Accounting for

Economic Activities

in Large Marine Ecosystems

and Regional Seas

UNEP Regional Seas Reports and Studies No. 181

UNEP/RSP and NOAA LME Partnership

Prepared by:

Porter Hoagland and Di Jin

Marine Policy Center

Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), Woods Hole, MA 02543 USA

UNEP 2006

Foreword

A healthy marine and coastal environment is essential for human well-being and for sustainable

development. It provides many different functions linked to public health, food security, transport,

recreation, and other economic and social benefits. The annual sales value of the goods and

services derived from the marine and coastal environment has been estimated in the tens of

billions of dollars. Some 80% of the pollution load in the oceans originates from land-based

activities, adversely affecting productive areas of the environment. A thorough evaluation of the net

economic value of goods and services that the oceans and coasts provide remains a challenge.

This report has been commissioned within the framework of the RS/LME partnership, which was

developed to link the coastal and marine activities of the global Regional Seas Programmes (RS)

coordinated by UNEP with the Large Marine Ecosystem (LME) approach. The joint initiative

contributes to one of the global Regional Seas Strategic Directions, which calls to "develop and

promote a common vision and integrated management, based on ecosystem approaches, of

priorities and concerns related to the coastal and marine environment and its resources in

Regional Seas Conventions and Action Plans, introducing amongst others proactive, creative and

innovative partnerships and networks and effective communication strategies."

The report compiles estimates of activity levels of the relevant marine sectors (e.g fisheries,

aquaculture, tourism, shipping, oil etc.) of countries bordering the world's LMEs and RSs. The

authors develop an index approach to assess the extent of the human uses of regional ocean

areas and regional socio-economic development. Two case studies have been included exploring

the scale of economic rents (revenues minus costs) and direct output impacts (gross revenues)

that could be a source of sustainable financing for conserving and managing regional marine

environments. It is targeted towards government policy- and decision-makers with the aim of

highlighting the potential value of goods and services provided by the marine and coastal

environment.

Positive actions are required on the part of governments and the civil society to manage and

sustain the marine and coastal environment and its resources. The Regional Seas Programmes

provide a policy framework for the regional implementation of the Global Programme of Action for

the Protection of the Marine Environment from Land-based Activities (GPA). The RS/LME

partnership and the GEF/LME approach to ecosystem-based management are crucial elements in

the implementation of the GPA. In addressing ecosystem approaches among other JPOI targets,

the 2nd Intergovernmental Review Meeting of the GPA (IGR2) provides a step forward in

international action for realistically assessing the value of goods and services provided by the

marine and coastal environment and for increasing ownership and commitment in allocating

sufficient resources for its conservation.

This report will be disseminated at the highest policy level to enhance the understanding of the

value of marine resources and to increase financial commitment and ownership in managing and

conserving the marine and coastal environment in the long-term.

Dr. Veerle Vandeweerd

United Nations Environment Programme

Head, Regional Seas Programme

Coordinator, GPA

Table of Contents

User Guide. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ii

Executive Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .iv

I. Introduction and Purpose . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1

II. Marine Activity Database. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

III. Methodology . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

A. Total economic value (TEV) as a single metric . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .5

B. Direct output impacts (DOIs) as a single metric . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .6

C. Marine activity indexes (MAIs) as a single metric . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .7

D. The problem of regional aggregation. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .8

IV. Calculation of the Marine Activity Index (MAI) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

V.

Results of the Index Approach . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .14

VI. Discussion. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .17

VII. Summary and Conclusions. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .20

VIII. References . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .21

Annex I: Case Study: Benguela Current Large Marine Ecosystem. . . . . . . . . A1-1

Annex II: Case Study: Yellow Sea Large Marine Ecosystem. . . . . . . . . . . . . .AII-1

i

USER GUIDE

Our purpose in producing this report is to provide a decision-making tool for international

financial and natural resource management institutions to use in setting priorities for allocating

financial resources toward the sustainable management of Large Marine Ecosystems (LMEs)

located within Regional Seas areas.

We develop an index that is a measure of the intensity of marine activities in these

regions. We compare this marine activity index (MAI) with an index of socioeconomic

development, the UNDP's human development index (HDI), across ocean regions. This

comparison identifies regions that may be capable of achieving on their own the sustainable

development of their regional marine environment and those that are less likely to do so. The

latter may be candidates for international financial or management assistance. We make no

predictions or normative judgments about whether these regions will or should manage for

sustainability.

Our index approach is meant as a tool for setting priorities, given limited international

financial and management resources for assisting regions in moving toward sustainable

development. The tool should be used in conjunction with additional information, such as data

and expertise on environmental conditions and ecological status. Knowledge of the national

and international legal institutions and the political context of each region is obviously important

as well.

The index approach is based on actual industrial and recreational activities occurring at

the national level in coastal nations. We compile publicly available worldwide data on marine

activities occurring in those coastal nations comprising large marine ecosystems (LMEs) and

Regional Seas. Data on marine activities include fish landings, aquaculture production,

shipbuilding orders, cargo traffic, merchant fleet size, oil production, oil rig counts, and tourism

arrivals.

These data can be used to compare activity levels in physical units (quantities, not

prices) for each individual marine activity across the coastal nations of the world. This kind of

comparison is valuable for gauging relative levels of economic activity by marine industrial

sector among coastal nations.

Without additional analysis or information, however, these data cannot be used to

compare the combinations of marine activities occurring in each nation across the coastal

nations of the world. Further, data in this format can provide only a very crude understanding of

activity levels for regional aggregates of all or portions of nations that are included in LMEs

and Regional Seas.

One method of creating a single metric that combines all marine activities is to express

the levels of each activity in units of a common monetary measure. There are several possible

monetary measures. The preferred monetary metric is "total economic value" (TEV). TEV

measures the net benefits (the sum of consumer and producer surpluses) that derive from a

nation's marine activities.

A readily available compilation of TEVs for marine activities in coastal nations does not

exist. TEVs would need to be calculated on activity- and location-specific bases, and there are

few studies that do so. In some cases, estimates of the producer surplus component of TEV

can be compiled. In particular, resource rents, or those producer surpluses (revenues in excess

of all costs) attributable to the exploitation of marine resources, may be estimated. If captured

by governments, resource rents provide a potential basis for financing the sustainable

ii

management of the marine environment. We present an application of the resource rent

approach in the case of the Benguela Current LME in Annex I.

A second possible monetary metric is known as "direct output impact" (DOI). DOI

measures the gross revenues or sales that derive from a nation's marine activities. As the

product of price times quantity, DOI represents the sum of benefits to producers (producer

surplus) and the costs of production. Because it includes costs and excludes benefits to

consumers, DOI is not an accurate measure of economic value. DOI can be conceptualized as

an upper bound on producer surplus, which again is only one component of TEV.

Despite the fact that a DOI metric can be readily calculated for some activities (e.g.,

offshore oil and natural gas production), it is problematic to calculate such an index for other

activities (e.g., tourism visits). As in the case of the resource rent approach, a DOI metric would

need to be calculated on an activity- and location-specific basis. We present an application of

the DOI approach in the case of the Yellow Sea LME in Annex II.

An alternative method for creating a single metric is the index approach that we present

in this report. The marine activity index (MAI) does not rely upon monetary values; it relies

instead on physical values. Each physical value is converted into an index that ranges from

zero to one. These indexes have no dimension; in other words, they are not measured in

specific units of any kind. Decision makers must make assumptions about the weights that

each activity is to be accorded when compiling an aggregate MAI from its individual activities.

Further assumptions must be made to combine each nation's MAI with others' from the relevant

region to produce a regional MAI. We present and rank regional MAIs for both LMEs and

Regional Seas.

Finally, we compare regional MAIs with a socio-economic index. This comparison is

presented in tables and in figures in our report. We classify ocean regions by low, moderate,

and high levels of both marine activity and socio-economic development. We expect that

nations involved in ocean regions characterized by high levels of socio-economic development

and moderate to high levels of marine activity are probably capable of sustainably managing

their marine environments themselves. Alternatively, we expect that nations involved in ocean

regions characterized by low to moderate levels of socio-economic development and moderate

to high levels of marine activity may need assistance in sustainable management. Special

opportunities may exist to place ocean regions that embody low levels of both socio-economic

development and marine activity on a sustainable path.

The framework developed in our study serves as a first step toward more detailed

analyses of socio-economic issues associated with LMEs and UNEP Regional Seas. Thus, the

index approach is a useful first cut at prioritizing regions that deserve closer attention as

candidates for international financial assistance to promote sustainable marine environmental

management. An important next step is to carry out detailed case studies designed to improve

our understanding of any specific ocean region, including its environmental circumstances, its

ecological conditions, its economic value, and the political feasibility of organizing a

collaboration among nations participating in the region to share the costs of sustainable

management.

iii

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Sixty-four large marine ecosystems (LMEs) have been identified around the

world's coastal margins. The LMEs are located within the boundaries of 18 Regional

Seas. The large ecological zones of these LMEs are economically important, producing

95 percent of the world's marine fisheries biomass, among other goods and services

valued at many trillions of dollars each year. Counterbalancing these economic benefits

is the fact that pollution is more severe in LMEs than in other ocean areas, and some

LME coastal habitats are among the most seriously degraded on earth. It is in the

world's interest to ensure that those marine resources and habitats at risk are protected

and managed sustainably for both present and future generations.

A pragmatic approach to the sustainable management of LMEs is now being

implemented by nations in Africa, Asia, Latin America, and Eastern Europe, supported

by $650 million in start-up funds from the Global Environment Facility (GEF) and other

international donors. This approach uses suites of environmental indicators to assess

the physical, biological, and human forcings on ecosystem productivity, fish and

fisheries, pollution and ecosystem health, economic development, and governance.

Over the past several years, a rapidly growing literature on LME studies has

emerged, focused mostly on issues of biological conservation; the sources, transport,

and fate of pollutants; and regional governance. In sharp contrast, analysis of the

socio-economic characteristics of LMEs has received relatively little attention to date.

Although a general framework for monitoring and assessing the socio-economic

aspects of LMEs has been developed, few detailed studies grounded in empirical data

iv

have been undertaken. In this report, we take an initial step toward the development of

a global overview of the socio-economic aspects of LMEs and Regional Seas.

We focus on the following two broad questions regarding the sustainable

management of the marine environment in an LME and Regional Sea:

1. Can the level of marine activity in an LME and Regional Sea be considered

sustainable?

2. Are the nations participating in the relevant LME and Regional Sea capable of

financing programs of sustainable management themselves?

In order to begin to address the first question, we develop a measure of marine

industry activities for each LME and Regional Sea. Given the nature of the data on

economic activity that is available on a consistent basis across nations, our preferred

measures of marine activities are sets of indexes. We expect that higher levels of

industrial activity exert greater pressure on the ecosystem, say, through pollution or

resource depletion, and that lower activity levels exert less pressure.

For a given activity level, however, the scale of negative ecological impacts may

not be the same for coastal nations in different stages of economic development, as

measured by income levels or some other metric. For example, the environmental

Kuznets hypothesis suggests that there exists an inverted U-shape relationship in an

economy between pollution intensity and income per capita. At low levels of income,

economic development would lead to increasing levels of pollution emissions. As

economic growth leads to income levels that exceed a threshold, however, a society's

demand for environmental quality increases, and its pollution emissions decline.

In order to begin to address the second question, we examine the relationship

between a measure of socio-economic development, namely UNDP's human

development index (HDI), and measures of marine activity. The HDI measure is useful

v

in thinking about the second question, because we expect that developed nations that

exhibit higher levels of income are more likely to be capable of financing programs of

sustainable LME management themselves.

We develop a ranking of LMEs and Regional Seas by various measures of

marine activity and by socio-economic development. This ranking process should

assist responsible international organizations and donors in developing funding and

assistance priorities based upon the revealed characteristics of LMEs.

Our study results include the following:

· the compilation of data and the construction of an international database on

marine activities for all coastal nations relating to fish landings, aquaculture

production, shipbuilding orders, cargo traffic, merchant fleet size, oil production,

oil rig counts, and tourism;

· the development of indexes for each of these marine activities, and the

aggregation of sets of activities into industry sector indexes;

· the adaptation of these indexes and a separate socio-economic index to

characterize the marine activity levels of LMEs and Regional Seas;

· the development of a ranking of LMEs and Regional Seas according to total

marine activity levels, industry sectoral activity levels, and socio-economic status;

· a graphical presentation of the rankings to facilitate the identification of

international management and development assistance priorities;

· the development of a case study exploring the scale of resource rents in the

Benguela Current LME and the management issues and sustainable

development priorities of the region;

· the development of a case study exploring the scale of direct output impacts in

the Yellow Sea LME and the regional management issues and sustainable

development priorities.

We reach six general conclusions relating to the potential for the sustainable

management of marine environments in LMEs or Regional Seas:

· Our examination of the two cases--one of an upwelling, the other of a

continental shelf LME--have reinforced our original opinions as to the benefit of

the GEF-sponsored efforts to encourage sustainable management. In particular,

the detailed studies, capacity building, and reorientation of the policy focus from

resource exploitation to sustainable management have been the most positive

vi

effects in these two cases. Based upon what we have been able to learn about

these two cases, we expect that the nations of the region will be fully capable

and willing to continue their programs of sustainable development in the future.

· The compilation of data and the development of an international database on

marine activity levels in coastal nations, LMEs, and Regional Seas is likely to be

of considerable value for conducting preliminary screening and prioritization of

marine regions that are in need of international attention and support for

organizing programs of sustainable development.

· For those LMEs or Regional Seas that are identified as priorities from the marine

activity and socio-economic development rankings, detailed case studies should

be conducted.

· Case studies should focus on the following:

· characterizing marine activities at the sub-national level within the LME

and Regional Sea;

· estimating the scale of resource rents that could obtain from the efficient

management of the marine resources of the LME and Regional Sea;

· clarifying, where relevant and necessary, the need for and the costs

involved in the international regulation of natural resources or the

management of transboundary environmental degradations;

· identifying the set of sustainable development policy priorities in each of

the nations of the region (including priorities unrelated to the marine

environment); and

· understanding the willingness of the nations participating in the region to

devote some fraction of rents from marine resources to the sustainable

management of their shared ecosystem.

· The efforts of international organizations to encourage the sustainable

development of LMEs and Regional Seas is obviously an important goal. We

recognize, however, that decisions about sustainable development are policy

decisions that must be made by each coastal nation independently and, where

feasible, in concert with the other nations of the region.

· Whether coastal nations will work together to solve the issues that pervade LMEs

or Regional Seas will depend upon the benefits that each nation expects from its

cooperation with others. Hence, clarifying in detail the nature of the benefits to

individual nations of international cooperation within LMEs and Regional Seas is

of fundamental importance.

vii

ACCOUNTING FOR ECONOMIC ACTIVITIES IN LARGE MARINE ECOSYSTEMS

AND THE REGIONAL SEAS

I. Introduction and Purpose

Over the past several years, a rapidly growing literature on large marine

ecosystems (LMEs) has emerged, focused mostly on issues of biological

conservation; the sources, transport, and fate of pollutants; and regional

governance (Duda and Sherman 2002; Sherman et al. 1996). Increasingly, the

results of scientific research have revealed the degradation of ocean regions,

including coastal pollution, the over-exploitation of fisheries, invasions of exotic

species, and blooms of harmful algae, among other effects. The hope is that

increased attention to these problems will motivate the nations of the relevant

regions to manage their marine environments more sustainably.

In sharp contrast to these scientific studies, analysis of the socioeconomic

characteristics of large ocean regions has received relatively little attention to

date.1 Although a general framework for monitoring and assessing the

socioeconomic aspects of LMEs has been developed (viz., Wang 2004; Sutinen

2000), few detailed studies grounded in empirical data have been undertaken.

Characterizing the socioeconomic features of ocean regions is critical to

developing an understanding of the extent to which nations have the financial

resources to undertake programs of sustainable development.

In this report, we take an initial step toward the development of a global

overview of the socioeconomic aspects of LMEs and Regional Seas. We focus

1 One exception is a calculation of the direct, indirect, and induced economic impacts of the marine sector

in the Northeast Shelf LME (Hoagland et al. 2005).

1

our attention on the development of measures of the intensity of human activities

in the marine environment that may be useful in identifying regions that may

need international assistance to initiate and carry out programs of sustainable

management. Although other types of economic measures may be preferable to

our measure of the intensity of marine activities, their practical use is severely

constrained by data limitations.

We focus on the following two broad questions regarding the sustainable

management of the marine environments of an LME and Regional Sea:

1. Can the level of marine activity in an LME and Regional Sea be

considered sustainable?

2. Are the nations participating in the relevant LME and Regional Sea

capable of financing programs of sustainable management

themselves?

In order to begin to address the first question, we develop a measure of

marine industry activities for each LME and Regional Sea. Given the nature of

the data on economic activity that is available on a consistent basis across

nations, our preferred measures of marine activities are sets of indexes. We

expect that, ceteris paribus, higher levels of industrial activity exert greater

pressure on the ecosystem, say, through pollution or resource depletion, and

vice versa.

For a given activity level, however, the scale of negative ecological

impacts may not be the same across different stages of economic development,

as measured by income levels or some other metric. For example, the

environmental Kuznets hypothesis suggests that there exists an inverted U-

shape relationship in an economy between pollution intensity and income per

2

capita. At low levels of income, economic development would lead to increasing

levels of pollution emissions. As economic growth leads to income levels that

exceed a threshold, however, a society's demand for environmental quality

increases, and its pollution emissions decline (Tisdell 2001; Grossman and

Krueger 1995).

In order to begin to address the second question, we examine the

relationship between a measure of socioeconomic development, namely UNDP's

human development index (HDI), and marine activity. The HDI measure is useful

in helping to answer the second question, because we expect that, ceteris

paribus, developed nations that exhibit higher levels of income are more likely to

be capable of financing programs of sustainable LME management themselves.

We develop a ranking of LMEs and Regional Seas by various measures of

marine activity and by socioeconomic development. This ranking process should

prove useful for responsible international organizations and donors in developing

funding and assistance priorities based upon the revealed characteristics of

LMEs.

II.

Marine Activity Database

This report presents the results of our efforts to compile data on marine

activities in the coastal nations comprising large marine ecosystems (LMEs) and

Regional Seas. In general, LMEs have been defined primarily in terms of

ecological characteristics. In contrast, Regional Seas have been defined

primarily in terms of geographic and political characteristics. Regional Seas tend

3

to be larger than LMEs, and Regional Seas comprise one or more (or

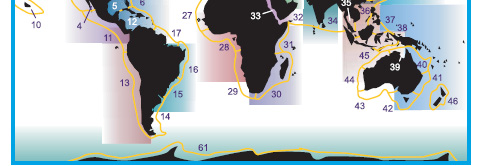

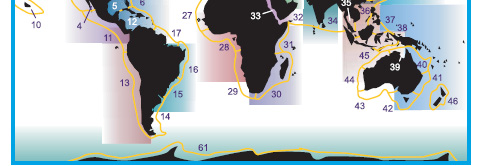

components of) LMEs. The identities of LMEs and Regional Seas (and a rough

concordance between the two types of regions) are presented in the map in Fig.

1.

Data on marine and relevant non-marine activities include fish landings

(metric tons), aquaculture production (metric tons), shipbuilding orders (gross

tons), cargo traffic (metric tons), merchant fleet size (deadweight tons), oil

production (average barrels per day), oil rig counts (numbers of facilities), and

tourism (international arrivals). The published sources, units, and vintage of the

data on marine activities are presented in Table 1. The actual data are

presented in Table 2.2 The data are from the most recent years available (i.e.,

between 2002 and 2004). Most data are measures of quantities, with the

exception of the dimensionless Human Development Index (HDI).

The data presented in Table 2 can be used to compare levels for each

individual marine activity across the coastal nations of the world. This kind of

comparison is valuable for analyzing relative levels of economic development by

industrial sector in coastal nations and, if collected over time, can help in

understanding changes in relative sectoral economic development for these

nations. Without additional analysis or information, however, these data cannot

be easily used to compare across the coastal nations of the world the

combination of marine activities occurring in each nation. Further, data in this

form can provide only a very crude understanding of activity levels for regional

2 We thank Jennifer Skilbred and Chris Vonderweidt for assisting us in the identification and compilation

of these data.

4

aggregates of all or portions of nations that are involved in LMEs or Regional

Seas.

III. Methodology

A. Total economic value (TEV) as a single metric

One method of creating a single metric that combines all marine activities

is to express the levels of each activity in units of a common monetary measure,

such as US dollars. In theory, the ideal monetary metric would be "total

economic value"(TEV).3 To calculate a single metric based upon TEV, one

would estimate the net benefits in dollars that obtain from each of a nation's

marine activities and sum these benefits across all activities. Net benefits are the

sum of consumer surpluses (what consumers are willing to pay over and above

the market price for a good or service) and producer surpluses (what firms earn

from the sale of goods and services over and above their costs of production).

Net benefits from non-market activities, such as environmental services, would

need to be estimated using one of several methods of environmental valuation,

and these benefits should be added to the TEV metric as well. The cost of

implementing government policies to help manage the marine environment

should be subtracted from TEV.

As a single metric, TEV could be compared across all coastal nations.4

Such a comparison would increase our understanding of the economic capacity

3 From the perspective of the theory of welfare economics, economic value is the only theoretically valid

measure of social welfare (viz., Mishan 1980).

4 The most important use of total economic value for each coastal nation or for regional aggregations of

nations would be to understand how it grows or shrinks with changes in both the mix of marine activities

5

of the nations participating in LMEs and Regional Seas Programs to conserve

and manage their marine ecosystems in a sustainable fashion. Unfortunately,

there is no readily available compilation of TEVs for marine activities across all

coastal nations, however, and the calculation of such values has occurred only

on a location- and activity-specific basis to date.

In our case study of the Benguela Current LME, which appears in Annex I,

we estimate for the region the scale of "resource rents," which are a constituent

of the producer surplus component of TEV, for the offshore oil, marine capture

fisheries, and marine diamond dredging activities in the region. Resource rents

are therefore a subset of TEV. In the context of sustainable management of the

marine environment, we note that resource rents could be a relevant source of

financing. We note further, however, that the use of rents for such a purpose is a

political decision that must be agreed upon at both regional (i.e., international)

and domestic levels.

B.

Direct output impacts (DOIs) as a single metric

Another single metric that can be constructed using a monetary measure

is called the "direct output impact" (DOI). DOIs are the product of the physical

quantities of goods or services flowing from marine activities (e.g., fish landings,

oil production, etc.) and their market prices.5 As in the case of calculating TEV,

one estimates a DOI for each activity, and these impacts are summed to create a

and the implementation of government policies. In principle, the combination of activities and policies can

be adjusted so as to maximize total economic value.

5 If the marine activities are "final" goods and services (i.e., they are consumed and not used to produce

another good or service in an economy), then the direct output impact measure would be equivalent to the

marine component of gross national product (GNP).

6

single metric. This metric is less difficult to construct than TEV, but it does not

account for the cost of inputs in production, including the degradation of the

environment, or the depreciation of capital assets or the depletion of natural

resource stocks.6

As in the case of TEV, there is no readily available compilation of DOIs for

all marine activities across all coastal nations, and the calculation of such values

has occurred only on a location- and activity-specific basis to date. Some

estimates of DOI can be calculated (using a world oil price times oil production,

for example) and others have been compiled on an ad hoc basis (FAO has

calculated for most nations the ex-vessel value of landed capture fisheries and

the farmgate value of some aquaculture industries). In our case study of the

Yellow Sea LME, which appears in Annex II below, we calculate and compile a

wider range of DOIs for the marine activities of the region.

C. Marine

activity

indexes

(MAIs) as a single metric

A third approach to the problem of constructing a single metric does not

involve the use of a monetary measure. Instead, indexes, ranging from zero to

one, are created for each marine activity by ranking each nation's activity level

relative to all others on a worldwide basis. These indexes can be combined in a

variety of ways into one or more aggregate indexes by assigning weights to each

6 Much recent effort has been directed at "greening" the national accounts, which would involve accounting

for changes (depletion) in natural resource stocks, such as offshore oil, capture fisheries, or marine minerals

(see Lange 2003). Green accounting involves the use of the net national product (NNP), which is GNP less

depreciation of capital assets. According to this approach, the depletion of natural resources through

changes in resource stocks are viewed as the analog to the depreciation of capital assets. Changes in green

NNP over time can then be used as measures of welfare change.

7

individual index and then summing across weighted index values. (We describe

one way of accomplishing this weighting process below.) The indexes are

dimensionless, but they convey information about the relative activity level (or the

"intensity" of activity) for nations in the marine environment. We develop the

index approach in this report because of data limitations that affect the use of

either the TEV or DOI metrics.

D.

The problem of regional aggregation

Once a single metric has been developed for each coastal nation, a

procedure needs to be established for aggregating individual national metrics to

a regional level.7 There are five possible scenarios to consider: an LME and

Regional Sea comprises: (i) the entire exclusive economic zone (EEZ)8 of only

one coastal nation (e.g., the Iceland Shelf); (ii) a portion of the EEZ of only one

coastal nation (e.g., the Northeast Shelf); (iii) the entire EEZs of two or more

coastal nations (e.g., the Humboldt Current); (iv) the entire EEZ of one or more

coastal nations and portions of the EEZs of one or more other coastal nations

(e.g., the Benguela Current); and (v) portions of the EEZs of multiple coastal

nations (e.g., the Yellow Sea). For each coastal nation, we need a method for

attributing national-level data on its marine activities to the one or more LMEs or

Regional Seas Programs in which it participates. This issue does not present

7 This issue applies to the marine activity indexes as well as to other single metrics that might be utilized,

including the TEV and DOI metrics.

8 We assume here that the geographic coverage of an LME or Regional Sea is limited to EEZs, although

that is not precisely true in practice.

8

itself for scenarios (i) or (iii), because we can readily use the national-level data

in both cases to develop aggregate indexes.

Scenarios (ii), (iv), and (v) involve situations in which only a portion of a

nation participates in an LME or Regional Sea project. In these situations, we

need to find a way in which to attribute only a portion of a nation's marine

activities to the LME or Regional Sea.9 One approach would be to calculate the

length of a nation's coastline within an LME and Regional Sea relative to that

nation's total coastline.10 That ratio could be used to weight national marine

activity.

We encounter two problems with this approach. First, although data exist

on total coastlines for all coastal nations, there are no data that measure the

coastline length of each nation for each LME and Regional Sea.11 Second, even

if such data exist, without a detailed case study of the geographic distribution of

marine activities for each nation, we might assign part of a nation's marine

activities to an LME or Regional Sea, even though those activities might not take

place in that region (e.g., the assignment of US offshore oil and natural gas

exploration and production to the Northeast Shelf, where no such activity occurs).

Given the data constraints, we design a method for weighting the marine

activity for each individual nation that participates in an LME and Regional Sea

relative to the other participating nations in the same LME and Regional Sea.

9 Ideally, we would like to have subnational-level data on marine activities for each coastal nation. With

such data, we could create a single metric for each region.

10 Other measures of national contribution could be used, such as the area of a nation's total EEZ or its

outer continental shelf that lies within an LME or Regional Sea.

11 Data exist in ARCVIEW format that permits the calculation of the shares, but not the length, of each

nation's coastline within any LME or Regional Sea.

9

We calculate the share of the total LME and Regional Sea coastline for each

nation participating in an LME and Regional Sea Program, and we use that share

to weight that nation's marine activity levels as its contribution to the marine

activity of the whole LME and Regional Sea. These shares are presented in

Table 4 for the world's LMEs.12 A concordance exists between LMEs and

Regional Seas (Table 5), and we use the concordance to develop a similar

weighting procedure for the world's Regional Seas based upon the area

coverage of LMEs. We emphasize that this procedure does not resolve the issue

of attributing all of a nation's marine activities to an LME and Regional Sea when

only a portion of that nation has been assigned to the LME and Regional Sea.

Resolution of that issue is an area for future research.

IV. Calculation of the Marine Activity Index (MAI)

Our methodology involves four basic steps: (i) compiling nation-level data

for a set of indicator variables; (ii) converting all indicator variables into indexes;

(iii) constructing weighted average indexes for each LME; and (iv) constructing

weighted average indexes for each Regional Sea Program (RSP). We focus on

two important descriptors for each LME and each RSP: a measure of marine

industry activities and a measure of socioeconomic development.

We construct marine activity indexes by ranking nations within each

activity category. For example, all nations would be ranked in terms of average

barrels per day of oil production from the highest to the lowest. Then each nation

12 We thank Roger Goldsmith (2005) for calculating the shares that appear in Table 4.

10

would be assigned a number that represents its scale of oil production from the

highest to the lowest value. The values for each index for each activity are

standardized to lie between zero and one. Specifically, for any marine industry

activity indicator variable j occurring in nation i, its measure (xij) (from an entry for

nation i in a column for activity j in Table 2) is converted into an index (Iij) as

follows:

x - min(x )

ij

j

I =

(1)

ij

max(x ) - min(x )

j

j

One can then combine indexes for different marine industry activities in

various ways.13 We construct a combined marine industry activity index for each

nation in two steps. First, a weighted average index AIi is calculated across n

related activities for nation i:

n

AI = w I

(2)

i

j ij

j=1

where the wj are weights (please see the last column in Table 3) assigned by the

analyst or decision maker across related marine activities, which are grouped

into "industry sectors" (e.g., fisheries landings and aquaculture production), and

wj = 1.

In our study, as an example, we have grouped related activities into five

marine industry sectors: marine fisheries and aquaculture, tourism, shipbuilding,

shipping, and offshore oil. In the case of the first industry sector, we consider

13 One way to make such a combination is to assign equal weights to each activity index by averaging

across indexes. In principle, unequal weights could be assigned to activity indexes, if such weights could

be estimated.

11

fisheries and aquaculture equally important, and we assign weights of 0.50 to

each. The next two sectors, tourism and shipbuilding, have one indicator each,

so there is no need to assign weights. In the case of the fourth sector (i.e.,

shipping), we consider cargo traffic more important than the size of fleet, and we

assign weights of 0.67 and 0.33, respectively. In a similar vein, we consider

offshore oil production more important than drilling (i.e., rig counts), and we

assign weights of 0.67 and 0.33, respectively, in the last sector.

Next, a weighted average across all m industry sectors is computed:

m

TAI =

v (AI )

(3)

i

k i

k =1

where TAIi is the total marine industry activity index for nation i, and vk is the

weight assigned by the analyst or decision maker for marine industry sector k

(please see the second column in Table 3). In our example, we assign equal

weights of 0.20 to each of the five industry sectors (see Table 3).

For any particular nation i, TAIi will be large if most of its marine industry

indicators are ranked relatively high in comparison with the rest of the world.

Importantly, a nation with only a few highly ranked industry sectors could have a

total activity index close in value to a nation with all of its industry sectors ranked

in the medium category. Thus, the total marine industry activity index (TAIi) can

be interpreted as the overall "intensity" of nation i's marine activities.

We use the Human Development Index (HDI) for each nation reported in

the United Nations Development Program's Human Development Report (UNDP

2004). HDI is a measure of a nation's socioeconomic development. It is based

upon three key indicators: life expectancy (at birth); education (i.e., adult literacy

12

rate and combined gross enrolment ratio for primary, secondary, and tertiary

schools); and GDP per capita (purchasing power parity in US dollars).14

The national-level TAI and HDI can be used to construct relevant indexes

for the LMEs, which often are combinations of nations (or parts of nations), and

then for the Regional Seas, which are in effect combinations of LMEs. As

described above, due to data constraints, the national TAI value must be used

even in cases in which only a portion of a nation's coastline occurs in an LME or

Regional Sea.

For each LME, we compute both the marine industry activity index (MAI)

and the socioeconomic index (SEI) as:

s

MAI

=

(4)

(

)

lTAI

LME RSP

i

i

i =1

s

SEI

=

(5)

(

)

l HDI

LME RSP

i

i

i =1

where i is the index for a nation bordering the LME, and li is the percentage

share of nation i's coastline length relative to the total coastline length of all s

nations bordering the LME (these shares are compiled in Table 4).15

Finally, for each RSP, the LME-level indexes are further aggregated as:

p

MAI

= a MAI

(6)

RSP

q

q

q=1

14 For a detailed description of HDI and its calculation, see UNDP (2004), p.259.

15 LME-level marine activity indexes (MAI) can also be calculated using the activity indexes (AI) for

industry sectors in lieu of the total activity index (TAI). We present calculations for three such industry

sectors in Table 7.

13

p

SEI

= a SEI

(7)

RSP

q

q

q =1

where q is the index for an LME within a Regional Sea (Table 5), and a is the

percentage share of the LME's area (Table 6) relative to the total area of all p

LMEs within the Regional Sea.

V.

Results of the Index Approach

We calculate the marine industry activity index (MAI) and the

socioeconomic index (SEI) for each LME using Equations (4) and (5).16 The

results are summarized in Table 7. Also included in Table 7 are calculations of

marine activity indexes based upon industry sectors: (i) the fishery and

aquaculture index and (ii) the tourism index, both of which depend upon a

relatively clean marine environment, and (iii) the shipping, shipbuilding, and oil

production index, which includes three industry sectors that do not necessarily

depend upon a clean environment and which, in some cases, may in fact be the

cause of environmental degradation.

One can compare LMEs based upon these different indexes. The data in

Table 7 are sorted by the socioeconomic index, which can be used as an

indicator of the potential for LMEs to undertake self-financing management

16 Five LMEs are not included in our analysis because of the paucity of datat on either the socioeconomic

index, marine activity, or both. These five LMEs are: the Arctic Ocean (64); Antarctica (61); the Faroe

Plateau (60); the East Greenland Shelf (19); and the West Greenland Shelf (18). Table 2 does not include

all the countries (or territories) listed in Table 4. This creates a data gap that leads to biased estimates for

LME indexes. To address the issue, we bridged the data gaps with data from related countries as follows:

Morocco for Western Sahara, UK for Falkland Islands, Suriname for French Guiana, US for Puerto Rico,

and Norway for Svalbard. Several countries with missing data and also with very small weights were

excluded from the calculation of weighted average indexes. We assigned HDI values for Liberia (0.3),

North Korea (0.5), Somalia (0.28), and Taiwan (0.9) based mostly on income levels.

14

programs. The Somali Coastal Current (#31), Agulhas Current (#30), Guinea

Current (#28), and Benguela Current (#29) are among the LME regions with

lowest SEI. In contrast, the Norwegian Shelf (#21) and several LMEs along the

Australian coast have the highest SEI.

In Table 8 and Fig. 2, we rank the data by MAI, which can be interpreted

as a measure of the intensity of marine activity in each LME. This ranking is

much different from the ranking in Table 7. Even so, the Somali Coastal Current

(#31), Guinea Current (#28), and Agulhas Current (#30) exhibit the lowest levels

of intensity of marine activity, consistent with their low levels of SEI. In contrast

to the results for the SEI ranking, the Yellow Sea (#48) and the East China Sea

(#47) exhibit the highest MAI levels. In Figs. 3 and 4, we also present rankings

of MAI normalized by total LME area (Fig. 3) and MAI/SEI (Fig. 4).

The precise relationship between marine industry activities and

socioeconomic development is a bit more complex (Figure 5). We group LMEs

according to their socioeconomic development levels and marine industry activity

levels, using data from Tables 7 and 8. We specify three development levels:

high (SEI 80), medium (50 SEI < 80), and low SEI < 50); and three marine

activity levels: high (MAI 30), medium (5 MAI < 30), and low (MAI < 5). The

resulting nine categories are shown in Table 9 and Figure 5.

In Table 9, the top two boxes on the left do not have entries, suggesting

that LME regions with low levels of economic development generally do not have

high levels of marine industry activities. In contrast, LME regions with high levels

of economic development may or may not have high levels of marine industry

15

activities. For example, the Iceland Shelf (#59) is a region with a high level of

socioeconomic development but a low level of marine industry activities, while

the Northeast Shelf (#7) is a region with high levels of both economic

development and marine industry activities. The Yellow Sea (#48) region is

unique in that it has a high level of marine industry activities and a medium level

socioeconomic development. This combination suggests a major management

challenge to achieve sustainability (i.e., balancing economic growth with

environmental and resource protection).

We aggregate the LME index estimates to get the indexes for the

Regional Seas, using Equations (6) and (7). We present the results of the

Regional Sea index estimates ranked in order of SEI (Table 10 and Fig. 6) and

MAI (Table 11 and Fig. 7). Within the Regional Seas Program, the Eastern

Africa region appears to be the least developed, while the Pacific (SPREP)

region has the highest level of socioeconomic development. The Northeast

Pacific and Northwest Pacific Regional Seas exhibit the highest intensities of

marine activity, while the West Central Africa and Eastern Africa Regional Seas

exhibit the lowest.

We develop groupings similar to those for LMEs for the regional seas (see

Table 12). In addition, we plot SEI against MAI for the regional seas in Fig. 8.

The two representative cases pictured in Fig. 8 include the BCLME (West Central

Africa RSP) and the YSLME (Northwest Pacific RSP). The interpretation of the

figure is similar to that for the plot of SEI vs. MAI for LMEs.

16

While the results in Tables 10, 11, and 12 are useful in providing a quick

overview of relative positions across Regional Seas, they must be used with

caution. LMEs are large areas that are often composed of heterogeneous

countries. Regional Seas are much larger areas than the LMEs, and the level of

heterogeneity in economic development and marine activity within a specific

regional sea may be substantial. Disparities in regional heterogeneity are

evident, for example, in the somewhat surprising result that the Pacific (SPREP)

RSP, which is extremely heterogeneous, has a higher level of socioeconomic

development than the much more homogeneous North-East Atlantic Regional

Sea.17

VI. Discussion

We have developed an index approach to provide an overview of the

socioeconomic dimension of different LMEs and Regional Seas. The study is

unique in its global perspective. The results may be used to address

management questions regarding sustainable development and sustainable self-

financing of regional programs.

The results may also be used to identify problem areas. Typically, regions

with high levels of marine industry activities demand high levels of management

attention to address issues related to resource depletion, environmental

degradation, and multiple use conflicts. This is particularly true in regions with

high marine activity levels and medium levels of socioeconomic development.

17 Also of relevance is the fact that only three of the 19 states that participate in the Pacific (SPREP)

Regional Sea Programme--Australia, New Zealand, and Papua New Guinea--border on, and are represented

in the data assembled for, the four LMEs that occur within that region (LMEs 40, 41, 42, and 46).

17

Efforts must be made to coordinate economic development and environmental

and resource protection. Regions with low socioeconomic development levels

and low marine activity levels at the present deserve international assistance in

preparation for possibly rapid development in the future.

The framework developed in our study serves as a first step toward more

detailed analyses of socioeconomic issues associated with LMEs and Regional

Seas. Thus, the index approach is a useful first cut at prioritizing regions that

deserve closer attention as candidates for international financial assistance to

promote sustainable marine environmental management. An important next step

is to carry out detailed case studies designed to improve our understanding of

any specific ocean region, including its environmental circumstances, its

ecological conditions, its economic value, and the political feasibility of organizing

a collaboration among nations participating in the region to share the costs of

sustainable management.

To illustrate this point, we present case studies in the Annexes of the

Benguela Current LME and the Yellow Sea LME. These two LMEs were selected

because they represent different types of marine ecosystems, different levels of

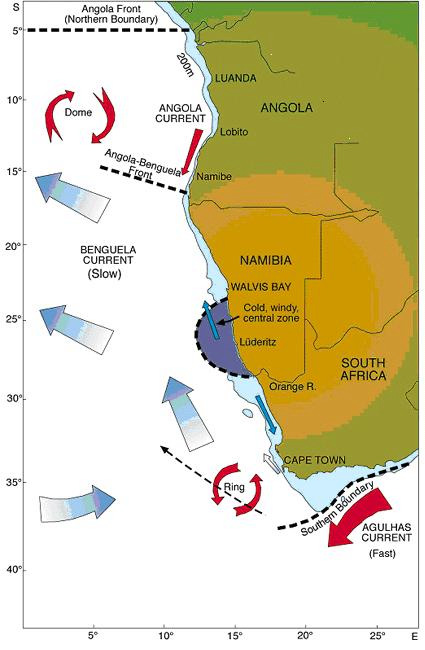

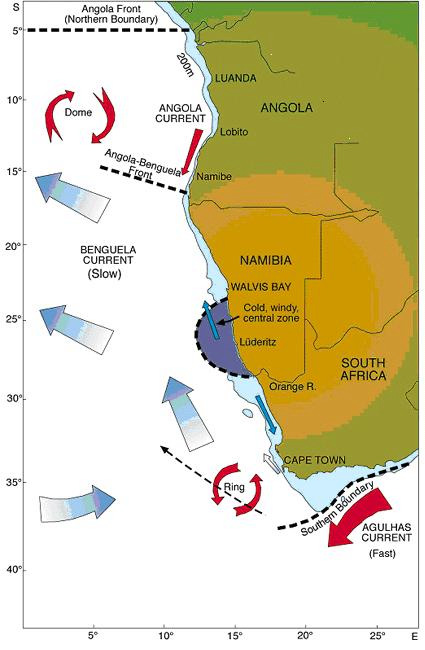

marine economic activity, and different geographic locations. The Benguela

Current LME, located along the southwest coast of Africa, is the world's most

powerful wind-drive coastal upwelling system, and it has a relatively low level of

marine economic activity. In contrast, the Yellow Sea LME, a sub-area of the

Northwest Pacific Regional Sea, is a continental shelf ecosystem with intense

marine activities.

18

The two case studies use two different approaches for estimating a

monetary measure of levels of economic activity in an LME. We present an

application of the resource rent approach in the case of the Benguela Current

LME in Annex I. In particular, we estimate resource rents, or those producer

surpluses attributable to the exploitation of marine resources. If collected by

governments, resource rents provide a potential basis for financing the

sustainable management of the marine environment.

In many cases, however, it can be difficult to obtain estimates of resource

rents. In Annex II, we present an application of the direct output impact (DOI)

approach for the Yellow Sea LME. DOI measures the gross revenues or sales

that obtain from a nation's marine activities; it can be conceptualized as an upper

bound on producer surplus. Although the DOI approach does not result in as

much information about economic value as the resource rent approach, it can be

used to gain a sense of the scale of economic activity and as a rough measure of

the capacity of the nations of an LME to finance sustainable management.

VII. Summary and Conclusions

Examination of the two cases--one of an upwelling, the other of a

continental shelf LME--have reinforced our original opinions as to the benefit of

the GEF-sponsored efforts to encourage sustainable management. In particular,

the detailed studies, capacity building, and reorientation of the policy focus from

resource exploitation to sustainable management have been the most positive

effects in these two cases. Based upon what we have been able to learn about

19

these two cases, we expect that the nations of the region will be fully capable

and willing to continue their programs of sustainable development in the future.

The compilation of data and the development of an international database

on marine activity levels in coastal nations, LMEs, and Regional Seas is likely to

be of considerable value for conducting preliminary screening and prioritization of

marine regions that are in need of international attention and support for

organizing programs of sustainable development.

For those LMEs or Regional Seas that are identified as priorities from the

marine activity and socioeconomic development rankings, detailed case studies

should be conducted. Case studies should focus on the following:

· characterizing marine activities at the sub-national level within the LME

and Regional Sea;

· estimating the scale of resource rents that could obtain from the efficient

management of the marine resources of the LME and Regional Sea;

· clarifying, where relevant and necessary, the need for and the costs

involved in the international regulation of natural resources or the

management of transboundary environmental degradations;

· identifying the set of sustainable development policy priorities in each of

the nations of the region (including priorities unrelated to the marine

environment); and

· understanding the willingness of the nations participating in the region to

devote some fraction of rents from marine resources to the sustainable

management of their shared ecosystem.

The efforts of international organizations to encourage the sustainable

development of LMEs and Regional Seas is obviously an important goal. We

recognize, however, that decisions about sustainable development are policy

decisions that must be made by each coastal nation independently and, where

feasible, in concert with the other nations of the region.

20

Notwithstanding the priority to devote resource rents from the

development of marine natural resources to improve environmental, public

health, and social welfare conditions, the scale of rents (in the case of BCLME)

and direct output impacts (in the case of YSLME) appear to be sufficient to

continue to support existing efforts to improve marine management. At the very

least, the sustainable management programs, involving scientifically based

assessments, which have been organized by GEF and the nations of both LMEs,

might be continued at the same or even a slightly expanded scale.

Whether coastal nations will work together to solve the issues that

pervade LMEs or Regional Seas will depend upon the benefits that each nation

expects from its cooperation with others. Hence, clarifying in detail the nature of

the benefits to individual nations of international cooperation within LMEs and

Regional Seas is of fundamental importance. In an optimistic future, as the

economies of the nations develop, and hopefully as their social problems begin

to be resolved, any residual problems of marine pollution and resource

misallocations can be accorded a higher priority in national and regional public

policy.

VIII. References

Duda, A.M. and K. Sherman. 2002. A new imperative for improving management

of large marine ecosystems. Ocean and Coastal Management 45:797-

833.

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). 2005. FAO

Fisheries Global Information System 2003.

http://www.fao.org/es/ess/meetings/figis.asp.

21

Goldsmith, R. 2005. Dataset concerning the shares of coastlines of nations within

large marine ecosystems. Woods Hole, Mass: Computer and Information

Systems, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

Grossman, G.M. and A.B. Krueger. 1995. Economic growth and the environment.

Quarterly Journal of Economics 110(2):353-377.

Hoagland, P., D. Jin, E. Thunberg and S. Steinback. 2005. Economic activity

associated with the Northeast Shelf Large Marine Ecosystem: application

of an input-output approach. Pages 157-179 in T. Hennessey and J.

Sutinen, eds. Sustaining Large Marine Ecosystems: The Human

Dimension. Elsevier Science.

Institute of Shipping Economics and Logistics (ISL). 2004. Shipping Statistics

Yearbook 2004. Bremen, Germany.

Lange, G-M. 2003. Policy applications of environmental accounting.

Environmental Economics Series Paper No. 88. Washington:

Environment Department, The World Bank.

Mishan, E.J. 1980. Introduction to Normative Economics. New York.

OGJ. 2004. Oil and Gas Journal (OGJ) Databook 2004 Edition. PennWell:

Tulsa, OK.

Sea Around Us Project. 2005. Large Marine Ecosystems.

http://saup.fisheries.ubc.ca/lme/ lme.aspx#.

Sherman, K., N.A. Jaworski and T. J. Smayda. 1996. The Northeast Shelf

Ecosystem: Assessment, Sustainability, and Management. Blackwell:

Cambridge, MA.

Sutinen, J.G. 2000. A framework for monitoring and assessing socioeconomics

and governance of large marine ecosystems. NOAA Technical

Memorandum NMFS-NE-158. Northeast Fisheries Science Center,

Woods Hole, MA.

Tisdell, Clem. 2001. Globalization and Sustainability: Environmental Kuznets

Curve and the WTO. Ecological Economics 39(2):185-196.

United Nations Development Program (UNDP). 2004. Human Development

Report 2004 http://hdr.undp.org/reports/global/2004/.

United Nations Environment Program (UNEP). 2004. Regional Seas Program

linked with Large Marine Ecosystems. NOAA Large Marine Ecosystem

Program. Narragansett, RI.

22

United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) and National Oceanic and

Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). 2005. "UNEP Regional Seas

Programme Linked With Large Marine Ecosystems: Assessment and

Management." Last accessed on 30 March 2005 at

http://www.unep.org/regionalseas/News/Regional_Seas_and_

LMEs/default.asp.

US Department of the Interior, Minerals Management Service (MMS). 2005. OCS

Production. http://www.mms.gov/stats/OCSproduction.htm.

World Bank. 2004. World Development Indicators.

http://www.worldbank.org/data/ wdi2004/

23

or offshore

orld Bank 2004)

(OGJ 2004)

r

c

e

(UNDP 2004)

(ISL 2004)

(ISL 2004)

(ISL 2004)

o

u

S

a

t

a

D

ack of separate statistics f

ent Indicators 2004 (W

e

lopment Report 2004

ies Global Information System 2003 (FAO 2005)

eries Global Information System 2003 (FAO 2005)

Human Dev

Fish

Fisher

World Developm

Shipping Statistics Yearbook 2004

Shipping Statistics Yearbook 2004

Shipping Statistics Yearbook 2004

Oil and Gas Journal Databook 2004 (OGJ 2004)

US Department of the Interior (2005)

Oil and Gas Journal Databook 2004

e

offshore fields and (2) l

r som

24

y

I

ndictors and Data Sources

e

a

r

Y

2002

2003

2003

2004

quarter

2004

2

0

0

2

2

0

0

4

nd 2

Jan. 1, 2004

Dec., 2003

i

ssing data fo

**

)

i

t

T

b

er

t tons, revenue tons, or harbor tons (see ISL 2004).

n

U

e

i

g

h

t

t

o

n

s

e

nsionless

(GT)

m

(DW

Num

Metric tons

b

er of visitors

Di

Gross tonnage

Metric tons

e

a

d

w

Metric tons (MT)

D

v

e

r

a

g

e

b

a

r

r

e

l

/

d

a

y

Table 1. Marine Industr

Num

A

**

*

**

number of

i

cile; ships of 1000 GT and over.

ent Index (HDI)

e

countries are partial due to (1) m

i

c

a

t

o

r

all fraction of ports are in freigh

d

*

**

I

n

t

fleet

a

n Developm

a

ls

Hum

Fishery landings

Aquaculture production

International tourism

arriv

Shipbuilding orderbook

Shipping cargo traffic

Merchan

Offshore oil production

Offshore rig count

* Ships of 100 GT and over.

** Units for a sm

*** By nation of dom

**** Data for som

(vs. onshore) production.

t

0

0

7

0

0

4

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

1

3

1

0

0

0

5

0

0

1

0

0

0

2

o

un

ber)

um

Offshore

Rig C

(n

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

2

3

3

7

5

ay)

3,

,0

uction

65

16

4

4

9

,

4

75

1

8

0

,

5

41

5

0

2

,

50

Offshore Oil

Prod

(bbl/d

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

3

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

3

0

0

0

0

0

0

T)

86

32

5,

4

,

7

9

1

4,

4

5,552

Fleet

(

100

DW

Merchant

c

0

0

0

0

7

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

3

2

0

0

0

20

4

9

0

7

6

09

g

fi

5,

3

,

4

9

3

3

,

4

6

9

3,

,0

5

,

9

9

7

9,

r

af

5

3

7

,

3

91

1

8

8

,

5

44

40

18

1

8

5

,

7

73

0 MT)

1

,

3

1

0

,

82

g

o T

Shippin

(

100

Car

g

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

3

0

8

0

0

0

)

39

3

2

T

2

3

9

1

5

3

1

7

,644

0 G

try Indicators by Nation

Shipbuildin

Orderbook

(

100

0

0

2

0

0

5

0

0

8

0

0

2

0

0

4

0

0

2

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

6

0

0

2

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

4

0

0

00

4

0

0

o

nal

,8

,2

40

1,

4,

8,

0,

5,

3,

1,

5,

2,

7,

7,

7,

4,

8,

10

24

34

02

54

23

50

21

3

6

,

8

0

0

15

79

80

9

9

8

,

0

00

2

2

3

,

4

00

8

5

,

6

0

0

16

41

50

2

3

,

8

0

0

1

5,167

urism

isitor)

1

,

1

4

5

,

2

00

2

,

5

8

7

,

0

00

5,

1,

1,

3

,

9

3

6

,

6

00

6

,

9

0

5

,

4

00

3,

1

,

0

2

1

,

6

67

3,

,5

1,

To

(v

20

4

9

,885

25

Internati

0

0

0

3

0

0

0

4

0

0

0

0

6

5

8

0

42

6

8

15

31

0

3

5

0

0

2

6

0

41

8,

,3

,5

T)

3

5

,

1

5

4

5

6

,

5

0

3

1

0

,

1

6

0

1

0

9

,

6

15

1

4

2

,

7

71

6

2

9

,

4

93

16

(M

n

omic and Marine Indus

Marine

2

0

,893

Aquaculture

y

7

7

0

0

3

0

5

1

53

5

3

0

5

3

9

58

1

1

1

4

3

0

9

4

3

8

2

0

9

3

1

1

0

7

0

1

63

3

5

1

5

,6

,6

9

0

8

50

,3

19

,8

0

4

6

98

,2

,6

,8

2

6

1

72

3

5

6

,6

,3

,1

1,

1,

1,

2,

3,

9,

12

13

1,

2,

26

5,

11

2,

1,

10

55

52

4,

8,

0,

97

14

2

6

,346

Socioeco

Fisher

T)

14

20

88

21

43

58

32

93

1,

3,

(M

1

4

,588

Marine

Table 2.

1

4

1

0

3

6

6

5

3

9

8

2

7

1

1

5

7

6

8

1

3

7

9

3

0

80

78

86

71

0

.

78

0

.

70

0

.

38

0.

0

.

85

0

.

94

0

.

74

0

.

81

0

.

84

0

.

50

0

.

88

0

.

94

0

.

73

0

.

42

0.

0

.

77

0.

0

.

79

0

.

56

0

.

50

0

.

94

0.

0

.

83

0

.

7

4

5

0

.

77

0

.

53

0

.

4

9

4

HDI

o

v

i

n

a

u

d

a

am

rzeg

tion

a

rb

al

He

Na

n

d B

r

u

ss

n

d

a

n

d

e

a

j

a

n

a

i

n

a

i

a

a

s

n

Da

a

b

i

a

ni

ri

nt

bai

a

d

e

s

h

d

o

s

a

a

l

a

o

r

o

s

ral

n

bodi

e

roo

ba

ge

g

o

l

a

i

g

ua a

ge

a

ham

a

hrai

a

ngl

a

rba

e

l

g

i

u

m

e

l

i

z

e

e

ni

o

sni

r

azi

r

u

n

ei

u

l

g

ari

a

m

a

m

a

n

a

d

a

a

pe Ver

h

i

l

e

in

o

l

o

m

o

m

ngo

Al

Al

An

Ant

Ar

Aust

Azer

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

C

C

C

C

C

Ch

C

C

Co

t

0

0

0

0

0

0

4

0

0

0

0

9

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

1

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

o

un

ber)

um

Offshore

Rig C

(n

6

9

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

8

0

0

0

0

0

1

8

ay)

,1

0,

0,

,3

6

,

0

0

0

3

,850

uction

16

37

20

1

5,000

16

Offshore Oil

Prod

(bbl/d

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

1

0

0

0

3

5

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

T)

64

,3

1

6

,

3

7

3

4,

48

Fleet

(

100

DW

156,385

Merchant

c

0

0

1

6

8

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

73

83

54

0

2

4

2

g

fi

7

,

0

3

3

2

,

5

9

6

7,

9,

4,

,3

,2

r

af

1

4

,

7

2

8

3

7

,

5

2

6

61

3

2

2

,

0

18

2

5

3

,

4

90

10

24,935

0 MT)

g

o T

Shippin

(

100

Car

g

0

0

0

7

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

2

0

0

0

0

0

0

)

1

5

20

T

24

2

5

7

47

53

2,

1

,

6

6

1

2,

0 G

Shipbuildin

Orderbook

(

100

0

0

0

0

0

8

0

0

8

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

8

0

0

6

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

2

0

0

6

0

0

8

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

o

nal

9,

2,

6,

,2

3,

7,

,6

1,

6,

,00

9,

2,

,000

7,

,2

16

75

99

66

75

71

58

36

03

0

1

,

2

0

0

1

92

8

0

,

2

1

9

28

5

2

,

4

0

0

54

13

53

1

2

6

,

2

00

urism

isitor)

1

,

2

3

7

,

0

00

8

,

5

7

6

,

2

00

1

,

8

9

9

,

6

00

2,

1,

3

,

2

1

9

,

4

00

5,

1

,

0

9

4

,

2

00

1

,

7

1

1

,

0

00

3,

,2

,1

1

,

0

0

4

,

0

00

To

(v

81

19

16,251

26

Internati

0

1

0

5

6

0

0

9

3

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

6

0

0

2

26

5

1

05

36

68

89

47

77

16

5,

4,

2,

1

,

7

3

1

,1

3,

T)

7

3

,

5

8

0

5

7

,

4

9

3

4

3

,

4

7

8

10

1

9

7

,

2

74

2

8

,

6

5

3

98,459