Southern African Development Community

(SADC)

Water Sector Coordination Unit

(WSCU)

Funded by the Government of France

Development of a Code of Good Practice for Groundwater

Development in the SADC Region

REPORT No.2 (Final)

GUIDELINES FOR THE GROUNDWATER DEVELOPMENT

IN THE SADC REGION

November 2001

GROUNDWATER CONSULTANTS

Bee Pee (Pty) Ltd.

P.O. Box 7885

Maseru 100

Lesotho

Southern African Development Community

(SADC)

Water Sector Coordination Unit

(WSCU)

Funded by the Government of France

PROJECT

Development of a Code of Good Practice for Groundwater

Development in the SADC Region

REPORT No.2 (Final)

TITLE

GUIDELINES FOR THE GROUNDWATER DEVELOPMENT

IN THE SADC REGION

November 2001

FOREWORD

On behalf of the Southern African Development Community (SADC) Water Sector, I

have the honour of presenting this document entitled "A Code of Good Practice and

Guidelines for Groundwater Development in the SADC Region".

The member States of SADC have agreed to cooperate on strategic sectors that will

contribute to and foster regional economical development and integration on the basis

of balance, equity and mutual benefit for all member States. As a result the Water

Sector was identified as one of such strategic sectors and thus was established in

1996, and coordination responsibility was given to the Kingdom of Lesotho. The

overall objective of the Water Sector is to promote cooperation in all water matters in

the region for sustainable and equitable utilisation, development and management of

water resources that contribute towards the upliftment of the quality of life of the

people of the SADC region.

There are a number of challenges faced by the Water Sector in order to meet its

objective that require concerted efforts by all member States to avert the effects of

those challenges. The major challenges that need to be addressed include the

provision of water of adequate quantity and quality and safe sanitation services

mainly to the people living in rural areas of the region, the majority of which still lack

access to these basic services.

A number of documented studies have shown that more than 60% of communities in

the region depend on groundwater, of which the majority (about 70%) live in rural

areas. Studies have also shown that two or more countries share a number of aquifers

from which water is abstracted for various purposes and services in member States.

The SADC Water Sector therefore acknowledges that groundwater resources are

finite and valuable and are recognised as playing a pivotal role in activities aimed at

alleviating or combating poverty in the region. The SADC Water Sector also

acknowledges that all member States are at different levels in terms of management

and development systems used in managing and developing groundwater resources as

shown by documented studies. Therefore proper development and management

systems need to be in place in order to jointly manage and harness this resource in an

economically, environmentally and socially sustainable manner. This is also in

pursuance of the Protocol on Shared Watercourses in the SADC Region underlying

joint water resources management principle.

The SADC Water Sector Coordinating Unit with the Water Sector Stakeholders in an

effort to address some of the concerns raised above, have attempted to put in place

preliminary management and development tools and mechanisms to be used by a

variety of agencies involved in the groundwater management and development

ranging from government departments, consultants and drilling companies. The

process leading to the development of this document has been very consultative and

has also involved a number of stakeholders in all SADC member States, including

other SADC Sectors such as the Trade and Industry Sector. Processes are underway

for the Trade and Industry Sector having the mandate of developing "Standards" for

the region to adopt this document.

The SADC Water Sector views this document as an on-going evolutionary process

with evolving technology, and therefore will continue consultations with a wider

range of stakeholders in an effort to improve this document through regular reviews.

We, therefore, appeal to and encourage all agencies involved in water resources

development and management to take cognisance of this document when developing

and managing groundwater resources. We also hope that the implementation and the

application of this Code of Good Practice and Guidelines will prove an effective

management and development approach for this resource.

The SADC Water Sector acknowledges the commitment and contribution of the

member States in this document. The SADC Water Sector is also most grateful to the

French Government for financial and technical support that made it possible to

produce this document.

........................

Phera S. Ramoeli

Chief Engineer Sector Coordinator

SADC Water Sector.

PREFACE

The project goal was to develop minimum common standards for groundwater development

in the Southern African Development Community (SADC) Member States, which would serve

as regional standards and guidelines to maintain uniform, good quality development in a

cost-effective manner. Implementation of the project is by the SADC Water Sector

Coordination Unit (SADC-WSCU) through the financial assistance of the French

Government. Groundwater Consultants (Pty) Ltd were commissioned to carry out the project

on behalf of SADC-WSCU.

SADC adopted a Regional Groundwater Management Programme (RGMP) consisting of 10

Projects within the overall framework of regional co-operation and development. The present

project was identified as the priority project for implementation.

To accomplish the project objectives the project was divided into two interdependent stages.

Stage 1 was basically the fact finding, data collection and situation analysis stage, while

Stage 2 focussed on the drafting of standards and guidelines based on the feedback received

during Stage 1.

The Stage 1 Report (Report No.1) was submitted and discussed in a workshop (Workshop

No.1) with the Hydrogeology Subcommittee on 25th and 26th September' 2000. It was agreed

in the meeting that the Report No.1 contains useful information for reference and therefore

should be produced in final form as a reference report to Report No.2.

The Draft Final Report of stage 2 (Report No.2) was submitted in February 2001. The report

was presented to the Hydrogeology Subcommittee on 27th and 28th March 2001 in a workshop

in Mauritius (Workshop No.2). Apart from the subcommittee members, the workshop was also

attended by the SADC STAN (SADC Cooperation in Standardization) experts as observers.

The present Final Report No.2 incorporates the comments and suggestions raised during the

workshop on the Draft Final Report.

During the Workshop No.1, there was a significant discussion on the use of the term

`Minimum Standard' versus `guidelines'. The primary difference between the terms being that

`standard', although effecting only voluntary compliance, has a more strict connotation to

most than the term `guideline', which implies more flexibility in implementation. At the time,

no specific consensus was reached on the preferred use of either term.

Similar to Workshop No.1, there was some discussion on the title of the report, following the

SADC STAN presentation that apprised the committee of the definition of the words,

`Standards', Guidelines' and `Code of Practice' during the Workshop No. 2. `Standards'

refer to a technical document that prescribes the quality characteristics of a product for it to

meet its intended use, while `Code of Practice' refers to a document that recommends

practices or procedures for the design, manufacture, installation, maintenance or utilisation

of equipment, structures or products. Therefore, a consensus was reached on the term `Code

of Practice' instead of `Standards'.

Following the presentation on the regional process of harmonisation of standards within the

SADC Region by the SADC STAN experts, it was realised that the present work on

groundwater standards needs to be incorporated within the framework of SADC STAN. It was

agreed that the present report should become a basis for the adoption of these groundwater

standards and guidelines as the formal `Code of Practice' by the SADC STAN through its

protocol. Therefore the document should be titled "Guidelines for the Groundwater

Development in the SADC Region" under the project title of "Development of a Code of

Good Practice for Groundwater Development in the SADC Region".

This `Code of Good Practice' document is very focused on technical aspects and recommends

the correct practices and/or procedures in relation to groundwater development. By and

large, the document follows sequentially the logical steps in a typical groundwater

development programme, starting from project implementation and planning until the

borehole equipping and reporting. In general, the rationale behind the recommendations and

current practices in the region is not discussed in this document. For this the reader is

referred to Report No.1 and other technical references provided with this document.

In the present document a word `desirable' has also been used frequently in relation to the

standards and guidelines. The standards and guidelines in this document refer to the

minimum level that should be implemented during groundwater development. In certain cases

it may be possible to easily improve the quality of works or data collected, and/or gain

additional confidence in results by implementing extra measures, that in some cases have

additional cost implications. In this report, these activities or procedures are defined as

`desirable'.

Implementing these codes of practice can have profound implications for advancement of the

hydrogeological science through improved integration of data collection and development

practices across national boundaries. Not only will it facilitate the institution of a proper

code of practice that will serve the end user much better, but it will also result in enhanced

exchange of resources across the region, be it technical, manpower, data, or equipment and

instruments.

In the opinion of the authors, this comprehensive document is a valuable guide in

groundwater project implementation in addition to setting a minimum level for groundwater

development practices. The intention of this document is not to rigidly enforce, but to

facilitate and improve the quality of, groundwater development as per the current state of the

science. This document further has the advantage of using terminology and reflecting

conditions that are common in (and sometimes specific to) the SADC region.

The need for this document is also appreciated in view of the considerable variation in the

level of groundwater development activities in the region, from poor or inappropriate to

extremely effective and sophisticated methodologies. In essence, it is desirable to have certain

Minimum Common Standards and Guidelines for optimal and sustainable development and

management of groundwater resources with the ultimate purpose of providing services to the

majority of the population in the region and providing maximum benefit to future generations.

It is important that this document be seen not as a static object but as an on-going,

evolutionary process. As such, regular review and up-dating of the document is imperative if

this first comprehensive document is to continue to serve the overall objective of effectively

implementing Regional Groundwater Management Programme for the SADC Region.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This document is a part of the Regional Groundwater Management Programme for the SADC Region.

The document is drafted by Groundwater Consultants, Bee Pee (Pty) Ltd. of Maseru, Lesotho under a

project of the SADC Water Sector. The project was managed by the SADC Water Sector Coordination

Unit (SADC-WSCU) of Maseru Lesotho, with technical back-up from the SADC Sub-Committee for

Hydrogeology, acting as Steering Committee for the Project.

The French Government (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Cooperation and Francophony), under a Grant

agreement with SADC, provided the source of funding for the project to SADC-WSCU.

Consultant Team

M M Bakaya Project Director

T B Bakaya Quality Reviewer

S K Pandey Consultant

F Linn Consultant

D Juizo Consultant

A Simmonds - Consultant

F Greiner Consultant

Steering Committee

Mr. P S Ramoeli (Coordinator, SADC WASCU)

Ms P Molapo (Senior Engineer- Groundwater, SADC-WSCU)

Dr. S Puyoô (Technical Advisor to SADC-WSCU under the French Assistance Programme)

Mr. G M Christelis (Chairperson, Namibia)

Ms. L Mokoena (Vice-chairperson, South Africa)

Mr. P J da Silva (Angola)

Mr. O Katai (Botswana)

Mr. M Tchimoa (Democratic Republic of Congo)

Mr. M Lesupi (Lesotho)

Mr. J T Banda (Malawi)

Mr. R Pokhun (Mauritius)

Mr. L A Chairuca (Mozambique)

Mr. D Labodo (Seychelles)

Ms. L Mokoena (South Africa)

Mr. O Ngwenya (Swaziland)

Mr. F Senguji (Tanzania)

Mr. L O Sangulube (Zambia)

Mr. L Sengayi (Zimbabwe)

Observers

The following members were observers and provided significant contribution and guidance on the

process:

Mr. B Aleobua (DWAF, South Africa)

Mr. M Chetty (SADC STAN Member, SABS, South Africa)

Mr. S Khodabux (SADC STAN Member, MSB, Mauritius)

Ms C Colvin (IAH Deputy Chairperson for Sub-Sahara Africa)

Mr. K Sami (Council for Geosciences, South Africa)

Mr. G Small (Council for Geosciences, South Africa)

Mr. B Kumwenda (SADC Mining Sector, Zambia)

Mr. R Ndhlovu (Geological Survey Department, Zambia)

Mrs. N Masuku (Geological Survey Department, Zimbabwe)

Document Ownership and Copyrights

This document is owned by the SADC WSCU. No part of this document should be reproduced in any

manner without full acknowledgement of the source.

The document is obtainable from the SADC WSCU, Ministry of Natural Resources, P/Bag A-440,

Maseru 100, Lesotho; Tel (+266) 310022; e-mail: sadcwscu@lesoff.co.za

MAIN REPORT

Development of a Code of Good Practice for Groundwater

Final Report

Development in the SADC Region

TABLE OF CONTENTS

SECTION 1:

GUIDELINES ON GROUNDWATER PROJECT

IMPLEMENTATION.............................................................................. 1-1

1.1

GENERAL ................................................................................................................ 1-1

1.1.1

Scope and Purpose ..................................................................................... 1-1

1.2

ROLE PLAYERS ....................................................................................................... 1-1

1.2.1

National Groundwater Regulatory Body (NGRB)...................................... 1-1

1.2.2

The Implementing Agency (IA)................................................................... 1-3

1.2.3

The Executing Agency ................................................................................ 1-3

1.3

IMPLEMENTATION STRATEGY ................................................................................ 1-3

1.3.1

Community Participation and Need Assessment ........................................ 1-3

1.3.2

Feasibility Study ......................................................................................... 1-4

1.3.3

Proposal and Financing ............................................................................. 1-5

1.3.4

Project Plan and Preparation of Tender Documents................................. 1-6

1.3.5

Tendering and Appointment of Executing Agencies................................... 1-7

1.3.6

Manpower Resource Input and Management Structure............................. 1-7

1.3.7

Execution of Groundwater Development Project..................................... 1-11

1.3.8

Monitoring and Evaluation (M&E).......................................................... 1-11

1.4

PRIVATE BOREHOLES ........................................................................................... 1-13

1.5

DATA CAPTURE AND MANAGEMENT ................................................................... 1-14

1.5.1

Recording Forms ...................................................................................... 1-14

1.5.2

Coordination............................................................................................. 1-14

1.5.3

Borehole Numbering System .................................................................... 1-15

1.5.4

Record Keeping and Data Management .................................................. 1-16

1.6

REGISTRATION OF CONSULTANTS AND CONTRACTORS....................................... 1-16

SECTION 2:

DESK STUDY AND RECONNAISSANCE SURVEY ......................... 2-1

2.1

GENERAL ................................................................................................................ 2-1

2.1.1

Scope and Purpose ..................................................................................... 2-1

2.2

BACKGROUND INFORMATION................................................................................. 2-1

2.2.1

Legal Aspects.............................................................................................. 2-1

2.2.2

Environmental Aspects ............................................................................... 2-1

2.2.3

Physical ...................................................................................................... 2-1

2.3

DESK STUDY........................................................................................................... 2-1

2.3.1

Existing Borehole Information ................................................................... 2-2

2.3.2

Maps ........................................................................................................... 2-2

2.3.3

Water Quality Analyses .............................................................................. 2-2

2.3.4

Existing Reports.......................................................................................... 2-3

2.3.5

Aerial Photograph Review ......................................................................... 2-3

2.3.6

Pumping-test Data...................................................................................... 2-3

2.3.7

Tentative Borehole Design ......................................................................... 2-3

2.3.8

Additional Activities ................................................................................... 2-4

2.4

RECONNAISSANCE FIELD SURVEY ......................................................................... 2-4

2.5

ADDITIONAL ACTIVITIES........................................................................................ 2-5

2.5.1

Limited Hydrogeologic Mapping / Data Collection................................... 2-5

2.5.2

Water Point Inventory ................................................................................ 2-5

2.6

TARGET AREA DELINEATION ................................................................................. 2-5

SECTION 3:

BOREHOLE SITING .............................................................................. 3-1

3.1

GENERAL ................................................................................................................ 3-1

3.1.1

Scope and Purpose ..................................................................................... 3-1

3.1.2

Principle ..................................................................................................... 3-1

3.2

CONTROLLING FACTORS ........................................................................................ 3-1

SADC Water Sector Coordination Unit, Lesotho

i

Development of a Code of Good Practice for Groundwater

Final Report

Development in the SADC Region

3.2.1

Legal Aspects.............................................................................................. 3-1

3.2.2

Social Aspect .............................................................................................. 3-1

3.2.3

Accessibility................................................................................................ 3-1

3.2.4

Environmental Aspects ............................................................................... 3-2

3.2.5

Yield Requirement ...................................................................................... 3-2

3.3

SITING TECHNIQUES AND METHODS ...................................................................... 3-2

3.3.1

Geological and Hydrogeological Technique.............................................. 3-2

3.3.2

Geophysical Techniques............................................................................. 3-3

3.4

MISCELLANEOUS .................................................................................................... 3-5

3.4.1

Number of Sites........................................................................................... 3-5

3.4.2

Prioritisation of Sites.................................................................................. 3-5

3.4.3

Marking of Sites.......................................................................................... 3-5

3.4.4

Site Selection Forms ................................................................................... 3-5

SECTION 4:

BOREHOLE DRILLING AND CONSTRUCTION............................. 4-1

4.1

GENERAL ................................................................................................................ 4-1

4.1.1

Scope and Purpose ..................................................................................... 4-1

4.1.2

Pre-requisite for Drilling of Boreholes ...................................................... 4-1

4.1.3

Supervision of Drilling ............................................................................... 4-1

4.1.4

Data Recording .......................................................................................... 4-1

4.1.5

Pre-mobilisation Meeting/Agreement......................................................... 4-1

4.2

DRILLING ................................................................................................................ 4-2

4.2.1

Choice of Drilling Method.......................................................................... 4-2

4.2.2

Drilling Equipment..................................................................................... 4-4

4.2.3

Formation Sampling and Record Keeping ................................................. 4-4

4.2.4

Drilling Fluids............................................................................................ 4-6

4.2.5

Drilling Diameter ....................................................................................... 4-7

4.2.6

Monitoring During Drilling Activities........................................................ 4-7

4.2.7

Borehole Geophysical Logging .................................................................. 4-8

4.3

BOREHOLE CONSTRUCTION.................................................................................... 4-9

4.3.1

Casings ....................................................................................................... 4-9

4.3.2

Screens...................................................................................................... 4-10

4.3.3

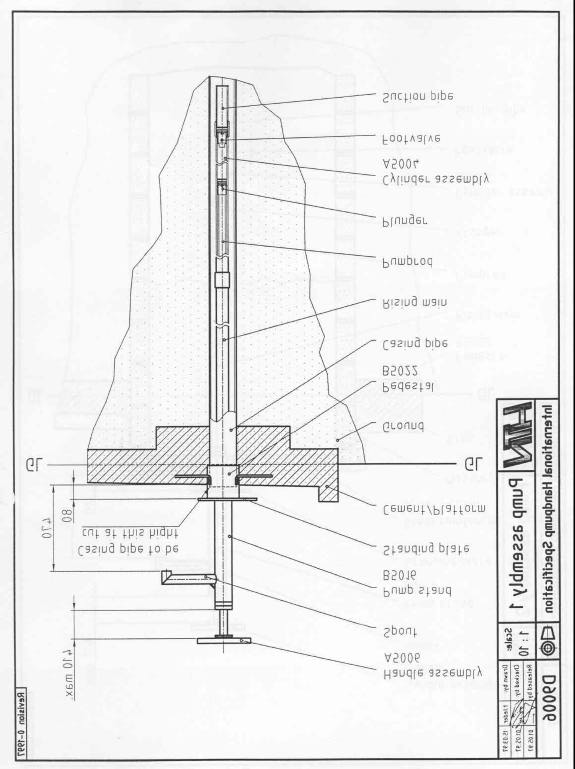

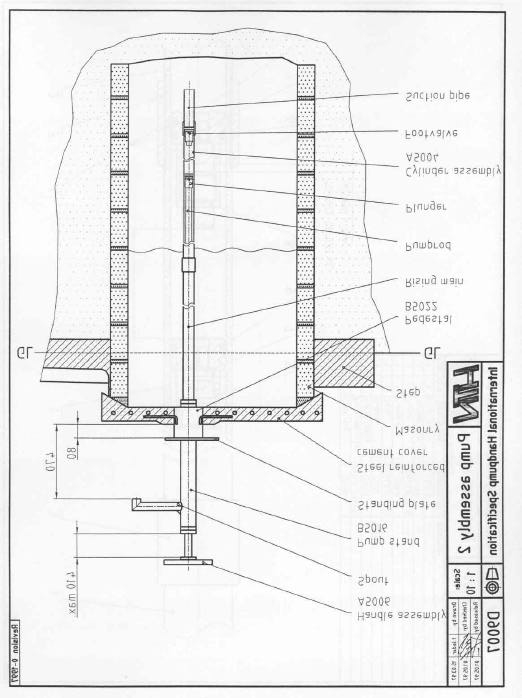

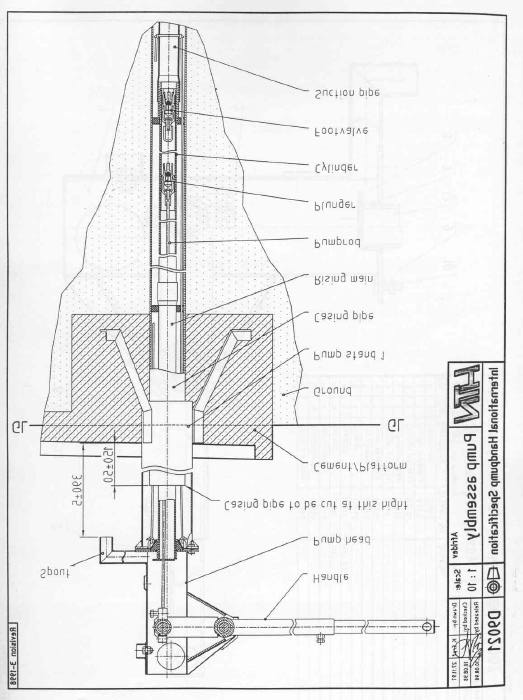

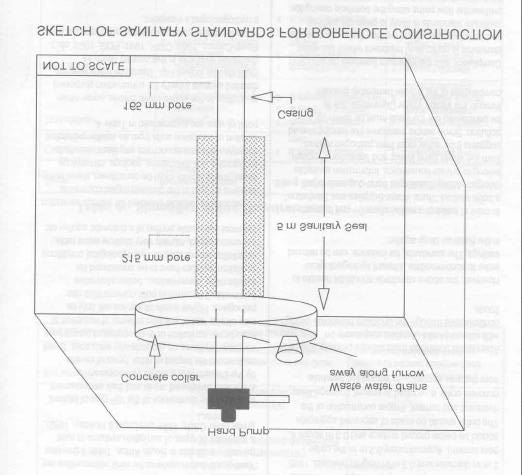

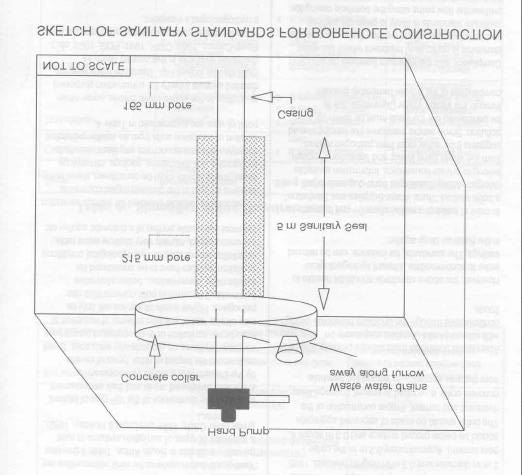

Typical Borehole Designs......................................................................... 4-12

4.3.4

Installation of Casing and Screens........................................................... 4-16

4.3.5

Gravel Pack.............................................................................................. 4-16

4.3.6

Grouting and Sealing ............................................................................... 4-18

4.3.7

Verticality and Alignment......................................................................... 4-18

4.4

BOREHOLE DEVELOPMENT................................................................................... 4-19

4.5

BOREHOLE DISINFECTION .................................................................................... 4-19

4.6

SITE COMPLETION ................................................................................................ 4-19

4.7

MISCELLANEOUS............................................................................................. 4-20

4.7.1

Drilling Site .............................................................................................. 4-20

4.7.2

Abandonment of Boreholes....................................................................... 4-20

SECTION 5:

BOREHOLE DEVELOPMENT............................................................. 5-1

5.1

GENERAL ................................................................................................................ 5-1

5.1.1

Scope and Purpose ..................................................................................... 5-1

5.1.2

Principles.................................................................................................... 5-1

5.1.3

Choice of Development Method ................................................................. 5-1

5.2

MECHANICAL DEVELOPMENT METHODS ............................................................... 5-2

5.2.1

Pumping Methods....................................................................................... 5-3

5.2.2

Surging Methods......................................................................................... 5-4

5.2.3

Jetting Methods .......................................................................................... 5-6

5.3

CHEMICAL METHODS ............................................................................................. 5-7

5.4

TESTING COMPLETENESS OF DEVELOPMENT ......................................................... 5-8

SADC Water Sector Coordination Unit, Lesotho

ii

Development of a Code of Good Practice for Groundwater

Final Report

Development in the SADC Region

5.4.1

Air Lift Pumping......................................................................................... 5-8

5.4.2

Short Constant Rate Test ............................................................................ 5-9

5.4.3

Short Step Test............................................................................................ 5-9

5.5

BOREHOLE ACCEPTANCE ....................................................................................... 5-9

SECTION 6:

GROUNDWATER SAMPLING............................................................. 6-1

6.1

GENERAL ................................................................................................................ 6-1

6.1.1

Scope and Purpose ..................................................................................... 6-1

6.2

THE SAMPLING PROGRAMME .................................................................................. 6-1

6.2.1

Single Water Point Sampling...................................................................... 6-1

6.2.2

Multiple Water Point Sampling .................................................................. 6-1

6.2.3

Laboratory Liaison..................................................................................... 6-2

6.3

GROUNDWATER SAMPLING METHODS................................................................... 6-2

6.3.1

Sample Collecting Devices ......................................................................... 6-2

6.3.2

Spring Sampling ......................................................................................... 6-3

6.3.3

Existing Borehole and Hand Dug Well Sampling ...................................... 6-3

6.3.4

New Borehole Sampling ............................................................................. 6-3

6.3.5

Multiple Horizon Sampling ........................................................................ 6-4

6.3.6

Preservation Methods................................................................................. 6-4

6.3.7

Labelling and Documentation .................................................................... 6-4

6.3.8

Analysis ...................................................................................................... 6-5

SECTION 7:

PUMPING TEST OF BOREHOLES ..................................................... 7-1

7.1

GENERAL ................................................................................................................ 7-1

7.1.1

Scope and Purpose ..................................................................................... 7-1

7.1.2

Conducting And Supervising the Pumping Test Operations ...................... 7-1

7.2

TYPES OF TESTS...................................................................................................... 7-2

7.3

CHOICE OF TYPE AND DURATION OF TEST............................................................. 7-3

7.4

PUMPING EQUIPMENT AND MATERIAL AND THEIR INSTALLATION .............. 7-4

7.4.1

Pumps ......................................................................................................... 7-4

7.4.2

Delivery Pipes ............................................................................................ 7-4

7.4.3

Discharge Control and Measuring Equipment .......................................... 7-5

7.4.4

Water Level Measurement Equipment........................................................ 7-6

7.4.5

Water Quality Monitoring Equipment........................................................ 7-6

7.5

PRE-TEST PREPARATIONS ....................................................................................... 7-7

7.5.1

Information to be collected......................................................................... 7-7

7.5.2

Pre-mobilization Meeting........................................................................... 7-7

7.5.3

Mobilisation and Installation of Test Unit ................................................. 7-7

7.5.4

Observation Boreholes/ Piezometers.......................................................... 7-8

7.6

PUMPING TEST ........................................................................................................ 7-8

7.6.1

Data and Records to be collected............................................................... 7-8

7.6.2

Testing ........................................................................................................ 7-9

7.7

MISCELLANEOUS .................................................................................................. 7-10

SECTION 8:

RECOMMENDATIONS ON PRODUCTION PUMPING.................. 8-1

8.1

GENERAL ................................................................................................................ 8-1

8.1.1

Scope and Purpose ..................................................................................... 8-1

8.2

REQUIRED PARAMETERS ........................................................................................ 8-1

8.2.1

Pumping test Data and Aquifer Parameters............................................... 8-1

8.2.2

Groundwater Recharge .............................................................................. 8-2

8.2.3

Groundwater Quality.................................................................................. 8-2

8.2.4

Abstraction Data from Nearby Production Boreholes ............................... 8-2

8.2.5

Monitoring Data......................................................................................... 8-2

8.2.6

Available Drawdown (sav) .......................................................................... 8-3

8.3

PRODUCTION PUMPING RECOMMENDATIONS ........................................................ 8-3

SADC Water Sector Coordination Unit, Lesotho

iii

Development of a Code of Good Practice for Groundwater

Final Report

Development in the SADC Region

8.3.1

Sustainable Yield ........................................................................................ 8-3

8.3.2

Pump Installation Depth........................................................................... 8-11

8.3.3

Water Quality ........................................................................................... 8-11

8.3.4

Water Quality Protection ......................................................................... 8-12

8.4

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS IN COASTAL AND INLAND SALINITY AREAS............ 8-12

8.5

ADJUSTMENTS IN PRODUCTION YIELD AND PUMPING HOURS AFTER

COMMISSIONING................................................................................................... 8-13

SECTION 9:

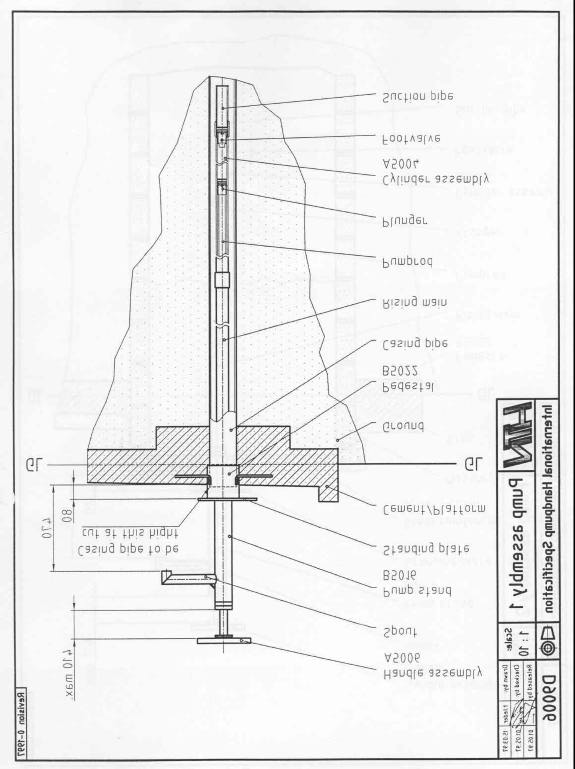

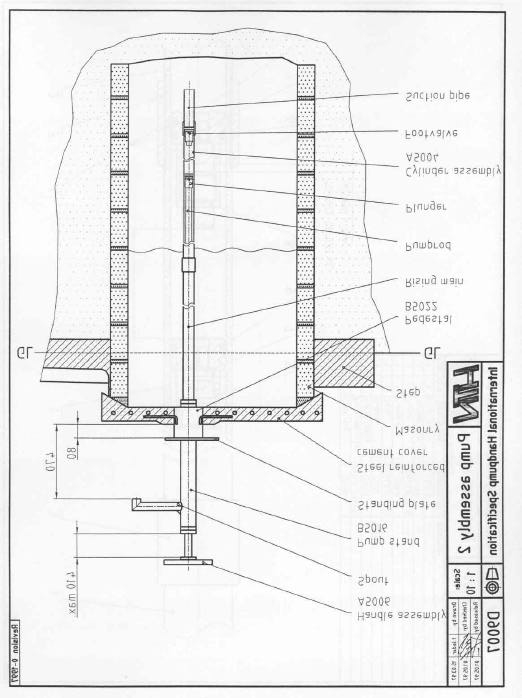

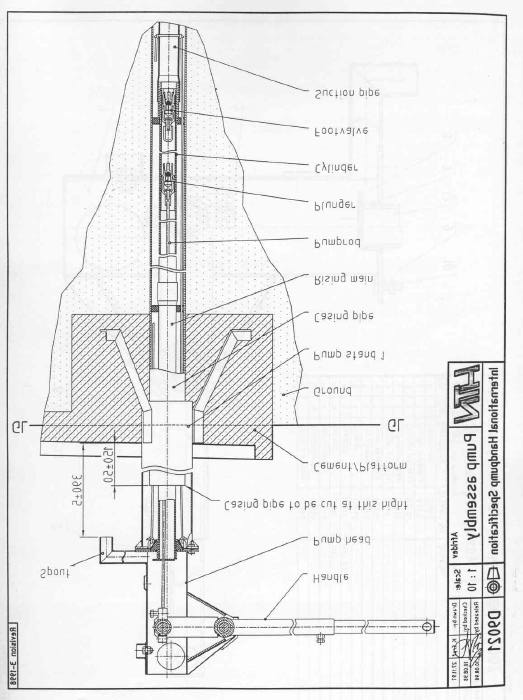

RECOMMENDATIONS ON EQUIPPING OF BOREHOLES .......... 9-1

9.1

GENERAL ................................................................................................................ 9-1

9.1.1

Scope and Purpose ..................................................................................... 9-1

9.2

BOREHOLES EQUIPPED WITH MOTORISED PUMPS................................................. 9-1

9.2.1

Design Requirements.................................................................................. 9-1

9.2.2

Pump Selection ........................................................................................... 9-1

9.2.3

Rising Mains............................................................................................... 9-3

9.2.4

Other Mechanical and Electrical Components .......................................... 9-4

9.2.5

Installation Of Pumping Equipment ........................................................... 9-4

9.3

BOREHOLES WITH NON-MOTORISED PUMPS.......................................................... 9-6

9.3.1

Handpumps................................................................................................. 9-6

9.3.2

Windmills.................................................................................................... 9-7

9.4

OPERATION AND MAINTENANCE............................................................................ 9-8

SECTION 10:

GUIDELINES ON HAND DUG WELLS AND SPRINGS ................ 10-1

10.1 HAND DUG WELLS ............................................................................................... 10-1

10.1.1

Siting......................................................................................................... 10-1

10.1.2

Well Excavation........................................................................................ 10-2

10.1.3

Well Lining ............................................................................................... 10-2

10.1.4

Installation of Liners ................................................................................ 10-3

10.1.5

Slotted or Perforated Pre-cast Concrete Rings, or in situ Cast Concrete

Liners. 10-4

10.1.6

Well Head Completion ............................................................................. 10-5

10.1.7

The Well Cover ......................................................................................... 10-5

10.1.8

Apron and Water Runoff Channel ............................................................ 10-6

10.1.9

Upgrading existing wells.......................................................................... 10-6

10.2 SPRINGS ................................................................................................................ 10-6

10.2.1

Spring Discharge (or Flow) and Water Quality Measurements .............. 10-6

10.2.2

Excavation of the Eye ............................................................................... 10-7

10.2.3

Spring Intake (Catchment) ....................................................................... 10-7

10.2.4

Water Supply System based on Spring Source ......................................... 10-9

10.2.5

Spring Catchment Protection and Monitoring ......................................... 10-9

10.2.6

Miscellaneous......................................................................................... 10-10

SECTION 11:

GUIDELINES ON REPORTING......................................................... 11-1

11.1 GENERAL .............................................................................................................. 11-1

11.1.1

Scope and Purpose ................................................................................... 11-1

11.2 REPORTING ........................................................................................................... 11-1

11.2.1

Inception Report ....................................................................................... 11-1

11.2.2

Siting Report or Site Selection Report...................................................... 11-2

11.2.3

Progress Reports ...................................................................................... 11-2

11.2.4

Final Report.............................................................................................. 11-2

11.2.5

Community Report.................................................................................... 11-3

SADC Water Sector Coordination Unit, Lesotho

iv

Development of a Code of Good Practice for Groundwater

Final Report

Development in the SADC Region

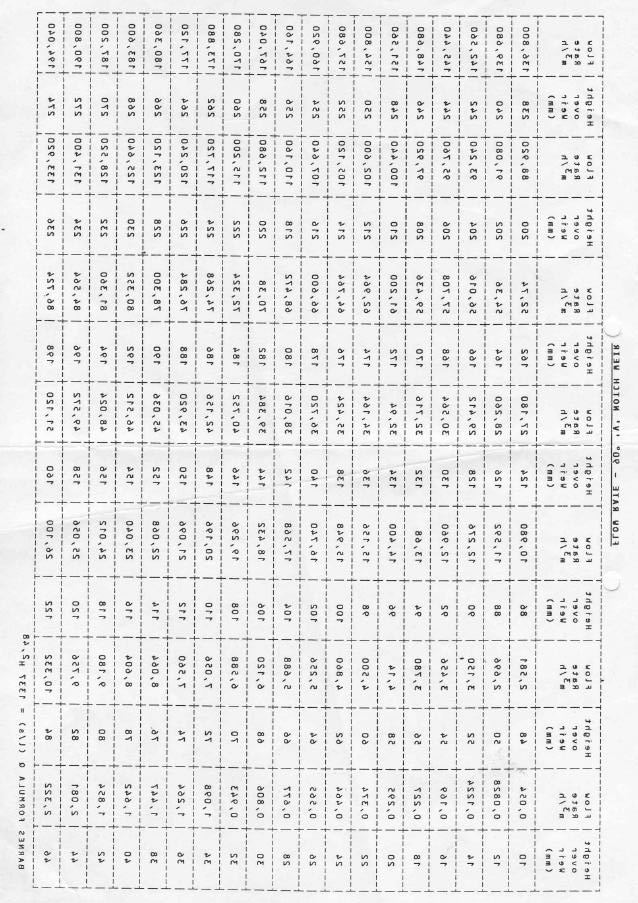

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1-1: Categorisitaion of Personnel Involved in a Typical Groundwater Development

Project/Programme ......................................................................................................... 1-7

Table 1-2 : Implementation Plan for Private Groundwater Development............................ 1-13

Table 4-1 : Summary of Drilling Methods ............................................................................. 4-3

Table 4-2 :Guidelines on Sampling Method .......................................................................... 4-5

Table 4-3: Types of Drilling Fluids........................................................................................ 4-6

Table 4-4 : Monitoring of Fluid Properties ............................................................................ 4-7

Table 4-5 : Characteristics of Sondes..................................................................................... 4-8

Table 4-6 :Screen Types....................................................................................................... 4-10

Table 5-1 : Borehole Development Methods and their Applicability .................................... 5-2

Table 5-2 : Orifice Size and Nozzle Pressure......................................................................... 5-6

Table 5-3 : Testing Methods to Assess Degree of Development .......................................... 5-8

Table 5-4 : Borehole Acceptance Criteria ............................................................................ 5-10

Table 6-1 : Minimum Requirements for Constituent Analysis .............................................. 6-5

Table 6-2 : Guidelines on Constituent Analysis..................................................................... 6-6

Table 7-1: Choice and Duration of Test ................................................................................. 7-3

Table 7-2 : Guidelines on Container Capacity for Discharge Measurements ........................ 7-5

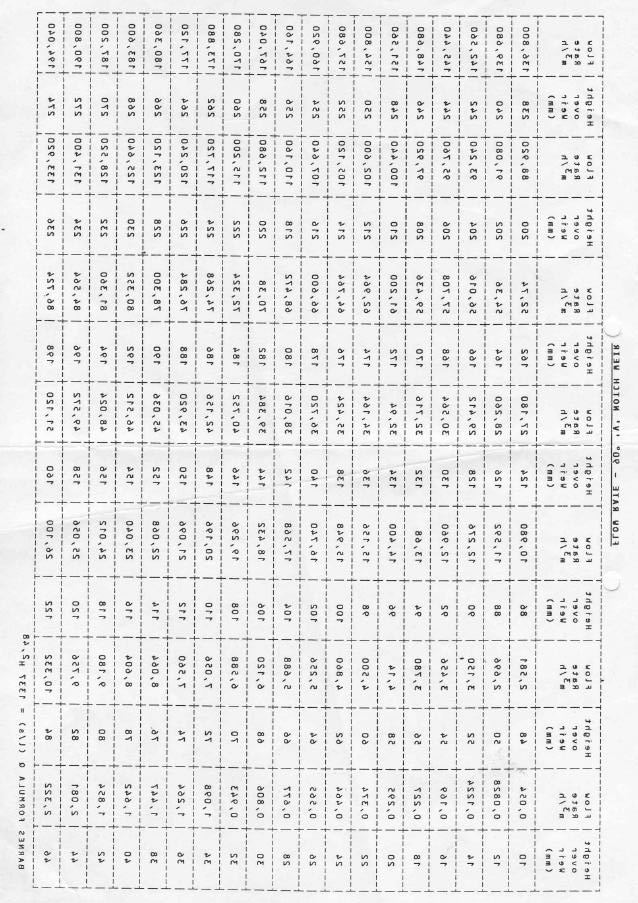

Table 8-1 : Guidelines on Pumping Hours ........................................................................... 8-10

Table 9-1 : Guidelines on Pump Types .................................................................................. 9-2

Table 9-2 : Guidelines on Borehole Protection Structure....................................................... 9-4

Table 9-3 : Guidelines on Handpump Selection..................................................................... 9-6

SADC Water Sector Coordination Unit, Lesotho

v

Development of a Code of Good Practice for Groundwater

Final Report

Development in the SADC Region

LIST OF ANNEXES

Annex A : References

Annex B : Data Recording Forms

Annex C : Reference Material

SADC Water Sector Coordination Unit, Lesotho

vi

Development of a Code of Good Practice for Groundwater

Final Report

Development in the SADC Region

ACRONYMS

BS British

Standards

CBM

Community Based Management

CMAs

Catchment Management Authority

CRT

Constant Rate Test

CSIR

Council for Scientific and Industrial Research

DWAF

Department of Water Affairs and Forestry

DWAs

Departments of Water Affairs

EA Executing

Agency

EIA

Environmental Impact Assessment

ESAs

External Support Agencies

EU European

Union

FIDIC

International Federation of Consulting Engineers

GDs Geohydrology

Divisions

HLEM

Horizontal Loop Elecetro-magnetic

HTN

Handpump Technology Network

IA Implementing

Agency

IGS

Institute for Groundwater Studies

IP Induced

Polarisation

ISO

International Standards Organisation

NGOs

Non Governmental Organisations

NGRB

National Groundwater Regulating Body

SABS

South African Bureau of Standards

SADC

Southern African Development Community

SADC-WSCU

SADC Water Sector Coordination Unit

SDT Step-drawdown

Test

SKAT

Swiss Centre for Development Cooperation in Technology and

Management

SP Self

Potential

TEM

Time Domain Electro-magnetic

UNICEF

United Nations Children Fund

UNDP

United Nations Development Project

VES

Vertical Electrical Sounding

WHO

World Health Organisation

WRC

Water Research Commission

SADC Water Sector Coordination Unit, Lesotho

vii

Development of a Code of Good Practice for Groundwater

Final Report

Development in the SADC Region

REFERENCED STANDARDS

SABS 719 (1971)

SABS 966 (1998)

SADC Water Sector Coordination Unit, Lesotho

viii

Development of a Code of Good Practice for Groundwater

Final Report

Development in the SADC Region

DEFINITIONS OF TERMS

Alluvium. A general term used for clay, silt, sand and gravel deposited in geologically recent

time by a river system.

Annular Space. The space between the wall of the borehole or the outer casing and the inner

casing or the drill stem.

Aquifer. A geological formation, or a part of a formation, or a group of formations below the

surface that is capable of yielding sufficient amount of water when tapped through

boreholes, dug wells or springs.

Aquitard. A geologic formation, or part of a formation, through which practically no water

moves

Artesian Well. A borehole in which the water level (or the head) is above the ground level

and as a result water flows out of the borehole without any mechanical means. In

some instances the term is also used for a well in which the water level stands above

the top of the aquifer but not necessarily above the ground surface.

Available Drawdown. The maximum allowable drawdown in a pumping borehole and is the

difference between the dry season rest water level and the upper level of first screen

or the water strike or the pump intake, whichever is shallower.

Backfill. A term used for filling a drilled borehole, usually a dry or unused borehole, with

drill cuttings or other appropriate material.

Bentonite. A colloidal clay used as a drilling fluid.

Blow-out Yield. Yield of borehole measured during the drilling using compressed air.

Casing. A pipe of steel, uPVC or any other suitable material inserted into a borehole to

support the screens and/or borehole against collapse.

Casing Shoe. A circular, short length of high tensile hardened steel fitting welded to the

bottom end of steel casing for protection against damage during installation into the

borehole.

Centralisers. A piece of folded steel (or uPVC) welded (or attached) to the casing/screen to

keep the casing and screens in the center of the borehole.

Cone of Depression. A depression in the groundwater level, or the head that develops,

around a pumping borehole with the pumping borehole being its axis.

Confined Aquifer. An aquifer that is confined from top and bottom by impervious layers and

the piezometric surface is above the top confining layer.

Contamination. The degradation of natural water quality as a result of man's activity.

Drawdown. The difference between the static water level and lowered water level in any

borehole within the cone of depression including the pumping borehole.

SADC Water Sector Coordination Unit, Lesotho

ix

Development of a Code of Good Practice for Groundwater

Final Report

Development in the SADC Region

Drilling Fluid. A water or air based fluid used in the drilling of a borehole to remove cuttings

from the borehole, to clean and cool the bit, to avoid collapse of borehole, to reduce

friction between the borehole wall and the drill stem and to seal the borehole.

Electrical Conductivity. A measure of the ease with which a conducting current flows

through the fluid. It is used to assess the salinity of the fluid.

Filter Pack. Same as Gravel Pack.

Formation Stabilizer. Same as the Gravel pack but is normally used to stabilize fractured

semi-consolidated or consolidated formation. The material may be of sub-rounded

nature.

Gravel Pack. Sand or gravel that is smooth, uniform, clean, well-rounded and siliceous. It is

placed in the annular space between the borehole wall and the well screen to

prevent the entry of formation material into the screen and borehole.

Grout. A fluid mixture of cement and water that is placed at a required depth within the

annular space to provide a firm support and impervious layer for protection against

contamination.

Head. Energy measured in the dimension of length (usually in meters) of a fluid produced by

elevation, velocity and pressure.

Heterogeneous. Non-uniform in structure and composition.

Homogeneous. Uniform in structure and composition.

Injection Borehole. A borehole through which water is poured back to the aquifer.

Interference. A condition occurring when the cone of depression of two nearby borehole

pumping from the same aquifer come in contact with each other or overlap.

Leakage Coefficient. It is a measure of spatial distribution of leakage through an aquitard

into a leaky aquifer. It has the dimension of Length.

Monitoring Borehole. A borehole used for monitoring of water level and/or water quality.

Porosity. It defines the pore spaces in an aquifer. It is expressed as a fraction and is the ratio

of void space to total volume for a unit volume of aquifer.

Production Borehole. A pumping borehole that is used for producing water for consumption.

Pumping Test. A test carried out to assess the aquifer or borehole characteristics.

Regolith. A general term used for soil, unconsolidated material or weathered material

overlying the country rock/bed rock.

Residual Drawdown. The difference between the static water level and the water level

measured in a borehole during the recovery following pumping.

Rest Water Level. A water level in a borehole that is not affected by the pumping. Also

referred to as Static Water Level (SWL) at times.

SADC Water Sector Coordination Unit, Lesotho

x

Development of a Code of Good Practice for Groundwater

Final Report

Development in the SADC Region

Rising Main. The pipe from the pump intake (or the pump) to the surface through which

water is pumped to surface.

Sanitary Seal. The seal, composed of a cement grout, with which the annular space between

the borehole wall and the surface casing is filled in order to prevent contamination

of the borehole.

Screen. A filtering device used to restrict the sediments from the formation entering the

borehole. (commonly made by perforation of steel or uPVC pipes with apertures of

various types and shapes)

Specific Capacity. It is the volume of water that is pumped from a borehole for a unit

drawdown of water level for a particular duration of pumping.

Static Water Level. refer Rest Water Level.

Storativity. It is the volume of water released from storage per unit surface area of the aquifer

per unit decline in the hydraulic head. It is dimensionless coefficient.

Sump. A term used to express the lowermost part of a borehole that is left for sediment

accumulation or any other debris falling into the borehole.

Surface Casing. The casing that is used to protect the top regolith/soil falling into the

borehole to facilitate drilling of rest of the borehole. It is also used to protect

contaminant entering into the borehole annulus through the regolith.

TDS (Total Dissolved Solid). The quantity of dissolved material in water expressed as

mg/liter.

Transmissivity. The rate of flow of water across the unit width of the entire saturated

thickness of the aquifer under a unit hydraulic gradient. It is expressed in terms of

m2/day or equivalent (dimensions L2/T).

Tremie Pipe. A pipe that is used to carry/install material (such as cement grout or gravel) at a

specified point or depth in a borehole.

Unconfined Aquifer. An aquifer in which the water is in direct contact with the atmosphere

through open spaces. It has a free water table and the true thickness of the aquifer is

more than or equal to the saturated thickness.

Unconsolidated Formations. Loose (or loosely cemented), soft rock material of any type of

rock that includes sand, gravel, breccia or weathered material.

Water Table. The upper surface of the zone of saturation in an unconfined formation, at

which the hydraulic pressure is equal to atmospheric pressure.

Note

More definitions related to groundwater can also be found in the UNESCO International

Glossary of Hydrology, 1992.

SADC Water Sector Coordination Unit, Lesotho

xi

Development of a Code of Good Practice for Groundwater

Final Report

Development in the SADC Region

Section 1: GUIDELINES ON GROUNDWATER PROJECT IMPLEMENTATION

1.1 GENERAL

1.1.1 Scope and Purpose

Effective groundwater development is contingent on structured, sufficiently funded and

coordinated programmes that are efficiently regulated through an appropriate policy and

institutional framework, and are implemented by technically competent personnel.

The present section outlines a generalised guideline on the key role players and the

implementation mechanism. These are only guidelines and should be viewed in the context of

the national institutional framework. It may be appropriate to accommodate these guidelines

in on-going sectoral and institutional reforms that are presently underway in many of the

SADC Member States.

1.2 ROLE

PLAYERS

A variety of role players are involved in groundwater development projects. These can be

broadly categorised as regulator and facilitator, implementer, executor and user. A general

hierarchical structure is presented in Figure 1-1.

1.2.1 National Groundwater Regulatory Body (NGRB)

A national regulatory body, with the sole responsibility for groundwater sector planning and

management (in coordination with other related sectors), is essential to oversee the

groundwater development activities on behalf of the government. These national agencies

could be a groundwater division, department or directorate within the department of water

affairs, water ministry or water authority. In other cases, where water resource management at

catchment level is gaining momentum, it could be a catchment management authority. NGRB

could be represented at regional or provincial level for logistical reasons.

Although at present some of these national agencies in the SADC Region are directly

involved in implementation of groundwater development, it is desirable for these agencies to

limit their involvement in direct implementation and rather play the role of a facilitator and

regulator. The key roles they could play particularly in relation to groundwater development

are:

· develop national policies, in close coordination with other relevant sectors, on

groundwater exploration, development and management;

· provide a larger framework of policies and technical assistance to various implementing

agencies on groundwater development (for example implementation of the guidelines and

standards outlined in this document) and associated macro planning;

· provide a framework for registration of professionals, drillers and suppliers engaged in

groundwater development activities;

· plan, coordinate and execute if necessary, groundwater assessment and research at

national level to facilitate the macro-planning of groundwater development;

· monitor and regulate groundwater development activities to ensure sustainable

development, quality data collection and good workmanship;

· ensure the protection of aquifers against the contamination and pollution; and

· develop and maintain a groundwater database to provide easy access to data for

groundwater development activities.

SADC Water Sector Coordination Unit, Lesotho

1-1

Development of a Code of Good Practice for Groundwater

Final Report

Development in the SADC Region

Figure 1-1 : A General Organisational Set-up for Groundwater Development Project

Implementation

National Government

(Represented by Appropriate Ministry)

National Groundwater Regulating Agency

(Groundwater division, department or directorate

within the department of water affairs, water ministry,

catchment management or water authority)

Implementing Agency

(Rural or urban water supply departments, water

utilities, boards, local governments & authorities,

municipalities, agricultural, educational or health

departments)

Executing Agency

(Implementing agency or parastatal organisation,

consultants, contractors, suppliers)

Users

(Communities, industries and other private users)

SADC Water Sector Coordination Unit, Lesotho

1-2

Development of a Code of Good Practice for Groundwater

Final Report

Development in the SADC Region

1.2.2 The Implementing Agency (IA)

These are the agencies that are directly responsible for the implementation of water supply

projects. In smaller member states this could be the department of rural water supplies or

water utilities departments while in larger member states these could be provincial and local

government authorities and municipalities. In addition there are other stakeholders such as

departments of education and health, agricultural departments, geological surveys, major

mining and industrial establishments, external support agencies (ESA's) and non-

governmental organisation (NGO's).

It is desirable to have clarity on the role and mandate of implementing agencies. For example

in the case of a rural water supply department/division being responsible for rural water

supplies, all the rural water supply implementation should either be channelled (particularly

for government bodies such as education and health department and ESA's) or coordinated

through (for NGO's involved in rural water supply implementation) this agency. It may be

necessary to have a regulatory framework to make the coordination effective amongst these

agencies.

1.2.3 The Executing Agency

The executing agency should comprise a competent group of people with appropriate

resources to undertake the execution of groundwater development projects. It is desirable that

the national regulatory bodies put in place an acceptable mechanism and criteria for the

recognition and registration of the executing agencies, as necessary, to engage in groundwater

development activities.

The Executing agency may be the implementing agency itself, a parastatal organisation or

private consulting and contracting companies that are appointed by the implementing agency.

1.3 IMPLEMENTATION

STRATEGY

1.3.1 Community Participation and Need Assessment

Community participation and their need assessment is the starting point of any water supply

system implementation. It includes:

· assessment of the community's need in regard to water requirement (water demand);

· the type of systems that are preferred by the community i.e handpumps, motorised

pumping systems etc.;

· aspects related to ease of running and maintenance of the water supply system with

reference to the community's skill level, availability of spares etc;

· the community's ability and willingness to pay for the water supply systems and take the

ownership;

· existing community organisation structure (such as water committees); and

· assessment of the impact of planned abstraction and other negative impact on other water

users in the area.

It is not the objective of the present document to cover the community aspects in detail.

However, it is important to note the significance of these aspects and maintain a continuous

interaction with the community during the entire decision making process, as it is essential for

the sustainability of the project. The level of interaction and involvement may depend on the

community's ability and willingness to take ownership of the system (also refer 9.4).

SADC Water Sector Coordination Unit, Lesotho

1-3

Development of a Code of Good Practice for Groundwater

Final Report

Development in the SADC Region

1.3.2 Feasibility

Study

Regardless of the size and the purpose of the scheme (i.e. rural, urban, domestic, non-

domestic etc.), a feasibility study must be carried by the implementing agency for any

groundwater development programme implementation. The elements of the study will

involve:

· All the basic elements of community participation, ability and need assessment, preferred

system etc. as outlined in 1.3.1.

· Population estimates from the existing demographic data (a direct head count can also be

made for smaller rural communities), including details on schools, clinics and any other

institution that may impact the water demand.

· Domestic water demand estimate, based on national standards on per capita consumption.

· Non-domestic water demand, such as industrial, recreational or agricultural demand, as

applicable.

· An assessment of the water quality of exiting and potential water supply sources as well

as an assessment of water quality requirements.

· A review of existing water supply systems, if present.

· A review of available water supply sources in the area.

· A review of alternate designs that might be required for a specific problem or

hydrogeological environment, e.g. in coastal areas alternate designs might be necessary to

optimise the exploitation of fresh water zones/aquifers.

· A review of macro-plans for water supply development for the area, if available.

Based on the above information and assessment, an analysis is carried with regard to the most

cost effective but sustainable scheme that could meet the requirement for the chosen design

period (i.e. 10 or 20 years). Policy and guidelines are generally available at national level as

well as at implementation agency level on details of the feasibility analysis.

Only after this stage of feasibility analysis should a decision be made on the extent and details

of planned groundwater development. In some cases, decisions on the source of water supply

are made without a proper feasibility study, leading to ineffective development. Similarly,

premature and general decisions are also made on the type of schemes. For example, often

either only handpump systems are chosen for all rural water supply systems or only pumping

systems are chosen within the urban areas. However, in many cases a combined system type

is often the optimal and most cost effective solution. These generalised practices should be

discontinued and these choices should be made specific to schemes. It is desirable to involve a

competent groundwater specialist at the feasibility stage.

With specific reference to groundwater development, the feasibility analysis should be able to

provide:

· the total water demand to be met by groundwater development;

· type of groundwater development that is found to be feasible (such as springs, open dug

well, handpumps, mechanised pumping boreholes etc.);

· total number of required boreholes (or other source) and expected yields; and

· estimated cost of development.

Although, from the above guidelines, a feasibility study may appear to be exhaustive and time

consuming, for smaller rural communities it may often take only a day or two to complete the

study, provided the base line data are available. On the other hand, the feasibility study for a

larger urban type water supply may take years depending upon the complexities involved.

SADC Water Sector Coordination Unit, Lesotho

1-4

Development of a Code of Good Practice for Groundwater

Final Report

Development in the SADC Region

An Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) should also be carried out independently as an

integral component of the feasibility study. The EIA should follow the national guidelines as

set by the respective national environmental authority/s. To clearly assess the impact of

development, these possible impacts should be clearly defined in terms of:

· direct or indirect;

· significant or insignificant;

· reversible or irreversible; and

· positive or negative.

With particular reference to groundwater development, the various possible components that

should be assessed for the environmental impact are (but not limited to):

· Impacts on flora and fauna, particularly on any endangered plant and animal specie,

caused during geophysical survey, drilling and testing operations, subsequent construction

of water supply system as well as production pumping.

· Impact of planned abstraction on the other users in the area that are already abstracting

water.

· Discharge or release of toxic chemicals, fuel, oil etc. during drilling, testing and

construction.

· Contamination or pollution of fresh water aquifers from another aquifer of poor quality

(e.g. in the coastal aquifers and in the areas of groundwater salinity) water during the

drilling and pump-testing.

· Possible movement of saline water interface in coastal areas due to planned abstraction

· Loss or damage or change to a scenic area/landscape over a long period.

· Negative impacts on human health during drilling and construction operations.

· Loss of any cultural, historical, archaeological site.

· Loss of any employment due to development activities.

The nature and scope of EIA should depend upon:

1. the scale of the groundwater development project; and

2. the sensitivity of the area.

In cases where the scale of the groundwater development project is smaller (such as drilling

of scattered boreholes for rural water supply), a detailed EIA may not be required. An initial

screening of the project should be done to assess the need and scope for the EIA. Similarly,

the sensitivity of the area should also be considered during the screening and scoping process.

It is recommended that the NGRB (in coordination with the national environmental authority)

should delineate sensitive areas where, irrespective of the scale of operation, a proper EIA

must be done.

It should be made mandatory that the completed feasibility study, together with the EIA

report, is forwarded to NGRB for final review and approval to ensure that it complies with

national policies and standards on groundwater development.

1.3.3 Proposal and Financing

Following the feasibility study, IA should prepare a proposal to meet the water demand. The

proposal should incorporate all the components of water supply in an integrated manner,

starting from water source development to commissioning of the water supply system. It may

be necessary to provide a breakdown of groundwater development activities.

IA should incorporate the project proposal into their financing plans or seek funding from an

appropriate agency within the framework of their mandate.

SADC Water Sector Coordination Unit, Lesotho

1-5

Development of a Code of Good Practice for Groundwater

Final Report

Development in the SADC Region

1.3.4 Project Plan and Preparation of Tender Documents

Based on the approved feasibility study, the implementing agency should combine schemes of

similar nature and/or similar logistical set-up to form a single project. A time frame and

resource input schedule should be prepared for the implementation.

In cases where the implementing agency does not have the resources to execute the project

itself, and has a mandate to outsource the execution, the implementing agency should prepare

appropriate tender documents. Two separate tenders should be prepared: one for the

consulting services including services such as desk study, borehole siting, borehole drilling

and pumping test supervision, production pumping recommendations, supervision of hand

pump installation and final reporting; and the other one for the works: to include drilling,

pumping test and equipping of handpumps or motorised pumps (as applicable). In order to

ensure quality of the product it is firmly recommended that the two functions should not be

mixed in any case.

Sometimes groundwater development becomes an integral part of a larger engineering/water

supply project. In such cases it is desirable that consulting and contracting issues for

groundwater development activities are identified clearly, and preferably should be separated

as parallel sub-contracts.

Although both tenders for services and works could be prepared by IA, it is desirable that

tender document for works should be prepared by the consultant (or by the IA where it carries

out the services itself and outsources the works only) during the execution. This provides an

extra opportunity to make the tender more specific to particular requirements as it is based on

additional knowledge gained during the feasibility study.

A typical tender for groundwater development should include:

· Terms of Reference (ToR) and specifications;

· Indicative manpower resources (for services only) and time schedule;

· Bill of quantities (BoQ);

· Draft contract document including the General and Special conditions of contract; and

· Form of agreement and other applicable forms for tender boards.

Terms of reference and specifications should clearly provide the details of the intended

groundwater development activities. They should either cross-refer to the relevant national

and regional (e.g. the present document) standards and guidelines on groundwater

development or be customised.

An indicative manpower resources and time schedule for the implementation should be

provided with the services tender, as it is often based on financial constraints and/or

implementation strategy of the implementing agencies.

The tender should be accompanied by a detailed bill of quantities based on the ToR and

specifications. A general BoQ for a groundwater development programme is provided as

guideline in Appendix B. Explanations and elaborations on items should be provided

wherever applicable. In general the BoQ's should be structured according to rated items and

measured quantities and not on based on Lump Sums. Broad items such as complete drilling

and installation per meter should be avoided and instead specific aspects (i.e. drilling, casing

installation, etc.) should be itemised for better control.

The Contract should broadly be according to the procedures and guidelines set by the relevant

national authorities or funding agencies. Standard FIDIC contract documents can also be used

as a basis.

SADC Water Sector Coordination Unit, Lesotho

1-6

Development of a Code of Good Practice for Groundwater

Final Report

Development in the SADC Region

If services and the works are carried out by the IA itself then an overall project execution

plan, including the resource input, implementation schedule and project monitoring

mechanism, should be prepared and approved by the regulatory body.

1.3.5 Tendering and Appointment of Executing Agencies

Once the tender documents are prepared these must be approved by the NGRB as well as any

other relevant authority at national level, if required (such as Tender Board).

Tender evaluation should be carried out by the implementing agency within the framework of

its own procedures. It is essential that the tender for services should be evaluated for its

technical merit first before opening the financial bid. It is also essential to involve at least one

groundwater professional (hydrogeologist, geophysicist, engineer) from the implementing

agency in the evaluation committee. Wherever this is not possible, assistance from the NGRB

should be requested.

Tendering and appointment of an executing agency will not be applicable in cases where IA is

directly involved in execution.

1.3.6 Manpower Resource Input and Management Structure

Manpower resource input and management structure varies primarily according to the

magnitude and complexity of groundwater development project implementation and available

financial resources.

Typical manpower resources are categorised to provide a general guideline on their input,

level of expertise and qualifications for typical personnel involved in groundwater

development. These are categorised and presented in Table 1-1 below. The table only

includes key manpower on typical technical aspects of groundwater development. Additional

manpower such as sociologist, environmentalist, sanitation expert, etc. may be required on

specific projects.

Table 1-1: Categorisitaion of Personnel Involved in a Typical Groundwater Development

Project/Programme

Category

Qualification and Experience

Hydrogeologist A competent hydrogeologist with a master's degree in an appropriate

Level A

discipline or higher and minimum 10 years of relevant experience

Or

A competent hydrogeologist with a bachelor's degree in an appropriate

discipline and minimum 13 years of relevant experience

Hydrogeologist A competent hydrogeologist with a master's degree in an appropriate

Level B

discipline or higher and minimum 5 years of relevant experience

Or

A competent hydrogeologist with a bachelor's degree in an appropriate

discipline and minimum 8 years of relevant experience

Hydrogeologist A competent hydrogeologist with a master's degree in an appropriate

Level C

discipline

Or

A competent hydrogeologist with a bachelor's degree in an appropriate

discipline and minimum 3 years of relevant experience

Hydrogeologist A competent hydrogeologist with a minimum of a bachelor's degree in an

Level D

appropriate discipline

Geophysicist

A competent geophysicist with a master's degree in an appropriate

Level A

discipline or higher and minimum 10 years of relevant experience

Or

SADC Water Sector Coordination Unit, Lesotho

1-7

Development of a Code of Good Practice for Groundwater

Final Report

Development in the SADC Region

A competent geophysicist with a bachelor's degree in an appropriate

discipline and minimum 13 years of relevant experience

Geophysicist

A competent geophysicist with a master's degree in an appropriate

Level B

discipline or higher and minimum 5 years of relevant experience

Or

A competent geophysicist with a bachelor's degree in an appropriate

discipline and minimum 8 years of relevant experience

Geophysicist

A competent geophysicist with a master's degree in an appropriate

Level C

discipline

Or

A competent geophysicist with a bachelor's degree in an appropriate

discipline and minimum 3 years of relevant experience

Geophysicist

A competent geophysicist with a minimum bachelor's degree in an

Level D

appropriate discipline

Technician

A competent technician with a diploma in an appropriate discipline and

Level A

minimum relevant experience of 10 years

Technician

A competent technician with a diploma in an appropriate discipline and

Level B

minimum experience of 5 years

Or

A competent technician with Standard 10 or higher level and minimum

relevant experience of 8 years

Technician

A competent technician with a diploma in an appropriate discipline

Level C

Or

A competent technician with Standard 10 or higher level and minimum

relevant experience of 3 years

Groundwater

A person of suitable qualification and experience and recognised in a

Specialist

specific field pertaining to groundwater such as modelling expert,

geochemist, drilling expert etc. These may not be hydrogeologist or

geophysicist but personnel required for specific aspects on a more complex

and larger scale groundwater development projects.

Handpump Programme

Project Management

Overall project management, quality control and technical support should be by a

Project Manager/Team Leader (PM) who is a hydrogeologist of level B or higher. In

case the project is an integrated project with other components of water supply/health

also involved, the PM could be a non-hydrogeologist but in that case the Team Leader

should be a hydrogeologist of level B or higher for groundwater development

component. His involvement should be continuous on the project. PM/TL should be

supported by a hydrogeologist of category C (may not be full time) wherever the scale

of operations and logistics require such support.

Target Delineation and Borehole Siting

A Hydrogeologist (HS) of category C should carry out target delineation for detailed

siting and geophysical survey (if required) with support from the PM and a