LAND-OCEAN INTERACTIONS IN THE COASTAL ZONE (LOICZ)

Core Project of the

International Geosphere-Biosphere Programme: A Study of Global Change (IGBP)

and the

International Human Dimensions Programme on Global Environmental Change (IHDP)

Nutrient fluxes in transitional zones of the Italian coast

Compiled and edited by G. Giordani, P. Viaroli, D.P. Swaney,

C.N. Murray, J.M. ZaldÝvar and J.I. Marshall Crossland

LOICZ REPORTS & STUDIES NO. 28

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

1.

OVERVIEW OF WORKSHOP AND BUDGETS RESULTS

1

2.

NORTH-EASTERN ITALIAN COASTAL SYSTEMS

18

2.1 Lagoon of Venice ş Gianpiero Cossarini, Chiara Castellani, Andrea

18

Barbanti, Alberto Giulio Bernstein, Giovanni Cecconi, Flaviano Collavini,

Stefano Guerzoni, Laura Montobbio, Roberto Pastres, Sandro Rabitti,

Giorgio Socal, Cosimo Solidoro, Marina Vazzoler and Luca Zaggia

29

2.2 Sacca di Goro ş Martina Austoni, Gianmarco Giordani, Giuseppe

Castaldelli, JosŔ Manuel ZaldÝvar, Dimitar Marinov and Pierluigi Viaroli

2.3 Pialassa Baiona Lagoon, Ravenna ş Massimo Ponti, Saverio Giaquinta and

41

Marco Abbiati

3.

SOUTH-EASTERN ITALIAN COASTAL SYSTEMS

49

3.1 Lagoon of Lesina ş Elena Manini, Paolo Breber, Raffaele D'Adamo,

49

Federico Spagnoli and Roberto Danovaro

3.2 Lagoon of Varano ş Elena Manini, Paolo Breber, Raffaele D'Adamo,

55

Federico Spagnoli and Roberto Danovaro

3.3 Torre Guaceto wetland ş Alessandro Pomes, Ilaria Cappello, Luigi

59

Palmisano, Maurizio Pinna, Giuseppe Cal˛, Roccaldo Tinelli, Alessandro

Ciccolella and Alberto Basset.

3.4 Torre Guaceto Bay ş Luigi Palmisano, Alessandro Pomes, Ilaria Cappello

69

and Alberto Basset

3.5 Acquatina Lake ş Ilaria Cappello, Luigi Palmisano, Alessandro Pomes,

75

Maria Rosaria Vadrucci and Alberto Basset

4.

COASTAL SYSTEMS OF SICILY AND SARDINIA

80

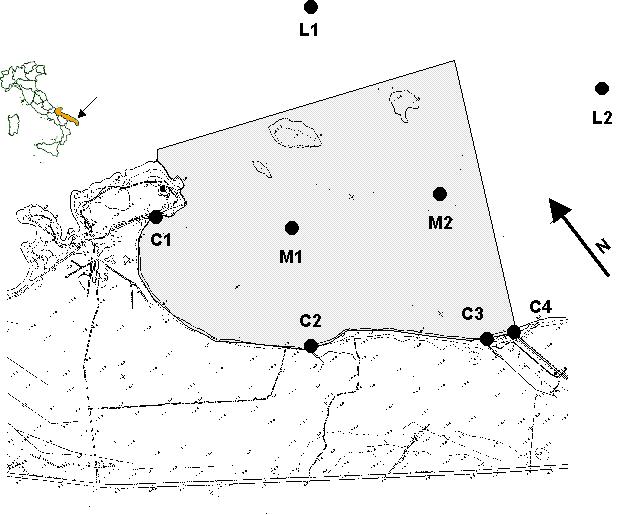

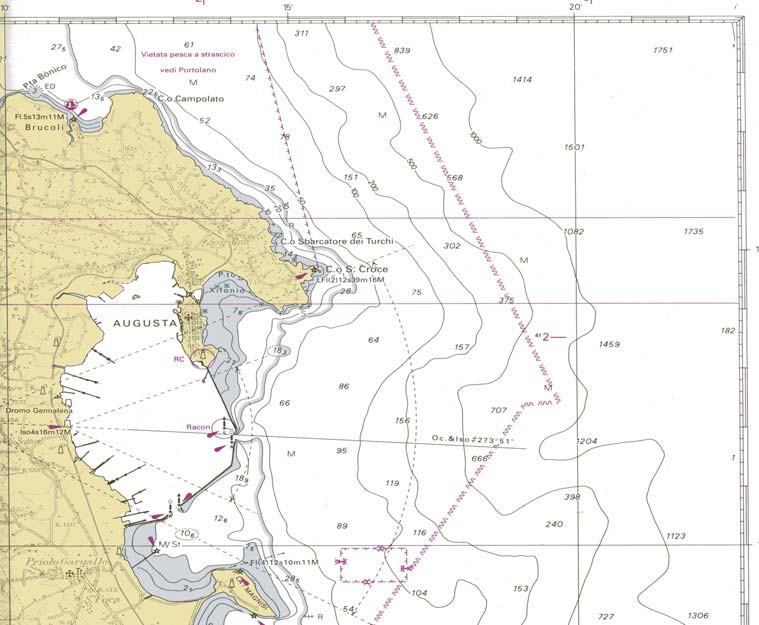

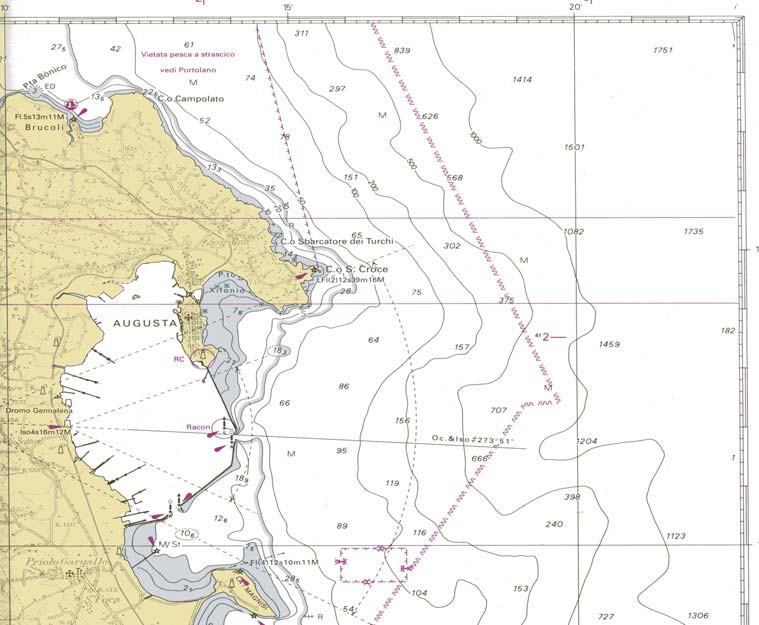

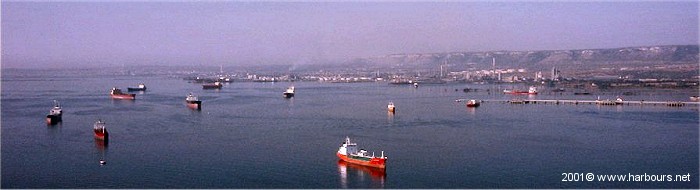

4.1 Rada di Augusta, eastern coast of Sicily ş Filippo Azzaro, Maurizio Azzaro,

80

Alessandro Bergamasco and Salvatore Giacobbe

4.2 Capo Feto marshland, south-west Sicilyş Giuseppe Pernice, Ignazio Patti,

85

Vincenzo Maccarrone and Francesca Apollo

4.3 Stagnone di Marsala Lagoon, western Sicily ş Sebastiano Calvo, Giuseppe

91

Ciraolo, Goffredo La Loggia, Antonio Mazzola, Agostino Tomasello and

Salvatrice Vizzini

4.4 Marinello coastal system, north-eastern Sicily ş Marcella Leonardi, Filippo

95

Azzaro, Maurizio Azzaro, Alessandro Bergamasco and Franco Decembrini

4.5 Ganzirri Lake, north-eastern Sicily ş Alessandro Bergamasco, Maurizio

103

Azzaro, Giuseppina Pulican˛, Giuseppina Cortese and Marilena Sanfilippo

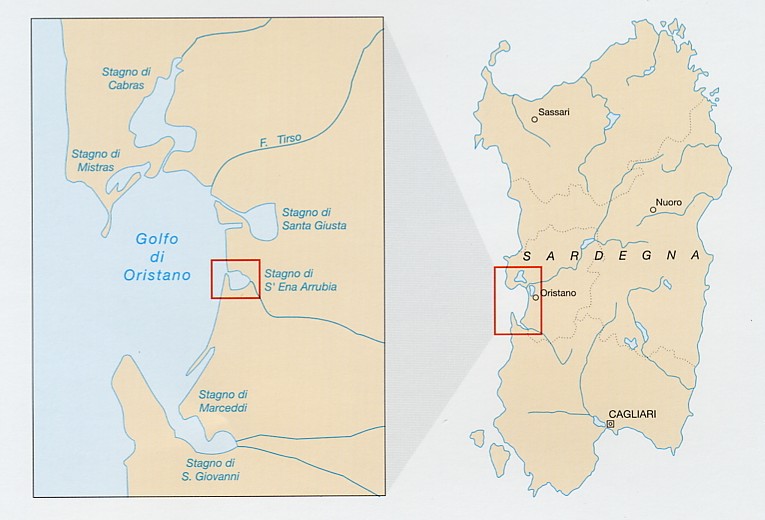

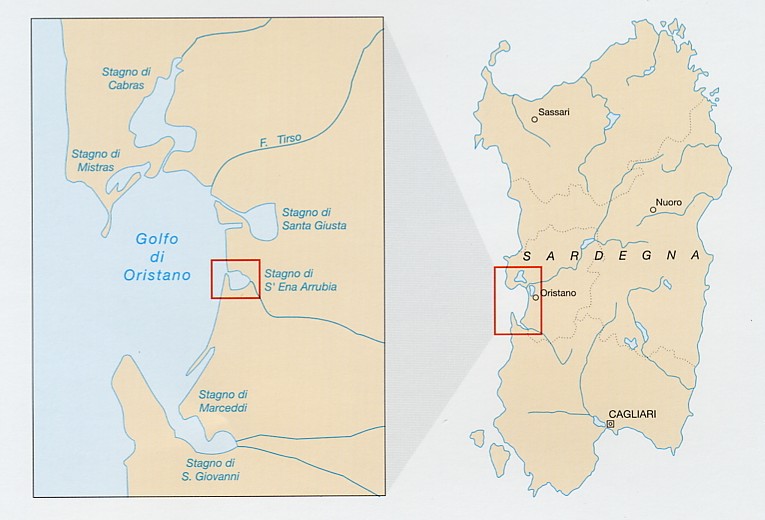

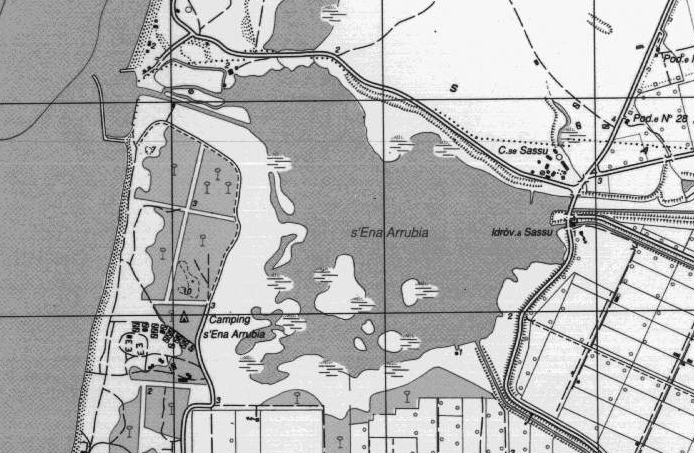

4.6 S'Ena Arrubia Lagoon, western Sardinia ş Felicina Trebini, Bachisio Mario

111

Padedda, Giulia Ceccherelli and Nicola Sechi

5.

COASTAL SYSTEMS OF THE TYRRHENIAN SEA (WEST COAST)

118

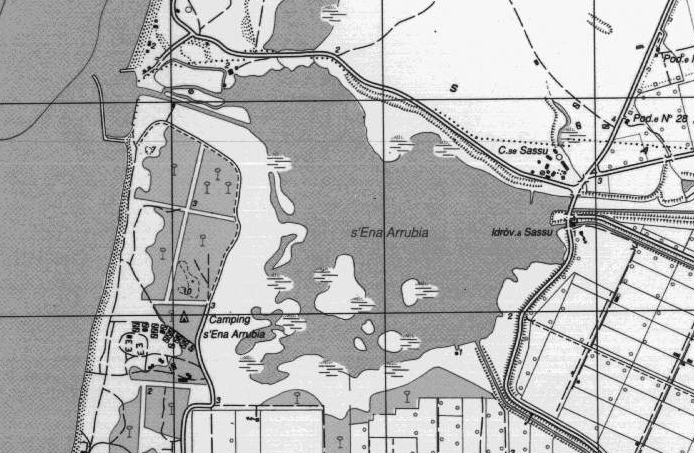

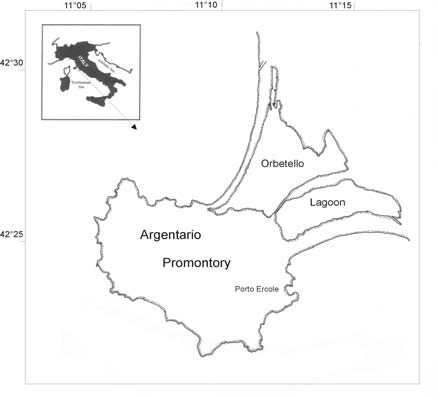

5.1 Lagoon of Orbetello, Tuscany ş Paola Gennaro, Mauro Lenzi and Salvatore

118

Porrello

6.

COASTAL SYSTEMS OF GENOA AND THE LIGURIAN COAST

123

6.1 Ligurian Coast (Gulf of Genoa) ş Paolo Povero, Nicoletta Ruggieri,

123

Cristina Misic, Michela Castellano, Paola Rivaro, Osvaldo Conio, Ezio

Derqui and Mauro Fabiano

6.2 Port of Genoa: Old Port, Multedo Oil Terminal and Voltri Container

128

Terminal ş Paolo Povero, Nicoletta Ruggieri, Cristina Misic, Michela

Castellano, Paola Rivaro, Osvaldo Conio, Ezio Derqui, Stefania Maggi and

Mauro Fabiano

i

Page

7. REFERENCES

136

APPENDICES

143

Appendix I

List of Participants and Authors contributing to this Report

143

Appendix II

Workshop Report

148

Appendix III Creation of a Southern European Lagoon Observational Network

150

Appendix IV A proposal of a Typology for Mediterranean transitional waters

152

Appendix V

List of acronyms

157

ii

Nutrient fluxes in transitional zones of the Italian coast

compiled and edited by

Gianmarco Giordani & Pierluigi Viaroli

Department of Environmental Sciences, University of Parma, Italy

Dennis P. Swaney

Boyce Thompson Institute for Plant Research

and Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Cornell University

Ithaca, NY, USA

Nicholas Murray & JosÚ Manuel Zaldivar Comenges

Institute for the Environment and Sustainability, Joint Research Centre, Ispra, Italy

and

Janet I. Marshall Crossland

LOICZ International Project Office

Texel, The Netherlands

LOICZ REPORTS & STUDIES NO. 28

Published in the Netherlands, 2005 by:

LOICZ International Project Office

Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research

P.O. Box 59

1790 AB Den Burg - Texel

The Netherlands

Email: loicz@nioz.nl

The Land-Ocean Interactions in the Coastal Zone Project is a Core Project of the International Geosphere-

Biosphere Programme: A Study Of Global Change (IGBP) and the International Human Dimensions Programme

on Global Environmental Change (IHDP), of the International Council of Scientific Unions (ICSU).

The LOICZ IPO is financially supported through the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO)

by: the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science (OCW); the National Institute for Coastal and Marine

Management of the Ministry of Transport, Public Works and Water Management (V&W RIKZ); the Netherlands

Ministry of Housing, Spatial Planning and the Environment (VROM), and the Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea

Research (NIOZ).

This report and allied workshops are contributions to the LOICZ biogeochemical budgeting and modeling core

project which started with global assessments under the name "United Nations Environment Programme project:

The Role of the Coastal Ocean in the Disturbed and Undisturbed Nutrient and Carbon Cycles (Project Number

GF 1100-99-07), financially supported by the Global Environment Facility (GEF) and implemented by IGBP-

LOICZ. This core project is being continued as work in progress into LOICZ II and the study presented has been

co-supported by the European Commission (Joint Research Centre, Ispra, Italy).

COPYRIGHT ę 2005, Land-Ocean Interactions in the Coastal Zone Core Project of the IGBP and the IHDP.

Reproduction of this publication for educational or other, non-commercial purposes is authorized

without prior permission from the copyright holder.

Reproduction for resale or other purposes is prohibited without the prior, written permission of

the copyright holder.

Citation:

G. Giordani, P. Viaroli, D.P. Swaney, C.N. Murray, J.M. ZaldÝvar and J.I. Marshall Crossland.

2005. Nutrient fluxes in transitional zones of the Italian coast. LOICZ Reports & Studies No. 28,

ii+157 pages, LOICZ, Texel, the Netherlands.

ISSN: 1383

4304

Cover:

The cover shows an image of Italy (GTOPO30 elevation map, courtesy Professor S.V. Smith),

with the budgeted estuaries indicated.

Disclaimer: The designations employed and the presentation of the material contained in this report do not

imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of LOICZ or the IGBP and the IHDP

concerning the legal status of any state, territory, city or area, or concerning the delimitations of

their frontiers or boundaries. This report contains the views expressed by the authors and may

not necessarily reflect the views of the IGBP and the IHDP.

_________________________________

The LOICZ Reports and Studies Series is published and distributed free of charge to scientists involved in global

change research in coastal areas.

1.

OVERVIEW OF WORKSHOP AND BUDGETS RESULTS

The key objectives of the Land-Ocean Interactions in the Coastal Zone (LOICZ) core project of the

International Biosphere-Geosphere Programme (IGBP) are to:

Ě gain a better understanding of the global cycles of the key nutrient elements carbon (C), nitrogen

(N) and phosphorus (P);

Ě understand how the coastal zone affects material fluxes through biogeochemical processes; and

Ě characterize the relationship of these fluxes to environmental change, including human intervention

(Pernetta and Milliman 1995).

To achieve these objectives, the LOICZ programme of activities has two major thrusts. The first is the

development of horizontal and, to a lesser extent, vertical material flux models and their dynamics

from continental basins through regional seas to continental oceanic margins, based on our

understanding of biogeochemical processes and data for coastal ecosystems and habitats and the human

dimension. The second is the scaling of the material flux models to evaluate coastal changes at spatial

scales to global levels and, eventually, across temporal scales.

It is recognized that there is a large amount of existing and recorded data and work in progress around

the world on coastal habitats at a variety of scales. LOICZ is developing the scientific networks to

integrate the expertise and information at these levels in order to deliver science knowledge that

addresses our regional and global goals.

LaguNet is an example of such a scientific observational network studying the fluxes of nutrients and

other contaminants from lagoon catchments to the near-coastal environment. The idea of developing a

network of Italian researchers involved in the study of lagoons and coastal transitional ecosystems was

developed during a workshop "Coastal and estuarine systems of the Mediterranean and Black Sea

regions: carbon, nitrogen and phosphorous fluxes" organized in Athens (2-5 February 2001) by LOICZ

(Land Ocean Interactions in Coastal Zones) with the support of UNEP and ELOISE. In the

proceedings of the workshop is included a first series of estimates on the fluxes of nitrogen and

phosphorus from selected transitional ecosystems of the Italian coast (Dupra et al. 2001) which

contributed to filling an information gap on information on the Mediterranean region.

LaguNet was inaugurated during the workshop "Nutrient fluxes in the transition zones along the Italian

Coast: evaluation of fluxes and derived ecosystem functions " held in Venice 14-15 April 2002, and

has the following objectives:

i.

Provide a forum for discussion and cooperation between researchers who are studying

biogeochemical processes in lagoons, wetlands and salt- marshes at sites along the Italian coast.

ii.

Evaluate available information and present understanding of the biogeochemistry of carbon,

nitrogen and phosphorous in transitional and coastal waters under the influence of catchment basins.

iii.

Discuss the feasibility of the application of the LOICZ Biogeochemical Model to such areas.

iv.

Promote an agreed common approach to studies of biogeochemical processes in these

transitional ecosystems that can provide support to management or policy applications.

Consider the feasibility of developing one or more projects either in Italy or in Europe (with

Mediterranean EU partners and eventually from Eastern Europe and North Africa).

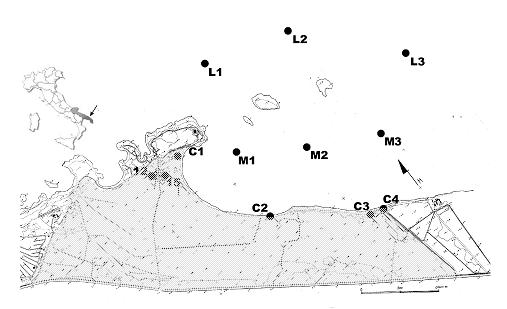

At present, LaguNet (www.dsa.unipr.it/lagunet ) comprises sites distributed around the entire Italian

peninsula and islands (Figure 1.1). Some, such as the Port of Genoa and the Marinello lakes, consist of

several independent systems (see Table 1.1). There are currently 22 ecosystems under investigation in

which the LOICZ Biogeochemical Model has been applied for a well-defined time period. In total, 94

flux estimations have been undertaken considering a wide range of systems and different time periods.

For some sites (for example, the S'Ena Arrubia Lagoon) it has been possible to compare the results

obtained with the model for different periods of time to obtain valuable information on the evolution of

the lagoon. Some results have already been published in LOICZ Reports and Studies Volume 19

1

(Dupra et al. 2001), while others are reported here. The preliminary results of the exercise have been

presented in various national and international conferences:

Ě Viaroli, P., G. Giordani, C.N. Murray and J.M. Zaldivar: LaguNet: Italian Lagoon

Observational Network. Presentation at the First Italian IGBP Conference: Mediterraneo e Italia

nel Cambiamento Globale: un ponte fra scienza e societÓ Paestum (Salerno) 14-16 November 2002

Ě Viaroli, P., G. Giordani, C.N. Murray, J.M. Zaldivar, S. Guerzoni, A. Bergamasco, C. Solidoro, S.

Rabitti, G. Castaldelli, M. Abbiati, M. Ponti, E. Manini, R. Danovaro, A. Basset, M. Azzaro, A.

Mazzola, T.L. Maugeri, S. Porrello, M. Lenzi, M. Innamorati, C. Melillo, M. Fabiano, P. Povero, P.

Magni, G. De Falco, F. Trebini and N. Sechi. Nutrient fluxes in the transition zones along the

Italian Coast: evaluation of fluxes and derived ecosystemic functions. Presentation at the III

National Congress of Marine Sciences, Bari, Italy, 27-30 November, 2002.

Ě Giordani, G., P. Viaroli, C.N. Murray, J.M. Zaldivar, M. Ponti, M. Abbiati, A. Barbanti, C.

Castellani,, A. Basset, I. Cappello, A. Pomes, L. Palmisano, S. Bencivelli, A. Bergamasco, M.

Azzaro, G. Carrada, G. Castaldelli, M. Mistri, A. E. Fano, A. Castelli, C. Lardicci, F. Maltagliati, G.

Ceccherelli, F. Trebini, B.M. Padedda, N. Sechi, S. Guerzoni, S. Rabitti, F. Collavini, L. Zaggia, R.

Zonta, R. Danovaro, A. Pusceddu, M. Fabiano, P. Povero, N. Ruggieri, S. Fonda Umani, P.

Giordani, M. Ravaioli, F. Frascari, P. Giordano, T.S. Hopkins, V. Hull, M. Falcucci, M. Innamorati,

S. Marsili-Libelli, G. Izzo, C. Creo, M. Lenzi, P. Magni, G. De Falco, E. Manini, F. Spagnoli, M.

Mauri, X.F. Niell, R. Pastres, G. Pernice, S. Porrello, P. Gennaro, V. Saggiomo, C. Solidoro, G.

Cossarini, M. Vazzoler, A. Mazzola, T.L. Maugeri, A. Bernstein, G. Cecconi, L. Montobbio.

Evaluation of fluxes and derived ecosystem functions in the transition zones along the Italian

Coast. Poster at the XIII National Congress of the Italian Society of Ecology (S.It.E.), Como 8-10

September 2003.

Ě Giordani, G., P. Viaroli, C.N. Murray, J.M. Zaldivar, M. Ponti, M. Abbiati, A. Barbanti, C.

Castellani,, A. Basset, I. Cappello, A. Pomes, L. Palmisano, S. Bencivelli, A. Bergamasco, M.

Azzaro, G. Carrada, G. Castaldelli, M. Mistri, A. E. Fano, A. Castelli, C. Lardicci, F. Maltagliati, G.

Ceccherelli, F. Trebini, B.M. Padedda, N. Sechi, S. Guerzoni, S. Rabitti, F. Collavini, L. Zaggia, R.

Zonta, R. Danovaro, A. Pusceddu, M. Fabiano, P. Povero, N. Ruggieri, S. Fonda Umani, P.

Giordani, M. Ravaioli, F. Frascari, P. Giordano, T.S. Hopkins, V. Hull, M. Falcucci, M. Innamorati,

S. Marsili-Libelli, G. Izzo, C. Creo, M. Lenzi, P. Magni, G. De Falco, E. Manini, F. Spagnoli, M.

Mauri, X.F. Niell, R. Pastres, G. Pernice, S. Porrello, P. Gennaro, V. Saggiomo, C. Solidoro, G.

Cossarini, M. Vazzoler, A. Mazzola, T.L. Maugeri, A. Bernstein, G. Cecconi and L. Montobbio.

LaguNet, the Italian lagoon observational network. Evaluation of fluxes and derived

ecosystem functions in the transition zones along the Italian Coast. Poster at the 17th Biennial

Conference of the Estuarine Research Federation (ERF). Estuaries on the Edge. Seattle, WA, USA,

September 14-18, 2003.

Ě Giordani, G., C.N. Murray, J.M. Zaldivar, P. Viaroli. LaguNet, the Italian lagoon observational

network. Evaluation of fluxes and derived ecosystem functions in the transition zones along the

Italian Coast. Presentation at the International Conference: Southern European Coastal Lagoons:

The Influence of River Basin-Coastal Zone interactions. Castello Estense (Ferrara, Italy), 10-12

November 2003.

Ě Viaroli P., The Italian network: LaguNet. Presentation at the national workshop: the Greek

lagoons in the framework of the European networks. Mytilini, Lesvos, Greece. March 20, 2004.

2

Figure 1.1 Map of Italy showing estuaries for which budgets are presented in this report.

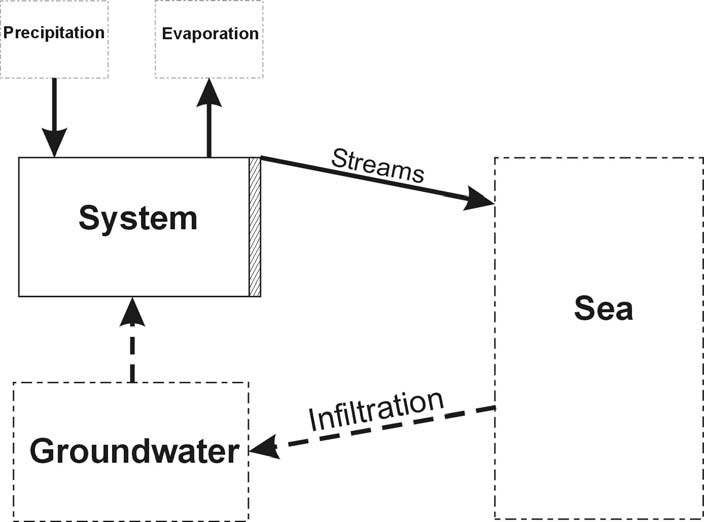

The common element in the site descriptions is the use of the LOICZ approach for biogeochemical

budget development, which allows for global comparisons and application of the typology approach.

The differences in the descriptive presentations reported here reflect the variability in richness of site

data, the complexity of sites and processes and the extent of detailed process understanding for the

sites. Support information for the various estuarine locations, describing the physical environmental

conditions and related forcing functions including history and potential anthropogenic pressure, is an

important part of the budgeting information for each site. These budgets, data and their wider

availability in electronic form (CD-ROM, LOICZ web-site) will provide opportunities for further

regional and global assessment, comparisons and potential use in evaluating patterns of coastal system

responses to human pressures. A LaguNet workshop organized by G. Carrada and A. Basset was held

17-19 June 2004 in Naples (Italy) to discuss the typology of coastal systems at national, southern

Europe and Mediterranean scales, (http://www.ecologia.ricerca.unile.it/TWTypology/). The final

document of the meeting is in Appendix IV.

The biogeochemical budget information for sites shown in Figure 1.1 is discussed individually in the

text that follows, and is reported as average daily rates for the period studied. To provide for an

overview and ease of comparison, the key data are presented in "annualized" form and non-

conservative fluxes are reported per unit area (Tables 1.1 and 1.2).

Due to the shape of the Italian peninsula, it has been possible to study systems that cover a wide range

of latitudes: from the Lagoon of Venice in the North (45.40░ N) to the Rada di Augusta in the South

(37.21░N) (Figure 1.1). Although the distances between these ecosystems are relatively modest

compared to other LOICZ studies that have been organized at continental scales, the network of sites

presented here represents a very wide range of characteristics and a very high density of data.

3

The exploitation and management of these systems are very varied: fish farming, oyster or mussel

farming, tourism, recreation and water sports or nature reserves are all represented. Many of the

ecosystems are in protected areas, others are subject to intense anthropogenic pressures, and still others

are exposed to only slight human impact and stress. Further the biological communities are very

diversified; in some systems the dominant primary producers are phytoplankton, whereas in others they

may be macroalgae or rooted phanerogams.

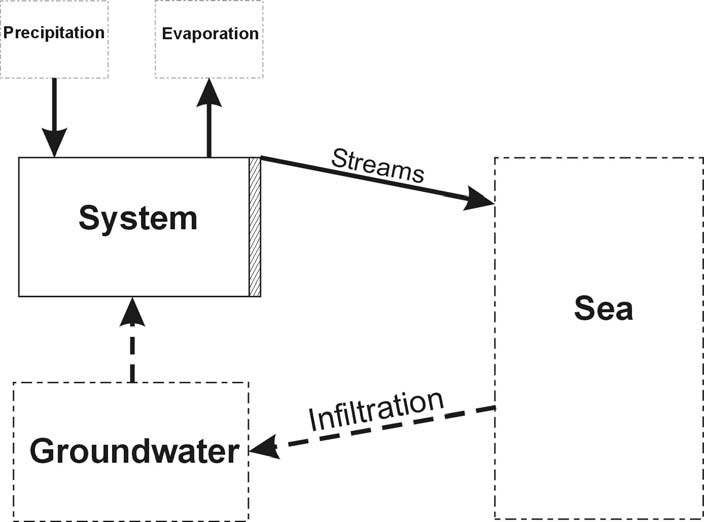

In the first applications of the LOICZ budgeting procedure to these systems, the simplest one-box, one-

layer model was generally applied. However, for some systems, it was necessary to apply more

complex versions of the procedure, such as the 2-box or 2-layer models. In the Old Port area of Genoa,

a mixed model was applied: the inner box of a 2-boxes model was separated in 2 layers. The budget of

dissolved organic phosphorus (DOP) and nitrogen (DON) was calculated for Sacca di Goro for 1992.

Most of the budgets were calculated using a dedicated MS Excel spreadsheet template

(http://www.dsa.unipr.it/lagunet/documenti/calcoliLOICZ.xls ) but an online tool for one-box one-

layer budgets, called LOICZ Calculator, was built and made available by M. Ponti and G. Giordani at

the web-site: http://www.ecology.unibo.it/LOICZ-Calculator/loicz_calculator.htm. This tool

represents yet another piece of software for LOICZ budgeting, to complement CABARET which was

built by L. David (http://data.ecology.su.se/MNODE/Methods/cabaret.htm ).

Most of the watersheds are subjected to intense agricultural exploitation; as a consequence the nutrient

loads are generally richer in DIN than DIP if we consider the theoretically balanced Redfield N:P ratio

(Figure 1.2). Higher loads were found for the Lagoon of Venice which is the largest LaguNet system.

The Sacca di Goro, which was investigated in the 1992 and 1997, shows a considerable decrease in

nutrient loads, partially due to the reduction of the Po di Goro input, a more efficient use of wastewater

treatment plants in the catchment and to the introduction of laws restricting the P concentrations in

detergents (Viaroli et al. in press). Of all the systems studied by LaguNet, the highest external loads of

dissolved inorganic phosphorus and nitrogen were estimated for the Pialassa Baiona Lagoon (290 and

6870 mmol m-2 y-1 respectively) (Figure 1.3), which receives large inputs from industrial wastewater

treatment plants plus many other sources around the city of Ravenna. The loads of S'Ena Arrubia are

rich in DIP even though this system is located in an agricultural area. The case of Torre Guaceto is

quite peculiar because the inputs are dominated by groundwater rich in DIN and poor in DIP. About

50% of the systems receive loads higher than 0.05 or 0.8 mol m-2 y-1 of DIP and DIN respectively,

indicating the heavy anthropic pressure to which they are subjected. Systems with the lowest nutrient

loads are the Stagnone di Marsala and the system of Capo Feto, which are located in areas with

minimal human activities. For all systems, DIP inputs directly from the atmosphere are considered

negligible; for S'Ena Arrubia, where a study on dry deposition was performed, such P input was

estimated at about 0.1% of the total DIP input. In contrast, DIN inputs from the atmosphere are

relevant, in particular in northern Italy where concentration of 100-300 mmol m-3 were measured along

the east coast and 50-60 mmol m-3 along the west coast. These high concentrations are probably

related to human activities which are more developed along the north-east coast of Italy. In southern

Italy, lower DIN concentrations were measured (Mosello 1993) but measuring stations were few and

not uniformly distributed. The DIN loads through precipitation are an important input for many

systems (Table 1.2): they are the main estimated DIN inputs for Valli di Comacchio, about 20 % for

the Lagoon of Venice, 5-10% for the Gulf of Genova and S'Ena Arrubia and 1-5 % for Sacca di Goro.

Sites range from very large ecosystems such as the Venice Lagoon (the area open to tidal expansion

and assessed as relevant for budgeting is 360 km2, the total area of the system is 550 km2) to extremely

small ones such as Marinello - Fondo Porto (0.013 km2), from deep coastal systems such as the Gulf of

Genoa (28 m) to very shallow ones such as Torre Guaceto or S'Ena Arrubia (0.40 m). Figure 1.4

illustrates the geomorphologic and hydrologic variability of the LaguNet systems. Large systems, as

the Lagoon of Venice, have relative low water residence time whilst small systems as the lakes of

Marinello, positioned in a dry area, have relative high . Most of the systems have surface area from 1

to 100 km2 (median value = 2.4 km2) and from 5 days to 1 year.

4

Among LaguNet sites, a relationship between DIP and DIP loads are observed (Figure 1.5). At low

loads, systems are more or less in balance or they act as a source of DIP (positive DIP) while at high

loads they act as sinks of DIP. The case of Pialassa Baiona is peculiar since even at the highest DIP

loads, the system shows a DIP close to zero. This can be due to the presence of heavy metals or other

toxic compound that inhibited P uptake and release. A trend similar to DIP input/DIP can be

observed also for DIN input/DIN (Figure 1.6).

The higher values (both positive and negative) of the estimated Net Ecosystem Metabolism, which

indicate that a system is highly heterotrophic or highly autotrophic, are estimated for systems

dominated by floating macroalgae such as Sacca di Goro and S'Ena Arrubia (-8 and +12 mol C m-2 y-1,

respectively) indicating that this kind of primary producer can be considered as a source of disturbance

within the system. As expected from Figure 1.5, since NEM is estimated from DIP and N/P ratio,

balanced or respiration dominated system prevail at low DIP load while production dominate at high

DIP load (Figure 1.7). No clear relationships exist among NEM and DIN loads (Figure 1.8).

The resulting (nfix-denit) is the difference between nitrogen fixation and denitrification in the system

(Figure 1.9). These 2 microbial processes are linked to the availability of nitrogen rather then to

production and respiration processes. In general, at high nitrogen loads, the LaguNet systems show a

dominance of denitrification over N fixation.

The principal component analysis (PCA) was applied to all the LaguNet sites, considering area, depth,

, annual DIP and DIN inputs and mean concentrations in the system, DIP, DIN, NEM and (nfix-

denit). The first four component explain the 76% of the system variance. The scattergram of the first 2

components (54% of the system variance) shows a separation of the most impacted lagoons from the

well preserved ones (Figure 1.10)

Comparing LaguNet budgets to the global budgets of the LOICZ database as of 2003, we can see

similar general trend (Figures 1.11-1.18). The median area of LaguNet sites is smaller than that of

global dataset (Figure 1.11). Median depth (Figure 1.12) and water residence time (Figure 1.13) of the

two distributions are roughly the same. The nutrient loads of LaguNet sites cover only the lower half of

the overall budget but follow the same trends (Figure 1.14). DIP and DIN distribution of the

LaguNet sites conform to the general global distribution with a dominance of negative values (Figures

1.15-1.16). As for the overall budgets, the LaguNet systems are mostly autotrophic with a dominance

of denitrification (Figures 1.17-1.18).

With this volume, we continue to increase the coverage of nutrient fluxes in much of the global coastal

zone. Some trends are emerging, such as the dominance of autotrophic systems and net-denitrifying

systems in the global coastal zone, though quantitative relationships with other variables seem to be

generally nonlinear and noisy. Other statistical approaches (principal components and cluster analysis)

may be more robust and have to be considered. In any case, extrapolating from individual budget sites

to the "global coastal zone" remains a challenge although the Italian sites appear to reproduce patterns

observed at the global scale

Input to national and European policy

Other than the application of LOICZ methodology for the purpose of studying the impact of climatic

change and human activities on fluxes of nutrients to coastal ecosystems, there is an increasing need of

policy-oriented scientific information.

Information on the impact of watershed processes on nearshore coastal environments is becoming

increasingly important for the protection of biodiversity and sustainability of terrestrial aquatic

ecosystems as well coastal systems under their influence. Such integrated systems require an approach

that closely links science and policy for a more efficient development and implementation of EU

Directives. Too often, available scientific information is not adequately assessed in the development of

5

policy, even if it is well prepared, or alternatively, the information is not presented in a form that can be

easily used for policy development. One role of networks of environmental researchers, such as

LaguNet, is to contribute to bridging the gap between science and policy. Such networks bring together

individual research groups working on similar or common themes, using benchmarked methodologies,

allowing comparison of processes over a wide range of ecosystems (under varying pressures and

impacts), and can thus identify information gaps and build a basis in solid science for the development

and implementation of Directives and input to national or EU policy discussions. We expect that

LaguNet will also provide a strong basis for cooperation with other national or European networks.

List of reference persons for groups collaborating in LaguNet

P. Viaroli, G. Giordani, Dipartimento di Scienze Ambientali, UniversitÓ di Parma (Coordination and

Secretariat). N. Murray, J.M. Zaldivar, JRC, European Commission, Ispra (Italy). M. Ponti, M.

Abbiati, Centro Interdipartimentale di Ricerca per le Scienze Ambientali in Ravenna, UniversitÓ di

Bologna. A. Barbanti, C. Castellani, S. Rabitti, Thetis S.p.A., Venezia. A. Bernstein, G. Cecconi, L.

Montobbio, Consorzio Venezia Nuova, Venezia. A. Basset, I. Cappello, A. Pomes, L. Palmisano, Dip.

di Scienze e Tecnologie Biologiche e Ambientali, UniversitÓ di Lecce. S. Bencivelli, Amministrazione

Provinciale di Ferrara. A .Bergamasco, M. Azzaro, CNR-Istituto Talassografico, Messina. G.

Carrada, Dipartimento di Zoologia, UniversitÓ Federico II, Napoli. G. Castaldelli, M. Mistri, A.E.

Fano Dipartimento di Biologia, UniversitÓ di Ferrara. A. Castelli, C. Lardicci, F. Maltagliati,

Dipartimento di Scienze dell'Uomo e dell'Ambiente, UniversitÓ di Pisa. G. Ceccherelli, F. Trebini,

B.M. Padedda, N. Sechi, Dipartimento di Botanica ed Ecologia Vegetale, UniversitÓ di Sassari. S.

Guerzoni, F. Collavini, L. Zaggia, R. Zonta, I. Scroccaro, G. Umgiesser, CNR-ISMAR, Venezia. R.

Danovaro, A. Pusceddu, Dipartimento di Scienze del Mare, UniversitÓ Politecnica delle Marche. M.

Fabiano, P. Povero, N. Ruggieri, DIPTERIS, UniversitÓ di Genova. S. Fonda Umani, Laboratorio di

Biologia del Mare, UniversitÓ di Trieste. P. Giordani, M. Ravaioli, F. Frascari, P. Giordano, CNR-

ISMAR, Sezione di Geologia Marina, Bologna. T.S. Hopkins, CNR-IAMC, Napoli. V. Hull, M.

Falcucci, Laboratorio Centrale di Idrobiologia, Roma. M. Innamorati, Dipartimento di Biologia

Vegetale, UniversitÓ di Firenze. S. Marsili-Libelli, Dipartimento di Sistemi e Informatica, UniversitÓ

di Firenze. G. Izzo, C. Creo, ENEA, Roma. M. Lenzi, LeaLab, Orbetello. P. Magni, G. De Falco,

IMC, Oristano. E. Manini, F. Spagnoli, CNR-ISMAR, Lesina. M. Mauri, Dipartimento di Biologia

Animale, UniversitÓ di Modena e Reggio. X.F. Niell, Universidad de Malaga (Spain). R. Pastres,

Dipartimento di Chimica Fisica, UniversitÓ di Venezia. G. Pernice, CNR-IAMC, Mazara del Vallo. S.

Porrello, P. Gennaro, ICRAM, Roma. V. Saggiomo, Stazione Zoologica A. Dohrn, Napoli. C.

Solidoro, G. Cossarini, OGS, Trieste. M. Vazzoler, Arpa Regione Veneto. G. Matteucci, CSA

Ricerche, Centro Studi Ambientali, Rimini.

Acknowledgments

This activity was performed with the support of the Joint Research Centre of the European

Commission (Ispra, Italy), the UE Project DITTY (contact n░ :EVK3-CT-2002-00084), Thetis S.p.A.

(Venice, Italy) and the Provincia di Ferrara ş Settore Ambiente (Italy). We are especially indebted to

A. Barbanti, S. Bencivelli and G.C. Carrada for the organisation of the LaguNet workshops in Venice,

Ferrara and Naples.

6

Table 1.1. Budgeted LaguNet sites for Italy - locations, system dimensions and water exchange

times.

Exchange

System Name/

Lat.

Long. Area Depth

Period

No. of

No. of

Province

time

Description

(+░N)

(+░E)

(km2)

(m)

studied

layers

boxes

(days)

1999,

Lagoon of Venice

Venezia

45.40

12.40

360

1.5

1

1 and 2

10-14

2001

1992

2

Sacca di Goro

Ferrara

44.80

12.29

26

1.5

1 1

1997

7

Ferrara-

Valli di Comacchio

44.60 12.17 114.5 0.8

1997

1

1

247

Ravenna

Valle Smarlacca

Ravenna

44.58

12.23

1.9

0.8

1997

1

1

434

Pialassa Baiona

Ravenna

44.50

12.25

9.9

0.9

2000

1

1

3

Lagoon of Lesina

Foggia

41.88

15.45

51.5

0.8

1998-99

1

1

100

Lagoon of Varano

Foggia

41.88

15.75

64.0

4.0

1997-99

1

1

1032

Torre Guaceto

Brindisi 40.71

17.80 1.19 0.3 2001-02 1

1

26

marshland

Torre Guaceto Bay

Brindisi

40.71

17.80

1.44

4

2001-03

1

1

na

Acquatina Lake

Lecce

40.44

18.24

0.45

1.0

1995

1

1

4

Lake Alimini Grande Lecce

40.20

18.45

1.4

1.5

1998-99

1

1

232

Rada di Augusta

Siracusa

37.21

15.23

23.5

14.9

1998-99

1

1

169

Capo Feto

Trapani

37.68

12.48

1.4

1.75

2001

1

1

105

Stagnone di Marsala

Trapani

37.83

12.45

21.35

0.95

1996

1

1

63

149*

Ganzirri Lake

Messina

38.26

15.62

0.34

2.5

1998-99

1

2

(44-15)

Marinello Lakes-

Messina 38.13

15.05

0.017 1.6 1997-98 1

1

156

Verde

Marinello Lakes -

Messina 38.13

15.05

0.013 1.5 1997-98 1

1

95

Fondo Porto

Orbetello Lagoon

Grosseto

42.44

11.23

25.25

1.0

1999-00

1

1

8

Ligurian Coast

summer

Genova 44.40 8.93 52 28.0

2 1 16

(Gulf of Genoa)

1996

Port of Genoa - Old

summer

11*

Genova 44.40 8.90 2.7 13.2

2/1 2

Port

2002

(20-7)

Port of Genoa

summer

- Multedo oil

Genova 44.40 8.90 1.4 15.0

1 1 60

2002

terminal

Port of Genoa ş

summer

Voltri Container

Genova 44.40 8.90 2.1 15.0

1 1 99

2002

Terminal

1994,

8

S'Ena Arrubia

Oristano

39.83

8.57

1.2

0.40

1995,

1 1 20

2001-02

4

* for the 2 boxes budgets, of the whole system is indicated with the values of the inner and outer boxes in brackets.

na= not available

7

Table 1.2 Budgeted LaguNet sites for Italy - loads and estimated (nfix-denit) and (p-r). Torre

Guaceto marine area budget is not considered due the uncertainty in the VX estimation (see the

relevant budget).

System Name/

DIP

DIN DIN

(nfix -

V

P

DIP DIN

(p-r)

Description

R

VX

load* load* load#

denit)

106 m3 yr-1 mmol

m-2 yr-1

Lagoon of Venice

-1216 19248 11.5 741 202 9.2 -511 -657 -986

1999

Lagoon of Venice

-1136 12511 12.4 751 202 -3.9 -694 -628 438

2001

Sacca di Goro

-726 6467 42.1

5517

56 3.3

-7230

-7099

1234

1992

Sacca di GoroSG

-361 1717 20.1

1227

58 24.6

1774 916 -8249

1997

Valle di ComacchioVC 18 117 0 0 59 0.4 -72 -80 -40

Valle SmarlaccaVS -2 0VS 4.0

182

58

-3.6

-226

-146 402

-3405 ş

354-

Pialassa Baiona

-472

667

291.3 6802

66

-3.3

-3459 -3343$ 1117$

Lagoon of Lesina

-45

105

43.3

954

naú -43.2 -911 -212 4636

Lagoon of Varano

-24

67

2.2

76

naú -2.1 -72 -37 234

Torre Guaceto

-5

0

0.1

3784

naú 0.8 -3134

-3146 -88

Acquatina Lake

-15

44

8.9

2300

naú -7.3 -651 -526 803

Alimini GrandeAG -2 7

0.2

242

naú -0.03 -11 -11

0

Rada di Augusta

-17

741

4.0

914

naú -0.4 -827 -818 44

Capo Feto marshland

0.04

8

0.3

8

naú 8.6 33 -106 -913

Stagnone di Marsala

7

110

0.0

0

naú 0.04 -0.5 -1.1 -18

Ganzirri Lake

-0.5

1.5

3.4

109

naú -3.0 -61 -13.2 319

Marinello-Verde -0.02

0.04

5.0

84

naú -3.9 -47 14.6 405

Marinello-Fondo

-0.01 0.07 0.6 10 naú -0.5 16 25.6 58

Porto

Orbetello Lagoon

-179

995

12.4

576

45

-1.4

1239

1347

1022

Ligurian Coast

198

ž 15968

ž 41.7 595 18 -48.9 -825 -44 5183

(Gulf of Genoa)

Port of Genoa ş

-27 1203

107.3

6558

150

-83

-6227

-4897

8813

Old Port

Port of Genoa ş

-4 124

8.1

130

149

87

145

-1256

-9271

Multedo oil terminal

Port of Genoa -

Voltri Terminal

-4 113 0 0

149

-1.2

-251

-237

110

Container

S'Ena Arrubia SEA

-9 14

159.1

1048

32

-111

-1034

767

11863

1994

S'Ena Arrubia SEA

-2 7

91.9

215

16

-45

-176

548

4818

1995

S'Ena Arrubia

-8 45

92.5

695

14

-34

-329

212

3599

2000-01

* = sum of loads from runoff (VQ), direct sources (Vo), groundwater (VG) if present and known,

expressed per unit area of the system (not the drainage basin)

# DIN loads from precipitation (Vp) if present and known, expressed per unit area of the system (not the

drainage basin)

naú data not available; DINP loads are assumed to be zero.

8

$ lower value obtained using Redfield ratio C:P; Higher value using macroalgal C:P from Atkinson and

Smith,1983

ž Vdeep is reported for VX; Vsurf-Vdeep for VR

SG see Viaroli et al. 2001b or

http://data.ecology.su.se/mnode/Europe/Med_Aegean_BlackSea/Italy/SaccadiGoro/saccadigorobud.htm

VC see Viaroli and Giordani 2001 or

http://data.ecology.su.se/mnode/Europe/Med_Aegean_BlackSea/Italy/comacchio/comacchiobud.htm

VS see Giordani and Viaroli 2001 or

http://data.ecology.su.se/mnode/Europe/Med_Aegean_BlackSea/Italy/smarlacca/smarlaccabud.htm

AG see Vadrucci et al. 2001 or

http://data.ecology.su.se/mnode/Europe/Med_Aegean_BlackSea/Italy/Alimini/aliminibud.htm

SEA see Giordani et al. 2001 or

http://data.ecology.su.se/mnode/Europe/Med_Aegean_BlackSea/Italy/arrubia/arrubiabud.htm

400

)

Venice

-1

300

l y

o

m6

1

0 200

t

(

u

p

i

n

N

Sacca

100

DI

di Goro

DIN = 16 DIP

0

0

1

2

3

4

5

DIP input (106 mol y-1)

Figure 1.2. DIP and DIN loads to the LaguNet systems.

9

8

Piallassa Baiona

)-1 6

y2

ol m

m

( 4

Torre Guaceto

DIN = 16 DIP

input

I

N

D 2

S'Ena Arrubia

0

0.0

0.1

0.2

0.3

DIP input (mol m2 y-1)

Figure 1.3. DIP and DIN loads to the LaguNet systems per square meter of lagoon.

10000

1000

ays)

100

d

(

10

1

0.0

0.1

1.0

10.0

100.0

1000.0

Surface area (Km2)

Figure 1.4. Surface area and estimated mean water residence time (log scales) among LaguNet

sites.

10

0.10

0.05

)

Piallassa Baiona

-1 y

2

0.00

l

m

o

0.00

0.05

0.10

0.15

0.20

0.25

0.30

m

(

P -0.05

DI

-0.10

-0.15

DIP input (mol m2 y-1)

Figure 1.5. Non-conservative behaviour of DIP in relation to DIP loads among the LaguNet sites.

3

2

1

0

)-1

y -1 0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

2

l

m -2

o

m

( -3

N

DI -4

-5

-6

-7

-8

DIN input (mol m2 y-1)

Figure 1.6. Non-conservative behaviour of DIN in relation to DIN loads.

11

15

10

)-1

5

y2

l

m

o

0

m

(

0.00

0.05

0.10

0.15

0.20

0.25

0.30

M

NE

-5

-10

-15

DIP input (mol m2 y-1)

Figure 1.7. Relationship between NEM and DIP loads in the LaguNet sites. NEM is the

difference between production and respiration processes in the system.

15

10

)-1

5

y2

l

m

o

0

m

(

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

M

NE

-5

-10

-15

DIN input (mol m2 y-1)

Figure 1.8. Relationship between NEM and DIN loads in the LaguNet sites. NEM is the

difference between production and respiration processes in the system..

12

2

1

0

)-1

y2 -1 0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

l

m

o -2

-3

i

t

r

) (m

e

n -4

x

-

d

-5

fi

(n -6

-7

-8

DIN input (mol m2 y-1)

Figure 1.9. Relationship between (nfix-denit) and DIN loads in the LaguNet sites. (nfix-denit) is

the difference between nitrogen fixation and denitrification in the system.

3

S'Ena Arrubia

2

Old Port

Gulf of

of Genova

Genova

1

Lesina

t

2

n

Venice

e

Varano

0

pon

Piallassa

m

o

Baiona

Orbetello

C

Acquatina

Torre

-1

Sacca di

Guaceto

Alimini

Goro 92

Multedo Oil

-2

Sacca di

Terminal

Goro 97

-3

-4

-3

-2

-1

0

1

2

Component 1

Figure 1.10. Ordination of the LaguNet sites as shown by the Principal Component Analysis of

morphometric data (area, depth, water residence time), DIP and DIN inputs and concentration

in the system, DIP, DIN, NEM and (nfix-denit). Component 1 (33%) correlates with (nfix-denit)

(r = +0.96), DIN (r = +0.92) and DIN input (r = -0.90); Component 2 (20%) correlates with NEM (r =

+0.91), DIP (r = -0.89) and DINsys (r = -0.66). The other 2 components (not indicated) (14 and 10 %)

correlate respectively with DIPsys (r = -0.70) and area (r = -0.88).

13

Figure 1.11. Comparison between the areas of LOICZ (blue) and LaguNet (red) sites as of 2003.

The areas of LaguNet sites span 4 orders of magnitude and the median area is smaller than that of

global budget dataset.

Figure 1.12. Comparison between the depth of LOICZ (blue) and LaguNet (red) sites as of 2003.

The depths of LaguNet sites span 3 orders of magnitude and the median area value is similar to that of

global budget dataset.

14

Figure 1.13. Comparison between water residence time of LOICZ (blue) and LaguNet (red) sites

as of 2003. Residence time distribution of the LaguNet sites spans over three orders of magnitude and

is centred on roughly the same median value as the overall distribution.

Figure 1.14. Comparison between nutrient loads of LOICZ (blue/green) and LaguNet (red) sites

as of 2003. Nutrient loads (unscaled) span over 3+ orders of magnitude. Overall budgets show a

bimodal distribution for both DIN and DIP LaguNet sites follow these general patterns even with low

values related to the smaller catchment areas.

15

Figure 1.15. Comparison between DIP of LOICZ (blue) and LaguNet (red) sites as of 2003.

Both distributions are unimodal and skewed left on a linear scale (negative values). Most LaguNet

sites fall in the same category as the global budget dataset.

Figure 1.16. Comparison between DIN of LOICZ (blue) and LaguNet (red) sites as of 2003.

Both distributions are unimodal and skewed left on a linear scale (negative values). Most LaguNet

sites fall in the same category as the global budget dataset.

16

Figure 1.17. Comparison between (p-r) of LOICZ (blue) and LaguNet (red) sites as of 2003. More

sites are autotrophic than heterotrophic. The distribution of the Italian sites is similar to the general

global distribution. Extreme values (beyond ▒ 104) are questionable.

Figure 1.18. Comparison between (nfix-denit) of LOICZ (blue) and LaguNet (red) sites as of

2003. More sites are denitrifiers. The distribution of the Italian sites is similar to the global

distribution pattern. Extreme values (beyond ▒ 5000) are questionable.

17

2

NORTH-EASTERN ITALIAN COASTAL SYSTEMS

2.1 Lagoon

of

Venice

Gianpiero Cossarini1, Chiara Castellani2, Andrea Barbanti2, Alberto Giulio Bernstein3, Giovanni

Cecconi3, Flaviano Collavini4, Stefano Guerzoni4, Laura Montobbio3, Roberto Pastres5, Sandro

Rabitti2, Giorgio Socal4, Cosimo Solidoro1, Marina Vazzoler6 and Luca Zaggia4

1Istituto Nazionale di Oceanografia e di Geofisica Sperimentale, Trieste;

2Thetis S.p.A., Venezia;

3Consorzio Venezia Nuova;

4Istituto di Scienze Marine, Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche, Venezia;

5UniversitÓ di Venezia;

6ARPAV - Agenzia Regionale per la Prevenzione e Protezione Ambientale del Veneto

Study area description

The Lagoon of Venice is the largest lagoon in Italy and one of the largest in Europe. It is located in the

northern part of the Adriatic Sea (45.2░N - 45.6░N 12.2 - 12.6░E). Three narrow inlets connect the

Lagoon of Venice to the Adriatic Sea, subdividing the lagoon into three sub-basins divided by two

watersheds, along which the intensity of the tidal currents is low. Part of the lagoon is devoted to

aquaculture and closed to water exchanges; the surface open to tidal exchange and assessed as relevant

for LOICZ computation (estimated from CVN 1990 bathymetry), is 360 km2, with a volume of 0.540

km3 and an average depth of 1.5 m.

Draina

Drain ge basin

Venice

c Lagoon

P.Marghera

Margher

Venice

Venic

The 3 se

The 3 a

se inl

i ets

et

Adriati

t c se

s a

Figure 2.1. The Lagoon of Venice and its drainage basin (Source: CVN).

18

The drainage basin is densely populated and carries into the lagoon both industrial and agricultural

wastewaters. The loads of nitrogen and phosphorus discharged into the lagoon by the tributaries were

assessed during the DRAIN project (DeteRmination of pollutAnt INputs from the drainage basin;

MAV-CVN 2001), in which the main tributaries were monitored for almost two years (1998 - 2000).

The largest fraction of these loads of nitrogen and phosphorus is discharged into the northern sub-

basin. Other relevant nutrient sources come from the industrial area of Porto Marghera (MAV-SAMA

2000-2002), from a civil wastewater treatment plant located close to the lagoon (ASPIV 2000; VESTA

2002) and from atmospheric deposition, which was investigated within the "2023 project" (MAV-CVN

2000a).

In the last few decades several projects have studied the lagoon environment. Data dealing with the

concentrations of dissolved nitrogen and phosphorus in the lagoon were systematically collected by

MAV-CVN (MELa1 Project, Monitoraggio Ecosistema Lagunare). Analysis of results shows that the

lagoon is a complex system, exhibiting spatial and temporal variability of dissolved nutrients,

chlorophyll a, dissolved oxygen and turbidity (MAV-CVN 2002a, MAV-CVN 2002b). Dissolved

nitrogen and phosphorus are higher in the northern sub-basin than in other sub-basins, while within

each basin concentrations are inversely correlated with salinity, suggesting the importance of nutrient

loads from freshwater sources.

The LOICZ budgeting approach was applied to the datasets presented in Table 2.1. These data allowed

us to estimate annual budgets of salt and nutrients for the years 1999 and 2001, which were computed

under the standard 1-box, steady-state hypothesis (Gordon et al. 1996). We also show and briefly

discuss the results of a seasonal analysis calculated for the year 1999, and of a steady-state analysis of

the 2001 annual budget which was based on the assumption that the lagoon could be divided into two

homogeneous boxes.

Single box analysis: 1999 and 2001 annual budgets

Water and salt budget

In 1999, river discharges (VQ) and direct atmospheric precipitation (VP) accounted for about 70% and

20% of the freshwater input (Table 2.2). The discharges from sewage treatment plants (VO) accounted

for the remaining 10%. The evaporation volume, VE, estimated according to Hargreaves' equation

(Hargreaves 1975) was about 7% greater than direct precipitation. As a result of the water balance, the

residual flow, VR, was -3.33x106 m3 d-1. The exchange flow, Vx, computed on the values of salinity of

system and sea and residual flow, was 52.74x106 m3 d-1.

Lacking more recent data, fluvial and atmospheric input for 2001 were considered to be as for 1999,

since precipitation into the lagoon during the two years was comparable, at least for the model aims

and on annual basis. For 2001, VR = ş3.11x106 m3 d-1 and VX = 34.28x106 m3 d-1, suggesting a change

with respect to 1999 values: VR increased 7% while VX decreased ~ 35%.

Residence time estimates using LOICZ methodology were 10 days for 1999 and 14 days for 2001.

These values are consistent with estimates of the residence time obtained by hydrodynamic model

simulations previously performed for the Lagoon of Venice (MAV-CVN 1998). LOICZ results are

within the range of variation of the model-simulated residence time of the lagoon, which exhibits

strong variability depending on the spatial heterogeneity of the system and tidal conditions. The net

exchange flow VX accounts about for 9-14% of the average daily volume of water flowing into the

lagoon from the sea through the three inlets (385x106 m3 d-1) (MAV-CVN 2000b). However, any

consideration of the VX and values must take into account their high sensitivity to the average salinity

values attributed to the lagoon and to the sea.

Results of the water and salt budget for the years 1999 and 2001 are summarized in Table 2.2 and

Figure 2.3.

19

Table 2.1. Data used in budget calculations for the Lagoon of Venice.

Frequency of

Year of

Type of data

Spatial resolution

sampling or

Sources

budget

estimation

1999-

V

2001

Q, DIPQ, DINQ

Main inflowing rivers

Monthly 1999 MAV-CVN 2001

Monthly from

1999-

V

August 1998 to MAV-CVN 2000a

2001

P, DIPP, DINP

4 stations in the lagoon

July 1999

Monthly 1999 ASPIV 2000

Campalto sewage treatment plant;

1999 VO, DIPO, DINO

Annual, 1999- MAV-SAMA

P. Marghera industrial discharge

2000

2000

VESTA 2002

Campalto sewage treatment plant;

Monthly 2001

2001 VO, DIPO, DINO

MAV-SAMA

P. Marghera industrial discharge

Monthly 2000 2002

Monthly from

26 stations located in the central January to July MAV-CVN 1999

part of the lagoon

1999

10 stations located near inland of

Sal

1999

sys,

Venice and urban centres of Lido

MAV-SAMA

DIPsys,DINsys

Monthly 1999

and Chioggia, and in southern sub-

2001

basin

7 stations located in northern sub- Monthly 1999 IBM-CNR

basin

Sal

MAV-CVN

2001

sys, DIPsys,

28 stations over the whole lagoon

Monthly 2001

DINsys

2002a,b

Interreg II Project

Sal

(IBM-CNR) and

1999

sea, DIPsea,

Transects along Adriatic coast

Monthly 2000

DINsea

ARPAV coastal

data

Interreg II Project

Sal

(IBM-CNR) and

2001

sea, DIPsea,

Transects along Adriatic coast

Monthly 2001

DINsea

ARPAV coastal

data

Table 2.2. Summary of salt and water budget for the 1-box model for the Lagoon of Venice

* = values estimated from the 1999 data

Year VQ

VO

VP

VE

Salsys Salsea VR

Vx

r

103 m3 d-1 103 m3 d-1 103 m3 d-1 103 m3 d-1 psu

psu

103 m3 d-1 103 m3 d-1 days

1999

2980.8 407.8 846.1 903.5 30.97

32.99

-3,331 52735 10

2001

2980.8*

407.8* 655.5 903.7 30.16

33.03

-3,113 34276 14

20

Budgets of non-conservative materials

The main sources of N and P were the discharges from the rivers, which in 1999 accounted for 67%

and 50% of the total annual inputs respectively (Table 2.4). Atmospheric precipitation was also

important, accounting for 27% and 21% of DIP and DIN inputs respectively. Because recent data are

lacking on inputs from the rivers and from atmospheric deposition, 1999 estimates are also used in the

annual budget for 2001. Inputs from the direct discharges, which were independently estimated for the

years 1999 and 2001, collectively accounted for about 23% and 11% of the total DIP and DIN inputs

for 1999 and 29% and 12% for 2001.

Table 2.3. DIP concentrations in the inflowing rivers, the Lagoon of Venice and the adjacent

Adriatic Sea.

*data obtained from VPDIPP of 1999 and VP 2001

Year DIPQ

DIPP

DIPO

DIPsys

DIPsea

DIPR

mmol m-3

mmol m-3

mmol m-3

mmol m-3

mmol m-3

mmol m-3

1999

1.92 3.56 6.45 0.45 0.08 0.27

2001

1.92 4.59* 8.64 0.38 0.16 0.27

Table 2.4. DIP budget for the Lagoon of Venice.

Year VQ DIPQ

VP DIPP

VO DIPO

VR DIPR

VxDIPx

DIP

DIP

mol d-1

mol d-1

mol d-1

mol d-1

mol d-1

mol d-1

Ámol m-2 d-1

1999 5723

3012 2630

-899

-19512 9046 25

2001 5723

3009 3523

-841

-7541 -3873 -11

The results of the budget calculations for DIP and DIN, presented in Tables 2.3-2.6 and Figures 2.4 and

2.5 show that VRDIPR and VRDINR obtained for the years 1999 and 2001 are of the same order of

magnitude. However, in 1999, the fluxes of DIP and DIN due to the mixing process (VX), which is the

most significant term, were in both cases higher than those calculated for the year 2001. The

difference is mainly due to the fact that in 1999 the DIP gradient between the system and the sea was

almost twice as high as that in 2001, while DIN was almost 50% higher in 1999 than in 2001. Average

values of the DIP gradient between system and sea were 0.37 mmol m-3 for 1999 and 0.22 mmol m-3

for 2001, while the DIN gradients were 6.49 mmol m-3 in 1999 and 5.44 mmol m-3 in 2001.

As a result of the balance between input and output flows of DIP, the lagoon mobilized 9046 mol d-1 in

1999 but took up 3873 mol d-1 in 2001. DIN estimates for the two years have the same sign, with a

higher consumption during 2001 than during 1999.

Table 2.5. DIN concentrations in the inflowing rivers, the Lagoon of Venice and the adjacent

Adriatic Sea.

*data obtained from VPDINP of 1999 and VP 2001

Year DINQ

DINP

DINO

DINsys

DINsea

DINR

mmol m-3

mmol m-3

mmol m-3

mmol m-3

mmol m-3

mmol m-3

1999

209.95 235.36 258.00 28.39 21.90 25.15

2001

209.95 303.80*

281.48 23.90 18.36 21.13

21

Table 2.6. DIN budget for the Lagoon of Venice.

Year VQ DINQ

VP DINP

VO DINO

VR DINR

VxDINx

DIN

DIN

mol d-1

mol d-1

mol d-1

mol d-1

mol d-1

mol d-1

mmol m-2 d-1

1999 625819 199138 105212 -83775 -342250 -504144 -1.40

2001 625819 199141 114788 -65778 -189889 -684081 -1.90

Stoichiometric calculations of aspects of net system metabolism

The non-conservative fluxes expressed as daily rates per unit area are summarized in Table 2.7. The

system was heterotrophic in 1999 and slightly autotrophic in 2001 as the NEM was -2.7 mmol C m-2 d-1

in 1999 and +1.2 mmol C m-2 d-1 in 2001. The values of (nfix-denit), which represents the balance of

the fixation and the denitrification processes of the two years, are in good agreement. In fact, the

estimation for 2001 was just 5% less than for 1999.

In Figure 2.2 the values of NEM (p-r) of the two annual budget calculations for the Lagoon of Venice

(red bars) are compared with the results from other northern Adriatic lagoons (black medium bars) and

some Mediterranean sites (thin grey bars) (Dupra et al. 2001). The NEM values for the Lagoon of

Venice are rather small relative to other LOICZ sites, implying a state of near-balance between

autotrophic and heterotrophic processes.

Table 2.7. Results of stoichiometric calculations for Lagoon of Venice.

Year NEM

(nfix-denit)

mmol m-2 d-1 mmol m-2 d-1

1999 -2.7

-1.80

2001 1.2

-1.72

20

15

10

5

0

/d

2

-5

-10

-15

-20

-25

mmol/m

Gulf of Lione

S'Ena Arrubia

Sacca of Goro

N-E Aegean Sea

Dnieper Estuary

o

macchio Valley

C

Smarlacca Valley

Inner Thermaikos G.

Malii Adzalik Estuar

Dnieper Bug Estuary

Alimini Grande Lake

Venice lagoon 1999

Venice lagoon 2001

Donuslav River Estua

Moulay Busselham L.

Figure 2.2. Comparison of NEM calculations between Lagoon of Venice and other Adriatic and

Mediterranean LOICZ sites.

22

Single box analysis: 1999 seasonal budget

Salt and water budget

Due to the high monthly variability of data for freshwater flows, lagoon and sea salinity, monthly data

were aggregated in order to obtain seasonal estimations of the residual and mixing flow and of the

residence time.

The results are summarized in Table 2.8, which shows that in 1999 seasonal variability of advective

and mixing fluxes was still quite high. As a consequence, the residence time ranged from 4-5 days in

the spring and autumn to 16-17 days during winter and summer. This can be explained by the higher

VQ and VP fluxes in spring and autumn. However, this pattern can be influenced by the salinity

difference between sea and lagoon, which in autumn and spring was slightly lower than 1 psu, the

minimum suggested value for a good estimation of Vx and .

Table 2.8. Seasonal salt and water budgets for the Lagoon of Venice in 1999.

VQ

VO

VP

VE

Sal sys Sal sea VR

Vx

r

103 m3 d-1 103 m3 d-1 103 m3 d-1 103 m3 d-1 psu

psu

103 m3 d-1 103 m3 d-1 d

Jan-Mar

2542.5 405.9 371.0 437.2 31.64

34.78

-2882 30481 16

Apr-Jun 3002.7 411.8 1039.0 1401.2 29.71 30.49 -3052 117776 4

Jul-Sep 2448.2 404.1 632.7 1350.1 31.48

33.82

-2135 29790 17

Oct-Dec 3574.7 409.4 1341.8 425.6 31.77 32.87 -4900 143971 4

Budgets of non-conservative materials and stoichiometric calculations

The DIP input was higher during summer than in the other seasons, while the advection and mixing

fluxes of DIP with the Adriatic Sea were both at the lowest levels (Table 2.10). This indicates that the

lagoon has a net uptake of DIP only in summer when the net ecosystem metabolism, NEM, was

positive (autotrophy) (see Table 2.13). During all the other seasons the system act as a source of DIP

as DIP was positive. The system was highly heterotrophic during spring and autumn when NEM was

-12.9 and -21.6 mmol d-1 m-2 respectively.

Table 2.9. DIP concentrations in the rivers, the Lagoon of Venice and the adjacent Adriatic Sea.

DIPQ

DIPP

DIPO

DIPsys

DIPsea

DIPR

mmol m-3

mmol m-3

mmol m-3

mmol m-3

mmol m-3

mmol m-3

Jan-Mar

1.46 8.33 6.67 0.41 0.06 0.24

Apr-Jun

1.82 3.16 6.13 0.55 0.09 0.32

Jul-Sep

2.64 6.16 6.85 0.29 0.05 0.17

Oct-Dec

1.88 1.16 6.13 0.69 0.12 0.41

Table 2.10. DIP budget for the Lagoon of Venice ş 1999.

VQ DIPQ VP DIPP VO DIPO VR DIPR VxDIPx DIP

DIP

mol d-1

mol d-1

mol d-1

mol d-1

mol d-1

mol d-1 Ámol m-2 d-1

Jan-Mar 3712 3276 2707 -692 -10668

1665

5

Apr-Jun 5465 3283 2524 -977 -54177

43882

122

Jul-Sep 6463 3897

2768 -363 -7150

-5615

-16

Oct-Dec 6720 1556 2510 -2009 -82063

73286

204

23

The seasonal budgets for DIN, summarized in Tables 2.11 and 2.12, indicate that the lagoon is a sink

of DIN during winter, spring and summer when fluxes toward the sea did not remove all DIN loads

that the system received. The maximal negative value of DIN was estimated for summer season,

during which both VXDINX and VRDINR were at the lowest levels and the input was at its maximum.

In autumn the DIN fluxes toward the sea were higher than the input and DIN was positive, indicating

a net release of 871255 mol DIN d-1.

The (nfix-denit) rate was negative in all seasons and maximal during spring (Table 2.13). Even in

autumn the DINexp is positive and higher that the DIN, due to the high heterotrophy of the system.

Also in this season the (nfix-denit) value was negative, meaning that denitrification processes prevail

over N-fixation during all seasons of the year.

Table 2.11. DIN concentrations in the rivers, the Lagoon of Venice and the adjacent Adriatic

Sea, 1999.

DINQ

DINP

DINO

DINsys

DINsea

DINR

mmol m-3

mmol m-3

mmol m-3

mmol m-3

mmol m-3

mmol m-3

Jan-Mar 213.97 341.14 253.84 27.79 16.34 22.07

Apr-Jun 219.58 263.07 264.16 34.26 30.07 32.17

Jul-Sep 135.42 496.14 251.02 12.69 10.04 11.37

Oct-Dec 238.17 63.73 262.31 43.19 31.15 37.17

Table 2.12. DIN budget for the Lagoon of Venice 1999, single-box analysis.

VQ DINQ VP DINP VO DINO VR DINR

VxDINx DIN

DIN

mol d-1

mol d-1

mol d-1

mol d-1

mol d-1

mol d-1

mmol m-2 d-1

Jan-Mar 544019 126563 103034 -63606 -349007 -361003 -1.00

Apr-Jun 659333 273330 108781 -98183 -493481 -449780 -1.25

Jul-Sep

331535 313907 101437 -24275 -78944 -643660 -1.79

Oct-Dec 851386 85513 107390 -182133 -1733411 871255 2.42

Table 2.13. Stoichiometric calculations for the Lagoon of Venice, single-box analysis 1999.

NEM

DINexp

(nfix-denit)

mmol m-2 d-1

mmol m-2 d-1

mmol m-2 d-1

Jan-Mar -0.5

0.08

-1.08

Apr-Jun -12.9 1.95 -3.20

Jul-Sep 1.7 -0.26 -1.53

Oct-Dec -21.6 3.26 -0.84

24

VE= 903.5 (1999)

VP= 846.1 (1999)

903.7 (2001)

655.5 (2001)

SR= 31.98 (1999)

31.60 (2001)

VQ= 2980.8 (1999-2001)

Lagoon of Venice

V

S

R = -3331 (1999)

Q = 0 (1999-2001)

Areasys = 360*106 m2

-3113 (2001)

Vsys = 540*106 km3

Ssys = 30.97 psu (1999)

VO = 407.8 (1999-2001)

30.16 psu (2001)

S

sys = 10 d (1999)

sea= 32.99 (1999)

VO SO = 0 (1999-2001)

14 d (2001)

33.03 (2001)

VX= 52735 (1999)

34276 (2001)

Figure 2.3. Water and salt budgets for the Lagoon of Venice, single-box analysis. Water fluxes

are expressed in 103 m3 d-1 and salinity in psu.

DIPP=3.56 (1999)

VPDIPP=3012 (1999)

4.59 (2001)

3009 (2001)

V

DIP

RDIPR= -899 (1999)

Q= 1.92 (1999-2001)

Lagoon of Venice

-841 (2001)

V

DIPsys = 0.45 mmol m-3 (1999)

DIP

Q DIPQ =5723 (1999-2001)

R = 0.27 (1999-2001)

0.38 mmol m-3 (2001)

DIPsys = 9046 mol d-1 (1999)

DIP

DIP

O = 6.45 (1999)

sea= 0.08 (1999)

- 3873 mol d-1 (2001)

8.64 (2001)

0.16 (2001)

DIPsys = 25 Ámol m-2d-1(1999)

-11 Ámol m-2d-1 (2001)

VO DIPO = 2630 (1999)

VXDIPX= -19512 (1999)

3523 (2001)

-7541 (2001)

Figure 2.4. DIP budget for the Lagoon of Venice, single-box analysis. Concentrations are in

mmol m-3 and fluxes in mol d-1.

25

DINP=235.36 (1999)

VPDINP=199138 (1999)

303.8 (2001)

199141 (2001)

VRDINR= -83775(1999)

DINQ= 209.95(1999-2001)

Lagoon of Venice

-65778 (2001)

VQ DINQ =625819 (1999-2001)

DINsys = 28.39 mmol m-3 (1999)

DINR = 25.15 (199)

23.90 mmol m-3 (2001)

21.13(2001)

DINsys = -504144 mol d-1 (1999)

DINO = 258.00 (1999)

-684081 mol d-1 (2001)

281.48 (2001)

DINsys = -1.40 mmol m-2d-1(1999)

DIN

-1.90 mmol m-2d-1(2001)

sea= 21.90 (1999)

18.36(2001)

VO DINO = 105212 (1999)

114788 (2001)

VXDIPX= -342250 (1999)

-189889 (2001)

Figure 2.5. DIN budget for the Lagoon of Venice, single-box analysis. Concentrations are in

mmol m-3 and fluxes in mol d-1.

Two-box 2001 analysis

As was mentioned in the introduction, the Lagoon of Venice has a rather high spatial variability of

salinity and concentrations of DIP and DIN, that can not be taken into account when using the 1-box

steady-state hypothesis. Therefore, the subdivision of the lagoon into boxes should improve the results

of the budget calculations. Furthermore, in order to obtain good results, the salinity gradient should not

be less than 1-2 psu (Gordon et al. 1996). Considering this constraint, only two boxes could be

defined.

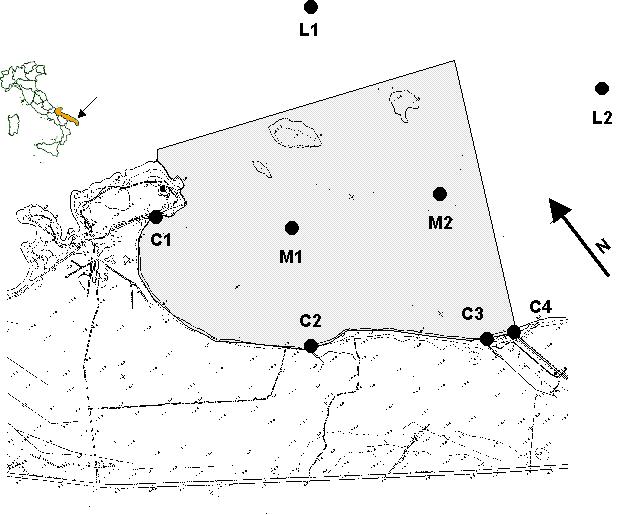

The MAV-CVN sampling stations, which covered the whole lagoon for the year 2001, were assigned

to the two boxes by statistical analysis. The results of Principal Component Analysis, Cluster Analysis

and K-means methodology, applied on standard water quality parameters (MAV-CVN 2002b), were

utilized in order to find the composition of the two clusters of stations that minimize the within-group

variability. The two groups of sampling stations identified the areas of the two boxes of the model,

which are indicated in Figure 2.6 as boxes A and B. Box A, close to the edge of the lagoon, has a

surface of 174.86 km2 with a mean depth of 0.85 m; Box B, directly affected by tidal flow from the

Adriatic Sea, has a surface of 185.28 km2 with mean depth of 2.14 m.

Nutrient loads from rivers and sewage systems enter Box A; atmospheric loads were divided between

the boxes in proportion to their surface areas (Table 2.14). The results of water, DIP and DIN budgets

for the two-box model for the year 2001 are given in Figure 2.7.

Table 2.14. Salinity, DIP, DIN concentrations in the two boxes budget for the Lagoon of Venice.

Units: salinity in psu, concentrations in mmol m-3.

Salinity DIPQ DIPP DIPo DIPsys DINQ DINP DINO DINsys

BOX A

27.83 1.92 4.59

8.64 0.53 209.95

303.80 281.48

31.68

(inner box)

BOX B

32.16

-- 4.59

-- 0.24

-- 303.80

-- 17.23

(outer box)

Sea

33.03

-- --

-- 0.16

-- -- -- 18.36

26

1B

1C

BOX A

2B

3B

2C

5B

4B

6B

7B

8B3C

4C

5C

9B

10B

11B12B

6C

BOX B

13B

7C

14B

15B

16B

18B

17B

19B

8C

20B

Figure 2.6. Subdivision of the Lagoon of Venice into two boxes. Sampling stations for MAV-

CVN 2001, used to define the area of the boxes, are superimposed on the bathymetric map.

Subdivision of the system into two boxes permitted the description of some spatial behaviour of the

ecosystem metabolism of the lagoon. Figure 2.7 shows that Box A was autotrophic (NEM positive),

while Box B was heterotrophic (NEM negative). This finding is in agreement with the results of

studies indicating the presence of a strong negative trophic gradient from the inner part to areas close to

lagoon inlets (MAV-CVN 2002b). The trophic gradient is also supported by the fact that on an annual

basis, the nutrient flux is from Box A toward Box B, meaning that Box A was richer in nutrients than

Box B.

The amount of nutrients exchanged with the sea is the second important difference obtained by the use

of the 2-box model compared to the 1-box. While the export of DIP from the lagoon to the Adriatic

Sea obtained with the 2-box model (9957 mol d-1) was in near agreement with the 1-box estimation of

8382 mol d-1, for DIN the two models behaved differently. With the 1-box model, DIN export to the

sea was estimated at 255,667 mol d-1, while with the two-box model a net import of 75933 mol d-1 was

estimated, because Box B received a higher input of DIN through mixing than was exported through

advective flow. This is in agreement with several studies which suggest that the Adriatic Sea could be

a source of DIN for the lagoon, at least for several months of the year and for some parts of the lagoon

close to the inlets (Sfriso et al. 1994, Cossarini et al. 2001). These results again support the idea that

the spatial complexity of the Lagoon of Venice ecosystem cannot be adequately and completely

represented by a single-box model. A higher spatial resolution allows a focus on processes which

otherwise remain hidden at lower resolution.

27

Finally, according to the two-box model, (nfix-denit) was negative in both boxes. For the whole

lagoon, it can be estimated at -2.72 mmol m-2 d-1 (weighted average of the two boxes), 58% greater

than the value estimated by the 1-box model. Therefore, the two-box model highlights the importance

of the denitrification process, which clearly dominates any nitrogen fixation processes.

V

V

P = 318.5 103 m3 d-1

P = 337.4 103 m3 d-1

V

V

PDIPP = 1462 mol d-1

PDIPP = 1549 mol d-1

V

V

PDINP = 96760 mol d-1 VE= 451.9 103 m3 d-1

PDINP = 102502 mol d-1

VE= 478.8 103 m3 d-

V

BOX A

BOX B

V

Q= 2980.8 103 m3

VR= 3255.2 103 m3

R= 3113.8 103 m3 d-1

VO= 407.8 103 m3

A=174.86 km2

V

A=185.28 km2 V

X=22553.3 103 m3 d-1

X=116678.0 103 m3 d-1

= 6 d

= 3 d

VQDIPQ= 5723 mol d-1

DIP=

V

DIP=

RDIPR= 1270 mol d-1

VRDIPR= 623 mol d-1

-17 Ámol m-2d-1

3 Ámol m-2 d-1

V

NEM (p-r) =

V

NEM (p-r) =

VXDIPX= 9334 mol d-1

ODIPO= 3523 mol d-1

XDIPX= 6540 mol d-1

1.8 mmol m-2d-1

-0.3 mmol m-2 d-1

VQDINQ=

625819 mol d-1

V

V

RDINR= 55395 mol d-1

DIN=

RDINR= 79622 mol d-1

DIN=

-2.47 mmol m-2 d-1

-3.15 mmol m-2 d-1

VODINO=

(nfix-denit) =

V

(nfix-denit) =

VXDINX=

114788 mol d-1

XDINX= 325895 mol d-1

-2.20 mmol m-2 d-1

-3.20 mmol m-2 d-1 131328 mol d-1

Figure 2.7. Budget calculations using the 2-box model for the Lagoon of Venice.

28

2.2

Sacca di Goro Lagoon

Martina Austoni1, Gianmarco Giordani1, Giuseppe Castaldelli2, JosŔ Manuel ZaldÝvar3, Dimitar

Marinov3, Pierluigi Viaroli1

1Dipartimento di Scienze Ambientali, UniversitÓ di Parma

2 Dipartimento di Biologia, UniversitÓ di Ferrara,

3 Institute for Environment and Sustainability, Joint Research Centre, European Commission, Ispra

Summary

The Sacca di Goro is an eutrophic lagoon located along the North Adriatic coast of Italy in the

southernmost part of the Po River delta. The lagoon was investigated in 1992, when annual and

monthly budgets were estimated with a single-box, single-layer LOICZ model. Exchange flows were

obtained from the application of COHERENS (COupled Hydrodynamical Ecological model for

REgioNal Shelf seas) 3-D model. A mean water residence time of 2 days was estimated. The annual

mean DIP was positive (0.01 mmol m-2 d-1) whereas DIN was negative (-20 mmol m-2 d-1), thus the

system can be considered as a source of DIP and a sink of DIN. Budgets for DOP and DON were

calculated from April onwards (except October). Dissolved nutrients from marine and freshwater

sources were dominated by the organic forms of P and the inorganic forms of N. In 1992, the lagoon

acted as a net sink of DOP and a net source of DON. The imbalance between input and output of

nutrients conformed to the seasonal trends of macroalgal biomass growth and decomposition. From

March to June macroalgal blooms were coupled to negative DIP (except for April), DOP and DIN.

In July and August, during the decay phase of macroalgae, DIP, DOP and DON were positive

indicating a high organic matter mineralisation and a release of inorganic and organic dissolved

nutrients. The C, N and P budgets were estimated considering the C:N:P ratios of both macroalgae and

phytoplankton. On an annual basis, the lagoon can be considered as slightly autotrophic, with a net

ecosystem metabolism (p-r) of about 3 mmol C m-2 d-1. The net nitrogen budget (nfix-denit) was

negative, indicating a dominance of denitrification over N-fixation even with values much higher than

those expected in this ecosystem.

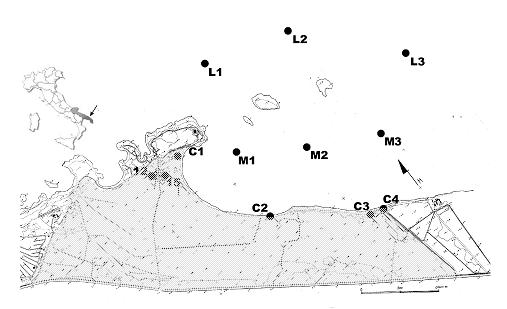

Figure 2.8. Map and location of the Sacca di Goro Lagoon.

29

Study area description

The Sacca di Goro (Figure 2.8) is a shallow-water embayment of the Po River Delta (44.78░N 12.25░E-

44.83░N 12.33░E). The surface area is 26 km2 with a mean depth of 1.5 m and the total water volume

is approximately 39x106 m3. Observation and numerical models have demonstrated a clear zonation of

the lagoon with the low-energy eastern area separated from two higher energy zones, the western area

which is influenced by freshwater inflow from the Po di Volano and the central area influenced by the

sea. Moreover, the eastern zone is very shallow (maximum depth 1 m) and accounts for half of the

total surface area and a quarter of the water volume.

The lagoon is surrounded by embankments. The main freshwater inputs are the Po di Volano River,

and the Canali Bianco-Romanina, Giralda and Bonello. Freshwater inlets are also located along the Po

di Goro River and are regulated by sluices. The freshwater system is mostly located in a subsident area

and is regulated by a system of pumping stations (scooping plants).

The bottom of the lagoon is flat and the sediment is composed of typical alluvial mud; the northern and

central zones exhibit high clay and silt content, while sand is more abundant near the southern

shoreline, and sandy mud occurs in the eastern area.

The climate of the region is mediterranean with some continental influence (wet mediterranean). Wet

deposition is approximately 600 mm yr-1, with late spring and autumn peaks. However, this pattern is

undergoing significant changes with an increase of short-term intense events.

The catchment is heavily exploited for agriculture, whilst the lagoon is one of the most important

aquacultural systems in Italy. About 8 km2 of the aquatic surface were exploited for Manila clam

(Tapes philippinarum) farming, with an annual production of about 15,000 tonnes in 1992.

The system was investigated in 1992 using the one box ş one layer model at monthly intervals.

Meteorological data from the Volano station were supplied by the Agenzia Regionale Prevenzione e

Ambiente (ARPA, Regione Emilia-Romagna). Temperature, salinity and nutrient concentrations of

coastal waters were provided by the Struttura Oceanografica Daphne, ARPA-Cesenatico (ARPA,

1992). Inorganic nutrient data were recorded at Station 2 (44.7853░N - 12.2625░E; depth: 3 m;

distance from coast 500 m), which is in front of the Sacca di Goro. Data of DON and DOP at stations

4 (44.6628░N - 12.2517░E, depth 3 m, distance from coast 500 m) and 304 (44.6628░N ş 12.2872░E,,

depth 8 m, distance from coast 3000 m) were used, since these data are not available for Station 2.