TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

List of Acronyms

iv

Executive Summary

vii

Unique contribution of PEMSEA

vii

Findings

vii

Recommendations

viii

A. All PEMSEA partners

viii

B. Donor support (GEF, UNDP, IMO and other donors)

viii

C. Governments

ix

D. PEMSEA management team

ix

Taking the recommendations forward

x

1.0 Project concept and design summary

1

Context of the problem

1

Effectiveness of the PEMSEA programme concept and design

1

Assessment of the fit of the SDS-SEA to the objectives of

4

Agenda 21, WSSD, MDG, Capacity 2015 and the results of

the Third Replenishment of the GEF Trust Fund

2.0 Project

results

11

3.0 Progress towards outcomes

14

Overall development objective, project development objectives

15

and planned outputs

Progress towards achievement of project outcomes

15

Knowledge management

18

4.0 Impacts of the PEMSEA programme

21

Review and evaluation of the extent to which project impacts

22

have reached the intended beneficiaries

Likelihood of continuation of project outcomes and benefits

23

after completion of GEF funding

Key factors and issues that require attention

25

Other concerns that the programme should look into

28

5.0 Project

Management

30

The project's adaptive management strategy

30

Roles and responsibilities of the various institutional

31

arrangements for project implementation and the level of

coordination between relevant players

Partnership arrangements with other donors

32

Public involvement in the project

33

Efforts of UNDP and IMO in support of the programme office

34

and national institutions

Use of the logical framework approach and performance

36

indicators as project management tools

Implementation of the projects' monitoring and evaluation plans

36

6.0 Main Lessons Learned

37

Strengthening country ownership/drivenness

37

Strengthening regional cooperation and inter-governmental

38

cooperation

Strengthening stakeholder participation

38

Application of adaptive management strategies

38

Efforts to secure sustainability

38

Role of monitoring and evaluation in project implementation

39

7.0 Recommendations

39

Overview

39

Specific Recommendations

40

All PEMSEA partners

40

Donor Support: Recommendations to GEF, UNDP, IMO

40

ii

and other donor partners

Governments

41

PEMSEA management team

41

Annexes

45

Annex 1 Progress towards meeting objectives of GEF

Operational Programs 8, 9 and 10

Annex 2 IMO Supported Trainings/Workshops

Annex 3 PEMSEA Logframe Matrix: Key Performance

Indicators

Annex 4 Internal Evaluation of ICM Sites Performance

Annex 5 Knowledge Management Strategies and

Applications

Annex 6 Knowledge Management Case Studies: Batangas

Bay and Bataan, Philippines

Annex 7 Resource Mobilization

Annex 8 PEMSEA Cooperation and Collaboration with

Partners

Annex 9 An example of implementation of a comprehensive

set of performance indicators

iii

LIST OF ACRONYMS

ADB

Asian Development Bank

ASEAN

Association of South East Asian Nations

BC

Benefit Cost

BCCF

Bataan Coastal Care Foundation

CITES

Convention on Trade in Endangered Species

CMC

Coastal Management Center

DA

Department

of

Agriculture

DANIDA

Danish Agency for Development Assistance

DENR

Department of Environment and Natural Resources

DSS

Decision Support System

EIA

Environmental Impact Assessment

ERA

Environmental Risk Assessment

GEF

Global Environment Facilty

GPA

Global Programme of Action

ICM

Integrated Coastal Management

IEIA

Integrated Environmental Impact Assessment

IIMS

Integrated Information Management System

IMO

International Maritime Organization

IRR

Internal Rate of Return

ISO

International Organization for Standardization

IT Information

Technology

ITC-CSD

International Training Center for Coastal Sustainable Development

IW

International Waters

JICA

Japan International Cooperation Agency

KM

Knowledge

Management

LFA

Logical Framework Approach

LUAS

Lembaga Urus Air Selangor

MBEMP

Manila Bay Environmental Management Project

MDG

Millennium Development Goals

MED

Marine Environment Division

MEG

Multidisciplinary Expert Group

MMCC

Marine Management and Coordination Committee

MOA

Memorandum of Agreement

MOU

Memorandum of Understanding

NGO

Non Government Organizations

PCC

Project Coordinating Committee

PEMSEA

Partnerships in Environmental Management for the Seas of East Asia

PG-ENRO

Provincial Government - Environment and Natural Resources Office

PIR

Project Implementation Review

PMO

Project Management Office

PMMP-EAS Prevention and Management of Marine Pollution of the East Asian Seas

PPP

Public-Private Partnerships

PSC

Project Steering Committee

PSEMS

Port Safety Environmental Management System

RNLG

Regional Network of Local Governments

RPD

Regional

Programme

Director

RPO

Regional Programme Office

RTF

Regional Task Force

iv

SIDA

Swedish International Development Agency

SDS-SEA

Sustainable Development Strategy for the Seas of East Asia

SMPR

Secretariat Managed Project Review

SOM

Senior Officials Meeting

TCD

Technical

Cooperation

Division

UN

United Nations

UNDP

United Nations Development Programme

UNEP

United Nations Environment Programme

UNFAO

United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization

WB

World

Bank

WSSD

World Summit on Sustainable Development

v

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Unique Contribution of PEMSEA

The unique and distinctive characteristic of Partnerships in Environmental Management

for the Seas of East Asia (PEMSEA) is that it is the first international programme to

develop a core base of practical knowledge in integrated management of coasts and

oceans within the Seas of East Asia based firmly on its network of local demonstration

and parallel sites. This has generated a wealth of intellectual capital that moves beyond

technical know-how and scientific endeavour towards developing a cohesive network of

relationships that makes the integrated management approach a living reality in this

region. This core competence of PEMSEA has enabled nations to accelerate their

progress in implementation of coastal and oceans governance through the development

of institutional frameworks, mutual sharing of lessons and greater South-South dialogue.

There are dangers that this international asset could be lost at the end of this

programme unless the intellectual capital is nurtured by national governments and donor

agencies.

Findings

The PEMSEA programme has achieved substantial progress in meeting the Overall

Development Objective "To protect the life support systems and enable the

sustainable use and management of coastal and marine resources through

intergovernmental, intersectoral and interagency partnerships for improved quality of life

in the East Asian Seas Region."

The ten stated Project Development Objectives and fourteen planned Outputs as set

out in the ProDoc are appropriate to the Overall Development Objective and are being

implemented within, or in advance of, the planned time frame and in a cost effective

manner. These achievements are the result of both good project design and innovative

and adaptive management, which are producing commendable outcomes and beneficial

social, economic and environmental impacts.

There are areas where the programme could be strengthened and the Evaluation Team

is confident that the PEMSEA will be able to address these in a manner that will

enhance the impact of the program at a local, national and regional level.

It is important for the Global Environment Facility (GEF), United Nations Development

Programme (UNDP), and International Maritime Organization (IMO) to fully recognize

the valuable information, experience and public and private support the PEMSEA

programme has developed by focusing on achieving tangible progress in environmental

improvements that help to form a sound basis for the expansion and diversification of

economic development. This has been achieved through implementation of an

Integrated Management approach and developing effective partnerships for

environmental improvements at a trans-national and wider regional level.

vi

Together, these achievements have created a very valuable asset that supports the

objectives of all three United Nations programs and forms a very sound foundation for

helping the nations of East Asia in achieving sustainable economic development that is

integrated with sound environmental management. This asset needs to be fostered and

developed further as it forms an invaluable resource to help in the implementation of

Agenda 21, the World Summit on Sustainable Development (WSSD) Plan of

Implementation, and the Millennium Development Goals (MDG) as well as related

international and national efforts to promote sustainable development of natural

resources and assets of the marine and coastal areas of the region.

Recommendations

The Evaluation Team recommends the following actions to be taken by the PEMSEA

partners:

A. All PEMSEA partners

1. Make full use of the momentum that has been achieved through the PEMSEA,

seek continuity in funding and other forms of support for PEMSEA beyond 2005

to maximize the potential benefits to the East Asian Region and beyond.

2. Seek the transformation of PEMSEA into a new regional arrangement for wider

exploitation and future development of its intellectual capital to improve the

integration of environmental management and economic and social development

through the further development of local, national and regional ICM and ocean

governance initiatives.

3. Implement the Sustainable Development Strategy for the Seas of East Asia

(SDS-SEA) as a collective international effort in the regional implementation of

the commitments of Agenda 21, WSSD, MDG and other international instruments

related to the sustainable development of coasts and oceans.

B. Donor support (GEF, UNDP, IMO and other donors)

1. The GEF, UNDP, IMO, international donors and other donor partners should

capitalize on the achievements of PEMSEA in helping each other meet their

respective sustainable development objectives by:

a) maintaining core roles especially in building national and local capacity in the

further development and implementation of PEMSEA and SDS-SEA;

b) fostering cooperation and partnerships with and among nations in Asia;

c) creating a wider partnership among international donors for supporting the

future of PEMSEA;

d) supporting an international working party made up of representatives from

East Asian nations with a remit to examine options for new institutional and

funding arrangements for taking PEMSEA forward.

vii

C. Governments

1. Give careful consideration to maximizing the potential benefits that could be

gained from what has been achieved by the PEMSEA programme, how this can

be extended and expanded to further support national and international

development objectives.

2. National Governments set up review panels to determine what they need most in

order to make integrated management of coasts and oceans more effective;

3. Initiate a country-driven donors meeting in 2003 to demonstrate support for the

future development of PEMSEA and to communicate priorities for funding and

technical assistance.

D. PEMSEA management team

1. Adopt a broader view of adaptive management so that a wider array of issues

are taken into consideration, while incremental, small-scale actions at the local

level are pursued towards solving problems and issues.

2. Strengthen national capacities in EIA system where required, as an interim

measure till zoning guidelines are put in place.

3. Accelerate national buy-in by using clear examples of the benefits of ICM,

supporting the finalization of national coastal policies, the replication of ICM sites

and mainstreaming of the approaches, policies, lessons learned in the

implementation of sites and in the program as a whole into major strategic

development plans.

4. Enhance efforts to establish public-private partnerships (PPP) in environmental

investments, particularly for small and medium sized enterprises.

5. Promote national commitment to the planned Senior Officials Meeting and the

Ministerial Meeting being organized by the program.

6. Develop a monitoring and evaluation system that takes into account activity-

based and cumulative impacts.

6. Target the development of an ISO 14001 Certification for ICM using the

PEMSEA experience and outcomes.

8. Fully implement the Port Safety Audits and the Port Safety Environmental

Management System (PSEMS) and further develop certification mechanisms.

9. Seek greater integration of river basin management, coastal land and water use

management, and sea use zoning.

10. Explore ways that knowledge management practices could help expand and

sustain the intellectual capital developed by PEMSEA.

viii

Taking the Recommendations Forward

The Evaluation Team recommends that an international working party be set up to

explore options for a new institutional mechanism and funding to take the PEMSEA

program forward. The Working Party should be made up of no more than 5 senior

government officials representing the countries taking an active part in the PEMSEA

program. Technical advice should be made available to the Working Group as and

when necessary. The Working Party should meet at least on a bi-monthly basis starting

as soon as possible to allow time to develop and test the feasibility of alternatives, with a

view to presenting their final recommendations by the end of 2004. This would allow

actions to be put in place in 2005 to allow a smooth transition and continuity in staffing

arrangements from the existing phase of PEMSEA to the new arrangements.

ix

I.0

PROJECT CONCEPT AND DESIGN SUMMARY

Context of the problem

1.1

East Asia is a region of dynamic economic growth amidst trends of globalization.

The financial crisis only strengthened the resolve of the countries of the region

for economic growth while the global economic recession gave focus for

intraregional trade and commerce, creating in the process a new East Asian

Economy comprised of Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) + 3.

1.2

At the same time, there is rapid urban population growth in the region. The

annual growth rate of the urban population of East Asia from the mid-1990's to

2025 is estimated to be four times that of the highest income countries. A large

number of this urban population will be coastal dwellers. Over the next 25 years,

half of the total population of the region will come from coastal urban centers with

more than 300 million inhabitants. Many of these inhabitants will belong to

sectors of the poor. Presently, majority of the 75 million people living in the

coastal areas of the region are below the poverty line.

1.3

This combination of aggressive drive for economic development, high population

growth and poverty will increasingly put pressure on the region's coastal

environment. Coastal environments in the countries of the region are in danger of

being overexploited and rapidly degraded. So too is the regional marine

environment given that the seas of the region are semi-enclosed with high

ecological interconnectivities.

1.4

While there is growing awareness of "sustainable development" as the vision for

development, there is also the lack of appropriate and practical mechanisms for

putting it into action. The need is to have a dynamic process that would deal with

conflicts of use, using the increasing recognition of the important role that could

be played by local governments, the private sector and other local stakeholders

as initiators.

1.5

One of the major benefits of the PEMSEA programme is the generation of

intellectual capital in the form of human capital, social capital, organisational

capital and stakeholder capital related to the implementation of ICM in the region.

This valuable intangible asset is difficult to assess quantitatively due to the lack

of sophistication of models for such applications. However, case studies, stories,

narratives and anecdotes provide useful guides to the strength and depth of

these intangible assets. Care needs to be exercised not to assume that

economic development is directly related to high levels of social and stakeholder

capital in ICM as this is often not the case in planned economies.

Effectiveness of the PEMSEA programme concept and design

1.6

The focus of the programme on starting at the local site level allowed fast action

to proceed at many sites. Practical field experience is developed. Appropriate

demonstration sites were also selected, sites that would later exemplify how

integrated management including ICM efforts could create a balance between

1

rapid economic growth and environmental management. Xiamen is a designated

international economic city. Danang has an aggressive plan to develop the city

for industry and for tourism. Batangas port was designated as an international

port. Port Klang is already an international port with planned expansion. In all of

these cases, there would be increased port activities, extensive infrastructure

development, rapid increase in population, and various economic activities. All

these will exert pressure on the environment, directly and indirectly. All these

sites require an ICM approach.

1.7

PEMSEA's strategy is to come in to speed up the process of ICM problem

solving. As such it selects sites where people and government are already keen

to do something. This has led to fast action. The downside to this is that the

experience of these sites will have low utility to sites where supportive local

people and governments do not yet exist unless public awareness is created.

1.8

The programme's comprehensive landscape approach (i.e. integrating the

coastal area with its linked land and sea-based ecosystems) provides more

effective management than a habitat approach. The close and direct ecological

as well as socio-economic interconnectivities of the various habitats or

ecosystems comprising the coastal area require an integrated approach.

1.9

An integrated approach such as ICM requires partnerships with different sectors

and at various levels. The shift from the Phase 1 programme title of "Regional

Programme for the Prevention and Management of Marine Pollution of the East

Asian Seas to the Phase 2 title of "Building Partnerships on the Environmental

Management of the Seas of East Asia" is thus very appropriate. The new title

also broadens the concern to extend beyond pollution management to that of

environmental management. This then appropriately covers many other relevant

concerns that should be part of the programme if it is to be called an ICM effort.

1.10 The partnerships that are developed are not only at various institutional levels

site, national, subregional and regional. There is also the partnership between

sectors particularly public-private partnerships. At the conceptual level, the

"partnership" or linking of environment and development underlies PEMSEA's

approach. As such the programme also becomes a way by which various global

agreements on maritime concerns as well as on the broader sustainable

development agreements of the WSSD Plan of Implementation, the MDG,

Agenda 21, Capacity 2015 and other environmental conventions could be

operationalized at the local level. It should be noted that partnerships are also

linked to the development of a critical mass of countries, organizations and

people which is the only way that these global agreements can be put into

practice. Using the PPP framework, there is considerable potential to develop

cost effective solutions especially when industries come together and generate

economies of scale for environmental facilities.

1.11 The diversity of sites implementing the programme provides an advantage.

Demonstration sites pioneer the ICM approach, provide for capacity building,

make lessons available for other sites, and are used to convince the country to

adopt ICM as a management approach. Parallel sites show that the effort could

be replicated using mostly local resources, provide a way to adapt lessons from

the demonstration sites to other situations, and would additionally convince the

2

country to adopt the ICM approach. Hotspot sites provide the opportunity to

address cross-boundary issues.

1.12 The sites cover a typology of governance mechanisms, from highly centralized

governance systems (Xiamen, Danang, Nampo), decentralized governance but

with strong central direction (Port Klang) and those with highly decentralized

governance practice (Batangas, Bataan, Manila Bay, Bali and Sihanoukville) as

shown in Figure 1. The sites also relate to different socio-economic situations.

Fast economic growth is exemplified by Xiamen and Port Klang. Relatively

slower economic growth areas are in Batangas, Bataan, and Manila Bay. Given

this diverse typology of sites the programme would be able to provide a variety of

models that could meet the needs of a region with countries of differing

environmental, socio-economic and governance situations.

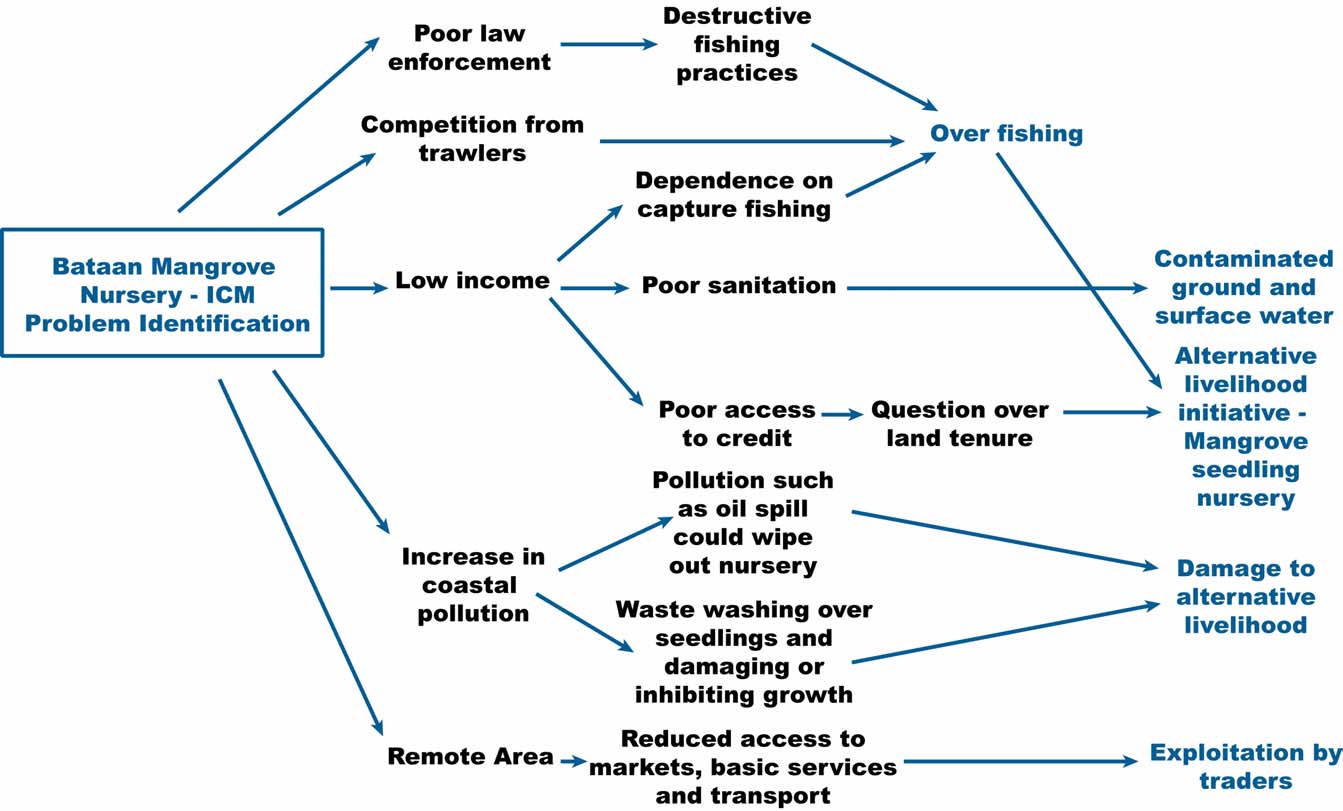

Bataan

Sihanoukville

Philippines

Cambodia

Danang

Vietnam

Batangas Bay

Philippines

Port Klang

Malaysia

COMMITTEE BASED

Xiamen

CENTRALISED

DECENTRALISED

COMMUNITY BASED

FASTER

PR China

LEARNING

LEARNING

SLOWER

PROGRESS

Chonburi

PROGRESS

Thailand

Bali

Indonesia

Nampo

DPR Korea

Shihwa

Sukabumi

RO Korea

Indonesia

Figure1. Organisational learning at demonstration and paral el sites

1.13 The programme has taken the "soft approach", employing resource use and

environmental concerns as the entry point and avoiding security and boundary

issues that could lead to inter-country conflicts and debate. Use of conventions

already agreed upon as a guide and with focus on sustainable development as a

goal, the programme is able to acquire immediate acceptance. In addition, with

the countries developing and implementing their national strategies following the

ICM approach, these countries are then in a sense already implementing the

programme's proposed regional strategy, the SDS-SEA. This would make it

easier for such a regional strategy to be approved and a regional mechanism for

its implementation to be agreed upon.

1.14 The programme's study tours, internships, cross-visits and Regional Task Force

(RTF) provided the opportunities for South-South exchange of experiences and

knowledge. Together with regional bodies such as the RNLG, Regional Experts

Group, and the Project Coordinating Committee (PCC), they have helped create

a feeling of regional programme participation.

1.15 The co-financing approach of the programme allows local ownership to be

developed. At the same time, the ability of PEMSEA to provide a certain level of

funding support and technical assistance allows it to stimulate attention and

3

participation at certain strategically important activities. It allows the programme

to be a catalyst of certain processes and decisions.

1.16 PEMSEA states that its budget allocation is more for "people management"

rather than the provision of physical facilities. This relatively low level of funding

allocated by the programme to sites builds not only capacity but also prevents

the creation of false expectations and dependence. Provision of knowledge,

through technical assistance and sharing mechanisms augments the funding

support and is well appreciated.

1.17 The most difficult aspect of PEMSEA is the many institutional levels involved in

the programme. It makes the programme an exercise in the "management of

complexity". Links have to be maintained with various focal points the focal

points of IMO, UNDP and GEF in the 12 countries involved. Relationships at the

local, national, subregional, and regional levels have to be developed and

appropriate coordinative mechanisms established. At the country level, there is

the complexity of linking agencies in-charged of land-based concerns with those

for marine and coastal resources. There are also the other coastal and marine

resources management projects at the regional and country levels that are

supported by other donor agencies. Differences in site and focal implementing

agency as well as the tendency to focus on its own approach make it difficult to

get coordination amongst these many programmes and projects. An

understanding of some of the levels of complexity are shown in Figure 2.

1.18 As the major outputs from this programme are developing tacit knowledge in

ICM, promoting best practice and sharing lessons learnt across the region, the

programme concept and design could be improved by making knowledge sharing

practices more central in its approach. There is a danger that the action

orientation of implementation processes could place the creation, organisation,

evaluation, storage and retrieval of new knowledge secondary to the primary

purpose of meeting outputs in the logframe.

Assessment of the fit of the SDS-SEA to the objectives of Agenda 21, WSSD, MDG,

Capacity 2015 and the results of the Third Replenishment of the GEF Trust Fund

1.19 PEMSEA's development objective "to protect the life support systems, and

enable the sustainable use and management of coastal and marine resources

through intergovernmental, interagency and intersectoral partnerships, for the

improved quality of life in the East Asian region" is in a sense an operational

definition of sustainable development. The coastal and ocean systems of the

East Asia is the region's natural heritage and source of food and livelihood for the

millions of poor in the region. In addition, the social and cultural values of the

people of the region are linked to these resources. Properties and investments

are also dependent on how well these resources are managed. PEMSEA's

activities on bringing ICM into the countries of the region, building sustainability

on such management through capacity building, scientific inputs, integrated

information management system (IIMS), stakeholder participation, environmental

investments, and national coastal/marine policies as well as upscaling and

complementing all these with efforts to create inter-country partnerships through

a regional mechanism are therefore not only for the environment's sake but also

for supporting two other pillars of sustainable development -- social development

4

and economic development. Bringing the sustainable development direction of

PEMSEA into the regional level would be facilitated by one of its outcomes, the

SDS-SEA.

1.20 The 2002 WSSD was quite unique from that of the United Nations Conference on

Environment and Development (UNCED) held in 1992 in that it emphasized good

governance within each country and at the international level as essential to

sustainable development. PEMSEA's efforts at getting local governments to take

the lead in ICM activities as well as in helping promote stakeholder participation

and national level policy-making support WSSD's call for strengthening good

governance at the country level. The process of developing the SDS-SEA, on the

other hand, supports the effort for strengthening good global governance, in

particular ocean governance.

1.21 The foundation of the SDS-SEA are based on the prescriptions of global and

regional instruments relevant to the environment as well as on the regional

programmes of action developed by ASEAN, UNEP Regional Seas Programme,

Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP), Asia-Pacific

Economic Cooperation (APEC) and others. As such it is implementing WSSD's

call for strengthening institutional arrangements for sustainable development at

the regional level. As stated in the WSSD Plan of Implementation, the

"implementation of Agenda 21 and the outcomes of the Summit should be

effectively pursued at the regional and subregional levels, through the regional

commissions and the other regional and subregional institutions and bodies".

1.22 The SDS-SEA provides for the active participation of all stakeholders and not just

national governments and international agencies as often is the case for regional

agreements and mechanisms. The participation of the local governments, the

private sector, civil society and communities are given importance, the same

importance that the WSSD Plan of Implementation, in numerous provisions,

gives to these stakeholders. The WSSD Plan of Implementation has called for

action to "enhance the role and capacity of local authorities", "enhance corporate

environmental and social responsibility and accountability", "foster full public

participation in sustainable development policy formulation and implementation"

and "to enhance partnerships between governmental and non-governmental

actors, including all major groups, as well as volunteer groups". The WSSD Plan

of Implementation and the SDS-SEA Action Programs both give importance to

community-based management and the recognition of the usefulness of

appropriate indigenous/traditional knowledge and practices. A slight difference is

in the weak reference of the WSSD Plan of Implementation to concerns of

artisanal fisherfolks. This is where the SDS-SEA is quite strong. Thus, the

Strategy augments that which should have been given importance but was

somehow not given enough attention at the WSSD negotiations.

1.23 The WSSD Plan of Implementation reiterates Chapter 17 of Agenda 21 which

calls for "integrated management and sustainable development of coastal areas,

including exclusive economic zones; marine environmental protection;

sustainable use and conservation of marine living resources; addressing critical

uncertainties for the management of the marine environment and climate

change; strengthening international, including regional cooperation and

coordination; and sustainable development of small islands". A close look at the

5

various action programs of the SDS-SEA shows that these programme areas

called for by WSSD and Agenda 21 are tackled at an operational level relevant to

the region.

1.24 The other output of the WSSD was the promotion of Type II partnerships. These

are partnerships that bring in not only donors and international bodies but most

especially civil society groups and the private sector as well. The objective is to

draw in additional resources for the immediate implementation of actions called

for by the WSSD Plan of Implementation. The SDS-SEA becomes a framework

to stimulate Type II partnerships for coastal and ocean governance in the region

as it is built on the pillar of "partnerships". The SDS-SEA is "meant to be

implemented by all the different stakeholders men and women, public and

private, local and national, non-government organizations, governments, and

international communities working in concert with each other".

1.25 In the SDS-SEA Action Programs, there are many elements that would facilitate

formation of Type II partnerships. Objective 3 of the "Develop" Section of the

Strategy is on "Partnerships in Sustainable Financing and Environmental

Investments". All the action programs under this objective are important in

supporting Type II partnerships. Similar action programs are similarly

emphasized in other sections of the Strategy. Some examples are action

programs for "institutionalizing innovative administrative, legal, economic and

financial instruments that encourage partnership among local and national

stakeholders" and "creating partnerships among national agencies, local

governments and civil society that vest responsibility in concerned stakeholders

for use planning, development and management of coastal and marine

resources". Some examples that would facilitate public-private partnership

include the following: "enhancing corporate responsibility for sustainable

development of natural resources through application of appropriate policy,

regulatory and economic incentive packages", "exploring innovative investment

opportunities, such as `carbon credits' for greenhouse gas mitigation, and user

fees for ecological services" and "levying economic incentives and disincentives".

For promoting partnerships at the regional level, the SDS-SEA Action Programs

call for "promoting south-south and north-south technical cooperation, technology

transfer and information-sharing networks" and working with international

financial institutions, regional development banks and other international financial

mechanisms to facilitate and expeditiously finance environmental infrastructure

and services". The communication action programs of the Strategy would further

strengthen the development of Type II partnerships by raising public awareness

and mobilizing various stakeholders to act.

1.26 The SDS-SEA, in many senses, also supports the MDG, in particular three of its

goals: (1) eradicate extreme poverty and hunger; (2) ensure environmental

sustainability, and; (3) develop a global partnership for development. As noted in

Agenda 21: "More than half the world's population lives within 60 km of the

shoreline, and this could rise to three quarters by the year 2020. Many of the

world's poor are crowded in coastal areas. Coastal resources are vital for many

local communities and indigenous people." The Strategy's Action Programs

under the sections on "Sustain" (East Asian countries shall ensure sustainable

use of coastal and marine resources), "Preserve" (East Asian countries shall

preserve species and areas of the coastal and marine environment that are

6

pristine or of ecological, social and cultural significance), "Protect" (East Asian

countries shall protect ecosystems, human health and society from risks which

occur as a consequence of human activity) all directly contribute to ensuring

environmental sustainability and consequently the maintenance of the coastal

resources and oceans as source of livelihood and food. The Strategy's "Develop"

section states the link between environment and development more succinctly:

"East Asian countries shall develop areas and opportunities in the coastal and

marine environment that contribute to economic prosperity and social well-being

while safeguarding ecological values". The Action Programs on the promotion of

sustainable economic development in coastal and marine areas and on building

partnerships in sustainable financing and environmental investments with their

implications on sustaining or increasing productivity and jobs generation directly

relate to eradication of poverty and hunger.

1.27 The effort for meeting environment needs as well as the eradication of poverty

and hunger extends beyond the local and national levels. Objective 2 of the

Strategy's "Develop" section relates to incorporating transboundary

environmental management programs in subregional growth areas or what is

alternatively known as East Asia's international growth triangles. The success of

SDS-SEA implementation of this will provide other developing country regions an

example to look at and adapt.

1.28 The link of the SDS-SEA to the MDG goal of developing a global partnership for

development is exemplified by its "Implement" section which states that "East

Asian countries shall implement international instruments relevant to the

management of the coastal and marine environment." Its action programs call for

national government accession to and compliance with relevant international

conventions and agreements and regional cooperation in integrated

implementation of international instruments. The Strategy, however, goes a step

further to deepen the reach of global partnership by calling for the execution of

obligations under international conventions and agreements at the local

government level.

1.29 The strong links between SDS-SEA implementation and that of meeting the

objectives of the WSSD Plan of Implementation and the MDG also then link the

Strategy to UNDP's Capacity 2015 programme. The goal of Capacity 2015 is to

develop the capacities needed by developing countries and countries in transition

to meet their sustainable development goals under Agenda 21 and the MDG. It

seeks to build local level capacities for sustainable development and local

implementation of Multilateral Environmental Agreements. The SDS-SEA

highlights this in its Action Programs.

1.30 Capacity 2015 also seeks to maximize benefits of globalization at the local level.

SDS-SEA reflects a similar objective by holistically linking the promotion of

regional cooperation and the incorporation of sustainable development in

subregional growth areas as a way to further support efforts (i.e. through South-

South or North-South exchanges of technical assistance and of environmental

investments for key coastal and marine sites) at the local level. The ASEAN + 3

framework of the Strategy is therefore very relevant not only because it allows

management of the ecological interconnectivities of the semi-enclosed East

Asian seas, including interconnectivities in risk due to a common pattern of oil

7

tanker routes in the region, but at the same time, the framework is able to draw in

the economic dynamism of fast growing economies of the region (Japan,

Republic of Korea, and China) and draws them to support the low and middle-

income economies. Trade between the countries of the region is growing and the

closer economic links that will develop could lead to a similar strengthening of

links on environmental investments. The mainstreaming of SDS-SEA action

programs in the national economic development plans of the countries of the

region as well as in the regional trade and other economic agreements will do

well to further strengthen the implementation of the Strategy.

1.31 The consistency of the SDS-SEA with GEF policy has been strengthened with

the results of the negotiations for the Third Replenishment of the GEF Trust

Fund. The Third Replenishment of the GEF Trust Fund underscored and affirmed

the critical importance of supporting the goals of the United Nations Millennium

Declaration and of Agenda 21. Other policy recommendations include the

following:

· GEF to support a more systematic approach to capacity building. Where

capacity is a need and acts as a barrier, then it should be addressed first.

· Country ownership is essential to achieving sustainable results. Thus

integration into national priorities, strategies and programs for sustainable

development is vital. Mainstreaming and co-financing are also important.

· Need to increase interagency cooperation between the UN system and

the Bretton Woods institutions at the country level such as linking the

Poverty Reduction Strategy Programme (PRSP) and the United Nations

Development Assistance Framework (UNDAF) processes to bring

together poverty reduction strategies and sustainable development

processes.

· Greater participation in the development and management of GEF

projects of other executing agencies (i.e. ADB) designated under

expanded opportunities.

· All activities of the GEF should be undertaken in a spirit of enhanced

partnership. Cross-learning should be strengthened and accelerated.

· Document best practices of stakeholder participation.

· Better engagement with the private sector.

1.32 All of the above is similar to the direction taken by SDS-SEA. The strategy also

puts great importance to capacity-building. The adoption of the Strategy will be

through a process that builds country ownership. The plan for adoption also

states that "consultations will be undertaken with a view to harnessing the

objectives of intergovernmental bodies and multilateral financial institutions,

including World Bank, ADB, GEF and official development assistance (ODA)."

Once the Strategy is adopted, this will be used by these same partners to act

decisively and proactively to conserve the Seas of East Asia. The Strategy puts

emphasis on partnership, particularly public-private partnerships. The

strengthening and acceleration of cross-learning and the documentation of best

practices of stakeholder participation can be found in the Strategy's

Objectives/Action Programs for the establishment of information technology (IT)

as a vital tool in environmental management programs, partnerships with

scientists and scientific institutions to encourage information and knowledge

8

sharing, and the utilization of innovative communication methods for the

mobilization of governments, civil society and the private sector.

1.33 The results of the GEF replenishment negotiation also points out that a new

strategic thrust would be to catalyze implementation that builds on foundational

work. The development of the SDS-SEA is one such foundational work which,

with more financial and political support, would contribute significantly to meeting

the action objectives of Agenda 21, the WSSD Plan of Implementation, and the

MDG.

1.34 The replenishment negotiation documents also pointed at indicators for meeting

the objectives of the International Waters portfolio. These indicators are:

· Global Coverage (transboundary waterbodies with management

framework of priority actions agreed by riparian countries);

· Agreed Joint Management Actions (countries with national policies,

regulations, institutions, etc. re-aligned to be consistent with agreed joint

management actions);

· Regional Cooperation (regional bodies and management authorities with

strengthened capacities);

· Local Technological Development (countries with demonstration

technologies and management practices viable under local conditions).

1.35 Note that these indicators could be the same indicators for monitoring the SDS-

SEA as the Strategy has strongly brought in Action Programs that lead to

meeting the same objectives served by these indicators.

1.36 The Beijing Declaration of the Second GEF Assembly contains the same focus

as that of the policy recommendations resulting from the replenishment

negotiations. The Beijing Declaration also emphasized the need for GEF to assist

in the implementation of the WSSD, in particular the importance placed by the

Summit on regional and sub-regional initiatives and on public participation,

stakeholder involvement and partnerships. It also pointed at the importance of

capacity building and the enhancement of technology transfer through public-

private partnerships and technology cooperation, both North/South and

South/South. As previously noted, the SDS-SEA has placed the same high level

of importance to these aspects.

1.37 The Beijing Declaration also noted that the expanded mandate of the GEF would

now include dealing with Persistent Organic Pollutants (POP). In as much as the

SDS-SEA also desires control of land-based pollutants getting into coastal and

marine areas, the implementation of the Strategy then also contributes to the

meeting this new mandate of the GEF.

1.38 The SDS-SEA indeed has strong links and consistency in objectives and action

programs with the WSSD Plan of Implementation, the MDG, the strategic

directions of the GEF coming out of the Third Replenishment negotiations, and

the Capacity 2015 programme. What now needs to be done is to move the

9

WSSD, MDG, Agenda 21, Capacity 2015, Conventions

Donor Agencies: GEF, UNDP, UNEP, IMO, World Bank, ADB, Bilateral donors

GLOBAL

ASEAN Ministerial

Meetings

Ministerial Conference,

Malaysia, December 2003

Competing projects

Regional Network of

such as USAID

Local Governments

and DANNIDA

(PMOs, NGOs, national

and local governments)

Gulf of

Thailand

Local

Govt.

PMO

REGIONAL

PCC

PPP

Roundtable

Discussions

Bohai Sea,

Manila Bay,

PR China

Philippines

Local

Local

Govt.

PMO

Govt.

PMO

PCC

PCC

NATIONAL

Bataan,

Philippines

Local

Govt.

PMO

PCC

Shihwa,

Korea

Batangas Bay,

Xiamen,

Local

Philippines

PR China

LOCAL

Govt.

PMO

Local

Local

Govt.

PMO

Govt.

PMO

PCC

PCC

PCC

Nampo,

DPR Korea

Chonburi,

Thailand

Local

Govt.

PMO

Local

Govt.

PMO

PCC

PCC

Sihanoukville,

Management

Cambodia

Sukabumi,

Team

Bali,

Indonesia

Local

Indonesia

Govt.

PMO

Local

Local

Govt.

PMO

Govt.

PMO

PCC

PCC

PCC

Danang,

Vietnam

Port Klang,

Local

Malaysia

Govt.

PMO

Local

Govt.

PMO

PCC

Site

PCC

Management

PEMSEA

Team

Figure 2. Organisational Networks at PEMSEA

10

Strategy forward beyond the endorsement of the 8th Programme Steering

Committee Meeting and that of the UNDP. The planned PEMSEA Ministerial

Meeting of countries participating in the programme would be a good opportunity

to get higher-level approval and commitment to SDS-SEA. UNDP's Capacity

2015 could then give it further impetus by providing immediate support in

translating its action programs for local level implementation. This would open up

additions which could further enhance its validity at the local level such as

bringing in a stronger reference to the participation of women and youth and a

special consideration for vulnerable groups. Where local coastal sites are

repositories of high levels of runoff from chemical-based agriculture, due

attention to POP issues could also be made. A link to the other expanded

mandate of the GEF which is land degradation primarily desertification and

deforestation could also be looked into especially where drought and siltation

impact on the coastal ecosystems.

2.0

PROJECT

RESULTS

2.1

This mid-term evaluation of the PEMSEA programme is based upon two

fundamental observations, namely:

2.1.1 Integrated management approaches attempt to address extremely complex

problems and issues affecting the sustainable development of highly dynamic

coastal ecosystems whose rich and diverse natural resources have generated

powerful and often competing demands from a wide array of economic sectors.

This means that ICM is perhaps the most complex form of human activity, far

more complex in fact than managing upland or purely marine areas and

activities. For this reason alone, the achievement of major outcomes takes a

considerable period of time and requires the development of strong political

commitment to integrated rather than sectoral approaches to the formulation and

implementation of human activities that influence the ability of coastal systems to

sustain planned development activities;

2.1.2 When evaluating the progress of the PEMSEA programme, the four most critical

features to examine are progress towards the development of:

a. A robust and self-sustaining process for applying ICM concepts,

frameworks, principles and good practices;

b. Strong ICM strategies and their practical implementation at a project level

that are also supported by strong political commitment at a national level;

c. A critical mass of successful ICM projects at a local level that inform and

support the development of national ICM policies and supporting

measures;

d. A regional mechanism to facilitate the sharing of knowledge, experience,

technical assistance, and lessons learned to help nations to work together

to a common purpose in solving problems and issues which affect the

achievement of sustainable development objectives.

11

2.2

Given the challenge of managing the very complex issues facing the coastal

nations in East Asia, it is important to understand a number of key issues that

influence the progress made by the PEMSEA programme towards the

development of ICM at a site, national and regional level. These include:

a. A long tradition of economic development planning based on

transformation of natural systems to meet the needs of individual sectoral

activities. This forms a barrier to multiple use management of complex

coastal systems, such as mangrove, which can sustain more than one

economic activity;

b. Different political systems characterized by strong, centralized policy

making where top-down decision making concerning investment and the

allocation of land and water resources takes precedence over local

decision making. In some countries, such as Indonesia, the recent move

towards decentralization and deconcentration of decision making has

created a hiatus where considerable adjustment in policy making and

adoption of local priorities for development is taking place;

c. Where local development priorities and plans to address coastal

management issues are being formulated, these are often obstructed by

a legacy of prior commitments and approvals of plans by centralized

agencies and powerful investors and political interests;

d. Awareness of the dynamics and functions of coastal systems, and the

hazards to life, property and investment from their inappropriate

development is generally low in most developing nations. This limits the

perceptions of problems and issues that hinder sustainable economic

development;

e. The direct and indirect linkages between coastal ecosystem functions and

economic development are poorly perceived. This lack of awareness

constrains the development of comprehensive and accurate analyses of

problems and issues affecting specific areas and limits the utility of risk

assessments and feasibility studies, and the evaluation of management

alternatives available to meet stated development objectives;

f. Where the use of the English language is not widespread its use as the

medium of communication can form a barrier to effective sharing of

knowledge and experience in the adoption and use of complex ICM

concepts, methodologies and examples of good practice;

g. Low level of understanding of ICM and acceptance of the PEMSEA

framework and process as viable and valuable planning and management

tools at a national and regional level.

2.3

These constraints add to the complexity of managing development processes in

coastal areas and help to explain why the achievement of even modest advances

in developing a robust ICM process take considerable time-often 5 to 10 years,

consistent technical assistance tailored to the needs of individual sites, continuity

12

of funding, and the progressive development of political acceptance of ICM as a

tool to help sustain development rather than adding bureaucratic hurdles.

2.4

It is clear that ICM frameworks and practices have a good deal to offer the

nations of East Asia in promoting effective solutions to very complex problems

and issues that undermine efforts to develop sustainable use of coastal areas

and natural resources.

2.5

The PEMSEA programme is well suited to meet the needs of the new

programmatic approach adopted by the GEF. Major advances have been

achieved in developing the practical implementation of ICM concepts and

practices across a wide spectrum of different environmental, social and economic

situations in six East Asian nations. The Evaluation Team has been impressed

by the commitment of the PEMSEA core staff, staff and counterparts at the 6

project sites visited, and the developing support for environmental investment

from the private sector. All involved are to be congratulated on their combined

achievements.

2.6

While the Evaluation Team is aware of the difficulties that the PEMSEA team and

their partners have overcome and that there have been advances in the adoption

and application of ICM, certification procedures for ports and the SDS-SEA, it

has proven very difficult to assess the actual impact of the Program. There are

good examples of ICM practice. Some have been catalysed by PEMSEA, while

others may not be a direct result of PEMSEA activities. For example, the LUAS

river basin framework in Selangor is designed to improve the integration and

sectoral planning for land and water use management in watersheds associated

with the environmental management of the Klang river which drains into the Port

Klang ICM project site. However, this initiative was in place before the Port Klang

coastal area was selected as a PEMSEA site. In fact, this initiative by the State

Government made the Port Klang area more attractive to the PEMSEA

management team and has helped strengthen the potential for longer-term

positive impacts of PEMSEA efforts.

2.7

The careful choice of sites based on evidence of political commitment, available

information, clearly perceived problems, and other criteria have helped form a

series of sites where PEMSEA should be able to demonstrate rapid results and

thus gain greater political buy-in to the ICM process. However, the Evaluation

Team believes that truly integrated forms of coastal management are at an early

stage of development in the sites visited. There remain major obstacles, such as

lack of understanding of how coastal systems function and continuing sectoral

emphases in planning for and managing human activities that will take a

considerable period of time and effort by the PEMSEA Team to overcome.

2.8

Having expressed these concerns, the Evaluation Team does believe that the

PEMSEA Program has achieved significant progress towards potentially very

beneficial outcomes and, in time, major positive impacts on environmental quality

and sustainable use of the coastal lands and waters of the East Asian Region.

The following paragraphs attempt to set out progress towards outcomes.

13

3.0

PROGRESS TOWARDS OUTCOMES

3.1

Given the above considerations and that the project is at the mid-point in the

implementation of the second phase, the evaluation team believes it is too early

to fully assess the outcomes and impact of the project beyond what we have

witnessed during field visits and through discussions with the intended

participants.

3.2

The Evaluation Team is convinced that the PEMSEA programme has achieved

substantial progress in the development and implementation of ICM frameworks,

processes and good management practices. There is substantial evidence of

emerging outcomes resulting from one or more program outputs. These include:

a.

Acceptance of ICM as a tool to help sectoral agencies reduce conflicts

with other sectoral agencies and improve the effectiveness of the

respective efforts to help fulfill mandates, improve the efficiency of public

investment, and meet national development objectives;

b.

Enhanced awareness of the added value ICM can bring to the resolution

of national, provincial and local development issues;

c.

Adoption of ICM in the project sites as a tool for resolving local

environmental, economic and social management issues;

d.

Major progress in developing practical measures for the formulation and

implementation of sustainable ICM initiatives;

e.

Learning shared between project sites, sharing of knowledge,

development of shared understanding of problems and potential for

complementary solutions at varying ecosystem and geographic levels;

f.

Innovative and usable technologies that is strengthening comprehension

of complex sets of data and information to inform ICM processes;

g.

Evolution of a local, sub-regional, national and transnational cooperation

and development of solutions to common problems;

h.

Development of a comprehensive data base that can be developed to

provide information to better inform planning and decision taking process

and investment. Examples include: environmental profiles, risk

assessments, feasibility studies, maps and scientific reports for the

project and parallel sites;

i.

Positive influence on investment in measures to improve environmental

conditions and reduce stress within coastal and marine ecosystems;

j.

Engaging private enterprises to focus on coastal management issues in

their corporate responsibility agendas;

k.

Support to national governments in the formulation of national coastal

policies.

14

3.3

All of the above contribute to meeting the project's regional and global

environmental objectives as per GEF Operational Programs 8 (Waterbody-Based

Operational Program), 9 (Integrated Land and Water Multifocal Area Operational

Program), and 10 (Contaminant-Based Operational Program). Progress in

meeting the targets and indicators that support these objectives are discussed in

the various sections of this evaluation. Additional discussion on PEMSEA

activities as they relate to the stipulations and expected outputs of GEF OP 8, 9,

and 10 is also in Annex 1.

Overall development objective, project development objectives, and planned outputs

3.4 The

stated

Overall Development Objective is "To protect the life support

systems and enable the sustainable use and management of costal and marine

resources through intergovernmental partnerships for improved quality of life in

the East Asian Seas Region." This is a most ambitious higher order objective or

longer-term goal. The emphasis upon protecting the life support systems that

underpin sustainable production of marine and costal resources is a key element

in enabling the sustainable use and management of these resources to help

improve the quality of life in the East Asian Seas Region.

3.5

The ten stated Project Development Objectives (See Annex 3 ) and fourteen

planned Outputs are appropriate to the Overall Development Objective.

Progress towards achievement of project outcomes

3.6

A clear distinction must be made between project outputs, outcomes and

impacts. The Logical Framework Approach is used to test the internal logic of a

project design and to monitor and assess the progress in meeting intended

objectives through the implementation of planned activities. The outputs are the

stated targets of the project activities. For example, training to enhance human

resource capacities may have a target of 12 people trained in Environmental Risk

Assessment (ERA) by the 7th month of the project. The intended output is 12

trained people. The outcome will be different depending on a number of factors,

including the additive or synergistic effects of other outputs from the project (e.g.

the design and implementation of an ERA system and the provision of

appropriate hardware and software), the starting competence of the trainee and

social and economic conditions beyond the control of the project managers.

3.7

The Evaluation Team concurs with the findings of the GEF Secretariat Managed

Project Review (SMPR) 2002 and the UNDP Project Implementation Review

(PIR) 2002 evaluations. It is clear from a comparison of the original logframe and

progress reports, verbal presentations of the staff, official reports, published

materials and interviews with participants that the project is performing very well

and that planned activities are on course for completion within the planned time

frame or ahead of schedule. There do not appear to be any significant cost-over-

runs and it is significant that additional funding from partners has enhanced the

use of the GEF funding and has made up for the unfortunate shortfall in planned

UNDP counterpart funding. Careful project management and energetic sourcing

of funding from participants and external funding bodies has allowed the project

team to expand participation in planned activities and to add new activities.

15

3.8

Internal evaluations indicate that there are specific areas where the achievement

of objectives has already been met, while some objectives are expected to be

fulfilled during the remaining life of the project. Please refer to Annex 4 for

illustrative charts prepared by the PEMSEA staff to denote progress in meeting

planned activities. The Evaluation Team sees a need to strengthen the

objectively verifiable indicators and methods used to track progress in the

implementation of activities and performance of the individual projects as these

may not give a full and accurate picture of what has been achieved. For

example, where an advisory group has been established this is counted as an

output. However, the actual range of expertise available in that advisory group

may be limited, essential disciplines may not be available, and there may be little

experience in the group of working in an inter-disciplinary mode and providing

scientific advice in a form that will be valued and applied by planners and

managers. By adopting more perceptive indicators to assess outputs, it would be

possible to identify areas where selective inputs or corrections by the PEMSEA

management team would help provide stronger support to local project activities

and thus enhance outcomes and impacts.

3.9

It is understood that the PEMSEA staff are preparing an assessment of indicators

and methods used to evaluate progress towards implementing activities and

achieving stated outputs directed towards fulfilling the ten project objectives. The

preliminary draft of this paper is most helpful. It explains how expanded criteria

and assessment techniques could be applied and reinforces the Evaluation

Team's assessment that the program is actively strengthening project

management tools.

3.10 The report of the Proceedings of the First Meeting of the Multidisciplinary Expert

Group (MEG) held in May 2002 makes specific reference to PEMSEA activities

that have helped strengthen scientific support to the program at a regional level

and at individual project level. Specific emphasis has been given to a) enriching

the application of "indigenous and emerging technologies", b) addressing

"cutting-edge scientific issues of leading environmental and resource concerns",

and c) promoting management-oriented research to support the demonstration

projects. These efforts are commendable and illustrate the determination of the

program staff to better integrate information from indigenous knowledge and

more formal science to enrich ICM in practice.

3.11 However, the Evaluation Team believe that action needs to be taken within the

remaining life of the project to strengthen specific activities to help PEMSEA

move further forward in addressing its Overall Development Objective. These

are set out below:

3.11.1 The Evaluation Team is concerned that insufficient emphasis is being given in

the implementation of planned activities to the protection of the life support

systems that enable the sustainable use and management of costal and marine

resources. Throughout the study tour of the six project and parallel sites visited it

was very clear that coastal ecosystems were under great stress from

inappropriate development. When this was raised with project staff it was clear

that the staff were operating under very difficult political, institutional and

economic conditions which made it almost impossible to protect and effectively

16

manage the coastal ecosystems on a sustainable basis. The Evaluation Team

have identified four principal areas where the implementation of the project could

be strengthened with the result that the protection of the life support systems

could be addressed more effectively, namely:

a. The Training Program needs to strengthen emphasis on the functions of

the coastal ecosystems. This would include: environmental linkages

among different ecosystems, established management guidelines and

good practices that help protect the functional integrity of the different

coastal ecosystems and the resources they generate, and the hazards to

life, property and public and private investment associated with the

inappropriate planning and management of human activities within both

the terrestrial and marine components of the coastal zone. The Risk

Assessment training materials and exercises do address some of the

risks associated with coastal systems, however the Evaluation Team

believes the design of the Training Program and materials need to be

strengthened to address these subjects as a matter of urgency;

b. Greater effort is required to enhance awareness of the role of coastal

ecosystems in sustaining human activities and the risks associated with

their inappropriate development on the part of participants and

stakeholders in the PEMSEA programme at all levels. The initial training

of all PEMSEA staff and participants needs to be reinforced by the

application of the materials in 1 above in a "refresher" program. This

should then be extended in a very carefully designed and highly graphic

and hard hitting manner to the senior managers, policy makers and

decision makers associated with the PEMSEA programme;

c. The IIMS is intended to provide a data base for factors relevant to the

management of coastal and marine areas. The Evaluation Team sees a

need to avoid the IIMS being data driven and for more emphasis to be

given to ensuring the data collected will be transformed into information

that will be effective in informing coastal and ocean management decision

making. For example, more attention could be given to the dynamics of

coastal systems and good management practices- such as soft

engineering- that would help coastal planners and managers develop

more sustainable and economically equitable uses;

d. The Stakeholder based Coastal Management Strategies for various sites

should more adequately address the risks associated with major

interventions in coastal processes. This would help avoid increased

hazards to life, property and investment.

3.11.2 Strengthening efforts to address these four factors can enhance the impact of the

PEMSEA program outputs and will help remove constraints that hinder progress

towards meeting Project Development Objectives and the Overall

Development Objectives of protecting the life support systems and enable the

sustainable use and management of costal and marine resources.

17

Knowledge Management

3.12 There have been local differences in organisational learning at demonstration

and parallel sites. One major distinction is between `centralised learning' and

`decentralised learning' as shown in Figure 1. Project sites based in command

economies such as China and Vietnam favoured centralised learning aimed

more at mobilising committees rather than communities. This is not to say that

public awareness and consultation was not important at these sites. Instead,

progress in ICM implementation was much faster at these sites due to strong

committee decision making structures in local government. In contrast,

decentralised learning was more evident at project sites such as Bali which is

based more on community oriented decision making. Progress at these sites was

much slower as considerable efforts were placed on mobilising local

stakeholders and community leaders. The distinction can be developed further as

a difference between `top down' approaches in centralised learning and `bottom

up' approaches in decentralised learning.

3.13 There are a number of examples of innovative and creative practices in Phase 2

arising from double-loop learning. Such double-loop learning involves

questioning underlying assumptions and moving beyond the confines of the

iterative ICM development cycle in Phase. These innovations have included:

a. The establishment of self funding parallel sites.

b. The development of `hotspots' exploring cross boundary issues.

c. The examination of PPP funding mechanism for sustainable development.

d. The establishment of the RNLG to promote greater South-South dialogue on

ICM implementation.

e. The promotion of a regional SDS through a Ministerial Conference in 2003.

DOUBLE-LOOP

Forms of

LEARNING (DLL)

DLL

Ministerial

Conference

RNLG

PPP

Initiating

Developing

Preparing

`Hotspots'

SINGLE-LOOP

LEARNING

Parallel Sites

Adopting

Development of further

Implementing

demonstration sites

Refining and

Consolidating

Figure 3. Single-loop and double-loop learning on the PEMSEA Programme

18

3.14 Some of the difficulties in effective impact with key stakeholders is likely to arise

from the fact that the current communications strategy is trying to cover too many

stakeholders at the same time with limited resources and giving each stakeholder

equal importance. The danger with the current strategy is that PEMSEA may be

`preaching to the converted' such as the 312 regular subscribers to `Tropical

Coasts'. The result is that the media approaches chosen may become too bland

as they try to please a wide variety of stakeholders and lose effective impact on

particular segments. Instead, an adaptive management strategy used in other

parts of the PEMSEA project could be used to help improve the communications

strategy. This could be based on a force field analysis1 identifying key

stakeholders actively driving PEMSEA's goals and stakeholders resisting

PEMSEA's goals at local, national and regional levels. Reinforcement

communications strategies could be used for supportive stakeholders and

awareness building strategies for stakeholders resistant to PEMSEA's approach.

In such cases, a few stakeholders are identified, segmented and the

communications activities are directly targeted at them.

3.15 Knowledge sharing across demonstration and parallel sites is currently limited. At

present, staff at PMO sites share their knowledge centrally with site managers at

the RPO rather than horizontally across other regional sites. The linkages in

knowledge sharing mechanisms between local and national levels are weak and

not well defined. The main knowledge sharing occurs formally through national

focal points reporting site activities to the Project Steering Committee (PSC) and

their local PCC. However, there is no direct linkage between staff at local site

level in the region. This needs to be addressed to consolidate ICM practices and

promote best practice more widely within the region. One future challenge at

local level is overcoming language barriers to ensure that shared understandings

are developed and similar mistakes are avoided across the East Asia Seas

region.

3.16 An ontology or taxonomy to describe the ICM knowledge domain is currently

implicit in PEMSEA's activities. A more explicit ontology would be useful to

provide a `knowledge map' of the area and develop shared conceptualisations of

how integration occurs between technological, social, economic and political

factors. Such ontologies could be used for codifying knowledge in a systematic

manner and provide a further mechanism for creating, organising and sharing

knowledge across sites. There have been attempts in the past to capture coastal

management ontologies through simulation models such as `Simcoast'. However,

the advantage of developing an ICM ontology at PEMSEA would be that it is

embedded in practice.

3.17 The poor standing of the IW: LEARN site on search engine rankings may be

principally due to its aim to develop global communities in international waters

rather than supply direct explicit knowledge through a search engine. One of the

difficulties in maintaining global communities of practice is sustaining the passion

and interest in any given area over time. Face to face meetings are essential to

renew and revitalise trust in these relationships. Community members need to

1 Force field analysis is a simple tool used in strategy to identify those forces driving a change process and those

forces retarding it. Strategies are developed to support and enhance the driving forces and examine ways to

undermine the restraining forces. Such an analysis has a background in military planning.

19

feel that they are contributing and receiving in equal measure. If these

relationships become unbalanced, commitment to such communities is likely to

waver. From the IW: LEARN brochure, there appears to be a few hundred solid

participants with a possible few thousand other interested parties globally.

However, there are a number of unanswered questions that arise from IW:

LEARN's e-forums:

1. How are the interest areas identified and promoted?

2. How are champions or e-forum co-ordinators selected to ensure that they

bring the necessary passion, commitment, contacts and expertise to

online discussions?

3. Are e-forums problem centred or theme based?

4. Is there a critical mass of participants to sustain these communities

globally with all the cultural differences and language problems?

5. What role does storytelling play in these communities of practice?

3.18 Currently, none of the staff at PEMSEA are actively engaged in IW: LEARN

communities of practice as there appears to be an imbalance in benefits gained

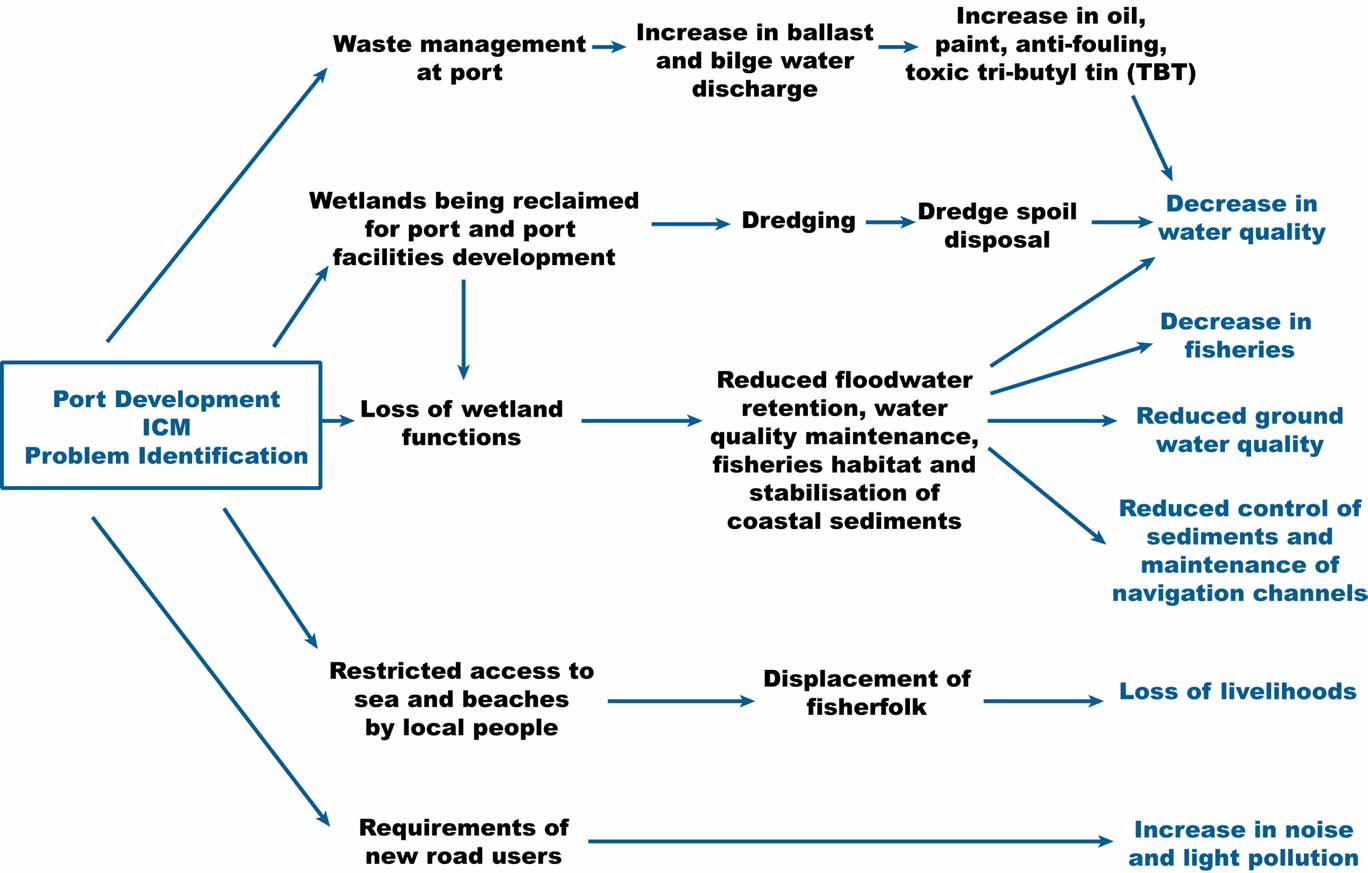

from their contributions and pressures on their time. For example, IW: LEARN