This report was compiled by:

Susan Taljaard (CSIR, Stellenbosch)

This report was reviewed by:

Dr Pedro M S Monteiro (CSIR, Stellenbosch)

Dr Des Lord (D. A. Lord & Associates Pty Ltd, Perth, Australia)

This report also includes feedback that was received from key stakeholders attending the work

sessions that were held in each of the three countries:

Namibia: January and August 2005

Angola: February and November/December 2005

South Africa: February and August 2005

The Desktop Assessment Studies (referring to Appendices A C) were prepared by:

Angola: Marina Paulina Paulo (Ministry of Urban Affairs and Environment, Angola) and Olivia

Fortunato Torres (Instituto de Investigação Marinha, Ministério das Pescas, Angola)

Namibia: Aina Iita (Minsitry of Fisheries and Marine Resources)

South Africa: Susan Taljaard (CSIR, Environmentek)

CSIR Report No CSIR/NRE/ECO/ER/2006/0010/C

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The United Nations Office for Project Services ("UNOPS") commissioned the CSIR (South

Africa) to conduct a baseline assessment of sources and management of land-based marine

pollution in the Benguela Current Large Marine Ecosystem (BCLME) Region.

The primary purpose of this project was to standardize the approach and methodology by

which land-based marine pollution sources in the BCLME region are managed. This was

achieved through the preparation of a generic (draft) management framework, including

protocols for the design of baseline measurement and long-term monitoring programmes.

An important secondary objective of this project was to initiate the establishment of a

BCLME coastal water quality network to provide a legacy of shared experience, awareness

of tools, capabilities and technical support. This network had to be supported by an

updatable web-based information system that could provide guidance and protocols on the

implementation of the management framework. The web-based information system also

had to contain a meta-database on available information and expertise.

The main outputs of this project, therefore, included:

· A proposed (or draft) framework for managing a land-based source of marine pollution,

U

U

including guidance on the implementation of such a framework

· Proposed protocols for the design of baseline measurement and long-term monitoring

U

programmes related to the management of land-based marine pollution sources in the

U

BCLME region

· An inventory and critical assessment of available information and data related to the

U

U

management of (land-based) marine pollution sources in Angola, Namibia and South

Africa

· Work sessions and training workshops in each of the three countries to which key

U

U

stakeholders, involved in the management of marine pollution, were invited

· Updatable web-based information system that provides guidance on the application of

U

U

the generic management framework, as well as a meta-database on available

information and expertise in the BCLME region.

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/01

Page i

Final

January 2006

The proposed framework is largely based on a process that was developed for the

Department of Water Affairs and Forestry (South Africa) as part of their Operational Policy

for the Disposal of Land-derived Wastewater to the Marine Environment of South Africa

(RSA DWAF, 2004) which, in turn, is based on a review of international best practice and

own experience in the South African context.

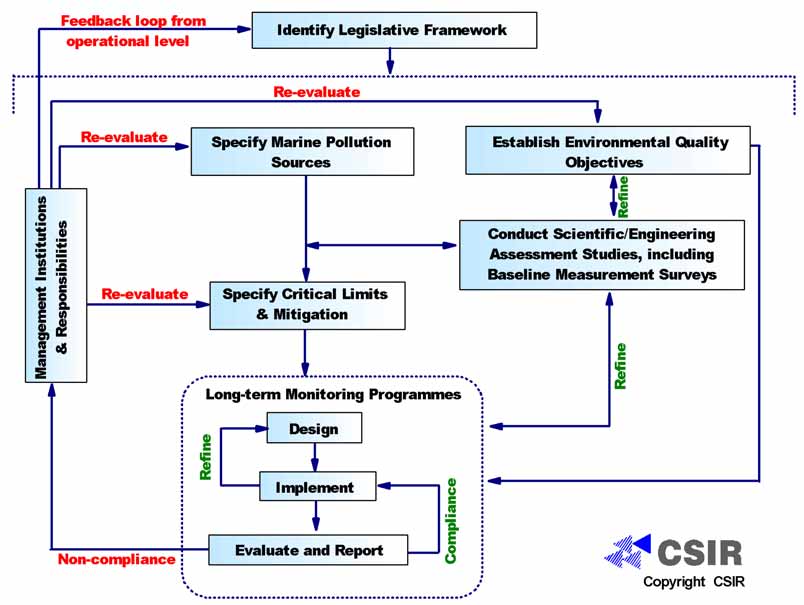

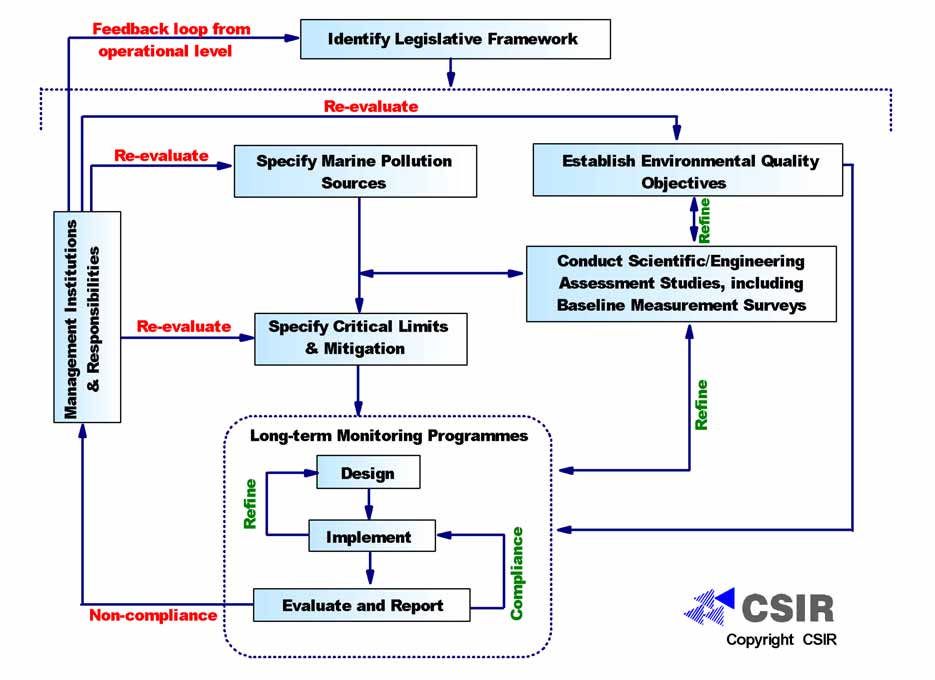

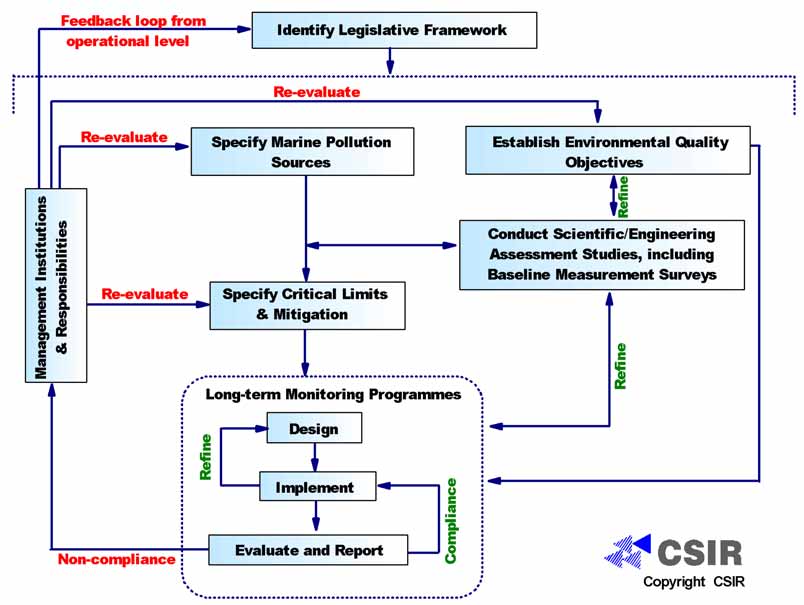

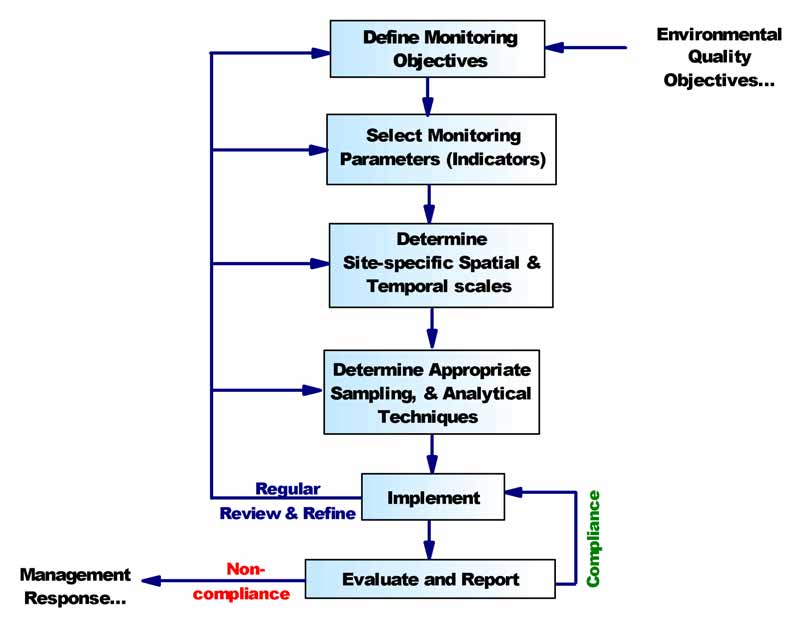

The proposed framework promotes an ecosystem-based approach, identifying different

components that need to be addressed as well as linkages between components. The

following are considered to be key components of such a management framework:

· Identification of legislative framework

· Establishment of management institutions and their responsibilities

· Determination of environmental quality objectives

· Specification of marine pollution sources

· Scientific assessment studies

· Specification of critical limits and mitigation measures

· Design and implementation of long-term monitoring programmes.

A schematic illustration of the inter-linkages between these components is provided below.

Each of the components is discussed in more detail in the document, with guidance on

implementation.

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/01

Page ii

Final

January 2006

An integral part of the management framework is baseline measurement and long-term

monitoring programmes. As a result, this report also considers proposed protocols in the

design of such programmes. In this regard it is important to note the difference between

baseline measurement programmes (usually part of Scientific Assessment Studies) and

U

U

monitoring programmes (implemented as part of Long-term Monitoring Programmes):

U

U

· Baseline measurement programmes (or surveys) usually refer to shorter-term or once-

off, intensive investigations on a wide range of parameters to obtain a better

understanding of ecosystem functioning

· Long-term monitoring programmes refer to ongoing data collection programmes (using

selected indicators) that are done to continuously evaluate the effectiveness of

management strategies/actions designed to maintain a desired environmental state so

that responses to potentially negative impacts, including cumulative effects, can be

implemented in good time.

The successful implementation of the proposed management framework relies on good

cooperation, not only between responsible government departments and industries, but also

with the scientific community (which plays a key role in providing the sound scientific base

for decision-making). It is for this reason, therefore, that key stakeholders in each of the

three countries should include members from:

· National and regional government departments

· Nature conservation authorities

· Local authorities

· Scientific

community

· Industries utilizing the marine environment.

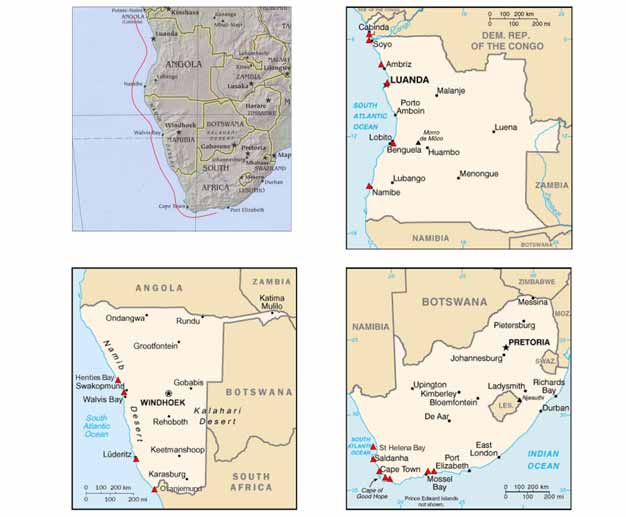

The inventory and critical assessment of available data and information relevant to the

management of land-based marine pollution sources in the BCLME region focused on main

development nodes in the area, as listed below:

ANGOLA

NAMIBIA

SOUTH AFRICA

Cabinda

Henties Bay

St Helena Bay

Soyo

Walvis Bay/Swakopmund

Saldanha Bay/Langebaan Lagoon

Ambriz

Luderitz

Cape Peninsula (western section)

Luanda

Oranjemund (diamond mining areas)

False Bay

Lobito

Walker Bay (Hermanus)

Namibe

Mossel Bay

Knysna Estuary

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/01

Page iii

Final

January 2006

The following points relate to the way forward:

· The proposed framework for the management of land-based sources of marine pollution

in the BCLME region still needs to be officially approved and adopted by responsible

government authorities in the different countries.

· The management framework developed as part of this project is closely linked to the

recommended water and sediment quality guidelines for the coastal areas of the

BCLME region (developed as part of another BCLME project BEHP/LBMP/03/04).

In the interim, until such time as a management framework and quality guidelines have

been incorporated in official government policy, it is proposed that the management

framework developed as part of this project, together with the recommended water and

sediment quality guidelines, be applied as preliminary tools towards improving the

management of the water quality in coastal areas of the BCLME region.

· The updatable web-based information system (temporary web address

www.wamsys.co.za/bclme), developed as part of this project, can be a very useful

H

T

U

U

T

H

decision-support and educational tool provided that it is maintained and updated

regularly. In the short to medium term, it is recommended that one or more of the

BCLME offices within the three countries take on this responsibility.

· To facilitate wider capacity building in the BCLME region of the management of marine

pollution in coastal areas, it is strongly recommended that the output of this project be

included in a training course. In this regard, the Train-Sea-Coast/Benguela Course

Development Unit is considered the ideal platform from which to develop and present

such training (www.ioisa.org.za/tsc/index.htm).

H

T

U

U

T

H

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/01

Page iv

Final

January 2006

RESUMO EXECUTIVO

O Gabinete das Nações Unidas para Prestação de Serviços (United Nations Office for

Project Services - "UNOPS") contratou o CSIR (África do Sul) para conduzir uma avaliação

primária das fontes terrestres e gestão da poluição marinha na região do Grande

Ecossistema Marinho da Corrente de Benguela (Benguela Current Large Marine

Ecosystem) (BCLME).

O objectivo primario deste projecto foi o de padronizar a abordagem e metodologia pelo

qual as origens de poluição marinha na região BCLME são geridas. Isto foi alcançado

através da preparação de uma estrutura genérica (rascunho) de gestão, incluindo

protocolos para a delineação de programas de monitorização a longo prazo.

Um segundo objectivo importante deste projecto foi dar início ao estabelecimento de uma

rede de comunicações sobre a qualidade da água costeira no BCLME, de modo a

providenciar uma partilha de experiência, conhecimentos sobre o tipo de instrumentos,

capacidades e apoio técnico. Esta rede tinha de ser apoiada por um sistema de informação

actualizável e apoiado na Internet que pudesse providenciar orientação e criasse protocolos

na implementação da estrutura de gestão. Este sistema de informação apoiado na Internet

deveria também incluir uma metabase de dados sobre informação disponível e experiência

técnica.

Os principais produtos deste projecto incluíam assim:

· Uma proposta (ou rascunho) da estrutura para gerir fontes terrestres de poluição

U

U

marinha, incluindo orientações quanto à implementação dessa mesma estrutura

U

U

· Proposta de Protocolos para a delineação de programas de monitorização a longo

prazo relacionadas com a gestão de fontes terrestres de poluição marinha na região do

U

U

BCLME

· Um inventário e availaç

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/01

Page v

Final

January 2006

· Um inventário e uma avaliação crítica da informação e dos dados disponíveis

U

relacionados com a gestão das fontes terrestres de poluição marinha em Angola,

U

Namíbia e África do Sul

· Sessões de trabalho e workshops de treino em cada um dos três paises aos quais os

"stakeholders" no campo de gestão de poluição marinha foram convidados

· Um sistema de informação actualizável com apoio na Internet que proporcione

U

U

orientação quanto à aplicação da estrutura de gestão genérica, bem como uma

metabase de dados sobre informação disponível e experiência técnica na região do

BCLME.

A estrutura proposta é largamente baseada num processo desenvolvido pelo Ministério dos

Assuntos de Água e Florestas (Department of Water Affairs and Forestry), da África do Sul,

como parte da sua Política Operacional para o Tratamento de Águas Residuais Oriundas de

Terra para o Ambiente Marinho da África do Sul (RSA DWAF, 2004), a qual por sua vez

assenta numa revisão do código de boa conduta internacional e na própria experiência no

contexto da África do Sul.

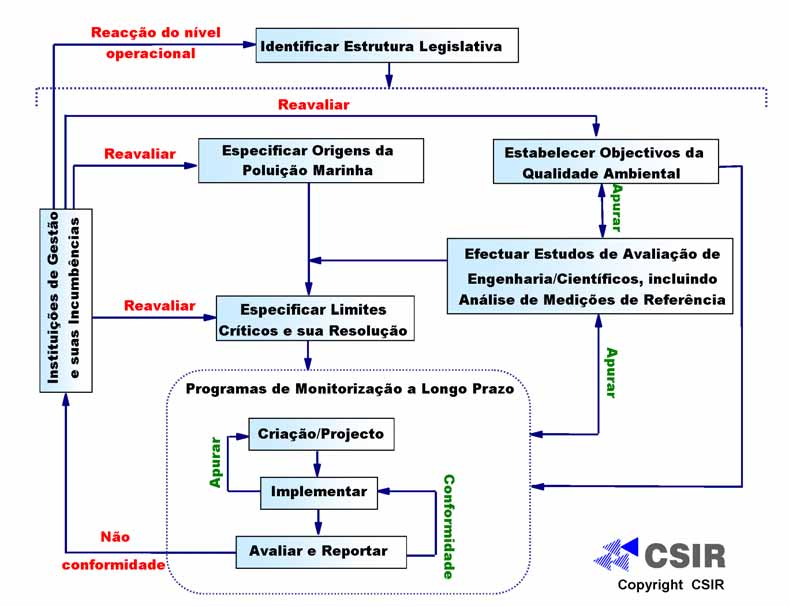

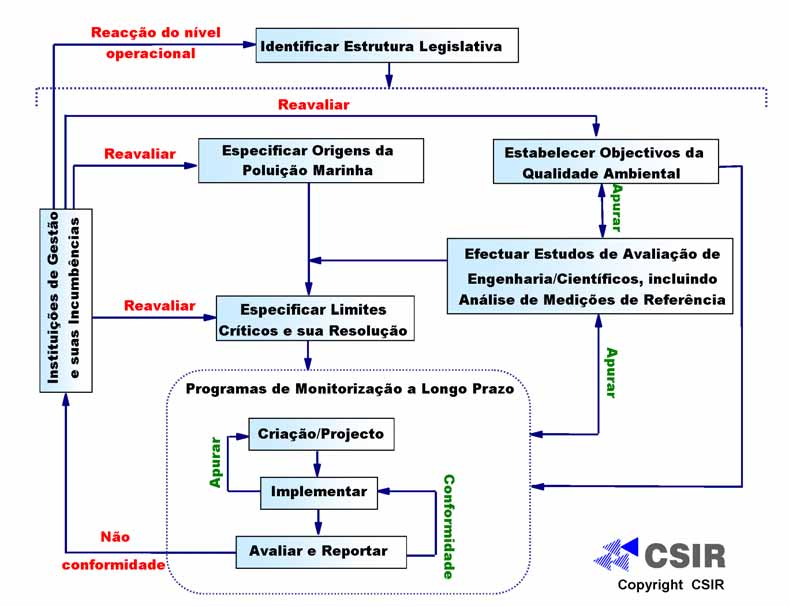

A estrutura proposta estimula uma aproximação com base no ecossistema, identificando

componentes diferentes que devem ser estudados, bem como ligações entre as

componentes. Abaixo identificam-se aqueles considerados como os componentes-chave

dessa estrutura de gestão:

· Identificação de uma estrutura legislativa

· Estabelecimento de instituições de gestão e suas incumbências

· Determinação de objectivos de qualidade ambiental

· Especificação das origens da poluição marinha

· Estudos de avaliação científica

· Especificação de limites críticos e medidas de atenuação

· Criação e implementação de programas de monitorização a longo prazo.

Uma ilustração esquemática das interligações entre estes componentes é dada abaixo.

Cada um dos componentes é discutido com maior pormenor no documento, com

orientações para execução.

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/01

Page vi

Final

January 2006

Uma parte integrante da estrutura de gestão é a medição de base e programas de

monitorização a longo prazo. Como consequência, este relatório contempla igualmente os

protocolos da criação desses mesmos programas. Quanto a este aspecto, torna-se

importante salientar a diferença entre programas de estudos de referência (habitualmente

U

U

fazendo parte de Estudos de Avaliação Científica) e programas de monitorização

U

(desenvolvidos como fazendo parte de Programas de monitorização a Longo Prazo):

U

· Programas de estudos básicos (ou pesquisa) referem normalmente a investigações

intensivas de um conjunto de parâmetros de curto-prazo ou realizadas de uma só com

a finalidade de um melhor entendimento do funcionamento do ecossistema.

· Programas de monitorização a longo prazo referem-se a programas em curso de

recolha de dados (usando indicadores seleccionados), feitos para avaliar continuamente

a eficácia das estratégias/acções de gestão criadas para manter um estado ambiental,

de modo a que as respostas aos impactos potencialmente negativos, incluindo os

efeitos cumulativos, possam ser implementadas em devido tempo.

A implementação com sucesso da estrutura de gestão proposta assenta numa boa

cooperação, não só entre os vários departamentos governamentais e indústrias, mas

também na comunidade científica (que desempenha um papel chave no fornecimento de

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/01

Page vii

Final

January 2006

uma base científica sólida para uma tomada de decisão). É por esta razão, por isso, que os

investidores potenciais em cada um dos três países devem incluir membros de:

· Departamentos governamentais nacionais e regionais

· Autoridades de conservação da natureza

· Autoridades locais

· Comunidade

científica

· Indústrias que utilizam o meio ambiente marinho.

O inventário e a avaliação crítica dos dados e da informação disponíveis relevantes para a

gestão das fontes terrestres de poluição marinha na região do BCLME focalizados nos

principais nós de desenvolvimento na área, são apresentados de seguida:

ANGOLA

NAMÍBIA

ÁFRICA DA SUL

Cabinda

Henties Bay

St Helena Bay

Soyo

Walvis Bay/Swakopmund

Saldanha Bay/Langebaan Lagoon

Ambriz

Luderitz

Cape Peninsula (secção ocidental)

Luanda

Oranjemund (áreas das minas de

False Bay

Lobito

diamantes)

Walker Bay (Hermanus)

Namibe

Mossel Bay

Knysna Estuary

Os pontos seguintes definem o caminho a seguir:

· A estrutura proposta para a gestão das fontes terrestres de poluição marinha na região

do BCLME necessita ainda de ser oficialmente aprovada e adoptada pelas

autoridades governamentais responsáveis nos diferentes países.

· A estrutura de gestão desenvolvida como parte deste projecto está intimamente ligada

às linhas mestras da qualidade da água e dos sedimentos para as áreas costeiras

do BCLME (desenvolvidas como parte de um outro projecto BCLME o

BEHP/LBMP/03/04).

Neste entretanto, até que uma estrutura de gestão e as linhas mestras da qualidade da

água tenham sido incorporadas numa política governamental oficial, é proposto que a

estrutura de gestão desenvolvida como parte deste projecto, juntamente com as

orientações recomendadas para água e sedimentos, sejam aplicadas como

ferramentas preliminares com vista a melhorar a gestão da qualidade da água nas

áreas costeiras da região do BCLME.

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/01

Page viii

Final

January 2006

· O sistema de informação actualizável com suporte na Internet (endereço web

temporário: www.wamsys.co.za/bclme) desenvolvido como parte deste projecto pode

H

T

U

U

T

H

ser útil para apoiar a tomada de decisão e como ferramenta educativa, desde que

mantido e actualizado com regularidade. A curto e médio prazo, recomenda-se que um

ou mais escritórios do BCLME no âmbito dos três países seja por esse facto

responsável.

A fim de facilitar uma maior e mais vasta capacidade de construção no seio da região do

BCLME no que respeita à gestão da poluição marinha nas áreas costeiras, é fortemente

recomendado que os resultados deste projecto sejam incluídos num curso de formação.

Assim sendo, a Unidade de Desenvolvimento do Curso(Train-Sea-Coast/Benguela Course

Development Unit) é tido como a plataforma ideal para desenvolver e apresentar essa

formação (www.ioisa.org.za/tsc/index.htm).

H

T

U

U

T

H

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/01

Page ix

Final

January 2006

TABLE OF CONTENTS

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.......................................................................................................................................... i

T

U

U

T

TABLE OF CONTENTS .......................................................................................................................................... x

T

U

U

T

LIST OF TABLES ...................................................................................................................................................xii

T

U

U

T

LIST OF FIGURES.................................................................................................................................................xii

T

U

U

T

ACRONYMS, SYMBOLS AND ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................................................xiii

T

U

U

T

INTRODUCTION ______________________________________________________________________ 1

T

U

U

T

1. SCOPE OF WORK ____________________________________________________________________ 2

T

U

U

T

T

U

U

T

2. APPROACH AND METHODOLOGY ______________________________________________________ 4

T

U

U

T

T

U

U

T

3. INTRODUCTION TO PROPOSED MANAGEMENT FRAMEWORK ______________________________ 7

T

U

U

T

T

U

U

T

SECTION 1. GUIDANCE ON IMPLEMENTATION OF PROPOSED FRAMEWORK FOR

T

U

MANAGEMENT OF LAND-BASED SOURCES OF MARINE POLLUTION________ 1-1

U

T

1.1

LEGISLATIVE FRAMEWORK _______________________________________________________ 1-2

T

U

U

T

T

U

U

T

1.2

MANAGEMENT INSTITUTIONS & RESPONSIBILITIES___________________________________ 1-4

T

U

U

T

T

U

U

T

1.3

ENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY OBJECTIVES____________________________________________ 1-8

T

U

U

T

T

U

U

T

1.4

MARINE POLLUTION SOURCES ___________________________________________________ 1-12

T

U

U

T

T

U

U

T

1.4.1 Municipal Wastewater (including Sewage) ________________________________________ 1-16

T

U

U

T

T

U

U

T

1.4.2 Fishing industry _____________________________________________________________ 1-18

T

U

U

T

T

U

U

T

1.4.3 Oil Refineries _______________________________________________________________ 1-19

T

U

U

T

T

U

U

T

1.4.4 Coastal Mining______________________________________________________________ 1-19

T

U

U

T

T

U

U

T

1.4.5 Power Stations ______________________________________________________________ 1-19

T

U

U

T

T

U

U

T

1.4.6 Urban Stormwater Run-off_____________________________________________________ 1-20

T

U

U

T

T

U

U

T

1.4.7 Agricultural Runoff___________________________________________________________ 1-23

T

U

U

T

T

U

U

T

1.4.8 Atmospheric Pollution ________________________________________________________ 1-24

T

U

U

T

T

U

U

T

1.4.9 Dredging___________________________________________________________________ 1-24

T

U

U

T

T

U

U

T

1.4.10 Offshore Exploration and Production ____________________________________________ 1-25

T

U

U

T

T

U

U

T

1.4.11 Maritime Transportation ______________________________________________________ 1-27

T

U

U

T

T

U

U

T

1.5

SCIENTIFIC & ENGINEERING ASSESSMENT STUDIES_________________________________ 1-29

T

U

U

T

T

U

U

T

1.6

CRITICAL LIMITS AND MITIGATING ACTIONS ________________________________________ 1-32

T

U

U

T

T

U

U

T

1.7

LONG-TERM MONITORING PROGRAMMES __________________________________________ 1-33

T

U

U

T

T

U

U

T

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/01

Page x

Final

January 2006

SECTION 2. PROPOSED PROTOCOLS FOR BASELINE MEASUREMENT AND

T

U

LONG-TERM MONITORING PROGRAMMES ______________________________ 2-1

U

T

2.1

INTRODUCTION __________________________________________________________________ 2-2

T

U

U

T

T

U

U

T

2.2

BASELINE MEASUREMENT PROGRAMMES __________________________________________ 2-2

T

U

U

T

T

U

U

T

2.2.1

Physical Data ________________________________________________________________ 2-3

T

U

U

T

T

U

U

T

2.2.2 Biogeochemical Data _________________________________________________________ 2-10

T

U

U

T

T

U

U

T

2.2.3 Biological data ______________________________________________________________ 2-14

T

U

U

T

T

U

U

T

2.3

LONG-TERM MONITORING PROGRAMMES __________________________________________ 2-15

T

U

U

T

T

U

U

T

2.3.1 Source Monitoring ___________________________________________________________ 2-16

T

U

U

T

T

U

U

T

2.3.2 Environmental Monitoring _____________________________________________________ 2-17

T

U

U

T

T

U

U

T

SECTION 3. PRELIMINARY IDENTIFICATION OF KEY STAKEHOLDERS INVOLVED

T

U

IN MANAGEMENT OF LAND-BASED MARINE POLLUTION SOURCES IN THE

BCLME REGION _____________________________________________________ 3-1

U

T

SECTION 4. DESKTOP ASSESSMENT STUDIES ON EXISTING INFORMATION

T

U

PERTAINING TO MANAGEMENT OF LAND-BASED SOURCES OF MARINE

POLLUTION _________________________________________________________ 4-1

U

T

SECTION 5. THE WAY FORWARD ______________________________________ 5-1

T

U

U

T

SECTION 6. REFERENCES ____________________________________________ 6-1

T

U

U

T

Appendix A

Desktop Assessment of Available Information and Initiatives: South Africa

Appendix B

Desktop Assessment of Available Information and Initiatives: Namibia

Appendix C

Desktop Assessment of Available Information and Initiatives: Angola

Appendix D

User Manual for Web-based Information System

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/01

Page xi

Final

January 2006

LIST OF TABLES

TABLE 2.1: Checklist for selection of measurement parameters (from ANZECC, 2000b) ............................2-21

T

U

U

T

T

U

U

T

TABLE 3.1: Preliminary list of key stakeholders in Angola ..............................................................................3-3

T

U

U

T

T

U

U

T

TABLE 3.2: Preliminary list of key stakeholders in Namibia ............................................................................3-3

T

U

U

T

T

U

U

T

TABLE 3.3: Preliminary list of key stakeholders in South Africa......................................................................3-4

T

U

U

T

T

U

U

T

TABLE 4.1: Development nodes selected for the BCLME region....................................................................4-2

T

U

U

T

T

U

U

T

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1:

Boundaries of the Coastal Zone of the BCLME region.................................................................... 2

T

U

U

T

T

U

U

T

Figure 2:

Proposed framework for the design and implementation of marine water quality management

T

U

U

T

T

U

programmes in the BCLME region .................................................................................................. 7

U

T

Figure 1.1: Mapping of important marine aquatic ecosystems and designated (beneficial uses in Saldanha

T

U

U

T

T

U

Bay/Langebaan along the west coast of South Africa (adapted from Taljaard & Monteiro,

2002) 1-10

U

T

Figure 1.2: Mapping of potential marine pollution sources in Saldanha Bay/Langebaan along the west coast

T

U

U

T

T

U

of South Africa (adapted from Taljaard & Monteiro, 2002) .........................................................1-15

U

T

Figure 1.3:

A schematic illustration of the different treatment processes for municipal wastewater (sewage)

T

U

U

T

T

U

(taken from RSA DWAF, 2004b)................................................................................................1-17

U

T

Figure 1.4:

A schematic illustration of components to be addressed as part of scientific and assessment

T

U

U

T

T

U

studies, highlighting key engineering aspects (e.g. related to the design of marine wastewater

disposal scheme) (adapted from RSA DWAF, 2004b)...............................................................1-31

U

T

Figure 2.1:

Example of bathymetric contour map and typical profile (taken form RSA DWAF, 2004b)..........2-4

T

U

U

T

T

U

U

T

Figure 2.2:

Typical diurnal land- sea breeze variations (taken from RSA DWAF, 2004b)..............................2-5

T

U

U

T

T

U

U

T

Figure 2.3:

Time series data showing current velocities, directions and vectors (taken from RSA DWAF,

T

U

U

T

T

U

2004b) ..........................................................................................................................................2-7

U

T

Figure 2.4: Spatial plot of the distribution of particle size in Saldanha Bay (South Africa) (Monteiro et al.,

T

U

U

T

T

U

1999) ............................................................................................................................................2-9

U

T

Figure 2.5:

Sub-bottom profile derived from a seismic trace (taken form RSA DWAF, 2004b) ......................2-9

T

U

U

T

T

U

U

T

Figure 2.6:

Dissolved oxygen variability (m/) in the bottom water layer in Saldanha Bay, South Africa (from

T

U

U

T

T

U

Monteiro et al., 1999) .................................................................................................................2-12

U

T

Figure 2.7:

Key aspects to be addressed as part of long-term monitoring programmes ..............................2-18

T

U

U

T

T

U

U

T

Figure 4.1:

Development nodes selected for the BCLME region....................................................................4-2

T

U

U

T

T

U

U

T

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/01

Page xii

Final

January 2006

ACRONYMS, SYMBOLS AND ABBREVIATIONS

ANZECC

Australia and New Zealand Environment and Conservation Council

ANZFA

Australia New Zealand Food Authority

BCLME

Benguela Current Large Marine Ecosystem

CCME

Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment

CEC

Council of the European Community

CTD

Conductivity-Temperature-Depth

DEAT

Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism (RSA)

DWAF

Department of Water Affairs and Forestry (RSA)

Group of Experts on the Scientific Aspects of Marine Pollution

GESAMP

(United Nations)

Global Programme of Action for the Protection of the Marine

GPA

Environment from Land-Based Activities

IMO

International Maritime Organization

PAH

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons

PCB

Polychlorinated biphenyls

RSA

Republic of South Africa

SBWQFT

Saldanha Bay Water Quality Forum Trust

UNCLOS

United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea

UNEP

United Nations Environmental Programme

US FDA

United States Food And Drug Administration

US-EPA

United States Environmental Protection Agency

WSSD

World Summit on Sustainable Development

WWTW

Wastewater Treatment Works

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/01

Page xiii

Final

January 2006

INTRODUCTION

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/01

Page 1

Introduction

January 2006

Final

1. SCOPE

OF

WORK

The United Nations Office for Project Services ("UNOPS") commissioned the CSIR to

conduct a baseline assessment of sources and management of land-based marine pollution

in the Benguela Current Large Marine Ecosystem (BCLME) Region.

The primary purpose of this project was to standardize the approach and methodology by

which land-based marine pollution sources in the BCLME region are managed. This was

achieved through the preparation of a generic (draft) management framework for the

management of such sources, including protocols for the design of baseline measurements

and long-term monitoring programmes. It is important to realize that, although it is possible

to put forward a generic management framework for such a large region, the implementation

of the management framework will ultimately be more site-specific.

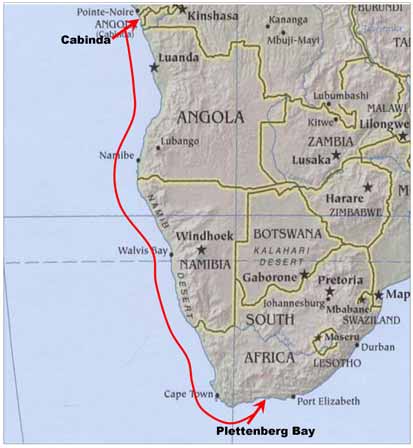

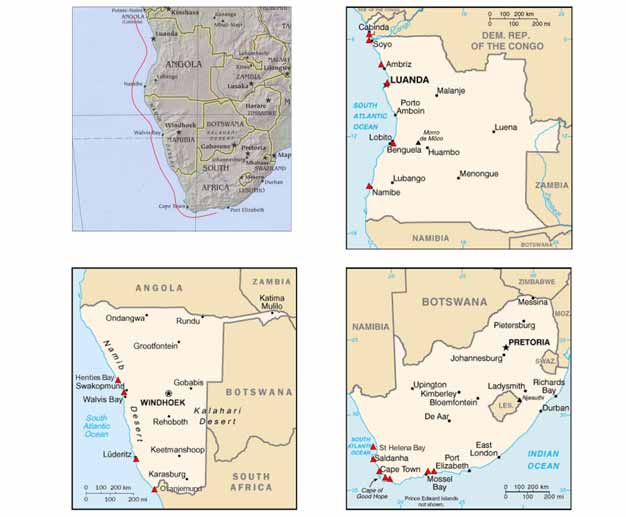

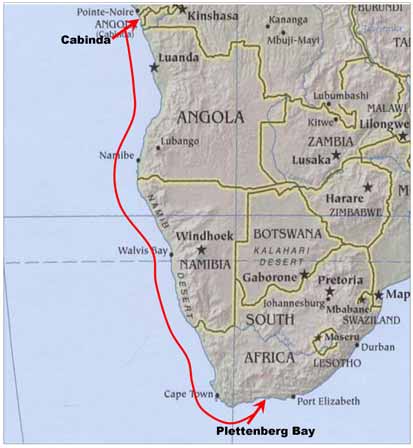

The BCLME region is situated along the coast of south- western Africa, stretching from east

of the Cape of Good Hope in the south (Plettenberg Bay) northwards to Cabinda in Angola,

and encompassing the full extent of Namibia's marine environment (Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Boundaries of the Coastal Zone of the BCLME region

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/01

Page 2

Introduction

January 2006

Final

An important secondary objective of this project was to initiate the establishment of a

BCLME coastal water quality network to provide a legacy of shared experience, awareness

of tools, capabilities and technical support. This network had to be supported by an

updatable web-based information system, providing guidance and protocols on the

implementation of the generic management framework. The web-based information system

also had to contain a meta-database on available information and expertise.

The main outputs of this project, therefore, are:

· A proposed (or draft) framework for managing a land-based source of marine pollution,

U

U

including guidance on the implementation of such a framework

· Propose protocols for the design of baseline measurement and long-term monitoring

U

programmes related to the management of land-based marine pollution sources in the

U

BCLME region

· A preliminary list of key stakeholders involved in the management of marine pollution in

U

U

each of the three countries

· An inventory and critical assessment of available information and data related to the

U

U

management of (land-based) marine pollution sources in Angola, Namibia and South

Africa

· Updatable web-based information system that provides guidance on the application of

U

U

the generic management framework, as well as a meta-database on available

information and expertise in the BCLME region.

In the Introduction to this Report, the Scope of Work (Chapter 1) is followed by a chapter

describing the Approach and Methodology (Chapter 2) that were used in the development of

the proposed management framework, followed in turn by a short Introduction to the

Proposed Management Framework (Chapter 3).

Thereafter the layout of the report is as follows:

· Section 1: Guidance on the implementation of the proposed management framework,

highlighting key aspects that need to be addressed within each of the identified

components

· Section 2: Proposed protocols (or guidance) for consideration in the design of baseline

measurement and long-term monitoring programmes

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/01

Page 3

Introduction

January 2006

Final

· Section 3: Preliminary list of key stakeholders involved in the management of marine

pollution sources in the BCLME region

· Section 4: Introduction to the Desktop Assessment Studies on existing information

pertaining to Land-based Sources of Marine Pollution in the BCLME region

· Appendices A, B and C: Detailed desktop assessment studies on existing information

pertaining to land-based sources of marine pollution for South Africa, Namibia and

Angola.

· Appendix D: User Manual for the Web-based Information System (temporary web

address: www.wamsys.co.za.

H

T

U

U

T

H

2. APPROACH

AND

METHODOLOGY

The challenge in ecosystem management is to ensure sustainable development, which is

defined as:

".. development which fulfils the needs of the present generation without jeopardizing the possibilities

of future generations to fulfill their needs."

This definition is echoed by the consensus agreement that was formed at the United

Nation's Conference on Environmental Development, which was held in Rio de Janeiro

(1992):

· The overall aim of the development of any society should be sustainable development

· Sustainable development encompasses environmental, economic, and social

dimensions

· Sustainable development demands not only a governmental effort, but also an effort

from all levels of society, from the global to the local perspective

· International co-operation is a prerequisite for sustainable development.

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/01

Page 4

Introduction

January 2006

Final

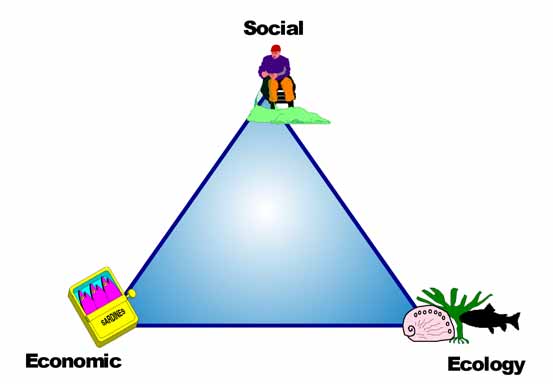

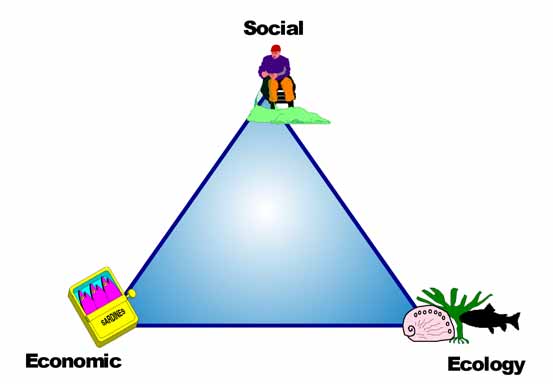

Thus, in order to be sustainable, development must be economically profitable, ecologically

proper, and socially acceptable. These three considerations are described as the

`sustainability triangle':

Since nature is a complex of dynamic processes, sustainable management of any

ecosystem implies that emphasis on the three priorities (i.e. various economic, ecological

and social considerations) over time may not always be equal. However, as long as the

management of the system does not go beyond the bounds of the `sustainability triangle',

the management and development of the system could be characterized as sustainable.

In this context, the ultimate goal in the management of coastal water resources is to keep the

environment suitable for all designated uses both existing and future uses. To achieve this

goal, is important to protect the biodiversity and functioning of marine aquatic ecosystems

U

U

(i.e. ecology) so as to support important (beneficial) uses of the marine environment (i.e.

U

U

social and economic values).

Land-based sources of marine pollution, amongst others, are posing an increasing threat to

the sustainability of the ecological, social and economic functions of the marine environment,

even though the associated activities and developments may create social and economic

benefits elsewhere. Towards combating this threat, the Global Programme of Action for the

Protection of the Marine Environment from Land-Based Activities (GPA), was adopted in

November 1995. It is designed to assist states in taking action individually or jointly within

their respective policies, priorities and resources that will lead to the prevention, reduction,

control or elimination of the degradation of the marine environment, as well as to its recovery

from the impacts of land-based activities (www.gpa.unep.org/).

T

T

H

T

U

U

T

H

T

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/01

Page 5

Introduction

January 2006

Final

In 2004, the CSIR assisted the South African Department of Water Affairs and Forestry with

the Development of an Operational Policy for the Disposal of Land-derived Wastewater to

the Marine Environment of South Africa (RSA DWAF, 2004a). As part of this operational

policy, a management framework was proposed for the management of land-based disposal

to the marine environment. The framework proposed for the management of land-based

sources of marine pollution in the BCLME region, as part of this project, is largely based on

this management framework, the motivation for this approach being:

· that the framework developed as part of South Africa's operational policy in 2004 was

already based on a review of international best practice and own experience in the

south(ern) African context

· rather adapt successful management practices that already exist in one or more

countries within the BCLME region, than `re-invent the wheel'.

The proposed management framework promotes an ecosystem-based approach, rather than

managing pollution sources on an individual basis. It identifies key components to be

addressed in the management of marine pollution sources, as well as the linkages between

such components. Baseline measurement and long-term monitoring programmes form an

integral part of the framework.

South Africa's operational policy also includes detailed guidance on the implementation of a

management framework, particularly aimed at managers, responsible authorities and

scientists who typically form part of such a process (RSA DWAF, 2004b). For the same

reasons as listed above, the guidance on implementation was also largely based on

approach and methods of this policy.

Also incorporated was the CSIR's experience in applying a similar framework in Saldanha

Bay, when it assisted local authorities with the development of a marine water quality

management plan for the area. Saldanha Bay is situated along the west coast of South

Africa, within the BCLME region (Taljaard & Monteiro, 2002; Monteiro & Kemp, 2004). A

similar exercise has also been conducted in False Bay, a large bay just south of Cape Town,

also within the BCLME region (Taljaard et al., 2000).

The framework proposed for the management of marine pollution in the BCLME region, as

part of this project, is also similar to the Framework for Marine and Estuarine Water Quality

Protection that forms part of the Coastal Catchments Initiative, which has been launched in

Australia to improve coastal water quality (Australian Government, 2005).

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/01

Page 6

Introduction

January 2006

Final

3. INTRODUCTION

TO

PROPOSED MANAGEMENT

FRAMEWORK

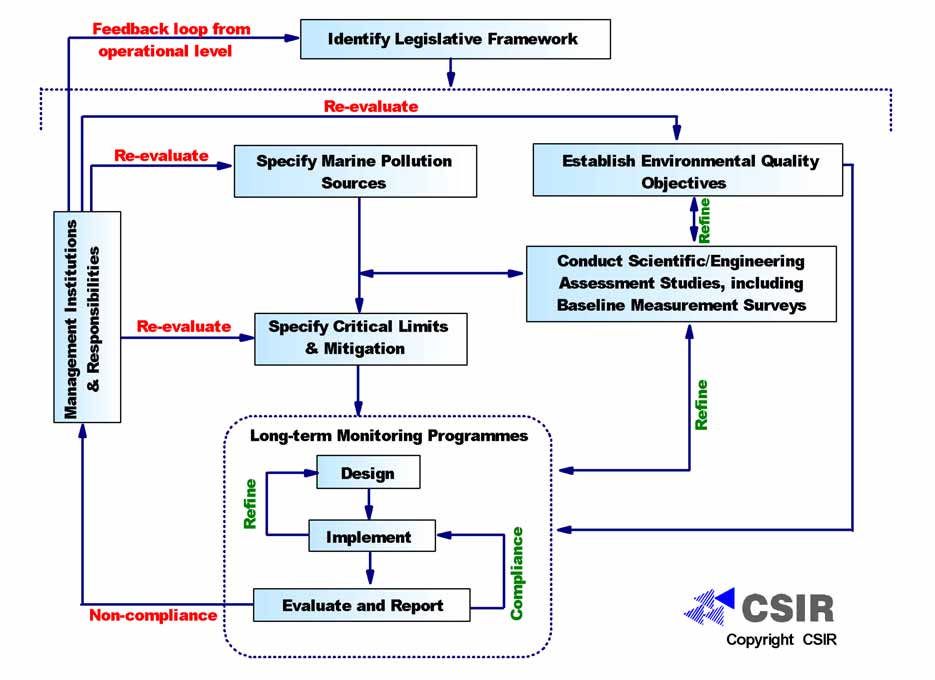

Based on a review of international practice and own experience in the South African context,

the following key components should be included in a management framework for marine

pollution (including land-based sources):

· Identification of legislative framework

· Establishment of management institutions and responsibilities

· Determination of environmental quality objectives

· Specification of marine pollution sources

· Scientific/engineering assessment studies

· Specification of critical limits and mitigation measures

· Design and implementation of long-term monitoring programmes.

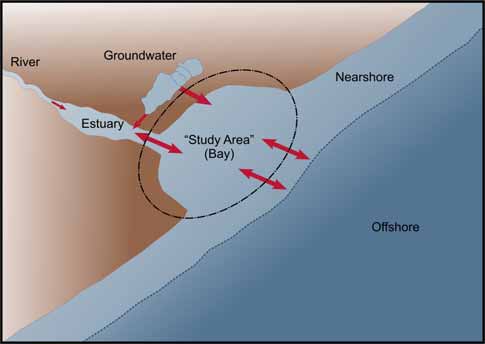

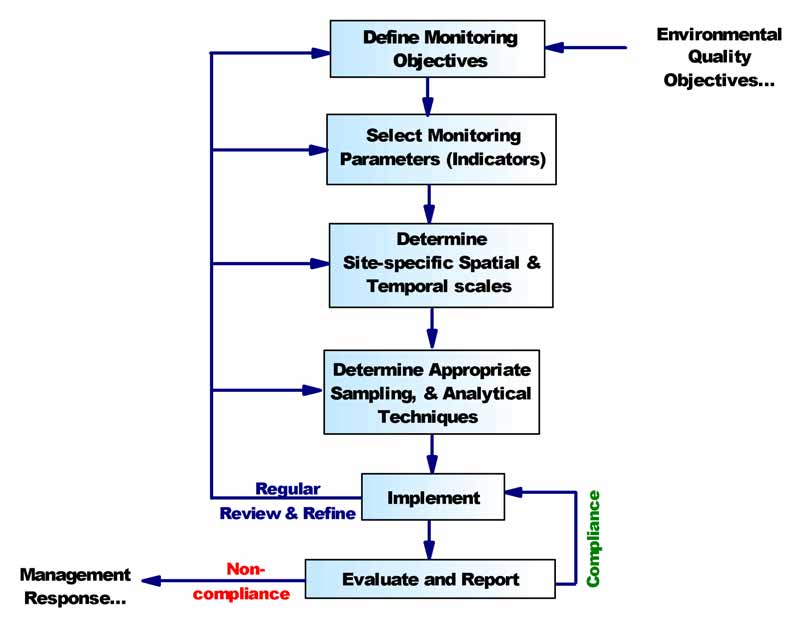

A schematic illustration of the inter-linkages between these components is provided in

Figure 2. Each of the components is discussed in more detail in Section 2, including

guidance on implementation.

Figure 2:

Proposed framework for the design and implementation of marine water quality

management programmes in the BCLME region

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/01

Page 7

Introduction

January 2006

Final

SECTION 1.

GUIDANCE ON IMPLEMENTATION OF

PROPOSED FRAMEWORK FOR MANAGEMENT

OF LAND-BASED SOURCES OF MARINE

POLLUTION

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/01

Page 1-1

Section 1

January 2006

Final

1.1 LEGISLATIVE

FRAMEWORK

A marine water quality management programme needs to be designed and implemented

within the statutory framework governing marine pollution, taking into account international

and national legislation. Assessments of the current legislative framework governing such

matters in each of the three countries in the BCLME region are provided in Appendix A

(South Africa), Appendix B (Namibia) and Appendix C (Angola).

Although the national legislative framework differs from one country to another, key

international programmes, treaties and conventions relating to the management of land-

based marine pollution sources that may apply, depending on whether a country is a

signatory to such agreements, include:

· Agenda 21, the internationally accepted strategy for sustainable development decided

upon at the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) held

in Rio de Janeiro in 1992. Agenda 21 is a plan for use by governments, local authorities

and individuals to implement the principle of sustainable development contained in the

Rio Declaration. This document has significant status as a consensus document adopted

by about 180 countries. Agenda 21 is, however, not legally binding on states, and merely

acts as a guideline for implementation (www.un.org/esa/sustdev/agenda21text.htm).

H

T

U

U

T

H

· Global Programme of Action for the Protection of the Marine Environment from

Land-Based Activities (GPA), which was adopted in November 1995 and which is

designed to assist states in taking action individually or jointly within their respective

policies, priorities and resources that will lead to the prevention, reduction, control or

elimination of the degradation of the marine environment, as well as to its recovery from

the impacts of land-based activities. The GPA builds on the principles of Agenda 21.

The GPA identifies the Regional Seas Programme of UNEP as an appropriate

framework for delivery of the GPA at the regional level (www.gpa.unep.org/).

H

T

U

U

T

H

· World Summit on Sustainable Development (WSSD) (2002) - the Johannesburg

summit formulated two new principles that are central to the philosophy of managing

marine water quality at the system scale (www.gpa.unep.org/news/gpanew.html):

H

T

U

U

T

H

- Firstly, the call for a shift away from individual resources towards ecosystem-based

management of coastal systems

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/01

Page 1-2

Section 1

January 2006

Final

- Setting of wastewater emission targets (WET), which limit the upper boundary of

land-based discharge fluxes into coastal systems to a level in which ecosystem

impacts are not measurable.

· United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP), which was initiated in 1972 and

which contains several programmes considering marine pollution, e.g. the Ocean and

Coastal Areas Programmes and the Regional Sea Programmes (www.unep.org/).

H

T

U

U

T

H

· United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) (1982) which lay down,

first of all, the fundamental obligation of all states to protect and preserve the marine

environment. It further urges all states to cooperate on a global and regional basis in

formulating rules and standards and to otherwise take measures for the same purpose.

It addresses six main sources of ocean pollution: land-based and coastal activities,

continental-shelf drilling, potential seabed mining, ocean dumping, vessel-source

pollution, and pollution from or through the atmosphere

(www.un.org/Depts/los/index.htm).

H

T

U

U

T

H

· United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity (1992), which came into force in

December 1993 and which has three main objectives, namely, the conservation of

biological diversity; the sustainable use of biological resources; and the fair and

equitable sharing of benefits arising from the use of genetic resources (www.biodiv.org).

H

T

U

U

T

H

Important international conventions that relate to marine pollution, but that are not

necessarily directly linked to land-based sources, include:

· London Convention for the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping of Wastes

and Other Matter (1972, amended 1978, 1980, 1989). In November 1996, the

contracting parties to the London Convention of 1972 adopted the 1996 Protocol, which,

when entered into force, replaces the London Convention

(www.londonconvention.org/London_Convention.htm) (related to dumping at sea)

H

T

U

U

T

H

· International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL

convention) (1973/1978), which is the main international convention covering

prevention of pollution of the marine environment by ships from operational or accidental

causes and includes regulations aimed at preventing and minimizing pollution from ships

- both accidental pollution and that from routine operations (www.imo.org/home.asp)

H

T

U

U

T

H

(related to maritime transportation).

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/01

Page 1-3

Section 1

January 2006

Final

Effective legislation (together with practical operational policies and protocols) is a key

requirement for the successful management of marine pollution in a particular country. A

sound legislative framework, for example, empowers responsible authorities to legally

challenge offenders, provided that such legislation is supported by sufficient resources (both

human and financial).

1.2 MANAGEMENT

INSTITUTIONS & RESPONSIBILITIES

A key driving factor in the successful operation of any management programme is the

establishment of the appropriate management institution/s, which includes identifying the

roles and responsibilities of the different parties. Again, the legislative framework within a

particular country should provide specifications and guidance in this regard.

In the management and control of marine pollution sources (including land-based sources),

responsibilities traditionally resided with the responsible government authorities as well as

the impactors (e.g. municipalities, industry and developers). Although these traditional

management structures are still important, the value of also involving other local interested

and affected parties through stakeholder forums or local management institutions, has

proved to add great value to the overall management process (Henocque, 2001; Van Wyk,

2001; Taljaard & Monteiro, 2002; Cape Metropolitan Coastal Water Quality Committee,

2003).

Not only do these local management institutions provide an ideal platform through which to

consult interested and affected parties on, for example, designated uses and environmental

quality objectives for a specific area, but they also fulfil the important role of `local

watchdogs' or `custodians'. Although such institutions usually do not have executive

powers, they have shown themselves to be very successful mechanisms through which to

empower (and often pressurize) responsible authorities to execute their legal responsibilities,

e.g. ensuring that licence agreements are issued or that corrective action is taken timeously

in instances of non-compliance.

The key to the success of local management institutions is a sound scientific information

base, containing explicit scientific assumptions and outcomes, by which authorities, and also

local stakeholders, are empowered to partake in the decision- making process.

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/01

Page 1-4

Section 1

January 2006

Final

It is also essential that local management institutions include all relevant interested and

affected parties in order to facilitate a participatory approach to decision-making. The

inclusion of responsible local, regional and national government authorities is also important,

as these usually form the routes through which local management institutions have/hold

executive powers. Local management institutions should therefore include representatives

from, for example:

· National and regional government departments

· Nature conservation authorities

· Local authorities

· Industries

· Tourism boards and recreation clubs

· Local residents, e.g. through ratepayers' association

· Non-government

organizations.

Where more than one source is responsible for pollution in a particular area (e.g. a bay

area), it is usually extremely difficult and financially uneconomical to manage marine

pollution issues in isolation because of potential cumulative or synergistic effects. In such

instances, collaboration is also best achieved through a joint local management institution.

A local management institution, being actively involved in the management of marine

pollution matters at local level, is also ideally positioned to test the effectiveness and

applicability of legislation and policies, which are normally developed at national or regional

levels. It is therefore also important that these institutions be utilized by higher tiers of

government as a mechanism for improving legislative frameworks related to the

management of marine pollution. Such practice supports the principle of Adaptive

Management.

For the BCLME region, the coastal water quality network group, initiated as part of this

study, will assist in empowering authorities in the different countries to fulfil their role as

national manager of marine water quality. Furthermore, it is envisaged that the web- based

information system will provide to all concerned easy access to guidance and protocols on

the implementation of the generic management framework, as well as a meta-database on

available information and expertise.

Within the BCLME region, the Saldanha Bay Water Quality Forum Trust (SBWQFT) is an

example of an existing local management institution that works very well. The forum was

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/01

Page 1-5

Section 1

January 2006

Final

established in June 1996 through the efforts of individuals with an interest in Saldanha Bay

who created an awareness of the need to address the deteriorating water quality in the Bay.

The SBWQFT is a voluntary organization comprising officials from local (municipality, Nature

conservation), regional (regional office of the Department of Water Affairs and Forestry) and

national authorities (Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism), representatives from

all major industries in the area (e.g. National Ports Authority, seafood processing industries,

marine aquaculture farmers) and other groups who have a common interest in the area (e.g.

tourism).

The main purpose of the SBWQFT is to work towards maintaining water quality and

ecosystem functioning so as to keep Saldanha Bay fit for all its designated uses. Although

the Trust does not have legislative powers, it acts as an advisory body to legislative

authorities that are also members of the forum (e.g. Department of Water Affairs and

Forestry, Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism, National Ports Authority,

Saldanha Bay Municipality). Through this route the Trust can thereby influence the decision-

making process. A quote from Bay Watch, the publication of the Trust (SBWQFT, 2004)

probably explains this best: `This is a most unique forum in that, as far as I am aware, it is a

the only non-government body that is totally successful in melding the private sector with

their contributions and the government with their overseeing capacity, to form a unit that is

ultimately functional and effective.'

The

organizational

structure of the

Trust is

illustrated below

(SBWQFT,

2004):

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/01

Page 1-6

Section 1

January 2006

Final

The SBWQFT raises funding by applying the principle of `Polluter Pays' whereby major

industries contribute. These financial resources are utilized towards:

· Commissioning scientific investigation to make informed decisions on the management

of the area, albeit through advising the relevant government authorities (e.g. CSIR was

commissioned to assist them with developing a management plan)

· Commissioning coordinated joint monitoring programmes in the area (e.g. CSIR was

commissioned to conducting a sediment monitoring programme, while the Trust

conducts its own microbiological programme)

· Producing communication tools to inform the wider community, such as the Bay Watch

publication.

Because the Trust has a mechanism in place to generate its own funds it can commission

scientific investigations (e.g. the development of the management plan for Saldanha Bay

was commissioned through a tender process). The Trust within itself also has water quality

management expertise, e.g. one of the members is responsible for running the

microbiological programme in the Bay. Local expertise is also sourced, e.g. at a recent

public meeting a local resident with experience in oil spill contingency planning provided his

services.

Analysis of the manner in which the SBWQFT operates highlights key success factors of a

local management institution that include:

· An enthusiastic executive chairperson who will keep things going!

· Active involvement of relevant government authorities (e.g. with executive powers in the

domain of marine pollution and related matters)

· A mechanism in place to generate funds to, for example:

- commission joint scientific investigations

- produce communication tools to inform the wider local community (e.g. local news-

letters

· Ensuring that all role players are on board, either actively through being members of the

Trust or by involving them through regular public feedback meetings (at least annually or

U

U

bi-annually).

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/01

Page 1-7

Section 1

January 2006

Final

1.3 ENVIRONMENTAL

QUALITY

OBJECTIVES

Environmental quality objectives must be set as part of the management framework to

provide a basis from which to assess and evaluate management strategies and actions.

This can be achieved through a four-step approach:

· Define geographical boundaries of study area

· Define important aquatic ecosystems and designated uses within area

· Define management goals for important aquatic ecosystems and designated use areas

· Determine site-specific (measurable) environmental quality objectives, pertaining to

sediment and water quality requirements.

A first and very important step in setting environmental quality objectives is to determine the

geographical boundaries of the area within which the management framework is to be

U

U

implemented. The anticipated influence of all major human activities and developments,

both in the near and far field, must be taken into account, including the location of and inputs

from different marine pollution sources. Important issues that need to addressed, include:

· Proximity of depositional areas in which pollutants introduced from one or more pollution

sources can accumulative these can be at distant locations for specific sources,

particularly where the source discharges into a very dynamic environment, but then gets

transported to an area of lower turbulence

· Possible synergistic effects in which the negative impacts from a particular source could

be aggravated through interactions with pollutants introduced by other pollution sources

in the area, or even through interaction with natural processes.

The ultimate goal in the management of the marine waters is to keep the environment

suitable for all designated uses both for existing and future uses (this includes the `use' of

designated areas for biodiversity protection and ecosystem functioning). The second step,

therefore, is to identify and map important aquatic ecosystems and designated uses within

U

U

the study area.

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/01

Page 1-8

Section 1

January 2006

Final

For the BCLME region, it has been proposed that three designated uses of the coastal

marine environment be recognised, namely:

· Marine aquaculture (including collection of seafood for human consumption)

· Recreational use

· Industrial uses (e.g. seawater intakes for seafood processing, cooling water intakes,

harbour and ports).

Management goals should be defined for each of the above uses. In the case of the

U

U

protection of the aquatic marine ecosystem, these can be quantified in terms of the level of

species diversity that needs to be maintained, while in the case of recreational or marine

aquaculture areas, the management goal could be to achieve a certain rating or

classification. Similar to the European Union's approach, it is proposed that, for the

BCLME region, in contrast to designated use areas where protection is required only in the

specific area where such a use occurs (e.g. popular recreation beach), protection of marine

aquatic ecosystems should be striven for in all waters (CEC, 2003). ,the exception to this

being perhaps in approved sacrificial zones (e.g. in proximity to wastewater discharges and

U

U

certain areas within ports) the rationale being that the natural environment needs to be

protected to a high level in its entirety.

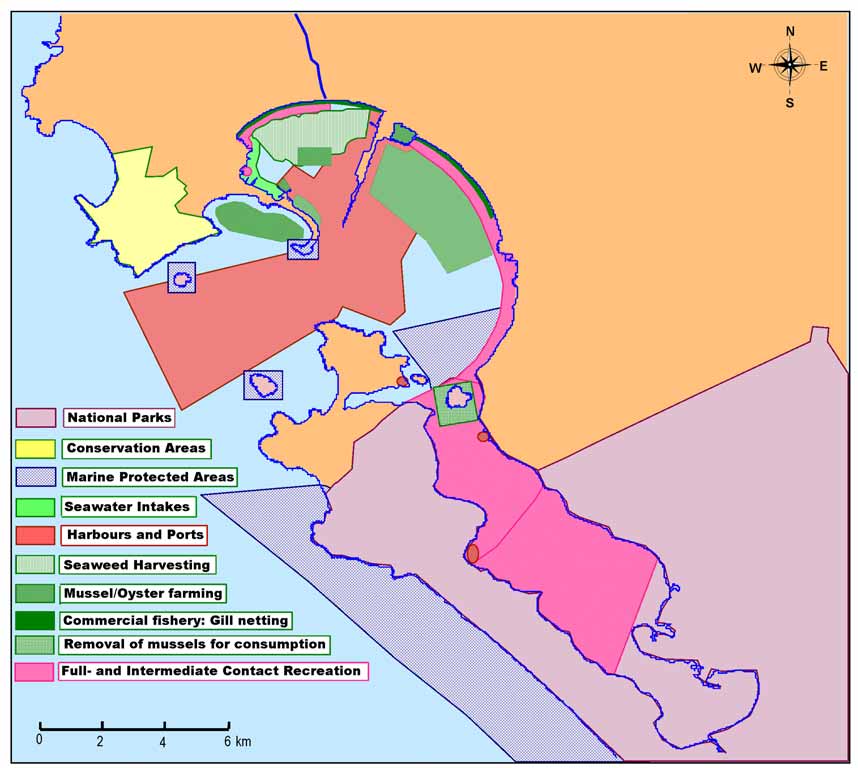

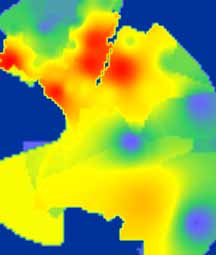

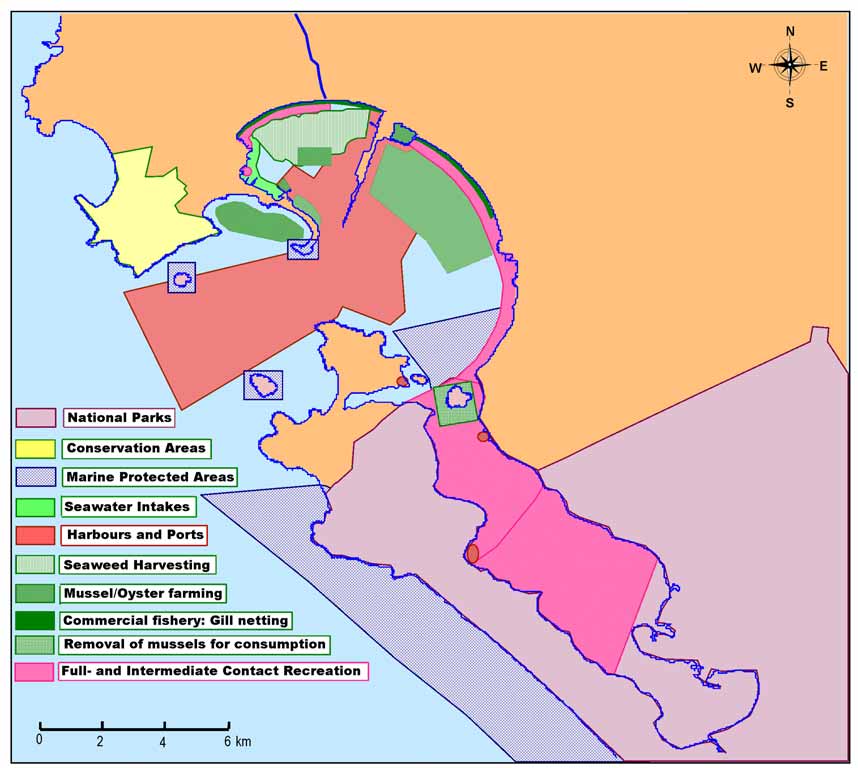

Agreement on the designated uses and management goals of a particular area should be

obtained in consultation with local interested and affected parties (or stakeholders) through,

for example, the local management institutions. An example of a designated (beneficial) use

map is that for the Saldanha Bay/Langebaan Lagoon area along the west coast of South

Africa (Figure 1.1). This map was compiled in consultation with local stakeholders, using the

Saldanha Bay Water Quality Forum Trust (local management institution) as vehicle.

Once agreement has been obtained on important aquatic ecosystems and designated uses,

their location, as well as the management goals for each particular area, site-specific

U

environmental quality objectives pertaining to sediment and water quality requirements need

U

to be derived. The rationale here is that, although management goals are the real

management end-points, the goals will only be achieved if certain sediment and water quality

targets are maintained, as the proximal causes in the causeeffect relationship (Ward and

Jacoby, 1992).

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/01

Page 1-9

Section 1

January 2006

Final

Figure 1.1:

Mapping of important marine aquatic ecosystems and designated (beneficial

uses in Saldanha Bay/Langebaan along the west coast of South Africa

(adapted from Taljaard & Monteiro, 2002)

It is in setting these site-specific environmental quality objectives that the national (or

regional) water and sediment quality guidelines provide valuable guidance to managers and

U

U

local governing authorities.

NOTE:

Recommended water and sediment quality guidelines for the coastal zone of the BCLME regions and its

beneficial uses are addressed as part of another BCLME project, namely The development of a common set

of water and sediment quality guidelines for the coastal zone of the BCLME region Project

BEHP/LBMP/03/04)

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/01

Page 1-10

Section 1

January 2006

Final

Quality objectives could also be prescribed in legislation. For example, the concentration of

U

U

pathogens and toxicants in seafood (which will be relevant to areas used for the culture of

shellfish) are typically prescribed in national legislation, such as in:

· South Africa, where limits for chemical and pathogens are specified under the

Foodstuffs, Cosmetics and Disinfectants Act (No. 54 of 1972) (Department of Health,

1973, 1994)

· European Union, where limits for shellfish flesh are specified in the Shellfish Hygiene

Directive (CEC, 1991).

· Australia and New Zealand, where these limits are specified under the Food Standards

Code (ANZFA 1996, and updates)

· United States Food and Drug Administration which specifies such limits for the United

States see website on Seafood Information and Resources (US FDA, 2004) and

National Shellfish Sanitation Program (US FDA, 2003)

· Canada, where the Canadian Food Inspection Agency specifies action levels (Canadian

Food Inspection Agency, 2004).

Development of site-specific environmental quality objectives requires knowledge of the

chemical, physical, and biological properties of a water body, as well as the social and

economic conditions of an area.

As a minimum, environmental quality objectives should protect the existing and potential

uses of a water body. Where water bodies are considered to be of exceptional value, or

where they support valuable biological resources, degradation of the existing water quality

should always be avoided. Similarly, site-specific objectives should not be made on the basis

of aquatic ecosystem characteristics that have arisen as a direct result of previous human

activities (CCME, 1995).

Social and economic factors need to be evaluated to determine if the environmental quality

objectives can realistically be attained. For example, when setting critical limits for pollution

sources (e.g. wastewater emission standards) so as to meet quality objectives, social and

economic factors can be factored in by giving longer deadlines to smooth out the transition

period. Periodic re-evaluations and refinements of environmental quality objectives are then

implemented to ensure that the desired water quality is ultimately maintained.

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/01

Page 1-11

Section 1

January 2006

Final

1.4 MARINE

POLLUTION

SOURCES

The United Nation's Group of Experts on the Scientific Aspects of Marine Pollution defines

marine pollution as the (GESAMP, 1999):

Introduction by man, directly or indirectly, of substances or energy into the marine

environment (including estuaries) resulting in such deleterious effects as to cause(?) harm to

living resources, hazard to human health, hindrance to marine activities including fishing,

impairment of quality for use of seawater, and reduction of amenities.

Effective management of marine pollution in a particular area requires, amongst other things,

quantitative data on marine pollution sources, as well as on other activities or developments

that directly (or indirectly) affect water and sediment quality. Although human perturbations

of marine water and sediment quality are usually perceived to be the result of marine

pollution sources, it is important to realize that developments that modify circulation

dynamics in the marine environment, such as harbour and marina structures, can also

modify these quality characteristics.

Marine pollution sources can broadly be categorized into the following groups of activities,

which occur either at sea or on land:

· Pollution or waste originating from land-based sources, including sewage effluent

U

U

discharges, industrial effluent discharges, stormwater run-off, agricultural and mining

return flows, contaminated groundwater seepage

· Pollution or waste entering the marine environment through the atmosphere, e.g.

U

U

originating from vehicle exhaust fumes and industries

· Maritime transportation (which includes accidental and purposive oil spills, and dumping

U

U

of ship garbage etc.)

· Dumping at sea (e.g. dredge spoil)

U

U

· Offshore exploration and production (e.g. oil exploration platforms).

U

U

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/01

Page 1-12

Section 1

January 2006

Final

Of the different sources of marine pollution, land-based sources are considered to be the

largest - based on studies by the International Maritime Organisation (IMO, 1977):

NOTE:

Depending on the type of impact on the aquatic organisms, communities, and ecosystems, pollutants can

further be grouped in the following order of increasing hazard (Patin, 2004):

· substances causing mechanical impacts (suspensions, films, solid wastes) that damage the respiratory

organs, digestive system, and receptive ability;

· substances provoking eutrophic effects (e.g., mineral compounds of nitrogen and phosphorus, and

organic substances) that cause mass rapid growth of phytoplankton and disturbances of the balance,

structure, and functions of the water ecosystems;

· substances with saprogenic properties (sewage with a high content of easily decomposing organic

matter) that cause oxygen deficiency followed by mass mortality of water organisms, and appearance

of specific microphlora;

· substances causing toxic effects (e.g., heavy metals, chlorinated hydrocarbons, dioxins, and furans)

that damage the physiological processes and functions of reproduction, feeding, and respiration;

· substances with mutagenic properties (e.g., benzo(a)pyrene and other polycyclic aromatic compounds,

biphenyls, radionuclides) that cause carcinogenic, mutagenic, and teratogenic effects.

Focusing on land-based marine pollution sources shows that these can be sub-divided into:

· Point sources (i.e. sources of which the volume and quality can be readily controlled)

· Non-point (or diffuse) sources (i.e. sources of which the volume and quality are difficult to

control).

Point sources mainly comprise:

· Municipal (or sewage) wastewater discharges

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/01

Page 1-13

Section 1

January 2006

Final

· Industrial wastewater discharges from industries these also include discharging of

contaminated seawater that was used for industrial purposes on land, e.g. coastal mining

activities and seafood processing industries.

Diffuse pollution sources include:

· Contaminated stormwater run-off, usually associated with urban areas

· Agricultural and mining return flows

· Contaminated groundwater seepage.

Within the BCLME region, contaminated urban stormwater runoff is probably the most

important diffuse source of marine pollution to the coastal areas.

Waste loads for point source (or controlled waste disposal practices), such as those

discharged through marine outfalls, can usually be measured quite easily. However, it is

much more difficult to quantify waste loads for non-point (or diffuse) sources, such as urban

storm-water run-off, mining return flows and contaminated groundwater seepage. Spatial

and temporal quantification and establishing of variation in waste loads from diffuse sources

are usually best achieved through application of appropriate statistical or mathematical

predictive models, although field measurements are required for calibration and verification

purposes.

Land-based activities potentially causing marine pollution are often situated in the coastal

U

zone, in which case waste or pollutants are directly disposed of into the coastal zone, e.g.

U

through marine outfalls or stormwater drains. However, land-based marine pollution sources

can also originate from activities and developments in adjacent river catchments in which

case the pollutant is routed to the marine environment via rivers.

U

U

As part of a management programme, specifications that are typically required for marine

pollution sources include:

· A description of the source, activity or development, including information on the manner

in which it will affect the quality of the marine environment, as well as a map indicating

the location of such sources

· Volume of waste - it is of particular importance to understand typical flow distribution

patterns, whether these are, for example, continuous flows, whether there are distinct

daily, monthly or seasonal patterns or whether the flow is determined by specific events

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/01

Page 1-14

Section 1

January 2006

Final

· Composition of waste this refers to the concentration of biogeochemical and

microbiological pollutants, including information on diurnal, seasonal or event-driven

variations in composition

· In the case of effluents, it is also important to have information on physical properties,

such as density, viscosity and temperature, including specification on diurnal and or

seasonal variations (e.g. for engineering design of marine disposal schemes).

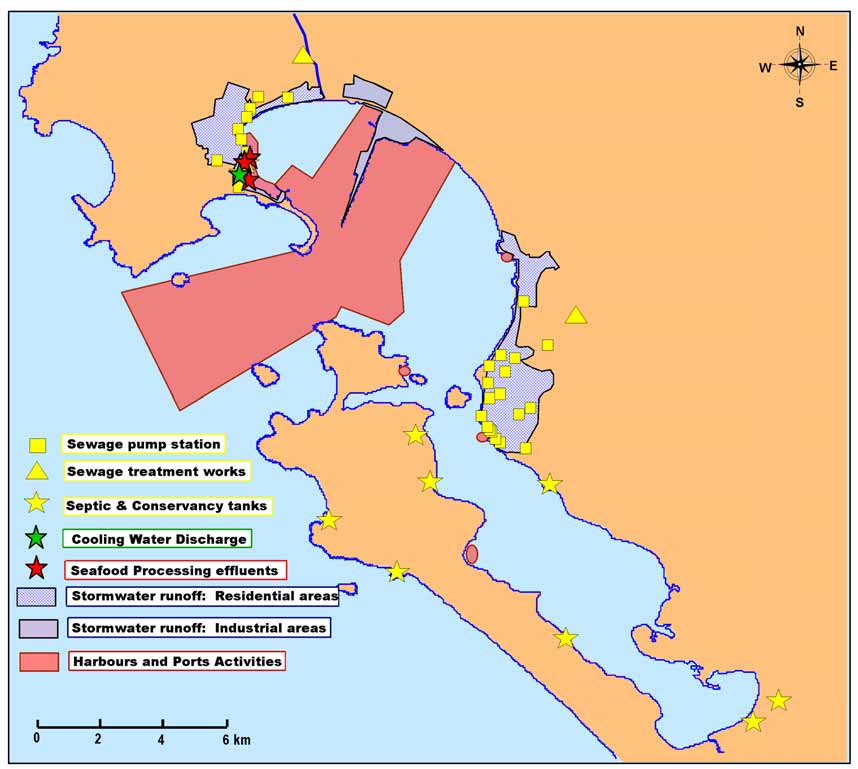

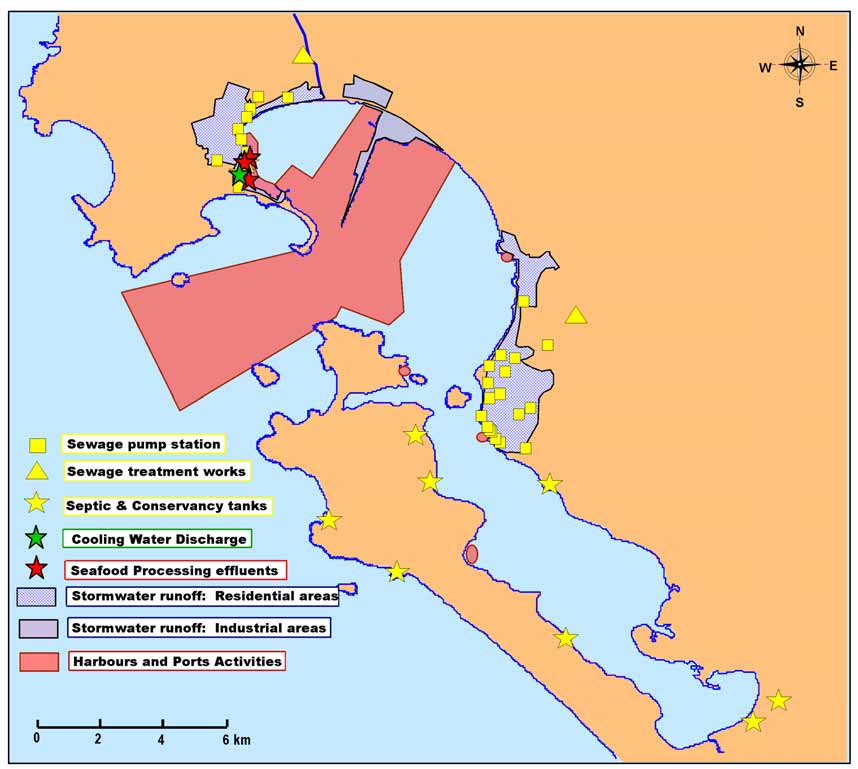

An example of a map indicating the location of potential marine pollution sources is that for

the Saldanha Bay/Langebaan Lagoon area along the west coast of South Africa (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2:

Mapping of potential marine pollution sources in Saldanha Bay/Langebaan

along the west coast of South Africa (adapted from Taljaard & Monteiro, 2002)

Ultimately, the management of land-based pollution sources cannot be isolated from other

marine pollution sources or other activities or developments that contribute to the

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/01

Page 1-15

Section 1

January 2006

Final

modification of water and sediment quality in the marine environment. Not taking other

sources into account may result in severe negative impacts due to, for example, cumulative

or synergistic effects not being accounted for. Also, although atmospheric sources of

marine pollution are traditionally categorized separately from land-based sources of

pollution, a large proportion of the former category originate from land, e.g. emissions from

land-based industries and vehicle exhaust fumes.

Therefore, although the focus of this project is on the management of land-based sources of

U

marine pollution, potential interactions with other categories of marine pollution sources, as

U

indicated above, cannot be ignored. The extent to which these need to be incorporated will

depend on site-specific conditions and will therefore need to be evaluated on a case-by-case

basis.

As a guide, a brief overview of the pollutant composition of major marine pollution sources in

the BCLME region is provided in the following sections (also included are a number of non

land-based sources that are considered important in the BCLME region).

1.4.1 Municipal Wastewater (including Sewage)

Municipal wastewater typically consists of:

T

· domestic wastewater (sewage) and/or

· industrial wastewater (also referred to as trade effluent) and/or

· urban storm-water run-off routed through wastewater treatment works (WWTW).

Municipal wastewater volumes tend to show diurnal variation with peaks during the morning,

midday and late afternoon. However, each area will have its own characteristic flow pattern,

depending on socio-economic factors, as well as the physical layout of the reticulation

systems and taking into account retention times. Volume and flow rates may also show

strong seasonal variation, particularly in small coastal towns where flows usually peak during

the summer holidays. Also, infiltration (due to damaged pipes) during the wet season or

during a rainstorm can also influence flow patterns (i.e. event driven).

The composition of municipal wastewater is largely dependent on the level of treatment, as

well as the composition of trade effluents entering the WWTW. The composition of

municipal wastewater (in particular the domestic sewage component) could contain

(although the actual concentrations are dependent on the level of treatment):[keep u/c in list]

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/01

Page 1-16

Section 1

January 2006

Final

· high suspended solids

· organic matter

· inorganic nutrients, particular nitrogen and phosphate

· microbiological contaminants (e.g. bacteria and viruses).

Different treatment levels of municipal wastewater (sewage) are schematically illustrated in

Figure 1.3 (RSA, DWAF, 2004b).

Treatment

Preliminary

Primary

Secondary

Tertiary

Potential effluent

Offshore

disposal option

Offshore

Offshore

Surf zone

Estuary

Effluent SS

300 - 400 mg/l

120 - 200 mg/l

30 - 40 mg/l

quality

BOD

300 - 500 mg/l

180 - 240 mg/l

30 - 40 mg/l

Effluent

Effluent

Effluent

Coarse

Fine

screens

screens

OR

OR

OR

Treatment

Solids

processes

To landfill

Aeration

tanks

Sedimentation

Sand filters

tanks

Reed beds

Ponds

Biological

filter

Sludge

To Sludge treatment

Figure 1.3:

A schematic illustration of the different treatment processes for municipal

wastewater (sewage) (taken from RSA DWAF, 2004b)

Treatment processes of municipal wastewater (sewage) include (RSA DWAF, 2004b):

· Primary treatment which removes settleable organic and inorganic solids by

sedimentation, and materials that will float (scum) by skimming. Approximately 25% to

50% of the organic matter (or biochemical oxygen demand) in the incoming wastewater,