REPORT

to

Danube - Black Sea Basin Stocktaking Meeting

Bucharest, 11-12 November 2004

Policy and legal reforms and

implementation of investment projects for

pollution control and nutrient reduction in

the Danube River Basin Countries

This report has been prepared by Mihaela Popovici, using information from the results of the ICPDR

Expert Groups, DABLAS report 2002 and preliminary results of the on going reporting to the ICPDR

Joint Action Program within the frame of EU DABLAS project, 2004.

Overall supervision: Philip Weller, Executive Secretary of the ICPDR

ICPDR Document IC WD 197

International Commission for the Protection of the Danube River

Vienna International Centre D0412

P.O. Box 500

A-1400 Vienna, Austria

Phone: +(43 1) 26060 5738

Fax:

+(43 1) 26060 5895

e-mail: icpdr@unvienna.org

web: http://www.icpdr.org/DANUBIS

Date: October 2004

PREFACE

The Danube is the most international river in the world. Thirteen countries together comprise 99% of

the territory of the basin and a further five countries have small amounts of land area in the basin.

These thirteen major countries and the European Union signed the Danube River Protection Convention

in 1994, that committed them to coordinated management of water resources.

To coordinate the work under the Convention the International Commission for the Protection of the

Danube River (ICPDR) was founded. The ICPDR has established a secretariat based in Vienna and

developed a work group structure involving the input of experts from each of the countries.

This report summarizes achievements that have been realized through work of the countries under the

ICPDR. A focus of this analysis is on identifying the challenges that remain in order to streamline and

target the implementation of the Strategic Partnership towards its objectives and indicators for further

reinforcement of cooperation in the Danube Black Sea Region.

In elaborating this report, emphasis has been given to the role of the ICPDR as a legal platform of

cooperation among Danube countries. The report also presents activities and results of the ICPDR work

relevant to D-BS Strategic Partnership objectives. In particular the report addresses the status of

implementation of the ICPDR Joint Action Programme (JAP), the ICPDR-BSC Memorandum of

Understanding (MoU), introduction of policy and legal reforms and implementation of investment

projects in the municipal, industrial and agricultural sectors for pollution control and nutrient reduction

in the Danube basin including cooperation with donor organizations and International Financing

Institutions.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1

MANDATE, ROLE AND OBJECTIVES OF THE ICPDR.................................... 11

1.1

Background .................................................................................................................. 11

1.2

Activities for transboundary cooperation in water management and

pollution control .......................................................................................................... 11

2

MEMBERS OF THE ICPDR, REGULAR CONTRIBUTIONS AND

SPECIAL FUNDS ....................................................................................................... 13

2.1

Members of the ICPDR............................................................................................... 13

2.1.1

ICPDR Membership..................................................................................... 13

2.1.2

ICPDR Observership.................................................................................... 13

2.2.

Annual contribution to the budget of the ICPDR since 1998 by

contracting parties....................................................................................................... 13

3

INSTITUTIONAL MECHANISMS OF BASIN WIDE

COOPERATION......................................................................................................... 15

3.1

Background .................................................................................................................. 15

3.2

Activities of selected ICPDR Expert Groups ............................................................ 15

3.2.1 MLIM EG........................................................................................................ 15

3.2.2 EMIS

EG......................................................................................................... 15

3.2.3 APC

EG........................................................................................................... 15

3.2.4 RBM

EG.......................................................................................................... 16

3.2.5 ECO

EG .......................................................................................................... 16

4

MECHANISMS FOR REGIONAL COOPERATION WITH THE

BSC - DANUBE BLACK SEA JOINT TECHNICAL WORKING

GROUP (DBS JTWG) ................................................................................................ 17

5

DEVELOPMENT OF POLICIES AND REGULATORY

MEASURES IN IMPLEMENTING THE DRPC.................................................... 18

5.1

Steps forward in adapting policy instruments to new challenges ........................... 18

5.1.1

Strategic Action Plan....................................................................................... 18

5.1.2 Transboundary

Analysis.................................................................................. 18

5.1.3

Joint Action Programme of the ICPDR........................................................... 19

5.1.4

Implementation of the EU WFD (RBM Plan) ................................................ 20

5.2

New policy guidelines for pollution control and nutrient reduction in

the DRB ........................................................................................................................ 21

5.3

New instruments of environmental policies in the DRB .......................................... 24

5.4

Barriers to the implementation .................................................................................. 24

6

REPORTING ON THE JOINT ACTION PROGRAM

IMPLEMENTATION................................................................................................. 25

6.1

Progress of implementing policy and regulatory measures at national

level in relation to JAP requirements........................................................................ 25

6.2

Policy objectives, priorities and general principles for water

management and pollution control and reduction................................................... 25

6.3

Status of legislation dealing with water management and pollution

control and reduction.................................................................................................. 27

6.4

Pollution reduction from point sources of pollution................................................. 29

6.4.1 Emission

inventories ....................................................................................... 29

6.4.2 Achieved and expected pollution reduction from point sources ..................... 30

6.5

Pollution reduction from diffuse sources................................................................... 31

6.6

Wetlands restoration and floodplain management. Inventory of

protected areas............................................................................................................. 34

6.7

Improvement of water quality monitoring and upgrading TNMN ........................ 35

6.7.1 Upgrading

TNMN ........................................................................................... 35

6.7.2

Joint Danube Survey ....................................................................................... 36

6.7.3

Analytical Quality Control (AQC) in the DRB............................................... 36

6.7.4

Load assessment programme .......................................................................... 37

6.8

Definition of basin wide priority substances and water quality

standards (ICPDR list of priority substances).......................................................... 37

6.9

Revision of the Accident warning system and definition of preventive

measures....................................................................................................................... 37

6.9.1

Operation and upgrade of the Danube Accident Emergency

Warning System .............................................................................................. 37

6.9.2

Inventory of accident risk spots in the Danube River Basin........................... 37

6.9.3

Inventory of contaminated sites in flood-risk areas ........................................ 37

6.10

Country progress in policy reforms ........................................................................... 38

7

IMPLEMENTATION OF THE EU WATER FRAMEWORK

DIRECTIVE ................................................................................................................ 40

7.1

Progress in developing the Danube River Basin Management Plan in

line with the WFD ....................................................................................................... 40

7.1.1

Harmonization of methodologies and reference conditions (i.e.

criteria for significant pressure and impact).................................................... 41

7.1.1.1 Characterisation of surface waters types and harmonised system

for reference conditions................................................................................... 41

7.1.2

Identification of significant pressures ............................................................. 42

7.1.2.1 Definition of significant point source pollution on the basin-

wide level ........................................................................................................ 42

7.1.3

Development of DRBD Overview map and preparation of

thematic maps.................................................................................................. 45

7.1.4

Development of public participation strategy ................................................. 45

7.1.5

Development of economic indicators.............................................................. 45

7.2

Progress on National reports ...................................................................................... 46

7.3

Response to bilateral an multilateral agreements..................................................... 46

8

IMPLEMENTATION OF THE JAP / NATIONAL INVESTMENT

PROGRAMMES ......................................................................................................... 47

8.1

National investments for pollution reduction and nutrient control in

the DRB since 1998 and efficiency of funding mechanisms .................................... 47

8.1.1

Estimation of total investment since 1997 for all Danube River

Basin countries ................................................................................................ 47

6

8.1.2

Estimation of financial requirements for identified priority

projects (up to 2009) ....................................................................................... 48

8.1.3. Achieved and expected results for above existing and proposed

projects in terms of reduced pollution in BOD, COD, N and P...................... 49

8.1.3.1 Implementation of the JAP, national investment programmes

municipal sector .............................................................................................. 50

8.1.3.2 Implementation of the JAP, national investment programmes

industrial sector .............................................................................................. 52

8.1.3.3 Implementation of the JAP, national investment programmes

agro-industrial sector....................................................................................... 52

8.1.3.4 Implementation of the JAP, national investment programmes

land use sector ................................................................................................. 52

8.1.3.5 Implementation of the JAP, national investment programmes

wetlands and floodplain restoration ................................................................ 52

8.2

Efficiency of existing mechanisms to facilitate funding of investment

projects ......................................................................................................................... 53

8.3

Role and mandate of DABLAS................................................................................... 54

8.4

Role and mandate of Danube (and Black Sea) Investment Facilities ..................... 55

8.5

Cooperation with other IFIs ....................................................................................... 55

8.6

Development and management of project data base and selection of

priority projects........................................................................................................... 55

9

PROGRESS AND EFFECTIVENESS OF IMPLEMENTING THE

WORK PROGRAMME OF THE MOU .................................................................. 57

9.1

Achieving mid - and long term goals.......................................................................... 57

9.1.1

Monitoring and evaluation indicators ............................................................. 58

9.1.1.1 Environmental status indicators ..................................................................... 62

9.1.2

Coastal zone part of the Danube river basin district .................................... 62

9.1.3 Reporting mechanisms in place/under discussion........................................... 62

10

SUSTAINABILITY OF THE PROJECT RESULTS REFLECTED

IN THE ICPDR ACTIVITIES AFTER UNDP GEF CO-

FINANCING ENDS .................................................................................................... 64

10.1

Building long term sustainability in the participation of Danube

countries ....................................................................................................................... 64

10.2

Further EC support to build national capacities for implementation of

EU directives and regulations for water quality control and pollution

reduction ...................................................................................................................... 64

10.3

Estimates on the cost for reforms and investments .................................................. 65

11

CONCLUSIONS .......................................................................................................... 68

7

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The report summarizes achievements that have been realized through work of the countries under the

ICPDR. A focus of this analysis is on identifying the challenges that remain in order to streamline and

target the implementation of the D-BS Strategic Partnership towards its objectives and indicators for

further reinforcement of cooperation in the Danube Black Sea Region.

In elaborating this report, emphasis has been given to the role of the ICPDR as a legal platform of

cooperation among Danube countries. Despite the difficulties of cooperation among the large number of

states within the Danube region there has been important progress in establishing the necessary

mechanisms for coordination and cooperation under the framework of the Danube River Protection

Convention. The main objective of the Convention is the sustainable and equitable use of surface waters

and groundwater and includes the conservation and restoration of ecosystems. To coordinate the work

under the Convention the International Commission for the Protection of the Danube River (ICPDR)

was founded. The ICPDR has established a secretariat based in Vienna and developed a work group

structure involving the input of experts from each of the countries.

From the early 1990s the European Commission and the United Nations Development

Programme/Global Environment Facility (UNDP/GEF) have supported the building of capacity at the

regional and national levels to develop mechanisms for cooperation under the DRPC. Currently

UNDP/GEF is providing 17 million USD financing under the Danube Regional Project to support the

countries of the region and the ICPDR in adopting new policies and measures for nutrient reduction and

for sustainable river basin management. Specific projects have been targeted at industrial pollution,

agriculture and supporting river basin management planning.

The first part of the report is presenting the mandate, role and objectives of the International ICPDR.

The ICPDR Contracting Parties are: European Union, Germany, Austria, Czech Republic, Slovakia,

Hungary, Slovenia, Croatia, Bulgaria, Romania, Moldova, Ukraine and Serbia & Montenegro. Bosnia

and Herzegovina is a participant with consultative status. 10 organisations have observership status to

the ICPDR.

A second substantial section of the report addresses the status of implementation of the ICPDR Joint

Action Programme (JAP), with particular attention to the introduction of policy and legal reforms and

implementation of investment projects in the municipal, industrial and agricultural sectors for pollution

control and nutrient reduction in the Danube basin.

The JAP 2001-2005 reflects the general strategy for the implementation of the DRPC for the respective

period. It deals i.a. with pollution from point and diffuse sources, wetland and floodplain restoration,

priority substances, water quality standards, prevention of accidental pollution, floods prevention and

control and river basin management. Important successes of Danube countries in implementing the JAP

include: Trans-national Monitoring Network (TNMN) operational with 79 sampling stations, Analytical

Quality Control (AQC) programme to ensure quality and comparability of data, Emissions Inventories

updated for point and diffuse sources of pollution, AEWS operational and upgraded, Action Plan for

Sustainable Flood Protection in the Danube River Basin developed, Accident prevention system in

place, Habitat and species protection areas defined and measures to restore and protect wetlands and

floodplains under implementation..

There has been substantial legislative reform and in particular the implementation of EU community

law within the DRB countries. The key challenge Danube countries face in the policy field is to identify

the most effective ways of transposing EU environmental directives. Country's choice on how to

achieve compliance with EU directives will have a significant influence on compliance costs.

The total investment foreseen in the JAP period 2001-2005 to respond to priority needs is estimated to

be about 4.404 billion , with priority projects mainly being:

· Municipal waste water collection and treatment plants: 3.702 billion

· Industrial waste water treatment: 0.267 billion

· Agricultural projects and land use: 0.113 billion

· Rehabilitation of wetlands: 0.323 billion

Recent reviews of activities conducted under ongoing EU DABLAS project highlight that many

investment and actions are happening. The DABLAS project has, however, highlighted both the

implementation efforts and deficits. This is especially the case for those EU Directives that require

substantial administrative reform and financial investments.

It is expected that the EU Danube Black Sea Task Force (DABLAS) shall play a coordinator and

facilitator role to foster political commitment and to assure implementation of the program and projects

for pollution reduction and sustainable management of water resources and ecosystems in the wider

Black Sea region. Political support and commitment are already mobilized to facilitate the

implementation of investment projects and to enhance the cooperation between participating countries

and the financing instruments of the EU, bilateral donors and International Financing Institutions (in

particular EBRD, EIB, WB etc).

Considerable attention is given in the report to the implementation of EU Water Framework Directive.

The WFD places obligations on member states to implement measures to achieve specific

environmental objectives for water bodies including rivers, lakes, groundwater and estuaries. The EU as

well as ICPDR member countries have agreed that the ICPDR will provide the platform for the

coordination necessary to develop and establish the River Basin Management Plan for the Danube

Basin. Required under the WFD are a series of reports which document the responsible authorities for

water management in each country, analyse and determine baseline and reference information to

achieve a characterisation of the waters, a pressure and impact analysis, and a programme of measures

which will eliminate or reduce those pressures and impacts. The final product is the Basin Management

Plan. The Danube River Basin Management Plan has been divided into two parts. Part A (roof of the

DRBMP) gives relevant information of multilateral or basin-wide importance, whereas Part B (national

input to DRBMP) gives all relevant further information on the national level as well as information

coordinated on the bilateral level. "River Basin Management Plans" (RBMPs) will provide the context

for setting out a comprehensive programme of measures designed to achieve the objectives that have

been set for water bodies.

This report is also reviewing the progress and effectiveness of implementing the work programme of

the Memorandum of Understanding between the ICPDR and BSC in achieving the mid and long term

goals. Indicators relevant for the assessment of the environmental status of the Black Sea, indicating

changes over time in Black Sea ecosystems due to nutrient inputs from the Danube River are agreed by

the DBS JTWG.

Building long term sustainability in the participation of Danube countries is the focus of the last part of

the report. The major measure of success to assure long-term sustainability of the ICPDR activities is

the country's commitment to continue to financially and technically support the Expert Groups

activities. The financial support for the ICPDR activities by the countries and strong commitment to the

work indicates a positive attitude for sustainability. Success will depend on thorough implementation of

actions and commitments of the countries and on effective and coordinated contribution of the

international community.

10

1 Mandate, role and objectives of the ICPDR

"The Danube is a river that binds and connects people. It is also a river that connects important parts of

Europe. Irrespectively of their relations with the EU, all peoples of the Danube share in the celebration

of being part of the Danube basin and at the same time share the responsibility to protect this river and

its ecosystems".

Catherine Day, ICPDR President

1.1 Background

The Danube River Basin is by far the most transboundary river basin in the world in terms of number of

interconnected countries - 18 countries contribute with small or large land areas. Initiatives, with a view

to finding appropriate solutions to the common pursuit of the long-term development and management

of Danube waters have been developed over recent decades.

The Environmental Programme for the Danube River Basin was established in 1991, with the aim to

build regional cooperation for water management and to initiate high priority actions, which would

support the finalisation and implementation of the Danube River Protection Convention (DRPC). The

DRPC is a legally binding instrument, which provides a substantial framework and a legal basis for

cooperation between the contracting parties. Austria, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Germany,

Hungary, Moldova, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Serbia and Montenegro, Ukraine and the European

Union have signed the DRPC. The ratification process is currently under way in Bosnia and

Herzegovina.

The main objective of the Convention is the protection and sustainable use of ground and surface waters

and ecological resources, directed at basin-wide and sub-basin-wide cooperation with transboundary

relevance.

In order to achieve substantial progress in implementing the Convention the following overall strategic

goals and targets have been agreed:

· maintain and improve the status of water resources;

· prevent, reduce and control water pollution;

· improve the environmental conditions of the aquatic ecosystems and biodiversity;

· contribute to the protection of the Black Sea from land-based sources of pollution.

1.2

Activities for transboundary cooperation in water management and pollution control

The ICPDR is acting as a platform coordinates joint activities and actions focused on enhancement of

policies and strategies aiming at sustainable use of the water and the natural resources of the Danube

Basin.

The Signatories to the Convention agreed on `conservation, improvement and the rational use of surface

and groundwater in the catchment area', to `control the hazards originating from accidents' and `to

contribute to reducing the pollution loads of the Black Sea from sources in the catchment area'. They

also agreed to cooperate on fundamental water management issues by taking `all appropriate legal,

administrative and technical measures to at least maintain and improve the current environmental and

water quality conditions of the Danube River and of the waters in its catchment area and to prevent and

reduce as far as possible adverse impacts and changes occurring or likely to be caused'. The Danube

River Protection Convention (Article 8) also foresees the need to develop `joint action programmes

aimed at the reduction of pollution loads both from industrial and municipal point sources as well as

from non-point sources'.

11

In response to challenges posed by DRPC, the Danube countries have established the International

Commission for the Protection of the Danube River (ICPDR) to strengthen regional cooperation. It is the

institutional frame not only for pollution control and the protection of water bodies but it also sets a

common platform for sustainable use of ecological resources and coherent and integrated river basin

management. International organizations such as UNDP, GEF, UNEP, the World Bank and UNOPS as

implementing agency, as well as the European Union (who is contracting party to the ICPDR) are

providing significant support to the ICPDR and to the individual member states to fulfil their obligations

under the DRPC.

Fig. 1. Organisational structure under the Danube River Protection Convention

Of current major importance is the GEF UNDP Danube Regional Project (17,2 million US$ for a 5 year

period) which is reinforcing the activities of the ICPDR to provide a regional approach to the

development of national policies and legislation and the definition of priority actions for pollution

control with particular attention to achieving sustainable ecological effect within the Danube River

Basin and the Black Sea Region.

A similar project (total investment 9 million US$) has been developed for the Black Sea, which will

reinforce the actions for nutrient reduction in the Black Sea and to strengthen the cooperation between

the Danube and the Black Sea Commissions. The actions of both projects are reinforced by the GEF-

World Bank Partnership Program, which is providing financial support for investment projects (70

million in GEF Grants and 210 million in loans).

The ICPDR set up a Secretariat based in Vienna, which coordinates the work of the countries under the

Convention and the work of the Expert Groups in particular. Expert Groups for Monitoring, Laboratory

and Information Management Systems (MLIM), Emissions (EMIS), Accident Prevention and Control

(APC), Ecology (ECO), Flood Protection (FP), and River Basin Management (RBM) have been

created. The organisation chart of the ICPDR can be seen in Figure 1. Each Expert Group is composed

of at least one expert from each country and meets twice or perhaps three times a year to undertake the

work needed. Of importance, it is the experts from the countries who do most of the work needed in

each of the groups. The Expert Groups report regularly to the ICPDR on their work progress and/or

seek guidance from the ICPDR on issues of policy.

12

2 Members of the ICPDR, regular contributions and special funds

2.1

Members of the ICPDR

2.1.1 ICPDR Membership

The ICPDR Contracting Parties are: European Union, Federal Republic of Germany, Republic of

Austria, Czech Republic, Slovak Republic, Republic of Hungary, Republic of Slovenia, Republic of

Croatia, Republic of Bulgaria, Romania, Republic of Moldova, Ukraine and Serbia & Montenegro.

Bosnia and Herzegovina is a participant with consultative status.

2.1.2 ICPDR Observership

The following organisations are observers to the ICPDR: Danube Commission, World Wide Found for

Nature, International Association for Danube Research, RAMSAR Convention, Danube Environmental

Forum, Regional Environmental Centre for Central and Eastern Europe, Black Sea Commission, Global

Water Partnership - Central and Eastern Europe, United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural

Organization International Hydrological Programme and International Association for Water Works

in the Danube Basin.

2.2.

Annual contribution to the budget of the ICPDR since 1998 by contracting parties

The contribution keys for the period 2001 to 2005 were agreed upon at the 1st Plenary Session of the

ICPDR (Vienna, Austria on 29 October 1998) taking into account whether a Contracting Party (CP) is

an EU member state, in the process of accession to the EU or none of both as the criterion for the CP“s

capability to contribute to the budget.

Furthermore a two-stage development of contribution keys (2001 to 2005 and 2006 to 2010) was agreed

anticipating a revision of the keys for the period 2006 to 2010 prior to 2006. The payments of first year

contribution of new a CPs was set to 5%. It was agreed that these contributions would be transferred

into the Working Capital Fund.

In 2004, the ICPDR has received payment for all countries with exception of Ukraine (which has

promised payment by the end of the year).

The ad-hoc Strategic EG of the ICPDR has revised the structure of budgetary contributions for the

period 2006 to 2010. Consideration was given to:

the criterion whether a CP is an EU member state by 2006;

a group of four countries that are not yet EU member states or in the next wave of accession

and their economic circumstances do not allow an equal share to the budget;

the request of Moldova that a 1% contribution is realistic for the foreseeable future, and since

the economic situation in Ukraine is similar, a 1% contribution was also proposed for Ukraine.

The contributions from these two CPs would be kept at this low level up to 2008, and then be

raised to 3% in 2009 and 5% in 2010;

the acknowledgement that the contribution from the EC remains at 2.5%.

In 2007 the contribution keys for Moldova and Ukraine for the years 2009 and 2010 shall be revised. In

the event of a new CP joining ICPDR the contribution keys will be reduced in an amount equal to the

additional contribution from the new CP. From the year 2006 onwards, for a transitional period of five

years, modified contribution keys as specified in the Table 1.

13

Table 1. Proposal on the contribution keys for the period 2005-2010

Proposed Development of Contribution Keys for the Period 2005 to 2010 [ % ]

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

CPs

Proposed

Contribution Keys

Germany

12.8233

11.2500

10.8250

10.4000

9.7341

8.7500

Austria

12.8233

11.2500

10.8250

10.4000

9.7341

8.7500

Czech Republic

10.6875

11.2500

10.8250

10.4000

9.7341

8.7500

Slovakia

9.2636

11.2500

10.8250

10.4000

9.7341

8.7500

Hungary

10.6875

11.2500

10.8250

10.4000

9.7341

8.7500

Slovenia

10.6875

11.2500

10.8250

10.4000

9.7341

8.7500

Croatia

9.2636

7.0000

7.6375

8.2750

8.2739

8.7500

Bosnia-Herzegovina

Serbia and Montenegro

5.00

7.0000

7.6375

8.2750

8.2739

8.7500

Bulgaria

5.00

7.0000

7.6375

8.2750

8.2739

8.7500

Romania

9.2636

7.0000

7.6375

8.2750

8.2739

8.7500

Moldova

1.00

1.00

1.00

1.00

3.00

5.00

Ukraine

1.00

1.00

1.00

1.00

3.00

5.00

EC

2.50

2.50

2.50

2.50

2.50

2.50

Total

100.00

100.00

100.00

100.00

100.00

100.00

Fig. 2. The ICPDR Budgetary contributions and Special Funds

ICPDR Budgetary Contributions

and Special Funds

1,500,000

] 1,000,000

[

500,000

Funds

0 1998 2000 2002 2004 2006

Total Annual Income

Special Funds [ ]

UA and CS [ ]

Contributions of CPs [ ]

14

3 Institutional mechanisms of basin wide cooperation

3.1 Background

In the ten years since the signing of the Convention, the International Commission for the Protection of

the Danube River (ICPDR) has been established and matured as the forum for cooperation among the

Danube countries. All the countries of the Danube have been actively participating in the Expert Groups

of the ICPDR and achieved important progress in their joint efforts to manage this shared river system.

The work undertaken under the DRPC has been reinforced by the adoption of a commitment to utilise

the EU Water Framework Directive (WFD) as a basis for organising water management efforts. All the

Contracting Parties of the Convention have committed themselves to implement the WFD although less

than half the parties are currently EU Member States. This commitment has been made with a political

objective of legally harmonising the countries of the Danube more closely with the European Union,

and in recognition of the value of this comprehensive legislation in providing (i) a regional approach to

the development of national policies and legislation and, (ii) a framework for further assessment and

identification of measures needed by Danube countries to ensure the basis for sustainable water

management.

These existing mechanisms have been supported by the UNDP GEF Danube Regional Project.

3.2

Activities of selected ICPDR Expert Groups

3.2.1 MLIM EG

The Laboratory and Information Management Expert Group is responsible for co-ordinating and

evaluating the Trans-National Monitoring Network (TNMN) for water quality in the Danube River

Basin. It is responsible for setting up programmes aimed at improving the laboratory analytical quality

assurance. It facilitates the preparation and exchange of (in-stream) water quality and quantity

information among the Contracting Parties.

The DRP has provided assistance to Danube countries to develop, upgrade and reinforce capacities

monitoring of water quality, laboratory and information management. In addition, the results of the

Joint Danube Survey (JDS), carried in 2001-2002 has provided comparable biological and chemical

characteristic data along the Danube in the main river bed as well as in the major tributaries.

3.2.2 EMIS

EG

The Emission Expert Group is responsible for developing actions to control pollution from point and

diffuse sources through regularly updating emission inventories. It establishes action programmes to

reduce pollution, e.g., from municipalities, industry and agriculture.

Several activities concerning industrial sector were successfully undertaken: (i) revision of policies and

relevant existing and future legislation for industrial pollution control and identification enforcement

mechanisms on a country level, (ii) discussion on existing ICPDR BAT concepts and relevant

complementary measures for the introduction of BAT, in addition to the experience of the introduction

of cleaner technologies to reduce the emissions of toxic substances and nutrients in particular in various

Danube countries, (iii) up-dating the basin-wide inventory on industrial and mining sectors, and (iv)

improvement of methodology of collecting information on discharges to facilitate the combined

approach of screening pressures and impacts basin-wide.

An important output is the Recommendations on Best Available Techniques at Agricultural Point

Sources.

3.2.3 APC

EG

The Accident Prevention and Control Expert Group is responsible for steering and evaluating the

effectiveness of the Accident Emergency Warning System (AEWS) for the Danube River Basin. The

15

Danube AEWS is activated in the event of transboundary water pollution danger or if warning threshold

levels are exceeded.

To facilitate the assessment of risk of (i) industrial sites (ongoing activities), and of (ii) contaminated

sites (closed-down waste disposal sites and industrial installations in flood-risk areas) reported by the

Danube countries, a specific methodology was developed to (i) identify potential ARS and (ii) establish

a ranking system to evaluate a real risk. This methodology will allow countries to take prompt actions at

priority ranked old contaminated sites.

The APC EG has also been supported by the DRP to (i) reinforce operational conditions of PIACs, and

for (ii) the maintenance and calibration of the Danube Basin Alarm Model (concept for calibration

options for the DBAM and the outline for the DBAM calibration manual), in order to predict the

propagation of the accidental pollution and evaluate temporal, spatial and magnitude characteristics in

the Danube river system and to the Black Sea. The assessment of definition of messaging formats of

AEWS has been completed as well as the concept and definition of detailed software requirements

(application design). The new communication software was developed and successfully tested by

national PIACs.

3.2.4 RBM

EG

The work of the River Basin Management Expert Group focuses on facilitating the implementation of

the EC Water Framework Directive, in particular on the preparation of the Danube River Basin

Management Plan.

All Danube countries stated their firm political commitment to support the implementation of the WFD

in their countries, and to cooperate in the framework of the ICPDR to achieve a single, basin-wide

coordinated Danube RBM Plan. Consequently, the ICPDR decided that it would provide the platform

for the coordination necessary to develop and established the River Basin Management Plan for the

Danube River Basin.

The implementation of the WFD is a demanding process for the Danube countries due to its extremely

challenging timetable, complexity of possible solutions to scientific, technical and practical questions.

Support was given by the UNDP GEF DRP for capacity building in specific countries and overall for

the development of standardized methodologies and guidelines for sub-river basin management plans

and for the methodology for the aggregation of the sub-river basin management plans to a basin wide

management concept.

The existing results prove the benefit of a close link between basin wide environmental objectives and

an appropriate legislative framework provided by the EU WFD. It provides an excellent basis for the

implementation of the Danube River Basin Management Plan given commonly shared principles such

as a basin-wide holistic approach.

3.2.5 ECO

EG

The main tasks of the ECO/EG are linked to the preparation of an inventory of protected areas that are

part of the riverine ecosystem in the DRB in line with WFD, and to provide guidance for the monitoring

of habitat and species protection areas according to EC Habitats Directive and WFD.

The ECO EG supervised the development of an inventory of protected areas, starting from a core data

set that was developed in 2003. The draft inventory from October 2003 lists around 250 sites officially

nominated to ICPDR by Danube countries. This list served to select 55 "Water-related Protected Areas

for Species and Habitats of basin-wide Importance" for the WFD Roof Report 2004/2005, i.e. national

parks, biosphere reserves, Ramsar sites and other internationally important national protected areas.

ECO EG has evaluated progress in implementation of the ICPDR Joint Action Programme 2001-2005

for restoration/rehabilitation and management of wetlands and floodplains.

16

4 Mechanisms for regional cooperation with the BSC - Danube Black Sea

Joint Technical Working Group (DBS JTWG)

The Memorandum of Understanding between the ICPDR and the BSC was signed by the Presidents of

the two Commissions on 26 November 2001 in Brussels at the occasion of the Ministerial Conference

convened for the creation of the DABLAS Task Force.

The ICPDR and the BSC Secretariats in cooperation with the UNDP GEF Regional Projects for the

Danube and the Black Sea have convened, until now, four meetings of the DBS JTWG, which was

established to the MoU.

The purpose of the first meeting was to discuss new terms of reference, the work programme, and the

composition of the Working Group. The modalities to assess nutrient inputs and hazardous substances

into the Black Sea, the establishment of a monitoring system for measuring input loads and for the

evaluation of the ecological status of the Black Sea have been discussed. The second meeting focused

on the selection of indicators relevant for the assessment of the environmental status of the Black Sea ,

indicating changes over time in Black Sea ecosystems due to nutrient inputs from the Danube River. At

the occasion of the 3rd DBS JTWG meeting, the Work Programme has been revised to respond to the

tasks related to the "Implementation of WFD requirements in regard to achieving the good status of

coastal waters in the Black Sea". The Work Programme has been approved by the ICPDR 1st StWG

meeting (June 2003, Prien). The most recent group meeting assessed the availability of the information

on the indicators on state of the Black Sea agreed by JTWG, revision of the work program, and

information on the progress with development monitoring and assessment in both Commissions.

Taking into account that the ICPDR has already developed major tools for monitoring and assessment

for water quality control (TNMN, AQC), it has been recognized that the BSC needs to deploy special

efforts to reach similar conditions of monitoring and emission control in the Black Sea Convention area.

Only then, joint reporting as required by the MoU can successfully be implemented.

In the course of the implementation of the WFD, JAP and MoU, the necessity of strengthening and the

further development of ties between the ICPDR and BSC was often underlined. In this connection the

ICPDR and the UNDP GEF DRP expressed readiness to render where appropriate overall assistance

and aid in enhancing the efficiency of cooperation with the Black Sea Commission.

17

5 Development of policies and regulatory measures in implementing the

DRPC

5.1

Steps forward in adapting policy instruments to new challenges

Since 1992 the European Community (PHARE and TACIS programs) and the UNDP/GEF (Danube

Pollution Reduction Program-1997 to 1999) have supported the efforts of the Danube countries to

develop the necessary mechanisms for effective implementation of the DRPC. The Danube

Environmental Program Investments 1992 2000 has included 27 million USD from the EU

Phare/Tacis, and 12.4 million USD were provided by the UNDP/GEF.

This support has enabled the elaboration of a regional Strategic Action Plan (SAP) based on national

contributions and the development of a Transboundary Analysis to define causes and effects of

transboundary pollution within the DRB and on the Black Sea.

Assistance has been provided to the Danube countries, the ICPDR EGs, and the ICPDR Secretariat to

reinforce the national capacities in terms of policy/legislative reforms and enforcement of environmental

regulations (with particular attention to the reduction of nutrients and toxic substances). An important

goal was to assure a coordinated, harmonised and transferable approach basin wide of policy and

legislative measures introduced at the national level of the participating countries.

5.1.1 Strategic Action Plan

The Strategic Action Plan provides guidance concerning policies and strategies in developing and

supporting the implementation measures for pollution reduction and sustainable management of water

resources enhancing the enforcement of the DRPC.

According to the Strategic Action Plan, the main problems in the Danube River Basin that affect water

quality use are: (i) high loads of nutrients and eutrophication, (ii) contamination with hazardous

substances, including oils, (iii) microbiological contamination, (iv) contamination with substances

causing heterotrophic growth and oxygen-depletion; and (v) competition for available water.

The SAP outlined regional policies and strategies for pollution reduction and environmental protection

in response to the Danube River Protection

The objectives and target of the SAP considered (i) the development of national policies, regulations

and actions, (ii) the development of coherent approaches to pollution reduction and transboundary

cooperation, (iii) reinforcing of coordination of interventions in relation to sub basin area, (iv)

encouraging transboundary cooperation for pollution reduction in Significant Impact Areas.

5.1.2 Transboundary Analysis

The Transboundary Report (TAR) provide a scientific analysis of the root causes of environmental

pollution in the DRB, identifying causes and effects of pollution with particular attention to

transboundary issues and nutrient transport to the Black Sea. TAR defined priorities for control and

management strategies at the regional and national levels.

Regional assessments such as the Black Sea Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis have indicated that the

Danube River Basin is the largest pollution contributor to the Black Sea in general and the Western part

of the Black Sea in particular. A significant fraction of the nutrients (58%-nitrogen, 66%-phosphorus)

received by the Black Sea come from the Danube River and these loads have resulted in the occurrence

of severe eutrophication problems.

Based on the National Review Reports more than 500 hot spots, in three sectors (municipal, industrial

and agricultural) have been identified and ranked.

In association with the work on the Danube Water Quality Model (DWQM) updated comprehensive

estimates of N and P emissions to surface waters of the Danube Basin were made for 1996 - 1997. The

sums of these estimates are:

· 898 kt/y of N - i.e., approximately 246 kt/y from point sources and 652 kt/y from diffuse sources.

· 108 kt/y of P - i.e., approximately 47.5 kt/y from point sources and 60.1 kt.y from diffuse sources

18

Updated estimations of point source emissions of N and P by country, were available for the TDA (May

1999) for (i) storm weather overflow, (ii) industry with and without treatment, (iii) municipal waste

water management and (iv) effluents from agricultural WWTPs as follows:

Table 2. N and P from point sources, 1999

Country D AT CZ SK H SI HR BA FRY RO BG MD UA Total

N

20 24 13 14 19 12 8 8 32 74 18 1 3 246

P

1.2 2.2 2.6 3.0 5.4 1.5 1.4 3.2 9.8 12.0 3.6 0.2 1.1 85

Updated estimations of diffuse source emissions of N and P by country (May 1999) for (i) base flow, (ii)

direct discharges from private households, (iii) erosion, runoff, (iv) discharge of untreated manure, (v)

surface runoff / forests and others and (vi) N fixation were as follows:

Table 3. N and P from diffuse sources , 1999

Country D AT CZ SK H SI HR BA FRY RO BG MD UA Total

N

100 72 19 40 63 12 27 29 74 157 16 12 31 652

P

5.8 4.6 0.8 2.6 7.8 1.3 2.7 1.9 7.9 15.6 2.5 2.0 4.6 133

Based on the Causal chain analyses of the three main sectors, the core problems that emerged for the

middle Danube basin were as follows:

· for the agricultural sector - "unsustainable agricultural practices"

· for the municipal sector - "inadequate management of municipal sewage and waste"

· for the industrial sector - "ecologically unfriendly industry".

For the lower Danube region, the corresponding core problems were considered as follows:

· for the agricultural sector - "missing implementation of sustainable agriculture"

· for the municipal sector - "inefficient management of waste waters and solid waste"

· for the industrial sector - "pollution prevention and abatement from industry not achieved"

Over the last 200 years, many floodplains have been cut-off from the river systems as to allow human

uses, such as energy and agricultural production, river transport or settlements development. Today, only

a fraction of the Danube basin floodplains continues to fulfil their natural functions because more than

80% of the original floodplain along Danube and its tributaries have been destroyed. The UNDP/GEF-

PRP analysis on wetland areas and floodplains 1999 has shown that a total of 350,000 ha of floodplains

are still existing with a potential to restore additional 300, 000 ha. To focus attention on the effects of

water pollution and other human interventions, 51 "Significant Impact Areas" have been identified in

1999 in the Danube River Basin, which were in particular affected by industrial pollution, COD and

toxic substances as well as from excessive nutrient loads.

5.1.3 Joint Action Programme of the ICPDR

The ICPDR developed a first Joint Action Programme (JAP) for the years 2001 - 2005, which was

adopted at the ICPDR Plenary Session in November 2000. The ICPDR Joint Action Programme 2001-

2005 reflects the general strategy for the implementation of the DRPC for the respective period. The

JAP deals i.a. with pollution from point and non-point sources, wetland and floodplain restoration,

priority substances, water quality standards, prevention of accidental pollution, floods prevention and

control and river basin management.

In the frame of the Danube Pollution Reduction Program 1999, based on the results of the

Transboundary Analysis, an investment portfolio has been developed with particular attention to

nutrient reduction. All the measures, projects and programs proposed to reduce emissions from both

point and non-point sources of pollution will improve water quality, considering a reduction of 50 % in

Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD) emissions and 70 % in Biological Oxygen Demand (BOD)

emissions and other toxic elements, and thus reduce transboundary effects within the Danube River

Basin. Once implemented, these measures would further substantially contribute to reducing nutrient

transport (Phosphorus by 27 % and Nitrogen by 14 %) to the Black Sea to further improve, over time,

environmental status indicators of Black Sea ecosystems of the western shelf. A total of 421 projects for

19

5.66 billion USD, primarily addressing hot spots have been identified for municipal, industrial and

agricultural projects.

In the frame of the ICPDR Joint Action Programme, 243 committed investment projects and strategic

measures have been identified out of which 156 are in the municipal sector and only 44 in the industrial

sector. This reflects the situation in most transition countries where industries are not operational or

using mostly outdated technologies. Most of these projects, listed generally as "hot spots" or point

sources of emission, are representing national priorities and taking equally into account the obligation to

mitigate transboundary effects. Particular attention was also given to the identification of sites for

wetland restoration, which play an important role not only as natural habitats but also for flood

protection and as nutrient sinks.

The total investment foreseen in the JAP period 2001-2005 to respond to priority needs is estimated to

be about 4.404 billion , with priority projects mainly being:

· Municipal waste water collection and treatment plants: 3.702 billion

· Industrial waste water treatment: 0.267 billion

· Agricultural projects and land use: 0.113 billion

· Rehabilitation of wetlands: 0.323 billion

From the total amount of investment of 4.4 billion for point sources reduction, 3.54 billion are

earmarked as national contributions.

It is expected that the EU Danube Black Sea Task Force (DABLAS) shall play a coordinator and

facilitator role to foster political commitment and to assure implementation of the program and projects

for pollution reduction and sustainable management of water resources and ecosystems in the wider

Black Sea region. Political support and commitment are already mobilized to facilitate the

implementation of investment projects and to enhance the cooperation between participating countries

and the financing instruments of the EU, bilateral donors and International Financing Institutions (in

particular EBRD, EIB, WB etc). In this frame, the two Commissions for the protection of the Danube

and the protection of the Black Sea will play a vital role in protecting transboundary waters and

ecosystems in the wider Black Sea Region.

5.1.4 Implementation of the EU WFD (RBM Plan)

On December 22, 2000 the Water Framework Directive 2000/60/EC (WFD) came into force. The EU

Member States (at the time this was Germany and Austria in the Danube basin) are obliged to fulfil this

Directive. The WFD brings major changes in water management practices. Most importantly, it:

· sets uniform standards in water policy throughout the European Union and integrates different

policy areas involving water issues,

· introduces the river basin approach for the development of integrated and coordinated river

basin management for all European river systems,

· stipulates a defined time-frame for the achievement of the good status of surface water and

groundwater,

· introduces the economic analysis of water use in order to estimate the most cost-effective

combination of measures in respect to water uses,

· includes public participation in the development of river basin management plans encouraging

active involvement of interested parties including stakeholders, non-governmental

organizations and citizens.

The WFD places obligations on member states to implement measures to achieve specific

environmental objectives for water bodies including rivers, lakes, groundwater and estuaries. The WFD

requires that for most surface water bodies, the target of "good ecological status" should be achieved

within 15 years of adoption of the Directive. For water bodies that already achieve this status and those

at "high ecological status" the objective is to maintain this. Some water bodies may not be capable of

achieving "good status", simply because they have been heavily physically modified, for example, in

the case of engineered river channels or flood defence measures. If so, a more appropriate ecological

quality objective may be set "good ecological potential". In case of disproportionate costs to achieve a

specific goal, a derogation of the timetable could be acceptable.

20

"River Basin Management Plans" (RBMPs) will provide the context for setting out a comprehensive

programme of measures designed to achieve the objectives that have been set for water bodies. One of

the key features of the Directive is its incorporation of economic considerations. For example, adequate

cost recovery for water services, and economic analysis of water use and review of the environmental

impact of human activity to support the development of the River Basin Management Plans are

included. Consequently, public consultation plays an important part in their preparation.

The EU as well as ICPDR member countries have agreed that the ICPDR will provide the platform for

the coordination necessary to develop and establish the River Basin Management Plan for the Danube

Basin.

What makes the implementation process in the Danube River Basin a particular challenge is the fact

that only some countries are EU Members and therefore obliged to fulfil the EU WFD. Besides Austria

and Germany, four additional Danube countries have become EU Members States on May 1, 2004.

Three other Danube countries are in the process of accession and are preparing to conform with the

complete body of EU legislation in order to become EU Members. Others have not initiated a formal

process to join the EU.

The ICPDR RBM EG is responsible for coordinating the technical work amongst the 13 participating

countries and according to the implementation time frame as set by the EU. All Contracting Parties

have agreed to make all efforts to arrive at a coordinated international River Basin Management Plan

for the Danube River Basin.

The work of the International Commission for the Protection of the Danube River is concentrated on the

development of a joint basin management plan and a harmonization of methodologies and approaches

for conducting the analysis needed. The first major step in that work which has been greatly benefiting

of UNDP GEF DRP support the characterization of the basin is completed and forms the basis for

identifying the problems and additional efforts and actions needed to reduce pollution, and minimize

other pressures negatively influencing the quality of water in the basin.

5.2

New policy guidelines for pollution control and nutrient reduction in the DRB

A fundamental objective of regulatory reforms in the Danube countries is to foster high quality

regulation that will improve the efficiency of national economies and environmental actions, and will

eliminate the substantial compliance costs generated by low quality regulations. By helping countries to

revise their legal and institutional arrangement, the ICPDR and the UNDP GEF DRP have contributed

to long-term economic prosperity and increased opportunities for investments to reduce pollution and

protect natural resources.

Countries in the DRB have increasingly recognised that developing and implementing regulation (at the

national, regional and local level) is a precondition for effectively responding to a range of key

challenges. Further assistance and efforts are still needed to building institutional capacity at central and

local government level to address the broad challenges of legal reforms.

In addressing environmental concerns, the Danube countries share certain principles: the precautionary

principle, best available technology (BAT), best environmental practice (BEP), control of pollution at

Following a challenging and demanding period the source, the "polluter pays" principle and the

of transition, all DRB countries have in the last

related "user pays" principle, the principle of

years developed a comprehensive hierarchic integrated river basin management approach, the

system of short, medium and long-term principle of shared responsibilities, respectively

environmental policy objectives, strategies and the principle of subsidiarity.

principles which reflect the political context of In addition to the WFD, there has been a high

each country, key country-specific environmental

level of transposition of the EU Directives into

problems and the sector priorities on national and

the national legislations of the DB countries.

regional levels.

The Urban waste water treatment and IPPC

Directives are considered as the most

challenging areas for compliance. This is reflected in the negotiated derogation periods and agreed long

transition periods.

21

With regard to agricultural policies it is worth mentioning that the current low use of agricultural

pesticides in the countries of the DRB presents a unique opportunity to develop and promote more

sustainable agricultural systems before farmers become dependent again upon the use of agro-chemical

inputs. There is concern that with EU enlargement and the expansion of the Common Agricultural

Policy (CAP) into the DRB countries joining the EU there is a risk of increasing fertilisers and pesticide

use due to (i) increasing areas cultivated with cereals and oilseeds due to the availability of EU direct

payments for farmers growing these crops in the new Member States, (ii) increased intensification of

crop production, including the greater use of mineral fertilisers and pesticides, particularly in the more

favourable areas with better growing conditions, and (iii) a reduction in mixed cropping and an increase

in large-scale cereal monocultures in some areas dependent upon agro-chemicals for crop protection.

The selection of the most appropriate policy instruments to control diffuse pollution coming from

agricultural activities, including nutrient and pesticide pollution of the DRB countries will depend also

upon the establishment of a clear policy strategy for controlling pollution, together with clear policy

objectives in line with DRPC and JAP.

In response to this concern, the UNDP GEF DRP has assisted the DRB countries in providing guidance

on the development of policies and legal and institutional instruments for the agricultural sector to

assure reduction of nutrients and harmful substances with particular attention to the use of fertilizers

and pesticides. Inventories of agricultural pesticide use and of fertilizer and manure use have been

completed in 2003. A concept of BAP and opportunities for promoting it through agricultural policy

changes has been also proposed in early 2004.

The following section summarizes the policy and legislation achievements in the countries.

In general terms, the 13 DRB countries can be categorized and characterized as follows: Germany and

Austria have substantially reformed their regulatory regimes to assure the functioning of their

democracies and market-based economies, with all legislation in compliance with the "highest

environmental standards". Significant efforts are also required for EU member states for reaching an

acceptable level of implementation. The experience of the new Member States having joined EU in

May 2004 is an important information for other Danube countries.

The core of water legislation in Austria is the Water Right Act, which was revised in 2003 to

accommodate the EU Directives principles. Austria is currently engaged in developing an Ordinance

defining water quality objectives for rivers as well as for lakes and an Ordinance for the management of

the Austrian Water Data Register.

In March 2004, the Czech Ministry of Environment prepared the updated State Environmental Policy

for 2004 2010. Considerable attention is paid to wetland ecosystems, to rehabilitation of aquatic

biotopes, to effective and sustainable protection of surface and ground water bodies, to harmful

contaminants, to integrated water protection and management. Through river basin management plans,

measures to protect wetlands and floodplains shall be implemented. The use of wetlands and water

resources should be sustainable in view of economic pressures and global changes, and this includes

principles referring to landscape and environmentally sound agricultural practice, wetland and

floodplain uniqueness, restoration, remediation and rehabilitation of damaged wetlands areas.

Slovenia has developed appropriate legislative tools that outline the objectives and strategies for

environmental regulation and water management. The lately approved Environmental Protection Act

(May 2004) primarily focuses on pollution from point sources and is consistent with EU environmental

requirements. The 1999 National Environmental Action Programme (NEAP) established a more

balanced relationship between the environment and economic sectors and introduced a system of

economic incentives to encourage manufacturers and consumers to use resources in a more

"environmentally successful" manner. The Water Act considers the whole water policy such as

protection of water, water use, management of water and protection of water depending ecosystems.

The National Environmental Programme of Hungary includes substantial provisions and measures for

the conservation and management of surface and groundwater resources. Some of the key targets and

approved policy directions are: regulation development to encourage sustainable and economical water

use; improvement of water quality for the main water bodies (Danube and Tisza Rivers, Lake Balaton);

gradual increase (to a level of 65%) of the number of settlements with sewers; at least biological

22

treatment of wastewater from sewers; nitrate and phosphorous load reductions for highly protected and

sensitive waters. By 2003 the Hungarian legislation on water quality protection was fully harmonized

with the EU regulations, including the appropriate institutional setup.

The implementation of the Slovak water management and protection policy is in compliance with EU

water policy, i.e the WFD, aiming at achieving of good water status for all waters by 2015. The

legislative tools for achieving policy objectives have been prepared. All EC directives have been

transposed into the national law system. The transposition was finished in 2004 through an updated

version of the Water Act (no. 364/2004). Main priority in relevant sectors (urban wastewater, industrial

wastewater, land use, wetlands) is the implementation of EC directives' requirements (urban and

industrial wastewater during the transition periods), namely reduction of nutrients and priority

substances and creation of effective water management that will be able to promote sustainable water

use based on long - term protection of available resources.

The need to implement a unified policy on the environment and the use of natural resources, which

integrates environmental requirements into the process of national economic reform, along with the

political desire for European integration, has resulted in the review of the existing environmental

legislation in Moldova. The current priorities for water management include the strengthening of

institutional and management capability through improvement of economic mechanisms for

environmental protection and the use of natural resources, setting internal environmental performance

targets and controls, self-monitoring, review of current legislation in line with European Union

legislation, and the adjustment or elaboration on a case-by-case basis of implementation mechanisms.

Bosnia and Herzegovina is faced with major challenges in the environmental and water management

area. Among specific objectives for environment is the development of an environmental framework in

Bosnia and Herzegovina based on the Acquis. The most important issues in the environment sector will

be identified in the Environmental Action Plan, which is being developed with World Bank support.

The EU is supporting a Water Institutional Strengthening Programme, which is complemented by two

Memoranda of Understanding (2000, 2004) between both Entities and the EC.

The proposed schedule for approximation with EU indicates a new Water Law and a Law on

Environment, compatible with the Acquis, to enter into force by January 2005.

Since the WFD was adopted, numerous and diverse activities were initiated in Serbia & Montenegro

to further develop and implement the Directive. The water management is faced with serious tasks that

require, above all: (i) the creation of a system of stable financing for water management, (ii) the

reorganization of water management sector, and (iii) the revision of water legislation and related

regulations, in compliance with requirements of European legislation.

The remaining accession countries Romania, Bulgaria, Croatia as well as those non accession countries

are experiencing the historic opportunity of European integration, which is the most important driver of

reforms but brings great challenges at the same time:

The adoption in 1999 of the Strategy for the Integrated Water Management marked the beginning of the

reforms in the water sector in Bulgaria in line with the WFD and assumed obligations under

international instruments. Several other programs such as Environmental Strategy to implement the

ISPA objectives, the Program for the UWWT Directive implementation or the National Strategy for

Management and Development of the Water Sector until 2015 complete the picture of on going efforts

in Bulgaria towards complying with EU legislation.

In Croatia, the current basic environmental and water legislation and regulations (such as the Water

Act, Water Management Financing Act, State Water Protection Plan) will be revised to meet the EU

directives requirements within the frame of two CARDS projects expected to start at the end of 2004.

Romania is about to close Chapter 22 on harmonisation of environmental legislation with EU

requirements. Basic water legislation (Water Law) and implementing regulations, standards and

ordinances regulations have already been fully harmonised with the EU directives.

Ukraine has not yet updated the environmental policy act (the Principal Direction, 1998). The update

version of the Sustainable Development Strategy, however, has been recently submitted for approval by

the Parliament. The Program of the Development of Water Economy is in force but still specific

23

legislation on water management is missing. The current Governmental Action Plan is a comprehensive

document which integrates economic, social and environmental concerns. Efforts are currently

undertaken to finalise in 2005 the revision of the Protocol on the Protection of the Black Sea Marine

Environment against Pollution from Land-Based Sources, in line with WFD principles. The Water Code

of Ukraine harmonised with EU Directives is submitted as well for approval.

5.3

New instruments of environmental policies in the DRB

The environmental policy of the past can be described as source, substance, and media - orientated.

Recent approaches try to connect isolated instruments such as directive based regulations - by

integrating existing measures into a comprehensive framework for sustainable development (market

based instruments and/or voluntary agreements). The main instruments used in the DRB countries today

are often grouped into three main clusters: (i) directive based regulations, (ii) market based

instruments and (iii) voluntary agreements.

According to the JAP, a joint decision for a voluntary agreement (Detergent industry (AISE) and the

ICPDR) on promoting the introduction and use of phosphate-free detergents to the market of the

Danube countries should be formulated. There are several voluntary agreements between governments

and industry to limit the use of phosphates in detergents by the detergent industry. In some countries

such as Germany the voluntary agreement is in effect equivalent to a "ban" of phosphates in household

laundry detergents.

The UNDP GEF DRP has already started to provide support to the ICPDR on the identification of best

alternative to introduce voluntary agreements instruments. As this process can only be successful in a

partnership with all relevant stakeholders, the detergent industry is actively involved in the dialogue.

5.4

Barriers to the implementation

Regulatory challenges facing Danube Countries are significant. Progress is slow but the governments

are gradually adopting modern regulatory and policies instruments to improve the quality of the

regulatory environment and management practices to send a clear signal to the foreign and national

financing institutions on their needs for investments.

Enforcement and compliance are considered as the main barriers to the effective implementation of the

EU Directives and the ICPDR JAP. The difference between high regulatory standards and compliance

capacity of the regulated bodies, without having designed flexible compliance schedules prevent

authorities from effectively enforcing their regulatory instruments. Lack of a unifying concept on

policies instruments choice and implementation across various levels of government still exist in some

countries (e.g Moldova, Ukraine, Serbia & Montenegro) where decentralization and democratization of

structures has not yet taken place. In some countries, problems with decentralization are associated with

absence of subsidiarity principle approach (clarifying of competencies by all authorities in

government, in regions, districts and municipalities).

Additionally, costs for fulfilment of EU directives requirements will increase of water services prices.

Implementation of Directive 76/464/EEC cost requires education of state water administration

concerning new permits for discharging of waste waters. Sometimes, weak enforcement is associated

with ineffective penalties system or with inconsistencies between the current structure/content of the

laws, and the conflicts and overlapped provisions in various other laws.

Other barriers impeding the implementation are linked to the insufficient capacity building, lack of

access to water and environmental relevant information, absence of public participation mechanisms in

the environmental decision-making process. High investment needs, sometimes more demanding

national legislation than that at the EU, administrative burdens, and insufficient co-operation between

governmental institutions can complete the barriers picture.

24

6 Reporting on the Joint Action Program implementation

6.1

Progress of implementing policy and regulatory measures at national level in relation to

JAP requirements

Responding to the DRPC requirements, the Danube countries have developed the Joint Action Program

(JAP), which includes policies and strategies for improvement of water quality, pollution reduction and

wetland restoration. Particular attention is given to both structural/investment and non structural/policy

reforms measures that address nutrient reduction and protection of transboundary waters and

ecosystems:

· Coordinating and developing the River Basin Management Plan for the Danube River Basin in

implementing the EU Water Framework Directive;

· Maintaining and updating emission inventories and implementing proposed measures for

pollution reduction from point sources and non point sources;

· Restoring wetlands and floodplains to improve flood control, to increase nutrient absorption

capacities and to rehabilitate habitats and biodiversity;

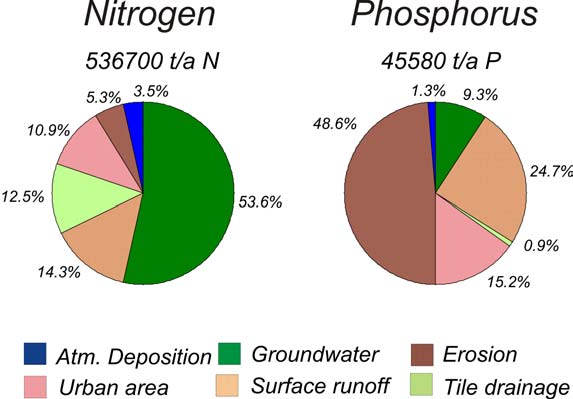

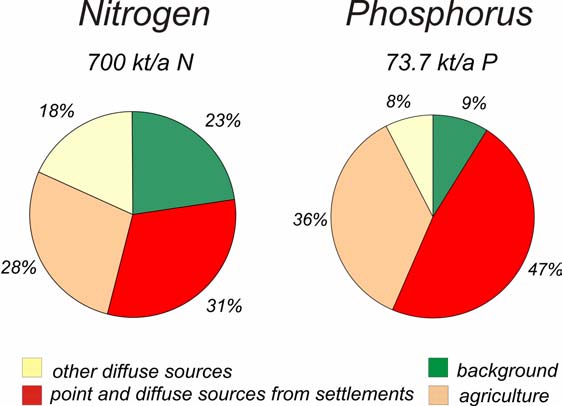

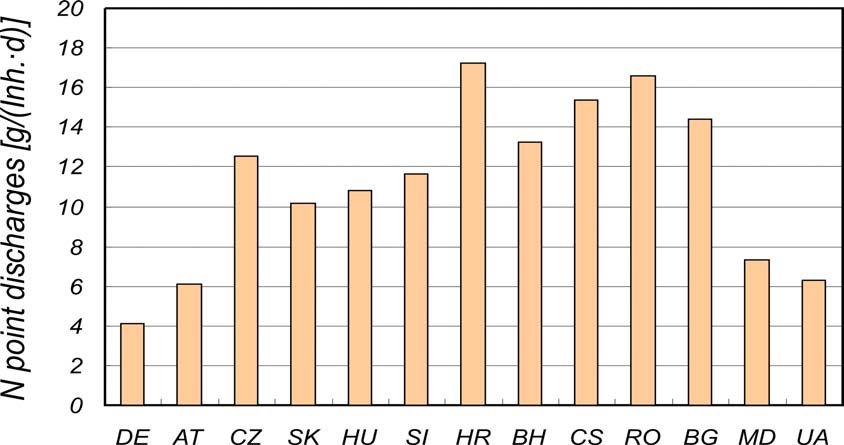

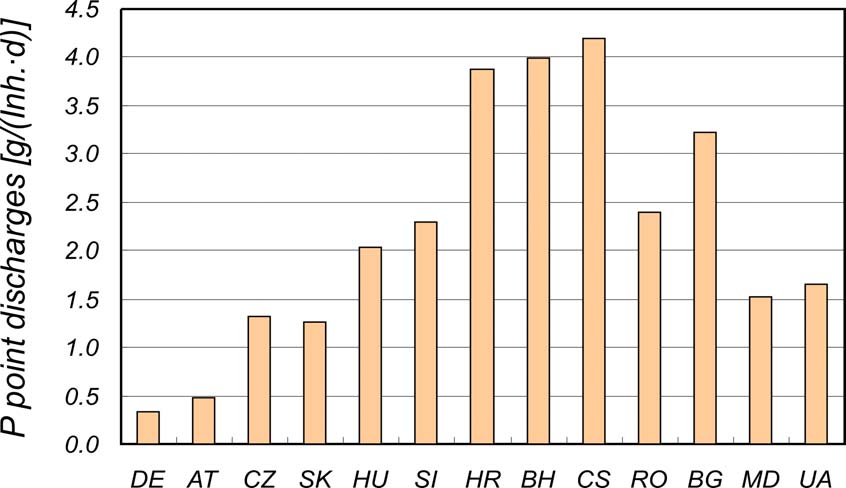

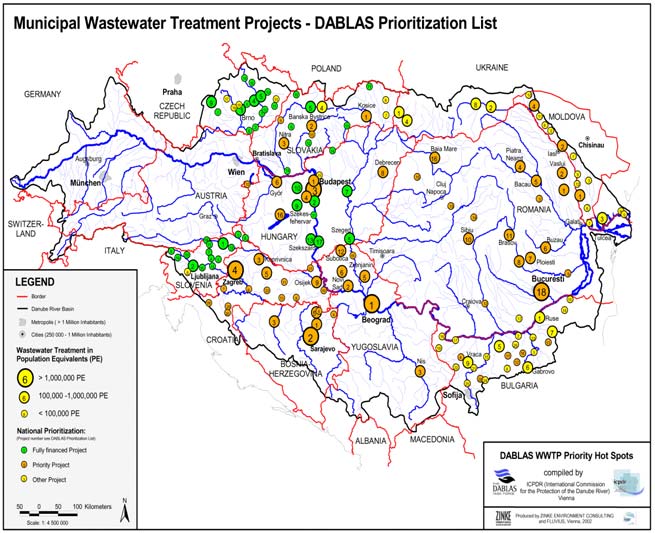

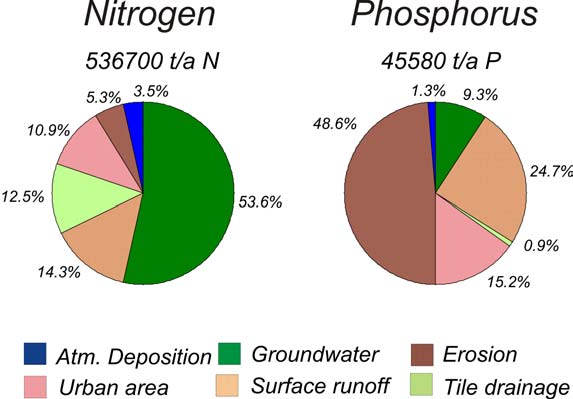

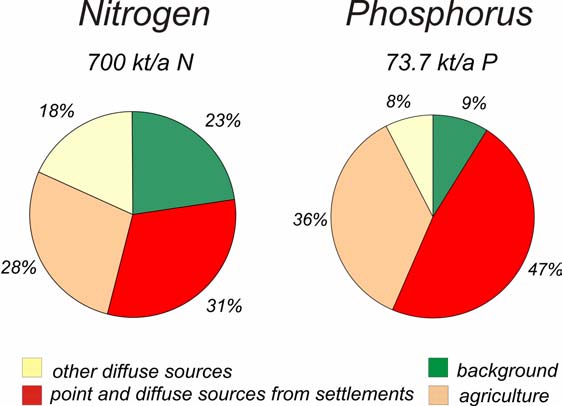

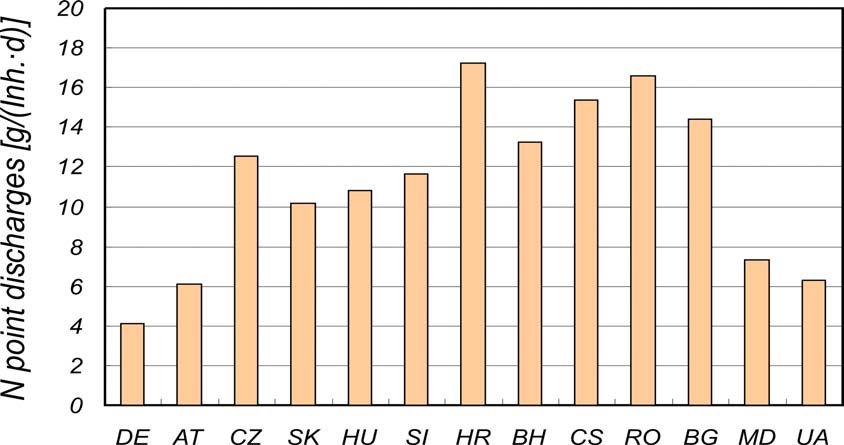

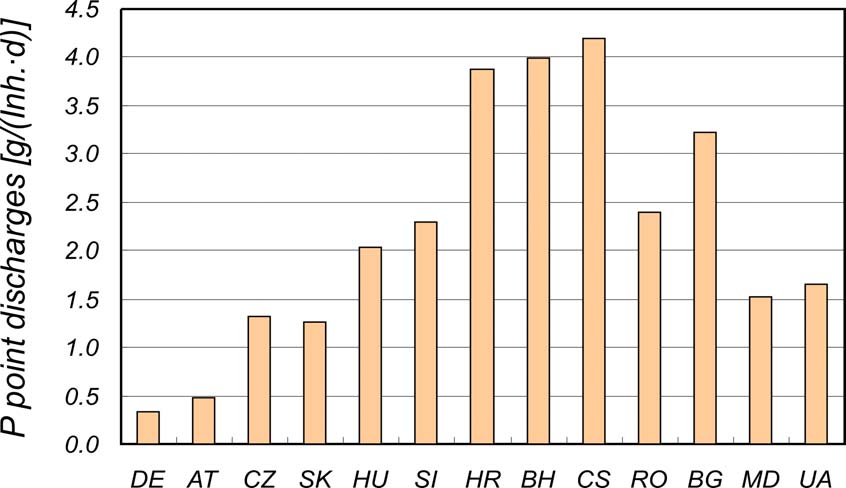

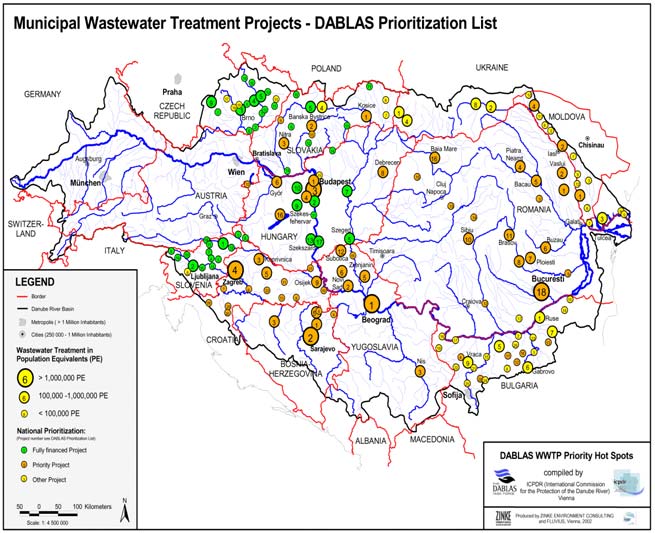

· Operating and further developing the Transnational Monitoring Network (TNMN) to assess the