September 2004

ASSESSMENT AND DEVELOPMENT OF

MUNICIPAL WATER AND WASTEWATER

TARIFFS AND EFFLUENT CHARGES IN

THE DANUBE RIVER BASIN.

Volume 2: Country-Specific Issues and

Proposed Tariff and Charge Reforms:

The Czech Republic National Profile

AUTHORS

Lenka Camrova / IREAS, o. p. s.

TARIFFS AND CHARGES VOLUME 2

PREFACE

The Danube Regional Project (DRP) consists of several components and numerous

activities, one of which was "Assessment and Development of Municipal Water and

Wastewater Tariffs and Effluent Charges in the Danube River Basin" (A grouping of

activities 1.6 and 1.7 of Project Component 1). This work often took the shorthand

name "Tariffs and Effluent Charges Project" and Phase I of this work was undertaken

by a team of country, regional, and international consultants. Phase I of the

UNDP/GEF DRP ended in mid-2004 and many of the results of Phase I the Tariffs and

Effluent Charges Project are reported in two volumes.

Volume 1 is entitled An Overview of Tariff and Effluent Charge Reform Issues and

Proposals. Volume 1 builds on all other project outputs. It reviews the methodology

and tools developed and applied by the Project team; introduces some of the

economic theory and international experience germane to design and performance of

tariffs and charges; describes general conditions, tariff regimes, and effluent

charges currently applicable to municipal water and wastewater systems in the

region; and describes and develops in a structured way a initial series of tariff,

effluent charge and related institutional reform proposals.

Volume 2 is entitled Country-Specific Issues and Proposed Tariff and Charge

Reforms. It consists of country reports for each of the seven countries examined

most extensively by our project. Each country report, in turn, consists of three

documents: a case study, a national profile, and a brief introduction and summary

document. The principle author(s) of the seven country reports were the country

consultants of the Project Team.

The authors of the Volume 2 components prepared these documents in 2003 and

early 2004. The documents are as up to date as the authors could make them,

usually including some discussion of anticipated changes or legislation under

development. Still, the reader should be advised that an extended review process

may have meant that new data are now available and some of the institutional detail

pertaining to a specific country or case study community may now be out of date.

All documents in electronic version Volume 1 and Volume 2 - may be read or

printed from the DRP web site (www.undp-drp.org), from the page Activities /

Policies / Tariffs and Charges / Final Reports Phase 1.

TARIFFS AND CHARGES VOLUME 2

We want to thank the authors of these country-specific documents for their

professional care and personal devotion to the Tariffs and Effluent Charges Project.

It has been a pleasure to work with, and learn from, them throughout the course of

the Project.

One purpose of the Tariffs and Effluent Charges Project was to promote a structured

discussion that would encourage further consideration, testing, and adoption of

various tariff and effluent charge reform proposals. As leaders and coordinators of

the Project, the interested reader is welcome to contact either of us with questions

or suggestions regarding the discussion and proposals included in either volume of

the Project reports. We will forward questions or issues better addressed by the

authors of these country-specific documents directly to them.

Glenn Morris: glennmorris@bellsouth.net

András Kis: kis.andras@makk.zpok.hu

TARIFFS AND CHARGES VOLUME 2

National Profile of Municipal Water and Wastewater Management in the Czech Republic

3

Table of Contents

Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................7

1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................9

1.1. Overview of the Morava River Basin .............................................................................9

1.2. Origins of the Municipal Water and Wastewater Industry ...........................................10

1.3. Future Direction ............................................................................................................11

2. Legal and Institutional Setting .............................................................................................13

2.1. National Laws and Regulations ....................................................................................13

2.1.1. Common Provision ................................................................................................13

2.1.2. Self Service............................................................................................................15

2.2. Management Units ........................................................................................................15

2.2.1. Administrative Unit ...............................................................................................15

2.2.2. Operating Units......................................................................................................15

2.2.3. Ownership of Facilities..........................................................................................16

2.3. Service Users ................................................................................................................16

2.3.1. Classification of Users...........................................................................................16

2.3.2. Special Legal Consideration by User ....................................................................17

2.4. Regulatory Units ...........................................................................................................17

2.4.1. The Overview of the Environmental Regulation...................................................18

2.4.2. The Overview of the Economic Regulation ..........................................................19

3. Data ......................................................................................................................................20

3.1. Water Production ..........................................................................................................20

3.1.1. Abstraction of Surface Water ................................................................................20

3.1.2. Abstraction of Groundwater ..................................................................................22

3.2. Water Processing/Cleaning ...........................................................................................24

3.3. Water Distribution ........................................................................................................24

3.4. Water Purchased ...........................................................................................................25

3.5. Water Consumption ......................................................................................................25

3.5.1. General Consumption of Water in the Czech Republic.........................................25

3.5.2. Water Consumption of PWSS&S..........................................................................26

3.6. Wastewater Production .................................................................................................26

3.7. Wastewater Collection and Processing .........................................................................28

3.8. Wastewater Effluent Discharge ....................................................................................28

4. Economic Data .....................................................................................................................29

4.1. Tariffs, Fees and Charges..............................................................................................29

4.1.1. Tariffs for PWSS&S Services ...............................................................................29

4.1.2. Payments to Cover Watercourse and River Basin Administration........................30

4.1.3. Charges for the Withdrawal of Groundwater ........................................................31

4.1.4. Fees for the Discharge of Wastewater into Surface Water (Effluent Charges) .....31

4.1.5. Fee for a Permitted Discharge of Wastewater into Groundwater ..........................31

4.2. Sales to Particular Service Users ..................................................................................31

4.3. Costs on Purchased Inputs ............................................................................................31

4.3.1. Effluent Charges ....................................................................................................33

4.4. Grants or Transfers........................................................................................................34

5. Infrastructure ........................................................................................................................35

5.1. Production, Processing and Distribution of Water........................................................35

5.2. Collection and Treatment of Wastewater......................................................................36

6. Management Units ...............................................................................................................37

6.1. Types of Management Units .........................................................................................37

6.2. Management Units Service Areas.................................................................................38

6.3. Population Served .........................................................................................................38

4

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

6.4. Special Obligations .......................................................................................................38

6.5. Financial Conditions .....................................................................................................38

6.6. Current Plans for Expansion and Investment................................................................39

7. Regulatory Units ..................................................................................................................40

7.1. National and Local Planning and Permitting ................................................................40

7.1.1. Data Collection ......................................................................................................40

7.1.2. Planning and Development....................................................................................40

7.2. Economic Regulations or Limitations...........................................................................41

7.2.1. Pricing (tariffs) ......................................................................................................41

7.2.2. Grants and Subsidies..............................................................................................41

7.3. Environmental Regulations and Restrictions ................................................................42

8. Service Users........................................................................................................................44

8.1. MU Customers ..............................................................................................................44

8.2. Self Supply Users..........................................................................................................44

9. Reform Proposals Connected with Tariffs and Charges ......................................................45

9.1. Tariff Structure..............................................................................................................45

9.2. Economic Regulation....................................................................................................45

9.3. Economic Sustainability ...............................................................................................46

9.5. Summary of Reforms ....................................................................................................46

10. References ..........................................................................................................................48

Lenka Camrova/IREAS

National Profile of Municipal Water and Wastewater Management in the Czech Republic

5

Abbreviations

Act on PWSS&S

Act No. 274/2001 Coll. on Public Water Supply Systems and Sewers

CSSR

Czech and Slovak Socialistic Republic

CZSO

Czech Statistical Office

CR

Czech Republic

CZK

Czech currency (1 Euro is about 32 CZK)

EU

European Union

MU

Management Units - municipalities or companies established or hired by

municipalities to run the system

PWSS&S

Public Water Supply Systems and Sewers - the official title for the MU in the

Czech Republic

RU

Regulatory Units, e.g. the government, Ministries and other offices of the public

administration, which impose some regulation on the MU

SU

Service Users are households and businesses

VaK

Vyskov Public Water Supply System and Sewerages in Vyskov (selected case

site)

VAT

Value Added Tax

Water Act

Act No. 254/2001 Coll. on Water

WWTP

Wastewater treatment plant

National Profile of Municipal Water and Wastewater Management in the Czech Republic

7

Executive Summary

The purpose of the National Profile is to analyse the current situation and future development in the

field of water and wastewater management in the Czech Republic, with a strong focus on providing

public water supply and sewerage. As a result of describing the historical consequences, the current

and future development, possible tariff and effluent charges reforms have been suggested.

The text is divided into 9 chapters, which are focused on different entities of the system, following the

basic division into three main groups: regulatory units, management units and service users. This

division facilitates defining the individual competences and obligations as well as mutual interactions

throughout the whole system.

Whenever possible the stated data and information are related to the Morava River basin the part of

the Czech territory, which belongs to the Danube river basin.

An integral part of the National Profile of Municipal Water and Wastewater Management in the Czech

Republic is A Case Study of Municipal Water System Management and the Impacts of Tariff and

Effluent Charges: Vyskov. The case study describes the situation of a particular management unit and

explores some hypothetical development and policy scenarios.

National Profile of Municipal Water and Wastewater Management in the Czech Republic

9

1. Introduction

This report is, first of all, a compilation of information and data that describes the institutions and

conditions that shape and characterize the provision of municipal water and wastewater service in the

Czech Republic. The purpose of this compilation is to provide a background and inspiration for

proposals to reform both the current system of water and wastewater tariffs and effluent charges and

coincident proposals to adjust or modify the legal and regulatory system within which the these tariffs

and effluent charges function in the Czech Republic.

Indeed, some chapters include brief analyses suggesting such reforms and Chapter 9 concludes this

report with preliminary proposals for reforms in the institutional setting and the design of these tariffs

and charges. The aim of these proposals is to improve the management of water and wastewater

resources used in the municipalities of the Czech Republic generally and including protecting water

resources from nutrient loading and toxic substances originating from municipal systems.

1.1. Overview of the Morava River Basin

The Czech Republic is a democratic state in Central Europe which was established in 1993 after the

federation ,,Czechoslovakia" split up into two republics: the Czech Republic and Slovak Republic. The

country is politically stable under the governance of the social democratic party since 1998. The Czech

Republic is joining the European Union in May 2004 in the first wave of enlargement.

The state is divided administratively into self-governing units, which are as follows:

a) municipalities in the first level of public administration (more than 6 000),

b) municipalities with enlarged competences (,,small districts") which administrate the territory

of more municipalities and also have some special competences under the government

administration, e.g. in the field of water management (about 200),1

c) regions as the highest level of public administration (13 regions).

For the purpose of administering watercourses, there is another division of the Czech Republic based

on the ,,river basin" approach. According to that, there are 5 main river basin territories: Elbe, Vltava,

Ohre, Odra and Morava. For the purpose of the report, only the Morava River has any relevance as a

part of the Danube river basin. The administrative units' borders do not correspond with particular

river basins, which causes some problems in data collection (see Chapter 3).

1 ,,small districts" partly replaced the competences of about 73 districts units of government administration - that were

abolished in 2002

10

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

Map 1.

River Basins in the Czech Republic

Ohre river basin

Vltava river basin

Elbe river basin

Morava River basin

Odra river basin

Source: www. povodi.cz

The Morava River basin covers about 21 423 km2, which is about 25% of the Czech territory. It covers

the area of 4 regions (South-Moravian, Zlin, Vysocina, Olomouc) and encompasses parts of another 3

regions (Pardubice, Moravskoslezsky, South-Bohemia). There are about 1 900 municipalities of

different size in the Morava River Basin, from which about 100 serve as a ,,small district".

The population living in the Morava River basin is about 3 mil., which is about 30% of the total

population.

1.2. Origins of the Municipal Water and Wastewater Industry

In the Czech Republic, the fundamental change in water legislation, in general, took place after the

political shift in 1948 (beginning of the socialist period). This change was based on a unified approach

to the whole territory and fixed the principles of planned management of the national economy.

Watercourses of major importance were declared as a national property. Water management was

directed by the Ministry of Public Works, which was responsible for canalising rivers, dams, public

water supply systems and sewers (PWSS&S) in selected industrial towns and spas. The Ministry of

Agriculture was responsible for the other watercourses, technical drainage, PWSS&S in the villages.

According to Act. No. 138/1974 Coll. on waters, the structure of water management used to have 4

hierarchical levels: the central authority at the national level (Ministry of Water Management and

Wood Industry of the CSSR), at the provincial level (the provincial national committee), at the

Lenka Camrova/IREAS

National Profile of Municipal Water and Wastewater Management in the Czech Republic

11

municipal or city level (municipal or city national committee) and at the local level (local national

committee). Most decisions were carried out at the municipal level, i.e. permissions to construct

waterworks, agreements on water management authorities, ... etc.

A significant step was the establishment of 6 basin administrations in 1966, which were linked to the

General Directorate for Watercourses. In 1970 the general directorate was closed down, and 5 River

Authority Companies were set up, together with the Water Management Development and Structures

Company.

In the period between 1971 and 1977 the district and provincial authorities responsible for drinking

water supplies and sewerage were fused into 7 provincial drinking water-sewerage system companies

(Central Bohemian, South Bohemian, West Bohemian, North Bohemian, East Bohemian, South

Moravian and North Moravian Water Supplies and Sewerage). However in Prague two independent

companies were kept, Prague Water Supplies and Prague Sewerage. This structure lasted until

practically 1989. In 1989, the Ministry of Water Management and Wood Industry was closed down

After 1990, the Ministry of the Environment was delegated to oversee water management at the

central level to play the role of Central Water Management Authority. Since 1990 some of the

responsibility for water management has also gradually been taken over by the Ministry of

Agriculture, including the function of setting up water management companies. This situation played a

significant role in their privatisation process. Most of the formerly centralised water management

companies were dissolved and new private companies have been established. On the basis of a

decision of the minister of agriculture, the River Basin Boards were converted into joint-stock

companies, where the only shareholder is the Czech State. This decision (which wasn't legally

justified) has been changed by Act No. 305/2000 Coll. on River Basin Administrators.

Currently, the Ministry of Agriculture plays the most significant role in the water sector as the central

water authority with regions and "small districts" at lower stages of administration. The Ministry also

co-finances and drive particular River Basin Boards as administrators of large watercourses.

Major changes have taken place in water supply and sewerage. The transformation followed the basic

principle of transferring ownership and responsibility from the state to the new owners, in this case to

self-administrating towns and villages. The transformation of public drinking water and sewer systems

took place within the second wave of coupon privatisation. Legislatively, this did not take the form of

a special act. A governmental decision was issued, which established the following conditions for the

approval of privatisation on projects:

a) the owners of the infrastructure may be only communities, groups of communities and/or joint

stock companies in which the communities are major shareholders (with a holding of 80 -

100% of the shares),

b) the so-called operational property of the former provincial water supply and sewerage

companies (buildings, transport and construction machinery) could be privatised using the

standard methods of privatisation,

c) each privatisation project should also take into account the standpoints of the communities

involved with respect to the process of privatisation.

1.3. Future Direction

The Czech Republic has become a member state of the EU, which brings the obligation to adopt and

enforce all environmental legislation according to European Union directives. The implementation has

been in process and for each directive an ,,Implementation Plan" has been adopted.

There is a amendment of the Water Act in the Czech Parliament, which should ensure the total

implementation of the EU Water Framework Directive into Czech legislation.

For the purpose of this study, two significant changes are suggested:

12

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

1) Municipalities that cause water pollution in excess of 2000 population equivalent are obliged

to ensure a functional sewage system and water treatment by the end of 2010. The limits of

discharged pollution will be set by a special Government Order. A system of grants and

subsidies has also been suggested (see Chapter 7.2.2.).

2) 50% of Charges for the Withdrawal of Groundwater will accrue to regional budgets (at present

all charges are revenues of the Czech State Environmental Fund). Therefore, central state

resources face a reduction of about 350 mil. CZK, but the position of Regional Offices as the

second level of the water administration will be stabilized. (for charges see Chapter 4.1.)2

In keeping with EU regulations, an amendment of the Law on Public Orders is being prepared. This

law is going to regulate investments of PWSS&S, because there is a tendency to over-invest in some

territories of particular PWSS&S, where the efficiency of such investments is very low and the

subsequent operating costs would be a big burden on the public. To support this regulation, regional

plans for development of PWSS&S have been elaborated. Recommendations are to be made by

independent experts and the main goal is to choose the economically and technically best option for

future development. The water administration should not allow construction other than that identified

in the plans.

Regarding municipal water and wastewater services in the Czech Republic generally, we can consider

them functioning systems on the whole but posing some potential risks in the future. These are

mostly analyzed in the following chapters. One of these risks is the current trend of municipalities

selling the infrastructure to private firms which are enormously interested in towns or agglomerations

over 10 000 inhabitants where running the system is profitable. The municipality often does not realize

the real value of its property (which is often formally depreciated, but will serve another 20 years

without any investment) and prefers the immediate revenues that come with possibly precipitous

privatisation. This behaviour is also promoted by the particular privatisation process used in the Czech

Republic in the early 90s' (for further information on MUs behaviour see Chapter 6.1.).

2 As further explained in Chapter 2.4., there is a hierarchy of water authorities in CR: Ministry of Agriculture regions

"small districts", through which the water sector is managed. All other institutions and organisation (River Basin Boards,

PWSS&S of particular municipalities) do not have executive power and are established only for purposes of better

administration or for ensuring basic needs of public.

Lenka Camrova/IREAS

National Profile of Municipal Water and Wastewater Management in the Czech Republic

13

2. Legal and Institutional Setting

The chapter introduces the main actors playing roles in municipal water management in the Czech

Republic and presents their position and power as stated in Czech legislation. These actors are divided

into 3 categories: regulatory units (RU), management units (MU) and service users (SU). An overview

of the Czech water management legislation is provided, too.

2.1. National Laws and Regulations

2.1.1. Common Provision

For a better orientation in the requirements and definitions set by the legislation, the area of water

management in the Czech Republic has been divided into 2 key parts:

1. General use of surface water and groundwater for different purposes.

2. Area of Public Water Supply Systems and Sewers.

2.1.1.1. General Use of Water

The area of the general use of surface water and groundwater (including drinking water) is addressed

by Act No. 254/2001 Coll. on Water (The Water Act). Granting of permits to extract water and to

discharge wastewater is described, and payments (fees, charges) for particular users are established.

The law also covers the area of planning in water management and defines the administrators of

watercourses. It implements parts of the requirements of the Water Framework Directive into Czech

legislation.

Scope: The law covers any withdrawals and discharges of/to surface water and groundwater which

exceed a volume of 6 000 m3 in one calendar year or 500 m3 of water in one calendar month.

Conditions of Use: Surface water and groundwater are not subject to ownership (administrators of

these watercourses are established by the law). Any water withdrawn from these sources is no longer

considered to be surface water or groundwater. In the Water Law, there is a list of activities for which

special permission from the water authority is required. The lowest level of water authority is

considered the ,,small district". The next grade up in water management is represented by the regions.

Both, municipal and regional offices operate with two types of power: independent activities (e.g.

cooperation with Ministry of Agriculture in creating River Basin Plans) and government transferred

activities (e.g. decision-making, permissions, controlling municipalities...etc.). The central water

management administration is represented by particular Ministries (see Chapter 2.4).

Reporting Requirements: For the purpose of water balance, the consumers of surface water and

groundwater and those discharging wastewater (= holders of permits) are obliged to report to the river

basin administrators (Act No. 305/2000 Coll. on River Basin Administrators) or the relevant

Ministries. This reporting is done annually and includes the quantity and quality of water

withdrawn/discharged. Also the Czech Environmental Inspection is authorised to ask for needed

information within its activities.

2.1.1.2. Public Water Supply Systems and Sewers

According to Act No. 274/2001 Coll. on Public Water Supply Systems and Sewers (Act on

PWSS&S), the service area of PWSS&S has been legally established as a special network branch

14

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

(public utilities subject the regulation, e.g. electricity, telecommunications). For clear understanding,

the expression PWSS&S means the entity (public, private or mixed) responsible for ensuring that

system operators (that operate the public, municipal water infrastructure) meet the basic needs of the

population (while subject to economic, including tariff, regulation. This entity can, but does not have

to be interconnected with the municipal bodies or the actual operation of the infrastructure. Various

legal status of PWSS&S will be discussed in Chapter 2.2.

Service Area: Historically particular PWSS&S were public companies operating the public

infrastructure, established and built as a decision of government or public administration (towns before

the Socialist period, the Central Government from 1948). From the 50s', particular construction and

supply systems mostly were organized according to districts.

Condition of service: In the legislation, three main categories of subjects are described: the owner of

the infrastructure, the service provider and the user of the system. Municipalities are usually the

owners of the infrastructure. The service provider is a legal person receiving the permission to do a

business from the regional office in a form of concession.

The owner or the service provider has to enable connection into the network (pipelines, sewers) for all

users without any discrimination. It is responsible for the reliable and safe operation of the system 24

hours a day. The quantity of the water consumed is usually measured by water meters in households

and the quantity of wastewater services estimated based on drinking water consumption. The price for

the service (water and sewage tariff) is under price regulation according to Act No. 526/1990 Coll. on

prices. The calculation has to be published every year. This means that before the given period (year),

PWSS&S itself has to estimate its costs and propose water and sewage tariffs per m3. These prices are

invoiced over the whole period. Subsequently, PWSS&S compares the real operating cost with the

previous calculation. If there are some differences, the surplus or the shortage has to be given back (or

invoiced) to consumers. In practice, an annual water account is sent to consumers with calculated

overcharge or surcharge. In some cases, the total of the estimate calculation per m3 and the real

calculation is the same.

The quality of the drinking water and harmful substances in wastewater has to be regularly measured

and reported to the water authorities.

The customers pay to PWSS&S per measured m3 and they can be disconnected if the invoice is not

paid in 30 days. If a new customer wants to join the system he has to pay costs for building the

distribution and collection lines on his property and he is an owner of this end part of the

infrastructure.

Reporting Requirements: The owner of the infrastructure has to do the record-keeping of his pipelines

and sewers (value of the property, sources and quality of used water, price calculations... etc.). This

information has to be submitted annually to the regional water authority. This regional authority

aggregates the data and sends it to the Ministry of Agriculture. The owner (or the service provider) has

to inform the user about the price calculation whenever asked.

Ownership of infrastructure: During the process of privatisation, most of the infrastructure was

transferred directly to associations of municipalities or joint-stock companies formed by

municipalities, according to their privatisation project (plan for operation of the business) that had to

be presented. About 16% of shares of particular companies (their operational property) went to the

voucher privatisation and could have been bought by any citizen. Within associations, shares were

distributed among municipalities according to two rules: No. of inhabitants or value of the

infrastructure, according to a decision of the constituent members. The large towns were mostly

agreeable to the process in which small municipalities were favoured (e.g. municipalities with no

infrastructure on their territory got some shares, too).

Originally, in most joint-stock companies, the Central Government held one ,,golden share" with

special rights, e.g. the right to block selling the infrastructure. At present, this share exists in about

20% of companies and there is a strong pressure to inconspicuously lower the power of the Central

Government in decision-making.

Lenka Camrova/IREAS

National Profile of Municipal Water and Wastewater Management in the Czech Republic

15

2.1.2. Self Service

According to the Water Act, any person can withdraw surface water without a permit if such a use

does not require special technical facilities.

In other cases (listed in Section 8 of the Water Act) the Permission for the Use of Surface Water or

Groundwater is required from the water authority. Every person holding this permit has to measure the

quantity and quality of the water used and submit the results to the river basin administrator. There is

an exception for small users withdrawing a volume of up to 6 000 m3 in one calendar year or 500 m3

of water in one calendar month or less.

According to the Act on PWSS&S, all water used for drinking purposes has to meet given hygienic

standards. The frequency and the process of controls is regulated by a special law from the Ministry of

Health.

Most of the self-supplying units in the Czech Republic are exempted from any reporting (especially

houses in small villages), therefore the quality of drinking water is very difficult to control. It is

assumed, that most of there resources (pump-wells) do not meet hygienic standards.

2.2. Management Units

2.2.1. Administrative Unit

In the Czech Republic, municipalities are responsible by law for providing the water supply and

sewage services for the population. Particular municipalities can contract service providers or establish

self-operating companies. The price for using the infrastructure depends on local policy.

2.2.2. Operating Units

Water supply and wastewater treatment is primarily organised in combination. There are about 1 400

1 600 registered PWSS&S in the Czech Republic and about 800 1 000 small municipal MUs running

the system without concession. There are about 120 large companies, which are covered by the central

records of the Ministry of Agriculture. About 22 of them operate in the Morava River basin.

These companies cover mainly district areas and are characterized by one large ,,compound" pipeline,

which usually determines the territory of the system (company).

There are many types of PWSS&S in the Czech Republic which can be organized into the following 3

groups:

1. Joint-stock companies which own the infrastructure and the operational property (so operates

the system themselves) and where a municipality (or Association of municipalities) has got a

majority ownership of the stock. In this case every municipality has some directly control of

the operations of the system. This control may be limited if a private firm has an ownership

position in the company and is responsible for providing services as the operator of the

system.

2. Association of municipalities, which owns the infrastructure and a separate private company

as a service provider which owns the operational property. The association of municipalities

hires the infrastructure to a service provider and indirectly controls operator's policies, prices

of services etc. through the terms of the contract or concession to provide service or any

oversight provisions included in that contract.

16

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

3. Small single municipalities, which own the infrastructure and the operational property and

run the system themselves or contract a service provider (if it has no own staff to do it). This

type is often similar to the first one, but it is established in small isolated villages in

mountains.

2.2.3. Ownership of Facilities

As mentioned before, the ownership of the property has been transferred from the Central Government

to a more diversified share-holder basis in the privatisation process. Originally, the state kept a

,,golden share" in most companies through which it could regulate important decisions.

At present, the owner of the infrastructure (pipelines, sewers) is mostly the municipality (or

association of municipalities). Other functional buildings, cars and other property necessary for

providing services belongs to the service provider. Pumping stations, water treatment and wastewater

treatment plants are considered as a part of infrastructure. The service provider can be the same entity

as the infrastructure owner.

Particular distributaries and collection lines on private property are the private property of the owner

of the connected land/building.

2.3. Service Users

2.3.1. Classification of Users

There are the following water users in the Czech Republic:

- PWSS&S,

- agriculture,

- industry and electricity producers,

- others.

Within the category of PWSS&S, a further sub-classification of Service Users can be made:

- households (consuming about 63 % of water invoiced in 20013),

- agriculture (1.3 %),

- industry (7.4%),

- others (28%).

All categories of users show a decreasing trend in surface water and groundwater withdrawals.

Of the total amount of wastewater annually discharged into the sewage system about 59% is domestic

wastewater and about 41% industrial and other wastewater.4

3 Source: Smrný vodohospodáský plán vstník, 2001, Ministry of the Environment

4 Source: Czech Statistical Office, www.czso.cz

Lenka Camrova/IREAS

National Profile of Municipal Water and Wastewater Management in the Czech Republic

17

2.3.2. Special Legal Consideration by User

The user (customer) of PWSS&S is the owner of the property or building connected to the water

supply or sewerage network. If there is more than one private independent owner of apartments in the

building, the user of PWSS&S is always an association of these owners.

In the case of national or municipal property, the user is an organizational constituent of the Czech

state, which administers the property.

2.4. Regulatory Units

Ministry of Agriculture is the major water authority in the Czech Republic and it shares its

responsibility with other central bodies. Its domain is:

- To control drainage systems on agricultural and forest land, irrigation networks, ponds and

small water reservoirs, if they serve agriculture and forestry,

- To administer watercourses important in water management via the River Board State

Companies,

- To develop the conceptual framework, international cooperation and centralize the PWSS&S

records (in practise done only for the large PWSS&S).

Other Ministries responsible for particular parts of water management are as follows:

- Ministry of the Environment in the field of natural water accumulation and water sources

protection (surface and underground water) and providing the central control for flood

protection ,

- Ministry of Health in the field of drinking water hygiene and quality,

- Ministry of Transport in the field of water transport,

- Ministry of Defence as a watercourse authority inside military training areas,

- Ministry of Finance in the field of distributing State Budget funds to selected water

construction works and the price regulation of MUs.

Watercourses are subject to administration. They are classified into significant watercourses and minor

watercourses. In a decree the Ministry of Agriculture, in co-operation with the Ministry of the

Environment, stipulates a list of significant watercourses.

Administrators of significant watercourses are 5 legal entities called River Boards State Companies

established by a special Act (River Board Elbe, River Board Vltava, River Board Ohre, River Board

Odra and River Board Morava).

Administrators of small watercourses belong to the following institutions:

a) Forests of the Czech Republic State Company in mountains where forests are the major part

of the territory;

b) Agricultural Water Management Administration;

c) Ministry of Interior in military zones;

d) Administration of national parks in the territory of national parks;

e) Municipalities through whose territory minor watercourses flow or a natural person of legal

entities using minor watercourses or to whose activity the minor watercourse is related and

they are permitted to do so by the Ministry of Agriculture.

18

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

The Ministry of Agriculture will appoint small watercourse administrators based on application. The

administrators established by this Ministry (River Boards State Companies, Forests of the CR State

Company and Agricultural Water Management Administration) cover about 95% of the entire length

of rivers in the CR.

According to the Water Act and the Act on PWSS&S, there is a general 3-level hierarchy of the

central and local water authorities driving the Czech water management as a whole (including the field

of PWSS&S): Ministry of Agriculture regions ,,small districts".

The Czech Environmental Inspection is the main controlling body in protecting the water

environment (as well as other folders of the environment, e.g. air, wastes). According to the Water

Act, the Inspection controls the use of surface water and groundwater, monitors accidents endangering

water quality, supervises compliance with the provisions on fees for discharging wastewater ... etc.

The superior body of the Inspection is the Ministry on the Environment. Inspectors are entitled to enter

into objects controlled and required all relevant documents.

Other ministries and local offices or citizens can announce their suspicions of the environmental risks

or failures against laws directly to the Inspection. In practice, there are not enough people and

resources in the Inspection that is why its power is limited.

The Czech State Environmental Fund represents an important resource for long-term financing in

water management. It was established in 1991 by Act No. 388/1991 Coll. as a supplementary financial

source to support environmental improvement. The Minister of the Environment is responsible for the

distribution of resources. Charges and fees related to water abstraction are important revenue for the

Fund. Its granting priorities are stated for the each year.

2.4.1. The Overview of the Environmental Regulation

Act No. 254/2001 Coll. on Water (The Water Act)

- general use, permissions and protection of watercourses,

- river basin district plans and protected and sensitive areas,

- supporting fish life, minimum residual flow, minimum level of groundwater,

- harmful substances, obligations in the case of accident.

Act No. 258/2000 Coll. on the protection of public health

- drinking water analyses,

- standards for drinking water and water in swimming pools.

Decree No. 376/2000 on drinking water standards and volume and frequency of controls.

Decree No. 20/2001 on the frequency of measuring the amount and quality of water.

Government order No. 103/2003 on protected zones.

Decree No. 241/2002 on watercourses where using boats with combustion engines is prohibited.

Decree No. 336/2002 on creating flood plain maps.

Government order No. 103/2003 on sensitive areas and using fertilizers, rotating agriculture and

carrying out anti-erosion measures.

Government order No. 71/2003 on establishing watercourses suitable for fish life.

Lenka Camrova/IREAS

National Profile of Municipal Water and Wastewater Management in the Czech Republic

19

2.4.2. The Overview of the Economic Regulation

Act No. 254/2001 Coll. on Water (The Water Act)

- water management structures,

- obligations of owners of water management structures,

- charges, fees and sanctions.

Act. No. 274/2001 Coll. on Public Water Supply Systems and Sewers

- determining the field of doing business in drinking water supply and sewerages generally,

- a region's public water supply and sewers plan,

- a region's permission to provide water supply services and sewers,

- delivering, measuring and pricing,

- sanctions.

Act. No. 305/2000 Coll. on River Basin Administrators

Act No. 200/1990 Coll. on Misdemeanours (with amendments)

- withdrawal or discharge of water without permission

Act No. 388/1991 Coll. on the State Environmental Fund of the Czech Republic

- fees for discharging wastewater,

- transfers for the area of water supply and sewerage systems.

Act No. 526/1990 Coll. on Prices

- regulation of water and sewage tariff.

Act No. 265/1992 Coll. on recording the property right belonging to real estates

- the obligation of the owner of the infrastructure to make a property record.

Decree No. 293/ 2002 on fees for the discharge of wastewater into surface water.

Decree No. 292/2002 on the river boards territories.

Decree No. 274/2001 on PWSS&S.

Financial Bulletin of the Ministry of Finance (rules for calculating prices).

20

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

3. Data

There is a general problem with data collection at river basins in the Czech Republic, which must be

separate from national statistics done according to municipalities, district and regions, especially for

all socio-economic indicators and PWSS&S. Both the regional division of the country and the borders

of particular PWSS&S, do not respect the river basins' borders. This problem affects the consistency

of the separate statistics made by River Boards Companies and (according to Water Framework

Directive requirements) it must be solved in the near future.

3.1. Water Production

About 98% of surface water and 80% of groundwater withdrawals are registered in the National Water

Statement. Other withdrawals are below the minimum level for registration (a volume of 6 000 m3 in

one calendar year or 500 m3 of water in one calendar month).

3.1.1. Abstraction of Surface Water

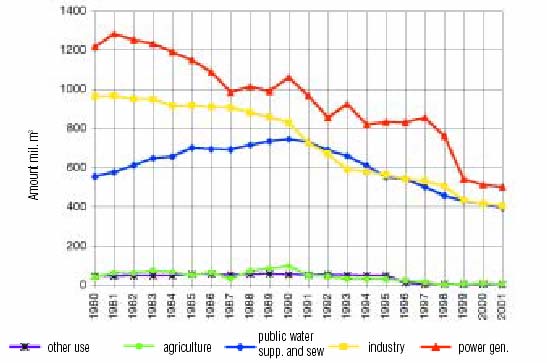

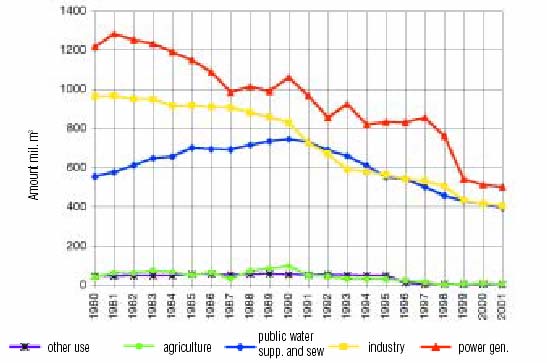

The structure of abstraction of surface water presented over time in Figure 1 and for 2001 and 2002 in

Table 1. From the national time series, the overall substantial downward trend in the abstraction of

surface water is emphatic, especially in light of the higher water tariffs for industry and households.

The total abstraction of surface water diminished from 1 342.7 mil.m3 in 2000 to 1 300.1 mil.m3 in

2001. The Morava River basin represents the only exception to this trend: total surface water

abstraction increased by 2.5% in comparison with 2000, although the decrease in the category of

PWSS&S withdrawal in 2001 was the most significant in the CZR (about 91.9% of the previous year

2000). There was a large increase in water consumption by industry in the Morava Basin.

Agricultural withdrawals decreased in all river basins. Industrial consumption accelerated to 106.8%

in 2001 (in comparison with the year 2000)5.

PWSS&S represented about 24% of the total amount of surface water withdrawn in the Morava River

basin in 2001.

5 Source: Smrný vodohospodáský plán vstník, 2001, Ministry of the Environment

Lenka Camrova/IREAS

National Profile of Municipal Water and Wastewater Management in the Czech Republic

21

Figure 1 Abstraction of Surface Water in the Czech Republic in 1980 2001

Source: Report of the State Water Management in the Czech Republic 2001

Table 1 Abstraction of Surface Water in Millions of m3

River

River Board

CR

Board

Morava in 2002*

in 2001

Morava

in 2001

Public water supply and sewers

-

amount in mil. m3

41.9

49.7

394.6

-

number of users

33

39

157

Agriculture

-

amount in mil. m3

4.3

4.4

6.9

-

number of users

19

15

58

Electricity generation

-

amount in mil. m3

98.5

96.3

500.0

-

number of users

3

2

19

Industry

-

amount in mil. m3

26.1

24.9

403.1

-

number of users

94

127

457

Other

-

amount in mil. m3

0.5

0.1

4.4

-

number of users

8

9

45

Total

-

amount in mil. m3

171.3

175.4

1 300.0

-

number of users

157

192

730

Source: Report of the State Water Management in the Czech Republic 2001

*Source: Recent statistics of River Board Morava

In Table 2, the difference between abstraction and consumption of water indicates the amount of

sewage water. In 2001, this consumption is about 20% in the category of PWSS&S, 100% in

agriculture and 12% in industry.

22

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

Table 2 Total Recorded Abstraction and Consumption of Surface Water (mil.m3/year, %) in

2001

River

Year

PWSS&S Agriculture

Industry

+

others Total

Basin

Abstract. Consump. Abstract. Consump. Abstract. Consump. Abstract. Consump.

1990

91.1 18.2 52.0 52.0 262.9 31.5 406.0 101.7

1995

53.8 10.8 11.2 11.2 164.0 19.7 229.0 41.7

Morava 2000

45.6 9.1 4.4 4.4 117.1 14.1 167.1 27.6

2001

41.9 8.4 4.3 4.3 125.1 15.0 171.3 27.7

01/00

91.9% 92.3% 97.7% 97.7% 106.8% 106.4% 102.5% 100.4%

01/95

77.9% 77.8% 38.4% 38.4% 76.3% 76.1% 74.8% 66.4%

1990

739.6 147.9 114.5 114.5 1

913.5 229.6 2

767.6 492.0

1995

544.4

108.8

28.4

28.4

1 408.6

169.1

1 981.4

306.3

CR

2000 408.3

81.6

8.8

8.8

925.6 111.1 1

342.7 201.5

2001 384.1

76.9

7.4

7.4

908.6 109.0 1

300.1 193.3

01/00

94.1% 94.2% 84.1% 84.1% 98.2% 98.1% 96.8% 95.9%

01/95

70.6% 70.7% 26.1% 26.1% 64.5% 64.5% 65.6% 63.1%

Source: Smrný vodohospodáský plán vstník, 2001, Ministry of the Environment

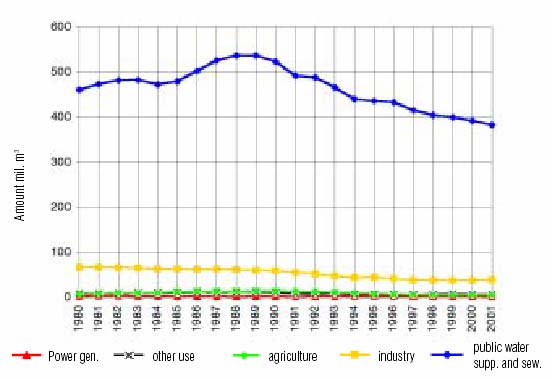

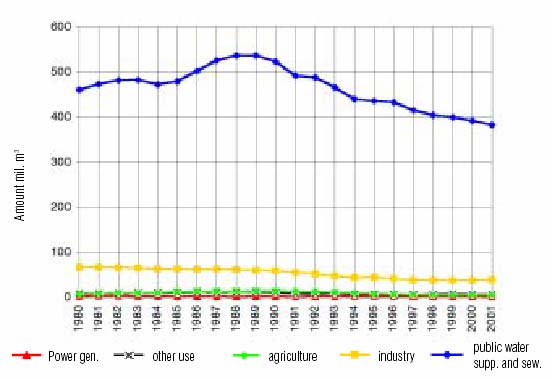

3.1.2. Abstraction of Groundwater

In the Czech Republic, the amount of abstracted groundwater dropped slightly in all the river basins in

comparison with the year 2000. Abstraction in the Morava River basin accounted for 34.2% of the

total amount groundwater withdrawn in the CR.

Withdrawing groundwater for the purpose of PWSS&S represented more than 90% of the total of

groundwater extracted in 2001. The reason is that the Water Act regulates use of groundwater

primarily for drinking water production. In addition, there was no abstraction payments levied on

PWSS&S for this sort of withdrawal in the past (see Chapter 4.1.3.).

In the Morava River basin, there are about 400 withdrawals in the category of PWSS&S, of which

about 20% exceeded production of 1,000 thous. m3.

Lenka Camrova/IREAS

National Profile of Municipal Water and Wastewater Management in the Czech Republic

23

Figure 2 Abstraction of Groundwater in the Czech Republic in 1980 2001

Source: Report of the State Water Management in the Czech Republic 2001

Table 3 Abstraction of Groundwater in the year 2001 in millions of m3

River Board River Board

CR in

Morava in

Morava in

2001

2001

2002*

Public water supply and sewers

-

amount in mil. m3

137.9

126.8

382.3

-

number of users

373

502

1 618

Agriculture

-

amount in mil. m3

2.2

1.6

5.1

-

number of users

68

87

156

Electricity generation

-

amount in mil. m3

0.0

0.0

1.1

-

number of users

0.0

0.0

3

Industry

-

amount in mil. m3

8.8

9.7

38.9

-

number of users

124

214

393

Other

-

amount in mil. m3

1.1

2.8

6.5

-

number of users

21

37

85

Total

-

amount in mil. m3

150

140.9

433.8

-

number of users

586

840

2 255

Source: Report of the State Water Management in the Czech Republic 2001

*Source: Recent statistics of River Board Morava

24

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

3.2. Water Processing/Cleaning

For the use of PWSS&S, the sources for the drinking water produced in the Czech Republic in 2001

were as follows:

· 48.9% groundwater

· 51.1% surface water.

According to the Act on PWSS&S, the service provider can withdraw surface water or groundwater if

the quality of the resource is satisfactory and the costs of processing and cleaning are not exorbitant. If

there is any uncertainty, the regional office (as a water authority at the second stage of approval)

decides.

The process of transforming raw water into drinking water (including methods, frequency of analysis,

...etc.) is described in Decree No. 274/2001 on PWSS&S. The requirement related to ensuring the

minimal quality of drinking water is included in Act No. 258/2000 Coll. on the protection of public

health.

3.3. Water Distribution

In Table 4, shows basic delivery information from the stated River Board Morava statistics. From the

time series, the following aspects can be emphasized:

- the Dukovany nuclear power station is situated in the Morava River basin, so that is why the

surface water consumption of industry is so high,

- the extraction of surface water for agricultural purposes (e.g. irrigation... etc.) became free of

charge,

- the extraction of groundwater for purposes of PWSS&S was free of charge until 2001.

Lenka Camrova/IREAS

National Profile of Municipal Water and Wastewater Management in the Czech Republic

25

Table 4 River Board Morava Basic Water Delivery Information in 1997 - 2001

1997 1998 1999 2000 2001

DELIVERY OF SURFACE WATER (thous. m3)

Total

205 819

187 546

165 541

167 158

171 303

Charged

201 655

171 842

156 247

141 902

132 680

Of this: - for PWSS&S

40 833

38 086

36 499

38 768

39 398

- for industry

156 612

133 731

119 566

103 134

93 282

Of that: - power stations and heat. Plant

130 093

111 105

48 783

43 518

43 269

- once-through water cooling

77 267

59 991

50 698

41 632

31 927

- for agriculture

4 210

25

182

0

0

EXTRACTION OF GROUNDWATER (thous. m3)

Total

x

161 804

156 750

152 770

147 752

Charged

x

3 608

3 890

3 935

3 646

PAYMENTS FOR ABSTRACTION OF SURFACE

WATER (thous. CZK)

Total

273 329

264 284

269 989

276 996

287 368

Of this: - for PWSS&S

78 397

79 982

86 406

98 083

105 006

- for industry

186 885

184 251

183 201

178 913

182 362

Of that: - power stations and heat. plant

136 096

107 339

110 738

110 101

115 095

- once-through water cooling

35 543

29 396

26 870

23 314

19 156

- for agriculture

8 047

51

382

0

0

PAYMENTS FOR EXTRACTION OF

x

7 216

7 779

7 871

7 294

GROUNDWATER (thous. CZK)

Payments for using water bodies for the electricity

15 324

15 176

15 153

15 215

15 602

production (thous.CZK)

Source: T. G. Masaryk Water Research Institute, 2002

3.4. Water Purchased

For particular price calculation items see Chapter 4.3.

3.5. Water Consumption

3.5.1. General Consumption of Water in the Czech Republic

Table 5 represents reconstructed data of water withdrawals according to final users as stated in the

National Water Statement in 2000 and 2001. This data represents all water withdrawals in the Czech

Republic in the given period. There are always several problems with gathering and reprocessing these

data (see notes under line).6

6 Problems with data reprocessing:

a) Public water supply systems and sewers cover only water produced, technological water (water delivered in lower quality

not for drinking purposes) is shown separately, that is why it is only partly included in the National Water Statement. River

Boards State Companies represent a higher number of withdrawals of surface water for public water supply than public

water supply systems and sewers, which only deal with produced drinking water.

b) Statistics of River Boards State Companies do not cover the area of other river basin administrators therefore their

numbers are lower than in the National Water Statement.

c) There are no data on private well withdrawal.

d) There is no data on small enterprises under the withdrawal limit established by the Water Act.

26

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

Table 5 Reconstructed Data of Water Withdrawals According to Final Users in CR (mil. m3)

Users

Total

Surface water

Ground water

2000 2001 2000 2001 2000 2001

Households

- public supply systems*)

808 779 404 399 404 380

- private wells (assumption)

48

48

-

-

48

48

- industry and services from public supply

-60 -56 -30 -29 -30 -27

systems**) ***)

- agriculture from public supply systems**)

-12 -13 -6 -5 -6 -8

***)

- others*) ***)

-218 -212 -109 -112 -109 -100

Households

-

total

566 546 259 253 307 293

Industry and services

-

from

private

sources

971 948 933 908 38 40

- from public supply systems**)

60 56 30 29 30 27

Industry and services total

1 031

1 004

963

937

68

67

Agriculture

-

irrigation

9 7 9 7 - -

- animal production from private sources

15

15

-

-

15

15

- agriculture from public supply systems**)

12 13 6 5 6 8

Agriculture

total

36 35 15 12 21 23

Others

- others from public supply systems*)

218 212 109 112 109 100

-

global

(assumed)

12 12 6 6 6 6

Others

-

total

230 224 115 118 115 106

TOTAL

1 863

1 809

1 352

1 320

511

489

National Water Statement - Total

1 804

1 744

1 363

1 310

441

434

Source: Smrný vodohospodáský plán vstník, 2001, Ministry of the Environment

*) including non-invoiced and technological water

**) including non-invoiced water

***) part of the amount of surface and groundwater were derived from the first row

3.5.2. Water Consumption of PWSS&S

In 2001, about 87% of the total number of inhabitants of the CR were supplied by water from

PWSS&S. A total of 753.8 mil.m3 of drinking water was produced in all companies. Losses of

drinking water for the main operators were about 25% of the water produced.

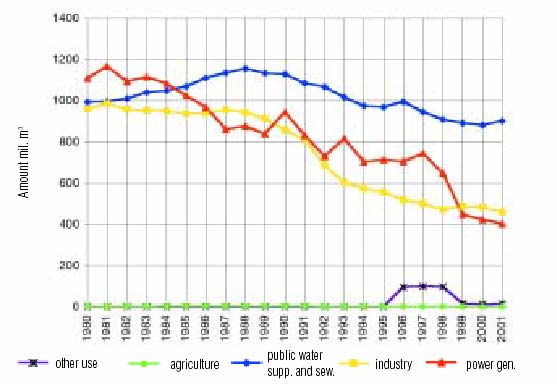

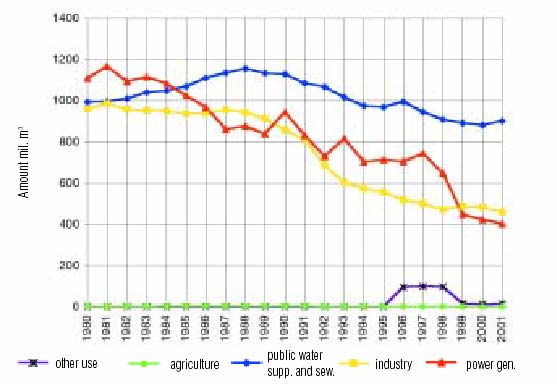

3.6. Wastewater Production

As stated in Table 6, the wastewater discharge of PWSS&S represented about 67% in 2001 in the

Morava River basin which is above the national average (50% in CR).

The total water abstraction of PWSS&S (groundwater + surface water) is lower than stated wastewater

discharge of PWSS&S in Morava River basin and the Czech Republic, too. This comparison

highlights the problems of data inconsistency.

Lenka Camrova/IREAS

National Profile of Municipal Water and Wastewater Management in the Czech Republic

27

Figure 3 Discharges into Surface Water in the Czech Republic in 1980 2001

Source: Report of the State Water Management in the Czech Republic 2001

Table 6 Discharges of Waste and Mine Water into Surface Water in Millions of m3

River Board River Board

CR in

Morava in

Morava in

2001

2001

2002*

Public water supply and sewers

-

amount in mil. m3

204.2

194.4

902.5

-

number of users

397

508

1 561

Agriculture

-

amount in mil. m3

0.1

0.0

1.7

-

number of users

2

0

12

Electricity generation

-

amount in mil. m3

69.3

66.6

403.4

-

number of users

3

2

41

Industry

-

amount in mil. m3

28.7

32.0

460.4

-

number of users

134

142

674

Other

-

amount in mil. m3

1.6

5.4

15.8

-

number of users

26

48

140

Total

-

amount in mil. m3

304

298.4

1 783.9

-

number of users

562

700

2 428

Source: Report on the State of Water Management in the Czech Republic 2001

*Source: Recent statistics of the River Board Morava

28

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

3.7. Wastewater Collection and Processing

In 2001, there were 7 706 200 inhabitants connected to public sewers in the Czech Republic, which is

about 74.9%. There is an increasing trend in this area. The difference between inhabitants supplied

with drinking water and inhabitants connected to public systems was about 12 % (1 275 mil.) and it is

stable over time. The portion of storm water in total wastewater treated is about 36% in 2001.

In regions, which are situated in the Morava River basin, the percentage of inhabitants connected to

public sewerages was about 75% in the South-Moravian Region and 75.5 % in the Zlin Region in

2001.

Table 7 Population and Public Sewers in CR between 1995 2001

Indicator Unit

1995

2000

2001

No. of population living in houses connected to

thous.

7 559.1

7 685.2

7 706.2

public sewers

Population living in connected houses in

% 73.2 74.8 74.9

relation to the total population of CR

No. of inhabitants connected to public sewers,

thous.

6 708.1

7 028.9

7 060.7

of which:

- No. of population connected to sewer with

thous.

5 784.2

6 571.2

6 692.8

sewage plant

Amount of discharged water, of which:

mil. m3 649.7 576.0 570.7

- sewage

%

56.0

64.0

66.9

- industrial

%

44.0

36.0

33.1

Amount of wastewater treated (including storm

mil. m3 866.3 854.3 886.2

water)

Amount of wastewater treated

mil. m3 581.3 546.1 544.8

Source: Smrný vodohospodáský plán vstník, 2001, Ministry of the Environment

3.8. Wastewater Effluent Discharge

Regarding Table 6 and Table 7, the total amount of wastewater discharged after processing in 2001

was between 886.2 mil. m3 and 902.5 mil. m3 in the Czech Republic.

Lenka Camrova/IREAS

National Profile of Municipal Water and Wastewater Management in the Czech Republic

29

4. Economic Data

In the following sub-chapters, the system of different payments for water and wastewater in the Czech

Republic will be analysed. This system includes fees and charges for using water (as national natural

wealth) and the amount is set by law. Apart from these there are also prices (tariffs) for the service of

water supply and wastewater discharge, as set by the MU. These prices are based on the cost

conditions of particular companies, but their amount is also regulated by the Act No. 526/1990 Coll.

on Prices. The RU is the Ministry of Finance and controls are done by its network of regional and

municipal Financial Offices (which are mostly focus on tax revenues of the state).

4.1. Tariffs, Fees and Charges

4.1.1. Tariffs for PWSS&S Services

Up until the end of 1990, tariffs for water supply and sewerage services were centralized by the

Government. For households the water tariff was 0.60 CZK/m3 and the sewage tariff was 0.20

CZK/m3, for other users these tariffs were about 3.70 CZK/m3 and 2.35 CZK/m3.

At present, in the field of drinking water treatment, the PWSS&S calculates ,,factually rectified" or

,,regulated" prices for the following types of services provided:

- drinking water and service water delivered directly to the customer;

- drinking water and service water delivered to the water network of another supplier;

- wastewater coming into the public sewers.

These tariffs are calculated per m3 and there was a possibility to distinguish between households and

other users according to the regulatory scheme as set out by the law. From the 1 January 2001 the

price levels for both categories were united, so each company is obliged to use only one level of tariffs

for all customers.

The price regulation imposed by the law is based on the notion that water and sewage tariffs can only

reflect economically eligible costs of production and an adequate "profit". It also has to consist of

"given" items (see Chapter 4.3.) and it has to be published annually and provided to customers

whenever requested. As mentioned in Chapter 2.1.1.2., every PWSS&S estimates the cost calculation

for the coming year and subsequently re-calculates real costs. That is the reason for the small

differences between calculated and realised prices in Table 8.

From 2002, tariffs can be charged as 2-component prices with a fixed component (for the privilege of

getting some minimal level of service) and floating part (a consumption charge or tariff per unit of

additional water consumed). The fixed part's maximum is 20% of the tariff and in the Act on

PWSS&S, there are strict rules for its calculation (e.g. metering of consumption). The main purpose of

creating this possibility is to impose some minimal charge on users with extremely low consumption

(e.g. cottages) and high charges for customers who are larger consumers of water (or wastewater)

services. Some PWSS&Ss have a problem with seasonal residences or cottages, because if such a

residence is connected into the network, the invoicing, checking the water meter and other services

have to be done throughout the year, even if the consumption is only a few m3 per year.

The PWSS&S can decide which type of tariff (1-component or 2-component) to use. The 2-

component price is not connected to the cost calculation, which means: the fixed component of the

price is not derived from fixed cost of the company, but from the formula given by the Ministry of

Agriculture.

As shown in Table 8 (maximum and minimum values), there are huge differences in water and sewage

tariffs between particular PWSS&S because of the different local cost conditions. The average water

tariff was about 18 CZK/m3 and the average sewage tariff was about 15 CZK/m3 in 2000.

30

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

Table 8 Water and Sewage Tariffs in the CR in 2000

CZK/m3

Water supply

Sewerages

Average Households Others Average Households Others

Calculated prices

17.19 16.68 18.04 14.45 13.62 15.40

(without VAT)

Calculated prices

18.05 17.52 18.94 15.17 14.30 16.17

(with VAT)

Realised prices

17.15 16.61 18.05 14.39 13.52 15.39

(without VAT)

Realised prices

18.00 17.44 18.96 15.11 14.20 16.16

(with VAT)

Minimum value

7.73 7.28 8.00 6.09 5.16 7.56

Maximum value

28.04 28.04 31.28 25.95 19.78 31.27

Source: T. G. Masaryk Water Research Institute, 2002

4.1.2. Payments to Cover Watercourse and River Basin Administration

According to the Water Act, any person authorised to withdraw surface water is obliged to pay for the

administration of the watercourse depending on the purpose for which the surface water is withdrawn.

The price for withdrawal differs according to the following purposes of withdrawal:

- single use cooling water for stream turbines;

- agricultural irrigation (free of charge from 2000);

- filling during artificial terrain activities (pits following raw material excavation ) in cases

requiring water pumping or transfer ;

- other withdrawals.

The payment for the withdrawal of surface water is assessed by the River Board Company in

accordance with a special act7. If the quantity of the water does not exceed 6 000 m3 per calendar year

or 500 m3 per calendar month, the subject is not obliged to make any payment. The payment accrues

directly to the River Board Morava and it is an important part of its revenues.

According to the legislation, this payment is also defined as a ,,factually rectified" or ,,regulated"

price. This means that (as in the case of PWSS&S) the River Basin Boards are obliged to develop a

price calculation of their operational costs per m3 withdrawn. This calculation can be controlled by the

Ministry of Finance. In practice, this payment is calculated by dividing the total assumed operational

cost by assumed number of m3 withdrawn in future period. The payment differs between river basins

according to the amount of water withdrawn for industrial, drinking and other purposes. Agricultural

withdrawn are free of charge. In the Morava River basin the payment is 2.66 CZK/m3. This is nearly

the highest level in the CR and is due to the large number of farmers in the territory.

7 Section 6 of Act 526/1990 Coll. on Prices

Lenka Camrova/IREAS

National Profile of Municipal Water and Wastewater Management in the Czech Republic

31

Table 9 River Board Morava: Payments for Surface Water Abstraction in Morava River Basin

in 1997 - 2001

CZK/m3

1997 1998 1999 2000 2001

without VAT

Single use 0.46 0.49 0.53 0.56 0.60

water cooling

Others

1.92 2.10 2.27 2.53 2.66

Source: T. G. Masaryk Water Research Institute, 2002

4.1.3. Charges for the Withdrawal of Groundwater

An authorized person withdrawing groundwater is obliged to pay charges for the actual quantity

according to the purpose of the water withdrawal. For drinking water supply, there is a rate of 2 CZK/

m3 and for other uses there is a rate of 3 CZK/ m3. Until 2001, PWSS&S were exempted and were not

subject to any payment. PWSS&Ss began paying the full for withdrawal charge in 2004.

Groundwater withdrawals from one resource not exceeding 6,000 m3 per calendar year or not

exceeding 500m3 per month are exempt from payment. The charges go to the Czech State

Environmental Fund and the State Budget as revenues.

4.1.4. Fees for the Discharge of Wastewater into Surface Water (Effluent Charges)

There is a fee for the level of the discharged wastewater's pollution and its volume. These fees are

imposed on individual sources of pollution. The charges go to the Czech State Environmental Fund as

revenues. For more detailed information see Chapter 4.3.1.

4.1.5. Fee for a Permitted Discharge of Wastewater into Groundwater

The authorised person shall pay a fee in respect of a permitted discharge of wastewater into

groundwater. The permission is given by the water authority (small districts), the quality of

wastewater is judged. If wastewater from a family dwelling is purified by a domestic treatment plant,

no fee applies to the discharge. In other cases, the permitted discharge is subject to a fee of 3 500 CZK

per year.

The fee is payable to the municipality in the area where the discharge takes place.

No national statistics on permitted discharges into groundwater are published.

4.2. Sales to Particular Service Users

---

4.3. Costs on Purchased Inputs

32

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

Due to large differences in tariffs between particular PWSS&S (see Table 8), the concrete calculation

of VaK Hodonin is used as an example. The calculation of PWSS&S Hodonin includes the main cost

categories as stated in the Financial Bulletin of the Ministry of Finance in which certain price

regulation conditions are regularly up-dated.

The Value Added Tax (VAT) is paid as a percentage from the price of PWSS&S services (see the last

row in Table 10). At present, VAT is 5%, but in the future we can assume an increase because of the

fiscal harmonization with EU requirements (VAT should vary from 15 to 25% for all goods and

services in all European countries). The current discussion in the Czech Parliament is to offset water

and wastewater services to the group of 19% VAT.

Lenka Camrova/IREAS

National Profile of Municipal Water and Wastewater Management in the Czech Republic

33

Table 10 Calculation of Prices in Vak Hodonin in 2002

CZK/m3

Water rate

Sewage charge

1. Direct material 2.37

1.24

1.1 Unprocessed water

0.42

0.00

1.2 Chemicals

0.25

0.44

1.3 Other material

1.70

0.80

2. Direct salaries

2.87

2.50

3. Other direct material

9.81

12.62

3.1 Depreciation

4.42

5.25

3.2 Reparations and services

0.89

1.82

3.3 Social cost

1.01

0.87

3.4 Fees for the discharge of wastewater

0.00

0.86

3.5 Charges for the withdrawal of groundwater

0.89

0.00

3.6 Energy

1.51

1.52

3.7 Others

1.09

2.32

Company's cost TOTAL

15.05

16.38

4. Manufacturing overheads

0.91

0.64

5. Administrative overhead expenses

2.20

2.19

TOTAL COSTS

18.16

19.21

Profit 0.72

0.77

PRICE (without VAT)

18.88

19.98

Source: http://www.vak-hod.cz

All categories must be in harmony with the price regulation schemes. The "Profit" represents the