September 2004

ASSESSMENT AND DEVELOPMENT OF

MUNICIPAL WATER AND WASTEWATER

TARIFFS AND EFFLUENT CHARGES IN

THE DANUBE RIVER BASIN.

Volume 2: Country-Specific Issues and

Proposed Tariff and Charge Reforms:

Romania National Profile

AUTHORS

Dr. Victor Platon

George Dulcu

TARIFFS AND CHARGES VOLUME 2

PREFACE

The Danube Regional Project (DRP) consists of several components and numerous

activities, one of which was "Assessment and Development of Municipal Water and

Wastewater Tariffs and Effluent Charges in the Danube River Basin" (A grouping of

activities 1.6 and 1.7 of Project Component 1). This work often took the shorthand

name "Tariffs and Effluent Charges Project" and Phase I of this work was undertaken

by a team of country, regional, and international consultants. Phase I of the

UNDP/GEF DRP ended in mid-2004 and many of the results of Phase I the Tariffs and

Effluent Charges Project are reported in two volumes.

Volume 1 is entitled An Overview of Tariff and Effluent Charge Reform Issues and

Proposals. Volume 1 builds on all other project outputs. It reviews the methodology

and tools developed and applied by the Project team; introduces some of the

economic theory and international experience germane to design and performance of

tariffs and charges; describes general conditions, tariff regimes, and effluent

charges currently applicable to municipal water and wastewater systems in the

region; and describes and develops in a structured way a initial series of tariff,

effluent charge and related institutional reform proposals.

Volume 2 is entitled Country-Specific Issues and Proposed Tariff and Charge

Reforms. It consists of country reports for each of the seven countries examined

most extensively by our project. Each country report, in turn, consists of three

documents: a case study, a national profile, and a brief introduction and summary

document. The principle author(s) of the seven country reports were the country

consultants of the Project Team.

The authors of the Volume 2 components prepared these documents in 2003 and

early 2004. The documents are as up to date as the authors could make them,

usually including some discussion of anticipated changes or legislation under

development. Still, the reader should be advised that an extended review process

may have meant that new data are now available and some of the institutional detail

pertaining to a specific country or case study community may now be out of date.

All documents in electronic version Volume 1 and Volume 2 - may be read or

printed from the DRP web site (www.undp-drp.org), from the page Activities /

Policies / Tariffs and Charges / Final Reports Phase 1.

TARIFFS AND CHARGES VOLUME 2

We want to thank the authors of these country-specific documents for their

professional care and personal devotion to the Tariffs and Effluent Charges Project.

It has been a pleasure to work with, and learn from, them throughout the course of

the Project.

One purpose of the Tariffs and Effluent Charges Project was to promote a structured

discussion that would encourage further consideration, testing, and adoption of

various tariff and effluent charge reform proposals. As leaders and coordinators of

the Project, the interested reader is welcome to contact either of us with questions

or suggestions regarding the discussion and proposals included in either volume of

the Project reports. We will forward questions or issues better addressed by the

authors of these country-specific documents directly to them.

Glenn Morris: glennmorris@bellsouth.net

András Kis: kis.andras@makk.zpok.hu

TARIFFS AND CHARGES VOLUME 2

National Profile of Municipal Water and Wastewater Management in Romania

3

Table of Content

1 Introduction....................................................................................................................... 7

1.1 General Considerations .............................................................................................................. 7

1.2 Administrative Structure of Romania ....................................................................................... 8

1.3 Aggregate Supply of Raw Water and Production .................................................................. 11

1.4 Quality of Surface Water.......................................................................................................... 13

1.5 Major Sources of Pollution....................................................................................................... 16

2 Legal and Institutional Framework .............................................................................. 16

2.1 Laws of the Water Sector ......................................................................................................... 16

2.2 Institutional Framework; Major RUs in the Water Sector................................................... 18

2.3 Water Permitting....................................................................................................................... 21

2.3.1 Water Management Approval (WMAp) ......................................................................................... 21

2.3.2 Water Management Authorization (WMAu) .................................................................................. 23

3 Water Used by Localities................................................................................................ 24

3.1 Production and Consumption of Drinking Water.................................................................. 24

3.2 Metering and Leakage of Drinking Water.............................................................................. 25

3.3 Wastewater from Localities...................................................................................................... 26

4 Pricing Water and Wastewater ..................................................................................... 27

4.1 Price for Raw Water Abstraction ............................................................................................ 28

4.2 Tariffs for Drinking Water....................................................................................................... 29

4.3 Tariffs for Wastewater.............................................................................................................. 32

5 Water and Wastewater Infrastructure ......................................................................... 32

5.1 Infrastructure for Drinking Water.......................................................................................... 32

5.2 Infrastructure for Wastewater................................................................................................. 33

5.3 Opportunities for Investment in Water and Wastewater Infrastructure ............................ 36

5.3.1 Urban Areas .................................................................................................................................... 37

5.3.2 Rural Areas ..................................................................................................................................... 37

6 Financing Water and Wastewater Services in Romania............................................. 38

6.1 Financing the Current Activities of Drinking Water and Wastewater Services ................. 38

6.2 Financing the Investment in Water and Wastewater Infrastructure ................................... 38

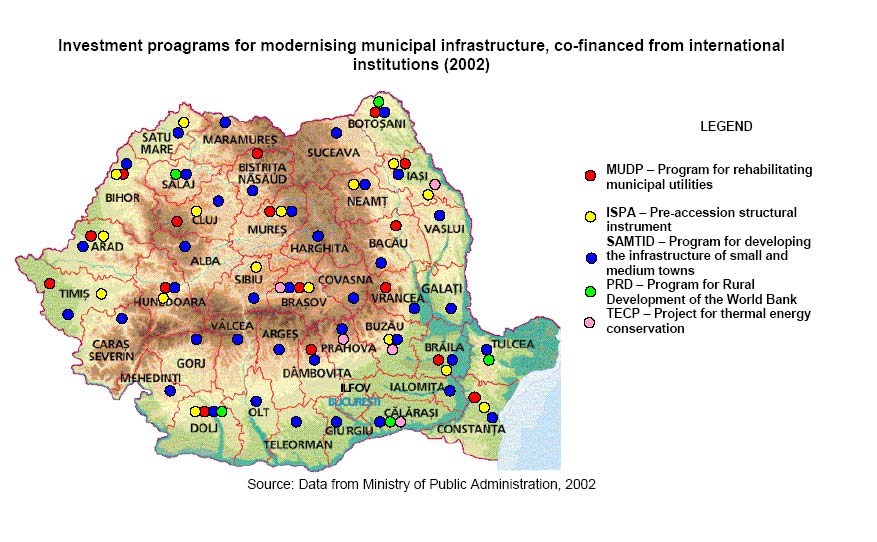

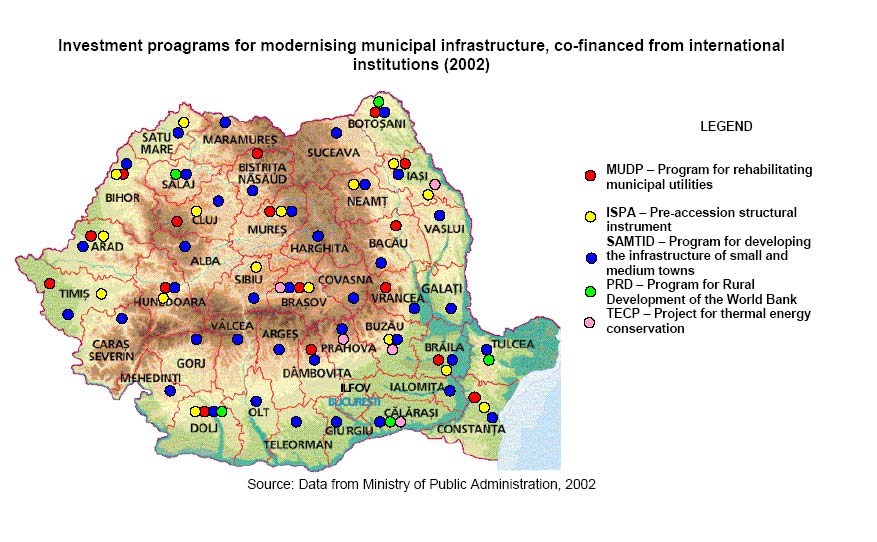

6.3 Water and Wastewater Investment Co-Financed with Foreign Aid .................................... 41

6.4 Bilateral Assistance Granted by Denmark.............................................................................. 44

6.5 Bilateral Assistance Granted by the US .................................................................................. 44

7 Management Units (MUs) .............................................................................................. 45

7.1 Types of Management Units and their Operation.................................................................. 45

7.2 Trends in Formation and Consolidation of MUs.................................................................... 46

8 Policy Issues..................................................................................................................... 47

8.1 Issue 1: Water Consumption and Wastewater Generation ................................................... 47

8.2 Issue 2: Municipal Water Tariffs............................................................................................. 49

8.3 Issue 3: Economic Sustainability of the Water Utility ........................................................... 49

9 ANNEXES ....................................................................................................................... 50

4

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

LIST OF TABLES

TABLE 1: CLASSIFICATION OF LOCALITIES IN ROMANIA (2001) .................................................. 9

TABLE 2: WATER RESOURCES, BY CATEGORIES, IN ROMANIA (2001) ........................................ 11

TABLE 3: RAW WATER DISTRIBUTED TO USERS, IN ROMANIA (1997-2001)............................... 12

TABLE 4: WATER QUALITY OF MONITORED RIVERS IN ROMANIA, 2001 .................................... 14

TABLE 5: WATER QUALITY OF MONITORED RESERVOIRS AND LAKES IN 2001 ........................... 15

TABLE 6: VOLUME OF DRINKING WATER DISTRIBUTED IN NETWORKS, IN 2001 ........... 24

TABLE 7: REGIONAL DISTRIBUTION OF DRINKING WATER AND POPULATION .............. 24

TABLE 8: VOLUME OF THE MUNICIPAL WASTEWATER TREATED ................................................. 26

TABLE 9: VOLUME OF THE MUNICIPAL WASTEWATER AND SLUDGE COLLECTED IN ROMANIA , BY

REGIONS, (2001) .......................................................................................................... 27

TABLE 10: PRICE OF THE RAW WATER (2002 AND 2003), BY SOURCES ..................................... 29

TABLE 11: TARIFF EVOLUTION FOR WATER SUPPLY, FOR HOUSEHOLDS, IN ROMANIA............... 29

TABLE 12: AVERAGE SEWAGE TARIFFS, IN ROMANIA....................................................... 32

TABLE 13: DISTRIBUTION NETWORK FOR DRINKING WATER AND CAPACITY OF DRINKING WATER

TREATMENT PLANTS, IN ROMANIA, BY REGIONS, (2001)................................................. 32

TABLE 14: NETWORK FOR WASTEWATER AND CAPACITY OF THE TREATMENT PLANTS, IN

ROMANIA, BY REGIONS, (2001)..................................................................................... 33

TABLE 15: EXISTING WASTEWATER TREATMENT PLANTS IN ROMANIA, 2001 ............................ 35

TABLE 16: EVOLUTION OF THE SEWERAGE NETWORK AND TREATMENT OF MUNICIPAL

WASTEWATER, IN ROMANIA (1997-2001) ...................................................................... 35

TABLE 17: WATER MANAGEMENT PROJECTS FINANCED BY THE NETHERLANDS ......................... 43

Dr. Victor Platon, George Dulcu

National Profile of Municipal Water and Wastewater Management in Romania

5

LIST OF ANNEXES

ANNEX 1: EVOLUTION OF THE EXCHANGE RATE - ROL/USD OR EURO - ................................. 50

ANNEX 2: EU WATER DIRECTIVES TRANSPOSED IN ROMANIAN LEGISLATION (MARCH 2003).... 52

ANNEX 3: NUMBER OF LOCALITIES WITH DRINKING WATER AND SEWERAGE NETWORKS, IN 2001

.................................................................................................................................... 54

ANNEX 4: DRINKING WATER DISTRIBUTED IN ROMANIA, IN 2001 .......................................... 56

ANNEX 5: LEAKAGE AND METERING OF DRINKING WATER, IN 2001 ....................................... 58

ANNEX 6: DATA ON SEWERAGE AND WASTEWATER FROM LOCALITIES, IN 2001 ....................... 60

ANNEX 7: SETTING UP TARIFFS IN PLOIESTI CITY .................................................................... 62

ANNEX 8: LEVELS OF PENALTIES FOR INFRINGEMENT OF THE NORMS CONCERNING MAXIMUM

POLLUTANT CONCENTRATION ADMITTED IN WASTEWATER DISCHARGED INTO THE SURFACE

WATER RESOURCES........................................................................................................ 64

ANNEX 9: INVESTMENT COSTS FOR THE MODERNIZATION, REHABILITATION AND DEVELOPMENT

OF THE WATER AND SEWERAGE SERVICES IN ROMANIAN TOWNS AND MUNICIPALITIES

(ESTIMATES) .................................................................................................................. 66

ANNEX 10: ESTIMATION OF THE NECESSARY INVESTMENT FOR SUPPLYING DRINKING WATER TO

THE ROMANIAN RURAL LOCALITIES ................................................................................ 68

ANNEX 11: WATER AND WASTEWATER PROJECTS FINANCED WITHIN ISPA FRAMEWORK, IN

ROMANIA ..................................................................................................................... 70

ANNEX 12: WATER AND WASTEWATER PROJECTS CO-FINANCED BY EIB AND EBRD IN ROMANIA

.................................................................................................................................... 72

ANNEX 13: WATER AND WASTEWATER PROJECTS CO-FINANCED BY THE DANISH GOVERNMENT 73

ANNEX 14: STRATEGIES AND ACTION PLANS.......................................................................... 74

6

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

ACRONYMS

Danish Environment Protection Agency

DEPA

European Bank for Reconstruction and Development

EBRD

European Investment Bank

EIB

Construction Authorization

CA

Consumer Price Index

CPI

Environmental Protection Inspectorate -

EPI

Local Authority

LA

Local Council

LC

Management Unit

MU

Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, Waters and Environment

MAFWE

Ministry of Economy

MoE

Ministry of Health and Family

MHF

Ministry of Public Finance

MPF

Ministry of Transport, Housing and Tourism

MTHT

Memorandum of Understanding

MoU

National Administration Romanian Waters

NARW

National Authority for Municipal Utilities

NAMU

National Environmental Action Plan

NEAP

National Institute for Research and Development of the Environment

ICIM

Pre Accession Instrument for Structural Policy Instrument

ISPA

Regulatory Unit

RU

River Basin Committees

RBC

Romanian Lei

RoL1

Romanian Water Association

RWA

Service User

SU

Unit of Measure

UM

Urbanism Certificate

UB

United State Agency for International Development

USAID

Water and Wastewater

W&WW

Water Management Approval

WMAp

Water Management Authorization

WMAu

1 Evolution of the exchanges rates RoL/ and RoL/$ is illustrated in the Annex 1

Dr. Victor Platon, George Dulcu

National Profile of Municipal Water and Wastewater Management in Romania

7

1 Introduction

This paper was drafted within the framework of the project "Assessment and Development of Water

and Wastewater Tariffs and Effluent Charges Designs for Nutrient Reduction in the Danube River

Basin (DRB)". The main purpose was to give an overview of the organization and functioning of the

management units in the Romanian water sector (Danube basin), regulatory framework, service users

etc. in order to improve both water resource management generally and protection of water bodies

from nutrification and hazardous substances. In this respect was explored the use of water and waste-

water service tariffs and effluent charges, fines and incentives as a tool for nutrient reduction. The

paper ends with policy issues that will need solutions and policies for suggested reforms.

1.1 General Considerations

Despite a relatively small surface area, the natural conditions of Romania are very diverse and the

different geographic areas cover small distances within the territory. The mountains cover most of the

central area of the country, the hills cover 30% of the area and are situated in the central part of the

country and the areas surrounding the mountains (see Map 1). The bigger towns of the country were

established and developed within the contact area situated between the mountains and the hills and in

those situated between the hills and the plains, forming three urban circles. The plains are situated in

the border areas and have a higher population density of important concentrations within the river

valleys.

Map 1. Relief of Romania

The Danube river basin can be divided into four parts: the upper region, the middle region, the lower

region and the Danube Delta. The lower region of the Danube is mainly the Romanian and Bulgarian

plain area and the plateaus and mountains of the higher areas surrounding the plain. From the mouth of

the Timok River to Silistra (km 374), the Danube defines the Romanian-Bulgarian border, flowing

eastward. In this part, the Danube flows as a wide river (800 m), with well-developed alluvial plains

on its left (Romanian) bank. The area flooded during flashfloods may reach a width of up to 10 km.

The right (Bulgarian) bank is a narrow floodplain flanked by a steep bank.

8

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

Romania is a Danube riparian country (see Map 2) and 98% of the territory lies within the Danube

river basin. The Danube river flows over Romanian territory for 1,575 kilometers. Raw water from the

Danube is used in Romania for the preparation of drinking water, for irrigation, industry, fisheries and

navigation.

Map 2. Danube, Riparian Countries

1.2 Administrative Structure of Romania

Romania has three territorial-administrative levels: central level, county level and communal level

(including communes, towns and villages). Romania's entire territory is divided into 41 counties2 plus

the Bucuresti municipality (see Map 3). Bucuresti municipality is the capital of Romania and has the

same standing as a county.

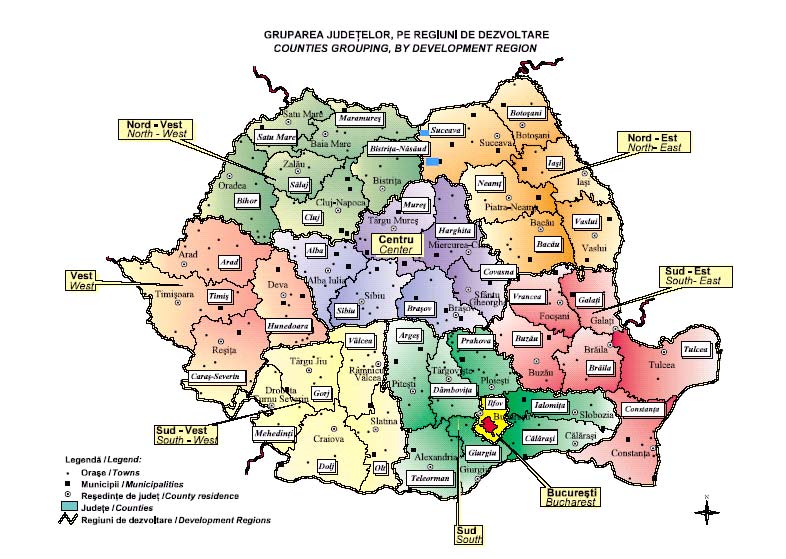

Map 3. Counties of Romania

2 A county consists of a county capital municipality, where the headquarters of the county public administration are located, several

municipalities, and all the towns and communes within that county's territorial limits. Law establishes the territorial limits of the counties,

municipalities, towns or communes, and their modifications.

Dr. Victor Platon, George Dulcu

National Profile of Municipal Water and Wastewater Management in Romania

9

Certain towns can be declared by law municipalities. The distinction between municipalities and

towns is made according the law taking into account the size and number of inhabitants, historical

traditions, and the social, economic and cultural importance. A city could become municipality by law

and this depends mainly on the level of infrastructure3 and could have a larger territory. Communes

may be formed of one or several villages and hamlets.

Table 1: Classification of Localities in Romania (2001)

Groups of

Locality units

Population

administrative

units

Number % Number %

Municipalities and Towns

Total 265

100

12243748

100

Under 2000

1

0.4

1798

0.0

2000 - 4 999

12

4.5

47463

0.4

5000 - 9999

59

22.3

450943

3.7

10000 - 19999

85

32.1

1165881

9.5

20000 - 49999

61

23

1910885

15.6

50000 - 99999

23

8.7

1744334

14.3

100000 - 199999

12

4.5

1729594

14.1

200000 - 999999

11

4.1

3196036

26.1

Over 1000000

1

0.4

1996814

16.3

Communes

Total 2686

100

10164645

100

Under 1000

56

2.1

40936

0.4

1000 - 1999

405

15.1

640850

6.3

2000 - 4999

1626

60.5

5412303

53.2

5000 - 9999

563

21.0

3637391

35.8

10000 and over

36

1.3

433165

4.3

Source: Romanian Statistics Yearbook., 2003

In 2001, in Romania were 265 towns and 2,686 communes (see Table 1). From the total towns the

most numerous group is that of towns with a population between 5,000-10,000 inhabitants and 10,000-

20,000 inhabitants; this group of towns represents 54.4% of the total number of towns but only 13.2%

of the total population. As regarding to communes the most important group is that having 2,000-

4,999 inhabitants; there are 1626 communes of this category cumulating 53.2% of the population

living in communes.

It should be mention that each year a number of villages are declared communes, communes are

declared towns and towns are declared municipalities. In the period 2001-2004 a number of 180

3 According to the law there is the next structure: level 0 Bucuresti, level 1 11 large towns, level 2 95 municipalities, level 3 other

towns (out from 270 towns in Romania).

10

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

villages have been declared communes, 33 communes4 have been declared towns and 10 towns have

been declared municipalities.

According to Romanian legislation, communes, towns, municipalities and counties are legal entities,

have full capacity, own a patrimony, and hold the initiative in everything related to the administration

of local public interests, exercising authority within their established territorial-administrative units.

For the purpose of ensuring local autonomy, the public administration authorities of communes, towns

and counties elaborate and approve the local budget and are entitled to collect local duties and taxes.

Local autonomy could be expressed within the limits of the local budget and other financing sources

as municipal bonds, grants or loans. This implies that W&WW services are not entitled to receive

subsidies from the central budget. All investments in communal and urban W&WW services should

be financed with local sources.

In 2002 there were 268 towns and 1,423 communes with systems for drinking water supply. Sewerage

systems were identified in 266 towns and in 378 communes.

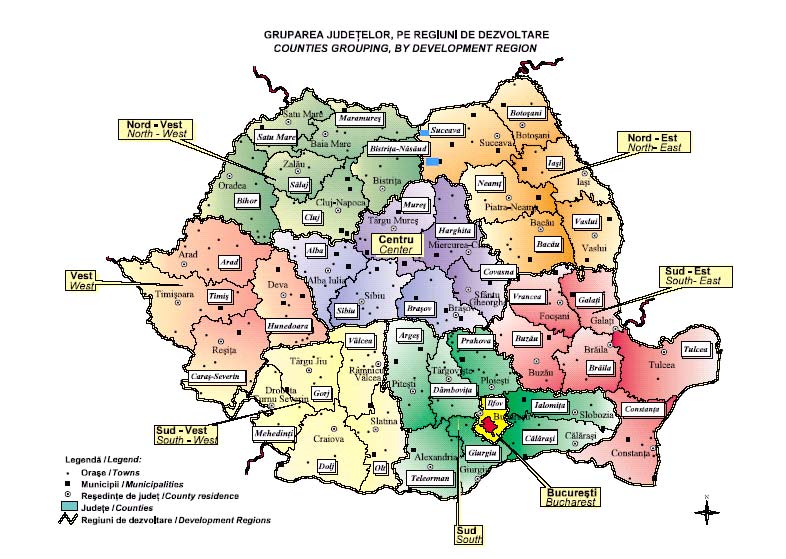

Map 4. Development Regions in Romania

4 According to the law 351/2001 on Spatial Planning, a commune could be declared town if: there are more than 5000 inhabitants and 75%

of them must be involved in non-agricultural activities, 70% of houses should be connected to the water network and 50% of them to have

bath and toilets. Other conditions should be fulfilled as well.

Dr. Victor Platon, George Dulcu

National Profile of Municipal Water and Wastewater Management in Romania

11

The Law 151/1998 on Regional Development introduced in Romania the development regions5 (see

Map 4), the regional development boards and the agencies for regional development (the eight regions

created are not administrative units). The existence and position of compact zones of similar

development characteristics and featuring similar problems has given rise to the need of creating new

development tools for solving problems. The regions (also named macro-regions) have been

delineated not in terms of similar levels of development, but as potential functional units and contain

several counties (see Map 4). The Law 15/1998 concerning the regional development in Romania

establishes the institutional frame, the principles, the purposes, the competence and the specific

instruments necessary for regional development.

At the national level it was created the National Council for Regional Development (NCRD) as a

Steering Body for policy guidelines. The executive body is the General Directorate within the Ministry

for EU Integration; this is entrusted with the elaboration and co-ordination of the policy for social

cohesion and regional development.

At the regional level there are eight Councils for Regional Development (CRD). These councils are

composed of the presidents of the county councils (elected persons) and majors and presidents of some

of the local town councils. The executive body is the Regional Development Agency (eight of them),

subordinated to the CRD.

So far the regional dimension was not important for public water utilities but in the future will play a

bigger role in financing regional infrastructure projects and in the W/WW sector6 as well.

1.3 Aggregate Supply of Raw Water and Production

The raw water industry has in Romania an old history starting with Roman Empire and even before. In

terms of quantity, the water resources are relatively unequally distributed in time and space. The major

sources are surface waters (inland rivers, lakes and reservoirs, the Danube River) and ground waters.

The quantitative structure of the raw water resources is illustrated in the Table 1.

Table 2: Water Resources, by Categories, in Romania (2001)

- Billion m3/ year -

Water resource category

Multi year average- Manageable

water

resource

Inland rivers, lakes

40

34

Danube River

85*

20

Underground water

9

5.8

TOTAL 134

39.8

* half of the annual flow at the country entrance

Source: Ministry of Waters and Environmental Protection., Yearbook on Environment in Romania., National Institute for

Statistics, 2002

The theoretical yield of water resources of the inland rivers and lakes is estimated at about 40 billions

m3/year, of which, in a natural flow regime (without reservoirs), only 5 billions m3/year are utilizable

and 14 billions m3/year, in the existing regime with water works (with reservoirs and dams).

5 These were proposed by the Green Paper for Regional Policy in Romania, published by the Romanian Government and the European

Commissions in May 1997.

6 For instance will be some PHARE projects within the heading PHARE 2004 2006 Economic and Social Cohesion Programme -

Regional Large Scale Infrastructure Projects that will finance W&WW investment.

12

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

Out of the Danube theoretical resources, Romania could get 85 billions m3/year, but the possibilities of

extraction are limited because of the river navigable character and its peripheral position etc.

Thus, only about 40 billions m3/year of the water resources could be used for consumption. The Black

Sea water resources, although very important, cannot be utilized for the time being because of the

technical and economical difficulties of seawater desalination.

Although in Romania there are about 3,450 natural lakes with a water capacity of 2 billions m3, these

are of local importance in water management because only 400 millions m3 are fresh water and the rest

are with salted water in the different degree of salinity.

Because only 12.5 % of the water resource potential can be used in natural flow regime, a lot of

reservoirs were developed to smooth water availability over the seasons. Inter-basin diversions for a

territorial reallocation of the water resources according to the local demands were developed as well.

In 2000, the existing 1300 water reservoirs (400 having a capacity of over 1 million m3 each) stored a

total volume of 14 billions m3 of which 5.5 billions m3 is water supply for population, industry and

irrigation and the rest for flood protection and hydroelectricity. There are also 2000 km of canals and

galleries for inter-basin water diversions and the reallocation of water resources according to the needs

of agricultural irrigation in dry periods and other demands for water. However, more than 70% of the

inland watercourses are in their natural state (unregulated).

Taking into account existing and the future reservoirs, from the inland rivers Romania could have

about 25 billions m3 in a waterless year, which represents the maximum limit that could be increased

only by a successive reuse of the wastewater discharged through the sewage systems, treatment plants

from localities and industrial units, as well as by intensifying the industrial wastewater recycling and

by reducing consumption .

Ground waters, generally have a better quality than that of the surface waters. The quantity being

estimated as available is 9 billions m3/year, of which about 5.8 billions m3/year could be used under

the existing technical and economical conditions. At the present, only 1.5 billion m3/year is used.

The main use of raw water resources is illustrated in

. T

Table 3 he general trend in water use is down.

In the period 1997-2001, the reduction in water use was 1.92 billion m3,( -21%). The biggest reduction

(-27%) was registered by the industry and by the domestic sector (-19%). Only Agriculture recorded a

small increase for irrigation purposes but this amount is small taking into account that before 1990

Romania has had an irrigation system that covered 3 million hectares.

Table 3: Raw Water Distributed to Users, in Romania (1997-2001)

- million m3/year -

Users

1997 1998 1999 2000 2001

2001/1997

Difference

2001-1997

Municipalities

2 946

2 887

2 776

2 609

2 391

81%

- 555

Industrial activities

5 247

4 823

4 728

4 388

3 833

73%

- 1414

(independent extraction

systems)

Agriculture (total) (out of

1 026

1 299

1 027

940

1 090

106%

+ 64

which):

· Irrigation

287 560 266 513 701 244% +

414

· Livestock

farms 92 79 69 46 36 39% -

56

· fishery

647 660 692 381 353 55% -

294

Other

users

45 42 45 30 29 64% -

16

TOTAL

9 264

9 051

8 576

7 967

7 343

79%

- 1921

Source: Ministry of Waters and Environmental Protection, Yearbook on Environment in Romania., National Institute for

Statistics, 2002. Water produced by NARW and distributed.

Dr. Victor Platon, George Dulcu

National Profile of Municipal Water and Wastewater Management in Romania

13

In Romania there are all types of water resources (rivers, lakes and underground water). The biggest

resource is the Danube river and inland rivers. There are 11 basin rivers with various water volume.

The biggest one is Siret basin with 224 m3/second or 7,083 million m3/year representing 17% of the

total water resources. The next basin is Mures with 14% and Olt basin with 13%. These three river

basins provide 44% of the total amount of water resources in Romania. Other basins, with the same

surface, have less water resources.

Another characteristic of the water resources in Romania is related to season variability of water

flows. In the spring the water debit represents 39.7% of the annual water total flow and in fall the

water debit is 14.2% of the annual debit. In the summer the debit is 26.7% and in the winter is 19.4%.

The numerous lakes (3450) have a small contribution to water resources.

1.4 Quality of Surface Water

About 40 physical, chemical, biological and microbiological parameters (such as oxygen content,

BOD - biological oxygen demand, COD - chemical oxygen demand, TDS - total dissolved solids,

nutrients, organic pollutants, heavy metals) are used to categorize the water.

Based on Romanian standard for surface waters (STAS 4706/1988), quality of the watercourses are

categorized as follows:

· Category I very good/drinkable, includes waters that can become drinkable to supply the

population centers or animal breeding units, the food industry, and bathing resorts (pools);

· Category II good, includes surface waters that can be used for industry, fish farms (for fish

that all not as sensitive to pollution as trout, and for urban and recreational use;

· Category III for industrial use, includes waters for irrigating agricultural land, electric

power production in hydroelectric power plants, industrial cooling installations, cleaning

units and other purpose;

· Category D degraded, includes degraded waters improper for development of aquatic

fauna.

Romania has 4864 watercourse with a total length of about 78,900 km, out of which 22,031 km are

monitored for water quality. In 2001, about 7% of the total length of monitored rivers was considered

as degraded (see Table 3).

The worst conditions, falling in degraded class Category D occurred within the following river basins:

Prut (21.9%); Ialomita (20%); Vedea (10.6%) (see Figure 1). In the period 1993-2001, there was a

substantial increase in category I class of total river length, as well as a decrease in category II class of

total river length since 1996, and a relative stabilization of the length of rivers within category III and

Degraded class of total river length.

14

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

Table 4: Water Quality of Monitored Rivers in Romania, 2001

Total number

Class of overall river water quality by Category I sections, 2001

of monitored sections

I II

III

Degraded

No. % No. % No. % No. %

318

198 63.5 64 20.5 25 8.0 25 8.0

Total monitored length, Class category of overall river water quality by monitored length, 2001

km

I II

III

Degraded

km % km % km % Km %

22,031

14,979 68.0 4,117 18,7 1,401 6.3 1,534 7.0

Source: National Company "Apele Române7", ,,Synthesis of water quality in Romania in 2001, 2002

In the past 10 years, water quality in Romania has slightly improved, but not because of increased

pollution control. Due to poor economic conditions, industrial and agriculture water consumption has

decreased, thus decreasing the quantity of wastewater discharged into surface water.

80.0

70.0

60.0

50.0

Class I

40.0

30.0

Class II

20.0

Class III

10.0

Degraded

0.0

1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001

Figure 1: Trends in River Water Quality, 1993-2001

Source: The impact on industry, agriculture and local utilities systems of implementing directives

91/271/EEC, 98/83/EC, 76/464/EEC (and the seven "daughter" directives) and 91/676/EEC., Phare Project

RO 9907-02-01: Pre-accession Impact Studies., FINAL Report

Non-point sources have decreased because smaller quantities of fertilizers and pesticides are used, but

ground water contamination, especially by nitrates, remains high. It is difficult to fully characterize

water contamination, because only a limited number of hazardous pollutants are monitored. Existing

7 This is the former name of NARW; owing to various institutional changes the same institution have had different names. In quoting a

range of papers and documents drafted in the past the original name was used.

Dr. Victor Platon, George Dulcu

National Profile of Municipal Water and Wastewater Management in Romania

15

wastewater treatment facilities, half of which are not working properly, will not be able to treat the

additional quantities of wastewater discharges from the industrial and agriculture sectors when

economic growth resumes. Therefore, water quality is likely to worsen.

The overall water quality and the trophic level of the reservoirs and lakes are shown in Table 5. The

percentage of eutrophic reservoirs and lakes could be explained by an existing high potential for

contamination, due to diffuse or "non-point" sources and specific hydraulic conditions, rather than to

point pollution sources.

The worst situation within the category degraded class was registered within the seaside area.

Table 5: Water Quality of Monitored Reservoirs and Lakes in 2001

Class category*)

Total

I II

III

Degraded

number of

monitored

No. %

No.

%

No.

%

No.

%

lakes and

63 67.0

16

17.0

6

6.4

9

9.6

reservoirs

Trophic level*

Oligotrophic Oligo-mesotrophic Mesotrophic

Meso-eutrophic

Eutrophic

No. % No. % No. % No. % No.

%

94

27 28.72 7

7.45 30 31.91 11 11.7 19

20.21

Source: National Company "Apele Române", ,,Synthesis of water quality in Romania in 2001", 2002

*) STAS 4706/1988 for surface waters, quality categories and conditions.

Water Monitoring

In Romania, water authorities8 use to monitor the quality of rivers in 22,000 km out of 78,900 km,

using 318 gauging stations. When flows are high, water quality data are transmitted daily from 65

control stations. When flows are low, surface waters are monitored in the 318 stations once a month.

About 40 physical, biological and microbiological parameters are measured.

Monitoring water quantity is carried out by 1,016 hydrometric stations by measuring the flows.

About 40% of the stations that monitor water quality also use to monitor the quantity. For the other

stations discharge information is transmitted from the nearest hydrometric station.

Groundwater is usually monitored in 3,695 hydrological stations, of which 1,434 take qualitative

measurements. In addition there are some 12,000 survey points situated in the vicinity of pollution

sources, drillings and water wells for water supply, mainly in rural areas. Eighteen general physical-

chemical parameters (temperature, pH, conductivity, total dissolved solids, oxygen regime, nutrients,

etc.) are measured in groundwater. As well, for the drinking water supply, bacteriological parameters

are measured too.

The monitoring of waste-water discharges (emission monitoring) of about 2,100 point pollution

sources is performed by water authorities, including municipalities' discharges points. As well, the

laboratories9 of the Environmental Protection Inspectorate (EPI) can perform environmental audits or

inspections. EPI laboratories can also perform water analyses on a commercial basis.

8 The description of Water Authorities is made in Section 2.2

9 The accreditation process, according to international standards (ISO 9000), has just started in Romania. At present the quality assurance

system consists mainly of parallel sampling and analysing (inter-calibration) between the laboratories of the water authorities and foreign

laboratories, followed by a spatial analysis of the results. Ten of the forty-one provincial laboratories are very close to accreditation at

national level, by RINAR, the national accreditation body.

16

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

1.5 Major Sources of Pollution

In 2001, the total volume of water discharged was 5.03 billion m3. Of this amount 52% are

wastewaters that require treatment.

From the total amount that require treatment (2595.3 m3/year) 16.5% have been adequate treated; out

of the rest 35% are waters not treated and 48.5% is water insufficient treated.

Local water utilities are the main dischargers of wastewaters that requires treatment with 1.87 billions

m3 in 2001; out of this amount 0.8 billion m3 was not treated and 0.91 billion m3 was insufficiently

treated. On the second place is the industry with a volume of 0.64 billion m3 of wastewaters that

requires treatment.

In Romania, the natural raw water resources, while technically utilizable, cannot be used without

making certain significant investments in complex development water works of the hydrographic

basins and in treatment installations because:

· one of the most important water resource, the Danube river, can be used in a small extent,

due to its eccentric position, at the Southern limit of the territory;

· the inland rivers are unequally distributed all over the territory, significant areas remaining

with insufficient resources, presenting at the same time important flow variations in time and

space;

· the pollution of certain inland rivers, exceeds the admissible limits, which makes difficult

and sometimes even prohibitive their use.

From the data presented we may see that municipalities are one important water polluter. The situation

is significant where localities are situated up stream and down stream of a river that is the only water

source. As it is mentioned in the Case Study, Pitesti is situated on the Arges river and, down stream an

agglomeration of more than 2.5 million (mainly Bucuresti city) is getting the drinking water. So, the

MUs should meet effluent standards in order to reduce the nutrient load and allow other entities to take

advantage of a natural resource without excessive processing costs.

2 Legal and Institutional Framework

In Romania, raw waters are considered a natural resource that is managed by a public body. The water

users are municipalities (trough MUs), industry that it is not linked to a municipal network and has its

own water source, agriculture for irrigation and other users. Municipal W&WW operators have to

observe water laws that are general for all users. This section describes the legal and institutional

framework in which the MUs and municipalities should operate. The legal framework is very

important for municipalities especially in this period when the whole environmental "acquis" was

transposed in Romania. As a consequence for municipalities, the targets of water infrastructure

development programmes are, to a large extent, externally determined by the EU laws. Some estimates

say that only for the water sector, Romanian municipalities will have to invest around 9 billion , in

order to implement all EU laws.

2.1 Laws of the Water Sector

I. Water Law

The main legal act regulating the water sector in Romania is the Law no 107 of 25 September 1996 on

waters, published in the Official Gazette Part I, no 244 of 8 October 1996, with its subsequent

modifications. This law aims at water sources preservation, development and protection, protection

against pollution, water quality modification and alteration of surface waters' beds and shores. Also,

the law provides for restoring the quality of surface and ground water, preserving aquatic ecosystems,

securing potable water supply, complex exploiting of water as an economic resource, its rational

distribution and the maintaining of waters' natural productivity, as well as at floods and other hydro-

meteorological risks management.

Dr. Victor Platon, George Dulcu

National Profile of Municipal Water and Wastewater Management in Romania

17

In Romania, waters are public property and their protection, exploitation and sustainable development

should be carried out in accordance with the public interest. For that reason, both the right of use and

corresponding obligations regarding water resources protection and preservation should be exercised

according to the water law, which establishes specific regulations with regard to different types of

water and their beds and shores. Law no 107 on waters, together with adjacent secondary legislation,

also rules on the construction works connected with waters and generating direct or indirect,

permanent or temporary modifications on waters' quality or flowing status. Underground water should

be used in accordance with relevant legal provisions.

Rivers, banks and riverbeds together with tributaries with lengths greater than 5 km or with basin

larger than 10 km2 are public property.

The water law provides for the setting up of special sanitary protected areas around potable water

supply sources and installations (Government Decision no 101 of 3 April 1997 on approving the

Special Norms regarding the characteristics and size of the sanitary protected areas, published in the

Official Gazette no 62 of 10 April 1997). Ministry of Health and Ministry of Water and Environmental

Protection are responsible for sanitary protected areas. Ministry of Health is also in charge of

monitoring drinking water quality. Standards have been set for surface waters intended for abstraction

of drinking water as well as for the quality of water destined for human consumption and bathing. The

law also establishes that in artificial lakes representing potable water supply sources, only natural fish

breeding is permitted, fish foddering and fungicide and veterinary drugs spreading being forbidden.

Even in cases different from above, fish foddering and chemicals utilization is allowed provided that it

does not alter water quality downstream and a valid water management authorization does exist.

The right of utilizing surface or ground water is established through the water management

authorization and is exercised according to the legislation (see details in Section 2.3). This right also

refers to the discharging of wastewater, drain, and storm water into water sources. Water users are

bound to observe certain norms on water consumption per production unit and per activity and to save

water through rational utilization and recycling. They are also legally responsible for ensuring the

maintenance and repair of water installations under their jurisdiction.

Taking into consideration the highest performance of existing technologies, water consumption norms

are proposed by water users, consented by stakeholder ministries and approved by the Ministry of

Water and Environmental Protection. These water consumption norms are regularly updated. In case

of divergences, the RUs should intervene.

On joint proposal of Environment and Health Ministries, limits concerning pollutants concentration in

wastewater discharged into water sources have been set by Government Decision no 730 of 10

November 1997 on approving the Norms10 on establishing limits regarding pollutants concentration in

wastewater discharged into water resources..

Carrying out any new investment on drinking or industrial water supply cannot take place without

appropriate and simultaneous extension of the sewerage network and sanitation equipment. The law

also prohibits the throwing of solid waste into any type of water and the discharging of wastewaters

into ground water or natural and artificial lakes. In cases of new

Potential investors or beneficiaries should apply for the water management approval during the

preparation phase of the feasibility study for a project and should show evidence of other permits11

previously acquired (see Section 2.3 for details).

Water users located in inhabited zones, suburbs or industrial areas may discharge wastewater into the

sewerage network only with the agreement of the sewerage system's administrator, in conformity with

the established conditions and provided that the terminal sanitation station has an adequate capacity

and technologic profile for the wastewater discharged.

10 The NORM "NTPA-001", published in the Official Gazette Part I no 327 of 25 November 1997

11 . An Annex to the Waters and Environmental Protection Minister's Order no 148 issued on 27 February 1997 and published in the

Official Gazette Part I no 100 bis of 26 May 1997 lists a number of nineteen approvals, consents and certificates issued by other

authorities, that may be required, on a case by case basis, before to start the water permitting procedure which is the last one.

18

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

II. Other Laws

Other important laws are:

· Minister's Order no 1100 of 28 December 2001 on the modification and completion of the

Water and Environmental Protection Minister's Order no 706/2001 was issued for approving

the Rules of Procedure regarding the organization of the certifying activity for institutions

specialized in accomplishing studies, projects, consultant work in the field of water

management and technical documentation supporting applications for water management

approvals and authorizations12.

· Law No. 215/2001, Law No. 216/2001, Law No.326/2001, Law No 213/1998 and Law No

219/1998 have created the legal framework for proper management and development of

public services of communal husbandry. The Law No. 326 of 28 June 2001 on the Public

Services for Communal Husbandry, a framework law of modern European conception,

which sets important tasks with regard to the responsibilities of the Government of Romania

and the structures of the central public administration regarding the general policy of the

state in this field. This law was followed by a series of sector regulations which, for the first

time in the post-war Romania, settle administrative, legal and technical rules for every

service of communal husbandry, namely for: drinking water and sewerage, production and

distribution of thermal energy, sanitation, waste management, local public transport for

passengers, roads and green areas and electric energy distribution in localities.

Other EU directives, with impact on the municipal water system, have been transposed so far (for

more details see Annex 2):

· Directive no. 91/271/EEC regarding urban sewage waters approximated by Government

Decision no. 188/2002 regarding some effluent norms regarding water discharged into

natural waters (Official Journal no.187/ 20 March 2002);

· Directive no. 75/440/EEC regarding the quality of surface waters designated for

drinking water is transposed in: Ministerial order no. 377/2001 regarding the approval of

the norms for surface water quality; Gov. Decision no. 100/2002 for the norms to measure

and associated frequency for analysis for the surface water designated for extraction and

preparation of drinking water and Ministerial order no. 1146/2002 for classification of the

quality of the surface waters (Official Journal 197/ 27 March 2003);

· Directive no. 98/83/EC regarding drinking water transposed in Law no. 458/2002

regarding drinking water (OF. Journal no552/29.07.2002);

· Directive no. 80/68/EEC regarding the protection of the underground waters from

pollution with some dangerous substances is transposed in Min. Order no. 1049 from

13.11.2002 for approving the Plan of Measures for reducing and eliminating the risk of

polluting underground waters.

2.2 Institutional Framework; Major RUs in the Water Sector

Public water resources are managed by the National Administration "Romanian Waters" (NARW)

which implements the national strategy and policy. NARW is the major regulatory unit (RU) in the

field of raw water.

Water management activity in Romania is planned and carried out across river basin units within

which surface and ground waters are considered as a unit both from a quantitative and qualitative

perspective, with the view to ensure sustainable development.

Law no 106/1996 refers to the "Romanian Waters" Regie Autonomous, the name of the national

authority on water resources management. Water management authority's name and status have

been changed twice since 1996. In 1998, by the Government Decision no 981/1998 the National

12 It has been published in the Official Gazette no 77 of 31 January 2002

Dr. Victor Platon, George Dulcu

National Profile of Municipal Water and Wastewater Management in Romania

19

Company "Romanian Waters" (joint stock corporation) was created. On 5 September 2002,

Government Decision no 981 has been repealed by the Government Emergency Ordinance no 107 on

the creation of the National Administration "Romanian Waters". This Emergency Ordinance

became effective13 on 20 September 2002, the date when it was published in the Official Gazette.

The National Administration Romanian Waters (NARW) is responsible for preparing water

management plans and programmes. Through its branches for each 11 river basins, (corresponding to

the river basins), it also responsible for enforcing water legislation and policy, monitoring, for

preparation of river basin management plans, floods and drought control etc.

NARW through its basin branches, is also responsible for the prevention and warning of accidental

pollution. In this regard, adequate planning is conducted, taking into consideration the specific

conditions of a hydrographic basin and the nature of hazardous substances involved and in accordance

with the methodology established by the former Ministry of Waters and Environmental Protection.

Water users should devise their own plans on preventing and combating accidental pollution. In case

an accidental pollution occur, the polluter should take urgent measures to address pollution's causes

and consequences, and to inform immediately the closest water management unit.

The public water management body should warn water users and local governments downstream

about the accident. Potential polluting companies, local governments and water management bodies

should be equipped with adequate intervention means for cases of accidental pollution. Downstream

water users suffering material losses from an accidental pollution, that could take place upstream, have

the right to receive compensations from the natural person or legal entity that, according to the law,

bears responsibility for the accident. The polluter should also compensate natural persons and legal

entities, including NARW for their expenses related to the neutralizing of accidental pollution effects.

The implementation and enforcement responsibilities involve other institutions including: ministries,

public institution, institutes and local authorities.

Ministry of Agriculture, Food, Forestry and Environmental Protection14 (MAFWE) plays the

main responsibility for implementing the environmental acquis; as well it has an important role in

implementing the Water Directives trough its Water Department. This ministry and its Water

Department is RU in the field of environment, waters and forestry.

Water Department, along with NARW, was entitled to set limits or suspend temporarily water

utilization in order to face the risk or consequences of accidents, drought and water shortage caused by

depletion of existing resources. Temporary restriction plans can be instituted during periods with water

deficit by NARW, after consultation with authorized users. These plans should be sanctioned by the

Ministry, approved by the water basin committees and made known to the public in a timely manner.

To implement restriction plans, in case of emergency, NARW devises certain measures that are

compulsory on all users and prevail on the provisions of the water management authorization. The

methodology for restriction plans' issuance and public information is established by the Ministry.

Ministry of Economy (ME) has legislative responsibilities related to the industrial sector, develops

strategies and plans etc.

Ministry of Health and Family (MHF) has joint implementation responsibilities for Urban

Wastewater, Nitrates and Air quality Directives, mainly for standards regarding drinking water.

Ministry of Transport, Housing and Tourism (MTHT) has primary responsibility, among others,

for drafting spatial development plans ensuring that the infrastructure works are correlated and issuing

requirements and norms for the implementation of heavy infrastructure investment. This ministry is

mainly responsible for large infrastructure projects at the national level (national roads, highways,

harbors, airports etc.) but not direct related to W&WW investment. It finances the infrastructure under

its authority.

13 It should be mentioned that the instability of the main institutions is significant. For instance, in the last four years, NARW changed its

status and name for several times as well as the regulatory authority, namely the Ministry of Water and Environmental Protection.

14 In mid August 2003, Ministry of Water and Environment Protection was dissolved and water and environmental attributions were

transferred to the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry. For the time being there is also a Water Department in MAFWE.

20

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

The Ministry of Public Finance (MPF) makes decisions on the state budget, allocations to local

budgets, taxation etc.

The National Institute for Meteorology, Hydrology and Water Management provides technical

support in air quality and emission control, water quality, radioactivity, data collection and emissions

inventory.

The Institute for Public Health is the expert agency of the Ministry of Health and Family, carries out

research, collects and processes data on various aspects of environment that might impact on human

health.

The Romanian Standards Institute develops technical standards for all domains.

The Romanian Research Marine Institute and the R&D Institute of the Danube Delta, play an

important role in conducting research and monitoring for the Black Sea and the Danube Delta,

respectively.

The National Institute for Research and Development for Environment (ICIM) carries out studies,

strategies, actions plans, legislations, norms, lab methodologies, national survey of wastes, water

resources quality, water use and water users.

At local and regional level the following institutions are responsible for the enforcement of water

regulations:

Environment Protection Inspectorates (42 EPIs), corresponding to the 41 counties and Bucharest,

are in charge with permitting, inspection, enforcement and monitoring. They report to the MAFWE,

but are partially self-financed.

Local Authorities (LA), at the county and municipal levels15, have the duty to insure that population

has access to public services and related infrastructure (i.e. wastewater treatment works, water and

sewage networks, landfills); as well LA identify and propose public projects for investment. Local

Authorities have certain obligations aimed at the rational utilization of water and preserving its

quality. They should employ installations with low water consumption and less polluting, to avoid

losses and wasting and reduce effluent concentration. LA as infrastructure owners should also ensure

the maintenance and operation of stations and installations for water quality processing at the

authorized capacity, monitor their efficiency through lab analyses and, in case of non-compliance, take

measures to bring emission/effluent indicators within the limits stipulated in the water management

authorization.

According to the water law, in urban and rural localities, the local authorities should ensure adequate

management of water supply, sewerage and sanitation, as well as storm water drainage, using local

legislation and local budgets. All investment in W&WW should be carried out with the local level

financial resources. There are no subsidies from the state budget in financing W&WW services16. As a

redistribution tools, the central budget is transferring some revenues from the richer counties to poorer

ones in order to cover some expenditures at the county level.

Local Agriculture Agencies at county level enforce and monitor, among other duties, the Nitrates

Directive.

River Basin Committees (RBC). The G.D. No. 1212 11.29.2000 (O.J. No. 644, 12.11.2000) lays

down the rules for the structure and operation of the River Basin Committees. The M.O. No. 678,

07.17.2001 (MWEP), not published in the Official Journal, established 11 River Basin Committees,

actually corresponding to the 11 River Basin Districts under the NCAR. The structure of the River

Basin Committees consists of 15 appointed, elected and selected members (in accordance with

specified procedures), representatives from MWEP, MHF, NCAR, local public authorities, legal water

users, NGOs, and consumer protection offices.

National regulatory units that affect MUs

15 Towns and communes

16 There are direct subsidies from the central budget in the case of local transport and household heating in the winter period.

Dr. Victor Platon, George Dulcu

National Profile of Municipal Water and Wastewater Management in Romania

21

The National Authority for Municipal Utilities17 (NAMU) is a new institution that has important

attributions in the field of communal utility services including water and wastewater. This new

institution has responsibilities in regulating, monitoring and controlling all communal activities that

are natural monopoly. Among other duties, NAMU has to:

· issue licenses to the operators of communal water services;

· collect and publish information regarding the activities of the operators of communal water

services and publish it;

· oversee the mechanism of the adjusting the prices or tariffs to the conditions of the contracts;

· adjudicate solutions in the conflict between the operator and the consumers;

· ask for improvement programs of the activity from the other operators, when their activity

does not meet the standards set by the operator license, namely the contract of delegating the

administration;

· withdraw the operating license, if the operator refuses to consider the measures means to

improve the activity.

NAMU is the RU for all MUs at municipal level in all cases where is a natural monopoly.

2.3 Water Permitting

2.3.1 Water Management Approval (WMAp)

All MUs should have a WMAp when is undertaking an investment or an old facility is modernized.

This rule should be observed by all entities that carry out a water work.

For a new water user or an old one that is undertaking a new investment or retrofitting an old one,

getting the construction emplacement approval does not exclude the obligation to apply for the water

management approval. Consequently, individual works can be performed only on the basis of the

water management approval issued by the territorial branches of the National Administration

"Romanian Waters" after reviewing the required documentation18. Potential investors or beneficiaries

should apply for the water management approval during the phase of preparation of the feasibility

study for a project and should show evidence of other permits previously acquired19. In addition, the

solicitor should present, as the case may be, proposed measures on providing sustainable management

of water resources, proposed measures on minimizing adverse impacts, proposed actions on securing

optimal water flow and aquatic ecosystems preservation. Technical documentation submitted to the

approving authority should be accompanied by a photocopy of the public information letter on the

intended activities that the solicitor should accomplish.

Water management approval - or substantiated refusal - should be issued within sixty days from the

date when the last document required has been submitted. Water management approval is valid

throughout the execution work on the objective for which it was issued; on the condition that full

compliance with the provisions set therein does exist. This permit looses validity after two years if

execution work does not begin within this interval. Yet, water management approval can be renewed

upon request submitted six months before the expiration date. A new water management approval is

required for the development or modernization of some technological processes or existing equipment

of water users if the planned change implies the modifying of the previous approval's provisions. By

water management approval provision, investors can be obliged to perform certain works not included

in the technical documentation but necessary to ascertain that proposed works, constructions and

installations will not cause damage to existing water users or riverside residents.

17 This is subordinated to the Ministry for Administration and Internal Affaires (created in mid 2003).

18 The standard application form is presented in annex 1d of the Procedure on water management approval and authorization issuance,

adopted by the Waters and Environmental Protection Minister's Order no 148 issued on 27 February 1997 and published in the Official

Gazette Part I no 100 bis of 26 May 1997.

19 Annex 1i to the above-mentioned Procedure lists a number of nineteen approvals, consents and certificates that may be required, on a

case by case basis, during the permitting procedure.

22

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

The law allows for performing of some minor works without a water management approval20 on the

basis of a notification to the National Administration "Romanian Waters" 20 days prior to the works'

start. Carrying out these works can take place in similar conditions, i.e. without an authorization but

upon previous notification.

Reference material supporting the application for water management approval21 should draw upon

meteorological, hydrological or hydro-geological studies, as the case may be, as well as on water

management studies and studies on the impact that individual works would have upon water resources

and riparian zones. These studies can be accomplished by authorized public and private institutions22

and should demonstrate that the water approval solicitor is able to comply with relevant legal

provisions.

The law points out that water management approval and construction emplacement approval are

separate permits but have to be in concordance. The same legal act specifies that getting water

management approval and authorization do not exclude the obligation to apply for the environment

approval and environment authorization in accordance with the law.

The steps in having all approvals for an investment or a modernization of an existing plant are in the

next table.

20Categories of works and activities for which the water management approval is not required are listed in annex 1c of the Procedure on

water management approval and authorization issuance. Categories of works and activities for which a water management approval is

required are listed in annex 1b of the same Procedure, which also establishes which is the approving authority for different categories of

works (annex 1g).

21 By the former Waters and Environmental Protection Minister's Order no 277 of 11 April 1997, Norms on the technical documentation

necessary to obtain the water management approval and authorization have been adopted. These norms have been published in the

Official Gazette Part I no 100 bis of 26 May 1997.

22 Minister's Order no 1100 of 28 December 2001 on the modification and completion of the Water and Environmental Protection Minister's

Order no 706/2001 on approving the Rules of Procedure regarding the organization of the certifying activity for institutions specialized in

accomplishing studies, projects, consultant work in the field of water management and technical documentation supporting applications for

water management approvals and authorizations has been published in the Official Gazette no 77 of 31 January 2002.

Dr. Victor Platon, George Dulcu

National Profile of Municipal Water and Wastewater Management in Romania

23

No.

Type of permit

Issuing institution

1. Urbanism Certificate (this document includes a list

Town Hall of the city or the County Council

with all approvals and consents needed in order to get

the CA)

2. Water Management Approval

NARW

3. Environmental Approval

EPI

4. Other approvals, if there are necessary or asked by the

Other institution as power generator, gas

Urbanism Certificate

supplier, MPWTH etc.

5. Construction Authorization (CA) (final document)

Town Hall of the city

The final document is the CA that allows to start construction works; this is usually valid for one year

and could be extended.

2.3.2 Water Management Authorization (WMAu)

All MUs operating in Romania should have a valid WMAu.

MUs and other operating business in the water sector (water extraction, mineral aggregates exploiting

etc.) can take place only after receiving the water management authorization (autorizatia de

gospodarire a apelor). In addition, Ministry of Transport's approval is required in case of works to be

accomplished into the navigable national waters. Applicants should pay for water management

approval and authorization services certain fees and tariffs due to the Water Fund.

As well, the water management authorization includes the discharge limits for water users . Surpassing

these limits is banned by law. The law also prohibits the opening of new economic objectives or

extending of existing ones, constructing new dwellings or replacing production technologies with new

ones that produce increased effluent concentration, without simultaneously opening new sewerage

systems and sanitation installations or taking other measures aimed at complying with the provisions

on wastewater set by the water management authorization.

Water management authorization is issued within sixty days from the application date and at the latest

on the date of inauguration for the economic objective to be authorized, on the basis of technical facts

finding conducted in the presence of the solicitor. WMAu is granted only if legal provisions regarding

water management are observed and information included in the application form23 and supporting

documentation24 prove to be accurate. WMAu can be issued for a period of time varying from one to

ten years, according to the type of activity to be authorized25.

In case of extending of activities, improvements of production technologies, etc., the water user (MUs

as well) have to apply for update the water management authorization.

WMAu is one of the documents that are needed, among other consents and permits from relevant

authorities, in order to have the Environmental Authorization. The Environmental Authorization

allows a company to run.

23 Standard application form for the water management authorization is presented in annex 1f of the Procedure on water management

approval and authorization issuance.

24 Standard application form should be accompanied by the water management approval, previous authorization if existing, a program for

compliance in cases of authorizations issued for a limited timeframe, a general plan of the water works, constructions and installations to

be authorized, mentioning their construction and operation parameters, the operation and maintenance rules of procedure, and the

agreement of the owners of the water supply and sewerage systems involved.

25 For example, mineral aggregates exploiting for individual household or local government's needs may be authorized for maximum one

year, but installations for water abstraction, treatment, pumping, transport, accumulation, distribution and cleaning can be authorized for

maximum five years. Other activities such as energy production, navigation, fish breeding, rafting and entertainment activities can be

authorized for a period up to ten years.

24

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

3 Water Used by Localities

From the 22.4 million inhabitants, living in Romania, only 14.7 million persons (65% of total) have

drinkable water supplied by public service; of this amount 11.3 million persons are in the urban area

(76.9 %) and 3.4 mil. in the rural area (23.1 %). In the last 25 years, there was an increase in the

number of households connected to the network from 29% to 65% of the population.

3.1 Production and Consumption of Drinking Water

A total number of about 304 drinking water treatment plants were identified in Romania by NARW,

during year 2001, operating in general using the classical treatment technology including: coagulation

settling- rapid sand filtration and chlorination (in certain cases pre-chlorination was used). The

capacity of these installations to produce drinking water was of 10.5 million m3/day.

According to the Romanian Statistic Yearbook, in 2001, the volume of drinking water pumped into

networks was 2.4 billion m3 and the volume of drinking water distributed to users was 1.53 billion m3

(for details see Annex 5). The share of water distributed to domestic users was 64.6% in 2001 and to

public users the share was 13.1% (see Table 6).

Table 6: Volume of Drinking Water Distributed in Networks, in 2001

Volume of drinking water distributed

million m3 %

At users, out of which:

1,530

100

· for domestic purpose

988.3

64.6

· for public purpose

200.2

13.1

Source: Data from Annex 5

Table 7: Regional Distribution of Drinking Water and Population

- (%) -

Drinking Water distributed

Population by regions

to users by regions

1. North-East

11.9 17.1

2. South-East

13.3 13.1

3. South

11.8 15.4

4. South-West

7.9 10.7

5. West

9.3 9.1

6. North-West

11 12.7

7. Center

14.8 11.8

8. Bucharest-Ilfov

19.9 10.1

Total

100 100

Source: Processed Data from Annex 5

At regional level, the Region 8 which is a big urban agglomeration, gets 19.9% of the water distributed

but only 10% of the population. The water is distributed across the eight regions in correspondence

with the population living in these regions (see Table 7).

According to the Ministry of Public Administration, by taking into account the losses and the share for

both public and economic uses, the water consumption in Romania has the following pattern: for the

urban area 335 l /inhabitant per day and for the rural area 126 l /inhabitant per day (in 2001). If

the calculation is made eliminating losses than the average consumption of drinking water was

Dr. Victor Platon, George Dulcu

National Profile of Municipal Water and Wastewater Management in Romania

25

160.7 l/inhabitant in urban areas (in 2002). This value is lower than the average consumption in

2001 that was 183 l/inhabitant.

3.2 Metering and Leakage of Drinking Water

In 2001, at national level, metering of drinking water progressed. From the volume of drinking water

distributed to users of 1,530 mil m3, a quantity of 1,124 mil m3 was metered which represented an

average of 73.4% (for details see Annex 5). The metering process started several years ago but in the

last two years it increased in intensity not only for drinking water but for hot water and apartment

heating as well.

For people living in single houses there is not a problem to introduce a meter (for this category of SUs

metering is a standard procedure) but for people living in block of flats there is still no an acceptable

approach. One solution was to introduce a meter at each stair of flats and a cluster of apartments

should divide the water bill. This division could be made according to the number of people living in

each apartment or each apartment to install meters to count the water. This last solution is very

complicated owing to the fact that usually, for each apartment in a block of flats, are needed 3-4

meters for drinking water without taking into account other 3-4 meters for heating. Having so many

meters it is time consuming to read them and to make calculations for the water bills. Not to mention

that in some localities the individual metering is not taken into account by the MUs because high

transaction costs. In such a situation the readings of the apartment meters are used only to split the

water bill among the people living in the same block of flats.

Another solution, experimented in Pitesti, is to install a more advanced meters that send by radio the

data to a central unit that processes these data and calculate the bill for each apartment. In this way the

huge cost of reading individual meters is diminished. This solution could be applied now only in

blocks of flats that have the adequate pipe network.

Across regions, the metering and losses are not uniform (see Figure 2). We could notice that losses of

drinking water are lower than the national average in six regions: South, Centre, North-West, West,