September 2004

ASSESSMENT AND DEVELOPMENT OF

MUNICIPAL WATER AND WASTEWATER

TARIFFS AND EFFLUENT CHARGES IN

THE DANUBE RIVER BASIN.

Volume 2: Country-Specific Issues and

Proposed Tariff and Charge Reforms:

Hungary Case Study

AUTHORS

Gabor Ungvari

TARIFFS AND CHARGES VOLUME 2

PREFACE

The Danube Regional Project (DRP) consists of several components and numerous

activities, one of which was "Assessment and Development of Municipal Water and

Wastewater Tariffs and Effluent Charges in the Danube River Basin" (A grouping of

activities 1.6 and 1.7 of Project Component 1). This work often took the shorthand

name "Tariffs and Effluent Charges Project" and Phase I of this work was undertaken

by a team of country, regional, and international consultants. Phase I of the

UNDP/GEF DRP ended in mid-2004 and many of the results of Phase I the Tariffs and

Effluent Charges Project are reported in two volumes.

Volume 1 is entitled An Overview of Tariff and Effluent Charge Reform Issues and

Proposals. Volume 1 builds on all other project outputs. It reviews the methodology

and tools developed and applied by the Project team; introduces some of the

economic theory and international experience germane to design and performance of

tariffs and charges; describes general conditions, tariff regimes, and effluent

charges currently applicable to municipal water and wastewater systems in the

region; and describes and develops in a structured way a initial series of tariff,

effluent charge and related institutional reform proposals.

Volume 2 is entitled Country-Specific Issues and Proposed Tariff and Charge

Reforms. It consists of country reports for each of the seven countries examined

most extensively by our project. Each country report, in turn, consists of three

documents: a case study, a national profile, and a brief introduction and summary

document. The principle author(s) of the seven country reports were the country

consultants of the Project Team.

The authors of the Volume 2 components prepared these documents in 2003 and

early 2004. The documents are as up to date as the authors could make them,

usually including some discussion of anticipated changes or legislation under

development. Still, the reader should be advised that an extended review process

may have meant that new data are now available and some of the institutional detail

pertaining to a specific country or case study community may now be out of date.

All documents in electronic version Volume 1 and Volume 2 - may be read or

printed from the DRP web site (www.undp-drp.org), from the page Activities /

Policies / Tariffs and Charges / Final Reports Phase 1.

TARIFFS AND CHARGES VOLUME 2

We want to thank the authors of these country-specific documents for their

professional care and personal devotion to the Tariffs and Effluent Charges Project.

It has been a pleasure to work with, and learn from, them throughout the course of

the Project.

One purpose of the Tariffs and Effluent Charges Project was to promote a structured

discussion that would encourage further consideration, testing, and adoption of

various tariff and effluent charge reform proposals. As leaders and coordinators of

the Project, the interested reader is welcome to contact either of us with questions

or suggestions regarding the discussion and proposals included in either volume of

the Project reports. We will forward questions or issues better addressed by the

authors of these country-specific documents directly to them.

Glenn Morris: glennmorris@bellsouth.net

András Kis: kis.andras@makk.zpok.hu

TARIFFS AND CHARGES VOLUME 2

A Case Study of Municipal Water System Management and the Impacts of Tariff and Effluent Charges: EDV, Hungary

3

Table of Contents

1

Description of the Case Study Area ............................................................................................. 5

1.1

Brief Historic Overview ...........................................................................................................5

1.2

Grouping of Territories and Users inside the Case Study Area ...............................................5

1.2.1

Description of Territories .................................................................................................5

1.2.2

Desription of Management Unit (MU), Operation Units (OU's), and

Regulatory Units (RU's) ...................................................................................................................8

1.2.3 Service Users....................................................................................................................8

1.2.4

User Groups in the Spreadsheet Model ..........................................................................10

2

Scenarios ...................................................................................................................................... 11

2.1

Lines of Investigation.............................................................................................................11

2.2 Economic

Sustainability.........................................................................................................12

2.2.1 The

Current Practice.......................................................................................................12

2.2.2

Comparison of Different Scenarios for Economic Sustainability ..................................12

2.2.3

Future Trends, Policies to Cover the Gap ......................................................................14

2.3

The Extension and Upgrade of the Service - Environmental Scenario ..................................15

2.3.1

System Extension and Upgrade......................................................................................15

2.3.2

The Potential Increase of Sewage Connection Rate.......................................................16

2.4 The

Cost Burden.....................................................................................................................17

2.5

The Distribution of Cost Burden Equity .............................................................................18

2.6

The Potential in Tariff Structure Reform ...............................................................................19

2.7

Sewerage Substitutions or Emission Tax ...............................................................................21

3

Policy Recommendations ............................................................................................................ 23

3.1

Local Decision on Financial Policy, Responsibility of Inter-Generational Burden

Allocation ..........................................................................................................................................23

3.2

Grant / Subsidy Allocation .....................................................................................................23

3.3

Equity and Complexity...........................................................................................................23

4

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

List of Abbreviations

AC Average

Cost

ASTEC Model

Accounts Simulation for Tariffs and Effluent Charges Model

CR Cost

Recovery

D Demand

EDV

Eszak-Dunantuli Vizmuvek, North-Transdanubian Waterworks, the site of the

case study

HUF

Hungarian Forint, the currency of Hungary

MC Marginal

Cost

MCP

Marginal Cost Pricing

MEWM

Ministry of Environment and Water Management

MU Management

Unit

RU Regulatory

Unit

RWW

Regional Water Works

SU Service

User

T1 through T8

The territorial categories applied in ASTEC modelling

Gábor Ungvári, MAKK, Hungary

A Case Study of Municipal Water System Management and the Impacts of Tariff and Effluent Charges: EDV, Hungary

5

1 Description of the Case Study Area

1.1 Brief Historic Overview

The examined area is a sub-system of the North-Transdanubian Waterworks (Eszak-Dunantuli

Vizmuvek, EDV)1. It is situated along the Danube riverbank where two towns and four villages are

located, as well as several small communities uphill from the river. The total population of the district

is around 80 thousand, half of the population lives in the two towns, and the other half in the villages,

with populations between 500 to 5000.

There are different kinds of heavy industry in the region with high volume water consumption

(machinery, glass production and power plant). All of them have their own water extraction facility

and some of them have their own treatment plant as well.

The district is a mix of state and local government owned subsystems, that (except for a few network

elements) are operated by a state owned regional water works company (RWW). The dominant owner

of the network is the state. The basis of the district is the regional water supply network that provides

water from a bank filtered water basis and a carstic well to the whole area and sells water to supply a

handful of small communities on the territory of the neighbouring regional system.

The sewage systems of the district show a more complex picture. The towns and the villages next to

them are serviced by a state owned network, operated by the regional waterworks company . The other

sewage systems service small groups of (one to three) municipalities, these are owned by the

municipalities. The RWW and a private firm run these small networks (based on concession

contracts). The RWW deposits the sewage sludge of its treatment plants on the landfill of the region's

solid waste management firm.

The examined area is part of a bigger service district where the mentioned state owned RWW is the

dominant service provider of both water and wastewater. Its network is separated from other districts

of the region, and it consists of two operation sub-units.

The predecessors of the RWW date back to the 19th century. The unification process of the region's

small waterworks started early in the 60's, and later during the decade a county wide service provider

was organised that operated all of the public water utilities of the county. Due to the development

program of the water utilities in the region its service districts reached beyond the administrative

boundaries of the county. Due to the ownership transfer of state property to the municipalities, some of

the new owners withdrew their sub-systems from the RWW's operation. The examined area has

approximately 25% of the total population serviced by the company.

1.2 Grouping of Territories and Users inside the Case Study Area

1.2.1 Description of Territories

To make the upcoming discussion easier to understand I show a territorial categorisation of the created

service user (SU) groups which reflect the most important patterns of service provision. These groups

will provide the base for the model's territorial differentiation.

T1.

Town A - Centre

T2.

Town A - suburban area

T3. Town

B

1 I would like to acknowledge the time and efforts of the colleagues at the Eszak-Dunantuli Vizmuvek Rt to

provide us the required information to evaluate this case study. The basic data was provided by EDV Rt

regarding a wider territory than of the company. The calculations and the conclusions express the opinion of the

author, not necessarily coincides with of the company.

6

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

T1,T2,T3 are the core settlements of the service area with 53% of the service area's

population. The reason of splitting them into three is the allocation of cost elements. T1 and

T2 have a common drinking water supply branch, while in case of the sewerage network T2

and T3 are components of a local system.

T4. "Mountain" group of 9 villages. These villages are on the same branch of the drinking water

network. There are three small sewage networks that service six of them. In the remaining three

villages sewerage substitution modules have to be developed until 2015.

T5. A village next to Town B, where the sewerage system will be built with connection to the

treatment plant of Town B

T6.

A village at the end of the network where the regional provider supplies drinking water and it

operates the wastewater system of the municipality

T7.

Two villages, where the regional provider supplies the drinking water and a private firm

services the wastewater.

T8. Three off-border villages, the waterworks sell drinking water to another waterworks to supply

these villages.

Basic data in the territory units is organised by households, public institutions, big industrial users (if

there is any) and other industrial users. The grouping inside one territory unit is based on the quantity

and the drinking water/sewage production similarities (the households always appears as an

independent group).

Gábor Ungvári, MAKK, Hungary

A Case Study of Municipal Water System Management and the Impacts of Tariff and Effluent Charges: EDV, Hungary

7

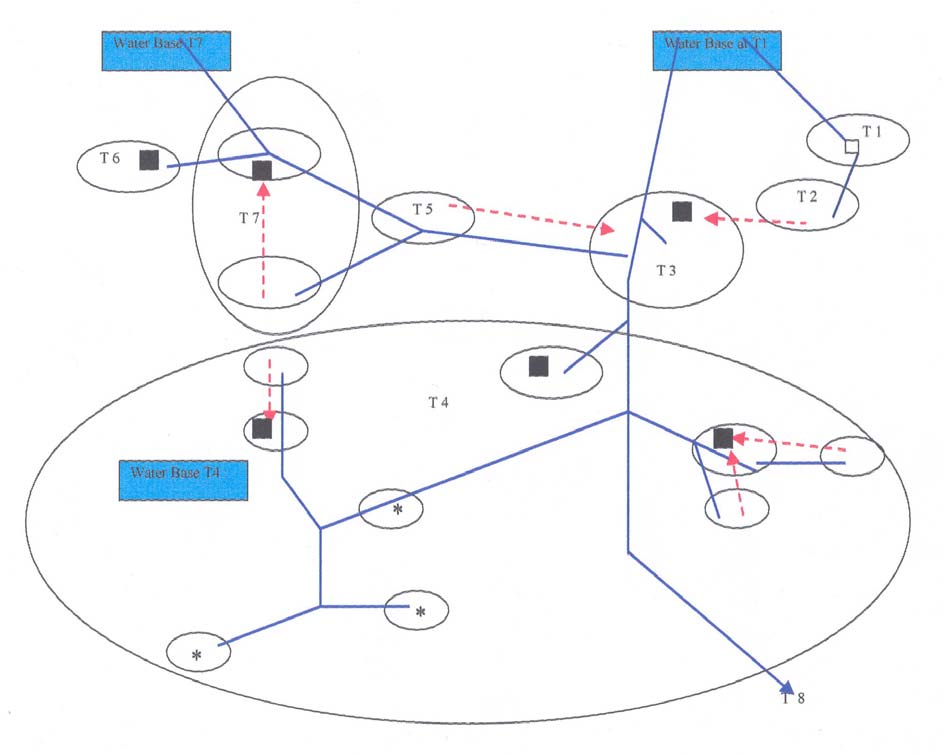

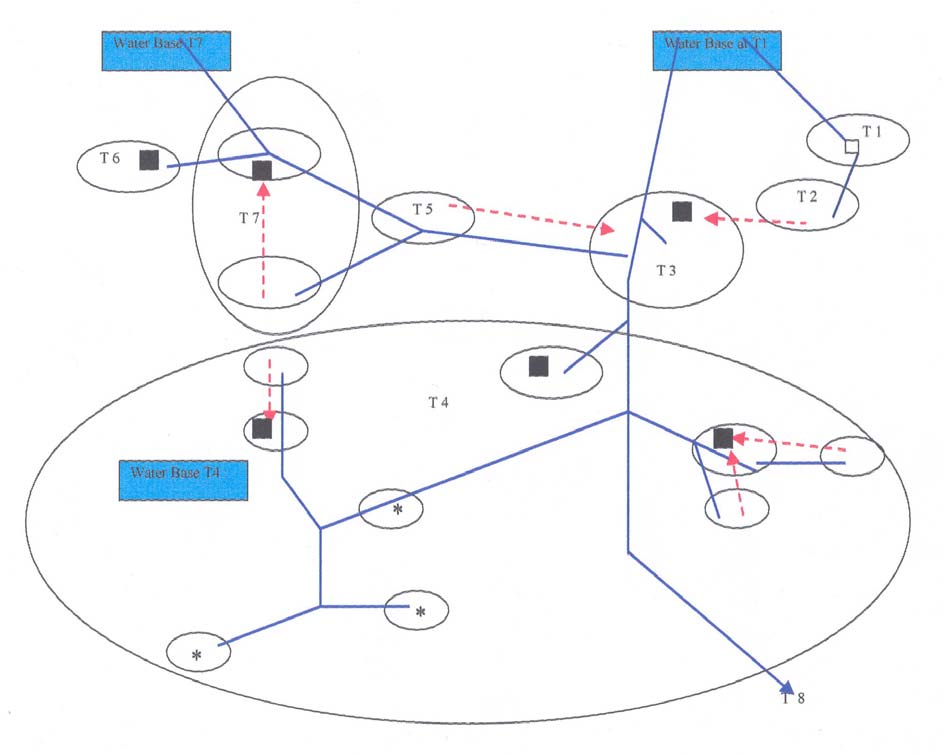

Figure 1

The Map of the Service District

Legend: Circles: municipalities Tx: territorial groups of analysis, the description is in the main text.

Blue (constant) line : drinking water network.

Red (staggered) line : sewerage networks.

Square: treatment plant. Star: there will be no sewerage network, only substitutions

8

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

1.2.2 Desription of Management Unit (MU), Operation Units (OU's), and Regulatory

Units (RU's)

1.2.2.1 Water Supply

The water supply network is one system, although it is operated from two bases. Accordingly, it

consists of two Operation Units. These units are responsible for maintenance, customer relations,

metering and the service of information. OU 1 is responsible for territories T1, T2, T6 and T7, OU 2

comprises T3, T4 and T5.

The MU of the case study district is the centre office of the RWW (that is located outside the area). It

runs the networks, decides on the necessary development investments from a technical point of view,

but it has to reach agreement on financial conditions with the owner - the Ministry of Environment and

Water Management (MEWM). The Ministry has MU licenses as it exercises the right to set prices

(annually by the modification of the concerned decree), decides about the amortisation measures. In

the past it provided financial sources of large development investments through grants and preferential

loans (the details see later).

The RU licences on drinking water supply are delegated to the owner, the Ministry of Environment

and Water Management.

1.2.2.2 Sewage System

Operation Units.

There are seven networks (collection and treatment included) in the area. Two of them (at T1 and T3 )

are owned by the state. The other five networks belong to the municipalities. Six of the networks are

operated by the RWW. One system (at T7.) is operated by a private service provider.

The function defined as of the MUs are allocated among several actors. There are two MU's that have

the responsibility on operation issues. These are the RWW and the private sewage service provider of

T6. The owners of the infrastructure have MU licences on tariff issues. In T1,T2,T3 the Ministry of

EWM has these licenses, in the other areas, from T4 to T7 the municipalities have this right each by

each. The municipalities' have concession contracts with the service providers that define the

algorithm of price modification.

The municipalities and the MEWM have RU licences over the sewerage networks they own.

1.2.3 Service Users

1.2.3.1 Households

The household groups mean residential customers in territory 1 to 7 (except 5). The portion of joint

metered apartment buildings is very low. The division of households follows the territorial units. The

average consumption based on the year 2001 is 84 m3/household(max 100 m3/household, min 75

m3/household).

1.2.3.2 Non-Household Groups, Public Institutions

I create public institution as a single consumer group only in T1 (the biggest town in the area). This is

because public institutions are concentrated in the towns, the proportion of their consumption in the

villages are very low. In T3 however the small scale industry and the public institutions have similar

water consumption/sewage production patterns, therefore there was no reason to differentiate among

them. The group called "other" aggregates their consumption.

1.2.3.3 Industry

Gábor Ungvári, MAKK, Hungary

A Case Study of Municipal Water System Management and the Impacts of Tariff and Effluent Charges: EDV, Hungary

9

There are some big industrial users in the area and several small ones. The big ones locate in T1, T3

and T7. All of them have access to the drinking water network, two have their own water extraction

facilities and all of them have installed pre-treatment devices on wastewater outflow to the public

network.

Industry "A" locates in T1. It is a heavy industry site. It has its own wells, applies advanced water re-

circulation technologies to optimise water consumption. The factory has a pre-treatment plant and

loads the sewage to the public sewerage system. For modelling purposes water use and wastewater

discharge are handled as independent services.

Industry "B" in T1 was distinguished from all other industry. As their consumption pattern differs

from Industry "A", for modelling purposes water use and wastewater discharge are handled as

composite services.

Industry "C" in T3 is a pharmaceutical factory. It has water supply from the public utility and has its

own treatment plant.

In T7 there is a glass producer, that consumption is 12% of the territories' consumption and 62% of

the industrial consumption, but the 15-group model capacity prescribe the compromise of merging all

non-household customer and this is the smallest "big" industrial user. Cost allocation of the

Spreadsheet model is based on the flow quantities a specific network element can be associated with.

Big industrial users' cost structure includes their location's distribution and collection costs with a

smaller weight (20%).

1.2.3.4 Purchase of Water

T8. The regional waterworks purchase water, and transfers it to the neighbouring regional waterworks.

10

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

1.2.4 User Groups in the Spreadsheet Model

Table 1

The Main Characteristics of the Defined User Groups in the Year 2001

User groups

No. of units

Drinking water Sewage quantity Consumption

consumption in in thousand m3

pattern of

thousand m3

drinking water

and sewage

services

Households in T1

7200

626

488

Composite

Public in T1 *

610

313

283

Composite

Industry A in T1

1

31

156

Independent

Industry B in T1 *

322

161

127

Composite

Households in T2

1862

167

103

Composite

Households in T3

4968

387

315

Composite

Industry C in T3

1

356

315

Independent

Other small users in T3

369

163

136

Composite

Households in T4

5529

417

175

Composite

Other users in T4

247

98

8

Independent

Households in T6

295 (12)

26

20

Composite

Households in T7

2948

295

-

-

Other small users in T7

227

105

-

-

Purchasing water to T5

941(53)

99

-

-

Purchasing water to T8

-

174

-

-

* Number of all non-households are divided by their consumption

Gábor Ungvári, MAKK, Hungary

A Case Study of Municipal Water System Management and the Impacts of Tariff and Effluent Charges: EDV, Hungary

11

2 Scenarios

2.1 Lines of Investigation

Baseline scenario

Current operation

This scenario deals with the current operation for up to one year. Computed cost include

variable costs, that change as the serviced volumes change, and fixed costs that do not change

with the volume of the services, but are necessary conditions of running the networks (i.e.

salaries, maintenance). This scenario does not include capital costs of assets or amortisation.

Economic sustainability scenarios

Medium term economic sustainability

This scenario incorporates capital cost elements up to seven year lifetime. Volumes and tariffs

are computed with the Cost Recovery requirement2.

Long term economic sustainability

This scenario consists of all the capital cost of system elements that are shown in the RWW's

book and system elements of municipalities owned networks that the RWW operates on a

contractual basis. Capital costs are computed assuming that the necessary assets to cover

future investments were provided from the capital market (present value of 4% real interest

rate). Because the sewerage network of T5 will be completed next year, the long term

restoration cost of this network part is included. Volumes and tariffs are computed with the

Cost Recovery requirement .

Sub-scenario: Extra Investments for further nutrient load decrease on the long run

Although this service district is not ranked as sensitive territory, the scenario shows increased

economic burdens if third phase (nutrient load reduction) devices were introduced. Volumes

and tariffs are computed with the Cost Recovery requirement.

Distribution of cost burden

This analysis is based on the allocation of costs among the distinguished network parts (T1-T8). In the

current situation there is a flat tariff for all the drinking water users and flat tariffs respectively by

ownership. The baseline scenario spreadsheet model counts the distribution effects of this tariff. The

model reflects the present financial flow, without cost recovery condition.

Efficiency gains of tariff structure reform

The Medium term sustainable scenario is the basis of the comparison of Cost Recovery and Cost

Recovery with marginal cost pricing scenarios. This comparison intends to show the efficiency

changes and the distribution effect of an optimal two-component tariff structure.

Incentive measure to increase connection rate to the sewerage network.

This analysis is based on the previous one. As an additional feature, it counts the volume of a specific

charge targeting households that do not connect to the sewerage network in spite of technical

possibilities.

2 Without Marginal Cost Pricing

12

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

2.2 Economic Sustainability

2.2.1 The Current Practice

During the pre-transition period the development of the system and the large scale maintenance needs

were financed from state sources. The transformation of the service providers into the market

compatible form of joint stock company raised the question of valuing the system's assets. The assets

were revalued in 1996. This forms the basis of our calculation on infrastructure.

The company operates system elements (both water and sewage) on a contractual basis; the

amortisation value of these are negotiated with the owner municipalities. Amortisation is collected as

part of the tariffs and usually the company itself uses the sum for maintenance. No additional funds are

set aside by the municipalities for this purpose.

Although the economic context has changed, some of the pattern of financing still remained. It was the

result of the valuation that an amortisation constant multiplier of 0.3 was created. This is the sum the

owner allows to impose for generating revenues to cover long term investment needs.

Meanwhile, on the average the same amount was transferred to the company from the owner Ministry

year by year for specified investment purposes such as the renewal of treatment sites etc. The

company can negotiate about its view on system needs, but the investment decision, the planning and

the execution of the investment is out of the scope of the management of the company. As years went

by the sum of reallocated investment has decreased. Due to these circumstances the company does not

have a long term financial plan for accumulating the necessary restoration fund.

In the economic sustainability issue emphasis has to be placed on changing the financial burden, if

new elements necessary for long term functioning are to be introduced.

2.2.2 Comparison of Different Scenarios for Economic Sustainability

Economic sustainability scenarios are based on the gross capital assets according to the bookkeeping

of the company. There are network elements that show up in the municipal books, especially in case of

the sewage network, but there is no coherent data on some of these units. Therefore, besides these

elements I use values that are based on the ministerial guidelines of per capita investment cost on

water and sewage development, as well as a guideline of the National Water Chief Directorate that

further elaborates these values based on research studies of development investments3.

3 The missing elements are based on the per capita investment guidelines of the Ministry, and their correction (OVF-Öko Rt,

1999).

Gábor Ungvári, MAKK, Hungary

A Case Study of Municipal Water System Management and the Impacts of Tariff and Effluent Charges: EDV, Hungary

13

Table 2

Comparison of Economic Sustainability Scenarios (total costs million HUF,

commodity charge HUF/m3)

Current revenue Costs of Current Costs of Medium

Long run

Operation

run Scenario, up

scenario with

Scenario up to

to 7 years

"borrow policy"

one year run

Water

supply

639 529 561 661

Sewage

service

254 256 409 701

Total 893

785

971

1

363

Water commodity charges HUF/m3

Uniform (average) price

190

190

163

201

Households T1-T7

171

216

Industry

117

130

Other

177

217

Sewage commodity charges HUF/m3

Uniform (average) price

-

122

227

417

Households T1-T3

122

199

293

Industry 122

148

213

Other* *

199

293

Highest household

290

547 1680

price**

rate 2.3

Rate of highest and lowest household sewage price

2.7

5.7

*There are several tariffs each by treatment plant, in T4 they ranges from 190 HUF to 290 HUF, at one plant charges 390

HUF for industry, in T6 the uniform tariff is 380 HUF

** In the investigated scenarios the highest tariffs resulted in T4, due to this, the basis of comparison at current revenues is

T4 not T6

14

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

Table 3

Balance of Current Revenues and Total Costs of Scenarios (million HUF)

Balance of Current

Short run

Medium run

Long run

Long run

Revenues and:

Operation

Scenario

Scenario with

Scenario with

Scenario

"borrow policy"

expansion and

environmental

upgrade, ,,borrow

policy"*

Water supply

110

78

-22

-14

Sewage

service

-2 -155 -447 -613

Total 108

-77

-470

-627

*The details of this scenario are discussed in the next chapter

The Table 2 shows different angles on the current financial policy. It shows the cost of different

scenarios of water and sewerage service compared to the present revenue stream. The first, Short Run

Operation Scenario indicates that without any amortisation (capital cost replacement) the overall

balance is positive, but there are differences between the two services.

The next column contains data that reveals the current scope of the accounted capital cost

(amortisation). If the capital cost of assets (with lifetime up to seven years) were accounted for, a

negative balance would result, which reaches 8 percent of the Medium run scenario's overall costs.

This reflects the practice that the sum received for amortisation is spent on the maintenance needs of

the network while there is no room for long term accumulation or restoration of the fundamental

elements such as pipes and treatment plant bases.

Next table shows the difference in total cost of the Operation Costs Scenario and the Long Run

Economic Sustainability Scenario with 4% real interest rate on borrowing the necessary funds.

2.2.3 Future Trends, Policies to Cover the Gap

What kind of considerations should be taken into account when deciding on the long-term capital

needs of the operation? The lack of suitable sewage infrastructure is the result of the state's previous

practice. It did not allocate the necessary funds to maintain the already existing networks, and did not

push the expansion of the sewage networks in line with the expanding (state funded) drinking water

supply network. The reason behind the state funded development activity was the sheer fact of income

centralisation.

From this point of view the burden lies on the state to provide for the missing infrastructure, without

any exception as to who owns or runs the regions' existing infrastructure, as there can be no difference

between settlements' financial burden based on whether the state financed the development earlier or

not (as they have to do it themselves now). Meanwhile it is unrealistic to take the position that the

burden of financing lies with the state, in spite of the goals the government issued in the National

Wastewater Program. (There are several other programs that have been halted or substantially delayed

due to the lack of even smaller public resource needs.) It is more reasonable to suppose some kind of

accumulation of own sources of the users themselves.

I consider two policies that aim at accumulating the necessary funds. Both target the full recovery of

capital costs. These scenarios are static ones, as they do not consider the process of gradual

replacement. Both calculate the effect of full capital replacement.

The "borrow" scenario assumes the financial market provides the necessary funds. It reflects the user

pays consideration, and implies that after the replacement of a certain system element the users will

pay the capital cost of investment through the fees. The consumers use the capital market to provide

themselves with the necessary funds for the lifetime of the operation.

Gábor Ungvári, MAKK, Hungary

A Case Study of Municipal Water System Management and the Impacts of Tariff and Effluent Charges: EDV, Hungary

15

The "self-financing" scenario uses the capital market to invest, and thus increase the value of the

accumulated fund that the community raises in advance to finance the necessary developments in the

future.

Both financial policy solutions have their advantages and disadvantages. The factors that have to be

taken into consideration at a local decision are numerous: Technical, geographical patterns, local

economic power, actual co-financing policies and the financial market's condition on long term

borrowing and savings. The decision also relies heavily on the inhabitants view about the future

prospect of their own settlement. Accumulation of local funds for future investments can put the

settlement in a better position in the long run as the local economy (as a whole) may pay less for the

provision of the necessary funds. Although the duration and the margins can change outcome of a

given policy dramatically, even turn it to disadvantageous. Most influential parameters (more precisely

their rate) are the real interest rate on borrowing, real interest rate on savings and the growth of

spending on a specific target due to economic expansion or necessity4. The longer the accumulation

period the more beneficial for a local community to choose savings instead of future use of external

sources. But the threshold of duration that marks the length of savings that could be more

advantageous than borrowing, shows great volatility. Although comparing different rate sets in case of

the around-and-over-25-years-long run savings the possibility that such an outcome is more probable.

As a consequence, such a savings policy will hardly take place without a regulatory frame and an

efficiently working financial market.

2.3 The Extension and Upgrade of the Service - Environmental Scenario

This chapter follows the previous chapter's line of thought. One of the main tasks of the program is

the reduction of nutrient load of the Danube basin. In this context the reduction of nutrient load can be

achieved by

- installation of third treatment phases in the plants and

- the increase of the connected consumers' rate.

2.3.1 System Extension and Upgrade

The next table shows the increase of costs due to the new system elements.

4 Above this calculation of circumstances, a local decision on financial policy even consider the other local activities'

alternative cost of capital use.

16

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

Table 4

The Changes of the Expansion and Upgrade Scenario

Current revenue

Costs of Short Long run Scenario

Run Operation

with expansion

Scenario up to

and

one year run

environmental

upgrade, borrow

policy

Water supply

639

529

651

Sewage service

254

256

867

Total 893

785

1

518

Drinking water commodity charge HUF/m3

Uniform (average) price

190

190

200

Households T1-T7

217

Industry

132

Other

210

Sewage water, commodity charge HUF/m3

Uniform (average) price

-

506

Households T1-T3

122

122

340

Industry 122

264

Other *

340

Highest household price

290

rate 2.3

1888

Rate of highest and lowest household sewage price

5.6

*the same considerations as the description of the other scenarios

2.3.2 The Potential Increase of Sewage Connection Rate

The difference between drinking water supply and sewage water provision is the main problem of the

service, although a considerable number of consumers do not use the sewerage network even if the

possibility of connection is given. In this system there is one village where the sewerage system (T5)

will soon be completed, and there are two small villages in T4 where the National Wastewater

Program does not provide for a sewerage system, only substitution for it, but with no specific deadline.

T5 will be part of the sewage network of T2 and T3, and the expansion of the network is included in

the Long term and environmental scenarios.

Beyond its environmental impact, the increase of connected users has economic benefits as well. The

higher the collected amount the lower the per cubic meter average fixed cost. The next table shows the

potential increase of wastewater at each of the territories and the resulting price changes. I assumed

that the drinking water / sewage water rate changes to 95% in towns, 90% in suburban areas and to

80% in villages.

Gábor Ungvári, MAKK, Hungary

A Case Study of Municipal Water System Management and the Impacts of Tariff and Effluent Charges: EDV, Hungary

17

Table 5

The Comparison of Medium Run CR Scenarios with the Current and a

Plausible Full Sewage Connection Rates

Present

Rate of Medium Run With full

Change of

Change of

Drinking /

D/SW at

CR tariff connect tariff

Total

total annual

Sewage

"full"

(HUF/m3)

(HUF/m3)

Sewage

revenue

Transformati connection

Volume

on rate

Households in T1

78%

95%

199

179

1.23

1.10

Public Inst. in T1

90%

90%

199

179

1.01

0.91

Households in T2

62%

90%

199

179

1.46

1.31

Households in T3

81%

95%

199

179

1.18

1.05

Other small users in T3

83%

90%

199

179

1.09

0.98

Households in T4

38%

69%

547

303

1.86

1.03

Households in T6

77%

80%

426

413

1.04

1.01

Although the connection between sewage collection efficiency and nutrient load reduction of the

Danube is more complex. Fostering connection without suitable third phase installments at the

treatment plants the higher rate of collection may even result the increase of load. Meanwhile the

precautionary principle rather suggests that collecting wastewater is more justifiable than the

prolonged use of leaking sink tanks.

2.4 The Cost Burden

The table below shows the changes of households' cost burden based on different scenarios. It reflects

that the less advantageous small facilities cost increase substantially as the capital intensity of the sites

grow. The comparison is based on the average household net income of the region. If the lower

income groups are considered, water and wastewater costs can have an even higher share. (The lowest

income deciles is 50%, the lowest quintile 62% and the second quintile 80% of the average income).

Moreover the distribution of income is unequal, it tends to be higher in urban areas.

Table 6

The Allocated Cost Burden of Households Compared to the Net Household

Income of the Region in 2001

Households

Current Operation Medium run with Long run scenario Long run scenario

Costs

cost recovery

with "borrow

with expansion and

policy"

environmental

upgrade, borrow

policy

T1 1.7%

2.1%

2.7%

2.9%

T2 1.6%

2.1%

2.7%

2.9%

T3 1.5%

1.8%

2.4%

2.6%

T4 1.4%

2.7%

6.5%

7.2%

T6 2.9%

3.0%

7.4%

8.0%

Households average incomes: KSH, 2001

18

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

2.5 The Distribution of Cost Burden Equity

As a result of the institutional changes of the last decade, the previously existing structure of service

provision was split, and one provider was replaced with several providers. This process was led by the

strong need for low cost areas to gain short term benefits from their geographical or system

advantages. This process has left other areas worse off. The central government answered this problem

by developing a subsidy scheme, which aims to subsidize the households that face the highest cost.

From the government's point of view it is reasonable to prevent the less capable rural population from

facing the exaggerated effect of the price changes. This policy tries to avoid shifting the

(environmental and health) cost to the more exposed segment of the population through the increase of

water use from lower quality local wells. But the current practice gives no incentives to municipalities

for regional co-operation and for finding less costly solutions to their common problems (in sight of

WFD for example). The present situation results in questionable differences between villages in cost

burdens in case of a basic service, as the differences can be random and are not based on the villages

own previous decisions or geographical patterns.

The investigated systems make it possible to determine the effect of further assignment of actual costs

to the users. The wastewater systems are separate local networks where differences in ownership have

resulted in different charges as well. The water system is a single network although there is a

possibility for a virtual separation of the system into smaller systems. The system could be divided by

the three water extraction points into sub districts if we suppose that the production of the wells is

constant in time and that they service only the nearby villages, at levels up to their production

volumes5.

Who finances whom?

The tariff scheme recently defined by the Ministry is quite simple. It defines one-component, flat

tariffs for drinking water provision and for the sewage service as well. There are no different tariff

measures for households and public institutions. This tariff scheme is valid throughout the district for

drinking water provision, and for the sewage systems run by the municipalities which are state owned

(T1, T2, T3), but not for other municipality sewage systems. The municipalities set their own sewage

prices in accordance with the concession contracts they have. Some of them differentiate between

households and other users, other apply a uniform tariff, but all of them have per cubic meter prices

more than twice as high as the uniform price of the state owned system.

The baseline scenarios show that the balance of costs and revenues for drinking water supply shows a

surplus, while sewage provision costs exceed revenues.

The cost allocation models reveal that the uniform tariff results in cross-subsidisation of households at

the expense of industry. The small villages benefit more from the current tariff structure than the cities

of T1, T2 and T3, in spite of the more cost based prices of the sewage service (where, due to the

municipal ownership the tariffs actually are two-three times higher). So the small settlements benefit

more from the uniform drinking water tariffs than they "lose" due to the unequal cross subsidisation of

sewage provision.

5This division results in mixed supply only in case of two municipalities.

Gábor Ungvári, MAKK, Hungary

A Case Study of Municipal Water System Management and the Impacts of Tariff and Effluent Charges: EDV, Hungary

19

Table 7

Rate of Total Revenues (Paid) per Total Costs (Allocated) by Consumer

Groups for Both Services Together

Current situation

Total Revenue / Total Cost ratio

Households in T1

1.09

Public Institutions in T1

1.06

Industry A in T1

1.16

Industry B in T1

1.36

Households in T2

0.91

Households in T3

1.05

Industry C in T3

1.49

Other small users in T3

1.05

Households in T4

0.83

Other users in T4

0.87

Households in T6

0.86

Households in T7

0.99

Other small users in T7

0.99

Purchasing water to T5

0.64

Purchasing water to T8

0.62

T7, T5, T8 only water provision.

The cost recovery scenario that I run to analyse the current situation supports this hypothesis. The

uniform cost recovery price is 8 HUF lower than the actual water tariffs, meanwhile the uniform

sewage tariff of T1, T2, T3 and the industry is 76 HUF higher than the actual tariff.

The revenue / cost ratios show that when considering both services, all the household groups are more

or less in balance, with the costs they are responsible for being roughly equal to the tariffs they pay for

the service, only the industry is worse off.

2.6 The Potential in Tariff Structure Reform

The allocation of costs (to territories T1-T7) revealed that the further reflection of real costs can result

in efficiency gains on network level. To show the effect I compare the shift from a one-component

tariff to a two-component tariff, both with Cost Recovery (the latter one includes marginal cost

pricing, MCP) in case of drinking water provision.

20

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

MCP pricing implicates two-component tariffs. The characteristics of the D, MC an AC curves imply

that the tariff contains a constant element that results in a relatively high burden compared to the

tariff's variable element. The question is whether the MCP pricing in case of infrastructure with big

spare capacity can result in gains that originate from higher levels of consumption6. The table shows

that overall, the proportional change in volume of water exceeds the proportional change of the sum it

costs to the consumers, making the average costs of water lower. That results in a 9% gain. But it is

still not a widely accepted technique due to the conflicts such a tariff change would generate on local

political fields.

The identification of cost elements is a technical problem, meanwhile introducing new cost-sharing

rules is a political one. The result of stricter allocation of costs borne by consumer groups reflects in

tariff differences. One of the arguments against this (two-component, MCP) tariff structure is that

definite customer groups (located in high cost areas or with low level of consumption) will be worse

off. This outcome emerges if the total price these groups pay for their consumption is lower than the

costs delegated to the fixed tariff element in the new tariff regime. This leads them to a

disadvantageous situation that - in case of constrained purchasing ability - has no simple solution to

adjust their consumption. The price increase in low consumption areas can cause an unfortunate

positive feedback. Due to the low consumption the further decrease of consumption results in a

disproportionately large increase in average costs that force the prices even higher... etc. The other

element is a substitution effect: if the only rational response of the consumer to an increase in price

levels is to leave the system and base his consumption on the existing old wells.

Meanwhile, the cross-subsidisation of household consumption contradicts the overall interest of the

region as it puts costs on industry that other regions may not. The political cost of price increase is

high. So tariff structures have to incorporate definite social or local political considerations.

6 The external costs of water extraction are not within the scope of our research, and we are not in a position to judge if this

solution is in accordance with environmental considerations.

Gábor Ungvári, MAKK, Hungary

A Case Study of Municipal Water System Management and the Impacts of Tariff and Effluent Charges: EDV, Hungary

21

Table 8

Volume Change / Total Tariff Payment Change Ratio due to Shift from

Medium Run Cost Recovery Scenario to Medium Run Cost Recovery with

Marginal Cost Pricing

Drinking

water

Households in T1

1.44

Public Institutions in T1

1.51

Industry A in T1

1.09

Industry B in T1

1.09

Households in T2

1.02

Households in T3

1.21

Industry C in T3

1.12

Other small users in T3

1.26

Households in T4

0.84

Other users in T4

0.88

Households in T6

0.80

Households in T7

0.99

Other small users in T7

1.04

Purchasing water to T5

0.65

Purchasing water to T8

1.03

Total 1.09

Drinking Water Cost Clusters: The costs are allocated by territory and inside a given territory the division of costs are based

on the used amount.

The table shows that T4, T5 and T6 would be worse off with this tariff change, these are the villages

that are among mountains, or at the far end of the network. Usually in village areas the average income

is lower.

2.7 Sewerage Substitutions or Emission Tax

A widespread problem of sewerage development is the low connection rate of households to the

existing networks. This feature has an environmental aspect as well, because leakage is a "built-in"

function of these sewerage substitution tanks. The waterworks offer free connection to the sewerage

network, but this has not resulted in an increase in the number of households connected.

How much would the connected user save if all the technically feasible households were connected?

The calculation is based on the above discussed Medium Run scenario with MCP. Except for T5, the

sewerage networks cover the area of the water supply network. It means that the lower number of

sewerage connection indicates the unwillingness of the population to use the service. These

households cause losses to their fellow citizens as the per capita fixed costs are higher for the ones

who co-operate, and they cause environmental damages as well. The remediation or the purification of

the polluted water imposes extra costs on the community. The low sewage water / consumed water

quantity rates of communities show the potential in increased use of the sewerage network.

22

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

A local environmental load fee imposed on the non-connected households can provide an incentive to

co-operate. The possible measures of this fee can be based on the MCP pricing method as this method

calculates by dividing fix and variable costs and gives an efficient quantity / tariff set.

The distribution of the investment cost among all households (connection charge) will bring the

previously non-connected households to a point where the costs they incur and the costs they are

responsible for are balanced (in the medium run). If the local environmental load fee consisted of the

per household fixed costs and the variable cost of an average household's consumption, then it would

be indifferent to the non-connected user if he was connected to the network or not. In fact, if users also

incur some cost of illegal disposal (e.g. maintenance of the septic tank or payment for transport of the

septics) then non-connected users would have an incentive to connect. The average fixed cost per

household in the district is 25,500 HUF (minimum 10,300 HUF, maximum 62,300 HUF) the fine

where the user charges cover the costs (adding the average consumption) is 28,300 HUF annually.

Introduction of such a charge may result in a 20 percent increase in the total collected sewage water

quantity (in case of currently under utilised systems).

Gábor Ungvári, MAKK, Hungary

A Case Study of Municipal Water System Management and the Impacts of Tariff and Effluent Charges: EDV, Hungary

23

3 Policy Recommendations

3.1 Local Decision on Financial Policy, Responsibility of Inter-

Generational Burden Allocation

Experience:

Lacking financial strategies to obtain own sources for investments in the medium and long run.

Recommendations:

1. Regulatory frame in order to oblige owners to start accumulate funds for future investments

2. Provide information to owner municipalities about possibilities of financial markets to better

represent the interest of present and future generations

3.2 Grant / Subsidy Allocation

Experience: misallocation of financial sources of sewerage investments

Recommendation: Tighter supervision by regulators pe.: State Audit Office

3.3 Equity and Complexity

Experience:

1. Efficiency gains on network level makes some user-groups worse off especially ones with small

consumption and less ability to adjust their consumption

2. Worse off groups may leave the system and apply illegal solution that impose extra charges and

costs to the communities

Recommendations:

1. Reconsider the conditions of current subsidy scheme of villages with extra high tariff

2. Tariff changes for efficiency gains have to be issued together in package with local initiatives

that targeted more sustainable environmental resource use of the district.

3. Create guidelines with official backing on proportional allocation of costs between different

consumer groups. These guidelines should provide information on how to match policy goals (express

local values) with suitable rules of financing the operation, in order

ˇ to facilitate self-reorganisation of the network for efficiency gains, or

ˇ to create alternative ways to exit existing technical solutions of the networks on their edge. In form

of: applying new small scale ecology driven solutions for small settlements, adjusting land-use

patterns for safer resource use and harness ecological services of abundant local access to land (pe:

Target oriented use of new financing possibilities of EU)

Document Outline