September 2004

ASSESSMENT AND DEVELOPMENT OF

MUNICIPAL WATER AND WASTEWATER

TARIFFS AND EFFLUENT CHARGES IN

THE DANUBE RIVER BASIN.

Volume 2: Country-Specific Issues and

Proposed Tariff and Charge Reforms:

Bulgaria National Profile

AUTHORS

Dr. Galia Bardarska / Institute of Water Problems at the Bulgarian Academy of

Sciences

TARIFFS AND CHARGES VOLUME 2

PREFACE

The Danube Regional Project (DRP) consists of several components and numerous

activities, one of which was "Assessment and Development of Municipal Water and

Wastewater Tariffs and Effluent Charges in the Danube River Basin" (A grouping of

activities 1.6 and 1.7 of Project Component 1). This work often took the shorthand

name "Tariffs and Effluent Charges Project" and Phase I of this work was undertaken

by a team of country, regional, and international consultants. Phase I of the

UNDP/GEF DRP ended in mid-2004 and many of the results of Phase I the Tariffs and

Effluent Charges Project are reported in two volumes.

Volume 1 is entitled An Overview of Tariff and Effluent Charge Reform Issues and

Proposals. Volume 1 builds on all other project outputs. It reviews the methodology

and tools developed and applied by the Project team; introduces some of the

economic theory and international experience germane to design and performance of

tariffs and charges; describes general conditions, tariff regimes, and effluent

charges currently applicable to municipal water and wastewater systems in the

region; and describes and develops in a structured way a initial series of tariff,

effluent charge and related institutional reform proposals.

Volume 2 is entitled Country-Specific Issues and Proposed Tariff and Charge

Reforms. It consists of country reports for each of the seven countries examined

most extensively by our project. Each country report, in turn, consists of three

documents: a case study, a national profile, and a brief introduction and summary

document. The principle author(s) of the seven country reports were the country

consultants of the Project Team.

The authors of the Volume 2 components prepared these documents in 2003 and

early 2004. The documents are as up to date as the authors could make them,

usually including some discussion of anticipated changes or legislation under

development. Still, the reader should be advised that an extended review process

may have meant that new data are now available and some of the institutional detail

pertaining to a specific country or case study community may now be out of date.

All documents in electronic version Volume 1 and Volume 2 - may be read or

printed from the DRP web site (www.undp-drp.org), from the page Activities /

Policies / Tariffs and Charges / Final Reports Phase 1.

TARIFFS AND CHARGES VOLUME 2

We want to thank the authors of these country-specific documents for their

professional care and personal devotion to the Tariffs and Effluent Charges Project.

It has been a pleasure to work with, and learn from, them throughout the course of

the Project.

One purpose of the Tariffs and Effluent Charges Project was to promote a structured

discussion that would encourage further consideration, testing, and adoption of

various tariff and effluent charge reform proposals. As leaders and coordinators of

the Project, the interested reader is welcome to contact either of us with questions

or suggestions regarding the discussion and proposals included in either volume of

the Project reports. We will forward questions or issues better addressed by the

authors of these country-specific documents directly to them.

Glenn Morris: glennmorris@bellsouth.net

Andrįs Kis: kis.andras@makk.zpok.hu

TARIFFS AND CHARGES VOLUME 2

National Profile of Municipal Water and Wastewater Management in Bulgaria

3

Table of Content

Abbreviations

1. Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 7

1.1. Purpose of the National Profile.................................................................................................... 7

1.2. Overview...................................................................................................................................... 7

1.3. Overview of the Origins and Status of the Municipal Water and Wastewater Industry ............ 10

1.4. Future Directions ....................................................................................................................... 11

2. Legal and Institutional Setting .......................................................................................................... 13

2.1. National Laws and Regulations Governing Provision of Municipal Water and Wastewater

Service............................................................................................................................................... 13

2.2. Management Units ..................................................................................................................... 20

2.3. Service Users ............................................................................................................................. 22

2.4. Regulatory Units ........................................................................................................................ 22

3. Production Quantity and Quality....................................................................................................... 29

3.1. Water Production, Distribution and Consumption..................................................................... 29

3.2. Wastewater Production, Collection and Discharge.................................................................... 32

4. Economic Data .................................................................................................................................. 38

4.1. Tariffs......................................................................................................................................... 38

4.2. Sales ........................................................................................................................................... 39

4.3. Costs and Purchased Inputs........................................................................................................ 40

4.4. Grants, Subsidies and Transfers................................................................................................. 44

5. Infrastructure of Municipal Water and Wastewater Services............................................................ 47

5.1. Production and Processing of Municipal Water......................................................................... 47

5.2. Collection, Processing and Discharge of Municipal Wastewater .............................................. 51

6. Management Units ............................................................................................................................ 53

6.1. Types and Numbers of Management Units................................................................................ 53

6.2. Financial Conditions of the MUs ............................................................................................... 54

7. Regulatory Units ............................................................................................................................... 57

7.1. National, Basin and Local Planning and Permitting .................................................................. 57

7.2. Economic Instruments and Regulations..................................................................................... 58

7.3. Environmental Regulations and Restrictions ............................................................................. 59

8. Service Users..................................................................................................................................... 61

8.1. Water System Customers ........................................................................................................... 61

8.2. Self-Service Users...................................................................................................................... 61

9. Reform Proposals connected to Tariffs and Charges ........................................................................ 62

9.1. State Reform Proposals.............................................................................................................. 62

9.2. Reform Proposals....................................................................................................................... 64

References ............................................................................................................................................. 67

Annex 1: Objectives of The Strategy and Implementation Measures ................................................... 69

Annex 2 Institutional Organization of the Water Supply and Sewerage Sector.................................. 70

Annex 3: Water Tariffs of Water Supply&Sewerage Companies in 2003............................................ 71

Annex 4: Matrix of the Water Supply&Sewerage Problems in Bulgaria.............................................. 75

Annex 5: Water Supply&Sewerage Action Plan for the period 2003 2015 in Bulgaria .................... 77

4

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

Abbreviations

BGN

Local currency: Bulgarian leva after denomination since 1999

BOD5

Biological Oxygen Demand after 5 days

BOT

Build, Operate, Transfer

Budget

Organizations

COD

Chemical Oxygen Demand

CA Commercial

Act

CoM

Council of Ministers

dka

Dekar or an area of 0.1 ha

EBRD

European Bank for Reconstruction and Development

EIB

European Investment Bank

EMEPA

Enterprise for Management of Environmental Protection Activities

EWSRC

Energy and Water State Regulatory Commission

GDP

Gross Domestic Product

IBRD

International Bank for Reconstruction and Development

ISPA

Instrument for Structural Policies for Pre-Accession

IWWTP

Industrial Wastewater Treatment Plant

LTPSMC

Law for Transformation and Privatization of State and Municipal Companies

LSGLAA

Local Self-government and Local Administration Act

MAF

Ministry of Agriculture and Forests

MoEW

Ministry of Environment and Water

MoH

Ministry of Health

MoRDPW

Ministry of Regional Development and Public Works

MU Management

Unit

NEPF

National Environmental Protection Fund

NSI

National Statistical Institute

NRW

Non Revenue Water

O&M

Operation and Maintenance

USD US

dollars

UWWTP

Urban Wastewater Treatment Plant

PE Population

Equivalent

PWTP

Potable Water Treatment Plant

SCWC

Supreme Consultative Water Council

SS Suspended

Solids

VAT

Value Added Tax

Dr. Galia Bardarska Institute of Water Problems at the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences

National Profile of Municipal Water and Wastewater Management in Bulgaria

5

WB World

Bank

WSSC

Water Supply and Sewerage Company

WWTP

Wastewater Treatment Plant

Exchange Rates

No.

1999

2000

2001

2002

1.

GDP:

1.1. in BGN

2898

3274

3754

4108

1.2. in USD

1577

1542

1718

1978

2.

Exchange rate: BGN for 1 USD

1.838

2.124

2.185

2.077

3.

Exchange rate: BGN for 1 Euro

1.95583

1.95583

1.95583

1.95583

Since July 1, 1997, Bulgaria is under a Currency Board Regime and the currency stabilized around the 1800 leva

per USD till 1999 when the lev was redenominated (three zeros were dropped).

6

GDP increase,%

Inflation, %

d

5

Annual incomes increase, %

an

P

4

D

c

r

e

a

s

e

, %

G

d

s

i

n

3

,

an

o

n

c

o

me

2

ati

i

n

fl

al

u

I

n

n 1

an

0

Year

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

Inflation, and GDP and annual incomes increase

6

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

Dr. Galia Bardarska Institute of Water Problems at the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences

National Profile of Municipal Water and Wastewater Management in Bulgaria

7

1. Introduction

1.1. Purpose of the National Profile

This report is a compilation of information and data that describe the institutions and conditions that

shape and characterize the provision of drinking water and wastewater service in Bulgaria. The

purpose of this compilation is to provide background and inspiration for proposals to reform both the

current system of water supply and wastewater tariffs and effluent charges and proposals to adjust or

modify the legal and regulatory system within which these tariffs and effluent charges function in

Bulgaria. The aim of the reform proposals is to improve the water supply and sewerage management

in Bulgaria generally, including protection of water resources from nutrient loading and toxic

substances originating from municipal wastewater systems.1

For most of Bulgaria the operation and management of local water and wastewater service is carried

out by Water Supply and Sewerage Companies (WSSCs). The provision of water supply and sewerage

services, associated investment planning, and implementation of those plans are their obligation

The trends in the organization of the water sector reflected the same divergent pressures experienced

by the rest of Bulgarian society. For the last 50 years, the State invested in building water services. 2

Social developments since 1989 can be seen as a process of devolution both in the transfer of power

from national to local (municipal) government, and, in reduction of State support for, and influence

on, local budgets.

1.2. Overview

The Republic of Bulgaria is situated in the northeastern part of the Balkan Peninsula between latitudes

41014' and 44013' North and longitudes 22021' and 28036' East. Its longitudinal extent defines the

climate of the country as a transitional between the typical oceanic climate of Western Europe and the

typical continental climate of the Eurasian land mass. Droughts are a characteristic feature of

Bulgaria's climate. Of highly varying duration and frequency, they strongly affect water run off, as

well the population's way of life and activities (Raev at al., 2003).

The total area of Bulgaria is 110993.6 km2 (land area 110630.9 km2, frontier river and sea islands

areas 101.3 km2 and territorial waters of frontiers rivers 261.4 km2). Administratively, the country

is divided into 6 planning regions, 28 districts and 262 municipalities.

1 A municipal water system includes those regional water systems whose service area includes multiple

municipalities and often also served industrial and commercial customers in that region. As discussed below, the

larger, regionally oriented systems are particularly prominent in Bulgaria.

8

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

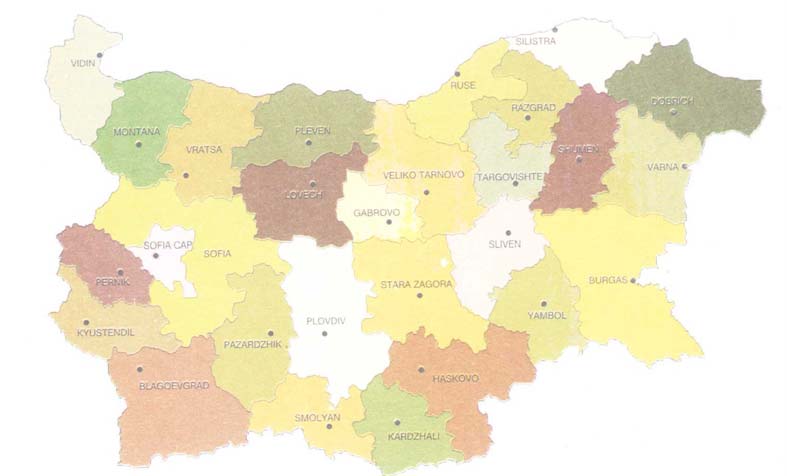

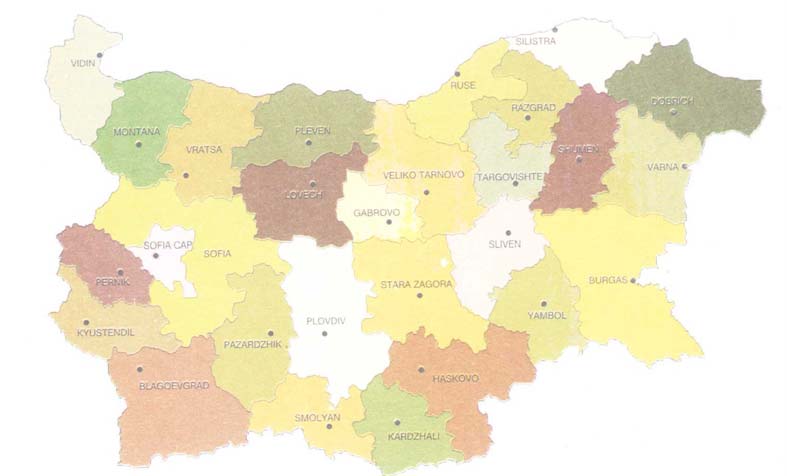

Figure 1.

Administrative Territorial Division of the Republic of Bulgaria 28 Districts

(North West region: district of Varna,Vratsza, Montana; North Central region: district of Veliko

Tarnovo, Gabrovo, Lovech, Pleven, Ruse; North-East Region: district of Varna, Dobrich, Razgrad,

Silistra, Targovishte, Shumen; South-East region: district of Burgas, Sliven, Yambol; South Central

region: district of Kardzali, Pazardzhik, Plovdiv, Smolyan, Stara Zagora, Haskovo; South-West

region: district of Blagoevgrad, Kyustendil, Pernik, Sofia and Sofia capital).

The population's decrease was 12.3% for the period 1985-2002 and was due mostly to emigration of

young people. Most of the population is concentrated in urban areas (64.8% in 1985 and 69.7% in

2002). The average density of the population decreased from 80.6 to 70.7 persons/km2 for the same

period of time.

Table 1. Population at the End of the Year (December 31)

No. Indices/year 1985 1992 2000 2001 2002

1. Total

population, 8948.6 8487.3 8149.5 7891.1 7845.5

thousands,

of which:

1.1.

Urban

5799.9 5704.5 5576.9 5473.0 5469.6

1.2.

Rural

3148.7 2782.7 2572.6 2418.1 2375.9

2.

Density per km2 80.6 76.5 73.4 71.1 70.7

Source: NSI

The population's forecast is for continued decline: from 7,785,091 inhabitants in 2003 to 7,323,708

inhabitants in 2014 e.g. 6% decrease of population (MoEW, 2003).

Dr. Galia Bardarska Institute of Water Problems at the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences

National Profile of Municipal Water and Wastewater Management in Bulgaria

9

Pop 7900

ulati 7800

on, 7700

1000 7600

7500

7400

7300

7200

7100

7000

2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014

Year

Figure 2.

Population Forecast for Bulgaria (MoEW, 2003).

The most urbanized parts of the country are: Sofia, with 1,192,031 inhabitants; Plovdiv, 713,060

inhabitants; and Varna 459,931 inhabitants (2002). Unemployment was 16.8% in 2002 and ranged

from 11.8% in the South-West region to 22.8% in the North West region.

According to art. 152, item 1 of the Water Act, the territory of Bulgaria is divided into four river

basins: Danube River Basin, Black Sea River Basin, West Aegean River Basin and East Aegean River

Basin. The Danube River Basin has its administrative centre in Pleven and covers the water catchment

areas of the rivers Iskar, Erma, Nishava, Ogosta and; to the west of the Ogosta river, Vit, Osam,

Yantra and Roussenski Lom, and the territory west of the groundwater watershed of the malm aquifer.

The Danube River Basin covers about 43% of the country and most of northern Bulgaria. Bulgaria

ratified the Convention on the Cooperation for the Protection and Sustainable Use of the Danube River

and implemented it on April 6, 1999.

Bulgaria is a formerly socialist country striving to enter the EU. It has experienced macroeconomic

stability and positive growth rates since a major economic downturn in 1996 led to the fall of the

socialist government. Bulgaria has already adopted most of the basic regulations that are meant to

ensure compliance with EU environmental directives.

10

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

1.3. Overview of the Origins and Status of the Municipal Water and

Wastewater Industry

The national level water management is exclusively the right of the Council of Ministers, performed

by the Ministry of Environment and Water (MoEW). The basin level management within one or

several catchment areas is done by Basin Directorates for River Management, which are bodies to the

above-mentioned Ministry and Basin Councils. The Basin Council is a state public consultative

commission for supporting the activities of the Basin Directorate. The Basin Council includes

representatives of the state administration, the municipal administration, the water users and the

environmental organizations within the range of the basin as well as representatives of the scientific

organizations connected with the water issues. For their activity the members of the Basin Council do

not receive remuneration.

The Supreme Consultative Water Council (SCWC) provides expert consultation to the Ministry of

Environment and Water. It was established on the basis of a Regulation issued by the MoEW. It has

representatives of the Ministry of Environment and Water; Ministry of Regional Development and

Public Works; Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry; Ministry of Industry, Ministry of Transport,

Ministry of Health; Ministry of Finance; Civil Defense; Ministry of Power Engineering and Energy

Resources; many institutes of the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, municipalities, and NGOs directly

related to waters.

State responsibilities related to the operation, construction, reconstruction and modernization of water

systems and facilities owned or partially-owned by the state are presently allocated to Ministries of the

National Government as follows:

1. The Ministry of Regional Development and Public Works (MoRDPW) water supply and

sewerage systems and facilities of the settlements, protection of the population from the water harmful

impact within settlements;

2. The Ministry of Agriculture and Forests (MAF) irrigation systems and facilities; protection of the

population from the water harmful impact beyond the settlement boundaries;

3. The Ministry of Energy and Energy Resources water energy systems;

4. The Ministry of Environment and Water (beside the above mentioned functions) water abstraction

facilities for mineral water, public state property.

For municipally-owned water and wastewater systems the operation, construction, reconstruction and

modernization of the water supply and sewerage systems is the responsibility of the municipal mayor.

There are currently 29 Regional WSSCs responsible for providing most water and sanitation services

throughout Bulgaria. The State exercises its prerogatives in the state-owned WSSCs according to a

Regulation adopted by Decree of the CoM No 7/1994 and amended several times since then.

According to this Regulation, the rights of the State as owner of a companies that is either wholly

state-owned or where the State has a share are exercised by the Minister responsible for the economic

sector in which the company is active.

The WSSCs have the status of Commercial Companies under the Commercial Act (CA). The

prerogatives of the municipality as owner of WSSCs are exercised under the Local Self-government

and Local Administration Act (LSGLAA). According to Art.21, p.9 of the LSGLAA, the Municipal

Council takes decisions for the creation, transformation and cessation of commercial companies with

municipal participation. The Municipal Council also nominates the representatives of the municipality

for a place on the governing bodies (Boards of Directors) of these companies. The Boards of Directors

of the WSSCs have the power to decide on choices of management or privatization for their

companies. In the Limited Companies, the municipalities are shareholders and have a vote through the

Boards of Directors in proportion to the percentage (%) of their ownership (according to the

Commercial Law).

Dr. Galia Bardarska Institute of Water Problems at the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences

National Profile of Municipal Water and Wastewater Management in Bulgaria

11

In the case of companies that are wholly or majority state-owned, the decision to privatize would be

taken by the Minister of Regional Development and Public Works, following consultation with the

municipalities served by the water companies.

Most dams and surface water reserves are exclusive state property, but WSSCs can use them based on

a contract with the CoM. The water supply and wastewater services assets infrastructure are owned by

the WSSCs. Though different WSSCs may own different parts of local water networks. The WSSCs

may be privatized under the Law for Transformation and Privatization of State and Municipal

Companies (LTPSMC) only through concession, or contracts for lease, management, or `build,

operate, and transfer" (BOT).

1.4. Future Directions

Bulgaria aspires to join the EU and works to harmonize the EU water-related legislation. Bulgaria has

received international technical assistance to support the legislative and institutional reform related to

the water sector and is in the process of transforming this sector, including its organization and tariff

setting process. The future direction will be outlined in the new Water Act that will be proposed by the

MoEW at the end of 2004. It is envisaged that full ownership of the WSSCs will be transferred to the

municipalities and the WSSCs future will be determined by them. This includes possibly granting

concession contracts to run the WSSCs.

The Government of Bulgaria has often expressed its interest in the evaluation of private sector

participation (PSP) options in the operation, management and financing of their water supply and

wastewater services in order to:

- increase the cost-efficiency of operations and development of the cities' water supply and sewerage

systems and introduce current managerial and technical practices;

- reduce contingent liabilities for the municipal governments, by having the private sector contribute

capital (if applicable) and share risks and incentives;

- increase consumer satisfaction and willingness to pay through the provision of a higher quality, more

responsive service;

- better delineate the role of the municipalities as regulator and representative of the customer's

interests and separate the municipalities from the day-to-day management of the WS&WW

companies;

- make tariff decisions more transparent by introducing an arms-length relationship between the

regulator and management.

Under the World Bank (WB) Project "Water Loan" a new study was initiated to examine private

sector participation in the water sector in Bulgaria. The Dutch consulting firm ARCADIS prepared the

concession bidding documents for the WSSCs of Varna and Shumen and the pre-qualification for

prospective bidders was completed. The next steps would be solicitation of bids and selection of a

winning concessionaire. For the time being, however, MoRDPW has stopped the process because of

objections by some members of the tender committee. These members are the mayors of the affected

municipalities they are presently opposed to the award of a private concession.

The Management and Development Strategy for Water Supply and Sewerage Sector in the Republic of

Bulgaria, recently adopted by the Council of Ministers, aims to improve the management of the water

supply and sewerage sector and increase the quality of services (MoRDPW, Annex 1, p. 69 . ). This

strategy would:

- establish a new law on water supply and sewerage;

- introduce an integrated approach to private sector participation, taking into account public interest

and identifying preferred management models for private sector participation;

12

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

- application of a structured management approach, taking into account regional planning and ensuring

economies of scale;

- elaboration of a regulatory act for water pricing.

An Act for Regulation of the Water Supply and Sewerage Services has been drafted. According to the

Art.5 (1) of the act a new Energy and Water State Regulatory Commission (EWSRC) will be

responsible for the quality of water services and for the establishment and control of water tariffs

beginning January 1, 2005 (MoRDPW, Annex 2 p. 70). Under this draft, there are many aspects of a

WSSC's performance that would be regulated. Drinking water quality and discharge wastewater

quality, would continue to be regulated by the relevant Ministries (MoH and MoEW), with regular

consultation with the EWSRC.

In the official EC No. CONF 13/01 position of the Republic of Bulgaria the transition period for the

Directive 91/271/ is proposed as follows as:

· to 01.01.2011 - construction of sewerage systems and WWTPs for settlements with more than

10000 PE;

· to 01.01.2015 - construction of sewerage systems and WWTPs for settlements with 2000-10000

PE.

Dr. Galia Bardarska Institute of Water Problems at the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences

National Profile of Municipal Water and Wastewater Management in Bulgaria

13

2. Legal and Institutional Setting

2.1. National Laws and Regulations Governing Provision of Municipal

Water and Wastewater Service

2.1.1. Common Provisions

Legislation, relevant to levels of services and required to be respected includes the following:

1. Water Act (SG 67/1999, in force since 28.01.2000, as amended in 2000 and 2003);

2. Environment Protection Act (SG 91/25.09.2002);

3. CoM Decree No 169/2003 for Regulation Determining and Impose the Penalties for Pollution

over the Permission Norms;

4. National Standardization Act (SG No. 55/1999 in force since 1999);

5. Act for Limitation of Harmful Impact of Waste on the Environment (SGNo 86/1987);

6. Norms for Designing of Water Supply Systems since 1987;

7. Technical &Building Norms to Control Outbreaks of Fire (SG No33/1994);

8. Regulation No. 11 for the Design and Use Requirements of Waste Treatment Facilities (SG

No. 152/1998);

9. Regulation No. 1 on the Study, Use and Protection of Groundwater (SG No. 57/2000);

10. Regulation No. 2 of Protection of Water against Pollution Caused by Nitrates from

Agriculture Sources (SG No. 87/2000);

11. Regulation No. 3 on Sanitary Protection Zones (SG No. 88/2000);

12. Regulation No. 4 on the Quality of Water for Fish and Shellfish (SG No. 88/2000);

13. Regulation No. 5 on the Operation of Water Monitoring System (SG No. 95/2000);

14. Regulation No. 6 on the Emission Limit of Substances in Wastewater Discharged into Water

Bodies (SG No. 97/2000);

15. Regulation No. 7 on Wastewaters Discharged into Sewer Systems (SG No. 98/2000);

16. Regulation No. 8 on the Quality of Coastal Sea Waters (SG No. 10/2001);

17. Regulation No. 9 on the Quality of Water intended for Drinking and Domestic Purposes (SG

No. 30/2001 and on the Use of Water Supply and Wastewater Systems, 16.03./2002;

18. Regulation No. 10 on Discharge Permits;

19. National Standards 17.13.02-82; 17.13.03-83; 17.13.04-84; 17.13.05-85; 17.13.06-85;

17.13.07-85; 17.13.08-86, obligatory one year after the enforcement of the National

Standardization Act.

These acts and regulations are listed above in rough order of importance. All of them are in accord

with the EU directives.

The Water Act, approved in 1999 by the 38th National Assembly, has undergone numerous

amendments and addenda in the period 2000-2001. An Amendment of and Addendum to the Water

Act was passed by the National Assembly in 2002. Analyses of 1999 legislation and its application

have shown some problems:

In general, no distinction is made between water as a common national and indivisible natural

resource and the use of water for water economic activities and provision of water services;

The rules of protection of waters and water ecosystems are not explicitly defined. Many of the

imperative regulations in the by-laws on water protection in actual fact develop further the

Water Act and that is inadmissible;

14

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

Three years after the enforcement of the Water Act, the provisions regulating the depreciation

of the capital stock and the requirements for submission of information by other institutions

and municipalities for the purposes of setting up an information system (data base) on water

management have not been fulfilled;

The issues related to the ownership rights and joint ownership rights on water infrastructure

and facilities are not adequately regulated;

The basic public relations with respect to the provision of water supply and sewerage as a

public service in human settlements and settlement clusters are not regulated;

The criteria for use of surface waters and water facilities are not adequately regulated and their

linking to public interest remains to be a matter of wishful nature;

After the approval of the 1999 Water Act other laws have been approved, which:

(i)

give new definition of notions, which are an integral part of the Water Act, and that in

actual fact changes the sense of the notion;

(ii)

settle in a new way issues of the ownership rights, thus blocking the application of

certain dispositions of the Water Act related to water management;

(iii)

settle in a different way the water economy activities, which are in principle an

integral part of the subject matter of the Water Act.

The recent passage of the EU Water Framework Directive (WFD) required still further harmonization

than was possible by The Amendment and Addendum to the 1999 Water Act. As noted above, the

Ministry of Environment and Water has drafted a new Water Act in 2004. It is expected that the new

legislation, including full transposition of the WFD into the national legislation, will be adopted by the

end of 2005.

The responsibility for the implementation of the WFD lies with the MoEW Water Directorate, and, for

the associated economic analysis, the MoEW Strategy, European Integration and International

Cooperation Directorate. The economic analysis, part of each WFD-mandated river basin management

plan, will most probably be performed by external consultants selected according to the procedures of

the Public Procurement Law. It is envisaged that the supporting information needed for the analysis

will be collected and managed by the Basin Directorates. These four directorates will also provide

guidance as to the source and availability of useful information. It still has to be decided how the data

provided by the directorates will be organized.

2.1.2. Service Area

The service area of WSSCs corresponds to the administrative regions in the country. As noted above,

there are 29 regional WSSCs set up in Bulgaria. 13 of these companies are 100% state owned, and 16

are jointly owned (51% by the state and 49% by the municipality). Besides these 29 WSSCs, there are

additional 20 municipal water companies serving only small areas and populations ( Table 2. ). These

20 municipal companies are not typical of Bulgaria. They were established due to the lack of

investments from the state (central budget). These municipalities used local financial resources to

provide basic infrastructure to their citizens.

Dr. Galia Bardarska Institute of Water Problems at the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences

National Profile of Municipal Water and Wastewater Management in Bulgaria

15

Table 2. Water Supply and Sewerage Companies with Different Ownership in Bulgaria

100% state ownership

51% state and 49% municipal

100% municipal ownership

1.

Blagoevgrad

Varna

Batak

2.

Burgas

Vratza

Belovo

3.

Vidin

Gabrovo

Berkovitsa

4.

Dobrich

Dimitrovgrad

Botevgrad

5.

Pazardjik

Isperih

Bratsigovo

6.

Pleven

Kardjali

Breznik

7.

Plovdiv

Kjustendil

Velingrad

8.

Razgrad

Lovech

Dupnitsa

9.

Smolyan

Montana

Kresna

10.

Sofia-district

Pernik

Kovachevtsi

11.

Stara Zagora

Russe

Kubrat

12.

Haskovo

Silistra

Panagyurishte

13.

Yambol

Sliven

Petrich

14.

Targovishte

Peshtera

15.

Shumen

Rakitovo

16.

Veliko Tarnovo

Sandanski

17.

Svishtov

18.

Sevlievo

19.

Sofia-city concession

20.

Strelcha

21.

Troyan

Source:MoRDPW

8 0 0 0 0 0

N u m

7 204

In h ab ita n ts s erv ed b y p u b lic w ater s u p p ly

7 0 0 0 0 0

b e r

1 6

o f

In h ab ita n ts c o n n ec ted to th e s ew erag e

4 611

6 0 0 0 0 0

in h a b

4 240

2 6

ita n ts

8 0

3 881

5 0 0 0 0 0

8 2

3 149

2 662

4 0 0 0 0 0

6 5

2 755

2 429

2 340

2 196

2 9

2 259

3 8

2 185

7 5

2 085

0 0

2 148

2 9

8 7

1 654

0 9

8 0

1 493

1 628

3 0 0 0 0 0

2 3

1 566

1 373

1 331

1 427

1 410

1 180

1 480

2 6

8 2

5 1

1 009

1 058

3 1

2 3

9 6

2 2

8 6

1 3

0 0

9 920

2 7

6 7

2 0 0 0 0 0

6 498

4 772

5

1

7

1 0 0 0 0 0

W S S C

B la g o

D im it

S o fia

S ta ra

0

G a b r

D o b r

T a rg

K a rd

K ju s t

P a za

P lo v d

H a s k

e v g ra

B u rg

V e lik

V ra tz

ro v g r

L o v e

P e rn i

P le v e

S ilis t

S m o l

Y a m

V a rn

V id i n

R a zg

o v o

Is p e r

M o n t

R u s s

-

S h u

ic h

S liv e

Z a g o

o v is h

ja li

e n d il

c h

rd jik

iv

ra d

o v o

d

a s

a

o

a

a d

ih

a n a

k

n

e

ra

n

y a n

b o l

d is tri

m e n

ra

te

c t

Figure 3.

Inhabitants Served by Water Supply & Sewerage Companies with State

Share

16

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

1400000

117

757

7

1200000

1094

410

1000000

Inh

abit

ants

serv

800000

ed

by

mun

Inhabitants served by public water supply

icip

Inhabitants connected to the sewerage

al

WS

600000

SC

400000

200000

650

500

517

412

414

2951

439

283

00

3500

3000

250

3870

3419

120

175

1652

2100

00

15

162

03

3600

50

2200

1400

0

310

43

700

0

0

7000

214

57

00

6

0

00

600

5

00 3000

66

01

9

4720

0

0

3000

00

0

0

0

0

0

Sofi

Bat

Belo

Ber

Bote

Veli

Kne

Kub

Pan

Petr

Pes

Svis

Rak

Stre

Dup

San

yska

ak

vo

kovi

vgra

ngr

itov

ja

rat

agy

ich

hter

htov

lcha

nits

dan

vod

tsa

d

ad

uris

a

a

o

ski

a

hte

Municipal WSSC

Figure 4.

Inhabitants Served by Municipal Water Supply& Sewerage Companies

In a singular example of privatization, in 1999 the foreign firm "International Water" signed a 25 year

concession for the water supply and sewerage services with the municipality of Sofia. In 2000

"International Water" and the municipality of Sofia registered a joint stock company, Sofiyska Voda

AD, for water supply and sewerage management.

2.1.3. Conditions of Service

The regional WSSCs are responsible for producing and distributing drinking water and receiving and

treatment of wastewater for all their private and public customers. Conditions of services provided by

WSSCs are specified and defined in the 1999 Water Act and its implementing Regulations. All

consumers shall be supplied with a minimum water pressure 2 bars in the towns and villages,

measured at customers` connection at the time of maximum daily and hourly peak demand. In the

areas with multi-dwelling houses, the minimum pressure shall not be less than 3.4 bars and maximum

water pressure shall not exceed 6 bars.

The WSSCs are responsible for maintaining the distribution network and provide connections at the

request from customers. Also, WSSCs are responsible to ensure inspection, repair, and/or replacement

of consumer meters. The proper functioning of water meters is ensured by establishing an action

program. As a result there is a very high percentage of connections to the drinking water supply

network (98%) and the very high percentage of customers connected to the network with meters (85%

to 90%). There is no "connection" charge. But the cost of monitoring a connection's conditions is

recovered by each WSSC (MoRDPW, 2004). The municipal street cleaners are responsible for

maintaining the municipality's storm sewers, but the WSSC is responsible for maintaining and

cleaning the link between the storm sewer and street's wastewater sewer.

When the user hinders the checking of the water meter the water tariff is based on the continuously

water consumption with water velocity 1.5 m/s (MoRDPW, 2004). In the rare cases when there is not

Dr. Galia Bardarska Institute of Water Problems at the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences

National Profile of Municipal Water and Wastewater Management in Bulgaria

17

possibility to install a water meter the water consumption is calculated on the basis if the number of

persons served by the connection. Here are some other "rules of thumb" for calculating monthly water

quantity (MoRDPW, 2004):

- 6 m3 water consumed per person in heated flat and 5 m3 for an unheated flat;

- 0.15 m3 water per m2 cultivated area;

- 0.1 m3 per m3 of offices, tourist house, villa etc.;

- 0.5 m3 per m3 of buildings during construction.

In drought periods the WSSC informs the regional administration that it is putting into operation water

restrictions to limit the quantity of the water consumed.

There are three tariff components: water supply, sewerage, and water treatment services. There

usually are two rate schedules in regard to these tariffs: one for households and one for non-household

customers. The WSSC has to announce a new water tariff in a popular newspaper for a three days

period (MoRDPW, 2004).

The standards of water services are similar across Bulgaria, with little, if any, variation locally or

regionally. These standards do not vary with a customers' ability to pay for service.

WSSCs are supposed to try to keep the required service levels and quality in order to comply with the

regulations. WSSCs are also supposed to establish tariffs for given time periods to reflect efficient

levels of operation, all with due regard to the affordability of the tariff.

Customers should receive a bill based on the metered consumption every month. If there is not

regular access to the meters during the year, for example in a villa area, the billing cycle may be

longer but should not be longer than a year.2

In multi-apartment buildings the meter reading is done one a month, and the payment is made on the

basis of the reported figures. The difference between the amounts registered on the main (block) water

meter and the sum of the individual apartment's meters is the value of water loss in the block of flats.

To recover all costs, this is divided among the apartments in proportion to the number of inhabitants of

the apartment and added to the amount of water registered on the meter.

For the purpose of reducing the amount of non-revenue water (NRW) produced by the WSSC, all

WSSCs have to establish teams to investigate the reasons for water losses. NRW arose due to physical

and administrative conditions including: illegal connections, bursts, non-metered water quantities, and

lack of pressure reduction valves in the lower zones. 3

There are also investigations into the water loss per km of water supply pipe above a certain diameter

(Dimitrov, Trichkov, 2001).

According to the 1999 Water Act the control of water sector is made by different ministries, basin

directorates and municipalities. The main assignments are as follows:

The mayor of the municipality shall control: the construction, maintenance and the proper operation of

the sewerage networks and of the installations for treatment of household wastewaters; the

construction, maintenance and operation of the water systems; the construction and the registration of

the wells for individual water use from the ground waters on the territory of the municipality.

The Minister of Health shall control: the quality of the water, designated for drinking-communal

needs; the quality of the mineral water, designated for drinking or used for prophylactic, healing and

hygienic purposes, including the bottled mineral waters in the retail trade network; the quality of the

water, designated for bathing.

The Minister of Regional Development and Public Works, the Minister of the Agriculture and Forests,

and the Minister of Power Engineering and Energy Resources shall control the state of the water

bodies, the water systems and installations in the scope of their competence.

2 Villas are, in this case, usually temporary summer residences in a country setting.

3 The definition for non-revenue water percentage is: (total volume distributed water-total volume billed

water)/total volume distributed water x 100 (%) per annum, or semi-annual period.

The total water loss percentage is defined as: (total volume of water loss during transport/ Total volume of

produced water in distribution system) x100 (%) per annum (NSI, 2004).

18

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

The Minister of Environment and Water issues: methodologies for control of the water resources;

preparation of the water balances of the water sources and the National Water Balance; distribution of

the waters from the dams and for use of the water resources; determining of the operational resources

of the ground waters.

The Ministry of Environment and Water shall control: the quantity and the emission status of the

waters; the observance of the requirements of the permit for water use when it is issued by the MoEW;

the observance of the conditions under the concession contracts for waters, which are exclusive state

property; the design parameters of the water installations and systems, elements of which are the

complex and important dams, the condition of their control and measuring devices, the condition of

the networks for quantitative and qualitative characteristics of the waters; the observation of the

prescribed regime for use of the waters of the complex and important dams.

The Director of the Basin Directorate shall: establish the boundaries of the waters and the water

systems which are public state property, together with the technical services cadastre services of the

municipalities; organize the preparation of the management plans for the respective basin; issue the

permits; realize the activity of the National Water Monitoring System at a basin level; keep and

maintain the water and water infrastructure cadastre and the registers of the issued permits; collect the

fees for the permits which he issues; control the observation of the conditions and the requirements of

the issued permits and of the conditions of the granted concessions; carry out supervision over the

control and measurement devices of the hydro-technical installations and the systems for monitoring

of their safety; carry out supervision over the state of the water systems and installations, issue

prescriptions and controls their observation; manage the waters which are exclusive state property and

were not granted as concession; manage the installations for ground waters, which are public state

property.

The Basin Directorates shall control: the condition and the flow capacity of the river beds and of the

discharging installations into the water recipients; the condition and the proper operation of:

a) the water intake installations, the installations for use of the surface and the ground waters

and the facilities for measuring the water quantities;

b) the treatment installations for wastewaters;

c) the sewerage systems;

d) the network for own monitoring of the waters;

e) the control and measuring devices of the hydro-technical installations, the tailings ponds,

the slag ponds, the solid waste deposits and the systems for control of their safety;

f) the implementation of the requirements of the issued permits;

g) the emission status of the waters in the water bodies;

h) the maintenance of the minimum admissible run-off in the rivers;

i) the pollution of the water recipients and the ground waters during emergency situations

and volley discharges; and

j) the wastewater treatment plants.

The Minister of Defense shall control the preparation of the emergency plans and the implementation

of their requirements.

2.1.4. Reporting Requirements

All State owned MSSCs, joint State/Municipal owned MSSCs, and Sofia City have the capacity to

provide regulatory data as, in most cases, the systems are already in place to provide data to the

MoRDPW and/or the World Bank. Annually, the regional (national or partly nationally owned)

WSSC managers report to the MoRDPW financial data including income, expenditure, cash flow, and

calculation of tariffs. Technical reports must be submitted that provide data on water produced, water

billed, water losses, wastewater quality, quantity of discharged wastewaters including charges and

penalties paid in respective year. There is a special department in the MRDPW dealing with state

owned utility companies (not only WSSCs) where these reports are submitting and checked. The

State, through MoRDPW, has majority ownership and could impose new reporting requirements on

Dr. Galia Bardarska Institute of Water Problems at the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences

National Profile of Municipal Water and Wastewater Management in Bulgaria

19

the MSSCs without resort to legislation. The public access to these annual WSSC reports is very

difficult.

The smaller, municipal companies, although making up over 40% of the total number of water

companies, only provide services to about 5% of the population served. They are not required to

supply the same information to the MoRDPW and therefore do not necessarily have in place the

systems of data gathering to provide this information.

Some data are available in a special publication "Environment", printed by National Statistical

Institute. The 2002 water data were published on January 30, 2004. All managers of WSSCs provide

the annual questionnaire of the National Statistical Institute with data on produced and consumed

water quantity, water quality, water tariffs etc. Information collected by the National Statistical

Institute does not differentiate between expenditure by the public sector, the private sector and

specialized producers according to the Eurostat definitions (NACE 90). Nor does it provide enough

information on foreign financial sources, for example, if the sources are loans or grants, etc. There is a

considerable discrepancy in the data published by the NSI, the Ministry of Environment and Water,

regarding foreign donors.

2.1.5. Self-Service of Water and Wastewater

Self service is allowed in accordance with the relevant Acts and Regulations, such as: Water Act,

Regulation No. 9 and the Territory Development Act. The self services include wells, septic tanks, and

public taps. Most of the industrial plants and/or factory utilize self-water supply, from surface or

groundwater sources, but for technological and process purposes only. If the quality meets the

requirements for drinking purpose, then the water could be used for that purpose.

Permission by the regional authorities of the Ministry of Health (Regional Hygienic Epidemically

Inspectorates) and regional authorities of the MoEW (Regional Inspectorate of Environment and

Water) is required in advance of any construction of a water or wastewater service installation.

Independent provision of water and wastewater service is widely used in the villas areas, villages, in

the areas with water rationing, and villages without sewerage systems that rely on septic tanks. The

water quality of self service systems should meet the standard requirements in accordance with the

Regulation No. 9 on the Quality of Water intended for Drinking and Domestic Purposes (SG No.

30/2001 and on the Use of Water Supply and Wastewater Systems, 16.03./2002. Households might

use water from their individual wells without any limitation.

Most of the water used by industry is self-supplied 5,098,693.103 m3 ( Table 3. ). The lower bound on

the quantity of self-supplied water is implied by the data for 2000, a drought year in Bulgaria. There

are no limitations on water quality when used for industrial process purposes, but there may be

quantity limits (see below).

Table 3. Water Used from Self-Supply, 1000 m3

No.

Water

used

1998 1999 2000 2001 2002

1.

Total 6,316,688 5,169,618 3,999,534 4,282,911

5,119,585

1.1.

Agriculture, hunting and forestry 28,033 22,588 18,722 10,332 8,176

(incl. fishing)

1.2.

Industry 6,269,079 5,125,240 3,963,853 4,257,629

5,098,693

1.3.

Domestic sector

19576 21,790 16,959 14,951 12,716

(other activities)

Source: NSI, 2004.

According to the Art. 43. (2) of the 1999 Water Act the owner or the user of an immovable property

has the right to gratuitous water use of the surface or groundwater or under the property in quantity not

20

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

more than 10 m3 per 24 hours. Apart from these cases, for the individual use of waters the user should

pay a water systems fees determined by the Council of Ministers. No fee is paid for water use for anti-

fire needs as well as for water use from surface waters out off the own property for irrigation of

individual farms with area up to 2 dka (0.2 ha) in quantity not bigger than 300 m3 monthly (Art. 194.

(2)). For industrial factories and plants there is a "water fee" for withdrawal quantity. The permission

is given from the MoEW in accordance with the technological needs of the user.

2.2. Management Units

Since 1989 much reorganization of the water supply and sewerage system has been undertaken:

- 1989 : the "Vodokanalproject" was changed by "Vodokanalinvest" (responsible for investment

functions) and "Vodokanalengineering" (for water supply and sewerage design). In this year the

right of municipalities to establish municipal firms for water supply and sewerage was approved

by the Council of the Ministers;

- 1991 : the Council of the Ministers stopped the establishment of municipal firms for water supply

and sewerage but "grandfathered" the existing municipal WSSCs;

- 1995: there were 29 state regional and 14 municipal WSSCs;

- 1995 : according to the signed Water Loan with World Bank the state should transfer 49% of their

shares to the municipalities that received investment financing based on the loan;

- 1995 1999 : 22 companies involved in the Water Loan of World Bank were scheduled for

transfer from state companies to state-municipal companies with 51% state shares and 49%

municipal shares. The allocation of the shares among municipalities was done according to

population. The first stage finished with establishment of 16 state-municipal companies. The aim

of this transition period is the penetration of the municipalities into the water management sector

and all management responsibilities to be taken by the municipalities before transferring of other

51% state shares to them in the near future;

- 1999 : the foreign firm International Water signed a 25-year concession for water supply and

sewerage services with the municipality of Sofia capital;

- 2000 : International Water and the municipality of Sofia registered the joint stock company

"Sofiyska Voda AD" for water supply and sewerage management in the city of Sofia;

- 2000-2001 : the Council of Ministers stopped the transfer of the water shares from the state to the

municipalities. The water management of three regional water supply and sewerage companies in

the towns of Veliko Tarnovo, Burgas and Sliven was transferred to private companies and water

associations;

- 2003 : the 2003 Amendment and Addendum to the Water Act suspended the contracts of Veliko

Tarnovo, Burgas and Sliven WSSCs because their activities had been nontransparent and deemed

contrary to the interests of consumers, the state and the municipalities. This unfavorable

privatization, made by former directors of these three WSSCs, showed the need for a transparent

privatization process.

The MoRDPW is responsible for the State owned WSSCs and acts as a majority shareholder in the

jointly owned WSSCs. It is the general beneficiary of international projects, funded by EU, WB etc.

and its main functions, according to the legislation, include: preparation and realization of the State

policy and conduct of State property in water supply & sewerage companies, overseeing the activities

of WSSCs and appointment of managers of state owned WSSCs, and assignment of concession

contracts.

The executive bodies in the MoRDPW are: the Trade Enterprises Directorate (where the managers

submit their reports) and Water Supply and Sewerage Department.

Finally, the MoRDPW oversees investment planning and implementation, as well as provision of

water and sanitation services. Under its umbrella are all 29 WSSCs, where the managers submit the

annual and semi-annual accounts and incomes and expenditure sheets and the balance of the entities.

Also here, the managers are obligated to announce and defend the new tariff proposals for the WSSC.

Dr. Galia Bardarska Institute of Water Problems at the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences

National Profile of Municipal Water and Wastewater Management in Bulgaria

21

The new tariffs need to be supported by calculations. Beginning in January 2005 a new water tariff

methodology is expected to be established by the new regulatory body, EWSRC.

The 16 Ltd WSSCs are directed by Boards of Directors, and the managers are appointed by these

Boards. The Minister of Regional Development and Public Works directly appoints the managers in

the 13-SPLtd WSSCs. Besides appointing a manager, the Board of Directors of the Ltds has the

power to appoint a controller, the owner's (minister's) representative, and an expert-accountant.

Through management contracts, the Boards of Directors and MoRDPW give a wide managerial

freedom to the 29 regional WSSCs` managers. The WSSC managers can define the internal structure

of their Companies, technical management, marketing and business development policy and financial

management (up to a certain delegated limit). These contracts define the obligations of the managers

vis a vis the MoRDPW: elaboration of a strategic development program, preparation of a program for

technical upgrading, with a secure financing plan, financial reporting, profit and profitability increases.

It is important to observe that in the management contracts there is a clause that sets manager

remuneration as a function of the reduction of water leakages in the service area of the WSSCs. This is

in accordance with their business plans and the World Bank requirements for the Sub-Lon

Agreement. If the managers don't succeed in implementing and/or completing the water leakages

reduction program, they will receive less salary. Such a provision also applies to the salaries of other

management staff.

For the whole-owned municipal WSSCs the managers are appointed by the Municipal Councils and

approved by the mayors. As noted above, they are not required to submit the annual/ semi-annual

reports to the ministry.

The manager is directly responsible for the financial-economic status of the entity; its prospective

running; the profit and profit abilities, receivables, or paying duties, personal salaries, the running and

future investments and construction and reconstructing policy, and so on. According to the manager's

order, the senior staff may organize and provide bids and conclude contracts for fulfillment of works,

supply of goods, consultant services, while properly observing the laws. The implemented project

should be technically feasible, financially affordable and economically viable. In addition to effective

leakage management, strategic planning and operational control of the water supply and distribution

network are used to measure the skills of management and staff of the WSSC.

The Administrative Units of WSSCs are: managers, senior engineers, chief accountant, departments'

chiefs, cashier, and as well as the chiefs of the regions (situated on the municipal territories, served by

that WSSC). All staff is appointed by the manager himself, in accordance with the Labor Code in

Bulgaria.

The World Bank Loan and WSSC Reorganization

In 1995 Bulgarian Government signed a Loan Agreement with the World Bank for USD 45 million

The Bulgarian public contributions was 30% (15% by the MoRDPW and 15% by the participated

WSSCs). The total amount of the investment pool was therefore USD 60 million. 21 WSSCs signed

sub-loans with the MoRDPW. The first condition for the loans was that they be restructured from

100% state-owned to 51% state owned and 49% municipal own WSSCs. Municipal ownership was to

be in proportion to the population served by the WSSC in each municipality. That is why 16 regional

WSSCs were restructured as Ltds, in accordance with the Trade Law.

The permission for this restructuring was given by the Council of Ministers. The WB Project was

successfully closed at the end of April 2003. The Implementation Competition Report (ICR) to the

WB Directors was completed.

In most of the cases the WSSCs are parts of physically integrated systems, encompassing all the

municipalities in the service area. The Operating Units within the MSSC are organized around specific

activities, such as: pumping stations (PS), distribution network, sewerage, WWTP, PWTP, incasso

system, NRW reduction program, illegal connections, water-meter reading, workshops (for calibration

and test of water meters, mechanical, electrical), elimination of bursts, public services, replacement of

depreciated pipes, water meters assembly and so on.

22

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

In accordance with the last amendment of the 1999 Water Act all government assets of the water

distribution and wastewater collection infrastructure with the exceptions of those that serve the

territory of more than one municipality will be municipal property. The state retains the right to most

of the water bodies and water supply and water and flood control infrastructure (1999 Water Act, esp.

Ch. 2).

At the conclusion of a concession contract for waters, water systems, water infrastructure and facilities

- municipal ownership, the municipal council determines:

1. the places for common use of waters and water bodies;

2. the existing rights for use of the waters in the water reservoir.

2.3. Service Users

2.3.1. Classification of Users

The classification of water users varies from institution to institution. According to the National

Statistical Institute, the classification is as follows as:

- agriculture (incl. irrigation), hunting, forestry (incl. fishing);

- industry (mining and quarrying; manufacturing industry- food processing industry, textiles, paper

and paper production, chemicals, refined petroleum, basic metals, transport equipment; electricity,

gas, steam and hot water supply incl. cooling, construction);

- domestic sector (households, other activities).

The Ministry of Regional Development and Public Works, classifies service users as:

- households;

- budgetary organizations,

- public sector.

According to the draft Act for Regulation of Water Supply and Sewerage Services, the users are:

- all legal and physical persons which are owners of property or flats supplied with water;

- enterprises, using the water from the public water supply network;

- enterprises which treat the water and use their own water supply system to distribute not drinkable

water.

All special legal considerations by user are described in Regulation No9/ / 16.03.2002, Territory

Development Act (SG1/2001and amendments: No41 and 111/ 2001; No 43/2002; No20/2003 and the

last one No65/2003) and 1999 Water Act (SG No067/1999, in force since 28.01.2000, as amended in

2000 and the last in 2003).

During the drought periods the drinking water supply used for households has preference when water

is rationed. There are some water quantity limits for industry supplied by a public water supply

system during a drought period. This is one of the reasons for construction of wells by industry and

agriculture farms; it reduces dependence on the less reliable supply of the WSSC.

2.4. Regulatory Units

2.4.1. Environmental Regulation

According to Art. 116. of the 1999 Water Act, all waters and water bodies are preserved from

depletion, pollution, and damage with objective of maintaining the quantity and quality of waters

necessary for a healthy environment, preservation of the ecosystems, preservation of the landscape,

Dr. Galia Bardarska Institute of Water Problems at the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences

National Profile of Municipal Water and Wastewater Management in Bulgaria

23

and prevention of economic damages. The waters and the water bodies are preserved from pollution

and damage through:

·

prohibition of discharge of dangerous substances in quantities threatening the life and the

health of people and biological diversity of water bodies;

·

restriction the discharge of harmful substances;

·

determining sanitary protection zones around the water sources and the facilities for

drinking and household water supply and around the sources of mineral waters;

·

construction of water treatment stations for wastewaters;

·

establishing of a regime for use and preservation of the flooded strips along the banks;

·

regulating prohibitions for depositing wastes and dangerous substances at places where could

happen pollution of waters;

·

determining measures for not admitting artificial mixing of ground waters with different

qualities.

For these purposes the programs for categorization of surface and ground waters, and programs for

decrease of the pollution of the waters have been developed. The persons who produce wastewaters

are obliged to construct the necessary treatment facilities in accordance with the requirements for

discharge into the water body when there is no public sewerage system. The discharge of wastewater,

containing hazardous substances into the ground waters is forbidden or restricted depending on the

degree of danger that they create. The storage of pesticides; the depositing and treatment of wastes; the

construction of cattle-breeding farms; the construction of economic and housing buildings; the

washing and maintenance of transport vehicles and equipment; and the planting of perennial

vegetation with shallow root system is forbidden on river banks and in coastal areas.

The national water management institutions are the Council of Ministers and the Minister of

Environment and Water. The water management bodies at a basin level are the Directors of the Basin

Directorates.

1. The Council of Ministers:

·

approves the National Water Economic Plan;

·

grants concessions for waters which are exclusive state property;

·

approves national programs in the sphere of protection and sustainable use of waters;

·

permits the use of waters for the purposes of the defense and the security of the country;

·

determines restrictions in the use of waters, in exclusive cases, concerning different districts of

the country;

·

determines the quantity of mineral waters, used by public health care institutions at a

grounded proposal by the Minister of Health; and

·

determines the tariffs for the fees, collected on the grounds pointed out in the 1999 Water Act.

2. The Minister of Environment and Water:

·

elaborates the policy of the state in the field of the use and protection of the waters and the

protection from their harmful impact;

·

elaborates the National Water Economic Plan;

·

approves the river basin management plans;

·

develops national programs in the sphere of protection and sustainable use of waters;

·

prepares the water and water economic balances of the country;

24

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

·

issues permits for water use and/or use within the scope of the cases provided for in the

present law;

·

determines the order and the way for use of the waters of the complex and important dams,

determined in appendix No 1 of the 1999 Water Act;

·

establishes the necessary organization, ensure the financing and make proposal for granting of

concessions;

·

organizes the maintenance of the water and water economic cadastre;

·

organizes and manages the National Water Monitoring System;

·

elaborates the state policy for bilateral and multilateral cooperation in the field of use and

protection of waters;

·

publishes a periodical bulletin about the status of the water resources of the Republic of

Bulgaria;

·

approves the design parameters and schemes for the water infrastructure and installations;

·

coordinates the starting of procedures for granting of concessions for water infrastructure and

installations, which are public state property; and

·

approves the exploitation resources and the project obtaining of the ground waters, including

the mineral waters.

2.4.2. Economic Regulation

The financial organization and economic regulation for the use, protection and restoration of the

waters and water infrastructure is guided by the 1999 Water Act in Art 192 is as follows:

1. such organizations and regulations should be devoted to protection of the interests of the population

in their use of water for drinking-communal purposes and mineral waters for drinking, healing -

prophylactic and recreation purposes;

2. payment for water and wastewater service depending on the volume, the quantity and the quality of

the used and discharged waters;

3. the offender pays for the incurred damages, disruptions, pollution and other to the waters and the

water bodies;

4. economic incentives for rational use, protection and restoration of the waters and water bodies.

The implementation of this guidance is changing, however, as new legislation directed at the

regulations of water and water management is, as was noted above, being developed.

he elements of economic regulation include:

- a new organization of WSSCs

- a new Energy and Water State Regulatory Commission. Its aims are to offer new measures for

water sector development and restructuring in order to guarantee effectiveness of all kind of

services in the field of water supply continuity of services and the services quality;

- economic instruments (tariffs, fines, charges, etc) ;

- economic analysis;

- water tariffs set up, using profitability (12% or to 30%);

- methodology for cost recovery tariffs and possibilities for capital investments to be included;

- annual adjustment of tariffs, which will be done by EWSRC;

- institutional strengthening and capacity building program in the WSSCs;

- investment planning and realization of the year program;

Dr. Galia Bardarska Institute of Water Problems at the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences

National Profile of Municipal Water and Wastewater Management in Bulgaria

25

- NRW reduction program;

- renewing the assets.

Water and Wastewater Tariffs

Until 1991, the same water tariff applied for the domestic sector of all country. Before 1991 the tariff

of drinking water for industry via public water supply system was 2-3 times higher than households'

drinking water. Now, each WSSC defines the water tariff according to the methodology adopted with

Decree No. 194/1995 issued by the Council of Ministers and promulgated in the SG No.

40/10.05.1996, amend. SG No. 60/ 02.07.1999. This methodology not refers to geothermal waters

used for heating and greenhouses, for the water used for heating and for the water used for irrigation.

There are other institutions' methodologies for calculation of these types of water supply.

The water tariff setting for different types (i.e. pure, sewage and treated) is based on the rules of: 1999

Water Act, Act for Protection of Users and for Trade Rights (Ordinance No. 85/1999 of the Bulgarian

President), Accountant Act, National Accountant Standards, and Regulation for Water Supply &

Sewerage Systems Use in Populated Sites. The water tariffs are meant to cover their operational

expenses, depreciation, and a certain "profit".4 The drinking water "profit" shall not exceed 12% for

the population and for the business needs and shall not exceed 30% in the cases when it has been

proven that funds are needed for financing an investment program for rehabilitation of the water or

wastewater distribution network and facilities. The water tariff is set on the basis of 1 m3 the three

classes of billed water: water supplied, wastewater collected, and wastewater treated.

WSSCs and municipal councils set tariffs for drinking water and wastewater services. The tariffs are

lower for households and cross-subsidized by other consumers. Currently, the drinking water supply

tariffs vary substantially with the technology of water extraction and delivery pumps, gravity or

mixed systems and on the associated electricity and other costs incurred by the operator. The

wastewater tariff is calculated on the same basis as the water supply tariff. Usually, the operator splits

its wastewater charge into two parts: for taking the water away to the main city collector and the

charge for wastewater treatment (if the WWTP is installed). The WSSC includes into the wastewater

tariff the costs of any effluent charge. The WSSCs make individual contracts with the local factory's

administration and the quantity and quality of wastewaters impact on the costs of wastewater service.

Twenty days after the end of each annual quarter the WSSCs send their report of actual expenditures

for the water services to the MoRDPW. The items that go into the calculation of the experience-based

final tariff are shown in Table 4.

4 The term profit is put in quotations here because it is very doubtful that these rules are guided by the concept of

economic profit. The concept of "profit" here is more likely some net-revenue concept but without a clear

understanding of prevailing accounting rules we can't say more precisely what this net revenue represents

despite the elaboration of some accounting elements below.

26

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

Table 4. Calculation of Water Tariff According to the Adopted Methodology

No. Item

Report for the Proposal for

% of increase

current year

the next year

1.

Expenditures, thousands BGN

of which for:

1.1.

Materials (right for withdrawal water,

buying of water, raw materials and materials

for production, spare parts of long-term

assets)

1.2.

Electricity and fuels

1.3.

Outside services incl. repairs

1.4.

Depreciation (depreciation of physical and

non physical long-term assets according to