United Nations

Environment Programme

Chemicals

Indian Ocean

REGIONAL REPORT

Regionally

Based

Assessment

of

Persistent

Available from:

UNEP Chemicals

11-13, chemin des Anémones

CH-1219 Châtelaine, GE

Switzerland

Phone : +41 22 917 1234

Fax : +41 22 797 3460

Substances

E-mail: chemicals@unep.ch

December 2002

http://www.chem.unep.ch

UNEP Chemicals is a part of UNEP's Technology, Industry and

Printed at United Nations, Geneva

Economics Division

GE.03-00153January 2003500

UNEP/CHEMICALS/2003/6

G l o b a l E n v i r o n m e n t F a c i l i t y

UNITED NATIONS

ENVIRONMENT

PROGRAMME

CHEMICALS

Regional y Based Assessment

of Persistent Toxic Substances

Bahrain, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Iran (Islamic Republic of),

Iraq, Kuwait, Maldives, Nepal, Oman, Pakistan, Qatar, Saudi

Arabia, Sri Lanka, United Arabic Emirates, Yemen

INDIAN OCEAN

REGIONAL REPORT

DECEMBER 2002

GLOBAL ENVIRONMENT FACILITY

This report was financed by the Global Environment Facility (GEF) through a global project with co-

financing from the Governments of Australia, France, Sweden, Switzerland and the United States of

America.

This publication is produced within the framework of the Inter-Organization Programme for the Sound

Management of Chemicals (IOMC).

This publication is intended to serve as a guide. While the information provided is believed to be

accurate, UNEP disclaim any responsibility for the possible inaccuracies or omissions and

consequences, which may flow from them. UNEP nor any individual involved in the preparation of

this report shall be liable for any injury, loss, damage or prejudice of any kind that may be caused by

any persons who have acted based on their understanding of the information contained in this

publication.

The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this report do not imply the

expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations of UNEP

concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning

the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries.

The Inter-Organization Programme for the Sound Management of Chemicals (IOMC), was

established in 1995 by UNEP, ILO, FAO, WHO, UNIDO and OECD (Participating

Organizations), following recommendations made by the 1992 UN Conference on

Environment and Development to strengthen cooperation and increase coordination in the

field of chemical safety. In January 1998, UNITAR formally joined the IOMC as a Participating

Organization. The purpose of the IOMC is to promote coordination of the policies and

activities pursued by the Participating Organizations, jointly or separately, to achieve the

sound management of chemicals in relation to human health and the environment.

Material in this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted but acknowledgement is requested

together with a reference to the document. A copy of the publication containing the quotation or

reprint should be sent to UNEP Chemicals.

UNEP

CHEMICALS

UNEP Chemicals11-13, chemin des Anémones

CH-1219 Châtelaine, GE

Switzerland

Phone: +41 22 917 8170

Fax:

+41 22 797 3460

E-mail: chemicals@unep.ch

http://www.chem.unep.ch

UNEP Chemicals is a part of UNEP's Technology, Industry and Economics Division

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PREFACE ............................................................................................................................VI

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.....................................................................................................VII

1

INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ 1

1.1

Overview of the RBA PTS Project........................................................................1

1.1.1 Objectives................................................................................................................................................ 1

1.1.2 Results ..................................................................................................................................................... 1

1.2

Methodology..........................................................................................................2

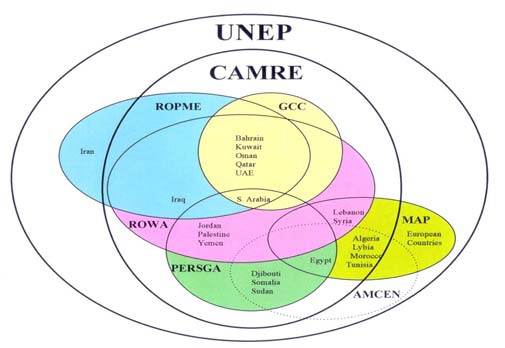

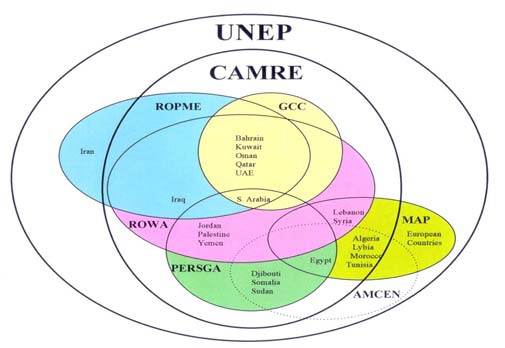

1.2.1 Regional divisions ................................................................................................................................... 2

1.2.2 Management structure ............................................................................................................................. 2

1.2.3 Data processing ....................................................................................................................................... 2

1.2.4 Project funding ........................................................................................................................................ 2

1.3

SCOPE OF THE INDIAN OCEAN REGIONAL ASSESSMENT......................3

1.4

EXISTING ASSESSMENTS ................................................................................3

1.5

OMISSIONS/WEAKNESSES ..............................................................................3

1.6

METHODOLOGY ................................................................................................4

1.7

EXISTING ASSESSMENTS ................................................................................4

1.8

OMISSIONS/WEAKNESSES ..............................................................................4

1.9

GENERAL DEFINITIONS OF CHEMICALS ....................................................4

1.9.1 Pesticides ................................................................................................................................................. 4

1.9.2 Industrial compounds .............................................................................................................................. 7

1.9.3 Unintended by-products .......................................................................................................................... 7

1.9.4 Regional specific ..................................................................................................................................... 8

1.10 DEFINITION OF THE INDIAN OCEAN REGION .........................................11

1.11 PHYSICAL SETTING ........................................................................................14

1.11.1

Freshwater Environment ................................................................................................................... 14

1.11.2

Marine Environment ......................................................................................................................... 14

1.11.3

Pattern of Development/Settlement .................................................................................................. 14

2

SOURCE CHARACTERISATION ............................................................................ 15

2.1

BACKGROUND INFORMATION ON THE SOURCES OF PTS ...................15

2.2

DATA COLLECTION AND QUALITY CONTROL ISSUES .........................15

2.3

PRODUCTION, USE AND EMISSION ............................................................15

2.3.1 POPs Pesticides ..................................................................................................................................... 15

2.3.2 Industrial Chemicals.............................................................................................................................. 16

2.3.3 Unintended By-Products ....................................................................................................................... 16

2.3.4 Other PTS of Emerging Concern .......................................................................................................... 17

2.4

HOT SPOTS ........................................................................................................18

2.4.1 PAHs in oil lakes in Kuwaiti desert....................................................................................................... 18

2.4.2 PCBs in old transformers....................................................................................................................... 18

2.5

DATA GAPS .......................................................................................................19

2.6

PRIORITISATON OF PTS CHEMICALS FOR SOURCES.............................19

2.7

CONCLUSIONS .................................................................................................20

2.8

REFERENCES ....................................................................................................21

3

ENVIRONMENTAL LEVELS, TOXICOLOGICAL AND ECOTOXICOLOGICAL

CHARACTERIZATION............................................................................................. 23

3.1

ENVIRONMENTAL LEVELS OF PTS.............................................................23

3.1.1 Air 23

3.1.2 Water ..................................................................................................................................................... 24

3.1.3 Soil and Sediment.................................................................................................................................. 25

3.1.4 Aquatic Biota......................................................................................................................................... 27

3.1.5 Terrestrial Biota..................................................................................................................................... 30

3.1.6 Food commodities ................................................................................................................................. 31

3.1.7 Human Tissue........................................................................................................................................ 34

3.1.8 Special Issues......................................................................................................................................... 36

3.2

TOXICOLOGY ...................................................................................................36

3.2.1 Overview ............................................................................................................................................... 36

3.2.2 National Reports on Toxicology and Ecotoxicology of PTS in Humans .............................................. 37

3.3

ECOTOXICOLOGY OF PTS OF REGIONAL CONCERN .............................39

3.3.1 Domestic Animal Poisonong................................................................................................................. 39

3.3.2 Wild Life and Birds Poisoning .............................................................................................................. 39

3.3.3 Loss in Biodiversity............................................................................................................................... 39

3.4

DATA GAPS .......................................................................................................39

3.5

CONCLUSIONS .................................................................................................40

3.6

REFERENCES ....................................................................................................41

4

MAJOR PATHWAYS OF CONTAMINANT TRANSPORT....................................... 50

4.1

INTRODUCTION ...............................................................................................50

4.1.1 General Features.................................................................................................................................... 50

4.1.2 Regionally Specific Features................................................................................................................. 50

4.1.3 Persistence and Long-Range Transport Potential.................................................................................. 51

4.2

OVERVIEW OF EXISTING MODELLING PROGRAMS ..............................52

4.2.1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 52

4.2.2 Atmospheric modelling ......................................................................................................................... 52

4.2.3 Freshwater systems................................................................................................................................ 53

4.2.4 Marine system modelling ...................................................................................................................... 53

4.3

ATMOSPHERE...................................................................................................54

4.3.1 General features..................................................................................................................................... 54

4.3.2 Single and multi-hop pathways ............................................................................................................. 54

4.3.3 Atmospheric transport ........................................................................................................................... 54

4.3.4 Atmospheric-surface exchange.............................................................................................................. 55

4.4

OCEANS .............................................................................................................55

4.4.1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 55

4.4.2 Rivers Discharge .................................................................................................................................. 56

4.4.3 Atmospheric deposition......................................................................................................................... 56

4.5

FRESHWATER...................................................................................................57

4.5.1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 57

4.5.2 Atmospheric deposition......................................................................................................................... 57

4.5.3 Local wastewater discharges ................................................................................................................. 57

4.5.4 Regional wastewater sources................................................................................................................. 57

4.5.5 Snow-pack and snowmelt...................................................................................................................... 57

4.5.6 Hydrology.............................................................................................................................................. 58

4.5.7 Ice 58

4.6

DATA GAPS .......................................................................................................58

4.7

CONCLUSIONS .................................................................................................59

4.8

REFERENCES ....................................................................................................59

5

PRELIMINARY ASSESSMENT OF THE REGIONAL CAPACITY AND NEED TO

MANAGE PTS.......................................................................................................... 63

5.1

INTRODUCTION ...............................................................................................63

5.2

MONITORING CAPACITY ..............................................................................63

5.2.1 Regional................................................................................................................................................. 63

5.2.2 National ................................................................................................................................................. 64

5.2.3 Human health ........................................................................................................................................ 64

5.3

EXISTING REGULATIONS AND MANAGEMENT STRUCTURE..............64

5.3.1 Regional................................................................................................................................................. 64

5.3.2 National ................................................................................................................................................. 66

5.4

STATUS OF ENFORCEMENT .........................................................................74

5.5

ALTERNATIVES ...............................................................................................74

5.5.1 Pesticides ............................................................................................................................................... 74

5.5.2 Industrial chemicals and unintentional by-products.............................................................................. 75

5.6

TECHNOLOGY TRANSFER ............................................................................75

5.7

IDENTIFICATION OF NEEDS .........................................................................75

5.7.1 Capacity Building.................................................................................................................................. 75

5.7.2 Establishment of Efficient PTS Management Systems ......................................................................... 76

5.8

CONCLUSIONS .................................................................................................80

5.9

REFERENCES ....................................................................................................81

6

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS ........................................................ 82

6.1

SOURCES OF PTS .............................................................................................82

6.2

LEVELS AND EFFECTS ...................................................................................83

6.3

TRANSBOUNDARY MOVEMENT .................................................................83

6.4

CAPACITY TO MANAGE PTS ........................................................................83

6.5

INTER-COUNTRY COLLABORATIVE EFFORTS........................................85

6.6

CONCLUDING REMARKS ..............................................................................85

ANNEX I.............................................................................................................................. 87

ANNEX II............................................................................................................................. 88

ANNEX III............................................................................................................................ 91

ANNEX IV ........................................................................................................................... 93

PREFACE

The enhanced agricultural and industrial activities have significantly helped in meeting the requirement of food,

thereby providing comfort and better quality of life. However, this has led to an increase in the number of

chemicals being released in the environment, many of which persist in nature due to their low biodegradability

and are termed as Persistent Toxic Substances (PTS). Reports of their accumulation, biomagnification in the

ecosystem and their possible adverse effects on human health have aroused great concern among the

ecotoxicologists and health scientists all over the world. This report for the Indian Ocean is one of twelve

regional reports compiled to assess selected PTS across the globe.

I am extremely grateful to my Regional Team Members, Dr. M.U. Beg, (Research Scientist, Kuwait Institute

for Scientific Research, Kuwait), Dr. M. Yousaf Hayat Khan (Senior Scientist/National Project Director,

National Agricultural Research Centre, Pakistan), Dr. G.K. Manuweera (Registrar of Pesticides, Department of

Agriculture, Sri Lanka) and Dr. M. Sengupta (Adviser, Ministry of Environment and Forests, India) without

whom it would not have been possible to put this report together. I am thankful to the country experts who have

provided information from their countries. My thanks are due to my colleagues, Dr. Kr. P. Singh, Scientist,

ITRC and Dr. P.N. Viswanathan, Former-Senior Deputy Director of this institute who both worked very closely

with me throughout this project.. The secretarial assistance of Mr. B.K. Jha, ITRC is highly appreciated. I

would also like to acknowledge the support of Er. K.K. Gupta, Deputy Director, ITRC in dealing with

substantive matters, administration, accounts and other departments in running the project.

I feel privileged and honoured for the opportunity given to me to serve as the Regional Coordinator. I thank

Director General, CSIR and Ministry of Environment and Forests for their support in running the project. I

extremely enjoyed working with Mr. Paul Whylie, Project Manager, who always guided, encouraged and

helped me and the team throughout the implementation of the project. I take great pleasure in acknowledging

his support and guidance. I am also thankful to the GEF and other donors for the financial assistance.

I sincerely hope that this regional report will go a long way in serving the cause of humanity and in assessing

the risk of PTS and guide the concerned governments, UNEP and other agencies to take further action to reduce

risks to chemical exposure.

P.K. Seth

Regional Coordinator, Indian Ocean Region

and Director, Industrial Toxicology Research Centre

Lucknow, India

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Introduction

This is the final report of the Regionally Based Assessment of Persistent Toxic Substances, under GEF/UNEP

terms of reference, for region VI (Indian Ocean). A regional team with Dr. P.K. Seth (Ph.D., FNA, Director,

Industrial Toxicology Research Centre, Lucknow, India) as Coordinator, Dr. M. Sengupta (Adviser, Ministry of

Environment and Forests, New Delhi, India), Dr. Gamini Manuweera (Registrar of Pesticides, Office of the

Registrar of Pesticides, Department of Agriculture, Peradeniya, Sri Lanka), Dr. M. Yousaf Hayat (Senior

Scientist/National Project Director, Ecotoxicology Research Institute, National Agricultural Research Centre,

Islamabad, Pakistan) and Dr. M.U. Beg (Research Scientist, Department of Environmental Sciences, Kuwait

Institute for Scientific Research, Safat, Kuwait) as members was constituted for the preparation of the report.

The committee had the 1st Regional Team Members meeting from July 31 to August 01, 2001 at Lucknow

India; 2nd Regional Team Members meeting from August 1-2, 2002 at Colombo, Sri Lanka; 1st Technical

Workshop on Sources and Environmental Levels of Persistent Toxic Substances (PTS) from March 10-13,

2002 at Kuwait; 2nd Technical Workshop on "Impacts and Transboundary Transport of Persistent Toxic

Substances" from July 29-31, 2002 at Colombo, Sri Lanka; and Priority Setting Meeting at New Delhi, India

from September 18-21, 2002. In these meetings, the information collected by the team and inputs kindly

provided by representatives of all the 16 countries of the region were evaluated and compiled. Based on further

suggestions and inputs by the country experts, and discussions during the regional meeting at New Delhi and

the final round of discussions at Lucknow on Oct. 26-27, 2002, the draft was modified and the present stage

was possible only through the commendable inputs by various experts.

The countries grouped under the region are: Bahrain, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Iran, Kuwait, Maldives,

Myanmar, Nepal, Oman, Pakistan, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Sri Lanka, United Arab Emirates and Yemen. The

following 21 compounds, or groups of compounds, were identified as priority PTS when magnitude of use,

environmental levels and human and ecological effects were taken into account: aldrin, chlordane, DDT,

dieldrin, endrin, heptachlor, hexachlorobenzene, mirex, toxaphene, PCBs, dioxins, furans, atrazene, endosulfan,

lindane, phthalates, PAHs, pentachlorophenol, organotin, organolead and organomercury compounds

The region has, in addition to the concerns of global nature, specific localised factors influencing the sources,

levels and effects of PTS. These include geoclimatic, socioeconomic, and ethnic factors and the recent trends in

industrial and agricultural development, urbanisation and activities aimed at a better quality of life . Personal

predisposition of the individuals due to genetic and health status, vulnerability of rich biodiversity to

ecotoxicity, petroleum production and transport, refuse burning, biomass fuels adding to PTS load are also

existing. Further, even though most of the PTS are regulated, their residues are still measured.

Sources

The need for further development and the continued dependence on some chlorinated pesticides for disease

vector control also make PTS problems distinct in the region. A detailed appraisal of the sources of PTS in the

various countries of the region has been presented on the basis of data collected through over 1650

questionnaire responses from all the countries, inputs from country experts, write ups and our own literature

search. From the amounts and potential of exposure, PAHs, dioxins and furans, appear to be the priorities in the

region. Due to past agricultural use and present restricted use in vector control, organochlorine pesticide-based

PTS may remain a local concern for some countries for some time, but not for the long-term. The pattern is

different between countries with petroleum based and those with agriculture based economies. However, most

of the direct sources of the PTS are already banned, being phased out or regulated so that further buildup may

be unlikely. Several data gaps were found in most countries regarding information on some or all of the PTS.

Generally, production of secondary PTS components through incineration or other sources or environmental

degradation is not yet quantified and there is no systematic inter-country collaborative surveillance programme.

Among the hot spots for quick remedial measures, the major ones are stockpiles of banned/outdated pesticides;

build up in marine food chains and sediment, discarded transformers, incineration sites and the areas of high

petroleum transport e.g. Gulf. A system of grouping different PTS by matrix and semi-quantitative scoring

based on sources and data gaps was developed. Based on this, 3 categories of PTS were identified for each

country and appended in the report (score 0 no concern, score 1 - local concern, score 2 - regional concern).

Consequently recommendations are made for further monitoring of sources and regulatory content.

vii

Environmental levels

Considerable information is available on PTS levels in various environmental compartments and matrices,

especially in countries such as India, Pakistan and Sri Lanka. Airborne levels of PTS, at present do not appear

to be a serious issue in any of the situations excepting perhaps localised sites of production, storage, use or

disposal. However, information is needed on transboundary migration in air and water for which monitoring

and modelling are suggested.

The levels of the organochlorine pesticide-based PTS, in surface and ground water in various countries,

especially those of agrarian and rural backgrounds could cause concern, including long-term low exposure

effects on man and livestock and wildlife. The build up of organochlorine pesticide residues in marine and fresh

water fauna and flora and wildlife, have also been reported in low levels. In food commodities like dairy

products and poultry, the levels also could be of concern. However, the levels of organochlorine pesticides

show declining trends. Since man is at the top of the food chain, human adipose tissue, blood, breast milk and

placenta show critical levels of PTS in the light of specific toxicity like carcinogenicity, mutagenicity,

immunotoxicity and endocrine toxicity. This situation deserves detailed systematic ecoepidemiological

assessment. The above problems with pesticide-based PTS are not serious in the Gulf countries. With the

present restrictions in use, further buildup may be unlikely. However, PCBs and PAHs appear of concern. The

oil lakes created after the war, wherein a lot of secondary chemical weathering is taking place, are considerd a

regional hot spot.

Ecotoxicological and Toxicological Characterisation

As expected, all the issues regarding toxicity of PTS, are reported in the region as in other regions. Due to the

large-scale use in the past for agriculture, several epidemiological surveys are available in India, Pakistan and

Sri Lanka and long-term low dose effects are also evident. Apart from the well recorded neuromuscular and

other target effects, endocrine desruption cases also have been known suggesting reproductive and

developmental toxicity. Cases of non-occupational and non-environmental exposure such as

intentional/accidental ingestion cause a large number of victims in many countries. This is much higher than in

temporate regions and low levels of awareness could be a factor, along with the lack of adequate medical

management facilities nearby in rural/agricultural areas. Also, chronic and sub-acute effects are very seldom

attended to and there is very little information on long-term low dose exposure in humans. Sprayers and cotton

pickers are considered major exposure groups.

In Pakistan, India and Sri Lanka several detailed epidemiological surveys and compilations of hospital records

are available on pesticide effects. Serious ecotoxicological effects have also been reported in most countries

due to chlorine containing PTS. Domestic animals in small agricultural situations are common targets of

pesticide toxicity due to contaminated fodder and water. With larger land holdings and organized agricultural

and animal husbandry, the problem is not serious. Adverse effects in other production avenues such as poultry,

apiary and aquaculture are also reported in isolated situations and wild life especially migrating birds are also

affected. However more detailed systematic survey based information on cause-effect-species relation are

needed. Data gaps are even more serious with PAHs, PCBs and Dioxin, excepting some study by the Regional

Organization for the Protection of the Marine Environmental (ROPME). The marine ecotoxicology component

in territorial and international water is virtually unstudied and potential hot spots like Gulfs, major riverine

estuaries, glaciers and coral reefs need coordinated international efforts.

Transboundary Pathways for PTS

Even when the sources are well characterised, the actual environmental burden is decided by the mechanism

and pathways of transport of the fugitative chemicals. Like sunlight, air or water, pollutants also are not

segregated by political or geographical boundaries. A clear partition in sources in the region is observed with

the Gulf countries having petroleum based development and the others being agriculture oriented. As a

consequence, major sources of PAH, PCBs, and pesticides are somewhat separated. This makes detailed

assessment of the intra-regional transport pathways essential and also its contribution to global pathways.

Atmospheric and hydrospheric transport are considered far more important in the region than biotic (migratory

birds, aquatic fauna) transport or import/export/dumping of chemicals/wastes. Residential kinetics of PTS in

different regions especially sensitive ones like Gulf, are not understood and so also are factors influencing

persistence. The contribution of monsoon turbulence, large inter-country rivers and ocean transport are not

quantified. However, observations after the gulf war show considerable widespread marine pollution by PTS.

The mechanisms of transport of chemicals depend on their chemical reactivity, solubility, volatilisation,

persistence and meteorological factors. So the situation in the region has been modelled based on earlier

viii

models. For this the special features of the Indian Ocean are complex such as monsoon patterns, cyclones, sea

currents and the geochemical characteristics of pollutant laden water, sludge and sediment have to be

quantified. Even though contribution by riverine discharges can be assessed, the contribution by localised waste

discharges/burning, and snow melt, water harvesting projects etc. are unknown. The need to develop models

suitable for the region and validation of these through field studies are considered priorities. The localised

efforts done in this direction by Industrial Toxicology Research Centre, Lucknow and in the Gulf countries can

be integrated in the light of other models and a suitable model developed for the region as a priority for

capacity building.

Capacity and Needs to manage PTS

After assessing the magnitude of sources, levels and effects of the priority PTS in the region, it was logical to

appraise the existing capacity and need to manage such problems. Based on questionnaires and other inputs,

detailed appraisal of the existing capacities for monitoring PTS as well as regulatory structures were made. The

existing laboratory capabilities are adequate by international state of the art standards to handle local problems

of general pollutants and pesticides. But for the specialised contaminants, the task of monitoring over 20 PTS,

using ultrasensitive, sophisticated equipment based monitoring in thousands of matrices regularly is not

currently possible. With additional facilities, financial support and human resource development in the

countries where facilities are inadequate at present, some improvement is possible. For intra-regional

collaborations a centralised facility specifically for PTS is desirable. Also networking of present organizations

along with their upgrading is suggested.

In this context, it is pertinent to mention that in the Indian Ocean region, ITRC, a constituent laboratory of

Council of Scientific and Industrial Research, has been in forefront in monitoring, assessment and managing

health effects of pesticides, heavy metals and other environmental pollutants which include the PTS. The

Institute has active collaborative research programmes with several countries including human resource

development. A network between ITRC (India), KISR (Kuwait), Pesticide Institute (Sri Lanka) and ERI

(Pakistan) can be evolved.

The existing regulations in the management of PTS during their entire life cycle, have been collected from all

the countries and discussed in the report. Wherever there is lacunae, they have been pointed out and a uniform

policy in approach to PTS is generally evident. It is hoped that recommendations in the present report will

greatly help in furthering efforts to reduce the build up and impact of PTS and to remediate any hstorical

damage that has occurred.

ix

1 INTRODUCTION

1.1 Overview of the RBA PTS Project

Following the recommendations of the Intergovernmental Forum on Chemical Safety1, the UNEP Governing

Council decided in February 1997 (Decision 19/13 C) that immediate international action should be initiated to

protect human health and the environment through measures which will reduce and/or eliminate the emissions

and discharges of an initial set of twelve persistent organic pollutants (POPs). Accordingly an

Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC) was established with a mandate to prepare an international

legally binding instrument for implementing international action on certain persistent organic pollutants. To

date three2 sessions of the INC have been held. These series of negotiations have resulted in the adoption of the

Stockholm Convention in 2001. The initial 12 substances fitting these categories that have been selected under

the Stockholm Convention include: aldrin, endrin, dieldrin, chlordane, DDT, toxaphene, mirex, heptachlor,

hexachlorobenzene, PCBs, dioxins and furans. Besides these 12, there are many other substances that satisfy

the criteria listed above for which their sources, environmental concentrations and effects are to be assessed.

Persistent toxic substances can be manufactured substances for use in various sectors of industry, pesticides, or

by-products of industrial processes and combustion. To date, their scientific assessment has largely

concentrated on specific local and/or regional environmental and health effects, in particular "hot spots" such as

the Great Lakes region of North America or the Baltic Sea. In response to the long-range atmospheric transport

of PTS, instruments such as the Convention on Long-Range Trans-boundary Air Pollution (LRTAP) under the

auspices of the UN Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) have been developed. The Basel Convention

regulates the trans-boundary movement of hazardous waste, which may include PTS. Some PTS are covered

under the recently adopted Rotterdam Convention on the Prior Informed Consent Procedure for Certain

Hazardous Chemicals and Pesticides in International Trade. FAO has initiated a process to identify and

manage the disposal of obsolete stocks of pesticides, including PTS, particularly in developing countries and

countries with economies in transition.

1.1.1 Objectives

There is a need for a scientifically-based assessment of the nature and scale of the threats to the environment

and its resources posed by persistent toxic substances that will provide guidance to the international community

concerning the priorities for future remedial and preventive action. The assessment will lead to the

identification of priorities for intervention, and through application of a root cause analysis will attempt to

identify appropriate measures to control, reduce or eliminate releases of PTS, at national, regional or global

levels (Annex D).

The objective of the project is to deliver a measure of the nature and comparative severity of damage and

threats posed at national, regional and ultimately at global levels by PTS. This will provide the GEF with a

science-based rationale for assigning priorities for action among and between chemical related environmental

issues, and to determine the extent to which differences in priority exist among regions.

1.1.2 Results

The project relies upon the collection and interpretation of existing data and information as the basis for the

assessment. No research will be undertaken to generate primary data, but projections will be made to fill

data/information gaps, and to predict threats to the environment. The proposed activities are designed to obtain

the following expected results:

1) Identification of major sources of PTS at the regional level;

2) Impact of PTS on the environment and human health;

3) Assessment of trans-boundary transport of PTS;

4) Assessment of the root causes of PTS related problems, and regional capacity to manage these

problems;

1

Conclusions of the IFCS sponsored Experts Meeting on POPs and final Report of the ad hoc working group on POPs, Manila, 17-

22 June 1996, "Persistent Organic Pollutants: Considerations for Global Action".

2

At the time of the submission of the project proposal, October 1999.

1

5) Identification of regional priority PTS related environmental issues; and

6) Identification of PTS related priority environmental issues at the global level.

The outcome of this project will be a scientific assessment of the threats posed by persistent toxic substances to

the environment and human health. The activities to be undertaken comprise an evaluation of the sources of

persistent toxic substances, their levels in the environment and consequent impact on biota and humans, their

modes of transport over a range of distances, the existing alternatives to their use and remediation options, as

well as the barriers that prevent their good management.

1.2 Methodology

1.2.1 Regional

divisions

To achieve these results, the globe is divided into 12 regions namely: Arctic, North America, Europe,

Mediterranean, Sub-Saharan Africa, Indian Ocean, Central and North East Asia (Western North Pacific), South

East Asia and South Pacific, Pacific Islands, Central America and the Caribbean, Eastern and Western south

America, Antarctica. The twelve regions were selected based on obtaining geographical consistency while

trying to reside within financial constraints.

1.2.2 Management

structure

The project is managed by the project manager situated at UNEP Chemicals in Geneva, Switzerland. Each

region is controlled by a regional coordinator assisted by a team of approximately 4 persons. The co-ordinator

and the regional team are responsible for promoting the project, the collection of data at the national level and

to carry out a series of technical and priority setting workshops for analysing the data on PTS on a regional

basis. Besides the 12 POPs from the Stockholm Convention, the regional team selects the chemicals to be

assessed for its region with selection open for review during the various workshops undertaken throughout the

assessment process. Each team writes the regional report for the respective region.

1.2.3 Data

processing

Data is collected on sources, environmental concentrations, human and ecological effects through

questionnaires that are filled at the national level. The results from this data collection along with presentations

from regional experts at the technical workshops, are used to develop regional reports on the PTS selected for

analysis. A priority setting workshop with participation from representatives from each country results in

priorities being established regarding the threats and damages of these substances to each region. The

information and conclusions derived from the 12 regional reports will be used to develop a global report on the

state of these PTS in the environment.

The project is not intended to generate new information but to rely on existing data and its assessment to arrive

at priorities for these substances. The establishment of a broad and wide- ranging network of participants

involving all sectors of society was used for data collection and subsequent evaluation. Close cooperation with

other intergovernmental organizations such as UNECE, WHO, FAO, UNPD, World Bank and others was

obtained. Most have representatives on the Steering Group Committee that monitors the progress of the project

and critically reviews its implementation. Contributions were garnered from UNEP focal points, UNEP POPs

focal points, national focal points selected by the regional teams, industry, government agencies, research

scientists and NGOs.

1.2.4 Project

funding

The project costs approximately US$4.2 million funded mainly by the Global Environment Facility (GEF) with

sponsorship from countries including Australia, France, Germany, Sweden, Switzerland and the USA. The

project runs between September, 2000 to April, 2003 with the intention that the reports be presented to the first

meeting of the Conference of the Parties of the Stockholm Convention projected for 2003/4.

Results from the project will be used by the GEF and other funding agencies to provide priorities for future

remedial action to reduce or eliminate these substances from the environment. In addition, the project will

provide support to international conventions such as the Rotterdam Convention, the UNECE LRTAP

Convention, the Regional Seas Agreement and the Stockholm Convention. It will present opportunities for

2

bilateral or multilateral action, network building and co-operation within and between regions and stimulate

research through the identification of data gaps.

1.3 SCOPE OF THE INDIAN OCEAN REGIONAL ASSESSMENT

The Indian Ocean region has several special features, unique in the context of persistent toxic substances (PTS)

and their long-term impact on man and environment. The high population density, increasing agricultural and

industrial activities, urbanisation and health care, have led to large-scale utilisation of energy and chemicals.

This adds to the possibility of gradual accumulation of PTS in the region. The tropical/sub tropical location is

conducive to large-scale proliferation and infestation by pests and disease vectors, which necessitates the use of

large amounts of pesticides. DDT and related compounds are still used in many countries in the region. It is

natural that many of the residues could persist in original form or as recalcitrant derivatives. Monsoon-fed

rivers and recurring floods also lead to runoff from fields and, in addition to air turbulence or ocean currents,

pour out large amounts into the ocean. The ocean itself comprises the most active route of oil tanker and

mineral transport enhances the chances of accumulation of fossil fuel related pollutants. Coastal wetland

agriculture, aquaculture and petrochemical and other coastal industries further aggravates the problem. The

common practice of burning industrial, municipal, agricultural and other waste without adequate safe

incineration facilities and pollution control leads to the generation of unintentional byproducts. Traditional use

of biomass for cooking in rural areas, cultural practices, accidental oil spillage and issues such as the Gulf War,

have also contributed to the problems specific to this region.

As with the diversity of sources of PTS, the factors influencing persistence are also unique to the region. The

hot humid climate, in many places and seasons, influence bio-availability, biological uptake, persistence and

effect different from other climate regions. Evapouration and photochemical transformation are also more

important and the native biota involved in primary conversion is also more diverse. The environmental half-

lives in this region could be much different than in temperate regions. Very little data from field studies are

available on this issue.

Transboundary rivers are a common feature in the region and water pollutant movement assumes serious

proportion e.g. the rivers of Punjab and Indus (India-Pakistan), Ganga, Brahmaputra systems (India-Nepal-

Bangladesh) and Shattalarab in northern Gulf region. The monsoon-fed rivers show wide variation in water

flow in various seasons and this also affects pollutant transport and sediment/soil bound PTS.

The vast literature on the sources, environmental levels, toxicological and ecotoxicological risks, transport and

persistence pathways were collected, appraised and compiled in this report. Regional capacity for the

management of PTS has also been evaluated and viable conclusions offered. This report covers the general

issues comprehensively followed by specific chapters. Source characterisation is described in Chapter II;

Chapter III is in two parts, one covering environmental levels and the other toxicological and ecotoxicological

characteristics. The major transport pathways of contaminants are discussed in Chapter IV. A critical appraisal

of regional capacity and the need to manage PTS is presented in Chapter V, with conclusions and

recommendations in Chapter VI.

1.4 EXISTING

ASSESSMENTS

So far only a few country specific assessments of some PTS have been carried out, except for an exhaustive

sub-regional assessment in the ROPME sea area. Due to the regional importance of pesticide residues, most of

the surveys have been done on this group of PTS. Information on PTS sources in many countries is either not

available or incomplete.

1.5 OMISSIONS/WEAKNESSES

Many of the country surveys done earlier, suffer from statistical limitations, lack of uniform standard

methodology and GLP as per today's requirement and lack correlation of residues with sources and effects.

Long-term effect monitoring through epidemiological and ecotoxicological field studies has been limited. Also

the bulk of data are on pesticides with very little information on other PTS.

3

1.6 METHODOLOGY

The methodology used is generally the same as in other regions, however, in some cases it is with region

specific details like preservation of samples, transport under local conditions etc. modified. Quality assurance

data is lacking in many studies.

1.7 EXISTING

ASSESSMENTS

So far only a few country specific assessments of some PTS have been carried out, except for an exhaustive

sub-regional assessment in the ROPME sea area. Due to the regional importance of pesticide residues, most of

the surveys have been done on this group of PTS. Information on PTS sources in many countries is either not

available or incomplete.

1.8 OMISSIONS/WEAKNESSES

Many of the country surveys done earlier, suffer from statistical limitations, lack of uniform standard

methodology and GLP as per today's requirement and lack correlation of residues with sources and effects.

Long-term effect monitoring through epidemiological and ecotoxicological field studies has been limited. Also

the bulk of data are on pesticides with very little information on other PTS.

1.9 GENERAL DEFINITIONS OF CHEMICALS

The description of the PTSs of concern to the Indian Ocean Region in terms of persistence, exposure

concentrations, toxicity and ecotoxicity including the twelve Stockholm Convention chemicals (aldrin, endrin,

dieldrin, chlordane, DDT, heptachlor, mirex, toxaphene, hexachlorobenzene, PCBs, dioxins and furans) and

other regionally specific chemicals including HCH, PAHs, endosulphan, pentachlorophenol, organic mercury

compounds, organic tin compounds, organic lead compounds, phthalates and atrazine are presented below. For

further information the MSDs (Material Safety Data sheets) and IPCS documents may be referred to.

1.9.1 Pesticides

1.9.1.1 Aldrin

Chemical Name: 1,2,3,4,10,10-Hexachloro-1,4,4a,5,8,8a-hexahydro-1,4-endo,exo-5,8-dimethanonaphthalene

(C12H8Cl6). CAS Number: 309-00-2

Properties: Solubility in water: 27 µg/L at 25°C; vapour pressure: 2.3 x 10-5 mm Hg at 20°C; log KOW: 5.17-

7.4.

Discovery/Uses: It has been manufactured commercially since 1950, and used throughout the world until the

early 1970s to control soil pests such as corn rootworm, wireworms, rice water weevil, and grasshoppers. It has

also been used to protect wooden structures from termites.

Persistence/Fate: Readily metabolised to dieldrin by both plants and animals. Biodegradation is expected to be

slow and it binds strongly to soil particles, and is resistant to leaching into groundwater. Aldrin was classified

as moderately persistent with half-life in soil and surface waters ranging from 20 days to 1.6 years.

Toxicity: Aldrin is toxic to humans; the lethal dose for an adult has been estimated to be about 80 mg/kg body

weight. The acute oral LD50 in laboratory animals is in the range of 33 mg/kg body weight for guinea pigs to

320 mg/kg body weight for hamsters. The toxicity of aldrin to aquatic organisms is quite variable, with aquatic

insects being the most sensitive group of invertebrates. The 96-h LC50 values range from 1-200 µg/L for

insects, and from 2.2-53 µg/L for fish. The maximum residue limits in food recommended by FAO/WHO

varies from 0.006 mg/kg milk fat to 0.2 mg/kg meat fat. Water quality criteria between 0.1 to 180 µg/L have

been published.

1.9.1.2 Dieldrin

Chemical Name: 1,2,3,4,10,10-Hexachloro-6,7-epoxy-1,4,4a,5,6,7,8,8a-octahydroexo-1,4-endo-5,8-

dimethanonaphthalene (C12H8Cl6O). CAS Number: 60-57-1

Properties: Solubility in water: 140 µg/L at 20°C; vapour pressure: 1.78 x 10-7 mm Hg at 20°C; log KOW:

3.69-6.2.

Discovery/Uses: Production began in 1948 after World War II and it was used mainly for the control of soil

insects such as corn rootworms, wireworms and catworms.

4

Persistence/Fate: It is highly persistent in soils, with a half-life of 3-4 years in temperate climates, and

bioconcentrates in organisms. Its persistence in air has been estimated as 4-40 hrs.

Toxicity: The acute toxicity for fish is high (LC50 between 1.1 and 41 mg/L) and moderate for mammals (LD50

in mouse and rat ranging from 40 to 70 mg/kg body weight). However, a daily administration of 0.6 mg/kg to

rabbits adversely affected the survival rate. Aldrin and dieldrin mainly affect the central nervous system but

there is no direct evidence that they cause cancer in humans. The maximum residue limits in food

recommended by FAO/WHO varies from 0.006 mg/kg milk fat to 0.2 mg/kg poultry fat. Water quality criteria

between 0.1 to 18 µg/L have been published.

1.9.1.3 Endrin

Chemical Name: 3,4,5,6,9,9-Hexachloro-1a,2,2a,3,6,6a,7,7a-octahydro-2,7:3,6-dimethanonaphth[2,3-

b]oxirene (C12H8Cl6O). CAS Number: 72-20-8

Properties: Solubility in water: 220-260 µg/L at 25 °C; vapour pressure: 2.7 x 10-7 mm Hg at 25°C; log KOW:

3.21-5.34.

Discovery/Uses: It has been used since the 1950s against a wide range of agricultural pests, mostly on cotton

but also on rice, sugar cane, maize and other crops. It has also been used as a rodenticide.

Persistence/Fate: Is highly persistent in soils (half-lives of up to 12 years have been reported in some cases).

Bioconcentration factors of 14 to 18,000 have been recorded in fish, after continuous exposure.

Toxicity: Endrin is very toxic to fish, aquatic invertebrates and phytoplankton; the LC50 values are mostly less

than 1 µg/L. The acute toxicity is high in laboratory animals, with LD50 values of 3-43 mg/kg, and a dermal

LD50 of 5-20 mg/kg in rats. Long-term toxicity in the rat has been studied over two years and a NOEL of 0.05

mg/kg bw/day was found.

1.9.1.4 Chlordane

Chemical Name: 1,2,4,5,6,7,8,8-Octachloro-2,3,3a,4,7,7a-hexahydro-4,7-methanoindene (C10H6Cl8). CAS

Number: 57-74-9

Properties: Solubility in water: 56 µg/L at 25°C; vapour pressure: 0.98 x 10-5 mm Hg at 25 °C; log KOW: 4.58-

5.57.

Discovery/Uses: Commercial production of chlordane began in 1945 and it was used primarily as an

insecticide for control of cockroaches, ants, termites, and other household pests. Technical chlordane is a

mixture of at least 120 compounds. Of these, 60-75% are chlordane isomers, the remainder being related to

endo-compounds including heptachlor, nonachlor, diels-alder adduct of cyclopentadiene and penta, hexa and

octachloro-cyclopentadienes.

Persistence/Fate: Chlordane is highly persistent in soils with a half-life of about 4 years. Its persistence and

high octanol-water partition coefficient promote binding to aquatic sediments and bioconcentration in

organisms.

Toxicity: LC50 from 0.4 mg/L (pink shrimp) to 90 mg/L (rainbow trout) have been reported for aquatic

organisms. The acute toxicity for mammals is moderate with an LD50 in rat of 200-590 mg/kg body weight

(19.1 mg/kg body weight for oxychlordane). The maximum residue limits for chlordane in food are, according

to FAO/WHO between 0.002 mg/kg milk fat and 0.5 mg/kg poultry fat. Water quality criteria of 1.5 to 6 µg/L

have been published. Chlordane has been classified as a substance for which there is evidence of endocrine

disruption in an intact organism and possible carcinogenicity to humans.

1.9.1.5 Heptachlor

Chemical Name: 1,4,5,6,7,8,8-Heptachloro-3a,4,7,7a-tetrahydro-4,7-methanoindene (C10H5Cl7). CAS

Number: 76-44-8

Properties: Solubility in water: 180 µg/L at 25°C; vapour pressure: 0.3 x 10-5 mm Hg at 20°C; log KOW: 4.4-

5.5.

Production/Uses: Heptachlor is used primarily against soil insects and termites, but also against cotton insects,

grasshoppers, and malaria mosquitoes. Heptachlor epoxide is a more stable breakdown product of heptachlor.

Persistence/Fate: Heptachlor is metabolised in soils, plants and animals to heptachlor epoxide, which is more

stable in biological systems and is carcinogenic. The half-life of heptachlor in soil is in temperate regions 0.75

2 years. Its high octanol-water partition coefficient provides the necessary conditions for bioconcentration in

organisms.

Toxicity: The acute toxicity of heptachlor to mammals is moderate (LD50 values between 40 and 119 mg/kg

have been published). The toxicity to aquatic organisms is higher and LC50 values down to 0.11 µg/L have been

5

found for pink shrimp. Limited information is available on the effects in humans and studies are inconclusive

regarding heptachlor and cancer. The maximum residue levels recommended by FAO/WHO are between 0.006

mg/kg milk fat and 0.2 mg/kg meat or poultry fat.

1.9.1.6 Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT)

Chemical Name: 1,1,1-Trichloro-2,2-bis-(4-chlorophenyl)-ethane (C14H9Cl5). CAS Number: 50-29-3.

Properties: Solubility in water: 1.2-5.5 µg/L at 25°C; vapour pressure: 0.2 x 10-6 mm Hg at 20°C; log KOW:

6.19 for pp'-DDT, 5.5 for pp'-DDD and 5.7 for pp'-DDE.

Discovery/Use: DDT appeared for use during World War II to control insects that spread diseases like malaria,

dengue fever and typhus. Following this, it was widely used on a variety of agricultural crops. The technical

product is a mixture of approx. 85% pp'-DDT and 15% op'-DDT isomers.

Persistence/Fate: DDT is highly persistent in soils with a half-life of up to 15 years and of 7 days in air. It also

exhibits high bioconcentration factors (in the order of 50000 for fish and 500000 for bivalves). In the

environment, the product is metabolised mainly to DDD and DDE.

Toxicity: The lowest dietary concentration of DDT reported to cause egg-shell thinning is 0.6 mg/kg for the

black duck. LC50 of 1.5 mg/L for largemouth bass and 56 mg/L for guppy have been reported. The acute

toxicity of DDT for mammals is moderate with an LD50 of 113-118 mg/kg body weight in rats. DDT has been

shown to exhibit oestrogen-like activity, and possible carcinogenic activity in humans. The maximum residue

level in food recommended by WHO/FAO ranges from 0.02 mg/kg milk fat to 5 mg/kg meat fat. The maximum

permissible DDT residue level in drinking water (WHO) is 1.0 µg/L.

1.9.1.7 Toxaphene

Chemical Name: Polychlorinated bornanes and camphenes (C10H10Cl8). CAS Number: 8001-35-2

Properties: Solubility in water: 550 µg/L at 20°C; vapour pressure: 3.3 x 10-5 mm Hg at 25°C; log KOW : 3.23-

5.50.

Discovery/Uses: Toxaphene has been in use since 1949 as a non-systemic insecticide with some acaricidal

activity, primarily on cotton, cereal grains fruits, nuts and vegetables. It was also used to control livestock

ectoparasites such as lice, flies, ticks, mange, and scab mites. The technical product is a complex mixture of

over 300 congeners, containing 67-69% chlorine by weight.

Persistence/Fate: Toxaphene has a half-life in soil of 100 days up to 12 years. It has been shown to

bioconcentrate in aquatic organisms (BCF of 4247 in mosquito fish and 76000 in brook trout).

Toxicity: Toxaphene is highly toxic to fish, with 96-hour LC50 values in the range of 1.8 µg/L in rainbow trout

to 22 µg/L in bluegill. Long-term exposure to 0.5 µg/L reduced egg viability to zero. The acute oral toxicity is

in the range of 49 mg/kg body weight in dogs to 365 mg/kg in guinea pigs. In long-term studies NOEL in rats

was 0.35 mg/kg bw/day, LD50 ranging from 60 to 293 mg/kg bw. Strong evidence exists of the potential of

toxaphene for endocrine disruption. Toxaphene is carcinogenic in mice and rats and is of carcinogenic risk to

humans, with a cancer potency factor of 1.1 mg/kg/day for oral exposure.

1.9.1.8 Mirex

Chemical Name: 1,1a,2,2a,3,3a,4,5,5a,5b,6-Dodecachloroacta-hydro-1,3,4-metheno-1H-cyclobuta-

[cd]pentalene (C10Cl12). CAS Number: 2385-85-5

Properties: Solubility in water: 0.07 µg/L at 25°C; vapour pressure: 3 x 10-7 mm Hg at 25°C; log KOW: 5.28.

Discovery/Uses: The use of Mirex in pesticide formulations started in the mid 1950s largely focused on the

control of ants. It is also a fire retardant for plastics, rubber, paint, paper and electrical goods. Technical grade

preparations of mirex contain 95.19% mirex and 2.58% chlordecone, the rest being unspecified. Mirex is also

used to refer to bait comprising corncob grits, soya bean oil, and mirex.

Persistence/Fate: Mirex is considered to be one of the most stable and persistent pesticides, with a half-life is

soils of up to 10 years. Bioconcentration factors of 2600 and 51400 have been observed in pink shrimp and

fathead minnows, respectively. It is capable of undergoing long-range transport due to its relative volatility

(VPL = 4.76 Pa; H = 52 Pa m 3 /mol).

Toxicity: The acute toxicity of Mirex for mammals is moderate with an LD50 in rat of 235 mg/kg and dermal

toxicity in rabbits of 80 mg/kg. Mirex is also toxic to fish and can affect their behaviour (LC50 (96 hr) from 0.2

to 30 mg/L for rainbow trout and bluegill, respectively). Delayed mortality of crustaceans occurred at 1 µg/L

exposure levels. There is evidence of its potential for endocrine disruption and possibly carcinogenic risk to

humans.

6

1.9.1.9 Hexachlorobenzene (HCB)

Chemical Name: Hexachlorobenzene (C6Cl6) CAS Number: 118-74-1

Properties: Solubility in water: 50 µg/L at 20°C; vapour pressure: 1.09 x 10-5 mm Hg at 20°C; log KOW: 3.93-

6.42.

Discovery/Uses: It was first introduced in 1945 as fungicide for seed treatments of grain crops, and used to

make fireworks, ammunition, and synthetic rubber. Today it is mainly a by-product in the production of a large

number of chlorinated compounds, particularly lower chlorinated benzenes, solvents and several pesticides.

HCB is emitted to the atmosphere in flue gases generated by waste incineration facilities and metallurgical

industries.

Persistence/Fate: HCB has an estimated half-life in soils of 2.7-5.7 years and of 0.5-4.2 years in air. HCB has

a relatively high bioaccumulation potential and long half-life in biota.

Toxicity: LC50 for fish varies between 50 and 200 µg/L. The acute toxicity of HCB is low with LD50 values of

3.5 mg/g for rats. Mild effects of the [rat] liver have been observed at a daily dose of 0.25 mg HCB/kg bw.

HCB is known to cause liver disease in humans (porphyria cutanea tarda) and has been classified as a possible

carcinogen to humans by IARC.

1.9.2 Industrial

compounds

1.9.2.1 Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs)

Chemical Name: Polychlorinated biphenyls (C12H(10-n)Cln, where n is within the range of 1-10). CAS Number:

Various (e.g. for Aroclor 1242, CAS No.: 53469-21-9; for Aroclor 1254, CAS No.: 11097-69-1);

Properties: Water solubility decreases with increasing chlorination: 0.01 to 0.0001 µg/L at 25°C; vapour

pressure: 1.6-0.003 x 10-6 mm Hg at 20°C; log KOW: 4.3-8.26.

Discovery/Uses: PCBs were introduced in 1929 and were manufactured in different countries under various

trade names (e.g., Aroclor, Clophen, Phenoclor). They are chemically stable and heat resistant, and were used

worldwide as transformer and capacitor oils, hydraulic and heat exchange fluids, and lubricating and cutting

oils. Theoretically, a total of 209 possible chlorinated biphenyl congeners exist, but only about 130 of these are

likely to occur in commercial products.

Persistence/Fate: Most PCB congeners, particularly those lacking adjacent unsubstituted positions on the

biphenyl rings (e.g., 2,4,5-, 2,3,5- or 2,3,6-substituted on both rings) are extremely persistent in the

environment. They are estimated to have half-lives ranging from three weeks to two years in air and, with the

exception of mono- and di-chlorobiphenyls, more than six years in aerobic soils and sediments. PCBs also have

extremely long half-lives in adult fish, for example, an eight-year study of eels found that the half-life of PCB

153 was more than ten years.

Toxicity: LC50 for the larval stages of rainbow trout is 0.32 µg/L with a NOEL of 0.01 µg/L. The acute toxicity

of PCB in mammals is generally low and LD50 values in rat of 1 g/kg bw. IARC has concluded that PCB are

carcinogenic to laboratory animals and probably also for humans. They have also been classified as substances

for which there is evidence of endocrine disruption in an intact organism.

1.9.3 Unintended

by-products

1.9.3.1 Polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins (PCDDs) and Polychlorinated dibenzofurans (PCDFs)

Chemical Name: PCDDs (C12H(8-n)ClnO2) and PCDFs (C12H(8-n)ClnO) may contain between 1 and 8 chlorine

atoms. Dioxins and furans have 75 and 135 possible positional isomers, respectively. CAS Number: Various

(2,3,7,8-TetraCDD: 1746-01-6; 2,3,7,8-TetraCDF: 51207-31-9).

Properties: Solubility in water: 0.43 0.0002 ng/L at 25°C; vapour pressure: 2 0.007 x 10-6 mm Hg at 20°C;

log KOW: in the range 6.60 8.20 for tetra- to octa-substituted congeners.

Discovery/Uses: They are by-products resulting from the production of other chemicals and from combustion

and incineration processes. They have no known use.

Persistence/Fate: PCDD/Fs are characterised by their lipophilicity, semi-volatility and resistance to

degradation (half life of TCDD in soil of 10-12 years). They are also known for their ability to bioconcentrate

and biomagnify under typical environmental conditions.

Toxicity: The toxicological effects reported refer to the 2,3,7,8-substituted compounds (17 congeners) that are

agonist for the AhR. All the 2,3,7,8-substituted PCDDs and PCDFs plus coplanar PCBs (with no chlorine

substitution at the ortho positions) show the same type of biological and toxic response. Possible effects include

dermal toxicity, immunotoxicity, reproductive effects and teratogenicity, endocrine disruption and

7

carcinogenicity. At the present time, the only persistent effect associated with dioxin exposure in humans is

chloracne. The most sensitive groups are fetus and neonatal infants.

Effects on the immune systems in the mouse have been found at doses of 10 ng/kg bw/day, while reproductive

effects were seen in rhesus monkeys at 1-2 ng/kg bw/day. Biochemical effects have been seen in rats down to

0.1 ng/kg bw/day. In a re-evaluation of the TDI for dioxins, furans (and planar PCB), the WHO decided to

recommend a range of 1-4 TEQ pg/kg bw, although more recently the acceptable intake value has been set

monthly at 1-70 TEQ pg/kg bw.

1.9.4 Regional

specific

1.9.4.1 Atrazine

Chemical Name: 2-Chloro-4-(ethlamino)-6-(isopropylamino)-s-triazine (C10H6Cl8).

CAS Number: 19-12-24-9

Properties: Solubility in water: 28 mg/L at 20°C; vapour pressure: 3.0 x 10-7 mm Hg at 20°C; log KowPartition

Coefficient: 2.3404.

Discovery/Uses: Atrazine is a selective triazine herbicide used to control broadleaf and grassy weeds in corn,

sorghum, sugarcane, pineapple, christmas trees, and other crops, and in conifer reforestation plantings. It was

discovered and introduced in the late 50's. Atrazine is still widely used today because it is economical and

effectively reduces crop losses due to weed interference.

Persistence/Fate: The chemical does not adsorb strongly to soil particles and has a lengthy half-life (60 to

>100 days)., Aatrazine has a high potential for groundwater contamination despite its moderate solubility in

water.

Toxicity: The oral LD50 for atrazine is 3090 mg/kg in rats, 1750 mg/kg in mice, 750 mg/kg in rabbits, and

1000 mg/kg in hamsters. The dermal LD50 in rabbits is 7500 mg/kg and greater than 3000 mg/kg in rats.

Atrazine is practically nontoxic to birds. The LD50 is greater than 2000 mg/kg in mallard ducks. Atrazine is

slightly toxic to fish and other aquatic life. Atrazine has a low level of bioaccumulation in fish. Available data

regarding atrazine's carcinogenic potential are inconclusive.

1.9.4.2 Hexachlorocyclohexanes (HCH)

Chemical Name: 1,2,3,4,5,6-Hexachlorocyclohexane (mixed isomers) (C6H6Cl6). CAS Number: 608-73-1 (-

HCH, lindane: 58-89-9).

Properties: -HCH: solubility in water: 7 mg/L at 20°C; vapour pressure: 3.3 x 10-5 mm Hg at 20°C; log KOW:

3.8.

Discovery/Uses: There are two principle formulations: "technical HCH", which is a mixture of various

isomers, including -HCH (55-80%), -HCH (5-14%) and -HCH (8-15%), and "lindane", which is essentially

pure -HCH. Historically, lindane was one of the most widely used insecticides in the world. Its insecticidal

properties were discovered in the early 1940s. It controls a wide range of sucking and chewing insects and has

been used for seed treatment and soil application, in household biocidal products, and as textile and wood

preservatives.

Persistence/Fate: Lindane and other HCH isomers are relatively persistent in soils and water, with half-lives

generally greater than 1 and 2 years, respectively. HCH are much less bioaccumulative than other

organochlorines because of their relatively low liphophilicity. On the other hand, their relatively high vapour

pressures, particularly of the -HCH isomer, make them susceptible to long-range transport in the atmosphere.

Toxicity: Lindane is moderately toxic to invertebrates and fish, with LC50 values of 20-90 µg/L. Acute toxicity

to mice and rats is moderate with LD50 values in the range of 60-250 mg/kg. A number of studies on Lindane

have not been found to have any mutagenic potential in but endocrine disrupting activity.

1.9.4.3 Endosulfan

Chemical Name: 6,7,8,9,10,10-Hexachloro-1,5,5a,6,9,9a-hexahydro-6,9-methano-2,4,3-benzodioxathiepin-3-

oxide (C9H6Cl6O3S). CAS Number: 115-29-7.

Properties: Solubility in water: 320 µg/L at 25°C; vapour pressure: 0.17 x 10-4 mm Hg at 25°C; log KOW: 2.23-

3.62.

Discovery/Uses: Endosulfan was first introduced in 1954. It is used as a contact and stomach insecticide and

acaricide in a great number of food and non-food crops (e.g. tea, vegetables, fruits, tobacco, cotton) and it

8

controls over 100 different insect pests. Endosulfan formulations are used in commercial agriculture and home

gardening and for wood preservation. The technical product contains at least 94% of two pure isomers, - and

-endosulfan.

Persistence/Fate: It is moderately persistent in the soil environment with a reported average field half-life of

50 days. The two isomers have different degradation times in soil (half-lives of 35 and 150 days for - and -

isomers, respectively, in neutral conditions). It has a moderate capacity to adsorb to soils and it is not likely to

leach to groundwater. In plants, endosulfan is rapidly broken down to the corresponding sulfate, on most fruits

and vegetables, 50% of the parent residue is lost within 3 to 7 days.

Toxicity: Endosulfan is highly to moderately toxic to bird species (Mallards: oral LD50 31 - 243 mg/kg) and it

is very toxic to aquatic organisms (96-hour LC50 rainbow trout 1.5 µg/L). It has also shown high toxicity in rats

(oral LD50: 18 - 160 mg/kg, dermal LD50: 78 - 359 mg/kg). Female rats appear to be 45 times more sensitive to

the lethal effects of technical-grade endosulfan than male rats. The -isomer is considered to be more toxic than

the -isomer. There is strong evidence of its potential for endocrine disruption.

1.9.4.4 Pentachlorophenol (PCP)

Chemical Name: Pentachlorophenol (C6Cl5OH). CAS Number: 87-86-5.

Properties: Solubility in water: 14 mg/L at 20°C; vapour pressure: 16 x 10-5 mm Hg at 20°C; log KOW: 3.32

5.86.

Discovery/Uses: It is used as insecticide (termiticide), fungicide, non-selective contact herbicide (defoliant)

and, particularly as wood preservative. It is also used in anti-fouling paints and other materials (e.g. textiles,

inks, paints, disinfectants and cleaners) as inhibitor of fermentation. Technical PCP contains trace amounts of

PCDDs and PCDFs

Persistence/Fate: The rate of photodecomposition increases with pH (t1/2 100 hr at pH 3.3 and 3.5 hr at pH

7.3). Complete decomposition in soil suspensions takes >72 days; other authors report a half-life in soils of 23-

178 days. Although enriched through the food chain, it is rapidly eliminated after discontinuing exposure (t

1/2 =

10-24 h for fish).

Toxicity: The 24-h LC50 values for trout were reported as 0.2 mg/L, and chronic toxicity effects were observed

at concentrations down to 3.2 µg/L. Mammalian acute toxicity of PCP is moderate-high. Oral LD50 in rats

ranging from 50 to 210 mg/kg bw have been reported. LC50 ranged from 0.093 mg/L in rainbow trout (48 h) to

0.77-0.97 mg/L for guppy (96 h) and 0.47 mg/L for fathead minnow (48 h).

1.9.4.5 Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs)

Chemical Name: PAHs are a group of compounds consisting of two or more fused aromatic rings. CAS

Number:

Properties: Solubility in water: 0.00014 -2.1 mg/L at 25ºC; vapour pressure: from 0.0015 x 10-9 to 0.0051

mmHg at 25°C; log KOW: 4.79-8.20

Discovery/Use: Most of these are formed during incomplete combustion of organic material and the

composition of PAHs mixture vary with the source(s) and also due to selective weathering effects in the

environment.

Persistence/Fate: The persistence of PAHs varies with molecular weight. The low molecular weight PAHs are

most easily degraded. The reported half-lives of naphthalene, anthracene and benzo(e)pyrene in sediment are 9,

43 and 83 hours, respectively, whereas for higher molecular weight PAHs, their half-lives are up to several

years in soils/sediments. The BCFs in aquatic organisms range between 100-2000 and increase with increasing

molecular size. Due to their widespread distribution, environmental pollution by PAHs has aroused global

concern.

Toxicity: The acute toxicity of low molecular weight PAHs is moderate with an LD50 of naphthalene and

anthracene in rat of 490 and 18000 mg/kg body weight respectively. The higher molecular weight PAHs exhibit

higher toxicity and LD50 of benzo(a)anthracene in mice is 10mg/kg body weight. In Daphnia pulex, LC50 for

naphthalene is 1.0 mg/L, for phenanthrene 0.1 mg/L and for benzo(a)pyrene is 0.005 mg/L. The critical effect

of many PAHs in mammals is their carcinogenic potential. The metabolic action of these substances produces

intermediates that bind covalently with cellular DNA. IARC has classified benz[a]anthracene, benzo[a]pyrene,

and dibenzo[a,h]anthracene as probably carcinogenic to humans. Benzo[b]fluoranthene and indeno[1,2,3-

c,d]pyrene were classified as possibly carcinogenic to humans.

9

1.9.4.6 Phthalates

Chemical Name: They encompass a wide family of compounds. Dimethylphthalate (DMP), diethylphthalate

(DEP), dibutylphthalate (DBP), benzylbutylphthalate (BBP), di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate (DEHP)(C24H38O4) and

dioctylphthalate (DOP) are some of the most common. CAS Nos.: 84-74-2 (DBP), 85-68-7 (BBP), 117-81-7

(DEHP).

Properties: The physico-chemical properties of phthalic acid esters vary greatly depending on the alcohol

moieties. Solubility in water: 9.9 mg/L (DBP) and 0.3 mg/L (DEHP) at 25°C; vapour pressure: 3.5 x 10-5

(DBP) and 6.4 x 10-6 (DEHP) mm Hg at 25°C; log KOW: 1.5 to 7.1.

Discovery/Uses: They are widely used as plasticisers, insect repellents, solvents for cellulose acetate in the

manufacture of varnishes and dopes. Vinyl plastic may contain up to 40% DEHP.