GEF/UNEP PDF-B

Western Indian Ocean

Preliminary

Transboundary

Diagnostic Analysis

For

Land-Based Activities

15 January 2002

DRAFT

Table of Contents

I. INTRODUCTION ..............................................................................................6

II. PHYSICAL AND BIOGEOCHEMICAL SETTING ...........................................8

II. 1 WATERSHEDS.......................................................................................................................... 8

II. 2 GEOLOGY AND GEOMORPHOLOGY ......................................................................................... 9

II. 3 OCEANOGRAPHY................................................................................................................... 10

II. 4 IMPORTANT ECOSYSTEMS..................................................................................................... 12

II. 4. 1 MANGROVES/COASTAL FORESTS ..................................................................................... 12

II. 4. 2 SEAGRASS BEDS................................................................................................................ 12

II. 4. 3 CORAL REEFS .................................................................................................................... 13

II. 5 ENDANGERED SPECIES.......................................................................................................... 14

II. 6 FISHERIES.............................................................................................................................. 14

II. 6. 1 ARTISANAL FISHERIES...................................................................................................... 14

II. 6. 2 COASTAL COMMERCIAL FISHERIES .................................................................................. 15

II. 6. 3 HIGH SEAS COMMERCIAL FISHERIES................................................................................ 15

III. SOCIO-ECONOMIC AND DEVELOPMENT SETTING ................................15

III. 1 HUMAN DEVELOPMENT....................................................................................................... 15

III. 2 TOURISM.............................................................................................................................. 17

IV. LEGAL AND REGULATORY SETTING ......................................................18

V. MAJOR TRANSBOUNDARY PERCEIVED PROBLEMS AND ISSUES......30

V.1 FRESH WATER SHORTAGE AND CONTAMINATION.................................................................. 32

V.2 DECLINE IN HARVESTS OF MARINE AND COASTAL LIVING RESOURCES .............................. 38

V.3 DEGRADATION OF COASTAL HABITATS (MANGROVES, SEAGRASS BEDS, AND CORAL

REEFS), LOSS OF BIODIVERSITY. .................................................................................................. 48

V.4 OVERALL WATER QUALITY DECLINE: DEGRADATION OF COASTAL WATERS, BEACHES

AND LIVING RESOURCES FROM LAND BASED ACTIVITIES............................................................ 60

i

VI. STAKEHOLDER ANALYSIS .....................................................................100

VII. ENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY OBJECTIVES ...........................................104

VIII. BIBLIOGRAPHY ......................................................................................115

ii

List of Figures

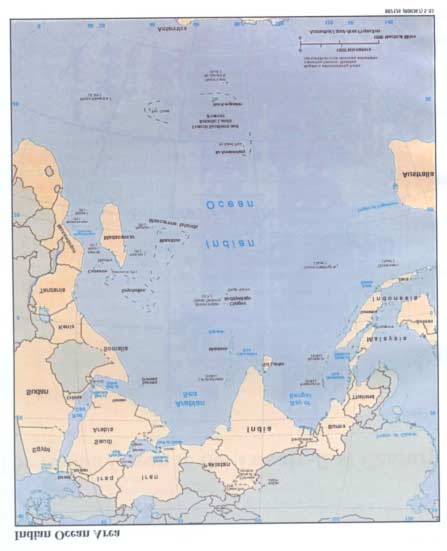

Figure 1.

Indian Ocean Area .........................................................................................11

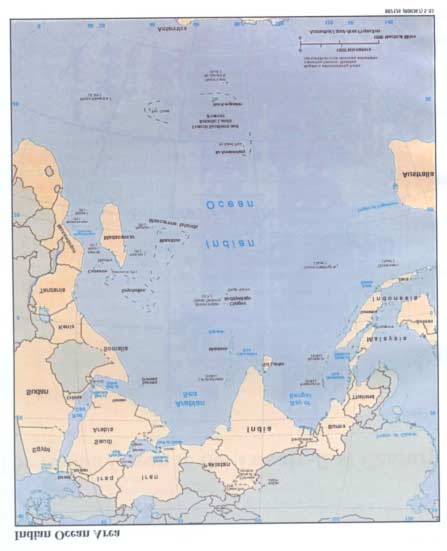

Figure 2. A New Generation: Projected population growth in the Eastern African

Region (1991-2020) .......................................................................................18

Figure 3.

Causal Chain Analysis: Fresh water shortage and contamination.................34

Figure 4.

Causal Chain Analysis: Decline in harvests of marine and coastal living

resources ........................................................................................................40

Figure 5.

Evolution of the catch rates of shrimp on Sofala Bank (Hoguane, 2000) .....43

Figure 6.

Causal Chain Analysis: Degradation of biodiversity and coastal habitats ....50

Figure 7.

Causal Chain Analysis: Overall water quality decline/contamination ..........64

iii

List of Tables

Table 1. Some characteristics of the major rivers of the Western Indian Ocean

Region .................................................................................................................8

Table 2. Coastal plains and continental and island shelf areas of the Western Indian

Ocean...................................................................................................................9

Table 3. Distribution of mangrove forests.......................................................................12

Table 4. The common breeding sites for different species of turtle................................14

Table 5. Human Development Index and Gross Domestic Product for some of the

countries in the Western Indian Ocean Region .................................................16

Table 6. Coastline usage in Mauritius in 1990 and 1996 ................................................16

Table 7. Population and population density for the countries of the region....................17

Table 8. Government Institutions Dealing with Different Aspects of Coastal and

Marine Environment in Zanzibar ......................................................................28

Table 9. Root Causes and Major Perceived Problems and Issues...................................31

Table 10. Number of cases of waterborne diseases reported in coastal provinces of

Mozambique (Anon, 1998). ...............................................................................33

Table 11. Annual river flows in cubic km, 1995...............................................................35

Table 12. Pollution Loads to Ground Water Sources (Kg/Day) in Dar es Salaam ...........37

Table 13. Rural Water Supply and Population Coverage by Administrative Coastal

Regions (Tanzania) in 1993 and Projected Demand to year 2002 ....................37

Table 14. Urban Water Supply/Demand for Coastal Districts (Tanzania) in 1993...........38

Table 15. The number of coastal fishermen deriving their livelihood from fisheries .......39

Table 16. Fishery resources, catch, and level of exploitation in Mozambique .................41

Table 17. Fish Catch (tons) by type of fisheries in Mozambique .....................................42

Table 18. Catch per Fisherman/Day (kg) in Mauritius......................................................44

Table 19. Production and Employment in Mauritius, 1995 ..............................................45

Table 20. Annual Catch from submerged Banks in Mauritius..........................................45

Table 21. Tuna Landing in Mauritius................................................................................45

Table 22. Annual coastal fish catch (tons) in Mauritius....................................................46

Table 23. Total Artisanal Catch (1994-1999) in Metric Tons in Seychelles.....................46

Table 24. Sea cucumber export from Tanzania.................................................................47

Table 25. Total marine fish production (in tons) for Tanzania mainland: 1985 1995. ...47

Table 26. Mangrove degradation in Mozambique, 1972-90 .............................................52

Table 27. Average cases of disease per year for the period 1993-1997 for Dar es

Salaam ...............................................................................................................62

Table 28. For Tanzania, disease incidence per 100,000 population..................................63

Table 29. Number of cases of waterborne diseases reported in coastal provinces of

Mozambique......................................................................................................63

Table 30. Concentration of nitrates (NO3) in wells around Maputo with time

(Casadei et al., 1985).........................................................................................67

Table 31. Concentration of nitrates (NO3) with distance from latrines around Maputo

(Casadei et al., 1985).........................................................................................67

Table 32. Concentration of nitrates (NO3) in wells around Maputo (Casadei et al.,

1985)..................................................................................................................67

iv

Table 33. Concentration of nitrates (NO3) in borehole waters around Maputo and

Matola cities (LNHAA, unpublished) ...............................................................68

Table 34. Summary of pollution loads from Mombasa District (Kenya)..........................70

Table 35. Pollution Load to Surface Water Resources (Kg/Day) in Dar es Salaam .........75

Table 36. Summary of pollution loads from Kwale District (Kenya)...............................81

Table 37. Summary of pollution loads from Kilifi District (Kenya).................................82

Table 38. Summary of pollution loads from Lamu District (Kenya) ................................82

Table 39. Concentration of heavy metals (mg l-1) in sediments of Elephant River at

Mamba (Loc 1) and Baule, in Kruger Park (Loc 2), in February-November

1994 (after Robinson and Avenant-Oldewage, 1994).......................................89

Table 40. Mercury concentration (mg l-1) in the water in Umbeluzi River (LNHAA,

1994)..................................................................................................................89

Table 41. Hot spots identified in the National Reports .....................................................94

Table 42. Sites of current and potential mineral exploitation and quarrying in coastal

areas...................................................................................................................98

Table 43. Environmental Quality Objectives, Targets, and Interventions ......................104

v

I. Introduction

TDA Content and Process

According to GEF guidance, the purpose of conducting a Transboundary Diagnostic

Analysis (TDA) is to scale the relative importance of sources and causes, both immediate

and root, of transboundary `waters' problems, and to identify potential preventive and

remedial actions. The TDA provides the technical basis for development of both the

National Action Plans (NAPs) and the Strategic Action Programme (SAP) in the area of

international waters of the GEF.

This TDA, therefore, summarizes information available from the region, gathered both as

part of ongoing national activities within the littoral states, as well as information made

available since from the variety of internationally supported activities in the region.

The methodology for a TDA consists of the following steps, at a minimum:

· Identification of major perceived problems and issues, including status and gaps

· Classification as national or Transboundary in nature

· Causal chain analysis (including root causes)

· Identification of interventions to address the root causes and primary perceived

problems and issues

Because the list of possible interventions and actions arising from the analysis of Western

Indian Ocean (WIO) problems is so large, a mechanism was needed in order to prioritize the

interventions. Borrowing from methodology commonly used in the European Union and

other regions, the present TDA identifies a series of Environmental Quality Objectives

(EQOs), which represent the regional perspective of major goals for the regional

environment. The use of EQOs helps to refine the TDA process by achieving consensus on

the desired status of the WIO. Within each EQO (which is a broad policy-oriented

statement), several specific targets were identified. Each target generally had a timeline

associated with it, as well as a specific level of improvement/ status. Thus, the targets

illustrate the logic chain for eventual achievement of the EQO. Finally, specific

interventions or actions were identified to permit realization of each of the targets, within the

time frame designated.

In summary, this TDA follows the general GEF TDA Guidelines for International Waters

projects. However, an additional step was achieved, that is, use of Environmental Quality

Objectives, in order to facilitate consensus on the desired state of WIO after the next pentade

or decade. The EQOs naturally led to identification of specific targets to be met within the

desired time frame, and from there identification of specific interventions and actions that

can be considered in the framework of the NAPs and SAP.

6

Geographic Scope of the TDA

The present analysis covers a vast region of the Western Indian Ocean from Somalia to

South Africa and includes the following countries: Comoros, Kenya, Madagascar,

Mauritius, Mozambique, Seychelles, Somalia, South Africa, and Tanzania. Only partial

information on the environmental status was provided by each country, so this TDA is a

summary of available information only. Where possible, additional sources of data were

sought.

This TDA relies on the preliminary TDA prepared by the Institute of Marine Sciences,

University of Dar es Salaam in 1998, National reports from the participating countries,

various technical publications available for the region prepared by UNEP, ACOPS, and

other organizations. The major sources of information are listed in the Bibliography

accompanying this TDA. Gaps in information available to this TDA can be filled during

the full GEF project.

This Preliminary TDA identifies the following list of major perceived problems and

issues. It includes four existing problems/issues:

1. Shortage and contamination of fresh water

2. Decline in harvests of marine living resources

3. Degradation of coastal habitats (mangroves, seagrass beds, and coral reefs), loss

of biodiversity.

4. Overall water quality decline: Contamination of coastal waters, beaches and

living resources.

Below, each of these problems and issues is addressed from a status perspective. It

answers the question: what do we know about each problem/issue? What data support the

quantification of the extent of the problem/issue? Do the data support these as real

problems and issues, or just as perceptions? This analysis took place on a scientific level,

including biological, oceanographic, physical, social, and other perspectives on the

problem. This is in effect the "status" assessment.

The next step was to perform the causal chain analysis; the major perceived problems and

issues were analyzed to determine the primary, secondary and root causes for these

problems/issues. Identification of root causes is important because root causes tend to be

more systemic and fundamental contributors to environmental degradation. Interventions

and actions directed at the root causes tend to be more sustainable and effective than

interventions directed at primary or secondary causes. However, because the linkages

between root causes and solutions of the perceived problems are often not clear to

policymakers, interventions commonly are erroneously directed at primary or secondary

causes.

This TDA attempts to clarify the linkages between root causes and perceived problems,

to encourage interventions at this more sustainable level. Fortunately, root causes are

7

common to a number of different perceived problems and issues, so addressing a few root

causes may have positive effects on several problems and issues (Table 9).

This TDA draft faced several challenges, including lack of complete information and

data, short time open for its final preparation, and limited time in the Region.

II. Physical and Biogeochemical Setting

The Western Indian Ocean (WIO) Region is comprised of the continental coastal states

(Somalia, Kenya, Tanzania, Mozambique and South Africa) and the island States

(Mauritius, Comoros, Reunion, Seychelles, and Madagascar). The ten Western Indian

Ocean nations are at different stages of both political and economic development. These

differences are reflected in the range of individual economic indicators from those with a

per capita gross national product of over $ 8,000 per annum, to those with $500 per

capita. Similarly, national institutions reflect comparable variations in strength and

infrastructure.

II. 1 Watersheds

The major watersheds are on the East African mainland and Madagascar. By far, the

largest is the Zambezi River which has a drainage basin estimated at more than one

million km2. Other large waterlands include the basins of the Rufiji, Juba, Limpopo and

Tana rivers.

Table 1.

Some characteristics of the major rivers of the Western Indian Ocean

Region

River Drainage

Area

Highest Recorded Flow

(1000 km2)

(m3/s)

Zambezi 1,300

8,625

Limpopo 358

n/a

Juba

200

n/a

Rufiji

158

5,754

Tana

132

5,400

Wami

36

348

Pangani

36

248

Ruvu

16

1,177

Source: Matondo (1989)

The coastal areas of the continental Western Indian Ocean countries are characterized by

a coastal plain which averages 15-20 km in width, and which rises inland to upland

savannahs and plateaux. In northern Somalia, the coastal plain is extremely narrow but

widens toward the south, where valleys and flood plains of the larger rivers accumulate

sediments. In some areas, the coastal plain ranges from a few hundred meters wide to

around 145 km, in particular in areas such as the Juba and Shebelle, Tana, Rufiji, and

Zambezi deltas.

8

The continental shelf is generally narrow, but varies considerably. On most headlands

and straight stretches of coastline there is virtually no shelf, and steep continental slopes

to the ocean floor are only a few kilometers offshore in many places along the continent.

The shelf sediments are generally sandy, especially in shallow areas, changing to mud in

deeper areas and near river mouths and estuaries.

The shelf surrounding Madagascar varies greatly, with a narrower shelf and steeper

continental slope on the east coast than on the continent. The shelf is wider on the west

side and is widest in the northwest.

Comoros and Mauritius are surrounded by deep waters from a few hundred meters to

several kilometers offshore. There are shallow banks around Rodriguez and other

Mauritian dependencies. The main islands of the Seychelles can be characterized as

steep granitic outcrops with the absence of extensive shelves; however, the Almirantes

Archipelago is basically a shelf area. There is an extensive shelf-platform on the axis

between the Seychelles and Mauritius.

Table 2.

Coastal plains and continental and island shelf areas of the Western

Indian Ocean

Country Land

Area

Coastal %Coastal

Shelf Coastline

(km2) Land Area Land Area

Area

Length

(km2)

(km2)

(km)

Comores

2,236

2,030

100

900

350

Kenya

582,650

32,447

6

655

500

Madagascar 595,790 242,745

41

135,000 4,000

Mauritius

1,865

1,328

100

1,600

200

Mozambique 738,030 162,938

21

120,000 2,500

Seychelles

443

455

100 48,000

600

Somalia

637,657

n/a

n/a 32,500

3,000

Tanzania

939,703

6

6 30,000

800

II. 2 Geology and Geomorphology

Many types of geological formations are found in the region, with ages ranging from 200

million years to recent. For instance, the coastal sediments of Tanzania vary in age from

Jurassic through Cretaceous to Tertiary and Quarternary and are composed of both

marine and terrestrial sedimentary rocks (Kent et al., 1971). The islands of Reunion,

Comoros, and Mauritius are essentially volcanic while those of the Seychelles are

granitic.

In terms of its geological structure, the coastline of Eastern Africa represents a passive

continental margin, from which through geological time continental fragments, large and

small, have separated and migrated across the adjoining oceanic crust. Some of these

detached continental fragments remain within the region, notably the Seychelles Bank

and Madagascar. This structural history has left the mainland states with generally

narrow continental shelves. Exceptions include the coasts of southern Mozambique and

9

central Tanzania in the vicinity of Unguja and Mafia islands. In the island states, wider

shelves exist in western Madagascar and part of the Seychelles. Pleistocene coral

limestones overlap older rocks along much of the mainland coastline and on some of the

islands. These limestones form extensive coastal terraces, cliffs, and intertidal platforms

(Arthurton, 1992).

Fringing, largely intertidal platforms, eroded mostly in these Pleistocene limestones,

dominate the coastal geomorphology in much of the region. Commonly cliff-bounded to

landwards, these platforms extend seawards from a few tens of meters to more than two

kilometers from the back shore, their seaward edges forming breaker zones for ocean

swell. Terraces and platforms alike are incised by major creeks draining the hinterland,

as at Dar Es Salaam and Mombasa. Holocene and Recent beach ridge and bar deposits

overlie the platform rocks in many places. Mangrove forests are developed in many of

the sheltered sedimentary embayments including those in deltaic areas, such as the

outflow of the Rufiji River in Tanzania. Coastal sand dunes are associated with river

mouths where there is a high discharge of terrigenous sediment, as from the Sabaki River

in Kenya (Arthurton, 1992). Water resources, including potable water supplies, are

dominated by groundwater in coastal areas of highly permeable Pleistocene limestone.

II. 3 Oceanography

The Western Indian Ocean is a tropical area where the air temperature at sea level rarely

falls below 20°C and seawater temperature is usually between 20-30°C. Ocean currents

are an important feature that strongly influence the distribution of marine organisms and

the availability of nutrients. The South Equatorial Current which flows at around 12°S is

the principal current flowing from east to west all year round. Part of the Current

branches off northeast of Madagascar to form the southeastward Madagascar Current,

while the main stream splits west of the northern tip of Madagascar into a southward

current which flows through the Mozambique forming the perennial Mozambique

Current, and a northward component which forms the East African Coastal Current

(EACC). EACC flows as far north as southern Somalia, after which its direction depends

on the season, becoming the Somali Current and later joining the Indian Monsoon

Current during the SE monsoon; during the NE monsoon it becomes the eastward

flowing Equatorial Counter Current. South of Madagascar, the East Madagascar Current

and the Mozamibique Current join at about 26°S to form the Agulhas Current.

Based on the Current systems prevailing in the Region, three Large Marine Ecosystems

(LMEs) have been identified, namely the Somali Coastal Current, the Agulhas Current,

and the Mascarene Plateau. These LMEs cover ecosystems and resources shared by

several countries as they extend beyond the boundaries of the EEZs of some countries in

the region.

10

Figure 1. Indian Ocean Area

11

II. 4 Important Ecosystems

The coastal ecosystems of the region are generally both rich in natural resources and

highly productive. Especially important habitats include mangrove forests, coral reefs,

and seagrass meadows. Of the 38 designated marine and coastal habitats, at least one

third are found within each country of the region; the greatest known diversity was

reported in Mozambique where 87% of all habitat types are recorded (UNEP, 1984).

These ecosystems sustain a great diversity of marine life and represent an important food

source for most coastal communities.

The conditions within each ecosystem are influenced by the adjacent ecosystems. For

example, mangrove ecosystems are a nursery ground for a variety of fish, some of which

mature in coral reefs and sea grass meadows. There is also nutrient, sediment, and

organic matter interchange between the ecosystems.

II. 4. 1 Mangroves/Coastal Forests

In the intertidal areas of the Western Indian Ocean, there are many areas with conditions

favorable for mangroves. These areas include estuaries, bays, protected shores, and

lagoons. While mangroves are found scattered along much of the Region shoreline, the

most significant stands occur in Kenya, Tanzania, Madagascar, and Mozambique.

The main species occurring are Rhizophora mucronata, Ceriops tagal, and Bruguiera

gvmnorrhiza. Other species include Avicennia marina, Avicennia officionalis, Heritiera

littolaris, Lumnitzera racemosa, Sonneratia alba, Xylocarpus granatum, and Xylocarpus

moluccensis.

Matthes and Kapetsky (1988) found that the Western Indian Ocean Region has a total of

654 species of algae, molluscs, crustaceans, echinoderms, and fishes of economic

importance which are associated with mangroves.

Table 3.

Distribution of mangrove forests

Country

Mangrove area (ha)

Comoros Negligible

Kenya

62,027

Madagascar

320,700

Mauritius Negligible

Mozambique

84,800

Seychelles Negligible

Tanzania

133,500

II. 4. 2 Seagrass Beds

The seagrass beds which occur throughout the region are a common feature of intertidal

mud and sand flats, coastal lagoons, and sandy areas around the bases of shallow fringing

and patch reefs. They are found in all countries of East Africa, the most extensive beds

12

being around Bazaruto archipelago in Mozambique. In Tanzania, seagrass beds are

found in all bays and the west side of Pemba, Unguija, and Mafia islands. In Kenya,

seagrass and algal beds are prominent in Mombasa, Diani, and Malindi, and in Seychelles

they are dominant in Platte, Coetivy, and Aldabra.

Worldwide there are 58 species of seagrasses of which twelve species are found in the

Western Indian Ocean region. These include Enhalus acoroides, Thalassia hemprichii,

Halophila ovalis, Halophila stipulacea, Zostera capensis, Cymodocea rotundata,

Cymodocea serrulata, Halodule uninervis, Halodule wrightii and Syringodium

isoetifolium.

Shallow-rooted seagrasses forms such as Halodule, Cymnodocea and Syringodium have

colonized unstable sediments in the intertidal as well as in the lagoon waters. Thalassia

sp. and Thalasodentron sp. dominate in lagoons areas with consolidated sediments.

Seagrass beds provide shelter, food and nursery area for some of the important and

valuable species of fish (siganids, lethrinids, lutjanids, scarids), shellfish, dugong

(Dugong dugong) and the green turtle (Chelonia mydas).

In Mozambique, the distribution of dugong and the green turtle are closely associated

with that of seagrass beds (National Report from Mozambique).

II. 4. 3 Coral reefs

Coral reefs are among the most biologically diverse ecosystems typical of the coast of

East Africa from Somalia to Mozambique featuring fringing and patch reefs along the

coastline, with Mozambique, Tanzania, Madagascar, and Kenya having the largest

coverage by area. They provide habitats for a wide variety of marine species and protect

coastal areas from erosion and storm damage. They occur at the margins of the fringing

platforms, mostly on the outer seaward facing slopes and in adjoining lagoons, on

shallow sub-tidal patches isolated from extensive platforms. The island states have a

wide variety of reef formation, including atoll formations such as in Aldabra Seychelles,

Comoros, Mauritius, and Rodriguez. The east coast of Madagascar, Kenya, and Tanzania

all have extensive fringing reefs except where they are broken in the vicinity of rivers and

bay mouths (delta areas of Zambezi and Limpopo in Mozambique and Rufiji in

Tanzania). The barrier reefs along the southern coast of Madagascar extend for 200 km

forming one of the largest true barrier reefs in the world.

According to Sheppard (1987), the total number of coral species recorded in different

parts of the region are as follows:

Kenya-Tanzania coastline

112 Species

Mozambique 149

Species

Reunion l27

Species

Mauritius l36

Species

Tulear, Madagascar

113 Species

13

Like mangrove forests, coral reefs are under pressure from human activities threatened by

land use practices and siltation, water turbidity, fishing practices involving dynamite,

poisoning, and over-harvesting to extract their rich biological and mineral wealth.

II. 5 Endangered Species

Five species of endangered marine turtles have been recorded in the region, of which the

most common ones are the hawksbill turtle and green turtle.

Table 4.

The common breeding sites for different species of turtle

Species Breeding

Area

Hawksbill

Aldabra and other small islands in the region

Green

Mainland and island beaches

Olive Ridley Northern Mozambique

Loggerhead Mozambique, South Africa

Leatherback Northern Natal, South Africa

Another endangered species is dugong. Dugong are normally found in shallow, sheltered

waters close to the coastline in bays and lagoons. There is only one species of dugong

(Dugong dugong). The largest population of dugong along the East African Coast is

found in Mozambique in Maputo Bay, Inhambane Bay, and Bazaruto Archipelago while

in Tanzania they are feared to have disappeared, as there are no recent reports of their

sightings.

II. 6 Fisheries

The marine fishery in the region is divided into three categories: Artisanal Fisheries,

Coastal Commercial Fisheries, and High Sea Commercial Fisheries. Total production

from marine fisheries in the region reached 211,000 tons in 1990, an increase of 72%

over 1980, with an estimated value of about US $670 million.

II. 6. 1 Artisanal Fisheries

The coastal fisheries is dominated by artisanal fisheries, which concentrates its fishing

activities in the coral reefs, seagrass beds, and reef flats. Artisanal fisheries are an

important source of food, employment, and income in most of the coastal communities in

the region.

For Tanzania, Kenya, Comoros, and Madagascar, the artisanal fisheries accounts for

more than 80% of the total marine fish catch. The artisanal fishery catch is dominated by

relatively limited number of specific groups, namely scavengers (rabbitfish, barracudas),

pelagic (sardines and mackerels), crustacea (crabs and lobsters), and molluscs (oysters

and octopus).

14

The productivity of coastal waters is dependent on the health of mangroves, coral reefs,

and seagrass beds as well as the amount and the quality of runoff from the rivers.

II. 6. 2 Coastal Commercial Fisheries

This type of fisheries is mainly dependent on the shrimp fisheries. Shrimp fishing occurs

mainly in the estuarine fishing grounds such as off Rufiji, Wami, and Rufiji rivers in

Tanzania, Ungwana Bay in Kenya, Sofala Bank and Maputo Bay in Mozambique, and off

the west coast of Madagascar. The catch is dominated by the species Penaeus indicus, P.

monodon, and Metapenaeus monoceros. In Madagascar, the shrimp export was the

second largest source of foreign currency in 1995.

II. 6. 3 High Seas Commercial Fisheries

There are two types of high seas fisheries in the region:

·

The purse-seine fishery concentrates mainly on surface schools of shipjack,

yellowfin, albacore and bigeye tuna. This fishery is dominated by Spanish and

French fleets.

·

The longline fishery concentrates on the larger, deep-swimming bigeye tuna,

yellowfin tuna, and bill fish. Most of the longliners are from Taiwan, Japan, and

Korea.

The tuna fishery based in Port Victoria is operated by foreign vessels. In 1995, there

were between 47 and 55 purse-seines which were licensed in Seychelles, generating total

license fee revenue of more than 47 million Seychelles Rupees. The same year, purse-

seine transhipment in Port Victoria was over 187, 145 metric tons, or about 61% of total

catch. Total net revenue accrued to Seychelles from the activities of tuna fleet (including

license fees, bunkering and other services) was SR. 102.7 million.

The tuna purse seine fishery accounts for about 60% of the total Mauritian annual fish

catch and provides a significant proportion of the raw material for canning industries.

Canned tuna represents more than 90% of the total export of fish. In 1995, the Mauritian

purse seines landed 736 tons of tuna, while 14,772 tons of tuna and related species were

transhipped by longliners during the same period.

III. Socio-Economic and Development Setting

III. 1 Human Development

The GDP of the countries considered in this overview indicates large differences in

economic development, from US$ 810 in Mozambique to US$ 9,000 in Mauritius. The

majority of the countries in the region are classified as 'poor' according to the World

Bank criteria. The social and economic implications of land-based activities are

concerned with water pollution, public health, and the sustainability of coastal resources.

15

Table 5.

Human Development Index and Gross Domestic Product for some of the

countries in the Western Indian Ocean Region

Country

HDI Rank (2000)

GDP/Capita (PPP 1999) ($)

Mauritius 71

8950

Kenya 138

1010

Tanzania 156

500

Madagascar 141

790

Mozambique 168

810

Source: UNDP (HDI) and World Bank (GDP)

The coastal zones of the mainland countries in particular are currently experiencing an

influx of people and expansion of economic activities such as tourism, which are

occurring spontaneously, with no thought given to the planning or provision of basic

infrastructure and services, protection of the marine environment, and sustainable use of

the natural resources base.

For example in Mauritius, residential and tourism development is located more or less

along the coast (Table 6). This is causing conflicts among users, as most of these

developments are blocking accessibility to beaches by fishermen as well as the general

public.

Table 6.

Coastline usage in Mauritius in 1990 and 1996

Coastline

% of Coastline % of Coastline

distribution

1990

1996

Public beaches

5.9

8.2

Hotels 9.0 13.0

Bungalows 16.0

16.0

Coastal Villages

7.7

7.7

Services 4.7 3.9

Agriculture 7.3

6.4

Fodder 5.3 8.9

Natural vegetation 32.4

24.2

Cliffs 3.2 3.2

Cliff/fodder 3.6

3.6

Total 100

100

In 1994 the combined population of the nine countries residing within coastal regions

was estimated at 19 million, of which Kenya, Mozambique, Tanzania, and Madagascar

constituted over 95% of the total (Table 7). The population growth rates of the mainland

states, the Comoros, and Madagascar are generally high, particularly in Kenya (3.3%),

Tanzania (2.8%), and Mozambique (2.8%). Growth rates in the large coastal cities, such

as Dar Es Salaam (6.7% per annum), Maputo (7.2% per annum), and Mombasa (5.0% per

annum), are even higher due to rural- urban migration. In addition to the local

population, the number of coastal tourists visiting the region has increased significantly

in recent years, which has increased the load of domestic sewage.

16

Table 7.

Population and population density for the countries of the region

Country Population

Coastal % of coastal

Population

(millions)

Population

population

Growth rate

1. Comoros

0.54

0.54

100%

2.7

2. Kenya

26.80

2.30

8.1%

3.3

3. Madagascar

12.10

4.80

36.6%

3.0

4. Mauritius

1.10

1.10

100%

1.2

5. Mozambique

18.53

6.50

39.3%

2.8

6. Seychelles

0.07

0.07

100%

1.5

7. Tanzania

28.90

4.61

16.2%

2.8

Source: Abdoulhalik (1997). Government of Kenya (1989). Ranaivoson (1997). National

Institute for Statistics (1996). Government Management and Information System (1996)

Bureau of Statistics, Ministry of Finance, Economic Affairs and Planning (1991).

III. 2 Tourism

Coastal tourism in Kenya accounts for 45% of the coastal economy. Agriculture

contributes 8%, fisheries 6%, forestry and mining another 6%, whereas industry and

harbor activities share the remaining 35%. The Nyali-Bambouri-Shanzu area,

traditionally a fishing economy, is now a tourist resort generating about 24% of all

coastal tourism earnings employing 13,000 people in hotels and another 10,000 in related

activities.

Mauritius is less dependent on tourism given the dominance of sugar production and

processing activities. It has three main tourist zones (a) the northern zone from Balaclava

to Grand Gaube, (b) the eastern zone from Roche Noire to Trout d'eau Douce, and (c) the

south-western zone from Flic-en-Flac to Le Monte. Tourist arrivals in 1995 had reached

422,463, grown by 8% a year since 1992, while foreign exchange receipts had reached

nearly 8,000 million Rupees, grown by 17% a year since 1992. Tourist accommodation

stock is 6,000 rooms plus 2,000 rooms in the informal sector. Hotels offer employment

to about 14,000 people, total tourism-induced employment reaches over 51,000

accounting for 10% of total employment.

Tourism in Comoros is limited. Arrivals in 1993 were 24,000, representing a small share

of only 4% of the arrivals in the countries of the West Indian Commission, totaling

600,000, while direct employment in tourism is about 500 people and 51 in related

activities. Foreign currency earnings are reported at 40 billion CF, roughly just over half

of the earnings from exports.

In Seychelles tourism is a significant activity described as "the mainstay of the

Seychelles economy today" (Lundin & Linden, 1995). Direct revenue from tourism

stand at 18% of the GDP, compared to 5% from agriculture, fishing and forestry,

amounting to 600 million Rupees accounting for 70% of total foreign exchange earnings.

Hotel beds exceed 2,000 and arrivals are estimated at about 60,000 tourists.

17

Figure 2. A New Generation: Projected population growth in the Eastern African

Region (1991-2020)

1991

2020

Each dot represents 25,000 people (source: World Bank)

IV. Legal and Regulatory Setting

In their endeavor to address the problems of their coastal and marine environments,

Governments of the Eastern African Region -Somalia, Kenya, Tanzania, Mozambique,

Comoros, Madagascar, Mauritius, Seychelles and France (Reunion)- came together under

the framework of UNEP's Regional Seas Programme in 1985 and endorsed the Eastern

African Action Plan (also called the Nairobi Convention) and related Protocols. The

Convention was broadly aimed at maintaining essential ecological processes and life

support systems, preserving genetic diversity, and ensuring sustainable utilization of

harvested natural resources.

18

Since then, the region has been contributing to and developing a number of initiatives

including the Arusha Resolution (April 1993) on Integrated Coastal Management in

Eastern Africa including the Island States; the first meeting of the Contracting Parties to

the Nairobi Convention, Mahé Seychelles, March 1997; the African Process on

Protection, Management and Development of the Marine and Coastal Environment,

which adopted the portfolio of actions arising from the Pan African Conference on

Sustainable Integrated Coastal Management (PACSICOM, Maputo, July 1998), and the

Cape Town Conference, (December 1998). The main activities identified were:

(a) Promotion and monitoring of long-term regional impacts caused by climate change

and adaptation planning to the effects of sea-level rise in the coastal areas,

(b) Inventory of potential hotspots in the region (shoreline changes - - coastal erosion,

land-based and marine sources of pollution, coral reefs and associated ecosystems), and

(c) Establishment and strengthening of regional measures of forecasting and early

warning capabilities to deal with natural disasters.

Today all nine East African countries have ratified the Convention: Comoros, France (La

Reunion), Kenya, Madagascar, Mauritius, Mozambique, Seychelles, Somalia, and

Tanzania. South Africa has asked to join.

Following a regional workshop in Zanzibar (6-9 October 1997), the GPA has produced a

regional overview and action plan on land-based pollution. Among its activities: to

assess pollution loads affecting the marine environment, and their harmful effects; to set

up monitoring programs and development strategies; to prepare and implement a regional

action plan; and to strengthen capacity of coastal States to intervene in case of accidents

and emergencies.

Countries are fulfilling their pledges to the regional Trust Fund in support of their

program, and welcome support for project activities has been forthcoming from

international sources: The EAF/5 project (Protection and Management of the Marine and

Coastal Areas of the Eastern Africa) received support from SIDA (Sweden); Belgium has

funded a series of activities for the preparation of databases and atlas under the project

entitled Eastern African coastal and marine environment resources database and atlas

(EAF/14); and the US has contributed US $30,000 to the UNEP Environment Fund for

the implementation of the International Coral Reef Initiative (ICRI) in Eastern Africa.

The recent high-level political commitment within the continent, as expressed in the

Maputo and Cape Town Declarations, set the stage and context of the second meeting of

the Contracting Parties to the Nairobi Convention, held in Mauritius, November 1999.

New perspectives were developed and priority focus of the Nairobi Convention and

related Action Plan in terms of delivery of services to the participating countries were

identified concurrent with global concerns for the coastal environment. At the second

Contracting Parties meeting in 1999, a joint bureau for the Nairobi and Abidjan (West

19

and Central African) Conventions met and agreed to set up a joint programming unit in

Nairobi to further cooperation on regional projects and international issues.

The Eastern African Regional Coordinating Unit, located in the Seychelles, coordinates

all activities of the Action Plan. UNEP is the secretariat of the Convention, while the

African Ministerial Conference on the Environment (AMCEN) provides guidance, as

well as political support, to the Nairobi Convention and its work program.

The countries of the WIO region are either parties to a number of regional initiatives or

actively participate in the activities promoted under these programs. These initiatives

include:

· Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission's Regional Committee for

Cooperative Investigations in the North and Central Western Indian Ocean

(IOCINCWIO)

· Eastern African and the Islands States Integrated Coastal Management Process

· Indian Ocean Commission (COI) for the island states

Despite existence of all these initiatives, the region is still faced with a number of

problems including: lack of sufficient capacity to address transboundary issues, poor

coordination among different initiatives, overlapping responsibilities, promotion of

sectoral approaches to coastal and marine environment issues, and lack of sustained

political and financial commitment to the coastal and marine environmental protection.

Below, the over-arching legal environmental context is presented country-by-country.

Mozambique

The Water Law, enacted in 1991, defines the general principles of water management, the

user rights, and the institutional control and monitoring of water use. Water is considered

as a property of the State and the public may be granted rights to the use of the water.

With regard to pollution and environment protection, the law establishes the polluters

pay principle. The law defines the concept of water contamination, to permit the

adoption of protective measures using scientific knowledge. The main objective for the

protection of water quality is stated and some prohibited activities are identified. If

pollution occurs, the law states that appropriate schedules be taken to guarantee that the

polluters gradually reduce the amount of dumping to acceptable standards, and that

whoever cause water pollution, should, at their own expense, restore the site to its normal

condition, and at the same time pay the fines.

In 1995, the government of Mozambique approved a new National Water Policy. The

policy has the same principles defined in the Water Law, but it puts emphasis on the

integrated water resources management to maximize the benefit. This is particularly

20

important during the negotiations with the neighboring countries for an equitable sharing

of water through integrated developments plans. It further ensures the protection of the

environment.

In June 1994, the government of Mozambique approved the National Environmental

Management Programme (NEMP), which is the master plan for the protection of the

environment in Mozambique. It contains a national environment policy, environment

umbrella legislation, and environmental strategy. The NEMP is also a program of

sectoral plans, containing projections for the medium and long term, aiming to lead the

country to sustainable socio-economic development. The Ministry for the Co-ordination

of Environment Affairs has taken the lead for the environmental management in

Mozambique.

One of the priority areas of NEMP is a number of activities related to integrated coastal

zone management. Specifically, the program states that the coastal zone management

should be based on an inter-institutional co-ordination among the relevant stakeholders.

The main objectives of the program are: fisheries, coastal and marine ecosystem

management, coastal and marine protection, marine parks and tourism. The program also

defines the activities for short, medium, and long term.

The creation of the Ministry for the Co-ordination of Environmental Affairs was the first

major step undertaken in the direction of an integrated management strategy for natural

resources. In fact, the co-ordination role that this institution plays stresses the adoption of

the principle of a collective, participatory and harmonized management process rather

than sectoral, isolated and not coordinated. One of the main recent achievements of this

process was the enactment of the Environmental Law by the Parliament in November,

1997. The Law was implemented in January, 1998, with the aim to guarantee that all the

activities related with the management of natural resources are undertaken in a correct

and coordinated way and involving all the stakeholders, including the planning and

decision-making level. This Law is the first attempt to introduce the concept of the

environment and a new vision and strategy for its management, both for the institution's

activities and for the public in general. Due to the comprehensive nature of this law,

complementary sectoral legislation will be produced to respond to specific situations and

needs.

With the objective of multi-sectoral coordination at the highest level, a ministerial body

was created by the enactment of the Environmental Law the National Council for

Sustainable Development. The Council is not yet in place, as there is a need for the

establishment of a proper regulation. However, this is the best way to solve the problems

of institutional relationship between the Ministry for the Coordination of Environmental

Affairs and other relevant Ministries such as the Ministry of Finances and Planning,

Agriculture and Fisheries and State Administration.

While producing national environmental legislation, the country has adopted and ratified

in the last years important international environmental conventions, such as:

21

(i). Biological

Diversity,

(ii). Climate

Change,

(iii). Desertification,

(iv). Basel and Bamako,

(v).

Law of The Sea,

(vi). Protection of the Ozone Layer, and

(vii). Protection, Management and Development of Marine Environment in the Western

African Region (Nairobi Convention)

Comoros

The Ministry of Agriculture, Marine Resources and Environment is the main

governmental body responsible for the protection of the environment in Comoros. The

Government also established a General Directorate for Environment and Regional

Environmental Services for each of the islands.

The government adopted a National Environment Policy as well as National

Environmental Action Plan. The Parliament has ratified the Environmental Law.

The Comoros have ratified the following international conventions:

· Ramsar Convention

· CITES Convention

· Biodiversity Convention

· UN Convention on the Law of the Sea

· Un Convention on Climate Change

· Vienna Convention

· Montreal Protocol

· Basel Convention

· Convention on Desertification

· MAB Convention

Seychelles

Water-related environment legislation operates within a general legal framework which is

formed by the constitution, cross-sectoral legislation (i.e. Legislation applying to all

sectors and branches of Government) and general environmental legislation reaching out

into all areas of environment protection and conservation.

Constitution (1993)

The new constitution of the Seychelles in 1993 addresses environmental and conservation

in various respects. The relevant passage solemnly declares that the Seychelles is

committed to preserve a safe, healthy and functioning environment for the present and

future generations.

Article 38 recognizes the right of everyone to a safe environment. The state undertakes

measures to promote the protection, preservation, and improvement of the environment;

22

to ensure sustainable socio-economic development by judicious use and management of

resources; and to promote public awareness of the need to protect, preserve and improve

the environment.

On the other hand, Article 40 of the constitution makes it a duty of every citizen to

protect, preserve and improve the environment. Two Articles concerning property may

be relevant in this context. Article 20 provides that no property be searched without the

owner's consent except where provided by law and in the interest of inter alia nature

conservation. Article 26 guarantees the private right to property; however, it also spells

out the limitations, which must be prescribed by law and may be those "necessary in a

democratic society." More and more it is recognized that the "democratic society"

limitation to fundamental rights includes environment protection and conservation duties.

Maritime Zones Act (1997)

The Maritime Zones Act of 1997 is another basic statute to be taken into account. The

Act declares national prediction over the territorial waters, the continental shelf and the

exclusive economic EEZ zone of the Seychelles. The use EEZ the Seychelles has

"exclusive prediction to preserve and control marines pollution." Furthermore, areas of

the continental shelf and the EEZ may be declared designated areas and special

provisions may be imposed to protect resources and the marine environment and regulate

the entry of foreign ships into the designated areas (section 9). The Maritime Zone Act

has been implemented by the Maritime Zones (EEZ) order (1978) demarcating the limits

of the EEZ, and the Maritime Zone (marine pollution) Regulations (1981).

District Councils Act (1994)

The District Councils Act, which has been amended in 1994 now, makes reference to

environment protection and conservation by establishing such powers and responsibilities

of District Councils.

I. Penal Code

The Penal Code (chapter 73 of the Laws of the Seychelles) contains a series of

environment protection and conservation related provisions.

II. Environment Protection Act 1994

The Environment Protection Act (EPA) of 1994 replacing the EPA of 1988 aims at

protecting improving and preserving the environment and preventing, controlling

pollution. It is mainly but not exclusively pollution control oriented. It establishes the

authority for environmental protection, which shall be the Ministry or the Department

within the Ministry responsible for the environment.

Two authorities have been legally established. In 1995, the Solid Waste Agency was

established (Environment Protection: Designation of Solid Waste Agency population).

More importantly, in 1996 the Marine Parks Authority (MPA) was established as a

parastatal institution (Environment Protection: Marine Parks Authority order 1996).

The 1994 EPA Framework (Major Instruments)

23

Environment Protection Act (1994)

Environment Protection (Designation of Solid Waste Agency Regulations 1995)

Environment Protection (Standard Regulations 1995)

Environment Protection (Marine Parks Authority order 1996)

Environment Protection (Impact Assessment Regulations 1996)

Tanzania

Tanzania lacks a coherent and harmonized coastal legislation for dealing with the marine

and coastal environment. This is further complicated by the existence of two different

types of legislation for Zanzibar Islands and Tanzania Mainland. Although Tanzania is a

federal state comprising Tanzania Mainland and Zanzibar, the latter maintains

administrative independence in most of its government matters. The National Assembly,

which includes members from Zanzibar, legislates on all matters and for the United

Republic of Tanzania on issues such as foreign affairs, finance, defense, immigration and

citizenship. All other matters concerning Zanzibar are within the exclusive jurisdiction

of the Zanzibar government and its legislative body, that is, the House of Representatives.

There are several sectoral legislations that have relevance for the management of marine

and coastal resources on Tanzania Mainland. These cover sectors such as fisheries,

agriculture, forestry, industry and trade, land use planning, culture, marine transport,

environment, energy and tourism.

Tanzania has adopted a wide range of approaches within their legal and regulatory

framework aimed at the protection of the coastal and marine environment. These

include:

· Setting out the environmental quality standards

· Protection of the key habitats such as coral reefs and mangroves

· Environmental impact assessment

· Pollutant discharge fee

· Monitoring, surveillance and inspection

· Penalties.

A number of environmental regulations exist in Tanzania. Such efforts notwithstanding,

serious gaps remain in policy, law and practice. There is also a shortage of reliable

information to guide implementation of both policy and legislation. However, previous

experiences clearly show that while enacting environmental laws with the accompanying

penalties is one thing, enforcing and implementing them is another. More often than not,

the problem lies with enforcement. However, the main contributing factors for weak

enforcement are limited financial and human resources, lack of technological capacity,

insufficient political support, pressure on government from interest groups, lack of

transparency, as well as the practical problems of administering environmental

regulations.

24

The Key Policies, Legislation and Plans Relevant to the Marine and Coastal Environment

of Tanzania are:

Natural Resources

· National Fisheries Sector Policy and Strategy Statement, 1997

· Fisheries Act, 1970

· Marine Parks and Reserves Act, 1994

· National Forest Policy, 1998

· Forest Ordinance, 1957

· National Forest Action Plan, 1990/91--2007/08

· Management Plan for the Mangrove Ecosystem in Tanzania, 1991

· The Territorial Sea and Exclusive Economic Zone, 1989--Union Government

· Deep Sea Fishing Authority Act, 1997

Land Use

· National Land Policy, 1995

· Town & Country Planning Ordinance, 1956, Cap. 378

· The Town & Country (Public beaches planning area) Order, 1991

· Government Notice No. 76 reducing the Beach Protection Line from 200 m to

60 m, 1992

Shipping

· Merchant Shipping Act of 1967

Cross-cutting

· National Environmental Policy, 1997

· Water Policy, 1991

· Water Utilization (Control & Regulation) (Amendment) No. 10, 1980

· National Land Policy, 1995

· Land Act, 1998

· Village Land Act, 1998

· Local Government Reforms

· Local Government (District & Urban Authorities) Acts, 1982

· Regional Administration Act, 1997

· District & Village by-laws

· Public Health (Sewerage & Drainage) Ordinance

· Mining (Environmental Management & Protection) Regulation, 1999

Similar to Tanzania Mainland, there is a serious deficiency in legislation guiding

development activities of marine and coastal areas in Zanzibar Islands. There is an

urgent need to review the legislation in order to address current and emerging issues as

well as to increase the level of penalties. However, Fisheries legislation has been updated

recently. The development of the Environmental Policy has increased the awareness of

islanders because it was done in a truly participatory manner. This consultative process

which was approved by the House of Representatives in February 1996 and acceded by

25

the President in July 1996 has generated a comprehensive and effective Environmental

Policy Legislation for Zanzibar.

The Key Legislation Relevant to Marine and Coastal Environment of Zanzibar Islands

are:

Natural Resources

· The Fisheries Legislation (Revised 1988)

· The Forest Reserve Decree (Cap. 120) and Wood Cutting Decree (Cap. 121)

· The Wild Animals Protection Decree (Cap. 128)

· The Wild Birds Protection Decree (Cap. 129)

Land Use

· The Land (Distribution) Decree, 1966

· The Town and Country Planning Decree (Cap. 85)

· The Public Land Decree (Cap. 93) Removal of Natural Produce Rules

Cross-cutting

· The Commission of Lands and Environment Act, 1988

· The Investment Promotion Act, 1986

· The Administrative Authorities Act, 1981

· The Local Government Act, 1986

· The Public Health Act (Cap. 73)

· The Dangerous Goods Act (Cap. 160)

· The Petroleum Act, 1980

· The Mining Act, 1979

Environmental Impact Assessment:

Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) is an important management tool and is a

relatively new management tool in Tanzania. EIAs are widely used to ensure that

development activities are environmentally, socially and economically sustainable.

The National Environment Management Council (NEMC) is the regulatory and

supervisory agency in environmental management. The issuing of a development

permit/license is subject to provision of environmental approval by NEMC. An EIA

Directorate was established at NEMC in 1996 to facilitate and implement the EIA

process. The national EIA guidelines and procedures have been developed by NEMC

since 1997 and they are currently awaiting formal government approval for them to be

legally binding. In addition, the process of development of Mariculture Guidelines is

almost complete.

A few legislations are currently requiring and taking into account the EIA before

approving development projects. These include:

26

· The Marine Parks and Reserves Act, 1994, includes provisions for Environmental

Impact Assessment (EIA)

· The Tanzania Investment Act, 1997, requires and takes into account EIA

· The new Mining Act, 1998, provides for EIA.

Currently, some EIAs have been conducted mainly through the initiative of the donor

community. Such development proposals have included, for instance, the proposed

development of a prawn farm at Rufiji River Delta, and the production of electricity from

natural gas at Songo Songo Island.

Institutional framework:

More than 10 national ministries and offices are mandated to manage some components

of marine and coastal resources and environmental issues. The main ones are:

· The Vice President's Office which is responsible for environment

· Prime Minister's Office which is responsible for Local Government

· The National Planning Commission which is responsible for national planning

· The Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism

· Ministry of Transport

· Ministry of Agriculture

· Ministry of Industries and Trade

· The Ministry of Judiciary, Attorney General's Office and the National Assembly

are responsible for law enforcement.

A similar structure exists for the Zanzibar Government (Table 8). Governance for

Tanzania's coastal zone is complicated by the existence of two national jurisdictions

the Zanzibar Government and the Union Government. Whereas certain issues such as

home affairs (law enforcement) and foreign affairs are under joint responsibility of the

Union Government, most of the coastal and marine management issues are non-union

matters. Most of the ministries are not coordinated and do not create a viable system for

managing coastal and marine resources. Authority is fragmented and often overlaps

between different departments, thus causing unnecessary competition. Both the Zanzibar

and the Union governments need to develop sound institutional linkages in order to

optimize the use of limited financial resources and support facilities.

The lack of a comprehensive institutional framework, which could act as a focal point in

coordinating all activities related to marine and coastal areas, is a major drawback in the

formulation of integrated coastal zone management. For example, as pointed above,

fisheries officers at the regional and district levels administratively report to two different

ministries (Prime Minister's Office and Ministry of Local Government) while

technically, they belong to the Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism. This poses a

major constraint to the efficient implementation and administration of the government's

fisheries development projects. The adoption of the Territorial Sea and Exclusive

Economic Zone Act of 1989 vested substantial powers for the control of coastal resources

in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The Ministry is responsible for the development of

27

the necessary framework for an integrated marine policy, but due to the diverse nature of

the coastal zone, progress is slow. However, it should be pointed out that the preparation

of this policy and related legislation should involve local and international interest groups

to ensure the adoption of sound and acceptable management practices.

In an attempt to coordinate environmental management, Tanzania has restructured the

former Ministry of Tourism, Natural Resources and Environment and has moved the

functions of Environment and associated institutions (National Environment Management

Council and Division of Environment) to the Vice President's Office. The Minister of

State responsible for the Environment heads these functions. However, to date, the Vice

President's Office has not issued guidelines on the way in which sector ministries and

parastatals will be engaged in a coordinated manner in addressing environmental issues.

Table 8.

Government Institutions Dealing with Different Aspects of Coastal and

Marine Environment in Zanzibar

Ministry Institution Specific

Responsibilities

Ministry of Water,

Department of

Environmental law

Construction, Energy

Environment

and setting of

environmental

standards

Lands and Environment

Department of Lands

Land

management,

administration, and

control

Department

of

Urban

Urban planning, land

Planning and

use planning,

Surveying

development control

and physical standards

Ministry of State for Regional Coordinates

all

Administration

aspects related to

regional and district

administration

and local government

(municipal councils,

wards and `shehias')

Ministry of Agriculture, Resources, Agriculture,

livestock,

Livestock and Fisheries

natural resources

fisheries and forestry

International Perspective:

Tanzania has signed and ratified several regional and international conventions and

agreements relevant to the marine and coastal management. These include:

28

· The African Convention on the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources,

Algiers, 1968. Tanzania ratified this Convention in 1974.

· The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species on Wild Fauna and

Flora (CITES or Washington Convention), Washington, DC, 1973. Tanzania

ratified this convention in 1980.

· The International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships

(MARPOL), London, 1973. Tanzania is signatory since 1978.

· United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, 1982. This is the only

convention for which Tanzania has a corresponding national legislation the

Territorial Sea and Exclusive Economic Zone Act of 1989. This act reduces the

territorial waters from the former 50 nautical miles to 12 nautical miles and

extended the EEZ to 200 nautical miles.

· The Nairobi Convention on Protection, Management and Development of Marine

and Coastal Environment in the Eastern Africa Region and Related Protocols,

1985. Tanzania ratified it in 1996.

· The International Convention on Climate Change. Tanzania is signatory since

1996.

· The Convention on Biological Diversity was ratified by Tanzania in 1996.

Tanzania is now developing a National Strategy for the Conservation of

Biological Diversity including compliance to the Jakarta Mandate.

Major International Agreements into which Tanzania has entered include:

· The Kenya and Tanzania agreement of 1995 concerning delimitation of territorial

waters boundary. This agreement also gives guidance on matters related to

fisheries.

· Fishing agreement between Tanzania and the European Union, which was

adopted in 1990. This agreement requires the parties to coordinate their activities

to ensure the sustainable management and conservation of living resources in the

Indian Ocean particularly with respect to migratory species. This agreement is in

force despite the fact that Tanzania is not party to the UN agreement on straddling

fish stocks and highly migratory fish stocks.

· Tanzania is also Member to some of the international and regional organizations

such as the Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission of UNESCO (IOC),

Regional Committee for Cooperative Investigations in the North and Central

Western Indian Ocean (IOCINCWIO); International Maritime Organization

(IMO); and the Indian Ocean Marine Affairs Commission (IOMAC).

As stated above, almost none of these conventions and agreements (except the Territorial

Sea and EEZ Act) have been translated into corresponding national legislation.

Zanzibar has had little involvement in these conventions although it has ratified some of

them indirectly by virtue of being in the Union Government. It is anticipated that the

Environmental Policy Programme will create a mechanism of sensitization, which will

lead to increased international cooperation, and in turn lead to government interest in the

international conventions of most relevance to it.

29

V. Major Transboundary Perceived Problems And Issues

The identification of the major perceived1 problems and issues (MPPI) is a first step in the

TDA process and it constitutes the justification for the subsequent in-depth analyses. The

significance of the perceived issues and problems should be substantiated on scientific,

environmental, economic, social, and cultural grounds.

The MPPIs represent the perceptions of the scientific and expert community on the

priority environmental issues of the region. The experts may come from the scientific

community, the NGO community, government, and other stakeholder groups. However,

not all stakeholders were included in the development of these MPPIs. Therefore, a

separate stakeholder analysis will be conducted before the finalization of the TDA during

the full GEF project.

This section of the TDA analyzes the MPPIs to identify the technical basis supporting or

refuting each MPPI as a priority issue in the WIO region. The intent is to provide a

technical rationale for prioritizing the MPPIs, to help guide the direction of future

interventions to improve the regional environment. It will be of no use to identify major

intervention efforts for an MPPI if the technical basis supporting its priority is missing. In

such a case, either the MPPI can be dismissed as a non-priority issue, or just as

importantly, gaps in knowledge can be identified, and filling the gaps can become the

next step towards addressing that particular MPPI.

This section, therefore, relies on the preliminary TDA prepared by the Institute of Marine

Sciences, University of Dar es Salaam in 1998, national reports from the participating

countries, various technical publications available for the region prepared by UNEP,

ACOPS and other organizations. The major sources of information are listed within each

individual section as well as in the Bibliography accompanying this TDA.

The Preliminary TDA identified the following list of major perceived problems and

issues. It includes four existing problems/issues:

I. Shortage and contamination of fresh water

II. Decline in harvests of marine and coastal living resources

III. Degradation of coastal habitats (mangroves, seagrass beds, and coral reefs), loss

of biodiversity.

IV. Overall water quality decline. Contamination of coastal waters, beaches and living

resources.

Below, each of these problems and issues is addressed from a status perspective. It

answers the question: what do we know about each problem/issue? What data support the

quantification of the extent of the problem/issue? Do the data support these as real

problems and issues, or just as perceptions? This analysis took place on a scientific level,

1 "Perceived" is used to include issues which may not have been identified or proved to be major problems as yet due to data

gaps or lack of analysis or which are expected to lead to major problems in the future under prevailing conditions.

30

including biological, oceanographic, physical, social, and other perspectives on the

problem. This is in effect the "status" assessment.

The next step was to perform the causal chain analysis; the major perceived problems and

issues were analyzed to determine the primary, secondary and root causes for these

problems/issues. Identification of root causes is important because root causes tend to be

more systemic and fundamental contributors to environmental degradation. Interventions

and actions directed at the root causes tend to be more sustainable and effective than

interventions directed at primary or secondary causes. However, because the linkages

between root causes and solutions of the perceived problems are often not clear to

policymakers, interventions commonly are mis-directed at primary or secondary causes.

This TDA attempts to clarify the linkages between root causes and perceived problems,

to encourage sustainable interventions at this more sustainable level. Fortunately, root

causes are common to a number of different perceived problems and issues, so addressing

a few root causes may have positive effects on several problems and issues (Table 9).

Table 9.

Root Causes and Major Perceived Problems and Issues

Root Causes

Perceived Problems

I. Fresh Water II. Decline in

III. Degradation of IV. Overall water

shortage and

harvests of marine coastal habitats

quality decline.

contamination

and coastal living (mangroves, seagrass Contamination of

resources

beds, and coral reefs) coastal waters,

loss of biodiversity,

beaches and living

resources.

1. Rapid growth in

coastal population and

urbanization

2. Lack of policies and

legal framework

3.Inadequate

knowledge

4. Institutional

Weakness

5. Lack of

management strategies

6. Inadequate

financing mechanisms

and support, lack of

investments

The TDA summary analysis of the major perceived problems and issues follows.

31

V.1 Fresh water shortage and contamination

a. Statement of the problem/issue

Freshwater shortage and the contamination of supplies are the single greatest

environmental constraints to economic and social activities in all countries of the region.

Fresh water shortage is equally serious in all the countries of the region with widespread

environmental and socio-economic impacts. Lack of regional legal agreements and

poorly articulated institutions for implementing effective international river basin

management and ground water conservation, are the dominant problems shared by the

whole region, with Mozambique being the prominent example including 8 of the 12

downstream parts of the region's international basins.

In the case of the Small Islands Developing States (SIDS), the small physical size and

geological nature of many SIDS means that reliable supplies of freshwater can be a major

constraints to development. The economic health of the island states of the WIO of

regional and intra-regional concern, partly as a result of the expanding tourist trade, the

tuna industry, and the fragile nature of the island ecosystems and biodiversity. Water

shortage, contamination and saline intrusions are among the main water problems

affecting SIDS.

b. Transboundary elements

The major transboundary patterns of the fresh water shortage and contamination can be

illustrated as follows:

- The West Indian Ocean region has rivers basins that transcend national

boundaries and the inputs from these rivers have long geographic impacts. The

negative effects experienced in estuarine and coastal areas are the result of

activities carried in upland areas including the landlocked countries.

- Most coastal areas in WIO region are arid; fresh water is therefore a scarce

resource. Many of the industries in the region are located in the coastal urban