Working paper

S

TRATEGIES FOR PUBLIC

PARTICIPATION IN THE

M

ANAGEMENT OF

TRANSBOUNDARY WATERS IN

C

OUNTRIES IN TRANSITION

Cases of Lake Peipsi/Chudskoe (Estonia/Russia) and

Lake Ohrid (Macedonia/Albania)

The working paper is based on a seminar "Strategies for Public Participation in the

Management of Transboundary Waters in Countries in Transition: Cases of Lake

Peipsi/Chudskoe (Estonia/Russia) and Lake Ohrid (Macedonia/Albania)"

Tartu, 15-16 October 2001.

The seminar was organised by Peipsi Center for Transboundary Cooperation (Peipsi CTC)

and the Alliance for Lake Cooperation in Ohrid and Prespa (ALLCOOP)

Edited by:

Margit Säre, Peipsi CTC

Gulnara Roll, Peipsi CTC

Piret Uus, Peipsi CTC

Jovanco Sekuloski, ALLCOOP

ISBN 9985-78-400-6

DECEMBER 2001

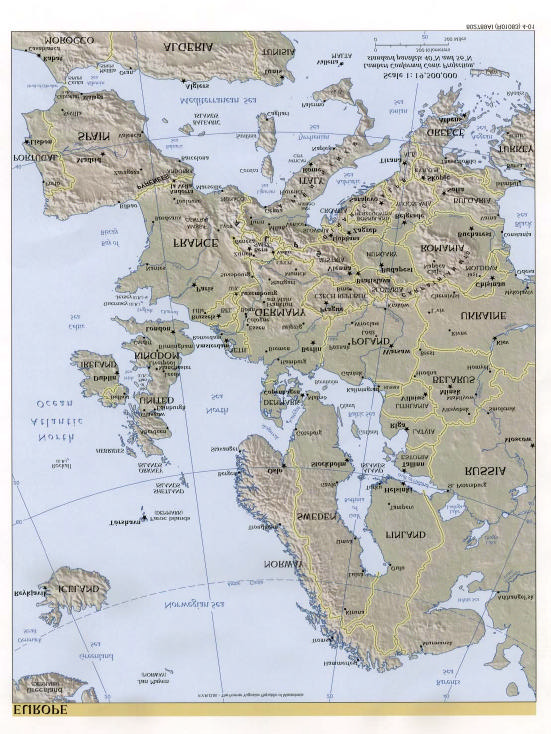

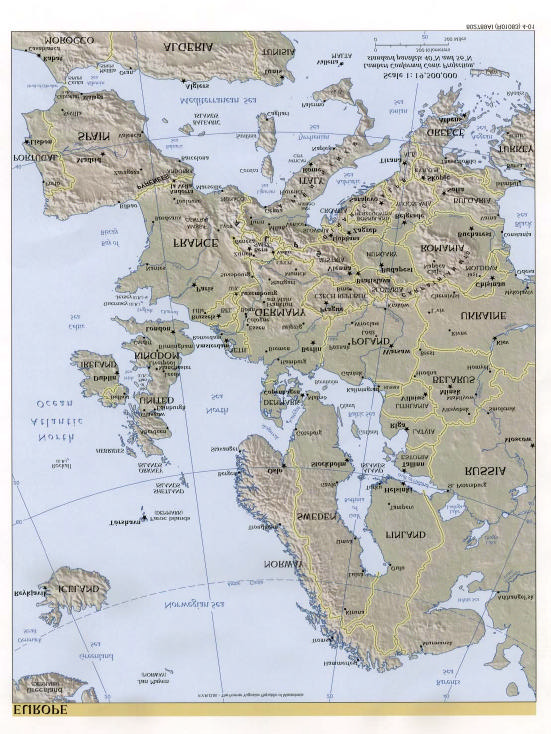

LAKE PEIPSI

LAKE OHRID

Map from http://www.lib.utexas.edu/maps/europe/europe_ref01.jpg

2

C O N T E N T :

1. FOREWORD ..................................................................................................................4

2. INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................5

3. INTERNATIONAL LEGAL FRAMEWORK FOR PUBLIC PARTICIPATION

IN WATER MANAGEMENT.........................................................................................6

THE DRAFT GUIDELINES ON PUBLIC PARTICIPATION IN WATER MANAGEMENT:

BRIDGING THE GAP BETWEEN THE WATER CONVENTION AND THE AARHUS CONVENTION

..........................................................................................................................................7

OVERVIEW OF IMPLEMENTATION IN ESTONIA AND POSSIBLE BARRIERS FOR COMPLIANCE

OF THE AARHUS CONVENTION ON ACCESS TO INFORMATION, PUBLIC PARTICIPATION

AND ACCESS TO JUSTICE IN ENVIRONMENTAL MATTERS..................................................9

PUBLIC PARTICIPATION IN THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE EU WATER FRAMEWORK

DIRECTIVE ......................................................................................................................12

4. LESSONS LEARNED: PROPOSALS FOR INVOLVEMENT OF

STAKEHOLDERS INTO THE ELABORATION OF THE RIVER BASIN

MANAGEMENT PLAN.................................................................................................15

5. CONCLUSIONS..........................................................................................................32

ANNEX I..........................................................................................................................36

WORKSHOP PROGRAMME...............................................................................................36

ANNEX II ........................................................................................................................42

WORKSHOP CONTRIBUTORS ...........................................................................................42

ANNEX III........................................................................................................................44

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS....................................................................................................44

ANNEX IV........................................................................................................................45

FOLLOW-UP PLANS.........................................................................................................45

ANNEX V..........................................................................................................................48

ALLCOOP - ALLIANCE FOR LAKE COOPERATION IN OHRID AND PRESPA.....................48

PEIPSI CENTER FOR TRANSBOUNDARY COOPERATION PEIPSI CTC ..............................49

3

1 . F O R E W O R D

The seminar on "Strategies for Public Participation in the Management of Transboundary

Waters in Countries in Transition: Cases of Lake Peipsi/Chudskoe (Estonia/Russia) and

Lake Ohrid (Macedonia/Albania)" was organized by two NGOs: Peipsi Center for

Transboundary Cooperation (Peipsi CTC) and the Alliance for Lake Cooperation in Ohrid

and Prespa (ALLCOOP). Peipsi CTC is working in the Estonian-Russian border area, Lake

Peipsi basin and ALLCOOP in the Macedonian-Albanian border area, Lake Prespa and Lake

Ohrid basins.

The seminar took place on 15-16 October 2001 in Tartu, Estonia and was attended by 60

participants from Estonian, Russian, Latvian, Macedonian, Albanian and Austrian NGOs,

ministries, local governments, research institutes, water companies etc.

The workshop was supported by Charity Know How Foundation, Open Society Institute

"East-East Program" and Regional Environmental Center for Central and Eastern Europe.

The Tartu seminar was a follow-up to the first joint workshop which took place in Ohrid,

Macedonia on 12-14 March 2001, focusing on introducing UN ECE Guidelines on Public

Participation and collecting comments and recommendations from the practitioners and

community leaders on these guidelines.

The main objective of the Tartu seminar was: to introduce experiences of public

participation in water management in different transboundary areas of Europe (Lake Peipsi,

Lake Ohrid, Lake Prespa, the Daugava River, Cherava river basins, other regions) and to

give an overview of the international legal framework of public participation in water

management, including the UN/ECE Water Convention and the UN/ECE Guideline on

Public Participation, the Aarhus Convention on Access to Information, Public Participation

and Access to Justice and the EU Water Framework Directive (WFD).

The second seminar day was devoted to work in smaller groups on the development of

guidelines for involving the public into the elaboration of water management plans in

transboundary basins of Lake Peipsi/Chudskoe and Lake Ohrid, based on the EU Water

Framework Directive. WFD recognizes that water respects physical and hydrological

boundaries, but not political and administrative units. The implementation of the WFD

should lead to a more rational water protection and use, to reduced water treatment costs, to

increased amenity value of surface waters and to a much more coordinated administration of

waters.

The seminar proceedings is prepared by Peipsi CTC, ALLCOOP and WWF Danube-

Carpathian Programme project experts and is available in English, Russian, Estonian,

Macedonian and Albanian languages (www.ctc.ee). The proceedings draw together the texts

of all the presentations made during the seminar; comments and discussions after the

presentations; working groups results and annexes containing; seminar programme and list

of participants; follow-up plans and the description of Peipsi CTC and ALLCOOP.

4

2 . I N T R O D U C T I O N

The main objectives of water management, ultimately, can be narrowed down to providing

safe water for drinking, appropriate sanitation, and enough food and energy at reasonable

cost in an equitable manner that works in harmony with nature. However, we are not

achieving these goals today, and we are on a path leading to crisis and to future problems for

a large part of humanity and many parts of the planet's ecosystems1. In fact this conclusion

can be easily extended to the environmental issues in general at global scale. A recent report

of the European Environmental Agency2 came up with a similar conclusion: "that the

general environmental quality in the European Union is not recovering significantly, and in

some areas, it is worsening, despite more than 25 years of Community Environmental

Policy".

This is why the 1990s for decision makers have been a period for exploring new directions

and novel policy approaches and instruments. In this respect, at global, international scale,

the most important event was the United Nations Conference on Environment and

Development, held in June 1992 in Rio de Janeiro. It focused the world's attention on the

need to promote environmentally sustainable development. The conference was attended by

representatives of 178 nations, including a number of European Heads of State and/or

Government and the President of the European Commission. Potentially the most

significant of the Conference achievements was the 800-page Agenda 21. Agenda 21

represents only the beginning rather than the end of a process, and a number of firm targets

were omitted during pre-conference negotiations.

Numerous international documents have expressed the importance of public participation

and the need to institutionalise it to move towards sustainable development. It is important

to mention Principle 10 of the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development signed by

more than 100 heads of State worldwide, in Rio de Janeiro in 1992, establishing that:

"Environmental issues are best handled with the participation of all concerned citizens, at the

relevant level. At the national level, each individual shall have appropriate access to information

concerning the environment that is held by public authorities, including information on hazardous

materials and activities in their communities, and the opportunity to participate in decision-making

processes. States shall facilitate and encourage public awareness and participation by making

information widely available. Effective access to judicial and administrative proceedings, including

redress and remedy, shall be provided".

1 World Water Vision,

http://www.worldwatercouncil.org/Vision/cce1f838f03d073dc125688c0063870f.htm

2 Environment in the European Union at the turn of the century. European Environment Agency, 1999

5

3 . I N T E R N A T I O N A L L E G A L F R A M E W O R K F O R

P U B L I C P A R T I C I P A T I O N I N W A T E R

M A N A G E M E N T

This publication is based on principles of three international documents which present the

framework for transboundary water management and public participation in Europe UN

ECE Water Convention, UN ECE Aarhus Convention and EU Water Framework Directive.

Legal framework

Geographical Content

Levels of

document

coverage

implementation

UN ECE

Countries

§ Prevention, control and

- International

Convention on the

ratified the

reduction of

transboundary

Protection and Use convention3

transboundary impacts;

river basins

of Transboundary

and riparian § Cooperation in research

Watercourses and

parties

into and development of

International Lakes

techniques for the

Entered into force

prevention, control and

6 Oct 1996

reduction;

§ Exchange and protection

of environmental

information

UN ECE Aarhus

Countries

§ Access to environmental - International

Convention

ratified the

information

river basin level

Entered into force

convention4

§ Public participation in

- National level

30 Oct 2001

environmental decision-

- Local level

making

§ Access to justice

EU Water

EU territory, § Tools for integrated river - International

Framework

bordering to

basin planning and

river basin level

Directive

EU basins

management;

- National level

Entered into force

§ Setting up River Basin

- Local level

22 Dec 2000

Districts;

§ Designing Programmes

of Measures and

developing River Basin

Management Plans

3 Ratified, accepted, approved or accessed by Albania, Austria, Azerbaijan, Belgium, Croatia, Czech Republic,

Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Kazakhstan, Latvia, Liechtenstein, Lithuania,

Luxembourg, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Republic of Moldova, Romania, Russian Federation, Slovakia,

Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Ukraine (Source: http://www.unece.org/unece/env/water/topfra1.htm)

4 Ratified, accepted, approved or accessed by Albania, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Denmark, Estonia, Georgia,

Hungary, Italy, Kazakhstan, Kyrgystan, Republic of Moldova, Romania, Ukraine, Tajikistan, The Former Yugoslav

Republic of Macedonia, Turkmenistan (Source: http://www.unece.org/env/pp/ctreaty.htm)

6

THE DRAFT GUIDELINES ON PUBLIC PARTICIPATION IN WATER

MANAGEMENT: BRIDGING THE GAP BETWEEN THE WATER CONVENTION AND

THE AARHUS CONVENTION

Oliver Avramoski

Alliance for Lake Cooperation in Ohrid and Prespa

The Legal Framework in the field of Water Management for the Pan-European

Region

Traditionally, the only means available for regulating the behaviour of nation states has been

through a system of international law, codified in treaties and conventions. Since the

beginning of the century more than 170 multilateral environmental treaties and instruments

have been established. The vast majority of these agreements are regional in their scope, and

many of them apply only to Europe. However, during the 1980s it became increasingly

apparent that placing reliance on environmental conventions, agreements and even

legislation to secure environmental protection could be only partially effective. A key

problem with all international environmental agreements is their implementation and

enforcement. Parties to international agreements generally find external monitoring and

enforcement systems unacceptable, and wish to control monitoring themselves. Information

gathered in this manner may be incomplete or inaccurate due to differing monitoring

methods and standards. As a result, treaties incorporating detailed targets and structures have

often taken years to draft, and even longer to ratify. The growing sense of urgency in

addressing increasingly complex problems has led to a shift in favour of 'softer' conventions

which can be drafted and signed within a relatively short time frame. These may include

codes of practice, guidelines or frameworks, which allow wide discretion in interpreting their

precise requirements. They may be easier to agree, but their very flexibility can reduce their

effectiveness.

For the pan-European region, cooperation with respect to transboundary waters was initially

based on various underlying principles. However, during the last decade, UN/ECE, UNEP

and other organizations have advocated a coordinated regional approach to resolving the

water problems. The new paradigm of cooperation at the European level was based upon

several principles: prevention of conflicts over water in accordance with the principles of

reasonable and equitable use of transboundary waters, the polluter-pays principle, the

precautionary principle and the ecosystem approach in water management. These principles

are built into the basis of the Convention on the Protection and Use of Transboundary

Watercourses and International Lakes (hereinafter referred to as the UN/ECE Water

Convention) which was adopted in Helsinki on 17 Marc h 1992 and entered into force on 6

October 1996.

Bridging the Gap

Following the growing acceptance that environmental regimes must be inclusive, that all

relevant stakeholders are involved in the decision-making process, soon after the adoption of

the Rio Declaration, the UN/ECE has quickly moved to the development of the UN/ECE

Convention on Access to Information, Public Participation in Decision-Making and Access

7

to Justice in Environmental Matters, adopted in Aarhus in 1998 (hereinafter referred to as

the Aarhus Convention).

A number of provisions in the UN/ECE Water Convention anticipated the principles of the

Aarhus Convention. For example Article 16 requires that The Riparian Parties shall ensure

that information on the conditions of transboundary waters, measures taken or planned to

be taken to prevent, control and reduce transboundary impact, and the effectiveness of those

measures, is made available to the public. However, on 17 June 1999, a supplementary

protocol to the Convention - the Protocol on Water and Health - was adopted in London on

the occasion of the Third Ministerial Conference on Environment and Health. Compared to

the Water Convention, The Protocol on Water and Health goes further in ensuring public

participation in decision-making (article 6, paragraph 2). Under Article 16, paragraph 3 (g),

the Parties shall:

...At their meetings consider the need for further provisions on access to information, public

participation in decision-making and public access to judicial and administrative review of decisions

within the scope of this Protocol, in the light of experience gained on these matters in other

international forums.

Another unique feature of the Protocol is the necessary provision for the involvement of

NGOs, whereby Article 16, paragraph 3 (f) requires that the Parties shall:

... Establish the modalities for the participation of other competent international governmental and

non-governmental bodies in all meetings and other activities pertinent to the achievement of the

purposes of this Protocol.

The Aarhus Convention, in addition to the requirement for Access to Environmental

Information (Article 4), also requires Parties to make appropriate practical and/or other

provisions for the public to participate during the preparation of plans and programmes

relating to the environment, within a transparent and fair framework (Article 7). In this

respect, the UN/ECE Water Convention alone, through the development of

bilateral/multilateral agreements drawn up under article 9, paragraph 1, provides

arrangements for public involvement in decision-making. Thereof, the second meeting of the

Parties to the Convention on the Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and

International Lakes, held at Hague from 23 to 25 March 2000 recognized the need to

develop guidelines to ensure that such bilateral or multilateral agreements are effective.

Consecutively, the Meeting of The Parties decided to include in the work plan 2000-2003

under the Convention a programme element aimed at finalizing the guidelines for public

participation in water management based on the outcome of the UN/ECE-UNEP project

on a "Strategy and framework for compliance and on draft guidelines on public participation in water

management", with the Netherlands as lead country.

The draft guidelines are intended to assist Governments and joint bodies in the UN/ECE

region and in other regions in the world in developing and implementing procedures to

enhance public participation in water management. They are particularly intended to assist

Governments and joint bodies in the UN/ECE region. The draft guidelines draw on the

experience of experts from Governments, joint bodies and NGOs from the pan-European

region.

8

è

OVERVIEW OF IMPLEMENTATION IN ESTONIA AND POSSIBLE BARRIERS FOR

COMPLIANCE OF THE AARHUS CONVENTION ON ACCESS TO INFORMATION,

PUBLIC PARTICIPATION AND ACCESS TO JUSTICE IN ENVIRONMENTAL

MATTERS

Kaidi Tingas

Danish-Estonian Co-operation Project to Implement the Aarhus Convention in Estonia

The Estonian efforts to implement the Aarhus Convention (AC) were supported by

Denmark by conducting the Project to Assist Estonia in the Implementation of the EU Access to

Information Directive and the Aarhus Convention. The main purpose of the Danish support was to

assist Estonian Ministry of the Environment in building the framework of regulations and

administrative systems necessary to implement the first two pillars of the AC access to

information (AI) and public participation (PP) in decision-making.

The statements and recommendations presented below were worked out during the project.

Estonia ratified the AC on 6th June 2001 and so the number of parties had passed the magic

16 and the Convention entered into force internationally 90 days later - on 30th October

2001.

General principles of the Convention

Firstly, the Aarhus Convention is not only an environmental policy instrument it is also an

instrument to emphasise certain participatory democratic values. It underlines the values of a

strong and stable participatory democracy. This implies:

§ An open and transparent public administration;

§ A positive attitude in the public administration towards servicing the citizens;

§ That politicians and the public administration see it as an advantage to have PP in

the decision-making process;

§ That the citizens believe and experience that PP in the decision-making process

does matter;

§ That the citizens have a fundamental trust and confidence in the politicians and the

public authorities.

An effective implementation of the Convention not only requires that it should be in

accordance with environmental objectives but also that it shows compliance between the

democratic spirit it embodies and the prevailing political culture in Estonia. It must be said

that achieving full compliance in Es tonia is possible but poses challenges to the political and

administrative system as well as the public.

9

Estonian laws

Estonia has incorporated most of the elements of the Aarhus Convention into its national

legislation. The 1st pillar access to information - is covered by the Public Information Act,

the Environmental Monitoring Act, the Act on Release of GMO-s, the Draft Act of

Environmental Registers and General Part of the Environmental Code (drafting process is

going on). The 2nd pillar public participation in the decision-making process is covered by

the Planning and Building Act, the Environmental Impact Assessment and Auditing Act, the

Water Act, the Ambient Air Act, the Waste Act and the Act on Integrated Pollution and

Prevention Control.

A solid legal foundation has thereby been established, guaranteeing public access to

environmental information and the right to participate in the environmental decision-

making. However, many challenges regarding the practical implementation of the newly

adopted legal framework and work on public possibility of gaining access to environmental

information and participating in the environmental decision making lie ahead.

Practical implementation historical, societal and economic barriers

The next step is to secure and develop an administration of the legislation. During the

project we have trained public officials; in addition, the guideline and the case handbook

have been developed in order to support public officials in their daily work within this field.

Nevertheless, the truth is also that Estonians in general are not familiar with the spirit of the

Convention. In the light of this, it becomes obvious that we have two complicated tasks

ahead. The authorities are faced with the task of not only implementing the Convention, but

also of informing the public of their rights to participate and how to do it in the most

effective way.

§ Direct participation is new to many people because of our past and they need to be

acquainted with their rights herewith. Because of our history we have a perception

that the authorities cannot be trusted and it is pointless to participate.

§ The authorities, therefore, have to be very outspoken on the rights of citizens to

instigate people to participate.

The implementation of the AC partly needs a new kind of relationship between the public

and public administration/government, more dialogue and interaction.

Example of good practice

By the governmental initiative the Internet portal Today I Decide was established in spring

2001. All draft regulations and laws are available there for comments and amendments.

Everyone can make suggestions for new regulations, etc., collect the signatures (according to

the Digital Signature Act) and send his/her idea or even a draft document to the relevant

ministry for further proceedings.

10

What has been done in the Ministry of the Environment

During the Project several Round Table meetings were organised among representatives of

different organisations/authorities/universities to get recommendations for adjustments to

the existing Estonian law or practice in order to fully comply with the requirements under

the Aarhus Convention.

The following discussion papers have been produced by the project (also available on the

project web site www.envir.ee/arhus):

§ Internal working documents

§ Confidential information

§ System of charges for information to the Public

§ Attitudes and barriers to PP in environmental decision-making in Estonia

§ PP in specific activities, plans, programmes, policies and legally binding

instruments

§ Collection and dissemination of information

Followed by the recommendations, discussions, existing laws and best possible practice a

guideline for public officials was developed. The guideline covers the aspects regarding

public access to environmental information and public participation in the decision making

process. This includes the environmental impact assessment procedures on public

participation, but also the public participation procedures related to the environmental

permitting procedure and planning process. The guideline contains a large section on public

participation tools and good advice.

A case handbook has also been developed. The case handbook contains a description of the

existing PP cases in Estonia and Denmark. By giving a description of how public

participation has been conducted in practice it is the aim of the case handbook to show how

the public and public officials interact. A learning experience can be drawn from these cases.

Some suggestions for better implementation

The Project made some suggestions to the Ministry of the Environment. Examples:

§ Develop best practices at service levels regarding access to information and public

participation in the regional departments;

§ Work out a procedure (to involve more stakeholders and interest groups) on how to

process the act before it reaches the Parliament;

§ The authorities shall develop information to the public about the data and

information in their possession (meta info). Better overview of what kind of

environmental info the individual authority or organisation holds needs to be

established;

§ The public officials shall be trained more extensively on how they can fulfil the new

publication to assist the public in obtaining access to information and public

participation;

11

§ The public needs to be trained in using their rights;

§ A lot of information is made available on the Internet. This is good, but it is however

recommended that other dissemination channels should also be utilised not

forgetting that many people do not have access to the Internet.

è

PUBLIC PARTICIPATION IN THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE EU WATER

FRAMEWORK DIRECTIVE

Piret Uus

Peipsi Center for Transboundary Cooperation

Charlie Avis

WWF Danube-Carpathian Programme

The Water Framework Directive

The Water Framework Directive (WFD) reforms the EU water legislation by introducing a

new model for water management. It entered into force on 22nd December 2000.

From an environmental point of view, the WFD's ultimate aim is preventing further

deterioration and achieving "good status" in all waters. The WFD' s managerial approach -

integrated water management at the river basin level - aims at ensuring overall coordination

of water policy in the EU. Being a "framework", the Directive focuses on establishing the

right conditions to encourage efficient and effective water protection at the local level, by

providing for a common approach and common objectives, principles, definitions and basic

measures. However, the mechanisms and specific measures required to achieve "good

status" will take place at the local level and are the responsibility of competent (national,

regional, local, or river basin) authorities.

The implementation of the WFD should lead to a more rational water protection and use, to

reduced water treatment costs, to increased amenity value of surface waters and to a much

more coordinated administration of waters. The ultimate benefit is that the sustainability of

water use should be ensured.

Public Participation and the WFD

Article 14 of the Directive demands public participation, but the mechanisms to achieve this

are not spelled out or otherwise specified. This is problematic, but it is nonetheless envisaged

that public participation is required. Effective participation means engagement and

involvement of target groups (e.g. specific stakeholders or the wider public) in implementing

12

the WFD. It is far more than the provision of information and the gathering of opinions,

though these are important preparatory elements.

An open, transparent and participatory approach can bring multiple advantages when it is:

§ Included in river basin planning and management from the beginning;

§ Adapted to the appropriate scale (i.e. the approach at river basin level will need to be

different from that used to engage communities at the local level) and target groups;

§ Managed carefully, so that the capacity to meet commitments to stakeholders is not

exceeded;

§ Adequately resourced.

The strategic implementation process should be based on the principles of openness and

transparency encouraging creative participation of interested parties. This is beginning to

happen. These parties may be involved both in the work of the strategic co-ordination group

(as observers) and in the specific working groups and other activities under the joint

implementation strategy (as participants).

Involvement should start at different levels of operation i.e. at general policy levels on the

European, river basin, and national scales (for ensuring integration of sectoral interests e.g.

nature conservation), at programmatic levels on a local, sub-basin, or national level (for

implementing measures such as wetland restoration, agri-environment activities with a

positive environmental effect), and for information and public awareness activities. The

involvement level should be decided on a case-by-case basis depending on scope and topic

of the relevant process or working group. By identifying the kind of involvement needed for

each situation of the implementation process, the EC and Member States intend to ensure

both the effective participation of and contribution from the interested parties and to

enhance their understanding of the different elements related to the process. The basic idea

is to promote an open and clear exchange of views and concerns between all the parties

directly responsible for the implementation of the framework directive and those who are

interested or affected by it.

Why Public Participation?

Recent years have seen a rapid growth of interest in public participation in a wide range of

sectors and contexts, including public health, environmental management, urban

regeneration, agriculture, conservation, national parks, and local economic development.

In all these sectors new forms of engagement are beginning to emerge, resulting in people

increasingly getting involved in their own communities and governments and influencing

decisions that affect their lives. The complexities of real-world problems need solutions

developed by all stakeholders, if they are to trust in and abide by the outcomes.

Traditional, non-participatory processes such as top-down direction and instruction have

been shown to not work. History shows that coercion does not work. The results are clear

in the decline in the state of the environment, the increase in social exclusion and the lack of

trust of the public in their governments and industry. On the one hand public participation

benefits both planning and management institutions and at the same time it benefits the

public in general.

13

Specifically, the following benefits could be summed up:

§ Public participation strengthens democracy by showing stakeholders that they do

have an influence over what decisions are made;

§ NGOs and the public provide locally held information and increased pools of ideas

and knowledge. Solutions to problems are found in new and productive

partnerships between the local and the external and are therefore better adapted to

being implemented locally;

§ Public participation creates awareness and ownership of decisions and plans which is

in turn essential for their successful implementation;

§ NGOs and stakeholder participation allows them to play a more constructive and

better informed "watchdog" role and ensure government accountability;

§ A continuous investment in the practice of public involvement will help build a

culture of co-operation to handle conflicts and tensions. Participation is an

investment in the social structures, institutions and relationships that will allow

stakeholders to go on to achieve much more in other areas;

§ Participation is being increasingly demanded from institutions, donors and the public

themselves as their right.

What has become clear in recent years and in a range of sectors is that public participation

can lead to improvements in performance and outcomes. There are significant opportunities

- if it is properly implemented - to set European water and other environmental management

onto a more sustainable path and environmental NGOs clearly have a significant role (and

responsibility) to assist in this process.

14

4 . L E S S O N S L E A R N E D : P R O P O S A L S F O R

I N V O L V E M E N T O F S T A K E H O L D E R S I N T O T H E

E L A B O R A T I O N O F T H E R I V E R B A S I N

M A N A G E M E N T P L A N

4.1 Identification of Stakeholders and the Public

Given the social, political and legislative5 trends at the EU, Member State and regional levels,

it is highly unlikely that any river basin management plan (RBMP) can be implemented

successfully if it does not meet with broad public acceptance and, in particular, if it is not

supported by key stakeholder groups within a river basin, including local residents and

sectoral land/water users.6

In this publication a distinction is made between `public' and `stakeholder' participation, to

stress the differing mechanisms and approaches that are likely to be needed for (a) the

general population living within an river basin district, and (b) those individuals and

organisations with a specific interest in water resources management. "The public" means

one or more natural or legal persons, and, in accordance with national legislation or practice,

their associations, organizations or groups (Aarhus Convention). "The stakeholder" means

natural or legal person, who has specific interest or active roll in water management.

The most important players in WFD implementation at the strategic level of dialogue will be:

§ Those that can really contribute to delivering solutions: water companies, wastewater

treatment companies, various vocational associations and unions (farmers, forestry,

irrigation, fishery), state bodies of control and supervision, local governments;

§ Those that have technical expertise and are `representative' of a particular

constituency: NGOs, National Parks, scientist and scientific institutions;

§ And those that pay for action: land-users (e.g. mining and tourism companies, health

sector), individual owners of land, potential investor, community and village leaders,

schools.7

Many solutions to water resource problems will be strategic in nature, requiring a `whole

river basin' rather than local, or sub-basin approach. But the success of the Directive relies

on "close cooperation and coherent action at Community, Member State and local level as

well as on information, consultation and involvement of the public, including users" (WFD,

consideration 14). Each of the levels has its own importance and the participation tools and

strategies are differing to a large extent. Following the several mechanisms for public

involvement are specified on international river basin, nation state and local level.

4 Notably the 1998 `Århus' Convention on Access to Information, Public Participation in Decision-making and Access

to Justice in Environmental Matters

6 Elements for Good Practice in Integrated River Basin Management a Practical Resource for

implementing the EU Water Framework Directive, WWF/EC

7 Based on working group results from the seminar on 16 Oct. 2001, contributed by all seminar participants

15

4.2 Cases of Public Involvement at International River Basin Level

One of the important overall concepts of the WFD is the organization and regulation of

water management at the level of river basins. To this effect, river basin districts are created

in such a way as to comprise not only the surface run-off through streams and rivers to the

sea, but the total area of land and sea together with the associated ground waters and coastal

waters.

In the case of international river basins whether they fall entirely within the EU or attend

beyond the boundaries of Community Member States are asked to ensure co-ordination

and co-operation with the aim of producing one single international RBMP. If such an

international RBMP cannot be produced for some reason or other, Member States are still

responsible for producing RBMP for the parts for the international river basin district falling

within their territory.8

Our seminar was based on investigation of two transboundary river basins in Europe Lake

Peipsi on the Estonian-Russian border and Lake Ohrid on the Macedonian-Albanian border.

Lake Peipsi Basin

The total length of the Estonian-Russian border is about 277 km where approximately two-

thirds of the border goes through Lake Peipsi (in Russian the lake is named Chudskoe) a nd

the Narva River. Lake Peipsi is the fourth largest lake in Europe after Ladoga, Onega, and

Vänern with respect to surface area, and is located in the Baltic Sea water basin. Both sides

of the Estonian-Russian border zone are mostly agricultural regions of their countries.

Arable lands, milk and cattle farms, small-scale fishery, timber enterprises and food

processing factories are located in this area; however, rural areas, especially on the Russian

side, are rather sparsely populated. Most of the population is urban and living in the two

largest towns - Tartu in Estonia with about 100,000 inhabitants and Pskov on the Russian

side with 300,000 inhabitants. The border on Lake Peipsi between Estonia and Russia was

re-established in 1991, a development which has caused severe social, economic and

environmental problems in areas that were formerly closely co-operating. Steps to improve

cross border cooperation and to ensure safe and secure borders have been made at different

levels of Estonian and Russian governments during the 1990s.

Lake Ohrid Basin

Lake Ohrid is situated in southeastern Europe with Albania and Macedonia as its riparian

states, excelling as a unique ecosystem including many endemic species of flora and fauna.

The lake has a shoreline of 87,5 km, a maximum depth of 289 m. Approximately 43,000

people live in the Albanian and 126,000 in the Macedonian part of the Lake Ohrid basin. At

present, agriculture, especially on the Albanian side is the most important economic sector

for the region, but in the future, tourism and industry may reduce the economic significance

of agriculture. During the last few years, industry in Macedonia has suffered from

8 Elements for Good Practice in Integrated River Basin Management a Practical Resource for

implementing the EU Water Framework Directive, WWF/EC, manuscript

16

considerable structural and economic problems. The unemployment rate of the region is

nearly 30%. Fishery is important for local groups but its importance is expected to decrease

with a growth in tourism and industry. High economic pressure and the absence of

regulations presently endanger an economic use of resources. The institutionalised bilateral

cooperation between Albania and Macedonia dates back to 1956 when an agreement

between Yugoslavia and Albania on "Questions of Water Management" was ratified.

However, the cooperation and even the communication, among the local authorities,

economic sector and the citizens, were very poor until 1991. Important progress was made

in 1996 with the signing of a memorandum of understanding aiming at transboundary

natural resources management and pollution problems in order to provide a basis for

sustainable economic development of the basin.

Assets

Lake Peipsi

Lake Ohrid

Surface Area (km2)

3558

358,2

Estonia: 44%

Albania: 30%

Russia: 56%

Macedonia: 70%

Basin Area (km2)

44,240

1,129

Volume (km3)

25.2

50.8

Average Depth (m)

7.1

163

Maximum Depth (m)

15.3

289

Maximum Length (km)

143

30.8

Maximum Width (km)

48

14.8

Shore Line (km)

520

87.5

Trophic State

Eutrophic

Oligotrophic

Population in the Basin

1,000,000

Macedonia: 108,000

Albania: 38,000

The river basin analyses and the establishment of river basin plans are the crucial processes

for the public to be part of the decision-making at the river basin level. To enable the public

to express its views, the authorities responsible for the river basin management plans need to

maximize transparency of the issues and intentions addressed by the plans. To explain the

pending environmental and water use problems in the river basin as well as the intended

measures to combat them via RBMP, a thorough documentation in written form is only a

first step. River basin conferences bringing all stakeholders and the public together are

another tool to improve communication between the people and officials. Exhibitions about

the river basin, existing challenges and intended future solutions appear to be the most

efficient strate gy to get the public involved. The attraction of water could be linked to the

interest in protecting the source.9

9 Lanz, K., Scheuer, S. 2001. EEB Handbook on EU Water Policy under the Water Framework Directive.

EEB.

17

Box 1.

The Role of the Lake Ohrid Conservation Project in the Capacity Building and

Involvement of the NGOs in the Protection and Management Activities of

Lake Ohrid Basin10

Although historically environmental NGOs in Macedonia and Albania have not actively

participated in environmental policy-making or management decisions, in recent years

NGOs have become increasingly influential in the environmental field. The program for

public awareness and participation initiated by Lake Ohrid Conservation Project (LOCP)

proposes a range of short- and long-term actions which are addressing some of the major

problems and threats affecting Lake Ohrid. The strategy is to strengthen and utilize local

environmental NGOs to develop and carry out programs and activities designed to reach the

above objectives. The strategy comprises three major sub-components:

- Capacity building of NGOs;

- Public awareness;

- Public action.

Under the Public Awareness sub-component two Green Centres were created in Struga and

Ohrid. The Green Centres are serving as a central clearinghouse for the public, providing

information about the Lake Ohrid Conservation Project, the lake ecology and environmental

problems affecting the lake. They operate as a sort of "watch dog", investigating and

reporting environmental violations around the lake to the municipal governments and

exchanging information across the border. The Green Centres are offering recreation

opportunities for tourists, thereby increasing public interaction with the lake environment

while simultaneously creating a mechanism for self-financing.

In the offices of the Green Centres both in Ohrid and in Struga, so far the Green

Telephone line has been working successfully. In this period, documentation has been

established for more than 400 cases, of local citizens calling to give information about the

environmental situation in the region. From this the Green Centres have made more than

100 reports to the Communal inspections about environmental problems, more than 25

reports to the Public Communal enterprises, more than 100 reports about disposed

crushed vehicles. Under Public Action sub-component Public meetings are organized as a

central tool to ensuring that information about the project is open to all members of the

Lake Ohrid community. The public meetings include:

- Roundtables focused on a specific topic, at which scientific and other expert participants

present data and results from their work in the project;

- Public Hearings in which journalists, NGOs, project participants and others discuss the

project;

- Direct personal contacts between project manager and participants with local government,

village community leaders, NGOs, academic institutions, and other public representatives;

- Joint declarations, agreements for cooperative work within and between Macedonia and

Albania.

10 Box 1 is based on the presentation by Dejan Panovski, Lake Ohrid Conservation Project, Macedonia

18

Box 2.

Proposals for Public Participation in Elaboration of Cherava River Basin

Management Plan at International Level

The most important facts concerning Cherava River Basin Management approach are that

the Cherava River is the only transboundary river in the Lake Ohrid Basin; it is the second

biggest source of pollution of Lake Ohrid; most of its flow is a part of Albania and a small

fragment, important for tourist business, is crossing Macedonia.

The key water management issues in the Cherava River Basin are the necessity of

establishing joint bodies for the management of the river basin; regular monitoring of water

quality agreed by the two states of Macedonia and Albania; regular reports of the state of

water quality; providing public information in three languages (Albanian, English,

Macedonian).

The main interests of stakeholders in the key water management issues are economic

interests (tourism, mining); water quality (with special concern for water supply systems and

quality of drinking water); biodiversity (important for National Parks and forestry);

production of electricity; development of the region (in the fields of agriculture, industry and

urban development) and potential effects (decrease the costs for using land and water).

The relevant sources of information for stakeholders are scientific and research institutions

at state level (Hydro-Biological Institute in Ohrid, Hydro-Meteorological Institute in Tirana

etc.), existing national and transboundary bodies (ISTF, MTF, WMC), state and local

governments, legislative and inspectorate system.

The methods and formats of communication that can be used in work with different groups

of stakeholders are regular correspondence; seminars, workshops and round tables; public

hearings; press conferences; public campaigns; study tours; contests.

The possible ways to involve the public within the RBMP development process could be: to

offer information about the existing situation in the Cherava River Basin; to develop a

summary of the action plan; to conduct a questionnaire among all inhabitants and evaluate

the questionnaire; to organise seminars with all stakeholders; to publish the action plan and

organise a second round of seminars with the stakeholders.

19

Box 3.

Latvian Experience - Daugava River Basin project11

On March 2000 the LatvianSwedish "Daugava River basin project" (Daugava project) has

started. The Daugava Project is carried through by: Public Organization "Daugavas fonds"

with a project group of 10 specialists (from the Latvian side) and Vattenresurs Sverige AB

(from the Swedish side).

The Daugava project is based on the EU Water Framework Directive. Implementation of

the new policy will give a cause for changes both in the legislative and institutional water

management systems. Latvia as a pre-accession country to the EU has to be ready for such

policy and the Daugava project is one of the first steps towards it.

The long range objective of the project is to contribute to the development of a modern

Latvian water management system by the elaboration of the Daugava River Basin

Management Plan according to EU legislation and by gaining the knowledge and experience

to be used later in the management of other river basins of Latvia.

So far groups of stakeholders are identified, a basic strategy developed and a database of

stakeholders and target groups is established and regularly updated. Stakeholders are divided

into three groups according to their role and interest in the elaboration of the Daugava River

Basin Management Plan.

1. Environmental and educational NGO's, General public (Mass media), Funds. This group

is informed by post, home page, mass media and network of NGO centre with

encouragement for further cooperation. Drafted documents were also sent directly to

representatives of this group.

2. Inter-ministerial coordination group (including representatives from different ministries

as well as NGO centre and Union of Local governments of Latvia), Project board. The

inter-ministerial coordination group has an essential role in the distribution of

information and promotion of the "Daugava project". There are two main forms of

cooperation with this group: case-by-case consultations and periodical group meetings.

The Project Board with representatives both from the Latvian and Swedish side has a

key role in decision-making concerning activities within the project.

3. Local governments within the Daugava River Basin, specialists of central governmental

institutions, Regional Environmental Boards within the Daugava River Basin, Scientific

and research institutions, Professional associations (farmers, industries, water users etc.).

One of the most important stakeholders of this group is local government. The "Daugava

project" has organized interactive seminars with all local governments in the basin. The

results of a questionnaire show that local governments are interested in water

management within their territory and recognize the link between development and

sustainable management of water resources.

11 Box 3 is based on the presentation by Vija Silina, "Daugavas fonds", Latvia

20

Specialists from central governmental institutions, Regional Environmental Boards, scientific

and research institutions, reference groups, professional associations as well as consultants

and experts is a core group for discussing specific issues, for example, the establishment of

reference conditions for different types of waters, setting criteria for good water quality,

assessment of most effective measures to improve water quality etc. A fruitful collaboration

has already started and will be continued further on.

Box 4.

The First Steps on the Cooperative Management of Transboundary Waters on the

Eastern European Fringe the Pilot Study of Lake Peipsi/Chudskoe

Cooperation in the Lake Peipsi/Chudskoe basin illustrates the management of an

international lake by countries in transition, which need outside technical, material and

intellectual support, reorganize its administrative and legal systems, start the promotion of

public participation.

Cooperation in the Lake Peipsi/Chudskoe basin embraces a wide variety of stakeholders

from both countries, which encourage public participation among a wider audience and

promotes confidence building between riparian countries. Promotion of public participation

in the decision-making process and cooperation between regions and local authorities are the

main policy areas in the water management of Lake Peipsi at the moment. The

implementation of the European Union Water Framework Directive in the basin will be the

challenge of the coming years.

The Lake Peipsi/Chudskoe case demonstrates lessons learned from the first steps of

developing integrated water management for the protection a nd sustainable use of a large

transboundary lake shared by countries in transition in the Baltic Sea Basin. The lessons

learned could be summed up as:

1. A successful start of cooperative environmental management of transboundary waters

after years of economic crisis and political problems is possible, if parties commit

themselves politically and create formal mechanisms and means (institutions) for

cooperation.

2. Common interests in transboundary water body combined with an adequate legal and

political framework and mutual trust result in effective joint environmental management

at the intergovernmental level.

3. Members of the joint commission should be elected from very different institutions so

that different interests and perspectives are represented in the process of decision-

making; therefore a joint commission is a good body for communication, contention and

compromises.

4. Activities of the commission must follow a logical rhythm: first the collection of

background information and then on the basis of the collected and analysed information

decision making for joint actions.

21

5. It is very important to involve from the very beginning NGOs, local authorities, the

public as well as third parties experts from other countries than those sharing a lake, -

into the lake transboundary water management. The governments have to express their

will to include into the cooperation structures local stakeholders and NGOs through

creating institutional arrangements: in the case of the Estonian Russian commission a

working group under the intergovernmental commission was created for cooperation

with local authorities and NGOs.

6. On international water bodies intercalibration of water monitoring sampling and analysis

techniques is critical; it requires on the one hand trust and commitment to cooperation

between the riparian states, on the other hand, considerable resources time, human and

financial resources to ensure that the same equipment and methods are applied in

monitoring.

7. The exchange of data and knowledge is a prerequisite for an effective cooperation and

water management in international water basins but it is often difficult to achieve

because of a lack of trust between partners.

8. Public participation at local, national and international levels should be promoted. It

requires considerable human and financial resources from the decision-makers to

promote public participation but involving the public will facilitate a more effective

implementation of water management measures.

22

4.3 Cases of Public Involvement at National Level

The crucial steps for the public to be part of the decision-making at national level are the

transposition of administrative provisions into national law as well as the establishment of a

national ecological assessment system. Transposition usually requires the consent of national

parliaments, so public pressure at that step would have to be at the level of competent

government ministries and members of parliament. It may be difficult for NGOs to

influence this rather technical process, but given the key importance of the ecological

assessment system, every attempt should be made to safeguard the highest possible

standards. The WFD requires the Member States to establish the necessary measures to

achieve at least a good status in all waters. So nothing keeps a Member State from adopting

programmes of measures which are more ambitious than that. Hence, stakeholders should

watch closely the legal requirements for programmes of measures put into national law.12

Box 5.

The Role of Estonian Water Association and Water Clubs in Elaboration of

River Basin Management Plan13

In Estonia, persons dealing with water management problems are united under the Estonian

Water Association this is a voluntary organisation, founded on October 26, 1993, aimed at

`the development of Estonian water management, especially the usage and protection of

water bodies and ground water, water supply, sewage, water hygiene and connected natural

sciences and legislation, and at dissemination of information regarding water management'.

Every year, numerous meetings, reporting and informative events and conferences have

been organised; training on water management issues has been developed and publishing

activities in the field of water have been promoted.

On August 17, 2001 a new working group was established in the framework of the Water

Association it is called the Water Club and its aim is to promote water management in a

wider range of public and inform the public of water problems. During the forthcoming

years, the Estonian Water Club sees the inclusion of the public in the discussion of river

basin management plans, as a main direction of its activity. As we know, nine river basin

districts have been established in Estonia, in the light of the European Union's Water

Framework Directive, all of them exceeding the administrative boundaries of the counties.

One head office shall be formed in each district, which, as a rule, shall be located in the

public relations office of the environmental authority of the county, which is closest to the

river mouth. As a first priority, it has been planned to create three Water Clubs on the basis

of the Water Association: in Tallinn, Tartu and Pärnu. Within the framework of the above-

mentioned project, the EU water policy and other necessary literature has been translated

into the Estonian language, currently available in the Tallinn Water Club, however, they will

be accessible also in all other Water Clubs. In the Water Clubs, all interested citizens and

groups can obtain information on drafted development plans, and they can also submit their

proposals and comments there.

12 Lanz, K., Scheuer, S. 2001. EEB Handbook on EU Water Policy under the Water Framework Directive.

EEB.

13 Box 5 is based on a presentation by Maret Merisaar, Estonian Green Movement, Estonia

23

Box 6.

Educating and Involving Stakeholders by Agency for Development and Promotion of

Agriculture of the Republic of Macedonia 14

Eutrophication is the main transboundary problem at Lake Ohrid. The annual phosphorus

load to Lake Ohrid is estimated at 240 t/y, 154 of which are in dissolved form, readily

available to the algae. More than 30% of the dissolved phosphorus originates from the

rivers and the springs, that is, from the non-point sources of pollution. The non-point

sources of pollution have proven to be more difficult to tackle and require different control

strategies than those applied for the point sources. Essentially, the problem stems from the

fact that diffuse sources do not lend themselves to command and control style oversight.

Because a limited amount of funding is available, efforts to reduce phosphorus should focus

on the sub-basins most affected by phosphorus.

Numerous agricultural activities today heavily relay on the use of different agrochemicals. In

their efforts to produce quality agricultural products, competitive on the open market, the

farmers have to use different pesticides to control the multiplicity of diseases, weeds and

harmful insects. Recognizing these facts, the Agency is focusing on educating the farmers on

the proper use of all those chemical substances (pesticides and fertilizers), that is, to be used

in a proper way, on time, no more, no less. Moreover, the Agency is promoting the

integrated pest management practices that have multiple benefits, both to the farmers and

the environment. However, this needs proper technical knowledge and monitoring

equipment that at the moment is not affordable for most of the farmers. Therefore, one of

the important activities of the Agency is to monitor different parameters pertinent to the

control of the growth of the plants as well of the different pests and distribute to the farmers

free-of-charge.

Education programs of the Agency focus on several areas:

1. Adequate use of agrochemicals, handling of surplus pesticides and agrochemicals,

controlling wash water from agrochemical application machines; dumping of the packing etc,

in order to protect the surface and ground waters;

2. New methods for maximum plant protection and minimum pollution, including:

- Solar radiation of the soil, by using sunbeams and PVC foil, soil can be protected from

diseases, weeds and harmful insects, and in this way it remains clean from chemicals.

- To pour boiling water through the soil for the same aim which is presented above.

- Using biological substances.

- Using bacteria to disintegrate surplus pesticides that have remained in the soil.

- Analysis of the soil to find out which chemical elements it consists; which fertilizers

and their quantity are important for the plant's growth.

14 Box 6 is based on a presentation by Slagjana Kaladzievska, Agency for the Development and Promotion

of Agriculture of the Republic of Macedonia

24

The basin approach as a whole and the control of the non-point sources of pollution in

particular, rely very much on the involvement of and contribution from the stakeholders and

the public in general. The ongoing educational and demonstration programs of the Agency

coincide with several important actions in the field of agriculture proposed by the Lake

Ohrid Watershed Committee for Macedonia. The regional river basin associations of citizens

can play a crucial role since they are familiar with the non-point pollution sources within the

sub-basins. Therefore, it rests heavily on public education and on creating an active public

participation and public support.

Box 7.

Public Participation in Water Management in Russia15

Environmental protection in general and, especially, protection of such an important,

irreplaceable and integral component, as water resources, is a problem not only nation-wide,

but also social, as far as it touches vital interests of all layers of the population.

Unfortunately, in the present situation in Russia the interaction of the bodies, which to some

extent engage in water management and the protection of water bodies, with the public is

extremely insignificant. That is caused by the reasons of an objective and subjective

character. To the list of objective reasons it is possible to include the following:

1. The problems of the economy and the social sphere are coming to the foreground

(unemployment, manufacturing crisis, wages non-payment etc.);

2. The general crisis of management, weakness of administrative structures and state control;

3. The backwardness of civil society institutes;

4. The inefficiency of the system aimed at providing the citizens with environmental

information, including data on the state of water bodies.

Among the subjective reasons we can list the following: disbelief of citizens in the

importance of public opinion for state structures on environmental questions and

unwillingness in this connection to be engaged in environmental public activity; the absence

of leaders - organizers of environmental movement capable to attract public attention to

environmental problems and to involve the citizens; environmental ignorance and

environmental nihilism of the population.

At the same time the existing Russian legislation gives the real rights to the citizens in the

sphere of environmental protection and various natural resources (in particular, water

bodies). The legal basis of public participation in the protection of water bodies is stated in

clauses 30, 42,58 of the Constitution of the Russian Federation, clause 3 of the law «About

environmental protection» etc. in the Water Code of the Russian Federation, Statute on the

Ministry of Natural Resources of the Russian Federation, the Civil Code of the Russian

Federation, the federal law «About public associations» and the federal law «About

environmental expertise».

15 Box 7 is based on an article by Vladimir Budarin, Head of the Neva-Ladoga Basin Water Administration,

Russia

25

The form of public participation in the management of the use and protection of the water

fund is the realization of referendums of various levels, which raise the questions of

environmental protection, construction of economic and other objects and realization of

other economic activities connected with the influence on the environment and natural

objects and conditions of population health of the territory in question. Thus the high degree

of legitimacy of administrative decisions is achieved through the economic and other

activities, which are based on these decisions and which influence the environment.

4.4 Cases of Public Involvement at Local Level

The most important factor contributing towards our earth's positive development is the sum

of all the local initiatives, decisions and actions put together. Local populations and

interested parties' influence on the development processes varies a lot, but limited

possibilities of taking local decisions can be compensated by voluntary actions, creative ideas

and co-operation. It is hardly an exaggeration to claim that most of the environmental

threats we are facing today can be solved through local initiatives if we only put our minds to

it.16

Inherent in our recognition that the most serious problems of water security are those at the

local level, is the attendant recognition that civil society is among the best suited to address

local issues.17 Each person has a stake in protecting and enhancing the environment and

citizens know the needs of their communities through work, play and travel.18

Box 8.

Pogradec Water Management Project19

The Pogradec Water Management Project was launched in the beginning of 1996. Two

feasibility studies which aimed at determining the most appropriate means of rehabilitating,

upgrading, and extending the water supply and waste water collection and treatment system

in the region of Pogradec for the long and for the short-term were prepared. One of the

studies covers the drinking water supply system, the other the wastewater collection and

treatment system.

The Pogradec Water Management Project is a part of an overall Albania Municipal Water

Supply and Wastewater Project. The overall purpose of this project is to improve the

provision of water supply and wastewater services to the cities of Elbasan, Fier, Vlore, Lezhe

and Pogradec and through that the environmental protection of Lake Ohrid by the

introduction of water pollution prevention and control for the Albanian side of the Lake.

16 Bovin, K., Magnusson, S. 49 Local Initiatives for Sustainable Development. 1997.

17 Wolf, A. T. 2001. Trahsboundary Waters: Sharing Benefits, Lessons Learned. Thematic Background

Paper for International Conference on Freshwater, Bonn 2001. Manuscript.

18 Public Participation in Making Local Environmental Decisions. The Aarhus Convention Newcastle

Workshop, 2000.

19 Box 8 is based on a presentation by Naum Gegprifti, Lake Ohrid Watershed Management Committee,

Albania

26

The first implementation phase would include the construction of a wastewater treatment

plant near Pogradec, a primary collector connecting the city of Pogradec with the treatment

plant and a secondary collecting system in the city of Pogradec. A workshop on the two

investigated wastewater concepts was held in Ohrid on February 9 and 10, 1999 with

representatives of Albania, Macedonia and different donors participating. The main result of

the workshop was a common agreement, based on its considerably lower unit costs, its

suitability for project phasing and its lower regulatory requirements.

In addition, the Albanian and Macedonian delegations signed a joint statement to fully

involve the Lake Ohrid Management Board and to join efforts in finding additional funding

from various donors for future project phases II and III. The Lake Ohrid Monitoring

Program should identify the need for evacuating their intent to include such evacuation in

the future project phases.

Public Participation has been present during all phases of implementation of the Lake Ohrid

Conservation Project. Since the early years of 1995 and 1996 a number of experts and

specialists from Albania and Macedonia participated in this process giving their opinions and

their scientific data. Later a lot of specialists of different fields related to this Project

participated and gave their special contribution and many of them gave interesting data.

Last year some meetings and seminars were organized with specialists, representatives of

Local Government and NGOs and they discussed a lot of topics to identify the real situation

and determine the priorities in this field.

Box 9.

Proposals for Public Participation in Elaboration of Gdovka River Basin

Management Plan in Russia

The key water management problems for the Gdovka River Basin are:

- Lack of management body in the regional local authorities

- Lack of reliable information

- Lack of essential means of subsistence

- Lack of state licences for land-users

The key water management issue of the Gdovka River is the absence of effective biological

treatment of sewage (for improvement for BOD and reduction of ammonia by 90%, and

pathogenic substances). There were several projects and plans prepared for construction of

the Gdov wastewater treatment plant but nevertheless neither of them was realised due to

lack of funds in Russia. At the same time, the major international funder of environmental

infrastructure projects, the Danish EPA, adopted a decision not to fund wastewater

treatment plants for municipalities with the population less than 10 000 (The Gdov

municipality population is 6 000 inhabitants). The re is a need to develop project proposals

to the government as well as to possible international funders, such as the EU TACIS

program, for construction of the Gdov municipal wastewater treatment plant and

preparation of the Gdovka River sub-basin management plan. The Gdov municipality can

prepare such a proposal in cooperation with the Pskov Regional Committee for Natural

Resources as well as with Pskov regional NGOs.

27

The Gdov municipality discussed with the local NGOs and stakeholders the possible

involvement of local stakeholders in developing of the Gdovka River Management Plan. It

was discussed that environmental information relevant to the river basin management plan

can obtain it from the following sources: the Pskov Centre of Hydrometeorology and

Environment Monitoring and Sanitary Epidemiological Service. Besides, information for

internal use can be found at The Federal State Water Management Institution of

"Pskovvodhoz" and from the Administration on the issues of Civil Defence and Extreme

Incidents. Based on that information, it would be useful to elaborate an ecological database

for the Gdovka River Basin, showing the main points of pollution and its statistics.

The means of communication and format of communication to be used working with

different target groups for preparation of the Management Plan are:

- Public hearings and referendums

- Mass media, films

- Newsletters and pamphlets

- NGOs' means of communication

It is crucial to inform the local population on significant pressures and impacts from human

activities in the river basin district and to invite the specialists; to provide such information

local newspapers, state newsletters and public meetings should be used. On the other hand it

is important to enhance feedback from the public by performing questionnaire studies and

collecting suggestions. It is important to provide information demanded by the population.

It is important not only to inform but also involve NGOs, educational institutions,

inhabitants, village headmen, and mass media into the process of the RBMP elaboration.

The crucial point is to organize a Public Council at the level of local authorities (village

headmen) on environmental development, announce in the local newspaper the possibility

of organising such a body and ask for interested parties to participate. The Public Council

will gather from time to time to discuss the questions of ecological development of the area

and provide local population with relevant information.

The elaborated RBMP should be transferred to the area administration and included into the

local Agenda 21. Federal structures elaborate such plans and present it to the local

authorities and interested parties calling for comments. The "pusher" in that process should

be a person with an environmental background, understanding of the fundamental issues or

some other initiator raising the problems in this field (representative of the local

administration or NGO). Besides, the problems can be stated and solved by the same

interested parties.

There is a necessity to create a database, as a basis for information providing a starting point

of the process. There could be an option to elaborate an environmental atlas showing the

river basin status. It is also important to make an agreement between the local authorities

and the bodies that provide information on the issues of data supply and also on the

interrelation of the local authorities and information providers. After the adoption of the

RBMP its implementation should be supported by the public.

28

Box 10.

Proposals for Public Participation in Elaboration of Lake Peipsi Management Plan in

Tartu and Jõgeva County in Estonia

The following could be mentioned as key problems of water management in the Lake Peipsi

water basin in Jõgeva and Tartu counties: water quality, availability and the level of

information; monitoring and accessibility of monitoring data; sustainable use of water

resources (especially that of the ground water); preservation of habitats and rare species; the

economy (agriculture, forestry, fishery, water transport, etc.); formation of water price (raw

water treatment, water supply and sewage systems, wastage) and the evaluation of

investment necessities.

In order to inform different interested groups, various formats should be used. The

following forms are the most efficient for the dissemination of information among local

inhabitants: articles in a local newspaper, various forms of data, reaching homes by way of

children, such as leaflets, stickers, information booklets, etc.; materials presented on the

notice boards of local governments, know-how disseminated by professional associations;

more definitely directed information of various forms distributed by way of non-

governmental organisations. The best information channels for enterprises, the second large

target group, are the following: technical and marketing information, disseminated via the

Internet; market and advertising news spread through media channels; more circumscribed

special data delivered at seminars and training events. The great importance of disseminating