BLACK SEA TRANSBOUNDARY

DAGNOSTC ANALYSS

May 2007

TABLE OF CONTENTS

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... 1

1.

INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................... 9

2.

METHODOLOGY ............................................................................................ 11

2.1 The 1996 Black Sea TDA ................................................................................... 11

2.2

The 2006 Black Sea TDA ................................................................................... 11

2.3

Identification of priority transboundary issues ................................................. 12

2.4

Development of thematic reports ....................................................................... 12

2.5

Development of causal chains for priority transboundary problems ............ 13

2.6

Hot-spots analysis ................................................................................................ 14

2.7

Stakeholder analysis ............................................................................................ 14

2.8

Governance analysis ........................................................................................... 14

3.

DESCRIPTION OF THE BLACK SEA REGION ........................................... 17

3.1

Physical and geographical characteristics ....................................................... 17

3.1.1 Geographic boundaries ....................................................................................... 17

3.1.2 Bathymetry .......................................................................................................... 18

3.1.3 Coastline characteristics ...................................................................................... 18

3.1.4 River discharge ................................................................................................... 19

3.1.5 Climate, agricultural production and river discharge ......................................... 19

3.2

Socio-economic situation .................................................................................... 22

3.2.1 Demographic trends ............................................................................................ 22

3.2.2 Economic indicators ............................................................................................ 24

3.2.3 Social indicators .................................................................................................. 28

3.3

Biodiversity and ecosystem health .................................................................... 30

3.1.1 Introduction ......................................................................................................... 30

3.1.1 Ecosystem and habitat types ............................................................................... 30

3.3.2 Phytoplankton and zooplankton .......................................................................... 31

3.3.3 Seaweeds and zoobenthos ................................................................................... 33

3.3.4 Large fauna ......................................................................................................... 35

3.3.5 Alien species introduction ................................................................................... 36

3.3.6

Loss/decline of biodiversity at the species level IUCN red list species ...... 37

3.3.7

Protected areas ................................................................................................ 37

3.3.8 Status of fisheries ................................................................................................ 38

3.4

Status of chemical pollutants .............................................................................. 39

3.4.1 Water column ...................................................................................................... 40

3.4.2 Sediment ............................................................................................................. 41

3.5

Status of the nutrient regime .............................................................................. 43

3.6

Institutional setting and stakeholders ................................................................ 45

3.6.1 Institutional setting.............................................................................................. 45

3.6.2 Stakeholders ........................................................................................................ 45

3.7

Public perception of environmental status, causes and responsibilities ..... 47

4.

PRIORITY TRANSBOUNDARY PROBLEMS .............................................. 49

4.1

Key transboundary problems and priority scores ............................................ 49

4.2

Nutrient over-enrichment/eutrophication .......................................................... 50

4.2.1

The problem .................................................................................................... 50

4.2.2

Environmental impacts and socio-economic consequences ........................... 51

4.2.3 Linkages with other transboundary problems ..................................................... 54

4.2.4 Immediate causes ................................................................................................ 55

4.2.5 Underlying causes ............................................................................................... 65

i

4.2.6 Knowledge gaps .................................................................................................. 68

4.2.7 Summary and preliminary recommendations ..................................................... 68

4.3

Changes in commercial marine living resources ............................................ 71

4.3.1

The problem .................................................................................................... 71

4.3.2 Environmental impacts and socio-economic consequences ............................... 74

4.3.3 Linkages with other transboundary problems ..................................................... 77

4.3.4 Immediate causes ................................................................................................ 79

4.3.5 Underlying causes ............................................................................................... 83

4.3.6 Knowledge gaps .................................................................................................. 85

4.3.7 Summary and preliminary recommendations ..................................................... 85

4.4

Chemical pollution, including oil ......................................................................... 88

4.4.1

The problem .................................................................................................... 88

4.4.2 Environmental impacts and socio-economic consequences ............................... 89

4.4.3 Linkages with other transboundary problems ..................................................... 90

4.4.4 Immediate causes ................................................................................................ 91

4.4.5 Underlying causes ............................................................................................... 99

4.4.6 Knowledge gaps ................................................................................................ 103

4.4.7 Summary and recommendations ....................................................................... 104

4.5

Biodiversity changes, including alien species introduction .......................... 107

4.5.1 The problem ...................................................................................................... 107

4.5.2 Environmental impacts and socio-economic consequences ............................. 107

4.5.3 Linkages with other transboundary problems ................................................... 111

4.5.4 Immediate and underlying causes ..................................................................... 112

4.5.5 Underlying socio-economic drivers .................................................................. 118

4.5.6 Knowledge gaps ................................................................................................ 118

4.5.7 Summary and preliminary recommendations ................................................... 119

5.

HOT-SPOTS ANALYSIS ............................................................................... 123

5.1

Identified capital investments completed ........................................................ 123

5.2

Identified capital investments started .............................................................. 125

5.3

Work still required............................................................................................... 125

6.

GOVERNANCE LEGAL AND INSTITUTIONAL ANALYSIS OF THE

BLACK SEA REGION ........................................................................................................ 127

6.1

Introduction .......................................................................................................... 127

6.2

Institutional analysis ........................................................................................... 127

6.2.1 Regional institutions ......................................................................................... 128

6.2.2 National institutions for regional cooperation .................................................. 131

6.3

Policy/legal analysis ........................................................................................... 137

6.3.1 International legislation and agreements .......................................................... 137

6.3.2 National legislation ........................................................................................... 138

6.4

Conclusions ......................................................................................................... 139

7.

STAKEHOLDER ANALYSIS ........................................................................ 141

7.1

Introduction .......................................................................................................... 141

7.2

Environmental perceptions of stakeholders ................................................... 141

7.3

Priority issues for stakeholder groups ............................................................. 146

7.4

Nutrient over-enrichment/eutrophication ........................................................ 148

7.5

Decline in commercial fish species/stocks ..................................................... 151

7.6

Chemical pollution (including oil) ..................................................................... 153

7.7

Habitat and biodiversity changes (including alien species introduction) ... 154

7.8

Summary and preliminary recommendations ................................................ 155

8.

CONCLUSIONS AND NEXT STEPS ............................................................ 157

ii

8.1

Conclusions ......................................................................................................... 157

8.2

Next steps ............................................................................................................ 159

REFERENCES ..................................................................................................................... 161

Annex 1:

GLOSSARY OF TERMS ................................................................................ 167

Annex 2:

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ........................................................ 171

Annex 3:

LIST OF CONTRIBUTING SPECIALISTS................................................... 175

Annex 4:

MAIN BLACK SEA HABITATS AND CRITICAL HABITATS AT

NATIONAL LEVEL ............................................................................................................ 177

Annex 5:

INVENTORY OF AQUATIC AND SEMI-AQUATIC RED LIST SPECIES,

ENDANGERED IN AT LEAST ONE COUNTRY AROUND THE BLACK SEA ........... 180

Annex 6:

INVENTORY OF AQUATIC AND SEMI-AQUATIC ALIEN SPECIES

INTRODUCED TO THE BLACK SEA AND COASTAL HABITATS ............................ 190

Annex 7:

GROUPS USED IN THE STAKEHOLDER ANALYSIS ............................. 212

Annex 8:

MINIMUM FISH SIZES FOR LANDING IN BLACK SEA COUNTRIES . 218

Annex 9:

LANDFILL DATA .......................................................................................... 220

Annex 10:BOD5 LOADS ...................................................................................................... 232

Annex 11:IMPLEMENTATION OF HOT-SPOTS CAPITAL INVESTMENTS

IDENTIFIED IN THE 1996 TDA ........................................................................................ 236

Annex 12:EXISTING PROTOCOLS TO THE BUCHAREST CONVENTION ................ 242

Annex 13:INTERNATIONAL CONVENTIONS AND THEIR RATIFICATION STAGE

244

Annex 14:INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION THROUGH BI/TRI-LATERAL

AGREEMENTS .................................................................................................................... 248

Annex 15:RELEVANT NATIONAL LEGISLATION ........................................................ 250

iii

iv

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Introduction

The Black Sea covers an area of 423,000 km2, is over 2 km deep and drains an area of 1.9

million km2 (one-third of continental Europe) containing over 160 million inhabitants. The

coastal zone1 contains a poulation of some 20 or 39 million people, depending on whether

the Istanbul administrative unit is included in the total. This has a short Black Sea coastline.

The Sea has six coastal countries: Bulgaria, Georgia, Romania, the Russian Federation,

Turkey and Ukraine.

The Sea is enclosed by land; its only connection with the World's Oceans being via the

Turkish Bosphorus Strait, which links it with the Mediterranean (via the Sea of Marmara).

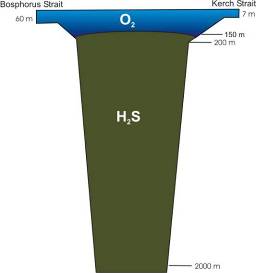

Some 90% of the Sea is naurally anoxic (contains no oxygen), but the top 150 m layer

represents an area of great biological productivity, providing the employment basis for

hundreds of thousands of people.

This report represents the second Black Sea transboundary diagnostic analysis (TDA), the

first of which was produced in 1996. It assesses the environmental status of the Sea, focusing

on the major transboundary problems, their causes and what should be done to improve its

status in the future. The structure and content of this document are different to that of the

1996 TDA, since guidance on TDA production has changed in the intervening years and

instead of the original seven major transboundary problems, it now focuses on only four:

· Eutrophication/nutrient enrichment

· Changes in marine living resources

· Chemical pollution (including oil)

· Biodiversity/habitat changes, including alien species introduction

For each of these a causal chain analysis is included, to assist in the identification of

solutions for each of the problems. The emphasis of this document is on changes that have

occurred since the original TDA was produced. However, socio-economic developments and

environmental data over a longer period of time are also considered to place the current

status in context, and describe the reasons underlying changes observed.

Socio-economic changes

The Black Sea Region has undergone major socio-economic changes over the past 20 years.

The regional economic collapse at the end of the 1980s, with the resulting break-up of the

Soviet Union and birth of the CIS2 countries, together with a much less dramatic but still

influential economic slow-down in 1997-98 have had major social and environmental

implications. Since 2000, personal wealth has increased, but not as rapidly as inflation.

Furthermore, this increase in wealth has been concentrated in the hands of a small number of

very rich individuals. The size of the middle class remains small. The economies and

infrastructure of all countries have been struggling with the problem of rural-urban migration

since the 1960s, a trend which is continuing and has led to the development of Istanbul,

spanning the Bosphorus Strait, as a city which now contains about 15 million people. The

lack of data provided on pollution inputs (nutrients and toxic substances) to the Black Sea

1 Defined as one `administrative unit' inland from the Sea

2 Commonwealth of Independent States.

1

from both the Bosphorus and Kerch straits is considered a major weakness of this

assessment.

As the economies have changed, so has the importance of different sectors in contributing to

national wealth. In particular, agriculture has slumped as a contributor to national GDP since

1994 (most dramatically in Georgia), with a less dramatic fall in manufacturing industry, but

these have been more than offset by the increase in importance of the service sector (again,

most notably in Georgia).

Ecological changes

For management and reporting purposes it is useful to consider environmental changes in

carefully-defined steps, stages or classes. Indeed, classification schemes are used in this

report. However, in reality the shift from pristine to catastrophic damage is a perfect

glissando; a smooth transition; albeit one in which the rates of change are different in

different areas of the Sea, with emphasis having been placed on the NW Shelf. The Sea is

still degraded, but substantial improvements have occurred over the past 10-15 years. This is

demonstrated by changes in the plankton, fish and benthic invertebrate communities. In

addition, the area affected by oxygen depletion (hypoxia) is now much smaller than in the

1980s and early 1990s, and those areas which are still affected by hypoxia are impacted to a

lesser extent. Ecological change was very rapid in the 1990s and has continued through the

early 2000s, with the emphasis of this change having been on both adaptation and recovery.

The introduction of so many exotic species has meant that even if the chemical environment

of the Sea is restored to its 1960s status, the ecology of the Sea would not return to its former

state.

Eutrophication/nutrient-enrichment

This decrease in the importance of agriculture as an economic powerhouse of the region has

been clearly shown by decreasing trends in livestock numbers and a shift from major

livestock farms to small-scale or subsistence-level farming. Livestock numbers (excluding

poultry) in 2004 were about two-thirds of those present 1997, and about one-third of the

numbers recorded in 1998. Likewise, inorganic fertiliser application rates in Romania in

2004 were about one-third of what they were prior to the collapse of the Soviet Union.

During the early years of this century fertiliser application rates were substantially higher in

Turkey than in other Black Sea countries; Bulgaria, Georgia and Romania formed a middle

group; and the lowest fertiliser application rates were found in the Russian Federation and

Ukraine. Indicators suggest that the decline in agriculture may have bottomed-out, so a

gradual re-intensification of agricultural practices may begin in the near future.

Direct discharges from large municipal/industrial plants to the Sea account for only about

2% of the inorganic nitrogen and 13% of the phosphate load discharged to the Sea via rivers,

of which the Danube is by far the most important. This accounts for about 84% of the river-

borne inorganic nitrogen load and 49% of the river-borne phosphate load, from a river

accounting for 67% of the freshwater input. Available information suggests that atmospheric

deposition of nitrogen to the Sea may be of a similar order of magnitude to river loads, but

there is considerable uncertainty over the data used.

Between 1996 and 2005 river-borne loads of both inorganic nitrogen and phosphate fell by

30. This is very encouraging for the future status of the Sea, but this decrease in nutrient

loads is overwhelmingly the result of economic decline and slump in agricultural

productivity rather than due to improved regional environmental management. For these

2

improvements to be maintained in the future it is essential that procedures and legislation are

put in place to prevent the situation from reversing as regional economic improvements

occur.

The following recommendations are made:

· Improve routine Black Sea nutrient monitoring/reporting in at least 3 countries:

Bulgaria, Georgia and Ukraine. All countries should monitor the Black Sea with the

same sampling frequency to improve data comparability.

· Measure riverine and municipal/industrial nutrient discharge concentrations (for the

estimation of loads) as total N and total P. Inorganic nitrogen and ortho-phosphate

measurements are a poor substitute for calculating loads.

· Place a much greater emphasis on nutrient management in agriculture, notably the

development, adoption and enforcement of best agricultural practice guidelines,

including revised guidance on fertiliser (organic and inorganic) fertiliser application

rates, together with a robust soil nutrient testing programme.

· Standardise and harmonise the quantification of river loads. Procedures giving

comparable results should be adopted for the assessment of loads at the most

downstream points in all major rivers discharging into the Black Sea.

· Develop a nutrient source apportionment model for the whole Black Basin to

improve existing understanding of nutrient sources.

Commercial marine living resources

Due to over fishing in the early 1970s-1980s, the structure of catches has shifted

significantly. Declining stocks of predatory species such as bonito, horse mackerel and

bluefish resulted in an increase in non-predatory species such as anchovy and sprat.

Consequently, fishing fleets have increasingly targeted these smaller species, resulting in

increased by-catches of larger, less abundant fish species.

Commercially important marine living resources have been greatly affected by alien species

introductions, eutrophication, over-fishing and habitats change/damage. Annual total fish

catch statistics show an improving situation, but these figures are dominated by catches of

anchovy and sprat. There have been recent improvements in catches of some other fish, such

as bonito, but turbot, dogfish and whiting catches have either shown no improvement or have

fallen over the past decade-or-so. Sturgeons remain endangered. There is an absolute need to

develop a regionally agreed fishery policy, for which background work on the development

of a legally binding document has started. This needs to include agreed methods on and

participation in: (i) regional stock assessment exercises, since those countries which

currently undertake these use different methodologies and many of the assessments are out

of date; and (ii) catch per unit effort (CPUE) assessments. No robust CPUE methodology

exists for the same assessments to be made by all coastal countries.

The importance of Rapana, the Japanese Snail has increased and has helped to off-set the

decline in mussel and clam landings (the decline being due, in large part, to predation by

Rapana anyway). The seafood industry is a major coastal employer, particularly in Turkey

which is responsible for some 80% of the total catch from the Sea. Aquaculture is not

strongly developed in the region and there is scope for this to be expanded, providing

environmental considerations are taken into account.

3

There contribution of illegal fishing activities to damage/change of marine living resources is

not clearly understood, but there a general acceptance that this is a causative factor. One

example cited from Romanian waters shows that this is, indeed, a considerable issue which

needs to be addressed.

The following recommendations are made:

· A regionally agreed system needs to be developed to match fishing effort to stocks

(prohibition periods, minimum admissible fish length, etc).

· Harmonise the methodologies for collection and collation of fisheries statistics at a

regional level

· Establish regionally agreed national fishing zones in all Black Sea countries

· Prohibit the use of non-sustainable fishing technologies (notably dragging and

bottom trawling).

· All countries should take greater effort to combat illegal fishing practices.

· Encourage expansion of the mariculture sector, but only if account is taken of

environmental considerations. The precautionary principal should be applied.

· Place a higher emphasis on ecological factors when making decisions on coastal

development.

Chemical pollution

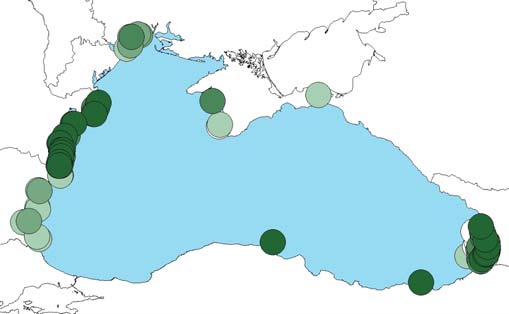

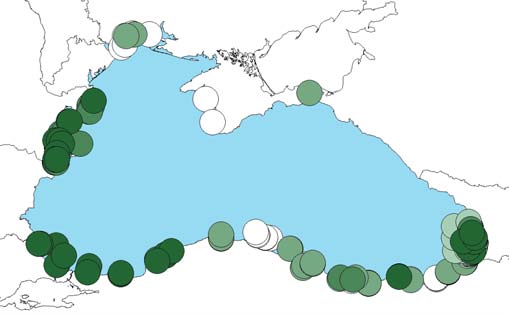

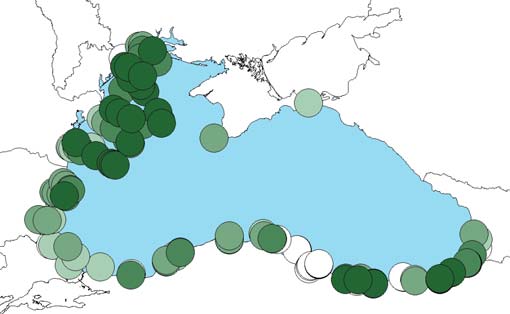

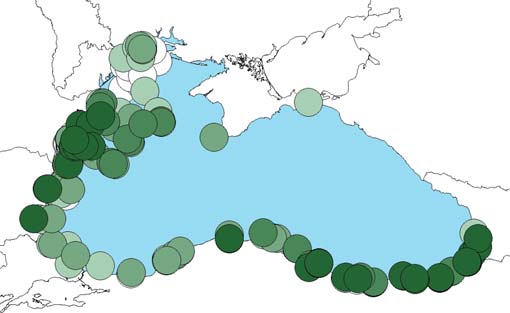

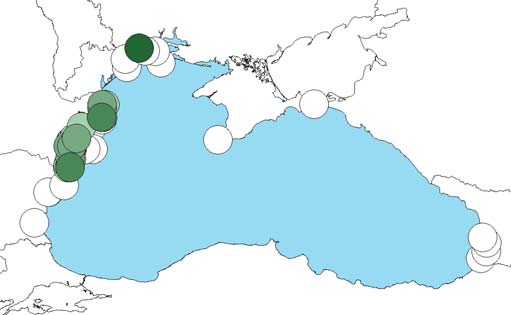

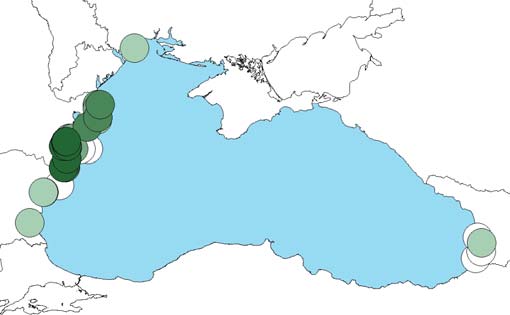

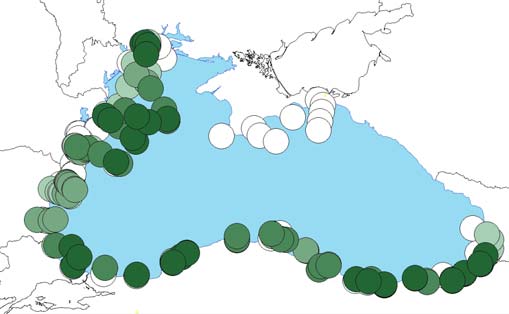

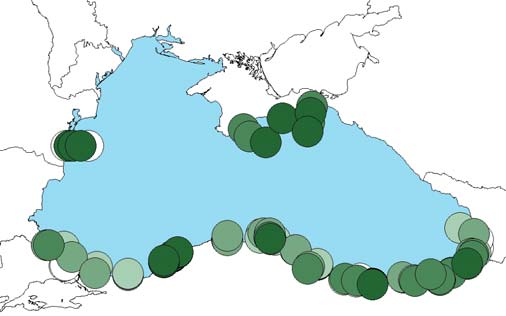

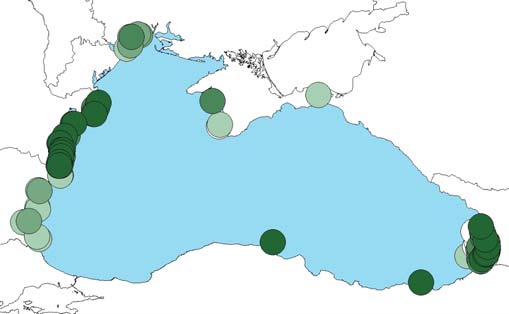

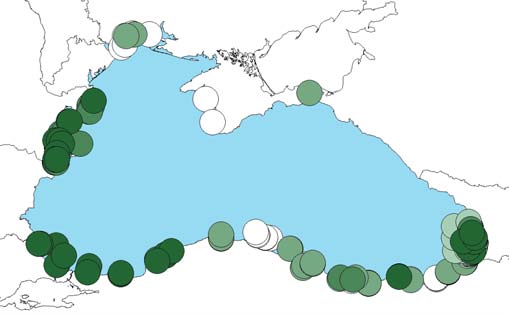

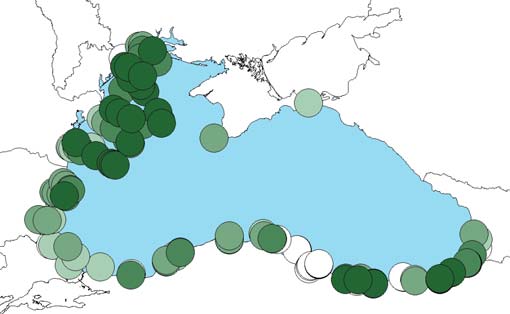

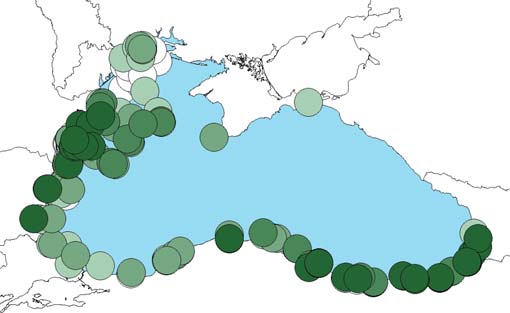

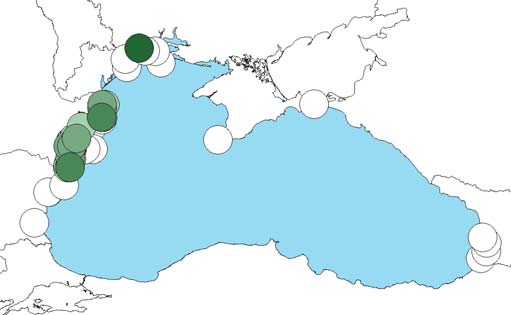

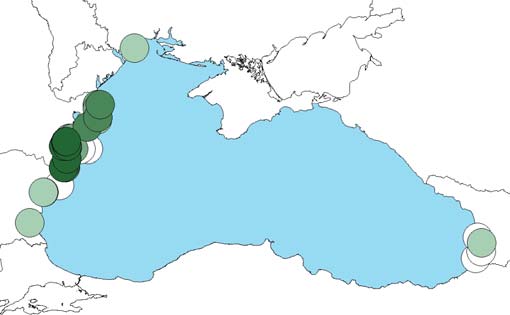

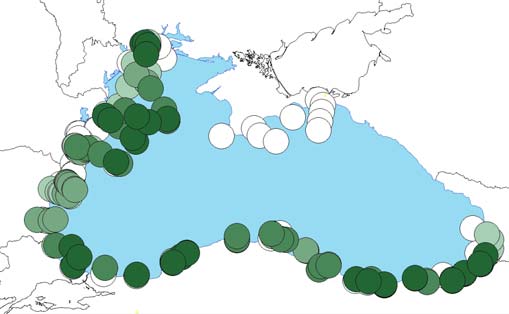

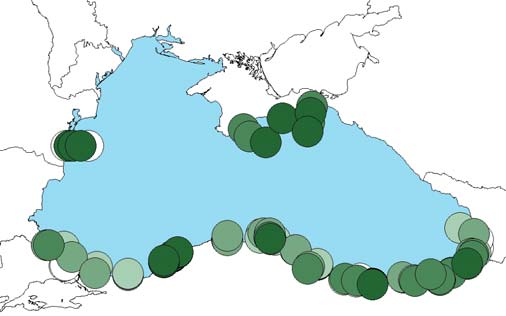

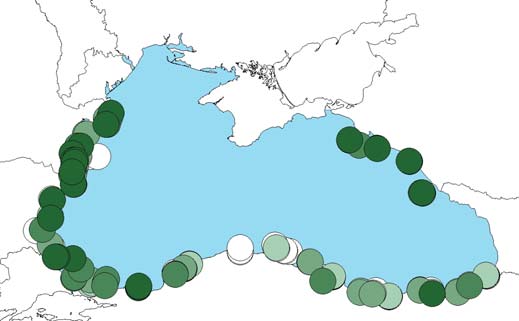

Available data on individual pollutants in the water column an sediments are mapped out,

illustrating large differences in the number of sites for which results of individual parameters

are available. In general terms, considerable amounts of data were made available from the

Western edge and NW Shelf, of the Sea, with good spatial coverage but limited sampling

frequency and period of coverage along the Turkish cosat. Data from a surprisingly high

number of Georgian coastal sites were made available, albeit with a low number of

determinations for each site. Relatively few Russian or Ukrainian data were available.

An assessment of pollutant loads from river and large direct municipal/industrial discharges

is also presented. However, the pollution loads data are very incomplete, BOD5 being the

only parameter (apart from nutrients) that is routinely monitored from major point sources

and rivers. Relatively high contamination levels of some pesticides, heavy metals and PCBs

are present at specific sites in the Black Sea. The concentrations of some substances are in or

above the ranges used as Ecotoxicological Assessment Criteria by OSPAR, with illegal

dumping/discharges (particularly of agrochemicals) being recognised as a particular

problem. The historical poor enforcement of discharge standards and a failure to consider the

Sea itself as a receiving waterbody for discharges to river are considered to be the principal

reasons underlying the pollution status of the Sea.

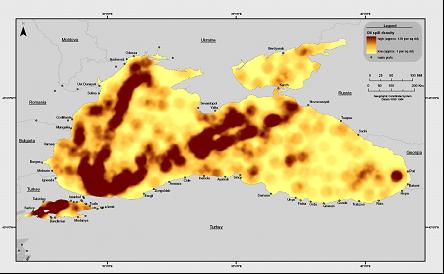

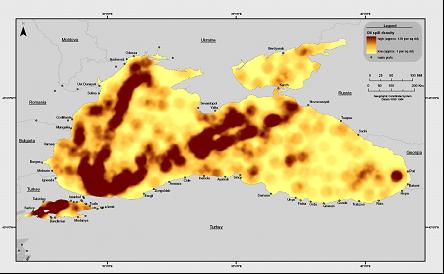

A huge increase in the volume of oil being transported across the Black Sea and oil/gas

extraction from beneath the Sea itself have greatly increased the risk of oil pollution. This

presents two types of problem: (i) localised chronic pollution stemming from frequent but

minor releases of oil; and (ii) acute pollution resulting from major oils spills. Remote sensing

data show that the majority of oil spills occur along major shipping routes, showing that

shipping, rather than land-based oil installations are the principal cause of concern. In

particular, where ships eneter the Sea through the Bosphorus Strait appears to be an area of

frequent ship-derived oil spills, with sediment total petroleum products results supporting the

remote sensing imagery data.

4

The following recommendations are made:

· Develop a regionally agreed list of priority pollutants for monitoring purposes.

· Develop robust national quality assurance programmes for the

intercomparation/intercalibation of chemical concentration and flow data from point

sources.

· Harmonise environmental standards (discharge and environmental water/sediment

quality standards) throughout the Region.

· Produce a regional manual for data handling.

· Establish national plans to reduce/prevent pollution of the Black Sea.

· Build the capacity of environmental authorities to enforce existing regulations on the

discharge of priority pollutants from both point and diffuse sources.

· Develop national/regional public awareness programmes to promote bottom-up

pressure on decision makers in order to improve the environmental status of the

Black Sea

· Establish an inter-state ministerial mechanism to enable a quick response to major

pollution events.

· Develop/adopt an agreed transboundary environmental impact assessment

methodology to assist with transboundary projects in the region

· Reduce pollution loads by the application of best available technology and

introduction/enforcement of best agriculture practice.

· Provide assistance to industrial sectors (including mining enterprises) to develop

Environmental Management Systems and practice cleaner production activities

· Develop a network of farmer support services for raising awareness in the application

of fertilizers, pesticides and herbicides.

· Production of a code of practice for data handling and transfer for use by all national

institutions reporting to the BSC and the Premanent Sectretariat itself.

Biodiversity

The structure of marine ecosystems differs from that of the neighbouring Mediterranean Sea

in that species variety is lower and the dominant groups are different. However, the

abundance, total biomass and productivity of the Black Sea are much higher than in the

Mediterranean Sea. Plankton community composition and biomass suggest that

improvements are taking place, albeit that a reduction in organic enrichment is key to this

recovery.

Formerly "dead" areas of the NW Shelf sediment are once again colonised by biota, with

evidence of biodiversity continuing to increase. The once massive area dominated by

Zernov's Phyllophora (a red seaweed) field has decreased hugely in area, having been

replaced by other, opportunistic macroalgae. Similarly, during the last two decades, the area

covered by eelgrass (Zostera) has decreased tenfold in shallow waters.

The Phyllophora field once provided a habitat for 118 species of invertebrates and 47 species

of fish. The Black Sea macrozoobenthos is represented by approximately 800 species, and

the fish fauna by 171 species. There are 320 bird species in the Danube Delta and 4 species

of Mammals are found in the Sea.

Higher species richness in shallower waters is associated with good dissolved oxygen

conditions whilst in deeper areas there is lower diversity due to natural oxygen depletion

5

with increasing depth in the Black Sea. Consequently, the number of macrobenthic species

decreases rapidly with increasing depth - only the polychaete worm Notomastus profundus is

found below a depth of about 120 m.

The invasion of Mnemiopsis leidyi (a comb jelly) contributed to a catostrophic decline in fish

productivity in the 1980s. The subsequent invasion of a another comb jelly (Beroe ovata),

which feeds on the original invader, means that opinions are now split as to whether

Mnemiopsis is still has a major impact on fish communities and catches.

The number of registered alien species at the regional level amounts to 217 (parasites and

mycelium excluded). Nearly half of them (102) are permanently established, a quarter -

highly or moderately invasive (20 and 35 species respectively). This high ratio of invasive

aliens suggests a serious impact on the Black Sea native biological diversity, with negative

consequences for human activities and economic interests.

Between 1996 and 2005 a total of 48 new alien species were recorded, which represents over

22 % of all registered aliens. The majority belong to phytoplankton (16) and zoobenthos

(15), followed by zooplankton (8), fish (5), macroalgae (3) and mammals (1).

Habitat status is a critical component of maintaining high levels of biodiversity within the

Black Sea. The status of marine habitats is therefore assessed. All 5 habitats within the

coastal margin ecotones category are considered to be in a critical status in at least one

country; both types of benthic pelagic habitat (neritic and open sea) are considered critical in

at least one country; and 13 of the 37 types of benthic habitat are considered to be critical in

at least one country. No data were available on Russian Black Sea habitats. The ecosystem(s)

of the Black Sea are, therefore, seriously damaged and in need of legal protection. Those

habitats most at risk include the neritic water column, coastal lagoons, estuaries/deltas and

wetlands/saltmarshes.

The following recommendations are made:

· Continue capacity-building and training of marine scientists.

· Allow environmentalists greater access to key decision-makers in organisations

throughout the Black Sea region.

· Undertake regular re-evaluations of major marine systematic (biological) groups in

each of the BS countries, using the latest IUCN criteria and guidelines for application

at the regional level.

· Develop a habitat- and ecosystem- oriented approach to biodiversity management.

Often it is clearer which impacts are responsible for the deterioration of habitats than

it is for individual species

· Once national Red Lists on habitats and biota have been completed, a Red Book of

Habitats, Flora and Fauna of the Black Sea should be created. This should serve as a

tool for conservation management at the regional level.

· Increase the number and area of Marine Protected Areas.

· Improve and back-up management strategies to prevent the introduction of new

invasive species. These should target the priority vectors of introduction ships

(ballast water) and aquaculture.

Causal chain analyses

6

Many of the immediate, underlying and root causes of individual problems are shared with

other problems. In particular, the causal chain analyses for nutrient enrichment and chemical

pollution are very similar, since the majority of sources of chemical pollution are also

sources of nutrients. For biodiversity, the failure to adequately treat ship ballast water is

regarded as being an important cause of the problem, and for changes commercial marine

living resources the remaining three major problems are clearly contributory factors. For

biodiversity-related problems, the importance of eutrophication is considered to have been

greatly under-estimated, both by stakeholders and, indeed, by contributors to this report.

It is clear, therefore that the four transboundary problems cannot be dealt with individually.

Improvements in management of one problem will have knock-on effects for other problems,

and addressing individual causes is likely to improve the situation with regard to at least two,

if not more, of the four environmental problems. For example, one of the causes of all four of

the environmental problems covered in this report is that of poorly regulated coastal

development. A brief tour around the Region reveals the huge scale of this, with the

economic importance of tourism increasing rapidly. The six countries all agree with the

`ecology tenet' underlying integrated coastal zone management, i.e. that coastal development

should take account of marine ecology, conservation and biodiversity, but the underlying

institutional structures vary considerably between countries. There are many examples where

money has spoken louder than words.

Hot-spots analysis

A review of planned and proposed capital investments on pollution point sources identified

from the 1996 TDA has shown disappoint results. Of the 50 investments initially identified,

only 12 have been completed and 2 are no longer required (mis-identification as the reason

for one site, and a change in use of the facility as the reason for the other). A decade later,

work is in progress on another 10 point sources, but over half of the capital investments

originally identified have either been insufficiently funded or not funded at all. Capital

investment costs to address the identified 50 hot-spots were originally estimated to be almost

$400 million. By the end of 2005 at least $143 million had been spent on addressing these

point sources, with a further $340 million planned to be spent by the end of 2015.

Legal and institutional analysis

The results of a legal and institutional analysis of the region are also presented. The major

regional document for protecting the Black Sea is the Bucharest Convention. This now

appears out-dated and is unusual in that it excludes the Sea of Azov, but protocols to the

Convention can (and do) include it. The Convention established a Permanent Secretariat

(PS), which has worked under difficult conditions with respect to the level of staffing and the

uncertainty created by the lack of consistency in receiving national annual contributions. The

PS is supported by sixteen subsidiary bodies: six activity centres (only two of which have

funding to support the PS), seven advisory groups and three ad hoc working groups.

The aims of the Permanent Secretariat have been over-ambitious, given its resources, with

the result that little progress has been achieved. There has been a lack of focus on outputs

from the Advisory Groups, and to date there has been little accountability. The outputs of

Advisory Groups are not generally used by decision makers in the Black Sea countries

because they are seen as being irrelevant to policy making or because national

funding/political back-up has been insufficient. One example of this is the development and

undertaking of the Black Sea Integrated Monitoring and Assessment Programme. Outputs of

this programme, robust monitoring results of the environmental status of the Black Sea,

7

should be one of the most important deliverables of the PS, but national funding of the

laboratories, staff and equipment to undertake this work has been lacking in a number of

countries.

National environmental legislation is relatively strong, but the enforcement of this legislation

has been weak. In Bulgaria and Romania, the EU Accession process has been (and is

continuing to be) good news for the environment. The capital investments (hot-spots)

analysis shows this to be the case, despite the fact that the majority of planned investments

are still to come on-line in the two EU Member States. Turkey is in the initial stages of its

EU accession negotiations and appears keen to comply with the capital investments and best

agricultural practice regulations required, so further environmental improvements should

accrue in the future. However, there is a need for improved cooperation between the

Environment and other Ministries in all countries.

Stakeholders analysis

Environmental management is complex, with huge numbers of individuals, ministries and

organizations involved; political changes further complicate the picture. The level of

complexity is illustrated in a Stakeholders analysis, which involved questioning

representatives of 42 stakeholder groups. This analysis revealed that 61% of respondents

considered the Black Sea to be unhealthy and, surprisingly, over 70% of people thought the

environmental health of the Black Sea region to be more important than economic

development. The vast majority of respondents agreed that the Sea was polluted and that

regional cooperation was important to address this issue. A considerable majority also agreed

that preserving endangered fish species was more important than meeting market demand for

seafood

Some 80% of respondents thought that if people knew more about the causes of

environmental problems they would want to make changes to improve matters, but overall,

they considered eutrophication to be less important than any of the other three transboundary

problems addressed in this document. The results are encouraging, but reveal that further

environmental education is required.

The following recommendations are made:

· Develop focused stakeholder involvement strategies for livestock industry and port

and harbour administrators to help them recognize and remedy actions that adversely

impact the Black Sea ecosystem.

· Target activities towards helping groups to adjust their current practices to more

environmentally sustainable approaches, in all areas and issues.

· Increase outreach efforts that emphasize the importance of biodiversity and habitat

conservation.

· Target efforts to inform stakeholder groupss about nutrient loading and

eutrophication, and provide alternative approaches to current waste water and

nutrient management practices.

· Develop an outreach programme that includes stakeholders from all fisheries sectors

to take steps towards addressing the causes of over-fishing.

· Develop targeted interventions for the tourism and recreation industry to help it to

take steps to avoid negatively impacting the waters of the Black Sea.

· Develop an outreach component for the BS Commission that links the economic

well-being of the region with the health of the Black Sea.

8

1. INTRODUCTION

The Black Sea is one of the most remarkable regional seas in the world. It is almost cut off

from the rest of the world's oceans, is over 2200 m deep and receives the drainage from a 1.9

million km2 basin covering about one third of the area of continental Europe. Its only

connection is through the Bosphorus Strait, a 35 km natural channel, as little as 40 m deep in

places. This channel has a two layer flow, carrying about 300 km3 of seawater to the Black

Sea from the Mediterranean along the bottom layer and returning a mixture of seawater and

freshwater with twice this volume in the upper layer. Every year, about 350 km3 of river

water enters the Black Sea from an area covering almost a third of continental Europe and

including significant areas of seventeen countries: Austria, Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina,

Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Georgia, Germany, Hungary, Moldova, Slovakia,

Slovenia, Romania, Russia, Turkey, Ukraine, Yugoslavia. Europe's second, third and fourth

largest rivers (the Danube, Dnipro and Don) all flow to the Black Sea.

Isolation from the flushing effects of the open ocean, coupled with its huge catchment, has

made the Black Sea particularly susceptible to eutrophication (the phenomenon that results

from an over-enrichment of the sea by plant nutrients). Eutrophication has led to radical

changes in the Black Sea ecosystem in the past three decades with a major transboundary

impact on biological diversity and human use of the sea, including fisheries and recreation.

Prior to the 1990s, little or no action had been taken to protect the Black Sea. Political

differences during the Soviet era, coupled with a lack of general knowledge of the

environmental situation resulted in an absence of effective response. In 1992 the Black Sea

countries signed the Bucharest Convention followed closely by the first Black Sea

Ministerial Declaration (the Odessa Declaration) in 1993. This inspired the GEF and other

donors, particularly the European Union, to provide more than US$17 million support to the

region to help implement the Odessa Declaration and to formulate the longer-term Black Sea

Strategic Action Plan (BS SAP).

The Black Sea Environmental Programme (BSEP) was launched in June 1993. The

Programme included a number of interventions by the GEF, including the development of

the first Black Sea Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis (TDA), finalised in June 1996. On

the basis of this comprehensive report senior government officials negotiated the Black Sea

Strategic Action Plan (BS-SAP), signed on October 31st at a Ministerial Conference in

Istanbul.

Following the signature of the BS-SAP, GEF funding was sustained in order to enable

countries to complete National Black Sea Strategic Action Plans and for the negotiations on

the institutionalisation of the Istanbul Commission's Secretariat to be completed. This was a

very protracted three-year process as countries struggled to overcome technical and legal

issues of establishing the Secretariat. In the meantime however, progress was made in

implementing part of the BS-SAP due to GEF seed money and considerable support from the

European Commission. In October 2000, the Secretariat for the Black Sea Commission

became operational.

Further GEF Full Project funding was secured in 2002 with the commencement of the Black

Sea Ecosystem Recovery Project (BSERP). The project was split into two implementation

phases - Phase I (Apr 2002 - Oct 2004) and Phase II (Nov 2004 - Oct 2007). The project

supports regional aspects of the Black Sea Partnership for Nutrient Control and assists and

9

strengthens the role of the Black Sea Commission.

Further, the project was set up to ensure the provision of a suite of harmonised legal and

policy instruments for tackling the problem of eutrophication, and release of certain

hazardous substances, and to facilitate ecosystem recovery. An important feature of the

project has been its encouragement of broad stakeholder participation.

A cornerstone of this project is the development of a revised Black Sea TDA and SAP based

on the existing 1996 documents. This document is an objective, non-negotiated analysis

using best available verified scientific information and examines the state of the environment

and the root causes for its degradation. It will provide the factual basis for the formulation of

a Black Sea Strategic Action Programme (BS SAP), which will embody specific actions

(policy, legal, institutional reforms or investments) that can be adopted nationally, usually

within a harmonized multinational context, to address the major priority transboundary

problems identified in the TDA, and over the longer term, enable the sustainable

development and environmental protection of the Black Sea.

10

2. METHODOLOGY

2.1

The 1996 Black Sea TDA

The 2006 Black Sea TDA is the first significant update of the original Black Sea TDA

finalized in June 1996 under the GEF Black Sea Ecosystem Protection (BSEP) project.

The 1996 Black Sea TDA was a technical document which examined the root causes of

Black Sea degradation and options for actions which could be taken to address them. It

examined each major environmental problem, the stakeholders involved in the problem and

the uncertainties in the information describing the problem. It then proposed solutions, time

frames and costs.

.

The development of the 1996 TDA was a carefully implemented technical process spanning

more than two years. Initially, a series of thematic analyses were conducted at a national

level and then integrated by a group of regional and international specialists in order to

construct the Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis (TDA) of the Black Sea3. On the basis of

this document, senior government officials negotiated the Black Sea Strategic Action Plan

(BS-SAP) which was signed on October 31st 1996, at the Black Sea Ministerial Conference

in Istanbul.

2.2

The 2006 Black Sea TDA

The 2006 Black Sea TDA was expected to build on the existing 1996 document and it was

anticipated that it wouldn't adhere to the traditional TDA development process (as generally

used in 1st phase International Waters projects). However, current GEF requirements for

TDA development mean that the process needed to follow the GEF IW TDA/SAP "best

practice" approach4. This required careful management of the process between the Black Sea

Project Implementation Unit (PIU) and the Secretariat of the Black Sea Commission.

Consequently, the 2006 Black Sea TDA, developed between 20th December 2005 and xxth

November 2006, is an objective, non-negotiated assessment using best available verified

scientific information which examines the state of the environment and the root causes for its

degradation. It will provide the factual basis for the formulation of the revised Black Sea

SAP, which will embody specific actions (policy, legal, institutional reforms or investments)

that can be adopted nationally, usually within a harmonized multinational context, to address

the major priority transboundary problems, and over the longer term restore or protect the

Black Sea ecosystem.

The process proceeded according to the following `Best Practice' steps:

· Identification and initial prioritisation of transboundary problems

· Gathering and interpreting information on environmental impacts and socio-

economic consequences of each problem

· Causal chain analysis (including root causes)

· Completion of an analysis of institutions, laws, policies and projected investments

3 Full reference of 1996 TDA

4 Full reference of the GEF best practice approach

11

The TDA focuses on transboundary problems without ignoring national concerns and

priorities and identifies information gaps, policy distortions and institutional deficiencies.

The analysis is cross-sectoral and examines national economic development plans, civil

society (including private sector) awareness and participation, the regulatory and institutional

framework and sectoral economic policies.

2.3

Identification of priority transboundary issues

The first step in the TDA process was to agree on an initial list of transboundary problems in

the Black Sea, examine their transboundary relevance and scope, and determine preliminary

priorities.

At the first TDA TTT meeting (11th April 2006), the TTT, made up of 22 experts from the

Black Sea countries5, brainstormed the list of 23 common GEF transboundary problems in

order to determine their relevance and transboundary nature in the context of the Black Sea.

The priority transboundary problems were identified by assigning a score to each problem of

between 0 (no importance), 1 (low importance), 2 (moderate importance) and 3 (high

importance) to determine the relevance of the problem from the perspective of the present

day and 10-15 years in the future. When examining future change the TTT were asked to

consider the effects of climate change. The scoring activity was based on the following suite

of criteria:

· Transboundary nature of a problem.

· Scale of impacts of a problem on economic terms, the environment and human

health.

· Relationship with other environmental problems.

· Expected multiple benefits that might be achieved by addressing a problem.

· Lack of perceived progress in addressing/solving a problem at the national level.

· Recognised multi-country water conflicts.

· Reversibility/irreversibility of the problem

2.4

Development of thematic reports

Thematic Reports were drafted by selected members of the TTT (Team Leaders). The list of

the Thematic Reports is shown below:

1. Thematic report on Habitat loss/ Biodiversity

2. Thematic report on Causal Chain Analysis

3. Thematic report on Fisheries

4. Thematic report on pollution loads

5. Thematic report on pollution assessment

6. Stakeholders Analysis

7. Socio- economic Assessment

8. Governance Analysis

Each review and report used a similar structure and the Team Leaders were asked to produce

reports that: described the particular problem; identified any gaps in knowledge; identified

the environmental impacts and socio-economic consequences; detailed the immediate and

5 A full list of the TTT experts is shown in Annex <>.

12

underlying causes of the impacts and consequences; and listed proposed options for

addressing the identified problem. Consequently, the Thematic Reports constituted the main

sources of information for the TDA.

2.5

Development of causal chains for priority

transboundary problems

The CCA methodology developed for this TDA was based on that described in the GEF

`Best Practice' approach and tried to relate the transboundary problems with their impacts,

immediate physical causes, underlying causes (divided into resource uses and socio-

economic causes) and root causes. A simple step by step guide to the process is shown in

Figure 2.1.

For a given transboundary problem,

identify the environmental impacts and

socio-economic consequences

For a given environmental impact or

and socio-economic consequence

identify the key sectors

For each sector, identify the immediate,

underlying and socio-economic, legal

and political root causes

Link each sector to the impacts and link

each set of immediate, underlying and

socio-economic, legal and political root

causes

Determine the over-arching root

causes

Figure 2.1

Stepwise sectoral analysis approach to developing a causal chain

The CCA process was iterative and consultative, with several versions being developed by

the CCA team leader after successive consultations with the international consultant, the

Black Sea Project Implementation Unit (PIU), the TDA TTT and CCA National Experts.

Draft CCAs were presented at the second TDA TTT Meeting (July 6th, 2006) and a Delphi

Exercise was performed during the meeting to help identify further causes. Based on this

input, sectoral CCAs were re-drafted.

The revised versions were reviewed by the PIU and the International Consultant and were

then sent to the TDA TTT leaders for further approval. These versions were checked by the

CCA National Experts for relevance in the 6 Black Sea countries.

13

2.6 Hot-spots

analysis

The hot-spots analysis presented in this TDA does not include an update of the list of 50 hot-

spots identified in the 1996 TDA, but rather an assessment of progress made in addressing

the original list of pollution sources in terms of undertaking the capital investments

originally identified. In addition, where data have been provided, the measured pollution

loads from individual hot-spots are calculated. The loads cited in the 1996 TDA were

modelled using the Rapid Assessment Methodology.

2.7 Stakeholder

analysis

The Black Sea Stakeholder Analysis involved conducting quantitative surveys of

stakeholders throughout the region. This analysis identifies stakeholders of the Black Sea

Ecosystem Recovery Project and provides insights into the concerns, priorities, capacities

and perceptions of stakeholder groups throughout the region in regards to specific

transboundary environmental issues. This also identifies where tensions or potential tensions

could emerge as a result of different expectations and priorities for Black Sea resource uses.

The stakeholder analysis methodology involves identifying stakeholder groups through desk

studies, consultation with project staff, and review of issues, thematic reports, historical

project materials socio-economic and government structures throughout the region.

Following this the survey was developed following consultation with earlier stakeholder

analyses in the region, surveys conducted by NGOs, reports from the project. The

conclusions of these were combined with findings of the Causal Chain Analysis conducted

within the scope of the current TDA and based on these sources, survey questions were

developed.

The survey was conducted in all six Black Sea countries among 42 different stakeholder

groups. Surveys were translated into local languages and were administered by national level

stakeholder consultants throughout the region. A total of 368 surveys were collected and

statistically analyzed for trends among and between groups. Areas of notably high and low

priority concern or high levels of variation within groups were detailed and analyzed for the

potential causality and significance of these trends. Issues which showed potential for

conflict between groups were highlighted.

2.8 Governance

analysis

The Governance Analysis involved a regional assessment of the institutional and policy/legal

instruments based on the existing analysis/reports under the Black Sea Ecosystem Recovery

Project. This analysis identifies institutional involvement in Black Sea related environmental

problems, as well as the existing global/regional/national policies and provides insights into

the coordination mechanisms, enforcement capacity and implementation results at regional

level in respect to the priority Black Sea transboundary problems. It also identifies the gaps

and obstacles in adapting or reforming the policy/legal framework.

The Governance Analysis methodology involved a review of the thematic reports as well as

desk studies and consultation with national experts. The Stakeholders Analysis findings and

the Causal Chain Analysis results conducted within the scope of the current TDA are also

included.

A questionnaire was developed in order to review the actual national institutional structures

capacity and resources, together with the current relevant legal instruments, with special

14

emphasis on their actual implementation, compliance and enforcement. The review was

conducted in all six Black Sea Countries by the TDA TTT National Experts.

15

Box 2.1:

Comparative analysis of the 1996 and 2006 TDA components

A comparison between the 1996 and 2007 was always going to be difficult to undertake, not least because the two methodologies are quite different and much

has been learnt about TDA design since the original TDA was produced. However, the table below outlines the key differences between the two approaches.

The 1996 TDA uses a tabular approach with linked tables and a small amount of supporting information. The methodology, although logical, is difficult to

navigate and lacks detail. The 2007 TDA follows a more conventional approach, in line with GEF `best practice'.

Components 1996

TDA

2006/7 TDA

Description of the Black

·

No Description of the Black Sea region was presented.

·

A detailed description of the Black Sea region was produced.

Sea region

·

This included the physical and geographical characteristics,, the socio-economic

situation, biodiversity and ecosystem health, the status of nutrient and toxic

pollutants, the institutional setting and stakeholders, and the public perception of

environmental status, causes and responsibilities

·

This description set the scene for the more detailed analysis of the priority problems

Transboundary Problems

·

Seven Major Perceived Problems were identified. These were:

·

Four Priority Transboundary Problems were identified. These were:

· Decline in Black Sea Commercial Fish Stocks

· Nutrient over-enrichment/eutrophication

· Loss of habitats, notably wetlands and shelf areas, supporting

· Decline in natural resources (e.g. fisheries)

important biotic resources

· Chemical pollution

· Loss or imminent loss of endangered species and their genomes

· Habitat and biodiversity changes - including alien species introduction

· Replacement of indigenous Black Sea species with exotic ones

Degradation of the Black Sea landscape

· Inadequate protection of marine and coastal resources from

maritime accidents

· Unsanitary conditions in many beaches, bathing and shellfish-

growing waters.

Environmental impacts

·

No analysis of environmental impacts or socio-economic

·

An analysis of environmental impacts and socio-economic consequences was

and socio-economic

consequences was carried out

undertaken

consequences

·

This was dependent on the level of information and data available and varied from

problem to problem

Causal Chain Analysis

·

No Causal Chain Analysis was undertaken.

·

A detailed Causal Chain Analysis was carried out. This focused on:

·

Five main root causes were identified and briefly described

· Immediate causes

· Underlying causes

· Underlying socio-economic drivers

·

The level of information and data available varied from problem to problem

Knowledge gaps

·

Uncertainties were identified in the problem matrices

·

Knowledge gaps were identified for each transboundary problem

Stakeholder Analysis

·

A stakeholder analysis was not presented in the TDA

·

A detailed quantitative survey of stakeholders throughout the region was presented

in the TDA

·

The analysis identified the stakeholders and provided insights into the concerns,

priorities, capacities and perceptions of stakeholder groups throughout the region in

regards to specific transboundary environmental issues.

Governance Analysis

·

A detailed governance analysis was not undertaken

·

A detailed governance analysis was presented in the TDA

·

The analysis identified institutional involvement in Black Sea related environmental

problems, as well as the existing global/regional/national policies and provided

insights into the coordination mechanisms, enforcement capacity and

implementation results at regional level in respect to priority transboundary problems.

·

It also identifies the gaps and obstacles in adapting or reforming the policy/legal

framework.

Actions and

·

Detailed actions were outlined in the TDA. The actions were also

·

The 2007 TDA was developed using current GEF `best practice' which states that the

recommendations

costed, and products and milestones identified

TDA should be a non-negotiated technical document. Consequently,

recommendations were briefly outlined but further actions, costings and milestones

were consigned to the SAP.

16

3. DESCRIPTION OF THE BLACK SEA REGION

3.1

Physical and geographical characteristics

The geographical scope of the Convention on the Protection of the Black Sea against

Pollution is applied to the Black Sea proper, with the Southern boundary constituted, for the

purposes of this Convention, by a line running between Capes Kelagra and Dalyan6.

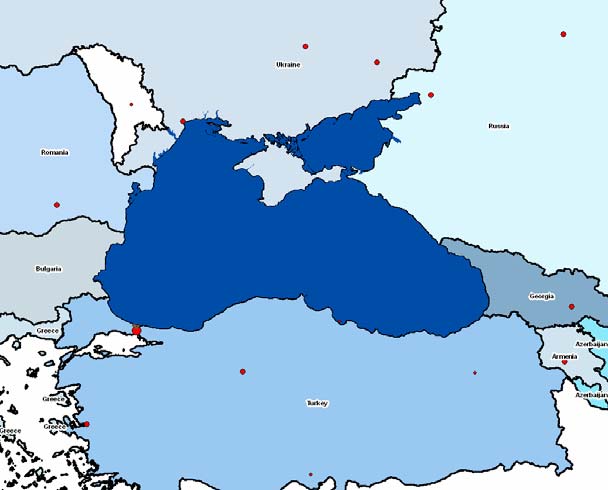

3.1.1 Geographic

boundaries

The Black Sea is an inland Eurasian sea bordering Ukraine and the Russian Federation to the

north, Bulgaria and Romania to the west, Georgia to the east and Turkey to the south (Fig.

3.1). The Black Sea is located between latitudes 40° 56'N and 46° 33'N, and longitudes 27°

27'E to 41° 42'E. It is located in the east-west depression between two alpine fold belts, the

Pontic Mountains to the south and the Caucasus Mountains to the northeast. The topography

of the north western coast (except for Crimea) is relatively low and flat.

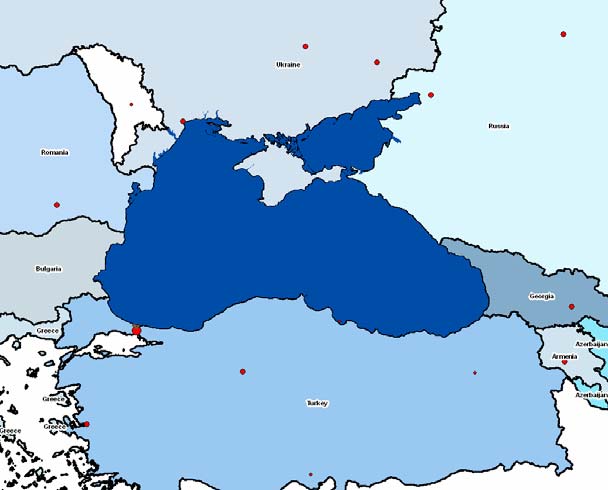

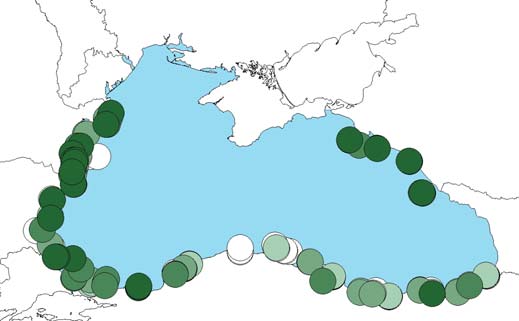

Figure 3.1

Geographical boundaries in Black Sea Region

The Black Sea is a semi-enclosed sea connected to the shallow (1020 m) Azov Sea through

the Kerch Straits and to the Mediterranean Sea through the Bosporus Straits, the Marmara

Sea and the Dardanelles Straits. The flat abyssal plain (20% of free surface, depth. 2000 m)

rises to the continental shelves. The northwestern shelf (mean depth 50 m) has a shelfbreak

at about 100 m between the Crimean peninsula and Varna in the South. The Danube and the

Kerch fans are gentle continental slopes. The other portions of the shelf are narrow (20 km),

fractured by canyons, abrupt ridge extensions and steep continental slopes.

The only connection to other marine water bodies is through the winding Istanbul (Bosporus)

Straits, a 35 km natural channel, as little as 40 m deep in places. The Black Sea is up to 2212

metres deep (North of nebolu) and receives the drainage from a 1.9 million km2 basin,

covering about one third of the area of continental Europe. The Bosporus has a two layer

6 http://www.blacksea-commission.org/main.htm

17

flow, carrying about 300 km3 of seawater to the Black Sea from the Mediterranean along the

bottom layer and returning a mixture of seawater and freshwater with twice this volume.

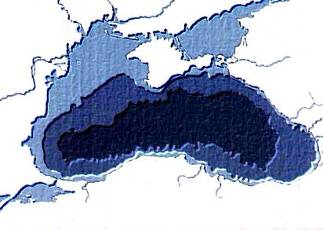

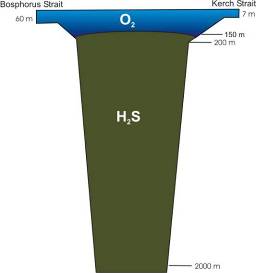

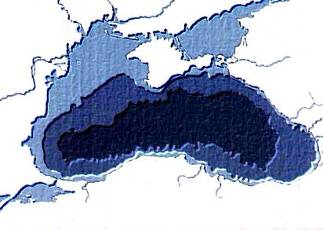

3.1.2 Bathymetry

The seabed is divided into the shelf, the continental slope and the deep-sea depression

(Figure 3.2). The shelf occupies a large area in the north-western part of the Black Sea,

where it is over 200 km wide and has a depth ranging from 0 to 160 m. In other parts of the

sea it has a depth of less than 100 m and a width of 2.2 to 15 km. Near the Caucasian and

Anatolian coasts the shelf is only a narrow intermittent strip. The thin upper layer of marine

water (up to 150 m) supports the unique Black Sea ecosystem. The deeper and more dense

water layers are saturated with hydrogen sulfide that has accumulated over thousands years

as a by-product of decaying organic matter (Figure3.3). Due to the unique geomorphological

structure and specific hydrochemical conditions, very specific organisms, including

protozoa, bacteria, and some multi-cellular invertebrates, inhabit the deep-sea waters.

Knowledge about forms of life in the deep waters of the Black Sea is very limited, but it is

clear that disturbance of the natural balance between the two layers could trigger irreversible

damage to the people and ecosystem of the Black Sea.

Figure 3.2

Black Sea bathymetry

3.1.3 Coastline

characteristics

The length of the Black Sea shoreline is approximately 4,340 km (Table 3.1). The Black Sea

has similar geological properties as the major oceans, and is classified geomorphologically

into three key sections namely: (i) the continental shelf, (ii) the continental side, and (iii) the

abrasion platform (2).The continental shelf covers 24.1% of the Black Sea surface area and

has a 0.5-5 slope. This area generally extends 0-90 m depth from the shoreline. The

continental shelf is very important for fishing, although it is quite narrow along the Anatolian

and Caucasus coasts.

18

Figure 3.3

Profile of the hydrogen sulfide zone in the Black Sea

The length of national Black Sea costlines is presented in Table 3.1, Ukraine having the

longest coast and Romania the shortest.

Table 3.1

Black Sea shoreline length (km)

Country

Length (km)

Bulgaria 300

Georgia 310

Romania 225

Russian Federation

475

Turkey 1,400

Ukraine 1,628

Total

4,338

3.1.4

River discharge

The main rivers in the Black Sea Region are the Danube, Dnipro, Rioni, Kodori, Inguri

Chorokh, Kizilirmak,Yeshilirmak, Sakarya, Southern Bug and Dnister. Every year, some

350 km3 of river water flows into the Black Sea. Discharges from the main rivers are

presented in Table 3.2, with inflows of water from the Sea of Marmara (via the Bosphorus

Strat) and the Sea of Azov (via the Kerch Strait) shown in Table 3.2. The areas of national

Black Sea sub-basins are shown in Table 3.3.

3.1.5 Climate,

agricultural

production and river discharge

In a major part of the Black Sea Basin, the climate is similar to the Mediterranean (warm

humid winters and hot dry summers) because the geography and macro circulation processes

existing in the Mediterranean influence the climate of the Black Sea Basin. The south-

eastern part, surrounded by the mountains, is characterized by a humid subtropical climate

(abundant precipitation, warm winter, hot summer). Average periods of sunshine vary

throughout the region 2,432 hours in the Bosporus area, 2,237 hours in the Varna area and

2,223 hours per year in the Yalta area. The total amount of precipitation from the Bosporus

to Varna is about 500-700 mm per year, in the north, near Odessa 300-400 mm, in the

19

southern coast of Crimea (Yalta) 586 mm. The amount of annual precipitation increases

eastward 1,600 mm between Novorossiysk and Sukhumi, to 2,465 mm in Batumi. In

general, the Black Sea Basin climate is very favorable for tourism and recreation.

Table 3.2

Annual river discharge into the Black Sea (m3/s)7

Country River

1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005

Kamchia

10.3

5.7

46.8

Aheloy

0.1

0.0

0.3

Veleka

4.1

2.2

18.3

Ropotamo

0.1

0.1

0.5

Batova

0.1

0.1

0.7

Bulgaria

Diavolska

0.0

0.0

0.1

Dvoinitza

0.2

0.1

0.9

Hadjiska

0.1

0.1

0.6

Karaach

0.2

0.1

0.7

Rezovska

1.8

1.0

7.9

Rioni

406.0 406.0 406.0 406.0 406.0 406.0 406.0 406.0 406.0 406.0 406.0

Supsa

46.0 46.0 46.0 46.0 46.0 46.0 46.0 46.0 46.0 46.0 46.0

Chorakhi

409.0 409.0 409.0 409.0 409.0 409.0 409.0 409.0 409.0 409.0 409.0

Georgia8

Natanebi

24.5 24.5 24.5 24.5 24.5 24.5 24.5 24.5 24.5 24.5 24.5

Khobi

50.5 50.5 50.5 50.5 50.5 50.5 50.5 50.5 50.5 50.5 50.5

Kubastskali

0.3

0.3

Romania Danube 6223.7 7035.8 6684.2 6654.1 7952.0 6580.6 6304.3 6837.1 5021.0 6524.0 8695.0

Sochi

25.6 15.7 20.1 14.6 15.4 13.6 27.7 18.8 14.4 16.8 14.3

Russian

Mzimta

66.4 49.0 55.1 - 42.8 48.4 63.1 70.9 54.5 60.2 72.3

Federation

Khosta

6.9 4.2 5.3 4.6 4.7 4.0 6.7 5.6 4.6 5.9 5.8

Tuapse

24.3

Sakarya

124.2 94.5 177.8 234.1 117.4 188.3 30.6 217.4 106.0 148.1 138.8

Kizilirmak

21.0

21.0

2.9

21.0

Turkey

Filyos

53.7

139.8

21.0

97.5

21.3

97.0

Yeilirmak

161.7 182.0 121.1 211.2 99.7 105.7 165.0 165.0 165.0 165.1 165.1

Coruh

219.8 279.9 185.9 170.0 151.6 215.0 215.0 210.0 215.0

Dniepro

1149.0 916.0 1160.0 1850.0 1820.0 1290.0 1390.0 1050.0 1100.0 1460.0 1460.0

Southern

Ukraine

70.1 121.0 97.8 109.0 93.7 88.5 94.7 80.5 121.0 81.6 103.0

Bug

Dniester

213.0 295.0 303.0 420.0 342.0 249.0 303.0 265.0 175.0 205.0 269.0

Table 3.3

Annual river discharge into the Sea of Azov (m3/s)

Country River

1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005

Russian

Kuban

421.0

382.0

626.0

439.0

317.0

367.0

306.0

544.0

311.0

Federation

Don

666.0

837.0

637.0

679.0

733.0

680.0

648.0

599.0

766.0

7 Data provided by in-country national experts

8 Discharge based on long-term investigations carried out before 1993

20

Table 3.4

Catchment area of the Black Sea (km2) Russian Federation and Ukraine are

only partially included

Country Catchment

Area

(km2)

Bulgaria 22,244

Georgia 32,816

Romania 90,894

The Russian Federation

49,8260

Turkey 246,525

Ukraine

367,230

Total 1,257,969

Because of its climate the Black Sea region is a productive farming area, where many

varieties of plant crops are grown. Thus, for those countries having only a part of their

territory included in the Basin, these national sub-basins represent important components of

their respective national agricultural production balance sheets For example, in Bulgaria,

land draining into the Black Sea contains.about 85% of the national cereal farmland, 76% of

the land on which oil bearing crops are grown, 37% of the land used for forage crops and

47% of the area of national vineyards (Petkova, 2005). The agricultural area in the Turkish

Black Sea sub-basin contains approximately one third of the total agriculture area of Turkey,

supporting the production of a wide range of agricultural crops. For example, all of the tea

grown in Turkey is produced in this area, 71% of national nut production, 57% of tuber

crops, 39% of industrial crops, 33% of cereals, 24% of pulses and vegetables, 18% of fruits

and 9 5% of oil seed production (Ulger 2005). For further comparison about one third of the

agricultural area of Georgia is contained in its Black Sea sub-basin, where all of its national

tea and citrus fruit ptoduction occurs, the vast majority (98%) of the country's volatile oil

bearing plant production, about 80% of nuts, over 50% of other fruits, 40% of cereals, and

over 30% of national vineyard production (Lagidze 2005 data exclude statistics from the

breakaway republic of Abkhazia). Similarly, the Black Sea coastal administrative areas of

the Russian Federation, particularly Krasnodar Krai, constitute a nationally important

agricultural region.

In addition to arable farming, the Black Sea Basin is also an important area for livestock

farming. This is dealt with in more detail in Section 4.2.4.2.

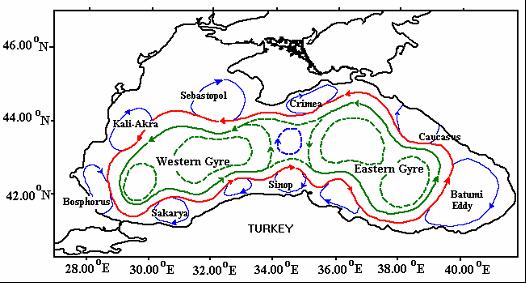

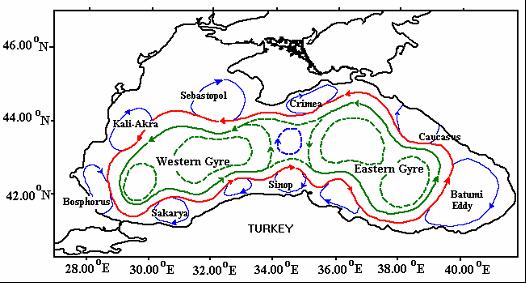

Ocean current circulation in the Black Sea is characterized by a cyclonic system of currents

Fig. 3.4). The dynamic system of the Black Sea has a distinct yearly cycle, with maximum

circulation activity occuring during winter and spring.

21

Figure 3.4

Schematic of Black Sea currents9

3.2 Socio-economic

situation

Social and economic changes within the Black Sea Basin both impact the ecosystem and are

impacted by many of the environmental changes that have been brought about during the last

century. The historical socio-economic conditions of the Black Sea have largely shaped

practices that continue to date. The shift from the Soviet economic system to a more free

market system in the Warsaw Pact States, the movement towards EU accession of some

countries, and economic fluctuations in the 1990s have influenced the ecosystem of the

Black Sea.

The Black Sea countries coastal zones10 are estimated to contain about 20 million people in

their coastal areas. However, the situation with regard to Istanbul is confusing, since the

coastal administrative unit which includes Istanbul has a short Black Sea coastline. Thus, if

the population of this area is also included, the value increases to over 39 million people.

The proportion of national populations living within Black Sea coastal administrative areas

varies widely: 0.6% in Russia, 4.5% in Romania, 10.5% in Turkey (excluding Istanbul),

14.4% in Ukraine, 26.5% in Bulgaria, 37.1% in Turkey (including Istanbul) and 38.6% in

Georgia.

Available data suggest the proportions of populations living in coastal administrative areas

which are connected to sewerage systems range from about 53% in Russia, through 70% in

Turkey (excluding Istanbul) to >90% in Bulgaria, Georgia and Romania. (No information

available for Ukraine). However, intuitively these values do appear to be on the high side,

and bear no relationship to the level of treatment that is applied to the wastewater produced.

A coastal population of some 7 million inhabitants are connected to sewerage systems

discharging directly into the Sea.

3.2.1 Demographic

trends

The population growth statistics in Fig. 3.5 demonstrate that the populations of the countries

of the Black Sea Basin are experiencing a negative growth rate, with the exception of

9 Data source: Tugrul and Besiktepe (2006) after Ouz et al, (1993)

10One national administrative unit (oblast, municipal area, etc.) inland from the coast.

22

Turkey. Even Turkey has shown a slowing growth rate since 1995. The years around 1998

and 1999 show a dramatic decline in Bulgaria, and Romania with a recovery in 2001 and

2002. Russia and Georgia both show increasing rates though the increase in Georgia slowed

significantly in 1998. Trends in population growth rate generally reflect the over all

optimism about social and economic development prospects, with people having more

children as they feel more confident about economic development. However in many