E R M E

H

S

Hotsp

s

o

a

t

e

E

S

c

n

os

ea

ystemResearchontheMarginsofEurop

Deep-sea

biodiversity and ecosystems

A scoping report

on their socio-economy, management and governance

Regional

Seas

E R M E

H

S

Hotsp

s

o

a

t

e

E

S

c

n

os

ea

ystemResearchontheMarginsofEurop

Deep-sea

biodiversity and ecosystems

A scoping report

on their socio-economy, management and governance

Regional

Seas

UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

219 Huntingdon Road,

The authors are grateful to Salvatore Arico, Claire Armstrong, Antje

Cambridge CB3 0DL,

Boetius, Miquel Canals, Lionel Carter, Teresa Cunha, Roberto

United Kingdom

Danovaro, Anthony Grehan, Ahmed Khalil, Thomas Koetz, Nicolas

Tel: +44 (0) 1223 277314

Kosoy, Gilles Lericolais, Alex Roger, James Spurgeon, Rob Tinch

Fax: +44 (0) 1223 277136

and Phil Weaver for their insightful comments on earlier versions

Email: info@unep-wcmc.org

of this report. Thanks also for the additional comments provided

Website: www.unep-wcmc.org

by UNEP Reginal Seas Programme Focal Points, and to all

individuals and institutions who gave permission to use their

©UNEP-WCMC/UNEP December 2007

pictures. Special thanks to Vikki Gunn and Angela Benn for their

input and support and to Stefan Hain from UNEP for his significant

ISBN: 978-92-807-2892-7

input, dedication and immense enthusiasm. Any error or

inconsistency, as well as the views presented in this report, remain

Prepared for

the sole responsibility of the authors.

UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre

(UNEP-WCMC) in collaboration with

HERMES (Hotspot Ecosystems Research on the Margins of

the HERMES integrated project

European Seas) is an interdisciplinary research programme

involving 50 leading research organisations and business partners

AUTHORS

across Europe. Its aim is to understand better the biodiversity,

Sybille van den Hove, Vincent Moreau

structure, function and dynamics of ecosystems along Europe's

Median SCP

deep-ocean margin, in order that appropriate and sustainable

Passeig Pintor Romero, 8

management strategies can be developed based on scientific

08197 Valldoreix (Barcelona)

knowledge. HERMES is supported by the European Commission's

Spain

Framework Six Programme, contract no. GOCE-CT-2005-511234.

Email: s.vandenhove@terra.es

For more information, please visit www.eu-hermes.net.

CITATION

UNEP (2007) Deep-Sea Biodiversity and Ecosystems:

A scoping report on their socio-economy, management

and governance.

A Banson production

URL

Design and layout Banson

UNEP-WCMC Biodiversity Series No 28

Printed in the UK by The Lavenham Press

(www.unep-wcmc.org/resources/publications/

UNEP_WCMC_bio_series)

UNEP Regional Seas Reports and Studies N° 184

UNEP promotes

(www.unep.org/regionalseas/Publications/Reports/Series

environmentally sound practices,

_Reports/Reports_and_Studies)

globally and in its own activities.

DISCLAIMER

This report is printed on 100% recycled

The contents of this report do not necessarily reflect the views or policies

paper, using vegetable-based inks and other

of UNEP or contributory organizations. The designations employed and

the presentations do not imply the expressions of any opinion whatsoever

eco-friendly practices.

on the part of UNEP or contributory organizations concerning the legal

Our distribution policy aims to reduce

status of any country, territory, city or area and its authority, or

concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries.

UNEP's carbon footprint.

For all correspondence relating to this report please contact:

info@unep-wcmc.org

Foreword

Foreword

"For too long, the world acted as if the oceans were somehow a realm apart as areas owned by none, free for all, with little

need for care or management... If at one time what happened on and beneath the seas was `out of sight, out of mind', that can

no longer be the case."

Kofi Annan, UN Secretary General, Mauritius, 2005

Billionsofpeopleliveat,orincloseproximityto,the depleted and regulated, commercial operations such as

world's coastlines. Many depend on the narrow strip

fishing, mining, and oil and gas exploration are increasingly

of shallow waters for their food, income and

taking place in deeper waters.

livelihoods, and it is here that most efforts to conserve and

In the light of these alarming findings and trends, various

protect marine ecosystems are concentrated, including the

international fora, including the UN General Assembly, are

sustainable management and use of the resources they

starting to consider the need for measures to safeguard

provide. We tend to forget that coastal waters less than 200

vulnerable deep-sea ecosystems, especially in areas beyond

metres deep represent only 5 per cent of the world's oceans,

national jurisdiction, and to ensure their sustainable use.

and that their health and productivity, indeed all life on Earth,

Amongst others, three key questions need to be answered:

is closely linked to the remaining 95 per cent of the oceans.

· What are key deep-sea ecosystems, and what is their

role and value?

THE DEEP SEA

· Are existing governance and management systems

Remote, hidden and inaccessible, we rely on deep-sea

appropriate to take effective action?

scientists using cutting-edge technology to discover the

· What are the areas for which we need further data and

secrets of this last frontier on Earth. Although only a tiny

information?

amount (0.0001 per cent) of the deep seafloor has so far been

subject to biological investigation, the results are remarkable:

In order to begin seeking answers, and to establish a direct

the bottom of the deep sea is not flat it has canyons,

link between the deep-sea science community and policy

trenches and (sea)mounts that dwarf their terrestrial

and decision makers, UNEP became a partner in the inter-

counterparts. The deep sea is not a uniform environment with

disciplinary, deep-sea research project HERMES in October

stable conditions and very little environmental change, but

2006. This report is the product of this fruitful partnership and

can be highly dynamic through space and time. The deep sea

demonstrates that the findings and discoveries from the deep

is not an inhospitable, lifeless desert but teems with an

waters of the European continental shelf can easily be

amazing array of organisms of all sizes and types. Indeed, it

transferred and are applicable to similar deep-sea areas

is believed to have the highest biodiversity on Earth.

around the world. It also highlights the benefits, and short-

One of the remaining misconceptions about this

comings, of looking from a socio-economic perspective

environment that the deep oceans are too remote and too

at deep-sea ecosystems and the goods and services

vast to be affected by human activities is also rapidly being

they provide.

dispelled. Destroyed or damaged deep-water habitats and

The intention of this report is to raise awareness of the

ecosystems, depleted fish stocks, and the emerging/predicted

deep-sea and the impacts and pressures this unique

effects of climate change and rising greenhouse gas

environment faces from human activities. We are confident

concentrations on the temperature, currents and chemistry of

that this report provides substantial input to the ongoing

the oceans are proof to the contrary. Further pressures and

discussions about vulnerable deep- and high-sea ecosystems

impacts on the deep sea are looming: with traditional natural

and biodiversity, so that action will be taken to preserve the

resources on land and in coastal waters becoming ever more

oldest and largest biome on Earth before it is too late.

Ibrahim Thiaw

Jon Hutton

Phil Weaver

Director of the Division of

Director

HERMES Coordinator

Environmental Policy Implementation

UNEP World Conservation

National Oceanography Centre

UNEP

Monitoring Centre

UK

Contents

FOREWORD.................................................................................................................................................................................3

CONTENTS..................................................................................................................................................................................5

LIST OF ACRONYMS ...................................................................................................................................................................8

INTRODUCTION ..........................................................................................................................................................................9

1 HABITATS, ECOSYSTEMS AND BIODIVERSITY OF THE DEEP SEA......................................................................................11

Continental slopes ................................................................................................................................................................14

Abyssal plains........................................................................................................................................................................15

Seamounts.............................................................................................................................................................................16

Cold-water corals .................................................................................................................................................................16

Deep-sea sponge fields........................................................................................................................................................17

Hydrothermal vents ..............................................................................................................................................................18

Cold seeps and gas hydrates...............................................................................................................................................19

2 ECOSYSTEM FUNCTIONS, GOODS, SERVICES AND THEIR VALUATION .............................................................................20

Valuation of ecosystems and the goods and services they provide..................................................................................20

Different types of values.....................................................................................................................................................20

Valuation methods ..............................................................................................................................................................23

Shortcomings of monetary environmental valuation.........................................................................................................23

Deep-sea goods and services and their valuation.............................................................................................................25

Deep-sea goods and services............................................................................................................................................25

Valuation of deep-sea goods and services .......................................................................................................................27

Research needs.....................................................................................................................................................................29

3 HUMAN ACTIVITIES AND IMPACTS ON THE DEEP SEA.......................................................................................................31

Direct impacts on deep-sea biodiversity and ecosystems ................................................................................................31

Deep-sea fishing .................................................................................................................................................................33

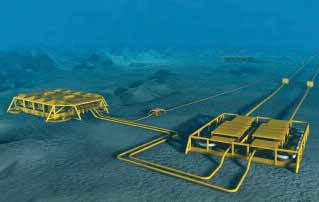

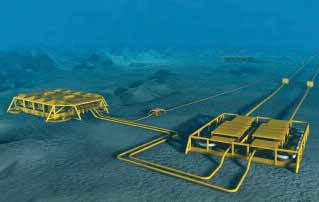

Offshore oil and gas operations.........................................................................................................................................37

Deep-sea gas hydrates.......................................................................................................................................................40

Deep-sea mining.................................................................................................................................................................42

Waste disposal and pollution .............................................................................................................................................44

Cable laying .........................................................................................................................................................................47

Pipeline laying .....................................................................................................................................................................48

Surveys and marine scientific research............................................................................................................................48

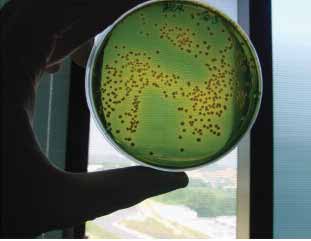

Bioprospecting ....................................................................................................................................................................50

Ocean fertilization ...............................................................................................................................................................51

Indirect impacts on deep-sea biodiversity and ecosystems .............................................................................................52

Research needs.....................................................................................................................................................................53

4 GOVERNANCE AND MANAGEMENT ISSUES ........................................................................................................................54

Key elements for environmental governance and management .....................................................................................55

Implementing an ecosystem approach.............................................................................................................................55

Addressing uncertainties, ignorance and irreversibility ..................................................................................................55

Multi-level governance .......................................................................................................................................................56

Governance mechanisms and institutional variety..........................................................................................................57

5

Deep-sea biodiversity and ecosystems

Information and knowledge ...............................................................................................................................................60

Equity as a cornerstone of environmental governance ...................................................................................................60

Key issues for deep-sea governance ..................................................................................................................................61

Deep-sea governance.........................................................................................................................................................61

Implementing an ecosystem approach in the deep sea .................................................................................................63

Governance mechanisms in the deep sea .......................................................................................................................64

Area-based management, marine protected areas and spatial planning ....................................................................65

Information and knowledge challenges............................................................................................................................67

Equity aspects .....................................................................................................................................................................67

Ways forward .......................................................................................................................................................................67

Research needs ...................................................................................................................................................................68

5 CONCLUSIONS.......................................................................................................................................................................69

Research needs on socio-economic, governance and management issues ..................................................................69

Research priorities .............................................................................................................................................................69

Integrating natural and social science research .............................................................................................................70

Training and capacity-building...........................................................................................................................................70

Improving the science-policy interfaces for the conservation and sustainable use

of deep-sea ecosystems and biodiversity ...........................................................................................................................71

GLOSSARY ..........................................................................................................................................................................................72

REFERENCES.....................................................................................................................................................................................75

6

FIGURES

Figure 1.1: The main oceanic divisions ...............................................................................................................................11

Figure 1.2: Marine biodiversity patterns in relation to water depth .................................................................................14

Figure 1.3: Species richness in relation to depth in the Atlantic and the Mediterranean..............................................14

Figure 1.4: Schematic showing cold seeps and other focused fluid flow systems/features discussed in the text .....19

Figure 2.1: Ecosystem services ...........................................................................................................................................20

Figure 2.2: Classification under Total Economic Value .....................................................................................................22

Figure 2.3: Examples of deep-sea goods and services .....................................................................................................26

Figure 3.1: Mean depth of global fisheries landings by latitude, from 1950 to 2000......................................................33

Figure 3.2: Oil and gas production scenario per type and region.....................................................................................38

Figure 3.3: Deep-water oil and gas production..................................................................................................................40

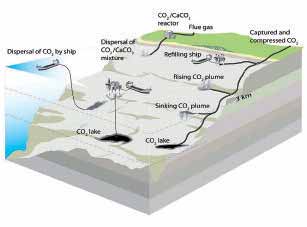

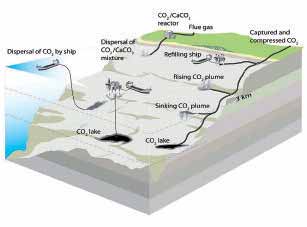

Figure 3.4: Methods of CO2 storage in the oceans.............................................................................................................46

Figure 4.1: Three key governance mechanisms ................................................................................................................58

Figure 4.2: Marine zones under the UNCLOS ...................................................................................................................61

TABLES

Table 1.1: Main geomorphologic features of the deep sea ...............................................................................................12

Table 2.1: Classification of environmental values ..............................................................................................................21

Table 2.2: Knowledge of the contribution of some deep-sea habitats and ecosystems to goods and services ..........27

Table 2.3: Total Economic Value components and deep sea examples ...........................................................................28

Table 3.1: List of the main human activities directly threatening or impacting the deep sea .......................................32

Table 3.2: Most developed human activities in the deep sea and main habitats/ecosystems affected ........................33

Table 3.3: Summary of the principal types of mineral resources in the oceans.............................................................43

Table 3.4: Estimated anthropogenic impacts on key habitats and ecosystems of the deep sea...................................52

Table 4.1: Different forms of incertitude and possible methodological responses.........................................................56

Table 4.2: Some major governance mechanisms and tools .............................................................................................57

Table 4.3: The relationship between the Responses and the Actors. ..............................................................................59

BOXES

Box 1.1: Biodiversity of the deep sea...................................................................................................................................13

Box 2.1: Valuation methods..................................................................................................................................................22

Box 2.2: Some key issues relating to monetary valuation of the environment ...............................................................24

Box 3.1: Deep-sea fishing gear............................................................................................................................................36

Box 3.2: Main potential sources of non-fuel minerals in the deep sea ...........................................................................41

Box 3.3: IPCC on geo-engineering ......................................................................................................................................51

Box 4.1: Risk, uncertainty, ambiguity and ignorance.........................................................................................................55

Box 4.2: The Precautionary Principle and Precautionary Appraisal.................................................................................57

Box 4.3: Adaptive Management ...........................................................................................................................................58

Box 4.4: Information and knowledge needs for environmental governance ...................................................................60

Box 4.5: Some key governance principles for sustainability .............................................................................................60

7

Deep-sea biodiversity and ecosystems

LIST OF ACRONYMS

ABNJ

Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction

BRD

Bycatch Reduction Device

EEZ

Exclusive Economic Zone

FAO

United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization

GHG

Greenhouse gases

HDI

Human Development Index

IEA

International Energy Agency

IMO

International Maritime Organization

ISA

International Seabed Authority

ITQ

Individual Transferable Quotas

IUU

Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated fishing

IWC

International Whaling Commission

MA

Millennium Ecosystem Assessment

MPA

Marine Protected Area

MSR

Marine Scientific Research

NGL

Natural Gas Liquids

NGO

Non-Governmental Organization

OSPAR

Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the Northeast Atlantic, 1992

PAH

Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon

PCB

Polychlorinated Biphenyl

RFMO

Regional Fisheries Management Organization

ROV

Remotely Operated Vehicles

SIDS

Small Island Developing States

TAC

Total Allowable Catch

TBT

Tributyltin

TEV

Total Economic Value

UN

United Nations

UNCLOS United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, 1982

UNFSA

United Nations Fish Stocks Agreement, 1995

8

Introduction

Theobjectiveofthisreportistoprovideanoverviewof atthegloballevel,suchastheUNGeneralAssembly(UNGA)

the key socio-economic, management and governance

and the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), the

issues relating to the conservation and sustainable use

UN Fish Stocks Agreement, the Convention on Biological

of deep-sea ecosystems and biodiversity. The report high-

Diversity (CBD), and under regional multilateral agree-

lights our current understanding of these issues and ident-

ments and conventions, for example. We are also in a time

ifies topics and areas that need further investigation to close

of rapid change in the way we think about marine resource

gaps in knowledge. It also explores the needs and means for

management both in shallow waters and offshore. We

interfacing research with policy with a view to contributing to

are moving away from sector-based management to

the political processes regarding deep-sea and high-seas

more holistic integrated ecosystem-based management

governance, which are currently ongoing in various inter-

approaches. Sustainable deep-sea governance presents

national fora within and outside the UN system. In addition,

additional specific challenges linked to the criss-cross of

this report provides guidance on the future direction and

legal and natural, vertical and horizontal, boundaries

focus of research on environmental, socio-economic and

applying to the deep-sea and deep-seabed areas. Deep-sea

governance aspects in relation to the deep sea.

waters and seabed can be within or beyond areas of national

The deep sea, as defined and used here, includes the

jurisdiction of coastal states, which further complicates

waters and seabed areas below a depth of 200 metres. This

policy design and implementation, and challenges the

corresponds to 64 per cent of the surface of the Earth and

establishment of effective links with shallow-water

90 per cent of our planet's ocean area. The average ocean

governance regimes.

depth is 3 730 metres and 60 per cent of the ocean floor lies

Despite existing political commitments, deep-sea

deeper than 2 000 metres. The volume of the oceans, incl-

resources are increasingly exploited. On the one hand, the

uding the seabed and water column, creates the largest

depletion of some shallow-water resources (in particular

living space on Earth, roughly 300 times greater than that of

fish stocks and fossil fuels) has drawn more commercial

the terrestrial environment (Gage, 1996).

interest in deep-water ones and, on the other hand, the

For millennia, the oceans have been used for shipping

advances in technology over the last decades have made the

and fishing. More recently, they became convenient sinks for

exploitation of the deep waters and deep seabeds feasible

waste. This usage was guided by the perception that the

and more economically attractive. The same technological

seas are vast, bottomless reservoirs that could not be

advances have also revolutionized deep-sea research. Until

affected by human activity. Today, we know that the seas are

recently, research on deep-sea ecosystems and biodiversity

not limitless, and that we are approaching (or in some cases,

was restricted by the complexity of the systems, their

may even have overstepped) the capacity of the marine env-

inaccessibility and the associated technological and

ironment to cope with anthropogenic pressures. In the light

methodological challenges. Our knowledge started to

of this knowledge, over the last 1015 years the international

expand with the rise of sophisticated sampling technologies,

community has adopted increasingly ambitious goals and

remotely operated vehicles, acoustic mapping techniques,

targets to safeguard the marine environment and its

ocean observatories and remote sensing (Koslow, 2007). We

resources. During the 2002 World Summit on Sustainable

now know that the deep sea harbours rich, complex and

Development held in Johannesburg, world leaders agreed

vulnerable ecosystems and biodiversity. As we discover the

inter alia on: the achievement of substantial reductions in

natural wonders of the last frontier on Earth, we also realize

land-based sources of pollution by 2006; the introduction of

that the deep biosphere is no longer too remote to remain

an ecosystems approach to marine resource assessment

unaffected by the human footprint. The enduring miscon-

and management by 2010; the designation of a network of

ception of the oceans as bottomless reservoirs of resources

marine protected areas by 2012; and the maintenance or

and sinks for wastes is rapidly eroding in the face of

restoration of fish stocks to sustainable yield levels by 2015

scientific evidence of the finiteness and fragility of the deep

(UN, 2002: Chapter IV).

oceans. We have proof that several deep-sea habitats and

In this context, issues related to deep-sea governance

ecosystems are impacted, threatened, and/or in decline

are increasingly appearing on the political agenda at diff-

because of human activity. But the knowledge gaps are still

erent levels. There is presently a heavy international policy

huge. It is estimated that the amount of properly mapped

focus on deep-sea ecosystems and resources in various fora

seafloor in the public domain is around 2 or 3 per cent

9

Deep-sea biodiversity and ecosystems

(Handwerk, 2005). This figure could reach 10 per cent if

open file seismic data from the hydrocarbon industry that

classified military information is taken into account. Only

provides information on the structure of the seabed in

0.0001 per cent (10-6) of the deep seafloor has been

certain areas). But socio-economic research in support of

scientifically investigated. Although we know that species

the sustainable use and conservation of deep-sea resources

diversity in the deep sea is high, obtaining precise data and

is lagging behind (Grehan et al., 2007). Collapsing fisheries,

information is problematic: current estimates range

degraded and destroyed habitats and ecosystems, changes

between 500 000 and 100 million species (Koslow, 2007). As

in ocean chemistry and qualities, are all indications of direct

of today, the bulk of these species remains undescribed,

and indirect human interactions with the deep-sea

especially for smaller organisms and prokaryotes (Danovaro

environment, which affect the role of the oceans, their buffer

et al., 2007).

functions and their future uses. There is a clear need to

Meanwhile, anthropogenic impacts on vulnerable

identify the societal and economic implications of these

ecosystems and habitats are rising. Direct impacts of human

activities and impacts, and for documenting the key socio-

activities relate to existing or future exploitation of deep-sea

economic and governance issues related to the conser-

resources (for example, fisheries, hydrocarbon extraction,

vation, management and sustainable use of the deep seas.

mining, bioprospecting), to seabed uses (for example,

This report constitutes a first step in that direction. It is

pipelines, cable laying, carbon sequestration) and to

structured along four chapters. Chapter 1 offers a short

pollution (for example, contamination from land-based

introduction to habitats, ecosystems and biodiversity of the

sources/activities, waste disposal, dumping, noise, impacts

deep sea. Chapter 2 explores ecosystem functions, goods

of shipping and maritime accidents). Indirect effects and

and services, and issues pertaining to their valuation. It then

impacts relate to climate change, ocean acidification and

turns more specifically to deep-sea goods and services and

ozone depletion.

their valuation. Chapter 3 describes the main human

The recent advances in research have also shown that

activities and impacts on deep-sea biodiversity and

deep-sea processes and ecosystems cannot be addressed in

ecosystems. Following the same structure as Chapter 2,

isolation. They are not only important for the marine web of

Chapter 4 identifies key elements for environmental man-

life; they also fundamentally contribute to global biogeo-

agement and governance and then turns more specifically to

chemical patterns that support all life on Earth (Cochonat et

deep-sea governance issues. Based on the gaps identified in

al., 2007). They also provide more direct goods and services

previous chapters, the Conclusions summarize strategic

that are of growing economic significance. Most of today's

research needs on socio-economic, governance and man-

understanding of the deep oceans comes from the natural

agement issues and suggests priority actions to improve

sciences, supplemented by data from industry (such as,

science-policy interfaces.

Coral, sponge, and feather star at 3 006 meters depth on the

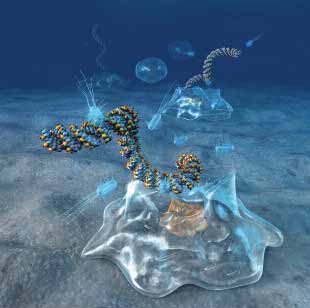

A jelly fish of the genus Crossota, collected from the deep

Davidson Seamount, located 120 kilometres to the

Arctic Canada Basin with an ROV.

southwest of Monterey, California (US).

2006

Raskoff/NOAA

NOAA/MBARI

Kevin

10

1. Habitats, ecosystems and

biodiversity of the deep sea

Deepwatersor"deepseas"aredefinedinthisreport bottom in areas of at least 200metres depth; and the

as waters and sea-floor areas below 200 metres,

seafloor itself (Figure 1.1).

where sunlight penetration is too low to support

The structure and topography of the deep-seafloor is as

photosynthetic production.

complex and varied as that of the continents or even more

From a biological perspective, the deeper waters below

so. Many submarine mountains and canyons/trenches dwarf

the sunlit epipelagic zone comprise: the mesopelagic or the

their terrestrial counterparts. Numerous larger and smaller

"twilight" zone (200 to about 1 000 metres), where sunlight

geomorphologic features (Table 1.1) strongly influence the

gradually dims depending, for example, on water turbidity,

distribution of deep-sea organisms. Many of these features

seasons, regions; the bathypelagic zone from approximately

rise above, or cut into, the seafloor, thereby creating a

1 000 metres down to about 2 000 metres; the abyssal

complex, three-dimensional topography that offers a

pelagic zone (down to 6 000 metres); the hadalpelagic

multitude of ecological conditions, habitats and niches for a

zone, which delineates the deepest trenches; the bentho-

wide variety of unique marine ecosystems.

pelagic zone, which includes waters directly above the

Biodiversity in the deep seas depends among other

Figure 1.1: The main oceanic divisions Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ocean

High

Pelagic

water

Neritic

Oceanic

Epipelagic

Photic

Low

200 m

water

Mesopelagic

Sublittoral or ice shelf

Littoral

10ºC

700 to 1,000 m

Bent

Bathypelagic

hal

4ºC

2,000 to 4,000 m

Aphotic

Benth

Abyssalpelagic

ic

Abyssal

6,000 m

Hada

Hadalpelagic

l

10,000 m

11

Deep-sea biodiversity and ecosystems

Table 1.1: Main geomorphologic features of the deep sea

Continental shelf

Seaward continuation of continents underwater, typically extending from the coast to depths of up to 150

to 200 metres. Ends at the continental shelf break at an average depth of 130 metres.

Continental slope

Beyond the shelf break, often disrupted by submarine landslides. Steeper slopes frequently cut by

canyons.

Continental rise

The gently sloped transitional area between the continental slope and the abyssal plain.

Continental margin

Submerged prolongation of the land mass of a coastal state, consisting of the seabed and subsoil of

the shelf, the slope and the rise.

Abyssal plains

Flat areas of seabed extending beyond the base of the continental rise.

Mid-ocean ridges

Underwater mountain range of tectonic origin commonly formed when two major plates spread

apart. They often host hydrothermal vents.

Back-arc basins

Submarine basins associated with island arcs and subduction zones, formed where tectonic plates

collide.

Dysoxic (anoxic)

Ocean basins in which parts (or all) of the water mass, often near the bottom, is depleted in basins

oxygen (for example the Black Sea below 160200 metres depth).

Submarine canyons

Valleys carved into the continental margin where they incise the continental shelf and slope, often off

river estuaries. Act as conduits for transport of sediment from the continent to the deep-ocean floor.

Their formation has been related both to subaerial erosion during sea level lowstands and to

submarine erosion.

Submarine channels

Wide, deep channels that may continue from canyons and extend hundreds to thousands of

kilometres across the ocean floor.

Deep sea trenches

Narrow, deep and steep depressions formed by subduction of one tectonic plate beneath

and hadal zones

another and reaching depths of 11 kilometres; the deepest parts of the oceans.

Seamounts

Submarine elevations of at least 1 000 metres above the surrounding seafloor, generally conical with

a circular, elliptical or more elongate base and a limited extent across the summit. Typically volcanic

in origin, seamounts can form chains and sometimes seamounts show vent activity.

Carbonate mounds

Seabed features resulting from the growth of carbonate-producing organisms and (current

controlled) sedimentation

Hydrothermal vents

Fissures in the seafloor commonly found near volcanically active places which release geothermally

super-heated and mineral-rich water.

Cold seeps

An area of the ocean floor where hydrogen sulphide, methane and other hydrocarbon-rich fluids (with a

temperature similar to the surrounding seawater) escape into seawater.

Mud volcanoes

Dome-shaped formations on the seafloor of up to 10 kilometres in diameter and 700 metres in

height, created mostly by the release of fluids charged with mud derived from the subseabed. A type

of cold seep.

12

Habitats, ecosystems and biodiversity

are horizontally and vertically interconnected with shallow

Box 1.1: Biodiversity of the deep sea

areas, for instance by ocean currents, which carry large

amounts of surface water continuously (for example, the

Mesopelagic: Biodiversity includes horizontally and

Meridional Overturning Circulation in the North Atlantic) or

vertically actively swimming species (nekton)

sporadically (by dense shelf water cascading, for example)

distributed over large geographic areas and

into the deep sea, and vice versa (upwelling of nutrient-rich

plankton (typically small metazoans, jelly fish and

deep waters to the surface, for example).

eukaryotic, as well as prokaryotic single cell

The mesopelagic zone is home to a large number of

organisms) living at depths ranging from 200 to

planktonic micro-organisms as well as a wide variety of

1 000 metres.

macro-organisms, which are widely distributed over large

geographic areas and undergo regular horizontal and

Bathypelagic: Biodiversity and biomass inhabiting

vertical migrations in search of food. In the bathypelagic

the water column comprised from 1 000 to 4 000

zone, the number of species and their biomass appear to

metres depth. Knowledge of biodiversity in the

decrease rapidly with depth. Very little is known about

bathy- and abyssal pelagic zones is limited. Typical

the organisms living in the deeper bathypelagic waters,

life forms include gelatinous animals, crustaceans

and even some of the large animals on Earth such as the

and a variety of fish.

giant squid are barely documented.

The study of the deep-seabed life (benthos) has revealed

Benthic: Species on the seabed (epibenthic) and in

that the fauna is as varied and highly diverse as and that

sediments (endobenthic) are abundant, although

their diversity is linked to the complexity of the seafloor it

not evenly distributed. Complex, 3-dimensional

is occupying. Some stretches of seafloor, especially on the

habitats such as seamounts have often a high

abyssal plains, seem to be sparsely populated by inter-

species richness and a high degree of endemism.

spersed macrobenthos and meiofauna (which account for

Emphasis on the levels of benthic biodiversity,

more than 90 per cent of total faunal abundance), whereas

especially in sediments, cannot be overrated

other areas can teem with life. Marine benthic biodiversity is

since estimates show close to 98 per cent of

highest from around 1 000 to 2 000 metres water depth.

known marine species live in this environment.

Biodiversity along the continental margins is, per equal

Microbial life can extend kilometres into the sea-

number of individuals, in terms of abundance, higher than

floor (deep biosphere).

that of continental shelves. In addition, continental slopes,

ridges and seamounts are expected to host most of the

undiscovered biodiversity of the globe (Figure 1.2).

parameters on depth (see Box 1.1). In this report we mainly

Recent results from the HERMES project suggest that in

(although not exclusively) focus on deep seabed and benthic

biodiversity and ecosystems. Although, in recent years,

Planktonic animals like this krill form a vital link in the marine

knowledge about biodiversity in the deep-sea water column

food chain.

has started to increase (Nouvian, 2007; Koslow, 2007) there

are still a number of mysteries and myths surrounding

deep-sea life. The deep sea was regarded as a vast, desert-

NOAA

like expanse void of life, until the first research expeditions in

the mid 19th century proved otherwise (Koslow, 2007). Deep-

sea organisms were believed to live in very stable conditions

with very little environmental change, relying completely on

food sinking down from surface waters. However, we now

know that certain biophysical conditions and parameters

that govern deep-water and deep-seabed systems are highly

dynamic both in spatial and temporal scales, and that there

are communities that thrive on minerals and chemicals,

rather than energy from the sun and organic matter.

Today, the deep sea is still commonly seen (and

addressed, for example, in policy processes) as distinct from

shallow coastal marine environments. Research in recent

years indicates that the deeper waters and the life therein

13

Deep-sea biodiversity and ecosystems

100

non-colonial marine invertebrate known, whereas a close

relative, Riftia pachyptila, living around hydrothermal vents,

80

number

reaches maturity and 1.5 metres length in less than two

60

years which makes these worms the fastest-growing

(200)

species

40

ES

marine invertebrate known (Druffel et al., 1995).

ed

The majority of deep-sea organisms rely on the input of

20

food and nutrients produced in the epipelagic zone; that is,

Expect

00

1

2

3

4

5

they depend indirectly on energy from the sun. Where food

Depth ('000 m)

availability is increased or more stable, such as around

Figure 1.2: Marine biodiversity patterns in relation to

seamounts and other seafloor features, organisms and

water depth. Highest biodiversity values occur from about

species can aggregate in large numbers, forming biodiversity

1 000 to 2 000 metre depths. Source Weaver et al., 2004,

hotspot communities such as those associated with cold-

compiled from various literature sources

water coral reefs. Hydrothermal vents and cold seeps are

types of ecosystems that are chemotrophic; that is they

some areas biodiversity can increase with depth down to the

benefit from non-photosynthetic sources of energy, such as

abyssal plains (Figure 1.3).

gas, hydrocarbons and reduced fluids as well as minerals

Despite the heterogeneity and variety of deep-sea life,

transported from the deep subsurface to the seafloor at a

there are a number of traits that the majority of deep-sea

wide range of temperatures from 2°C of up to 400°C.

organisms share. Most are adapted to life in environments

Another frequent characteristic of deep-sea fauna is the

with relatively low and/or sporadic levels of available energy

high level of endemism (for example, Brandt et al., 2007).

and food (Koslow et al., 2000; Gage, 1996). Most deep-sea

Due in part to the unique conditions of deep-sea habitats,

organisms grow slowly and reach sexual maturity very late.

and the distances or physical and chemical obstacles that

Reproduction is often characterized by low fecundancy (that

often separate them, in some areas 90 per cent of species

is, number of offspring produced) and recruitment. Some

are endemic (UN, 2005).

deep-sea organisms can reach astonishing ages: orange

Out of the variety of deep-sea environments, this report

roughy, a commercially exploited fish species, can live up to

focuses on the deep-seabed features and ecosystems

200 years or more, and gold corals (Gerardia spp.) found for

described below, which are (or have the potential to be)

example, on seamounts may have been alive for up to 1 800

important from a socio-economic point of view, and for

years, making them the oldest known animals on Earth

which some information is available, although big gaps of

(Bergquist et al., 2000). However, slow growth is not necess-

knowledge still exist in most cases.

arily consistent even within the same group: the vestimenti-

feran tube worm Lamellibrachia living near cold seeps

CONTINENTAL SLOPES

requires between 170 and 250 years to grow to a length of

Continental slopes and rises, commonly covering water

two metres which makes these worms the longest-lived

depths of about 2003 000 metres, constitute 13 per cent of

the Earth's area. They consist of mostly terrigenous

a

140

sediments angled between 1 and 10 degrees, and are often

in

heavily structured by submarine canyons and sediment

120

specimen

slides. These large-scale features, together with ocean

100

species

currents, create a varied seafloor topography with a wide

of

200

of 80

range of substrates for organisms to settle in or on,

e 60

including large areas of soft sediments, boulders and

number

sampl 40

exposed rock faces. The geomorphologic diversity of

ed

continental slopes, combined with favourable ocean-

20

Expect

r

andom

ographic and nutrient conditions (for example, through

00

1

2

3

4

5

upwelling or cascading-down of nutrient-rich waters from

Depth ('000 m)

deeper or shallower areas, respectively), create an array of

Atlantic

Mediterranean

conditions suitable for a great abundance and variety of

marine

life.

Several

marine

biodiversity

"hotspot

Figure 1.3: Species richness in relation to depth in the

ecosystems" can be found on continental slopes such as

Atlantic and the Mediterranean.

cold-water coral reefs or ecosystems associated with slope

Source: preliminary unpublished data from the HERMES

features (for example, canyons, seamounts, carbonate

project (R. Danovaro, pers. com.)

mounds or cold seeps).

14

Habitats, ecosystems and biodiversity

NOCS

Gunn,

Vikki

Three-dimensional map of the seafloor off the Atlantic coast of the Iberian Peninsula, showing various submarine canyons cut

into the continental shelf.

ABYSSAL PLAINS

on the abyssal plains, which support a distinct community of

Abyssal plains, commonly occurring in water depths of about

organisms. Cadavers of large marine mammals (for

3 0006 000 metres, constitute approximately 40 per cent of

example, whale falls) or fish sinking to the bottom of the

the ocean floor and 51 per cent of the Earth's area. They are

abyss attract a succession of specialized organisms that feed

generally flat or very gently sloping areas formed by new

on these carcasses over months to years. Polymetallic

oceanic crust spreading from mid-oceanic ridges at a rate of

20 to 100 millimetres per year. The new volcanic seafloor

near these ridges is very rough, but soon becomes covered in

Hawaiii

most places by layers of fine-grained sediments,

of

predominantly clay, silt and the remains of planktonic

organisms, at a rate of appromimately two to three

centimetres per thousand years. The main characteristics of

University

abyssal plain ecosystems are (1) low biomass, (2) high

Smith,

species diversity, (3) large habitat extension and (4) wide-

scale, sometimes complex topographic and hydrodynamic

Craig

features. Species consist mostly of small invertebrate

organisms living in or burrowing through the seabed (Gage,

1996), as well as an undiscovered plethora of micro-

organisms. Given the relative homogeneity of abyssal plains,

small organisms (larvae, juveniles and adults) can drift over

For over four years, the bones of this 35-tonne gray whale

long distances. The percentage of endemic species found on

have rested on the seabed at 1 670 metres depth in the Santa

abyssal plains may therefore not be as high as elsewhere in

Cruz Basin (Eastern Pacific) and are now covered with thick

the deep sea. In certain areas, special conditions are found

mats of chemosynthetic bacteria.

15

Deep-sea biodiversity and ecosystems

and are, increasingly targeted by commercial fisheries.

Bottom trawling causes severe impacts on benthic

Azores

seamount communities, and without sustainable manage-

the

of

ment can deplete fish stocks within a few years ("boom and

bust" fisheries). The flanks of some seamounts, especially in

the equatorial Pacific, contain cobalt-rich ferromanganese

University

crusts, which are attracting deep-water mining interest.

Thus, the commercial fisheries close to seamounts are

unlikely to remain the only source of direct human impact on

IMAR/DoP,

seamounts (ISA, 2004). Moreover, as a consequence of the

diversity and uniqueness of species on seamounts, research

and bioprospecting programmes may increase, and likewise

their associated impacts (Arico and Salpin, 2005).

Bashmachnikow,

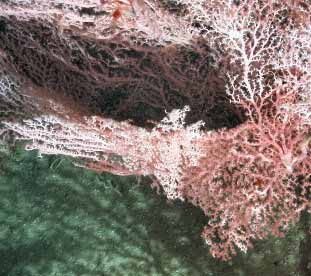

COLD-WATER CORALS

Igor

Cold-water corals thrive in the deeper waters of all oceans.

Unlike their tropical shallow-water cousins, cold-water

corals do not possess symbiotic algae and live instead by

feeding on zooplankton and suspended particulate organic

matter. Cold-water corals belong to a number of groups

including soft corals (for example, sea fans) and stony

corals, and are most commonly found on continental

shelves, slopes, seamounts and carbonate mounds in

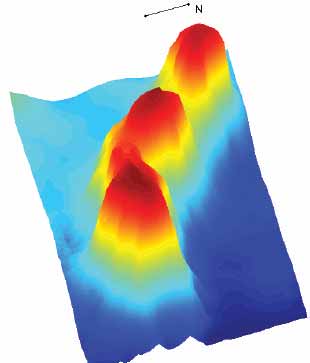

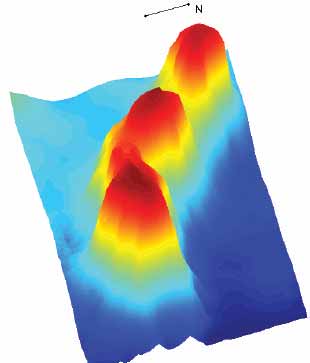

3D map of the Sedlo Seamounts, north of the Azores,

depths of 200 to 1 000 metres at temperatures of 413ºC

Atlantic. Base depth ca. 2 500 metres, minimum summit

(Freiwald et al., 2004). Most cold-water corals grow slowly

depth 750 metres.

(Lophelia pertusa, 4-25 millimetres per year). Some stony

coral species can form large, complex three-dimensional

manganese nodules, found on some abyssal plains, support

structures on continental shelves, slopes and seamounts.

distinct ecosystems (Wellsbury et al., 1997).

The best-known examples are the cold-water coral reefs in

the Northeast Atlantic, which are part of a Lophelia belt

SEAMOUNTS

stretching on the eastern Atlantic shelf from northern

Seamounts are underwater mountains of generally tectonic

Norway to South Africa. The largest individual reef dis-

and/or volcanic origin, often (but not exclusively) found on

covered so far (Røst reef off the coast of Norway) measures

the edges of tectonic plates and mid-ocean ridges.

40 kilometres in length and 23 kilometres in width.

Seamounts are prominent and ubiquitous geological

Growing at a rate of 1.3 millimetres a year (Fosså et al.,

features. Based on satellite data, the location of 14 287 large

2002), this reef took about 8 000 years to form. In the deeper

seamounts with summit heights of more than 1 000 metres

waters of the North Pacific, dense and colourful "gardens"

above the surrounding area has been predicted. This is likely

of soft corals cover large areas, for example, around the

to be an underestimate: there may be up to 100 000 large

Aleutian Islands. What these cold-water coral reefs or

seamounts worldwide. Seamounts often have a complex

gardens have in common with their tropical counterpart is

topography of terraces, pinnacles, ridges, crevices and

their ecological role. Cold-water coral ecosystems are

craters, and they are subject to, and interact with, the water

among the richest biodiversity hotspots in the deep sea,

currents surrounding them. This leads to a variety of living

providing shelter and food for hundreds of associated

conditions and substrates providing suitable habitat for rich

species, including commercial fish and shellfish. This

and diverse communities. Although only a few large

makes cold-water corals, like seamounts, a prime target

seamounts have been subject to detailed biological studies

for trawling. There is some evidence that some com-

(Clark et al., 2006), it appears that seamounts can act as

mercially targeted fish are more abundant close to cold-

biodiversity hotspots, attracting top pelagic predators and

water coral reefs; more detailed studies that demonstrate

migratory species, such as whales, sharks, tuna or rays, as

their role and potential as nursery grounds have yet to be

well as hosting an often-unique bottom fauna with a large

carried out (Freiwald et al., 2004; Clark et al., 2006). Cold-

number of endemic species (Richer de Forges et al., 2000).

water coral reefs formed by stony corals are also

The deep-water fish stocks around seamounts have been,

threatened by the indirect impacts of anthropogenic CO2

16

Habitats, ecosystems and biodiversity

emissions. With increasing CO2 emissions in the atmos-

phere, large amounts of CO2 are absorbed by the oceans,

which results in a decrease in pH ("ocean acidification") and

reduced number of carbonate (CO32-) ions available in

seawater (see Chapter 3). Scientists predict that, due to this

T.Lundalv/TMBL

phenomenon, by 2100 around 70 per cent of all cold-water

corals will live in waters undersaturated in carbonate,

especially in the higher latitudes (Guinotte et al., 2006). The

decline in carbonate saturation will not only severely affect

cold-water corals it will also impede and inhibit a wide

array of marine organisms and communities (such as

shellfish, starfish and sea urchins) with carbonate

skeletons and shells.

DEEP-SEA SPONGE FIELDS

Sponges are primitive, sessile, filter feeding animals with

no true tissue, that is, they have no internal organs,

muscles and nervous system. Most of the approximately 5

000 sponge species live in the marine environment attached

to firm substrate (rocks etc.), but some are able to grow on

soft sediment by means of a root-like base. As filter

feeders, sponges prefer clear, nutrient-rich waters.

Continued, high sediment loads tend to block the pores of

Above: A colony of the gorgonian coral Primnoa

sponges, lessening their ability to feed and survive. Under

resedaeformis at 310m depth in the Skagerrak, off the coast

suitable environmental conditions, mass occurrences of

of Sweden.

large sponges ("sponge fields") have been observed on

continental shelves and slopes, for example, around the

Below: Sponge field dominated by Aplysilla sulphurea

Faroe Islands, East Greenland, around Iceland, in the

covering Stryphnus ponderosus. Still image from HD video

Skagerrak off Norway, off the coast of British Columbia, in

filmed at 271 metres depth in the North East Atlantic off the

the Barents Sea and in the Antarctic ocean. Some of these

coast of the Finnmark area, northern Norway.

fields originated about 8 5009 000 years ago. Most deep-

water sponges are slow-growing (Fosså and Tendal,

undated), and individuals may be more than 100 years old,

weighing up to 80 kg (Gjerde, 2006a). Similar to cold-water

Norway

coral reefs, the presence of large sponges adds a three-

dimensional structure to the seafloor, thus increasing

Research,

habitat complexity and attracting an invertebrate and fish

fauna at least twice as rich as that on surrounding gravel or

Marine

soft bottom substrates. Sponge fields around the Faroe

of

Islands are associated with about 250 species of

invertebrates (UN, 2006b), for which the sponges provide

Institute

shelter and nursery grounds. Most of the approximately 65

sponge

species

known

from

sponge

fields

are

characterized by their large size, slow growth rates and

Mortensen,

weak cementation, which makes them very fragile and

P.B.

vulnerable to the direct physical impact from bottom

trawling and to emothering by the sediment blooms this

and

gear causes. Sponges are also a very important marine

Fosså

source of chemicalls and substances with potential

J.H.

pharmaceutical and biotechnological purposes/value. Most

of the more than 12 000 marine compounds isolated so far

stem from these animals.

17

Deep-sea biodiversity and ecosystems

Ifremer

Sampling of hydrothermal vent chimneys in the North East Pacific at 260 metre depth using ROV Victor.

HYDROTHERMAL VENTS

depths of 850 to 2 800 metres and deeper, with one of the

Hydrothermal vents were discovered in 1977 and are

largest fields at 1 700 metres below sea level off the

commonly found in volcanically active areas of the seafloor

Azores in the Atlantic (Santos et al., 2003). On contact with

(for example, mid-ocean ridges, tectonic plate margins,

the surrounding cold deep-ocean seawater, the minerals

above magma hotspots in the Earth's crust), where

in the superheated (up to 400ºC) plumes precipitate and

geothermally heated gases and water plumes rich in

form the characteristic chimneys (which can grow up to 30

minerals and chemical energy are released from the

centimetres a day and reach heights of up to 60 metres)

seafloor. Vents have been documented in many oceans at

and polymetallic (copper, iron, zinc, silver) sulphide

deposits. Hydrothermal vents host a unique fauna of

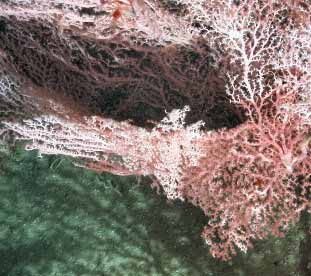

Gorgonian corals at the Carlos Ribeiro mud volcano in the

microbes, invertebrates (for example, mussels and crabs)

Gulf of Cadiz, south of the Iberian Peninsula.

and fish. The local food chains are based on bacteria

converting the sulphur-rich emissions into energy, that is,

are independent from the sun as an original source for

energy. The chemosynthesis of minerals, and the extreme

cruise

physical and chemical conditions under which hydro-

thermal vent ecosystems thrive, may provide further clues

on the evolution of life on Earth. Although hydrothermal

NOCS/JC10

vent communities are not very diverse in comparison with

those in nearby sediments (Tunnicliffe et al., 2003), the

biomass around such vents can be 500-1 000 times that of

the surrounding deep sea, rivalling values of some of the

most productive marine ecosystems. Over 500 vent

species have so far been identified (ChEss, 2007).

Community composition varies among sites with success-

ional stages observed. Different ages of hydrothermal

flows can be distinguished by the associated fauna

(Tunnicliffe et al., 2003).

The activity of individual vents might vary over time. The

temporary reduction or stop of the water flow, for example,

18

Habitats, ecosystems and biodiversity

due to its diversion to a new outlet, will also affect the supply

ecosystems on the basis of microbial chemosynthesis,

of hydrogen sulphide on which the organisms depend. If the

which makes them prime potential targets for biopros-

flow stops altogether, all non-mobile animals living in the

pecting (Arico and Salpin, 2005). Cold seep communities are

surrounding of the particular chimney will starve and

characterized by a high biomass and a unique and often

eventually die. The mineral deposits around hydrothermal

endemic species composition. Biological communities

vents are of potential interest for commercial mining

include large invertebrates living in symbiosis with chemo-

operations, and the "extromophile" fauna of hydrothermal

trophic bacteria using methane and/or hydrogen sulphide as

vent ecosystems might become a source of organic

their energy source. The fauna living around cold seeps often

compounds (for example, proteins with a wide range of heat

display a spatial variability, depending on the distance to the

resistance) for industrial and medical applications (ISA,

seep. Communities of microbes oxidizing methane thrive

2004). Even when the original vent community becomes

around these cold seeps, despite the extreme conditions of

extinct, vent chimneys may continue to provide a basis for

pressure and toxicity (Boetius et al., 2000; Niemann et al.,

life as hard-substrate for a new community of corals and

2006). Research recently showed the relevance of such

other species to grow.

microbes and their genetic makeup in controlling green-

house gases (GHG) such as methane, which is a much more

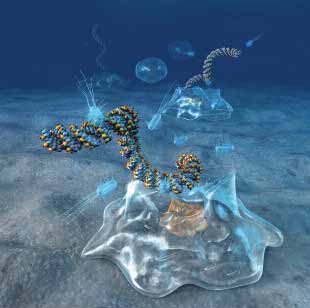

COLD SEEPS AND GAS HYDRATES

potent GHG than CO2 (Krueger et al., 2003).

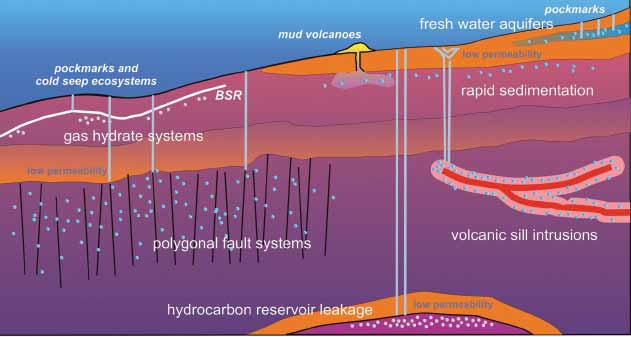

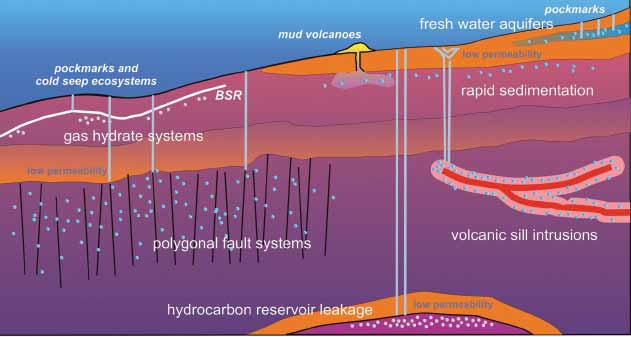

Cold seeps are areas on the ocean floor where water,

Cold seeps are often associated with gas hydrates

minerals, hydrogen sulphide, methane, other hydrocarbon-

(Figure 1.4), naturally occurring solids (ice) composed of

rich fluids, gases and muds are leaking or expelled through

frozen water molecules surrounding a gas molecule, mainly

sediments and cracks by gravitational forces and/or

methane. The methane trapped in gas hydrates represents

overpressures in often gas-rich subsurface zones (Figure

a huge energy reservoir. It is estimated that gas hydrates

1.4). In contrast to hydrothermal vents, these emissions are

contain 500-3 000 gigatonnes of methane carbon (WBGU,

not geothermally heated and therefore much cooler, often

2006), over half of the organic carbon on Earth (excluding

close to surrounding seawater temperature. Cold seeps can

dispersed organic carbon), and twice as much as all fossil

form a variety of large to small-scale features on the sea-

fuels (coal, oil and natural gas) combined (Kenvolden, 1998).

floor, including mud volcanoes, pockmarks, gas chimneys,

However, the utilization of gas hydrates as energy sources

brine pools and hydrocarbon seeps. As in the case of hydro-

poses great technological challenges and bears severe risks

thermal vents, cold seeps sustain exceptionally rich

and geohazards (see Chapter 3).

Figure 1.4: Schematic showing cold seeps and other focused fluid flow systems/features discussed in the text. (BSR:

bottom-simulating reflector) (Source: Berndt, 2005)

19

Deep-sea biodiversity and ecosystems

2. Ecosystem functions, goods,

services and their valuation

Ecosystem functions are processes, products or biogeochemicalconditions.Humansocietiesandeconomic

outcomes arising from biogeochemical activities

systems fundamentally depend on the stability of

taking place within an ecosystem. One may

ecosystems and their functions (Srivastava and Vellend,

distinguish between three classes of ecosystem functions:

2005). The provision of ecosystem goods and services is

stocks of energy and materials (for example, biomass,

likely to be reduced with biodiversity loss (for example, Worm

genes), fluxes of energy or material processing (for

et al., 2006).

example, productivity, decomposition), and the stability of

The notion of ecosystem goods and services has been

rates or stocks over time (for example, resilience,

put forward as a means to demonstrate the importance of

predictability) (Pacala and Kinzig, 2002).

biodiversity for society and human well-being, and to trigger

Ecosystem goods and services are the benefits human

political action to address the issue of biodiversity change

populations derive, directly or indirectly, from ecosystem

and loss. The provision of ecosystem goods and services,

functions (Costanza et al., 1997). This definition includes

however, is a sufficient but by no means necessary

both tangible and intangible services and was adopted by

argument for biodiversity and ecosystem conservation.

the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MA), which

Other arguments, based on precaution or ethics in

identifies four major categories of services (supporting,

particular, are equally legitimate. Hence, the goods and

provisioning, regulating and cultural) (Figure 2.1). The

services approach adds value to conservation strategies that

concepts of ecosystem functions and services are related.

argue for conservation on moral or ethical grounds.

Ecosystem functions can be characterized outside any

human context. Some (but not all) of these functions also

VALUATION OF ECOSYSTEMS AND THE GOODS AND

provide ecosystem goods and services that sustain and

SERVICES THEY PROVIDE

fulfil human life.

The human enterprise depends on ecosystem goods and

Maintained biodiversity is often essential to the stability

services in an infinite number of ways, often divided into

of ecosystems. The loss of species can temporarily or

direct and indirect contributions. Directly, with the

permanently move an ecosystem into a different state of

provision of goods as essential as food or habitat, and

indirectly with multiple services that maintain appropriate

Figure 2.1: Ecosystem services Source: MA (2005a)

biochemical and physical conditions on Earth. Providing

value evidence for ecosystem goods and services is

important for at least two reasons. First, to measure the

Provisioning services

human dependence upon ecosystems (Daily, 1997) and

· Food

· Freshwater

second, to better account for the contribution of

· Wood and fibre

ecosystems to human life and well-being so that more

· Fuel

efficient, effective and/or equitable decisions can be made

· ...

(DEFRA, 2006). Hence, a key question for the conservation

and management of biodiversity and ecosystems is how to

Supporting services

Regulating services

value ecosystems themselves and the goods and services

· Nutrient recycling

· Climate regulation

· Soil formation

· Food regulation

they provide, in particular those goods and services that

· Primary production

· Disease regulation

are not (and cannot be) traded in markets.

· ...

· Water purification

· ...

Different types of values

Valuation of ecosystem goods and services is restrictive in

Cultural services

the sense that it caters to humans only. However, as shown

· Aesthetic

· Spiritual

in Table 2.1, anthropocentric values are only two of four

· Educational

categories of environmental values. The other two categ-

· Recreational

ories cannot be completely accounted for, as by definition it

· ...

is hard or impossible for humans to comprehend non-

20

Ecosystem functions, goods and services and their valuation

anthropocentric values. Focusing on the total economic

value only (the top left corner of Table 2.1), in particular

through monetary valuation, is often the preferred answer to

the question of how to account for ecosystem goods and

NOAA/MBARI

services in policy and decision making (see, for example,

Costanza et al., 1997; Costanza, 1999; Beaumont and Tinch,

2003). There are, however, strong arguments for the use of

non-monetary types of valuation in decision-making

processes (see section on shortcomings of monetary

environmental valuation below).

Several typologies of values exist. Environmental econo-

mists often divide Total Economic Value (TEV) into various

types of (in principle) quantifiable values before adding them

up. A major division is between use and non-use values. Use

values are further divided into direct and indirect use as well

as option-use values, while non-use value includes bequest

and existence values (Beaumont and Tinch, 2003). Figure 2.2

summarizes this classification of value.

The components of TEV can be defined as follows:

Use values relate to the actual or potential, consumptive or

Deep-sea blob sculpin (Psychrolutes phrictus); yellow

non-consumptive, use of resources:

Picasso sponge (Acanthascus (Staurocalyptus) sp.); and

Direct-use values come from the exploitation of a

white ruffle sponge (Farrea sp.) at 1 317 meters depth on

resource for both products and services. Sometimes

the Davidson Seamount off the coast of California.

market prices and proxies can be used to estimate

such values.

biodiversity. Some species may prove valuable in the

Indirect-use values are benefits that humans derive

future, either as the direct source of goods (for example,

from ecosystem services without directly intervening.

the substances they secrete or their genes for

They correspond to goods and services mostly taken

pharmaceutical or industrial applications) or as a key

for granted and stem from complex biogeochemical

component of ecosystem stability.

processes, which are often not sufficiently understood to

Non-use values essentially refer to the benefits people

be properly valued.

attach to certain environmental elements independently of

Option-use values consist of values attached to possible

their actual or future use:

future uses of natural resources. Future uses are

Bequest value is associated with people's satisfaction

unknown, a reason to want to keep one's options open.

that (elements of) the natural environment will be

As such, option-use values are intrinsically linked with

passed on to future generations.

Table 2.1: Classification of environmental values

Source: Adapted from DEFRA, 2006

Anthropocentric

Non-anthropocentric

Instrumental

Total Economic Value (TEV): use

The values to other animals, species, ecosystems,

and non-use (including value

etc. (independent of humans). For instance, each

related to others' potential or

species sustains other species (through different

actual use)/ utilitarian.

types of interactions) and contributes to the evolution

and creation of new species (co-evolution).

Intrinsic

"Stewardship" value (unrelated

Value an entity possesses independently of any

to any human use)/ non-

valuer.

utilitarian.

21

Deep-sea biodiversity and ecosystems

Total Economic Value

(TEV)

Use values

Non-use values

Direct use

Indirect use

Option

Bequest

Existence

value

value

value

value

value

Figure 2.2: Classification under Total Economic Value (Beaumont and Tinch, 2003)

Existence value is associated with people's satisfaction

such as the deep seas, which may never be witnessed

to know that certain environmental elements exist,

without proxy.

regardless of uses made. This includes many cultural,

aesthetic and spiritual aspects of humanity as well as,

Although TEV represents only a fraction of the overall value

for instance, people's awe at the wonders of nature,

of the natural environment, it is a useful notion to signal

Box 2.1: Valuation methods

Source: DEFRA 2006

Monetary valuation methods are based on economic theory and aim to quantify all or parts of the Total Economic Value (TEV).

These methods assume that individuals have preferences for or against environmental change, and that these preferences are

affected by a number of socio-economic and environmental factors and the different motivations captured in the TEV

components. It is also assumed that individuals can make trade-offs, both between different environmental changes and

between environmental changes and monetary amounts, and do so in order to maximize their welfare (or happiness, well-being

or utility). Several methods can be used to estimate individual preferences in order to monetarize individual values. They are

based on individuals' willingness to pay (WTP) for an improvement (or to avoid a degradation) or willingness to accept (WTA)

compensation to forgo an improvement (or to tolerate a degradation). Methods include: market price proxies; production

function; hedonic property pricing; travel cost method; random utility model; contingent valuation and choice modelling1.

Non-monetary valuation methods, often called deliberative and participatory methods, also examine the values underlying