United Nations

Intergovernmental

Educational, Scientific and

Oceanographic

Cultural Organization

Commission

Seamounts, deep-sea corals

and fisheries

Census of Marine Life on Seamounts (CenSeam)

Data Analysis Working Group

Regional

Seas

Seamounts, deep-sea corals

and fisheries

Vulnerability of deep-sea corals to fishing on

seamounts beyond areas of national jurisdiction

Regional

Seas

UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

219 Huntingdon Road,

The authors would like to thank Matt Gianni Advisor, Deep Sea

Cambridge CB3 0DL,

Conservation Coalition and Dr Stefan Hain, Head, UNEP Coral

United Kingdom

Reef Unit for promoting the undertaking of this work and for many

Tel: +44 (0) 1223 277314

constructive comments and suggestions. Adrian Kitchingman of

Fax: +44 (0) 1223 277136

the Sea Around Us Project, Fisheries Centre, University of British

Email: info@unep-wcmc.org

Columbia, kindly provided seamount location data, and Ian May at

Website: www.unep-wcmc.org

UNEP-WCMC re-drew most of the original maps and graphics.

Derek Tittensor would like to thank Prof. Ransom A Myers and Dr

Jana McPherson, Department of Biological Sciences, Dalhousie

©UNEP-WCMC/UNEP 2006

University and Dr Andrew Dickson, Scripps Institute of

Oceanography for discussions, comments, and advice on

ISBN: 978-92-807-2778-4

modelling of coral distributions and ocean chemistry; Dr Alex

Rogers would like to thank Prof. Georgina Mace, Director of the

Institute of Zoology and Ralph Armond, Director-General of

A Banson production

the Zoological Society of London for provision of facilities for

Design and layout J-P Shirreffs

undertaking work for this report. Dr Amy Baco-Taylor (Woods

Printed in the UK by Cambridge Printers

Hole Oceanographic Institution) provided very useful comments

Photos

on a draft of the manuscript. Three reviewers provided comments

Front cover: Left, Cold-water coral (Lophelia pertusa), André Freiwald,

on the final manuscript. Dr Christian Wild, GeoBiocenter LMU

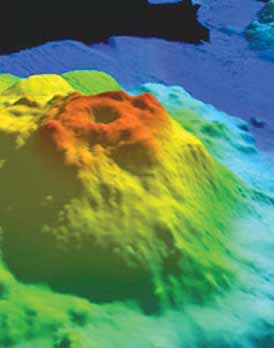

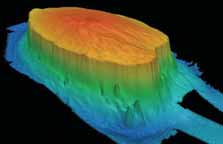

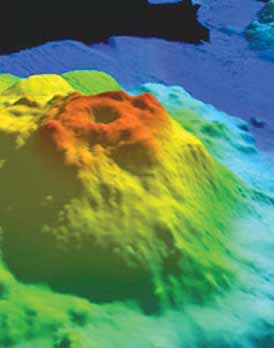

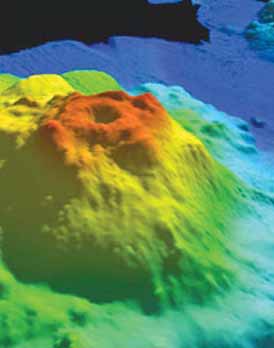

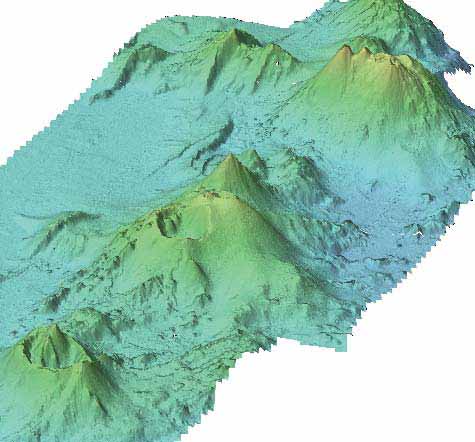

IPAL-Erlangen; Centre, Multibeam image of Ely seamount (Alaska) with

Muenchen reviewed and guided the report on behalf of UNESCO-

the caldera clearly visible at the apex. Jason Chaytor, NOOA Ocean

IOC. The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the

Explorer (http://oceanexplorer.noaa.gov/ explorations/04alaska); Right,

Census of Marine Life programmes FMAP (Future of Marine

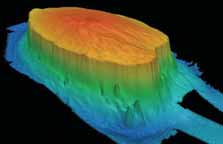

Orange roughy haul. Image courtesy of M Clark (NIWA). Back: Multibeam

Animal Populations) and CenSeam (a global census of marine life

image Brothers NW, NIWA.

on seamounts). The Netherlands' Department of Nature, Ministry

We acknowledge the photographs (pp 16, 21, 25, 26, 29, 31, 47) from

of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality are gratefully

the UK Department of Trade and Industry's offshore energy Strategic

acknowledged for funding the original workshop and NIWA for

Environmental Assessment (SEA) programme care of Dr Bhavani

hosting the meeting. Hans Nieuwenhuis is additionally

Narayanaswamy, Scottish Association for Marine Science and Mr Colin

acknowledged for help in bringing this report to fruition. The

Jacobs, National Oceanography Centre, Southampton.

UNEP Regional Seas Programme and the International

Oceanographic Commission of UNESCO kindly provided funding

DISCLAIMER

for the publication of this report.

The contents of this report are the views of the authors alone. They are not

an agreed statement from the wider science community, the organizations

the authors belong to, or the CoML.

Citation: Clark MR, Tittensor D, Rogers AD, Brewin P, Schlacher T,

The contents of this report do not necessarily reflect the views or

Rowden A, Stocks K, Consalvey M (2006). Seamounts, deep-sea

policies of the United Nations Environment Programme, the UNEP World

corals and fisheries: vulnerability of deep-sea corals to fishing

Conservation Monitoring Centre, or the supporting organizations. The

on seamounts beyond areas of national jurisdiction. UNEP-

designations employed and the presentations do not imply the expressions

WCMC, Cambridge, UK.

of any opinion whatsoever on the part of these organizations concerning

the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or its authority, or

URL: www.unep-wcmc.org/resources/publications/

UNEP_

concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Moreover, the

WCMC_bio_series/

views expressed do not necessarily represent the decision or the stated

and

policy of UNEP or contributory organizations, nor does citing of trade

www.unep.org/regionalseas/Publications/Reports/

names or commercial processes constitute endorsement.

Series_Reports/Reports_and_Studies

2

Seamounts, deep-sea corals and fisheries

The work was initiated with data compilation and analysis in 2005

AUTHORS

supported by CenSeam, followed by a workshop funded by the

Malcolm R Clark*

Department of Nature, Ministry of Agriculture, Nature and Food

National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research

Quality, Netherlands, which was held at the National Institute of

PO Box 14-901, Kilbirnie, Wellington, New Zealand

Water and Atmospheric Research (NIWA) in Wellington, New

Zealand, from 8 to 10 February 2006.

Derek Tittensor*

Department of Biological Sciences

CENSUS OF MARINE LIFE AND CENSEAM

Life Sciences Centre

The Census of Marine Life (CoML) is an international science

1355 Oxford Street

research programme with the goal of assessing and explaining

Dalhousie University

the diversity, distribution and abundance of marine life past,

Halifax, Nova Scotia, B3H 4J1, Canada

present and future. It involves researchers in more than 70

countries working on a range of poorly understood habitats. In

Alex D Rogers*

2005 a CoML field project was established to research and sample

Institute of Zoology

seamounts (Stocks et al. 2004; censeam.niwa.co.nz). This project,

Zoological Society of London

termed CenSeam (a Global Census of Marine Life on Seamounts),

Regent's Park, London NW1 4RY, United Kingdom

provides a framework to integrate, guide and expand seamount

research efforts on a global scale. It has established a `seamount

Paul Brewin

researcher network of almost 200 people around the world, and is

San Diego Supercomputer Center

collating existing seamount information and expanding a data-

University of California San Diego

base of seamount biodiversity. Its Steering Committee comprises

9500 Gilman Drive, La Jolla, CA 92093-0505, USA

people who are at the forefront of seamount research, and can

therefore contribute a wealth of knowledge and experience to

Thomas Schlacher

issues of seamount biodiversity, fisheries and conservation.

Faculty of Science, Health and Education

One of the key themes of CenSeam is to assess the impacts of

University of the Sunshine Coast

fisheries on seamounts, and to this end, it has established a Data

Maroochydore DC Qld 4558, Queensland, Australia

Analysis Working Group (DAWG) that includes people with a wide

range of expertise on seamount datasets and analysis and

Ashley Rowden

modelling techniques.

National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research

PO Box 14-901, Kilbirnie, Wellington, New Zealand

Karen Stocks

San Diego Supercomputer Center

University of California San Diego

9500 Gilman Drive, La Jolla, CA 92093-0505, USA

Mireille Consalvey

National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research

PO Box 14-901, Kilbirnie, Wellington, New Zealand

*These authors made an equal contribution to this report and

are therefore joint first authors.

3

Supporting organizations

Regional

Seas

UNEP's Regional Seas Programme aims to address the

Department of Nature, Ministry of Agriculture, Nature and Food

accelerating degradation of the world's oceans and coastal areas

Quality, Netherlands.

through the sustainable management and use of the marine and

coastal environment, by engaging neighbouring countries in

comprehensive and specific actions to protect their shared marine

environment.

The Census of Marine Life (CoML) is a global network of

researchers in more than 70 nations engaged in a ten-year

initiative to assess and explain the diversity, distribution and

abundance of marine life in the oceans past, present and future.

The UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP-WCMC)

is the biodiversity assessment and policy implementation arm of

the United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP), the

world's foremost intergovernmental environment organization.

UNEP-WCMC aims to help decision makers recognize the value of

The National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research

biodiversity to people everywhere, and to apply this knowledge to

(NIWA) is a research organization based in New Zealand, and is an

all that they do. The Centre's challenge is to transform complex

independent provider of environmental research and consultancy

data into policy-relevant information, to build tools and systems

services.

for analysis and integration, and to support the needs of nations

and the international community as they engage in programmes

of action.

The Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (IOC) of the

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization

(UNESCO) provides Member States of the United Nations with an

essential mechanism for global cooperation in the study of the

ocean. The IOC assists governments to address their individual

and collective ocean and coastal problems through the sharing of

knowledge, information and technology and through the

coordination of national programmes.

4

Foreword

Foreword

`How inappropriate to call this planet Earth, when it is quite clearly Ocean'

attributed to Arthur C Clarke

Alook at a map of the world shows how true this and described. However, the same observations also

statement is. Approximately two-thirds of our planet

provided alarming evidence that seamount habitats are

is covered by the oceans. The volume of living space

increasingly threatened by human activities, especially from

provided by the seas is 168 times larger than that of

the rapid increase of deep-sea fishing.

terrestrial habitats and harbours more than 90 per cent of

The United Nations General Assembly has repeatedly

the planet's living biomass.

called upon States and international organizations to

The way most world maps depict the oceans is

urgently take action to address destructive practices, such

deceiving: while the land is shown in great detail with

as bottom trawling, and their adverse impacts on the

colours ranging from greens, yellows and browns, the sea

marine biodiversity and vulnerable ecosystems, especially

is nearly always indicated in subtle shades of pale blue.

cold-water corals on seamounts.

This belies the true structure of the seafloor, which is

This report, compiled by an international group of

as complex and varied as that of the continents or even

leading experts working under the Census of Marine Life

more so. Some of the largest geological features on Earth

programme, responds to these calls. It provides a

are found on the bottom of the oceans. The mid-ocean

fascinating insight into what we know about seamounts,

ridge system spans around 64 000 km, four times longer

deep-sea corals and fisheries, and uses the latest facts

than the Andes, the Rocky Mountains and the Himalayas

and figures to predict the existence and vulnerability of

combined. The largest ocean trench dwarfs the Grand

seamount communities in areas for which we have no or

Canyon, and is deep enough for Mount Everest to fit in with

only insufficient information.

room to spare.

The deep waters and high seas are the Earth's final

Only in the last decades, advanced technology has

frontiers for exploration. Conservation, management and

revealed that there are also countless smaller features

sustainable use of the resources they provide are among the

seamounts arising in every shape and form from the sea

most critical and pressing ocean issues today.

floor of the deep sea, often in marine areas beyond national

Seamounts and their associated ecosystems are

jurisdiction. Observations with submersibles and remote

important and precious for life in the oceans, and for

controlled cameras have documented that seamounts

humankind. We hope that this report provides inspiration to

provide habitat for a large variety of marine animals and

take concerted action to prevent their further degradation,

unique ecosystems, many of which are still to be discovered

before it is too late.

Veerle Vandeweerd, Head,

Jon Hutton, Director,

Patricio Bernal, Executive Secretary,

United Nations Environment

UNEP World Conservation

Intergovernmental Oceanographic

Programme (UNEP) Regional

Monitoring Centre

Commission (IOC) of the United

Seas Programme,

Nations Educational, Scientific and

Coordinator, GPA

Cultural Organization (UNESCO)

5

Seamounts, deep-sea corals and fisheries

Executive summary

The oceans cover 361 million square kilometres, almost on seamounts and identifies the seamounts on which

three-quarters (71 per cent) of the surface of the Earth.

they are most likely to occur globally;

The overwhelming majority (95 per cent) of the ocean

3. compares the predicted distribution of stony corals on

area is deeper than 130 m, and nearly two-thirds (64 per

seamounts with that of deep-water fishing on

cent) are located in areas beyond national jurisdiction.

seamounts worldwide;

Recent advances in science and technology have provided an

4. qualitatively assesses the vulnerability of communities

unprecedented insight into the deep sea, the largest realm

living on seamounts to putative impacts by deep-water

on Earth and the final frontier for exploration. Satellite and

fishing activities;

shipborne remote sensors have charted the sea floor,

5. highlights critical information gaps in the development

revealing a complexity of morphological features such as

of risk assessments to seamount biota globally.

trenches, ridges and seamounts which rival those on land.

Submersibles and remotely operated vehicles have

SEAMOUNT CHARACTERISTICS AND DISTRIBUTION

documented rich and diverse ecosystems and communities,

A seamount is an elevation of the seabed with a summit of

which has changed how we view life in the oceans.

limited extent that does not reach the surface. Seamounts

The same advances in technology have also documented

are prominent and ubiquitous geological features, which

the increasing footprint of human activities in the remote

occur most commonly in chains or clusters, often along

and little-known waters and sea floor of the deep and high

the mid-ocean ridges, or arise as isolated features from the

seas. A large number of video observations have not only

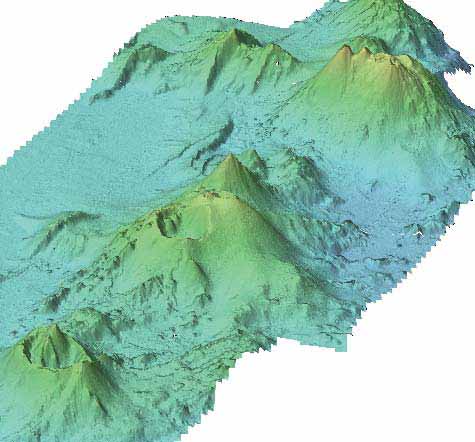

sea floor. Generally volcanic in origin, seamounts are often

documented the rich biodiversity of deep-sea ecosystems

conical in shape when young, becoming less regular with

such as cold-water coral reefs, but also gathered evidence

geological time as a result of erosion. Seamounts often have

that many of these biological communities had been

a complex topography of terraces, canyons, pinnacles,

impacted or destroyed by human activities, especially by

crevices and craters telltale signs of the geological

fishing such as bottom trawling. In light of the concerns

processes which formed them and of the scouring over time

raised by the scientific community, the UN General

by the currents which flow around and over them.

Assembly has discussed vulnerable marine ecosystems and

As seamounts protrude into the water column, they are

biodiversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction at its

subject to, and interact with, the water currents surrounding

sessions over the last four years (2003-2006), and called,

them. Seamounts can modify major currents, increasing the

inter alia, `for urgent consideration of ways to integrate and

velocity of water masses that pass around them. This often

improve, on a scientific basis, the management of risks to

leads to complex vortices and current patterns that can

the marine biodiversity of seamounts, cold-water coral reefs

erode the seamount sediments and expose hard substrata.

and certain other underwater features'.

The effects of seamounts on the surrounding water masses

This report, produced by the Data Analysis Working

can include the formation of `Taylor' caps or columns,

Group of the global census of marine life on seamounts

whereby a rotating body of water is retained over the summit

(CenSeam), is a contribution to the international response to

of a seamount.

this call. It reveals, for the first time, the global scale of the

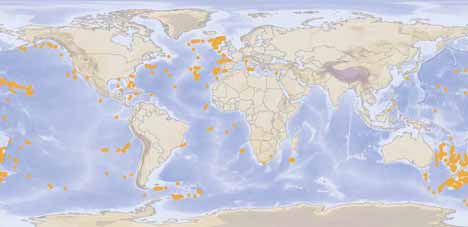

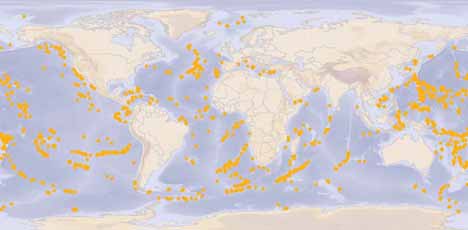

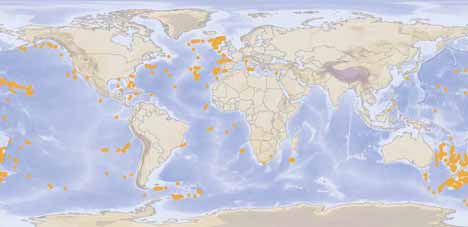

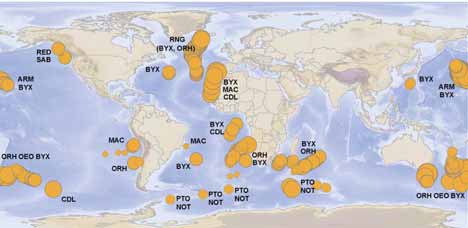

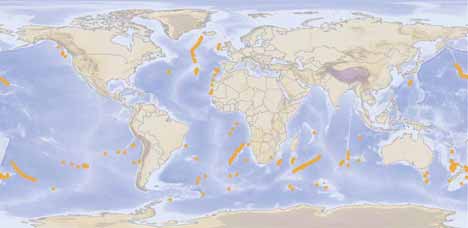

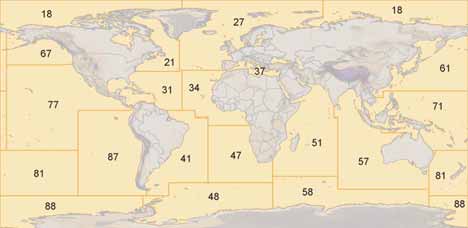

In the present study the global position of only large

likely vulnerability of habitat-forming stony (scleractinian)

seamounts (>1 000 m elevation) were taken into account due

corals, and by proxy a diverse assemblage of other species,

to methodological constraints. Based on an analysis of

to the impacts of trawling on seamounts in areas beyond

updated satellite data, the location of 14 287 large sea-

national jurisdiction. In order to support, focus and guide the

mounts has been predicted. This is likely an underestimate.

ongoing international discussions, and the emerging

Extrapolations from other satellite measurements estimate

activities for the conservation and sustainable management

that there may be up to 100 000 large seamounts worldwide.

of cold-water coral ecosystems on seamounts, the report:

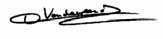

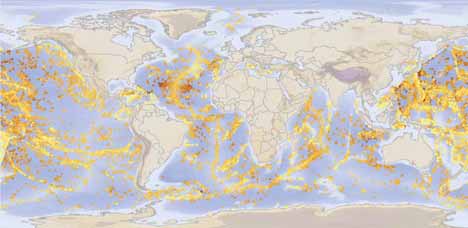

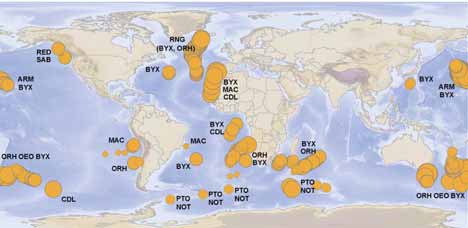

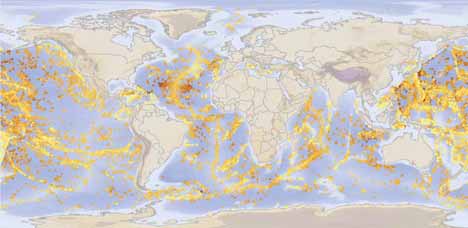

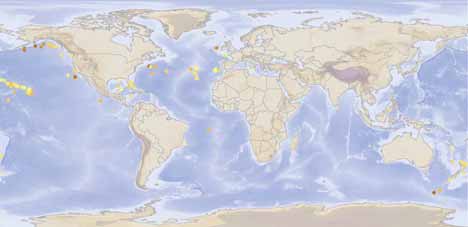

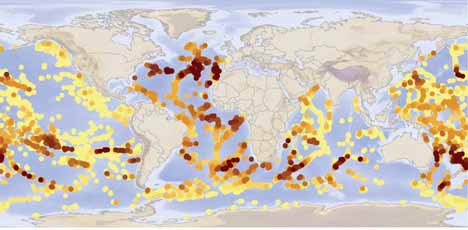

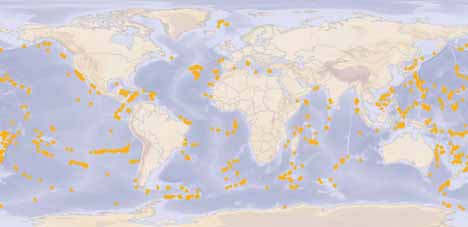

Numbers of predicted seamounts peak between 30ºN

1. compiles and/or summarizes data and information on

and 30ºS, with a rapid decline above 50ºN and below 60ºS.

the global distribution of seamounts, deep-sea corals on

The majority of large seamounts (8 955) occur in the

seamounts and deep-water seamount fisheries;

Pacific Ocean area (63 per cent), with 2 704 (19 per cent) in

2. predicts the global occurrence of environmental

the Atlantic Ocean and 1 658 (12 per cent) in the Indian

conditions suitable for stony corals from existing records

Ocean. A small proportion of seamounts are distributed

6

Executive Summary

between the Southern Ocean (898; 6 per cent), the

animals that contains the corals, hydroids, jellyfishes and

Mediterranean/Black Seas (59) and Arctic Ocean (13) (both

sea anemones). A recent study recorded more than 1 300

less than 1 per cent).

species associated with the stony coral Lophelia pertusa on

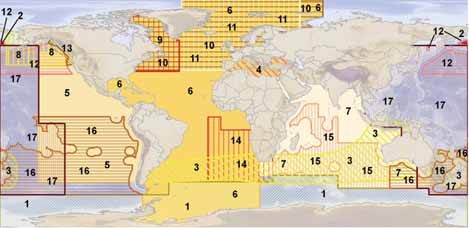

An analysis of the occurrence of these seamounts inside

the European continental slope or shelf. Thus some cold-

and outside of Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) indicates

water corals may be regarded as `ecosystem engineers'

that just over half (52 per cent) of the world's large

because they create, modify and maintain habitat for other

seamounts are located beyond areas of national jurisdiction.

organisms, similar to trees in a forest.

The majority of these seamounts (10 223; 72 per cent) have

Cold-water corals can form a significant component

summits shallower than 3 000 m water depth.

of the species diversity on seamounts and play a key

ecological role in their biological communities. The assess-

DEEP-SEA CORALS AND BIODIVERSITY

ment of the potential impacts of bottom trawling on corals is

Compared to the surrounding deep-sea environment,

therefore a useful proxy for gauging the effects of these

seamounts may form biological hotspots with a distinct,

activities on seamount benthic biodiversity as a whole. A

abundant and diverse fauna, and sometimes contain many

comprehensive assessment of biodiversity is currently

species new to science. The distribution of organisms on

impossible because of the lack of data for many faunal

seamounts is strongly influenced by the interaction between

groups living on seamounts.

the seamount topography and currents. The occurrence of

hard substrata means that, in contrast to the mostly soft

DISTRIBUTION OF CORALS ON SEAMOUNTS

sediments of the surrounding deep sea, seamount

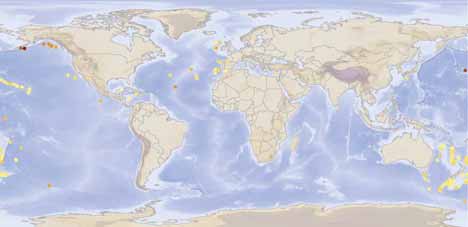

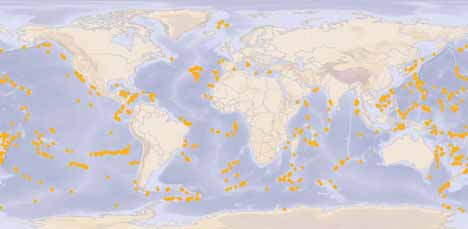

One of the data sources utilized for this report was a

communities are often dominated by sessile, permanently

database of 3 235 records of known occurrences of five

attached organisms that feed on particles of food

major coral groups found on seamounts, including some

suspended in the water. Corals are a prominent component

shallower features <1 000 m elevation. Existing records

of the suspension-feeding fauna on many seamounts,

show that the stony corals (scleractinians) were the most

accompanied by barnacles, bryozoans, polychaete worms,

diverse and commonly observed coral group on seamounts

molluscs, sponges, sea squirts and crinoids (which include

(249 species, 1 715 records) followed by Octocorallia (161

sea lilies and feather stars).

species, 959 records), Stylasterida (68 species, 374 records),

Most deep-sea corals belong to the Hexacorallia,

Antipatharia (34 species, 159 records) and Zoanthidea (14

including stony corals (scleractinians) and black corals

species, 28 records). These records included all species of

(antipatharians), or the Octocorallia, which include soft

corals, including those that were reef-forming, contributed

corals such as gorgonians.

to reef formation, or occur as isolated colonies.

Three-dimensional structures rising above the sea

The most evident finding in analysing the coral database

floor in the form of reefs created by some species of

is that sampling of seamounts has not taken place evenly

stony coral, as well as coral `beds' formed by black corals

across the world's oceans, and that there are significant

and octocorals, are common features on seamounts and

geographic gaps in the distribution of studied seamounts.

continental shelves, slopes, banks and ridges. Coral

For some regions, such as the Indian Ocean, very few

frameworks add habitat complexity to seamounts and other

seamount samples are available. In total, less than 300

deep-water environments. They offer refugia for a great

seamounts have been sampled for corals, representing

variety of invertebrates and fish (including commercially

only 2.1 per cent of the identified number of seamounts in

important species) within, or in association with, the living

the oceans globally (or 0.03 per cent when assuming there

and dead coral framework. Cold-water corals are frequently

are 100 000 large seamounts). Only a relatively small

concentrated in areas of the strongest currents near ridges

number of coral species have wide geographic distributions,

and pinnacles, providing hard substrata for colonization

and very few have near cosmopolitan distributions. Many of

by other encrusting organisms and allowing them better

the widely distributed species are the primary reef, habitat

access to food brought by prevailing currents. Although the

or framework-building stony corals such as Lophelia

co-existence between coral and non-coral species is in most

pertusa, Madrepora oculata and Solenosmilia variabilis.

cases still unknown, recent research is showing that some

In most parts of the world, stony corals were the most

coral/non-coral relationships may show different levels

diverse group, followed by the octocorals. However, in the

of dependency. A review of direct dependencies on cold-

northeastern Pacific, octocorals are markedly more diverse

water corals globally, including those on seamounts, has

than stony corals. Most stony corals and stylasterid species

shown that of the 983 coral-associated species studied, 114

occur in the upper 1 000-1 500 m depth range.

were characterized as mutually dependent, of which 36

Antipatharians also occurred in the upper 1 000 m, although

were exclusively dependent on cnidarians (group of

a higher proportion of species occurs in deeper waters than

7

Seamounts, deep-sea corals and fisheries

the two previous groups. Octocorals were distributed to

total alkalinity; total dissolved inorganic carbon;

greater depths, with most species in the upper 2 000 m. Very

aragonite saturation state).

little sampling has occurred below 2 000 m.

There are a number of reasons for the differences in the

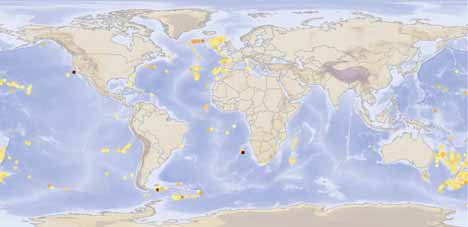

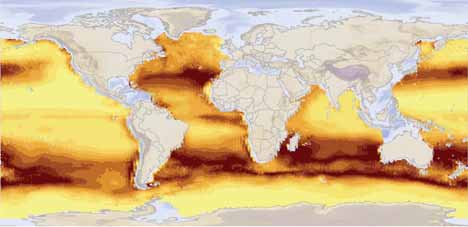

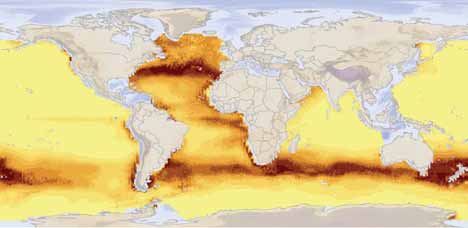

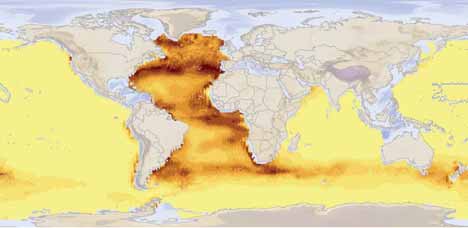

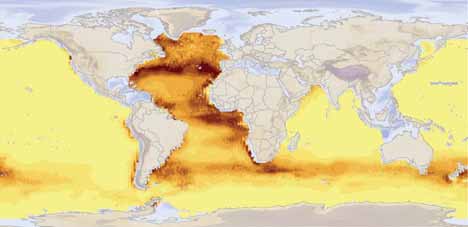

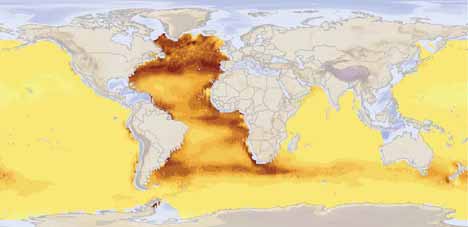

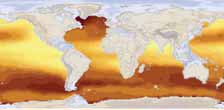

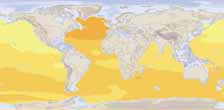

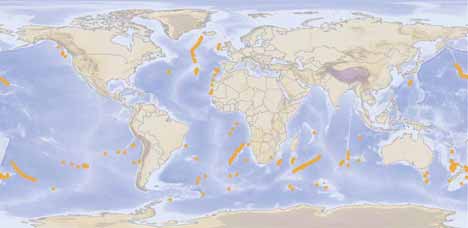

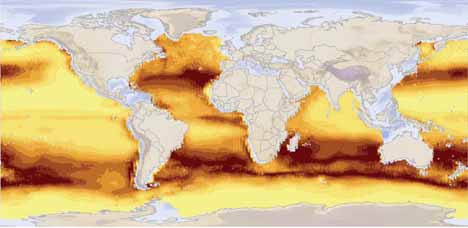

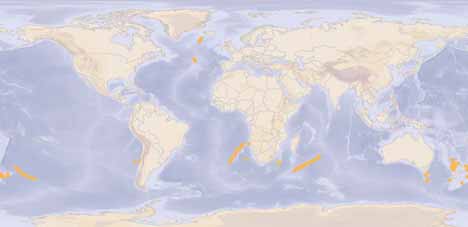

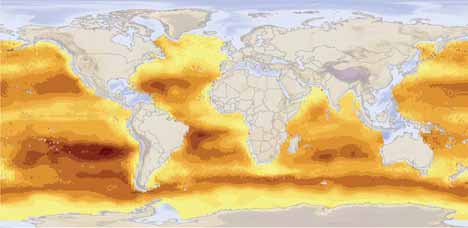

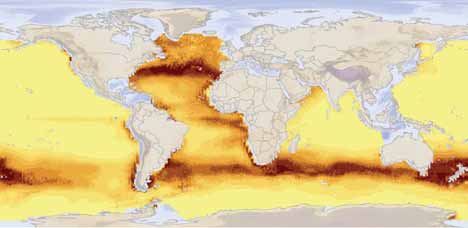

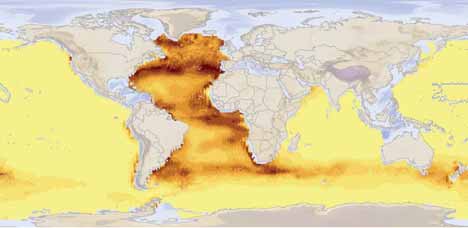

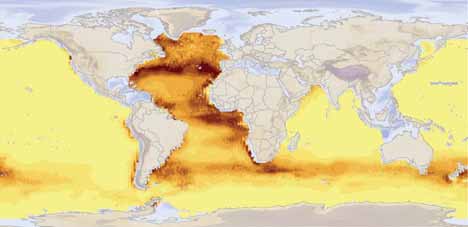

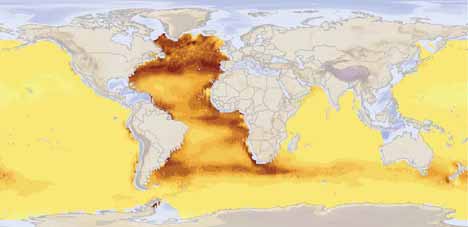

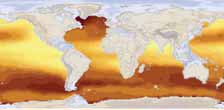

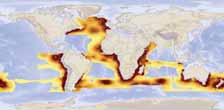

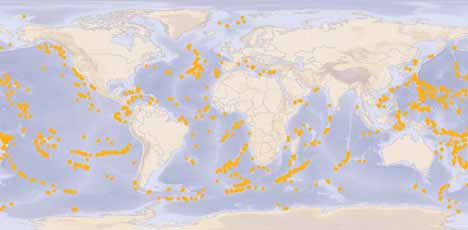

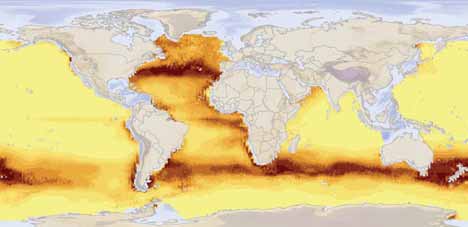

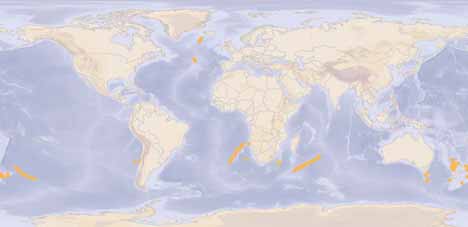

The model predictions were as follows: in near-surface

depth and regional distribution of the coral groups, including

waters (0-250 m), habitat predicted to be suitable for stony

species-related preferences of the nature of substrates

corals lies in the southern North Atlantic, the South

available for attachment, quantity, quality and abundance

Atlantic, much of the Pacific, and the southern Indian

of food at different depths, the depth of the aragonite

Ocean. The Southern Ocean and the northern North

saturation horizon, temperature and the availability of

Atlantic are, however, unsuitable. Below 250 m depth, the

essential elements and nutrients.

suitability patterns for coral habitat change substantially.

In depths of 250-750 m, a narrow band occurs around

PREDICTING GLOBAL DISTRIBUTION OF STONY CORALS

30ºN ± 10º, and a broader band of suitable habitat occurs

ON SEAMOUNTS

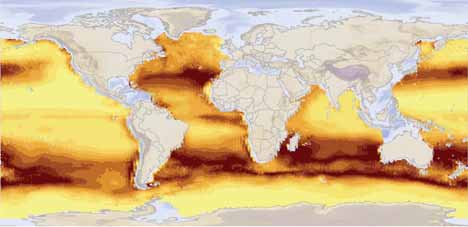

around 40ºS ± 20º. In depths of 750-1 250 m, the North

The dataset for corals on seamounts revealed significant

Pacific and northern Indian Ocean are unsuitable for stony

areas of weakness in our knowledge of coral diversity and

corals. The circum-global band of suitable habitat at

distribution on seamounts, especially the lack of sampling

around 40ºS narrows with increasing depth (to ± 10º).

on seamounts at equatorial latitudes. Thus, to make a

Suitable habitat areas also occur in the North Atlantic and

reasonable assessment of the vulnerability of seamount

tropical western Atlantic. These areas remain suitable

corals to bottom trawling (and, by proxy, determine

for stony corals with increasing depth (1 250-1 750 m;

the potential impacts of this activity on non-coral

1 750-2 250 m; 2 250 m-2 500 m), whereas the band

assemblages), it was necessary to fill the sampling gaps by

at 40ºS breaks up into smaller suitable habitat areas

predicting the global occurrence of suitable coral habitat

around the southeast coast of South America and the tip

by modelling coral distribution.

of South Africa.

An environmental niche factor analysis (ENFA) was used

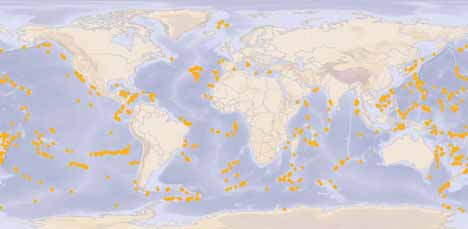

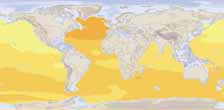

The global extent of habitat suitability for seamount

to model the global distribution of deep-sea stony corals on

stony corals was predicted to be at its maximum between

seamounts and to predict habitat suitability for unsampled

around 250 m and 750 m. The majority of the suitable

regions. Other groups of coral, such as octocorals, for

habitat for stony corals on seamounts occurs in areas

example, can also form important habitats such as coral

beyond national jurisdiction. However, suitable habitats are

beds. These corals may have very different distributions

also predicted in deeper waters under national jurisdiction,

to stony corals, which would also be useful to appreciate in

especially in the EEZs of countries:

the context of determining the vulnerability of seamount

1. between 20ºS and 60ºS off Southern Africa, South

communities to bottom trawling. The available data for

America and in the Australia/New Zealand region;

octocorals are, unfortunately, currently too limited to enable

2. off Northwest Africa; and

appropriate modelling.

3. around 30ºN in the Caribbean.

ENFA compares the observed distribution of a species to

the background distribution of a variety of environmental

Combining the predicted habitat suitability with the

factors. In this way, the model assesses the environmental

summit depth of predicted seamounts indicates that the

niche of a taxonomic group i.e. how narrow or wide this

majority of seamounts that may provide suitable habitat

niche is identifies the relative difference between the niche

for stony corals on their summits are located in the

and the mean background environment, and reveals those

Atlantic Ocean. The rest are mostly clustered in a band

environmental factors that are important in determining the

between 15ºS and 50ºS. A few seamounts elsewhere, such

distribution of the studied group.

as in the South Pacific, with summits in the depth range

The model used and combined:

between 0 m and 250 m, are highly suitable. In the Atlantic,

(i). the location data of 14 287 predicted large seamounts;

a large proportion of suitable seamount summit habitat is

(ii). the location records of stony corals (Scleractinia) on

beyond national jurisdiction, whereas in the Pacific, most of

seamounts; and

this seamount habitat lies within EEZs. In the southern

(iii). physical, biological and chemical oceanographic data

Indian Ocean, suitable habitat appears both within and

from a variety of sources for 12 environmental

outside of EEZs. When analysing habitat suitability on the

parameters (temperature; salinity; depth of coral

basis of summit depth, it should be noted that suitable

occurrence; surface chlorophyll; dissolved oxygen; per

habitat for stony corals might also occur on the slopes of

cent oxygen saturation; overlying water productivity;

seamounts, i.e. at depths greater than the summit.

export primary productivity; regional current velocity;

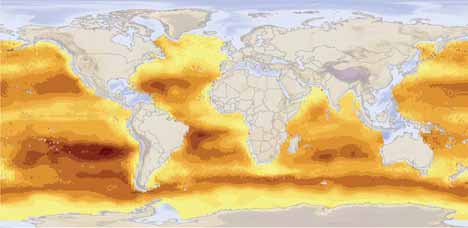

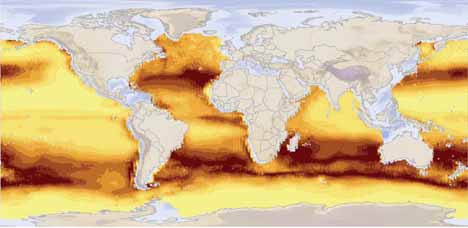

The analysis found the following environmental factors

8

Executive Summary

were important for determining suitable habitat for stony

and target species for smaller-scale line fisheries (e.g. black

corals: high levels of aragonite saturation, dissolved oxygen,

scabbardfish Aphanopus carbo).

per cent oxygen saturation, and low values of total dissolved

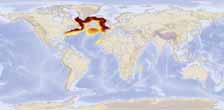

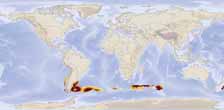

The distribution of four of the most important seamount

inorganic carbon. Neither surface chlorophyll nor regional

fish species (for either their abundance or commercial

current velocity appears to be important for the global

value) is as follows:

distribution of stony corals on seamounts. Nevertheless,

1. ORANGE ROUGHY is widely distributed throughout the

these factors may be important for the distribution of corals

Northern and Southern Atlantic Oceans, the mid-

at smaller spatial scales, such as on an individual seamount.

southern Indian Ocean and the South Pacific. It does

The strong dependency of coral distribution on the

not extend into the North Pacific. It is frequently

availability of aragonite (a form of calcium carbonate) is

associated with seamounts for spawning or feeding,

noteworthy. Stony corals use aragonite to form their hard

although it is also widespread over the general

skeletons. A reduction in the availability of aragonite, for

continental slope.

example through anthropogenically induced acidification of

2. ALFONSINO has a global distribution, being found in all

the oceans due to rising CO2 levels, will limit the amount

the major oceans. It is a shallower species than orange

of suitable habitat for stony corals.

roughy, occurring mainly at depths of 400-600 m. It is

associated with seamount and bank habitat.

SEAMOUNT FISH AND FISHERIES

3. ROUNDNOSE GRENADIER is restricted to the North

Seamounts support a large and diverse fish fauna. Recent

Atlantic, where it occurs on both sides, as well as on the

reviews indicate that up to 798 species are found on and

Mid-Atlantic Ridge, where aggregations occur over

around seamounts. Most of these fish species are not

peaks of the ridge.

exclusive to seamounts, and occur widely on continental

4. PATAGONIAN TOOTHFISH has a very wide depth range

shelf and slope habitats. Seamounts can be an important

and is sometimes associated with seamounts, but it is

habitat for commercially valuable species, which may form

also found on general slope and large bank features.

dense aggregations for spawning or feeding targeted by

large-scale fisheries.

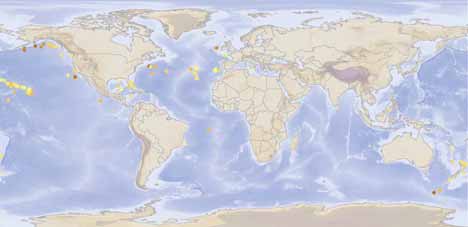

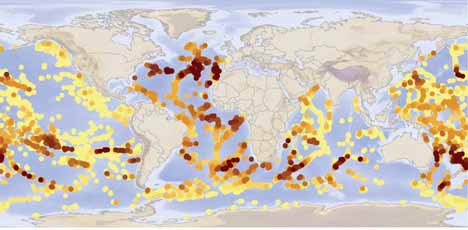

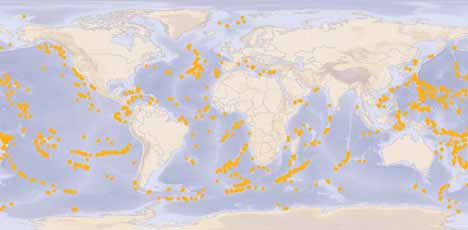

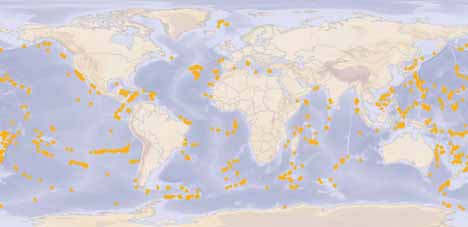

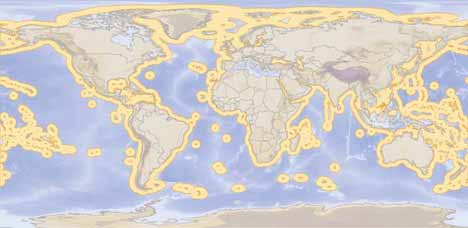

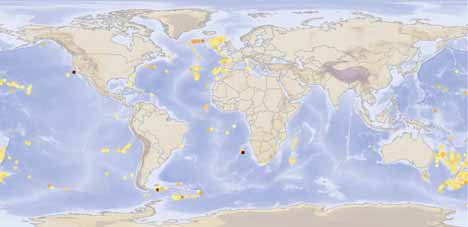

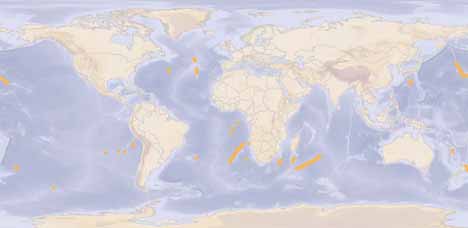

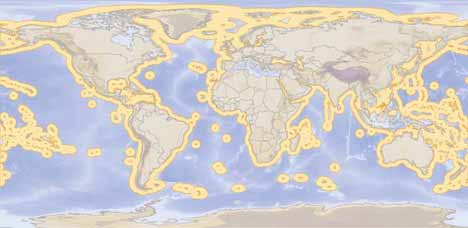

The distribution of historical seamount fisheries includes

For the purpose of this report, the distribution and depth

heavy fishing on seamounts in the North Pacific Ocean

ranges of commercial fish species were compiled from a

around Hawaii for armourhead and alfonsino; in the South

number of Internet and literature sources, including

Pacific for alfonsino, orange roughy and oreos; in the

seamount fisheries catch data of Soviet, Russian and

southern Indian Ocean for orange roughy and alfonsino; in

Ukrainian operations since the 1960s; published data on

the North Atlantic for roundnose grenadier, alfonsino,

Japanese, New Zealand, Australian, European Union (EU)

orange roughy, redfish and cardinalfish; and in the South

and Southern African fisheries; Food and Agriculture

Atlantic for alfonsino and orange roughy. Antarctic waters

Organization of the United Nations (FAO) catch statistics;

have been fished for toothfish, icefish and notothenioid cods.

and unpublished sources. Although known to be incomplete,

The total historical catch from seamounts has been

this is the most comprehensive compilation attempted to

estimated at over 2 million tonnes. Many seamount fish

date for seamount fisheries, and is believed to give a

stocks have been overexploited, and without proper and

reasonable indication of the general distribution of

sustainable management, they have followed a `boom

seamount catch over the last four decades.

and bust' cycle. After very high initial catches per unit

Deep-water trawl fisheries occur in areas beyond

effort, the stocks were depleted rapidly over short time

national jurisdiction for around 20 major species. These

scales (<5 years) and are now closed to fishing or no longer

include alfonsino (Beryx splendens), black cardinalfish

support commercial fisheries. The life history character-

(Epigonus telescopus), orange roughy (Hoplostethus

istics of many deep-water fish species (e.g. slow growth

atlanticus),

armourhead and southern boarfish

rate, late age of sexual maturity) make the recovery and

(Pseudopentaceros spp.), redfishes (Sebastes spp.),

recolonization of previously fished seamounts slow.

macrourid rattails (primarily roundnose grenadier

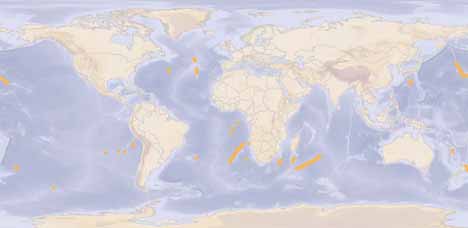

Over the last decade, exploratory fishing for deep-

Coryphaenoides rupestris), oreos (including smooth oreo

water species in many areas beyond national jurisdiction

Pseudocyttus maculatus, black oreo Allocyttus niger) and

has focussed on alfonsino and orange roughy. The depth

Patagonian toothfish (Dissostichus eleginoides), and in

distribution of the two main target fisheries for alfonsino

some areas Antarctic toothfish (Dissostichus mawsoni),

and orange roughy differ. The former is primarily fished

which has a restricted southern distribution. Many of these

between 250 and 750 m, and includes associated

fisheries use bottom-trawl gear. Other fisheries occur over

commercial species like black cardinalfish and southern

seamounts, such as those for pelagic species (mainly tunas)

boarfish. The orange roughy fisheries on seamounts,

9

Seamounts, deep-sea corals and fisheries

between 750 and 1 250 m depth (deeper fishing can occur

or recolonization. Trawling's impact on sea floor biota differs

on the continental slope), include black and smooth oreos

depending on the gear type used. The most severe damage

as bycatch. Seamount summit depth data was used to

has been reported from the use of bottom trawls in the

indicate where such suitable fisheries habitat might occur

orange roughy fisheries on seamounts. Information is

in areas beyond national jurisdiction. Combined with

currently lacking about the potential impact of trawling

information on the geographical distribution of the

practices for alfonsino, where mid-water trawls are often

commercial species, various areas where fishing could

used on seamounts. These may have only a small impact if

occur were broadly identified. Many of these areas are in

they are deployed well above the sea floor. However, in many

the southern Indian Ocean, South Atlantic and North

cases the gear is most effective when fished very close to, or

Atlantic. The South Pacific Ocean also has a number of

even lightly touching, the bottom. Thus, it is likely that the

ridge structures with seamounts that could host stocks of

effects of the alfonsino fisheries on the benthic fauna would

alfonsino and orange roughy. Many of these areas have

be similar to that of the orange roughy fisheries.

already been fished and some are known to have been

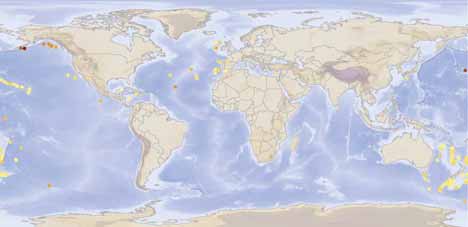

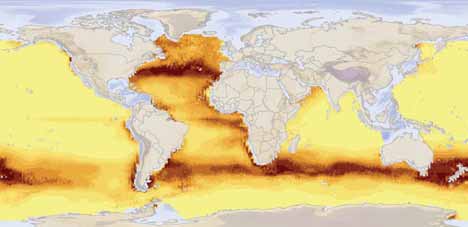

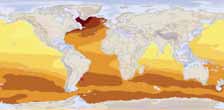

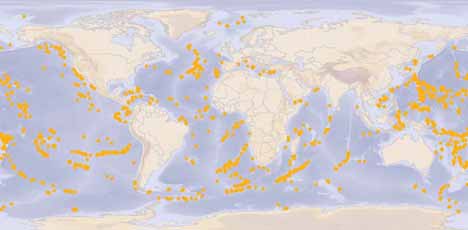

The comparison between the distributions of

explored, but commercial fisheries have not developed.

commercially exploited fish, fishing effort and coral habitat

on seamounts highlighted a broad band of the southern

ASSESSING THE VULNERABILITY OF STONY CORALS

Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans between about 30°S and

ON SEAMOUNTS

50°S, where there are numerous seamounts at fishable

In order to assess the likely vulnerability of corals and the

depths, and high habitat suitability for corals at depths

biodiversity of benthic animals on seamounts to the impact

between 250 m and 750 m (the preferred alfonsino

of fishing, the report examines the overlap and interaction

fisheries depth range), and again but somewhat narrower

between:

between 750 m and 1 250 m depth (the preferred orange

1. the predicted global distribution of suitable habitat for

roughy fisheries depth range).

stony corals;

This spatial concordance suggests there could be

2. the location of predicted large seamounts with summits

further commercial exploration for alfonsino and orange

in depth ranges of alfonsino and orange roughy

roughy fisheries on large seamounts in the central-

fisheries; and

eastern southern Indian Ocean, the southern portions

3. the distribution of the fishing activity on seamounts for

of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge in the South Atlantic, and

these two species, and combines this with information

some regions of the southern-central Pacific Ocean.

on the known effects of trawling.

Importantly, since these areas also contain habitat suitable

for stony coral, impacts on deep-water corals and

Many long-lived epibenthic animals such as corals have an

seamount ecosystems in general are likely to arise in such

important structural role within sea floor communities,

a scenario. However, it is uncertain whether fisheries

providing essential habitat for a large number of species.

exploration will result in economic fisheries.

Consequently, the loss of such animals lowers survivorship

and recolonization of the associated fauna, and has spawned

A WAY FORWARD

analogies with forest clear-felling on land. A considerable

This report has identified sizeable geographical areas with

body of evidence on the ecological impacts of trawling is

large seamounts, which are suitable for stony corals and

available for shallow waters, but scientific information on the

are vulnerable to the impacts of expanding deep-sea fishing

effects of fishing on deep-sea seamount ecosystems is

activities. To establish and implement adequate and effective

much more limited to studies from seas off northern

management plans and protection measures for these

Europe, Australia and New Zealand. These studies

areas beyond national jurisdiction will present major

suggested that trawling had largely removed the habitats

challenges for international cooperation. In addition, the

and ecosystems formed by the corals, and thereby

report has identified that there are large gaps in the current

negatively affected the diversity, abundance, biomass and

knowledge of the distribution of seamounts and the

composition of the overall benthic invertebrate community.

biodiversity they harbour.

The intensity of trawling on seamounts can be very high.

In light of these findings, the report recommends a

From several hundred to several thousand trawls have been

number of activities to be carried out collaboratively by all

carried out on small seamount features in the orange

stakeholders under the following headings:

roughy fisheries around Australia and New Zealand. Such

intense fishing means that the same area of the sea floor

How can the impacts of fishing on seamounts be managed

may be trawled repeatedly, causing long-term damage to

in areas beyond national jurisdiction?

the coral communities by preventing any significant recovery

Management initiatives for seamount fisheries within

10

Executive Summary

national EEZs have increased in recent years. Several

them to report detailed catch and effort data, but many

countries have closed seamounts to fisheries, established

do not. Therefore it is difficult at times to know where

habitat exclusion areas and stipulated method restrictions,

certain landings have been taken.

depth limits, individual seamount catch quotas and bycatch

2. Ensuring compliance with measures, especially in

quotas.

areas that are far offshore and where vessels are

In comparison, fisheries beyond areas of national

difficult to detect. Compliance monitoring is also acute

jurisdiction have often been entirely unregulated. There

in southern hemisphere high seas areas, where there

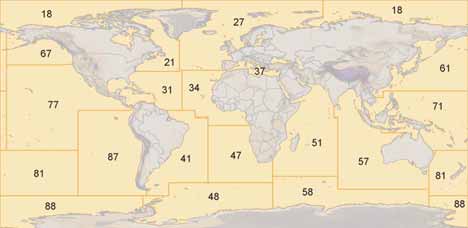

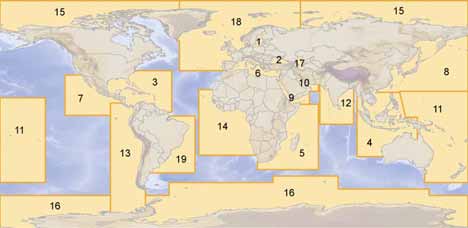

are 12 Regional Fisheries Management Organizations

are no quotas for offshore fisheries.

(RFMOs) with responsibility to agree on binding measures

3. Facilitating RFMOs, where necessary, to undertake

that cover areas beyond national jurisdiction, including

ecosystem-based management of fisheries on the high

some of the geographical areas identified in this report that

seas.

might see further expansion of exploratory fishing

4. Establishing, where appropriate, dialogue to ensure

for alfonsino and orange roughy on seamounts. An

free exchange of information between RFMOs,

RFMO covers parts of the eastern South Atlantic where

governments, conservation bodies, the fishing industry

exploratory fishing has occurred in recent decades, and

and scientists working on benthic ecosystems.

where further trawling could occur. However, the western

side of the South Atlantic is not similarly covered by an

The experiences gained by countries in the protection of

international management organization. There have been

seamount environments in their EEZs and in the

recent efforts to improve cooperative management of

management of their national deep-water fisheries can

fisheries in the Indian Ocean, although there are no areas

provide useful case examples for the approach to be taken

covered by an RFMO. In addition, efforts are underway in

under RFMOs. Other regional bodies, such as Regional Sea

the South Pacific, for example to establish a new regional

Conventions and Action Plans, might be able to provide

fisheries convention and body, which would fill a large gap

lessons learned from regional cooperation to conserve,

in global fisheries management. However, it should be

protect and use coastal marine ecosystems and resources

noted that only the five RFMOs for the Southern Ocean,

sustainably, including the implementation of an ecosystem

Northwest Atlantic, Northeast Atlantic, Southeast Atlantic

approach in oceans management and the establishment of

and the Mediterranean currently have the legal competence

networks of marine protected areas (MPAs). Regional Sea

to manage most or all fisheries resources within their areas

Conventions and Action Plans also provide a framework for

of application, including the management of deep-sea

raising awareness of coral habitats in deep water areas

stocks beyond national jurisdiction. The other RFMOs have

under national jurisdiction, and coordinating and supporting

competence only with respect to particular target species

the efforts of individual countries to conserve and manage

like tuna or salmon.

these ecosystems and resources sustainably.

In the light of the recent international dialogues

In calling for urgent action to address the impact of

concerning the conservation and sustainable management

destructive fishing practices on vulnerable marine

and use of biodiversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction

ecosystems, Paragraph 66 of UN General Assembly

held within and outside the United Nations system, various

Resolution 59/25 places a strong emphasis on the need to

fisheries bodies are more actively updating their mandates

consider the question of bottom-trawl fishing on seamounts

and including benthic protection measures as part of their

and other vulnerable marine ecosystems on a scientific and

fisheries management portfolios. It appears that a growing

precautionary basis, consistent with international law. The

legislation and policy framework, including an expanding

UN Fish Stocks Agreement (FSA) Articles 5 and 6 `General

RFMO network, particularly in the southern hemisphere,

principles' and the `Application of the precautionary

could enable the adequate protection and management of

approach' also establish clear obligations for fisheries

the risks to vulnerable seamount ecosystems and

conservation and the protection of marine biodiversity and

resources identified in this report. In order to be

the marine environment from destructive fishing practices.

successful, a number of challenges will have to be

The Articles also establish that the use of science is

overcome, including:

essential to meeting these objectives and obligations. At the

1. Establishing adequate data reporting requirements for

same time, the FSA recognizes that scientific understanding

commercial fishing fleets. Some unregulated and

may not be complete or comprehensive, and in such

unreported fishing activities take place, even in areas

circumstances, caution must be exercised. The absence

where there are well-defined fishery codes of practice

of adequate scientific information shall not be used as a

and allowable catch limits (e.g. Patagonian toothfish

reason for postponing or failing to take conservation and

fishery). Some countries require vessels registered to

management measures.

11

Seamounts, deep-sea corals and fisheries

A precautionary approach, consistent with the general

taxonomists; increased accessibility of full (non-aggregated)

principles for fisheries conservation contained in the FSA,

datasets from seamount expeditions through searchable

as well as the UN FAO Code of Conduct for Responsible

databases; and the further development of integrated,

Fisheries and the principles and obligations for biodiversity

Internet-based information systems such as Seamounts

conservation in the Convention on Biological Diversity

Online and the Ocean Biogeographic Information System.

(CBD), would require the exercise of considerable caution

It should be noted that the activities under the two

in relation to permitting or regulating bottom-trawl fishing

headings above are closely interrelated and linked.

on the high seas on seamounts. This is because of the

Increased research and collaboration between scientists

widespread distribution of stony corals and associated

and fishing companies will not only improve the amount and

assemblages on seamounts in many high seas regions, and

quality of data, it will also expand the scientific foundation for

the likelihood that seamounts at fishable depths may also

reviewing existing measures (e.g. those which were taken on

contain other species vulnerable to deep-sea bottom

a precautionary basis in the light of information gaps), and

trawling even in the absence of stony corals. In this regard,

for developing new, focussed management strategies to

a prudent approach to the management of bottom-trawl

mitigate against negative human impacts on seamounts and

fisheries on seamounts on the high seas would be to

their associated ecosystems and biodiversity. Requirements

ascertain whether vulnerable species and ecosystems are

in this context include:

associated with a particular area of seamounts of potential

1. obtaining better seamount location information;

interest for fishing, and only then permitting well-regulated

addressing geographic data gaps (including the

fishing activity provided that no vulnerable ecosystems

sampling of other deep-sea habitats);

would be adversely impacted.

2. assessing the spatial scale of variability on and between

seamounts; increasing the amount and scope of genetic

Further and improved seamount research

studies;

The conclusions of this report apply only to the association

3. undertaking better studies to assess trawling impacts;

of stony corals with large seamounts. In order to consider

assessing recovery from trawling impacts; undertaking

other taxonomic groups on a wider range of seamounts,

a range of studies to improve functional understanding

further sampling and research is required.

of seamount ecosystems; and

Spatial coverage of sampling of seamounts is poor and

4. implementing the means to obtain better fisheries

data gaps currently impede a comprehensive assessment of

information.

biodiversity and species distributions. Only 80 of the 300

biologically surveyed seamounts have had at least a

Without a concerted effort by a number of organizations,

moderate level of sampling. Existing surveys have tended to

institutions, consortia and individuals to attend to the

concentrate on a few geographic areas, thus the existing

previously identified gaps in data and understanding, the

data on seamount biota are highly patchy on a global scale,

ability of any body to effectively and responsibly manage and

and the biological communities of tropical seamounts

mitigate the impact of fishing on seamount ecosystems will

remain poorly documented for large parts of the oceans.

be severely constrained. Considering what this report has

Most biological surveys on seamounts have been relatively

revealed about the vulnerability of seamount biota

shallow and thus the great majority of deeper seamounts

particularly deep-sea corals to fishing, now is the time for

remain largely unexplored. Very few individual seamounts

this collaborative effort to begin in earnest.

have been comprehensively surveyed to determine the

variability of faunal assemblages within a single seamount.

In addition to the previous spatial gaps in sampling

coverage, there are a number of technical issues that make

direct comparisons of seamount data sometimes

problematic. These issues relate to the availability of non-

aggregated data, differences in collection methods and

taxonomic resolution.

In order to expand the type of analyses conducted for this

report to other faunal groups common on seamounts, and to

work at the level of individual species, certain steps should

be taken. These include the adoption of a minimum set of

standardized seamount sampling protocols; more funding

for existing taxonomic experts and training of new

12

Contents

Acknowledgements...............................................................................................................................................................2

Supporting organizations...............................................................................................................................................................4

Foreword ...............................................................................................................................................................................5

Executive summary...............................................................................................................................................................6

1. INTRODUCTION ..........................................................................................................................................................15

Study objectives.....................................................................................................................................................................17

2. SEAMOUNT CHARACTERISTICS AND DISTRIBUTION................................................................................................18

Small and large seamounts.................................................................................................................................................18

How many large seamounts are there?..............................................................................................................................18

Where are the large seamounts located?...........................................................................................................................19

The origin and physical environment of seamounts......................................................................................................... 21

What environmental conditions influence life on seamounts?........................................................................................ 21

3. DEEP-SEA CORALS AND SEAMOUNT BIODIVERSITY ................................................................................................23

The diversity of life on seamounts...................................................................................................................................... 23

The relationship between corals and other life................................................................................................................. 25

Attempting to determine the global seamount fauna ...................................................................................................... 27

Global distribution of sampling on seamounts ................................................................................................................. 27

A preliminary assessment of global seamount faunal diversity...................................................................................... 30

How to alternatively assess seamount faunal diversity.................................................................................................... 30

4. DISTRIBUTION OF CORALS ON SEAMOUNTS ............................................................................................................31

The need to assess the distribution of corals ................................................................................................................... 31

The task of compiling useful data ...................................................................................................................................... 31

Global distribution of records for seamount corals.......................................................................................................... 32

Patterns of coral diversity ................................................................................................................................................... 33

The relative occurrence and depth distribution of the main coral groups ..................................................................... 35

Getting a better understanding of coral distribution on seamounts............................................................................... 35

5. PREDICTING GLOBAL DISTRIBUTION OF STONY CORALS ON SEAMOUNTS.............................................................37

Known coral distribution ..................................................................................................................................................... 37

Using habitat suitability modelling to predict stony coral distribution............................................................................ 38

Stony coral distribution and environmental data .............................................................................................................. 38

Predicted habitat suitability for stony corals ..................................................................................................................... 39

What environmental factors are important in determining stony coral distribution? ................................................... 40

6. SEAMOUNT FISH AND FISHERIES ............................................................................................................................ 46

Fish biodiversity.................................................................................................................................................................... 46

Deep-water fisheries data................................................................................................................................................... 46

Global distribution of deep-water fishes............................................................................................................................ 47

Global distribution of major seamount trawl fisheries .................................................................................................... 49

Areas of exploratory fishing in areas beyond national jurisdiction.................................................................................. 50

7. ASSESSING THE VULNERABILITY OF STONY CORALS ON SEAMOUNTS ..................................................................55

Rationale............................................................................................................................................................................... 55

13

Seamounts, deep-sea corals and fisheries

Overlap between stony corals and fisheries...................................................................................................................... 56

Vulnerability of corals on seamounts to bottom trawling ................................................................................................ 58

Where are the main areas of risk and concern?............................................................................................................... 60

8. A WAY FORWARD .......................................................................................................................................................61

How can the impact of fishing on seamounts be managed in areas beyond national jurisdiction?............................ 61

Further and improved seamount research........................................................................................................................ 63

Acronyms .............................................................................................................................................................................. 66

Glossary ................................................................................................................................................................................ 67

References............................................................................................................................................................................ 69

Selection of institutions and researchers working on seamount and cold-water coral ecology ................................. 76

Selection of coral and seamount resources...................................................................................................................... 78

APPENDICES

Appendix I: Physical data .................................................................................................................................................... 79

Appendix II: The habitat suitability model.......................................................................................................................... 80

14

Introduction

1. Introduction

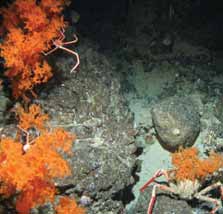

A)

M. Clark (NIW

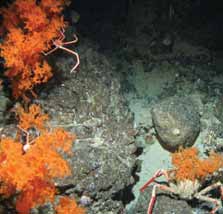

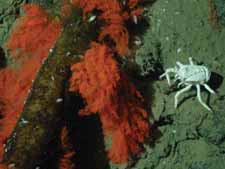

Seamounts are prominent and ubiquitous features can provide important habitat for a great variety of

found on the sea floor of all ocean basins, both within

associated invertebrates and fish, which use the coral as

and outside marine areas under national jurisdiction.

food, attachment sites and/or for protection and shelter.

With food availability on and above seamounts often higher

Deep-water corals can support a rich fauna of closely

than that of the surrounding waters and ocean floors,

associated animals with, for example, greater than 1 300

seamounts may function as biological hotspots, which

species reported living on Lophelia pertusa reefs in the

attract a rich fauna. Pelagic predators such as sharks, tuna,

northeastern Atlantic alone (Roberts et al., 2006). Many fish

billfish, turtles, seabirds and marine mammals can

species, including several of commercial significance, show

aggregate in the vicinity of seamounts (Worm et al., 2003).

spatial associations with deep-water corals (e.g. Stone,

Deep-sea fish species such as orange roughy (Pankhurst,

2006), and fish catches have been found to be higher in, and

1988; Clark, 1999; Lack et al., 2003) and eels (Tsukamoto,

around, deep-water coral reefs (Husebø et al., 2002).

2006) form spawning aggregations around seamounts.

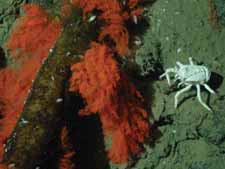

The fragility of cold-water corals makes them highly

The bottom fauna on seamounts can also be highly

vulnerable to fishing impacts, particularly from bottom

diverse and abundant, and they sometimes contain many

trawling (Koslow et al., 2001; Fosså et al., 2002; Hall-Spencer

species new to science (Parin et al., 1997; Richer de Forges

et al., 2002), but also from gill nets and long-lining gear

et al., 2000; Koslow et al., 2001). Suspension-feeding

(Freiwald et al., 2004; ICES, 2005, 2006). Ground-fishing gear

organisms, such as deep-sea corals, are frequently prolific

can completely devastate coral colonies (Fosså et al., 2002),

on seamounts, mainly because the topographic relief

and such direct human impacts can be extensive. For

creates fast-flowing currents and rocky substrata, providing

example, coral bycatch in the first year of the orange roughy

suspension feeders with a good food supply and attachment

fishery on the South Tasman Rise was estimated at 1 750

sites (Rogers, 1994). Corals are recognized as an important

tonnes, but this fell rapidly to 100 tonnes by the third year of

functional group of seamount ecosystems, as they can

the fishery as attached organisms on the seabed were

form extensive, complex and fragile three-dimensional

progressively removed by repeated trawling (Anderson and

structures. These may take the form of deep-water reefs

Clark, 2003). Because corals provide critical habitat for many

built by stony corals (scleractinians) (Rogers, 1999; Freiwald

other seamount species, destruction of corals has `knock-

et al., 2004; Roberts et al., 2006), or coral gardens or beds

on' effects, resulting in markedly lower species diversity and

formed by black corals and octocorals (e.g. Stone, 2006). All

biomass of bottom-living fauna (Clark et al., 1999; Koslow et

15

Seamounts, deep-sea corals and fisheries

Benthoctopus sp. and crinoid, Davidson Seamount,

Brisingid sea star, Hatton Bank.

2 422 m. (NOAA/MBARI)

(DTI SEA Programme, c/o Bhavani Narayanaswamy)

al., 2001; Smith, 2001; Clark and O'Driscoll, 2003).

2004). Most of this is taken from shelf and slope areas of the

Importantly, recovery of cold-water coral ecosystems from

Northwest Atlantic, but outside this region fishing effort

fishing impacts is likely to be extremely slow or even

tends to focus on deep-water species from seamounts. Over

impossible, because corals are long lived and grow extremely

77 fish species have been commercially harvested from

slowly (in the order of a few millimetres per year). Individual

seamounts (Rogers, 1994), including major fisheries for

octocorals can reach ages of several hundred (Andrews et al.,

orange roughy (Hoplostethus atlanticus), pelagic armour-

2002; Risk et al., 2002; Sherwood et al., 2006) or even more

head (Pseudopentaceros spp.) and alfonsino (Beryx

than a thousand years old (Druffel et al., 1995), and larger

splendens). Most of these fisheries have not been managed

reef complexes, formed by stony corals, may be more 8 000

in a sustainable manner, with many examples of `boom and

years old (Freiwald et al., 2004; Roberts et al., 2006). Corals

bust' fisheries, which rapidly developed and then declined

also have specific habitat requirements and may be sensitive

sharply within a decade (Koslow et al., 2000; Clark, 2001;

to alteration of the character of the seabed by fishing gear,

Lack et al, 2003). In most cases there is insufficient infor-

or to increased sedimentation resulting from trawling

mation on the target fish species, let alone the seamount

(Commonwealth of Australia, 2002; ICES, 2006). Such effects

ecosystem, to provide an adequate basis for good manage-

may prevent recovery of cold-water coral reefs or octocoral

ment (Lack et al., 2003). Furthermore, the life-history

gardens permanently (Rogers, 1999; ICES, 2006).

characteristics of many exploited deep-sea fish are unlike

There has been a dramatic expansion of fishing over the

those of shallow-water species, rendering some fisheries

last 50 years (Royal Commission on Environmental

management practices inappropriate (Lack et al., 2003).

Pollution, 2004) and the exploitation of deep-sea species of

In the light of the evidence found in numerous in situ

fish in the last 25 years (Lack et al., 2003). The expansion of

observations, the scientific community raised concern about

deep-sea fisheries has been driven by the depletion of

the damage that trawling can have on the bottom-dwelling

shallow fisheries based on the continental shelf, the

(benthic) communities in deep-waters and on seamounts

establishment of the 200 nautical mile economic exclusion

(MCBI, 2003 et seq.). Taking into account that most of the

zones by states under the UN Convention on Law of the Sea

potential areas affected by the expanding deep-sea fishing

(UNCLOS), overcapacity of fishing fleets, technological

activities are in areas beyond national jurisdiction, the United

advances in fishing including developments in navigation,

Nations General Assembly (UNGA) addressed the issue in its

acoustics and capture gear and in the power of vessels and

58th (2004), 59th (2005) and 60th sessions (2006), both in its

the availability of subsidies for building new fishing vessels

discussions on `Oceans and the Law of the Sea' and

equipped for deep-sea fishing (Lack et al., 2003; Royal

`Sustainable Fisheries'. Seamounts and cold-water corals/

Commission on Environmental Pollution, 2004). It is

reefs were specifically mentioned in the following

estimated that 40 per cent of the world's trawling grounds

resolutions:

are now located in waters deeper than the continental shelf

UN resolutions on oceans and the law of the sea (UN

(Roberts, 2002). The catch of commercial fish species

General Assembly, 2003, 2004a, 2005a, 2006)

beyond areas of national jurisdiction by bottom trawling has

Reaffirms the need for States and competent

been estimated at about 200 000 tonnes annually (Gianni,

international organizations to urgently consider ways

16

Introduction

to integrate and improve, based on the best available

paragraph 52 of Resolution 58/240). Following the

scientific information and in accordance with the

examination of this report in 2004, the UNGA decided to

Convention [UN Convention on Oceans and the Law of

establish an Ad Hoc Open-ended Informal Working Group to

the Sea, 1982] and related agreements and

study issues relating to the conservation and sustainable

instruments, the management of risks to the marine

use of marine biological diversity beyond areas of national

biodiversity of seamounts, cold-water corals,

jurisdiction (cf. Paragraph 73 in Resolution 59/24). The

hydrothermal vents and certain other underwater

outcome of their first meeting (New York, 13-17 February

features; (Resolution 60/30, Paragraph 73, following

2006) will be presented to the 61st session of the UNGA.

similar text in the previous resolutions 59/24, 58-240

Furthermore, the UNGA requested in 2005 the Secretary

and 57-141)

General, in cooperation with the FAO, to include in his next

Calls upon States and international organizations to

report concerning fisheries a section on the actions taken by

urgently take action to address, in accordance with

States and regional fisheries management organizations

international law, destructive practices that have

and arrangements to give effect to Paragraphs 66 to 69 of

adverse impacts on marine biodiversity and

Resolution 59/25, in order to facilitate discussion of the

ecosystems, including seamounts, hydrothermal

matters covered in those paragraphs. The UNGA also

vents and cold-water corals; (Resolutions 60/30,

agreed to review, within two years, progress on action taken

Paragraph 77 and 59/24)

in response to the requests made in these paragraphs, with

UN resolutions on sustainable fisheries (UN General

a view to further recommendations, where necessary, in

Assembly, 2004b, 2005b)

areas where arrangements are inadequate.

Requests the Secretary-General, in close cooperation

From the above, it is apparent that the UNGA

with the Food and Agriculture Organization of the

discussions on:

United Nations (FAO), and in consultation with States,

(i). conservation and sustainable management of

regional and subregional fisheries management

vulnerable marine biodiversity and ecosystems

organizations and arrangements and other relevant

(including seamount communities) in areas beyond

organizations, in his next report concerning fisheries

national jurisdiction, and

to include a section outlining current risks to the

(ii). the role of regional fisheries management organizations

marine biodiversity of vulnerable marine ecosystems

or arrangements in regulating bottom fisheries and the

including, but not limited to, seamounts, coral reefs,

impacts of fishing on vulnerable marine ecosystems

including cold-water reefs and certain other sensitive

are set to continue.

underwater features related to fishing activities, as

well as detailing any conservation and management

It is hoped that the scientific findings presented in this report

measures in place at the global, regional, subregional

by members of the Census of Marine Life programme

or national levels addressing these issues; (Resolution

CenSeam will help and guide policy and decision makers to

58/14, Paragraph 46).

make progress on these issues.

Calls upon States, either by themselves or through

regional fisheries management organizations or

STUDY OBJECTIVES

arrangements, where these are competent to do so, to

The study presented here aimed to:

take action urgently, and consider on a case-by-case

1. compile and/or summarize data for the distribution of

basis and on a scientific basis, including the

large seamounts, deep-sea corals on seamounts and

application of the precautionary approach, the interim

deep-water seamount fisheries;

prohibition of destructive fishing practices, including

2. predict the global occurrence of environmental

bottom trawling that has adverse impacts on

conditions suitable for stony corals from existing records

vulnerable marine ecosystems, including seamounts,

on seamounts and identify the seamounts on which they

hydrothermal vents and cold-water corals located

are most likely to occur globally;

beyond national jurisdiction, until such time as

3. compare the predicted distribution of stony corals on

appropriate conservation and management measures

seamounts with that of deep-water fishing on

have been adopted in accordance with international

seamounts worldwide;

law; (Resolution 59/25, Paragraph 66)

4. qualitatively assess the vulnerability of communities

living on seamounts to putative impacts by deep-water

In 2003, the UNGA requested the Secretary General to

fishing activities; and

prepare a report on vulnerable marine ecosystems and

5. highlight critical information gaps in the development of

biodiversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction (cf.

risk assessments to seamount biota globally.

17

Seamounts, deep-sea corals and fisheries

2. Seamount characteristics

and distribution

SMALL AND LARGE SEAMOUNTS

Seamounts are masses of rock and give rise to anomalies

Seamounts are submarine elevations with a limited in the usual straight-down force of gravity. These minute

extent across the summit and have a variety of

variations in the Earth's gravitational pull cause seawater to

shapes, but are generally conical with a circular,

be attracted to seamounts. This means that the sea surface

elliptical or more elongate base (Rogers, 1994). The slopes

is pitched up over a seamount with a shape that reflects

of seamounts can be extremely steep, with some showing

the underlying topographic feature (Wessel, 1997 and 2001).

gradients of up to 60º (e.g. Sagalevitch et al., 1992), although,

Satellite sensors can detect the anomalies in the Earth's

in general, slopes are less steep (generally less than 20º in

gravitational field (e.g. Seasat gravity sensor) or the small

the New Zealand region; Rowden et al., 2005). Younger

differences in sea-surface height (e.g. Geosat/ERS1 alti-

seamounts tend to be more conical and regular in shape,

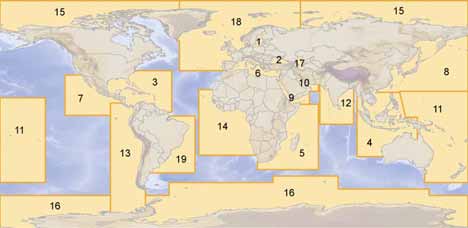

meter) (Stone et al., 2004). Efforts to estimate the number

whereas older seamounts that have been subject to