XVI SOUTH WEST ATLANTIC

XVI 52 North Brazil Shelf LME

XVI 53 East Brazil Shelf LME

XVI 54 South Brazil Shelf LME

XVI 55 Patagonian Shelf LME

700

XVI South West Atlantic

XVI South West Atlantic

701

XVI-52 North Brazil Shelf LME

S. Heileman

The North Brazil Shelf LME extends along northeastern South America from the

boundary with the Caribbean Sea to the Parnaíba River estuary in Brazil (Ekau &

Knoppers 2003). It has a surface area of about 1.1 million km2, of which 1.69% is

protected, and contains 0.01% of the world's coral reefs and 0.06% of the world's sea

mounts (Sea Around Us 2007). The hydrodynamics of this region is dominated by the

North Brazilian Current, which is an extension of the South Equatorial Current and its

prolongation, the Guyana Current. Shelf topography and external sources of material,

particularly the Amazon River with its average discharge of 180,000 m3s-1 (Nittrouer &

DeMaster 1987), exert a significant influence on the LME. This is complemented by

discharge from other rivers such as Tocantins, Maroni, Corantyne, and Essequibo. A

wide continental shelf, macrotides and upwellings along the shelf edge are some other

features of this LME. Book chapters and reports pertaining to the LME include Bakun

(1993), Ekau & Knoppers (2003), UNEP (2004a, 2004b).

I. Productivity

The North Brazil Shelf LME is considered a Class I, highly productive ecosystem

(>300 gCm-2yr-1), with the Amazon River and its extensive plume being the main source

of nutrients. Primary production is limited by low light penetration in turbid waters

influenced by the Amazon, while it is nutrient-limited in the clearer offshore waters (Smith

& DeMaster 1996). Primary productivity on the continental shelf has been found to be

greatest in the transition zone between these two types of waters, occasionally exceeding

8 gCm-2day-1 (Smith & DeMaster 1996). In addition to high production, the food webs in

this LME are moderately diverse. Brazil's coral fauna is notable for having low species

diversity, yet a high degree of endemism.

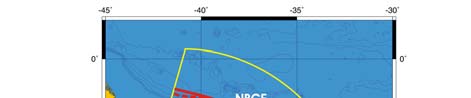

Oceanic Fronts (Belkin et al. 2008)(Figure XVI-52.1): Major fronts within this LME are

associated with outflow from the Amazon River and, to a lesser extent, that of the

Orinoco River. The Amazon plume initially turns northwestward and flows along the

Brazil coast as the North Brazil Current. Off the Guiana coast, between 5°N and 7°N, the

North Brazil Current retroflects and flows eastward. This retroflection develops

seasonally and produces anticyclonic rings of warm, low-salinity water that propagate

northwestward toward Barbados, the Lesser Antilles Islands and eventually the

Caribbean Sea. The second major source of fresh water is the Orinoco River plume.

Most thermal fronts are associated with salinity fronts related to freshwater lenses and

plumes originated at the Amazon and Orinoco estuaries. Such fronts are relatively

shallow, sometimes just a few meters deep. Nonetheless, these fronts are important to

many species whose ecology is related to the upper mixed layer. Fresh lenses

generated by the Amazon and Orinoco outflows persist for months, largely owing to the

sharp density contrasts across TS-fronts that form their boundaries (in case of fresh,

warm tropical lenses, the temperature and salinity contributions to the density differential

reinforce each other).

North Brazil Shelf LME SST (Belkin 2008)(Figure XVI-52.2):

Linear SST trend since 1957: 0.22°C.

Linear SST trend since 1982: 0.60°C.

702

52. North Brazil

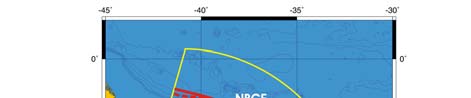

Figure XVI-52.1. Fronts of the North Brazil Shelf LME. Acronyms: NBCF, North Brazil Current Front.

SSF, Shelf Slope Front (most probable location. Yellow line, LME boundary. After Belkin et al. (2008).

The North Brazil Shelf's thermal history over the last 50 years started with a long-term

cooling that culminated in the all-time minimum of 27.3°C in 1976, followed by warming

until present. Using the year of 1976 as a true breakpoint, a linear trend would yield a

0.9°C increase over 30 years, which would place the North Brazil Shelf among moderate-

to-fast warming LMEs. The North Brazil Shelf thermal history is decorrelated from the

adjacent South Brazil Shelf. This can be explained by decoupling of their oceanic

circulations. Indeed, the North Brazil Shelf is strongly affected by the North Equatorial

Current and Amazon Outflow, whereas the South Brazil Shelf is affected by sporadic

inflows of Subantarctic waters from the south and also by offshore oceanic inflows from

the east.

Figure XVI-51.2. North Brazil Shelf LME annual mean SST (left) and SST anomalies (right), 1957-2006,

based on Hadley climatology. After Belkin (2008).

XVI South West Atlantic

703

North Brazil Shelf LME Chlorophyll and Primary Productivity: The North Brazil Shelf

LME is a Class I, highly productive ecosystem (>300 gCm-2yr-1)(Figure XVI-51.3).

Figure XVI-51.3. North Brazil Shelf LME trends in chlorophyll a (left) and primary productivity (right),

1998-2006, from satellite ocean colour imagery. Values are colour coded to the right hand ordinate.

Figure courtesy of J. O'Reilly and K. Hyde. Sources discussed p. 15 this volume.

II. Fish and Fisheries

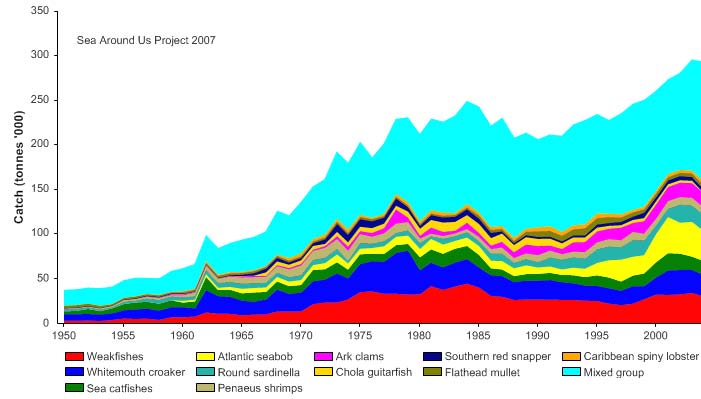

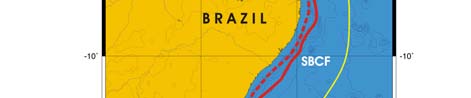

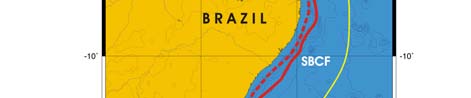

The multispecies and multigear fisheries of the North Brazil Shelf LME are targeted by

both national and foreign fleets (FAO 2005 and see below). Major exploited groups

include a variety of groundfish such as weakfish (Cynoscion sp.), whitemouth croaker or

corvina (Micropogonias furnieri) and sea catfish (Arius sp.). The shrimp resources, such

as southern brown shrimp (Penaeus subtilis), pink spotted shrimp (P. brasiliensis),

southern pink shrimp (P. notialis), southern white shrimp (P. schmitti) as well as the

smaller seabob (Xiphopenaeus kroyeri) support one of the most important shrimp

fisheries in the world. Tuna is also exploited, and although its catch weight is relatively

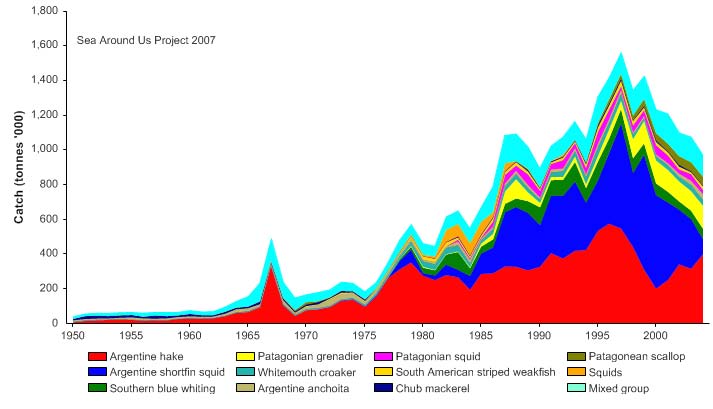

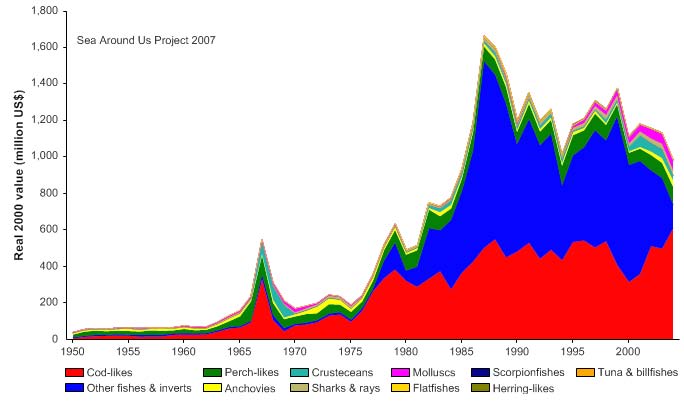

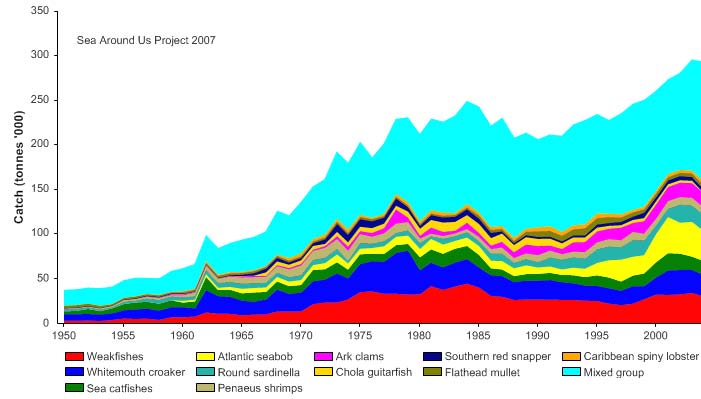

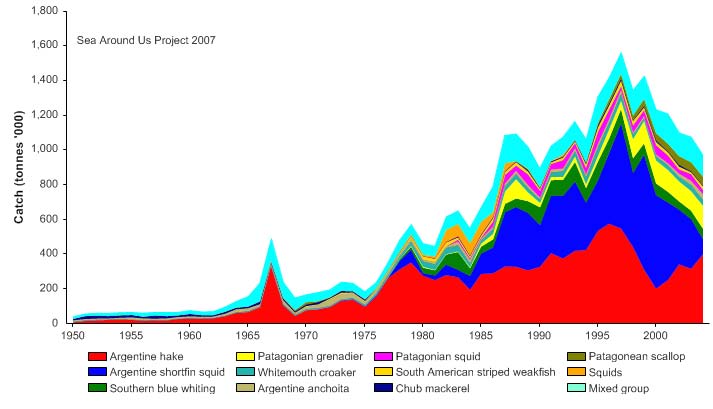

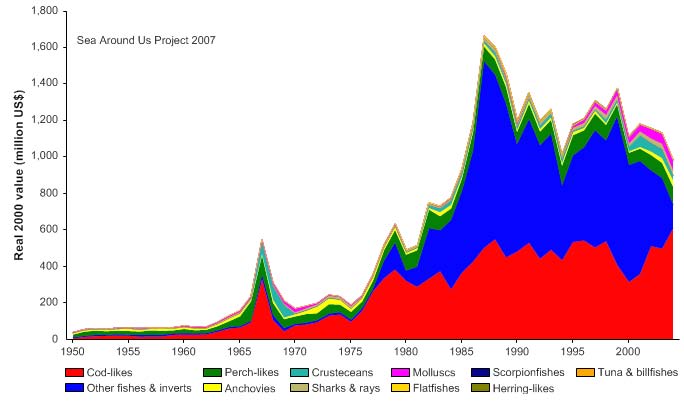

small, its value is significant. Total reported landings in this LME underwent a steady

increase from 1950 to just over 290,000 tonnes in 2004 (Figure XVI-52.4) and the value

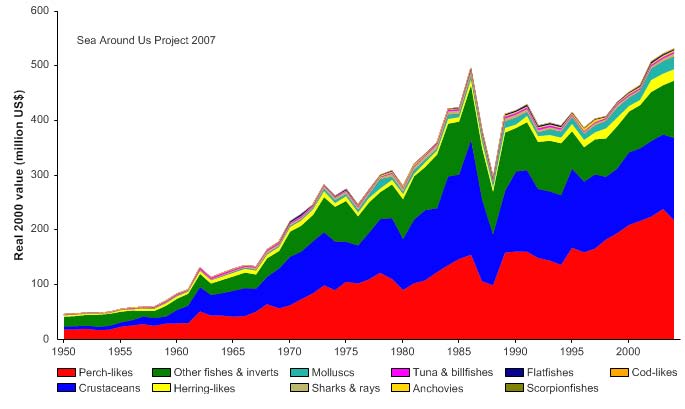

of the reported landings reached US$532 million (in 2000 US dollars) in 2004 (Figure

XVI-52.5).

Figure XVI-52.4. Total reported landings in the North Brazil Shelf LME by species (Sea Around Us 2007).

704

52. North Brazil

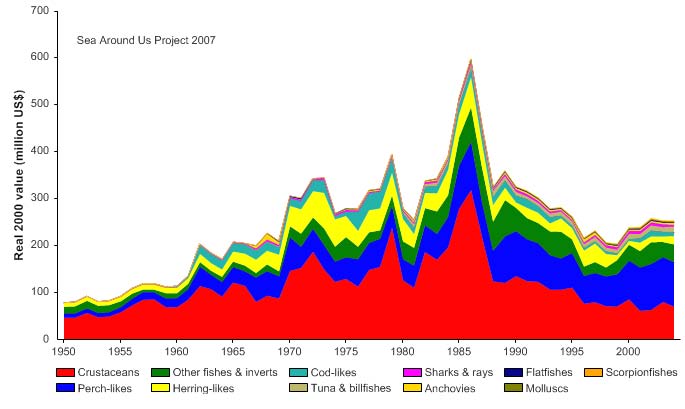

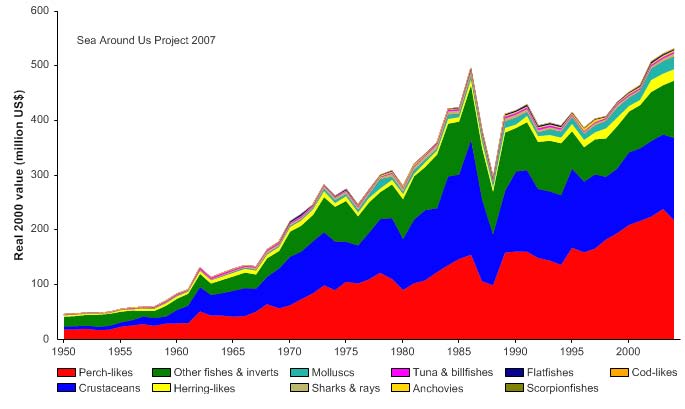

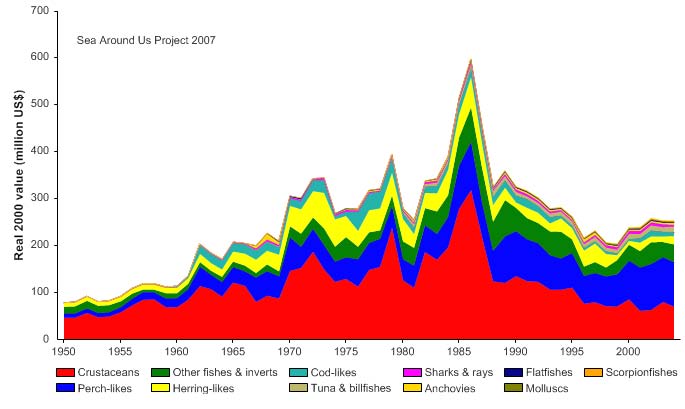

Figure XVI-52.5. Value of reported landings in the North Brazil Shelf LME by commercial groups (Sea

Around Us 2007).

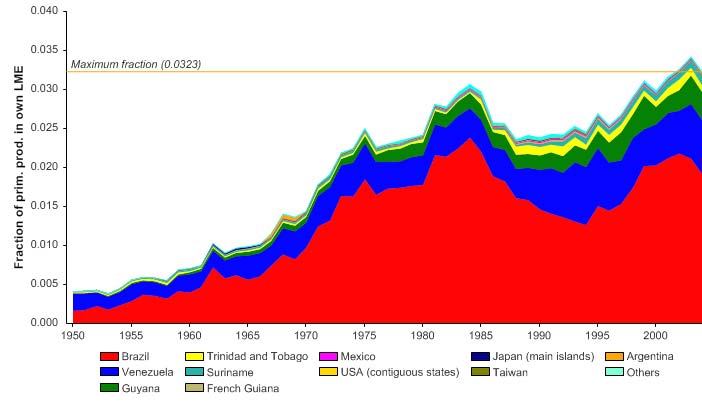

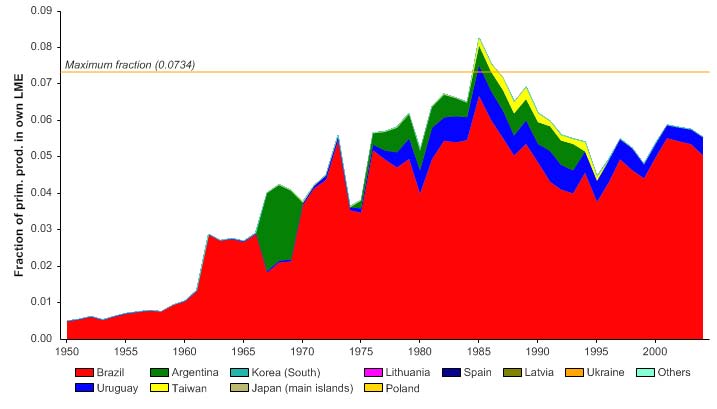

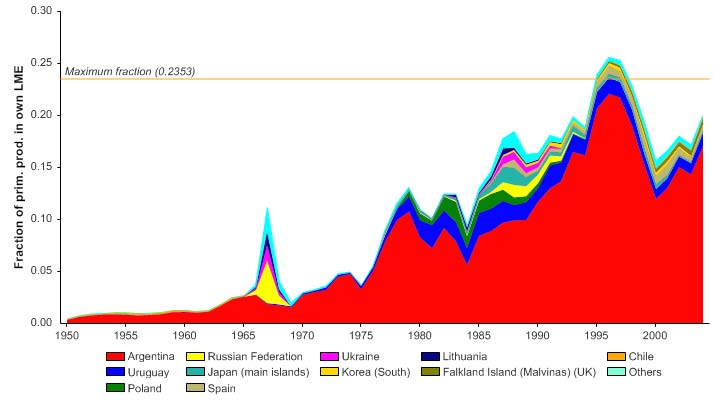

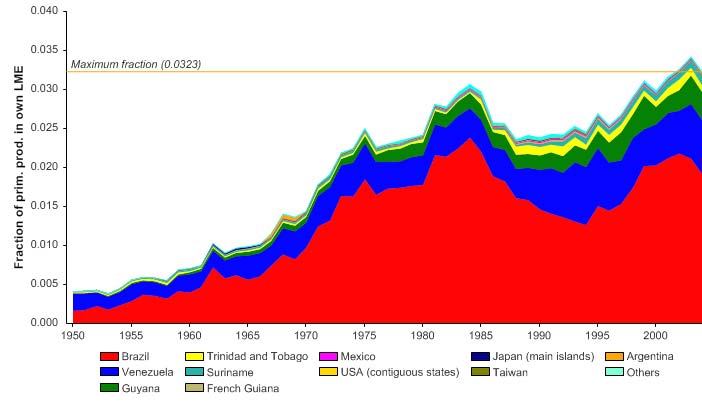

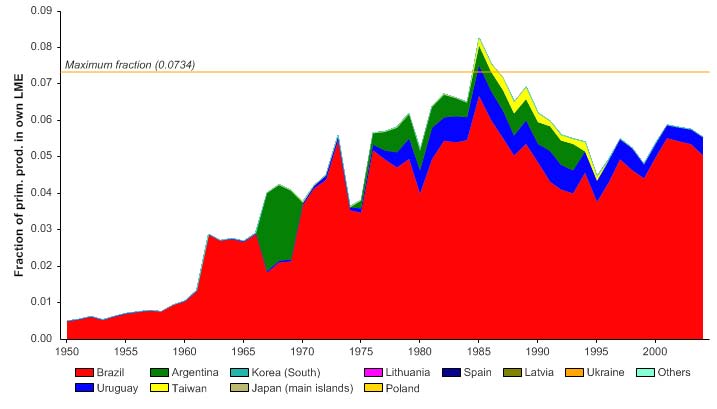

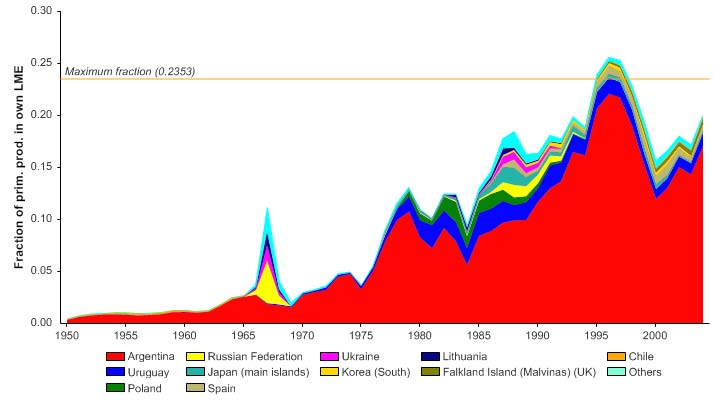

The primary production required (PPR; Pauly & Christensen 1995) to sustain the reported

landings in this LME is low, currently at 3% of the observed primary production (Figure

XVI-52.6). Brazil has the largest share of the ecological footprint in this LME, followed by

Venezuela and Guyana.

Figure XVI-52.6. Primary production required to support reported landings (i.e., ecological footprint) as

fraction of the observed primary production in the North Brazil shelf LME (Sea Around Us 2007). The

`Maximum fraction' denotes the mean of the 5 highest values.

From the mid 1980s, the mean trophic level of the reported landings (i.e., the MTI; Pauly

& Watson 2005) has undergone a steady decline (Figure XVI-52.7, top), a trend

indicative of a `fishing down' of the food webs (Pauly et al. 1998) in the LME, while the

flatness of the FiB over the same period (Figure XVI-52.7, bottom) implies that the

increase in the reported landings have not compensated for the decline in the mean

XVI South West Atlantic

705

trophic level. A detailed study of ecosystems in the region by Freire (2005) has found

similar trends using local catch data.

Figure XVI-52.7. Mean trophic level (i.e., Marine Trophic Index) (top) and Fishing-in-Balance Index

(bottom) in the North Brazil Shelf LME (Sea Around Us 2007).

The Stock-Catch Status Plots indicate that over 60% of commercially exploited stocks in

the LME are either overexploited or have collapsed (Figure XVI-52.8, top). However,

70% of the reported landings come from fully exploited stocks (Figure XVI-52.8, bottom).

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

0%

100

10%

90

20%

)

80

%

(

s

30%

u

70

at

st

40%

y

60

b

ks

50%

c

50

o

f

st

60%

o

40

er

b

70%

m

30

Nu

80%

20

90%

10

100%0

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

(n = 4573)

developing

fully exploited

over-exploited

collapsed

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

0%

100

10%

90

20%

80

)

%

30%

(

70

s

u

at

40%

60

k st

c

50%

o

50

st

y

60%

b

h

40

t

c

a

70%

C

30

80%

20

90%

10

100%0

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

(n = 4573)

developing

fully exploited

over-exploited

collapsed

Figure XVI-52.8. Stock-Catch Status Plots for the North Brazil Shelf LME, showing the proportion of

developing (green), fully exploited (yellow), overexploited (orange) and collapsed (purple) fisheries by

number of stocks (top) and by catch biomass (bottom) from 1950 to 2004. Note that (n), the number of

`stocks', i.e., individual landings time series, only include taxonomic entities at species, genus or family

level, i.e., higher and pooled groups have been excluded (see Pauly et al, this vol. for definitions).

706

52. North Brazil

Detailed analysis of the fisheries in this LME confirms this diagnosis of severe

overexploitation. There is evidence that some of the fisheries may be fully exploited or

overexploited in relation to MSY, particularly some of the groundfish stocks. Where

assessments have been undertaken, there are clear signs of overexploitation of the

southern red snapper (Lutjanus purpureus) resource (UNEP unpubl), with declining catch

rates and a decrease in the size of this species (Charuau et al. 2001, Charuau & Medley

2001). Recent trends in catch per unit effort and other analyses indicate that the corvina

is now overexploited in some areas, with the low stock levels of this species being

commensurate with exploitation levels beyond the MSY level (Alió et al. 2000, Alió 2001).

Similarly, lane snappers (L. synagris), bangamary (Macrodon ancylodon) and sharks are

also showing signs of overexploitation (Alio 2001, Ehrhardt & Shepard 2001a).

Moreover, a decrease in the average size of some groundfish species has raised

sustainability issues (Booth et al. 2001, Chin-A-Lin & IJspol 2001). The increasing

capture of small individuals is potentially compromising recruitment to the spawning stock

(Souza 2001). For instance, in Brazil, immature southern red snappers comprise over

60% of the catch of this species (Charuau et al. 2001). Trawl and Chinese seines

harvest bangamary at ages far below the age at maturity (Ehrhardt & Shepherd 2001a).

In general, all the shrimp species in the region are subjected to increasing trends in

fishing mortality (Ehrhardt 2001) and the fishery is generally overcapitalised (Chin-A-Lin

& M. IJspol 2001). Stocks of brown and pink spotted shrimp may be close to being fully

exploited (Charuau & Medley 2001, Ehrhardt 2001, Ehrhardt & Shepherd 2001b,

Negreiros Aragão et al. 2001), with the latter being overexploited in some areas (Ehrhardt

& Shepherd 2001b). There has been a general downward trend in the abundance of

brown and pink shrimps, particularly during the late 1980s and throughout the 1990s.

The trends in fishing mortality were not high enough to have created the very

conspicuous decline in abundance, which implies that environmental factors (seasonal

river run-off and rainfall) may be more significant than fishing in determining recruitment

in these species.

Excessive bycatch and discards and destructive fishing practices are severe, and are of

concern throughout the LME. The shrimp bycatch issue is well known in the region,

where the bycatch/shrimp ratios are typically between 5 and 15:1 (Villegas & Dragovich

1984, Marcano et al. 1995). Many commercial species, predominantly young individuals,

comprise the bycatch, most of which is discarded dead at sea. Several species have

practically disappeared from the bycatch, indicating a dramatic shrinking of their

populations, notably in the case of sharks (Charlier 2001). The operation of trawlers in

shallow areas also causes extensive physical damage to benthic habitats and their

communities (Charlier 2001). The use of explosives and poisons on the reefs (bleach for

capturing octopus) and mangroves (toxic chemicals to capture crabs), capture of

immature individuals through diving as well as the use of nets to catch lobsters, which

drag sediments, animals and calcareous algae from the sea floor, have also been

reported in this region (UNEP 2004a).

III. Pollution and Ecosystem Health

Pollution: Overall, pollution was found to be moderate, but severe in localised hotspots

near urban areas. Most of the pollution is concentrated in densely populated and

industrialised coastal basins, and not widespread across the region. Water quality in the

coastal areas is threatened by human activities that give rise to contamination from

sewage and other organic material, agrochemicals, industrial effluents, solid wastes and

suspended solids (EPA/GEF/UNDP 1999).

Effluents from industries are released, sometimes untreated, into the water bodies.

Contamination by mercury as well as by chemical agricultural wastes is the main source

XVI South West Atlantic

707

of chemical pollution in the Amazon Basin (UNEP 2004b). Gold is exploited in all the

countries of the region and mercury from gold mining operations is dispersed into the air.

It is assumed that the largest part ends up in rivers, transforms into methyl-mercury and

other chemical compounds and concentrates along the food chain. Mercury

contamination could, on the longer-term, become a hazard for the coastal marine

ecosystem and for human health, if suitable measures to limit its use are not

implemented. There is also the potential risk of pollution from oil extraction, both in the

coastal plain and the sea.

Agricultural development is concentrated along the coast and includes intensive

cultivation of sugarcane, bananas and other crops. This involves the application of large

quantities of fertilisers and pesticides, which eventually end up in the coastal

environment. Sugarcane plantations along the coast are also suspected to contribute

persistent organic contaminants, which are widely used in pest control, to the coastal

habitats (UNEP 2004b).

As a result of the coastal hydrodynamics in this LME, the potential for transboundary

pollution impacts is significant. River outflow is deflected towards the northwest and

influences the coastal environment in an area situated west of each estuary. It has been

estimated that 40-50% of the annual Amazon run-off transits along the Guyana coast

(Nittrouer & DeMaster 1987). In fact, Amazon waters can be detected as far away as the

island of Barbados (Borstad 1982). As a result, most of the coastal area of the Brazil-

Guianas region has been described as an `attenuated delta of the Amazon' (Rine &

Ginsburg 1985). This implies that contaminants in river effluents, particularly those of the

Amazon, could be transported across national boundaries and EEZs.

Habitat and community modification: Human activities have led to severe habitat

modification in this LME. Mangroves, which dominate a major part of the shoreline, have

been seriously depleted in some areas, for example, in Guyana, where mangrove

swamps have been drained and replaced by a complex coastal protection system (EPA

2005. Likewise, on the Brazilian coast, the original mangrove area has been significantly

reduced by cutting for charcoal production and timber, evaporation ponds for salt and

drained and filled for agricultural, industrial or residential uses and development of tourist

facilities (Marques et al. 2004). In Brazil, erosion also threatens coastal habitats and

some coastal lagoons have been cut off from the sea.

In the past, the coral reefs were mined for construction material. Currently, they are

exposed to increased sedimentation due to poor land use practices and coastal erosion,

chemical pollution from domestic sewage and agricultural pesticides, overfishing, tourism

and development of oil and gas terminals (Maida & Ferreira 1997). Additionally, there

has been some coral bleaching associated with climate variation (Charlier 2001).

Trawlers often operate without restriction in the shallower areas of the shelf, over

ecologically sensitive areas inhabited by early life stages of shrimp. The environmental

impact of such activities is likely to be high, considering the intensity of shrimp trawling

operations in these areas (Ehrhardt & Shepherd 2001b). Evidence from other regions

suggests that precautionary measures should be undertaken in environmentally sensitive

areas of the continental shelf (Ehrhardt & Shepherd 2001b). Trawlers also catch

significant quantities of finfish as bycatch, of which dumping at sea is still a widespread

practice in the region (FAO 2005). This is especially damaging to the stocks when the

bycatch includes a significant portion of juvenile fish. In Suriname, small-scale fishers

have reported the incidence of `dead waters', in shallow areas, following fishing activity

by trawlers (Charlier 2001). These dead waters were scattered with dead fish in larger

amounts than could have been discarded by the trawlers. Vast areas were devoid of live

708

52. North Brazil

fish, as they had apparently died or moved out of the area. Such mortality could be the

result of local oxygen depletion, caused by the re-suspension of anoxic sediment

combined with the presence of organic matter dumped from the vessels.

Growth of the local human population and pressures associated with urban and industrial

development will continue to threaten the health of the LME. The problems are, however,

potentially reversible, considering that there is a greater public and governmental

awareness about environmental issues and several measures at national and regional

levels are being taken to address some of these problem.

IV. Socioeconomic Conditions

Brazil (states of Amapá, Pará, Maranhão), French Guiana, Guyana, Suriname and the

southeastern part of Venezuela border this LME. A high percentage of the total

population consists of indigenous communities. Human uses of the coastal zone include

subsistence agriculture, fisheries, exploitation of clay and sand and limited ecotourism.

Marine fisheries constitute an important economic sector in the region, providing foreign

exchange earnings, employment and animal protein. A significant portion of the region's

population depends upon fishing for its survival and is unable to substitute other sources

of animal protein for fish protein (UNEP 2004b). In Guyana, the fishery sector is of

critical importance to the economy and to social well-being. The economic contribution of

Guyana's fisheries has grown dramatically in recent years, contributing about 6% to GDP

and employing about 10,000 persons (FAO 2005). Furthermore, fish protein is the major

source of animal protein in Guyana, with per capita consumption of about 60 kg in 1996,

more than four times the world average (FAO 2005). In general, unsustainable

overexploitation of living resources as well as environmental degradation may result in

threats to the food security of fishers and loss of employment, as well as loss of foreign

exchange to the countries of this LME. Because of shrinking resources and degradation

of habitats, a number of development projects have been implemented to support local

communities.

V. Governance

Fisheries management issues in the countries bordering the North Brazil Shelf LME are

complicated because of the variety of gears used, and the multi-species and multinational

nature of the groundfish fisheries. This situation is further complicated by the paucity of

data pertaining to the biology and productivity of the region's fish stocks and catch and

fishing effort. As a consequence, confidence in stocks assessments is low (Booth et al.

2001). The countries have ongoing programmes for environmental and natural resource

management and coastal zone management and most have established several national

marine parks and protected areas.

The countries are parties to several international environmental agreements, for example

CBD, UNFCCC, UNCLOS, MARPOL and Ramsar Convention on Wetlands. Brazil,

Guyana, Peru, Suriname and Venezuela, along with Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador and

Peru have developed a project for support by GEF: `Integrated Management of Aquatic

Resources in the Amazon' For the Brazilian Amazon River Basin. The project, approved

for Work Program Entry in June 2005, recognises the close linkages between integrated

water resource management and the protection of marine habitats. The general

objective of this project is to strengthen the institutional framework for planning and

executing, in a coordinated and coherent manner, activities for the protection and

sustainable management of the land and water resources of the Amazon River Basin,

based upon the protection and integrated management of transboundary water resources

and adaptation to climatic change.

XVI South West Atlantic

709

The first phase of the project will involve strategic planning and institutional

strengthening, including the development of a TDA of the Basin and preparation of a

Framework SAP. Brazil has applied for the GEF biodiversity project `Strengthening the

Effective Conservation and Sustainable use of Mangrove Ecosystems in Brazil through

its National System of Conservation Units'. The aim of the project is to develop

conservation and sustainable management of mangrove ecosystems in Brazil to

conserve globally significant biodiversity and key environmental services and functions

important for national development and the well-being of traditional and marginalised

coastal communities.

References

Alió, J.J. (2001). Venezuela, Shrimp and Groundfish Fisheries. FAO Fisheries Report 651:115-119.

Alió, J.J., Marcano, L., Soomai, S., Phillips, T., Altuve, D., Alvarez, R., Die, D., and Cochrane, K.

(2000). Analysis of industrial trawl and artisanal fisheries of whitemouth croaker (Micropogonias

furnieri) of Venezuela and Trinidad and Tobago in the Gulf of Paria and Orinoco River Delta.

FAO Fisheries Report 628:138-148.

Bakun, A. 1993. The California Current, Benguela Current, and Southwestern Atlantic shelf

ecosystems A Comparative Approach to Identifying Factors Regulating Biomass Yields, p

199-221 in: Sherman, K., Alexander, L.M. and Gold, B.D. (eds), Large Marine Ecosystems

Stress Mitigation, and Sustainability AAAS, Washington D.C., U.S.

Belkin, I.M. (2008) Rapid warming of Large Marine Ecosystems, Progress in Oceanography, in

press.

Belkin, I.M., Cornillon, P.C., and Sherman, K. (2008). Fronts in Large Marine Ecosystems of the

world's oceans. Progress in Oceanography, in press.

Booth, A., Charuau, A., Cochrane, K., Die, D., Hackett, A., Lárez, A., Maison, D., Marcano, L.A.,

Phillips, T., Soomai, S., Souza, R., Wiggins, S. and IJspol, M. (2001). Regional assessment of

the Brazil-Guianas groundfish fisheries. FAO Fisheries Report 651:22-36.

Borstad, G.A. (1982). The influence of the meandering Guiana Current and Amazon River

discharge on surface salinity near Barbados. Journal of Marine Research 40:421-434.

Charlier, P. (2001). Review of environmental considerations in management of the Brazil-Guianas

shrimp and groundfish fisheries. FAO Fisheries Report 651:37-57.

Charuau, A. and Medley, P. (2001). French Guiana, snapper fishery. FAO Fisheries Report 651:77-

80.

Charuau, A., Cochrane, K., Die, D., Lárez, A., Marcano, L.A., Phillips, T., Soomai, S., Souza, R.,

Wiggins, S. and IJspol, M. (2001). Regional Assessment of red snapper, Lutjanus purpureus.

FAO Fisheries Report 651:15-21.

Chin-A-Lin, T. and IJspol, M. (2001). Suriname, groundfish and shrimp fisheries. FAO Fisheries

Report 651:94-104.

Ehrhardt, N. M. and Shepherd, D. (2001a). Guyana, groundfish fisheries. FAO Fisheries Report

651:85-89.

Ehrhardt, N.M. (2001). Comparative regional stock assessment analysis of the shrimp resources

from northern Brazil to Venezuela. FAO Fisheries Report 651:1-14.

Ehrhardt, N.M. and Shepherd, D. (2001b). Guyana, shrimp fisheries. FAO Fisheries Report 651:81-

84.

Ekau, W. and Knoppers, B. A. (2003). A review and redefinition of the Large Marine Ecosystems

of Brazil, p 355-372 in: Sherman, K. and Hempel, G. (eds), Large Marine Ecosystems of the

World: Trends in Exploitation, Protection and Research. Elsevier Science. Amsterdam, The

Netherlands.

EPA (2005). Issues and Importance of Guyana's Coastal Zone. Environmental Protection Agency

Guyana. http://www.epaguyana.org/iczm/articles.htm

EPA/GEF/UNDP (1999). Guyana National Biodiversity Action Plan. www.epaguyana.org/

downloads/National-Biodiversity-Action-Plan.pdf

FAO (2005). Fishery Country Profile. The Federative Republic of Brazil. www.fao.org/fi/fcp

/en/BRA/profile.htm

Freire, K. (2005). Fishing impacts on marine ecosystems off Brazil, with emphasis on the north-

eastern region. PhD thesis, University of British Columbia, 254 p.

710

52. North Brazil

Freire, K.M.F. and Pauly, D. (2005). Richness of common names of Brazilian marine fishes and its

effect on catch statistics. Journal of Ethnobiology. 25 (2): 279-296.

Maida, M. and Ferreira, B.P. (1997).Coral reefs of Brazil: An overview, p 263-274 in: Proceedings

of the 8th International Coral Reef Symposium, Vol. 1.

Marcano, L., Alió, J.J., Altuve, D.E. and Celaya, J. (1995). Venezuelan shrimp fisheries in the

Atlantic margin of Guyana. National report of Venezuela. FAO Fisheries Report 526 (Suppl.):1-

29.

Marques, M., da Costa, M.F., de O. Mayorga, M.I. and Pinheiro, P.R.C. (2004). Water

environments: Anthropogenic pressures and ecosystem changes in the Atlantic drainage basins

of Brazil. Ambio (33)1-2:68-77.

Negreiros Aragão, J.A., de Araújo Silva, K.C., Ehrhardt, N.M., Seijo, J.C. and Die, D. (2001). Brazil,

Northern Pink Shrimp Fishery. Regional Reviews and National Management Reports Fourth

Workshop on the Assessment and Management of Shrimp and Groundfish Fisheries on the

Brazil-Guianas Shelf. FAO Fisheries Report 651.

Nittrouer, C.A. and DeMaster, D.J. (1987). Sedimentary Processes on the Amazon Continental

Shelf. Pergamon Press, New York, U.S.

Pauly, D. and Christensen, V. (1995). Primary production required to sustain global fisheries.

Nature 374: 255-257.

Pauly, D. and Watson, R. (2005). Background and interpretation of the `Marine Trophic Index' as a

measure of biodiversity. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society: Biological Sciences

360: 415-423.

Pauly, D., Christensen, V., Dalsgaard, J., Froese R. and Torres, F.C. Jr. (1998). Fishing down

marine food webs. Science 279: 860-863.

Rine, J.M. and Ginsburg, R.N. (1985). Depositional facies of the mudshorefave in Suriname, South

America: A mud analogue to sandy, shallow-marine deposits. Journal of Sedimentary Petrology

55(5):633-652.

Sea Around Us (2007). A Global Database on Marine Fisheries and Ecosystems. Fisheries Centre,

University British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada. www.seaaroundus.org/lme/

SummaryInfo.aspx?LME=17

Smith, W.O. and DeMaster, D.J. (1996). Phytoplankton biomass and productivity in the Amazon

River plume: Correlation with seasonal river discharge. Continental Shelf Research 16(3):291-

319.

Souza, R. (2001). Brazil, northern red snapper fishery. FAO Fisheries Report 651:3-70.

UNEP (2004a). Marques, M., Knoppers, B., Lanna, A.E., Abdallah, P.R. and Polette, M. Brazil

Current, GIWA Regional Assessment 39. University of Kalmar, Kalmar, Sweden.

www.giwa.net/publications/r39.phtml

UNEP (2004b). Barthem, R. B., Charvet-Almeida, P., Montag, L. F. A. and Lanna, A.E. Amazon

Basin, GIWA Regional Assessment 40b. University of Kalmar, Kalmar, Sweden.

www.giwa.net/publications/r40b.phtml

Villegas, L. and Dragovich, A. (1984). The Guianas-Brazil shrimp fishery, its problems and

management aspects, p 60-70 in: Gulland, J.A. and Rothschild, B.J. (eds), Penaeid Shrimps -

Their Biology and Management. Fishing News Books, Farnham, U.K.

XVI South West Atlantic

711

XVI-53 East Brazil Shelf LME

S. Heileman

The East Brazil Shelf LME encompasses that part of the Brazilian coast from the

Parnaíba Estuary in the North to Cape São Tomé in the South (Ekau & Knoppers 2003).

It covers a surface area of about 1.1 million km2, of which 0.86% is protected, and

contains 0.33% of the world's coral reefs and 0.58% of the world's sea mounts (Sea

Around Us 2007). The South Equatorial Current, which splits into the North Brazil

Current and the southward-flowing Brazil Current, dominates the LME. Coastal upwelling

of nutrient-rich South Atlantic Central Waters characterises the area south of Abrolhos

Bank in spring and summer (Summerhayes et al. 1976). About 35 rivers, the largest of

which are the Jequitinhonha, Mucuri, Doce and Paraíba do Sul rivers, drain into the

coastal areas. Estuaries include São Francisco and Paraíba. Apart from the Abrolhos

Bank, this LME has a narrow continental shelf. A tropical climate characterises this LME.

LME book chapters and articles pertaining to the South Brazil Shelf LME include Bakun

(1993), Ekau & Knoppers (2003), UNEP (2004).

I. Productivity

The East Brazil Shelf LME is a typical oligotrophic system, poor in nutrients and

phytoplankton biomass, except in areas of upwelling where primary production is

enhanced (Gaeta et al. 1999). The oligotrophic character of the eastern shelf system and

its diverse food web structure is in clear contrast to the Southeast-South shelf system

(Ekau & Knoppers 1999). The LME can be considered a Class II, moderate productivity

ecosystem (150-300 gCm-2yr-1). Highest biomass and densities of pico-, nano-, micro-

and macro-plankton typify the southern coast and the Abrolhos Bank (Susini-Ribeiro

1999). The macro-zooplankton is dominated by calanoid and cyclopoid copepods.

Mesopelagic species dominate the ichthyofauna community in waters more than 200 m

deep. On the Abrolhos Bank, demersal ichtyoplankton species, largely herbivorous fish,

dominate the system possibly relying on the primary production of benthic algae. The

Abrolhos Bank and the Vitória-Trindade Ridge form a topographical barrier to the Brazil

Current, inducing fundamental changes and spatial variability in physical, chemical and

biological features over the shelf and along the shelf edge (Castro & Miranda 1998, Ekau

& Knoppers 1999).

Oceanic Fronts (Belkin et al. 2008)(Figure XVI-53.1): This LME includes the bifurcation

of the westward South Equatorial Current near Cabo de São Roque (5.5°S; Belkin et al.

2008) that gives rise to two currents and associated fronts: the northward North Brazil

Current Front (NBCF) and the southward South Brazil Current Front (SBCF). Within this

LME the SBCF is most noticeable in salinity; it becomes distinct as a temperature front

from the South Brazil Bight southward (see South Brazil Shelf LME). The NBCF is year-

round, best defined in austral winter; it extends along the coast into the North Brazil Shelf

LME. The Southern Bahia Front (15°S-19°S) and the Cabo Frio Front (20°S-24°S) are

caused by wind-induced upwelling and are best developed during austral summer and

fall, from January through June.

East Brazil Shelf LME SST (Belkin 2008)(Figure XVI-53.2):

Linear SST trend since 1957: 0.57°C.

Linear SST trend since 1982: 0.30°C.

712

53. East Brazil Shelf LME

Figure XVI-53.1. Fronts of the East Brazil Shelf LME. Acronyms: NBCF, North Brazil Current Front;

SBCF, south Brazil current Front; SSF, Shelf Slope Front (most probable location). Yellow line, LME

boundary. After Belkin et al. (2008).

Like the adjacent South Brazil Shelf, the East Brazil Shelf experienced a long-term

warming at a slow-to-moderate rate. The most significant event since 1957 was a 1°C

warming in 1981-84, similar to and concurrent with the South Brazil Shelf warming. Both

LMEs are linked by shelf-slope along-frontal currents that transport SST anomalies from

one LME to another; therefore the observed synchronism can be explained by advection,

although large-scale atmospheric forcing spanning both LMEs also could have played a

role.

Figure XVI-53.2. East Brazil Shelf LME annual mean SST (left) and SST anomalies (right) , 1957-2006,

based on Hadley climatology. After Belkin (2008).

XVI South West Atlantic

713

East Brazil Shelf Chlorophyll and Primary Productivity: This LME is a Class II,

moderate productivity ecosystem (150-300 gCm-2yr-1)(Figure XVI-53.3).

Figure XVI-53.3. East Brazil Shelf trends in chlorophyll a (left) and primary productivity (right), 1998-

2006, from satellite ocean colour imagery. Values colour coded to the right hand ordinate. Figure

courtesy of J. O'Reilly and K. Hyde. Sources discussed p. 15 this volume.

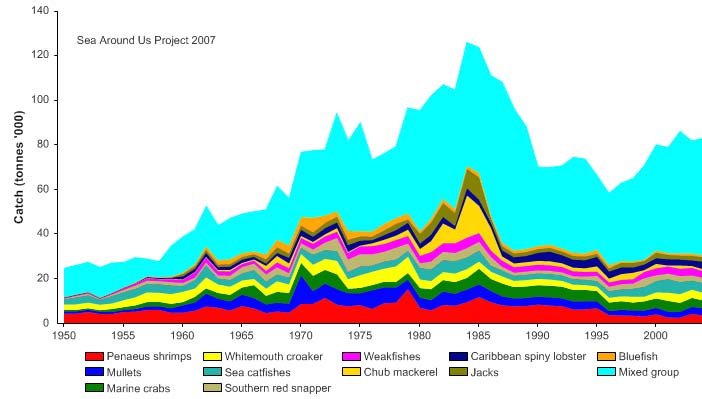

II. Fish and Fisheries

The fisheries are mainly artisanal although commercial fisheries for lobster, shrimp and

southern red snapper are significant in the states of Ceará, Rio Grande do Norte and

Espírito Santo (Ekau & Knoppers 1999). Tuna (mainly bigeye) are fished in offshore

areas and landed mainly in Rio Grande do Norte and Paraíba. Total reported landings in

the LME increased to 300,000 tonnes in 1973 with Brazilian sardinella (Sardinella

brasiliensis) accounting for two-third of the landings, but have decline over the past three

decades, recording 130,000 tonnes in 2004 (Figure XVI-53.4). However, a large quantity

of fish bycatch from shrimp trawlers is not included in the underlying statistics and, there

are reasons to believe that a substantial fraction of the landings from small artisanal

fisheries (predominantly fishes) may not be included in the statistics as well (Freire 2003).

The high likelihood of misreporting in the underlying statistics makes `ecosystemic'

diagnosis of catch trends difficult if not impossible (see below).

Figure XVI-53.4. Total reported landings in the East Brazil Shelf LME by species (Sea Around Us 2007).

714

53. East Brazil Shelf LME

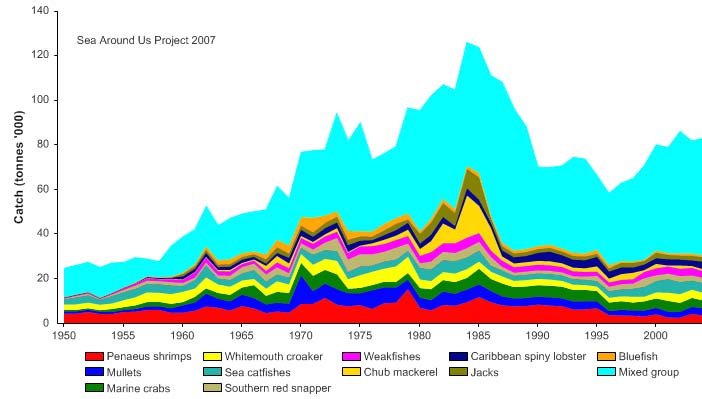

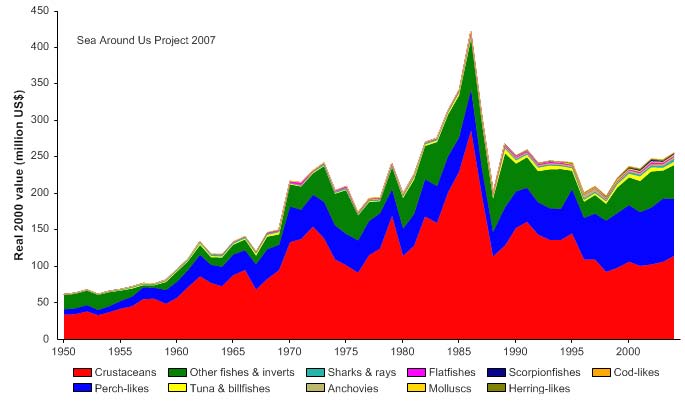

The value of the reported landings peaked at US$400 million (in 2000 US dollars) in

1986, with landings of crustaceans accounting for the largest share (Figure XVI-53.5).

Figure XVI-53.5. Value of reported landings in the East Brazil Shelf LME by commercial groups (Sea

Around Us 2007).

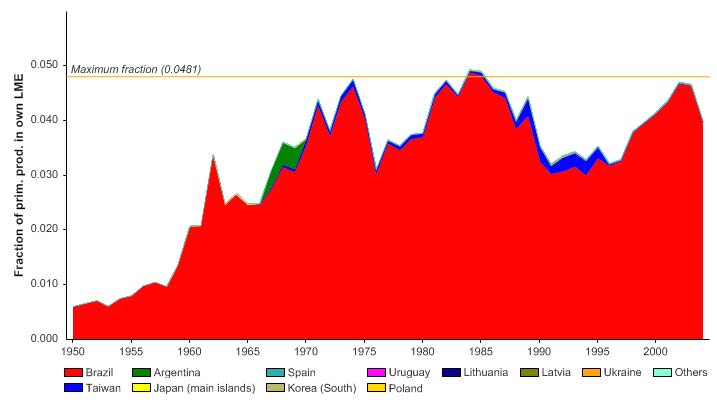

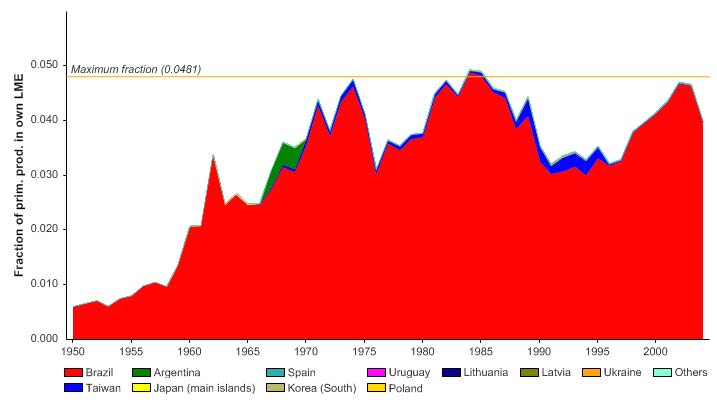

The primary production required (PPR; Pauly & Christensen 1995) to sustain the reported

landings for the LME approached 5% of the observed primary production in the early

1970s, and has fluctuated between 3 to 5% in recent years (Figure XVI-53.6). This is

probably an underestimate due to the large under-reporting of catch in the region (see

above). Brazil account for almost all of the ecological footprint in this LME, which has

little foreign fishing (Figure XVI-53.6).

Figure XVI-53.6. Primary production required to support reported landings (i.e., ecological footprint) as

fraction of the observed primary production in the East Brazil Shelf Sea LME (Sea Around Us 2007). The

`Maximum fraction' denotes the mean of the 5 highest values.

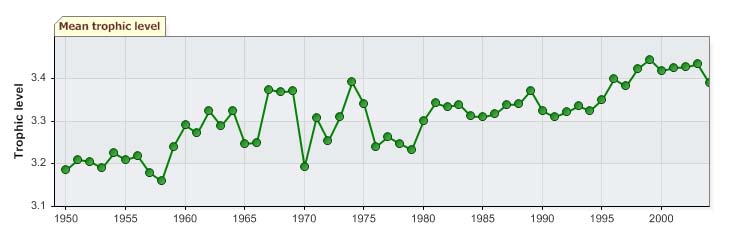

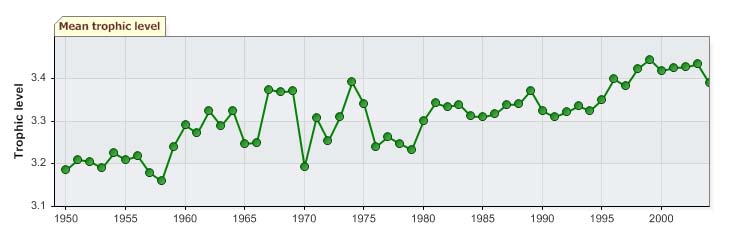

The mean trophic level of the reported landings (i.e., the MTI, Pauly & Watson 2005) has

increased steadily (with variation) from around 3.2 in the early years to 3.4 in recent

years (Figure XVI-53.7, top).. As for the FiB index, the expansion of the fisheries in the

XVI South West Atlantic

715

1950s and 1960s is represented by an increase in the FiB index, though it has since

been on a generally flat trend (Figure XVI-53.7, bottom).

Figure XVI-53.7. Mean trophic level (i.e., Marine Trophic Index) (top) and Fishing-in-Balance Index

(bottom) in the East Brazil Shelf LME (Sea Around Us 2007).

The Stock-Catch Status Plots indicate that over 70% of commercially exploited stocks in

the LME are either overexploited or have collapsed (Figure XVI-53.8, top). With regard to

the contribution to the reported landings biomass, approximately 60% of the landings are

supplied by overexploited and collapsed stocks (Figure XVI-53.8, bottom). However,

given the quality of the underlying catch statistics (see text), this diagnosis is tentative.

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

0%

100

10%

90

20%

)

80

(

%

s

30%

u

70

t

at

s

40%

y

60

b

ks

50%

c

o

50

f

st

60%

o

40

er

b

70%

m

30

u

N

80%

20

90%

10

100%0

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

(n = 3296)

developing

fully exploited

over-exploited

collapsed

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

0%

100

10%

90

20%

80

)

%

30%

(

70

s

t

u

a

40%

60

ck st

50%

o

50

st

y

60%

b

h

40

t

c

a

70%

C

30

80%

20

90%

10

100%0

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

(n = 3296)

developing

fully exploited

over-exploited

collapsed

Figure XVI-53.8. Stock-Catch Status Plots for the East Brazil Shelf LME, showing the proportion of

developing (green), fully exploited (yellow), overexploited (orange) and collapsed (purple) fisheries by

number of stocks (top) and by catch biomass (bottom) from 1950 to 2004. Note that (n), the number of

`stocks', i.e., individual landings time series, only include taxonomic entities at species, genus or family

level, i.e., higher and pooled groups have been excluded (see Pauly et al., this volume, for definitions).

716

53. East Brazil Shelf LME

Overexploitation is considered to be severe in this LME, with both artisanal and

commercial fishing contributing to the significant decrease of the region's fish stocks.

Several valuable species (e.g., shrimp, lobster, tuna, crabs and mussels) are fully

exploited or exploited above MSY (FAO 1997, UNEP 2004. As a result, declining fish

catches are evident in several areas (e.g., Paiva 1997, Hilsdorf & Petrére 2002) and

overfishing has drastically reduced the stocks of some commercially important fish or

eliminated them from the catches. In fact, marine and estuarine fisheries for red snapper,

prawns and mangrove crabs have declined as a result of overfishing.

Excessive bycatch and discards range from slight to severe (UNEP 2004. Non-selective

fishing methods are used extensively and up to 30% of fisheries catches in the northeast

areas consists of accidental captures and/or discards. In the oceanic fisheries, bycatch

comprises 80% of the catch (on the Sergipe and Alagoas coast this can reach 90%) with

discards amounting to 60% of the catch. Small-meshed nets used in commercial shrimp

trawling capture a number of non-target species, such as finfish, lobster, crab and turtle.

This bycatch, which is normally returned dead to the sea, can reach up to 8 kg for each

kilogram of shrimp captured. Destructive fishing practices are moderate to severe

(UNEP 2004). Trawling has also destroyed many habitats. The use of bombs and

poison is seen in most estuaries in the state of Sergipe while the use of explosives is

common along the entire Bahia coast.

Measures aimed at recovery and sustainability of the principal species may help to

address overexploitation in the LME (FAO 2005). However, improved fisheries statistics

are necessary for the development of fisheries management plans. Fisheries statistics

continue to be a difficult issue in Brazil, due to several factors including the lack of

institutional stability among the regulatory agencies in charge of the fisheries sector

(Freire 2003), the multitude of common names used for reporting landings (Freire &

Pauly 2005), the large geographical extension of the coast, the uneasy coexistence of

artisanal and commercial fisheries and the large number of species and landing sites

related to the artisanal fisheries (Paiva 1997).

III. Pollution and Ecosystem Health

Pollution: Pollution is a growing concern, especially around densely populated and

industrialised coastal areas where hotspots have been identified. In general, pollution

was found to be moderate in this LME, but severe in localised hotspots (UNEP 2004,

UNEP unpubl). The main sources of marine pollution are linked to land-based activities,

especially unplanned coastal development and tourism and recreation centres, as well as

ocean transport and industrial activities (e.g., Suape industrial port complex in the State

of Pernambuco) and agriculture. As a result of the disposal of untreated sewage in

coastal areas, microbial contamination is evident in the estuaries and coastal waters near

major cities. In fact, beaches located downstream of densely populated urban centres are

likely to be contaminated by faecal coliform bacteria in concentrations above the

threshold limit (FEMAR 1998). Estuaries, bays and lagoons encircled by large urban

areas show varying degrees of eutrophication from sewage and other organic pollution,

increased sediment loads and limited water circulation (FEMAR 1998, Kjerfve et al.

2001). Low oxygen levels (<3 mgl-1) occur in estuaries and coastal lagoons and

significantly affect coastal embayments (Lacerda et al. 2002). As a result, fish kills due to

low concentration of dissolved oxygen associated with the proliferation of harmful algal

blooms are not uncommon in some areas (Sierra de Ledo & Soriano-Serra 1999).

Chemical pol ution arises mainly from industry and agricultural plantations. Mercury

concentrations reach about 2-5 times baseline levels in some hotspots (Seeliger & Costa

1998). Deforestation, coastal plantations and mining have facilitated soil erosion, which

XVI South West Atlantic

717

has resulted in increasing suspended solids in estuaries and other coastal areas

(Knoppers et al. 1999a, 1999b).

Oil exploitation and shipping in the coastal zone, although on a lesser scale than offshore

oil and gas activities, represent one of the greatest pressures on the coastal environment

of this LME (IBAMA 2002). Several small-, medium- and large-scale spills of oil, grease

and a number of hazardous substances have been detected in coastal and marine

waters (UNEP 2004). Oil spills are becoming more frequent along the northeast coast of

Brazil. The refuelling of boats and the washing of ship tanks is normally carried out a few

kilometres from the coastline, resulting in the occurrence of tar and sometimes weathered

oil slicks in coastal habitats such as sandy beaches and coral reefs.

Habitat and community modification: Human activities in the coastal zone have

resulted in moderate to severe habitat modification in this LME, with the East Atlantic

Basins and NE Brazil Shelf being the most affected (UNEP 2004, UNEP unpubl).

Destruction of mangrove forests for charcoal production, timber, urban and tourist

developments, salt production, agriculture and shrimp farms is widespread throughout

the region. It is estimated that the area of mangrove swamp on the entire Brazilian coast

has been reduced by up to 30% of its original area, with the probability of further

reduction (UNEP unpubl). Only in the state of Piauí can significant areas of non-

impacted mangrove forest be found. The conversion of the mangrove to shrimp farms

has drastically changed the natural and ecological balance of the region's estuaries. The

highest rate of mangrove deforestation and conversion to aquaculture occurs on the

coast of Rio Grande do Norte, which has lost about 2,000 ha of its original area. The

states of Paraíba and Pernambuco are no exception, with almost all of its estuaries

having shrimp farms of various sizes. This industry is expanding in Piauí, where the total

loss of mangrove has already reached 600 ha.

The coral reefs of Brazil are mostly spread over a distance of 2,000 km between 0o50'

and 19° S latitude from the state of Maranhão in the North Brazil Shelf LME to southern

Bahia. They are the southernmost reefs in the Atlantic Ocean and are characterised by

relatively low species diversity and the endemism of the hard coral species, with six

endemic species (Castro 1994). The largest and richest reefs of Brazil occur on the

Abrolhos Bank in the southern part of the state of Bahia. In the past, the coral reefs of

the North Brazil Shelf LME were mined for construction material, but at present they

come under a growing number of threats. These include increased sedimentation due to

unsustainable land use as well as coastal erosion, pollution from domestic sewage and

pesticides from sugar cane plantations, overfishing and use of explosives for fishing,

tourism, as well as port and oil/gas terminals development (Amado-Filho et al. 1997,

Maida & Ferreira 1997, Leão 1999).

In the state of Bahia, an acceleration of generally unplanned urbanisation and

indiscriminate use of septic tanks in urban centres have resulted in contamination of

groundwater (Marques et al. 2004). As a consequence, nutrient enrichment through

groundwater seepage has resulted in eutrophication of adjacent coastal areas (Costa et

al. 2000). This has affected the trophic structure of the reefs in these areas, with

increasing turf and macroalgae growth, reduction of available light to coral colonies and

competition for space preventing the settlement of new coral larvae. Coral bleaching

resulting from high sea surface temperature has also affected the reefs in this LME (Leão

1999). There was extensive coral bleaching in 1998 in North Bahia and the Abrolhos

region, with levels of 80% reported in important species such us Agaricia agaricites,

Mussismilia hispida and Porites astreoides (Garzón-Ferreira et al. 2002). However, all

corals recovered after six months. The reefs of the Abrolhos Archipelago have been

impacted by coastal zone development, tourism, overexploitation of natural resources

and pollution from urbanisation as well as industrial activities, including the exploitation of

718

53. East Brazil Shelf LME

fossil fuel in deep waters (Amado Filho et al. 1997, Coutinho et al. 1993, Leão 1996,

1999).

Changes in sediment transport dynamics due to land-based activities are considered one

of the most serious environmental issues in this region (IBAMA 2002). The lower São

Francisco River and its estuary have suffered significant morphological changes as a

consequence of the construction of dams. Significant reduction of sediment/nutrient

transport has caused sediment deficit in coastal areas, erosion and modification of

ecological niches (Marques 2002). Some marine turtles, such as the green, loggerhead,

hawksbill, Pacific ridley and leatherback, marine mammals such as the humpack whale,

as well as the marine manatee have suffered significant reductions in their populations

and are in danger of extinction (Fundação CEPRO 1996).

IV. Socioeconomic Conditions

The East Brazil Shelf LME is bordered by the Brazilian states of Piauí, Ceará, Rio

Grande do Norte, Paraíba, Pernambuco, Alagoas, Sergipe, Bahia and Espírito Santo. It

shows an extremely high social, cultural and economic diversity (UNEP 2004). The

estimated population is about 53 million inhabitants, with a large percentage living in

urban areas (IBGE 2000). In most states, the increasing concentration of the population

and economic activities in coastal cities is notable. For example, the state of

Pernambuco has the highest coastal population density in the country (over 800 persons

km-2). This is ten times greater than the population density of the rest of the state and

twice above the national average (Costa & Souza 2002). A large number of the

inhabitants of this region are among the poorest in the country, with a wide social and

economic gap separating the few rich and the mass of poor people (UNEP 2004).

The main economic activities are linked to agriculture, livestock farming,

fisheries/aquaculture and tourism. The LME's fisheries represent an important source of

food and income for coastal communities, although they make a small contribution to the

country's GDP. Shrimp farming is also an important economic activity, with farms in the

northeastern part representing 75% of the national total. Tourism is one of the most

important drivers of coastal development in Brazil, and is expected to expand further

during the coming years.

Artisanal fisheries are an important subsistence activity not accounted for in the formal

economy of Brazil. Fishing represents a labour-intensive activity, responsible for about

800 000 direct jobs. Approximately four million people depend on this sector. The

decline in marine fisheries in the region has been accompanied by reduced economic

returns over the years. Severe impacts are seen on the fisheries sector economy,

affecting the population that is directly dependent on the sector. Several fishing

associations have been closed and the labour force diverted into other sectors, such as

tourism. As a consequence of the declining stocks and interruption of industrial fishing

activities, unemployment in the seafood processing sector has increased.

The socioeconomic impacts of pollution and habitat modification and loss in the East

Brazil Shelf LME include loss of revenue and employment opportunities from tourism and

fisheries, loss of property value, increased cost of surveillance, restoration of degraded

areas as well as penalties against companies responsible for accidents (UNEP 2004).

More frequent are the health impacts related to water-borne diseases such as

microbiological and parasitic diseases (Governo do Estado de São Paulo 2002).

Increasing gastrointestinal symptoms related to exposure to polluted beaches were

described by Ciência e Tecnologia a Serviço do Meio Ambiente (CETESB) (Governo do

Estado de São Paulo 2002). Among the social and other community impacts are the loss

of recreational and aesthetic value of many coastal areas. Pollution and habitat

XVI South West Atlantic

719

modification are also thought to cause reduction of fish stocks, leading to loss of

sustainable livelihoods in hundreds of fishing communities along the coast of this LME.

Habitat and community modification have also resulted in increased costs for coastal

areas maintenance due to higher vulnerability to erosion and lower coastline stability.

This concern has also created generational inequity and loss of scientific and cultural

heritage through the disappearance of aquatic species (UNEP 2004).

V. Governance

The Brazilian Government became involved in coastal preservation and management

during the 1970s when habitat degradation increased due to industrialisation and urban

growth (Lamardo et al. 2000). Coastal management is supported by the Federal

Constitution in Brazil, which defined the coastal zone as national property (UNEP 2004).

In 1988, the government implemented the National Coastal Management Plan. In 1995

the National Programme of Coastal Management (Programa Nacional de Gerenciamento

Costeiro, GERCO) proposed decentralisation, with the objective of stimulating initiatives

by the states and municipalities, according to the local conditions and demands. The

main objective of GERCO is to realign public national policies, which affect the coastal

zone, in order to integrate the activities of the states and municipalities and incorporate

measures for sustainable development (UNEP 2004). In parallel with the Ecological-

Economic Diagnosis, the Ministry of the Environment has coordinated the implementation

of the National Programme for Coastal Management involving all 17 coastal states and

their municipalities. The programme's main objective is the assessment and diagnosis of

the coastal zone uses and conflicts for better planning and management of its living and

non-living resources.

Some of the requirements for sustainable development in Brazil include the alleviation of

poverty, innovative development strategies, technological improvements as well as sound

conservation policies. The greatest constraints are the lack of harmonised legal

instruments and financial mechanisms, as well as discrepancies in the capabilities of

national and regional experts and managers. The Centre of Fisheries Research and

Development of Northeast (CEPENE) is a regional department of the Brazilian Institute of

Environment and Natural Renewable Resources and is responsible for the northeastern

and eastern coast from Rio Parnaíba to north of Abrolhos Bank. CEPENE has played an

important role in supporting research and technological development and promoting

technical and social assistance to the local labour force.

The East Brazil Shelf LME, along with the South Brazil Shelf LME and the Patagonian

Shelf LME, forms the Upper South-West Atlantic Regional Sea Area. In 1980 UNEP's

Governing Council launched a programme for the marine and coastal environment of

Argentina, Brazil and Uruguay. In 1998, in cooperation with the UNEP/GPA Coordination

Office and the UNEP Regional Office for Latin America and the Caribbean (ROLAC), a

Regional Programme of Action (POA) on Land-based Activities and a regional

assessment for the Upper South-West Atlantic were prepared and endorsed by

representatives of the three governments. The first steps in implementing the

programme, which covers the coast from Cape São Tomé in Brazil to the Valdés

Peninsula in Argentina, are under development. Under this regional POA, the Brazilian

National Programme of Action for the Protection of the Marine Environment from Land-

based Activities in the Brazilian Section of the Upper South-West Atlantic has been

developed. This national POA covers the area from São Tomé Cape to Chuí, in Rio

Grande do Sul state.

720

53. East Brazil Shelf LME

References

Amado-Filho, G.M. Andrade, L.R., Reis, R.P., Bastos, W. and Pfeiffer, W.C. (1997). Heavy metal

concentration in seaweed species from the Abrolhos Reef Region, Brazil, p 183-186 in:

Proccedings of the VIII International Coral Reef Symposium, Panama, 2. Panama.

Bakun, A. 1993. The California Current, Benguela Current, and Southwestern Atlantic shelf

ecosystems A Comparative Approach to Identifying Factors Regulating Biomass Yields, p

199-221 in: Sherman, K., Alexander, L.M. and Gold, B.D. (eds), Large Marine Ecosystems

Stress Mitigation, and Sustainability AAAS, Washington D.C., U.S.

Belkin, I.M. (2008) Rapid warming of Large Marine Ecosystems, Progress in Oceanography, in

press.

Belkin, I.M., Cornillon, P.C., and Sherman, K. (2008). Fronts in Large Marine Ecosystems of the

world's oceans. Progress in Oceanography, in press.

Castro, B.M. and Miranda, L.B. (1998). Physical Oceanography of the Western Atlantic Continental

Shelf Located Between 4° N and 34° S, in: Robinson, A.R. and Brink, K.H. (eds), The

Sea 11:209-252.

Castro, C.B. 1994. Corals of Southern Bahia, p 161-176 in: Hetzel, B. and Castro, C.B. (eds),

Corals of Southern Bahia. Nova Fronteira, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Costa, M.F. & Souza, S.T. (2002). A zona costeira Pernambucana e o caso especial da Praia da

Boa Viagem: Usos e conflitos, in: Construção do Saber Urbano Ambiental: A Caminho da

Trasdisciplinaridade. Editora Humanidades, Londrina, Brazil.

Costa, O.S.Jr., Leão, M.A.N., Nimmo, M. and Atrill, M.J. (2000). Nutrification impacts on coral reefs

from northern Bahia, Brazil. Hydrobiologia 440:307-315.

Coutinho, R, Villaça, R.C., Magalhães, C.A., Apolinário, M and Muricy, G. (1993). Influência

antrópica nos ecosistemas coralinos da Região de Abrolhos, Bahia, Brasil. Acta Biológica

Lepoldensia 15(1):133-144.

Ekau, W. and Knoppers, B. A. (2003). A review and redefinition of the Large Marine Ecosystems of

Brazil, p 355-372 in: Sherman, K. and Hempel, G. (eds), Large Marine Ecosystems of the

World: Trends in Exploitation, Protection and Research. Elsevier Science. Amsterdam, The

Netherlands.

Ekau, W. and Knoppers, B.A. (1999). An introduction to the pelagic subregion of the east and

northeast Brazilian Shelf. Archive of Fishery and Marine Research 47(2/3):113-132.

FAO (1997). Review of the State of World Fishery Resources: Marine Fisheries. Southwest

Atlantic. FAO Fisheries Circular 920 FIRM/C920.

FAO (2005). Fishery Country Profile The Federative Republic of Brazil. http://www.fao.org/fi/fcp/

en/BRA/profile.htm

FEMAR (1998). Uma Avaliação da Qualidade das Águas Costeiras do Estado do Rio de Janeiro.

Projeto Planágua SEMA/GTZ. Fundação de Estudos do Mar. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Freire, K. (2003). A database of landings on Brazilian marine fisheries, 1980-2000, p. 181-189. in:

Zeller D., Booth, S., Mohammed, E. and Pauly, D. (eds.). (2003). From Mexico to Brazil:

Central Atlantic fisheries catch trends and ecosystem models. Fisheries Centre Research

Reports 11(6).

Freire, K.M.F. and Pauly, D. (2005). Richness of common names of Brazilian marine fishes and its

effect on catch statistics. Journal of Ethnobiology. 25 (2): 279-296.

Fundação CEPRO (1996). Fundação Centro de Pesquisas Econômicas e Sociais do Piauí.

Macrozoneamento Costeiro do Estado do Piauí: Relatório Geoambiental e Sócio-econômico.

Teresina, Brazil.

Gaeta, A.S., Lorenzetti, J.Á., Miranda, L.B., Susini-Ribeiro, S.M.M., Pompeu, M. and De Araujo,

C.E.S. (1999). The Victoria eddy and its relation to the phytoplankton biomass and primary

productivity during the Austral Fall of 1995. Archive of Fishery and Marine Research

47(2/3):253-270.

Garzón-Ferreira, J., Cortés, J., Croquer, A., Guzmán, H., Leao, Z. and Rodríguez-Ramírez, A.

(2002). Status of coral reefs in southern tropical America in 2000-2002: Brazil, Colombia,

Costa Rica, Panama and Venezuela, p 343-360 in Wilkinson, C. (ed), Status of Coral Reefs of

the World: 2002. Australian Institute of Marine Science, Townsville, Australia.

Governo do Estado de São Paulo (2002). Water Resources Management, in: Agenda 21 in São

Paulo: 1992-2002. Ciência e Tecnologia a Serviço do Meio Ambiente. Governo do Estado de

São Paulo, Brazil.

XVI South West Atlantic

721

Hilsdorf, A.W.S. and Petrére, M. (2002). Concervação de peixes na bacia do rio Paraíba do Sul.

Ciência Hoje 30(180):62-65.

http://www.seaaroundus.org/lme/SummaryInfo.aspx?LME=16

IBAMA (2002). Geo-Brasil 2002: Perspectivas do Meio Ambiente no Brasil. Instituto Brasileiro de

Meio Ambiente, Brasília, Brazil.

IBGE (2000). Brazil in Figures. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Kjerfve, B., Seeliger, U. and Lacerda, L.D. (2001). A summary of natural and human-induced

variables in coastal marine ecosub-regions of Latin America, p 341-353 in: Seeliger, U. and

Kjerfve, B. (eds), Coastal Marine EcoSub-regions of Latin America. Springer Verlag, Berlin,

Germany.

Knoppers, B., Ekau, W. and Figueiredo, A.G. (1999a). The coast and shelf of east and northeast

Brazil and material transport. Geo-Marine Letters 19:171-178.

Knoppers, B., Meyerhöfer, M., Marone, E., Dutz, J., Lopes, R., Leipe, T. and Camargo, R. (1999b).

Compartments of the pelagic system and material exchange at the Abrolhos Bank coral reefs,

Brazil. Archive of Fishery and Marine Research 47(2/3):285-306.

Lacerda, L.D., Kremer, H.H., Kjerfve, B., Salomons, W., Crossland, J.I.M. and Crossland, C.J.

(2002). South American Basins: LOICZ Global Change Assessment and Synthesis of River

Catchment-Coastal Sea Interaction and Human Dimension. Land-Ocean Interactions in the

Coastal Zone. LOICZ Reports and Studies 21. Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Lamardo, E.Z., Bícego, M.C., Castro-Filho, B.M., Miranda, L.B. and Prósperi, V.A. (2000). Southern

Brazil, p 731-747 in: Sheppard, C.R.C. (ed), Seas at the Millennium: An Environmental

Evaluation I. Pergamon Press, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Leão, Z.M.A.N. (1996). The coral reefs of Bahia: Morphology, destruction and the major

environmental impacts. Anais Academia Brasileira de Ciências 68(3): 439-452.

Leão, Z.M.A.N. (1999). Abrolhos The South Atlantic largest coral reef complex, in:

Schobbenhaus, C., Campos, D.A., Queiroz, E.T., Winge, M. and Berbert-Born, M. (eds), Sítios

Geológicos e Paleontológicos do Brasil. http://www.unb.br/ig/sigep/sitio090/sitio090.htm

Maida, M. and Ferreira, B.P. (1997). Coral reefs of Brazil: An overview. Proceedings of the 8th

International Coral Reef Symposium 1:263-274.

Marques, M. (2002). Analise da Cadeia Causal da Degradação dos Recursos Hidricos: Proposta

de Modelo Conceitual do Projeto GIWA UNEP/GEF. 2o Simposio de Recursos Hidricos do

Centro Oeste. Campo Grande, Brazil.

Marques, M., da Costa, M.F., de O. Mayorga, M.I. and Pinheiro, P.R.C. (2004). Water

environments: Anthropogenic pressures and ecosystem changes in the Atlantic Drainage

Basins of Brazil. Ambio (33)1-2:68-77.

Paiva, M.P. (1997). Recursos Pesqueiros Estuarinos e Marinhos do Brasil. Universidade Federal

do Ceará-UFC. Fortaleza, Brazil.

Pauly, D. and Christensen, V. (1995). Primary production required to sustain global fisheries.

Nature 374: 255-257.

Pauly, D. and Watson, R. (2005). Background and interpretation of the `Marine Trophic Index' as a

measure of biodiversity. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society: Biological Sciences

360: 415-423.

Sea Around Us (2007). A Global Database on Marine Fisheries and Ecosystems. Fisheries Centre,

University British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada.

Seeliger, U. and Costa, C.S.B. (1998). Impactos Naturais e Humanos, p 205-218 in: Seeliger, U,

Odebrecht, C, Castello, J. P. (eds), Os Ecosistemas Costeiro e Marinho do Extremo sul do

Brasil. Ecoscientia, Rio Grande, Brasil.

Sierra de Ledo, B. and Soriano-Serra, E., eds. (1999). O Ecosistema da Lagoa da Conceição.

Fundo Especial de Proteção ao Meio Ambiente. Governo do Estado de Santa Catarina.

IOESC/FEPEMA 4.

Summerhayes, C.P., De Melo, U. and Barretto, H.T. (1976). The influence of upwelling on

suspended matter and shelf sediments off southeastern Brazil. Journal of Sedimentary

Petrology 46(4):819-828.

Susini-Ribeiro, S.M.M. (1999). Biomass distribution of pico, nano and micro-phytoplankton on the

continental shelf of Abrolhos, East Brazil. Archive of Fishery and Marine Research

47(2/3):271-284.

UNEP (2004). Marques, M., Knoppers, B., Lanna, A.E., Abdallah, P.R. and Polette, M. Brazil

Current, GIWA Regional Assessment 39. University of Kalmar, Kalmar, Sweden.

http://www.giwa.net/publications/r39.phtml

722

53. East Brazil Shelf LME

XVI Southwest Atlantic

723

VI-54 South Brazil Shelf LME

S. Heileman and M. Gasalla

According to the re-definition of the Brazilian LMEs (Ekau & Knoppers 2003), the South

Brazil Shelf LME extends from 22°-34°S along the South American southeast coast and

is bordered by the Brazilian states of Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo, Paraná, Santa Catarina

and Rio Grande do Sul. This LME has a surface area of about 565,500 km2, of which

1.47% is protected (Sea Around Us 2007), with a wide continental shelf that reaches

220 km in some areas. Another feature is its mixed climate and composite structure of

environmental conditions that imprints a warm-temperate characteristic (Semenov &

Berman, 1977). According to Gasalla (2007), the South Brazil LME would extend over 3

sub-areas: (a) the Southern shelf (28-34°S), influenced by estuarine outflows; (b) the

Southeastern Bight (23-28°S), also termed the South Brazil Bight, characterized by

seasonal upwellings and cool intrusions; and (c) a slope and oceanic system at its

eastern fringe, with the occurrence of meso-scale eddies. The Brazilian continental shelf

lies within the path of the South Equatorial Current, which gives rise to the North Brazil

Current and the southward flowing Brazil Current (Ekau & Knoppers 2003). The latter

influences the South Brazil Shelf LME which is also under regional effects of the Malvinas

current and the La Plata River plume edging northwards along the coast (Piola et al.

2008). Thus, the Brazil-Malvinas confluence system in the southwestern corner of the

subtropical gyre also shapes this LME characteristics. Major rivers and estuaries include

Patos-Mirim and Cananeia-Paranaguá Lagoon systems, Ribeira de Iguape and Paraiba

do Sul rivers, and the Santos/São Vicente estuarine complex. Book chapters, articles and

reports pertaining to the South Brazil Shelf LME include Bakun (1993), Vasconcellos &

Gasalla (2001), Ekau & Knoppers (2003),UNEP (2004) and MMA (2006).

I. Productivity

The South Brazil Shelf LME is subjected to relatively intense shelf edge and wind-driven

coastal upwelling of the South Atlantic Central Water (SACW), pumped by alongshore

winds and by cyclonic vortexes originated from the Brazil Current, particularly in summer

and at Cape Santa Marta (28° S) (Bakun 1993; Vasconcellos & Gasalla 2001). It is the

most productive coast of the Brazil Current region and considered a Class II ecosystem

with moderately high productivity (150-300 gCm-2yr-1). Productivity is higher in summer

when upwelling of the SACW is frequent, and decreases towards the north (Metzler et al.

1997; Ekau & Knoppers 2003). In addition to coastal, shelf-edge and offshore upwelling,

production is also sustained by various terrigenous sources such as the Patos-Mirim

Lagoon system and La Plata River plume (Seeliger et al. 1997; Piola et al. 2008). This

LME sustains higher production and fisheries than the East Brazil LME to the north (Ekau

& Knoppers 2003).

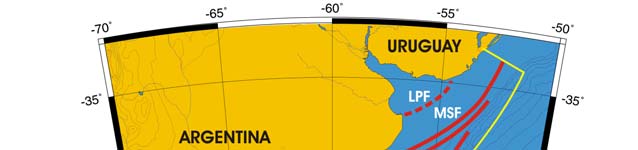

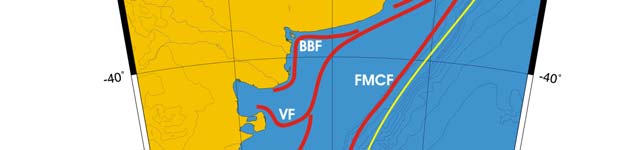

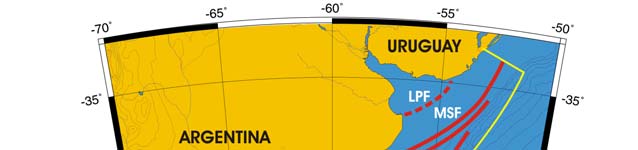

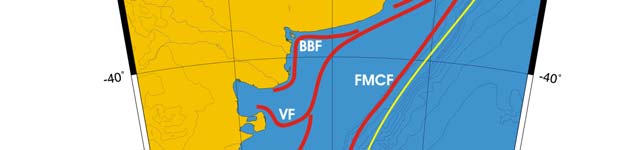

Oceanic fronts (Belkin et al. 2008) (Figure XVI-54.1): The Brazil Current Front forms the

offshore boundary of this LME. This current transports equatorial waters from off Cabo

de São Roque (5° 30'S) down to 25°S, where the thermal contrast with colder shelf

waters is enhanced in winter-spring by an equatorward flow of cold, fresh Argentinean

shelf water reaching as far north as 23°S (Campos et al. 1995, 1999, Ciotti et al. 1995,

Lima & Castello 1995, Lima et al. 1996). Shelf-slope fronts in the South Brazil Bight and

off Rio Grande do Sul are year-round, but best defined from April through September

(Castro 1998; Belkin et al. 2008). The Subtropical Shelf Front off southern Brazil has

724

54. South Brazil Shelf LME

been recently described by Piola et al. (2000), Belkin et al. (2008) and Campos et al.

(2008).

Figure XVI-54.1. Fronts of the South Brazil Shelf LME. Acronyms: SSF, Shelf Slope Front (most

probable location). Yellow line, LME boundary. After Belkin et al. (2008).

South Brazil Shelf LME SST (Belkin 2008) (Figure XVI-54.2):

Linear SST trend since 1957: 1.12°C.

Linear SST trend since 1982: 0.53°C.

The South Brazil Shelf remained relatively cold or cooled down until the relatively

abrupt warming by 1°C between 1981 and 1984 that commenced the modern epoch of

steady warming. The post-1982 warming of 0.53°C over 25 years is moderate compared

to other LMEs. The warming event of 1981-1984 was concurrent with a similar warming

in the East Brazil Shelf LME. In both LMEs, the maximum warming rate was observed

between 1982 and 1983. This synchronism can be explained either by large-scale

forcing spanning both LMEs or by ocean currents that connect these LMEs and transport

SST anomalies along shelf and shelf-slope fronts (Belkin et al. 2008).

Figure XVI-54.2. South Brazil Shelf LME annual mean SST (left) and SST anomalies (right), 1957-2006,

based on Hadley climatology. After Belkin (2008).

XVI Southwest Atlantic

725

South Brazil Shelf Chlorophyll and Primary Productivity

This LME is a Class II ecosystem with moderately high productivity (150-300 gCm-2yr-1)

(Figure XVI-54.3).

Figure XVI-54.3. South Brazil Shelf trends in chlorophyll a (left) and primary productivity (right), 1998-

2006, from satellite ocean colour imagery; courtesy of J. O'Reilly and K. Hyde.

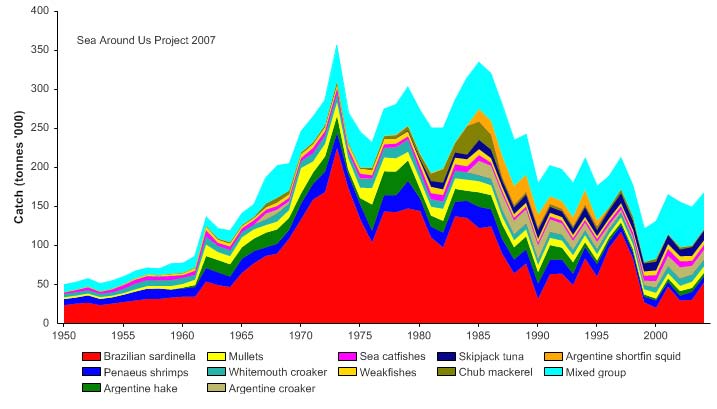

II. Fish and Fisheries

The South Brazil Shelf contributes about half of Brazil's commercial fisheries yield. In

2002, artisanal fisheries accounted for about 22 % of the total commercial catch in this

LME (IBAMA 2002). Sardines represent the most important group in shelf catches (FAO

2003), while the important demersal species are the whitemouth croaker (Micropogonias

furnieri), the argentine croaker (Umbrina canosai) and other sciaenids, the skipjack tuna

Katsuwonus pelamis, and penaied shrimps (Paiva 1997; Valentini & Pezzuto, 2006).

There is increasing expansion and importance of the oceanic fisheries in Brazil,

particularly for tuna (FAO 2005a). In 2002, 23,128 tonnes of skipjack and 3,116 tonnes of

yellowfin tuna were landed (IBAMA 2002). Deep fisheries initiated in the late 1990s

including serranids, Aristaid shrimps, crabs and monkfish have shown unsustainable

(MMA 2006).

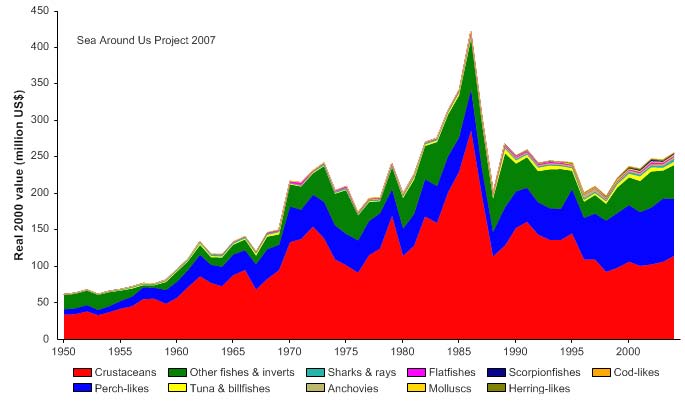

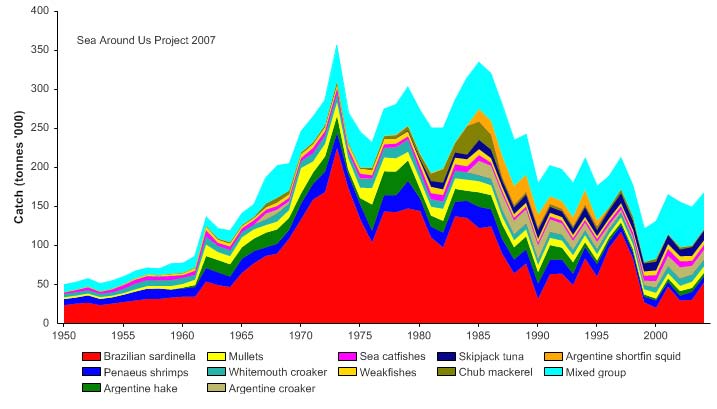

Total reported landings showed an increase up to the early 1970s, when landings peaked

at 356,000 tonnes, but have since declined to 160,000 tonnes in 2004 (Figure XVI-54.2).

Historically, catches have been dominated by the Brazilian sardinella (Sardinella

brasiliensis). Overexploitation as well as oceanographic anomalies are believed to have

accounted for the fluctuations of the sardine and anchovy fisheries in this LME (Bakun &

Parrish 1991, Paiva 1997, Matsuura 1998). Some recent changes in fishing strategies

and their ecosystem effect has been investigated by Gasalla & Rossi-Wongtschowski

(2004).The value of the reported landings reached nearly US$600 million (in 2000 US

dollars) in 1986, with crustaceans accounting for a significant fraction (Figure XVI-54.3).

726

54. South Brazil Shelf LME

Figure XVI-54.4. Total reported landings in the South Brazil Shelf LME by species (Sea Around Us 2007).

Note: Argentine shortfin squid and Whitemouth croaker trends are being reviewed.

Figure XVI-54.5. Value of reported landings in the South Brazil Shelf LME by commercial groups (Sea

Around Us 2007).

The primary production required (PPR; Pauly & Christensen 1995) to sustain the reported

landings in this LME reached 8% of the observed primary production in the mid 1980s,

and has fluctuated between 4 to 6% in recent years (Figure XVI-54.6). However,

Vasconcellos and Gasalla (2001) estimated that fisheries utilize 27 and 53% of total

primary production in the southern most shelf and in South Brazil Bight regions,

respectively. Brazil seems to account for almost all of the ecological footprint on this

LME, with very small fisheries by foreign fleets.

XVI Southwest Atlantic

727

Figure XVI-54.6. Primary production required to support reported landings (i.e., ecological footprint) as

fraction of the observed primary production in the South Brazil Shelf LME (Sea Around Us 2007). The

`Maximum fraction' denotes the mean of the 5 highest values.

Both the mean tropic level of the reported landings (i.e., the MTI, Pauly & Watson 2005;

Figure XVI-54.7 top) as well as the FiB index (Figure XVI-54.7 bottom) show an increase

from the late 1950s, somehow consistent with what was previously found by

Vasconcellos and Gasalla (2001). This pattern is indicative of the geographical expansion

of the fisheries, the collapse of the sardine fishery and an increase of offshore fishing for

higher trophic levels in the LME (Vasconcellos and Gasalla, 2001).

Figure XVI-54.7. Mean trophic level (i.e., Marine Trophic Index) (top) and Fishing-in-Balance Index

(bottom) in the South Brazil Shelf LME (Sea Around Us 2007).

The Stock-Catch Status Plots indicate that about 80% of commercially exploited stocks in

the LME are either overexploited or have collapsed (Figure XVI-54.8 top) with only 20%

of the reported landings biomass supplied by fully exploited stocks (Figure XVI-54.8,

bottom).

728

54. South Brazil Shelf LME

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

0%

100

10%

90

20%

)

80

%

(

s

30%

u

70

at

st

40%

y

60

b

ks

50%

c

o

50

f

st

60%

40

r

o

e

b

70%

m

30

u

N

80%

20

90%

10

100%0

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

(n = 3556)

developing

fully exploited

over-exploited

collapsed

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

0%

100

10%

90

20%

80

)

30%

(

%

70

s

u

at

40%

60

ck st

50%

o

50

st

y

60%

b

h

40

c

70%

Cat

30

80%

20

90%

10

100%0

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

(n = 3556)

developing

fully exploited

over-exploited

collapsed

Figure XVI-54.6. Stock-Catch Status Plots for the South Brazil Shelf LME, showing the proportion of

developing (green), fully exploited (yellow), overexploited (orange) and collapsed (purple) fisheries by

number of stocks (top) and by catch biomass (bottom) from 1950 to 2004. Note that (n), the number of

`stocks', i.e., individual landings time series, only include taxonomic entities at species, genus or family

level, i.e., higher and pooled groups have been excluded (see Pauly et al, this vol. for definitions).

Overexploitation of fisheries, excessive bycatch and discards and destructive fishing

practices were found to be severe, particularly for the inshore fisheries (UNEP 2004). In

some coastal areas, the stocks have been particularly overfished. For example, fish

stocks in Sepetiba Bay have declined by 20% during the last decade (Lacerda et al.

2002). In the mangrove areas of Babitonga Bay, crab, shrimp and mollusc have also

been overexploited (UNEP 2004). Recently, national evaluations showed that this LME

is the Brazil's most impacted by overfishing, with 55% of fishery resources been

overexploited and 29%, totally exploited (MMA, 2006). On the other hand, the oceanic