XV WIDER CARIBBEAN

XV-49 Caribbean Sea LME

XV-50 Gulf of Mexico LME

XV-51 Southeast U.S. Continental

Shelf

LME

656

XV Wider Caribbean

XV Wider Caribbean

657

XV-49 Caribbean Sea LME

S. Heileman and R. Mahon

The Caribbean Sea LME is a tropical sea bounded by North America (South Florida),

Central and South America and the Antilles chain of islands. The LME has a surface

area of about 3.3 million km2, of which 3.89% is protected, and contains 7.09% and

1.35% of the world's coral reefs and sea mounts, respectively (Sea Around Us 2007).

The average depth is 2,200 m, with the deepest part, the Cayman Trench, at 7,100 m.

Most of the Caribbean islands are influenced by the nutrient-poor North Equatorial

Current that enters the Caribbean Sea through the passages between the Lesser

Antilles. A significant amount of water is transported northwestward by the Caribbean

Current through the Caribbean Sea and into the Gulf of Mexico, via the Yucatan Current.

Run-off from two of the largest river systems in the world, the Amazon and the Orinoco,

as well as numerous other large rivers dominates the north coast of South America

(Müller-Karger 1993). A book chapter and reports pertaining to this LME have been

published by Richards & Bohnsack (1990) and UNEP (2004a, 2004b, 2006).

I. Productivity

The Caribbean Sea LME can be considered a Class II, moderate productivity ecosystem

(150-300 gCm-2yr-1). There is considerable spatial and seasonal heterogeneity in

productivity throughout the region. Areas of high productivity include the plumes of

continental rivers, localised upwelling areas and nearshore habitats such as coral reefs,

mangroves and seagrass beds. Relatively high productivity occurs off the northern coast

of South America where nutrient input from rivers, estuaries and wind-induced upwelling

is greatest (Richards & Bohnsack 1990). The remaining area of the LME is mostly

comprised of clear, nutrient-poor waters.

The Wider Caribbean Region is a biogeographically distinct area of coral reef

development within which the majority of corals and coral reef-associated species are

endemic (Spalding et al. 2001, Wilkinson 2002), making the entire region particularly

important in terms of global biodiversity. Among the LME's coral reefs is the Meso-

American Barrier Reef, the second largest barrier coral reef in the world. There have

been yearly migrations of marine mammals such as the humpback, sperm and killer

whales. Manatees not as common as they once were along many of the river mouths.

Sea turtles, such as hawksbill, green and leatherback nest on beaches within this LME.

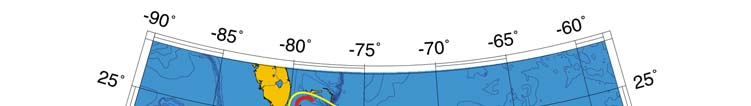

Oceanic Fronts (Belkin et al. 2008)( Figure XV-49.1): In the southern Caribbean Sea,

fronts are generated by coastal wind-induced upwelling off Venezuela and Colombia at

75°-78°W, 70°-75°W, and 62°-66°W. A 100-km-long front dissects the Gulf of Venezuela

along 70°40'W, likely caused by the brackish outflow from Lake Maracaibo combined with

coastal upwelling. Two shelf-break fronts off Cuba encompass two relatively wide shelf

areas off the southern Cuban coast, east of Isla de la Juventad (83°W) and along the

Jardines de la Reina island chain (79°-80°W), both best developed in winter. The

Windward Passage Front between Cuba and Hispaniola (73°W) separates the westward

Atlantic inflow waters moving into the Caribbean in the western part of the passage from

the Caribbean outflow waters heading eastward in the eastern part of the passage. A

200-km-long front in the Gulf of Honduras peaks in winter, likely related to a salinity

differential between the Gulf's apex and offshore waters caused by high precipitation in

southern Belize (Heyman & Kjerfve 1999).

658

49. Caribbean Sea LME

Figure XV-49.1. Fronts of the Caribbean Sea LME. Acronyms: BF, Belize Front; DOM.REP., Dominican

Republic; EVF, East Venezuela Front; GVF, Gulf of Venezuela Front; IGBBF, Inner Great Bahama Bank

Front; JHF, Jamaica-Haiti Front; NCF, North Colombia Front; OGBBF, Outer Great Bahama Bank

Front; PR, Puerto Rico (U.S.); SECF, Southeast Cuba Front; SJF, South Jamaica Front; SWCF,

Southwest Cuba Front; WPF, Windward Passage Front; WVF, West Venezuela Front. Yellow line, LME

boundary. After Belkin et al. (2008).

Caribbean Sea LME SST (Belkin 2008)(Figure XV-49.2):

Linear SST trend since 1957: 0.03°C.

Linear SST trend since 1982: 0.50°C.

The Caribbean Sea went through three phases over the last 50 years: (1) cooling until

1974; (2) cold phase with two cold spells of 1974-1976 and 1984-1986; (3) warming since

1986. Using the year of 1985 as a true breakpoint, the post-1985 warming amounted to

>0.6°C over the last 20 years. Both cold spells were synchronous with cold events

across the Central American Isthmus, in the Central American Pacific LME. The first

cooling period was interrupted by a major warm event (peak) of 1968-1970, when SST

reached its all-time maximum of 28.2°C in 1969. This event was confined to the

Caribbean Sea. None of the adjacent LMEs experienced a pronounced warming in

1968-1970. If the warm event of 1968-1970 cannot be explained by anomalous

atmospheric conditions, the reason should be in the open ocean east of the Caribbean

Sea, in the trade winds zone, where the Canary Current LME experienced a warm event

that peaked in 1969.

Virtually all significant maxima and minima of SST in the Caribbean Sea correlate

strongly with El Niños and La Niñas respectively (National Weather Service/Climate

Prediction Center 2007). This strong correlation is a good example of atmospheric

teleconnections across the Central American Isthmus. This link is so strong that El

Niños' and La Niñas' effects in the Caribbean Sea have comparable magnitudes with

their counterparts in the Pacific Central-American Coastal LME on the other side of the

Isthmus.

XV Wider Caribbean

659

Figure XV-49.2. Caribbean Sea LME annual mean SST (left) and SST anomalies (right), 1957-2006,

based on Hadley climatology. After Belkin (2008).

Caribbean Sea LME Chlorophyll and Primary Productivity

The Caribbean Sea LME is a Class II, moderate productivity ecosystem (150-300 gCm-

2yr-1)(Figure XV-49.3).

Figure XV-49.3. Caribbean Sea LME trends in chlorophyll a (left) and primary productivity (right), 1998

2006, from satellite ocean colour imagery. Values are colour coded to the right hand ordinate. Figure

courtesy of J. O'Reilly and K. Hyde. Sources discussed p. 15 this volume.

II. Fish and Fisheries

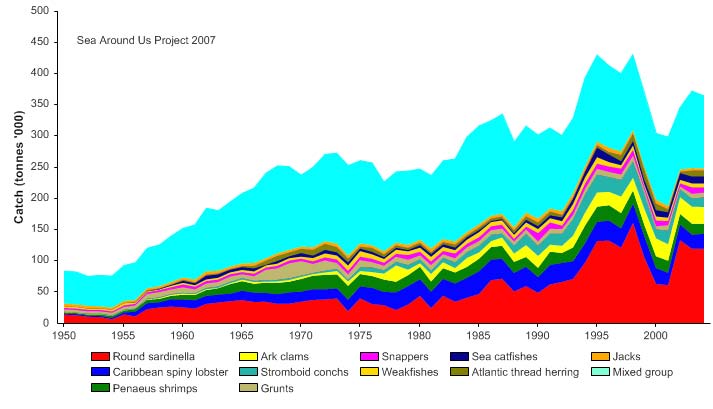

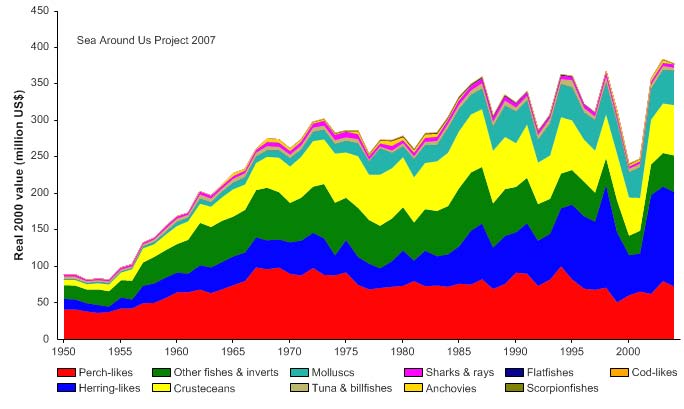

The fisheries of the Caribbean Sea LME are based on a diverse array of resources

(Mahon 2002). Those of greatest importance are spiny lobster (Panulirus argus), queen

conch (Strombus gigas), penaeid shrimps, reef fish, continental shelf demersal fish, deep

slope and bank fish and large coastal pelagics such as king mackerel (Scomberomorus

cavalla), Spanish mackerel (S. maculatus), dolphinfish (Coryphaena hippurus) and

amberjack (Seriola spp.). In addition, fisheries based on stocks of large oceanic fish

such as yellowfin tuna, skipjack tuna, Atlantic blue marlin and swordfish, several of which

have been considered underexploited, have expanded considerably in recent years

(Chakalall & Cochrane 2004). All of the large pelagic stocks are transboundary or Highly

Migratory Species (HMS) and Straddling Stocks (SS), moving in and out of all or most of

the EEZs and extending into the High Seas (Mahon 2003, Die 2004). The distribution of

the large coastal pelagics, which occur largely within the EEZs of Caribbean countries,

660

49. Caribbean Sea LME

also extends into the High Seas (Mahon 2003). The fishery resources are mostly coastal

and intensively exploited by large numbers of small-scale fishers using a variety of gears,

while foreign fleets from distant water fishing nations are known to exploit the region's

High Seas fisheries (Singh-Renton & Mahon 1996). Caribbean countries are often

perceived to be fishing for HMS & SS on the High Seas when they flag foreign vessels on

their open registries (Mahon 2003). This has resulted in problems for several countries of

the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) and there are attempts to eliminate this practice

(FAO 2002). Recreational fishing is an important activity in some of the countries,

particularly for large pelagic fishes (Mahon 2004). Developments in fishing technology,

as well as growing demands for fish have resulted in increasing pressure on the LME's

fish stocks. Additionally, government initiatives have led to substantial increases in

fishing effort, despite the inadequate institutional capacity to manage and monitor the

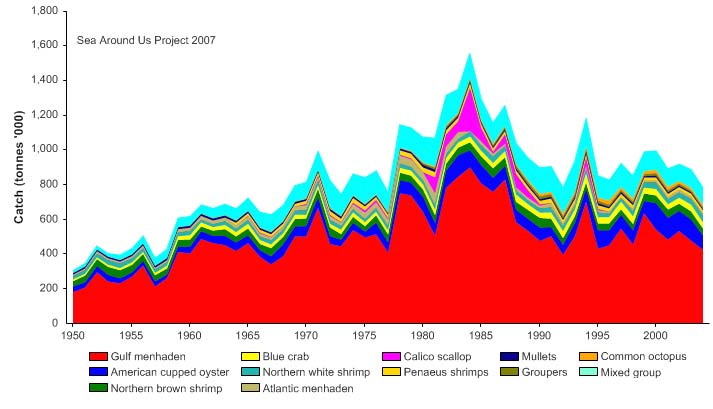

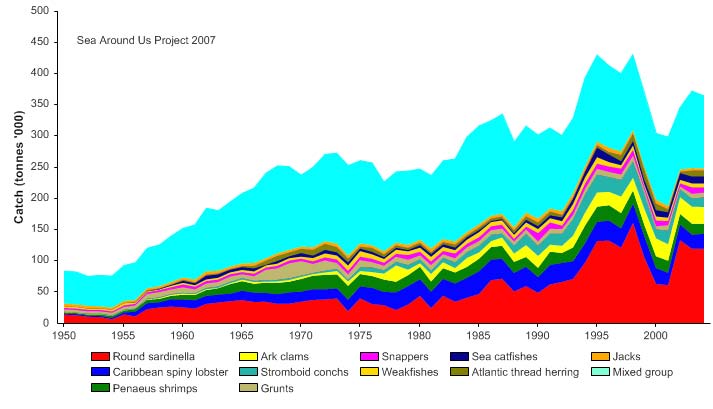

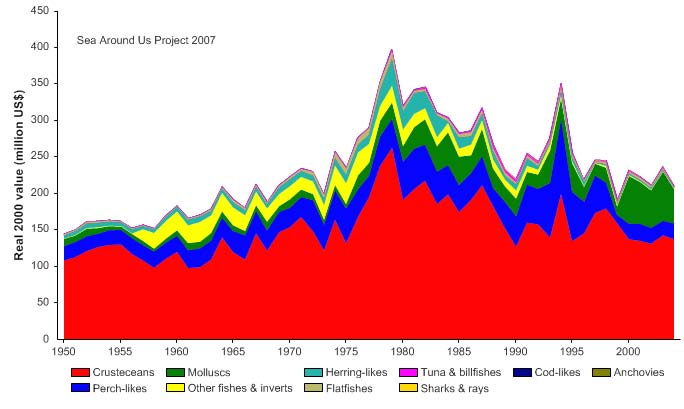

fishing industry. Total reported landings in this LME, which are probably underestimated

(see e.g., contributions in Zeller et al. 2003) showed a general increase to about 430,000

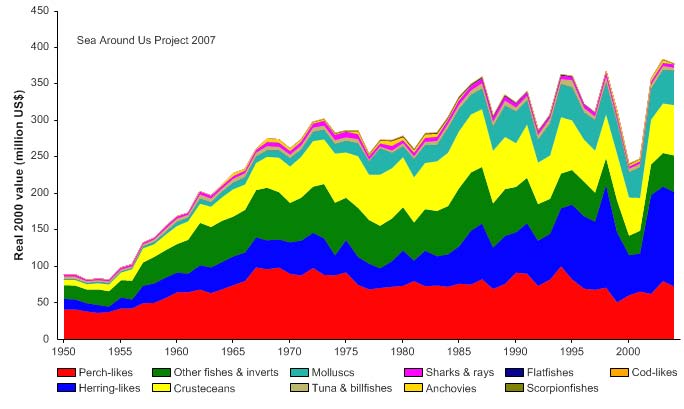

tonnes in the mid-1990s, followed by a slight decline (Figure XV-49.4). In the mid 1990s,

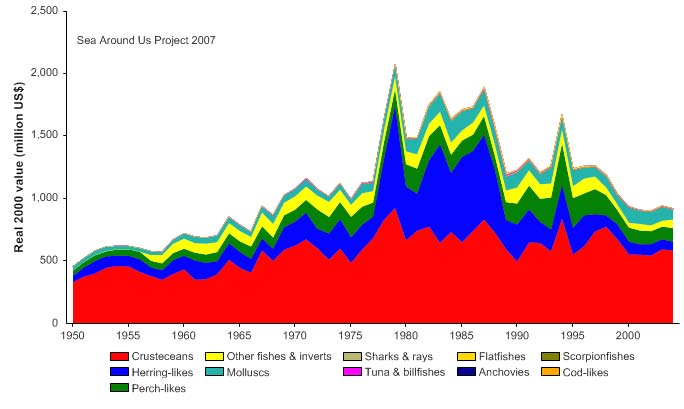

the reported landings were valued at over US$360,000 (in 2000 US dollars; Figure XV-

49.5).

Figure XV-49.4. Total reported landings in the Caribbean Sea LME by species (Sea Around Us 2007).

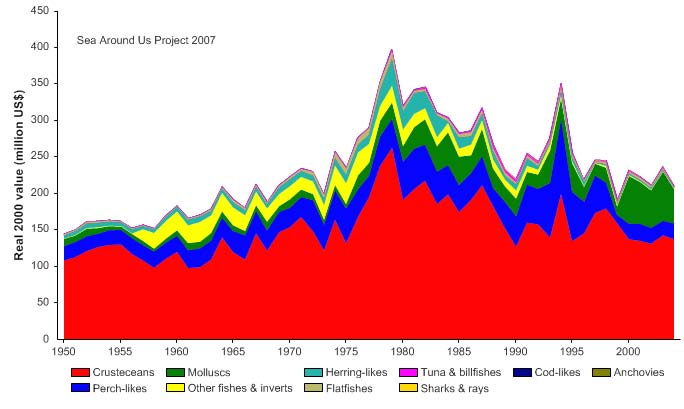

Figure XV-49.5. Value of reported landings in the Caribbean Sea LME by commercial groups (Sea

Around Us 2007).

XV Wider Caribbean

661

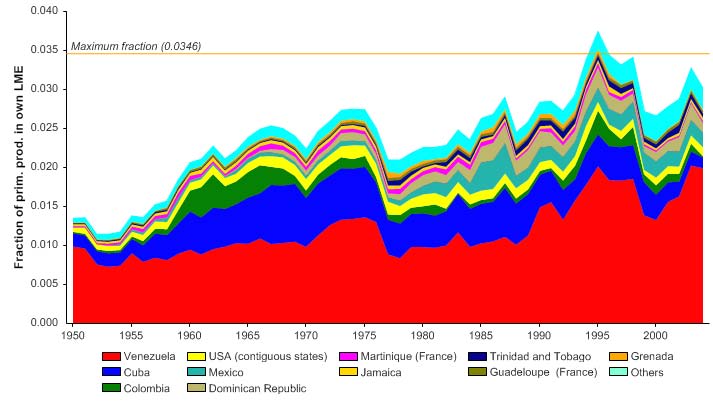

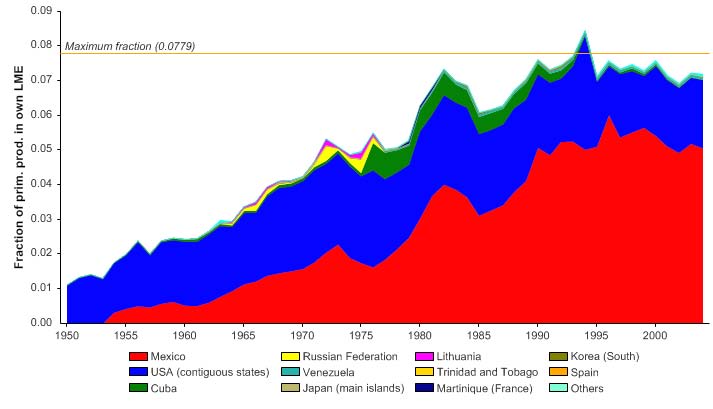

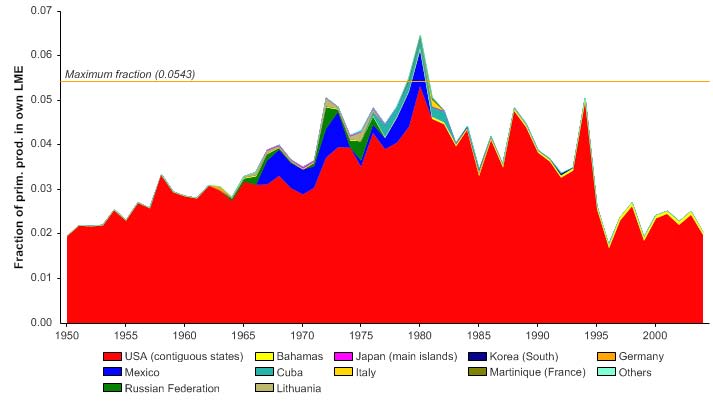

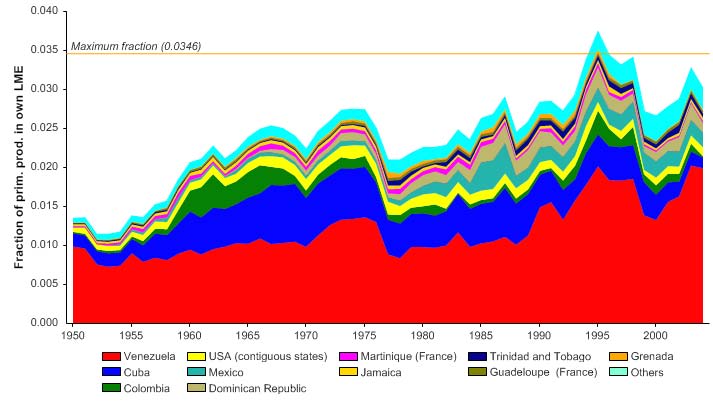

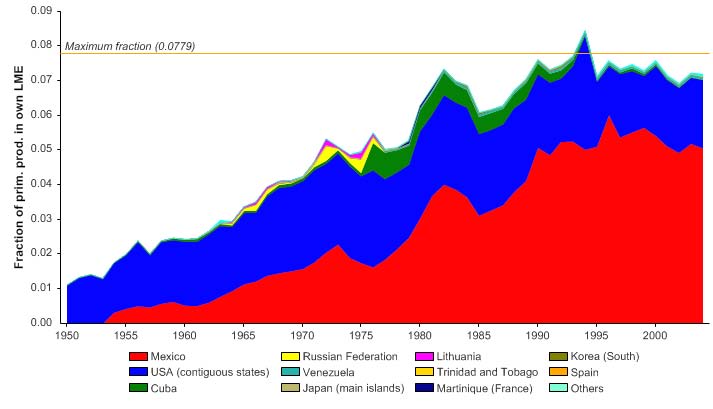

The primary production required (PPR; Pauly & Christensen 1995) to sustain the reported

landings in the LME reached 3% of the observed primary production in 1994 and have

fluctuated between 2.5 to 3% in recent years (Figure XV-49.6). Venezuela accounts for

the largest share of the ecological footprint in this LME.

Figure XV-49.6. Primary production required to support reported landings (i.e., ecological footprint) as

fraction of the observed primary production in the Caribbean Sea LME (Sea Around Us 2007). The

`Maximum fraction' denotes the mean of the 5 highest values.

The decline of the mean trophic level of the reported landings (i.e., the MTI, Pauly &

Watson 2005) is almost linear over the reported period (Figure XV-49.7, top),

representing a classic case of a `fishing down' of the food web in the LME (Pauly et al.

1998). This confirms Pauly & Palomares (2005), who performed a preliminary analysis of

MTI in this region. Indeed, the decline in the mean trophic level would have been greater

were it not for the expansion of the fisheries from the mid 1950 to the mid 1980s as

implied by the increasing FiB index (Figure XV-49.7, bottom).

Figure XV-49.7. Mean trophic level (i.e., Marine Trophic Index) (top) and Fishing-in-Balance Index

(bottom) in the Caribbean Sea LME (Sea Around Us 2007).

662

49. Caribbean Sea LME

The Stock-Catch Status Plots indicate that nearly 80% of the commercially exploited

stocks in the LME are either overexploited or have collapsed (Figure XV-49.8, top) and

these stocks now contribute 60% of the reported landings (Figure XV-49.8, bottom).

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

0%

100

10%

90

20%

)

80

%

(

s

30%

u

70

at

st

40%

y

60

b

50%

cks

o

50

f

st

60%

o

40

er

b

70%

m

30

u

N

80%

20

90%

10

100%0

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

(n = 5582)

developing

fully exploited

over-exploited

collapsed

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

0%

100

10%

90

20%

80

)

30%

(

%

70

t

us

40%

t

a

60

s

k

c

50%

t

o

50

s

60%

h by

40

t

c

a

70%

C

30

80%

20

90%

10

100%0

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

(n = 5582)

developing

fully exploited

over-exploited

collapsed

Figure XV-49.8. Stock-Catch Status Plots for the Caribbean Sea LME, showing the proportion of

developing (green), fully exploited (yellow), overexploited (orange) and collapsed (purple) fisheries by

number of stocks (top) and by catch biomass (bottom) from 1950 to 2004. Note that (n), the number of

`stocks', i.e., individual landings time series, only include taxonomic entities at species, genus or family

level, i.e., higher and pooled groups have been excluded (see Pauly et al,, this volume, for definitions).

Overexploitation was found to be severe throughout the Caribbean Sea LME (UNEP

2004a, 2004b, 2006). Most coastal resources are considered to be fully or overexploited

and there is increasing evidence that pelagic predator biomass has been depleted

(Mahon 2002, Myers & Worm 2003). Many local fisheries had collapsed by the mid-

1980s following the depletion of lobster, conch and finfish stocks (UNEP 2000).

Overfishing, particularly of herbivorous species, has been identified as a key-controlling

agent on Caribbean reefs leading to shifts in species dominance (Aronson & Precht

2000, Eakin et al. 1997; Hughes, T.P. 1994).

There is concern over the long-term sustainability of spiny lobster stocks due to an

increase in fishing effort for this species. Furthermore, the minimum legal size of lobsters

is well below the size of reproductive maturity in some areas (Richards & Bohnsack

1990). The conch fishery has collapsed in many areas and it is unlikely that conch

catches can be sustained (Richards & Bohnsack 1990, Smith et al. 2000). Several

species of sea turtles are threatened or endangered in many areas as a result of

overexploitation (FAO 1997). Overfishing and reduced abundance of large-sized

carnivorous reef fish such as snappers (Lutjanus spp.) and groupers (Epinephelus spp.)

have been observed in several locations throughout the LME (e.g., Manickchand-

Heileman and Phillip 1999, Charuau et al. 2001, Kramer 2003). Regardless of location,

XV Wider Caribbean

663

legal designation or local fishing regulations, these species have been overexploited in

the entire Western Atlantic region (Ginsberg & Lang 2003). The sustainability of the

groundfish fisheries in the southern Caribbean is also of concern in countries such as

Venezuela and Trinidad and Tobago (Booth et al. 2001). These stocks have experienced

high fishing pressure, particularly from trawlers. In the Gulf of Paria (between Trinidad

and Venezuela), intense pressure from bottom trawling is thought to have contributed to

a reduction in the abundance of species at higher trophic levels and the predominance of

low trophic-level species (Manickchand-Heileman et al. 2004).

There is a clear trend of increasing landings of large pelagic fishes, both coastal and

HMS and SS, by Caribbean countries. This indicates that these fisheries are expanding

steadily, despite the absence of any indication of the levels that may be sustainable

(Mahon 2003). In fact, some of these HMS and SS are already considered to be

overfished, based on assessments carried out by the International Commission for the

Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT) (Die 2004). These include the Atlantic swordfish

(ICCAT 2001a) and Atlantic blue marlin and white marlin (ICCAT 2001b). As a result of

both management interventions and high recruitment levels in recent years, the swordfish

stock has been slowly recovering (ICCAT 1999). The Atlantic yellowfin tuna stock is

considered to be fully fished (ICCAT 2001a) but there is concern that the tendency for

fishing effort to increase will ultimately result in overfishing of this species (ICCAT 2001a).

The abundance of Western Atlantic sailfish fell dramatically in the 1960s and has not

increased much since. Current catches seem sustainable, but it is not known how far the

current levels are from maximum sustainable yield (ICCAT 2001b).

The quantity of bycatch and discards in the Caribbean Sea LME is significant, with

bottom trawling for shrimp producing the greatest quantity of bycatch (UNEP/CEP 1996).

Immature individuals of commercially important species generally dominate the shrimp

bycatch. Moreover, the bycatch species composition has changed over the years and

several species have practically disappeared, indicating a dramatic shrinking of their

populations, notably in the case of sharks (Charlier 2001). Considerable quantities of

bycatch, which includes sharks and large coastal pelagics, are also taken in the longline

and other High Seas fisheries (Mahon 2003).

Destructive fishing practices such as dynamite and poison fishing are also contributing to

the decline of some fish species throughout the region (Garzón-Ferreira et al. 2000).

There is a lack of monitoring and enforcement to prevent these illegal practices, except

for coast-watching by communities and coast guards.

Overfishing could have significant transboundary implications in the Caribbean Sea LME.

In addition to the large migratory pelagic fishes, reef organisms, lobster, conch and small

coastal pelagics are also likely to be shared resources by virtue of planktonic larval

dispersal. In many species, larval dispersal lasts for many weeks or months, resulting in

transport across EEZ boundaries (Richards & Bohnsack 1990). Therefore, even these

coastal resources have an important transboundary component to their management.

Therefore, fisheries management should be based on the status of the stock evaluated at

the scale of the entire stock (Die 2004).

III. Pollution and Ecosystem Health

Pollution: Pollution of marine and coastal areas of the Caribbean Sea LME is a major

and recurrent transboundary environmental issue in the region. Land-based pollution

and physical alteration and destruction of habitats are among the major threats to the

coastal and marine environments of the Caribbean Small Island Developing States

(SIDS) (Heileman & Corbin 2006). In addition to land-based sources of pollution, the

discharge of solid waste, wastewater and bilge water from both commercial and cruise

664

49. Caribbean Sea LME

ships as well as other offshore sources are of increasing concern (CAR/RCU 2000,

GEF/CEHI/CARICOM/UNEP 2001). Pollution is moderate in general and severe in some

coastal hotspots particularly around the large cities, especially in the Central

America/Mexico sub-region (UNEP 2004a, 2004b, 2006). The entire Caribbean Sea may

be considered a hotspot in terms of risks from shipping and threats to coral reefs

(Heileman & Corbin 2006).

Sewage is one of the most significant pollutants affecting the coastal environments of the

Wider Caribbean Region (CAR/RCU 2000). Rapid population growth, urbanisation and

the increasing number of ships and recreational vessels have resulted in the discharge of

increasing amounts of poorly treated or untreated sewage into the coastal waters

(CAR/RCU 2000). Of even greater concern are the high bacterial counts that have been

detected in some areas, including in bays where there is a large concentration of boats

and berthing facilities. In addition to microbiological contamination, the input of sewage

contributes high levels of nutrients to coastal areas. This, as well as inputs of fertilisers

from agricultural run-off, have promoted hotspots of eutrophication as well as harmful

algal blooms in some localised areas throughout the region (UNEP 2004a, 2004b). The

estimated nutrient load from land-based sources is 130,000 tonnes nitrogen yr-1 and

58,000 tonnes phosphorus yr-1 (UNEP 2000). Discharges of suspended and dissolved

solids have intensified through human activities, such as deforestation, urbanisation and

agriculture. The region's rivers supply about 300 million tonnes suspended solids per

year to the Greater Caribbean Region (PNUMA 1999). High turbidity and sedimentation

have reduced biodiversity in shallow coastal waters throughout the region (UNEP 2000).

Of growing concern is the increasing amount of solid waste generated within the

Caribbean countries. Because of inadequate collection and disposal facilities, much of

this material eventually ends up on beaches and other coastal areas. About 70-80% of

marine debris originates from the intense shipping traffic, especially cruise ships and oil

tankers that cause an important transboundary movement of marine debris and tar balls

(UNEP 2004a, 2004b). In addition to reducing the aesthetic value of the coastal areas,

solid waste such as plastics are of considerable threat to marine fauna such as turtles,

marine mammals and sea birds.

Chemical contamination from industrial and agricultural activities is severe in some

localised areas (UNEP 2004a, 2004b). For example, pollution by copper, lead and zinc

was found in water and sediments in Cuba, the Dominican Republic and Jamaica

(GEF/UNDP/UNEP 1998). Coastal areas near to oil installations show significant heavy

metal concentrations in sediments, for example, the Santo Domingo coastal zone and

Havana Bay (GEF/UNDP/UNEP 1998, Beltrán et al. 2001). Chemical pollution is severe

in some coastal areas of Central America, which has the highest use of pesticides per

capita and which is expected to increase in the future.

One of the biggest potential threats to the Caribbean Sea LME is that of oil spills.

Because of their petroleum-based industry, countries such as Trinidad, Tobago and

Venezuela continue to have a higher risk of oil spills within their marine environments.

Large volumes of hydrocarbons are discharged from tankers and private vessels in the

region. More than one third of oil spilled at sea between 1983 and 1999 was caused by

accidents at ports and oil installations located in the coastal zone (UNEP 2000).

Thousands of large vessels, including those passing through the Panama Canal,

transport nuclear and other hazardous materials through the Caribbean Sea annually,

which increases the threat of spills of these materials.

Habitat and community modification: The coastal areas of the Caribbean Sea LME

are comprised of habitats such as mangrove wetlands, seagrass beds and coral reefs,

XV Wider Caribbean

665

which dominate the land-sea margin and harbour high biological diversity. These

habitats, however, are being impacted by a range of anthropogenic activities that have

resulted in severe habitat and community modification, particularly around the smaller

islands and along the mainland coast (UNEP 2004a, 2004b, 2006).

Signs of stress are particularly evident in the shallow-water coral reef habitats (Richards

& Bohnsack 1990). Major threats to coral reefs are linked to overexploitation of reef fish

communities, sewage, industrial and agricultural pollution, as well as tourism and

sedimentation (Bryant et al. 1998, Garzón-Ferreira et al. 2000) and global warming.

Recent studies have revealed a trend of serious and continuing long-term decline in the

health of Caribbean coral reefs (Wilkinson 2002, Gardner et al. 2003, Lang 2003,

Wilkinson and Souter 2005). About 30% of Caribbean reefs are now considered to be

either destroyed or at extreme risk from anthropogenic threats (Wilkinson 2000). More

was lost in the 2005 bleaching event (Wilkinson and Souter 2008). Another 20% or more

are expected to be lost over the next 10-30 years if significant action is not taken to

manage and protect them over and beyond existing activities. Dramatic changes in the

community structure of coral reefs have taken place over the past two decades. Prior to

the 1980s, scleractinian (stony) corals dominated Caribbean coral reefs and the

abundance of macroalgae was low. Over the past two decades a combination of

anthropogenic and natural stressors has caused a reduction in the abundance of hard

corals and an increase in macroalgae cover (Richards & Bohnsack 1990, Kramer 2003).

This has been exacerbated by the mass mortality of an important algal grazer, the sea

urchin Diadema sp., in 1983 (Lessios et al. 2001). The worldwide mass coral bleaching

events of 1997-1998 resulting from elevated sea surface temperatures affected coral

reefs in almost the entire Wider Caribbean region (Hoegh-Guldberg 1999), where

bleaching continued until the severe event of 2005. The impact of the bleaching events

varied across the Wider Caribbean, with the Meso-American Barrier Reef sustaining

severe damage.

Hurricanes have also impacted coral reefs in localised areas, for example, in Mexico and

Belize, with varying degree of recovery (Gardner et al. 2005). A range of diseases has

also affected Caribbean coral reefs, starting with black band disease in the early 1970s

followed by white band disease in the late 1970s. Diseases of stony corals and

gorgonians have been reported with increasing frequency (Woodley et al. 2000).

The major threats to the region's mangroves include coastal development and charcoal

production. Many islands have reported deforestation of mangroves for fuel wood, often

by squatters (GEF/CEHI/CARICOM/UNEP 2001). Between 1990 and 2000, 21 out of

26 countries showed decreasing mangrove cover, with annual rates of decline ranging

from 0.3% in the Bahamas to 3.8% in Barbados (FAO 2003). Clearing of mangrove

forests has made the coast more vulnerable to erosion and destroyed the habitat of many

species (UNEP/CEP 1996). Sandy foreshores have also been severely destroyed and

modified due to sand mining and poorly-devised shoreline protection structures (BEST

2002). Seagrass beds in some areas are affected by chronic sedimentation. Habitat

destruction and alteration is significantly impacting the LME's biodiversity. For example,

the population of the West Indian manatee has dramatically declined because of

degradation of essential habitats and because they have been hunted (UNEP/CEP

1995).

Recognising the importance of the Caribbean Sea LME and its resources to economic

development and human well-being, the countries are embarking on numerous

programmes and activities to address the degradation of the marine environment. As a

result, some improvements in the health of this LME are expected in the coming decades

(UNEP 2004a, 2004b).

666

49. Caribbean Sea LME

IV. Socioeconomic Conditions

The Caribbean Sea LME is bordered by 38 countries and dependent territories of the

U.S., France, U.K. and the Netherlands. Sixteen of the independent states and the

14 dependent territories are Small Island Developing States (SIDS). The population of

the Caribbean Sea region is approximately 107 million, with the majority inhabiting the

coastal zones. In addition, each year the population increases considerably due to the

influx of large numbers of tourists during the tourist season. The Caribbean countries,

especially the SIDS, are highly dependent on the marine environment for their economic,

nutritional and cultural well-being. There is a high dependence of the economies of the

islands on tourism, with revenues from tourism ranging between 15 to 99% of total

exports in 90% of the islands (CIA 2005). Marine fisheries also play an important social

and economic role, and are an important source of protein, employment and foreign

exchange earnings in many of the countries.

The socioeconomic impacts of overexploitation vary among the countries, but are

generally slight to moderate (UNEP 2004a, 2004b). The Lesser Antilles Islands suffer

the greatest socioeconomic impacts of overexploitation. Decreasing inshore resources,

increasing harvesting expenses and increasing demand have led to an increase in the

market prices of fish as well as conflicts between traditional and recreational fishers.

Reduced employment opportunities in the fisheries sector have forced fishers to seek

other sources of income. Declining fisheries resources also threaten the food security of

fishers and others who are dependent on fisheries resources.

The socioeconomic impacts of pollution are moderate to severe, particularly in the Lesser

Antilles and the Central American countries (UNEP 2004a, 2004b). Human health is

threatened and the propagation of disease vectors promoted by the discharge of non-

treated sewage and other contaminants (UNEP 2000). Where algal biomasses are

significantly elevated due to eutrophication, such as in nutrient/sewage-enriched areas,

the risk of disease and ciguatera poisoning is high (PNUMA 1999). Pollution has also

diminished the aesthetic value of some parts of the region resulting in a loss of revenue

from tourism (UNEP/CEP 1997).

The socioeconomic impacts of habitat modification range from slight to severe (UNEP

2004a, 2004b). The Caribbean islands are particularly affected by habitat degradation,

as are the Central American countries. The impacts include medium to long-term loss of

employment and income opportunities in the tourism sector, loss of recreational, cultural,

educational, scientific values as well as costs of restoration of modified ecosystems

(UNEP 2004a, 2004b). Habitats, such as mangroves and coral reefs, perform an

important role in coastal protection and stabilisation. Therefore, the destruction of these

coastal habitats has serious implications for the Caribbean Sea countries, particularly the

SIDS, in view of rising sea levels and an increase in the frequency and intensity of storms

and hurricanes (UNEP 2005).

V. Governance

With 38 countries and dependencies in the LME, the EEZs form a complete mosaic,

resulting in many transboundary resource management issues, even at relatively small

spatial scales. The need for countries of the Wider Caribbean to pay attention to the

management of transboundary marine resources is well documented (Mahon 1987, FAO

1997). The fisheries initiatives in the region are partly governed by international

frameworks such as UNCLOS, the UN Fish Stocks Agreement and the FAO Code of

Conduct for Responsible Fisheries. At the regional level, there are several initiatives for

the coordination of fisheries management (Mahon 2003). These are broad in scope,

XV Wider Caribbean

667

covering resources that range in distribution from coastal/national to HMS & SS. Among

them are the FAO Western Central Atlantic Fisheries Commission, the Latin American

Organisation for Fishery Development, CARICOM Regional Fisheries Mechanism, the

Caribbean Fisheries Management Council and the Intergovernmental Oceanic

Commission Sub-commission for the Caribbean (IOCARIBE). Operating at the

international level are ICCAT and the International Whaling Commission. In 2001, the

UN Fish Stocks Agreement that seeks to implement the provisions of UNCLOS related to

conservation and management of HMS & SS came into force.

Despite a recognised need, there is no Regional Fisheries Management Organisation for

the Wider Caribbean, including the Caribbean Sea LME, with a mandate to manage the

fisheries resources. The most established and operational fisheries management

organisation with relevance to the Caribbean Sea LME is ICCAT, which has the mandate

to manage all tuna and tuna-like species in the Atlantic. The coastal species are

perceived as being western Atlantic stocks that could be managed by the countries of the

Wider Caribbean, whereas the oceanic stocks require a level of collaboration that would

be best facilitated by an organisation such as ICCAT (Mahon 2003).

Regional programmes related to the marine environment include the UNEP's Regional

Seas Programme, the Caribbean Coastal Marine Productivity Programme and the

Caribbean Environment Programme (CEP), a sub-programme of UNEP's Regional Seas

Programme. The aim of CEP is to promote regional cooperation for the protection and

development of the marine environment of the Wider Caribbean Region. CEP, which is

facilitated by the Caribbean Regional Coordinating Unit located in Jamaica, is involved in

several regional projects and initiatives including the International Coral Reef Initiative

and its Action Network.

A number of marine environmental policy frameworks have been developed in the

Caribbean. These include the 1981 CEP Caribbean Action Plan and the Convention for

the Protection and Development of the Marine Environment in the Wider Caribbean

Region (the Cartagena Convention) and its three protocols (Protocol Concerning

Cooperation in Combating Oil Spills in the Wider Caribbean Region, Protocol Concerning

Specially Protected Areas and Wildlife in the Wider Caribbean Region, and Protocol

Concerning Marine Pollution from Land-Based Sources and Activities). In 1991, the

Marine Environment Protection Committee of the International Maritime Organisation

designated the Gulf of Mexico and the Wider Caribbean Region as a Special Area under

Annex V of the MARPOL Convention. An ongoing initiative to have the Caribbean Sea

internationally recognised as a special area in the context of sustainable development led

to the adoption in 2003 by the UN General Assembly of the resolution `Promoting an

integrated management approach to the Caribbean Sea area in the context of

sustainable development'.

GEF is supporting the project `Integrating Watershed and Coastal Area Management in

Small Island Developing States of the Caribbean'. The overall objective of this project is

to assist participating countries in improving their watershed and coastal zone

management practices. The project `Sustainable Management of the Shared Living

Marine Resources of the Caribbean Large Marine Ecosystem and Adjacent Regions' has

been developed by IOCARIBE and is being implemented. The goal of this project is the

sustainable management of the shared living marine resources of the LME and adjacent

areas through an integrated management approach. The project is focused on aligning

institutions on the national and regional scales to sustainably manage near shore and

deep-water fisheries and related habitats of the LME, including the development and use

of a knowledge base to support institutional decision-making. One of the objectives of

this project is the preparation of a Transboundary Diagnostic analysis (TDA) and

Strategic Action Plan (SAP) for the Caribbean Sea LME and Adjacent Regions.

668

49. Caribbean Sea LME

References

Aronson, R.B. and Precht, W.F. (2000). Herbivory and algal dynamics on the coral reef at

Discovery Bay, Jamaica. Limnology and Oceanography 45:251255.

Belkin, I.M. (2008) Rapid warming of Large Marine Ecosystems, Progress in Oceanography, in

press.

Belkin, I.M., Cornillon, P.C., and Sherman, K. (2008). Fronts in Large Marine Ecosystems of the

world's oceans. Progress in Oceanography, in press.

Beltrán, J., Martín, A., Ruiz, F., Regadera, R., Mancebo, H. and Ramírez, M. (2001). Control y

Evolución de la Calidad Ambiental de la Bahía de La Habana y el Litoral Adyacente. Informe

Final Vigilancia Ambiental para la Bahía de La Habana. Centro de Ingeniería y Manejo

Ambiental de Bahías y Costas (Cimab), Cuba.

BEST (2002). Bahamas Environmental Handbook. Bahamas Environment Science and Technology

Commission. The Government of the Bahamas. Nassau, New Providence.

Booth, A., Charuau, A., Cochrane, K., Die, D., Hackett, A., Lárez, A., Maison, D., Marcano, L.A.,

Phillips, T., Soomai, S., Souza, R., Wiggins, S. and IJspol, M. (2001). Regional Assessment of

the Brazil-Guianas Groundfish Fisheries. FAO Fisheries Report 651: 22-36.

Bryant, D., Burke, L., McManus, J.W. and Spalding, M. (1998). Reefs at Risk: A Map-based

Indicator of Threats to the World's Coral Reefs. World Resource Institute, Washington, D.C.,

U.S.

CAR/RCU (2000). An Overview of Land Based Sources of Marine Pollution. Caribbean

Environment Programme/Regional Coordinating Unit, Kingston, Jamaica. www.cep.unep.org

/issues/lbsp.html

Chakalall, B. and Cochrane, K. (2004). Issues in the management of large pelagic fisheries in

CARICOM countries, p 1-4 in: Mahon, R. and McConney, P. (eds), Management of Large

Pelagic Fisheries in CARICOM Countries. FAO Fisheries Technical Paper 464.

Charlier, P. (2001). Review of environmental considerations in management of the Brazil-Guianas

shrimp and groundfish fisheries. FAO Fisheries Report 651: 37-57.

Charuau, A., Cochrane, K., Die, D., Lárez, A., Marcano, L., Phillips, T., Soomai, S., Souza, R.,

Wiggins, S. and IJspol, M. (2001). Regional assessment of red snapper, Lutjanus purpureus.

FAO Fisheries Report 651: 15-21.

CIA (2005). World Factbook. www.cia.gov/cia/publications/factbook/

Die, D. (2004). Status and assessment of large pelagic resources, p 15-44 in: Mahon, R. and

McConney, P. (eds), Management of Large Pelagic Fisheries in CARICOM Countries. FAO

Fisheries Technical Paper 464.

Eakin, C.M., McManus, J.W., Spalding, M.D. and Jameson, S.C. (1997). Coral reef status around

the world: Where are we and where do we go from here? p 277-282 in: Lessios, H.A. and

MacIntyre, I.G., (eds), Proceedings of the 8th International Coral Reef Symposium, Smithsonian

Tropical Research Institute, Republic of Panama.

FAO (1997). Western Central Atlantic Fishery Commission Report of the Seventh Session of the

Working Party on Marine Fishery Resources, Belize City, Belize 2-5 December 1997. FAO

Fisheries Report 576.

FAO (2002). Preparation for Expansion of Domestic Fisheries for Large Pelagic Species by

CARICOM Countries. Large Pelagic Fisheries in CARICOM Countries: Assessment of the

Fisheries and Options for Management. FI: TCP/RLA/0070 Field Document 1.

FAO (2003). Report of the Fourth Session of the Advisory Committee on Fisheries Research

(ACFR). FAO Fisheries Report 699 (FIPL/R699).

Gardner, T.A., Côté, I.M., Gill, J.A., Grant, A. and Watkinson, A.R. (2003). Long-term region-wide

declines in Caribbean corals. Science 301: 958-960.

Gardner, T. A., I. M. Cote, J. A. Gill, A. Grant, and A. R. Watkinson. 2005. Hurricanes and

Caribbean coral reefs: Impacts, recovery patterns, and role in long-term decline. Ecology

86:174-184.

Garzón-Ferreira, J., Cortés, J., Croquer, A., Guzmán, H., Leao, Z. and Rodríguez-Ramírez, A.

(2000). Status of Coral reefs in Southern Tropical America: Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica,

Panamá and Venezuela, p 331-348 in: Wilkinson, C. (ed), Status of coral reefs of the world:

2000. Australian Institute of Marine Sciences, Townsville, Queensland, Australia.

XV Wider Caribbean

669

GEF/CEHI/CARICOM/UNEP (2001). Integrating Watershed and Coastal Area Management in

Small Island Developing States of the Caribbean. At www.cep.unep.org/programmes/

amep/GEF-IWCAM/GEF-IWCAM.htm

GEF/UNDP/UNEP (1998). Planning and Management of Heavily Contaminated Bays and Coastal

Areas in The Wider Caribbean. Regional Project RLA/93/G41. Final Report. Havana, Cuba.

Ginsberg, R.N. and Lang, J.C. (2003). Foreword, p xvxiv in: Lang, J. C. (ed), Status of Coral

Reefs in the Western Atlantic. Results of Initial Surveys, Atlantic and Gulf Rapid Reef

Assessment (AGRRA) Programme. Atoll Research Bulletin 496. National Museum of Natural

History, Smithsonian Institute, Washington, D.C., U.S.

Heileman, S. and Corbin, C. (2006). Caribbean SIDS, p. 213 245 in: UNEP/GPA (2006), The

State of the Marine Environment: Regional Assessments. UNEP/GPA, The Hague.

Heyman, W. D. and Kjerfve, B. (1999) Hydrological and oceanographic considerations for

integrated coastal zone management in southern Belize, Environmental Management 24(2):

229-245.

Hoegh-Guldberg, O. (1999). Climate Change, Coral Bleaching and the Future of the World's Coral

Reefs. Greenpeace International, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia.

Hughes, T.P. (1994) Catastrophes, phase shifts, and large-scale degradation of a Caribbean coral

reef. Science 265:1547-1551.

ICCAT (1999). International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tuna. Report for Biennial

Period, 19981999, Part 1. Madrid, Spain.

ICCAT (2001a). International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tuna. Report for Biennial

Period, 20002001, Part 1. Madrid, Spain.

ICCAT (2001b). International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tuna. Report of the

Fourth ICCAT Billfish Workshop. ICCAT Collective Volume of Scientific Papers 53:1-130.

Kramer, P. (2003). Synthesis of coral reef health indicators for the Western Atlantic: Results of the

AGGRA Programme (1997-2000), p 1-57 in Lang J.C. (ed), Status of Coral Reefs in the

Western Atlantic: Results of Initial Surveys, Atlantic and Gulf Rapid Reef Assessment (AGGRA)

Programme. Atoll Research Bulletin 496. National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian

Institute, Washington, DC, U.S.

Lang, J. C. (2003). Caveats for the AGGRA `Initial Results' Volume, p xvxx in: Lang, J. C. (ed),

Status of Coral Reefs in the Western Atlantic. Results of Initial Surveys, Atlantic and Gulf Rapid

Reef Assessment (AGRRA) Programme. Atoll Research Bulletin 496.

Lessios, H.A., Garrido, M.J. and Kessing, B.D. (2001). Demographic history of Diadema antillarum,

a keystone herbivore on Caribbean reefs. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, Series

B Biological Sciences 22; 268(1483):2347-2353.

Mahon, R. (2002). Living Aquatic Resource Management, p 143-218 in: Goodbody, I. and Thomas-

Hope, E. (eds), Natural Resource Management for Sustainable Development in the Caribbean.

Canoe Press, UWI, Kingston, Jamaica.

Mahon, R. (2003). Implementation of the Provisions of the UN Fish Stocks Agreement: Conditions

for Success The Case of the Wider Caribbean. IDDRA, Portsmouth, U.K.

Mahon, R. (2004). Harvest Sector, p 45-78, in: Mahon, R. and McConney, P. (eds), Management of

Large Pelagic Fisheries in CARICOM Countries. FAO Fisheries Technical Paper 464.

Mahon, R., ed. (1987). Report and Proceedings of the Expert Consultation on Shared Fishery

Resources of the Lesser Antilles Region. FAO Fisheries Report 383.

Manickchand-Heileman, S. and Phillip, D.A.T. (1999). Contribution to the biology of the vermilion

snapper Rhomboplites aurorubens in Trinidad and Tobago, West Indies. Environmental Biology

of Fishes 55:413-421.

Manickchand-Heileman, S., Mendoza, J., Lum Kong, A. and Arocha, F. (2004). A trophic model for

exploring possible ecosystem impacts of fishing in the Gulf of Paria, between Venezuela and

Trinidad. Ecological Modelling 172:307-322.

Müller-Karger, F.E. (1993). River Discharge Variability Including Satellite-observed Plume-dispersal

Patterns, p 162-192 in: Maul, G. (ed), Climate Change in the Intra-Americas Sea. United

Nations Environmental Programme (Wider Caribbean Region) and Intergovernmental

Oceanographic Commissions (Caribbean and Adjacent Regions).

Myers, R.A. and Worm, B. (2003). Rapid worldwide depletion of predatory fish communities. Nature

423:280-283.

National Weather Service/Climate Prediction Center (2007) Cold and warm episodes by seasons [3

month running mean of SST anomalies in the Niño 3.4 region (5oN-5oS, 120o-170oW)][based on

the 1971-2000 base period], www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/analysis_monitoring/

ensostuff/ensoyears.shtml

670

49. Caribbean Sea LME

Pauly, D. and Christensen, V. (1995). Primary production required to sustain global fisheries.

Nature 374: 255-257.

Pauly, D. and Palomares, M.L. (2005). Fishing down marine food webs: it is far more pervasive

than we thought. Bulletin of Marine Science 76(2): 197-211.

Pauly, D. and Watson, R. (2005). Background and interpretation of the `Marine Trophic Index' as a

measure of biodiversity. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society: Biological Sciences

360: 415-423.

Pauly, D., Christensen, V., Dalsgaard, J., Froese R. and Torres, F.C. Jr. (1998). Fishing Down

Marine Food Webs. Science 279: 860-863.

PNUMA (1999). Evaluación sobre las Fuentes Terrestres y Actividades que Afectan al Medio

Marino, Costero y de Aguas Dulces Asociadas en la Región del Gran Caribe. Informes y

Estudios del Programa de Mares Regionales del PNUMA 172. Oficina de Coordinación del

PAM, Programa Ambiental del Caribe.

Richards, W.J. and Bohnsack, J.A. (1990). The Caribbean Sea: A Large Marine Ecosystem in

crisis, p 44-53 in: Sherman, K., Alexander, L.M. and Gold, B.D. (eds), Large Marine

Ecosystems: Patterns, Processes and Yields. AAAS, Washington D.C., U.S.

Sea Around Us (2007). A Global Database on Marine Fisheries and Ecosystems. Fisheries Centre,

University British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada. www.seaaroundus.org/lme/

SummaryInfo.aspx?LME=12

Singh-Renton, S. and Mahon, R. (1996). Catch, Effort and CPUE Trends for Offshore Pelagic

Fisheries in and Adjacent to the Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) of Several CARICOM

States. CARICOM Fishery Report 1.

Smith, A.H., Archibald, M., Bailey, T., Bouchon, C., Brathwaite, A., Comacho, R., Goerge, S.,

Guiste, H., Hasting, M., James, P., Jeffrey-Appleton, C., De Meyer, K., Miller, A., Nurse, L.,

Petrovic, C. and Phillip, P. (2000). Status of the Coral Reefs in the Eastern Caribbean: The

OECS, Trinidad and Tobago, Barbados, the Netherlands Antilles and the French Caribbean, in:

Wilkinson, C. (ed), Status of Coral Reefs of the World 2000. Australian Institute of Marine

Science, Australia.

Spalding, M., Ravilious, C. and Green, E.P. (2001). World Atlas of Coral Reefs. United Nations

Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre, Cambridge, U.K.

UNEP (2000). Global Environment Outlook 2000. Earthscan Publications Ltd., London.

UNEP (2004a). Bernal, M.C., Londoño, L.M., Troncoso, W., Sierra- Correa, P.C. and Arias-Isaza,

F.A. Caribbean Sea/Small Islands, GIWA Regional Assessment 3a. University of Kalmar,

Kalmar, Sweden. http://www.giwa.net/publications/r3a.phtml

UNEP (2004b). Villasol, A. and Beltrán, J. Caribbean Islands, GIWA Regional Assessement 4.

Fortnam, M. and Blime P. (eds), University of Kalmar, Kalmar, Sweden.

http://www.giwa.net/publications/r4.phtml

UNEP (2005). Caribbean Environment Outlook. UNEP, Nairobi, Kenya.

UNEP (2006). Isaza, C.F.A., Sierra-Correa, P.C., Bernal-Velasquez, M., Londoño, L.M. and W.

Troncoso. Caribbean Sea/Colombia & Venezuela, Caribbean Sea/Central America & Mexico,

GIWA Regional assessment 3b, 3c. University of Kalmar, Kalmar, Sweden.

http://www.giwa.net/publications/r3bc.phtml

UNEP/CEP (1995). Regional Management Plan for the West Indian Manatee, Trichechus manatus.

CEP Technical Report 35. UNEP Caribbean Environment Programme, Kingston, Jamaica.

UNEP/CEP (1996). Directrices y Criterios Comunes para las Áreas Protegidas en la Región del

Gran Caribe. Identificación, Selección, Establecimiento y Gestión. Informe Técnico del PAC 37.

UNEP Caribbean Environment Programme, Kingston, Jamaica.

UNEP/CEP (1997). Coastal Tourism in the Wider Caribbean Region: Impacts and Best

Management Practices. CEP Technical Report 38, UNEP Caribbean Environment Programme,

Kingston, Jamaica.

Wilkinson, C., ed. (2000). Status of Coral Reefs of the World 2000. Australian Institute of Marine

Science, Australia.

Wilkinson, C., ed. (2002). Status of Coral Reefs of the World 2002. Australian Institute of Marine

Sciences, Townsville, Australia.

Wilkinson, C. L., and Souter, D.. (eds) 2008. Status of Caribbean coral reefs after bleaching and

hurricanes in 2005 Global Coral Reef Monitoring Network, and Reef and Rainforest Research

Centre, Townsville. Available at: http://www.coris.noaa.gov/activities/caribbean_rpt/

Wilkinson, C.L. and Souter, D. (eds) 2008. Status of Caribbean coral reefs after bleaching and

hurricanes in 2005 Global Coral Reef Monitoring Network, and Reef and Rainforest Research

Centre, Townsville.

XV Wider Caribbean

671

Woodley, J., Alcolado, P., Austin, T., Barnes, J., Claro-Madruga, R., Ebanks-Petrie, G., Estrada,

R., Geraldes, F., Glasspool, A., Homer, F., Luckhurst, B., Phillips, E., Shim, D., Smith, R.,

Sullivan-Sealy, K., Vega, M., Ward, J. and Wiener, J. (2000). Status of Coral Reefs in the

Northern Caribbean and Western Atlantic. In: Wilkinson, C. (ed), Status of Coral Reefs of the

World 2000. Australian Institute of Marine Science, Townsville, Australia.

Zeller D., Booth, S., Mohammed, E. and Pauly, D. (eds). (2003). From Mexico to Brazil: Central

Atlantic fisheries catch trends and ecosystem models. Fisheries Centre Research Reports

11(6), 264 p.

672

49. Caribbean Sea LME

XV Wider Caribbean

673

XV-50 Gulf of Mexico LME

S. Heileman and N. Rabalais

The Gulf of Mexico LME is a deep marginal sea bordered by Cuba, Mexico and the U.S.

It is the largest semi-enclosed coastal sea of the western Atlantic, encompassing more

than 1.5 million km2, of which 1.57% is protected, as well as 0.49% of the world's coral

reefs and 0.02% of the world's sea mounts (Sea Around Us 2007). The continental shelf

is very extensive, comprising about 30% of the total area and is topographically very

diverse. Oceanic water enters this LME from the Yucatan channel and exits through the

Straits of Florida creating the Loop Current, a major oceanographic feature and part of

the Gulf Stream System (Lohrenz et al. 1999). The LME is strongly influenced by

freshwater input from rivers, particularly the Mississippi-Atchafalaya, which accounts for

about two-thirds of the flows into the Gulf (Richards & McGowan 1989). Forty-seven

major estuaries are found in this LME (Sea Around Us 2007). Important hydrocarbon

seeps exist in the southernmost and northern parts of the LME (Richards & McGowan

1989). A major climatological feature is tropical storm activity, including hurricanes.

Book chapters pertaining to this LME are by Richards & McGowan (1989), Brown et al.

(1991). A volume on this LME is edited by Kumpf et al. (1999).

I. Productivity

The Gulf of Mexico LME is a moderately high productivity ecosystem (<300 gCm-2/yr-1).

Conditions range from eutrophic in the coastal waters to oligotrophic in the deeper ocean.

Lohrenz et al. (1999) distinguished among local scale, mesoscale and synoptic scale

processes that influence primary productivity in the LME. Upwelling along the edge of

the Loop Current as well as its associated rings and eddies are major sources of

nutrients to the euphotic zone. It has been suggested that this upwelling causes a 2- to

3-fold increase in the annual rate of primary production in the Gulf (Wiseman & Sturges

1999). The region of the Mississippi River outflow has the highest measured rates of

primary production (Lohrenz et al. 1990). The Gulf's primary productivity supports an

important global reservoir of biodiversity and biomass of fish, sea birds and marine

mammals. Each summer, widespread areas on the northern continental shelf are

affected by severe and persistent hypoxia (Rabalais et al. 1999a).

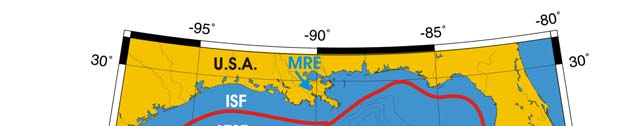

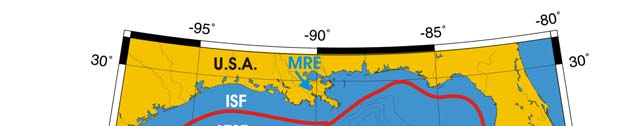

Oceanic Fronts (Belkin et al. 2008)(Figure XV-50.1): From December through March,

two major fronts emerge over two shelf areas, the West Florida Shelf (WFS) and

Louisiana-Texas Shelf (LTS). The WFS Front (WFSF) extends over the mid-shelf,

whereas the LTS Front (LTSF) is located closer to the shelf break. Both fronts form

owing to cold air outbreaks (e.g., Huh et al. 1978). Huge freshwater discharge from the

Mississippi River Estuary (MRE) and rivers of the Florida Panhandle contributes to the

fronts' development and maintenance. Compared to these northern fronts, the

Campeche Bank Shelf-Slope Front (CBSSF) and Campeche Bank Coastal Front (CBCF)

in the south are weak and unstable. The Loop Current Front (LCF) is always present at

the inshore boundary of the namesake front, best defined in winter.

674

50. Gulf of Mexico LME

Figure XV-50.1. Fronts of the Gulf of Mexico. Acronyms: CBCF, Campeche Bank Coastal Front;

CBSSF, Campeche Bank Shelf-Slope Front (most probable location); ISF, Inner Shelf Front; LCF, Loop

Current Front; LTSF, Louisiana-Texas Shelf Front; MRE, Mississippi River Estuary; WFSF, West

Florida Shelf Front. Yellow line, LME boundary. After Belkin et al. (2008).

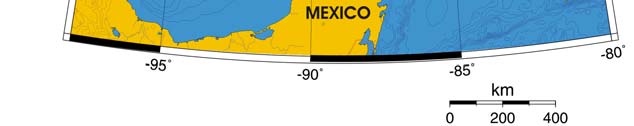

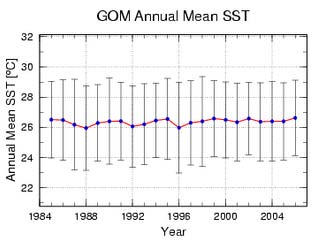

Gulf of Mexico LME SST (Belkin 2008)(Figure XV-50.2):

Linear SST trend since 1957: 0.19°C.

Linear SST trend since 1982: 0.31°C.

The Gulf of Mexico thermal history is quite peculiar. The global cooling of the 1960s

transpired here as an SST drop of <1°C, followed by a slow warming until present. The

relatively slow warming of the last 50 years was modulated by strong interannual

variability with a typical magnitude of 0.5°C. The all-time record high of 26.4°C in 1972

was a major event since SST increased by nearly 0.8°C in just two years. This event

was probably localized with the Gulf of Mexico. An alternative explanation involves a

gradual drift of a record-strong positive SST anomaly of 1969 from the Caribbean Sea

LME. The time lag of three years between the Caribbean Sea SST maximum and the

Gulf of Mexico SST maximum makes this correlation tenuous.

The relatively slow warming, if any, of the Gulf of Mexico is also evident from satellite

SST data from 1984-2006 assembled and processed at NOAA/AOML (Figure XV-50.2a).

Even though the annual mean SST change little since 1957, summer SST in the Atlantic

tropical areas rose substantially since the 1980s, which is thought to have resulted in a

recent increase of destructiveness of tropical cyclones, including those that hit the Gulf of

Mexico (Emanuel 2005).

XV Wider Caribbean

675

a

b

Figure XV-50.2a. Time series of annual mean SST in the Gulf of Mexico derived from satellite data,

1984-2006, processed at NOAA's Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, Miami,

Florida. Source: www.aoml.noaa.gov/phod/regsatprod/gom/sst_anm.php. Figure XV-50.2b. Gulf of

Mexico LME annual mean SST (left) and SST anomalies (right), 1957-2006, based on Hadley climatology.

After Belkin (2008).

Gulf of Mexico LME Chlorophyll and Primary Productivity: The Gulf of Mexico LME

is a Class II, moderately-high productivity ecosystem (150-300 gCm-2/yr-1)(Figure XV-

50.3).

Figure XV-50.3. Gulf of Mexico LME trends in chlorophyll a (left) and primary productivity (right), 1998-

2006, from satellite ocean colour imagery Values are colour coded to the right hand ordinate. Figure

courtesy of J. O'Reilly and K. Hyde. Sources discussed p. 15 this volume.

676

50. Gulf of Mexico LME

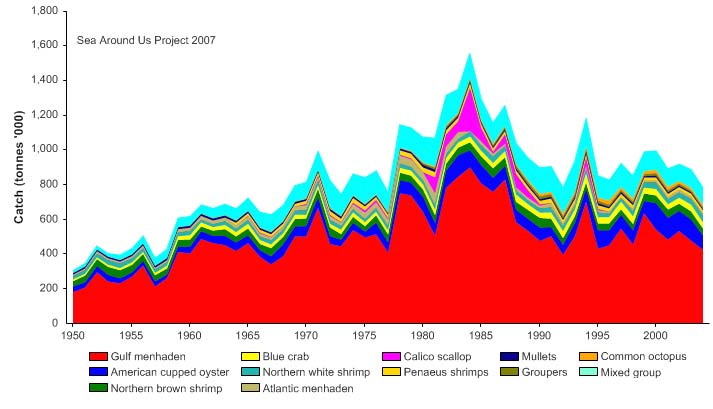

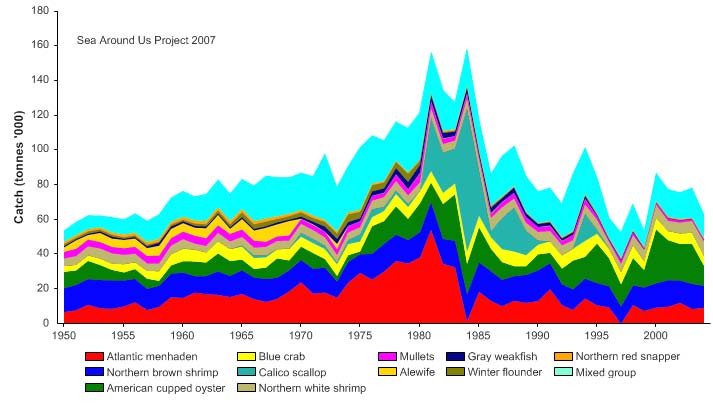

II. Fish and Fisheries

The Gulf of Mexico LME fisheries are multispecies, multigear and multifleet in character

and include artisanal, commercial and recreational fishing. Species of economic

importance include brown shrimp (Farfantepenaeus aztecus), white shrimp (Litopenaeus

setiferus), pink shrimp (Farfantepenaeus duorarum), Gulf menhaden (Brevoortia

patronus), king mackerel (Scomberomorus cavalla), Spanish mackerel (S. maculatus),

red grouper (Epinephelus morio), red snapper (Lutjanus campechanus), seatrout, tuna

and billfish (NOAA/NMFS 1999). Reported landings from this LME are dominated by

herrings, sardines and anchovies (FAO 2003), but they underestimate total catches, due

to non-inclusion of much of the discarded fish bycatch of shrimp trawlers (see e.g.

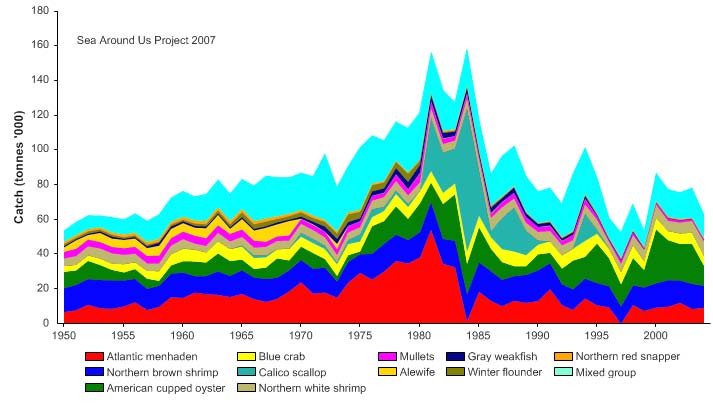

contributions in Yañez-Arancibia, 1985). Total reported landings increased to over

1.5 million tonnes in 1984, and then declined to 780,000 tonnes in 2004 (Figure XV-50.4).

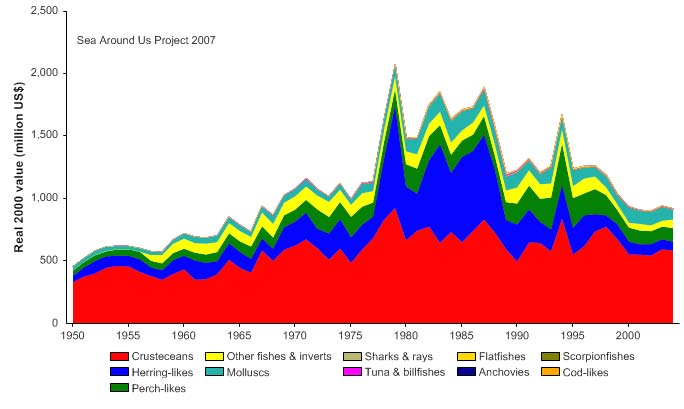

Between 1969 and 1999, the annual value of the reported landings has been over US$1

billion (in 2000 US dollars) and reached US$2 billion in 1979 (Figure XV-50.5).

Figure XV-50.4. Total reported landings in the Gulf of Mexico LME by species (Sea Around Us 2007).

Figure XV-50.5. Value of reported landings in the Gulf of Mexico LME by commercial groups (Sea

Around Us 2007).

XV Wider Caribbean

677

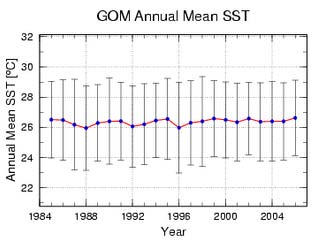

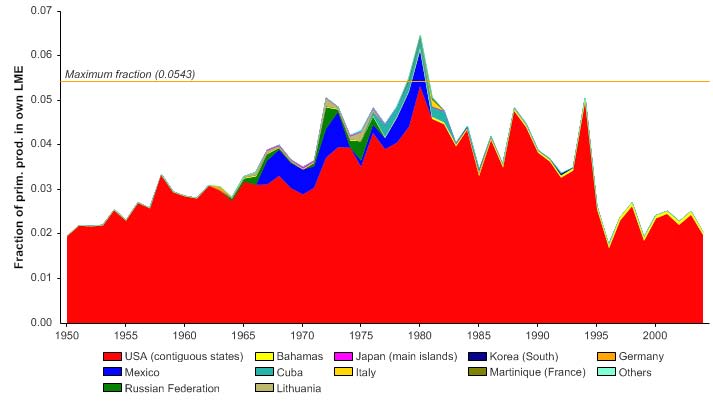

The primary production required (PPR; Pauly & Christensen 1995) to sustain the reported

landings in the LME reached 8% of the observed primary production in 1994 (Figure XV-

50.6), but this PPR underestimate due to the high level of shrimp bycatch not included in

the underlying statistics. Mexico and the USA account for the majority of the ecological

footprints in this LME.

Figure XV-50.6. Primary production required to support reported landings (i.e., ecological footprint) as

fraction of the observed primary production in the Gulf of Mexico LME (Sea Around Us 2007). The

`Maximum fraction' denotes the mean of the 5 highest values.

The mean trophic level of the reported landings (i.e., the MTI; Pauly & Watson 2005) has

increased slightly from the early 1950s to 2004 (Figure XV-50.7, top). The very low value

of MTI (2.3-2.5) is due to the high proportion of small low trophic pelagic fishes,

especially Gulf menhaden and shrimps in the landings, and the exclusion of the shrimp

trawler bycatches in valuation of the mean trophic level.

Figure XV-50.7. Mean trophic level (i.e., Marine Trophic Index) (top) and Fishing-in-Balance Index

(bottom) in the Gulf of Mexico LME (Sea Around Us 2007).

678

50. Gulf of Mexico LME

As for the observed increase in MTI, this may also be an artefact, as can be inferred from

the work of Baisre (2000). He found, based, on detailed catch data from Cuba that

included bycatch and covered an extended period (1935-1995), that a `fishing down' of

food webs (Pauly et al. 1998) is occurring in the region. The decline of the FiB index

from the mid 1980s (Figure XV-50.7, bottom) is likely a result of the diminished reported

landings.

The Stock-Catch Status Plots indicate that collapsed and overexploited stocks now

account for over 70% of all commercially exploited stocks in the LME (Figure XV-50.8,

top), with overexploited stocks contributing 60% of the reported landings (Figure XV-50.8,

bottom).

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

0%

100

10%

90

20%

)

80

%

(

s

30%

u

70

at

st

40%

y

60

b

ks

50%

c

50

t

o

f

s

60%

40

r

o

e

70%

mb

30

u

N

80%

20

90%

10

100%0

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

(n = 4739)

developing

fully exploited

over-exploited

collapsed

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

0%

100

10%

90

20%

80

)

%

30%

(

70

s

u

at

40%

60

st

ck

50%

t

o

50

s

y

60%

b

h

40

t

c

a

70%

C

30

80%

20

90%

10

100%0

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

(n = 4739)

developing

fully exploited

over-exploited

collapsed

Figure XV-50.8. Stock-Catch Status Plots in the Gulf of Mexico LME, showing the proportion of

developing (green), fully exploited (yellow), overexploited (orange) and collapsed (purple) fisheries by

number of stocks (top) and by catch biomass (bottom) from 1950 to 2004. Note that (n), the number of

`stocks', i.e., individual landings time series, only include taxonomic entities at species, genus or family

level, i.e., higher and pooled groups have been excluded (see Pauly et al, this volume for definitions).

Overexploitation was found to be moderate as a whole, but severe on the Campeche

Bank in the southwestern Gulf. Intensive fishing is the primary force driving biomass

changes in the LME, with climatic variability the secondary driving force (Sherman 2003).

In general, the fish stocks of this LME are impacted by excessive recreational and

commercial fishing pressure (Birkett & Rapport 1999). Both the traditional and the more

recent fisheries have reached their harvesting limits and several species are

overexploited (Arreguín-Sánchez et al. 1999, Brown et al. 1991, NOAA/NMFS 1999,

Shipp 1999). Spanish mackerel, shark and coastal pelagics showed severe declines

under intense fishing pressure during the late 1980s (Shipp 1999). Other commercially

important species that have been overexploited are the red drum and spotted seatrout,

and there has been concern over the sustainability of the fishery for amberjack and gag

grouper (Shipp 1999). The Gulf menhaden stocks fluctuated and then declined under

XV Wider Caribbean

679

heavy fishing pressure and other stresses (Birkett & Rapport 1999). Several stocks of

reef fish, including red, Nassau and goliath groupers, are also overexploited

(NOAA/NMFS 1999). The red snapper is considered the most severely overexploited

species in the Gulf, and its recovery is deterred by the high mortality of its juveniles in

shrimp trawl bycatch. Stocks of large migratory pelagic fish are also under threat from

overfishing. Landings of bluefin tuna dropped precipitously in the late 1970s and the

stocks are also considered to be severely overexploited. Likewise, other large pelagics

such as swordfish and blue and white marlin are also thought to be overexploited.

In the early 1980s, the shrimp fishery on the continental shelf off Campeche in the

southwestern Gulf of Mexico LME formed the base of the economy in this area (Arreguín-

Sánchez et al. 2004). This fishery, particularly for the pink shrimp has collapsed, with

annual harvests falling from 27,000 tonnes in the early 1970s to 3,000 tonnes or less

(Arreguín-Sánchez et al. 1997). There has been evidence of marked declines in the

abundance of pink and white shrimps in this area as a result of heavy fishing on juveniles

inshore as well as on spawners in offshore areas (Gracia & Vasquez-Bader 1999). Also

in this area, the red grouper and the brackish water clam fisheries collapsed in the late

1980s (Arreguín-Sánchez et al. 1999). As a result of these declines, the fisheries in the

Campeche area focus on other, less valuable species, such as finfish and octopus

(Arreguín-Sánchez et al. 2004).

Many of these fisheries are now under management (e.g., seasonal closures, size limits,

quotas) and some have started to show recovery (Arreguín-Sánchez et al. 1999, Brown

et al. 1991, NOAA/NMFS 1999, Shipp 1999). For example, Spanish mackerel, Gulf

menhaden as well as white, pink and brown shrimps are now considered to be either in a

state of recovery or at least are no longer overexploited. However, concern still exists

over continued overcapitalisation and the shift of fishing to lower tropic levels and smaller

sizes of fish, which are the prey of species supporting valuable, fully developed fisheries

(Brown et al. 1991, UNDP/GEF 2004). Harvest of prey species may therefore have long-

term negative impacts on the production of currently harvested species in the Gulf and

should be accompanied by research into important ecological relationships and

multispecies effects (Brown et al. 1991, Pauly et al. 1999). Several studies along these

lines have already been undertaken (e.g., Browder 1993, Manickchand-Heileman et al.

1998, Arreguín-Sánchez et al. 2004, Vidal-Hernandez & Pauly 2004).

Excessive bycatch and discards are associated with the shrimp trawl fishery, in which

small mesh nets are used. The 10:1 ratio of bycatch to shrimp implies that vast

quantities of non-target species are caught in shrimp trawls. Juveniles of sciaenids (e.g.,

croaker, seatrout, spot) constitute the bulk of the finfish bycatch, with many billion

individuals discarded every year (NOAA/NMFS 1999). The populations of species that

are heavily fished as bycatch in the shrimp fishery have declined significantly, in parallel

with the increase in shrimping effort (Brown et al. 1991). This loss through bycatch may

slow the recovery of overfished stocks (NOAA/NMFS 1999). Results from mass-balance,

trophic models suggest the ecosystem is rather robust as a whole, although continued

increases in fishing effort, especially by bottom (shrimp) trawlers, will have serious

impacts, reverberating through the entire shelf subsystem (Vidal-Hernandez & Pauly

2004).

III. Pollution and Ecosystem Health

Pollution: Shoreline development, the oil and gas industry, pollutant discharges and

nutrient loading are among the principal sources of stress on the Gulf of Mexico LME

(Birkett & Rapport 1999). In general, pollution was found to be slight to severe in this

LME. Most notable is the high input of nutrients and associated eutrophication and

hypoxia in the northern areas of the Gulf. Agricultural activities, artificial drainage and

680

50. Gulf of Mexico LME

other changes to the hydrology of the U.S. Midwest, atmospheric deposition, non-point

sources and point discharges, particularly from domestic wastewater treatment systems,

industrial discharges and feedlots all contribute to the nutrient load that reaches the Gulf

(Goolsby et al. 1999). The outflows of the Mississippi and Atchafalaya Rivers, however,

dominate the nutrient loads to the continental shelf (Rabalais et al. 1999a, 2002b). The

input of nutrients in the Mississippi River has increased dramatically in the last century

and has accelerated since 1950, coinciding with increasing fertiliser use in the Mississippi

Basin (Turner & Rabalais 1991). The high input and regeneration of nutrients result in

high biological productivity in the immediate and extended plume of the Mississippi River

(Lohrenz et al. 1990).

Most of the primary production fluxes to the bottom waters and the seabed, fuelling

hypoxia in the bottom waters. The areal extent of the hypoxic or `dead' zone during the

mid-summer of 1993-1995 ranged from about 16,600 to 18,200 km2 (Rabalais et al.

1999a, 1999b). The EPA predicted size of the dead zone by the end of summer 2007

was 22,127 km2 or more than 8,500 mi2. This is the largest zone of anthropogenic

coastal hypoxia in the western hemisphere. Evidence from chemical and biological

indicators in sediment cores shows the worsening hypoxic conditions in this LME

(Rabalais et al. 1996, 2002a). The U.S. EPA has classified the estuaries in the northern

Gulf as poor in terms of eutrophication (EPA 2001). In addition, HABs are of concern in

this LME. They debilitate fisheries for shellfish and affect tourism in Florida and Texas

(Anderson et al. 2000).

Inadequate management of sewage in the region has led to sewage contamination of

bays, lagoons and wetlands (Wong Chang & Barrera Escorcia 1996, Birkett & Rapport

1999). In some areas, microbiological pollution levels exceed permissible limits (Wong

Chang & Barrera Escorcia 1996). For example, high coliform levels (up to 300 faecal

coliforms MPN1/100

ml), greatly exceeding the sanitary regulation of 14

faecal

coliforms MPN/100 ml, have been detected in waters of Mecoacán, Tabasco and

Terminos Lagoons. In Galveston Bay, Texas, oysters have been severely affected by

pollution, and many public reefs have had to be closed due to organic pollution from

municipal sewage (Birkett & Rapport 1999).

Direct discharges and non-point sources of chemical pollutants are a major

environmental threat in the Gulf of Mexico LME (Birkett & Rapport 1999). The high use

of pesticides in agricultural areas has contributed to considerable levels of these

substances in the Mississippi and other rivers. These contaminants ultimately reach the

coastal waters. Heavy metals are released into the LME from numerous sources such as

municipal wastewater-treatment plants, manufacturing industries, mining and rural

agricultural areas. Elevated levels of heavy metals and pesticides have been detected in

water and sediments, in some cases exceeding permissible limits (Villaneuva Fragoso &

Paez-Osuna 1996, EPA 2001). The oil and gas industry has also had a significant

environmental and ecological impact on the LME (Botello et al. 1996, Birkett & Rapport

1999). Furthermore, the Gulf is a major thoroughfare for shipping, and accidental oil

discharges from tankers and oil installations are a constant threat. The Mississippi River

also delivers hydrocarbons to the Gulf, primarily from non-point source runoff. The

chronic exposure to oil residues from marine oil production is a significant source of

stress on the coastal habitats.

There is evidence of bioaccumulation of heavy metals, petroleum residues and PCBs in

the tissue of some finfish and invertebrate species (e.g., Botello et al. 1996, Villaneuva

Fragoso & Paez-Osuna 1996, Birkett & Rapport 1999, EPA 2001). In 2000, 10 out of

1 Most Probable Number

XV Wider Caribbean

681

14 fish consumption advisories for the coastal and marine waters of the northern Gulf

coast were issued for mercury, with each of the five US Gulf states having one state-wide

coastal advisory for mercury in king mackerel (EPA 2001). The widespread incidence of

fish diseases (e.g., lymphocytosis, ulcers, fin erosion, shell disease) thought to be related

to pollution has been reported in marine and estuarine species in the northern Gulf

(Birkett and Rapport 1999). The overall coastal condition for the U.S. part of this LME,

according to the EPA's primary indicators is: fair water quality, poor eutrophic condition,

poor condition of sediment and fish tissue (in terms of contaminants) and poor condition

of benthos (EPA 2001). In addition to the fish consumption advisories, the poor coastal

condition has also led to many beach closures throughout the northern Gulf coast, which

also has the lowest percentage of approved shellfish growing waters in the U.S. (EPA

2001).

Habitat and community modification: The LME's coastal and marine habitats are

threatened by both natural processes and anthropogenic factors and their modification is

severe throughout the LME (UNEP, unpublished). Hypoxia in the northern Gulf has

reduced the suitable habitat for living organisms and modified the benthic communities in

the affected area (Rabalais & Turner 2001). The more stressed community is

characterised by limited taxa, characteristic resistant fauna and severely reduced species

richness, abundances and biomass. The effects of hypoxia on fisheries resources

include direct mortality, altered migration, changes in food resources and disruption of life

cycles. Anectodal information from the 1950s to 1960s shows low or no catches by

shrimp trawlers from `dead' waters in this zone (Rabalais et al. 1999b).

Wetlands in particular have experienced severe loss and degradation due to coastal

development, interference with normal erosional/depositional processes, sea level rise

and coastal subsidence (EPA 2001). The EPA coastal wetlands indicator for the northern

Gulf of Mexico shows these wetlands to be in poor condition (EPA 2001). The periodic

sediment input to the Mississippi deltaic plain has been reduced by the construction of

flood control levees and dams upstream, the changing agricultural and urban water-use

practices and increasing alteration of the river system for navigation. The suspended

sediment load of the lower Mississippi decreased by about 50% during the period 1963-

1982 in response to dams built on the Arkansas and Missouri rivers (Meade 1995).

Wetlands are being converted to open water at an alarming rate because wetland

accretion is insufficient to compensate for the natural process of subsidence. In addition,

large areas of wetland have been drained for industrial, urban and agricultural

development. Wetland habitats are also being altered by increased salinities due to

saltwater intrusion, which is destroying coastal flora. This loss of wetlands also increases

erosion by waves and tidal currents and is exacerbated by sea level rise.

The effects of natural processes combined with human actions at large and small scales

have produced a system on the verge of collapse. Wetland losses in the U.S. Gulf of

Mexico from 1780s to 1980s are among the highest in the nation, with 50% having been

lost in this time period (EPA 2001). The rate of coastal land loss in Louisiana, which

contains the largest coastal wetland complex in the U.S., has reached catastrophic

proportions. Within the last 50 years, land loss rates have exceeded 104 km2yr-1,

representing 80% of the coastal wetland loss in the entire continental U.S. (Day et al.

2000).

In the coastal waters of the State of Campeche in Mexico, unregulated fishing, the use of

destructive fishing methods, as well as cutting of mangrove for aquaculture and other

purposes have destroyed fish habitats and reduced shrimp and other shellfish stocks

(Yañez Arancibia et al. 1999). The Usumacinta/Grijalva deltaic system is also being

modified because of changes in land use and the growing human population in this area.

682

50. Gulf of Mexico LME

As a consequence, coastal habitats and communities are being degraded and lost. For

example, the populations of some species such as the horseshoe crab (Limulus

polyphemus) and West Indian manatee (Trichechus manatus) have diminished as a

result of habitat and community modification in this system. Activities related to the oil

industry are also thought to have affected the distribution and abundance of commercially

important fisheries resources such as shrimp on the continental shelf and coastal

lagoons, particularly in the south of Tabasco and Campeche (Arreguín-Sánchez et al.

2004).

The LME's coral reefs are also threatened by natural and anthropogenic pressures.

Almost all the reefs of the Florida Keys are under moderate threat, largely from coastal

development, inappropriate agricultural practices, overfishing of target species such as

conch and lobster as well as pollution associated with development and farming (Bryant

et al. 1998). Other major threats in the last 20 years have arisen from direct human

impacts such as grounding of boats in coral, anchor damage and destructive fishing

(Causey et al. 2002). Reduced freshwater flow has resulted in increase of plankton

bloom, sponge and seagrass die-offs as well as the loss of critical nursery and juvenile

habitat for reef species, which affects populations on the offshore coral reefs. Serial

overfishing has dramatically altered fish and other animal populations. Alien species

introduced on the reefs in the last decade through ship hull fouling or ballast water

dumping have placed additional stress on the reefs (Causey et al. 2002).

Stresses from distant sources are also involved in the degradation of the region's reefs.

Waters from the Mississippi River periodically reach the Florida Keys while Saharan dust

has been implicated in the origin of nutrients and possibly disease spores, particularly

during El Niño years (Bryant et al. 1998). Florida reefs have been repeatedly stressed in

the past 25 years by coral bleaching, which has contributed to the dramatic declines in

coral cover in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary since 1997 (Causey et al.

2002). Disease is also a serious problem. Two of the most important reef-building

species (Acropora palmata and A. cervicornis) are now relatively uncommon due to

white-band disease, while others have proved particularly susceptible to black-band

disease (Bryant et al. 1998). Algae continue to dominate all sites, with average cover

generally above 75% in the Keys and above 50% in the Dry Tortugas (Causey et al.