XIX NON-REGIONAL SEAS LMES

XIX-58 West Greenland Shelf LME

XIX-59 Newfoundland-Labrador Shelf LME

XIX-60 Scotian Shelf LME

XIX-61 Northeast U.S. Continental Shelf LME

XIX-62 Hudson Bay LME

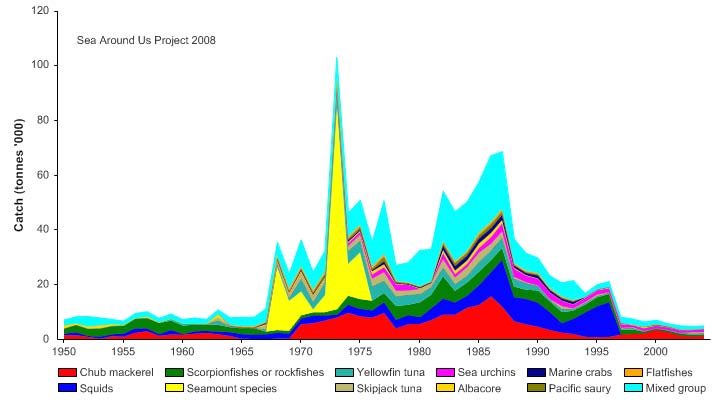

XIX-63 Insular Pacific-Hawaiian LME

XIX-64 Southwest Australian Shelf LME

776

XIX Non-Regional Seas LMEs

XIX Non Regional Seas LMEs

777

XIX-58 West Greenland Shelf LME

M.C. Aquarone and S. Adams

The West Greenland Shelf LME extends along Greenland's west coast in the Atlantic

Ocean, and encompasses a number of banks, including the Fyllas Bank. It has an area

of 375,000 km2, of which 1.37% is protected, and contains one major estuary, the

Tasersuaq (Sea Around Us 2007). It is characterised by its subarctic climate, as well as

by ice cover for parts of the year. For a map of sea currents and geography, see

Pedersen & Rice (2002). Climate is the primary force driving this LME, with intensive

fishing as the secondary driving force. Nutrient enrichment and mixing depend on

changes in sea and air temperature. Book chapters and articles pertaining to this LME

include Hovgård & Buch (1990), Blindheim & Skjoldal (1993), Pedersen & Rice (2002)

and UNEP (2004).

I. Productivity

The West Greenland Shelf LME is a Class III, low productivity (<150 gCm-2yr-1)

ecosystem. The waters of the West Greenland Current come from Greenland's south

coast, the Labrador Sea and from East Greenland's strong Irminger Current. For a map

of surface currents in the northern part of the Atlantic Ocean, see Hovgård & Buch (1990,

p. 39). Hydrographical conditions seem to be changing in the Irminger Sea to the east.

For more information on variations in climate, see Hovgard & Buch (1990). There is a

relatively long time series of plankton and hydrographic samples allowing an exploration

of the links between climate, physical oceanography and abundance of major

zooplankton and ichthyoplankton species (see Pedersen & Rice 2002). Investigations on

selected fish larvae and zooplankton in relation to hydrographic features are currently

undertaken as part of the monitoring programme NuukBasic. The marine component of

the monitoring program was initiated in 2005, and is managed by the Center of Marine

Ecology and Climate Effects at Greenland Institute of Natural Resources. Results from

the monitoring programme are published in annual reports, as well as peer-reviewed

scientific papers when appropriate. Currents carry cod eggs and larvae in a clockwise

direction around the southern part of Greenland, but there is a need to learn more about

the patterns of occurrence of selected fish larvae and zooplankton over time and space

and how those patterns relate to hydrographic features. For more information on the

variable inflow of cod larvae from Iceland, see Hovgard & Buch (1990). Studies showed

a decreasing trend in zooplankton abundance. Information on current velocity is scarce.

For a study of factors affecting the distribution of Atlantic cod, Greenland halibut, redfish,

long rough dab, wolf fish, sandeel and northern shrimp, see Pedersen & Rice (2002).

The decline of cod, redfish and long rough dab stocks can be seen mostly as

consequences of changes in climate, temperature and salinity. NORWESTLAND has

conducted surveys along 3 transects in the West Greenland coast, Store Hellefiske bank,

Sukkertop bank and Fyllas bank, where sea temperatures and salinities have been

measured.

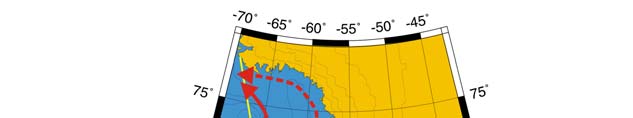

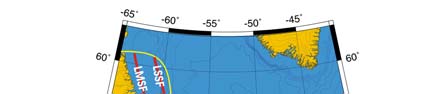

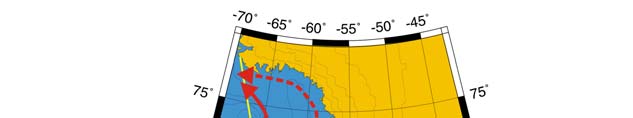

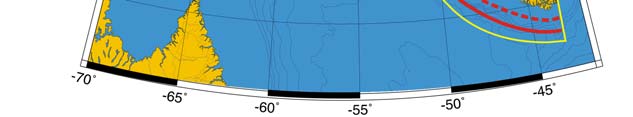

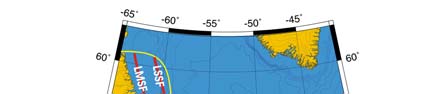

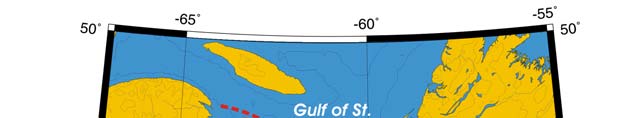

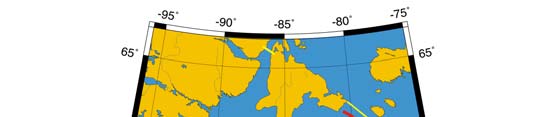

Oceanic fronts (Belkin et al. 2008) (Figure XIX-58.1): The West Greenland Current Front

(WGCF) closely follows the shelf break and the steep upper slope until 52°W, where the

slope becomes notably less steep and therefore no longer stabilises the WGCF. The

front instability results in eddy generation that enhances cross-frontal exchange of heat,

salt and nutrients as well as larvae and juvenile fish. The WGCF waters originate partly

in the cold, fresh East Greenland Current and partly in the warm and salty Irminger

Current. The Mid-Shelf Front (MSF) runs over mid-shelf roughly parallel to the coast and

778

58. West Greenland Shelf LME

carries very cold, low-salinity polar water originated in the East Greenland Current

augmented by melt water from the Greenland Ice Sheet.

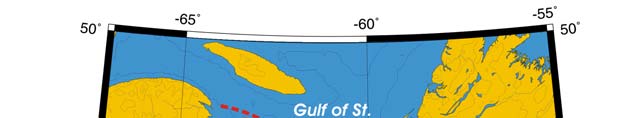

Figure XIX-58.1. Fronts of the West Greenland Shelf LME. MSF, Mid-Shelf Front (most probable

location); WGCF, West Greenland Current Front. Yellow line, LME boundary. After Belkin et al. (2008).

West Greenland Shelf SST (Belkin 2008) (Figure XIX-58.2):

Linear SST trend since 1957: 0.42°C.

Linear SST trend since 1982: 0.73°C.

The long-term 50-year warming of the West Greenland Shelf was interrupted by cold events that

peaked in 1970, 1983-84, and 1996. These cold anomalies were associated with low-salinity,

high-sea-ice cover anomalies dubbed "Great Salinity Anomalies" or GSAs since they are best

detected in the salinity time series (Dickson et al., 1988; Belkin et al., 1998; Belkin, 2004). The

GSAs form in the Arctic and are transported by oceanic currents into the northern North Atlantic

either through Fram Strait between Greenland and Svalbard or through the straits of the

Canadian Arctic Archipelago; some GSAs could also form locally in the Labrador Sea. The West

Greenland Shelf is one of a few LMEs where the GSAs are conspicuous in temperature records

as well as in salinity time series. As the GSAs travel along the Subarctic Gyre, they affect

spawning and fishing grounds; generally, their impact is detrimental to fish stocks. The first

anomaly (GSA'70s) led to a collapse of cod stock in this area, ultimately replaced by shrimp. The

ensuing cod-to-shrimp transition of local fisheries has had profound societal ramifications at the

regional level (Hamilton et al., 2003). The cold episodes of the early 1980s and early-to-mid

1990s have been caused by the harshest climatic conditions ever recorded in this area since the

XIX Non Regional Seas LMEs

779

beginning of meteorological observations at Godthab (now Nuuk) in the mid-19th century. During

these events, enhanced export of cold and fresh Arctic waters to the Baffin Bay and Labrador

Sea (through Canadian straits and also through Fram Strait) likely contributed to the formation of

the GSA'80s and GSA'90s. The all-time maximum SST of >1.4°C in 2003-2004 may have been

advected from the upstream-located East Greenland Shelf LME where SST peaked at >2.6°C in

2003.

Figure XIX-58.2. West Greenland Shelf LME annual mean SST (left) and SST anomalies, 1957-2006,

based on Hadley climatology. After Belkin (2008).

West Greenland Shelf LME Chlorophyll and Primary Productivity

This LME is a Class III, low productivity (<150 gCm-2yr-1) ecosystem (Figure XIX-58.3).

Figure XIX-58.3. West Greenland Shelf LME trends in chlorophyll a (left) and primary productivity

(right), 1998-2006, from satellite ocean colour imagery. Values are colour coded to the right hand

ordinate. Figure courtesy of J. O'Reilly and K. Hyde. Sources discussed p. 15 this volume.

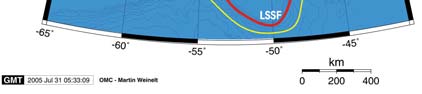

II. Fish and Fisheries

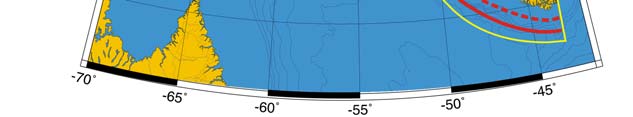

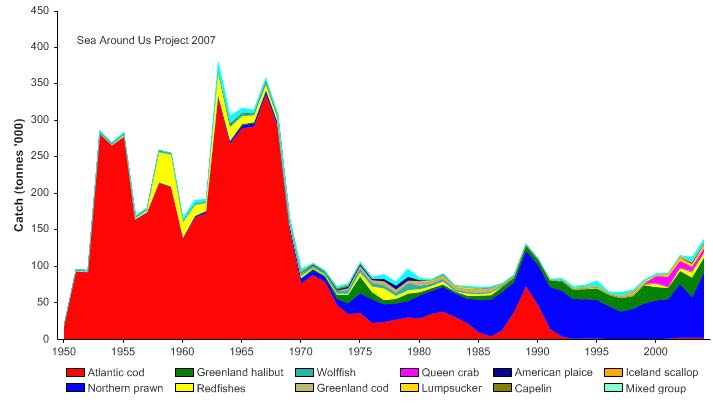

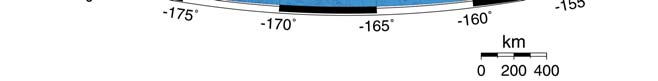

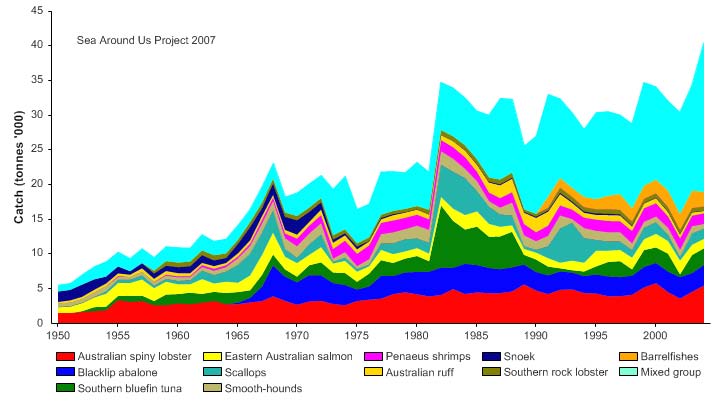

The most important species group in terms of shelf catches for recent years is the

northern prawn (Pandalus borealis), representing more than two-thirds of the total catch.

Another important species group is flatfish. For a study of changes in the West

Greenland fisheries, see Pedersen & Rice (2002). Reported landings of commercial fish

species show major changes over the past century, from a system dominated by Atlantic

cod landings to one defined by prawn landings Reported landings were at a historical

780

58. West Greenland Shelf LME

peak of over 350,000 tonnes in the 1960s (Figure XIX-58.4). They subsequently showed

significant declines to under 100,000 tonnes, with the decline in cod landings, but have

shown an increasing trend over the last few years (Figure XIX-58.4). As northern prawn

now contributes the majority of the reported landings, a potentially large amount of fish

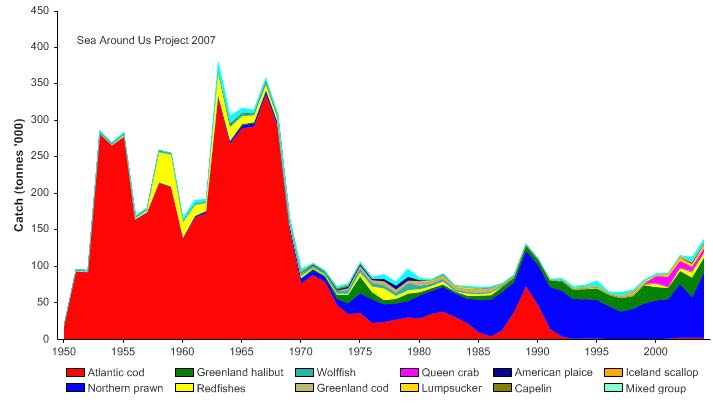

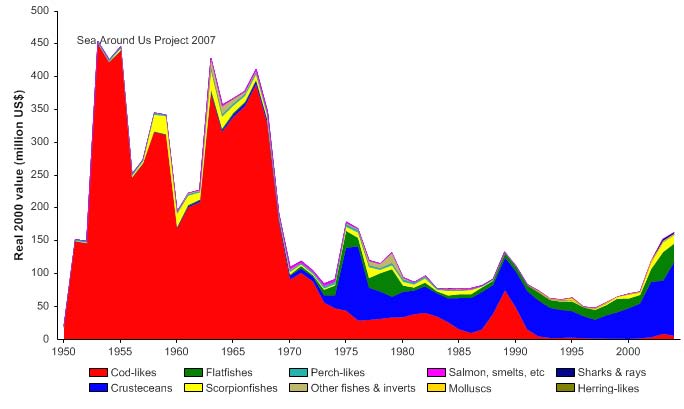

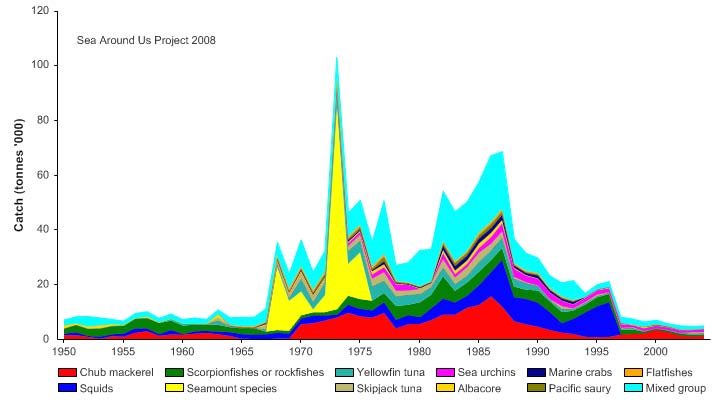

bycatch can be assumed to remain unreported. The value of the reported landings

reached US$400 million (in 2000 US dollars) in the 1950s and 1960s, but has since

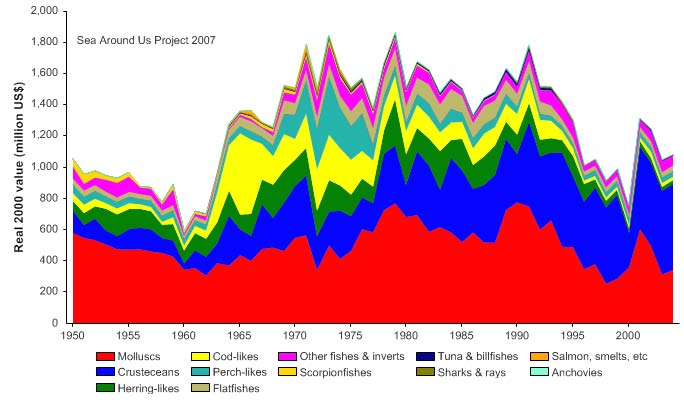

reduced to US$163 million in 2004 (Figure XIX-58.5).

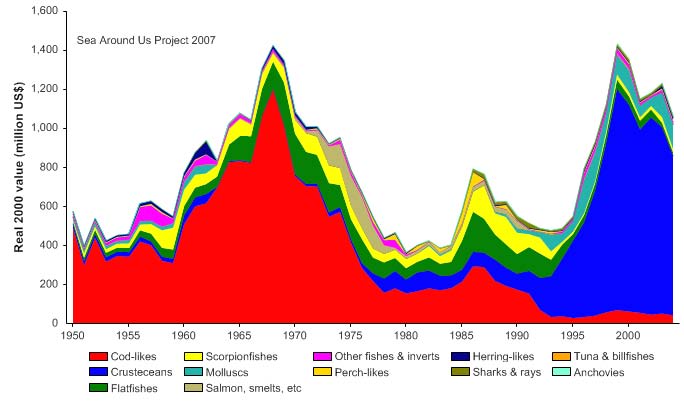

Figure XIX-58.4. Total reported landings in the West Greenland Shelf LME by species (Sea Around Us

2007).

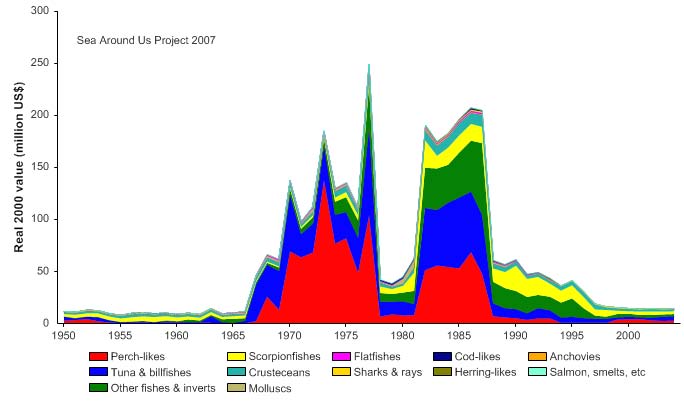

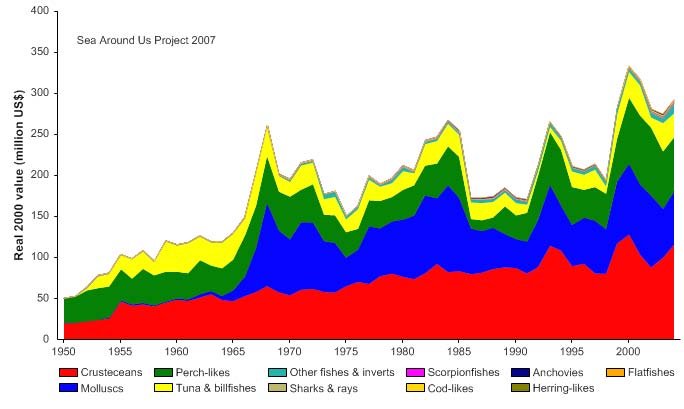

Figure XIX-58.5. Value of reported landings in the West Greenland Shelf LME by commercial groups

(Sea Around Us 2007).

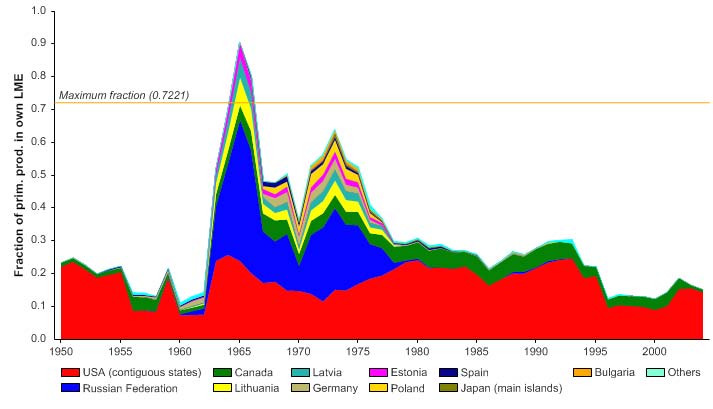

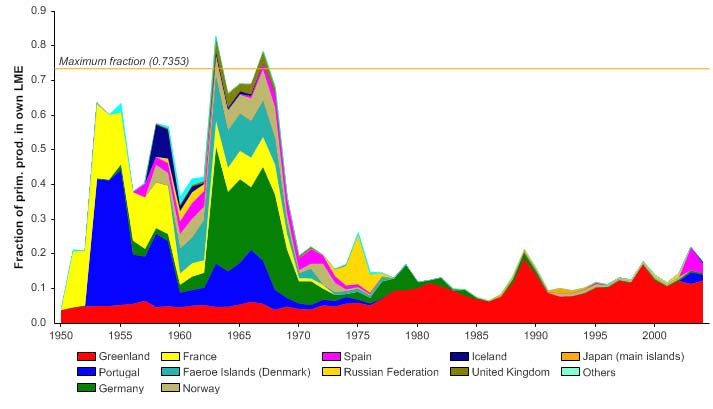

The primary production required (PPR; Pauly & Christensen 1995) to sustain the reported

landings in this LME was over 70% of the observed primary production in the 1960s

before declining to less than 2% over the last three decades. The extremely high PPR

recorded in the 1960s is likely a result of the high level of accumulated biomass of cod

stocks being exploited, not due to the exploitation of annual surplus production.

XIX Non Regional Seas LMEs

781

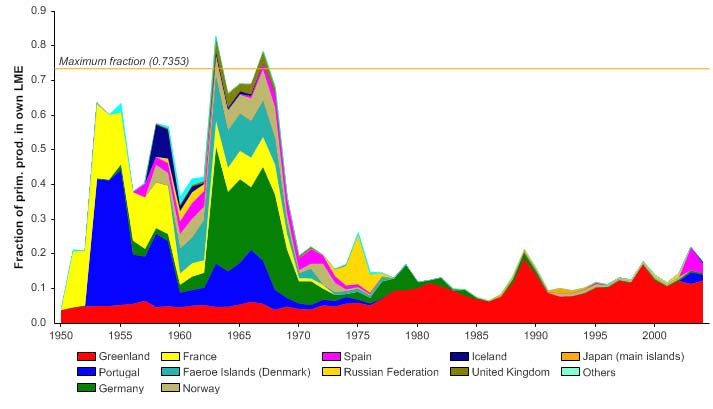

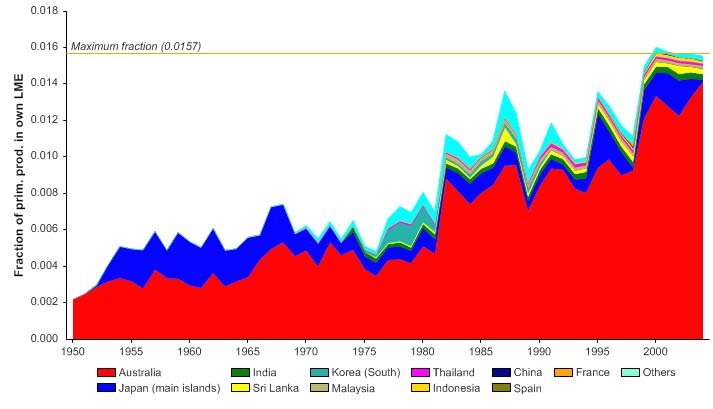

Greenland accounts for the largest share of the ecological footprint in this LME, although

European countries accounted for the majority of the footprint in the 1950s and 1960s.

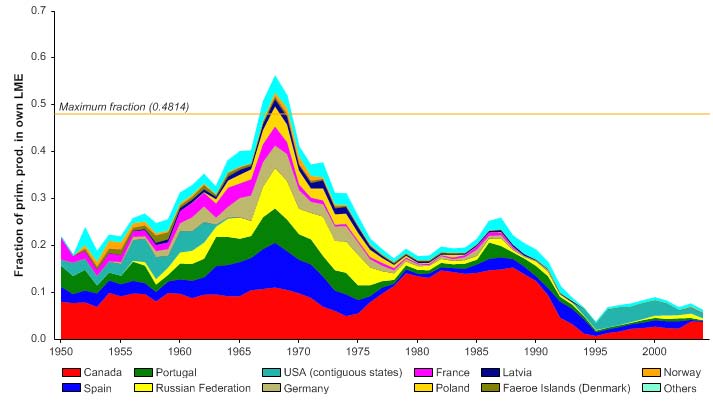

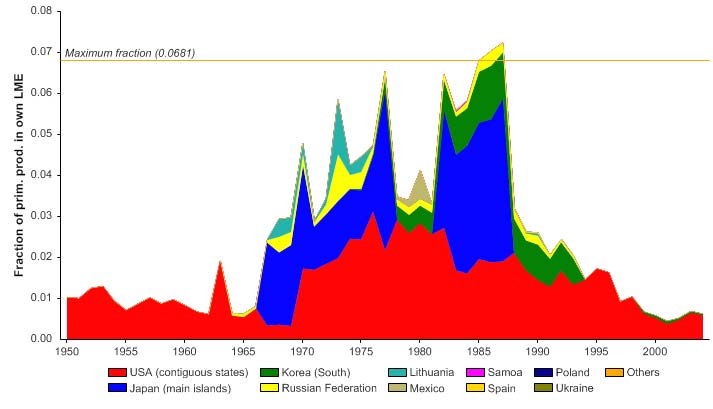

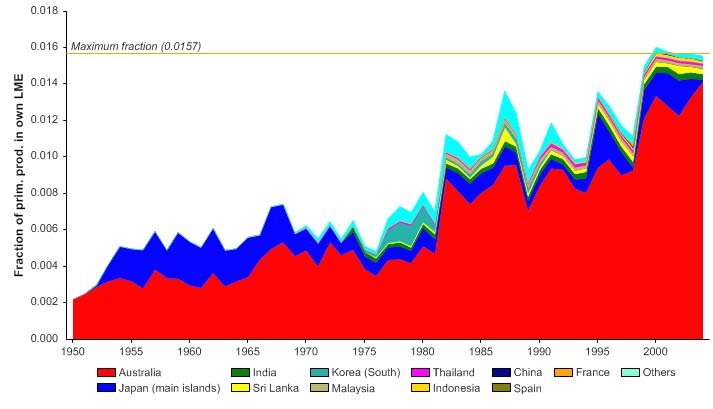

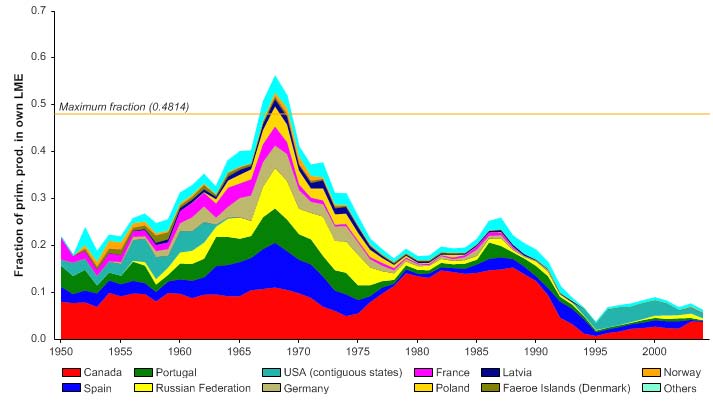

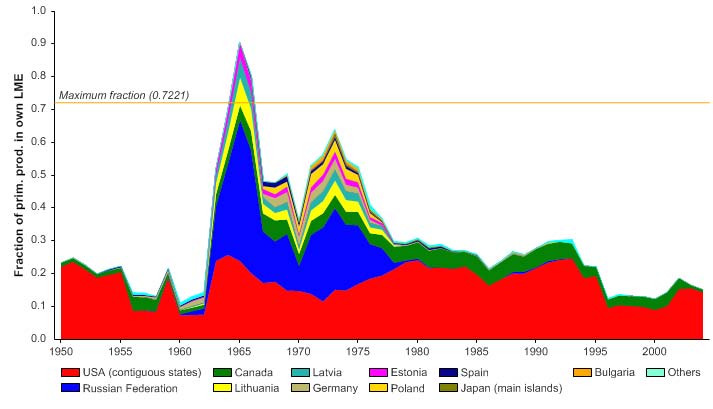

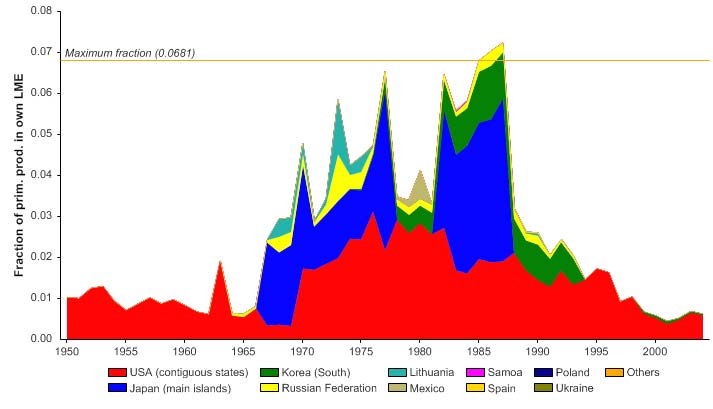

Figure XIX-58.6. Primary production required to support reported landings (i.e., ecological footprint) as

fraction of the observed primary production in the West Greenland Shelf LME (Sea Around Us 2007).

The `Maximum fraction' denotes the mean of the 5 highest values.

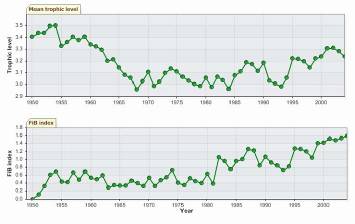

From 1950 to 1970, cod was dominant in the reported landings in this LME and as a

result, the mean trohic level (i.e., the MTT, Pauly & Watson 2005) remained high. It then

showed a decline with the change from cod to prawn dominance in the ecosystem

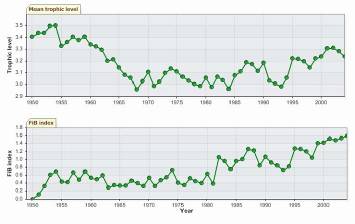

(Figure XIX-58.7, top).

Figure XIX-58.7 Mean trophic level (i.e., Marine Trophic Index) (top) and Fishing-in-Balance Index

(bottom) in the West Greenland Shelf LME (Sea Around Us 2007).

782

58. West Greenland Shelf LME

This trend, by its definition, implies a `fishing down' of the food web (Pauly et al. 1998).

The FiB index showed a similar trend (Figure XIX-58.7, bottom), suggesting that the

reported landings did not compensate for the decline in trophic levels during that period.

However, it must be noted that inclusion of bycatch may alter the trends in the indices

observed here. Furthermore, it is known that the system shift from cod to prawn was to a

large extent driven by environmental changes (see, e.g., Pedersen & Zeller 2001).

The Stock-Catch Status Plots indicate that more than 70% of commercially exploited

stocks in this LME have collapsed (Figure XIX-58.8, top), however, with 90% of the

landings still from fully exploited stocks, more specifically from the northern prawn (Figure

XIX-58.8, bottom). Considering the decrease in the reported landings over the past three

decades (Figure XIX-58.4), the observed trends in these plots present a stark reminder

that they must be examined as a pair, not in isolation from each other.

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

0%

100

10%

90

20%

)

80

%

(

s

30%

u

70

at

st

40%

y

60

b

50%

cks

50

o

f

st

60%

40

er o

b

70%

m

30

Nu

80%

20

90%

10

100%0

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

(n = 741)

developing

fully exploited

over-exploited

collapsed

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

0%

100

10%

90

20%

80

)

%

30%

(

70

s

u

at

40%

60

ck st

50%

o

50

st

y

60%

b

h

40

c

70%

Cat

30

80%

20

90%

10

100%0

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

(n = 741)

developing

fully exploited

over-exploited

collapsed

Figure XIX-58. 8. Stock-Catch Status Plots for the West Greenland Shelf LME, showing the proportion

of developing (green), fully exploited (yellow), overexploited (orange) and collapsed (purple) fisheries

by number of stocks (top) and by catch biomass (bottom) from 1950 to 2004. Note that (n), the number

of `stocks', i.e., individual landings time series, only include taxonomic entities at species, genus or

family level, i.e., higher and pooled groups have been excluded (see Pauly et al, this vol. for definitions).

Landings of cod, redfish and long rough dab have declined. Low recruitment played an

important role in the collapse of the cod fishery. The periodic fluctuations of cod stocks

have been linked to changes in sea and air temperature (see Hovgård & Buch 1990).

These authors also examine the southern displacement of the cod fishery, and provide

information on the development of the cod stock since 1956. For more information on the

biological effects of the temperature and salinity anomaly on the West Greenland cod,

see Blindheim & Skjoldal (1993). In the same period, catches of Greenland halibut and

XIX Non Regional Seas LMEs

783

northern shrimp increased. For nominal catches of Atlantic cod, redfish, Greenland

halibut and northern shrimp, see Pedersen & Rice (2002, p. 153). The present

abundance of shrimp in this LME may partly be the result of a lower abundance of cod

and redfish (see Horsted 2000). Large numbers of redfish, Greenland halibut, polar cod,

cod and others are caught and discarded in the West Greenland shrimp fishery (see

Pedersen & Kanneworff 1995). It is important to also consider the added influence of

changes in fishery technology and effort on cod stocks. The International Cod and

Climate Change Programme (ICCC) studies the response of different cod populations to

climate changes in various regions of the cod's North Atlantic range. Pedersen, Madsen

and Dyhr-Nielsen (2004) report that fishing mortality on cod has been too high due to by-

catch in the shrimp fishery and due to unregulated fishery directed for cod in the fjords

(GIWA 2004).

III. Pollution and Ecosystem Health

The waters of the West Greenland Shelf LME are little polluted. Information about

pollutants and their transport vectors in the Arctic region including Greenland is available

from the Arctic Marine Assessment Program (AMAP) (www.amap.no). Larsen et al.

(2001) et al. reported in Environmental Pollution (2001) that elevated levels of lead and

zinc have been found in sediments and biota in the fjord at Maarmorilik, West

Greenland--a legacy from the mining once done in the area. Bindler et al. (2001)

concluded that the lead in Søndre Strøfjord (W. Greenland) sediments dated since WW II

bears isotopic signatures suggesting W European sources as well as Russian sources.

Larsen et al. (2001) et al. conclude that this has important implications for future

depositions of eco-toxicologically important pollutants such as Hg and POPs. Pedersen

et al.(2004) cite studies showing that the cold Arctic climate creates a sink for Hg and

POPs, and that the already high levels of mercury in the Arctic are not declining despite

significant emissions reductions in Europe and North America.

IV. Socioeconomic Conditions

Greenland made the transition from a nation of hunters to a nation of fishers, primarily for

cod, over the course of the last century. A rich Atlantic cod fishery started in the 1920s

after a general warming of the Arctic. It developed from a local, small-boat fishery to an

international offshore fishery of primarily trawlers. Today the fishery is dominated by

shrimp, crab and halibut. The industries of West Greenland include fish processing, gold,

uranium, iron and diamond mining, handicrafts, hides and skins, and small shipyards.

Pedersen et al. (2004) suggest that economic diversification is not yet sufficient to offer

alternative income possibilities to professional fishermen and hunters.

V. Governance

Both Canada and Greenland share jurisdiction over this LME. After 1945 Canadian

fisheries were regulated under the International Commission for the Northwest Atlantic

Fisheries (ICNAF), consisting of all the industrialised fishing nations of the world

operating in that area (see www.nafo.ca/about/icnaf.htm). ICNAF's effectiveness,

however, was limited by the voluntary nature of compliance to its rules. With the increase

in foreign fishing fleets after World War II, the cod fishery expanded greatly. The limited

development of Canada's domestic fleet prompted Canada to establish a 200-mile EEZ

in 1977. The Greenland Institute of Natural Resources is responsible for providing

scientifically sound management advice to the Government of Greenland. Pedersen et

al. (2004) point out that chemical contamination of the waters and ecosystems of

Greenland come there from Europe, Asia and North America. Concerted international

effort should be focused on control of these emissions and to enforce existing

agreements.

784

58. West Greenland Shelf LME

References

Belkin, I.M. (2004) Propagation of the "Great Salinity Anomaly" of the 1990s around the northern

North Atlantic, Geophysical Research Letters, 31(8), L08306, doi:10.1029/2003GL019334.

Belkin, I.M. (2008) Rapid warming of Large Marine Ecosystems, Progress in Oceanography, in

press.

Belkin, I.M., Cornillon, P.C., and Sherman, K. (2008). Fronts in Large Marine Ecosystems of the

world's oceans. Progress in Oceanography, in press.

Belkin, I.M., Levitus, S., Antonov, J. and Malmberg, S.-A. (1998) "Great Salinity Anomalies" in the

North Atlantic, Progress in Oceanography, 41(1), 1-68.

Bindler, R., Anderson, N.J., Renberg, I. & Malmquist. C. (2001). Palaeolimnological investigation of

atmospheric pollution in the Søndre Strømfjord region, southern West Greenland:

accumulation rates and spatial patterns. Geology of Greenland Survey Bulletin 189:48-53.

Blindheim, J. and Skjoldal, H.R. (1993). Effects of climatic changes on the biomass yield of the

Barents Sea, Norwegian Sea, and West Greenland Large Marine Ecosystems, p 185-198 in:

Sherman, K., Alexander, L.M. and Gold, B.D. (eds), Large Marine Ecosystems: Stress,

Mitigation and Sustainability. AAAS Press, Washington, D.C., U.S.

Buch, E., Pedersen, S.A. and Ribergaard, M.H. (2003). Ecosystem variability and regime shift in

West Greenland waters. Journal of Northwest Atlantic Fishery Science 34:13-28.

Dickson, R.R., Meincke, J., Malmberg, S.-A., and Lee, A.J. (1988) The "Great Salinity Anomaly" in

the North Atlantic, 19681982, Progress in Oceanography 20(1), 103151.

GIWA (2004) Regional Assessment 18, 15, 16--Arctic Greenland, East Greenland Shelf, West

Greenland Shelf available at www.giwa.net/publications/r1b_15_16.phtml.

Hamilton, L.C., Brown, B.C. and Rasmussen, R.O. (2003) West Greenland's cod-to-shrimp

transition: Local dimensions of climate change, Arctic, 56(3), 271-282.

Horsted, S.A. (2000). A review of the cod fisheries at Greenland, 1910-1995. Journal of Northwest

Atlantic Fishery Science 28:1-109.

Hovgård, H. and Buch, E. (1990). Fluctuation in the cod biomass of the West Greenland Sea

ecosystem in relation to climate, p 36-43 in: Sherman, K., Alexander, L.M. and Gold, L.M. (eds),

Large Marine Ecosystems: Patterns, Processes and Yields. AAAS, Washington, D.C. U.S.

Larsen, T.S., Kristensen, J.A., Asmund, G. and Bjerregaard, P. (2001) Lead and zinc in sediments

and biota from maarmorilik, West Greenland: An assessment of the environmental impact of

mining wastes on an Arctic fjord system. Environmental Pollution 114(2): 275-283.

Pauly, D. and Christensen, V. (1995). Primary production required to sustain global fisheries.

Nature 374: 255-257.

Pauly, D. and Watson, R. (2005). Background and interpretation of the `Marine Trophic Index' as a

measure of biodiversity. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society: Biological Sciences

360: 415-423.

Pauly, D., Christensen, V., Dalsgaard, J., Froese R. and Torres, F.C. Jr. (1998). Fishing down

marine food webs. Science 279: 860-863.

Pedersen, S.A. and Kanneworff, P. (1995). Fishes on the West Greenland shrimp grounds, 1988-

1992. ICES Journal of Marine Science 53:165-182.

Pedersen, S.A., Madsen, J. And Dyhr-Nielsen, M. (2004) Arctic Greenland, East Greenland Shelf,

West Greenland Shelf--GIWA Regional assessment 1b, 15, 16. Available electronically at

www.giwa.net/publications/r1b_15_16.phtml.

Pedersen, S.A. and Rice, J.C. (2002). Dynamics of fish larvae, zooplankton, and hydrographical

characteristics in the West Greenland Large Marine Ecosystem 1950-1984, p 151-194 in:

Sherman, K. and Skjoldal, H.R. (eds), Large Marine Ecosystems of the North Atlantic:

Changing States and Sustainability. Elsevier, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Pedersen, S.A. and Zeller, D. (2001). Multispecies interactions in the West Greenland marine

ecosystem: importance of the shrimp fisheries. p 111-127 in: Guenette, S., Christensen, V. and

Pauly, D. (eds), Fisheries Impacts on North Atlantic Ecosystems: Models and Analyses.

University of British Columbia Fisheries Centre Research Reports 9(4).

Pedersen, S.A., and Smidt, E.L.B. (2000). Zooplankton distribution and abundance in West

Greenland waters, 1950-1984. Journal of Northwest Atlantic Fishery Science 26:45-102.

Pedersen, S.A., Simonsen, C.S and Storm, L. (2002). Northern shrimp (Pandalus borealis)

recruitment in West Greenland waters. Part I. Distribution of Pandalus shrimp larvae in relation

to hydrography and plankton. Journal of Northwest Atlantic Fishery Science 30:19-46.

Petersen, H., Meltofte, H., Rysgaard, S., Rasch, M., Jonasson, S., Christensen, T.R., Friborg, T.,

Søgaard, H. and Pedersen, S.A. (2001). The Arctic, p 303-330 in: Climate Change Research -

XIX Non Regional Seas LMEs

785

Danish Contributions. Danish Meteorological Instititute, Ministry of Transport. Gads Forlag,

Copenhagen, Denmark.

Sea Around Us (2007). A Global Database on Marine Fisheries and Ecosystems. Fisheries Centre,

University British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada. http://www.seaaroundus.org/lme/

SummaryInfo.aspx?LME=18

UNEP (2004). Pedersen, S.A., Madsen, J. and Dyhr-Nielsen, M. Arctic Greenland, East Greenland

Shelf, West Greenland Shelf, GIWA Regional Assessment 1b, 15, 16. University of Kalmar,

Kalmar, Sweden. http://www.giwa.net/publications/r1b_15_16.phtml

786

58. West Greenland Shelf LME

XIX Non Regional Seas LMEs

787

XIX-59 Newfoundland-Labrador Shelf LME

M.C. Aquarone and S. Adams

The Newfoundland-Labrador Shelf LME extends some distance off the eastern coast of

Canada, encompassing the areas of the Labrador Current and the Grand Banks. It has

an area of about 896,000 km2, of which 0.44% is protected, and contains 14 major

estuaries (Sea Around Us 2007). The seabed of the shelf is structurally complex. As in

some other LMEs, overexploitation is the principal driver of changes within this LME,

although fluctuations in the ocean climate have also been implicated. The ability to

explain the dynamics of this LME is severely limited by the lack of time series of data on

living components of the system, except for a few species of fishes and seals. A

description of the changing conditions of the fish and fisheries of this LME is given in Rice

(2002).

I. Productivity

The Newfoundland-Labrador Shelf LME is considered a Class II, moderately productive

ecosystem (150-300 gCm-2yr-1). For productivity information, see the GLOBEC Working

Group Summary of the Newfoundland and Labrador Shelves (1993). Harsh

environmental conditions, extensive and persistent sea ice, extreme cold anomalies,

changes in distribution of the area occupied by a Cold Intermediate Layer water mass

(CIL), as well as overfishing, have all contributed to fish population collapses (see Fish

and Fisheries module) in the 1990s. The crab and shrimp that have increased the most

are the favoured prey of cod and other major predators that have collapsed. The new

population densities that have appeared may have redistributed energy flows in ways that

have made it difficult to return to earlier system configurations. There have been several

local studies on plankton dynamics (see Prasad & Haedrich 1993). There was a

continuous plankton recorder transect through this area in the 1950s to the early 1970s.

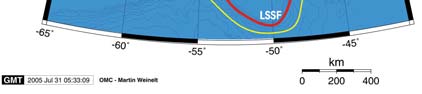

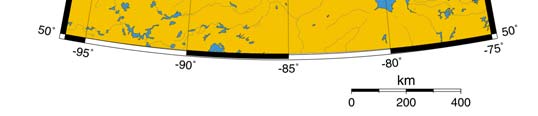

Oceanic fronts (Belkin et al. 2008) (Figure XIX-59.1): The Labrador Shelf-Slope Front

(LSSF) extends along the shelf break and upper slope. The Labrador Mid-Shelf Front

(LMSF) recently identified from satellite data runs inshore of the LSSF, parallel to

Labrador. Farther downstream, the LMSF hugs Newfoundland and merges with the

LSSF south of Newfoundland, near 45°N and 55°W. The Flemish Cap, a shallow bank

that supports important fisheries, is surrounded by the Flemish Cap Front (FCF) that

isolates on-bank waters from direct contact with off-bank oceanic waters. The FCF can

be considered an offshore branch of the LSSF. The main branch of the LSSF continues

south via Flemish Pass between the Grand Banks of Newfoundland and Flemish Cap.

Newfoundland Labrador Shelf SST (Belkin 2008) (Figure XIX-59.2):

Linear SST trend since 1957: 0.77°C.

Linear SST trend since 1982: 1.04°C.

788

59. Newfoundland-Labrador Shelf LME

Figure XIX-59.1. Fronts of the Newfoundland-Labrador Shelf LME. FCF, Flemish Cap Front; LMSF,

Labrador Mid-Shelf Front; LSSF, Labrador Shelf-Slope Front. Yellow line, LME boundary. After Belkin et

al. (2008).

The thermal history of the Newfoundland-Labrador Shelf LME is different from that of the

adjacent Scotian Shelf LME. There was no cold spell in the 1960s. Instead, long-term

steady warming was observed since 1957, punctuated by strong interannual variability

with a magnitude of ~1°C. This warming accelerated since the mid-1990s. Since the

near-all-time minimum of 4.6°C in 1991, the SST has risen to 6.4°C in 2006, a 1.8°C

increase in just 15 years. Despite a single large reversal in 2000-2002, this increase was

one of the fastest regional warming events of the last 25 years. The minima of 1972,

1985 and 1991 may have been associated with large-scale cold, fresh anomalies "Great

Salinity Anomalies" or GSAs (Dickson et al., 1988; Belkin et al., 1998; Belkin, 2004).

These anomalies form in the Arctic Ocean; enter the northern North Atlantic either via

Fram Strait or through the straits of the Canadian Archipelago; and propagate around the

Subarctic Gyre, where they profoundly affect regional ecosystems. The GSAs could also

form in the Labrador Sea (Belkin et al., 1998; Belkin, 2004).

Figure XIX-59.2. Newfoundland-Labrador Shelf LME annual mean SST (left) and SST anomalies (right),

1957-2006, based on Hadley climatology. After Belkin (2008).

XIX Non Regional Seas LMEs

789

Newfoundland-Labrador Shelf LME Chlorophyll and Primary Productivity

This LME is a Class II, moderately productive ecosystem (150-300 gCm-2yr-1) (Figure

XIX-59.3).

Figure XIX-59.3. Newfoundland-Labrador Shelf LME trends in chlorophyll a (left) and primary

productivity (right), 1998-2006, from satellite ocean colour imagery. Values are colour coded to the

right hand ordinate. Figure courtesy of J. O'Reilly and K. Hyde. Sources discussed p. 15 this volume.

II. Fish and Fisheries

Commercially exploited fish species in this LME include cod, haddock, salmon (see

salmon stock assessment for 1997), American plaice, redfish, yellowtail and halibut. Also

harvested are lobster, shrimp and crab. Historic records of catches of Atlantic cod can be

reconstructed back to 1677 (see Forsey & Lear 1987, for a time series of cod catches).

For a stock by stock assessment and recommendation, see Canada's Department of

Fisheries and Oceans website.

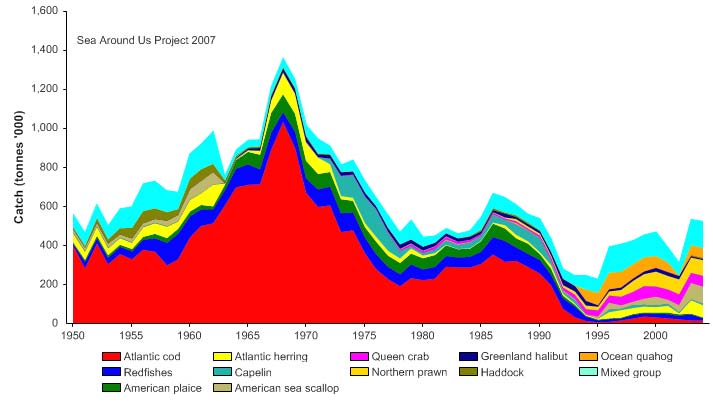

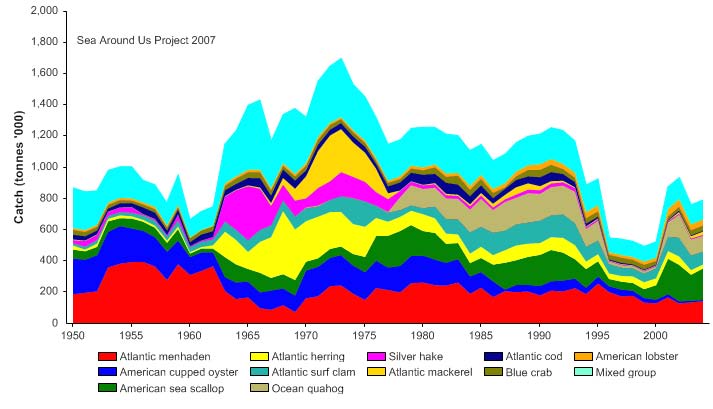

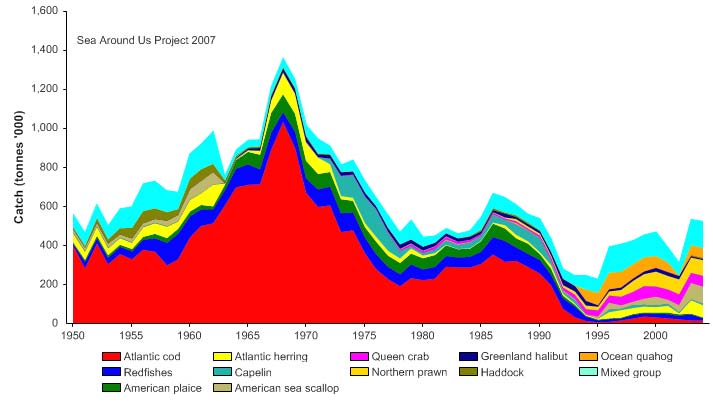

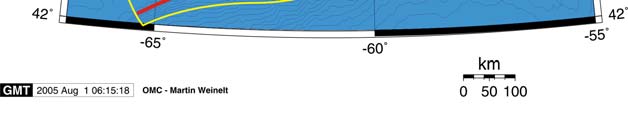

Total reported landings, dominated by cod until the 1990s, exceeded 1 million tonnes

from 1967 to 1970, but declined to 525,000 tonnes in 2004 (Figure XIX-59.4).

Figure XIX-59.4. Total reported landings in the Newfoundland-Labrador Shelf LME by species (Sea

Around Us 2007).

790

59. Newfoundland-Labrador Shelf LME

The cod landings, in particular, declined from a historic high of over 1 million tonnes in

1968 to 16,000 tonnes in 2004 with landings of less than 10,000 tonnes recorded in 1995

and 1996. With the collapse of the cod stock, landings in more recent times are

dominated by invertebrates (crabs, prawns and scallops) and herring (Figure XIX-59.4).

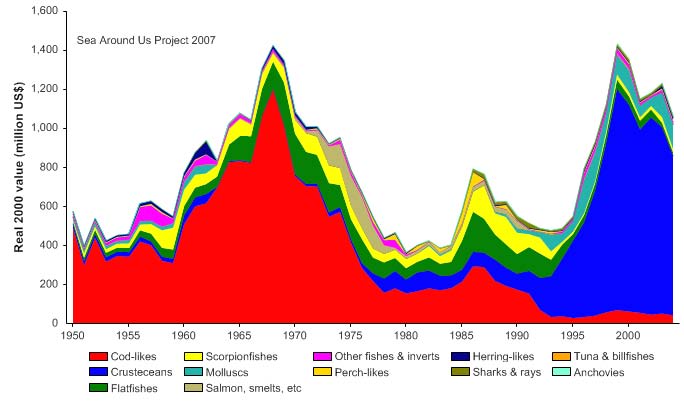

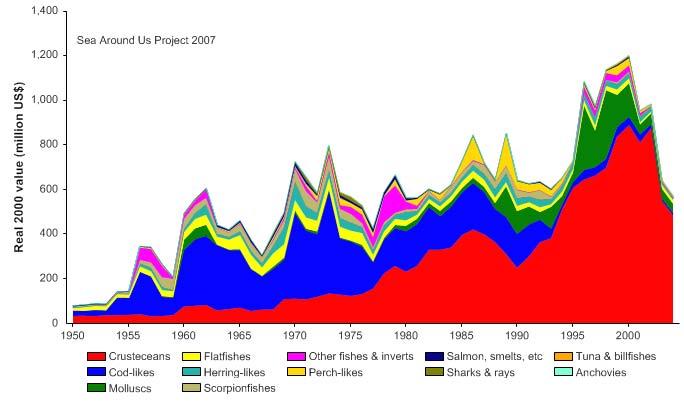

The reported landings of the LME were valued at over US$1.2 billion (in 2000 US dollars)

in the late 1960s, most of which was attributed to cod landings, while in recent years

similarly high values are produced by its invertebrate landings (Figure XIX-59.5).

Figure XIX-59.5. Value of reported landings in the Newfoundland-Labrador Shelf LME by commercial

groups (Sea Around Us 2007).

The primary production required (PPR; Pauly & Christensen 1995) to sustain the reported

landings in the LME reached 60% of the observed primary production in the mid 1960s,

but has declined in recent year (Figure XIX-59.6). The peak level achieved in the 1960s

is likely a result of the high level of accumulated biomass of cod stocks being exploited,

not due to the exploitation of annual surplus production.

Figure XIX-59.6. Primary production required to support reported landings (i.e., ecological footprint) as fraction

of the observed primary production in the Newfoundland-Labrador Shelf LME (Sea Around Us 2007). The

`Maximum fraction' denotes the mean of the 5 highest values.

XIX Non Regional Seas LMEs

791

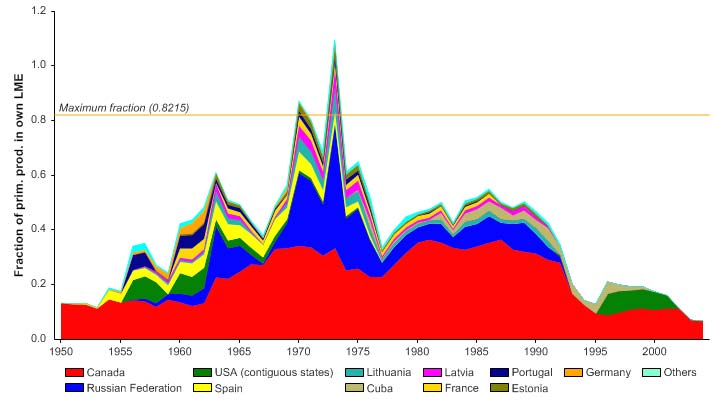

Since the late 1970s Canada accounts for the largest share of the ecological footprint in

this LME, although in the 1960s, a number of European countries also had a large share.

The mean trophic level of the reported landings (i.e., the MTI; Pauly & Watson 2005)

remained high until the 1990s, when the cod stock began to collapse (Figure XIX-59.7,

top), a clear case of `fishing down' the food web in the LME (Pauly et al. 1998, 2001).

The FiB index shows a similar trend (Figure XIX-59.7, bottom), indicating that the

reported landings did not compensate for the decline in the MTI over that period.

However, these landings do not account for the discarded bycatch from the shrimp

fishery, which now accounts for half of the value of the landings (Figure XIX-59.5).

Figure XIX-59.7 Mean trophic level (i.e., Marine Trophic Index) (top) and Fishing-in-Balance Index

(bottom) in the Newfoundland-Labrador Shelf LME (Sea Around Us 2007)

The Stock-Catch Status Plots shows that over 60% of commercially exploited stocks in

the LME have collapsed with another 20% overexploited (Figure XIX-59.8, top). Over

50% of the reported landings biomass is now supplied by fully exploited stocks (Figure

XIX-59.8, bottom).

0%

100

10%

90

20%

)

80

%

(

s

30%

u

70

t

at

s

40%

y

60

b

s

k

50%

c

o

50

f

st

60%

o

40

er

70%

mb

30

u

N

80%

20

90%

10

100%0

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

(n = 2341)

developing

fully exploited

over-exploited

collapsed

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

0%

100

10%

90

20%

80

)

%

30%

(

70

s

u

at

40%

60

k st

c

50%

o

50

st

y

60%

b

h

40

t

c

a

70%

C

30

80%

20

90%

10

100%0

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

(n = 2341)

developing

fully exploited

over-exploited

collapsed

Figure XIX-59.8. Stock-Catch Status Plots for the Newfoundland-Labrador Shelf LME, showing the

proportion of developing (green), fully exploited (yellow), overexploited (orange) and collapsed (purple)

fisheries by number of stocks (top) and by catch biomass (bottom) from 1950 to 2004. Note that (n), the

number of `stocks', i.e., individual landings time series, only include taxonomic entities at species,

genus or family level, i.e., higher and pooled groups have been excluded (see Pauly et al., this volume,

for definitions).

792

59. Newfoundland-Labrador Shelf LME

Instability, variability and overexploitation have characterised the entire history of

fisheries off the coast of Newfoundland and Labrador. Over time, the LME has shown

major changes, which have been greater in recent decades than in any other period in

history. There was a rapid expansion of distant water fleets during the late 1950s, as well

as an intensification of fishing effort. This affected the major fish stocks of the shelf

(Murawski et al. 1997). Overfishing of cod, haddock, redfish and major flatfish in the

1960s and 1970s led to fisheries collapses. There were also declines in the abundance

of broadhead wolffish and thorny skate. These collapses led to a fishing moratorium for

cod in 1992 (Walters & Maguire 1996), and the eventual closure of the fishery a decade

later. At the same time, other fisheries (notably for crab and shrimp, formerly prey of cod)

experienced record high yields.

III. Pollution and Ecosystem Health

Given the low population density of Newfoundland, pollution from land-based sources is

mostly limited to urban coastal areas. However, there is an increasing threat to the

region from the oil and gas industry's exploitation of the Hibernia, Terra Nova, White

Rose, and the Hebron Complex oil reserves, for example. The Canadian Wildlife

Federation (CWF) reported three spills in November of 2004 at the Terra Nova oil field off

the coast of Newfoundland and Labrador, the first spill releasing 170,000 litres into the

ocean. Additionally, CWF asserts that deliberate dumping, the primary source of oil

pollution in Atlantic Canada, is a chronic problem that is both illegal and preventable

(2004). The Economic Research and Analysis Division of the Government of Canada

(2007) reports that oil production in the province is expected to increase by 30%, that

prices will remain high, and more exploratory drilling will likely occur in 2008 and 2009.

There have been Oikopleura blooms in this LME. The International Cod and Climate

Change Programme studies the response of different cod populations to climate changes

in various parts of the cod's North Atlantic range. Canada is a key participant in the

Scientific Committee on Ocean Research (www.jhu.edu/~scor/) and the International

Council for Exploration of the Sea (www.ices.dk).

IV. Socioeconomic Conditions

The Grand Banks of Newfoundland and Labrador have been fished since the 1400s, with

fleets arriving annually from several of Europe's fishing nations. The banks and coastal

areas, being rich and productive, formed the basis for human settlement. The Atlantic

cod fishery was the base of the economy. About 30,000 people have been adversely

affected by the collapse of the cod fishery and its associated economy. However, the

value of the annual fisheries catch is approaching that of the cod fishery, with recent

increases in the crab and shrimp landings (Rice 2002). Hamilton and Butler (2001)

caution that the cod to crustaceans transition, while roughly an even exchange for the

Newfoundland economy, should not be taken for a new stable state. They point out that

shrimp size has been decreasing, depressing catch value and raising uncertainty about

the stock's future. Gear has been changed to prevent the female snow crab from being

caught, but the biomass of snow crab declined in 1999 and 2000. Greenland halibut, are

slow-growing, long-lived deepwater fish that cannot support intensive exploitation and are

thought to be on the verge of collapse (Hamilton and Butler 2001).

Newfoundland's population has been declining and no longer compensates for

outmigration. If this trend continues, it will be difficult for the province to provide services

to those who remain. Department of Finance Canada (2004) points to high economic

growth rates because of the development of offshore oil and gas projects--growth that

helps the Government of Newfoundland and Labrador to provide essential public services

in the face of a high provincial debt burden and the declining population in the region

XIX Non Regional Seas LMEs

793

(www.fin.gc.ca). The Minister of Natural Resources, Gary Lunn, addressed the

Newfoundland Offshore Industry Association on 19 June 2007 and urged increased oil

and gas investment in the Newfoundland and Labrador province. He cites 2,800 people

directly employed by the oil and gas projects and another 14,000 employed in support

industries and businesses--8% if all the people employed in Newfoundland and

Labrador. Tim Appenzeller (2004) in "The End of Cheap Oil," quotes Thomas Ahlbrandt,

the geologist who led the USGS 2000 study asserting 50% more world oil remaining than

feared, as saying "Oil and gas are limited; my personal feeling is, we have a concern in

the next couple of decades."

Hamilton and Butler point out that Rural Newfoundland hosts a strong informal economy

(Felt and Sinclair 1992) including country foods such as moose meat or fish and local

firewood cut for heating. Barter or cash-based exchanges of goods and services such as

home-building and vehicle maintenance are common.

V. Governance

Canada and France (the islands of St. Pierre and Miquelon) share jurisdiction of this

LME. The establishment by Canada of a 200-mile EEZ in 1977 effectively excluded

foreign fleets from most of the Grand Banks. The Government of Canada has

guaranteed that Newfoundland and Labrador will receive 100 percent of royalties from its

offshore oil and gas production, some offset benefits per the Atlantic Accord, and some

protection from reductions in revenues.

Single species quota management continues. The Fisheries Resource Conservation

Council (FRCC) was created in 1993 with a mandate to contribute to a more

comprehensive approach to the management of the Atlantic fisheries on a sustainable

basis, to integrate stock assessments at the ecosystem level and recommend to the

Minister and industry appropriate action to ensure sustainable fisheries. While there is a

stated desire to change to an ecosystem level approach, there are no explicit objectives

within fisheries management plans for the ecosystem. This ambiguity in management

objectives underscores the need for the many single function management agencies to

be integrated. See the West Greenland Shelf LME for further information on the

International Commission for the Northwest Atlantic Fisheries.

References

Appenzeller, T.( 2004). End of Cheap Oil. National Geographic Magazine (June, volume 205(6):80-

100. Online at http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/ngm/0406/feature5/fulltext.html.

Belkin, I.M. (2008) Rapid warming of Large Marine Ecosystems, Progress in Oceanography, in

press.

Belkin, I.M., Cornillon, P.C., and Sherman, K. (2008). Fronts in Large Marine Ecosystems of the

world's oceans. Progress in Oceanography, in press.

Department of Finance, Canada. (2004) Backgrounder on Status of Offshore Resource Revenue

Discussions with Newfoundland and Labrador. www.fin.gc.ca/FEDPROV05/OffshoreResAcc/

backgroundere.html.

Economic Research and Analysis Division, Government of Canada (2007). Oil and Gas report at

www.economics.gov.nl.ca pages 20-23.

Fisheries and Oceans (1993). Charting a new course: Towards the fishery of the future. Report of

the task force on incomes and adjustment in the Atlantic fishery. Communications Directorate,

Fisheries and Oceans, Ottawa, Canada.

Fisheries Resource Conservation Council (FRCC).(1993) www.frcc.ca/mandate.htm

794

59. Newfoundland-Labrador Shelf LME

Forsey, R and Lear, W.H. (1987). Historical catches and catch rates of Atlantic cod at

Newfoundland during 1677-1833. Canadian Data Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Science 662.

GLOBEC Working Group Summary of the Newfoundland and Labrador Shelves (1993) at

www.globec-canada.mun.ca/globec/documents/science_plan/node14.html

Hamilton, L.C. and M.J. Butler (2001) Outport adaptations: Social indicators through

Newfoundland's cod crisis. Human Ecology Review 8(2): 1-11.

www.seaaroundus.org/lme/SummaryInfo.aspx?LME=9

Murawski, S.A., Maguire, J-J., Mayo, R.K. and Serchuk, F.M. (1997). Groundfish stocks and the

fishing industry, p 27-69 in: Boreman, J., Nakashima, B.S., Wilson, J.A. and Kendall, R.L. (eds),

Northeast Atlantic Groundfish: Perspectives on a Fishery Collapse. American Fisheries Society.

Washington D.C., U.S.

Pauly, D. and Christensen, V. (1995). Primary production required to sustain global fisheries.

Nature 374: 255-257.

Pauly, D. and Watson, R. (2005). Background and interpretation of the `Marine Trophic Index' as a

measure of biodiversity. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society: Biological Sciences

360: 415-423.

Pauly, D., Christensen, V., Dalsgaard, J., Froese R. and Torres, F.C. Jr. (1998). Fishing down

marine food webs. Science 279: 860-863.

Pauly, D., Palomares, M.L., Froese, R., Sa-a, P., Vakily, M., Preikshot, D., and Wallace, S. (2001).

Fishing down Canadian aquatic food webs. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Science

58: 51-62.

Prasad, K.S. and Haedrich, R.L. (1993). Satellite observations of phytoplankton variability on the

Grand Banks of Newfoundland during a spring bloom. International Journal of Remote Sensing

14:241-252.

Rice, J. (2002). Changes to the Large Marine Ecosystem of the Newfoundland-Labrador Shelf, p

51-104 in: Sherman, K. and Skjoldal, H.R. (eds), Large Marine Ecosystems of the North Atlantic

Changing States and Sustainability. Elsevier Science, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Rivard, D., McKone, W.D. and Elner, R.W. (1988). Resource prospects for Canada's Atlantic

fisheries: 1989-1993. Communications Directorate, Fisheries and Oceans, Ottawa, Canada.

Scarratt, D.J., ed. (1982). Canadian Atlantic Offshore Fishery Atlas. Canadian Special Publication

of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 47. (Revised)

Sea Around Us (2007). A Global Database on Marine Fisheries and Ecosystems. Fisheries Centre,

University British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada.

USGS (2000) World Petroleum Assessment at <pubs.usgs.gov/fs/fs-062-03/FS-062-03.pdf>.

Walters, C. and Maguire, J.J. (1996). Lessons for stock assessments from the Northern cod

collapse. Review of Fish Biology and Fisheries 6: 125-137.

XIX Non Regional Seas LMEs

795

XIX-60 Scotian Shelf LME

M.C. Aquarone and S. Adams

The Scotian Shelf LME is bordered by the Canadian province of Nova Scotia and

extends offshore to the shelf break, more than 200 nautical miles from the coast. The

area of this LME is 283,000 km2, of which 0.87% is protected, and contains one major

estuary, the St. Lawrence (Sea Around Us 2007). To the north the LME is separated

from the Newfoundland Labrador Shelf LME by the Laurentian Channel, while to the

south it extends to the Fundian Channel (Northeast Channel). The Scotian Shelf LME

has a complex topography consisting of numerous offshore shallow banks and deep mid-

shelf basins. It can be divided into eastern and western subsystems. The eastern

Scotian Shelf LME includes Emerald Bank. The Nova Scotia Current hugs the coastline

in a southwestward direction and enters the Gulf of Maine through the Northeast channel

(Zwanenburg et al. 2002, Zwanenburg 2003). Book chapters pertaining to this LME are

by Zwanenburg et al. (2002) and Zwanenburg (2003).

I. Productivity

The Scotian Shelf LME is considered a Class II, moderately high productivity ecosystem

(150-300 gCm-2yr-1). Productivity is influenced by changes in environmental conditions

and temperature. A decrease in ambient temperature is noted on the eastern Scotian

Shelf for the period 1980-1992 (Zwanenburg et al. 2002). The recent changes to

research vessel survey protocols broaden the collection of ecosystem monitoring data to

include abundance and distribution of phytoplankton, zooplankton, as well as an

increased suite of physical oceanographic parameters. A monthly Continuous Plankton

Recorder Survey is being conducted in collaboration with the Allister Hardy Foundation,

Plymouth, England. There has been an exponential increase in grey seal abundance

since the 1960s. Harp, hooded and harbour seals are found in the Gulf of St. Lawrence

and so are Beluga whales.

Oceanic fronts (Belkin et al. 2008) (Figure XIX-60.1): The Shelf-Slope Front (SSF)

along the Scotian Shelf/Slope bounds this LME and is associated with the southward

cold, fresh Labrador Current, augmented by fresh discharge from the Gulf of St.

Lawrence. The Gulf component is strongly seasonal and reflects in the SSF

characteristics (Linder & Gawarkiewicz 1998). The newly-identified Gully Front (GF) is

observed at 43.5°N over the Gully, the largest canyon that incises the Scotian Shelf and

Slope. Medium-scale thermohaline fronts in the southern Gulf of St. Lawrence are

generated seasonally by spring freshet, followed by summertime warming. The Cabot

Strait Front (CSF) is also related to the Gulf of St. Lawrence fresh outflow. The Cape

North Front (CNF) develops north of the Cape Breton Island.

The Scotian Shelf LME SST (Belkin 2008) (Figure XIX-60.2):

Linear SST trend since 1957: 1.15°C.

Linear SST trend since 1982: 0.89°C.

796

60. Scotian Shelf LME

Figure XIX-60.1. Fronts of the Scotian Shelf LME. CNF, Cape North Front; CSF, Cabot Strait Front (most

probable location); GF, Gully Front; SSF, Shelf-Slope Front. Yellow line, LME boundary. After Belkin et

al. (2008).

The thermal history of the Scotian Shelf LME is similar to that of the Northeast U.S.

Continental Shelf LME. These LMEs are connected by the Slope Current, which flows

southwestward along the shelf break and upper continental slope. This connection

explains the observed similarities between thermal histories of these LMEs: first of all,

the cold spell of the mid-1960s, with the all-time minimum of 6.7°C in 1965 and the

subsequent steady warming until the present. As in the Northeast Shelf LME, 1965 can

be taken as a true breakpoint between two regimes characterized, respectively, by long-

term cooling before 1965 and long-term warming after 1965. The post-1965 warming

amounted to approximately 2°C over 40 years, making the Scotian Shelf as a geographic

whole, one of the fastest warming LMEs. Note that smaller processes like the rapid

cooling of the eastern Shelf during the 1980s, drive significant changes in the biota.

Generalizations about the entire Scotian Shelf do not examine important differences

between the eastern and western sections of this LME.

Over the late 1990s, the Scotian Shelf interannual variability was in sync with the

Northeast U.S. Continental Shelf LME as evidenced by the simultaneous minimum in

1997, maximum in 1999, minimum in 2004, and the sharp increase in 2004-2006, in both

LMEs. The most recent SST increase in 2004-2006 led to the all-time maximum of

>9.0°C in 2006 over the Scotian Shelf, consistent and concurrent with the near-all-time

maximum of 13.0°C over the Northeast U.S. Shelf Continental LME and the all-time

maximum of 6.4°C over the Newfoundland-Labrador Shelf LME, both in 2006. The

above simultaneity suggests large-scale forcing on the order of 2,000 km as a dominant

factor over these distinct but adjacent ecosystems.

XIX Non Regional Seas LMEs

797

The minima of 1986 and 1997 may have been related to passages of the decadal-scale

Great Salinity Anomalies (GSA) associated with low temperatures (Belkin et al., 1998;

Belkin, 2004).

Figure XIX-60.2. Scotian Shelf LME annual mean SST (left) and SST anomalies (right), 1957-2006, based

on Hadley climatology. After Belkin (2008).

Scotian Shelf LME Chlorophyll and Primary Productivity

This LME is a Class II, moderately-high productivity ecosystem (150-300 gCm-2yr-1)

(Figure XIX-60.3).

Figure XIX-60.3. Scotian Shelf LME annual trends in chlorophyll a (left) and primary productivity (right),

1998-2006, from satellite ocean colour imagery. Values are colour coded to the right hand ordinate.

Figure courtesy of J. O'Reilly and K. Hyde. Sources discussed p. 15 this volume.

II. Fish and Fisheries

Commercially exploited species include cod, haddock, pollock, silver hake, halibut, white

hake, and turbot. Pelagic species include the Atlantic herring and the Atlantic mackerel.

Invertebrates include snow crab, northern shrimp and short fin squid. Both snow crab

and northern shrimp prefer cold water and the increased landings for both those species

coincide with the cooling of the eastern shelf (Zwanenburg 2003). Systematic fishery

surveys of the shelf made between the 1960s and the present are the most consistent

source of information available concerning this LME.

798

60. Scotian Shelf LME

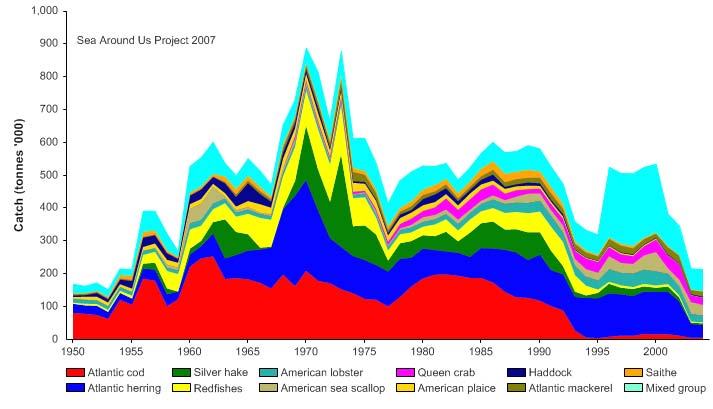

Total reported landings recorded a peak of 889,000 tonnes in 1970 and declined to less

than a quarter of this level or 213,000 tonnes in 2004 (Figure XIX-60.4). Major changes

include a dramatic decline in landings of cod, silver hake and redfish. However, the value

of the reported landings reached its peak of US$1.2 billion (in 2000 US dollars) in 2000,

as a result of high value commanded by its landings of crustaceans (Figure XIX-60.5).

Figure XIX-60.4. Total reported landings in the Scotian Shelf LME by species (Sea Around Us 2007).

Figure XIX-60.5. Value of reported landings in the Scotian Shelf LME by commercial groups (Sea

Around Us 2007).

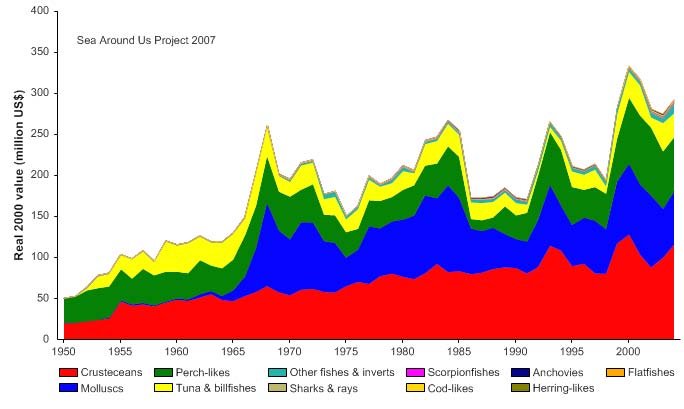

The primary production required (PPR; Pauly & Christensen 1995) to sustain the reported

landings in this LME exceeded the observed primary production in the mid 1970s, but

has declined in recent years (Figure XIX-60.6). The extremely high PPR recorded in the

mid 1970s was likely due to the accumulated biomass of cod stocks being exploited and

not from exploitation of annual surplus production. Canada accounts for almost all of the

ecological footprint in this LME (Figure XIX-60.6), although in the 1960s and 1970s, a

number of European countries also had a large share.

XIX Non Regional Seas LMEs

799

Figure XIX-60.6. Primary production required to support reported landings (i.e., ecological footprint) as

fraction of the observed primary production in the Scotian Shelf LME (Sea Around Us 2007). The

`Maximum fraction' denotes the mean of the 5 highest values.

The mean trophic level of the reported landings (i.e., the MTI; Pauly & Watson 2005)

remained high until the early 1990s, when the cod stock collapsed (Figure XIX-60.7, top),

a clear case of `fishing down' of the food web (Pauly et al. 1998, 2001). The FiB index

showed a similar trend (Figure XIX-60.7, bottom), suggesting that the reported landings

did not compensate for the decline in the MTI over that period.

Figure XIX-60.7. Mean trophic level (i.e., Marine Trophic Index) (top) and Fishing-in-Balance Index

(bottom) in the Scotian Shelf LME (Sea Around Us 2007).

800

60. Scotian Shelf LME

The Stock-Catch Status Plot shows that over 90% of commercially exploited stocks in the

LME are either overexploited or have collapsed (Figure XIX-60.8, top) with less than 30%

of the reported landings biomass supplied by fully exploited stocks (Figure XIX-60.8,

bottom).

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

0%

100

10%

90

20%

)

80

(

%

s

30%

u

70

at

st

40%

y

60

b

s

k

50%

c

o

50

f

st

60%

o

40

er

70%

mb

30

u

N

80%

20

90%

10

100%0

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

(n = 2726)

developing

fully exploited

over-exploited

collapsed

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

0%

100

10%

90

20%

80

)

%

30%

(

70

s

t

u

a

40%

60

ck st

50%

t

o

50

s

y

60%

b

h

40

t

c

a

70%

C

30

80%

20

90%

10

100%0

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

(n = 2726)

developing

fully exploited

over-exploited

collapsed

Figure XIX-60.6. Stock-Catch Status Plots for the Scotian Shelf LME, showing the proportion of

developing (green), fully exploited (yellow), overexploited (orange) and collapsed (purple) fisheries by

number of stocks (top) and by catch biomass (bottom) from 1950 to 2004. Note that (n), the number of

`stocks', i.e., individual landings time series, only include taxonomic entities at species, genus or family

level, i.e., higher and pooled groups have been excluded (see Pauly et al., this volume, for definitions).

There have been significant declines in abundance and sizes for many commercially

exploited fish species (Zwanenburg 2000), indicating that the limits of exploitation had

been reached (Pauly et al. 2001). The decrease in size, related to fishing effort, occurred

both on the eastern and western shelves. Fishing effort increased rapidly with the

establishment of Canada's 200-mile EEZ in 1977. Recent analyses of changes in the

productivity and biomass yields of the Scotian Shelf LME revealed the consequences of

the removal of top predators on the trophic structure of an ecosystem (Choi et al. 2004,

Frank et al. 2005). The dominant change in the biomass yield was a sharp decline in

groundfish landings and biomass from the mid-1980s through the mid-1990s. The

trawlable demersal biomass declined from 450,000 tonnes in 1973 to less than 15,000

tonnes in 1997. Coincident with this decline was an increase of pelagic fish as well as of

shrimp and snow crab. At the lower trophic levels, increases were observed for a 40-

year period from 1960 to 2000 in phytoplankton concentrations based on colour index

values from CPR, and in the increase in numbers of zooplankters, less than 2 mm in

length. The principal fisheries are now directed toward pelagic fish and

macroinvertebrates, and are dominated by herring, shrimp and snow crab.

XIX Non Regional Seas LMEs

801

A management scheme taking into account species interaction and biomass production

is being initiated to address the overexploitation of the LME's main fisheries (cod,

haddock, flounder, and other demersal fish). When the cod fishery collapsed on the

Eastern shelf, a cod moratorium was imposed in 1993 and remains in effect. Overfishing

led to a number of fishery closures in the early 1990s.

III. Pollution and Ecosystem Health

For information on marine pollution and the protection of this LME's offshore

environment, consult the Fisheries and Oceans Canada site at www.mar.dfo-mpo.gc.ca.

The report section on Ocean Disposal and Marine Environmental Quality, Scotian Shelf:

An Atlas of Human Activities (2005), lists illegal spills and discharges such as the chronic

introduction of oil from vessel traffic, marine debris, chemical contaminants from vessels

and offshore hydrocarbon development activities, and the introduction of invasive species

and pathogens through ballast water as significant ongoing environmental concerns.

Also listed are shipwrecks and post-war chemical and unexploded ordinance dump sites

that need new assessments for risk. There have been several large-scale environmental

emergencies, including the wreck of the Arrow oil tanker and other vessel sinkings. The

DFO reports no concentrations of heavy metals above the PEL (probable effects level) on

the Scotian Shelf.

Hollingworth recognized the need to assess the wider ecological costs of over

exploitation of the fisheries resource (2000). The International GLOBEC Cod and

Climate Change Programme studies the response of different cod populations to climate

changes in various regions of the cod's North Atlantic range, including the Scotian Shelf.

The ESSIM project (Eastern Scotian Shelf Integrated Management Project) described in

its first Ecosystem Status Report for the Eastern Scotian Shelf (DFO 2003) the shift in the

ecosystem from groundfish to pelagic species and invertebrates (see also Zwanenburg et

al. 2006). O'Boyle and Jamieson (2006) point to an ongoing paradigm shift in ocean

management, exemplified by explicit consideration of the impacts of all ocean sectors on

the marine environment, both separately and in aggregate. The authors recommend

adaptive management, and include both conceptual and operational level management

goals to achieve ecosystem-based management. Climate change is a priority issue, and

on 12 December 2007 the Government of Canada announced at the UN Climate Change

Conference in Indonesia new mandatory regulations for industry for emissions reduction.

Industries must submit air emissions data to the Government of Canada within the next

six months as part of the "toughest plan in Canadian history" to clean up air, tackle

climate change and protect our environment" said Environment Minister John Baird. The

air emissions action is part of Canada's "Turning the Corner: An Action Plan to Reduce

Greenhouse Gases and Air pollution launched in April 2007.

IV. Socioeconomic Conditions

The Nova Scotia Department of Finance, Economics and Statistics, reports that the

population of Nova Scotia on 1 October 2007 was 935,106 persons of whom 452,000

were employed and per capita income in 2006 was $29,459. Health Canada posts a

report by Dr. Ronald Colman (2005) on the socioeconomic gradient in health in Atlantic

Canada based on evidence from Newfoundland and Nova Scotia 1985-2001 finding high

socioeconomic inequality in health in Newfoundland and Glace Bay and Kings County,

Nova Scotia compared to Canada as a whole, Europe and Australia. Income was found

to be the most important contributor to socioeconomic inequality in health; education and

economic status also contributed to health status (Colman 2005).

The trophic cascade changed the structure of the Scotian Shelf LME from an economic

perspective, with the recent value of shrimp and crab landings exceeding the previous

802

60. Scotian Shelf LME

value of the demersal fishery. With regard to other marine resources, the Canada-Nova

Scotia offshore petroleum Board is responsible for the regulation of petroleum affairs in

the province. The presence of oil raises issues of multiple uses of the marine

environment.

V. Governance

Federal jurisdiction over Canada's coastal and inland fisheries dates to the Constitution

Act of 1867. In 1979 the federal government established the Department of Fisheries

and Oceans. However, the provinces are responsible for certain areas of fisheries

jurisdiction, including fish processing and the training of fishermen (The Canadian

Encyclopedia at www.thecanadianencyclopedia.com). In November 2007 the DFO

announced a new framework for the management of fisheries resources. Drivers for the

new management framework include the need to certify that Canadian seafood products

are sustainably harvested, domestic legislation including Bill C-45, and International

agreements and protocols signed by Canada. The Framework and the international

agreements emphasise the Precautionary Approach, the Ecosystem Approach, and

Sustainable Development.

References

Belkin, I.M. (2004) Propagation of the "Great Salinity Anomaly" of the 1990s around the northern

North Atlantic, Geophysical Research Letters, 31(8), L08306, doi:10.1029/2003GL019334.

Belkin, I.M. (2008) Rapid warming of Large Marine Ecosystems, Progress in Oceanography, in

press.

Belkin, I.M., Cornillon, P.C., and Sherman, K. (2008). Fronts in Large Marine Ecosystems of the

world's oceans. Progress in Oceanography, in press

Belkin, I.M., S. Levitus, J. Antonov, and S.-A. Malmberg (1998) "Great Salinity Anomalies" in the

North Atlantic, Progress in Oceanography, 41(1), 1-68.

Brown, S.K., Mahon, R., Zwanenburg, K.C.T., Buja, K.R., Claflin, L.W., O'Boyle, R.N., Atkinson, B.,

Sinclair, M., Howell, G., and Monaco, M.E. (1996). East Coast of North America Groundfish:

Initial Explorations of Biogeography and Species Assemblages. NOAA, Silver Springs,

MD/Department of Fisheries and Oceans, Dartmouth, Canada.

Choi, J.S., Frank, K.T., Leggett, W.C., and Drinkwater, K.F. (2004). Transition to an alternate state

in a continental shelf ecosystem. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 61:505-

510.

Colman, R. (2005) The Socioeconomic Gradient in Health in Atlantic Canada: Evidence from

Newfoundland and Nova Scotia 1985-2001. www.hc-sc.gc.ca/finance/hprp-prpms/results-

resultats/20

DFO (Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada) (2007) A New Resource Management

Sustainable Development Framework at www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/communic/fish_

man/consultations/RMSD

DFO (Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada) (2005) Report on Ocean Disposal and Marine

Environmental Quality, Disposal of Material in the Ocean, Scotian Shelf: An Atlas of Human

Activities. www.mar.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/oceans/e/essim/atlas/odmeq-e.htm

DFO (Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada) (2003) State of the Eastern Scotian Shelf

Ecosystem. DFO. Can. Sci. Advisory Sec. Ecosystem Status Report 2003/004.

Frank, K.T., Perry, R.I. and Drinkwater, K.F. (1990). Predicted response of northwest Atlantic

invertebrate and fish stocks to CO2-induced climate change. Transaction American Fisheries

Society 119:353-365.

Frank, K.T., Perry, R.I., Drinkwater, K.F. and Lear, W.H. (1988). Changes in the fisheries of Atlantic

Canada associated with global increases in atmospheric carbon dioxide: A preliminary report.

Canadian Technical Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 652.

XIX Non Regional Seas LMEs

803

Frank, K.T., Petrie, B., Choi, J.S. and Leggett, W.C. (2005). Trophic cascades in a formerly cod-

dominated ecosystem. Science 308:1621-1623.

Hollingworth, C.E. (2000). Ecosystem effects of fishing. Proceedings of an ICES/SCOR

Symposium, Montpellier, France, 16-19 March 1999. ICES Journal of Marine Science 57(3).

Linder, C. A. and Gawarkiewicz, G. (1998). A climatology of the shelfbreak front in the Middle Atlantic

Bight. Journal of Geophysical Research 103(C9):18,405-18,423.

Mills, E.L. and Fournier, R.O. (1979). Fish production and the marine ecosystems of the Scotian

Shelf, eastern Canada. Marine Biology 54:101-108.

Nova Scotia Department of Finance Economics & Statistics (2007) Common Statistics at

www.gov.ns.ca/finance/statistics/agency/index.asp

O'Boyle, R. and Jamieson, G. (2006) Observations on the implementation of ecosystem-based

management: Experiences on Canada's east and west coasts. Fisheries Research 79:1-12.

Pauly, D. and Christensen, V. (1995). Primary production required to sustain global fisheries.

Nature 374: 255-257.

Pauly, D. and Watson, R. (2005). Background and interpretation of the `Marine Trophic Index' as a

measure of biodiversity. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society: Biological Sciences

360: 415-423.

Pauly, D., Christensen, V., Dalsgaard, J., Froese R. and Torres, F.C. Jr. (1998). Fishing down

marine food webs. Science 279: 860-863.

Pauly, D., Palomares, M.L., Froese, R., Sa-a, P., Vakily, M., Preikshot, D. and Wallace, S.

(2001). Fishing down Canadian aquatic food webs. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic

Science 58:51-62.

Prescott, J.R.V. (1989). The political division of large marine ecosystems in the Atlantic Ocean and

some associated seas, p 395-442 in: Sherman, K. and Alexander, L.M. (eds), Biomass Yields

and Geography of Large Marine Ecosystems. AAAS Selected Symposium 111. Westview

Press, Boulder, U.S.

Sea Around Us (2007). A Global Database on Marine Fisheries and Ecosystems. Fisheries Centre,

University British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada. www.seaaroundus.org/lme/

SummaryInfo.aspx?LME=8

Zwanenburg, K. C. T. (2000). The effects of fishing on demersal fish communities of the Scotian

Shelf, ICES J. Mar. Sci. 57:503-509.

Zwanenburg, K.C.T. (2003). The Scotian Shelf, p 75-91 in: Hempel, G. and Sherman, K. (eds),

Large Marine Ecosystems of the World: Trends in Exploitation, Protection, and Research.

Elsevier, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Zwanenburg, K.C.T., Bowen, D., Bundy, A., Drinkwater, K., Frank, K., O'Boyle, R., Sameoto, D.

and Sinclair, M. (2002). Decadal changes in the Scotian Shelf Large Marine Ecosystem, p 105-

150 in: Sherman, K. and Skjoldal, H.R. (eds), Large Marine Ecosystems of the North Atlantic:

Changing States and Sustainability. Elsevier, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Zwanenburg, K.C.T., A. Bundy, P. Strain, W.D. Bowen, H. Breeze, S.E. Campana, C. Hannah, E.

Head, and D. Gordon. 2006. Implications of ecosystem dynamics for the integrated

management of the Eastern Scotian Shelf. Can. Tech. Rep. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2652: xiii + 91 p.

804

60. Scotian Shelf LME

XIX Non Regional Seas LMEs

805

XIX-61 Northeast U.S. Continental Shelf LME

M.C. Aquarone and S. Adams

The Northeast U.S. Continental Shelf LME extends from the Gulf of Maine to Cape

Hatteras in the Atlantic Ocean. It is characterised by its temperate climate. Structurally,

this LME is complex, with marked temperature and climatic changes, winds, river runoff,

estuarine exchanges, tides and multiple circulation regimes. It is historically a very

productive LME of the Northern Hemisphere. The LME has an area of 310,000 km2, of

which 1.96% is protected, and has 28 major estuaries and river systems (Sea Around Us

2007), including Casco Bay (Kennebec), Chesapeake (including the Potomac River),

Delaware, and Long Island Sound (Connecticut River). Four major sub-areas are the

Gulf of Maine, Georges Bank, Southern New England, and the Mid-Atlantic Bight. Book

chapters and articles pertaining to this LME include Falkowski (1991), Sissenwine &

Cohen (1991), Sherman et al. (1996a, 1996b, 2002, 2003) and Murawski (1996, 2000).

A Northeast Shelf Ecosystem volume, edited by Sherman et al., was published in 1996.

I. Productivity

This LME is bounded on the seaward side by the Gulf Stream, with its circulation and

seasonal meanders and rings influencing the LME. The gyre systems of the Gulf of

Maine and Georges Bank, and the nutrient enrichment of estuaries in the southern half of

the LME contribute to the maintenance on the shelf of relatively high levels of

phytoplankton and zooplankton prey fields for planktivores including menhaden, herring,

mackerel, sand lance, butterfish, and marine birds and mammals. For a map of surface

circulation, see Sherman et al. (2003). For an overview of the physical oceanography of

the shelf, see Brooks (1996). The Northeast U.S. Continental Shelf LME is a Class I,

highly productive ecosystem (>300 gCm-2yr-1), and is one of the world's most productive

LMEs. Since 1977, the NOAA Northeast Fisheries Science Centre (NEFSC) has

monitored this LME for primary productivity, chlorophyll-a, zooplankton biomass and

species diversity. Productivity varies in the 4 major sub-areas, and from season to

season. Zooplankton is used as an indicator of major changes in stability of the lower

levels of the food web and of biofeedback responses to oceanographic changes (Durbin

& Durbin 1996). Over the past two decades, zooplankton has been stable with regard to

biomass and the abundance of dominant species. Sufficient biodiversity and abundance

of zooplankton within the ecosystem supported the recovery of herring and mackerel

from their low levels in the mid-1970s and initiated the recovery of demersal fish stocks

beginning in the mid-1990s (Sherman et al. 2003).

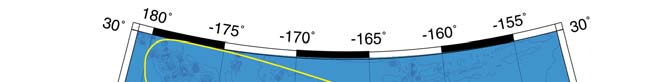

Oceanic fronts (Belkin et al. 2008)(Figure XIX-61.1): The Shelf-Slope Front (SSF) is

associated with a southward flow of cold, fresh water from the Labrador Sea. The Mid-

Shelf Front (MSF) follows the 50-m isobath (Ullman and Cornillon, 1999). The Nantucket

Shoals Front (NSF) hugs the namesake bank/shoals along 20-30-m isobaths. The

Wilkinson Basin Front (WBF) and Jordan Basin Front (JBF) separate deep basins from

Georges Bank and Browns Bank and are best defined in winter. Georges Bank is

surrounded by a tidal mixing front, GBF (Mavor and Bisagni, 2001). The Maine Coastal

Front (MCF) and Cape Cod Front (CCF) are seasonal (Ullman and Cornillon, 1999).

Northeast U.S. Continental Shelf LME SST (Belkin 2008)(Figure XIX-61.2):

Linear SST trend since 1957: 1.08°C.

Linear SST trend since 1982: 0.23°C.

806

61. U.S. Northeast Continental Shelf LME

Figure XIX-61.1. Fronts of the Northeast U.S. Continental Shelf LME. CCF, Cape Cod Front; GBF,

Georges Bank Front; MCF, Maine Coastal Front; MSF, Mid-Shelf Front; NSF, Nantucket Shoals Front;

SSF, Shelf-Slope Front. Yellow line, LME boundary. After Belkin et al. (2008).

The Gulf Stream brings warm waters from the Gulf of Mexico into the Southeast U.S.

Shelf, creating oceanographic conditions dramatically different from those of the

Northeast U.S. Continental Shelf LME. The Southeast U.S. Shelf is protected from

northern influences by the convergence of the Gulf Stream with the coast near Cape

Hatteras, which leaves very little opening for the leakage of shelf/slope waters from the

Mid-Atlantic Bight into the South Atlantic Bight. Subarctic influences can reach the Mid-

Atlantic Bight of the NE Shelf LME but not the South Atlantic Bight of the SE Shelf LME

(Greene and Pershing, 2007). Additionally the Gulf Stream, deflected offshore past Cape

Hatteras, indirectly impacts the Northeast U.S. Shelf by warm-core rings, whereas the

Southeast U.S. Continental Shelf is directly affected by the meanders of the Gulf Stream.

A cold spell in the 1960s resulted in a 2°C SST drop down to 10.5°C by 1965; the

recovery took four years. From 1969 on, the Northeast U.S. Continental Shelf

experienced a gradual warming with substantial interannual variability. The linear trend

for 1957-2006 yields a warming of 1.08°C, whereas the linear trend for 1982-2006 yields

a much smaller warming of 0.23°C.

XIX Non Regional Seas LMEs

807

Figure XIX-61.2. Northeast U.S. Continental Shelf annual mean SST (left) and SST anomalies (right),

1957-2006, based on Hadley climatology. After Belkin (2008).

Northeast Shelf LME Chlorophyll and Primary Productivity

The Northeast U.S. Continental Shelf LME is a Class I, highly productive ecosystem

(>300 gCm-2yr-1)(Figure XIX-61.3),

Figure XIX-61.3. Northeast U.S. Continental Shelf LME trends in chlorophyll a (left) and primary

productivity (right), 1998-2006, from satellite ocean colour imagery. Values are colour coded to the

right hand ordinate. Figure courtesy of J. O'Reilly and K. Hyde. Sources discussed p. 15 this volume.

II. Fish and Fisheries

Much has been published on Northeast U.S. Shelf LME fisheries, including population

assessments (Sherman et al. 1996c; Kenney et al. 1996; Mavor & Bisagni 2001) and the

status of living marine resources in Our Living Oceans (NOAA 1999) and in the NEFSC

Status of Stocks reports. The catch composition of this LME is diverse, and is comprised

of demersal fish (groundfish) dominated by Atlantic cod, haddock, hakes, pollock,

flounders, monkfish, dogfish, skates and black sea bass, pelagic fish (mackerel, herring,

bluefish and butterfish), anadromous species (herrings, shad, striped bass and salmon),

and invertebrates (lobster, sea scallops, surfclams, quahogs, northern shrimp, squid and

red crab). In the late 1960s and early 1970s there was intense foreign fishing within the

808

61. U.S. Northeast Continental Shelf LME

LME. The precipitous decline in biomass of fish stocks during this period was the result

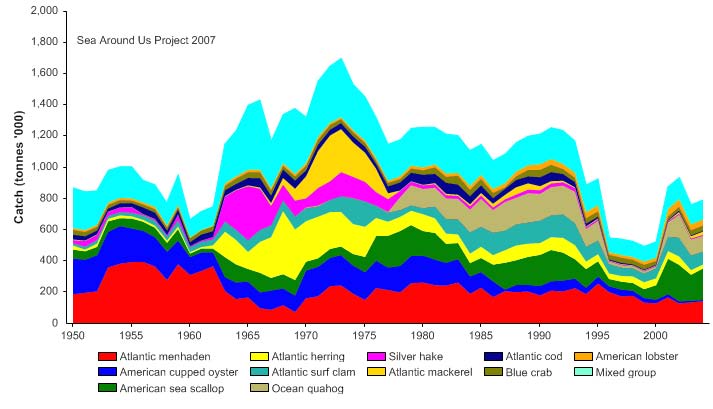

of excessive fishing mortality (Murawski et al. 1999). Total reported landings declined

from more than 1.6 million tonnes in 1973 to less than 500,000 tonnes in 1999, before

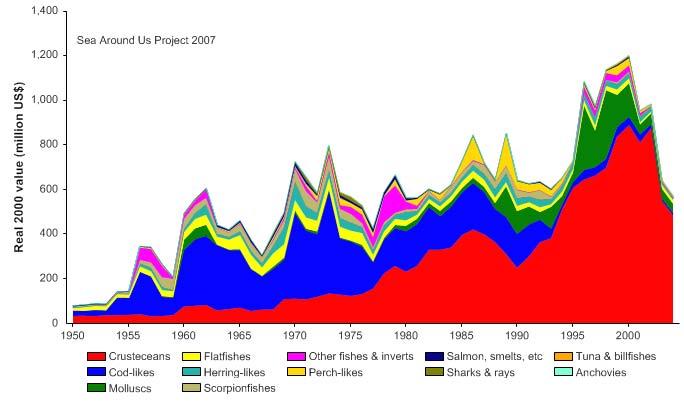

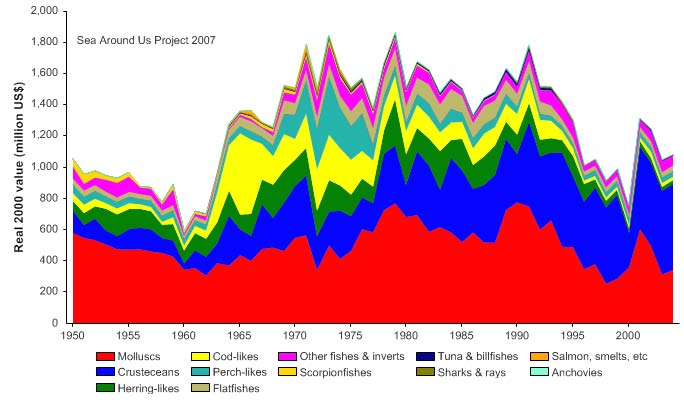

increasing to just under 800,000 tonnes in 2004 (Figure XIX-61.4). The value of the

reported landings reached US$1.8 billion (in 2000 US dollars) in 1973 and in 1979, and

has maintained a level above US$1 billion except for the three-year period between1998

and 2000 (Figure XIX-61.5). Among the most valuable species are lobster, sea scallops,

monkfish and summer flounder.

Figure XIX-61.4. Total reported landings in the Northeast U.S. Continental Shelf LME by species (Sea

Around Us 2007).

Figure XIX-61.5. Value of reported landings in the Northeast U.S. Continental Shelf LME by commercial

groups (Sea Around Us 2007).

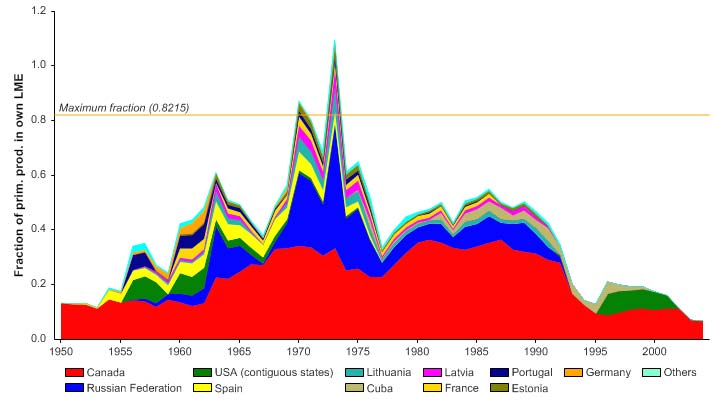

The primary production required (PPR) (Pauly & Christensen 1995) to sustain the

reported landings in the LME reached 90% of the observed primary production in the mid

1960s, but has declined to less than 20% in recent years (Figure XIX-61.6). The

XIX Non Regional Seas LMEs

809

extremely high PPR recorded in the 1960s and 1970s was likely due to the exploitation of

the accumulated biomass of cod stocks rather than from the exploitation of annual

surplus production in the LME. The USA accounts for most of the ecological footprint in

this LME, and Canada for some, although European countries also had a major share in

the 1960s and 1970s.

Figure XIX-61.6. Primary production required to support reported landings (i.e., ecological footprint) as

fraction of the observed primary production in the Northeast U.S. Continental Shelf LME (Sea Around

Us 2007). The `Maximum fraction' denotes the mean of the 5 highest values.

The mean trophic level of the reported landings (Pauly & Watson 2005) has declined

since the early 1960s, when the rate of exploitation of demersal fish in the LME was high

(Figure XIX-61.7, top), the consequence of a clear case of `fishing down' of the food web

(Pauly et al. 1998). The Fishing in Balance index showed a similar decline (Figure XIX-

61.7, bottom), implying that the increase in reported landings in the 1970s did not

compensate for the decline in the Marine Trophic Index over that period.

Figure XIX-61.7. Mean trophic level (i.e., Marine Trophic Index) (top) and Fishing-in-Balance Index

(bottom) in the Northeast U.S. Continental Shelf LME (Sea Around Us 2007).

810

61. U.S. Northeast Continental Shelf LME

The Stock-Catch Status Plots show that over 70% of commercially exploited stocks in the

LME have collapsed, with another 20% being overexploited (Figure XIX-61.8, top).

Slightly over 30% of the reported landings biomass is supplied by fully exploited stocks

(Figure XIX-61.8, bottom). The US National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) includes

"overfished" but not "collapsed" in its stock status categories. Currently overfished are

several demersal stocks (NMFS 2009).

1950