XIV NORTH EAST PACIFIC

XIV-44 California Current LME

XIV-45 East Bering Sea LME

XIV-46 Gulf of Alaska LME

XIV-47 Gulf of California LME

XIV-48 Pacific Central-American

Coastal LME

592

XIV North East Pacific

XIV North East Pacific

593

XIV-44 California Current LME

M.C. Aquarone and S. Adams

The California Current LME is bordered by the USA and Mexico, between subtropical and

subarctic LMEs. It has a surface area of around 2.2 million km², of which 1.31% is

protected, and it contains 0.01% of the world's coral reefs and 1.04% of the world's sea

mounts (Sea Around Us 2007). The LME shoreline is more than two thousand miles long.

The LME features more than 400 estuaries and bays, including the Columbia River, San

Francisco Bay and Puget Sound, which constitute 61% of the estuary and bay acreage.

This LME is characterised by its temperate climate and strong coastal upwelling. Book

chapters and articles pertaining to this LME include MacCall (1986), Mullin (1991), Bakun

(1993), Bottom et al. (1993), McGowan et al. (1999), Brodeur et al. (1999) and Lluch-

Belda et al. (2003). Additional information on this well-studied LME is available from the

Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory at< www.pmel.noaa.gov>.

I. Productivity

The effects of coastal upwelling, ENSO and the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO) result

in strong interannual variability in the productivity of the ecosystem and, consequently, of

the catch levels of different species groups (Bakun 1993). ENSO events are

characterised locally by an increase in temperature, a rise in coastal sea level,

diminished upwelling and increased coastal rainfall (Bakun 1993). Miller (1996) reports a

significant deepening of the thermocline off California, which he attributes to a weakening

of the Aleutian Low (decadal scale), and to waves propagating through the ocean from

the tropics (interannual scale). There is speculation as to what causes changes in the

eastern bifurcation of the Subarctic Current into the California Current, and the possible

effects of these changes on biological production in this LME.

The CCLME is one of the world's five LMEs that undergo seasonal upwellings of cold

nutrient rich water that generate localised areas of high primary productivity that support

fisheries for sardines, anchovy, and other pelagic fish species. (e.g. California Current,

Canary Current, Guinea Current, Benguela Current, and Humboldt Current LMEs). The

California Current LME can be considered a Class III, low productivity ecosystem (<150

gCm-2yr-1) (Figure XIV-44.3). The Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO) is a 20-30-year

cooling and warming cycle between a cool and productive ocean regime and a warm and

unproductive ocean regime. The latest warm regimes were in 1977-1998 and 2003-2006.

Apparent biological consequences of these regime shifts are changes in primary and

secondary production and changes in the abundance of eastern Pacific fish stocks. For

example, there was a sharp decline in primary and secondary production following the

1977 regime shift (CalCOFI Atlas 35, 2002). The California Cooperative Oceanic

Fisheries Investigations (CalCOFI) programme has sampled zooplankton biomass almost

continuously from 1951 to present. Observed decline in zooplankton abundance related

to water column stratification has been described by Roemmich & McGowan (1995a and

1995b), Haywood (1995), and McGowan et al. (1999). These biomass changes appear

to be inversely related to those occurring in the Gulf of Alaska LME to the north (Brodeur

& Ware 1995, Brodeur et al. 1999). For a study of interannual variability impacts on the

LME, see Lluch-Belda et al. (2003), Peterson and Schwing (2003), and Hooff and

Peterson (2006). There is a need to better understand the role of climate and seasonal

change in the energy flow and population dynamics of species inhabiting the LME. For

an analysis of chlorophyll and sea surface temperature changes during the El Niño/La

Niña period of 1998/1999, see Kahru & Mitchell (2000). For an article on observing and

modelling the California Current system, see Miller and Schneider (2000). Information on

594

44. California Current LME

the U.S. GLOBEC Northeast Pacific Programme is available at:

http://globec.coas.oregonstate .edu/

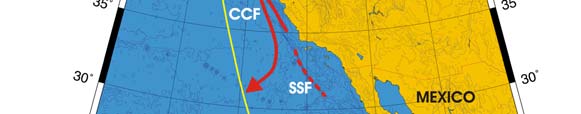

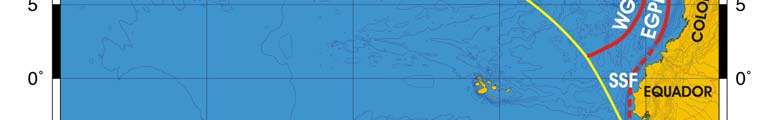

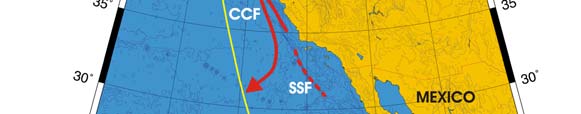

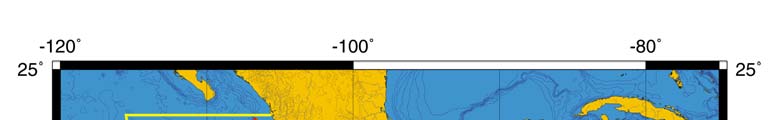

Oceanic fronts (Belkin et al. 2008): The California Current Front (CCF) separates

relatively cold, low-salinity waters of the southward California Current from warmer and

saltier waters inshore (Hickey 1998) (Figure XIV-44.1). The Subarctic Front (SAF)

separates the northward Subarctic Current from inshore waters. On the inshore side of

the California Current, upwelling fronts develop in summer (Belkin & Cornillon 2003,

Belkin et al. 2003). Offshore frontal filaments, sometimes a hundred km long, carry the

upwelled cold, nutrient-rich water across the entire LME (Belkin & Cornillon 2003). In

winter, a second and seasonal poleward current develops over the shelf and slope, giving

rise to the seasonal Davidson Current Front (DCF) between warm saline subtropical

waters inshore and colder, fresher temperate waters offshore. This front can be traced

from off southern California (35°N) to the northern Washington coast (48-49°N).

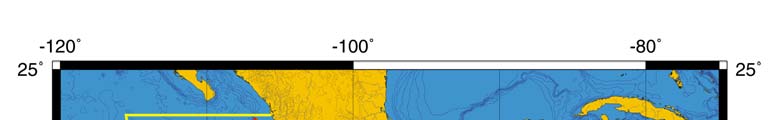

Figure XIV-44.1. Fronts of the California Current LME. CCF, California Current Front; DCF, Davidson

Current Front (winter only); SAF, Subarctic Front; SSF, Shelf Slope Front; Yellow line, LME boundary.

After Belkin et al. (2008).

California Current LME SST (Belkin 2008)(Figure XIV-44.2).

Linear SST trend since 1957: 0.32°C.

Linear SST trend since 1982: -0.07°C.

Like the East Bering Sea and Gulf of Alaska LMEs, the California Current cooled

dramatically, by nearly 2°C, from 1958 to 1975, then warmed in 1977 as a result of the

North Pacific regime shift (Mantua et al., 1997), and remained relatively warm in 1998.

Cooling was again observed from 1999-2002, then warming in 2003-2006. The absolute

minimum of 1975 was synchronous with the absolute minima in two other LMEs of the

East Pacifi, the Gulf of California and Pacific Central American. The absolute maximum

of 18.3°C in 1997 is attributable to El Niño, whereas the dramatic 1.8°C cooling in 1999

was associated with La Niña. The California Current LME and the Humboldt Current LME

XIV North East Pacific

595

have experienced a slight cooling over the last 25 years. Both LMEs are situated in

similar oceanographic regimes of East Pacific wind-induced coastal upwelling systems.

These regimes feature strong and persistent alongshore winds directed towards the

Equator, causing Ekman offshore transport of warm surface waters and upward flux of

cold subsurface waters (coastal upwelling). The above-noted long-term cooling in these

areas is suggestive of a long-term increase in the upwelling intensity, which in turn may

have resulted from a long-term increase in the strength and/or persistence of upwelling-

favorable along-coast winds. This hypothesis is supported by observed data and

numerical modeling experiments (Schwing and Mendelsson, 1997; and GLOBEC at

www.usglobec.org). There is no significant time lag between major thermal events in the

California Current, Gulf of Alaska and East Bering Sea LMEs. The observed

synchronicity among these regions suggests ocean-scale if not global forcing in the

Northern and Northeast Pacific. The North Pacific regime shifts of 1976-1977 and 1999-

2002 were broad scale events.

Figure XIV-44.2 California Current LME annual mean SST (left) and SST anomalies (right) based on

Hadley climatology. 1957-2006. After Belkin ( 2008).

California Current LME Chlorophyll and Primary Productivity: The California Current

LME is a Class III, low productivity ecosystem (<150 gCm-2yr-1)(Figure XIV-44.3).

Figure XIV-44.3. California Current LME trends in chlorophyll a (left) and primary productivity (right),

1998-2006, from satellite ocean colour imagery. Values are colour coded to the right hand ordinate.

Figure courtesy of J. O'Reilly and K. Hyde. Sources discussed p. 15 this volume..

596

44. California Current LME

II. Fish and Fisheries

Fisheries resources in the California Current LME include salmon, pelagic fisheries,

groundfish, and invertebrates. Salmon fisheries harvest 5 species of salmon (Chinook,

coho, sockeye, pink, and chum). The abundance of salmon stocks fluctuates

considerably. Chinook and coho are harvested recreationally and commercially in Puget

Sound and in freshwater rivers. Fisheries management for salmon is complex, with

conflicting jurisdictions and salmon originating from several rivers. For all salmon species

there is excess fishing power and overcapitalization of the fishing fleet. For coho and

Chinook there is a sharp decline in abundance that has led to the closure of all salmon

fisheries off the coasts of Oregon and California. Small pelagic resources in the LME are

Pacific sardine, northern anchovy, jack mackerel, chub (Pacific) mackerel, and Pacific

herring. Sardine, anchovy and mackerel are mostly harvested off California and Baja

California. Sardine and anchovy fluctuate widely in abundance (NMFS 2009). Natural

environmental change and intensive fishing are causing long-term shifts in their

abundance in this LME. The CalCOFI programme was initiated to examine the reasons

for the decline of the Pacific sardine and to study its physical and biotic habitat (CalCOFI

1990 results at www.calcofi.org). The collapse of the Pacific sardine has had cascading

effects on other ecosystem components including marine birds. The variability in

abundance levels of sardine and anchovy spawning biomass from 1930 to 1985 is

analysed in MacCall (1986). Sardine catches declined after World War II, and the stock

collapsed in the late 1950s. The sardine crash is one of the earliest well documented

major fishery crashes (Radovich 1982) and is attributed to overfishing that accelerated a

long term pattern of natural decline. Sardines today are taken for human consumption,

bait, and aquaculture feed. Consumer demand for canned anchovy is low. Anchovy are

harvested for reduction into fishmeal, bait, human consumption and oil. In recent years,

low prices and market problems continue to prevent a significant anchovy fishery. The

endangered brown pelican depends on anchovy as an important food source, and the

wellbeing of the ecosystem is an important factor in resource management. Mackerel

supported a major fishery in California but the stock collapsed in the 1970s. It has since

reopened under a quota system. Sardine, anchovy, and mackerel are transboundary

stocks exploited by both US and Mexican fleets. Squid is an important fishery in

California in terms of revenue and tons landed. The vast majority is frozen for human

consumption and exported to China, Japan and Europe. Landings depend on cyclical

oceanographic regimes, with increases when relatively warm water events are displaced

by cool water. Herring landings declined with an El Niño episode. Groundfish fisheries

include sole, thornyheads, sablefish, rockfish, ligcod and cabezon, flatfish, and Pacific

hake. Harvest rates have been reduced in recent years and gear designs to reduce

bycatch. Nearshore fisheries are for invertebrate species including crabs, shrimps,

abalones, clams, scallops and oysters (NMFS 2009). A recent compilation of species

inhabiting the nearshore California Current LME can be reviewed at the California

Department of Fish and Game site at: www.dfg.ca.gov/mrd/.

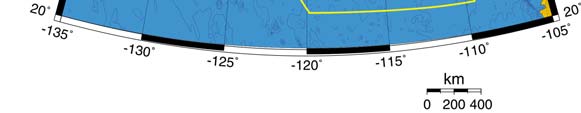

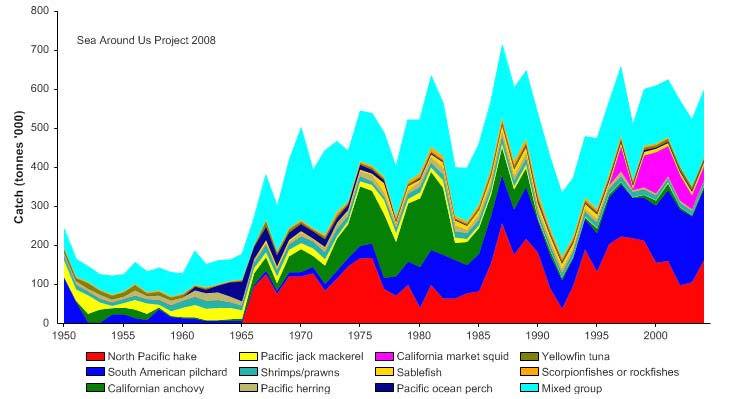

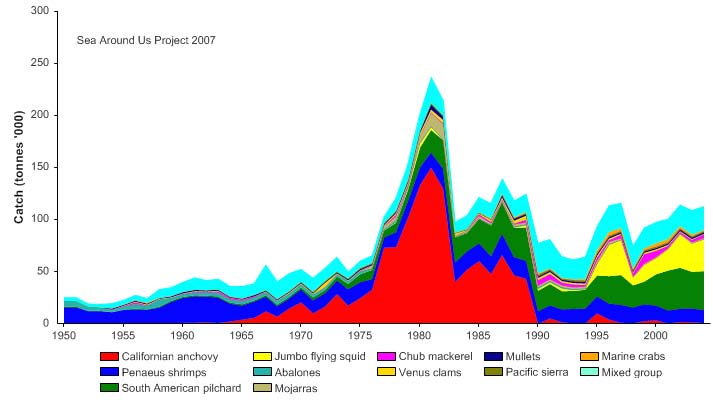

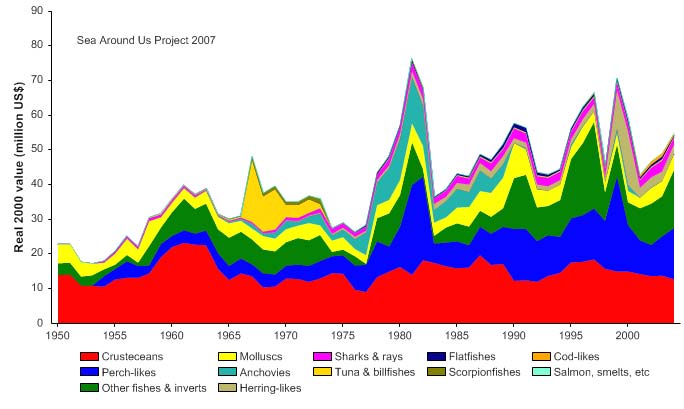

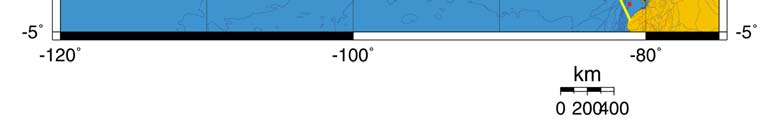

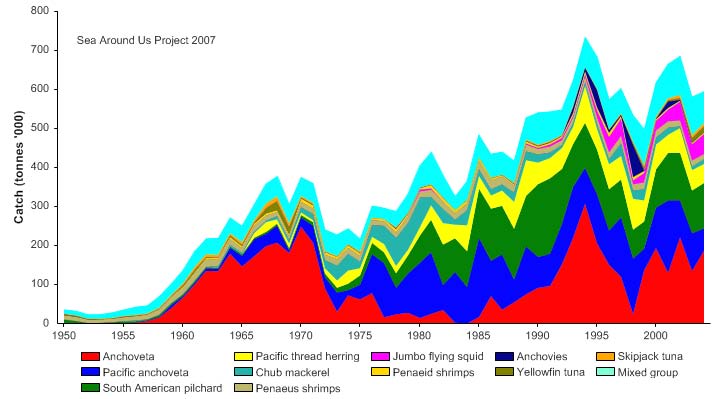

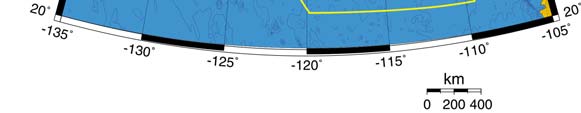

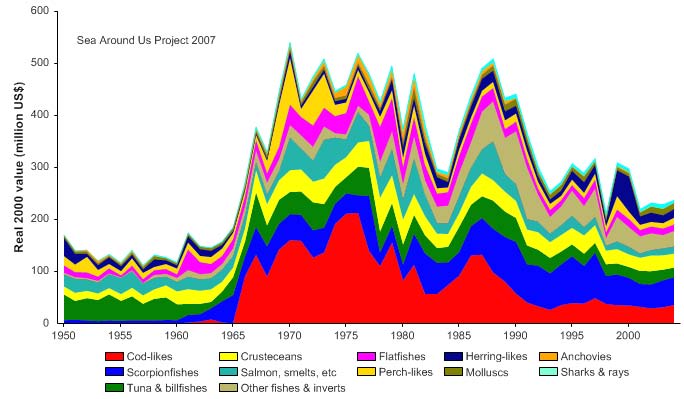

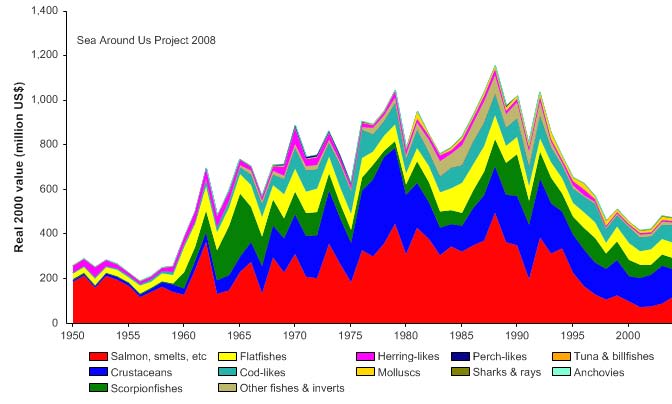

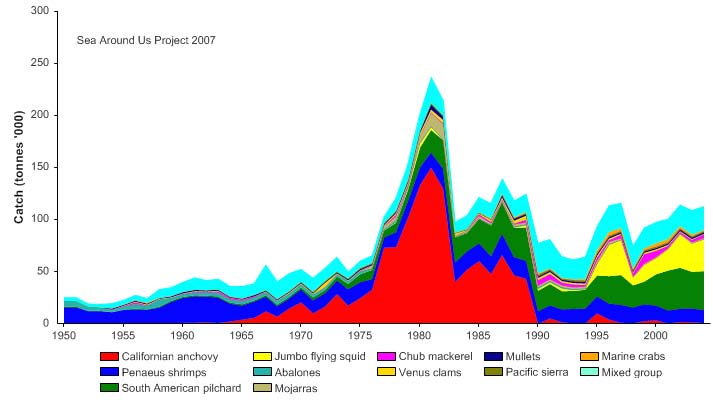

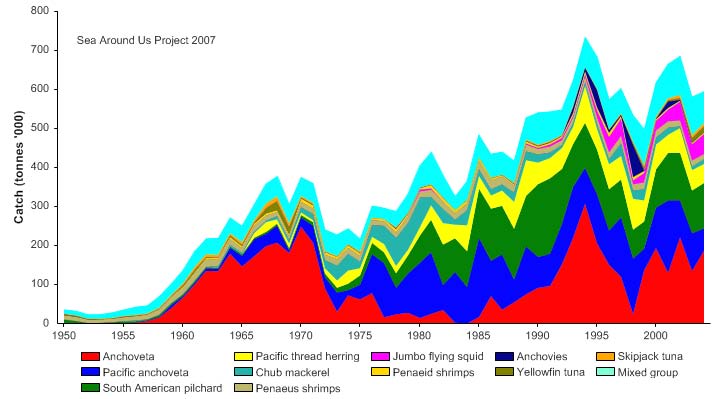

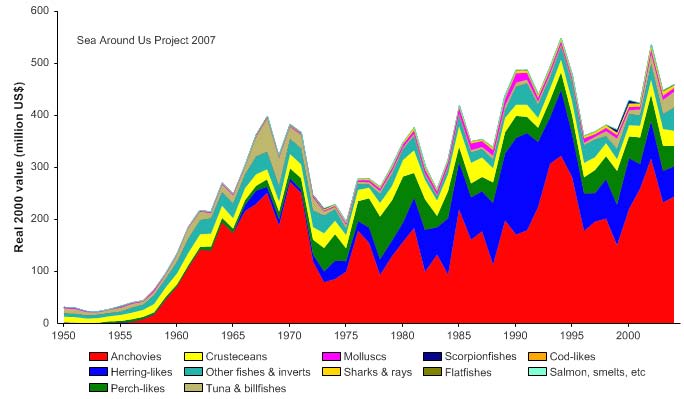

Total reported landings peaked at 710,000 tonnes in 1987 (Figure XIV-44.4). The value

of reported landings peaked in 1970 at US$540 million (in 2000 US dollars) with a similar

level recorded in 1988 (Figure XIV-44.5). The major commercial fish species are Pacific

salmon, hake, albacore tuna, Pacific sardine (also known as South American pilchard),

northern anchovy, jack mackerel, chub (Pacific) mackerel, Pacific herring, and Pacific

halibut. Shrimp, squid, crab, clam and abalone have high commercial value.

XIV North East Pacific

597

Figure XIV-44.4. Total reported landings in the California Current LME by species (Sea Around Us

2007).

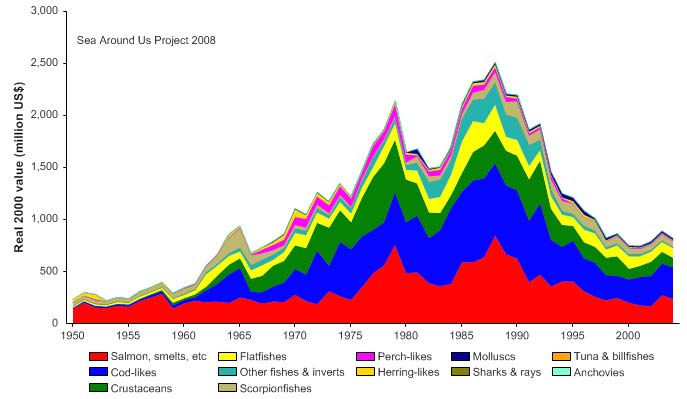

Figure XIV-44.5. Value of reported landings in the California Current LME by commercial groups (Sea

Around Us 2007).

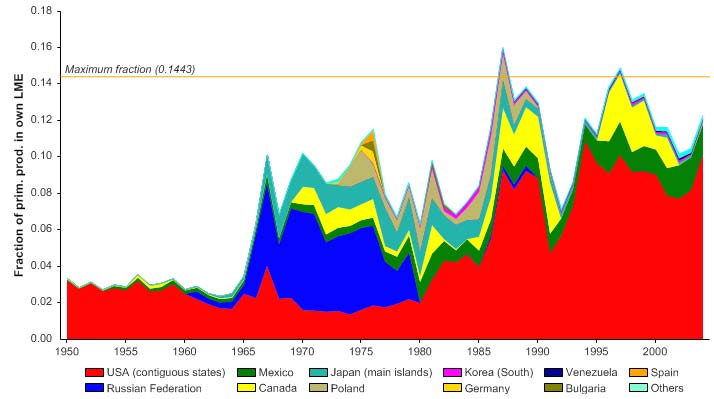

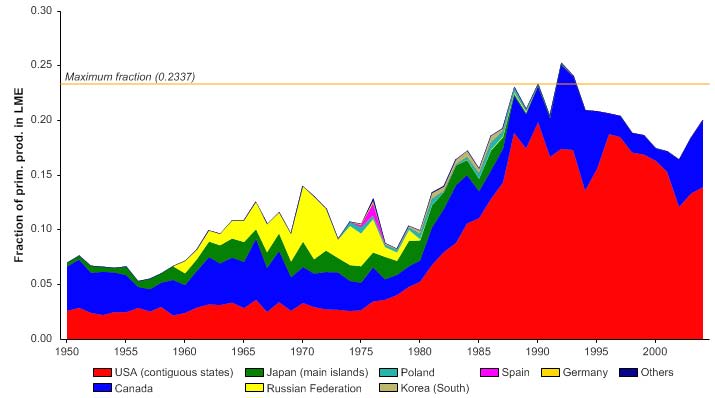

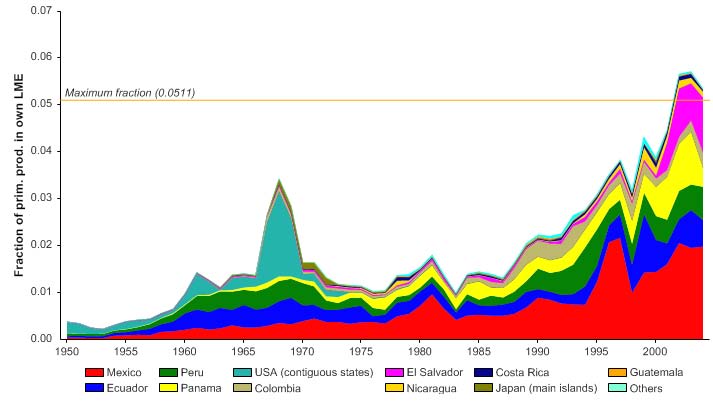

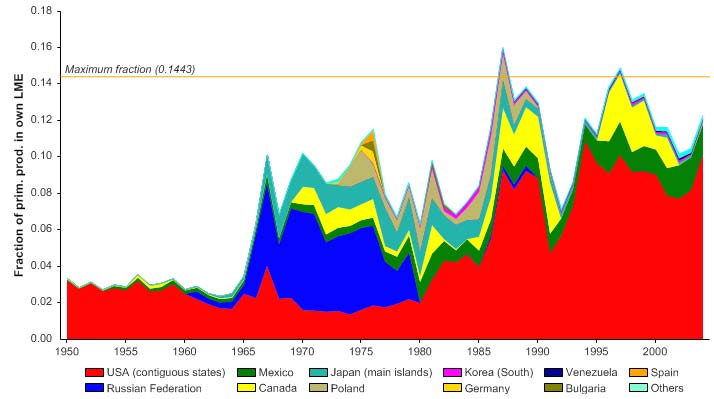

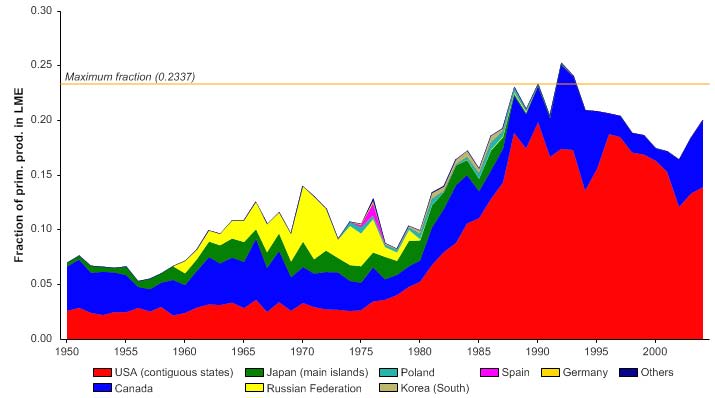

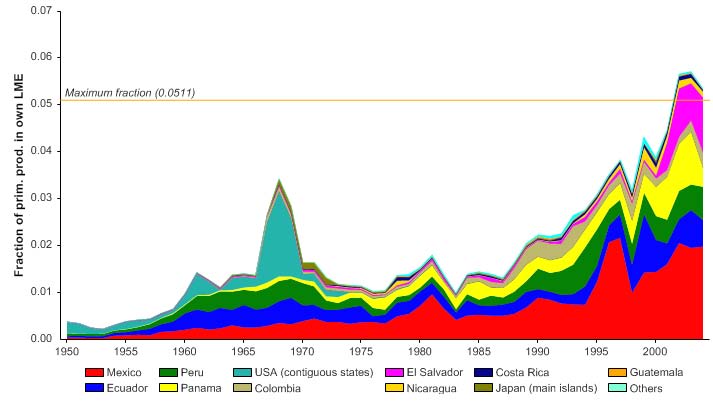

The primary production required (PPR) (Pauly & Christensen 1995) to sustain reported

landings in this LME reached 16% of the observed primary production in the late 1980s,

and has fluctuated between 7 to 15% in recent years (Figure XIV-44-6). The USA has

the largest share of the ecological footprint in the LME.

598

44. California Current LME

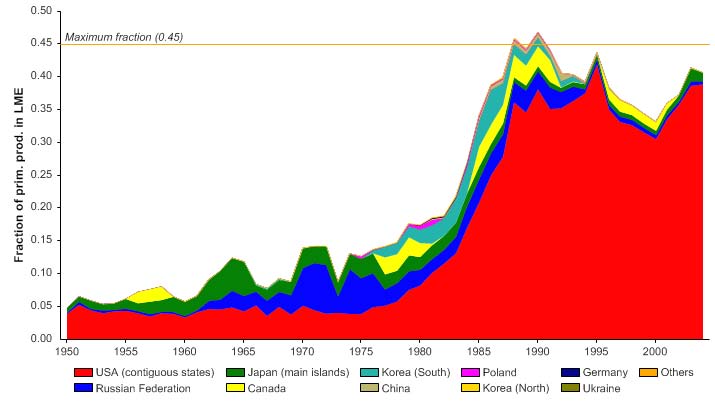

Figure XIV-44.6. Primary production required to support reported landings (i.e., ecological footprint) as

fraction of the observed primary production in the California Current LME (Sea Around Us 2007). The

`Maximum fraction' denotes the mean of the 5 highest values.

Both the mean trophic level of the reported landings (Pauly & Watson 2005; figure XIV-

44.7, top) and the Fishing-in-Balance index (Figure XIV-44.7, bottom) show considerable

fluctuation over the reported period with no clear trend, except for the initial increase in

the FiB index corresponding to a growth in fisheries during the 1960s.

Figure XIV-44.7. Mean trophic level (i.e., Marine Trophic Index) (top) and Fishing-in-Balance Index

(bottom) in the California Current LME (Sea Around Us 2007).

The Stock-Catch Status Plots indicate that over 80% of the stocks in the LME have

collapsed or are currently over-exploited (Figure XIV- 44.8, top). Half of the reported

landings biomass is still supplied by fully exploited stocks (Figure XIV-44.8, bottom). The

US National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) includes "overfished" but not "collapsed" in

its stock status categories. Currently overfished are Chinook and coho salmon, thought to

be impacted by environmental conditions resulting in poor ocean survival. The other

salmon species are considered fully exploited. Six other overfished species are among

XIV North East Pacific

599

groundfish stocks. Hake and lingcod have been rebuilt to target levels. Jack mackerel

and northern anchovy are underutilized species (NMFS 2009).

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

0%

100

10%

90

20%

)

80

%

(

s

30%

u

70

t

at

s

40%

y

60

b

s

k

50%

c

o

50

f

st

60%

40

er o

b

70%

m

30

Nu

80%

20

90%

10

100%0

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

(n = 4148)

developing

fully exploited

over-exploited

collapsed

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

0%

100

10%

90

20%

80

)

%

30%

(

70

s

t

u

a

40%

60

st

ck

50%

t

o

50

s

y

60%

b

h

40

t

c

70%

Ca

30

80%

20

90%

10

100%0

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

(n = 4148)

developing

fully exploited

over-exploited

collapsed

Figure IV-44.8. Stock-Catch Status Plots for the California Current LME, showing the proportion of

developing (green), fully exploited (yellow), overexploited (orange) and collapsed (purple) fisheries by

number of stocks (top) and by catch biomass (bottom) from 1950 to 2004. Note that (n), the number of

`stocks', i.e., individual landings time series, only includes taxonomic entities at species, genus or

family level. Higher and pooled groups have been excluded (see Pauly et al, this vol. for definitions).

Comprehensive plans for the management of marine resources in this LME are being

developed. Efforts are underway to implement ecosystem management in this LME.

There is a need to know more about competitive and predatory interactions, and about

climate effects on the fish stocks.

III. Pollution and Ecosystem Health

The major stressors in this LME are the effects of shifting oceanic climate regimes, the

intensive harvesting of commercial fish, releases of captive-bred salmon, and low-level,

chronic pollution from multiple sources (Bottom et al. 1993). Population growth rates

suggest that human pressures on coastal resources will increase substantially in many

coastal areas (EPA 2004). Hypotheses concerned with the growing impacts of pollution,

overexploitation and environmental changes on sustained biomass yields are under

investigation. Pacific salmon in the California Current LME depend on freshwater habitat

for spawning and rearing of juveniles. There are concerns about the interactions of

hatchery and natural wild salmon regarding the genetic integrity of native stocks and

productivity levels. The quality of freshwater habitat is largely a function of land

management practices. Coastal habitat degradation and shoreline alteration have

resulted from dam construction, logging, agriculture, increased urbanisation, grazing and

atmospheric pollution. In 1990-2000, the coastal areas experienced a loss of 1720 acres,

a low figure compared with other regions of the country but high in relation to existing

wetlands in the California Current LME. Ecological conditions in West Coast estuaries, a

600

44. California Current LME

valuable resource in this LME, are considered fair to poor (EPA 2004). Eighty seven

percent of estuaries assessed are impaired by some form of pollution or habitat

degradation. Some estuaries have extensive areas with elevated phosphorus

concentrations and decreased water clarity. Considerable areas have poor light

penetration. DIN concentrations in estuaries are rated good. Summer wind conditions

result in an upwelling of nutrient rich deep water that enters estuaries during flood tides

(EPA 2004). DIP concentrations in estuaries are rated fair. Chlorophyll a concentrations

in estuaries are rated good.

The EPA rated water clarity and dissolved oxygen as good, benthos and fish tissue as

fair, and coastal wetlands, eutrophic condition and sediment as poor in this LME (EPA

2001). In 2004 the EPA assessed the water quality index as fair, the sediment quality

index slightly improved, and the coastal habitat index and fish tissue index as poor (EPA

2004). The primary problem in California Current estuaries continues to be degraded

sediment quality, with 14% of estuaries exceeding thresholds for sediment toxicity or

sediment contaminants. Seventeen different contaminants were responsible for fish

advisories in this LME in 2002. Toxic sediments in Puget Sound were contaminated with

DDT and metals. For a study of water quality and one on sediment contamination in

Puget Sound, see EPA 2004. High concentrations of metals and PAHs were observed in

the Los Angeles harbour. The potential for benthic community degradation and fish

contamination is increasing. A decline in seabirds such as the sooty shearwater has

been observed. The LME contains a large seabird and marine mammal population

(Bakun 1993) that includes sea lions and elephant seals. Since the late 1970s, pinnipeds

have been increasing and are consuming large quantities of fish (DeMaster 1983;

California Department of Fish and Game 2005). For more information on marine

mammals as indicators of LME health, see NOAA (1999, p. 238). Of 274 coastal

beaches, 178 were closed or under an advisory for some period of time in 2002.

IV. Socioeconomic Conditions

Three major estuaries, the San Francisco Bay, the Columbia River and Puget Sound,

contribute to the local economy and enhance the quality of life of the inhabitants. Human

population pressures are increasing in Puget Sound, the Seattle-Tacoma region, San

Francisco Bay and southern California. California's population approached 37.7 million

persons on January 1, 2007 (www.dof.ca.gov), up almost 3.8 million persons from the

2000 census. The coastal population increased by 45% between 1970 and 1980 (U.S.

Census Bureau 1996). Forty seven coastal and estuarine countries bordering the

California Current LME increased their population by 13% between 1990 and 2000 (U.S.

Census Bureau 2001). In 2008 the combined population increase of San Diego, San

Bernardino, Orange and Riverside counties in California was estimated at 12 percent of

the total U.S. coastal population increase (www.oceanservice.noaa.gov). These

pressures require continued environmental monitoring to ensure that environmental

indicators currently demonstrating fair condition do not deteriorate. The California Current

LME supports important commercial and recreational fisheries. All salmon species are

harvested by Native American tribes for subsistence and ceremonial purposes. The value

of recreational catches is not easily measured. Recent prices for salmon have declined

due to market competition from record landings of Alaskan salmon and increasing

aquaculture production. Northern anchovy landings fluctuate more in response to market

conditions than to stock abundance. Commercial fishing is heavily regulated in an effort

to achieve sustainability. In 1998 there were 9,843 commercial fishermen licensed to fish

in California waters, down from 20,363 in 1980-1981. In 2006, there were 6,354

commercial fishing licenses purchased (California Department of Fish and Game

Statistics, online at <www.dfg.ca.gov/licensing/statistics>). Recreational fishing in

California generates US$4.9 billion and supports 43,000 jobs paying US$1.2 million in

salaries and wages (Bacher 2007). An increase in the demand for oil, gas and mineral

XIV North East Pacific

601

resources (e.g., chromite-bearing black sands and titanium sands off the Oregon and

Washington coasts; sand and gravel dredging) has stimulated an exploration of the non-

living resources of the LME.

V. Governance

Some critical issues requiring management include wild salmon stocks and significant

loss of their spawning and nursery habitats (EPA 2001, p.153). The Pacific Fishery

Management Council (PFMC) is responsible for managing fisheries off the coasts of

California, Oregon and Washington, with cooperation form states and tribal fishery

agencies. Within Puget Sound and the Columbia River, fisheries for Chinook and coho

salmon are managed by the states and tribes. The Pacific Salmon Commission, the

State of Washington, and tribal fishery agencies manage fisheries for pink, chum, and

sockeye salmon. All species of pink salmon have been listed as threatened or

endangered under the US Endangered Species Act. There is a legally mandated tribal

allocation of Coho salmon. The Pacific Salmon Treaty with Canada determines the share

of Canada and the US in the transboundary stock (NMFS 2009). There are more than 80

species managed under the Pacific Coast Groundfish Fishery Management Plan (FMP)

of the PFMC, no less than eight of which have been declared overfished. Many

groundfish stocks have geographic ranges that extend beyond the US EEZ into Canada

and Mexico. Groundfish stocks support many commercial, recreational, and Indian tribal

fishing interests in state and Federal waters off the coasts of Washington, Oregon, and

California. Groundfish are also caught incidentally in other fisheries, such as the trawl

fisheries for pink shrimp and ridgeback prawns. Current management measures include

trip limits, bag limits size limits, time/area closures, and gear restrictions. A trawl permit

buy-back program was implemented in 2003 to reduce the capacity of the groundfish

fishery. NOAA Fisheries Service, in cooperation with the PFMC, is assessing the impacts

of groundfish fisheries on the human, biological and physical environment. A preliminary

set of alternatives will be developed to take into account new stock assessments for 23 of

the groundfish species managed under the FMP (NOAA Fish News 2005). For

information concerning the San Francisco Bay Estuary Project, see www.abag.ca.gov/.

In Northern California, commercial, recreational, and Native American fishermen have

recently targeted both State and Federal water management on the Klamath River and in

the California Delta charging that historic fish runs in Northern California have been

destroyed by illegal pumping in the Delta area and by hydroelectric dams (Bacher, 2007).

Since the passage of the Marine Mammal Protection Act in 1972, populations of seals

and sea lions have increased. Killer whales are listed as an endangered species. In the

south, the Mexican portion of the LME has minimal fisheries regulation, with limited fauna

and marine mammal protection. The Mexican part of this LME falls within a non-UNEP

administered Regional Seas Programme, the North-East Pacific Region, which covers 8

central American countries (Colombia, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras,

Mexico, Nicaragua and Panama). The Convention for Cooperation in the Protection and

Sustainable Development of the Marine and Coastal Environment of the North-East

Pacific (Antigua Convention) was signed in 2002. The governments also approved an

Action Plan detailing how the countries concerned will improve the environment of the

North-East Pacific for the benefit of people and wildlife. The Action Plan's secretariat is

COCATRAM (Central America Marine Transport Commission). For information on

PICES, see the East China Sea LME (Chapter X). The States of California, Oregon, and

Washington are developing and implementing a network of marine protected areas.

602

44. California Current LME

References

Bacher, D. California fishermen target water policies. California Progress Report, June 26, 2007.

Accessed July 2007 at <californiaprogressreport.com>

Bakun, A. (1993). The California Current, Benguela Current, and Southwestern Atlantic Shelf

Ecosystems: A comparative approach to identifying factors regulating biomass yields, p 199-

221 in: Sherman, K., Alexander, L.M. and Gold, B.D. (eds), Large Marine Ecosystems: Stress,

Mitigation and Sustainability. AAAS, Washington D.C., U.S.

Belkin, I.M. (2008) Rapid warming of Large Marine Ecosystems, Progress in Oceanography, in

press.

Belkin, I.M., and Cornillon, P.C. (2003). SST fronts of the Pacific coastal and marginal seas. Pacific

Oceanography 1(2):90-113.

Belkin, I.M., Cornillon, P. and Ullman, D. (2003). Ocean fronts around Alaska from satellite SST

data, Paper 12.7 in: Proceedings of the American Meteorological Society, 7th Conference on

the Polar Meteorology and Oceanography. Hyannis, U.S.

Belkin, I.M., Cornillon, P.C., and Sherman, K. (2008). Fronts in Large Marine Ecosystems of the

world's oceans. Progress in Oceanography, in press.

Bottom, D.L., Jones, K.K., Rodgers, J.D. and Brown, R.F. (1989). Management of living marine

resources: a research plan for the Washington and Oregon continental margin. National

Coastal Resources Research and Development Institute. Publication NCRI-T-89-004,

Newport, U.S.

Bottom, D.L., Jones, K.K., Rodgers, J.D., Jeffrey, D. and Brown, R.F. (1993). Research and

management in the northern California Current ecosystem, p 259-271 in: Sherman, K.,

Alexander, L.M. and Gold, B.D. (eds), Large Marine Ecosystems: Stress, Mitigation and

Sustainability. AAAS Washington D.C., U.S.

Brodeur R.D. and Ware, D.M. (1995). Interdecadal variability in distribution and catch rates of

epipelagic nekton in the Northeast Pacific Ocean. Canadian Special Publication of Fisheries

and Aquatic Sciences 121:329-356.

Brodeur, R.D., Frost, B.W., Hare, S.R., Francis, R.C. and Ingraham, W.J., Jr. (1999). Interannual

variations in zooplankton biomass in the Gulf of Alaska, and covariation with California Current

zooplankton biomass, p 106-138 in: Sherman, K. and Tang, Q. (eds), Large Marine

Ecosystems of the Pacific Rim: Assessment, Sustainability, and Management. Blackwel

Science, Malden, U.S.

CalCOFI Committee (1990). Fortieth Anniversary Symposium of the CalCOFI Conference.

CalCOFI Report 31:25-59.

CalCOFI. Atlas 35. (2002) online at www.calcofi.org/newhome/publications/CalCOFI

Reports/calcofi_reports.htm

California Department of Fish and Game (2005). Overview of pinnipeds and their prey. Retrieved

June 2006 from: www.dfg.ca.gov/mrd/mlpa/pdfs/agenda_090705a7.pdf.

California Deptartment of Fish and Game (1990). Review of some California fisheries for 1989.

CalCOFI Report 31:9-21.

DeMaster, D. 1983. Annual consumption of northern elephant seals and California sea lions in the

California Current (abstract). Calif. Coop. Ocean. Fish. Invest. Annual Conference 1983,

Program and Abstracts.

EPA (2001). National coastal condition report. EPA-620/R-01-005. Office of Research and

Development/Office of Water, Washington D.C. U.S.

EPA (2004). National coastal condition report 2. EPA-620/R-03-002. Office of Research and

Development/Office of Water, Washington D.C. U.S.

Hare, S.R., and Mantua, N.J. (2000) Empirical evidence for North Pacific regime shifts in 1977 and

1989, Progress in Oceanography, 47(2-4), 103-145.

Haywood, V.E., ed. (1995). Global Biodiversity Assessment. UNEP, Cambridge University Press,

Cambridge, U.S.

Hickey, B.M. (1998). Coastal oceanography of western North America from the tip of Baja to

Vancouver Island, p 345-393 in: Robinson, A.R. and Brink, K.H. (eds), The Sea, The Global

Coastal Ocean: Regional Studies and Syntheses, Vol. 11. Wiley, New York, U.S.

Hooff, R.C. and W.T. Peterson. 2006. Copepod biodiversity as an indicator of changes in ocean

and climate conditions of the northern California current ecosystem. Limnol. & Oceanogr.

51(6): 2607-2620.

Kahru, M. and Mitchell, B.G. (2000). Influence of the 1997-1998 El Niño on the surface chlorophyll

in the California Current. Geophysical Research Letters 18:2937-2940.

XIV North East Pacific

603

Lluch Belda, D., Lluch Cota, D.B. and Lluch Cota, S. (2003). Interannual variability impacts on the

California Current Large Marine Ecosystem, p 195-226 in: Hempel, G. and Sherman, K. (eds),

Large Ecosystems of the World: Trends in Exploitation, Protection, and Research. Elsevier,

Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

MacCall, A.D. (1986). Changes in the biomass of the California Current ecosystem, p 33-54 in:

Sherman, K. and Alexander, L.M. (eds), Variability and Management of Large Marine

Ecosystems. AAAS Selected Symposium 99. Westview Press, Boulder, U.S.

Mantua, N.J., S.R. Hare, Y. Zhang, J.M. Wallace, and R.C. Francis (1997) A Pacific decadal

climate oscillation with impacts on salmon, Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, Vol.

78, pp. 1069-1079.

McGowan, J.A., Chelton, D.B. and Conversi, A. (1999). Plankton patterns, climate, and change in

the California Current, p 63-105 in: Sherman, K. and Tang, Q. (eds), Large Marine Ecosystems

of the Pacific Rim: Assessment, Sustainability, and Management. Blackwell Science, Malden,

U.S.

Miller, A.J. (1996). Recent advances in California Current modeling: decadal and interannual

thermocline variations. California Cooperative Oceanic Fisheries Investigations Report 37.

Miller, A.J. and Schneider, N. (2000). Interdecadal climate regime dynamics in the North Pacific

Ocean: Theories, observations and ecosystem impacts. Progress in Oceanography 47:355-

379.

Morgan, J. (1989). Large Marine Ecosytems in the Pacific Ocean, p 377-394 in: Sherman, K, and

Alexander, L.M. (eds), Biomass Yields and Geography of Large Marine Ecosystems. Westview

Press, Boulder, U.S.

Mullin, M.M. (1991). Spatial-temporal scales and secondary production estimates in the California

Current Ecosystem, p 165-192 in: Sherman, K., Alexander, L.M. and Gold, B.D. (eds), Food

Chains, Yields, Models, and Management of Large Marine Ecosystems. Westview Press,

Boulder, U.S.

NMFS. (2009). Our living oceans. Draft report on the status of U.S. living marine resources, 6th

edition. U.S. Dep. Commer., NOAA Tech. Memo. NMFS-F/SPO-80. 353 p.

NMFS (1999). Our Living Oceans. Report on the status of U.S. Living Marine Resources. U.S.

Department of Commerce, Washington D.C., U.S.

NOAA Fish News (2005). Pacific Coast: Public invited to participate in examining scope of

alternatives for the 2007-2008 groundfish fisheries. October 31:2.

Pauly, D. and Christensen, V. (1995). Primary production required to sustain global fisheries.

Nature 374: 255-257.

Pauly, D. and Watson, R. (2005). Background and interpretation of the `Marine Trophic Index' as a

measure of biodiversity. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society: Biological Sciences

360: 415-423.

Peterson, W.T.and Schwing, F.B. (2003). A new climate regime in northeast pacific ecosystems.

Geophysical Research Letters 30(17) 1896, doi:10.1029/2003GL017528,2003

PMEL Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory at www.pmel.noaa.gov

www.pmel.noaa.gov/np/pages/seas/npmap4.html

Radovich, J. (1982). The collapse of the California sardine industry: What have we learned?

CalCOFI Reports 23: 56-78.

Roemmich, D. and McGowan, J. (1995a). Climatic warming and the decline of zooplankton in the

California Current. Science 267:1324-1326.

Roemmich, D. and McGowan, J. (1995b). Sampling zooplankton: Correction. Science 268:352-353.

San Francisco Bay Estuary Project at www.abag.ca.gov/bayarea/sfep

Schwing, F. B., and R. Mendelssohn (1997), Increased coastal upwelling in the California Current

System, J. Geophys. Res., Vol. 102, No. C2, pp. 34213438.

Sea Around Us (2007). A Global Database on Marine Fisheries and Ecosystems. Fisheries Centre,

University British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada. www.seaaroundus.org/lme/Summary

Info.aspx?LME=3

US Census Bureau online at www.census.gov

US GLOBEC at www.usglobec.org/reports/ebcip/ebcip.histvar.html

604

44. California Current LME

XIV North East Pacific

605

XIV-45 East Bering Sea LME

M.C. Aquarone and S. Adams

The East Bering Sea LME is characterised by an extremely wide, gradually sloping shelf,

and by a seasonal ice cover that in March extends over most of this LME. The LME is

bounded by the Bering Strait to the North, by the Alaskan Peninsula and Aleutian Island

chain to the South, and by a coastline to the east that is thousands of miles in length. The

surface area is about 1.4 million km², of which 0.87% is protected. It contains 0.07% of

the world's sea mounts. This LME receives freshwater discharge from major rivers

including the Yukon and Kuskokwim (Sea Around Us 2007). Book chapters and articles

pertaining to this LME include Incze & Schumacher (1986), Carleton Ray & Hayden

(1993), Livingston et al. (1999) and Schumacher et al. (2003).

I. Productivity

Temperature, currents and seasonal oscillations influence the productivity of this LME.

For information on oceanographic and climate forcing in the East Bering Sea ecosystem,

and the recruitment responses of many Bering Sea fish and crabs linked to decadal scale

patterns of climate variability, see EPA (2004) and PICES (2005). The East Bering Sea

LME is a Class II, moderately high productivity ecosystem (150-300 gCm-2yr-1). This LME

is undergoing a climate driven change in species dominance and species abundance in

some ecological groups (PICES 2005). On the temporal variability of the physical

environment over the LME, see Stabeno et al., 2001. There is much to understand about

its carrying capacity during the present period of climate change. For example, there

have been nearly ice-free conditions in the mid shelf from January to May in 2000-2004.

Accompanying this change are shifts in the trophic structure with walrus populations

moving northward with the ice, and Alaska pollock moving east.

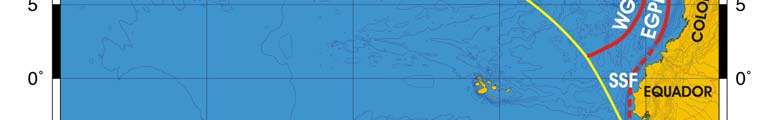

Oceanic fronts: Five major fronts can be found over the East Bering shelf and slope

(Belkin et al., 2003; Belkin & Cornillon 2005; Belkin et al., 2008). The Coastal Front

consists of three segments, the Bristol Bay Front (BBF), the Kuskokwim Bay Front (KBF),

and the Shpanberg Strait Front (SSF), all extending approximately parallel to the Alaskan

Coast at a depth of 10 to 20 meters (Figure XIV-45.1). Farther offshore, the Inner Shelf

Front (ISF) is located at a depth of 20 to 40 meters while the Mid-Shelf Front (MSF) is

found at 40 to 60 meters. These two fronts are also approximately isobathic. The most

distant offshore fronts, the Outer Shelf Front (OSF; 60-100-m depth) and the Shelf-Slope

Front (SSF; 100-200-m depth within this LME) are not isobathic. They extend from

relatively shallow depths in the east, off Bristol Bay, to significantly greater depths in the

west, where the SSF crosses the shelf break and slope to continue over the deep basin

as it leaves the East Bering Sea LME and enters the West Bering Sea LME.

East Bering Sea SST (Belkin 2008)(Figure XIV-45.2)

Linear SST trend since 1957: 0.46°C.

Linear SST trend since 1982: 0.27°C.

The annual mean SST averaged over the East Bering Sea increased by 0.46°C between

1957 and 2006. The 50-year warming was not uniform: instead, the time span included

two periods with opposite SST trends. In 1957 the average Bering Sea SST reached a

maximum that has not been surpassed until recently (Niebauer et al., 1999). From 1957

to 1971, the SST decreased by 1.3°C. The SST drop was especially abrupt in the late

1960s-early 1970s; in 1969-71 SST decreased from 5°C to 4°C. The cold spell lasted

606

45. East Bering Sea LME

through 1976. In the winter of 1976-77, the East Bering Sea underwent an abrupt regime

shift to warm conditions, with the SST rising by 1°C in a single year and remaining

relatively high through 2006. The 1°C SST jump from 4.1°C to 5.1°C between 1976-77

was a regional manifestation of a trans-North Pacific "regime shift" that occurred during

the winter of 1976-77, caused by a major shift of the North Pacific atmospheric pressure

pattern captured in three indexes, ENSO, PDO, and the Aleutian Low index (Mantua et

al., 1997; Hare and Mantua, 2000). This has helped species such as salmon stocks

rebound from previous low years of abundance. The atmosphere-ocean system shift

was followed by an ecosystem shift around and across the entire North Pacific. For

some species, the effects of this ecosystem shift were beneficial, for others they were

detrimental. The most recent cold episode, in 1999, was short-lived. The East Bering

Sea has returned to warm conditions.

Figure XIV-45.1. Fronts of the East Bering Sea LME. BBF, Bristol Bay Front; ISF, Inner Shelf Front; KBF,

Kuskokwim Bay Front; MSF, Mid-Shelf Front; OSF, Outer Shelf Front; PF, Polar Front; SSF, Shelf-Slope

Front; SSNSF, Shpanberg Strait-Norton Sound Front. Yellow line, LME boundary. After Belkin et al.

(2008).

The bathymetry of this LME is critically important while analyzing the area-averaged SST

time series. The most important feature is the presence of two different oceanographic

regimes within this LME, namely an extremely wide, nearly horizontal continental shelf

and a deep-sea basin. This co-existence of shallow shelf and deep sea might explain the

observed discrepancy between the LME-averaged SST time series and the SST

observations over the East Bering Sea Shelf alone. Indeed, the most recent

observations over the southeastern Bering Sea Shelf revealed a dramatic summertime

warming by 3°C in the 2000s, likely caused by a synergy of several mechanisms,

including (a) persistent northward winds since 2000; (b) a later fall transition combined

XIV North East Pacific

607

with an earlier spring transition that resulted in a shorter sea ice season; (c) an increased

flux of warm waters from the Gulf of Alaska LME through Unimak Pass; and (d) the

feedback mechanism between warm summertime oceanic temperatures and the

wintertime southward advection of sea ice (Stabeno et al., 2007).

Figure XIV-45.2. East Bering Sea LME annual mean SST (left) and annual SST anomalies (right), 1957-

2006, based on Hadley climatology. After Belkin (2008).

East Bering Sea LME Chlorophyll and Primary Productivity: The East Bering Sea

LME is a Class II, moderately high productivity ecosystem (150 300 gCm-2yr-1)(Figure

XIV-45.3).

Figure XIV-45.3. East Bering Sea LME trends in chlorophyll-a (left) and primary productivity (right),

1998-2006, from satellite ocean colour imagery. Values are colour coded to the right hand ordinate.

Figure courtesy of J. O'Reilly and K. Hyde. Sources discussed p. 15 this volume.

II. Fish and Fisheries

The LME's thousands of miles of coastline support populations of five species of salmon

(pink, sockeye, chum, Coho and Chinook). The high abundance of salmon is due to a

number of factors including favourable ocean conditions that promote high survival rates

of juveniles, hatchery production, and reduction of bycatch (EPA 2004). Sockeye salmon

(in Bristol Bay, Alaska Peninsula and Aleutian Islands) is the most valuable of the salmon

species but has had recent declines, along with chum salmon. In some years, significant

numbers of chum salmon are caught as bycatch in fisheries that target pollock and other

608

45. East Bering Sea LME

groundfish. Despite relatively stable Chinook stocks there is concern over abundance

trends. A quota under the provisions of the Pacific Salmon Treaty regulates the Chinook

salmon harvest in this LME. Coho salmon is the most popular recreational species.

Salmon bycatch in US groundfish fisheries continues to be a problem in fisheries

management (NMFS 2009). Groundfish (Pacific halibut, Walleye pollock, Pacific cod,

flatfish, sablefish, and Atka mackerel) are the most abundant fisheries resource off the

East Bering Sea LME. The dominant species harvested are pollock and cod. Catch

quotas have been capped at 2 million tons for groundfish in the fishery management plan

for the East Bering Sea and Aleutian Islands. Reported annual landings of Alaska

pollock (Theragra chalcogramma), the largest catch of any species harvested in the US

EEZ, now range between 1.0 and 1.5 million tonnes, a level thought to be sustainable.

Pollock has fluctuated in the past decades as a result of variable year classes. Other

commercially valuable species include herring, rockfish, skate, Greenland turbot, sole,

plaice and crab. The centers of abundance for pelagic herring are in northern Bristol Bay

and Norton Sound (EPA 2004). This fishery occurs within state waters and is managed

by the Alaska Department of Fish and Game. From catch records it is clear that herring

biomass fluctuates widely due to the influence of strong and weak year-classes.

Species such as herring, pollock and Pacific cod show interannual variability in

recruitment that might be related to climate variability (EPA 2004). Herring biomass

fluctuates widely due to strong and weak year classes. Years of strong onshore

transport, typical of warm years in the East Bering Sea, correspond with strong

recruitment of Pollock (NMFS 2009). Annual summaries of pollock catches and other

groundfish, flatfish and invertebrates in the Eastern Bering Sea from 1954 to 1998 are

presented in Schumacher et al. (2003).

Major shellfish fisheries in the LME are king and snow crab. King and Tanner crab

fisheries are managed by the state of Alaska with advice from federal fisheries. Crab

resources are fully utilized. Catches are restricted by quotas, seasons, size and sex

limits. Shrimp are also managed by the state of Alaska. For biomass trends of crab

species from 1979 to 1993, and for finfish fishery exploitation rates compared with crab

recruitment in this LME, see Livingston et al. (1999). Nearshore fishery resources are

those coastal and estuarine species found in the 0-3 nautical mile zone of coastal state

waters. Pollock is targeted in the `Donut Hole' that exists in the high seas area outside of

the U.S. and Russian EEZs.

Historical catches in this area were very high and unsustainable. Since 1999, however,

there has been evidence of increased abundance of Alaska pollock in the Donut Hole,

coincident with the reduction of annual sea-ice cover (Overland et al. 2005). Another

species that appears to be increasing in abundance in response to warming conditions in

this LME is pink salmon (Overland et al. 2002 and 2005, Overland & Stabeno 2004),

whose catches were about 100 thousand tonnes in 2003 and 2004. Patterns of

production for salmon are inversely related to those in the California Current LME.

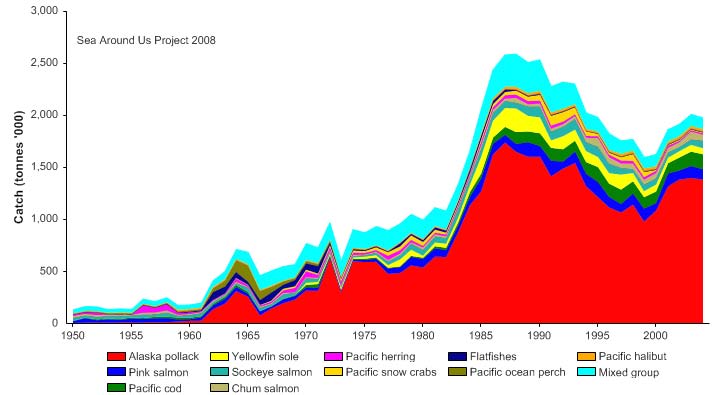

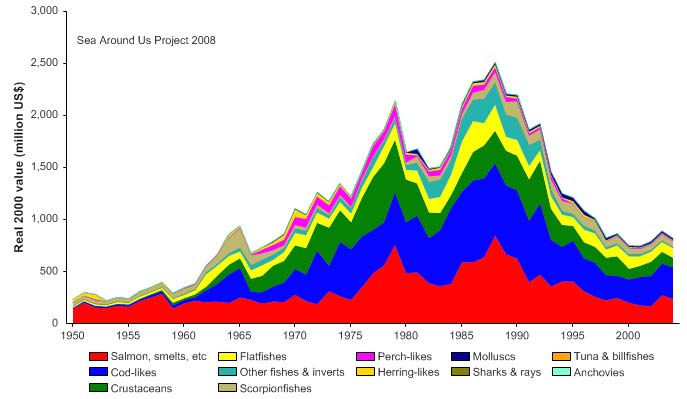

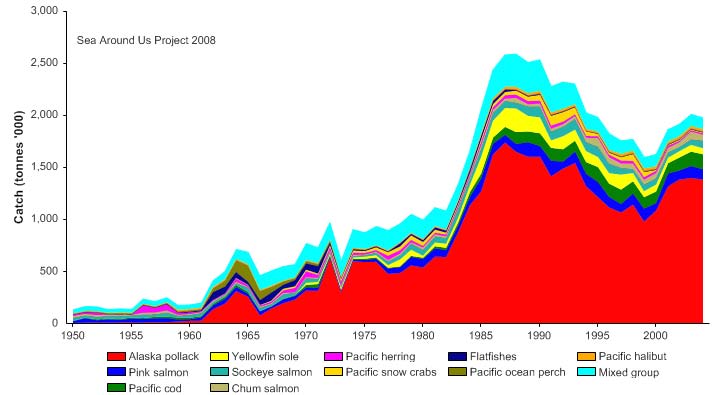

Total reported landings experienced a historic high of over 2.5 million tonnes between

1995 and 1990 (Figure XIV-45.4), with Alaska pollock dominating. In that period, the ex-

vessel value of the catches from the East Bering Sea LME was US$2.5 billion (Figure

XIV-45.5). The value of the salmon catch has declined due to a number of complex

worldwide factors (see IV. Socioeconomic Conditions).

XIV North East Pacific

609

Figure XIV-45.4. Total reported landings in the East Bering Sea LME by species (Sea Around Us 2007).

Figure XIV-45.5 Value of reported landings in the Eastern Bering Sea LME by commercial groups (Sea

Around Us 2007)

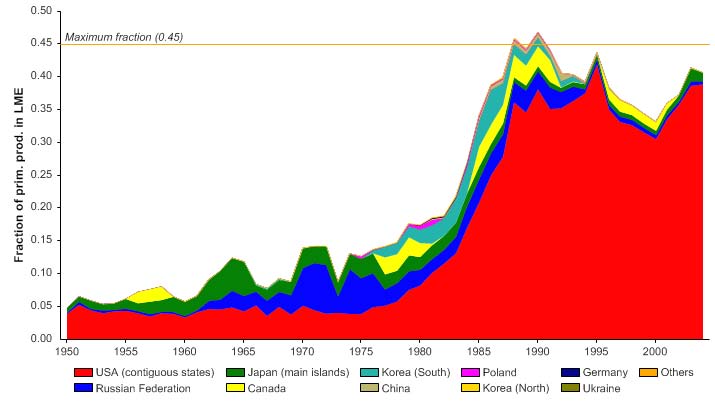

The primary production required (PPR) (Pauly & Christensen 1995) to sustain the

reported landings in this LME exceeded 45% of observed primary production in the late

1980s, and has remained around 40% in recent years (Figure XIV-45.6). The USA has

the largest share of the ecological footprint in this LME. The mean trophic level of the

reported landings (i.e., the MTI, Pauly & Watson 2005) declined from the 1950s to the

early 1970s, but has since leveled off at around 3.5 due to the high catch of Alaska

pollock. (Figure XIV-45.7, top). The geographic expansion which led to this dominance of

Alaska pollock is represented by the increase of the FiB index from the mid 1970s to the

mid-1980s (Figure XIV-45.7 bottom). The system appears sustainable according to

these two indices, although it must be stressed that such an interpretation is based on

the overwhelming effect of a single species.

610

45. East Bering Sea LME

Figure XIV-45.6. Primary production required to support reported landings (i.e., ecological footprint) as

fraction of the observed primary production in the East Bering LME (Sea Around Us 2007). The

`Maximum fraction' denotes the mean of the 5 highest values.

Figure XIV-45.7. Mean trophic level (i.e., Marine Trophic Index) (top) and Fishing-in-Balance Index

(bottom) in the East Bering Sea LME (Sea Around Us 2007)

The Stock-Catch Status Plots indicate that over 70% of the commercially exploited stocks

are now generating catches of 10% less than the historic maximum, corresponding to the

`collapsed' status in Figure XIV-45.8 (top). This is in line with the findings of Armstrong et

al. (1998), who reported, for an area immediately adjacent to the one considered here, on

serial depletion of the (frequently small) stocks of commercial invertebrates. However, the

overwhelming bulk of the reported landings for this LME is supplied by fully exploited

stocks of Alaska pollock (Figure XIV-45.8, bottom). The US National Marine Fisheries

Service (NMFS) includes "overfished" but not "collapsed" in its stock status categories. All

five species of Alaska salmon are fully utilized, and stocks in the LME have rebuilt to near

or beyond previous high levels. There is concern for some salmon stocks (especially

Chinook and chum salmon) along the East Bering Sea LME, due to overfishing,

XIV North East Pacific

611

incidental take of salmon as bycatch in other fisheries, and loss of freshwater spawning

and rearing habitats. There is however growing evidence of population increases of pink

salmon in Norton Sound and Kotzebue Sound, due perhaps to climatic changes. The

halibut fishery is not subject to overfishing. A Pacific halibut cap constrains these

fisheries. The Walleye Pollock stock in the LME is considered fully utilized and is well

managed for bycatch and other issues which include minimizing impacts on Steller sea

lion populations. Flatfish species are underutilized. The sablefish stock is fully utilized and

is harvested under an IFQ system. Skates and squids are underutilized. Alaska crab

resources are fully utilized (NMFS 2009). The difference between the two panels of

Figure XIV-45.8 is the greatest of all LMEs included in this volume. It illustrates the

contrast between the effect of prudent management in a few abundant stocks (bottom),

combined with serial depletion of what might be seen as minor stocks (top).

0%

100

10%

90

20%

)

80

%

(

s

30%

u

70

at

st

40%

y

60

b

s

k

50%

c

o

50

f

st

60%

40

er o

70%

mb

30

Nu

80%

20

90%

10

100%0

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

(n = 3724)

developing

fully exploited

over-exploited

collapsed

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

0%

100

10%

90

20%

80

)

%

30%

(

70

t

us

40%

t

a

60

s

k

c

50%

t

o

50

s

60%

h by

40

t

c

a

70%

C

30

80%

20

90%

10

100%0

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

(n = 3724)

developing

fully exploited

over-exploited

collapsed

Figure XIV-45.8. Stock-Catch Status Plots for the East Bering Sea LME, showing the proportion of

developing (green), fully exploited (yellow), overexploited (orange) and collapsed (purple) fisheries by

number of stocks (top) and by catch biomass (bottom) from 1950 to 2004. Note that (n), the number of

`stocks', i.e., individual landings time series, only include taxonomic entities at species, genus or family

level, i.e., higher and pooled groups have been excluded (see Pauly et al, this vol. for definitions).

The management regime annually updates fishing quotas based on biomass estimates,

including those for Alaska pollock. Because of the Steller sea lion interaction with

pollock, research is underway to study the dynamics and distribution of Steller sea lion

prey and predators, and to evaluate the connection with commercial fishing

(www.etl.noaa.gov/). An ecosystem approach is being implemented for the assessment

and management of fisheries biomass yields in the East Bering Sea LME. The basic

ecosystem consideration is a precautionary approach. All groundfish stocks are

considered healthy, providing sustained yields of approximately 2 mmt annually. Actions

are taken by the North Pacific Fisheries Management Council to annually cap a total

groundfish TAC based on NOAA-Fisheries survey operations (Witherell et al. 2000).

612

45. East Bering Sea LME

III. Pollution and Ecosystem Health

The coastal resources in this LME are generally in pristine condition. Coastal habitats

are favourable to, for instance, the high abundance of salmon and with minimal impact

from extensive development. Salmon being anadromous depend on freshwater streams,

rivers and lakes. Their health is directly influenced by land management practices. The

conservation of the region's salmon resource requires the conservation of the thousands

of miles of riparian habitat that support salmon production. Competing uses for this

habitat include logging, mining, oil and gas development, and industrial and urban

development. Contaminant levels are consistently below the EPA's level of concern

(EPA 2001 and 2004). Hypotheses concerned with the growing impacts of pollution,

overexploitation and environmental changes on sustained biomass yields are under

investigation. Concerns for the health of this LME focus on petroleum hydrocarbons

found in the tissue of marine mammals, and the effects of the growing industrialisation of

the region. Population levels of marine mammals in the coastal areas are low compared

to other shallow seas. For statistics concerning the harbour seal, Beluga whale and

harbor porpoise, see NOAA (1999, p. 231). Current regulations restrict the Aleutian

Islands pollock quota due to concerns over food competition with Steller sea lions in this

area, which contains critical habitat for the species. Marine mammal interactions with fish

and fisheries are a major concern in fishery resource management in this LME. Fisheries

compete for prey items that marine mammals and seabirds depend on for food and are a

major factor in the decline of sea lion populations. The Steller sea lion is listed as

threatened under the Endangered Species Act.

The East Bering Sea LME has low levels of toxic contaminants, but these have been

rising over the last 50 years due to increased human activities (mining, fishing and oil

exploration). This increase is linked to the long-range transport of contaminants through

the ocean and atmosphere from other regions. Cold region ecosystems such as the East

Bering Sea LME are more sensitive to the threat of contaminants than warmer regions

because the loss and breakdown of these contaminants are delayed at low temperatures.

Also, animals high in the food web with relatively large amounts of fat tend to accumulate

organic contaminants such as pesticides and PCBs (EEA 2004). This causes concerns

for human health in the region, particularly for Alaska natives, including the Aleut

community, who rely on marine mammals and seabirds as food sources. The EPA and

Indian Health Service contribute $20 million annually for water and sanitation projects

now underway in rural Alaska so that 85% of all Alaska households will have access to

safe water and basic sanitation (www.dced.state.ak.us.AEIS).

IV. Socioeconomic Conditions

The Alaskan coast east of the LME has a low population relative to its size and is distant

from major urban or industrial areas. More than 65,000 Native Americans live on the

shores of the East Bering Sea LME, with a long tradition of relying on salmon and other

marine resources for economic, cultural and subsistence purposes. Pacific salmon plays

an important and pivotal role, along with mining, timber, and furs, keystone natural

resources that led to the settling and development of the US's 49th state by non-native

peoples. Many Alaskans still depend heavily on salmon for recreation, food, and

industry. Recent declines in chum and sockeye salmon runs have added to the

hardships experienced by fishermen in Bristol Bay. The value of the salmon catch has

declined over the past decade, along with a rising trend in total worldwide salmon

production with the rapid growth of farmed salmon especially in Norway, Chile and the

United Kingdom. Nearshore fishery resources provide important subsistence and

recreational fishing opportunities for Alaskans of the East Bering Sea LME. Subsistence

fishing is distributed all along the coastline of the LME. The East Bering Sea herring

fishery began in the late 1920s, with a small salt-cure plant in Dutch Harbor in the

Aleutian Islands. Commercial harvesting and processing, along with rapidly growing

XIV North East Pacific

613

tourism and sport fishing, provide the region with big employment opportunities (NMFS

2009). According to statistics from the State of Alaska Department of Labor and

Workforce Development in 2005, nearly 80% of the private sector population was

engaged in fish harvesting or seafood processing in the Aleutian Islands. In the Bristol

Bay Region, 75%, of which 40% were non-residents, were employed in the regional

seafood industry (harvesting or processing). In the Yukon Delta Region, about 28%.were

engaged in fish harvesting or seafood processing. Recreational fishing continues to grow

due to an increase in guided fishing trips for visitors and tourists.

The East Bering Sea is home to a valuable offshore fishing industry. The interests of US

factory trawlers differ markedly from those of small fisheries. Much of the groundfish

catches are exported, particularly to Asia. This trade is a major source of revenue for US

fishermen. For an article on the political economy of the walleye pollock fishery, see

Criddle & Mackinko (2000). There are increasing demands from extractive industries to

log and drill for oil and gas development. Climate change is having and is expected to

have a profound influence on the socioeconomics of natural resources, goods and

services of the East Bering Sea LME. The U.S. National Science Foundation supports

studies of the physical, chemical and biological processes and human impacts to be

expected by the reduction of sea ice in the East Bering Sea (BEST 2003).

V. Governance

The East Bering Sea LME is bordered by the USA (State of Alaska). The Alaska Board

of Fisheries deals with the allocation of fish resources and quotas among various

fisheries. The North Pacific Fishery Management Council (NPFMC) has primary

responsibility for groundfish management within the US Exclusive Economic Zone (3 to

200 nautical miles) off the coasts of the East Bering Sea and Aleutian Islands, with the

goal of maintaining stable yields by regulating harvest allocations among species. It is

addressing the issue of salmon bycatch through time-area closures and bycatch limits set

for different gear types in groundfish fisheries. The Alaska native populations benefit

from individual fishing quotas or IFQs. There are also community development quotas

(CDQs). Pelagic and salmon fisheries occurring within 3 miles are managed by the

Alaska Department of Fish and Game. Improved management of the salmon fishery by

state and federal agencies has contributed to the high abundance of Pacific salmon.

High seas drift net fisheries by foreign nations for salmon has been eliminated through

UN Resolution 46/215. The management of high seas salmon is under the North Pacific

Anadromous Fish Commission. Initial signatories of the Commission are Canada, Japan,

Russian Federation, Korea, and the United States. The Convention for the Conservation

of Anadromous Stocks in the North Pacific Ocean has eliminated a former high seas

salmon fishery by Japan. An area involving salmon and negotiations with Canada

concerns the stocks and fisheries of the 2,000 mile long Yukon River system. The

agreement sets harvest quotas for Chinook and chum salmon stocks. The Magnuson-

Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act extended federal fisheries

management jurisdiction to 200 nautical miles and stimulated the growth of a domestic

Alaskan groundfish fishery that rapidly replaced foreign fisheries. The former

unregulated pollock fishery in the "Donut Hole" now comes under the Convention on the

Conservation and Management of Pollock Resources in the Central Bering Sea. The

Convention has been signed by the Russian Federation, Japan, Poland, China, Korea,

and the United States. A moratorium on pollock fishing was voluntarily imposed in 1993

(NMFS 2009). The Bureau of Indian Affairs has responsibility to protect and improve

trust assets of Alaska natives. Alaska has a Department of Environmental Conservation

(ADEC) responsible for assessing and controlling potential environmental degradation.

.

614

45. East Bering Sea LME

References

Armstrong, J., D. Armstrong and R. Hilborn 1998. Crustacean resources are vulnerable to serial

depletion the multifaceted decline of crab and shrimp fisheries in the Greater Gulf of Alaska.

Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries. 8(2): 117-176.

Belkin, I.M. (2008) Rapid warming of Large Marine Ecosystems, Progress in Oceanography, in

press.

Belkin, I.M. and Cornillon, P.C. (2005). Bering Sea thermal fronts from Pathfinder Data: Seasonal

and interannual variability. Pacific Oceanography 3(1):6-20.

Belkin, I.M., Cornillon, P.C., and Sherman, K. (2008). Fronts in Large Marine Ecosystems of the

world's oceans. Progress in Oceanography, in press.

Belkin, I.M., P.C. Cornillon, and D. Ullman (2003). Ocean fronts around Alaska from satellite SST

data, Proceedings of the Amer. Met. Soc. 7th Conf. on the Polar Meteorology and

Oceanography, Hyannis, MA, Paper 12.7, 15 pp.

BEST (2003). Workshop agenda, 2003. Bering Sea Ecosystem Study. www.arcus.org/Bering

/agenda.html

Carleton Ray, G. and Hayden. B.P. (1993). Marine biogeographic provinces of the Bering, Chukchi

and Beaufort seas, p 175-184 in: Sherman, K., Alexander, L.M. and Gold, B.D. (eds), Large

Marine Ecosystems: Stress, Mitigation and Sustainability. AAAS, Washington D.C., U.S.

Criddle, K.R. and Mackinko, S. (2000). Political economy and profit maximization in the Eastern

Bering Sea fishery for walleye pollock. IIFET 2000 Proceedings.

www.orst.edu/dept/IIFET/2000/papers/criddle.pdf

EEA (2004). Arctic environment European perspectives. Environmental Issue Report 38/2003.

http://reports.eea.eu.int/environmental_issue_report_2004_38/en

EPA (2001). National Coastal Condition Report. EPA-620/R-01-005. Office of Research and

Development/Office of Water, Washington D.C., U.S.

EPA (2004). National Coastal Condition Report 2. EPA-620/R-03-002. Office of Research and

Development/Office of Water. Washington D.C., U.S.

ETL (NOAA, Earth System Research Laboratory , Marine Ecological Studies and Physical

Sciences Division) at www.etl.noaa.gov/programs/marine/

Hare, S.R., and N.J. Mantua (2000) Empirical evidence for North Pacific regime shifts in 1977 and

1989, Progress in Oceanography, 47(2-4), 103-145.

Incze, L. and Schumacher, J.D. (1986). Variability of the environment and selected fisheries

resources of the Eastern Bering Sea Ecosystem, in: Sherman, K. and Alexander, L.M. (eds),

Variability and Management of Large Marine Ecosystems. AAAS Selected Symposium 99.

Westview Press, Boulder, U.S.

Livingston, P.A., Low, L.L. and Marasco, R.J. (1999). Eastern Bering Sea Ecosystem trends, p 140-

162 in: Sherman, K. and Tang, Q. (eds), Large Marine Ecosystems of the Pacific Rim:

Assessment, Sustainability and Management. Blackwell Science, Malden, U.S.

Mantua, N.J., S.R. Hare, Y. Zhang, J.M. Wallace, and R.C. Francis (1997) A Pacific decadal

climate oscillation with impacts on salmon, Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society,

78(6), 1069-1079.

Niebauer, H.J., Bond, N.A. Yakunin, L.P. and Plotnikov V.V. (1999) An update on the climatology

and sea ice of the Bering Sea, in Dynamics of the Bering Sea, edited by T.R. Loughlin and K.

Ohtani, pp. 2959, Alaska Sea Grant College Program, AK-SG-99-03, University of Alaska

Fairbanks.

NMFS (2009). Our living oceans. Draft report on the status of U.S. living marine resources, 6th

edition.

U.S. Dep. Commer., NOAA Tech. Memo. NMFS-F/SPO-80. 353 p.

NOAA (1999). Our living oceans. Report on the status of U.S. living marine resources. US

Department of Commerce, Washington D.C., U.S.

Overland, J.E. and Stabeno, P.J. (2004). Is the climate of the Bering Sea warming and affecting the

ecosystem? Transactions of the American Geophysical Union 85:309-310, 312.

Overland, J.E., Boldt, J. and Stabeno, P.J. (2005). Multiple indicators track major ecosystem shifts

in the Bering Sea. ICES CM 2005/M:21.

Overland, J.E., Wang, M. and Bond, N.A. (2002). Recent temperature changes in the western

Arctic during spring. Journal of Climate 15:1702-1716.

Pauly, D. and Christensen, V. (1995). Primary production required to sustain global fisheries.

Nature 374: 255-257.

XIV North East Pacific

615

Pauly, D. and Watson, R. (2005). Background and interpretation of the `Marine Trophic Index' as a

measure of biodiversity. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society: Biological Sciences

360: 415-423.

PICES (2005). Fisheries and Ecosystem Response to Recent Regime Shifts. Report of the Study

Group. North Pacific Marine Science Organisation. www.pices.int/publications/

scientific_reports/Report28/Rep_28_default.aspx

Schumacher, J.D., Bond, N.A., Brodeur, R.D., Livington, P.A., Napp, J.M. and Stabeno, P.J.

(2003). Climate change in the Southeastern Bering Sea and some consequences for its biota,

p 17-40 in: Hempel, G. and Sherman, K. (eds), Large Marine Ecosystems of the World: Trends

in Exploitation, Protection and Research. Elsevier Science, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Sea Around Us (2007). A Global Database on Marine Fisheries and Ecosystems. Fisheries Centre,

University British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada. www.seaaroundus.org/lme/Summary

Info.aspx?LME=1

Stabeno, P.J., Bond, N.A, Kachel, N.B., Salo, S.A. and Schumacher, J.D. (2001) On the temporal

variability of the physical environment over the south-eastern Bering Sea, Fisheries

Oceanography, 10(1), 8198.

Stabeno, P.J., N.A. Bond, S.A. Salo (2007) On the recent warming of the southeastern Bering Sea

Shelf, Progress in Oceanography, accepted.

State of Alaska Department of Labor and Workforce Development at www.labor.state.ak.us/

research/trends/nov07reg.pdf

Witherell, D., Pautzke, C. and Fluharty, D. (2000) An ecosystem-based approach for Alaska

groundfish fisheries. ICES Journal of Marine Science 57:771-777.

616

45. East Bering Sea LME

XIV North East Pacific

617

XIV-46 Gulf of Alaska LME

M.C. Aquarone and S. Adams

The Gulf of Alaska LME lies off the southern coast of Alaska and the western coast of

Canada. It is separated from the East Bering Sea LME by the Alaska Peninsula. The

cold Subarctic Current, as it bifurcates towards the south, serves as the boundary

between the Gulf of Alaska and the California Current LME. For a description of the Gulf

of Alaska's major currents, see www.pmel.noaa.gov/np/. The LME has a sub-Arctic

climate and is subject to interannual and interdecadal climate variations (Brodeur et al.

1999). The area of this LME is about 1.5 million km², of which 1.50% is protected, and

includes 0.52% of the world's sea mounts (as defined in Sea Around Us 2007 and

Kitchingman et al. 2007). There are 14 estuaries and river systems, including the Stikine

River, Copper River, and Chatham Sound (Skeena River). A book chapter pertaining to

this LME is by Brodeur et al. (1999).

I. Productivity

The Gulf of Alaska LME is considered a Class II, moderately productive ecosystem (150-

300 gCm-2yr-1). The LME's cold, nutrient-rich waters support a biologically diverse

ecosystem. Large-scale atmospheric and oceanographic conditions affect the productivity

of this LME. Changes in zooplankton biomass have been observed in both the Gulf of

Alaska LME and the adjacent California Current LME. These biomass changes appear

to be inversely related to each other (Brodeur et al. 1999). A well-documented climatic

regime shift occurring in the late 1970s caused the Alaska gyre to be centred more to the

east (Lagerloef 1995, Anderson & Piatt 1999). Brodeur and his co-authors suggested a

possibility of increases in the future production of salmon as a consequence of long-term

oceanographic shifts resulting in increases in plankton biomass in the last decade. More

information is available on climate variability and its effect on the abundance and

production of marine organisms in this LME (Hollowed et al. 1998). For more information

on the production dynamics of Alaska salmon in relation to oscillating periods of `warm'

and `cool' regimes, see Francis (1993), Francis & Hare (1994), and Hare & Francis

(1995).

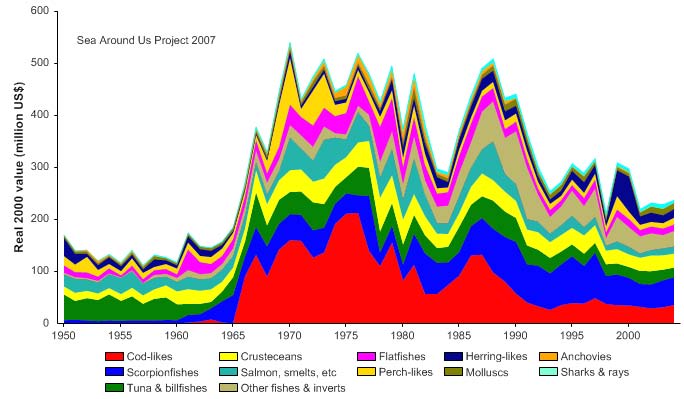

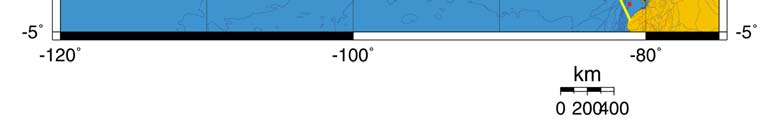

Oceanic Fronts (Belkin et al. 2008): The Polar Front (PF) exists year-round in the

western part of the Gulf (Belkin et al. 2002) (Figure XIV-46.1). This front is associated

with the Subarctic Current that crosses the North Pacific from Hokkaido to the Gulf of

Alaska where it retroflects and flows along the Aleutian Island Chain, branching first into

the Eastern Bering Sea, then into the Western Bering Sea. Several fronts develop in

summer over the Alaskan Shelf (Belkin & Cornillon 2003, Belkin et al. 2003). The

conspicuous Kodiak Front (KF) is observed east and south of Kodiak Island, where its

quasi-stable location is controlled by local topography. The Inner Passage Front (IPF) is

located in a strait between the Queen Charlotte Islands and the British Columbia coast.

Gulf of Alaska LME SST (Belkin 2008)(Figure XIV-46.2)

Linear SST trend since 1957: 0.38°C.

Linear SST trend since 1982: 0.37°C.

Temporal SST variability in the Gulf of Alaska (GOA) LME is strong (Figure XIV-46.2). In

1957-2006, three successive regimes were: (1) rapid cooling by nearly 2°C from the

sharp peak of 1958 until 1971; (2) a cold spell in 1971-1976; (3) a warm epoch, from

1977 to the present. These epochs are best defined in the central GOA and off the

Queen Charlotte Islands (Mendelssohn et al., 2003, and Bograd et al., 2005). The

618

46. Gulf of Alaska

transition from the cold spell to the present warm epoch occurred during the North Pacific

regime shift of 1976-77 (see East Bering Sea LME). In general, the SST history of the

GOA is very similar to the East Bering Sea (EBS). In particular, SST swings in 1996-2006

were synchronic, from the absolute maximum in 1997 to a 1.4°C drop in 1999, to a

maximum in 2003-2005, followed by a drop in 2006. The observed synchronicity

between the GOA and EBS is suggestive of large-scale forcing that spans the eastern

North Pacific.

Figure XIV-46.1. Fronts of the Gulf of Alaska LME. IPF, Inner Passage Front; KF, Kodiak Front; PF, Polar

Front; SSF, Shelf-Slope (most probable location). Yellow line, LME boundary. After Belkin et al. (2008).

Figure XIV-46.2. Gulf of Alaska LME annual mean SST (left) and SST anomalies (right), 1957-2006,

based on Hadley climatology. After Belkin (2008).

XIV North East Pacific

619

Gulf of Alaska LME Chlorophyll and Primary Productivity: The Gulf of Alaska LME is

a Class II, moderately productive ecosystem (150-300 gCm-2yr-1)(Figure XIV-46.3).

Figure XIV-46.3. Trends in Gulf of Alaska LME chlorophyll a (left) and primary productivity (right), 1998-

2006, from satellite ocean colour imagery. Values are colour coded to the right hand ordinate. Figure

courtesy of J. O'Reilly and K. Hyde. Sources discussed p. 15 this volume.

II. Fish and Fisheries

This LME supports a number of commercially important fisheries for crab, shrimp,

scallops, walleye pollock, Pacific cod, rockfishes, sockeye salmon, pink salmon and

halibut. For information on salmon, pelagic, groundfish, shellfish and nearshore fisheries

in Alaska, see NMFS (1999). The largest fisheries for sockeye salmon, the salmon

species of highest commercial value in the US portion of the LME, occur in Cook Inlet,

Kodiak Island, and Prince William Sound. Chum salmon hatcheries produce a significant

portion of the catch. A quota, under the provisions of the Pacific Salmon Treaty between

Canada and the US, regulates the Chinook salmon harvest in this LME. Pacific herring is

the major pelagic species harvested in the LME. In Alaska, spawning fish concentrate in

Prince William Sound and around the Kodiak Island-Cook Inlet area (EPA 2004). The

groundfish complex (walleye pollock, Pacific cod, flatfish, sablefish, rockfish, and Atka

mackerel) is an abundant fisheries resource in the Gulf of Alaska LME but less so than in

the neighboring East Bering Sea LME. The extreme variation in pollock abundance is

primarily the result of environmental forcing. For information on abundance of larval

pollock, see Duffy-Anderson et al., 2002. Pollock are carefully managed due to concerns

about the impact of fisheries on endangered Steller sea lions for which pollock is a major

prey. Sea lion protection measures include closed areas and determinations of the

acceptable biological catch. The western part of the Gulf (Kodiak Island and along the

Alaska Peninsula) is a major area of operation for the shrimp fishery. Shrimp landings

rose and are now declining. King crab catches peaked in the mid 1960s. Almost all Gulf

of Alaska king crab fisheries have been closed since 1983. Dungeness crabs are

harvested in the Yakutat and Kodial areas of the Gulf of Alaska. Most nearshore fisheries

take place in the Gulf of Alaska LME near population centers (NMFS 2009). Current

information regarding US fisheries in the GOA is available from the NMFS Alaska Region

(www.fakr.noaa.gov), the Alaska Fisheries Science Center (www.afsc.noaa.gov), and the

Alaska Department of Fish and Game (www.cf.adfg.state.ak.us). Current information

regarding Canadian fisheries is available from Fisheries and Oceans, Canada, Pacific

Region (www.pac.dfo-mpo.gc.ca).

620

46. Gulf of Alaska

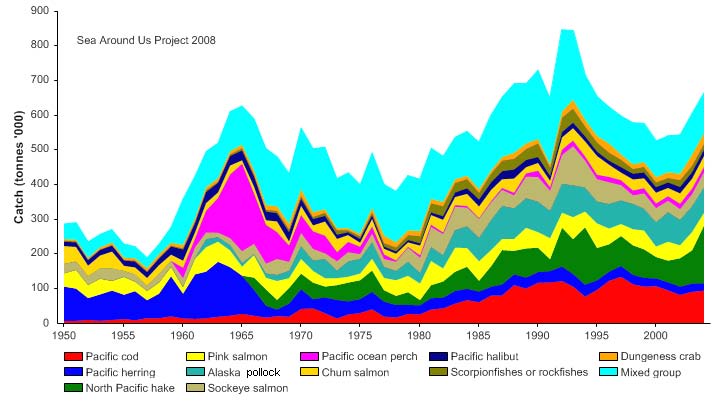

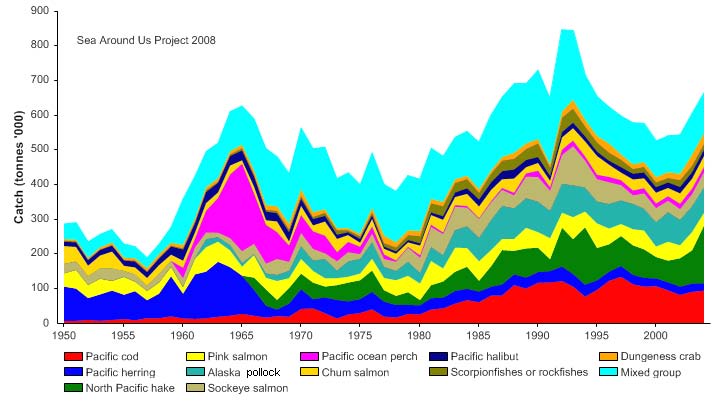

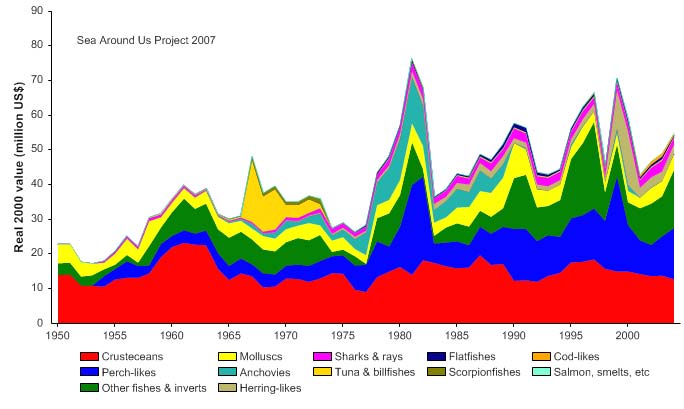

Total reported landings in this LME is in the order of 600 to 700 thousand tonnes, with a

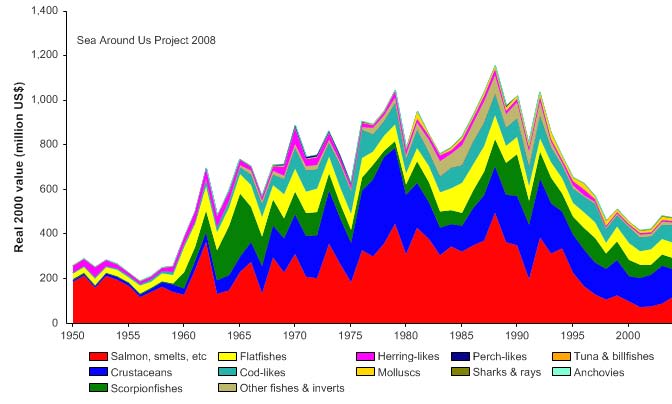

peak of 800 thousand tonnes in 1993 (Figure XIV-46.4). The value of the reported

landings peaked in 1988 at nearly US$1.2 billion (calculated in 2000 US dollars) but has

since declined to about US$500 million in 2004 (Figure XIV-46.5).

Figure XIV-46.4. Total reported landings in the Gulf of Alaska Sea LME by species (Sea Around Us

2007)

Figure XIV-46.5. Value of reported landings in the Gulf of Alaska LME by commercial groups (Sea

Around Us 2007)

The primary production required (PPR) (Pauly & Christensen 1995) to sustain the

reported landings in this LME reached over 25% of the observed primary production in

XIV North East Pacific

621

the late 1980s, but leveled off at around 20% in recent years (Figure XIV-46.6). The USA

and Canada now account for all landings (i.e. ecological footprint) in this LME.

Figure XIV-46.6. Primary production required to support reported landings (i.e., ecological footprint) as

fraction of the observed primary production in the Gulf of Alaska LME (Sea Around Us 2007). The

`Maximum fraction' denotes the mean of the 5 highest values.

The mean trophic level of the fisheries landings (MTI) (Pauly & Watson 2005) is rather

high, especially in recent years (Figure XIV-46.7 top), while the increase in the Fishing-in-

Balance index in the early 1980s reflects the increased landings reported during that

period (Figure XIV-46.7 bottom).

Figure XIV-46.7. Mean trophic level (i.e., Marine Trophic Index) (top) and Fishing-in-Balance Index

(bottom) in the Gulf of Alaska LME (Sea Around Us 2007).

The Stock-Catch Status Plots indicate that over 30% of the commercially exploited stocks

are now generating catches of 10% or less than the historic maximum, corresponding to

622

46. Gulf of Alaska

the `collapsed' status (Figure XIV-46.8, top). Another 40% are generating catches from

50 to 10%, corresponding to the `overexploited ' status (see Pauly et al. this vol.). This is

explained by Armstrong et al. (1998), who reported on the serial depletion of (frequently

small) stocks of commercial invertebrates. However, 80%. (in bulk) of the reported