VIII EAST ASIAN SEAS

VIII-11 Gulf of Thailand LME

VIII-12 Indonesian Sea LME

VIII-13 North Australian Shelf LME

VIII-14 NW Australian Shelf LME

VIII-15 South China Sea LME

VIII-16 Sulu-Celebes Sea LME

VIII-17 West-Central Australian

Shelf LME

254

VIII-11 Gulf of Thailand LME

S. Heileman and R. Chuenpagdee

The Gulf of Thailand LME is located in Southeast Asia and bordered by Cambodia,

Malaysia, Thailand and Vietnam. It covers a surface area of about 400,000 km2, of which

0.80% is protected, and contains about 0.46% of the world's coral reefs and 18 major

estuaries (Sea Around Us 2007). The mean depth is 45 m and maximum depth 80 m

(Piyakarnchana 1989, 1999). The tropical climate is governed by the northeast and

southwest monsoon regimes, which have profound effects on the conditions within the

Gulf (Piyakarnchana 1989, 1999). Geographically, the LME can be divided into the inner

and outer Gulf. The inner Gulf is primarily influenced by river outflow while the outer Gulf

is influenced by seawater intrusion from the South China Sea. Water circulation is

complex and influenced by tides and wind as well as differences in water densities.

These and other aspects of the oceanography and biogeochemical characteristics are

discussed in Wyrtki (1961) and Longhurst (1998). Book chapters and reports pertaining

to this LME are by Piyakarnachana (1989, 1999), Talaue-McManus (2000), Pauly &

Chuenpagdee (2003) and UNEP (2005).

I. Productivity

This LME is considered a Class I, highly productive ecosystem (>300 gCm-2yr-1). Its high

primary production is the result of high nutrient input through rivers and from agricultural

fertilisers, household sewage and shrimp farms (Piyakarnchana 1999). The Chao Phraya

watershed is the largest watershed in Thailand, covering approximately 35% of the

nation's land, and draining an area of 157,924 km². Nutrient content and dissolved

oxygen levels vary seasonally in the inner Gulf, with most nutrients except nitrate being

higher and oxygen concentration being lower, in the rainy season. Peaks in

phytoplankton densities are correlated with the rainy season. Higher productivity also

occurs close to estuaries. Increasing input of nutrients is leading to the occurrence of

phytoplankton blooms, including Harmful Algal Blooms (HABs) (Piyakarnchana 1999).

The coastal development in the GoT has been very rapid during the last decade

especially for medium and small industries. Shrimp farming, on the other hand, has been

largely terminated in the inner Gulf area. This is likely to affect the productivity in the

LME.

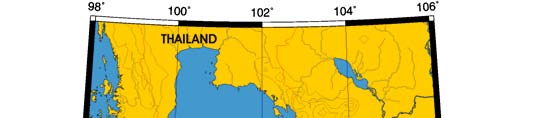

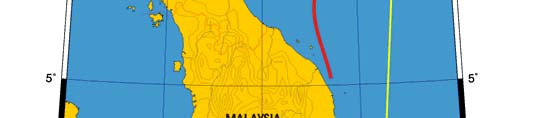

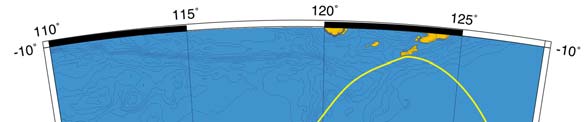

Oceanic fronts: The Gulf of Thailand Front (GTF) is the only major front within this LME

located near its boundary, at the entrance to the Gulf (Figure VIII-11.1). This front is

largely a salinity front between low-salinity waters of the Gulf, diluted by the Mekong

River outflow, and the saline waters of the South China Sea. The salinity contrast

between the Gulf waters and South China Sea waters varies seasonally and

interannually depending on the Mekong River discharge and the South China Sea

circulation that brings Mekong River waters into the Gulf. This contrast can be as high as

3 ppt across the front (Belkin & Cornillon 2003, Belkin et al. 2008). The attendant thermal

front has the cross-frontal range of 2°C to 3°C. The monsoon plays a major role in the

front's seasonal evolution since the Mekong River discharge is largely monsoon-

dependent; the snowmelt component of the Mekong runoff is of secondary importance.

Gulf of Thailand SST

Linear SST trend since 1957: 0.40°C.

Linear SST trend since 1982: 0.16°C.

256

11. Gulf of Thailand

In general, the thermal history of the Gulf of Thailand shows a moderate-to-slow

warming, which is strongly correlated with the one of the South China Sea LME, as could

be expected since the Gulf of Thailand is the largest gulf of the South China Sea. The

relative magnitude of corresponding peaks and troughs is however different among these

LMEs. The Gulf of Thailand's steady, slow warming was modulated by relatively strong

interannual variability with year-to-year variations exceeding 0.5°C. The SST peak of

1998 stands out. This event was likely related to the El Niño 1997-98. Other pronounced

events are:

(1) near-all-time minimum of 1963, simultaneous with a SST minimum in the South

China Sea LME;

(2) absolute minimum of 1976, which corresponds to a minimum in the South China

Sea.

The major warm event of 1998 caused the first extensive coral bleaching in the Gulf in

April-June 1998, which resulted in severe degradation of coral reefs; the smaller warm

event of 2003 caused mild bleaching (Yeemin, 2004).

Seasonal variability of vertical stratification plays a significant role in the Gulf of

Thailand's thermal regime (Yanagi et al., 2001). Stratification is best developed in spring

owing to strong surface heating and weak winds. The Mekong River runoff also affects

stratification over most of the Gulf. The above parameters incident solar radiation,

winds and runoff eventually depend on monsoon, therefore interannual variability of

monsoon is expected to strongly modulate SST regime of the Gulf.

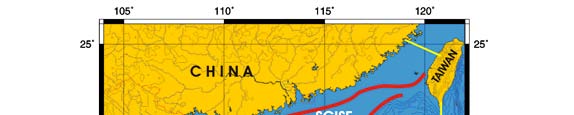

Figure VIII-11.1. Fronts of the Gulf of Thailand LME. GTF, Gulf of Thailand Front. Yellow line, LME

boundary (from Belkin et al. 2008).

VIII East Asian Seas

257

Figure VIII-11.2. Gulf of Thailand LME, annual mean SST (left) and SST anomalies (right), 1957-2006,

based on Hadley climatology. After Belkin (2008).

Gulf of Thailand LME Trends in Chlorophyll and Primary Productivity: This LME is

considered a Class I, highly productive ecosystem (>300 gCm-2yr-1).

Figure VIII-11.3. Gulf of Thailand LME, trends in chlorophyll a and primary productivity, 1998-2006.

Values are colour coded to the right hand ordinate. Figure courtesy of J. O'Reilly and K. Hyde. Sources

discussed p. 15 this volume.

II. Fish and Fisheries

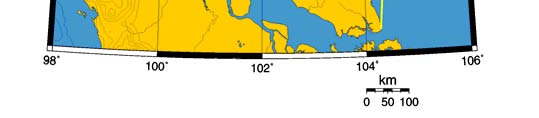

The catch composition of the Gulf of Thailand LME is a tropical multi-species mix and

includes food fish, trash fish, squid and cuttlefish, shrimp, shellfish and crab. Until the

early 1960s, the fisheries were dominated by small pelagics (mainly Indian mackerels,

Rastrelliger spp. and anchovies, Stolephorus spp.), which were caught by artisanal

fishers for the local market (Pauly & Chuenpagdee 2003). In the 1960s, the introduction

of trawl gear led to the development of demersal trawl fisheries (Piyakarnchana 1989,

Chuenpagdee and Pauly 2004), targeting threadfin bream (Nemipterus spp.), big-eye

(Pempheris adspersa), lizardfish (Saurida elongata), croaker (Johnius sp., Larimichthys

sp., Pennahia sp.), shrimps (Penaeus spp.), flatfish and squid.

258

11. Gulf of Thailand

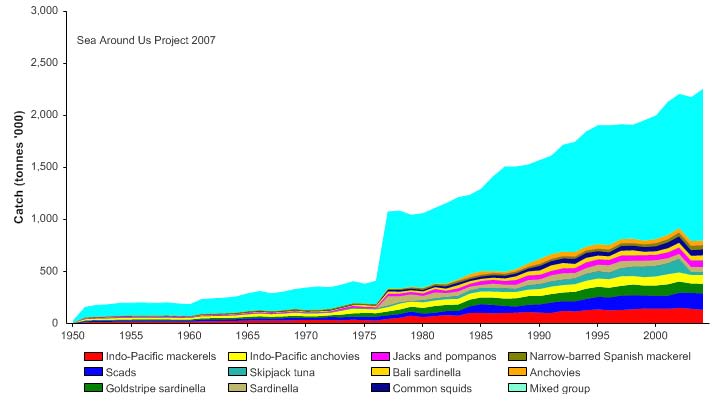

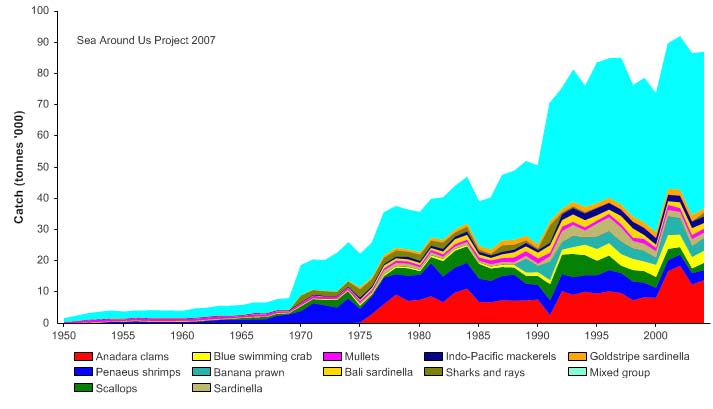

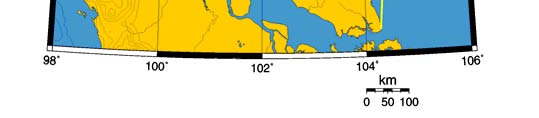

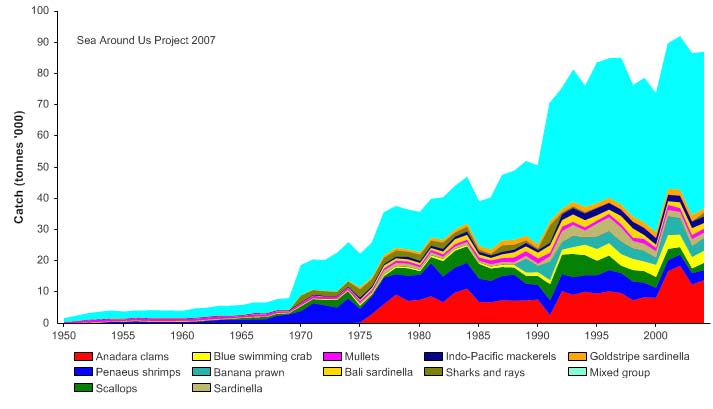

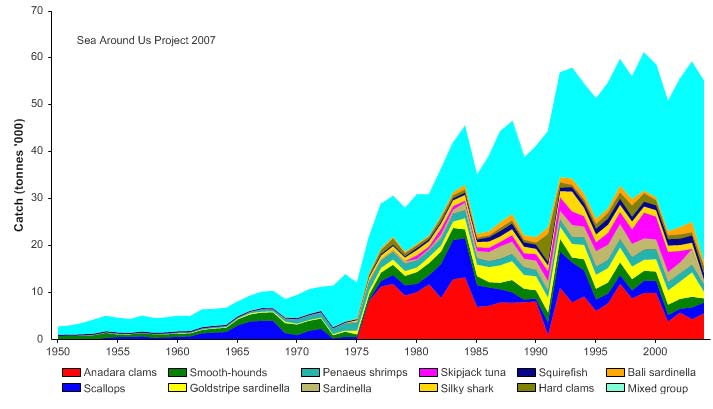

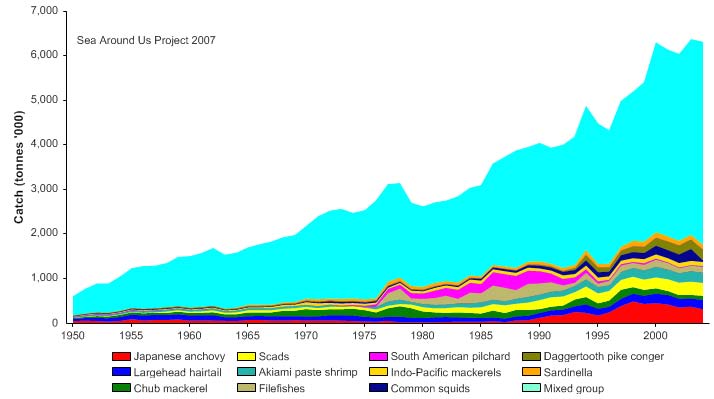

Total reported landings rose to over a million tonnes in 1969, but this is probably due to

misreporting of fish caught outside the Gulf. After 1969, the landings declined to less

than 500,000 tonnes by the late 1970s, but gradually returning to 700,000 tonnes by

2004 (Figure VIII-11.4). Again, a large fraction of the increased landings in recent years

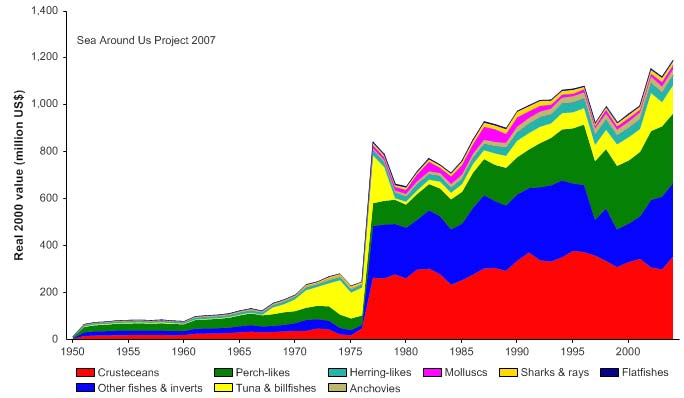

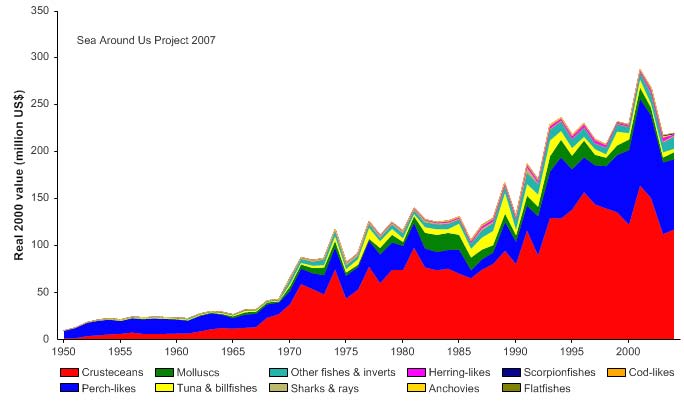

was probably caught outside of the LME, particularly for large pelagic species such as

tuna.. Note the high level of `mixed group' in the reported landings, due to the poor

quality of the underlying statistics which report a majority of the landings simply as

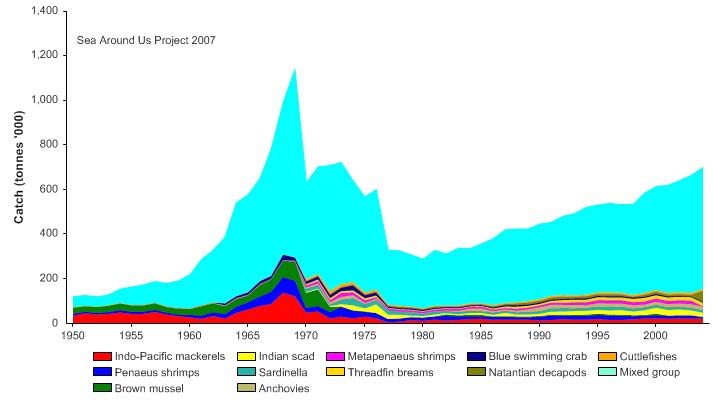

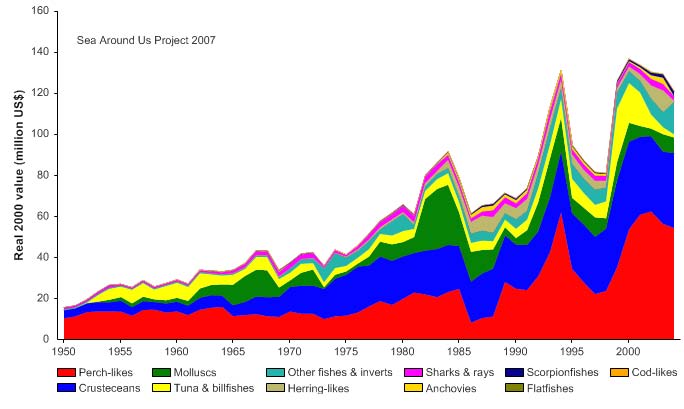

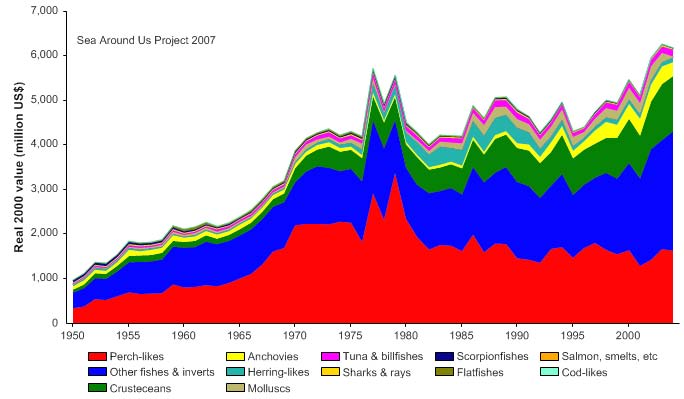

unidentified marine fish. The value of the reported landings peaked at about 1.1 billion

US$ (in 2000 real US$) in 1968 (Figure VIII-11.5).

Figure VIII-11.4. Total reported landings in the Gulf of Thailand LME by species (Sea Around Us 2007).

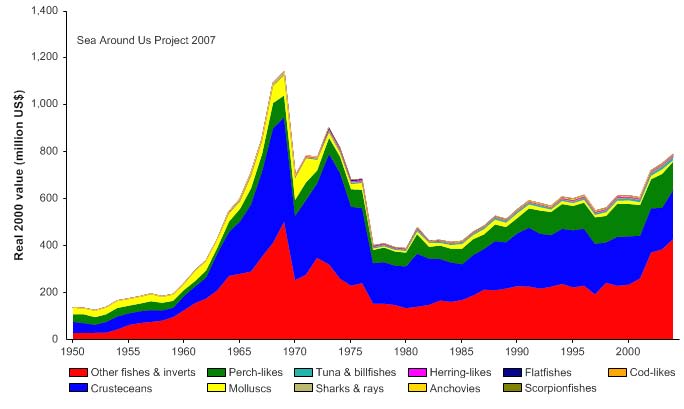

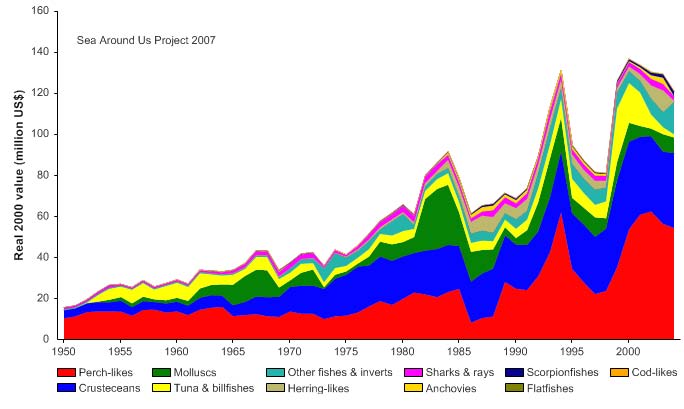

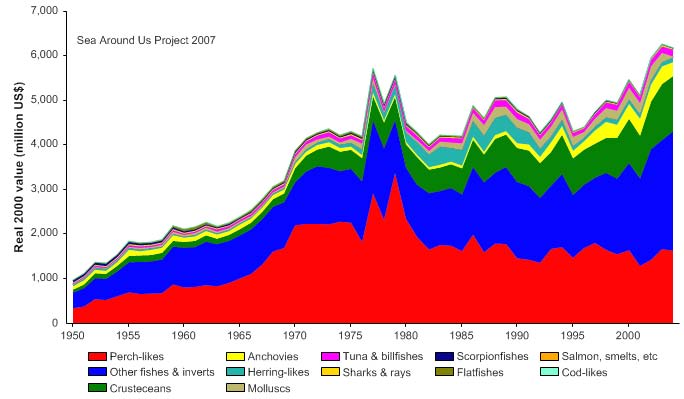

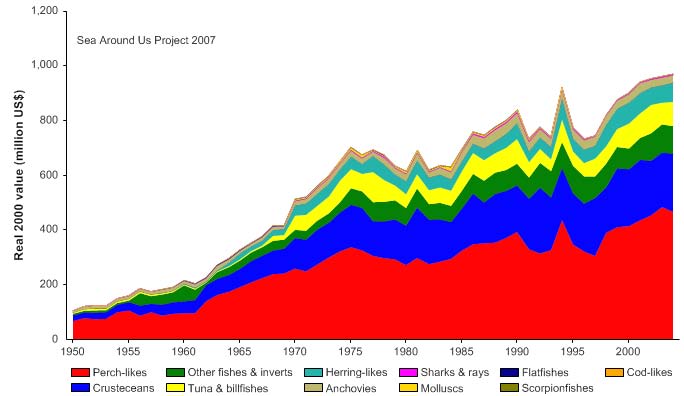

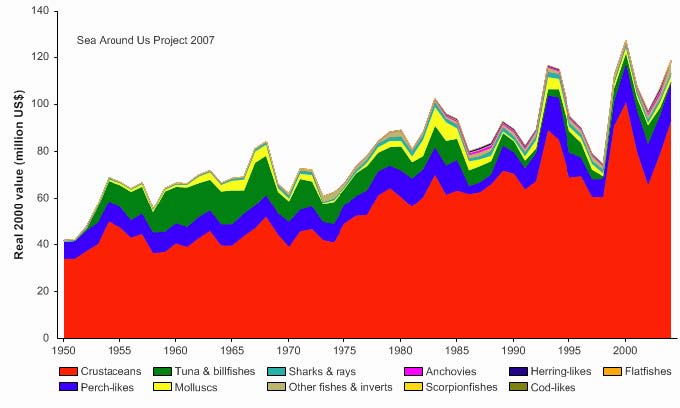

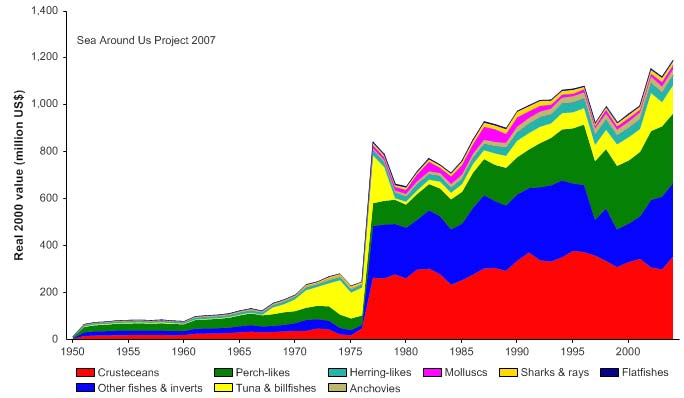

Figure VIII-11.5. Value of reported landings in the Gulf of Thailand LME by commercial groups (Sea

Around Us 2007).

VIII East Asian Seas

259

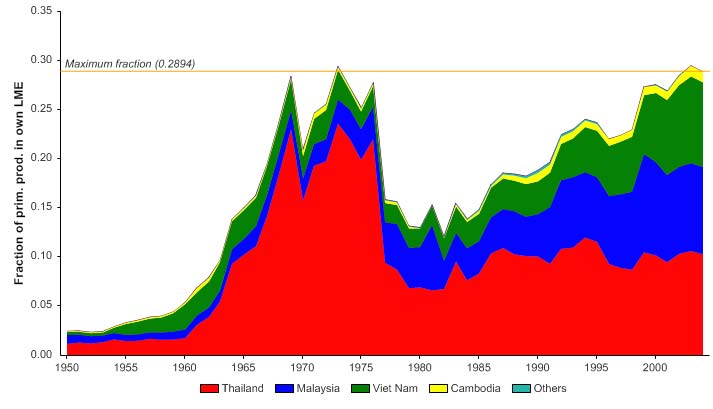

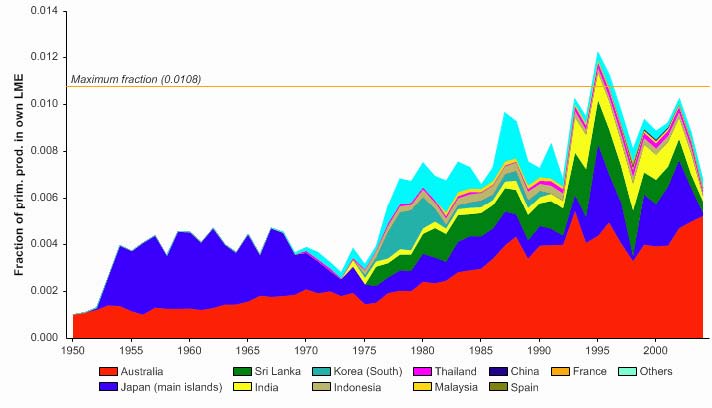

The primary production required (PPR; Pauly & Christensen 1995) to sustain the reported

landings in this LME peaked in the early 1970s at 30% of the observed primary

production, and following a period of low PPR, has reached this level in recent years

(Figure VIII-11-6). The countries bordering the LME, namely Thailand, Malaysia and

Vietnam, account for most of the ecological footprint in this LME.

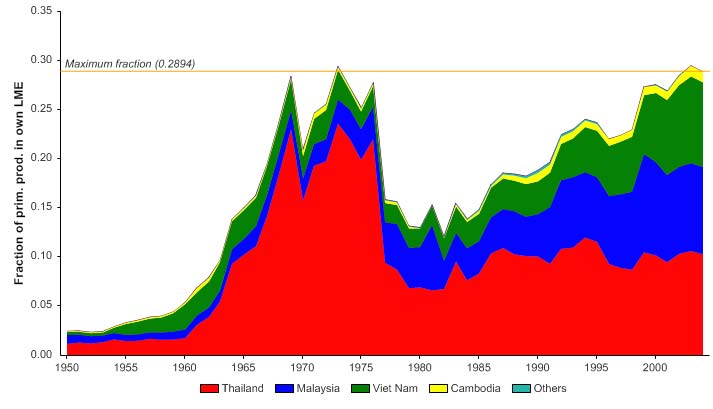

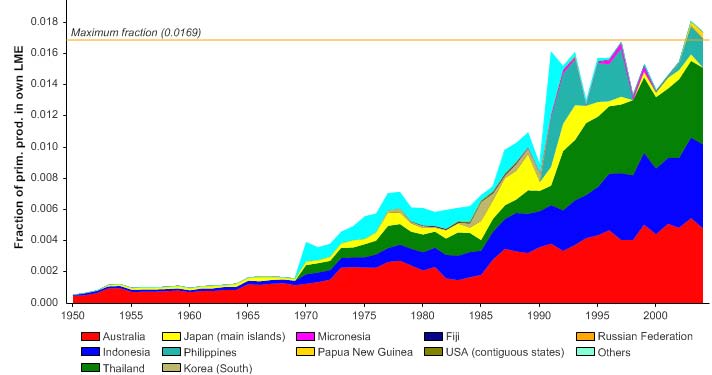

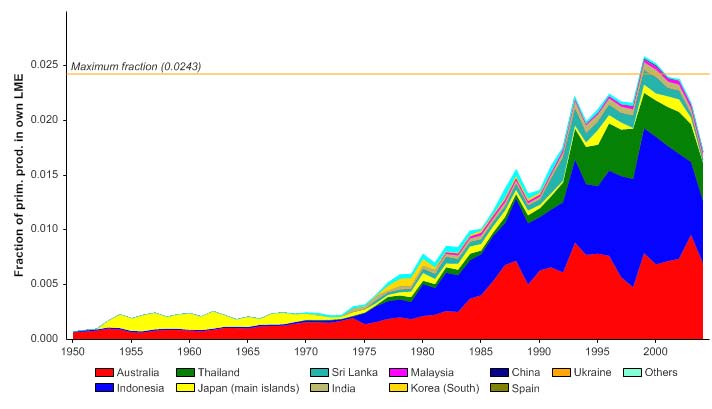

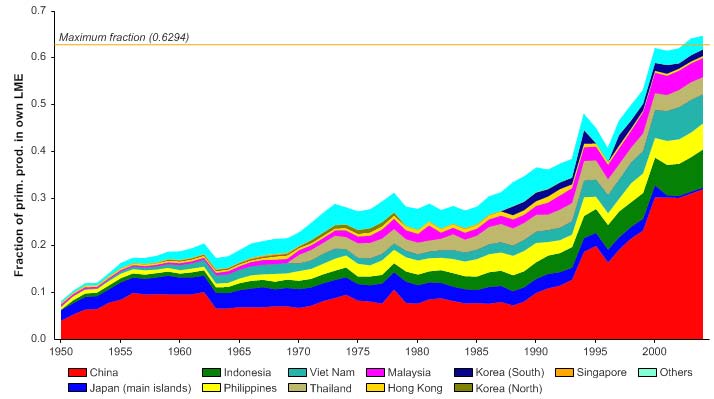

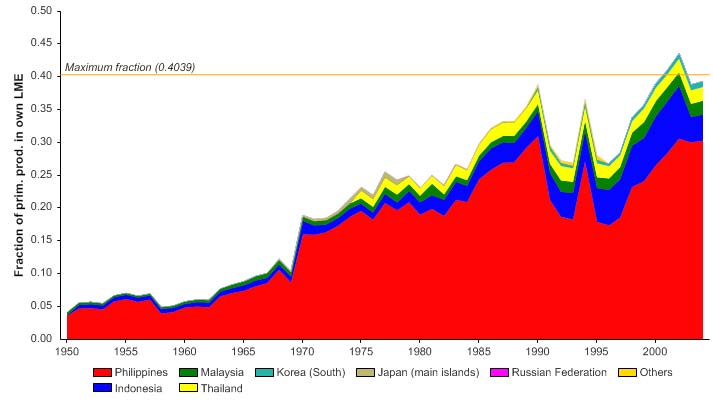

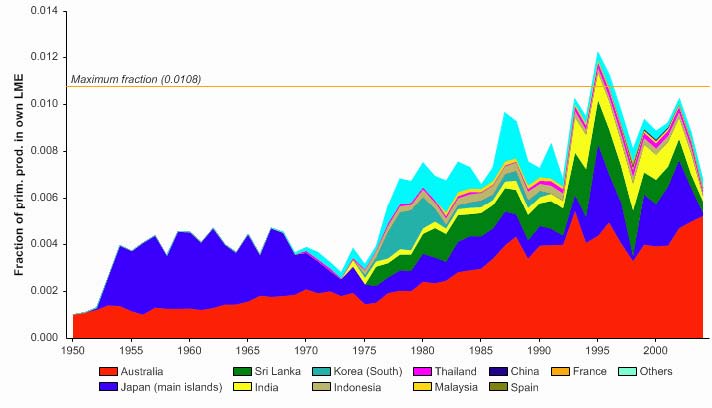

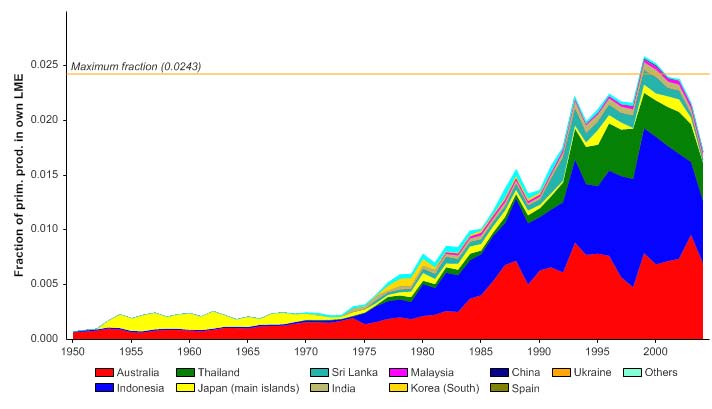

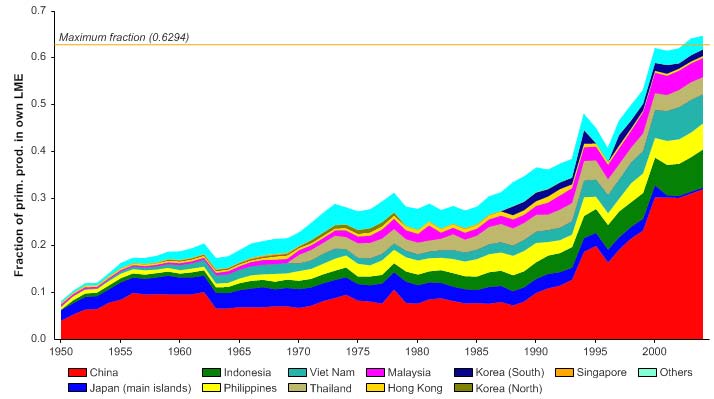

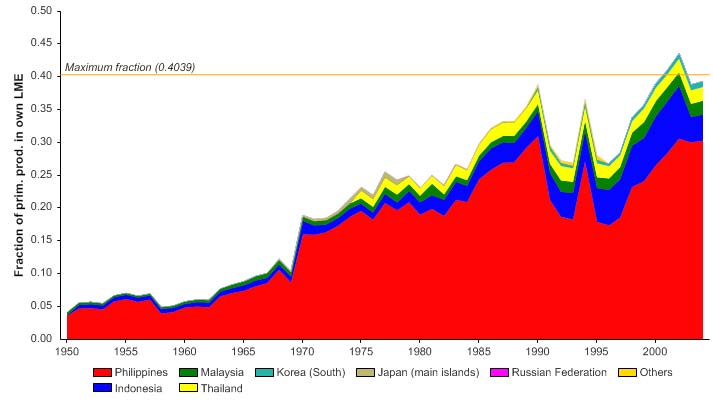

Figure VIII-11.6. Primary production required to support reported landings (i.e., ecological footprint) as

fraction of the observed primary production in the Gulf of Thailand LME (Sea Around Us 2007). The

`Maximum fraction' denotes the mean of the 5 highest values.

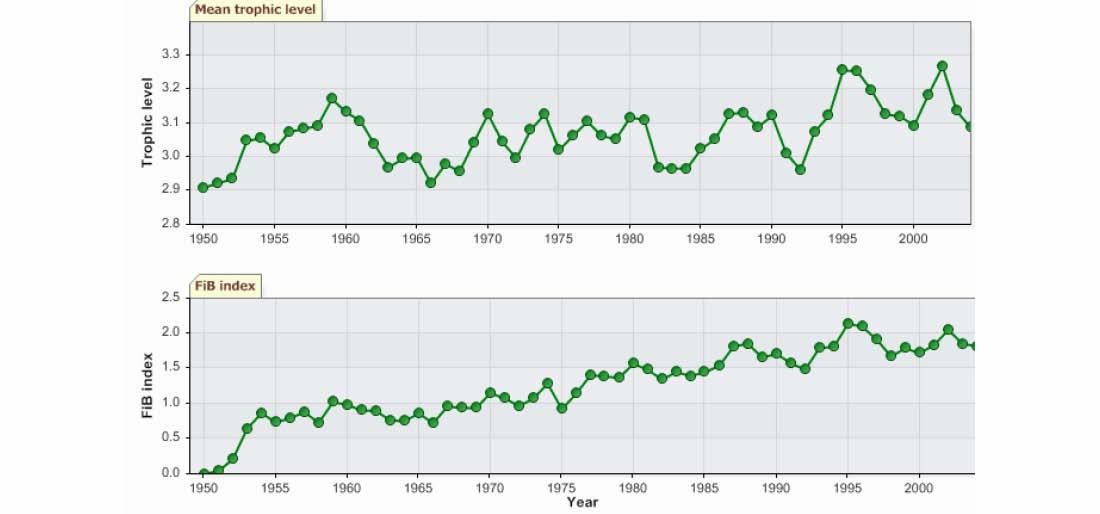

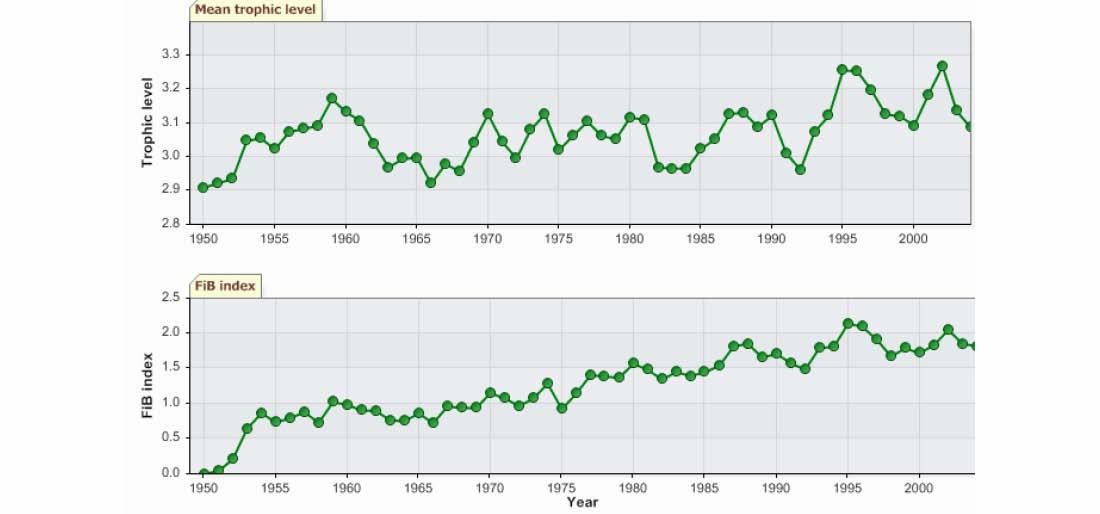

The trends in the mean trophic level (i.e., the MTI; Pauly & Watson 2005) and the FiB are

indicative of growing fisheries in the LME (Figure VII-11.7). However, due to the poor

taxonomic details in the underlying landings statistics (Figure VII-11.4), it is highly likely

that such diagnosis is incorrect.

Figure VIII-11.7. Mean trophic level (i.e., Marine Trophic Index) (top) and Fishing-in-Balance Index

(bottom) in the Gulf of Thailand LME (Sea Around Us 2007).

260

11. Gulf of Thailand

The Stock-Catch Status Plots indicate that over 60% of the stocks in the LME are either

collapsed or overexploited (Figure VIII-11.8, top), and that they contribute over 60% of

the catch (Figure VIII-11.8, bottom). Again, the high degree of taxonomic aggregation in

the underlying statistics must be noted in regards to problems in the interpretation of

these plots.

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

0%

100

10%

90

20%

)

80

(

%

s

30%

u

70

at

st

40%

y

60

b

s

k

50%

c

50

t

o

f

s

60%

40

er o

b

70%

m

30

u

N

80%

20

90%

10

100%

0

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

(n = 3486)

developing

fully exploited

over-exploited

collapsed

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

0%

100

10%

90

20%

80

)

%

30%

(

70

s

u

at

40%

60

k st

c

50%

o

50

st

y

60%

b

h

40

t

c

a

70%

C

30

80%

20

90%

10

100%0

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

(n = 3486)

developing

fully exploited

over-exploited

collapsed

Figure VIII-11.8. Stock-Catch Status Plots for the Gulf of Thailand LME, showing the proportion of

developing (green), fully exploited (yellow), overexploited (orange) and collapsed (purple) fisheries by

number of stocks (top) and by catch biomass (bottom) from 1950 to 2004. Note that (n), the number of

`stocks', i.e., individual landings time series, only include taxonomic entities at species, genus or family

level, i.e., higher and pooled groups have been excluded (see Pauly et al, this vol. for definitions).

There is, in spite of uncertainties in the available statistics, much evidence that fishing

has impacted the LME at the ecosystem level and has become a primary driving force of

biomass change. A `fishing down' of the food web (Pauly et al. 1998) has been

documented for the Gulf of Thailand (Christensen 1998, Pauly & Chuenpagdee 2003)

and is fundamentally altering ecosystem structure and impacting its productive capacity.

Overfishing caused by overcapacity of the local trawl fisheries is well documented (e.g.,

Pope 1979, Pauly 1979. Christensen 1998, Piyakarnchana 1999, Pauly & Chuenpagdee

2003, Silvestre et al. 2003, Chuenpagdee & Pauly 2004) and the South China Sea TDA,

which includes the Gulf of Thailand LME, has identified loss in fisheries productivity as a

major transboundary issue in this region (Talaue-McManus 2000). As a consequence of

high fishing effort by non-selective trawl gear, its demersal catch composition has

changed towards smaller individuals and a mix of predominantly small, short-lived

species or `trash fish' (Pauly & Chuenpagdee 2003). There is also a rapid decrease in

the catch per unit effort, from over 300 kg per hour in the early 1960s to 50 kg per hour in

the 1980s, and a further decline to 20-30 kg per hour in the 1990s (Eiamsa-Ard &

Amornchairojkul 1997).

In addition to overexploitation, destructive fishing was found to be severe in the region

(UNEP 2005) and the use of small meshes in trawl nets has contributed to

overexploitation of the local demersal fish stocks (Christensen 1998). Impacts from

VIII East Asian Seas

261

fishing with explosives and poisons are also severe, particularly on coral reefs (Bryant et

al. 1998, Talaue-McManus 2000, (UNEP SCS 2008) and other types of fishing gear, such

as push nets and mackerel purse seines, have contributed further to the unsustainable

condition of the local fisheries (Pauly & Chuenpagdee 2003). Excessive bycatch is also a

severe problem (UNEP 2005). Small mesh sizes and minimal use of bycatch-exclusion

devices have resulted in massive overexploitation of fisheries resources as bycatch. Yet,

discarding is insignificant, as virtually all of the bycatch is utilised, with smaller 'trash' fish

taken in trawls being used as aquaculture feed. There is widespread capture, either

intentional or accidental, of rare, threatened and endangered species such as turtles and

dugong, by artisanal and commercial fisheries. In 2003 an international training course

on the use of turtle excluder devices (TEDs) and juvenile and trash excluder devices

(JTEDs) was conducted by the Southeast Asian Fisheries Development Center in

cooperation with FAO and GEF to train participants in how to minimize bycatch in the

fisheries of Southeast Asia, particularly in the excluding of turtles from shrimp trawling.

Substantial, though unquantified, levels of bycatch are also produced by distant waters

fleets, through use of blast fishing and poison, and in the shrimp fry fisheries, where

juvenile fishes are often discarded (UNEP SCS 2008).

Fish stocks in the inner Gulf have been affected by rapid environmental deterioration,

including eutrophication, HABs and oxygen depletion (Eiamsa-Ard & Amornchairojkul

1997, Piyakarnchana 1999). The relative effects of environmental deterioration and

overexploitation on the region's fisheries resources need to be further explored but, at the

same time, there is growing recognition that there is an urgent need for Thailand to

reduce and manage fishing capacity (Stobutzki et al. 2006; Pauly & Chuenpagdee 2003,

Ahmed et al. 2007).

As with the neighbouring LMEs, the status and future viability of the fisheries are not well-

understood, and there are significant gaps in data. In fact, the status of many fisheries

may be summarised as Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated (IUU; UNEP 2005). Based

on present consumption and population growth patterns, pressure on the fisheries

resources is likely to increase significantly in the immediate future and overexploitation is

expected to remain severe or get worse if adequate measures are not taken to address

this problem (UNEP 2005). A substantial reduction of fishing effort, especially of bottom

trawlers, may reduce the fishing pressure on the local stocks and slow further ecological

degradation in the region (Pauly & Chuenpagdee 2003; Stobutzki et al. 2006; Ahmed et

al. 2007).

III. Pollution and Ecosystem Health

Pollution: Rapid economic development and population growth in the coastal areas have

caused pollution that is severe in localised coastal hotspots (UNEP 2005). Liquid wastes

from domestic, agricultural and industrial sources, as well as sediments and solid wastes

are the major land-based pollutants affecting the coastal areas (Talaue-McManus 2000,

Fortes 2006). Outflow from the Chao Phraya River, is critical to the productivity of the

system, especially since it contains nutrients and other substances, including pollution.

As a consequence, problems such as eutrophication, sedimentation, and shallowness of

the inner Gulf are common. Pollution has potential transboundary impacts due to the

possibility of long-shore transport of pollutants as a result of the water circulation pattern

on the Sunda Shelf (Talaue-McManus 2000). Water quality is lower than acceptable

standards in the inner Gulf region, especially at river mouths, the popular tourist spots

along the coast and near certain islands. Many cities have no sewage treatment and

discharge raw sewage directly into the coastal areas (UNEP 2005).

Eutrophication is a growing problem, due to the increasing input of nutrients from land-

based sources (Piyakarnchana 1999). The increased nutrient loading has caused

262

11. Gulf of Thailand

phytoplankton blooms in several areas, reducing water clarity as well as dissolved

oxygen in bay areas and this pattern is reportedly spreading. There have been frequent

occurrences of toxic and non-toxic algal blooms, as well as cases of paralytic shellfish

poisoning in parts of the region (Talaue-McManus 2000).

High levels of suspended solids have severe impacts in coastal waters throughout most

of the region (UNEP 2005). Major changes in turbidity and levels of suspended

sediments have resulted from activities such as extensive deforestation, logging, land

reclamation, dredging and urban development. Pollution from solid wastes is also severe

in localised areas, particularly around many towns and villages where waste

management is poor or non-existent.

The use of agricultural pesticides and industrial effluents creates a significant problem in

some areas such as near river mouths and industrial discharges (UNEP 2005). Releases

of chemical and other forms of pollution from shipping in harbours also commonly occurs

since regulations and controls relating to ship-derived pollution are rarely enforced.

Pollution by petroleum hydrocarbons and the occurrence of oil spills have been reported

in the Gulf (Piyakarnchana 1999).

Habitat and community modification: Habitat and community modification was

assessed as severe (UNEP 2005), with land use and land cover changes being the major

contributors (Piyakarnchana 1999). The causes of mangrove destruction along the

coastlines bordering the South China Sea, including the Gulf of Thailand LME, include

conversion to aquaculture ponds, particularly of shrimp, clear felling of timber for

woodchip and pulp production, land clearance for urban and port development and

human settlements and harvest of timber products for domestic use (UNEP 2004a).

However, as noted by Talaue-McManus (2000) and UNEP (2004a), shrimp culture

appears to be the most pervasive economic imperative for mangrove conversion in the

region. In 1961, mangrove forests surrounding the LME covered 367,000 ha, but by

1991 this was reduced to 173,600 ha, with at least three out of 24 provinces having lost

all their mangrove forests (Piyakarnchana 1999). The clearing of these forests has led to

a deterioration of the coastal zone (Piyakarnchana 1999). From a global perspective, the

major transboundary issues surrounding the loss of mangrove habitats include the loss of

unique biological diversity and the loss of mangrove services (UNEP 2004a).

Over the past 15 years, progressive degradation of coral reefs in several locations of the

South China Sea (including the Gulf of Thailand LME) has been noted, with reefs located

near large human population centres having suffered the most serious degradation

(UNEP 2004b). Rapid population growth, coastal development, land-based pollution,

tourism, overfishing and destructive fishing practices all contribute to this decline (Sudara

& Yeemin 1997, Talaue-McManus 2000, UNEP 2004b). Heavy sedimentation resulting

from various anthropogenic disturbances in the coastal areas and poor land use practices

in the watersheds has also impacted the region's reefs (Sudara et al. 1991). In addition,

global warming of the sea surface has caused considerable and widespread damage to

the LME's reefs after the severe 1998 bleaching event (UNEP 2004b). A comprehensive

reef survey programme covering 251 sites in the Gulf of Thailand showed 16.4% of the

reefs to be in excellent condition, 29% good, 30.8% fair and 23.8% poor (Chou et al.

2002).

Seagrass beds are subjected to a number of threats from various sources, the root cause

being associated with coastal human populations (UNEP 2004c). High sediment loads

associated with deforestation (including of mangroves), dredging and land reclamation;

fluctuation in freshwater input due to irrigation and land clearing; increased pollution;

coastal development; and destructive fishing methods are among the causes of

degradation of the region's seagrass habitats (UNEP 2004c). There is evidence of

VIII East Asian Seas

263

widespread modification of seagrass habitats throughout the region. For example,

between 20% to 50% of seagrass beds in Malaysia and Thailand have been damaged

(Talaue-McManus 2000) and Vietnam has lost an estimated 40% to 50% over the past

two decades (UNEP 2004c).

Ecosystem health may deteriorate further as a consequence of expected future increases

in pollution and habitat modification (UNEP 2005). Despite increasing measures for

pollution mitigation and control (e.g., sewage treatment), environmental quality is likely to

worsen, primarily because of the predicted increase in deforestation and agriculture, as

well as a major increase in population overriding the improvements in infrastructure.

Some positive steps are being taken to address habitat modification, including mangrove

rehabilitation programmes, watershed protection and establishment of marine protected

areas. Both the direction of change and the rates of environmental deterioration or

improvement, however, will depend on the success of ongoing and planned interventions.

IV. Socioeconomic Conditions

The population in the Gulf of Thailand LME region is 112 million (Talaue-McManus 2000;

UNEP 2005). For the larger South China Sea region, some 270 million people (5% of the

world's population) inhabit coastal areas and this population is expected to double in the

next three decades. The LME and its resources have provide important benefits to the

region's coastal communities, with fisheries, mariculture and tourism being key economic

activities in the bordering countries. Marine fisheries in particular play a significant

socioeconomic role. Subsistence fishing is the major activity of large numbers of people

outside of the main urban and industrial centres. Fisheries are an important source of

food, employment and foreign exchange. Despite nutritional requirements and current

population growth rates, South China Sea countries in general are net exporters of

fishery products (Talaue-McManus 2000). Fishing contributes about 2% to the GDP of

Thailand, which is a major world exporter of fishery commodities and among the leading

exporters of farmed shrimp (FAO 2005).

The socioeconomic impacts of overexploitation of fisheries and environmental

deterioration are significant (UNEP 2005). There have been reduced economic returns

and loss of employment from the collapse of fisheries in the region. Higher investment is

now required per unit of commercial catch, reducing the profitability of fishing enterprises.

The degradation of mangrove forests, seagrass and coral reefs, critical for fish spawning,

feeding and recruitment, has also contributed to declining fish catch, especially in near-

shore areas. This has had a marked negative impact on the livelihoods of poor artisanal

fishing communities. Competition for fisheries resources among fishers has also been

increasing.

The socioeconomic impacts of pollution include economic losses in mariculture and the

shellfish industry as a result of high levels of toxicity and HABs and risk to human health.

Other socioeconomic impacts of pollution are associated with the costs of clean-up and

coastal restoration. Land-use conflicts have also arisen. The socioeconomic impacts of

habitat and community modification range from slight to severe (UNEP 2005), primarily

because of reduced capacity of local populations to meet basic human needs and loss of

employment. Other impacts include loss or reduction of existing and future income and

foreign exchange from fisheries and tourism and increased risks to capital investment

(e.g., failure of coastal aquaculture projects in many parts of the region, costs of

restoration of modified ecosystems and intergenerational inequity).

264

11. Gulf of Thailand

V. Governance

Governance of the LME is shared by the four bordering countries. A range of measures

and programmes has been established to arrest and reverse overexploitation as well as

environmental degradation in the LME. Following on its adoption of the FAO Code of

Conduct for Responsible Fisheries, the Thai Department of Fisheries issued licensing

regulations to control the number of trawlers and push nets. The number of registered

trawlers has gradually decreased from about 10,500 units in 1980 to 8,000 units in early

2000 (DoF 2002). The Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives in Thailand governs the

Department of Fisheries. The Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment governs

coastal resources and the environment. The countries have made a commitment to

devolve authority for natural resources management from state to community and from

central to more local levels of government (Ratner et al. 2004). For instance, in Thailand

the 1999 Decentralization Act has placed a range of decision-making powers with sub-

district government units (Tambon Administrative Organisations).

The Gulf of Thailand LME comes under the UNEP-administered East Asian Regional

Seas Programme. The Action Plan for the Protection and Development of the Marine

and Coastal Areas of the East Asian Region was approved in 1981, and currently

involves 10 countries. There is no regional convention. Instead, the programme

promotes compliance with existing environmental treaties and is based on member

country goodwill. The Action Plan is steered from Bangkok by its coordinating body,

COBSEA. The East Asian Seas Regional Coordinating Unit serves as the secretariat

and is responsible for coordinating the activities of governments, NGOs, UN and donor

agencies and individuals in caring for the region's marine environment. Other regional

action plans include the ASEAN Strategic Plan of Action on the Environment, ASEAN

Cooperation on Transboundary Pollution and Regional Action Programme for

Environmentally Sound and Sustainable Development. Regional research programmes

include the International Cooperative Study of the Gulf of Thailand for the sustainable

management of the Gulf, sponsored by the UNESCO Intergovernmental Oceanographic

Commission-Sub Commission for the Western Pacific (IOC-WESTPAC), the Southeast

Asian Programme in Ocean Law, Policy and Management and the Southeast Asia

START Global Change Regional Centre.

The Council of Directors of the Southeast Asian Fisheries Development Centre approved

a programme for the `regionalisation' of the FAO Code of Conduct in 1998. It has also

produced three volumes of Regional Guidelines for Responsible Fisheries in Southeast

Asia -- Responsible Fishing Operations, Responsible Aquaculture and Responsible

Fisheries Management (SEAFDEC 2003). The Asia-Pacific Fishery Commission is

assisting its member countries to achieve accelerated fisheries development and

management.

To help address the problems in the coastal fisheries of Asia, the WorldFish Centre

joined forces with fisheries agencies from Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, The

Philippines, Sri Lanka, Thailand and Vietnam and the Asian Development Bank, to

implement the project `Sustainable Management of Coastal Fish Stocks in Asia'

(TrawlBase project) between 1998 and 2001 (Silvestre et al. 2003). Among the main

achievements of this partnership was the development of a database called `Fisheries

Resource Information System and Tools' (FiRST), which contains trawl research survey

data and socioeconomic information for selected fisheries, and facilitates its analysis.

The project has also strengthened national capacity in coastal fisheries assessment,

planning and management, and illustrated the benefits of collaborative efforts in

addressing issues of regional concern.

VIII East Asian Seas

265

GEF is currently supporting three projects involving this LME. The project `Reversing

Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand' aims to

foster and encourage regional collaboration and partnership in addressing transboundary

environmental problems between all stakeholders and at all levels. The project also

seeks to enhance the capacity of the participating governments to integrate

environmental considerations into national development planning. A comprehensive TDA

for the South China Sea, which includes the Gulf of Thailand LME, has been produced

under this project.

The project `Building Partnerships for the Environmental Protection and Management of

the Seas of East Asia' (PEMSEA) aims to enable the East Asian Seas Region to

collectively protect and manage its coastal and marine environment through inter-

governmental and inter-sectoral partnerships (www.pemsea.org). Through partnership

building, the project will help countries to develop scientifically-based environmental

management strategies and action plans in order to deal with land-based pollution,

promote closer regional and sub-regional collaboration in combating environmental

disasters arising from maritime accidents as well as increase regional commitments in

implementing international conventions that they ratify. The project `East Asian Seas

Region: Development and Implementation of Public-Private Partnerships in

Environmental Investments' aims to build confidence and capabilities in public-private

sector partnerships as a viable means of financing and sustaining environmental facilities

and services for the protection and sustainable use of the marine and coastal resources

of the East Asian Seas region.

References

Ahmed, M., Boonchuwongse, P., Dechboon, W. and Squires, D. (2007) Overfishing in the Gulf of

Thailand: Policy challenges and bioeconomic analysis. Environment and Development

Economics 12 (1): 145-172.

Belkin, I.M. (2008). Rapid warming of Large Marine Ecosystems. Progress in Oceanography, in

press.

Belkin, I.M. and Cornillon, P.C. (2003). SST fronts of the Pacific coastal and marginal seas. Pacific

Oceanography 1(2): 90-113.

Belkin, I.M., Cornillon, P.C., and Sherman, K. (2008) Fronts in large marine ecosystems of the

world's oceans: An atlas. Progress in Oceanography, in press.

Bryant, D., Burke, L., McManus, J. and Spalding, M. (1998). Reefs at Risk. A Map-based Indicator

of Threats to the World's Coral Reefs. WRI/ICLARM/WCMC/UNEP, Washington D.C., U.S.

Chou, L.M., Wilkinson, C., Gomez, E. and Suraphol, S. (2002). Status of Coral Reefs in the ASEAN

Region, p 8-17 in: Wilkinson, C.R. (ed), Living Coastal Resources of Southeast Asia: Status

and Management. Report of the Consultative Forum 3rd Association of Southeast Asian

Nations-Australia Symposium on Living Coastal Resources. Chulalongkorn University Bangkok,

Thailand. Australian Institute of Marine Science, Townsville, Australia.

Christensen, V. (1998). Fishery induced changes in a marine ecosystem: insight from models of the

Gulf of Thailand. Journal of Fish Biology 53 (Suppl. A):128-142.

Chuenpagdee, R. and Pauly, D. (2004). The Gulf of Thailand trawl fisheries, p 203-220 in: Swan, J.

and Gréboval, D. (comps), Report and Documentation of the International Workshop on the

Implementation of International Fisheries Instruments and Factors of Unsustainability and

Overexploitation in Fisheries, Mauritius, 3-7 February 2003. FAO Fisheries Report 700. FAO,

Rome.

DoF (2002). Thai Fishing Vessels Statistics 2000. Department of Fisheries, Ministry of Agriculture

and Cooperatives. Bangkok, Thailand. Document 16/2002.

Eiamsa-Ard, M. and Amornchairojkul, S. (1997). The marine fisheries of Thailand, with emphasis

on the Gulf of Thailand trawl fishery, p 85-95 in: Silvestre, G. and Pauly, D. (eds), Status and

Management of Tropical Coastal Fisheries in Asia. International Centre for Living Aquatic

Resources Management Conference Proceedings 53.

266

11. Gulf of Thailand

FAO (2005). Fishery Country Profiles. www.fao.org/fi/fcp/fcp.asp

Fortes, M. (2006). Seas of East Asia, p 177 -192 in: UNEP/GPA (2006), The State of the Marine

Environment: Regional Assessments. UNEP/GPA, The Hague.

Longhurst, A.R. (1998). Ecological Geography of the Sea. Academic Press, California, U.S.

Pauly, D, Christensen, V., Dalsgaard, J., Froese, R. and Torres, F. Jr. (1998). Fishing down marine

food webs. Science 279:860-863.

Pauly, D. (1979). Theory and management of tropical multispecies stocks: a review, with emphasis

on the southeast Asian demersal fisheries. ICLARM Studies and Reviews 1, 35 p.

Pauly, D. and Christensen, V. (1995). Primary production required to sustain global fisheries.

Nature 374: 255-257.

Pauly, D. and Chuenpagdee, R. (2003). Development of Fisheries in the Gulf of Thailand Large

Marine Ecosystem: Analysis of an Unplanned Experiment, p 337-354 in: Hempel, G. and

Sherman, K. (eds), Large Marine Ecosystems of the World: Trends in Exploitation, Protection

and Research. Elsevier, The Netherlands.

Pauly, D. and Watson, R. (2005). Background and interpretation of the `Marine Trophic Index' as a

measure of biodiversity. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society: Biological Sciences

360: 415-423.

Piyakarnachana, T. (1989). Yield Dynamics as an Index of Biomass Shifts in the Gulf of Thailand, p

95-142 in: Sherman, K. and Alexander, L.M. (eds), Biomass Yields and Geography of Large

Marine Ecosystems. AAAS Symposium 111, Westview Press, Inc., Boulder, U.S.

Piyakarnchana, T. (1999). Changing State and Health of the Gulf of Thailand Large Marine

Ecosystem, p 240-250 in: Sherman, K. and Tang, Q. (eds), Large Marine Ecosystems of the

Pacific Rim Assessment, Sustainability and Management. Blackwell Science, Malden, U.S.

Pope, J.A. (1979). Stock Assessment in Multispecies Fisheries. South China Sea Fisheries, with

Special Reference to the Trawl Fishery in the Gulf of Thailand. South China Sea Development

and Coordinating Programme. SCS/DEV/79/19. Manila, Philippines.

Ratner, B.D., Thanh-ha, D., Kosal, M., Nissapa, A. and Chanphengxay, S. (2004). Undervalued

and Overlooked: Sustaining Rural Livelihoods through Better Governance of Wetlands.

WorldFish Center Studies and Reviews 28.

Sea Around Us (2007). A Global Database on Marine Fisheries and Ecosystems. Fisheries Centre,

University British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada. www.seaaroundus.org/lme/SummaryInfo.

aspx?LME=35

SEAFDEC (2003). Regional Guidelines for Responsible Fisheries in Southeast Asia: Responsible

Fisheries Management. Southeast Asian Fisheries Development Centre. MFRDMD/SP/3.

Sherman, K. (2003). Physical, Biological and Human Forcing of Biomass Yields in Large Marine

Ecosystems. ICES CM 2003/P: 12.

Silvestre, G.T., Garces, L.R., Stobutzki, I., Ahmed, M., Santos, R.A.V., Luna, C.Z. and Zhou, W.

(2003). South and South-East Asian coastal fisheries: Their status and directions for improved

management. Conference synopsis and recommendations, p 1- 40 in: Silvestre, G., Garces, L.,

Stobutzki, I., Ahmed, M., Santos, R.A.V., Luna, C., Lachica-Aliño, L., Christensen, V., Pauly, D.

and Munro, P. (eds), Assessment, Management and Future Directions for Coastal Fisheries in

Asian Countries. WorldFish Center Conference Proceedings 67.

Stobutzki, I.C., Silvestre, G.T., Talib, A. Abu, Krongprom, A., Supongpan, M., Khemakorn, P.,

Armada, N., Garces, L.R. (2006). Fisheries Research 78:130-142.

Sudara, S. and Yeemin, T. (1997). Status of Coral Reefs in Thailand, p 135-144 in: Grigg, R.W.

and Birkeland, C. (eds), Status of Coral Reefs in the Pacific. Sea Grant College Program,

School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology, University of Hawaii, U.S.

Sudara, S., Sanitwongs, A., Yeemin, T., Moordee, R., Panutrakune, S., Suthanaluk, P. and

Natekanjanalarp, S. (1991). Study of the Impact of Sediment on Growth of the Coral Porites

lutea in the Gulf of Thailand, p 107-112 in: Alcala, A.C. (ed), Proceedings of the Regional

Symposium on Living Resources in Coastal Areas. Marine Science Institute, University of the

Philippines.

Talaue-McManus, L. (2000). Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis for the South China Sea. East

Asian Seas Regional Coordination Unit Technical Report Series 14, United Nations

Environment Programme, Bangkok, Thailand.

UNEP (2004a). Mangroves in the South China Sea. UNEP/GEF/SCS Technical Publication 1.

UNEP (2004b). Coral Reefs in the South China Sea. UNEP/GEF/SCS Technical Publication 2.

UNEP (2004c). Seagrass in the South China Sea. UNEP/GEF/SCS Technical Publication 3.

UNEP (2005). Wilkinson, C., DeVantier, L., Talaue-McManus, L., Lawrence, D. and Souter D.

South China Sea, GIWA Regional Assessment 54. University of Kalmar, Kalmar, Sweden.

www.giwa.net/publications/r54.phtml

VIII East Asian Seas

267

UNEP SCS (2008) Establishing a regional system of fisheries refugia in the Gulf of Thailand and

South China Sea. Report available online at:http://refugia.unepscs.org/Fisheries_Refugia_

Information/About_Fisheries_Refugia/About_Fisheries_Refugia.html

Wyrtki, K. (1961). Dynamics of the Demersal Fish Resources in the Sunda Shelf Area of the South

China Sea. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Washington, Seattle, U.S.

Yanagi T., Sachoemar, S.I., Takao, T. and Fujiwara S. (2001) Seasonal variation of stratification in

the Gulf of Thailand, Journal of Oceanography, 57(4), 461-470.

Yeemin, T. (2004) Status of coral reefs in the Gulf of Thailand and the Andaman Sea, poster

presented at the 10th ICRS, Okinawa, Japan, 28 June - 2 July 2004.

268

11. Gulf of Thailand

VIII East Asian Seas

269

VIII-12 Indonesian Sea LME

S. Heileman

The Indonesian Sea LME is situated at the confluence of the Pacific and Indian Oceans,

and is bordered by Indonesia and East Timor. It covers an area of 2.3 million km2, of

which 1.49% is protected, and contains 9.98% and 0.75% of the world's coral reefs and

sea mounts, respectively (Sea Around Us 2007). Indonesia is one the world's largest

archipelagic nations, with a coastline exceeding 84,000 km. The warm ocean acts as a

`heat engine' of global atmospheric circulation, with complex ocean-atmospheric

dynamics, including the ENSO phenomenon. The convergence of three tectonic plates

the Eurasian, the Indo-Australian and the Pacific Plates makes the region geologically

as well as topographically diverse. Many of Indonesia's islands are subject to tectonic

instability including volcanic activity. Seasonal monsoons, during which ocean currents

reverse directions, exert a significant influence on the LME. The seas around Indonesia

have complex and rapid currents owing to energetic tides over rough topography and

also owing to the Indonesian Throughflow, which is the flow and exchange of oceanic

water between the Pacific and Indian Oceans. Books, book chapters, articles and reports

pertaining to this LME are Dalzell & Pauly (1989), Morgan (1989), Pauly & Martosubroto

(1996), Pitcher et al. (2007), Zijlstra & Baars (1990) and UNEP (2005).

I. Productivity

The Indonesian Sea LME is considered a Class I ecosystem with high productivity

(>300 gCm-2yr-1). The Banda Sea and the Aru Basin in particular, are areas of extensive

seasonal upwelling and downwelling related to the monsoonal system. During upwelling

periods, biomasses and productivity at all levels in the food chain are greatly enhanced

(Zijlstra & Baars 1990). Stocks of small pelagic fish were also found to be considerably

higher during the upwelling period. The changing oceanographic conditions in this LME

also influence phytoplankton and zooplankton species composition.

The region is located in the Indo-West Pacific centre of biodiversity, supporting mega-

diversity (Roberts et al. 2002). For example, more than 500 species of reef-building

corals, 2,500 species of marine fish, 47 species of mangroves and 13 species of

seagrasses are found in this region (Chou 1997, Tomascik et al. 1997, Veron 2000,

Spalding et al. 2001). The pelagic realm is an important habitat, which supports high

biodiversity of large and small migratory marine species, including a wide variety of

cetaceans, including the blue, fin and humpback whales and other species that frequently

migrate through the region (Kahn & Pet 2003).

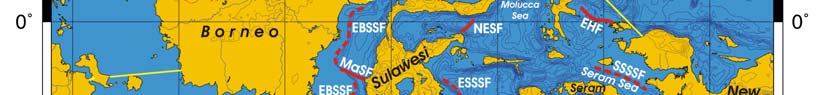

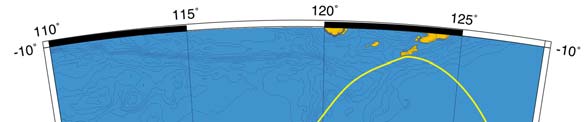

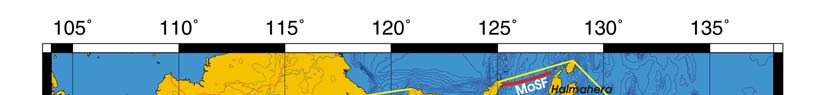

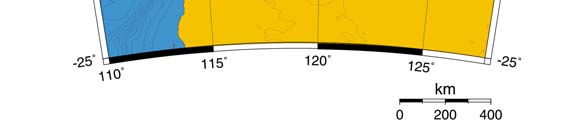

Oceanic fronts Belkin et al. (2008): Straits connecting this LME with the other marginal

seas are sites of front formation due to topographic effects caused by flow constrictions

(Figure VIII-12.1). Internal tide interaction with sills in these straits is one of such front-

genetic processes. Local (basin-scale) fronts are observed east of Borneo (EBSSF),

northeast of Sulawesi (NESF), east of Halmahera (EHF), in the eastern parts of the Java

Sea (EJSF) and Flores Sea (EFSF), across the Makassar Strait (MaSF), in the Molucca

Sea (MoSF) and in the southern Banda Sea (SBSF).

270

12. Indonesian Sea LME

Figure VIII-12.1. Fronts of the Indonesian Sea LME. EBSSF, East Borneo Shelf-Slope Front; EFSF, East

Flores Sea fronts; EHF, East Halmahera Front; EJSF, East Java Sea fronts; ESSSF, East Sulawesi Shelf-

Slope Front; MaSF, Makassar Strait Front; MoSF, Molucca Sea Front; NESF, Northeast Sulawesi Front;

SBSF, South Banda Sea Front; SSSSF, Seram Sea Shelf-Slope Front. Dashed lines show most probable

locations of shelf-slope fronts. Yellow line, LME boundary. After Belkin et al. (2008) and Cornillon

(2003).

Indonesian Sea SST (after Belkin 2008)

Linear SST trend since 1957: 0.53°C.

Linear SST trend since 1982: 0.24°C.

The thermal history of the Indonesian Sea since 1957 included brief cooling through 1967

and steady warming ever since (Figure VIII-12.2). The all-time minimum of 1967

occurred simultaneously with the all-time minimum in the Sulu-Celebes Sea LME and

only a year prior to the all-time minimum of 1968 in the West-Central Australian Shelf

LME and a minimum of 1968 in the North-West Australian Shelf LME.

Figure VIII-12.2. Indonesian Sea LME mean annual SST (left) and SST anomalies (right), 1957-2006,

based on Hadley climatology. After Belkin (2008).

VIII East Asian Seas

271

This sequence of events can be explained by advection of the low-temperature signal of

1967 from the Indonesian Sea toward Western Australia with the Indonesian

Throughflow. The 1982 minimum occurred simultaneously in the North and Northeast

Australian Shelf LMEs, but not off Western Australia; this can be explained by the long-

time variability of circulation pattern. The 1998 all-time maximum was likely caused by El

Niño 1997-98. Despite the relatively uniform SST field, local anomalies up to 10°C are

generated by the Indonesian Throughflow and tides, e.g. east of Bali in the Lombok

Strait, where SST drops to 16°C vs. 28°C in adjacent waters (Vantier et al., 2005, p. 56).

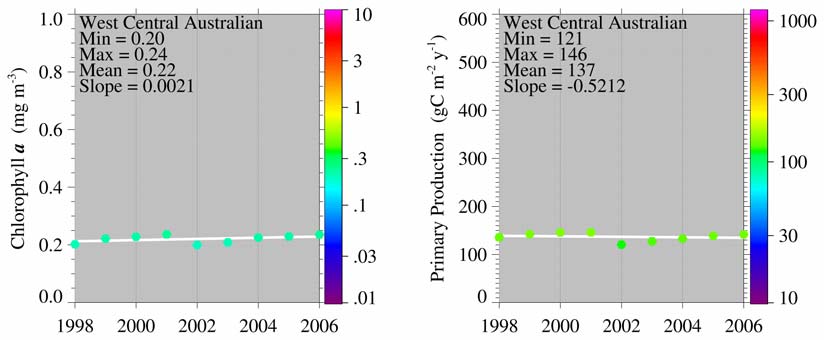

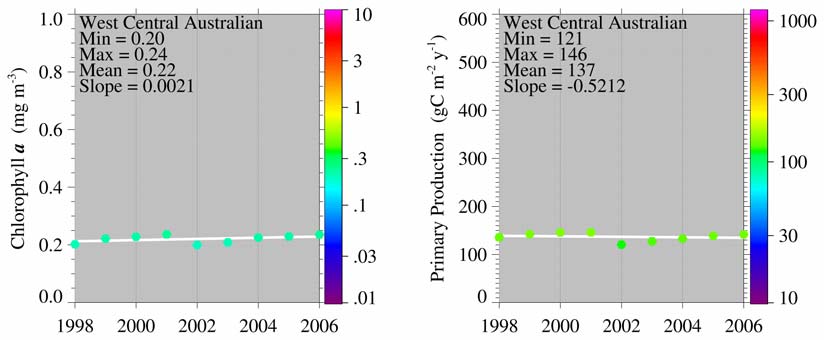

Indonesian Sea LME trends in Chlorophyll and Primary Production: The Indonesian

Sea LME is considered a Class I ecosystem with high productivity (>300 gCm-2yr-1).

Figure VIII-12.3. Indonesian Sea LME annual trends in chlorophyll a (left) and primary productivity

(right), 1998 2006. Values are color coded to the right hand ordinate. Figure courtesy of J. O'Reilly

and K. Hyde. Sources discussed p. 15 this volume.

II. Fish and Fisheries

The fisheries of the Indonesian Sea LME are very complex and diverse, reflecting the

region's extraordinarily heterogeneous geography and species variance (Pauly &

Martosubroto 1996; FAO 2005). While most of the catch comes from its artisanal sector,

industrial fisheries contribute considerably more in terms of value, since they target high-

value shrimp and tuna stocks. Major species caught in the LME include tuna, sardines,

anchovy, mackerel, as well as a range of reef fishes (Morgan 1989). Reef fisheries are

vital to subsistence fishers and their families in the region but are also important in

supplying high value products for expanding international, national and local markets

(Cesar et al. 2000). Aquaculture of shrimps in coastal ponds has also increased rapidly

during the last two decades in Indonesia.

As noted by Kahn & Fauzi (2001) for the adjacent Sulu-Celebes Sea, but also applicable

in the Indonesian Sea, great uncertainties exist on the status of the local fish stocks due

to serious discrepancies in fisheries data and a potentially significant level of Illegal,

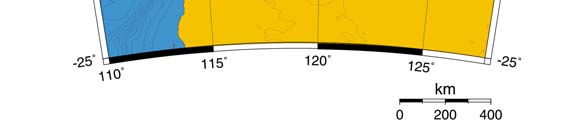

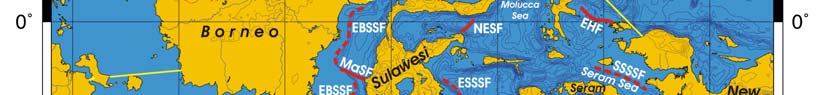

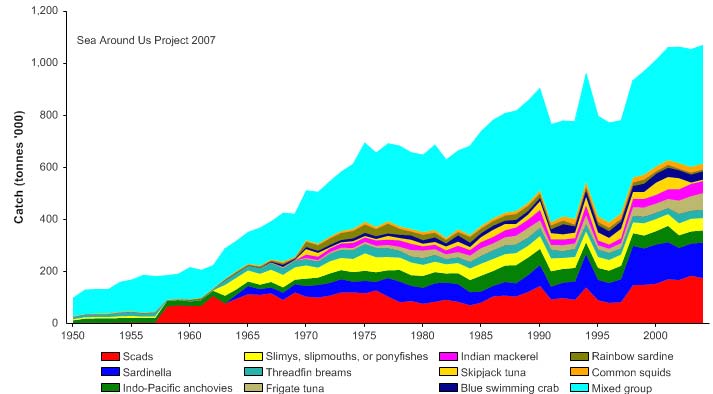

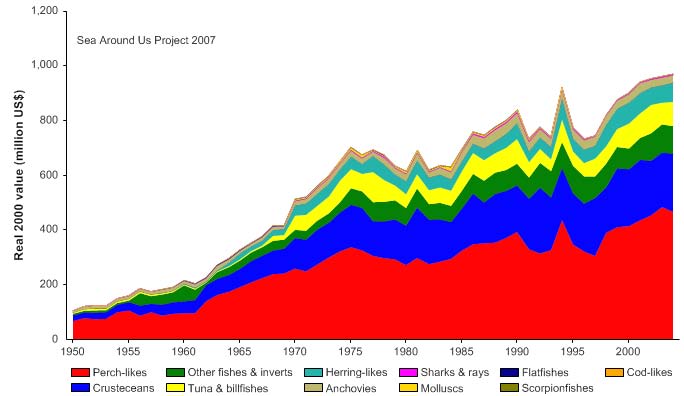

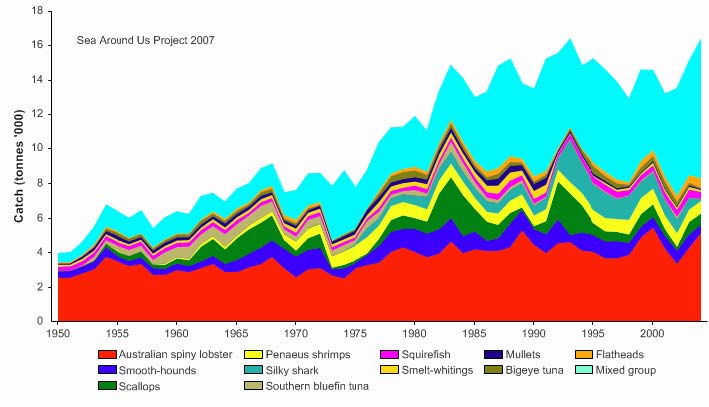

Unreported and Unregulated (IUU) catches. Total reported landings in the LME have

increased steadily from the 1950s, with a sharp increase from less than half a million

tonnes to over one million tonnes in the mid 1970s (Figure VIII-12.4). This distinct

increase in the reported landings may be associated with developments related to the

declaration of the EEZ. In 2004, the total reported landings reached 2.2 million tonnes

272

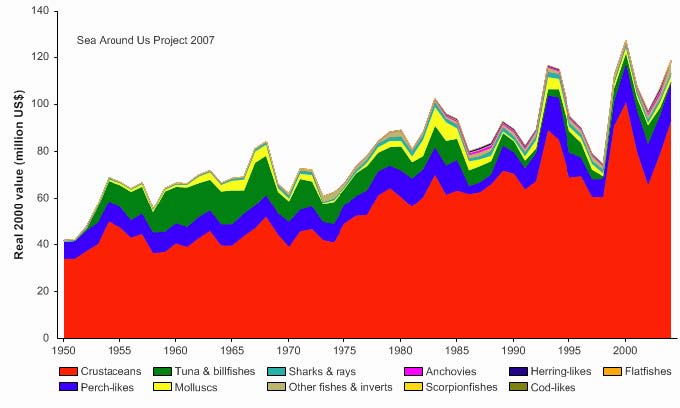

12. Indonesian Sea LME

and the value of the reported landings, showing a trend similar to landings, reached close

to US$1.2 billion (in 2000 US dollars) in 2004 (Figure VIII-12.5)..

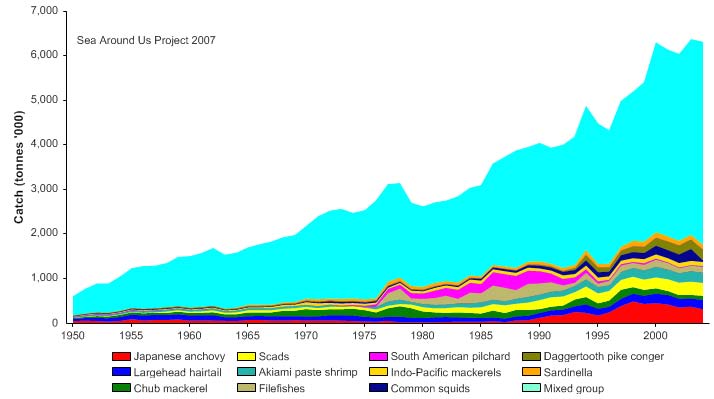

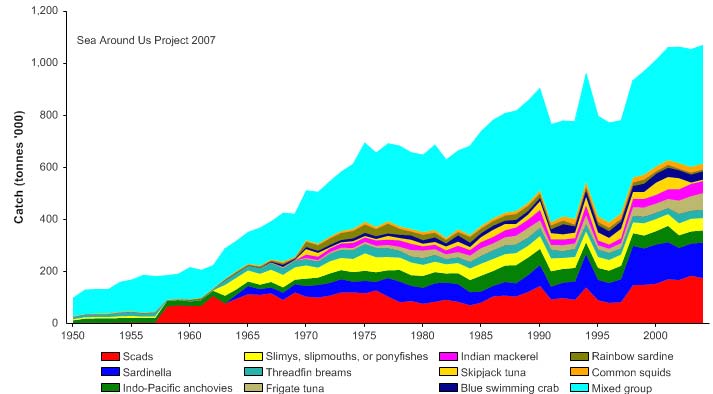

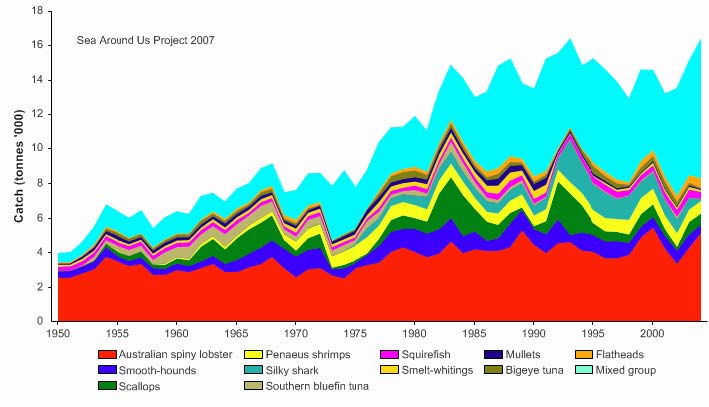

Figure VIII-12.4. Total reported landings in the Indonesian Sea LME by species (Sea Around Us 2007).

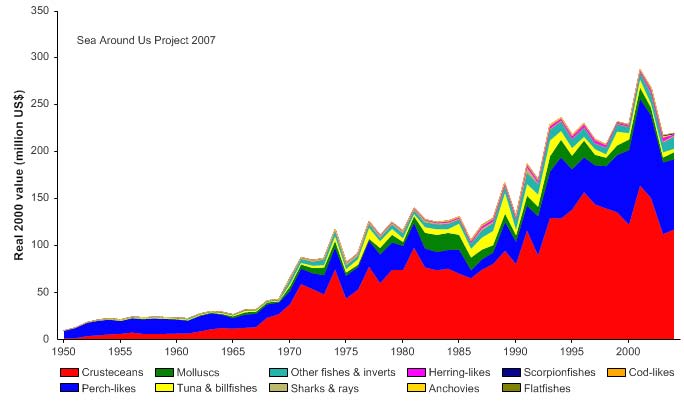

Figure VIII-12.5. Value of reported landings in the Indonesian Sea LME by commercial groups (Sea

Around Us 2007).

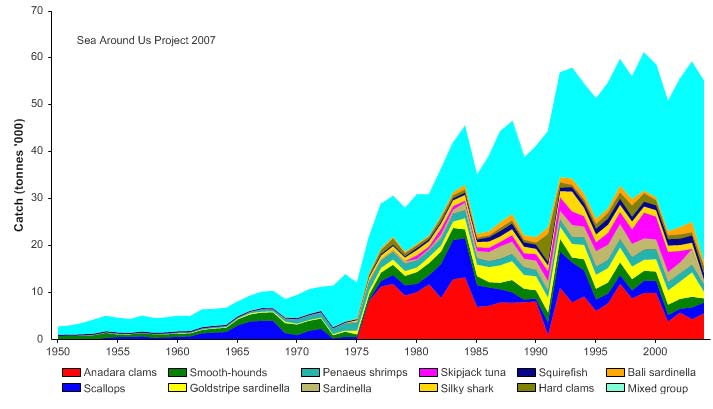

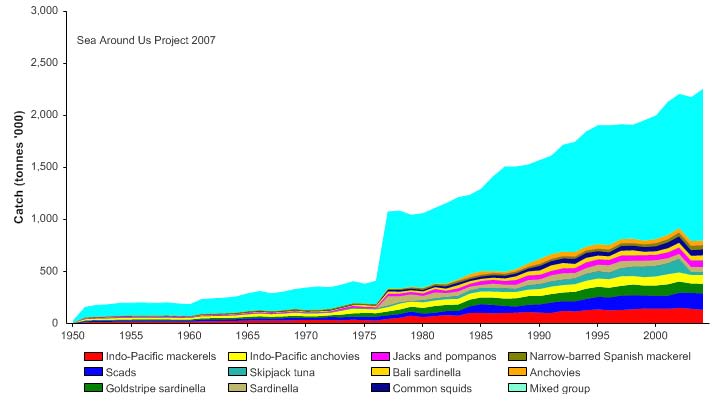

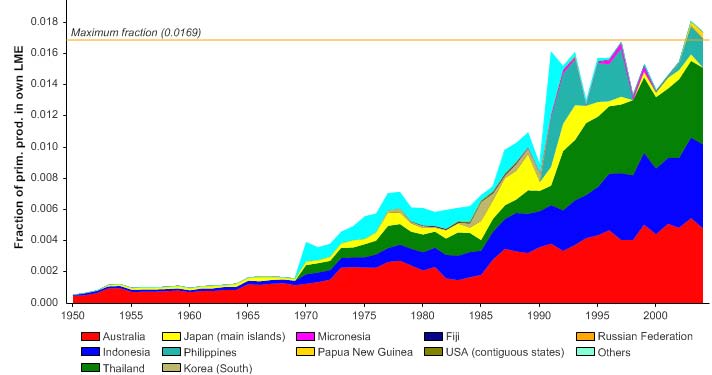

The primary production required (PPR; Pauly & Christensen 1995) to sustain the reported

landings in this LME is increasing, and is currently at 30% of the observed primary

production (Figure VIII-12.6). Indonesia and Thailand account for the largest shares of

the ecological footprint in the LME.

VIII East Asian Seas

273

Figure VIII-12.6. Primary production required to support reported landings (i.e., ecological footprint) as

fraction of the observed primary production in the Indonesian Sea LME (Sea Around Us 2007). The

`Maximum fraction' denotes the mean of the 5 highest values.

The mean trophic level of fisheries landings (i.e. the MTI; Pauly & Watson 2005) shows

an increase from the early 1980s, an indication of increased reported landings of high

trophic species such as tuna (Figure VIII-12.7 top). Such interpretation is also inferred by

the increase in the FiB index during the same period (Figure VIII-12.7 bottom) denoting a

steady expansion of the fisheries in the region. It must, however, be noted that these

indices may be skewed by the high level of unidentified fishes in the underlying landings

statistics.

Figure VIII-12.7. Mean trohpic level (i.e., Marine Trophic Index) (top) and Fishing-in-Balance Index

(bottom) in the Indonesian Sea LME (Sea Around Us 2007).

274

12. Indonesian Sea LME

The Stock-Catch Status Plots indicate that only a small number of the stocks in the LME

are either overexploited or have collapsed (Figure VIII-12.8, top) with 80% of the catch

from fully exploited stocks. Again, the high level of taxonomic aggregation in the

underlying landings statistics must be noted here.

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

0%

100

10%

90

20%

)

80

%

(

s

30%

u

70

at

st

40%

y

60

50%

cks b

o

50

f

st

60%

40

er o

b

70%

m

30

Nu

80%

20

90%

10

100%0

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

(n = 4260)

developing

fully exploited

over-exploited

collapsed

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

0%

100

10%

90

20%

80

)

%

30%

(

70

t

us

40%

t

a

60

s

k

50%

t

oc

50

s

60%

h by

40

t

c

a

70%

C

30

80%

20

90%

10

100%0

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

(n = 4260)

developing

fully exploited

over-exploited

collapsed

Figure VIII-12.8. Stock-Catch Status Plots for the Indonesian Sea LME, showing the proportion of

developing (green), fully exploited (yellow), overexploited (orange) and collapsed (purple) fisheries by

number of stocks (top) and by catch biomass (bottom) from 1950 to 2004. Note that (n), the number of

`stocks', i.e., individual landings time series, only include taxonomic entities at species, genus or family

level, i.e., higher and pooled groups have been excluded (see Pauly et al, this vol. for definitions).

Overexploitation is widespread in this LME, with many fish stocks exploited well beyond

the biological limits (Dwippongo et al. 1987), especially in the coastal zone, which is

exploited by 85% of Indonesian fishers (Hopley & Suharsono 2000). In addition, foreign

fleets continue to threaten Indonesia's fisheries, but again, accurate data on the extent,

the number of vessels and their mode of operations are inadequate (Kahn & Fauzi 2001,

Perrin et al. 2002). Coral reefs have been exploited for a long time, even in the more

remote areas of Eastern Indonesia (Palomares & Heymans 2006), and are now

considered to be under severe fishing pressure. Of particular concern is the live reef fish

trade in the Southeast Asian region, including in the Indonesian Sea LME. The use of

fish poisons to catch aquarium and food fishes is a serious problem in many Pacific

countries, but more so in Indonesia and the Philippines (Johannes & Riepen 1995). Use

of explosives is also of a grave concern throughout the region (see Pollution and

Ecosystem Health).

About 85% of aquarium fish traded internationally has been caught using cyanide,

targeting about 380 species from a few families such as Labridae, Pomacentridae,

Chaetodontidae, Pomacanthidae and Scaridae (Pratt et al. 2000). The live food fish

trade primarily targets groupers (especially Epinephelus spp. and Plectropomus

leopardus), Napolean wrasse (Cheilinus undulates) and barramundi cod (Cromileptes

altivelis) (Pet & Pet-Soede 1999). Because of their particular life-history attributes,

VIII East Asian Seas

275

groupers are highly susceptible to overexploitation and the targeting of their spawning

aggregations is a serious concern (Licuanan & Gomez 2000). In addition to taking adult

groupers for direct food consumption, the live reef fish food trade also involves capture of

wild fry and fingerlings supplying the grouper mariculture industry in Southeast Asia,

predominantly in Taiwan and Thailand (Sadovy & Pet 1998).

Over the past several centuries many of Indonesia's coral reefs have been heavily and

chronically overfished, with a major loss of productivity and cascading effects to other

components of the ecosystem. Overexploited stocks include many species of reef fish

such as groupers and threatened and endangered species such as sea turtle and

dugong. Benthic invertebrate species such as sea cucumbers, trochus and clams are

also overexploited, particularly around major coastal population centres. Overexploitation

of pelagic species such as shark, tuna and billfish is also evident. Catch per unit effort for

these fisheries has declined sharply, as has the size of fishes caught. There have also

been local extinctions and reductions in market availability (UNEP 2005). Of major

importance in this context has to be the realization that much of the true catch may not be

accounted for by official landings statistics, e.g., as shown for northern Sabah, Malaysia

(Teh et al. 2007). While these examples pertain to other LME areas, the same problem

applies to the Indonesian Sea LME.

The problem of excessive bycatch was assessed as severe (UNEP 2005). However,

there are little or no discards because virtually all of the bycatches, except those

produced by distant waters fleets and through the use of blast fishing and poisons, are

consumed. Sharks are also caught as bycatch in trawl as well as tuna long-line fisheries.

Perrin et al. (2002) noted that bycatch is a major threat to all marine mammals in

Indonesian waters, especially to cetaceans and dugong, and can lead to major losses in

biodiversity. Impacts of destructive fishing on fisheries resources and marine habitats are

increasingly becoming a problem, even within national parks (Pet-Soede & Erdmann

1999, UNEP 2005). There is a widespread habitat destruction of coral reefs from blast

and poison fishing including extensive damages to soft-bottom communities from trawling

(see Pollution and Ecosystem Health). The impacts of destructive fishing have major

transboundary implications, both in terms of target species population dynamics and in

terms of international market demand. Although these practices are illegal, regulations

are difficult to enforce, especially in remote areas.

III. Pollution and Ecosystem Health

Pollution: Urban expansion and industrialisation have resulted in coastal pollution from

domestic, agricultural and industrial wastes in the Indonesian Sea LME. Industrial forms

of water pollution are concentrated in the major urban centres, primarily the large cities of

northern Java. Oil spills, slowly degrading toxic wastes from chemical as well as non-

chemical industries, agricultural runoff and heavy metals threaten coastal waters. This

has resulted in severe pollution in some areas, such as Sunda (UNEP 2005). Because of

inadequate sewage disposal and treatment throughout the region, microbiological

pollution is severe, especially around urban centres. Eutrophication is also severe

around urban centres, particularly in areas with limited water circulation and where

sewage, agricultural and/or industrial discharges are present.

Siltation rates in this LME are among the highest in the world (Hodgson & Dixon 1992).

Pollution by suspended solids is severe in coastal waters, particularly in north Java and

Sumatra, with high turbidity over wide areas. Close to the major urban centres, the

affected zone extends up to 50 km offshore (Hopley & Suharsono 2000). This has mostly

resulted from extensive deforestation in many watersheds, compounded by high rates of

erosion as well as industrial mining. Solid waste is a severe problem locally, particularly

276

12. Indonesian Sea LME

in the Java Sea and around the cities, towns and villages where waste management is

inadequate.

Chemical pollution from agricultural pesticides and industries is severe in localised areas.

Mercury contamination from gold mining is widespread and is generating serious health

as well as environmental risks in Indonesia (Limbong et al. 2003). Studies conducted by

Kambey et al. (2001) showed that mercury levels in the tissue of fish near gold mines

were higher than that recommended by the WHO for total restriction on fish consumption.

The disposal of toxic materials from mines via submarine tailings placement is of special

relevance to Indonesian marine life (Perrin et al. 2002). In the next decade, the world's

biggest copper and gold mine situated in Indonesia will discharge more than one

billion tonnes of tailings over a wide area. This LME forms part of both the main and

Ultra Large Crude Carrier oil tanker routes between the Indian and Pacific Oceans.

Furthermore, there is regular discharge of ship ballast waters in this LME. In addition to

spills, chronic pollution from oil production facilities and refineries is evident in some

areas such as Sunda (Hopley & Suharsono 2000).

Habitat and community modification: The Indonesian Sea LME has a large diversity

of coastal habitats, including extensive mangroves, coral reefs and seagrass beds. The

area of Indonesia's mangroves has been estimated to range from 24,000 km2 (Tomascik

et al. 1997) to 42,500 km2 (Wilkinson et al. 1994), representing over two thirds of the area

of mangroves in Southeast Asia. Seagrass beds are even more extensive (30,000 km2

according to Tomascik et al. 1997). Estimated coral reef areas range from 50,000 to

90,000 km2 (Spalding et al. 2001) to 85,707 km2 (Tomascik et al. 1997). Overall, habitat

and community modification was assessed as severe in the Sunda and Wallacea sub-

regions, and moderate in the Sahul (UNEP 2005). Extensive cutting for timber,

conversion for aquaculture and other forms of coastal development, heavy siltation,

pollution and destructive fishing have caused major fragmentation and reduction in

mangrove area. For example, more than 30% of the mangroves in north Java

disappeared during the last 150 years. About 80% of the reefs are at extremely high risk

of further damage from human activities (Bryant et al. 1998, Burke et al. 2002). In the

last 50 years, the proportion of degraded reefs has increased from 10% to 50% (Hopley

& Suharsono 2000). In central Indonesia, 40% of coral reefs are currently classified as

being in poor condition and only 6% in excellent condition (Hopley & Suharsono 2000).

Damage to coral reefs from the use of explosives and poisons is catastrophic. Johannes

& Riepen (1995) forecast the collapse of the live fish industry in Indonesia and this does

appear to be happening in many areas (Bentley 1999). On regularly bombed reefs, coral

mortality can range from 50% to 80%, even in National Parks (Pet-Soede & Erdmann

1999). The effects of cyanide fishing are multiple. In addition to being broken to retrieve

stunned fish, corals are also bleached by the cyanide (Johannes & Riepen 1995) and

recovery may take up to half a century (Cesar 1996). As reefs become damaged and

unproductive, they are abandoned by fishers who move to new reefs to continue this

pattern of destruction. Indonesian coral reefs are also impacted by pollution. Reefs

subject to land-based pollution (sewage, sedimentation and/or industrial pollution) show

30% to 50% reduced diversity at 3 m and 40% to 60% reduced diversity at 10 m depth

relative to unpolluted reefs (Edinger et al. 1998). This implies a dramatic, rapid decrease

in Indonesian reef-based fisheries resources. Mining and quarrying of coral is another

significant threat to the LME's coral reefs and is widespread at both subsistence and

commercial levels, despite being banned by various provincial governments (Hopley &

Suharsono 2000). Indonesia's reefs have also been impacted by the 1997-1998 El Niño

event that triggered widespread bleaching, with western and west-central Indonesia most

affected.

VIII East Asian Seas

277

Modification of coastal habitats has resulted in major changes in population structure as

well as functional group composition, notably on coral reefs, and massive changes in

ecosystem services of coral reefs and mangroves (DeVantier et al. 1999). For instance,

the important nursery and feeding ground role of mangroves as well as seagrass beds for

fish and marine mammals have been lost over extensive areas. Habitat modification and

loss have also contributed to the decline in populations of marine mammals such as

dugong (Marsh et al. 2001). Habitat degradation has significant transboundary

implications in terms of reduced fish recruitment and impacts on migratory species as

well as on biodiversity throughout the region.

Unless there are improvements in regulation and expansion and improved management

of protected areas, the health of the LME is likely to deteriorate further primarily because

of the predicted increases in fisheries, deforestation, agriculture, aquaculture, mining and

industrialisation as well as a major increase in population without the required

improvements in infrastructure.

IV. Socioeconomic Conditions

The population of Indonesia as a whole is about 222 million in 2006 (Indonesian Central

Statistics Bureau, 2006), with some 200 million people living in the LME region. The total

population is expected to double to 400 million by 2035. Subsistence farming and fishing

are the major activities of large numbers of people outside the main urban centres. Most

of the approximately 6,000 coastal communities are directly dependent on the sea as

their primary source of food and income (Dahuri & Dutton 2000). Coastal and marine

industries, including oil and gas production, transportation, fisheries and tourism, account

for 25% of the nation's GDP, in addition to employing a significant percentage of

Indonesia's workforce (Dahuri & Dutton 2000).

The socioeconomic impacts of overexploitation of fisheries include reduced economic

returns as well as loss of employment of fisher families, conflicts between user groups,

loss of food sources for human and animals and injury or loss of human life from diving

accidents (Johannes & Djohani 1997). Losses in revenue to the Indonesian economy as

a result of poaching by foreign boats may top four billion US dollars (Perrin et al. 2002).

The reefs of Indonesia provided annual economic benefits of US$1.6 billion per year in

2002, based on their value in food security, employment, tourism, pharmaceutical

research and shoreline protection. However, over the next 20 years, human impacts,

notably overfishing, destructive fishing and sedimentation, could cost Indonesia some

US$2.6 billion (Burke et al. 2002). The cost from fish bombing alone over the next

20 years will be at least US$570 million (Cesar 1996, Pet-Soede et al.2000), while the

economic loss from cyanide fishing is estimated to be US$46 million annually (Hopley &

Suharsono 2000).

Pollution has severe socioeconomic impacts, especially around major urban centres and

coastal villages (UNEP 2005). Water pollution is found in virtually all populated and/or

highly industrialised areas of Indonesia and is known to cause massive fish kills, harvest

failure from aquaculture and threats to human health (Dahuri 1999, Hopley & Suharsono

2000). Habitat and community modification impact local fisheries, cause increased

beach erosion and have adverse consequences for tourism, due to loss of aesthetic

value and the cost of mitigation measures.

V. Governance

The Indonesian Sea LME is governed by Indonesia and the recently independent state of

East Timor. Indonesia uses the `Archipelagic Doctrine' to define its territorial waters;

most of this LME is within archipelagic waters. Marine governance in Indonesia is very

complex as there are three levels of government district, provincial and national with

278

12. Indonesian Sea LME

marine jurisdiction. The government has sponsored the Coral Reef Rehabilitation and

Management Programme, a 15-year initiative aimed at strengthening the management of

the country's coastal resources while considering the needs of coastal communities.

Since the 1980s, there have been major advances in the regional capacity for

development of policy and legislation based on sound science. For example, a `critical

mass' of regional expertise now resides in government, inter-governmental agencies,

academic institutions and NGOs. There is also an extensive literature on the marine

environment in Indonesia that is published locally in the Indonesian language.

An urgent priority regarding the management of the country's coastal and marine living

resources is the development of a functional, integrated network of MPAs (UNEP 2005).

This must be accompanied by the establishment of substantial no-take zones as well as

the development of appropriate policy and legal frameworks. The National Parks Service

manages six National Marine Parks and several other Terrestrial National Parks with

marine areas. These parks cover a total sea space of 41,129 km2, equivalent to 1.3% of

the country's territorial and archipelagic seas (Putra & Mulyana 2003). Indonesia is

developing co-management strategies for improving the management of these parks.

The LME falls within the UNEP-administered East Asian Regional Seas Programme (see

Gulf of Thailand LME). Indonesia participated in the GEF-supported project `Regional

Programme for Marine Pollution Prevention and Management in the East Asian Seas

region' from 1994 to 1999. This country is also participating in the GEF-supported

PEMSEA (see Gulf of Thailand LME) and Bay of Bengal LME projects (see Bay of

Bengal LME and www.fao.org/).

References

Belkin, I.M. (2008) Rapid warming of Large Marine Ecosystems, Progress in Oceanography, in

press.

Belkin, I. M. and Cornillon, P.C. (2003) SST fronts of the Pacific coastal and marginal seas. Pacific

Oceanography 1(2): 90-113.

Belkin, I.M., Cornillon, P.C. and Sherman, K. (2008). Fronts in Large Marine Ecosystems of the

world's oceans. Progress in Oceanography, in press.

Bentley, N. (1999). Fishing for Solutions: Can the Live Trade in Wild Groupers and Wrasses From

Southeast Asia be Managed? A report for TRAFFIC Southeast Asia.

Bryant, D., Burke, L., McManus, J. and Spalding, M. (1998). Reefs at Risk. A Map Based Indicator

of Threats to the World's Coral Reefs. WRI, ICLARM, WCMC and UNEP, Washington D.C.,

U.S.

Burke, L, Selig, E. and Spalding, M. (2002). Reefs at Risk in Southeast Asia. World Resources

Institute.

Cesar, H. (1996). Economic Analysis of Indonesia Coral Reefs. World Bank, Washington D.C., U.S.

Cesar, H.S.J., Warren, K.A., Sadovy, Y., Lau, P., Meijer, S. and van Ierland, E. (2000). Marine

market transformation of the live reef fish food trade in Southeast Asia, in: Cesar, H.S.J. (ed),

Collected Essays on the Economics of Coral Reefs. CORDIO, Department of Biology and

Environmental Sciences, Kalmar University, Sweden.

Chou, L.M. (1997). Southeast Asia as the global center of marine biodiversity. Tropical Coasts 4: 4-

8.

Dahuri, R. (1999). Coastal zone management in Indonesia: Issues and approaches, p 60-72 in:

Rais, J., Dutton, I.M., Pantimena, L., Plouffe, J. and Dahuri, R. (eds), Integrated Coastal and

Marine Resource Management Proceedings International Symposium, Malang, 1998.

Dahuri, R. and Dutton, I. (2000). Integrated Coastal and Marine Management Enters a New Era in

Indonesia. Integrated Coastal Zone Management 1:11-16.

Dalzell, P. and Pauly, D. (1989). Assessment of the fish resources of Southeast Asia, with

emphasis on the Banda and Arafura Seas. Netherlands Journal of Sea Research 24(4): 641-

650.

VIII East Asian Seas

279

DeVantier, L.M., Suharsono, Budiyanto, A., Tuti, J., Imanto, P. and Ledesma, R. (1999). Status of

the Coral Communities of Pulau Seribu, Java Sea, Indonesia, p 1-24 in: Soemodihardjo, S.

(ed), Contending with Global Change Study 10. Proceedings Coral Reef Evaluation Workshop

Pulau Seribu, Jakarta, Indonesia. UNESCO/Indonesian Institute of Sciences.

Dwiponggo, A., Hariati, T., Banon, S., Palomares, M.L. and Pauly, D. (1987). Growth, mortality and

recruitment of commercially important fishes and penaeid shrimps in Indonesian waters.

ICLARM Technical Reports. 17, 91 p.

Edinger, E.N., Jompa, J., Limmon, G.V., Widjatmoko, W. and Risk, M.J. (1998). Reef degradation

and coral biodiversity in Indonesia: Land-based pollution, destructive fishing practices and

changes over time. Marine Pollution Bulletin 36 (8):617-630.

FAO (2005). Fishery Country Profiles Indonesia. www.fao.org/countryprofiles/index

Feng, M., Meyers, G., Pearce, A. and Wijffels, S. (2003) Annual and interannual variations of the

Leeuwin Current at 32°S, Journal of Geophysical Research, 108(11), 3355,

doi:10.1029/2002JC001763.

Hodgson, G. and Dixon J.A. (1992). Sedimentation damage to marine resources: Environmental

and economic analysis, in: Marsh J.B. (ed), Resources and Environment in Asia's Marine

Sector. Taylor and Francis, Washington, U.S.

Hopley, D. and Suharsono (2000). The Status of Coral Reefs in Eastern Indonesia. Australian

Institute of Marine Science, Townsville, Australia.

Indonesian Central Statistics Bureau (1 September 2006). "Tingkat Kemiskinan di Indonesia

Tahun 20052006" (in Indonesian). Press release.

Johannes, R.E. and Djohani, R. (1997). Reducing the incidence of the bends in Indonesian fishing

villages: Education may not be enough. SPC Live Reef Fish Bulletin 3.

Johannes, R.E. and Riepen, M. (1995). Environmental, Economic and Social Implications of the

Live Reef Fish Trade in Asia and the Western Pacific. Report for the Nature Conservancy and

South Pacific Forum Fisheries Agency.

Kahn, B. and Fauzi, A. (2001). Fisheries in the Sulu Sulawesi Seas Indonesian Country Report.

Assessment of the State of Biophysical, Socio-economic and Institutional Aspects of Coastal

and Pelagic Fisheries in the Indonesian Part of the Sulu-Sulawesi Seas. WWF Sulu-Sulawesi

Marine Eco-region Fisheries Project.

Kahn, B. and Pet, J. (2003). Long-term Visual and Acoustic Cetacean Surveys in Komodo National

Park, Indonesia 1999-2001: Management Implications for Large Migratory Marine Life, in:

Proceedings and Publications of the World Congress on Aquatic Protected Areas 2002.

Australian Society for Fish Biology.

Kambey, J.L., Farrell, A.P. and Bendell-Young, L.I. (2001). Influence of illegal gold mining on

mercury levels in fish of north Sulawesi's Minahasa Peninsula, (Indonesia). Environmental

Pollution (114)3: 299-302.

Licuanan, W.Y. and Gomez, E.D. (2000). Philippine Coral Reefs and Associated Fisheries Status

and Recommendations to Improve their Management. Global Coral Reef Monitoring Network.

Institute of Marine Science, Townsville, Australia.

Limbong, D., Kumampung, J., Rimper, J., Arai, T. and Miyazaki, N. (2003). Emissions and

environmental implications of mercury from artisanal gold mining in North Sulawesi, Indonesia.

The Science of the Total Environment (302)1-3:227-236.

Marsh, H., Penrose, H., Eros, C. and Hugues, J. (2001). Dugong Status Report and Action Plans

for Countries and Territories. Early Warning and Assessment Report Series.

UNEP/DEWA/RS.02-1.

Morgan, J. (1989). Large Marine Ecosystems in the Pacific Ocean. p 377-394 in: Sherman, K.,

Alexander, L.M. and Gold, B.D. (eds). Biomass Yields and Geography of Large Marine

Ecosystems. AAAS Selected Symposium 111. Westview Press. Boulder, U.S.

Palomares, M.L.D. and Heymans, J.J. (2006). Historical Ecology of the Raja Ampat Archipelago,

Papua Province, Indonesia, Fisheries Centre Research Report 14(7), 64 pp

Pauly, D. and Christensen, V. (1995). Primary production required to sustain global fisheries.

Nature 374: 255-257.

Pauly, D. and Martosubroto, P. (eds). (1996). Baseline studies in biodiversity: the fish resources of

western Indonesia. ICLARM Studies and Reviews 23. 390 p.

Pauly, D. and Watson, R. (2005). Background and interpretation of the `Marine Trophic Index' as a

measure of biodiversity. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society: Biological Sciences

360: 415-423.

Perrin, W.F., Reeves, R.R., Dolar, M.L.L., Jefferson, T.A., Marsh, H., Wang J.Y. and Estacion, J.,

eds. (2002). Report of the Second Workshop on the Biology and Conservation of small

280

12. Indonesian Sea LME

Cetaceans and Dugongs of SE Asia. Silliman University, Dumaguete City, Philippines 24-26

July, 2002.

Pet, J. and Pet-Soede, L. (1999). A note on cyanide fishing in Indonesia. SPC Live Reef Fish

Bulletin 5:21-22.

Pet-Soede, L. and Erdmann, M. (1999). An overview and comparison of destructive fishing

practices in Indonesia. SPC Live Reef Fish Bulletin 4:28-36.

Pet-Soede, L., Cesar, H. and Pet, J. (2000) Blasting away: The economics of blast fishing on

Indonesian coral reefs, p 77-84 in: Cesar, H. (ed), Collected Essays on the Economics of Coral

Reefs. CORDIO, Kalmar University, Kalmar, Sweden.

Pitcher, T.J., Ainsworth, C.H. and Bailey, M. (eds). (2007). Ecological and economic analyses of

marine ecosystems In the Bird's Head Seascape, Papua, Indonesia. Fisheries Centre

Research Report 15(5) 184 pp.

Pratt, V. R., Mamauag, S., Alban, J., Parfan, E. and Donaldson, T. (2000). Status Report on the

Philippine Live Reef Fish Trade and Strategies to Combat its Destructive Fishing Practices.

Workshop on the Status of Philippine Reefs, 24 January 2000, Marine Science Institute,

University of the Philippines.

Putra, S. and Mulyana, Y. (2003). Linking Coral Reef Conservation into Integrated Coastal

Management as Part of Indonesia Sea Large Marine Ecosystem. An Experience of Coral Reef

Rehabilitation and Management Program, COREMAP Phase II.

Roberts, C.M., Colin, J.M., Veron, J.E.N., Hawkins, J.P., Allen, G.R., McAllister, D.E., Mittermeier,

C.G., Schueller, F.W., Spalding, M., Wells, F., Vynne, C. and Werner, T.B. (2002). Marine

biodiversity hotspots and conservation priorities for tropical reefs. Science 295:1280-1284.

Sadovy, Y. and Pet, J. (1998). Wild collection of juveniles for grouper mariculture: Just another

capture fishery? SPC Live Reef Fish Information Bulletin 4:36-39.

Sea Around Us (2007). A Global Database on Marine Fisheries and Ecosystems. Fisheries Centre,

University British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada. www.seaaroundus.org/lme/

SummaryInfo.aspx?LME=38

Spalding, M., Ravilious, C. and Green, E.P. (2001). World Atlas of Coral Reefs. United Nations

Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre, Cambridge, U.K.

Teh, L., Zeller, D., Cabanban, A., Teh, L. and Sumaila, U.R. (2007). Seasonality and historic trends

in the reef fisheries of Pulau Banggi, Sabah, Malaysia. Coral Reefs 26: 251-263.

Tomascik, T., Mah, A.J., Nontji, A. and Moosa, M.K. (1997). The Ecology of the Indonesian Seas.

Periplus 2 Volumes.

UN (2002). Johannesburg Summit (2002) Indonesia Country Profile. United Nations Department of

Economic and Social Affairs. Division for Sustainable Development. www.un.org/esa/

agenda21/ natlinfo/wssd/indonesia.pdf

UNEP (2005). DeVantier, L., Wilkinson, C., Lawrence, D. and Souter, D., eds. Indonesian Seas,

GIWA Regional Assessment 57. University of Kalmar, Kalmar, Sweden. www.giwa.net/

publications/r57.phtml

Vantier, L.,. Wilkinson, C., Lawrence, D. and Souter, D., editors (2005) Indonesian Seas, GIWA

Regional assessment 57, University of Kalmar on behalf of United Nations Environment

Programme, Kalmar, Sweden, 140 pp., xv.

Veron, J.E.N. (2000). Corals of the World. Australian Institute of Marine Science, Townsville,

Australia.

Wilkinson, C., Gomez, E. and Sudara, S. (1994). Status of coral reefs in the ASEAN region, p 8-12

in: Wilkinson, C.R. (ed), Living Coastal Resources of Southeast Asia: Status and Management.

Report of the Consultative Forum Third ASEAN-Australia Symposium on Living Coastal

Resources, May 1994, Thailand. Australian Agency for International Development.