VII South Asian Seas

236

10. Bay of Bengal LME

VII South Asian Seas

237

VII-10 Bay of Bengal LME

S. Heileman, G. Bianchi and S. Funge-Smith

The Bay of Bengal LME is a relatively shallow embayment in the northeastern Indian

Ocean encompassing the Bay of Bengal, Andaman Sea and Straits of Malacca. It is

bordered by Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Maldives, Myanmar, Sri Lanka and

Thailand. The LME covers an area of about 3,660,130 km2, of which 0.49% is protected,

and contains 3.63% and 0.12% of the world's coral reefs and sea mounts, respectively

(Sea Around Us 2007). It is influenced by the second largest hydrologic region in the

world, the Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna (GBM) Basin, which covers nearly 1.75 million

km2 spread over five countries (Bangladesh, Bhutan, China, India and Nepal).

Located in the tropical monsoon belt, the LME is strongly affected by monsoons, storm

surges, cyclones and tsunamis. During the northeast monsoon, an anticyclonic gyre

forms in the Bay and reverses during the southwest monsoon (Wyrtki 1973, Longhurst

1998). The LME shows considerable spatial and temporal variability because of

seasonal river discharges, particularly the surface water along the coast. Monsoon rain

and flood waters produce a warm, low-salinity, nutrient and oxygen-rich layer to a depth

of 100 - 150 m; this layer floats above a deeper, more saline, cooler layer that does not

change significantly with the monsoons (Dwivedi & Choubey 1998). Large quantities of

fresh water and sediment discharged into the LME have also contributed to the formation

of the largest mangrove system in the world, the Sunderbans, covering an area of 12,000

km2 and shared by India and Bangladesh. Books and book chapters, reports and articles

pertaining to this LME include Dwivedi (1993), Aziz et al. (1998), Desai & Bhargava

(1998), Dwivedi & Choubey (1998), Ittekot et al. (2003), Silvestre and Pauly (1997),

Silvestre et al. (2003) and UNEP (2006).

I. Productivity

The Bay of Bengal LME can be considered a Class I, highly productive ecosystem (>300

gCm-2yr-1).While large nutrient input from river run-off supports high primary production in

coastal waters, the central parts of the bay are less productive because of the absence of

large-scale mixing or upwelling (Dwivedi 1993). The presence of different water masses

in coastal areas has produced sub-systems along the coast that differ in their

environmental characteristics and community composition. These sub-systems are

described by Dwivedi (1993). Secondary production is highest in the post-monsoon

period (October to January) and lowest during the monsoon period from June to

September (Desai & Bhargava 1998). Zooplankton biomass is low near the shore but

increases towards the EEZ boundary (Desai & Bhargava 1998). Further information on

biological production and fishery potential in India's EEZ is given in Desai & Bhargava

(1998). Wetlands, marshes, mangroves, backwaters and coastal lakes play an important

role in overall productivity (Dwivedi 1993). The coastal forested areas of Sri Lanka and

Malaysia are biodiversity hotspots, with a large number of threatened endemic plants and

animals (Aziz et al. 1998).

Oceanic fronts (after Belkin et al. (2008)): The principal front in the Bay of Bengal is

maintained by the huge fresh outflow from the Ganges-Brahmaputra estuary (Figure VII-

10.1). This is a year-round front, whose cross-frontal TS-ranges vary seasonally.

Another estuarine front is maintained by the Irravadi River outflow in the northern

238

10. Bay of Bengal LME

Andaman Sea. In both cases the location of estuarine fronts coincides with the shelf

break. A front east of Sri Lanka has been recently described from satellite data (Belkin et

al. 2005); its origin is related to the wind-induced upwelling off the east coast of Sri

Lanka. A bathymetrically-trapped front exists along a sill at the northern entrance to the

Palk Strait between India and Sri Lanka.

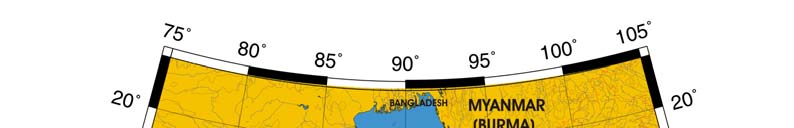

Figure VII-10.1. Fronts of the Bay of Bengal LME. ECF, East Ceylon Front; GBEF, Ganges-Brahmaputra

Estuarine Front; IEF, Irravadi Estuarine Front; MSSF, Myanmar Shelf-Slope Front; PSF, Palk Strait

Front; TSSF, Thailand Shelf-Slope Front. Red dashed lines, most probable locations of fronts. Yellow

line, LME boundary. Belkin et al. (2008).

Bay of Bengal SST (after Belkin 2008)

Linear SST trend since 1957: 0.50°C.

Linear SST trend since 1982: 0.24°C.

The steady, slow warming of the Bay of Bengal was modulated by quasi-regular

interannual variability with an average magnitude of <0.5°C. The dominant mode of

variability has a scale of 3 to 5 years, whereas decadal variability is not distinct. The all-

time maximum of 1998 occurred simultaneously with other Indian Ocean LMEs and could

be linked to El Niņo 1997-1998. It is more difficult to correlate other extrema with similar

events elsewhere since the Bay of Bengal LME has no immediate LME neighbors. For

example, the all-time minimum of 1961 has no contemporary counterparts elsewhere in

the Indian Ocean and therefore must be explained locally.

The temperature history of the Bay of Bengal is strongly coupled with its salinity regime,

since the upper layer stability here is largely dependent on the freshwater discharge of

VII South Asian Seas

239

three great rivers, the Ganges, Brahmaputra and Irrawaddy. The river discharge is

seasonal to the extreme, governed by the Indian monsoon, which brings heavy

precipitation to the Indian subcontinent (e.g. Salahuddin et al. 2006). Therefore

interannual variability of the Indian monsoon largely determines the river discharge,

hence salinity regime and eventually SST variability, in the Bay of Bengal. The Bay of

Bengal is not spatially uniform, notwithstanding the existence of a quasi-stationary gyre

circulation encompassing the Bay. The horizontal non-uniformity is caused by the

perennially low salinity in the northern Bay owing to the Ganges-Brahmaputra river

discharge. As a result, the upper mixed layer in the northern Bay is much shallower than

in the south. The boundary between these two regimes runs zonally along ~15°N

(Narvekar and Kumar 2006). This separation of the Bay of Bengal into two parts,

northern and southern, with different SST regimes, must have important ecosystem

ramifications.

Figure VII-10.2. Bay of Bengal LME annual mean SST (left) and SST anomalies (right), 1957-2006, based

on Hadley climatology. After Belkin (2008).

Bay of Bengal LME trends in Chlorophyll and Primary Productivity: The Bay of

Bengal LME can be considered a Class I, highly productive ecosystem (>300 gCm-2yr-1).

Figure VII-10-3. Bay of Bengal LME annual trends in chlorophyll a (left) and primary productivity (right),

1998-2006. Values are colour coded to the right hand ordinate. Figure courtesy of J. O'Reilly and K.

Hyde. Sources discussed p. 15 this volume.

240

10. Bay of Bengal LME

II. Fish and Fisheries

Fisheries of the Bay of Bengal LME target a wide range of species, including sardine,

anchovy, scad, shad, mackerel, snapper, emperor, grouper, pike-eel, tuna, shark,

ornamental reef fish, shrimp, bivalve shellfish and seaweed (Preston 2004). Catches

from commercial and subsistence fishing equal or exceed those from industrial fisheries.

In Bangladesh, for example, less than 5% of marine landings are estimated to come from

industrial fishing, with the rest coming from the artisanal sector (Hossain 2003;

Chuenpagdee et al. 2006). During the last decade, some countries have developed

offshore fishing for tuna, notably Indonesia, Thailand and Sri Lanka and while most of the

tuna catch comes from coastal fisheries, offshore fisheries provide the majority of export-

grade tuna (Preston 2004). Crustacean catch is slightly less than 15% of the total catch,

with penaeid shrimp accounting for about 40% of the total crustacean catch and being

the major export earner (FAO 2003). Most of the countries are also major producers of

farmed shrimps, with Thailand and Indonesia among the world's top producers (FAO

2005a).

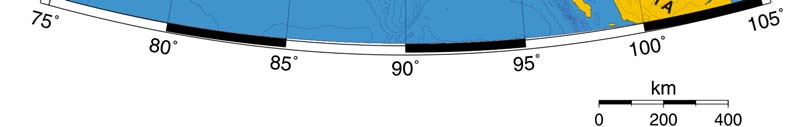

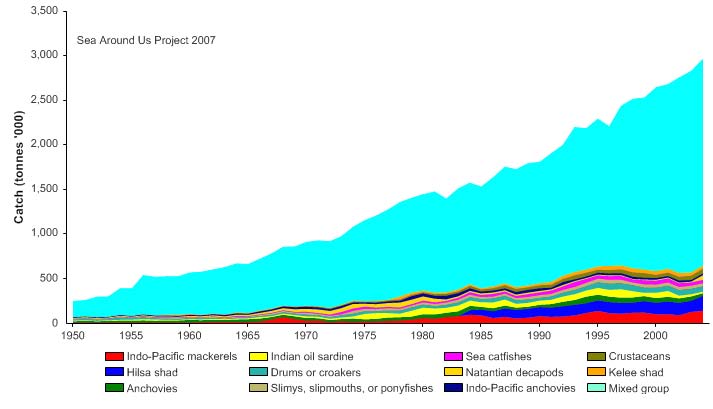

Statistics on fisheries catch and effort are highly fragmented, especially in the artisanal

and subsistence fisheries, two very important sectors in the region (Preston 2004). There

are also indications that a continuous increase in the reported landings, particularly of

unidentified fishes (included in `mixed group' in Figure VII-10.4), may be a product of

deficiencies in the underlying statistics, rather than improvements in the performance of

the fisheries in the LME (Figure VII-10.4. If so, such deficiencies would have serious

implications on the effectiveness of the fisheries management regimes in the LME and

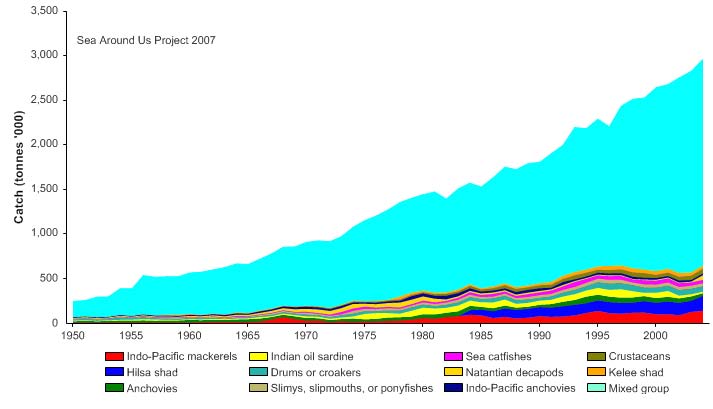

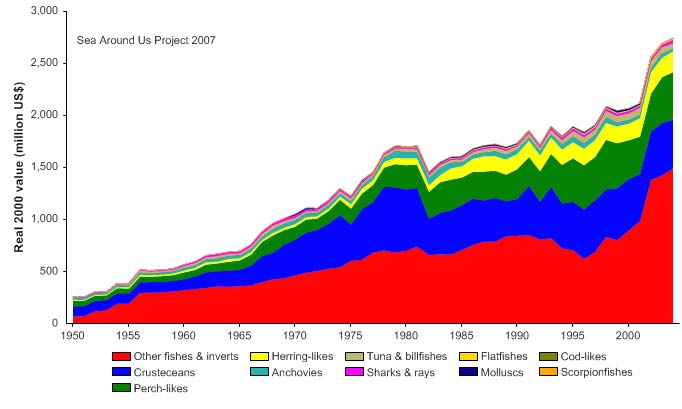

would also affect the value of the reported landings, which, according to Figure VII-10.5,

rose to about over 2.7 billion US$ (in 2000 real US$) in 2004.

Figure VII-10.4. Total reported landings in the Bay of Bengal LME by species (Sea Around Us 2007).

VII South Asian Seas

241

Figure VII-10.5. Value of reported landings in the Bay of Bengal LME by commercial groups (Sea

Around Us 2007).

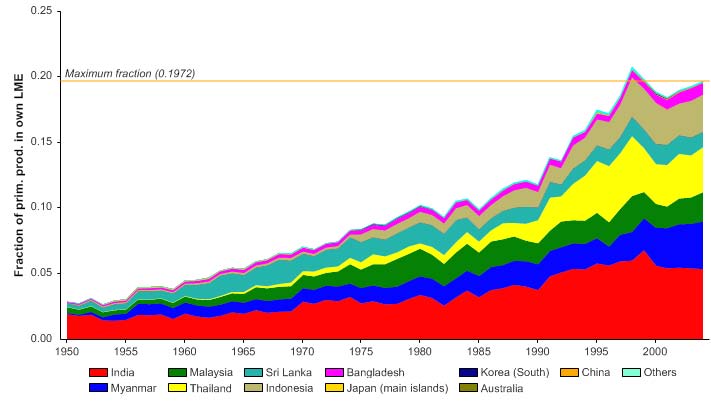

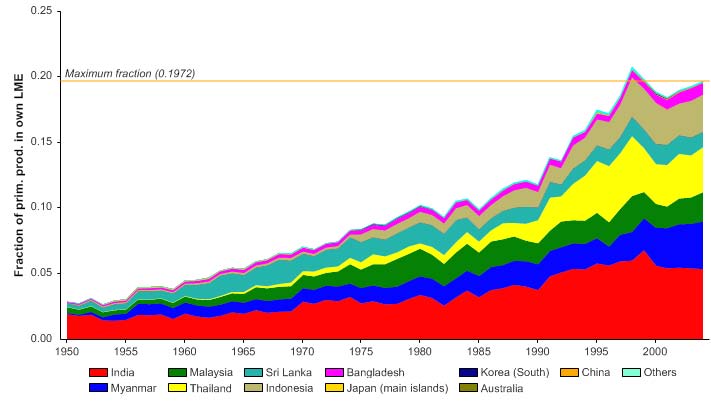

The primary production required (PPR; Pauly & Christensen 1995) to sustain the reported

landings in this LME has increased over the years, and reached 20% of the observed

primary production in 1998 (Figure VII-10.6). Such high PPR is another indication that

the reported landings for this LME may be exaggerated. Bordering countries, namely

India, Myanmar, Malaysia and Thailand account for the largest shares of the ecological

footprint in the region.

Figure VII-10.6. Primary production required to support reported landings (i.e., ecological footprint) as

fraction of the observed primary production in the Bay of Bengal LME (Sea Around Us 2007). The

`Maximum fraction' denotes the mean of the 5 highest values.

The mean trophic level of the reported landings (i.e., the MTI; Pauly & Watson 2005)

show a steady decline over the past 50 years (Figure VII-10.7 top) while the FiB index

increased over the same period (Figure VII-10.7 bottom). Due to the nature of the

242

10. Bay of Bengal LME

underlying landings statistics, it is not possible to draw any reasonable conclusions from

these indices, however, a detailed analysis of the MTI and FiB index of Western India,

based on independently validated catch data from the States and Union Territories

(Bhathal 2005), found that a `fishing down' of the food webs (Pauly et al. 1998) is indeed

occurring in the region (Bhatal and Pauly, in press).

Figure VII-10.7. Mean trophic level (i.e., Marine Trophic Index) (top) and Fishing-in-Balance Index

(bottom) in the Bay of Bengal LME (Sea Around Us 2007).

The Stock-Catch Status Plots indicate that the number of collapsed and overexploited

stocks in the LME is low but on the rise (Figure VII-10.8, top), with over 80% of the

reported landings from fully exploited stocks (Figure VII-10.8, bottom). Again, the

questionable quality of the underlying landings statistics must be noted.

As should be expected, given the amount of fishing pressure present in this LME (Gelchu

and Pauly 2007), both the catch per unit effort and the average size and weight of the

catches have been on a decline (Preston 2004). Excess fishing capacity in many of the

region's coastal fisheries is reducing the productivity of the local stocks and threatening

their long-term sustainability (Preston 2004). In fact, intensive fishing has been identified

as the primary force driving biomass changes in the LME (Sherman 2003). These

changes are well illustrated on the southeast coast of India, where high density of coastal

fishing craft is inducing changes in the ecosystem, as evident in the trophic level declines

(Bhathal 2005, Vivekanandan et al. 2005). India, for example, is experiencing serial

depletions of coastal fish stocks, where the increase in its fisheries catch is maintained

only by the expansion of its range. Indeed, there are now signs that this expansion

phase has reached its limit, with stagnation of its catch (Bhathal 2005). Other indicators

of unsustainable resource use are described in the Bay of Bengal LME national reports

for a wide range of resources including finfish, shark, crustacean, mollusc and

echinoderm (Preston 2004).

Destructive fishing practices of various kinds are commonplace in the LME. Continued

growth of commercial fishing effort, especially by trawlers, is increasing the fishing

mortality of non-reef species. In the southern Indian maritime states of Tamil Nadu and

VII South Asian Seas

243

Andhra Pradesh, the decline in the catch has been associated with an increase in

unregulated trawling for shrimps.

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

0%

100

10%

90

20%

)

80

%

(

30%

t

us

70

t

a

s

40%

60

by

s

k

50%

50

t

oc

s

60%

40

r

of

e

b

70%

m

30

u

N

80%

20

90%

10

100%0

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

(n = 6022)

developing

fully exploited

over-exploited

collapsed

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

0%

100

10%

90

20%

80

)

%

30%

(

70

s

u

at

40%

60

ck st

50%

o

50

st

y

60%

b

h

40

t

c

70%

Ca

30

80%

20

90%

10

100%0

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

(n = 6022)

developing

fully exploited

over-exploited

collapsed

Figure VII-10.8. Stock-Catch Status Plots for the Bay of Bengal LME, showing the proportion of

developing (green), fully exploited (yellow), overexploited (orange) and collapsed (purple) fisheries by

number of stocks (top) and by catch biomass (bottom) from 1950 to 2004. Note that (n), the number of

`stocks', i.e., individual landings time series, only include taxonomic entities at species, genus or family

level, i.e., higher and pooled groups have been excluded (see Pauly et al, this vol. for definitions).

Excessive bycatch is of concern, although all captured fish are generally used either for

human consumption or as aquaculture feed. The accidental capture of endangered fish

species, dolphin and sea turtle is also of concern. The large-scale collection of fish and

shrimp larvae for aquaculture using destructive methods may be seriously damaging wild

stocks of both shrimp and other species (FAO 2005a), which typically make up more than

99% of the catch (Preston 2004). Dynamite fishing, often for small pelagic species, and

the use of cyanide and other toxins for capturing ornamental and live food fish, are both

increasing, and may lead to long-term damage, not only to the target resources, but to

their associated habitats (FAO 2002, Preston 2004).

Expanding human populations of the Bay of Bengal LME region has created an

increasing demand for fish as a source of animal protein. Furthermore, trade

liberalisation and rising demand for export have contributed to the rapid development of

marine fisheries and aquaculture in recent years. The steady decline in the abundance

of the fisheries resources is expected to continue, despite a number of regulatory

244

10. Bay of Bengal LME

measures in force in some of the bordering countries. Bilateral or multilateral

collaboration would greatly assist the efforts of individual countries in addressing the

problem of overexploitation, given the transboundary nature of most of the fish stocks.

III. Pollution and Ecosystem Health

Pollution: Human activities are causing serious environmental degradation, threatening

the sustainable management and health of the near-coastal waters. Among the major

threats to the LME's health and productivity is pollution from land-based sources,

particularly related to sewage, agriculture, aquaculture and industries (Kaly 2004,

Samarakoon 2006). These are also the main land-based pollution categories of

transboundary significance in the region. The mobilisation of pol utants through rivers,

run-off and floods, as well as cross-border movements of pollutants through international

rivers, are of concern (Kaly 2004). Pollution from sea-based sources (oil spills, oil

exploration and production) is also among the main recognised threats (Kaly 2004).

Sewage was identified as a major priority issue (Chia & Kirkman 2000). This includes

nutrients, POPs, household chemicals, medical wastes, excreted pharmaceuticals and

sediments. The use of chemicals and irrigation in agriculture and aquaculture, as well as

sediment inputs to the coastal areas compounds this problem. High amounts of organic

and inorganic nutrients reach the LME (Kaly 2004). Although the ecological effect of

nutrient enrichment of the coastal environment of the LME are poorly documented and

understood, reported localised problems of eutrophication, hypoxia and algal blooms are

likely to be related. Over the past 20-30 years, an increase in both the frequency and

persistence of algal blooms in coastal waters and enclosed sea areas in India has been

reported (Sampath 2003). The GBM river system is a major recipient of waste from

industries in Bangladesh and India. High levels of pesticides can be found along the

coast, especially near cities and ports (Dwivedi 1993).

Pollution by suspended solids is common to the entire LME, including the Andaman Sea.

Although sediment mobilisation occurs with urban and port developments, the most

important sources are probably deforestation together with agriculture and aquaculture

(Kaly 2004). The GBM river system delivers 30% of the world's total load of river

sediment (Milliman & Meade 1983), and provide high turbidity in the coastal waters, as

has been shown in satellite photos.

Oil spills are a major concern. There is heavy oil tanker traffic between Japan and the

Middle East, with the main shipping route passing south of Sri Lanka before entering the

Straits of Malacca. Along the Indian coastline, there is also intense shipping traffic, and

associated chronic oil pollution through operational discharge of waste, mostly by

medium and small ships where installation of oil-water separators is not mandatory

(Sampath 2003). Increasing shipping activity and increasing emphasis on offshore oil

exploration in many countries of the region makes the northern Indian Ocean very

vulnerable to oil pollution.

Habitat and community modification: Among the coastal habitats of the Bay of Bengal

LME are several wetlands of international importance (WRI 2005). Six areas of critical

biological diversity are the Sundarbans, Palk Bay and the Gulf of Mannar, the Marine

(Wandur) National Park in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, the Maldives Atolls, Mu Ko

Similan National Park and Mu Ko Surin National Park in Thailand. The Sundarbans, a

UNESCO World Heritage Site, represents the most economically important production

forest and natural wildlife habitat in Bangladesh.

Extensive habitat modification has occurred, but was considered to be moderate in

Bangladesh, India, and Sri Lanka, and severe in the Andaman Sea. The major problems

VII South Asian Seas

245

are sedimentation and siltation, reclamation, coastal aquaculture, illegal fishing, and oil

pollution, as well as global warming and sea level rise (Angell 2004). Climate change is

likely to have severe impacts on the LME as it is closed in the north, preventing the

migration of endemic species to higher latitudes. The impact on the ecosystem of the

recent start of dredging in the Gulf of Mannar for the Sethusamudram Ship Canal is also

of grave concern.

Weakened traditional common property management, growing human population in

coastal areas, and development of brackish water shrimp farming have contributed to the

increasing pressure on mangrove forests and their resources in the last few decades

(Angell 2004, Samarakoon 2004). With a few exceptions, most mangrove habitats in the

Bay of Bengal LME region are degraded or threatened. For instance, in the Sundarbans,

some 150,000 ha of mangrove forest disappeared during the past 100 years, as a result

of reclamation for agriculture settlement sites, industrial estates and roads (Govindasamy

et al. 1997). More than half of the total area (some 208,220 ha) of Thailand's mangrove

forests disappeared between 1961 and 1993 (GESAMP 1993). Between 1991 and 1995,

approximately 50,000 ha of coastal wetlands along the east coast of India were

converted to shrimp farms (Government of India 2002). In Sri Lanka, mangrove

conversion to shrimp ponds has considerably reduced mangrove forest (Joseph 2003).

Agriculture and land reclamation for urban settlements have also reduced the mangroves

and peat swamps of the Malacca Straits by about 50-60% (Thia-Eng et al. 1997).

Similarly, the Merbok mangroves in Malaysia, with one of the highest recorded levels of

species diversity in the world, have been reduced by about 65% through conversion to

rice paddies, shrimp farms and housing estates (Samarakoon 2004).

Among the pressures on the region's coral reefs are destructive fishing practices, siltation

and pollution, unplanned tourism development and coral mining (Angell 2004) are

prominent. Coral reefs have also been damaged by bleaching, as a consequence of

periodic increases in sea surface temperatures. The most notable bleaching event

occurred in 1997-1998, and caused extensive bleaching and in numerous instances, over

90% mortality of corals, in some parts of the LME (Wafar 1999, Chou et al. 2002,

Wilkinson 2002). Pollution and related disease are also threatening some reefs. For

instance, oil spills and ballast water discharges are a significant threat to 85% of

Thailand's reefs (Angell 2004). Destructive fishing practices such as the use of cyanide

and explosives are a major cause of coral reef degradation in most of the countries,

particularly in Indonesia, where 67%-98% of the reefs are seriously degraded.

Furthermore, reefs are generally depleted of high value food fish due to the demand for

both the local tourism industry and export. Although this practice has been banned, coral

mining has destroyed coral reefs in many areas, including in Sri Lanka, India and, to a

lesser extent, in Bangladesh. Only the Maldives government has had some success in

reducing this destructive practice by subsidising the import of alternative materials.

Extensive damage to coastal and marine habitats was caused by the tsunami of 26

December 2004 (CORDIO 2005a, 2005b, IUCN/CORDIO 2005). Places along the coast

that were most affected were those that have been previously disturbed by anthropogenic

activities. For example, mangroves and vegetated coastal dunes seem to have

dissipated the wave energy and provided protection to coastlines, coastal inhabitants and

infrastructure. Surveys have shown significant damage to coral reefs over extensive

areas from mechanical damage, deposition of debris, sand, silt, and rubble, as well as

impacts on the diversity of benthic organisms and fish. Fish populations, which in many

cases were depleted by overexploitation, showed varying levels of impact, seemingly

correlated with loss of habitat. In general, a higher impact was observed on smaller fish,

notably damselfish, gobies, butterfly fish and wrasse; this may have adverse

consequences for the ornamental fish trade.

246

10. Bay of Bengal LME

The impact of the tsunami is also very visible on turtle nesting sites (Kulkarni 2005,

CORDIO 2005b). The nesting beaches of leatherback, green, hawksbill and olive ridley

turtles in South Andaman, Little Andaman and the Nicobar Group of islands have almost

vanished. Sand and sediment deposited on sea grass beds will have a long term-impact

on dugongs, which feed in these areas. Severe beach erosion has occurred at all sites,

with some beaches suffering over 50% reduction in width and up to one meter loss in

height.

IV. Socioeconomic Conditions

The eight countries bordering the Bay of Bengal LME include some of the most populous

in the world, with India, Indonesia and Bangladesh being among the world's top ten. An

estimated 400 million people live in the LME's catchment area (Preston 2004). The LME

and its natural resources are of considerable social and economic importance to the

bordering countries, with activities such as fishing, shrimp farming, tourism and shipping

contributing to food security, livelihoods, employment and national economies. Marine

fisheries make a modest contribution to the GDP of the bordering countries, with the

exception of the Maldives, where this sector contributes 11% to GDP and 74% of the

country's export commodities (FAO 2005a). Primary export commodities are shrimp and

tuna, which make a significant contribution to national foreign exchange earnings. For

example, in Bangladesh, fisheries account for more than 11% of annual export earnings,

while in Indonesia, the value of fisheries exports amounted to about US$1.6 billion in

1998 (FAO 2005a).

Rapid development of aquaculture, mainly of shrimp, in the extensive coastal and

brackish-water areas has made a significant contribution to the growth of national export

earnings, and aquaculture is now an important element in both the local and national

economies. Based on statistics in FAO (2005b), the combined output of the region's

farmed shrimp and fish in 2003 was estimated at about 5.3 million tonnes, equivalent to

35% of total production from capture and aquaculture. It should be noted, however, that

these statistics are based on the countries' total production, and not only that from the

LME, although most of the aquaculture production comes from the LME. Tourism also

makes a substantial contribution to the national economies of some of the Bay of Bengal

LME countries. Coastal tourism in western Thailand, Peninsular Malaysia, Sri Lanka and

the Maldives continue to gather momentum and is being promoted in India and

Bangladesh.

Many of the region's poor are dependent primarily or entirely on marine resources, and

have few, if any alternatives to fishing, even when overfishing is clearly occurring

(Preston 2004, Samarakoon 2004). Fisheries also provide employment for millions of

people. For example, in Indonesia, over 5 million people are directly involved in fishing

and fish farming. Together with their families, they make up at least 4 percent of the total

population (FAO 2005a). In Bangladesh, this sector provides income to some 1.5 to

2 million full-time and around 12 million part-time fishers, while in the Maldives, fisheries

account for 20% of employment. Fisheries also make a very important contribution to the

national diet in the bordering countries (FAO 2005a). For example, about two-thirds of

Bangladesh, Indonesia and Sri Lanka national protein supply come from fish. This is

even higher in Mayanmar, where fish makes up 80% of the animal protein for most

people.

The socioeconomic impacts of over-exploitation were assessed as severe in the Bay of

Bengal LME countries, particularly for the millions of poor coastal fisher families.

Increasing fishing effort and declining resources are leading to increased competition for

access to these resources, with negative impacts, especially on poorer resource users

(Townsley 2004). Reduced benefit flows from resource use lead to reduced livelihood

VII South Asian Seas

247

security, including reduced food security. The localised decline of fisheries resources

also forces resource users to migrate to other areas in search of new opportunities. This

creates new vulnerabilities for those affected as it means abandoning familiar

environments and social support networks. Without the capacity to adopt alternative

strategies, poorer groups continue to exploit fisheries resources, further exacerbating the

decline of the resources (Townsley 2004).

Pollution is affecting both critical habitats in coastal and marine areas, and the livelihoods

that depend on them. Those making direct use of these resources see decreasing

access to resources, declining environmental conditions that may affect their access to

safe water and necessary livelihood resources and specific health risks generated by

increased pol ution (Townsley 2004). Over 60% of reported diseases in the two countries

are linked to pollution discharged from point and diffuse sources. Pollution impacts are

often particularly severe in coastal areas where pollution from multiple sources may be

concentrated.

The coastal and marine habitats of the Bay of Bengal LME serve as nursery areas for fish

and shellfish species that contribute substantially to income, livelihood, food security and

employment in the bordering countries. These benefits are lost or threatened when such

habitats are destroyed. The extent to which this affects other countries around the LME

is unclear, but the interconnectedness of marine ecotones suggests that there are likely

to be impacts, particularly in adjacent areas but also potentially further away (Townsley

2004; Bhattacharya and Sarkar 2003). For instance, distant fisheries may be affected by

the destruction of habitats that are critical to the life cycle of their target species.

Many of the marine and coastal environmental problems faced by the Bay of Bengal LME

are inextricably linked with the large populations of the region's coastal areas, and their

impoverished status. Continued population growth, and the increasing concentration of

people in coastal areas will exacerbate these problems in the future. Unless addressed,

environmental degradation and unsustainable resource use practices will reduce the

capacity of fisheries to provide sustenance and income for coastal people, thus leading to

increased poverty in a spiralling effect. Preston (2004) notes the growing need to

address coastal management, pollution, fishery management and alternative livelihood

issues in parallel.

V. Governance

The LME is bordered by Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Maldives, Myanmar, Sri

Lanka and Thailand. At the national level, a range of environmental and fisheries

regulations and management initiatives have been developed by the countries bordering

the LME (Edeson 2004, FAO 2005a). However, their results have been mixed, with

effectiveness hampered largely by inadequate implementation, surveillance and

enforcement. Attempts to conserve coral reefs focus on the establishment of MPAs.

These may be internationally recognised biosphere reserves or nationally established

marine protected areas or parks (Angell 2004). For instance, the Sundarbans and the

Gulf of Manner were named biosphere reserves in 1986 and are recognised by UNESCO

under their `Man in the Biosphere' programme. The effectiveness of these MPAs,

however, varies considerably. Problems include intrusion of local fishers, weak to non-

enforcement of MPA regulations, and lack of coordination among responsible

government agencies.

A multitude of international, regional, and sub-regional organisations and programmes

operate in the Bay of Bengal LME. The only regional fisheries management organisation

whose jurisdiction extends into the LME is the Indian Ocean Tuna Commission. There

are also numerous stakeholder groups and policy frameworks (Aziz et al. 1998). In March

248

10. Bay of Bengal LME

1995, the South Asian Seas Action Plan (SASAP) was adopted by Bangladesh, India,

Maldives, Pakistan and Sri Lanka. The South Asia Cooperative Environment Programme

is the Action Plan secretariat. Although there is not yet a regional convention, SASAP

follows existing global environmental and maritime conventions and considers the Law of

the Sea as its umbrella convention. One of SASAP's priorities focuses on National

Action Plans and pilot programmes to implement the GPA.

The regional Bay of Bengal Programme (BOBP) started out in 1979 as a fisheries

development oriented-programme, and moved progressively towards fisheries

management. The BOBP has been succeeded, in a reduced form, by the Bay of Bengal

Programme Inter-Governmental Organisation, which continues to promote responsible

management of small-scale fisheries and related activities. This organization has a

membership of Maldives, India, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh and focuses largely on coastal

fisheries related issues of these countries.

Recognising the need for integrated and coordinated management of their coastal and

near-shore living marine resources, the eight countries bordering the LME have

embarked on the development of a Bay of Bengal Large Marine Ecosystem Project with

support from GEF to address critical threats to the coastal and marine environment, and

to promote ecosystem-based management of the LME's coastal and marine resources.

This project has recently been endorsed by GEF and will be implemented 2008-2013 by

FAO with the aim of increased national institutional capacity in participating countries.

Through this process, the outcomes will be a Trans-boundary Diagnostic Analysis,

including assessments of critical coastal/marine habitats providing a location-specific

assessment of critical transboundary concerns and the identification of "hotspots". As a

part of regional cooperative arrangements, a permanent, partially financially-sustainable

institutional arrangement will be established, that will support the continued development

and broadening of commitment to a regional approach to BOBLME issues. The Strategic

Action Plan that will be developed will guide future BOBLME Programme activities

leading to improved wellbeing of rural fisher communities through incorporating regional

approaches to resolving resource issues and barriers affecting their livelihoods.

The BOBLME will be largely based around regional and sub-regional activities for

collaborative ecosystem approaches leading to changes in sources and underlying

causal agents contributing to trans-boundary environmental degradation. The

programme also envisages action to promote the restoration of depleted stocks and

develop a better understanding of the BOBLME's large-scale processes and ecological

dynamics. Basic health indicators in the BOBLME will be established as part of this. As

a goal over the longer-term, and foreseen within the Strategic Action Plan, the sustained

commitment from the BOBLME countries to collaborate will be achieved through adoption

of an agreed institutional collaborative mechanism.

References

Angell, C.L. (2004). Review of Critical Habitats- Mangroves and Coral Reefs. Bay of Bengal Large

Marine Ecosystem (BOBLME) Theme report, FAO-BOBLME Programme.

Aziz, A.H., Ahmed, L., Atapattu, A., Chullasorn, S., Pong Lui, Y., Maniku, H.M., Nickerson, D.J.,

Pimoljinda, J., Purwaka, T.H., Saeed, S., Soetopo, S., and Yadava, Y.S. (1998). Regional

stewardship for sustainable marine resources management in the Bay of Bengal, p 369-378 in:

K. Sherman, E. Okemwa and M. Ntiba (eds), Large Marine Ecosystems of the Indian Ocean:

Assessment, Sustainability, and Management. Blackwell Science.

Bhattacharya, A. and Sarkar, S.K. (2003) Impact of overexploitation of shellfish: Northeastern

coast of India. Ambio 32(1) 70-75.

VII South Asian Seas

249

Belkin, I.M. (2008) Rapid warming of Large Marine Ecosystems, Progress in Oceanography, in

press.

Belkin, I.M., Cornillon, P.C., and Sherman, K. (2008). Fronts in Large Marine Ecosystems of the

world's oceans: An atlas. Progress in Oceanography, in press.

Bhathal, B. (2005). Historical reconstruction of Indian marine fisheries catches, 1950-2000, as a

basis for testing the `Marine Trophic Index'. Fisheries Centre Research Reports 13(4), 122 p.

Bhathal, B. and Pauly, D. (in press). `Fishing down marine food webs' and spatial expansion of

coastal fisheries in India, 1950-2000. Fisheries Research

Chia, L.S. and Kirkman, H. (2000). Overview of Land-Based Sources and Activities Affecting the

Marine Environment in the East Asian Seas. UNEP/GPA Coordination Office and EAS/RCU

(2000). Regional Seas Report and Studies Series.

Chou, L. M., Tuan, V.S., Philreefs, Yeemin, T., Cabanban, A., Suharsono and Kessna, I. (2002).

Status of Southeast Asia coral reefs, p 123-152 in: Wilkinson, C.R. (ed), Status of Coral Reefs

of the World 2002. GCRMN Report, Australian Institute of Marine Science, Townsville,

Australia.

Chuenpagdee, R., Liguori, L., Palomares, M.L.D. and Pauly, D. (2006). Bottom-up, Global

Estimates of Small-Scale Marine Fisheries Catches. Fisheries Centre Research Reports 14(8).

Fisheries Centre, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada, 105 pp.

CORDIO (2005a). Assessment of tsunami damage in the Indian Ocean: First Report CORDIO

online document. www.cordio.org/news_article.asp?id=11

CORDIO (2005b). Assessment of tsunami damage in the Indian Ocean: Second Report CORDIO

online document. www.cordio.org/news_article.asp?id=12

Desai, B.N. and Bhargava, R.M.S. (1998). Biologic production and fishery potential of the Exclusive

Economic Zone of India, p 297-309 in: Sherman, K., Okemwa, E. and Ntiba, M. (eds), Large

Marine Ecosystems of the Indian Ocean: Assessment, Sustainability, and Management.

Blackwell Science Inc. Cambridge, MA.

Dwivedi, S.N. (1993). Long-term variability in the food chains, biomass yield and oceanography of

the Bay of Bengal Ecosystem, p 43-52 in: Sherman, K., Alexander, L.M. and Gold, B.D. (eds),

Large Marine Ecosystems: Stress, Mitigation, and Sustainability. AAAS Press. Washington,

D.C.

Dwivedi, S.N. and Choubey, A.K. (1998). Indian Ocean Large Marine Ecosystems: Need for

National and Regional Framework for Conservation and Sustainable Development, p 361-368

in: K. Sherman, E. Okemwa and M. Ntiba (eds), Large Marine Ecosystems of the Indian Ocean:

Assessment, Sustainability, and Management. Blackwell Science Inc. Cambridge, MA.

Edeson, W. (2004). Review of Legal and Enforcement Mechanisms in the BOBLME Region. Bay of

Bengal Large Marine Ecosystem (BOBLME) Theme report. GCP/RAS/179/WBG. FAO-

BOBLME Programme.

FAO (2002). The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture. Food and Agriculture Organisation of

the United Nations, Rome, Italy.

FAO (2003). Trends in Oceanic Captures and Clustering of Large Marine Ecosystems - 2 Studies

based on the FAO Capture Database. FAO Fisheries Technical Paper 435.

FAO (2005a). Fishery Country Profiles at.www.fao.org/fi/fcp/fcp.asp.

FAO (2005b). World fisheries production, by capture and aquaculture, by country (2003). FAO

Yearbook of Fisheries Statistics: Summary Tables 2003. www.fao.org/fi/statist/statist.asp

FAO (2007) Bay of Bengal LME Prospectus, www.fao.org/fi/boblme/website/index.htm

Gelchu, A. and Pauly, D. (2007). Growth and distribution of part-based fishing effort within

countries' EEZ from 1970 to 1995. Fisheries Centre Research Reports, 15(4), 99 p.

GESAMP (1993). Joint group of experts on the scientific aspects of marine protection, impact of oil

and related chemicals and wastes on the marine environment. Reports and Studies 50. IMO,

London, U.K.

Government of India (2002). National Biodiversity Action Plan for the East Coast of India.

http://sdnp.dehi.nic/nbsap/dactionp/ecoregion/ecoast/ecoast.html

Govindasamy C., Viji Roy, A.G., Prabhahar, C., Valarmathi, S. and Azariah, J. (1997). Bioethics in

India, in: Azariah, J., Azariah, H. and Macer, D.R.J. (eds), Proceedings of the International

Bioethics Workshop in Madras: Biomanagement of Biogeoresources, 16-19 Jan. 1997,

University of Madras.

Hossain, M.M.M. (2003). National Report of Bangladesh on the Sustainable Management of the

Bay of Bengal Large Marine Ecosystem. Bay of Bengal LME Project, FAO GCP/ RAS/ 179/

WBG, Chennai, India.

Ittekot, V., Kudrass, H.R., Quaddfasel, D. and Unger, D. (eds.) (2003). The Bay of Bengal. Deep

Sea Research, Part II:Topical Studies in Oceanography. 50(5): 853-1045.

250

10. Bay of Bengal LME

IUCN/CORDIO (2005). Initial Rapid Assessment of Tsunami Damage to Coral Reefs in Eastern Sri

Lanka, 2-5 March 2005. www.cordio.org/news_article.asp?id=20

Joseph, L. (2003). National Report of Sri Lanka on the Formulation of a Transboundary Diagnostic

Analysis and Strategic Action Plan for the Bay of Bengal Large Marine Ecosystem Programme.

BOBLME Report. FAO-BOBLME Programme

Kaly, U.L. (2004). Review of Land-based sources of pollution to the coastal and marine

environments in the BOBLME Region. Bay of Bengal Large Marine Ecosystem Theme Report.

FAO-BOBLME Programme.

Kulkarni, S. (2005). Tsunami Impact Assessment of Coral Reefs in the Andaman and Nicobar.

CORDIO online document. www.cordio.org/news_article.asp?id=13.

Longhurst, A.R. (1998). Ecological Geography of the Sea. Academic Press, California, USA.

Milliman, J.D. and Meade, R.H. (1983). Worldwide delivery of river sediment to the oceans. Journal

of Geology 91:1-21.

Narvekar, J., and Kumar, S.P. (2006) Seasonal variability of the mixed layer in the central Bay of

Bengal and associated changes in nutrients and chlorophyll Deep-Sea Res. Part I, 53(5), 820-

835.

Pauly, D. and Christensen, V. (1995). Primary production required to sustain global fisheries.

Nature 374: 255-257.

Pauly, D. and Watson, R. (2005). Background and interpretation of the `Marine Trophic Index' as a

measure of biodiversity. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society: Biological Sciences

360: 415-423.

Pauly, D., Christensen, V., Dalsgaard, J., Froese R. and Torres, F.C. Jr. (1998). Fishing down

marine food webs. Science 279: 860-863.

Preston, G.L. (2004). Review of the Status of Shared/Common Marine Living Resource Stocks and

of Stock Assessment Capability in the BoBLME Region. Bay of Bengal Large Marine

Ecosystem (BOBLME) Theme report, FAO-BOBLME Programme.

Salahuddin, A., Isaac, R.H., Curtis, S. and Matsumoto, J. (2006) Teleconnections between the sea

surface temperature in the Bay of Bengal and monsoon rainfall in Bangladesh, Global and

Planetary Change, 53(3), 188-197.Samarakoon, J. (2004). Issues of livelihood, sustainable

development and governance: Bay of Bengal. Ambio 33(1-2): 34- 44.

Samarakoon, J. (2006). South Asian Seas Region, p 137 155 in: UNEP/GPA (2006), The State of

the Marine Environment: Regional Assessments. UNEP/GPA, The Hague.

Sampath, V. (2003). National Report on the Status and Development Potential of the Coastal and

Marine Environment of the East Coast of India and its Living Resources. BOBLME, FAO GCP/

RAS/ 179/ WBG, Chennai, India.

Sea Around Us (2007). A Global Database on Marine Fisheries and Ecosystems. Fisheries Centre,

University British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada. www.seaaroundus.org/lme/SummaryInfo

.aspx?LME=34

Sherman, K. (2003). Physical, biological, and human forcing of biomass yields in Large Marine

Ecosystems. ICES CM 2003/P:12.

Silvestre, G and Pauly, D. (eds). (1997). Status and Management of tropical coastal fisheries in

Asia. ICLARM Conference Proceedings 53, 208 p.

Silvestre, G.T, Garces, L.R., Stobutzki, I., Ahmed, M., Valmonte-Santos, R.A., Luna, C.Z., Lachica-

Aliņo, L., Munro, P., Christensen, V. and Pauly, D. (eds). (2003). Assessment, Management

and Future Directions for Coastal Fisheries in Asian Countries. WorldFish Center Conference

Proceedings 67, 1120 p. [Also available as CD-ROM]

Thia-Eng, C., Ross, S.A. and Hu, Y. (1997). Malacca Straits Environmental Profile.

GEF/UNDP/IMO Regional Programme for the Prevention and Management of Marine Pollution

in the East Asian Seas.

Townsley, P. (2004). Review of Coastal and Marine Livelihoods and Food Security in the Bay of

Bengal Large Marine Ecosystem Region. Report prepared for the Bay of Bengal Large Marine

Ecosystem Programme. FAO-BOBLME Programme.

Vivekanandan, E., Srinath, M. and Kuriakose, S. (2005). Fishing the marine food web along the

Indian coast. Fisheries Research 72 (2-3): 241-252.

Wafar, M.V.M. (1999). Status report India, p.25-26 in: Linden, O. and Sporrong, N. (eds), Coral

Reef Degradation in the Indian Ocean (CORDIO). Status Reports and Project Presentations

1999. Stockholm, Sweden.

Wilkinson, C. (2002). Coral bleaching and mortality - the 1998 event 4 years later and bleaching to

2002, p 33-44 in: Wilkinson, C.R. (ed), Status of Coral Reefs of the World: 2002. GCRMN

Report, Australian Institute of Marine Science, Townsville, Australia.

VII South Asian Seas

251

WRI (2005). Coastal and Marine Ecosystems: Country Profiles. http://earthtrends.wri.org/

country_profiles/index.cfm?theme=1&rcode=1

Wyrtki, K. (1973). Physical Oceanography of the Indian Ocean, p 18-36 in Zeitzschel, B. (ed),

Biology of the Indian Ocean. Springer-Verlag, Berlin.

252

10. Bay of Bengal LME