IX SOUTH PACIFIC

IX-18 East-Central Australian Shelf LME

IX-19 New Zealand Shelf LME

IX-20 Northeast Australian Shelf LME

IX-21 Southeast Australian Shelf LME

338

IX South Pacific

IX South Pacific

339

IX-18 East-Central Australian Shelf LME

M.C. Aquarone, S. Adams, I.M. Suthers and M.E. Baird

The East-Central Australian Shelf LME extends from the southern edge of the Great

Barrier Reef off Fraser Island, Queensland (24.5ºS) to Cape Howe (37.5 ºS), at the

southern end of the state of New South Wales. It covers a surface area of 650,000 km2,

of which 2.66% is protected, and contains 0.18% of the world's coral reefs and 0.20% of

the world's sea mounts, as well as 15 major estuaries (Sea Around Us 2007). A narrow

continental shelf (only 20-60 km wide) that is bordered by the Tasman abyssal plain and

a temperate climate characterise the LME. The South Equatorial Current from the Pacific

Ocean gyre flows westward towards the Australian coast, bifurcates with the southern

branch bending south (left) under the influence of wind stress and topography to become

the East Australian Current (EAC, Ridgeway and Dunn 2003). The EAC is Australia's

largest current and is typically 30 km wide, 200 m deep and traveling up to 4 knots (2 ms-

1), with a variable annual transport variously estimated as 20-30 Sv (Ridgeway & Dunn

2003 and references therein). For comparison, the EAC has ~5 fold greater volume

transport than the seasonally flowing Leeuwin Current on the west coast. The EAC

intensifies in the northern part of this LME, before separating from the coast 31-33 ºS,

leaving behind a southward trending eddy field. The EAC's mesoscale variability is so

large that a single continuous current can often not be identified, and distinguishes it from

other western boundary currents. After separation the EAC retroflects northward and can

feed back into the EAC, as an anticyclonic eddy. Further separations and retroflections

are evident along the NSW coast around 34 and 37ºS (Ridgeway & Dunn 2003). The

eddies are formed at 90 to 180 d intervals driven in part by intrinsic instabilities

(Marchesiello and Middleton 2000; Bowen et al. 2005). The anticyclonic eddies may

transport considerable amounts of heat into the Tasman Sea, or may turn northeast and

coalesce back into the main current. The strengthening of the EAC is predicted to warm

Australian waters by 1-2ºC by 2030 and 2-3 ºC by 2070s, particularly off Tasmania

(Poloczanska et al. 2007). This has already affected growth rates of commercial fish

(Thresher et al. 2007). Ridgeway (2007) and others have noted the remarkable impact of

the EAC's southward penetration off Tasmania. Using the Maria Island long term quasi-

monthly monitoring station (since 1944), they report the warming rate of 2.3 ºC per

century and increasing salinity of 0.34 per century. A book chapter and report pertaining

to this LME are Morgan (1989) and UNEP (2003).

I. Productivity

The East-Central Australian Shelf LME is considered a Class III, low productivity

ecosystem 86 177 gCm-2yr-1) (Sea Around Us 2007; www.science.oregonstate.

edu/ocean.productivity/). At this latitude, water temperature, levels of wind mixing and

light intensity go through seasonal cycles. During the winter, strong winds and cool

surface water temperatures enhance vertical mixing processes, breaking down vertical

density gradients and allowing nutrient-rich waters to mix into the surface layer.

However, the overall productivity of this temperate Australian LME is restricted by the

poleward transport of low-nutrient tropical waters along the continent's eastern margin by

the EAC. There are no widespread seasonal blooms producing large surpluses of

organic matter. Localised coastal blooms occur as a result of wind-driven and current-

driven upwelling and occur throughout the year (Ajani, 2001; Baird et al., 2006).

Localised blooms can produce ecosystem responses such as red-tides (Dela-Cruz et al.,

2003), but are not sufficiently large to support a large demersal fishery such as those

which characterise northern hemisphere continental shelf systems.

340

18. East Central Australia LME

For a general understanding of oceanographic processes affecting the nutrient dynamics

and productivity of Australian marine ecosystems, see the Australian State of the

Environment Reports at www.deh.gov.au/soe where the reports are listed by date. For

more information on productivity, see Furnas (1995). For information on ocean surface

environmental data (currents, temperatures, winds), see the website

www.marine.csiro.au for the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research

Organisation, CSIRO, and David Griffin's CSIRO site at www.marine.csiro.au/%7Egriffin/.

Regularly updated information on climate impact, fisheries and marine sciences,

including an online Atlas of Australian Marine Fishing and Coastal Communities is

available from the Australian Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry, Bureau

of Rural Sciences at http://adl.brs.gov.au together with lists of publications on species,

bycatch, the role of marine reserves and other important topics broken out by regions.

Oceanic fronts: The westward South Equatorial Current impinges on the east coast of

Australia and bifurcates, with the two branches flowing north or south, along the coast

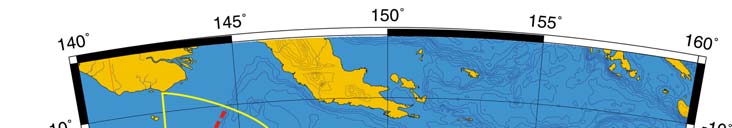

(Belkin & Cornillon 2003, Belkin et al. 2008) (Figure IX-18.1). The southward branch is

the East Australian Current (EAC), a strong poleward flowing western boundary current

that carries tropical waters into the LME. A distinct front exists between tropical Coral Sea

waters and the Tasman Sea waters at between 31-37ºS, the Tasman Front. The EAC is

a highly energetic current that shifts between a dominating poleward extension that flows

past Tasmania, and a Tasman Front extension, which flows eastward towards Lord Howe

Island, eventually forming the East Auckland Current. With currents more than 1 ms-1,

water flowing in from the north, surface waters can move though the LME in as little as a

month. The poleward extension of the EAC has strengthened due to recent climatic

changes, resulting in a significant warming of waters of southern NSW and Tasmania

(Cai, 2006).

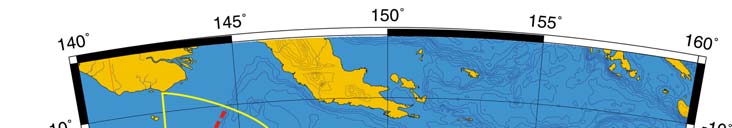

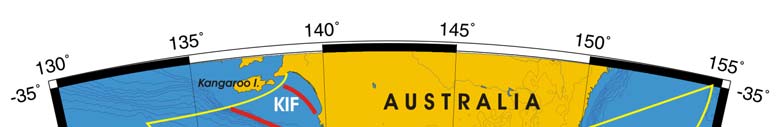

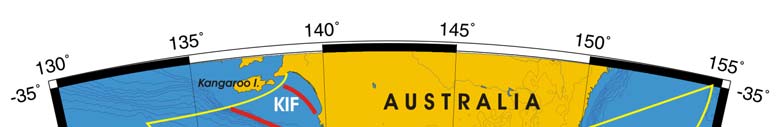

Figure IX-18.1. Fronts of the East-Central Australian Shelf LME. EAC, East Australian Curent; TF,

Tasman Front. Yellow line, LME boundary (after Belkin et al. 2008).

IX South Pacific

341

East-Central Australian Shelf SST

Linear SST trend since 1957: 0.56°C.

Linear SST trend since 1982: 0.35°C.

The steady warming of the East-Central Australian Shelf was punctuated by two warm

events, in 1973 and 1998. The 1973 peak was a large-scale event that occurred

simultaneously in the Indonesian Sea LME, North Australian Shelf LME, and Northwest

Australian Shelf LME. The above-noted synchronism can only be explained by large-

scale atmospheric forcing (teleconnections). Indeed, oceanic advection by currents must

be ruled out because the entire Northeast and East Australian coastal and offshore

region (basically, most of the Coral Sea and northern part of the Tasman Sea) is

dominated by the South Equatorial Current and its extension, East Australian Current,

whereas the Indian Ocean inflow via Torres Strait is negligible.

The 1998 all-time maximum was a manifestation of the 1997-98 El Niño. The summer of

1997-1998 was the hottest recorded on the Great Barrier Reef, causing bleaching of two

thirds of inshore reefs (Berkelmans and Oliver 1999).. Otherwise, the interannual

variability of this ecosystem was rather small, with year-to-year variations less than 0.5°C

(CSIRO 2007). Causes of the annual variation in the EAC eddies are still a puzzle,

driven by intrinsic instabilities (Bowen et al. 2005).

Figure IX-18.2. East Central Australian Shelf LME Mean Annual SST, 1957-2006 (top) and SST

anomalies, 1957-2006 (bottom) based on Hadley climatology, after Belkin et al. 2008.

342

18. East Central Australia LME

East Central Australian Shelf LME, Chlorophyll and Primary Productivity: The East-

Central Australian Shelf LME is considered a Class III, low productivity ecosystem at 86

177 gCm-2yr-1 (Sea Around Us 2007; www.science.oregonstate. edu/ocean.productivity/).

Figure IX-18.3. East Central Australian Shelf trends in chlorophyll a and primary productivity, 1998-

2006. Values are colour coded to the right hand ordinate. Figure courtesy of J. O'Reilly and K. Hyde.

Sources discussed p. 15 this volume.

II. Fish and Fisheries

Australian waters are relatively nutrient-poor and unable to sustain large fish populations.

Approximately 1 in 4 of the 4,482 species found in Australian waters are endemic (Hoese

et al. 2006). Off the coast of New South Wales, 1,748 fish species are recorded of which

22% are Australian endemics. For information on South-East Fisheries, see the AFMA

websites or DEWR reports. Federal, commercial fishing is not large in the Australian

East Marine Planning region (approximates the East Central Australian LME) valued in

2002-2006 at around $320 m and 1% of the national value of commercial fisheries.

These AFMA managed fisheries http://www.afma.gov.au/fisheries/default.htm include the

East Coast Deepwater trawl fisheries, (10 concessions, using demersal and midwater

trawling); the Commonwealth Trawl Sector (formerly South East Trawl Fishery), with

nearly 60 concessions, 54 vessels using otter trawl and danish seine methods, some

midwater trawling; the Eastern Tuna and Billfish Fishery (ETBF) with over 100 permits,

72 vessels using pelagic longline, minor line (handline, troll, rod and reel). The vast bulk

of the landings are restricted to the very narrow continental shelf (Moore et al. 2007).

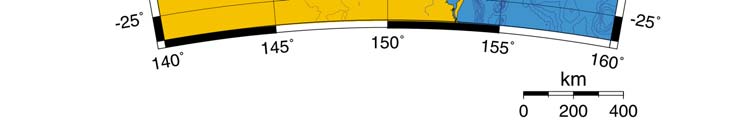

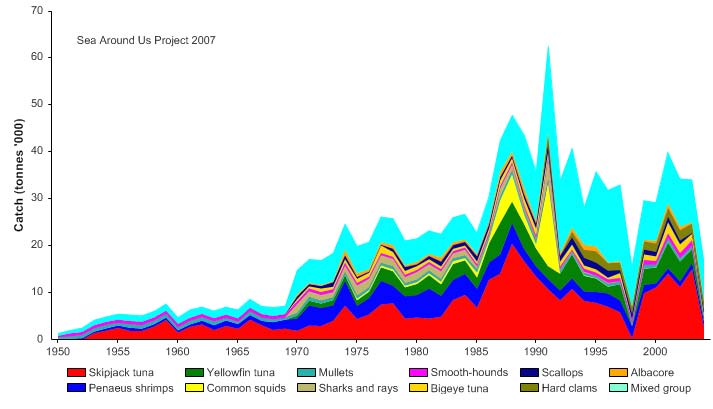

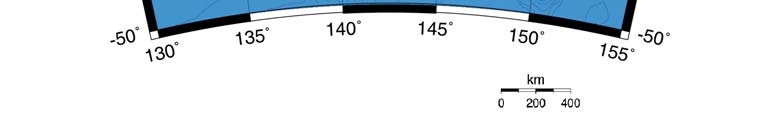

Three of the more significant commercial fisheries are the various estuarine and ocean

prawn trawl fisheries to 3 nautical miles, and the federally managed South East Trawl

and the East Coast tuna fishery. FAO provides information on Australia's fisheries and

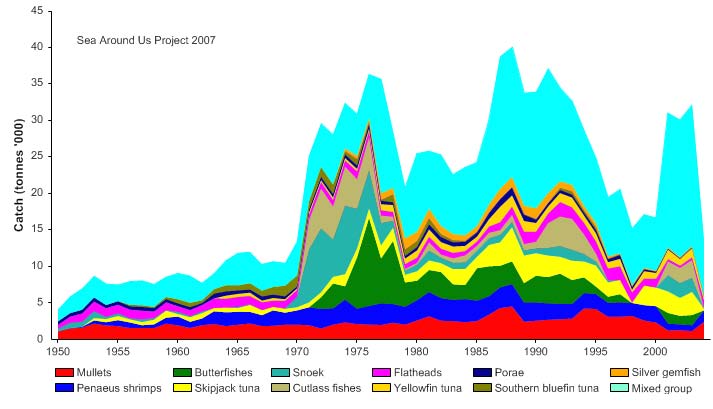

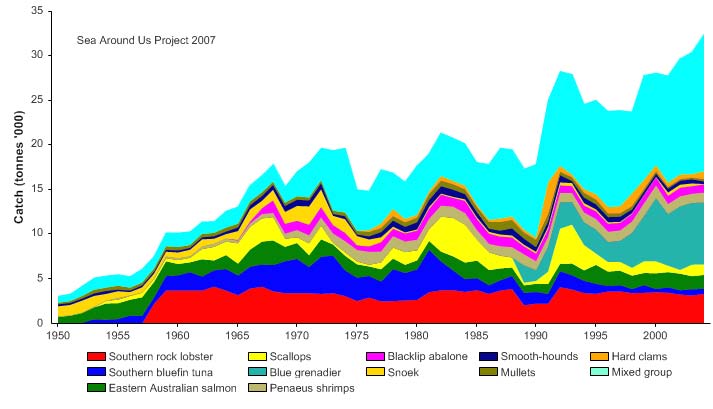

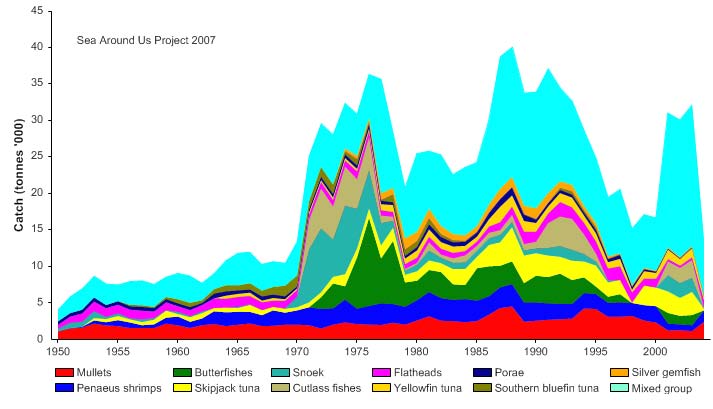

the characteristics of the industry (www.fao.org). Reported landings in the LME include

mullet, shrimps and prawns, butterfishes and tunas (skipjack, yellowfin and bluefin) and

have fluctuated over the last 50 years with peaks in the mid 1970s, late 1980s and early

2000s with over 30,000 tonnes recorded in mid 1970s, late 1980s and again in 2002-

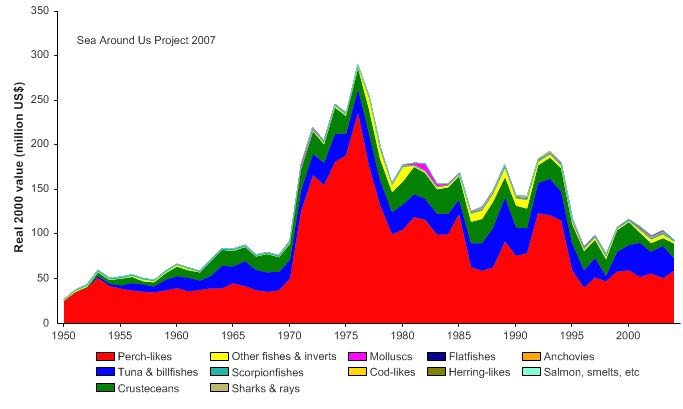

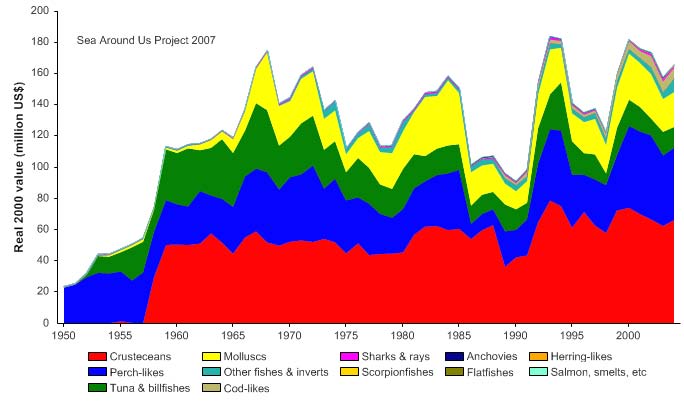

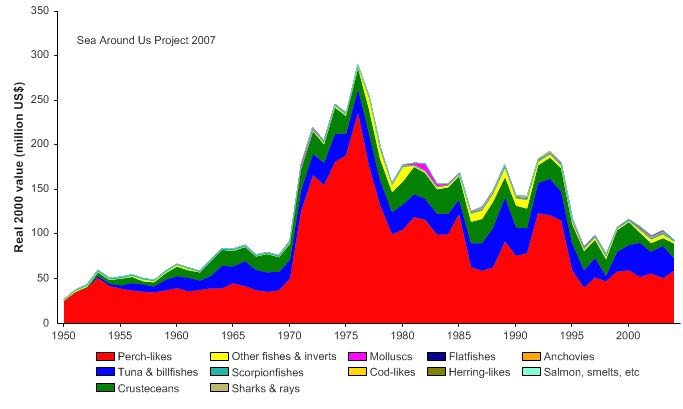

2005 (Figure IX-18.4). The value of the reported landings reached nearly 300 million

US$ (in 2000 real US$) in the mid 1970s and 100 million US$ in recent years (Figure IX-

18.5). For 2000/01, FAO reports landed catch in Queensland fisheries alone at 31,250

tonnes (excluding aquaculture), valued at 741 millions $AUD. The ADL Bureau of Rural

Science estimates that the Eastern Central Region's commercial fisheries caught 31,500

tonnes with Gross Value of Products (GVP) at 315 million $AUD in 2002.

IX South Pacific

343

Figure IX-18.4. Total reported landings in the East-Central Australian Shelf LME by species (Sea

Around Us 2007). Note that Porae =Blue Morwong.

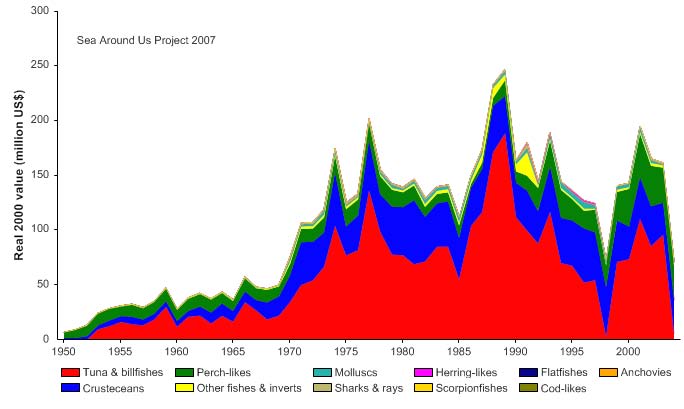

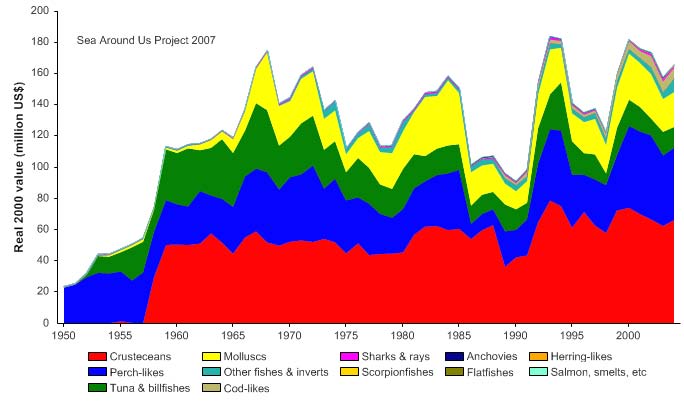

Figure IX-18.5. Value of reported landings in the East-Central Australian Shelf LME by commercial

groups (Sea Around Us 2007).

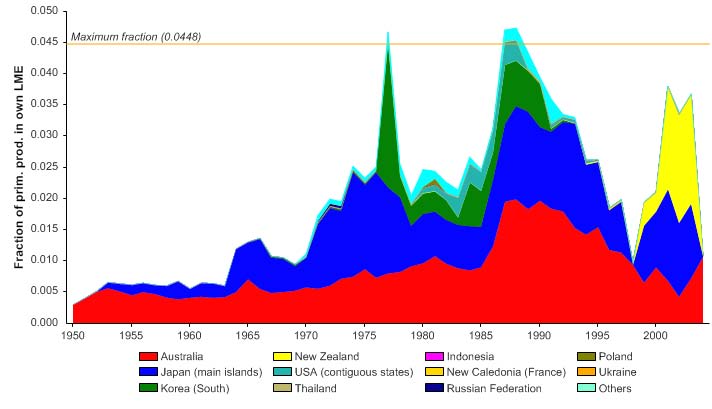

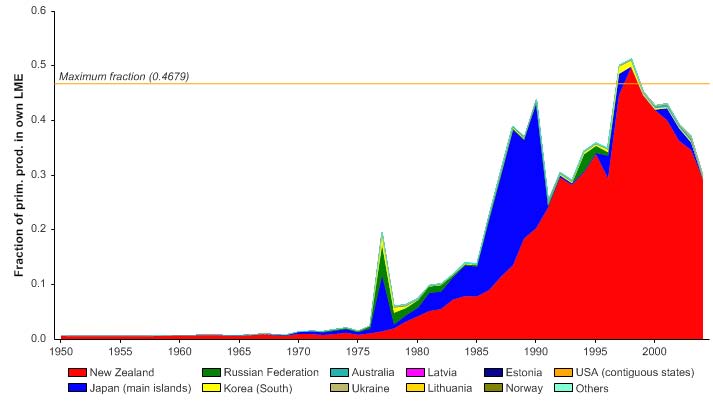

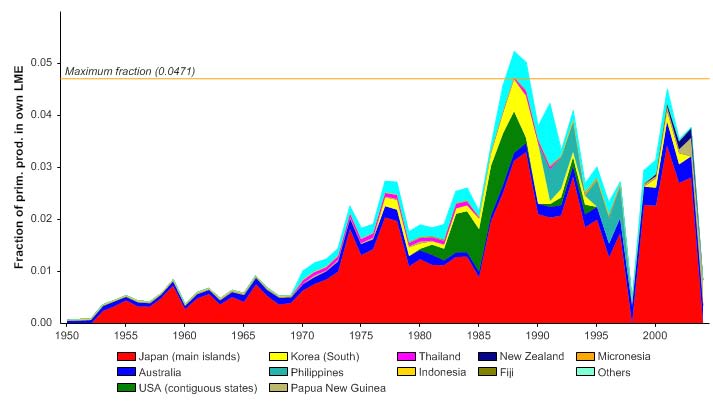

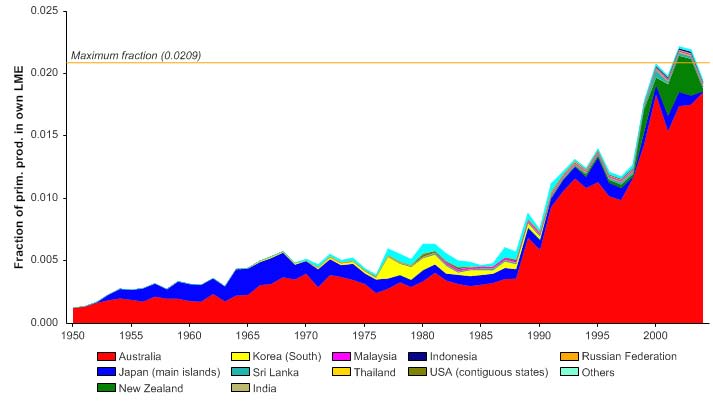

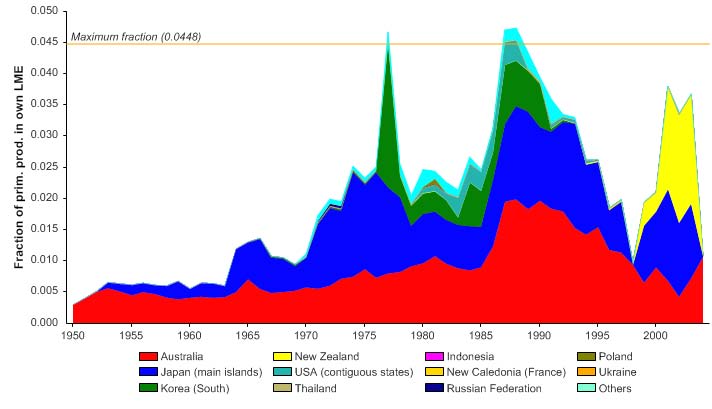

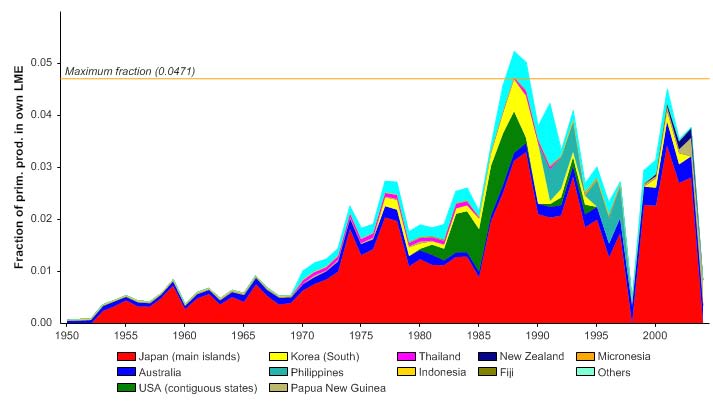

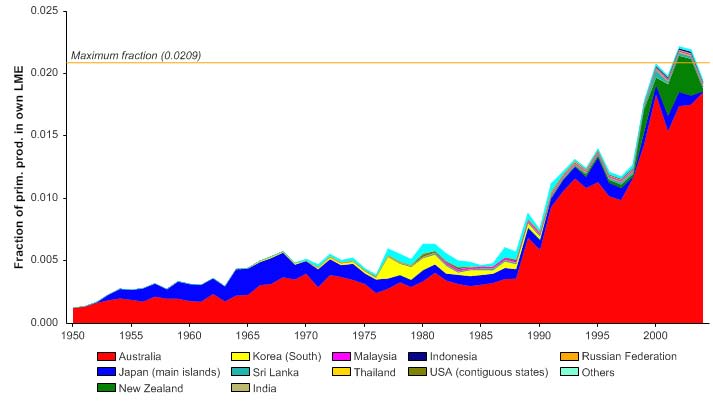

The primary production required (PPR; Pauly & Christensen 1995) to sustain the reported

landings in this LME is currently below 4% with Australia and New Zealand, as well as

few distant water fishing countries, namely Japan and South Korea, historically

accounting for the large share of the ecological footprint (Figure IX-18.6).

344

18. East Central Australia LME

Figure IX-18.6. Primary production required to support reported landings (i.e., ecological footprint) as

fraction of the observed primary production in the East-Central Australian Shelf LME (Sea Around Us

2007). The `Maximum fraction' denotes the mean of the 5 highest values.

Both the mean trophic level (i.e., the MTI; Pauly & Watson 2005) and the FiB index vary

widely and no clear interpretation on the state of the LME or its fisheries can be made

based on these indices (Figure 18.7). It is likely that such variation in the two indices is

due to the low level of exploitation in the region.

Figure IX-18.7. Mean trophic level (i.e., Marine Trophic Index) (top) and Fishing-in-Balance Index

(bottom) in the East-Central Australian Shelf LME (Sea Around Us 2007)

The fluctuations in the reported landings are also making interpretation of the Stock-

Catch Status Plots difficult (Figure IX-18.8). Whilst these plots imply approximately 20%

and 40% of stocks being collapsed and overexploited, respectively (Figure IX-18.8 top),

the causes are complex including changes to gear and management, price and

IX South Pacific

345

especially multispecies effects (over 200 species are processed by the Sydney Fish

Markets, Moore et al. 2007).

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

0%

100

10%

90

20%

)

80

%

(

s

30%

u

70

at

st

40%

y

60

b

ks

50%

c

50

o

f

st

60%

o

40

er

b

70%

m

30

u

N

80%

20

90%

10

100%0

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

(n = 2640)

developing

fully exploited

over-exploited

collapsed

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

0%

100

10%

90

20%

80

)

%

30%

(

70

s

u

at

40%

60

ck st

50%

o

50

st

y

60%

b

h

40

c

70%

Cat

30

80%

20

90%

10

100%0

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

(n = 2640)

developing

fully exploited

over-exploited

collapsed

Figure IX-18.8. Stock-Catch Status Plots for the East-Central Australian Shelf LME, showing the

proportion of developing (green), fully exploited (yellow), overexploited (orange) and collapsed (purple)

fisheries by number of stocks (top) and by catch biomass (bottom) from 1950 to 2004. Note that (n), the

number of `stocks', i.e., individual landings time series, only include taxonomic entities at species,

genus or family level, i.e., higher and pooled groups have been excluded (see Pauly et al, this vol. for

definitions). See also Moore et al. (2007) for a fisheries status overview.

III. Pollution and Ecosystem Health

The major problems for this coastline are real estate value, urbanization, water quality,

freshwater, and beach erosion. The coastline of NSW alone has over 450 coastal

discharge sites along the NSW coast, the largest three being off Sydney amounting to

nearly 1000 ML.d-1 or primary treated sewage Desalination plants are planned or being

constructed for the Gold Coast, Sydney (Kurnell) and Melbourne (at Wonthaggi on the

South Gippsland coast). There are no mining activities in the LME but there is potential

for sand mining, manganese nodule harvesting, or base/precious metals on the Lord

Howe Rise. Sand mining has the greatest potential for NSW in light of beach erosion and

construction needs. There is a pilot wave-energy generator at the breakwater of Port

Kembla www.oceanlinx.com/ .

For 2005-2006, ports of the East Marine Planning region (mostly Newcastle, Sydney,

Brisbane and Port Kembla) accounted for 42% of the nation's exports and 51% of

national imports by tonnage (Anon. 2007). These ports accounted for 18% of freight

loaded and 67% unloaded by all Australian ports. The busiest sea lanes are through the

Coral Sea. The LME may be threatened by an increase in shipping. Ship ballast water

has been shown to contain organisms including bacteria, viruses, algal cells, plankton

346

18. East Central Australia LME

and the larval forms of many invertebrates and fish. Two of Australia's largest three cities

and four of the largest 10 ports are located in this LME, and it is the most urbanized

coastline in Australia. Pressure is increasing on natural environments, productive

agricultural land, water resources, sewage treatment and waste disposal systems. There

are environmental impacts caused by tourism and related infrastructure (airports, power

generation facilities, accommodation, sewage treatment and disposal facilities, moorings

and marine transport). For more information on coastal and marine pollution issues in

this LME, see the Australia State of the Environment Reports indexed by date at

www.deh.gov.au/soe/index.html.

.

IV. Socioeconomic Conditions

Australia's Bureau of Rural Sciences estimates that, on average, 5% of the population of

the Eastern Central and Norfolk Regions is employed in the fishing industry

(http://adl.brs.gov.au/). FAO provides information on the characteristics and

socioeconomic benefits of Australia's fishing industry (www.fao.org/). The Eastern

Central region contains 165 towns, and large cities and ports, including Sydney (Port

Jackson and Botany Bay), Brisbane, Newcastle, and Port Kembla. Shipping and marine

tourism are major economic activities and the cities absorb much of the country's

population growth. The Australian Bureau of Statistics http://www.abs.gov.au/ estimates

the current coastal population in this LME at 8 million, mostly living in Sydney and

Brisbane, with a quarter in the large coastal non-metropolitan centres like Newcastle,

Wollongong, Gold and Sunshine Coasts, Coffs and Bundaberg (http://adl.brs.gov.au/).

The largest marine industry is marine tourism, contributing 22% of the national marine

industry ($27 billion in value added during 2002-03, The Allen Report 2004). The value

of the marine industry (i.e. all recreational and light commercial vessels) in NSW is

valued at over $2 billion pa and employs over 11,000 both figures are almost equivalent

to all other states combined (mostly Victoria and Queensland,

http://www.bia.org.au/data.html ). Over a third of the national marine industry employment

(36%) is in NSW and mostly in marine tourism. These figures are more remarkable

considering that our estuaries, while numerous (>130) are small and we have the nation's

narrowest continental shelf. The Australian Bureau of Statistics estimates at

www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/ that, in the entire country, over 5 million Australians take part

in recreational fishing in Australia as a leisure activity (i.e. 20% fish at least once a year),

with some 120,000 people identified as members of fishing clubs in 1996-97, and that

recreational fishing supports about 90,000 Australian jobs especially in industries

supplying tackle and bait and recreational boating. The Bureau of Statistics estimates

that international tourists spend over $200m on fishing in Australia each year. A survey

undertaken by the ABS in the early 1990s showed that recreational fishing accounted for

23,000 tonnes of fish, 2,800 tonnes of crabs and approximately 1,400 tonnes of

freshwater crayfish. In NSW the recreational catch is about 30% of the commercial

catch, but for 6 major species the recreational catch is actually greater than the

commercial. In NSW the recreational fishing fee bought out commercial fishing licenses

in 25 estuaries in 2001, now described as recreational fishing havens. Most of Australia's

recreational fishing is undertaken along the coast and estuaries of New South Wales,

Queensland and Victoria, reflecting both the excellent fishing areas and the geographic

spread of Australia's population.

V. Governance

The East-Central Australian Shelf LME is bordered only by Australia and falls within the

non-UNEP administered Pacific Regional Seas Programme. In 2003, Australia's Natural

Resource Council endorsed a framework for a national cooperative approach to

Integrated Coastal Zone Management. State jurisdiction is generally limited to the 3

IX South Pacific

347

nautical mile limit, but many state managed fisheries extend into federal waters to 200

nautical miles. Governance issues in this LME pertain to fisheries management and to

the establishment of marine reserves. Lord Howe Island (33.5S, 159E) and the Solitary

Islands (30.2S off northern NSW) were declared state marine parks in 1998/1999. Four

other NSW marine parks have been declared over the past 6 years, which extend out to

the 3 nm mile limit of state waters: Cape Byron (22,000 ha), Batemans Bay (85,000 ha),

Jervis Bay (21,000 ha) and the largest, Port Stephens-Great Lakes (98,000 ha). The

Batemans Bay and Port Stephens parks have been the most controversial with the

recreational fishing community, and have challenged in state parliament the science on

which they are based. The NSW Marine Parks Authority (MPA) through NSW

Department of Environment and Climate Change aims to establish and manage a system

of multiple-use marine parks designed to conserve marine biodiversity, maintain

ecological processes and, provide for ecologically-sustainable use, public appreciation,

education, understanding and enjoyment of the marine environment. Key issues

remaining are larval connectivity amongst areas, and the degree of "spill-over".. See the

North Australian Shelf LME (Chapter VIII, this volume) for more information. NSW

Department of Primary Industries is the principal agency responsible for conserving the

aquatic environment and managing the fisheries resources of this LME. It is responsible

for protecting and restoring fish habitats, promoting responsible and viable commercial

fishing and supporting aquaculture industries.

The South Pacific Regional Environment Programme (SPREP), a regional

intergovernmental organisation now based in Apia, Samoa, was initially established in

1982 as a programme of the South Pacific Commission. SPREP is the primary regional

organisation concerned with environmental management in the Pacific, and serves as the

Secretariat for three Conventions. The 1986 Convention for the Protection of the Natural

Resources and Environment of the South Pacific region entered into force in 1990. The

1976 Convention on the Conservation of Nature in the South Pacific (Apia Convention),

came into force in 1990. The Pacific Islands Forum is the key regional political

organization in the Pacific representing the 14 Island countries as well as Australia and

New Zealand. Australia ratified the United Nations Law of the Sea Convention (UNCLOS)

in 1996. The 1995 Convention to Ban the Importation into Forum Island Countries of

Hazardous and Radioactive Wastes and to Control the Transboundary Movement and

Management of Hazardous Wastes within the South Pacific Region (Waigani

Convention) entered into force in 2001. Australia's indigenous peoples are re-emerging

in the environmental management process as a result of native title rights. The Pacific

Islands Forum is the key regional political organization in the Pacific, representing the 14

island countries as well as Australia and New Zealand. The Action Plan has identified

four broad priorities for the region: natural resources management, pollution prevention,

climate change and variability, and sustainable economic development. The Australian

Government's Department of the Environment and Heritage regularly updates a coasts

and oceans website at: www.deh.gov.au/coasts/.

References

Ajani, P., Hallegraeff, G.M., Pritchard, T., 2001. Historic overview of algal blooms in marine and

estuarine waters of New South Wales, Australia. Proc. Linn. Soc. N. S. W. 123, 1 22.

Australia State of the Environment (2006) at www.deh.gov.au

Australian Bureau of Agriculture and Resource Economics (ABARE) www.abare.gov.au/

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) www.abs.gov.au/

Australian Bureau of Statistics at www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs

Australian Government, Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry, Bureau of Rural

Sciences at www.daff.gov.au/fisheries_marine

348

18. East Central Australia LME

Australian Marine Fishing and Coastal Communities,"Pilot" Atlas, Eastern Central and Norfolk

regions at http://adl.brs.gov.au/mapserv/fishcoast/eastern_central_norfolk_region

Anonymous 2007. East Marine Planning Region. Non-fisheries resource use activities in the east

marine planning region. Sinclair Knight Mertz report to DEWR. www.environment.gov.au

/coasts /mbp/publications/general/marine-economic.html

ABARE 2007, Australian Fisheries Statistics 2006, Canberra June. ISSN 1037-6879

Baird, M. E., Timko, P. G., Suthers, I. M., and Middleton, J. H. (2006). Coupled physicalbiological

modelling study of the East Australian Current with idealised wind forcing. Part I: Biological

model intercomparison. Journal of Marine Systems 59, 249270

Belkin, I. M. and Cornillon, P. C. (2003). SST fronts of the Pacific coastal and marginal seas.

Pacific Oceanography 1(2):90-113.

Belkin, I.m., Cornillon, P.C., and Sherman, K. (2008). Fronts in large marine ecosystems of the

world's oceans: An atlas. Progress in Oceanography, submitted.

Berkelmans R and Oliver JK. 1999. Large-scale bleaching of corals on the Great Barrier Reef.

Coral Reefs 18(1):55 - 60

Bureau of Rural Sciences (BRS) www.brs.gov.au/, fisheries and the marine environment, and

Marine Matters reports.

Cai, W. 2006. Antarctic ozone depletion causes an intensification of the Southern Ocean super-

gyre circulation, Geophys. Res. Lett. 33: L03712.

CSIRO. (2007) Commonwealth Scientific and Industry Research Organization at www.csiro.gov.au/

59th Annual Report.

Dela-Cruz, J., Middleton, J.H., Suthers, I.M., 2003. Population growth and transport of the red tide

dinoflagellate, Noctiluca scintillans, in the coastal waters off Sydney Australia, using cell

diameter as a tracer. Limnol. Oceanogr. 48, 656 674

Fisheries Research Development Corporation (FRDC) www.frdc.com.au/

Furnas, M. J. 1995. Land-sea interactions and oceanographic processes affecting the nutrient

dynamics and productivity of Australian marine ecosystems, p. 61-74. In L. P. Zann

(ed.),SOMER Technical Annex 1. Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, Townsville,

Australia.

Henry GW, Lyle JM (2003) 'The national recreational and indigenous fishing survey.' Australian

Government Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry, Canberra.

Hoese, D.F., Bray, D.J., Paxton, J.R. & G.R. Allen. 2006. Fishes. In Beesley, P.L. & A. Wells.

(eds) Zoological Catalogue of Australia. Volume 35. ABRS & CSIRO Publishing: Australia. parts

1-3, Pp. 1-2178.

Moore et al. 2006. Regional Profile East Marine Region. Description of commercial, recreational

and charter fishing activities. Report for Bureau of Rural Science.

www.environment.gov.au/coasts/mbp/publications/general/marine-economic.html

Morgan, J. (1989). Large Marine Ecosystems in the Pacific Ocean, p 377-394 in: Sherman, K. and

Alexander, L.M. (eds), Biomass Yields and Geography of Large Marine Ecosystems. AAAS

Selected Symposium 111. Westview Press, Boulder, U.S.

Pauly, D. and Christensen, V. (1995). Primary production required to sustain global fisheries.

Nature 374: 255-257.

Pauly, D. and Watson, R. (2005). Background and interpretation of the `Marine Trophic Index' as a

measure of biodiversity. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society: Biological Sciences

360: 415-423.

Pogonoski, J.J., Pollard, D.A. and Paxton, J.R. (2002). Conservation overview and action plan for

Australian threatened and potentially threatened marine and estuarine fishes. Environment

Australia, February 2002. www.deh.gov.au/coasts/publications/marine-fish-action /index.html

Ridgway, K. R., and J. R. Dunn. 2003. `Mesoscale structure of the mean East Australian Current

System and its relationship with topography'. Progress in Oceanography 56:189-222.

Sainsbury, K.J. (1988). The ecological basis of multispecies fisheries, and management of a

demersal fishery in tropical Australia, p 349-382 in: Gulland, J.A. (ed), Fishery Population

Dynamics: The Implications for Management. John Wiley and Sons, New York, U.S.

Sea Around Us (2007). A Global Database on Marine Fisheries and Ecosystems. Fisheries Centre,

University British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada. www.seaaroundus.org/lme/

SummaryInfo.aspx?LME=41

The Allen Report. 2004. The economic contribution of Australia's marine industries.

1995-96 to 2002-03. Report to the National Oceans Office.

UNEP (2003). Wilkinson, C., Reichelt, R., DeVantier, L. and Lawrence, D. Great Australian Bight

and Murray Darling Basin. GIWA Regional Assessment 61. University of Kalmar, Kalmar,

Sweden.

IX South Pacific

349

IX-19 New Zealand Shelf LME

M.C. Aquarone and S. Adams

The New Zealand Shelf LME stretches across from the subtropics to the sub-Antarctic. It

covers a surface area of nearly one million km2, of which 0.03% is protected, and

contains 0.08% of the world's sea mounts (Sea Around Us 2007). The shelf surrounding

New Zealand's North Island and South Island vary in width from a few tens to several

hundred kilometres. This LME is characterised by its temperate climate, influenced by

the warm Tasman and North Cape currents in the north and by the cooler Southland

Current in the South. The marine environment is diverse and includes estuaries,

mudflats, mangroves, seagrass and kelp beds, reefs, sea mount communities and deep

sea trenches. Morgan (1989) and UNEP (2003) pertain to this LME.

I. Productivity

The New Zealand Shelf LME is a Class III, low productivity (<150gCm-2yr-1) ecosystem.

See also Bradford-Grieve et al. (2003, 2006). While the southern Plateau region

subantarctic water, limited by iron availability, is low a productionsystem, the productivity

of the Chatham Rise, eastern Cook Strait, and the NE shelf are considerably more

productive. For a study of ocean fronts and their contribution to marine productivity in this

LME, see the National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research website,

www.niwa.co.nz. View a SeaWiFS image of ocean chlorophyll in New Zealand coastal

waters at www.niwa.cri.nz. In the southern part of this LME, there is higher productivity in

the fiord ecosystems. The current definitive data on marine species in the New Zealand

flora and fauna from the National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research of New

Zealand (NIWA) are a maximum of 16,214 species in total, including known, undescribed

species.

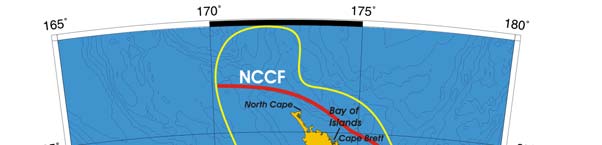

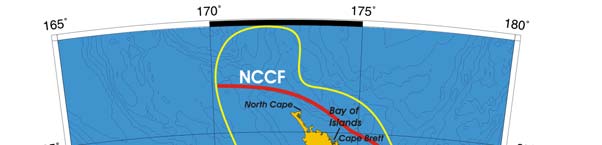

Oceanic fronts: This LME features several well-defined fronts (Figure IX-19.1) that

together determine the ecological regime of the New Zealand shelf (Belkin and Gordon

1996; Belkin and Cornillon 2003; Belkin et al. 2008). In the north, the Tasman Front and

its extension associated with the North Cape Current bring warm and salty tropical waters

to the east coast of North Island. This influx, together with vigorous tidal mixing thanks to

rough bathymetry, is largely responsible for the exceptionally high productivity off the Bay

of Islands, where big game fish like marlins and kingfish come unusually close to the

mainland coast, forming fishing grounds just a few miles offshore, for example, off Cape

Brett. West of North Island, the southern branch of the Tasman Front heads toward

Cook Strait. In the south, the Southland Current Front runs northward along the east

coast of South Island toward Banks Peninsula. East of New Zealand, the double

Subtropical Frontal Zone that consists of the North and South STF extends eastward

along the north and south flanks of the Chatham Rise up to Chatham Island and beyond.

This double Subtropical Frontal Zone is similar to the double frontal zones found in other

subtropical oceans (Belkin, 1988, 1993, 1995, 2005; Belkin and Gordon, 1996). See also

Bradford-Grieve et al. (2006).

New Zealand Shelf SST (Belkin 2008)

Linear SST trend since 1957: 0.11°C.

Linear SST trend since 1982: 0.32°C.

The New Zealand Shelf features strong interannual variability, with a magnitude

exceeding 1°C, superimposed over a slow-warming trend (Figure IX-19.2). Any

correlation between this LME and the upstream LMEs off Australia can only be rather

350

19 New Zealand Shelf LME

tenuous since different parts of the New Zealand Shelf are advectively affected by

different Australian LMEs. For example, the North Island is oceanographically linked to

the Northeast Australian Shelf LME, whereas the South Island is linked to the Southeast

Australian Shelf LME. The all-time maximum of 1971 in New Zealand occurred two years

prior to the near-all-time maximum of 1973 in the East Central Australian Shelf LME,

therefore these events could not have been advectively connected.

Figure IX-19.1. Fronts of the New Zealand Shelf LME. ETSF, East Tasman Front; NCCF, North Cape

Current Front; NSTF, North Subtropical Front; SCF, Southland Current Front; SSTF, South Subtropical

Front. Yellow line, LME boundary. After Belkin et al. (2008), Belkin and Cornillon (2003), and Belkin and

Gordon (1996).

Another warm peak, of 1974, occurred off New Zealand a year after the 1973 warm peak

in the East-Central Australia LME; these events may have been advectively connected.

The warm events of 1971-1974 were confined to these two LMEs connected by the East

Australian Current and its eastward extensions, namely Tasman Front (TF), North Cape

Current Front (NCCF), and East Tasman Sea Front (ETSF) (Figure IX-19.1).

IX South Pacific

351

Figure IX-19.2. New Zealand Shelf LME annual mean SST (left) and SST anomalies (right), 1957-2006,

based on Hadley climatology. After Belkin (2008).

New Zealand Shelf LME Chlorophyll and Primary Productivity

Figure IX 19.3. New Zealand Shelf LME annual trends in chlorophyll a (left) and primary productivity

(right), 1998-2006. Values are colour coded to the right hand ordinate. Figure courtesy of J. O'Reilly and

K. Hyde. Sources discussed p. 15 this volume.

I. Fish and Fisheries

The New Zealand Ministry of Fisheries estimates about 750,000 tonnes of seafood is

harvested annually from New Zealand's fisheries--70% from deepwater and midwater

fisheries, 11% pelagic, 10% farmed species, and 9% from their inshore fisheries. Note

that the Chatham Rise and the Southern Plateau, 2 major fishing regions, are not entirely

included in the LME. The Ministry also estimates that 20% of the population engages in

marine recreational fishing annually and that the expenditure made by recreational

fishers to catch five key recreational species is nearly NZ$1 billion per year

(www.govt.nz/en-nz). Among the important fisheries in this LME are those for migratory

apex predators such as tuna, billfish, and shark, squid, hoki, orange roughy, rock lobster,

mussels (cultured) and snapper are key export species. According to the Ministry, the

value of fish exports in 2004 grew more than the volume and generated NZ$1.2 billion,

NZ$1.0 billion from capture fisheries and NZ$200 million from aquaculture.

352

19 New Zealand Shelf LME

Fisheries policies in New Zealand hope to secure a long-term future for the industry by

setting sustainable catch limits and providing harvesting rights to benefit all New

Zealanders, including the indigenous Maori. Fiords in the southern part of this LME

support commercial and recreational fisheries as well as traditional Maori fisheries.

Information on the fisheries in this LME is available on the FAO website (www.fao.org/).

For information on areas closed to fishing, see the New Zealand Department of

Conservation (www.doc.govt.nz/).

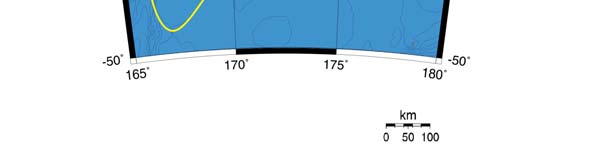

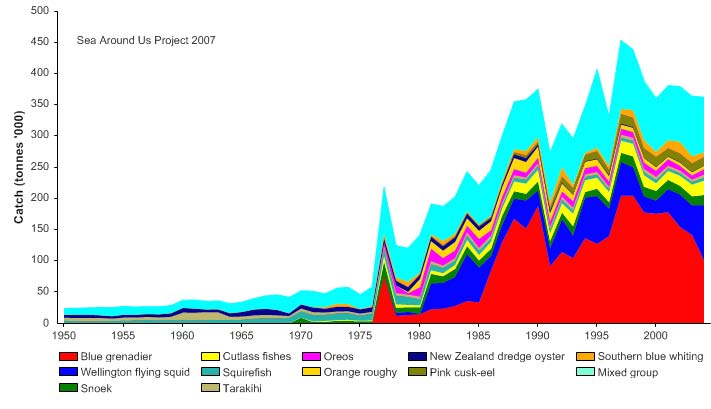

Total reported landings show a sharp spike in 1977 of 220,000 tonnes, likely associated

with the declaration of the 200 nautical mile Exclusive Economic Zone around this LME

by New Zealand, followed by a continuous increase through the 1980s and 1990s and a

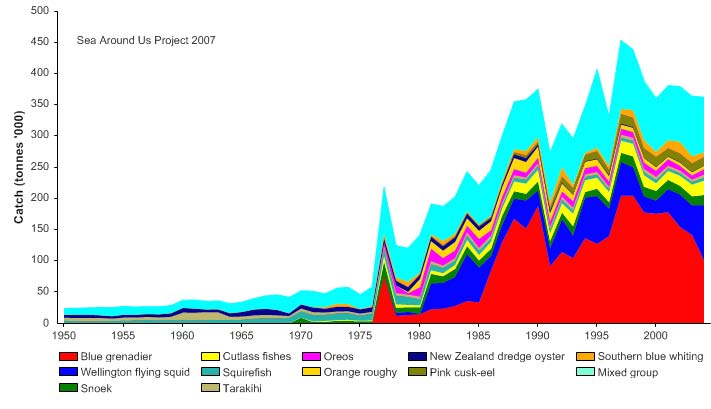

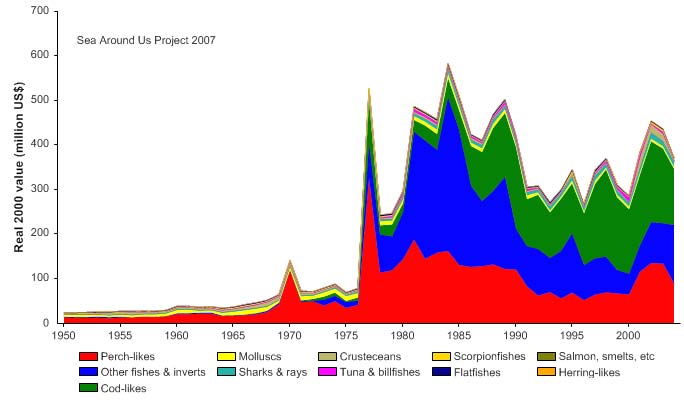

decline in the 2000s (Figure IX-19.4). The value of the reported landings reached

US$583 million (in 2000 US dollars) in 1984, followed by a decline to between US$260

million and US$450 million in recent years (Figure IX-19.5).

Figure IX-19.4. Total reported landings in the New Zealand Shelf LME by species (Sea Around Us 2007).

Figure IX-19.5. Value of reported landings in the New Zealand Shelf LME by commercial groups (Sea

Around Us 2007).

IX South Pacific

353

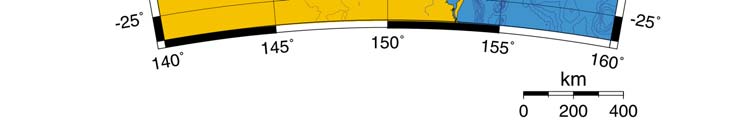

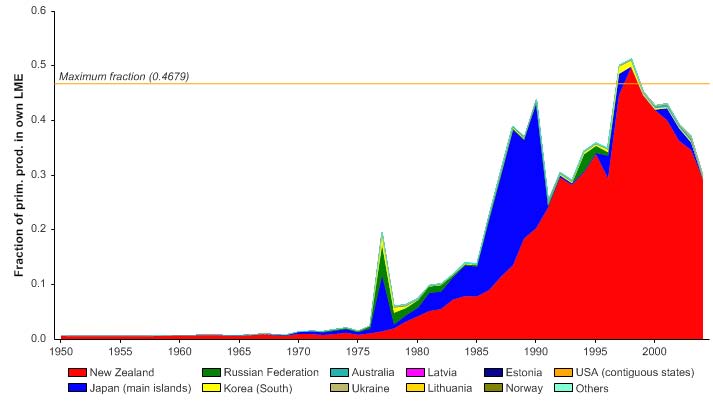

The primary production required (PPR; Pauly & Christensen 1995) to sustain the reported

landings is currently below 4% with New Zealand accounting for the great majority of the

ecological footprint in the LME (Figure IX-19.6).

Figure IX-19.6. Primary production required to support reported landings (i.e., ecological footprint) as

fraction of the observed primary production in the New Zealand Shelf LME (Sea Around Us 2007). The

`Maximum fraction' denotes the mean of the 5 highest values.

The mean trophic level of the reported landings (i.e., the MTI; Pauly & Watson 2005) has

been on a rise since the mid-1970 (Figure IX-19.7, top) as has the FiB index (Figure IX-

19.7, bottom). Together with the data presented in Figure IX-19.6, such trends suggest

the development of previously under-utilized, high trophic fisheries resources by local as

well as foreign fleets.

Figure IX-19.7. Mean trophic level (i.e., Marine Trophic Index) (top) and Fishing-in-Balance Index

(bottom) in the New Zealand Shelf LME (Sea Around Us 2007).

354

19 New Zealand Shelf LME

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

0%

100

10%

90

20%

)

80

%

(

s

30%

u

70

at

st

40%

y

60

b

ks

50%

c

o

50

f

st

60%

40

r

o

e

b

70%

m

30

u

N

80%

20

90%

10

100%0

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

(n = 2695)

developing

fully exploited

over-exploited

collapsed

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

0%

100

10%

90

20%

80

)

%

30%

(

70

t

us

40%

t

a

60

s

k

50%

t

oc

50

s

y

60%

h b

40

t

c

a

70%

C

30

80%

20

90%

10

100%0

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

(n = 2695)

developing

fully exploited

over-exploited

collapsed

Figure IX-19.8. Stock-Catch Status Plots for the New Zealand Shelf LME, showing the proportion of

developing (green), fully exploited (yellow), overexploited (orange) and collapsed (purple) fisheries by

number of stocks (top) and by catch biomass (bottom) from 1950 to 2004. Note that (n), the number of

`stocks', i.e., individual landings time series, only include taxonomic entities at species, genus or family

level, i.e., higher and pooled groups have been excluded (see Pauly et al, this vol. for definitions).

The Stock-Catch Status Plots for the LME illustrate that more than half of the stocks in

the region are currently either overexploited or have collapsed (Figure IX-19.8, top).

However, the majority of the reported landings are supplied by stocks classified as `fully

exploited' (Figure IX-19.8, bottom).

III. Pollution and Ecosystem Health

Fisheries impacts on the environment are not completely understood and the data is

incomplete. Gill nets pose a risk to marine birds, particularly if set near feeding or

breeding areas. Yellow-eyed penguins appear most at risk from nets set by commercial

fishermen for bottom dwelling species such as rig and dogfish. The nets are set well

within the feeding range of these penguins. Fiord ecosystems in the southern part of this

LME are in need of protection. In that region, the crested penguin, Eudyptes

pachyrhynchus, is at risk. Native flora and fauna are affected by invasions of the Asian

kelp, Undaria, and toxic micro-algae. Additional information on marine invasions, ballast

water, marine toxins, harmful algal blooms and diarrheic shellfish poisoning, is given

www.cawthron.org.nz. Studies are underway to assess trawling damage to benthic

species and to deepwater seamount habitat.

It has been suggested that changes in sea surface conditions have contributed to the

spread of toxic algae and invasive seaweeds in New Zealand waters. Toxic algal blooms

occurring in the 1990s have killed marine life and caused illness in humans. Other issues

IX South Pacific

355

affecting the marine environment are waste and hazardous substances. New Zealand

produces a higher rate of municipal waste (two thirds of a tonne per person each year)

than most other developed countries. Industrial waste is estimated at 300,000 tonnes a

year. Another ecosystem health issue is climate change. Gases released into the

atmosphere are enhancing the natural greenhouse effect at a rate that could extensively

damage the LME's biophysical systems. Atmospheric levels of carbon dioxide and

methane - two of New Zealand's major greenhouse gases are rising. Studies are

underway to assess the impact of terrestrial runoff on coastal ecologies and marine

communities.

IV. Socioeconomic Conditions

The population of New Zealand is exceeds 4 million and impacts the marine environment

through commerce, recreation (including whale watching), indigenous fishing (Maori and

Pacific Islanders), commercial fisheries, marine aquaculture, trade, defence and security.

The ocean floor is explored and mined for minerals, natural gas and oil. Ports and

harbours in this LME are Auckland, Christchurch, Dunedin, Tauranga and Wellington.

Statistics New Zealand has developed socioeconomic indicators for the environment that

complement the Ministry for the Environment's Environmental Performance Indicators

programme (www.stats.govt.nz/). The Ministry of Fisheries estimates direct full-time

employment in commercial fisheries and aquaculture at 10,500, and direct and indirect

full-time employment in those jobs at 26,000 (www.fish.govt.nz/). Commercially

important species are managed under the quota management system (the QMS). The

Ministry lists 2,200 persons as holding a quota and a total quota value of $3.5 billion.

The Mori now own 40% of quota and have additional involvement in 20% of quota

(www.fish.govt.nz/). Recommended TACs for various species for 2006/2007are listed at

www.fish.govt.nz/ and in 2006 it was thought that some TAC levels were still too high to

be sustainable. Of the 93 stocks on which New Zealand has information for current stock

size, 76 (82%) are at or near target levels.

V. Governance

This LME is governed by New Zealand, and is included within the UNEP Pacific Regional

Seas Programme. Managing the marine environment is a complex process involving

overlapping and conflicting interests, agencies and legislation. Issues arising between

commercial fisheries and conservation interests are addressed under different

regulations administered by the Department of Conservation and the Ministry of

Fisheries. The latter, since the 1930s, has been responsible for the sustainable use of

fisheries for the social, economic and cultural well-being of the people. All stakeholders

of the marine environment are included in the advancement of sustainable management.

There are currently 97 species groupings in the QMS, divided into 629 fishstocks or

geographic Quota Management Areas (QMAs). Of the 629 fishstocks, 280 have TACCs

of 10 tonnes or less, leaving approximately 349 significant fishstocks that need to be

closely monitored (www.fish.govt.nz).

New Zealand is in the process of developing a comprehensive National Oceans Policy

which aims to address a range of marine issues including fisheries, maritime transport

and protection of the marine environment. New Zealand's Department of Conservation is

responsible for marine reserves and for marine mammals such as dolphins, whales, sea

lions and fur seals. New Zealand has a number of coastal national parks (Bay of Islands

Maritime and Historic Park, Hauraki Gulf Maritime Park).. The New Zealand Biodiversity

Strategy (2000) goal includes having 10% of the marine environment in a network of

Marine Protected Areas by 2010. For more information on marine reserves see the

Department of Conservation website at (www.doc.govt.nz/). The Ministry of Foreign

Affairs and Trade is responsible for New Zealand's international effort to address

356

19 New Zealand Shelf LME

environmental pressures arising from climate change, conservation of species, protection

of ocean biodiversity, hazardous substances, and international agreements on

environmental goods and services. The Environment Division leads this work and all

multilateral environmental agreements, such as the United Nations Framework

Convention on Climate Change (ministry web site at www.mfat.govt.nz/).

References

Belkin, I.M. (1988) Main hydrological features of the Central South Pacific, in: Ecosystems of the

Subantarctic Zone of the Pacific Ocean, edited by M.E. Vinogradov and M.V. Flint, Nauka,

Moscow, 21-28 [Translated as "Pacific Subantarctic Ecosystems", pp.12-17, New Zealand

Translation Centre Ltd., Wellington, 1996].

Belkin, I.M. (1993) Frontal structure of the South Atlantic, in: Pelagic Ecosystems of the Southern

Ocean, edited by N.M. Voronina, Nauka, Moscow, 40-53.

Belkin, I.M. (1995) Remote sensing and in situ observations of subtropical fronts, in: Proceedings of

the COSPAR Colloquium "Space Remote Sensing of Subtropical Oceans", September 12-16,

1995, Taipei, Taiwan, 14B3-1÷14B3-5.

Belkin, I.M. (2008) Rapid warming of Large Marine Ecosystems, Progress in Oceanography, in

press.

Belkin, I.M., and Gordon, A.L. (1996) Southern Ocean fronts from the Greenwich meridian to

Tasmania, J. Geophys. Res., 101(C2), 3675-3696.

Belkin, I.M., Cornillon, P.C., and Sherman, K. (2008). Fronts in Large Marine Ecosystems of the

world's oceans. Progress in Oceanography, in press.

Belkin, I.M., and Cornillon, P.C. (2003). SST fronts of the Pacific coastal and marginal seas. Pacific

Oceanography 1(2), 90-113.

Boyd, P.W., LaRoche, J., Gall, M., Frew, R. and McKay, R. (1999). Role of iron, light, and silicate in

controlling algal biomass in subantarctic waters SE of New Zealand. Journal of Geophysical

Research 104(13):391-404.

Bradford-Grieve, J.M., Boyd, P., Chang, F.H., Chiswell, S., Hadfield, M., Hall, J.A., James, M.R.,

Nodder, S.D. and Shushkina, E.A. (1999). Ecosystem functioning in the subtropical front

region east of New Zealand in austral winter and spring 1993. Journal of Plankton Research

21(3):405-428.

Bradford-Grieve, J.M., Probert, P.K.; Baker, A.N., Best, H.A., Boyd, P., Broekhuizen, N.,

Childerhouse, S., Clark, M.; Hadfield, M., Hall, J.A.; Hanchet, S.; Nodder, S.D.; Safi, K.;

Thompson, D.; Wilkinson, I.; Zeldis J. (2003) Pilot trophic model for subantarctic water over the

Southern Plateau, New Zealand: a low biomass, high efficiency system. Journal of

Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 289(2): 223 262.

Bradford-Grieve, J., Probert, K., Lewis, K., Sutton, P., Zeldis, J., Orpin, A. (2006). Chapter 36. New

Zealand shelf region. In: The Sea, Volume 14: "The Global Coastal Ocean: Interdisciplinary

Regional Studies and Syntheses" Part B. (eds) A. Robinson and H. Brink, Wiley, New York. Pp

1451-1492.

Cawthron (2007) www.cawthron.org.nz//what_biosecurity_main.htm. (for information on

invasive species ). Cawthron's funding comes from the Foundation for Research, Science &

Technology and a range of commercial clients to which it provides consulting and analytical

services. Cawthron scientific and technical staff are based in Nelson and Marlborough.

FAO. Fisheries at www.fao.org/docrep/003 /w4248e/AREA81

Forrest, B., Taylor, M. and Hay, C. (1997). Foreign marine species in New Zealand: Towards a risk

assessment and management model. Cawthron Report 424.

Gall, M., Hawes, I. and Boyd, P. (1999). Predicting rates of primary production in the vicinity of the

subtropical convergence east of New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater

Research 33(3):443-455.

Hall, J.A., James, M.R. and Bradford-Grieve, J.M. (1999). Structure and dynamics of the pelagic

microbial food web of the subtropical convergence region east of New Zealand. Aquatic

Microbial Ecology 20(1):95-105.

Hay, C. (1998). Marine and freshwater invaders. Water and Wastes in New Zealand

November/December issue:27-29.

IX South Pacific

357

Hay, C. and Taylor, M. (1999). Biosecurity in ports: Pros and cons of an "Insurance Assessment"

approach, in: Hillman, S.P. (ed), The Ballast Water Problem - Where to from here?

Proceedings of a workshop, 5-6 May 1999, Brisbane, Australia. EcoPorts Monograph Series

19.

Hunter K.A. and Boyd, P.W. (1999). Biogeochemistry of trace metals in the ocean. Marine and

Freshwater Research 50(8):739-754.

Morgan, J. (1989). Large Marine Ecosystems in the Pacific Ocean, p 377-394 in: Sherman, K. and

Alexander, L.M. (eds), Biomass Yields and Geography of Large Marine Ecosystems. AAAS

Selected Symposium 111. Westview Press. Boulder, U.S.

New Zealand National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research at www.niwa.cri.nz/

pgsf/Ocean Fronts/images/nz2/gif for Sea WiFS image.

New Zealand Department of Conservation at www.doc.govt.nz/ Conservation/Marine-and-

coastal/index.asp

New Zealand Government Environment Publications at www.govt.nz/en-nz/Publications/);

www.stats.govt.nz/domino/external/web/prod_serv.nsf/htmldocs/Socioeconomic+indicators+in

dicators+for+the+environment)

New Zealand Ministry of Fisheries at www.fish.govt.nz

www.fish.govt.nz/en-nzFisheries+at+a+glance/default.htm (for labor statistics)

www.fish.govt.nz/en-nz/Press/September+2006/Sustainability (for 2006-2007 TAC statistics)

www.fish.govt.nz/en-nz/Publications/Ministerial+Briefing+04/F (for Maori catch quotas)

NOAA (1991). Report of the ad hoc Committee on Large Marine Ecosystems. NOAA Technical

Memorandum NMFS-F/NEC-92.

Paulin, C., Stewart, A., Roberts, C. and McMillan, P. (1989). New Zealand Fish A complete guide.

National Museum of New Zealand Miscellaneous Series No 19.

Pauly, D. and Christensen, V. (1995). Primary production required to sustain global fisheries.

Nature 374: 255-257.

Pauly, D. and Watson, R. (2005). Background and interpretation of the `Marine Trophic Index' as a

measure of biodiversity. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society: Biological Sciences

360: 415-423.

Roberts, R., Hay, C. and Rhodes, L. (1997). Marine invaders. The Royal Society of New Zealand,

Alpha Series 92.

Safi, K.A. and Hall, J.A. (1999). Mixotrophic and heterotrophic nanoflagellate grazing in the

convergence zone east of New Zealand. Aquatic Microbial Ecology 20(1):83-93.

Sea Around Us (2007). A Global Database on Marine Fisheries and Ecosystems. Fisheries Centre,

University British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada. www.seaaroundus.org/lme/

SummaryInfo.aspx?LME=46

UNEP (2003). Deese, H., de Ronde, C., DeVantier, L., Hall, J., Howard-Williams, C., Johnson, D.,

Mosbauer, A., Murdoch, R., Nodder, S., Pearson, C., Reichelt, R. and Wilkinson, C. Tasman

Sea, GIWA Regional Assessment 63. University of Kalmar, Kalmar, Sweden.

358

19 New Zealand Shelf LME

IX South Pacific

359

IX-20 Northeast Australian Shelf LME

M.C. Aquarone, S. Adams, and J. Brodie

The Northeast Australian Shelf/Great Barrier Reef LME lies in the Pacific Ocean off the

coast of the State of Queensland, Australia. It is bounded by the Coral Sea to the east

and by the Torres Strait, which separates Australia from Papua New Guinea, to the north,

covering an area of 1.3 million km2 of which 28.06% is protected (Sea Around Us 2007).

The LME is characterised by a tropical climate, with tropical cyclones being common

seasonal events. The South Equatorial Current, a part of the Pacific Ocean

counterclockwise gyre, and the Great Barrier Reef (GBR), a system of coral reefs that

stretches 2,000 km along Australia's northeast coast, are notable features of the LME

(Brinkman et al., 2002). It has the largest system of corals and related life forms in the

world, with 13.51% of the world's coral reefs, in addition to 0.26% of the world's sea

mounts (Sea Around Us 2007). Nutrient enrichment is due to land-based sources as well

as small upwelling areas and advection while mixing in this LME is due to tidal effects

and the wind regime in inshore areas. Intensive fishing is an important force driving the

LME but the combined stresses of climate change, terrestrial pollution and over-

harvesting are degrading the system in similar ways to other global coral reef systems

(Pandolfi et al., 2003; Bruno and Selig, 2007). Book chapters and articles pertaining to

this LME include Bradbury & Mundy (1989), Morgan (1989), Kelleher (1993), Brodie

(1999, 2003), Furnas (2003), Hopley et al. (2007), Johnson and Marshall (2007), and

UNEP (2003).

I. Productivity

The Northeast Australian Shelf LME is considered a Category III, low productivity

(<150 gCm-2yr-1) ecosystem. Ocean currents and wind systems along this coast inhibit

the development of highly productive upwelling systems. On this continental shelf,

sources of nutrients are Coral Sea surface water, Coral Sea local upwellings of deep sea

water, terrestrial runoff and atmospheric inputs. Tidally-induced mixing in the GBR is a

major contributor to the nutrient dynamics of this ecosystem. For more information on

oceanographic processes in this LME, see Wolanski, 1994, Wolanski et al., 2001 and

Brinkman et al., 2002. For large-scale shifts in biomass of the GBR, see Bradbury &

Mundy (1989).

There has been a steady accumulation of knowledge and understanding of the structure

and dynamics of this system. There is high biological diversity in this LME, with high

numbers of rare species. On the GBR are found 350 species of hard corals, along with

1,500 species of fish, 240 species of seabirds, and at least 4,000 species of molluscs

(see Brodie 1999). The physical and biological structure of the GBR is complex. For a

map of the GBR region, see Kelleher (1993). The abundance of hard corals has been

reduced by at least 50% in areas where there is intense crown-of-thorns starfish activity.

For more information about the large-scale effects of crown-of-thorns starfish outbreaks

on the benthic community, and for the propagation of effects into the fish and plankton

communities, see Bradbury & Mundy (1989) and Brodie et al. (2005).

Oceanic fronts: From satellite data (Belkin & Cornillon 2003, Belkin et al. 2008), the

GBR is marked by a seasonal thermal front (GBRF) that peaks during the austral winter

(Figure IX-20.1). This front is better defined off southern Queensland, whereas the

fronts' extension off northern Queensland is less robust. Satellite data analysis revealed

another, inner shelf front that runs off the Queensland coast (QISF). This front appears

to consist of three segments, northern, central and southern, whose possible connectivity

is not yet established. In addition, a coastal region affected by terrestrial material is

360

20. Northeast Australia LME

evident (Brodie et al., 2007) separated from the oceanic regions off the shelf in deeper

waters.

Figure IX-20.1. Fronts of Northeast Australian Shelf/Great Barrier Reef LME. NGBRF, North Great

Barrier Reef Front (most probable location); QISF, Queensland Inner Shelf Front; SGBRF, South Great

Barrier Reef Front. Yellow line, LME boundary. After Belkin et al. (2008).

Northeast Australian Shelf SST (after Belkin 2008)

Linear SST trend since 1957: 0.46°C.

Linear SST trend since 1982: 0.37°C.

Interannual and long-term variability of SST in this LME (Figure IX-20.2) are correlated

with a few neighboring LMEs. For example, the twin peaks of 1970-1973 occurred

simultaneously in the North Australian Shelf LME. The local minimum of 1982 occurred

at the same time in the Indonesian Sea LME and in the Australian Shelf LME. The all-

time maximum of 1998 was a local manifestation of the global warming effect of the El

Niño 1997-98. The absolute minimum of 1964-65 occurred concurrently with the

Southeast Australian Shelf LME. This cold anomaly probably originated upstream, in the

South Equatorial Current.

High SST exceeding the coral colony' tolerance threshold is the primary cause of coral

bleaching (Hoegh-Guldberg, 1999; Liu et al., 2003). In 2002, the Great Barrier Reef

suffered from the worst coral bleaching event ever, which affected up to 60% and

severely damaged 5%, of reefs surveyed (Berkelmans et al., 2004). Further severe

bleaching and damage is predicted under the current climate change predictions and in

association with ocean acidification (Lough, 2008, Hoegh-Guldberg et al., 2007).

IX South Pacific

361

Figure IX-20.2. NE Australian Shelf mean annual SST (left) and SST anomalies (right), 1957-2006, based

on Hadley climatology. After Belkin (2008).

Northeast Australian Shelf Chlorophyll and Primary Productivity

Figure IX-20.3. Northeast Australian Shelf Trends in chlorophyll-a and primary productivity, 1998-2006.

Values are colour coded to the right hand ordinate. Figure courtesy of J. O'Reilly and K. Hyde. Sources

discussed p. 15 this volume.

II. Fish and Fisheries

The relatively nutrient-poor waters of the Northeast Australian Shelf are unable to sustain

large fish populations. The trawl fishery (Brodie 1999) targets tiger prawns, banana

prawns and king prawns. Commercial and recreational fishing remain a huge industry in

the Northeast Australian Shelf/Great Barrier Reef LME. The commercial sector in the

state of Queensland annually harvests about 24,000 tonnes of seafood while the 800,000

recreational fishers in Queensland annually catch between 3,500 and 4,300 tonnes

(www.oceanatlas.org). The Bureau of Rural Sciences estimates a total commercial

fisheries production in national waters in 2002 at 15,600 tonnes with a value of AU$165

million (http://adl.brs.gov.au/). The annual catch of scallops and prawns is about 8,000

tonnes. Scallops are caught in the southern section of the GBR Marine Park. The Torres

Strait prawn fishery is fully-exploited while the Torres Strait lobster is still underexploited.

Information on Australia's fisheries is also available on the FAO website (www.fao.org/).

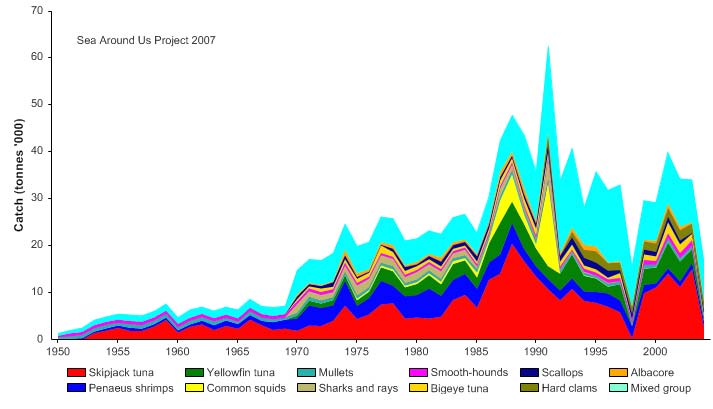

Total reported landings of the LME comprised mainly of tunas (mostly of skipjacks but

also yellowfin, bigeye and albacore), shrimps and prawns, and squids (from the late

362

20. Northeast Australia LME

1980s to early 1990s) and recorded 62,000 tonnes in 1990 (Figure IX-20.4). The

landings have since declined to about half of the peak landings. The trend in the value

reflected that of the landings, rising to about US$250 million (in 2000 US dollars) in 1989

(Figure IX-20.5).

Figure IX-20.4. Total reported landings in the Northeast Australian Shelf LME by species (Sea Around

Us 2007)

Figure IX-20.5. Value of reported landings in Northeast Australian Shelf LME by commercial groups (Sea

Around Us 2007).

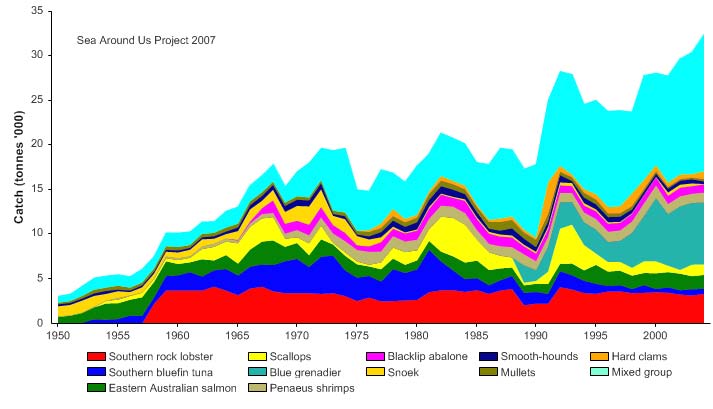

The primary production required (PPR; Pauly & Christensen 1995) to sustain the reported

landings in this LME reached to 5% of the observed primary production in the late1980s,

but still is relatively low, considering the high proportion of high trophic pelagic species in

the landings (Figure IX-20.6). Japan, with its distant water tuna fleets, account for the

largest footprint in the region.

IX South Pacific

363

Figure IX-20.6. Primary production required to support reported landings (i.e., ecological footprint) as

fraction of the observed primary production in the Northeast Australian Shelf LME (Sea Around Us

2007). The `Maximum fraction' denotes the mean of the 5 highest values.

The mean trophic level of the reported landings (i.e., the MTI; Pauly & Watson 2005;

Figure) in the LME is still high, except for 1998 and 2004 when the landings of tuna were

unusually low (Figure IX-20.7, top), while the FiB index has been stable following an

increase from 1950 to the mid-1970s (Figure IX-20.7, bottom). These trends imply a

growth of fisheries in the region with no clear signs of a `fishing down' (Pauly et al. 1998)..

Figure IX-20.7. Mean trophic level (i.e., Marine Trophic Index) (top) and Fishing-in-Balance Index

(bottom) in the Northeast Australian Shelf LME (Sea Around Us 2007).

364

20. Northeast Australia LME

The Stock-Catch Status Plots indicate that more than half of the stocks in the region are

currently either overexploited or have collapsed (Figure IX-20.8, top) and that half of the

reported landings is supplied by such stocks (Figure IX-20.8, bottom).

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

0%

100

10%

90

20%

)

80

%

(

s

30%

u

70

at

st

40%

y

60

50%

cks b

50

o

f

st

60%

o

40

er

70%

mb

30

Nu

80%

20

90%

10

100%0

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

(n = 2266)

developing

fully exploited

over-exploited

collapsed

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

0%

100

10%

90

20%

80

)

%

30%

(

70

s

u

at

40%

60

k st

c

50%

o

50

st

y

60%

b

h

40

t

c

a

70%

C

30

80%

20

90%

10

100%0

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

(n = 2266)

developing

fully exploited

over-exploited

collapsed

Figure IX-20.8. Stock-Catch Status Plot for the Northeast Australian Shelf LME, showing the proportion

of developing (green), fully exploited (yellow), overexploited (orange) and collapsed (purple) fisheries

by number of stocks (top) and by catch biomass (bottom) from 1950 to 2004. Note that (n), the number

of `stocks', i.e., individual landings time series, only include taxonomic entities at species, genus or

family level, i.e., higher and pooled groups have been excluded (see Pauly et al, this vol. for definitions).

III. Pollution and Ecosystem Health

The Northeast Australia LME has been perturbed by the crown-of-thorns starfish

(Acanthaster planci) that has devastated reefs (Kelleher 1993). There is uncertainty as to

whether the outbreaks are human-induced or a natural part of the ecological variability of

the GBR (Brodie 1999). Possible anthropogenic causes are the overfishing of crown-of-

thorns predators such as fish or the triton shell, and enhanced nutrient runoff from coastal

development (Brodie et al., 2005). The large-scale effects of crown-of-thorns starfish

outbreaks on the benthic community have been discussed in Bradbury & Mundy (1989)

and in the State of the Environment Report (www.deh.gov.au/soe/index ).

The GBR is also threatened by increased shipping. A number of ports line the GBR

coastline (Brodie 1999), and navigation in the Torres Strait is intense. Ballast water

introductions of toxic dinoflagellates have caused serious ecological problems in other

parts of Australia but so far no undesirable introduction has been detected in the GBR

region. One significant anthropogenic impact on the GBR region is the change in the

IX South Pacific

365

water quality of terrestrial runoff (Brodie 1999). Excess nutrients affect coral and coral

reef systems (Kinsey 1991). There is considerable evidence that reefs, particularly

inshore fringing reefs, are now muddier and have less coral cover and more algal cover

(Fabricius et al., 2005). Reef ecosystem damage is evident in a large area of the north-

central GBR (Devantier et al., 2006) coinciding with the area known to be exposed to

polluted terrestrial runoff (Devlin and Brodie, 2005). Recreational fishermen tend to

target reef ecosystems and remove larger predatory species. The effects of this selective

removal of fish are largely unknown. Shore-based recreational fishing can affect shore

populations of invertebrates that are collected for bait in intensively visited areas.

Environmental impacts on the Great Barrier Reef also stem from tourism. Large numbers

of people are engaged in recreational fishing, SCUBA diving and boating. The expanding

marine tourism industry is a major contributor to the Australian economy and now

supports more than 820 operators, generates $4.2 billion annually, and accommodates

1.8 million visitors each year (www.oceansatlas.org). Activities associated with this level

of recreational use can affect the environment through the pollution of water by boats and

the disturbance of species and habitats (including mangroves). A major source of

environmental impacts is the provision of infrastructure to support tourism (airports,

power generation facilities, accommodation, sewage treatment and disposal facilities,

moorings, and marine transport, including high-speed ferries). Often, this infrastructure is

located in fragile or pristine environments that are susceptible to disturbance and

fragmentation. For more information on pollution control in the GBR, see Kelleher

(1993).

IV. Socioeconomic Conditions

According to the Bureau of Rural Statistics, the North Eastern Region of Australia has a

population of 441,300 of whom 90% reside in 66 medium-to-large coastal towns.

(http://adl.brs.gov.au). Employment within the fishing sector is heavily concentrated in

the commercial sector, and involves from 1% to 5% of total employment. Total

commercial fisheries production for the region in 2002 was estimated at 15,600 t with a

GVP of AU$165 million (http://adl.brs.gov.au/). FAO provides information on Australia's

fisheries and the socioeconomic benefits of the industry (www.fao.org/fi). Marine and

coastal-based tourism is the main industry of the GBR, an internationally recognised

tourist site and one of Australia's six World Heritage Sites (see Brodie 1999). In the

1980s, tourism in the GBR was evaluated at 150,000 visitor-days. In the late 1990s,

tourism was worth US$1 billion, with 1.5 million visitor-days. Whale-watching takes place

off the coast of Queensland. Tourism clearly depends on sustaining environmental and

heritage values. Tourism can affect the lifestyle of community residents in ways they

perceive as intrusive. In terms of fisheries, for instance, there can be tensions between

recreation, commercial and indigenous interests. Traditional fishing by Aborigines and

Torres Strait islanders is confined to areas close to Aboriginal communities (Brodie

1999). Shipping is a major activity. Mining including extraction of petroleum is not

permitted within the Marine Park boundary. For more information about human uses of

the GBR, see Kelleher (1993) and Brodie (2003).

V. Governance

This LME falls within the Pacific Regional Seas Programme (see the East-Central

Australian Shelf LME). The main governance issues in this LME pertain to fisheries

management and to the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park and Great Barrier Reef World

Heritage Area. See the North Australian Shelf LME (Chapter VIII) for more information.

For sustainable fishing issues in the GBR, see Kelleher (1993). Under the offshore

constitutional settlement between the Australian states and the federal government, the

management of most fisheries within the GBR is the responsibility of the Queensland

366

20. Northeast Australia LME

government (Brodie 1999). Fishery Management methods covering recreational and

commercial fishing are: input controls (gear restrictions, limited entry licenses, area and

seasonal closures); output controls (TAC, ITQs, bag limits and size limits), measures for

species and habitat protection. There is often a `user pays' approach in which users

(usually fishers) pay the full cost of supporting management and compliance for their

fisheries, including substantial license or access fees (www.fao.org/). In 2003 the

Australian Government Representative Areas Program for the GBR was introduced

where the area of highly protected status (no take) was increased from 6 to 30 % of the

total (Fernandes et al. 2004). More information on the governance of Australia's fisheries

is available at the FAO website.

The GBR Marine Park Act was one of the first pieces of legislation in the world to apply

the concept of sustainable development to the management of a large natural area. The

GBR Marine Park Authority was established in 1975 to manage the multi-use park. The

Authority aims to protect the natural ecosystems of the GBR, and ensures that fishing

does not have unacceptable ecological impacts on the fished areas and the reefs. For

more information on the history and zoning system of the GBR Marine Park, see Brodie

(1999) and Kelleher (1993). Compulsory pilotage in the area reduces the risk of collision

with reefs.

On the national level, the Commonwealth Government developed a National Action Plan

for Tourism in 1998. The Plan, which identifies conservation and careful management of

the environment as essential to the long-term viability of the tourism industry, makes a

commitment to ecologically sustainable tourism development and recognises that

environmental considerations should be an integral part of economic decisions.

References

Belkin, I.M. (2008) Rapid warming of Large Marine Ecosystems, Progress in Oceanography, in

press.

Belkin, I.M. and Cornillon, P.C. (2003). SST fronts of the Pacific coastal and marginal seas. Pacific

Oceanography 1(2):90-113.

Belkin, I.M., Cornillon, P.C., and Sherman, K. (2008) Fronts in large marine ecosystems of the

world's oceans: An atlas. Progress in Oceanography, in press.

Bell, P.R.F. (1991). Status of eutrophication in the Great Barrier Reef lagoon. Marine Pollution

Bulletin 23:89-93.

Berkelmans, R., De'ath, G., Kininmonth, S. and Skirving, W. (2004) A comparison of the 1998 and

2002 coral bleaching events on the Great Barrier Reef: spatial correlation, patterns and

predictions, Coral Reefs, 23(1), 74-83.

Bradbury, R.H. and Mundy, C.N. (1989). Large-scale Shifts in biomass of the Great Barrier Reef

ecosystem, p 143-168 in: Sherman, K. and Alexander, L.M. (eds), Biomass Yields and

Geography of Large Marine Ecosystems. AAAS Selected Symposium 111. Westview Press,.

Boulder, U.S.

Brinkman, R., Wolanski, E., Deleersnijder, E., McAllister, F. and Skirving, W.: 2002, Oceanic inflow

from the Coral Sea into the Great Barrier Reef. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 54, 655-

668.

Brodie, J. (1999). Management of the Great Barrier Reef as a Large Marine Ecosystem, p 428-437

in: Sherman, K. and Tang, Q. (eds), Large Marine Ecosystems of the Pacific Rim

Assessment, Sustainability and Management. Blackwell Science, Malden, U.S.

Brodie, J. (2003). The Great Barrier Reef: 25 years of management as a Large Marine Ecosystem,

p 313 - 336 in: Hempel, G. and Sherman, K. (eds), Large Marine Ecosystems of the World:

Trends in Exploitation, Protection and Research. Elsevier, The Netherlands.

Brodie, J. and Furnas, M. (1994). Long term monitoring programmes for eutrophication and the

design of a monitoring programme for the Great Barrier Reef. Proceedings of the Seventh

International Coral Reef Symposium, Guam 1:77-84.

IX South Pacific

367

Brodie, J.E. (1995). Management of sewage discharges in the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park, p

457-465 in: Bellwood, O., Choat, H. and Saxena, N. (eds), Recent advances in Marine

Science and Technology '94. James Cook University, Townsville, Australia.

Brodie J., Fabricius K., De'ath G. and Okaji K. 2005. Are increased nutrient inputs responsible for

more outbreaks of crown-of-thorns starfish? An appraisal of the evidence. Marine Pollution

Bulletin, 51 (1-4): 266-278.

Brodie, J., De'ath, G., Devlin, M., Furnas, M., and Wright, M. 2007. Spatial and temporal pattern of

near-surface chlorophyll-a in the Great Barrier Reef lagoon. Marine and Freshwater

Research, 58: 342-353.

Bruno, J. and Selig, E. 2007. Regional decline of coral cover in the Indo-Pacific: timing, extent and

sub-regional comparisons. PLoSONE, 8.

DeVantier, L., De'ath, G., Turak, E., Done, T. Fabricius, K. 2006. Species richness and community

structure of reef-building corals on the nearshore Great Barrier Reef. Coral Reefs, 25: 329-

340.

Devlin, M.J. Brodie, J. 2005. Terrestrial discharge into the Great Barrier Reef Lagoon: nutrient

behaviour in coastal waters. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 51: 9-22.

Fabricius, K.E., De'ath, G., McCook, L.J., Turak, E., Williams, D. (2005). Coral, algae and fish

communities on inshore reefs of the Great Barrier Reef: Ecological gradients along water

quality gradients. Marine Pollution Bulletin 51: 384-398.

FAO. (2003). Information on Fisheries Management in Australia. www.fao.org/

fi/fcp/en/AUS/body.htm (for access fees); www.fao.org/ fi/FCP/FICP_AUS_E.ASP)

Fernandes, L., Day, J., Lewis, A., Slegers, S., Kerrigan, B., Breen, D., Cameron, D, Jago, B., Hall,

J., Lowe, D., Innes, J., Tanzer, J., Chadwick, V., Thompson, L., Gorman, K., Simmons, M.,

Barnett, B., Sampson, K., De'ath, G., Mapstone, B., Marsh, H., Possingham, H., Ball, I., Ward,

T., Dobbs, K., Aumend, J., Slater, D. and K. Stapleton (2005) Establishing representative no-

take areas in the Great Barrier Reef: large-scale implementation of theory on marine

protected areas. Conservation Biology: 1733-1744.

Furnas, M.J. (1995). Land-sea interactions and oceanographic processes affecting the nutrient

dynamics and productivity of Australian marine ecosystems. www.ea.gov.au/coasts/

publications/somer/annex1/land-sea.html#HDR7

Furnas, M.J. (2003). Catchments and Corals: Terrestrial Runoff to the Great Barrier Reef.

Australian Institute of Marine Science and Reef CRC, Townsville.

Hoegh-Guldberg, O. (1999) Coral bleaching, climate change and the future of the world's coral

reefs, Marine and Freshwater Research, 50(8), 839-866.

Hoegh-Guldberg, O., Mumby, P.J., Hooten, A.J. et al (2007). Coral reefs under rapid climate

change and ocean acidification. Science 318, 1737-1742.

Hopley D, Smithers SG, Parnell KE 2007 The Geomorphology of the Great Barrier Reef:

development, diversity, and change, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0-521-85302-6.

Johnson JE and Marshall PA (editors) (2007) Climate Change and the Great Barrier Reef. Great

Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority and Australian Greenhouse Office, Australia

Kelleher, G. (1993). Sustainable development of the Great Barrier Reef as a Large Marine

Ecosystem, p 272-279 in: Sherman, K., Alexander, L.M. and Gold, B.D. (eds), Large Marine