LMEs and REGIONAL SEAS

100

LMEs and Regional Seas

I WEST AND CENTRAL AFRICA

1. Benguela Current LME

2. Guinea Current LME

3. Canary Current LME

102

I West and Central Africa

I West and Central Africa

103

I-1 Benguela Current LME

S. Heileman and M. J. O'Toole

The boundaries of the Benguela Current LME extend from the Agulhas Current to

27o E longitude, and to the northern boundary of Angola. It encompasses the Exclusive

Economic Zones (EEZs) of Angola and Namibia, and part of the EEZ of South Africa,

with an area of 1.5 million km2 of which 0.59% is protected, and contains 0.06% of the

world's sea mounts (Sea Around Us 2007). One of its unique features is that it is

bounded in the north and south by two warm water systems, the Angola Current and

Agulhas Current, respectively. These boundaries are highly dynamic and the

neighbouring warmer waters directly influence the ecosystem as a whole as well as its

living resources. A strong wind-driven coastal upwelling system, with the principal

upwelling centre located off Lüderitz (27°S, southern Namibia), dominates this LME. The

system is complex and highly variable, showing seasonal, interannual, and decadal

variability as well as periodical regime shifts in local fish populations (Shannon & O'Toole

1998, 1999, 2003). The Benguela Current LME has a temperate climate, and plays an

important role in global climate and ocean processes (GEF/UNDP/UNOPS/NOAA 1999).

Its major estuaries and river systems include the Kwanza and Cunene Rivers. Books,

book chapters, articles and reports on this LME include Crawford et al. (1989),

Palomares and Pauly (2004), O'Toole et al. (2001), Shannon & O'Toole (2003), Shannon

et al. (2006) and UNEP (2005).

I. Productivity

The Benguela Current LME is a Class I, highly productive ecosystem (>300 gCm-2y-1).

The distinctive bathymetry, hydrography, chemistry and trophodynamics of the Benguela

Current LME make it one of the most productive marine areas of the world. The plankton

has been generally regarded as a diatom-dominated system, but this perception is to

some extent an artefact of past sampling (Shannon & O'Toole 1998). Copepods, which

are numerically the most abundant and diverse zooplankton group, play an important role

in the trophodynamics of this LME since they are the principal food of sardines,

anchovies, and other pelagic fish including the larval and juvenile stages of both fish and

squid. The high level of primary productivity supports an important global reservoir of

biodiversity and biomass of fish, seabirds, crustaceans, and marine mammals.

Favourable conditions exist for a high production of small pelagic fishes such as

sardines, anchovies, and round herrings. The LME's estuaries provide nursery areas for

a number of fish stocks that are shared among the bordering countries, while both the

estuaries and coastal lagoons provide critical feeding grounds for migratory birds.

The LME's considerable climatic and environmental variability is the primary driving force

of biomass change in the Benguela Current LME (Sherman 2003, Shannon et al. 2006).

Harmful Algal Blooms (HABs) regularly occur, and have been associated with fish

mortalities as a result of oxygen depletion in the water during and after major blooms

(Shannon & O'Toole 1998). Satellite images show frequent and widespread eruptions of

toxic hydrogen sulphide off the coast of Namibia (Weeks et al. 2004). Eruptions often

seem to be coincident with either increased intensity of wind-driven coastal upwelling or

the passage of a low-pressure weather cell. In 2001, nine major hydrogen sulphide

eruptions occurred, with the largest covering 22,000 km2 of ocean. Their relevance to the

fishery resources, including lobsters, is likely to be high. For example, a widespread

depletion of oxygen is blamed for the deaths of two billion young hake in 1993

(Hamukuaya et al. 1998, Weeks et al. 2004).

104

1. Benguela Current LME

Since 1995, efforts have been underway in the BENEFIT and Benguela Current LME

project (see Governance) to better understand this highly variable and complex system of

physical, chemical, and biological interactions and processes (Shannon et al. 2006).

Systematic surveys have been conducted to assess oceanographic conditions using both

shipboard sensors and satellite remote sensors for temperature, chlorophyll, nutrients,

and primary productivity.

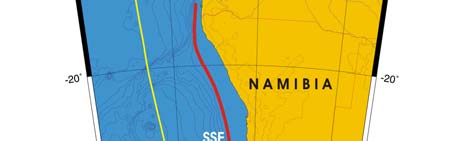

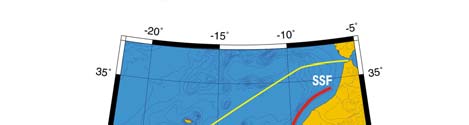

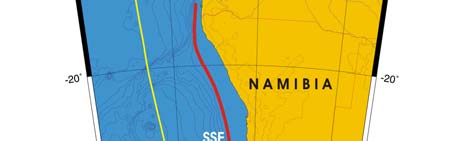

Oceanic fronts: The coastal upwelling zone off South Africa extends from Cape of Good

Hope (34.5°S) north to 13°S and consists of the two major areas, the northern and

southern Benguela upwelling frontal zones (UFZ) separated by the so-called Lüderitz line

(LL) at 28°S, where the shelf's width is at a minimum (Shannon 1985, Shillington 1998)

(Figure I-1.1). The northern UFZ is year-round, whereas the southern UFZ is seasonal).

A peculiar double front is observed within the southern UFZ, between 28°S-32°S, with the

inshore front close to the coast (a few tens of km) and the offshore front over the shelf

break (150-200 km off the coast). This double-front pattern can be explained by the

conceptual model put forth by Barange and Pillar (1992). A vast frontal zone develops

seasonally off the Angolan coast. This zone consists of numerous fronts; most fronts

extend ESE-WNW; the entire zone seems to protrude seaward from the Angolan coast

north of 20°S (Belkin et al. 2008). This zone is likely related to the Angola-Benguela

Front (ABF) (Shannon et al. 1987, Meeuwis & Lutjeharms 1990).

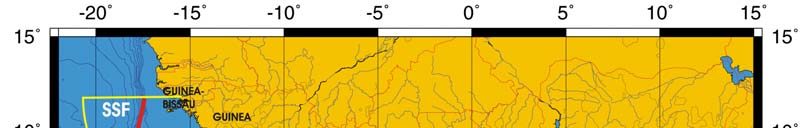

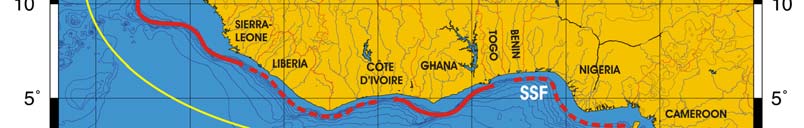

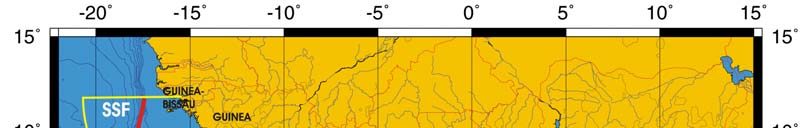

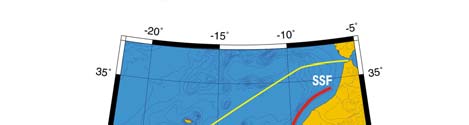

Figure I-1.1. Fronts of the Benguela Current. ABF, Angola-Benguela Front; LL, Lüderitz Line; SSF, Shelf-

Slope Front. Yellow line, LME boundary. (Belkin et al. 2008)

I West and Central Africa

105

Benguela Current SST

Linear SST trend since 1957: 0.26°C.

Linear SST trend since 1982: 0.24°C.

The Benguela Current's thermal history was punctuated by warm and cold events

associated with Benguela El Niños and La Niñas, Atlantic counterparts of the Pacific El

Niños and La Niñas. Fidel and O'Toole, in a presentation made at the 2nd Global

Conference on Large marine Ecosystems in Qingdao, distinguished five major Benguela

El Niños over the last 50 years. The most pronounced warming of >1.2°C occurred after

the all-time minimum of 1958 and took 5 years to peak in 1963. Other warm events

peaked in 1973 and 1984, alternated with cold events of 1982 and 1992. Clearly,

decadal variability in the Benguela Current was strong through the last warm event of

1984. After that, the Benguela Current experienced a shift to a new, warm regime, in

which decadal variability is subdued. Some researchers also note the 1995 warm event,

although this maximum is not conspicuous from Hadley SST data. The post-1982

warming of the Benguela Current LME was spatially non-uniform: whereas SST in some

areas of northern Benguela (between 12-26°S) increased by 0.6 to 0.8°C, the inshore

shelf area of southern Benguela experienced a slight cooling (Fidel and O'Toole, 2007,

after Pierre Florenchie, University of Cape Town, personal communication).

The thermal history of this LME bears limited commonality with either the Guinea Current

LME (its northern neighbor) or to the Agulhas Current LME (its southern neighbor). This

is not at all surprising since these three LMEs are oceanographically disconnected.

Indeed, the Agulhas Current retroflects southwest of Cape Agulhas and therefore does

not feed the Benguela Current, save possibly for small occasional alongshore leakages.

In the north, the Angola-Benguela Front (ABF) blocks any direct along-shelf connection

between two neighbors, the Benguela Current LME and Guinea Current LME.

Correlation analysis suggests different responses to environmental forcing in the

northern, central, and southern parts of the Benguela Current region (Jury and Courtney,

1995). For example, the lower correlation in the southern Benguela between SST and

local winds suggests that SST variability here is often driven by advection, likely by the

Agulhas Current and its extension. The higher correlation in the central Benguela

between SST and local winds indicates that SST variability here is largely driven by local

upwelling.

Figure I-1.2. Benguela Current LME mean annual SST (left) and annual SST anomalies (right), 1957

2006, based on Hadley climatology (after Belkin 2008).

106

1. Benguela Current LME

Benguela Current Trends in Chlorophyll a and Primary Productivity: The Benguela

Current LME is a Class I, highly productive ecosystem (>300 gCm-2y-1).

Figure I-1.3. Benguela Current LME trends in chlorophyll a (left) and primary productivity (right) 1998-

2006; values are color coded to the right hand ordinate. Courtesy of J. O'Reilly and K. Hyde. Sources

discussed p.15 this volume.

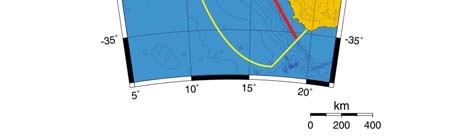

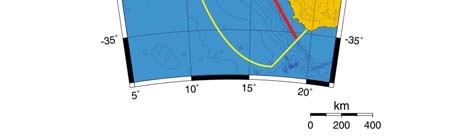

II. Fish and Fisheries

The Benguela Current LME is very rich in pelagic and demersal fish. Most of the LME's

major fisheries resources are shared between the bordering countries or migrate across

national jurisdictional zones, and include sardine (Sardinops sagax), anchovy (Engraulis

capensis), hake (Merluccius capensis and M. paradoxus), horse mackerel (Trachurus

trachurus and T. trecae), sardinella (Sardinella spp.), and rock lobster (Jasus lalandii).

Artisanal, commercial (industrial) and recreational fisheries are all of significance in the

LME, with artisanal fisheries being particularly important for Angola. Total reported

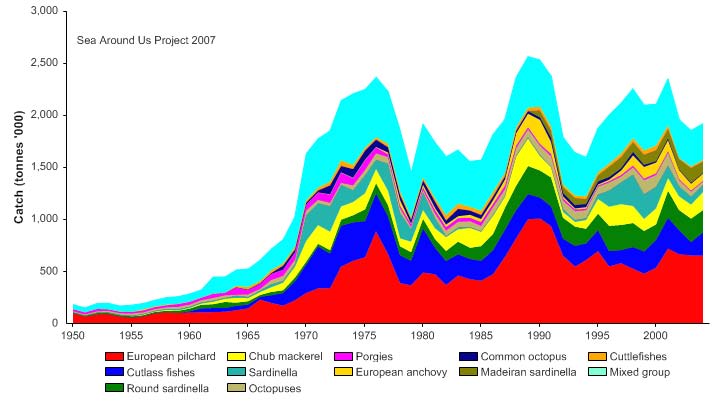

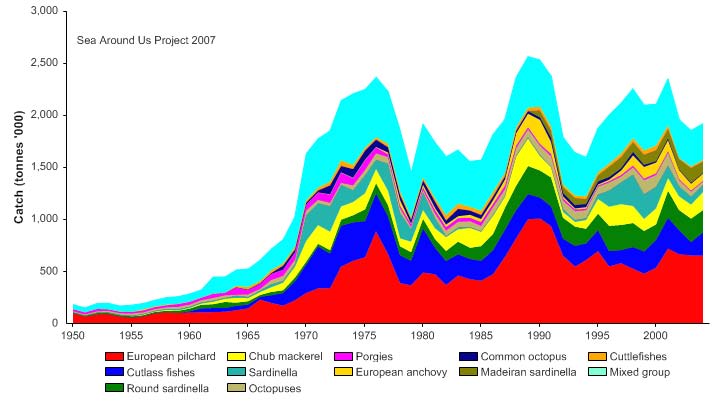

landings of the LME increased steadily from 1950 to a peak of about 3 million tonnes in

1978 (Figure I-1.4). In the subsequent years, however, the landings show a general

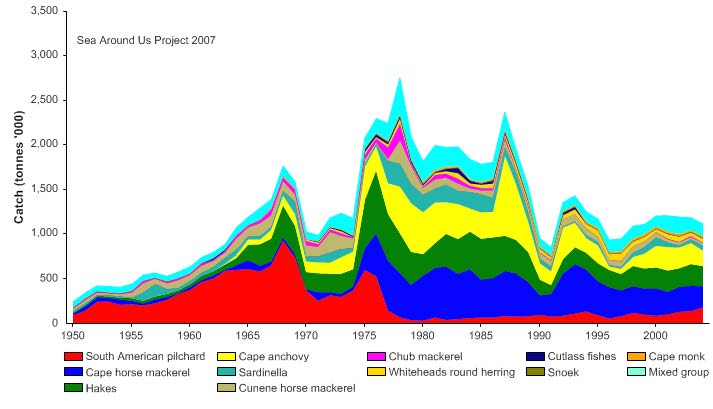

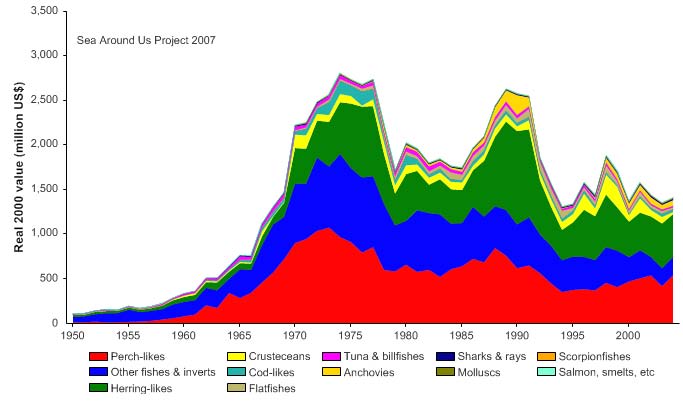

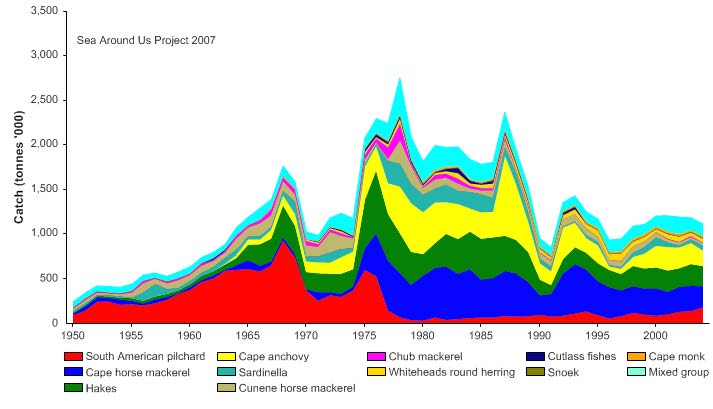

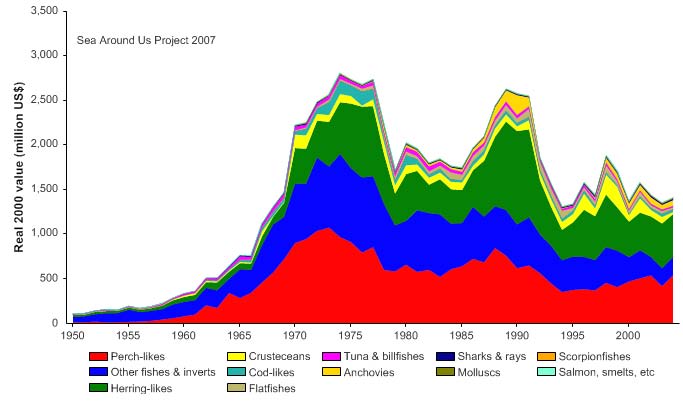

decline, down to about 1.1 million tonnes in 2004. The trend in the value of the reported

landings closely resembles that of the reported landings, peaking at just under 3 billion

US$ (in 2000 real US$) in 1978 (Figure I-1.5).

Figure I-1.4. Total reported landings in the Benguela Current LME by species (Sea Around Us 2007).

I West and Central Africa

107

Figure I-1.5. Value of reported landings in the Benguela Current LME by commercial groups (Sea

Around Us 2007).

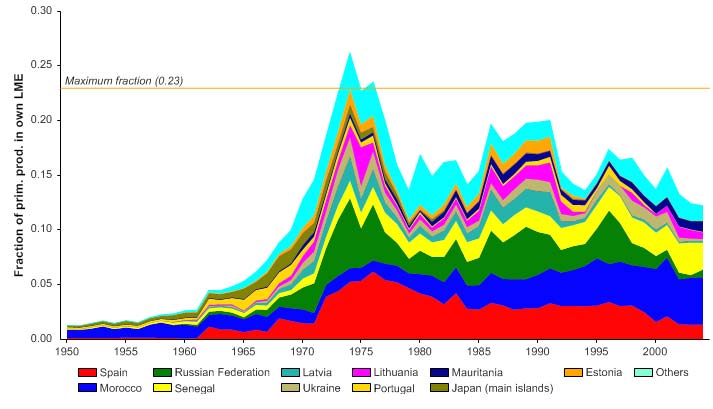

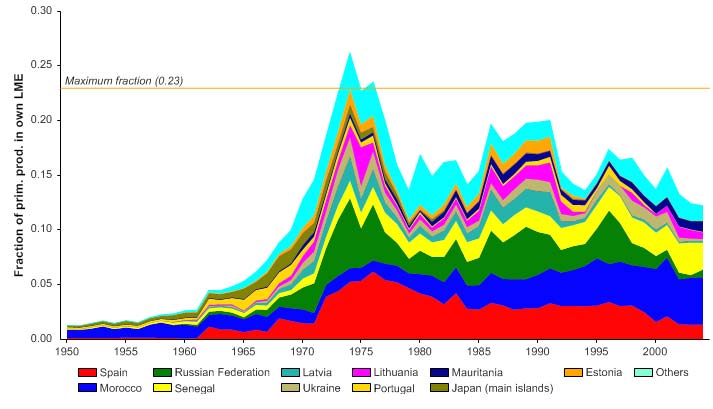

The primary production required (PPR; Pauly & Christensen 1995) to sustain the reported

landings in the LME reached one third of the observed primary production by the mid

1970s, but has since declined to half that level (Figure I-1.6). Although there were large

numbers of foreign fleets operating in the LME in the 1970s and 1980s, since the early

1990s, Namibia and South Africa have the largest ecological footprints in the region.

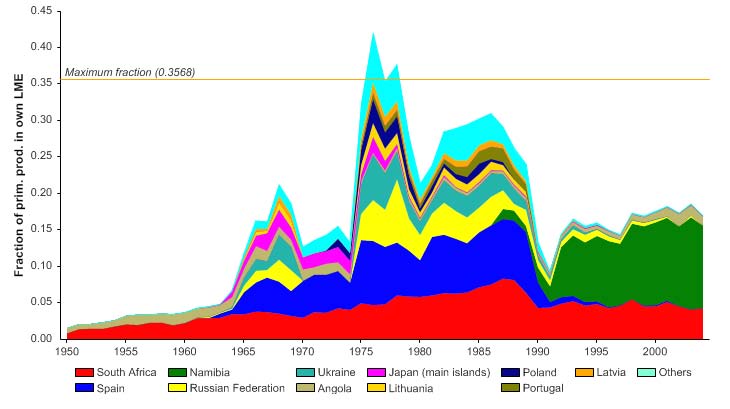

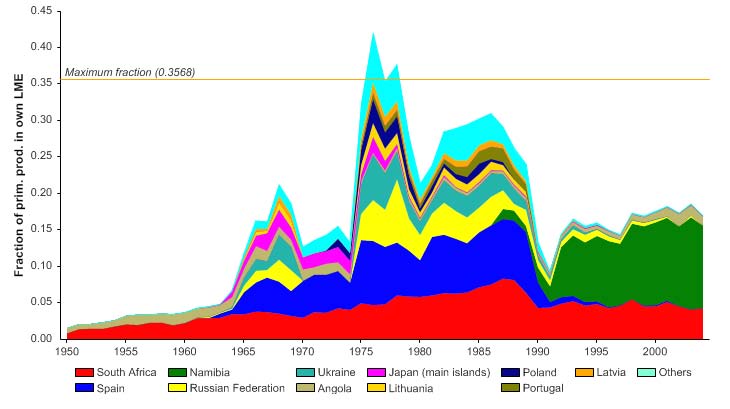

Figure I-1.6. Primary production required to support reported landings (i.e., ecological footprint) as

fraction of the observed primary production in the Benguela Current LME (Sea Around Us 2007). The

`Maximum fraction' denotes the mean of the 5 highest values.

Since the mid 1970s, the mean trophic level of the reported landings (i.e, the MTI, Pauly

& Watson 2005) has been relatively stable in this LME, (Figure I-1.7 top), but as the

amount of catch (tonnage) has declined over the same period, the FiB index shows a

rapid decline (Figure I-1.7 bottom).

108

1. Benguela Current LME

Figure I-1.7. Trophic level (i.e., Marine Trophic Index) (top) and Fishing-in-Balance Index (bottom) in the

Benguela Current LME (Sea Around Us 2007).

This decline of the FiB index is particularly strong off Namibia (Willemse and Pauly 2004),

where the ecosystem has been greatly modified, with jellyfish now dominating the food

web (Lynam et al. 2006). This is a case of `fishing down marine food webs' (Pauly et al.

1998), but one in which the species that replaced the exploited species are presently not

targeted by fisheries.

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

0%

100

10%

90

20%

)

80

%

(

s

30%

u

70

t

at

s

40%

y

60

ks b

50%

c

50

t

o

f

s

60%

o

40

er

b

70%

m

30

Nu

80%

20

90%

10

100%0

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

(n = 3894)

developing

fully exploited

over-exploited

collapsed

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

0%

100

10%

90

20%

80

)

%

30%

(

70

t

us

40%

t

a

60

s

k

c

50%

t

o

50

s

60%

h by

40

t

c

a

70%

C

30

80%

20

90%

10

100%0

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

(n = 3894)

developing

fully exploited

over-exploited

collapsed

Figure I-1.8. Stock-Catch Status Plots for the Benguela Current LME, showing the proportion of

developing (green), fully exploited (yellow), overexploited (orange) and collapsed (purple) fisheries by

number of stocks (top) and by catch biomass (bottom) from 1950 to 2004. Note that (n), the number of

`stocks', i.e., individual landings time series, only include taxonomic entities at species, genus or family

level, i.e., higher and pooled groups have been excluded (see Pauly et al. this vol. for definitions).

I West and Central Africa

109

The Stock-Catch Status Plots indicate that about 60% of commercially exploited stocks in

the LME has collapsed, with another 10% overexploited (Figure I-1.8 top), with fully-

exploited stocks contributing 50% of the catch (Figure I-1.8, bottom). However, fully

exploited stocks, while accounting for less than 30% of the stocks, provide over 50% of

the reported landings (Figure I-1.8).

Major changes in the key harvested species have occurred in the last century (Hampton

et al. 1999, Shannon & O'Toole 2003). While environmental variability has been a

contributing factor, some of these changes were undoubtedly the consequence of

overexploitation (FAO 2003, Sherman 2003). The decline in these fisheries is caused, in

part, by excessive fishing effort and overcapacity of fleets, excess processing capacity,

catching of under-sized fish, and inadequate fisheries management

(GEF/UNDP/UNOPS/NOAA 1999). As a result, the fisheries in the LME have

experienced years of catches well below the maximum or optimal sustainable yields, with

dramatic declines in stock sizes and catch per unit effort.

Decline in commercial fish stocks and non-optimal fishing of living resources is now a

major transboundary problem in the LME (GEF/UNDP/UNOPS/NOAA 1999). In all three

countries bordering the LME, major fisheries resources have undergone significant

changes in annual catch (Hampton et al. 1999, Tapscott 1999) and this is also true for

exploitation of invertebrate resources. For example, rock lobster catches have declined

dramatically since the early 1960s, particularly off Namibia, where catches are now well

below their 1960s peak. Assessments of the South African rock lobster resource have

shown it to be seriously depleted, and estimates of recruitment in recent decades are

only about 35% of its pre-exploitation condition (Hampton et al. 1999). The abalone

stock has also been declining since 1996 (Tarr et al. 2000) and the stock is considered to

be on the brink of collapse as a result of illegal fishing (Tarr 2000) and an ecological shift

in abundance (Tarr et al. 1996).

Some of the major stock fluctuations have undoubtedly been influenced by the large-

scale environmental perturbations that occur periodically in the system (Shannon &

O'Toole 1998, Shannon et al. 2006). System-wide changes in abundance of species and

species shifts (e.g., sardine and anchovy) are well-documented in this LME (e.g.,

Hampton et al. 1999, Shannon & O'Toole 2003). Fluctuations in abundance of the LME's

fish stocks have also been detected through acoustic surveys for pelagic species such as

sardines and anchovies (Barange et al. 1999, Hampton et al. 1999), and trawl surveys for

demersal species (Hampton et al. 1999). The geographic displacement of stocks (e.g.,

Sardinella aurita and S. maderensis in Angola into Gabon) is also a common

phenomenon with alongshore migration of fish populations across national boundaries in

the Benguela Current LME having important implications for resource management.

Global warming and associated phenomena are also expected to influence the LME's

upwelling system, with potentially significant impact on the local food webs and the entire

ecosystem, including fish recruitment and fisheries production.

Fluctuations in fish stocks can also have effects on top predators such as seabirds and

seals (Crawford 1999, Crawford et al. 1992). For example, the distribution of Cape

gannets, Cape cormorants, and African penguins has changed over the past three

decades in response to changes in the distribution and relative abundance of sardine and

anchovy (Crawford 1998). The high mortality and breeding failure of Cape fur seal

colonies in Namibia in 1994 and 1995 can be attributed to low food availability resulting

from low sardine abundance, a consequence of the catastrophic environmental variability

and anomalous low oxygen events (O'Toole 1996).

110

1. Benguela Current LME

Despite the vast scale of the fisheries in the LME, bycatch is not a major problem, and is

taken mostly in the large pelagic and demersal fisheries. Discarding is controlled by strict

regulations as well as by observers in some fisheries (e.g., Patagonian toothfish) but by

self-policing where the bycatch is used as a luxury product. In the demersal trawl fishery

of South Africa, 10% of the total catch is discarded (Walmsley-Hart et al. 2000). Both

South African and Angolan purse seine fisheries yield bycatch rates between 10-20% of

the total catch (Crawford et al. 1987).

The status of the fisheries is problematic, as the countries develop and implement

national and regional fisheries policies and management programmes (GEF/ UNDP/

UNOPS/ NOAA 2002). Furthermore, some stocks show signs of response to

environmental variability, e.g., recently correlated with a movement of sardines from

Namibian waters to the south and southwest coasts toward the Agulhas Bank (van der

Lingen et al. 2006). Sardine stocks in South Africa showed signs of recovery from the

mid-1990s as a result of careful control of bycatch of juveniles, and the introduction of an

operational management procedure which focused on rebuilding sardine stocks while

optimally utilising the anchovy. However, recent stock assessment surveys of sardines

around the Cape indicate a decline to very low levels compared with the mid 1990s.

III. Pollution and Ecosystem Health

Pollution: Virtually the entire coastline of the Benguela Current LME is exposed to the

open ocean and experiences a relatively high degree of wave action. Strong wave action

and currents tend to rapidly dissipate any pollution reaching the marine environment.

Pollution is not a serious problem in the open marine areas of most of the LME, and is

mostly evident in localised areas or hotspots such as ports and enclosed lagoons in all

three countries. Poorly planned coastal developments, inadequate waste management,

chronic oil pollution, inappropriate agricultural practices, contaminated stormwater run-off,

as well as industrial and sewage wastewater discharges are among the factors that

contribute to the deterioration of coastal and marine environments in the LME (UNEP

2005, Taljaard et al. 2006). Levels of pollution, with the exception of hotspots, are

considered moderate (UNEP 2005). With poor urban infrastructure, there is a very real

danger that a rapidly expanding urban population will pose a serious pollution threat, as

untreated sewage is discharged into the sea in increasing volumes. HABs have been

identified as a major transboundary problem, and their frequency of occurrence, spatial

extent, and duration appear to be increasing (GEF/UNDP/UNOPS/NOAA 1999).

Although HABs occur naturally in all three bordering countries (Tapscott 1999), several

factors, including nutrient loading from anthropogenic activities (e.g., discharge of

untreated sewage), can promote their incidence and spread. Toxins produced by HABs

have led to mortalities of fish, shellfish, and humans, as well as anoxia in inshore waters

that can cause mass mortality of marine organisms (GEF/UNDP/UNOPS/NOAA 1999).

Diamond mining operations impact negatively on the marine environment. Certain

mining activities are conducted close to national boundaries (e.g., diamond mining near

the Orange River mouth on both sides of the border between South Africa and Namibia),

across which negative consequences may be transmitted. Diamond mining is also

thought to affect marine living resources. For instance, although the dramatic decrease

in Namibian rock lobster catches in the 1990s may be attributed to large scale

environmental perturbations, it is evident that stock abundance might have also been

influenced by marine diamond mining (Tapscott 1999). While mining is the primary

cause of increased suspended solids in the marine areas, poor agricultural practices also

contribute to this problem, particularly in estuaries, lagoons, and sheltered bays. Marine

litter from land and shipping poses a serious growing problem throughout the LME, with

significant transboundary consequences (GEF/UNDP/UNOPS/NOAA 1999). Oil and gas

exploration and production are considered to pose a major threat, particularly off Angola,

I West and Central Africa

111

with oil spills sometimes causing severe local pollution which impacts artisanal fisheries.

A substantial volume of oil is transported through the region, and poses a significant risk

of contamination to coastal environments, damage to shared and straddling fish stocks,

and to coastal infrastructure (GEF/UNDP/UNOPS/NOAA 1999).

Habitat and community modification: Four estuaries and five coastal lagoons in the

Benguela Current LME are considered to be of transboundary significance. Several

lagoons have been designated as Ramsar sites. Species that are endemic to only one or

two estuarine systems within the LME are also present. The rare estuaries represent the

only sheltered marine habitat in the LME, and are important both for biodiversity and as a

focus of coastal development.

Habitat and community modification was assessed as severe in the Benguela Current

LME (UNEP 2005). The TDA produced by the GEF-supported Benguela Current Large

Marine Ecosystem (BCLME) Project has identified habitat destruction and alteration,

including modification of the seabed and coastal zone, and degradation of coastscapes,

as a transboundary problem in this LME (GEF/UNDP/UNOPS/NOAA 1999).

Nevertheless, compared to other parts of the world, these effects are minor in the

Benguela Current LME.

Modification of the few estuarine systems was found to be severe in the Benguela

Current LME (UNEP 2005). There is some loss of rocky and sandy foreshores in the

region due to port construction, seawalls, resort development, and coastal diamond

mining particularly in South Africa and Namibia, and some sand mining in Angola. The

invasion of a significant stretch of coastline by the alien mussel (Mytilus galloprovincialis)

has drastically altered community structure and functional group composition on the

shore. Exploitation of some species in the kelp beds and mangroves has led to changes

in community structure within these habitats.

The potential impacts of sea level rise on the coastal areas of the Benguela Current LME

include increased coastal erosion and inundation of coastal areas. Available evidence

suggests that variability and extremes in rainfall pattern are increasing in the south,

particularly in the drier western parts (Tyson 1986, Mason et al. 1999). The resulting

projected changes in stream flow are likely to have serious consequences for the

estuaries.

Pollution, particularly microbiological, chemical and solid waste as well as eutrophication,

is expected to become worse in the future, if poorly planned urbanization and economic

development in the coastal areas of this LME continue (UNEP 2005). Habitat

modification and loss are also expected to become worse if current practices continue,

increasing the concern over the cumulative future effects on the health of this ecosystem.

IV. Socioeconomic Conditions

A large part of the population of the countries bordering the Benguela Current LME lives

in urban areas, many of which are situated near the coast. The LME and its resources

are of considerable socioeconomic importance to the bordering countries. For example,

the production of oil and gas off the coast is the most important economic activity in

Angola, contributing 90% of the total Gross Domestic Product (GDP). The fisheries

sector is an important source of revenue, food, and employment in the three countries.

Traditionally, fisheries have contributed significantly to the livelihoods of coastal

communities. In Angola, this sector currently rates third after oil and diamond mining,

and is estimated to provide half of the animal protein consumed in the country. Fishing

contributes 9% to Namibia's GDP (SADC 2003), with annual fisheries exports worth over

225 million US$. Although the fisheries sector plays a small part in South Africa's

112

1. Benguela Current LME

economy, contributing about 1% to GDP (FAO 2006), it makes a significant contribution

to the regional economy of the Western Cape, which is the centre for the industrial

fisheries. In some coastal areas of South Africa, this sector is the dominant employer.

Fisheries constitute an important contribution to national revenue, employment, and food

security in the bordering countries. These include a variable and uncertain job market,

loss of national revenue, loss of food security, erosion of sustainable livelihoods, missed

opportunities through underutilisation and wastage, and loss of competitive edge on

global markets (GEF/UNDP/UNOPS/NOAA 1999). Unpredictable fisheries yields have

sometimes resulted in closure of fish processing plants. Conflicts between subsistence,

artisanal, commercial, and recreational fisheries also arise when resources become

scarce. Subsistence fisheries depletion may adversely affect the diet and consequently

the health of those dependent on fisheries. In many coastal settlements fishing is the only

source of livelihood for the poorer segments of the population. Reduced fisheries

resources also lead to migration of human populations from rural coastal areas to cities,

resulting in expansion of urban poverty. Regime shifts as well as factors possibly related

to climate change may displace fish stocks, contributing to socio-economic difficulties and

threats to breeding populations of endemic species, e.g. African penguin.

V. Governance

The Benguela Current LME is located within the UNEP Regional Seas for the West and

Central Africa Region, which was forged in the early 1980s. The West and Central

African Action Plan for the Protection and Development of the Marine Environment and

Coastal Areas of the West and Central African Region, the Abidjan Convention for Co-

operation in the Protection and Development of the Marine and Coastal Environment of

the West and Central African Region (Abidjan Convention) and associated Protocol

Concerning Co-operation in Combating Pollution in Cases of Emergency were adopted

by the Governments of the region in 1981. Projects on contingency planning, pollution,

coastal erosion, environmental impact assessment, environmental legislation and marine

mammals soon followed. A Conference of Plenipotentiaries, which met in Dakar,

Senegal, in 1991, adopted the Regional Convention on Fisheries Cooperation among

African States bordering the Atlantic Ocean (Dakar Convention), to which Angola has

acceded.

There is a strong need for harmonising legal and policy objectives and for developing

common strategies for resource surveys, as well as investment in sustainable ecosystem

management in the Benguela Current LME. In 1997 a major regional cooperative

initiative (BENEFIT: BENguela-Environment-Fisheries-Interaction and Training

Programme) was launched jointly by Angola, Namibia, and South Africa, together with

foreign partners (Norway and Germany) to enhance science capacity required for the

optimal and sustainable utilization of living resources of the Benguela Current LME. This

programme has been remarkably successful in developing cooperation among the three

countries and in helping to strengthen marine scientific capacity in the region. A GEF

grant and in-kind support of 38 million US$ to Angola, Namibia and South Africa, the

three countries participating in the Benguela Current LME assessment and management

project, will allow for significant additional support for initiating time-series measurement

of selected indicators of the ecosystem's productivity, fish and fisheries, pollution and

ecosystem health, and socioeconomics.

In March 2000, this regional cooperation was further enhanced with the initiation of the

implementation phase of the Benguela Current LME Programme (www.bclme.org), to

assist Angola, Namibia, and South Africa to assess and manage the marine resources of

the LME in an integrated and sustainable manner. This programme, which is funded in

part by the GEF and the 3 participating countries, chiefly addresses transboundary

I West and Central Africa

113

problems in three key areas of activity: the sustainable management and utilisation of

living resources; the assessment of environmental variability, ecosystem impacts and

improvement of predictability; and maintenance of ecosystem health and management of

pollution. Through this project, the Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis (TDA) and

Strategic Action Plan (SAP) were used to review the existing knowledge on the status of,

and to identify the threats to the Benguela Current LME. One of the main goals of the

BCLME Programme was the creation of the Benguela Current Commission. This

process was formalised through the signing of an Interim Agreement by the three

countries on 29 August 2006 in Cape Town. This transitional management entity, which

will last for four years, will be the precursor of the fully-fledged Benguela Current

Commission whose function and responsibilities will be to implement an ecosystem

approach to ocean governance in the Benguela region. This will include annual stock

assessments of key economic species, annual ecosystem reports, the provision of advice

on harvesting resource levels and other matters related to sustainable resource use,

particularly fisheries and the management of the Benguela Current LME as a whole.

References

Barange, M., Hampton, I. and Roel, B.A. (1999). Trends in the abundance and distribution of

anchovy and sardine on the South African continental shelf in the 1990s, deduced from

acoustic surveys. South African Journal of Marine Science 21: 367-391.

Barange, M. and Pillar, S.C. (1992). Cross-shelf circulation, zonation and maintenance

mechanisms of Nyctiphanes capensis and Euphausia hanseni (Euphausiacea) in the northern

Benguela upwelling system. Continental Shelf Research 12(9): 1027-1042.

Belkin, I.M. (2008) Rapid warming of Large Marine Ecosystems, Progress in Oceanography, in

press.

Belkin, I.M. , Cornillon, P.C., and Sherman, K. (2008) Fronts in Large Marine Ecosystems of the

world;s oceans. Progress in Oceanography, in press.

Crawford, R.J.M., Shannon, L.V. and Shelton, P.A. (1989). Characteristics and management of the

Benguela as a Large Marine Ecosystem, p 169-219 in: Sherman, K. and Alexander, L.M. (eds),

Biomass Yields and Geography of Large Marine Ecosystems. AAAS Selected Symposium 111.

Westview Press. Boulder, Colorado.

Crawford, R.J.M. (1998). Responses of African penguins to regime changes of sardine and

anchovy in the Benguela System, p 355-364 in: Pillar, S.C., Moloney, C.L. Payne, A.I.L. and

Shillington, F.A. (eds), Benguela Dynamics: Impacts of Variability on Shelf - Sea Environments

and their Living Resources. South African Journal of Marine Science 19.

Crawford, R.J.M. (1999). Seabird responses to long-term changes in prey resources off Southern

Africa, p 688-705 in: Adams, N. and Slotow, R. (eds), Proceedings of 22nd International

Ornithological Congress, Durban. Birdlife South Africa, Johannesburg, South Africa.

Crawford, R.J.M., Shannon, L.V. and Pollock, D.E. (1987). The Benguela Ecosystem. Part VI. The

major fish and invertebrate resources. Oceanography and Marine Biology 25:353-505.

Crawford, R.J.M., Underhill, L.G., Raubenheimer, C.M., Dyer, B.M. and Martin, J. (1992). Top

predators in the Benguela ecosystem implications of their trophic position, p 95-99 in: Payne,

A.I.L., Brink, K.J., Mann, K.J. and Hilborn, R. (eds), Benguela Trophic Functioning. South

African Journal of Marine Science 12.

FAO (2003). Trends in Oceanic Captures and Clustering of Large Marine Ecosystems Two

Studies Based on the FAO Capture Database. FAO Fisheries Technical Paper 435.

FAO (2006). Fisheries country profiles. www.fao.org/fi/fcp/fcp.asp

Fidel, Q. and O'Toole, M.J. (2007). Changing State of the Benguela LME: Forcing, Climate

Variability and Ecosystem Impacts. Presentation to the 2nd Global Conference on Large Marine

Ecosystems,11-13 September 2007,Qingdao, PR China. Available online at

www.ysfri.ac.cn/GLME-Conference2-Qingdao/ppt/18.1.ppt.

GEF/UNDP/UNOPS/NOAA (1999). Benguela Current Large Marine Ecosystem Transboundary

Diagnostic Analysis.

GEF/UNDP/UNOPS/NOAA (2002). Benguela Current Large Marine Ecosystem Strategic Action

Programme.

114

1. Benguela Current LME

Hampton, I., Boyer, D.C., Penney, A.J., Pereira, A.F. and Sardinha, M. (1999). Integrated Overview

of Fisheries of the Benguela Current Region: A Synthesis Commissioned by the United Nations

Development Programme (UNDP) as an Information Source for the Benguela Current Large

Marine Ecosystem (BCLME) Programme. Thematic Report 1: Synthesis and Assessment of

Information on the BCLME. UNDP, Windhoek, Namibia.

Hamukuaya, H., M.J. O'Toole and P.M.J. Woodhead (1998). Observations of severe hypoxia and

offshore displacement of Cape hake over the Namibian shelf in 1994. S. Afr. J. Mar. Sci. 19:57-

59.

Lynam, C.P., Gibbon, M.J., Axelsen, B.E., Sparks, C.A.J., Coetzee, J., Heywood, B.G. and

Brierley, A.S. (2006). Jellyfish overtake fish in a heavily fished ecosystem. Current Biology 16

(13): R492-R493.

Mason, S.J., Waylen, P.R., Mimmack, G.M., Rajaratnam, B. and Harrison, M.J. (1999). Changes in

extreme rainfall events in South Africa. Climate Change 41:249-257.

Meeuwis, J.M. and Lutjeharms, J.R.E. (1990). Surface thermal characteristics of the Angola-

Benguela front. South African Journal of Marine Science 9: 261-279.

O'Toole, M.J., Shannon L.V. de Barros Neto, and Malan, D.E. (2001). Integrated Management of

the Benguela Current Region A Framework for Future Development. P.228-251 In: B. von

Bodungen and R.K. Turner (eds): Science and Integrated Coastal Management, Dahlem

University Press, Berlin.

O'Toole, M.J. (1996). Namibia's marine environment. Namibia Environment 1:51-55.

Palomares, M.D. and Pauly, D. (2004). Biodiversity of the Namibian Exclusive Economic Zone: a

brief review with emphasis on online databases. p. 53-74 in: U.R. Sumaila, Boyer, D., Skogen,

M.D. and Steinshamm, S.I. (eds.) Namibia's fisheries: ecological, economic and social aspects.

Eburon Academic Publishers, Amsterdam.

Pauly, D. and Christensen, V. (1995). Primary production required to sustain global fisheries.

Nature 374: 255-257.

Pauly, D., Christensen, V., Dalsgaard, J., Froese R. and Torres, F.C. Jr. (1998). Fishing down

marine food webs. Science 279: 860-863.

Pauly, D. and Watson, R. (2005). Background and interpretation of the `Marine Trophic Index' as a

measure of biodiversity. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society: Biological Sciences

360: 415-423.

SADC (2003). Official SADC Trade Industry and Investment Review 2003. www.sadcreview.com/

Sea Around Us (2007). A Global Database on Marine Fisheries and Ecosystems. Fisheries Centre,

University British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada. www.seaaroundus.org/lme/SummaryInfo

.aspx?LME=29

Shannon, L.V., ed. (1985). South African ocean colour and upwelling experiment. Sea Fisheries

Research Institute, Cape Town.

Shannon, L.V., Agenbag, J.J. and Buys, M.E.L. (1987). Large- and mesoscale features of the

Angola-Benguela Front. South African Journal of Marine Science 5: 11-34.

Shannon, L.V. and O'Toole, M.J. (1998). An Overview of the Benguela Ecosystem. Collected

papers, First Regional Workshop, Benguela Current Large Marine Ecosystem (BCLME)

Programme, UNDP. 22-24 July 1998, Cape Town, South Africa.

Shannon, L.V. and O'Toole, M.J. (1999). Integrated Overview of the Oceanography and

Environmental Variability of the Benguela Current Region: Thematic Report 2, Synthesis and

Assessment of Information on BCLME: October 1998, UNDP, Windhoek, Namibia.

Shannon, L.V. and O'Toole, M.J. (2003). Sustainability of the Benguela: Ex Africa semper aliquid

novi, p 227-253 in: Hempel, G. and Sherman, K. (eds), Large Marine Ecosystems of the World

Trends in Exploitation, Protection and Research. Elsevier, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Shannon, V., Hempel, G., Melanotte-Rizzoli, P., Moloney, C. and Woods, J. eds. (2006). Benguela:

Predicting a Large Marine Ecosystem. Elsevier Science

Sherman, K. (2003). Physical, biological, and human forcing of biomass yields in Large Marine

Ecosystems. ICES CM2003/P: 12.

Shillington, F.A. (1998). The Benguela upwelling system off southwestern Africa, p 583-604 in:

Robinson, A.R. and Brink, K.H. (eds), The Sea, Vol. 11: The Global Coastal Ocean, Regional

Studies and Syntheses. John Wiley and Sons, New York.

Taljaard, S., Morant, P.D., van Niekerki, L. and Lita, A. (2006). Southern Africa, p 29 - 49 in:

UNEP/GPA (2006), The State of the Marine Environment: Regional Assessments. UNEP/GPA,

The Hague.

Tapscott, C. (1999). An Overview of the Socioeconomics of some Key Maritime Industries in the

Benguela Current Region (Draft): A Synthesis Commissioned by the United Nations

Development Programme (UNDP) as an Information Source for the Benguela Current Large

I West and Central Africa

115

Marine Ecosystem (BCLME) Programme. Thematic Report 6: Synthesis and Assessment of

Information on theBCLME. UNDP, Windhoek, Namibia.

Tarr, R.J.Q. (2000). The South African abalone (Haliotis midae) fishery: A decade of challenges

and change. Journal of Shellfish Research 19(1):537.

Tarr, R.J.Q., Williams, P.V.G. and Mackenzie, A.J. (1996). Abalone, sea urchins and rock lobster: a

possible ecological shift may affect traditional fisheries. South African Journal of Marine

Science 17:319-324.

Tarr, R.J.Q., Williams, P.V.G., Mackenzie, A.J., Plaganyi, E. and Moloney, C. (2000). South African

fishery independent abalone surveys. Journal of Shellfish Research 19(1):537.

Tyson, P.D. (1986). Climate Change and Variability in Southern Africa. Oxford University Press,

Cape Town, South Africa.

UNEP (2005). Prochazka, K., Davies, B., Griffiths, C., Hara, M., Luyeye, N., O'Toole, M.,

Bodenstein, J., Probyn, T., Clark, B., Earle, A., Tapscott, C. and Hasler, R. Benguela Current,

GIWA Regional assessment 44. University of Kalmar, Kalmar, Sweden.

http://www.giwa.net/publications/r44.phtml

van der Lingen, C.D., Shannon, L.J., Cury, P., Kreiner, A., Moloney, C.L., Roux, J-P, Vaz-Velho, F.

(2006). Resource and ecosystem variability, including regime shifts, in the Benguela Current

system. P.156 in Shannon, V., Hempel, G., Malanotte-Rizzoli, Paola, Moloney, C., Woods, J.,

eds. Benguela: Predicting a Large marine Ecosystem. Elsevier, Amsterdam, p.156.

Walmsley-Hart, S.A., Sauer, W.H.H. and Leslie, R.W. (2000). The quantification of by-catch and

discards in the South African demersal trawling industry. 10th Southern African Marine Science

Symposium (SAMSS 2000): Land, Sea and People in the New Millennium.

Weeks, S.J., Currie, B., Bakun, A. and Peard, K.R. (2004). Hydrogen sulphide eruptions in the

Atlantic Ocean off Southern Africa: Implications of a new view based on SeaWiFS satellite

imagery. Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers 51(2):153-172.

Willemse, N.E. and Pauly, D. (2004). Reconstruction and interpretation of marine fisheries catches

from Namibian waters, 1950 to 2000. p. 99-112 in: U.R. Sumaila, Boyer, D., Skogen, M.D. and

Steinshamm, S.I. (eds.) Namibia's fisheries: ecological, economic and social aspects. Eburon

Academic Publishers, Amsterdam.

116

1. Benguela Current LME

I-2 Guinea Current LME

S. Heileman

The geographical boundaries of the Guinea Current LME extend from the intense

upwelling area of the Guinea Current in the north, to the northern seasonal limit of the

Benguela Current in the south. While the northern border of the Guinea Current is

distinct, but with seasonal fluctuations, its southern boundary is less well-defined, and is

formed by the South Equatorial Current (Binet & Marchal 1993). Sixteen countries border

the LME - Angola, Benin, Cameroon, Congo, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Côte

d'Ivoire, Gabon, Ghana, Equatorial Guinea, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Nigeria, São

Tomé and Principe, Sierra Leone and Togo. The tropical climate of the region is

influenced by the northward and southward movements of the Inter-Tropical

Convergence Zone (ITCZ) associated with the southwest monsoon and the Northeast

Trade Winds. This LME covers an area of about 2 million km2, of which 0.33% is

protected, and includes 0.15% of the world's sea mounts and 0.20% of the world's coral

reefs (Sea Around Us 2007). Twelve major estuaries and river systems (including the

Cameroon, Lagos Lagoon, Volta, Niger-Benoue, Sanaga, Ogooue, and Congo rivers)

form an extensive network of catchment basins enter this LME, which has the largest

continental shelf in West Africa, although it should be noted that the West Africa's shelf is

relatively narrow compared with many other shelves of the World Ocean. A volume on

this LME was edited by McGlade et al. (2002), while another (Chavance et al. 2004)

contains numerous accounts on this system. Other articles and reports include Binet &

Marchal (1993), UNEP (2004) and Ukwe & Ibe (2006).

I. Productivity

The Guinea Current LME is a Class I, highly productive ecosystem (>300 gCm-2y-1). The

Guinea Current LME is characterised by seasonal upwelling off the coasts of Ghana and

Côte d'Ivoire, with intense upwelling from July to September weakening from about

January to March (Roy 1995). Seasonal upwelling drives the biological productivity of

this LME, which includes some of the most productive coastal and offshore waters in the

world. The cold, nutrient-rich water of the upwelling system is subject to strong seasonal

and inter-annual changes (Demarcq & Aman 2002, Hardman-Mountford & McGlade

2002), linked to the migration of the ITCZ. The LME is subject to long-term variability

induced by climatic changes (Binet & Marchal 1993). Changes in meteorological and

oceanographic conditions such as a reduction of rainfall, an acceleration of winds, an

alteration of current patterns, and changes in nearshore biophysical processes might

have significant consequences for biological productivity (Koranteng 2001). The coastal

habitats and marine catchment basins also play an important role in maintaining the

LME's productivity (Entsua-Mensah 2002).

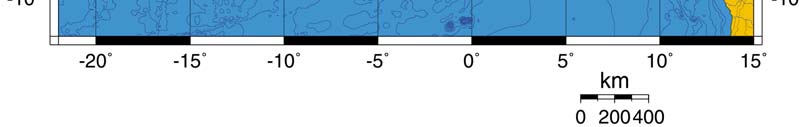

Oceanic fronts (Belkin et al. 2008): Fronts in the Guinea Current occur mainly off its

northern coast, in winter and summer (Figure I-2.1). The winter front appears to be the

easternmost extension of the coastal Guinea Current that penetrates the Gulf; the front

fully develops in January-February, reaching 5°E by March. The summer front emerges

largely off Cape Three Points (2°W), usually in July-September, the upwelling season in

the Gulf, and sometimes extends up to 200 km from the coast. Wind-induced upwelling

develops east of Cape Palmas (7.5°W) and Cape Three Points owing to the coast's

orientation relative to the prevailing winds. Current-induced upwelling and wave

118

2. Guinea Current LME

propagation also contribute to the observed variability in the Gulf (Ajao & Houghton

1998).

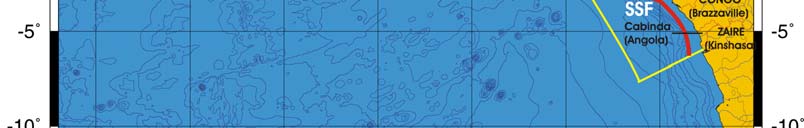

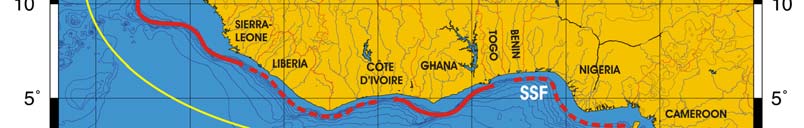

Figure I-2.1. Fronts of the Guinea Current LME. EF, Equatorial Front; SSF, Shelf-Slope Front (solid line,

well-defined path; dashed line, most probable location). Yellow line, LME boundary. After Belkin (2008).

Guinea Current LME SST (after Belkin 2008)

Linear SST trend since 1957: 0.58°C.

Linear SST trend since 1982: 0.46°C.

The thermal history of the Guinea Current (Figure 1-2.2) included (1) a relatively stable

period until the all-time minimum of 1976; (2) warming until the present at a rate of ~1°C

in 30 years. Interannual variability of this LME is rather small, with year-to-year variations

of about 0.5°C. The only conspicuous event, the minimum of 1976, cannot be linked to a

similar cold event of 1972 in the two adjacent LMEs (Canary Current, Benguela Current)

because of the 4-year time lag between the two events, which seems too long for oceanic

advective transport of cold anomalies from one LME to another. The only plausible

explanation invokes a cold offshore anomaly, probably localized within the equatorial

band. Indeed, the North Brazil Shelf LME located on the western end of the equatorial

zone saw the all-time SST minimum in 1976, the same year as the all-time minimum in

the Guinea Current LME. Since the equatorial zone offers a fast-track conduit for

oceanic anomalies, it remains to be seen from high-resolution data if both minima were

truly synchronous hence caused by large-scale (ocean-wide) forcing or whether this

cold anomaly propagated along the equator from one LME to another across the Atlantic

Ocean.

I West and Central Africa

119

The above results are consistent with an analysis of AVHRR SST data from 1982-1991

(Hardman and McGlade, 2002). The latter study has found 1982-1986 and 1987-1990 to

be cool and warm periods respectively, with 1984 being exceptionally warm. As can be

seen from Hadley data, 1984 was exceeded first by 1988 and then by 1998, when SST

reached the all-time maximum probably linked to El-Niño. The SST variability mirrors the

upwelling intensity, with strong upwelling in 1982-83, and weak upwelling in 1984 and

1987-1990 (Hardman and McGlade, 2002).

Figure I-2.2 Guinea Current LME mean annual SST (left) and SST anomalies (right), 1957-2006, based

on Hadley climatology. After Belkin (2008).

Guinea Current Trends in Chlorophyll and Primary Productivity: The Guinea

Current LME is a Class I, highly productive ecosystem (>300 gCm-2y-1).

Figure I-2.3 Guinea Current LME trends in chlorophyll a (left) and primary productivity (right), 1998-

2006. Values are colour coded to the right hand ordinate. Figure courtesy of J. O'Reilly and K. Hyde.

Sources discussed p. 15 this volume.

II. Fish and Fisheries

The Guinea Current LME is rich in living marine resources. These include locally

important resident stocks supporting artisanal fisheries, as well as transboundary

straddling and migratory stocks that have attracted large commercial offshore foreign

120

2. Guinea Current LME

fishing fleets. Exploited species include small pelagic fishes (e.g., Sardinella aurita,

Engraulis encrasicolus, Caranx spp.), large migratory pelagic fishes such as tuna

(Katsuwonus pelamis, Thunnus albacares and T. obesus) and billfishes (e.g., Istiophorus

albicans, Xiphias gladius), crustaceans (e.g., Penaeus notialis, Panulirus regius),

molluscs (e.g., Sepia officinalis hierredda), and demersal fish (e.g., Pseudotolithus

senegalensis, P. typus, Lutjanus fulgens) (Mensah & Quaatey 2002). Several fishery

resource surveys have been conducted in the LME (Koranteng 1998, Mensah & Quaatey

2002), with the Guinean Trawling Survey conducted in 1963-1964 having been the first

large-scale survey in West African waters (Williams 1968). Data from this survey have

recently been recovered (Zeller et al. 2005).

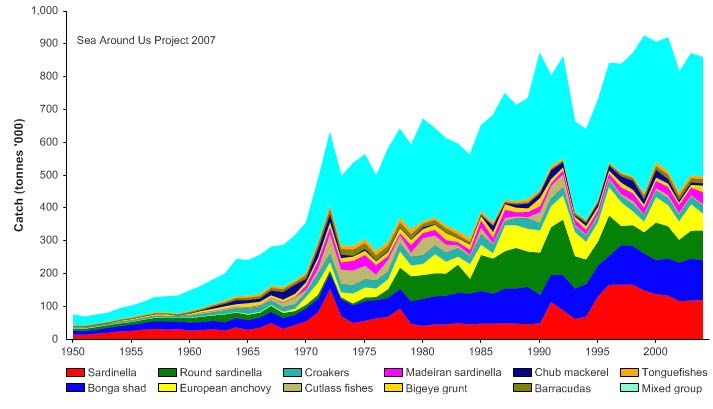

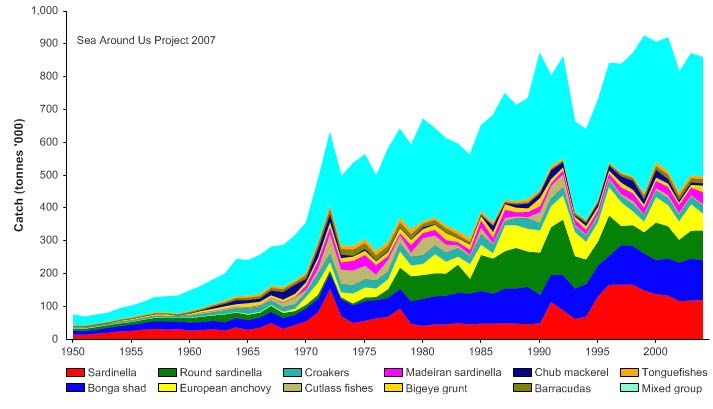

Total reported landings show a series of peaks and troughs, although there has been an

overall trend of a steady increase from 1950 to the early 1990, followed by fluctuations

with a peak at just over 900,000 tonnes (Figure I-2.4). Due to the poor species break-

down in the official landings statistics, a large proportion of the landings falls in the

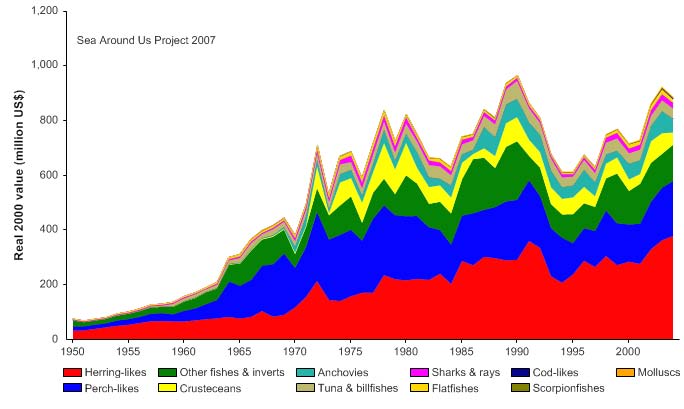

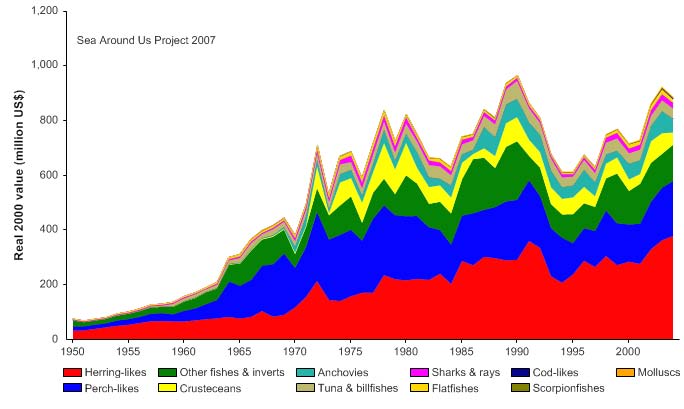

category named `mixed groups'. The trend in the value of the reported landings

increased to a peak of around US$ 1 billion (in 2000 US dollars) in 1991 and thereafter

declined considerably until the mid 1990s, before recovering to just over US $800 million

(Figure I-2.5). Nigeria and Ghana account for about half of the reported landings in this

LME, while European Union countries such as Spain and France, as well as Japan, are

among the foreign countries fishing in the LME in recent times. Since the 1960s, high

fishing pressure by foreign and local industrial fleets has placed the fisheries in the LME

at risk (Bonfil et al.1998; Kacynski & Fluharty 2002).

Figure I-2.4. Total reported landings in the Guinea Current LME by species (Sea Around Us 2007).

I West and Central Africa

121

Figure I-2.5. Value of reported landings in the Guinea Current LME by commercial groups (Sea Around

Us 2007).

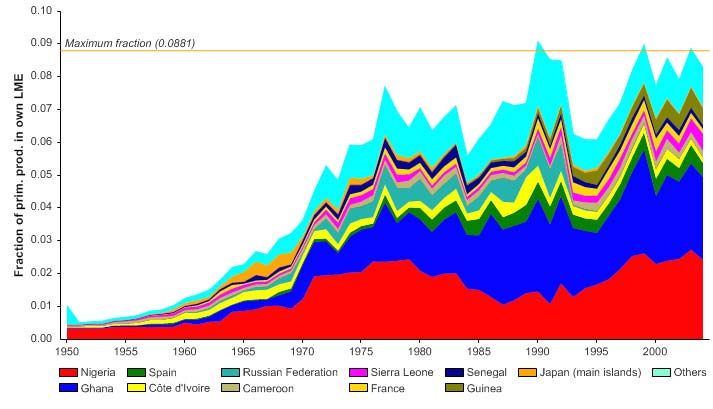

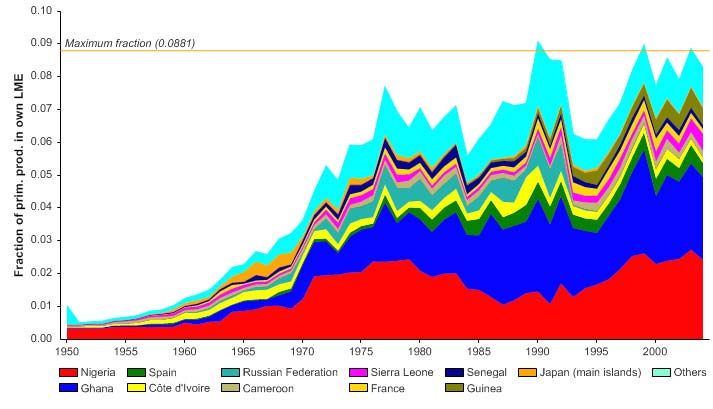

The primary production required (PPR; Pauly & Christensen 1995) to sustain the reported

landings in the LME reached 9% of the observed primary production in the early 1990s

and has fluctuated between 6 to 9% (Figure I-2.6). Nigeria and Ghana account for the

two largest ecological footprints in the LME.

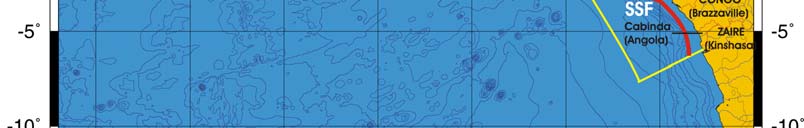

Figure I-2.6. Primary production required to support reported landings (i.e., ecological footprint) as

fraction of the observed primary production in the Guinea Current LME (Sea Around Us 2007). The

`Maximum fraction' denotes the mean of the 5 highest values.

Since the mid 1970s, the mean trophic level of the reported landings (i.e., MTI; Pauly &

Watson 2005) has declined (Figure I-2.7 top), an indication of a `fishing down' of the local

food webs (Pauly et al. 1998). The FiB index, on the other hand, has remained stable

122

2. Guinea Current LME

(Figure I-2.7 bottom), suggesting that the increase in the reported landings over this

period has compensated for the decline in the MTI (Pauly & Watson 2005).

Figure I-2.7. Trophic level (i.e., Marine Trophic Index) (top) and Fishing-in-Balance Index (bottom) in the

Guinea Current LME (Sea Around Us 2007).

The Stock-Catch Status Plots show that fisheries on collapsed stocks are rapidly

increasing in numbers (Figure I-2.8, top). However, the catch is still overwhelmingly

supplied by stocks in the fully exploited category (Figure I-2.8, bottom), which account for

just under 30% of the stocks.

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

0%

100

10%

90

20%

)

80

%

(

s

30%

u

70

at

st

40%

y

60

b

50%

cks

50

o

f

st

60%

o

40

er

70%

mb

30

Nu

80%

20

90%

10

100%0

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

(n = 4762)

developing

fully exploited

over-exploited

collapsed

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

0%

100

10%

90

20%

80

)

30%

(

%

70

s

u

at

40%

60

st

ck

50%

o

50

st

y

60%

b

h

40

c

70%

Cat

30

80%

20

90%

10

100%0

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

(n = 4762)

developing

fully exploited

over-exploited

collapsed

Figure I-2.8. Stock-Catch Status Plots for the Guinea Current LME, showing the proportion of

developing (green), fully exploited (yellow), overexploited (orange) and collapsed (purple) fisheries by

number of stocks (top) and by catch biomass (bottom) from 1950 to 2004. Note that (n), the number of

`stocks', i.e., individual landings time series, only include taxonomic entities at species, genus or family

level, i.e., higher and pooled groups have been excluded (see Pauly et al., this vol. for definitions).

I West and Central Africa

123

While some fish stocks such as skipjack tuna, small pelagic fish in the northern areas of

the Gulf of Guinea, and offshore demersal fish and cephalopods are underexploited

(Mensah & Quaatey 2002), the level of exploitation was found to be significant in this

LME (UNEP 2004). The Guinea Current LME TDA (see Governance) has identified the

decline in fish stocks and unsustainable fishing as a major transboundary problem

(UNIDO/ UNDP/ UNEP/ GEF/ NOAA 2003) and reviews of the status of the LME's

fisheries resources indicate that several fish stocks are either overexploited or close to

being fully exploited (Ajayi 1994, Mensah & Quaatey 2002). These include small

pelagics and shrimps in the western and central Gulf of Guinea and coastal demersal

resources throughout the LME. There is also evidence of depletion of straddling and

highly migratory fisheries stocks, with heavy exploitation of yellow-fin and big-eye tunas

(Mensah & Quaatey 2002). Overexploitation has resulted in declining stock biomass and

catch per unit effort (CPUE), particularly for inshore demersal species, and this decline

has been attributed to trawlers operating in inshore areas (Koranteng 2002, Koranteng &

Pauly 2004).

The use of small-sized mesh, especially in trawl, purse and beach seine nets is a

widespread problem, especially in the central part of the region. This practice leads to

excessive bycatch, but because these catches, mainly of juvenile fishes, are generally

utilised, they are discarded only in a few fisheries (e.g., the shrimp fishery). Other

destructive fishing practices such as the use of explosives and chemicals are also

common in the inshore areas (e.g., see Vakily 1993).

There are indications that overexploitation has altered the ecosystem as a whole, with

impacts at all levels, including top predators. Species diversity and average size of the

most important fish species have declined as a result of overexploitation (Koranteng

2002, FAO 2003). Strong patterns of fish variability in the LME are thought to be related

to strong interactions between species or communities, as well as to environmental

forcing (Cury & Roy 2002). The influence of environmental variability on fish stock

abundance and distribution in the LME has been demonstrated, for example, by Williams

(1968), Koranteng et al. (1996), and Roy et al. (2002). Several oceanographic features

that influence fish recruitment have also been identified (Hardman-Mountford & McGlade

2002). For instance, the abundance and distribution of small pelagic fish species are

controlled mainly by the intensity of the seasonal coastal upwelling, which also

determines the period of the main fishing season (Bard & Koranteng 1995).

The most significant changes in species abundance are reflected in sardinella (Sardinella

aurita) and triggerfish (Balistes capriscus). The sardinella fishery experienced a collapse

in 1973, and was followed by a vast increase in the abundance of triggerfish between

1973 and 1988. The decline of the triggerfish after 1989 was followed by an increase of

the sardinella to unprecedented levels during the 1990s (Binet & Marchal 1993, Cury &

Roy 2002). Koranteng & McGlade (2002) attributed the almost complete disappearance

of the triggerfish after the late 1980s to environmental changes and an upwelling

intensification off Ghana and Côte d'Ivoire. The highly variable environment of the

Guinea Current LME contributes to uncertainty regarding the status of fisheries stocks

and yields which is likely to increase considering the impact of global climate change

(UNIDO/UNDP/ UNEP/ GEF/ NOAA 2003). Therefore, environmental variability must be

considered in the sustainable use and management of the region's fisheries resources.

Cooperation among the countries bordering this LME in the management of the fisheries

resources would help to improve the fisheries situation in the future.

124

2. Guinea Current LME

III. Pollution and Ecosystem Health

Pollution: LMEs have experienced various stresses as a result of the intensification of

human activities. The coastal and marine environments of the Guinea Current are

seriously polluted in the vicinity of large cities (Scheren & Ibe 2002). An assessment of

the state of the environment with respect to the GPA land-based sources of pollution in

this region is given by Gordon & Ibe (2006). More than 60% of existing industries are

concentrated in the coastal areas and an estimated 47% of the population lives within

200 km of the coast. Pollution from land-based sources is particularly important, and

together with sea-based sources, has contributed to a deterioration of water quality in the

bordering countries. The TDA has identified the deterioration of water quality from land

and sea-based activities as one of the four broad environmental problems in the LME

(UNIDO/UNDP/UNEP/GEF/NOAA 2003). Overall, pollution was assessed as moderate,

but more serious in coastal hotspots associated with the larger coastal cities (UNEP

2004). Despite being mainly localised, pollution also has transboundary impacts in this

LME through the transport of contaminants by wind and water currents along the coast.

Sewage is one of the main sources of coastal pollution in the LME (UNEP 1999) and

arises from generally poor treatment facilities and widespread release of untreated

sewage into coastal areas (Scheren & Ibe 2002). Microbiological pollution is localised

around coastal cities and remains a problem in terms of human health. Organic pollution

from domestic, industrial and agricultural wastes has resulted in eutrophication and

oxygen depletion in some coastal areas (Awosika & Ibe 1998, Scheren & Ibe 2002).

While the incidence of eutrophication is not widespread and tends to be episodic, there

are instances of continuous and persistent causes of eutrophication in large coastal water

bodies (e.g., the Ebrié Lagoon in Abidjan). The increasing occurrence of HABs is of

concern to the bordering countries (Ibe & Sherman 2002). Pollution from solid waste

originating from domestic and industrial sources and offshore activities is severe across

the entire region, with the enormous bulk of solid waste produced daily being a serious

threat. Pollution from suspended solids is moderate along the coast, and arises mainly

from soil loss from farms and deforested areas. Although much of the silt is trapped in

dams and reservoirs, this has caused extensive siltation of coastal water bodies.

Chemical pollution is serious in coastal hotspots. Some chemical contaminants enter the

aquatic environment through the use of pesticides, agro-chemicals including persistent

organic pollutants (POPs) and as industrial effluents. Large quantities of residues (e.g.,

phosphate, mercury, zinc) from mining operations are discharged into coastal waters. Oil

production is an important activity in some of the countries, especially Nigeria, and most

of these countries have important refineries on the coast, only a few of which have proper

effluent treatment plants. Moreover, the LME's coastline lies to the east and downwind of

the main oil transport route from the Middle East to Europe. Pollution from spills is

significant, and arises mainly from oil spills from production points, loading and discharge

points and from shipping lanes. Significant point sources of marine pollution have been

detected around coastal petroleum mining and processing areas, releasing large

quantities of oil, grease and other hydrocarbon compounds into the coastal waters of the

Niger delta and off Angola, Cameroon, Congo and Gabon. It is estimated that about

4 million tonnes of waste oil are discharged annually into the LME from the Niger Delta

sub-region (UNIDO/ UNDP/ UNEP/ GEF/ NOAA 2003). Much of the oil found on

beaches originates from spills or tank washing discharged from tankers in the region's

ports (Portmann et al.1989). Because of the wind and ocean current patterns in the

Guinea Current LME, any oil spill from the offshore or shore-based petroleum activities

could easily become a regional problem.

Habitat and community modification: The Guinea Current LME is interspersed with

diverse coastal habitats such as lagoons, bays, estuaries and mangrove swamps.

I West and Central Africa

125

Besides being important reservoirs of biological diversity, these habitats provide

spawning and breeding grounds for many fish, including transboundary species and

shellfish in the region, and therefore are the basis for the regenerative capacity of the

region's fisheries (Ukwe et al. 2001). Both anthropogenic activities and natural

processes threaten these habitats. Although this is mainly localised, there are

transboundary impacts related to migratory and straddling fish stocks that may use these

habitats as spawning and nursery grounds.

It is estimated that 30% of habitat modification has been caused by natural processes,

including erosion and sedimentation due to wave action and strong littoral transport.

Coastal erosion is the most prevalent coastal hazard in the LME. Human activities, on

the other hand, are thought to be largely responsible for habitat modification in this LME

(UNEP 1999). Habitat and biodiversity loss due to hydrocarbon exploration and

exploitation is significant. Many coastal wetlands have been reclaimed for residential and

commercial purposes, with accompanying loss of wetland flora and fauna. The

introduction of exotic species is also recognised as a transboundary problem

(UNIDO/UNDP/UNEP/GEF/NOAA 2003).

Mangroves and estuaries have suffered the most losses, followed by sandy foreshores

and lagoons. The LME has large expanses of mangrove forests (the mangrove system

of the Niger Delta is the third largest in the world). However, these mangrove forests are

under pressure from over-cutting, conversion into agricultural farms or saltpans, erosion,

salinity changes, and other anthropogenic impacts (e.g., pollution). About 60% of

Guinea's original mangroves and nearly 70% of the original mangrove vegetation of

Liberia is estimated to be lost (Macintosh & Ashton 2002). The grass Paspalum

vaginatum is replacing the original mangrove vegetation in these countries. In other

areas the extent of mangrove destruction is: 45% in the Lake Nokoue area (Benin), 33%

in the Niger delta (Nigeria), 28% in the Warri Estuary (Cameroon) and 60% in Côte

d'Ivoire. Dam construction has led to reduction of freshwater and sediment discharge in

the lower estuarine reaches of the rivers and altered the extent of intrusion of the

estuarine salt wedge inland. This has important ecological effects on the flora and fauna

of the coastal habitats.

Climate change is expected to also lead to habitat modification and loss. The IPCC

(2001) has reported that Africa is highly vulnerable to climate change and sea level rise.

Studies conducted in Nigeria estimated that over 1,800 km2, or 2% of Nigeria's coastal

zone, and about 3.68 million people would be at risk from a 1 m rise in sea level (Awosika

et al. 1992). Moreover, Nigeria could lose over 3,000 km2 of coastal land from floods and

coastal erosion by the end of the 21st Century. Sea level rise would result in modification

or loss of flora, fauna and biodiversity in flooded lands and coastal habitats, particularly in

brackish waters (Ibe & Ojo 1994).

The LME is an important reservoir of marine biological biodiversity and has natural

resources of global significance. Green, leatherback, hawksbill, loggerhead and olive

ridley turtles are found in the LME. The LME is also inhabited by marine mammals

(whales, dolphins, and manatees), among which are the Atlantic humpback dolphin and

the African manatee, both of which appear on the IUCN Red List of endangered species

(IUCN 2002). The humpbacked dolphin is classified as highly endangered and the

African manatee as vulnerable under the Convention on International Trade of

Endangered Species (CITES).

IV. Socioeconomic Conditions

The 16 countries bordering the Guinea Current LME have an estimated total population

of 300 million. At the present rate of population growth, this is expected to double in 20-

126

2. Guinea Current LME

25 years. Approximately 47% of the people live within 200 km of the coast (GIS analysis

based on ORNL 2003). Rapid expansion of coastal populations with areas of high

population densities has resulted from high population growth rates and movements

between rural and urban areas (UNEP 1999). In addition, many of the region's poor are

crowded in the coastal areas for subsistence activities such as fishing, farming, sand and

salt mining and production of charcoal.

The Guinea Current LME and its natural resources represent a source of economic and

food security for the bordering countries. In addition to being of major importance for

food security in this region, fisheries also provide employment for thousands of people

and are a substantial source of foreign exchange for countries such as Angola, Côte

d'Ivoire, Ghana, and Guinea. A large proportion of the population could potentially be

affected by overexploitation of fisheries (UNEP 2004). A reduction in the size and quality

of the fish catch has widespread socioeconomic impacts, since more than 500,000 men

and women along the coast from Mauritania to Cameroon are employed in the artisanal

fishery (Bortei-Doku Aryeetey 2002). In Ghana, the national fish requirement has been

estimated at 794,000 tonnes for a population of about 17.9 million, but fisheries

production in 1998 achieved only 57% of the required volume (Akrofi 2002).

Over the past three decades, there has been evidence of reduced economic returns, loss

of employment and user conflicts between artisanal and large commercial trawlers for

access to the fishery resources (ACOPS/UNEP 1998). Côte d'Ivoire reported losses of

about US$80 million in 1998 due to decreased fishing activities. This loss was attributed

to the degradation of the coastal zone and its resources (GEFMSP/ACOPS/UNESCO

2001). The overexploitation of transboundary and migratory fish by offshore foreign

fleets is having a detrimental effect on artisanal fishermen as well as on those coastal

communities that depend on the near-shore fisheries resource for food. Local

communities are at risk if artisanal fishing cannot proceed. This becomes particularly

serious in the context of exploding demographics in the coastal areas and the fact that

most of the fish catch is exported out of the region where all the countries, except Gabon,

were classified by the FAO as Low Income Food Deficit Countries in 1998 (FAO 2002).

The socioeconomic impacts of pollution and habitat degradation include loss of

recreational resources, pollution of food sources, decline in living coastal resources, and

subsequent loss of subsistence livelihoods and reduction in food security and economic

activity. In addition, increased pressure on governments to produce alternative

livelihoods, and political instability at local or national levels may also arise. Coastline

erosion also causes some concern because of the threat to coastal settlements, tourist

infrastructure, agricultural and recreational areas, harbour and navigation structures, and

oil producing and export handling facilities. The costs of coastal protection and habitat

restoration can be high. For example, the restoration of the Korle Lagoon in Ghana has

cost the government nearly US$65 million (Government of Ghana 2000). Public health

risks from the presence of sewage pathogens and HABs are of concern. The cost of

treatment of water-borne diseases is significant. For example, the Korle Lagoon

Ecological Restoration Project (Government of Ghana 2000) estimated the cost of

treatment to range from US$10 to US$50 per person, depending on the duration and

intensity of the disease.

V. Governance

The countries bordering the Guinea Current LME participate in numerous bodies that

work together on various aspects of coastal degradation and protection of living marine

resources. The LME comes under the UNEP Regional Seas Programme for the West

and Central Africa Region (see the Benguela Current LME for more information). They

I West and Central Africa

127

have adopted several international environmental conventions and agreements, among

which is the Abidjan Convention and the Dakar Convention.

Mechanisms to provide regional collaboration on transboundary issues in the form of a

regional coordination unit, and regionally agreed environmental quality standards and

monitoring protocols and methods have been limited. These and other environmental

issues are being addressed through joint projects. The GEF-supported Guinea Current

Large Marine Ecosystem Project (Ibe & Sherman 2002, Ukwe et al. 2006) is an

ecosystem-based effort to assist countries adjacent to the Guinea Current LME to

achieve environmental and resource sustainability by shifting from short-term sector-

driven management objectives to a longer-term perspective and from managing

commodities to sustaining the production potential for ecosystem-wide goods and

services (www.chez.com/gefgclme/). The pilot phase of this project (Water Pollution

Control and Biodiversity Conservation in the Gulf of Guinea Large Marine Ecosystem)

involved Côte d'Ivoire, Ghana, Togo, Benin, Nigeria and Cameroon, and ended in

November, 1999. In 1998, the Ministerial Committee of this pilot project signed the Accra

Declaration on Environmentally Sustainable Development of the Guinea Current LME, as

an expression of their common political will for the sustainable development of marine

and coastal areas of the Gulf of Guinea.

The second phase of this project `Combating Living Resource Depletion and Coastal

Area Degradation in the Guinea Current LME through Ecosystem-based Regional

Actions', has extended the pilot phase to include 10 additional countries (Angola, Congo

Brazzaville, Congo-Kinshasa, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau,

Liberia, São Tomé and Príncipe, and Sierra Leone). This phase includes the preparation

of a TDA and a SAP. A project goal is to build capacity of the countries to work jointly

and in concert with other nations, regions and with GEF projects in West Africa to define

and address priority transboundary environmental issues within the framework of their

existing responsibilities under the Abidjan Convention and the UNEP Regional Seas

Programme. The Ministers of Environment of Angola, Benin, Cameroon, Congo, Côte

d'Ivoire, Democratic Republic of Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Ghana, Guinea,

Guinea Bissau, Liberia, Nigeria, Sao Tome and Principe, Sierra Leone and Togo,

gathered in Abuja, Nigeria, 21 22 September, 2006 on the occasion of the First Meeting

of Ministers responsible for the implementation of the Guinea Current Large Marine

Ecosystem (GCLME) Project; the Ministers signed the Abuja Declaration on 22

September, establishing the framework for an Interim Guinea Current Commission. The

Interim Commission was brought into force on 22 September 2006 in Abuja, Nigeria, and

is presently operating from Accra, Ghana. The focus of the Interim Commission is on

achieving sustainable development through integration of environmental concerns in

planning,accounting and budgeting, building capacity through multi-sector participation,

management of transboundary water bodies and living resources of land, forests and

biodiversity conservation, and development of information and data exchanges.

References

ACOPS/UNEP (1998). Background Papers to the Conference on Cooperation for the Development

and protection of the Coastal and Marine Environment in Sub-Saharan Africa, 30 November-4

December 1998, Cape Town, South Africa.

Ajao, E. A. and Houghton, R.W. (1998). Coastal ocean of Equatorial West Africa from 10°N to

10°S. p 605-630 in: Robinson, A.R. and Brink, K.H. (eds). The Sea, Vol. II: The Global Coastal

Ocean, Regional Studies and Syntheses. John Wiley and Sons, New York, U.S.

Ajayi, T.O. (1994). The Status of Marine Fishery Resources of the Gulf of Guinea, in: Proceedings

of the 10th Session Food and Agricultural Organisation of the United Nations, CECAF, 10-13

October 1994, Accra, Ghana.

128

2. Guinea Current LME

Akrofi, J.D. (2002). Fish utilisation and marketing in Ghana: State of the art and future perspective,

p 345-354 in: McGlade, J., Cury, P. Koranteng, K. and Hardman-Mountford, N.J. (eds), The

Gulf of Guinea Large Marine Ecosystem: Environmental Forcing and Sustainable Development

of Marine Resources. Elsevier, The Netherlands.

Awosika, L.F. and Ibe, C.A. (1998). Geomorphic features of the Gulf of Guinea shelf and littoral drift

dynamics, p 21-27 in: Ibe, A.C., Awosika, L.F. and Aka, K. (eds). Nearshore Dynamics and

Sedimentology of the Gulf of Guinea. IOC/UNIDO. CEDA Press, Cotonou, Benin.

Awosika, L.F., French, G.T. Nicholls, R.J. and Ibe, C.A. (1992). The impacts of sea level rise on the

coastline of Nigeria, in: O'Callahan, J. (ed). Global Climate Change and the Rising Challenge of

the Sea. Proceedings of the IPCC Workshop at Margarita Island, Venezuela, 913 March 1992.

National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration, Silver Spring, U.S.

Bard, F. and Koranteng, K.A. eds. (1995). Dynamique et Usage des Ressources en Sardinelles de

l'Upwelling Cotier du Ghana et de la Cote d'Ivoire. ORSTOM Edition, Paris.

Belkin, I.M. (2008) Rapid warming of Large Marine Ecosystems. Progress in Oceanography, in

press.

Belkin, I.M., Cornillon, P.C. and Sherman K. (2008). Fronts in Large Marine Ecosystems of the

world's oceans. Progress in Oceanography, in press.

Binet, D. and Marchal, E. (1993). The large marine ecosystem of shelf areas in the Gulf of Guinea:

Long-term variability induced by climatic changes, p 104-118 in: Sherman, K., Alexander, L.M.

and Gold, B. (eds), Large Marine Ecosystems: Stress, Mitigation, and Sustainability. AAAS,

Washington D.C., U.S.

Bonfil, R., Munro, G., Sumaila, U.R., Valtysson, H., Wright, M., Pitcher, T., Preikshot, D., Haggan,

N. and Pauly, D. (1998). Impacts of distant water fleets: an ecological, economic and social