THE UNEP

LARGE MARINE ECOSYSTEMS

REPORT

A PERSPECTIVE ON CHANGING CONDITIONS IN

LMES OF THE WORLD'S REGIONAL SEAS

ii

This report may be cited as:

Sherman, K. and Hempel, G. (Editors) 2008. The UNEP Large Marine Ecosystem Report: A

perspective on changing conditions in LMEs of the world's Regional Seas. UNEP Regional Seas

Report and Studies No. 182. United Nations Environment Programme. Nairobi, Kenya.

Bound and printed in the United States

DEP/089I/HA

ISBN 978-92080702773-9

iii

A Message from the Executive Director of UNEP

The world's 64 Large Marine Ecosystems

are as much economic as they are

environmental assets contributing around

12 trillion dollars annually to the global

economy.

Increasingly the management of these

assets is beginning to reflect that

importance. Combined efforts among

coastal countries in Africa, Asia, Latin

America, and eastern Europe are now contributing to assessment and

management actions aimed at tackling coastal pollution, restoration of degraded

habitats, and recovery of depleted fish stocks.

They have been joined by United Nations agencies, the Global Environment

Facility, and a growing number of northern hemisphere countries and principle

stakeholders in fish and fisheries, coastal transportation, tourism, gas and oil

production, and diamond and mineral extraction operations.

The effort to reverse the degraded status of LMEs will take time, well-focused

and creative policies and funding. However it is clear that with the financial

assistance of the GEF and in partnership with the UN the effort has begun,

especially among the economically developing nations.

The work reflects the targets put forward at the World Summit on Sustainable

Development in Johannesburg in 2002 to achieve substantial reductions in land-

based sources of pollution; introduce an ecosystems approach to marine

resource assessment and management by 2010; designate a network of marine

protected areas by 2012 and restore and maintain fish stocks to maximum

sustainable yield levels by 2015. UNEP is among several agencies and donors

assisting developing countries to achieve these targets.

Climate change adds new urgency to this effort. Indeed the original findings in

this report have been up-dated to reflect new findings showing that in many of

the LMEs warming is proceeding at two to three times the global rate. Some of

this most rapid warming is being witnessed in northeastern North Atlantic and

around Europe and in the East Asian seas.

Pollution, such as high levels of nutrients coming from the land and the air, may

be aggravating the effect. So we must not only secure a deep and decisive

climate regime post 2012 but also tackle the wider sustainability issues to ensure

the abundant productivity of not only LMEs but the Regional Seas and oceans in

general for this and future generations.

Achim Steiner,UN Under-Secretary General and UNEP Executive Director

iv

v

A Message from the Chief Executive Officer, GEF

We live on the land yet we often forget the sea.

We forget that 70% of our planet is made up of

coastal and marine ecosystems and that our

coastal economies depend on these ecosystems

to generate sustainable communities.

Many do not know that more than half of the

carbon sequestered on the planet is attributed to

marine ecosystems; our planet's temperature is

regulated by the oceans. We take them for granted as we do the fact that

international trade in coastal and marine fisheries is a $70 billion a year business

that drives coastal economies.

While we tend to focus on a plethora of terrestrial environmental problems over

the last 35 years, we have neglected coastal and marine water pollution. The

Large Marine Ecosystems (LMEs) of our planet that span the continental shelves

and enclosed marine waters are warming, over-fished, and becoming ever more

degraded with nitrogen.

This book represents the first attempt at establishing the baseline environmental

conditions of the world's LMEs and comes from a partnership among the United

Nations Environment Programme, the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric

Administration, the Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission of UNESCO,

and the Global Environment Facility. Eighty percent of marine capture fisheries

are taken in these LMEs where billions of people reside in coastal areas.

The satellite-based time series of warming of LMEs presented in this baseline

assessment presents a stark picture. The trend of over-fishing of valuable and

less desirable species of fish based on many decades of data from the Food and

Agriculture Organization and the University of British Columbia's Sea Around Us

Project shows vast depletion of species in many LMEs to the point of

overexploitation and collapse. The authors also found there is an increased

trend expected for nitrogen pollution from land-based sources--this promises to

create more dead zones of oxygen depletion and hazardous algal blooms that

threaten human, ecosystem, and economic health.

We at the Global Environment Facility hope that the release of this global

assessment will call attention to the degraded state of many coasts and marine

waters as well as the high risk that human behavior is placing on loss of perhaps

trillions of dollars of annual goods and services. We need to stop taking these

precious resources for granted.

Monique Barbut, CEO Global Environment Facility

vi

vii

The UNEP

Large Marine Ecosystems

Report

A Perspective on Changing Conditions in LMEs of

the World's Regional Seas

Edited by

Kenneth Sherman

Director, Narragansett Laboratory and Office of Marine Ecosystem Studies,

NOAA-NMFS, Northeast Fisheries Science Center

Narragansett, Rhode Island, USA

Adjunct Professor of Oceanography, Graduate School of Oceanography

University of Rhode Island, Narragansett, RI, USA

Adjunct Professor, School of Marine Science and Technology, University of

Massachusetts, Dartmouth.

Gotthilf Hempel

Science Advisor, Senate of Bremen, Germany

Professor emeritus, Bremen and Kiel Universities

Director, Alfred-Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research, Bremerhaven

until 1992

Director, Center for Tropical Marine Ecology, Bremen until 2000

Director, Institute for Baltic Research, Rostock until 1997

viii

ix

Preface

The world's coastal ocean waters continue to be degraded by unsustainable fishing

practices, habitat degradation, eutrophication, toxic pollution, aerosol contamination, and

emerging diseases. Against this background is a growing recognition among world

leaders that positive actions are required on the part of governments and civil society to

redress global environmental and resource degradation with actions to recover depleted

fish populations, restore degraded habitats and reduce coastal pollution. No single

international organization has been empowered to monitor and assess the changing

states of coastal ecosystems on a global scale, and to reconcile the needs of individual

nations to those of the community of nations for taking appropriate mitigation and

management actions. However, the World Summit on Sustainable Development

convened in Johannesburg in 2002 recognized the importance for coastal nations to

move more expeditiously toward sustainable development and use of ocean resources.

Participating world leaders agreed to pursue 4 marine targets: (i) to achieve substantial

reductions in land-based sources of pollution by 2006; (ii) to introduce an ecosystems

approach to marine resource assessment and management by 2010; (iii) to designate a

network of marine protected areas by 2012; and (iv) to maintain and restore fish stocks to

maximum sustainable yield levels by 2015. At present, 110 developing countries are

moving toward these targets in joint international projects supported, in part, by financial

grants by the Global Environment Facility (GEF) in partnership with scientific and

technical assistance from UN partner agencies, donor countries and institutions, and non-

governmental organizations including the World Conservation Union (IUCN). Many of

these projects are linked to ecosystem-based initiatives underway in Europe and North

America.

This report is a result of a collaborative effort to promote a global view of conditions within

LMEs across the North-South divide. It was generously coordinated by UNEP Regional

Seas Programme, and the Global Programme of Action for the Protection of the Marine

Environment from Land-based Activities (GPA Coordination Office) in The Hague,

Netherlands. In summer 2005 it was agreed that UNEP, in partnership with the GEF-

supported Global International Waters Assessment (GIWA) project, and NOAA's Large

Marine Ecosystem Program, would provide synopses of ecological conditions for each of

the worlds' Large Marine Ecosystems (LMEs). In accordance with the outcome of a

series of consultations among the three parties, it was concluded that the five-module

LME assessment framework of productivity, fish and fisheries, pollution and ecosystem

health, socioeconomics, and governance, would provide a useful basis for describing

ecological conditions within the world's LMEs.

The synopses are relatively brief for the LMEs adjacent to the more economically

developed countries where ecological conditions are fairly well documented by

periodically released reports, published in print or electronically, on various sectoral

interests including: fisheries, pollution, habitats, tourism, shipping, oil and gas production

and mineral extraction. Sources for this summary information are provided for the

reader. Whereas, for the LMEs bordering countries less economically developed in

Africa, Asia, and Latin America, the synopses are longer. They are based on information

collected through GIWA and the GEF-LME project planning and implementation process

using information that would otherwise not be readily available in the published marine

assessment and management literature. The synopses were prepared by two principal

authors, Dr. Sherry Heileman and Dr. Marie Christine Aquarone. For several LME

synopses, where one or more of the peer reviewers added substantially to the description

of ecological conditions, they are listed as co-authors of the synthesis. Each of the 64

x

synopses of ecological conditions includes standardized information on productivity

(gCm-2y-1), ocean fronts, multi-decadal time series of trends in annual fishery yields, and

changes in mean annual trophic levels of fish catch, as well as data on the physical

extent (km2) of LMEs, the presence of sea mounts, coral reefs and linked rivers,

watersheds and estuaries.

Chapters I, through XVIII describe conditions of LMEs within the Regional Seas areas,

followed by chapter XIX on the LMEs bordering Regional Seas areas. Three generic

issues recur in the synopses: (1) the issue of encroachment of industrial fisheries into

near coastal community based fisheries in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, and the need

for application of the precautionary principle to protect the food security and livelihood of

coastal communities; (2) the need for improved forecasting of climate driven events

affecting LME resources, especially during present extensive global climate change, and

(3) the global scale increasing frequency and extent of eutrophication stress on

ecosystem integrity and health. Examples of these issues are included in the

introductory chapter.

The substantial contribution in start-up funding by the GEF to 110 developing countries is

enabling a global effort to go forward in initiating movement in Asia, Africa, and Latin

America towards the WSSD marine targets. Although the way ahead is costly, a

concerted and focused effort has been initiated. Within the context of the baseline

initiated in this report, UNEP in partnership with other actors in the conservation and

management of the marine and coastal environment will aim at measuring progress

regularly through further editions of this report or through contributing to other reports

such as the Global Marine Assessment (GMA).

The Editors

xi

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this initial report on the ecological conditions of the LMEs in the Regional

Seas has been a collaborative effort. We are greatly indebted to the GEF-LME

Programme Managers for their pioneering contributions to the LME assessment and

management process and their willingness to take the time from busy schedules to

provide reviews of the LME descriptions in this report. Special appreciation is extended

to: Andrew Cooke (Canary Current LME), Gerardo Gold-Bouchot (Gulf of Mexico LME),

Chidi Ibe (Guinea Current LME), Yihang Jiang, Qisheng Tang and Hyung Tack Huh

(Yellow Sea LME), Robin Mahon (Caribbean Sea LME), Jan Thulin (Baltic Sea LME),

and Michael O'Toole (Benguela Current LME).

The GEF had tasked the Global International Waters Assessment (GIWA) to identify the

ecological conditions of the GEF-eligible LMEs, thereby allowing, on the basis of these

assessments, the GEF to prioritize the activities or areas needing more financial,

scientific and technical support. The reports on the ecological condition for 34 LMEs, for

which bordering countries are eligible for GEF financial support, were prepared by Dr.

Sherry Heileman, marine and fisheries biologist, Paris, France. We are indebted to Dr.

Heileman for her carefully prepared reports. We are indebted to Dr. Marie Christine

Aquarone for her expert synthesis of ecological conditions in the 30 LMEs bordering the

more economically advanced countries. We are indebted as well to Dr. Sara Adams,

Technical Editor, for recent updates to LME descriptions and for extraordinary care and

expertise in producing this volume for publication.

The following experts gave much of their time, effort, and considerable expertise to

review the LME reports in Africa, Asia, Latin America and eastern Europe: Dr. Johann

Augustyn (South Africa), Dr. Andrew Bakun (USA), Dr. Ratana Chuenpagdee (Nova

Scotia), Dr. Andrew Cooke (Senegal), Brian Crawford (South Africa), Dr. Werner Ekau

(Germany), Dr. Li Haiqing (China), Dr. Kwame Koranteng (Kenya), Dr. Daniel Lluch

Belda (Mexico), Johann Lutjeharms (South Africa), Dr. Robin Mahon (Barbados), Dr.

Gennady G. Matishov (Russia), Dr. Laurence Mee (United Kingdom), Dr. Sunilkumar

Kolliyil Mohamed (India), Dr. Dirar Nasr (Saudi Arabia), Dr. Michael O'Toole (Namibia),

Dr. Nancy Rabalais (USA), Dr. Claude Roy (France), Rodolfo Serra (Chile), Jerker

Tamelander (Sri Lanka), Dr. Jan Thulin (Sweden), Professor Dr. Matthias Wolff

(Germany), Jiang Yihang (Korea) and Dr. Sinjae Yoo (Korea).

The LME descriptions for North America, Europe and East Asia were originally made

possible by LME experts who prepared syntheses of ecosystem productivity, fish and

fisheries, pollution and ecosystem health, socioeconomics, and governance that have

been published in the 14 LME volumes. These experts include P. Cury, S. J. Heymans,

P. Hoagland, S. Levin, P.A. Livingston, J.M. McGlade, J.E. Overland, J. Rice, V.

Shannon, H. R. Skjoldal, Q. Tang, and K.C.T. Zwanenburg.

We thank Dr. Daniel Pauly and other members of the Sea Around Us Project (Fisheries

Centre, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada, for contributing graphs of

fisheries catch time series and related statistics for each of the LMEs covered here, and

embedding these graphs and their explanatory text into the LME descriptions.

Finally, we acknowledge with gratitude the support and encouragement of Dr. Veerle

Vandeweerd, former coordinator of UNEP/GPA and Head of the Regional Seas Program

in the Hague, and Anjan Datta, Officer in Charge of the UNEP/GPA Coordination Office,

Nairobi, Kenya, and Annie Muchai of UNEP, Nairobi, Kenya

The Editors

xii

xiii

Expert Reviewers

I West and Central Africa

Michael J. O'Toole (Namibia and Ireland); Johann Augustyn (SouthAfrica);

Johann R.E. Lutjeharms (South Africa); Kim Prochazka (South Africa);

Chidi Ibe (Nigeria); Julius Wellens-Mensah (Ghana); Jean Folack (Cameroon); Bradford

Brown (USA); Andrew Cooke (Senegal); Claude Roy (France); Merete Tandstad (Italy);

Tayaa Mhammed (Morocco)

II Eastern Africa

Lucy E.P. Scott (South Africa); Johann R.E. Lutjeharms (South Africa); Chris Magadza

(Zimbabwe); Renison K. Ruwa (Kenya)

III Red Sea and Gulf of Aden

Khulood Tubaishat (Saudi Arabia); Dirar Nasr (Saudi Arabia); David Aubrey (USA)

IV Mediterranean

Paul Mifsud (Athens)

V Black Sea

Yegor Volovik (Turkey); William Parr (Turkey); Felix Stolberg (Ukraine)

VI ROPME Sea Area

Peyman Eghtesadi-Araghi (Iran); Najah T. Mistafa (Sweden)

VII South Asian Seas

Simon Funge-Smith (Rome); Gabriella Bianchi (Rome)

VIII East Asian Seas

Ratana Chuenpagdee (Canada); Clive Wilkinson (Australia)); Miles Furnas, (Australia);

David Souter (Australia); John Keesing (Australia); Tennille Irvine (Australia);

Nick D'Adamo, (Australia)

IX South Pacific

Iain Suthers (Australia); M.E. Baird (Australia); Janet Bradford-Grieve (New Zealand);

Jon Brodie (Australia); Stewart Frusher (Australia)

X North West Pacific

Qisheng Tang (P.R. China); Jing Zhang (P.R. China); Igor Belkin (U.S.A);

Arkady V. Alekseev (Russia); Yihang Jiang (Republic of Korea);

Teng Seng-Keh (P.R. China)

XI Arctic

Gennady Matashov (Russia); Igor Belkin (USA); NMFS, Alaska Fisheries Science

Center (AFSC), U.S.A.; Alla Tsyban (Russia); Natalia Golubeva (Russia);

Mogens Dyhr-Nielsen (Russia)

XII Baltic Sea

Jan Thulin (Denmark); Ain Lääne (Estonia)

xiv

XIII North East Atlantic

Hein Rune Skjoldal (Norway); Natalia Golubeva (Russia); Luis Valdés (Spain);

Michael J. O'Toole (Ireland); Eilif Gaard (Faroe Islands); Ditte Mickelsson (Greenland);

Thomas Juul Pedersen (Greenland); Ólafur S. Ástþórsson (Iceland)

XIV North East Pacific

NMFS, Northwest Fisheries Science Center (USA); Igor Belkin (USA);

NMFS, Alaska Fisheries Science Center (AFSC; Daniel Lluch Belda (Mexico);

Edgar Arias Patron (Mexico)

XV Wider Caribbean

Robin Mahon (Barbados); NMFS, Southeast Fisheries Science Center (SEFC) (USA);

Nancy Rabelais (USA)

XVI South West Atlantic

Igor Belkin (USA); Marcia Marques (Brazil); Maria Gasalla (Brazil);

Ana Mugetti (Argentina)

XVII South East Pacific LME

Renato Guevara (Perú); Francisco Chavez (USA); Arnau Bertrand (France);

Adm. Hector Soldi (Perú); Ulises Munaylla Alarcón (Ecuador)

XVIII Antarctic

NMFS Southwest Fisheries Center (USA)

XIX LMEs Outside Regional Sea Areas

Ditte Mickelsson (Greenland); Thomas Juul Pedersen (Greenland); Igor Belkin (USA);

Kees C.T. Zwanenburg (Canada); Robert Siron (Canada);

NMFS Pacific Island Fishery Center (USA); John Keesing (Australia);

Tennille Irvine (Australia); Nick D'Adamo (Australia)

xv

Contents

Message from the Executive Director of UNEP

iii

Message from the Executive Director of GEF

v

Preface

ix

Acknowledgments xi

Expert Peer Reviewers

xiii

Contents

xv

BACKGROUND REPORTS

1

Perspectives on Regional Seas and the Large Marine Ecosystem Approach

3

K. Sherman and G. Hempel

Fisheries in Large Marine Ecosystems: Descriptions

and Diagnoses

23

D. Pauly, J. Alder, S. Booth, W.W.L. Cheung, C. Close, U.R. Sumaila, W. Swartz,

A. Tavakolie, R. Watson, L. Wood and D. Zeller

Accelerated Warming and Emergent trends in Fisheries Biomass Yields of the

World's Large marine Ecosystems

41

K. Sherman, I. Belkin, K. Friedland, J. O'Reilly, K. Hyde

Land-Based Sources of Nutrients to Large marine Ecosystems

81

S. Seitzinger and R. Lee

LMEs and REGIONAL SEAS

99

I West and Central Africa

101

1. Benguela Current LME

103

2. Guinea Current LME

117

3. Canary Current LME

131

II Eastern Africa

143

4. Agulhas Current LME

145

5. Somali Current LME

159

III Red Sea and Gulf of Aden

173

6. Red Sea LME

175

IV Mediterranean

187

7. Mediterranean Sea LME

189

V Black Sea

201

8. Black Sea LME

203

VI ROPME Sea Area

219

9. Arabian Sea LME

221

xvi

VII South Asian Seas

235

10. Bay of Bengal LME

237

VIII East Asian Seas

253

11. Gulf of Thailand LME

255

12. Indonesian Sea LME

269

13. North Australia LME

281

14. Northwest Australia LME

289

15. South China Sea LME

297

16. Sulu Celebes Sea LME

309

17. West-Central Australia LME

321

IX Pacific (SPREP)

337

18. East-Central Australia LME

339

19. New Zealand Shelf LME

349

20. Northeast Australia LME

359

21. Southeast Australia LME

369

X North-West Pacific

381

22. East China Sea LME

383

23. Kuroshio Current LME

393

24. Oyashio Current LME

403

25. Sea of Japan/ East Sea LME

413

26. Sea of Okhotsk LME

423

27. West Bering Sea LME

433

28. Yellow Sea LME

441

XI Arctic

453

29. Arctic Ocean LME

455

30. Beaufort Sea LME

463

31. Chukchi Sea LME

469

32. East Siberian Sea LME

477

33. Kara Sea LME

483

34. Laptev Sea LME

491

XII Baltic Sea

497

35. Baltic Sea LME

499

XIII North-East Atlantic

511

36. Barents Sea LME

513

37. Celtic-Biscay Shelf LME

527

38. Faroe Plateau LME

535

39. Greenland Sea LME

545

40. Iberian Coastal LME

553

41. Iceland-Shelf LME

563

42. North Sea LME

573

43. Norwegian Sea LME

581

XIV The North-East Pacific

591

44. California Current LME

593

45. East Bering Sea LME

605

46. Gulf of Alaska LME

617

47. Gulf of California LME

627

48. Pacific Central-American LME

643

xvii

XV Wider Caribbean

655

49. Caribbean Sea LME

657

50. Gulf of Mexico LME

673

51. Southeast U.S. Continental Shelf LME

689

XVI South-West Atlantic

699

52. North Brazil Shelf LME

701

53. East Brazil Shelf LME

711

54. Patagonian Shelf LME

723

55. South Brazil Shelf LME

735

XVII South-East Pacific

747

56. Humboldt Current LME

749

XVIII Antarctic

763

57. Antarctic LME

765

XIX LMEs Outside Regional Sea Areas

775

58. West Greenland Shelf LME

777

59. Hudson Bay LME

787

60. Insular Pacific-Hawaiian LME

795

61. Newfoundland-Labrador Shelf LME

805

62. Northeast U.S. Continental Shelf LME

817

63. Scotian Shelf LME

829

64. Southwest Australia LME

839

xviii

BACKGROUND REPORTS

2 Background

Reports

Perspectives on Regional Seas and the Large

Marine Ecosystem Approach

K. Sherman and G. Hempel

UNEP REGIONAL SEAS PROGRAMME LINKS WITH LARGE MARINE

ECOSYSTEMS ASSESSMENT AND MANAGEMENT

A new partnership has been developed that links the coastal and marine activities of the

global Regional Seas Programme (RSP), coordinated by the United Nations Environment

Programme (UNEP), with the Large Marine Ecosystem (LME) approach to the

assessment and management of living marine resources and environments. The joint

initiative assists developing countries in using LMEs as operational units for translating

the Regional Seas Programme into concrete actions. With substantial support in over

one billion dollars in financial grants from the Global Environment Facility (GEF) and

investment funds from the World Bank in partnership with other UN agencies and

government and industrial donors, countries in Africa, Asia, the Pacific, Latin America

and the Caribbean, and Eastern Europe are presently engaged in LME assessment and

management projects that implement actions to restore and sustain living marine

resources in coastal waters.

THE LARGE MARINE ECOSYSTEM APPROACH

The LME approach to the assessment and management of marine resources and their

environments was first introduced at an international symposium convened at the annual

meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, in 1984. At the

outset, it was understood that the LME approach would provide a framework for utilizing

ecologically defined Large Marine Ecosystems as place-based areas around the globe, to

focus the methods of marine science, policy, law, economics and governance on a

common strategy for assessing, managing, recovering, and sustaining marine resources

and their environments (Sherman and Alexander 1986).

There are two important features in the LME approach. First and foremost, the

physical extent of the LME and its boundaries are based on 4 linked ecological

rather than political or economic criteria. These are: (i) bathymetry, (ii)

hydrography, (iii) productivity, and (iv) trophic relationships. It is the bathymetry or

bottom topography that greatly influences water column structure and flow. Within the

water column, the nutrient flux, vertical circulation and advective processes determine to

a large extent the levels of primary productivity of the phytoplankton of the LME--

productivity that is a determinant of zooplankton biomass and species composition

(biodiversity), and subsequent energy-flow (trophodynamics), from plankton to fish and

shellfish to marine birds and marine mammals, through the food web of the LME. Based

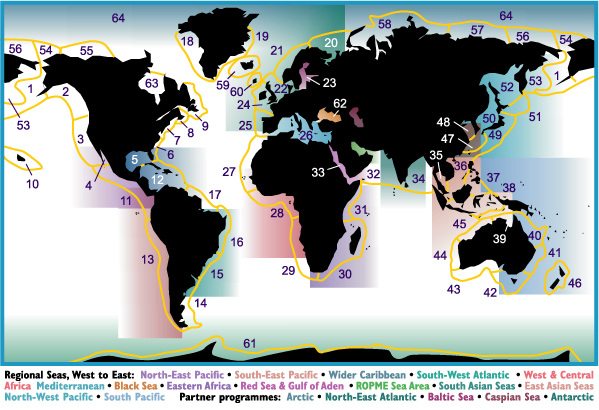

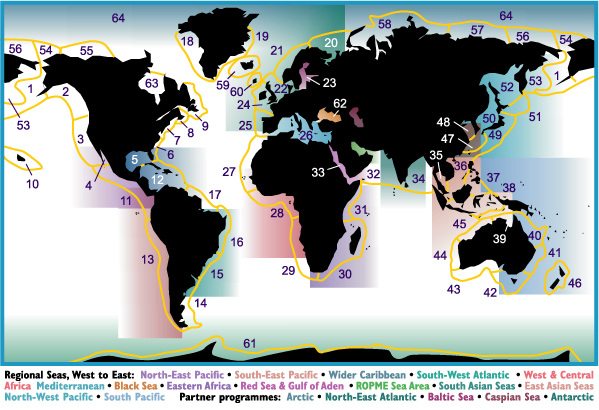

on the 4 ecological criteria, 64 distinct LMEs have been delineated around the coastal

margins of the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans (Figures 1a and 1b).

Frontal maps and quantitative assessments of the sea surface temperature (SST) and

temperature anomalies for each of these LMEs are provided by Dr. Igor Belkin. SST was

selected as the only thermal parameter routinely measured worldwide that can be used to

characterize thermal conditions in each and every LME. Subsurface hydrographic data,

albeit important, lack spatial and temporal density required for reliable assessment of

thermal conditions at the LME scale worldwide.

4

K. Sherman and G. Hempel

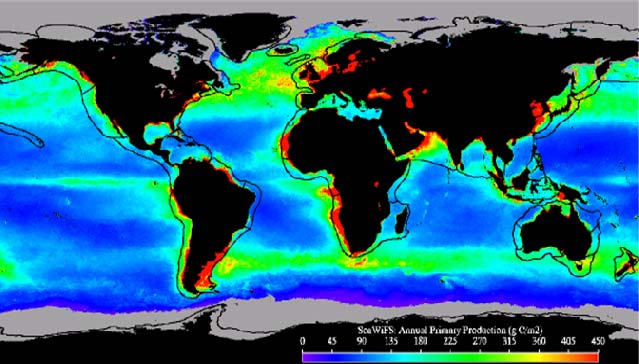

Figure 1a. Map showing 64 Large Marine Ecosystems of the world. LMEs in this map are numbered as

they are on the LME website, www.lme.noaa.gov.

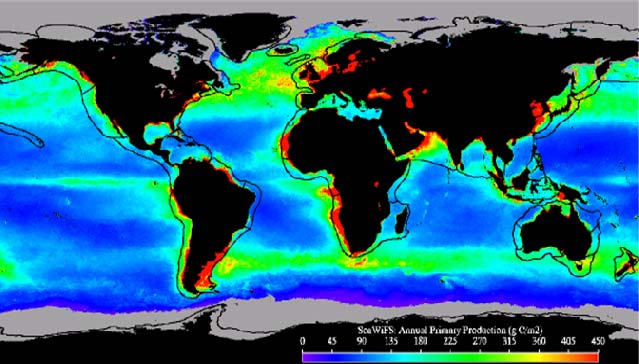

Figure 1b. Global map of average primary productivity and the boundaries of the 64 Large Marine

Ecosystems (LMEs) of the world, available at www.lme.noaa.gov. The annual productivity estimates are

based on Sea WiFS satellite data collected between September 1998 and August 1999, and the model

developed by M. Behrenfeld and P.G. Falkowski (Limnol. Oceangr. 42(1): 1997, 1-20). The color-

enhanced image provided by Rutgers University depicts a shaded gradient of primary productivity from

a high of 450 gCm-2yr-1 to a low of 10gCm-2y-1.

Regional Seas and Large Marine Ecosystems

5

All LMEs are relatively large areas of ocean space, of approximately 200,000 km2 or

greater, adjacent to the continents in coastal waters where primary productivity is

generally higher than in open ocean areas. It is within the boundaries of the LMEs that

80% of the world's annual marine fish catch is produced, degraded habitats are most

prevalent and the frequency and effects of pollution and eutrophication of ocean waters

are most severe. The LMEs are also centers of marine gas and oil production; mining for

sand, gravel, diamonds and other extractive minerals; coastal shipping; and tourism.

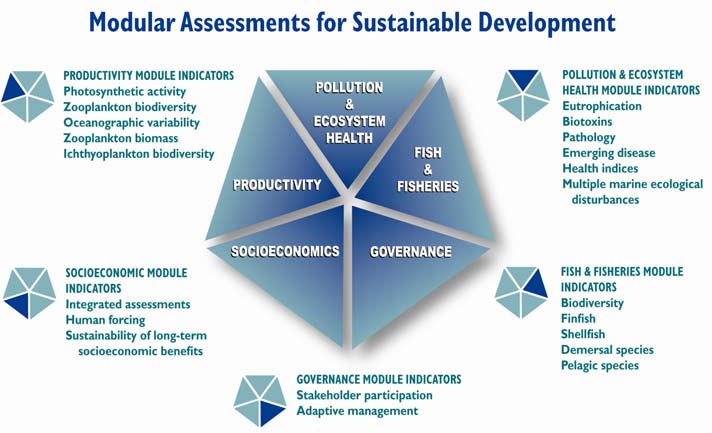

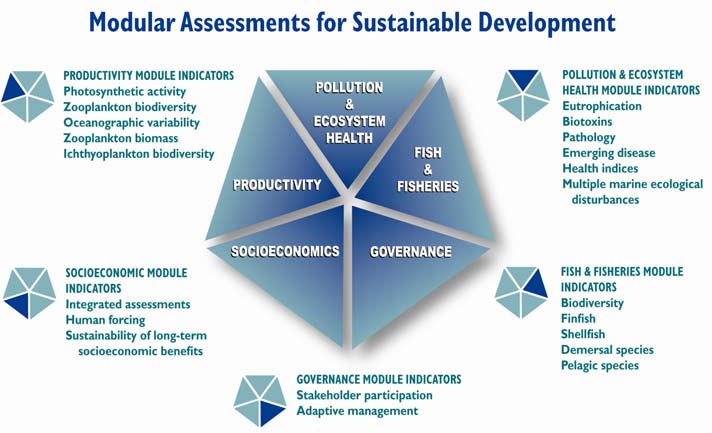

A second important feature of the LME approach is the use of a 5-module strategy

for measuring the changing states of the ecosystem and for taking remedial

actions toward recovery and sustainability of degraded resources and

environments. From a management perspective it is essential to establish a baseline

condition against which to measure the success or failure of management actions

directed toward recovery of degraded conditions within the LMEs. The 5 modules are

focused on the application of suites of indicators measuring LME (1) productivity, (2) fish

and fisheries, (3) pollution and ecosystem health, (4) socio-economics, and (5)

governance.

LMES AND THE UNEP REGIONAL SEAS PROGRAMME

Since 1984, the LME approach has matured into the planning and implementation

activities of 16 projects in 110 countries bordering on LMEs in Africa, Asia, Latin America

and countries in economic transition in eastern Europe (Sherman et al. 2007). The

projects are country driven, wherein the direction and priorities of assessment and

management actions are "driven" by nations sharing the transboundary goods and

services of the LMEs.

There is a growing body of peer-reviewed published reports on the application of the LME

approach to the assessment and management of marine resources. As of 2006, the

American Association for the Advancement of Science, Westview Press, Blackwell

Science, and Elsevier Science have published a total of fourteen peer-reviewed volumes

with contributions by 445 authors (www.noaa.lme.gov).

The LME approach is a way forward for advancing ecosystem-based management of

coastal and marine resources within a framework of sustainable development. Country-

driven GEF-LME assessment and management projects are linked to the WSSD Plan of

Implementation and to the global Regional Seas Programme, coordinated by UNEP. The

descriptions in this report of the general ecological conditions of the LMEs, with regard to

their productivity, fish and fisheries, pollution and ecosystem health, socioeconomics and

governance, are arranged in accordance with the Regional Seas designations (Figure 2).

Regional Seas, LMEs and the 2002 World Summit on Sustainable Development

In December 2004, at the 6th Global Meeting of the Regional Seas Conventions and

Action Plans, new strategic directions were adopted, in order to strengthen the Regional

Seas Programme at the global level and address evolving challenges and priorities, while

continuing to implement the individual work programmes of the Conventions and Action

Plan secretariats. One of the directions calls to "Develop and promote a common

vision and integrated management, based on ecosystem approaches, of priorities

and concerns related to the coastal and marine environment and its resources in

Regional Seas Conventions and Action Plans, introducing amongst others

proactive, creative and innovative partnerships and networks and effective

communication strategies." In 1982, UNEP began to address issues related to

impacts on the marine environment from land-based activities. Some 80% of the

6

K. Sherman and G. Hempel

pollution load in the oceans originates from land-based activities (municipal, industrial

and agricultural wastes, run-off, and atmospheric deposition). These contaminants affect

the most productive areas of the marine environment, including estuaries and near-shore

coastal waters.

Figure 2. Regional Seas map with boundaries (in yellow) of the 64 Large Marine Ecosystems. Numbers

correspond to the LME map numbers for the 64 LMEs.

The health and, in some cases, the very survival of coastal populations depend upon the

health and well being of coastal systems such as estuaries and wetlands. In response to

intense pressures put on coastal systems, 108 governments and the European

Commission adopted the 1995 Washington Declaration, to establish a Global Programme

of Action for the Protection of the Marine Environment from Land-based Activities (GPA).

To support the GPA activity, a UNEP/GPA office was established in The Hague,

Netherlands.

During the World Summit on Sustainable Development (WSSD), held in Johannesburg in

2002, participating world leaders agreed to pursue 4 marine targets: (i) to achieve

substantial reductions in land-based sources of pollution by 2006; (ii) to introduce an

ecosystems approach to marine resource assessment and management by 2010; (iii) to

designate a network of marine protected areas by 2012; and (iv) to maintain and restore

fish stocks to maximum sustainable yield levels by 2015. In an effort to encourage the

global movement toward the 4 WSSD targets, UNEP along with other partnering UN and

non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and the GEF and its partners, is assisting

developing countries in operationalizing LME projects to serve as operational and

management units for translating the legal frameworks and objectives of the Regional

Seas Programmes into concrete actions to restore, sustain, protect and manage coastal

environments and linked watersheds. Assessments of the state of most LMEs in GEF

eligible regions were carried out by the Global International Waters Assessment (GIWA)

between 2000 and 2005. The GIWA Regional Reports can be downloaded from their

website www.giwa.net/publications/.

Regional Seas and Large Marine Ecosystems

7

TRANSBOUNDARY DIAGNOSTIC ANALYSIS AND STRATEGIC ACTION PROGRAM

The GEF Operational Strategy recommends that nations sharing an LME begin to

address coastal and marine issues by jointly undertaking strategic processes for

analyzing science-based information on transboundary concerns, their root causes, and

by setting priorities for action on transboundary concerns. This process is referred to as

a Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis (TDA) and it provides a useful mechanism to foster

participation of policy makers, scientists, management experts, stakeholders, and civil

society at local, regional, national and international levels of interest. Countries then

determine the national and regional policy, legal, and institutional reforms and

investments needed to address the priorities, and based on the strategies prepare and

initiate an LME wide Strategic Action Program (SAP). This allows sound science to

assist policy making within a specific geographic location for an ecosystem-based

approach to management that can be used to engage stakeholders (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Summary of Transboundary Diagnostic Analyses (TDA) and Strategic Action Plans (SAP) for

GEF sponsored LME projects planned and underway. An additional 2 projects outside the Regional

Seas areas have completed TDAs.

In the GEF-LME projects either approved or in the preparation stage, 110 countries are

moving to meet WSSD ecosystem-related targets and to address overfishing, fishing

down food webs, destruction of habitat and accelerated nitrogen export. Countries

engaged in the TDA process have already begun to scientifically characterize the LME, to

identify the root causes of trends in LME biomass yields and the most pressing

transboundary characteristics of coastal pollution, damaged habitats and depleted fish

stocks, in order to prioritize these issues. Seven country-driven GEF-LME Projects are

advancing to the drafting of the SAP, in which the countries commit to making institutional

arrangements and taking policy actions, based on sound science, to address the issues

identified in the TDA. The SAP addresses actions to correct institutional fragmentation,

ecosystem assessment gaps, lack of cooperation and weak coastal policies and is signed

by high-level government authorities of each participating country. The strategic

framework for developing TDAs and SAPs is guided by the geographic area of LMEs and

the application of the 5-module approach to LME assessment and management.

Examples of TDA and SAP documents for the Benguela Current LME Project are

available at www.bclme.org.

These processes are critical for integrating science into management in a practical way

and for establishing appropriate governance regimes. The five modules consist of 3 that

are science-based indicators focused on: productivity, fish/fisheries, pollution/ecosystem

health; the other two, socio-economics and governance, are focused on economic

benefits to be derived from a more sustainable resource base and implementing

8

K. Sherman and G. Hempel

governance mechanisms for providing stakeholders and stewardship interests with legal

and administrative support for ecosystem-based management practices (Figure 4). The

first four modules support the TDA process while the governance module is associated

with periodic updating of the Strategic Action Program or SAP (Duda and Sherman,

2002; Wang 2004). Adaptive management regimes are encouraged through periodic

assessment processes (TDA updates) and updating of SAPs as gaps are filled.

CHANGING STATES OF THE LMES: INDICATOR MODULES

Figure 4. The Large Marine Ecosystem (LME) approach to sustainable development includes 5 modules

with indicators.

The five-module indicator approach to the assessment and management of LMEs has

proven useful in ecosystem-based projects. The modules are customized to fit the

situation within the context of the TDA process and SAP development process for the

groups of nations or states sharing an LME.

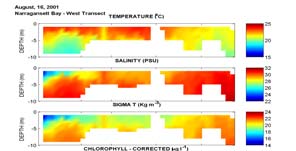

Productivity module indicators

Primary productivity can be related to the carrying capacity of an ecosystem for

supporting fish resources (Pauly & Christensen 1995). Measurements of ecosystem

productivity can be useful indicators of the growing problem of coastal eutrophication. In

several LMEs, excessive nutrient loadings to coastal waters have been related to algal

blooms implicated in mass mortalities of living resources, emergence of pathogens (e.g.,

cholera, vibrios, red tides, and paralytic shellfish toxins), and explosive growth of non-

indigenous species (Epstein 1993, Sherman 2000). The ecosystem parameters

measured and used as indicators of changing conditions in the productivity module are

zooplankton biodiversity and species composition, zooplankton biomass, water-column

structure, photosynthetically active radiation, transparency, chlorophyll-a, nitrite, nitrate,

and primary production, (Aiken 1999, Berman & Sherman 2001, Melrose et al. 2006),

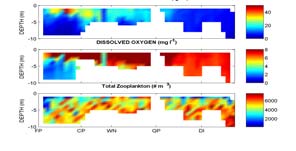

(Figure 5).

Regional Seas and Large Marine Ecosystems

9

Figure 5. A Mariner Shuttle, towed behind a ship is used to collect measurements for assessing

changing conditions of temperature, salinity, density, chlorophyll and primary productivity, oxygen and

zooplankton within LMEs.

Fish and Fisheries module indicators

Changes in biodiversity and species dominance within fish communities of LMEs have

resulted from excessive and selective exploitation, environmental shifts due to climate

change and coastal pollution. Changes in biodiversity and species dominance in a fish

community can cascade up the food web to apex predators and down the food web to

plankton and benthos components of the ecosystem.

The Fish and Fisheries Module includes both fisheries-independent bottom-trawl surveys

and pelagic-species acoustic surveys to obtain time-series information on changes in fish

biodiversity and abundance levels (Figure 6). Standardized sampling procedures, when

employed from small, calibrated trawlers, can provide important information on changes

in fish species (Sherman 1993). The fish catches on the surveys provide biological

samples for stock identification, stomach content analyses, age-growth relationships,

fecundity, and for coastal pollution monitoring, based on pathological examinations.

Figure 6. The Norwegian Research Vessel Dr. Fridtjof

Nansen readies to depart from Accra, Ghana on the Third

Guinea current LME Survey (June 4 July 15, 2005) of the

fish and fisheries of the Guinea Current LME Project

(GCLME). Scientists and technicians from all of the

GCLME countries participated in this survey. The

countries represented were Angola, Benin, Cameroon,

Congo, Democratic Republic of Congo, Côte d'Ivoire,

Ghana, Equatorial Guinea, Guinea, Liberia, Nigeria, Sierra

Leone and Togo.

Fish stock demographic data are used for preparing stock assessments (NAFO 2005)

and for clarifying and quantifying multispecies trophic relationships (NAFO 2005). NOAA

Fisheries information is available at http://nft.nefsc.noaa.gov (username: nft; password:

nifty) for development of a standard suite of methods for standardizing assessment tasks.

The survey vessels can also be used as platforms for obtaining water, sediment, and

benthic samples for monitoring harmful algal blooms, diseases, anoxia, and structure of

benthic communities.

10

K. Sherman and G. Hempel

Pollution and Ecosystem Health module indicators

In semi-enclosed LMEs, pollution and eutrophication can be important driving forces of

change in biomass yields. Assessing the changing status of pollution and health of an

entire LME is scientifically challenging. Ecosystem health is a concept of wide interest for

which a single precise scientific definition is difficult. The health paradigm is based on

multiple-state comparisons of ecosystem resilience and stability, and is an evolving

concept that has been the subject of a number of meetings (Sherman 1993). To be

healthy and sustainable, an ecosystem must maintain its metabolic activity level and its

internal structure and organization, and must resist external stress over time and space

scales relevant to the ecosystem (Costanza 1992). The modules are all used to a

greater or lesser extent in the US, in ICES, and are now being introduced in the GEF-

LME Projects.

The Pollution and Ecosystem Health Module measures pollution effects on the

ecosystem through the pathobiological examination of fish, and through the estuarine and

nearshore monitoring of contaminant effects in the water column, the substrate, and

selected groups of organisms. Where possible, bioaccumulation and trophic transfer of

contaminants are assessed, and critical life history stages and selected food web

organisms are examined for indicators of exposure to, and effects from, contaminants.

Effects of impaired reproductive capacity, organ disease, and impaired growth from

contaminants are measured. Assessments are made of contaminant impacts at both

species and population levels. Implementation of protocols to assess the frequency and

effect of harmful algal blooms, emergent diseases, and multiple marine ecological

disturbances (Sherman 2000) are included in the pollution and ecosystem health module.

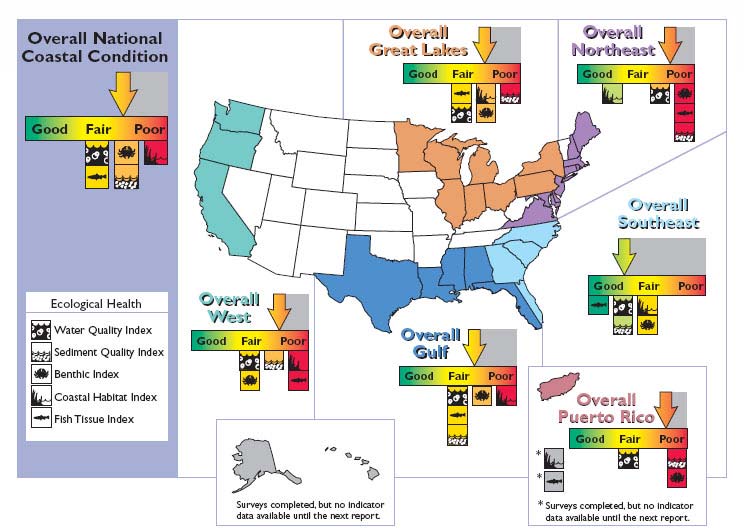

In the United States, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has developed a suite

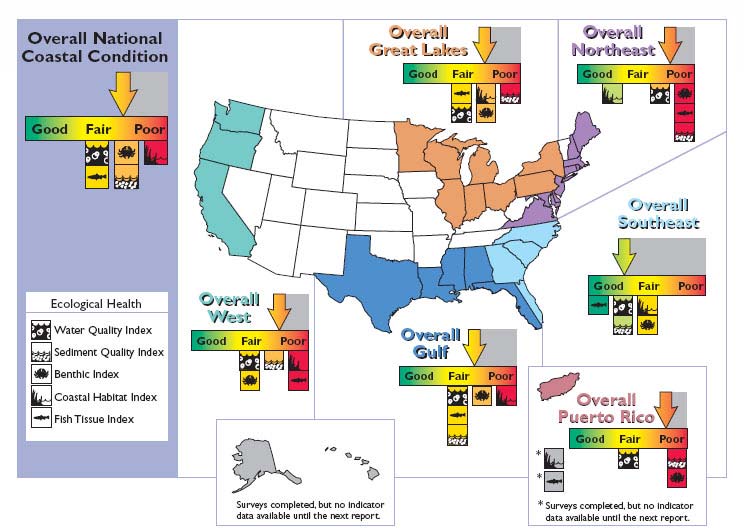

of 5 coastal condition indicators: water quality index, sediment quality index, benthic

index, coastal habitat index, and fish tissue contaminants index (Figure 7) as part of an

ongoing collaborative effort with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

(NOAA), the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS),

and other agencies representing states and tribes.

Figure 7. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) 2004 indicators of coastal condition A

stoplight approach is used to indicate relative conditions: poor (red), moderate (orange) or good

(green). (National Coastal Condition Report II. 2004).

Regional Seas and Large Marine Ecosystems

11

The 2004 report, "National Coastal Condition Report II," includes results from EPA's

analyses of coastal condition indicators and NOAA's fish stock assessments by LMEs

aligned with EPA's National Coastal Assessment (NCA) regions (USEPA 2004). Several

GEF supported LME projects are adapting EPA's 5 coastal condition indicators for

assessing the health of near coastal areas of LMEs (Figure 7).

Socioeconomic module indicators

This module emphasizes the practical application of scientific findings to the

management of LMEs and the explicit integration of social and economic indicators and

analyses with all other scientific assessments to assure that prospective management

measures are cost-effective. Economists and policy analysts work closely with ecologists

and other scientists to identify and evaluate management options that are both

scientifically credible and economically practical with regard to the use of ecosystem

goods and services.

In order to respond adaptively to enhanced scientific information, socioeconomic

considerations must be closely integrated with science findings. Both the socioeconomic

and governance indicators are used in the planning and implementation actions as

summarized in Figure 8.

PLANNING ACTIONS

1. Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis (TDA) provides

consensus priorities from analysis and ranking of water-related

resources issues, their environmental and socioeconomic impacts,

immediate and root causes and possible remedies

Integrated Ecosystem

2. Strategic Action Program (SAP) provides national and

regional commitments to policy, legal and institutional reforms, and

Assessment and

investments to remedy root causes of priority transboundary issues

Adaptive Management

identified in TDA

IMPLEMENTATION ACTIONS

3. Ecosystem-based assessment and management strategy for

TDA and SAP

3.1 Productivity indicators and assessments

3.2 Fish and fisheries indicators and assessments

3.3 Pollution and ecosystem health indicators and assessments

3.4 Socioeconomic indicators and assessments

3.5 Governance indicators and assessments

Year 1

Year 2

Year 3

Year 4

Years 5-10

Assessments &

Assessments &

Assessments &

Toward Self-

Management

Management

Management

financing

Actions

Actions

Actions

Assessments

and adaptive

management

Figure 8. Integrated Ecosystem-based assessment and adaptive management planning actions over 10

years.

The new ecosystem accounting paradigm requires that resource managers of the

different sectors of stakeholder interests incorporate the cumulative assessments of

changing ecosystem productivity, fish and fisheries, pollution and ecosystem health and

their effects on socioeconomic conditions and governance jurisdictions, as both additive

12

K. Sherman and G. Hempel

and integrative effects on ecosystem conditions. These latter components of the LME

approach to marine resources management have recently been described as the human

dimensions of LMEs (Hennessey & Sutinen 2005). A framework has been developed by

the Department of Natural Resource Economics at the University of Rhode Island for

monitoring and assessment of the human dimensions of LMEs and for incorporating

socioeconomic considerations into an adaptive management approach for LMEs (Sutinen

et al. 2000; Juda et al. 2006, Olsen et al. 2006). One of the more critical considerations,

a method for economic valuations of LME goods and services, has been developed using

framework matrices for indexing economic activity (Sherman et al. 2005, Hoagland & Jin

2006).

Governance module indicators

The Governance Module is evolving, based on demonstration projects now underway in

several ecosystems, that are being managed from an ecosystem perspective. In LME

assessment and management projects supported by the Global Environment Facility for

the Yellow Sea, the Guinea Current, and the Benguela Current LMEs, agreements have

been reached among the several ministries in each country bordering the LMEs

(ministries responsible for ocean resources for the environment, fisheries, energy,

tourism, finance and foreign affairs, for example), to enter into joint resource assessment

and management activities as the framework for ecosystem-based management

practices. Elsewhere, the Great Barrier Reef LME and the Antarctic LME are also being

managed from an ecosystem perspective, the latter under the Commission for the

Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources. Governance profiles of LMEs are

being explored to determine their utility in promoting long-term sustainability of

ecosystem resources (Juda and Hennessey 2001). In each of the LMEs, governance

jurisdiction can be scaled to ensure conformance with existing legislated mandates and

authorities. An example of multiple governance-related jurisdictions that includes areas

designated for fisheries management, pollution control and marine protected areas, is

described in Sherman et al. (2004).

Within the context of ecosystem-based management the integration of data and

information for decision making is additive and vertically integrated for the five modules,

and adaptive contingent on annual assessment findings horizontally across years. From

Year 1, the GEF supported projects move toward the goal of self-financing of the

ecosystem assessment and management process by year 10 (Figure 8).

GEF-SUPPORTED LME PROJECTS

An increasing number of countries and organizations are engaged in LME projects aimed

at moving toward the WSSD marine targets. The LME approach to the assessment and

management of marine resources and their environments is being applied with financial

assistance from GEF to developing countries who are planning and implementing LME

projects focused on introducing an ecosystem-based approach to the (1) recovery of

depleted fish stocks; (2) restoration of degraded habitats; and (3) reduction of coastal

pollution and eutrophication. GEF-LME projects are presently located in 16 LMEs that

provide goods and services in bordering countries containing over half the world's

population. These LMEs produce 46% of the world's annual marine fish catch while also

being subjected to significant eutrophication in near coastal waters. These stressors

have been identified during the TDA and SAP process. Taken together, the 16 projects

represent a significant movement toward the WSSD targets, and will be the subject of

future UNEP and partners' ecological condition reports.

Regional Seas and Large Marine Ecosystems

13

The new generation

The LME projects themselves as well as their academic, administrative and political

environment have to be scientifically and technically strong. The complexity of the

modern ecosystem oriented approach of fisheries and other marine activities calls for a

new generation of professionals addressing the sustainability issue in a much broader

sense than before. Not only do the preservation of the fish stocks and the other goods

and services of the ecosystem including the protection of marine biodiversity have to be

taken care of, but also the socio-economic development of the region. Management

goals have to be defined and defended under the pressure of conflicting ecological

interests and societal and political constraints.

On the one hand, in order to address all five modules of the LME concept, specialists are

needed like ichthyologists and oceanographers and plankton experts, fish stock

assessment biologists, sociologists, economists and experts in international law. There

is an increasing demand for reliable data sets of adequate length and resolution in space

and time to feed modern data-driven models on the medium- and long-term

consequences of various management strategies. On the other hand experienced

generalists and modelers are required to put the facts and findings together and to create

such management scenarios. Those generalists are rather rare and not easy to recruit.

Therefore, capacity development has to be continued in all parts of the world, not only in

developing countries. Much of it can now be done in the regions themselves through

mutual assistance.

To a certain extent a fair division of research work between the rich and the poorer

countries might be envisaged. Rich countries have the capacity and hence the

responsibility of advancing science in the broadest possible way in natural and social

sciences per se but also in theory and analysis of the interactions in the sustainability

triangle of environment, economy and society. Those interactions differ in structure from

region to region. Working in collaboration with colleagues and institutions in poorer parts

of the world, including developing countries with their rich and diverse perspectives, is a

win-win situation.

In a nutshell

The LME approach is the pathway towards sustainable use of marine ecosystems

provided the interaction between the various players becomes much stronger amongst

the various science sectors and between scientists and stakeholders, the general public

and the national and international administration. Partnership and communication are

required on all levels and on all geographical scales. What is lacking is not so much the

money but rather the political will and the vision of enthusiastic and competent experts on

the way to apply the LME concept for the sustainable development of the use and

conservation of the marine environment in many parts of the World Ocean.

TECHNICAL DESCRIPTION OF THE DATA SETS CONTAINED IN THIS REPORT

ECOLOGICAL INDICATORS OF LME CONDITION AND METHODOLOGY

Ocean front maps

Igor Belkin of the University of Rhode Island provided descriptions and maps of LME

oceanographic fronts for each of the 64 LMEs (Belkin et al. 2008, Belkin & Cornillon

2003). An oceanographic front is a relatively narrow zone of enhanced horizontal

gradients of physical, chemical and biological properties (e.g. temperature, salinity,

nutrients). Fronts occur on a variety of scales, from several hundred meters up to many

thousand kilometers. Some of them are short-lived, but most are quasi stationary and

14

K. Sherman and G. Hempel

seasonally persistent: they emerge and disappear at the same locations during the same

season, year after year. The temperature and salinity ranges across the strongest fronts

can be as high as 10-15 degrees C and 2 to 3 parts per thousand (ppt) salinity, although

somewhat smaller numbers, such as 5 degrees C and 1 ppt, are far more common. The

width of fronts varies widely: from less than 100 m to 200 km. Vertically, many fronts

extend several hundred meters in depth. Major fronts can extend as deep as 2,000 m.

Fronts are crucial in various processes that evolve in the ocean and at the ocean

interfaces with the atmosphere, sea ice and sea bottom. Fronts are important for climate

change monitoring and prediction, the fishing industry, pollution control, waste disposal

and hazards mitigation, marine transportation, marine mining, including the oil and gas

industry, submarine navigation and integrated coastal management.

· Fronts are associated with current jets, so that any frontal pattern represents a

circulation pattern;

· The along-frontal current jets are accountable for the bulk of water/heat/salt

transport;

· Fronts separate different water masses and spawn rings responsible for the bulk

of cross-frontal and meridional transport of water, heat and salt;

· Fronts usually coincide with major biogeographical boundaries associated with

zones of enhanced bio-productivity, including fisheries grounds;

· The surface heat fluxes, wind stress and other meteorological parameters may

differ drastically between the warm and cold sides of a front. Fronts strongly

interact with the marine atmospheric boundary layer and separate regions with

different response to atmospheric forcing, so they are crucial for weather

forecasting and climate monitoring;

· Some high-latitude fronts are directly related to sea ice conditions, so the front

locations are determined by the maximum extent of the sea ice cover;

· Fronts profoundly influence acoustic environment so that solving any sound

propagation problem requires knowledge of the fronts' locations and

characteristics;

· Ocean sedimentation regimes are largely determined by the circulation (hence

frontal) pattern, therefore the interpretation of paleo-oceanographic and

paleoclimatic information recorded in marine sediments requires a priori

knowledge of the modern frontal situation;

· Because fronts are associated with convergent currents, oceanic and riverine

pollutants can be concentrated thousands of times on fronts, thus endangering

the fish, sea birds and marine mammals that inhabit the frontal zones.

The descriptions and maps provide both textual and visual summaries of dominant frontal

patterns and principal individual fronts. The frontal schematics are annual long-term

means, based largely on a 12-year data set of frontal maps assembled at the University

of Rhode Island. They are the result of a comprehensive global analysis, based on

Pathfinder Sea Surface Temperatures. The maps show the most robust and well-defined

fronts, regardless of the seasons during which they develop and peak.

Sea Surface Temperature

The U.K. Meteorological Office Hadley Center SST climatology data was selected for its

superior resolution (1 degree latitude by 1 degree longitude globally); for the historic

reach of the data; and for its high quality. A highly detailed, research-level description of

this data set has been published by Rayner et al. (2003). The Hadley data set consists of

monthly SSTs calculated for each 1° x 1° rectangular cell (spherical trapezoid, to be

exact) between 90°N-90°S, 180°W-180°E. To calculate and visualize annual SSTs for

each LME, the annual SST for each 1° x 1° cell was calculated and the area-averaged

annual 1° x 1° SSTs within each LME. Since the square area of each trapezoidal cell is

Regional Seas and Large Marine Ecosystems

15

proportional to the cosine of the middle latitude of the given cell, all SSTs were weighted

by the cosine of the cell's middle latitude. After integration over the LME area, the

resulting sum of weighted SSTs was normalized by the sum of the weights, that is, by the

sum of the cosines. Annual anomalies of annual LME-averaged SSTs were calculated

by computing the long-term LME-averaged SST for each LME by a simple long-term

averaging of the annual area-weighted LME-averaged SSTs. Then, annual SST

anomalies were calculated by subtracting the long-term mean SST from the annual SST.

Both SST and SST anomalies were visualized using adjustable temperature scales for

each LME in order to bring out details of temporal variability that otherwise would be

hardly noticeable if a unified temperature scale were used. The resulting plots of SST

and SST anomalies are for 63 LMEs. Ice cover precludes a meaningful assessment of

the LME-averaged SST for the Arctic Ocean. John O'Reilly (NOAA) kindly provided a

data set of the LME coordinates for these processes.

Primary productivity data

The LME descriptions include primary productivity estimates derived from satellite borne

data of NOAA's Northeast Fisheries Science Center, Narragansett Laboratory. These

estimates originate from SeaWiFS (satellite-derived chlorophyll estimates from the Sea-

viewing Wide Field-of-view Sensor), Coastal Zone Color Scanner (CZCS), a large archive

of in situ near-surface chlorophyll data, and satellite sea surface temperature (SST)

measurements to quantify spatial and seasonal variability of near-surface chlorophyll and

SST in the LMEs of the world. Daily binned global SeaWiFS chlorophyll a (CHL, mg m-3),

normalized water leaving radiances, and photosynthetically available radiation (PAR,

Einsteins m-2 d-1) scenes at 9 km resolution for the period January 1998 through

December 2006) are obtained from NASA's Ocean Biology Processing Group. Daily

global SST (oC) measurements at 4 km resolution are derived from nighttime scenes

composited from the AVHRR sensor on NOAA's polar-orbiting satellites and from NASA's

MODIS TERRA and MODIS AQUA sensors. Daily estimates of global primary

productivity (PP, gC m-2 d-1) are calculated using the Ocean Productivity from Absorption

and Light (OPAL) model (Marra, personal communication), a derivative of the model first

formulated in Marra et al. (2003). The OPAL model generates profiles of chlorophyll

estimated from the SeaWiFS chlorophyll using the algorithm from Wozniak et al. (2003)

and uses the absorption properties in the water column to vertically resolve estimates of

light attenuation in approximately 100 strata within the euphotic zone. Absorption by pure

water is assumed to be a constant value over PAR wavelengths; chlorophyll-specific

phytoplankton absorption is parameterized empirically (Bricaud et al., 1998); absorption

by photosynthetic pigments is distinguished from total absorption; and absorption by

colored dissolved organic matter (CDOM) is calculated according to Kahru and Mitchell

(2001). The chlorophyll-specific phytoplankton absorption is used to calculate

productivity, while absorption by photosynthetic pigments, water, and CDOM are used to

vertically resolve light attenuation. SST, which is used as a proxy for seasonal changes

in the phytoplankton community, is related to the chlorophyll-specific absorption

coefficient. The quantum efficiency is obtained from a hyperbolic tangent and a constant

max. Productivity is calculated for the 100 layers in the euphotic zone and summed to

compute the integral daily productivity (gC m-2 d-1).

Monthly and annual means of PP were extracted for each LME and a simple linear

regression of the annual PP was used to determine the rate of change over time. The

significance (alpha = 0.01 and 0.05) of the regression coefficient was calculated using a

t-test according to Sokal and Rohfl (1995)(Table 1). The data allowed for classifying the

LMEs into 3 categories: Class I, high productivity (>300 gCm-2 year-1), Class II, moderate

productivity (150-300 gCm-2year-1), and Class III, low (<150 gCm-2 year-1) productivity.

16

K. Sherman and G. Hempel

LME Chl

PP

Barents Sea

+ **

Bay of Bengal

- *

California Current

+ *

East Greenland Shelf

+ *

East Siberian Sea

- *

Hudson Bay

+ **

+ *

Humboldt current

+ *

Indonesian Sea

+ *

New Zealand Shelf

+ *

North Australian Shelf

+ *

Red Sea

+ **

+ *

Sea of Okhosk

+ *

Table 1. Significance of T test on chlorophyll (Chl) and primary productivity (PPD) regression

coefficients for SeaWiFS time series data on chlorophyll and primary productivity (1998-2006). Only

cases where p<.05 are listed. All other comparisons were nonsignificant. Plus and minus signs are

used to designate the direction of the slope of the trend line. * Indicates P<.05 ** Indicates P<.01

Fisheries catch and values trends, and ecosystem state indicators

Trends in fisheries biomass yields and catch value, provided by the Sea Around Us

Project, Fisheries Centre, University of British Columbia (see www.seaaroundus.org), are

also included in the LME descriptions. The datasets and methods used for deriving the

catch trends and the concepts behind the indicators are described in Pauly et al. (this

volume).

THE GLOBAL INTERNATIONAL WATERS ASSESSMENT

The assessments presented in this volume on state and trends in LMEs in GEF eligible

regions are based mainly on the data collections and regional reports compiled by the

Global International Waters Assessment (GIWA), supplemented by information from

other sources (see Appendix 2). GIWA was designed as a globally comparable

assessment of the present state and future trends of transboundary aquatic resources in

the world`s shared waters. On a regional basis, a bottom-up and multidisciplinary

approach was adopted that involved nearly 1,500 natural and social scientists from

around the world, particularly in developing regions (Hempel & Daler 2004, UNEP 2006).

The GIWA project divided the world into transboundary water regions, each comprising

one or more major drainage basin(s) with adjacent LMEs. Regional teams conducted the

assessment based on existing regional data and information, and adapted the

methodology to the local conditions. In many GIWA regions, the assessment process

has strengthened communication between social and natural scientists, as well as

managers. It has also fostered new partnerships within the regions and between

neighbouring regions. The GIWA project was initiated and largely funded by GEF and

led by UNEP. The key products of GIWA are 35 regional reports, most of them published

in print and/or electronically. The GIWA Final Report (UNEP 2006) summarises the

findings of the regional reports in a global perspective and provides information on

GIWA's methodology and theoretical background.

Regional Seas and Large Marine Ecosystems

17

Globally comparable results were achieved by a common and consistent methodology

applied by all of the regional teams. The GIWA methodology provides criteria for

assessing water-related environmental concerns, and for identifying their immediate and

root causes and potential policy options. Regional experts assessed and compared the

severity of impacts from a regional perspective (Belausteguigoitia 2004).

The numerous and complex transboundary water-related environmental problems were

grouped into five major concerns:

1) Freshwater

shortage

2) Pollution

3) Overfishing and other threats to aquatic living resources

4) Habitat and community modification

5) Global

change

The GIWA methodology is comprised of four major steps:

1) Scaling defines the geographic boundaries of the GIWA region, boundaries

generally demarcated by a large drainage basin and its adjacent marine

areas. The boundaries of the marine parts of the GIWA regions often

correspond with those of LMEs.

2) Scoping assesses and scores the severity of present and predicted

environmental and socioeconomic impacts caused by each of the GIWA

concerns.

3) Causal chain analysis traces the cause and effect pathways from the socio-

economic and environmental impacts back to their root causes.

4) Wherever possible, the causal chain analysis was followed by policy option

analysis which outlined potential courses of action that aim to mitigate or

resolve environmental and socioeconomic problems in the region.

The GIWA provided baseline information at the regional level for the preparation of TDAs

and SAPs initiated by GEF. At the same time, many GIWA regional assessments have

benefited from completed TDAs. GIWA has been the largest global assessment of

ecosystem-wide water issues from a transboundary perspective, linking international river

basins to their adjacent LMEs. It was designed to provide policy makers and managers

with the information they need to improve transboundary resources management.

RECENT TRENDS IN LMES WITHIN REGIONAL SEAS,

IDENTIFIED THROUGH THE 5-MODULE ASSESSMENTS

During the review of the LME condition descriptions, three major challenges emerged: (1) the

need to apply the precautionary approach, especially in LMEs with limited access to science-

based stock assessments, to control the industrial fishing effort that threatens the community-

based artisanal fisheries, (2) The need to improve forecasts of climate effects on abundances

of key species, and (3) the need to reduce nutrient inputs into estuaries to levels that protect

coastal waters from eutrophication.

Need for Precautionary Approach:

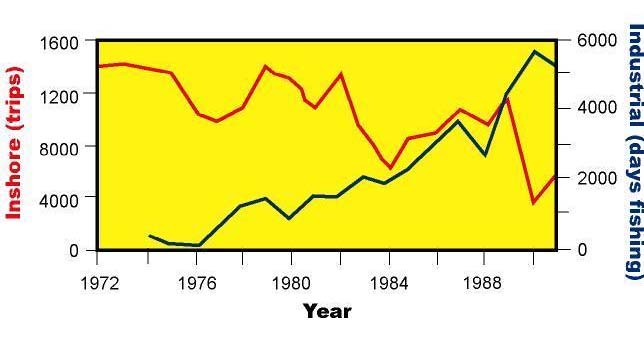

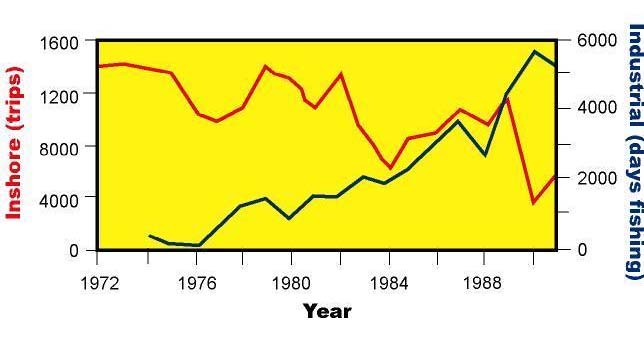

One example illustrating the need for a precautionary approach is the encroachment of

industrial globalized fisheries on artisanal fisheries in the Guinea Current LME. Findings

from a time series analysis of Catch-Per-Unit-Effort for both small-sized inshore artisanal-

type vessels and industrialized fishing fleets from the European Union showed that the

large industrialized trawlers are fishing species in near-shore areas previously not fished

by the industrial fishmeal extraction enterprises that provide product to industrialized

farms in the developed world as animal feed or fertilizer (Figure 9). The analysis found a

consistent rise in industrial trawling coinciding with a downward trend during the late

18

K. Sherman and G. Hempel

1980s in inshore seasonal artisanal fishing, which raises concerns for the community-

based fish harvest, available to meet the growing nutritional needs of the 300 million

people living along the Guinea Current coast (Korentang 2002, Figure 9).

Figure 9. Negative influence of industrial fisheries (days fished) on catch based in shore fishing fishing trips

along the coast of Ghana in the Guinea Current LME (from Koranteng, 2002)

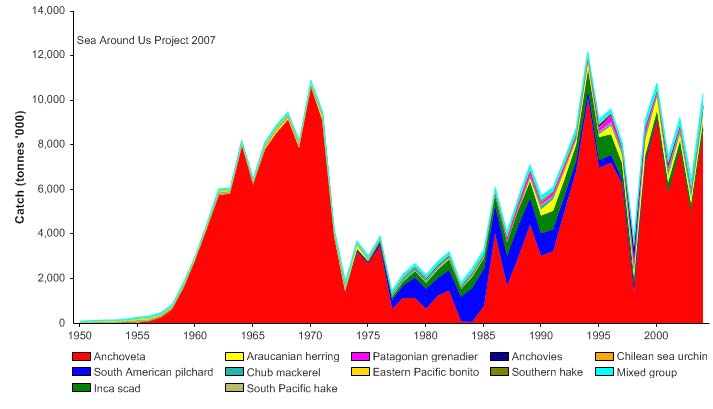

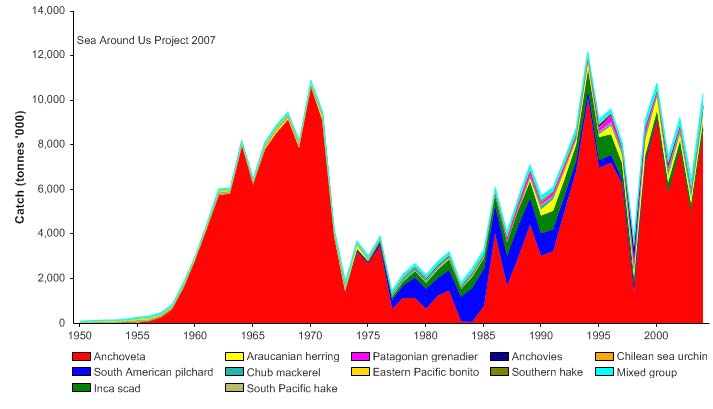

Need for improved forecasts of fishery fluctuations during climate change:

The variability in mean-annual fisheries catch of Humboldt Current LME provides one

illustration of the need for improved forecasts of fishery fluctuations in order to move toward

long-term sustainability of pelagic and demersal fish stocks. The Humboldt Current LME

contains the world's largest upwelling system and is the world's most productive marine

ecosystem, providing between 15% and 20% of the world's annual marine catch. Anchovy,

sardine and horse mackerel are used for fish meal and for human consumption. Fishing

sustains thousands of fishermen and their families. The sharp decline in landings in the early

1970s and increases in the late 1980s and 1990s are related to El Niño climate effects (see

Humboldt Current description, this volume).

Figure 10.--Humboldt Current LME multi-decadal fish catch (1950-2004). Source: Sea Around Us Project

2007.

Regional Seas and Large Marine Ecosystems

19

While the high productivity of the Humboldt Current LME is the result of upwelling processes

governed by strong trade winds, the upwelling is subjected to considerable annual climatic

variability, which causes variations in marine populations and catch (Figure 10). The normal

seasonal upwelling can be interrupted by the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO), which

results in intrusions of warm water. For the long-term sustainability of the pelagic and

demersal fish stocks of this LME, improved forecasts of climate-driven fishery fluctuations are

required. Polar region LMEs are now also changing from extensive global climate warming

and ice melt (see East Bering Sea and Gulf of Alaska descriptions, this volume).

Need to curb excessive nitrogen loading:

Models of nitrogen affecting LMEs predict significant increases. Excessive levels of nitrogen

contribution to coastal eutrophication constitute a growing global environmental problem that

is cross-sectoral in nature. Excessive nitrogen loadings have been identified as problems

inter alia in the Baltic Sea, Black Sea, Adriatic portion of the Mediterranean, Yellow Sea,

South China Sea, Bay of Bengal, Gulf of Mexico, and Patagonian Shelf LMEs.

16

14

12

2050

10

-1 r

1990

8

Tg N y

6

4

2

0

N o rth

S o u th Afric a E u ro p e N o rth

E a s t

S o u th

A m e ric a A m e ric a

e a s t

A s ia

A s ia

A s ia

Figure 11. Model-predicted nitrogen (dissolved inorganic N) export by rivers to coastal systems in 1990

and in 2050--based on a business-as-usual (BAU) scenario. Figure modified from Kroeze and

Seitzinger (1998).

Model-predicted global estimates of dissolved inorganic nitrogen (DIN) export from

freshwater basins to coastal waters in 1990 and 2050 have been developed by Kroeze

and Seitzinger (1998). These estimates, based on a business-as-usual (BAU) scenario,

are cause for concern for the future condition of LME coastal waters with expected

nitrogen exports doubling between 1990 and 2050 (Figure 11). Given the expected

future increases in human population size and in fertilizer use, without significant nitrogen

mitigation efforts, LMEs will be subjected to a future of increasing harmful algal bloom

events, reduced fisheries, and hypoxia that will further degrade marine biomass and

biological diversity.

REFERENCES

Aiken, J., Pollard, R., Williams, R., Griffiths, G., Bellan, I. (1999). Measurements of the upper ocean

structure using towed profiling systems. In: Sherman, K. and Q. Tang, eds. Large Marine

Ecosystems of the Pacific Rim: Assessment, Sustainability, and Management. Malden:

Blackwell Science, Inc. 346-362.

20

K. Sherman and G. Hempel

Behrenfeld, M. and Falkowski, P.G. (1997). Limnol. Oceangr. 42(1):1-20.

Belausteguigoitia, J.C. (2004). Causal chain analysis and root causes: the GIWA approach. Ambio

33:7-12.

Belkin, I.M. (2008) Rapid warming in Large Marine Ecosystems. Progress in Oceanography, in

press.

Belkin, I.M., and Cornillon, P.C. (2005). Bering Sea thermal fronts from Pathfinder data: Seasonal

and interannual variability, Pacific Oceanography 3(1): 6-20.

Berman, M.S. and Sherman, K.. 2001. A towed body sampler for monitoring marine ecosystems.

Sea Technology 42(9):48-52.

Bouvet M., Hoepffner, N. and Dowell, M.D. (2002). Parameterization of a spectral solar irradiance model

for the global ocean using multiple satellite sensors. Journal of Geophysical Research, 107(C12),

3215, doi:10.1029/2001JC001126.

Bricaud, A., A. Morel, M. Babin, K. Allali, and H. Claustre. 1998. Variations of light absorption by

suspended particles with chlorophyll a concentration in oceanic (case 1) waters: Analysis and

implications for bio-optical models. Journal of Geophysical Research 103(C13):31033-31044.

CBD (2004). Annex I, Decision VII/30, p 351 in: The 2020 Biodiversity Target: a Framework for

Implementation. Decisions from the Seventh Meeting of the Conference of the Parties of the

Convention on Biological Diversity, Kuala Lumpur, 9-10 and 27 February 2004. Secretariat of

the CBD, Montreal.

Costanza, R. (1992). Toward an operational definition of ecosystem health. In: Costanza R, B.G.

Norton, B.D. Haskell, eds. Ecosystem Health: New Goals for Environmental Management.

Island Press, Washington DC. 239-256.

Duda, A. and Sherman, K. (2002). A new imperative for improving management of large marine

ecosystems. Ocean & Coastal Management 45:797-833.

Epstein, P.R. (1993). Algal blooms and public health. World Resource Review 5(2):190-206.

FAO'S Fisheries Agreement Register (FARISIS). 1998. Committee on Fisheries. Twenty-third

Session Rome, Italy, 15-19 February 1999 www.fao.org/docrep/meeting/w9885e.htm

GEF. 2007. Operational Programs , available online at http://gefweb.org/Operational_Policies/

Operational_Programs/OP_8_English.pdf.

Hempel, G. and Daler, D.. (2004). Why a Global International Waters Assessment (GIWA)? Ambio

33:2-6.

Hennessey, T. and Sutinen, J., eds. (2005). Sustaining Large Marine Ecosystems: The Human

Dimension. Elsevier. Amsterdam. 368p.

Hoagland, P. and Jin, D. (2006). Accounting for Marine Economic Activities in Large Marine