Land-based Nutrient Loading to LMEs: A Global

Watershed Perspective on Magnitudes and Sources

Sybil P. Seitzinger and Rosalynn Y. Lee

Abstract

Land-based nutrient (nitrogen and phosphorus) inputs to coastal systems around the

world have markedly increased due primarily to the production of food and energy to

support the growing population of over 6 billion people. The resulting nutrient enrichment

has contributed to coastal eutrophication, degradation of water quality and coastal

habitats, and increases in hypoxic waters, among other effects. There is a critical need

to understand the quantitative links between anthropogenic activities in watersheds,

nutrient inputs to coastal systems, and coastal ecosystem effects. As a first step in the

process to gain a global perspective on the problem, a spatially explicit global watershed

model (NEWS) was used to relate human activities and natural processes in watersheds

to nutrient inputs to LMEs, with a focus on nitrogen.

Many LMEs are currently hotspots of nitrogen loading in both developed and developing

countries. A clear understanding of the relative contribution of different nutrient sources

within an LME is needed to support development of effective policies. In 73% of LMEs,

anthropogenic sources account for over half of the dissolved inorganic nitrogen (DIN)

exported by rivers to the coast. In most of these, agricultural activities (fertilizer use and

wastes from livestock) are the dominant source of DIN loading, although atmospheric

deposition and, in a few LMEs, sewage can also be important.

Over the next 50 years, human population, agricultural production, and energy production

are predicted to increase especially rapidly in many developing regions of the world.

Regions of particular note are in southern and eastern Asia, western Africa, and Latin

America. Unless substantial technological innovations and management changes are

implemented, this will lead to further increases in nutrient inputs to LME coastal waters

with associated water quality and ecosystem degradation. An approach is needed such

as that being developed in GEF-sponsored LMEs programs where all stakeholders

including scientists, policy makers and private sector leaders work together to develop

a better understanding of the issues and to identify and implement workable solutions.

Introduction of the Problem

Human activities related to food and energy production have greatly increased the

amount of nutrient pollution entering the coastal environment from land-based sources

(Howarth et al. 1996; Seitzinger and Kroeze 1998; Galloway et al. 2004; Green et al.

2004). Small amounts of nutrient enrichment can have beneficial impacts to some

coastal waters and marine ecosystems by increasing primary production which can have

potentially positive impacts on higher trophic levels. However, a high degree of nitrogen

and phosphorus enrichment, causing eutrophication of coastal and even inland waters,

tends towards detrimental effects including degradation of fisheries habitats. The

negative effects of eutrophication begin with nutrient uptake by primary producers that

can result in blooms of phytoplankton, macroalgae, and nuisance/toxic algae. When

phytoplankton blooms die and sink, decomposition of the biomass consumes and may

deplete dissolved oxygen in the bottom water resulting in hypoxic or "dead zones." There

are many other effects of nutrient over-enrichment including increased water turbidity,

82

Land-based sources of nutrients in LMEs

loss of habitat (e.g., seagrasses), decreases in coastal biodiversity and distribution of

species, increase in frequency and severity of harmful and nuisance algal blooms, and

coral reef degradation, among others (National Research Council 2000; Diaz et al. 2001;

Rabalais 2002).

Nutrient over-enrichment and associated coastal ecosystem effects are occurring in

many areas throughout the world and a number of recent assessments have begun to

document their regional and global distribution. The European Outlook reported that in

2000, more than 55% of ecosystems were endangered by eutrophication. This includes

the notable hypoxic/anoxic zones in the Baltic Sea, Black Sea and Adriatic Sea, among

many others. In the USA, a recent assessment of over 140 coastal systems by the

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration found that in 2004 50% of the

assessed estuaries had a high chlorophyll a (phytoplankton) rating and 65% of the

assessed estuaries were moderately to highly eutrophic (Bricker et al. 2007). In a recent

literature review by the World Resources Institute (Selman et al. 2008), 375 eutrophic

and hypoxic coastal systems were identified around the world, including many areas in

developing countries.

The need to address nutrient over-enrichment as a priority threat to coastal waters and

Large Marine Ecosystems (LMEs) has been recognized at national and global levels.

The Global Plan of Action for the Protection of the Marine Environment from Land-based

Activities (GPA), which was adopted by 108 Governments and the European

Commission in 1995, recognized the need for global, regional and national action to

address nutrients impacting the coastal and marine environment. Continued widespread

government support to address nutrients has been noted in both the Montreal and Beijing

Declarations. In 2002, the World Summit on Sustainable Development convened in

Johannesburg identified substantial reductions in land-based sources of pollution by 2006

as one of their 4 marine targets. Over 60 countries have developed national policies or

national action plans to address coastal nutrient-enrichment within the context of

sustainable development of coastal areas and their associated watersheds.

Over the next 50 years, human population, agricultural production, and energy production

are predicted to increase especially rapidly in many developing regions of the world

(Hassan et al. 2005). Unless substantial technological innovations and management

changes are implemented, this will lead to further increases in nutrient (nitrogen and

phosphorus) inputs to the coastal zone with associated water quality and ecosystem

degradation. In order to optimize use of land for food and energy production while at the

same time minimizing degradation of coastal habitats, there is a critical need to

understand the quantitative links between land-based activities in watersheds, nutrient

inputs to coastal systems, and coastal ecosystem effects.

In this chapter we primarily address the links between land-based activities in watersheds

and nutrient inputs to coastal systems around the world. Here we use a global watershed

model (NEWS) to examine the patterns of nutrient loading and source attribution at global

and regional scales and then apply the model at the scale of large marine ecosystems

(LMEs) (Sherman & Duda 1999). Within all LMEs, 80% of the world's marine capture

fisheries occur (Sherman 2008) which emphasizes the importance of cross political-

boundary management of these international marine ecosystem units, as in the Global

International Waters Assessment (GIWA; UNEP 2006). Various aspects including

ecosystem productivity, fish and fisheries, pollution and ecosystem health,

socioeconomic conditions, and governance, have been examined for many individual

LMEs, but limited assessments across all LMEs have been made with a primarily

fisheries emphasis (e.g., Sea Around Us Project 2007). In individual LMEs, few

estimates of nutrient loading have been made, and only in the Baltic Sea LME has source

Seitzinger and Lee

83

apportionment been investigated (HELCOM 2004, 2002). At the end of the chapter we

return to coastal ecosystem effects.

A Watershed Perspective

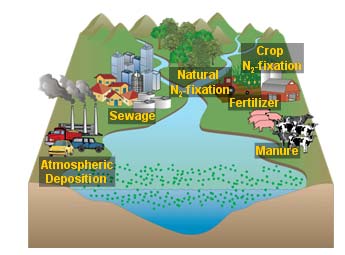

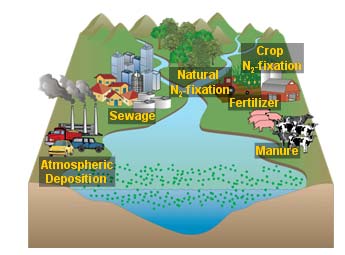

Rivers are a central link in the chain of nutrient transfer from watersheds to

coastal.systems. Nutrient inputs to watersheds include natural (biological N2-fixation,

weathering of rock releasing phosphate) as well as many anthropogenic sources. At the

global scale, anthropogenic nitrogen inputs to watersheds are now greater than natural

inputs (Galloway et al. 2004). Anthropogenic nutrient inputs are primarily related to food

and energy production to support the over 6 billion people on Earth with major sources

including fertilizer, livestock production, sewage, and atmospheric nitrate deposition

resulting from NOx emissions from fossil fuel combustion.

Figure 1. Watershed schematic of nitrogen inputs and transport to coastal systems. Symbols for

diagram courtesy of the Integration and Application Network (ian.umces.edu/symbols), University of

Maryland Center for Environmental Science.

Uneven spatial distribution of human population, agriculture, and energy production leads

to spatial differences in the anthropogenic alterations of nutrient inputs to coastal

ecosystems (Howarth et al. 1996; Seitzinger and Kroeze 1998; Green et al. 2004;

Seitzinger et al. 2005). While many site-specific studies have documented river transport

of nutrients (nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), carbon (C) and silica (Si)) to coastal systems,

there are many more rivers for which there are no measurements; sustained monitoring

of temporal changes in exports is rarer still. A mechanism is needed to develop a

comprehensive and quantitative global view of nutrient sources, controlling factors and

nutrient loading to coastal systems around the world under current conditions, as well as

to be able to look at past conditions and plausible future scenarios.

A Global Watershed Nutrient Export Model (NEWS)

In order to provide regional and global perspectives on changing nutrient transport to

coastal systems throughout the world, an international workgroup (Global NEWS

Nutrient Export from WaterSheds; http://www.marine.rutgers.edu/globalnews) has

developed a spatially explicit global watershed model that relates human activities and

natural processes in watersheds to nutrient inputs to coastal systems throughout the

world (Beusen et al. 2005; Dumont et al. 2005; Harrison et al. 2005a and b; Seitzinger et

al. 2005). Global NEWS is an interdisciplinary workgroup of UNESCO's

Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (IOC) focused on understanding the

relationship between human activity and coastal nutrient enrichment.

84

Land-based sources of nutrients in LMEs

In addition to current predictions, the NEWS model is also being used to hindcast and

forecast changes in nutrient, carbon and water inputs to coastal systems under a range

of scenarios. In this chapter we briefly describe the NEWS model and then present

results for mid-1990's conditions at both global scales and as specifically applied to LME

regions.

NEWS Model Basics. The NEWS model is a multi-element, multi-form, spatially explicit

global model of nutrient (N, P, and C) export from watersheds by rivers (Table 1). The

model output is the annual export at the mouth of the river (essentially zero salinity).

The NEWS model was calibrated and validated with measured export near the river

mouth from rivers representing a broad range of basins sizes, climates, and land-uses.

Over 5000 watersheds are included in the model with the river network and water

discharge defined by STN-30 (Fekete et al. 2000; Vörösmarty et al. 2000a and b). The

input databases are at the scale of 0.5o latitude by 0.5o longitude.

Table 1. Nutrient forms modeled in Global NEWS. DIC and DSi sub-models (in italics) are currently in

development.

Dissolved

Particulate

Inorganic Organic

N DIN DON PN

P

DIP

DOP

PP

C

DIC

DOC

POC

Si

DSi

Whereas previous efforts have generally been limited to a single element or form, the

Global NEWS model is unique in that it can be used to predict magnitudes and sources

of multiple bio-active elements (C, N, and P) and forms (dissolved/particulate,

organic/inorganic). It is important to know coastal nutrient loading of multiple elements

because different elements and elemental ratios can have different ecosystem effects.

The various forms of the nutrients (dissolved inorganic and organic and particulate forms)

also have different bioreactivities. For example, the dissolved inorganic nitrogen (DIN)

pool is generally considered to be bio-available, while only a portion of river transported

dissolved organic nitrogen (DON) is readily available for uptake by micro-organisms,

including bacteria and some phytoplankton (Bronk, 2002; Seitzinger et al., 2002a).

However, DON can be an important N source and it is implicated in the formation of

some coastal harmful algal blooms (Paerl, 1988; Berg et al., 1997 and 2003; Granéli et

al., 1999; Glibert et al., 2005a and b). Particulate and dissolved species can also have

very different impacts on receiving ecosystems.

The NEWS model predicts riverine nutrient export (by form) as a function of point and

non-point nutrient sources in the watershed, hydrological and physical factors, and

removal within the river system (Figure 2) (Beusen et al. 2005; Dumont et al. 2005;

Harrison et al. 2005a and b; Seitzinger et al. 2005). A further feature of the model is that

it can be used to estimate the relative contribution of each watershed source to export at

the river mouth. The NEWS model builds on an earlier model of dissolved inorganic N

(DIN) export (Seitzinger and Kroeze 1998).

Seitzinger and Lee

85

Figure 2. Schematic of some of the major inputs and controlling factors in the Global NEWS watershed river

export model.

There is considerable detail in the input databases and model parameterizations that

reflect food and energy production and climate (Figure 2). For example, crop type is

important in determining fertilizer use, the amount of manure produced is a function of

animal type (e.g., cows, camels, chickens, goats, etc.), nutrient loading from sewage

depends not only on the number of people in a watershed but also on their connectivity to

a sewage system and level of sewage treatment, atmospheric nitrate deposition is related

to fossil fuel combustion. A number of hydrological and physical factors are important in

transferring nutrients from soils to the river, with water runoff being important for all

elements and forms. Once in the river, N and P can be removed by biological and

physical processes during river transport within the river channels, in reservoirs, and

through water removal for irrigation (consumptive water use).

NEWS Model Output: The NEWS model has provided the first spatially distributed

global view of N, P and C export by world rivers to coastal systems. At the global scale

rivers currently deliver about 65 Tg N and 11 Tg P per year according to NEWS model

predictions (Tg = tera gram = 1012 g) (Figure 3). For nitrogen, DIN and particulate N (PN)

each account for approximately 40% of the total N input, with DON comprising about

20%. This contrasts with P, where particulate P (PP) accounts for almost 90% of total P

inputs. However, while DIP and dissolved organic P (DOP) each contribute only about

10% of total P, both of these forms are very bioreactive and thus may have a

disproportionate impact relative to PP on coastal systems.

Figure 3. Global N and P river export to coastal systems by nutrient form based on the NEWS model (Dumont

et al. 2005; Harrison et al. 2005a).

86

Land-based sources of nutrients in LMEs

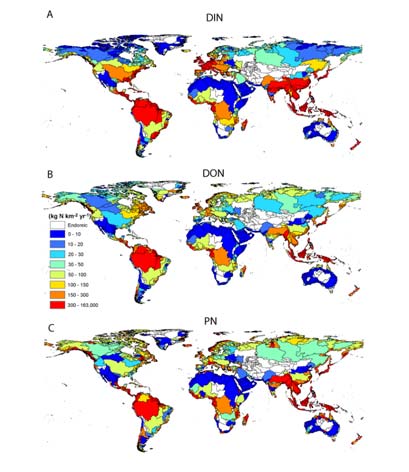

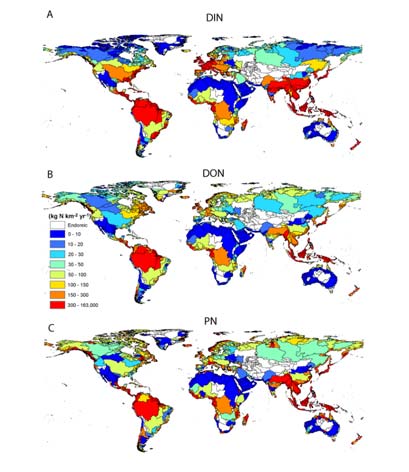

There is large spatial variation around the world in river nutrient export, including different

patterns for the different nutrient forms (DIN, DON and PN) (Figure 4). Using N yield (kg

N per km2 watershed per year that is exported to the river mouth), DIN yield shows

considerable variation at regional and continental scales, as well as among adjacent

watersheds. As might be expected based on past measurements of river nutrient export,

the NEWS model predicts relatively high watershed yields in the eastern USA, the

Mississippi basin, and much of western Europe. Of particular note, however, are also the

high DIN yields from developing regions including much of southern and eastern Asia,

Central America and small coastal watersheds in western Africa.

The large spatial variation in N yield reflects the variable magnitudes of the different

nutrient sources and controlling factors among watersheds. This underscores the

importance of the need for a clear understanding of the nutrient sources and controls

within LMEs at many scales in order to develop effective policies and implementation

strategies to control coastal nutrient loading.

Figure 4. NEWS-model-predicted A) DIN, B) DON, and C) PN yield (kg N km-2 yr-1) to coastal systems

from basins globally. Model output replotted from Harrison et al., 2005b, Dumont et al 2005, and

Beusen et al. 2005.

Seitzinger and Lee

87

N and P differ markedly in the relative contribution of different nutrient sources to river

nutrient export (Seitzinger et al. 2005). At the global scale, natural sources account for

about 40% of DIN and DIP river export (biological N2-fixation and rock weathering,

respectively) (Figure 5). Anthropogenic sources for DIN export are dominated by

agriculture (fertilizer and manure) in contrast to DIP where sewage accounts for ~60% of

river export. This difference in major sources, illustrates the need for different strategies

to reduce nitrogen or phosphorus loading to coastal systems.

Of course there is considerable variation in the relative contribution of nutrient sources at

continental, regional and watersheds scales, and this must be known and taken into

consideration when developing nutrient reduction strategies. At the continental scale, for

example, in South America livestock production (manure) is by far the largest

anthropogenic N source contributing to river DIN loading to coastal systems (Figure 6).

This contrasts with Asia where fertilizer use is about twice as great as livestock

production in contributing to river DIN loading.

Figure 5. Contribution of different sources to DIN and DIP river export globally.

Figure 6. Contribution of N sources in watersheds to model predicted DIN river export to the coastal

zone of each continent. (Figure from Dumont et al. 2005)

88

Land-based sources of nutrients in LMEs

NEWS Model Application to LMEs

Land-based pollution of coastal waters in LMEs can have sources in multiple countries

often located upstream at a considerable distance from the coastal zone. The release of

nutrients into rivers can cross national borders and create environmental, social and

economic impacts along the way - until reaching the coastal zone, which may be in a

different country. Thus an LME transboundary approach is essential for identifying

watershed nutrient sources and coastal nutrient loading to support policy development

and implementation in LMEs that will reduce current and future coastal eutrophication.

Few estimates of nutrient loading have been made in individual LMEs, and only in the

Baltic Sea LME has source apportionment been investigated (HELCOM 2004, 2002). As

a first step in bridging the gap between land-based activities and LME waters, we

examined the relative magnitudes and distribution of DIN loading from watersheds to

LMEs globally. We focused on N because it is often the most limiting nutrient in coastal

waters and thus important in controlling coastal eutrophication. DIN is often the most

abundant and bioavilable form of nitrogen, and therefore contributes significantly to

coastal eutrophication.

Watershed DIN export to rivers predicted by the NEWS model described above was

compiled for each of the 64 LMEs (2002 delineation; Duda & Sherman 2002) except for

the Antarctic (LME 61) where database information was limited. Total DIN load to each

LME was aggregated from all watersheds with coastlines along that LME for point

sources and only those watersheds with discharge to that LME for diffuse sources. This

work was part of the GEF Medium-Sized Project: Promoting Ecosystem-based

Approaches to Fisheries Conservation and LMEs (Component 3: Seitzinger and Lee

2007).

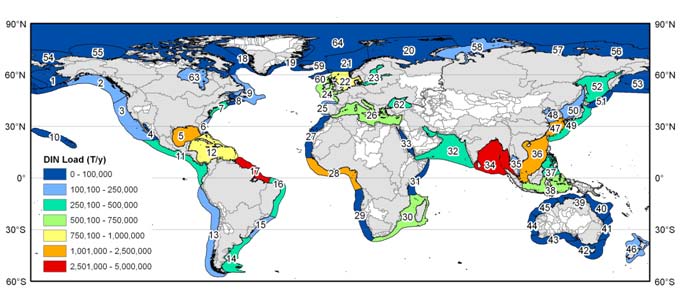

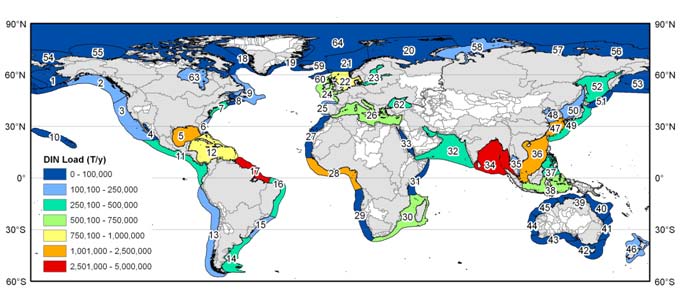

Figure 7. DIN inputs to LMEs from land-based sources predicted by the NEWS DIN model. Watersheds

discharging to LMEs are grey; watersheds with zero coastal discharge are white. Units: Tons N/y. See

Table 2 for LME identification. (Figure from Lee and Seitzinger submitted).

Seitzinger and Lee

89

Table 2. LMEs identified by name and number (see Fig. 7 and 8)

LME

LME

LME name

LME name

#

#

1

East Bering Sea

33

Red Sea

2

Gulf of Alaska

34

Bay of Bengal

3

California Current

35

Gulf of Thailand

4

Gulf of California

36

South China Sea

5

Gulf of Mexico

37

Sulu-Celebes Sea

6 Southeast

U.S.

Continental Shelf

38

Indonesian Sea

7

Northeast U.S. Continental Shelf

39

North Australian Shelf

Northeast Australian Shelf-Great Barrier

8 Scotian

Shelf

40 Reef

9

Newfoundland-Labrador Shelf

41

East-Central Australian Shelf

10

Insular Pacific-Hawaiian

42

Southeast Australian Shelf

11

Pacific Central-American Coastal

43

Southwest Australian Shelf

12

Caribbean Sea

44

West-Central Australian Shelf

13

Humboldt Current

45

Northwest Australian Shelf

14

Patagonian Shelf

46

New Zealand Shelf

15

South Brazil Shelf

47

East China Sea

16

East Brazil Shelf

48

Yellow Sea

17

North Brazil Shelf

49

Kuroshio Current

18

West Greenland Shelf

50

Sea of Japan

19

East Greenland Shelf

51

Oyashio Current

20

Barents Sea

52

Okhotsk Sea

21

Norwegian Sea

53

West Bering Sea

22

North Sea

54

Chukchi Sea

23

Baltic Sea

55

Beaufort Sea

24

Celtic-Biscay Shelf

56

East Siberian Sea

25

Iberian Coastal

57

Laptev Sea

26

Mediterranean Sea

58

Kara Sea

27

Canary Current

59

Iceland Shelf

28

Guinea Current

60

Faroe Plateau

29

Benguela Current

61

Antarctic (not included in this analysis)

30

Agulhas Current

62

Black Sea

31

Somali Coastal Current

63

Hudson Bay

32

Arabian Sea

64

Arctic Ocean

DIN export from watersheds to LMEs varies globally across a large range of magnitudes

(Figure 7). The smallest loads are exported to many polar and Australian LMEs, while

the largest loads are exported to northern tropical and subtropical LMEs. Of particular

90

Land-based sources of nutrients in LMEs

note are the large loads exported to the Gulf of Mexico, South China Sea, East China

Sea, and North Sea LMEs in which high anthropogenic activity occurs in their

watersheds. The Carribean Sea, Mediterranean Sea and Indonesian Sea LMEs, among

others, also receive substantial DIN loads.

The NEWS model also predicts substantial DIN export from the North Brazil Shelf LME

which has relatively low anthropogenic activity in its watersheds. Further investigation is

underway to evaluate the NEWS model for these large and relatively pristine tropical river

basins. The high DIN load may reflect a number of factors including the large role that

high water runoff from tropical rivers plays in the export of DIN, high biological N2-fixation,

low denitrification, and model uncertainty.

Identification of Land-based Nutrient Sources to LMEs. DIN loading to each LME

was attributed to diffuse and point sources including natural biological N2-fixation,

agricultural biological N2-fixation, fertilizer, manure, atmospheric deposition and sewage.

Dominant sources of DIN to LMEs were also identified which may be useful for the

management of land-based nutrient loading to LMEs.

Figure 8. Histogram of anthropogenic contribution to total DIN load to LMEs. LME numbers are shown

in each bar. See Table 2 for LME identification.

Land-based sources of DIN include natural sources (biological N2-fixation in natural

landscapes) and anthropogenic activities. In watersheds draining to LMEs,

anthropogenic activities contribute to over half of the total DIN load in 73% of LMEs

(Figure 8). These anthropogenic DIN dominant LMEs are distributed across most

continents, except sub-Saharan Africa and most polar regions. Some of the highest

proportions (> 90%) of anthropogenic DIN loads are to European LMEs, such as the

North Sea and Mediterranean LMEs, and East Asian LMEs, such as the Yellow Sea and

East China Sea LMEs.

Agriculture is a major source of the anthropogenic DIN export to LMEs (Lee and

Seitzinger submitted). In 91% of the LMEs with agriculture occurring in their related

watersheds, over half their anthropogenic export is due to agricultural sources such as

agricultural biological fixation, manure, and fertilizer. Attribution of agricultural DIN export

Seitzinger and Lee

91

to these three sources reveals the predominance of fertilizer and manure over agricultural

biological fixation. For example, LMEs with the largest agricultural loads have less than

20% of the total DIN load due to biological fixation and over 50% due to either fertilizer

(e.g., in many northern temperate and Southeast Asian LMEs such as the Bay of Bengal,

East China Sea and South China Sea LMEs), to manure (e.g., in most Central and South

American LMEs such as the Caribbean and North Brazil Shelf LMEs) or to a combination

of both (e.g., in the North Sea and Celtic-Biscay Shelf LMEs) due to local agricultural

practices. There is no agricultural export to most polar LMEs.

Atmospheric deposition is important in regions where there are few other land-based

inputs (e.g., in polar regions such as the West and East Greenland Shelf LMEs), where

fossil fuel combustion from development is extreme (e.g., in the North- and Southeast

U.S. Continental Shelf LMEs), or where extensive landscape burning occurs (e.g., in the

Guinea Current LME which is fed by savannah fires in Western Central African

watersheds; Barbosa et al. 1999). Sewage is an important source of DIN to only a few

LMEs (as a primary source to the Kuroshio Current, Red Sea, West-Central Australian

Shelf, and Faroe Plateau LMEs), while agricultural fixation plays an even lesser role as a

primary source to only the Southwest Australian Shelf LME and a secondary source to

the Benguela Current, North Australian Shelf, and West-Central Australian Shelf LMEs.

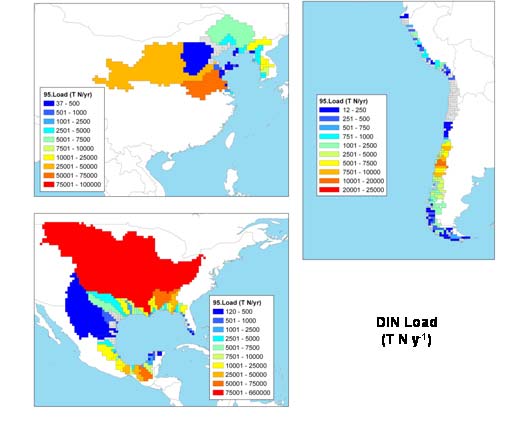

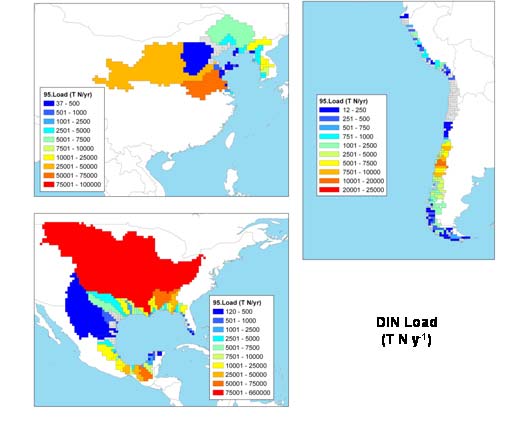

Figure 9. DIN export predicted by the NEWS DIN model from watersheds within the Yellow Sea,

Humboldt Current and Gulf of Mexico LMEs. Units: Tons N/yr.

The variability in watershed DIN export and source attribution within individual LMEs

exhibits comparably large differences as with across LMEs. Examples from different

world regions including Asia, South America and the US-Latin America are presented

below. Among the Yellow Sea, Humboldt Current and Gulf of Mexico LMEs, the DIN load

92

Land-based sources of nutrients in LMEs

from individual watersheds ranges over several orders of magnitude across both small

and large watersheds (Figure 9). For example, similarly sized watersheds in both the

Yellow Sea and Humboldt Current LMEs exhibit both the largest and smallest

magnitudes of watershed DIN export. In contrast, the Mississippi watershed is the

largest watershed contributing to the Gulf of Mexico LME and also exports the largest

load of DIN to the Gulf of Mexico.

Figure 10. Source attribution of DIN export predicted by the NEWS DIN model to the Yellow Sea,

Humboldt Current and Gulf of Mexico LMEs. Units: Tons N/yr.

The relative importance of different watershed sources of DIN to LME loading also varies,

e.g., among the Yellow Sea, Humboldt Current and Gulf of Mexico LMEs (Figure 10).

Agricultural sources dominate the DIN export in all of these LMEs, but fertilizer

contributes the most to export to the Yellow Sea and Gulf of Mexico LMEs while manure

is relatively more important than fertilizer to the Humboldt Current LME. In the Yellow

Sea LME, sewage is also a significant source (19%) to DIN export, while less so to the

Humboldt Current and Gulf of Mexico LMEs. Nitrogen fixation occurring in natural

landscapes is a significant source (28%) to the DIN export to only the Humboldt Current

LME. Atmospheric deposition is a lesser source of DIN export to all three example

LMEs, but contributes the relatively largest percentage (11%) to the Gulf of Mexico LME.

The identification of dominant sources of DIN and their relative contribution at the

individual LME level is essential for developing effective nutrient management strategies

on an ecosystem level.

Implications of Future Conditions in LME Watersheds

At the global scale, river nitrogen export to coastal systems is estimated to have

approximately doubled between 1860 and 1990, due to anthropogenic activities on land

(Galloway et al., 2004). Over the next 50 years the human population is predicted to

increase markedly in certain world regions, notably Southern and Eastern Asia, South

America, and Africa (United Nations, 1996). Growing food to feed the expanding world

population will require increased use of nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizers (Alcamo et al.,

1994; Bouwman et al., 1995; Bouwman, 1997). Increased industrialization, with the

associated combustion of fossil fuels and NOx production, is predicted to increase

atmospheric deposition of N (Dentener et al., 2006; IPCC, 2001). Thus, unless

substantial technological innovations and management changes are implemented,

increasing food production and industrialization will undoubtedly lead to increased export

of N to coastal ecosystems (Galloway et al. 2004), with resultant water quality

degradation.

Based on a business-as-usual (BAU) scenario, inorganic N export to coastal systems is

predicted to increase 3-fold by the year 2050 (relative to 1990) from Africa and South

Seitzinger and Lee

93

America (Figure 11) (Kroeze and Seitzinger, 1998; Seitzinger et al., 2002b). Substantial

increases are predicted for Europe (primarily eastern Europe) and North America.

Alarmingly large absolute increases are predicted for eastern and southern Asia; almost

half of the total global increased N export is predicted for those regions alone.

Figure 11. Predicted DIN export to coastal systems in 1990 and 2050 under a business-as-usual (BAU)

scenario. Modified from Kroeze and Seitzinger (1998).

The above scenario for 2050 was based on projections made from early 1990 trajectories

and using a relatively simple DIN model (Seitzinger and Kroeze 1998). The NEWS

model has more parameters and more detail behind the inputs (e.g., fertilizer use by crop

type, level of sewage treatment, etc.) (Figure 2) thus facilitating more advanced scenario

development and analyses. For example, it is now possible to explore the effects of a

range of development strategies, effects of climate change, production of biofuels,

increase in dams for hydropower, and consumptive water use (irrigation) on coastal

nutrient loading. Using the NEWS model, we are currently analyzing a range of

alternative scenarios for the years 2030 and 2050 based on the Millennium Ecosystem

Assessment (www.millenniumassessment.org) to provide insights into how changes in

technological, social, economic, policy and ecological considerations could alter future

nutrient export to coastal systems around the world (Seitzinger et al. in prep.).

Coastal Ecosystem Effects

As noted at the beginning of this chapter, nutrient over-enrichment can lead to a wide

range of coastal ecosystem effects. The most direct response of coastal ecosystems to

increased nutrient loading is an increase in biomass (e.g., chlorophyll a) of primary

producers or primary production rates (Nixon 1995). How might land-based DIN loading

be affecting primary production in LMEs? As a preliminary examination, we compared

land-based DIN loads predicted by the NEWS model to LME primary production

(modeled SeaWiFS data; Sea Around Us Project 2007) (Figure 12). This analysis

suggests that land-based DIN export supports a significant portion of primary production

at the level of an entire LME. In areas with upwelling, nutrient-rich bottom waters support

high rates of photosynthetic production. This is reflected in the generally higher primary

productivity than predicted by the regression solely with land-based DIN inputs in LMEs

characterized by upwelling (the Guinea Current, Arabian Sea, Pacific Central-American,

Humboldt Current, California Current, Gulf of Alaska, Benguela Current, Canary Current,

Northwest Australian, and Southwest Australian LMEs).

94

Land-based sources of nutrients in LMEs

Figure 12. Phytoplankton production vs. DIN load to the 63 LMEs. Orange points are LMEs in upwelling

regions. Phytoplankton production rates are from the Sea Around Us Project; DIN loads are from the

NEWS model (Dumont et al. 2005). Figure from Lee and Seitzinger submitted.

The above analysis compares land-based N loading to average primary production for

waters in the entire LME. In the near shore areas of LMEs, land-based N loading likely

supports a much higher proportion of primary production than suggested by the overall

relationship in Figure 12 and should be investigated. The additional effects of high

nutrient loading to estuaries and near shore waters in LMEs on hypoxia, biodiversity,

toxic and nuisance algal blooms, habitat quality, and fisheries yields also warrants further

analysis.

Future Needs

We are beginning to make significant advances in understanding the relationship

between human activities in watersheds and coastal nutrient loading at a range of scales

(e.g., watershed, LME, and global) as illustrated by the application of the NEWS model.

However, this is only a start. For example, to date the LME, regional, and global

analyses have relied on input databases at the scale of 0.5 o latitude x 0.5o longitude.

The use of higher spatial resolution input databases based on local knowledge from

specific LME regions could significantly improve the model predictions. Similarly,

additional data for model validation is need. Development of scenarios based on local

projections of population, agricultural production, biofuels, dam construction, and climate

change, among others could provide information of use to policy makers.

Development of nutrient reduction policies and effective mitigation strategies also

requires widely applicable, quantitative relationships between nutrient loading and coastal

ecosystem effects. While there is considerable information on nutrient sources and

coastal impacts, this information is often much dispersed and has not yet been compiled

into a consistent database so that nutrient sources in specific LMEs can be linked to

impacts in their associated coastal system. This is a critical next step in order for a

toolbox to be developed so that effective policy measures can be formulated and

measures taken, and for the outcomes of those policies and measures to be evaluated.

Many technical and political options are available to reduce fertilizer use, decrease

nutrient runoff from livestock waste, decrease NOx emissions from fossil fuel burning,

Seitzinger and Lee

95

and enhance sewage treatment. The fact that many of these tools have not yet been

implemented on a significant scale suggests that additional technological options and

new policy approaches are needed. In addition, policy approaches to address non-point

source pollution are often nonexistent or very limited. To ensure that the science used to

develop these technologies and polices is sound and complete, existing data on nutrient

sources, mobilisation, distribution, and effects need to be assessed. An approach is

needed such as that being developed in GEF-sponsored LME programs and as

promoted by the International Nitrogen Initiative (INI: INitrogen.org) where all

stakeholders including scientists, policy makers and private sector leaders work

together to develop a better understanding of the issues and to identify and implement

workable solutions.

Literature Cited

Alcamo, J., Kreileman, J.J.G., Krol, M.S., and Zuidema, G. (1994). Modeling the global society-

climate system: Part 1: Model description and testing. Water Air Soil Pol. 76, 1-35.

Barbosa, P.M., Stroppiana, D., Gregoire, J.-M., and Pereira, J.M.C. (1999). An assessment of

vegetation fire in Africa (1981-1991): Burned areas, burned biomass, and atmospheric

emissions. Global Biogeochemical Cycles 13:933-950.

Berg, G. M., Glibert, P.M., Lomas, M.W., and Burford, M.A. (1997) Organic nitrogen uptake and

growth by the chrysophyte Aureococcus anophagefferens during a brown tide event. Marine

Biology 129, 377-87.

Berg, G.M., Balode, M., Purina, I., Bekere, S., Bechemin, C., and Maestrini, S.Y. (2003). Plankton

community composition in relation to availability and uptake ofoxidized and reduced nitrogen.

Aquatic Microb. Ecol. 30, 263-74.

Beusen, A., Dekkers A.D., Bouwman, A.F., Ludwig, W., and Harrison, J.A.. (2005). Estimation of

global river transport of sediments and associated particulate C, N and P. Global

Biogeochemical Cycles 19(4):GB4S06.

Bouwman, A.F. (1997). Long-term scenarios of livestock-cropland use interactions in developing

countries. Land Wat. Bull. 5. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome,

Italy.

Bouwman, A.F., Vanderhoek, K.W., and Olivier, J.G.J. (1995). Uncertainties in the global sources

distribution of nitrous oxide. Journal of Geophys Res-Atmos. 100, 2785, 2800.

Bricker, S., Longstaff, B., Dennison, W., Jones, A., Boicourt, K., Wicks, C., and Woerner, J. (2007).

Effects of nutrient enrichment In the nation's estuaries: A decade of change. NOAA Coastal

Ocean Program Decision Analysis Series No. 26. National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science,

Silver Springs, MD. Pp. 328.

Bronk, D.A. (2002). Dynamics of DON, Chapter 5, pp. 153-247, In: D.A. Hansell, and C.A. Carlson

(eds.) Biogeochemistry of marine dissolved organic matter. Academic Press, San Diego,

California.

Diaz., R.J. (2001). Overview of hypoxia around the world. J. Environ.Qual. 30: 275-281.

Dentener, F., Drevet, J,. Lamarque, J.F., Bey, I., Eickhout B., Fiore, A.M., Hauglustaine, D.,

Horowitz, L.W., Krol, M., Kulshrestha, U.C., Lawrence, M., Galy-Lacaux, C., Rast, S., Shindell,

D., Stevenson, D., Van Noije, T., Atherton, C., Bell, N., Bergman, D., Butler, T., Cofala, J.,

Collins, B., Doherty, R., Ellingsen, K., Galloway, J., Gauss, M., Montanaro, V., Müller, J.F.,

Pitari, G., Rodriguez, J., Sanderson, M., Solmon, F., Strahan, S., Schultz, M., Sudo, K., Szopa,

S. and Wild, O. (2006). Nitrogen and sulfur deposition on regional and global scales: A

multimodel evaluation, Global Biogeochem. Cycles, 20, GB4003, doi:10.1029/2005GB002672.

Duda, A.M., and Sherman, K. (2002). A new imperative for improving management of large marine

ecosystems. Ocean and Coastal Management 45:797-833.

Dumont, E., Harrison, J.A., Kroeze, C., Bakker, E.J., and Seitzinger, S.P. (2005). Global distribution

and sources of dissolved inorganic nitrogen export to the coastal zone: results from a spatially

explicit, global model. Global Biogeochemical Cycles 19:19(4): GB4S02.

Fekete, B.M., Vorosmarty, C.J., and Grabs, W. (2000). Global, composite runoff fields based on

observed river discharge and simulated water balances, Report 22. World Meteorological

Organization-Global Runoff Data Center, Koblenz, Germany.

96

Land-based sources of nutrients in LMEs

Galloway, J.N., Dentener, F.J., Capone, D.G., Boyer, E.W., Howarth, R.W., Seitzinger, S.P.,

Asner, G.P., Cleveland, C., Green, P., Holland, E., Karl, D.M., Michaels, A.F., Porter, J.H.,

Townsend, A., and Vorosmarty, C. (2004). Nitrogen cycles: past, present and future.

Biogeochemistry 70:153-226.

Glibert, P.M., Seitzinger, S., Heil, C.A., Burkholder, J.M., Parrow, M.W., Codispoti, L.A., and Kelly,

V. (2005a). The role of eutrophication in the global proliferation of harmful algal blooms.

Oceanography, 18: 199-209.

Glibert, P.M., Harrison, J., Heil, C. and Seitzinger, S. (2005b). Escalating worldwide use of urea -- a

global change contributing to coastal eutrophication. Biogeochemistry. DOI 10.1007/s10533-

3070-0.

Global International Waters Assessment (GIWA; UNEP 2006). Challenges to International Waters;

Regional Assessments in a Global Perspective. United Nations Environment Programme.

February 2006. ISBN 91-89584-47-3.

Granéli, E., Carlsson, P., and Legrand, C. (1999). The role of C, N, and P in dissolved and

particulate organic matter as a nutrient source for phytoplankton growth, including toxic

species. Aquat. Ecol. 33, 17-27.

Green, P.A., Vörösmarty, C.J., Meybeck, M., Galloway, J.N., Peterson, B.J., and Boyer, E.W.

(2004). Pre-industrial and contemporary fluxes of nitrogen trough rivers: a global assessment

based on topology, Biogeochemistry 68, 71-105

Harrison, J., Seitzinger, S.P., Caraco, N., Bouwman, A.F., Beusen, A., and Vörösmarty, C. (2005).

Dissolved inorganic phosphorous export to the coastal zone: results from a new, spatially

explicit, global model (NEWS-SRP). Global Biogeochemical Cycles 19(4): GB4S03.

Harrison, J.H., Caraco, N.F., and Seitzinger, S.P. (2005). Global patterns and sources of dissolved

organic matter export to the coastal zone: results from a spatially explicit, global model. Global

Biogeochemical Cycles 19(4): GBS406.

Hassan, R., Scholes, R., and Ash, N. (eds). (2005). ECOSYSTEMS AND HUMAN WELL-BEING:

CURRENT STATE AND TRENDS Vol. 1 Findings of the Condition and Trends Working Group.

Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. Island Press, Washington, DC.

HELCOM; Helsinki Commission. (2002). Environment of the Baltic Sea Area 1994-1998. Baltic Sea

Environmental Proceedings, No. 82B. Helsinki Commission, Helsinki, Finland.

HELCOM; Helsinki Commission. (2004). The Fourth Baltic Sea Pollution Load Compilation (PLC-

4) Baltic Sea Environment Proceedings No. 93. Helsinki Commission, Helsinki, Finland.

Howarth, R.W., Billen, G., Swaney, D., Townsend, A., Jaworski, N., Lajtha, K., Downing, J.A.,

Elmgren, R., Caraco, N., Jordan, T., Berendse, F., Freney, J., Kudeyarov, V., Murdoch, P.,

and Zhao-Liang, Z. (1996). Regional nitrogen budgets and riverine N & P fluxes for the

drainages to the North Atlantic Ocean: Natural and human influences. Biogeochemistry 35, 75-

139.

IPCC, Climate Change 2001: Synthesis Report. A Contribution of Working Groups, I, II, and III to

the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Cambridge,

United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, Cambridge University Press, pp. 398, 2001.

Kroeze, C., and Seitzinger, S.P. (1998). Nitrogen inputs to rivers, estuaries and continental

shelves and related nitrous oxide emissions in 1990 and 2050: A global model. Nutrient

Cycling in Agroecosystems 52: 195-212.

Lee, R.Y., and Seitzinger, S.P. In prep. Land-based dissolved inorganic nitrogen export to Large

Marine Ecosystems.

National Research Council. (2000). Clean waters: Understanding and reducing the effects of

nutrient pollution. National Academy of Science Press, Washington, D.C.

Nixon, S.W. (1995). Coastal marine eutrophication: A definition, social causes, and future

concerns. Ophelia 41:199-210.

Paerl, H.W. (1988). Nuisance phytoplankton blooms in coastal, estuarine, and inland waters.

Limnol. Oceanogr. 33, 823-847.

Rabalais, N.N. (2002). Nitrogen in aquatic ecosystems. Ambio 31, 102-112.

Sea Around Us. (2007). A global database on marine fisheries and ecosystems. World Wide Web

site www.seaaroundus.org. Fisheries Centre, University British Columbia, Vancouver, British

Columbia, Canada. [Accessed 15 May 2007].

Seitzinger, S.P. and Lee. R.Y. (2007). Eutrophication: Filling Gaps in nitrogen loding forecasts for

LIMEs. Component Three in GEF MSP Promoting Ecosystem-based Approaches to Fisheries

Conservation and LMEs. Final report to Global Environmental Facility.

Seitzinger and Lee

97

Seitzinger, S.P., Harrison, J.A., Dumont, E., Beusen, A.H.W., and Bouwman, A.F. (2005). Sources

and delivery of carbon, nitrogen and phosphorous to the coastal zone: An overview of global

nutrient export from watersheds (NEWS) models and their application. Global Biogeochemical

Cycles 19(4):GB4S01.

Seitzinger, S.P., Sanders, R.W., and Styles, R.V. (2002a). Bioavailability of DON from natural and

anthropogenic sources to estuarine plankton. Limnology and Oceanography 47(2):353-366.

Seitzinger, S.P., Kroeze, C., Bouwman, A.F., Caraco, N., Dentener, F., and Styles, R.V. (2002b).

Global patterns of dissolved inorganic and particulate nitrogen inputs to coastal systems:

Recent conditions and future projections. Estuaries 25(4b):640-655.

Seitzinger, S.P., and Kroeze, C. (1998). Global distribution of nitrous oxide production and N

inputs in freshwater and coastal marine ecosystems. Global Biogeochemical Cycles 12(1): 93-

113.

Selman, M., Greenhalgh, S., Diaz, R., and Zachary S. (2008). Eutrophication and hypoxia in

coastal areas: a global assessment of the state of knowledge. Washington, DC: World

Resources Institute.

Sherman, K., and Duda, A.M. (1999). An ecosystem approach to global assessment and

management of coastal waters. Marine Ecology Progress Series. 190:271-287.

Sherman, K. (2008). The UNEP Large Marine Ecosystem Report: A perspective on changing

conditions in LMEs of the World's Regional Seas. UNEP Regional Seas Report and Studies No.

182. United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi.

United Nations (1996). Country population statistics and projections 1950-2050, Report, Food and

Agricultural Organization of the United Nations, Rome, Italy, 1996.

UNEP/MAP/MED POL. (2003). Riverine transport of water, sediments and pollutants to the

Mediterranean Sea. MAP Technical Reports Series. Athens: United Nations Environment

Programme-Mediterranean Action Plan. 141, 1-111.

Vörösmarty, C.J., Fekete, B.M., Meybeck, M., and Lammers, R. (2000a). Geomorphometric

attributes of the global system of rivers at 30-minute spatial resolution. Journal of Hydrology

237:17-39.

Vörösmarty, C.J., Fekete, B.M., Meybeck, M., and Lammers, R. (2000b). A simulated topological

network representing the global system of rivers at 30-minute spatial resolution (STN-30).

Global Biogeochemical Cycles 14:599-621.

98

Land-based sources of nutrients in LMEs