Accelerated Warming and Emergent Trends in

Fisheries Biomass Yields of the World's Large

Marine Ecosystems

K. Sherman, I. Belkin, K. Friedland, J. O'Reilly and K. Hyde

Introduction

The heavily exploited state of the world's marine fisheries has been well documented

(FAO 2004; Garcia and Newton 1997; González-Laxe 2007). Little, however, is known of

the effects of climate change on the trends in global fisheries biomass yields. The Fourth

Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change stated with "high

confidence" that changes in marine biological systems are associated with rising water

temperatures affecting shifts in pelagic algae and other plankton, and fish abundance in

high latitudes (IPCC 2007). The Report also indicated that adaptation to impacts of

increasing temperatures in coastal systems will be more challenging in developing

countries than in developed countries due to constraints in adaptive capacity. From a

marine resources management perspective, the 8 regions of the globe examined by the

IPCC (i.e. North America, Latin America, Europe, Africa, Asia, the Australia and New

Zealand region and the two Polar regions), are important fisheries areas but at a scale

too large for determination of temperature trends relative to the assessment and

management of the world's marine fisheries biomass yields produced principally in 64

large marine ecosystems (LMEs) (Figure 1). These LMEs, in coastal waters around the

globe, annually produce 80% of the world's marine fisheries biomass (Figure 2).

Large Marine Ecosystems are areas of an ecologically based nested hierarchy of global

ocean biomes and ecosystems (Watson et al. 2003). Since 1995, LMEs have been

designated by a growing number of coastal countries in Africa, Asia, Latin America, and

eastern Europe as place-based assessment and management areas for introducing an

ecosystems approach to recover, develop, and sustain marine resources. The LME

approach to the assessment and management of marine resources is based on the

operationalization of five modules, with suites of indicators for monitoring and assessing

changing conditions in ecosystem: (i) productivity, (ii) fish and fisheries (iii) pollution and

ecosystem health, (iv) socioeconomics, and (v) governance (Duda and Sherman 2002).

The approach is part of an emerging effort by the scientific community to relate the scale

of place-based ecosystem assessment and management of marine resources to policy

making and to tighten the linkage between applied science and improved management of

ocean resources within the natural boundaries of LMEs (COMPASS 2005; Wang 2004).

Since 1995, international financial organizations have extended explicit support to

developing coastal countries for assessing and managing goods and services using the

modular approach at the LME scale. At present, 110 countries are engaged in LME

projects along with 5 UN agencies and $1.8 billion in financial support from the Global

Environment Facility (GEF) and the World Bank. Sixteen LME projects are presently

focused on introducing an ecosystems approach to the recovery of depleted fish stocks,

restoration of degraded habitats, reduction and control of pollution, conservation of

biodiversity, and adaptation to climate change. In recognition of the observational

evidence of global warming from the 4th Assessment Report of the (IPCC 2007) and the

lack of information on trends in global warming at the LME scale where most of the

world's marine fisheries biomass yields are produced, we undertook a study of the

physical extent and rates of sea surface temperature trends in relation to fisheries

biomass yields and SeaWiFS derived primary productivity of the world's LMEs.

42

Sherman et al.

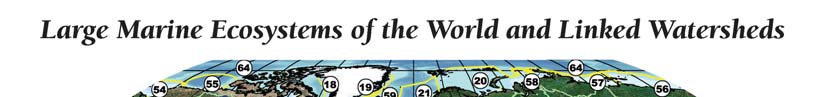

Figure 1. Large Marine Ecosystems of the World

Figure 2. Annual global marine fisheries biomass yields in metric tons in world LMEs (Sea Around Us Project)

Accelerated warming and emergent trends in fisheries biomass yields

43

METHODS

Fisheries biomass yields are not presented here as representative of individual fish stock

abundances. They are representative of fisheries catches and are used here to compare

the effects of global warming on the fishery biomass yields of the World's LMEs. The

comparative analysis of global temperature trends, fisheries biomass yields, and primary

productivity is based on available time-series data at the LME scale on sea surface

temperatures, marine fisheries biomass yields, and Sea WiFS derived primary

productivity values.

LME Sea Surface Temperatures (SST)

Sea surface temperature (SST) data is a thermal parameter routinely measured

worldwide. Subsurface temperature data, albeit important, are limited in the spatial and

temporal density required for reliable assessment of thermal conditions at the Large

Marine Ecosystem (LME) scale worldwide. The U.K. Meteorological Office Hadley

Center SST climatology was used in this analysis (Belkin 2008), as the Hadley data set

has resolution of 1 degree latitude by 1 degree longitude globally. A detailed description

of this data set has been published by Rayner et al. (2003). Mean annual SST values

were calculated for each 1° x 1° cell and then were area-averaged by annual 1° x 1°

SSTs within each LME. Since the square area of each trapezoidal cell is proportional to

the cosine of the middle latitude of the given cell, all SSTs were weighted by the cosine of

the cell's middle latitude. After integration over the LME area, the resulting sum of

weighted SSTs was normalized by the sum of the weights, that is, by the sum of the

cosines. Annual anomalies of annual LME-averaged SST were calculated. The long-

term LME-averaged SST was computed for each LME by a simple long-term averaging

of the annual area-weighted LME-averaged SSTs. Annual SST anomalies were

calculated by subtracting the long-term mean SST from the annual SST. Both SST and

SST anomalies were plotted using adjustable temperature scales for each LME to depict

temporal trends. Comparisons of fisheries biomass yields were examined in relation to

intervals of 0.3°C of increasing temperature.

LME Primary Productivity

The LME primary productivity estimates are derived from satellite borne data of NOAA's

Northeast Fisheries Science Center, Narragansett Laboratory. These estimates originate

from SeaWiFS (satellite-derived chlorophyll estimates from the Sea-viewing Wide Field-

of-view Sensor), Coastal Zone Color Scanner (CZCS), a large archive of in situ near-

surface chlorophyll data, and satellite sea surface temperature (SST) measurements to

quantify spatial and seasonal variability of near-surface chlorophyll and SST in the LMEs

of the world. Daily binned global SeaWiFS chlorophyll a (CHL, mg m-3), normalized water

leaving radiances, and photosynthetically available radiation (PAR, Einsteins m-2 d-1)

scenes at 9 km resolution for the period January 1998 through December 2006 were

obtained from NASA's Ocean Biology Processing Group. Daily global SST (oC)

measurements at 4 km resolution were derived from nighttime scenes composited from

the AVHRR sensor on NOAA's polar-orbiting satellites and from NASA's MODIS TERRA

and MODIS AQUA sensors. Daily estimates of global primary productivity (PP, gC m-2 d-1)

were calculated using the Ocean Productivity from Absorption and Light (OPAL) model, a

derivative of the model first formulated in Marra et al. (2003). The OPAL model

generates profiles of chlorophyll estimated from the SeaWiFS chlorophyll using the

algorithm from Wozniak et al. (2003) that uses the absorption properties in the water

column to vertically resolve estimates of light attenuation in approximately 100 strata

within the euphotic zone. Productivity is calculated for the 100 layers in the euphotic

zone and summed to compute the integral daily productivity (gC m-2 d-1). Monthly and

annual means of primary productivity (PP) were extracted and averaged for each LME.

Significance levels (alpha=0.01 and 0.05) of the regression coefficients of the nine years

of Sea WiFS mean annual primary productivity data were determined using a t-test

44

Sherman et al.

according to Sokal and Rohfl (1995). Time series trends plotted for each LME are

available online (www.lme.noaa.gov).

Fisheries Biomass Yield Methods

Prior to the Sea Around Us Program, projections of marine fisheries yields at the LME

scale, were largely defined by the range of vessels exploiting a given resource (Pauly

and Pitcher 2000). The need for countries to manage fisheries within EEZ's under

UNCLOS initiated efforts to derive fisheries yields at the national level(Prescott-Allen

2001) and consistent with the emergence of ecosystem-based management at the LME

scale(Sherman et al. 2003) (Pauly et al. 2008). The time series of fisheries biomass

yields (1950-2004) used in this study are based on the time-series data provided at the

LME scale by the Sea Around Us Project at the University of British Columbia (Pauly et

al. 2008) The method used by the Sea Around Us Project to map reported fishery

catches onto 180,000 global spatial cells of ½ degrees latitude and longitude was applied

to produce profiles of 54-yr. mean annual time-series of catches (biomass yields) by 12

species or species groups for the world's LMEs (Pauly et al. 2008; Watson et al. 2003).

In addition, plots on the status of the stocks within each of the LMEs according to their

condition (e.g. undeveloped, fully exploited and overexploited) in accordance with the

method of Froese and Kesner-Reyes (2002), and illustrated by Pauly et al. (2008), were

used to examine trends in yield condition among the LMEs. Fisheries biomass yields

were examined in relation to warming trends for 63 LMEs for the period 1982 to 2004.

Fisheries biomass yield trends were plotted for each LME using the LOESS smoothing

method (tension=0.5) and the emergent increasing and decreasing patterns examined in

relation to LME warming data (Cleveland and Devlin 1988). Observed trends were

compared to earlier studies for emergent spatial and temporal global trends in LME

fishery biomass yields.

RESULTS

Comparative SST Clusters

The LME plots of SST and SST anomalies are presented in 2 sets of 4 plates, with each

set containing a total of 63 figures: four plates for SST and four plates for SST anomalies

1957-2006. These can be viewed at www.lme.noaa.gov. The Arctic Ocean LME was not

included in this analysis because of the perennial sea ice cover. Other Arctic LMEs also

feature sea ice cover that essentially vanishes in summer, thus making summer SST

assessment possible. The 1957-2006 time series revealed a global pattern of long-term

warming however, the long-term SST variability since 1957 was not linear over the

period. Specifically. most LMEs underwent a cooling between the 1950s and the 1970s,

replaced by a rapid warming from the 1980s until the present. Therefore we re-

calculated SST trends using only the last 25 years of data (SST data available at

www.lme.noaa.gov, where SST anomalies are calculated for each LME. Net SST

change in each LME between 1982 and 2006 based on SST trends is summarized in

Table 1 (after Belkin, 1998).

The most striking result is the consistent warming of LMEs, with the notable exceptions of

two, the California Current and Humboldt Current. These LMEs experienced cooling over

the last 25 years. Both are in large and persistent upwelling areas of nutrient rich cool

water in the Eastern Pacific. The SST values were partitioned into 0.3°C intervals to

allow for comparison among LME warming rates. The warming trend observed in 61

LMEs ranged from a low of 0.08°C for the Patagonian Shelf LME to a high of 1.35°C in

the Baltic Sea LME (Table 1). The relatively rapid warming exceeding 0.6°C over 25

years is observed almost exclusively in moderate- and high-latitude LMEs. This pattern

is generally consistent with the model-predicted polar-and-subpolar amplification of global

warming (IPCC 2007). The warming in low-latitude LMEs is several times slower than

the warming in high-latitude LMEs (Table 1). In addition to the Baltic Sea, the most rapid

Accelerated warming and emergent trends in fisheries biomass yields

45

Table 1. SST change in each LME, 1982-2006 (sorted in descending order)

LME# SST

Change

Slope of Linear

Standard Error of

(°C)

Regression

Slope (°C/year)

1982-2006

(°C/year)

LME23='BALTIC SEA';

1.35

0.0563 0.0151

LME22='NORTH SEA';

1.31

0.0544 0.0099

LME47='EAST CHINA SEA';

1.22

0.0509 0.0077

LME50='SEA OF JAPAN'/'EAST SEA';

1.09

0.0453 0.0098

LME9='NEWFOUNDLAND-LABRADOR SHELF';

1.04

0.0435 0.0108

LME62='BLACK SEA';

0.96

0.0401 0.0124

LME8='SCOTIAN SHELF';

0.89

0.0370 0.0105

LME59='ICELAND SEA';

0.86

0.0360 0.0091

LME21='NORWEGIAN SEA';

0.85

0.0356 0.0072

LME49'KUROSHIO CURRENT';

0.75

0.0312 0.0062

LME60='FAROE PLATEAU';

0.75

0.0311 0.0078

LME33='RED SEA';

0.74

0.0309 0.0048

LME18='WEST GREENLAND SHELF';

0.73

0.0304 0.0064

LME24='CELTIC-BISCAY SHELF';

0.72

0.0301 0.0076

LME26='MEDITERRANEAN SEA';

0.71

0.0294 0.0055

LME54='CHUKCHI SEA';

0.70

0.0290 0.0087

LME25='IBERIAN COASTAL';

0.68

0.0283 0.0072

LME48='YELLOW SEA';

0.67

0.0279 0.0097

LME17='NORTH BRAZIL SHELF';

0.60

0.0252 0.0049

LME51='OYASHIO CURRENT';

0.60

0.0250 0.0086

LME15='SOUTH BRAZIL SHELF';

0.53

0.0221 0.0068

LME27='CANARY CURRENT';

0.52

0.0217 0.0082

LME12='CARIBBEAN SEA';

0.50

0.0208 0.0050

LME19='EAST GREENLAND SHELF';

0.47

0.0197 0.0074

LME28='GUINEA CURRENT';

0.46

0.0194 0.0063

LME10='INSULAR PACIFIC HAWAIIAN';

0.45

0.0187 0.0056

LME36='SOUTH CHINA SEA';

0.44

0.0182 0.0063

LME53='WEST BERING SEA';

0.39

0.0162 0.0064

LME2='GULF OF ALASKA';

0.37

0.0154 0.0081

LME40='NE AUSTRALIAN SHELF-GREAT BARRIER REEF';

0.37

0.0153 0.0101

LME56='EAST SIBERIAN SHELF';

0.36

0.0149 0.0092

LME41='EAST-CENTRAL AUSTRALIAN SHELF';

0.35

0.0145 0.0056

LME55='BEAUFORT SEA';

0.34

0.0140 0.0066

LME46='NEW ZEALAND SHELF';

0.32

0.0135 0.0105

LME4='GULF OF CALIFORNIA';

0.31

0.0130 0.0069

LME5='GULF OF MEXICO';

0.31

0.0130 0.0161

LME52='SEA OF OKHOTSK';

0.31

0.0129 0.0053

LME16='EAST BRAZIL SHELF';

0.30

0.0126 0.0062

LME63='HUDSON BAY';

0.28

0.0117 0.0076

LME1='EAST BERING SEA';

0.27

0.0113 0.0070

LME32='ARABIAN SEA';

0.26

0.0110 0.0048

LME29='BENGUELA CURRENT';

0.24

0.0100 0.0072

LME34='BAY OF BENGAL';

0.24

0.0098 0.0061

LME38='INDONESIAN SEA';

0.24

0.0098 0.0067

LME45='NORTHWEST AUSTRALIAN SHELF';

0.24

0.0098 0.0049

LME7='NORTHEAST U.S. CONTINENTAL SHELF';

0.23

0.0096 0.0043

LME37='SULU-CELEBES SEA';

0.23

0.0096 0.0125

LME30='AGULHAS CURRENT';

0.20

0.0085 0.0079

LME42='SOUTHEAST AUSTRALIAN SHELF';

0.20

0.0084 0.0042

LME31='SOMALI COASTAL CURRENT';

0.18

0.0074 0.0059

LME39='NORTH AUSTRALIAN SHELF';

0.17

0.0070 0.0068

LME6='SOUTHEAST U.S. CONTINENTAL SHELF';

0.16

0.0067 0.0061

LME35='GULF OF THAILAND';

0.16

0.0067 0.0064

LME58='KARA SEA';

0.16

0.0066 0.0065

LME11='PACIFIC CENTRAL-AMERICAN COASTAL';

0.14

0.0059 0.0101

LME20='BARENTS SEA';

0.12

0.0051 0.0092

LME57='LAPTEV SEA';

0.12

0.0048 0.0088

LME43='SOUTHWEST AUSTRALIAN SHELF';

0.09

0.0039 0.0057

LME44='WEST-CENTRAL AUSTRALIAN SHELF';

0.09

0.0038 0.0093

LME14='PATAGONIAN SHELF';

0.08

0.0034 0.0059

LME61='ANTARCTIC';

0.00

0.0001 0.0011

LME3='CALIFORNIA CURRENT';

-0.07

-0.0030 0.0119

LME13='HUMBOLDT CURRENT';

-0.10

-0.0042 0.0112

LME64='ARCTIC OCEAN';

46

Sherman et al.

warming exceeding 0.96°C over 25 years is observed in the North Sea, East China Sea,

Sea of Japan/East Sea, and Newfoundland-Labrador Shelf and Black Sea LMEs.

Comparisons of warming were made among three temperature clusters of LMEs. 1)

Super fast warming LMEs with D(SST) between >0.96°C -1.35°C are combined with fast

warming LMEs .67°C 0.84°C. Moderate warming LMEs have D(SST) between >0.3-

0.6°C; slow warming LMEs, have D(SST) between 0.0°C-0.28°C. Of the fast warming

LMEs (0.67°C to 1.35°C), 18 are warming at rates 2x to 4x times higher than the global

air surface temperature increase of 0.74°C for the past 100 years as reported by the

IPCC (2007) (Figure 3, after Belkin, 2008, Figure 5).

SST Net Warming in Large Marine Ecosystems, 1982-2006

1.2

1.1

1

0.9

°C 0.8

i

ng, 0.7

m

0.6

e

t

War 0.5

T N 0.4

SS 0.3

0.2

0.1

0

Slow LME

Moderate LME

Fast LME

Super-Fast LME

Global SST

(IPCC-2007;

1979-2005)

Figure 3. SST Net Warming in Large Marine Ecosystems, 1982-2006

Primary Productivity

No large scale consistent pattern of either increase or decrease in primary productivity

was observed. Of the 64 LMEs examined, only four 9-year trends were significant

(P<.05) (Figure 4). Primary productivity declined in the Bay of Bengal, and increased in

the Hudson Bay, Humboldt Current and Red Sea LMEs). The general declining trend in

primary productivity with ocean warming reported by Behrenfeld (2006) was limited to

the Bay of Bengal LMEs. No consistent trend among the LMEs was observed (Table 1).

However, as previously reported (Chassot et al. 2007; Nixon et al. 1986; Ware and

Thomson 2005) fisheries biomass yields did increase with increasing levels of primary

productivity (P<.001) in all 63 LMEs, and for LMEs in each of the warming clusters

(Figure 5A and 5B).

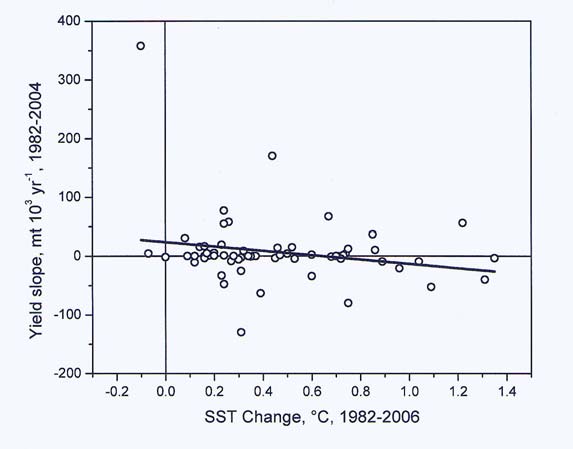

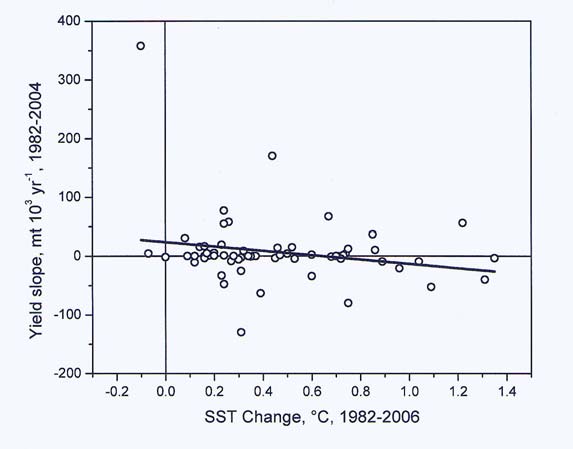

Fisheries biomass yield trends

The effects of warming on global fisheries biomass yields were non-uniform in relation to

any persistent global pattern of increasing or decreasing yields. The relationship

between change in LME yield and SST change was not significant; the slight suggestion

of a trend in the regression, was influenced by the data for the Humbolt LME (Figure 6).

Partitioning of the results into LMEs with increasing trends in fisheries biomass yields,

and those with declining trends divided the trends into two groups. Increasing yields

were observed in 31 (49.2%) and decreasing trends in 32 (50.8%) of LMEs. Differences

Accelerated warming and emergent trends in fisheries biomass yields

47

Figure 4. Primary productivity trends (1998-2006): Bay of Bengal, Hudson Bay, Humboldt Current and

Red Sea.

Figure 5A. Comparison of 5-yr mean annual fisheries biomass yield with 9-yr mean annual primary

production in fast warming (red), moderately warming (yellow) and slower warming (green) LMEs. The

two blue circles represent cooling LMEs.

48

Sherman et al.

Figure 5B. Comparison of 5-yr mean annual fisheries biomass yield with 9-yr mean annual primary

production in fast warming (red), moderately warming (yellow) and slower warming (green) LMEs.

Figure 6. The relationship between change in LME yield and SST change was not significant; the slight

suggestion of a trend in the regression, was influenced by the data for the Humbolt LME

Accelerated warming and emergent trends in fisheries biomass yields

49

;

land

e

n

ing LMEs

Fast

m

C5

st Gre

st Bering Sea

te War

odera

of the NW Atlantic;

South China Sea, Ea

C4

n-Clustered, M

No

n Seas;

ral

heast Shelf, the Barents Sea, Ea

e

ve

Es.

ropea

M

S

s

.

Gulf of California;

i

c.

sed Eu

a

cif

P

s

tal LME

n/East Sea L

SW

Coa

u

lf

of Alaska,

st Shelf, the U.S. Sout

Semi-Enclo

C10

i

c;

C3

a

cif

Sea of Japa

P

S. Northea

e

a

n

;

W

ntral American

N

rop

n

t and

cific Hawaiian, G

C9

Es in Relation to SSTs, 1987-2006:

de the U.

Es;

a

r Pa

hern Eu

Pacific Ce

o

Curre

M

i

n

clu

rs.

Sout

n

t and

C2

Kuroshi

nt Wate

C6

:

ing LMEs

s

ter;

a

ce

m

a Curre

Eastern Atlantic L

:

ean Clu

ng: NE Australia, Insul

;

C8

n and Adj

Slow War

E WARMING

d,

st Asian LMEs;

warmi

c

ea

rn Europ

LMEs

n

Shelf, Benguel

an O

tere

derate

-

clus

Northe

rming Ea

Atlantic

Indi

Figure 7. Warming Clusters of LM

FAST WARMING C1 Wa

MODERAT C7 are mo Shelf;

SLOW WARMING: C11 Non Patagonia

50

Sherman et al.

were similar in Fast Warming (8 increasing, 10 decreasing) and Moderate Warming

LMEs (10 increasing, 8 decreasing). In the Slower Warming LMEs, most (14) were

undergoing increasing biomass yields and 6 were in a decreasing condition (Table 2).

Linear warming trends from 1982 to 2006 for each LME were distributed in distinct global

clusters, (i) the Fast Warming LME clusters were in the Northeast Atlantic, African and

Southeast Asian waters; (ii) the Moderate Warming LMEs were clustered in the Atlantic

and North Pacific waters; and (iii) the Slow Warming LME clusters were located

principally in the Indian Ocean, and also in locations around the margins of the Atlantic

and Pacific Oceans (Figure 7). Comparisons of fisheries biomass yield trends for eleven

LME warming clusters were examined.

Table 2. Fisheries biomass trends in countries adjacent to developing and developed countries.

Fisheries biomass

Status of adjacent

Fisheries biomass in

Percentage of total

trend

countries

million metric tons

Increasing fisheries (20

Developing countries

32.0

49%

LMEs)

Decreasing fisheries (9

Developing countries

6.2

9%

LMEs)

Increasing fisheries (11

Developed countries

4.4

6%

LMEs)

Decreasing fisheries 15

Developed countries

11.0

17%

LMEs)

California Current,

11.4

19%

Humboldt Current, and 7

Arctic LMEs (9 LMEs)

Total fisheries biomass

All categories

65.0

100%

Comparative fisheries biomass yields in relation to warming: Fast

warming European LMEs

In the Norwegian Sea, Faroe Plateau, and Iceland Shelf, the fisheries biomass yield is

increasing. These three LMEs account for 3.4 million tons, or 5% of the world biomass

catch, (Figure 8A). This cluster of LMEs is influenced from bottom-up forcing of

increasing zooplankton abundance and warming hydrographic conditions in the northern

areas of the North Atlantic, where stocks of herring, blue whiting and capelin are

benefiting from an expanding prey field of zooplankton (Beaugrand and Ibanez 2004;

Beaugrand et al. 2002) supporting growth and recruitment of these three species. The

warming trend in the Norwegian Sea driving the increase in biomass of herring, capelin

and blue whiting yields has been reported by (Skjoldal and Saetre 2004). On the Faroe

Plateau LME, Gaard et al. (2002) indicate that the increasing shelf production of plankton

is linked to the increased production of fish and fisheries in the ecosystem. Astthorsson

and Vilhjálmsson (2002) have shown that variations of zooplankton in Icelandic waters

are greatly influenced by large scale climatic factors and that warm Atlantic water inflows

favor zooplankton that supports larger populations of capelin that serve as important prey

of cod. The productivity and fisheries of all three LMEs are benefiting from the increasing

strength of the sub-Polar gyre bringing warmed waters to the LMEs of the region

generally in the northern northeast Atlantic and contributing to decreasing production and

fisheries yields in the relatively warmer southern waters of the northeast Atlantic

(Richardson and Schoeman 2004).

In southern Europe three LMEs, the North Sea, Celtic Biscay, and Iberian Coastal

LMEs in fast warming clusters are experiencing declines in biomass trends representing

4.1 mmt (6.4%) of the mean annual global biomass yield (Figure 8B). It has been

Accelerated warming and emergent trends in fisheries biomass yields

51

(A)

2,000,

2,

000

00

600,000

600,

1,

1 600,

,

00

600, 0

00

1,

1 500,

,

00

500, 0

00

500,000

500,

1,

1 400,

,

00

400, 0

00

1,500,

1,

000

00

1,

1 300,

,

00

300, 0

00

400,000

400,

_21

_60

1,

1 200,

,

00

200, 0

_59

00

_59

1,000,

1,

000

E

00

E

E

E 1,1100,

,

00

100, 0

00

LM

LM 300,000

300,

LM

1,

1 000,

,

00

000, 0

00

500,000

00

200,000

200,

900,00

900, 0

00

800,00

800, 0

00

0

100,000

100,

700,00

700, 0

00

1981

1989

1997

200

2 5

00

1981

1989

1997

1

200

2 5

00

1981

19

1989

1

1997

200

20 5

0

YEA

YE R

A

YEA

YE R

A

YEA

YE R

A

Norwegian Sea LME

Faroe Plateau LME

Iceland Shelf LME

(B)

4,000,

4,

0

000, 00

0

1,700,

70 000

00

500,000

0

1,600,

60 000

00

3,500,

3,

0

500, 00

0

400,000

0

1,500,

50 000

00

_22

_24

_25

3,000,

3,

0

000, 00

E

0

E

E

E

LM

LM 1,400,

40 000

00

LM

300,000

0

2,500,

2,

0

500, 00

0

1,300,

30 000

00

2,000,

2,

0

000, 00

0

1,200,

20 000

00

200,000

0

1981

19

1 89

9

1997

200

20 5

0

19

1 8

9 1

8

19

1 8

9 9

8

19

1 9

9 7

9

20

2 0

0 5

0

19

1 81

9

19

1 89

9

1997

2005

200

YEA

YE R

A

YEA

YE R

A

YEA

YE R

A

North Sea LME

Celtic Biscay LME

Iberian Coastal LME

(C )

1,100,

10 000

00

900,0

900, 00

0

1,250,

25 000

00

800,0

800, 00

0

1,000,

00 000

00

1,200,

20 000

00

700,0

700, 00

0

900,

90 000

00

1,150,

15 000

00

600,0

600, 00

0

_23

_62

_26

E

E

E

LM

500,0

500, 00

0

800,

80 000

00

LM

LM 1,100,

10 000

00

400,0

400, 00

0

700,

70 000

00

1,050,

05 000

00

300,0

300, 00

0

600,

60 000

00

200,0

200, 00

0

1,000,

00 000

00

1981

198

1989

19

19

1 97

9

20

2 0

0 5

0

1981

1989

198

1997

200

2 5

00

19

1 81

9

19

1 8

9 9

8

199

19 7

9

200

20 5

0

YEA

YE R

A

YEA

YE R

A

YEA

YE R

A

Baltic Sea LME

Black Sea

Mediterranean Sea

150,

1

0

50, 0

0 0

0

100,

1

0

00, 0

0 0

0

_33

E

LM

50,

50 0

, 0

0 0

0

0

1981

19

19

1 8

9 9

8

1997

19

20

2 0

0 5

0

YEA

YE R

A

Red Sea LME

Figure 8. Fisheries biomass yield trends (metric tons) in fast warming clusters A. Norwegian, Faroe

Plateau and Iceland Shelf LMEs (C1) B. North Sea, Celtic Biscay and Iberian Coastal LMEs (C2) and C.

Baltic Sea, Black Sea, Mediterranean Sea and Red Sea (C3) LMEs

reported that zooplankton abundance levels in the three LMEs are in decline, reducing

the prey field for zooplanktivores (Beaugrand et al. 2002; Valdes and Lavin 2002; Valdés

et al. 2007). Although we did not detect any significant decline in primary productivity in

52

Sherman et al.

the three LMEs, the declining phytoplankton level in the region (Richardson and

Schoeman 2004) is consistent with the declines in primary productivity in warming ocean

waters reported by Behrenfeld (2006). The fisheries biomass yields of 80% of the

targeted species are in an overexploited or fully exploited condition (Table 3), suggesting

that the observed decline in biomass yield of pelagic species is related to both heavy

exploitation and warming.

The three semi-enclosed European LMEs, the Mediterranean, the Black Sea, and the

Baltic Sea, and the adjacent area of the Red Sea (Figure 8C), are surrounded by

terrestrial areas and are fast warming, with heavy fishing as a dominant feature. The four

LMEs contribute 2.4 mmt (3.7%) of the mean annual global biomass yield. In three

European LMEs, the fisheries biomass trend is decreasing, while in the Red Sea it is

increasing. In the case of the Black Sea, the fisheries biomass is severely depleted, with

85% of fisheries stocks overexploited due to heavy fishing and a trophic cascade

(Daskalov 2003). In the Baltic Sea, Red Sea and Mediterranean Sea LMEs, 78% of the

stocks are in a fully exploited condition. Mixed species dominate in the Red Sea, where

88% of the species fished are fully exploited and 10% are overexploited (Table 3). It

appears that heavy exploitation is the dominant driver of the biomass trends observed in

all four LMEs.

Comparative fisheries biomass yields (in metric tons) in the fast

warming clusters of the Northwest Atlantic (C4) LMEs and the Asian

(C5, C6) LMEs

The three LMEs in this region contribute 1.1 mmt (1.7%) to the global biomass yield. In

two LMEs of the Northwest Atlantic, the downward trends in fisheries yield have been

attributed to the cod collapse in the Newfoundland-Labrador Shelf (Rice 2002), and to

the cod collapse and collapse of other demersal fisheries in the Scotian Shelf LME from

excessive fishing mortality (Choi et al. 2004; Frank et al. 2005). In the West Greenland

Shelf LME, where the cod stock has collapsed from excessive fishing mortality, there is a

recent increase in the landings of shrimp and other species (Aquarone and Adams

2008b) (Figure 9A).

Biomass yields of the fast warming LMEs of East Asian Seas

The 7.5 million metric tons (mmt) biomass yields of the Yellow Sea and East China Sea

LMEs constitute 11% of the global yield. In both LMEs, yields are increasing (Figure 9B).

The principal driver of the increase is food security to accommodate the needs of the

People's Republic of China and Korea (Tang 2003; Tang 2006; Tang and Jin 1999;

Zhang and Kim 1999). Biomass yields are dominated by heavily fished "mixed" species.

Seventy percent or more of the species constituting the yields are fully exploited or

overexploited (Table 3), suggesting that the principal driver of increased biomass yields is

full exploitation rather than global warming.

The fast warming Kuroshio Current and Sea of Japan/East Sea LMEs show declining

fisheries trends (Figure 9B). They contribute 1.9 mmt (2.9%) to the global marine

fisheries yield. For these two LMEs, exploitation levels are high with 90% of the species

in a fully exploited to overexploited condition (Table 3). The fisheries are also subjected

to periodic oceanographic regime shifts affecting the abundance of biomass yields

(Chavez et al. 2003). Among the fast warming East Asian Seas LMEs, no analysis has

been conducted for the ice-covered Chukchi Sea LME, as the data is limited and of

questionable value.

Accelerated warming and emergent trends in fisheries biomass yields

53

(A)

1,000,

1,

000

000,

600,0

600, 00

0

200,

2

0

00, 0

0 0

0

900,000

900,

500,0

500, 00

0

800,000

800,

150,

1

0

50, 0

0 0

0

9

400,0

400, 00

0

700,000

8

_ 700,000

_

_

E

E

_18

E

LM 600,000

600,

LM 300,0

300, 00

0

LM

100,

1

0

00, 0

0 0

0

500,000

500,

200,0

200, 00

0

400,000

400,

300,000

300,

100,0

100, 00

0

50,

50 0

, 0

0 0

0

1981

1989

1

1997

200

20 5

0

1981

1989

1997

1

200

2 5

00

1981

19

19

1 8

9 9

8

1997

19

20

2 0

0 5

0

YEA

YE R

A

YEA

YE R

A

YEA

YE R

A

Newfoundland/Labrador Shelf LME Scotian Shelf LME West Greenland Shelf LME

(B)

4,000,

4,

000

000,

5,000

00 ,

0 00

, 0

00

3,000,

00 000

00

3,000,

3,

000

000,

4,000

00 ,

0 00

, 0

00

2,000,

00 000

00

_48

_47

_49

E

E

E

LM

LM

LM

2,000,

2,

000

000,

3,000

00 ,

0 00

, 0

00

1,000,

00 000

00

1,000,

1,

000

000,

2,000

00 ,

0 00

, 0

00

0

1981

1989

1

1997

1

200

20 5

0

1981

198

198

1 9

98

1997

199

200

2 5

00

1981

198

19

1 8

9 9

8

1997

1

200

2 5

00

YEA

YE R

A

YEA

YE R

A

YEA

YE R

A

Yellow Sea LME

East China Sea LME

Kuroshio Current LME

2,500

50 ,

0 00

, 0

00

2,000

00 ,

0 00

, 0

00

_50

E

LM

1,500

50 ,

0 00

, 0

00

1,000

00 ,

0 00

, 0

001981

198

1989

198

199

1 7

99

2005

200

YEA

YE R

A

Sea of Japan/East Sea

Figure 9. Comparative fisheries biomass yields (in metric tons) in the fast warming clusters of the (A)

Northwest Atlantic (C4) LMEs and the(B) Asian (C5, C6) LMEs

Comparative Fisheries Biomass Yields (in metric tons) in Moderate

Warming Western Atlantic LMEs (C7), Eastern Atlantic (C8) LMEs, and

LMEs of the Asian Northwest Pacific region

A large cluster of moderately warming LMEs can be found in the Trade Winds region of

the Atlantic Ocean. This is an important cluster of LMEs contributing 5.1 mmt (7.9%) to

the mean annual global biomass yield. Five LMEs are clustered in the Western Atlantic,

and two in the Eastern Atlantic. In the West Atlantic Ocean, the Gulf of Mexico LME

fisheries biomass yields are decreasing, while in the Caribbean, North Brazil, East

Brazil, and South Brazil Shelf LMEs fisheries biomass yields are increasing (Figure

10A).

54

Sherman et al.

The fisheries biomass yield trends in the Atlantic Ocean region appear to be driven

principally by heavy exploitation rather than climate warming. The Caribbean, North

Brazil, and East Brazil Shelf LMEs are in a fully exploited and over-exploited fisheries

condition equal to or greater than 88% of the stocks. In the South Brazil Shelf, 60% of

fisheries are fully exploited or overexploited (Table 3). The East Brazil Shelf and South

Brazil Shelf LMEs are dominated by small pelagics and/or "mixed species"

(A)

2,000,

2,

000

000,

500,

5

00

00, 0

00

35

3 0,

5 00

0, 0

00

1,500,

1,

000

500,

400,

4

00

00, 0

00

30

3 0,

0 00

0, 0

00

5

_

E

_12

_17

E

E

LM

LM

LM

1,000,

1,

000

000,

300,

3

00

00, 0

00

25

2 0,

5 00

0, 0

00

500,000

500,

200,

2

00

00, 0

00

20

2 0,

0 00

0, 0

00

1981

1989

1

1997

200

20 5

0

19

1 81

9

1989

19

1997

19

2005

200

1981

1

1989

19

1997

19

2005

200

YEA

YE R

A

YEA

YE R

A

YEA

YE R

A

Gulf of Mexico LME

Caribbean LME

North Brazil LME

300

30 ,

0 0

, 0

0 0

0

250

25 ,

0 0

, 0

0 0

0

250

25 ,

0 0

, 0

0 0

0

200

20 ,

0 0

, 0

0 0

0

_16

_15

200

20 ,

0 0

, 0

0 0

E

0

E

E

LM

LM

150

15 ,

0 0

, 0

0 0

0

150

15 ,

0 0

, 0

0 0

0

100

10 ,

0 0

, 0

0 0

0

100

10 ,

0 0

, 0

0 0

0

1981

1

1989

19

1997

19

2005

200

1981

1

1989

19

1997

19

2005

200

YEA

YE R

A

YEA

YE R

A

East Brazil LME

South Brazil LME

(B)

3,000,

3,

000

00

1,100,

1,

000

00

1,000,

1,

000

00

2,500,

2,

000

00

900,000

00

_27

_28

E

E

LM

LM 800,000

00

2,000,

2,

000

00

700,000

00

1,500,

1,

000

00

600,000

00

1981

1989

1997

200

2 5

00

1981

1989

1

1997

2005

200

YEA

YE R

A

YEA

YE R

A

Canary Current LME

Guinea Current LME

(C)

1,100,

1,

000

100,

5,0

5, 00,

0

000

2,0

2, 00,

0

000

1,000,

1,

000

000,

900,000

900,

4,0

4, 00,

0

000

1,5

1, 00,

5

000

800,000

800,

700,000

_51 700,

_51

_52

_53

E

3,0

3, 00,

0

000

E

1,0

1, 00,

0

000

E

600,000

600,

LM

LM

LM

500,000

500,

2,0

2, 00,

0

000

500,

5

000

400,000

400,

300,000

300,

200,000

200,

1,0

1, 00,

0

000

0

1981

1989

1

1997

200

20 5

0

1981

19

1989

198

1997

199

2005

200

1981

19

1989

198

1997

199

2005

200

YEA

YE R

A

YEA

YE R

A

YEA

YE R

A

Oyashio Current LME

Sea of Okhotsk LME West Bering Sea LME

Figure 10. Comparative Fisheries Biomass Yields (in metric tons) in Moderate Warming (A) Western

Atlantic LMEs (C7), (B) Eastern Atlantic (C8) and (C) Pacific LMEs

Accelerated warming and emergent trends in fisheries biomass yields

55

The two LMEs of the Eastern Atlantic are important sources of food security to the over

300 million people of West African countries adjacent to the LMEs. The Canary Current

and the Guinea Current are showing increasing trends in biomass yield with "mixed

species" dominant (Heileman 2008) (Figure 10 B&C. The fisheries stocks in both LMEs

are at risk. Oceanographic perturbations are also a source of significant variability in

biomass yields in the Guinea Current (Hardman-Mountford and McGlade 2002;

Koranteng and McGlade 2002) and in the waters of the Canary Current LME (Roy and

Cury 2003)(www.thegef.org, IW Project 1909).

Three LMEs, the Sea of Okhotsk, the Oyashio Current, and the West Bering Sea,

contribute 2.3 mmt (3.5%) to the mean annual global biomass yield. They are in a

condition where 78% of the fisheries stocks are overexploited (Table 3). The Oyashio

Current and the West Bering Sea LMEs show decreasing trends in fisheries yields

(Figure 10C. In the Sea of Okhotsk, the biomass yields are dominated by targeted table

fish including pollock and cod. The increasing yield trend in the Sea of Okhotsk LME is

related principally to a high level of overexploitation (Shuntov et al. 1999).

Comparative Fisheries biomass yields in Moderately Warming Southwest

Pacific LMEs (C10) and other Non-clustered, Moderately Warming LMEs

The three moderately warming LMEs, two on the east coast of Australia (Northeast and

East Central Australia LMEs) and the New Zealand Shelf LME, contribute 0.4 mmt

(0.7%) to the mean annual global biomass yield. Biomass yields are decreasing in the

Australian LMEs, whereas they are increasing in the New Zealand Shelf LME (Figure 11)

under the present condition of full exploitation (Table 3). Whether their conditions are the

result of top down or bottom up forcing is not clear. However, Individual Transferable

Quota (ITQ) management to promote the recovery and sustainability of high priority

fisheries stocks is in place. Stewardship agencies in Australia and New Zealand have

implemented management actions for the recovery and sustainability of the overexploited

species.

Six moderately warming LMEs occur in separate locations. Taken together they

contribute 7.7 mmt (11.8%) to the mean annual global biomass yields. In the Pacific,

landings are too low in the moderately warming Insular Pacific Hawaiian LME to draw

any conclusion on biomass yield. In the moderate warming Gulf of Alaska LME, the

overall 25-yr. fisheries biomass trend is decreasing. However, this LME shows evidence

of a relatively recent upturn in yield, attributed to increases in biomass of Alaska Pollock

and Pacific salmon populations in response to climate warming (Overland et al. 2005).

The biomass of the moderately warming Gulf of California LME is in a declining trend

(Figure 11). The dominant biomass yield in this LME is from small pelagics and "mixed

species," suggestive of top down fishing as the principal driver of the decline. The South

China Sea fisheries biomass yields are increasing. The dominant biomass yield of the

LME is of "mixed species" and the level of exploitation is high with 83% fully exploited

and 13% overexploited (Table 3). In this case, high population demand for protein by the

adjacent countries contributes to drive the biomass yield upward.

The Arctic region's Beaufort Sea LME, landings data are unavailable. The moderate

warming East Greenland Shelf fisheries biomass yields are increasing with capelin,

redfish and shrimp dominant; following the earlier collapse of cod and other demersal

species. The role of global warming in relation to cause and effect of increasing yields is

not known.

56

Sherman et al.

Table 3. LMEs, rates of warming, 5-yr. mean fisheries biomass yields, adjacent to developing or

developed countries, status of stocks exploitation.

Accelerated warming and emergent trends in fisheries biomass yields

57

58

Sherman et al.

80,

80 0

, 0

0 0

0

50,000

50,

60

6 0,

0 00

0, 0

00

70,

70 0

, 0

0 0

0

40,000

40,

50

5 0,

0 00

0, 0

00

60,

60 0

, 0

0 0

0

50,

50 0

, 0

0 0

0

_40

_41

_46

E

30,000

E 30,

E

40

4 0,

0 00

0, 0

E

00

E

40,

40 0

, 0

0 0

LM

0

LM

LM

LM

30,

30 0

, 0

0 0

0

20,000

20,

30

3 0,

0 00

0, 0

00

20,

20 0

, 0

0 0

0

10,

10 0

, 0

0 0

0

10,000

10,

20

2 0,

0 00

0, 0

00

1981

19

1989

19

1997

19

20

2 0

0 5

0

1981

1989

19

1997

200

20 5

0

19

1 81

9

1989

19

1997

19

2005

200

YEA

YE R

A

YEA

YE R

A

YEA

YE R

A

NE Australia LME

East Central Australia LME

New Zealand Shelf

80,000

80,

1,500

50 ,

0 00

, 0

00

300,

3

0

00, 0

0 0

0

70,000

70,

1,400

40 ,

0 00

, 0

00

60,000

60,

1,300

30 ,

0 00

, 0

00

200,

2

0

00, 0

0 0

0

50,000

0 50,

0

1,200

20 ,

0 00

, 0

00

2

4

_

1

_

_

40,000

E 40,

E

E 1,100

10 ,

0 00

, 0

00

E

LM

LM

LM

30,000

30,

1,000

00 ,

0 00

, 0

00

100,

1

0

00, 0

0 0

0

20,000

20,

900

90 ,

0 00

, 0

00

10,000

10,

800

80 ,

0 00

, 0

00

0

700

70 ,

0 00

, 0

00

0

1981

1989

19

1997

200

20 5

0

1981

198

1989

198

1997

199

200

2 5

00

1981

19

19

1 8

9 9

8

1997

19

20

2 0

0 5

0

YEA

YE R

A

YEA

YE R

A

YEA

YE R

A

Insular Pacific Hawaiian LME

Gulf of Alaska LME

Gulf of California

7,0

7, 00,

0

000

200,

2

000

00

6,0

6, 00,

0

000

150,

1

000

00

5,0

5, 00,

0

000

_36

E

_19 100,

1

000

E

00

E

LM 4,0

4, 00,

0

000

LM

50,000

00

3,0

3, 00,

0

000

2,0

2, 00,

0

000

0

1981

19

1989

198

1997

199

2005

200

1981

19

1989

1997

1

200

20 5

0

YEA

YE R

A

YEA

YE R

A

South China Sea LME East Greenland Shelf LME

Figure 11. Comparative Fisheries Biomass Yields (in metric tons) in Moderately Warming Southwest

Pacific LMEs (C10) and other Moderately Warming LMEs

Comparative Fisheries Biomass Yields in Slow Warming Indian Ocean and

Adjacent LMEs (C11)

The 10 LMEs of the Indian Ocean, Arabian Sea, Bay of Bengal, Agulhas Current,

Somali Current, Indonesian Sea, North Australia, Northwest Australia, West Central

Australia, Southwest Australia and Southeast Australia LMEs are in the slow range

of climate warming and their biomass trends are all increasing. This group of LMEs

contributes 8.6 million metric tons, or 13.2% of the global biomass yield. The slow

warming is consistent with the IPCC forecast of slow but steady warming of the Indian

Ocean in response to climate change (IPCC 2007). While biomass yields are

increasing, the landings adjacent to developing countries are composed primarily of

mixed species and small pelagics (Heileman 2008) and the stocks are predominantly fully

exploited and/or overexploited (Table 3), suggesting that top down fishing is the

predominant influence on the condition of biomass yield. In the adjacent Southwest

Pacific waters, the slow warming Sulu-Celebes and Gulf of Thailand LMEs contribute 1.8

mmt (2.8%) to the mean annual global biomass yield. The consistent pattern of

Accelerated warming and emergent trends in fisheries biomass yields

59

increasing yields of the Indian Ocean LMEs adjacent to developing countries is driven

principally by the demand for fish protein and food security (Ahmad et al. 1998; Dwivedi

and Choubey 1998). In the case of the 5 LMEs adjacent to Australia, the national and

provincial stewardship agencies are promoting stock recovery and sustainable

management through ITQs. The fisheries stocks in the LMEs adjacent to developing

countries are under national pressure to further continue to expand the fisheries to

provide food security for the quarter of the world's population inhabiting the region. Given

the demands on fisheries for food security for the developing countries bordering the

Indian Ocean, there is a need to control biomass yields and sustain the fisheries of the

bordering African and Asian LMEs.

3,000,

000 0

, 00

0

4,000,

000 0

, 00

0

400,00

0 0

0

2,500,

500 0

, 00

0

3,000,

000 0

, 00

0

300,00

0 0

0

3

2

_

_34

_30

2,000,

000 0

, 00

E

0

E

E

E

LM

LM

LM

2,000,

000 0

, 00

0

200,00

0 0

0

1,500,

500 0

, 00

0

1,000,

000 0

, 00

0

1,000,

000 0

, 00

0

100,00

0 0

0

1981

198

19

1 8

9 9

8

1997

1

2005

200

1981

19

19

1 8

9 9

8

1997

19

2005

200

1981

1989

1997

2005

200

YEA

YE R

A

YEA

YE R

A

YEA

YE R

A

Arabian Sea LME

Bay of Bengal

Agulhas Current LME

3,000,

000 0

, 00

0

70,000

00

200,00

0 0

0

60,000

00

2,500,

500 0

, 00

0

150,00

0 0

0

50,000

00

3

9

_31

_38

_

E

2,000,

000 0

, 00

E

0

E

E

LM 40,000

00

LM

LM

100,00

0 0

0

1,500,

500 0

, 00

0

30,000

00

20,000

00

1,000,

000 0

, 00

0

50,000

00

1981

1989

1997

199

20

2 0

0 5

0

1981

198

19

1 8

9 9

8

1997

1

2005

200

1981

1989

1997

2005

200

YEA

YE R

A

YEA

YE R

A

YEA

YE R

A

Somali Current LME

Indonesian Sea LME

North Australia LME

22

2 ,

2 000

50,

50 000

70,00

70, 0

00

21

2 ,

1 000

45,

45 000

60,00

60, 0

00

4 20

2 ,

0 000

3

_45 50,00

50, 0

E

00

E

E_4

40,

40 000

E_4

LM

LM 19

1 ,

9 000

LM

40,00

40, 0

00

35,

35 000

18

1 ,

8 000

30,00

30, 0

00

17

1 ,

7 000

30,

30 000

1981

1989

1997

199

20

2 0

0 5

0

1981

1989

1997

2005

200

1981

19

1989

19

1997

199

2005

200

YEA

YE R

A

YEA

YE R

A

YEA

YE R

A

Northwest Australia LME

West-Central Australia Southwest Australia LME

40,

40 000

0

35,

35 000

0

2

_

4

30,

30 000

E

0

E

LM

25,

25 000

0

20,

20 000

0 19

1 8

9 1

8

1989

19

1997

19

20

2 0

0 5

0

YEA

YE R

A

Southeast Australia LME

Figure 12. Comparative Fisheries Biomass Yields (in metric tons) in Slow Warming Indian Ocean and

Adjacent LMEs (C11)

60

Sherman et al.

The biomass yields of other slow warming LMEs of the Northwest Atlantic

and the United States East Coast, Barents Sea, East Bering Sea,

Patagonian Shelf, Benguela Current, and Pacific Central American Coastal

LMEs

There is slow warming taking place in the Northeast US Shelf and in the Southeast US

Shelf. The LMEs contribute 1.0 mmt (1.6%) to the mean annual global marine biomass

yield. For both LMEs, the declines are attributed principally to overfishing (NMFS 2006)

For these two LMEs and the Gulf of Mexico, the Gulf of Alaska, the East Bering Sea,

Chukchi Sea, Beaufort Sea, Insular Pacific Hawaiian Islands, and the Caribbean, the

United States has underway a fisheries stock rebuilding program for increasing the

spawning stock biomass of overfished species(NMFS 2007).

Biomass yields of the slow warming LMEs of the Arctic region

For several of the slow warming LMEs bordering the Arctic including the Laptev Sea,

Kara Sea, East Siberian Sea and Hudson Bay, biomass yield data is at present

incomplete and is not included in the trend analyses. In the case of the Barents Sea

LME, there is a decreasing biomass trend attributed to the over-exploited condition of

many fish stocks inhabiting the LME (Table 3)(Figure 13). During the present warming

condition, variability in ice cover has an important influence on biomass yields (Matishov

et al. 2003)

Biomass yields of other LMEs

Four widely separated LMEs, the East Bering Sea, the Patagonian Shelf, Benguela

Current, and Pacific Central American LMEs are located in slow warming waters

(Figure 13). Together they contribute 3.3 mmt (5.1%) to the mean annual global biomass

yield. In the North Pacific Ocean, the slow warming East Bering Sea has an overall

decline in fisheries biomass yield. However, in recent years there has been an upturn in

yield, attributed to climate warming and increases in biomass of Alaska Pollock and

Pacific Salmon populations (Overland et al. 2005). In the Southwest Atlantic Ocean

Patagonian Shelf LME, increasing biomass yields are reflective of a very high level of

fisheries exploitation, overshadowing any climate change effects, where 30% of fisheries

are fully exploited, and 69% are overexploited (Table 3). The increasing biomass trends

of the Pacific Central American Coastal LME are the result of high levels of exploitation

(Table 3) driven principally by the need for fish protein and food security of the adjacent

developing countries and secondarily by oceanographic regime shifts (Bakun et al. 1999).

The biomass yields of the Benguela Current (BCLME), southwest African coast are in a

declining trend (Figure 13). The living resources of the BCLME have been stressed by

both heavy exploitation and environmental perturbations during the past 25 years (van

der Lingen et al. 2006) The southwestward movement of sardines (Sardinella)

populations from the coastal areas off Namibia to southeastern South Africa has been

attributed to recent warming. The southerly migration has disrupted the Namibian

fisheries. A further southerly movement of sardines and anchovies from the vicinity of

island colonies of African penguins off South Africa led to a decrease in availability of

small pelagic fish prey of penguins resulting in a 40% penguin population decline (Koenig

2007).

Accelerated warming and emergent trends in fisheries biomass yields

61

1,500,

500 0

, 00

0

200,000

2,000,

000 0

, 00

0

1,400,

400 0

, 00

0

1,300,

300 0

, 00

0

1,500,

500 0

, 00

0

1,200,

200 0

, 00

0

150,000

1,100,

100 0

, 00

0

E_7

E_6

_

20

1,000,

000 0

, 00

E

0

E

1,000,

000 0

, 00

LM

0

LM

LM

LM

900,

900 0

, 00

0

100,000

500,

500 0

, 00

0

800,

800 0

, 00

0

700,

700 0

, 00

0

600,

600 0

, 00

0

50,000

0

1981

198

19

1 8

9 9

8

1997

1

2005

200

1981

1989

1997

2005

200

1981

198

19

1 8

9 9

8

1997

1

2005

200

YEA

YE R

A

YEA

YE R

A

YEA

YE R

A

U.S. Northeast shelf LME

U.S. Southeast Shelf LME

Barents Sea LME

2,500,

500 0

, 00

0

2,

2 00

0 0,

0 00

0, 0

00

3,000,

000 0

, 0

0 0

0

2,000,

000 0

, 00

0

1,

1 50

5 0,

0 00

0, 0

00

2,000,

000 0

, 0

0 0

0

9

_

1

14

E

_

2

1,500,

500 0

, 00

0

E_

E

LM

LM

LM

1,

1 00

0 0,

0 00

0, 0

00

1,000,

000 0

, 0

0 0

0

1,000,

000 0

, 00

0

500,

500 0

, 00

0

50

5 0,

0 00

0, 0

00

0

1981

198

19

1 8

9 9

8

1997

1

2005

200

1981

198

1989

19

19

1 97

9

2005

200

1981

198

1989

19

19

1 97

9

2005

200

YEA

YE R

A

YEA

YE R

A

YEA

YE R

A

East Bering Sea LME

Patagonian Shelf LME Benguela Current LME

1,

1 00

0 0,

0 00

0, 0

00

90

9 0,

0 00

0, 0

00

80

8 0,

0 00

0, 0

00

11

70

7 0,

0 00

0, 0

E_

00

E_

LM

60

6 0,

0 00

0, 0

00

50

5 0,

0 00

0, 0

00

40

4 0,

0 00

0, 0

001981

198

1989

19

19

1 97

9

2005

200

YEA

YE R

A

Pacific Central American LME

Figure 13. Comparative Fisheries Biomass Yields (in metric tons) in Slow Warming LMEs of the United

States East Coast, Barents Sea, East Bering Sea, Patagonian Shelf, Benguela Current and Pacific

Central American Coastal LMEs

Discussion

Emergent trends

From the analysis, we conclude that in four LME cases the warming clusters of LMEs are

influencing 7.5 mmt or 11.3% of the world's fisheries biomass yields. The first and

clearest case for an emergent effect of global warming on LME fishery yields is in the

increasing biomass yields of the fast warming temperature clusters affecting 3.4 mmt

(5.0%) of global yields for the Iceland Shelf, Norwegian Sea, and Faroe Plateau LMEs in

the northern Northeast Atlantic. Warming in this region has exceeded levels expected

from entering the warm phase of the Atlantic Multi-decadal Oscillation (Trenberth and

Shea 2006). The increase in zooplankton is related to warming waters in the northern

areas of the Northeast Atlantic (Beaugrand et al. 2002) leading to improved feeding

conditions of three zooplanktiverous species that are increasing in biomass yields.

Herring, blue whiting, and capelin yields are increasing in the Iceland Shelf and

Norwegian Sea LMEs, and blue whiting yields are increasing in the Faroe Plateau LME.

The second case is in the contrasting declines in biomass yields of the fast warming

cluster of more southern Northeast Atlantic waters including the North Sea, the Celtic-

62

Sherman et al.

Biscay Shelf, and Iberian Coastal LME where declines in warm water plankton (Valdés et

al. 2007) and northward movement of fish (Perry et al. 2005) are a negative influence on

4.1 mmt (6.3%) of the mean annual global biomass yields. Recent investigations have

found that SST warming in the northeast Atlantic is accompanied by increasing

zooplankton abundance in cooler more northerly areas, and decreasing phytoplankton

and zooplankton abundance in the more southerly warmer regions of the northeast

Atlantic in the vicinity of the North Sea, Celtic-Biscay Shelf and Iberian Coastal LMEs

(Richardson and Schoeman 2004). Due to tight trophic coupling fisheries are adversely

affected by shifts in distribution, reduction in prey and reductions in primary productivity

generated by strong thermocline stratification inhibiting nutrient mixing (Behrenfeld et al.

2006).

In the third case, recent moderate warming of the Gulf of Alaska, and slow warming of

the East Bering Sea are supporting increasing levels of zooplankton production and

recent increasing biomass yields of Alaska Pollock and Pacific Salmon (Grebmeier et al.

2006; Hunt et al. 2002; Overland et al. 2005).

The biomass yields of the fourth case are more problematic. Biomass yields of all 10

LMEs (8.6 mmt) (13.2%) around the western and central margin of the Indian Ocean are

increasing (Figure 12). The increasing yields of the five LMEs adjacent to developing

countries, the Agulhas Current, Somali Current, Arabian Sea, Bay of Bengal and

Indonesian Sea are dominated by mixed species and small pelagic species, driven by the

fish protein and food security needs of nearly one quarter of the world's population

inhabiting the bordering countries of Africa and Asia (Heileman and Mistafa 2008). The

overexploited condition of most species is at present masking any gains in biomass yield

that may be attributed to the slow and steady warming of waters predicted for the Indian

Ocean by the IPCC (2007) and observed during the present study. In contrast, the slow

warming five Australian LMEs on the eastern margin of the Indian Ocean are driven

principally by economic considerations and are closely monitored by governmental

stewardship agencies that practice an adaptive management system of Individual

Transferable Quotas (Aquarone and Adams 2008a). Taken together, the 8.6 mmt mean

annual biomass yield of the Indian Ocean LMEs are critical for food security of the heavily

populated adjacent countries. In this region there is a need to exercise a precautionary

approach (FAO 1995) to recover and sustain the fisheries in the LMEs of east Africa and

Asia, in the slow warming clusters.

Precautionary Cap and Sustain Action

From a global perspective 38.2 mmt or 58% of the mean annual 2001-2006 biomass

yields are being produced in 29 LMEs adjacent to developing countries (Table 2). This

vital global resource is at risk from serious overexploitation (Table 3). Given the

importance for sustaining 58% of the world's marine fisheries biomass yield, it would be

prudent for the GEF supported LME assessment and management projects to

immediately cap the total biomass yield at the annual 5-year mean (2000-2004) as a

precautionary measure and move toward adoption of more sustainable fisheries

management practices.

The management strategies for protecting the 26.8 mmt or 42% of global marine biomass

yields in LMEs adjacent to the more developed countries (Table 2) have had variable

results ranging from highly successful fisheries biomass yield recovery and sustainability

actions for stocks in LMEs adjacent to Australia, New Zealand, the United States,

Norway, and Iceland to the less successful efforts of the European Union and LMEs

under EU jurisdiction in the Northeast Atlantic (Gray and Hatchard 2003). An ecosystem-

based cap and sustain adaptive management strategy for groundfish based on an annual

overall total allowable catch level and agreed upon TACs for key species is proving

Accelerated warming and emergent trends in fisheries biomass yields

63

successful in the management of the moderately warming waters of the Gulf of Alaska

LME and slow warming East Bering Sea LME Alaska Pollock and Pacific Salmon stocks,

providing evidence that cap and sustain strategies can serve to protect fisheries biomass

yields (NPFMC 2002; Witherell et al. 2000).

In LMEs where primary productivity, zooplankton production and other ecosystem

services are not seriously impaired, exploited, overexploited and collapsed stocks as

defined by Pauly and Pitcher (2000) can be recovered where the principal driver is

excessive fishing mortality and the global warming rates are moderate or slow. The

principal pelagic and groundfish stocks in the slow warming US Northeast Shelf

ecosystem have been targeted for rebuilding from the depleted state of the 1960s and

1970s by the New England Fisheries Management Council and the Mid Atlantic Fisheries

Management Council. In collaboration with NOAA-Fisheries and the results of

productivity and fisheries multi-decadal assessment surveys it was concluded that the

principal driver of the declining trend in biomass yield was overfishing. Reductions in

foreign fishing effort in the 1980s resulted in the recovery of herring and mackerel stocks.

Further reductions in US fishing effort since 1994 initiated recovery of spawning stock

biomass of haddock, yellowtail flounder and sea scallops. Similar fish stock rebuilding

efforts are underway in all 10 of the LMEs in the US coastal waters (NMFS 2007).

From our analysis, it appears that the emerging increasing trends in biomass yields can

be expected to continue in fast warming LMEs of the northern North Atlantic (Iceland

Shelf, Faroe Plateau, Norwegian Sea) and the moderate and slow warming LMEs of the

northeast Pacific (Gulf of Alaska, East Bering Sea and the U.S. Northeast Shelf). The

countries bordering these LMEs (U.S., Norway, Faroes Islands) have in place sufficiently

advanced ecosystem-based capacity to support adaptive assessment and management

regimes for maintaining sustainable levels of fishery biomass yields.

In the absence of the capacity for conducting annual assessments for a large number of

marine fish species in many developing countries, and in recognition of the uncertainties

of effects of climate warming, in the observed slow warming and increasing fisheries

biomass yields of LMEs adjacent to east Africa and south Asia along the margins of the

Indian Ocean, it would be prudent for the bordering countries to implement precautionary

actions to protect present and future fishery yields with a cap and sustain strategy aimed

at supporting long term food security and economic development needs.

REFERENCES

Ahmad HbA, Ahmed L, Atapattu A, Chullasorn S, Lui YP, Maniku MH, Nickerson DJ,

Pimoljinda J, Purwaka TH, Saeed S and others. 1998. Regional stewardship for

sustainable marine resources: Management in the Bay of Bengal. In: Sherman K,

Okemwa EN, Ntiba MJ, editors. Large Marine Ecosystems of the Indian Ocean:

Assessment, sustainability, and management. Malden, MA: Blackwell Science. p 369-

378.

Aquarone MC, Adams S. 2008a. VIII East Asian Seas: 13 North Australia LME; 17 West-Central

Australia LME; IX Pacific (SPREP): 21 Southeast Australia LME. In: Sherman K,

Hempel G, editors. The UNEP Large Marine Ecosystems Report: A perspective on

changing conditions in LMEs of the world's Regional Seas. Nairobi, Kenya: UNEP

Aquarone MC, Adams S. 2008b. XI Arctic: 30 Beaufort Sea LME; XIII North-East Atlantic: 39

East Greenland Shelf LME. In: Sherman K, Hempel G, editors. The UNEP Large Marine

64

Sherman et al.

Ecosystems Report: A perspective on changing conditions in LMEs of the world's

Regional Seas. Nairobi, Kenya: UNEP.

Astthorsson OS, Vilhjalmsson H. 2002. Iceland Shelf large marine ecosystem. In: Sherman K,

Skjoldal HR, eds, editors. Large marine ecosystems of the North Atlantic: Changing

states and sustainability. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science. p 219-244. 449p.

Bakun A, Csirke J, Lluch-Belda D, Steer-Ruiz R. 1999. The Pacific Central American Coastal

LME. In: Sherman K, Tang Q, editors. Large Marine Ecosystems of the Pacific Rim:

Assessment, sustainability, and management. Malden, MA: Blackwell Science. p 268-

279.

Beaugrand G, Ibanez F. 2004. Monitoring marine plankton ecosystems. II: Long-term changes in

North Sea calanoid copepods in relation to hydro-climatic variability. Mar Ecol Prog Ser

284(December 21):35-47.

Beaugrand G, Reid PC, Ibanez F, Lindley JA, Edwards M. 2002. Reorganization of North Atlantic

Marine Copepod Biodiversity and Climate. Science 296:1692-1694.

Behrenfeld MJ, O'Malley R, Siegel D, McClain C, Sarmiento J, Feldman G, Milligan A,

Falkowski P, Letelier R, Boss E. 2006. Climate-driven trends in contemporary ocean

productivity. Nature 444:752-755.

Belkin IM. 2008. Rapid warming of Large Marine Ecosystems. Progress in Oceanography

submitted.

Chassot E, Mélin F, Le-Pape O, Gascuel D. 2007. Bottom-up control regulates fisheries

production at the scale of eco-regions in European seas. Marine Ecology Progress Series

343(7 August 2007):45-55.

Chavez FP, Ryan J, Lluch-Cota SE, Ñiquen C. M. 2003. From anchovies to sardines and back:

Multidecadal change in the Pacific Ocean. Science 299(10 January 2003):217-221.

Choi JS, Frank KT, Leggett WC, Drinkwater K. 2004. Transition to an alternate state in a

continental shelf ecosystem. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 61:505-510.

Cleveland WS, Devlin SJ. 1988. Locally weighted regression: An approach to regression analysis

by local fitting. Journal of the American Statistical Association 83:596-610.

COMPASS. Communication Partnership for Science and the Sea: Scientific Consensus Statement

on Marine Ecosystem-Based Management Released 21 March 2005.

www.compassonline.org/pdf_files/ EBM_Consensus_Statement_v12.pdf.; 2005 August

2007.

Daskalov GM. 2003. Overfishing drives a trophic cascade in the Black Sea. In: Hempel G,

Sherman K, editors. Large Marine Ecosystems of the World: Trends in Exploitation,

Protection, and Research. the Netherlands: Elsevier Science. p 171-191.

Duda AM, Sherman K. 2002. A new imperative for improving management of large marine

ecosystems. Ocean and Coastal Management 45(2002):797-833.

Dwivedi SN, Choubey AK. 1998. Indian Ocean Large Marine Ecosystems: Need for national and

regional framework for conservation and sustainable development. In: Sherman K,

Okemwa EN, Ntiba MJ, editors. Large Marine Ecosystems of the Indian Ocean:

Assessment, sustainability, and management. Malden, MA: Blackwell Science. p 361-

368.

FAO. 1995. Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries; Precautionary Principle. In: FAO, editor:

FAO Document Repository.

FAO. 2004. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2004. Rome: FAO Corporate

Document Repository.

Frank KT, Petrie B, Choi JS, Leggett WC. 2005. Trophic cascades in a formerly cod-dominated

ecosystem. Science 308:1621-1623.

Froese R, Kesner-Reyes K. 2002. Impact of fishing on the abundance of marine species. ICES CM

2002/L:12, 15p.

Gaard G, Hansen B, Bergur Olsen JR. 2002. Ecological Features and Recent Trends in the

Physical Environment, Plankton, Fish Stocks, and Seabirds in the Faroe Shelf Ecosystem.

In: Sherman K, Skjoldal HR, editors. Large Marine Ecosystems of the North Atlantic:

Changing States and Sustainability. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Accelerated warming and emergent trends in fisheries biomass yields

65

Garcia SM, Newton C. 1997. Current situation, trends,and prospects in world capture fisheries. In:

Pikitch EL, Huppert DD, Sissenwine MP, editors. Global trends: fisheries management.

Bethesda, Maryland: American Fisheries Society Symposium 20. p 3-27.

González-Laxe F. 2007. Territorialisation processes in fisheries management. Ocean and Coastal

Management 51:259-271.

Gray T, Hatchard J. 2003. The 2002 reform of the Common Fisheries Policy'ssystem of

governance--rhetoric or reality? Marine Policy 27(6):545-554.

Grebmeier JM, Overland JE, Moore SE, Farley EV, Carmack EC, Cooper LW, Frey KE, Helle JH,

McLaughlin FA, McNutt SL. 2006. A major ecosystem shift in the northern Bering Sea.

Science 311(10 March 2006):1461-1464.

Hardman-Mountford NJ, McGlade JM. 2002. Variability of physical environmental processes in

the Gulf of Guinea and implications for fisheries recruitment. An Investigation using

remotely sensed sea surface temperature. In: McGlade JM, Cury P, Koranteng KA,

Hardman-Mountford NJ, editors. The Gulf of Guinea Large Marine Ecosystem:

Environmental forcing and sustainable development of marine resources. Amsterdam: