GEF FINAL EVALUATION

Transfer of Environmentally Sound Technologies

(TEST) to Reduce Transboundary Pollution in the

Danube River Basin

PROJECT TITLE:

Transfer of Environmentally Sound Technology (Test) to Reduce

Transboundary Pollution In The Danube River Basin

PARTICIPATING COUNTRIES: Bulgaria, Croatia, Hungary, Romania and Slovak Republic

UNDP PROJECT NUMBER : RER/00/G35

GEF Project Number:

867

Project Evaluator:

David H. Vousden

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Acronyms

1. Executive Summary

2. Evaluation Process (Purpose and methodology)

3. Project Background and Landscape

3.1

Objectives

3.2

Justification for the Project

3.3

Project Components and Outputs

4. Findings and Evaluation

4.1 Project Delivery

4.1.1

Outputs and Activities

4.1.2

National Delivery The Demonstrations

4.1.3

Summary of Demonstration Enterprise Delivery

4.1.4

Threats and Root Causes Effective Resolution

4.1.5

Global and National Benefits

4.1.6

Stakeholder Participation and Public Involvement

4.1.7

Capacity Building

4.1.8

Policy and Legislative Reform and Improvement

4.1.9

Replicability

4.1.10

Risks and Sustainability

4.2 Project Management and Implementation

4.2.1

Project Design and Planning

4.2.2

Project Management

4.2.3

Project Execution and Implementation

4.2.4

Country ownership/Drivenness

4.2.5

Workplan and Budget (including cost effectiveness)

4.2.6

Monitoring and Evaluation

4.3 Overall Project Impact

4.3.1

Objective Achievements

4.3.2

Constraints

5. Conclusions of Evaluation

6. Recommendations

7. List of Annexes

Acknowledgements

2

The Evaluator would like to thank all of the people interviewed during this evaluation procedure

(whether in person or by email), all of whom proved to be helpful, courteous and informative, and

all of whom were clearly fully supportive of the project and its delivery.

The Evaluator would like especially to thank UNIDO for its hospitality and for the efforts made by

them to ensure a smooth and successful evaluation, and in particular the Project Coordinator.

David H. Vousden - GEF Project Design Specialist and Evaluator. March 2005.

3

Acronyms

AB

Advisory Board

APR

Annual Progress Review

BAT

Best Available Technology

BOD

Biological Oxygen Demand

CEE

Central and Eastern Europe

CESD

Centre for Environmentally Sustainable Development

COD

Chemical Oxygen Demand

COMFAR

Computer Model for Feasibility Analysis and Reporting

CP

Cleaner Production

CPA

Cleaner Production Assessment

CPC

Cleaner Production Centre

DRP

Danube Regional Programme

EA

Executing Agency (of GEF)

EMA

Environmental Management Accounting

EMIS

Danube Regional Project's Expert Group on Emissions

EMS

Environmental Management System

EST

Environmentally Sound Technology

EU

European Union

GEF

Global Environment Facility

IA

Implementing Agency

ICPDR

International Convention for the Protection of the Danube River

IPPC

Integrated Pollution Prevention and Control

ISO

International Organisation for Standardisation

M&E

Monitoring and Evaluation

M&EB

Mass and Energy Balance

MSP

Medium-Sized Project

NCPC

National Centre for Pollution Control

NGO

Non-Governmental Organisation

NPO

Non-Product Output

OP

Operational Programme (of GEF)

PDF

Project Development Facility (of GEF)

POPS

Persistent Organic Pollutants

QMS

Quality Management System

REC

Regional Environmental Centre

SAP

Strategic Action Plan

SES

Sustainable Enterprise Strategy

SQA

Semi-Quantitative Score

TDA

Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis

TEST

Transfer of Environmentally Sound Technology

UNDP

United Nations Development Programme

UNEP

United Nations Environment Programme

UNIDO

United Nations Industrial Development Organisation

USAID

United States Agency for International Development

VOC

Volatile Organic Compounds

4

1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The GEF Transfer of Environmentally Sound Technologies project was implemented by UNDP

and Executed by UNIDO. In the three-year period of the MSP, the project successfully completed

training and knowledge transfer related to capacity building and institutional strengthening at both

the level of the selected demonstration enterprises and at the level of the national counterpart

institutions (Cleaner Production Centres, Pollution Control Centres, etc). The actual demonstrations

of the TEST approach in 17 enterprises was equally as successfully with considerable investment

made by the selected companies into the adoption of cleaner production processes and

environmentally sound technology.

There are some concerns related to Project Design, which should be noted for future consideration.

Activities for replication and transfer of lessons from the Project's achievements to other

beneficiaries and stakeholders within the countries and the Danube Basin as a whole were weak.

These can be related to the absence of any specific transfer and replication mechanism or linkages,

and the fact that the Project was constrained by its MSP modality and funding limitations (and, to

some extent, 3-year time limitation). Furthermore, the total funding identified in the Project

Document was not fully realised. The Project Document also has no reference to sustainability of

the Project's objectives or of the GEF investment.

In this respect, it must be stated that the Project Management and the Execution Process achieved a

very high level of success from the point-of-view of completion of the Project activities and

delivery of intended outputs. Any criticism has to rest with the Project Design and not its Execution

or Management.

The Terminal Evaluation finds this project to have been most notably successful and a very

worthwhile example of a GEF MSP investment from which many valuable lessons and practices

can be captured. The Evaluation provides a number of recommendations, including the proposal

that serious consideration be given to further investment to transfer these lessons and best practices

and to build on the substantial achievements of the TEST project. The Evaluator applauds the

Executing Agency, the Project Coordinator and the in-country Coordinators and Project Teams for

a praiseworthy achievement.

2. EVALUATION PROCESS (PURPOSE AND METHODOLOGY)

The purpose of a GEF Independent Terminal Evaluation is to enable all of the direct stakeholders

OF the project (Government, private sector, the Implementing Agency, the Executing Agency,

GEF, NGOs, etc.) to review achievements and delivery, and to identify valuable lessons and

practices that need to be captured and sustained. To this end it is important that such an evaluation

gathers as much input and feedback as is possible from a broad spectrum of all project stakeholders

and beneficiaries related to the project objectives.

The Evaluation attempts to determine, as systematically and objectively as possible, the relevance,

efficiency, effectiveness, impact and sustainability of the project. The Evaluation will assess the

achievements of the project against its objectives, including a re-examination of the relevance of

the objectives and of the project design. It will also identify factors that have facilitated or impeded

the achievement of the objectives. While a thorough review of the project design and

implementation is in itself very important in order to explain or justify project trends and/or

amendments, such an in-depth evaluation is ultimately an important tool for providing detailed

recommendations with regard to the current project and its outputs, and for capturing best practices

and lessons which can be used to structure and drive future initiatives.

5

The Evaluation places its emphasis on results and delivery, with reference to any measurable

indicators as defined within the Project Document or subsequent Annual Project Reviews/Project

Implementation Reviews. However, the evaluation also recognises that GEF Projects are, by nature,

dynamic and constantly evolving, and that this requires flexibility and understanding when

reviewing a project in the context of its original objectives and intended outputs.

It is important to see the Evaluation not merely as a monitoring process required by GEF but more

as the final opportunity to scrutinise and review what the project has achieved and learned. The

Evaluation is the instrument that helps all parties to identify valuable lessons, document successes

(and failures) and best practices (as well as those to be avoided). It provides closure to a project

while allocating a degree of achievement, but it should also identify any logical next steps and

potentially valuable follow-up exercises. Of course, most importantly, it also provides guidance for

similar GEF project design and implementation in the future.

Further details regarding the Monitoring and Evaluation requirements of UNDP/GEF and the

Objectives and Purpose of this Evaluation can be found under the Terms of Reference for the

Evaluation (Annex I). Annex II provides a list of the persons/agencies/bodies interviewed during

the course of the evaluation. Annex III gives a list of the documents reviewed.

In looking at the achievements of any Project, it is necessary to review the Outputs against any

measurable indicators provided by various Project documents. This often requires some level of

rating or quantitative scoring. To this effect, the Evaluator has used a Semi-Quantitative

Assessment approach which aims to assess the actual achievements of the project up to the time of

completion against the anticipated achievements as defined in the Project Document and/or

APR/PIR.

This SQA approach assigns a scale of achievement for each output (based on the expected delivery

and the success criteria for measuring that delivery) This provides a useful and quite accurate

guideline to which components were completed, which were not, and what the reason may be for

any lack of delivery. This is not intended to be an exercise in criticism, but more importantly one

whereby valuable lessons and practices can be identified and captured both for the sake of the

current project and for future GEF projects.

This assessment uses a judgement of the percentage of achievement per activity or output against

the original intention of the Project. To smooth-out the subjective nature of this approach, this

percentage is then converted to a scale from 1-5 whereby:

0 1.1 =

Almost No Delivery The Project has effectively failed in its objectives.

1.1-2.0 =

Limited effective delivery - generally poor and unsustainable. Project unlikely to

have secured its objectives.

2.1-3.0 =

Borderline Some notable achievements and delivery in specific areas but weak in

others. Considerable additional effort necessary to secure intended objectives.

3.1-4.0 =

Good, Effective Delivery Most activities or outputs have delivered as expected.

Project has met majority of its objectives and has produced benefits consistent with

GEF operational strategy. Project could have benefited from some changes in design

or realignment of priorities. Some possible areas of weakness that could be

strengthened through follow-up activities.

4.1-5.0 =

Excellent Delivery All outputs delivered as planned. Full stakeholder support.

Project undoubtedly successful and sustainable.

6

The SQA scores for Project Delivery, Management and Implementation are presented and

discussed at the end of each section.

Section 5 (Conclusions of Evaluation) of this report presents the SQA scores for the overall

objectives and components of the Project as defined both in the Project Document and subsequent

APR/PIRs, as well as by the GEF criteria for Projects and discusses their implications. This

includes an extrapolated composite score for the Project Outputs and Activities.

This Evaluation was conducted during the February-March 2005. The Evaluator conducted

interviews and made observations in Bulgaria, Croatia and Slovakia as well as at UNIDO

Headquarters in Vienna, Austria. This included field-trips to selected enterprises in Croatia and

Slovakia as well as the opportunity to observe and ask questions at the final TEST National

Dissemination Workshop in Sofia, Bulgaria. Further follow-up consultations were carried out in the

3 weeks following the Evaluation Mission in order qualify any concerns and to fine-tune the

Evaluation report.

3. PROJECT BACKGROUND AND LANDSCAPE

3.1. Objectives

Overall Project Objective and Description

The UNDP/GEF Pollution Reduction Programme identified 130 major manufacturing enterprises

of concern (known as hot spots) within the Danube River Basin; a significant number of these were

contributing to transboundary pollution in the form of nutrients and/or persistent organic pollutants.

In spite of the environmental problems they were causing, there was a lack of convincing evidence

that it is possible to comply with environmental norms while still maintaining or perhaps enhancing

their competitive position. This project set out to build capacity in existing cleaner production

institutions in five Danubian countries to apply the UNIDO programme on Transfer of

Environmentally Sound Technology (TEST) at selected pilot enterprises that were contributing to

transboundary pollution in the Danube River Basin and the Black Sea. The aim of the assistance

was to bring these pilot enterprises into compliance with environmental norms of the Danube River

Protection Convention while at the same time taking into account their needs to remain competitive

and to deal with the social consequences of major technology upgrading. The enhanced institutional

capacity would then be available to assist other enterprises of concern in these countries as well as

other Danubian countries.

Development Objective from the 2003 APR/PIR

· To improve industrial environmental management by major industrial enterprises in the

Danube River Basin, resulting in Major reductions in pollutant loading and consequently

risk to the Danube River and Black Sea aquatic environments.

· To build capacity in networks of national cleaner production institutions to advise the

enterprises in the five participating countries on how to implement the TEST approach.

3.2. Justification for the Project (Taken from the Project Document)

The Danube River Basin

7

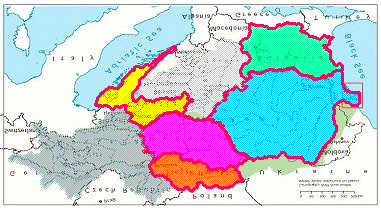

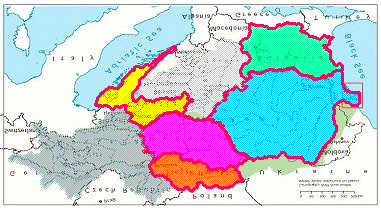

The Danube River basin is the heartland of central Europe. The main river is 2,857 km long and

drains 817,000 sq. km including all of Hungary; most parts of Romania, Austria, Slovenia, Croatia,

and Slovakia; and significant parts of Bulgaria, Germany, the Czech Republic, Moldova and

Ukraine. Territories of FR Yugoslavia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and small parts of Italy,

Switzerland, Albania and Poland are also included in the basin. The Danube River discharges into

the Bla ck Sea through a delta which is the second largest natural wetland area in Europe.

Water Quality Problems in the Danube

The Transboundary Analysis (TDA) for the Danube River Basin (1999) identified the following

main problems that affect water quality use: high load of nutrients and eutrophication;

contamination with hazardous substances, including oils; microbiological contamination;

contamination with substances causing heterotrophic growth and oxygen depletion and competition

for available water. The human activities contributing significantly to these problems are human

settlements, agriculture and industry.

Industry, atmospheric deposition, etc. cause about 20-30 per cent of the problem of excessive

nitrogen and phosphorus in the Danube Basin. Old-fashioned fertilizer factories are major

dischargers of nitrogen and their outdoor piles and lagoons of phosphor-gypsum are a special case

of pollution by nutrients. Even if production on these sites is reduced or stopped, the gypsum

stores will continue to be serious pollution sources in the future.

Industry and mining are responsible for most of the direct and indirect discharges of hazardous

substances into the Danube Basin. Depending on the type of industry, the effluent might contain

heavy metals (smelting, electroplating, chlorine production, tanneries, metal processing, etc.),

organic micro-pollutants (pulp and paper, chemical, pharmaceuticals, etc.) or oil products and

solvents (machine production, oil refineries, etc.). Mining activities result in drainage water from

the mines, run off from tailings and from process water containing metals and sometimes organic

solvents. Data on loadings of hazardous pollutants are available from only a few individual

enterprises. Sewage is a main source of ammonia.

Organic materials discharged by human settlements and industry consume available dissolved

oxygen. The impact is dependent on the total load, the type of organic substances, the water

temperature, the dilution capacity and the initial oxygen concentration of the recipient. Serious

oxygen deficiencies are most likely to occur in slow -flowing and stagnant waters. Downstream of

major outlets, the oxygen concentration may drop below the level that can support aquatic life

forms including fish populations and render the receiving waters unsuitable for drinking water

supply and recreation. Such situations are occurring in the Danube tributaries: for example, the Vit

River in Bulgaria is unable to support fish downstream of the city of Plevin, primarily due to

discharges from a sugar factory, and discharges from the pulp and paper factory in Pietra Neamt

have made one of the Siret tributaries unfit for most uses. The main stream of the Danube,

however, has a very large dilution and oxygen mixing capacity that enables it to cope with heavy

loads of organic materials.

Industrial Polluters

In the frame of the UNDP/GEF Pollution Reduction Programme (PRP) in 1998/1999, country

expert teams under the guidance of the respective country programme coordinators undertook a

new, comprehensive review of the sources of pollution and their effects in the Danube River Basin

and the Black Sea. Each national team developed a national review for their respective countries

based on a common methodology. The results were then compiled and analysed at the regional

8

level in the TDA. Based on the TDA and the ICPDR Emission Expert Group, 130 industrial

enterprises of concern (known as hot spots) were identified within the Danube River Basin.

The specifics of the transboundary pollution problems in the Danube River Basin and Black Sea

originating from the industrial plants in the five countries selected to participate in the TEST

programme can be briefly summarized: Bulgaria -- 8 plants contributing to nutrient loadings of 50

tons/year or greater; Croatia -- 3 plants contributing to nutrient loadings of 50 tons/year or greater

and 2 plants with other pollutant loading affecting a SIA in a neighbouring country; Hungary -- 4

plants contributing to nutrient loadings of 50 tons/year or greater and 2 plants with other pollutant

loadings affecting a SIA in a neighbouring country; Romania--33 plants contributing to nutrient

loadings of 50 tons/year and 5 plants with other pollutant loadings affecting a SIA in a

neighbouring country and Slovakia-- 2 plants contributing to nutrient loadings of 50 tons/year or

greater and 9 plants with other pollutant loadings affecting a SIA in a neighbouring country. Full

details are available in the UNDP UNIDO GEF Project Document.

The major polluting industrial sub-sectors in terms of numbers of enterprises are food; paper,

chemicals, and iron. Together these four sub-sectors account for about 75 per cent of the major

industrial pollutant dischargers.

Thus despite the period of transition in most of Central and Eastern Europe that has lead to serious

changes in the level of industrial and agricultural activity, industrial pollution still remains a

significant problem to be addressed by Danube Countries. Moreover, it can be expected that as

economies in the region recover and industrial production increases, industrial pollution will also

increase unless the source of pollution is adequately addressed.

3.3. Project Components and Outputs:

COMPONENT I. Institutional Strengthening

Objective: To set up national focal points that would facilitate the transfer of ESTs to

industrial enterprises in five Danubian countries

The first step for successful implementation of the project is to strengthen national focal points that

would facilitate the transfer of ESTs to industrial enterprises in five Danubian countries. The focal

points will be working units within an already established NCPC or PCC. Success under this

objective would be strengthened institutional capacity to apply the TEST approach. The availability

of the strengthened capacity would be measured in terms of the availability of trained national team

leaders and their deputies in the TEST approach, of operating information management systems

and of boards of advisors actively involved in enterprises selection and oversight of activities.

COMPONENT II. ENTREPRISE DEMONSTRATIONS

Objective: To apply the TEST approach to at least twenty enterprises located in the Danube

River Basin

The outputs and activities under this objective are the core of the project. Under this objective

national teams will apply the TEST approach in the five countries in order to show 20 enterprises

that it is possible to comply with environmental norms and still remain or perhaps enhance their

competitive positions. Success under this objective would be enterprise application of the TEST

approach, both individual components and of all seven components. Successful application would

be measured in terms of at least 15 out of the 20 participating enterprises applying the full TEST

9

approach to their operations and a larger number of firms applying most of the seven components.

In addition, there should be significant pollutant reduction (at least 30 per cent) by at least ten of the

20 enterprises and some pollutant reduction by the other ten enterprises at the end of the project.

Full compliance with environmental norms will take additional years because of the need to install

the EST packages at the enterprises.

COMPONENT III. Diffusion of Results

Objective: The diffusion of e xperience with the twenty pilot enterprises to other enterprises in

the five participating countries and to other Danubian countries

The ultimate aim of the project is to persuade other polluting enterprises in the Danube that national

institutions are available and capable of assisting them to devise cost effective plans for compliance

with environmental norms. Success under this objective would be wide spread awareness and

demand for the TEST approach among the major industrial enterprises causing pollution of the

Danube.

4. FINDINGS AND EVALUATION

4.1. Project Delivery

The overall objective of the Project was to build capacity in existing cleaner production institutions

to apply the UNIDO Transfer of Environmentally Sound Technology (TEST) procedure to

technology transfer to 17 enterprises that are contributing to transboundary pollution, and primarily

nutrients, in the Danube River Basin and the Black Sea.

Existing CPCs were functional within 3 of the Project countries (Croatia, Hungary and Slovakia) at

the start of the Project. Other pertinent institutions had to be identified for the other two countries

(Bulgaria and Romania). The institutes initially proposed at the national level within these latter

two countries were found to be inappropriate once the project was under way and new counterpart

institutes had to be identified. In the case of Romania this change was almost immediate and did

not cause any significant delays in project activities and delivery. In Bulgaria however, the situation

was much more complicated and the project went through two inappropriate counterpart

institutions before finally identifying the necessary capacity and effective project ownership within

the Technical University of Sofia. In this respect, a preparatory phase would have been helpful (in

this case a PDF A which is the only option available for an MSP) during which the counterpart

institutions could have been identified after working closely with one or two national potential

candidate institutes as part of the process of stakeholder involvement in project preparation. This

would have allowed the Executing Agency and Project Coordinator to `get to know' the institutes

and personalities first before committing the project to a particular counterpart. A more elongated

project preparation phase would have been possible with a Full GEF Project and raises the question

of whether a Full project would have been more appropriate to such a detailed multi-country

demonstration approach. This will be discussed further.

The following statement from the Evaluation Terms of Reference provides some useful guidance

for the evaluation process in this respect:

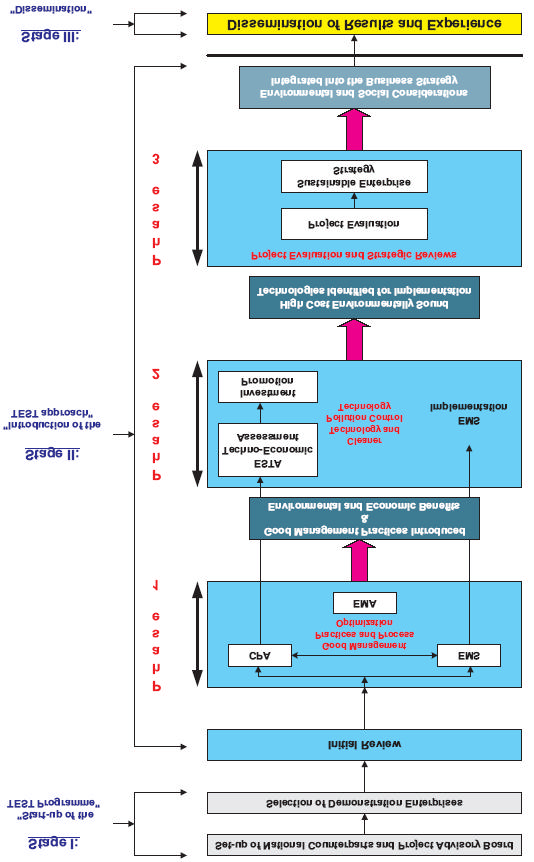

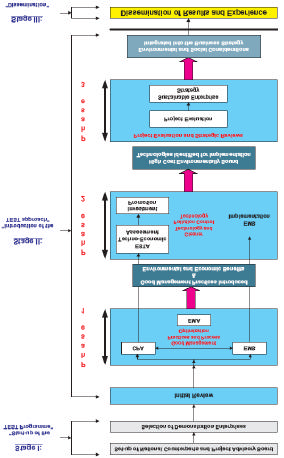

TEST Project Implementation Strategy

10

The project implementation strategy has been adjusted during project implementation, as indicated

in the UNDP/GEF Project Implementation Report (PIR1) June 2003 (section 3) in order to reflect

country specific conditions and to achieve the project objectives in a timely and cost-effective way.

By replacing the original step-by-step approach with the integrated approach, the revised TEST

project implementation strategy promotes synergies between different and complementary

environmental management tools supporting top management decision-making processes in

medium and long-term planning toward environmental compliance and eco-efficiency.

The TEST integrated approach to industrial environmental management developed by UNIDO, has

been designed to assist enterprises in the developing and transitional countries to effectively adopt

Environmentally Sound Technology (EST). The application of the TEST integrated approach and

its tools, leads to continuous improvement of the economic and environmental profiles of

companies.

The integrated TEST approach is based on three basic principles:

First, it gives priority to the preventive approach of Cleaner Production (systematic preventive

actions based on pollution prevention techniques within the production process) and it considers

the transfer of additional technologies for pollution control (end-of-pipe) only after the cleaner

production solutions have been explored. This leads to a transfer of technologies aimed at

optimizing environmentally and financially optimized elements transfer of technologies: a win-

win solution for both areas.

Second, the integrated TEST approach addresses the managerial aspects of environmental

management as well as its technological aspects, by introducing tools like such as

Environmental Management System (EMS) and Environmental Management Accounting

(EMA).

Third, it puts environmental management within the broader strategy of environmental and

social business responsibilities, by leading companies towards the adoption of sustainable

enterprise strategies (SES).

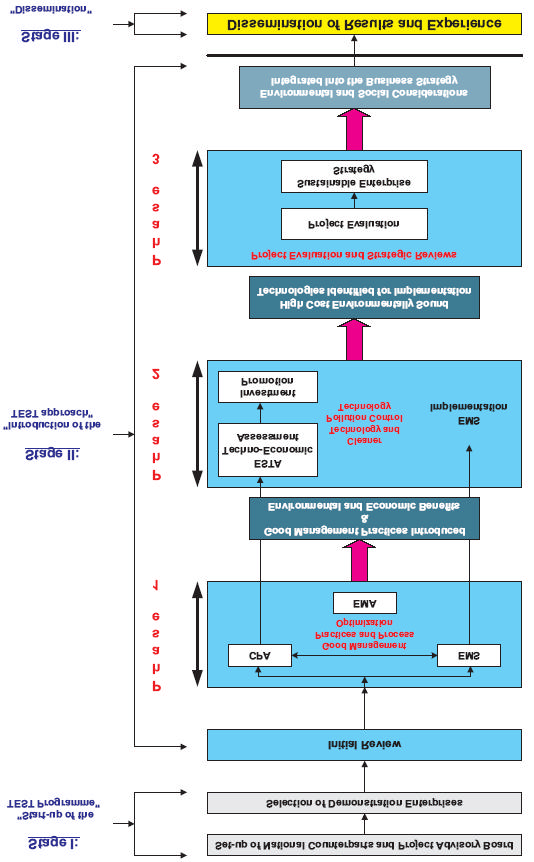

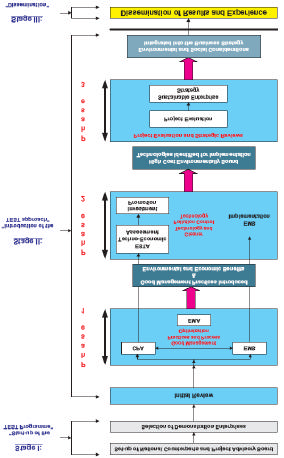

The schematic diagram below shows the stages of the revised TEST implementation strategy.

1 For additional details on the revised implementation strategy see the related PIR - June 2003

11

Consequently, it should be noted that the original Project Document had proposed to use a stepwise

approach to promoting EST, CP and an EMS. However, once the project started implementation,

the stakeholders discussed the actual merits of this approach versus other options and agreed that a

12

more integrated parallel development approach was necessary rather than the intended A->B->C

serial approach

As a result of these modifications, the project then realigned itself to build capacity and expertise

within the CPCs and related institutes to be able to deliver this new integrated approach, and to

demonstrate the approach through the project implementation and through the individual industrial

enterprise demonstrations. The original approach was defined within the Project Document as a

series of steps through the selection, training and re-education process whereby the industrial

enterprises either met the requirements of the project or dropped out of the demonstration. The

original TEST approach was expensive (requiring almost continuous assessment of many potential

enterprises) and would not capture the investment by GEF and the stakeholders efficiently. It

allowed too many chances for enterprises to drop out or opt out of the demonstration process even

once considerable time and investment had been made in support of those enterprises. This

modification of the project approach was pragmatic and necessary particularly in view of the

shortage of available budget within the constraints of a GEF MSP. Furthermore, the stepwise

approach was technically inefficient. Instead, enterprises were pre-selected on the basis of existing,

published information. Once the enterprises realised that they would also need to contribute time,

financial and human resources to the project aims there was a natural selection process through

attrition and lack of `ownership' for the project concepts and outcomes. In the end 17 enterprises

volunteered for the demonstration process.

The Project was effectively providing capacity building, training and delivery in the following

TEST tools (definitions derived from descriptions in `Increasing Productivity and Environmental

Performance: An Integrated Approach. Know-how and experience from the UNIDO project -

Transfer of Environmentally Sound Technology (TEST) in the Danube river basin' (Authors:

Roberta De Palma, Vladimir Dobes):

Cleaner Production (CP): The continuous application of an integrated preventive environmental

strategy applied to industrial processes, products and services to increase overall efficiency and

reduce risk to humans and the environment. The process includes conservation of raw materials,

water and energy, the elimination of toxic and dangerous raw materials, and the reduction of the

quantity and toxicity of all emissions and wastes. CP generates financial as well as environmental

benefits by encouraging companies to use processes that are more productive and cost-effective.

Environmental Management System: This is partly evolved from the Quality Management

Systems that are commonly developed within companies. It can be defined as that part of the

overall management system that includes the organised structure, planning activities,

responsibilities, practices, procedures, processes and resources for developing, implementing,

achieving, reviewing and maintaining the environmental policy. It should be an integral part of the

existing management system and should be harmonised with any existing quality management

system in the company.

Env ironmental Management Accounting: Monetary EMA is a sub-system of environmental

accounting that deals only with the financial impacts of a company's environmental performance. It

allows management to better evaluate the monetary aspects of products and projects when making

business decisions. EMA assists business managers in making capital investment decisions, costing

determinations, process/product design decisions, performance evaluation and a host of other

forward-looking business decisions. As such, EMA has an internal company-level function and

focus, as opposed to being a tool for reporting environmental costs to external stakeholders. This

gives EMA the flexibility to take into consideration the special needs and conditions of the

company. EMA tends to focus more on materials, energy flow, and environmental cost

considerations.

13

Environmentally Sound Technology: This is a combination of best available techniques and best

available practices. In most cases the introduction of good management practices alone are

insufficient to solve a company's environmental problems and to bring it into compliance with

environmental norms, or to greatly improve environmental performance. Investments in

technological changes or end-of-pipe solutions are also usually necessary. The concept of EST also

builds on the concept of BAT (Best Available Practices) where `Best' refers to best environmental

performance while `available' refers to economic feasibility as well as availability of the

technology on the market.

Sustainable Enterprise Strategy: The purpose of the SES is to assist management of the company

to turn the core strategic environmental/social success factors (as identified during the

implementation of the TEST approach) into formal performance objectives aligned with the

objectives of the company's business strategies (financial, marketing and operational). This means

that the environmental and social objectives of the company are not `stand-alone' objectives, but

are connected to the other objectives of the company and ultimately contribute to achieving the

financial goals of the business. Integration of the added dimensions of environmental and social

considerations should therefore demonstrate a clear competitive advantage within the business plan.

COMFAR: A Computer Model for Feasibility Analysis and Reporting. This is a software tool

developed by UNIDO and intended as an aid in the analysis of investment projects. The program is

applicable for the analysis of investment in new projects, and for the expansion or rehabilitation of

existing enterprises.

The above tools cannot, however, be treated in isolation and should be seen as a series of

overlapping and even interwoven modules that can be plugged in or omitted depending on the

conditions prevailing within the company, and on the assessment and investment needs of that

company. The adopted procedure for TEST within each enterprise would be decided through the

Initial Review prior to initiation of the CPA, but also through the outcomes and recommendations

of the CPA itself.

So, the procedure for building improved production linked to environmentally sound processes was

re-structured prior to its implementation to be a more phased approach. Enterprises were now

expected to complete a logical series of integrated activities before moving onto the next phase. For

example, the first phase focussed on introducing management tools in support of cleaner production

and more environmentally sound approaches, and demonstrating their use and value. The next

phase addressed the need to change the technology through investment in new technology where

appropriate, coupled with on-going changes to company policy and management through improved

awareness. The final phase was to deliver the final outcome of the demonstration package which

was the EST assessment linked into a business plan which effectively constituted a Sustainable

Enterprise Strategy (SES) for the company.

To this effect, the project itself acted now as an overall demonstration exercise for a new integrated

and phased approach to improving productivity while increasing environmental performance and

for evolving an effect mechanism for the adoption of environmental management accounting at the

industrial enterprise level. This resulted in a set of concrete project outputs in the form of two

UNIDO-funded publications:

1. Increasing Productivity and Environmental Performance: An Integrated Approach. Know-

how and experience from the UNIDO project "Transfer of Environmentally Sound

Technology (TEST) in the Danube river basin" (Authors: Roberta De Palma, Vladimir

Dobes)

14

2. Introducing Environmental Management Accounting at Enterprise Level. Methodology and

Case Studies from Central and Eastern Europe. (Authors: Roberta de Palma, Maria

Csutora).

These two publications carry most of the pertinent information and explanation of the revised

TEST process and methodology, how it should be applied, along with a selection of case studies

which demonstrate its effective application. This information has been shared with all of the

countries of the Danube basin along with the national TEST publications. These national

publications identify achievements at each national enterprise by way of economic improvements,

reduced emissions and discharges, low raw material costs, and proposed longer-term TEST-related

investments.

Undoubtedly the project has succeeded in its role of institutional strengthening and capacity

building as is discussed in further detail below. All of the counterpart CPCs and institutes have

received significant training in the TEST procedure both at the desk-top level and through actual

experience in assisting the enterprises themselves. At the end of the MSP this has left all of the

counterpart agencies in a strong position to provide a significant level of national and regional

support to industry in cleaner production assessment and techniques, environmental systems and

environmental management accounting, right through the modular TEST process to the

identification of environmentally sound technologies and the development of long-term sustainable

enterprise strategies. Of course, this capacity building has also been established within the

enterprises that have served as demonstrations. All of the enterprises now have a raised level of

awareness and understanding of the TEST process and associated improvements, not only in

cleaner production, but also in more cost-effective management of resources and wastes. Generally

speaking, the concepts demonstrated to the enterprises by the TEST project have now become

adopted into company policy on a day-to-day basis.

Furthermore, the overall objective of demonstrating reductions in discharges, and more efficient

use of water resources in industrial processes, whilst maintaining economic sustainability and

market competitiveness has been clearly demonstrated. There are still many improvements that can

be made at the individual level of each enterprise that could improve discharge reductions and

water use efficiency, but these are now mostly long-term changes in technology and will require

reconstruction and consequent high investment costs. Serious consideration is necessary as to the

next steps in this respect if GEF's investment to date is to be consolidated and improved. Within

the context of a Medium Sized Project the achievements are considerable and noteworthy. It should

also be noted that the TEST MSP went somewhat beyond its remit at a number of enterprises and

considered the issue of energy efficiency and its implications to the Danube environment. This was

a logical and sensible move as the concepts of energy efficiency dovetail well into the TEST

process and can significantly effect both cleaner production as well as the overall cost-effective

nature of a company's sustainable enterprise strategy.

The diffusion of results has been somewhat less successful at the regional level, although some

significant steps have been taken at the national level. Clearly each country has undertaken

dissemination activities and there has been at least one regional dissemination exercise but there is

a need for a more effective replication and transfer mechanism for lessons and best practices.

However, this should be seen in the context of financial constraints imposed on the project by the

design and modality and does not deter from the significant achievements made in the

implementation of the TEST demonstrations. This is discussed further under the relevant sections

below.

4.1.1 Outputs and Activities

15

Component 1: Institutional Strengthening. Component Outcome - Establishment of Test Focal

Points in each Country

TEST National Focal Points were effectively established for each country either within National

Cleaner Production Centres or in other relevant Pollution Control Centres/Institutes. Three

countries had existing CPCs (Croatia, Hungary and Slovakia).

In Romania, there was a CPC which had been established by USAID. However, the Executing

Agency and Project Management had no knowledge of their capacity and skills. The Project

decided to review several possible candidate institutions and finally settled with ECOIND

(Industrial Ecology Institute) which was considered to be best suited to the requirements of a

National Counterpart Institute and had some of the necessary expertise already in place.

In Bulgaria, the project had an unfortunate start as the original counterpart proved to be

inappropriate and had to be replaced. This regrettable situation was repeated a second time until the

Executing Agency and the Project Coordinator managed to identify an efficient source of expertise

(both for a national counterpart person and for other technical support to the Project) within the

Technical University of Sofia. This caused a delay for Bulgaria of around one year as far a project

implementation was concerned.

One lesson that can be captured here is the need for a more careful and drawn-out process of

selection of national counterparts. In hindsight, a period of preparatory stakeholder input and

assessment (such as a PDF phase of several months) would have been advantageous. This raises a

concern as to whether the MSP (GEF Medium Size Project) modality was appropriate to a regional

project of this nature. Although intended as a `fast-track' mechanism for releasing GEF funds more

efficiently, the MSP modality has two drawbacks that are relevant to the TEST project. One is the

financial limitation (with a ceiling of $1 million in GEF funds). The other is the lack of a prolonged

PDF B phase (MSPs may only access PDF A preparatory funding). This latter concern was

somewhat academic in the case of the TEST project as the MSP actually underwent no formal PDF

phase. This concern regarding the MSP modality is discussed further under the section on Project

Design below.

In the final analysis, strong project management and the selection (ultimately) of appropriate and

committed national counterpart personnel and institutions allowed the TEST Project to implement

an effective programme of capacity building and training for the TEST process which remains

firmly embedded within those personnel and institutions at the closure of the project, and can be

seen as a national and regional asset for further promotion and replication of the TEST process. The

Counterpart institutions have already demonstrated their ability (as well as market demand) to sell

their new expertise and services. A number of the CPCs have already been approached by both the

original demonstration enterprises and those outside of the project to provide further assistance

which the companies are prepared to pay for themselves. Also, a strong level of networking has

been developed between the national counterpart agencies, with countries providing special

expertise to each other and assisting each other in the development of further TEST-related

initiatives. Examples of this include close cooperation between Slovakia and Bulgaria, Hungarian

assistance and funding towards a Croatian project initiative for joint implementation and

dissemination of an Environmental Management Accounting module, and assistance beyond the

TEST countries to non-TEST Danubian partners. The CPC's themselves saw this as a very

effective and important result of the TEST project. Although UNIDO has established such a CPC

network in principle, this was the first time that the CPCs saw it work in action. They were very

complimentary regarding the training and the coordination meetings associated with this

16

networking process. Capacity building is discussed in further detail below under the relevant

section of this report.

The lack of a formal information management system was noted as this was an original output cited

in the Project Document for this Component. However, the project did have an active website that

provided useful information but this could have been improved with links to ICPDR and other

TEST-related initiatives. It was noticeable that there were also no direct links back from the ICPDR

website to TEST.

TABLE 1:

SQA SCORES FOR COMPONENT 1 DELIVERY

%ge

COMPONENT 1: Institutional Strengthening

Verifiable Indicators

Delivery

TEST Focal Point and count erpart institute identified and

All 5 Counterpart Institutes engaged

initiated

and actively delivering TEST products

100

Adoption of TEST Advisory Board

ABs functional with at least 2 meetings

per year

100

Training of TEST Counterpart Team and Consultants in TEST

Intended Number of trainees = 50.

procedures

Actual = 90. Intended number of man-

days of training =300. Actual = 369

100

Information Management System and networking established

Internet linkages to relevant databases

(including EU, ICPDR, etc). Effective

networking established between

CPCs/Institutes and Coordinator and

active sharing of lessons and

expertise between all parties

80

Total for Component

95

Table 1 shows the allocated SQA score for Component 1 delivery as being 95 which is equivalent

to a rating of 4.75 Excellent Delivery. All outputs have been fully successful and have achieved

maximum or very high SQAs. The Information Management System has delivered effectively as

far as the establishment of networks between the CPCs/Institutes and the project is concerned. A

substantial number of Internet linkages have been identified, and the sharing of lessons and

expertise has been very effective. The only missing activity indicator is internet linkage to ICPDR

and the Danube Regional Programme which would have been valuable. The Component has met its

main objectives (institutional strengthening, training of counterparts, establishment of Advisory

Boards, networking and sharing of information, etc) very successfully.

Component 2: Enterprise Demonstrations. Component Outcome - Application of the TEST

Procedure at Demonstration Enterprises within Danube River Basin.

Under the Project Document it had originally been intended to apply TEST to a total of 20

enterprises. However, in the final analysis 17 projects were selected as being suitable and viable

and, in view of the time-constraints imposed by the GEF MSP modality, it was decided to move

ahead with these 17. This is not construed as a shortfall or failure on the part of the Project as the

overall concept of enterprise selection necessitates elimination of non-viable companies.

Furthermore, there was no real basis or justification given within the Project Document for the

selection of 20 companies and this was presumably an arbitrary figures based on 4 demonstrations

per country. It should also be noted that in Slovakia (the only one of the five participating countries

17

to have only two selected enterprises) the official number of hotspots at the start of the project

(2001) was half of the original number included in the SAP (1997). As is discussed later, many of

the hotspots identified by the original SAP were no longer relevant or in existence by the time the

TEST project came to implementation. This situation inevitably affected the enterprise selection

process in some countries, and was unsurprisingly most evident in those countries that first joined

the EU (i.e. Slovakia and Hungary).

The criteria for selecting the enterprises, along with some of the inherent problems in the selection

process, were clearly defined in the 2003 APR/PIR as follows:

Selection of enterprises was a difficult step due to the fact that the participating countries are

characterized by lack of enforcement of environmental legislation and by limited understanding

of environmental concerns. Financial viability of companies was not easy to assess on a

preliminary basis, due to lack of reliable data. Moreover many companies do not have formal

medium-long term strategies, which further complicated the identification of focus areas for

project implementation. This is a common situation in transition economies where companies

are rushing to produce what is requested; and their focus on near-term survival may overcome

that of building a medium-long-term strategy.

In order to properly select the participating enterprises, local counterparts, in cooperation with

the UNIDO project manager, had to identify the right combination of tools for marketing the

project concept to local enterprises trying, on the one hand, to present the expected benefits for

the company and at the same time clarifying the level of commitment and necessary internal

resources. Being a hot spot was never sufficient reason for a company to join the project and as

it happened in several cases, not all hot spots were suitable for the TEST project (most of the

hot spot companies are in very difficult financial circumstances at the moment). Nevertheless

given the difficult situation and the lack of enforcement of environmental legislation, the

required number of enterprises was successfully identified. It seems then that economic drivers

are much stronger then the environmental ones and are pushing companies in the direction of

improving the efficiency of their operations and in acquiring EMS certification.

The 2003 APR/PIR recognises that appropriate marketing tools need to be used to properly select

the demonstration industrial enterprises. The APR/PIR also notes that medium to large size

enterprises fitted the TEST project requirements best (smaller enterprises generally do not have the

human resources necessary to successfully implement TEST procedures), and that the criteria for

selection of the most representative enterprises related to their willingness to cooperate, along with

the influence of regulators, market and community pressures. The Advisory Boards adopted

guidelines on which enterprises should be considered for invitation to take part in TEST.

Discussions were held with relevant government agencies to ensure the shortlist included the best

companies for the demonstrations, and to ensure that every company had been considered and

reviewed.

It is important to note that the changes in the TEST process itself resulted in alterations to the

procedure for CPA and TEST assessment. It has already been mentioned earlier that the project

revised the TEST implementation process in the early stages based on discussion and approval with

all national counterparts and Advisory Boards. This led to a more modular approach to TEST using

an integrated approach to assessment and management rather than a stepwise approach as had been

initially proposed in the Project Document. The original step-by-step approach was considered to

be too linear and time-consuming (as well as generalised and inflexible) with more opportunities

for enterprises to fall out of the process along the way. The modular, integrated approach allowed

TEST to be fine-tuned for the needs of each enterprise. It also included the addition of the

Environmental Management Accounting concept, which all of the counterpart teams and agencies

18

were strongly in favour of adopting into the TEST approach. One noticeable effect that this new

approach had was to alter the emphasis on and within the Sustainable Enterprise Strategy. The

original idea of the SES was to include the business plan for the EST investments (the main output

from the EST assessment), a social action plan, and a negotiated compliance scheme based on the

implementation of the EST solution identified. The EST assessment is the critical component of the

SES. However, it became clear during project implementation that the other two components of the

SES (the social plan and compliance scheme) were not feasible for certain companies.

The social action plan was not always applicable since a) the new technology did not necessarily

imply any redundancy of workers and b) some companies were already undergoing severe

downsizing as a result of the transitional dynamics and associated economics symptomatic within

the CEE (new owners, division of companies, etc). The companies were therefore dealing with

these issues on a larger and more general level with local labour unions.

The environmental compliance plan was already subject to a well-established mechanism for

negotiation between the companies and the local environmental inspectorates on an annual basis.

So, based on these considerations the SES concept was refocused and broadened so that the new

SES tool included elements of strategic management (as well as the EST business plan). This new

SES strategy was implemented in 10 of the 17 enterprises. It was not possible to apply SES to all of

the enterprises. The main reasons for exclusion included a) companies with public ownership where

it was difficult to address top management directly b) lack of a formal business plan c) lack of

interest by top management, often due to on-going restructuring of the company and its assets, and

d) limited resources and time-constraints within the Project. However, it is important to note that

while the SES tool was re-focused, the business plan for the EST investments (the most important

part of the original SES concept) was implemented in all companies.

In effect, this modification of the process gave a much stronger emphasis to identification and

adoption of Environmentally Sound Technologies rather than to the concept of Sustainable

Enterprise Strategy as an end-product of the GEF project. SES was now seen as more of a logical

next step, and in the company's interests as a conclusion to TEST in order to capture the cost-

effective components of the TEST process. All of the enterprises went through the modular

process, and EST options were developed for all 17 enterprises. This is an important change from

the original Project outputs as it presents a proactive and conceptual alteration of the TEST process.

This modification is explained and justified within the 2003 APR/PIR and was clearly supported by

all stakeholders. It does have certain implications for the Evaluation in that some original indicators

needed to be revised also. This requirement for revised indicators is not clearly captured in either

the 2003 or 2004 APR/PIR although it is to some extent implied within the text. The need to

address this oversight in the APR/PIR format is discussed further under the section on Monitoring

and Evaluation.

The concrete delivery from this component were the various options for cleaner production and for

environmentally sound technologies. These were referred to as Type A, B and C options and these

can be defined as follows:

Type A options : Good management practices and process optimisation no cost or low cost.

Type B options : Introduction of cleaner technologies low cost and short-term payback period

Type C options : Larger-scale environmentally sound technologies high cost and long-term

payback period.

A good example of how the TEST process was implemented for Croatia is given below under 4.1.3

National Delivery The Demonstrations.

19

The Project performed extremely well as far as the demonstration of the TEST process is

concerned. Despite some shortcomings in the selection process (related more to project design and

time constraint), all of the enterprises identified valuable CP and EST options, and nearly all of

them implemented a significant number of these, with a clear intention to implement more as and

when investment funding becomes available.

TABLE 2:

SQA SCORES FOR COMPONENT 2 DELIVERY

%ge

COMPONENT 2: Enterprise Demonstrations

Verifiable Indicators

Delivery

Selection of enterprises and viability asses sment

Original intention to select 20

enterprises. Actual selection of 17.

80

Training of the Test Teams in enterprises in TEST procedures

intended number of enterprise staff

trained = 500. Actual = 622. Intended

man-days of training = 1500. Actual =

1673

100

Application of the TEST procedures at selected enterprises

TEST modules selected and

implemented at each enterprise. All 17

enterprises undertaken at least IR,

CPA and EST. EMA and EMS at

selected enterprises.

100

Identification of Type A, B and C improvements

Type A,B and C options specified

through CPA and TEST process,

approved by enterprises and included

in Action Plan

100

Implementation of Type A options for improvements

One or more CP/Housekeeping

measures adopted per enterprise

100

Adoption/implementation of Type B options for improvement

One or more Type B low -cost, early

payback small investments made for

CPA and EST per enterprise

100

Adoption of Type C options for improvement

Type C high-cost, longer payback

measures adopted by company as

part of business strategy, and

investment being actively sort (or, in

some cases, under implementation)

100

Noticeable improvement to identified environmental threat at

Measurable reduction in discharge

each enterprise.

volume and/or toxicity, water usage, or

general waste production for each

enterprise

70

Total for Component

94

Table 2 Shows the SQA scores for this Component. Delivery of outputs has been very high,

equivalent to a rating of 4.5 Excellent Delivery. There could have been improvements in the

enterprise selection process to ensure that CPA and EST options were directly addressing IW

concerns at the level of water pollution, water use efficiency and wastewater management. It is fair

to remember that for the Project Management process, two of the pre-conditions for enterprise

selection were A) Their financial viability and sustainability and B) Their voluntary commitment to

the project. This suggests that the selection procedures should have been more clearly defined in

the project design. Although the actually delivery on the TEST procedure at most enterprises was

commendable, these did not always address real threats at the river basin level. This is further

reflected in the output addressing improvements to identified environmental threats. Furthermore,

20

there is a need for each enterprise to keep more detailed records of improvements, reductions in

pollution and waste discharges, toxicity levels, etc if the data presented to the Project is to be fully

credible. Otherwise, the training of the in-house TEST teams, the application of the TEST

procedures, and the identification and adoption of Type A-C improvements has been remarkable

within the constraints of the time period for the project.

Component 3: Diffusion of Results . Component Outcome - Disseminating Results to other

Enterprises and Countries.

The primary objective of this component was to raise awareness among other industrial enterprises

in the Danube region regarding the TEST process, and to further ensure that they were aware of the

presence of national institutions that could assist them in using the process to develop cost-effective

business plans and Sustainable Enterprise Strategies that would help them to comply with new

environmental directives and regulations.

To this end, every country hosted a National Dissemination Seminar to which at least 10 industrial

companies were invited to review the results of TEST in the Demonstration enterprises.

Furthermore, in certain countries some of the enterprises that attended these seminars and showed a

strong interest were given a demonstration two-day in-plant assessment (4 in Romania and 3 in

Croatia). A regional seminar was also organised in cooperation with ICPDR, and the results of the

TEST Project were disseminated at the national level through many different conference and

workshops.

UNIDO supported the distribution of TEST methodologies and result through the development of

two publications on `Increasing Productivity and Environmental Performance' and on

`Environmental Management Accounting' (as discussed above under Project Delivery). A project

web-page has also been created by UNIDO where the two publications can be downloaded for free

(www.unido.org/doc/26190).

The original Project Design had intended that teams in 4 other Danube countries would be trained

in using the TEST Approach. This was successful in one country (Bosnia) but proved unfeasible for

other countries due to a general lack of project resources along with the difficulties in identifying

national counterparts as there are no CP institutions within the remaining countries of the Danube.

It should be noted that the activities undertaken in Bosnia relating to this component went much

further than was proposed or intended in the original Project Document. As well as the workshop

held in Bosnia which included the participation of several companies and national institutions, a

full project document for the replication of TEST in Bosnia was prepared by UNIDO in

cooperation with the CP centre of Croatia, and the Centre for Sustainable Development (CESD) in

Sarajevo. This project proposal is currently with UNDP for review and funding is being actively

sought to support its implementation. In reality, and considering the constraints of funding and lack

of effective institutional capacity, it would seem that the Project Design has been somewhat

ambitious and optimistic in this respect. A more structured and planned approach to building

further capacity for TEST within the other Danube countries would have been appropriate, and

almost certainly beyond the financial and time constraints of an MSP of this nature.

This Component is the weaker of the 3 project components in that a lot more transfer of

information, lessons and practices could have been done and a more effective replication process

initiated. However, the Evaluator is inclined to see this as a fault in the project design coupled to

the constraints of inadequate funding, and not as a management or implementation fault as such. So

much was achieved in the relatively short project lifecycle that shortfalls in this component should

not be allowed to cloud these achievements. Having said that, there is a risk in losing GEF's

investment here if the lessons and practices are not captured and if the TEST demonstration is not

21

replicated effectively throughout the Danube region. This will be the subject of further discussion

under Conclusions and Recommendations .

TABLE 3:

SQA SCORES FOR COMPONENT 3 DELIVERY

%ge

COMPONENT 3: Diffusion of Results

Verifiable Indicators

Delivery

National Dissemination Seminars to share results

Dissemination seminars completed for

all 5 TEST Project countries. National

reports published

100

TEST training materials and case studies

Test Manual and Case Studies

published and disseminated

100

Introduction of TEST approach to 25 other enterprises in 5

Other (non-demonstration) enterprises

TEST participating countries

engaging the CPCs and Institutes to

undertake TEST process

40

Regional dissemination to other Danube countries

Regional Workshop/seminar (e.g. on

BAT, Industrial Pollution Control,

TEST processes) plus dissemination

of published materials to relevant

institutes in other DRB countries

80

Introduction of TEST approach to other enterprises in Danube

Teams from other Danube countries

River Basin

trained in TEST approach

35

Component Total

71

Table 3 presents the SQA scores for Component 3 which is equivalent to a rating of 3.5 which is

within the Good, Effective Delivery category. Dissemination at the national level has been good as

far as sharing the results of the enterprise demonstrations with the national stakeholders is

concerned. This component has been weaker on delivery than the other 2 components in that a lot

more was expected and intended as far as the transfer of results and lessons and the replication of

the TEST process. The two publications relating to the TEST process are comprehensive and

valuable but there is still a need for a summary report for the entire project which captures all of the

lessons from the 17 enterprises as an overall case study for TEST. Also, there is still a need to

disseminate the overall success and value of the TEST process to more enterprises within the

project Countries. The original Project Document Output identifies the following activities:

· Hold regional seminar for nine countries (including the five participating countries) to

present results and determine interest/capacity building needs for undertaking TEST

programme in other Danubian countries. This has been achieved through the ICPDR two-

day regional workshop.

· Prepare requests for technical assistance as needed (this has been done in the case of

Bosnia).

Less has been achieved at the level of those Danube countries outside of the project. The Project

Document had intended the following activities to occur:

· Identify team members in four other countries with input from country programme

coordinators, NCPC/PPC, UNIDO national focal points and UNIDO staff. This was

achieved in Bosnia

22

· Hold one week training course on TEST approach using selected national experts from the

five participating countries. Croatian CPC experts undertook this training in Bosnia

· Match one team from each participating country with new team from another country.

· Mission to each country to advise on enterprise selection and application of TEST approach.

The Project Coordinator confirmed that this had been addressed during the ICPDR

workshop.

· Provide limited technical advice as requested by new teams from the teams in the five

participating countries.

It is the opinion of the Evaluator that this Component was somewhat optimistic within the

timeframe and funding of the original project design, and in view of the need to complete TEST

procedures at 17 enterprises first before the lessons and best practices could be consolidated into

results for dissemination and training. To this effect, a somewhat lower score and rating for this

component is a reflection of over-ambitious project design rather than an implied criticism of

project management and implementation, or of stakeholder commitment and effort. This is

reflected in the rating which falls just within Good, Effective Delivery rather than Borderline.

The accumulative SQA score for the Project Outputs and Activities comes to 87.6% or a rating

equivalent of 4.5 which amounts to Excellent Delivery for the Outputs and Activities.

4.1.2. National Delivery The Demonstrations

The Evaluator visited three of the 5 countries involved in the TEST Project. Selected stakeholders

from the other two countries were asked to respond to a questionnaire (see Annex IV). The

following descriptions and comments relate to the enterprises in the 3 countries visited during the

mission:

BULGARIA:

There were 3 demonstration enterprises selected for Bulgaria, in alcohol production, fish processing

and textile production. The primary incentive for the alcohol production enterprise was the demand

from government to clean up their wastewater discharge which has been a cause of concern for

some 25 years. The other two enterprises were conscious of the need to get ISO 14000 accreditation

as Bulgaria expects to sign the pre-accession agreement to the EU in early 2007.

In Bulgaria, the project had a poor start due to selection of an inappropriate counterpart. The project

only started to delivery effectively when the Technical University of Sofia was selected as the

counterpart. This institute was chosen because of its staff capabilities and expertise in industrial

production and engineering. The evaluator was unable to visit any of the enterprises in Bulgaria but

did manage to attend the final dissemination workshop where presentations were given on each

enterprise, and was then able to meet with company representatives. The Evaluator also spoke in

detail with the National Counterpart team at the Technical University.

The selection of the companies followed a step-by-step approach. In the first place the project was

advertised among the local industries in order to illustrate the main objective, the methodology, as

well as the expected benefits and the requirements for participation. Secondly, enterprises that

expressed an interest were contacted and visited by the local counterpart. During these visits a more

detailed explanation was given of the TEST Project targets, objectives and expected results.

Finally, enterprises were selected on the basis of their financial viability, magnitude of

environmental problems and management commitment.

23

The Counterpart Institute decided to include energy efficiency and energy auditing into the TEST

process as they had a recognised level of expertise in that field. The Institute staff received several

seminars from outside experts who explained the process of CPA, EST, EMA and SES, etc and

provided general technical assistance and training. The teams from each of the enterprises were

introduced and mixed with each other to exchange ideas and share thoughts. For the EMS module

(carried out at the textile plant) they had assistance from the CPC in Slovakia and for the EMA they

were assisted by the Hungarian CPC experts.

Zaharnia Zavodi AD, a sugar and alcohol production company, carried out all of the TEST modules

except the Environmental Management System module. The company was established in 1913 and

is the biggest sugar and alcohol production company in Bulgaria. Prior to their involvement in the

TEST Project they were unable to sell their alcohol products throughout Europe due to quality

constraints. Furthermore, they had been threatened with closure by the government unless they

cleaned up their waste discharges. The TEST Project was therefore a very timely piece of

assistance for them and the attention within the TEST project was concentrated on the alcohol

production unit which had the greatest environmental problems. The main waste from the process

was the slop from the beer production which was discharged directly into the river, plus liquid

wastes from the distillation process. The energy (thermal) losses were found to be enormous,

especial from the slop and the cooling water. These losses were also going directly into the river.

The Company had no recycling for cooling water, which also went directly into the river.

Through the CP Assessment it was possible to identify the aim of the TEST process at this

enterprises as a) a decreases in organic pollution though reduction of the slop water flow and its

high COD load in to the Yantra river, b) reduction in thermal pollution and re-use of wasted heat

energy, c) reduction of water losses through re-cycling and re-use of cooling water. Various options

to clean up the discharge process were studied including thermal, membrane, biological and

combined processes.

The EST Assessment looked at the investment plans and priorities of the company and its owners,

taking into consideration the results and recommendations from the CPA. This led the EST to focus

on changes to raw materials along with appropriate changes in pure alcohol production technology.

As a consequence the project identified a viable option for the reduction of organic pollution as

being the replacement of molasses with grain in the alcohol production process. As a consequence

of the TEST project, the company made a decision to change from sugar-based to cereal-based

alcohol production which reduced the chemical oxygen demand in the slop and produced a much

higher quality of alcoholic product. These changes also create a value-added by-product, as the slop

could now be used as animal feed. The water used in the process is also recyclable. Step by step the

company has gradually introduced these more cost-effective and environmentally appropriate

changes in process and technology, and is looking for funding to make further improvements. The

total cost for the modifications and reconstruction are estimated to be around $6 million (As of

2003). The company is hoping to introduce more TEST approaches. They have 6 such plants in

total and are planning to build the TEST process into their new construction plans.

The EMA process undertaken at Zaharnia Zavodi AD, was of considerable value to the company

and as a demonstration of hidden losses. Prior to the project, the non-product output (NPO) costs

(effectively the cost to the company to produce waste products) were not considered by the

company in their environmental and financial auditing. In reality, having identified these costs it is

their magnitude and the enormous losses to the company of these `hidden' production costs which

are the greatest incentives to improvement in cleaner production and elimination of waste by-

products. This is discussed further below under the dissemination workshop results.

24

Another enterprises, Slavianka JSC was established in 1948 and is one of the biggest fish

processing companies in Bulgaria and is situated in the town of Bourgas. The production process is

divided into sterilisation and metal packaging. The sterilisation department is equipped with a

production line for the processing of frozen and fresh fish. A second department provides the

necessary metal cans for packaging. The steam boiler house, providing the steam for the production

processes, and the wastewater treatment installation are also part of the facilities. The equipment in

all sections is old and needs replacing and modernising in order to reduce the energy expenses and

to meet the growing requirements related to the treatment of organic matter in the wastewater.

Slavianka also followed all of the TEST procedures except the EMS. This helped them to identify

the extent of their pollution problems. The main problem was fish waste from cleaning, washing

and defrosting, as well as the cleaning of the packing cans, along with an excessively high

consumption of water and energy. The development of the CP and Energy Efficiency opportunities

under the TEST Project therefore focused on three main directions a) water consumption and

related wastewater flows, b) reduction of pollution load and the volume of effluent generated, and

c) improvement of energy efficiency.

The CPA at Slavianka gave rise to two specific requirements 1. the need for a new de-frosting

mechanism and technology ( a major source of wastewater pollution) and 2. The need for a more