G l o b a l E n v i r o n m e n t F a c i l i t y

GEF/ME/C.24/Inf.3

November 4, 2004

GEF Council

November 17-19, 2004

PROGRAM STUDY ON INTERNATIONAL WATERS

(Prepared by the GEF Office of Monitoring and Evaluation)

GEF INTERNATIONAL WATERS PROGRAM STUDY

OCTOBER 2004

STUDY TEAM

PROF. LAURENCE MEE, TEAM LEADER, ALSO RESPONSIBLE FOR

PLATA BASIN AND EAST ASIAN CASE STUDIES

PROF. JOHN OKEDI, ALSO RESPONSIBLE FOR THE AFRICAN LAKES

CASE STUDY

MR. TIM TURNER, ALSO RESPONSIBLE FOR THE BLACK SEA

CASE STUDY

MS. PAULA CABALLERO, ALSO RESPONSIBLE FOR THE STUDY

OF GLOBAL DEMONSTRATION PROJECTS

DR. MARTIN BLOXHAM, REVIEW OF TDA/SAP INFORMATION

MR. AARON ZAZUETA MANAGED THE STUDY FOR THE GEF

OFFICE OF MONITORING AND EVALUATION

The study team presents this final main report. It addresses the points raised by the

International Waters Task Force following the frank and informative discussions on

the earlier versions and includes technical clarifications submitted by project

managers. Our appreciation is expressed to the many people who have given valuable

assistance to this work and without whom it would not have been possible.

ii

Foreword

One of the key tasks of the GEF Office of Monitoring and Evaluation is to review the progress

and results of the focal areas of the Global Environment Facility. Independent studies of the

Biodiversity, Climate Change and International Waters focal areas were conducted during 2003-

2004. These studies provide the GEF stakeholders with an assessment of how the focal areas are

performing and recommendations on how to continue their development. Together, these three

areas represent more than 1,100 projects with funding of just over 4 billion US$. Obviously, it is

difficult to do full justice to the wealth and depth of such a vast portfolio.

The studies report notable contributions from interventions for global environmental benefits. The

present study on international waters concludes that GEF support has extended to almost

every GEF-eligible large catchments and large marine ecosystems. Impressive achievements can

be observed on new legal regimes,; basin and sea agreements, treaties and conventions. The IW

Focal Area is also contributing to the enhancement of regional security, another role that can only

increase in importance with time.

The studies report weaknesses that are common to the three focal areas. The impact of GEF

efforts could be enhanced by refining strategic frameworks and concepts, tools and processes, as

well as communicating these better to stakeholders. Furthermore, there is a call for improvements

in monitoring, evaluation, indicators and knowledge sharing.

The three studies were undertaken by staff from Office of M & E and independent and external

consultants. Mr. Aaron Zazueta managed the study and ably coordinated the many contributions.

The support of Professor Laurence Mee, was indispensable both in his function as Team Leader

and for specific case studies. Professor John Okedi, Mr. Tim Turner, Ms. Paula Caballero and

Dr. Martin Bloxham contributed useful case studies. The study addresses the points raised by the

International Waters Task Force following the frank and informative discussions on earlier

versions and includes technical cla rifications submitted by project managers. Our appreciation is

expressed to the many people who have given valuable assistance to this work and without whom

it would not have been possible.

The three program studies will serve as inputs the Third Overall Performance Study of the GEF

during 2004-05, the GEF Trust Fund replenishment process and the GEF Assembly. The GEF

Council will find, in each of the program studies, findings and numerous recommendations

ranging from improvements in the definition of GEF policy and mechanisms to maximize impacts

and outcomes to recommendations on how to enhance project design, preparation and

implementation. The GEF focal area Task Forces have a particularly important role to play in the

implementation of the management response to the studies. We also believe that the lessons will

be relevant to other international programs in sustainable development, in a collective effort to

understand which strategies work best, under which circumstances, in protecting our global

environment.

Robert D. van den Berg

Director

GEF Office of Monitoring and Evaluation

iii

Table of Contents

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY..............................................................................................1

1.

INTRODUCTION TO THE STUDY..................................................................................5

1.1 Purpose of the Study.......................................................................................5

1.2 Background .....................................................................................................5

1.3 Context and Objectives of This Study ............................................................6

1.4 Methodology ...................................................................................................7

1.5 Structure of the Present Report .......................................................................8

2.

COVERAGE

2.1 Development and Current Status of the IW Focal Area .................................9

2.2 Coimplementation of Projects by IAs ...........................................................11

2.3 Comparison of IAs' Project Start-Up Times ................................................14

2.4 Questionnaire Survey....................................................................................15

2.5 Coherence and Information Availability for the GEF Operational

Programs ......................................................................................................16

2.6 Concluding Remarks.....................................................................................17

3.

ANALYSIS OF CASE STUDIES ...................................................................................18

3.1 Introduction and Criteria Used......................................................................18

3.2 Criterion 1: Coherent, Transparent, and Practicable Design .......................19

3.3 Criterion 2: Achievement of Global Benefits ..............................................24

3.4 Criterion 3: Country Ownership and Stakeholder Involvement ..................30

3.5 Criterion 4: Replication and Catalysis .........................................................33

3.6 Criterion 5: Cost-Effectiveness and Leverage .............................................39

3.7 Criterion 6: Institutional Sustainability........................................................45

3.8 Criterion 7: Incorporation of Monitoring and Evaluation Procedures .........51

3.9 Conclusions ...................................................................................................55

4.

THE EFFECTIVENESS OF THE TDA/SAP AS A KEY TOOL FOR GEF

INTERNATIONAL WATERS ENABLING ACTIVITIES ..................................................56

4.1 Introduction...................................................................................................56

4.2 Methodology .................................................................................................56

4.3 Information from the Questionnaire .............................................................59

4.4 Information from the TDA/SAP Reviews ....................................................59

4.5 Inconsistencies in Reporting .........................................................................63

4.6 Conclusions ...................................................................................................64

5.

LESSONS LEARNED .................................................................................................64

The Project Cycle..........................................................................................64

The Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis ......................................................65

The Value of Demonstration Projects ...........................................................66

Selection of Appropriate Scales for Assessment and Management ..............67

iv

The Value of Strategic Planning ...................................................................67

The Interministry Process .............................................................................69

Project Operational Arrangements and Support ...........................................70

6.

IMPLEMENTATION OF THE RECOMMENDATIONS OF THE PREVIOUS STUDY ............71

6.1 Introduction...................................................................................................71

6.2 Conclusions ...................................................................................................75

7.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS................................................................76

7.1 Preamble........................................................................................................76

7.2 Overarching Conclusions ..............................................................................76

7.3 Recommendations .........................................................................................79

BOXES

Box 3.1 Altered Sediment Fluxes as a Global Issue in the Plata Basin? A

Question of Setting Appropriate Scales ........................................................21

3.2 An Innovative Management Framework for the Project "Reversing

Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf

of Thailand ....................................................................................................23

3.3 Complex Realities for Achieving Global Benefits: The Mekong Water

Utilization Project .........................................................................................27

3.4 The Project Implementation Phase: Achieving Global Benefits

Through Strategic Partnerships .....................................................................29

3.5 GloBallast: Cornerstone of a New Global Regime ......................................34

3.6 Managing the Human Footprint of Xiamen: A Question of Scales .............37

3.7 An Unexpected Output ..................................................................................38

3.8 Impact of Project Execution Modalities on Project Performance.................43

3.9 Public-Private Partnerships in South East Asia ............................................45

3.10 The Incremental Cost of Achieving Sustainable Institutions .......................47

3.11 Developing a Knowledge-Based GEF IW Community................................54

4.1 Main Questionnaire Findings Regarding the TDA/SAP Process .................60

FIGURES

Figure 2.1 Approval of Finance for IW Projects Since 1991 .........................................10

2.2 Comparison of GEF Funding and Cofunding, by Year ................................10

2.3 GEF Funding per Region..............................................................................12

2.4 GEF Cofunding per Subregion .....................................................................12

2.5 Distribution of All Approved Projects According to the OPs ......................13

2.6 Distribution of Projects by IAs .....................................................................13

2.7 Development of Coimplemented Projects by GEF Replenishment Cycle ...14

2.8 Full-Scale Project Document Development Times.......................................15

4.1 TDA Development Status in Projects Selected for Appraisal

by Questionnaire ...........................................................................................57

4.2 SAP Development Status in Projects Selected for Appraisal

by Questionnaire ...........................................................................................58

v

TABLES

Table 2.1 Distribution of Projects Approved by Council .............................................10

2.2 Response Rates to the Questionnaire ............................................................16

3.1 Leverage by PEMSEA Pilot Projects ...........................................................44

4.1 TDAs and SAPs Examined in the Current Chapter ......................................58

6.1 Degree of Achievement from Previous Recommendations ..........................72

vi

Executive Summary

The present study of the Global Environment Facility's (GEF's) International Waters

Focal Area is a contribution toward the Third Study of GEF's Overall Performance

(OPS3). A team of experienced international specialists conducted this study between

February and July 2004 based on a review of previous evaluations (at the project and

program level), questionnaires to all current projects, and field visits to four geographical

regions and to a number of global demonstration projects. The study regions selected, the

Black Sea (and Danube) Basin, the Plata Basin, the African Great Lakes, and part of the

East Asian seas, jointly make up more than half of the US$691.59 million GEF funding

invested in the Focal Area to date. An evaluation of the transboundary diagnostic analysis

and strategic action program (TDA/SAP) tools used by the foundational projects of the

portfolio was also conducted.

The study had three major objectives:

· An assessment of the impacts and results of the International Waters (IW) focal

area to the protection of transboundary water ecosystems

· An assessment of the approaches, strategies, and tools by which results were

achieved

· Identification of lessons learned and formulation of recommendations to improve

GEF IW operations.

Case studies were examined according to seven criteria: coherent, transparent, and

practicable design; achievement of global benefits; country ownership and stakeholder

involvement; replication and catalysis; cost-effectiveness and leverage; institutional

sustainability; and incorporation of monitoring and evaluation procedures. A number of

generic lessons were derived from the detailed analysis of the various studies. Four

overarching operational recommendations were also made.

The IW portfolio now extends to almost every GEF-eligible large catchment and large

marine ecosystem. The study revealed an impressive portfolio of well-managed GEF-IW

interventions, and there is increasing success at leveraging collateral funding, including

investments. The leveraging ratio is currently 1:2, and the total portfolio exceeds US$2

billion, evincing the largest effort in history to support sustainable use and protection of

transboundary waters. This task has not diminished in its global relevance; on the

contrary, water issues have grown in significance in policy statements such as the

Millennium Goals, the Johannesburg Declaration, and the targets set by the Commission

for Sustainable Development. We present clear evidence that the IW Focal Area is

contributing to the enhancement of regional security, another role that can only increase

in importance with time.

The GEF IW Focal Area has already generated some impressive achievements, including

new policy tools such as the legal regime for avoiding the transfer of opportunistic

species in ships' ballast water, the Caspian Sea Convention, the Dnipro Basin Agreement,

the Protocol for Sustainable Development of Lake Victoria Basin, the Lake Ohrid Treaty,

1

and the Pacific Tuna Treaty (the first under the 1995 Fish Stocks Agreement). It provided

the practical support necessary for actions such as successfully combating water hyacinth

overgrowth of Lake Victoria, the creation of protected areas as part of several integrated

management projects, capacity building for hundreds of public officials worldwide, and

opportunities for nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) to assume a greater role in

resource management. Most of its work is not spectacular, however; it is the vital

groundwork behind sustainable development: providing evidence, developing strategies

and innovative solutions, improving awareness, promoting stakeholder dialogue, helping

to build new institutions, testing new approaches through demonstration projects, and

creating opportunities for investment. This is a gradual process of stepwise change

toward shared goals, and progress is often difficult to assess. The central paradigm is best

summarized with this quotation (Monitoring and Evaluation [M&E] Working Paper 10):

"The GEF international waters operational strategy aims at assisting countries to jointly

undertake a series of processes with progressive commitments to action and instilling a

philosophy of adaptive management. Further, it seeks to simplify complex situations into

manageable components for action. "

We paid special regard to examining the overall performance (measured by outputs and

outcomes) of projects classified as foundational, demonstration, or SAP implementation.

Progress on foundational projects was encouraging, and there have been clear

improvements between each iteration of the TDA/SAP (transboundary diagnostic

analysis/strategic action program) process. Difficulties sometimes occur when projects

make a poor distinction between global and local benefits, do not identify social and

economic root causes of transboundary problems, or fail to identify and incorporate

stakeholders. A particularly difficult challenge has been the development of sustainable

transboundary institutional mechanisms and Interministry Committees at a national level

with the high-level participation of all relevant sectors.

Demonstration activities have been very successful in generating local participation and

home-grown solutions to problems. The GEF-IW Focal Area has more than 10 years of

experience in their development and growing success in replication (indeed, there are

now examples of self-financed demonstration projects). The early success of one of the

global demonstration projects (GloBallast) to catalyze an international agreement is a

particularly noteworthy achievement. There are some limitations with the approach:

attempts to upscale demonstration projects have met with difficulties, because each scale

requires a different solution and policy framework. We conclude that projects combining

demonstration and strategic planning (TDA/SAP) activities are most likely to succeed;

they maintain stakeholder confidence while endeavoring to ensure longer-term

sustainability of local and global benefits.

Of the SAP implementation projects, we paid special attention to the Black Sea Strategic

Partnership, a concerted attempt to integrate the comparative advantages of all

Implementing Agencies (IAs) and counterpart donors to prevent the return of devastating

eutrophication to the Black Sea during the economic recovery of countries in its basin.

The partnership has generated more than US$110 million in grant funds and leveraged at

least three times as much in investment. Its first phase has resulted in a number of very

2

successful large demonstration projects that are incremental to national development

initiatives (for example, agricultural reform). One difficulty that should be corrected at

the forthcoming regional stocktaking meeting is that the initial partnership concept

underestimated the interagency coordination needs and the measures required to enhance

government buy-in to joint institutional arrangements in the Black Sea. This has led to

some fragmentation of the overall effort and diminished momentum.

Interagency coordination was examined closely in the current study. There is evidence of

steady improvement of Implementing Agency (IA) cooperation within projects (some 20

percent of all new full-sized projects are co-implemented). We noted continued

shortcomings in regional cooperation between projects in all case study regions,

particularly between IAs and between focal areas. The apparently large differences

between IAs in the time taken to develop and negotiate full-sized projects from Project

Development Facility - Block B (PDF-B) signature to GEF Chief Executive Officer

(CEO) endorsement also merits further study.

A significant number of project staff and stakeholders demonstrated insufficient

knowledge of the concepts, processes, and tools that give the GEF IW Focal Area its

unique role. Ambiguities remain in the descriptions of Operational Programs (OPs), and

the language and terminology used is not readily accessible. We noted criticism that

mechanisms for project analysis and approval are insufficiently transparent. Many

midterm and final evaluations also commented on overambitious and excessively

complex project documents. We consider that most of the above points can be improved

with stronger supervision combined with clearer documentation and its use for

management training.

Articulation of adaptive management requires robust indicators of environmental and

socioeconomic status, stress reduction, and process. Process indicators are particularly

important for monitoring and evaluation, but more work is needed to strengthen the

current indicators to make them more coherent and objective.

We have examined the implementation of recommendations from the previous study. We

estimate that about half of the 15 recommendations have been implemented (most have

been at least partially implemented). The pending recommendations (these focus on

clarification of procedures, M&E, and supervision) have been rolled into our own

recommendations outlined below.

We register our concern that the supervisory capacity of the IAs, Executing Agencies,

GEF Secretariat, and International Waters Task Force (IWTF) has not increased in

proportion to the magnitude and complexity of the IW Focal Area. We strongly

recommend an independent review of this situation, with a view to proposing a revision

of the current 9 percent cap on management costs.

To address the issues identified in the study, we have made four overarching

recommendations, indicated below and fully detailed in the report. In addition, we

identified key lessons learned, and we recommend their analysis by the IWTF.

3

· The production and use of an accessible GEF International Waters Focal Area

manual to clarify the concepts, tools, and processes that are giving rise to recurrent

difficulties for project design and implementation.

· Development of a comprehensive M&E system for IW projects that ensures an

integrated system for information gathering and assessment throughout the lifespan of

a project.

· The incorporation of a regional-level coordination mechanism for IW projects to

increase the synergies between IW projects within defined natural boundaries and

their focus on global benefits, to enable communication and coordination with

relevant projects in other focal areas, to enhance feedback between projects and the

IW Task Force, and to facilitate implementation of the M&E strategy at the regional

level.

· The redefinition of the GEF International Waters Task Force to enhance its role

in the definition of technical guidelines and policies, to ensure the optimum use of

comparative advantages of the Implementing Agencies within each intervention, and

also to examine the selection of Executing Agency in accordance with agreed on

criteria.

Note regarding the methodology:

This report was prepared by an experienced team of consultants drawn from Europe, Africa, and Latin

America, appointed following consultation with the GEF International Waters Task Force (IWTF). The IWTF

also commented upon the Terms of Reference (TOR) for the study. The team's work comprised the

following steps:

(1) Initial briefing from the M&E Unit and agreement on methodology

(2) Desk studies of the overall IW portfolio and the case study regions

(3) Field studies in the Black Sea Basin (Danube, Black Sea, Dnipro, Black Sea Strategic Partnership); the

African Great Lakes (L. Victoria, L. Tanganyika, L. Malawi); the Plata Basin and associated maritime

areas (Upper Paraguay, Bermejo, Guarani Aquifer, Plata and its Maritime Front, Patagonia Shelf, Plata

Basin Project); the East Asian seas (South China Sea, Mekong River, "Building Partnerships for the

Environmental Protection and Management of the East Asian Seas PEMSEA"); and selected global

demonstration projects (GloBallast, Global Mercury) (full project titles may be found in Annex 1

(4) Team meeting to discuss overall results

(5) Drafting of preliminary version of the main report

(6) Meeting of extended IWTF to discuss preliminary report and provide feedback based on their

experience and internal consultations (it was previously agreed that all feedback should be channeled

through IWTF members)

(7) Further consultations on conclusions with GEFSec representative

(8) Preparation of second draft (incorporating all factual clarifications from the IWTF members, plus

information on additional projects requested by them but not included in the original TOR)

(9) Receipt of additional factual clarifications from any projects not involved in step (6), plus final comments

of IWTF members

(10) Production of final report.

The study team has taken great care to ensure accuracy in factual content of this report and objectivity in the

analysis through the use of defined assessment criteria. As with all studies of this kind, however, some

elements of the study required the considered judgment of the team. The team recognizes that there may be

other viewpoints and sensitivities on some of these issues and that the opinions presented in this document

are not necessarily the products of a full consensus with all of the parties involved.

4

1. INTRODUCTION TO THE STUDY

1.1. PURPOSE OF THE STUDY

The present independent study of the Global Environment Facility's (GEF's) International

Waters Focal Area (referred to here as the IW Study) is a contribution toward the Third Study

of GEF's Overall Performance (OPS3). The purpose of OPS3 is to assess the extent to which

the GEF has achieved, or is on its way to achieving, its main objectives. It will contribute to

the fourth replenishment and the third Assembly of the GEF. Because the portfolio is fast

maturing, OPS3 will focus more than its predecessors on program and project outcomes, the

sustainability of those outcomes, and the move toward impact. Specifically, OPS3 will

provide an overall assessment of the results achieved through GEF support, from the

restructuring in 1994 to June 2004; assess the effectiveness of GEF policies, strategies, and

programs in achieving those results; and draw key lessons and provide clear and forward-

looking recommendations to the GEF and its partners on how to render GEF support more

effective in contributing to global environmental benefits.

The IW Study team comprises a number of expert independent consultants drawn from the

European, Asian, Latin American, and African regions, working closely with a GEF

Monitoring and Evaluation (M&E) specialist and staff from the GEF Secretariat and

consulting with Implementing Agencies (IAs), the Scientific and Technical Advisory Panel

(STAP), and other consultants. The IW Study integrates findings and lessons from other GEF

M&E studies and reports, such as specially managed project reviews (SMPRs), the program

performance report (PPR), review of midterm and terminal evaluations, and the local benefits

study currently in progress. The study includes site visits to projects in regions where there

has been a high or long-standing investment of GEF funds in IW projects.

1.2. BACKGROUND

The GEF operational strategy defines GEF's objective in the International Waters Focal Area

as "to contribute primarily as a catalyst in the implementation of a more comprehensive,

ecosystem-based approach to managing international waters and their drainage basins as a

means to achieve global environmental benefits." According to the operational strategy, the

overall strategic thrust of GEF-funded international waters activities is to meet the agreed on

incremental costs of:

· "Assisting groups of countries to better understand the environmental concerns of their

international waters and work collaboratively to address them

· Building the capacity of existing institutions (or, if appropriate, developing the capacity

through new institutional arrangements) to utilize a more comprehensive approach for

addressing transboundary water-related environmental concerns

· Implementing measures that address the priority transboundary environmental concern."

The goal of GEF international waters projects is to "assist countries to use the full range of

technical, economic, financial, regulatory, and institutional measures needed to operationalize

5

sustainable development strategies for international waters."1 The GEF also seeks to act as a

catalytic agent that lays the foundations for investment.

There are three Operational Programs in the IW Focal Area:2

· OP8, Water Body-Based Operational Program:

"Projects in this Operational Program focus mainly on seriously threatened water bodies

and the most imminent transboundary threats to their ecosystems as described in the

Operational Strategy 1. Consequently, priority is placed on changing sectoral policies and

activities responsible for the most serious root causes or needed to solve the top priority

transboundary environmental concerns."

· OP9, Integrated Land and Water Multiple Focal Area OP:

"Projects . . . are aimed at achieving changes in sectoral policies and activities as well as

in leveraging donor and regular Implementing Agency (IA) program participation. These

projects focus on integrated approaches to the use of better land and water resource

management practices on an area-wide basis."

· OP10, Contaminant-Based Operational Program

"This includes projects that help demonstrate ways of overcoming barriers to the adoption

of best practices that limit contamination of the International Waters environment."

We have reviewed the descriptions and guidance information for the OPs in Chapter 2 of this

report and in more detail in Annex 2.

1.3. CONTEXT AND OBJECTIVES OF THIS STUDY

The study has three objectives.

· An assessment of the impacts and results3 of the IW Focal Area to the protection of

transboundary water ecosystems.

· An assessment of the approaches, strategies, and tools by which results were achieved.4

1 Duda, A. "Monitoring and Evaluation Indicators for GEF International Waters Projects." M&E Working Paper

10. GEF, Nov. 2002, p. 2.

2 Quoted texts are from the GEF OP guidance documents, available on www.thegef.org.

3 This study focuses on the analysis of the impact and results of GEF activities on selected water bodies by

conducting in-depth case studies that address GEF-supported activities performance, results, and impacts. By

adopting a geographical approach, the study assesses the cumulative impacts and results of multiple GEF IW

activities in assisting governments in improving the environmental management of transboundary waters.

Demonstration activities are assessed independently in as far as they do not target specific water bodies.

Relevant projects in other GEF focal areas are taken into account during each water body assessment.

4 The study also examines the extent to which current approaches, strategies, and tools respond to the GEF's IW

goals. Special attention is given to the assessment of the quality of project design, the tools and approaches used

and promoted by the GEF to identify and address environmental transboundary water issues, and the

incorporation of lessons into program operations (that is, the transboundary diagnostic analysis /strategic action

program approach). The geographical approach adopted by this review also permits an assessment of the

interactions between IW and selected activities from other focal areas, especially biodiversity.

6

· Identification of lessons learned and formulation of recommendations to improve IW GEF

operations.

This study also assesses the global distribution of GEF IW activities among eligible water

bodies. This is to determine the water bodies in which the GEF has been involved, issues

addressed and types of activities supported by the GEF, patterns of IA participation in GEF

projects, and patterns in the allocation of GEF resources across water bodies.

1.4. METHODOLOGY

A. Case Studies

The study carried out four in-depth case studies that address the results and impacts of GEF

activities in four geographical regions, as well as the particular case of the IW global

demonstration projects. The four water bodies were:

· The Black Sea Basin (including the Danube and Dnipro River Basins)

· The La Plata River Basin (including the adjacent Patagonia Shelf)

· African lakes and their catchments (Tanganyika, Malawi, and Victoria)

· The East Asian seas (including the Gulf of Thailand and the South China Sea).

Following a review of available documentation,5 site visits to these areas were conducted in

the period from March to May 2004. This enabled the following questions to be addressed:

· How effectively have the GEF foundational activities assisted countries or groups of

countries to identify root causes of key transboundary environmental issues and to

develop agreed on programs and effective approaches to address root causes and other

key environmental transboundary water issues? What are the impacts and results?

· How effectively has the GEF assisted countries or groups of countries to develop the

policy, legal, and institutional frameworks to address transboundary environmental

stresses jointly identified? In selected cases, what are the impacts and results in stress

reduction and in environmental status?

· To what extent have GEF IW catalytic actions resulted in the additional non-GEF

investments that address the identified environmental stresses in the selected water

bodies?

B. Assessment of the Approaches, Strategies, and Tools by Which Results Are Achieved

Based on the regional studies and responses to a questionnaire prepared with the participation

of the GEF International Waters Task Force in accordance with the IW Focal Area

Performance Indicators for the GEF International Water Programs,6 the following questions

were examined:

5 The study also draws on previous program studies and reviews of midterm and final evaluations and other

relevant materials to the GEF.

6 Program Performance Indicators for International Water Programs, GEF/C.22/Inf.8.

7

· To what extent have the TDA and SAP approach been adopted by projects since the

endorsement of this methodology in OPS2? How effective has the use of GEF-

financed transboundary diagnostic analysis (TDA) been to assist countries to

discriminate between transboundary and domestic problems and identify root causes

of transboundary water problems? Is there clear evidence that the TDAs have been

developed with broad stakeholder participation?

· To what extent have SAPs identified a manageable number of interventions that

address root causes and identify solutions that are compatible with country capacities?

How effective have GEF approaches been to assist riparian countries to develop

programs to address transboundary issues? Have the proposed interventions been

agreed on by a broad range of stakeholders? What approaches have worked well under

different circumstances?

· In the case of projects involving demonstration projects, what evidence exists of their

successful replication within or between projects?

· What lessons have GEF activities derived from experience? Have these lessons been

systematically used to improve project design and implementation?

1.5. STRUCTURE OF THE PRESENT REPORT

The present report comprises six substantive chapters, including the present one. In Chapter 2,

we present an overview of the development of the IW project portfolio, its coverage, finance,

and comparative rates of delivery of the three IAs, and we conclude with an analysis of the

coherence of the Operational Programs. Chapter 3 presents an in-depth analysis of the case

studies and the implications of the findings for the development of the IW Focal Area.

Chapter 4 includes a study of the implementation of the transboundary diagnostic

analysis/strategic action program (TDA/SAP) approach, based on the questionnaires received

and a review of relevant completed TDA/SAPs. In Chapter 5, we list a number of key lessons

learned from the proceeding chapters. Chapter 6 contains overall conclusions to the study and

key recommendations.

The main text of the study is kept as concise as possible, and footnotes are provided to give

clarifications and to present substantiating evidence or additional information. Boxes are used

to provide in-depth case study information to support the main text or to provide conceptual

guidance. A number of annexes are included that detail the current status of the IW Portfolio.

Some recommendations are provided throughout the text; Chapter 6 is reserved for the key

overarching recommendations.

8

2. COVERAGE

2.1. DEVELOPMENT AND CURRENT STATUS OF THE IW FOCAL AREA

The GEF IW Focal Area portfolio currently includes 95 projects at various stages of

completion (see Annex 1). This represents a total investment (from the beginning of the GEF)

of US$691.59 million, with declared7 cofunding of US$1,466.84 million. The total investment

could therefore be as much as US$2.16 billion, by far the largest sum ever invested in the

transboundary aquatic environment, but still miniscule compared with investments in other

sectors. In the present section, we shall examine the development of the portfolio since 1991

and the current distribution of GEF IW projects.

Before presenting our analysis however, we will explain the geographical divisions employed

for presentation. Data on GEF projects are gathered by the GEF Secretariat according to the

political divisions employed by the World Bank (that is, Latin America and the Caribbean

LAC, Africa AFR, South and East Asia ASIA, and Europe and Central Asia ECA),

together with global projects (GLO) and interregional projects (REGIONAL). Though this

system is convenient from the terrestrial perspective, it has a very coarse scale and can

complicate the practical analysis of international waters projects that follow the ecosystem

approach (for example, large marine ecosystems) because these employ natural rather than

national boundaries. For our current, more detailed analysis, therefore, we have presented

information according to the 66 large catchments and associated marine areas (marine areas

are identical to LMEs) defined for the Global International Water Assessment (GIWA)

project. Some 42 of these cover GEF-eligible countries. We recognize the limitations of this

division, but pending further consideration by the Scientific and Technical Advisory Panel

(STAP), find it to be the only alternative system currently available that covers both

freshwater and marine areas.

The development of the GEF IW Focal Area is illustrated in Figure 2.1. Funding for both OP8

and OP9 projects has more than doubled since the approval of the Operational Programs. The

average GEF finance for individual OP8 projects is US$9.07 (range 0.75 36.8) million, and

for OP8, US$8.55 (range 0.7521.45) million. The average cofunding is US$23.09 million for

OP8 and US$19.28 million for OP9. The funding of both OPs is therefore remarkably similar.

Figure 2.2 shows the evolution of cofunding during the development of the portfolio. The

increase in cofunding in recent years appears to attest to increasing leveraging. This is partly

due to World Bank SAP implementation projects that are closely related to loans or other

investments.

The overall distribution of the portfolio of approved projects is shown in Table 2.1. To date

there have been 35 OP8 projects, 26 in OP9, 25 in OP10, and 7 of stated joint OPs. The

distribution of these projects among the IAs is World Bank, 34; United Nations Development

Programme (UNDP), 38; and United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), 21.

Interestingly, only three projects are declared as being joint with other focal areas, and only

one of these is with OP2 (which has a clear focus on the coastal zone).

7 The cofunding amounts are those recorded in project documents. We are aware that these figures have not

always been achieved, but lack detailed information on the entire portfolio to explore this issue fully.

9

Table 2.1. Distribution of Projects Approved by Council

Implementing

OP8

OP9

OP10

Joint OPs

Agency

Number

Type

WB

15

8

10

1

8,6

UNDP

17

11

7

3

8,10; 8,9; 9,2

UNEP

3

7

8

3

10,14; 10,2,9;

9,1

Total

35

26

25

7

Funding for IW projects by year and OP

120

100

80

OP 10

Million US$ 60

OP9

OP8

40

20

0

1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003

Figure 2.1. Approval of Finance for IW Projects since 1991

Total GEF and co-financed funding

600

500

400

Cofinance

Million US$ 300

GEF

200

100

0

1991

1992

1993 1994

1995

1996

1997 1998

1999

2000 2001

2002

2003

Year

Figure 2.2. Comparison of GEF Funding and Cofunding, by Year

10

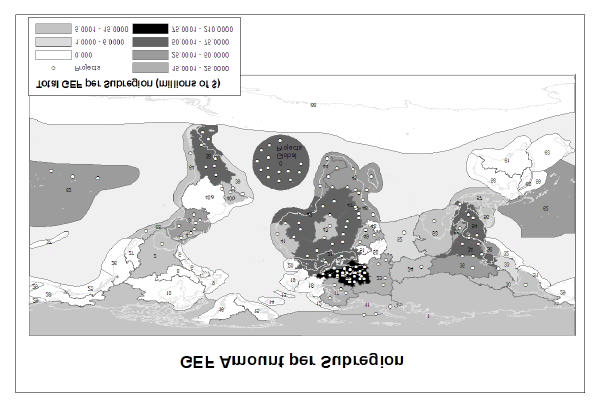

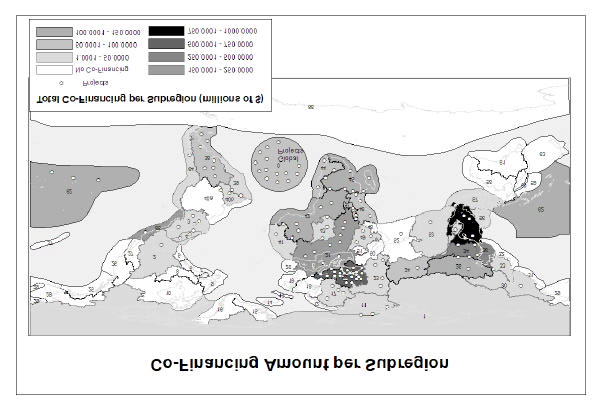

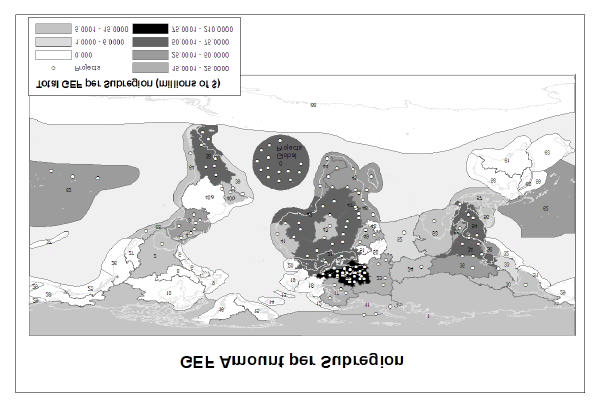

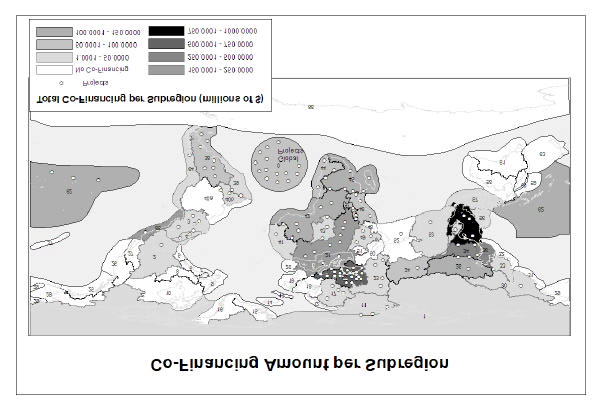

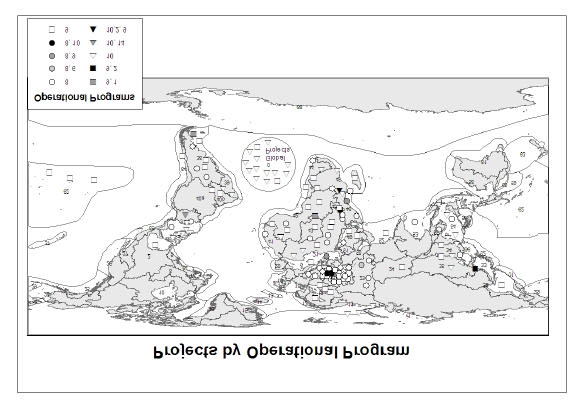

The distribution of project funding by subregion (as defined in paragraph 3) is provided as a

map in Figure 2.3 (GEF funding) and Figure 2.4 (declared cofunding--see footnote 7). Note

that the gray scales used in the two figures are different because of large differences in the

investment levels. Global projects are indicated in a circle in the South Atlantic. The

information has been pooled for each of the subregions. Although this should not be taken to

imply that all of the subregion is covered by GEF interventions, it shows the approximate

distribution of GEF effort in the IW Focal Area on a global scale. Also, the position of the

markers in each section does not describe the exact position of each project; it merely

signifies a single intervention within the region.

The results of this analysis are self-evident. GEF IW investments have been made in virtually

every eligible region, and there are new investments in the pipeline for most of the subregions

not presently covered. By far the highest GEF investment has been in the Black Sea Basin

(US$149.12 million, 20 projects). Other regions of high investment include those of Southeast

(SE) Asia (including China's river basins and the South China Sea), the Plata Basin, and

several African river and lake basins and large marine ecosystems (LMEs), including the Gulf

of Guinea and the Mediterranean Sea. The regions of highest cofunding (Figure 2.4) have

been the Black Sea and the SE Asian basins and seas.

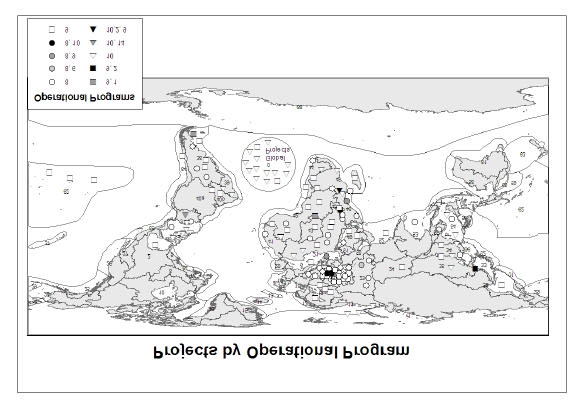

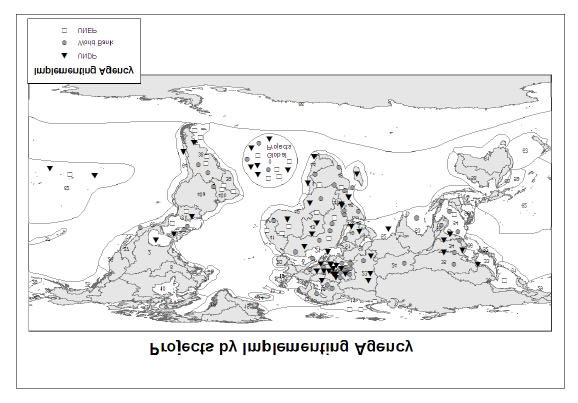

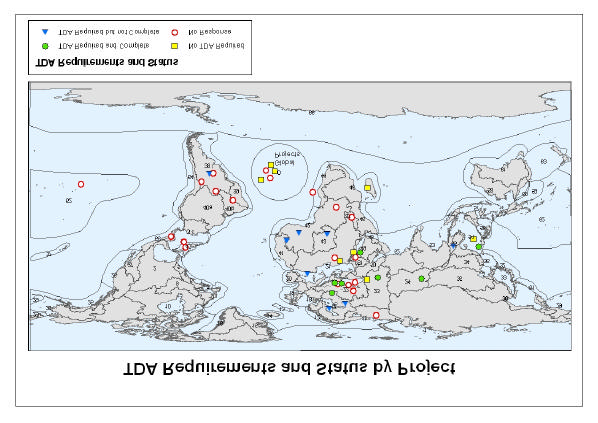

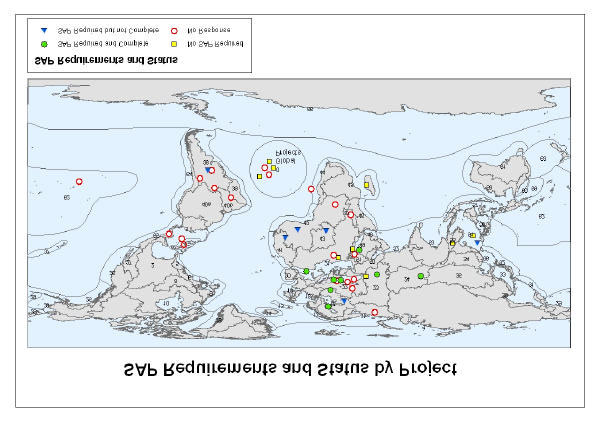

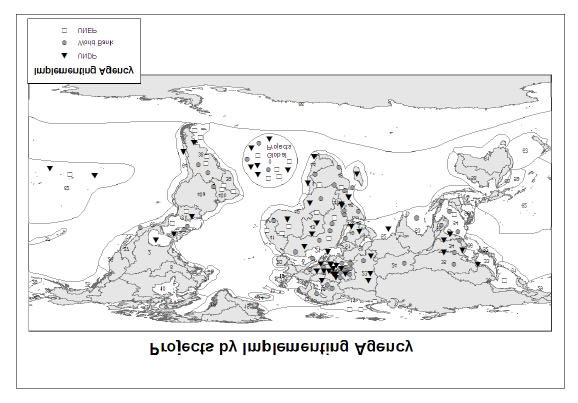

We have also examined the distribution of projects according to the Operational Program

(Figure 2.5) and Implementing Agency (Figure 2.6). The figure clearly shows the high density

of OP8 projects in the Black Sea Basin. In most other regions, there is a mixture of OP8 and

OP9 projects, though OP9 tends to dominate in Africa (except for the African lakes water

body projects and the LME projects). Most of the global projects are in OP10, as are the

earlier ship waste projects. Figure 2.6 also illustrates the division of lead agency

responsibilities among IAs. The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the

World Bank dominate projects in Europe and in Central and East Asia, whereas the United

Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) has a greater role in Latin America (largely

through the Organization of American States). To some degree, however, all three IAs are

responsible for interventions in all geopolitical regions of the world.

Figures 2.42.6 also explain our choice of regions for site visits. The study areas were

selected in close cooperation with the IW Task Force according to regional representation, the

highest density of mature projects, the magnitude of GEF investment, and the use of a wide

range of approaches (TDA/SAPs, demonstration projects, and so forth). In this manner, we

were able to collect firsthand information from projects that account for more than 50 percent

of the total GEF investment to date. In doing so, however, we recognize that we have missed

important and innovative interventions, particularly those related to large marine ecosystems

(LMEs). At the request of the IW Task Force, we have included information from additional

key projects in our detailed analysis in Chapter 3.

2.2. COIMPLEMENTATION OF PROJECTS BY IAS

There are clear operatio nal advantages with close cooperation between IAs at the project

level. UNDP (working with a number of Executing Agenc ies and their own network of

Country Offices) are particularly adept at managing complex multicountry projects that

require many small contracts and procurements. The World Bank's more centralized approach

and strict procurement procedures have been a source of considerable frustration to project

11

Figure 2.3. GEF Funding per Region (Note: Many of the projects cover only a small part of each region.)

Figure 2.4. GEF Cofunding per Subregion (see footnote 7)

12

Figure 2.5. Distribution of All Approved Projects (1991 to the Present) according to the OPs (see Table 2.1)

Figure 2.6. Distribution of Projects (1991 to the Present) by Implementing Agency (see text for details)

13

managers, but the Bank has excelled at leveraging cofunding and investments. UNEP's

approach to information gathering and its relationship with regional conve ntions and the

STAP have given it a comparative advantage in many technical areas. Earlier reviews of

the IW Focal Area commented on the deficiencies in operational coordination between

IAs. In this context, we examined the development of co-implemented projects within the

overall portfolio (Figure 2.7).

Co-implemented Projects in the IW portfolio (total: 15)

25.0

20.8

20.0

17.4

15.0

Percentage

IW Portfolio 10.0

7.7

5.0

5.0

0.0

0.0

Pilot

GEF1

GEF2

GEF3

PDFA/B

Phase

Replenishment Cycle

Figure 2.7. Development of Co-implemented Projects by GEF Replenishment Cycle

The results of the analysis demonstrate a steady increase in coimplementation. Numbers

are still relatively low (one in five of projects approved in the current cycle) and the

degree of coimplementation highly variable, but the trend is positive. There is clearly an

increasing willingness to cooperate, fuelled by successful experiences such as the

Caspian Sea project. Currently however, only one Project Development Facility B (PDF-

B) is coimplemented, and this may herald a retreat from the positive trend. Our

investigations suggest that this may be a consequence of the 9 percent cap on

management costs imposed on IAs by the GEF Council. Successful co-implementation

requires the mobilization of appropriate in-house specialists from the IAs to project

meetings, and this is difficult to achieve if the limited fees must be shared between

agencies, especially where projects are relatively small. A full cost-benefit analysis and

review of the management fee system are urgently needed.

2.3. COMPARISON OF IAS' PROJECT START-UP TIMES

We conducted a survey of the time taken to complete PDF-B phases and generate CEO-

endorsed project documents. IAs were requested to supply the dates of PDF-B signature,

project brief approval by Council, and CEO endorsement. It was evident that a

consolidated database is urgently required; these simple data were not always readily

available and often incomplete, and the format varies markedly between agencies.

14

Figure 2.8 illustrates the results of this survey for projects that have been endorsed by the

CEO since early 2002.

Full Scale project document development times (for FSPs

endorsed from 2002 onwards)

UNEP

Completion of

PDF-B

World Bank

Completion/

negotiation of FS

Pro Doc

UNDP

0

1

2

3

4

5

years from PDF-B signature

Figure 2.8. Full-Scale Project (FSP) Development Times . (Notes: "Completion of PDF-B" refers to the

average time between signature of the PDF-B and the approval of the project brief for the FSP by Council.

"Completion/negotiation of FS Pro Doc" refers to the average time from Council approval of the project brief

to the endorsement of the project document by the CEO.)

The figure appears to show striking differences between the IAs, and we tested these

statistically (F-test) to determine which of them were highly significant. The times taken

for the PDF-B phase in the World Bank and UNDP were indistinguishable and averaged

22 months, whereas that of UNEP averaged 40 months. Completion and negotiation of

the full-scale project document took an average of 15 months for the World Bank and

UNEP, and significantly shorter (7 months) for UNDP. The average overall start-up

process varied from 28 months (UNDP) to 54 months (UNEP), a difference of more than

two years. Actual time to FSP start-up was longer because operation does not begin

immediately after CEO endorsement. It is easy to explain the difference between project

document completion/negotiation between UNDP and the World Bank: UNDP has

streamlined its procedures, whereas the World Bank follows strict standard policies and

generates comparatively far more detailed project documents. The reason for UNEP's

tardy process is less clear, however, and merits further investigation. The process should

not be seen as a race aga inst the clock, however; it may take a considerable time to

achieve full buy-in of all stakeholders. (We will discuss the consequences of gaps

between PDF-B implementation and FSP start-up in Chapter 3.)

2.4. QUESTIONNAIRE SURVEY

To gather additional information on the IW portfolio, a questionnaire was prepared by the

GEF M&E Unit in close consultation with the IW Task Team before the beginning of the

current study. The questionnaire was "trialled" in autumn 2003, and a modified version

15

was distributed through the IAs to 44 ongoing full-sized projects in spring 2004. Much of

the questionnaire was designed to examine the experience of projects with the

transboundary diagnostic analysis (TDA) and strategic action program (SAP) processes,

and this will be discussed in Chapter 4. Some general points are worth reporting at this

juncture, however. First, the response to the questionnaires was very poor (see Table 2.2).

Of the 44 projects, only 23 responded. There was only one response from Latin America

and the Caribbean (WB Guarani project), and none from the UNEP projects in the region.

This severely constrained the usefulness of the exercise and suggests that M&E is not

taken very seriously in the region. The 23 responses did, however, represent a reasonable

sample of the three OPs (7 from OP8, 11 from OP9, and 4 from OP10) and provided

valuable information that will be used in later chapters of this report.

Table 2.2. Response Rates to the Questionnaire

Submitted

IW Projects

Questionnaires IW

Geopolitical Region

Selected for Study

Projects

E. Europe & Central Asia

13

8

Africa

7

5

Latin America and Caribbean

8

1

Global

5

3

Middle East and North Africa

4

3

East Asia and the Pacific

4

3

Total

44

23

Second, the design of the questionnaire proved inadequate. It was based on the agreed on

performance indicators8 for the IW Focal Area, but in some cases these proved to be

ambiguous and insufficiently quantitative to permit their effective use as a monitoring

tool. (We shall examine this point in Section 3.8 of the current report.)

Third, the survey, together with examination of annual project implementation reports

(PIRs), leads us to question the heavy reliance on self-assessment as a tool for project and

program monitoring. There are some surprising inaccuracies in responses, as we shall

demonstrate in Chapter 4. An example however, is that 40 percent of the respondents

were not sure under which OP their project was financed. This leads us to question

general knowledge of the GEF and its IW Focal Area at the project level. Is the

information available understandable, up-to-date, and communicated to projects? (We

shall explore this further in the next section.)

2.5. COHERENCE AND INFORMATION AVAILABILITY FOR THE GEF OPERATIONAL

STRATEGY AND OPERATIONAL PROGRAMS IN THE INTERNATIONAL WATERS FOCAL AREA

We examined9 the guidance documents for the International Waters Operational

Programs (OPs) from the perspective of their clarity and to determine whether they

clearly differentiate between OPs 8 and 9, and we also examined the operational strategy

(OS) to determine whether it provides understandable guidance on the concept of

8 Program Performance Indicators for International Water Programs, GEF/C.22/Inf.8

9 A full comparative review was conducted and is available as a separate report.

16

incremental costs and eligibility for GEF funding. This clarity is important to determine

which priorities identified in the TDA/SAP qualify for GEF funding under a SAP

implementation project. (The analysis of OP descriptors is presented in tabular form in

Annex 2.) Our conclusion is that the OP guidance documents contain much ambiguous

wording (resulting from inevitable compromises during their initial negotiations) and

their review and updating would be timely, especially given the incorporation of OP15

(land degradation) in the suite of GEF OPs and the wealth of new case studies that could

be used to illustrate the IW OPs.

In this context, we noted the publication of M&E Working Paper 10 (see footnote 1),

"Monitoring and Evaluation Indicators for GEF International Waters Projects." This

document, written in plain English, provides valuable insights into the objectives and modus

operandi of the IW Focal Area and builds upon a decade of lessons learned. Unfortunately,

its distribution has been very limited--perhaps the narrow title discourages wider readership.

It sets a precedent, however, for providing guides that explain some of the more impenetrable

GEF technical documents. We feel that better and more cons olidated guidance would

improve the transparency and effectiveness of GEF mechanisms.

In addition to examining the descriptors of OPs, we also considered the guidance

provided on incremental costs for the IW Focal Area. (The details of our analysis are

provided in Annex 2.) We concluded that the operational strategy does provide sufficient

guidance regarding the concept of incremental costs. The problem is that much of this is

couched in "GEF-speak" (the GEF's own technical jargon) and there is a need to provide

a bridge between this and the practitioners who need to understand and implement the

guidance. Such a document could be illustrated by practical examples from the IW

portfolio.

2.6. CONCLUDING REMARKS

In this chapter, we have demonstrated the impressive growth in scope and scale of the

GEF International Waters Focal Area. This has resulted from the gradual geographical

extension of enabling actions (such as TDA/SAPs), the development of new global

initiatives under OP10, and the emergence of the first SAP implementation activities,

particularly those in the Black Sea Basin. The SAP implementation and demonstration

site projects are also responsible for much of the increased cofunding of GEF activities

shown in Figure 2.2 (see detailed analysis in Chapter 3).

The maps of coverage in Figures 2.32.6 must be interpreted carefully; the patchwork

quilt of projects is far from complete. In the next chapter, we shall also examine problems

of fragmentary and inconsistent coverage at a basin scale, as well as project overlaps.

Questionnaires distributed to key projects through the IAs resulted in a relatively poor

level of response. This may reflect fatigue from excessive gathering of information that

appears trivial or repetitive, rather than a low level of importance given to M&E activities

at the project level. However, there is also a worrying lack of knowledge regarding the

GEF-IW Focal Area itself at the project level (this was also corroborated during site

visits). We feel that this is partly due to the style and content of documentation available

17

describing the Operational Programs. Operational Programs also provide insufficient

guidance to distinguish between activities that contribute to global benefits (and thus

qualify for GEF support) and activities that would be considered as generating national

benefits and would not qualify for GEF funding.

We noted major differences between IAs in the time required to complete project

preparatory processes. IW projects are fairly evenly distributed between the

Implementing Agencies, and there are gradually increasing numbers of multiple IA

initiatives such as the Red Sea (completed) and the Caspian (entering the second phase).

The costs and benefits of multiple agency implementation merit further study. Explicit

multiple focal area interventions remain rare.

In the next chapter, we shall investigate many of these issues in depth, based on field

visits and case studies.

3. ANALYSIS OF CASE STUDIES

3.1. INTRODUCTION AND CRITERIA USED

The study sites visited represent a broadly representative array of ongoing and completed

GEF interventions within OPs 8, 9, and 10. The five areas covered (Black Sea Basin,

Plata Basin, African lakes, East Asian seas, and the Global Demonstration Projects)

represent about half of the GEF IW Focal Area expenditure to date and an even higher

proportion of cofinancing. The study team visited almost every ongoing project in the

study areas to gather firsthand information from project staff, government officials, and

stakeholder representatives. (Summary reports of each of the five studies are included as

Annexes 37.)

The current section analyzes the results of these studies in relationship to a set of

common criteria. The objective is not to conduct a critical evaluation of each project (this

is the purpose of the mid- and final-term evaluation process and the independent SMPR),

but to illustrate the development of the IW Focal Area, based on strengths and

weaknesses of the projects (or elements of the projects) visited. Text boxes and footnotes

are used to illustrate particular points or to give greater insight into individual projects. At

the request of the International Waters Task Force, some projects are referenced from

outside the study regions, including LME projects and IW:Learn (see Box 3.11).

The criteria employed for the evaluation are the following (see footnotes for further

explanations):

· Coherent,10 transparent, and practicable design

· Achievement of global benefits11

· Country ownership and stakeholder involvement12

10 By "coherent," we refer to coherence with the operational program, with findings of the TDA, and with

the institutional capacity in the region.

11 In the case of IW projects, "global" also refers to transboundary environmental benefits related to the

aquatic system.

18

· Replication and catalysis13

· Cost-effectiveness and leverage14

· Institutional sustainability15

· Incorporation of monitoring and evaluation16 procedures.

The above criteria are fully compatible with the evaluation criteria employed by the GEF

Secretariat and by most of the Implementing Agencies.

3.2. CRITERION 1: COHERENT, TRANSPARENT, AND PRACTICABLE DESIGN

Context

The M&E Working Paper 10 (see footnote 1) gives an elegant statement of what the

operational strategy seeks to achieve: "The GEF international waters operational strategy

aims at assisting countries to jointly undertake a series of processes with progressive

commitments to action and instilling a philosophy of adaptive management. Further, it

seeks to simplify complex situations into manageable components for action. "

In most cases, there was a high level of coherence between PDF-B and subsequent phases

of the project cycle. With some exceptions, transboundary diagnostic analyses (TDAs)

led to strategic action programs (SAPs) that provided a firm basis for subsequent actions.

(We will review the TDA/SAP process in Chapter 4.)

As the IW portfolio develops, project design has improved, and innovations have

gradually been incorporated. As we shall demonstrate in Section 3.5, there is a move

toward projects that combine strategic planning with demonstration projects to maintain

stakeholder interest and articulate the adaptive management process. Our comments are

provided within this context of a focal area that is moving forward, but requires continual

critical review to assist its progress.

Analysis

Gaps between PDF-B completion and the start-up of the full-sized project (see Section

2.4) often cause difficulties for the overall efficiency of project implementation. In the

case of the South China Sea project, for example, the TDA was already four years old

when project implementation began. The implementation phase of the Black Sea

12 We recognize that country ownership and stakeholder involvement are not the same; however, we

consider that these two elements of "ownership" should coexist in any effective IW project.

13 "Replication" refers to a project or project element that can be repeated at another place and time;

"catalysis " refers to the ability of a project to galvanize effective actions at a larger scale than the GEF

intervention itself.

14 We recognize that cost-effectiveness is not the same as leverage--an intervention does not necessarily

have to leverage cofunding to be cost-effective.

15 This aspect of GEF interventions is considered to be critically important. (Our interpretation of a strategy

for institutional sustainability is explained in Box 3.10.)

16 "Monitoring and evaluation" is used in the broad sense, not only from the perspective of the formal GEF

M&E criteria. Monitoring is a key element in an adaptive management strategy.

19

project--the Black Sea Ecosystem Recovery Project (BSERP)--began six years after

TDA completion. Though there were no gaps in interventions in the case of the Black

Sea, the small bridging project and patchwork of funding used to keep the Project

Implementation Unit alive during the five years between SAP completion and BSERP

resulted in a considerable loss of momentum and credibility.17 In the case of the Lake

Malawi/Nyasa and Lake Tanganyika projects, the five-year discontinuity in funding

continues, and many technical outcomes of the projects have remained underutilized. In

both cases, however, other donors have continued some level of support and, in the case

of Tanganyika, a Convention and Lake Authority have now emerged. Long gaps

generally lead to difficulties in applying an adaptive management approach because of

lost momentum and the limited shelf life of technical documents produced in earlier

interventions.

From these examples, it would also appear that some interventions were conceived

without an adequate exit strategy or a big picture of the scale and scope of the overall

GEF contribution. This does not imply a failure of the SAP approach, however, because

many of the projects cited were originally developed in the pilot phase of the GEF itself.

There was a problem of regional coherence, however, between projects in the Plata

Basin. For pragmatic political reasons, the early projects in the region--Bermejo, Upper

Paraguay, Plata, and its Maritime Front (FREPLATA)--were established with little or no

interrelation and without a full understanding of the Plata as an integral transboundary

system. This made it difficult to maximize the global benefits of interventions (see Box

3.1), a problem that has been recognized and will be addressed through a new regionwide

Plata Basin project. There is also a chronic problem of poor coordination between the

GEF Focal Areas in most of the regions studied.

Inadequate project design has been a problem cited in a number of project midterm and

final evaluations. Part of the problem is in the way some project documents are written

and negotiated following Council approval of the project brief. The logical framework

matrix should provide an overall vision of the project design, though we found little

evidence of its regular use in project implementation. The most detailed and carefully

prepared project documents are undoubtedly those of the World Bank, which take an

almost turnkey approach. Some project coordinators18 claimed that this left them with

limited flexibility to adapt to small unforeseen changes,19 but others20 have suggested that

their task managers21 have helped them overcome procedural issues. At the other

17 The problem was compounded by the need to keep the coordination unit alive as a first priority, leaving

very limited funding for in-country activities. This irony is common in international projects; the struggle

to maintain institutions and institutional memory leads to a loss of credibility, given that the stakeholders

see few on-the-ground benefits.

18 We refer to "project coordinator" as the person in the field with immediate responsibility for

implementation ("CTA" in UNDP terminology).

19 The Patagonia Shelf project was an example of this.

20 Such as the Guarani Aquifer and Mekong Water Utilization Project.

21 It has been suggested that task managers often have large portfolios to manage, including projects that

are considerably larger than those of the GEF, and it may be difficult to allocate sufficient time to respond

quickly to all requests from the field.

20

Box 3.1. Altered Sediment Fluxes as a Global Issue in the Plata Basin? A Question of

Setting Appropriate Scales

In virtually every sub-basin of the Plata system, the

It can be argued that the navigation issue is

alteration of sediment fluxes by human activity has

exclusively a domestic one within the region

been singled out as a problem of particular concern.

because the dredging costs reflect the costs of

There is plenty of evidence to illustrate the problem

adapting the river for a singular local and regional

and its impacts. In the upper Paraguay Basin in

economic benefit as a waterway and that the high

Brazil, for example, huge changes in land use due

maintenance costs are externalities from

to the rapid development of agriculture (mostly soy

inappropriate land use practices inland (channeling

beans) and cattle grazing since the early 1970s

the river also creates new externalities). The same

have accelerated land erosion. There are some 23

argument does not apply to the loss of habitat,

million cattle in the State of Mato Grosso do Sul

however. The region contains unique habitats such

alone (10 for every human resident). The sediments

as the Pantanal wetlands or those of the Parana

washed into rivers are deposited downstream. In the

River, and the maintenance of these systems and

case of the Taquari River that flows through the

the ecological corridors of the rivers are of immense

Pantanal wetlands, the buildup of sediments has

global value.

caused it to break its banks and permanently flood

vast areas of wetland. The ecology of the Pantanal

One note of caution is needed. As a result of

relies on seasonal drying of the system , and the

damming, sediment fluxes are not always

flooding is lowering its productivity, threatening

increasing. Decreased loads can cause the

biodiversity and causing a loss of employment.

downstream river to cut more deeply into its bed,

drying out adjoining wetlands. It can also result in

Further south, in the basin of the Bermejo River that

insufficient sediment supply to coasts and beaches

flows from Bolivia through Argentina to join the main

downstream, resulting in serious erosion. Sediments

Parana, there is also evidence of huge natural

are currently trapped by large dams such as the

erosion exacerbated by land use changes that

Itaipu on the Parana or the Salto Grande on the

began during the earliest period of colonization of

Uruguay River. The Itaipu reservoir, one of the

the region, four centuries ago. The Bermejo is now

largest in the world, traps almost all of the

the main source of sediments to the Parana.

sediments passing from the upper Parana.

According to a report submitted to the World

To what degree are these problems transboundary?

Commission on Dams, sediment supply to the lower

There is evidence of large natural sediment loads in

Parana is currently balanced by recent increases in

the system (though an order of magnitude less than

loads from the Bermejo River that join downstream

the Amazon). The Pantanal, for example, is a

from the dam. These increases are thought to be

natural sediment trap that is full of relict riverbeds

related to recent increases in rainfall in the Bermejo

and oxbow lakes , and there are plenty of historical

Basin.

accounts of the turbid waters of the Plata estuary

itself. There are two main issues at stake, however:

Understanding sediment balances requires complex

·

Impediment of the use of the system for

studies and models and must be tackled on a

navigation. It has long been an essential trade

system wide basis. A piecemeal approach cannot

route into the heart of the continent, but

work, and strategic assessment of the

increasing vessel size requires deeper waters

transboundary and global implications of changing

and expensive constant dredging in the Parana. sediment loads will require measurements and

·

The concern that the current rate of change of

models as part of a coordinated basinwide

sedimentation is leading to alterations in habitat

approach.

that are occurring too quickly for adaptation by

the natural ecosystem.

21

extreme, the midterm evaluators of the UNDP FREPLATA project commented that the

descriptions of implementation mechanisms in the project document were insufficient to

guide the project coordinator in his duties. The Dnipro River Basin project document

appears to have achieved a balance between the two extremes, giving just enough

flexibility for the project coordinator to deal with the problems of political change that

arose in the region but also clear descriptions of the roles of each of the collateral

partners.

From a practical perspective, project documents are often too bulky for careful analysis

(for example, by Council members) and have executive summaries that are

uninformative. In some cases of non-U.N.-language countries, neither the project briefs

nor project documents have been translated into national languages, hampering

transparency from the outset.

Another problem with project design, frequently cited in midterm and final evaluations, is

excessive ambition and complexity.22 This seems to accrue during project negotiations as

each partner (including the Executing and Implementing Agencies and the GEF

Secretariat themselves) demands changes23 to meet its various needs and constraints.

Activities are added, but rarely dropped. The reason for this is that it is difficult to

remove some of the original activities (given that they were proposed by governments)

and easier to add the new ones that help the proposal to meet the demands of the OPs.

Perhaps it would be useful to prioritize activities from the outset, enabling some to be

removed if the IA detects excessive complexity.

In some cases, project start-up was considerably delayed by the need to negotiate

memoranda of understanding or similar arrangements with the various entities involved

in project delivery. One GEF Focal Point suggested that this could be avoided or

minimized by making the completion of such agreements (at least at a framework level) a

prerequisite to project approval. He suggested that adequate institutional arrangements

were sometimes not properly negotiated at the time of approval of project briefs to gain

time. Examples of problems that develop at this stage are assignment of roles that are

outside the jurisdiction or competence of the coordinating institution,24 over-

concentration of effort on one ministry or sector,25 misjudgment of existing capacity,26

22 This also applies to projects beyond the study area (for example, Red Sea, IW:Learn, Pacific SIDS)

23 This often happens during a period of frenzied activity following the bilateral review of projects between

the IA and the GEFSec and before its submission in time for the next GEF Council meeting.

24 The MTE for FREPLATA, for example, demonstrated that the host Commissions (for the Plata and for

its Maritime Front) had no jurisdiction over the coastal zones from where much of the pollution entering

the system was arriving.

25 The Black Sea interventions, for example, have focused mainly on the environment sector, despite

evidence of very poor interministry coordination.

26 Assignment of responsibility to some institutions as activity centers in the Black Sea did not match their

capacity nor national plans for capacity development. Many of these centers are still struggling, despite

more than a decade of support.

22

Box. 3.2. An Innovative Management Framework for the Project "Reversing Environmental

Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand" (SCS)

The SCS project has successfully gathered objective

number of needs , such as to engage the best available

information that has enabled the participant countries to

regional expertise while recognizing the special role of

select demonstration sites for the sustainable use of

government agencies, to enable efficient information

mangroves, sea grass beds, non-oceanic coral reefs , and

transfer, to enable specialists to work together on

wetlands. It is also working on the fisheries of the Gulf of

transboundary issues (including those that are common to

Thailand and the control of land-based pollution in the

two or more countries), and to balance sectoral interests

study area and will complete a revised SAP. In developing

at a national level and national interests at a regional level.

its management framework, the project had to consider a

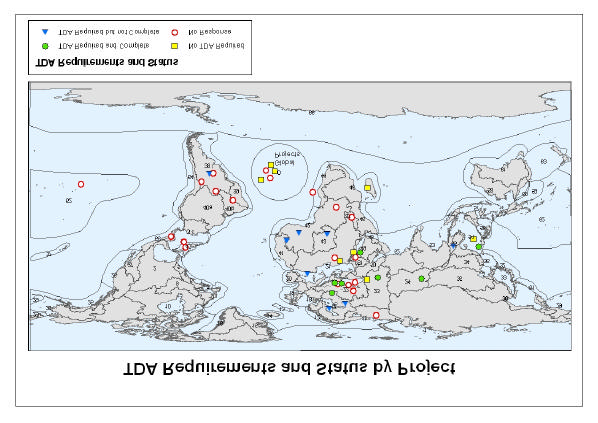

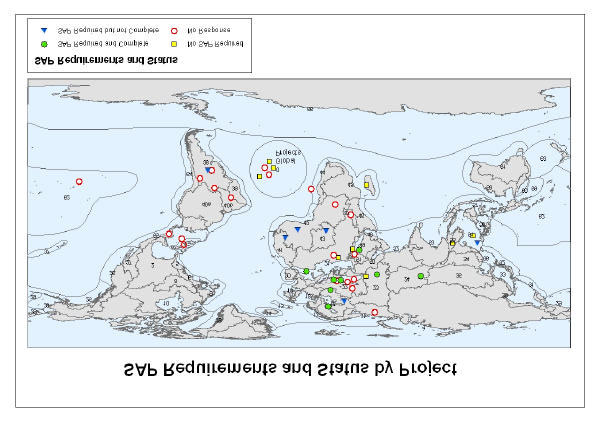

Project Steering Committee