OPS3: PROGRESSING TOWARD

ENVIRONMENTAL RESULTS

THIRD OVERALL PERFORMANCE STUDY OF THE GEF

June 2005

© 2005 Office of Monitoring and Evaluation of the Global Environment Facility

1818 H Street, NW

Washington, DC 20433

Internet : www.thegef.org

E-mail : gefteam@thegef.org

All rights reserved.

The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily

reflect the views of the GEF Council or the governments they represent.

The GEF Office of Monitoring and Evaluation does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work.

The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any

judgment on the part of the GEF concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such

boundaries.

Rights and Permissions

The material in this work is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without

permission may be a violation of applicable law. The GEF encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant

permission promptly.

Global Environment Facility

Director of the Office of Monitoring and Evaluation: Robert D. van den Berg

Task Manager, Office of Monitoring and Evaluation: Claudio R. Volonte

OPS3 Team: ICF Consulting and partners

1725 I Street, NW, Suite 1000

Washington, DC 20006

www.icfconsulting.com

A FREE PUBLICATION

OPS3: PROGRESSING TOWARD ENVIRONMENTAL RESULTS

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Foreword ............................................................................................................................................................................... vii

Preface..................................................................................................................................................................................... x

Third Overall Performance Study Teams ............................................................................................................................... xii

Acronyms and Abbreviations................................................................................................................................................ xiii

Section I: Introduction and Approach

1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................. 1

1.1 Purpose and Scope............................................................................................................................................. 1

1.2 GEF Instrument and Mandate......................................................................................................................... 1

1.2.1 Establishment of the GEF.................................................................................................................... 1

1.2.2 GEF Program Activities........................................................................................................................ 3

1.2.3 GEF Entities--Roles and Responsibilities......................................................................................... 4

1.3 Historical Context for OPS3 ............................................................................................................................ 5

1.4 Organization of the Report............................................................................................................................... 6

2. OPS3

Approach........................................................................................................................................................... 6

2.1 Developing Thematic Areas of Assessment .................................................................................................. 6

2.2 Evaluation Challenges and Strategies.............................................................................................................. 6

2.2.1 Results of GEF Activities...................................................................................................................... 6

2.2.2 Sustainability of Results at the Country Level and the GEF as a Catalytic Institution ............... 8

2.2.3 GEF Policies, Institutional Structure, and Partnerships, and GEF

Implementation Processes..................................................................................................................... 9

2.3 Elements of the OPS3 Approach .................................................................................................................. 10

2.3.1 Research Agenda................................................................................................................................... 10

2.3.2 Desk Study............................................................................................................................................. 10

2.3.3 Field Study: Participatory Stakeholder Consultations..................................................................... 10

2.3.4 Development of Evidence to Support Findings.............................................................................. 10

2.3.5 Organization of Findings..................................................................................................................... 11

Notes, Section I................................................................................................................................................................. 12

Section II: Focal Area Analysis

3. Focal Area Portfolio Analysis.................................................................................................................................. 13

3.1 Biodiversity (TORs 1A, 1B, and 1E)............................................................................................................. 14

3.1.1 Scientific and Historical Context: Biodiversity ................................................................................ 14

3.1.2 Biodiversity Portfolio Analysis ........................................................................................................... 16

3.1.3 Contributions of the GEF to Biodiversity Conservation............................................................... 19

3.1.4 Challenges and Strategic Tradeoffs.................................................................................................... 26

3.1.5 Recommendations ................................................................................................................................ 28

3.2 Climate Change (TORs 1A, 1B, and 1E)...................................................................................................... 29

3.2.1 Scientific and Historical Context: Climate Change ......................................................................... 29

3.2.2 Climate Change Portfolio Analysis .................................................................................................... 30

3.2.3 Results of the GEF in Climate Change............................................................................................. 33

3.2.4 Challenges and Strategic Tradeoffs.................................................................................................... 36

3.2.5 Recommendations ................................................................................................................................ 41

iii

OPS3: PROGRESSING TOWARD ENVIRONMENTAL RESULTS

3.3 International Waters (TORs 1A, 1B, and 1E) ............................................................................................. 42

3.3.1 Scientific and Historical Context: International Waters ................................................................. 42

3.3.2 International Waters Portfolio Analysis............................................................................................ 43

3.3.3 Contribution of the GEF to the Health of International Waters ................................................. 45

3.3.4 Challenges and Strategic Tradeoffs.................................................................................................... 51

3.3.5 Recommendations ................................................................................................................................ 53

3.4 Update to the 2000 "Study of Impacts of GEF Activities on Phase-Out of Ozone

Depleting Substances" (TORs 1A, 1B, and 1E).......................................................................................... 54

3.4.1 Scientific and Historical Context: Ozone Depletion ...................................................................... 54

3.4.2 Ozone Portfolio Analysis .................................................................................................................... 54

3.4.3 Contributions of the GEF to ODS Phaseout.................................................................................. 55

3.4.4 Update to 2000 Study of Impacts--Results..................................................................................... 57

3.4.5 Challenges and Strategic Tradeoffs.................................................................................................... 60

3.4.6 Recommendations ................................................................................................................................ 61

3.5 Land Degradation (TORs 1C and 1E).......................................................................................................... 61

3.5.1 Scientific and Historical Context: Land Degradation ..................................................................... 62

3.5.2 Land Degradation Portfolio Analysis ................................................................................................ 62

3.5.3 Current Evidence on Meeting Global Priorities.............................................................................. 63

3.5.4 Challenges and Strategic Tradeoffs.................................................................................................... 65

3.5.5 Recommendations ................................................................................................................................ 66

3.6 POPs (TORs 1C and 1E)................................................................................................................................ 67

3.6.1 Scientific and Historical Context: POPs ........................................................................................... 67

3.6.2 POPs Portfolio Analysis...................................................................................................................... 68

3.6.3 Current Evidence on Meeting Global Priorities.............................................................................. 68

3.6.4 Challenges and Strategic Tradeoffs.................................................................................................... 71

3.6.5 Recommendations ................................................................................................................................ 72

3.7 Responsiveness of the GEF to Conventions (TOR 4C) ........................................................................... 72

3.7.1 Biodiversity (CBD) ............................................................................................................................... 73

3.7.2 Climate Change (UNFCCC) ............................................................................................................... 77

3.7.3 Ozone Depletion (Montreal Protocol).............................................................................................. 80

Notes, Section II ............................................................................................................................................................... 81

Section III: Sustainability and the Catalytic Effects of the GEF

4. Achieving and Sustaining Global Environmental Benefits ................................................................................ 84

4.1 Achieving Global Environmental Benefits .................................................................................................. 84

4.2 Sustaining Global Environmental Benefits.................................................................................................. 85

4.3 Achieving versus Sustaining Global Environmental Benefits: Where to Draw the Line? ................... 85

4.4 Factors for Achieving and Sustaining Global Environmental Benefits

(TORs 1D, 2A, 2B, and 2C) ........................................................................................................................... 86

4.4.1 Historical Context................................................................................................................................. 86

4.4.2 Factors for Achieving and Sustaining Results.................................................................................. 87

4.4.3 Extent of Sustainability........................................................................................................................ 98

4.5 Challenges and Strategic Tradeoffs ............................................................................................................. 101

4.5.1 Ensuring the Will ................................................................................................................................ 101

4.5.2 Ensuring the Way ............................................................................................................................... 101

4.6 Recommendations.......................................................................................................................................... 102

iv

OPS3: PROGRESSING TOWARD ENVIRONMENTAL RESULTS

5. Cross-Cutting Factors Contributing to Global Environmental Benefits ....................................................... 103

5.1 The GEF as a Catalyst (TORs 3A and 3B)................................................................................................ 104

5.1.1 Historical Context............................................................................................................................... 105

5.1.2 Current Evidence................................................................................................................................ 107

5.1.3 Challenges and Strategic Tradeoffs.................................................................................................. 119

5.1.4 Recommendations .............................................................................................................................. 120

5.2 National Priorities of Recipient Countries (TOR 4E).............................................................................. 122

5.2.1 Historical Context............................................................................................................................... 122

5.2.2 Responsiveness to National Priorities ............................................................................................. 123

5.2.3 Challenges and Strategic Tradeoffs.................................................................................................. 124

5.2.4 Recommendations .............................................................................................................................. 125

5.3 Varying Capacities of SIDS, LDCs, and CEITs (TOR 4F)..................................................................... 126

5.3.1 Historical Context............................................................................................................................... 127

5.3.2 Responsiveness to Varying Capacities............................................................................................. 127

5.3.3 Challenges and Strategic Tradeoffs.................................................................................................. 130

5.3.4 Recommendations .............................................................................................................................. 131

Notes, Section III ........................................................................................................................................................... 132

Section IV: Effects of the GEF's Institutional Structure and Procedures on Results

The Institutional Form of the GEF............................................................................................................................. 134

Is the GEF's Institutional Form an Appropriate One for Meeting Its Mandate and Operations?................... 135

Measuring Institutional Effectiveness ......................................................................................................................... 136

The Evolutionary Nature of the GEF......................................................................................................................... 138

Structure of Section IV .................................................................................................................................................. 138

6. Effects of the GEF's Institutional Structure ...................................................................................................... 138

6.1 How Effectively Is the GEF Meeting Its Challenges? (TOR 4D) ......................................................... 138

6.1.1 Communication and Alignment of Goals....................................................................................... 139

6.1.2 Coordinating Partners on Multiple Levels and Managing Increasingly Complex

Interdependence.................................................................................................................................. 140

6.1.3 Maintaining an Inclusive Approach................................................................................................. 142

6.1.4 Structured Informality (Balance between Control and Empowerment).................................... 143

6.1.5 Overcoming Capacity Shortages ...................................................................................................... 144

6.1.6 Managing in a Permanently Evolving World .................................................................................145

6.1.7 Maintaining Effective Relations with External Stakeholders ...................................................... 146

6.1.8 Challenges and Strategic Tradeoffs.................................................................................................. 147

6.1.9 Recommendations .............................................................................................................................. 147

6.2 A Discussion of the GEF Entities: Evolving Roles and Responsibilities (TORs 4A and 4G) ......... 148

6.2.1 GEF Secretariat................................................................................................................................... 149

6.2.2 Implementing Agencies ..................................................................................................................... 152

6.2.3 Executing Agencies ............................................................................................................................ 156

6.2.4 Scientific and Technical Advisory Panel ......................................................................................... 158

6.2.5 Trustee.................................................................................................................................................. 159

6.2.6 Monitoring and Evaluation ............................................................................................................... 161

6.2.7 Nongovernmental Organizations..................................................................................................... 165

6.2.8 Participant Countries.......................................................................................................................... 166

6.3 Challenges and Strategic Tradeoffs ............................................................................................................. 166

6.4 Recommendations.......................................................................................................................................... 167

v

OPS3: PROGRESSING TOWARD ENVIRONMENTAL RESULTS

7. GEF

Procedures...................................................................................................................................................... 170

7.1 GEF Project Cycle (TOR 5A)...................................................................................................................... 170

7.1.1 Historical Context............................................................................................................................... 170

7.1.2 Current Evidence................................................................................................................................ 171

7.1.3 Challenges and Strategic Tradeoffs.................................................................................................. 174

7.1.4 Recommendations .............................................................................................................................. 175

7.2 Lessons Learned and the Use of Knowledge Gained (TOR 5B) ........................................................... 176

7.2.1 Lessons Learned and Knowledge Management ............................................................................ 176

7.2.2 Management and Information Systems (MIS) ............................................................................... 180

7.2.3 Recommendations .............................................................................................................................. 182

Notes, Section IV............................................................................................................................................................ 183

Section V: Main Findings and Recommendations

8. Main

Findings .......................................................................................................................................................... 185

8.1 Focal Area Results.......................................................................................................................................... 185

8.2 Strategic Programming for Results--Focal Area Level ........................................................................... 186

8.2.1 Improving Coherence of Strategic Guidance................................................................................. 186

8.2.2 Tracking Indicators............................................................................................................................. 187

8.3 Strategic Programming for Results--Country Level................................................................................ 187

8.4 Responsiveness to Conventions................................................................................................................... 189

8.5 Information Management within the GEF Network............................................................................... 190

8.6 Network Responsibilities and Administration........................................................................................... 191

8.6.1 Network Administrative Office........................................................................................................ 191

8.6.2 Competition versus Collaboration ................................................................................................... 191

8.6.3 Scientific and Technical Advisory Panel ......................................................................................... 192

8.6.4 Monitoring and Evaluation ............................................................................................................... 192

8.6.5 Private Sector....................................................................................................................................... 193

8.7 Small Grants Programme.............................................................................................................................. 193

9. Major

Recommendations ....................................................................................................................................... 194

9.1 Programming for Results--Focal Area Level............................................................................................ 195

9.2 Programming for Results--Country Level ................................................................................................ 196

9.3 Responsiveness to Conventions................................................................................................................... 197

9.4 Information Management within the GEF Network............................................................................... 197

9.5 Network Responsibilities and Administration........................................................................................... 197

9.6 Small Grants Programme.............................................................................................................................. 198

Notes, Section V ............................................................................................................................................................. 199

Annex A: Clarification of OPS3 Terms of Reference.............................................................................................. 200

Annex B: High-Level Advisory Panel......................................................................................................................... 203

Annex C: List of Interviews and Country Trips ....................................................................................................... 205

Annex D: Comparison to Similar Institutions (TOR 4B)........................................................................................ 222

Annex E: Progress on Recommendations from the Third Replenishment (TOR 5C) ...................................... 226

Annex F: Bibliography .................................................................................................................................................. 237

vi

OPS3: PROGRESSING TOWARD ENVIRONMENTAL RESULTS

FOREWORD

The Global Environment Facility is replenished by donors every four years. Ideally, any replenishment should

be based on the achievements so far and the problems that need to be addressed in the coming years. The

fourth replenishment, which will be negotiated and agreed in the second half of 2005, will be informed on the

achievements of the GEF through the present "Overall Performance Study," which is the third of its kind. It

provides an overview of the results in dealing with global environmental problems and it also looks at how

the GEF functions as a network and partnership of institutions and organizations. Given the fact that the

GEF is the main financial mechanism for several global environmental conventions, the report amounts to a

review on what governments are doing to improve the global environment. It also provides an indication of

the status of some of the most important global environmental issues.

Any impression that the GEF on its own would be able to solve global environmental problems needs to be

qualified immediately. The world community currently spends approximately US $ 0.5 billion a year on

solving these issues through the GEF. The problems are immense. Any solution would need the strong

involvement of many other actors. The amount of Green House Gases emissions continues to increase.

Extinction of animal and plant species continues. Pollution and waste treatment pose enormous challenges.

Access to safe water is not ensured and even endangered for many people. Land degradation is a huge

problem in many countries across the world. The only global environmental problem that is almost solved is

that of the elimination of ozone depleting substances. For all of these problems, the GEF contribution needs

to be seen in its proper perspective as a catalyst or innovator rather than as the direct purveyor of

international public goods.

My personal assessment of this study is that it provides a solid basis for discussion and decisions on the

fourth replenishment of the GEF. The questions of the Terms of Reference of the study have been

addressed. It provides an authoritative overview of the current state of knowledge in the GEF about its

results. Furthermore, it gives a challenging picture of the GEF as a network of organizations and institutions.

The report is consistent with the methodology presented in Inception and Interim Reports. The study draws

on data gathering and analysis based on literature review, evaluative evidence in the GEF (mainly from

studies of the GEF Office of Monitoring and Evaluation) and extensive stakeholder consultations and

country visits.

The current state of knowledge about results in the GEF is well presented, as well as shortcomings

concerning these results. Furthermore, the strategic choices are identified that the GEF is facing in reaching

(and maintaining) these results. The difficulties of sustaining results is highlighted and the catalytic role of the

GEF receives due attention. Last but not least the study contains many recommendations and suggestions for

increasing the results orientation of the GEF in the fourth replenishment period.

It should be noted that OPS3 did not do an independent empirical assessment of the environmental results

that were achieved by the GEF. This was not possible given the time limitations of the study. To explain why

this is the case, let me turn back to the origin of OPS3. The GEF Council attached great importance to the

independence of the OPS3 team from GEF management, and devoted extra time and energy to ensure that

this would be the case. In the first half of 2004, when preparations for the Third Overall Performance Study

started, the monitoring and evaluation unit of the GEF Secretariat was not yet fully independent. As a result,

Council decided to take the final drafting of the terms of reference for the study in its own hands. This took

longer than initially expected, which meant that the tendering process for the study started relatively late in

June 2004. The study started in September 2004, which meant that the actual time available was reduced

significantly, since it still had to be finalized in April 2005 in order to feed into the replenishment process.

This meant that given the scope and range of the questions in the terms of reference, no empirical data

gathering on environmental results was possible.

vii

OPS3: PROGRESSING TOWARD ENVIRONMENTAL RESULTS

The tendering process was handled by the Operations Evaluation Department of the World Bank in July and

August of 2004 in a timely and professional manner. The tender was won by ICF Consulting and its

international partners. In August and early September 2004 contract negotiations took place. Furthermore, in

early September I started in my position as Director of Monitoring and Evaluation. My arrival meant that the

monitoring and evaluation unit of the GEF Secretariat changed into the independent GEF Office of

Monitoring and Evaluation. As required by the Terms of Reference of OPS3, as Director of Monitoring and

Evaluation I provided oversight of the process, ensuring that the terms of reference were being followed.

Furthermore, a High Level Advisory Panel was established as part of the technical backstopping, reporting

directly to me and providing written comments on all deliverables.

The GEF Council in its session in November 2004 requested me to work with the study team to ensure

consistency and high quality in the field analyses to be undertaken by the team. To this end, further

discussions were held with the study team on the composition of field teams and the preparation of field

visits. I participated fully in one field visit and regional meeting to witness the team in operation. This led to a

satisfactory conclusion on the preparedness and openness of the team concerned.

The primary way in which the time limitations were addressed by the study team was through fielding a large

team of mostly senior experts. This approach is sound in itself, but led to some unanticipated difficulties

when it turned out that no proper sequencing of efforts could take place. Ideally, the desk review of

evaluative evidence would have finished before the field visits and interactions with stakeholders took place.

A more systematic agenda for checking the reality behind literature and evaluative findings in field visits could

have been developed if there had been sufficient time. In reality, the desk review and the field visits and

consultations had to run in parallel. It seems to me that these difficulties raised concerns on first the quality of

the field work and second on the (lack of) emergence of findings in early stages of the analysis. These

concerns were raised by several Council members in November 2004 (on the quality of field visits) and in

February 2005 (on the lack of emerging findings on results of the GEF) and by the High Level Advisory

Panel at several occasions.

The field visits were logistically difficult to arrange for. Often dates and agendas had to be changed,

sometimes at the last moment. In November, the study team promised to involve itself at an adequate level

(senior and mid-level participation) and that counterparts from developing countries would participate. This

was realized for most, but not all, of the workshops and field visits. The workload was increased when some

workshops were added on the request of the Council (notably Cuba and Fiji), as well as an informal exchange

with Council members in Paris in February 2005. The regional workshops were generally well attended.

Although these constraints and added milestones and meetings limited the time available even further the

process has been managed by the team in a truly exemplary manner. Many evaluation managers would have

buckled under the pressure and have asked for a delayed delivery of the final product. The study team, under

the leadership of Mark Wagner, has not done this and has excelled in keeping the whole process within the

time limits set for it. Given the scale and the scope, this is to be applauded.

During the study, the team did take the advice of the High Level Panel on board in various ways.

Furthermore, the interactions of the team with the GEF Council and with GEF Council members have

helped to focus the study on the issues that are important for the replenishment process.

In many respects the Third Overall Performance Study was a global effort and therefore there are many

people from around the globe that should be acknowledged in making it possible. The ICF Consulting OPS3

team, led by Mark Wagner, and the GEF Office of Monitoring and Evaluation OPS3 support team, led by

Claudio Volonte, should be recognized first of all. Both of these teams ensured that the final report was

technically sound and prepared with high professional standards. The entire GEF Office of Monitoring and

Evaluation was involved in the exercise and provided essential inputs through the preparation of studies of

the three main GEF focal areas which constituted the basis for OPS3's assessments on results. The High

viii

OPS3: PROGRESSING TOWARD ENVIRONMENTAL RESULTS

Level Advisory Panel, chaired by Nancy McPherson, provided critical comments that pushed the study team

to improve the quality of the analysis and final report.

Council members also should be acknowledged for their active participation from the preparation and

approval of the Terms of Reference to extensive comments on several of the products produced by the study

team. Staff of the GEF Secretariat, GEF Implementing Agencies and global convention Secretariats as well

as many of the STAP members provided many valuable hours of their time throughout the process. I would

also like to acknowledge the very active and open contribution made by GEF Focal Points and

representatives of the many NGOs from around the globe that participated in the extensive consultation

process conducted by the study team, probably the most extensive one so far in the history of the GEF.

Finally, but not least, I would like to thank the national and local governments as well as the GEF project

teams that opened their doors to share their experiences during the visits conducted by the OPS3 teams.

Although it is impossible to accurately portrait the extensive tapestry of GEF activities in a report like this

one the projects that were visited helped the study team to recognize the richness and uniqueness of GEF

experience.

Rob D. van den Berg

Director of Monitoring and Evaluation

ix

OPS3: PROGRESSING TOWARD ENVIRONMENTAL RESULTS

PREFACE

The team for the Third Overall Performance Study of the GEF (OPS3), which took place between

September 2004 and June 2005, was charged with evaluating the 1) results of GEF activities, 2) sustainability

of results at the country level, 3) GEF as a catalytic institution, 4) GEF policies, institutional structure and

partnerships, and 5) GEF implementation processes. From the onset, our team viewed the evaluation as an

opportunity to evaluate the progress of GEF activities, and also to set the stage for future evaluations.

This perspective was essential to avoid the development of a static evaluation (a "snap shot") for a dynamic

and evolving institution such as the GEF. As such, OPS3 attempted to place all analyses, findings, and

recommendations in the context of the future. In particular, we asked the question, "What information will

OPS4 and future evaluations need to conduct analysis, and how will having this information ensure the

success of the GEF?"

One of the key challenges for OPS3 was collecting and assessing results. While results are critical to project

success and aggregated results are essential to the evaluation process, this information is not always available

in the GEF system. This difficulty is attributable to a range of factors, but most importantly to limited

baseline data, inconsistency on what will be measured and how, a vast array of projects with differing goals,

and nascent centralized data collection systems. All of these issues are overlaid by very high expectations for

achieving global environmental benefits.

While there clearly has been progress in the GEF system and while all stakeholders are more informed, and

processes are better off, than they were 4 years ago, when OPS2 took place, further attention is needed in

certain core areas. In particular, if the GEF is to be robust, there must be continued dialogue on baseline

setting and, specifically, how to define baselines in the face of a moving target, for example, as additional

species are catalogued or abandoned stockpiles of POPs are uncovered.

Additionally, measuring results relative to these often shifting baselines can be difficult, and while

improvements are being made in data collection, verification, and analysis, it is critical that simple procedures

for gauging results be agreed upon. Simple measures of results will be more practical for tracking progress

than the use of complex, resource intensive measurement schemes. To house this ever growing universe of

data, transparent, centralized data systems, accessible to all parties will be necessary to enable future

evaluations.

Collaboration is critical to success. Improving outcomes and results will depend on furthering the emerging

acknowledgement of the GEF as a network collaboration between the parts of various institutions that

focus on the GEF. By realizing the advantages of this network arrangement, the effectiveness of the GEF can

be improved, but it will take compromise and a willingness to work towards the utility of all to sacrifice self

interest for the overall good of the system.

During the field study portion of our evaluation, the OPS3 team spoke to more than 600 GEF stakeholders

from country governments, Implementing and Executing Agencies, NGOs, GEF project managers, and

representatives from the private sector and civil society, in addition to representatives of the GEF Council,

the GEF Secretariat, and the Scientific and Technical Advisory Panel. The leadership of the Office of

Monitoring and Evaluation, especially the newly appointed director Robert van den Berg and his staff,

notably Claudio Volonte, was integral to the success of this study and made our work more targeted than

would have otherwise been possible. Their help in establishing a High Level Advisory Panel and in

orchestrating panel interactions also was instrumental. Further, the contributions of the High Level Advisory

Panel itself improved the quality of the evaluation.

x

OPS3: PROGRESSING TOWARD ENVIRONMENTAL RESULTS

Across all of the groups with whom we interacted, there was a great commitment to the GEF and its

mandate, a great enthusiasm for the work being undertaken, and eagerness to demonstrate success. We hope

that the recommendations put forward by OPS3 will be helpful in moving the GEF's agenda forward in

achieving global environmental benefits in a sustainable way.

Finally, I would like to personally acknowledge my colleagues at ICF Consulting and our regional partners for

their creativity, thoughtfulness, and dedication to this evaluation.

Mark C. Wagner

OPS3 Team Leader

and Senior Vice President

ICF Consulting

xi

OPS3: PROGRESSING TOWARD ENVIRONMENTAL RESULTS

THIRD OVERALL PERFORMANCE STUDY TEAMS

Core OPS3 Team

ICF Consulting

Partners

Mark Wagner, Team Leader

ICF-EKO (Russian Federation)

Christopher Durney

Olga Varlamova

Will Gibson

Abyd Karmali

Walter Palmer

Polly Quick

OPS3 Support Team

ICF Consulting

Partners

Paula Aczel

Africon (South Africa)

Joana Chiavari

Joseph Asamoah

Chiara D'Amore

Thomas van Viegen

Craig Ebert

Centre for Environmental Education (India)

David Hathaway

R. Gopichandran

Alan Knight

ICF-EKO (Russian Federation)

Johanna Kollar

Svetlana Golubeva

Daniel Lieberman

Mexican Institute of Water Technology (Mexico)

Pamela Mathis

Alberto Guitron

Jeremy Scharfenberg

Marian Martin Van Pelt

Jessica Warren

GEF Monitoring and Evaluation Office OPS3 Team

Robert van den Berg, Director

Claudio Volonte, Senior Monitoring and Evaluation Specialist

Aaron Zazueta, Senior Monitoring and Evaluation Specialist

Siv Tokle, Senior Monitoring and evaluation Specialist

Juan Jose Portillo, Project Officer

Joshua Brann, Junior Professional Associate

OPS3 High Level Advisory Panel

Professor Zhaoying Chen, Director, China's National Centre for Science and Technology Evaluation

Dr. Lawrence Haddad, Director, Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex, United

Kingdom

Dr. Alcira Kreimer, independent consultant

Dr. Uma Lele, Sr. Adviser, Operations Evaluation Department, World Bank

Ms. Nancy MacPherson, Senior Adviser, Performance Assessment, IUCN The World Conservation

Union

xii

OPS3: PROGRESSING TOWARD ENVIRONMENTAL RESULTS

ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS

ABS

Access and benefit sharing

FUNBIO

Brazilian Biodiversity Fund

ACTUAR

Asociación Costarricense de

GEF

Global Environment Facility

Turismo Rural Comunitario

GEF-1

Restructured GEF, fiscal 1995/98

ADB Asian

Development

Bank

GEF-2 Restructured

GEF,

fiscal

AfDB

African Development Bank

1999/2002

ARPA Amazon

Region

Protected Areas

GEF-3

Restructured GEF, fiscal 2004/06

Program

GEF-4

Restructured GEF, fiscal 2007/10

ASP

African Stockpile Program

GEFM&E

GEF Monitoring and Evaluation

BPS

Biodiversity Program Study

Unit

CAS

Country Assistance Strategy

GEFSEC GEF

Secretariat

CBD

Convention on Biological

GHG Greenhouse

gas

Diversity

GTZ

German Agency for Technical

CCPS

Climate Change Program Study

Cooperation (Deutsche

CCS

Carbon capture and sequestration

Gesellschaft für Technische

Zusammenarbeit)

CDM

Clean Development Mechanism

GWP Global-warming

potential

CDW

Country Dialogue Workshop

HCFC Hydrochlorofluorocarbon

CEITs

Countries with economies in

transition

HFC Hydrofluorocarbon

CEO

Corporate Executive Officer

HLP

OPS3 High-Level Advisory Panel

CFC Chlorofluorocarbon

IA Implementing

agency

CO

IADB Inter-American

Development

2 Carbon

dioxide

Bank

COP

Conference of the Parties

ICR

Implementation completion report

CPAP

Country Programme Action Plan

[UNDP]

IFAD

International Fund for Agricultural

Development

DDT Dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane

[a POP]

IGO Intergovernmental

organization

EA Executing

agency

IPCC

Intergovernmental Panel on

Climate Change

EBRD

European Bank for

Reconstruction and Development

IPO Indigenous

peoples'

organization

EU European

Union

IUCN

World Conservation Union

(formerly International Union for

FAO

Food and Agriculture

the Conservation of Nature)

Organization of the United

Nations

IW:LEARN The International Waters Learning

Exchange and Resource Network

FCCC

Framework Convention on

Climate Change

IWPS International

Waters

Program

Study

FSP Full-size

project

IWTF

GEF International Waters Task

FSU

Former Soviet Union

Force

xiii

OPS3: PROGRESSING TOWARD ENVIRONMENTAL RESULTS

KM Knowledge

management

OECD

Organisation for Economic Co-

LDCs

Least developed countries

operation and Development

LME Large

marine

ecosystem

OFP Operational

focal

point

M&E

Monitoring and evaluation

OME

GEF Office of Monitoring and

Evaluation (after 2004)

MAR Management

action

record

OP Operational

Program

MBC Meso-American

Biological

Corridor

OP1

Arid and Semi-Arid Zone

Ecosystems

METT Management

Effectiveness

Tracking Tool

OP2

Coastal, Marine, and Freshwater

Ecosystems

MIS Management

and

information

systems

OP3 Forest

Ecosystems

MLF

Multilateral Fund of the Montreal

OP4 Mountain

Ecosystems

Protocol

OP5

Removal of Barriers to Energy

MMTCO

Efficiency and Energy

2Eq Million metric tons of carbon

dioxide equivalent

Conservation

MOP

Meeting of the Parties to the

OP6

Promoting the Adoption of

Montreal Protocol

Renewable Energy by Removing

Barriers and Reducing

MOU

Memorandum of understanding

Implementation Costs

MSP Medium-size

project

OP7

Reducing the Long-Term Costs of

MT Metric

tons

Low Greenhouse Gas Emitting

Energy Technologies

NAI Non-Annex

I

OP8 Waterbody-Based

Operational

NAP

National Action Program (to

Program

combat desertification)

OP9

Integrated Land and Water

NAPA

National Adaptation Programme

Multiple Focal Area Operational

of Action

Program

NBF

National Biosafety Framework

OP10 Contaminant-Based

Operational

NBSAPs

National Biodiversity Strategies

Program

and Action Plans

OP11 Promoting

Environmentally

NCSA

National Capacity Self-Assessment

Sustainable Transport

NDI

National Dialogue Initiative

OP12 Integrated

Ecosystem

Management

NEPAD

New Partnership for Africa's

Development

OP13

Conservation and Sustainable Use

of Biological Diversity Important

NGO

Nongovernmental organization

to Agriculture

NIPs

National Implementation Plans

OP14

Persistent Organic Pollutants

(under POPs)

OP15

Sustainable Land Management

ODP Ozone-depleting

potential

OPS

Overall Performance Studies

ODS Ozone-depleting

substance

PCBs

polychlorinated biphenyls (a POP)

OED Operations

Evaluation

Department [World Bank]

PDF

Project preparation and

development facility

xiv

OPS3: PROGRESSING TOWARD ENVIRONMENTAL RESULTS

PEMSEA

Partnership in Environmental

UNEP

United Nations Environment

Management for the Seas of East

Programme

Asia

UNFCCC

United Nations Framework

PIR

Project Implementation Review

Convention on Climate Change

PMIS

GEF Project Tracking and

UNIDO

United Nations Industrial

Management Information System

Development Organization

POP Persistent

organic

pollutant

WCMC

World Conservation Monitoring

POV

Point of view

Centre

PPR

Project Performance Report

WCST

Wildlife Conservation Society of

Tanzania

PROBIO

Brazilian National Biodiversity

Project

WSSD

World Summit for Sustainable

Development

PTMS

Project Tracking and Mapping

System

PV Photovoltaic

QAG

Quality Assurance Group

QEA

Quality at Entry Assessment

QSA

Quality Supervision Assessment

RAF

Resource allocation framework

SAP

Strategic Action Program

SCCF

Special Climate Change Fund

SGP Small

Grants

Programme

SIDS

Small island developing states

SLM

Sustainable land management

STAP

Scientific and Technical Advisory

Panel

STRMs

Short-term response measures

TDA Transboundary

Diagnostic

Analysis

TE Terminal

evaluation

TEAP

Technology and Economic

Assessment Panel

TER

Terminal evaluation review

TOR

Term of reference

UN United

Nations

UNAIDs

Joint United Nations Programme

on HIV/AIDS

UNCCD

United Nations Convention to

Combat Desertification

UNDP

United Nations Development

Programme

xv

OPS3: PROGRESSING TOWARD ENVIRONMENTAL RESULTS

SECTION I: INTRODUCTION AND APPROACH

1. Introduction

1.1 Purpose and Scope

The purpose of the Third Overall Performance Study (OPS3), commissioned by the Global Environment

Facility (GEF) Council, is "to assess the extent to which GEF has achieved, or is on its way towards

achieving its main objectives, as laid down in the GEF Instrument and subsequent decisions by the GEF

Council and the Assembly, including key documents such as the Operational Strategy and the Policy

Recommendations agreed as part of the Third Replenishment of the GEF Trust Fund." (GEF/C.23/4)

OPS3 follows two previous studies that were similar in nature to that of OPS3; however, as the GEF and its

portfolios have matured, so the purpose of an overall performance study has evolved. OPS3 is part of a

larger, longitudinal study that will build on the concepts and recommendations of the previous studies and

look forward to improvements in GEF operations to set the stage for OPS4. The OPS3 team also recognizes

that this study is taking place at a critical time and will provide input that is relevant to the Fourth

Replenishment of the GEF Trust Fund, which will be taking place shortly after the publication of the OPS3

study. A primary goal of OPS3 is to provide relevant, timely, and actionable recommendations for each of the

Terms of Reference (TOR) areas to support the replenishment process and associated programming.

The scope of OPS3 is defined by the "Terms of Reference for the Third Overall Performance Study of the

GEF" (GEF/C.23/4. 2004) approved by the GEF Council on May 21, 2004, and it covers five main themes:

· Results of GEF activities

· Sustainability of results at the country level

· GEF as a catalytic institution

· GEF policies, institutional structure, and partnerships

· GEF implementation processes.

1.2 GEF Instrument and Mandate

As the only existing multiconvention financing mechanism, the GEF serves as such for the Convention on

Biological Diversity (CBD), United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC),

Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs), and the United Nations Convention to

Combat Desertification (UNCCD). The GEF also supports the Montreal Protocol and activities related to

international waters. Drawing on the financial contributions of developed-country GEF participants, the

GEF provides new and additional funding for the incremental costs of projects in six focal areas:

Biodiversity, Climate Change, POPs, Land Degradation, International Waters, and Ozone Layer Depletion.

1.2.1 Establishment of the GEF

In 1991, the GEF was established in the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (the World

Bank) as a pilot facility to assist in the protection of the global environment by providing new and additional

funding in the areas of climate change, biodiversity, ozone layer depletion, and international waters.

Participants in this phase agreed to a collaborative management arrangement among the three Implementing

1

OPS3: PROGRESSING TOWARD ENVIRONMENTAL RESULTS

Agencies (IAs)--the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the United Nations Environment

Programme (UNEP), and the World Bank--with the understanding that the three-year program would be

exploratory.

In 1994, after several years of negotiation, the GEF was restructured under the guidance of the "Instrument

for Establishment of the Restructured Global Environment Facility" (GEF 1994a) (hereafter referred to as

the Instrument) and became a permanent mechanism to promote international cooperation and fund projects

to achieve global environmental benefits. The network design of the GEF emerged from these restructuring

negotiations, during which it was determined that a new, stand-alone institution would not be created.

The Instrument was accepted by representatives of 73 countries and formally adopted by the three IAs. The

GEF was mandated to "...operate, on the basis of collaboration and partnership among the IAs, as a

mechanism for international cooperation for the purpose of providing new and additional grant and

concessional funding to meet the agreed incremental costs of measures to achieve agreed global

environmental benefits" (GEF 1994a) in the stated focal areas.

In 1996, the GEF put forth its Operational Strategy, based on the objectives of the UNFCCC and CBD, the

Instrument, and Council decisions. The Operational Strategy was developed through GEF Secretariat

(GEFSEC) consultations with the IAs, the GEF Scientific and Technical Advisory Panel (STAP),

Conferences of the Parties (COPs) for the two conventions, and regional stakeholders. The GEF Council

approved the strategy at its October 1995 meeting. Exhibit 1 presents the 10 operational principles to which

the GEF pledged to adhere in carrying out its mission.

The third operational principle of the GEF states that the GEF will provide funding to meet the agreed

incremental costs of activities to achieve global environmental benefits. As outlined in the 1996 Council

document "Incremental Costs" (GEF/C.7/Inf.5), to calculate incremental costs, "[t]he cost of GEF eligible

activity should be compared to that of the activity it replaces or makes redundant. The difference between the

two costs--the expenditure on the GEF supported activity and the cost saving on the replaced or redundant

activity--is the incremental cost. It is a measure of the future economic burden on the country that would

result from its choosing the GEF supported activity in preference to one that would have been sufficient in

the national interest."

Exhibit 1. Operational Principles of the GEF

1) For purposes of the financial mechanisms for the implementation of the Convention on Biological Diversity

and the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, the GEF will function under the guidance

of, and be accountable to, the Conference of the Parties (COPs). For purposes of financing activities in the focal

area of ozone layer depletion, GEF operational policies will be consistent with those of the Montreal Protocol

on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer and its amendments.

2) The GEF will provide new, and additional, grant and concessional funding to meet the agreed incremental costs

of measures to achieve agreed global environmental benefits.

3) The GEF will ensure the cost-effectiveness of its activities to maximize global environmental benefits.

4) The GEF will fund projects that are country-driven and based on national priorities designed to support

sustainable development, as identified within the context of national programs.

5) The GEF will maintain sufficient flexibility to respond to changing circumstances, including evolving guidance

of the Conference of the Parties and experience gained from monitoring and evaluation activities.

6) GEF projects will provide for full disclosure of all nonconfidential information.

7) GEF projects will provide for consultation with, and participation as appropriate of, the beneficiaries and

affected groups of people.

8) GEF projects will conform to the eligibility requirements set forth in paragraph 9 of the GEF Instrument.

9) In seeking to maximize global environmental benefits, the GEF will emphasize its catalytic role and leverage

additional financing from other sources.

10) The GEF will ensure that its programs and projects are monitored and evaluated on a regular basis.

2

OPS3: PROGRESSING TOWARD ENVIRONMENTAL RESULTS

To provide the needed funding to meet these incremental costs, contributing participants pledge resources

every four years. The First Replenishment of the GEF was undertaken in 1994, and subsequent

replenishments were carried out in 1998 and 2002. The Fourth Replenishment of the GEF is scheduled for

2006, and input from OPS3 will contribute to the negotiations of this replenishment.

1.2.2 GEF Program Activities

As described, the GEF operates in six focal areas that align with the objectives of their respective

conventions. In addition to the Biodiversity, Climate Change, Ozone Layer Depletion, and International

Waters focal areas, in 2002, the Second GEF Assembly established two new focal areas: Land Degradation

(primarily desertification and deforestation) and POPs, and the Instrument was amended accordingly.

Projects proposed for funding under the GEF must be consistent with the Instrument and the GEF

Operational Strategy. In particular, in funding activities, the GEF aims to emphasize its catalytic role and to

leverage additional financing from other sources. IAs also aim to avoid transfer of negative environmental

impacts between focal areas and to take advantage of synergies between focal areas.

Once funding eligibility is confirmed, projects are generally classified in one of three inter-related ways:

enabling activities, short-term response measures (STRMs), or Operational Programs (OPs). Additionally,

since 1997, limited amounts of GEF funding have also been occasionally granted for goal-oriented research

that supports the GEF operational strategy.1

· Enabling activities "are a means of fulfilling essential communication requirements to a Convention, provide

a basic and essential level of information to enable policy and strategic decisions to be made, or assist

planning that identifies priority activities within a country" (GEF Operational Strategy 1996).

· Short-term response measures are activities that are considered sufficiently important for funding, even though

they may not be strictly related to an OP or enabling activity. STRMs are expected to provide short-term

benefits at a relatively low cost.

· OPs represent "a conceptual and planning framework for the design, implementation, and coordination of

a set of projects to achieve a global environmental objective in a particular focal area" (GEF Operational

Strategy 1996).

Initially, OPs were developed for the Biodiversity and Climate Change focal areas conforming to the program

priorities approved by the COPs to those conventions, and for the International Waters focal area based on

the priorities determined by the Council. It was decided that the Ozone Layer Depletion focal area would not

have an OP, but that activities in that focal area would be focused on STRMs and enabling activities. OPs

have since been developed for the Land Degradation and POPs focal areas.

In addition to enabling activities, STRMs, and projects approved under the OPs, projects may also be

submitted under the Small Grants Programme (SGP). Established in 1992 to grant funding for community-

based initiatives, the SGP currently provides up to US$50,000 per project in the Climate Change, Biodiversity,

International Waters, Land Degradation, and POPs focal areas. The SGP incorporates a separate, streamlined

project cycle that is conducted at the national level.

To further direct GEF resources in a way that catalyzes action to maximize global environmental benefits, a

strategic planning framework was introduced in GEF's fiscal 2004/06 Business Plan. As part of this

framework, Strategic Priorities were identified in each of the six focal areas. These Strategic Priorities are

"consistent with the OPs, guidance from the Conventions, and country priorities...and...reflect the major

themes or approaches under which resources are programmed within each of the focal areas"

(GEF/C.24/9/Rev.1).

3

OPS3: PROGRESSING TOWARD ENVIRONMENTAL RESULTS

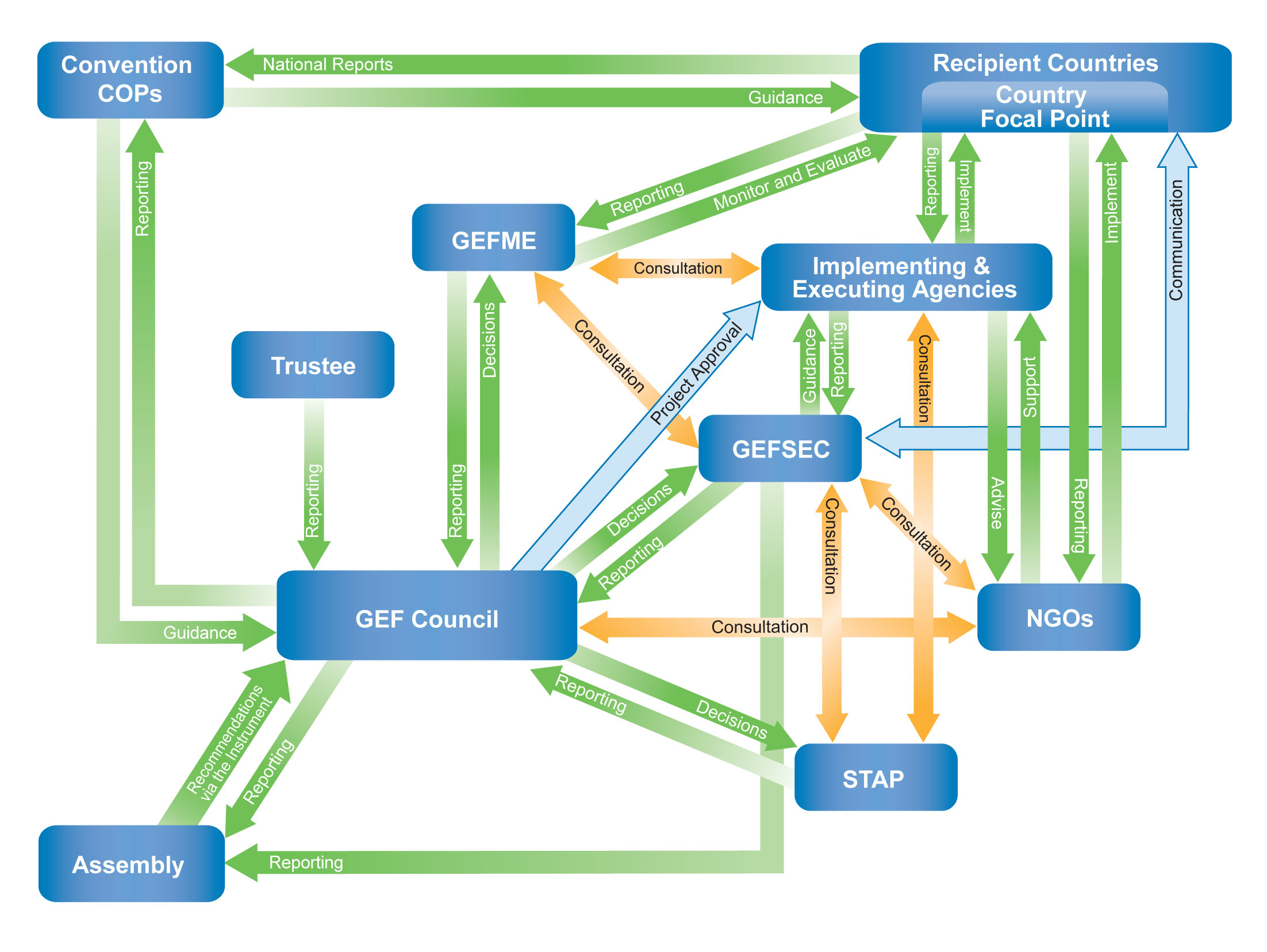

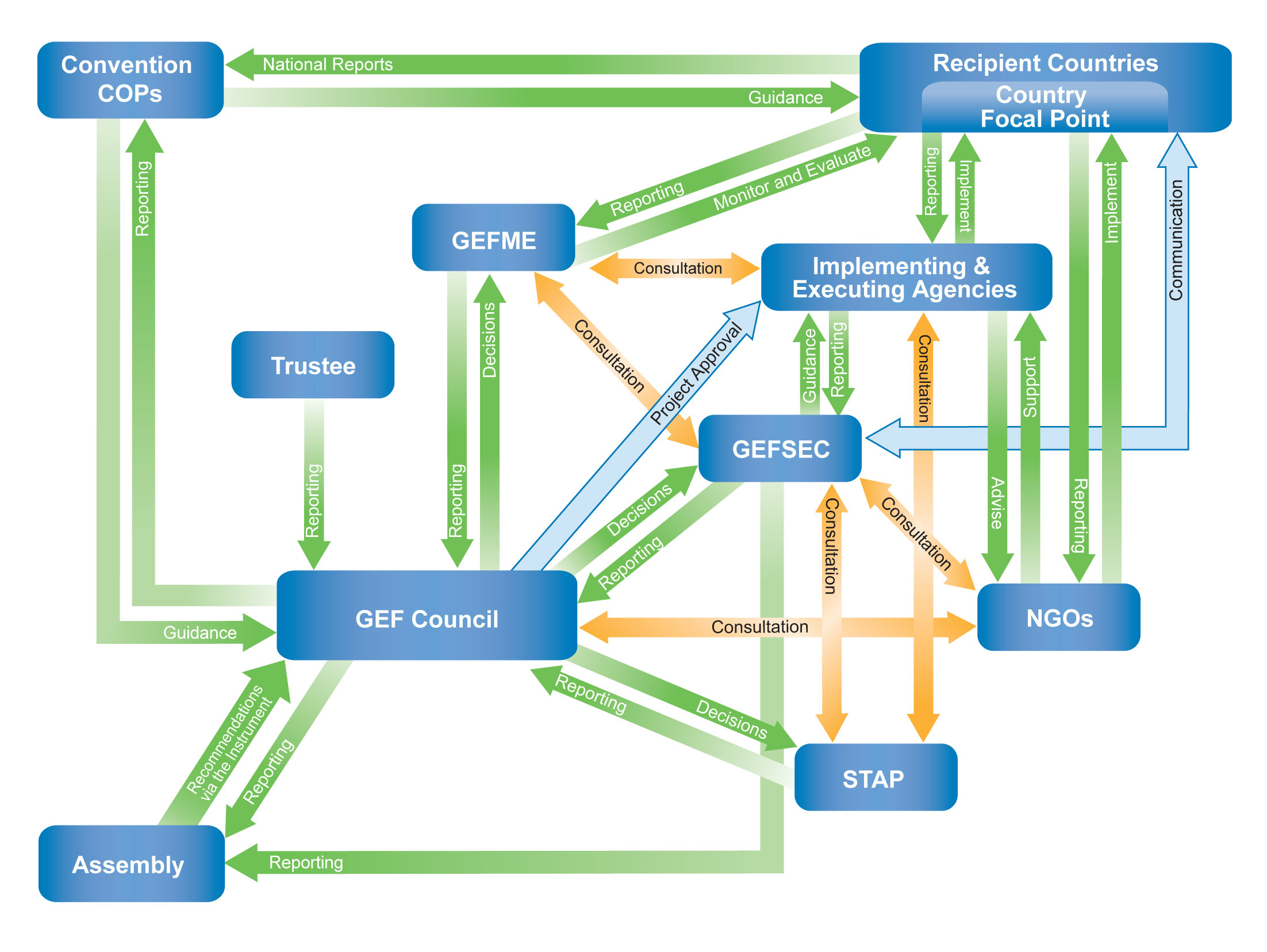

1.2.3 GEF Entities--Roles and Responsibilities

Based on the Instrument, the following GEF entities were charged with these mandates:

· Assembly, consisting of representatives of all participants, meets once every three years to "(a) review the

general policies of the Facility; (b) review and evaluate the operation of the Facility on the basis of reports

submitted by the Council; (c) keep under review the membership of the Facility; and (d) consider, for

approval by consensus, amendments to the present Instrument on the basis of recommendations by the

Council."

· Council, made up of 32 members that represent regional constituency groupings, is responsible for

developing, adopting, and evaluating the operational policies and OPs for GEF-financed activities in

accordance with the Instrument and guidance from the Assembly. The Council acts in accordance with

program priorities and eligibility criteria as decided by the COPs for the conventions. Among other

responsibilities, the Council also reviews and approves work programs and provides guidance to the

GEFSEC, IAs, the Office of Monitoring and Evaluation, the Trustee, STAP, and other bodies. The

Council meets twice each year.

· GEFSEC, headed by the Corporate Executive Officer (CEO)Chairperson of the GEF, supports and

reports to the Assembly and Council. To assist the Council, the GEFSEC (a) implements the decisions of

the Assembly and the Council and, in consultation with the IAs, ensures the implementation of the

operational policies adopted by the Council; (b) coordinates the development and oversees the

implementation of the activities in the work program; and (c) coordinates with the secretariats of the

conventions for which the GEF is a financial mechanism and other bodies.

· IAs, which include the UNDP, UNEP, and World Bank, develop and implement GEF activities within

each of their respective technical competences.

· STAP serves a scientific and technical advisory role for the GEF. For example, members of the STAP

expert roster review and advise on individual projects.

· Trustee of the Fund is the World Bank, which is responsible for the financial management of the Fund,

including investment of assets, disbursement of funds to IAs and Executing Agencies (EAs), and

monitoring and reporting on the investment and use of the Fund's resources.

In addition to these entities that received specific mandates in the Instrument, the following entities are

important partners in the GEF network and have had evolving roles and responsibilities over the lifetime of

the GEF:

· Monitoring and evaluation (M&E): In October 1996, the GEF Council approved a budget and work program

for an M&E function. The Third Replenishment of the GEF Trust Fund recommended in 2002 that the

M&E unit (GEFM&E) become an independent entity. The TOR for an independent M&E function were

approved by the Council in July 2003, and the unit was granted full independence and renamed the Office

of Monitoring and Evaluation (OME) in 2004.

· EAs: In the Instrument, IAs were allowed to cooperate with EAs to prepare and implement GEF

activities. In 1999, the GEF Council approved a policy to expand the number of international

organizations that can directly access funding from the GEF Trust Fund through the GEFSEC to prepare

and implement GEF-financed activities. This policy of expanded opportunities for EAs was eventually

extended to the Asian Development Bank (ADB), African Development Bank (AfDB), European Bank

for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), Inter-American Development Bank (IADB), Food and

Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), United Nations Industrial Development

Organization (UNIDO), and International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD).

4

OPS3: PROGRESSING TOWARD ENVIRONMENTAL RESULTS

· Nongovernmental organizations (NGOs): In the Instrument, IAs were permitted to cooperate with NGOs to

promote the purposes of the GEF and to prepare and implement GEF activities. NGOs may also

participate in the semi-annual GEF-NGO consultations and the NGO network, the representative of

which can make interventions at GEF Council meetings. Additionally, NGOs can prepare and execute

medium-size projects as well as projects under the SGP.

1.3 Historical Context for OPS3

The GEF Monitoring and Evaluation Unit (GEFM&E) has coordinated two previous OPSs to evaluate the

global impacts and policies that result from the GEF programs. OPSs are conducted by external experts every

four years and generate a number of recommendations for the GEF. These recommendations are taken into

consideration by the GEF Assembly and used for financial negotiations and decision making.

In 1997, the first OPS (OPS1 [GEF/A.1/4]) was conducted at the request of the GEF Council. The report

focused on the GEF's provision of resources as well as country and institutional issues. However, so few

GEF projects had been completed at the time that OPS1 could not evaluate program results. By the time

OPS2 was conducted in 2001, a subset of projects had been completed and their success documented,

allowing reviewers to focus on whether the GEF objectives were being met. Despite the different focuses,

OPS1 and OPS2 posed many common questions and came to similar conclusions in many areas. Common

themes and issues raised by both reports include:

· Need for additional financial leveraging, including stronger involvement of private sector funds and

entities

· Concerns about the functionality of focal point system

· Concerns about IA coordination

· Prioritization of convention guidance and GEF implementation of convention guidance

· Concerns about outreach to stakeholders and GEF visibility

· Effectiveness of institutional organization and management strategies

· Role of the STAP.

In addition to the OPS, every four years, coinciding with the GEF replenishment cycle, the GEFM&E

conducts a round of evaluations and studies on all GEF programs. These reviews are fundamental elements

of the GEFM&E's work program and are major inputs to the OPS, the GEF replenishment process, and the

GEF Assembly. In preparation for the OPS3, the fourth2 major GEF-wide review, the following program

studies (and other key non-program-area studies) were conducted in 2004:

· GEF Biodiversity Program Study (BPS2004)

· International Waters Program Study (IWPS2004)

· Climate Change Program Study (CCPS2004)

· Progress Report on Implementation of the GEF Operational Program on Sustainable Land Management

(GEF/C.23/Inf.13.Rev.2)

· Local Benefits Study (GEFM&E 2004a.2004h.)

These studies are an essential contribution to OPS3. Their key findings and recommendations are drawn on

to complement OPS3 findings in this report.

5

OPS3: PROGRESSING TOWARD ENVIRONMENTAL RESULTS

1.4 Organization of the Report

The remainder of this report is organized around the OPS3 TORs:

· Chapter 2 discusses the approach and methodology employed by OPS3.

· Chapter 3 addresses findings and recommendations related to results of GEF activities.

· Chapter 4 gives findings and recommendations related to the sustainability of GEF results.

· Chapter 5 discusses the success of the GEF as a catalytic institution.

· Chapter 6 presents the effects of the GEF network structure on results.

· Chapter 7 addresses the effects of GEF procedures on results.

· Chapter 8 presents the main findings of OPS3.

· Chapter 9 puts forth the major recommendations of OPS3.

2. OPS3

Approach

2.1 Developing Thematic Areas of Assessment

Based on its review of the five main areas of assessment outlined in the study TOR, OPS3 grouped the

subject matter of the TOR into three broad points of view (POVs) for purposes of data collection and

analysis. This allowed for a more focused and thematic approach to research and assessment of GEF

performance. These POVs, presented in exhibit 2, are the:

· Focal area point of view, which includes each of the six GEF focal areas

· Cross-cutting point of view, which includes issues concerning, among other things, sustainability,

contributions to global benefits, replicability, incremental cost, country-drivenness, the GEF's role as a

catalytic institution, and similar issues that can be observed across the GEF's operations

· Institutional point of view, which includes the effectiveness of the GEF's structure, roles, and

responsibilities and the core processes the GEF uses for conducting its work

Exhibit 2 describes this general POV framework and indicates which specific TOR areas were considered

within each POV grouping. A detailed list of the indexed TOR topics is included in annex A.

2.2 Evaluation Challenges and Strategies

In addressing the various areas of the OPS3 TOR, there were several distinct challenges and requirements

that contributed to the OPS3 approach. These are outlined below.

2.2.1 Results of GEF Activities

Given the increasing maturity level of certain GEF portfolios, and in the context of recent dialogue on the

results of the GEF, there was a clear focus on assessing results as part of OPS3 (TOR 1). In addition, this is

an area where OPS1 and OPS2 were not able to provide any comprehensive assessment, and where

expectations for OPS3 were high.

6

OPS3: PROGRESSING TOWARD ENVIRONMENTAL RESULTS

Exhibit 2. Organization of TOR Questions by POV

The OPS3 Role in Results Assessment

During initial consultations with the OME, discussions were held on how OPS3 would address the results

assessment issue, given the objectives of the study, other major recent analyses that had contributed to the

study (for example, Program Studies), and various other constraints, such as the general unavailability of

impact-level results data and the study timeframe. Three consensus points emerged from these discussions:

· OPS3 should focus on assessing overall results of the GEF at the level of the focal areas, based on

available data synthesized in reports such as the recent Program Studies, data gathered through a series of

country visits to assess results observed at the country level, and other available summary data.

· The recently completed Program Studies for Biodiversity, Climate Change, and International Waters

would serve as one of the primary existing sources of detailed data concerning specific results and related

issues at the project and focal area level. Consideration of the Program Studies as part of the OPS3

assessment was supported by the Council in the November 2004 summary meeting documentation.

(GEF. "Joint Summary of the Chairs, GEF Council Meeting." November 2004.)

· The research conducted by the OPS3 team during the desk and field study components would look to

provide an overview of GEF activities, and would not try to corroborate data at the project level. Instead,

the OPS3 team would use information collected in the field to corroborate findings from the Program

Studies, OPS1 and OPS2, and the rest of the desk study.

Key Challenges to Results Measurement

After conducting an initial desk review, it was clear that the TOR 1 would be problematic. In particular, there

would be problems relating to reporting at the level of long-term quantifiable results or impacts (global

environmental benefits). This difficulty had been reported by OPS2 (GEFM&E 2002d) and was similarly

raised in the 2004 Program Studies, which also indicated that more recent projects have made progress in

including baselines and indicators. However, the results of these newer projects will not be seen for several

years. These observations by OPS3, in addition to the scientific literature, pointed to problems such as:

· Most projects do not generate information at the level of long-term quantifiable impacts and, more

important, many projects still do not have clear and agreed baselines, indicators of impacts, or

methodologies to calculate them.

7

OPS3: PROGRESSING TOWARD ENVIRONMENTAL RESULTS

· Although environmental change may take decades to be perceived or measured, GEF projects on average

span a four- to five-year period.

· The GEF does not systematically conduct postcompletion studies to look at long-term results.

· The GEF, as an institution, does not have an overall results measurement framework or methodology to

aggregate from project-level impacts to program-level or GEF-wide impacts. There is no existing unified

framework in place for systematically defining, measuring, and aggregating results of GEF activities,

particularly in terms of global environmental benefits for each of the GEF focal areas.

OPS3 observed that although mechanisms appeared to be in place to guide development of goals and results

during project design, implementation, and reporting (for example, project log-frames), and individual

projects have been assessed against their implementation performance as part of various annual, mid-term,

and completion reports, there remains a large gap in the effectiveness of such project-level mechanisms in

capturing results at the impact level. Apart from this constraint, there were not mechanisms in place to

support the roll-up of impacts should they be identified. In summary, the OPS3 team was presented with a

situation where basic questions concerning what to measure, how to measure, and how to scale up results to