G l o b a l E n v i r o n m e n t F a c i l i t y

GEF/ME/C.28/5

May 12, 2006

GEF Council

June 6-9, 2006

Agenda Item 6

GEF COUNTRY PORTFOLIO EVALUATION -

COSTA RICA (1992 - 2005)

(Prepared by the GEF Evaluation Office)

Recommended Council Decision

The Council, having reviewed the document GEF/ME/C.28/5, GEF Country Portfolio

Evaluation Costa Rica (1992 2005), takes note of the findings and

recommendations. The Council requests the GEF Evaluation Office to report through

the Management Action Record on the follow-up to the following decisions:

(a) The GEF Evaluation Office should continue conducting GEF Country Portfolio

Evaluations in other countries, selected with transparent criteria.

(b) The GEF Evaluation Office should conduct an evaluation of GEF regional

projects in Central America, as a cohort. A budget for such an evaluation will be

presented to Council at its next session.

(c) The GEF Secretariat needs to improve the information mechanisms in the GEF,

most notably the GEF website, to make essential operational information

available at the national level.

(d) The GEF Evaluation Office is invited to continue its interaction with the

government of Costa Rica on the evaluation report and to report back to Council

on Costa Rica's experience implementing the RAF and their attempt at defining

the country's potential national contribution to global environmental benefits

and how it has used it in the prioritization of projects for future GEF funding, as

part of the review of the RAF in 2 years time.

Council reiterates its decision of June 2005 that "the transparency of the GEF project

approval process should be increased" and requests the GEF secretariat to reinforce its

efforts to improve this transparency.

ii

Table of Contents

Executive Summary .................................................................................................................. 1

CHAPTER 1. MAIN CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS.............................................. 4

Background ............................................................................................................................. 4

Conclusions ............................................................................................................................. 4

Recommendations ................................................................................................................... 8

Observation............................................................................................................................. 9

CHAPTER 2. DESCRIPTION OF THE EVALUATION ............................................................... 10

Background ........................................................................................................................... 10

Objectives of the Evaluation................................................................................................. 10

Key Questions for the Evaluation......................................................................................... 11

Focus and Limitations of the Pilot Phase.............................................................................. 11

Methodology ......................................................................................................................... 12

CHAPTER 3. CONTEXT OF THE EVALUATION ..................................................................... 13

General Description .............................................................................................................. 13

Brief Description of Environmental Resources in Key GEF Support Areas ........................ 13

The Environmental Legal Framework of Costa Rica ........................................................... 18

The Environmental Political Framework of Costa Rica ....................................................... 21

Global Environment Facility................................................................................................. 22

CHAPTER 4. ACTIVITIES FUNDED BY THE GEF IN COSTA RICA ........................................ 25

Introduction........................................................................................................................... 25

Activities Considered in the Evaluation ............................................................................... 26

Areas Addressed in Projects and Enabling Activities........................................................... 30

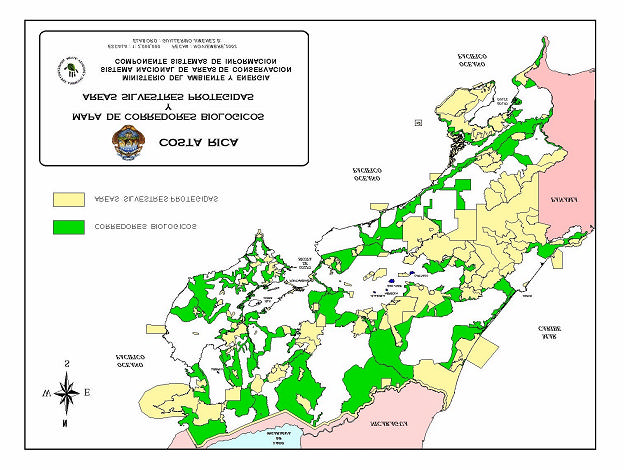

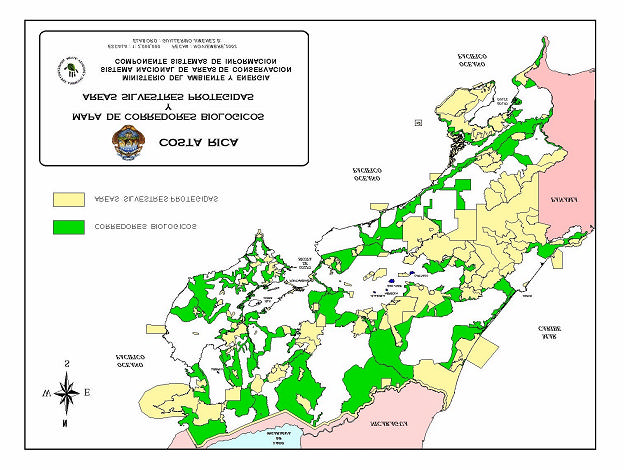

Activities Over Time............................................................................................................. 33

Evolution of the GEF Funding to Costa Rica ....................................................................... 35

CHAPTER 5. RESULTS OF GEF SUPPORT TO COSTA RICA................................................. 39

Global Environmental Impacts ............................................................................................. 39

Catalytic and Replication Effects.......................................................................................... 39

Institutional Sustainability and Capacity Building ............................................................... 40

Details of Project Results ...................................................................................................... 40

CHAPTER 6. RELEVANCE OF GEF SUPPORT TO COSTA RICA ........................................... 43

Relevance of GEf Support to the Country's Sustainable Development

Agenda and Environmental Priorities .............................................................................. 43

Relevance of GEF Support to Country's Development Needs and Challenges ................... 45

Relevance of GEF Support to National Action Plans Within GEF Focal Areas .................. 46

Relevance of GEF Support to Global Environmental Indicators.......................................... 47

Relevance of GEF Portfolio to Other Global and National Organizations........................... 49

iii

CHAPTER 7. EFFICIENCY OF GEF SUPPORTED ACTIVITIES IN COSTA RICA .................... 51

How much time, effort and money does it take to develop and implement a project, by type

of GEF support modality?................................................................................................. 51

Roles and Responsibilities Among Different Stakeholders in Project Implementation....... 56

The GEF Focal Point Mechanism in Costa Rica .................................................................. 58

Lessons Learned Between GEF Projects .............................................................................. 59

Synergies Between GEF Stakeholders and Projects ............................................................. 59

ANNEXES (available in a separate document)

Annex 1. Terms of Reference

Annex 2. List of documents reviewed

Annex 3. List of participants to consultation workshops

Annex 4. List of people interviewed

Annex 5. Complete list of activities funded by GEF in Costa Rica

Annex 6. Brief description of activities funded by GEF not included in the evaluation

Annex 7. Results of projects included in the evaluation

Annex 8. Relevance of projects objectives and results to National Development Plans

iv

Executive Summary

1.

Costa Rica and the GEF have worked successfully together as partners in the effort

against the decline in global environmental conditions since the beginning of the GEF. Costa

Rica has been the recipient of GEF financial support since 1992 through a variety of projects and

activities in collaboration with the GEF's Implementing and Executing Agencies. The activities

supported by the GEF have assisted Costa Rica in the development of its environmental and

national development strategies. Costa Rica's rich natural endowments, well developed

environmental sector and national human resources capacity have helped the many achie vements

attained in the country with GEF support.

2.

The present evaluation is the first of its kind produced by the GEF Evaluation Office.

This type of evaluation was requested by the GEF Council with two main objectives (1) to

provide Council with additional information on the results of the GEF supported activities and

how they are implemented, and (2) to evaluate how GEF supported activities fit into the national

strategies and priorities as well as within the global environmental issues mandated to the GEF.

Costa Rica was selected for the first evaluation as a pilot with the additional objective of learning

and assessing if this new evaluation modality can actually be implemented in other countries in

the future.

3.

The evaluation focused on a portfolio of 12 full and medium size projects, some

completed and others still under implementation, approved between 1992 and 2005 for a total of

$32 million. In addition, the evaluation includes the Small Grants Programme, established in

Costa Rica since 1993 with an accumulated investment of $5 million in 354 small projects. The

GEF support to Costa Rica has been concentrated in the biodiversity focal area (almost 70% of

the GEF investment) but there are examples of projects in all the other GEF focal areas.

4.

The Costa Rica Country Portfolio Evaluation produced very good results and proved that

this kind of evaluation is indeed valid and feasible. The evaluation is relevant to the GEF

system, in particular to establish a historic assessment of how the GEF has been implemented in

the country. Based on this experience the evaluation produced recommendations to improve GEF

functioning in its new phase, under the implementation of the RAF.

5.

The evaluation reached the following conclusions:

Relevance of the portfolio

(1) GEF support to Costa Rica has been relevant to the progress of the country's

environmental agenda.

(2) The GEF's support could be more relevant in terms of the country's contribution to

global benefits.

Results of the portfolio

(3) GEF support of Costa Rica has produced global benefits and has been in accordance

with the GEF's mandate.

1

Portfolio's efficiency

(4) The duration of project preparation and approval varied greatly from very short to

very long. No common problem areas, constituting bottlenecks for all projects, were

found in this evaluation.

(5) The mechanisms available for tracking project preparation and negotiation processes

are generally very limited and the parties involved in these processes at the national

level do not have direct access to them. This limitation is particularly severe in the

pre-pipeline and post-GEF Council approval stages.

(6) GEF operational information (project procedures and requirements, decisions of

Council, etc.) is not easily available and is presented in a confusing way.

(7) Costa Rica is beginning to prepare for the challenges of the GEF's new Resource

Allocation Framework (RAF), though with some delay, particularly with regards to

institutional coordination and project prioritization.

Country Portfolio Evaluations

(8) GEF portfolio evaluations at the country level are valid and feasible despite the fact

that there is no national GEF program or strategy.

6.

The evaluation provides two set of recommendations:

(a) to the Council:

(1) Continue with GEF portfolio evaluations in other countries

(2) Evaluate Regional Projects for Central America

(3) Reinforce the effort to improve transparency in the GEF project cycle

(4) The information mechanisms in the GEF, most notably the GEF website, need to be

improved to make essential operationa l information available at the national level

(b) to the government of Costa Rica:

(1) Explicitly define the potential national contribution to global environmental benefits

and use this definition in prioritizing the country's proposals to the GEF in the future.

(2) Speed up processes for meeting the challenges inherent to the introduction of the

RAF.

7.

In addition, the evaluation also recommends that the on-going joint evaluation of GEF

activities and modalities conducts further investigation for developing proper support or

mitigation actions for GEF project proponents particularly during the pre-pipeline part of the

project cycle when most of the investments of counterpart organizations take place.

8.

The document begins with a presentation of main conclusions and recommendations

coming from the evaluation. The following chapters present the information collected and the

analysis conducted and how they support the conclusions and recommendations.

2

9.

The evaluation was conducted by a team of consultants under the leadership of Claudio

Volonte (Sr. Evaluation Officer, GEF Evaluation Office) and Alejandro Imbach (consultant). A

draft document was presented in Costa Rica on April 20, 2006 to national stakeholders, including

national government, Implementing and Executing Agencies, NGOs and other civil society

partners. Feedback was very positive. Comments received are included in this final version. The

Office remains fully responsible for the contents of this report.

3

CHAPTER 1. MAIN CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Background

10.

Costa Rica has been the recipient of GEF financial support since 1992 through a variety

of projects and activities in collaboration with the GEF's Implementing and Executing Agencies.

From the end of 2005 until April 2006 the GEF Evaluation Office undertook an evaluation of the

GEF support to Costa Rica. This is the first time that the Office has performed such an

evaluation. The GEF Council asked the Office to begin conducting evaluations of activities

supported by the GEF at the country level with the goal of providing pertinent information to the

Council on how those activities relate to the country's sustainable development agenda, national

environmental strategies and priorities and the GEF's mandate. Costa Rica was selected as a

pilot case for testing the methodology and, based on that experience, for drawing up terms of

reference for similar future evaluations.

11.

The focus of the evaluation is a portfolio of 12 projects funded by the GEF during the

period from 1992 to the present with an investment of almost $32 million. Eight of those

projects were completed and four are under execution. This portfolio was not developed based

on a predetermined program or strategy, but consists of various projects with different aims and

objectives, developed and implemented over a 14-year period.

12.

All the focal areas are represented in this group, as are all GEF Implementing Agencies

(World Bank, UNDP and UNEP) and the IADB. In addition to those projects, the evaluation

included the Small Grants Programme, which has been under implementation in Costa Rica since

1993 and has funded 354 projects worth $5 million.

Conclusions

Relevance of the portfolio

13.

On the relevance of GEF support for the country's sustainable development agenda and

its environmental priorities, as well as its relevance to the GEF's mandate and programs, the

following conclusions were reached.

Conclusion 1. GEF support to Costa Rica has been relevant to the progress of the country's

environmental agenda.

14.

The analysis of the GEF portfolio shows that it was in line with National Development

Plans and national environmental strategies. Also, an analysis of the origins and results of

completed projects shows that Costa Rica has full ownership of the GEF's portfolio in the

country and has managed it in accordance with the national agenda. Projects that were completed

several years ago demonstrated catalytic and replication effects.

15.

Over the years the GEF support has become increasingly important relative to

development grants, given the relative constancy of the former compared to the drastic reduction

of the latter in the last few years.

4

Conclusion 2. The GEF's support could be more relevant in terms of the country's

contribution to global benefits.

16.

Although the preceding conclusion points out the relevance of GEF support of Costa

Rica's agenda and indicates that this agenda is clearly in line with the GEF's global agenda,

Costa Rica has not clearly defined its potential contribution to global benefits, even though it has

the capabilities and information needed to do so, as is evidenced by the work done in preparing

the GEF Programmatic Framework (2000) on biodiversity. Doing so would allow even better

alignment of the GEF's mandate, the country's priorities and projects.

17.

Given the fact that the activities supported by the GEF in Costa Rica were carried out

without a programmatic focus (the GEF does not require this in any of its programs), GEF

support puts special emphasis on the area of biodiversity (almost 70% of total funds) and little on

other major areas such as land degradation, and marine and coastal areas. This might be due to

the fact that other donors supported the country in those areas1, which was not studied further in

this evaluation.

Results of the portfolio

Conclusion 3. GEF support of Costa Rica has produced global benefits and has been in

accordance with the GEF's mandate.

18.

The analysis shows that there are many success stories related to:

· Impacts at the global environmental level, particularly in biodiversity conservation

through protected area management programs and payment for environmental services

and the abetment of CO2 emissions through wind energy projects.

· Replication and catalytic effect in terms of wind energy, payment for environmental

services, persistent organic pollutants national plan.

· Improvement in institutional sustainability for the Institute for Biodiversity (INBIO), the

national fund for forestry financing (FONAFIFO through Full Size Projects and other

local organizations through the Small Grants Programme and capacity building on areas

such as protected area management, taxonomy, payment for environmental services and

wind energy.

The portfolio's efficiency

19.

Efficiency questions focus on determining the time, energy and financial resources

needed to develop and implement GEF projects; the roles, coordination, lessons and synergies

among the various players and GEF projects; and the various challenges that are critical to the

entire GEF operation (communications, information on projects, GEF focal point and level of

preparation for the RAF).

1 As put forward during the workshop on the draft evaluation report in San José, Costa Rica, April 20, 2006.

5

Conclusion 4. The duration of project preparation and approval varied greatly from very

short to very long. No common problem areas emerged constituting bottlenecks for all

projects.

20.

As with other evaluations performed by the Office, the main problem when attempting to

conduct an analysis of this kind is the lack of systematized information on the progress of

projects during the project cycle.

21.

Analysis of existing information compiled for the evaluation shows considerable

variability in the duration of the phases for the same funding modality. It was noted that, on

average, preparation (from entry into the pipeline until start of execution) for Full Size Projects

took much longer than for Medium Size Projects (33 mo nths and 10 months respectively), while

this time was only about 4 months for Enabling Activities. There is no readily available

information on time spent on preparing projects before they enter the pipeline.

22.

Variability in the duration of the various phases of the project cycle seems to be

explained by factors particular to each project, such as prolonged negotiations between executors

and IAs/EAs, technical discussions among the various players involved, conflicts with public

finance regulatory entities in Costa Rica, staff rotation in IAs/EAs and changes in GEF priorities.

Conclusion 5. The mechanisms available for tracking project preparation and negotiation

processes are generally very limited and the parties involved in these processes at the

national level do not have direct access to them. This limitation is particularly severe in the

pre-pipeline and post-GEF Council approval stages.

23.

During interviews and visits, it was noted that there is no access to mechanisms for

tracking the progress of project proposals by parties acting at the national level (in both

implementing agencies and national organizations), which leads to apprehension and frustration.

Several cases were found where many months went by without project proponents at the national

level receiving any information on progress in reviewing their proposals. It was also noted that

there are mechanisms for doing this at the level of the central headquarters of the implementing

agencies, but the public does not have access to them.

Conclusion 6. GEF operational information (project procedures and requirements,

decisions of Council, etc.) is not easily available and is presented in such a way that

sometimes it leads to confusion.

24.

One area in which there is confusion and unawareness at the level of all national parties

(including some of the IAs/EAs local representatives) is the lack of knowledge and information

on the GEF in general, its operation, and the differing operating procedures of the Implementing

and Executing Agencies and the GEF for submitting projects and navigating them successfully

throughout the project cycle. Performance in these areas was deemed to be poor, deficient or

non-existent by most of the national executors interviewed and is confirmed by the experience of

the evaluation team. The GEF webpage is not visited regularly since it is perceived as being

confusing and not user-friendly. In general, it is hard to access operational information that is

relevant to national players. Council decisions are not indexed by subject on the webpage. This

was pointed out as a serious deficiency. Also, various people interviewed mentioned the lack of

direct communications between the GEF Secretariat and interested national parties.

6

Conclusion 7. Costa Rica is beginning the preparation process for dealing with the

challenges of the GEF's new Resource Allocation Framework (RAF), though with some

delay, particularly in relatively weak areas such as institutional coordination and project

prioritization.

25.

There are no GEF-related participatory mechanisms in operation at the national level for

analyzing the country's priorities based on requirements arising from the implementation of the

RAF, which is scheduled to begin operation in July 2006. Progress in this area can be shown

within the national capabilities self-assessment project funded by the GEF, which is beginning to

look into operational and strategic RAF issues and expects to address this subject. Pertinent

lessons can also be drawn from the process set up by the Small Grants Programme to give

priority to participatory mechanisms to efficiently allocate the GEF resources.

26.

At the same time, there is still no country program that sets specific priorities for

processes supported by the GEF. Existing instruments (Biodiversity Strategy, National

Environmental Agenda and others) are still very generic and require adaptation to become

operational for this particular source of funding.

Country portfolio evaluations

27.

A parallel goal for the GEF portfolio evaluation in Costa Rica was to evaluate the

feasibility of this new kind of evaluation at the GEF.

Conclusion 8. GEF portfolio evaluations at the country level are valid and feasible despite

the fact that there is no national GEF program or strategy.

28.

The pilot evaluation conducted in Costa Rica made it possible to satisfactorily answer

key questions regarding the relevance and efficiency of the portfolio. In addition, it was possible

to identify results and achievements of projects terminated several years ago, although it should

be pointed out tha t the results of the projects cannot be aggregated at the national level, but only

at the focal area level. The choice of Costa Rica as a pilot case was satisfactory, particularly as

an experiment in evaluating countries with small and medium GEF portfolios.

29.

A significant added value of this kind of evaluation is the ability to assess project results

several years after they are completed, creating a perspective that it is not possible to achieve

with the end-of-project evaluations that are normally done when particular projects are

completed.

30.

A fuller picture would emerge if the contributions of regional and global projects would

be included. However, unless the coordination offices of such projects are based in the country in

question, inclusion of these projects would substantially raise the costs of this kind of evaluation.

Furthermore, inclusion would increase the complexity of the evaluation by introducing contexts

different from the national ones, for example regional environmental problems and agreements.

7

Recommendations

(a) Recommendations to the GEF Council

(1) Continue with GEF portfolio evaluations in other countries.

31.

Continuing with these evaluations will allow a greater body of evidence on GEF support

at the country level to be built up. Moreover, such evaluations will add evidence and possibly

confirm the findings and conclusions of other evaluations with different focuses such as program

evaluations or global results evaluations, as well as provide inputs and questions to explore in

future exercises.

(2) Evaluate Regional Projects for Central America.

32.

This country evaluation demonstrated that this methodology is not an efficient way of

analyzing regional projects. In the case of Central America, regional projects on the whole have

constituted a large part of the GEF support to the region. Any comprehensive evaluation of these

projects should consider their performance, costs and relevance at the national and regional

levels, given the various regional environmental agreements and treaties in place in Central

America.

(3) Reinforce the effort to improve transparency in the GEF on project proposals in

the approval process.

33.

The GEF Council should reiterate its decision on the 2004 Annual Performance Report

that "the transparency of the GEF project approval process should be increased". The Costa Rica

portfolio evaluation highlights the difficulties at the national level to follow the project approval

process and reinforces the need for action on this issue, which was also emphasized in OPS3.

(4) The information mechanisms in the GEF, most notably the GEF website, need to

be improved to make essential operational information available to the national

level.

34.

On the national level it is difficult to ascertain whether the information provided on the

GEF's operations is up-to-date and in line with the decisions of the GEF Council. This could be

addressed by improving the accessibility of the website.

(b) Recommendations to the Government of Costa Rica

(1) Explicitly define the potential national contribution to global environmental

benefits and use this definition in prioritizing its proposals to the GEF in the

future.

35.

Costa Rica has an opportunity and the ability to increase its national contribution to

achieve global benefits. To do that, it must develop a strategic focus based on its environmental

potential and its national environmental and development strategies. The strategic spirit that

powered the preparation of the Programmatic Framework for Biodiversity (2000) could be

improved and extended to the entire range of actions supported by the GEF.

8

(2) Speed up processes for meeting the challenges inherent in the introduction of the

RAF.

36.

Implementation of the RAF will provide specific funding to countries for the biodiversity

and climate change focal areas. This will require developing new institutional processes for

prioritizing the use of those limited resources, mainly as regards climate change, where Costa

Rica will be sharing in group funding. Although Costa Rica has already begun this process, with

the implementation of the RAF in July 2006, it is recommended that this process be sped up to

avoid missing opportunities in areas such as climate change that will be open to competition.

Observation

37.

The GEF Evaluation Office is conducting an evaluation in conjunction with the

Evaluation Units of Implementing and Executing Agencies on GEF activities and modalities and

their respective cycles. The subject of efficiency, which is dealt with in Chapter 7, is an input for

this evaluation, especially as regards certain suggestions proposed to mitigate the negative

effects of long project preparation times.

9

CHAPTER 2. DESCRIPTION OF THE EVALUATION

Background

38.

The GEF Council asked the GEF Evaluation Office to conduct an evaluation of the GEF

portfolio at the country level. Such evaluations will provide the Council with additional

information on how the GEF functions at the country level and on the results of the activities it

supports, allowing it to better understand how these activities respond both to the country's

sustainable development, national strategies and priorities and the GEF mandate. Interestingly,

no evaluations of this kind using a country as the evaluation unit have ever been conducted

within the GEF system. Since the recently approved "Resource Allocation Framework" (RAF)

will be implemented in the next phase of the GEF (GEF 4, 2006-2010), it is expected that

evaluations of GEF support at the national level will provide useful feedback on work at that

level.

39.

The Council approved this new evaluation modality, as a pilot plan, for evaluating its

viability and developing a methodology for future country evaluations based on this experiment

as part of the EO's 2006 work program. The evaluation of the Costa Rica pilot case was

conducted in accordance with the Terms of Reference prepared by the Office and discussed with

Implementing Agencies, the GEF Secretariat and the Government of Costa Rica (see the Terms

of Reference attached as Annex 1).

40.

The Office selected Costa Rica for this first pilot evaluation for a number of reasons

including that the GEF portfolio in Costa Rica entails a wide variety of national, regional and

global projects, enabling activities and small grants implemented by all the implementing and

executing agencies. Also important is the fact that Costa Rica has a very good knowledge base

on the country's development and the environmental sector.

Objectives of the Evaluation

41.

The GEF support to Costa Rica pilot evaluation has three objectives:

1) Independently evalua te the relevance and efficiency of GEF support in the country

from various points of view: sustainable national development and the environmental

work framework; the GEF's mandate; achievement of global environmental benefits;

and the GEF's policies and procedures;

2) Explore methodologies that might be used to measure the results and effectiveness of

the GEF's portfolio at the aggregated and country levels; and

3) Provide feedback and knowledge to be shared with (1) the GEF Council in its

decision-making process on distributing resources and developing policies and

strategies (2) Costa Rica regarding its participation in the GEF.

10

Key Questions for the Evaluation

42.

The key questions explored during the evaluation of GEF support to Costa Rica were:

1) Is GEF support relevant to: (a) the national sustainable development agenda and

environmental priorities? (b) national development needs and challenges (e.g.

direction and appropriation by the country of the various kinds of GEF activities?;

(c) action plans for the GEF's national focal areas (e.g. enabling activities)?; and

(d) the GEF's mandate and focal area programs and strategies, and particularly what

is the relationship between the results of GEF support and impacts (proposed and

actual) and the global environmental indicators of each focal area?

2) Is GEF support efficient? (a) how much time, effort and money is involved in

developing and implementing GEF projects (e.g. based on the various kinds of GEF

support); (b) are the roles and responsibilities of the various players involved with the

GEF during the project design and implementation phases clear? (c) are execution

agreements, partnerships and synergies created within the GEF and between it and

other project donors and the national projects funded? and (d) how efficient are the

various kinds of GEF activities (e.g. comparison of full and medium-size projects)?

3) What methodologies are available for measuring GEF results (products, results and

impacts) and the effectiveness of its support: (a) at the project, focal area and work

framework levels and to explore various indicators for measuring these factors (e.g.

aggregation to measure progress in achieving global environmental benefits); and

(b) how can we determine what achievements are attributable to the GEF?

Focus and Limitations of the Pilot Phase

43.

The evaluation included all the activities supported by the GEF at the national level (full

and medium-size projects, enabling activities and Small Grants Programme) at various stages of

implementation (completed, on-going and in the pipeline) and implemented by all implementing

and executing agencies in all the local areas. This set of projects is defined as the GEF portfolio

in the country.

44.

In this evaluation exercise, environmental sector activities supported by other funding

sources, whether national, binational or multinational, were not included since the base

information for performing an analysis of this kind has not been compiled or systematized. At

the evaluation results presentation and validation meeting (April 20, 2006), the participants

pointed out the importance of those supplementary funding sources. As far as possible, mention

is made of them in the results analysis sections of this document and it is recommended that this

subject be considered in future evaluations of this kind.

45.

The way in which the GEF has operated at the country level causes various difficulties

for evaluations of this kind. For example, the GEF does not have national strategic programs.

Thus, there is no GEF national framework against which to evaluate results or effectiveness. On

the other hand, the GEF rarely supports work in isolation, but does in association with different

institutions. This makes it hard to attribute results. On the positive side, an evaluation with the

objectives described above might lead to important findings and increased understanding that

11

will allow the GEF to be more effective at the country level and within the RAF's operational

context.

46.

The evaluation of the GEF portfolio in this pilot project is not intended to be an

evaluation of the performance of the GEF, the implementing agencies or the country, taking into

account their effectiveness and the results achieved. The focus of this evaluation was on the

effectiveness and relevance of the overall GEF support.

47.

Also, given financial and time constraints and those described above, these evaluations

cannot be considered exhaustive, but limited, based mainly on existing literature (for example,

independent evaluations of projects and countries and reports from various studies and

evaluations carried out by the Office) and consultations with the major stakeholders involved.

48.

This evaluation of GEF support to Costa Rica was carried out by staff at the GEF's EO

and by local and international consultants who made up the evaluation team.

Methodology

49.

The methodology used included a combination of quantitative and qualitative methods:

· An in-depth review and analysis of over 10 documents containing information of the

development of Costa Rica's environmental, political and legal sectors, over 20 on

the GEF and the implementation of the assistance programs of GEF implementing

and executing agencies in Costa Rica and almost 100 documents with information on

progress in implementation and evaluative information on the results of projects

supported by the GEF (see the list in Annex 2).

· Two consultation workshops with key members in the implementation of the GEF in

Costa Rica, including the government, NGOs and other civil society stakeholders

(Annex 3 lists participants at various workshops). The first workshop discussed the

evaluation's the terms of reference, including the methodology. The second one

presented the first draft of the report and received feedback from all major

stakeholders.

· Extensive coverage of interviews with over 30 individuals and 20 global, national and

local institutions associated with the GEF and analysis of their contents (Annex 4 lists

the people interviewed).

· Field visits to 5 projects.

12

CHAPTER 3. CONTEXT OF THE EVALUATION

50.

In the preceding chapter, it was explained that one of the fundamental objectives of this

evaluation is to analyze the relevance of GEF support, both for Costa Rica and for the GEF itself.

Thus, it will be useful to present a brief summary of the context of the evaluatio n related to the

environmental sector in Costa Rica and the mandate and operations of the GEF, while pointing

out that there are a number of detailed documents that treat this subject in depth. Those

documents are listed in Annex 2.

General Description

51.

Costa Rica is a small country (land area: 51,100 km2; marine area: 589.000 km2) located

in the Central American tropics to the north of the Equator. It is a country of medium population

density (80 inhab/km2) with a total population of 4,200,000 inhabitants (2002), of whom

approximately half live in urban areas (48% en 2000).

52.

Costa Rica is a High Human Development country, in position 45 on the pertinent list

(UNDP, 2004), because of its high rating for various key indicators such as:

· Child mortality (9.5 per 1000, 2005)

· Life expectancy at birth (2000-2005): 79.7 years (women) and 75.0 years (men)

· Literacy (general adult population) 95.8% (UNESCO)

· Per capita GDP: (US$) 4,271 and per capita Purchasing Power Parity: (US$) 8,840

· Equality. Gini Index for income distribution by quintiles. 46.4. This index is high, being

the fourth highest among high human development countries, surpassed only by Mexico,

Chile and Argentina.

· Gender. The Gender-related Development Index lists Costa Rica in position 44, which is

consistent with its general position in the HDI (45), while on the Gender Empowerment

Measure (GEM), it is in position 19 on the list.

53.

In 2005, the Environmental Sustainability Index presented at the World Economic Forum

placed Costa Rica in position 18 among 146 nations. That index analyzes the performance and

the ability of countries to protect the environment in coming decades, considering investment in

natural resources, past and present pollution levels, environment management efforts and

society's ability to improve its management in that area (Programa Estado de la Nacion, 2005)

Brief Description of Environmental Resources in Key GEF Support Areas

a) Biodiversity and its conservation

54.

Based on the Costa Rican Institute of Biodiversity (INBIO) documentation and website

Costa Rica is among the 20 most biologically diverse countries in the world, having over

500,000 living species, of which 300,000 are insects (4% of the planet's land species).

Furthermore, approximately 11% of plant species are endemic, as are 14% of freshwater fish,

16% of reptiles and 20% of amphibians. To protect some of this extensive endowment, Costa

Rica has developed a world-class model of Protected Areas System. The development of this

13

system began in the mid-20th century and currently covers over 25% of the country. The table

below summarizes the System's status in 2001.

Table 1: Protected land area management categories in Costa Rica (SINAC 2001)

Management categories

Number

Area (ha)

% of the

country's Area

National parks

26

621,267

12.23

Biological reserves

8

21,663

0.42

Buffer zones

32

166,604

3.06

Forest reserves

11

227,545

4.47

Wildlife refuges

65

182,473

3.53

Wetlands

15

62,195

1.53

Other categories

12

23,264

0.34

Total

169

1,305,011

25.58

Figure 1. Map of biological corridors and protected areas in Costa Rica (SINAC-MINAE, 2002)

55.

In addition to the numbers mentioned above, there are over 55,000 hectares in 10 Private

Reserves (2001) and over 320,000 hectares in 21 Indigenous Territories. The latter are not

protected areas but, in general, they contain critical biodiversity and are important part in the

conservation system.

14

56.

This Protected Areas System is supplemented by a network of biological corridors being

developed that is intended to ensure the System's effectiveness and viability, playing an

important role in the migration and dispersion of plant and animal species, thus reducing the

vulnerability of protected areas to global and local threats. This biological corridor strategy has

become more relevant nationally and regionally because of the Mesoamerican Biological

Corridor project funded by the GEF through the World Bank and the impetus given by the

CCAD (Central American Commission for Environment and Development) to the concept as

such (Programa Estado de la Nacion, 2005). Moreover, both the Ecomarkets project (funded by

the World Bank and the GEF) and the GEF Small Grants Programme have designated biological

corridors as high-priority intervention areas.

57.

In recent years, this concept has been extended to the marine sector through a new

initiative aimed at establishing the Eastern Tropical Pacific Marine Conservation Corridor

through Costa Rica, Ecuador and Panama. In 2004, the MINAE set up the "Interdisciplinary

Exclusive Economic Zone Marine Coastal Committee" to determine the feasibility of dedicating

up to 25% of the exclusive economic zone to the conservation, restoration, management and

sustainable use of existing species and ecosystems (Decree 31832-MINAE, Program Estado de

la Nacion, 2005). This decree puts Costa Rica on the road to protecting an area in the ocean

equal to that on land.

b) Contribution to climate change and vulnerability

58.

According to the World Resources Institute (2000), Costa Rica has quantifiable emissions

in just three sectors: liquid fuels, cement production and land use change. In all three sectors, its

global and regional contribution is marginal. However, its emissions are increasing, with

domestic transportation being the sector with the greatest impact (66% of emissions).

Table 2: CO2 emissions in 2000 (World Resources Institute, 2000)

CO2 EMISSIONS, YEAR 2000 (thousands of metric tons)

LIQUID FUELS

CEMENT

LAND USE

PRODUCTION

CHANGE

World

10,636,592

824,400

7,618,621

Mesoamerica and the Caribbean

445,575

23,137

303,227

Costa Rica (country)

4,851

573

9,876

Costa Rica (% of Mesoamerica and the

1.1

2.5

3.3

Caribbean)

Costa Rica (% of world)

0.0

0.1

0.1

Costa Rica 1990

2,609

309

14,076

Costa Rica 2000

4,851

573

9,876

Change (%)

85.9

85.4

-29.8

SOURCE: Carbon Dioxide Information Analysis Center; World Resources Institute

15

SECTORIAL EMISSIONS (%) - (2001)

Electricity

2.1

Industry

1.0

Construction

15.9

Domestic transportation

66.0

Residential

2.9

Other commercial, public and agricultural

11.3

uses

99.2

SOURCE: International Energy Agency

59.

As regards to energy, Costa Rica's consumption is derived from three main sources:

petroleum derivatives, electricity and biomass (MINAE, First National Communication to the

Framework Convention on Climate Change, 2000). Energy demand has increased over the past

decade. This increase has been covered mainly by importing hydrocarbons and, to a lesser

extent, by producing energy domestically (Program Estado de la Nacion, 2005). In 2004, 70% of

commercial energy consumption came from imported hydrocarbons, 20% from electricity and

the remaining 10% from biomass resources. Energy consumption by the residential sector

(including family and personal vehicles) is dominated by electricity (42%). (2004 CENCE

report, ICE 2005).

60.

In 2004, 97% of the country was electrified. The population without access to the

electricity network is located in very remote areas where it is not feasible to extend the network.

In those cases, the government has been undertaking a rural electrification program with isolated

sources of renewable energy, in cooperation with international agencies and financial support

from the GEF.

61.

This energy overview gives a clear picture of Costa Rica's carbon emissions profile,

which is concentrated in liquid fuels and land use change, and shows the domestic transportation

sector as the main emitter (Table 2).

62.

On the other hand, Costa Rica is vulnerable to climate change impacts in various ways.

In its first communication to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, Costa Rica

presented a study on the vulnerability of various sectors to possible climate change impacts:

(1) according to simulations, runoff patterns in most basins could be altered; (2) changes in sea

levels would negatively impact the present coastline and extend areas subject to flooding;

(3) temperature changes could affect planting dates and cultivation areas; and (4) climate

changes might also reduce tropical and mountain zone areas and increase foothill floor life areas.

c) International waters

63.

The country has 589,000 km2 of oceans, 210 km of coastline on the Caribbean and 1,106

km on the Pacific. The broad continental shelf along the Pacific coast is one of the main factors

contributing to its fishing wealth. The Gulf of Nicoya is the most degraded marine area, both

because of overexploitation of its resources and because of pollution, particularly that resulting

16

from waste carried by the Río Grande de Tárcoles. Various migratory marine species have

routes that pass through the country's oceans (5 species of turtles, whales, lobster and others).

64.

The development of Marine Protected Areas is beneficial but limited compared to the

country's coastal and marine extension, as is indicated in the table below:

Table 3: Marine wildlife protected areas in Costa Rica (INBIO, 1997)

Management class

Area (ha)

National park

368,120

Biological reserve

2,700

National wildlife refuge

12,436

Total

383,256

65.

The Cocos Island marine ecosystems are noteworthy for their coral reefs and their

abundant highly endemic fish communities (approx. 17% of the 300 species), as well as for their

importance as a distribution center for many species of the Indo-Pacific region.

66.

In addition to marine environments, the country shares two transborder basins with

neighbouring countries: to the north with Nicaragua (San Juan River) and to the south with

Panamá (Sixaola-Yorquin Rivers). The San Juan River begins in Lake Nicaragua and flows into

the Caribbean Sea. At its head, the river runs through Nicaraguan territory and then forms the

international border. The river basin (i.e. excluding the Lake Nicaragua basin) covers 38,500

km2, of which 64% belongs to Nicaragua and 36% to Costa Rica. The river has various large

sub-basins in both countries and borders very important protected areas such as the Indio-Maíz

Reserve in Nicaragua and the Barra del Colorado Wildlife Reserve in Costa Rica. The Sixaola

River begins in the Talamanca mountain range, which divides the waters between the Pacific

Ocean and the Caribbean Sea, and empties into the Caribbean. In its lower course, it forms

Panama's northern border with Costa Rica. It is 146 km long and its basin covers 5,094 km².

Biodiversity and natural resources are safeguarded by six protected areas (155,848 has.), two

national biological corridors and six indigenous territories (112,789 has.) legally established by

the governments of Costa Rica and Panama.

d) Persistent organic pollutants

67.

Costa Rica has signed the main international conventions on chemical pollutants: Basel,

Rotterdam and Stockholm. Consistent with them, Costa Rica has prohibited, through decrees,

the production, importation, transportation, registration, trade in and use of raw materials and

manufactured products that contain polychlorinated or polybrominated biphenyls, heptachlor,

pentachlorophenol, aldrin, clordane, DDT, dieldrin, endrin, mirex or toxaphene. As will be seen

in later chapters, the country is currently in the process of inventorying toxic substances,

developing an action plan for them and creating the organizations needed to work effectively in

that area.

17

e) Land degradation

68.

Costa Rica has also signed and ratified the UN Convention to Combat Desertification and

set up an official advisory committee on the matter in 1998: the Land Degradation Advisory

Commission (CADETI). Work in this area has progressed as far as approval of the Soils General

Law and the creation of the National Action Program to Combat Land Degradation, while the

various requirements of the pertinent Convention have been fulfilled. The land degradation

situation in the country is summarized in Table 4.

Table 4: Current use of land in Costa Rica (National Land Degradation in Costa Rica Action

Programme, 2004)

Use class (Land)

Area (hectares)

Area (percent)

Well used (W)

2,714,977

54.9

Used in accordance with its use capacity, but requires special

521,598

10.5

conservation measures (Wt)

Underutilized (U)

732,217

14.8

Over-utilized (O)

475,204

9.6

Severely over-utilized (Ot)

504,584

10.2

TOTAL

4,948,580

100.0

The Environmental Legal Framework in Costa Rica

69.

Environmental legislation, including biodiversity and natural resources, is well developed

and up-to-date in Costa Rica. The national legal system consists of approximately 20,000 in-

force instruments, of which approximately 10% (2,000) deal with environmental matters in

general. Although the number of instruments mentioned above may seem high, the Attorney

General's Office, as the official attorney of the State, operates and periodically updates the

National System of In-Force Legislation, resolving any contradictions or overlapping in the

legislation being produced.

70.

The country's laws are based on the Roman/Germanic tradition and the hierarchy of legal

rules in Costa Rica is in line with that tradition. That hierarchy is set out in the Political

Constitution and the General Public Administration Law, as follows:

18

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

· GOVERNING FRAMEWORK

· OPERATIONAL FRAMEWORK

o Political Constitution of the Republic

o Executive Branch decrees

o International Treaties, Conventions and

o Regulations

Protocols

o Directives

o Laws

o Standards

§ Organic

§ Specific

a) Constitution of the Republic of Costa Rica and the environment

71.

In 1994, an amendment to Article 50 of Costa Rica's Political Constitution to read as

follows was approved2:

"The State shall attempt to ensure the greatest welfare of all inhabitants of the country,

organizing and stimulating the most appropriate production and distribution of wealth. All

persons have a right to a healthy and ecologically balanced environment and thus may denounce

any acts that infringe upon that right and demand that any damage caused be repaired. The

State shall guarantee, defend and preserve that right. The law shall determine the pertinent

responsibilities and sanctions."

72.

This amendment is very pertinent since by incorporating the right of "ecological balanced

environment" in the Constitution, no administrative rule or act may oppose it and it is protected

against all infraction.

b) Relevant International Treaties, Conventions and Protocols

73.

Costa Rica has signed and ratified most international treaties and conventions, including

the seven major international instruments monitored by the UNDP, as well as those related to

biodiversity and natural resources. The main ones are:

2 This is not an official translation of the original Constitution article; it was translated just to illustrate the

importance of the environmental sector in the country.

19

Table 5: Main international environment-related treaties, conventions and protocols

in Costa Rica over the last 30 years

Year

Milestone

1975

·

Ratification of CITES, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of

Wild Fauna and Flora (Law 5605).

·

Ratification of the Montreal Protocol (Law 7223).

·

Ratification of the Vienna Convention (Law 7228).

1991

·

Ratification of the RAMSAR Convention on Wetlands of International Importance (Law

7224).

·

Ratification of its joining the CBD (Law 7416).

·

Ratification of its joining the UNFCCC (Law 7414).

·

Ratification of the Convention for the Conservation of Biodiversity and the Protection of

1994

Priority Protected Wildlife Areas in Central America (Law 7433).

·

Ratification of its acceptance of the Basel Concordat on the Control of Transborder

Movements of Dangerous Waste (Law 7438) and then ratification of the pertinent

Regional Agreement in 1995 (Law 7520).

1995

·

Ratification of the Regional Convention (Central American) on Climate Change (Law

7513).

·

Ratification of the UNCCD.

·

Ratification of the Kyoto protocol.

1997

·

Signature of the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants (not yet

ratified).

·

Signature of the Cartagena Biosecurity Protocol (not yet ratified).

c) Relevant Laws

74.

In 1995, the Environmental Organic Law (Law 7554) was passed. Under its various

sections, this law establishes guidelines in numerous sectors and resources (protected areas;

marine, coastal, wetland, biodiversity, forest, air, water, soil, and energy resources) and on

numerous matters (administration and public participation; environmental education and

research; environmental impacts; protection and improvement of environment in human

settlements; land use planning; funding; sanctions, Environmental Controller, pollution, and

environmentally-friendly production)

75.

In the following years, various laws dealt with many of those issues in greater detail.

Some that might be mentioned are:

· 1996. Forest Law (7575). Established the Forest Fund and the FONAFIFO

· 1998. Soil Use, Management and Conservation Law (7779)

· 1998. Biodiversity Law (7788). Created the CONAGEBIO and the SINAC

20

76.

As regards deficiencies and weaknesses, the Water Law should be mentioned which it is

still being actively discussed in the Assembly, but has not yet been approved. Likewise, the legal

planning of coastal and marine areas still has weaknesses.

d) Operational framework

77.

The operational part that supplements and applies the legal framework is broad and

covers all existing legislation. Even more, certain important areas such as that related to

agrochemicals are almost totally regulated by various decrees.

78.

Finally, but very importantly, the existence and recognition in Costa Rica of

administrative careers should be pointed out. That means that technical level and middle

management personnel in state institutions remain in their positions when administrations change

and are not replaced automatically when a government is formed by a different political party.

Only officials of a "political" nature (senior managers and high officials) are replaced when

administrations change. That means that good institutional memory is maintained in most state

institutions because employees' jobs are secure.

Environmental Political Framework in Costa Rica

79.

The legal framework described in the preceding chapter is the legal structure that governs

national life despite political dynamics and the regular changes in government that have occurred

in the country since 1948. However, the various administrations (or governments) by different

political parties have left their mark on the national process through instruments such as plans

and strategies.

80.

Some of the instruments mentioned were created in response to obligations contracted

under international conventions such as the National Biodiversity Strategy. Notable among those

relevant to this evaluation include:

· ECODES National Conservation and Development Strategy (1989)

· National Conservation and Sustainable Use of Biodiversity Strategy (1999)

· 2001-2020 National Forest Development Plan (NFDP)

· NFDP action plan (2001)

· National Environmental Strategy 2005-2020

81.

The meshing of the political agendas of the various administrations with the current legal

framework is achieved through the National Development Plan (NDP), developed by the

different government institutions and coordinated by MIDEPLAN. This is a medium-term plan,

the duration of which coincides with the 4-year term of each administration, prepared at the

beginning of each democratically elected administration's mandate. Recently, the NDP has been

harmonized with state budget allocation mechanisms and with follow-up and account rendering

processes through the National Evaluation System (SINE). Public participation and national

discussions on environmental issues are a fundamental aspect of the formation of the

environmental political framework in Costa Rica, contributing to a high level of awareness and

involvement by civil society in decision-making. This social capital is particularly notable in the

environmental sector.

21

82.

Work with international organizations such as multilateral banks, the GEF and others has

also been subject to some extent to political dynamics, since it is with high-ranking officials from

the various administrations that they negotiate regarding a variety of issues. As was already

stated, all this activity takes place within the prevailing legal framework, but with political and

ideological nuances introduced by the rotation of different political parties in the government.

Global Environmental Facility

83.

The GEF is an international cooperation financial mechanism whose goal is to provide

new and additional funding, in the form of grants and concessionary funding, to cover the

additional agreed cost of measures necessary to achieve the agreed global environmental benefits

in the areas of:

· Biological diversity, in coordination with the Convention on Biological Diversity

· Climate change, in coordination with the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change

· International waters

· Depletion of the ozone layer, in coordination with the Montreal Protocol

· Persistent Organic Pollutants, in coordination with the Persistent Organic Pollutants

Convention

· Land degradation, in coordination with the UN Convention to Combat Desertification

· Multifocal Area for initiatives that combine two or more of the above thematic areas.

84.

The GEF is governed by an Assembly of almost 150 member countries that meet every

four years and a 32-member Council (representing all the member countries), which meets semi-

annually. A Secretariat located in Washington (USA) is responsible for the institution's

operational matters.3

85.

GEF activities are implemented through three implementing agencies: the World Bank,

the UNDP and the UNEP. Since 2004, seven executing agencies have been approved (regional

banks: Inter-American, African, European and Asiatic), the FAO, the IFAD and the UNIDO) to

execute GEF activities, although the great majority of projects are still being implemented

through the three implementing agencies.

GEF support modalities can be summarized as follows:

· Full-size projects (funding over $ 1 million)

· Medium-sized projects (total funding under $ 1 million)

· Small grants, with funding under $ 50,000, directed to NGOs and local organizations.

Small GEF grants are structured into a global program (Small Grants Programme)

administered by the UNDP and support initiatives included in any of the GEF's four focal

areas

· Enabling activities, intended to help countries meet their obligations under the various

conventions which the GEF services

3 More information may be found on the GEF's web page at http://www.thegef.org.

22

· Project development funds (PDFs), which are organized into three classes based on the

amount of support (PDF A up to $ 50,000, PDF B up to $ 500.000 and PDF C up to $1

million).

86.

Activities funded by the GEF are governed by Operational Programs and Priority

Strategies in each of the focal areas. Global conventions provide the GEF with guidelines on

projects that should be funded, the GEF Council approves those guidelines and the Secretariat

makes them operational.

87.

At the national level, the GEF operates through a Focal Point mechanism, which is

structured differently in each national context. The GEF recommends that two Focal Points be

established (one political and the other operational) and the establishment of transparent

mechanisms with strong participation. As for the structure of the Focal Point function, there are

several different models ranging from single-person models (as is the case in Costa Rica, which

has one person designated by the government as both the political and operation Focal Point) to

schemes based on multi-institutional committees (Colombia), mulit-sector committees (Bolivia),

specific offices within the formal state structure (China) and others. The GEF provides

guidelines defining the functions and responsibilities of the Focal Point mechanism. There are

also basic support programmes for those functions.

88.

The GEF trust fund is made up of contrib utions from donor countries plus interest on

them generated over time. This fund is administered by the World Bank. Once the trust fund is

replenished (every 4 years), funding is allocated through grants as countries develop projects and

the Council approves them.

89.

Officially, the GEF began with a 2-year pilot phase from 1992 to 1994. This was

followed by 3 regular 4-year phases: GEF I (1994-1998), GEF II (1998-2002) and GEF III

(2002-2006). In mid-2006, GEF IV will be initiated and will continue until 2010. During those

phases, grants were allocated by means of a funding windows process where a global amount

was allocated to each of the seven thematic areas listed above (and not by country). GEF

member countries submitted their requests to the various windows through the different

Implementing Agencies, which take appropriate action before the GEF.

90.

GEF III donors recommended the establishment of a system for allocating resources by

country, specifically for biodiversity and climate change, to be implemented in GEFIV. The

GEF Council approved this new framework in August 2005 and it will be implemented

beginning in July 2006 for the duration of GEF IV (until June 2010) under the name RAF

(Resource Allocation Framework).4 Unlike the mechanism used previously, the RAF sets

funding allocations for each country in each of the two areas mentioned. Depending on the

importance of the country in each of area, these allocations might be made individually (country

allocation) or for countries within a group of countries (group allocation). For example, in the

case of Costa Rica, the country will receive an individual allocation for Biodiversity but a group

allocation for Climate Change, reflecting its great importance in the first case and its limited

relevance to emissions abatement.

4 More information about the RAF is provided in the GEF website: www.thegef.org

23

91.

Since this evaluation focuses on projects approved before July 2006, the subject of the

RAF is considered to be outside its terms of reference despite the fact that it is considered as the

framework of relevance for any recommendatio ns and suggestions that might be made.

24

CHAPTER 4. ACTIVITIES FUNDED BY THE GEF IN COSTA RICA

Introduction

92.

The GEF has supported a wide and diverse range of activities and projects in Costa Rica

in collaboration with national and multinational partners5. The GEF portfolio of projects is

formed by a series of individual initiatives that were approved and implemented in relative

isolation since neither the GEF nor Costa Rica have developed a strategic plan or program to

guide GEF support. It is thus not possible to speak of a country program or other instruments

that involve a pre-existing higher-level design.

93.

It should be pointed out that in 2000 a group of national experts prepared a strategic

document to guide biodiversity-related activities to be funded by the GEF, following

recommendations on the matter contained in GEF Council Resolution C14-11 of December

1999. That document (Programmatic Framework for Biodiversity GEF, 2000) was developed

to the level of project profiles, but was never used in practice.6

94.

In short, GEF support to Costa Rica can only be described as a portfolio or group of

projects that have been approved over the years in different areas. In this and following chapters,

it will be discussed whether this was a weakness in GEF support or if, in reality, projects in

Costa Rica in some way succeeded in filling gaps in the national environmental strategy.

95.

For analysis purposes, the portfolio may be broken down into six basic groups:

a) All Projects (full and medium-size) completed or being implemented within the country.

b) Project Development Facilities (PDF A, PDF B and others) that constitute the country's

"pipeline".

c) Enabling Activities.

d) The Small Grants Programme.

e) Regional Projects (shared by Costa Rica and other Latin American and Caribbean

countries).

f) Global Projects (shared by Costa Rica and countries on other continents).

96.

A complete list of the activities funded by the GEF in Costa Rica may be found in

Annex 5.

5 As was indicated above, there are other sources of support and funding for the environmental sector in Costa Rica.

However, the analysis presented in this chapter is limited to the GEF portfolio supported by the GEF and the co-

funding.

6 In the late 1990s and early 2000s, a number of countries, including Costa Rica, developed guide strategies and

programs for GEF intervention at the national level. None of those initiatives were formalized or approved by the

GEF Council or the GEF Secretariat.

25

Activities Considered in the Evaluation

97.

In this pilot evaluation, not all activities supported by the GEF were included because of

time and financial limitations only those that met the following criteria:

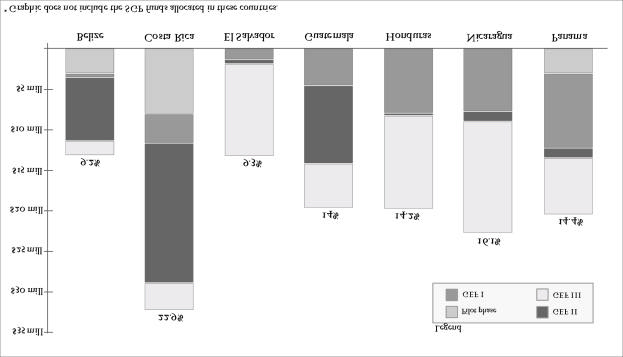

a. Activities carried out exclusively in Costa Rica i.e. all regional and global activities

were excluded

b. Activities completed and under implementation, excluding current project development

facilities i.e. PDF A and PDF B and pipeline activities.

98.

Those criteria were used to define a group of homogeneous and feasible activities to be

analyzed with available resources (money and time). A very brief description of activities that

were not considered is given in Annex 6. Based on those criteria, the group of activities

considered in this evaluation are presented in the following table:

Table 6: List of activities supported by the GEF in Costa Rica included in the evaluation

GEF

ID/Focal

Name/Implementing Agency

Type

Area

Completed Projects

60/CC

Tejona Wind Power (World Bank/IADB)

FSP

103/BIO

Biodiversity Resources Development (World Bank)

FSP

364/BIO

Conservation of Biodiversity and Sustainable Development in the Osa and La Amistad

FSP

Conservation Areas (UNDP)

671/BIO

Ecomarkets (World Bank)7

FSP

672/BIO

Conservation of Biodiversity in the Talamanca-Caribbean Biological Corridor (UNDP)

MSP

979/BIO

Conservation of Biodiversity in Agroforestry with Cacao (World Bank)

MSP

Projects Under Implementation

1132/CC

National Off-grid Electrification Based on Renewable Sources of Energy Programme

FSP

Phase 1 (UNDP)

1713/BIO

Improvement in Management and Conservation Practices for the Cocos Island

MSP

Conservation Area (UNDP)

Completed Enabling Activities

213/BIO

National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (Report to the CBD) (UNDP)

EA

1659/CC

Inventory of Greenhouse Gases (Second National Communication to the UNFCCC

EA

Climate Change-) (UNDP)

Enabling Activities in Execution

2207/MFA

National Global Environmental Management Capacity Self-Assessment (UNDP)

EA

2426/POPs

National Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants Implementation Plan (UNEP)

EA

Small Grants Program

Small Grants Programme (UNDP)

SGP

99.

As presented in the previous table, most of the focal areas and all GEF's implementing

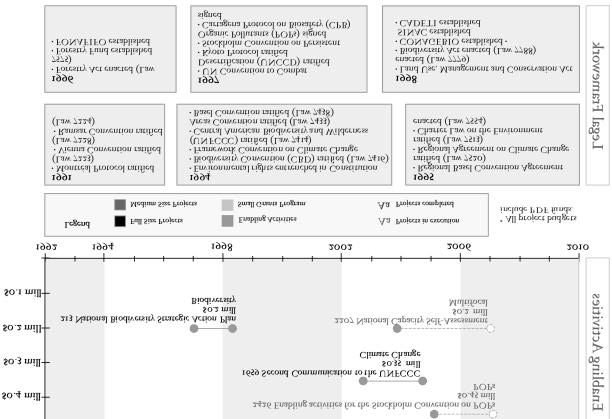

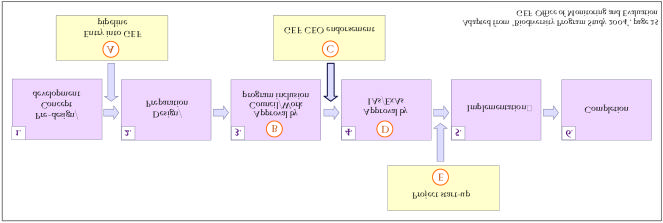

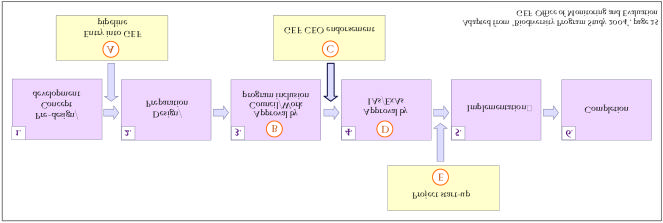

agencies are present in the selected projects.8. On the next page, Figure 3 showing types of

7 This project will be completed as June 30, 2006

26

activities, implementing agencies and the GEF focal area to which projects belong is presented to

illustrate how the group of activities selected in relation to those variables is visualized. In this

figure, each block of color (shades of gray) represents one of the activities implemented or under

implementation with GEF funds in Costa Rica. The height of each block is proportional to the

budget assigned to it. The color of each block indicates the GEF focal area to which each activity

belongs. In addition, each block has the unique GEF identification number, the name of the

project and its budget. The dark text indicates completed projects and in the light text represents

projects in execution.

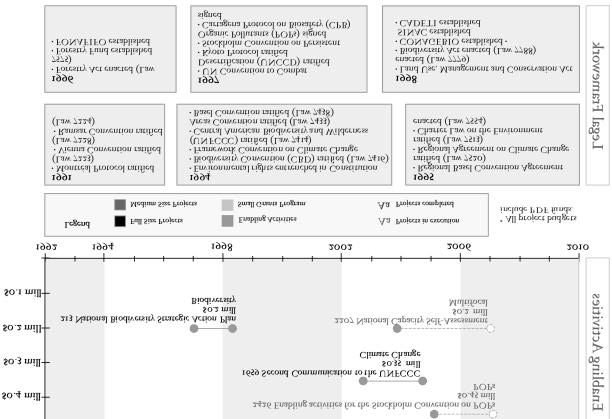

Figure 3: Activities supported by the GEF in Costa Rica, by IA/EA

100. As can be seen in the above graphic, the main implementing agencies are the World Bank

(which has executed 53.2% of GEF funds) and the UNDP (which has executed 45.5% of GEF

funds). The World Bank has participated in fewer activities than the UNDP, but with larger

budgets in all of them. The above graphic shows that the WB:

· has participated in 4 activities

§ 3 Full-size Projects (2 in Biodiversity and 1 in Climate Change)

§ 1 Medium-sized Project in Biodiversity

· has executed a total budget of $19.67 million

· the average budget is $4.92 million per activity

· currently has no activities in execution

101. In the case of the UNDP, its participation has been more varied, including all the funding

modalities available through the GEF. The above graphic shows that UNDP:

8 The IADB was recently added to the list of executing agencies but its national projects are still

in the development phase.

27

· has participated in 7 activities

§ 2 Full-size Projects (1 in Biodiversity and 1 in Climate Change)

§ 2 Medium-size Projects, both in Biodiversity

§ 3 Enabling Activities (1 in Biodiversity,1 in Climate Change and 1 Multifocal)

· has executed the Small Grants Programme for 13 years

· has executed a total budget of $11.75 million (not including the SGP)

· the average budget is $1.68 million per activity

· the SGP has distributed approximately U$ 5.08 million in 354 projects (an average of

$14,350)

· currently has 3 activities in execution, plus the SGP.

102. The UNEP has participated only marginally in the execution of GEF funds at the national

level only $450,000, equal to 1.2% of all GEF funds executed in Costa Rica. As is usual in

most countries, the UNEP's portfolio includes regional and global projects but, as was

mentioned earlier, activities of that type were not included in this analysis.

103. The GEF Executing Agencies do not appear in the graphic since they do not currently

have any activities in execution or completed.9

104. On the next page, another graphic similar to the preceding one is presented, but using

other criteria that make it possible to look at GEF activities in Costa Rica by focal area and

extract useful information. As in the preceding figure, in this one each color block (gray

shadings) represents one of the activities executed or in execution in Costa Rica with GEF funds.

The height of each block is proportional to the budget assigned to each activity. In this graphic,

the color of each block indicates the Implementing Agency associated with each activity. Each

block also has a brief text giving the GEF identification number, the name of the activity and its

budget. For completed projects, the text appears in dark black. For projects in execution, it

appears in light black.

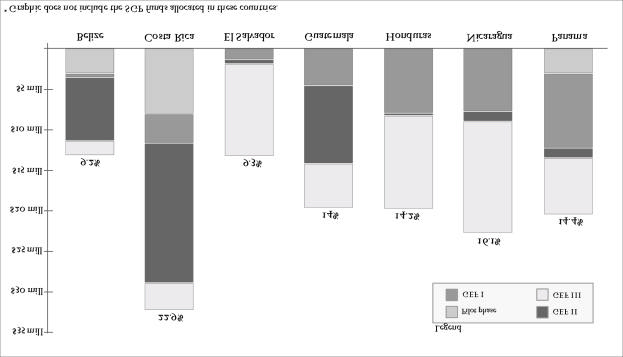

105. This graphic clearly shows the particular emphasis placed in the Biodiversity focal area

(68.6% of funds) on activities supported by the GEF in Costa Rica. In second place is the SGP,

which has executed approximately 13.2% of GEF funds. In third place are activities related to

the Climate Change focal area (12.5% of funds). Finally comes the Persistent Organic Pollutants

focal area (1.2% of funds) and the Multifocal area (0.5%).

106. The preceding graphic shows that for the Biodiversity focal area:

· 7 activities have been executed

o 3 by the World Bank and 4 by the UNDP

o 3 Full-size Projects, 3 Medium-size Projects and 1 Enabling Activity

o 6 activities have been completed and 1 is still in execution

· A total of $ 26.4 million has been executed for an average of $3.8 million per activity

107. In the case of the Climate Change focal area, we observe that:

9 The IADB executed the Tejona Project but through the World Bank since at that time the IADB was not one of the

seven Executed Agencies under Expanded Opportunities.

28