Lake Champlain

Experience and Lessons Learned Brief

William G. Howland*, Lake Champlain Basin Program, Grand Isle, VT, USA, whowland@lcbp.org

Barry Gruessner, Lake Champlain Basin Program, Grand Isle, VT, USA

Miranda Lescaze, Lake Champlain Basin Program, Grand Isle, VT, USA

Michaela Stickney, Lake Champlain Basin Program, Grand Isle, VT, USA

* Corresponding author

1. Overview

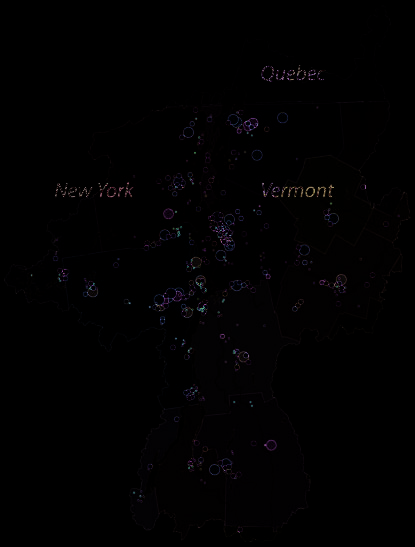

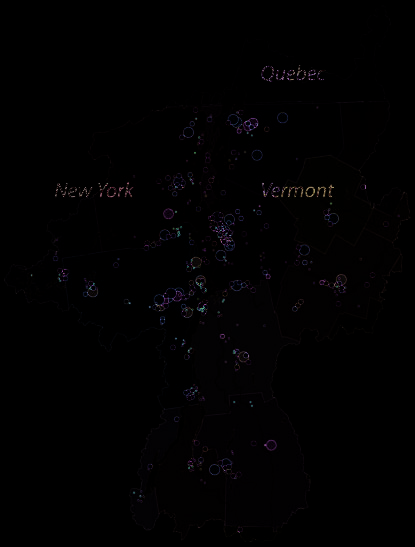

The Lake Champlain basin

(Figure 1) is home to a diverse

and signifi cant array of natural,

cultural, and recreational re-

sources. Extending west into New

York's Adirondack region, east

into Vermont's Green Mountains,

and north onto Québec's fertile

fl atlands, the basin's rich history

of human inhabitance is inter-

woven with its natural features.

Not long after glaciers retreated

from the area over 10,000 years

ago, Native Americans hunted,

fi shed, and later farmed along the

lake's shoreline. In 1609, explorer

Samuel de Champlain sailed into

the lake that would later bear his

name, initiating European settle-

ment in the basin. The basin was

the site of numerous important

military battles during the French

and Indian War, the American

Revolution, and the War of 1812

(LCBP 1999, 2003).

The economy of the basin has al-

ways relied on its natural resourc-

es to support the agricultural,

forestry, fi shing, ice, maple syrup,

iron ore and marble industries.

The natural beauty of the region

made it a popular destination for

vacationers beginning soon after

the Civil War. Boat building and

railroads satisfi ed the demand to

move people and goods through

a major transportation corridor

for both commerce and recre-

ation (LCBP 1999). Today more Figure 1. The Lake Champlain Basin.

than 600,000 people make their

home in the basin, and millions of

visitors are drawn to its waters and other natural and historic

1.1 Quantitative

Description

features each year. Nearly everyone in the basin depends on

the lake for a wide variety of uses, from drinking water and

The following quantitative facts about the Lake Champlain

recreation to agriculture, industry and waste disposal (LCBP

basin were adapted from the Lake Champlain Basin Atlas,

2003).

online version (LCBP 2002).

The basin's living natural resources are part of a complex ·

The Lake Champlain basin covers 21,325 km2 (8,234

ecosystem of interconnected aquatic and terrestrial habitats,

mi2). About 56% of the basin lies in the State of Vermont,

including broad open water, rivers and streams, wetlands,

37% in the State of New York, and 7% in the Province of

forests, agricultural lands, and other areas. Much of the Lake

Québec.

Champlain basin lies in the 650 km (400 mile) long Northern

Forest, extending from the Canadian Maritime Provinces ·

Lake Champlain is 193 km (120 mi) long, fl owing north

to eastern New York. Within the basin are extensive forest

from Whitehall, NY to the Richelieu River in Québec, with

lands under various levels of protection and management,

945 km (587 mi) of shoreline.

including a large section of the six million acre Adirondack

Park region, parts of the Green Mountain National Forest, ·

The Lake consists of fi ve distinct segments (depicted

and the Missisquoi National Wildlife Refuge. Diverse natural

in Figure 2), each with its own physical and chemical

communities are preserved at these and numerous other

characteristics:

State, Provincial, and private-owned lands. Besides humans,

·

The South Lake: The South Lake is narrow and

the basin supports about 81 species of fi sh, 318 species of

shallow, much like a river.

birds, 56 species of mammals, 21 species of amphibians and

·

The Main Lake: The Main (or Broad) Lake holds

20 reptile species, a number of which are at the northern edge

most of the lake's water and its deepest and

of their range (LCBP 1999). In 1989, the basin and adjoining

widest points.

Adirondack Park were designated a Biosphere Reserve by the

·

Mallets Bay: Mallets Bay is largely restricted

United Nations Man and the Biosphere Programme.

hydrologically due to railroad causeways.

·

The Inland Sea: The Inland Sea (or Northeast Arm)

The health of the economy of the Lake Champlain Basin is

is a lake segment lying east of the Champlain

tightly linked to its natural, cultural and recreational resources.

Islands.

One-third of the total employment in the Lake Champlain

·

Missisquoi Bay: Missisquoi Bay is a shallow bay

region was in the service industries in 1990, with recreation

at the northernmost part of the lake whose waters

and tourism as major components (Holmes & Associates

fl ow south to the Inland Sea.

1993). Tourism in the basin creates an estimated US$3.8 billion

in economic activity annually (LCBP 2003). In Vermont, tourism

·

The lake is 19 km (12 miles) at widest point, covering a

makes up 15% of the state's economy, 23% of the jobs and

surface area of 1,127 km2 (435 mi2). There are over 70

23% of total statewide personal income, and over two thirds

islands in the lake.

of this sector of the Vermont economy occurs in the Lake

Champlain basin (Holmes & Associates 1993). Towns along ·

At its deepest point, the lake is over 120 m (400 ft) deep,

Lake Champlain's shore benefi t from US$1.5 billion in tourism

but its average depth is 19.5 m (64 ft). The maximum

expenditures from visitors, with US$228 million of that spent

depth of some of the lake's bays is less than 4.5 m

on Lake Champlain related activities (e.g., boating, camping,

(15 ft).

fi shing, motels, etc.) (LCBP 2003). Agriculture in the basin,

which depends on clean water and productive soil, generated

·

The volume of the lake averages 25.8 million m3 (6.8

about US$526 million in sales of agricultural products--such

trillion gallons).

as milk, cheese, maple syrup, and apples--in 1997 (LCBP

2003). Recreation-related industries also depend on a clean

·

Precipitation averages 76 cm (30 in) annually in the Lake

lake. Residents within thirty-fi ve miles of Lake Champlain

Champlain valley, and 127 cm (50 in) in the mountains.

spent US$118 million in 1997 on water-based recreational

Rivers and streams contribute more than 90% of the

activities on Lake Champlain, while visitors from outside the

water which enters Lake Champlain.

area spent an additional US$228 million (Gilbert 2000).

·

The surface of the lake has an average elevation of 29 m

Clearly, life in the Lake Champlain basin is inextricably

(95.5 ft) above mean sea level.

connected to the natural resources found there. Every resident

and visitor to the towns and villages of the basin in some way

·

The basin includes the highest elevations in both New

enjoys the natural beauty of the region, its economic and

York (Mt. Marcy at 1629 m (5344 ft)) and Vermont (Mt.

recreational opportunities, and a sense of connection with the

Mansfi eld at 1339 m (4393 ft)). The growing season

basin's cultural and natural heritage.

averages from 150 days on the shoreline to 105 days in

the higher altitudes.

94 Lake

Champlain

·

Due to Lake Champlain's low water temperatures, the

best collection of underwater shipwrecks in North

America has been well preserved through more than

two centuries. Several shipwrecks in Vermont and

New York are included in an Underwater Preserve

network, supported by the LCBP, where SCUBA divers

can visit them and learn about the rich history of Lake

Champlain.

1.2 Landscape

The landscape of the basin was shaped by geologic events

over millions of years. The basin consists of fi ve physiographic

regions: the Champlain Valley, the Green Mountains, the

Adirondack Mountains, the Taconic Mountains and the Valley

of Vermont (Figure 3). The Adirondack Mountains, formed over

one billion years ago, were bordered to the east by the Iapetus

Ocean, an ocean over 500 million years older than the present

day Atlantic Ocean. Marine fossils can be found throughout

the basin, including the Chazy Reef in Isle La Motte, Vermont,

well known as the world's oldest reef. When the Iapetus Ocean

closed over 400 million years ago, the sedimentary rocks

of the shoreline and eastern continental shelf were folded

and faulted to form the Green Mountains. During this time,

portions of the earth's crust began to break and move as

large fault blocks, where younger rocks have been pushed

up and over metamorphosed continental shelf rocks beneath.

Geologists and students come to Lake Champlain from around

the world to view the exposed thrust faults at cliffs and road

cuts (LCBP 1996, 2002).

The Great Ice Age brought several glacial advances to the

Lake Champlain basin beginning about 1 million years ago,

covering the entire basin with a sheet of ice more than one

mile thick. About 12,500 years ago, the glaciers retreated and

Lake Vermont formed from the melted ice. When the glaciers

retreated further about 10,000 years ago, marine waters

from the St. Lawrence estuary fl ooded the basin, forming

the Champlain Sea, an arm of the Atlantic Ocean (Figure 4).

Evidence from this period includes a Beluga whale skeleton

found in Charlotte, Vermont. As the glacial ice disappeared

from the region, the earth's surface rebounded and the sea

was again cut off from the Atlantic Ocean, isolating the present

day freshwater Lake Champlain (LCBP 1996, 2002).

The land use and land cover in the Lake Champlain basin varies

from alpine meadow to lakeside fl oodplain forest. Much of the

vegetative land cover in the basin has been altered by human

activities ranging from logging to agriculture. Today, forested

areas dominate the landscape, covering over 70% of the

basin overall and continuing to increase from 100 years ago,

when approximately 30% was forested. Agricultural land is

the second largest cover category in the basin covering about

15%. The amount of land in agricultural use is decreasing as

abandoned crop and grazing lands revert back to forest or they

are converted to urban and suburban uses, which, as of 1999,

Figure 2. Lake Champlain Bathymetry and Lake Segments

represent about 5% of the total area of the basin (Hegman et

(Source: Adapted from fi gure available at

al. 1999).

http://www.lcbp.org).

Experience and Lessons Learned Brief

95

Agricultural lands in the basin are primarily concentrated in

by the President of the United States and the Prime Minister

the Lake Champlain valley and along the fertile fl oodplains

of Canada. The IJC convened a Champlain-Richelieu Board to

of the major river tributaries to the lake. The basin's human

examine a controversial proposal to regulate water levels in

population is largely dispersed in many towns, villages, and

Lake Champlain during the 1970s, with a new control structure

hamlets. Major population centers with urban and suburban

in the upper Richelieu River. After careful research and

land use include Clinton County, New York (including the City

deliberation, the IJC recommended that no control structure be

of Plattsburgh, total population of nearly 80,000 in 2000), permitted to regulate lake level, and both the US and Canada

Chittenden County, Vermont (including the Cities of Burlington,

have accepted this resolution of the issue.

South Burlington, and Essex and other towns, total population

of over 146,000 in 2000) and the City of Rutland, Vermont 2.1.2 Interstate Commission on Lake Champlain

(population 17,292 in 2000) (LCBP 2002).

(INCOCHAMP)

Formed in 1949, INCOCHAMP was intended to coordinate and

2.

Lake Management Issues and Activities

foster cooperation for environmentally sound development in

the basin. The INCOCHAMP became a pro forma organization

2.1

Cooperative Management Efforts

in 1968. Vermont ended its participation in the commission in

1990, while New York has never formally done so.

Because the Lake Champlain basin spans state and

international borders, the need for interjurisdictional 2.1.3 New England River Basins Commission (NERBC)

cooperation has been recognized for decades. The following

The NERBC existed from 1969-1981 as a federal-state

organizations have at various times played an important role

partnership composed of the six New England States and New

in the cooperative management of the basin's resources (LCBP

York, 10 federal and six interstate agencies. Its mission was to

1996, 2003).

encourage the conservation, development, and utilization of

water and related land resources on a coordinated basis by

2.1.1 International Joint Commission (IJC)

federal, state, and local governments and private enterprise.

Formed by the Boundary Waters Treaty in 1909 between Its activities included developing a Level B Study and

Canada and the United States, the IJC coordinates activities

Management Plan for Lake Champlain in 1979. The program

related to United States-Canada boundary waters. The IJC terminated shortly after completion of the Management Plan,

membership is comprised of six commissioners appointed due to cuts in US federal funding.

Figure 3. Physiographic Regions of Lake Champlain Basin

Figure 4. The Champlain Sea (Source: Adapted from fi gure

(Source: Adapted from fi gure available at

available at http://www.lcbp.org).

http://www.lcbp.org).

96 Lake

Champlain

2.1.4 Lake Champlain Fish and Wildlife Management

facilitating and coordinating resource conservation activities;

Cooperative (LCFWMC)

and exchanging information.

The LCFWMC was created in 1973 and continues as a federal-

state cooperative between the United States Fish and Wildlife

2.1.8 Lake Champlain Research Consortium (LCRC)

Service, the New York State Department of Environmental The Consortium is a multidisciplinary research and education

Conservation, and the Vermont Fish and Wildlife Department,

program for Lake Champlain established in 1991. Membership

that manages the fi sh and wildlife resources of Lake in the Consortium currently consists of selected academic

Champlain. The Cooperative Agreement, which was updated

institutions conducting research within the basin boundaries.

in 1995, created a Policy Committee consisting of program The LCRC periodically prepares a list of research needs and

directors from the three agencies, and Management and priorities related to the management issues identifi ed by the

Technical Committees of agency staff. Organizations in Québec

Lake Champlain Basin Program.

are not formal partners within the LCFWMC, but coordinate and

communicate with it regularly. The LCFWMC leads the program

2.2

Major Issues and Management Activities

to control the sea lamprey, an invasive, parasitic fi sh species.

Although Lake Champlain remains a vital and attractive lake

2.1.5 Memorandum of Understanding on

with many assets, there are several serious environmental

Environmental Cooperation on Lake Champlain

problems that demand action.

(MOU)

This MOU between New York, Vermont, and Québec was fi rst

2.2.1 Phosphorus

signed in 1988 and has been renewed at regular intervals Phosphorus is necessary for life, but concentrations of this

since, most recently in 2003. The MOU established the Lake

nutrient in parts of Lake Champlain are high enough to cause

Champlain Steering Committee with representatives from the

excessive growth of algae and other aquatic plants. This

three jurisdictions, as well as Citizen Advisory Committees growth results in reduced water transparency and oxygen

from Vermont and New York. The Steering Committee currently

levels, odors, and poor aesthetics, thereby posing the single

guides the activities of the Lake Champlain Basin Program.

greatest threat to water quality, living organisms, and human

Through this MOU, several cross-boundary protocols have use and enjoyment of Lake Champlain.

been established, including a Joint Toxic Spill Response

Agreement that mandates prompt communication between Wastewater treatment and industrial discharges are the

governments in the event of a spill, and a Québec-Vermont

main point sources of phosphorus, contributing about 20%

phosphorus reduction agreement for Missisquoi Bay. The MOU

of the total phosphorus entering Lake Champlain. Nonpoint

and subsequent agreements provide an opportunity to test

sources, which account for about 80% of the phosphorus

regulatory cooperation. In practice, the three jurisdictions treat

load, include lawn and garden fertilizers, dairy manure and

these agreements as binding covenants, though they are not

other agricultural wastes, pet wastes, and areas of exposed

strictly enforceable.

or disturbed soil, such as construction areas and eroding

streambanks (LCBP 2003). Agricultural activities contribute

2.1.6 Lake Champlain Basin Program (LCBP)

approximately 55% of the annual nonpoint phosphorus load

The LCBP is a partnership between the States of New York and

to the lake. Forests cover a majority of the basin's surface area

Vermont, the Province of Québec, the USEPA, other federal

but contribute only an estimated 8% of the average annual

and local government agencies, and local groups. Created by

nonpoint source phosphorus load. Urban land covers only a

Congress through the Lake Champlain Special Designation Act

small portion of the basin, yet it produces approximately 37%

of 1990 (Public Law 101-596) and updated with a continuing

of the average annual nonpoint source phosphorus load to

authorization in 2002 (Public Law 107-303), the LCBP works

the lake--much more phosphorus per unit area than either

cooperatively with many partners to protect and enhance agricultural or forested land (Hegman et al. 1999). The average

the environmental integrity and the social and economic phosphorus concentrations for each segment of the lake are

benefi ts of the Lake Champlain basin. The LCBP serves as the

presented in Figure 5. It is essential to note that many decades

coordinating body for the development and implementation

of high phosphorus inputs to the lake have also resulted in the

of the comprehensive management plan for Lake Champlain

accumulation of a large amount of phosphorus in lake-bottom

known as Opportunities for Action.

sediments which contribute to water quality problems through

internal loading.

2.1.7 Lake

Champlain

Ecosystem

Team

Established by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service, the

Since the 1970s, phosphorus loads have been dramatically

Ecosystem Team is an association of organizations throughout

reduced through actions such as banning phosphate

the Lake Champlain basin involved in the conservation of detergents, regulating wastewater treatment plants and

plants, animals, and their habitats. The Team's mission is industrial discharges, and voluntary pollution control efforts

to maintain and enhance ecological integrity throughout on farms. In 1993, after completion of an extensive diagnostic

the basin. Its work includes enhancing interdisciplinary feasibility study of the lake and its tributaries, New York,

cooperative partnerships among federal and state agencies,

Vermont, and Québec signed a Water Quality Agreement

conservation organizations, and academic institutions; establishing in-lake phosphorus concentration criteria (goals)

Experience and Lessons Learned Brief

97

Figure 5. Phosphorus Levels in Segments of Lake Champlain, 1990-2003 (Source: Adapted from fi gure available at

http://www.lcbp.org).

98 Lake

Champlain

for thirteen lake segments (Figure 5), and committing to urban uses is offsetting some of the gains achieved to date by

measure point and nonpoint source phosphorus loads to the

point and nonpoint source reduction efforts. Potential options

lake and develop a load reduction strategy to attain the in-lake

for achieving the additional phosphorus reductions necessary

criteria (VTDEC and NYSDEC 1997).

to account for these increases include both additional point

and nonpoint source treatment.

Using an optimization procedure to determine the cost-

effectiveness of various strategies for attaining the in-lake 2.2.2 Toxic Substances

phosphorus criteria (Holmes and Artuso 1995), load reduction

Toxic substances are elements, chemicals, or chemical

targets considered both fair and cost-effective were then compounds that can poison plants and animals, including

developed (Figure 5). Vermont and New York have committed

humans. Recent efforts to improve the understanding of toxic

to reducing the difference between the 1995 loads and the

pollution in Lake Champlain suggest that, while levels are

target loads in each lake segment watershed by at least 25%

low compared to more industrialized areas such as the North

for each fi ve-year period over 20 years, pending available American Great Lakes, there is already cause for concern.

federal and/or state funds to support implementation. Vermont

The presence of toxic substances, such as polychlorinated

and Québec have also developed an agreement dividing biphenyls (PCBs) and mercury, has caused New York and

responsibility for phosphorus reductions in the Missisquoi Vermont to issue health advisories suggesting limiting

Bay lake segment (QMENV and VTANR 2002; MBTF 2000). consumption of certain fi sh species. A survey of lake-bottom

The loading and in-lake concentration targets agreed to by

sediments funded by the Lake Champlain Basin Program has

the two states have become the basis of a federally mandated

identifi ed three areas in Lake Champlain (Cumberland Bay,

phosphorus Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) plan for Lake

Inner Burlington Harbor, and Outer Mallets Bay) where lake-

Champlain, prepared jointly by Vermont and New York (VTANR

bottom sediments are contaminated with toxic substances at

and NYSDEC 2002). The development and implementation of

levels that may be harmful to aquatic biota or human health

the TMDL are consistent with the priority actions detailed in

(Figure 6). A list of Toxic Substances of Concern has also been

Opportunities for Action.

prepared to help direct management actions (Table 1) (LCBP

2003).

In 2000, the LCBP released a Preliminary Evaluation of

Progress Toward Lake Champlain Phosphorus Reduction In recent years, hazardous waste cleanup and containment

Goals (LCBP 2000). The report estimated that Vermont, New

projects have been undertaken at the Pine Street Barge

York, and Québec reduced the phosphorus inputs to Lake Canal in Burlington, Vermont and in Cumberland Bay near

Champlain by about 38.8 metric ton/yr by 2001, far exceeding

Plattsburgh, New York. Cleanup of other less-contaminated

the fi rst fi ve-year interim reduction goal of 15.8 metric ton/yr.

sites called brownfi elds is also underway to protect water

The report also concluded, however, that not all lake segments

quality and encourage economic development. Additional

can be brought to the loading targets needed to meet the in-

research and monitoring efforts are needed to better

lake phosphorus criteria by relying solely on existing reduction

understand the sources and effects of toxic pollutants in the

programs. The report indicated that, because developed land

basin. Efforts to promote pollution prevention, from household

generates signifi cantly more phosphorus per unit area than

hazardous waste collections to reducing pesticide use, must

other land uses, conversion of land use from agricultural to

be continued and increased.

Table 1. Toxic Substances of Concern Found in the Lake's Biota, Sediment, and Water.

Priority

Toxic Substances

Criteria for Selection

Persistent contaminants found lake-wide (in either sediment,

water, or fi sh) at levels above standards, indicating potential risk

Group 1

PCBs, mercurya

to human health, wildlife, or aquatic biota. These are highest

priority for management action.

Arsenic, cadmium, chromium, dioxins/

Persistent contaminants found in localized areas (in either

furans, lead, nickel, PAHs, silver,

sediment, water, or fi sh) at levels above standards or guidelines,

Group 2

zinc, copper, persistent chlorinated

indicating potential risk to human health, wildlife, or aquatic

pesticidesb

biota. These are next highest priority for management action.

Ammonia, phthalates, chlorinated

Contaminants found above background levels in localized areas

Group 3

phenols, chlorine, atrazine, alachlor,

of the lake, but below appropriate standards or guidelines.

and pharmaceuticals

VOCs, such as benzene, acetone,

pesticides, strong acids and bases,

Contaminants known to be used or known to occur in the Lake

Group 4

and other potential pollutants, such as

Champlain Basin environment.

fl uoride

Source: LCBP

(2003).

Notes:

a) Based on US FDA standards.

b) Based on a variety of guidelines (NOAA, Ontario, USEPA) regarding toxics in sediments.

Experience and Lessons Learned Brief

99

2.2.3 Nonnative Aquatic Nuisance Species

Sea lamprey are primitive parasitic fi sh that feed on the body

The fi sh, wildlife, and other living resources of the Lake fl uids of other fi sh, resulting in reduced growth and sometimes

Champlain basin have been negatively impacted by the causing the death of the host fi sh. Evidence collected on

introduction of nonnative aquatic nuisance species, such as

Lake Champlain indicates that sea lamprey have a profound

sea lamprey, water chestnut, Eurasian watermilfoil, zebra negative impact upon native and sport fi sh populations. Their

mussels, and recently alewives. At least 23 nonnative aquatic

presence has thwarted efforts to establish and restore new

nuisance species are known to live in the waters of the Lake

and historical sport fi sheries. The Lake Champlain Fish and

Champlain basin (Eliopoulos and Stangel 2002). These Wildlife Management Cooperative (LCFWMC) completed an

species can interfere with the recreational use and ecological

eight-year experimental sea lamprey control program in 1998.

processes of the Lake. Zebra mussels, for example, can clog

The LCFWMC is now implementing a long-term sea lamprey

residential, municipal, and industrial water intake pipes, foul

management program, including chemical and non-chemical

boat hulls and engines, and obscure priceless underwater approaches.

archeological artifacts. Because nonnative species are often

transported across borders to reach the basin, coordination

Zebra mussel densities have increased dramatically since their

among the different management agencies is required to discovery in Lake Champlain in 1993. A monitoring program

prevent their introduction and spread. The Lake Champlain is in place to document the spread of zebra mussels and to

Aquatic Nuisance Species Management Plan was approved by

characterize the conditions that may limit their growth (see

New York and Vermont in 1999 and accepted by the National

Figure 9 below). Additional effort is needed in educating

Aquatic Nuisance Species Task Force in 2000. The plan is a

people about zebra mussel issues and to determine the long-

comprehensive action strategy to protect ecologically valuable

term effect of zebra mussels on the aquatic food web.

habitats, to control the spread of nuisance species, and

prevent additional introductions of nonnative species.

Eurasian watermilfoil, fi rst discovered in the basin in 1962,

now occupies an extensive range throughout the lake and at

least 40 other waterbodies in the basin. Because Eurasian

watermilfoil is spread by plant fragments transported by

waves, wind, currents, people, and to some extent, animals,

its spread is not easily controlled. Control techniques using

chemical and biological agents such as aquatic moths and

weevils are being investigated in the basin.

Like Eurasian watermilfoil, water chestnut displaces other

aquatic plant species, is of little food value to wildlife, and

forms dense vegetative mats that change habitat and interfere

with recreational activities. The most extensive infestations

are limited to southern Lake Champlain. Water chestnut has

also been found in Québec near Missisquoi Bay. In recent

years, a consistent, well-funded lakewide spread prevention

and control program of surveying, mechanical harvesting, and

handpulling of water chestnut has successfully pushed the

northern extent of the South Lake infestation back nearly 40

miles (Figure 7).

2.2.4 Human Health

There are potential health threats associated with poor water

quality in the Lake Champlain basin, including drinking water,

eating fi sh and wildlife, and swimming in the lake. Pathogens

are disease-causing agents such as bacteria, viruses, and

parasites. Water-related pathogens cause gastrointestinal

illnesses when ingested. Exposure to pathogens is primarily

through ingestion, either accidentally while swimming, or when

drinking water from the lake. Drinking water suppliers depend

on high quality source water to produce the highest quality

drinking water as economically as possible. The presence of

pathogens causes occasional beach closings in some areas

of the lake. Sources of pathogens include agricultural wastes,

Figure 6. Sites of Concern for Toxic Substances in Sediments

(Source: Adapted from fi gure available at

failed septic tanks, combined sewer overfl ows and sanitary

http://www.lcbp.org).

sewer overfl ows, and urban stormwater runoff.

100 Lake

Champlain

Blue-green algae, also known as cyanobacteria, are normally

limitations on fi sh consumption due to mercury contamination,

harmless and widely scattered through the surface waters are not consistent among the three jurisdictions, and therefore

of Lake Champlain. Under favorable conditions for growth, may be confusing to the public. It is important to develop

however, thick blue-green algae blooms develop, especially in

effective means to alert the public about these health risks

calm and shallow waters. Some strains of common blue-green

(LCBP 2003).

algae species can produce toxins that can damage the nervous

system or liver. These toxins have been detected sporadically

2.2.5 Fish and Wildlife

in Lake Champlain, although the conditions that result in the

Fish and wildlife provide tremendous social, economic, and

production of toxins have yet to be fully characterized. In recent

environmental benefi ts to the Lake Champlain basin. The

years, the deaths of several pets that ingested large amounts

structure and function of the food web affect water quality,

of blue-green algae laden water indicate that the health risk

bioaccumulation of toxins, and habitat suitability for fi sh

associated with blue-green algae blooms has increased. and wildlife. Abundant fi sh and wildlife attract recreational

Late in the summers of 2002 and 2003, signifi cant areas in

hunters, bird watchers, and anglers, resulting in signifi cant

Missisquoi Bay were contaminated by toxins associated with

economic benefi t to local communities. The complex array

large blooms of blue-green algae, resulting in public health

of plants and animals also provides other important benefi ts

advisories. Current research is focused on developing a to humans, such as pollution fi ltration through wetlands

coordinated health advisory program among Vermont, New and other vegetated areas, scenic beauty, and recreational

York, and Québec, and an examination of the factors that opportunities. Natural species diversity is a highly valued part

trigger these extreme conditions.

of the region's natural heritage and a critical component of the

ecosystem that supports all life on earth.

Mercury and PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyls) are a human

health concern because they accumulate to high levels in some

Populations of some rare, threatened, and endangered plant

fi sh species. State Health Departments have issued health and animal species and rare natural communities in the

advisories for several species of fi sh and waterfowl caught in

Lake Champlain basin are declining as a result of habitat

Lake Champlain. The fi sh sampling programs for Vermont, New

degradation, invasions of non-native species, collection, and

York, and Québec are currently not well coordinated, and do

other factors. Of the approximately 487 vertebrate species of

not yet provide a comprehensive database, making it diffi cult

fi sh and wildlife thought to be in the basin, 30 species are

to discover trends or provide statistically valid conclusions.

offi cially listed by federal and state agencies as endangered

and threatened. More information on the status of and threats

Communicating risks is an important part of any effort to to these species and natural communities, in addition to

protect human health. New York and Vermont have worked

more public education, is necessary for their protection and

together to inform each other of any press releases or health

restoration. A comprehensive inventory of these species and

advisories before they are released, and both states use their habitats for the entire Lake Champlain basin is essential,

similar methods of educating the public and communicating

as is close coordination by various agencies on all aspects of

risks. However, some of the general advisories, for example

protection and restoration (LCBP 2003).

Figure 7. Lake Champlain Water Chestnut Management: Annual Funding and Northernmost Mechanical Harvesting Site

(Source: Adapted from fi gure in LCBP (2003)).

Experience and Lessons Learned Brief

101

2.2.6 Wetlands, Streams and Riparian Habitats

tourism-related expenditures in the basin were estimated at

The Lake Champlain basin includes some of the highest US$3.8 billion in 1998-99.

quality wetlands in the northeastern United States, including

extensive lakeside wetland complexes and many rare or Efforts are being made to support initiatives that promote

declining natural wetland communities. In addition to ecologically sustainable economic activity utilizing natural,

providing critical habitat and nourishment for fi sh and wildlife,

cultural, and historical resources in the basin, while minimizing

the more than 300,000 acres of wetlands improve water quality

congestion and confl icts between users. Protection and

by fi ltering sediments, pollutants, and nutrients. Wetlands also

enhancement of the environment and cultural and recreation

help control fl ooding, protect groundwater and drinking water

resources is clearly important to visitors to the basin, as

supplies, stabilize shorelines, prevent erosion, and provide these resources are often the main focus of their experience.

recreational opportunities. Despite federal, state, and local Fostering more opportunities for diverse groups to access

wetlands protection regulations, threats to wetlands in the and enjoy the lake will encourage more people to value it

Lake Champlain basin persist. Wetlands are often drained or

and support water quality protection, ultimately increasing

fi lled for agricultural, residential, or commercial purposes.

the number of people engaged in lake stewardship. Issues

of congestion and confl icts of use can be addressed through

Human impacts on stream and riparian habitats have also user cooperation and/or education on a site-by-site basis.

been severe and wide ranging. For the last three centuries,

For example, the Lake Champlain Basin Program funded a

people have altered the landscape and the fl ow of streams and

demonstration project that identifi ed solutions to the boating

rivers for fl ood control, bridges and roads, power generation,

congestion and other problems in Malletts Bay, the Malletts

agriculture, development, and even erosion control or Bay Recreation Resources Management Plan.

bank stabilization. Adverse impacts include loss of historic

fl oodplains, increased river channel instability, degradation Plans are underway to commemorate the 400th anniversary

of water quality, decreased water storage and conveyance of Samuel de Champlain's arrival in the basin (2009). Both

capacity, loss of habitat for fi sh and wildlife, and decreased

New York and Vermont have established State Commissions

recreational and aesthetic value. Unfortunately, in the past,

to coordinate and promote the preparations for this

most stream manipulation did not take into consideration quadricentennial event. The focus in quadricentennial

the natural dynamic processes at work in the stream channel,

preparations will be on developing the regional infrastructure

riparian habitat, and fl oodplain, or the need for streams and

so that this celebration of regional heritage will be successful

rivers to transport both fl ow and sediment. Adequate riparian

and will shape the economy in a sustainable way. Associated

buffers are one of the most effective tools for limiting nonpoint

with this anniversary is a comprehensive initiative to

sources of pollution and promoting the long-term stability signifi cantly improve lake water quality by 2009 through a

of stream banks and channels, as well as providing wildlife

rapid and effective implementation of the TMDL program. The

habitat corridors and thermal protection to the stream.

National Park Service (1999) recently completed a study of the

Champlain Valley that assesses the potential for establishing

The Lake Champlain Basin Program sponsored a wetland a national heritage corridor in the region. A follow-up project

acquisition strategy that laid the groundwork for a four-phase,

to develop a framework for heritage tourism in the region that

multiyear program to permanently protect almost 9,000 acres

is compatible with local interests has been completed by the

of wetlands in the Champlain Valley. By 2001, US$1.4 million

LCBP. Other initiatives--the Lake Champlain Birding Trail, the

in federal funds had been provided to the project, which had

Lake Champlain Paddlers' Trail, Lake Champlain Walkways, the

conserved 4,000 acres of wetlands and surrounding areas Lake Champlain Underwater Preserve System, the Waterfront

in the basin. Other projects in the basin being conducted Revitalization Program in New York, Lake Champlain Byways

by citizens groups and public agencies include numerous and Lake Champlain Bikeways--have also made notable

streambank restorations using natural channel design progress in promoting low impact, non-motorized tourism

techniques, designating an ecological preserve in Québec, and

in the basin. Continuing and expanding these and similar

creating miles of buffer areas along streams and rivers (LCBP

initiatives in a more coordinated manner fosters stewardship

2003).

for the lake and its surrounding natural, cultural, recreational,

and historic resources within the basin, while also contributing

2.2.7 Recreation and Cultural Heritage Resources

to the economic vitality of the region (LCBP 2003).

The history of humans in the Lake Champlain basin spans more

than 10,000 years. It includes Native American and early Euro-

3.

Socioeconomic Threats to Sustainable Use

American settlements, French and British explorations and

occupations, pivotal military confl icts, and a dynamic period

3.1

Pressures from Within the Basin

of 19th century commerce. Many archaeological and historic

sites provide a context and sense of place to people today.

Socioeconomic factors in the Lake Champlain basin are tightly

Lake Champlain is also a popular recreation resource for basin

linked to the natural, cultural, and recreational resources

residents and visitors alike. Swimming, fi shing, scuba diving,

there. Protecting these resources and enhancing access to

and boating are just a few of the activities enjoyed on the

them generates substantial economic revenues (LCBP 2003).

lake. Recreation also contributes to the local economy. Total

In turn, increased awareness and use of resources can result

102 Lake

Champlain

in a greater concern and need for their protection. However,

in the basin provide milk, cheese, meat, and other products,

economic activity can also threaten the very resources on while preserving open space and maintaining the character

which it depends if it is not carried out in a sustainable way.

of the rural landscape that is so attractive to basin residents

Sustainable development is an economic development concept

and visitors alike. At the same time, farm activities are a

that gives full consideration to the social, economic, quality of

major source of pollutants to the basin's surface and ground

life, and environmental aspects of development decisions and

waters. Small farms need considerable assistance to manage

seeks to avoid depleting or degrading the economic resource

manure in an environmentally responsible manner. With milk

base. To promote sustainable development, it is essential to

prices low, small farms are being forced to increase milk

work closely with economic development agencies, chambers

production (i.e., the number of cows they keep) or go out

of commerce, business and industry groups, real estate of business. Although economies of scale can be realized,

development interests, local government, and environmental

larger farms also face proportionately larger challenges

organizations to identify actions and programs that can in effectively managing the manure from their facilities. In

lead to sustained economic activity, good wages, long-term

addition to manure management issues, low milk prices also

employment, affordable housing, and a cleaner environment

tend to discourage farmers from taking land out of production

(LCBP 2003).

to install streamside buffers that provide habitat and fi lter

pollutants from the stormwater runoff that fl ows from fi elds.

3.1.1 Local

Economies

It is then diffi cult for government assistance programs to offer

Local economies in the basin must remain vital to support

payments to create such buffers that are high enough to make

sustainable development and implementation of effective them attractive to farmers.

pollution controls, such as phosphorus removal in wastewater

treatment and upgrading failing septic systems. In addition

3.1.3 Forest

Products

to tourism, major sectors of the basin economy include Forest products include a wide diversity of commodities

manufacturing, agriculture, retail and wholesale trade, and manufactured items such as building materials, paper,

healthcare, universities, prisons, and state government. In the

maple syrup, and furniture. The importance of specifi c forest

1990s, employment in the service sector comprised 35% of

products-related industries to local economies varies from one

basin employment, followed by trade (22%), and manufacturing

part of the basin to another. In Vermont, Caledonia, Orleans,

(15%). The trend in the last 20 years has been towards an

and Windsor counties each account for 14% of the volume of

increase in the service and trade sectors and a decrease in

sawlogs produced in the state. Of those, Orleans is considered

the manufacturing sector. Income from wages, especially a basin county, and about half of the county lies within the

in the rural portions of the basin, lags behind the national

basin. In the New York portion of the basin, a signifi cant

average. In the Adirondack Park region, average annual wages

amount of the land area is classifi ed as commercial forestland:

in 1992 were US$20,621, in contrast to US$32,411 for all of the

Clinton County (69%), Franklin County (61%), Essex County

State of New York and US$25,903 nationwide. In Vermont, (48%), Warren County (59%), and Washington County (48%).

non-metropolitan earnings per job were US$24,774 in 1999,

while metropolitan earnings were US$28,039. Nationally, the

Maple syrup contributes signifi cantly to local rural economies

averages for non-metropolitan earnings were US$24,408 and

in the basin. In 1999, Vermont was the largest maple syrup

metropolitan earnings were US$36,526. In several locations

producing state in the nation, accounting for 31% of the total

around the basin, businesses related to agriculture, mining,

US maple production. Vermont's maple syrup production was

and forestry are the major employers (Holmes & Associates

valued at US$10.5 million in 1999, while production in the New

and Artuso 1996; LCBP 2003; US Department of Commerce's

York portion of the Lake Champlain basin was valued at US$1

1990 Census).

million.

3.1.2 Agriculture

Manufacturing of paper and paper products makes a

In the ten counties of New York and Vermont that lie signifi cant economic impact on rural economies as well. For

predominately within the basin, there were approximately example, in 2000, International Paper's Ticonderoga Mill

4,840 farms in 1987, roughly one-third in New York and two-

employed 690 people and had a payroll of US$36 million. In

thirds in Vermont. According to the 1997 Census of Agriculture,

2000, the mill purchased more than US$30 million in goods

the number of acres of farmland in Vermont decreased by and services in the Ticonderoga area of New York State. The

one percent from 1992 to 1997, to 1.3 million acres, while mill also purchased US$20 million of fi ber, wood chips, and

the number of full-time farms decreased six percent to bark from the Adirondack region, and 285 private truckers

3,300. By 1997, sales from Vermont farms totaled US$476 were involved in bringing wood to the mill. In 1997, the mill

million, indicating that the total value of Lake Champlain received the New York State Governor's Award for Pollution

basin agricultural products of US$526 million. Dairy products

Prevention for eliminating chlorine and hypochlorite in its pulp

account for the majority of farm sales in both New York and

bleaching process, resulting in reduced dioxin and chloroform

Vermont basin areas (LCBP 2003).

emissions.

Farming in the basin, the dairy industry in particular, is subject

According to recent research on the forest-based economy

to potentially confl icting resource management goals. Farms

of the northern forest region of New York, Vermont, New

Experience and Lessons Learned Brief

103

Hampshire, and Maine, jobs in lumber, wood, and paper the Lake Champlain Basin Program has characterized the land

products have declined from 1987 to 1997. There is local cover and land use of the basin, using data from 1993. Updated

evidence of that decline in the closing of several sawmills and

land use information and new "smart growth" initiatives will be

plywood mills during 2000-2001 in the New York portion of the

increasingly important for local municipalities (LCBP 2003).

basin, and related reductions in the workforce in paper mills

in the region. However, wood manufacturing of value-added

Population change can be an indicator of economic activity--

products, such as furniture, is a growing and strong economic

or lack of economic opportunity--and can indicate high

sector (LCBP 2003).

growth areas where land use planning is needed to protect

water quality. Preliminary 2000 Census data indicates that

The forest products industry is clearly a large economic driver

approximately 45% of Lake Champlain basin residents live in

in the basin. It is important to encourage sustainable forestry

lake shoreline towns. As shown in Table 2, the Vermont portion

practices that also balance consumptive use, recreational of the Main Lake area, which includes the Winooski River basin

access, and wildlife habitat values in the basin's forests. and contains the cities of Burlington and Montpelier, comprises

Expanding the production of value-added products from forests

almost one-half of the population in the basin (47%). The other

that are managed in a sustainable manner will add revenue to

main population center is the Plattsburgh area of New York

the local economy while reducing pressure to use practices

which includes the Saranac and Chazy River basins where

that produce short-term profi ts at the expense of long-term

15% of the population resides. Between 1990 and 2000, high

economic stability and balanced use of forest resources.

growth areas included Mallets Bay, Lake George, Missisquoi

Bay, and the Inland Sea watershed areas (LCBP 2003).

3.1.4 Population, Development and Land Use Change

A major landscape issue facing the basin is known as sprawl,

Seasonal residents and visitors are also very important to the

a cumulative development process that results from the basin economy. According to the 1990 Census data, there were

incremental growth of low density, single-use development,

38,530 seasonal homes in the basin, or approximately 14.6%

typically scattered along a highway. Sprawl generally begins at

of all basin housing units. Approximately 9,118 of the seasonal

the edge of traditional community centers and moves outward

homes are located in the Lake Champlain shoreland areas,

into previously rural areas, requiring new or larger roads, water

representing 24% of all seasonal homes in the basin. These

and sewer capacity, and utility lines. Although sprawl is not a

seasonal homes bring a large population increases to parts of

new phenomenon in the basin, the amount and rate of this

the basin each summer.

form of development has made it a topic of concern and study.

3.2

Pressures from Outside of the Basin

The effects of sprawl often include water quality degradation

from increased urban runoff and wetland losses. As the 3.2.1 Air Deposition of Pollutants

landscape becomes increasingly fragmented, wildlife habitat,

In addition to pollutants generated by activities within the Lake

farmlands, and forests also become less productive. The Champlain basin, mercury, PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyls)

discussion of both the positive and negative impacts of sprawl

and other pollutants from sources hundreds of miles away

on the landscape, culture, and economy of the basin has taken

travel through the air and are deposited to the land and water

on a new sense of importance in view of recent development

of the basin. According to the United States Environmental

trends. Information about land use change is an important

Protection Agency (USEPA 2000), atmospheric deposition is

resource for communities to guide their own economic destiny

a signifi cant source of certain pollutants to Lake Champlain

and to ensure the future quality of life in the basin. To this end,

and other surface waters in the United States. These pollutants

Table 2. Population Change in Lake Champlain Watershed Areas, 1950 to 2000.

Lake Champlain

Percent Change

Lake Segment/Watershed

1950-60

1960-70

1970-80

1980-90

1990-2000

1950-2000

Missisquoi

Bay

-6.4

3.2

13.6

10.7

11.4

35.4

Inland

Sea

5.0

7.3

5.2

14.7

10.6

50.3

Mallets

Bay

1.3

43.2

37.2

20.1

16.1

177.4

Broad

Lake,

VT

8.3

18.4

11.4

9.5

7.4

67.9

South

Lake,

VT

13.0

-0.2

11.7

10.6

6.5

48.6

South

Lake,

NY

-2.5

8.5

2.0

10.2

3.8

23.5

Lake

George

29.5

14.9

12.2

-3.2

13.6

83.7

Broad

Lake

South,

NY

7.7

-2.1

9.8

5.5

5.2

28.5

Broad Lake North, NY

30.3

-2.3

10.8

6.2

-6.1

40.6

Total

Change 10.2

11.4

12.7

9.8

6.1

61.1

Source: LCBP

(2003).

104 Lake

Champlain

may occur at levels that can be harmful to both human and

4.1

The Lake Champlain Basin Program

ecological health. For humans, the risk is greatest for those

who consume large amounts of fi sh. Although it appears that

To address the need for cooperative, basin-wide management,

the amount of deposition of mercury and other pollutants the Lake Champlain Basin Program (LCBP) was created by the

is decreasing or holding steady, it is likely that atmospheric

United States Congress through the Lake Champlain Special

deposition will continue to be a source of several pollutants for

Designation Act of 1990 (Public Law 101-596). The LCBP is

some time to come and that they will continue to be found in

a partnership among the States of New York and Vermont,

water, sediments, and biota.

the Province of Québec, the USEPA, other federal and local

government agencies, and many local groups, both public

The USEPA (1997) has concluded that coal-fi red power plants

and private, working cooperatively to protect and enhance the

and municipal trash incinerators are the two largest sources of

environmental integrity and the social and economic benefi ts

mercury emissions in the United States, and that the Federal

of the Lake Champlain basin (LCBP 2003).

Drug Administration "action level" for mercury consumption

must be lowered to adequately protect human health. The Steppacher and Perkins (1999) have summarized the

states in the northeastern United States and the eastern formation and workings of the LCBP through the management

Canadian Provinces have joined forces to develop a Mercury

plan development phase. Following previous management

Action Plan which sets a goal of virtual elimination of man-

efforts, the Special Designation Act called for a comprehensive

made mercury releases in the region (USEPA 2000).

planning process that would involve stakeholders with diverse

interests throughout the basin. It also encouraged the process

The release of sulfur (SO2) and nitrogen (NOX) compounds from

to consider the interconnected nature of the Lake Champlain

fossil fuel combustion can create acid deposition (also known

basin ecosystem, from plants to animals and humans. The

as acid rain). The source of nearly two-thirds of the SO2 and

31-member Lake Champlain Management Conference (LCMC)

one-fourth of all NOX is from electric power generation using was initiated in 1991 to lead the planning effort, including

fossils fuels such as coal. While in the air, these pollutants

development of a comprehensive plan, conducting research

can reduce visibility and be harmful to human health. When

and monitoring studies, and implementing an education and

they fall to earth, either in rain, fog or snow, or as particles

outreach program.

and gases, they cause acidifi cation of surface waters, and can

damage trees, soils, and building materials. The United States

In 1996, the LCMC completed the management plan,

Federal Clean Air Act Amendments of 1990 set a goal to reduce

Opportunities for Action: An Evolving Plan for the Future

annual SO

of the Lake Champlain Basin

2 emissions by 50%, and annual NOX emissions by

. The LCMC dissolved and the

two million tons, compared to 1980 levels, primarily through

leadership of the LCBP was passed on to an expanded Lake

restrictions on fossil fuel-fi red power plant emissions in Champlain Steering Committee established in the 1988 MOU.

eastern and midwestern states (USEPA 2002).

Howland (2001) has described the structure and operation

of the LCBP in the current plan's implementation phase. Like

3.2.2 Non-native Aquatic Nuisance Species

the LCMC, the Steering Committee is comprised of a broad

As discussed above, controlling the introduction of non-native

spectrum of representatives of government agencies, the

aquatic nuisance species from outside the basin is a key part

chairs of advisory groups representing citizen lake users,

of protecting the Lake Champlain basin ecosystem. Additional

scientists, and educators. These advisory groups include:

safeguards, educational efforts, and intergovernmental a Technical Advisory Committee, composed of resource

coordination are needed to restrict further introduction of managers, physical and social scientists, and economic

these species as many of them are inadvertently transported

experts; Citizens Advisory Committees from New York,

here by people from regions outside of the basin.

Vermont, and Québec; an Education and Outreach Advisory

Committee; and a Cultural Heritage and Recreation Advisory

4.

Policy, Legislative and Institutional Reforms

Committee. The LCBP continues to be jointly administered by

the USEPA, the States of Vermont and New York, and the New

Managing the natural and cultural resources of the Lake England Interstate Water Pollution Control Commission. Other

Champlain basin is a complex undertaking. Various cooperating agencies include the US Fish and Wildlife Service,

management agencies and programs have made signifi cant

the US Department of Agriculture, the US Geological Survey,

progress in areas such as controlling point source discharges

the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration,

of pollution from industry and wastewater treatment plants

and the National Park Service. The Province of Québec is

and strengthening the lake's sports fi shery (LCBP 2003). The

also represented on the Steering Committee and each of the

Clean Water Act (i.e., Federal Water Pollution Control Act of

advisory committees.

1972 and subsequent amendments) has been the driving

force behind many of the water quality improvements for the

4.2

Strengths and Successes

past three decades. However, effective management of these

resources requires action from all levels of private and public

4.2.1 Partnerships

organization, from homeowners and businesses, from local The success of the LCBP is rooted in the maintenance of

governments, and state and federal agencies.

partnerships and collaborations, a multiple stakeholder

Experience and Lessons Learned Brief

105

approach, sharing of information with the public, and basing

through other means. While the consensus process employed

management decisions on good science (LCBP 2003; Stickney

by the LCBP tends to minimize the polarization of hard

et al. 2001). Successful implementation of the management

ideological positions, it does require that common goals (such

plan is achieved by developing many partnerships among as drinkable, swimmable waters) be shared by all participants.

natural resource agencies, citizens, and other lake and The motivating infl uence of the policy accord expressed by

watershed stakeholders throughout the basin (LCBP 2003). The

the Governors and the Premier in the 1988 MOU (reaffi rmed

fi rst revision of the management plan was a two-year process

in 2003) and in the management plan Opportunities for Action

that began in 2001 and relied extensively on partnerships with

(2003), together with the universal appeal of a clean lake and a

stakeholder groups, public meetings and citizen involvement.

thriving economy, can hardly be overstated.

Stakeholder involvement in the revision of the management

plan is described by Howland and Hoerr (2002).

5.

Constraints to Environmentally Sound

Management

Since its inception, the LCBP has evolved into an internationally

recognized natural resource management initiative 5.1 Investments

characterized by inter-jurisdictional management, and the

enhancement of the stewardship role of local leaders (Stickney

Since the establishment of the LCBP, efforts to protect and

et al. 2001). Transboundary relations are guided by a sequence

preserve the resources in the Lake Champlain basin have been

of nonbinding, nonregulatory consensus-based agreements.

well-supported by the States of New York and Vermont, the

Since the 1988 Memorandum of Understanding, 14 additional

Province of Québec, and the US federal government, as well as

agreements have been signed, ranging from joint declarations

local governments, businesses, and citizens. Because funding

and watershed plans to in-lake phosphorus criteria and toxic

support for activities related to Lake Champlain basin resource

spill responses. These agreements are typically renewable and

protection comes from such varied sources, it is diffi cult to

this incremental approach has enhanced cooperation and trust

quantify exactly the level of funding committed each year.

among the jurisdictions (Stickney 2003; Harris et al. 2001).

Highlights of typical funding are presented below. Note that

the funds below are in addition to those spent through the

4.2.2 Consensus

base operations of local, state, provincial, and federal agency

Principles of consensus and trust-building helped overcome

programs.

initial policy differences among the three jurisdictions

during the plan development phase, and they are still being

·

From 1991-2001, Vermont has spent over US$20 million

utilized today. This approach to decision-making creates a

dollars on reducing phosphorus discharges from

"win-win" atmosphere where minority opinions are normally

municipal wastewater treatment plants in the Lake

incorporated into Steering Committee decisions, and motions

Champlain basin. During the same period, New York

pass by unanimous vote, refl ecting the full consensus of

spent over US$10 million dollars building and enhancing

the group. However, on rare occasions when consensus is

wastewater treatment plants. From 1991-1998, Québec

not possible, votes are held and the majority prevails. The

invested over US$13 million in wastewater treatment

latter prospect provides an incentive for all parties to work

plant construction for areas discharging to the Lake

assiduously to achieve consensus, while ensuring that timely

Champlain basin and Richelieu River (LCBP 2000).

decisions may be made. The LCBP process encourages open

and public discussion, with subsequent meeting summaries

·

Approximately US$9.6 million was applied to controlling

(but without recorded transcript), so that committee members

nonpoint sources of phosphorus in the Vermont

can freely explore decisions before making commitments.

portion of the basin between 1996 and 2001. The funds

supported cost-share projects with farmers. About 58%

Many management policy debates arise from different

of the funds came from the US federal government

perspectives on issues about which there is inadequate

(United States Department of Agriculture--Natural

information. Flexibility in the decision-making process has

Resource Conservation Service), 22% from Vermont,

enabled the LCBP to take an adaptive management approach

and 20% from farmers. New York has committed over

to diffi cult issues. When scientifi c information is not adequate

US$15 million to environmental projects in the basin

to guide a management decision, the LCBP allocates funds to

through the Clean Water/Clean Air Bond Act of 1996

support focused and timely research or monitoring to address

and the Environmental Protection Fund. Québec spent

the knowledge gap. When the needed information thus is

nearly US$1.8 million to help farmers manage manure in

made available, an appropriate management decision may

the Lake Champlain basin, representing 70% of the total

be more easily reached by the group. In this way, research

project costs that were shared by farmers (LCBP 2000).

and monitoring has an essential role in informing policy

development.

·

The USEPA generally provides US$1-2 million annually

toward operation of the Lake Champlain Basin Program

The consensus building process gives all participants a

offi ce and its technical and local grant projects.

meaningful role in developing viable solutions and results in

Additional EPA funding has been directed toward

a sense of group ownership of decisions that is unattainable

wastewater treatment plant upgrades in the basin,

106 Lake

Champlain

stormwater management demonstration projects, and

·

An estimated US$139 million will be needed to fully

development of a lakefront laboratory and science

implement the TMDL phosphorus reduction plan for the

museum.

Vermont sector of the Lake Champlain basin (VTANR and

NYSDEC 2002). The timeline for achieving phosphorus

·

The US Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) generally

load reduction goals has been accelerated (from 2016 to

provides about US$400,000 annually toward invasive

2009) by Vermont and Québec largely in response to the

species management, primarily for the harvesting of

increasing blue-green algae problems in the Missisqoui

nuisance aquatic plants. In recent years, the Corps

Bay, a part of the lake shared by these two jurisdictions.

also has provided additional funds for restoring the

Annual recommendations by the Technical Advisory

Burlington Harbor breakwater. The USACE is presently

Committee and its workgroups for vital technical

working with the LCBP to develop a Corps General

projects needed to implement Opportunities for Action

Management Plan for Lake Champlain that will bring

are typically many times the amount available for such

signifi cant new funds (US$500,000 in 2004) to the

projects.

support of Opportunities for Action and an enhanced

partnership with the Corps.

·

The total annual amount of technical and local grant

project proposals to the Lake Champlain Basin Program

·

The US Geological Survey spends US$400,000-500,000

is typically four times the amount available for such

annually on Lake Champlain tributary fl ow gauging and

projects.

research projects.

5.2

Human Resources and Institutional Capacity

·

The USDA NRCS has spent about US$300,000 annually

since 2001 on research and demonstration of alternative

The Lake Champlain basin is fortunate to have a broad

manure management techniques. Many of these assemblage of committed and knowledgeable people who

programs have been managed by the LCBP on behalf of

are interested in protecting the basin's resources, from local

the NRCS.

citizens joining in wildlife monitoring programs and cleanup

days, to watershed and lake groups planting vegetation

·

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

along streambanks and shorelines, to professional scientists

(NOAA) has provided US$150,000 annually toward and managers studying water quality and restoring cultural

research in hydrodynamics and atmospheric processes,

treasures. Over the past decade, these individuals have

awarded on a competitive basis through the Lake become increasingly skilled and effective in their work.

Champlain Research Consortium. The NOAA also

contributes approximately US$150,000 annually for Many of the actions included in Opportunities for Action

the Lake Champlain Sea Grant program in New York and

call for greater coordination among the groups working on

Vermont.

particular issues. Dedicated human resources are generally

needed to provide the level of coordination needed to address

Despite these commitments, signifi cantly expanded funding is

issues through a cooperative process that brings together the

needed to meet the goals that have been set for protecting and

strengths and resources of participating partners.

restoring the Lake Champlain basin's resources.

·

The Lake Champlain Basin Program supports several

·

Preliminary cost estimates from Opportunities for

staff positions involved in coordination work. The

Action (LCBP 2003) suggest that implementing actions

LCBP also helps to support a number of state agency

in the plan will require at least US$12 to US$15 million

staff positions involved with particular aspects of

annually, and at least US$170 million for the period

implementing Opportunities for Action. Lastly, the

through 2016. Estimates were not developed for all

LCBP supports the staff of local watershed, cultural

actions.

and recreation groups, primarily through project grants,

but also through small professional development and

·

In 1999, it was estimated that over US$62 million would

organizational support grants (Figure 8).

be needed to implement phosphorus management

on all remaining farms in the Vermont portion of the

·

Vermont has hired several basin planners to oversee

basin. However, additional nonpoint or point source

watershed planning in river basins throughout the state,

phosphorus controls will be needed to achieve the

including those in the Lake Champlain basin. These

phosphorus goals in sub-basins where farm treatments

efforts are being coordinated with the LCBP and are

are not expected to result in the needed load reductions

consistent with Opportunities for Action.

(LCBP 2000).

·

Federal funds have been made available for controlling

·

Québec has estimated that implementing needed

pollution from agricultural sources, but these funds

erosion control projects for nonpoint phosphorus

are often restricted to costs related to design and

control would cost nearly US$14 million (LCBP 2000).

construction of waste storage structures. Additional

Experience and Lessons Learned Brief

107

funding or expanded access to existing funding is 6. Lessons

Learned

needed to provide the technical staff who plan and

implement projects and provide services such as 6.1

Involve Stakeholders in the Design and

developing Comprehensive Nutrient Plans that will also

Implementation of Programs

signifi cantly reduce agricultural pollution in addition to

structural approaches.

A diverse array of stakeholders participate in the management

of Lake Champlain basin's resources, from citizen watershed

·

The state environmental conservation agencies in groups concerned about the health of their local streams

the basin have minimal staff resources to administer

to government agencies mandated to implement the laws

and enforce the environmental regulations under designed to protect these resources. These stakeholders

their purview. Additional staff are needed to facilitate

understand the close connection between the condition of the

sub-watershed level planning and assessment work. basin's resources and their quality of life, including economic

Additional staff are also needed to address stormwater

opportunity, health, heritage, and aesthetics. Because

pollution. Stormwater management and permitting stakeholders have been involved from the beginning of the

issues have recently become litigious in the basin.

planning process, they have shown a greater acceptance of the

policies and actions developed, and a greater willingness to

·

Small watershed and lake associations engage numerous

form partnerships to work toward implementation.

restoration and education activities, often with funding

from small grants and member contributions. It is often

The Lake Champlain Basin Program sponsored 28 formal public

diffi cult for these groups to consistently maintain even

meetings around the basin while developing the fi rst version of

part-time staff to oversee their operations, implement

Opportunities for Action, and countless informal meetings. A

projects, and provide a point of contact for ongoing similar process was used when Opportunities for Action was

business. Organizational Support Grants from the LCBP

revised in 2003. Hundreds of local citizens and representatives

in recent years have done much to build capacity that will

of various organizations attended these meetings and provided

make these small organizations become fully functional

comments on draft plan materials throughout the planning

and sustainable. Additional funding is needed to sustain

process. The Lake Champlain Management Conference also

these local groups.

established a series of advisory committees, subcommittees,

and workgroups whose members represented the various

interests associated with specifi c areas of the plan. LCBP staff

and committee members made presentations and conducted

outreach activities for hundreds of groups during the fi ve-year

planning phase.

The LCBP continues to invite stakeholders to participate

in its annual budget planning process, soliciting advice on

management priorities and ideas for projects related to

implementing the management plan. The LCBP's Technical

Advisory Committee (TAC) plays a key role in informing

the development of policy by the Lake Champlain Steering

Committee, especially through recommendations of

scientifi cally sound approaches to management issues in the

basin. Steering Committee policies characteristically refl ect

the technical advice provided by the TAC.

Local river and lake associations play a key role in organizing

watershed protection efforts (LCBP 2003). These associations

accomplish a great deal through education and outreach

programs, participation in local planning, development

reviews, and citizen monitoring and restoration activities.

Watershed associations also act as catalysts for developing

nonregulatory protection programs. River and lake associations

can encompass several local jurisdictions, sometimes even

spanning state boundaries. Watershed associations work

closely with local government, where most land use planning

occurs, respecting a wide variety of interests, including

Figure 8. Lake Champlain Basin Program Local Grants

Projects, 1992-2002 (Source: Adapted from fi gure

property rights, environmental protection, and economic

available at http://www.lcbp.org).

development.

108 Lake

Champlain