Trainee Manual

Module 3

TRAINING COURSE ON THE TDA/SAP APPROACH IN THE GEF

INTERNATIONAL WATERS PROGRAMME

TRAINEE MANUAL

MODULE 3: JOINT FACT-FINDING I - IDENTIFICATION

AND PRIORITISATION OF PROBLEMS AND THE

ANALYSIS OF IMPACTS

Training course on the TDA/SAP approach in the GEF

International Waters Programme

Page 1 of 52

Trainee Manual

Module 3

MODULE 3

JOINT FACT-FINDING I

9

Identification and Prioritisation of Problems

9

Impact Analysis

1. This Module

This module and Module 4 cover the two stages of the execution of the TDA, which are

carried out by the Technical Task Team after the project development phase (covered in

Module 2).

This module deals with the identification and prioritisation of the transboundary problems

and the determination of their environmental impacts and socio-economic consequences.

Module 4 covers the development of causal chains for the priority transboundary

problems, the role of governance analysis and the integration of the component parts of the

TDA.

The formulation of the SAP is covered in Module 5.

1.1 Stepwise approach to joint fact-finding

The flow diagram shown in Figure 1 identifies the major steps taken towards the

development of the TDA document in both Modules 3 and 4.

Each step described in this flow diagram is further expanded in Sections 3 and 4 of this

module.

You will find a contents list of Module 3 at the end of this document.

Training course on the TDA/SAP approach in the GEF

International Waters Programme

Page 2 of 52

Trainee Manual

Module 3

Description

Module

section

TDA preparation

Module 3

information and data `stock taking' exercise

3.1

Identification and initial prioritisation

Module 3

Identification of transboundary problems

3.2

Initial prioritisation of transboundary problems

3.3

Analyse impacts/consequences of each problem

Module 3

Analysis of environmental impacts

4.1

Assessment of socio-economic consequences

4.2

Detailed final prioritisation of transboundary problems

4.4

Causal chain analysis

Module 4

Analysis of causal chains (identification of immediate,

3.1

underlying and root causes of each priority transboundary

problem)

Governance analysis

3.4

Production and Submission of Complete Draft TDA

Module 4

Integration of the component parts of the TDA

4.1

Drafting the TDA

4.2

The TDA review process and submission for final approval

4.3

Figure 1 Major steps taken towards the development of the Transboundary

Diagnostic Analysis

Training course on the TDA/SAP approach in the GEF

International Waters Programme

Page 3 of 52

Trainee Manual

Module 3

1.2 Module Objectives

At the end of the module, you should be able to:

A. Identify and prioritise transboundary problems

1. Describe the principal types of transboundary problems.

2. Explain the process of identifying and prioritising the problems.

3. Explain the need to take account of current developments and future risks in

deciding on priority problems.

4. Describe common criteria and scoring systems for assessing problems and methods

of prioritisation.

5. Describe how to conduct a `Delphi Exercise'

B. Determine the environmental impacts and socio-economic consequences

6. Describe methods for examining the impact of a problem from an environmental

and socio-economic perspective.

7. Describe the types of information necessary to demonstrate the scale and scope of

an problems:

a. environmental impacts; and

b. socio-economic consequences.

8. Explain the usefulness of quantitative data on socio-economic effects, as measures

of potential benefit when assessing policy options.

9. Identify potential sources for the information indicated in item 6 above, and

develop an initial plan for obtaining such information in a given situation.

1.3 Module Activities

In this module, you will be invited to:

1. Study a series of texts and case-studies.

2. Complete a short self-assessment test.

3. Complete three exercises analysing the approach used in several real case-

studies.

Training course on the TDA/SAP approach in the GEF

International Waters Programme

Page 4 of 52

Trainee Manual

Module 3

2. General principles

2.1 Transboundary problems

The majority of GEF-funded IW projects are concerned with environmental problems

which are transboundary. A "transboundary problem" is any form of anthropogenic

degradation in the natural status of a water body that concerns more than one country.

Anthropogenic means caused by the activities of people rather than natural phenomena.

A transboundary problem can originate in, or be contributed by, one country and affect (or

impact) another. For example, the chemicals associated with eutrophication may be emitted

predominantly by one country in a region but the effects felt in several countries. The

transboundary impact may be damage to the natural environment (e.g. algal blooms) and/or

damage to human welfare (e.g. health problems).

In international waters management, transboundary problems can be classified under one

of the following headings:

Box 1 - Common transboundary problems

Major Concern I. Freshwater Flow Modifications

1

Excessive withdrawals of surface and/or groundwater for human uses

2

Changes in freshwater availability

3

Changes in flow regimes from structures

Major Concern II: Pollution

4

Pollution of existing drinking water supplies

5 Microbiological

pollution

6 Nutrient

overenrichment

7 Hydrocarbon

pollution

8

Heavy metal pollution

9 Radionuclide

pollution

10

Suspended solids/accelerated sedimentation

11 Excessive

salinity

12 Thermal

pollution

Major Concern III: Habitat and community modification

13

Loss of ecosystems or ecotones

14

Modification of ecosystems or ecotones

15 Invasive

Species

Major Concern IV: Exploitation of fisheries & other living resources

16 Over-exploitation

17

Excessive bycatch and discards

18

Destructive fishing practices

19

Decreased viability of stocks through contamination and disease

20

Impact on biological and genetic diversity

Major Concern V: Fluctuating Climate

21

Freshwater flow fluctuations such as drought and floods

22

Fluctuating ocean circulation patterns

23

Sea level change (including saltwater intrusion)

Training course on the TDA/SAP approach in the GEF

International Waters Programme

Page 5 of 52

Trainee Manual

Module 3

2.2 The Driver-Pressure-State-Impact-Response (DPSIR)

Framework

A problem can have multiple causes and impacts. This is illustrated in the Driver-

Pressure-State-Impact-Response (DPSIR) framework in Figure 2, below.

SOCIO-ECONOMIC

DRIVERS

· Enhanced food production

via use of fertilisers in

crop production

· Intensification of animal

EXTERNAL VARIABILITY

production resulting in

· The immediate causes

increased animal waste

where these result from,

production

INSTITUTIONAL

or are coupled to natural

processes.

BARRIERS FOR

CHANGE

POLICY RESPONSE

· Inadequate

development

OPTIONS

and/or

ENVIRONMENTAL

· Current and future

enforcement of

PRESSURES

interventions

regulations

· Enhanced nutrient inputs

ENVIRONMENTAL STATE CHANGES

· Decrease in the transparency of water

· Development of anoxic conditions (low

oxygen levels)

· Increased algal blooms

· Loss of habitat (e.g. Sea grass beds)

· Change in dominant biota (e.g. Changes

in plankton and macrophyte community

SOCIO-ECONOMIC

structure or changes in fish composition)

CONSEQUENCES

· Decrease in species diversity

· Change in the aesthetic

value of the water body

· Loss of recreational use

· Changed employment

opportunities

Figure 2 - DPSIR framework for the transboundary problem of eutrophication

In this module we are concerned with two elements in the DPSIR framework, shown in the

diagram as "Environmental State Changes" and "Social and Economic Consequences".

We will call these "Environmental impacts" (or simply "impacts") and "Socio-economic

consequences" (or simply "consequences"), defining these terms as follows:

Environmental impacts

The effects of a transboundary problem on the integrity of an ecosystem.

Socio-economic consequences

Changes in the welfare of people attributable to the problem or its environmental

impacts.

In the eutrophication example, a high concentration of a chemical pollutant might be

detected in a lake, but the question then is: what are the impacts and consequences of this?

An environmental impact might be a reduced fish population. This could mean that the

Training course on the TDA/SAP approach in the GEF

International Waters Programme

Page 6 of 52

Trainee Manual

Module 3

nutrition of people living around the lake suffers, which is an indirect consequence of the

problem. However, there may also be direct consequences, in this case the impact on

health from polluted drinking water.

PROBLEM

ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT

Eutrophication

Reduced fish population

Health impacts from drinking water

Loss of source of food

SOCIO-ECONOMIC CONSEQUENCES

2.3 GEF indicators: How these relate to DPSIR

GEF does not use the DPSIR framework. However, GEF Monitoring and Evaluation

(M&E) indicators can be considered as analogous to this approach.

Three types of monitoring and evaluation indicators have been proposed by GEF:

· process indicators;

· stress reduction indicators; and,

· environmental status indicators.

Process indicators are used to measure progress in project activities. The complex nature

of many GEF international waters projects and the emphasis on collaborative processes in

a TDA followed by reforms and investments to address these priorities in a SAP, all call

for additional process indicators to reflect the extent, quality, and eventual on-the-ground

effectiveness of the multi-country, inter-ministerial, and cross-sectoral efforts that are at

the heart of the GEF international waters approach.

Whereas process indicators relate to needed reforms or programs, Stress Reduction

Indicators indicate the rate of success of specific on-the-ground actions implemented by

the collaborating countries. Often a combination of stress reduction indicators in several

nations may be needed to produce detectable changes in transboundary waters.

It can take a number of years before sufficient stress reduction measures are implemented

in a sufficient number of countries to detect a change in the transboundary water

environment. Environmental Status Indicators are measures of actual success in restoring

or protecting the targeted waterbody.

Training course on the TDA/SAP approach in the GEF

International Waters Programme

Page 7 of 52

Trainee Manual

Module 3

Although serving different purposes, there is a relationship between process indicators,

stress reduction indicators and environmental status indicators on the one hand, and the

components DPSIR. These are shown in Figure 3.

Process

Stress

Reduction

Response

Driver

Impact

Pressure

State

Status

Figure 3 Relationship between GEF M & E indicators and the DPSIR

framework

Although we are using the DPSIR framework to describe aspects of the TDA and SAP, all

GEF projects must adhere to the GEF M&E approach when developing, preparing and

implementing a project.

2.4 The Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis (TDA)

The role of the TDA has been discussed in Module 1 (Overview of the TDA/SAP Process),

but it is worthwhile recalling that its purpose is to identify the relative importance of the

sources and causes of transboundary waters problems. The development of a TDA

followed by the formulation of a Strategic Action Programme (SAP) is a requirement for

most projects proposed for financing in Operational Programmes 8 and 9 of the GEF

International Waters Focal Area.

The TDA is an objective assessment and not a negotiated document. It uses the best

available verified scientific and technical information to examine the state of the

environment and the root causes for its degradation. The analysis is carried out in a cross

sectoral manner, focusing on transboundary problems without ignoring national concerns

and priorities.

Training course on the TDA/SAP approach in the GEF

International Waters Programme

Page 8 of 52

Trainee Manual

Module 3

The TDA is preceded by a full consultation with all stakeholders in the problem, and the

stakeholders are involved throughout the subsequent process (For more information on

stakeholder involvement please refer to Module 6). The key features of a TDA, according

to the GEF M & E Working paper (2002)1 are presented in Box 2, below.

Box 2 - Features of the Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis (TDA)

The process of jointly developing a TDA is important for countries so that they learn to

exchange information and work together. Interministry committees are often

established in each country sharing a water body to provide that country's input of

factual information on the shared basin or marine ecosystem. This helps to determine

the transboundary nature, magnitude, and significance of the various problems

pertaining to water quality, quantity, biology, habitat degradation, or conflict.

After the threat is identified, the countries can determine which problem or problems

are priorities for action, relative to less significant problems and those of solely

national concern. In addition, the root causes of the conflicts or degradation, and

relevant social problems, are also included in the analysis so that actions to address

them may be determined later. The science community from each country is often

involved because the TDA is intended as a factual, technical document, and key

stakeholders are expected to participate. If a stakeholder identification or social

analysis was not done in preparation, it should be included in the TDA process.

This TDA process provides an opportunity for the countries to understand the linkages

among the problems and the root causes of environmental problems in economic

sectors. As a result, more holistic, comprehensive solutions may be identified to

enable responding to many different conventions in a cost-effective manner. The TDA

process allows complex transboundary situations to be broken up into smaller, more

manageable components for action as specific sub-areas of degradation or priority

"hotspots "are geographically identified (with their specific problem and root

cause)within the larger, complex system. Some of these may be deemed high priority;

others may not.

In the case of the large marine ecosystems (LME) component of OP8, it is essential to

examine linkages among coastal zones, LMEs, and their contributing freshwater

basins as part of the TDA process so that necessary linkages to root causes in

upstream basins can be included in the subsequent SAP. In this manner, different

transboundary problems existing in different portions of an LME and its basins or in

large river basins can be managed for the diagnosis of root causes and the

development of geographically specific actions.

This module is concerned with the identification and prioritisation of transboundary

problems and the subsequent analysis of their impacts and consequences but it is important

to be aware of how this fits in with the purpose and nature of the TDA as a whole.

1 Duda, A. (2002) Monitoring and Evaluation Indicators for GEF International Waters Projects, M & E

Working Paper 10, GEF, Washington, USA.

Training course on the TDA/SAP approach in the GEF

International Waters Programme

Page 9 of 52

Trainee Manual

Module 3

The methodology for a TDA consists of the following steps (also outlined in Figure 1,

above):

· Identification and initial prioritisation of transboundary problems (often termed

Scaling Scoping Screening)

· Gathering and interpreting information on environmental impacts and socio-

economic consequences of each problem

· Final prioritisation of transboundary problems

· Causal chain analysis (including root causes)

· Completion of an analysis of institutions, laws, policies and projected investments

The development of the TDA is the job of the Technical Task Team (TTT), coordinated by

the Project Manager (PM). Remember that the TTT is formed of technical experts from

the stakeholder organizations, augmented with additional external specialists as necessary.

The three steps that you will study in this module are briefly described below.

2.4.1 Identification and initial prioritisation of transboundary problems

The main analytical and diagnostic work has often been called Scaling Scoping

Screening. This means that the scale (or timescale and geographical area) of each problem,

and its scope (magnitude) must be determined, and then the problems must be screened to

sort out those of high priority from the low.

The initial stakeholder consultation will have already highlighted the main problems, but it

is important for the TTT to revisit them, agree on whether or not the list is complete,

examine their transboundary relevance, determine preliminary priorities and examine the

scope of each.

The initial prioritisation does not need to be a complex one. To prioritise, ranking criteria

have to be established. Criteria will generally include some assessment of the severity of

the problem in terms of its impacts. In addition, criteria may be included to reflect:

a. the level and nature of uncertainties

b. likely future developments.

The significance of future developments is that currently or historically observed impacts

of the problem may not be a useful guide to the future position.

The ranking of problems may be conducted simply by discussion among stakeholders

and/or technical experts, at both national and regional levels. Alternatively, a uniform

scoring system may be involved.

Training course on the TDA/SAP approach in the GEF

International Waters Programme

Page 10 of 52

Trainee Manual

Module 3

An advantage of using a scoring system is that it is more formal, and can be used

consistently at both national and regional level. The national scores can be aggregated to

reveal national priorities at one level, and regional priorities at the other.

2.4.2 Analysis of environmental impacts and socio-economic consequences

The environmental impacts and socio-economic consequences of the relevant

transboundary problems should also be identified. Much of this information should arise

from the stakeholder consultation process since stakeholders may identify impacts or

consequences and it is on this basis that problems are identified. However, the TTT must

ensure that the entire range of impacts and consequences are identified, and this may

require additional research.

2.4.3 Final prioritisation of transboundary problems

After the completion of the analysis of impacts/consequences, a final prioritisation should

be carried out. Final prioritisation is vital since it ensures that the causal chain analysis

concentrates on those problems that are the most significant to stakeholders and represent

the best investment of their resources.

2.5 Risk of Confusion

It is important not to confuse the problem identified with the causes or the impacts of the

problem. This can cause difficulty when carrying out the impact and causal chain analysis.

For example, a cause of eutrophication could be inadequate infrastructure capacity.

Eutrophication can result in harmful algal blooms (an environmental impact) and

diminished amenity (a socio-economic consequence).

If you examine the Case Studies in Boxes 4 to 9 below, you will see that there are

examples of where the confusion between problem, causes and impacts has occurred.

Another common difficulty is the interchangeability of terms. For example, we use the

term transboundary `problem'. However, you will see the use of other terms including

transboundary problem, environmental concern, perceived major problem, and major

threat, amongst others. These are also highlighted in Boxes 4 to 9.

Whatever terminology is used, it must be fully explained and understood by the TTT from

the start and be satisfactorily described in the TDA.

Training course on the TDA/SAP approach in the GEF

International Waters Programme

Page 11 of 52

Trainee Manual

Module 3

Self-assessment Test 3.1

1. Who carries out the TDA fact-finding?

2. Who are the people that are consulted?

3. Match the three words on the left with the three four definitions on the right (one of

these is false), by drawing lines connecting them.

A. Screening

1. Determining the magnitude of a problem.

2. Determining the time-scale and

geographical area of an problem

B.

Scaling

3. Examining the resources needed to

resolve an problem

C. Scoping

4. Sorting out the priority of problems.

4. State in one sentence what is the TDA step before the prioritization of problems?

5. State in one sentence what is the TDA step after prioritisation of problems?

Correct answers are given in the pink pages

at the end of this module.

Training course on the TDA/SAP approach in the GEF

International Waters Programme

Page 12 of 52

Trainee Manual

Module 3

3. Initial TDA preparation, and identification and

prioritisation of transboundary problems

3.1 Information and data stock taking exercise

There is often a wealth of information and data available. However, it generally comes

from multiple sources, its generation and use is often uncoordinated, and it is frequently

neither accessible nor entirely appropriate. Therefore, prior to developing the TDA, a

simple information and data `stock taking' exercise should be initiated (often termed a

meta data study). This will ascertain the sources of information/data, its availability and

gaps in knowledge.

The TDA should employ information that is already available within the region.

It is not the intention of the TDA to repeat the valuable

studies already conducted on environmental impacts and

socio-economic consequences merely to assemble them

in a more holistic manner.

Often it will be necessary to rely on measurement data which will have already been

collected at a national rather than a regional level. As consequence of this, aggregation

and disaggregation of information and data will be required. Full recognition should be

given to all sources of information employed.

The members of the TTT and Interministry Committees (IMCs) will generally be aware of

the sources of information that are available in their respective countries, but you will need

to confirm that all the following sources have been checked for relevant data:

National and Provincial Government departments and agencies

· departments of the environment, health , employment

· departments of trade or economic affairs responsible for monitoring and/or

forecasting economic activity;

· environmental protection agencies;

· marine organisations, water authorities and fisheries organisations.

International Organisations

· UNDP, UNEP, UNIDO programmes and projects (GIWA);

· EU INTAS programmes and projects.

Non-Governmental Organisations (NGO's) concerned with, for example

· general environmental preservation, protection of endangered species;

· human health and welfare

· security of freshwater supplies, poverty alleviation.

Training course on the TDA/SAP approach in the GEF

International Waters Programme

Page 13 of 52

Trainee Manual

Module 3

Commercial Consultancies, Companies and Trade Bodies, including Trade Unions that

have a commercial interest in the area under study (this information may not be freely

available if it is considered commercially sensitive).

Academic Institutions

· university research, local, national and foreign

· publications that can be searched for with a standard bibliographic database;

· regional research institutes.

In some instances it may be prudent to prepare Country

Reports prior to the development of the TDA. This material

can then be used as the backbone of the final TDA document.

3.2 Identification of Transboundary Problems

The first stage in the TDA process is to agree on the transboundary problems. The initial

stakeholder consultation will have already highlighted the main problems but the TTT

must revisit them, agree on whether the list is complete, and for each problem reach a view

on:

·

What is the transboundary relevance?

·

What are preliminary priorities?

·

What is the geographical scope?

·

What is the temporal scope?

·

What are the impacts/consequences of the problem?

The experts should brainstorm the list of problems with particular regard to their

transboundary status, and assign priorities (high-medium-low) from an environmental and

social/economic standpoint. The geographical extent of the problems associated with each

problem can then be stated and described on a map.

The initial meeting of the TTT also serves as an agenda-setting exercise. The expertise

needed for the subsequent stages can be discussed, as well as the availability of

information.

Agreement on a preliminary contents page for a TDA is a useful means of ensuring that

the entire process has been thoroughly discussed.

The identification of problems is a crucial part of the TDA process since those that are not

brought to light at this stage may not be captured at a later stage. The difficulty and effort

involved in this initial stage will vary widely depending on the particular circumstances of

the region. Generally, the key determinants are likely to be the extent to which:

Training course on the TDA/SAP approach in the GEF

International Waters Programme

Page 14 of 52

Trainee Manual

Module 3

· potential transboundary problems have been the subject of scientific research:

- at the national level

- at the level of the water body

· environmental problems have already been recognised as essentially

transboundary in nature (particularly where supra-national/regional bodies have

been involved in investigating such problems).

For example, the identification of problems in the Mediterranean TDA was based on a

review of some 20 year's work under the auspices of the Mediterranean Action Plan

(MAP). In other cases, such as the Volta River Basin, international meetings were

conducted in order to discuss the problems identified at the national level and establish

those of common concern. Some further key points to consider when identifying and

prioritising transboundary problems are highlighted in Box 3, below.

Box 3 - Some Key Points:

· In the absence of some pre-existing body of research or a relevant

supra-national body, a structured TDA/SAP process is necessary to

identify potentially relevant problems and then subject these to review

by an international panel of experts.

· The initial identification of potential problems is commonly undertaken

at the national level by stakeholder consultation including convening

meetings of relevant experts. The reports of these bodies are then

discussed at international gatherings to decide on which problems

should be treated as transboundary in nature.

· Identification of a transboundary problem entails more than simply

defining the problem its geographic extent and possible causes

should be specified at this stage. The latter information is significant

because there must be agreement that there is a traceable human

cause that is susceptible to intervention. Further, this initial information

will be important when carrying out causal chain analysis (Module 4).

3.2.1 Examples of transboundary problems

Transboundary problems will vary from region to region. As a possible starting point for

your TDA, you may be interested to look at the generic list of transboundary problems

shown in Box 1, above.

There have been a number of different approaches used to determine transboundary water

problems. A summary of those developed for the Case Studies are presented in the

following boxes.

Training course on the TDA/SAP approach in the GEF

International Waters Programme

Page 15 of 52

Trainee Manual

Module 3

Box 4 - The Dnipro Basin TDA

Major Transboundary problems

· Modification of hydrological regime

· Changes in the water table

· Flooding and elevated ground and surface waters and elevated groundwater

levels in various parts of the Basin

· Chemical

pollution

· Microbiological

pollution

· Pollution by radionuclides

· Suspended

solids

· Eutrophication

· Solid

waste

· Accidental spills and releases

· Loss/modification of ecosystems or ecotones and decreased viability of

stocks due to contamination and diseases

· Impact on biological and genetic diversity

Box 5 - The Mediterranean Sea TDA

Existing problems/problems

·

Degradation of coastal and marine ecosystems

·

Unsustainable exploitation of coastal and marine resources

·

Loss of habitats supporting living resources

·

Decline in biodiversity, loss of endangered species and introduction of

non-indigenous species

·

Inadequate protection of the coastal zone and marine environment and

increased hazards and risks

·

Worsened human related conditions

·

Inadequate implementation of existing regional and national legislation

Training course on the TDA/SAP approach in the GEF

International Waters Programme

Page 16 of 52

Trainee Manual

Module 3

Box 6 - The Benguela Current TDA

Perceived Major Problems:

· Decline in Benguela Current LME commercial fish stocks and non-optimal

harvesting of living resources

· Uncertainty regarding ecosystem status and yields in a highly variable

environment

· Deterioration in water quality - chronic and catastrophic

· Habitat destruction and alteration, including inter alia modification of seabed

and coastal zone and degradation of coastscapes

· Loss of biotic integrity (changes in community composition, species and

diversity, introduction of alien species, etc.) and threat to

biodiversity/endangered and vulnerable species

· Inadequate human and infrastructure capacity to assess the health of the

ecosystem as a whole (resources and environment, and variability thereof)

· Harmful algal blooms (HABs)

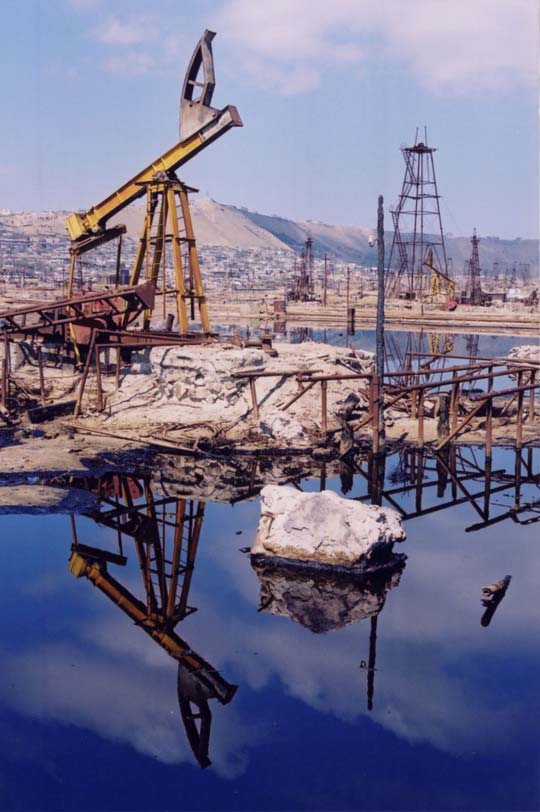

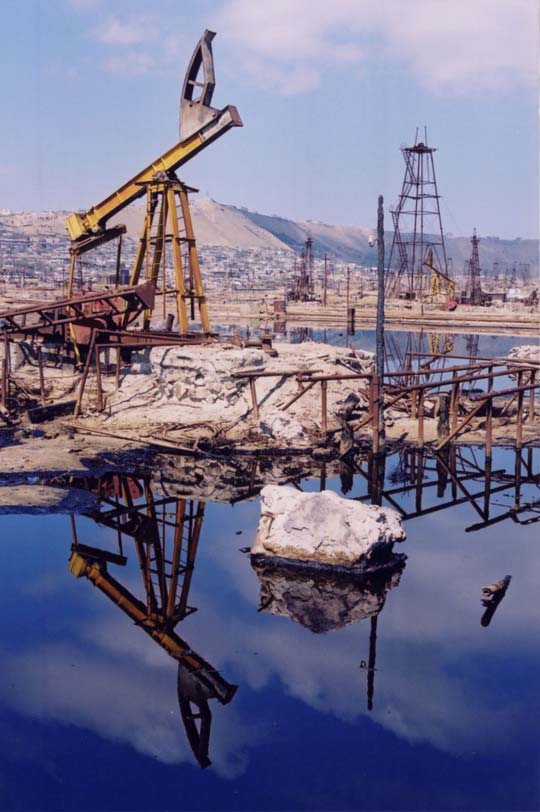

Box 7 - The Caspian Sea major perceived problems and problems

(MPPI)

Existing problems/problems

· Decline in certain commercial fish stocks, including sturgeon

· Degradation of coastal landscapes and damage to coastal habitats

· Threats to Biodiversity

· Overall decline in environmental quality

· Decline in human health

· Damage to coastal infrastructure and amenities

Emerging problems/problems

· Contamination from oil and gas activities

· Introduced

species

Training course on the TDA/SAP approach in the GEF

International Waters Programme

Page 17 of 52

Trainee Manual

Module 3

Box 8 - The Bermejo River TDA

Environmental problems:

· Soil

degradation

· Water scarcity and use Restrictions

· Water

Resource

Degradation

· Loss of Biodiversity And Biotic Resources

· Floods and Other Natural Hazard Events

· Diminished Quality of Life and Endangered Cultural Re-sources

Box 9 - Lake Tanganyika TDA

Main threats:

· Unsustainable

Fisheries

· Increasing

Pollution

· Excessive

Sedimentation

· Habitat

Destruction

You should next carry out the tasks in Case-study

Exercise 3.1.

The case-studies are contained on the Course CD-

ROM

You should set aside a substantial amount of time for

these tasks, and you may want to discuss your

conclusions with your colleagues and the tutor.

Short answers only are given in the Correct Answer

section on the pink pages.

Training course on the TDA/SAP approach in the GEF

International Waters Programme

Page 18 of 52

Trainee Manual

Module 3

Exercise 3.1 Case Study Questions on Identification of

Transboundary Problems

A.

The Caspian Sea, Benguela Current, and Bermejo River

Please examine these Case Studies and consider how systematic you find each,

as regards the distinction between problems, causes and impacts.

B.

The Mediterranean Sea

The aim of this 1997 TDA was to identify the perceived problems and problems

associated with land-based activities affecting the Mediterranean Sea.

On Page 7 of the TDA, the major perceived problems were:

1. Degradation of coastal and marine ecosystems

2. Unsustainable exploitation of coastal and marine resources

3. Loss of habitats supporting living resources

4. Decline in biodiversity, loss of endangered species and introduction of non-

indigenous species

5. Inadequate protection of the coastal zone and marine environment and

increased hazards and risks

6. Worsened human related conditions

7. Inadequate implementation of existing regional and national legislation

Questions

1. Is there consistency in the terminology used? Is there consistency between the

perceived major problems in Table 1.1 and the Tables identifying the Problems

and Root Causes (pp 13-33)?

2. Regarding the identification of transboundary problems, do you feel the 2003

Mediterranean TDA is an improvement on the 1997 TDA? Why?

Training course on the TDA/SAP approach in the GEF

International Waters Programme

Page 19 of 52

Trainee Manual

Module 3

C.

The Caspian Sea

In the Caspian Sea TDA, problems were initially prioritised by the expert TTT and

subsequently re-analysed by a more inclusive stakeholder group who ranked the

concerns as low, medium or high priority (pp. 52-58 and Table 2.2).

The following are a list of the major perceived problems and problems in the Caspian

Sea. It includes six existing problems/problems, and two emerging

problems/problems:

Existing problems/problems

1. Decline in certain commercial fish stocks, including sturgeon

2. Degradation of coastal landscapes and damage to coastal habitats

3. Threats to Biodiversity

4. Overall decline in environmental quality

5. Decline in human health

6. Damage to coastal infrastructure and amenities

Emerging problems/problems

1. Contamination from oil and gas activities

2. Introduced species

Questions

1. Do you feel that the prioritised problems are problems or the immediate causes of

specific problems? Does this matter?

2. In your opinion, was the initial prioritisation by the TTT and the subsequent ranking

by the stakeholder group an effective approach?

After you have checked your answers and discussed

them with the tutor, you might like to take a break before

moving on to the next section the Criteria for

Prioritisation.

Training course on the TDA/SAP approach in the GEF

International Waters Programme

Page 20 of 52

Trainee Manual

Module 3

3.3 Initial prioritisation of transboundary problems

You will recall that the objective of prioritising transboundary problems is to rank them

according to their "importance" - broadly meaning those problems most worthy of

attention. This ensures that limited resources are applied to yield the greatest benefits.

Resources (time, expertise and finance) are limited in two senses:

· the resources that can be devoted to the TDA process and the subsequent

preparation of the SAP

· those that can be applied in implementing the SAP.

The second constraint is the more important, because even if there were resources available

to conduct the TDA/SAP process, it would still be necessary to decide which of the

proposals in the SAP should be implemented first.

It will not always be possible to produce a strict ordering of the problems. There may be

problems considered of equal importance, or there may be so much uncertainty that the

ordering is unreliable. It is not essential to aim for a "perfect" strict ordering. The

important thing is to distinguish those problems that should be considered further in the

TDA from those that need not.

For the purpose of the initial prioritisation, the problems need to be assessed by reference

to criteria - features of a problem that contribute to its relative importance.

For example, one criterion might be the severity of environmental impacts, in terms of the

extent of disturbance from the "natural" level and its geographical spread. In this case,

each problem would need to be assessed against this criterion. If this were the only

criterion, the problems could be ranked according to the depth and geographical extent of

their environmental impacts.

There is no single set of criteria that should be employed in every TDA. Each TDA will be

different. Similarly, the importance given to each criterion will vary, depending on the

views of those doing the prioritisation. For example, how one type of environmental

impact should be judged against another, or how environmental impacts should be judged

against their socio-economic consequences.

The remainder of this section describes criteria that would generally be considered relevant

and how they might be balanced off against each other in assessing the importance of a

problem.

Figure 4 illustrates how prioritisation can be carried out at several alternative levels:

- Using a simple set of general criteria for all problems (indicated by the dotted red

line). This approach is described in 3.3.1 below.

Training course on the TDA/SAP approach in the GEF

International Waters Programme

Page 21 of 52

Trainee Manual

Module 3

- Based on criteria which assess the severity of the environmental impacts and the

socio-economic consequences of a particular problem (the black line). See 3.3.2 and

3.3.3 below.

- In addition, considering other prioritisation criteria future severity, uncertainty and

feasibility (the blue line). See 3.3.4 below.

Prioritisation

criteria

Environmental

impacts

Current

severity

of issue

Socio-economic

consequences

Assessment of

issue

Importance

of issue

Future severity of issue

Uncertainties related to the

issue

Feasibility of solutions

Overall

Figure 4 Illustration of the different levels of prioritisation

The use of simple transboundary problem based

prioritisation criteria is ideal for the initial prioritisation

process. However, the TTT experts must have substantial

knowledge and experience in all the problems. It also

requires a very experienced chairperson.

Criteria which assess the severity of the environmental

impacts and the socio-economic consequences of a

particular problem can be used to initially prioritise

transboundary problems. However, it is likely that these

approaches are more applicable to the final prioritisation

step once the impacts for each problem have been

ascertained.

Training course on the TDA/SAP approach in the GEF

International Waters Programme

Page 22 of 52

Trainee Manual

Module 3

3.3.1 Prioritisation criteria: problem-based

Assessment of the severity of a problem does not have to be detailed or exhaustive; the

level of detail required is only such as to enable distinctions to be drawn between

problems. But the breadth of impacts and consequences of each problem must be

recognised and considered in each country.

Prioritisation carried out at the problem level is the simplest approach but it requires that

the experts have substantial knowledge and experience in all the problems. It also requires

a very experienced chairperson.

A simple set of criteria for determining priority problems are:

1. Transboundary nature of a problem.

2. Scale of impacts of a problem on economic terms, the environment and human

health.

3. Relevance of a problem from the perspective of national priorities reflected in

existing national policies and action plans, and international conventions.

4. Scope of the systemic relationship with other environmental problems and

economic sectors.

5. Expected multiple benefits that might be achieved by addressing a problem.

6. Lack of perceived progress in addressing/solving a problem at the national level.

7. Recognised multi-country water conflicts.

8. Reversibility/irreversibility of the problem

9. Relationship of problem to Millennium Goals and World Summit on

Sustainability Development (WSSD) Targets.

Each transboundary problem can then be assigned a score (e.g. between 0 and 3) on the

basis of its severity

3.3.2 Prioritisation criteria: Environmental impacts

This approach uses pre-defined, culturally unbiased, uniform criteria which assess whether

a specific problem causes: no known impact, slight impact, moderate impact or severe

impact.

Each problem can then be assigned a score between 0 and 3. Scoring is dealt with in the

next section.

An example of environmental impact criteria for chemical pollution is shown on the next

page. A full set of problem-specific criteria developed for the GIWA can be found in the

supporting materials for this module. However, it should be noted that these criteria are

not definitive, because the particular circumstances of each TDA will dictate the type of

criteria that are relevant.

Training course on the TDA/SAP approach in the GEF

International Waters Programme

Page 23 of 52

Trainee Manual

Module 3

Score

No observed impact

0

Slight 1

Moderate 2

Severe 3

Definition: Chemical pollution refers to the adverse effects of chemical contaminants

released to standing or marine water bodies as a result of human activities. Chemical

contaminants are here defined as compounds that are toxic and/or persistent and/or

bioaccumulating

Score 2 = Moderate Impact when one or more of the following criteria are met or exceeded

Chemical contaminants are above the threshold limits defined for

LEVELS

the country or region (e.g. by a regional or national Commission).

Large area advisories by public health authorities concerning

PROXIES

fisheries product contamination but without associated catch

restrictions or closures, OR

EFFECTS

High mortalities of aquatic species near outfalls.

If there is no available data use the following criteria:

PRESSURES

- Large-scale use of pesticides in agriculture and forestry; or

- Presence of major sources of PCDD/PCDF such as large

municipal or industrial incinerators or large Bleached Kraft Pulp

Mills using chlorine as a bleaching agent; or

- Considerable quantities of other contaminants described in the

UNEP GPA.

Figure 5 - Example of criteria used for assigning scores: Chemical Pollution

Training course on the TDA/SAP approach in the GEF

International Waters Programme

Page 24 of 52

Trainee Manual

Module 3

3.3.3 Prioritisation criteria: Socio-economic consequences

There is a vast range of possible socio-economic consequences, all of which must be

recognised if the analysis is to be complete. A useful framework is based on the idea that

the individual's welfare is built on three types of values for the natural environment:

·

Use value

·

Non-use value

·

Bequest value

These are described in Table 1, below. Generally, most socio-economic consequences will

fall into the use value category, although they may not necessarily be the most important.

Table 1 - Types of value for the natural environment

Use value

The environment provides resources and services that people use to

support their welfare. For example, water bodies might provide:

· freshwater for human consumption or for use in agriculture or

industry,

· sources of food for local consumption or trade,

· recreational activities etc.

Degradation of the environment can therefore impair these uses.

In assessing the impact, many indirect consequences may need to be

taken into account. For example, there may be profound effects on social

structures because of changes in employment patterns and population

distributions.

In extreme cases, communities may disappear because of large scale

movements of human population.

Non-use value

Whether or not the water body currently has direct human uses, it may

(sometimes

have non-use value. This might stem from preserving the option of future

called passive

use, or simply because people want to feel that the environment is as

use or

undisturbed or as near-natural as possible (so-called existence value).

existence)

Existence value may also arise from a cultural significance attached to the

water body and its ecosystems or particular species. While loss of

biodiversity can have effects on use value in the long-term, its impact in

the shorter term may be a loss of existence value for people.

Bequest value

Bequest value stems from the concept of stewardship: leaving the

environment intact for future generations. Bequest value can have use

and non-use components, but for convenience here it is dealt with as part

of non-use value.

Training course on the TDA/SAP approach in the GEF

International Waters Programme

Page 25 of 52

Trainee Manual

Module 3

The procedure for assessing the severity of each transboundary problems socio-economic

consequences is the same as that for environmental effects.

Again, the consequences of each problem have to be recognised and considered in each

country. It is generally worthwhile for country teams to agree at the outset a list of

potential consequences for each problem. Some consequences may be irrelevant in a given

country but at least this ensures that they have been considered.

Table 2 - Types of criteria for assessing severity of problems

Value

Types of Use

Types of Criteria for Assessing Severity of problems

Use

Direct consumption Extent of health impacts.

by local people

Freshwater availability for human consumption.

Food availability for human consumption.

Loss of recreation opportunities.

Loss of aesthetic value (if sight or smell of water or the water

body itself become unpleasant).

Production

Freshwater availability for use in agriculture or industry.

activities

Loss of tradable commodities (e.g. fish) that can be

sustainably harvested.

Loss of tourism activity.

Indirect uses

Negative social changes associated with the impairment or

loss of above direct uses, e.g. unemployment, collapse of

local economy, enforced migrations, loss of local self-

sufficiency.

Loss of educational and scientific values.

Nonuse/

Loss of potential uses, e.g. future development of commercial

Bequest

fishery or exploitation of pharmaceutical resources.

Loss of symbolic or cultural value associated with ecosystem

integrity or particular species.

Each of the above types of criteria can be broken down into specific criteria. For example:

Health impacts:

- Increases in the prevalence of illnesses

- The extent to which the specified problem contributes to deaths over a

particular period

- The costs of treatment

Training course on the TDA/SAP approach in the GEF

International Waters Programme

Page 26 of 52

Trainee Manual

Module 3

Freshwater availability

- In literal terms (how often and for how many people is supply impaired or

lost)

- Costs that have to be incurred in countering the problem, e.g. additional

water treatment costs.

When assessing the problems against the criteria, several dimensions of socio-economic

consequences have to be taken into account

Depth of impact How major is the impact of the problem for individuals? For

example, in terms of health impacts, does the problem cause a mild/treatable

infection that passes quickly, or are its effects generally associated with death?

Affected population How many people suffer the consequences connected with

the problem? For example, are the consequences concentrated in a small areas with

a relatively small total population, or are they felt over a wide area by the majority

of the population dwelling near the water body?

Timing How often and for how long are the consequences felt? For example, do

the health impacts of a problem occur rarely and last a short time, or do they occur

frequently and persist

3.3.4 Other prioritisation criteria

The criteria for environmental impacts and socio-economic consequences focus on the

observed position, and thus address the current severity of the problem. Other criteria

should also be considered since they contribute to the overall objective of prioritisation

ensuring resources are focused where they can do most good.

Three considered below are:

-

Likely Future Severity

-

Uncertainty

-

Feasibility

Likely Future Severity

Problems that are currently having little impact may become very important in the future,

or vice versa. This should be taken into account; otherwise resources could be devoted to

resolving a problem that is not of the highest priority, particularly during the lengthy

period over which the SAP may be implemented.

Assessing "likely future severity" relies on judgement, but the following approach

described in Box 10 can make the outcome more rational and reliable.

Training course on the TDA/SAP approach in the GEF

International Waters Programme

Page 27 of 52

Trainee Manual

Module 3

Box 10 Approach for assessing "likely future severity"

1. Time horizon

A date in the future, at which the forecast is to apply, should be specified. This should be far

enough into the future that there is time for the current position to radically change, but not

so far that it becomes infeasible to have any realistic idea what conditions might be at that

time. 20 years into the future might generally be considered reasonable. But there is no

hard and fast rule.

2. Definition of "most likely" scenario

a. Often many different scenarios can be envisaged. It would be very complex to

assign probabilities to each possible scenario and calculate an expected value for

the prioritisation criteria, and this would not necessarily yield more reliable results.

Therefore, the "most likely" scenario should be selected as the context for

assessing future severity. This is the scenario which stakeholders feel is the most

probable to apply at the specified time horizon.

b. Characterization of scenarios: The range of features that could be used to

characterize a future scenario is vast. To make the assessment task more

manageable, it should be restricted to those features that are likely to be the most

salient. Generally, these will include:

·

the size of the population living in proximity to the water body and its physical

distribution (note, concentrated centres of population may put more pressure

on the environment than a more even distribution)

·

utilization of the water body resources in production activities both as a

"source" (e.g. of freshwater, food, minerals etc.) and as a "sink" (i.e. as a

means of disposing of waste)

·

technological changes from the present day that will reduce (or perhaps

increase) environmental degradation attributable to direct usage by the

population and production activities

·

policy changes that would arise regardless of the TDA/SAP process (e.g.

there may already be a commitment by countries concerned with the water

body to cooperate in reducing pressures on fisheries through a long-term

quota system).

3. Standard Criteria

To simplify the process as far as possible, the same criteria are used for assessing severity

at the time horizon as are used in assessing current severity.

Training course on the TDA/SAP approach in the GEF

International Waters Programme

Page 28 of 52

Trainee Manual

Module 3

When assessing future severity the fundamental question that should be addressed to the

TTT is:

"If we were undertaking the assessment of severity:

·

at the specified time in the future, and

·

assuming the most likely scenario existed at that time,

·

what would our assessment of severity be, using the

criteria we have used to assess current severity? "

Once this exercise has been undertaken, it is possible to arrive at a ranking of problems for

the future that can be compared to the current ranking. Where the ranking is radically

different then some method has to be agreed for deciding how the two types of information

should be weighted in arriving at the final assessment. This is discussed further in the next

sub-section on prioritisation methods.

If the TTT find it impossible to reach any consensus on "likely future severity", then an

alternative approach is to consider "likely changes in severity" over the period specified.

Again the concepts of the "most likely scenario" should be applied, but now it is only

necessary to consider whether the current severity will increase or diminish.

Uncertainty

With a reasonable level of data and experience, the TTT should be able to arrive at an

adequate preliminary judgement. But in some cases an additional criterion of uncertainty

may need to be introduced to reflect some shortfall in information available. For example,

it may be suspected that some form of pollution is connected with a health impact but data

may not have been collected for long enough to assess current severity with any

confidence.

What effect uncertainty has on the prioritisation process will depend on the nature of the

impacts. This can work both ways. For example, if the health impact is of relatively minor

severity (e.g. the symptoms are not incapacitating and the illness is of short duration) then a

high level of uncertainty may be argued to diminish the importance that should be attached

to the relevant problem. Conversely, if the health impact is death, then a high level of

uncertainty arguably increases the importance of the problem.

This sort of complication means that a criterion of uncertainty should be introduced at this

stage only where it is essential because of shortage of information. It will also be

necessary to establish how uncertainty is interpreted in the prioritisation process.

Feasibility

Finally, the feasibility of a solution to a problem (in other words the tractability of the

problem) may be used as a criterion.

Training course on the TDA/SAP approach in the GEF

International Waters Programme

Page 29 of 52

Trainee Manual

Module 3

Strictly, this factor is not relevant until later stages in the TDA/SAP process, when the

feasibility of the options for addressing a problem are considered. However, in certain

circumstances, the TTT may feel a problem (or problems) will be so difficult to tackle that

further consideration is not worthwhile.

When this happens, then the ranking both with and without this criterion should be

reported. This enables users of the TDA to make their own judgement as to whether the

question of feasibility should be pursued further, depending on the relative importance of

the problems.

3.3.5 Approaches Used to Prioritise Problems

Conducting a Simple `Delphi' Exercise

As has already been mentioned, the process of determining preliminary priorities does not

need to be complex. A powerful, iterative and structured survey approach that can be

employed to aid in this process is the `Delphi' exercise. This is described in more detail in

Box 11 below.

Scoring approaches

There are a number of different approaches that can be used to score the relative

importance or priority of transboundary problems. Whatever approach is used, it must be

applied in a systematic manner.

A simple approach that has been applied in a number of IW projects (e.g. Dnipro Basin

TDA and GIWA) uses a 4 point scoring system. The scoring could relate to impact (e.g. 0

= no observed impact; 3 = severe impact) or priority (e.g. 0 = little or no priority; 3 = high

priority). This will depend on the criteria system used (see Sections 3.3.1 to 3.3.4, above).

Prioritisation of Problems in the Case Studies

You may now want to look at the case-studies to see what approaches they used.

In the Dnipro Basin TDA an approach was used that was similar to the Delphi exercise

described above.

You do not need to study the Dnipro Basin TDA at this point,

because it is used in the Case-Study Exercise 3.2 soon.

An alternative approach was used by the Caspian Sea TDA. In this, problems were

initially prioritised by the expert TTT and subsequently re-analysed by a more inclusive

stakeholder group who ranked the concerns as low, medium or high priority.

Training course on the TDA/SAP approach in the GEF

International Waters Programme

Page 30 of 52

Trainee Manual

Module 3

Box 11 What is a Delphi Exercise?

Description

The objective is the creative exploration of ideas to produce suitable information for decision making. The

Delphi Method is based on a structured process for collecting and distilling knowledge from a group of

experts by means of a series of questionnaires interspersed with controlled opinion feedback. The main

advantage of the Delphi method is that it overcomes the problems of conventional committee action. The

group interaction in Delphi is anonymous: comments, forecasts, and the like are not identified as to their

originator, but are presented to the group in such a way as to suppress any identification. An excellent tool

for gaining input from recognised sources of expertise, without the need for face to face meetings. It

provides a highly disciplined way of addressing or solving a problem. It can be time consuming and the

information gained is only as good as the selection of the experts.

Method

1. Pick a facilitation leader

2. Select a panel of experts (the TTT)

3.

Identify a "straw man" problem list from the panel

In a brainstorming session, draft a list of problems that all think appropriate to the region. Include in this

the inputs from the stakeholder analysis. At this point, there is no "correct" criteria.

4.

The panel ranks the problems

For each problem, the panel ranks it as 3 (high priority), 2 (medium priority), or 1 (low priority) according

to criteria defined prior to the meeting. Each panellist ranks the list individually and anonymously if the

environment is charged politically or emotionally.

5. Calculate the median values and standard deviations

For each problem, find the median value and standard deviations. Place the problems in rank order and

show the (anonymous) results to the panel. Discuss reasons for problems with high standard

deviations. The panel may insert removed problems back into the list after discussion.

6. Re-rank the problems

Repeat the ranking process among the panellists until the results stabilize. The ranking results do not

have to have complete agreement, but a consensus such that the all can live with the outcome. Two

passes are often enough, but four are frequently performed for maximum benefit. In one variation,

general input is allowed after the second ranking in hopes that more information from outsiders will

introduce new ideas or new criteria, or improve the list.

Outcomes

The outcome of a Delphi sequence is nothing but opinion. The results of the sequence are only as valid as

the opinions of the experts who made up the panel. The panel viewpoint is summarized statistically rather

than in terms of a majority vote.

Difficulties faced

On the surface, Delphi seems like a very simple concept that can easily be employed. Because of this, it is

tempting to use the procedure without carefully considering the problems involved in carrying out such an

exercise.

Some of the common reasons for the failure of a Delphi are:

· Imposing view's and preconceptions of a problem upon the respondent group by overspecifying

the structure of the Delphi and not allowing for the contribution of other perspectives related to the

problem

· Assuming that Delphi can be a surrogate for all other human communications in a given situation

· Poor techniques of summarising and presenting the group response and ensuring common

interpretations of the evaluation scales utilized in the exercise

· Ignoring and not exploring disagreements, so that discouraged dissenters drop out and an artificial

consensus is generated

Training course on the TDA/SAP approach in the GEF

International Waters Programme

Page 31 of 52

Trainee Manual

Module 3

Prioritisation of problems was not carried out in the Benguela Current LME TDA (or the

Black Sea TDA from which the methodology was developed). The principal problems

were highlighted at the first regional workshop, backed up through a suite of Thematic

Reports subsequently prepared by regional/international experts and finally synthesised

and condensed into a series of analytical tables which were ultimately presented in the

TDA document. This TDA presented 3 main over-arching problems and 7 sub-problems.

Lake Tanganyika TDA was also based closely on the analysis used in the Black Sea

TDA, although the specific problems were ranked (low, medium or high) according to the

severity of problem, the feasibility of the potential solutions and any additional benefits

gained.

The 1997 Mediterranean TDA lists 7 main problems but does not prioritise them. In

contrast, the 2003 Mediterranean TDA examines a range of environmental, human health

and socio-economic problems that relate specifically to transboundary pollution from land

based sources. The impacts of each problem were scored between 0 and 3 (not known,

slight, moderate and severe impact). In addition, transboundary impacts were highlighted.

In the South China Sea TDA 4 major concerns and 15 principle problems were defined

prior to the development of the national reports However, after submission and evaluation

of the national reports the concerns and problems were prioritised and weighted at a second

meeting of the national coordinators at which leading scientists from the region were also

invited. The prioritisation and weighting exercise was based on the data, information and

evidence assembled during the preparation of the national reports (including causal chain

analysis).

Training course on the TDA/SAP approach in the GEF

International Waters Programme

Page 32 of 52

Trainee Manual

Module 3

Exercise 3.2 - Case Study on Prioritisation Criteria

The Dnipro Basin TDA

Background

The Dnipro Basin TDA was based on a modified version of the GIWA methodology. It

used information already gathered and drafted by the TDA authors/expert groups drawn

from the Thematic Centres.

A simple prioritisation exercise was carried out in order to determine the severity of

the environmental and socio-economic effects of the 12 Dnipro Basin problems, and also

to determine the relevance and transboundary nature of each problem. Each

transboundary problem was scored by the TTT on a scale of 0 (no impact) to 3 (severe

impact) for both environmental impacts and socio-economic effects. The level of

prioritisation was assessed based on the median response. Although not strictly using

the Delphi approach, voting was done using a `secret ballot' and discussed in an open

plenary session.

The outcome of this exercise was a prioritised list of 6 transboundary problems that

required more detailed impact and causal chain analysis. A suite of criteria, listed on p.

52, were used to prioritise 6 major transboundary problems in the Basin:

1.

Chemical pollution (Priority A)

2.

Loss/modification of ecosystems or ecotones and decreased viability of stocks

due to contamination and diseases (Priority A)

3.

Eutrophication (Priority A)

4.

Radionuclide pollution (Priority A)

5.

Modification of the hydrological regime (Priority B)

6.

Flooding events and elevated groundwater levels (Priority B)

Priority A problems are those with an environmental and/or socio-economic impact score

of 3. Priority B problems are those that scored less than 3 for either environmental

and/or socio-economic impacts.

Your task is to review the priority transboundary problems in Chapter 4 (pp. 52-53 and

p. 110) and the text describing the environmental impacts of each problem (e.g. chemical

pollution p. 73) and then consider the questions on the next page.

Training course on the TDA/SAP approach in the GEF

International Waters Programme

Page 33 of 52

Trainee Manual

Module 3

Exercise 3.2 (continued)

Questions

Please make short notes in answer to each of the following questions, then discuss your

answers with your CTA and colleagues as appropriate.

1. Is the method of prioritisation adequately explained?

2. Is there consistency in the terminology used?

3. How effective is the scoring system? Are the criteria well defined?

4. Was the initial prioritisation of the transboundary problems consistent with the

outcomes of the causal chain analysis (p.110)?

5. Are the environmental impacts adequately described and quantified in the

text?

6. Do you feel that the socio-economic consequences of each priority problem

are adequately reflected in the TDA?

Training course on the TDA/SAP approach in the GEF

International Waters Programme

Page 34 of 52

Trainee Manual

Module 3

4. Analysis of the Impacts/Consequences of

Transboundary problems

So far we have discussed how to identify and prioritise the transboundary problems.

Detailed information must next be gathered on each of the priority problems in the region.

The TTT and selected additional experts (including joint government and local groups)

should work together to help gather information, further define the key transboundary

problems and analyse their impacts and consequences. This will involve putting objective

and quantitative information in final reports.

The process should:

· Describe the problem itself (using available survey data showing changes over

time, etc.).

· Examine the impact of the problem on the environment.

· Examine social and Economic consequences of the problem.

In describing the impact of the problem from an environmental perspective, a distinction

will be made between problems and impacts (e.g. high concentrations of chemical

pollutants may be the problem but what is the evidence of impact on the natural

environment?).

When examining the social and economic consequences, figures will need to be put on

such parameters as: How many people have their health impaired by chemical pollution?

What is the economic cost of the damage to health?

The information gathered should concentrate on the transboundary impacts. However,

national or localised impacts can also be described if they are relevant.

Even at this early stage it is useful to agree on a set of indicators and present the data in the

form of these indicators. This will later give important monitoring and evaluation tools for

the SAP.

The work will normally be conducted by selected individual specialists, who should

produce final reports that are fairly brief (typically some 5 pages per problem). From

these, the TTT must write a summary text to explain the overall significance of the

problems in the region. A good example of reporting for this stage of the process is the

South China Sea TDA, which you may like to study if you are especially interested.

4.1 Analysis of environmental impacts

The purpose of this step is to examine the impact of each priority problem on the

environment. This should not be confused with an environmental impact assessment (EIA)

Training course on the TDA/SAP approach in the GEF

International Waters Programme

Page 35 of 52

Trainee Manual

Module 3

which is an instrument to identify and assess the potential environmental impacts of a

proposed project.

The analysis of environmental impacts is simpler and more straightforward than the

analysis of the socio-economic consequences. However, the process can be easily derailed

if the TTT fails to identify, select and interpret the appropriate data and information.

A logical approach to facilitate this process is the development of robust, relevant

environmental status, impact and pressure indicators for which data is available.

These indicators will have several uses:

- Status indicators: will be used in the TDA to describe physical and

geographical characteristics, socio-economic status and the environmental

status.

- Impact indicators: will describe and quantify the impacts of the each

transboundary problem.

- Pressure indicators will substantiate the causal chains developed for the

priority transboundary problems (Module 4).

In addition, some of the indicators developed (particularly environmental status) may

ultimately be used in the SAP for Monitoring & Evaluation purposes (Module 5).

Remember - One good indicator that describes the impact and its

relevance is worth 20 indicators that don't.

For example, changes in long term monthly averages of stream

flow say very little in isolation, whereas the loss of habitat due to

erosion does.

4.1.1 Baselines

Impact indicators show change over time. Therefore it is important to determine the

`baseline'.

1. The baseline will normally be chosen assuming that the most recent information is

generally the most complete.

2. It is recommended to gather information in at least 10 year horizons where possible

(i.e. 1990s, 1980s etc).

3. Further it will be necessary to determine the baseline for which information was

last available (i.e. 1990 to 2000; 1994 to 2004 etc).

Training course on the TDA/SAP approach in the GEF

International Waters Programme

Page 36 of 52

Trainee Manual

Module 3

4.1.2 Environmental Indicator Assessment Tool (EIAT)

A method that can help this process is the Environmental Indicator Assessment Tool

(EIAT), currently being developed by IW:LEARN. A Microsoft Word version of the EIAT

can be found in the supporting materials for this module.

This web-based toolbox describes 160 pressure, state and impact indicators and quotes

units of measure. Inevitably, many of the indicators listed are specific to a particular

feature of a biogeographical region (e.g. coral reefs, mangroves, boreal wetlands) and are

not applicable generally.

An example of Using the IW:LEARN Environmental Indicator Analysis Tool is given on

the next page.

Box 12 - Example of the indicator selection process using the IW:LEARN

Environmental Indicator Analysis Tool

Problem 13: Modification of ecosystems or ecotones

Habitat 4. Wetlands related to running water

= View Profile

ID

Title

1

HYD1: Peak stream flow

3

HYD6: Stream flow- Long Term Monthly Averages

5

HYD8: Delta front movements

6

HYD9: Changes in sediment flux

7

HYD10: Land subsidence

8

HYD12: Precipitation

9

HYD13: Loss of habitat due to erosion

10

HYD14: Disappearance of perennial springs

13

SAT1: Change in the extent of each land cover class- Satellite derived vegetation index

14

SAT2: Changes in the extent of habitat/community types compared with historic and current baselines

17

SAT5: Changes in gross habitat fragmentation compared with historic and current baselines

18

BIO1: Changes in macrophyte community structure

21

BIO4: Changes in the area of wetland macrophyte communities

24

BIO7: Change in the Number/proportion of taxa

25

BIO8: Changes in native species or higher taxa

26

BIO9: Changes in endemic species or higher taxa

27

BIO10: Invasive alien species

28

BIO13: Species arrivals

29

BIO14: Nesting population densities

30

BIO15: Confirmed breeding population densities

31

BIO17: Number and abundance of species wintering at a given habitat

91

FW2: Loss of habitat due to rate of growth of urban areas

92

FW3: Loss of river floodplains due to artificial banking of river margins

Training course on the TDA/SAP approach in the GEF

International Waters Programme

Page 37 of 52

Trainee Manual

Module 3

4.2 Assessment of socio-economic consequences

The purpose of this step is to identify the socio-economic consequences of each priority

transboundary problem. It is likely that the TTT will need to hire particular expertise to

undertake this process, unless it can identify a good environmental economist from the

region. However, the following sections will give you an indication of the general

approach that will need to be undertaken.

4.2.1 Measures of socio-economic consequences

How the extent of socio-economic consequences can be presented in the TDA calls for

some explanation of the types of measure that are available. The socio-economic

consequences for impact analysis are the same as those used in prioritisation, described in

Section 3.3.3 but the detail with which consequences are assessed and reported is higher.

More detail means the use of measurements wherever possible. As the examples in Table 3

suggest, there are many ways of assessing the extent of socio-economic consequences, and