UNEP SCS/SAP Ver. 3 (24/2/99)

Page 1

UNEP SCS/SAP Ver. 3

Strategic Action Programme

for the South China Sea

(Draft Version 3, 24 February 1999)

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1

BACKGROUND & RATIONALE: ........................................................................................... 6

1.1 GLOBAL AND REGIONAL SIGNIFICANCE OF THE SOUTH CHINA SEA (SCS) AND ITS ASSOCIATED

FRESHWATER CATCHMENTS ................................................................................................. 6

1.2

BASIS FOR PREPARATION OF THE STRATEGIC ACTION PROGRAMME......................................... 7

2 CAUSES OF DEGRADATION AND THREATS TO THE AQUATIC ENVIRONMENT AND

RESOURCES OF THE SOUTH CHINA SEA.............................................................................. 9

2.1

CAUSES OF ENVIRONMENTAL DEGRADATION ........................................................................ 9

2.2

FUTURE THREATS TO THE SOUTH CHINA SEA ..................................................................... 11

3 ESTABLISHMENT OF TARGETS FOR ENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY IN THE SOUTH CHINA

SEA ....................................................................................................................................... 12

3.1

GENERAL...................................................................................................................... 12

3.2

OBJECTIVES, RATIONALE AND PRIORITIES FOR THE SAP...................................................... 12

3.3

TARGETS AND PRIORITY ACTIONS..................................................................................... 13

3.3.1

Mangroves...........................................................................................................13

3.3.2

Coral reefs ...........................................................................................................16

3.3.3

Seagrass .............................................................................................................17

3.3.4 Estuaries and Wetlands .........................................................................................21

3.4

OVER EXPLOITATION OF FISHERIES.................................................................................... 22

3.5

LAND-BASED POLLUTION................................................................................................. 24

3.5.1

Urban/Municipal Waste.........................................................................................24

3.5.2

Industrial Waste ...................................................................................................26

3.5.3

Agricultural Waste ................................................................................................26

3.5.4

Hydrocarbons.......................................................................................................27

3.5.5

Suspended Solid/Sedimentation............................................................................28

3.5.6

Regional Cooperation ...........................................................................................30

4

COST BENEFIT ANALYSIS OF PROGRAMME ACTIONS.................................................... 31

4.1

VALUATION CONSIDERATIONS.......................................................................................... 31

4.2

VALUATION OF RESOURCES............................................................................................. 32

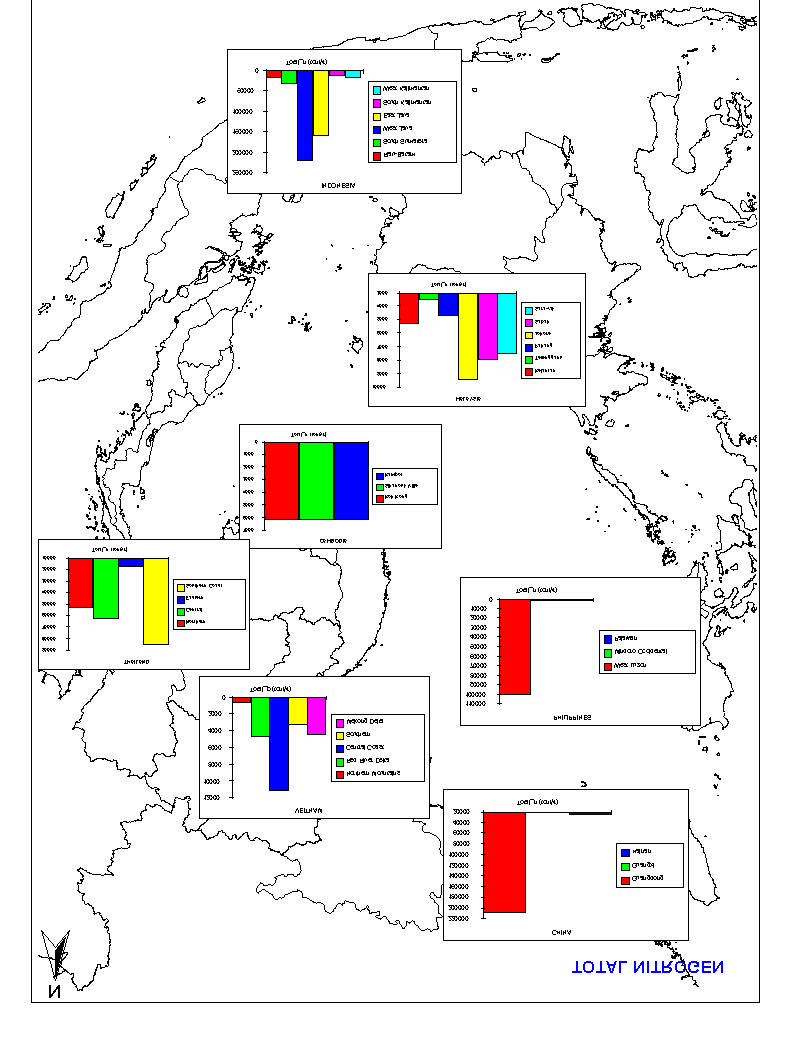

4.2.1

Mangrove.............................................................................................................33

4.2.2

Coral Reefs ..........................................................................................................42

4.2.3

Seagrass .............................................................................................................42

4.2.4

Wetlands .............................................................................................................43

4.2.5

Total habitat values ..............................................................................................43

4.2.6

Overexploitation of fishery resources .....................................................................44

4.2.7

Pollution...............................................................................................................46

UNEP SCS/SAP Ver. 3 (24/2/99)

Page 2

4.2.8 Regional Cooperation ...............................................................................................47

4.4

ASSESSING THE BENEFITS FROM THE PROGRAMME ............................................................. 47

4.5

ESTIMATED COST OF THE STRATEGIC ACTION PROGRAMME.................................................. 48

5

INCREMENTAL PARTNERSHIPS ....................................................................................... 64

5.1

JUSTIFICATION FOR FORMING PARTNERSHIPS ..................................................................... 64

5.2

PARTNERSHIPS AVAILABLE FOR ACHIEVING MAXIMUM ENVIRONMENTAL BENEFITS.................... 64

5.3

EXAMPLES OF POTENTIAL FOR EXISTING AND PLANNED INVESTMENTS.................................... 65

5.3.1

Regional..............................................................................................................65

5.3.2

National...............................................................................................................65

5.3.3

Donor Countries ...................................................................................................65

5.3.4

Non Government Organisations ............................................................................66

5.3.5

United Nations Organisations................................................................................66

6

PRIORITY REGIONAL AND NATIONAL ACTIONS TO ADDRESS THE CAUSES OF

ENVIRONMENTAL DEGRADATION AND THREATS TO THE ENVIRONMENT OF THE SOUTH

CHINA SEA................................................................................................................................ 67

6.1

PRIORITIES.................................................................................................................... 67

6.2

EXAMPLES OF ACTIONS THAT WILL FULFIL SOME OF THE OBJECTIVES OF THE STRATEGIC ACTION

PROGRAMME............................................................................................................................ 67

6.2.1

Support a regional programme in cleaner production technologies and best

environmental practices.......................................................................................................67

6.2.2

Monitoring of demonstration conservation sites ......................................................68

6.2.3

Review national EIA regulations to promote greater public participation ...................68

6.2.4

Demonstration site for local community conservation activity...................................69

6.2.5

Develop guidelines on preparation of national plans for protection of marine and

coastal environments...........................................................................................................69

6.2.6

A regional GIS database and a mathematical model on pollution and its impact on

ecosystems.........................................................................................................................69

6.2.7

Collect information on trade in "minor" and endangered marine products..................70

UNEP SCS/SAP Ver. 3 (24/2/99)

Page 3

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1.1

Ranking Of Importance Of Various Issues By Country

Table 2.1

Loss And Causes Of Mangrove Destruction.

Table 2.2

Ranked Sources Of Pollution Among Participating Countries In The South

China Sea1.

Table 4.1

Valuation Of Ecosystems

Table 4.2

Rates And Amounts Of Habitat Loss Under High And Low Pressure On The

Habitats

Table 4.3

Calculation Of Areas Saved By Action Programme: Low Pressure Scenario

Table 4.4

Calculation Of Values Saved By Action Programme: Low Pressure Scenario

Table 4.5

Net Present Value (NPV) Year 1999-2010

Table 4.6

Calculation Of The Rate Of Loss

Table 4.7

Calculation Of Areas Saved By Action Programme: High Pressure Scenario

Table 4.8

Calculation Of Values Saved By Action Programme: High Pressure Scenario

Table 4. 9

Net Present Value (NPV) Year 1999-2010

Table 4.10

Key Indicators Using The Gordon-Schaefer Model Results In The Philippines

Marine Fisheries 1994

Table 4.11

South China Sea Fishery Yield

Table 4.12 Summary Of Programme Cost

Table 4.13 Cost Of Action: Mangrove

Table 4.14 Cost Of Action: Coral Reefs

Table 4.15 Cost Of Action: Seagrass

Table 4.16 Cost Of Action: Seagrass

Table 4.17 Cost Of Action Exploitation Of Fisheries

Table 4.18

Cost Of Action: Land-Based Pollution

Table 4.19 Cost Of Action: Regional Co-operation

Table 5.1

Organisations Willing To Collaborate In Programme

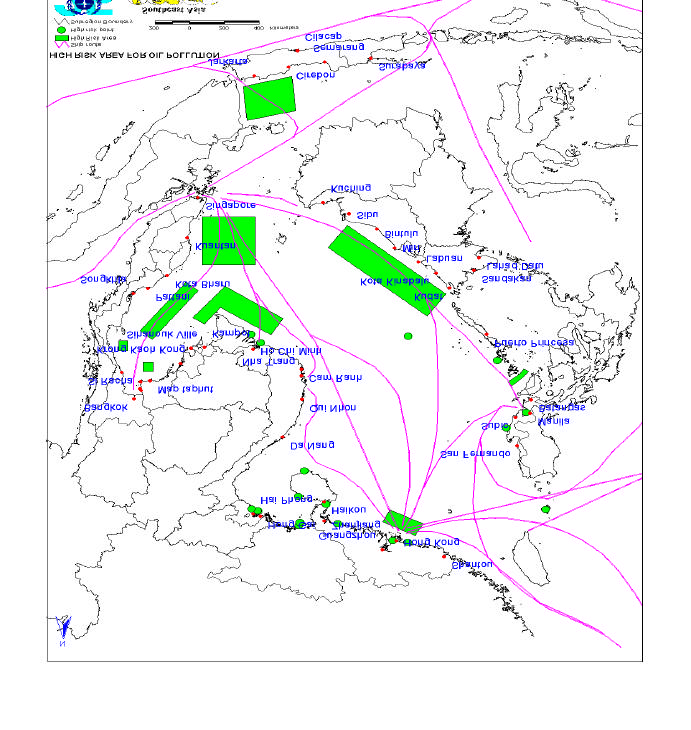

LIST OF FIGURES

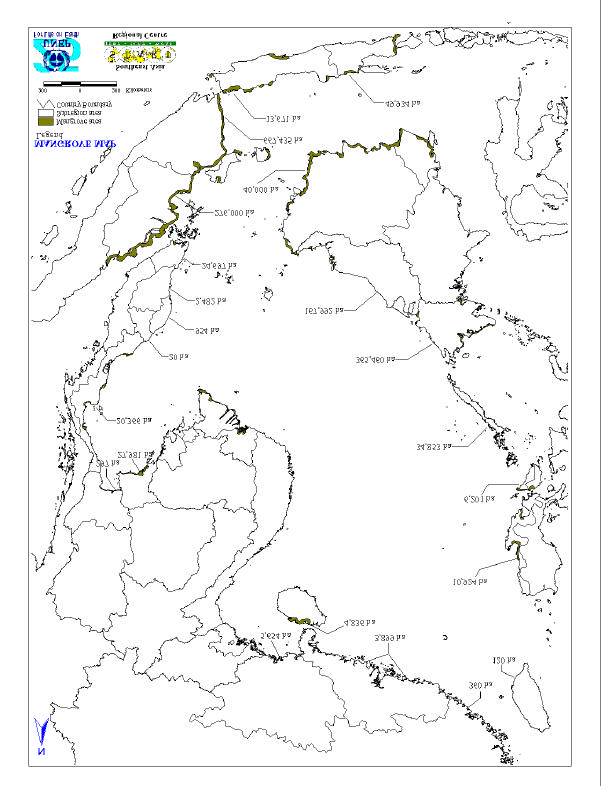

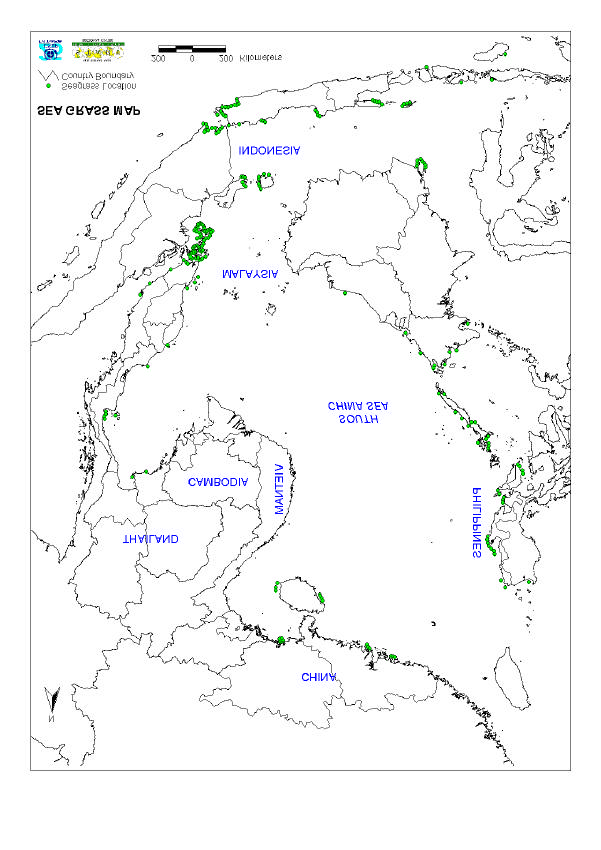

Figure 3.1

Distribution Of Mangroves In The South China Sea

Figure 3.2

Distribution Of Coral Reefs In The South China Sea

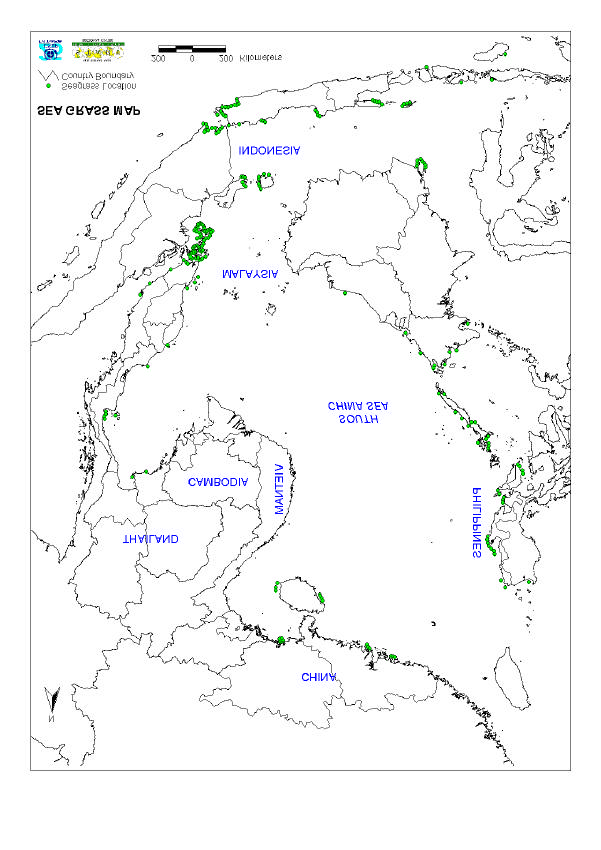

Figure 3.3

Distribution Of Seagrass In The South China Sea

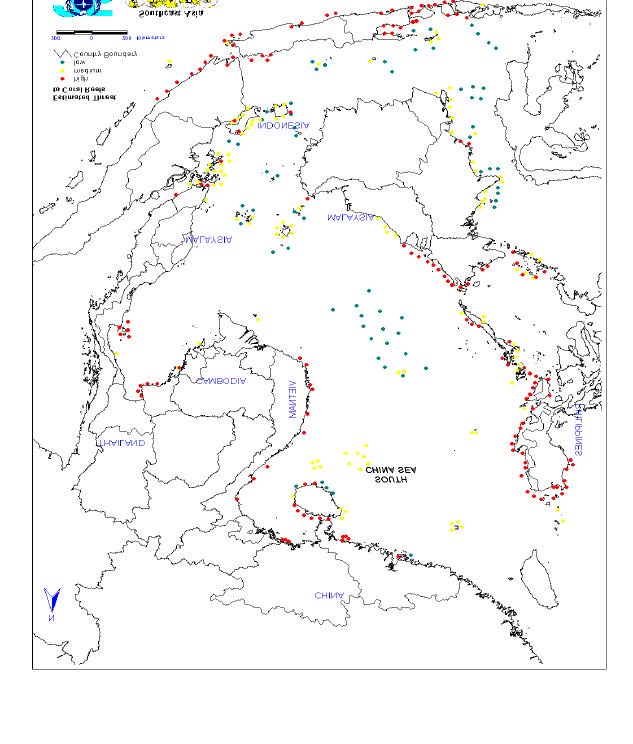

Figure 3.4

Distribution Of Pollution "Hot Spots" In The South China Sea

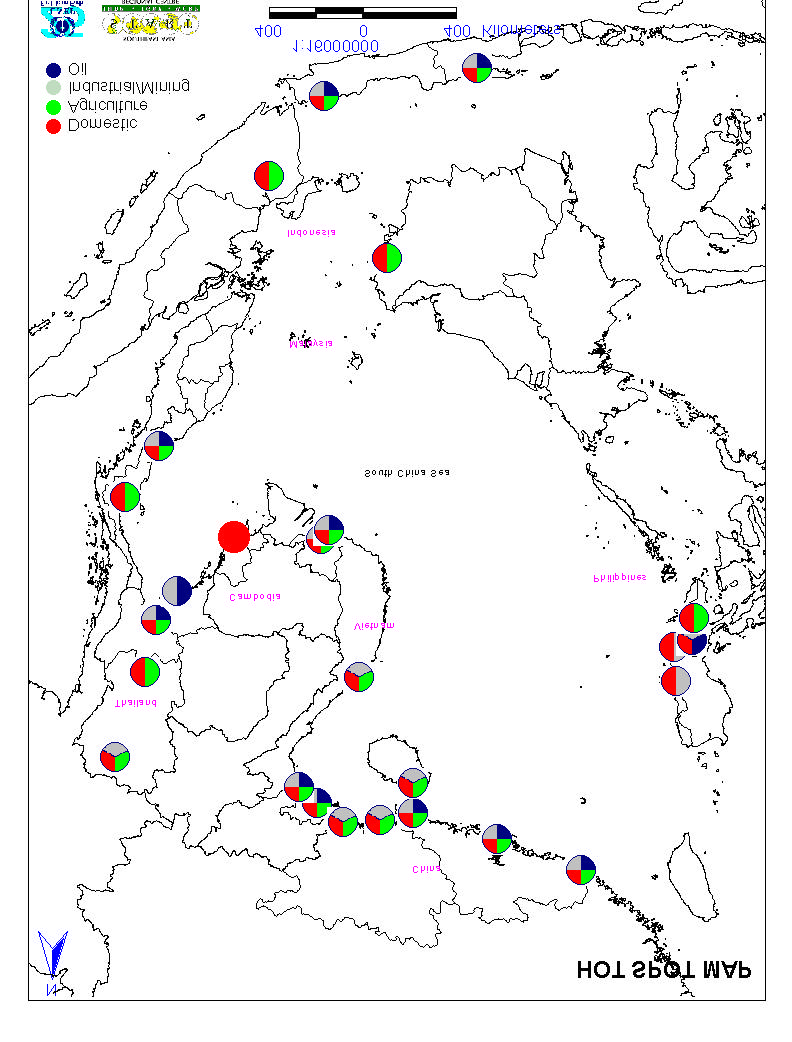

Figure 3.5

Biological Oxygen Demand From Domestic Sources In The South China Sea

Figure 3.6

Total Nitrogen In The South China Sea

Figure 3.7

High Risk Areas For Oil Pollution In The South China Sea.

UNEP SCS/SAP Ver. 3 (24/2/99)

Page 4

PREFACE

Development of the Strategic Action Programme

The South China Sea is a unique environment with rapid economic development and

rapid population increase in the coastal areas during the part two decades and with rapid

degradation of marine and coastal environments. The South China Sea is shared by many

countries, and the environmental problems they have are common and of a transboundary

nature with similar root causes.

Recognising that actions are urgently needed to halt degradation of the environment

of the South China Sea, the countries of the region sought the assistance of UNEP and the

Global Environment Facility (GEF) in preparing a Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis of the

issues and problems and their societal root causes as the basis for development of this

Strategic Action Programme. The Twelfth intergovernmental meeting of the Coordinating

Body for the Seas of East Asia (COBSEA) in December 1996 endorsed the proposal and the

GEF made available a project preparation and development facility grant (PDF-B) to enable

countries to prepare the necessary analyses and reviews.

In accordance with the GEF Operational Strategy these analyses and reviews

included the preparation of a Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis (TDA) (UNEP SCS/TDA

ver. 3) and Strategic Action Programme (SAP, this document). In preparing the

Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis, national committees were formed in each participating

country. Headed by a coordinator, each committee prepared a comprehensive, country-

based analysis of water-related environmental problems and concerns. An outline for the

content of these reports was agreed at a first meeting of coordinators held in March 1997.

The first drafts of the national reports were submitted and evaluated prior to a second

meeting of national coordinators in June, 1998. During this meeting, and on the basis of the

causal chain analysis done by each country for each identified water-related problem, a

weighting of all identified major issues was prepared by the national coordinators and invited

experts from the region. The identified regional concerns and principal issues became the

focus for the regional TDA, which was discussed and agreed by the national coordinators

and regional resource persons.

This draft Strategic Action Programme is based on the findings of the regional

Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis (TDA) that represents a regional synthesis of issues

identified from the national reports. The TDA identifies the priorities among water-related

problems and concerns, their socio-economic root causes, the sectoral implications of

actions needed to mitigate them and the extent to which the problems are transboundary in

either origin or effect.

The National reports, the draft Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis, and the draft

Strategic Action Programme were all submitted to The Third Meeting of National Co-

ordinators and regional experts for review and endorsement prior to their submission to the

Thirteenth Intergovernmental Meeting of COBSEA (document UNEP/(WATER)/EAS IG9/3).

This meeting endorsed the draft SAP and requested UNEP to formulate a project brief for

submission to the GEF that addresses the priority actions identified in the SAP. A key

element of this project must be actions that will lead to the further elaboration and

development of the present draft Strategic Action Programme. It is the intention of

UNEP SCS/SAP Ver. 3 (24/2/99)

Page 5

participating governments that this process of elaboration be undertaken over the next two

years with a view to governments endorsing a final draft during the next intergovernmental

meeting of COBSEA to be held in December 1999.

The actions proposed in the framework of the draft Strategic Action Programme are

wide ranging in both context and proposed areas for action. Successful implementation of

the Programme will depend upon co-ordination of actions by diverse organisations,

agencies, non-governmental organisations, private sectors, and stakeholder groups at both

the national and regional levels. Recognising the mandate of the United Nations

Environment Programme to co-ordinate environmental actions across the United Nations

System, the widest possible range of appropriate partners at national and regional levels will

be encouraged and assisted to participate in the execution of the Programme. It is the

intention of the participating countries that all actions be undertaken in a spirit of

collaboration and partnership, to enhance synergy between on-going initiatives at national

and regional levels, and eliminate duplicative and conflicting actions.

UNEP SCS/SAP Ver. 3 (24/2/99)

Page 6

1

BACKGROUND & RATIONALE:

1.1

Global and Regional Significance of the South China Sea (SCS) and its

Associated Freshwater Catchments

The South China Sea is a strategic body of water, surrounded by nations that are

currently at the helm of industrialisation and rapid economic growth in the Asia-Pacific

region. Bordered by the People's Republic of China to the north, the Republic of Philippines

to the east; Malaysia, the Republic of Singapore, The Republic of Indonesia and Brunei to

the south; and the Kingdom of Thailand, the Kingdom of Cambodia and the Socialist

Republic of Viet Nam to the west; the South China Sea has always been central to issues of

economic and political stability in Southeast Asia and adjacent regions (Fig. 1.1). Today, it is

central to environmental sustainability and food security for rapidly expanding populations of

these coastal and archipelagic nations.

The coastal subregions of these nations are home to 270 million people or 5% of the

world's population. About 125 major rivers drain 2.5 X 106 km2 of catchment area and

deliver, water, sediments, nutrients and pollutants to the South China Sea.

The South China Sea lies at the centre of the Indo-West Pacific biogeographic

Province the world's most diverse shallow-water marine area. Such richness in flora and

fauna contributes to the area's high natural rates of primary and secondary production.

Capture fisheries from the South China Sea contribute 10% of the world's landed catch at

around. 5 X 106 tons year-1. From the standpoint of aquaculture, five of the eight top shrimp

producers in the world, are countries bordering the South China Sea, namely: Indonesia,

first, Viet Nam, second, China, third, Thailand, sixth, and the Philippines, eighth.

Forty-five mangrove species out of a global total of 51 (Spalding et al. 1997); 50 of 70

coral genera (Tomascik et al. 1997); 20 of 50 seagrasses species (Sudara et al. 1994); and

7 of 9 giant clam species (Tomascik et al. 1997), are found in the nearshore areas of the

South China Sea. Compared to the Atlantic, the tropical Indo-West Pacific is highly diverse.

Only 5 mangrove species and some 35 coral species are found in the Atlantic compared with

51 mangrove and over 450 coral species are recorded from the Philippines compared with

200 species from the Red Sea, 117 from South East India and 57 from the Persian Gulf.

The richness and productivity of the natural environment of the South China Sea are,

however, seriously threatened by high rate of population growth, pollution, excessive

harvesting and habitat modification, resulting in rapid loss of habitat and impairment of the

regenerative capacities of living systems. The socio-economic impacts of environmental

deterioration are significant for the newly developed economies of this region. While the

economy of these countries is becoming increasingly dominated by developments in the

industrial and service sectors, food consumption patterns rely heavily on cheap protein

derived from fishery resources. The agriculture sector (including fisheries) remains not only a

significant source of revenue but also an important basis for food security in the countries of

the region.

An economic crisis in mid 1997 caused development to slow and a reduction in

funding to non-essential services. Under conditions of fiscal restraint environmental

protection tends to receive priority.

UNEP SCS/SAP Ver. 3 (24/2/99)

Page 7

1.2

Basis for Preparation of the Strategic Action Programme

The Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis [UNEP SCS/TDA ver.3] is based on national

reports prepared by Cambodia, China, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Thailand and

Viet Nam. The national reports present the key national priorities amongst the many issues

and concerns relating to the aquatic environment of the South China Sea basin. The TDA

provides an assessment of the regional and wider significance of these issues; an analysis

of the socio-economic causes of environmental degradation; an evaluation of the sectoral

implications of actions needed to mitigate them; and an analysis of priorities from the

national and regional perspectives.

The Strategic Action Programme (this document) is based on the preliminary findings

of the regional Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis and in particular upon the priorities

identified by the second meeting of National Co-ordinators and regional experts. This

preliminary ranking is presented in Table 1. 1

This Strategic Action Programme was prepared in collaboration and cooperation with

other regional institutions, organisations and bodies having interests in many issues in the

region, including:

· Food and Agricultural Organisation of the UN;

· South East Asia (START) Regional Centre;

· The South China Sea Informal Working Group at the University of British Columbia;

· IOC Sub-Commission for the Western Pacific (WESTPAC);

· GEF/UNDP/IMO Regional Programme for the Prevention and Management of

Marine Pollution in the East Asian Seas.

UNEP SCS/SAP Ver. 3 (24/2/99)

Page 8

Table 1.1 Ranking Of Importance Of Various Issues By Country

ISSUE

Cambodi

China

Indonesia

Malaysia

Philippines

Thailand

Viet Nam

TOTAL

RANK

a

Litter/Solid waste

3

1

3

1

3

1

12

7

Nitrate - domestic

1

3

2

3

3

3

1

16

3

Nitrate Rural

n.a.

3

1

1

2

2

1

10

9

Phosphate domestic

1

3

1

3

3

3

1

15

4

Phosphate rural

n.a.

3

-

1

2

2

1

9

10

Sediments mining

2

1

2

1

1

3

10

9

Sediments Rural

3

1

3

3

2

1

13

6

Hydrocarbons

n.a.

3

3

21

2

2

2

14

5

Organics domestic

3

2

3

3

3

3

1

18

2

Organics Rural

2

2

1

2

2

2

11

8

POPs

n.a.

1

1

1

1

1

5

12

E. Coli

n.a.

1

3

3

3

3

1

14

5

Heavy metals domestic

n.a.

1

1

1

1

4

13

Heavy Metals Industrial

2

1

3

1

3

1

1

12

7

Harmful Algal Blooms

n.a.

3

1

12

3

8

11

Industrial Chemical

2

1

2

2

3

2

1

13

6

Natural Catastrophes

1

2

2

3

2

10

9

Overfishing

3

1

3

3

3

3

3

19

1

Habitat loss

2

2

3

3

3

3

16

3

A

Overfishing

B

Sewage municipal

C

Habitat loss

D

Hydrocarbons

1 Potential problems in future

E

Industrial chemicals & HM

2 Sabah & Swak only

F

Rural (N, P, sed.org.)

n.a not available

G

Solid waste/litter

H

Natural catastrophes

H

Mining Sediments

I

Harmful algal blooms

J

POP's

UNEP SCS/SAP Ver. 3 (24/2/99)

Page 9

2

CAUSES OF DEGRADATION AND THREATS TO THE AQUATIC ENVIRONMENT

AND RESOURCES OF THE SOUTH CHINA SEA

2.1

Causes of Environmental Degradation

The root causes of the degradation of marine habitats and environment in the South

China Sea are the increased populations and the demands made upon the marine

environment as the population strives to achieve higher levels and standards of living. These

socio-economic causes are manifested in overexploitation of resources, human and

industrial waste dumping and destruction of habitat during development. These causes have

resulted in large losses of mangrove and seagrass area and destruction of coral reefs.

For instance, as indicated in the TDA, Table 2.1 shows that mangroves in the seven

participating countries constitute 10% of the current global area of slightly over 18 million ha.

The total amount of area lost over different time spans (70 years for the Philippines) is

estimated to be 4.3 million ha or 24% of the current global mangrove area. The causes for

mangrove destruction include conversion to pond culture, tree felling for woodchip and pulp

production, urban development and human settlements, and harvest of products for

domestic use. The impact of each economic activity is difficult to quantify for each country.

Nonetheless, shrimp culture would seem to be the most pervasive economic imperative for

mangrove conversion. However, the rate of destruction wrought by each cause must be

taken into account when known, for a more thorough analysis.

Table 2.1 Loss And Causes Of Mangrove Destruction.

Country

Area

Area now

%

Causes of mangrove destruction

before (ha)

(ha)

Are

a

Shrimp

Wood-

Urban

Domestic

lost

culture

chip and

developme

use

pulp

nt/Human

settlement

s

Cambodia

170,000

85,100

50

ü

ü

China

42,001

14,749

65

ü

ü

Indonesia

4,254,312

733,000

83

ü

ü

ü

Malaysia

505,000

446,000

12

ü

ü

ü

Philippines

400,000

160,000

80

ü

ü

ü

Thailand

550,000

247,000

70

ü

Vietnam

400,000

252,500

37

ü

ü

TOTAL

6,321,313

1,938,349

GLOBAL

18,107,700

TOTAL

Sources: Spalding et al., 1997; ISME 1993.

UNEP SCS/SAP Ver. 3 (24/2/99)

Page 10

The immediate causes for degradation in coral reefs in the participating countries and

in Southeast Asia in general are varied, but the major ones are commonly identified in the

national reports. Regional assessments like those of Wilkinson et al (1994) state that

pollution and sediments are major causes in countries of the Sunda shelf, and in the shallow

areas of the Philippines and Indonesia. However, overfishing causes greatest degradation in

the deeper areas of the archipelagoes including those in the oceanic shoals. Bryant et al.

(1998) enumerates overfishing, destructive fishing practices, sedimentation and pollution

associated with coastal development as the major culprits. These causes were weighted in

determining the three risk levels used in their evaluation.

Catchment areas are not managed with an eye to marine environments and the

forest fires, deforestation and inappropriate agricultural practices which occur in the region

considerably degrade the marine environment, particularly by allowing excess runoff of soil

and sediments into the rivers and hence, the sea. Rivers are dammed and their courses

changed which alters the stream flow and the erosion or accretion of sedimentary loads.

It is not clear, for underwater habitats, how much damage has been done as there is

no complete map of underwater habitats. Fisheries catch records and stock assessment are

not available for the South China Sea It is obvious that monitoring of marine resources and

habitats is not adequate. Monitoring should be to determine what the situation is, detect the

damage done and to test whether remedial efforts are successful.

Land based pollution is another priority area identified by the countries involved in

this project. Table 2.2 summarizes the sources of pollution among the participating countries

in the South China Sea, the quality of the database, and the perceived contribution of these

sources to the state of aquatic environments in each country. Wastes from domestic,

agricultural, and industrial sources, along with sediments and solid wastes are the major

sources of pollutants that impinge on both freshwater and coastal systems in the seven

countries. Land-based sources play a major role in both inland and coastal pollution. Ship-

based sources contribute relatively small amounts, but may have severe impacts when large

volumes are released such as during major oil spills. Atmospheric inputs may seem

innocuous at the present time because of a very poor database and because their impacts

are harder to establish given the nature of atmospheric chemistry and the larger scales

needed to carry out appropriate studies of air sheds. It must be pointed out however, that

atmospheric pollutants are most potent in being transported across national boundaries. This

was made evident during the extensive forest fires that occurred in Indonesia that caused

haze to shroud Malaysia and western Philippines. On a global scale, the ashfall debris

injected into the stratosphere by Mt. Pinatubo's eruption caused major weather anomalies

worldwide.

The Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis provides more detailed information on the

root causes and sources of the problems identified.

UNEP SCS/SAP Ver. 3 (24/2/99)

Page 11

Table 2.2 Ranked Sources Of Pollution Among Participating Countries In The South

China Sea1.

Source

Rank &

Contribution to pollution of national aquatic

Data

environments

base

(L=Low, M= Moderate, H= High)

Ca

Ch

Indo

Mal

Phil

Tha

Viet

· Domestic waste

1-Fair

M

H

H

M

H

H

H

· Agricultural waste

2-Poor

M

H

H

M

H

H

H

· Industrial waste

2-Poor

M

H

H

H

H

H

H

· Sediments

3-Poor

M

H

H

M

H

H

H

· Solid waste

4-Fair

H

H

H

M

H

H

H

· Hydrocarbons

5-Poor

L

M

H

M

M

M

M

· Ship-based sources

6-Poor

L

M

M

M

M

M

M

· Atmospheric

7-Poor

L

M

H

M

H

M

M

1Ranking of pollution sources was done during the Second Meeting of National Coordinators

(June 1998).

2.2

Future Threats to the South China Sea

Unless countries realise that there is unsustainable exploitation and irreversible

damage being done to marine ecosystems the current situation of losing habitat will

continue. Inventories of what is there, records of the state of the marine environment

determined by monitoring and a realistic outlook on exploitation of resources will give

countries a guide as to what should be done to relieve the current situation. To this end the

TDA and the SAP are leading documents. The population of most countries of the South

China Sea is growing and in 50-100 years time, however well managed the marine

environment is, it will not be able to support the predicted number of people.

As analysed in the TDA, the future treats for mangrove as an example mainly

include:

(i) Loss of biodiversity. The incomplete inventory of associated flora and fauna in the seven

participating countries nonetheless indicates the high biodiversity associated with mangrove

areas in the South China Sea region. The rich species diversity is reflected in the high

number of mangrove trees, finfish and penaeid shrimps, among others, that are associated

with mangrove swamps. Because of the severe pressure exerted on mangroves, a number

of associated species are among those classified as endangered. These include the

proboscis monkey, Nasalia larvatus, which eat young shoots and growing tips of Sonneratia

and Avicennia trees, the crocodile Crocodilus porosus, swamp birds like Ardea and Egretta,

among others (Low et al., 1994).

(ii) Loss of fisheries productivity. Mangroves act as nursery and feeding grounds for finfish

and shellfish at some stage or throughout their life cycles. Singh et al. (1994) obtained

studies that show high correlation between catch in coastal fisheries and the area of

adjacent mangroves in study sites such as Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Australia and

the US. Although correlation does not imply causation, ecological studies have established

the connectivities among mangroves, coral reefs and seagrass as far as supporting the life

cycles of coastal organisms (Robertson and Duke, 1987; Twiley 1988). Based on the

precautionary principle, it is not necessary to unequivocally prove that mangrove destruction

UNEP SCS/SAP Ver. 3 (24/2/99)

Page 12

will cause a decline in the productivity of dependent biota, and consequently a decrease in

their yields. There is sufficient evidence to believe that it will and does.

3

ESTABLISHMENT OF TARGETS FOR ENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY IN THE

SOUTH CHINA SEA

3.1

General

The national reports and the transboundary diagnostic analysis identified the priority

problems of the South China Sea as being, environmental pollution, over exploitation of

biotic resources, and ecosystem loss. Associated with these issues are the growing

problems of freshwater quality and quantity for human use. For a number of these issues

and problems quantitative indicators of loss or degradation are not available, or the data and

information are not uniform throughout the region, thus, further studies are required in order

to establish definitive targets for protection and management of the environment and its

resources. Nevertheless, recognising the urgency of the issues and problems, the

Governments agreed to establish preliminary targets for the key issues identified for priority

action in the immediate future.

Underlying the process of degradation of the various resources described in the TDA

is the lack of an effective institutional framework at national and regional levels, for collective

management of the environment and resources. This problem is addressed among the

priority actions outlined in this draft Strategic Action Programme.

3.2

Objectives, Rationale and Priorities for the SAP

The ultimate goal of the Strategic Action Programme is to halt or slow the current rate

of environmental degradation and as such it contains priority actions that need to be

undertaken at both national and regional levels. It is designed to assist participating states

in taking actions individually or jointly within their respective policies, priorities and

resources, which will lead to the prevention, reduction, control and/or elimination of the

causes of degradation of the marine and freshwater environment. Achievement of the aims

of the SAP will contribute to the protection of human health; promote the conservation and

sustainable use of marine living resources; and contribute to the maintenance of globally

significant biological diversity.

The general objectives of the SAP are:

· Formulation of principles, approaches, measures, timetables and priorities for

action;

· Preparation of a priority list for intervention and investments;

· Detailed analysis of expected baseline and additional actions needed to resolve

each transboundary priority problem;

· Identification of the elements and preparation of guidelines for the formulation of

national action plans for the protection of the marine environment and rational use of

marine and coastal resources consistent with the regional SAP;

· Foster the involvement of regional and, where appropriate, national Non-

Governmental Organizations and the private sector in the implementation of the

SAP;

UNEP SCS/SAP Ver. 3 (24/2/99)

Page 13

· Foster collaboration and co-operation between all regional entities having interests

in the environment of the South China Sea in an attempt to reduce or eliminate

duplication of effort and waste of scarce human and financial resources.

The countries of the South China Sea region are at different levels of socio-

economic, scientific and technological development. However, the basic infrastructure for the

protection of the environment and for the sustainable use of marine resources exists in all

countries of the region, including competent institutions having authority for protection of the

environment, and adopted legislation and regulations. However, the governments of the

region have recognised that past actions at national and regional levels have not been

adequate to halt the rate of degradation and that a more strategic approach is required.

Consequently, targets have been defined and endorsed by the governments, for each of the

priority areas of concern identified in the TDA, namely:

· Habitat conversion and loss

· Unsustainable exploitation of living aquatic resources

· Land-based pollution

· Freshwater shortage and low water quality

3.3

Targets and Priority Actions

Habitat Conversion and Loss

The loss of important habitats is a priority in the region. This is a concern in the case

of mangroves, coral reefs, seagrass and coastal wetlands. In most countries, laws and

regulations concerning land use planning and coastal development exist and important

areas of habitat have been declared as protected areas. The enforcement of these legal

measures is not effective in the face of continued economic pressures for the conversion of

these areas to alternative uses. The main reasons for continuing habitat loss are the failure

to deal with the socio-economic pressures for development and a failure to integrate

environmental concerns into the development process. The national reports identified the

need to prepare master plans of institutional and legal reform and action to deal with these

problems in an integrated way.

3.3.1 Mangroves

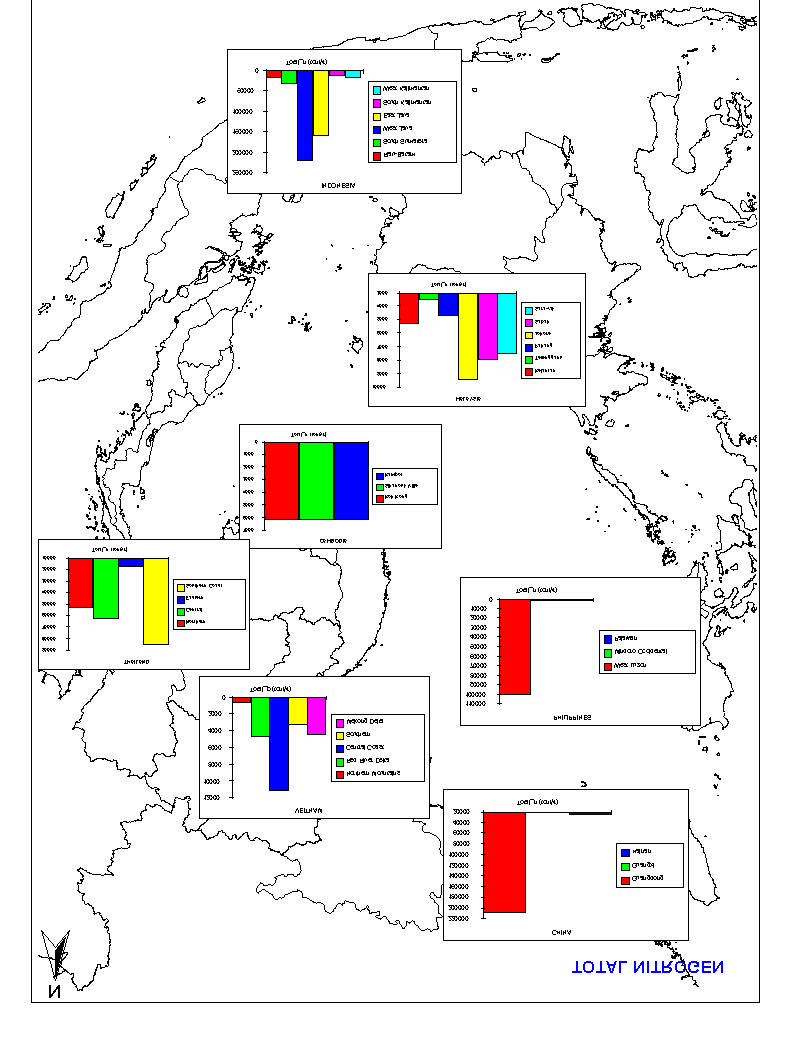

Over the last 70 years the area of mangrove bordering the South China Sea has

decreased from 6,321 km2 to 1,938 km2 a loss of nearly 70% of the original area.

Continuation of losses at the present rate will result in all mangrove being lost by the year

2030. The present distribution of mangrove forests is illustrated in Figure 3.1. Ecologically,

mangroves provide valuable habitat for juvenile fish and crustacea of commercial and

recreational value, protect the shore from erosion, and provide timber and other products for

human use. The value of the products and ecological services provided by the mangrove

systems of the South China Sea is estimated at about US$ 15,984 million per year ( based

on total area of 1.6 million ha as indicated in TDA, and a value of US$ 9990 ha-1 year-1).

The main causes of mangrove loss result from conversion of the land to other uses,

such as shrimp farms, urban development and logging for timber and woodchips.

As the global centre of mangrove biodiversity such losses in this region have both

global and wider regional significance. Loss of biodiversity and fisheries productivity are

major transboundary issues at a regional scale but trading in mangrove wood products i.e.

UNEP SCS/SAP Ver. 3 (24/2/99)

Page 14

pulp, charcoal, woodchips and building materials, are also transboundary being driven by

international trade in such products. The countries of the region dominate the mariculture

production of shrimp which results from high prices

on the world market that encourage low capital, extensive farming systems dependent on

tidal regimes for water and natural food inputs, in cleared mangrove areas.

UNEP SCS/SAP Ver. 3 (24/2/99)

Page 15

Figure 3.1 Distribution of Mangroves in the South China Sea

UNEP SCS/SAP Ver. 3 (24/2/99)

Page 16

Proposed Targets

By 2010, to maintain the area of mangroves in the region at no less than 90% of the present

(1998) area.

Proposed Activities at the Regional level

· Develop criteria for selection of mangrove areas for protection/sustainable management,

particularly those of transboundary importance;

· Identify and prioritise specific areas for future management and protection and develop

regional and national action plans to maintain regionally important mangroves areas;

· Develop and establish management regimes for the identified areas;

· Establish a regional mangroves database;

· Build the capacity of the governments of the region to understand the issues concerning

mangroves and to raise public awareness concerning the national and regional

importance of such ecosystems.

Proposed Activities at the national level

· Carry out and/or update inventories of mangrove areas and classify them according to

potential ecological functions, using a GIS database;

· Prepare national legislation and action plans for mangrove management;

· Implement and coordinate mangrove restoration projects wherever relevant;

· Study and assess the techniques and methods of mangrove restoration currently in use

in the Region with a view to improve restoration projects;

· Build the national capacity to understand the issues concerning mangroves and raise

public awareness.

3.3.2 Coral reefs

Coral reefs are habitats for marine life, for sequestration of carbon, and provide

economic return for fisheries and tourism. Coral reefs are one of the most diverse habitats

on earth. They also act as a barrier to swell waves and storm surges thus preventing erosion

of other inshore ecosystems and the coast.

Twenty seven percent of the world's mapped coral reefs are in South East Asia (Fig.

3.2) and 84% of these fringe Indonesia and the Philippines. All countries in the South China

Sea have degraded reefs, from 95% in Hainan to an unknown amount in Viet Nam. They all

identified overexploitation as an immediate cause of degradation, five cited destructive

fishing and sedimentation, and coastal development was also a cause of damage.

A more insidious cause of destruction is high nutrient and/or suspended solids in the

water either favoring seaweed to overgrow the coral or smothering the zooxanthellae (the

synergistic plants that grow in coral polyps). There is also coral bleaching occurring in the

region which may be caused by slightly higher water temperatures. The status of coral

bleaching is currently being examined.

Loss of coral reefs has long-term implications because of the time that they take to

recover. Protection of coral reefs is best carried out by means of declaring protected areas,

such as marine parks. A lack of data on the location and status of existing reefs hampers

efforts in controlling and preventing further damage.

UNEP SCS/SAP Ver. 3 (24/2/99)

Page 17

The value of the products and ecological services provided by the coral reef systems

of the South China Sea is estimated at US$ 13,792 million per year (considering one third of

coral areas of the South East Asia are located in the South China Sea, and have value of

US$ 6076 ha-1 year-1)

The transboundary issues associated with coral reef degradation are: loss of

biodiversity, reduction in reef fisheries, coastal tourism, threatened or endangered species,

and trade in coral, shells and associated biota. There is biodiversity connectivity when

ocean currents move planktonic larvae to recruit fringing reefs and oceanic shoals,

suggesting the strategic establishment of marine protected areas between interconnected

reef systems.

Proposed Targets

· By 2010, to maintain the area of coral reef with more than 50% live cover at the present

(1998) level.

Proposed Activities at the Regional level

· Develop criteria for selection of coral reef areas for protection/sustainable management,

particularly those of transboundary importance;

· Identify and prioritise specific areas for future management and protection and develop

regional and national action plans to maintain regionally important coral reef areas;

· Establish demonstration sites for implementing management models, based on the

agreed model of management for the rest of the Region to study;

· Develop and agree on scientific and technical guidelines on the economic evaluation of

coral reefs as resources;

· Develop, agree on and implement guidelines on the preparation of national legislation

and action plans for preservation of coral reefs;

· Coordinate with other organizations standardising and regionalising coral monitoring,

mapping and status and ensuring these are updated on a regional database;

· Build the capacity of the governments of the region to understand the issues concerning

coral reefs and to raise public awareness concerning the national and regional

importance of such ecosystems.

Proposed Activities at the national level

· Map and describe the status of coral reefs using, where appropriate the organizations

currently performing these tasks;

· Establish coral reef protection areas and to implement proper management of coral reef

resources;

· Prepare and implement national legislation and action plans for preservation of coral

reefs, such as legislating marine parks in the region;

· Actively participate in activities organized by the relevant coral reef monitoring networks

and provide information for the use of interested parties;

· Build the capacity of each nation in understanding coral reef based issues.

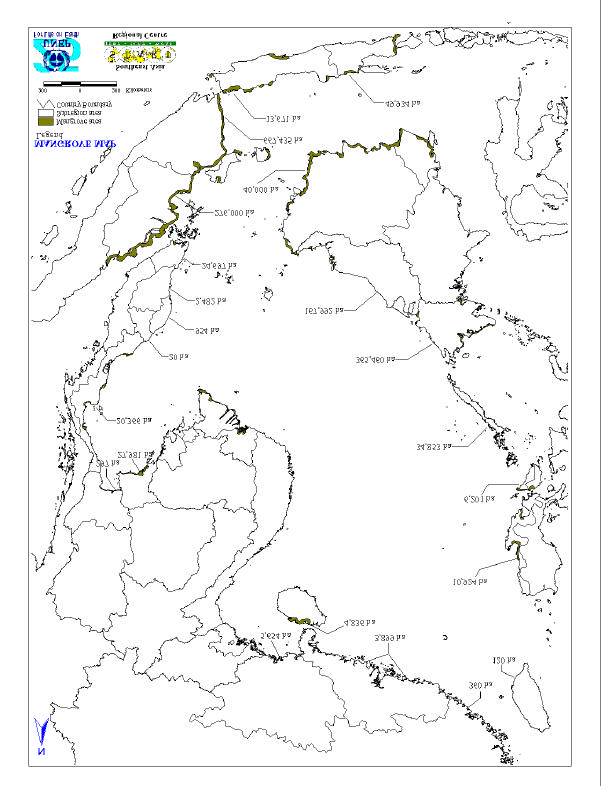

3.3.3 Seagrass

Seagrasses form the basis of many complex marine ecosystems and provide a

valuable nursery for commercially important fish and crustaceans such as crabs and

shrimps. When the seagrasses decline the links in the productivity chain are broken and the

UNEP SCS/SAP Ver. 3 (24/2/99)

Page 18

whole ecosystem collapses. Seagrasses also play an important role in the cycling of marine

nutrients. Dugong and green sea turtles graze on seagrass leaves and rhizomes but other

fish do not generally eat seagrasses.

Seagrasses have rhizomes that hold the sediments and form a mat over the bottom

preventing erosion along the coastal fringes where they grow. The leaves slow the water

movement over them thus causing particulate matter in the water to fall out into the seagrass

meadow. Some of this particulate matter is organic and provides food for animals dwelling in

the meadows.

Under natural conditions seaweeds (epiphytes) grow on seagrass leaves and stems,

but when excessive amounts of nutrients are introduced to the coastal waters this seaweed

can bloom (grow unnaturally rapidly). Under bloom conditions the seaweed can smother the

seagrass host by blocking out the light the plants need to survive. Without photosynthesis

the plant quickly uses up its stored food and dies. Light is also reduced by excessive

suspended solids in the water coming from runoff from the land due to deforestation, forest

fires, poor agricultural practices and inappropriate engineering works. Seagrass meadows

are also damaged in the region by inappropriate fishing methods such as push nets and

trawling which mechanically uproots the seagrass.

Seagrass meadows growing in shallow waters close to the shore renders them very

susceptible to unplanned and unmanaged urban and industrial development and tourism.

These problems are compounded by a lack of environmental assessment procedures for

developments, awareness about the importance of seagrasses, and information on their

distribution.

Seagrasses are the least studied marine habitats compared to coral reefs and

mangroves. An assessment of the extent of habitat modification in the South China Sea is

based on a few studied areas in some countries. Anywhere between 20 and 50% of

seagrass areas in Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines and Thailand are damaged. Main

seagrass meadows in the region are shown in Fig. 3.3.

As with the other marine ecosystems the main transboundary issues are losses of

biodiversity and fisheries productivity. The seagrass nursery areas provide commercial fish

for fishing grounds a long way from the habitat of the juveniles. There is also a trade in

seahorses and green turtles that live in seagrass meadows.

The best ways to preserve seagrass is by leaving it undisturbed, mainly by

preventing trawling, maintaining water quality by reducing nutrient and suspended solids

loads and by using appropriate fishing gear.

The value of the products and ecological services provided by the seagrass systems

of the South China Sea is estimated at US$ 22,400 ha-1 year-1. (The area of seagrass is not

known. To determine this area is one of the aims of the project).

Proposed Targets

· By the year 2010, to maintain at least 80% of the present area of seagrass in good

condition.

Proposed Activities at the Regional level

UNEP SCS/SAP Ver. 3 (24/2/99)

Page 19

· Develop criteria for selection of seagrass areas for protection/sustainable management,

particularly those of transboundary importance;

· Identify and prioritise specific areas for future management and protection and develop

regional and national action plans to maintain regionally important seagrass areas;

· Develop and establish management regimes for the identified areas;

· Establish an accessible database containing maps and status of environmental health of

sea grass beds in the South China Sea;

· Conduct training workshops on seagrass management;

· Build the capacity of the governments of the region to understand the issues concerning

seagrass and to raise public awareness concerning the national and regional importance

of such ecosystems.

Proposed Activities at the national level

· Provide and implement national legislation and action plans for the preservation of

seagrass areas;

· Establish seagrass protection areas and implement proper management;

· Encourage monitoring, mapping and research on seagrass for a better understanding of

the economic and ecological implications of conserving seagrass beds;

· Conduct economic valuation of seagrass areas as a resource;

· Conduct training on seagrass management.

UNEP SCS/SAP Ver. 3 (24/2/99)

Page 20

Figure 3.3

Distribution of Seagrass in the South China Sea

UNEP SCS/SAP Ver. 3 (24/2/99)

Page 21

3.3.4 Estuaries and Wetlands

Wetlands are defined by IUCN in the "Ramsar Convention on Wetlands of

International Importance" as "areas of marsh, fen, peat, land or water whether natural or

artificial, permanent or temporary, in which water is static or flowing, fresh, brackish or salt

including areas of marine water the depth of which at low tide does not exceed six metres."

There is no simple definition of the wetlands that do not include mangrove forests, seagrass

meadows and coral reefs to six m deep. In this report we will refer to wetlands as peat

swamps, swamps, fens and saltmarshes.

Wetlands are the seasonal home to many migratory birds, they have their own suite

of animals and plants of great diversity and are the nursery area of some commercial fish

and crabs. They function as nutrient traps and some wetlands are used for aquaculture

Wetlands are under threat from urban expansion (land reclamation), pollution from

urban sources, and changes to coastal morphology from up stream development (dam

building causing downstream erosion through lack of replacement sediment). Their small

size makes them especially vulnerable to pollution. Those that are easily accessible or have

a high concentration of birds and mammals, tend to attract large numbers of visitors, whose

wastes are deleterious to the wetlands. Straightening the meanders of wetland streams and

rivers changes the hydrology and/or salinity regime that is deleterious to wetlands.

Introduced plants may dominate some wetlands and the classic example of this in many

parts of the world is water hyacinth.

The value of the products and ecological services provided by the wetlands systems

of the South China Sea is estimated at US$ 190,726 million per year (from Table W1 of the

TDA, the total area of wetlands is about 12.9 million ha, and US$ 14,785 ha-1 year-1 is its

estimated ecological and economic value)

Proposed Targets

· By the year 2005, to have management plans for all wetlands, excluding mangroves, in

the Region, with emphasis on those in the coastal zone.

Proposed Activities at the Regional level

· Develop criteria for selection of wetland areas for protection/sustainable management,

particularly those of transboundary importance;

· Identify and prioritise specific areas for future management and protection and develop

and implement regional and national action plans to maintain regionally important

wetland areas;

· Develop, establish and implement management regimes for the identified areas;

· Develop and agree on scientific and technical guidelines on the economic valuation of

wetlands as resources;

· Establish a GIS-type database providing the necessary information on wetlands in the

Region;

· Build the capacity of the governments of the region to understand the issues concerning

mangroves and to raise public awareness concerning the national and regional

importance of such ecosystems.

Proposed Activities at the national level

UNEP SCS/SAP Ver. 3 (24/2/99)

Page 22

· Develop and implement guidelines, standards and measures to control development

impinging on wetland areas;

· Establish and implement management plans for wetland "hot spots" to conserve their

ecological and economic functions, including encouraging nations to ratify the

International Convention on Wetlands (Ramsar);

· Enhance public awareness of wetlands and assist with capacity building.

3.4

Over exploitation of fisheries

The problem of unsustainable exploitation of living aquatic resources is found in all

the national reports. Almost all countries bordering the South China Sea suffer from an

ineffective fisheries management system, allowing the non-sustainable use of living marine

resources.

The deteriorating resource base, as described in 1.1 and 2.1, is compounded by

socio-economic problems. Typically, many small-scale fishermen compete for resources with

a few large-scale more capitalised entrepreneurs. Current management policies may

exacerbate the problems by providing incentives for over-exploitation, e.g. subsidies for

capital investment or fuel, and provision of infrastructure and industrial incentives.

Different levels of development in the countries of the South China Sea lead to

uneven resource capabilities. Some countries have large fleets of large vessels that have

depleted local resources and are now encroaching on others which have not had the means

to fully exploit their resources. This transboundary movement of fishing fleets results in

conflicts among countries where territorial water limits are violated.

Where the level of exploitation is now excessive, guidelines to reduce that level to a

more sustainable one should be prepared. This sustainable level of fishing can be at many

optimal levels, from open access, where a limit on the amount of fish caught is laid down but

not on the effort required to catch them, to maximum economic yield, where the catch is

limited by the economic return. The maximum ecological yield lies somewhere between.

The prevailing situation is one of open access, where the level of exploitation is in

access of the ecological and the economical optimal levels. The choice is thus between

whether to continue with open access or to reduce the level of exploitation to either

ecological or economic optimum. Economic theory does not provide a clear-cut answer;

rather, the choice is between social preference, and the likely response of the ecosystem

productivity.

From the perspective of welfare, the main concern is with the maximisation of valued-

added product, and the aim of the intervention should be to achieve the level of long-term

exploitation that is maximising welfare with maximum economic yield. The target should take

into account costs of effort and the productive potential of the ecosystem.

The target for the issue of excessive exploitation should be to reduce the level of

effort to the level that is economically welfare-maximizing and still preserve the resource

base. The decisions on the form and amount of intervention should establish the actual

target levels of exploitation for these resources, and the economic cost to capture them. It

should concentrate on the targeted living aquatic resources of each country, and consider

the social implications. The question of large versus small-scale fishermen has to be

thoroughly recognised and dealt with in these studies realising that the removal of fishing

UNEP SCS/SAP Ver. 3 (24/2/99)

Page 23

boats and employment will cause hardship and short-term problems. These issues must be

included in the action programme.

Proposed targets

· By 2005 to determine regional catch levels of key economic/commercially important

species according to levels that are economically welfare maximising, while still

preserving the resource base;

· By the year 2005, to have established a regional system of marine protected areas

for fishery stock conservation and care for endangered species;

· By the year 2005 to have prepared and implemented at chosen sites, a management

system that will sustain the exploited resources.

·

Proposed activities at the Regional level

· Develop criteria for selection of marine habitats and areas critical to the maintenance

of regionally important fish stocks, particularly those of transboundary importance;

· Identify and prioritise specific areas for future management and protection and

develop regional and national action plans to develop a regional system of refugia for

maintenance of regionally important fish stock;

· Develop and establish management regimes for the identified areas;

· Review destructive fishing activities with the aim of removing and replacing them;

· Review fisheries management systems;

· Review compliance to international fisheries conventions.

Proposed activities at the national level

· Establish marine protected areas in areas identified as critical habitats for fish stock

conservation and protection of endangered species;

· Implement programmes to provide information on fish stock conservation and

sustainable fishery practices among small and artisanal fishing communities;

· Conduct resource assessment of fishery resources to determine the level of optimal

catch and effort for different fishing grounds in the Region;

· Develop educational and public awareness materials on sustainable fishery practices

for dissemination in countries;

· Establish in selected pilot sites a good management system which can be tested to

determine if it is leading to sustainable exploitation of resources;

· Promote the Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries through workshops,

awareness building, translate into local languages and educate people about the

Code.

UNEP SCS/SAP Ver. 3 (24/2/99)

Page 24

There should be close co-ordination and co-operation with the Regional Office of

Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) for the implementation of the actions identified.

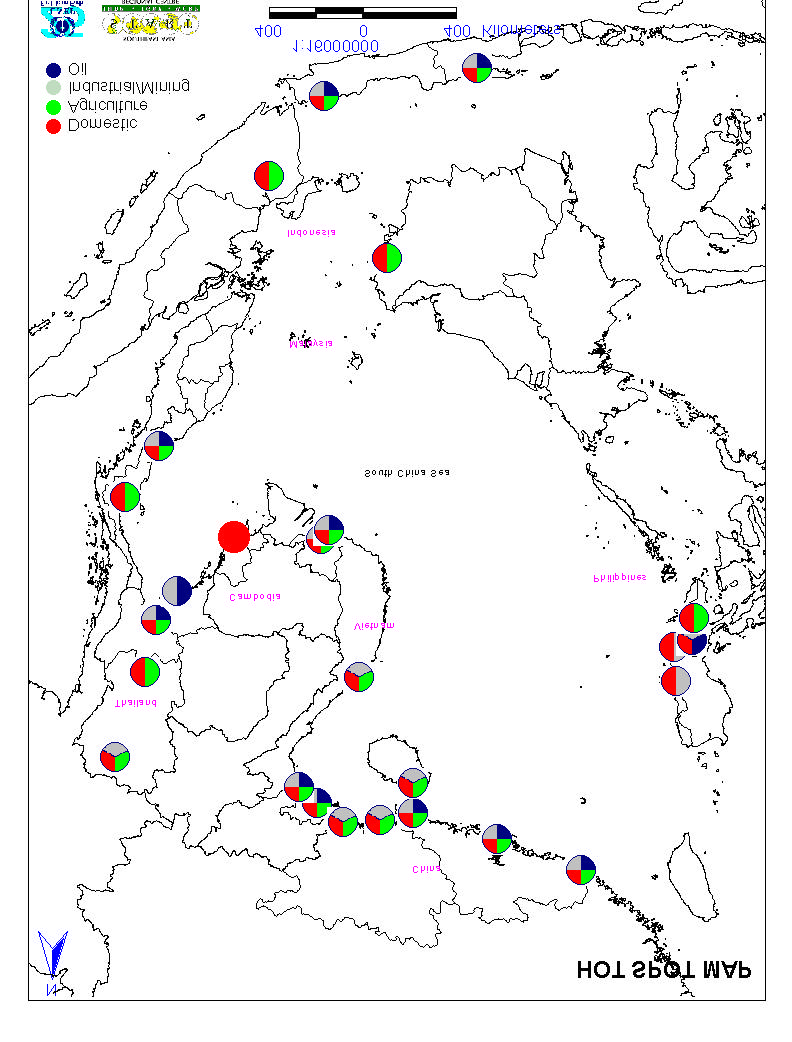

3.5

Land-based Pollution

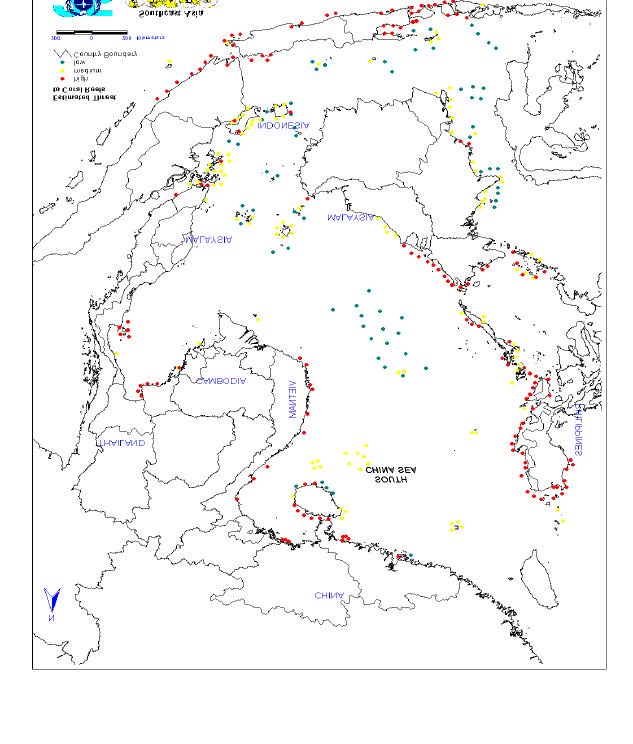

Most of the polluting elements that occur in the sea come from the land, waste from

large cities includes sewage, industrial waste and hydrocarbons, while agricultural runoff has

nutrients, pesticides and sediment that may pollute the marine environment. The "hotspots"

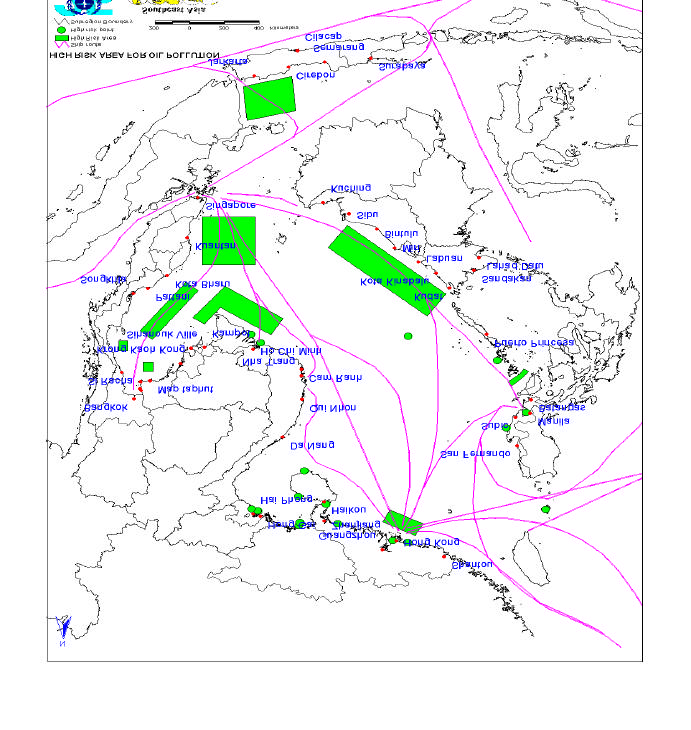

or areas of most concern are shown in Fig 3.4.

3.5.1 Urban/Municipal Waste

Urban waste consists of solid waste, such as plastic, glass, cans etc.; and sewage

consisting of organics which increase BOD, nutrients and bacterial coliforms that can

damage human health. Solid waste is unpleasant to the eye, can choke marine life and may

calm water to such an extent that alga blooms are allowed to concentrate in the mass of

floating debris. High BOD loading reduces dissolved oxygen available to fish and other

marine life. Usually the pelagic fish swim away from these areas but demersal fish, worms,

crustaceans and sessile animals are killed. Lowered oxygen in the water also kills plants

such as seaweed and seagrasses. The populations of the seven countries of the South

China Sea generate about six million tons per year of organic matter. Only 11% of this is

removed from four countries with treatment plants. The main producers of BOD are shown in

Fig 3.5.

Nutrients from treated or untreated sewage enhance the growth of phytoplankton that

may concentrate to such an extent that they form algal blooms. Sometimes these algal

blooms are toxic and fish kills and worse, human poisoning, may occur. Excess nutrients in

the water column may also be harmful to seagrass meadows. Epiphytes on the seagrass

leaves adsorb the nutrients, grow quickly and shade the seagrass so that it can no longer

photosynthesise enough food to sustain it. Storage material is used up and the seagrass

dies. With the death of the seagrass the organic matter, made up of epiphytes, seagrass

detritus and associated flora and fauna, fall to the bottom, use up oxygen as they decay and

the BOD rises, eventually leading to anaerobic conditions and virtual desertification of the

seafloor. This excess of nutrients is called eutrophication.

Usually, in the sea, nitrogen is the limiting nutrient to plant growth so it is usually

monitored in preference to phosphorus if monitoring facilities are limited. Total nitrogen

includes organic nitrogen as well as the inorganic form taken up readily by plants. Total

nitrogen from different sub-regions or districts of the South China Sea is shown in Fig. 3.6.

Untreated sewage contains much organic matter that has a deleterious effect on demersal

communities. The organics from sewage are most easily removed in the treatment plant and

can be used for mulch and organic fertilizer. High coliform counts in rivers, estuaries and

coastal waters cause health problems to users of the water bodies. E. coli is killed by

sunlight and settling ponds usually reduce coliform counts. Another sources of bacteria in

coastal waters is urban runoff from roads, gardens and footpaths where domestic animals'

faeces are washed into the drains, rivers and out to sea.

UNEP SCS/SAP Ver. 3 (24/2/99)

Page 25

Figure 3.5

Biological Oxygen Demand from Domestic Sources in the South China Sea

UNEP SCS/SAP Ver. 3 (24/2/99)

Page 26

Cities in the coastal areas of the South China Sea are large and growing, e.g. Guang

Zhou, Hong Kong, in China, Ho Chi Minh City in Viet Nam, Bangkok in Thailand, Manila in

Philippines, Jakarta in Indonesia and Singapore. Few have sewage treatment facilities, so

that waste is released directly into the rivers and seas. This inappropriate management

results in severe pollution through high BOD loadings, eutrophication, fish kills, red tides,

damage or loss of seagrass habitat and public health hazards.

Some of these problems can be addressed by installing waste treatment facilities.

However, this approach has been hampered by lack of finance and cost recovery of

facilities. Information on the damage caused by sewage pollutants and the economic loss

due to pollution should be provided to the governments and public. There are alternatives to

coastal dumping, such as using the two scarce commodities, freshwater and fertilizer, in

forestry, crop growing or playing field management.

3.5.2 Industrial Waste

Urban centres are also the location for major industrial agglomerations, e.g.

Bangkok, Maptaphut, Guang Zhou, Haiphong, with significant discharge of industrial wastes

to the marine and coastal environments, which can be highly toxic and damaging to marine

life. Causes of industrial pollution are lack of or poor enforcement of industrial pollution laws

and regulations, poor facilities and the desire of factories to promote competitiveness in the

international market by ignoring environmental and social costs. These problems can be

reduced by incentives and regulations to recycle wastes.

One of the environmental services provided by the oceans is its capacity to

assimilate or absorb wastes. However this capacity is being exceeded in many coastal

areas in the South China Sea region. The pollutants from industrial waste range from

nutrients to specific persistent organic pollutants that will, in most cases, be toxic.

3.5.3 Agricultural Waste

The reliance of countries of the South China Sea on agriculture for food and exports

means that much of the land surface is used for growing crops or rearing animals.

Successful farming relies on adequate applications of fertiliser to enhance plant growth and

the use of herbicides and insecticides to reduce pests that lower crop or animal yields.

Far too often fertiliser is over applied and applied at the wrong time thus making it

available to be washed away. Apart from the economic waste of losing fertiliser to runoff

after rain, there is a major problem of high nutrient levels in the marine environment once the

runoff enters rivers and hence the sea. Animal waste from piggeries and poultry farming and

the effluent from aquaculture also contain nutrients which can damage marine ecosystems.

Very often these wastes are allowed to run into waterways in times of flood or rainfall.

Shrimp and fish farms are major sources of nutrients to the marine environment as they are

usually close to the sea and excess feed and faeces are not treated in settling ponds. These

non-point sources of nutrients enter the sea and may cause transboundary problems if they

are not immediately absorbed by plants (phytoplankton, seagrasses, seaweed or

mangroves).

Economic loss due to poor water quality, loss of nursery habitat for commercial

species and disease in fish and shrimp ponds, means that attempts should be made to

reduce loss of nutrients to the marine environment.

UNEP SCS/SAP Ver. 3 (24/2/99)

Page 27

As insects and weeds become more immune to chemicals, larger applications are

made. Cost benefit analysis often suggests that applying the extra pesticide to kill the last 5-

10% of a pest is not economic and the extra pesticide is often wasted by also entering

waterways. These pesticides have varying effects on the marine environment. Some may be

persistent and accumulate in animal or plant tissue, others may accumulate in the sediment

and be released during storms. The damage they do is also variable and ranges from

causing impotence in gastropods to moving up the food-chain to human food.

3.5.4 Hydrocarbons

Oil-spills from wrecked ships are not the major cause of oil pollution in the sea. The

UNEP The State of the World Environment 1987 states that half a million tonnes of the 1.6

million tonnes annually discharged into the sea by shipping is released accidentally: The

remainder results from regular discharge by ships of contaminated ballast water and water

used for flushing out tanks. Later figures estimated total marine pollution at 3.5 million

tonnes, with 48% coming from land (World Resources, 1987). Municipal and industrial

wastes represent the single largest source.

Marine sources of hydrocarbon pollution in coastal and marine waters are ships and

oil and gas exploration and production platforms. The high risk areas for oil pollution from

marine sources are shown in Fig. 3.7. The amount of ship traffic - commercial, fishing,

leisure and bulk oil carriers, is likely to increase in the region and with it the risk of pollution

from ship-based oil. Hydrocarbon pollution may be limited in extent but have severe

consequences for the marine environment because some of the substances are not easily

biodegradable and highly toxic. Methods exist to contain the effects of major oil spills and

there are standards established for oil and gas exploration and production activities to

reduce pollution. These need to be followed and monitored. Yet, in spite of precautions,

accidents will occur, and countries need to be prepared to deal with these emergencies in

order to contain the damage.

The main difficulty of preventing marine-based sources from polluting the sea,

however, is in dealing with dispersed sources of pollution from small boats because they are

small scale and widespread, but the effect can be cumulative. The best way to deal with this

is to encourage people to adopt good practices in dealing with oil based substances through

education and provision of adequate facilities to dispose of waste oils etc. at landing sites.

Land-based activities like oil refining, oil-well blow-outs and leakages, and fallout

from the atmosphere are sources of hydrocarbons in the sea, but most comes via run-off

from rivers and city drains. More oil enters the coastal areas from car exhausts and oil-

changes in city garages that are then dumped down the drain, than from any other source

(Elsworth, S. A Dictionary of the Environment, 1990.).

Because of its persistence, oil in the marine environment is a transboundary issue.

Oil is driven by both currents and wind action across the sea surface. For large oil-spills from

wrecked tankers or blowouts from sea-based oil exploration platforms the responsible

companies usually have oil-spill contingency plans. Often the companies have not co-

ordinated these operations among themselves. For a large spill there is not

UNEP SCS/SAP Ver. 3 (24/2/99)

Page 28

enough equipment to contain the oil and not enough is known of the whereabouts of

vulnerable areas to make decisions on where to place limited clean-up equipment. A

mapping program to map vulnerable underwater habitats would be useful if seagrass

meadows and coral reefs are to be saved. Co-ordination between companies and countries

within the Region may help save some of the more valuable ecosystems if a large spill

occurred.

3.5.5 Suspended Solid/Sedimentation

Inappropriate agricultural practices and deforestation may leave bare soil available to

erosion by wind and rain. Land clearing of forests for agricultural crops is a major supply of

suspended solids and silt in rivers and coastal areas. The recent floods in China, although

the largest on record did not result from the largest rainfall on record, rather, the amount of

deforestation caused vast areas of loose sediment to be removed which silted up rivers and

hence river water broke over the rivers' banks and flooded the land.

Inappropriate engineering practices also lead to large volumes of sediment being

washed into rivers and the sea. The slope of unprotected earth walls in shrimp farms,

causeways, bridge approaches and roadsides are potential sites for erosion. With long-term

planning it should be obvious to engineers that repairs will be needed after a few years of

erosion. Artificial coverings such as Geotextile can be used, or slopes and banks can be

revegetated using seed of a fast growing annual which will stabilise the bare soil long

enough for more robust perennials to take over.

Eroded soil is washed into waterways and this suspended solid material reduces

water quality. Reduced water quality in this case means less light to benthic plants and may

result in a loss of benthic vegetation. Many of the rivers of the South China Sea are heavily

laden with suspended solids and some of these rivers have picked up these solids in

countries other than that in which the river enters the sea, thus a transboundary problem

occurs. Rivers that discharge large volumes of water often have plumes of suspended solids

which cross ocean boundaries and are therefore transboundary on their effect on the marine

environment.

There is an amount of suspended solids which has always washed out to sea caused

by floods and natural erosion, in recent years this natural loss of soil and sediment has

increased due to human activities. It is necessary to determine what is an acceptable flow of

suspended solids and what is caused by inappropriate human activities. Some of these

activities may be irreversible and this should be identified before attempts are made to

change the situation.

River-borne sediments are a major contribution to the water bodies in the South

China Sea region. Sediments perform useful functions by replenishing the coastline,

maintaining the land area for human habitation and supplying nutrients to the water bodies.

However, human actions in the upstream regions significantly affect the process of river

sedimentation. Dam construction can trap the flow of sediments and reduce the supply to

replace the beach material eroded by tidal action, resulting in eroding shorelines and threat

to coastal structures.

Proposed Targets

UNEP SCS/SAP Ver. 3 (24/2/99)

Page 29

· By 2003 develop and agree on regional water quality objectives; make recommendations

for water quality standards for use in coastal waters; make recommendations for effluent

standards/or mitigation measures for municipal, industrial and agricultural (including

aquaculture) activities;

· By 2003 develop guidelines for monitoring coastal waters, taking into account already

published guidelines;

· By 2003 determine principal pollutants in the region, estimate the carrying/assimilative

capacity of relevant ecosystems for relevant pollutants - BOD, nutrients, metals,

sediments etc.

· Establish a regional contingency plan for South China Sea to handle incidents of oil and

chemical or hazardous waste spillage;

· By 2004 develop a regional South China Sea Plan of Action for land-based activities to

meet regional water quality objectives;

· By 2005 identify 10 Priority Discharge Sites for action and develop appropriate mitigation

activities;

· By 2005 develop regional funding mechanisms for mitigation activities;

· By 2006 initiate mitigation activities on the Priority Discharge Sites;

· By 2008 review recommended water quality standards in national legislation.

Proposed Activities:

Determine regional water quality objectives and water quality and effluent standards:

· First meeting to review and assess existing knowledge of regional water quality,

determine information gaps, set a programme for carrying/assimilation capacity

evaluation, discuss GPA-land-based activities guidelines/action programmes (2002);

· Second meeting to agree on water quality objectives, determine a regional South China

Sea Plan of Action (based on GPA-land-based activities);

· Third meeting to agree on regional water quality and effluent standards;

· National meetings for endorsement of South China Sea Plan of Action (2005);

· International organisations, such as UNEP EAS/RCU, will initiate the production of

package programmes to help member countries facing problems associated with land-

based activities that pollute the South China Sea.

Determination of Regional Priority Hot Spots (2005)

· Discuss and agree on criteria for evaluating the regional importance of nationally

identified pollution "hot spots" (severity of pollution, feasibility/ease of mitigation,

transboundary effects);

· Assess and evaluate data relating to national "hot spots" and prepare and agree on

regional priorities;

· Conduct a preliminary evaluation of the costs and benefits of alternative mitigation

measures for selected "hot spots";

· Develop and agree on a South China Sea strategic approach to mitigating regional "hot

spots", including priority investment portfolio, cofinancing arrangements, national and

regional actions.

· Carry out capacity building activities that lead to improvement in water quality testing and

hence cleaner water. Determine the carrying capacity of ecosystems for specific

pollutants, realising that the carrying capacity of a human-made toxic chemical is zero.

UNEP SCS/SAP Ver. 3 (24/2/99)

Page 30

Analyse secondary data and, where appropriate, carry out some primary studies to

improve water quality testing and hence water quality. (2003)

3.5.6 Regional Cooperation

To achieve collaboration and co-operation among countries it is usual to have legal

frameworks that cover the areas of interest between the interested parties. However, there is

no legal framework that directly relates to forming a marine environment protection co-

ordinating body and few that relate to the marine pollution problems prioritised by the