"Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends

in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand"

WETLANDS BORDERING THE SOUTH CHINA SEA

UNEP/GEF

Regional Working Group on Wetlands

First published in Bangkok, Thailand in 2004 by the United Nations Environment Programme.

Copyright © 2004, United Nations Environment Programme

This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit purposes

without special permission from the copyright holder provided acknowledgement of the source is made. UNEP

would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication that uses this publication as a source.

No use of this publication may be made for resale or for any other commercial purpose without prior permission in

writing from the United Nations Environment Programme.

UNEP/GEF Project Co-ordinating Unit, United Nations Environment Programme,

UN Building, 9th Floor Block A, Rajdamnern Avenue, Bangkok 10200, Thailand.

Tel.

+66 2 288 1886

Fax.

+66 2 288 1094

http://www.unepscs.org

DISCLAIMER:

The contents of this report do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of UNEP or the GEF. The

designations employed and the presentations do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part

of UNEP, of the GEF, or of any cooperating organisation concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city

or area, of its authorities, or of the delineation of its territories or boundaries.

Cover Photo:

Migratory Birds in Pearl River Delta, China Professor Guizhu Chen.

Photo credits:

Page 3

Dumping of waste in coastal wetlands, Philippines Marlynn Mendoza

Page 3

Collection of molluscs from mudflats replanted with mangrove, Vietnam Mai Trong Nhuan

Page 4

Khao Sam Roi Yot Marine National Park, Thailand Sansanee Choowaew

Page 5

Coastal pond development in Sembilang, Indonesia Dibyo Sartono

Page 5

Erosion Prevention Dike in Ham Tien, Vietnam Mai Trong Nhuan

Page 7

Mui Ne Fishing Port, Vietnam Mai Trong Nhuan

Page 8

Harvesting of mollusc Solen regularis at Don Hoi Lot, Thailand Sarakhadee Magazine

Page 8

Harvest the edible seaweed Gracilaria tenuistipitata var. liui in Shantou, China Guizhu Chen

Authors:

Dr. Sansanee Choowaew, Dr. Liwei Chen, Mr. Sok Vong, Professor Guizhu Chen, Mr. Dibyo Sartono, Dr. Ebil Bin

Yusof, Ms. Marlynn Mendoza, Mr. Narong Veeravaitaya, Dr. Mai Trong Nhuan, and Ms. Sulan Chen.

This publication has been compiled as a collaborative document of the Regional Working Group on Wetlands of

the UNEP/GEF Project entitled "Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of

Thailand."

For citation purposes this document may be cited as:

UNEP. 2004. Wetlands Bordering the South China Sea. UNEP/GEF/SCS Technical Publication No. 4.

W ETLANDS BORDERING THE SOUTH CHINA SE A 1

FOREWORD

The South China Sea region has experienced high rates of economic growth and rapid coastal development in

recent decades. Each country bordering the South China Sea has actively and in certain respects very

successfully engaged in its economic development. This is a region where economic development has imposed,

and will continue to place increasing stress on the ecological systems.

In 1981, under the sponsorship of UNEP, the East Asian Seas Action Plan was adopted by five Southeast Asian

countries: Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand. At that time, obstacles to engaging all the

South China Sea border countries in a single programme were seemingly insurmountable. Two decades after the

adoption of East Asian Seas Action Plan, the region has witnessed a trend of deepening interdependence,

integration, cooperation and prosperity. Despite the 1997-1998 financial crisis, the region remains the fastest

industrializing area. However, economic development was not achieved without negative impacts. Fast economic

development was accompanied by urbanization, population growth and deterioration of environment.

In 1996, realizing the urgency to collaboratively tackle regional marine environmental problems in the South China

Sea, the countries bordering the South China Sea requested assistance from UNEP and the Global Environment

Facility (GEF) in addressing the issues and problems facing them in the sustainable management of their shared

marine environment. From 1996 to 1998 initial collection of data and information was conducted by each country

to provide inputs for the development of a Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis, which identified the major water

related environmental issues and problems of the South China Sea. In 1999 the governments, through the

Coordinating Body for the Seas of East Asia endorsed a framework Strategic Action Programme that established

targets and timeframes for action.

The endorsement of the UNEP/GEF South China Sea Project by all the major countries around the South China

Sea ushered in a new era of environmental cooperation in the region. It demonstrates the determination of the

littoral countries to take an holistic approach to addressing shared environmental problems, despite the continuing

existence of certain political disputes or disagreements. Under the framework of the Project, the wetlands sub-

component focuses its activities on five types of wetlands, i.e. intertidal flats, estuaries, lagoons, peat swamps

and non-peat swamps. During the first phase of the Project, data and information have been collected and

compiled for regional use, which provides baseline information for the operational phase of the project.

We are delighted to have been asked to write the Foreword to this booklet, and we consider this booklet a valid

contribution to accumulate regional knowledge and understanding on wetlands bordering the South China Sea. It

reflects the collective effort of the Regional Working Group on Wetlands in exchanging and sharing data and

information. We hope it reaches the possible widest audience and inspires new political and financial

contributions to promote the protection and sustainable management of wetlands in the global marine biological

divers ity centre--the South China Sea.

Dr. Sansanee Choowaew & Dr. Liwei Chen

Bangkok, Thailand

January 2004

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

INTRODUCTION

regions and almost 1/3 are located in Asia (Mitsch

and Gosselink, 2000).

Wetlands are defined as "areas of marsh, peatland

or water, whether natural or artificial, permanent or

Wetland ecosystems are cradles of biological

temporary, with water that is static or flowing, fresh,

diversity. Countless species of plants and animals

brackish or salt, including areas of marine water, the

depend on them for survival. Fishes in wetlands

depth of which at low tide does not exceed six

number around 20,000 species worldwide. Diversity

meters" (Ramsar Convention, 1971). This definition

amongst aquatic species groups is highest in the

encompasses reef flats and seagrass beds in

tropics: South America has the most species with

coastal areas, mudflats, mangroves, estuaries,

2,220 species, of which more than 1,000 are in the

rivers, freshwater marshes, swamp forests and

Amazon River basin; Africa has 2,000 species, with

lakes, saline marshes and lakes as well as

more than 700 occurring in the Zaïre River basin;

underground water resources.

Europe has about 200 species; and, Asia has an

estimated 1,600 species but this number is

Under the UNEP/GEF South China Sea Project,

increasing as additional research is undertaken

activities in the wetland sub-component are focused

[WCMC, Global Biodiversity, 1992].

on five specific types of wetlands, namely intertidal

flats, estuaries, lagoons, peat swamps and non-peat

The Southeas t Asian Region is rich in marine

swamp, since mangroves, coral reefs and seagrass

biodiversity. Field records of hermatypic coral

beds are the subjects of separate sub-components.

genera indicate that Indonesia, Malaysia and

Activities at national level include establishment or

Philippines form the centre of coral diversity.

re-vitalisation of national committees or technical

Countries bordering the South China Sea largely

working groups; review of national data relating to

depend on wetlands for their livelihood. In

wetlands; development of national meta database;

Cambodia, Over 30% of its territory is wetlands.

development or update of national management

Following internationally accepted criteria for

plan. At the regional level, the Regional Working

wetland identification (defined by the Ramsar

Group on Wetlands develops regional criteria and

Convention), over 20 % (36,500 Km2) of the

procedures in identifying, prioritising, and ranking

Kingdom may be classified as wetlands of

the importance of sites by environmental and socio-

international impor tance (Cambodia Wetland

economic indicators.

Report, 2003).

About 6% or 5.7 million square kilometres of the

Despite the importance of wetlands of high

Earth's surface is wetlands. The greatest proportion

biodiversity in the South China Sea, loss and

is made up of bogs (30%), fens (26%), swamps

degradation of wetlands and their biodiversity have

(20%) and floodplains (15%), with lakes accounting

been continuing at a high rate due to the increasing

for just 2% of the total. Mangroves cover about

human population size, particularly in coastal areas,

240,000km2 of coastal area and an estimated

poverty, and people's dependency on wetland

600,000km2 of coral reefs remain worldwide

resources. Actions are urgently needed to halt the

(WCMC, Global Biodiversity, 1992). About 56% of

degradation of coastal wetlands around the South

wetlands are found in tropical and subtropical

China Sea.

Reversing Environmental Degradation in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand.

Cambodia, China, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand, Viet Nam

In 1996, the countries bordering the South China Sea requested assistance from UNEP and the GEF in

addressing the issues and problems facing them in the sustainable management of their shared marine

environment. From 1996 to 1998 initial country reports were prepared that formed the basis for the development

of a Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis, which identified the major water related environmental issues and

problems of the South China Sea. Of the wide range of issues identified the loss and degradation of coastal

habitats, including mangrove, coral reefs, seagrass and coastal wetlands were seen as the most immediate

problem. Over-exploitation of fisheries resources and land-based sources of pollution were also considered

significant issues requiring action.

In 1999 the governments, through the Co-ordinating Body for the Seas of East Asia endorsed a framework

Strategic Action Programme that established targets and timeframes for action. In December 2000, the GEF

Council approved this project with UNEP as the sole Implementing Agency operating through the Environmental

Ministries in the seven participating countries and with over forty specialised Executing Agencies at national level

directly engaged in the project activities

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

W ETLANDS BORDERING THE SOUTH CHINA SE A 3

Rate of Wetland Loss. It has been estimated that

being drainage for agriculture, settlement and

about 50% of wetlands have been lost worldwide

urbanization, pollution and hunting.

since 1900. This has mostly occurred in the

northern temperate zone, however, since the 1950s,

Global Importance of Wetlands in the South

tropical and subtropical wetlands especially swamp

China Sea. The South China Sea is a strategic

forests and mangroves have been rapidly

body of water, surrounded by nations that are

disappearing (Stuip, et al., 2002).

currently at the helm of industrialization and rapid

economic growth in the Asia-Pacific Region. It is

In Southern and Eastern Asia, wetland loss has

bordered by China to the north; Philippines to the

been occurring for thousands of years. Lowland rice

east; Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia and Brunei to

cultivation began in Southeast Asia about 6,500

the south; and, Thailand, Cambodia and Vietnam to

years ago, and sophisticated drainage and irrigation

the west (Talaue-McManus, 2000).

systems had been developed in parts of the Middle

East by the 4th millennium BC (Scott, 1993). Over

The South China Sea has always been central to

the centuries, vast areas of wetland in Southern and

issues of economic and political stability in

Eastern Asia have been converted into rice fields or

Southeast Asia and adjacent regions. Its richness in

drained for agricultural use and human settlement.

flora and fauna contributes to the area's high natural

For example, no trace remains of the natural

rates of primary and secondary production. Capture

floodplain wetlands of the Red River delta in

fisheries from the South China Sea contribute 10%

Vietnam, which originally covered 1.75 million

of the world's total landed catch.

hectares.

The South China Sea is a region of important

In China, during the period of 1966-1996, the total

interaction between extensive watershed areas and

reclaimed area in the entire Pearl River delta

the marginal sea, where a large number of riverine

was344km2, which represents an average rate of

systems discharge a globally significant and high

11.47 km2 per year (China Wetland Report, 2003). It

volume of water and sediment into coastal waters.

has been estimated that approximately 69% of the

original mangrove forest area in the South China

About 40 marine protected areas have been

Sea was destroyed during the past century (Talaue-

established along the South China Sea coastline.

McManus, 2000). Logging and woodcutting affect

Twelve wetlands sites, with a total area of 364,832

about 30% of all wetlands sites in the Southeast

ha, have been designated as Ramsar sites around

Asian countries (ASEAN, 2001).

the South China Sea (Figure 1). The Ramsar sites

bordering the South China Sea are Koh Kapik

(Cambodia), Dongzhaigang (China), Huidong

Harbor Sea Turtle National Nature Reserve (China),

Mai Po Marshes and Inner Deep Bay (Hong Kong,

China), Shankou Mangrove Nature Reserve

(China), Zhanjiang Mangrove National Nature

Reserve (China), Berbak National Park (Indonesia),

Tasek Bera Peatswamp (Malaysia), Don Hoi Lot

intertidal mudflats (Thailand), Thale Noi Wildlife

Non-Hunting Area (Thailand), Phru To Daeng

Peatswamp Wildl ife Sanctuary (Thailand), and Xuan

Thuy National Park (Viet Nam).

Figure 1

Distribution of Ramsar Sites in Asia.

Dumping of waste in coastal wetland, Philippines

Agriculture is consider ed the principal cause for

wetland loss worldwide. By 1985, it was estimated

that 56%-65%, 27%, 6% and 2% of available

wetlands in Europe and North America, Asia, South

America and Africa, respectively, had been drained

for agriculture (Stuip et al., 2002) . Scott (1993)

quoted an overall wetland loss of 31%, 78%, and

22% in Indonesia, Philippines and Thailand,

respectively. In their review, Immirzi et al. (1992)

quoted peatland losses of 82%, for Thailand; 71%

for West Malaysia; 18% for Indonesia; 13% for

China; and, 11% in Sarawak in East Malaysia.

The Ramsar Site Database provides insight to the

Source: www.wetlands.org

main threats to wetlands. In 1999, 84% of Ramsar-

listed wetlands had undergone or were threatened

by ecological change. The most widespread threats

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

4

WETLANDS DISTRIBUTION AND DIVERSITY IN THE SOUTH CHINA SEA

WETLANDS DISTRIBUTION AND DIVERSITY IN THE SOUTH

CHINA SEA

Southeast Asian countries have at least 334

wetland sites, with a total area of 192,363,601 ha, of

which Indonesia has the greatest number, 129 sites

scattered throughout the country (ASEAN, 2001).

Along China's South China Sea coast, a total area

of 15,333.35 hectares has been identified under the

five types of wetlands with relevance to the

UNEP/GEF South China Sea Project. These

wetlands support local communities and habitats

that are home to a variety of rare, endemic,

endangered and threatened species of global

significance.

Khao Sam Roi Yot Marine National Park, Thailand

Wetlands are dynamic and complex ecosystems.

They exhibit enormous diversity in size and shape

Coastal wetlands play a critical role in protecting

according to their origins and geographical location,

coastal land from the influence of violent coastal

their physical structure, as well as their chemical

weather by providing a buffer against storm surges

composition. The characteristics of the flora and

and protecting coastlines from erosion. In Malaysia,

fauna are largely defined by the water depth, current

it has been estimated that the economic gain is

and intensity, underlying soil structure, sediment

US$300,000 per kilometre from intact mangrove

composition, and water temperature and, in coastal

swamps for storm protection and floo d control

regions, influence of the tide. Levels of diversity vary

alone, which is the cost of replacing them with rock

between different wetland types--some exhibit high

walls. This role of coastal wetlands may become

levels of diversity and endemism while others

even more important under conditions of changed

support little life.

climate over the next 50-100 years.

Ecological Functions of Wetlands in the South

The UNEP/GEF South China Sea Project focuses

China Sea. Wetlands are the ecotone and buffer

its activities on five wetland types, namely: estuaries

zone for inland and marine habitats with great

(including deltas), lagoons, intertidal mudflats, peat

importance for their "ecological functions," that

swamps, and non-peat swamps. Their functions,

support economic activities of significant value.

products and attributes are shown in Table 1.

These ecological functions include regulation of

water regimes; flood buffering and control;

Estuary. A wetland type where the river mouth

groundwater recharge and discharge; wind breaks

widens into a marine ecosystem, the salinity of

and storm protection; shoreline stabilization and

which is intermediate between salt and fresh water

erosion control; retention of nutrients, sediments

where tidal action is an important biophysical

and contaminants; nutrient processing, provision of

regulator.

nutrient-rich and sheltered habitats, spawning and

nursery areas for fish and aquatic organisms;

Lagoon. A semi-enclosed coastal basin with limited

retention of carbon dioxide and regulation of local

freshwater input, high salinity and restricted

and global climates.

circulation which of ten lies behind sand dunes,

barrier islands or other protective features like coral

reef of an atoll.

Intertidal mudflat. A wetland type that is usually an

unvegetated area, dominated by muddy substrate.

Peat swamp. Under normal oxygen-rich conditions,

dead plant matter decomposes eventually into

carbon dioxide and water. When under low

temperature, high acidity, low nutrient supply, water-

logging, and oxygen deficient conditions, the

process of decomposition is retarded and dead

plant matter accumulates as peat.

Non-peat swamp. A wetland type having still water

areas around lake margins, and in parts of

floodplains such as oxbows, where the water rests

Collection of molluscs from mudflats replanted with

for longer periods. Their precise characteristics vary

mangrove, Vietnam

according to geographical location and environme nt.

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

W ETLANDS BORDERING THE SOUTH CHINA SE A

5

Table 1

Functions, Products and Attributes of Wetlands. (X = present; = common and important value)

Estuaries

Lagoons

Intertidal

Mudflats

Peatswamps

Non-

peatswamps

Functions (Services)

Groundwater recharge

X

X

Groundwater discharge

X

X

X

X

Flood control

X

X

X

Shoreline stabilization/

erosion control

X

X

X

Sediment/toxicant retention

X

X

X

Nutrient retention

X

X

X

Biomass export

X

X

X

Storm protection

X

X

Water transport

X

X

Recreation/tourism

X

X

X

X

X

Products

Forest resources

X

Wildlife resources

X

X

X

X

Fisheries

X

X

X

Agricultural resources

X

X

Water supply

X

X

X

Energy Resources

Attributes

Biological diversity

X

X

Uniqueness to culture/heritage

X

X

X

X

X

Source: Dugan, P.J. (eds) 1990

ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACTS CONSEQUENCES OF

WETLAND LOSS

Floods and storms. Loss of coastal wetlands and

their ecological functions of storm and flood

Causes of wetland loss. Wetlands have been lost

protection, and coastal erosion control leads to

or altered because of the disruption of natural

severe damage and loss of life and property among

processes by agricultural intensification,

coastal communities. For example, between May

urbanization, pollution, water transfer, dam

and September 1994 Southeast Asia was

construction, and other forms of intervention in the

devastated by 5 months of storms and floods that

ecological and hydrological systems.

destroyed 220,000 houses in the Mekong Delta of

Vietnam and caused major losses in the rice crop.

Population growth remains high in the SCS

Tropical storms battered and drenched southern

countries (e.g. 2.6% in Cambodia and 1.7% in

China, Vietnam and Thailand during the period of

Vietnam, exceeding the East Asia/Pacific regional

June-November 1995.

average of 1.6%). It is estimated that some 37% of

the population in Vietnam, 36% in Cambodia, and

In 2000, the Mekong River delta experienced the

13% in Thailand live below the poverty line. These

longest-lasting and most severe flooding to affect

people in poverty are often those depending on

the area in 40 years. Floodwaters exceeded Alarm

wetland resources for their subsistence livelihoods.

Level III (very dangerous flood conditions) and

Wetland loss and degradation has led to loss of

flooding was reported in Thailand, Cambodia and

occupation and income.

Laos (IRI Climate Digest, 2000). The floods affected

almost 9 million people and killed 800. Damage was

estimated at more than US$ 455 million. Without

wetlands preventing such losses, investment in

coastal and flood plain protection are required.

Coastal pond development in Sembilang, Indonesia

Erosion Prevention Dike in Ham Tien, Vietnam

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

6

WETLAND LOSS AND DEGRADATION

WETLAND LOSS AND DEGRADATION

believed that the salt-water intrusion was

caused by decreased outflow from the lakes

Black Rivers. In 1979, 42 of the major rivers in

and rivers of the Makaham system as a

Peninsular Malaysia were declared dead as a result

result of extensive forestry clear felling in the

of pollution, primarily from oil palm and rubber

catchment.

effluents, sewage and industrial wastes. These

rivers no longer support fish, shellfish, or

·

In Malaysia and Indonesia, more than 1 and

crustaceans, and are unfit for drinking or washing

3 million hectares of peatland respectively,

(Sababat Alam Malaysia cited in Jayal, 1984;

have been converted into agricultural land.

Dugan, 1990).

Such conversion destroys not only the

developed peatland and its associated

In the Philippines, the National Pollution Control

biodiversity but has flow-on effects on the

Commission estimated that copper mining has

remaining peatlands by enhancing drainage

severely polluted 14 rivers in Luzon, the Visayas,

and loss from fire.

Palawan, and Marinduques. Where these rivers

enter the sea, fishing yields have declined by 50%

·

An intensive eel aquaculture scheme has

(Aditjondro, 1989 cited in Dugan, 1990).

been set up in the South East Pahang Peat

Swamp Forest on the east coast of

Wetland degradation. The following are further

Peninsular Malaysia. Huge quantities of

examples of wetland destruction or degradation and

groundwater have been extracted for the

their economic, social or ecological consequences:

ponds, resulting in the drying up of wells

used by local communities for their domestic

·

in the Philippines, some 300,000 ha of the

needs.

country's mangrove resources were lost in 60

years from 1920-1980, leading to a decline in

·

The Central plains of Thailand used to be

marine fishery production

swamp plains supporting populations of

wetland dependent wildlife such as

·

in Sumatra the average coastal fishpond

Schomburk's deer (Cervus schomburgki).

produces 287 kg/ha/year of fish but the loss

Drainage of the plains for rice cultivation

of one hectare of mangrove leads to a loss of

during the early 20th century destroyed most

approximately 480 kg/yr of offshore fish and

of the riverine wetlands and led to the

shrimp

extinction of the deer.

·

Local people of Samarinda (East Kalimantan)

·

Another consequence of wetland destruction

report that seawater formerly intruded

is the increasing number of threatened

upstream in the Makaham river as far as the

species as seen from Table 2.

town only in the very few years with a dry

season of ten or eleven months . In 1991

Within the framework of the UNEP/GEF South

saline water intruded upstream of Samarinda

China Sea Project, 102 ecologically and socially

after only six months of the dry season. This

important wetlands sites have been identified and

had significant impact on agriculture, industry

characterized (Table 3). Among these, 58 wetland

and the health of the community. It is

sites are already afforded some degree of

protection.

Table 2 Numbers of globally threatened wetland Species in countries bordering the South Chin Sea. (Numbers in parentheses

are species endemic to the country concerned)

Mammals Birds

Reptiles Amphibians Fishes

Invertebrates

Brunei

2-3

9-10

3-5

0

2 (1)

0

Cambodia

3

15-17

10-12

0

7

0

Indonesia

6 (1)

28-29 (8)

23 (3)

0

67 (54)

4 (2)

Malaysia

6-7 (2)

16-17

18-19

0

16 (10)

2 (1)

Philippines

1

16 (5)

7 (2)

26 (26)

30 (26)

4 (2)

Singapore

1-2

8

3-4

0

2

0

Thailand

5

22-29 (1)

17-20

0

19-20 (8)

1

Vietnam

4

21-26

20-24

1 (1)

6

0

Table 3 Number and areas of important wetlands bordering the South China Sea.

Cambodia

China

Indonesia

Malaysia

Philippines

Thailand

Viet Nam

No. of Wetlands Sites

3

6

40

9

16

13

15

Total Area (ha)

22,000

20,276

5,179,660

76,560

630,288

271,311

629,954

Range in Area (ha)

4500-13,000 218-12,783 7-1,000,000 348-35,750 420-193,195 140-65,000 16,000-160,000

No. of Sites with

protection measures

1

6

24

4

12

6

5

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

WETLANDS BORDERING THE SOUTH CHINA SE A 7

COASTAL DEVELOPMENT AND WETLANDS LOSS IN CHINA'S PEARL RIVER DELTA

Since the late 1970s, the Pearl River Delta has been the fastest developing area in China, acting as an engine for

the country's economic development. In the period 1978 to 1990, Guangdong's real gross domestic product

(GDP) increased at an average annual rate of 12.3% while its real per capita GDP grew at 10.4%. Due to

population increase, urbanization and industrialization, many wetlands in the Pearl River Delta have been

destroyed and reclaimed for agriculture, aquaculture, and industrial or residential uses.

Large areas of wetlands have been exploited or converted for farming, or city expansion, resulting in the reduction

of wetland area and decline of wetland functions. There were about 400,000 ha of mangrove in Guangdong in the

1950's, however, only 147,000 ha was left in the 1990s. The rate of mangrove loss has been especially high since

the 1980s. A total of 7,911.2 ha of mangrove have been destroyed or occupied since 1980, most of which has

been converted to aquaculture ponds (7,767.5 ha); reclaimed for construction projects (139.4ha), or converted to

salt pans (5.3 ha). From 1966 to 1996, the total reclaimed area in the entire Pearl River delta is 344 km2, an

average annual rate of 11 km2 yr-1 of reclamation, much greater than that experienced during recent historical

times.

Wetland degradation and loss have resulted in the disappearance of coastal vegetation, reducing the

effectiveness of coastal protection from typhoon winds and flood . In September 2003, Typhoon Dujuan, the

strongest storm to hit the Pearl River delta since 1979, killed 38 people, injured more than 1,000 and up-rooted

30% of all trees in the area. The direct economic losses were estimated at US$ 242 million and the severe

impacts of this typhoon can be partly attributed to the loss of natural coastal protection: coastal wetlands.

Guizhu Chen, China Wetland Focal Point

STATE OF WETLANDS AND PRESENT THREATS

Coastal wetlands continuously receive water,

sediment, nutrient and contaminants via inflows

The view that wetlands are wastelands, results from

from the inland catchment areas. Land-based

ignorance and misunderstanding of the value of the

pollution from industries, tourism, urban areas,

goods and services provided by wetlands, and has

agriculture, and aquaculture have impacts on

resulted in their conversion to intensive agricultural,

noteworthy fauna, and reduce the value of the

industrial or residential uses. Driven by short-term

benefits and services derived from estuaries,

economic gains and encouraged by government

mudflats, and other coastal wetlands. In the context

development policies, large coastal development

of climate variability and change, the projected sea

projects, along with scattered individual excessive

level rise and increases in storm surges are likely to

or inappropriate utilization of wetlands has

affect coastal wetlands significantly. Such changes

contributed to the rapid loss and degradation of

may cause substantial ecological, and economic

wetlands bordering the South China Sea.

losses.

Population growth and increasing demand for

economic development place tremendous pressure

on wetland ecosystems. The loss and degradation

of coastal wetlands bordering the South China may

trigger serious and long-term ecological, and socio-

economic consequences. For example loss of

coastal mangrove swamps in Viet Nam has resulted

in increasingly severe coastal erosion, affecting, for

example, at least 20% of Viet Nam's coastline,

leading to the loss of agricultural land and even

entire villages.

Major threats which are common to wetlands of all

countries bordering the South China Sea include

over-exploitation through over-fishing resulting in

Mui Ne Fishing Port, Vietnam

declining fish productivity; alteration of the

hydrological regimes, through draining and wetland

Many wetlands bordering the South China Sea are

reclamation schemes; conversion to other use such

protected as, national parks, wildlife sanctuary,

as agriculture or urban expansion, aquaculture,

wildlife non-hunting areas, and nature reserves.

agriculture, construction of coastal roads, and

Many of them however, are not well manag ed and

physical barriers for coastal protection against

the lack of appropriate and efficient management

erosion.

and unsustainable use remain threats to wetlands in

all countries.

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

8

USE AND VALUE OF W ETLANDS BORDERING THE SOUTH CHINA SEA

USE AND VALUE OF WETLANDS BORDERING THE SOUTH

and well-known as an attractive tourist destination.

CHINA SEA

Attractions include the natural environment,

traditional fisheries and fishing technologies,

The dependency of people on the coastal areas of

seafood and fishery products.

the South China Sea can be shown by the high

proportion of the total population living within 100

km of the coast: Cambodia, 24%; Indonesia, 96%;

Malaysia, 98%; Philippines, 100%; Thailand, 39%;

and Viet Nam, 83% (ASEAN, 2001). Whatever type

of wetland, their processes are based on the

interaction of the basic components of the natural

system, the physical and chemical components

including soil, and water, together with the biological

components, the plants and animals. It is the

wetland processes that generate the products,

services and attributes that are valued by humans.

Values are realized when people decide that

something is important to them. Human interactions

with the environment are diverse and so there are

many specific values that are applicable to

individual sites and to different stakeholder groups.

Harvesting the edible seaweed Gracilaria tenuistipitata var.

These can be categorized according to the principal

liui in Shantou, China

types of use and non-use values.

Wetlands are of significant importance to

Direct or extractive use values. The most tangible

subsistence communities in the South China Sea.

values, relating to the products and materials that

For generations, a large proportion of the population

can be derived from the wetland, such as food, and

of the South China Sea coastal area has depended

fibre.

on wetland ecosystems and their products for direct

use, and as sources of trade goods and for cash

Indirect or non-extractive use values. May be

income (see box on page 9).

seen as the value of wetlands for recreational use,

for tourism, or for research.

The countries bordering the South China Sea are

significant producers and consumers of captured

Service values. Reflect the services wetlands

and cultivated fish. In the coastal areas of the seven

provide for flood control, or as a windbreak.

participating countries, the marine capture fisheries

and culture production account for 8.2% and 54%

Existence value. The most difficult to determine,

respectively of the total world production. Globally,

such values reflect the intrinsic value of individual

two thirds of all fish consumed are dependent on

species and systems.

coastal wetlands at some stage in their life cycle.

Marine fishery aquaculture is mainly conducted in

wetlands or areas associated with wetlands.

Southeast Asia is the global centre of marine

aquaculture. In 1994, six of the seven countries

participating in this project accounted for 61% of

shrimp imports by Japan, and 6 of the ten top

shrimp producing countries border the South China

Sea. This dominant role has grown rather than

declined in recent years and the internal market

within the region has also grown significantly as

economic growth has lead to increasing levels of

disposable income.

On average, people in ASEAN countries consume

Harvesting of mollusc Solen regularis at Don Hoi Lot,

about 20 kg of fish per capita per year, which

Thailand

provides nearly half of their animal protein intake.

The figure can be much higher in some low -income

Don Hoi Lot Inter-tidal Mudflats on the Gulf of

countries. For example, in Cambodia, fish and fish

Thailand is the only major productive area of Solen

products are the single most important sources of

regularis, an economic, endemic mollusc species,

protein, for the Cambodian population, representing

which, unique to Thailand and to the region, is an

75% of the animal protein intake.

important source of fisheries production, occupation

and income. Solen regularis is harvested by 200-

300 mollusc harvesters at 1,360-3,025 kg/day and

sold at US$2.5/kg of fresh flesh. The site is famous

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

WETLANDS BORDERING THE SOUTH CHINA SE A

9

COMMUNITY LIVELIHOOD IN THALE NOI WILDLIFE NON-HUNTING AREA OF THAILAND

Thale Noi Wildlife Non-Hunting area, is a very important wetland site in the south of Thailand, covering

approximately 45,700 hectares. It includes various ecosystems, a freshwater lake, swamp forests, inundated

grassland, reed swamps and paddy fields. Phru Khuan Khi Sian, a permanently inundated swamp with

Melaleuca cajeputi, and dense stands of Cyperus imbricus , Scirpus mucronatus and Eleocharis dulcis is a

designated Ramsar site. This wetland is the nesting site of waterbirds such as the little cormorant, purple heron,

cattle egret, little egret and black-crowed night-heron and provides important habitats to over 187 species of

waterfowl. The area is also used by large groups of birds, estimated at over 10,000 individuals during the

migratory season.

There are fifty villages in the wildlife non-hunting area, with 7,813 households and 37,662 individuals. Most of the

population depends on farming for a living. Benefits of Thale Noi to local populations include its role as a

transport route, for recreation and for fishing. The area also provides timber for household usage, reeds for

handicraft, feed for livestock and sources of protein, including edible birds, reptiles and amphibians. The resident

communities have depended on this wetland for resources to generate cash income. Of the households resident

in the area, 4,771 households are engaged in rice farming, 1,073 households in rubber plantation, 1,579

households in reed harvesting, 2,894 households in handicraft production, and 41 households in tourist activities.

The average annual income from reed harvesting and handicraft production is estimated at US$525.09 and

US$462.67 per household, respectively (Office of Environmental Policy and Planning, 1999).

Narong Veeravaitaya, Thailand Wetland Focal Point

PURPOSE OF THE DEMONSTRATION SITES

·

function related sites which might include

existing sites that demonstrate sustainable

As stated in previous sections, the coastal wetlands

use for specific purpose;

of the South China Sea have been suffering from

·

process related sites which might include

serious degradation and rapid rates of loss over the

existing sites that demonstrate innovative

recent past. Due to limited available financial

management interventions and/or regimes

resources, it is not possible to fund activities at all

at the site level;

wetlands sites under severe threat. Sites therefore,

·

problem related sites, which might

should be selected with care according to agreed

demonstrate new modes of managing

priorities in order to maximize the environmental

specific problems or causes of

and socio-economic benefits of the investment.

environmental degradation.

The primary goal of the demonstration sites within

Whilst all the participating countries have identified

the context of the habitat component of this Project

national priority wetlands for conservation action

is to "demonstrate" actions that, either of

and sustainable management the determination of

themselves, "reverse" environmental degradation or,

national priority has rarely included a consideration

will demons trate methods of reducing degradation

of transboundary, regional or global considerations,

trends if adopted and applied at a wider scale.

beyond the inclusion of their status or potential

Demonstration sites could be sites where actions

status under the RAMSAR Convention as one

are directed towards:

criterion amongst many. Since the present project

takes a regional approach to intervention it was

·

Maintaining existing biodiversity; or,

necessary to develop a process by which regional

as opposed to national priority could be determined

·

Restoring degraded biodiversity to former

in as objective a manner as possible.

levels; or,

PROCESS OF SELECTING DEMONSTRATION SITES

·

Attempting to remove or reduce the cause,

and hence reduce the existing rates of

The Project has undertaken a transparent, scientific

degradation; or,

and objective regional procedure to rank and select

demonstration sites based on environmental and

·

Attempting preventive actions that halt the

socio-economic criteria and indicators discussed

adoption of unsustainable patterns of use,

and agreed at the regional level. To achieve

before it commence.

maximum impact from a limited number of

interventions, the Project Steering Committee

In the context of this Project, the demonstration site

adopted a three-step regional procedure to prioritise

proposals need not only to consider the goals and

and select demonstration sites.

purposes of the sites themselves but also what is

being demonstrated, to whom is it being

Full details of this procedure are contained in the

demonstrated, and how is it being demonstrated.

reports of the Regional Working Group (RWG-W)

An initial consideration of what is to be

meetings (UNEP, 2002a; 2002b; 2003a; in press)

demonstrated leads to three types of potential

but it may be outlined as follows:

demonstration site:

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

10

PRIORITISING AND SELECTING DEMONSTRATION SITES

·

Step 1. A cluster analysis was conducted

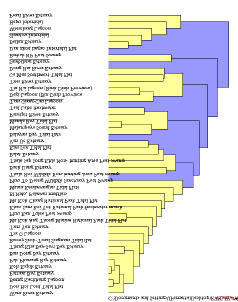

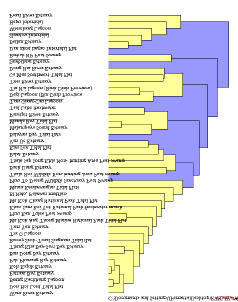

Figure 2 Results of Cluster Analysis of Wetlands Sites.

to review the similarities and differences of

all proposed sites, using data and

information assembled at the national level

that described the physical and biological

characteristics of the systems under

consideration. This analysis was used to

group sites of high degrees of similarity

within which priority could be determined.

·

Step 2. The Regional Working Group on

Wetlands developed a set of criteria and

indicators with an associated numerical

scoring system, encompassing

environmental and socio-economic

characteristics;

·

Step 3. The proposed sites were scored

according to the agreed system and

ranked within each cluster. Rank order was

considered to represent regional priority.

Site Characterization. The collection of data and

information at the national level is critical and

formed the fundamental basis for initiating the

regional comparis on. To ensure data compatibility

and comparability, the Regional Scientific and

Technical Committee (RSTC) provided initial

It was agreed to use socio-economic indicators in

guidance to the working groups on assembling

ranking of those sites with proposals. The socio-

regional level data and information; developing site

economic indicators include threats, national

characterisations; and commencing the process of

significance, financial considerations and level of

prioritising or ranking sites. A total of forty-three

local stakeholder involvement. reversibility of

sites were fully characterised and included in the

threats, national priority, level of stakeholder direct

raw data set for cluster analysis and prioritisation.

involvement in management, potential for co-

financing The scoring system developed for the

Cluster Analysis. To maximize the range of

socio-economic characteristics indicates a stronger

biological diversity covered by a limited number of

demonstration sites, selected sites should represent

weight for a site with stronger commitment from the

government and other stakeholders, in terms of co-

the greatest range of conditions represented in the

financing and level of involvement.

region as possible. The Clustan Graphic6 software

programme was used to conduct the cluster

Final rank scores for an individual site were

analysis, the results of which are shown in Figure 2.

determined using a combination of the

The RWG-W noted that the number of sites was not

environmental and socio-economic criteria and

evenly distributed among the six clusters in the

indicators in a 7:3 ratio. The combined scores and

cluster analysis; the first cluster having many more

final ranking are presented in Table 4.

sites (17) than any other cluster. It was decided

therefore that three major groups should be

Table 4 Ranking Proposed Demonstration Sites.

considered, with the second and third clusters being

Socio-

Weighted

grouped as one, and the fourth, fifth, and sixth

Environ.

Score

econ

Total

groups being combined as a third cluster.

Score

Cluster 1

Site Prioritisation and Ranking. Two sets of

Vietnam Tra O Lagoon

46

62

51

indicators with assigned scores were developed and

Cambodia Koh Kapik

26

69

39

agreed by the RWG-W; environmental and

Cambodia Beung

biological criteria and indicators; and socio-

Kachhang

15

50

26

economic criteria and indicators. Environmental

Cluster 2

criteria included specific measures of biological

Vietnam Balat Estuary

68

90

75

diversity, transboundary significance and

Thale Noi Non-hunting

regional/global significance. Criteria and indicators

Area

56

70

60

included area, number of fish, bird, plant, and

Malampaya Sound

46

76

55

mammal species, number of wetland types, number

Pansipit River

42

66

49

of migratory species, number of endemic species

Cluster 3

and number of endangered species. Priority for

China Pearl River

94

82

90

development of demonstration site proposals was

China Shantou

80

72

78

based on the total score and assigned to sites with

China Hepu

86

48

75

higher ranking in each of the identified groups of

Vietnam Ca Mau

69

67

68

sites.

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

W ETLANDS BORDERING THE SOUTH CHINA SE A

11

REFERENCES

Aditjondro, G. 1989. Irian Jaya: Copper Mining Boom Endangers River Systems. World Rivers Review 4: 8.

ASEAN. 2001. Second ASEAN State of Environment Report 2000. Jakarta: ASEAN Secretariat.

Chan, S., Benstead, P., Davies, J. and Grubh, R. 2001. The Wetland Management Handbook for South East

Asia. Ministry of the Environment, Japan.

Davies, J. and Claridge, C.F. (eds.) 1993. Wetland Benefits, The Potential for Wetlands Support and Maintain

Development. Asian Wetland Bureau Publications No. 87. IWRB Special Publication No. 27. Wetlands

for the Americas Publication No. 11.

Dugan, P.J. (ed.). 1990. Wetland Conservation: A Review of Current Issues and Required Action. IUCN, Gland,

Switzerland.

International Research Institute for Climate Change (IRI). 2000. IRI Climate Change Information Digest

September 2000 (http://iri.Columbia.edu/climate/cid/) accessed 12 January 2004.

Immirzi, C.P. et al. 1992. The Global Status of Peatlands and their Role in Carbon Cycling. Department of

Geography. University of Exeter. Friends of the Earth. London.

Jayal, N.D. 1984. Destruction of Water Resources the Most Critical Ecological Crisis of East Asia. Paper

presented at the 16th IUCN General Assembly, 5-14 November 1984. Madrid, Spain.

Mitsch, W.J. and Gosselink, J.G. 2000. Wetlands. 3rd edition. John Wiley & Sons. http://www.ramsar.org

Moser, M., Prentice, C. and Frazier, S. 1996. A Global Overview of Wetland Loss and Degradation. 6th Meeting

of the Conference of the Contracting Parties to the Ramsar Convention in Brisbane, Australia.

Office of Environmental Policy and Pl anning. 1999. The Conservation and Protection of the Important Wetland

namely Thale Noi Non-Hunting Area, Phatthalung Province. Bangkok, Thailand.

Ramsar Convention Bureau. 1971. Convention on Wetlands of International Importance especially as Waterfowl

Habitats. Gland, Switzerland.

Ramsar Convention Bureau. 1996. Wetlands and Biodiversity. 3rd Meeting of the Conference of the Parties to

the Convention on Biological Diversity in Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Ramsar Convention Bureau. 2000. Wetlands Values and Functions. Gland, Switzerland.

Scott, D.A. (ed) 1993. Wetland inventories and assessment of wetland loss: a global overview. Proceeding of the

IWRB Symposium St. Petersburg, Florida, November 1992. IWRB Special Publication 26.

Stuip, M.A.M., Baker, C.J. and Oosterberg, W. 2002. The Socio-economics of Wetlands. Wetlands International

and RIZA, The Netherlands.

Talaue-McManus, L. 2000. Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis for the South China Sea. EAS/RCU Technical

Report Series No. 14. UNEP, Bangkok, Thailand

UNEP/GEF South China Sea Project. 2003. National Reports from Wetland Subcomponent. UNEP, Bangkok,

Thailand.

UNEP, 2002a. First Meeting of the Regional Working Group for the Wetland Sub-component of the UNEP/GEF

Project "Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand".

UNEP/GEF/SCS/RWG-W.1/3. 44 pp In: UNEP, "Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South

China Sea and Gulf of Thailand", report of the First Meetings of the Regional Working Groups on Marine

Habitats. 179 pp. UNEP, Bangkok, Thailand.

UNEP, 2002b. Second Meeting of the Regional Working Group for the Wetland Sub-component of the UNEP/GEF

Project "Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand". Report

of the meeting, UNEP/GEF/SCS/RWG-W.2/3. 25 pp. In: UNEP, Report of the Second Meetings of the

Regional Working Groups on Mangrove & Wetlands. UNEP, Bangkok, Thailand.

UNEP, 2002b. Third Meeting of the Regional Working Group for the Wetland Sub-component of the UNEP/GEF

Project "Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand". Report

of the meeting, UNEP/GEF/SCS/RWG-W.2/3. 38 pp. UNEP, Bangkok, Thailand.

WCMC. 1992. Global Biodiversity. in Moser, M., Prentice, C. and Frazier, S. 1996. A Global Overview of Wetland

Loss and Degradation. 6 th Meeting of the Conference of the Contracting Parties to the Ramsar Convention

in Brisbane, Australia.

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

MEMBERS OF THE REGIONAL W ORKING GROUP ON WETLANDS

Dr. Ebil Bin Yusof, Department of Wildlife and National Parks, Peninsular Malaysia, KM10, Jalan Cheras, 56100

Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, Tel: (603) 9075 2872; 016 3807344, Fax: (603) 9075 2873,

E-mail: ebil@wildlife.gov.my; ebilyusof@hotmail.com

Professor Guizhu Chen, Institute of Environmental Sciences, Zhongshan University, 135 West Xingang Road,

Guangzhou 510275, Guangdong Province, China, Tel: (86 20) 8411 2293; 8403 9737, Fax: (86 20)

8411 0692; 8403 9737, E-mail: chenguizhu@yeah.net

Dr. Liwei Chen, Program Officer, Freshwater and Marine Programme, WWF-China Program Office, Room 1609,

Wenhua Palace, Laodong, Renmin Wenhua Gong, Dongcheng District, Beijing 100006, China, Tel: (86 10)

6522 7100 ext 238, Mobile: (86) 13 6510 46407, Fax: (86 10) 6522 7300, E-mail: lwchen@wwfchina.org

Ms. Sulan Chen, Associate Expert, UNEP/GEF Project Co-ordinating Unit, United Nations Environment

Programme, United Nations Building, 9th Floor, Block A, Rajdamnern Avenue, Bangkok 10200, Thailand,

Tel: (66 2) 288 2279, Fax: (66 2) 288 1094; 281 2428, E-mail: chens @un.org

Dr. Sansanee Choowaew, Programme Director, (Natural Resource Management), Mahidol University, Faculty of

Environment and Resource Studies, Salaya, Nakhonpathom 73170, Thailand, Tel: (66 2) 441 5000

ext. 162, Mobile: (66 1) 645 1673, Fax: (66 2) 441 9509-10, E-mail: enscw@mucc.mahidol.ac.th

Ms. Marlynn M. Mendoza, Protected Areas and Wildlife Bureau, APWNC Compound, North Avenue, Diliman,

Quezon City, Philippines 1101, Tel: (632) 925 8950; 9246031; 0916 7475492, Fax: (632) 924 0109;

925 8950, E-mail: mmmendozapawb@netscape.net; mmendoza@i -manila.com.ph

Dr. Mai Trong Nhuan, Vietnam National University, Hanoi, 165 Khuong Trung Street, Thanh Xuan, Hanoi,

Vietnam, Tel: (844) 834 2015; 853 1142, Mobile: (84) 91 334 1433, Fax: (844) 834 0724,

E-mail: nhuanmt@vnu.edu.vn; mnhuan@yahoo.com

Mr. Dibyo Sartono, Wetland International Indonesia Programme, JL Jend A Yani 53 BOGOR 16161, P.O. Box

254/BOGOR 16002, Indonesia, Tel: (62 251) 312 189, Fax: (62 251) 325 755,

E-mail: dibyo@wetlands.or.i d

Mr. Narong Veeravaitaya, Department of Fisheries Biology, Faculty of Fisheries, Kasetsart University,

50 Paholyothin Road, Bangkhen, Bangkok 10900, Thailand, Tel: (66 2) 579 5575 ext. 315; 01 741 0024,

Fax: (66 2) 940 5016, E-mail: ffisnrv@ku.ac.th

Mr. Sok Vong, Department of Nature Conservation and Protection, Ministry of Environment, 48 Samdech Preah

Sihanouk, Tonle Bassac, Chamkarmon, Cambodia, Tel: (855 23) 213908; 12 852904, Fax: (855 23)

212540; 215925, E-mail: sok_vong@camintel.com; sokvong@yahoo.com

UNEP/GEF South China Sea Project Co-ordinating Unit

United Nations Building

Rajadamnoern Nok

Bangkok 10200

Thailand

Ministry of Environment,

Department of Nature Conservation and Protection

48, Samdach Preah Sihanouk

Tonle Bassac, Chamkarmon

Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Institute of Environmental Sciences

Zhongshan University

135 West Xingang Road

Guangzhou 510275

Guangdong Province, China

Wetland International Indonesia Programme

JL Jend A Yani 53 BOGOR 16161

P.O. Box 254/BOGOR 16002

Indonesia

Department of Wildlife and National Parks

Peninsular Malaysia

KM10, Jalan Cheras

56100 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Protected Areas and Wildlife Bureau

NAPWNC Compound, North Avenue, Diliman

Quezon City, Philippines 1101

Department of Fisheries Biology

Faculty of Fisheries

Kasetsart University

50 Phanolyothin Road

Bangkhen, Bangkok 10900

Thailand

Vietnam National University, Hanoi

165 Khuong Trung Street

Thanh Xuan, Hanoi

Viet Nam