United Nations

UNEP/GEF South China Sea

Global Environment

Environment Programme

Project

Facility

"Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends

in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand"

National Reports

on

Wetlands in South China Sea

First published in Thailand in 2008 by the United Nations Environment Programme.

Copyright © 2008, United Nations Environment Programme

This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit

purposes without special permission from the copyright holder provided acknowledgement of the

source is made. UNEP would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication that uses this

publicationas a source.

No use of this publication may be made for resale or for any other commercial purpose without prior

permission in writing from the United Nations Environment Programme.

UNEP/GEF

Project Co-ordinating Unit,

United Nations Environment Programme,

UN Building, 2nd Floor Block B, Rajdamnern Avenue,

Bangkok 10200, Thailand.

Tel.

+66 2 288 1886

Fax.

+66 2 288 1094

http://www.unepscs.org

DISCLAIMER:

The contents of this report do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of UNEP or the GEF. The

designations employed and the presentations do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever

on the part of UNEP, of the GEF, or of any cooperating organisation concerning the legal status of

any country, territory, city or area, of its authorities, or of the delineation of its territories or boundaries.

Cover Photo: A vast coastal estuary in Koh Kong Province of Cambodia. Photo by Mr. Koch

Savath.

For citation purposes this document may be cited as:

UNEP, 2008. National Reports on Wetlands in the South China Sea. UNEP/GEF/SCS Technical

Publication No. 13.

United Nations

UNEP/GEF South China Sea

Global Environment

Environment Programme

Project

Facility

NATIONAL REPORT

on

Wetlands in South China Sea

CAMBODIA

Mr. Koch Savath

Focal Point for Wetlands

Department of Nature Conservation and Protection, Ministry of Environment

48 Samdech Preah Sihanouk

Tonle Bassac, Chamkarmon, Cambodia

NATIONAL REPORT ON WETLANDS IN SOUTH CHINA SEA CAMBODIA

Table of Contents

1. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................1

2. COASTAL WETLAND ECOSYSTEM.............................................................................................1

3. CURRENT WETLAND SYSTEMS ..................................................................................................2

3.1 WETLAND CLASSIFICATION SYSTEM.............................................................................................2

3.2 COASTAL WETLAND TYPES .........................................................................................................3

3.2.1

Marshes.............................................................................................................................3

3.2.2

Swamps.............................................................................................................................3

3.2.3

Peatlands...........................................................................................................................3

3.3 INTERNATIONALLY SIGNIFICANT WETLAND SITES ..........................................................................4

3.3.1

Brackish Water Wetland Sites...........................................................................................4

3.3.2

Marine Wetland Sites ........................................................................................................4

4. WETLAND REOURCES AND ECONOMIC VALUATION..............................................................6

4.1 COASTAL WETLAND RESOURCES.................................................................................................6

4.2 ECONOMIC VALUATION OF WETLANDS .........................................................................................7

5. CAMBODIAN DATA AND INFORMATION ON WETLANDS ........................................................9

5.1 GENERAL DATA ..........................................................................................................................9

5.2 INFORMATION RELATED TO WETLANDS ......................................................................................10

5.3 MAPPING DATA RELATED TO WETLANDS....................................................................................10

6. CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS ...............................................................................11

REFERENCES......................................................................................................................................12

List of Tables and Figures

Table 1

Relationship between Shrimp Farm Productivity and Age

Table 2

Price of Charcoal Production from 1997-2000

Table 3

Direct Use Value per ha of the Mangrove by the Local Populations

Table 4

Indicative Economic Value of Major Coastal Ecosystems

Table 5

Total Value within the Three Wetland Sites per Year

Figure 1

System for the Classification of Wetlands

Figure 2

Description of the Classification of Wetland Systems

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

NATIONAL REPORT ON WETLANDS IN SOUTH CHINA SEA CAMBODIA 1

1. INTRODUCTION

The Kingdom of Cambodia is rich in wetland environments. Over 30 percent of the country is

considered wetlands (according to the wetlands inventory and management project). Following

internationally accepted criteria for wetland identification (defined by the Ramsar Convention) over 20

percent (36,500km2) of the country may be classified as wetlands of international importance. This

represents over five percent of Asia's total area of wetlands of international importance.

Wetland areas support rice and fish production the primary sources of food for the vast majority of

the population and currently Cambodia's most economically productive sectors. Fish and fish products

are the single most important sources of protein for the Cambodian population, representing 75

percent of the animal protein intake. Wetlands provide nutrient-rich and sheltered habitats for fish

(breeding, spawning and nursery areas or habitats for adults) and therefore they play a central role in

the supply of animal protein in Cambodia. Agriculture is supported by water from wetlands. Wetland

water may be stored for use in the dry season or withdrawn for irrigation purposes. Other economic

activities utilizing wetland resources include aquaculture, tourism, inland transport, and energy (hydro-

electricity).

Wetlands serve a wide variety of ecological functions that support economic activities or are of

economic value. In addition to supporting agriculture and fisheries, they play a vital role in maintaining

the water cycle and protecting inland areas from flooding. Coastal wetlands act as barriers against

storm surges and protect the coastline from erosion. Many wetlands are important as filtering systems

- cleaning up polluted water and removing silt, encouraging plant growth, and further improving water

quality. Cambodia's wetlands are important sanctuaries for birds and other species of wildlife not

commonly found in other countries in the world. They are also important for research and educational

purposes.

2.

COASTAL WETLAND ECOSYSTEM

The Cambodian coastline extends along 435km of some of the least populated areas in all of tropical

Asia. The coastal region features a number of closely interrelated ecosystems, embracing beach

forest and strand vegetation, mangroves (including a Melaleuca dominated swamp forest referred to

as "rear mangrove," estuarine ecosystems, seagrass, coral reef and the unstudied marine

ecosystems of the gently sloping, relatively shallow seabed (only 80 meters of water depth at the

outer limit of the 200 nautical mile Executive Economical Zone), and of the water column above.

Estuaries are semi-enclosed bodies of water that are connected to the sea and in which salt water is

diluted by fresh water from land drainage. Estuaries are often highly productive areas due to the

nutrients they receive from the land and the sheltered environments that they provide.

The major estuarine areas in Cambodia occur in the region around Koh Kong province and near

Kampot province. The Stung Koh Pao and Stung Kep estuaries are recognized as wetlands of

international significance. Both rivers originate in the Cardamom range and discharge their flow into

Koh Kong Bay. The Bay is protected from southwest storms by the large island of Koh Kong. The

estuarine system is "a complex of channels and creeks, low islands, mangrove swamps, tidal

mudflats and coastal lagoons."

Mudflats occurs when sediment settles out of the water due to a decrease in current and/ or wave

action. Mudflats are often associated with estuaries, but also occur in low-energy, coastal

environments, such as in large bays or in the lees of islands. They are commonly continuous with

mangrove areas. Mudflats can be very productive system as a result of nutrients recycling through the

sediments. Typically there are high diversities of invertebrates living in and on the mud, and as a

result, the mudflats provide rich feeding grounds for vertebrates such as fish and waterbirds.

Mudflats adjacent to the mangroves and in natural mangrove streams are exploited for cockles,

although this is generally an unrewarding activity practiced only by those with no alternative form of

income.

The productivity of estuaries and mudflats is threatened by pollution from a range of sources, e.g.

construction activities outside mudflats can have adverse effects by causing the inflow of water, which

either erodes the mudflats or prevents further deposition. The location, extent, and significance of

mudflat areas in Cambodia have not been adequately studied.

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

2 NATIONAL REPORT ON WETLANDS IN SOUTH CHINA SEA CAMBODIA

3. CURRENT

WETLAND

SYSTEMS

3.1

Wetland Classification System

In the Cambodian Wetlands Inventory, for a site to be classified as a wetland, it must meet one of the

following criteria:

· Plants able to tolerate inundation by water for a period of greater than six weeks

(hydrophilic plants);

· Soils are classified as hydric soils; and

· The area is inundated by water for a period on an annual and periodic basis (see below for

further explanation).

A system for the classification of wetlands has been developed for Cambodia since 2000. This system

provides for the classification of wetlands based on a number of functional characteristics. These

characteristics allow for the classification into systems, categories, sub- categories, and modifiers that

describe the wetland sites (Figure 1). This classification system proposes to describe the important

characteristics of particular wetland sites. It considers the wetlands in terms of water regime,

substrate, vegetation type, etc. In combination, these definable characteristics should be able to

provide a clear categorization of each wetland type.

This system can be called a "Hierarchical approach" to the classification of wetlands. This is a

process to evaluate a particular set of characteristics through a series of levels related to the

characteristics of each particular site. At each step of this process more detailed information is

gathered to refine the description of the area. At the end of this process, the unique characteristics to

identify the wetland habitat will have been identified.

System

Wetland

Category

Wetland

Plant

Sub-category

Dominace

THE MODIFIERS

Water

Artificial

Salinity

regime

Modifier

Figure 1

System for the Classification of Wetlands.

The first level of classification is the system. The system level allows for the classification of wetland

habitats into broad functional ecosystems. The system is classified into Saltwater Wetland Systems

and Freshwater Wetland Systems. Saltwater Wetland Systems are classified into Marine and

Estuarine. Freshwater Wetland Systems are classified into Riverine, Lacustrine and Palustrine. Figure

2 represents the classification of the wetland system of Cambodia.

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

NATIONAL REPORT ON WETLANDS IN SOUTH CHINA SEA CAMBODIA 3

Wetlands

Freshwater

Saltwater

Wetlands

Wetlands

Marine

Estuarine

Riverine

Lacustrine

Palustrin

Figure 2

Description of the Classification of Wetland Systems.

3.2

Coastal Wetland Types

3.2.1 Marshes

Marshes have a number of specific characteristics: they are usually dominated by reeds, rushes,

grasses and sedges. These plants are commonly referred to as emergents since they grow with their

stems partly in and partly out of the water. Marshes are sustained by water sources other than direct

rainfall. They can vary a lot in response to often-subtle hydrological and chemical differences.

Marshes include some of the most productive ecosystems in the world.

Dominant plants in most freshwater marshes include species of reeds (Phragmites; traing), bulrush

(Typha), clib rush (Scirpus; kok), spike rushes (Eleocharis) and grasses such as paragrass

(Brachiaria mutica; smau barang). In Cambodia a good example of a marsh can be found close to

Phnom Penh in the Bassac marshes, which is an area between the Mekong and Bassac Rivers that

floods very year.

3.2.2 Swamps

Swamps are often confused with marshes. They are, however, very different. Swamps generally have

saturated soil or are flooded for most, if not all of the growing season. They are often dominated by a

single emergent herb species or are forested (e.g. the Plain of Reeds in the Mekong Delta). The

Tonle Sap lake, for example, was until recently surrounded by a belt of freshwater swamp forest (the

flooded forest).

According to a study by the Mekong Secretariat in 1991, there are 1.2 million ha of grassland and

other swampy areas associated with the flooded forests in Cambodia (MRC, 1997).

3.2.3 Peatlands

Peat is formed when decomposition fails to keep up with the production of organic matter. This is a

result of water logging, a lack of oxygen or of nutrients, high acidity or low temperatures. Peat can be

found in many types of wetland, including floodplains and coastal wetlands such as mangroves.

Where the peat deposits are deeper than 300 to 400 mm, they create a variety of distinctive wetland

ecosystem such as bogs and fens.

· Bogs from where a high water table, fed directly by rain, results in waterlogged soil with reduced

levels of oxygen. Rainfall leaches out nutrients in the soil, and the slow fermentation of organic

matter produces acids. Bogs are characterized by acid loving vegetation, including mosses.

Sphagnum bog mosses are likely sponges and can hold more than ten times their dry weight of

water. Bogs are not very common in Cambodia, but some have been reported from Bokor.

· Fens are fed by ground water rather than by rain. They produce wetlands higher in nutrient

content than bogs, but still able to accumulate peat. The combination of more nutrients and low

acidity results in very different vegetation, often a species rich cover of reeds, sedges and herbs.

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

4 NATIONAL REPORT ON WETLANDS IN SOUTH CHINA SEA CAMBODIA

3.3 Internationally

Significant Wetland Sites

Totally, 29 wetland sites were identified as significant habitats, or internationally important sites for

migratory birds. These sites have been classified into freshwater, brackish or marine wetlands. The

identification of these wetlands are based on the criteria of size, habitat, biodiversity richness,

distribution of species and cultural, landscape, and recreational values.

3.3.1 Brackish Water Wetland Sites

These types of coastal wetlands are located on the coastal plain and are linked to the sea. The water

component seasonally changes into brackish during the rainy season and saline during the dry

season. The main vegetation types in these wetlands are mangroves and rear mangroves, which

support reptiles, small mammals, and aquatic species. There are two brackish wetland sites:

1) Stung Metoek Mangrove and Creek System

Coordination:

11o 32' 00" 11o 51' 00" N

102o 51' 00" 103o 06' 00" E

Location:

About 1km north of Koh Kong Provincial town

Total

Area:

22,500ha

-

Water

surface:

10,000ha

-

Marshes:

12,500ha

Altitude:

Average:

116.6m

Maximum:

153m

Wetland Types:

Mangrove, creek systems, rear mangrove and shrimp ponds

Soil Types:

Coastal

complex

2) Prek Piphot Creek System and Swamp Mangroves

Coordination:

11o 04' 30" 11o 19' 00" N

103o 18' 30" 103o 36' 30" E

Location:

10km north of Sre Ambel, Koh Kong Province

Total

Area:

21,250ha

-

Water

surface:

12,750ha

-

Marshes:

85,000ha

Altitude:

Average:

62m

Maximum:

262m

Wetland Types:

Mangrove, creek systems, mud, sand and a little rear mangrove

Soil Types:

Acid lithosol and alumisol

3.3.2 Marine Wetland Sites

Marine wetlands are located in coastal areas similar to the brackish wetlands, however the water

regime is permanent although the water table can move with the start of the rainy season.

Six sites have been identified as internationally important habitats for migratory birds or marine

aquatic species:

1) Kampong Trach Marshes and Salt Ponds

Coordination:

10o 24' 30" 10o 33' 30" N

104o 24' 00" 104o 36' 00" E

Location:

About 2 km east of Kep town

Total

Area:

7,500ha

- Water surface: 2,500ha

-

Marshes:

15,000ha

Altitude:

Average:

89.7m

Maximum:

144m

Wetland Types:

Salt ponds, marshes, mangrove swamps, sand and seagrass

Soil Types:

Coastal

complex

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

NATIONAL REPORT ON WETLANDS IN SOUTH CHINA SEA CAMBODIA 5

2) Prek Kampong Bay, Creek System, Mangrove and Marshes

Coordination:

10o 30' 00" 10o 41' 00" N

104o 08' 30" 104o 18' 00" E

Location:

Kampot Provincial town

Total

Area:

16,250ha

- Water surface: 7,500ha

- Marshes:

8,800ha

Altitude:

Average:

94m

Maximum:

351m

Wetland Types:

Mangrove, swamps, sand and creek systems

Soil Types:

Coastal complex and red-yellow podzol

3) Prek Toek Sap Creek System, Mangrove and Marshes

Coordination:

10o 24' 00" 10o 37' 30" N

103o 40' 00" 103o 59' 00" E

Location:

15km east of Ream Navy Base, Sihanouk Ville

Total

Area:

21,250ha

-

Water

surface:

12,250ha

- Marshes:

8,750ha

Altitude:

Average:

328m

Maximum:

564m

Wetland Types:

Mangrove, creek systems, coral reef, seagrass and rear mangrove

Soil Types:

Acid lithosol and red-yellow podzol

4) Chhok Veal Rinh

Coordination:

11o 05' 00" 11o 15' 00" N

103o 47' 30" 103o 58' 30" E

Location:

170km southwest of Phnom Penh

Total

Area:

14,900ha

- Water surface: n/a

- Marshes:

n/a

Altitude:

Average:

3m

Maximum:

5m

Wetland Types:

Mangrove, marshes, rear mangrove and rice fields

Soil Types:

Peat, mud and sand

5) Koh Kapik Ramsar Site

Coordination:

11o 24' 00" 11o 32' 00" N

102o 59' 10" 103o 09' 45" E

Location:

Koh Kong Province

Total

Area:

12,000ha

- Water surface: n/a

- Marshes:

n/a

Altitude:

Average:

3.3m

Maximum:

5m

Wetland Types:

Estuary, mangrove, creek and tidal mudflats

Soil Types:

Mud, sand and peat

6) Prek Kampong Som Mangrove, Swamp and Marshes

Coordination:

11o 01' 30" 11o 09' 00" N

103o 37' 30" 103o 45' 15" E

Location:

About 52.5km north of Sihanouk Ville

Total

Area:

10,800ha

-

Water

surface:

3,300ha

-

Marshes:

7,500ha

Altitude: Average: 2.5m

Maximum:

10m

Wetland Types:

Mangrove, swamps, marshes and rice fields

Soil Types:

Mud, sand and brown soil

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

6 NATIONAL REPORT ON WETLANDS IN SOUTH CHINA SEA CAMBODIA

4.

WETLAND REOURCES AND ECONOMIC VALUATION

4.1

Coastal Wetland Resources

There is a 435km-long strip of coastal wetlands stretching from the border with Thailand eastwards to

the border with Viet Nam. Several areas of mangrove and Melaleuca forest are of potential

international importance. In addition, there is one large estuarine system with about 16,000ha of

mangrove forest near Koh Kong in the north. Smaller areas of mangrove are found along the shores

of the Veal Renh and Kompong Som Bays. It may be assumed that over 20 percent of Cambodia is

one or another type of wetland.

Some areas, such as Prek Kaoh Pao, are formed mainly by two communities, namely: mangrove and

melaleuca. In most places, the mangrove fringe is narrow, but contains a variety of species. Many

epiphytes including orchids and Asplenium nidens are found in mangrove forest. Immediately behind

the mangrove fringe, Melaleuca occurs, either as a monoculture or in a mixed assemblage. This

assemblage has often been called the rear mangrove formation. Melaleuca occurs above tidal

influence at an elevation around two meters above sea level, where there is the possibility of seasonal

freshwater inundation. The monoculture is due to repeated burning. The mixed assemblage consists

of Melaleuca with licualaspinosa, Pandanus, Acrosthicum aureum, A. speciosum, Hibiscus tiliaceus,

Xylocarpus granatum, Heritiera littoralis, and Phoenix paludosa. However, some areas, such as Koah

Kapik, are formed by three main communities, namely: Mangrove forest, Melaleuca forest, and Beach

strand vegetation. Beach strand vegetation is dominated by Casuarina equisitifolia.

The coastal zone is composed of alluvial islands, river estuaries, creeks, sand flats, rivers with

brackish water influence, rivers with tidal influence, mixed Melaleuca woodland, freshwater-influenced

mangrove, mangrove and Melaleuca, shrimp ponds, and mud flats. The catchments are comprised

mainly of the southern slopes of the Cardamom Mountains, which are mainly forested.

Mangrove: Most of the mangrove communities are characterized by areas that are inundated only at

some high tides, and where there is a large degree of freshwater influence. The islands and creeks

are typically fronted by Rhizophora apiculata, one of the most common of the mangrove species

present, and stands of Nypa fruticans. Immediately behind this fairly narrow strip of Rhizophora there

is an interesting mixture of other mangrove species, of which the following are most common:

Brugiera gymnorrhiza, B. sexangula, Ceriops tagal, Lumnitzera littorea, Heritiera littoralis, Xylocarpus

granatum, hibiscus tiliaceus, Phoenix paludosa, Acrosthicum speciosum, Aegialitis sp., and Acanthus

sp. Avicennia and Sonneratia are relatively infrequent in Koh Kapik.

Rear mangrove community: On some of the islands and on the mainland between Prek Khlang Yai

and Prek Thngo, the mangrove community is only a narrow band and is replaced by a community

which is above the high tide mark and is probably only subject to fresh water inundation during the

wet season. This community is dominated by Melaleuca leucadendron. In many places, there is an

almost pure stand of this tree, but this may be due to repeated burning rather than it being a layer of

humus. Other plants typical of this community are: Pandanus, licuala spinosa, Acrosthicum aureum,

A. speciosum. Hibiscus tiliaceus, Xylocarpus granatum, Heritiera littoralis, Phoenix paludosa,

Melostoma sp. (in more distributed areas), and Scleria sp. This is found together with several rattans

and epiphytes such as orchids and the bird nest fern Asplenium niden.

Beach strand vegetation: At the southwest side of Koh Kapik and on sandy areas of some of the

islands, there are small areas of typical beach strand vegetation dominated by Casuarina equisitifolia,

with some Terminalia catappa.

Fisheries resources: Common fisheries include: fish (grouper and sea bass), wild shrimp, crabs

(mostly mangrove mud crabs), and squid. Some aquatic fauna migrate depend on the season. There

is no exact data about the aquatic fauna in this area yet. However, the research conducted at Peam

Krosop Wildlife Sanctuary showed that this area is rich in aquatic fauna including the Dolphin and Sea

Cow.

Wildlife: The research conducted in Peam Krasop Wildlife Sanctuary, Koh Kong Province, showed

that more than 190 species of birds have been identified. Some are present over the whole year, but

some use this area as a migration place. There are also 29 species of reptiles that are present in the

Peam Krasop Wildlife Sanctuary. Some species are rare species such as Dermochelys sp,

Eretmochelys sp, and Scaly anteater. In addition, around ten species of mammals have been found.

This number has decreased because of destruction of the mangrove habitat.

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

NATIONAL REPORT ON WETLANDS IN SOUTH CHINA SEA CAMBODIA 7

Corals: Little data exists for coral within the mangrove ecosystem. Local Cambodian coral experts

have identified 56 different types of hard and soft corals within wetlands in Peam Krasop. This area is

a good habitat for Greasy grouper and Yellow grouper, and the habitats have been disturbed by

fishing.

The land and water is state owned, but some land may be privately leased. The water and mangrove

areas are under the jurisdiction of the Fishery Department, while the Melaleuca areas beyond the tidal

influence are under the jurisdiction of the Department of Forestry and Wildlife. Some areas, such as

Peam Krasop, along with much of the catchments, have recently been designated as the Wildlife

Sanctuaries.

4.2

Economic Valuation of Wetlands

Koh Kapik Ramsar Wetland Site

In 1997, a case study was conducted to find out the socioeconomics of protected areas provided a

short data of logging activities including Peam KraSop, where Koh Kapic is located. Both Khmer and

Thai logging companies are operating in the upland areas in Koh Kong. The logs are typically sold

directly to Thailand. Companies employ 200-300 workers. In addition, many workers from Peam

Krasop are involved in the collection of timber from nearby Koh Kong Island, which is under the

control of the navy. It is estimated that more than 100 electric saws are in use on the island (one

owner may have 2-3 saws). One machine can cut 1-2m3 wood per day. Soldiers are paid 10,000

Baht/month (US$400) per machine. Anyone can cut wood provided they pay the soldiers. The

workers, who carry wood from the island, can earn 400-1000 Baht per m3 depending on the distance

the wood is carried. A worker can transport on average 2-3m3 per day, thereby earning between 800-

2000 Baht per day (US$32-$80). Workers operating cutting machines are paid between 500-700 Baht

(US$20-28)/m3 (i.e., US$40-$56 per day including food). Trees are reportedly cut indiscriminately,

often on steep slopes.

Commercial Shrimp Farms

Investment at the construction stage includes the cost of a license and expenditure on farm

construction and equipment (e.g., dike construction, gates, fan for aerating water). The average

expenditure at the construction stage was estimated to be US$28,662 per hectare.

Only 25 percent of farms surveyed were operating under licenses. Licenses are valid for the lifetime of

the farm and cost between US$800-$1,200. Technically, the fisheries department needs to be

informed each year of the farm's intention to continue its operations.

Productivity per harvest ranges from 3-16 tonnes per hectare, with an average of five tonnes per

hectare. Sixteen tonnes per hectare is very high and represents the first harvest of a newly

constructed farm. Excluding this figure, productivity per harvest ranges from 3.1-4.4 tonnes per

hectare, with an average of 3.6 tonnes per hectare. Relationship between shrimp farm productivity

and shrimp age is shown in Table 1.

Table 1

Relationship between Shrimp Farm Productivity and Age.

Age of farm /

Yield/ha/Harvest Gross value US$ Gross value US$ Gross value US$

years

per hectare /

per hectare /

per hectare /

harvest

harvest @

harvest @ 185

@120Baht/kg

35Baht/kg

Baht/kg

1

16

76, 800

22, 400

118, 4000

2

3.78 18,

144 13,

230 27,

972

3

3.26 15,

648 4,564 24,

124

4

3.12 14,

976 4,368 23,

088

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

8 NATIONAL REPORT ON WETLANDS IN SOUTH CHINA SEA CAMBODIA

The price of shrimp ranges from 30-185 Baht/kg depending on size and quality. The shrimp are sold

to Thailand. Prices are dependent on the international market and have fallen over recent years from

a high of 210 Baht. Using a price of 120 Baht/kg (weighted average) and using the average

productivity of 5.1 tonnes/hectare/harvest, the average gross income from shrimp production per

harvest can be estimated at US$24,480 per hectare.

Assuming a five-year productive life of a shrimp farm, and two successful harvests per year at 5.1

tonnes/hectare/harvest, net income per farm is estimated at US$4,451 per hectare. If however, one

harvest fails because of disease or technical problems (very common), the farm will lose US$20,029

per hectare. A year of loss in which both harvests fail means losses of US$44, 509. At 120 Baht/kg,

productivity has to be at least 4.7 tonnes/kg to break even. At a productivity rate of 3.6 tonnes per

harvest, a loss of US$9,949 per hectare is incurred.

Given the risks facing shrimp farming, it is becoming increasingly rare for farms to have two

successful crops a year. Half of the farms surveyed have incurred losses ranging from 1-6 million

Baht (US$40,000-$240,000).

The calculations for each of the eight farms surveyed revealed that 50 percent of farms are making

profits of between US$17,508-$100,880 (US$1,782-$100,880 per hectare), and 50 percent to be

incurring losses of between US$3,602-$162, 216 (US$1,125-$20,481 per hectare).

Excluding the farm with the unrealistically high productivity rate of 16 tonnes/harvest, profits range

from US$74,658-17,508 per farm (US$11, 109-1,782 per hectare). Overall, the farms are incurring a

loss of US$8,826, or US$1,103 per hectare.

Calculations for individual farms are based on the investment, operating and productivity figures, and

selling price of shrimp of the individual farms covered in the survey. Shrimp prices ranged from

98-158 Baht/kg and obviously affected profit margins.

Therefore the TEV of the Koh Kapic can be calculated and mentioned as important in reference to the

general studies of Peam Krasom, where Koh Kapic is located within this area. There have been no

specific research studies on the economic valuation of the site yet, due to the lack of financial and

technical support. Even though it is fair enough to show the general picture of the economic, social,

and cultural values that come purely from the wetland site.

Table 2

Price of Charcoal Production from 1997-2000.

Year

Price

Cost per kg in Thai Baht

Price per kg in $ US

1997 2.15

Baht

$0.05

1998 2.4

Baht

$0.05

1999 2.55

Baht

$0.06

2000 4

16

Baht

$0.1

Source: PMMR (2000).

Sragnam-Russey Srok Wetland Site

In the actual case of the Russey Srok-Tourl Sragnam site, not every household earns income from the

mangrove forest. The forest is not as productive as it was before it was degraded, although it is

recovering. The case of Russey Srok-Tourl Sragnam represents villages that are mangrove, salt farm

and fishing dependent. Since there is no real data on the case, the assumption was made that every

household earns the same average net annual return per household as in the case for a sustainable

basis. The local use value per ha per year has been calculated (Table 2). The local use value is per

hectare/year in the case with charcoal production has been calculated and shown in Table 3.

Table 3

Direct Use Value per ha of the Mangrove by the Local Populations.

Cases

Direct use value per ha per year (baht)

The Case of a Mangrove without Charcoal Production

1,937.98

The Case of a Mangrove with Charcoal Production

4,237.16

Total 6,175.14

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

NATIONAL REPORT ON WETLANDS IN SOUTH CHINA SEA CAMBODIA 9

The total value of the economic valuation of wetlands, as well as others, is indicated below in US

dollars and illustrates in Table 4.

Table 4

Indicative Economic Value of Major Coastal Ecosystems1.

Estimated Net

Estimated Existing

Total Estimated Net Annual

Ecosystem

Annual Benefits

Area in Cambodia

Benefits

(US $/ha/yr)

(ha)

(million US $/yr)

Mangrove Forest

183

26,650

4.9

Coastal Wetlands

130

54,500

7.1

Coral Reefs

300

476

0.14

Seagrass

300

175

0.05

Total

81,801

12.2

Source: ADB (1996).

Based on the table referenced above, the direct use value of the three wetland areas per year can be

computed in

Table 5

Total Value within the Three Wetland Sites per Year.

N Site

Cost (US$)

1

Koh Kapic Wetland Site

1,755,000

2 Beung

Kachhang

585,000

3

Tourl Sragnam-Russey Srok

650,000

5.

CAMBODIAN DATA AND INFORMATION ON WETLANDS

5.1 General

Data

The general data provides a description of the existing situation that excludes the data depicted

above, and is not mappable data. This includes the biodiversity, socio-economic, and education data.

1. Biodiversity data: this database covers all the natural resources, as well biodiversity that includes

the fauna and flora explored during the past. It was set up by the Support Programme to the

Environment Sector in Cambodia, European Union in 1998, and the direct collaboration with the

Ministry of Environment, especially the department of Nature Conservation and Protection. It accounts

totally for more than 3,000 species. And it includes some site surveys at Bokor National Park, and

Tonle Sap areas.

2. Socio-economic data: this section logically came from the Cambodian National Census in 1998

that was supported by the UNFPA programme (National Institute of Statistic 1998). The database

includes four systems:

- Pop Map: this is a population map;

- Priority Data: this is a table with the priority data for Cambodia;

- Village level: this is the detail for the village level;

- WinR+: the system of database that was set up for using multi-purposes and facilitation for

the easy extraction of data with many compatible formats.

3. Education: The school census is a database system that was created by the EMIS, Ministry of

Education, Youth and Sport and supported by the UNESCO and UNICEF. It includes all the

information and data related to Cambodia's education statistics and indicators from preschool until the

university degrees. It is an annual census for Cambodian education that comprises the number of

students (enrolment, drop-out, repeater), teachers, schools, classes, and its facilities in all grades.

Overall, the quality of physical, biological, environmental, and socio-economic data and information

for the coastal and marine areas of Cambodia is inadequate for good planning and management:

ix

1 These economic valuations simply measure the annualized Net Present Value of some of goods and services provided by

these ecosystems. A comparison of different types of uses for these ecosystems (e.g., shrimp farm conversion, agriculture,

etc.) could show even higher economic values for existing ecosystems (e.g., Sathirathai 1998 estimates that the economic

value of mature mangrove ecosystems increases to about US $250/ha/yr when compared to shrimp farming).

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

10 NATIONAL REPORT ON WETLANDS IN SOUTH CHINA SEA CAMBODIA

5.2

Information Related to Wetlands

The information collected relates purely to environment, natural resources and wetlands within

Cambodia. It is mainly focusing on the coastal areas in Cambodia. Furthermore, the information

includes the report formats written in different reports for each activity, research project, or

programme in the Cambodia's Coastal zone (see the meta-database for Cambodian Wetlands in

spreadsheet as attached).

Referring to this meta-database, the information can be seen as made up of different parts, where

each part represents different areas, scales, and subjects. However the information generally

represents the Nation, the entire coastal zone, each protected area (such as Bokor National Park,

Ream National Park, Peam Krasop, Dong Peng) and/or each province as indicated as the whole

image. Most information was produced by the Coastal Zone Management Project supported by

DANIDA since 1997, and the Participatory Management of Mangrove Resources Project that has

been supported by IDRC since 1997 (IRIC and IDRC, 1997). The information basically describes the

physical infrastructures in place, water quality, some sources of pollution, mangrove plantations,

tourism issues, source of mangrove destruction and fishing activities.

Despite a great deal of information, it has only been interpreted and analysed from community

approaches. This means that approaches to evaluate and assess it were through the consultations,

meetings, discussions and interviews. This is good in some ways, however it is not scientifically

based. The information is just the vision of the people involved. Moreover the information indicated

the holistic management issues for the whole nation or coastal zone.

On the other hand, the coastal wetland classification has not yet been planned or considered. In order

to maximize the use of the existing data and information, we need to adjust the information to focused

areas. This is the main challenge and sometimes is not feasible. There is not any specific research

yet on wetland areas and the issues in coastal areas.

5.3

Mapping Data Related to Wetlands

The mapping data refers to the data that can be produced in a GIS map. The mapping data is from

different sources of databases in Cambodia, such as the Department of Geography, Support Unit of

the MRC, DoF/LUMO/MAFF, JICA/MPWT, MoE/GIS/RS Unit, MoP/NIS, MoEYS/EMIS, WFP/UN and

EU projects/programmes (please see the Cambodian Wetland Meta-database that was produced in

the spreadsheet).

After reviewing all these data, there are fives mains parts including:

1. Administrative data: This includes information on national boundaries, provinces, districts,

communes' polygon as boundaries, and central points with the points of the villages. These data are

updated annually and managed by the Department of Geography, Ministry of Land Management,

Urbanization and Construction. There is collaboration between the department with the Ministry of

Public Works and Transport that is supported by JICA.

2. Infrastructure: this includes information on all roads (national roads, main roads, secondary,

paved roads), all the railways (two lines, 1st to Sihanouk ville and the 2nd to Battambang/Banteay

Meanchey), all rivers (entire the main rivers, 2nd rivers, 3rd rivers, up till to the small streams), Oceans

and lakes (Tole Sap, all other lakes). These maps were produced from the Ministry of Public Works

and Transport, in collaboration with the JICA project. There are two phases, the 1st phase was already

finished in 2000, and the 2nd phase began, and is nearly finished.

3. Physical and chemical condition of the land: this includes information on watershed classes,

contour lines, soil, climate, catchment's areas, geology, landforms, hydrogeology, and landscape

conditions. These data were produced from the MRC, FAO, JICA, and collaborations with the national

institutions such as the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, Ministry of Environment,

Ministry of Land Management and Ministry of Public Works and Transport.

4. Land Use, Land Cover and Forest Cover: these data came from different sources at various

times, including the FAO, UNEP, Department of Forestry, Land Use Management Office of the

Ministry of Agriculture and the MRC. The data was found in 1971 for vegetation, then 1992-93 and

96-97 for forest and land cover of Cambodia (MRC 1997).

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

NATIONAL REPORT ON WETLANDS IN SOUTH CHINA SEA CAMBODIA 11

5. Population: there is a population density map that was produced from the National Institute of

Statistics, Ministry of Planning (National Institute of Statistic, 1998). Its source is mainly based on the

data from the National Census in 1998 and using the PopMap application that is more or less similar

to the MapInfo application. The data within the application not only produced the population density,

but also the distribution of population activities, of education, of age groups, households, gender, and

utilization of water, light and cooking. This map can be produced at the commune, district, and

provincial scales. Moreover, there was an old map of the Ethnic distribution that describes the

different ethnic groups in Cambodia.

6. CONCLUSION

AND

RECOMMENDATIONS

According to the descriptions above, the data and information is still very limited, especially for the

specific issues such as Wetlands in local areas. Most of the supports are likely to work at this stage

on the national level. In other words, nobody takes care yet for the local level, even though Cambodia

is in the process of decentralization. Regarding the local data and information, it mostly focuses on

the socio-economic and health issues, which are the immediate objectives to help people to survive,

maintain, and develop their own life. Environmental issues are the secondary or long-term objectives.

Therefore, the national self-management of the data and information is the key issue. Concerning its

management, there are a lack of knowledge and skills in information and data management and its

supporting infrastructures. People do not appropriately consider the data and information for decision

making, planning, and monitoring as well as evaluation. The principle causes are lack of mechanisms

for data and information sharing among other people, and lack of dissemination, which would allow

people to understand its importance, and to use and manage it effectively.

In order to maintain and keep records up to date, the key issue is to compile and manage the existing

data and information in a national database system that can be used by other people. As Cambodian

human resources are very limited, thus the capacity building in data and information use and

management is a prerequisite as an immediate objective.

Gathering and giving data and information are the principle issues to promote and maximize its

sharing and dissemination. There needs to be established the coordination for data and information

management with the enhancement of flow mechanisms with its free access.

Good information is crucial for sound coastal and marine environmental management and, by and

large, this good information does not yet exist in Cambodia. There has been a lack of data and

information, especially for coastal and marine resources, throughout the history of Cambodia.

Although the DANIDA coastal zone project prepared coastal resource profiles and mapping, as well

as community socio-economic survey reports, more information, and more up to date information,

especially data and information relevant to the biophysical characteristics of the natural resources, is

required for proper coastal and marine zone planning and management. Because of this, one of the

first items of work in the coastal and marine zone has to be basic gathering and assembly of data and

information.

The collection of data in and of itself should not be the goal. Resources are too scarce in Cambodia

for collecting data and information that do not meet practical needs. It is also impossible to substitute

for local knowledge of coastal conditions and resources. Sometimes dismissed with regards to

essentially anecdotal, unsystematic, or unverifiable, local knowledge may represent the distillation of

the experience of generations of those who have had 'hands-on' knowledge of a particular matter with

a particular issue.

There is an important institutional issue with respect to the sharing of information. Coastal and marine

environmental management is: (i) always multi-sectoral, meaning that many different types of

information are needed, and (ii) should be integrated, meaning that institutions often need information

collected by other institutions to provide a necessary and useful contribution. Overcoming this barrier

requires particular effort on the part of the practitioners of coastal and marine environmental

management.

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

12 NATIONAL REPORT ON WETLANDS IN SOUTH CHINA SEA CAMBODIA

Finally, coastal and marine environmental management cannot wait for perfect information. In fact, not

all of the scientific and technical issues germane to many of the proposed programs have been

resolved. For example, feasible farm models may not yet be perfectly tested, or the best method of

rehabilitating abandoned shrimp ponds may not be well known. This must be balanced against the

need to take steps quickly in some cases and locations to halt or reverse natural resource

degradation. Coastal and marine environmental projects in Cambodia will have to be implemented

with incomplete knowledge. This reality demands an adaptive approach to program implementation

and delivery. This adaptive approach will require environmental monitoring so that unanticipated

effects can be detected quickly, and lessons learned can be used to quickly modify and re-design

investments and technical assistance.

REFERENCES

ADB (1996). Coastal and Marine Environment Management for Kingdom of Cambodia (Final Draft).

RETA: Coastal and Marine Environment Management in the South China Sea.

IRIC and IDRC, (1997). Project on re-monitoring of nature and fishery resources in Cambodia coastal

zone. Ministry of Environment. Phnom Penh, Cambodia.

MRC (1997). The Study of Wetlands in Cambodia. Ministry of Planning. Phnom Penh, Cambodia.

National Institute of Statistic (1998). National Population Census. Phnom Penh, Cambodia.

PMMR (2000). Mangroves Meanderings: Learning about life in Peam Krasop Wildlife Sanctuary.

IDRC/Canada and Ministry of Environment of Project: Participatory Management in the Coastal Zone

of Cambodia. Ministry of Environment, Phnom Penh, Cambodia.

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

United Nations

UNEP/GEF South China Sea

Global Environment

Environment Programme

Project

Facility

NATIONAL REPORT

on

Wetlands in South China Sea

CHINA

Ms. Chen Guizhu

Focal Point for Wetlands

Institute of Environmental Sciences

Zhongshan University, 135 West Xingang Road

Guangzhou 510275

Guangdong Province, China

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

NATIONAL REPORT ON WETLANDS IN SOUTH CHINA SEA CHINA

Table of Contents

1. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................1

2. REVIEW OF CHINA'S WETLAND RESOURCES..........................................................................1

2.1 GENERAL STATUS OF WETLANDS IN CHINA.................................................................................1

2.1.1 China's Wetland Resources..........................................................................................1

2.1.2 Chinese Wetlands on the Ramsar Convention List of Wetlands of International

Importance ....................................................................................................................2

2.2 DISTRIBUTION OF WETLANDS IN CHINA ALONG THE SOUTH CHINA SEA.........................................2

2.3 TOTAL AREAS OF WETLANDS IN CHINA .......................................................................................4

3. UTILIZATION OF, AND THREATS TO, WETLANDS ....................................................................4

3.1 UITILISATION OF WETLANDS.......................................................................................................4

3.1.1 Land-use Resources .....................................................................................................4

3.1.2 Coastal Beach Wetland Resources ..............................................................................5

3.1.3 Mineral Resources ........................................................................................................6

3.1.4 Estuary Resources........................................................................................................6

3.1.5 Utilisation for Tourism ...................................................................................................6

3.2 CAUSAL CHAIN ANALYSIS FOR THREATS TO WETLANDS ..............................................................7

3.2.1 Global Climate Change .................................................................................................7

3.2.2 Typhoons and Storm Tides ...........................................................................................7

3.2.3 Red Tides ......................................................................................................................8

3.2.4 Enclosing Beaches for Land Reclamation ....................................................................8

3.2.5 Urbanization and Industrial Development .....................................................................8

3.2.6 Other Causes of Destruction.........................................................................................9

4. THE ASSESSMENT OF THE ENVIRONMENTAL ECONOMIC VALUE OF THE WETLANDS

ALONG THE SOUTH CHINA SEA ................................................................................................9

4.1 THE ENVIRONMENTAL ECONOMIC VALUE OF WETLANDS..............................................................9

4.2 THE ECONOMIC VALUE OF EXPLOITATION AND UTILIZATION OF THE WETLANDS ALONG THE SOUTH

CHINA SEA................................................................................................................................9

4.2.1 Total Benefit Value of the Coastal Wetland Ecosystem in the South China Sea .......10

4.2.2 Assessment and Analysis of the Value of Wetland Tourism along the South China

Sea ..............................................................................................................................10

4.2.3 Environmental Economic Analysis of the Value of Land Resources along the South

China Sea....................................................................................................................11

4.2.4 Analysis of the Transportation Value of Wetlands along the South China Sea..........11

4.2.5 Value of Ecological Services of Wetlands along the South China Sea ......................11

5. THE LEGISLATION AND MANAGEMENT SYSTEM FOR WETLANDS PRESERVATION IN

THE SOUTH CHINA SEA REGION .............................................................................................13

5.1 RELEVANT ADMINISTRATIVE BODIES AND CONSERVATION ACTION PROGRAMS ...........................13

5.1.1 Establishment of Administrative Bodies......................................................................13

5.1.2 Conservation Action Programs ...................................................................................15

5.2 INTRODUCTION TO THE CREATION OF NATURE RESERVES .........................................................15

5.2.1 Wetlands and Wetland Nature Reserves in Guangdong Province .............................15

5.2.2 Wetlands and Wetland Nature Reserves in the Guangxi Zhuangzu Autonomous

Region .........................................................................................................................16

5.2.3 Wetlands and Wetland Nature Reserves in Hainan Province ....................................17

5.3 MANAGEMENT OF WETLANDS AND WETLAND NATURE RESERVES..............................................17

5.3.1 Management of Wetlands in Guangdong Province ....................................................17

5.3.2 Management of Wetlands in the Guangxi Zhuangzu Autonomous Region................18

5.3.3 Management of Wetlands in Hainan Province............................................................20

5.3.4 The Wetland Management System and Legislation of the Hong Kong Special

Administrative Region (HKSAR) .................................................................................20

5.3.5 The Wetland Management System and Legislation of Macau ...................................21

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

NATIONAL REPORT ON WETLANDS IN SOUTH CHINA SEA CHINA

5.4 WETLAND LAWS AND REGULATIONS .........................................................................................22

5.4.1 Legislation on Land and Maritime Resources.............................................................22

5.4.2 Legislation on Protection of Wetland Animal and Plant Species ................................25

5.4.3 Legislation on Wetland Nature Reserves....................................................................27

5.5 PROBLEMS AND RESOLUTIONS WITH WETLAND MANAGEMENT...................................................28

5.5.1 General Problems .......................................................................................................28

5.5.2 Resolution of Problems ...............................................................................................28

6. CONCLUSION...............................................................................................................................28

REFERENCES......................................................................................................................................29

List of Tables and Figures

Table 1

Total Area of Coastal Wetlands of the South China Sea (km2).

Table 2

Land Reclamation in the Lingdingyang Area of the Pearl River Estuary from1966 to 1996

(unit km2).

Table 3

The Gross Product of the Main Industries Associated with Coastal Wetlands along the

South China Sea from 1996 to 1999 (unit: billion YMB Yuan)

Table 4

Total Economic Income of Tourism of South China Sea Wetlands

Table 5

Analysis of Land Resource Value along the South China Sea

Table 6

Economic Income from Transportation at Wetland Seaports and Gulfs along the South

China Sea (1999-2001)

Table 7

Assessment of the Principle Ecological Services Values of the Shantou Wetland

Demonstration Area

Table 8

Assessment of the Principle Ecological Services Values of the Pearl River Estuary

Wetland Demonstration Area

Table

9

Assessment of the Principle Ecological Services Values of the Hepu Wetland

Demonstration Area

Figure 1

Map of Coastal Wetland Types along the South China Sea based on Remote Sensing

Images.

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

NATIONAL REPORT ON WETLANDS IN SOUTH CHINA SEA CHINA 1

1. INTRODUCTION

China has 6,888 kilometres of coastline along the South China Sea (including 403 kilometres of

coastline in Hong Kong and Macau) from Raoping County in Guangdong Province, to the Beilun

Estuary in the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region. There are five administrative regions located

along the coast of the South China Sea: 1) Guangdong Province, 2) Hong Kong Special

Administrative Region, 3) Macau, 4) the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, and 4) Hainan

Province.

The majority of relevant data was totalled from the county to the city level, from the city to the

provincial or autonomous region level and finally to the national level. Therefore, the analysis of

China's coastal area along the South China Sea is divided into five sub regions, which are: 1)

Guangdong, 2) Hong Kong, 3) Macau, 4) Guangxi, and 5) Hainan.

2.

REVIEW OF CHINA'S WETLAND RESOURCES

2.1

General Status of Wetlands in China

China is located in the southeastern part of the Eurasian mainland. Its territory spans 9,600,000km2

and extensive territorial waters. China is a large country with diverse physical characteristics,

geography, and environmental and climatic conditions that also contains large numbers of varied

wetlands.

2.1.1 China's Wetland Resources

1)

Characteristics of China's Wetlands

There are many types of wetlands in China. They span large areas, appear in large numbers, and are

widely distributed. Differences among regions are notable and biodiversity is plentiful.

(1)

Types of Wetlands: According to the Ramsar convention, there are 31 types of natural

wetlands, and nine types of artificial wetlands in China. The primary types include marsh wetlands,

lake wetlands, river wetlands, estuary wetlands, coastal wetlands, wetlands in the neritic zone,

reservoirs, garden ponds, and paddy fields.

(2)

Expansive area: The area of wetlands in China is approximately 65,940,000hm22 (not

including rivers, garden ponds etc.) This represents ten percent of the total global wetlands, the

largest amount in Asia, and the fourth largest in the world. Chinese wetlands include 25,940,000hm2

of natural wetlands and 40,000,000hm2 of artificial wetlands.

(3)

Wide distribution: In China, wetlands extend from the frigid-temperate region to the tropics,

from coastal to inland areas, from plain to altiplano. Many types of wetlands exist in the same region

and one type of wetland can exist in many regions. This high degree of variation makes for a colourful

composition of different types of wetlands.

(4)

Notable differences among regions: There are many river wetlands in eastern China, many

marsh wetlands in north-eastern China, few wetlands in the west, and abundant lake wetlands in the

middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River and Qingzang Altiplano. Many salt lakes and saline

lakes exist in the Qingzang Altiplano and the arid area of northwest China. Special mangrove forests

and tropical and subtropical artificial wetlands spread from Hainan Island to the foreland of northern

Fukien. The Qing Zang Altiplano has the highest altitude and amplitude marshes and lakes, forming a

particular habitat.

(5)

Rich biodiversity: China has many wetland habitat types with numerous species. Not only are

the number and quantity of species large, but many of them are endemic to China. Thus, the wetlands

are important to science, research, and the economy. According to recent statistics, there are

approximately 172 families (15.5 percent), 495 genera (48.7 percent), and 1642 species (5.5 percent)

of national plants found in Chinese wetlands. More than 100 species are endangered. There are 770

species or sub-species of fresh water fish, including many migratory fish stocks whose reproduction

depends on wetland ecosystems. There are numerous waterfowl in Chinese wetlands, amounting to

i

2 1 square hectometer = 0.01 square kilometer.

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

2 NATIONAL REPORT ON WETLANDS IN SOUTH CHINA SEA CHINA

280 species, including crane, umbrettes, wild geese, gulls, and storks. There are many rare or

endangered waterfowl found in Chinese wetlands, including 15 national Class-A protected rare birds,

such as the Red-crowned Crane, and 45 Class-B protected rare birds, such as swans, Black-faced

Spoonbill, and Tringa guttifer. There are 57 species of endangered birds in Asia, out of which 31

species of endangered birds are present in Chinese wetlands, accounting for 54 percent of the total.

There are 166 species of wild geese in the world, with 50 species present in Chinese wetlands,

accounting for 30 percent of the total. There are 15 species of cranes, and nine of them are found in

China. Moreover, China is home to many migratory birds. Several Chinese wetlands provide the only

wintering grounds for some species along their migratory routes.

2)

Status of Primary Types of Chinese Coastal Wetlands

Coastal wetlands and wetlands in the Neritic Zone: Coastal wetlands in China are primarily distributed

among 11 littoral provinces and districts, and the Hong Kong-Macau-Taiwan area. There are

approximately 1,500 rivers flowing into oceans in China. They form six types of coastal/marine

wetlands with more than 30 types of ecosystems.

The northern section of Hangzhou Bay consists of sandy and silty beaches, except for the rocky

beach of the Shandong Byland and sections of the Liaodong Byland. Wetlands in the Huan-bohai Sea

and Jiangsu littoral area have the same composition. The Yellow River delta and Liaohe River delta

are important littoral wetlands in the Huan-bohai Sea. The Huanbohai Sea littoral area also contains

the Laizhou Bay Wetland, Mapengkou Wetland, BeidaGang Wetland, and Beitang Wetland. The total

area is 6,000,000hm2. The Jiangsu littoral wetland is made up of sections of the Yangtze River delta

and Yellow River delta. The total beach area amounts to 550,000hm2, including the Yancheng

Wetland, Nantong Wetland, and Lianyungang Wetland.

The southern part of Hangzhou Bay primarily consists of rocky beach. The major estuaries and gulf

are located at the mouth of the Qiantangjaing Huangzhou Bay, Jinjiangkou Quanzhou Bay, Pearl

River, and North Gulf.

2.1.2 Chinese Wetlands on the Ramsar Convention List of Wetlands of International

Importance

There are 21 Chinese wetlands included on Ramsar Convention list of Wetlands of International

Importance. The Chinese wetlands of international importance are 1) Zhalong Nature Reserve; 2)

Xianghai Nature Reserve; 3) Dongzhaigang Nature Reserve; 4) Qinghai Birds Island Nature Reserve;

5) East-Dongting Lake Nature Reserve; 6) Poyang Lake Nature Reserve; 7) Mipu and Back Gulf; 8)

Dongtan Nature Reserve; 9) Dalian National Harbour Seal Nature Reserve; 10) Dafeng Elk Nature

Reserve; 11) Inner-Mongolia Dalai Lake Nature Reserve; 12) Zhanjiang Mangrove Nature Reserve;

13) Honghe Nature Reserve; 14) Chelonian Nature Reserve; 15) Larus relictus Nature Reserve; 16)

Sanjiang National Nature Reserve; 17) Sankou National Mangrove Nature Reserve; 18) Wetland and

Waterforwl Nature Reserve; 19) Westdongting Lake Nature Reserve; 20) Xingkai Lake National

Nature Reserve; and 21) Yancheng Nature Reserve.

2.2

Distribution of Wetlands in China along the South China Sea

(1)

Estuarine Waters: These wetlands include the river water areas from the non-tidal reach to

the division of saltwater and freshwater. The estuarine waters are mainly distributed in the reaches of

tidal flats, which meets the mouth of the river, such as the reaches from the Xijiang River, Dongjiang

River and Beijiang River to the Pearl River Estuary (Lingdingyang Estuary) in the Pearl River Delta in

Guangdong; the estuary reaches of the Ganjiang River and Rongjiang River in the east of

Guangdong; the estuary reaches of the Moyangjiang River, Loujiang River and Zhanjiang River in the

west of Guangdong; the estuary reaches of the Kangjiang River in Beihai in Guangxi; the estuary

reaches of the Qingjiang River in Qingzhou, Guangxi; the estuary reaches of the three river systems

of Hainan, that is the Wanquanhe River, Nanduhe River and Changhuajiang River.

(2)

Intertidal Flats: These wetlands lie from the shoreline to the lowest low water limit that is the

beach land which comes out when the seawater falls to the lowest low water limit. The intertidal flats

include sandy gravel beaches, sands beaches, mud beaches, grass beaches, and mangrove

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

NATIONAL REPORT ON WETLANDS IN SOUTH CHINA SEA CHINA 3

swamps. Most of the mud beaches, mangrove swamps, and grass beaches are distributed in the

estuaries, both sides of the bays or the bay heads. The sandy gravel beaches are mostly distributed

on the rocky shores.

(3)

Coastal Lagoons: These wetlands are mostly formed in bays with a narrow mouth. When a

sand bank, sand spit, or sand bar appears in the bay mouth resulting from a washed deposit, a

lagoon will form--a salt water lake with one or more outlets, such as the Pinqing Lake in Shanwei,

Guangdong, the Dazhou Bay in Huidong, Guangdong, the Qingzhou Bay in Guangxi, the Dongzai

Port, the Gangbei Port and the Qinglan Port in Hannan.

(4)

Shallow Marine Waters: These wetlands cover the area between the depths of 0m to 6m at

low tide, which can be determined with reference to charts. Another method is to obtain the tidal

levels corresponding to the imaging time of the satellite images, and the depths of 0m to 6m can be

determined roughly through image processing.

(5)

Rocky Marine Shores: Because the shoreline of the South China Sea is meandering with a

large number of ports, rocky marine shores are distributed in each province, especially in the

Guanghai Bay in the west of Guangdong, and the Daya Bay, Dapeng Bay and the Dapeng Island in

the east of Guangdong. These wetlands also exist in the Pearl River delta, the Tieshan Port in Beihai,

Guangxi, the Qingzhou Port in Qingzhou, Guangxi, and the Yulin Port, Sanya Port and Yazhou Port in

Sanya, Hainan.

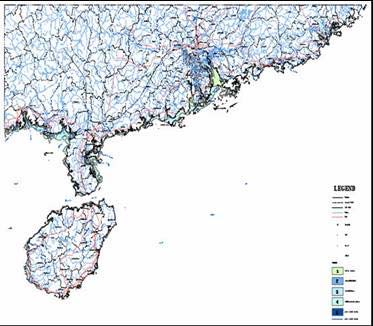

Based on the data from Remote Sensing, Geographic Information Systems, and Global Positioning

Systems, the resources of the coastal wetlands in China are shown to be plentiful (refer to Map 3-2).

The statistics show that there are: 1) estuarine waters with a total area of 4,550.12km2; 2) intertidal

flats with a total area of 2,824.71km2; 3) coastal lagoons with a total area of 365.83km2; 4) shallow

marine waters with a total area of 6,908.15km2; and 5) rocky marine shores with a total area of

666.55km2.

Figure 1 shows Map of Coastal Wetland Types along the South China Sea based on Remote Sensing

Images.

Figure 1

Map of Coastal Wetland Types along the South China Sea based on Remote Sensing

Images.

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

4 NATIONAL REPORT ON WETLANDS IN SOUTH CHINA SEA CHINA

2.3

Total Areas of Wetlands in China

Based on the above map of the coastal wetland classification at a scale of 1:250,000, the area of the

map polygons of each type of wetland was measured by GIS software (Arc/info) and summarised

according to the district divisions of the UNEP/GEF project, county, city, and province respectively.

Thus, the statistics of the coastal wetlands in the South China Sea have been obtained (Table 1). In

the tables, the data are area statistics from 2002 obtained from the remotely sensed images as

described above.

Table 1

Total Area of Coastal Wetlands of the South China Sea (km2).

Guangdong Hongkong Macau Guangxi Hainan

Total

Estuary Waters

3,974.56

28.08 11.97 403.31 160.28

4,578.20

Intertidal Flats

1,582.03

11.10

0.00 853.72 392.73

2,839.57

Coastal Lagoon

119.67

20.25 0.00 0.00

245.29

385.21

Shallow marine Waters

4,502.66

295.59 61.24

1,390.87 933.13

7,183.49

Rocky marine Shores

374.63 17.37 0.00 2.30 12.98

407.29

Total 10,553.55

372.39

73.21

2,650.20 1,744.40 15,393.75

3.

UTILIZATION OF, AND THREATS TO, WETLANDS

3.1

Uitilisation of Wetlands

3.1.1 Land-use

Resources

1)

Enclosing Beaches for Fisheries and Aquaculture in Shallow Seawater

The total aquaculture products from the South China Sea over the period from 1999 to 2001 were

44,570 thousand tonnes. In Guangdong Province from 1999-2001, beach enclosure and land

reclamation created 40,683 ha for aquaculture, and the total aquaculture products was 24,110

thousand tonnes. These areas became important sites for fisheries and aquaculture production.

2)

Coastal Mangrove Swamp Wetlands

Mangrove swamp wetlands are important resources that are mainly distributed in estuaries. They

provide many important ecosystem functions, such as shielding against wind and erosion, maintaining

banks, enduring huge waves, providing reproduction sites for fish, shrimp, crabs, and shellfish, and

providing nesting grounds for water birds. The area of coastal mangrove wetlands in the South China

Sea (including Hong Kong and Macao) was 22,121hm2 during the period from 1950-1959. From

1990-1999 the area of coastal mangrove wetlands fell to 14,567hm2, and 7,554hm2 currently. Land

reclamation is the primary cause of wetland loss. Land reclamation of these mangrove swamps has

provided the land to develop the Guanghai Farm in Taishan, Niutianyang Farm in Shantou, the

Huanggang tax-free Industrial Park in Shenzhen, the Mawan Oil Dock in Shenzhen, the Huangtian

Airdrome in Shenzhen, and the Aotou Industrial Park in Dayawan.

3)

Land Resources for Coastal Salt Fields

The natural conditions in the South China Sea are very advantageous for the salt industry, especially

in western Guangdong Province and in western Hainan Province. The salinity of the South China Sea

is 33 percent. The area of salt fields in the South China Sea was 21,613hm2 in 1992, including

11,656.92hm2 in Guangdong, 4,512.64hm2 in Hainan, and 5,444.16hm2 in Guangxi; the original

output of salt was 659,100 tonnes, including 351,700 tonnes in Guangdong, 152,000 tonnes in

Hainan, and 155,200 tonnes in Guangxi. Over the period from 1996 to 1999, the economic value of

salt industry production was 0.6 billion, and the annual mean was 0.15 billion.

4)

Delta Low Plane Land Resources

The important delta wetlands in the South China Sea include the Pearl River Delta, Hanjiang Delta,

Jianjiang Delta, Nanliujiang Delta, and Nandu River Delta. These areas have mainly been used for

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

NATIONAL REPORT ON WETLANDS IN SOUTH CHINA SEA CHINA 5

agriculture and aquaculture in the past. Today, these areas have become developed industrial areas.

In Wanqingsha of Panyu, a new town named Xinken was reclaimed in ten years; other areas that

have been reclaimed from deltas include the town of Maofengwei in Zhongshan, Baitenghu in Zhuhai,

the Yanan Farm in Xinhui, the Huangtian Airdrome in Shenzhen, the Zhuhai Airdrome, and the

Yantian Port in Shenzhen amation.

3.1.2 Coastal Beach Wetland Resources

The total area of coastal beach wetlands in the South China Sea is 3,535.7hm2, which is mainly used

for aquaculture, the salt industry, enclosing beaches for land reclamation, and building mangrove

wetlands. Through remote sensing and GIS techniques, it has been determined that 210.00km2 of

beaches were enclosed for land reclamation from 1978 to 1997 in the Pearl River Estuary. Of the

210.00km2, 160.00km2 occurred in the western Pearl River Estuary, and 50km2 in the eastern Pearl

River Estuary. In the eastern Pearl River Estuary, land reclamation in the south was mainly used for

urban development, industrial development, and establishment of foundations, while land reclamation

in the north was mainly used for agriculture and aquaculture. In the western Pearl River Estuary, land

reclamation was mainly used for agriculture and aquaculture. In recent years, land reclamation of

wetlands was mainly conducted to develop cities, transportation networks, airports, harbours,

industrial lands, and aquaculture.

Over the past 100 years, the siltation rate of the delta and evolution of the coastline has increased

rapidly, especially over the past 30 years. The natural rate of beach formation was approximately

1,000hm2/year, while the enclosure rate of beaches for land reclamation was approximately

1,100hm2/year.

Wetland Utilization in the South China Sea region mirrors that in the Pearl River Delta estuary as

described below:

The Pearl River Delta estuary is one of the largest estuaries in the world, which was densely covered

by networks of rivers. The beach resources were mainly distributed along the coast of the

Lingdingyang and Huangmaohai Districts, while the shallow areas were distributed in the Modaomen

and Jitimen districts. The pushing rate of Xijiang and Beijing delta was increased to 4,050m/year.

Delta pond wetlands are very famous in China. In this ecosystem, mulberry, fruit, sugar cane, and

other economic crops were planted along the banks, fish were cultivated in the ponds, and the leaves

of the mulberry gave birth to the silkworm.

In the Pearl River Delta Estuary, land reclamation is a serious problem. At the present time, the

proportion of enclosing and silting is three to five. There is a delay in construction of the protected

zone.

The Pearl River empties into the South China Sea through eight outlets in the delta. The evolution of

the outlets, the rates of delta reclamation, and the changes in the coastline from 1966 to 1996 has

been quantitatively studied through remote sensing and GIS techniques. The total reclaimed area in

the entire delta during the period has been calculated to be 344km2, at the average rate of

11.47km2/year, which is much greater than in the historical period. Of this total, 146km2 has been

reclaimed in the Lindingyang District, where four eastern outlets (Humen, Jiaomen, Hongqili and