EFA Namibia Socio-economics

Okavango River Basin Technical

Diagnostic Analysis:

Environmental Flow Module

Final Specialist Report

Country: Namibia

Discipline: Socio-economics

J. Barnes & D. Wamunyima

November 2009

1

EFA Namibia Socio-economics

Okavango River Basin Technical

Diagnostic Analysis:

Environmental Flow Module

Final Specialist Report

Country: Namibia

Discipline: Socio-economics

Authors: J Barnes & D. Wamunyima

Date: 20-11-2009

2

EFA Namibia Socio-economics

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................... 6

1INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 7

1.1 Background ........................................................................................................ 7

1.2 Okavango River Basin EFA objectives and workplan ........................................ 7

1.3 Layout of this report ............................................................................................ 8

1.4 Methods for data collection and analysis............................................................ 8

1.5 Description of the Okavango Basin .................................................................... 9

1.6 Delineation of the Okavango Basin into Integrated Units of Analysis ............... 11

2RESULTS - THE SITES .............................................................................................. 13

2.1 Overview of Namibian sites .............................................................................. 13

2.2 Socio-economic description of Namibian sites ................................................. 15

2.3 Habitat integrity of the sites in Namibia ............................................................ 19

3RESULTS - THE INDICATORS .................................................................................. 21

3.1 Indicators .......................................................................................................... 21

3.2 Flow categories river sites ............................................................................. 26

4RESULTS - RESPONSES AND IMPACTS ................................................................. 30

4.1 Socio-economic responses to potential changes in the flow regime ................ 30

5VALUES AND FLOW-RESPONSE RELATIONSHIPS IN THE OKAVANGO EFA

MODEL ................................................................................................................ 34

5.1 Base values ...................................................................................................... 34

5.2 Flow responses ................................................................................................ 36

6CONCLUSION ............................................................................................................ 68

7REFERENCES ............................................................................................................ 69

APPENDIX A: STAKEHOLDERS PARTICIPATION ..................................................... 70

REPORT ....................................................................................................................... 70

3

EFA Namibia Socio-economics

TABLE OF FIGURES

Figure 1. 1: Upper Okavango River Basin from sources to the northern end of the Delta10

Figure 1. 2: The Okavango River Basin, showing drainage into the Okavango Delta and

................................................................................................. 11

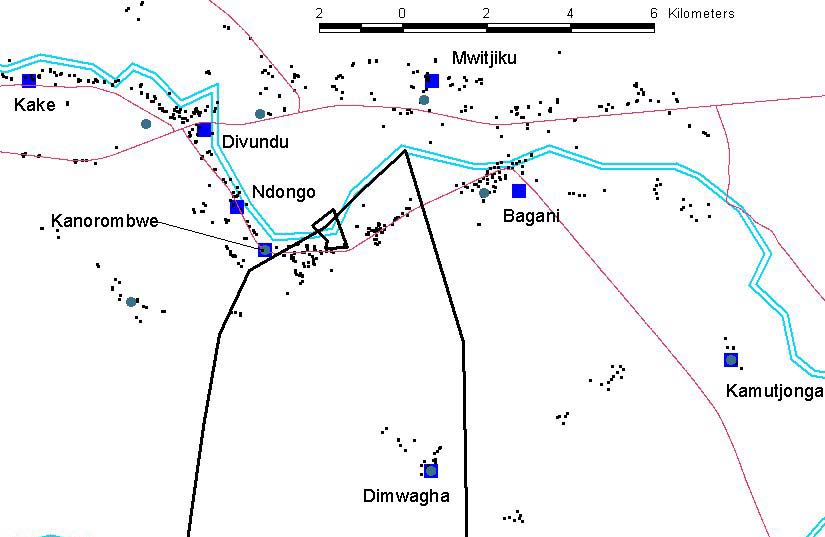

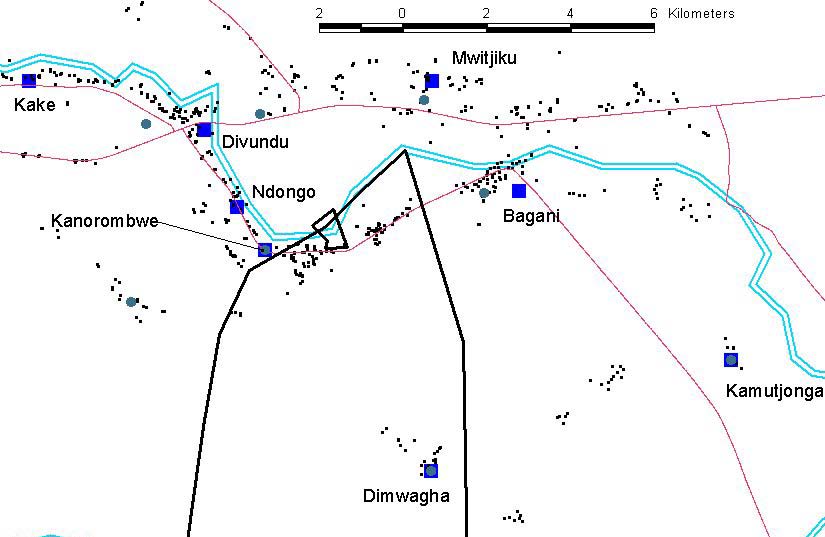

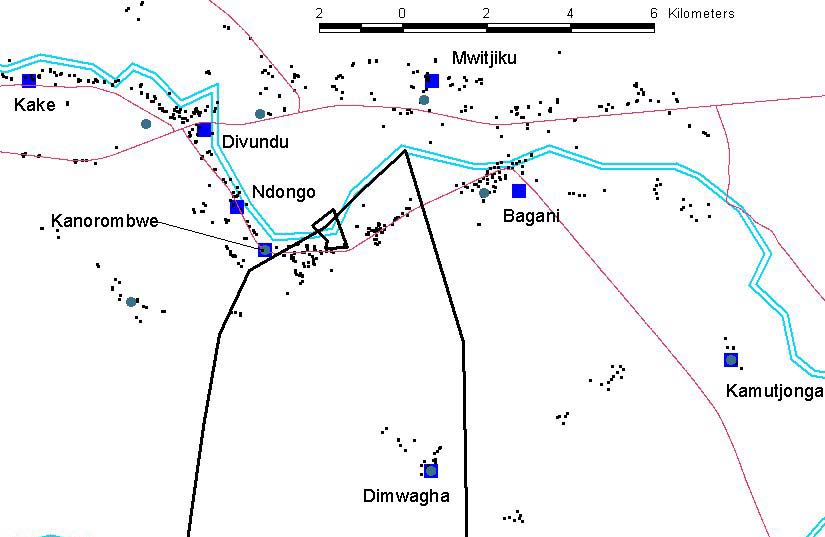

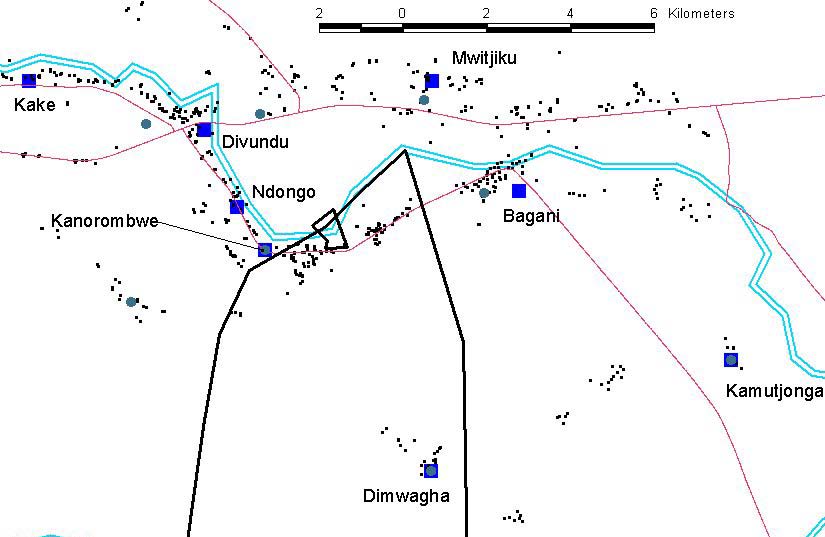

Figure 2. 1: Location of Site 4 at Kapako ...................................................................... 14

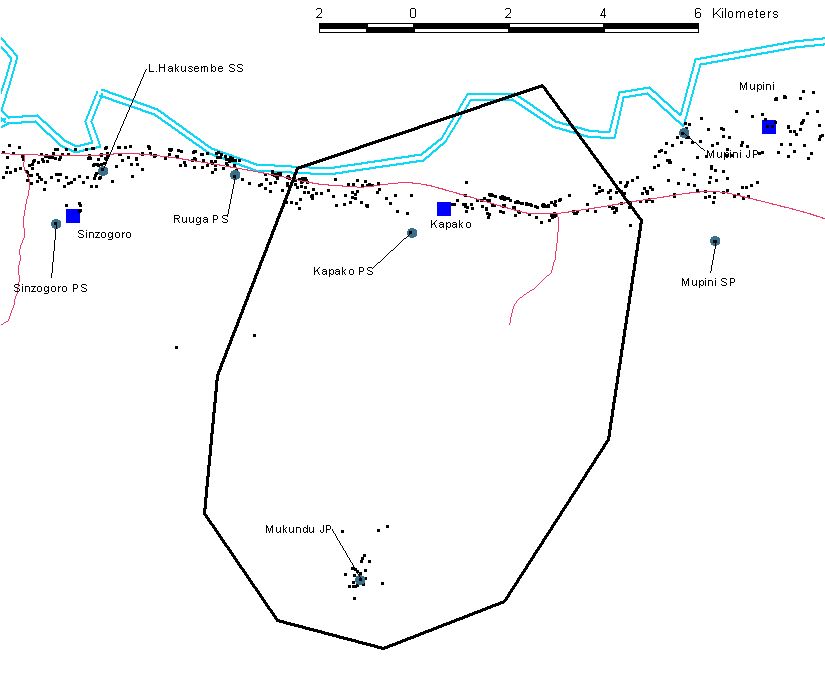

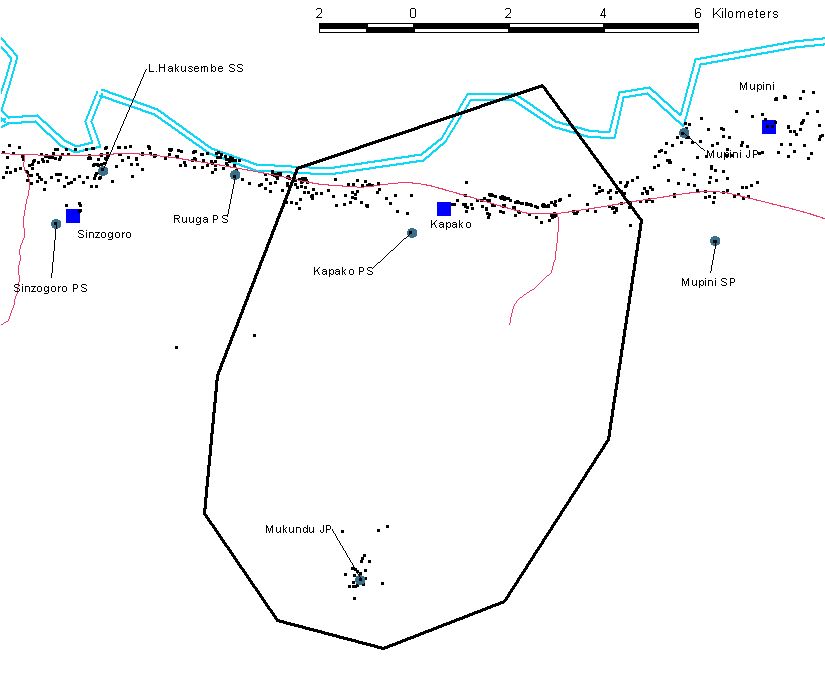

Figure 2. 2: Location of Site 5 at Popa Falls ................................................................. 15

Figure 3. 1: Three representative years for Site 1: Cuebe River @ Capico, illustrating 27

Figure 3. 3: Three representative years for Site 3 Cuito River @ Cuito Cuanavale,

illustrating the ........................................................................... 28

Figure 3. 4: Three representative years for Site 4: Okavango River @ Kapako

(hydrological data ..................................................................... 28

Figure 3. 5: Three representative years for Site 5: Okavango River @ Popa (hydrological

data .......................................................................................... 28

TABLE OF FIGURES

Table 2. 1: Population estimates for the Namibian Okavango river basin ..................... 16

Table 3. 1: List of socio-economic indicators and their links to the broader economy .. 22

4

EFA Namibia Socio-economics

ABBREVIATIONS

AIDS

Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome

DTM

Digital terrain model

EFA

Environmental flow assessment

EPSMO

Environmental Protection and Sustainable Management of the

Okavango River Basin Project

FAO

Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations

GDP

Gross domestic product

GEF

Global Environment Facility

GNI

Gross national income

GNP

Gross national product

HDI

Human development index

HIV

Human immunodeficiency virus

IUA

Integrated unit of analysis

MET

Ministry of Environment and Tourism

NGO Non-governmental

organisation

OBSC

Okavango Basin Steering Committee

OKACOM

Permanent Okavango River Basin Water Commission

PRB

Population Reference Bureau

SAM

Social accounting matrix

TDA

Transboundary diagnostic analysis

UN-FAO

Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations

5

EFA Namibia Socio-economics

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was funded by the Global Environment Facility (GEF), and managed by the

EPSMO Project, through the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) of the United Nations,

and under the overall guidance of OKACOM.

We wish to thank the EPSMO TDA Project Management Team, the Environmental Flows

Assessment (EFA) team, and the Namibia Nature Foundation administrative team. The

Namibian country team for the TDA project assisted greatly in providing us with essential

data, and advice.

Special assistance was received from Chaminda Rajapakse, Manuel Quintino, Jackie King,

Cate Brown, Alison Joubert, Casper Bonyongo, Shirley Bethune and Laura Namene, and

those others who were in the Namibian country team

We are grateful to all the people in the basin, natural resource users, farmers, tourism

operators officials, and others (too numerous to mention by name) who provided data,

information, and responses during surveys and research.

6

EFA Namibia Socio-economics

1 INTRODUCTION

1.1 Background

An Environmental Protection and Sustainable Management of the Okavango River Basin

(EPSMO) Project is being implemented under the auspices of the Food and Agriculture

Organization of the United Nations (UN-FAO). One of the activities is to complete a trans-

boundary diagnostic assessment (TDA) for the purpose of developing a Strategic Action Plan

for the basin. The TDA is an analysis of current and future possible causes of transboundary

issues between the three countries of the basin: Angola, Namibia and Botswana. The

Okavango Basin Steering Committee (OBSC) of the Okavango River Basin Water

Commission (OKACOM) noted during a March 2008 meeting in Windhoek, Namibia, that

future trans-boundary issues within the Okavango River basin are likely to occur due to

developments that would modify flow regimes. The OBSC also noted that there was

inadequate information about the physico-chemical, ecological and socioeconomic effects of

such possible developments. OBSC recommended at this meeting that an Environmental

Flow Assessment (EFA) be carried out to predict possible development-driven changes in

the flow regime of the Okavango River system, the related ecosystem changes, and the

consequent impacts on people using the river's resources.

The EFA is a joint project of EPSMO and the Biokavango Project. One part of the EFA is a

series of country-specific specialist studies, of which this is the socio-economic Report for

Namibia.

1.2

Okavango River Basin EFA objectives and workplan

1.2.1 Project objectives

The goals of the EFA are:

· To summarise all relevant information on the Okavango River system and its users, and

collect new data as appropriate within the constraints of the EFA

· to use these to provide scenarios of possible development pathways into the future for

consideration by decision makers, enabling them to discuss and negotiate on sustainable

development of the Okavango River Basin;

· to include in each scenario the major positive and negative ecological, resource-

economic and social impacts of the relevant developments;

· to complete this suite of activities as a pilot EFA, due to time constraints, as input to the

TDA and to a future comprehensive EFA.

The specific objectives are:

· to ascertain at different points along the Okavango River system, including the Delta, the

existing relationships between the flow regime and the ecological nature and functioning

of the river ecosystem;

· to ascertain the existing relationships between the river ecosystem and peoples'

livelihoods;

· to predict possible development-driven changes to the flow regime and thus to the river

ecosystem;

· to predict the impacts of such river ecosystem changes on people's livelihoods.

· To use the EFA outputs to enhance biodiversity management of the Delta.

· To develop skills for conducting EFAs in Angola, Botswana, and Namibia.

7

EFA Namibia Socio-economics

1.3

Layout of this report

This report contains the following elements: A description of the methods used is followed by

a description of the findings including a description of the socio-economic characteristics of

the study area, i.e., the Namibian part of the Okavango river basin. This includes delineation

of the Namibian basin into integrated units of analysis (IUAs), the identification of river

/wetland based natural resource uses, and the identification of the socio-economic indicators

for the EFA model. The characteristics of all these indicators are described and this is

followed by a description on the responses to scenario flow change in terms of livelihoods

and economic contribution.

1.4

Methods for data collection and analysis

The Namibian socio-economic team collated, reviewed and summarised all available

published and unpublished information on the social and economic characteristics in the

Namibian part of the basin. Other related, published and unpublished information on

livelihood and economic values in similar environments and in other river systems of the

southern African region was also scanned.

A rapid multidisciplinary field survey was carried out by the TDA/EFA core team, with

assistance within each country from the relevant country teams. Among eight target sites in

the basin, two in Namibia (Kapako and Popa) were visited to collect basic data for all

disciplines. Socio-economic data was collected at these sites through focus group discussion

meetings with basin community members and from key informants. The following tasks were

carried out.

i.

The key social and economic indicator resources, which can be linked to the river and

flow changes at each site were identified. These included those of the indicators

identified at the EFA Delineation Workshop (fish, reeds, papyrus, floodplain grass and

water lilies), that are used at the site.

ii.

Local key informants and/or focus groups regarding the use of the resources in

question were identified and located. Interviews were conducted with these. Particular

note was taken of harvest techniques, effort (particularly time invested),

equipment/gear (capital requirements), input and product prices, spatial and seasonal

patterns of use, perceptions about sustainability, and the relative importance of the

use to households/users compared to other resource use.

iii.

In interviews and focus group discussions it was determined as far as possible, how

all uses and their spatial and seasonal patterns relate to flow conditions. Examples

were uses that take place on seasonally on floodplains or uses that depend on

particular depth of flow or flood.

iv.

In the discussions with local informants, any signs or local knowledge of any other

indicators, such as those for health, culture, social well-being, that may be linked to

flows were recorded.

Of the 12 integrated units of analysis (IUAs) delineated as relatively homogeneous socio-

economic zones for the whole basin, two were selected for the Namibian basin. These were

used to guide data gathering, and as the basis for extrapolation and aggregation of livelihood

and economic values.

8

EFA Namibia Socio-economics

During the EFA/TDA process, two specific surveys were carried out to address important

data gaps. One was a detailed household and community level survey, carried out in the

Angolan part of the basin. The results are presented in Saraiva (2009). The other was a

small quantitative questionnaire survey was carried out among tourism operators in the

Botswana part of the basin. Here a systematic sample of 48 tourism operators, were

surveyed with the aim of measuring the likely effects that river flow change, and associated

flood change, might have on tourism incomes. The results of this were described by Mbaiwa

& Mmopelwa (2009).

Empirical results from literature and the surveys were used to develop natural resource use

and tourism enterprise models. These formed the basis for valuation. Most of the enterprise

models were adapted from those developed during a recent, detailed valuation of wetland

values in the Okavango delta (Turpie et al. 2006).The economic analysis for the EFA model

was focused only on the river and wetland values, i.e., those values that could be affected by

flow change. These included values for household use of river-based natural resources such

as fish, reeds, floodplain grass, floodplain gardens and floodplain grazing, as well as

commercial river- and floodplain-based tourism.

The socio-economic analyses measured the private wellbeing of the basin inhabitants, as

well as the national wellbeing of the basin countries. Private wellbeing was measured as the

net change in household livelihoods. This is the net gain in welfare, due to the resources of

the river basin and its functions, experienced by households. It is the net profits earned by

households in their income-earning activities. Private wellbeing as affected by intangible

factors such as water quality was subjectively assessed, but not included in livelihood

measures. National wellbeing was measured as the direct net change in national income. In

this case the enterprise models were used to measure the value added to the national

income by the enterprise. The specific national income measure used was gross national

product.

Measurement of the direct contribution to the national income was extended to illustrate the

total direct and indirect impact of resource use the on national economies. This was done

using multipliers calculated from the Namibian social accounting matrix (SAM) model (Lange

et al. 2004). National wellbeing as affected by indirect use values, or ecosystem services,

and national wellbeing as affected by non-use value (existence, bequest and option value)

was not assessed directly in the EFA process.

In the Namibian basin valuation work, values were first estimated in Namibia dollars (N$).

Where impacts of scenarios were compared between scenarios, these values were

converted to United States Dollars (US$) to allow basin-wide comparison. During the study in

2008, US$1.00 was worth N$8.16.

1.5

Description of the Okavango Basin

The Okavango River Basin consists of the areas drained by the Cubango, Cutato, Cuchi,

Cuelei, Cuebe, and Cuito rivers in Angola, the Okavango River in Namibia and Botswana,

and the Okavango Delta (). This basin topographically includes the area that was drained by

the now fossil Omatako River in Namibia. Outflows from the Okavango Delta are drained

through the Thamalakane and then Boteti Rivers, the latter eventually joining the

Makgadikgadi Pans. The Nata River, which drains the western part of Zimbabwe, also joins

the Makgadikgadi Pans. On the basis of topography, the Okavango River Basin thus

includes the Makgadikgadi Pans and Nata River Basin (). This study, however, focuses only

on the perennial parts of the basin in Angola and Namibia, and the Panhandle/Delta/Boteti

River complex in Botswana. The Omatako and other ephemeral drainages to the south west

as well as the and Makgadikgadi Pans and Nata River to the south east are not included.

9

EFA Namibia Socio-economics

Upper Okavango River Basin

N

W

E

S

C

u

ta

Cu

#

to

ch

i

#

C

C

u

u

#

it

a

o

nava

#

le

Cu

#

C

Menongue

ba

u

n

c

g

h

#

Major settlement

o

i

# Cuito Cuanavale

River

C

#

ue

Fossil river

be

C

Panhandle

ANGOLA

uiri

Permanent swamps

ri

#

Seasonal swamps

Cubango

Cuito

NAMIBIA

Okavango

#

Rundu

#

#

#

0

300 Kilometers

#

Figure 1. 1: Upper Okavango River Basin from sources to the northern end of the Delta

10

EFA Namibia Socio-economics

Okavango River Basin

N

W

E

S

Cu

t

a

Cu

#

t

o

c

h

i#

C

C

ui

ua

#

t

o

nava

#

l

e

C

# Menongue

ub

C

a

u

n

c

g

h

o

i

# Cuito Cuanavale

# Cuebe

C

ANGOLA

uirir

#

i

Cubango

Cuito

NAMIBIA

Okavango

#

Rundu #

# #

#

##

#

#

#

Maun

#

Makgadikgadi Pans

# Ghanzi

#

Major settlement

River

Fossil river

Panhandle

0

600 Kilometers

Permanent swamps

Seasonal swamps

Figure 1. 2: The Okavango River Basin, showing drainage into the Okavango Delta and

1.6

Delineation of the Okavango Basin into Integrated Units of Analysis

Within the Okavango River Basin, no study could address every kilometre stretch of the river,

or every person living within the area, particularly a pilot study such as this one. Instead,

representative areas that are reasonably homogeneous in character may be delineated and

used to representative much wider areas, and then one or more representative sites chosen

in each as the focus for data-collection activities. The results from each representative site

can then be extrapolated over the respective wider areas.

Using this approach, the Basin was delineated into Integrated Units of Analysis

(EPSMO/Biokavango Report Number 2; Delineation Report) by:

· dividing the river into relatively homogeneous longitudinal zones in terms of:

· hydrology;

· geomorphology;

· water

chemistry;

· fish;

· aquatic

invertebrates;

11

EFA Namibia Socio-economics

· vegetation;

· harmonising the results from each discipline into one set of biophysical river zones;

· dividing the basin into relatively homogeneous areas in terms of social systems;

· harmonising the biophysical river zones and the social areas into one set of Integrated

Units of Analysis (IUAs).

The recognised IUAs were then considered by each national team as candidates for the

location of the allocated number of study sites:

· Angola:

three

sites

· Namibia:

two

sites

· Botswana:

three

sites.

The sites chosen by the national teams are given in .

EFA Site No

Country

River

Location

1 Angola Cuebe

Capico

2 Angola

Cubango Mucundi

3 Angola Cuito Cuito

Cuanavale

4 Namibia

Okavango

Kapako

5 Namibia

Okavango Popa

Falls

6

Botswana

Okavango

Panhandle at Shakawe

7

Botswana

Khwai

Xakanaka in Delta

8 Botswana Boteti

Chanoga

Table 1. 1: Location of the eight EFA sites

This report deals only with the Namibian sites as well as their respective IUAs. Namibia was

divided into two IUAs each of which, in turn, subdivided into sub IUAs. Thus IUA 8 extended

along the basin from the Angolan border post at Katwitiwi to Mukwe, and it was divided into

two: 8a - above the junction with the Angolan Cuito tributary, and 8b - below this. IUA 9

extended along the Namibian basin from Mukwe to the Botswana border, and it was also

divided into two: 9a - the stretch between Mukwe and the Mahango core area of the

Bwabwata National Park, and 9b - the short section of the river wholly within the park. Site 4

at Kapako was representative of IUA 8 and in particular 8a. Site 5 at Popa Falls was

representative of IUA 9 in particular 9a.

Functionally, the river basin represented by IUAs 8 and 9 occupies both sides of the river

while the river forms the border between Namibia and Angola. There is relatively free

movement of people across the river, and resources are used on both sides, but about 80%

of the population lives on the Namibian side, including many Angolans, and nearly all the

economic activity is attributable to the Namibian side. From the point of view of the EFA

analytical work IUAs 8 and 9 are treated as part of Namibia. Adjustments were only made

when extrapolating the values between countries.

12

EFA Namibia Socio-economics

2 RESULTS - THE SITES

2.1 Overview

of

Namibian sites

The sites are specific localities, selected primarily so that their hydrological and biophysical

characteristics can be measured where needed. They need to be representative not only of

the IUA within which they fall, because the information gained from site visits needs to be

extrapolated to the whole IUA. Furthermore, this information needs to be suitable for

extrapolation to those IUAs which do not have sites. This is particularly the case with the

socio-economic component of the EFA, since the impacts of flow change need to be

measured in terms of their impact on aggregate household welfare and economic income

within the IUAs, the countries, and the basin as a whole.

From the socio-economic perspective the sites provided only reference points where field

visits were enabled, but the field literature and research was aimed more at the broader IUA

concerned. When the EFA field trip took place in Kavango Region, between the 17th and 23rd

of October, 2008, communities in the vicinity of Sites 4 and 5 were interviewed using focus

group and key informant methods.

2.1.1 Site 4: Okavango River at Kapako

Site 4 was located 20km upstream from Rundu on the Okavango river and was

representative of integrated unit of analysis (IUA) number 8. As stated, IUA 8 stretched from

the Angolan border post at Katwitiwi to Mukwe. This part of the river is characterised by

having a sandy substrate and a narrow floodplain. The division of IUA 8 into two: 8a - above

the junction with the Angolan Cuito tributary, and 8b - below this, reflects the fact that above

the Cuito junction, floods are more marked and seasonal river flow more varied. Inflows from

the Cuito are more constant and seasonally stable and this stabilises the flow regime in 8b.

Map 2.1 shows the locality of Site 4 at Kapako. Land is state owned with communal use

rights, and households live concentrated along the river. The locality of a strip of households

can be seen in the map.

13

EFA Namibia Socio-economics

Figure 2. 1: Location of Site 4 at Kapako

2.1.2 Site 5: Okavango River at Popa Falls

As stated, Site 5 is representative of the river between Mukwe and the Botswana border at

Mohembo or IUA 9. Here the river flows over a mixture of rock and sand and, for most of its

length, characteristically does not have a floodplain. It has also been divided into two: 9a -

the populated stretch between Mukwe and the Mahango core area of the Bwabwata National

Park, and 9b the section of the river wholly within the park. Section 9b does have a

moderately developed floodplain, which in Botswana's IUA 10, downstream widens

considerably into the delta panhandle.

Map 2.2 shows the locality of Site 5 at Popa Falls. The land is state owned under communal

tenure and households are scattered along the river as in IUA 8. These can be seen in the

map.

14

EFA Namibia Socio-economics

Figure 2. 2: Location of Site 5 at Popa Falls

2.2 Socio-economic

description of Namibian sites

2.2.1 Site 4: Kapako

The work of Mendelsohn & el Obeid (2003, 2004) and Mendelsohn et al. (2002) as well as

Yaron et al. (1992) provided significant amounts of data relevant to the descriptions that

follow.

The floodplain in IUA 8 effectively distinguishes it from IUA 9 which generally has a rocky

substrate and no floodplain. The river is at the heart and core of the Okavango Basin, and a

variety of aquatic plants animals live in and make good use of the river water. The river

channels are often flanked with broader margins consisting of floodplains, particularly so as

one progresses down the basin from the source. Away from the rivers and floodplains there

are uplands dominated by drier, deciduous woodlands. A variety of organisms are

specialised inhabitants of the river channels and floodplains.

The fish communities can be divided into two categories according to food habits, with

species that feed on plant materials and species that are predators of other fish. Further fish

communities tend to be broadly divided according to habitat, with different fish preferring the

mainstream channels, rocky areas and rapids, backwaters, permanent swamps and the

seasonal floodplains. The floodplains are of greatest value as places in which most fish

breed.

15

EFA Namibia Socio-economics

The floodplains are also of importance for the harvest of other resources. The wetter parts

contain reeds, and some papyrus which can be used for construction and crafts

manufacture. In permanent pools and backwaters some water lilies can be harvested as

food. In the less frequently or heavily flooded floodplain areas, Specific grasses grow which

can be harvested for building, and used as grazing. Crops can also be grown on the

floodplains, where receding floods, associated water tables, and more fertile, humic soils can

provide more favourable conditions than those on the uplands.

The Kavango region, through which the Okavango river flows in Namibia, is state land under

communal land tenure. An estimated 219,090 people in 35,120 households are estimated to

live in the Namibian part of the Basin, or within some 20 km of the river in Namibia, as

demarcated in the EFA/TDA delineation exercise. This amounts to some 80% of the total

population of the Kavango region. The river provides water and a number of resources that

attract people to settle. Infrastructure in the form of roads and the regional capital, Rundu,

are concentrated along the river. Of the estimated 219,090 people, some 94% live within 5

km of the river, on raised river terraces, in a strip served by a river road. Rundu contains 20%

of the people. Nearly half of the Namibian basin population speak Rukwangali, with other

languages, mostly Rumanyo, Nyemba and Thimbukushu spoken by the rest.

Population growth rates in the Namibian basin population have been very high, up to 7% per

annum between 1981 and 1991. This was due in part to the prevalent underdeveloped and

rural setting, but also to influx of Angolans from across the river, displaced as a result of civil

war and poverty. Some 20% of the Namibian basin population is estimated to be of Angolan

origin. Since 1991 there has been a noticeable decline in average fertility rates in the

Namibian basin population, from 7.1 children per woman per lifetime, to 4.2. This is due to

urbanisation, but also the impact of HIV and AIDS.

Table 2.2 shows the breakdown of the population in the IUAs of the Namibian part of the

basin. 98% of the population, or 214,050 people in 34,360 households, reside in IUA 8 which

represented by Site 4 at Kapako. 74% of the IUA 8 population is in IUA 8a which contains

Site 4.

The population mostly lives on river terraces above the floodplain where soils are more fertile

than in the sandy hinterland. Households grow rain-fed crops, graze livestock and harvest

woodland products away from the river, as well as making use of river-based resources.

Kapako where Site 4 was situated has a population of approximately 2,500 people within

10km.

Zone

No. of people

No. of households

Integrated Unit of Analysis 8a (Site 4, Kapako)

157,690

25,720

Integrated Unit of Analysis 8b

56,360

8,640

Integrated Unit of Analysis 9a (Site 5, Popa Falls)

5,040

760

Integrated Unit of Analysis 9b

0

0

Total for Namibian Okavango Basin

219,090

35,120

Table 2. 1: Population estimates for the Namibian Okavango river basin

16

EFA Namibia Socio-economics

The rural economy in the in the communal land is dominated by the small scale traditional

agriculture sector. Households derive a living from a strategic range of activities, including

small scale low input crop production, small scale livestock keeping, harvest of natural plant

products, fishing, formal employment and crafts production. Pension payments also

contribute to this living. Most agricultural and natural resource harvesting products are

consumed directly and only a small amount is traded in markets. Formal employment is

gained in government services, tourism, and commercial agriculture.

As stated, most of the population of Kavango Region is within the Namibian part of the

Okavango river basin. A recent poverty analysis (CBS 2008) shows that Kavango has the

highest incidence of poverty among all 13 regions in Namibia. In Kavango, 57% of

households are classified as poor (with expenditure of N$262 or less per adult equivalent per

month), and 36% of households are classified as severely poor (with expenditure of N$186

or less per adult equivalent per month). This can be compared with the incidence for the

whole country where 27.6% of households are poor or severely poor, and 13.8% are

severely poor.

In Kavango the incidence of poor among rural households (which make up 80% of the total

number) is 62%, while that among the urban population (20% of the total) is only 33%.The

high incidence of poverty in IUA 8 would underline the importance of natural resources

harvesting in the coping strategies of households. Government has an obligation both to

target these households for poverty reduction as well as to avoid interventions which might

exacerbate their poverty. Levine (2007) used a multi-dimensional human poverty index (HPI)

which accounts for survival, literacy and income to show that poverty in Kavango, despite

remaining the highest among the nation's regions, has declined between 1991-1994 and

2001-2004.

The high levels of poverty are associated with high dependency ratios (around 46% of the

population is below 15 years, or older than 64 years, of age). A very high rate of HIV

infection, as measured among pregnant women visiting hospitals and clinics, has been

recorded. This rate rose from 7.5% in 1994 to 20% in 2002 (Mendelsohn & el Obeid 2003).

Average life expectancy has declined from 57 in 1991 to 40 years in 2000, as a result of

AIDS, and this has impacted negatively on the human development index (HDI), despite

improvements in other HDI component measures such as education and income. Levine

(2007) showed that the average HDI for Kavango declined from 0.48, between 1991 and

1994, to 0.41, between 2001 and 2004. As expected, the human development index (HDI)

for Kavango is lower than that for Namibia as a whole. Between 2001 and 2004 the average

HDI was 0.41 for Kavango, while it was 0.56 for Namibia.

High poverty levels have also contributed to high incidence of tuberculosis (TB), malaria,

acute respiratory infections, diarrhoea, and urinary bilharzia, intestinal bilharzia, and

malnutrition in Kavango and IUA 8. Some of these are secondary to AIDS and increased as

a result of the AIDS epidemic. Others such as malaria, which affects half the population each

year, is linked to the summer rains and associated standing water. Urinary and intestinal

bilharzia are water borne and both prevalent in the river. Their incidence appears to have

increased dramatically (Mendelsohn & el Obeid 2003).

Seasonal flooding in February, March and April has a significant impact on the fish

populations which spike during this period. Fish catches from floodplain channels are very

high during the floods, and they are lower from the river channel in the rest of the year. The

floodplain results in a number of other resources being available for household livelihoods.

Communities harvest reeds, Phragmites sp., from upper wet banks and lower floodplain

reaches. They harvest specific grasses for thatching material (notably Miscanthus junceus)

from lower floodplain and middle floodplain vegetation zones. They grow crops in lower and

middle floodplain sites, deriving enhancement of yield from the more humic soils and wetter

17

EFA Namibia Socio-economics

soils. They also derive some of their livestock grazing in middle and upper floodplain

vegetation zones benefitting from enhanced productivity from the moister soils.

Compared with IUA 9 downstream, a higher portion of household income in IUA 8 is derived

from harvest of river resources. This is the direct result of the floodplain. IUA 8 also contains

an estimated 24 private tourism establishments, sited along the river, about 20 of these are

close to Rundu, and another 4 are scattered downstream from this. These facilities host

business travellers and leisure tourists passing through Kavango region and they make use

of the river and river-associated scenery for their tourism product. Households in the IUA

derive some of their income from employment in these facilities. Beyond these household

incomes the tourism sector also contributes value added to the national income through

private sector profits, taxes and returns to and of capital. The location of Site 4 was

representative of the IUA8 with respect to the household harvest of natural resources, but did

not contain any tourism establishments which are concentrated in the IUA downstream of

this.

Irrigation, mostly undertaken by government agencies and sometimes involving private

sector contractors, is practised on some 2,600 hectares at 11 sites along the river, for

commercial crop production. Various high value crops are grown along with staple grains.

Better quality soils on the river terraces are used rather than the sandy upland soils. The

setting is remote from input and product markets and the financial viability is difficult. Only

production dominated by high value cash and horticultural crops is economically attractive

(Liebenberg 2009; Shuh et al. 2006) and all require subsidisation. Nevertheless commercial

agriculture, at the scale practised, generates very significant income and significant amounts

of employment.

Focus group discussions at Kapako, Site 4, confirmed these findings, generally. During the

focus group discussion the basin residents described the flooding process where rising river

and channel waters push out over flat surrounding ground and the most extensive floods

form in years when river levels are highest. Floods provide access for fish to extensive

vegetation and detritus for feed and breed. They also offer the young fish refuge from larger,

predatory species and greatest survival of young fish and overall increase in fish population

occur in years when water levels are high and flooding lasts longest

Local people have recognised the quality of water and fish recourses is decreasing in the

Okavango River. Fish remain a significant income source in the lives of people at Kapako,

who fish for food or earn incomes by selling their catches or providing trips for tourists. In

terms of numbers, the fish stock explodes during flood times. On the flooded plains fish

numbers can be four times higher there than in the main river channel. Fish are caught by

households using both traditional and modern methods. Traditional gear includes fish

funnels, kraal traps, scoop baskets, push baskets, bows and arrows, set fish hooks and

spears. Modern gear consists of line and hooks, mosquito nets, and gill and seine nets.

The use of fish for recreational angling forms part of the tourism value associated with the

river. However, only a small part of tourism values is attributable to angling. The increase in

human population on the southern bank in IUA 8 means that the natural riparian landscape,

consisting of the main Okavango river channel and the floodplains are being subjected to

considerable pressure. The vegetation along the river bank and floodplain on the Namibian

side is heavily grazed and depleted. Thus, at Kapako, the residents graze their livestock

across the river on the Angolan floodplain

Despite the increase in grazing pressure and deforestation on the southern bank and

although the extent of bare ground has increased residents consider that overall water

quality has not declined substantially with the exception of very localised increase in

phosphorus concentration and a very slight decrease in water clarity from an increase in

18

EFA Namibia Socio-economics

suspended sediments. They perceive short term seasonal variation in water quality than long

term change.

2.2.2 Site 5: Popa Falls

IUA 9 is relatively small, compared with IUA 8, and it includes significant areas of national

park. As a result, and as can be seen from Table 2.2, it contains only 3% of the total

population of the Namibia portion of the basin. Many of the socio-economic characteristics

associated with the IUA 8 are the same for IUA 9 and Site 5. However the lack of a floodplain

in IUA 9 means that many of the benefits that people derive from the river in IUA 8 are

absent. Fishing is restricted to the river channel resulting in constant, but relatively lower

catches during the year. Use of mokoros (canoes) along with hook-and-line and gill nets is

necessary for effective fishing in the main channel. Community representatives, in focus

group discussion, confirmed that fishing is a secondary activity for most people in the Popa

area, contributing little to the overall cash or in-kind incomes of the majority of households.

People thus pay much less attention to fishing than to farming and other activities. Fishing

actually declines somewhat during the higher water levels around March as it is more difficult

to fish the strongly flowing channel then. Fishing is small-scale and mostly for home

consumption. A commercial fishing operation involving drag and gill nets, started by a

person, non-resident to the area, was asked to cease operations by the community,

demonstrating the existence of some property rights in fishing.

The use of reeds and floodplain grasses is restricted to a very narrow wet bank strip and

floodplain crops and floodplain derived grazing are absent. Species used are reed,

Phragmites australis, for building, the sedge, Cyperus papyrus for mats, and the grass,

Miscanthus, junceus for thatch. Communities in IUA 9 derive a lower proportion of their

household income from the harvest of river resources than those in IUA 8. According to

community informants interviewed during a focus group meeting at Popa Falls, Site 5,

tourism is a major source of income to the Popa residents; most of them are employed within

the lodges around Popa area. They value tourism as their major source of income. Indeed

estimations confirm that a large proportion of the river-derived incomes for households

comes from employment in tourism. There are some 6 private sector tourism lodges and

camps which make use of the river and the river associated wildlife in Bwabwata National

Park downstream for their tourism product.

As in IUA 8, households reported being dependent on a mix of incomes, including wages,

business earnings, pensions and remittances. Households also derive income from small

scale livestock keeping, small-scale low-input upland crops, and use of wild upland plant

resources for thatch, fuelwood, and poles. Farming activity is considered an important source

of income; households engage in both crop and livestock farming activity. Planting is

staggered through the rain season and is undertaken after there has been good rainfall. This

increases the chance of crop survival during the hot dry periods. Livestock farming is

dominated by cattle and goats, which are grazed in upland woodlands under common

tenure. They are moved between grazing and sources of water, mainly the Okavango river

2.3

Habitat integrity of the sites in Namibia

The concept of habitat integrity is applied in the socio-economic report in terms of the degree

to which natural resource uses are sustainable or not. This was assessed, based on

information gleaned from communities during focus group meetings, key informant

interviews, discussions with members of the EFA bio-physical team and the literature.

19

EFA Namibia Socio-economics

Generally, more so than at all other sites and IUAs in the basin, natural resources harvesting

at least in parts of IUAs 8 and 9, is at levels close to or exceeding sustainable limits. Thus

livestock grazing pressure on open access uplands and floodplains is very high,

deforestation in upland river terraces and woodlands has resulted in reduced woodland cover

on the southern bank of the river. In terms of the river-based natural resources, fish are being

used at close to the sustainable limits (B. van der Waal, 2008, pers. comm.). Reeds and

floodplain grass is being used intensively in most of the IUAs.

Utilisation pressure on natural resource in the populated southern bank of the river, in both

IUA 8 and IUA 9, can only increase in the future, as the population grows, at a rate,

estimated at between 0.9% and 1.5% per annum (Mendelsohn et al. 2002; Mendelsohn & el

Obeid 2003, 2004).

Currently the resources on the north bank of the river in Angola are underutilised, and these

are being used increasingly by people based on the southern bank, for example for

floodplain grazing, harvesting of reeds, harvesting of grass, etc. The protected Bwabwata

National Park in IUA 9 contains a pristine array of resources with significant value as a

reservoir for breeding and dispersal, as well as a base for tourism.

During the derivation of response curves in the EFA models during water use scenario

analysis, no consideration was given to population growth and the impact that this will have

on the resources in question. This was to prevent excessive complexity. However, in the

extrapolation of livelihood and economic values to measure impacts during scenario

analysis, discounted future streams of values incorporation the effects of future change were

used. These included consideration of change driven by population growth.

20

EFA Namibia Socio-economics

3 RESULTS - THE INDICATORS

3.1 Indicators

3.1.1 Introduction

Biophysical indicators are discipline-specific attributes of the river system that respond to a

change in river flow by changing in their:

· abundance;

· concentration;

or

· extent

(area).

Social indicators are attributes of the social structures linked to the river that respond to

changes in the availability of riverine resources (as described by the biophysical indicators).

The indicators are used to characterise the current situation and changes that could occur

with development-driven flow changes.

3.1.2 Indicator list for socio-economics

In order to cover the major characteristics of the river system and its users many indicators

may be deemed necessary. For any one EFA site, however, the number of indicators is

limited to ten (or fewer) in order to make the process manageable. The full list of socio-

economic indicators was developed collaboratively by country representatives for the

discipline, and is provided in Figure 1. With a few exceptions all of the indicators are

applicable to all of the sites. The exceptions apply where, for example, there is no floodplain

of significance, and thus no floodplain grazing or floodplain crop production.

It is important to note that the indicators selected are limited to values that are expected to

change under differing water use scenarios. Some natural resource uses associated with the

riverine environment provide livelihood and economic value but are unlikely to change with

flow change. An example would be use of riparian tree fruits. Another is the use of water for

irrigated commercial agricultural production. Some 2,610 hectares are irrigated in this way in

IUA 8, contributing significant income and employment for local residents. But irrigated crop

production would draw water in any case, regardless of flow change. It would also

presumably be augmented and expanded as part of the water use scenarios, itself affecting

water flow.

Possible indicators affecting human wellbeing are those related to health and disease, such

as malaria, bilharzia and diarrhoea were examined. These although their incidence is linked

to the aquatic environment were found to not be affected specifically by flow change. Other

possible indicators included natural resource uses such as water lily use (Nymphaea sp.) for

food, and use of the sedge (Cyperus papyrus) for mat making, were rejected as indicators

either because they were considered of small import or because in some sites their use was

unlikely to be affected by flow changes. Further not all indicators have been assigned values.

Where data are unavailable some have been treated only in discussion, despite being

recognised as likely to be affected by flow change.

The indicators in Figure 3.1 are divided into those affecting local household income, or

livelihoods (1 to 8) as well as the broader economy, and those impacting directly on the

broader economy or on societal well-being (9.1 to 9.4). The table shows how these all

21

EFA Namibia Socio-economics

contribute ultimately to overall social and economic wellbeing. All indicators were considered

relevant at Site 4 (IUA 8). At Site 5 (IUA 9) indicator 4 (floodplain crops) and indicator 5

(floodplain grazing for livestock) were not measured due to the general absence of a

floodplain.

Indicator

1. Household income - fish

2. Household income - reeds

3. Household income - floodplain grass

Total income

a. Household income

change as %

4. Household income - floodplain gardens (e.g. molapo)

%PD

PD

ng

A. SOCIAL WELL-

ei

5. Household income and wealth - livestock

BEING FOR

l

-

b

LOCAL

6. Household income - tourism

HOUSEHOLDS

i

c

wel

(=a+b+c)

b. Potable

7. Potable water/water quality

water/water quality

-

econom

%PD

cio

so

c. Wellbeing/welfare

l

8. Wellbeing/welfare from intangibles

from intangibles %Pd

Overal

9.1 Macro effects from tourism income excluding hh

(including multipliers)

(=A+B).

9.2 Macro effects from hh income 1-6 (including

d. National income

B. ECONOMIC-

C

multipliers etc.)

(=9.1+9.2+9.3+9.4)

WELL BEING

%PD

(nationally)

9.3 Indirect use

9.4 non-use

Table 3. 1: List of socio-economic indicators and their links to the broader economy

3.1.3 Description and location of indicators

Socio-economic Indicator 1

Name:

Household income - fish

Description:

Small-scale household-based fishing activity, using traps,

and/ or gill nets, hook and line and mokoros (canoes), for

own use as fresh food product, and very limited marketing,

with very limited processing (drying).

Representative species:

Vegetarian and predatory bream (Cichlidae), tiger, barbel

(Claridae),

Flow-related location:

Channels, floodplains during floods, residual floodplain

pools

Known water needs:

Perennial flows in channels, regular seasonal floods on

floodplains

22

EFA Namibia Socio-economics

Socio-economic Indicator 2

Name:

Household income - reeds

Description:

Small-scale household-based harvesting of reeds using

sickles, for own use in housing and compound wall

construction, and very limited marketing

Representative species:

Reed, Phragmites australis

Flow-related location:

Upper wetbank 1, river lower floodplain

Known water needs:

Perennial flows in channels, regular seasonal floods on

upper wetbank 1 and river lower floodplain

Socio-economic Indicator 3

Name:

Household income floodplain grass

Description:

Small-scale household-based harvesting of grass using

sickles for own use as specialised construction thatch and

very limited marketing

Representative species:

Thatch grass, Miscanthus junceus, other species

Flow-related location:

River lower floodplain, river middle floodplain

Known water needs:

Regular seasonal floods on floodplains

Socio-economic Indicator 4

Name:

Household income floodplain gardens (e.g. molapo)

Description:

Small-scale household-based flood-recession crop

production using animal draft power and manual labour, on

floodplains for own consumption as food and very limited

marketing and with home milling, complementary to

household upland rain-fed crop production.

Representative species:

Maize, sorghum, millet, vegetables

Flow-related location:

River lower floodplain, river middle floodplain

Known water needs:

Regular seasonal floods on floodplains and regular

transitional season 2 to allow crop growth

Socio-economic Indicator 5

Name:

Household income and wealth - livestock

Description:

Small-scale household-based open access grazing of

livestock on floodplain as part of broader upland small-

scale livestock keeping for meat milk, transport and as a

store of wealth, with limited marketing

Representative species:

Local breeds of cattle (Bos indicus) and goats

23

EFA Namibia Socio-economics

Flow-related location:

River middle floodplain and river upper floodplain

Known water needs:

Regular seasonal floods on floodplains

Socio-economic Indicator 6

Name:

Household income - tourism

Description:

Household-based and migratory, full- and part-time

employment in local tourism industry as labour, skilled

labour, and occasionally management

Representative species:

General wildlife, including semi aquatic animals, lower,

middle, and outer floodplain grazers, associated predators

and birds generally, general scenic habitats and attributes

linked to a mosaic of all the vegetation indicators

Flow-related location:

Sited commonly on upper dry banks but making use of all

vegetation indicators as part of product dependent on dry

season low flow and flood volume

Known water needs:

Perennial flows in channels, regular seasonal floods on

floodplains

Socio-economic Indicator 7

Name:

Potable water/water quality

Description:

Small-scale household-based use of river water for

household needs

Representative species:

None water quality indicators generally

Flow-related location:

Channels, floodplains during floods, residual floodplain

pools

Known water needs:

Perennial flows in channels, good water quality

Socio-economic Indicator 8

Name:

Wellbeing/welfare from intangibles

Description:

Small-scale household-based welfare linked to income

from indicators 1 to 7 but also to general individual,

household and community feeling on ecosystem integrity

in the face of flow change

Representative species:

None specific, but linked to indicators 1 to 7 as well as

overall ecosystem integrity

Flow-related location:

Channels, floodplains, all habitats associated with

ecosystem integrity

24

EFA Namibia Socio-economics

Known water needs:

Perennial flows in channels, regular seasonal floods on

floodplains

Socio-economic Indicator 9.1

Name:

Macro-effects from tourism income, excluding household

income (including multipliers)

Description:

Medium to large scale lodge based, non-consumptive

wildlife viewing and some consumptive hunting or angling

tourism, hosting middle- and up-market foreign and

regional tourists for water and/or land-based activities

Representative species:

General wildlife, including semi aquatic animals, lower,

middle, and outer floodplain grazers, associated predators

and birds generally, general scenic habitats and attributes

linked to a mosaic of all the vegetation indicators

Flow-related location:

Sited commonly on upper dry banks but making use of all

vegetation indicators as part of product dependent on dry

season low flow and flood volume

Known water needs:

Perennial flows in channels, regular seasonal floods on

floodplains

Socio-economic Indicator 9.2

Name:

Macro-effects from household income 1-6, (including

multipliers, etc)

Description:

All small-scale household-based activities described under

indicators 1 to 6

Representative species:

All species, ecosystems, attributes listed under indicators

1 to 6

Flow-related location:

All locations described under indicators 1 to 6

Known water needs:

perennial flows in channels, regular seasonal floods on

floodplains

Socio-economic Indicator 9.3

Name:

Indirect use

Description:

Indirect use values, i.e., off-site local, national, regional, or

global use values associated with river-based ecosystem

services, including carbon sequestration, wildlife refuge,

groundwater recharge, flood attenuation, scientific and

educational value, among others etc., poorly studied

Representative species:

General ecosystem integrity, providing the range of

ecosystem services referred to above

25

EFA Namibia Socio-economics

Flow-related location:

No specific location associated with a range of geo-

morphological and ecological features, including

vegetation and wildlife, which affect seasonal flooding

patterns as well as perennial nature of flow

Known water needs:

Perennial flows in channels, regular seasonal floods on

floodplains, generally

Socio-economic Indicator 9.4

Name:

Non-use

Description:

Existence bequest and option values for preservation,

manifested as local, national, regional and global

willingness to pay for preservation of resources in the river

system, values poorly researched and/or known

Other characteristics:

General wildlife, including semi aquatic animals, lower,

middle, and outer floodplain grazers, associated predators

and birds generally, general scenic habitats and attributes

linked to a mosaic of all the vegetation indicators

Flow-related location:

Embracing the broader ecosystem including all the

vegetation and wildlife indicators, mostly in the better

known lower parts of the basin (Okavango delta)

Known water needs:

Perennial flows in channels, regular seasonal floods on

floodplains

3.2

Flow categories river sites

One of the main assumptions underlying the EF process to be used in the TDA is that it is

possible to identify parts of the flow regime that are ecologically relevant in different ways

and to describe their nature using the historical hydrological record. Thus, one of the first

steps in the EFA process, for any river, is to consult with local river ecologists to identify

these ecologically most important flow categories. This process was followed at the

Preparation Workshop in September 2008 and four flow categories were agreed on for the

Okavango Basin river sites:

· Dry

season

· Transitional

Season

1

· Flood

Season

· Transitional

Season

2.

Tentative seasonal divisions for river Sites 1-5 are shown in to . These seasonal divisions

will be formalised by the project hydrological team in the form of hydrological rules in the

hydrological model. In the interim they provide useful insights into the flow regime of the

river system suggesting a higher within-year flow variability of the Cuebe River and a higher

year-on-year variability of the Cubango River.

It is planned to use similar flow seasons for the remaining river sites: 6 and 8.

26

EFA Namibia Socio-economics

120

Wet

100

Trans 1

Trans 2

Dry

80

Year

Y

2

ear

60

Year

Y

1

ear

Year

Y

3

ear

40

20

0

O

N

D

J

D

F

M

A

M

J

J

M

J

A

S

Figure 3. 1: Three representative years for Site 1: Cuebe River @ Capico, illustrating

1200

Wet

1000

Trans 1

Trans 2

Dry

800

Year 1

Y

600

Year 2

Y

Year 3

Y

400

200

0

O

N

D

J

D

F

M

A

M

J

J

M

J

A

S

Figure 3. 2: Three representative years for Site 2: Cubango River @ Mucundi, illustrating the

27

EFA Namibia Socio-economics

250

1

Wet

2

Dry

200

a

ns

a

ns

Tr

Tr

150

Year 1

ear

Year 2

ear

100

Year 3

ear

50

0

O

N

D

J

F

M

A

M

J

J

M

J

A

S

Figure 3. 3: Three representative years for Site 3 Cuito River @ Cuito Cuanavale, illustrating the

1000

900

Wet

We

800

Dry

Dr

Tra

Tr n

a s

n 1

s

Tra

Tr n

a s

n 2

s

Dry

Dr

700

600

Year 1

500

Year 2

400

Year 3

300

200

100

0

O

N

D

J

F

M

A

M

J

J

M

J

A

S

Figure 3. 4: Three representative years for Site 4: Okavango River @ Kapako (hydrological data

1800

1600

Wet

1400

Dry

Trans

n 1

Trans 2

Dry

1200

1000

Year 3

00

Year 2

800

Year 1

600

400

200

0

O

N

D

J

F

M

A

M

J

J

M

J

A

S

Figure 3. 5: Three representative years for Site 5: Okavango River @ Popa (hydrological data

28

EFA Namibia Socio-economics

The data collection and analysis exercises were focused on addressing what is initially

expected to be nine main questions related to these flow seasons (Table 3.2).

Question

Season

Response of indicator if:

number

1

Onset is earlier or later than natural mode/average

2

Dry Season

Water levels are higher or lower than natural mode/average

3

Extends longer than natural mode/average

Duration is longer or shorter than natural mode/average - i.e. hydrograph is

4

Transition 1

steeper or shallower

5

Flows are more or less variable than natural mode/average and range

Onset is earlier or later than natural mode/average synchronisation with rain

6

Flood season

may be changed

7

Natural proportion of different types of flood year changed

8

Onset is earlier or later than natural mode/average

Transition 2

Duration is longer or shorter than natural mode/average i.e. hydrograph is

9

steeper or shallower

Table 3. 2: Questions addressed at the Knowledge Capture Workshop, per indicator per site. In

29

EFA Namibia Socio-economics

4 RESULTS - RESPONSES AND IMPACTS

4.1

Socio-economic responses to potential changes in the flow regime

The socio-economic discipline differs to some extent from the biophysical ones, in that the

ultimate answer is not simply how much of an indicator natural resource there, but how much

does a change impact on livelihoods and on the economy. First the status of the particular

natural resource or attribute contributing to the livelihood and economic income is taken into

account. This usually comes out of biophysical response to flow change. If the example of

fish is taken, the abundance and availability of fish for fish catch may respond to change in

flood season flood type. The first socio-economic response curve follows this by measuring

how fish catches respond to fish abundance. In the example, if fish abundance rises

dramatically, fishers may only be able to catch some of these by virtue of limits to their

capacity and or the markets.

The second stage in the socio-economic process can be seen as the valuation of fish catch

within the fishing enterprise. Thus the short term response to change in fish catch is

measured in terms of private net income (livelihood), and contribution made to national

economic income (economic impact). This done using financial and economic budget cost

benefit models for fishing enterprises. Thus response curves for livelihoods and national

income contribution are made.

The socio-economic responses are thus related to resource abundance/availability and not

directly related to the flow categories in the previous section except in a few cases. One such

case is in the tourism sector which benefits from a complex array of natural attributes.

Operators are each faced with a unique and complex set of flow/flood characteristics. These

differ, depending on things like if they are on river bank, wetter middle delta or in the drier

lower delta, and if they specialise in water-based and/or land-based products or both. Nearly

every lodge site has permanently, frequently, occasionally, and rarely flooded areas of

varying quantity and in a complex mosaic, and this makes up their tourism product (along

with all the other attributes of the site). Here key to success are the abundance of wildlife, the

degree and nature of flooding and the dry season low flow characteristics. Tourism is

important in the basin and most important for the response curves is an understanding of

how flow/flood changes are likely to affect tourism income in the short to long term. As part of

the TDA process, a simple survey was conducted among some 50 tour operators in

Botswana. This was focused on their perceptions on how flow/flood changes (in ceteris

parabis), might affect tourism. Mbaiwa & Mmopelwa (2009) give the results of this.

Table 4.1 shows how these flow categories can affect tourism numbers, and thus the socio-

economic values.

30

EFA Namibia Socio-economics

Table 4. : Predicted response to possible changes in the flow regime of tourism numbers in the Okavango River ecosystem

Confidence in

Question

prediction (very

Season

Possible flow change

Predicted response of indicator

number

low, low, medium,

high)

Onset is earlier or later than

Small effect

1

natural

Dry

Water levels are higher or

The dry season low flow is expected to reduce tourism volumes

2

Season

lower than natural

(tourism numbers) if it drops to very low levels.

3

Extends longer than natural

Small effect

Duration is longer or shorter

Nil

4

than natural - i.e. hydrograph

Transition

is steeper or shallower

1

Flows are more or less variable Nil

5

than natural

Onset is earlier or later than

Small effect

6

natural synchronisation with

rain may be changed

Flood

The degree and nature of flooding measured primarily in terms of

season

volume and level have important effects on the amount of permanent,

Natural proportion of different

7

frequently, occasionally, and rarely flooded land in the tourism

types of flood year changed

concessions. This affects the amount of tourism with both high floods

and low floods generally having detrimental short term impacts.

Onset is earlier or later than

Nil

8

natural

Transition

2

Duration is longer or shorter

Nil

9

than natural i.e. hydrograph

is steeper or shallower

31

EFA Namibia Socio-economics

The scenarios which were tested in the environmental flows assessment (EFA)

model were four; the 'present day' plus three alternative water use development

scenarios. The present day (PD) scenario included all existing water resource

developments, notably:

Some 2,600 ha of irrigation in Namibia

The urban water demands of Menongue and Cuito Cuanavale (Angola), Rundu

(Namibia), and Maun (Botswana)

A low growth (Low Dev) scenario was based on the continuation of historical growth

in water demands in the three countries. Growth rates in Angola reflected recent

acceleration associated with resettlement in demined areas. Increased water

consumption was mainly due to growth in urban and rural domestic, livestock and

irrigation water demands. The largest water demands were represented by:

Some 3,100 ha of irrigation in Namibia

Some 18,000 ha of irrigation along the Cuebe River in Angola

One storage based and three runofriver hydropower stations in Angola

A medium growth (Med Dev) or "businessasusual" scenario included:

Some 8,400 ha of irrigation in Namibia

Development of a first phase of the Eastern National Carrier (17 Mm3/a) for water

supply from the Kavango to Grootfontein and Windhoek,

Some 198,000 ha of irrigation at various locations in Angola

One storage based and four runofriver hydropower stations in Angola

A high growth (High Dev) scenario included:

Some 15,000 ha of irrigation in Namibia

Some 338,000 ha of irrigation at various locations in Angola

Completion of all planned hydropower stations in Angola, i.e. one storage based and

nine runofriver hydropower stations in Angola ,

Completion of a second phase of the Eastern National Carrier (total capacity

100Mm3/a),

Development of a scaled down version of the Southern Okavango Integrated Water

Development Scheme (SOIWD) for urban and industrial water supply from the Delta

to Maun. At these levels of demand, it was necessary to introduce a hypothetical

dam in the upper basin (Cuchi River) with a capacity of some 500 million m3 to

provide for shortfalls in irrigation water supply and interbasin transfers.

Below, response curves from the EFA model are presented, for all the socio-

economic indicators at the two study sites in the Namibian basin. The EFA analysis,

though the response curves, captures the short term changes in the socio-economic

livelihoods and economic contributions. It does not deal with the longer term question

of how communities and investors in river/wetland natural resource use will adapt to

changes in the flow. The EFA process thus contained a further step where prediction

of future changes in resource uses and their socio-economic values was made.

These future streams of value extended over 40 years and were discounted, at a 4%

discount rate, to measure the net present value (NPV). These NPVs included

expected future population growth, tourism demand growth and expected long term

32

EFA Namibia Socio-economics

adaptations where relevant. Thus, growth in natural resources use due to population

increase was assumed to be 1.5% per annum in Namibia. Tourism demand was

anticipated to grow at 5% per annum on average in all scenarios. Where tourism was

found to collapse in the short term it was assumed to adapt, with its output settling at

between 5% and 25% depending on the scenario. Further, carrying capacity limits to

growth for certain activities were assumed, +75% of starting output in the case of

tourism, and +100% of starting output in the case of fishing. The adaptation

assumptions were subjective, while assumptions on growth in tourism demand and

populations were more analytical. The Bar charts below which show long term

impacts incorporate all these considerations.

Direct contribution to the national income is a comprehensive measure that includes

the basin household net income, as well as the income to other basin investors, and

stakeholders. Household net income has been used as a useful indicator, but the

direct economic contribution provides a better measure the true impact on socio-

economic welfare attributable to activities in the basin. It has thus been used as the

critical measure to value change as discussed below.

33

EFA Namibia Socio-economics

5 VALUES AND FLOW-RESPONSE RELATIONSHIPS

IN THE OKAVANGO EFA MODEL

5.1 Base

values

Current aggregate values estimated for the household income derived from each

socio-economic indicator in the Namibian basin are shown in Figure 5.1. It is clear

that tourism is an important river/wetland based contributor to livelihoods, while fish

and floodplain grass are also important. Aggregate livelihood values for each of the

two IUAs (8 and 9) in the Namibian basin are shown in Figures 5.2 and 5.3. IUA 8

has livelihood characteristics more typical of the Namibian river as a whole. In IUA 9,

which does not have a floodplain and is partly occupied by protected area, the

river/wetland-based livelihoods are dominated by tourism.

Figure 5.4 shows the aggregate direct and indirect economic contribution to the

national income derived from use of those resources constituting the socio-economic

indicators in the Namibian basin. Here the picture is similar to that for livelihoods,

except that the values are much higher, and the share attributable to tourism is

greater. The values are higher because all income is measured, not just that

accruing to households, and the multiplier effect is included. The multiplier effect

reflects the impact of these uses and the broader economy. It is greater for tourism

than it is for the other river/wetland based resource uses.

Namibia Household income from Okavango River

US$ 8.2 million

18%

Fish

Reeds

45%

7%

Grass

Gardens

Grazing

21%

Tourism

5% 4%

Figure 5. 1: Estimated livelihood value of Okavango river/wetland based natural

resource use in Namibia in 2008 (US$1.00 = N$ 8.16)

34

EFA Namibia Socio-economics

IUA 8 (Kapako Site) Household income from River US$ 7.3

million

Fish

19%

Reeds

40%

7%

Grass

Gardens

Grazing

23%

5%

Tourism

4%

Figure 5. 2: Estimated livelihood value of river/wetland based natural resource use in

IUA 8 in Namibia, 2008 (US$1.00 = N$ 8.16)

IUA 9 (Popa Site) Household Income from River

US$837,000

4% 1%5% 1% 1%

Fish

Reeds

Grass

Gardens

Grazing

88%

Tourism

Figure 5. 3: Estimated livelihood value of river/wetland based natural resource use in

IUA 9 in Namibia, 2008 (US$1.00 = N$ 8.16

35

EFA Namibia Socio-economics

Namibia Total Economic Impact of Okavango River

US$43 million

1%

3%

Fish

10%

12%

Reeds

Grass

10%

1%

Gardens

2%

Grazing

Tourism

61%

Function

Nonuse

Figure 5. 4: Estimated total direct and indirect impact of Okavango river/wetland based

natural resource use in the Namibian basin on the Namibian economy in

2008 (US$1.00 = N$ 8.16)

5.2 Flow

responses

Indicator 1 - Fish

KAPAKO - IUA 8 - Study site 4

Fishing at present day is near biological capacity. Floodplain here allows annual

large increases in fish abundance. Large changes will be only partly matched in

catch by volume, but demand will rise with some commercialisation. Decrease in fish

abundance will result in some over harvesting but this is offset by lower ability to

catch.

250

200

150

100

50

0

0

50

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

Fish catch response to fish abundance (% of present day)

36

EFA Namibia Socio-economics

900

800

700

600

500

400

300

200

100

0

0

50

100

150

200

250

Household net income response to fish catch (N$ per household per annum)

5000

4000

3000

2000

1000

0

0

50

100

150

200

250

Economic impact response to fish catch (N$ per household per annum)

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

2

140

1800

1600

120

1400

100

D

1200 rs

f

P

80

l

l

a

1000

% o

Do

60

800 ia

i

b

600

40

m

400 Na

20

200

0

0

1

2

3

4

5