TDA RIVER BASIN SOCIO-ECONOMIC ASSESSMENT.

Economic Valuation of Basin Resources:

Final Report to EPSMO Project of the UN

Food & Agriculture Organization as an

Input to the Okavango River Basin

Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis:

Final Draft

Bruce Aylward

October 2009

1

TDA River Basin Economic Valuation

Economic Valuation of Basin Resources

Final Report to EPSMO project of the UN Food & Agriculture

Organization as an input to the Okavango River Basin

Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis

Final Draft October 2009

Bruce Aylward

PO Box 2602, Bend, OR 97709, USA

bruce@ecosystemx.com

(541) 480-5694

2

TDA River Basin Economic Valuation

CONTENTS

1.

Introduction ................................................................................................................... 6

2. Macroeconomic Status ..................................................................................................... 7

2.1 Country Status and Trends .............................................................................................. 7

2.2 Sectoral Baseline: Angola ................................................................................................ 9

2.3 Sectoral Baseline: Namibia .............................................................................................. 9

2.4 Sectoral Baseline: Botswana.......................................................................................... 10

2.5 Basin Macroeconomic Issues and Opportunities .......................................................... 11

3. Transboundary Analysis, Market Failure and Basin Water Allocation ............................ 13

4.

Quantitative Evaluation Framework: Costs, Benefits and Water Resource Withdrawal

Alternatives ......................................................................................................................... 15

4.1 Valuation of Basin Resources ........................................................................................ 15

4.2 Formulation of the Alternatives Analysis ...................................................................... 16

4.2.1 Countries .................................................................................................................... 16

4.2.2 Alternatives ................................................................................................................ 16

4.2.3 Sectors ........................................................................................................................ 17

4.3 Economic Issues in Deriving Changes in Values ............................................................ 21

4.3.1 Gross Value vs Net Value Added ................................................................................ 21

4.3.2 Value Added and Alternatives Analysis ...................................................................... 22

4.3.3 Direct vs. Indirect Economic Impacts ......................................................................... 22

4.3.4 Financial vs. Economic Values .................................................................................... 24

4.4 Data Collection .............................................................................................................. 25

4.4.1 Ecosystem Values ....................................................................................................... 26

4.4.2 Water Resource Projects ............................................................................................ 26

5. Quantitative Evaluation ................................................................................................... 28

5.1 Model Development: General Parameters and Assumptions ....................................... 28

5.2 Domestic Water Supply: Ecosystem Direct Use Values and Water Supply & Sanitation

Values .................................................................................................................................. 29

5.3 Hydropower ................................................................................................................... 44

5.4 Irrigation ........................................................................................................................ 45

5.5 Summary of Economic Results ...................................................................................... 50

5.5.1 The Tradeoff Analysis ................................................................................................ 50

5.5.2 Angola ......................................................................................................................... 52

5.5.3 Namibia ...................................................................................................................... 54

5.5.4 Botswana .................................................................................................................... 56

3

TDA River Basin Economic Valuation

5.5.5 A Basin Perspective .................................................................................................... 58

5.5.6 Comparing sustainable development, stagnation and high water withdrawal paths 61

6. Investment in the Presence of Uncertainty, Irreversibility and Choice of Timing .......... 66

6.1 Analytical Framework .................................................................................................... 66

6.2 The Theory and Argument: The Incompleteness of CBA in the Presence of Uncertainty,

Irreversibility and Choice of Timing ..................................................................................... 67

6.3 Application to Water Resource Development ............................................................... 68

Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis of the Botswana Portion of the Okavango River Basin:

Land Use Planning ............................................................................................................... 73

Table of Figures

FIGURE 5 1 ............................................................................................................................................. 53

FIGURE 5 2 ............................................................................................................................................. 55

FIGURE 5 3 ............................................................................................................................................. 57

FIGURE 5 4 ............................................................................................................................................. 59

Table of Tables

TABLE 1: SUMMARY OF MACROECONOMIC INDICATORS ....................................................................... 8

TABLE 2: ANGOLA, GDP BREAKDOWN BY SECTOR, 2006 ......................................................................... 9

TABLE 3: NAMIBIA, GDP BREAKDOWN BY SECTOR, 2007 ...................................................................... 10

TABLE 4: BOTSWANA, GDP BREAKDOWN BY SECTOR, 2007 .................................................................. 11

TABLE 5: ALTERNATIVES MATRIX ........................................................................................................... 19

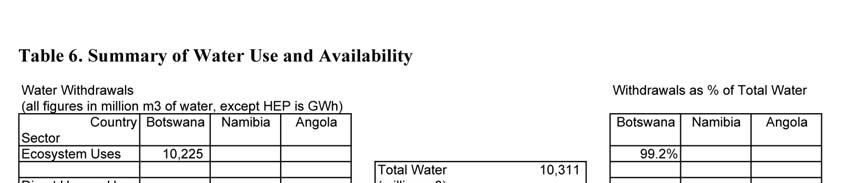

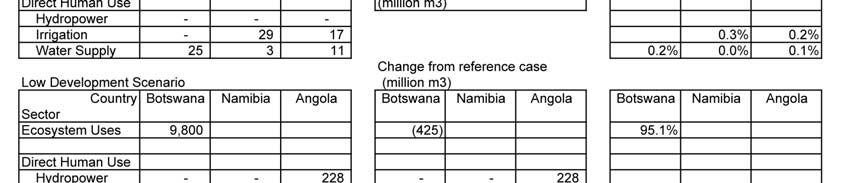

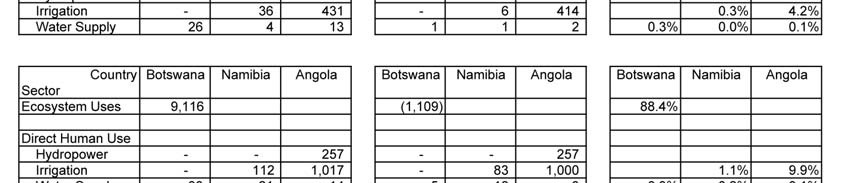

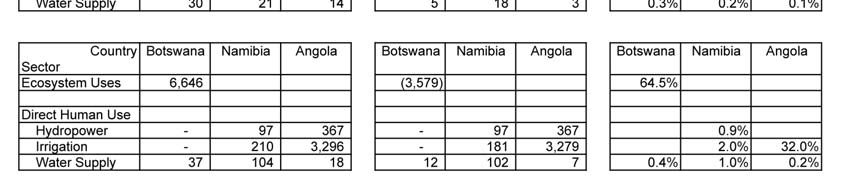

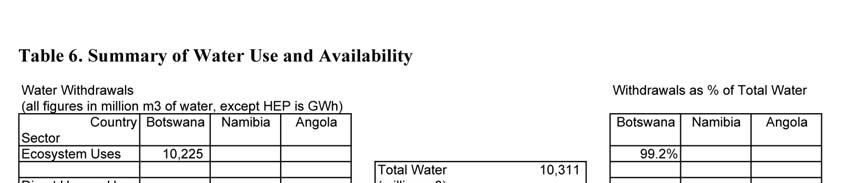

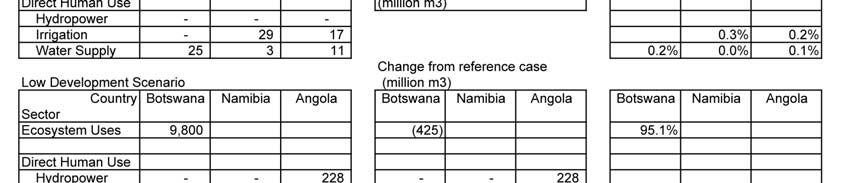

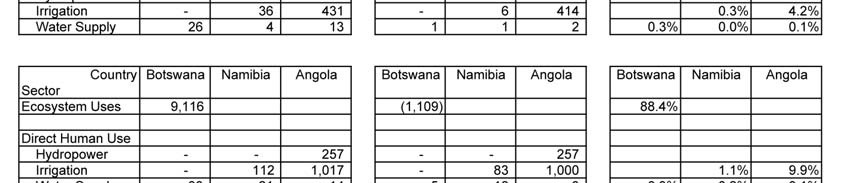

TABLE 6: SUMMARY OF WATER USE AND AVAILABILITY ....................................................................... 20

TABLE 7: ACCESS TO IMPROVED WATER SUPPLY AND SANITATION, OKAVANGO RIPARIAN COUNTRIES

...................................................................................................................................................... 29

TABLE 8: HOUSEHOLD ACCESS TO WATER SOURCES, NGAMILAND, BOTSWANA, 1991 AND 2001 ...... 31

TABLE 9: PER CAPITA REQUIREMENTS FOR WATER SERVICE LEVEL TO PROMOTE HEALTH .................. 32

TABLE 10: PRESENT DAY WATER USE, BOTSWANA ................................................................................ 32

TABLE 11: ESTIMATED WATER USE BY SOURCE, NAMIBIA ..................................................................... 33

TABLE 12: POPULATION SERVED AND DOMESTIC WATER USE, BOTSWANA ......................................... 37

TABLE 13: POPULATION SERVED AND DOMESTIC WATER USE, NAMIBIA ............................................. 38

TABLE 14: ESTIMATED WATER USE BY SOURCE, ANGOLA ..................................................................... 39

TABLE 15: ECOSYSTEM DIRECT USE VALUES, CHANGES DUE TO SHIFT IN WATER SUPPLY SOURCES,

BOTSWANA ................................................................................................................................... 40

TABLE 16: ECOSYSTEM DIRECT USE VALUES, CHANGES DUE TO SHIFT IN WATER SUPPLY SOURCES,

NAMIBIA ........................................................................................................................................ 42

TABLE 17: ECOSYSTEM DIRECT USE VALUES, CHANGES DUE TO SHIFT IN WATER SUPPLY SOURCES,

ANGOLA ........................................................................................................................................ 42

TABLE 18: COST AND BENEFIT PARAMETER VALUES FOR DOMESTIC WATER SUPPLY .......................... 44

TABLE 19: HYDROPOWER PROJECTS ...................................................................................................... 45

TABLE 20: HYDROPOWER COST AND BENEFIT PARAMETERS ................................................................ 45

TABLE 21: IRRIGATION PROJECTS, AREA ................................................................................................ 46

TABLE 22: IRRIGATION PROJECTS, WATER WITHDRAWALS ................................................................... 47

TABLE 23: IRRIGATION PROJECT COST AND BENEFIT PARAMETERS ...................................................... 49

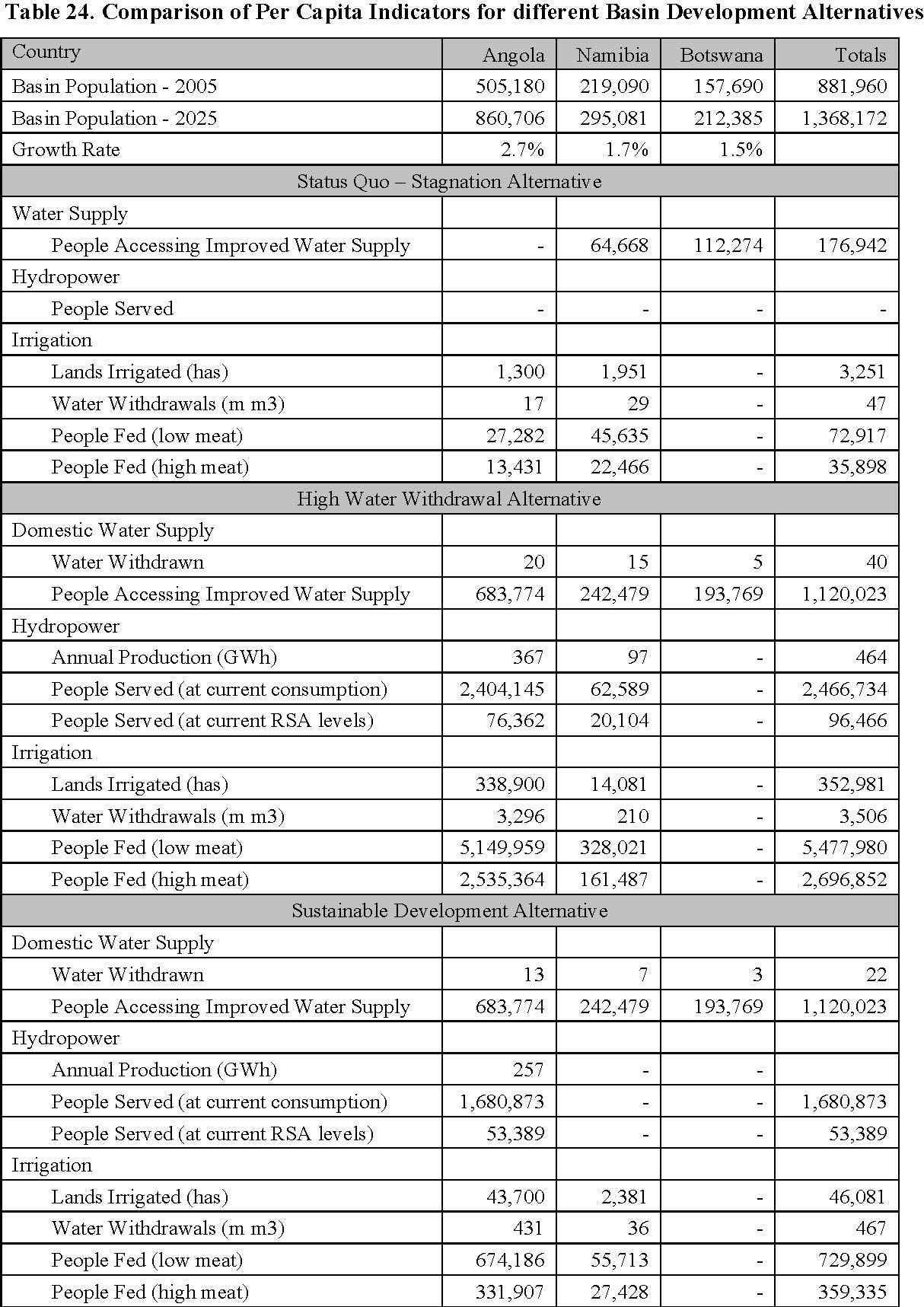

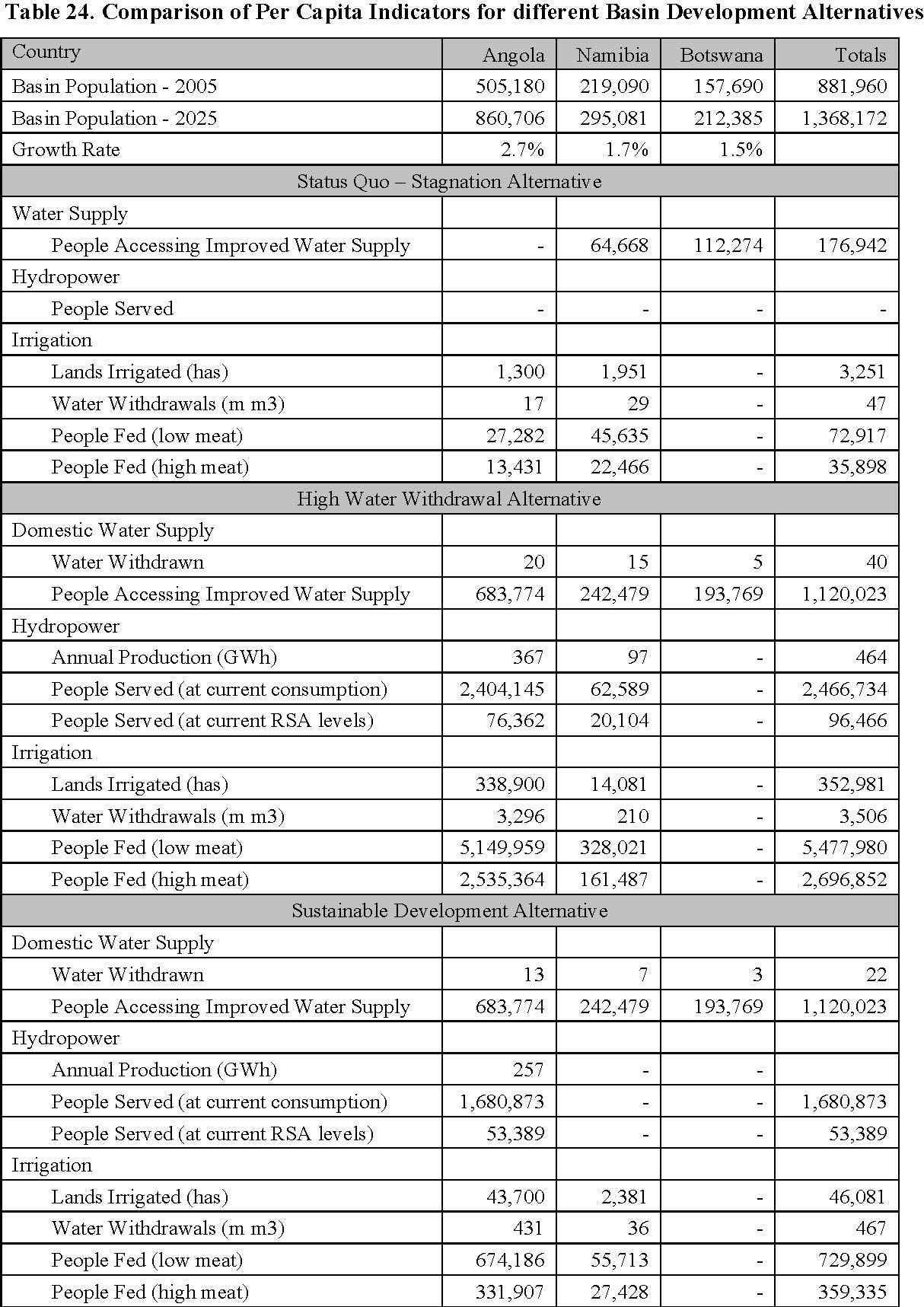

TABLE 24: COMPARISON OF PER CAPITA INDICATORS FOR DIFFERENT BASIN DEVELOPMENT

ALTERNATIVES .............................................................................................................................. 64

TABLE 25: PERCENTAGE OF THE POPULATION SERVED UNDER DIFFERENT BASIN DEVELOPMENT

ALTERNATIVES .............................................................................................................................. 65

4

TDA River Basin Economic Valuation

ACRONYMS

EPSMO

Environmental Protection and Sustainable Management

of the Okavango

FAO

UN Food and Agriculture Organization

BRD

International Bank for Reconstruction and Development

IDA

International Development Association

IFA

Integrated Flow Assessment

GDP

Gross Domestic Product

GEF

Global Environmental Facility

HEP

Hydroelectric power or hydropower

M&I

Municipal and Industrial

O&M

Operations and maintenance

TDA

Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis

UN

United Nations

UNDP

United Nations Development Programme

WTP

Willingness to pay

WHO

World Health Organization

NOTES

All $ (dollar) figures refer to US $. References to other national currency are

made explicit as follows:

N$ = Namibian dollar

Pula = Botswana Pula

Kwanza = Angolan Kwanza

ZAR = South African Rand

5

TDA River Basin Economic Valuation

1. Introduction

This report serves as a portion of the work carried out under the auspices of the

EPSMO project, which is a Global Environment Facility grant under the GEF's

International Waters Program. A Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis (TDA) for the

Okavango River Basin along with the preparation of a Strategic Action Program

forms the basis of the work under EPSMO. The UN Food and Agriculture

Organization is the executing agency under arrangement with the United Nation

Development Program. This report serves as an input to the TDA.

The terms of reference for the consultancy entitled "Value of Basin Resources" calls

for the following outputs:

an economic valuation of the basin resources (including ecosystem services) under

current

· development and use patterns;

· total for the basin

· disaggregated by sector and

· disaggregated by country

1. valuation of direct and indirect contribution of basin resources

(including ecosystem services) to the national economies in all three

countries

2. analysis of macro-economic benefits of three specified water

resources development scenarios and corresponding costs of

possible losses in ecosystem services

3. a sectoral analysis (i.e. tourism, agriculture, forestry, ecosystem

services etc) focusing on feasible development pathways

corresponding to the specified water resources development

scenarios.

During the course of the work the unfolding scope of the companion Integrated

Flow Analysis (IFA), in particular the socio-economic component, as well as the

specific demands of the TDA itself helped to shape the ultimate interpretation of

the terms of reference and the research tasks. The end result of this work is

incorporated in the TDA document, however, a full write up of the approach, data

and results is provided here as a reference for those so interested.

The document begins with a brief review of the macroeconomic context in order to

provide the setting within which the resources of the Okavango River will be

managed. A brief section then outlines the economic issues confronted by the

TDA, principally being the existence of market failure at the regional with regard to

water allocation between countries and the resulting uncertainty of water

management in the Basin. The quantitative analysis of potential economic

consequences of future alternatives for the management of water in the basin is

then explored, with sections on the analytical framework and then the data and

assumptions employed and results. Given issues of uncertainty, the timing of future

investment decisions, as well as the reversibility of the alternatives considered, the

report concludes by briefly suggesting the basis for a qualitative analysis that might

be employed to better frame investment decisions in the basin regarding water

infrastructure in the future.

6

TDA River Basin Economic Valuation

2. Macro-economic Status

2.1 Country Status and Trends

Angola has the largest economy of the three basin countries, in large part due to its

much larger population (eight times as large as Namibia or Botswana, as shown in

the table below). The Angolan economy is also growing at a much faster rate,

currently almost 20%, then the other two economies which are growing at about

5% per year. In large part this reflects the rapid economic gains Angola is making

after two decades of internal strife. The recent run up in the price of oil has also

been fortuitous as Angola is now the leading oil exporting country in Africa.

Meanwhile Namibia and Botswana, while growing more slowly, have had decades

of steady but significant growth. Botswana's gross domestic product (GDP) per

capita at 5,739 is by far the largest of the three countries.

Botswana also has the largest level of government expenditure at 35% of GDP,

reflecting the government's efforts to provide basic services to its rural populations.

In part this factor, plus the higher level of GDP may explain the lower level of

household consumption at 24% in Botswana. With similar GDP per capita levels,

household consumption in Namibia is much higher than that in Angola, with figures

at 53% and 32%. This most likely reflects much lower living standards of the bulk

of population in Angola. In other words, Angola's GDP has grown rapidly but is not

as well distributed as that in Namibia which has had a longer period to develop

post-independence. As expected gross capital formation is higher in Angola,

reflecting its early stage in development and the capital intensive nature of the oil

industry.

The latest UNDP figures on gini coefficients suggest that income inequality

remains more exaggerated in Namibia (74) than Botswana (60). No inequality

measure was available for Angola, however, it is likely to exceed that of both of the

other countries. Exploitation of the countries oil reserves, the rapid rise in the price

of oil and the resulting windfall profits are likely exacerbating the gap between the

urban elites, the urban poor and rural populations. Unemployment and

underemployment in Angola are major issues for the country as it demobilizes

forces and works to create economic opportunities. No unemployment numbers

are reported by UN agencies for Angola. Unemployment in Botswana is relatively

low for the region at 17.5%, while in Namibia the rate is fully double this at 33.8%.

Finally, all three countries have strong export-led economies, reflected in positive

or near-positive trade balances, as well as current account balances. In terms of

liquidity, at the end of 2007 Angola had $19 billion in liquid reserves (not counting

gold). Botswana had half this amount, but Namibia had just $1.2 million. The World

Bank classifies Namibia and Botswana as upper-middle-income countries. Neither

Namibia nor Botswana are currently IDA eligible for grants from the World Bank

Group, but could qualify for IBRD loans. Namibia has developed an Interim

Strategy Notes with the Bank and may engage in borrowing in the future.

Botswana recently completed a Country Partnership Strategy with the Bank, which

looks to reengage in lending with Botswana in the near future.

Angola is classified as a lower-middle-income country by the Bank and is IDA-

eligible. The Bank and other donors have been supporting Angola's transition since

the war ended and with recent rapid growth the European Union, the African

Development Bank and the Bank are all updating their country strategies to focus

on governance, particularly development of an effective private sector, as well as

7

TDA River Basin Economic Valuation

continuing the attempt to provide social services and assist in providing economic

opportunities for the poor. The World Bank reports that Angola received $442 in

international assistance in 2006 and that the country had programmed investments

of up to $7 billion in new infrastructure between 2008 -2010.

Table 1: Summary of Macroeconomic Indicators

Indicator

Angola

Namibia

Botswana Source

Population 2007 (millions)

17.02

2.07

1.88 UNPD

Unemployment rate 2006/7

20%

33.8%

17.5% Various

Gini Coefficient 2007/8

n/a

74.3

60.5 UNDP

HDR

Gross Domestic Product 2007

GDP (NC millions)

4,006,900

52,208

66,287 UNSD

GDP (US$ millions)

52,237

7,410

10,798 UNSD

GDP per capita (US$)

3,068

3,573

5,739 UNSD

GDP growth (average, 5 yrs)

14.96

4.68

5.92 UNSD

GDP growth (average 10 yrs)

9.87

4.27

5.91 UNSD

Composition of GDP (as % of GDP)

Household Consumption

32%

53%

24% UNSD

Gross Capital Formation

12%

26%

18% UNSD

Government Expenditure

22%

24%

35% UNSD

Exports

71%

49%

58% UNSD

Prices

CPI - 2007 (%)

12.25

6.73

7.08 IMF IFS

GDP Deflator (average, 2002-07))

20%

14%

20% UNSD

Exchange Rates

NC/$ -2007 average (NC/$)

76.71

7.05

6.14 IMF IFS

2008 end of period (NC/$)

75.17

9.31

7.52 IMF IFS

Balance of Payments 2007 (US$

millions)

Goods Imports

(13,662)

(3,102)

(3,447) IMF IFS

Goods Export

44,396

2,922

5,158 IMF IFS

Trade Balance

30,734

(180)

1,711 IMF IFS

Goods& Service Balance

18,402

(95)

1,675 IMF IFS

Current Account Balance

9,402

693

2,434 IMF IFS

International Liquidity (US$ millions)

Reserves 2007 (less Gold)

18,359

1,293

9,118 IMF IFS

Sources: UNPD = United Nations Population Division, UNDP HDR = United Nations Development

Program, Human Development Report, UNSD= Statistical Division of the United Nations, IMF IFS =

International Monetary Fund, International Financial Statistics

8

TDA River Basin Economic Valuation

2.2 Sectoral Baseline: Angola

As alluded to earlier, the dominant feature of Angola's economy is the extractive

sector, particularly oil and gas, which accounts for over half of GDP. The resources

sectors agriculture, hunting, forestry and fishery are together the third most

prominent sector making up 7.8% of GDP or US$ 3.8 billion in 2006. Despite their

relatively small participation in GDP, the resource sector employs a large share of

the workers in the country, by some estimates up to 85%. Further, a large

percentage of this activity is of a subsistence nature. Just 10% of agricultural land

is being used on a commercial basis. Despite this high level of activity in the

agricultural sector the country recently became a net importer of foodstuffs.

Table 2: Angola, GDP Breakdown by Sector, 2006

Economic Activity

Share of

GDP Value

GDP Employment

(in

change

GDP (%)

US$ million)

(%)

rate (%)

Oil and gas

57.1

28,350

n/a

n/a

Services

14.0

6,951

13.3

10.0

Agriculture, hunting, forestry and

7.8

3,873

18.3

60 to 85%

fishery

Manufacturing

4.9

2,433

17.1

n/a

Construction and public works

4.4

2,185

17.0

0.3

Mining and utilities

2.4

1,192

3.9

n/a

Source: UNSD, World Bank and African Development Bank, in Boccalon (2008)

2.3 Sectoral Baseline: Namibia

Namibia probably has the most diversified economy of the three countries. Trade,

transport, manufacturing and mining all contribute around 10% of GDP. Agriculture

and forestry contribute 6.6% or US$ 491 million. Farming itself is fairly limited due

to climate and soils, but large areas are in communal conservancies or private

lands are devoted to livestock and game ranching/wildlife. Tourism is also a

significant factor in the economy earning 2% or US$ 139 million. A portion of this

tourism comes from the Okavango region, though probably the bulk of it is

associated with Etosha, the coast and the dunes. Water and electricity contribute

an additional $99 million, or on average $50 per capita.

9

TDA River Basin Economic Valuation

Table 3: Namibia, GDP Breakdown by Sector, 2007

Economic Activity

Share of

GDP Value

GDP

Employment rate

(in

change

(%)

GDP (%)

US$ million)

(%)

General Government

20.65

1,530

(0.5)

56 (services

overall)

Trade

12.18

903

6.0

Transport

11.70

867

7.5

Manufacturing

11.20

830

13.0

12 (industry

overall)

Mining and quarrying

10.46

775

0.2

a. Diamond mining

8.26

612

(0.8)

b. Other mining

2.19

162

4.1

Agriculture and forestry

6.62

491

3.2

31

a. Commercial

4.32

320

6.5

b. Subsistence

2.30

170

(2.4)

Construction

5.44

403

32.7

Banks, Insurance and

4.36

323

2.4

Business

Services

Fishing

2.80

207

(16.2)

Hotels and Restaurants

1.88

139

3.8

Water and Electricity

1.33

99

(18.2)

Social and Personal

0.94

70

2.6

Services

Source: Central Bureau of Statistics (Namibia), in Boccalon (2008)

2.4 Sectoral Baseline: Botswana

Botswana, like Angola, is heavily reliant on extractive industries for its economic

well-being. Diamond mining brings in 40% of GDP. Manufacturing is limited at just

3.7% of GDP. Given the climate agriculture is limited, making only a 1.6%

contribution to GDP, the lowest of the three countries. As a consequence, services

government, banking, trade, transport, tourism, utilities and social services

make up a large portion of the remainder of the economy. Tourism plays a modest

role in the country's economy providing almost US$ 200 million, a large share of

which comes from the Okavango (as discussed later in this report). Water and

electricity are also responsible for US$ 200 million in value added. The higher level

of development in the country compared to its neighbors is revealed by the higher

level of spending on these basic services at $100/per capita.

10

TDA River Basin Economic Valuation

Table 4: Botswana, GDP Breakdown by Sector, 2007

Economic Activity

Share of GDP Value (in

GDP change Employment

GDP

(%)

(%)

US$ millions)

rate (%)

Mining

40.7

3,775

5.2

2.63

General Government

15.6

1,447

1.7

19.18

Banks, Insurance and

10.3

955

6.6

1.56

Business

Services

Trade

8.3

770

15.5

14.36

Construction

4.5

417

8.7

5.12

Social and Personal

3.8

352

1.6

4.56

Services

Manufacturing

3.7

343

12.0

6.67

Transport

3.5

325

20.3

2.98

Water and Electricity

2.2

204

5.9

0.77

Hotels and Restaurants

2.1

195

19.7

2.72

Agriculture

1.6

148

2.9

28.35

Source: Central Statistics Office (Botswana), in Boccalon (2008)

2.5 Basin Macroeconomic Issues and Opportunities

The brief macroeconomic review provided above shows that each of the three

countries in the basin have strong, open economies that have benefited from

sound macro-economic management and the intelligent use of their natural

endowments. That said the Okavango Basin region clearly is on the periphery of

the economy for each of the countries. Probably the most significant economic

activity in the basin is that of the tourism in Botswana's Delta region (and in the

panhandle in Namibia). Even in this case the contribution to GDP is small in

relative terms. Still, given the low populations in the basin there is no need for the

basin to be a dominant economic force in each country's economy. In fact, it may

be useful going forward to consider what the areas in each country within the basin

have in common and to try and build off these regional strengths in further

developing the basin economy.

With this in mind a number of macroeconomic issues and opportunities were

identified in the process of preparing the TDA. These relate more to the macro-

economy of the basin, linked as it is by the water resource, rather than the

macroeconomy of each country.

Regional Integration. There is a need to consider how to achieve closer social and

economic integration between the basin areas in each of the three countries. Such

integration would assist in building forwards and backwards economic linkages in

the basin. One idea that surfaced was to consider whether there are artificial trade

barriers, particularly in the panhandle area where all three countries come

together. Finding ways such as through including Angola, or the basin in the

existing Customs Union to promote the movement of tourists, workers, families,

as well as goods and capital within the border area or the basin as a whole might

yield considerable economic efficiencies and create new opportunities.

11

TDA River Basin Economic Valuation

Basin Comparative Advantage. While natural endowments of water, land, carbon,

flora and fauna, ecosystem goods and services in the basin appear advantageous

it is largely only in the Delta that commercial use of the resources occurs. The

majority of basin inhabitants live are engaged in subsistence activities. While it is

fortunate that resources are plentiful enough to supply this subsistence there are

two routes for the basin to develop. The first is for each country's province in the

basin to remain on the periphery and rely on resources from the center to provide

basic services while waiting for economic opportunities to arise. The second is for

the basin to determine what is its comparative advantage and market this

advantage to bring in the revenues needed to bring sustained livelihoods and

economic development to the basin. Central to this conversation over comparative

advantage will be the discussion over how to deploy the water resource to further

rather than retard development. At present if the basin has a comparative

advantage it is its reliance on wildlife tourism and its relatively undeveloped state.

Its comparative disadvantage remains its geographic isolation and hence the

distance to central markets and populations in each country.

Further effort is required to evaluate these issues and then strategize and plan in

what direction to move the basin macro-economy. Using the water resource as the

driver for this effort is sensible given its importance to livelihoods and income under

present conditions, as well as its role in linking communities in each of the three

countries. In the next section a brief description of the overarching economics

driving water allocation and use in the basin is provided and its relevance to the

transboundary analysis.

12

TDA River Basin Economic Valuation

3. Transboundary Analysis, Market Failure and Basin Water

Allocation

From an economic perspective the need for a transboundary analysis presupposes

the existence of some critical market failure between countries. For example if all

goods and services in the Okavango Basin, including those in the three countries

of Angola, Namibia and Botswana were private goods, traded in markets and not

subject to any unusual degree of government regulation then a transboundary

analysis would not be necessary. The economy of each country could be

segregated into tradable and non-tradable sectors (or goods and services).

Economic exchange across borders (i.e. trade) would take place between willing

sellers and willing buyers at prices established on the international market. The

private sector would invest in economic activities with attractive risk and rate of

return profiles, taking into account the local market for non-tradables and the

international market for tradables. These choices would be determined by a

number of factors, including the natural resource endowment at hand in each

country.

In the Okavango Basin, it is precisely the natural resource endowment that raises

the need for a transboundary analysis. Each country has its own endowment of

natural resources. Many of these resources are fixed and unchanging pending their

transformation by humans, for example soil, minerals and trees. Some resources

are mobile or migratory like wildlife, birds, fish or water. Each of these has it's own

natural range. In the case of the Okavango Basin, the primary migratory resource

is surface water. It starts in the headwaters of the Basin in Angola, travels

downstream through a large portion of Angola, briefly transits Namibia and then

spreads out across the Okavango Delta in Botswana, where it is stored as

groundwater, evaporated from surface water bodies, or evapotranspired by plants,

animals and human activities.

Over the course of geologic and human history the water resources of the

Okavango Basin have been informally shared between the countries, based on the

one hand on climate, geomorphology and vegetation, and on the other hand, the

limited efforts to date by humans to use and develop the resource. From the

perspective of its water resources the Okavango River is generally regarded as in

about as pristine a condition as any found in Africa today (Milzow et al. 2009). In an

arid environment increasing development pressure from the upstream riparian

states, as well as new uses in Botswana is inevitable. In economic terms this

shared water resource is a perfect example of a common pool resource. No one

country can exclude the other from using the resource and the use of the resource

by any one of the countries effectively to limit its consumption by another. The non-

excludability of common pool resources is the source of market failure. In effect at

present the Okavango River is largely used by Botswana, the downstream country

to provide a variety of ecosystem goods and services that have local and

international value. To the extent that the River really is congestible and therefore

rival in consumption i.e. that the use of water by an upstream riparian country will

affect the downstream uses and values then exercise of upstream location in the

form of extraction of water or re-regulation of flow is an act with economic

consequences, creating opportunity costs for Botswana, and those people outside

of Botswana that visit the delta or care about its continued existence (in its present

state).

The lack of an explicit and enforceable regime for managing the sharing of the

waters of the Okavango River is a source of market failure and may impede its

13

TDA River Basin Economic Valuation

efficient allocation and the equitable sharing of its benefits. While resolving this

dilemma is beyond the scope of the present work or the TDA, it is expected that

clearly defining the present and potential allocations of the water resource and then

estimating the associated values and their distribution across sectors and countries

should serve to stimulate further discussion between the countries.

For example, one possibility for the future governance of the Okavango would be

to make an explicit allocation of the water between states. In this case an

understanding of the economic consequences of water resource development,

would provide information to the states and the larger community of states about

the values inherent in the allocation of shares. The tradeoffs between different

uses of these allocations would thus be clear and open up a basis for negotiations

between states and with the international community over how to share the

benefits and costs of any master plan for the Okavango.

In order to shed light on the nature and extent of the choices that basin countries

are presented a quantitative analysis of the potential costs and benefits of

alternative future courses of action is presented below.

14

TDA River Basin Economic Valuation

4. Quantitative Evaluation Framework: Costs, Benefits and

Water Resource Withdrawal Alternatives

In its present allocation the Okavango River sustains the Okavango Delta in

Botswana, an important environmental and economic asset for the country and the

global community. The river and its derivative groundwater have also been

"developed" by humans for a number of uses in each of the three countries.

However, these uses remain minimal to date. Previous authors have noted that

withdrawing more of the flow of the River for off-stream uses will at some point

imply some loss of downstream economic benefits that exist today. This is

expected to occur as changes to the flow regime downstream lead to a loss of the

ecosystem goods and services provided by the river and its derivative groundwater

in the Okavango Delta. These foregone net ecosystem benefits would be the

opportunity cost of taking action to deploy the water resource to off-stream uses. In

a similar vein, any decision not to develop the water resource potential in the

upstream countries implies giving up the net economic benefits of hydropower,

irrigation, and municipal and industrial (M&I) uses. These would be the opportunity

costs of not withdrawing additional amounts of the water resource. The main

components of any economic analysis of future states of the system are future

changes in net ecosystem benefits and water withdrawal benefits, each with its

component changes in costs and benefits. In this document alternative paths for

developing the water resource are examined and therefore the economic gains

from water withdrawals are contrasted with the losses in ecosystem goods and

services.

4.1 Valuation of Basin Resources

The ToR call for a valuation of basin resources under current development and use

patterns (ToR output #1). This valuation is to be disaggregated by sector and by

country (ToR output #1), and this is to include not only direct, but indirect (including

ecosystem services), contributions of basin resources to the national economies

(TOR output #2). This analysis is not sought in and of itself but rather to set the

stage to then analysis what changes in value occur as different water withdrawal

alternatives are imposed on current conditions (TORs outputs #3 and #4). The

analysis of alternatives is to include not only water resource development benefits

but any costs in terms of the loss of ecosystem services.

Ultimately, then the valuation of basin resources is required for the purpose of

evaluating the impacts of gains and losses in economic welfare associated with

decisions to develop or not develop the water resources of the Okavango River

(and its tributaries, distributaries and groundwater). For this reason the analysis of

basin resources is best circumscribed to include only those resources and sectors

that will be affected by changes in the timing and amount of the flow regime

either in terms of impacts from changes in flow and timing downstream or in terms

of the development benefits and impacts from the changes in development and

land use patterns that accompany the water resource developments themselves.

The ensuing sub-section attempts to specify how such an analysis will be

constructed, indicates what data will be needed to this effect, and reports on data

already identified and in hand.

15

TDA River Basin Economic Valuation

4.2 Formulation of the Alternatives Analysis

The analysis involves assessing the economic impacts on sectors in each country.

In order to construct the matrices for each alternative the countries, alternatives

and sectors are identified.

4.2.1 Countries

The three riparian states are Angola, Namibia and Botswana. Typically, the scale

of an economic analysis needs to be at the level that incorporates all relevant

welfare changes. An economic analysis of the Okavango that did not include the

upstream (Angola) or downstream (Namibia) states, for example, would be of little

use in decision-making. In the case of the Okavango River, the environmental

asset represented by the Okavango Delta has value that is not realized only within

the three states. Tourists travel from all around the world to experience and use the

resource. The economic impacts of that travel are experienced well beyond the

three countries. Further, as a Ramsar site and one of the world's few remaining

pristine wetland areas, as well as the larger reservoir of biodiversity, the Okavango

Delta has value to the international community that goes beyond mere travel and

tourism. As such a comprehensive economic analysis would need to incorporate a

fourth "country" or region, represented by these international stakeholders.

4.2.2 Alternatives

Three alternatives are analyzed in companion efforts by the TDA team. These

alternatives (called "scenarios" in the IFA analysis) each involve a mix of additional

hydropower, irrigation and M&I projects to those already in existence. The

alternatives are identified as future possible combinations of these projects that

yield low, medium and high water withdrawal levels. Each successive alternative

includes the projects from the prior alternative and adds in more projects. Thus the

high withdrawal alternative includes all the projects in the medium alternative

(which in turn includes all the projects in the low alternative). These alternatives are

thus not independent sets of projects. Rather the analysis of these alternatives

investigates the impacts of a progression of projects that could be developed.

A reference case alternative is necessary to represent the valuation of basin

resources under current development and use patterns, i.e. present day,

extrapolated forward for the full duration of the analysis. Analysis of each

successive alternative will lead to new valuations of basin resources. The

difference between these outcomes and that of the reference case represent the

net change in economic welfare (by sector and country) of each water withdrawal

alternative, including the impacts on biodiversity and ecosystem goods and

services. Positive results indicate that there is a net increase in economic welfare

of the withdrawal alternative. Negative results indicate a net decrease. The choice

of which alternative is preferable to a given stakeholder group should be informed

by these results, but will likely incorporate other decision criteria.

16

TDA River Basin Economic Valuation

4.2.3 Sectors

The variable that changes in each alternative is how the water of the Okavango

River and its tributaries are used. Changes in flow lead to changes in economic

welfare and, therefore, it is necessary to only examine those basin resources and

sectors that are likely to respond to new water resources projects and the

subsequent, downstream impacts of alterations in the timing and amounts of flows.

On the water resources side the changes will occur in hydropower production,

irrigated lands and production, and water supply for M&I. On the ecosystem side,

changes in flows are expected to alter the production of natural resources, tourism,

ecosystem services and nature conservation.

A brief characterization of each sector and discussion of issues that may need to

be addressed is provided below.

· Tourism. Tourism is best understood as a result of biodiversity and

ecosystem services. The surface water discharge of the Okavango River

underpins the wetland ecosystems, the groundwater system and a rich oasis

of biodiversity in the Delta. Thus, while tourists may visit to marvel at the

wildlife, this wildlife is effectively reliant on the ecological function of the

Delta which in turn depends in large part on the timing and availability of

water. As a major service sector in the economy of Botswana this one sector

is separated out from the other natural resource sectors for special attention

and prominence.

· Natural Resources. Natural Resources is a catch all sector that will be used

here to capture the impacts of changes in river flows on the direct use values

of resources like water, food, fibre, timber, wildlife etc that can be

categorized as components of local livelihoods for communities in the Basin.

In the context "natural resources" are in effect ecosystem "goods." The

emphasis here is on distinguishing between the primary goods provided by

new water resource projects. Water projects may increase water supply and

food, for example, but the manner in which they do so oftentimes means that

there are impacts on those communities previously relying on this water (or

flow). New projects mean that these goods are provided through different

economic production systems and, at times, to different groups of people.

So, modern irrigated agriculture has often come at the expense of traditional,

flood recession agriculture, for example. Thus, under the natural resources

heading the impacts of changes in river flows and subsequent effects on the

full variety of natural resources that enter into household production and

consumption will be captured.

· Ecosystem Services. Ecosystem Services is used consonant with the

interpretation provided in Turpie et al (2006) and thus refers to carbon

sequestration, water supply, water purification, etc. In other words these are

the natural hydrological and ecological functions that only indirectly enter

into the economy. For example, boreholes support a variety of livestock and

agricultural uses in and around

· the Delta. These uses of water may not be considered in the reference case

as they do not reflect formal sector M&I water supply. As development

proceeds these groundwater uses may be affected with knock-on impacts on

livelihoods in the Delta. The value of the groundwater is derived from its end

use in this case, and end use reflected in the natural resources produced (as

above). A key consideration then with respect to natural resources and

ecosystem services is to ensure that benefits, or the ensuing welfare

17

TDA River Basin Economic Valuation

changes, are not double-counted. Thus, the analysis needs to be clear in

this case as to whether the resource production based on groundwater

extraction is classified under natural resources or ecosystem services (but

not both). Priority is given to recording those services that lead to the

production of direct use values as natural resources. Measuring the change

in these direct use values under different flow regime could then be used to

demonstrate the ecological value of the ecosystem services provided by the

natural flow regime. However, these are not added back in to the analysis as

that would be double counting.

· Nature Conservation. This sector is again not a typically recognized

economic sector. However, this heading is used to reflect the economic

importance of conserving the Okavango Delta as a Ramsar Site - a world

renown wetland rich in biodiversity. In other words, this category is designed

to capture the global willingness to pay to conserve nature, as represented

in this case by the Delta. This value is separate from that reflected under

Tourism, as an additional value above and beyond that which actual tourists

engage in when they purchase tourism services. People who have never

visited the Delta and never will may still be willing to pay to conserve this

environmental asset. Similarly, people who have not visited the Delta may

wish to preserve their option (and that of their children) to someday visit

and this value may be reflected in an option value for the delta. Probably

most importantly, is that those who have visited the Delta may come away

from the experience convinced of the importance of protecting this rare intact

system and may be willing to contribute to efforts to implement such actions.

So this sector is considered as global, which is not meant to say that only

those outside the region value nature, but rather that any effort to capture

this values would be global in scope.

· Hydropower (HEP). The hydropower sector is a subsector of the national

energy sector and changes in hydropower production will need to be placed

in the context of their expected benefits to the national energy sector.

However, the energy sector may also include biomass energy, which in the

Basin may be a natural resource sector that is affected by changes in river

flows and water availability (decrease in biomass if water is not available) or

by water resources development (i.e. availability of agricultural or livestock

wastes for use as fuel). In order to keep these impacts separated out, we will

keep the hydropower designation separate from these other energy sector

impacts.

· Irrigation. Irrigated agriculture or irrigation is likewise a sub sector of the

agriculture sector and is defined here as such for similar reasons as for the

hydropower/energy distinction, i.e. in order to keep any impacts on

traditional agriculture separated out from the impacts of water resource

development.

· Water supply. Water supply is used here to reflect large-scale infrastructure

to provide M&I water to settlements, commerce and industry. Domestic

water supply is used to refer to water supplied to homes and communities

for the purpose of household use.

The resulting sectoral and country matrix that needs to be created for the current situation

and each of the three alternatives is shown in Table 5.

18

TDA River Basin Economic Valuation

Table 5: Alternatives Matrix

Country Sector

Botswana

Namibia

Angola

Global

Tourism

Natural Resources

Ecosystem Services

Nature Conservation

Hydropower

Irrigated Agriculture

Water Supply

Table 6 below takes a very rough cut at stating where water is currently used and

where it will be used based on information from the TDA team about each of the

alternatives. For the three alternatives the new usage and change in absolute usage

of water is compiled along with an indication of the percent of mean water available

that is consumed by each use in each country. As hydropower uses are non-

consumptive (except for some evaporation at two reservoir sites) and use and reuse

the same water as it flows downstream they are included in terms of the Gwh of

power produced.

In the reference scenario the bulk of the flow in the Okavango River is ultimately

used in Botswana (in the Delta and outlying areas). As this water supports

ecosystem function it is called "ecosystem use" even though a good portion of it

probably indirectly supports human uses of water and water-related ecosystem

goods and services. The physical use of the water in Botswana clearly supports

global nature conservation values, although for simplicity sake the global scale is not

included in the charts.

19

TDA River Basin Economic Valuation

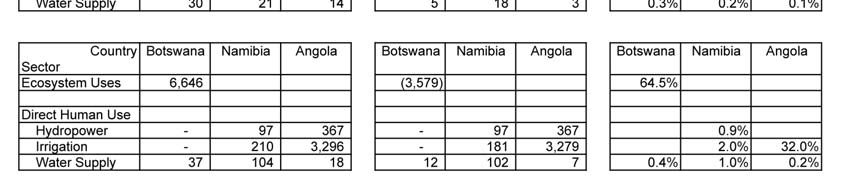

Table 6: Summary of Water Use and Availability

20

TDA River Basin Economic Valuation

Please note that the changes in water withdrawals in the middle portion of the table

are calculated by subtracting current withdrawals of water in the reference case

from the numbers for each alternative. This is not the same change in value that

would occur under these alternatives against a negotiated allocation of the water

resources of the Okavango River. Given, that any such negotiations would be

unlikely to grant the downstream country more than the current use allocation of

water these changes would be unlikely to increase in magnitude. Thus, as

calculations in the table suggest it is the downstream state, Botswana, is currently

consumptively using the vast majority of the flow of the Okavango river.

4.3 Economic Issues in Deriving Changes in Values

Quite a number of challenges exist in gathering, interpreting, compiling and

aggregating the economic information that may be available for these different

values, sectors and countries. These are too numerous to mention here, however, a

number of basic challenges are discussed here along with the suggested approach

to handing these.

4.3.1 Gross Value vs Net Value Added

In simple terms there are three concepts associated with value: production costs,

price of market transactions, and consumer willingness to pay (WTP). The value to

the economy represented by a market good is reflected by the total willingness to

pay for goods traded in the marketplace. This total WTP will typically exceed the

price paid by the consumer in the marketplace. The difference between these two is

called consumer surplus and represent the economic gains received by the

consumer. The difference between the total amount paid (quantity times price) by

consumers and the total production costs represents the economic gains garnered

by producers in the market, or the producer surplus. Production costs reflect

payments for land, labor, equipment and capital made by the producer. Each of

these payments is therefore part of the total payment made in other markets, i.e. the

markets for land, labor, equipment and capital.

Gross value added in a particular market should be represented by total WTP.

However, in practice WTP of consumers is not known and only market purchases

are observed. Thus Gross Value Added typically reflects the value of purchased

goods and services in the markets that make up a national economy. This gives the

gross size of the economy but does not accurately reflect the true value added

provided by the economy. This, as some of the items bought and sold in the

economy are imported or exported. So, for example, the gross value of automobiles

sold in a country may be quite large, but if the automobiles are imported attributing

the full gross value to the country would not accurately measure economic value

added in the country. In this case it the local economic contribution would simply be

the set of services needed to import, distribute and market the vehicles, which would

be just a portion of the purchase price. Net Value Added is therefore a more

appropriate measure of the size of an economy. Net value for a given market is

arrived at by taking the gross value and subtracting the costs of production. The net

value added for the input costs are in turn valued in their respective markets. So for

example local labor employed to bring imported automobiles to market is valued at

what it is paid. Assuming labor has no cash costs then all labor contributed to the

automobile market would represent net value added to the economy. Conversely,

amounts paid by automobile importers to foreign vendors are imports and are not

registered as national value added.

21

TDA River Basin Economic Valuation

With regard to natural resources like timber, fish, wildlife and water it is often

assumed in conventional economics that the resource has no cost. In the simplest

case, hunters provide their time and equipment, harvest animals and sell them in

meat, hide and other markets. Ultimately, in this case the amount paid for

purchased products is the sum of all the different net value added associated with

the wildlife markets. Even if it is assumed that there is some real opportunity cost

associated with the resource it probably does not change this calculation as long as

that opportunity cost is local. However, if this opportunity cost is borne by those

outside the country then the situation will differ. In other words, if all external effects

were compensated and an upstream country wished to use water already in use

and, therefore, impose costs on its downstream riparian neighbors then implicitly the

net value added associated with the upstream use of water would need to be

reduced proportionately (i.e. as if the water was being imported).

4.3.2 Value Added and Alternatives Analysis

In evaluating policy or projects the analyst is not so much interest in static measures

of gross value added for the entire economy, as in tracing through how shifts in

particular markets will play out and what the net effect will be on the economy. In

this regard it is important to be clear that economic measures are typically only

reliable when the changes that are evaluated take place within the range of

observed data. Quantities and prices in observed markets are always in flux, rising

and falling, and in some cases are subject to large shocks. However, when it comes

to large increases or decreases in supply or demand, these may push the analysis

beyond the bounds of existing data making it hard to predict price and quantity

response. For the analysis contemplated here this is an important point, both in

terms of any large decrease in water and ecosystem services available in Botswana

and any large increase in food production and hydropower in the upstream

countries.

For cases where these responses can be estimated the question is whether they

should be calculated as changes in gross value or net value added. For a specific

change in a specific market the best metric would be the change in net value added.

Ideally this would reflect both consumer and producer surplus, but at a minimum it

would consist of producer surplus for the measurement reasons described in the

prior sub-section. One rationale for not including any changes in production costs in

the market is the assumption that markets are in equilibrium. For example, if tourism

declined slightly in the Delta due to changes in water availability the change in the

quantity and price of labor employed in tourism is reflected in the change in

production costs. It is assumed that any labor freed up in tourism goes to its next

best use in the economy and that the price of labor adjusts to keep labor "fully"

employed. On this basis, the change in net value added is the best measure of the

welfare changes resulting from the water withdrawal alternatives evaluated here.

This said, once again it is clear that for marginal changes this assumption may hold,

but for rapid and large changes that might accompany such projects there will

clearly be volatility in these markets as labor may be constrained by location and

wages may be "sticky."

4.3.3 Direct vs. Indirect Economic Impacts

As suggested above an economic analysis of water withdrawal alternatives will

involve examination of welfare changes in a number of sectors. Each of these

sectors may involve a number of markets, i.e. so the irrigation sector will involve a

range of crop and livestock markets depending on what plants and animals are

22

TDA River Basin Economic Valuation

grown in a given irrigation projects. As stated above estimating the change in net

value added in each and every product market associated with each of the

development projects associated with each alternative will yield the best measure of

the economic impacts associated with that alternative (relative to the reference

case).

However, the economic impacts from irrigation, for example, are not limited just to

the market for wheat, beef or milk, but the markets for inputs to agricultural

production, as well as those for further processing of agricultural products. So, for

example, dramatic expansion in agricultural production in Angola may stimulate the

market for fertilizer, tractors and farm labor. Similarly, the onset of milk production in

the Okavango region may lead to new businesses for the processing and production

of a variety of diary products for internal or external consumption. Recalling the

discussion above this is the same as saying that the change in agricultural

production may increase the gross value in agricultural production which of course

includes the wages and prices paid for agricultural inputs. It may also create or

expand agricultural processing markets leading to new opportunities to create value

for the economy. These impacts are secondary to the impacts in the markets for

agricultural products per se. Oftentimes the primary impacts are refereed to as the

direct economic impacts and the secondary impacts as the indirect economic

impacts. These indirect economic impacts are what is being referred to when people

talk of the "multiplier" impacts of a given project or action. This reflects the idea that

the specific action in a given market generates economic benefits (direct), which are

then multiplied through backward (inputs) or forward (processing) linkages to other

markets. The idea being that $1 of direct benefit actually creates, for example, $1.5,

of value as it circulates through the economy.

It is safe to say that there is some debate as to what role these indirect economic

impacts should play in decision-making. From the perspective of positive economic

analysis there are conditions under which these indirect economic benefits might be

legitimately included along with the direct economic impacts in considering whether

a given project (or alternative) will maximize economic efficiency. But generally it is

recommended that they not be included (as explained further below) and that

decisions be made on the basis of the direct benefits alone (Aylward et al. 2001;

etc). The explanation for this mirrors that found above which is basically that in a

well-functioning economy resources will be priced at their opportunity cost and as

economic activity shifts will move from sector to sector. If resources to be devoted to

a proposed project are priced at their opportunity cost the only thing that matters is

whether it is worth dedicating these resources to the project and that is only the

case if net benefits are generated. In other words the inputs will generate more

economic value to the economy in the new, proposed use than in their alternative

use.

The crucial exception to this is, of course, if the resources will be un- or under-

employed if the project does not go ahead. This argument has been used to tout

large dam projects for a very long time. This is where the perspective of normative

economics applies. Oftentimes considerations of political economy have driven the

development of large water resource projects on the premise of employment and

large multiplier benefits, the interests of the unemployed coincide with that of

politicians seeking popular support. However, it needs to be clear that positive

economic analysis does not support the contention that devoting idle resources to a

project that generates net economic losses (and not net gains) is not an effective

way to build a national economy. The question that needs to be answered is what

other activity could be funded with the same development monies that would

provide employment and generate net economic benefits.

23

TDA River Basin Economic Valuation

A further difficulty is that once marginal economic projects are funded and input

and processing markets develop, the existence of these multipliers becomes a

normative argument for continuing these projects and activities. For example, in

developed countries where full employment of resources is largely taken as a given

(subject to the ups and downs of economic cycles) the argument that restricting the

use of water for agriculture and putting it to ecosystem uses will have adverse

affects on local economies in rural areas is now a frequently heard argument. A

recent review of the literature however, provides little support for the contention that

these multipliers are of a significant magnitude (MacDonnell et al. 2009). The

inclination to place undue importance on these indirect economic benefits, therefore,

can be seen as a potential poverty trap first lowering the bar to investment in

unproductive activities and then raising the bar to abandoning these activities.

A final point with regard to indirect economic benefits is that these are often

considered as unmitigated positives of water resource development activities.

Implicitly this reflects the view that there is no opportunity cost to developing the

water resource. But, as discussed in detail above, in the case of the Okavango it is

clear that the resource is already being used for the production of tourism,

ecosystem goods and services, and global existence value. In other words, an

increase in agricultural production in Angola or Namibia may be accompanied by a

decline in tourism in Botswana. These alternative economic uses of water also have

indirect economic, as well as direct, benefits. The point being that if the indirect

benefits are to be included on one side of the equation they may well need to be

included on the other. This issue also, therefore, needs to be considered in the

economic analysis. Indeed, this would be one argument for just focusing in the

alternative analysis on the direct changes in net value added.

The approach taken in the analysis is therefore to focus on these direct impacts and

leave the indirect impacts for future consideration. Predicting the multipliers

associated with processing industries that may or may not emerge alongside

irrigation projects would be haphazard at best in any case. The one exception here

would be to explicitly consider potential employment multipliers from labor markets

directly engaged in irrigation developments under the alternatives.

4.3.4 Financial vs. Economic Values

Prices and quantities appearing in national accounts are typically what can be

observed by data collectors or what is reported by producers and consumers. As

indicated above, in the first instance then these figures reflect prices of real market

transactions. These are typically referred to as financial values. However, there are

a large number of market and policy failures that may skew market quantities and

prices away from what they would be in an efficient market that allocates goods and

services to their highest and best use from an economic perspective (Anandarup

1984: ; Asian Development Bank 1997: ; Belli et al. 1998: ; Gittinger 1982: ; Jenkins

and Harberger 1989). This underlying "true" economy and its associated economic

values can be derived from market transaction data and knowledge of the

distortions imposed by market failures and distortionary policies. This type of

analysis is often undertaken in evaluating projects, although actual practice lags that

recommended as best practice (Jenkins 1997). Thus, there would be a financial

cost-benefit analysis carried out at market prices and quantities and an economic

cost-benefit analysis carried out at so-called "shadow" market prices and quantities.

Where market and policy distortions are significant it is very useful to undertake an

economic analysis, as otherwise a project that looks good in financial terms but is

24

TDA River Basin Economic Valuation

actually deleterious to the economy might be approved. Some of the typical issues

that arise and are usefully dealt with through economic analysis include:

· transfers i.e. where costs are not borne by the purchaser and thus do

not appear in the financial accounts even though the resources deployed

in the activity have an economic opportunity costs. Examples include free

provision of inputs, lack of cost recovery on infrastructure and failure to

account for opportunity costs of resources that can be extracted or

harvested for "free."

· own labor in particular small scale production oftentimes pays the

owner in profits not in hourly wages and thus economic analysis involves

specifying the labor hours and valuing them at the appropriate wage rate

in order to accurately convey not just financial but economic profit

· wages the true economic market-clearing price for labor of different

categories may diverge from that observed in the market place, for example,

in Botswana and Namibia the shadow price of unskilled labor is suggested to

be 35 to 50% of market price due to high unemployment levels (Barnes 1994)

· trade barriers i.e. where import or export subsidies or tariffs lead to under-

or over-valuing the costs and benefits to the economy of resources

· taxes and subsidies where the government partially subsidizes (or taxes)

inputs, provides direct subsidies (taxes) to the production and sale of goods,

or puts sales or other taxes on consumption or income appropriate discounts

or increase in values may be needed

· price controls i.e. where the government exerts direct control over the price

of inputs or outputs

· opportunity cost of foreign exchange i.e. manipulation or setting of foreign

exchange rates, which will effectively have same impacts as trade barriers

· opportunity cost of capital whereas financial analysis uses market lending

and borrowing rates of interest, economic analysis should account for

intragenerational equity (not penalize future generations) and therefore lower

rates for the cost of capital are generally recommended although the range of

views on this is large. This becomes an issue only where projects are likely to

have costs and benefits that vary greatly over longer time horizons. In this

case working with a future annual expected value may be sufficient to avoid

this problem.

In gathering data for the quantitative analysis some studies and figures

encountered will have applied shadow-pricing methods and in others this will not

have been done. This poses a consistency problem that will be hard to eliminate.

An effort will however be made to use economic values and not financial values

where these are available. Where these are not available an effort will be made to

indicate the likely net direction and magnitude of expected changes in any financial

values. In this regard the paper by Barnes (1994) provides useful guidance for the

region.

4.4 Data Collection

As alluded to in the discussion above a comprehensive and internally consistent (in

terms of methods and results) quantitative analysis will not be possible within the

frame of this consultancy. In large, part this is due to the scale of the alternatives that

need to be analyzed, the sheer number of projects in each alternative, and the gaps

25

TDA River Basin Economic Valuation

in information that will be available regarding these projects. However, the analytical

framework will be employed in making a first approximation at compiling and

evaluating such data as is available and filling in the alternative matrices to the extent

possible. Again, the interest is not in reaching some overarching conclusion about

what should be done, but providing the riparian countries with formatted information

that begins to indicate the values involved and the tradeoffs that need to be

discussed in future negotiations. A further objective will to highlight which information

remains to be gathered in order to attain a more comprehensive analysis going

forward.

The discussion below presents the approach taken in gathering information to fill in

the matrices with the efforts divided into those related to the ecosystem uses of

water and those for the water resource developments themselves.

4.4.1 Ecosystem Values

This category covers the tourism, natural resource, ecosystem service and global

nature conservation sectors. For the tourism, natural resource and ecosystem

service sectors the socio-economic results from the IFA were extended by the TDA

Team's Socio-Economist, in coordination with the author of the present study, and

thus could be incorporated directly into the quantitative analysis.

For the global nature conservation values, no primary research exists on the

existence values held by the global community with respect to the Okavango Delta.

Nonetheless there is the assumption that the willingness to pay is significant in total.

Literature review and where feasible benefits transfer could be used to see if at least

a range in order of magnitude can be assigned to this value. Due to time and

resource constraints, as well as the nature of the initial results for values within each

countries, these were not pursued for this study. If as expected, a policy option to be

considered would be having the global community engage with the three countries in

a system of compensated payments for development rights foregone based on a

negotiated sharing of the waters of the Okavango River carrying out such a review

would be a useful exercise and could be included in the Strategic Action Programme.

4.4.2 Water Resource Projects

For each alternative and each project within each alternative there are a number of

ways to arrive at alternative-level or project-by-project costs and benefits, or perhaps

simply the net benefits of water use in irrigation, water supply and hydropower:

1. detailed project economic cost-benefit analysis

2. project-level cost-benefit analysis at some level of detail and precision in

terms of reconnaissance through engineering/cost design proposal and

financial/economic analysis

3. costs and benefits from similar projects already implemented (along the

continuum of financial/economic cost-benefit analyses)

4. net values derived from larger evaluation datasets of similar projects (for

example the World Commission on Dams case studies, cross-check

analysis, and similar evaluation reports from development agencies such

as the World Bank)

26

TDA River Basin Economic Valuation

5. net values for irrigation, hydropower and water supply projects found in

the grey and academic literature as selected for their likely applicability

alternative

These sources are organized in order of preference. Project and site-specific

numbers as indicated in items 1 and 2 above were not available or obtained under

items 1-2. However, a range of information of the type mentioned in items 3 through

5 are available and were employed to identify likely cost, benefits or net values of

these activities. Depending on the type of value some of the methodological issues

mentioned above were dealt with, but it remains the case that the distinction

between, for example, financial and economic values was not apparent in much of

the literature. Where possible an economic as opposed to financial approach was

taken but given the crude nature of the extrapolations required the lack of consistent

economic data is probably not a major constraint.

It is also worth emphasizing that to some extent figures obtained from actual

evaluation work or research are probably more reliable indicators that early stage

reconnaissance project work. Indeed, one of the lessons learned from the World

Commission on Dams process is that pre-project economic analysis has often

understated project costs and overstated project benefits. For this reason, even if

information was available under item 1, it might still need to be adjusted to account

for this bias in pre-project analysis. In the end, the objective of the analysis was to

ensure that rough orders of magnitude for the alternatives were first achieved

knowing that this first approximation would probably clarify which projects would be

worthy of further scrutiny with more site and project numbers.

27

TDA River Basin Economic Valuation

5. Quantitative Evaluation

5.1 Model Development: General Parameters and

Assumptions

The analysis is undertaken over a 40-year time horizon. In order to synchronize with

a number of varying population estimates and water supply information the analysis

begins with 2008 and extends to 2048. All costs and benefits are discounted at an

8% cost of capital. To evaluate the sensitivity of results to a lower discount rate,

perhaps reflective of a lower social opportunity cost of capital, net present values are

also calculated at a 4% discount rate. These rates are chosen to be consistent with

those employed in the socio-economic analysis under the EPSMO project.

The projects that make up the alternatives are phased in over the first 20 years of

the time horizon. Broadly speaking the projects set forth in the IFA for each of the

three "scenarios" make up the alternatives. The low water withdrawal alternative

assumes a limited set of developments that are completed in the first five years (i.e.

by 2013); the medium water use alternative includes a more aggressive