5

Chapter 3

Recent Change in the Arctic and the Arctic Oscillation

Because the AO is usually `smoothed', it does not ade-

3.1. The Arctic Oscillation

quately represent events and short-term variations

During the 1990s, a quiet revolution took place in the

which are known to be important for the delivery of

perception of the Arctic (Carmack et al., 1997; Dickson,

contaminants to the Arctic and possibly also locally im-

1999; Johannessen et al., 1995; Johnson and Polyakov,

portant in forcing ice and surface water motion (see for

2001; Kerr, 1999; Levi, 2000; Macdonald, 1996; Mac-

example, Sherrell et al., 2000; Welch et al., 1991). It is

donald et al., 1999a; Maslanik et al., 1996; Maslowski

important to note that one of the projections of climate

et al., 2000; McPhee et al., 1998; Morison et al., 1998,

change is that cyclonic activity will increase; extreme

2000; Parkinson et al., 1999; Polyakov and Johnson,

events may therefore become a prominent component of

2000; Quadfasel et al., 1991; Smith, 1998; Steele and

atmospheric transport in the coming century. The earli-

Boyd, 1998; Vanegas and Mysak, 2000; Vörösmarty et

est significant rain event on record (May 26, 1994),

al., 2001; Walsh, 1991; Welch, 1998; Weller and Lange,

which was observed widely throughout the Canadian

1999). Despite early evidence of cyclical change in north-

Arctic Archipelago may have represented an example of

ern biological populations and ice conditions (e.g., Bock-

this (see also Graham and Diaz, 2001; Lambert, 1995).

stoce, 1986; Gudkovich, 1961; Vibe, 1967), the general

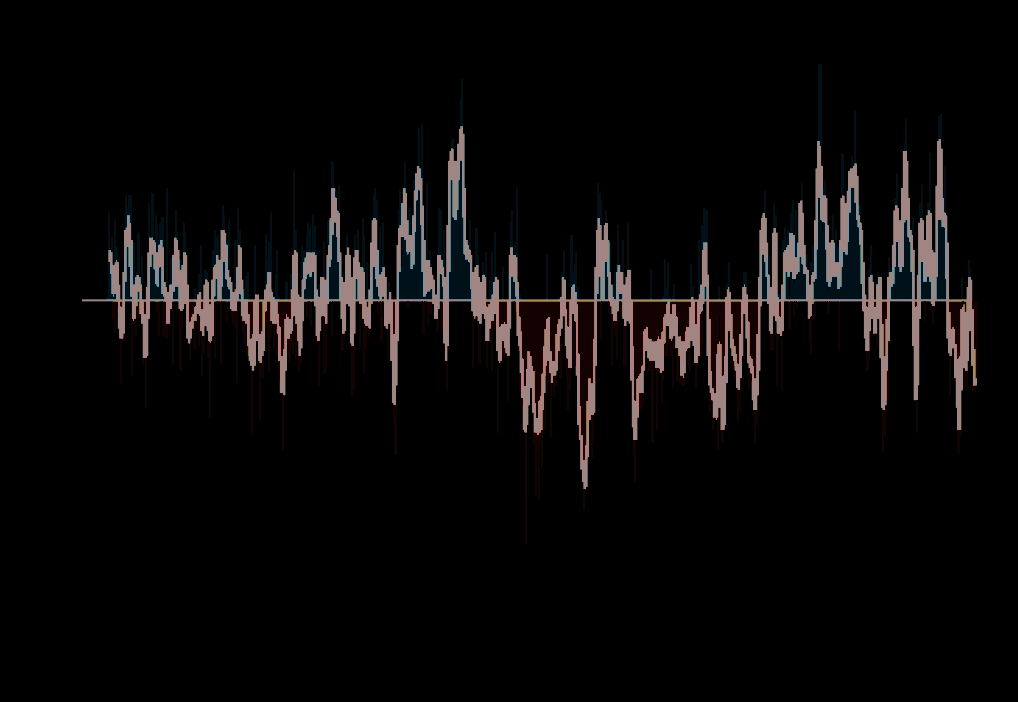

Around 1988 to 1989, the AO entered a positive

view among many western physical scientists through-

phase of unprecedented strength (Figures 3·1 a and c,

out the 1960s to 1980s was that the Arctic was a rela-

next page). The sea-level pressure (SLP) distribution pat-

tively stable place (Macdonald, 1996). This view has

tern of the AO for winter and summer (Figures 3·1 b and

been replaced by one of an Arctic where major shifts can

d) shows that this positive shift in AO is characterized

occur in a very short time, forced primarily by natural

by lower than average SLP distributed somewhat sym-

variation in the atmospheric pressure field associated

metrically over the pole (the blue-isoline region on Fig-

with the Northern-hemisphere Annual Mode.

ures 3·1 b and d) and higher SLP over the North Atlantic

The Northern-hemisphere Annual Mode, popularly

and North Pacific in winter and over Siberia and Europe

referred to as the Arctic Oscillation (AO) (Wallace and

in summer. As might be expected from examination of

Thompson, 2002), is a robust pattern in the surface man-

the AO SLP pattern (Figures 3·1 b and d), when the AO

ifestation of the strength of the polar vortex (for a very

index is strongly positive conditions become more `cy-

readable description, see Hodges, 2000). The AO corre-

clonic' i.e., atmospheric circulation becomes more

lates strongly (85-95%) with the more commonly used

strongly counterclockwise (Proshutinsky and Johnson,

indicator of large-scale wind forcing, the North Atlantic

1997; Serreze et al., 2000).

Oscillation (NAO) (the NAO is the normalized gradient

In discussing change it is important to distinguish be-

in sea-level air pressure between Iceland and the Azores

tween variability, which can occur at a variety of time

see for example, Deser, 2000; Dickson et al., 2000;

scales (Fischer et al., 1998; Polyakov and Johnson,

Hurrell, 1995; Serreze et al., 2000). In this report the

2000) and trends caused, for example, by GHG warm-

AO and NAO are used more or less interchangeably be-

ing. It has been suggested that locking the AO into a

cause they carry much the same information. It is recog-

positive mode might actually be one way that a trend

nized, however, that in both cases the term `oscillation'

forced by GHGs can manifest itself in the Arctic (Shin-

is rather misleading because neither index exhibits quasi-

dell et al., 1999). Others, however, consider that the ex-

periodic behaviour (Wallace and Thompson, 2002). The

traordinary conditions of the 1990s were produced nat-

AO captures more of the hemispheric variability than

urally by a reinforcing of short (5-7 yr) and long (50-80

does the NAO which is important because many of the

yr) time-scale components of SLP variation (Polyakov

recent changes associated with the AO have occurred in

and Johnson, 2000; Wang and Ikeda, 2001), and that

the Laptev, East Siberian, Chukchi and Beaufort Seas a

GHG forcing will affect the mean property fields rather

long way from the NAO's center of action (Thompson

than alter the AO itself (Fyfe, 2003; Fyfe et al., 1999).

and Wallace, 1998). Furthermore, the Bering Sea and the

Longer records of the NAO index (Figure 3·16 a, page

Mackenzie Basin are both influenced to some degree by

18) indeed suggest that there have been other periods of

atmospheric processes in the North Pacific (e.g., the Pa-

high AO index during the past 150 years (e.g., 1900-

cific Decadal Oscillation; see also Bjornsson et al., 1995;

1914), but none as strong as that experienced during the

Niebauer and Day, 1989; Stabeno and Overland, 2001),

early 1990s. Recent data suggest that the AO index has

whereas the Baffin Bay ice climate appears to have an as-

decreased and that the Arctic system has to some degree

sociation with the Southern Oscillation (Newell, 1996),

begun to return to `normal conditions' (Björk et al.,

and the Canadian Arctic Archipelago and Hudson Bay

2002; Boyd et al., 2002; Johnson et al., 1999).

probably respond to various atmospheric forcings as yet

The contrast in conditions between the Arctic in the

not fully understood.

1960s, 1970s and 1980s (with a generally low/negative

Although the AO is an important component of

AO index) and the Arctic in the early 1990s (with an ex-

change in Arctic climate, it accounts for only 20% of the

ceptionally high/positive AO index) provides an extraor-

variance in the atmospheric pressure field and many

dinary opportunity to investigate how the Arctic might

other factors can determine the atmospheric forcing.

respond to climate change. Similarity between climate-

6

AMAP Assessment 2002: The Influence of Global Change on Contaminant Pathways

Winter Arctic Oscillation index

Summer Arctic Oscillation index

+1

+1

a

c

0

0

1

1

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

Winter Arctic Oscillation pattern

Summer Arctic Oscillation pattern

b

d

0

0

2

1

1

4

2

0

1

2

Figure 3·1. The Arctic Oscillation. The figure illustrates a) variability in the AO index between 1958 and 1998 in winter; b) the associated

winter sea-level pressure pattern; c) variability in the AO index between 1958 and 1998 in summer; and d) the associated summer sea-level

pressure pattern. To recreate atmospheric pressure patterns during the period in question, the winter (b) and summer (d) AO patterns would

be multiplied by their respective indices (a, c) and added to the mean pressure field. Thus the high winter AO index in the early 1990s implies

anomalously low pressure over the pole in the pattern shown in (b). Small arrows show the geostrophic wind field associated with the AO

pattern with longer arrows implying stronger winds.

change projections and AO-induced change suggests

the Atlantic Ocean through the deep connection at Fram

that examining the differences between AO and AO+

Strait. Ocean circulation within the Arctic is tightly tied

states should provide insight into the likely effects of cli-

to bathymetry through topographic steering of currents

mate change forced by GHG emissions. Variation in

(Rudels et al., 1994). Considering these kinds of con-

SLP, as reflected by the AO index, demonstrates that the

straints, rapid change can occur in ocean-current path-

Arctic exhibits at least two modes of behaviour (Mori-

ways or in the source or properties of the water carried

son et al., 2000; Proshutinsky and Johnson, 1997) and

by currents when, for example, fronts shift from one ba-

that these modes cascade from SLP into wind fields, ice

thymetric feature to another (McLaughlin et al., 1996;

drift patterns, watermass distributions, ice cover and

Morison et al., 2000), when a given current strengthens

probably many other environmental parameters.

or weakens (Dickson et al., 2000), when source-water

The Arctic is to a large degree constrained by overar-

composition alters (Smith et al., 1998; Swift et al.,

ching structures and processes in how it can respond to

1997), or when relative strength of outflow varies be-

change. As illustrated in previous assessments, the Arctic

tween the Canadian Arctic Archipelago and Fram Strait

Ocean is, and will remain, a `mediterranean' sea, much

(Macdonald, 1996), but not by reversal of flow in

influenced by landocean interaction and with restricted

boundary currents or reversal of mean flow in the Bering

exchange with other oceans (Figure 1·1). Topography,

Strait or out through the Archipelago.

bathymetry and global distribution of salinity in the

Change associated with the Northern-hemisphere

ocean, require that water from the Pacific Ocean will

Annual Mode requires that consideration be given to

predominantly flow in to the Arctic and the shallow sill

large-scale variability in the Arctic; the fact that physical

at Bering Strait (50 m) guarantees that only surface

pathways can change rapidly needs to be recognized in

water will be involved in this exchange. Pacific water

greater detail, and the potential effects of GHG emis-

will remain above Atlantic Layer water which is denser.

sions against this naturally variable background should

Deep-basin water communicates predominantly with

be assessed.

Recent Change in the Arctic and the Arctic Oscillation

7

Positive Arctic Oscillation Index (AO+)

Negative Arctic Oscillation Index (AO )

(cyclonic)

(anticyclonic)

Aleutian Low

Winter

1015

a

1015

b

L

L

1015

1015

1015

1025

H

H

L

L

1005

1015

H

Icelandic Low

Siberian High

Positive Arctic Oscillation Index (AO+)

Negative Arctic Oscillation Index (AO )

(cyclonic)

(anticyclonic)

Beaufort High

H

Summer

H

c

d

1018

1018

1014

1014

1010

1010

1014

1014

L

L

L

1010

1018

1014

1018

1006

H

H

Figure 3·2. Atmospheric pressure fields and wind stream lines in the Northern Hemisphere. The figure illustrates a) strong AO+ conditions in

winter; b) strong AO conditions in winter; c) strong AO+ conditions in summer; and d) strong AO conditions in summer.

2001; Proshutinsky and Johnson, 1997) thereby indi-

3.2. Winds

rectly affecting transport by these two media as well.

Winds transport contaminants directly to the Arctic by

To understand how swings in the AO can affect at-

delivering volatile and semi-volatile chemicals, and chem-

mospheric circulation, AO+ and AO wind field/SLP

icals attached to fine particulates, from the south in

maps have been constructed for winter (Figures 3·2 a

timescales as short as a few days (Bailey et al., 2000;

and b) and summer (Figures 3·2 c and d) by adding

Barrie et al., 1998; Halsall et al., 1998; Hung et al.,

(AO+) or subtracting (AO) the patterns in Figures 3·1 b

2001; Stern et al., 1997). Over the longer term, spanning

and d to/from the mean pattern for the period of record

months to years, winds deliver volatile and semi-volatile

in the time series (1958-1998). The changes discussed in

contaminants through a series of hops, as airborne

the following paragraphs can be considered generally as

chemicals become deposited onto surfaces (water, soil or

representing the difference between conditions during

vegetation) and then re-volatilized during, for example,

the 1960s to 1970s (low/negative AO index) and during

summer warming. Winds also provide the primary forc-

the early 1990s (high/positive AO index) (see for exam-

ing for ice drift and surface ocean currents (Mysak,

ple, Proshutinsky and Johnson, 1997).

8

AMAP Assessment 2002: The Influence of Global Change on Contaminant Pathways

In winter (Figures 3·2 a and b), the lower tropos-

cording to Iversen (1996) summer accounts for only

pheric circulation is dominated by high pressure over the

20% of the annual south-to-north air transport (souther-

continents and low pressure over the northern Pacific

lies in the Norwegian Sea (10%), Eastern Europe/Siberia

Ocean (Aleutian Low) and Atlantic Ocean (Icelandic

(5%), and Bering Sea (5%)). The streamlines show that

Low). The Siberian High tends to force air on its western

winds provide a means to transport contaminants from

side into the Arctic, acting as an effective atmospheric

industrialized North America and Europe to the North

conduit from industrialized regions of Siberia and East-

Atlantic but penetration into the Arctic weakens. In the

ern Europe to the High Arctic. The high-pressure ridge

North Pacific, there remain atmospheric pathways to

over North America then forces air southward giving a

move air masses into the Gulf of Alaska from the east

net transport out of Eurasia into the Arctic, across the

coast of Asia (Figures 3·2 c and d). During AO+ condi-

Arctic and south over North America. The Icelandic

tions in particular, the Beaufort High weakens or disap-

Low produces westerly winds over the eastern North At-

pears (Figures 3·2 a and c), altering mean wind fields.

lantic and southerly winds over the Norwegian Sea pro-

viding a second conduit by which airborne contaminants

3.3. Surface air temperature

from eastern North America and Europe can rapidly

reach the Arctic. Finally, the Aleutian Low tends to steer

A strong trend of warming has been observed in the Arc-

air that has crossed the Pacific from Asia up into Alaska,

tic for the period from 1961 to 1990 (Figure 3·3 a). This

the Yukon, and the Bering Sea (Bailey et al., 2000; Li et

warming, which has been especially evident over north-

al., 2002; Wilkening et al., 2000). During winter, these

western North America and Siberia, has been accompa-

three routes into the Arctic southerlies in the Norwe-

nied by cooling in northeastern Canada, Baffin Bay, and

gian Sea (40%), over Eastern Europe/Siberia (15%), and

West Greenland. An almost identical pattern of warming

over the Bering Sea (25%) account for about 80% of the

to that shown in Figure 3·3 a is produced by taking the

annual south-to-north air transport (Iversen, 1996).

difference between mean surface air temperatures during

With a higher AO index (Figure 3·2 a), the Icelandic

periods of AO+ and AO conditions (Wallace and Thomp-

Low intensifies and extends farther into the Arctic

son, 2002). Due to an extensive temperature record col-

across the Barents Sea and into the Kara and Laptev Seas

lected from drifting buoys, manned drifting stations, and

(Johnson et al., 1999). This has the effect of increasing

land stations, direct relationships can be drawn between

the wind transport east across the North Atlantic, across

air surface temperature over sea and land in the Arctic

southern Europe and up into the Norwegian Sea. During

and the changes in pressure field discussed in section

high NAO winters, westerlies onto Europe may be as

3.2. Over the period 1979 to 1997, a trend of +1°C per

much as 8 m/s (~700 km/day) stronger (Hurrell, 1995).

decade was found for winter surface air temperature

At the same time, strong northerly winds are to be found

(SAT) in the eastern Arctic Ocean, offset by a trend of

over the Labrador Sea (Mysak, 2001).

1°C per decade in the western Arctic Ocean (Rigor et

The extension of the Icelandic Low into the Arctic

al., 2000). However, in spring almost the entire Arctic

also implies an effect of the AO on storm tracks. During

Ocean shows significant warming as much as 2°C per

the strong AO+ conditions of the early 1990s, there was a

decade in the eastern Arctic where a trend toward

remarkable increase in the incidence of deep storms, to

lengthened melt season was also observed. The trend in

around 15 per winter, and these storms penetrated farther

increasing SAT over the ocean is matched by tempera-

into the Arctic (Dickson et al., 2000; Maslanik et al., 1996;

ture increases over Arctic land masses of 2°C per decade

Semiletov et al., 2000). Increased cyclone activity increases

during winter and spring and annual increases of per-

poleward transport of heat and other properties carried by

haps 0.8°C per decade (Figure 3·3 a). Records of annual

the air masses involved. Anomalous southerly airflow over

temperature anomalies since 1900 (Figure 3·3 b) clearly

the Nordic Seas enhances the connection between indus-

show the warming trend since the 1970s, but note also

trial regions of North America and Europe and the Arctic.

that a similar episode of warming occurred in the 1930s

At the same time, increased cyclones enhance transfer of

to 1940s. Taken together, the trends in SAT over the cen-

contaminants from the atmosphere to the surface as a con-

tral Arctic Ocean suggest that warming has occurred

sequence of increased precipitation. Deep within the Arc-

predominantly during January to July (Figure 3·3 c).

tic, the high SLP ridge that extends across Canada Basin

Over half of the change in SAT in Alaska, Eurasia and

during AO conditions (the Beaufort High), disappears

the eastern Arctic Ocean has been ascribed to the AO,

and withdraws toward Russia (Johnson et al., 1999;

but less than half in the western Arctic (see Dickson et

Morison et al., 2000). It is worth noting that the Pacific

al., 2000; Rigor et al., 2000; Serreze et al., 2000). The

mean atmospheric pressure field and wind patterns appear

temperature changes associated with the AO are consid-

to change little between strong positive and strong nega-

ered large enough to have an immediate effect on polar

tive phases of the AO in winter. Penetration of air from the

circulation (Morison et al., 2000).

Pacific into the Arctic is hindered by the mountain barrier

along the west coast of North America where intensive

3.4. Precipitation and runoff

precipitation also provides a mechanism to transfer con-

taminants and aerosols to the surface (Figures 3·2 a and b).

Precipitation is a key pathway for contaminant transport

Summer pressure fields and air-flow patterns are

(Figure 1·2); rain, snow and fog scavenge aerosols and

markedly different from those of winter (compare Fig-

gasses from the atmosphere to deposit them at the sur-

ures 3·2 a, b, c, and d). In summer, the continental high-

face (Chernyak et al., 1996; Li et al., 2002; Macdonald et

pressure cells disappear and the oceanic low-pressure

al., 2000a; Mackay and Wania, 1995; Malcolm and

cells weaken with the result that northward transport

Keeler, 2002; Wania and Mackay, 1999). Scavenging by

from low latitudes weakens (Figures 3·2 c and d). Ac-

precipitation may be relatively weak in the desert-like

Recent Change in the Arctic and the Arctic Oscillation

9

Temperature change,

Temperature anomaly, °C

55-85°N

1961-1990

1.0

°C per decade

b

0.6 - 0.8

0.5

Average

0.5 - 0.6

0

1951-1980

0.4 - 0.5

0.5

1.0

0.2 - 0.4

North Pole

1900

1920

1940

1960

1980

0.1 - 0.2

Variation in surface air temperature, °C

0.1 - 0.1

0.6

c

Central Arctic Ocean

0.2 - 0.1

0.4

0.3 - 0.2

0.2

0.4 - 0.3

0.5 - 0.4

0

a

0.2

J

F

M

A

M

J

J

A

S

O

N

D

Figure 3·3. Temperature trends for the Arctic. This figure illustrates a) surface temperature trends over the Northern Hemisphere between

1961 and 1990 (courtesy of the Climate Monitoring and Data Interpretation Division of the Atmospheric Environment Service of Canada;

Stewart et al., 1998); b) annual temperature anomalies (55-85°N) for the period 1900 to 1995 set against the average for 1951 to 1980,

showing that the high temperatures of the late 1980s and 1990s are matched by equally high temperatures during the 1930s and 1940s

(adapted from Serreze et al., 2000); and c) the average monthly variation in surface air temperature of the central Arctic Ocean between 1979

and 1995 showing that recent warming is mainly a winterspring phenomenon (adapted from Serreze et al., 2000).

conditions that prevail over much of the High Arctic. For

ality (Serreze et al., 2000). Due to sparse monitoring

example, mean precipitation for the Arctic Ocean is esti-

networks and short time-series, it is difficult to assess

mated to be about 25.2 cm/yr and evaporation about

with confidence the spatial or temporal variation of

13.6 cm/yr, yielding a net moisture flux to ground of 11.9

precipitation within the Arctic. Nevertheless, records

cm/yr (Barry and Serreze, 2000). The precipitation over

suggest that precipitation has increased over northern

land in the Arctic drainage basins is somewhat greater as

Canada by about 20% during the past 40 years (Serreze

implied by runoff yield (precipitation minus evaporation

et al., 2000). The increase in southerly winds in the

(P E)) estimates of 21.2 cm/yr from the network of

Norwegian Sea in winter and the penetration of cy-

gauged discharge by rivers (Lammers et al., 2001).

clones from the Atlantic into the Barents, Kara and

Given the changes in winds (Figure 3·2) and temper-

Laptev Seas, when the AO (or NAO) index is high, is re-

ature that occur with shifts in the AO, it is to be ex-

flected in increased moisture flux and precipitation dur-

pected that precipitation and evaporation within the

ing autumn and winter, especially in the area between

Arctic will also be affected, both in amount and season-

10°W and 50°E (Figure 3·4 a; Dickson et al., 2000; Ser-

Vertically integrated moisture flux crossing 70°N, kg/m/s

35

a

b

30

Mean of months

with extreme positive NAO index

25

Mean of months with

extreme negative NAO index

20

15

10

5

0

5

10

180°W 150°

120°

90°

60°

30°

0°

30°

60°

90°

120°

150° 180°E

70°N

Difference in

winter precipitation

1.5

1.2

0.9

0.6

0

0.3

0.6

0.9

1.2 mm/ day

Figure 3·4. The effect of the North Atlantic Oscillation / Arctic Oscillation on precipitation in the Arctic; the NAO and AO are highly corre-

lated and this figure is based on the NAO for which a longer time series exists. The figure illustrates a) the mean vertically integrated merid-

ional flux crossing 70°N in winter for extreme NAO conditions (blue) and extreme NAO + conditions (red) and b) the change in winter pre-

cipitation between extreme NAO and extreme NAO+ conditions (modified from Dickson et al., 2000).

10

AMAP Assessment 2002: The Influence of Global Change on Contaminant Pathways

reze et al., 2000; Walsh, 2000). The composite differ-

the AO and snow cover in Eurasia for the period from

ence in precipitation (Figure 3·4 b), which may actually

1972 to 1997 suggests that a change from minimum to

underestimate the change between index extremes (Dick-

maximum AO index is accompanied by a loss of about

son et al., 2000), shows an increase of up to 15 cm/yr

4 106 km2 of snow cover, which could account for

precipitation during winter in the NorwegianGreen-

much of the trend described above (Vörösmarty et al.,

land Sea atmosphereocean conduit to the Arctic when

2001). The snow-cover anomalies plotted by Armstrong

the NAO is strongly positive. The response over the cen-

and Brodzik (2001) show a downward step around

tral Arctic to changes in the AO/NAO index is clearly

1989 when the AO index sharply increased. The late

much less, but it is likely that conditions there become

1980s up to at least 1998 has been identified as a period

wetter during index highs (Serreze et al., 2000). Over-

of low snow cover for both Eurasia and North America

all, it is estimated that P E north of 70°N is 36%

with the largest changes occurring in springsummer

higher during periods of high index compared to low

(Serreze et al., 2000); for Canada, there has been a de-

index (Serreze et al., 1995). Over central and northern

crease in snow depth, especially in spring, since 1946

Canada, flux of moisture out of the Arctic increases

(Brown and Goodison, 1996).

when the AO/NAO is high, but toward the western

Precipitation minus evaporation integrated over a

Beaufort Sea moisture flux into the Arctic again in-

drainage basin should be equivalent to river discharge

creases (Figure 3·4 a).

for the basin (if changes in groundwater or glacial

Whether precipitation falls as snow or as rain, and

storage are ignored). Arctic rivers exhibit large inter-

how long snow covers surfaces are important compo-

annual variation (Semiletov et al., 2000; Shiklomanov

nents of climate that control the interaction of contami-

et al., 2000; Stewart, 2000) making it difficult to link

nants with the hydrological cycle (Macdonald et al.,

river flow to precipitation or temperature trends or to

2002c; Wania, 1997). Snow cover in the Arctic varies

climatic variables such as the AO. For example, Shik-

from a maximum of about 46 106 km2 to as little as

lomanov et al. (2000) suggested little change in mean

4 106 km2 (Serreze et al., 2000). As might be predicted

annual discharge for Arctic rivers between the 1920s

from recent warming trends over Arctic land masses

and 1990s, whereas Semiletov et al. (2000) found re-

(Figure 3·3 a), there is evidence that the average area

cent increases for several Eurasian rivers, and Lam-

covered by snow has been decreasing by about 2%

mers et al. (2001) found evidence of increased winter

(450 000 km2) per decade between 1979 and 1999

discharge from rivers in Siberia and Alaska in the

(Armstrong and Brodzik, 2001). A correlation between

1980s relative to the 1960s and 1970s. Within Can-

Discharge,

Figure 3·5. Variability in river discharges.

1000 m3/s

Mackenzie River monthly discharge

30

The figure illustrates a) monthly river dis-

Dec

28

charges for the Mackenzie River between

a

Nov

26

1973 and 1995 as inferred from observa-

24

Oct

tions at Arctic Red River and the Peel

22

Sep

River (after Stewart, 2000) and b) the re-

20

lationship between AO+ and AO condi-

Aug

18

tions and the three-year smoothed month-

Jul

ly river discharges for the Ob, Yenisey,

16

Jun

and Mackenzie Rivers (after Johnson et

14

May

al., 1999).

12

10

Apr

8

Mar

6

Feb

b

4

Jan

2

19 75

1980

1985

19 90

1995

Discharge, 1000 m3/ s

13

AO+

Ob

12

AO

11

Mean discharge

10

22

Yenisey

20

18

Mean discharge

16

10

Mackenzie

9

Mean discharge

8

7

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

Recent Change in the Arctic and the Arctic Oscillation

11

Winter maximum

Summer minimum

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;

a

b

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;

Arctic Ocean region

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;

Total ice cover

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;

;;;

Partial ice cover (>15%)

;;

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;

;

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;

;;;

Open water

Figure 3·6. Arctic sea-ice cover derived from satellite imagery at the time of a) the winter maximum and b) the summer minimum (Johan-

nessen and Miles, 2000). The red line delimits the Arctic Ocean area as defined for the ice trends shown in Figure 3·7 (Parkinson et al., 1999).

ada, the Mackenzie Basin has undergone an excep-

3.5. The Arctic Ocean

tional warming between 1961 and 1990 (Figure 3·3 a);

3.5.1. Sea ice

nevertheless, increased basin temperatures are not ob-

3.5.1.1. Sea-ice cover

viously evident in this river's hydrology (Figure 3·5 a)

or in other Arctic rivers (Shiklomanov et al., 2000). In-

Sea ice controls the exchange of heat and other proper-

stead, there is evidence of 3- to 4-year periodicity in

ties between the atmosphere and the ocean and, together

peak flow and alterations in the seasonal shape of the

with snow cover, determines the penetration of light into

hydrograph with higher flows delayed well into Au-

the sea. Ice also provides a surface for particle and snow

gust, suggesting changes in both total annual discharge

deposition, a biological habitat above, beneath and with-

and its seasonality and possibly also changes in the rel-

in the ice and, when it melts in summer, creates stratifi-

ative importance of the river's sub-drainage basins.

cation of the upper ocean.

Such patterns appear to be only partially related to the

During the 1990s, the science community recognized

AO, as evidenced by significant correlations between

(with some alarm) that Arctic sea ice had been undergo-

runoff and precipitation for the Mackenzie Basin and

ing retreat over the previous three decades. Observed

variation in North Pacific storm tracks (Bjornsson et

changes include: a reduction in area covered by sea ice

al., 1995). These correlations suggest that trans-Pacific

(Johannessen et al., 1999; Levi, 2000; Maslanik et al.,

transport of airborne contaminants may be the domi-

1996; Parkinson et al., 1999; Vinnikov et al., 1999), an

nant component of contaminant loading for north-

increase in the length of the ice-melt season (Rigor et al.,

western Canada, which is supported by air monitoring

2002; Smith, 1998), a loss of multi-year ice (Johannes-

time-series data collected at Tagish in the Yukon (Bai-

sen and Miles, 2000), a general decrease in the thickness

ley et al., 2000). Hence, change related to atmospheric

of ice over the central Arctic Ocean (Rothrock et al.,

contaminant pathways for this region is more likely to

1999), and an increase of ice melt in the Beaufort Sea

come from the North Pacific, and it is possible that

(Macdonald et al., 1999a; McPhee et al., 1998).

such change might be manifested as an alteration in

Analyses of satellite data from 1978 to 1987 indicate

the domains of influence of Pacific air masses versus

a decrease in Arctic sea-ice area of about 2.4% per de-

Eurasian air masses.

cade (Gloersen and Campbell, 1991). Subsequent analy-

Discharges for the Ob, Yenisey, and Mackenzie rivers

ses have revised that figure upward to 4% per decade for

appear to show a positive relationship with the North

the period from 1987 to 1994 with an estimated average

Pole pressure anomaly, with a lag in discharge of about

loss during the entire period (1978 to 1997) of 3% per

0.5 to 0.7 years (Figure 3·5 b), but such a relationship

decade, which corresponds to the disappearance of

runs counter to the enhanced precipitation observed

0.3

106 km2 per decade of sea ice (Cavalieri et al.,

during AO+ (cyclonic) conditions (Figure 3·4). Even if all

1997; Parkinson et al., 1999). The Siberian shelves con-

variation in Arctic river discharge at the 4- to 5-year

tribute significantly to the estimated ice losses. Multi-

time scale is assigned to shifts in AO/NAO index, the

year ice is apparently being lost at an even greater rate,

maximum effect on annual flow would be about 5 to

estimated at 7% per decade, partly replaced by first-year

15% which is within the range of interannual variability

ice (Johannessen and Miles, 2000).

(for example see Johnson et al., 1999; Semiletov et al.,

The large seasonal amplitude in area covered by ice

2000).

(Figure 3·6) makes it difficult to assess trends. Further-

12

AMAP Assessment 2002: The Influence of Global Change on Contaminant Pathways

Arctic sea-ice extent, million km 2

of ice from shelves is a phenomenon of the 1990s, timed

8.0

with (Russian shelves) or slightly delayed from (Beaufort

Monthly averages

7.0

shelves) the shift to strong AO+ conditions in 1989. In the

Beaufort Sea, Macdonald et al. (1999a) used stable iso-

6.0

tope data ( 18O) collected from 1987 to 1997 to show

5.0

a

that amounts of ice melt contained in the water column

4.0

increased substantially at the same time as the AO index

1.0

increased in 1989. During such conditions, the cyclonic

Monthly deviations

circulation leads to greater ice divergence, more new ice in

0.5

Slope: 8500 ± 2300 km2/yr

leads, enhanced heat flux, and reduced ridging, all of

0

which imply thinning (Flato and Boer, 2001; Macdonald

et al., 1999a; Rigor et al., 2002). Maslanik et al. (1996)

0.5

b

draw the connection between increased penetration of cy-

1.0

1980

1985

1990

clones, which is observed during AO+ conditions, and in-

1995

creased poleward transport of heat, and the absence of ice

Arctic sea-ice extent, change per decade, %

in late summer over the Siberian shelves. Based on results

0.5

of a coupled sea/ice/ocean model, Zhang et al. (2000) sug-

0

gest that there is a strong correlation between sea-ice thin-

0.5

ning and the AO (~ 80%) due to dynamical effects, and

1.0

that the Eurasian and Canada Basins respond differently

1.5

to the AO forcing. The removal of the supply of ice from

2.0

the Beaufort to the East Siberian Sea when the index be-

comes strongly positive (discussed in section 3.5.1.2.) re-

2.5

sults in depletion of thick ice in the eastern Arctic Ocean

3.0

but may enhance thick ice-buildup in the western Arctic.

3.5

c

This is important in light of the findings from repeat sub-

4.0

J

F

M

A

M

J

J

A

S

O

N

D

marine surveys that ice thickness has decreased over the

central Arctic by about 1.3 m between 1958 and 1976 and

Figure 3·7. Trends in sea-ice cover in the Arctic Ocean. The figure il-

the 1990s (Rothrock et al., 1999; Wadhams, 1997, 2000).

lustrates a) monthly average sea-ice cover between 1979 and 1996

According to several models (Holloway and Sou, 2002;

for the Arctic Ocean as delimited by Parkinson et al. (1999), see Fig-

ure 3·6 a; b) monthly deviations in sea-ice cover for this area show-

Polyakov and Johnson, 2000; Zhang et al., 2000), the

ing the transition in 1990 to seasonally clear shelves; and c) the

submarine observations may have been conducted prima-

change in monthly sea-ice extent in percent per decade (1979-1995)

rily in that part of the ocean that underwent thinning in

showing ice loss to be predominantly a springsummer phenome-

response to a shift to AO+ conditions. The conclusion con-

non (after Serreze et al., 2000).

cerning reduction of ice thickness, while valid for the do-

more, various authors have partitioned the Arctic differ-

main of submarine measurements, is not necessarily true

ently to assess changes in ice cover or have compared

for the whole Arctic Ocean and an alternative hypothesis

different years and/or different seasons (Dickson et al.,

that ice-thickness distribution changed but ice volume

2000; Johannessen and Miles, 2000; Maslanik et al.,

may not have changed in response to the AO needs to be

1996, 1999; Parkinson et al., 1999). Despite these diffi-

carefully evaluated. The loss of ice cover between NAO

culties, the satellite data available since the late 1970s

clearly indicate a reduction of 2% per decade of total ice

Ice cover

area in winter (Johannessen et al., 1999), and a significant

shift in the marginal seas toward first-year ice which is

1958

1990s

easier to melt than multi-year ice because it is thinner and

saltier. The total area of Arctic sea ice, including the

marginal seas, varies from about 13 106 km2 in winter

to 5 106 km2 in summer, and has shrunk by about

Canada

0.6 106 km2 between 1978 and 1997 (Johannessen and

Miles, 2000). The Arctic Ocean component, as defined by

Russia

Parkinson et al. (1999) (Figure 3·7), which is about

7 106 km2 in area, began to exhibit a much stronger sea-

sonal modulation in ice cover in about 1989 (Figures

3·7 a and b) with the East Siberian and Beaufort Seas ex-

periencing anomalous areas of open water in late summer

at various times during the 1990s (Maslanik et al., 1999;

Greenland

Parkinson et al., 1999; Rigor et al., 2002; Serreze et al.,

1995). That the loss of sea-ice cover is predominantly a

springsummer phenomenon is clearly shown by seasonal

monthly trends for which June to October show the great-

est change (Figure 3·7 c; Serreze et al., 2000).

What part does the AO play in the variation of Arctic

Figure 3·8. The contrast in ice cover between pronounced AO con-

sea-ice distribution? The trends in ice cover with time

ditions (1958) and pronounced AO+ conditions (1990s) (Dickson et

(Figures 3·7 a and b) suggest that the wholesale clearing

al., 2000; Maslanik et al., 1999; Serreze et al., 1995).

Recent Change in the Arctic and the Arctic Oscillation

13

Low Arctic Oscillation index

Russia

High Arctic Oscillation index

Laptev Sea

Chukchi Sea

Siberia

Kara Sea

Barents

Sea

Alaska

Transpolar Drift

Transpolar Drift

Beaufort Gyre

Beaufort Gyre

Fram

Strait

Canada

a

b

Greenland

2 cm/s

2 cm/s

Figure 3·9. Ice drift patterns for a) years with pronounced AO (anticyclonic) conditions and b) pronounced AO + (cyclonic) conditions (after

Maslowski et al., 2000; Polyakov and Johnson, 2000; Rigor et al., 2002). The small arrows show the detailed ice drift trajectories based on

an analysis of sea level pressure (Rigor et al., 2002). The large arrows show the general ice drift patterns long recognized as the Beaufort Gyre

to the left and the Transpolar Drift to the right.

and NAO+ conditions is estimated at 590 000 km2 in the

penetration and mixing, may also alter primary produc-

Barents and Greenland Seas (Dickson et al., 2000), and if

tion and carbon flux (Gobeil et al., 2001b) which then

the remarkably open ice in the East Siberian Sea in 1990

alters the vertical flux of particle reactive and bio-active

and the Beaufort Sea in 1998 (Figure 3·8) is a product of

contaminants from the ocean surface to depth.

the strong AO+ conditions of the early 1990s then per-

haps half as much again ice loss occurred over the Rus-

3.5.1.2. Sea-ice drift

sian and North American shelves due to AO forcing.

In light of the changes observed in ice cover during

General ice motion in the Arctic Ocean follows the

the 1990s, it is worth noting that over a century ago the

Transpolar Drift (TPD) on the Eurasian side of the

Pacific whaling fleet experienced similar dramatic changes

ocean and the Beaufort Gyre in Canada Basin (Figure

in ice conditions in the western Arctic. Extraordinarily

1·1; Barrie et al., 1998). Although it has long been rec-

open water from 1861 to 1867 may have contributed to

ognized that large-scale ice-drift patterns in the Arctic

a complacency that resulted in the loss of 32 ships, crushed

undergo change (Gudkovich, 1961), it was not until the

in the ice along the Alaskan coast in 1871 (Bockstoce,

International Arctic Buoy Programme (IABP) that

1986). In this respect it is interesting to remember the

sufficient data became available to map the ice drift in

caution given by Polyakov and Johnson (2000), that

detail and thereby directly evaluate the role of the AO

both short (decadal) and long (60-80 yr) time-scale vari-

in changing ice drift trajectories. The IABP data from

ations are associated with the AO.

1979 to 1998 suggest two characteristic modes of Arctic

From data collected between 1979 and 1997, Rigor et

ice motion, one during low index (AO) and the other

al. (2000) determined that sea-ice melt begins in the mar-

during high index (AO+) periods (Figures 3·9 a and b;

ginal seas by the first week of June and advances rapidly

Proshutinsky and Johnson, 1997; Rigor et al., 2002).

to the pole within two weeks. Freezing begins at the pole

The ice-motion scheme shown by drifting buoys is rea-

on 16 August, returning to the marginal seas by late Sep-

sonably well corroborated by models that are being used

tember for a total melt season length of about 58 days at

to investigate the influence of the atmospheric variability

the pole and 100 days toward the margin. Based on satel-

inherent in the AO (Maslowski et al., 2000; Polyakov

lite data (SSMR and SSM/I) predominantly from the Beau-

and Johnson, 2000). There are two overarching differ-

fort Sea, Smith (1998) estimated that the length of the melt

ences between the two ice circulation modes:

season has been increasing by about 5.3 days per decade

1) during AO conditions (Figure 3·9 a), ice in the TPD

during the period 1979 to 1996. In contrast, Rigor et al.

tends to move directly from the Laptev Sea across the

(2000) found a shortening of the melt season in the west-

Eurasian Basin and out into the Greenland Sea, whereas

ern Arctic of 0.4 days per decade and an increase of about

during strong AO+ conditions (Figure 3·9 b) ice in the

2.6 days per decade in the eastern Arctic. These trends in

TPD takes a strong cyclonic diversion across the Lo-

length of melt season parallel the general observations of

monosov Ridge and into Canada Basin (Mysak, 2001);

a 1°C per decade decrease in temperature for the Beaufort

and

Sea compared to a 1°C per decade increase in the eastern

Arctic for the same time period (Rigor et al., 2000).

2) during AO+ conditions (Figure 3·9 b), the Beaufort

Change in ice cover and its seasonality are especially

Gyre shrinks back into the Beaufort Sea and becomes

important for contaminants like hexachlorocyclohexa-

more disconnected from the rest of the Arctic Ocean, ex-

nes (HCHs), toxaphene, and polychlorinated biphenyls

porting less ice to the East Siberian Sea and importing

(PCBs) where airsea exchange is a significant compo-

little ice from the region to the north of the Canadian

nent of regional budgets (Macdonald et al., 2000a,b).

Arctic Archipelago a region known to contain the Arc-

Furthermore, change in sea-ice cover, which alters light

tic's thickest multi-year ice (Bourke and Garrett, 1987).

14

AMAP Assessment 2002: The Influence of Global Change on Contaminant Pathways

Low Arctic Oscillation index

Russia

High Arctic Oscillation index

Laptev Sea

A

Chukchi Sea

Siberia

Kara Sea

3

3

4

5

4

2

2

Barents

Sea

Alaska

1

5

1

6

Fram

B

Strait

Canada

a

b

Greenland

2 cm/s

2 cm/s

Figure 3·10. Time taken in years for sea ice at that location to reach Fram Strait during a) pronounced AO conditions and b) pronounced

AO+ conditions (after Rigor et al., 2002). Line A-B represents the transect used to describe change in sea ice during drift shown in Figure 3·12.

There are also changes in the time required for ice to

crease in the 900 000 km2 of ice advected out of the Arc-

transit the ocean (Figures 3·10 a and b) and in the desti-

tic through Fram Strait (Morison et al., 2000; Rigor et

nations of ice exported from shelves. During winter,

al., 2002). Interestingly, increased ice export through

under AO+ conditions there is an increase in ice advec-

Fram Strait can be produced by shifts to both negative

tion away from the East Siberian and Laptev Sea coasts,

and positive AO states (Dickson et al., 2000).

leading to the production of more new, thin ice in the

Comparing the two modes of ice drift (Figures 3·9 a

coastal flaw leads (Figure 3·11; Polyakov and Johnson,

and b), it is apparent that during AO conditions the

2000; Rigor et al., 2002), a decrease in the advection of

East Siberian Sea imports much of its ice from the Beau-

ice from the western Arctic into the eastern Arctic, possi-

fort Sea and that there is an efficient route to carry ice

bly an increased advection of ice from the Arctic Ocean

clockwise around the Arctic margin of the East Siberian

to the Barents Sea through the SvalbardFranz Josef

Sea and out toward Fram Strait. Under the strong AO+

Land passage (Polyakov and Johnson, 2000), and an in-

conditions of the early 1990s, the Beaufort Sea ice be-

Winter sea-ice boundary

Major shore lead polynyas

Concentrations of polynyas

Catchment area for Arctic Ocean

and adjacent seas

Catchment area for Hudson Bay,

Baffin Bay, and adjacent seas

Yukon, 195

River outflow, km3/ y

Kolyma, 132

Mackenzie, 330

Indigirka, 61

Lena, 525

Khatanga, 85

Yenisey, 620

Ob, 429

Pechora, 131

Severnaya Dvina, 110

Figure 3·11. The Arctic Ocean drainage

basin, river discharge, and the distribution

of polynyas.

Recent Change in the Arctic and the Arctic Oscillation

15

came more isolated, whereas ice from the Kara, Laptev

sediment entrained over the shelf migrates to the surface

and East Siberian Seas was displaced into the central

of the ice. Additionally, atmospheric particulates deposit

Arctic and toward the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. It is

and accumulate on the ice along its transport route.

not clear from the IABP data how much ice from the

Consequently, an increase or decrease in the time taken

Russian shelves might transport into the Canadian Arc-

for ice to cross the Arctic Ocean (Figure 3·10) respec-

tic Archipelago or the Beaufort Gyre under AO+ condi-

tively increases or decreases the time for accumulation

tions, but models (Maslowski et al., 2000; Polyakov and

of atmospheric aerosols and sediments at the ice surface.

Johnson, 2000), paleo-studies of Eurasian wood (Dyke

Each step in the ice pathway can be altered by climate

et al., 1997; Tremblay et al., 1997), and sediment rec-

change. For example, fine river sediments (known to

ords (Darby et al., 2001) all suggest that such transport

carry contaminants) become trapped in estuaries by the

is likely and may at times be important.

so-called `marginal filter' (Lisitzin, 1995). Sea level rise,

Sea ice provides a rapid means to accumulate and

change in the ice climate, or change in the river's hydrol-

transport contaminants long distances without dilution

ogy can all alter the location of this filter. The process of

(Pfirman et al., 1995; Wadhams, 2000). The response in

suspension freezing might be enhanced by larger amounts

ice-drift trajectories to change in AO index (Rigor et al.,

of open water over shelves in the autumn whereas more

2002) therefore carries immense implication for the con-

sediment might be lost from the ice during transport due

nectivity between contaminant source and sink regions

to predominance of thin, first-year ice and augmented

for ice pathways within the Arctic Ocean.

melting. Finally, the location at which ice melts and

drops its particulate and dissolved loads can change.

There are no direct data on how these components of

3.5.1.3. Sea-ice transport of material

the ice-transport pathway respond either individually or

Sea ice is an important mechanism for the transport of

collectively to the AO; however, long-term sediment

coastal and continental shelf sediments to the interior

records (Darby et al., 2001), disequilibria in sediments

Arctic Ocean and out into the Greenland Sea (Barrie et

(Gobeil et al., 2001b), and the distribution of sediments

al., 1998; Dethleff et al., 2000b; Nürnberg et al., 1994).

within the Arctic Ocean (Stein, 2000) suggest that cli-

Sediments become incorporated into ice formed over

mate forcing akin to the AO probably occurs.

shelves. Although all the shelves of the Arctic are impli-

cated in this process, the Laptev Sea has proven so far

3.5.2. Ocean currents and water properties

to be the most efficient exporter of sediment-laden ice

(Eicken et al., 1997, 2000; Reimnitz et al., 1992, 1993,

3.5.2.1. Surface water

1994). This transport process involves several steps in-

For ocean currents that deliver contaminants to Arctic

cluding: 1) the delivery of sediment to the shelf by rivers

ecosystems, surface water is most important because it in-

or from coastal erosion where much of it may become

teracts more directly with biota and ecosystems. Surface

trapped; 2) the incorporation of sediment into the ice, ei-

water pathways will to some extent reflect ice-drift trajec-

ther through ice grounding or through suspension freez-

tories (Morison et al., 2000), responding in like manner

ing in mid-shelf flaw polynyas; 3) the export of ice from

to the state of the AO (Figure 3·9). In strong AO+ condi-

the shelf to the interior ocean; 4) the transport of ice

tions, water in the TPD makes a diversion into the

across Arctic basins, potentially with some loss of sedi-

Makarov Basin and the Beaufort Gyre contracts and re-

ment during transport; and 5) the release of sediment at

treats into Canada Basin. However, the AO results in

the location where the ice melts (Figure 3·12). During

other critical changes in surface water not represented by

transport, the ice `weathers', ablating at the surface dur-

ice drift. With the enhanced inflow and spreading of

ing summer and incorporating more ice on the bottom

water in the Atlantic Layer, a retreat of the cold halocline

during winter, with the consequence that some of the

in the Eurasian Basin under AO+ conditions was also

A T M O S P H E R I C D E P O S I T I O N

Transpolar Drift

East Greenland Current

A

Aerosols

B

River

Sediment-laden ice

discharge

Clean sea ice

Sediment

Suspension

accumulation

freezing

Particle release

Figure 3·12. A schematic diagram show-

ing the accumulation and transport of

sediments and contaminants by sea ice

over the transect marked A-B on Figure

Siberian shelves

Eurasian Basin

Fram Strait

3·10 b (modified from Lange and Pfir-

man, 1998).

16

AMAP Assessment 2002: The Influence of Global Change on Contaminant Pathways

Normal placement of the Atlantic-Pacific front

Ice

Atlantic-Pacific front

Polar mixed layer

during high Arctic Oscillation Index, early 1990s

Pacific halocline

Atlantic halocline

Bering Strait

Fram Strait

Depth, m

75°N

80°N

85°N

90°N

85°N

80°N

0

ca. 10 years

200

Pacific water

ca. 10 years

400

Atlantic water

ca. 25 years

600

ca. 30 years

Atlantic Layer

800

1000

Arctic Deep Water

Norwegian Sea

and Greenland Sea

ca. 75 years

deep water

2000

Canada

Makarov

Basin

Basin

ca. 300 years

Bering

3000

Amundsen

Strait

Alpha-Mendeleev

Basin

Nansen

Ridge

ca. 290 years

Basin

Nansen

Lomo-

Fram

Gakkel

4000

Strait

nosov

Ridge

Ridge

Bold figures denote residence times

Figure 3·13. The stratification of the Arctic Ocean, showing the polar mixed layer, the Pacific and Atlantic domains of influence and the halo-

clines. The red lines show the normal placement and the displacement of the Atlantic-Pacific front during the high Arctic Oscillation index of

the early 1990s.

noted (Steele and Boyd, 1998). The halocline (Figure 3·13)

(Figures 3·13 and 3·15). Although there does not appear

provides stratification between the Atlantic Layer and sur-

to be a strong AO signal in the Pacific inflow through

face water thereby preventing or reducing the transfer of

Bering Strait (~ 0.8 Sv, there has been a general decline of

properties such as heat or contaminants between deep and

about 15% since the early 1940s (Coachman and Aa-

surface layers. The increase in salinity of surface water in

gaard, 1988; Roach et al., 1995) and the flow may also

the Eurasian Basin noted by Steele and Boyd (1998), how-

have freshened due to runoff and precipitation in the

ever, was not due to enhanced inflow from the Atlantic,

Bering Sea (Weingartner, pers. comm., 2001).

which actually freshened slightly with the high AO/NAO

index of the late 1980s, but rather to the diversion of river

3.5.2.2. The Atlantic Layer

inflow at the margins of the Arctic Ocean.

Models (Figures 3·14 a and b; Dickson, 1999; John-

Repeat hydrographic surveys of Arctic basins, com-

son and Polyakov, 2001; Maslowski et al., 1998) and

mencing in 1987 (Aagaard et al., 1996; Anderson et al.

geochemical measurements (Ekwurzel et al., 2001; Guay

1989; Carmack et al., 1995; McLaughlin et al., 1996;

et al., 2001; Macdonald et al., 1999a, 2002a; Schlosser

Morison et al., 1998; Quadfasel et al., 1991; Swift et al.,

et al., 2002) clearly show that with the high AO+ index

1997), have revealed an Arctic Ocean in transition. The

of the late 1980s, river water entering the Laptev and

timing of that transition in the late 1980s implicates the

Kara shelves was forced to the east rather than directly

AO (or NAO) as a major source of forcing that has al-

off the shelf and into the TPD. Under strong AO+ condi-

tered connections between the Atlantic and the Arctic

tions, perhaps 1000 km3/yr or more of runoff from the

Oceans and so changed the distribution of Atlantic water

Lena, Ob, and Yenisey rivers stopped entering the Eur-

within the Arctic, both in the surface layer, as discussed

asian Basin and entered, instead, the East Siberian shelf

in section 3.5.2.1, and in the deeper Atlantic Layer

and thence the Canadian Basin, possibly to exit the Arc-

water (Dickson, 1999; Macdonald, 1996). Ironically,

tic Ocean via the Canadian Arctic Archipelago (Figures

some of the clearest evidence of these changes has come

3·14 c and d) (Morison et al., 2000). A consequence of

from contaminant time series, in particular the tracing

this diversion was a reduction of stratification in the

of artificial radionuclides released from European repro-

Eurasian Basin (Steele and Boyd, 1998) and an increase

cessing plants into the waters of the eastern North At-

in stratification in the Canadian Basin (Macdonald et al.,

lantic (Carmack et al., 1997; Smith et al., 1998).

1999a, 2002a). The drop in the AO index toward the

A major change, starting in about 1989, was a possi-

end of the 1990s (Figure 3·1) appears to have initiated a

ble intensification of flow from the Atlantic into the Arc-

return to the former pathways for river water in the

tic through Fram Strait and the Barents Sea in response

Eurasian Basin (Björk et al., 2002; Boyd et al., 2002).

to the shift to strong AO+ or NAO+ conditions (Figure

At the same time, Atlantic surface water invaded the

3·15 for detailed reviews see Dickson et al., 2000;

Makarov Basin, displacing water of Pacific origin from

Morison et al., 2000; Serreze et al., 2000). The winds as-

the top 200 m of the water column (McLaughlin et al.,

sociated with AO+ conditions (Figure 3·2) increased the

1996); this represents a rapid change of water source

rate of northward transport of surface water in the Nor-

and properties for about 20% of the Arctic Ocean's area

wegian Sea and produced warmer air temperatures,

Recent Change in the Arctic and the Arctic Oscillation

17

1979

1990-1994

Freshwater runoff distribution

Russia

a

b

Greenland

Alaska

Salinity

Low

High

c

620

d

430

85

525

600+

600+

Atlantic-Pacific

2000

Front

Atlantic-Pacific

Front

200

200

?

Pre 1990

Post 1990

330

330

Low Arctic Oscillation index

High Arctic Oscillation index

Freshwater discharge, km3/yr

Freshwater discharge, km3/yr

Figure 3·14. Transport of freshwater runoff across the Arctic Ocean. This figure illustrates a) freshwater pathways during pronounced AO

conditions (1979); b) freshwater pathways during pronounced AO+ conditions (1990-94) (both a and b are based on model results by

W. Maslowski reproduced in Dickson, 1999); c) the amounts and changes in pathways for freshwater inflows during AO conditions; and

d) the amounts and changes in pathways for freshwater inflows during AO+ conditions.

Low Arctic Oscillation Index

19

High Arctic Oscillation index

Surface water circulation

a

Alaska

b

Russia

Greenland

Temperature

Warm

Cold

Figure 3·15. The change in Atlantic water inflow to the Arctic and distribution within the Arctic produced by the exceptionally strong shift to

AO+/NAO+ conditions around 1989. The figure illustrates a) the distribution of Atlantic Layer water prior to the late 1980s and b) the dis-

tribution of Atlantic Layer water during the early to mid 1990s. The distribution of the Atlantic Layer (see Figure 3·13) is based on Hodges

(2000), Maslowski et al. (2000), McLaughlin et al. (1996), and Morison et al. (1998, 2000). The Atlantic Layer boundary currents, which are

relatively fast, transport properties along basin margins at about 1-5 cm/s (300-1600 km/yr; Woodgate et al., 2001).

18

AMAP Assessment 2002: The Influence of Global Change on Contaminant Pathways

North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) index (December-March)

3.6. Adjacent polar seas and regions

4

a

3.6.1. The Nordic and Barents Seas

2

The Nordic Seas (Greenland, Iceland and Norwegian

Seas) are dominated by a northward flow of warm At-

0

lantic water on the eastern side and a southward flow of

cold Arctic water on the western side (Figure 3·17). The

2

northward flows are large, estimated at 7 to 8 Sv in the

Norwegian Atlantic Current (NwAC). About 2 Sv of the

4

NwAC enters the Barents Sea and the remainder contin-

1860

1880

1900

1920

1940

1960

1980

2000

ues north where part enters the Arctic Ocean through

Fram Strait and part re-circulates toward the west (Bar-

Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO) index

rie et al., 1998; Dickson et al., 2000).

4

The currents that transport warm Atlantic water to

b

the Barents Sea are important for regional climate, keep-

2

ing the entire Norwegian Sea and large areas of the Bar-

ents Sea ice free and open for biological production.

0

These same currents provide a significant pathway for

2

contaminants from the western coast of Europe and per-

haps from as far as the eastern North American sea-

4

board. The volume flux for these currents and the distri-

1900

1920

1940

1960

1980

2000

bution of Atlantic water in the Norwegian Sea is

Figure 3·16. a) The North Atlantic Oscillation index from 1860 to

strongly influenced by wind forcing (e.g., Blindheim et

2000 (source: Hurrell, 2002) and b) the Pacific Decadal Oscillation

al., 2000; Hansen et al., 2001; Mork and Blindheim,

index 1900 to 2000.

2000; Orvik et al., 2001), with a large component of

which, together with the shorter transit times, contrib-

variation accounted for by the NAO index (Figure 3·17).

uted to warming by about 2.3°C of the Atlantic water

entering the Arctic Ocean (Swift et al., 1997). The At-

High North Atlantic Oscillation

lantic water also exhibited slightly decreased salinity (by

index

0.03-0.05), probably reflecting increased precipitation in

Barents

Sea

the Nordic Seas during NAO+ conditions (Figure 3·4 b).

Within the Arctic Ocean, the changes in the distribu-

Greenland

Sea

tion and composition of the Atlantic Layer water were

Norwegian

spectacular when set against the traditional perception

Sea

of a quiet, steady-state ocean (see Figures 3·13 and 3·15

Iceland

Sea

for the position of the Atlantic Layer within the water

column). The front between Atlantic water and Pacific

water, traditionally located over the Lomonosov Ridge

Irminger

was forced over to the Alpha-Mendeleev Ridge (Figure

Sea

Labrador

3·13 and see McLaughlin et al., 1996; Morison et al.,

Sea

2000). At the same time, the inflowing water could

be detected in the Atlantic Layer by an approximately

Atlantic water

a

1.5°C temperature rise above the climatological norm

Arctic water

(Carmack et al., 1995). The changes in volume and com-

position of Atlantic water entering the Arctic Ocean

Low North Atlantic Oscillation

through Fram Strait continue to cascade through the

index

Arctic basins, first as changes in properties along the

boundaries (McLaughlin et al., 2002; Newton and So-

tirin, 1997), then as changes propagated into the basin

interiors along surfaces of constant density (Carmack et

al., 1997) (Figure 3·13). Woodgate et al. (2001) esti-

mated that in 1995 to1996, the boundary flow over the

southern margin of the Eurasian Basin was transporting

5 ±1 Sv at about 1 to 5 cm/s (300 -1600 km/yr). When

water in the boundary current reached the Lomonosov

Ridge, the flow split with around half entering the Cana-

dian Basin along its margin and half returning toward

Fram Strait along the Lomonosov Ridge. The high NAO

index of the late 1980s (Figure 3·16 a) also strengthened

b

and warmed the inflowing Barents Sea branch of At-

lantic water, perhaps by as much as 25% relative to

Figure 3·17. Main features of the circulation of Atlantic waters

1970 (Dickson et al., 2000), which probably led to a

(red) and Arctic waters (blue) in the northern North Atlantic and

parallel warming and increase in salinity of the Barents

Nordic Seas under a) pronounced NAO+ conditions and b) pro-

Sea (Zhang et al., 2000).

nounced NAO conditions (source: Blindheim et al., 2000).

Recent Change in the Arctic and the Arctic Oscillation

19

Year, NAO

nants. In the Greenland Sea, deep or intermediate water

1960

'65

'70

'75

'80

'85

'90

'95

masses are created by winter cooling of the upper layer,

NAO 4

6°E Long.

a process which has weakened or even ceased since the

winter

index

4

beginning of the 1970s (e.g., Bönisch et al., 1997). In the

°E

2

Barents Sea, vertical mixing takes place down to 300 m

2°E

in cold years, which means the whole water column is well

0

NAO

mixed from the surface to the bottom. In addition to ver-

0

2

tical mixing due to cooling in the open sea, vertical mix-

2°W

ing also takes place in frontal zones of the Nordic and Ba-

4

rents Seas. Cold and warm water masses meet and mix

4°W

to create a very productive area where there is likely to

6

35 PSU

6°W

be a high organic sedimentation rate. The fronts also act

as a barrier for distribution of both plankton and fish.

8

8°W

1965 '70

'75

'80

'85

'90

'95

2000

Year, longitude of salinity 35

3.6.2. The Bering and Chukchi Seas

Figure 3·18. A comparison of the western extent of Atlantic Water

The eastern Bering and Chukchi Seas are contiguous

(brown curve) and the NAO index (blue curve). The brown curve

reflects three-year moving averages of the longitude of maximum

shelves that extend nearly 2000 km northward from the

western extent of water with salinity of 35 in the section along

Alaskan Peninsula to the continental slope of the Arctic

65°45'N (source: Blindheim et al., 2000). The blue curve reflects a

Ocean's Canada Basin (Figure 3·19). Both shelves are

three-year moving average of NAO winter values (Dec- March) (up-

broad and shallow with typical depths on the Bering and

dated from Hurrell, 1995). The two lines are strongly correlated

Chukchi shelves being <100m and < 60m, respectively.

with a time-lag of ca. 2-3 years between respective peaks.

The Bering Strait provides a continuous pathway by

A high winter NAO index (December-March) is associ-

which approximately 25 000 km3 of water from the

ated with more south-westerly winds and storms which

North Pacific Ocean enter the Arctic Ocean annually

increase the volume flux of the inner (eastern) branch of

(Roach et al., 1995). The nutrient-rich, but moderately

the NwAC (compare Figure 3·17 a with Figure 3·17 b;

M

Orvik et al., 2001). Under these conditions, more At-

inimum

Beaufort

lantic water reaches the Barents Sea and the Arctic

East

Sea

70°N

Siberian

Ocean, and less Atlantic water is transported into the

Sea

central Norwegian Sea (Blindheim et al., 2000). Coinci-

Chukchi

Sea

dentally, more Arctic water from the East Greenland

Maximum

Current, which is fresher and cooler, enters the central

Norwegian Sea. During periods of low NAO index (Fig-

Siberia

Alaska

ure 3·17 b), weaker south-westerlies result in a weaker 65°N

inner branch of the NwAC and a greater extension of

Atlantic water to the west in the Norwegian Sea. The

eastwest extent of Atlantic water passing through the

Yukon River

M

Norwegian Sea predictably follows the winter NAO

inimum

index with a lag of 2 to 3 years (Figure 3·18).

60°N

Large-scale atmospheric features, as represented by

the NAO, appear to affect the strength of the Atlantic

aximum

M

inflow to the Barents Sea (Figure 3·17; Dippner and Ot-

tersen, 2001; Ingvaldsen et al., 2002) but this inflow

seems also to be closely related to regional atmospheric

Bering Sea

55°N

circulation (Ådlandsvik and Loeng, 1991). Low atmos-

pheric pressure over the inflow area favours increased

Gulf of Alaska

inflow of Atlantic water resulting in higher than average

Aleutian Islands

temperatures in the Barents Sea.

500 km

From the mid-1960s the NAO index has increased

progressively with relatively high values in the early- to

180°W

175°W

170°W

165°W

160°W

155°W

0

Depth, m

mid-1990s (Figure 3·16 a). Increased atmospheric car-

Beaufort Gyre

Siberian Coastal Current

20

bon dioxide (CO

Alaska Coastal Water

2) is projected to increase storm fre-

Bering Shelf Water

100

quencies and weaken thermohaline circulation (IPCC,

Aleutian North Slope Bering Slope Anadyr Waters

200

2002) probably producing upper ocean circulation more

Alaskan Stream

September ice edge maximum and minimum extents

1000

like that observed during NAO+ conditions (Figure

March ice edge maximum and minimum extents

7000

3·17 a). The increased wind-induced transport may be

Figure 3·19. A schematic diagram of circulation in the Bering

partly compensated for by a reduced thermohaline circu-

Chukchi region of the Arctic. Flow over the Bering Sea shelf consists

lation with the net effect of a relatively large transport of

of waters from the Alaskan Stream, which feeds the Bering Slope

Atlantic water to the Barents Sea and the Arctic Ocean,

Current, and fresher water from the Gulf of Alaska shelf which con-

and increased influence of Arctic water masses on the

tributes to northward transport over the eastern Bering Shelf. In the

Chukchi region, the Siberian Coastal Current transports fresh, cold

western and central Norwegian Seas.

water from the East Siberian Sea. Maximum (March) and minimum

Vertical mixing of water masses is important for bio-

(September) ice coverage and their variations are shown by dashed

logical production and for redistribution of contami-

lines (adapted from NOCD, 1986).

20

AMAP Assessment 2002: The Influence of Global Change on Contaminant Pathways

Water transport, m3/s

100 000

Bering Strait

Roach et al., 1995

80 000

Measured

Coachman and Aagaard, 1988

60 000

Jan-Aug

a

40 000

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

Total annual precipitation, m

Bering Sea shelf

0.8

St. Paul

0.6

Average

Nome

Figure 3·20. Time series of a) mean

0.4

Average

annual transport of water through

Bering Strait from 1946 to 1996

(adapted from Roach et al., 1995)

and b) precipitation over the Be-

0.2

b

ring Sea shelf based on annual pre-

cipitation measurements.

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

fresh Pacific inflow plays an important role in stratifying

and Chukchi Seas following atmospheric transport across

the upper 200 m of the Canada Basin (Carmack, 1986;

the North Pacific from Asia (Li et al., 2002; Macdonald

Coachman and Aagaard, 1974) and can be detected as

and Bewers, 1996; Macdonald et al., 2002b; Wilkening

far away as Fram Strait (Jones and Anderson, 1986;

et al., 2000).

Newton and Sotirin, 1997). The freshness of Pacific wa-

Salinity variations of ~1 in the inflowing Pacific water

ters is supported by river runoff onto the Bering Sea

(Roach et al., 1995) correspond to a range in injection

shelf, relatively fresh inflow from the Gulf of Alaska

depth into the Arctic Ocean halocline of 80 m or more,

(Royer, 1982), and greater precipitation than evapora-

which is significant in determining whether, or how, con-

tion over the North Pacific Ocean (Warren, 1983).

taminants from the Pacific Ocean might enter Arctic

Any alteration in the global thermohaline circulation

Ocean food webs. Salinity variation over the Bering shelf

(occurring at time scales of hundreds of years) will prob-

is controlled partly by sea-ice production and melting

ably lead to change in the amount and composition of

and partly by net precipitation, this latter process being,

water passing through Bering Strait (see, for example,

itself, an important pathway for some contaminants

Wijffels et al., 1992). Interannual and decadal scale vari-

(e.g., Li et al., 2002). Precipitation exhibits interannual

ations in water transport, which may account for 40%

variations that are as high as 50% of the long-term aver-

of the variation in the long-term mean, are predomi-

age, and also decadal or longer cycles with, for example,

nantly forced by the regional winds (Figure 3·20 a)

the 1960s to 1970s being relatively dry (Figure 3·20 b).

whose strength and direction depends on the intensity

The ice edge in the BeringChukchi Seas migrates an-

and position of the Aleutian Low (Figure 3·2). Variation

nually as much as 1700 km between the southern Bering

on the decadal scale (water transport was 15% lower

shelf in winter (lowest dashed line on Figure 3·19) to the

during 1973 to 1996 than during 1946 to 1972) has also

northern Chukchi shelf in summer (highest dashed line

been inferred from wind records (Figure 3·20 a).

on Figure 3·19) with interannual variability of as much

Upwelled Pacific waters support one of the world's

as 400 km (Niebauer, 1998; Walsh and Johnson, 1979).

most productive ecosystems in the northern Bering

Variability in ice cover is governed by the strength and po-

southern Chukchi Seas (Springer et al., 1996; Walsh et

sition of the Aleutian Low and East Siberian High (Figure

al., 1989), including both oceanic fauna and shelf fauna

3·2) which influence storm tracks across the North Pa-

transported within the surface water flowing northward

cific (Niebauer, 1998; Overland and Pease, 1982). In the

over the Bering shelf (Walsh et al., 1989). These shelves