Arctic Oil and Gas 2007

Contents

Preface. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . i i

OGAExecutiveSummaryandRecommendations. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . v

I.

Introduction. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

PurposeoftheAssessment

ScopeoftheAssessment

TheArctic

Oilandgasactivities

Lifecyclephases

Thechemicalsassociatedwithoilandgasactivities

Typesofeffectsfromoilandgasactivities

ImplicationsofclimatechangeforoilandgasimpactsintheArctic

I .

OilandGasActivitiestothePresent. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .13

Extensiveoilandgasactivityhasoccurred,withmuchoilandgasproducedandmuchmoreremaining

Naturalseepsarethemajorsourceofpetroleumhydrocarboncontaminationinthearcticenvironment

Petroleumhydrocarbonconcentrationsaregeneral ylow

Onland,physicaldisturbanceisthelargesteffect

Inmarineenvironments,oilspil sarethelargestthreat

Impactsonpeople,communities,andgovernmentscanbebothpositiveandnegative

Humanhealthcansufferfrompol utionandsocialdisruption,butrevenuescanimprovehealthcare

andoveral wel -being

Respondingtomajoroilspil sremainsachal engeinremote,icyenvironments

Technologyandregulationscanhelpreducenegativeimpacts

I I.

OilandGasActivitiesintheFuture. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .31

Moreoilandgasactivityisexpected

Seasonalpatternsdeterminevulnerabilityinarcticecosystems

Manyrisksremain

Planningandmanagementcanhelpreducerisksandimpacts

KeyFindings. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 38

AMAP

ArcticMonitoringandAssessmentProgramme

Oslo2007

ii

Arctic Oil and Gas 2007

ISBN 978-82-7971-048-6

© Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme, 2007

Published by

Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme (AMAP), P.O. Box 8100 Dep., N-0032 Oslo, Norway (www.amap.no)

Ordering

AMAP Secretariat, P.O. Box 8100 Dep, N-0032 Oslo, Norway

This report is also published as electronic documents, available from the AMAP website at www.amap.no

AMAP Working Group:

John Calder (Chair, USA), Per Døvle (Vice-chair, Norway), Yuri Tsaturov (Vice-chair, Russia), Russel Shearer (Canada), Ruth McKechnie

(Canada), Morten Olsen (Denmark), Outi Mähönen (Finland), Helgi Jensson (Iceland), Erik Syvertsen (Norway), Yngve Brodin (Sweden),

Tom Armstrong (USA), Jan-Idar Solbakken (Permanent Participants of the Indigenous Peoples Organizations).

AMAP Secretariat:

Lars-Otto Reiersen, Simon Wilson, Yuri Sychev, Inger Utne.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Author:

Henry P. Huntington (Huntington Consulting, hph@alaska.net).

Contributing experts:

R. Aanes

J. Christian

A.V. Goncharov

M. Kandiah

J. Meyer

G. Reinson

T. Stubbs

P.J. Aastrup

D. Cobb

I. Goudie

J. Klungsøyr

M. Meza

J.D. Reist

O.I. Suprinenko

P.-A. Amundsen

R. Connel y

W. Greenal

C. Knoechel

G. Morrel

C. Reitmeier

V.V. Suslova

J.M. Andersen

N. Cournyea

S. Haley

V. Krykov

A. Mosbech

G. Robertson

E.E. Syvertsen

S. Andresen

J. Cowan

A.B. Hansen

E. Kvadsheim

S. Munroe

G. Romanenko

A. Taskaev

T. Anker-Nilssen

R.P Crandal

J. Hansen

R. Lanctot

H. Natvig

D. Russel

J. Tate

M. Baffrey

W.E. Cross

T. Haug

T. Lang

H. Nexø

V. Savinov

C. Thomas

T. Baker

S. Dahle

T. Heggberget

A. Lapteva

M. Novikov

T. Savinova

D. Thomas

A. Bambulyak

W. Dal mann

D. Hite

A. Lis

D. Nyland

Yu. Seljukov

D. Thurston

A. Banet

M. Dam

A.H. Hoel

L. Lockhart

B. Olsen

I.N. Senchenya

P. Bates

I. Davies

V. Hoffman

C. Macdonald

A.Yu. Opekunov

G. Shearer

G. Timco

M. Bender

G. Einang

D. Housenecht

R. Macdonald

V.I. Pavlenko

L. Sheppard

A. Tishkov

S. Blasco

A. Elvebakk

K. Hoydal

C. Macktans

J.F. Pawlak

T. Siferd

O. Titov

V. Bobrovnikov

H. Engel

A.M.J. Hunter

P. Makarevich

A.Ø. Pedersen

H.R. Skjoldal

J. Traynor

D.M. Boertmann D. Faulder

H.P. Huntington

C. Marcussen

O.L. Pedersen

D. Smith

T. Tuisku

S. Boitsov

R. Fisk

G. Ivannov

M. Markarova

A. Petersen

A. Solovianov

G. Ulmishek

R. Bolshakov

B. Forbes

M. Jankowski

A.M. Mastepanov S. Petersen

S. Sørensen

K.G. Viskunova

P.J. Brandvik

E. Fuglei

H. Jensson

F. McFarland

V. Petrova

P. Spencer

T. Warren

B. Buchanan

M. Gavrilo

S.R. Johnson

R. McKechnie

N. Plotitsina

F. Stammler

Ø. Wi g

D.M. Burn

G. Gilchrist

V. Johnston

T.Yu. Medvedeva

E. Pospelova

F. Steenhuisen

T. Wil iams

D. Cantin

A. Gilman

V. Jouravel

H. Mel ing

M. Pritchard

D.B. Stewart

S.J. Wilson

F. Carmichael

R. Glenn

S. Kalmykov

S. Melnikov

B. Randeberg

F. Straneo

L. Ystanes

G. Chernik

A. Glotov

V.D. Kaminsky

H. Meltofte

O. Raustein

H. Strøm

A. Zhilin

Indigenous peoples organizations, AMAP observing countries, and international organizations:

Aleut International Association (AIA), Arctic Athabaskan Council (AAC), Gwitch'in Council International (GCI), Inuit Circumpolar

Conference (ICC), Russian Association of Indigenous Peoples of the North (RAIPON), Saami Council.

China, France, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Poland, Spain, United Kingdom.

Advisory Committee on Protection of the Sea (ACOPS), Arctic Circumpolar Route (ACR), Association of World Reindeer Herders (AWRH),

Circumpolar Conservation Union (CCU), European Environment Agency (EEA), International Arctic Science Committee (IASC), International

Arctic Social Sciences Association (IASSA), International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), International Council for the Exploration of the Sea

(ICES), International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFFCRCS), International Union for Circumpolar Health (IUCH),

International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), International Union of Radioecology (IUR), International Work Group for Indigenous

Affairs (IWGIA), Nordic Council of Ministers (NCM), Nordic Council of Parliamentarians (NCP), Nordic Environment Finance Corporation

(NEFCO), North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission (NAMMCO), Northern Forum (NF), OECD Nuclear Energy Agency (OECD/NEA),

OSPAR Commission (OSPAR), Standing Committee of Arctic Parliamentarians (SCAP), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP),

United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UN ECE), United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), University of the Arctic

(UArctic), World Health Organization (WHO), World Meteorological Organization (WMO), World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF).

Graphical production of Arctic Oil and Gas 2007

Lay-out and technical production management:

John Bel amy (johnbel amy@swipnet.se).

Design and production of computer graphics:

Simon Wilson and John Bel amy.

Cover design:

John Bel amy.

Printing and binding:

Narayana Press, Gyl ing, DK-8300 Odder, Denmark (www.narayanapress.dk).

Copyright holders and suppliers of photographic material reproduced in this volume are listed on page 40.

iii

Preface

This assessment of oil and gas activities in the Arctic is prepared

the preparation of this assessment. AMAP would also like to thank

in response to a request from the Ministers of the Arctic Council.

IHS Incorporated for contributing information that was vital to

The Ministers cal ed for engagement of al Arctic Council Working

the preparation of this assessment. A list of the main contributors

Groups in this process, and requested that the Arctic Monitor-

is included in the acknowledgements on the previous page of this

ing and Assessment Programme (AMAP) take responsibility for

report. The list is based on identified individual contributors to

coordinating the work.

the scientific assessment, and is not comprehensive. Specifical y, it

The objective of the 2007 `Assessment of Oil and Gas Ac-

does not adequately reflect the contribution of the many national

tivities in the Arctic' is to present an holistic assessment of the

institutes, laboratories and organizations, and their staff, which

environmental, social and economic, and human health impacts

have been involved in the various countries. Apologies, and no

of current oil and gas activities in the Arctic, and to evaluate the

lesser thanks, are given to any individuals unintentional y omitted

likely course of development of Arctic oil and gas activities and

from the list.

their potential impacts in the near future.

Special thanks are due to the lead authors responsible for the

The assessment updates information contained in the AMAP

preparation of the scientific assessments that provide the basis for

1997/98 assessment reports, including several aspects not covered

this report, and also to the author of this report, Henry Huntington.

in the earlier assessments regarding impacts of oil and gas activities,

The author worked in close cooperation with the scientific experts

aiming to offer a balanced and reliable document to decision mak-

and the AMAP Secretariat to accomplish the difficult task of distil -

ers in support of sound future management of oil and gas activities

ing the essential messages from a wealth of complex scientific infor-

in the Arctic. The assessment also includes recommendations to

mation, and communicating this in an easily understandable way.

the Ministers for their consideration.

The support of the Arctic countries is essential for the produc-

This `State of the Arctic Environment Report' is intended to

tion of assessments such as this, with much of the information

be readable and readily comprehensible, and does not contain

presented being based on ongoing activities within the Arctic

extensive background data or references to the scientific literature.

countries. The countries also provide the necessary support for

The complete scientific documentation, including sources for all

most of the experts involved in the preparation of the assessments.

figures reproduced in this report, is contained in a related report,

In particular, AMAP would like to express its appreciation to

`Assessment 2007: Oil and Gas Activities in the Arctic - Effects and

Norway and the United States for undertaking the lead role in

Potential Effects', which is ful y referenced. For readers interested

supporting the Assessment of Oil and Gas Activities in the Arctic.

in the scientific background to the information presented in this

Special thanks are also offered to the Nordic Council of Ministers

report, we recommend that you refer to the scientific report. This

for their financial support to the AMAP parts of the work on this

report is the fifth `State of the Arctic Environment Report' that has

assessment, and to sponsors of other bilateral and multilateral

been prepared by AMAP in accordance with its mandate.

projects that have delivered data for use in this assessment. Fi-

A large number of experts from the Arctic countries (Canada,

nances from the Nordic Council of Ministers and some countries

Denmark/Greenland/Faroe Islands, Finland, Iceland, Norway,

also support the participation of indigenous peoples' organizations

Russia, Sweden, and the United States), together with experts from

in the work.

indigenous peoples' organizations, from other organizations, and

The AMAP Working Group is pleased to present this State of

from other countries have participated in the preparation of this

the Arctic Environment Report, the fourth in the series, for the

assessment. AMAP would like to express its appreciation to al of

consideration by governments of the Arctic countries. This report

these experts, who have contributed their time, effort, and data for

is prepared in English, which constitutes the official version.

Oslo, November 2007

iv

v

OGA Executive Summary and

Recommendations

The Arctic Council's assessment of oil and gas activities in the Arctic is prepared in response to a request from Ministers of the eight Arctic coun-

tries. The Ministers cal ed for engagement of al Arctic Council Working Groups in this process, and requested that the Arctic Monitoring and

Assessment Programme (AMAP) take responsibility for coordinating the work. 1

This Executive Summary is in three parts. Part A presents the main findings of the assessment and related recommendations. Part B is struc-

tured in the same manner as Part A and provides additional information for those interested in examining the basis for the conclusions and rec-

ommendations that are presented in Part A. Part C presents information on `gaps in knowledge' and recommendations aimed at fil ing these gaps.

PARTA:ConclusionsandRecommendations2

neering practice can greatly reduce emissions, discharges, and the

risk of accidents. Physical impacts and disturbance are likewise

Arctic Petroleum Hydrocarbon Resources and Oil

inevitable wherever industry operations occur; their effects can,

and Gas Activities

however, be minimized. Increased activity may extend these im-

pacts and effects into additional areas of the Arctic.

The importance of oil and gas development to the economy of the

It is therefore recommended that:

Arctic means that, with the possible exception of climate change,

· Oil and gas activities and their consequences for the environment

this activity wil pose the most significant chal enges to balancing

and humans should be given increased priority in the future work

resource development, socio-cultural effects, and environmental

of the Arctic Council, focussing in particular on:

protection in the Arctic in the next few decades.

Extensive oil and gas activity has occurred in the Arctic, with

- research, assessment and guidelines to support prevention of oil

much oil and gas produced and much remaining that could be

spil s and reducing physical disturbances and pol ution;

produced. More activity is expected in the next two decades, how-

- research, as es ment and guidelines leading to improved manage-

ever projections farther into the future become increasingly specu-

ment of social and economic effects on local communities; and

lative since the pace of activity is affected by a number of factors

- research, assessment, and guidelines in relation to the interac-

including economic conditions, societal considerations, regulatory

tions between oil and gas activities and climate change. 3

processes, and technological advances. Global climate change may

Specific recommendations in this respect are included under the

introduce additional factors that need to be taken into account.

heading `Managing Oil and Gas Activities', below.

Activities in the early decades of Arctic oil and gas exploration

and development typical y had larger impacts than corresponding

· Arctic oil and gas activities should be conducted in accordance with

activities today. Reduced impacts today are the result of improved

the precautionary approach as reflected in Principle 15 of the Rio

technology, stricter regulations, and a better understanding of

Declaration as wel as in Article 3, paragraph 3 of the UN Frame-

environmental effects of human activity in the region. Technological

work Convention on Climate Change; and with the pol uter pays

advances are likely to continue to change the way oil and gas activi-

principle as reflected in Principle 16 of the Rio Declaration.

ties are conducted. Even so, the presence of oil and gas activities

· Recognizing the trans-boundary context of pol ution hazards

both onshore and offshore is substantial in many parts of the Arctic.

associated with certain oil and gas activities, the Arctic Council

The history of oil and gas activities, including recent events,

should support improvements in bilateral (and multilateral)

indicates that risks cannot be eliminated. Tanker spil s, pipeline

cooperation among the Arctic countries to institute or improve

leaks, and other accidents are likely to occur, even under the most

coordination of preparedness and response measures across the

stringent control systems. Transportation of oil and gas entails risk

circumpolar region, in particular cooperation in the Barents,

to areas beyond production regions. Pol ution cannot be reduced

to zero, although adherence to strict regulations and sound engi-

Chukchi and Bering Seas.

1Ministers representing the eight Arctic States, convening in Reykjavík, Iceland, for the Fourth Ministerial meeting of the Arctic Council. Request AMAP, in cooperation with the other relevant Arctic

Council working groups, to continue work to deliver the assessments of oil and gas in the Arctic ... and propose effective measures in this regard, (Ministerial Declaration, Reykjavik 2004).

2Some Arctic governments are already implementing some or al of the activities described in the recommendations in this document.

3A focus on climate change should address both climate change effects on oil and gas activities in the Arctic and the influence of development of Arctic oil and gas resources on climate change, given the

special, and sometimes local, sensitivity of the Arctic climate to emissions of methane, nitrous oxides, formation of tropospheric ozone and other pol utants and agents affecting climate change in the Arctic.

vi

Social and Economic Effects

This assessment confirms AMAP's previous findings that

petroleum hydrocarbon concentrations are general y low in the

Oil and gas activities provide a significant contribution to the

Arctic environment. Furthermore, this assessment indicates that the

regional and national economies of the countries that currently

majority of petroleum hydrocarbons in the Arctic environment come

produce oil and gas from their Arctic territories.

from natural sources. From human activity, oil spil s are the largest

Effects on individuals, communities, and governments can be

contributor of petroleum hydrocarbons in the Arctic environment,

both positive and negative. Detriments and benefits are unlikely to

fol owed by industrial activity. The oil and gas industry is responsible

reach everyone in the same way. Some people wil receive greater

for some spil s but other sources such as shipping, fishing fleet opera-

benefits and others wil experience greater negative effects. The de-

tions, and spil s at local storage depots also account for much of the

velopment and construction lifecycle phases of oil and gas activity

oil spil ed. With the exception of spil s, oil and gas activities are, at

typical y have the largest social and economic effects, but they are

present, relatively modest contributors to overal petroleum hydro-

also the most rapid and transient.

carbon levels found in the Arctic. Although human inputs comprise

Oil and gas are non-renewable resources and, as such, are finite

a smal proportion of the total petroleum hydrocarbons in the Arctic

resources that wil eventual y be exhausted; however the benefits

environment, they can create substantial local pol ution.

resulting from oil and gas development may be sustainable if

If oil and gas activities in the Arctic reach levels projected by some

properly managed. Setting aside part of the revenue from oil and

countries, these activities may contribute an increasingly significant

gas production, for example in long-term support or investment

proportion of the input of petroleum hydrocarbons to the Arctic dur-

funds, or through provisions of land claims settlements can pro-

ing the next few decades.

vide means of securing benefits for communities over the longer

Oil spil s and other pol ution arising from oil and gas activities

term, including when oil and gas activity declines or ceases.

can damage ecosystems, but the extent of the impact depends on

Society in general has a responsibility to manage the positive

many factors. Seabirds and some marine mammals are particularly

and negative effects that oil and gas activities have on people.

sensitive if oil fouls the feathers or fur they depend on for insulation,

Involvement of local people in al stages of the decision-making

frequently resulting in death. Animals living under cold Arctic condi-

process, and planning for the longer-term are key elements in this

tions are particularly vulnerable in this respect. Seasonal aggregations

process. In some parts of the Arctic, the political influence of local

of some animals such as seabirds, marine mammals, and spawning

and indigenous peoples is a driving force in modern oil and gas

fish make them particularly vulnerable to a spil at those times and

industry supervision.

places. Leads, polynyas, and the marginal ice zones are particularly

It is therefore recommended that:

important habitats where such aggregations occur.

· Prior to opening new geographical areas for oil and gas explora-

Arctic plants and animals may be exposed to a large number of

tion and development, or constructing new infrastructure for

compounds released by oil and gas activities in a number of ways. In

transporting oil and gas, local residents including indigenous

general, Arctic plants and animals may be expected to exhibit effects

communities should be consulted to ensure that their interests are

from petroleum hydrocarbon exposure similar to those shown by

considered, negative effects are minimized and advantage is taken

plants and animals elsewhere in the world. For most of the Arctic,

of opportunities afforded by the activity, especial y during the

with the exception of local spil situations, petroleum hydrocarbon

early, intensive phases of development and construction.

levels are below known thresholds for effects. Aquatic animals may be

· Consideration should be given to securing lasting benefits from

sensitive to exposures to crude and refined oils and to numerous pure

petroleum hydrocarbons, with larval stages of fish among the most

oil and gas activities for Arctic residents, for example through the

sensitive. Experience from the Exxon Valdez oil spil has shown that

establishment of infrastructure and health-care facilities, so that

such effects can persist for decades. To date, no major oil spil s have

northern economies and people benefit over the longer-term and

occurred in the Arctic seas.

so that infrastructure and services are maintained in the period

Human health can suffer from pol ution and disturbance. Expo-

after the activity has declined or ceased.

sure to petroleum hydrocarbons at levels high enough to cause adverse

health effects is rare outside of occupational situations or accidental

Effects on the Environment and Ecosystems

releases such as spil s. Spil s can also lead to changes in the quality,

The Arctic surface environment is one of the most easily impacted

quantity or availability of traditional foods. Oil and gas revenues can

on Earth. On land, physical disturbance has the largest effect. In

also improve health care and overal wel -being. Demonstrating a con-

marine environments, oil spil s are the largest threat.

nection between petroleum hydrocarbons and human health in the

In some areas, the tundra has been damaged by tundra travel

Arctic is complex at best. Many factors contribute to overal health.

and construction of infrastructure related to oil and gas explora-

It is therefore recommended that:

tion and development. Direct physical impacts and disturbances

· Measures should be adopted to enforce stringent controls on activities

from oil and gas activities contribute to habitat fragmentation.

in sensitive areas, especial y during periods when vulnerable species

New technology and methods have significantly reduced damage

are present, and in particular on activities that involve a risk of

caused by operations, but the impacts may be cumulative.

impacts from spil s. Governments need to play an active role in this.

vii

· Where relevant, consideration should be given to staged opening of

increasingly common. There is, however, scope for making these

areas for oil and gas exploration and development or application of

types of assessment more relevant and useful.

seasonal restriction on activities to minimize effects on ecosystems.

Responding to major oil spil s remains a major chal enge in

· Consideration should be given to the need for additional protected

remote, icy environments. This is especial y true for spil s in waters

areas and areas that are closed for oil and gas activities, to ensure

where ice is present. Many areas along Arctic coasts that are vulner-

protection of vulnerable species and habit; the need for such areas

able to spil s from oil and gas activities, especial y transportation,

should also be considered in areas already designated as appropriate

do not have spil response equipment stationed nearby. Most oil

for oil and gas development.

combating equipment that is currently stored in Arctic depots was

· Improved mapping of vulnerable species, populations, and habi-

designed for use in non-ice-covered waters and may be inadequate for

tats in the Arctic should be carried out, also taking into account

combating spil s under typical Arctic conditions. Research on oil spill

seasonal, annual and longer-term changes, in order to facilitate

response technology and techniques has progressed in recent years,

oil spil contingency planning.

resulting in new technology and techniques with improved potential,

however, these have yet to be ful y-tested. For these reasons, spill

Managing Arctic Oil and Gas Development

prevention should be the first priority for al petroleum activities.

Experiences with leakages from older pipelines underline the

Economic benefits have accrued in those regions where oil and

necessity to use the highest engineering and environmental stand-

gas activities have occurred, but with some negative social and

ards, including right-of-way selection, inspection and maintenance,

environmental effects as wel . The benefits tend to be widespread

monitoring, and environmental studies.

(geographical y and across society), whereas the negative effects

Tanker transport of oil in the Arctic seas, especial y from Norwe-

tend to be more local.

gian and Russian fields, has increased and is likely to increase further.

It is difficult, however, to balance tangible (economic) benefits

Differences exist in the laws, regulations, and regulatory regimes

against risks of damage to the environment or ecosystems that, until

and their implementation among oil and gas producing countries

a major spil occurs, remain essential y `potential' or `hypothetical'.

in the Arctic. Some countries have enacted and enforced laws and

The regulatory process in most Arctic countries is modern and re-

regulations providing a robust regulatory regime for oil and gas

sponsive. However, in many cases it is also complex, involving many

activities. However, further measures may be warranted in areas with

agencies and jurisdictions. The continued improvement of regula-

vulnerable ecosystems and low accessibility.

tory systems, including the use of adaptive management, is necessary

It is therefore recommended that:

to ensure adequate control and enforcement as conditions and

Laws and regulations

technology change, and as new areas are explored and developed.

· Laws and regulations in al Arctic countries and their regional and

When oil and gas activities cease, the final steps in environmen-

local subdivisions should be enacted, periodical y reviewed and

tal protection are appropriate decommissioning and remediation.

evaluated and where neces ary strengthened and rigorously enforced,

Because these activities take place after revenues from production

in order to minimize any negative effects and maximize any posi-

have ended, it may be necessary to establish the respective respon-

tive effects of oil and gas activity on the environment and society.

sibilities of government and industry in regard to such activities.

· The requirement to use best industry and international standards

One option is for industry to contribute to a government-man-

should be addres ed in laws and regulations. Management systems

aged fund, to be used for decommissioning and remediation.

and regulations should be clear and flexible, and reviewed regularly

Offering incentives to operators to clean-up old sites in areas

to ensure that they are effective, adequate, consistently applied, and

of their current operations may represent a cost-efficient way to

accommodate changes in technology in a timely manner.

facilitate remediation in some remote areas.

· Monitoring of compliance and implementation of regulations

The environmental and negative social effects of oil and gas

should be improved in the Arctic countries, and appropriate au-

activities in the Arctic can only be minimized if existing regula-

thorities acros the Arctic should be encouraged to adhere to and to

tions are effectively implemented and new regulations addressing

enforce compliance with regulations.

current weaknesses are developed. Enforcing regulations requires

commitment by governments, which can be aided by strong pub-

· An as es ment of the oil and gas industry's degree of compliance with

lic pressure and industry cooperation.

applicable domestic regulations and monitoring programmes should

In the United States (Alaska) and Canada, land claim settlements

be undertaken.

and agreements have given, and continue to give indigenous people

· Guidelines for oil and gas activities in the marine environment,

a role in environmental assessment, permitting, and regulation of oil

and the legal framework for planning and control ing oil spil re-

and gas activities.

sponse operations in the Arctic, should be improved where neces ary

Planning can help reduce risks and impacts. Preparation of

to reduce risks and minimize environmental disturbances.

environmental impact assessments and risk assessments prior to new

· Oil and gas companies should be responsible for the costs as ociated

development is a standard and required procedure; strategic environ-

with risk reduction, spil response, remediation and decommis ion-

mental assessments that have a more holistic approach are becoming

ing activities, and be prepared to share in the costs for studies and

viii

for monitoring of effects on the environment and on society as oci-

· Emergency preparednes should be of the highest levels, including

ated with oil and gas development

continued review of contingency plans, training of crews to operate

· Environmental impact as es ments, strategic environmental as es -

and maintain equipment, and conducting regular (and unsched-

ments, and risk as es ments should continue to be rigorously applied

uled) response dril s. Cooperation and emergency communications

and streamlined to increase their relevance and usefulnes for all

between operators and local, regional, national and international

stakeholders.

authorities on routes and schedules of transport and response capa-

· The ways in which local and indigenous knowledge has been and

bilities need to be established and maintained.

can be used in project planning, environmental as es ment and

· Oil spil response capabilities should be maintained and, where

monitoring, and regulatory decision-making should be evaluated to

neces ary, strengthened. Spil response technology should be further

determine how best to involve such knowledge and its holders.

developed, especial y technology or techniques for dealing with spil s

Technology and practices

in water where ice is present. More (modern) combating equipment

4

· Oil and gas industry should adopt the best available Arctic technol-

should be deployed in the Arctic, and distributed more widely to en-

ogy and practices currently available in al phases of oil and gas

able a rapid and effective response to the chal enges as ociated with

activity when undertaking such activities in the Arctic.

an acute spil in the Arctic environment.

· Oil and gas industry should take action to reduce the physical

· Countries should evaluate current funding levels to ensure full

impacts and disturbances as ociated with oil and gas activities, in-

support for oil spil prevention, preparednes and response measures,

cluding, where appropriate: using `road-les' development techniques

including enforcement of these measures.

to reduce physical impacts of roads; conducting as much activity as

Remediation

pos ible in winter months to avoid effects on tundra, permafrost,

· Oil and gas industry should be encouraged to continue their efforts

streams, and water bodies.

to reduce emis ions and discharges to the environment, including

· Where appropriate, real-time monitoring should be used to mini-

as appropriate: consideration of `zero discharge' policies for harmful

mize disturbances and impacts on wildlife, and scientifical y-based

substances; reducing the amounts of produced water discharged to

best practices used to avoid adverse effects on marine mammals

surface waters or the terrestrial environment; improved treatment

during seismic operations.

of wastes prior to discharge; use of materials and chemicals that are

les harmful to the environment; employment of closed-loop dril ing

· Tanker operations in Arctic waters should employ the strictest

practices for waste management; reducing the use of sumps and

measures for spil prevention and response, including improved

ensuring safe disposal of spent muds and cuttings; and discontinua-

communication, training, and cargo handling techniques and the

tion of flaring of as ociated solution-gas except in emergencies or for

use of ice-strengthened and double-hul ed ves els. International

safety reasons.

coordination of oil transport information should be improved.

International standards and national legislation for ships engaged

· The benefits and costs of decommis ioning and removing aban-

in oil transportation in seas with potential for ice problems should

doned oil and gas facilities and remediation of affected areas should

be reviewed for adequacy and strengthened as appropriate.

be evaluated on a case-by-case basis. Action is required to remediate

sites that are pol uted or severely contaminated in order to signifi-

· Al pipeline projects should use the best available Arctic engineering

cantly reduce or prevent threats to the environment and the health

and environmental standards, including right-of-way selection, in-

of affected local populations.

spection using state-of-the-art leak and corrosion detection systems,

monitoring and environmental studies. Arctic design, engineering,

· Where not already defined, countries should ensure that the respec-

construction and monitoring standards, and response capabilities,

tive responsibilities of government and industry for undertaking

should be strictly adhered to and, if neces ary, improved. Existing

appropriate actions for decommis ioning and remediation of all

pipelines should be properly maintained and, if neces ary, replaced.

sites and infrastructure as ociated with ongoing and new oil and gas

activities are clearly defined, and that measures are implemented to

Spil prevention and response

ensure that these obligations are met.

· Consideration should be given to whether Arctic areas should be

opened for oil and gas activities or transportation where the meth-

· Where neces ary, a mechanism should be put in place for the

ods of dealing with a spil or other major accident are lacking.

clean-up of sites stil seriously pol uted as a result of past oil and gas

activities where the operators of the sites can no longer be identified.

· Actions should be evaluated and applied to reduce risks of marine

and terrestrial oil spil s, especial y aiming to prevent the occurrence

· Facilities for handling wastes from the oil and gas industry, includ-

of marine spil s in the presence of sea ice.

ing port reception facilities for transportation and ancil ary ves els,

should be extended to reduce environmental pol ution, including

pol ution resulting from il egal discharges.

4Different definitions of Best Available Technology (BAT) and Best Available Practices (BAP) exist. In the context of this assessment, these terms are used to imply the most advanced technology

and practices currently available that are appropriate to Arctic operations.

ix

PARTB:SupplementaryInformation

decline to shut down. Exploiting Arctic oil and gas resources

is difficult and expensive, as is transporting the products to

Arctic Petroleum Hydrocarbon Resources and Oil and

markets; much of the region currently lacks the necessary infra-

Gas Activities

structure to transport oil and gas to the major markets.

4. With rising global demand, and the desire for stable and

1. Oil and gas are among the most valuable non-renewable

secure supplies, oil and gas activity in the region is expected

resources in the Arctic today. The Arctic is known to contain

to increase. Plans for new pipelines and for evaluation and

large petroleum hydrocarbon reserves, and is believed to con-

development in new areas are underway. A major discovery

tain (undiscovered) resources that constitute a significant part

could transform the prospects for oil and gas development

of the World's remaining resource base.

in offshore areas around Greenland and the Faroese Shelf.

2. Unique characteristics of the Arctic mean that development

These areas, together with offshore areas in northern Norway,

of oil and gas activities within the region faces a number

northern Russia, the United States (Alaska) and Canada,

chal enges or considerations that do not apply in other parts

are of particular interest to both government and indus-

of the World.

try. During the next two decades, the construction of new

3. Since the 1970s, Arctic regions of the United States (Alaska),

infrastructure for development and particularly transporta-

Canada, Norway and, in particular, Russia have been pro-

tion wil likely extend into wilderness areas. The depletion of

ducing large volumes of both oil and (with the exception of

existing reserves worldwide may also lead to greater inter-

Alaska) gas. With over 75% of known Arctic oil and over 90%

est in unconventional resources such as heavy oil, coal-bed

of known Arctic gas resources and vast estimated undiscovered

methane, and potential y vast methane hydrate deposits that

oil and gas resources, Russia wil continue to be the dominant

exist both onshore and offshore in the Arctic. The many

Arctic producer of oil and gas. In some Arctic areas, activities

factors involved in development decisions, and their complex

have peaked and in others they are increasing or are changing

interactions, make it difficult to project future activity levels

phase from exploration to development or from production

with confidence.

SelectedkeycharacteristicsoftheArcticrelevanttooilandgasactivitiesandtheireffects

Characteristic

Relevance

Physical environment

Cold

Difficultworkconditions,especial yinwinter

Slowweatheringofoilcompounds

Light/darkregime

Difficultworkconditionsinwinter

Extremeseasonalityofbiologicalproduction

Permafrost

Surfaceeasilydisturbed,withlong-lastingeffectsandslowrecoveryofsurfacevegetation

Seaice

Difficultaccess;difficulttorespondtooilspil s

Biological environment

Seasonalaggregationsofanimals

Majorimpactspossibleevenfromlocalizedoilspil sorotherdisturbance

Migration

EffectsintheArcticimpactotherpartsoftheworld

EffectselsewhereimpacttheArctic

Intacthabitats

Landscapesandwide-rangingspeciessusceptibletomajordevelopmentsandto

incrementalgrowth

Short,simplefoodchains

Disruptiontokeyspecies(lichen,polarcod)canhavemajorimpactstomanyotherspecies

Human environment

Remote,largelyroadless

Difficulttoreach,especial yinresponsetodisaster

Expensivetodevelop,transportoilandgas

Majorimpactspossiblefromnewroads

Improvedaccess

Fewpeople

Majordemographicchangespossiblefromindustrialactivities

Limitedhumanresourcestosupportindustry;manyworkersrequiredfromelsewhere

Manyindigenouspeoples

Alreadychangingculturessusceptibletofurtherimpactsonsociety,environment

Indigenousrightsandinterests,includinglandownership

Businessandemploymentopportunities

Accesstoservices(healthcarefacilities,schools)

x

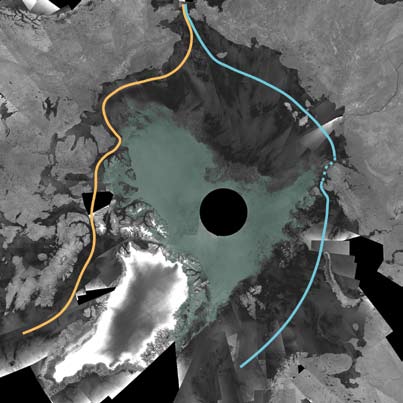

5. Climate change is expected to increase access to Arctic resources.

household for extended periods due to employment in the oil

Tanker shipment is increasing rapidly in Arctic waters. Initial

and gas industry can also chal enge traditional lifestyles.

plans for possible north-east and north-west trans-Arctic ship-

12. As oil and gas resources are exhausted, activity in a region

ping lanes are under development due to expected decreases in

wil eventual y close down. Closure of an oil or gas operation

sea-ice cover. Permafrost melting, however, may reduce access

means the loss of employment and of public revenue. Public

for development on land and wil present new chal enges with

or private investment funds may al ow some benefits to persist

respect to infrastructure and pipeline construction.

past the life of the operation. In some areas where oil and

6. Oil and gas activities include several `lifecycle stages'. In some

gas operations have declined, populations have decreased as

oil and gas regions, several phases may be taking place at the

has overal economic activity. The long-term effects of such

same time.

declines are as yet unknown for Arctic regions.

7. Early prospecting and resource delineation were conducted

13. Some degree of risk to people and society is unavoidable.

using methods that have unacceptable levels of environmental

Increased awareness of, and protection against, potential effects

impact under modern standards. Improved technology and

to the environment and people living and working in the

practices have reduced, and in some cases eliminated, the `foot-

Arctic remain important considerations in whether deposits are

print' of oil exploration and extraction activities in the Arctic

developed. An essential part of reducing negative effects and

compared with that of previous times.

capturing benefits is effective governance, which entails clear

8. Regulatory systems in the Arctic have evolved in recent decades.

decision-making, public involvement, and an effective regula-

Since 1992, Russia has been constructing a new system of

tory regime.

regulatory control. Greenland, the Faroe Islands, and Iceland

14. Oil and gas activities can lead to higher standards of living,

are in the early stages of regulatory development, while the ma-

including better health care and public health services and

ture systems used in Canada, the United States, and Norway

infrastructure. However, introduction and spread of diseases

have undergone and are stil undergoing changes. Regulations

through worker movements can occur at oil and gas activity

and the use of best available technology (BAT) are, however,

centres and in other industrial areas, and exposure of humans

not consistent across the Arctic. Despite comprehensive regula-

to oil and petroleum hydrocarbons fol owing spil s may result

tory systems and considerable public scrutiny, incidents such as

in a variety of reversible chemical-mediated health effects. Psy-

spil s and fires stil occur.

chological y, the trauma of an oil spil or other major accident

Social and Economic Effects

can be profound, especial y if ways of life are undermined.

Stress and il ness can lead to sociological effects when family

9. In the regions where they occur, oil and gas activities are major

and community networks are overburdened or disrupted.

contributors to regional and national economies. Oil and gas

activities are drivers of social and economic change. Oil and

Effects on the Environment and Ecosystems

gas activities have both positive and negative effects on people

15. Although anthropogenic inputs are a smal proportion of the

within the Arctic; populations outside of the Arctic general y

total petroleum hydrocarbon pol ution in the Arctic environ-

benefit from Arctic oil and gas activities.

ment, they can create substantial local pol ution. Some areas

10. Industrial activity creates employment opportunities and can

around oil facilities are pol uted by petroleum hydrocarbons

also stimulate local businesses leading to higher standards of

and other substances. Chronic spil s along some pipelines have

living. Public revenues from taxes and royalties can be used

led to severe local pol ution. Even where stringent regulations

to pay for improved public services, including schools and

and maintenance regimes exist, the costs to the environment

health care. The Arctic has relatively few inhabitants, and thus

and to the economy can be considerable if these regimes are

a smal potential labour pool; as a consequence, oil and gas

not strictly adhered to.

industry workers are typical y brought in from other regions,

16. Although many oil- and gas-related sources and unacceptable

in particular during the early, intensive stages of development

practices have been greatly reduced or eliminated, a complete

and construction. While providing many new opportunities,

and balanced assessment of the extent and significance of oil

this influx of people and industrial activity has the potential to

and gas activity impacts and oil field pol ution has been ham-

disrupt traditional ways of life cause social disruption, and also

pered by a lack of detailed information from some countries.

introduce or increase the spread of diseases.

Other countries have considerable information available, but

11. Many different indigenous peoples live in the Arctic. The

often in forms that make it difficult to access and evaluate.

subsistence hunting, fishing, herding, and gathering activities

17. Arctic plants and animals may be exposed in a number of

practiced by Arctic indigenous peoples extend over large areas

ways to a large number of compounds released by oil and gas

of land and sea. Environmental effects of oil and gas activities

activities. One of the greatest effects on birds and other animals

within these areas can be disruptive to traditional ways of life.

comes from physical coating by oil in the event of an oil spil .

A sudden increase in income or absence of adults from the

Even smal amounts of oil on part of an organism may cause

xi

death. Seals and whales that use blubber for insulation appear

24. The largest effect of oil and gas activities on land in the Arctic

relatively insensitive to being coated with oil; baleen whales

has been physical disturbance. Because Arctic landscapes typi-

could be vulnerable if their baleen plates become fouled with

cal y recover slowly, decades-old effects are stil visible. Notwith-

oil, although this effect has not been found to date.

standing the major improvements in industry practices in recent

18. Fish readily take up oil, but they metabolize most hydrocar-

decades, recent improvements cannot change the fact that large

bons quickly. In the aftermath of an oil spil , however, fish

areas of tundra have been damaged by tundra travel and con-

may retain sufficient quantities of hydrocarbons to affect their

struction of infrastructure related to oil and gas exploration and

quality as food for people. Even the suspicion of tainting can

developments. In addition to these direct physical `footprints' on

result in refusal to eat fish and wildlife products, affecting local

the terrestrial environment, there are also more diffuse physi-

consumers as wel as potential y damaging valuable markets

cal near-zone impacts. Dust from roads may have an effect on

for Arctic food products. Many organisms are adapted to the

physical conditions and vegetation out to a few hundred meters.

natural environmental occurrence of petroleum hydrocarbons

Roads and other infrastructure may influence the hydrology

and show no major biological effects from exposure to small

of flat tundra landscapes. Pipelines and roads may represent

amounts of many hydrocarbons.

impediments to migrations of animals, and traffic and human

19. For most of the Arctic, petroleum hydrocarbon levels are below

presence cause avoidance in some species. Other species may be

known thresholds for effects. In areas of local contamina-

attracted to human infrastructure and habitation.

tion, including contamination from natural sources, however,

25. The direct physical impacts and disturbances from oil and

concentrations are high enough to expect effects. In the Arctic,

gas activities contribute to habitat fragmentation, along with

low temperatures usual y mean that hydrocarbons wil persist

impacts and disturbances from other human activities. Habitat

longer in the environment, thus having more time to be taken

fragmentation can affect wildlife, disrupt traditional migration

up by plants and animals.

or herding routes, and reduce the aesthetic value; fragmenta-

20. The Arctic is considered to be general y vulnerable to oil spil s

tion of habitat may adversely affect many species, particularly

due to increased environmental persistence of petroleum hy-

large predators. Even without pol ution or incidents, oil and gas

drocarbons, slow recovery, highly seasonal ecosystems, and the

activities can reduce the wilderness character of a region.

difficulty of clean up in remote regions. Ice-edge communities

26. Although new technology and methods have significantly

are particularly vulnerable.

reduced damage caused by operations, the changes are cumula-

21. Oil spil s in aquatic environments, and in particular in marine

tive, and as activities overlap or expand the ultimate impact may

areas, have the potential to spread and affect animal life over

in some cases be increasing.

large areas and distances from the spil site.

27. Many affected areas, especial y in Russia, appear not to have

22. At sea, large oil spil s are general y considered to be the largest

been characterized with respect to the risks they pose.

environmental threat, though smal er, diffuse releases of oil

28. Arctic ecosystems experience high variability from year to year,

can also have substantial impacts. Seabirds and mammals

including large swings in population sizes. Some species and

depending on fur for insulation are particularly at risk from

populations wil recover more quickly from population effects

spil s. Due to the sensitivity of fish larval stages to exposures

than others. Smal changes in population are likely to remain

to crude and refined oils, an oil spil in a major spawning area

undetected. Even large changes may be the result of other

could severely reduce that year's recruitment to the population.

factors, including natural population cycles. In the event of

If a species or stock is already depleted, the impact of such a

significant population-level effects, ruling out other factors may

loss could adversely affect its recovery. A smal er spil in a time

be difficult or impossible.

and place with congregations of fish, birds, or mammals (for

Managing Arctic Oil and Gas Development

example during wintering, breeding, feeding, and migrations)

could have greater impacts on populations than a larger spil in

29. With Arctic oil and gas activity likely to increase risk is unavoid-

a time and place where animals are dispersed. Residual oil and

able. Sound planning and management can nonetheless help

other ecosystem effects may be as significant to seabird popula-

reduce negative effects and increase the benefits of oil and gas

tions as the initial oiling. Ecosystems are also vulnerable to

activity in the Arctic. Effective governance does not occur by

chronic pol ution, as contaminants or their effects may persist

chance.

and accumulate.

30. The gain in influence by indigenous groups can prove advanta-

23. Oil and gas activities that have the potential to cause impacts

geous for industry and governments, for example in settling

in the marine environment include seismic exploration and

land claims. In many cases, local residents desire not so much

dril ing and production operations that make loud noises that

to slow or stop development as to have a hand in determin-

are carried far underwater. Avoiding dril ing and seismic testing

ing how it occurs. Generating lasting benefits from oil and gas

during migratory and other sensitive periods can reduce effects

activity, while at the same time reducing major disruptions, is a

on sensitive species such as whales.

common goal for both national and local governments.

xii

31. While accidents such as oil spil s cannot be eliminated, plan-

Monitoring and Research:

ning and preparedness can reduce the likelihood of a disaster

and the impacts if and when a disaster occurs. Prevention is

Overal , knowledge about effects on the environment and human

the best approach and best practises and technologies should

health of oil and gas activities is limited, either because consist-

always be employed when oil and gas activities are undertaken

ent information has not been col ected, because incidents are

in the Arctic.

relatively few, or because information is not standardized across

scientific disciplines, regions or countries.

32. Stricter regulations and better operating practices have

More research is needed into the many (positive and negative)

reduced, and can further reduce, environmental and social

factors influencing human health if the net effect of oil and gas

impacts. However, in order for these measures to be effective,

industry on human health is to be determined in different areas of

strict enforcement of existing regulations and adherence by in-

the Arctic.

dustry to accepted international standards are essential. Better

Comparative studies should address the effectiveness of socio-

understanding of the nature and scope of effects can improve

economic mitigation and opportunity measures.

the ability to plan effectively. Resources need to be al ocated to

ensure that necessary monitoring and research are conducted.

Assessments:

33. Responding to a marine spil in the Arctic is particularly chal-

The oil and gas assessment has provided a number of valuable

lenging. Many oil and gas activities are in locations far from

lessons for the conduct of similar future assessments and possible

population centres. Detection of oil or gas leaks is vital in re-

fol ow-up assessments.

ducing the likelihood of environmental damage or health risks.

Employment of the best technology and practices for flaw

Recommendations

detection al ows defective or corroded pipelines to be replaced

To fil information gaps:

before an accident happens. Many oil and gas pipelines in Rus-

· Governments and industry should develop better reporting

sia need reconstruction and repair using up-to-date technolo-

procedures for compiling and reporting in a consistent man-

gies. Despite stringent engineering and environmental regula-

ner, appropriate data on releases from oil and gas operations at

tions, smal oil spil s are a common occurrence. Pipelines leak,

al instal ations and facilities, including data on waste disposal

accidents happen, and chronic and acute pol ution is the result.

and contamination around these facilities. Similar information

34. Although environmental clean-up (decommissioning) is

should be compiled for harbours.

required, it is not yet clear how much actual work wil be

· Governments and industry should be encouraged to provide better

done once an oil or gas instal ation is closed down. In some

information on infrastructure related to oil and gas activities, and

areas, sites of previous (historical) oil and gas activities urgently

as ociated physical disturbances.

require remediation and clean-up.

· Countries should be encouraged to continue and where neces ary

PARTC:GapsinKnowledge

implement new monitoring programmes to obtain baseline informa-

tion neces ary to detect pos ible population-level effects for both key

Information:

species and species at risk from oil and gas activities.

Arctic ecosystems experience high variability from year to year,

· Countries should be encouraged to col ect and compile comparable

including large swings in population sizes. Baseline information is

Arctic oil- and gas-related socio-economic statistics, including de-

often inadequate or unavailable. Such information is necessary if

velopment of a set of key social and economic indicators (relating to

population-level effects are to be identified and the effects of oil and

income, employment, revenue, social infrastructure, and health and

gas activities distinguished from other possible contributing factors.

safety) to measure effects of oil and gas activities on a circumpolar

There is a lack of detailed information about pol ution in the vicin-

basis and to al ow meaningful comparisons to be made regarding the

ity of oil and gas facilities and instal ations, including information

role of oil and gas or its proportional contribution to specific effects.

on practices used for waste handling and amounts of chemicals

· Comprehensive baseline investigations should be undertaken by gov-

emitted or discharged to the environment. This prevented a thor-

ernment and industry to al ow detection of potential adverse effects

ough assessment of the extent and significance of local pol ution

on ecosystems, and to identify existing seafloor hazards or archeologi-

associated with Arctic oil and gas activities, especial y in Russia.

cal sites, before petroleum activities commence.

The Arctic petroleum hydrocarbon budget represents a useful tool

· Governments and industry should provide the Arctic Council with

for investigating current sources of contamination and considering

improved acces to relevant and appropriate data to enable the Arc-

future scenarios and potential effects of Arctic oil and gas activities.

tic Council to establish an inventory of facilities and infrastructure

However, key components of the budget are based on assumptions

with potential for releases or spil s as ociated with oil and gas and

due to lack of relevant information.

compile and maintain an updated inventory of accidental releases

from oil and gas activities in the Arctic as a basis for conducting

periodic risk as es ments.

xiii

· A fol ow-up effort should be undertaken to obtain data from long-

· Continue existing research and where necessary, conduct new

term monitoring efforts in regions that have experience with large

research and monitoring to better understand short- and longer-

oil spil s.

term effects on the ecosystem, focusing on risks associated with oil

· Spil s under Arctic conditions should be used as an opportunity

spil s, including prevention, clean-up, and response.

to test and validate experience from experimental, e.g. laboratory

· Conduct further research on indicators of the cumulative effects

studies, and from spil s outside of the Arctic. Preparations should be

of activities, which can be applied across the Arctic in the next

made to al ow rapid mobilization of neces ary personnel and equip-

twenty years to help document the extent of changes.

ment to undertake such studies in the event of a future Arctic spil .

· Continue research to improve or develop new technologies for

· Monitoring programmes should be developed to improve the compat-

dril ing and seismic operations to reduce potential impacts.

ibility and comparability of the data, including bridging the gap

· Conduct comparative research on social and economic effects to

between the more persistent, high-molecular components currently

evaluate the effectivenes of various measures for mitigating negative

monitored and specific compounds of petroleum hydrocarbons

effects and achieving positive benefits with regard to economic op-

that elicit most of the toxicological effects (e.g., volatile aromatic

portunity, cultural traditions and practices, and social wel -being.

compounds) that are general y not included in monitoring pro-

· Conduct research to develop better approaches to document

grammes but which are recorded in laboratory experiments, to al ow

population-level and ecosystem-level effects of oil- and gas-related

as es ment of the environmental concentrations of these more toxic

activities and oil spil s.

compounds.

· Enhance research on ecosystem and social vulnerability to oil and

To fil knowledge gaps:

gas activities, with particular emphasis on cumulative effects.

· Undertake new research and continue existing research to provide

· Undertake health studies in communities affected or likely to be

better information on the behaviour and fate of oil in ice-covered

affected by oil and gas activities taking into account multiple

water.

determinants of health.

· Continue existing research necessary for developing effective tech-

· Institute monitoring of infectious disease among the work force

niques for dealing with oil spil s in areas of sea ice, and with large

at oil and gas facilities to enable more prompt and effective treat-

spil s on land.

ment of the occupational cohort and reduce the transfer of disease

· Better integrate environmental monitoring and toxicological stud-

from workers to communities as oil and gas activities expand in

ies so that results from these two fields can be compared.

the Arctic.

· Continue existing research and where necessary conduct more

· Expand research on the sensitivity of Arctic flora and fauna to oil

studies using oil spil trajectory models to determine areas most

and gas activities and oil spil s.

at risk from oil spil s and set priorities for response strategies, in

· Support continued research into unconventional resources to de-

particular in sensitive areas.

termine their economic viability, to develop technology to extract

· Continue existing monitoring and, where necessary undertake

them safely, and to determine the environmental consequences of

new monitoring to provide the necessary data for improving the

their development.

petroleum hydrocarbon budget of the Arctic, in particular to

· Increase research on the link between ozone reduction, associated

al ow better estimates of inputs associated with natural seeps, riv-

UV increase, and toxicity of released oil.

erine transport, and produced waters (disposal methods, location,

volumes, and composition).

To address future assessment needs:

· Conduct research into natural petroleum seeps especial y offshore

· Consideration of the effects of climate change on oil and gas

and quantify their output volumes.

activities and associated infrastructure as wel as the longer-term

effects of Arctic oil and gas activities and their impact on the

· Use natural seeps for research purposes.

Arctic environment and climate should be included in any future

· Before petroleum activities commence, monitoring should be insti-

fol ow-up to the Arctic Climate Impact Assessment (ACIA).

tuted in a programme designed to document the effects of oil and

· Consideration should be given to conducting a further assessment

gas activities and distinguish these from other sources of contami-

of information on contamination around oil and gas instal ations

nation or disturbance, including clear identification of methods

and facilities, and in harbours; waste management procedures;

utilized to assure quality control for al aspects of the monitoring

and the status of oil and gas pipeline infrastructure in the cir-

process. The monitoring programme should continue through

cumpolar region.

the decommissioning and reclamation phase. Prior to initiating

oil and gas activities, Arctic States should ensure that funding is

· An assessment should be made of the extent to which plans exist

available within government and/or industry for monitoring.

for decommissioning unused infrastructure and rehabilitating the

environment.

· Continue existing monitoring and where necessary conduct new

monitoring of groundwater reservoirs and water systems near

onshore wel s and pipelines.

I

n

t

r

o

d

u

c

t

i

o

n

Introduction

Oil and gas are among the most

valuable non-renewable resources in

the Arctic today. Oil seeps have been

known and used for thousands of

years in northern Alaska, Canada, and

Russia. Commercial oil extraction

started in the 1920s and expanded

greatly in the second half of the 20th

century. More activity is expected in

the future. Oil and gas activities will

remain a major economic driver in

E

R

D

the Arctic, extending across many

regions and ecosystems, affecting

many peoples and communities, both E R R Y A L E X A N H C &

inside and outside of the Arctic. The

B

R

Y

A

N

effects of these activities should be

assessed, both to establish a baseline

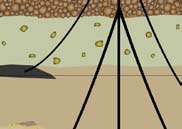

Nenetsreindeer

herderscampby

against which future changes can be

gasdril ingriginthe

measured, and to help understand the

Bovanenkovofield,

consequences of oil and gas develop-

Yamal,WesternSiberia,

ment over time.

Russia

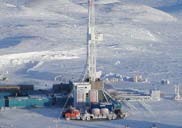

Gasdril ingplatform

PurposeoftheAssessment

onthetundrainthe

In 1997/98, the Arctic Monitoring and Assessment

Bovanenkovofield,

Programme produced its first assessment, Arctic

Yamal,WesternSiberia,

Pol ution Issues (see Box). That report included a

Russia.

chapter on petroleum hydrocarbon contamination in

E

R

D

the Arctic. The new assessment, Oil and Gas Activi-

ties in the Arctic: Effects and Potential Effects, updates

and expands upon the 1997/98 report. In addition to

E

R

R

Y

A

L

E

X

A

N

H

covering petroleum hydrocarbon pol ution in greater

C

&

detail, the new assessment addresses additional topics

B

R

Y

A

N

related to oil and gas activities in the Arctic. A detailed

history of each country's oil and gas operations

where sea ice is present. Seasonal aggregations of

and possible future activities has been added. Also

some animals such as seabirds, marine mammals, and

included is a chapter on social and economic effects,

spawning fish make them particularly vulnerable to a

which were not previously considered by AMAP.

spil at those times and places. Oil spil s and industrial

Furthermore, the assessment examines effects at levels

activities excluding oil and gas activities remain the

of biochemistry, individual organisms, populations,

largest human sources of petroleum hydrocarbons in

and the ecosystem, the last of which has not previ-

the Arctic. Routine oil and gas operations currently

ously been done. The assessment does not address

contribute a very smal fraction of the total input.

contributions of the use of arctic fossil fuels to climate

Natural sources, particularly natural seeps, are larger

change, nor does it address pol ution issues such as

than human sources.

heavy metals and radionuclides, which are associated

One motivation for producing this report is

with oil and gas activities in addition to other human

the increasing demand for oil and gas worldwide

activities. AMAP has already produced assessments on

combined with more interest in and access to arctic

climate, persistent organic pol utants (POPs), metals,

resources. Since the 1970s, arctic regions have been

and radionuclides.

producing bil ions of dol ars worth of both oil and gas.

The main findings of the 1997/98 report have

There is considerably more that could be developed.

been confirmed and extended. Petroleum hydrocar-

In arctic Alaska, offshore oil and gas activity is likely

bon contamination is not a widespread problem in

to increase. In Canada, natural gas field development

the Arctic, apart from areas where human activity

and pipeline construction may begin in the Mackenzie

has been intensive. The Arctic is general y considered

Delta, subject to approval, with oil and gas exploration

to be vulnerable to oil spil s due to slow recovery of

and development expected to fol ow in the nearshore

cold, highly seasonal ecosystems, and the difficulty of

Beaufort Sea. In Norway, Barents Sea gas production

clean up in remote, cold regions, especial y in waters

is about to begin, while exploration and development

The1997/98AMAPAssessmentofpetroleum andsummarizedhere.The1997/98assessmentrecommendedac-

hydrocarbon

tiontoreducetheriskofoilspil sandfurtherstudytoidentifyareas

ofparticularvulnerabilitytosuchoilpol ution.Thisrecommendation

hasbeenactedon(seepages34-35).

In1998,theAMAP Assessment Report: Arctic Pol ution Issuesawaspub-

lished,presentingthefirstAMAPscientificassessmentofcontami-

nantsintheArctic.Theresultsofthisassessmentwerealsopresented

inaplain-languageversionoftheassessment,Arctic Pol ution Issues:

A State of the Arctic Environment Reportb,releasedin1997.Thepub-

licationsaddressedanumberofdifferentcontaminantsandrelated

issues,includingpersistentorganicpol utants,heavymetals,radioac-

tivity,acidification,climatechange,andpetroleumhydrocarbons.

ThefindingsfromAMAP'sfirstassessmenthaveledtoaseriesof

furtherinvestigationsofmostofthetopicscoveredatthattime.For

petroleumhydrocarbons,theresultsofthelatestassessmentarepre-

sentedinOil and Gas Activities in the Arctic: Effects and Potential Effects

aAMAP, 1998. AMAP Assessment Report: Arctic Pol ution Issues. Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme (AMAP), Oslo, Norway. xi +859 pp.

bAMAP, 1997. Arctic Pol ution Issues: A State of the Arctic Environment Report. Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme (AMAP), Oslo, Norway. xi +188 pp.

continue. In Russia, onshore and offshore develop-

I

n

t

r

ment and production is already ongoing or is on the

Assessment2007: Oil and Gas Activities in the Arctic:

o

d

horizon in many regions, including some without

u

c

Effects and Potential Effects

t

previous oil and gas activity. Tanker shipment is also

i

o

n

increasing rapidly in Russian and Norwegian arctic

Chapter1providestherationaleforandlimitationsofthe2007oilandgas

waters. Greenland and the Faroe Islands continue to

assessment.Chapter2reviewsthehistoryofoilandgasactivitiesintheArc-

explore for offshore oil and gas, and exploration activi-

tic,includingtechnology,regulation,monitoring,andoilspillpreparedness

ties are starting around Iceland.

andresponsecapabilities,aswellasotherfactorsthatinfluencethecourse

As oil and gas activities continue, society must

ofindustryactivity.Chapter3presentsseveralcasestudiesonsocialand

respond to the positive and negative impacts that they

economiceffects,coveringlocal,regional,andnationalperspectives.Chapter

have on people and the environment. The purpose of

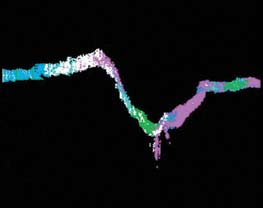

4describesthesourcesandconcentrationsofpetroleumhydrocarbonsin

the assessment is to document what is known about

theArctic,includingthefirstpetroleumhydrocarbonbudgetfortheregion.

the effects of past and current oil and gas activities, to

Italsoaddressesinputsofotherchemicalsusedintheoilandgasindustry.

project the likely course of such activities and impacts

Chapter5discusseseffectsofpetroleumhydrocarbonsandoilandgas

for the years to come, and to make recommendations

activityonterrestrialandaquaticenvironmentsandhumanhealth.Chapter

based on the assessment. Such information can then be

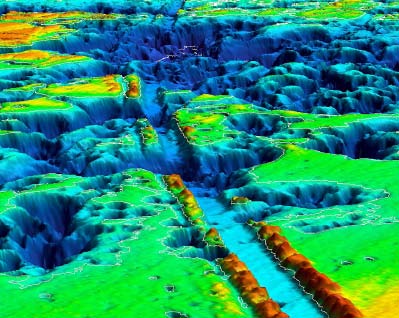

6examinesenvironmentalimpactassessmentsandvulnerabilityofspecies

used by al concerned with the decisions that are to be

andhabitatswithinthearcticecosystem,includingthemappingofvulner-

made about if and how oil and gas activities proceed.

abilitytooilandgasimpacts.Chapter7givesthekeyfindingsoftheentire

As is the nature of assessments, there is insufficient

assessment,andisthebasisforthisoverviewreport.

information to ful y answer al questions or address all

topics of concern. Nonetheless, a great deal of mate-

rial has been compiled and assessed in the scientific

background report, Oil and Gas Activities in the Arctic:

findings accessible beyond the scientific community.

Effects and Potential Effects, which draws on more than

Al statements in this overview are supported by Oil

a thousand studies to investigate many aspects of oil

and Gas Activities in the Arctic: Effects and Potential

and gas activities and their effects on the environment

Effects. The lead authors of the scientific report and

and people. Teams of scientists with expertise in the