Fostering a Culture

through Greater Pu

Y LEWIS--CORBIS

BARR

©

of Environmental Compliance

In conjunction with

blic Involvement the goals of the

by Ruth Greenspan Bell, Jane Bloom Stewart,

Aarhus Convention,

and Magda Toth Nagy

a pilot project in

Hungary and Slovenia

aimed to improve

access to information

to reduce pollution in

the Danube River.

lthough the Blue Danube may

conjure images of a scenic river

Asweeping through Europe,these

days the Danube River is severely

polluted. Raw sewage from major Cen-

tral and Eastern European cities, many

years of untreated industrial waste, agri-

cultural runoff, the results of the Balkan

war, and mining accidents such as the

Baja Mare incident in Romania all con-

tribute to pollution, which then finds its

way to the Black Sea and contaminates it

as well. This widespread problem and the

various sources of pollution have led

This article was published in the October 2002 issue of Environment.

Volume 44, Number 8, pages 34-44. Posted with permission.

© Heldref Publications, 2002. www.heldref.org/html/env.html

many reformers to conclude that en-

hanced public participation in environ-

mental decisionmaking and problem-

solving is one of the keys to reducing

pollution in the Danube basin and other

areas with similar problems.

A convention that entered into force in

2001--the United Nations Economic

Commission for Europe (UNECE) Con-

vention on Access to Information, Public

Participation in Decision-Making and

Access to Justice in Environmental Mat-

ters, popularly known as the Aarhus

ANOS PICTURES

Convention--helps provide a framework

for reaching that goal. The convention

TLEY--P

was adopted in 1998 in Aarhus, Den-

mark, and signed by 29 countries and the

EREMY HAR

European Union (EU). The convention

©J

entered into force on 30 October 2001

Traditional ribbon agriculture is used in Aggletek National Park, Hungary. Pollution in the

after ratification by the first 16 countries.

Danube River originates from many sources, including agricultural runoff.

Since then, 6 more have ratified, most

recently France on 8 July 2002.

UN Secretary-General Kofi A. Annan

land, the Netherlands, Norway, and Swe-

Unlike traditional agreements that are

has called the Aarhus Convention a "giant

den--offer these opportunities to their

designed to solve specific environmental

step forward" and an "ambitious venture

citizens at the same level.4 The United

problems, the Aarhus Convention pur-

in the area of `environmental democra-

Kingdom's FOIA was written with a

sues a less tangible but potentially more

cy.'"2 The Aarhus Convention grew out

built-in lag period, so that it did not begin

promising goal: to invite diverse voices

of the process of European and global

to come into effect until April 2002,

into environmental decisionmaking.

international environmental law drafting,

although it was enacted earlier. As a

Under the convention, signatory coun-

which has included the notions of envi-

result, experience in the United Kingdom

tries--including many that historically

ronmental democracy, transparency, and

is quite limited.5 Information access is a

have excluded the public from the deci-

public participation increasingly since the

novel concept in many Central and East-

sionmaking process--have pledged to

early 1990s. The convention includes

ern European countries that are currently

share documents that might provide

three "pillars"--in addition to access to

in economic and political transition

detailed, timely, and accurate infor-

environmental information, Aarhus con-

from state socialism to democracy and

mation about environmental quality,

tains provisions about public participa-

market economies. In these countries,

enforcement, and the data that govern-

tion and so-called access to justice, or

the process of opening government to

ments use to make environmental policy.

mechanisms to safeguard the explicit

public view began in the early 1990s.

The information obtained as a result

rights afforded under the first two pillars

Central and Eastern European coun-

increases the power of nongovernmental

and under national environmental law.

tries have several incentives to turn his-

organizations (NGOs) and ordinary citi-

The convention's requirements for

tory around. In addition to their commit-

zens, who can use it to lobby, conduct

public access to environmental informa-

ment to democratization, many of them

information campaigns, and influence

tion were influenced by the 1969 U.S.

aspire to EU membership and must

public policy in many other ways.1

Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) and

demonstrate "approximation" of their

Many countries are accustomed to

by experience gained during implemen-

laws with EU legislation. The body of

signing international environmental

tation of the 1990 EU Directive on Free-

EU law soon will include a new direc-

agreements and doing little about them,

dom of Access to Information on the En-

tive on freedom of access to environ-

despite being pushed toward imple-

vironment.3 In the United States, which

mental information with requirements

mentation by NGOs and others. Be-

has neither participated in the Aarhus

similar to those of the Aarhus Conven-

cause so many international environ-

negotiations nor signed or ratified the

tion. Also, some signatory Central and

mental agreements have failed to live up

agreement, FOIA is a vibrant but relative-

Eastern European countries, including

to their promise in achieving on-the-

ly recent step in an uneven 200-year

Hungary and Slovenia, participate in

ground improvements, the crucial issue

process of opening the government to

other pan-European environmental ef-

is how to make Aarhus more than a

public scrutiny. In Western Europe, only

forts in which public engagement is a

paper commitment.

a handful of countries--including Fin-

central component. Hungary ratified the

36

ENVIRONMENT

OCTOBER 2002

Aarhus Convention on 3 July 2001, and

risk.6 Even technical tools for environ-

outcome. Some U.S. studies suggest that

Slovenia is poised to do so in the future

mental decisionmaking such as risk

people who disagree with the final deci-

because of its plans to enter the EU.

assessment and cost-benefit analysis

sion may agree to go along with it if they

include significant subjective judgments

feel that the process itself has been fair

The Case for Public Involvement

that are most appropriately made with

and their views have been heard.

explicit attention to public values.7

According to Tom Tyler, professor of

There are several reasons to believe

The public, writ large, must be an

psychology at New York University,

that, in the long run, genuine public par-

active part of ongoing environmental pro-

"When legitimacy diminishes, so does

ticipation in Central and Eastern Euro-

tection implementation activities. For ex-

the ability of legal and political authori-

pean countries will enhance environ-

ample, many people throughout society--

ties to influence public behavior and

mental regulation and speed the way

not just a small number of large-scale

function effectively."8 The history of

toward a cleaner Danube River. One rea-

dischargers--contribute to poor water

mandated laws may be one reason that

son is that environmental laws are more

quality. Therefore, cleanup must engage

environmental laws written by previous

likely to be effective when the people

the cooperation of numerous factory

regimes in Central and Eastern European

who must obey the laws have respect

owners and employees, farmers, garden-

countries simply rested on the books

and confidence in the decisionmaking

ers, and urban residents. Attacking more

without significant genuine practice.9

system. Environmental laws typically

diffuse nonpoint sources (or point sources

require a high level of public engage-

that have long-lasting effects on a whole

Challenges to Progress

ment and mutual responsibility if they

river basin)--as Danube cleanup efforts

are to be effective.

seek to do--requires widespread knowl-

To be sure that requests for informa-

Information flow to and from govern-

edge, commitment, and mobilization.

tion will be honored, each country

ment can enhance the quality of environ-

Public involvement and open process-

implementing public-access measures--

mental rules and help develop a belief

es build public trust in the legitimacy of

whether motivated by the Aarhus Con-

that laws fairly represent shared con-

the decisionmaking process. In each

vention or other factors--must make

cerns. When lawmakers and environ-

case, after disputes on policy and sci-

significant operational changes. In addi-

mental protection officials obtain data,

ence have been resolved, there in-

tion to writing appropriate laws to pro-

lessons from experience, and opinions

evitably will be compromises, if not out-

vide a legal basis for information access,

from the affected public, NGOs, and

right winners and losers. But even those

each country must build government

industry, they can write more realistic and

who disagree with the final result should

infrastructure, systems of records, ways

achievable requirements. But to engage

be persuaded to work together on imple-

to track and respond to requests from cit-

in this dialog, the government must be

mentation, not to ignore or sabotage the

izens, and methods to ensure that gov-

willing to communicate its deci-

sionmaking process, the data it

relies on, and its goals--and it

must be willing to listen to those

who express concern or bring for-

ward data. The process should

focus not only on writing achiev-

able requirements but also on

respecting the rights of citizens to

live in a healthy environment, and

it should take into account how

they are affected by the policies

and programs that result.

Because environmental deci-

sions involve a great deal more

than good science, it is not enough

ANOS PICTURES

simply to engage experts in this

interactive process. Families con-

ARD--P

cerned about their drinking water

or about their asthmatic children

BRIAN GODD

breathing polluted air contribute

©

important insights about the

A small boat navigates the Danube Delta in Romania. Because the river flows through many countries,

human context and tolerance for

efforts to protect it require the cooperation of multiple jurisdictions and stakeholders.

VOLUME 44 NUMBER 8

ENVIRONMENT

37

ernment workers respond to requests in a

vestment is superficially easier, even if

The Pilot Project

timely fashion.

the improved factories never turn on or

in Hungary and Slovenia

However, even after considerable

maintain the equipment because basic

effort, there is no guarantee that this

attitudes toward the values inherent in

The authors recently worked with

investment in government infrastructure

environmental protection are unchanged.

Hungarian and Slovenian NGO experts

and human resources will immediately

For example, some projects financed

and governmental officials from envi-

lead to demonstrably improved environ-

through international financial institu-

ronment, water management, and other

mental quality. It would be difficult to

tions and development banks in China

bodies to build understanding and infra-

show a one-for-one correlation between a

have been built with state-of-the-art pol-

structure in support of information ac-

single FOIA request or particular lobby-

lution control, specific to the donors'

cess. This project, which began in the

ing campaign in the United States and

requirements. However, when a plant is

spring of 2000 and ended in early 2002,

improved environmental protection. No

turned over, managers may save operat-

was called "Building Environmental

human enterprise, particularly one as

ing costs by turning on the pollution-

Citizenship to Support Transboundary

complex as improving the environment,

control equipment only when an inspec-

Pollution Reduction in the Danube

moves in such a predictable pattern. It is

tor is about to arrive, for example, or

River: A Pilot Project in Hungary and

probably for this reason that funders of

during the day but not during night pro-

Slovenia." It was a collaborative effort

international environmental assistance

duction. The donors can say they have

of the Regional Environmental Center

have preferred to finance the installation

supported environmental protection, but

for Central and Eastern Europe, in Szen-

of technology and the creation of plan-

because they have disregarded the culture

tendre, near Budapest; Resources for the

ning documents rather than to support

in which the plants operate, their efforts

Future, in Washington, D.C.; and New

more qualitative efforts. The "bean

result in little environmental progress.

York University School of Law and was

counting" of the installation of tangible

The same can occur in efforts to retrofit

funded by the Global Environment

technology and the return for donor in-

plants with pollution-control technology.

Facility (GEF). The project serves as a

case study of what it takes to

move a country's commitments

from paper to practice, and it

demonstrates some of the perils

and opportunities of "soft" assis-

tance--which seeks to change

basic attitudes as well as laws,

institutions, and procedures.

Hungary and Slovenia have

GE

different histories and politics,

but they face common chal-

lenges. Since the fall of commu-

nism in the region, these two

countries have made greater

progress toward democratization

and the development of a market

CE FLIGHT CENTER, AND ORBIMA

A

economy than many of their

neighbors have, but both are still

ARD SP

emerging from political and

legal cultures dominated since

the end of World War II by the

, NASA/GODD

Marxist-socialist legal system.

OJECT

Under the communist regimes,

impressive laws and constitu-

WIFS PR

tions formally provided for pub-

THE SEA

lic participation in government

decisionmaking--but in fact, the

IDED BY

V

Communist Party maintained

O

PR

absolute control over every

aspect of society, including the

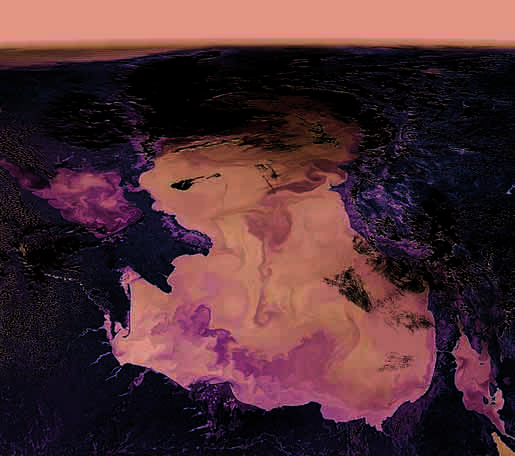

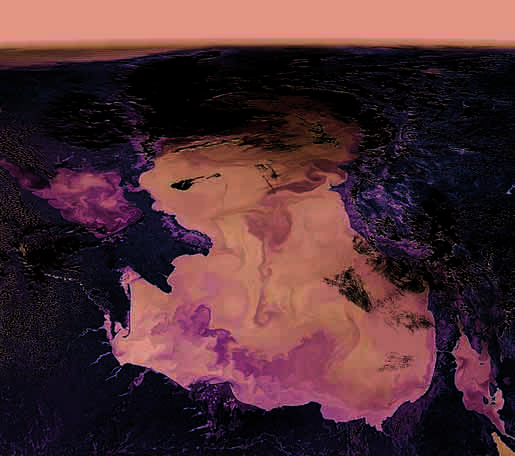

This satellite image shows eutrophication in the Black Sea, possibly due to agricultural runoff brought

in by the Danube River. (The Danube empties into the sea at the bottom of the image.)

creation of laws.10 The legacy of

38

ENVIRONMENT

OCTOBER 2002

government secrecy persists today in

many respects, but it is balanced by

efforts to build a more open society.

In addition to Hungary's and Slove-

nia's part in the Aarhus Convention and

their interest in joining the EU, the two

countries are part of a GEF-supported

process to clean the Danube River.11

International organizations including the

UN Development Programme, GEF, and

the EU's Phare and Tacis programs have

worked since 1991 with Danube River

basin countries--including Austria,

Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, the

ANOS PICTURES

Czech Republic, Germany, Hungary,

Moldova, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia,

TLEY--P

Ukraine, and Yugoslavia--to develop

successive programs to improve the

Danube. The Convention on Cooperation

EREMY HAR

©J

for the Protection and Sustainable Use of

In Hungary's Bukk National Park, wood is made into charcoal. In other areas, logging is

the River Danube and the Strategic

illegal; improved relations between a nongovernmental organization and a government agency

Action Plan for the Danube Basin, for

led to a prompt resolution in one instance of illegal logging in the Danube valley.

example, develop regional water-man-

agement cooperation to halt the deteriora-

regional meetings over the course of 18

and government participants were not

tion of water quality in the Danube basin

months, a study tour to Western Europe

Aarhus novices--some of them were rec-

and to begin the process of making

and the United States, and the creation

ognized experts and had experience with

improvements. Although the Aarhus Con-

of models and guides for participants to

the Aarhus negotiations as well as in-

vention is separate from these programs,

use in generating their own solutions.12

country efforts related to the convention.

the Danube efforts also include a public

Throughout the project, participants

Practical problems--such as a gov-

outreach component, and Danube partici-

were provided with technical assistance

ernment official who is uncertain about

pants have expressed strong interest in the

through consultations, conference calls,

how to handle a particular request or the

implications of the Aarhus Convention

and e-mails.

difficult logistics of tracking an infor-

for achieving goals for the Danube.

Consistent with what has become cli-

mation request from its receipt to a final

ché in the assistance world but is rarely

response--often are the greatest barri-

Project Approach

actually followed, the project's approach

ers to implementation of public-access

The assistance project in Hungary and

was "bottom-up," practical, and country-

legislation. This project focused on

Slovenia fit into numerous other pan-

driven. It emphasized working in a partic-

helping people overcome these often

European efforts to raise consciousness

ipatory fashion with people on the front

mundane problems.

of the Aarhus Convention. The project

lines of environmental information

The country-driven approach raises

focused mainly on information access.

access. These were government person-

complex issues about the nature of assis-

However, because that pillar of Aarhus

nel--mostly mid- and lower-level water

tance efforts. Assistance has the best

can lead to stronger public participation,

and environment ministry officials and

chance of succeeding if the proposed

the project also helped mobilize people.

experts at the national, regional, and local

activities and goals are tailored to meet

Effective assistance is a balancing act

levels--rather than exclusively high-level

the particular circumstances and needs

between identifying the needs and facil-

policy makers. These personnel receive

of each country's participants and if

itating the objectives of the partners and

and are responsible for responding to

there is demand--in the form of real

helping them gain deeper insights into

information requests from the public.

interest--on the part of country partici-

how to achieve their goals. Although this

NGOs also played a significant role, as

pants. But at the same time, the purpose

balancing act required complex interac-

they did in the Aarhus negotiations, by

of the assistance is to provide the in-

tions among many different ideas and

advising on country conditions, preparing

region experts with a wider perspective

participants, the basic structure of this

the initial needs-assessment research,

to help them achieve their goals. Al-

process was relatively simple. Project

participating in all meetings and in the

though it is relatively easy to provide

activities first included a needs assess-

study tour, and taking the lead in prepar-

information about how some Americans

ment and then--to build skills--six

ing the various project outputs. The NGO

and Europeans manage particular envi-

VOLUME 44 NUMBER 8

ENVIRONMENT

39

ronmental or information-access

problems, the result must be solu-

tions that are viable in Hungary

and Slovenia.13 "Paper" solutions

that do not work in practice often

are the outcome when approaches

from more mature environmental

regimes are replicated rather than

carefully adapted.14

Each of the project leaders had

something different to contribute.

The Regional Environmental Cen-

ter has deep roots in the region--

it was intensely involved in the

Aarhus negotiations and has long

spearheaded regional efforts to

.

increase public participation in

, INC

environmental decisionmaking.

The U.S. partners emphasized

their varied experience imple-

menting FOIA from the perspec-

tive of government, NGOs, and

the private sector. The EU exper-

ILSON--BIOS/PETER ARNOLD

.G

tise of several Hungarian and

©F

Slovenian participants was rein-

Industrial pollution--such as emissions from this power station in Romania--can contribute to

forced by that of an expert on EU

far-reaching and long-lasting environmental effects in Central and Eastern Europe.

environmental directives and the

accession process.

requests is even more problematic in

Identifying Objectives and Options

Slovenia; the needs assessment identified

Initial Assessment

major legislative gaps and institutional

The series of in-region meetings began

At the beginning of the project, local

deficiencies. Whether information was

with a joint meeting of both countries to

environmental law experts were com-

provided often depended on whether the

identify priority problems and practical

missioned to examine current laws,

requester actually knew the official

means of addressing them within the 18-

policies, and practices in Hungary and

behind the government desk.

month time frame. This set the course for

Slovenia. Their assessments showed

Most public officials in both countries

the project's training sessions, subse-

that both countries have basic but often

are unaccustomed to sharing informa-

quent meetings, and the documents and

inadequate environmental information

tion with the public, especially those

aids that each country team later pro-

provision laws in place. Government

outside the environment sector. Some

duced. Public officials and NGO repre-

officials need more specific guidance;

are apathetic and see little value in

sentatives from both countries agreed on

without it, they are left to interpret laws

informing lay members of the public or

the need for specific guidance. They

in an ad hoc fashion.

incorporating their opinions. Typically,

wanted to spell out procedures and rules

The needs assessment revealed that

many officials still believe that the only

for government employees tasked to

without clear definitions, implementa-

"public" views that should be considered

respond to public requests, and they

tion rules, or guidelines, officials tend to

are those of scientists and experts.15

wanted guidance to clarify laws or fill in

err on the side of caution and withhold

Even when officials want to com-

gaps. NGOs in Hungary recommended

information. For example, although Hun-

ply with requests, inefficient record-

that a citizen guide be created to remedy

garian law clearly states that no need

keeping and information systems some-

insufficient public know-how.

must be proved to request environmental

times make it difficult for them to find

The first meeting also demonstrated

information, when the project tested the

appropriate information. On the demand

that the two countries had slightly differ-

law, it found that Hungarian government

side, although many NGOs skillfully

ent objectives and that the project would

officials often demand justification and

pursue information, unaffiliated citizens

need to be adjusted accordingly. The proj-

deny access to those they deem not inter-

often do not know their rights, how to

ect leaders had planned to conduct all in-

ested enough. The inconsistent manner

frame requests, or what to do if they are

region meetings jointly and in English,

in which government officials handle

denied information.

the one common language between the

40

ENVIRONMENT

OCTOBER 2002

two groups. It soon became clear that

study tour to the Netherlands and the

The project also attempted to show

complex issues could be discussed more

United States also was organized for

how Hungary and Slovenia could learn

fluidly and country-specific solutions

some of the key government and NGO

from U.S. mistakes. These include EPA's

better crafted with separate, national-

experts.16 Tour participants met with offi-

continuing lack of a centralized, agency-

language sessions. Consequently, the

cials in those countries who administered

wide system of records and its initial

content, types of participants, and venues

FOIAs, managed docket rooms, and con-

track record of responding to requests

of the training sessions were modified.

ducted public outreach. They also heard

with vague promises to "get back to you

The Slovenians' principal objective

from NGOs and citizen groups who used

if or when we find something." The pub-

was to develop consensus among top-

information to protect shared water bod-

lic's persistence, through complaints,

level officials about more appropriate

ies such as the Chesapeake Bay and the

appeals, and litigation, has helped to

interpretation and implementation of

Hudson River. These two examples were

reform the agency system over time.

existing legislation and what amend-

used because Danube protection requires

Nonetheless, to date there is still no cen-

ments are necessary to fully incorporate

the close cooperation of multiple jurisdic-

tral filing office, and programs (and

the Aarhus Convention's access-to-

tions--the many countries through which

often sub-offices) maintain their own

information provisions. Most of the ses-

the Danube flows--as well as the engage-

records. Some of EPA's programs, such

sions were therefore held in the capital

ment of multiple stakeholders, some of

as the Toxic Substances Control Act, the

city, Ljubljana, with national ministry

which are located in the watershed but not

Resource Conservation and Recovery

officials, agency experts, and national

along the river itself.

Act, and the Comprehensive Environ-

NGO representatives participating.

Demonstrating how mature, well-

mental Response, Compensation, and

The Hungarians thought their basic

funded environmental information-

Liability Act, have learned lessons from

information-access law was adequate

access regimes work while emphasizing

the older programs--they plan in

but wanted to ensure that all levels of

the low-cost, low-tech elements that can

advance for the necessary filing systems

government would apply it more consis-

be more readily adapted in Central and

and dockets.

tently and would do a better job of rec-

Eastern European countries was a signif-

Project Results

onciling the various relevant laws. Meet-

icant challenge. For example, at last

ings were therefore held with a diverse

count (in 1995), the U.S. Environmental

The project saw sustainable progress

group of participants, principally outside

Protection Agency's (EPA) general

but very different results in each coun-

Budapest in regions impacted by Dan-

information-access system was funded

try. It is easy to identify tangible

ube water pollution: in Szolnok, a Tisza

at about $3.5 million and had more than

results--written products such as the

River city concerned that valuable tour-

25 full-time personnel in headquarters

good practices manual, Hungarian- and

ist revenues might be lost after a devas-

alone. The U.S. regime clearly cannot be

Slovenian-language documents, and

tating upstream cyanide leak, and in

transported wholesale to countries

models for writing Hungarian-language

Dobogokõ, another resort area that looks

whose entire environment ministries run

guidance documents for government em-

down on the Danube and across to the

on far smaller budgets.

ployees and citizens. But equally impor-

Slovak Republic. Each Hungarian meet-

ing attracted more than 50 specialists--

from regional environmental inspec-

torates, water directorates, municipalities,

the Ministry of Environment, the Min-

istry of Transport and Water Manage-

ment, local and national NGOs and busi-

nesses, the Office of the Ombudsman,

and health, agricultural, and plant and

soil protection authorities.

.

Two central tools were used to identify

,

INC

options. The project team wrote a "good

practices" manual that offered concrete

examples of how government officials in

the mature regimes of the United States

and Western Europe and the developing

information-access systems in Central

AMAS REVESZ--PETER ARNOLD

and Eastern Europe respond to public

©T

requests. The manual was distributed

A power plant in the Czech Republic dumps waste. International organizations have worked

broadly via Internet and print media. A

with the Czech Republic and other Danube basin countries to improve the Danube.

VOLUME 44 NUMBER 8

ENVIRONMENT

41

tant intangible results were achieved in

of the proposed revisions to the environ-

achieve deeper change and ratified the

the form of changes in officials' attitudes

mental law with respect to freedom of

Aarhus Convention in 2001. Two im-

and strengthened cooperation and under-

information. The extent of the expert's

portant products have been created

standing. As expertise and commitment

influence became evident at a post-

as a result of the project. A detailed

grew, the project leaders witnessed the

project public hearing to introduce and

Hungarian-language guidance manual

formation of a Hungarian-Slovenian

discuss principles of the proposed new

for public officials was released recently.

team and began to see how this team

law, when a draft reflecting the NGO

Its very specific and practical guidance

could share its experience with counter-

expert's input was presented.

on public access to environmental infor-

parts in other Central and Eastern Euro-

The project's independent evaluator

mation, public participation, and access

pean countries seeking to improve ac-

confirmed the project leaders' confi-

to justice will increase the likelihood

cess to information.

dence that these Slovenian recommenda-

that requests will be responded to

The Slovenian participants produced

tions for amendments, combined with

promptly and properly at all levels of

guidance for public officials that clari-

the strengthened NGO-government rela-

Hungarian administration. Its chief

fies ambiguities in the current Slovenian

tionship and mutual respect forged

author calls it a first edition, which will

law--specifically, provisions within the

through the project, have laid important

be revised as experience grows. Also, an

Environmental Protection Act that are

groundwork for legislative reform. He

empowering citizen guide prepared by

relevant to information access.17 With

noted momentum toward changed atti-

NGOs has been disseminated across

the support of the project, the Slovenian

tudes among Slovenian public officials:

Hungary. It includes sample letters,

participants also provided recommenda-

The number of officials who support

practical instructions on how to submit

tions for legislative amendments to

public release of important water-quality

requests, and advice on how to protest

Slovenia's current environmental protec-

data (such as crucial emissions data) has

incomplete responses and how to find

tion law that, if and when they are enact-

grown, and the opposition has become

information on the Internet. One review-

ed, will seal the major elements of the

more isolated. The project also has

er characterized the guide as "informal

guidance (and thus the requirements of

helped build a more effective and united

and helpful, and yet not insultingly sim-

the Aarhus Convention) into binding

Slovenian constituency for ratification

ple--a hard balance to strike when one

legal requirements. In addition, the proj-

and implementation of the Aarhus Con-

writes in Hungarian."

ect enhanced the access and influence of

vention and has helped open government

The project also has helped Hungary

the principal NGO expert, who had been

generally by spreading acceptance of the

open the water sector by building better

part of all meetings and the study tour.

principle of transparency--a process

cooperation between the Ministry of

As she participated in and helped pre-

that continues beyond the project.

Environment and the Ministry of Trans-

pare project workshops, she worked

Because Hungary could build on an

port and Water Management as well as

alongside official Slovenian law drafters

established legal framework for public

between NGOs and the water ministry.

who were shaping important principles

access to information, it was able to

Historically, the adversarial relationship

between these ministries has thwarted

cooperative actions for public access to

information and for protection of the

Danube River. Relations were improved

largely through the inclusion of repre-

sentatives from both of the ministries as

well as NGOs in all project activities.

These representatives had the opportu-

nity to work collaboratively toward a

common goal. One manifestation of this

newfound cooperation came shortly

after a joint workshop in an effort

involving an NGO--the Clean Air

Action group--and the Central Danube

ANOS PICTURES

Valley Water Authority in Hungary. The

level of trust between the NGO and the

government agency led to an exception-

ally prompt resolution to illegal logging

HEIDI BRADNER--P

©

in the Danube valley. These good rela-

tions will come in handy as Hungary

It is hoped that increased public involvement in environmental decisionmaking will help

address pollution, such as this toxic waste dump in the Czech Republic.

undertakes the hard work of implement-

42

ENVIRONMENT

OCTOBER 2002

ing several water-related EU directives

Aarhus Convention and implement its

pliance. This pilot project aimed to give

in the coming years.

requirements. Because the environment

participants a glimpse of how a relative-

In both countries, government partic-

ministry apparently has postponed adop-

ly mature information-access system

ipants' attitudes have improved. At the

tion of the project-developed guide-

like FOIA responds to individual re-

beginning of the project, some officials

lines until a new, general access-to-

quests and also how it provides informa-

used workload to excuse their failure to

information law is adopted, proponents

tion to the public without specific

act on public requests for information.

of improved information access must

requests (so-called "active" information

But they gradually gained interest,

redouble their efforts to ensure that the

provision, by which individuals can

understanding, and respect for NGO

recommended legislative amendments

obtain vast quantities of information

objectives, and they demonstrated will-

actually are enacted and the guidelines

from a government office through its

ingness to find systemic, workable

are used in the interim. The local

web site). The participants in the study

solutions. Some officials began to re-

Regional Environmental Center Country

tour to the United States were impressed

evaluate their role in providing infor-

Office was able to obtain a U.K. grant

by the way government-sponsored web

mation. In the project's concluding

for further capacity-building in coopera-

sites reduce the burden on public offi-

meeting, a key participant explained

tion with interested government and

cials to respond to individual requests

how the project had significantly

NGO experts.

for information. It became apparent,

expanded her perception of how to be

Hungary has a larger population and

however, that the near-term prospect of

successful in her job, which was to col-

more environmental NGOs than does

using high-tech or resource-intensive

lect and manage water-related data in

Slovenia. Perhaps by virtue of democra-

active information provision in the

Hungary. She no longer saw herself

tization initiatives and donor attention in

countries of Central and Eastern Europe

merely as a government data collector

the early part of the transition--which

was not great. The immediate problem

and manager; instead, she understood

produced Hungary's general access-to-

that some of these countries face is how

that she could help develop a broader

information law--Hungary already had

to put basics into place.

constituency for Danube pollution

internalized many of the Aarhus con-

The project generated a renewed re-

reduction. Her views echoed a similar

cepts when the project began. Hungarian

spect for process. Big changes are diffi-

statement made at the end of the U.S.

leaders and government officials were

cult, and good ideas take a long time to

portion of the study tour by a senior

ready for the new guidance manual for

settle into people's minds. Some early

water official from Slovenia.

public officials, and there is reason

meetings in Hungary initially seemed

to believe that the citizen guide will

unfocused or repetitious, but in time it

Assessing Progress

be widely used. Additional capacity-

became clear that these more broad-

building and training are likely to occur,

ranging discussions served to widen the

The project leaders are confident that

and they will increase understanding and

circle of understanding in Hungary and

the officials involved in the project will

use of both documents.

produced the greatest successes of the

be emissaries for their new viewpoints

In the final project meeting, govern-

project. In the end, a Hungarian con-

among their peers in government--and

ment employees and NGOs from other

sensus emerged that allowed signifi-

that similar efforts undertaken with a

Central and Eastern European countries

cant progress.

broader range of public officials can

were invited to hear what had been

A long-term issue that remains is how

yield the same positive results. Nonethe-

accomplished in Hungary and Slovenia

to acquire funding for projects like this

less, a great deal of follow-up work will

and to discuss the relevance of this work

that involve qualitative results and

need to be conducted in both countries to

for their own countries. They expressed a

therefore are not very susceptible to

ensure that these gains are sustained

strong desire to engage in a similar

bean counting. Despite widespread

over the long term.

process and a shared belief that they

agreement about the importance of

In Slovenia, a country of 2 million

could benefit from Hungary's and Slove-

efforts to implement the Aarhus Con-

people, the project leaders initially got

nia's experience. The challenge is to find

vention, it took several years to find

the attention of high-level officials

adequate financial support for a broader

financial support to take on this chal-

through their compelling desire to do

effort while interest is strong and while

lenge in Hungary and Slovenia. GEF

what it takes to join the EU. But Slove-

there is a Hungarian-Slovenian team will-

envisioned that the project could be

nia, like other countries hoping to

ing to cooperate in the effort.

replicated in other Danube basin coun-

accede, is engaged in a Herculean task--

Americans tend to assume that FOIA

tries. However, the vicissitudes of the

harmonizing domestic laws with about

always has been a well-functioning fea-

funding process have made it unclear

200 environmental directives (and about

ture of the U.S. landscape. It is impor-

whether support will be provided to tai-

1,500 directives in other areas). This

tant to remember that, in fact, it took

lor these ideas and to use the energy and

reality may have diminished the political

many years of training, litigation, and

expanded knowledge of the Hungarian

will to press forward quickly to ratify the

learning to force U.S. government com-

and Slovenian participants for countries

VOLUME 44 NUMBER 8

ENVIRONMENT

43

such as Romania, Bulgaria, Ukraine,

good practices of public participation in Central and

7. Ibid., page 295.

Eastern Europe. The authors were partners in a Global

Moldova, and Croatia.

8. T. R. Tyler, Why People Obey the Law (New

Environment Facility (GEF)funded project conducted

Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1990), 16162.

jointly by RFF, NYU School of Law, and REC.

9. Public participation and increasing the flow of

The authors acknowledge the ideas and support of Mar-

Building on Success

information do not guarantee either public acceptance

ianna Bolshakova, Isaac Flattau, and Stephen Stec and

of individual decisions or that such decisions will max-

thank Alfred Duda of GEF, Andrew Hudson of the

imize social welfare. Nonetheless, an RFF analysis

The international environmental com-

United Nations Development Programme, and Richard

concluded: "[P]ublic involvement in the policymaking

Lanier of the Trust for Mutual Understanding for their

process is fundamental to the health and vitality of

munity increasingly emphasizes the

support and encouragement. This article is dedicated to

American democracy. Public involvement influences

importance of public participation, but

the memory of the authors' friend, Gabi Varga, of Tisza

not only the success of a given program but also the

Klub of Hungary, a valued member of the project and

public's perception of its success" (J. C. Davies and J.

there still is little understanding of how to

study tour who was instrumental in drafting the citizen

Mazurek, Pollution Control in the United States: Eval-

make it work in practice. This pilot proj-

guide. She died of cancer at the age of 41, shortly after

uating the System (Washington, D.C.: RFF, 1998),

the project concluded. Bell may be contacted by e-mail

152). A separate concern is whether the values embod-

ect took on the challenge to build infra-

at bell@rff.org, Stewart at jbs6@nyu.edu, and Nagy at

ied in the U.S. Freedom of Information Act are theories

structure and comprehension that will

tmagdi@rec.org.

that uniquely explain Western countries with long-

standing democratic traditions or whether they also

facilitate information access and provide

apply to countries in transition to democracy.

a basis for genuine public engagement in

10. See, for example, H. S. Brown, D. G. Angel, and

environmental decisionmaking.

P. Derr, Effective Environmental Regulation: Learning

NOTES

from Poland's Experience (Westport, Conn.: Praeger,

The best outcomes from much hard

2000), 29, 3739, which describes the 1980 Polish

work in this field--new attitudes and

1. See, for example, S. Casey-Lefkowitz, "Global

Environmental Protection and Development Act that

explicitly granted nongovernmental organizations the

commitments to improved practices--

Trends in Public Participation," Environmental Law

Reporter International News & Analysis, accessible via

right to file public-interest lawsuits and to access infor-

are intangible but essential parts of

the Environmental Law Insitute web site at http://

mation about firms; and M. Schwarzschild, "Variations

on an Enigma: Law in Practice and Law on the Books

achieving substantive environmental

www.eli.org/elrinternationalna/elrinternationalna.htm

(this site is password-protected), accessed 22 July

in the USSR," book review, Harvard Law Review 99

goals such as reducing Danube pollu-

2002; and E. Petkova with P. Veit, "Environmental

(1986): 685, 691.

11. Nongovernmental and international organizations

tion. As a consequence of this project,

Accountability beyond the Nation-State: The Implica-

tions of the Aarhus Convention," in World Resources

played a major role in fashioning and drafting the

two Danube basin countries have taken

Institute Environmental Governance Notes (April

Aarhus Convention, and it was conceived and negotiat-

ed in somewhat the same time period as the Danube

major strides toward making informa-

2000), accessed via http://www.wri.org/governance/

publications.html on 30 July 2002.

efforts. Danube basin countries have worked with inter-

tion access a working reality for their cit-

national organizations to develop programs for the

2. K. A. Annan, foreword to The Aarhus Conven-

Danube.

izens. Hungary's and Slovenia's efforts

tion: An Implementation Guide, by S. Stec and S.

Casey-Lefkowitz with J. Jendroska (New York and

12. The documents created by the project may be

can be models for their neighbors and for

Geneva: United Nations, 2000).

downloaded through the Regional Environmental Cen-

the international community struggling

ter for Central and Eastern Europe web site at http://

3. European Union (EU), Council Directive

www.rec.org/REC/Programs/PublicParticipation/

to make progress on global environmen-

90/313/EEC (7 June 1990).

DanubeInformation/Outputs.html.

4. Many commentators have noted the comparative-

tal problems of huge magnitude and

13. One example is the very different role courts play

ly low levels of transparency, accountability, and pub-

in enforcing government duties in civil law countries.

seeming intractability. Environmental

lic involvement in decisionmaking by EU institutions,

See, for example, R. G. Bell and S. Bromm, "Lessons

including environmental policy. See, for example, E.

protection everywhere works at a seem-

Learned in the Transfer of U.S.-Generated Environ-

Rehbinder and R. Stewart, Environmental Protection

mental Compliance Tools: Compliance Schedules for

ingly glacial pace, but experience sug-

Policy (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter & Co., 1988). A more

Poland," Environmental Law Reporter News & Analy-

recent paper stated, "The secrecy and lack of access to

gests that public involvement can help

sis 27, June 1997.

documentation relevant to the development of EU leg-

move the agenda forward. Ultimately, it

islation has been subject to criticism and can be con-

14. See, for example, R. G. Bell, "Are Market-Based

sidered a major factor for the often-quoted `democratic

Instruments the Right First Choice for Countries in Tran-

is the responsibility of each country and

deficit' of the European Union. For example, even the

sition?" Resources 146 (2002), accessible via http://

the project participants to help build a

European Parliament could not, for a long time, access

www.rff.org/resources_archive/pdf_files/146.pdf.

certain documents used and developed by various com-

15. For a discussion of parallel attitudes in Poland,

culture of environmental compliance.

mittees which assist the Commission in discharging its

see Brown, Angel, and Derr, note 10 above, page 56,

responsibilities to developing implementing rules

which states: "In practice, however, there are still seri-

under various directives and regulations" (A. A. Hal-

ous obstacles to broad participation in policy making

Ruth Greenspan Bell is director of International Insti-

paap, doctoral student paper, Yale University, New

and implementation, especially by the general public. .

tutional Development and Environmental Assistance at

Haven, Conn., 8 January 2001. A copy of the paper is

. . [One is] the Bureaucracy's deeply entrenched

Resources for the Future (RFF) in Washington, D.C.

on file at Resources for the Future (RFF) in Washing-

administrative resistance to external scrutiny and its

Her work focuses on environmental institutions and

ton, D.C.).

disdain for the value of lay persons' contribution to

tools for environmental compliance in the developing

data analysis and policy making. . . . [Also] all parties

world and countries in transition, public participation

5. The United Kingdom's Official Secrets Act has

are strongly influenced by the prevailing cultural

as a means of facilitating or accelerating the process of

been considered a substantial barrier to opening up the

mores, which, in Poland, favor delegating problems to

environmental compliance, and implementation of

closed nature of policymaking within the U.K. govern-

experts who solve them in closed meetings." Brown

international environmental agreements. Jane Bloom

ment. After considerable controversy, the Freedom of

and her colleagues also note that "the independent eco-

Stewart is an environmental lawyer and director of the

Information Act finally received Royal Assent on 30

logical organizations have no traditions of participative

International Environmental Legal Assistance Program

November 2000 and is to be implemented in stages.

legal process and are too fragmented to mobilize their

at the New York University (NYU) Center on Environ-

See Her Majesty's Stationery Office, "Freedom of

limited resources necessary for such participation" and

mental and Land Use Law. She served as pro bono

Information Act 2000," United Kingdom Legislation,

that enterprises continue to be recipients of regulations

legal counsel to the Regional Environmental Center for

accessible via http://www.legislation.hmso.gov.uk/

rather than participants in their formulation. At the time

Central and Eastern Europe (REC) and has provided

acts/acts2000/20000036.htm. Countries with long-

she wrote, Brown noted that the situation was slowly

environmental law and policy advice to governments in

standing traditions of open government include Swe-

changing.

the region since 1991. Magda Toth Nagy directs the

den (see The Campaign for Freedom of Information,

Public Participation Program at REC, in Szentendre,

"Open and Shut Case: Access to Information in Swe-

16. Budgetary restrictions limited the study tour to

Hungary. She was a key actor in developing the Aarhus

den and the E.U.," accessed via http://www.cfoi.org.uk/

four participants from each country.

Convention and is a member of the Aarhus Convention

sweden1.html on 31 July 2002) and the Netherlands.

17. Article 14 (1) and (2), Environmental Protection

Advisory Board. She has been involved in managing

6. See, for example, D. J. Fiorino, "Technical and

Act, framework environmental law (1993), published

and overseeing various projects related to the imple-

Democratic Values in Risk Analysis," Risk Analysis 9,

in Official Gazette of the Republic of Slovenia, nos.

mentation of the convention and to the promotion of

no. 3 (1989).

32/93, 44/95, 1/96, 9/99, 56/99, and 22/00.

44

ENVIRONMENT

OCTOBER 2002