Mekong River Commission

Fish migrations of the

Lower Mekong River Basin:

implications for development,

planning and environmental

management

MRC Technical Paper

No. 8

October 2002

Published in Phnom Penh in October 2002 by the

Mekong River Commission

This document should be cited as:

Poulsen A.F. , Ouch Poeu, Sintavong Viravong, Ubolratana Suntornratana and Nguyen Thanh Tung.

2002. Fish migrations of the Lower Mekong River Basin: implications for development, planning

and environmental management. MRC Technical Paper No. 8, Mekong River Commission, Phnom

Penh. 62 pp. ISSN: 1683-1489

The opinions and interpretations expressed within are those of the authors

and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Mekong River Commission.

Editor: Ann Bishop

Layout: Boonruang Song-ngam

© Mekong River Commission

P.O. Box 1112, 364 M.V. Preah Monivong Boulevard

Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Telephone: (855-23) 720-979 Fax: (855-23) 720-972

E-mail: mrcs@mrcmekong.org

Website: www.mrcmekong.org

Acknowledgements

This report was prepared with financial assistance from the government of Denmark (through

Danida), under the auspices of the Assessment of Mekong Fisheries Component (AMFC)

of the MRC Fisheries Programme.

The authors wish to thank staff at the Department of Fisheries (Cambodia), LARReC (Lao

PDR, Department of Fisheries (Thailand) and the Research Institute for Aquaculture number

2 (RIA2) in Ho Chi Minh City (Viet Nam) for their contribution in compiling the ecological

information, on which much of this report is based.

The authors also wish to thank Dr. Chris Barlow and Kent Hortle from the MRC Fisheries

Programme, and Dr. Ian Campbell from the MRC Environment Programme, for reviewing

early drafts of the report.

Table of Contents

Summary - English............................................................................................... 1

Summary - Khmer................................................................................................. 5

Summary - Lao................................................................................................... 9

Summary - Thai.................................................................................................. 13

Summary - Vietnamese......................................................................................... 17

1. INTRODUCTION........................................................................................... 21

1.1 Background............................................................................................21

1.2 The purpose of this report................................................................................ 22

2 ANIMAL MIGRATIONS...................................................................................... 23

2.1 Fish migrations and life cycles..........................................................................24

3. FISH MIGRATION IN THE MEKONG RIVER.......................................................25

3.1 Important fish habitats in the Mekong Basin.........................................................26

3.2. Fish migrations and hydrology in the Mekong Basin................................................31

3.3. Major migration systems of the Mekong ..........................................................32

4. MANAGING MIGRATORY FISHES....................................................................... 41

4.1. Key issues for the maintenance of ecological functioning of

the Mekong ecosystem, with reference to migratory fishes........................................42

5. POTENTIAL IMPACTS OF DEVELOPMENT ACTIVITIES......................................... 47

5.1 Human impacts on the Mekong fisheries ..........................................................47

REFERENCES..................................................................................................... 59

Fish migrations of the Lower Mekong River Basin

Summary

In the Mekong River Basin, most fishes are migratory. Many of them migrate long distances, often

across international borders during their seasonal movements. People throughout the basin depend,

directly or indirectly, upon the migrating fish for food and livelihood. Water management projects

such as hydroelectric dams could adversely impact those migrations and thus negatively effect the

livelihoods of a large number of people.

This report identifies some key features of the Mekong River ecosystem that are important for the

maintenance of migratory fishes and their habitats. The report further discusses ways in which

available information about migratory fishes can be incorporated in planning and environmental

assessments.

Three distinct, but inter-connected, migration systems have been identified in the lower Mekong

River Basin, each involving multiple species. These are respectively the lower (LMS), the middle

(MMS) and the upper (UMS) Mekong migration systems. These migration systems have evolved as

a response to the hydrological and morphological shape of the Mekong in its lower, middle and

upper sections.

In a complex, multi-species ecosystem, such as the Mekong River Basin, single-species management

is not feasible. Instead, a more holistic ecosystem approach is suggested for management and planning.

The migration systems mentioned above could be used as the initial, large-scale framework under

which ecosystem attributes can be identified and, in turn, transboundary management and basin

development planning can be implemented.

The important ecological, or ecosystem, attributes of migratory fishes are identified for each migration

system. The emphasis is on maintaining critical habitats, the connectivity between them and the

annual hydrological pattern responsible for the creation of seasonal floodplain habitats.

The Lower Mekong Migration System (LMS)

Dry season refuge habitats: Deep pools, particularly in the Kratie-Stung Treng stretch of the

Mekong mainstream.

Flood-season feeding and rearing habitats: Floodplains in the Mekong Delta in Viet Nam, in

southern Cambodia, and in the Tonle Sap system.

Spawning habitats: Rapids and deep pool systems in Kratie-Khone Falls, and in the Sesan

catchment. Floodplain habitats in the south (e.g. flooded forests associated with the Tonle Sap

Great Lake).

1

Fish migrations of the Lower Mekong River Basin

Migration routes: The whole Mekong mainstream from the Mekong Delta to the Khone Falls,

including the Tonle Sap River (longitudinal connectivity). Between floodplain habitats and river

channels (lateral connectivity). Between the Mekong mainstream and the Sesan

sub-catchment (including the Sekong and Srepok Rivers).

Hydrology: The annual floods that inundate large areas of southern Cambodia (including the

Tonle Sap system) and the Mekong Delta, and the annual reversal of the Tonle Sap River, are

essential for fisheries productivity.

The Middle Mekong Migration System (MMS)

Dry season refuge habitats: Deep pool stretches of the Mekong mainstream and within major

tributaries.

Flood-season feeding and rearing habitats: Floodplains of this system that are mainly associated

with major tributaries.

Spawning habitats: Rapids and deep pool systems in the Mekong mainstream. Floodplain

spawning habitats associated with tributaries.

Migration routes: Connections between the Mekong River (dry season habitats) and major

tributaries (flood season habitats).

Hydrology: The annual flood pattern that causes inundation of floodplain areas along major

tributaries.

The Upper Mekong Migration System (UMS)

Dry Season refuge habitats: Occur throughout the extent of the Upper Mekong Migration

System, but are most common in the downstream stretch from the mouth of Loei River to Louang

Prabang.

Flood-season feeding and rearing habitats:Floodplain habitats are restricted to the floodplains

that border the main river, as well as smaller floodplains along some of the tributaries.

Spawning habitats: Spawning habitats that are situated mainly in stretches where rapids alternate

with deep pools.

Migration routes: Migration corridors between downstream dry-season refuge habitats and

upstream spawning habitats.

Hydrology: The annual flood pattern that triggers fish migrations and causes inundation of

floodplains.

These ecosystem attributes should be taken into account when assessing impacts of development

activities. A pre-requisite for impact assessments is a valuation of the impacted resource (e.g. migratory

fishes) from a fishery perspective. Undertaking such a valuation of migratory fishes is extremely

difficult because they are targeted throughout their distribution range in many different ways, and

2

Fish migrations of the Lower Mekong River Basin

with many different fishing gears and operations. Given the scale and complexity of such an

undertaking in the Mekong River, it is probably not possible to fully assess the economic value of

migratory fishes.

However, a partial assessment of value, together with an assessment of information gaps is in many

cases sufficient for planning and assessment purposes. It is also important to emphasise that in the

decision-making process, qualitative information and knowledge from various sources should be

included on equal terms with quantitative data. Furthermore, along with the direct value of fishery

resources, the Mekong River ecosystem provides numerous intrinsic, non-quantifiable goods and

services.

To ensure that the Mekong River Basin can continue to provide these important goods and services,

we propose that development planning and environmental assessment should be based on an ecosystem

approach within which the ecological functioning, productivity and resilience of the ecosystem are

maintained. Experiences from other river basins suggest that from an economic, social and

environmental point of view, this is best way to utilise a river.

3

Fish migrations of the Lower Mekong River Basin

xøwmsarsegçb³

enAkñúgGagTenøemKgÁ RtIPaKeRcInCaRbePTRtIbMlas;TI. PaKeRcInénBBYkRtIbMlas;TIEtgeFIV

cracrpøÚvq¶ayedayqøgkat;RBMRbTl;GnþrCatikñúgrdUvbMlas;TIrbs;BYkva. RbCaCnkñúgGagTaMgmUl

BwgEp¥kedaypÞal; rWedayRbeyaleTAelIRbePTRtIbMlas;TIsMrab;;CamðÚbGahar nigCIvPaBrs;enA.

KMeragRKb;RKgTwkCaeRcIn dUcCaTMnb;varIGKÁIsnIGacCH\Ti§BlGaRkk;y:agF¶n;F¶rdl;karbMlas;TI rbs;RtI

nigCalT§plpþl;plb:HBal;CaGviC¢mandl;CIvPaBrs;enArbs;RbCaCnCaeRcIn.

GtßbTenHnwgbgðajnUvlkçN³BiessCaKnwøHmYYycMnYnénRbB½§neGkUTenøemKgÁ Edlmansar³sMxan;

dl;karEfrkSaRbePTRtIbMlas;TI nigCMrkrbs;RtIRbePTenH. GtßbTenHnwgpþl;CabEnßmnUvviFIEdl

eyIgGacTTYl)anB'tmansþIGMBIRbePTRtIbMlas;TIEdlRtUv)aneKdak;bBa©ÚleTAkñúgEpnkar nigkar

vaytMélbrisßannana.

RbB½§nbMlas;TIcMnYnbIepSg²KñaEdlmanTMnak;TMngKñaeTAvijeTAmk RtUv)aneKkt;sMKal;eXIjman

enAkñúgGagTenøemKgÁeRkamEdlRbB½n§nimYy²Cab;Tak;TgKñaCamYyBUCRtICaeRcIn. TaMgGs;enHCa

RbB½§nbMlas;TIdac;edayELk²BIKñarvagEpñkxageRkam EpñkkNþal nigPaKxagelIénTenøemKgÁ.

RbB½§nbMlas;TITaMgenH)aneqIøytbeTAnwgRTg;RTayClviTüa nigrUbsaRsþénTenøemKgÁenAEpñkxageRkam

kNþal nigxagelIrbs;TenøenH.

kñúgRbB½§neGkUcMruHRbePT nigsaMjauMmYydUcCaGagTenøemKgÁ karRKb;RKgRbePTeTalNamYyenaHKW

minGaceFIV)aneLIy. pÞúyeTAvij eK)anesñIeGaymankarRKb;RKgmYy nigkardak;EpnkartamTis

edAsMrab;RbB½§neGkUTaMgmUl. ral;RbB½§nbMlas;TIEdl)anbriyayxagelIGaceRbIR)as;kñúgRkbx½NÐ

énkarcab;epþIm b£kñúgvisalPaBmYyTUlayEdlkñúgenaHGtþsBaØaNénektn³P½ÐNRbB½§neGkUTaMg

enH)anRtUvbgðajeGayeXIj nigCabnþ eTIbkarRKb;RKgqøgEdn nigkareFIVEpnkarGPivDÆn¾kñúgGag

GacGnuvtþeTA)an.

ektn³P½ÐNd¾sMxan;rbs;RbB½§neGkU rWeGkULÚsIuénRbePTRtIbMlas;TIRtUv)aneKsMKal;eXIjcMeBaH

RbB½§nbMlas;TInimYy². sar³sMxan;KWkarEfrkSaral;CMrksMxan;² PaBTak;TgKñaeTAvijeTAmkrvagCMrk

nigdMeNIrClviTüaRbcaMqñaMEdlFanadl;karbegIáteGaymanCMrkenAdMbn;licTwktamrdUvCaeRcInkEnøg.

5

Fish migrations of the Lower Mekong River Basin

RbB½§nbMlas;TIenATenøemKgÁPaKxageRkam

CMrkrs;enArdUvR)aMg³ GnøúgeRCA² CaBiessenAextþRkecH nigextþsÞwgERtgtambeNþayTenøemKgÁ.

cMNIGaharnardUvTwkdMeLIg nigCMrkbnþBUC³ TMnablicTwkkñúgdMbn;dIsNþrTenøemKgÁénRbeTs evotNam

dMbn;PaKxagt,ÚgRbeTskm<úCa nigtamRbB½§nTenøsab.

CMrkBgkUn³ RbB½§nGnøúgeRCA² nigfµb:RbHTwkenAkñúgextþRkecH l,ak;exan nigdMbn;rgTwkePøóg énTenøessan.

CMrkCaeRcInenAkñúgdMbn;licTwkPaKxagt,Úg ¬]> dMbn;éRBlicTwkCMuvijbwgTenø sab¦.

pøÚvcracrRtI³ RbB½§nTenøemKgÁTaMgmUlcab;BIdMbn;dIsNþrTenøemKgÁrhUtdl;l,ak;exan rYmbBa©Úl

TaMgTenøsab ¬TMnak;TMngExSry³beNþay¦. rvagCMrkdMbn;licTwk nigTenønana ¬TMnak;TMngépÞ lat¦.

rvagTenøemKgÁ nigGnudMbn;rgTwkePøógénTenøessan ¬rYmbBa©ÚlTaMgTenøeskug nigTenøERsBk¦.

ClsaRsþ³ CMnn;RbcaMqñaMy:agFMlwVgelIVyEdllicdMbn;CaeRcInénPaKxagt,ÚgRbeTskm<úCa ¬Kit

bBa©ÚlTaMgRbB½§nTenøsab¦ nigdMbn;dIsNþremKgÁ RBmTaMgkarhUrRtLb;rbs;Tenøsabmansar³

sMxan;Nas;cMeBaHplitPaBClpl.

RbB½§nbMlas;TIenATenøemKgÁPaKkNþal

CMrkrs;enArdUvR)aMg³ manenAtamGnøúgeRCA²énTenøemKgÁ nigenAtamédFM²énTenøemKgÁ.

cMNIGaharnardUvTwkdMeLIg nigCMrkbnþBUC³ CMrktamdMbn;licTwkPaKeRcInCaBiessCab;tam édTenøFM².

CMrkBgkUn³ enAtamRbB½§nGnøúgeRCA² nigdMbn;fµb:RbHTwkTenøemKgÁ. enAtamCMrkBgkUndMbn;

licTwktamédTenø.

pøÚvcracrRtI³ Cab;KñarvagTenøemKgÁ ¬CMrkrdUvR)aMg¦ nig tamédTenøFM² ¬CMrkrdUvCMnn;¦.

ClsaRsþ³ RbePT RTg;RTay nigvisalPaBTwkCMnn;RbcaMqñaMbNþaleGaymankarlicdMbn;TMnab

énédTenøFM².

6

Fish migrations of the Lower Mekong River Basin

RbB½§nbMlas;TIenATenøemKgÁPaKxagelI

CMrkrs;enArdUvR)aMg³ ekItmanenATUTaMgRbB½§nTenøemKgÁelI b:uEnþPaKeRcInmanenAkñúgdMbn;PaKxag

eRkamcab;BImat;énTenøelIydl;lYgR)a)ag.

cMNIGaharnardUvTwkdMeLIg nigCMrkbnþBUC³ CMrkdMbn;licTwkCaeRcInmanenAdMbn;licTwkEdl

CaRBMRbTl;énTenøFM² k¾dUcCadMbn;valTMnabtUc² tambeNþayédTenøtUc²mYycMnYn.

CMrkBgkUn³ CMrkBgkUnfitenACaBiesstamtMbn;fµb:RbHTwkEdlmanGnøúgeRCA².

pøÚvcracrRtI³ pøÚvrebogbMlas;TImanenAcenøaHCMrkrs;enAnardUvR)aMgenAPaKxageRkam nigCMrkBg

kUnenAPaKxagelI.

ClsaRsþ³ RbePT RTg;RTay nigvisalPaBTwkCMnn;RbcaMqñaMCaKnwøHCMrujeGaymankarbMlas;TI rbs;RtI

nigeGaymanTwkCMnn;dl;TMnabkNþal.

ektn³sm,tiþRbB½§neGkUTaMgenHKb,IRtUv)aneKykcitþTukdak;enAeBleFIVkarvaytMélBIplb:HBal;

bNþalmkBIskmµPaBGPivDÆn¾nana. kartRmUveGaymankarvaytMélCamunBIplb:HBal;KWCakar

vaytémønUvFnFanEdlGacTTYlrgkarb:HBal; ¬]> RbePTRtIbMlas;TII¦ elIvis½yClpl. kareFIV

karvaytMélRbePTRtIbMlas;TIEbbenHKWmankarlM)akCaTIbMput BIeRBaHeKRtUvkMNt;eKaledArbs;

vatamry³karerobcMCaRkum²edayviFIepSg²cMeBaHRbePTRtITaMgenaH nigtamrebobénkareFIV ensaTnig

RbePT]bkrN¾ensaTepSg²eTot. edaysarEtvisalPaB nigPaBsµúRKsµajénkar

Gnuvtþn¾EbbenHenAkñúgTenøemKgÁdUecñHehIy eTIbeKminGacvaytémøCarYm)anGMBIsar³sMxan;dl;

esdækic©rbs;RbePTRtIbMlas;TI .

7

Fish migrations of the Lower Mekong River Basin

eTaHCay:agNakþI kñúgkrNICaeRcInkarvaytMélmYyEpñkNaRBmCamYynwgkarvaytMélelIkgVH

xatEpñkB'tmanGacRKb;RKan;sMrab;kareFIVEpnkar nigbMerIeKaledAkarvaytémø. vaCakard¾caM)ac;

pgEdrEdlfa kñúgdMeNIrkareFIVesckIþsMerccitþ cMeNHdwg nigB'tmanEdlmanKuNPaBBIRbPBepSg

²Kb,Idak;bBa©ÚleGayesµIKñanwgTinñn½yCabrimaNpgEdr. bEnßmelIsenHeTotrYmCamYynwgtMél

pÞal;énRbPBFnFanClpl RbB½§neGkUTenøemKgÁpþl;eGaynUvmCÄniþk³y:agsem,Im RTBüsm,tþi

minGackat;éfø)an nigesvaCaeRcIn.

edIm,IFana)anfa GagTenøemKgÁGacbnþpþl;nUvRTBüsm,tiþ nigesvad¾mantMélTaMgenH eyIgxJMúesIñfa

kark¾sagEpnkarGPivDÆn¾ nigkarvaytMélbrisßanKb,IQrelImUldæanTsSn³RbB½§neGkUEdlkñúg

enaHeyIgRtUvrkSaeGay)annUvkarRbRBwtþieTAénRbB½§neGkULÚsIu plitPaB nigKµankarb:HBal;dl; RbB½§neGkU

. bTBiesaFn¾TaMgLayEdl)anmkBIbNþaGagTenøepSg²pþl;eyabl;fa cMeBaHvis½y brisßan sgÁm

nigesdækic©enHCaviFImYyd¾l¥bMputkñúgkareRbIR)as;Tenø.

8

®ö©¦½¹ì÷®¨Ó

Ã-ºÈ¾¤Á´È-Õ¢º¤, ¯¾¦È¸-¹ì¾¨Á´È-´ó¡¾-À£^º-¨É¾¨ (¢oe-OEìȺ¤). §^¤´ó¯¾¹ì¾¨§½-ò© À£^º-

¨É¾¨À¯ñ-Ä쨽꾤ġ ¢É¾´°È¾-À¢©Á©-ì½¹¸È¾¤¯½Àê© Ã-콩ø¡¾-À£^º-¨É¾¨. ¯½§¾§ö-Ã-

긺Ⱦ¤Á´È-º¾Ä¦§È¸¤©,,¤¡È¾¸ê¿¡¾-¥ñ®¯¾À²^º®ðìò²¡ Áì½ ¡¾-©¿ìö¤§ó¸ó©. £¤¡¾- ¡¾-

²ñ©ê½-¾¡È¼¸¡ñ®¡¾-çÉ-ժȾ¤Å À§,,- À¢^º-ij³É¾ ¦¾´¾©À¯ñ-º÷¯½¦ñ¡¡ó©¢¸¾¤ê¾¤À£^º-¨É¾¨

¢º¤¯¾Ä©É Áì½ ¡ÒùÉÀ¡ó©°ö-¡½êö®ê¾¤ìö®ªÒ ¡¾-©¿ìö¤§ó¸ò©¢º¤ ¯½ §¾§ö-¥¿-¸-¹ì¾¨.

®ö©ì¾¨¤¾-¦½®ñ®-s ĩɧsùÉÀ¹ñ-®¾¤ìñ¡¦½-½êÀ¯ñ-¢ð¡½Á¥ ¢º¤ì½®ö®-òÀ¸© ¢º¤Á´È-Õ¢º¤

ꦿ£ñ- À²^º»ñ¡¦¾ êµøº¾Ä¦¢º¤¯¾ê´ó-òĦÀ£^º-¨É¾¨. ®ö©ì¾¨¤¾- ¨ñ¤Ä©É¡È¾¸À«ó¤§Èº¤ê¾¤Ã-

¡¾--¿Àºö¾¢Ó´ø-¡È¼¸¡ñ®¡¾-À£^º-¨É¾¨¢º¤¯¾À¢í¾Ã-¡¾-¸¾¤Á°- Áì½ ¡¾-¯½À´ó- 꾤©É¾-

¦...¤Á¸©ìɺ´.

´ó 3 ì½®ö®Áª¡ªÈ¾¤¡ñ-Ã-¡¾-À£^º-¨É¾¨¢º¤¯¾ ê£í-£É¸¾²ö®Ã-ºÈ¾¤Á´È-Õ¢º¤, ÁªÈ¸È¾ ÁªÈì½

ì½®ö®Á´È-´ó¡¾-²ö¸²ñ-§^¤¡ñ- Áì½ ¡ñ-, ÁªÈì½ì½®ö®Á´È-´ó¹ì¾¨§½-ò©¯¾À£^º-¨É¾¨»È¸´

¡ñ-. 3 ì½®ö®À£^º-¨É¾¨©,,¤¡È¾¸ £õ: À¢©Á´È-Õ¢º¤ªº-ÃªÉ (LMS), À¢©Á´È-Õ¢º¤ªº-¡¾¤

(MMS) Áì½ À¢©Á´È-Õ¢º¤ªº-ÀÎõº (UMS). ì½®ö®À£^º-¨É¾¨©,,¤¡È¾¸ Á´È-Ä©É¥¿Á¨¡

©¨ºó¤Ã¦Èìñ¡¦½-½ 꾤º÷¹ö¡¡½¦¾© Áì½ »ø®»È¾¤ ìñ¡¦½-½¢º¤ Á´È-Õ¢º¤ ÁªÈì½²¾¡ À§,,-:

ì÷È´, ¡¾¤ Áì½ ÀÎõº.

Ã-£¸¾´¦½ìñ®§ñ®§Éº- ¢º¤ì½®ö®-òÀ¸©OE-¾-¾²ñ- À§,,- ºÈ¾¤Á´È-Õ¢º¤-s, ¡¾-£øÉ´£º¤¯¾

§½-ò©-¤ §½-ò©©¼¸ Á´È- À¯ñ-įĩɨ¾¡. Ã-꾤¡ö¤¡ñ-¢É¾´, ¥^¤Á-½-¿¸È¾£¸-¸¾¤Á°- £øÉ´

£º¤êñ¤ì½®ö®-òÀ¸©Â©¨ì¸´. ì½®ö®¡¾-À£^º-¨É¾¨¢º¤¯¾ê¡È¾¸Ä¸É¢É¾¤Àêò¤-~- Á´È-¦¾´¾©

çÉÀ¯ñ-¡¾-Àìs´ªí-Àê¾-~-, ÁªÈÃ-¢º®À¢©ê¡É¸¾¤¢oe-¢º¤ì½®ö®-òÀ¸© ¦¾´¾©¡¾¨À¯ñ-®ñ-¹¾

¡¾-£øÉ´£º¤°ö-¡½êö®¢É¾´§¾¨Á©- Áì½ ¦¾´¾©-¿À¢í¾¯½ªò®ñ©Ä©ÉÃ-Á°-¡¾-²ñ©ê½-¾ ºÈ¾¤.

£¸¾´¦¿£ñ-¢º¤-òÀ¸©¸ò꽨¾ ¹ìõ ì½®ö®-òÀ¸© À»ñ©Ã¹É´ó£¸¾´¦¾´¾©¥¿Á-¡Ä©ÉÀ«ó¤¯¾ ê

´ó-òĦÀ£^º-¨É¾¨ Ã-ÁªÈì½ì½®ö®À£^º-¨É¾¨. ªÉº¤Àºö¾Ã¥Ã¦È ¯ö¡¯ñ¡»ñ¡¦¾ ®Èº-µøȺ¾Ä¦ êÀ¯ñ-¥÷©

¹ìÒÁ¹ì´, ê´ó¡¾-À¦º´ªÒ ì½¹¸È¾¤ 꺾Ħ-~- ¡ñ® 콩ñ®º÷êö¡¡½¦¾©¯½¥¿¯ó ê´ó£¸¾´

¦¿²ñ-Ã-¡¾-¡ÒùÉÀ¡ó© êµøȺ¾Ä¦¢oe-Ã-À¢©-իɸ´¯½¥¿¯ó.

ì½®ö®À£^º-¨É¾¨¢º¤¯¾Ã-Á´È-Õ¢º¤ªº-ì÷È´ (LMS)

OEêµøȺ¾Ä¦ ìsIJÃ-콩øÁìɤ: ¸ñ¤Àìò¡, ©¨¦½À²¾½Ã-À¢© ¡½Á¥½ ¹¾ §¼¤Áª¤ (¡¿¯øÀ¥¼)

Ã-ì¿Á´È-Õ¢º¤.

OEêµøȺ¾Ä¦êÀ¯ñ-®Èº-º½-÷®¾-Áì½Á¹ìȤº¾¹¾-Ã-콩ø±ö-: À¢©-Õ«¸É´Ã- À¢©¦ñ-©º-

¯¾¡Á´È-Õ¢º¤ (Mekong Delta) ¢º¤¹¸¼©-¾´, ²¾¡ÃªÉ ¡¿¯øÀ¥¼ Áì½ ê½À즾®-Õ¥õ©

(Tonle Sap System) ¢º¤¡¿¯øÀ¥¼.

OE®Èº-¯½¦ö´²ñ- ¸¾¤Ä¢È: À¢©À¯ñ-Á¡É¤ Á콸ñ¤Àìò¡ ÁªÈ ¡½Á¥½ ¹¾ -Õªö¡£º-²½À²ñ¤, Áì½

À¢©Á´È-ÕÀ§¦¾-. À¢©-իɸ´Ã-²¾¡ÃªÉ (À§,,-: À¢©¯È¾-Õ «É¸´ ºÉº´ ê½À즾®-Õ¥õ© (Great

Lake) ¢º¤¡¿¯øÀ¥¼).

OEÀ¦~-꾤À£º-¨É¾¨¢º¤¯¾: Ã-ì¿Á´È-Õ¢º¤ ¥¾¡À¢© Mekong Delta ¹¾ -Õªö¡£º-²½ À²ñ¤

츴êñ¤ Á´È-Õªö¤À즾® (À¯ñ-À¦~-꾤ªò©ªÒ꾤¨¾¸). 콹ȸ¾¤ À¢©-իɸ´ ¹¾ ì¿-Õ

(À¯ñ-À¦~-꾤ªò©ªÒ꾤 ¢¸¾¤). ì½¹ú¸¾¤ ì¿-Õ¢º¤ Á콺Ⱦ¤ÂªÈ¤À§¦¾- (츴Àºö¾ À§¡º¤

À§¦¾- Áì½À§ë¯º¡)

OEº÷êö¡¡½¦¾©: -իɸ´¯½¥¿¯ó Áì½À¢©-իɸ´ ê¡û¸¾¤Ã¹¨ÈÃ-²¾¡ÃªÉ¢º¤ ¡¿¯øÀ¥¼ (츴êñ¤

Á´È-Õªö¤À즾®) Áì½ Mekong Delta, Á콡¾-Ĺì¡ñ®£õ-¯½¥¿¯ó¢º¤Á´È-Õªö¤À즾®

Á´È-´ó£¸¾´ ¦¿£ñ- ªÒ°ö-²½ìò©¯¾.

ì½®ö®À£^º-¨É¾¨¢º¤¯¾Ã-Á´È-Õ¢º¤ªº-¡¾¤ (MMS)

OEêµøȺ¾Ä¦ ìsIJÃ-콩øÁìɤ: ¸ñ¤Àìò¡ª¾´ì¿Á´È-Õ¢º¤ Á콦¾¢¾Ã¹¨ÈÅ¢º¤Á´È-Õ¢º¤

OEêµøȺ¾Ä¦êÀ¯ñ-®Èº-º½-÷®¾-Áì½Á¹ìȤº¾¹¾-Ã-콩ø±ö-: À¢©-իɸ´ ª¾´ìɺ¤Á´È-Õ

¦¾¢¾¢º¤Á´È-Õ¢º¤

OE®Èº-¯½¦ö´²ñ- ¸¾¤Ä¢ú: ª¾´Á¡É¤ Á콸ñ¤Àìò¡ª¾´ì¿Á´È-Õ¢º¤. À¢©-իɸ´ª¾´ìɺ¤-Õ

¦¾¢¾Á´È-Õ¢º¤.

OEÀ¦~-꾤À£º-¨É¾¨¢º¤¯¾: 콹ȸ¾¤ ì¿Á´È-Õ¢º¤ (꺾µøÈĦÃ-콩øÁìɤ) Áì½

¦¾¢¾Ã¹¨ÈÅ¢º¤Á´È-Õ¢º¤ (꺾µøÈĦÃ-콩ø±ö-)

OEº÷êö¡¡½¦¾©: 콩ñ®-իɸ´ ¯½¥¿¯ó êÀ¡ó©´ó-Õ¢ñ¤ ª¾´À¢©-իɸ´ ì¼®ª¾´¦¾¢¾Ã¹ÈÅ

¢º¤Á´È-Õ¢º¤

ì½®ö®À£^º-¨É¾¨¢º¤¯¾Ã-Á´È-Õ¢º¤ªº-ÀÎõº (UMS)

OEêµøȺ¾Ä¦ ìsIJÃ-콩øÁìɤ: ´óµøÈê¸Ä¯Ã-À¢© ªº-ÀÎõº(UMS), ÁªÈ¦È¸-¹ì¾¨´óµøȦȸ- êÉ

¥¾¡ ¯¾¡Á´È-ÕÀìó¨ ¹¾ ¹ì¸¤²½®¾¤.

OEêµøȺ¾Ä¦êÀ¯ñ-®Èº-º½-÷®¾-Áì½Á¹ìȤº¾¹¾-Ã-콩ø±ö-: ®ðÀ¸--իɸ´ Ã-ªº--s¥½´ó

¢º®À¢©¥¿¡ñ© µøÈì¼®ª¾´Á£´Á´È-Õ Áì½À¢©-իɸ´-ɺ¨Å ª¾´êªÔ Àì¾½ª¾´ì¿-Õ.

OE®Èº-¯½¦ö´²ñ- ¸¾¤Ä¢ú: ®ºÈ-¯½¦ö´²ñ-¸¾¤Ä¢È Á´È-´óµøÈê¸Ä¯ ª¾´ì¿Á´È-Õ¢º¤ Á콦ȸ-

¹ì¾¨¥½Á´È-®Èº-êÀ¯ñ-Á¡É¤ êªò©¡ñ®¸ñ¤Àìò¡

OEÀ¦~-꾤À£º-¨É¾¨¢º¤¯¾: Áú´-À¦~-꾤À¦^º´ªÒ콹ȸ¾¤ êìsIJ콩øÁìɤÃ-À¢©ÃªÉ¢º¤

ªº-ÀÎõº ¹¾ ®Èº-¯½¦ö´²ñ-¸¾¤Ä¢ÈÃ-À¢©ÀÎõº¦÷©

OEº÷êö¡¡½¦¾©: 콩ñ®-իɸ´¯½¥¿¯óê ¡½ª÷É-ùɯ¾ê¿¡¾-À£^º-¨É¾¨ Áì½À»ñ©Ã¹É´ó-Õ«ñ¤

Ã-À¢©-իɸ´.

£÷-¦ö´®ñ©¢º¤ì½®ö®-òÀ¸©À¹ì¾-s £¸--¿À¢í¾Ã-¢½®¸-¡¾-¯½À´ó-°ö-¡½êö® Ã-£¤¡¾-²ñ©

ê½-¾ªÈ¾¤Å. ¡¾-¦ô¡¦¾ ¯½À´ó-°ö-¡½êö®À®oeº¤ªí- Á´È-´ó¯½Â¹¨©ªÒ°ö-¡½êö® ꥽´óÁ¡È§ñ®

²½¨¾¡º- (À§,,-: ¯¾ê´ó¡¾-À£^º-¨É¾¨) ê¡È¼¸¡ñ®¡¾-¯½´ö¤. À´^º¡È¾¸À«¤£÷-£È¾¢º¤¯¾ê´ó-ò

ĦÀ£^º-¨É¾¨Áìɸ Á´È-¨¾¡¥½ê¿¡¾-¯½À´ó-, À²¾½¸È¾ ´ñ-¡½¥¾¨µøÈê¸ê÷¡Á¹ìȤ-Õ ¦¾¢¾

-Õ¢º¤, ¹ì¾¨»ø®Á®® Áì½ ¹ì¾¨¸òêò¡¾-¥ñ® ©¨Ã§ÉÀ£^º¤´õ¹ì¾¨»ø®Á®®. À-º¤¥¾¡ £¸¾´

¦½ìñ®§ñ®§Éº-©,,¤¡È¾¸¢º¤Á´È-Õ¢º¤, ¥^¤®Òº¾©¦¾´¾©À¯ñ-Ä¯Ä©É ê¥½¯½À´ó-´ø-£È¾ê¾¤©É¾-

À¦©«½¡ò© ¢º¤¯¾êê¿¡¾-À£^º-¨É¾¨. À«ó¤µÈ¾¤Ã©¡Òª¾´, ¡¾-¯½À´ó-´ø-£È¾À¯ñ-®¾¤¦È¸-

²Éº´¡ñ®¡¾-¯½À´ó-§Èº¤¸È¾¤¢º¤¢Ó´ø-¢È¾¸¦¾- ê²¼¤²ð¦¿¹ìñ®¡¾-¸¾¤Á°-¡¾-. ¦¿£ñ-į

¡È¸¾-~-Á´È-¢½®¸-¡¾-À²^º¡¾-ªñ©¦ò-Ã¥, £÷--½²¾®¢º¤¢Ó´ø- Áì½ £¸¾´»øÉê´¾¥¾¡

¹ì¾¨ÅÁ¹ìȤ£¸-¯½¡º®À¢í¾Ã¹É´ó£¸¾´¦½ÀÏ󲾮꾤©É¾-®ðìò´¾©¢º¤¢Ó´ø-. ¨¤Ä¯¡È¸¾-~-,

´ø-£È¾Â©¨¡ö¤¢º¤§ñ®²½¨¾¡º-©É¾-¯½´ö¤, ¡¾-¯½¡º®¦È¸-¢º¤ ì½®ö®-òÀ¸© ¢º¤Á´È-Õ¢º¤

ê´ó£¸¾´¦¿£ñ-Ã-¡¾-°½ìò©ê®Ò¥¿¡ñ©¯½ìò´¾- Áì½ ¡¾-®ðìò¡¾-.

À²^º£¸¾´Á-È-º- ꥽À»ñ©Ã¹ÉºÈ¾¤Á´È-Õ¢º¤ À¯ñ-®Èº-°½ìò© Áì½ ®ðìò¡¾-ꦿ£ñ--s¦õ®ªÒį,

²¸¡À»ö¾¦½ÀÎó¸È¾ Á°-¡¾-²ñ©ê½-¾ Áì½ ¡¾-¯½À´ó-©û¾-¦...¤Á¸©ìɺ´ £¸-ºó¤Ã¦Èêȸ¤êȾ

¢º¤ì½®ö®-òÀ¸© ²¾¨Ã-¢½®¸-¡¾-¢º¤ì½®ö®-òÀ¸©ê¡¿ìñ¤Ïø-į, £¸¾´º÷©ö´¦ö´®ø- Áì½

£¸¾´¯È¼-Á¯¤®Òµ÷©µ~¤ ¢º¤ì½®ö®-òÀ¸©ªÉº¤Ä©É¯ö¡¯ñ¡»ñ¡¦¾. ®ö©»¼-¥¾¡ ¹ì¾¨ÅºÈ¾¤Á´È-Õ

§s®º¡Ä¸É¸È¾ ¸òêó꾤©,,¤¡È¾¸´¾-s Á´È-À¯ñ-꾤ê©ó ê¦÷©Ã-¡¾--¿Ã§ÉÁ´È-ÕÃ-Á¤È À¦©«½¡ò©,

¦ñ¤£ö´ Áì½ ¦...¤Á¸©ìɺ´.

(Lower Mekong migration system; LMS),

(Middle Mekong migration system; MMS)

(Upper Mekong migration system;

UMS)

:

(Kratie) (Stung Treng)

:

(Tonle Sap River)

: (Khone Falls)

(Sesan) (

)

:

() (

) ( (Srepok))

:

()

:

:

:

: ()

()

:

:

:

:

:

:

( )

DI C CA CÁ H LU SÔNG MÊ CÔNG

NHNG VN LIÊN QUAN

TI QUI HOCH PHÁT TRIN VÀ QUN LÝ MÔI TRNG

Anders F. Poulsen, Ouch Poeu, Sitavong Viravong,

Ubolratana Suntonratana và Nguyn Thanh Tùng

Tóm tt

a s cá lu vc sông Mê công là cá di c. Rt nhiu loài trong mùa di c ca

chúng di chuyn c ly khá xa, vt qua biên gii quc t. Ngi dân sng trong lu vc

trc tip hoc gián tip ph thuc vào cá di c ly thc phm và sinh nhai. Các d án

qun lý nc nh các p thu in có th gây hi cho s di c, t ó nh hng xu

n cuc sng ca mt b phn ln dân c.

Báo cáo này xác nh mt s c tính then cht ca h sinh thái sông Mê Công

liên quan n vic bo v cá di c và ni c trú ca chúng. Báo cáo này còn tho lun

phng hng s dng thông tin v cá di c trong vic hp tác xây dng k hoch và

ánh giá môi trng.

h lu sông Mê Công ngi ta ã xác nh c 3 h di c riêng bit liên

quan n nhiu loài cá, có liên h mt thit vi nhau ó là: h h lu (LMBS), h trung

lu (MMMS) và h thng lu (UMBS). Nhng h di c này c hình thành t vic

thích nghi vi iu kin thy vn và hình thái ca các vùng h, trung và thng lu ca

sông Mê Công.

Trong

h sinh thái tng hp, a loài nh lu vc sông Mê Công thì vic ch qun

lý n loài là không kh thi. Trái li, ngi ta xut s tip cn c h qun lý và

qui hoch. Nhng h di c ã nói trên s c s dng nh mu ban u, xác nh

nó thuc h sinh thái nào, và t ó có th vn dng bin pháp qun lý xuyên biên gii

và qui hoch phát trin lu vc.

Mi h di c c xác nh bi nhng thuc tính sinh thái quan trng ca cá di

c. Bo v ni c trú có tính nguy c, duy trì mi liên h gia chúng và mô hình các

yu t thy vn hàng nm ã to ra ni c trú theo mùa vùng ngp là nhng iu cn

c nhn mnh.

H thng di c h lu sông Mê Công (LMS)

Ni n náu trong mùa khô: Vc sâu chy dc theo dòng chính sông Mê Công c bit

là tnh Kra Chiê, Stung Treng .

1

Ni kim n và v béo trong mùa l: Vùng ngp ng bng sông Cu Long Vit

Nam, min nam Cam Pu Chia và trong h thng bin h Tông Lê Sáp.

Bãi : h thng thác ghnh và vc sâu t Kra Chiê n thác Khôn và lu vc sông Sê

San. Vùng ngp phía nam (nh rng ngp nc khu vc bin h Tông Lê Sáp).

ng di c: Trên dòng chính t ng bng sông Cu long n thác Khôn bao gm c

sông Tông Lê Sáp (chy theo hàng dc); gia ni c trú vùng ngp và các nhánh sông

(chy theo hàng ngang); gia dòng chính sông Mê Công và tiu lu vc sông Sê San

(bao gm c sông Sê Công và sông Srê Pc).

Thu vn: l hàng nm làm ngp c vùng rng ln phía nam Cam Pu Chia (bao gm c

h thng sông Tông Lê Sáp) và ng bng sông Cu Long và thi gian sông Tông Lê

Sáp chy ngc li là thi gian rt quan trng i vi sn lng cá.

H thng di c trung lu sông Mê Công (MMS)

Ni n náu trong mùa khô: Vc sâu chy dc theo dòng chính sông Mê Công và các

nhánh chính .

Ni kim n và v béo trong mùa l: Vùng ngp ca h thng này ph thuc ch yu

vào các nhánh chính.

Bãi : h thng thác ghnh và vc sâu dòng chính sông Mê Công. Bãi trng vùng

ngp liên quan n các chi lu.

ng di c: Ni gia dòng chính sông Mê Công (ni c trú mùa khô) vi các chi lu

(ni c trú mùa l).

Thu vn: l hàng nm gây nên s ngp khu vc dc theo chi lu chính.

H thng di c thng lu sông Mê Công (UMS)

Ni n náu trong mùa khô: Xut hin trong sut h thng UMS nhng ph bin là

phn h lu t ca sông Loei n Luông Prabang.

Ni kim n và v béo trong mùa l: ni c trú trong vùng ngp b thu hp trong

phm vi vùng ngp ca dòng chính cng nh dc theo vùng ngp ca các chi lu .

Bãi : ni trng phân b dc theo dòng chy ni thác ghnh k tip vc sâu.

ng di c: hành lang di c ni ni c trú mùa khô h lu vi các bãi thng

lu.

Thu vn: l hàng nm gây nên s ngp và kích thích cá di c.

2

H thng sinh thái trên ây cn phi c tính n khi ánh giá nh hng ca các hot

ng phát trin. iu kin tiên quyt ánh giá nh hng là ánh giá ngun tài

nguyên b nh hng ( ây là cá di c) i vi vin cnh ngh cá. Tin hành ánh giá

cá di c nh vy là vic rt khó vì nhng cá này c khai thác theo nhng vùng phân

b khác nhau, ng c khác nhau và thao tác khác nhau. Tin hành a ra mc và

tng th khi ánh giá v giá tr kinh t ca cá di c sông Mê Công là không th c.

Tuy nhiên, ánh giá mt phn giá tr i ôi vi ánh giá s thiu ht thông tin trong

nhiu trng hp là thích hp cho vic d oán và xây dng k hoch. Mt iu quan

trng cn phi nhn mnh là trong quá trình a ra quyt nh thì thông tin v cht

lng và s hiu bit t nhiu ngun khác nhau cn phi coi ngang giá tr vi thông tin

v s lng. Ngoài ra, i ôi vi giá tr ngun li cá trc tip, h thng sinh thái sông

Mê Công còn cung cp nhng ca ci quí và dch v khác.

m bo cho sông Mê Công có th tip tc cung cp ca ci và dch v ó chúng tôi

kin ngh vic xây dng phát trin và ánh giá môi trng phi da trên c s s tip

cn sinh thái, trong ó chc nng sinh thái, sn phm và tính mm do ca h sinh thái

phi c duy trì. Kinh nghim t các h thng sông khác cho thy xut phát t quan

im kinh t xã hi và môi trng, ây là con ng tt nht khai thác dòng sông.

3

Fish migrations of the Lower Mekong River Basin

Introduction

1

1.1 Background

The Agreement on the Cooperation for the Sustainable Development of the Mekong River Basin

(The Mekong Agreement), which was signed in 1995 by the four countries of the lower Mekong

Basin (LMB), Cambodia, Lao PDR, Thailand and Viet Nam, is the legal foundation for the Mekong

River Commission (MRC). Through this Agreement the four countries are committed to:

"...cooperate in all fields of sustainable development, utilization, management and

conservation of the water and related resources of the Mekong River Basin including,

but not limited to irrigation, hydro-power, navigation, flood-control, fisheries, timber

floating, recreation and tourism, in a manner to optimize the multiple-use and mutual

benefits of all riparians and minimize the harmful effects that might result from natural

occurrences and man-made activities" (Article 1 of the Agreement).

Article 1 of the Agreement thus clearly reflects the fact that the Mekong River ecosystem provides

a wide range of benefits and resources, including fisheries. The fishery of the Mekong River Basin

is probably one of the largest and most important inland fisheries in the world 1 . The main reasons

for this are:

The river contains an unusually large number of species (probably more than 1,200).

A large number of people are involved in fisheries activities in the basin.

Large areas of floodplain remain accessible for fish production.

The annual flood pulse, which drives fish production on the floodplain, has not been greatly

affected, in contrast to most other large rivers.

In most of the basin, large-scale fish migrations provide the basis for the seasonal fisheries along

their migration routes. These migrations have not been affected as in most other large rivers.

The issue of fish migration is of particular interest to the MRC, since many migratory fish stocks

constitute transboundary resources, i.e. resources shared between two or more of the riparian

countries. Resolving transboundary issues is one of the main reasons for the existence of the MRC

and, therefore, one of its core working areas.

Although much is still to be learned about fish migrations in the Mekong, documented knowledge

has substantially increased in the past decade. During this period, the Fisheries Programme of the

MRC has carried out field surveys and research that have confirmed the importance of the Mekong

fisheries and documented some of the ecological processes and functional characteristics that support

these fisheries, including the role that fish migrations play in ecosystem functioning and productivity.

1

The total annual catch of the lower Mekong River Basin has been estimated at 1.5 2 million tonnes, and is particularly

important for food security and income generation for the large rural population of the basin.

21

Fish migrations of the Lower Mekong River Basin

1.2 The purpose of this report

The intention of this report is to promote the integration of ecological information into future basin

planning processes and environmental assessment (EA) procedures for the Mekong Basin. The

emphasis is on migratory fishes and the critical habitats and ecosystem attributes that sustain this

important resource.

The main targets of the report are the three core programmes of the MRC, the Basin Development

Plan (BDP), the Water Utilisation Programme (WUP) and the Environment Programme (EP).

Specifically, the report aims to provide inputs to: (1) the basin-wide and sub-catchment planning

process of the BDP; (2) the transboundary analysis work carried out under Working Group 2 of the

WUP; and (3) the Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) process, which is part of the

Environmental Assessment guidelines currently being developed under the Environment Programme.

The report will also be of use as a framework for Environmental Impact Assessment purposes for

specific development projects within the basin.

The report is mainly based on basin-wide surveys of local ecological knowledge carried out by the

assessment component of the MRC Fisheries Programme during 1999 and 2000. Information from

other sources is included (and referenced) where appropriate in order to support and complement

the surveys of local knowledge.

The methods that were applied during the local knowledge surveys have been described extensively

in other publications and will not be described here (Valbo-Jørgensen and Poulsen 2000; Poulsen

and Valbo-Jørgensen 1999).

Since the report covers the highest ecological scale (i.e. the entire Lower Mekong Basin), focus on

details is limited. We will, for example, not discuss species-specific information, but will instead

describe general patterns of large-scale migration systems. Individual species are included as

examples only.

22

Fish migrations of the Lower Mekong River Basin

Animal migrations

2

Animal migrations represent some of the greatest spectacles of nature. Furthermore, they also play

a key role in the culture and livelihoods in many human societies. Many hunting societies, for

example, have adjusted their seasonal movements and social structures to the movements of their

prime target animals (see for example, Berkes 1999).

Fish migrations in the Mekong River Basin are equally significant to the local people. Many fishing

communities along the rivers of the basin have adapted their way of life to the seasonal patterns of

fish migrations. A few of the most conspicuous examples are:

Throughout the basin, villages have adapted to the seasonal migration of groups of small cyprinid

fishes belonging to the genus Henicorhynchus which takes place at the beginning of the dry

season (October-February). These migrations support very large fisheries and the surplus yield

creates the foundation for a variety of fish processing activities.

From December to February, villages near certain sites along the river exploit the seasonal

spawning migration of the large

cyprinid Probarbus jullieni (and also

Probarbus labeamajor), one of the high-

profile `flagship' species of the Mekong.

The seasonal spawning migration of the

giant Mekong catfish (Pangasianodon

gigas) has experienced a dramatic

decline in recent decades, and today

only one site along the entire Mekong

River sustains a small traditional fishery

for the giant catfish (during the 2001

and 2002 season no fish were caught).

Probarbus jullieni one of the many migratory fishes of

the Mekong

Many authors have devoted considerable

effort trying to define the term migration

(see for example, Dingle 1996; McKeown 1984; and others). For the purposes of this report, we

share the view of Barthem and Goulding (1997) that a rigid definition does not seem useful. But we

find it important to emphasise two issues concerning migration:

Migration is one type of movement, distinguished from more diffuse types such as foraging for

food within a single habitat. It normally involves the "cyclic and predictable movements of a large

proportion of animals within the species, or populations of species" (as defined by the International

Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals, the CMS Convention).

Migration is an integrated element of the entire life cycle of the animal.

Animals migrate because key habitats essential for their survival are separated in time and space.

Often, movements are guided by seasonal changes in living conditions (e.g. escaping winters or

23

Fish migrations of the Lower Mekong River Basin

seasonal droughts) and/or by seasonal reproductive patterns (e.g. migrating to suitable breeding

sites). These movements have evolved with, and thus are finely tuned to, the environment within

which they occur. Migratory animals thus depend on a wide range of habitats, and their distribution

ranges cover large geographical areas. Since they move regularly between different habitats, they

are considered "living threads that tie or link widely scattered ecosystems together" (Glowka 2000).

Such links often reach beyond national borders, as is, for example, the case with many of the

migrating fishes of the Mekong Basin.

Migratory animals are well adapted to naturally occurring environmental fluctuations and changes,

but are particularly vulnerable to the abrupt environmental changes caused by human activities.

Therefore, many migratory animals are at risk of becoming endangered (see for instance the IUCN

Red list of Endangered Animals, 1996).

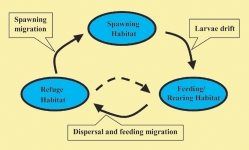

2.1 Fish migrations and life cycles

In rivers, fishes have adapted to life in running water and to seasonal changes in habitat availability.

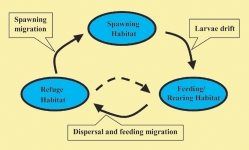

The need to migrate is part of this adaptation. Figure 1 illustrates how migrations are integrated into

the life cycles of migrating fishes.

Fish movements take place at all stages of life, even the earliest stages. In rivers, movements of fish

eggs and larvae, in the form of downstream passive drift are common, and are integrated events of

the overall movement patterns of migrating fishes. Often, migration routes and the spatial position

of spawning areas are finely tuned to hydrological and environmental circumstances, ensuring that

eggs and/or larvae drift back downstream to their rearing habitats with the flowing water.

In an ecological context, fish migrations

Figure 1 A: Simplified schematic representation of life

cannot be described without at the same

time describing essential fish habitats and

the environment within which these

habitats are embedded.

Therefore, impacts of development

scenarios on fish migrations are not

confined to the blocking of migration

routes caused by damming of rivers.

Impacts on the environment, and thereby

on fish habitats, and changes in

hydrological patterns are equally

important.

Figure 1 B: Corresponding habitat

requirements for the successful completion

of lifecycle of fish. Depending on species,

arrows may represent short movements (e.g.

from lake to adjacent floodplain), or long-

distance migration. The broken arrow

represents longer-lived species, which may

move several times between refuges and

feeding habitats.

cycle of fish.

24

Fish migrations of the Lower Mekong River Basin

Fish migration in

3

the Mekong River

In a multi-species fisheries environment such as the Mekong system, it is useful to distinguish

different species groups based on different life history strategies. The broadest classification of

fishes in the Mekong fisheries context is the classification of fishes into black-fishes and white-

fishes (Welcomme 1985).

Black-fishes are species that spend most of their life in lakes and swamps on the floodplains

adjacent to river channels and venture into flooded areas during the flood season. They are

physiologically adapted to withstand adverse environmental conditions, such as low oxygen levels,

which enable them to stay in swamps and small floodplain lakes during the dry season. They are

normally referred to as non-migratory, although they perform short seasonal movements between

permanent and seasonal water bodies. Examples of black-fish species in the Mekong are the

climbing perch (Anabas testudineus), the clarias catfishes (e.g. Clarias batrachus) and the striped

snakehead (Channa striata).

White-fishes, on the contrary, are fishes that depend on habitats within river channels for the main

part of the year. In the Mekong, most white-fish species venture into flooded areas during the

monsoon season, returning to their river habitats at the end of the flood season. Important

representatives of this group are some of the cyprinids, such as Cyclocheilichthys enoplos and

Cirrhinus microlepis, as well as the river catfishes of the family Pangasiidae.

Figure 1 is representative for both black-fishes and white-fishes. However, for black-fishes, the

arrows represent only short movements between `neighbouring' habitats, whereas for white-fishes,

they represent migrations between distant habitats.

Recently, an additional group within this classification has been identified. It is considered an

intermediate between black-fishes and white-fishes and therefore has been referred to as grey-

fishes (Welcomme 2001). Species of this group undertake only short migrations between floodplains

and adjacent rivers and/or between permanent and seasonal water bodies within the floodplain

(Chanh et al. 2001; Welcomme 2001).

Virtually all fishes of the Mekong are exploited and therefore constitute important fishery resources.

All fishes are also vulnerable to impacts from development activities, including transboundary

impacts. However, long-distance migratory species (i.e. white-fish species) are particularly vulnerable

because they depend on many different habitats, are widely distributed, and require migration

corridors between different habitats. For these important fishes, the term `transboundary' has double

meaning: they are transboundary resources that may be affected by transboundary impacts of human

activities.

25

Fish migrations of the Lower Mekong River Basin

3.1 Important fish habitats in the Mekong Basin

Since the separation of critical fish habitats within the overall ecosystem that constitutes the lower

Mekong Basin is the main cause for fishes to migrate, it is useful to identify these habitats before

discussing migrations, i.e. the cause (habitats) first, then the response (migrations).

3.1.1 Floodplains

The flood-pulse during the monsoon season is the driving force of the Mekong River ecosystem. As

is the case for most tropical floodplain river systems, the seasonal habitats on the floodplains created

by the monsoon floods are the main "fish production sites" of the Mekong (Sverdrup-Jensen 2002).

These areas are very rich in nutrients, food and shelter during the flood season, and most Mekong

fishes depend on these resources for at least certain parts of their early life cycle.

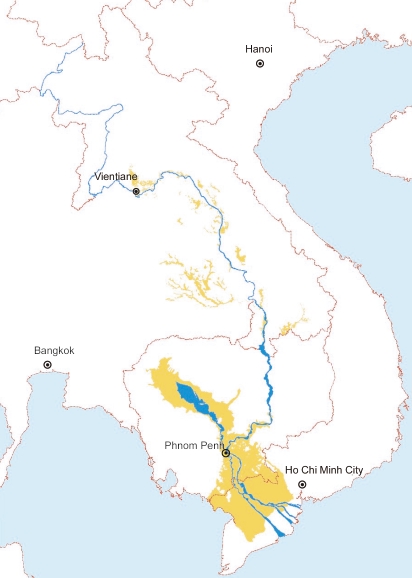

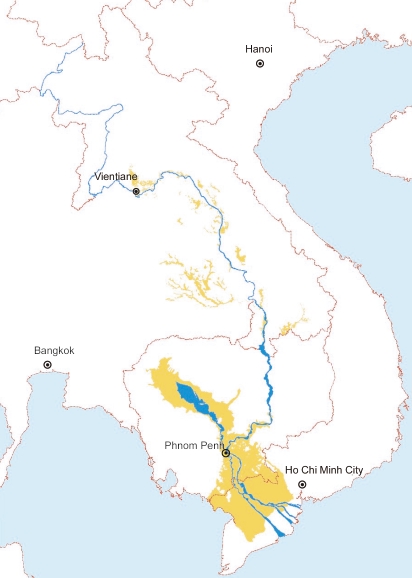

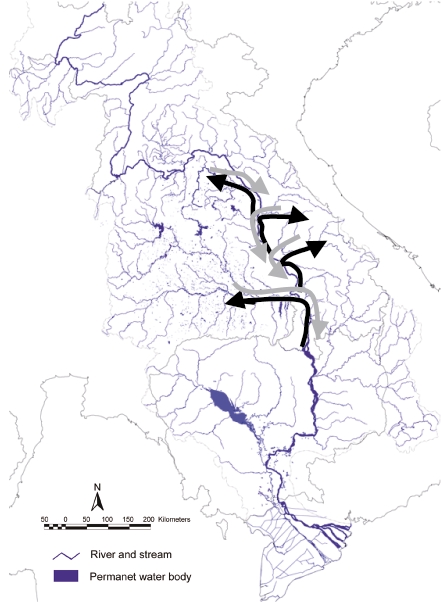

Figure 2: Main floodplain areas of the Lower Mekong Basin.

26

Fish migrations of the Lower Mekong River Basin

Figure 2 shows a map of the flooded areas of the Lower Mekong River Basin. As can be seen, the

main floodplain habitats occur in the lower part in southern Cambodia and the Mekong Delta in

Viet Nam. The most important floodplain complex is associated with the Tonle Sap River/Great

Lake system in Cambodia. In the upper parts of the basin, in Thailand and Lao PDR, floodplain

areas are smaller and are mainly associated with Mekong tributaries. In the upper parts of the basin,

i.e. approximately upstream from Vientiane, floodplain habitats become more and more scarce as

the river gradually changes to become a typical mountain river with steep riverbanks.

The migratory behaviour of many fishes

is an adaptation to these hydrological

and environmental conditions. The

timing of migrations is "tuned" to the

flood-pulse, and although different

species may have tuned their migrations

in different ways, some general patterns

can be elucidated. In general, most

species spend the dry season "fasting"

in refuge habitats. The arrival of the

monsoon and its floodwaters is an

ecological trigger for both spawning and

migration. Spawning at the right time

Floodplains are important fish habitats during the monsoon season

and place will enable offspring to enter

floodplain habitats, where they can feed. Some species spawn on the floodplain itself, whereas

others migrate upstream to spawn within the river channel and then rely on the river current to bring

the offspring to the downstream rearing habitats. Many larger juveniles and adult fish actively migrate

from dry-season shelters to the floodplains to feed. Thus, the life cycles of migrating fish species

ecologically connect different areas and habitats of rivers. From their point of view, the river basin

constitutes one ecological unit interconnecting upstream spawning habitats with downstream rearing

habitats.

3.1.2 Dry season refuge habitats

When water recedes from flooded areas at the end of the flood season, fishes have to move out of

the seasonal habitats and return to their dry season refuges. In a broad sense, two types of dry

season refuge habitats exist:

1) permanent floodplain lakes and swamps

2) river channels

Floodplain lakes are mainly used by the group of black-fish species, whereas river channel refuges

are mainly used by whitefishes. In the context of this report, the focus is on refuge habitats associated

with river channels, which are mainly used by migrating, transboundary fish stocks belonging to

the group of white-fish species.

Within rivers, deep areas are particularly important as dry season refuges. These areas are most

often referred to as deep pools. The importance of deep pools in the Mekong River Basin has

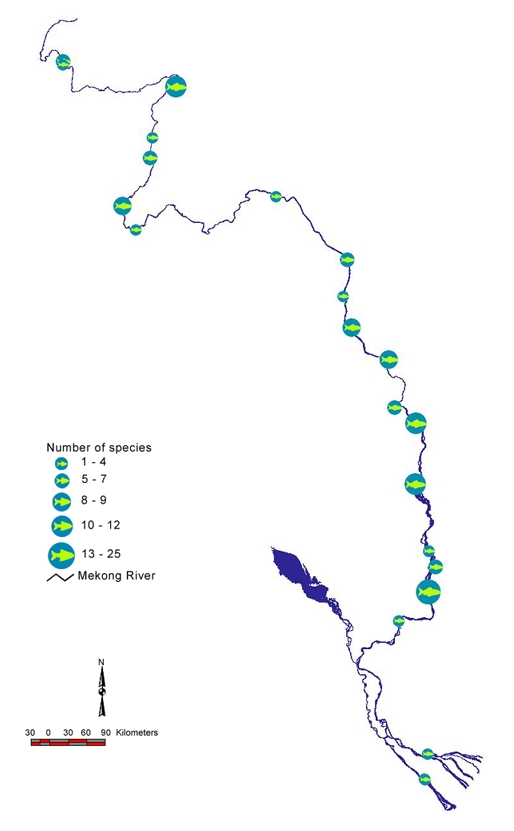

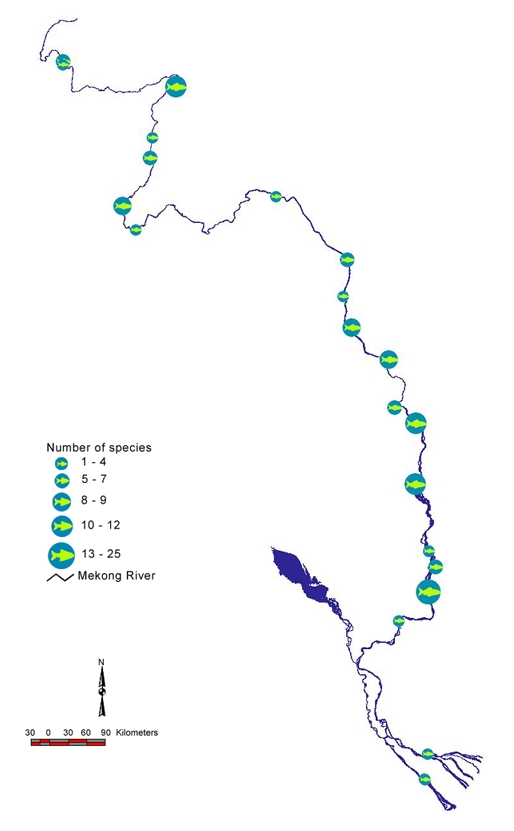

recently been documented by the MRC Fisheries Programme (Poulsen et al. 2002), in which Figure

3 shows the distribution of important deep pool habitats within the Mekong mainstream, based on

local ecological knowledge.

27

Fish migrations of the Lower Mekong River Basin

Figure 3. Number of species reported using deep pools at each study site in the Mekong mainstream (based

on Local Ecological Knowledge. See: Poulsen et.al. (2002); Poulsen and Valbo-Jørgensen (1999);

Valbo-Jørgensen and Poulsen 2000)

28

Fish migrations of the Lower Mekong River Basin

Certain stretches of the Mekong River emerge as important locations for deep pools. In particular,

the stretch from Kratie to the Khone Falls in northern Cambodia contains a large number of deep

pools that are used by many species during the dry season.

The river stretch immediately

upstream from the Khone Falls, as

far upstream as Khammouan/

Nakhon Phanom, and the stretch

from the Loei River to Louang

Prabang also contains many deep

pool habitats.

Interestingly, there are also

stretches that appear to contain

relatively few deep pool habitats.

Most notably, there are very few

River dolphins surfacing at a deep pool near Kratie

deep pools along the stretch from

Kratie in northern Cambodia all the

way to the Mekong Delta. Further upstream, within the stretch from Paksan/Beung Khan to Vientiane/

Sri Chiang Mai, deep pool habitats are also scarce.

3.1.3. Spawning habitats for migratory fishes

Although little is known about spawning habitat requirements for most Mekong fishes, spawning

habitats are generally believed to be associated with: (1) rapids and pools of the Mekong mainstream

and tributaries; and (2) floodplains (e.g. among certain types of vegetation, depending on species).

River channel habitats are, for example, used as spawning habitats by most of the large species of

pangasiid catfishes and some large cyprinids such as Cyclocheilichthys enoplos, Cirrhinus microlepis,

and Catlocarpio siamensis. Floodplain habitats are used as spawning habitats, mainly by black-fish

species.

Other species may spawn in river channels in the open-water column and rely on particular

hydrological conditions to distribute the offspring (eggs and/or larvae) to downstream rearing habitats.

Information on spawning habitats for migratory species in the river channels of the Mekong Basin

is scarce. Only for very few species, such as Probarbus spp. and Chitala spp., spawning habits are

well described because these species have conspicuous spawning behaviour at distinct spawning

sites. For most other species, in particular for deep-water mainstream spawners such as the river

catfish species, spawning is virtually impossible to observe directly.

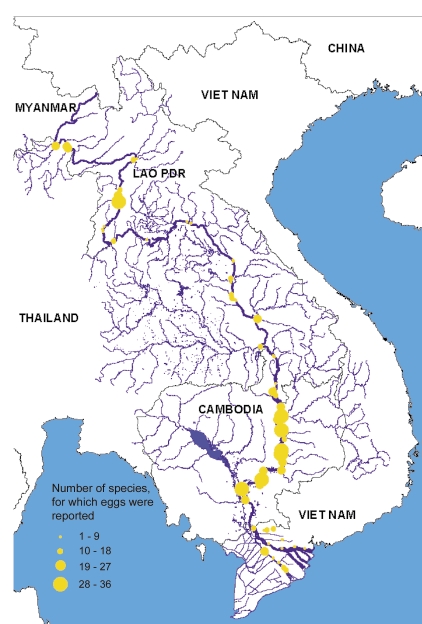

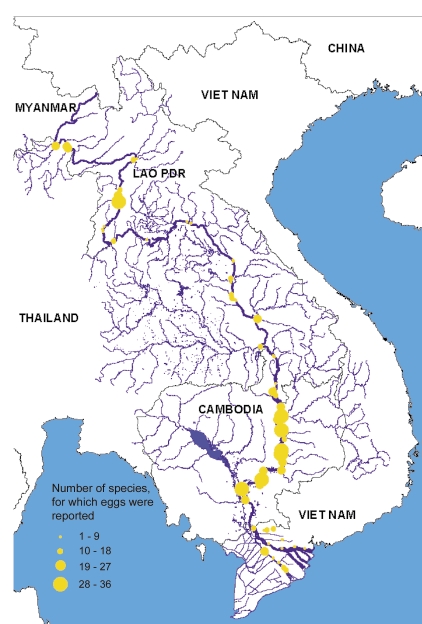

Information about spawning can instead be obtained through indirect observations such as

observations of ripe eggs in fishes. Figure 4 shows the number of species with eggs that have been

observed by fishers (each "pie" in Figure 4 represents the number of species carrying ripe eggs, as

observed by fishers). For fishes that spawn in main river channels, spawning is believed to occur in

stretches where there are many rapids and deep pools, e.g. (1) the KratieKhone Falls stretch; (2)

the Khone Falls to Khammouan/Nakhon Phanom stretch; and (3) from the mouth of the Loei River

to Bokeo/Chiang Khong.

Figure 4 indicates that the Kratie-Khone Falls stretch and the stretch from the Loei River to Luang

Prabang are particularly important for spawning.

29

Fish migrations of the Lower Mekong River Basin

Figure 4: Number of species along the Mekong mainstream reported to have eggs in their

abdomen (see text for further explanation).

30

Fish migrations of the Lower Mekong River Basin

View of the Mekong

near Kratie, northern

Cambodia. This area is

believed to be important

for spawning for many

migratory fish species.

3.2. Fish migrations and hydrology in the Mekong Basin

There is an intimate link between fish life cycles, fish habitats, and hydrology. Migrating fishes

respond to hydrological changes and use hydrological events as gauges for the timing of their

migrations. This is illustrated in Figure 5, where peak migration periods are correlated with the

annual hydrological cycle. Most species migrate at the start of the annual flood and return at the end

of the flood, producing the two peaks shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5: Relationship between migratory activity levels and water discharge in the Lower Mekong Basin

(modified from Bouakhamvongsa and Poulsen, 2000) Blue Line: average monthly discharge

(m3/sec) of the Mekong River at Pakse, Southern Lao PDR (data provided by MRC Secretariat).

Red Line: Number of migration reports (based on 50 species from 51 sites along the Mekong

mainstream).

Also, the spawning season is tuned according to river hydrology, and almost all species spawn at

the onset of the monsoon season. Only a few species, such as Probarbus spp. and Hypsibarbus

malcolmi, are exceptions to that rule: they spawn during the dry season.

31

Fish migrations of the Lower Mekong River Basin

3.3. Major migration systems of the Mekong

For a complex ecosystem, which involves such a large number of species, it is beyond the scope of

this report to discuss individual species. Although different species have developed different life

strategies to cope with the environmental circumstances, generalisations can be made, e.g. on migratory

patterns. Some of these general patterns will be outlined below (see also Sverdrup-Jensen 2002).

One of the major results of these surveys has been the identification of three main migration systems

associated with the lower Mekong River mainstream (Sverdrup-Jensen 2002). These three systems

have been termed the Lower Mekong Migration System (LMS), the Middle Mekong Migration

System (MMS), and the Upper Mekong Migration System (UMS).

It is important to note that the different migration systems are inter-connected and, for many species,

overlapping. Furthermore, their classification as `systems' is based on the fact that migration patterns

are different in each. In general, the migration patterns are determined by the spatial separation

between dry season refuge habitats and flood season feeding and rearing habitats within each system.

This, again, demonstrates how migration habits are deeply embedded in the environment within

which they occur.

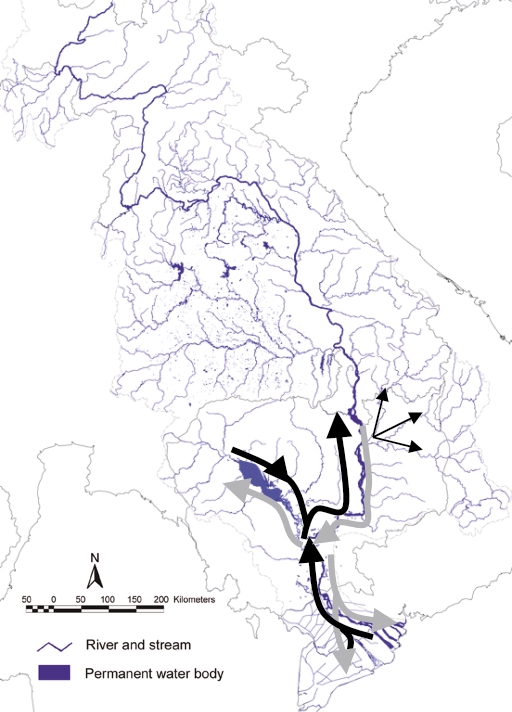

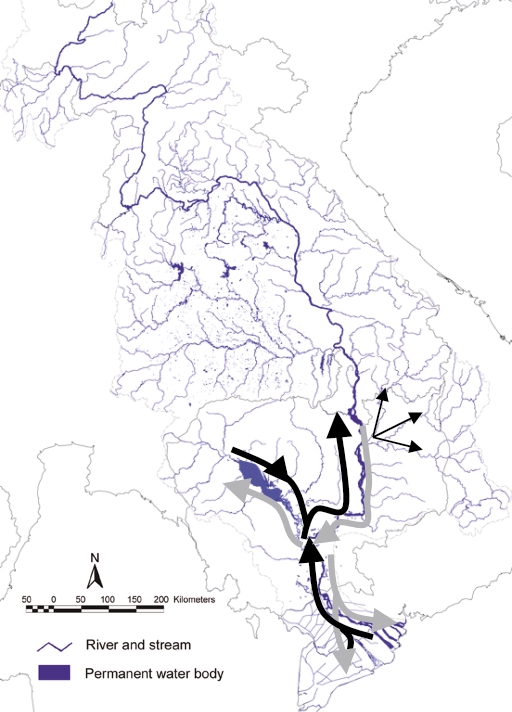

3.3.1 The Lower Mekong Migration System (LMS)

This migration system covers the stretch from the Khone Falls downstream to southern Cambodia,

including the Tonle Sap system, and the Mekong Delta in Viet Nam (Figure 6). As described above,

this migration is driven by the spatial and temporal separation of flood-season feeding and rearing

habitats in the south with dry-season refuge habitats in the north. The rise in water levels at the

beginning of the flood season triggers many migrating fishes to move from the dry season habitats

just below the Khone Falls, e.g. in deep pools along the Kratie-Stung Treng stretch, towards the

floodplain habitats in southern Cambodia and the Mekong Delta in Viet Nam. Here they spend the

flood season feeding in the fertile floodplain habitats. Some species spawn on, or near the floodplain,

whereas others spawn far upstream, i.e. above Kratie, and rely on the water current to bring offspring

to the floodplain rearing areas. One of the key factors for the integrity of this system is the Tonle

Sap/Great Lake system a vast and complex system of rivers, lakes and floodplains. As a result of

increasing water discharge from the Mekong River at the onset of the flood season, the water

current of the Tonle Sap River changes its direction, flowing from the Mekong into the Tonle Sap

River and towards the Great Lake. This enables fish larvae and juveniles to enter the Tonle Sap

from the Mekong by drifting with the flow. Together with the floodplains of the Mekong Delta in

Viet Nam, these floodplains are the main "fish factories" of the lower basin.

An important group of species, which undertakes this type of migration, belongs to the genus

Henicorhynchus. In terms of fisheries output, these fishes are among the most important of the

Lower Mekong. For example, in the Tonle Sap River dai fishery, species of the genus Henicorhynchus

account for 40 percent of the total annual catch (Lieng et al. 1995, Pengbun and Chanthoeun 2001).

Larger species, such as Catlocarpio siamensis, Cirrhinus microlepis, Cyclocheilichthys enoplos,

and Probarbus jullieni, as well as several members of the family Pangasiidae, also participate in

this migration system.

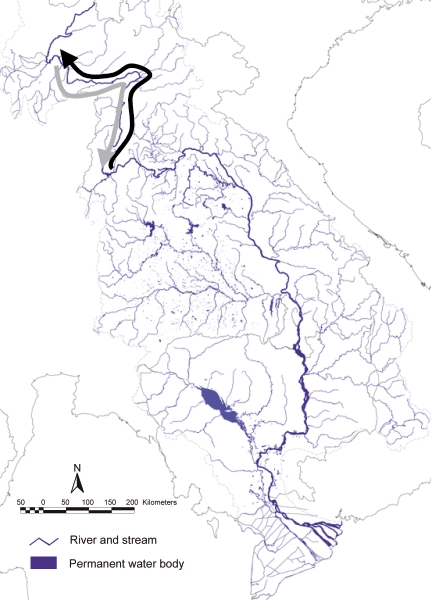

The Sesan tributary system (including the Sekong and Srepok Rivers) deserves special mention

here (Figure 7). This important tributary system is intimately linked with the Lower Mekong

Migration System, as evidenced by many species such as Henicorhynchus sp. and Probarbus jullieni

extending their migration routes from the Mekong River mainstream into the Sesan tributary system

(Chanh Sokheng, personal communication, December 2001). In addition, the Sesan tributary system

also appears to contain its own migration system.

32

Fish migrations of the Lower Mekong River Basin

Figure 6: A simplified illustration of the Lower Migration System (only the major routes are illustrated).

Black arrows represent migrations at the beginning of the dry season; grey arrows represent

migration at the beginning of the flood season. See text for further explanation.

33

Fish migrations of the Lower Mekong River Basin

Figure 7: The dry-season migration of Henicorhynchus spp. from the Mekong into the Sesan Tributary

system

Many of the species (e.g. all the species mentioned above) are believed to spawn within the Mekong

mainstream in the upper stretches of the system (from Kratie to the Khone Falls, and beyond) at the

beginning of the flood season in May-June. Eggs and larvae subsequently drift downstream with

the current to reach the floodplain feeding habitats in southern Cambodia and Viet Nam. The

importance of drifting larvae and juveniles has been documented through intensive sampling of

larvae fisheries in the Mekong Delta in Viet Nam (Tung et al. 2001). During a sampling period of

only 45 days in June-July 1999 from two sites (one in the Mekong River and one in the Bassac

River in An Giang Province of Viet Nam), 127 species were identified from the larvae and juvenile

drift. Fish eggs were not sampled. This illustrates how important hydrology is for the completion of

life cycles of fishes in the lower Mekong River.

Fishing for fish larvae in the

Mekong Delta (An Giang

Province of Viet Nam).

34

Fish migrations of the Lower Mekong River Basin

Table 1: The 127 species caught during the larvae sampling of the Mekong and Bassac rivers, in An

Giang Province of Viet Nam. M = Mekong; B = Bassac (from Tung, et. al., unpublished AMFC

report)

35

Fish migrations of the Lower Mekong River Basin

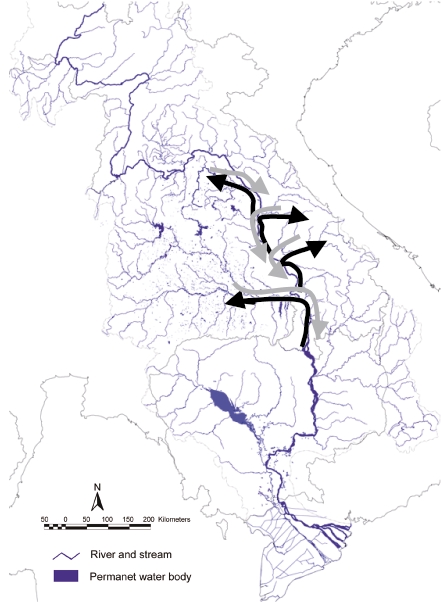

3.3.2 The Middle Mekong Migration System (MMS)

From just above the Khone Falls and upstream to the Loei River, Thailand, the migration patterns

are determined by the presence of large tributaries connecting to the Mekong mainstream. Within

this section of the river, floodplain habitats are mainly associated with the tributaries (e.g. the Mun

River, Songkhram River, Xe Bang Fai River, Hinboun River, and other tributaries), so fishes migrate

seasonally along these tributaries from mainstream dry season habitats to floodplain feeding/rearing

habitats. At the onset of the flood season, fishes generally move upstream within the Mekong

mainstream until they reach the mouth of one of these major tributaries. They swim up the tributary

until they can move into floodplain habitats. At the end of the monsoon, fishes move in the opposite

direction, from floodplains through the tributary river and, eventually, to the Mekong mainstream,

where many fishes spend the dry season in deep pools. An example is given in Figure 8, based on

local ecological knowledge.

Figure 8. Simplistic illustration of the Middle Migration System.

36

Fish migrations of the Lower Mekong River Basin

This is of course a very simplistic description of the main movements, and there are considerable

variations in the general pattern, both between different species and within species. Furthermore,

there are complex interconnections to the lower migration system described above, i.e. many of the

same species participate in both systems, either as genetically-distinct populations, or at different

stages of their life cycle (see later).

Figure 9.

Variation in occurrence of a group of 9 Pangasiid species in the Songkhram River and adjacent

Mekong, based on Local Ecological Knowledge. See text further for explanation. The species

are: Heligophagus waandersii, Pangasianodon hypophthalmus, Pangasius bocourti,

P. conchophilus, P. djambal, P. krempfi, P. larnaudiei, P. polyuranodon, P. sanitwongsei.

The movement of fish between the Songkhram River and the Mekong mainstream, is illustrated

in Figure 9. Each bar chart illustrates reported occurrence by month at each station over the year.

The occurrence level for each month was reported as `high occurrence', `low occurrence', or `no

occurrence'. It shows that all these species use the Mekong mainstream as a dry season refuge and

the Songkhram River floodplain as feeding grounds during the flood season.

37

Fish migrations of the Lower Mekong River Basin

It is important to emphasise

that the two different

migration systems (LMS

and MMS) are not "closed"

ecological systems, isolated

from each other. The two

systems are in fact

interconnected. Many

species are known to

migrate over the Khone

Falls, both during the flood

season and during the dry

season, thereby demonstrating

that the Falls is not a barrier

for fish movements (Baird

1998; Roberts 1993; Roberts

Fish trap in the upper Mekong River

and Baird 1995; Roberts and

Warren 1994; Singanouvong et al. 1996a and 1996b). For some species, the same fish may be part

of the lower migration system as a juvenile, and part of the middle migration system as a mature

adult. For example, important species such as Cyclocheilichthys enoplos and Cirrhinus microlepis

are mainly reported as juveniles and sub-adults in the Lower Mekong Migration System and as

adults in the Middle Mekong Migration System. The same may be true for a number of other

species, including the Giant Mekong Catfish. For other species, it may be the case that genetically

distinct sub-populations are involved in the different migration systems. However, further research

is needed before conclusions can be made on this issue.

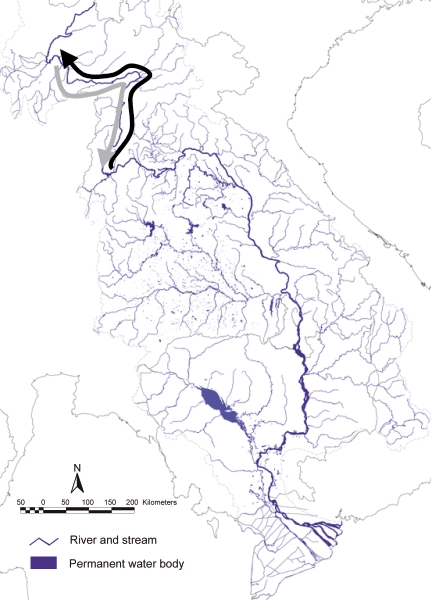

3.3.3 The Upper Mekong Migration System (UMS)

The third migration system occurs in the upper section of the river, approximately from the mouth

of the Loei River and upstream towards the border between Lao PDR and China (probably continuing

into China, although we have no data to confirm this). This section of the river (Figure 10) is

characterised by its relative lack of floodplains and major tributaries (although there are some

floodplains associated with tributaries in the far north, i.e. the Nam Ing River, in Thailand). This

migration system is dominated by upstream migrations at the onset of the flood season, from dry

season refuge habitats in the main river to spawning habitats further upstream. This is also a multi-

species migration system, and some of the species participating in the previous migration systems

further downstream also participate in this migration, although the total number of species may be

lower.

The most conspicuous member of this migration system is the Giant Mekong Catfish, Pangasianodon

gigas. The Henicorhynchus sp., which is so important for the fishery further downstream, is also

important along this stretch of the river. For example, a fisherman from Bokeo in northern Lao PDR

reported a catch of between 100 and 200 kg per day of this fish during the month of October 2001

(Bouakhamvongsa, in prep.) This may be a genetically distinct stock compared with downstream

stocks (although further research is needed to confirm this).

Whereas the LMS and the MMS are inter-connected to a large degree, the UMS appears to be

relatively isolated, with little "exchange" between the UMS and the other migration systems. As

can be seen from Figure 3, deep pool habitats are rare for a long stretch of the Mekong between the

MMS and the UMS. Along the same stretch, observations of mature fishes with eggs are also rare.

This indicates that for many migratory species, the stretch from Paksan to the mouth of the Loei

River is a functional barrier.

38

Fish migrations of the Lower Mekong River Basin

Figure 10. Simplistic illustration of the Upper Migration System.

Interestingly, the geographical extent of these three migration systems corresponds with elevation

contours of the lower Mekong Basin (Figure 11). In particular, there is a clear area overlap between

the extent of the Lower Mekong Migration System and the extent of the 0-149 m elevation of the

Mekong Delta/Cambodian lowlands. A correlation also occurs between the Middle Mekong

Migration System and the 150-199 m elevation represented largely by the Korat Plateau. The Upper

Mekong Migration System correlates with a plateau of 200-500 m elevation. This demonstrates

how fish migration has evolved within the surrounding physical environment.

39

Fish migrations of the Lower Mekong River Basin

Figure 11: Elevation map of the Lower Mekong Basin. Note the overlap between the Lower Migration

System and the region with the dominant elevation between 0-149 m (the Mekong Plain); between

the Middle Migration System and the region with the dominant elevation between 150-199 (the

Korat Plateau) and between the Upper Migration System and the region with elevation mainly

above 250 m (Northern Highlands).

40

Fish migrations of the Lower Mekong River Basin

Managing

4

migratory fishes

The two main intervention areas for the sustainable management of the fishery resources of the

Mekong are:

management of habitats and ecosystems (environmental management)

management of resource use (fisheries management).

Traditionally, fisheries management in the Mekong (and elsewhere) has focussed solely on `within-

the-sector' issues and management activities (e.g. gear restrictions, access restriction, seasonal

restrictions). In a complex setting like the Mekong Basin, it is particularly important that fisheries

resources are managed within an overall management framework, where environmental management

is seen as a pre-requisite for fisheries management (see, for instance Coates, 2001). Fisheries

management, in its conventional application, would be of limited use in the Mekong, unless the

environment that sustains the fisheries are managed first in a sustainable manner. This requires a

multi-disciplinary approach, involving all the different `users' of the river. The focus of this report,

therefore, is on environmental management (i.e. management of habitats and ecosystem attributes),

and not on conventional fisheries management.

With regards to the management of migratory, transboundary fish stocks, an additional requirement

is that regional, cross-border management initiatives are implemented. This is the area where the

MRC is well placed to play a key role. All the three migration systems mentioned previously extend

across international borders and thus, by nature, fall under the responsibility of the MRC.

The 1995 Agreement that established the Mekong River Commission, serves as the natural framework

under which management guidelines for migratory fishes of the lower Mekong Basin can be designed

and implemented. In addition to the 1995 Agreement, another instrument deserves mentioning here:

the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). The CBD is the most comprehensive international

instrument in existence for the management of natural resources. It commits signatory states to

"...the conservation of biodiversity, the sustainable use of its components and the fair and equitable

sharing of the benefits arising out of the utilisation of genetic resources...". It further makes special

reference to the need for states to manage transboundary (i.e. migratory) stocks (e.g. Article 3:

"...contracting parties shall ensure that activities within their jurisdiction or control do not cause

damage to the environment of other states or of areas beyond the limits of national jurisdiction". The

Convention specifically refers to the cooperation, among contracting parties in research, management

and monitoring of biodiversity, including migratory, transboundary elements of biodiversity. The

CBD has been signed by all the six riparian countries of the Mekong Basin, including China and

Myanmar. However, Cambodia, Lao PDR and Thailand have yet to ratify it.

41

Fish migrations of the Lower Mekong River Basin

The main reason for mentioning the CBD in the context of this report is that the two remaining

riparian countries, China and Myanmar, which are not members of MRC, are signatories of, and

have ratified, the CBD. Therefore, the CBD commits them to the conservation and sustainable use

of biodiversity (part of which are fishery resources). Some of the fish migrations extend into China

and Myanmar and, in addition, activities undertaken in the two upper countries may impact on

downstream fishery resources, including fish migration systems.

Another reason for the relevance of the CBD is that there is a direct link between the high fish

diversity and the fisheries productivity of the Mekong (Coates 2001). This link is important to

emphasise, because fisheries issues have traditionally been viewed in separation from biodiversity

conservation, often even seen as threats to biodiversity conservation. The Mekong fisheries demonstrate

the intimate linkages between biodiversity and fisheries: biodiversity conservation can be achieved

through the promotion of sustainable use (fisheries), and fisheries productivity can be sustained only

through biodiversity conservation.

The fish diversity of the Mekong is reflected in the diversity of fishing gears

used to catch them.

4.1. Key issues for the maintenance of ecological functioning of

the

Mekong ecosystem, with reference to migratory fishes

Based on the ecological information that has been described above, key attributes of importance for

the ecological functioning and productivity of the Mekong ecosystem will be listed in the following

section. Although the emphasis is on issues related to migratory fishes, the issues are equally relevant

for all fish species and indeed for the ecosystem as a whole.

Basically, the most important issue in relation to the ecological functioning of the Mekong River

from the point of view of migratory fishes is that critical habitats are maintained in time and space.

This includes the maintenance of connectivity between them, i.e. through migration corridors. The

importance of the annual hydrological pattern is emphasised, including its role in the creation of

seasonal floodplain habitats, as well as its role as a distributor of fish larvae and juveniles through

passive drift.

42

Fish migrations of the Lower Mekong River Basin

The following key ecological attributes for migratory species are identified, based on the three major

migration systems described above along the Mekong mainstream.

The Lower Mekong Migration System (LMS).

General ecological attributes

Mekong-specific ecological attributes

Dry season refuge habitats:

Deep pools in the Kratie-Stung Treng stretch of the Mekong

mainstream. These habitats are extremely important for

recruitment for the entire lower Mekong Basin, including

floodplains in southern Cambodia (including the Tonle Sap/

Great Lake System) and the Mekong Delta in Viet Nam.

Flood season feeding and

Floodplains in the Mekong Delta in Viet Nam, in southern

rearing habitats:

Cambodia, and in the Tonle Sap system. These habitats

support the major part of Mekong fisheries.

Spawning habitats:

Rapids and deep pool systems in the Kratie Khone Falls,

and in the Sesan catchment. Floodplain habitats in the south

(e.g. flooded forests associated with the Great Lake).

Migration routes:

The Mekong River from Kratie Stung Treng to southern

Cambodia and the Mekong Delta in Viet Nam.

Between the Mekong River and the Tonle Sap River

(longitudinal connectivity).

Between floodplain habitats and river channels (lateral

connectivity).

Between the Mekong mainstream and the Sesan sub-

catchment (including Sekong and Srepok Rivers).

Hydrology:

The annual flood pattern responsible for the inundation of

large areas of southern Cambodia (including the Tonle Sap

system) and the Mekong Delta is essential for fisheries

productivity of the system (see above).

The annual reversal of the flow in the Tonle Sap River is

essential for ecosystem functioning. If the flow is not

reversed (or if reversal is delayed), fish larvae drifting from

upstream spawning sites in the Mekong River cannot access

the important floodplain habitats of the Tonle Sap System.

A delayed flow reversal would also lead to a reduced

floodplain area adjacent to the river and lake, and thus,

reduced fish production.

Changed hydrological parameters, e.g. as a result of water

management schemes, result in changed flow patterns,

which in turn may change sedimentation patterns along

the river. Examples of this already exist in some tributaries

where hydropower dams have been constructed, resulting

in sedimentation, and thus in disappearance of deep pool

habitats.

43

Fish migrations of the Lower Mekong River Basin

The Middle Mekong Migration System (MMS)

General ecological attributes

Mekong-specific ecological attributes

Dry season refuge habitats:

Deep pool stretches of the Mekong mainstream and within

major tributaries. Of particular importance is the stretch

from the Khone Falls to Kammouan/Nakhon Phanom. Deep

pools immediately downstream from the Khone Falls also

are important for this migration system (thereby linking

the MMS and the LMS)

Flood-season feeding and

Floodplains of this system are mainly associated with major

rearing habitats:

tributaries (e.g. the Mun/Chi system, Songkhram River, Xe

Bang Fai River, Hinboun River).

Spawning habitats:

Rapids and deep pool systems in the Mekong mainstream

(particularly along the stretch from the Khone Falls to

Khammouan/Nakhon Phanom).

Floodplain habitats associated with tributaries.

Migration routes:

Connections between the Mekong River (dry season

habitats) and major tributaries (flood season habitats).

Access to floodplain habitats from main river channels must

be maintained.

Hydrology:

The annual floods that inundate floodplain areas along

major tributaries must be maintained.

The Upper Mekong Migration System (UMS)

General ecological attributes

Mekong-specific ecological attributes

Dry season refuge habitats:

Occur throughout the extent of the UMS, but are most

common in the downstream stretch from the mouth of the

Loei River to Louang Prabang.

Flood season feeding and

The UMS occurs within a section of the Mekong, which is

rearing habitats:

dominated by mountainous rivers with limited floodplain

habitats. Floodplain habitats therefore play a less important

role, compared to MMS and LMS. Large catches of

Henicorhynchus sp. in Bokeo Province of Lao PDR suggest

that even the limited areas of available floodplains are

important.

Spawning habitats:

Spawning habitats occur mainly in the upper stretches of

the system. They are mainly situated in stretches with

alternating rapids and deep pools.

Migration routes:

Migration corridors between downstream dry season refuge

habitats and upstream spawning habitats should be

maintained.

Hydrology:

The annual flood pattern that triggers fish migrations and

causes innudation of floodplains.

44

Fish migrations of the Lower Mekong River Basin

Khone Falls

The Khone Falls are situated on the border between Cambodia and Lao PDR and thus also demarcate

the "border" between the LMS and the MMS. It is important to emphasise that the Khone Falls are

not a barrier to migration. The Khone Falls area is probably the most studied site along the whole of

the Mekong, and large-scale migrations involving a large number of species have been documented

through intensive sampling programmes over the past decade (Baird 1998; Roberts 1993;

Singanouvong et al. 1996a and 1996b). Thus, the LMS and the MMS are in fact inter-connected.

What makes the LMS and the MMS different from each other is not that they are geographically

isolated.The difference is that in the LMS, the dry season refuge habitats are situated upstream

from the flood season feeding and rearing habitats, whereas in the MMS, they are situated

downstream from the flood season habitats. Therefore, at the onset of the flood season, in the LMS

fishes migrate downstream towards flood season habitats, whereas in the MMS, fishes migrate

upstream towards flood season habitats. As mentioned earlier, in some cases the same fish may

participate in both migration systems at different stages of their life cycle.

The UMS may be relatively isolated from the two migration systems further downstream. It thus

may represent genetically distinct populations of fishes. If so, these populations should be regarded

as separate management units. Further research, particularly on population genetics, is needed to

clarify this issue.

45

Fish migrations of the Lower Mekong River Basin

Potential impacts

5

of development

activities

In order to be able to optimise the basin planning process it is necessary to identify and assess

potential impacts of different development scenarios on fisheries and the environment that sustain

them. In this section some of the potential human impacts on migratory fishes of the Mekong are

discussed.

5.1 Human impacts on the Mekong fisheries

Some of the potential impacts of development activities and projects within the Mekong River

Basin will be discussed below. Human impacts on rivers have been divided into four categories: (1)

supra-catchment (e.g. inter-basin water transfer); (2) land-use change within the basin catchment

(e.g. agricultural development, urbanisation, deforestation, land drainage, flood protection); (3)

corridor engineering (e.g. dams and weirs, channelisation, dredging, mining); and (4) in-stream

impacts (e.g. pollution, navigation, water abstraction, exploitation of native species, introduction of

exotic species) (Arthington and Welcomme 1995).

These impacts affect all the fisheries resources of the Mekong, including both black-fish and white-

fish. However, the migratory white-fish species are particularly vulnerable, because they depend on

large areas, many different habitats, and the un-hindered access to these habitats through the migration

corridors linking them. Thus, potential impacts on black-fish species can be regarded as a sub-set of

impacts on white-fish species. In the following section, we will try to identify some potential impacts

in the context of migratory fishes of the Mekong River.

An assessment of impacts should ideally contain the following processes:

A valuation of migratory fishes as a fishery resource

An assessment of ecosystem attributes and processes that are required in order to sustain the

resources

Based on the two first points, an assessment of the degree of impacts (i.e. will the resource

disappear, or will part of it be able to persist in spite of the impacts?).

In the following section, we will discuss these three points with particular emphasis on the Lower

Mekong Migration System.

47