Mekong River Commission Secretariat

Flood situation report

August, 2008

MRC Technical Paper

No. 21

September 2008

Meeting the Needs, Keeping the Balance

Mekong River Commission Secretariat

Flood situation report, August 2008

MRC Technical Paper

No. 21

1st September 2008

Published in Vientiane, Lao PDR, in September 2008 by the Mekong River Commission

Cite this document as: MRC (2008) Flood situation report, August 2008. MRC Technical

Paper No 21, Mekong River Commission, Vientiane. 20 pp.

The opinions and interpretation expressed within are those of the authors and do not necessarily

reflect the views of the Mekong River Commission.

Author: Peter Adamson

Contributors: Tien Truong Hong, Janejira Tospornsampan, Chusit Apirumanekul, and Christoph Mor

Graphic design: Tim Burnhill

Photographs: Stanislas Fradelizi, www.laophoto.com

© Mekong River Commission

184 Fa Ngoum Road, Unit 18, Ban Sithane Neua, Sikhottabong District,

Vientiane 01000, Lao PDR

Telephone: (856-21) 263 263 Facsimile: (856-21) 263 264

E-mail: mrcs@mrcmekong.org

Website: www.mrcmekong.org

ii

Contents

1.

Summary

1

2.

Meteorological conditions

3

3.

Water levels

5

4.

Flood discharges

6

5.

Flood volumes

7

6.

The role of the mainstream dams in China on the events of August 2008

8

7.

Risk of occurrence

10

8.

Prospects for the rest of the 2008 flood season

10

9.

Damage

13

10. Performance of the RFMMC flood forecasting

15

11. Lessons learnt and recommendations

16

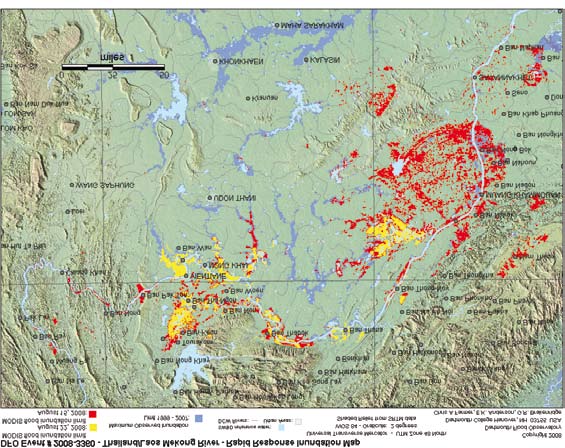

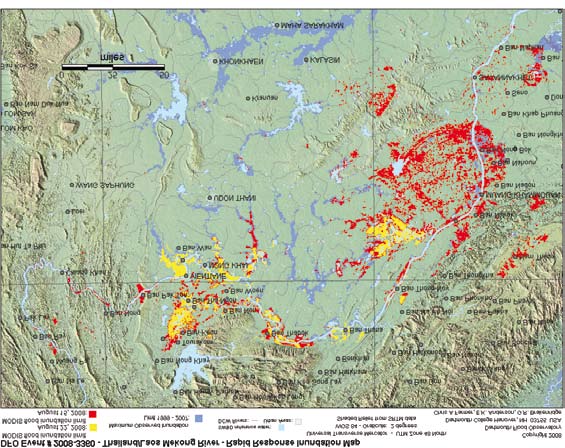

MODIS ood inundation limit August 22. 2008

Maximum observed inundation 1999 - 2007

MODIS ood inundation limit August 15. 2008

SWBD reference water

Figure 1.

Flood extent maps in the Vientiane to Savannaketh reach for 15th and 22nd August 2008.

(Source: G. Robert Brakenridge, Dartmouth Flood Observatory, Dartmouth College,

USA.)

iii

Upper Mekong Basin

China

Lower Mekong Basin

Manwan

Operational mainstream dams

Dachaoshan

Hydrological station

Jinghong

Myanmar

Man An

Viet Nam

Chiang Saen

Lao PDR

Luang Prabang

Chiang Khan

Vientiane

Nakhon Phanom

Nong Khai

Mukdahan

Savannakhet

Thailand

Khong Chiam

Pakse

Cambodia

Stung Treng

Kratie

Prek Kdam

Kampong Cham

Phnom Penh Port

Bassac Chaktomouk

Neak Luong

Koh Khel

Chau Doc

Tan Chau

0

200 kilometres

Figure 2.

Locations referred to in the text.

iv

1. Summary

During the second week of August 2008, flood water levels in the Mekong Basin reached

extreme levels, particularly at Luang Prabang, Vientiane and Nong Khai. The flood resulted

from tropical storm Kammuri that tracked westwards across northern Lao PDR and southern

Yunnan on the 8th, 9th and 10th of the month. Generally this produced 100 150 mm of rainfall,

though locally figures were as high as 250 mm. Catchments were already saturated as a result of

strong monsoonal conditions during May, June, and July, with the consequence that flood runoff

was maximised.

Flood water levels at Chiang Saen and Luang Prabang were such that large areas were

inundated, and it was only as a result of effective action by the authorities that the city centres

of Vientiane and Nong Khai were generally protected from inundation. Although water levels at

Vientiane (specifically at the stream gauge at Kilometre 4) were 1 m higher than in 1966, when

the city centre was flooded, the peak discharges were of the same order. These higher water

levels for similar discharge conditions are explained by the raising of flood protection levees

on both banks of the river after the 1966 event, and the resulting containment of the flood flow

within the channel.

At most locations along the mainstream, levels reached at least the alarm stage, and in the

Delta water levels remained above the alarm stage on 2nd September1. The flood runoff was

almost entirely generated in the area between Jinghong and Luang Prabang, and as a result the

most critical flood conditions occurred in the upstream reaches. Nevertheless, the continuing

strong SW Monsoon and significantly above-average seasonal rainfalls resulted in water levels

remaining very high in the middle reaches of the basin. With at least six to eight weeks of the

flood season remaining, and the peak of the cyclone season still to come, the flood situation

remains critical. Though water levels have decreased somewhat, continuing storms have not

seen them decrease to levels that provide acceptable factors of safety. The region remains

highly vulnerable to the impacts of additional tropical storms tracking across the basin during

the remainder of the season.

Analysis of the available storage behind the three dams currently operational on the Mekong

mainstream in Yunnan reveals this to be insignificant compared to the volumes of runoff that

occurred during the course of the flood. Any releases from these dams would have played

no role in the conditions that developed, which were the result of natural meteorological and

hydrological circumstances.

The August 2008 event was the first regional flood episode for which the RFMMC provided

forecasting services, on the whole results were encouraging. However, lessons to be learnt

include:

1 Alarm levels are always reached at Chao Doc and Tan Chao.

Page 1

Flood situation report August 2008

· Forecast rainfall data and resulting predicted tributary runoff tend to cause substantial

oscillations in the forecasted water levels from day to day. `Learning algorithms'

incorporated within the model could refine and dampen flood forecasts as the event

evolves.

· The performance of the forecasting underscored data deficiencies and the poor

understanding of the flood hydrology of the major tributaries in the Lao PDR north of

Luang Prabang. Here, calibration of the hydrological component of the overall model

needs to be addressed.

· However, even given these limitations regarding the data, the forecast given on 10th

August for Vientiane correctly indicated that the flood level would be exceeded.

Furthermore, the maximum flood level in Vientiane was forecast on the 13th August to

within 20 cm of that actually observed two days later on the 15th.

· Hydrometric data supplied by China under the agreement with the MRC proved to be

extremely important, as it provides a solid starting point for the flood routing on the

mainstream. However, this information is not yet used to its full potential. Respective

parts of the forecasting model require review and improvement.

· At least three-hourly updates of water levels from the AHNIP (Appropriate Hydrological

Improvement Project) and HYCOS (Hydrological Cycle Observation System) stations

are required. Data loggers can be placed in an automatic one- to three-hourly automatic

transmission mode during the critical flood season.

· Following the event a systematic review of the performance of the flood forecasting

technology in the Mekong Basin, both hydrologically and statistically, will be conducted.

· In the short term, institutional arrangements to disseminate MRC forecasts and early

warning need to be reviewed, in terms of their usefulness for counterpart agencies, their

distribution channels and comprehensive coverage of recipients.

Page 2

Flood situation report August 2008

2. Meteorological conditions

Tropical storm Kammuri struck southern China on the 6th August and moved west into northern

Viet Nam and on into northern Lao PDR and southern Yunnan over the following days (Figure 3).

Upper Mekong Basin

Lower Mekong Basin

Manwan

Operational mainstream dams

Dachaoshan

Hydrological station

Jinghong

Path of Tropical Storm Kam

Viet Nam

muri

Chiang Saen

Lao PDR

Luang Prabang

Vientiane

Mukdahan

Thailand

Pakse

Bangkok

Cambodia

Kratie

Phnom Penh

Ho Chi Minh City

Chau Doc

Tan Chau

0

200 kilometres

Figure 3.

Track of tropical storm Kammuri -- first week of August, 2008. (Map based upon data

obtained from the Hong Kong Meteorological Bureau http://weather.gov.hk )

As it moved into the Mekong Basin, the major areas of associated storm rainfall lay in northern

Lao PDR and southern Yunnan (Figure 4):

· In the Lao PDR most rainfall occurred upstream of Luang Prabang. Accumulated rainfall

over the nine days between the 6th and 14th August was generally between 100 and

150 mm, though locally these recorded figures were as high as 200 250 mm.

Page 3

Flood situation report August 2008

· In Yunnan the cumulative rainfall was similar and generally confined to the extreme

south, downstream of Jinghong.

Upper Mekong Basin

Lower Mekong Basin

Mekong mainstream

Hanoi

Vientiane

Cumulative rainfall (mm)

0-5

5-10

Bangkok

10-20

20-40

40-60

60-80

Phnom Penh

80-100

100-150

Ho Chi Minh City

150-200

200-250

250-300

300-350

350-400

> 400

0

200 kilometres

Figure 4.

Accumulated rainfall over the Mekong Region: 6th 14th August 2008 (based on data

provided on a daily basis by the United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric

Administration to the MRC).

Page 4

Flood situation report August 2008

These areas therefore generated virtually all of the consequent flood runoff. Elsewhere in the

lower basin the rainfall was much more scattered and not directly linked to Kammuri. However,

some central and southern areas did receive up to 150 mm over the same period. The 2008

monsoon has so far produced considerable amounts of rainfall over the basin as a whole since

its onset in early May. These conditions have led to saturated catchments throughout the basin

(Figure 5) and therefore flood runoff from tropical storms such as Kammuri was at a maximum.

1-10 August 2008

Percent soil moisture (%)

90 - 100

80 - 90

70 - 80

60 - 70

50 - 60

40 - 50

30 - 40

20 - 30

10 - 20

0 - 10

no data

Figure 5.

Regional soil moisture conditions during early August 2008, indicating that catchments

were saturated. This would have maximised the flood runoff that resulted from tropical

storm Kammuri. (Source: USDA, http://gcmd.nasa.gov/records/GCMD_USDA_FAS_

Percent_Soil _Moisture.html.)

This year, 2008, is a strong La Niña year, during which there is the probability of a more

intense SW Monsoon over SE Asia. The above-average regional rainfall thus far in 2008 tends

to confirm this link. La Niña conditions are also associated with a higher frequency of tropical

storm formation in the Western Pacific.

3. Water levels

The water level at reached Vientiane on the 15th of August was the highest recorded since

records began in 1913. At 13.7 m above the gauge datum, it was 1 m more than the maximum

levels achieved in 1966, 1971 and 2002 (Table 1).

Page 5

Flood situation report August 2008

Table 1. Comparative maximum historical flood water levels at Chiang Saen,

Vientiane and Mukdahan.

Year

Maximum water level achieved above gauge datum (m)

Chiang Saen

Vientiane2

Mukdahan

1924

No data

12.7

No data

1929

..

12.4

..

1942

..

12.2

..

1966

13.8

12.7

13.6

1970

9.8

12.2

13.2

1971

11.0

12.5

12.5

2002

10.4

12.6

12.3

2008

10.6

13.7

12.7

2 Levels recorded at the river gauge at Kilometre 4.

Upstream at Chiang Saen and downstream at Mukdahan, the August 2008 maximum water

levels were lower than those experienced in 1966, being over 3 m lower at Chiang Saen. This

reveals that the situation in 1966 was somewhat different to that in 2008. In September 1966

tropical storm Phyllis tracked further north than did Kammuri in 2008. So while most of the

floodwater in 1966 originated in Yunnan, in 2008, the origin of the floodwater was more or less

evenly split between China below Jinghong and the large left-bank tributaries in northern Lao

PDR.

It is worth noting that the rapid water level rise at Luang Prabang occurred one day before

water levels rose at Man An tributary station in China. This also strongly suggests that the flood

event was primarily caused by heavy rainfall in the basins of the Mekong tributaries in the north

of the Lao PDR.

At Mukdahan, the 2008 water levels were lower than in 1966 and 1970, indicating a

modest contribution from the central Lao tributaries and some attenuation of the August peak

downstream of Vientiane.

Water levels within the Cambodian floodplain and the Delta continued to increase and on the

25th August were 0.47 m above the alarm stage at Tan Chau and 0.26 m above it at Chau Doc.1

4. Flood discharges

The relationship between maximum water level and discharge achieved at Vientiane on the 15th

August is revealing when compared to those of 1966. Although the water level reached in 2008

was 1m higher than that of 1966, the discharge was slightly less. In 1966 peak flood discharge

was 26,000 cumecs, while that in 2008 was 23,500 cumecs. The explanation may lie with the

1 Alarm levels for Tan Chao and Chao Doc are always reached during the flood season.

Page 6

Flood situation report August 2008

flood protection works that were undertaken after 1966 on both the Thai and Lao banks of the

river, subsequent to the inundation of Vientiane, Si Chiang Mai and Nong Khai. These works

involved raising flood protection levees that contain the river within its channel up to

14 m above the gauge datum. This may explain why for a given discharge, water levels are now

higher while the river did not overtop the embankment as it did in 1966.

At Chiang Saen the maximum discharge reached on the 12th August was 13,300 cumecs,

which has only been exceeded three times (in 1966, 1970 and 1971) since records began in

1960.

Further downstream at Pakse and Kratie the peak discharges observed so far in 2008 have

been average. This confirms the fact that peak inflows from the large left-bank tributaries in the

Lao PDR downstream of Vientiane were not excessive, and that the Mekong flood of August

2008 was very much the result of meteorological and hydrological conditions in the northern

regions of the basin, upstream of Vientiane.

30000

1966

25000

2008

20000

cumecs)

ge (

15000

10000

Daily dischar

5000

0

J

F

M

A

M

J

J

A

S

O

N

D

Figure 6.

Comparative discharge hydrographs for the Vientiane Nong Khai reach of the

Mekong, for 1966 and 2008.

5. Flood volumes

Although the peak discharges downstream of Vientiane have so far in 2008 been average, the

flood volumes were, and remain, considerably above normal. This situation indicates that flood

runoff remains high, though to date there have been no individual storm events in the central

and southern areas of the basin that have generated excessive peak discharges. The importance

of assessing the flood volumes is that they are the best indicator of the potential duration of

inundation and the severity of flooding in the Cambodian floodplain and the Delta. In 2008

Page 7

Flood situation report August 2008

the flood season in the Lower Mekong Basin began during the first week of July, which is the

expected time of onset.1

· At Chiang Saen the volume of floodwater over the flood season from then to the

19th of August was 29 km3, which is average and indicates that flows out of China were

relatively low until the commencement of the August flood event.

· At Vientiane the equivalent figure is 64 km3, which is virtually the same as those during

the recent flood years of 2000 and 2001 in the Cambodian floodplain and the Delta. This

figure is much higher figure than that at Chiang Saen and indicates substantial early

season flood runoff from the left bank tributaries in northern Lao PDR. A volumetric

comparison with conditions in 1966 is not possible as that event did not occur until later

in the flood season, in the first week of September.

· By the 25th of August the total flood volume at Pakse and Kratie had tailed off to figures

significantly below those of 2000 and 2001.

· At Kratie the figure on the 25th of August was 150 km3, compared to 290 km3 in 2000

and 260 km3 in 2001. These figures confirm that flood runoff from the large tributaries

downstream of Vientiane has, so far in 2008, been modest and representative of that in an

average year.

Nonetheless water levels in the Cambodian floodplain and the Delta, specifically at Chau

Doc and Tan Chau, are such that the area remains vulnerable to flooding given the

oncoming peak of the cyclone season.

6. The role of the mainstream dams in China on the events of August 2008

The potential role of the three existing mainstream reservoir storages in Yunnan on the volume

and peak discharge of major floods in the northern areas of the Lower Mekong Basin is

insignificant. In other words, they do not have the capacity to materially modify natural flood

conditions.

Their combined active storage is less than 1 km3 (Table 2) and only a small portion of this

could be released practically. The effective drawdown releases would be very small compared

to the volumes of mainstream flood flow, and would be controlled by those from Jinghong, the

downstream dam in the cascade. The rates of release would also be minor compared to the peak

flood discharges.

1 The flood season is defined as the period of the year in which flows exceed the long-term mean annual discharge. This definition

permits the timing of the onset and end of the flood season to be compared from year to year.

Page 8

Flood situation report August 2008

Table 2. Active and gross storage volumes of the Mekong mainstream dams in Yunnan.

(Source: http://adb.org/Documents/Studies/Cumulative-Impact-Analysis/A3-Reservoir-

Hydropower-Data.pdf )

Dam

Gross Storage

Active Storage

km3

km3

Manwan

0.92

0.25

Dachaoshan

0.96

0.37

Jinghong

1.04

0.25

Total

2.92

0.87

In relation to the volumes of flood water that actually occurred during August 2008, any

releases from the reservoirs could not have been a significant factor in this natural flood event.

At Chiang Saen the flood peaked on the 12th, by which time the accumulated flood runoff for

the month had reached 8.5 km3, an order of magnitude greater than anything that could be

realistically released through reservoir drawdown. At Vientiane the flood peaked several days

later on the 15th, by which time the accumulated flood volume there from the beginning of the

month had reached 23 km3.

30

Peak level observed

Mekong at Vientiane

at Vientiane

)3

25

m

Mekong at Chiang Saen

Mekong at Jinghong

20

olume (k

ugust 2008 15

In ows from Lao and Thai

A

tributaries upstream of Vientiane

th

e ood runo v

t

o 19

st

10

1

In ows from tributaries in China and

C

umulativ

5

Myanmar downstream of Chinese dams

Contribution from catchment upstream of Chinese dams

0

Active storage volume of China dams(= 0.87 km3)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19

Date

(August 2008)

Figure 7.

Cumulative Mekong flood runoff volume (km3) between the 1st and 19th of August, 2008

at Chiang Saen and Vientiane, compared to the combined active storage of Manwan,

Dachaoshan and Jinghong reservoirs on the mainstream in Yunnan.

Page 9

Flood situation report August 2008

The flood was the result of natural meteorological and hydrological processes, with

approximately 50% of the overall volumes of floodwater entering the lower basin as flood

runoff from Yunnan (Figure 7). The rest of the floodwater that reached Vientiane and Nong

Khai was mainly contributed by the large left-bank tributaries in northern Lao PDR, such as the

Nam Tha, Nam Ou and Nam Khan.

7. Risk of occurrence

The statistical analysis of water levels to determine the annual risk of flood occurrence is

constrained by the fact that flood protection works have influenced historical levels, and

therefore do not a represent a consistent statistical sample. In terms of discharge, the flood of

August 2008 is estimated to have the following risk of occurrence:

Table 3. Estimated annual recurrence interval of the maximum discharge of

August 2008 (MRCS).

Station

Peak discharge

Annual recurrence interval

(cumecs)

Chiang Saen

13,300

1:5 years

Luang Prabang

23,100

1:30 years

Vientiane/Nong Khai

23,500

1:25 years

Pakse

35,000

1:2 years

Kratie

40,000

1:2 years

These figures confirm that the combination of the flood runoff from China with that from

the tributaries upstream of Luang Prabang, combined to produce a relatively extreme peak

discharge at Luang Prabang and at Vientiane. The peak discharge at Chiang Saen indicates that

the peak discharge from China was not significantly above average, while those downstream of

Vientiane were average due to the fact that flood runoff from the large tributaries in the central

and southern areas of the basin were not affected by tropical storm Kammuri.

8. Prospects for the rest of the 2008 flood season

Since basin-wide water levels remain high, rainfall conditions remain above normal, and the

peak of the cyclone and tropical storm season will not arrive until September and October,

the prospect of the onset of potential further critical flood conditions remains significant.

Regionally, tropical storm development is active.

Two intense systems were identified on the 27th August (Figure 8) to the NW and SE of the

Philippines. These were forecast to move north west and make landfall over southern China,

and significantly affected Hong Kong.

Page 10

Flood situation report August 2008

MTSAT-1R 2008 08 27 00:30 UTC

Image produced by Meteorological Services Division, NEA, Singapore

Figure 8.

Tropical storm activity over the Western Pacific on the 27th of August 2008.

(Source. Singapore Weather Information Portal www.weathe.gov.sg/wip/

web/ASMC/Satellite- imagary/Southeast_Asia /MTSAT-1r )

The development of further tropical storms is inevitable as the season progresses. The peak

seasonal incidence of tropical storms in the south of Viet Nam occurs in October (Figure 9).

35

30

June

y

ms

or 25

equenc

Viet Nam

opical st 20

Lao PDR

15

centage seasonal fr

yphoons and tr 10

Vientiane

P

er

of t

Thailand

5

0

J

F

M

A

M

J

J

A

S

O

N

D

Bangkok

Cambodia

Month

Phnom Penh

Ho Chi Minh City

Upper Mekong Basin

Lower Mekong Basin

December

Figure 9.

The seasonal percentage frequency and average seasonal tracks of typhoons and

tropical storms.

As the season progresses the storm systems moving westwards from the

South China Sea tend to make landfall progressively further south along

the coast of Viet Nam (based on data in Giang, L.T., 2005.)

Page 11

Flood situation report August 2008

As the season progresses their path westwards from the South China Sea and the Gulf of

Tonkin tends to move from north to south, though there are common exceptions to this general

pattern, as Kammuri proved. The average annual number of such events is five, though the

number can be as high as eighteen, as in 1964. The basin, particularly towards the south,

therefore remains vulnerable to the incursion of further storm systems, all the more so if water

levels remain as they currently are.

Although the flood levels at Vientiane and Nong Khai have fallen, history suggests that there

remains a significant probability that they will increase again before the end of the flood season.

By way of example, in Figure 10 water level trajectories are set out for the Vientinae Nong

Khai reach from the 19th August onwards for those years prior to 2008, during which water

levels in mid-August stood at 11 m or more above the gauge datum. Although water levels

can fall by as much as three metres by late August early September, history indicates that in

many years levels rise once again close to or in excess of the August flood level, and that these

conditions can occur as late as the last week of September.

Flood plain storage and the water levels of the Great Lake are slightly above average and

rising in response to the arrival of the floodwater from upstream (Figure 11). Since September

and October are likely to see the occurrence of tropical storms in these southern areas of the

basin, vigilance needs to be maintained. This vigilance is particularly important with regard to

tropical storm development in the Western Pacific, which, as Figure 6 shows, remains active.

15

14

Average levee level

13

Flood level

12

Alarm level

11

10

9

8

2008

v

el

7

Historic

er le

at

6

W ve gauge datum)

5

(m abo

4

3

2

1

0

J

F

M

A

M

J

J

A

S

O

N

D

Figure 10. Mekong at the Vientiane Nong Khai reach.

Daily water level trajectories from the 19th August onwards for those years prior to 2008

during which water levels in mid August were > 11 m above the gauge datum.

Page 12

Flood situation report August 2008

10

Tonle Sap at Prek Kdam

9

average, 1960-2004

8

2008 (to 25th August)

7

6

v

el

5

er le

at

W ve gauge datum) 4

3

(m abo

2

1

0

J

F

M

A

M

J

J

A

S

O

N

D

Figure 11.

Water levels in the Tonle Sap system in 2008 compared to their long term average.

9. Damage

It is very early to assess the damage caused by the event, but already the scale of losses is

apparent. Comprehensive damage assessments are being carried out, but preliminary accounts

indicate that the major impact of tropical storm Kammuri occurred in the northern provinces of

Viet Nam. News reports suggest that 120 people died and that 20,000 houses were damaged or

destroyed by floods, landslides and high winds.

According to the Interior Ministry in Thailand (reported by Reuters on the 18th August),

the flood was the worst in 100 years, claiming six lives, and causing damage estimated at

223 million baht (US$66.5 million) thus far in the country. Initial estimates suggest 92,000

households and 200,000 ha of agricultural land were directly affected.

In Lao PDR, on the 22nd of August the Vientiane Times published initial damage assessment.

The paper reports that damage in Luang Prabang province alone could be as high as 100

billion kip (US$12 million). Reported losses in Vientiane province are close to 148 billion

kip (US$17.5 million). Six deaths have since been reported. In Khammuan province alone,

the flood damage is initially assessed to be at least 31 billion kip (US$3.6 million). The floods

destroyed rice fields, irrigation systems, roads, and schools in the province. Almost 6,000

hectares of rice fields were damaged along with 167 hectares of other crops, 48 irrigation

systems, and 41 schools. In Borikhamxay province authorities estimate damage to the

agriculture sector is worth at least 90 billion kip (US$ 10 million). Road Number 13 South was

Page 13

Flood situation report August 2008

damaged, as were unpaved roads which had linked villages. It should be stressed that these are

preliminary assessments and the responsible authorities will release more detailed reports in due

course.

Figure 12. Flooding in Ban Kao Liao, Vientiane, 13th August 2008.

Page 14

Flood situation report August 2008

10. Performance of the RFMMC flood forecasting

The flood of August 2008 was centred within the upstream regions of the lower basin, with

significant further contributions of flood water from the far south of Yunnan. The major scrutiny

of the performance of the flood forecasting technology therefore lies with its ability to predict

water levels to an acceptable degree of accuracy in these areas of primary impact, and the

subsequent consequences further south as the floodwater moved downstream. The outputs

required are:

· The timing of water level increases and decreases and the potential duration of critical

periods above flood and warning levels, and;

· The water levels that are estimated to occur over time.

These temporal and quantitative aspects are combined by attempting to forecast the levels

over one to five day lead times using information on storm rainfall and catchment condition,

and then routing the estimated flood runoff downstream. Obviously, as lead time increases

accuracy reduces. Figure 13 shows the forecast accuracy of the predicted levels between Chiang

Saen and Chau Doc as the mean absolute error in metres between observed and predicted water

levels, over the period 19th July 22nd August 2008.

1.8

Forecast accuracy for one-day to ve-day lead times

1.6

between 19 July - 22 August 2008

1.4

1.2

r

or (m)

e er 1.0

0.8

ean absolut

M 0.6

5 day

0.4

4 day

3 day

0.2

2 day

1 day

0.0

t

han

hai

hek

het

or

hel

oc

rabang

dahan

Treng Kratie

uong dam

T

hanomhak

Vientiane

enh P

omouk

Koh K

T

Nong K

Muk vannak

Chau D

an Chau

Prek K

Chiang Saen Chiang K

hon P

Sa

Stung

Neak L

Luang P

Nak

K

Phnom P

ompong Chiam

Bassac Chakt

Figure 13. Forecast accuracy of the predicted levels between Chiang Saen and Chau Doc

over the period 19th July 22nd August, 2008.

The general picture that emerges is of significant more accurate forecasting for stations

downstream of Kompong Cham. This coincides with the fact that upstream of this station,

Page 15

Flood situation report August 2008

the errors and unknowns associated with the contributions of flood water to the mainstream

from the large left bank tributaries in the Lao PDR reduce accuracy. Downstream the tributary

contributions are small, so that prediction is almost entirely based on flood routing and therefore

much more precise.

Reduced accuracy is observed at the stations upstream of Vientiane and Nong Khai. This is

exclusively the result of limited data on the mainstream contributions of the major tributaries

in this reach, principally the Nam Ou, Nam Khan and Nam Tha. Rainfall data are particularly

deficient, with the exception of those for the right bank Thai tributaries, though in the main

these are smaller.

It is also evident that the current information received from China allows a one day forecast

at Chiang Saen of flood levels within an order of +/- 0.30 m, and a five-day forecast within an

order of +/- 1 m.

The performance of the flood forecasts increased significantly between the 10th and 13th of

August, with the peak water level at Vientiane predicted to within 20 cm over a lead time of two

days (Figure 14).

11. Lessons learnt and recommendations

The August 2008 event was the first regional flood episode for which active forecasting

was instigated by the RFMMC, and on the whole results were encouraging. Clearly, certain

questions have arisen and there are lessons to be learnt. These fall into three categories: (i) those

with regard to the data, (ii) those with respect to the modelling and accuracy of the forecasts,

and (iii) those concerning the dissemination and communication of the outputs.

Data and information

· The role of the rainfall data in forecasting water levels needs to be reviewed. As the lead

times increase, rainfall data assumes a greater role over the routing in determining overall

accuracy. However, the fall off in precision suggests that more rainfall data are needed

in many areas of the basin, particularly where the major volumes of flood runoff are

generated.

· Improvements in data coverage are particularly needed within the major tributaries in

the Lao PDR north of Luang Prabang, where at least half of the August flood runoff was

generated. Here data for calibrating the hydrological component of the overall model

are limited. A start could be made by considering the historical role that these tributaries

played in past events, with that of 1966 providing the benchmark.

Page 16

Flood situation report August 2008

Water level forecast on the 10th August

14.0

13.5

Forecast

1.

The forecast on the 10th accurately predicted that

Observed

13.0

water levels would exceed the ood level of 12.5 m

within 24 hours. However, the forecast was for this

12.5

v

el

exceedance to last for only one day, after which

12.0

er le

levels would decrease steadily. In fact they

at

11.5

continued to increase until the 15th when the

W ve gauge datum)

maximum of 13.67 m was reached, more than 1.5

11.0

m greater than the forecast peak water level. This

(m abo 10.5

shows the decrease in accuracy beyond the

10.0

two-day forecast.

10th

11th

12th

13th

14th

15th

August

Water level forecast on the 11th of August

14.0

13.5

2.

One day later, on the 11th, the forecast of the

13.0

maximum water level was much better, with only a

20 cm error in the predicted peak water level.

12.5

v

el

However, while this was expected to occur on the

12.0

er le

13th, it actually happened on the 15th.

at

11.5

W ve gauge datum) 11.0

Forecast

(m abo 10.5

Observed

10.0 11th 12th 13th 14th 15th 16th

August

Water level forecast on the 13th of August

14.0

13.5

3.

The forecast of the 13th predicted peak water

13.0

levels to occur on 14th. However, the peak

occurred one day later, on the 15th. The forecast of

12.5

v

el

the height of the peak was good, being only 15

12.0

er le

cm in error. However, the water level fell more

at

11.5

slowly than forecast.

W ve gauge datum) 11.0

Forecast

(m abo 10.5

Observed

10.0 13th 14th 15th 16th 17th 18th

August

Water level forecast on the 15th of August

14.0

13.5

4.

By the 15th, the day on which the peak water level

13.0

occurred, the rate of ood recession was predicted

accurately.

12.5

v

el

12.0

er le

at

11.5

W ve gauge datum) 11.0

Forecast

(m abo 10.5

Observed

10.0 15th 16th 17th 18th 19th 20th

August

Figure 14. Performance of the one- to five-day forecast of water levels at Vientiane on the 10th,

11th, 13th, and 15th of August.

Page 17

Flood situation report August 2008

· Satellite imagery of flooded areas is most valuable. The MRC has already contracted

a specialised agency to provide images, so that flood situation reporting can be

complemented by near real-time visuals.

· Inundation maps should be made available for the whole basin, and risk maps should be

prepared for those areas under significant threat of flooding. Some exist for certain areas,

and this activity should be expanded prior to the next flood season.

· During the course of the event, it also became apparent that along with the daily

provision of water levels from the AHNIP (Appropriate Hydrological Improvement

Project) and HYCOS (Hydrological Cycle Observation System) stations, at a minimum

of three-hourly updates is required. Data loggers should be placed in an automatic one- to

three-hourly automatic transmission mode during the flood season.

· Even though the role of the three existing mainstream reservoir storages in Yunnan on the

volume and peak discharge of major floods in the northern areas of the Lower Mekong

Basin remained insignificant, the flood event clearly demonstrated the usefulness of

early notifications of planned reservoir releases during flood events. Information with (if

possible) a lead time of five days would be most useful with regard to the three existing

mainstream reservoir storages, as well as from larger tributary reservoirs and construction

sites in the Lower Mekong Basin countries. The MRC is well placed to provide advice

on the sequencing and timing of potential releases from a regional flood management

perspective, particularly for larger schemes currently under construction.

Flood modelling capability and forecast accuracy

· The weight given to the rainfall data, and therefore to the tributary runoff, tends to cause

fairly substantial oscillations in the predicted water levels from day to day, particularly

for the longer lead times. This is not reassuring for the end user, and the day-to-day

variance of the forecasts needs to be reduced. Attention is required with regard to the

implementation of `learning algorithms' and feedback methods which the flood forecasts

allow to be refined and `damped' as the event evolves. In the short term a knowledge base

should be built up of major regional storm events. This could can be used develop flood

modelling capability.

· Hydrometric data provided by China proved to be extremely important, as it provides a

solid starting point for the flood routing on the mainstream. However, this information

is not yet used to its full potential. The relevant parts of the forecasting model require

review and improvement.

· All in all this recent flood has provided an excellent opportunity to build on

improvements being implemented, and to continue to review the performance of the

flood forecasting technology in the Mekong Basin, both hydrologically and statistically. A

formal report on the review is planned.

Page 18

Flood situation report August 2008

Dissemination of flood forecasts and early warning

· Institutional arrangements to disseminate MRC forecasts and early warning need to be

reviewed, in terms of their usefulness for counterpart agencies, their distribution channels

and selection of recipients. For instance, in addition to the web based dissemination of

forecasts, the RFMMC communicates forecasts and early warnings via daily emails to

some 50 subscribers. A pro-active and more strategic approach to identify and target

additional interested parties could be warranted.

· This is the first year that flood forecasts have been featured through the MRC's home

webpage. Feedback on further improvement in presentation and communication with

the media will be actively considered.

Flood preparedness

· The recent event may also provide practical lessons to improve and further focus flood

preparedness activities in selected provinces in Cambodia, the Lao PDR and Viet Nam,

which are carried out under FMMP Component 4.

The MRC's Flood Management and Mitigation Programme (FMMP) has developed a

preliminary plan of action to address these points and this will be discussed at a forthcoming

Steering Committee Meeting on 12th September 2008 in Hanoi.

Page 19

Mekong River Commission

P.O.Box 6101,Vientiane 01000,

Lao PDR.Telephone: (856) 21 263 263 Facsimile: (856) 21 263 264

E-mail: mrcs@mrcmekong.org

Website: www.mrcmekong.org

Document Outline

- 1. Summary

- 2. Meteorological conditions

- 3. Water levels

- 4. Flood discharges

- 5. Flood volumes

- 6. The role of the mainstream dams in China on the events of August 2008

- 7. Risk of occurrence

- 8. Prospects for the rest of the 2008 flood season

- 9. Damage

- 10. Performance of the RFMMC flood forecasting

- 11. Lessons learnt and recommendations

- Data and information

- Flood modelling capability and forecast accuracy

- Dissemination of flood forecasts and early warning

- Flood preparedness