ISSN: 1683-1489

Mekong River Commission

Biomonitoring of the lower Mekong

River and selected tributaries,

2004 2007

MRC Technical Paper

No. 20

December 2008

Meeting the Needs, Keeping the Balance

Mekong River Commission

Biomonitoring of the lower Mekong

River and selected tributaries

2004 2007

MRC Technical Paper

No. 20

December 2008

Published in Vientiane, Lao PDR in December 2008 by the Mekong River Commission

Cite this document as:

MRC (2008) Biomonitoring of the lower Mekong River and selected tributaries, 2004 2007,

MRC Technical Paper No 20, Mekong River Commission, Vientiane. 77 pp.

ISSN: 1683-1489

The opinions and interpretation expressed within are those of the authors and do not necessarily

reflect the views of the Mekong River Commission.

Editors: B.C. Chessman, V.H. Resh and T.J. Burnhill

Graphic design: T.J. Burnhill

© Mekong River Commission

184 Fa Ngoum Road, Unit 18, Ban Sithane Neua, Sikhottabong District,

Vientiane 01000, Lao PDR

Telephone: (856-21) 263 263 Facsimile: (856-21) 263 264

E-mail: mrcs@mrcmekong.org

Website: www.mrcmekong.org

ii

Table of Contents

Summary

xvii

1. Introduction

1

1.1. The need for river monitoring

1

1.2. The value of biological monitoring

1

1.3. The types of organisms included in biological monitoring

2

1.4. Biological monitoring in Asia

4

1.5. Development of the MRC biomonitoring programme

8

2. Sampling sites

11

2.1. Rationale for site selection

11

2.2. Designation of reference sites

15

3. Environmental variables

21

3.1. Introduction

21

3.2. Methods

21

3.3. Results

21

3.4. Discussion

27

4. Benthic diatoms

29

4.1. Introduction

29

4.2. Methods

29

4.3. Results

31

4.4. Discussion

32

5. Zooplankton

35

5.1. Introduction

35

5.2. Methods

35

5.3. Results

37

5.4. Discussion

40

6. Littoral macroinvertebrates

41

6.1. Introduction

41

6.2. Methods

41

6.3. Results

43

7. Benthic macroinvertebrates

47

7.1. Introduction

47

7.2. Methods

47

7.3. Results

49

iii

7.4. Discussion

50

8. The use of biological indicators to classify and rate sites

53

9. Future directions

59

10.References

61

Appendix 1. Physical and chemical variables and site disturbance

67

Appendix 2. Species lists and counts per site and sampling occasion

71

Appendix 3. Summary of biological indicator values

73

iv

Table of figures

Figure 2.1 Maps of sites surveyed in 2004, 2005, 2006, and 2007.

14

Figure 2.2 Plates illustrating sites with anthropogenic impacts

17

Figure 3.1 Relationship between river width and altitude.

22

Figure 3.2 Relationship between average water temperature and altitude.

22

Figure 3.3 Relationship between average water temperature and average dissolved oxygen

concentration.

23

Figure 3.4 Relationship between average electrical conductivity and average pH.

23

Figure 3.5 Relationship between average turbidity and average transparency.

24

Figure 3.6 Relationship between average transparency (Secchi depth) and average

chlorophyll-a concentration (plotted on a logarithmic scale).

24

Figure 3.7 Relationships between electrical conductivity values measured at the

same site in different years.

25

Figure 3.8 Relationships between dissolved oxygen values measured at the same

site in different years.

26

Figure 4.1 Statistically significant relationships of average richness of diatoms to

environmental variables.

31

Figure 4.2 Statistically significant relationship of average abundance of diatoms

to Secchi depth.

32

Figure 4.3 Statistically significant relationships of average ATSPT of diatoms to

environmental variables.

33

Figure 5.1 Statistically significant relationships of average richness of zooplankton to

environmental variables.

37

Figure 5.2 Statistically significant relationships of average abundance of zooplankton to

environmental variables.

38

Figure 5.3 Statistically significant relationships of ATSPT of zooplankton to

environmental variables.

39

Figure 6.1 Statistically significant relationships of average richness of littoral

macroinvertebrates (sweep samples) to environmental variables.

43

Figure 6.2 Statistically significant relationships of average richness of littoral

macroinvertebrates (sweep samples) to environmental variables.

44

Figure 6.3 Statistically significant relationships of average ATSPT of littoral

macroinvertebrates (sweep samples) to environmental variables.

45

Figure 7.1 Statistically significant relationships of average richness of benthic

macroinvertebrates to environmental variables.

49

v

Figure 7.2 Statistically significant relationship of average abundance of benthic

macroinvertebrates to electrical conductivity.

50

Figure 7.3 Statistically significant relationships of average ATSPT of benthic

macroinvertebrates to environmental variables.

51

Figure 8.1 Ratings of sites in the Lower Mekong Basin.

55

vi

Table of tables

Table 1.1 Percentage of sources describing an attribute as an advantage of a group of

organisms for biomonitoring.

3

Table 1.2 Percentage of sources describing an attribute as a disadvantage of a group of

organisms for biomonitoring.

4

Table 1.3 Examples of freshwater biomonitoring in Asia.

5

Table 2.1 List of sites sampled in 2004 2007.

11

Table 2.2 Evaluation of all sites against reference site criteria.

18

Table 3.1 Probability and R2 values resulting from linear regression analyses of selected

environmental variables on the Site Disturbance Score.

27

Table 8.1 Interim guidelines for biological indicators of harm to the ecosystem.

53

Table 8.2 Definition and characteristics of the classification system.

54

Table 8.3 Assessment of all sites against suggested guidelines.

56

vii

viii

Acknowledgements

This paper is the result collaborative work between international and riparian biologists

and ecologists over a number of years. The principal contributing authors are: Yuwadee

Peerapornpisal, Tatporn Kunpradid, Sutthawan Suphan, (benthic diatoms); Chanda

Vongsambath, Niane Sivongxay (littoral macroinvertebrates); Pham Anh Duc (benthic

macroinvertebrates); Nguyen Thi Mai Linh (zooplankton); Supatra Parnrong Davidson, Sok

Khom, and Monyrak Meng (environmental variables).

Monyrak Meng of the MRC's Environment Programme coordinated the sampling

programme, analysis, and write up of 2004 2007 field seasons. Representatives from the

National Mekong Committees of Cambodia, Lao PDR, Thailand, and Viet Nam, provided

invaluable help in the organisation of the field campaigns, and provided support for the

monitoring programme as a whole.

Vince Resh and Bruce Chessman, provided expertise and guidance from the inception of

the project to its completion. They also made major contributions to the writing, drafting, and

editing the paper.

ix

x

Abbreviations and acronyms

ATSPI

Average Tolerance Score Per Individual

ATSPT

Average Tolerance Score Per Taxon

BDP

Basin Development Programme of the MRC

DO

Dissolved Oxygen

EC

Electrical Conductivity

MRC

Mekong River Commission

MRCS

Mekong River Commission Secretariat

NTU

Nephelometric Turbidity Units

SDS

Site Disturbance Score

xi

xii

Glossary of biomonitoring terms

Abundance: This is a measurement of the number of individual plants or animals belonging

to a particular biological indicator group counted in a sample. Low species abundance is

sometimes a sign that the ecosystem has been harmed.

Benthic macroinvertebrates: In this report, the use of this term refers to animals that live in

the deeper parts of the riverbed and its sediments, well away from the shoreline. Because many

of these species are not mobile, benthic macroinvertebrates respond to local conditions and,

because some species are long living, they may be indicative of environmental conditions that

are long standing.

Biological indicator group: These are groups of animals or plants that can be used to

indicate changes to aquatic environments. Members of the group may or may not be related

in an evolutionary sense. So while diatoms are a taxon that is related through evolution,

macroinvertebrates are a disparate group of unrelated taxa that share the character of not having

a vertebral column, or backbone. Different biological indicator groups are suitable for different

environments. Diatoms, zooplankton, littoral and benthic macroinvertebrates, and fish are the

most commonly used biological indicator groups used in aquatic freshwater environments. In

addition, although not strictly a biological group, planktonic primary productivity can also be

used as an indicator. However, for a number of logistical reasons fish and planktonic primary

production are not suitable for use in the Mekong.

Diatom: Single celled microscopic algae (plants) with a cell wall made of silica. They drift

or float in the river water (planktic/planktonic) or are attached to substrate such as rocks on

the riverbed and aquatic plants growing in the river (benthic/benthonic). They are important

primary producers in the aquatic food chain and are an important source of food for many

invertebrate animals. Diatoms are a diverse group that respond in many ways to physical and

chemical changes to the riverine environment. Because, they have a short generation time

diatom populations respond rapidly to changes in the environment.

Environmental variables: These are chemical and physical parameters that were recorded at

each sampling site at the same time as samples for biological indicator groups were collected.

The parameters include, altitude, water transparency and turbidity, water temperature,

concentration of dissolved oxygen (DO), electrical conductivity (EC), acidity (pH), and

concentrations of chlorophyll-a, as well as the physical dimensions of the river at the site.

xiii

Littoral macroinvertebrates: In this report, the use of this term refers to animals that live on,

or close to, the shoreline of rivers and lakes. They are the group of animals that are most widely

used in biomonitoring exercises worldwide. They are often abundant and diverse and are found

in a variety of environmental conditions. For these reasons littoral macroinvertebrates are good

biological indicators of environmental changes.

Littoral organisms: Those organisms that live near the shores of rivers, lakes, and the sea.

Macroinvertebrate: An informal name applied to animals that do not have a vertebral column,

including snails, insects, spiders, and worms, which are large enough to be visible to the naked

eye. Biomonitoring programmes often use both benthic and littoral macroinvertebrates as

biological indicators of the ecological health of water bodies.

Primary producer: Organisms at the bottom of the food chain, such as most plants and some

bacteria and blue-green algae, which can make organic material from inorganic matter.

Primary production: The organic material made by primary producers. Therefore, planktonic

primary production is the primary production generated by plants (including diatoms), bacteria

and blue-green algae that live close to the surface of rivers lakes and the sea.

Primary productivity: The total organic material made by primary producers over a given

period of time.

Reference sites: These are sampling sites that are in almost a natural state with little

disturbance from human activity. To be selected as a reference site in the MRC biomonitoring

programme, a site must meet a number of requirements including pH (between 6.5 and 8.5),

electrical conductivity (less than 70 mS/m), dissolved oxygen concentration (greater than 5

mg/L) and average SDS (between 1 and 1.67). Reference sites provide a baseline from which to

measure environmental changes.

Richness: This is a measurement of the number of taxa (types) of plants or animals belonging

to a particular biological indicator group counted in a sample. Low species richness is often a

sign that the ecosystem has been harmed.

Sampling sites: Sites chosen for single or repeated biological and environmental sampling.

Although locations of the sites are geo-referenced, individual samples may be taken from the

different habitats at the site that are suitable for particular biological indicator groups. Sites

xiv

were chosen to provide broad geographical coverage of the basin and to sample a wide range

of river settings along the mainstream of the Mekong and its tributaries. There are 51 sampling

sites from which 14 reference sites were selected.

Site Disturbance Score (SDS): This is a comparative measure of the degree to which the site

being monitored has been disturbed by human activities, such as urban development, water

resource developments, mining, and agriculture. In the MRC biomonitoring programme, the

SDS is determined by a group of ecologists who attribute a score of 1 (little or no disturbance)

to 3 (substantial disturbance) to each of the sampling sites in the programme after discussion of

possible impacts in and near the river.

Richness: This is a measurement of the number of taxa (types) of plants or animals belonging

to a particular biological indicator group counted in a sample. Low species richness is often a

sign that the ecosystem has been harmed.

Taxon/taxa (plural): This is a group or groups of animals or plants that are related through

evolution. Examples include species, genera, or families.

Tolerance, or Average Tolerance Score per Taxon (ATSPT): Each taxon of a biological

indicator group is assigned a score that relates to its tolerance to pollution. ATSPT is a measure

of the average tolerance score of the taxa recorded in a sample. A high ATSPT may indicate

harm to the ecosystem, as only tolerant taxa survive under these disturbed conditions.

Zooplankton: Small or microscopic animals that drift or float near the surface of rivers, lakes,

and the sea. They can be single celled or multi-cellular. They are often secondary producers that

live off phytoplankton (including diatoms) or other zooplankton. Zooplankton can be useful

biological indicators of the ecological health of water bodies because they are a diverse group

that have a variety of responses to environmental changes. Because they have a short generation

time, zooplankton populations tend to respond more rapidly to changes in the environment.

xv

xvi

Summary

A biological monitoring programme was established for the lower Mekong River and its major

tributaries by the MRC and its member nations in response to article 7 of the 1995 Agreement

that established the Commission. The biomonitoring programme complements the previously

established monitoring programmes on physical-chemical water quality, and helps to determine

whether harmful effects on aquatic ecosystems are resulting from the development and use of

the water resources of the Lower Mekong Basin.

The groups of organisms to be monitored in the programme were nominated in 2003 for

their relevance to the interests of the general public, practicality of measurement in a broad-

scale, routine monitoring programme, and likely sensitivity to water resources development

and waste discharge, as indicated by international experience in biomonitoring over the past

century. A pilot study in 2003 tested and refined the groups to be measured. As a result, diatoms,

zooplankton, littoral macroinvertebrates and benthic macroinvertebrates were retained in the

programme. Unfortunately, fish could not be retained for reasons of cost and logistics, but this

could be re-considered in the future. Selected environmental measurements were also included

in the programme to assist in interpretation of the biological data and testing of biological

indicators.

Full-scale data collection with standardized methods began in 2004, when 20 sites were

sampled. In 2005, 16 sites were sampled, in 2006, 21 sites, and in 2007, 20 sites. In total, 51

sites were sampled, with some sites being sampled in two or more years. All sampling was done

in the dry season (March) because high water levels and rapid currents made sampling in the

wet season impossible or dangerous.

Specific indicators of ecological harm were calculated for each sample of diatoms,

zooplankton, littoral macroinvertebrates and benthic macroinvertebrates collected during the

programme. These were richness (number of types of organisms in the sample), abundance

(number of individual organisms in the sample) and average tolerance (a measure of how

resistant the species in the sample are to stresses caused by humans). Because biological

indicators can vary naturally as well because of human activities, data from reference sites

were used to define thresholds of harm. Reference sites with low levels of development were

selected from the total set of sites sampled after consideration of chemical water quality data,

human activity at the site, and human activity upstream. Data from 14 reference sites were used

to generate 12 interim biological guidelines, similar to the physical and chemical guidelines

proposed for the MRC water quality assessment programme. Data from all sites were then

compared with guideline values.

Potentially harmful effects at a sampling site were inferred if the average richness or

abundance of a group of organisms was below the applicable guideline, because reduced

richness or abundance can be construed as harm. For tolerance, potential harm was inferred

xvii

Biomonitoring of the lower Mekong River and selected tributaries, 2004 2007

if the average value calculated for a site was above the applicable guideline, because a more

tolerant fauna indicates a loss of sensitive species. In order to produce an overall assessment ,

each site was classified for each sampling occasion according to the number of guidelines met:

Class A (excellent): 10 12 guidelines met

Class B (good): 7 9 guidelines met

Class C (moderate): 4 6 guidelines met

Class D (poor): 0 3 guidelines met.

Of the 77 sampling events conducted over four years, 28 were in Class A, 32 in Class B, and

17 in Class C. None was in Class D. This rating suggests that the principal rivers of the Lower

Mekong Basin have not yet suffered severe harm from the development of water resources or

waste disposal. However, some rivers are showing signs of stress.

The data collected in this programme provide a basis for actions to avoid, minimise and

mitigate harm to the river's ecosystems, as required by the 1995 Agreement. They also provide

a sound baseline from which to monitor future change.

Page xviii

1. Introduction

1.1 The need for river monitoring

The people of the Lower Mekong Basin and their governments are naturally concerned about

the ecological well being of the river, its major tributaries, and their associated floodplains,

lakes and wetland habitats. This is because the river system supports plant and animal life on

which the livelihoods and food supply of the great majority of the population of 60 million

people have traditionally depended. These concerns are embedded in the 1995 Agreement that

established the MRC. In particular, Article 7 of the agreement states that `harmful effects on

aquatic ecosystems resulting from the development and use of the water resources of the lower

Mekong Basin, or the discharge of wastes and return flows, are to be avoided, minimised or

mitigated.'

However, the governments of the four riparian countries (Cambodia, Lao PDR, Thailand,

and Viet Nam) also want to alleviate poverty in their countries and to raise the standard of

living of their people using the revenue gained from developing other uses of the river, such

as hydropower generation, irrigated agriculture, improved navigation, and tourism. Although

these new developments will inevitably change the natural state of the river system, predictions

about how these modifications will affect people's livelihoods is made difficult by the complex

ecological relationships among the river system, its plant and animal life, and the people who

make a living from the river's resources. Therefore, governments and their line agencies need

monitoring systems that will give them early warning of changes in the ecology of the river, so

that they can take remedial action if it is necessary.

The MRC, acting on behalf of its member states, already has routine monitoring systems in

place for hydrology and climate (water level, flow, and rainfall) and water quality (the chemical

and physical properties of the river water, including natural and man-made pollutants). These

systems are designed for regional-scale monitoring reflecting the MRC's remit to address issues

that cross the national borders of its member states. However, there was no routine biological

monitoring of the Mekong River system prior to the programme described in this paper.

1.2 The value of biological monitoring

Biological monitoring, or biomonitoring, of fresh waters began in Germany at the start of the

20th century (Rosenberg and Resh, 1993). Routine, broad-scale biomonitoring has been well

established in Australia, Europe, Japan and North America for 20 30 years (Bonada et al.,

2006; Carter et al., 2006 a, b; Ziglio et al., 2006). More recently, biomonitoring has expanded

into developing countries, where it has been advocated because its relatively low cost and the

ability of biomonitoring to involve local populations in decision making (Resh, 1995, 2007).

Page 1

Biomonitoring of the lower Mekong River and selected tributaries, 2004 2007

Biomonitoring provides a third type of monitoring that complements physical and chemical

monitoring (Campbell, 2007). Biomonitoring provides important additional information

because plants and animals are sensitive to a wide range of environmental factors, including

many that are not practical to measure routinely in physical and chemical monitoring

programmes. Biomonitoring can therefore provide an indication of environmental problems that

are not detected by physical and chemical monitoring.

In addition, plants and animals are affected by episodic or intermittent pollution that may

not be present at the times when physical and chemical sampling takes place. Populations of

animals and plants that are sensitive to pollution take time to recover after pollutants have

dispersed, and so are indicative of water quality in the recent past as well as quality at the time

of sampling. For this reason, biomonitoring has been likened to a `video replay' of conditions

that existed in the recent past, rather than a `snapshot' of conditions at a single moment in time

(Carter et al., 2006a).

Equally importantly, biomonitoring records the condition of living things that are very

important to people's way of life, and to which they can relate. For example, people will notice

declines in fish populations, changes in vegetation, and the disappearance of certain types of

animals. These sorts of changes cannot be predicted accurately from physical and chemical

monitoring because of the complexity of ecological relationships and the huge variety of

physical and chemical variables that can affect animals and plants.

1.3 The types of organisms included in biological monitoring

Early biomonitoring of fresh waters in Germany focused on bacteria because of concerns

about public health (Hynes, 1960). However, as other management issues emerged, additional

organisms, and eventually entire aquatic communities, were included (Cairns and Pratt, 1993;

Bonada et al., 2006; De Pauw et al., 2006). When Hellawell (1986) reviewed the scientific

literature to determine which biological groups were most popular for monitoring, he found that

benthic macroinvertebrates were recommended in 27% of studies, and followed by algae (25%),

protozoa (17%), bacteria (10%), and fish (6%). Other biotic groups such as macrophytes, fungi,

yeasts, and viruses were seldom recommended.

More recently, most attention has been paid to three groups: benthic macroinvertebrates,

algae (especially diatoms), and fish (De Pauw et al., 2006). In the USA, all states monitor

benthic macroinvertebrates except Hawaii, where a programme is under development; two-

thirds of the states monitor fish and one-third monitor algae (Carter et al., 2006b). Resh (2007)

examined 50 recent biomonitoring studies conducted in developing countries and found that 34

of these used benthic macroinvertebrates, 9 involved fish, 3 algae, and 2 aquatic macrophytes.

Gallacher (2001) reported that benthic macroinvertebrates are the most widely used organisms

in biomonitoring in Asia (in 10 of 12 countries examined), followed by bacteria (8), algae and

fish (7), and protozoans.

Page 2

Introduction

Resh (2008) reviewed 65 journal articles, websites, and books that listed attributes as

advantages and disadvantages of different groups of organisms for biomonitoring. His

results are summarized in Tables 1.1 and 1.2. The number of sources listing advantages and

disadvantages of the different groups follows the pattern of frequency of use in biomonitoring

programmes.

Table 1.1 Percentage of sources describing an attribute as an advantage of a group of organisms for

biomonitoring (after Resh, 2008).

Attribute

Benthic

Algae (periphyton) Fish

Zooplankton

macroinvertebrates (22 sources)

(15 sources)

(9 sources)

(42 sources)

Widespread: Group is abundant,

common, ubiquitous, etc.

60%

36%

17%

33%

Diverse: Group has many species,

varying in responses to environmental

81%

45%

26%

67%

change

Important to ecosystem: Group has

important trophic positions or ecological

29%

23%

63%

56%

roles

Limited mobility: Group is sedentary

and therefore useful for inferring local

69%

14%

0%

0%

conditions

Longer generation time: Group is

useful for tracking over time, long-term

55%

5%

63%

0%

integrators, bioaccumulate toxins

Shorter generation time: Groups

has rapid responses to change, quick

14%

45%

0%

33%

recovery

Economic: Group is inexpensive to

conduct research with, has good benefit-

21%

9%

11%

0%

cost ratio

Easy taxonomy: Group has easily

identified specimens, good taxonomic

36%

23%

58%

0%

keys are available

Easy sampling: Group requires low field

effort

60%

50%

22%

22%

Pre-existing information: Group with

good background information, existing

19%

18%

53%

0%

expertise

Easy transport/storage: Group is easily

taken back from the field, moved, stored

2%

14%

0%

0%

for future use

Field examination: Group could be at

least partly processed/identified while

2%

0%

21%

0%

in the field

Low impact of sampling: Group for

which sampling has a low impact on its

7%

14%

5%

0%

own population and of other fauna

Stable/persistent populations: Group

with populations that are predictable,

and remain in the environment over

0%

5%

16%

0%

time and through various conditions

Use by agencies/volunteers: Group

has been used for biomonitoring by an

7%/7%

0%/0%

11%/0%

0%/0%

agency/volunteer group

Page 3

Biomonitoring of the lower Mekong River and selected tributaries, 2004 2007

Table 1.2 Percentage of sources describing an attribute as a disadvantage of a group of organisms

for biomonitoring (after Resh, 2008).

Attribute

Benthic

Algae (periphyton) Fish

Zooplankton

macroinvertebrates (9 sources)

(14 sources)

(6 sources)

(19 sources)

Sampling difficulties: Group requires

high effort, or has seasonal/daily

fluctuations, patchy spatial distributions,

68%

33%

36%

67%

equipment needs, variable populations

Identification: Group requires expertise

for identification, fewer taxonomic keys

58%

67%

7%

17%

available

Undesirable response levels: Group has

low sensitivity, with tolerances

42%

11%

4%

0%

Lack of social recognition by public:

Public does not consider group

5%

11%

0%

0%

important

Affected by natural conditions: Group

affected by predators, changes in

21%

22%

7%

50%

physical conditions

Mobile: Group swims, drifts, not useful

as a local indicator, affected elsewhere

21%

0%

64%

0%

(e.g. spawning grounds)

Problems with methods/use: Group has

poor metrics/indices available, poor

documentation, laboratory difficulties,

21%

78%

21%

67%

requires expertise

Not found/abundant in certain habitats:

Group does not regularly inhabit area

11%

0%

14%

33%

Short generation time: Poor integrators,

do not show bioaccumulation

0%

33%

0%

33%

Signs of stress hard to trace to source:

Changes in population/community

structure of group does not necessarily

21%

11%

7%

0%

point to cause of change

1.4 Biological monitoring in Asia

Table 1.3 provides examples of freshwater biomonitoring in Asian countries. Some countries

not included in the table, such as India and Indonesia, also have biomonitoring in place (e.g.

Sivaramakrishnan et al., 1996; Sudaryanti et al., 2001). Asian countries have made varying

levels of progress in the establishment of biomonitoring, with Japan being most advanced and

Thailand having made excellent progress, particularly within the Ping River system. Several

studies (e.g. Mustow, 2002) have applied methods developed outside of Asia to examine their

applicability to Asian water bodies (e.g. Thailand). This is a common approach in water quality

monitoring in developing countries.

Page 4

Introduction

Table 1.3 Examples of freshwater biomonitoring in Asia (based on information in Resh, 1995;

Gallacher, 2001; Resh, 2007; Morse et al., 2007)

et

.,

ang

., 1982;

W

Vshivkova

et al

.,; 1992, ., 1994;

., 2005.

et al

et al

et al

., 2003,

et al

Y

ang, 2004;

., 2000,

ang, 2002;

ang

References

Vshivkova and Nikulina, 1998,Vshivkova al et al Vshivkova 2005

Hwang Yang Morse W and W

Future needs and issues

T

axonomic and applied research needed. Development of university courses and mentors. Investment in modern, ecological and taxonomical literature. Environmental monitoring by government agencies based on obsolete methods, with very little use of macroinvertebrates. General public uninformed and uninterested in ecology and nature conservation. Little or no ecological monitoring carried out by private consultants.

Biological monitoring is lagging behind chemical monitoring.

Requirements exist for faunal inventories, establishment of tolerance values, University training programs, training programs for government agencies and specific protocols.

ater Center (CWC) aim to

ater Project (RCWP)

W

geon implemented.

W

and Clean

ganizes regular freshwater clean-ups.

Current practices

Russian Clean developing policies to protect freshwater resources.

RCWP develop rapid bioassessment technology using macroinvertebrates.

Network of public ecological agencies provides extensive monitoring.

Bioassessment data and conclusions passed through CWC to federal and regional nature protection departments, who then investigate sources of pollution.

Rapid bioassessment protocols adapted from those used in the USA.

CWC or

Ecological monitoring by remote sensing implemented.

Conservation programs for Chinese alligator and Chinese stur

Legislation on chemical effluents implemented.

40 NGOs active in China, but biological monitoring by them is rare.

ater

W

issued in 1993.

, Zhujiang and other rivers in late

iener Diversity Index used by

Y

ellow

ater Quality Biomonitoring'

W

Y

angtze,

published in 1994.

orkshops held at several universities and volunteer

Previous studies

Hydrobiologists at Institute of Biology and Soil Sciences began using macroinvertebrates for water quality monitoring in 2001.

National survey of hydrobiological measures and environmental variables for major aquatic resources began in late 1950s.

Point-source, pollution studies began in 1963.

Biotic indices and species diversity indices used to evaluate 1970s.

Modified Shannon-W government agencies in 1982.

`Manual for

`Aquatic Insects of China Useful for Monitoring Quality'

W monitoring groups established.

T

olerance values in east China developed in 2004.

Benthic index of biotic integrity developed in 2005.

Country

Asian Russia

China

Page 5

Biomonitoring of the lower Mekong River and selected tributaries, 2004 2007

T

suda,

Y

ule

Y

ap,

T

anida,

Azrina

Abu-

Y

ong, 2004;

., 2005; Che-

References

T

suda, 1962; 1964; Kawai, 1985; Kawai and 2005.

Bishop, 1973; and Chin, 2003; et al Salmah and Hassan, 2005; 2005.

f required.

ater pollution management requires

Future needs and issues

National and public institutions rarely involved in surveys.

No standardization of sampling or analysis methods.

Some taxonomic problems with databases.

Macroinvertebrates poorly known and relatively few species have been described.

More intensive monitoring of rivers using macroinvertebrates needed.

Increased protection and rehabilitation of aquatic ecosystems required.

T

raining programs for taxonomists and aquatic biologists needed. Educational programs required for the general public and government officials. Laws and regulations must keep pace with accelerating degradation of water resources. W prioritisation. Biomonitoring data need to form a resource for management decisions. Data on species responses to defined toxicant levels need to be made available to monitoring agencies. Adequate training and equipment for biomonitoring staf

The

ganic

status.

ganisms

pollution

.

.

determines

and

Academy of Sciences (supported

orld Bank and US National Science

W

estern Lakes Survey Project focuses on

Current practices

National biomonitoring programme for or pollution.

Nationwide survey of aquatic or (macroinvertebrates) has 800,000 participants.

30 species of macroinvertebrates used as indicators.

National census of river environments (109 rivers) describes macroinvertebrates, fish and riparian plants.

Huge volunteer programs, with participation by 23% of NGOs and 74% of public schools.

Biomonitoring uncommon; most studies focus on biodiversity

National monitoring network (902 stations, 462 rivers) measures various abiotic water quality parameters only biological data collected are for microbial analysis.

72% of rivers considered polluted or slightly polluted.

Biomonitoring carried out through National Institute of Meteorology and Hydrology to investigate biodiversity and evaluate water quality and ecology

Aquatic insect research carried out at National Institute of Meteorology and Hydrology and Mongolian by Foundation).

W diatoms, ostracods and Chironomidae.

Selenge River Basin insect survey project provides inventory of entomofauna.

Selenge River Basin insect survey project provides inventory of entomofauna.

The two projects above aim to establish baseline data on biota for use in biomonitoring programmes and to develop indigenous expertise and infrastructure.

ganic pollution since

.

gely unpublished.

Previous studies

Biomonitoring with macroinvertebrates adapted from German practices in late 1950s.

Comprehensive species lists compiled in 1962.

Introduction of saprobic system and biotic index in 1962.

T

esting of indices to measure or 1980s. Identification guides produced in 1985 and 2005.

One of the first studies of the macroinvertebrate fauna of a tropical river in 1973.

Guide to macroinvertebrates published in 2004.

Impact of a variety of disturbances on macroinvertebrate distribution studied by university research groups, but lar

Comparative study of macroinvertebrate fauna in urban and pristine streams in 2005.

Several macroinvertebrate species identified as potential bioindicators in 2005 study

Hydrobiological studies carried out by Russian and Mongolian scientists since late 1800s.

Interest in aquatic insects as bioindicators began in late 1990s with the introduction of university courses.

Country

Japan

Malaysia

Mongolia

Page 6

Introduction

.,

.;

et

et al

illiams,

et al

., 2002; W

., 2005; Bae,

et al

et al

Thorne and

illiams, 1997;

., 2005; PCD, 2005.

References

Bae and Lee, 2001; Bae 2005a; Bae, 2005b; Yoon, 2005.

Sangpradub 1996 W Kanjanavanit and Moonchinda, 1999; Luadee Thorne and 2002; Inmuong 2003, Boonsoong al

Thai macroinvertebrates.

Future needs and issues

Insufficient taxonomic knowledge.

Educational programs and materials for public participation required.

Research is needed on the taxonomy and biology of

Calibration of bioassessment procedures is required.

to

.

.

Thailand.

protocols are in progress in northern

A

ater quality of inland surface waters is

Current practices

Ministry of Environment of Korea (MEK) requires macroinvertebrate studies in environmental impact assessments.

Long-term `Eco-technopia 21 project' develop technology

Protocols using macroinvertebrates, fish and algae are being investigated in order to establish regular biomonitoring at check points throughout the country

MEK supports long-term biomonitoring in major freshwater systems.

Biomonitoring popular in schools.

Governmental and NGO public education programs include biomonitoring subjects.

W monitored with physical and chemical analysis. Total coliforms and fecal coliforms are the only biological parameters included.

Preliminary rapid bioassessment studies using USEP and north-eastern

orld Foundation started river and stream

Thailand to detect environment disturbance.

W

Previous studies

Community indices introduced in 1970s.

Nature conservation and restoration promoted in 1990s.

Korean biotic index introduced and modified in 1995.

Neural network methods introduced in 1996.

Dominant species index created in 2005.

Physiological measures and molecular biomarkers introduced in 2002.

Green investigation project for youth in 1997 (58 schools participated).

Report on water quality in 48 major rivers published by Pollution Control Department in 2005 (51% moderately polluted).

Studies on adult stages of aquatic insects carried out in northern

Pollution surveillance system using macroinvertebrates initiated along Ping River after 1996.

Country

South Korea

Thailand

Page 7

Biomonitoring of the lower Mekong River and selected tributaries, 2004 2007

Various short-term or issue-specific studies of freshwater organisms have been done in the

Mekong River basin. Fish have been the best studied organisms but this has mainly been from

the perspective of fish taxonomy and fishery productivity. Lists of invertebrates and algae have

also been prepared but vary greatly in their completeness and accuracy. Perhaps the best studied

organism that occurs in the river is the snail Neotricula aperta, which is the intermediate host of

Schistosoma mekongi, the vector of schistosomiasis in the Mekong region.

Grimås (1988) examined 28 sites for benthic macroinvertebrates in Lao PDR, Thailand

and Viet Nam, specifically to consider water quality issues. Concurrently, the Ministry of

Fisheries of Viet Nam conducted a series of studies on the Cambodian section of the Mekong

and included zooplankton, phytoplankton, and benthic invertebrates in their analysis. However,

neither study was detailed, and the results are best considered as preliminary to the programme

described here.

1.5 Development of the MRC biomonitoring programme

In 2003, the MRC undertook a pilot survey in the four riparian countries to test the potential

of five biological groups, and one ecological process, for routine monitoring of the Mekong

River and its major tributaries. These groups and process, selected in consideration of prior

international experience in freshwater biomonitoring, were as follows:

1. Planktonic primary production (a process critical to the well being of the Mekong's

fisheries);

2. Benthic algae, including microscopic diatoms and macro-algae such as the `river weed'

that is processed and sold or eaten by local people;

3. Zooplankton, which are microscopic animals floating and drifting in open water;

4. Littoral macroinvertebrates (invertebrate animals visible to the naked eye), living in the

shallow water at the river's edge;

5. Benthic macroinvertebrates, living in or on the sediments at the bottom of the river;

6. Fish.

The pilot study confirmed that diatoms, zooplankton, littoral macroinvertebrates and benthic

macroinvertebrates were practical and cost-effective for routine sampling and identification

with standard protocols. However, the pilot study showed that planktonic primary production,

macro-algae, and fish were not practical for immediate adoption in the Mekong River system.

The measurement of planktonic primary production required mooring a boat on site for several

hours through the middle part of the day, and transporting a large amount of equipment,

including chemicals, from site to site. These logistical requirements meant that measuring

Page 8

Introduction

primary production was a costly exercise relative to other components. Macro-algae were

not present in sufficient quantities to allow representative sampling at most sites. And pilot

sampling of fish showed that not enough specimens for reliable assessment could be collected

with nets, even when most of the day was spent in sampling one site.

A routine biomonitoring programme began in 2004, based on the four groups of organisms

and associated sampling protocols that proved most successful in the pilot, and continued

annually through to 2007. The overall objectives of this programme were to:

1. Survey the priority biological groups at a set of sites of interest for management

purposes, across all of the sub-areas of the Lower Mekong Basin;

2. Choose a set of reference sites to create a biological benchmark against which data from

any site in the Lower Mekong Basin can be compared;

3. Specify characteristics of the biological groups that indicate harm to the aquatic

ecosystem (biological indicators);

4. Use values of the biological indicators measured at the reference sites to develop a set of

guidelines to rate and classify the sites;

5. Prepare a `report card' that provides non-specialists and the general public with

information on the purpose and methods of biomonitoring, and indicates the current

condition of the river's ecosystems.

The programme was undertaken by biologists and ecologists from the member states,

supported by the MRC secretariat and international experts in the field of biomonitoring. All

sampling was confined to the dry season (March) because sampling in the wet season would be

too logistically difficult and dangerous. However, because of the long life span of many of the

organisms collected, the data reflect prior conditions as well as conditions during the time of

sampling.

This paper summarises and interprets the results of the four years of monitoring. It describes

the sampling locations and dates, the sampling protocols, the environmental variables measured

at each site, and the types and numbers of plants and animals recorded at each site. It analyses

the statistical significance of relationships among these factors and describes the rating and

classification of all the sites sampled.

Page 9

Biomonitoring of the lower Mekong River and selected tributaries, 2004 2007

Page 10

2. Sampling sites

2.1 Rationale for site selection

Biomonitoring sites were chosen to provide broad geographical coverage of the basin,

to include each of the sub-basins defined by the MRC's Basin Development Plan (BDP),

and to sample the mainstream of the Mekong River and each of its major tributaries. Sites

were selected each year by the MRC secretariat in consultation with the National Mekong

Committees.

The four years of sampling covered 51 sites spread across the Lower Mekong Basin (Table

2.1, Figure 2.1). Some sites were visited more than once, and so the study included 77 sampling

occasions. The sites covered a wide range of river settings, including rocky channels in northern

Lao PDR and northeast Thailand, the alluvial channels and floodplains of southern Lao PDR

and Cambodia, and the distributary system of the Mekong Delta in Cambodia and Viet Nam.

The sites also had a range of disturbances from human activity. Some were located in or close

by villages or cities, some were next to fields where crops are grown and livestock graze, some

were upstream or downstream of dams and weirs, and at some there was heavy river traffic.

Table 2.1 List of sites sampled in 2004 2007.

Site

River

Location

Year sampled

Coordinates (UTM)

code

CKL

Bassac

Koh Khel

2006

48P E0503327

N1246641

CKM Se Kong

River mouth

2005

48P E0615596

N1500691

2006

48P E0615508

N1500632

2007

48P E0615573

N1500696

CKT

Mekong

Kampi pool

2004

48P E0610951

N1393569

2006

48P E0609207

N1393544

CMR Mekong

Stung Treng Ramsar site

2005

48P E0607964

N1537129

2006

48P E0604976

N1539456

2007

48P E0605696

N1539736

CNL

Mekong

Nak Loeung

2006

48P E0528321

N1250852

CPP

Tonle Sap

Phnom Penh Port

2004

48P E0492492

N1279903

2006

48P E0491666

N1280205

CPS

Pursat

4 km upstream of Prek Thot

2004

48P E0381258

N1382944

CPT

Prek Te

2006

48P E0613899

N1374811

CSJ

Se San

Downstream of confluence with

2005

48P E0621005

N1499145

Sre Pok

2006

48P E0620973

N1499412

2007

48P E0615573

N1500688

Page 11

Biomonitoring of the lower Mekong River and selected tributaries, 2004 2007

Site

River

Location

Year sampled

Coordinates (UTM)

code

CSK

Stoeng Sangke

Battambang

2006

48P E0348375

N1465699

CSN

Stoeng Sen

Kapongthom

2006

48P E0490998

N1401845

CSP

Sre Pok

Kampong Saila, Lumpat

2004

48P E0716971

N1490691

2005

48P E0716971

N1490691

2006

48P E0717424

N1490804

2007

48P E0717104

N1490800

CSS

Se San

Veunsai District, Rattanakiri

2004

48P E0696445

N1545480

Province

2005

48P E0695488

N1546145

CSU

Se San

Pum Pi village, Rattakiri Province

2005

48P E0764687

N1526041

2006

48P E0764506

N1526065

2007

48P E0764707

N1526063

CTU

Tonle Sap

Prek Kdam ferry

2004

48P E0477884

N1309367

2006

48P E0478364

N1307071

LBF

Se Bang Fai

2007

48Q E0498437

N1888075

LBH

Se Bang Hieng

2007

48Q E0540315

N1779816

LDN Mekong

Done Ngieu island

2007

48P E0596621

N1650516

LKD Nam Ka Ding

Haad Sai Kam

2004

48Q E0398871

N2023713

2007

48Q E0398583

N2023903

LKL

Se Kong

Ban Xou Touat, Attapeu Province

2005

48P E0673642

N1622904

2007

48P E0670721

N1623450

LKU Se Kong

Ban Xakhe, Attapeu Province

2005

48P E0701679

N1653515

2007

48P E0702400

N1653117

LMH Mekong

Near Houa Khong water quality

2005

47Q E0723733

N2383320

station

LMX Mekong

Near Ban Xieng Kok, Muang

2005

47Q E0670860

N2311778

Luang

LNG Nam Ngum

Upstream of confluence with Nam

2004

48Q E0240744

N2050118

Lik

2007

48Q E0237411

N2049992

LNK Nam Khan

Between Hat Hian and Ban Houay

2005

48Q E0203428

N2200953

Ung

LNM Nam Mo

Upstream of bridge near mine

2007

48Q E0280667

N2088210

LNO Nam Ou

About 5 km from river mouth

2004

48Q E0212495

N2222855

LNT

Nam Ton

50 km from Vientiane

2007

48Q E0208083

N2016581

LOU Nam Ou

Between Ban Pak Ou and Ban

2005

48Q E0219345

N2229380

Hat Mat

LPB

Mekong

Above Luang Prabang, upstream

2004

48Q E0201739

N2203028

of Pak Nam Karn

2005

48Q E0206113

N2206957

LPS

Mekong

Pakse, upstream of Se Done mouth

2004

48P E0587623

N1671756

LSD

Se Done

Ban He, upstream of Pakse

2007

48P E0586345

N1673985

Page 12

Sampling sites

Site

River

Location

Year sampled

Coordinates (UTM)

code

LVT

Mekong

Upstream of Vientiane

2004

48Q E0239871

N1988731

2007

48Q E0229378

N1990015

TCH

Nam Chi

Wat Sritharararm, Yasothon

2004

48P E0407724

N1745362

TKO Nam Mae Kok

About 15 km upstream of Chieng

2004

47Q E0576165

N2205993

Rai Weir

2005

47Q E0576410

N2205793

TMC Mekong

Wiangkhain, between Sop Ing Tai

2005

47Q E0655974

N2231281

and Ban Huai Ian, near Cham Pong

TMI

Nam Mae Ing

Near Ban Ten

2005

47Q E0640355

N2213637

TMM Nam Mun Chi

Mekong (Mun - Kong Chiam)

2007

48P E0552854

N1692378

TMU Nam Mun

Ban Tha Phae, Ubon Ratchathani

2004

48P E0553283

N1692193

TNK Nam Kham

Na Kae

2007

48Q E0450473

N1874626

TSK

Nam Songkhram About 8 km from river mouth

2004

48Q E0438501

N1946480

2007

48Q E0440989

N1948666

TSM Nam Songkhram Mekong

2007

48Q E0444135

N1951422

VCD Bassac

Chau Doc

2004

48P E0515263

N1187502

2006

48P E0510969

N1188413

VCL

Cao Lanh

2006

48P E0563807

N1153868

VCT

Bassac

Can Tho

2006

48P E0588365

N1110673

VLX Long Xuyen

2006

48P E0551878

N1143546

VSP

Sre Pok

Ban Don hydrographic station

2004

48P E0802270

N1426825

VSR

Sre Pok

Upper Sre Pok

2006

48P E0817329

N1396950

VSS

Se San

Kon Tum hydrographic station

2004

49P E0180575

N1587838

2006

48P E0180527

N1588158

VTC

Mekong

Tan Chau

2004

48P E0528931

N1194535

2006

48P E0524259

N1195808

VTR

Vinh Long

Vinh Long

2006

48P E0603976

N1135759

2004 survey

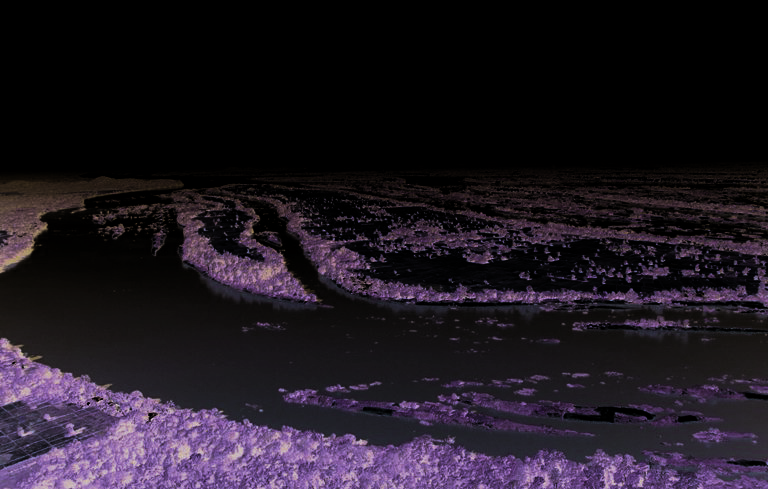

The sites surveyed in 2004 were chosen to provide a broad geographic coverage across the

Lower Mekong Basin. They included localities on the Mekong and its major tributaries, in each

of the BDP sub-areas and MRC member states.

2005 survey

The geographic coverage was more focused for the 2005 survey. The sites fell into two groups:

(i) northern Lao PDR and the northern provinces of Thailand (mainly Chiang Rai), which lie

in BDP sub-areas 1 (Northern Lao PDR) and 2 (Chiang Rai), and (ii) southern Lao PDR and

eastern Cambodia, which lie largely in sub-area 7 (Se San/Sre Pok/Se Kong).

Page 13

Biomonitoring of the lower Mekong River and selected tributaries, 2004 2007

Viet Nam

LMH

Viet Nam

LMX

TMC

LOU

LNO

LPB

TKO

LPB

TKO

TMI

LNK

Lao PDR

Lao PDR

LNG

LKD

LVT

TSK

Thailand

TCH

Thailand

TMU

LKU

LPS

LKL

VSS

CSS

CSS

CMR

CSP

CKM

CSU

Cambodia

CSJ

CSP

Cambodia

VSP

CPS

CKT

CTU

CPP

Viet Nam

Viet Nam

VCD

VTC

Biomonitoring Survey 2004

Biomonitoring Survey 2005

Sampling locality

0

100

200 kilometres

Sampling locality

0

100

200 kilometres

Viet Nam

Viet Nam

Lao PDR

Lao PDR

LNM

LNG

LNT

LKD

LVT

TSM

TSK

LBF

TNK

LBH

Thailand

Thailand

TMM

LSD LKU

LDN

LKL

VSS

CMR

CSU

CMR

CSU

CKM

CKM

CSK

Cambodia

CSJ CSP

Cambodia

CSJ CSP

CSN

CKT

VSR

CPT

CTU

CPP

CKL

CNL

Viet Nam

Viet Nam

VCD

VTC

VCLVTR

VLX

VCT

Biomonitoring Survey 2006

Biomonitoring Survey 2007

Sampling locality

0

100

200 kilometres

Sampling locality

0

100

200 kilometres

BDP Sub-area

1. Northern Laos

4. Central Laos

7. Se San/Sre Pok/Se Kong

2. Chiang Rai

5. Mun/Chi

8. Kratie

3. Nong Khai/Songkhram

6. Southern Laos

9. Tonle Sap

10. Delta

Figure 2.1 Maps of sites surveyed in 2004, 2005, 2006, and 2007.

Page 14

Sampling sites

2006 survey

The 2006 survey focused on the mainstream and its major tributaries downstream of the

Ramsar site at Stung Treng in northern Cambodia. The survey included localities in sub-areas 6

(Southern Lao), 7 (Se San/Sre Pok/Se Kong), 8 (Kratie), 9 (Tonle Sap), and 10 (Delta).

2007 survey

The 2007 survey covered a large area of the lower Mekong Basin in central Lao PDR, and

along the border of Lao PDR and Thailand. Sites from previous years were re-sampled in the

Se Kong river in Lao PDR and Cambodia, and the Se San and Sre Pok rivers in Cambodia. The

sites included fell in sub-areas 3 (Nong Khai/Songkhram), 4 (central Lao PDR), 5 (Mun Chi),

6 (southern Lao PDR), and 7 (Se San/Se Kong/Sre Pok).

2.2 Designation of reference sites

Reference sites are used in both physical-chemical monitoring (e.g. to set water-quality criteria)

and biological monitoring programmes worldwide. In biomonitoring, the sites chosen to be

reference sites are usually selected on the basis of water quality and the degree of disturbance

caused by human activities. They are commonly those sites that are in a most natural, or

pristine, state. Reference sites for the Mekong provide benchmark data against which all sites in

the system can be compared. They are located where anthropogenic impacts, such as from water

resource development or waste disposal, are minimal.

Accordingly, reference sites were selected from those sampled in the biomonitoring

programme by the application of six criteria related to water quality, human disturbance in the

vicinity of the site, and human disturbance upstream. The water quality criteria were based on

those proposed for the MRC's Environment Programme Water Quality Index (MRC 2008).

Site disturbance was scored by the national and international experts present on each sampling

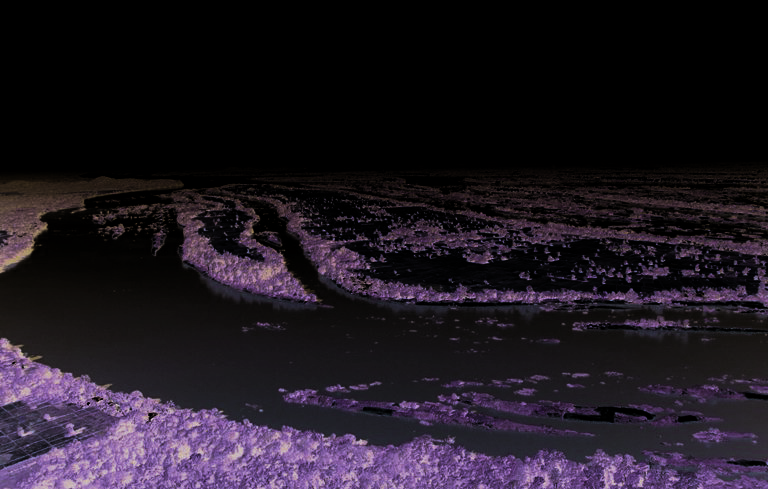

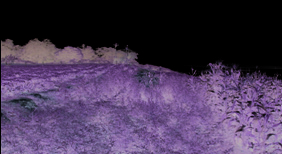

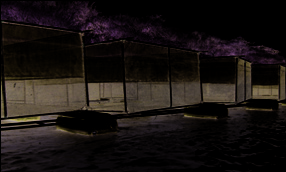

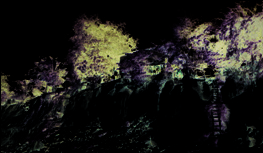

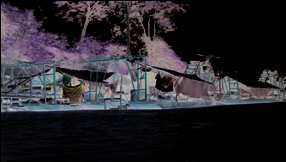

occasion, having regard to site-scale activities such as the following (Figure 2.2):

1. Sand and gravel extraction;

2. Dredging and mining;

3. Removal of natural riparian vegetation for agriculture or housing;

4. Agricultural cultivation;

5. In-stream aquaculture;

6. Fishing intensity;

Page 15

Biomonitoring of the lower Mekong River and selected tributaries, 2004 2007

7. Road building;

8. Unnatural bank erosion;

9. Cattle and buffalo grazing;

10. Boat traffic;

11. Waste disposal from villages, farms, towns etc.;

12. Village activities such as bathing and washing of clothes;

13. Unnatural fluctuations in water level.

A Site Disturbance Score (SDS) ranging from 1 (little or none of any of these types of

disturbance) to 3 (substantial disturbance of one or more types) was assigned independently by

each of the participants following group discussion about potential anthropogenic impacts (on

average there were eight participants, with a range of between five and nine). The individual

scores were then averaged to determine a measure of human disturbance at a site. Visual

assessment was used because it was not possible to make quantitative measurements of all of

these types of disturbance. Visual scoring systems are widely used in stream assessments for

features that are not amenable to quantitative measurement. Averaging of the scores of several

observers evens out the influence of individual differences, in the same way that scores are

averaged among judges of sporting and artistic competitions.

To be selected as a reference site, a site had to meet all of the following requirements:

1. The pH of the site at the time of biological sampling was between 6.5 and than 8.5.

2. The electrical conductivity at the time of biological sampling was less than

70 mS/m.

3. The dissolved oxygen concentration at the time of biological sampling was greater than

5 mg/L.

4. The average SDS was between 1 and 1.67 on a scale of 1 to 3, that is, in the lowest

one-third of possible scores. A typical site with a score between 1 and 1.67 might

have low-level rural development, such as low-density village activities, but not major

urbanization, intensive agriculture or waste disposal.

5. There was no major dam or city within 20 km upstream of the site, and flow at the site

was not affected by inter-basin water transfers. Downstream development was also

considered where a site has upstream flow because of tidal influence.

Page 16

Sampling sites

i

ix

ii

viii

iii

vii

iv

vi

v

Figure 2.2 Clockwise from top left (i) reference site; examples of disturbance caused by human

activity (ii) bank erosion, (iii) over-fishing, (iv) mining, (v) waste disposal,

(vi) agricultural discharge, (vii) urban development, (viii) aquaculture, and (ix)

agricultural cultivation.

Page 17

Biomonitoring of the lower Mekong River and selected tributaries, 2004 2007

Fourteen of the 51 sites sampled in the programme met all criteria and were selected as

reference sites (Table 2.2).

Table 2.2 Evaluation of all sites against reference site criteria.

Site

Number of pH

Maximum EC Minimum DO

Site

Upstream and downstream

Reference site

sampling (range if

(mS/m)

(mg/L)

disturbance disturbance

(yes or no)

occasions applicable)

score

CKL

1

7.17

12.32

7.56

2.19

Phnom Penh City

N

CKM

3

5.16 7.77

7.30

6.32

1.33

N

CKT

2

7.69 8.40

19.62

6.89

1.19

Y

CMR

3

7.74 8.41

23.02

8.15

1.59

Y

CNL

1

7.54

19.35

7.02

1.97

N

CPP

2

7.18 7.94

10.47

3.94

2.88

Phnom Penh City

N

CPS

1

7.30

8.40

5.07

2.22

N

CPT

1

7.13

11.03

4.56

2.33

N

CSJ

3

7.22 7.48

4.93

6.00

1.34

Dam 200 km upstream

Y

CSK

1

6.99

18.18

3.76

2.00

Battambang City and

N

agriculture

CSN

1

7.22

8.10

7.13

2.00

N

CSP

4

7.32 7.63

6.85

5.91

1.22

Y

CSS

2

7.24 7.52

4.23

6.19

1.75

N

CSU

3

7.05 7.32

4.30

6.98

1.95

N

CTU

2

7.00 7.01

9.08

3.79

2.08

N

LBF

1

8.05

32.88

7.54

1.72

N

LBH

1

7.86

15.25

7.70

1.63

Interbasin transfer

N

LDN

1

8.27

22.87

8.51

1.53

Y

LKD

2

7.71 7.97

10.70

7.67

1.50

Dam 100 km upstream with

N

interbasin transfer

LKL

2

7.18 7.24

7.07

5.56

1.59

Dam next year

Y

LKU

2

6.98 7.18

5.14

5.99

1.33

Dam next year

Y

LMH

1

8.19

34.80

9.34

1.94

N

LMX

1

8.10

33.00

8.25

1.94

N

LNG

2

6.87 7.45

7.51

6.93

1.67

Dam 3 km upstream

N

LNK

1

8.27

25.10

7.47

1.38

Y

LNM

1

7.95

9.65

8.87

2.31

Gold mine

N

LNO

1

8.46

24.72

8.59

1.00

Y

LNT

1

7.43

14.67

8.69

1.69

Town

N

LOU

1

8.15

21.27

8.16

1.00

Y

LPB

2

8.17 8.47

27.40

7.87

1.48

Y

LPS

1

8.38

22.86

7.17

1.57

Y

LSD

1

7.80

11.90

7.42

1.97

Rubber plantation

N

Page 18

Sampling sites

Site

Number of pH

Maximum EC Minimum DO

Site

Upstream and downstream

Reference site

sampling (range if

(mS/m)

(mg/L)

disturbance disturbance

(yes or no)

occasions applicable)

score

LVT

2

7.79 8.63

28.80

8.61

1.78

N

TCH

1

7.83

18.38

7.71

1.86

N

TKO

2

6.62 7.95

11.75

6.22

1.87

N

TMC

1

6.80

22.68

7.60

1.64

Y

TMI

1

6.80

10.18

6.40

2.25

N

TMM

1

7.52

20.94

7.25

2.17

Dam 10 km upstream

N

TMU

1

7.30

9.59

7.44

1.71

Ubon City

N

TNK

1

7.15

16.92

7.11

2.44

Series of weirs

N

TSK

2

7.47 8.01

76.66

7.15

2.05

N

TSM

1

8.12

24.95

8.65

1.86

N

VCD

2

7.10 7.68

18.05

3.91

2.50

Town downstream and tidal

N

movement; agriculture;

shipping

VCL

1

7.58

18.87

8.01

1.91

Town upstream; agriculture;

N

shipping

VCT

1

7.18

18.60

5.20

2.64

City upstream and

N

downstream; agriculture;

shipping

VLX

1

7.13

18.57

6.59

2.69

City upstream; agriculture;

N

shipping

VSP

1

7.77

6.26

5.87

1.29

Y

VSR

1

7.14

5.15

7.31

2.00

Dam 7 km upstream

N

VSS

2

6.62 7.66

3.97

7.28

2.14

N

VTC

2

7.64 8.33

18.28

5.70

2.39

Town downstream and tidal

N

movement; agriculture;

shipping

VTR

1

7.33

18.11

6.70

2.44

Town downstream and tidal

N

movement; agriculture;

shipping

Page 19

Biomonitoring of the lower Mekong River and selected tributaries, 2004 2007

Page 20

3. Environmental variables

3.1 Introduction

In the past, physical and chemical information was often the sole basis for monitoring the

environmental quality of rivers and lakes. Today, with the widespread implementation of

biological monitoring programmes, physical and chemical information is complemented by

biological data. Physical and chemical data can assist in the interpretation of information

obtained from biological monitoring programmes by revealing potential causes of biological

changes. For this reason, physical and chemical measurements were included in the

biomonitoring programme.

This chapter describes the physical and chemical environment of the sites sampled in the

biomonitoring programme from 2004 to 2007. Information is provided on site locations and

dimensions, water transparency and turbidity, water temperature, the concentration of dissolved

oxygen (DO), electrical conductivity (EC), pH, and concentrations of chlorophyll-a. Later

chapters relate these physical and chemical measurements to biological indicators.

3.2 Methods

The map coordinates and altitudes of the sampling sites were determined with a Garmin GPS

12xL device, and river width was measured with a Newcon Optik LRB 7x50 laser rangefinder.

All water quality measurements were taken in three sections of the river at each site, near the

left bank, near the right bank, and in the centre of the river, and averaged. Temperature, DO,

EC, and pH were measured with Enviroquip TPS meters and later with a YSI 556MP5 meter,

calibrated according to the manufacturer's instructions. Readings were taken at the surface and

at a depth of 3.5 m, or the maximum of the river, whichever was less. A Secchi disc was used

to determine water transparency. The disc was slowly lowered into the water, and the depth

at which it could no longer be seen was recorded. The disc was then lowered another metre

and slowly pulled up until it reappeared. If it reappeared at a depth more than 0.05 m different

from the depth at which it disappeared, the procedure was repeated. Water turbidity and the

concentration of chlorophyll-a were measured at the water surface in 2006 and 2007 only, with

a Hach 2100P turbidity meter and Aquaflour handheld fluorimeter respectively.

3.3 Results

Overall variability and relationships among variables

Site averages of the environmental variables had a broad range across the 51 study sites over 77

visits during the four years (Appendix 1). Altitude varied from 3 to 565 m above sea level, with

Page 21

Biomonitoring of the lower Mekong River and selected tributaries, 2004 2007

most of the lowland sites being in Cambodia and Viet Nam and the high-altitude sites in Lao

PDR, Thailand, and Viet Nam. Water width in the rivers varied from 11 to 2660 m, and tended

to be greater as the altitude decreased (Figure 3.1).

3000

2500

2000

1500

er width (m)

R

iv

1000

500

00

100

200

300

400

500

600

Altitude (m)

Figure 3.1 Relationship between river width and altitude.

Water temperature ranged from 16.7 ºC in a small, high-altitude river in Lao PDR to

31.4 ºC at a site in Cambodia, with an overall average of 27.7 ºC. As would be expected,

temperature tended to be lower at the higher altitudes, although there was considerable variation

(Figure 3.2).

35

30

C

)

o e (

a

tur

25

T

emper

20

150

100

200

300

400

500

600

Altitude (m)

Figure 3.2 Relationship between average water temperature and altitude.

Page 22

Environmental variables

The concentration of dissolved oxygen was generally high, ranging from 2.7 to 10.5 mg/L

with an average of 7.1 mg/L. DO was generally lower where temperature was higher, usually

in low-elevation sites, which was expected because the solubility of oxygen is lower in warmer

water (Figure 3.3).

11

10

9

8

7

x

y

gen (mg/L)

6

ed o

5

Dissolv

4

3

215

20

25

30

35

Temperature (oC)

Figure 3.3 Relationship between average water temperature and average dissolved oxygen

concentration.

The water was slightly alkaline at most of the sites, with pH varying between 5.2 and 8.6,

with an overall average of 7.5. EC was generally low, varying from 3.9 to 76.7 mS/m with an

average of 15.3 mS/m. Lower conductivity was found in tributary sites, whereas higher values

were found at the sites in the main channel and those with human disturbance or in limestone

catchments. Higher pH values tended to be associated higher EC (Figure 3.4).

9

8

pH

7

6

50

20

40

60

80

Electrical conductivity (mS/m)

Figure 3.4 Relationship between average electrical conductivity and average pH.

Page 23

Biomonitoring of the lower Mekong River and selected tributaries, 2004 2007

Water transparency (Secchi depth) was variable, and ranged from 0.2 m to 3.4 m with an

overall average of 1.0 m. Turbidity ranged from 2.4 to 71.1 NTU with an average of 15.3 NTU,

and as expected was inversely related to transparency (Figure 3.5).

3.5

3.0

2.5

y (m)

2.0

enc

1.5

T

r

anspar

1.0

0.5

0.00

20

40

60

80

Turbidity (NTU)

Figure 3.5 Relationship between average turbidity and average transparency. Turbidity was not

measured in 2004 or 2005.

Chlorophyll-a concentrations were generally low, ranging between 0.2 and 4.0 µg/L, except

for a value of 33.6 µg/L in Tonle Sap at Phnom Penh Port. Chlorophyll-a concentration was

negatively related to transparency, suggesting that phytoplankton levels were limited by light

availability (Figure 3.6).

100

10

yll-a (ug/L)

oph

Chlor

1

0.1 0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

3.5

Secchi depth (m)

Figure 3.6

Relationship between average transparency (Secchi depth) and average chlorophyl -a

concentration (plotted on a logarithmic scale). Chlorophyll a was not measured in 2004 or 2005.

Page 24

Environmental variables

Inter-annual changes

Twenty of the 55 sites were sampled in two or more years. Often, values of environmental

variables were similar at the same site in different years, for example EC (Figure 3.7). Other

variables such as DO varied more at a site between years (Fig. 3.8). However, DO typically

fluctuates even within the same day, because of variations in sunlight and temperature and

consequent differences in oxygen exchange with the atmosphere, the release of oxygen by

aquatic organisms via photosynthesis, and uptake for respiration. The most notable inter-annual

difference in pH was a low value of 5.2 at site CKM in 2006 compared to 7.5 and 7.8 in 2005

and 2007 respectively.

80

80

60

60

y 2005 (mS/m)

y 2006 (mS/m)

tivit 40

tivit 40

onduc

onduc

ical c 20

ical c 20

tr

tr

Elec

Elec

0

0

0

20

40

60

80

0

20

40

60

80

Electrical conductivity 2004 (mS/m)

Electrical conductivity 2004 (mS/m)

80

80

60

60

y 2007 (mS/m)

y 2006 (mS/m)

tivit 40

tivit 40

onduc

onduc

ical c 20

ical c 20

tr

tr

Elec

Elec

0

0

0

20

40

60

80

0

20

40

60

80

Electrical conductivity 2004 (mS/m)

Electrical conductivity 2005 (mS/m)

80

80

60

60

y 2007 (mS/m)

y 2007 (mS/m)

tivit 40

tivit 40

onduc

onduc

ical c 20

ical c 20

tr

tr

Elec

Elec

0

0

0

20

40

60

80

0

20

40

60

80

Electrical conductivity 2005 (mS/m)

Electrical conductivity 2006 (mS/m)

Figure 3.7 Relationships between electrical conductivity values measured at the same site in

different years.

Page 25

Biomonitoring of the lower Mekong River and selected tributaries, 2004 2007

11

11

10

10

9

9

8

8

7

7

x

y

gen 2005 (mg/L)

6

x

y

gen 2006 (mg/L)

6

ed o

5

ed o

5

4

4

Dissolv

Dissolv

3

3

2

2

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9 10 11

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9 10 11

Dissolved oxygen 2004 (mg/L)

Dissolved oxygen 2004 (mg/L)

11

11

10

10

9

9

8

8

7

7

x

y

gen 2007 (mg/L)

6

x

y

gen 2006 (mg/L)

6

ed o

5

ed o

5

4

4

Dissolv

Dissolv

3

3

2

2

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9 10 11

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9 10 11

Dissolved oxygen 2004 (mg/L)

Dissolved oxygen 2005 (mg/L)

11

11

10

10

9

9

8

8

7

7

x

y

gen 2007 (mg/L)

6

x