Mekong River Commission

Yield and value of the wild fishery of

rice fields in Battambang Province,

near the Tonle Sap Lake, Cambodia

MRC Technical Paper

No. 18

July 2008

Meeting the Needs, Keeping the Balance

Mekong River Commission

Yield and value of the wild fi shery of

rice fi elds in Battambang Province,

near the Tonle Sap Lake, Cambodia

MRC Technical Paper

No. 18

July 2008

Published in Vientiane, Lao PDR in July 2008 by the Mekong River Commission

Cite this document as:

Hortle K.G., Troeung R., and S. Lieng (2008) Yield and value of the wild fi shery of rice fi elds

in Battambang Province, near the Tonle Sap Lake, Cambodia. MRC Technical Paper No.18.

Mekong River Commission, Vientiane. 62 pp.

The opinions and interpretation expressed within are those of the authors and do not necessarily

refl ect the views of the Mekong River Commission.

Editor: T.J. Burnhill

Graphic design: T.J. Burnhill

Photographs: K.G. Hortle, S. Chan, R. Troueng, and J.G. Garrison

© Mekong River Commission

184 Fa Ngoum Road, Unit 18, Ban Sithane Neua, Sikhottabong District,

Vientiane 01000, Lao PDR

Telephone: (856-21) 263 263 Facsimile: (856-21) 263 264

E-mail: mrcs@mrcmekong.org

Website: www.mrcmekong.org

ii

Table of Contents

Summary

xi

1. Introduction

1

2. Methods

3

2.1 Study

area

3

2.2 General features of the fi shery

4

2.3 Study

sites

5

2.4 Rainfall

8

2.5 Inundation of rice fi elds and rice growing

8

2.6 Catch

assessment

9

2.7 Standing

crop

10

2.8 Socio-economic information on fi shers

11

2.9 Statistics

11

3. Results

13

3.1 General socioeconomic observations

13

3.2 Fishing gears, effort and total catch

14

3.3 Yield and composition of the catch

19

3.4 Composition and catch by gear

22

3.5 Value of the catch

22

3.6 Disposal of the catch

24

3.7 Comparison between sites

24

3.8 Relationship to habitat variables

26

3.9 Standing

Crop

27

3.10 Catches as a proportion of standing crop

30

3.11 Length-frequency data

31

4. Discussion

37

4.1 Comparison with rice-fi eld fi sheries elsewhere

37

4.2 Signifi cance to livelihoods and food security

40

4.3 Implications

for

fi shery yield estimates

40

4.4 Integration

of

fi sheries and agriculture

43

5. References

45

Appendix 1. Effort, total catches and CPUE for all gears and sites combined

49

Appendix 2. Total effort, catch and CUPE for all gear types

51

iii

Appendix 3. List of species of fi sh and taxa of OAAs recorded, with proportions of total weight

in catches and standing crop estimation, and categorisation by diet and as black or white/

grey fi shes

53

Appendix 4. Total catch of each species by each type of gear

55

Appendix 5. Taxa recorded in this study with total catch quantities and value

59

Appendix 6. Length frequency distributions for the fi ve most abundant species of fi shes

61

iv

Table of Figures

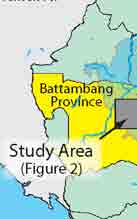

Figure 1. Location of study area.

3

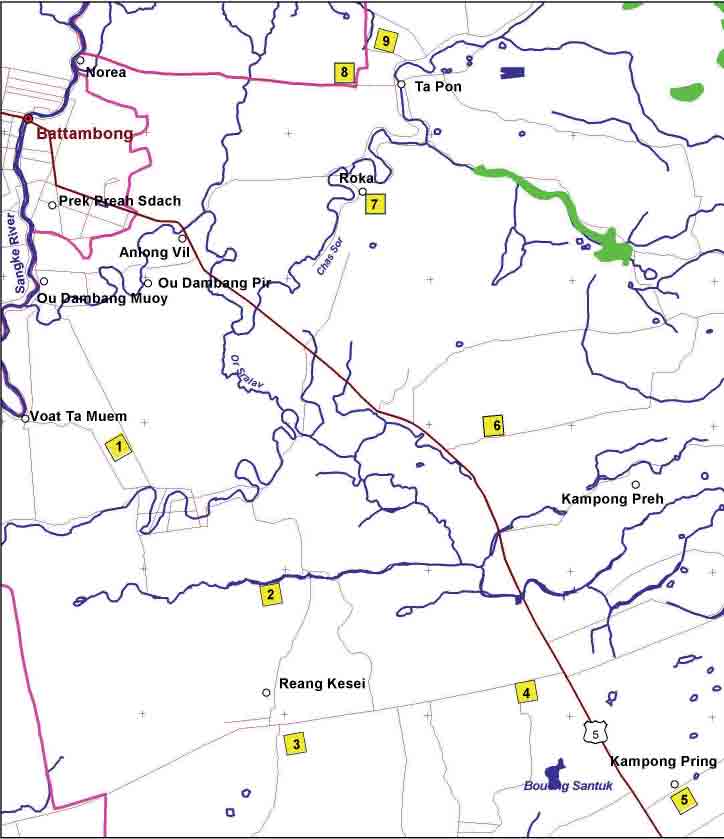

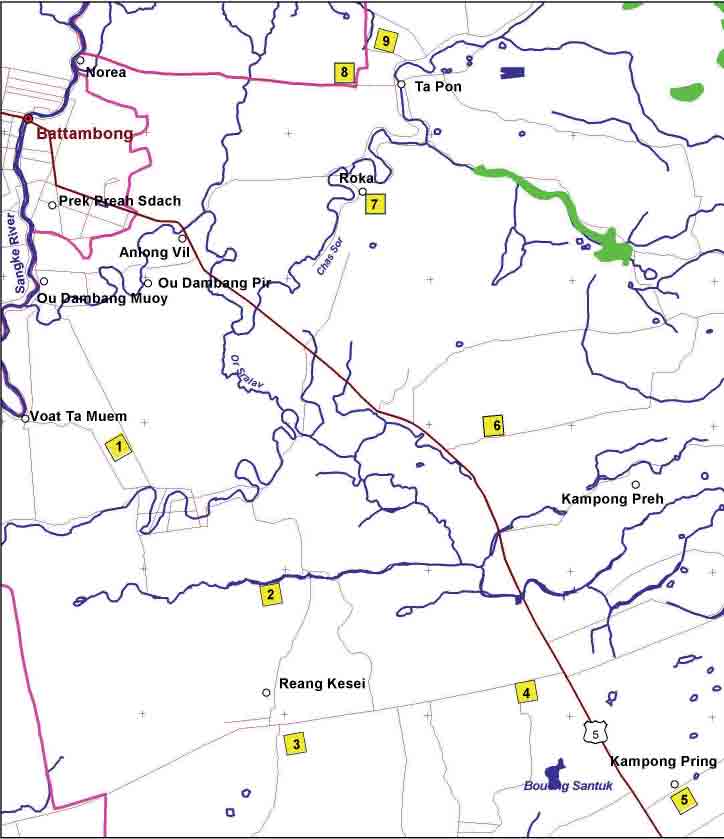

Figure 2. Map of the study sites.

6

Figure 3. Rainfall in Battambang in 2003 and 2004, compared with the long-term mean

from1920 2004.

8

Figure 4. Total catches by each of 26 kinds of gear versus total effort for that gear.

18

Figure 5. Total catches of fi sh and OAAs at each site each month.

18

Figure 6. Composition of the total catch of 26,730 kg.

20

Figure 7. Proportions of the total weight and total value of fi sh of different trophic

guilds in the catches.

21

Figure 8. Composition of the total catch of fi sh each month, showing the six species

comprising most of the weight in catches, nine sites combined.

21

Figure 9. Total catch and weighted average price of all fi sh and OAAs each month.

23

Figure 10. Monthly prices of the six fi sh species which contributed the most to total

catches by weight.

23

Figure 11. Dendrograms of site similarity based on total catches.

26

Figure 12. Proportional composition by weight of the dominant fauna in catches

compared with the fauna recorded by pumping rice fi elds to estimate

standing crop.

29

Figure 13. Ordination of sites based on multi-dimensional scaling of faunal composition.

29

Figure 14. Length-frequency for catches of Channa striata at Site 1.

32

Figure 15. Apparent changes in length, as exemplifi ed by Anabas testudineus at Site 5.

33

v

vi

Table of Tables

Table 1. The area of agricultural land in Cambodia in 1992 and 2004.

1

Table 2. Selected features of the study sites as determined from dry-season aerial

photographs and ground-truthing.

7

Table 3. General pattern of rice growing for wet season rain-fed rice in Battambang.

9

Table 4. The dates of the two occasions when sites were pumped for standing crop

estimation. 10

Table 5. Summary of age and gender data from fi sher interviews.

13

Table 6. The main income-earning activities of fi shers interviewed during the study

period. 14

Table 7. Types of gear used by fi shers in this study.

15

Table 8. Fishing effort as total fi sher-days, summed for all nine sites, total area 225 ha.

16

Table 9. Total catch of fi sh & OAAs (kg) by each gear, summed for all nine sites.

16

Table 10. CPUE as mean catch by each category of gear (kg/fi sher-day), summed for

all sites.

17

Table 11. Summary statistics for catches, value, no. of taxa and effort at each site.

25

Table 12. Summary statistics for standing crop on the fi rst and second occasions of

pumping 1-ha plots in rice fi elds.

28

Table 13. Comparison of the proportions of the main taxa in catches and pump samples

at each site.

30

Table 14. Correlation matrix for comparison of total catches with total standing crop

from pumping.

31

Table 15. Summary of fi sh measured from sub-samples of fi sher catches and from

pumping on two occasions for standing crop estimation.

33

Table 16. Increase in total length of identifi able cohorts of three common species

between pumping occasions.

34

Table 17. Estimates of yields from rain-fed rice fi elds and fl oodplain habitat.

39

Table 18. Estimated wetland areas in the LMB and Cambodia.

40

Table 19. Estimated annual inland catches for Cambodia, based on information from

1994 1997.

41

vii

viii

Acknowledgements

The following provincial fi sheries offi cials are thanked for assisting with fi eld data collection:

Mr Heng Piseth, Mr Chhea Hav, Mr Kheng Makkhen, Mr Sam Mardy, Mr Yim Hour, Mr Uy

Sarun, Mr Chan Tey, Mr Chhem Sophea, and Mr Ouch Chham. Drs Matthias Halwart and

Andrew Noble are thanked for their helpful comments on a draft manuscript. The senior author

acknowledges the support of the Water Studies Centre, Monash University, Australia, for

providing offi ce space and computer support during the preparation of this report.

ix

x

Summary

For most rural people in Cambodia, rice fi elds and associated habitats are important sources

of fi sh and other aquatic animals (OAAs), which provide both nutrition and income. A lack of

quantitative information contributes to a general neglect of rice fi eld fi sheries in development

planning, which usually favours intensifi cation of rice production that may negatively impact

the fi shery. The main objective of this study was to quantify the yield and value of the rice

fi eld fi shery in an area typical of the rain-fed, lowland, wet-season rice fi elds that surround the

fl oodplain of the Tonle Sap-Great Lake system.

At nine sites, each 25 ha in area, the fi shing effort and catches of fi sh and OAAs by local

fi shers were monitored for one season (July 2003 February 2004), and standing crop was

measured twice by pumping and sieving water from one-hectare plots adjacent to each site in

the late wet season.

Fishing activity was greatest during October and November, when paddy water levels were

highest, rice was in the vegetative stage and other work opportunities were limited. Fisher

numbers peaked at about 2 persons/ha; most fi shers (82%) were male and most (79%) were

aged 16 50 years. Ten main types of gear were used. Traditional traps and hook and line were

the most used and most productive (accounting for 72% of the total catch), because they can be

used around rice fi elds without disturbing the crop.

Catches included 35 species of fi sh, which made up 77% of the total catch weight, with

air-breathing `black fi sh' accounting for about 88% of the fi sh catch by weight. Most of the

fi sh catch consisted of carnivores, which were more valuable than omnivores (based on market

values); no herbivores were recorded. About 80% of the total fi sh catch by weight comprised six

species: Channa striata (chevron snakehead), Macrognathus siamensis (peacock eel), Anabas

testudineus (climbing perch), Clarias batrachus (walking catfi sh), Trichogaster trichopterus

(three-spot gourami), and Monopterus albus (swamp eel). Six taxa of OAAs comprised 23% of

the total catch, and crabs, frogs and shrimps were the most abundant OAAs.

Catches at each site appeared to refl ect hydrology; in general sites that were deeper and

inundated for longer periods attracted greater total fi shing effort and produced larger total

catches. Catches were also infl uenced by proximity to permanent waters, as the two sites with

the most fi sh species were close to a permanent river. The mean yield (fi sh plus OAAs) was

119 kg/ha/season (±25 as 95% confi dence limits) with a mean value of US$102/ha (±$23/ha),

based on market prices. This study underestimates the yield and value of the fi shery, because

additional catches are made by fi shers using unmonitored illegal gears, and unmonitored

catches are also made during the dry season.

Mean standing crop in the one-hectare rice fi eld plots was 64.7 kg/ha (±4.9), of which

about 70% was fi sh. Carnivorous black fi shes, and crabs and snails were proportionately more

xi

Yield and value of the wild fi shery of rice fi elds in Battambang Province, near the Tonle Sap Lake, Cambodia

abundant than in catches, and fewer species were recorded than in catches, which refl ect a

diversity of habitats targeted by fi shers. The biomass of fi sh in standing-crop samples increased

signifi cantly between sampling occasions, but the biomass of OAAs declined, a fi nding

consistent with growth of fi sh and predation on OAAs. The composition of the fauna was

similar in all of the standing crop samples, refl ecting general homogeneity of rice fi elds as a

habitat. The composition of catches was more variable between sites, refl ecting the response of

the fauna to small and heterogeneous areas of non-rice fi eld habitats.

Most of the fi sh in catches were small; among fi ve common species all individuals were

less than 32 cm and half were less than 10 cm in length. Analyses of length-frequency data

suggested growth rates of 1 4 cm/month, which indicates that virtually all fi sh were caught in

their fi rst or second year of life.

The gross income from rice production at the time of the study was about $150 /hectare/

year with a single crop, so with some level of management (for example development of trap-

ponds), the capture fi shery could become more valuable than rice farming. The indigenous

carnivorous fi sh species may be signifi cant agents for controlling the pests of rice, and fi sh feed

upon organisms, including insects, crabs and snails, which would otherwise be inaccessible as

food for people. Research and development of rice-fi sh culture should include these indigenous

fi sh species that are hardy, adaptable, preferred as food and generally more valuable than the

introduced herbivorous/omnivorous species that are usually promoted in rice-fi sh culture.

The rice-fi eld fi shery is accessed by most rural people for some part of the year; it is a

common-property resource, which limits the incentive for farmers to invest in its conservation.

Land holdings are generally small, often fragmented, and distant from their owners' houses.

Farmers are usually not present to prevent others fi shing on their land or to prevent theft of

aquacultured fi sh. Increasing the yield from the fi shery is a technically feasible way to improve

output from rice fi elds, but the management problems which arise from current ownership

patterns and small fragmented landholdings need to be addressed if the full potential of rice-

fi eld fi sheries is to be realised.

The yield fi gure found in this study is consistent with the values that have been found in

other studies in the Lower Mekong Basin and elsewhere in Asia. Previously published estimates

for the total fi shery yield from Cambodian rice fi elds are based on unrealistically low values for

yield per unit area and under-estimates of the area of rice fi eld habitat, leading to a signifi cant

under-estimate for the total national yield from rice fi elds. Moreover, rice fi elds probably

produce a much larger share of the total yield of inland fi sheries in Cambodia than is generally

recognised. Elsewhere in the Lower Mekong Basin, rice fi eld habitats' contribution to fi sheries

is also under-recognised; in each country rice fi elds are the most extensive aquatic habitat and

there are general similarities in fi shing methods, target species and high participation rates.

Rice-fi eld habitats should be given appropriate emphasis in research to quantify inland fi sheries

yield in each country and to improve management for fi sheries, especially given their particular

importance in supporting livelihoods and nutrition for the rural poor.

xii

1. Introduction

Wild capture fi sheries are important sources of food and income for rural people throughout

Asia. Assessment of fi sheries should take into account the contribution from the large areas

of agricultural land that are typically used for rice farming, an industry that is based on vast

areas of anthropogenic wetlands, which can be referred to as `rice-based ecosystems' because

they support a wide biodiversity. In the four countries of the Lower Mekong Basin (LMB)

up to 100 species of wild fi sh, other aquatic animals and plants are harvested by rural people

in any particular location, supporting their livelihoods and providing essential protein and

micronutrients (Balzer et al. 2005; Halwart 2006). A recognition that rice-farming landscapes

produce much more than rice led the International Rice Commission to recommend that

member countries should promote the sustainable development of aquatic biodiversity in rice-

based ecosystems, that management measures should enhance the living aquatic resource base,

and that attention should be given to the nutritional contribution of aquatic organisms to the

diet of rural people (IRC, 2002). To support this recommendation, quantitative data are required

which show the actual yield and economic value of the fi shery and how best to optimise the

value of all forms of production from rice-based ecosystems.

Table 1. The area of agricultural land in Cambodia in 1992 and 2004.

Based on offi cial national data summarised by ACI and CamConsult (2006, Table 284).

Year

Area (ha) of land used for:

Percentage of Area

Rice

Other Crops

Total

Rice

Other Crops

Total

1992

1,844,100

187,000

2,031,100

90.8%

9.2%

100.0%

2004

2,374,175

440,348

2,814,523

84.4%

15.6%

100.0%

In Cambodia, rice is the most important crop by area farmed, production tonnage and value

(ACI and CamConsult, 2006), and the estimated area of planted to rice increased by about 29%

between 1992 and 2004 to about 2.4 million ha (Table 1). This increase can be attributed to

intensifi cation of land use (i.e. on fallow or un-worked land) and to clearing of forest or scrub,

both in the fl ood recession zone and on the surrounding terraces where rain-fed rice is grown.

According to ACI and CamConsult (2006, Table 294) 81.3% of Cambodia's rice farming land is

terraces, i.e. land surrounding fl oodplains where `rain-fed' rice is grown during the wet season.

Only 11.1% of the rice-fi eld area is within fl oodplains and comprises recession rice (8.1%) and

fl oating rice (3.0%); the remaining area is riverbank rice (5.4%) and others (2.1%). Irrigation is

relatively undeveloped, as only 22% of the rice-fi eld area in Cambodia receives supplemental

irrigation. However, only one percent is fully irrigated and able to produce more than one crop

per year.

Most of Cambodia's rice-farming land is within the Lower Mekong Basin, which includes

the Tonle Sap system, other lowland tributaries, and distributaries in south-east Cambodia. It

should be noted that `rice fi elds' as a land-use class in GIS data covers a much larger area than

Page 1

Yield and value of the wild fi shery of rice fi elds in Battambang Province, near the Tonle Sap Lake, Cambodia

the planted areas as indicated in Table 1, e.g. about 26,097 km2 in 1992 3 (MRCS, 1994).

Associated habitats include small water bodies (ponds and canals), other wetland crops, such as

lotus, and small patches of brush.

Cambodian's main sources of animal protein are inland fi sh and OAAs; which are estimated

to provide about 80% of the average intake of animal-derived protein (Hortle, 2007). About

84% of Cambodians are rural (Anonymous, 1999), and virtually all rural households would

directly access rice fi elds for food and seasonal income from the fi shery The large and

seasonally spectacular river-fl oodplain fi sheries along the Tonle Sap and Mekong River have

been relatively well-studied, but rice-fi eld fi sheries are relatively innocuous, being often

referred to as `the invisible fi shery' (Halwart, 2006), so they are poorly researched.

This study was carried out to provide a quantitative estimate of fi sheries yield (kg/ha/season)

and value (fi rst-sale prices in Battambang) from accurately defi ned areas in typical lowland

rain-fed rice-fi eld habitat in Cambodia. In addition, we estimated standing crop (kg/ha of fi sh

and OAAs) in rice-fi elds to complement the estimate of yield. The study also aimed to provide

information on the usage of gears and the composition of the catch.

The data obtained in this study represent a baseline for the yield that is currently being

obtained in the absence of any management from a wild fi shery in typical lowland rain-fed

Cambodian rice-fi elds. The results provide the basis for a valuation of the fi shery and illustrate a

methodology to use for assessing yield prior to enhancements or changes to management.

In a wider context, because of the vast extent of rice-fi eld habitat, the yield and composition

of this part of the fi shery needs to be quantifi ed throughout the lower Mekong Basin generally,

if the yield of the system as a whole is to be understood and if fi sheries are to be managed

effectively.

Page 2

2. Methods

2.1 Study area

Battambang is a large province in Cambodia which borders the north-western edge of the Tonle

Sap (or Great) Lake, which is the largest lake in South-East Asia and is the centre of inland

fi sh production in the Mekong River system (Figure 1). Population density in the province is

about 68 persons per km2, and 83% of the population is rural (Anonymous, 1999), with most

households still employed directly or indirectly in agriculture or related activities. The mean

household size is 5.3 persons, and most people live in small villages or communes which are

spread fairly evenly through the province along unclassifi ed roads in proximity to the farms.

Single-crop rain-fed rice farming is the dominant land use, as is usual in Cambodia. Formerly,

fl oating rice was cultivated in the zone around the Great Lake that fl oods each year as a result of

backing-up of the Mekong and Tonle Sap fl oodwaters, but recession rice farming is now more

common in this zone. In many respects the pattern of rice-farming and fi sheries resembles that

described in detail by Balzer et al. (2005) in Kampong Thom Province, which lies along the

north-east edge of the Tonle Sap.

Lao PDR

Thailand

Battambang

Mek

Province

CAMBODIA

ong

Great Lake

Study Area

(Figure 2)

Tonle Sa

p

Phnom Penh

Viet Nam

Gulf of Thailand

Mekong Delta

0

100 Kilometres

Figure 1. Location of study area

This study was carried out in Sangke District, which extends from the provincial capital,

Battambang, to the dry-season shoreline of the Tonle Sap Lake. The landscape is generally

Page 3

Yield and value of the wild fi shery of rice fi elds in Battambang Province, near the Tonle Sap Lake, Cambodia

fl at alluvial plains; although the study area is about 500 km inland (i.e. from the mouth of the

Mekong) the elevation is less than 20 mASL, with a general slope towards the Tonle Sap or

its tributaries (Figure 1). The main rivers that drain to the lake are incised several metres into

the plain. The Tonle Sap Great Lake system fl oods regularly each year, peaking around late

September, mainly because of the infl ow and backing up of water from the Mekong. In the

wettest years, Tonle Sap fl oodwaters extend to the main highway, which runs from Phnom Penh

in the south-east to Battambang town. In most years, including during the years of this study,

the sites on the eastern side of the highway are not reached by Tonle Sap fl oodwaters, but are

inundated by local rainfall.

Rice farming is the main land use in the Sangke district. About two-thirds of the rice

cultivation area is rain-fed rice and about one third is fl oating/recession rice, according to data

from the provincial Department of Agriculture. Most houses, with their associated fruit and

vegetable gardens, are sited along roads (usually unsurfaced), which are built on natural levees

or spoil beside rivers and canals. Families typically own one to two parcels of land that are

usually at some distance from their houses; in Cambodia land ownership averages one hectare

per family (ACI and CamConsult, 2006), as is probably also the case in Battambang.

Agriculture has long been practised in this part of Cambodia, so most natural vegetation

has been cleared and the land surface extensively modifi ed to trap rainwater in paddies and to

control drainage. Some remnant `fl ooded forest' to the east of the study area is important wet-

season habitat for fi sh which migrate seasonally from the Great Lake. Paddy walls are typically

about 0.5 m high, and larger levees have been formed from spoil from the main drainage

canals; such levees support the roads used by tractors, buffaloes and motorcycles. Drainage is

controlled via canals and along the remnants of modifi ed stream courses.

Rice cultivation in this area, as is usual in Cambodia, is not highly intensive. One crop

is grown each year, relying mainly on natural rainfall, with limited use of canal water for

irrigation of seedlings or some low-lying fi elds. Yield of wet-season rice averages about 2.2 t/

ha in Battambang, higher than the national average of 1.7 t/ha, but less than half of what can be

achieved under intensive cultivation (ACI and CamConsult, 2006).

2.2 General features of the fi shery

In the study area, the fi shery is entirely based upon naturally occurring fi sh and other aquatic

animals (OAAs), with little evidence of stocking or any kind of management for the rice-fi eld

fi shery. Most people live at some distance from their rice fi elds so they cannot control fi shing

activity on their land. Fishing is apparently open-access, but in this province most fi shers are

local people, so farmers generally know who fi shes in their fi elds and are often given some of

the catch, as well as fi shing themselves.

The fi shery is highly seasonal, because most of the landscape is dry for about half of the

year (Dec. Jan. to May June). Fish and other aquatic animals (OAAs) that have survived the

Page 4

Methods

dry season locally in remnant water bodies or by aestivating in mud, breed at the onset of and

during the wet season and their fry or larvae rapidly colonise newly-fl ooded rice fi elds. The

common `black fi sh' are hardy and fecund species that are widespread in the lowlands because

they can tolerate anoxia -- all gulp air at the water surface and have accessory respiratory

structures.1

Fish and OAAs disperse by moving along the small channels connecting paddies and many

species at times may also move overland. The fry of fi sh from the Tonle Sap Great Lake

and its tributary rivers -- `white' or `grey' fi sh -- are intolerant of anoxia but also colonise

rice-fi eld habitats by swimming up drainage canals and streams. The paddies and associated

canals and ponds are fi shed throughout the wet season, using a wide range of gears, but fi shing

activity peaks during the vegetative phase of the rice crop, when other seasonal employment

opportunities are limited.

2.3 Study sites

Nine sites were selected east and southeast of Battambang Town, the capital of the province

as shown in Figure 2. The sites were selected to be representative of the dominant rice-fi eld

habitats in the surrounding areas and the district generally. Sites were chosen to be accessible

from motorbike paths and to be in reasonably well-frequented areas, because in this part of

Cambodia lawlessness is still a problem. The fi shing gears were a mixture of small-scale

artisanal gears; i.e. there were no medium or large-scale commercial gears, because the sites

were not close to any very large canals or rivers where such licensed gears operate. The sites

were also selected only where the owners allowed access for surveyors and for pumping of a

part of the site in their rice fi elds for standing crop assessment.

The study sites were all 500 metres square, i.e. 25 ha in area. The position of the corners

of each site was recorded by GPS to provide data that was used to locate the sites accurately

on a district map and on dry-season aerial photographs which were linked to GIS data. The

photographs had a resolution of about 0.5 m. From the aerial photographs the area of brush

(scrub and trees) was estimated by planimetry, the number of paddy fi elds was counted, and

the areas of the smallest and largest paddy fi elds were also measured by planimetry. Ground-

truthing was carried out during the wet season, and in the following dry season to identify

remnant water bodies. The aerial photographs and GIS images were examined to confi rm the

location of larger temporary and permanent watercourses and ponds. Table 2 shows that the

sites varied in elevation from 12 to 17 mASL, and on most sites brush occupied less than 2%

of the area, with only three sites having signifi cant remnant vegetation. The number of paddy

fi elds varied from 40 to 123 in each 25 ha site, with sites having mean paddy fi eld areas of 0.2

to 0.6 ha. Overall, paddy fi elds varied from 0.04 to 1.97 ha in size. In general, paddy fi elds

1 Black fi sh are air-breathing fi sh that can spend their entire lives on fl oodplain habitats and are well-defi ned morphologically and

behaviourally. Grey and white fi sh migrate short and long distances respectively from rivers and streams onto fl ood plains to

feed; they are intolerant of anoxia and generally require dry-season refuges in well-oxygenated water, typically deep pools. There

are insuffi cient data to classify many Mekong system fi shes as grey or white, so they are combined in one group here.

Page 5

Yield and value of the wild fi shery of rice fi elds in Battambang Province, near the Tonle Sap Lake, Cambodia

are smaller (and hence more numerous in a given area) where slopes are steeper. The sites had

varying degrees of exposure to seasonal and permanent watercourses and farm ponds.

103°14'

103°16'

103°18'

103°20'

9

Norea

8

Ta Pon

BATTAMBONG

13°06'

Roka

Prek Preah Sdach

7

Anlong Vil

Ou Dambang Pir

13°04'

Ou Dambang Muoy

6

Voat Ta Muem

13°02'

1

Kampong Preh

5

13°00' LEGEND

13°00'

2

Provincial centre

Commune centre

District boundary

Reang Kesei

4

Road

12°58'

12°58'

River

3

Swampy area

Kampong Pring

0

2

4 kilometres

Study site

5

103°14'

103°16'

103°18'

103°20'

Figure 2. Map of the study sites

Page 6

Methods

Table 2. Selected features of the study sites as determined from dry-season aerial photographs and

ground-truthing.

Site

Elev.

Trees/scrub

Paddy Fields

No. of farm ponds Distance to Watercourses

(mASL)

in the 25-ha plot

permanent

and state in

Area/fi eld (ha)

watercourse

dry season

(April)

Area

% cover Number

Mean

Min.

Max.

Perm.

Seas.

(ha)

1

13

0.23

0.90%

57

0.44

0.09

0.87

2

200

Large

canal

along east

edge, some

residual water

2

15

0.34

1.40%

85

0.29

0.05

1.31

50

Large

stream

parallel to

north edge,

some residual

water

3

17

4.89

19.60%

71

0.35

0.08

1.33

2

>200

No

major

watercourses

near site

4

12

0.07

0.30%

40

0.63

0.17

1.97

2

>200

No

major

watercourses

near site

5

14

0.04

0.20%

67

0.37

0.06

1.41

3

>200

Large

canal

along south

edge, some

residual pools

6

13

0.23

0.90%

66

0.38

0.06

1.14

2

>200

Small

canals

connecting to

ponds hold

some water

7

12

0.05

0.20%

111

0.23

0.05

0.84

100

Large

river

(S. Chas) to

the west

8

12

0.00

0.00%

50

0.5

0.05

1.38

2

0

Canals

along

south and

east edges,

residual pools

9

12

0.19

0.80%

123

0.2

0.04

0.72

>200

No

major

watercourses

near site

Page 7

Yield and value of the wild fi shery of rice fi elds in Battambang Province, near the Tonle Sap Lake, Cambodia

2.4 Rainfall

Battambang receives most of its rainfall during the Southwest Monsoon from about May to

November, as is usual for most of Cambodia. Long-term rainfall between 1920 and 2004, with

60 years of complete data, averaged 1318 mm/year. Typically, there is very little rainfall from

December to March (on average 5.6% of the annual total), and because of high temperatures

and evaporation rates through May there is usually little standing water in most paddy fi elds

until June. Over the period April 2003 March 2004, encompassing the study period, rainfall

was 1,221 mm, or 93% of the annual average. (Figure 3).

300

mean

250

study

200

150

ainfall (mm)

R

100

50

0

Apr

May

Jun

Jul

Aug

Sep

Oct

Nov

Dec

Jan

Feb

Mar

Month

Figure 3. Rainfall in Battambang in 2003 and 2004, compared with the long-term mean

from1920-2004. Based on daily rainfall records from the Cambodian Department of Water

Resources and Meteorology.

2.5 Inundation of rice fi elds and rice growing

The general pattern of inundation and of rice-growing is as follows. Seeds are planted (to grow

seedlings) from May through to July in nursery areas where the seedlings can be watered from

canals. Transplanting of seedlings starts in June and continues through to September, when

most of the paddy fi elds are fully inundated. In this area, most strains of rice are traditional

slow-growing varieties that are harvested after about fi ve to seven months, so the earliest-

planted paddies are harvested during November while the latest are harvested during February.

Page 8

Methods

Table 3. General pattern of rice growing for wet season rain-fed rice in Battambang.

Activity

Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Jan Feb Mar

Land

preparation

Seedbed

Transplanting

Harvesting

Through October and most of November 2003, 100% of the area of the study sites was

under water. On the western side of the highway the paddies were typically 0.4 0.6 m deep,

and held signifi cant water through to December, as drainage was constrained by having to pass

through a limited number of culverts under the highway. On the eastern side of the highway, the

paddies were generally shallower, 0.3 0.5 m deep, and drained earlier (through canals to the

east) so that at least half the area was dry by November. In terms of apparent depth and duration

of fl ooding, Sites 5, 6 and 7 were the driest and shallowest, Sites 8 and 9 were intermediate, and

sites 1 to 4 were the wettest.

2.6 Catch assessment

The plots were visited four times each month for seven months (August 2003 February 2004);

a total of 28 times. During the other fi ve months there was relatively limited fi shing in the study

sites, although some catches were made in residual water bodies and in fi elds where fi shers dig

and rake through mud to catch aestivating fi sh, crabs, molluscs and frogs.

On each survey occasion, two surveyors visited each plot to interview fi shers and to measure

their catches. The local surveyors generally knew the villagers who fi shed in each area, so they

could organise the interviews in advance. The total numbers of fi shers and the gears used by

each fi sher in each plot were recorded based on direct observation and by interviewing fi shers.

About 30 50% of people fi shing on a surveyed day were interviewed regarding their use of

gear and their catches and the results. They were also asked to estimate their effort (number

of days fi shing) over the period since the previous interview (about one week). The exact time

each gear was being used during each day was not recorded, so effort was expressed as `fi shing

days' only. The catch per gear and the effort data were used to estimate the catches of those who

were not interviewed in detail, based on their reported gear and effort.

Interviews were based on a standard format that included basic information on the people

fi shing, effort and gears. Identifi cations were based on a chart of photos of about 150 species

found in the area, as well as by reference to drawings and keys in Rainboth (1996), and names

were updated from FishBase (Froese and Pauly, 2007). Fishers kept their catches for the

surveyors to identify and weigh. Animals were weighed using calibrated pan balances accurate

to fi ve grams. Representative sub-samples of the fi ve most common fi sh species were selected

Page 9

Yield and value of the wild fi shery of rice fi elds in Battambang Province, near the Tonle Sap Lake, Cambodia

from all gears at each site on all occasions, and the total lengths of fi sh were measured to the

nearest centimetre using fi sh measuring boards. The price of each taxon was determined from

interviews as the sale price in the nearby Battambang market in Riel/kg for each species.

2.7 Standing crop

Standing crop was estimated for plots one hectare in area that were adjacent to, and considered

representative of, each 25 ha plot. Standing crop estimation followed a pumping procedure.

Each one-hectare plot was already enclosed by the walls of paddy fi elds; inlet and outlet

channels were blocked and the walls were repaired where necessary to fully isolate each fi eld.

Water was pumped from each plot using an agricultural diesel-powered pump with the intake

in the deepest corner of the plot. A fence of 2 mm nylon mesh around the intake prevented

animals from passing through the pump. While the water level was falling, collectors walked

through the plot and collected fi sh and OAAs by hand and by using dip-nets of 5 mm mesh.

Complete removal of water took up to two days in each plot as the depth varied from 0.1 0.6

m. After most of the water had been pumped from a plot, animals were collected using dipnets

from the remaining small pool of water. The total weight of each taxon was recorded and then

the lengths of representative sub-samples of animals were measured to the nearest millimetre.

Representative sub-samples of the fi ve most common fi sh species were selected and the total

lengths of fi sh were measured to the nearest centimetre using fi sh measuring boards.

The plots were pumped twice, in September and November 2003, as shown in Table 4.

After pumping, the plots rapidly re-fi lled with water from adjacent paddies. During the period

between sampling it was assumed that fi sh and OAAs could readily colonise the plots, directly

via connecting channels and through locally overtopped paddy walls, or by moving overland, a

common behaviour of many species of fi sh and OAAs in this area.

Table 4. The dates of the two occasions when sites were pumped for standing crop estimation.

Site

Occasion

Elapsed Days

1

2

1

13 Sep 03

02 Nov 03

50

2

14 Sep 03

07 Nov 03

54

3

27 Sep 03

12 Nov 03

46

4

28 Sep 03

13 Nov 03

46

5

25 Oct 03

22 Nov 03

28

6

24 Oct 03

23 Nov 03

30

7

23 Oct 03

21 Nov 03

29

8

16 Oct 03

25 Nov 03

40

9

17 Oct 03

26 Nov 03

40

Page 10

Methods

2.8 Socio-economic information on fi shers

During interviews, data were also recorded on the age and gender of fi shers and their usual

income-earning occupations at the time of the survey. Fishers were asked to estimate the

proportion of their catch that was eaten by themselves or their families and the proportion sold.

2.9 Statistics

To estimate the similarity of the fauna at each site two indexes were used (Hellawell, 1978),

calculated for pair-wise comparisons of the fauna at each site with every other site. Sorensen's

index (S) takes account only of the presence of each taxon at each site; these included all taxa

of OAAs and all species of fi sh. The index is defi ned as:

S=

2c/(a+b)

where: a = no. of species at Site a,

b = no. of species at site b and

c = no. of species present at both sites.

Spearman's non-parametric correlation coeffi cient (Rho) takes account of the relative

abundance of each species at each site, in terms of rank. This coeffi cient was calculated using

the six taxa of OAAs and the ten fi sh species at each station which contributed most of the

weight of catches. Rho is defi ned as:

= 1 6d2/(n3-n)

where d is the difference in the magnitude of the rank of each species for the pair of stations and

n is the total number of species in the comparison.

For each index, dendrograms were constructed by single linkage clustering, i.e. by joining

site pairs with the highest values fi rst, then joining site pairs with the next highest values, and so

on, until all sites were connected.

Page 11

Yield and value of the wild fi shery of rice fi elds in Battambang Province, near the Tonle Sap Lake, Cambodia

Page 12

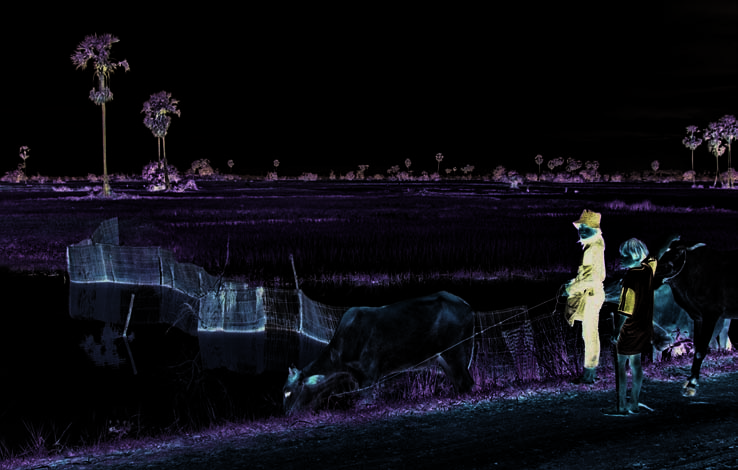

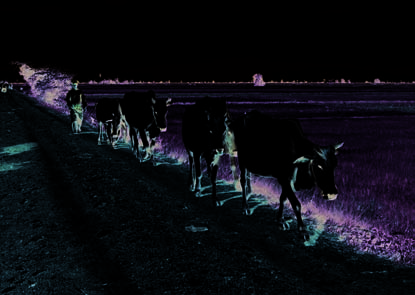

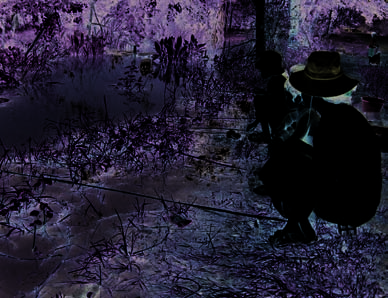

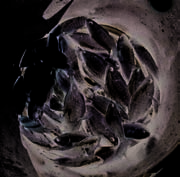

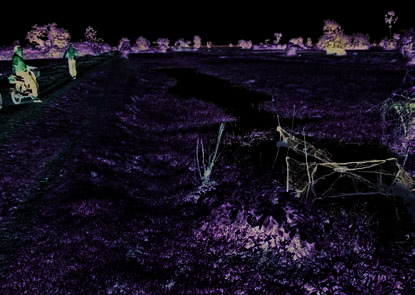

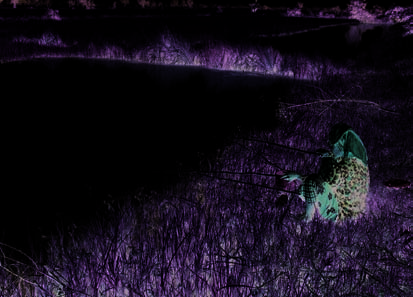

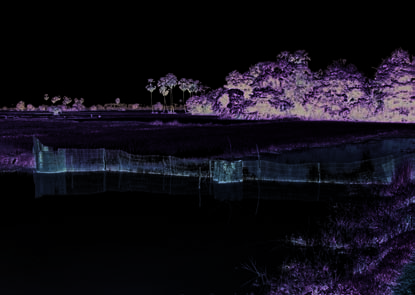

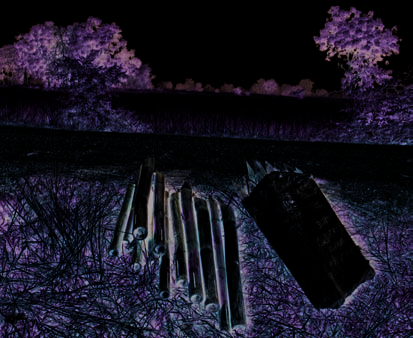

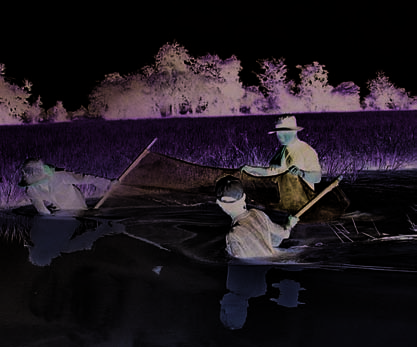

Plate 1. Ploughing fields prior to planting in July creating a temporary but fertile aquatic environment in

which plankton grows rapidly. There is little fishing at this time.

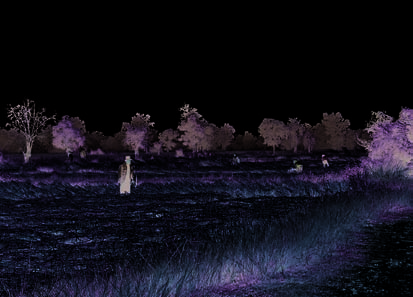

Plate 2. Planting rice seedlings in late July. Vast expanses of dry land become wetlands.

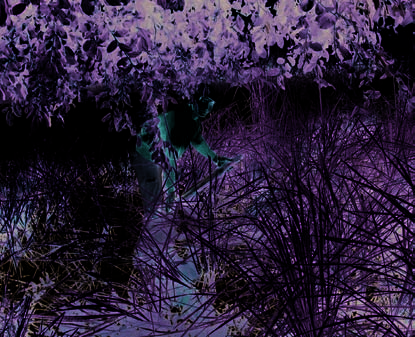

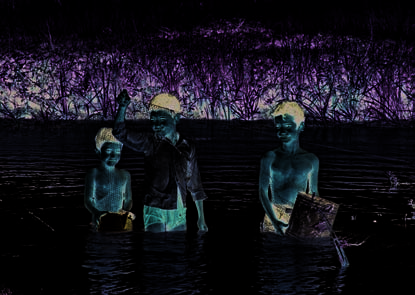

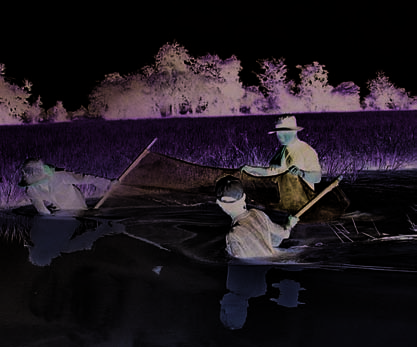

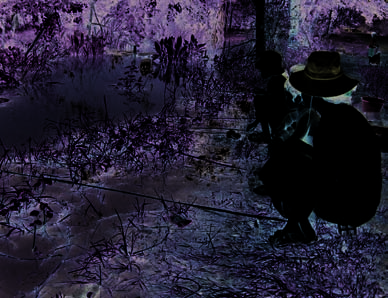

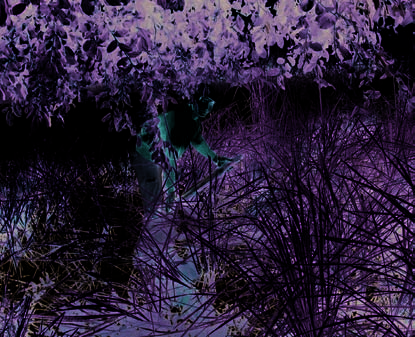

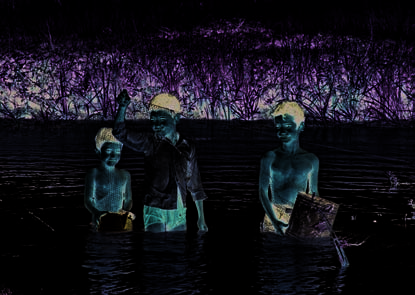

Plate 3. Fishing activity is most intense in October November, when the rice is growing and ripening and

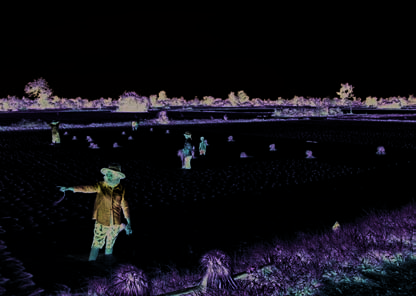

there is less labour needed in farming or other occupations.

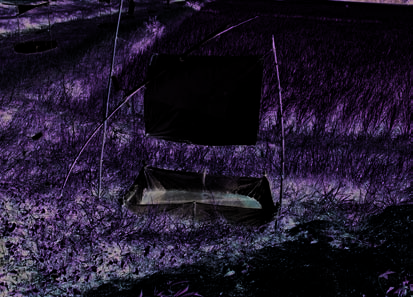

Plate 4. Small holes (anlung) are made to trap fish that exit rice fields, a simple but effective method that

requires little or no equipment.

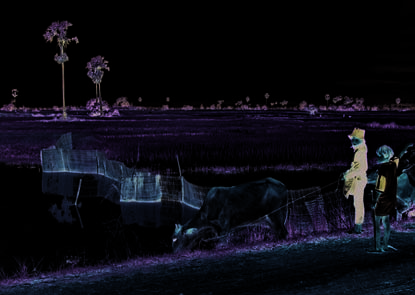

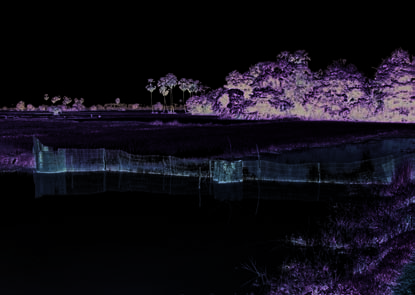

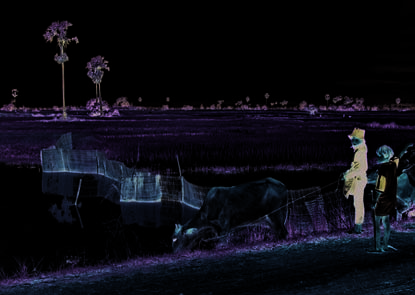

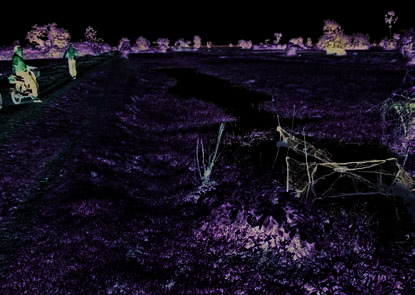

Plate 5. Access for most fishers is by foot, cycle, or motorcycle along levee roads.

Plate 6. Bullocks are still commonly used as draught animals by farmers, and manure is the most-used

fertiliser in a farming system that continues to support production of other common-property

resources, including the wild capture fishery.

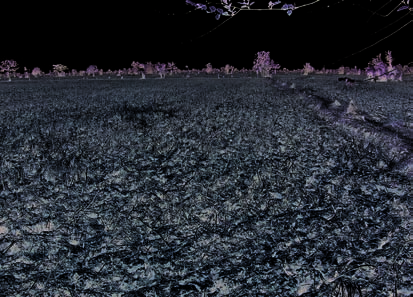

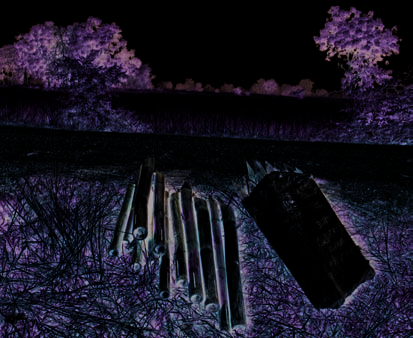

Plate 7. Harvesting rice by hand in December. Most water has gone.

Plate 8. Most of the landscape is very dry from February to May, but some fish and OAAs are still present

in deep cracks and in a few residual water bodies.

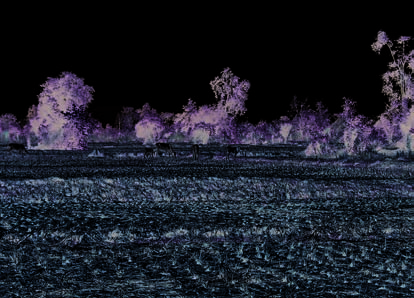

Plate 9. During the dry season, people continue to catch fish and OAAs from drying mud or ponds, but

catches from March to July were not included in this study, so the study underestimates total catches

and value of the wild fishery.

Plate 10. Many people make large catches of aquatic insects by light-trapping at night. Insects are attracted

to the light, hit the plastic sheet and fall into the pool of water. The yield and value of this `aerial

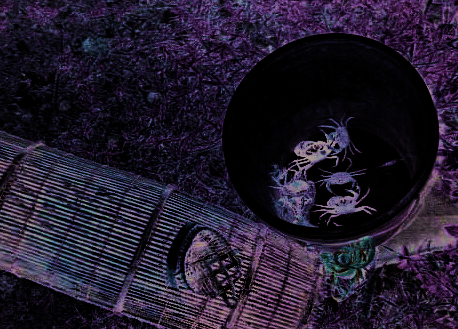

fishery' is not known, but would add to the unaccounted economic value of the wild fishery.

Plate 11. Weighing and measuring snakeheads (Channa striata) and large snails.

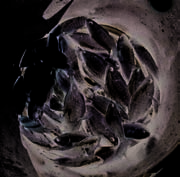

Plate 12. Pumping to estimate standing crop.

Plate 13. Single-hook set pole and line (santuch bangkai) was the most commonly used and productive

gear, accounting for about 23% of the weight of all fish caught, and 19% of all fisher-days. It is

particularly effective for snakeheads and other carnivorous fish.

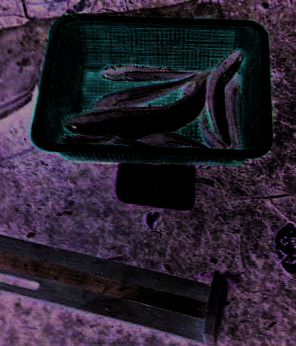

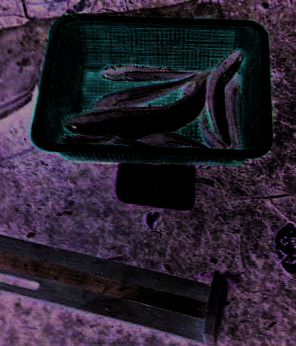

Plate 14. Typical catches from single-hook set pole and line. Left: snakeheads (Channa striata), climbing

perch (Anabas testudineus) and walking catfish (Clarias macrocephalus). Right: peacock eel (Macrognathus

siamensis), climbing perch (Anabas testudineus) and silver catfish (Mystus atrifasciatus).

Plate 15. Single hand-held hook and line (santuch ple muoy) -- simple, commonly used and

productive, accounting for about 7% of all fish caught and 9% of all fisher-days.

Plate 16. Among traditional traps, horizontal cylinder traps (tru) are the most commonly used (about 14% of

all fisher-days) and most productive (about 14% of all catches).

Plate 17. One kind of horizontal cylinder trap, specially designed for catching crabs.

Plate 18. Horizontal cylinder traps with bamboo fences (lop phsom pruol) are the second most productive trap,

accounting for about 12% of the total catch and 8% of fisher-days.

Plate 19. Traps are widely used in a range of habitats, here deploying vertical rice field cylinder

traps (lop nheuk).

Plate 20. Active collecting with a wedge-shaped scoop basket (Chhnieng chunhchot) -- commonly used by the

end of the fishing season in February, with a catch of climbing perch, Anabas testudineus.

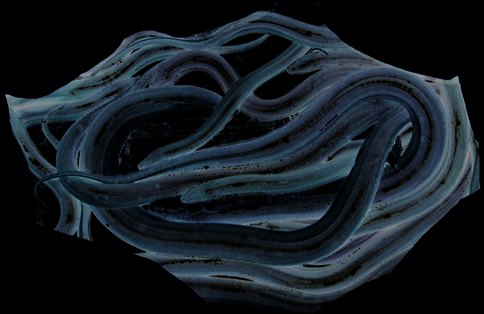

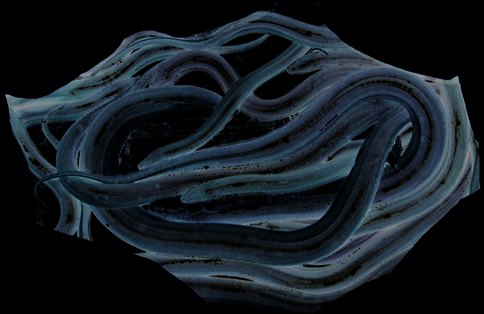

Plate 21. A specialised gear, bamboo tube trap (loan) for eels, with the catch of swamp eels, Monopoterus albus,

one of the most commonly caught species. These traps accounted for 4% of all fish and 3% of

fisher-days.

Plate 22. Vertical bamboo vase traps (tom) are specialised gears that accounted for only 1% of fisher-days

and catches.

Plate 23. Despite policing efforts by fisheries inspectors, fine-mesh fyke nets are commonly seen -- here in

the early wet season. These illegal gears block migration routes and catch all kinds of fish and their

fry before they access inundated areas where they would feed and grow through the wet season.

Plate 24. Cast nets (samnanh) are commonly used in all open-water areas, accounting for about 10% of

all catches by weight and about 9% of the total fisher-days. Sometimes they are used in pairs to

increase efficiency.

Plate 25. Gillnets (mong reay sre) are less popular in the rice field environment than in larger rivers or lakes

where they may be the dominant gear. In this study they accounted for only 6% of fisher days and

5% of catches.

Plate 26. Small-handle seine net (anchorng), a relatively uncommon gear accounting for 2% of catches and

fisher-days. In this example it is technically illegal because of the fine mesh.

Plate 27. Larger fish, especially snakeheads and walking catfish are sold on roadsides or in local markets.

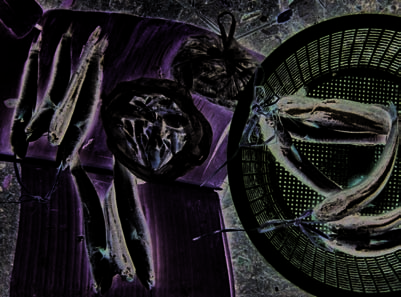

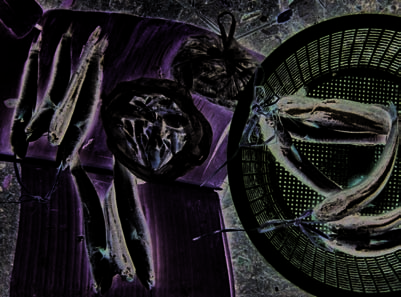

Plate 28. Peacock eels (Macrognathus siamensis) and swamp eels (Monopterus albus) on sale in Battambang market.

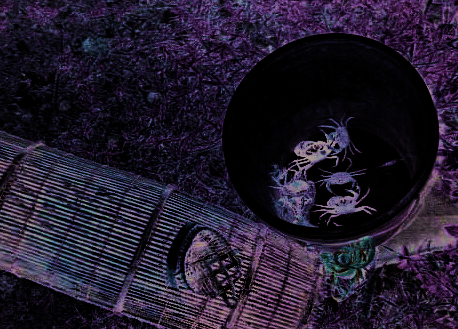

Plate 29. The forgotten animals of the `invisible fishery' on sale in Battambang -- common other aquatic

animals include frogs, crabs, snails and shrimps. OAAs accounted for about 23% of the weight and

11% of the value of all catches.

Plate 30. Trey riel and other fish from the commercial catches in the Tonle Sap Great Lake tributaries begin

to arrive in Battambang in December, so fish prices tend to remain stable despite the declining

supply of rice-field fish.

3. Results

3.1 General socioeconomic observations

Over the period of the study a total of 1217 fi sher interviews were made, with the number of

interviews being approximately proportional to the number of people fi shing at a site each

month, so that interviews varied from a high of 428 people in November 2003, when fi shing

activity was most intense, to only 27 people in February 2004, when most fi shing had ceased.

Some people were interviewed more than once, so the total does not refl ect the actual number

of interviewees, but because interviewees were randomly selected the results should accurately

refl ect the characteristics of the fi shers. Table 5 shows that most fi shers (about 82%) were male,

and most fi shers (79%) were aged 16 50 years, with fairly similar proportions at each site.

There were more children at Sites 5, 6 and 7, probably refl ecting proximity to settlements and

better access from the highway.

At the study sites there were at least 463 fi shers, the number estimated to be fi shing in the

peak month, which was October 2003 at Sites 5, 6 and 7, and November 2003 at the other sites.

Therefore, at the peak of the season there were about 2 fi shers per hectare.

Table 5. Summary of age and gender data from fi sher interviews.

Based on interviewees in each category over the seven-month period of the study.

Location

Total interviewees

Age Group (years)

All

Male

Female

% male % female

<15

16 30

31 50

>50

Site1

151

119

32

78.8%

21.2%

7.3%

38.4%

43.7%

10.6%

Site2

168

138

30

82.1%

17.9%

5.4%

38.1%

45.2%

11.3%

Site3

167

134

33

80.2%

19.8%

4.8%

38.3%

44.9%

12.0%

Site4

170

135

35

79.4%

20.6%

4.1%

38.2%

47.1%

10.6%

Site5

124

100

24

80.6%

19.4%

18.5%

36.3%

39.5%

5.6%

Site6

98

70

28

71.4%

28.6%

24.5%

36.7%

26.5%

12.2%

Site7

125

107

18

85.6%

14.4%

20.0%

34.4%

35.2%

10.4%

Site8

113

100

13

88.5%

11.5%

8.0%

34.5%

46.9%

10.6%

Site9

101

92

9

91.1%

8.9%

8.9%

38.6%

41.6%

10.9%

Total

1217

995

222

81.8%

18.2%

10.3%

37.2%

42.0%

10.5%

Rice growing is the main economic activity in the study area, but people with small holdings

or who own no rice-growing land usually gain seasonal income as wage labourers, either in

cultivation (e.g. harrowing using buffalos or small tractors), rice planting, or rice harvesting

(Table 6). Rice fi elds also support other important industries: large-scale harvesting of insects,

based on light-trapping (Hortle et al., 2005), capture and sale of rats, which are sold as food

Page 13

Yield and value of the wild fi shery of rice fi elds in Battambang Province, near the Tonle Sap Lake, Cambodia

for people or farmed crocodiles, and capture and sale of waterbirds. These wild products are

typically sold in Battambang town and some are exported to Thailand. Their harvest is seasonal,

based on rainfall and abundance of food, including rice. Fishers also earn other income from

labouring and from selling vegetables and fruits.

Table 6. The main income-earning activities of fi shers interviewed during the study period.

The table is a summary of the activities reported by fi shers.

Activity

Aug-03 Sep-03

Oct-03

Nov-03 Dec-03

Jan-04

Feb-04

Wage labour cultivation of rice-fi

elds

Wage labour rice planting

Wage labour rice harvesting

Vegetable selling

Vegetable selling corn and beans

Fruit

selling

Insect (especially crickets) selling

Rat

selling

Water bird selling

Wage labour house building

Wage labour brick factory

Transport motor taxi fee

3.2 Fishing gears, effort and total catch

Fishers used 26 types of gear in ten main categories, classed by mode of action, as shown in

Table 7. Four kinds of gears were observed to be usually lined with nylon mosquito-netting

mesh of 2 mm aperture, illegal under Cambodian fi sheries law1, which specifi es the minimum

mesh for all gears as 15 mm aperture. Other `illegal' methods, including electro-fi shing and

poisoning, were also being practised, but no data could be collected on catches from these

gears.

The usual number of gears per fi sher was estimated and is shown in Table 7, but could

not be recorded on each occasion, so effort is expressed as fi sher-days for each gear; i.e. the

number of days per month each fi sher was estimated to be using a gear at a site. The exact time

spent fi shing during a fi sher-day could not be determined, but would usually be several hours

each day. Most fi shers specialised in one type of gear on any occasion; about 90% of all fi sher

records were for only one kind of gear on one day, but fi shers change their gears during the

season to adjust to changing environmental conditions and target species. Seasonal changes in

effort and catch are tabulated in the summary tables in Appendix 1, which were simplifi ed by

combining effort and catches by gear category to produce Tables 8 10.

1 The Fisheries Law 2004 is open to interpretation on private land.

Page 14

Results

Table 7. Types of gear used by fi shers in this study. Page numbers and codes follow Deap et al. (2003)

yes

yes

yes

yes

Often used with mosquito net mesh

fi

shers

fi

shers

fi

shers

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

5

5

7

6

5

6

1

1

1

fi

sher

3

several

1 5

, 2

, 2

20 100

10 50

20 30

10 40

1 5

1 gear

1 gear

Approximate number used by a typical

usually

x

x3

x3

x3

x3

x3

x5

x1

x

day + night

x

x

x

night

Fishing Period

day

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

e

e

r

ey Chhlonh

ob

m

u

Khmer Name

Bach Bat Pralay

Chap Dai

Chhnieng Chunhchoat

Thnorng Moul

Kangva Kongkaep

Chamr

Kangva T

Santuch Bobok Kongkaep

Santuch Phlay Muoy

Santuch Bongkai

To

Chongnoum

Lop Nhek Sr

Tr

Lawn Antong

Lop Kongkaep

Lop Rungvel

Lop Phsom Pruol

Anlung Ungkoup

Mong Reay Sr

Uon Hum

Anchorng

Chheub

Kantrup Kongkaep

Samnanh

Lu Sbai Mong

fi

eld cylinder trap

mesh)

fi

eld cylinder trap

f

fi

ne

edge-shaped scoop basket

Name

Capture by hand in dried ditch or canal

Capture by hand in water

W

Long-handled circular scoop bag

Frog gaf

T

wo-pronged eel fork

Eel clamp

Pole and line for catching frogs

Hand-held single hook and line

Single-hook set pole and line

V

ertical bamboo vase trap

Bamboo funnel basket trap

V

ertical rice

Horizontal rice

Bamboo tube trap for eel

Horizontal cylinder trap for frogs

Big horizontal cylinder trap

Horizontal cylinder trap with bamboo fences

Hole trap

Gill net

Small hand-dragged seine net

Small-handle seine net

Hand-held scissors push net

Frog trap net

Cast net

Fyke net (

ounding gear

ounding gear

ounding gear

Category

Capture by hand

Capture by hand

Scoop nets

Scoop nets

W

W

W

Hook & line

Hook & line

Hook & line

T

raps

T

raps

T

raps

T

raps

T

raps

T

raps

T

raps

T

raps

T

raps

Gill nets

Seine nets

Seine nets

Pushed Gear

Covering nets

Covering nets

Bag nets

Cat. No.

1

1

2

2

3

3

3

4

4

4

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

6

7

7

9

1

1

1

1

12

Code

1.1

1.1

2.1.1

2.2.1

3.1.1

3.2.1

3.3.1&2

4.1.3

4.1.4

4.2.1

5.1.1.2

5.1.1.2

5.1.1.6

5.1.2.1

5.1.2.2

5.2.3

5.1.2.6

5.1.2.8

5.4.1

6.1.1

7.1.1

7.3.1

9.1.2

1

1.1.2

1

1.2.1

12.1.1

Page No.

14

14

16

22

32

34

38-40

70

72

76

93

95

102

104

108

1

10

1

19

131

147

165

175

182

202

214

216

224

Page 15

Yield and value of the wild fi shery of rice fi elds in Battambang Province, near the Tonle Sap Lake, Cambodia

During the period when rice is growing in inundated paddies, fi shers may not move through

rice fi elds, so are restricted to using hook and line and small traps around the edges of paddies,

and using other gears such as gillnets, cast nets, small seines, traps and fyke nets in adjacent

canals and ponds. Some specialised gears for frogs and eels are used only after rice fi elds have

been wet for several months and the population of these target species has increased. After

water levels fall and where rice has been harvested, fi shers can move through the fi elds using

active methods, including capture by hand and, using wounding gears such as clamps and

gaffs. Pumping water out of fenced-off parts of canals is a common (but illegal practice) when

water levels are low, and capture by hand, sometimes aided with wedge-shaped scoop baskets

is practised in shallow residual water through rice fi elds. Tabulations of the number of fi shers

using each category of gear each month, and for the number of sites at which the gear was being

used, showed similar patterns to Table 10 so are not presented here.

Table 8. Fishing effort as total fi sher-days, summed for all nine sites, total area 225 ha

Category

Aug 03 Sep 03 Oct 03 Nov 03 Dec 03 Jan 04 Feb 04 Total

%

Traps (9 types)

696

1148 1963 3964 2104

72

9947 43.3%

Hook & line (includes hand-held & set single hooks) 912

904

2413 2189

208

80

6706 29.2%

Covering nets (cast nets & frog trap nets)

751

1228

80

2059 9.0%

Gill nets (one type)

712

732

1444 6.3%

Bag nets (one type fyke nets)

50

560

610

2.7%

Wounding gear (eel clamps, eel forks & frog gaffs)

48

148

396

307

899

3.9%

Pushed gear (hand-held scissors net)

112

132

244

1.1%

Seine nets (2 types of small hand-pulled seines)

160

144

216

32

552

2.4%

Capture by hand (in water or in canals pumped dry)

164

168

80

412

1.8%

Scoop nets (2 types of small hand-held nets)

12

80

92

0.4%

Total

1608 2052 6061 8865 3032

880

467 22,965 100.0%

Table 9. Total catch of fi sh & OAAs (kg) by each gear, summed for all nine sites.

Category

Aug 03 Sep 03 Oct 03 Nov 03 Dec 03 Jan 04 Feb 04 Total

%

Traps (9 types)

1070

976

3130 4582 2819

63

12,641 47.3%

Hook & line (includes hand-held & set single hooks) 382

791

1752 3431

87

93

6537 24.5%

Covering nets (cast nets & frog trap nets)

1021 1595

56

2672 10.0%

Gill nets (one type)

808

643

1451 5.4%

Bag nets (one type - fyke nets)

173

847

1020 3.8%

Wounding gear (eel clamps, eel forks & frog gaffs)

6

160

315

382

863

3.2%

Pushed Gear (hand-held scissors net)

96

432

529

2.0%

Seine nets (2 types of small hand-pulled seines)

158

203

150

14

525

2.0%

Capture by hand (in water or in canals pumped dry)

131

97

57

285

1.1%

Scoop nets (2 types of small hand-held nets)

30

178

208

0.8%

Total

1452 1767 7073 11,307 3500 1015

617 26,730 100.0%

Note: Totals may not sum due to rounding.

Page 16

Results

Table 10. CPUE as mean catch by each category of gear (kg/fi sher-day), summed for all sites.

Category

Aug 03 Sep 03 Oct 03 Nov 03 Dec 03 Jan 04 Feb 04 Mean

Traps (9 types)

1.54

0.85

1.59

1.16

1.34

0.88

1.27

Hook & line (includes hand-held & set single hooks)

0.42

0.88

0.73

1.57

0.42

1.16

0.97

Covering nets (cast nets & frog trap nets)

1.36

1.30

0.70

1.30

Gill nets (one type)

1.13

0.88

1.00

Bag nets (one type - fyke nets)

3.46

1.51

1.67

Wounding gear (eel clamps, eel forks & frog gaffs)

0.13

1.08

0.80

1.24

0.96

Pushed gear (hand-held scissors net)

0.86

3.27

2.17

Seine nets (2 types of small hand-pulled seines)

0.99

1.41

0.70

0.43

0.95

Capture by hand (in water or in canals pumped dry)

0.80

0.58

0.71

0.69

Scoop nets (2 types of small hand-held nets)

2.50

2.23

2.26

Total

0.90

0.86

1.17

1.28

1.15

1.15

1.32

1.16

Note: Totals may not sum due to rounding.

Tables 8 and 9 show that the largest total catches were made with the most-used gears, with

catch rates varying between 0.1 and 3.5 kg/fi sher-day for any type of gear (Appendix 1). The

highest catch rate was recorded for fi ne-mesh fyke nets, which could explain why they are

widespread and popular, despite efforts by fi sheries inspectors to destroy these illegal gears.

Overall, mean CPUE (catch per unit effort) was 1.16 kg/fi sher-day, averaged across all gears.

Allowing for the use by some fi shers of two kinds of gear (approximately 10% of fi sher-days)

the mean catch per fi sher was about 1 kg/day, averaged across all gears, sites and months.

Traps accounted for about 43% of the effort and 47% of the weight of catches, and three

categories of gear (traps, hook and line, and covering nets) accounted for about 82% of the total

effort and the total weight of catches (Tables 8 and 9). Some types of gear that are commonly

used in other environments, such as gill nets, bag nets and seines were relatively unimportant

in the fi shery, as dense vegetation in and near rice fi elds tends to limit the effectiveness of such

gears.

As shown in Figure 4, total catches depend largely upon total effort. The data for this graph

are shown in Appendix 2. The gears which are apparently more effective, in terms of catch per

fi sher-day, correspond with points above the line in Figure 4; including for example horizontal

cylinder traps with fences (HTF) and vertical rice-fi eld cylinder traps (VRT), whereas less

apparently effi cient gears correspond with points below the line in the centre of the graph, such

as hole traps (HT) and hand-held single hook and line (HSH). If the graph were to take into

account the total investment in terms of actual effort per gear or method, and the time and cost

of preparation and materials, the relationship might be improved, because points above the

line (such as HTF and VRT) would be moved to the right, whereas points below the line (such

as HT and HSH) would be moved to the left. Combining gears within the ten main categories

results in an even better correlation (r2=0.98), because within each group lower CPUE by less

effi cient gears tends to be balanced by higher CPUE by more effi cient gears.

Page 17

Yield and value of the wild fi shery of rice fi elds in Battambang Province, near the Tonle Sap Lake, Cambodia

6000

5000

4000

HTF

3000

y = 1.16x

ch by each gear

VRT

R2 = 0.92

2000

T

otal cat

HSH

1000

HT

0 0

500

1000 1500 2000 2500 3000 3500 4000 4500 5000

Effort (fisher - days)

Figure 4.

Total catches by each of 26 kinds of gear versus total effort for that gear.

Labelled points are HTF horizontal cylinder trap with bamboo fences; VRT vertical rice-fi eld

cylinder trap; HT hole trap and HSH hand-held single hook and line; refer to text for discussion.

3000

Site 1

Site 2

2500

Site 3

Site 4

g) 2000

Site 8

Site 9

ch (k 1500

T

otal cat 1000

500

0 Aug 03 Sep 03 Oct 03 Nov 03 Dec 03 Jan 04 Feb 04

Month

3000

Site 5

Site 6

2500

Site 7

g) 2000

ch (k 1500

T

otal cat 1000

500

0 Aug 03 Sep 03 Oct 03 Nov 03 Dec 03 Jan 04 Feb 04

Month

Figure 5.

Total catches of fi sh and OAAs at each site each month

Page 18

Results

Total effort, total catches and mean CPUE were all highest in October and November.

Figure 5 shows that the seasonal pattern of catches varied between two groups of sites: at Sites

5, 6 and 7 catches were highest in October, whereas at the other sites catches were highest in

November; similarly the second-highest catches were in November at Sites 5, 6 and 7, and

during December at the other sites. Peak catches were approximately one month early at Sites

5, 6 and 7 because these sites were shallower and drained faster than the other sites. The months

of peak catches coincided for fi sh and for OAAs at all sites, except at Site 1, where highest

catch of OAAs was in August 2003.

Of the total weight of all fi sh and OAAs, 57% was caught during the peak month, with

between 44% and 78% of the total at any site being caught in the peak month. During the two

peak months (i.e. the months of the largest and second largest catch at a site) about 74% of the

total catch was made, with 62 95% being caught at any site. Therefore, a very large proportion

of the catch is made in the period of about two months between the last transplanting of rice

seedlings and the fi rst harvest, when labour is not needed for other work and when inundation

of most of the landscape prevents many other activities. For a family in which three people

fi shed most days, catches of about 100 kg/month could readily be achieved over the two-month

peak period, providing a signifi cant boost for household consumption and supplementary

income.

3.3 Yield and composition of the catch

Fishers caught 35 species of fi sh, as well as six taxa of OAAs which were not identifi ed

to species (Appendix 3). Of the total catch of 26.7 tonnes (from the nine sites), about 77%

comprised fi sh and 23% comprised OAAs. As shown in Figure 6, most of the total catch of

fi sh (about 88% by weight) was made up of 12 species of `black fi shes', species that gulp air

and have modifi ed respiratory structures, features that allow them to tolerate anoxic conditions

in wetland habitats; black fi shes typically do not migrate far when water levels fall. The other

fi shes (i.e. the 24 species making up 7% of the weight of fi sh) are relatively intolerant of

anoxia and migrate to dry-season refuge habitats in permanent water bodies, such as canals,

streams and the Great Lake Tonle Sap system; those that migrate to local refuges are termed

`grey' fi shes whereas species that migrate long-distances are termed `white' fi shes, as noted in

Appendix 3.

Most of the catch of OAAs consisted of crabs, frogs and shrimps in approximately equal

proportions (Figure 6), and it is interesting to note that the total catch of each of these taxa was

greater than the catch of most of the individual species of fi sh. All OAAs are eaten, but some

are fed to animals; for example crabs are commonly fed to pigs and shrimps are fed to ducks.

As shown in Figure 7, the fi sh catch was dominated by carnivores, including snakeheads,

peacock eels, gouramies and walking catfi sh; a full list is presented in Appendix 3. The

omnivores mainly comprised species which eat only small proportions of plant material,

Page 19

Yield and value of the wild fi shery of rice fi elds in Battambang Province, near the Tonle Sap Lake, Cambodia

and there were no purely herbivorous fi sh. Carnivores were generally more valuable than

omnivores, which increased their proportional contribution to total value, as discussed below.

Figure 8 (top) shows that the same species of fi sh tended to dominate catches each month,

whereas Figure 8 (bottom) shows that among OAAs, crabs were more abundant early in the

season while frogs became relatively more abundant later in the season, as might be expected

based on their life cycles. Large numbers of crabs survive the dry season deep in rice-fi eld mud

and are caught early in the season soon after they emerge, whereas tadpoles require time to

grow and metamorphose into frogs, which are mostly caught later in the wet season and in the

early dry.

Other fish (24 species)

Other black fish (6 species)

Channa striata

12.3%

Chevron snakehead

28.0%

7.3%

Monopterus albus

Swamp eel

6.2%

Trichogaster trichopterus

6.3%

Three-spot gourami

17.9%

9.2%

Clarias batrachus

Macrognathus siamensis

17.7%

Walking catfish

Peakcock eel

Anabas testudineus

Climbing perch

Snakes

Small water snails

Large water snails

2.9%2.4%

Crabs

7.1%

35.5%

Shrimps

22.5%

29.6%

Frogs

Figure 6.

Composition of the total catch of 26,730 kg. Fish 20,469 kg (top), OAAs 6,261 kg,

(bottom). For fi sh, only species comprising more than 5% of the total weight are shown.

Page 20

Results

Omnivores

Carnivores

36.6%

32.3%

63.4%

67.7%

Proportion of

Proportion of the

total fish catch

total value of fish

Figure 7.

Proportions of the total weight and total value of fi sh of different trophic guilds in the

catches. Appendix 3 shows the composition by species. Value was derived from Appendix 5.

10000

9000

Monopterus albus

Trichogaster trichopterus

8000

Clarias batrachus

7000

Anabas testudineus

g) 6000

Macrognathus siamensis

ch (k 5000

Channa striata

Other Species

4000

T

otal cat

3000

2000

1000

0

Aug 03

Sep 03

Oct 03

Nov 03

Dec 03

Jan 04

Feb 04

Month

2500

Snakes

Small water snails

2000

Big water snails

Shrimps

g) 1500

Frogs

ch (k

Crabs

1000

T

otal cat

500

0

Aug 03

Sep 03

Oct 03

Nov 03

Dec 03

Jan 04

Feb 04

Month

Figure 8.

Composition of the total catch of fi sh each month, showing the six species comprising

most of the weight in catches, nine sites combined (Top). Composition of the total catch

of OAAs each month, nine sites combined (Bottom).

Page 21

Yield and value of the wild fi shery of rice fi elds in Battambang Province, near the Tonle Sap Lake, Cambodia

3.4 Composition and catch by gear

The catch of each species by each type of gear is shown in Appendix 4. Gears tended to be

selective for certain species. For example, the larger carnivores including Channa striata,

Clarias spp. and Ompok bimaculatus were caught disproportionately by hook and line, whereas

several smaller fi sh species were caught disproportionately by traps. For OAAs, shrimps were

caught disproportionately by bag nets, but the other fi ve taxa were all caught mainly by traps.

Three main groups of gears caught about 82% of the total catch weight; traps accounted for

about 47% of the catch, about 25% was taken with hook and line, and about 10% was caught

using cast nets. Gill nets caught about 5% of the catch and the other seven main types of gears

each caught less than 5% of the total catch.

3.5 Value of the catch

Over the period of the study fi shers caught about 26,730 kg of fi sh and OAAs with a total

value of about US$22,912, calculated as a weighted average based on 647 individual site-date

price records (Appendix 5). Mean prices varied between US$0.05/kg and $1.36/kg; snails and

crabs were the lowest-value animals (US$0.05 0.07/kg) and were predominantly used to feed

animals; the most valuable fi sh (all worth more than US$1.20/kg on average) were the larger

good-eating fi sh, which were carnivorous or primarily carnivorous, these included Channa

striata, Monopterus albus, Macrognathus siamensis, Clarias macrocephalus, Clarias batrachus

and Ophisternon bengalense. The value of carnivorous fi sh averaged US$1.06/kg and the value

of omnivorous fi sh averaged US$0.88/kg, as weighted means across all catches. Similarly,

carnivorous OAAs (frogs and snakes) were far more valuable than omnivorous or herbivorous

OAAs (Appendix 5). Over the entire area of 225 ha that was surveyed, the mean value of the

catch was approximately US$101 per hectare.

The price of fi sh and OAAs overall appears to be insensitive to the quantity caught from

rice fi elds and associated habitats, as shown in Figure 9, because prices in markets also depend

upon the supply from other sources. For example, markets also receive fi sh and OAAs from

large catches which are made in the Tonle Sap Great Lake system during the fl ood recession

from December to February. This supply would tend to offset the effect of lower rice fi eld

catches in those months. The prices of individual species or taxa varied to some extent between

months, which might refl ect short-term changes in supply (Figure 10). However, there was

no evident relationship between quantity and price for all taxa combined (r2 = 0.36, p > 0.05,

n = 7 months), nor for 11 of 12 individual taxa tested for such a relationship. For one fi sh,

Trichogaster trichopterus, quantity and price were positively correlated (r2 = 0.77, p = 0.01),

perhaps a spurious correlation related to catches for this species peaking in October, prior to

catches of most other species peaking (i.e. the price might refl ect lower availability of fi sh

overall).

Page 22

Results

12000

4500

Catch

4000

10000

Price

3500

8000

3000

g)

g)

ch (k

2500

iel/k

6000

2000

r

ice (R

T

otal cat

P

4000

1500

1000

2000

500

0

0

Aug 03

Sep 03

Oct 03

Nov 03

Dec 03

Jan 04

Feb 04

Figure 9.

Total catch and weighted average price of all fi sh and OAAs each month.

US$ = Riel 4000.

10000

Channa striata

9000

Macrognathus siamensis

Anabas testudineus

8000

Clarias batrachus

7000

Trichogaster trichopterus

Monopterus albus

g)

6000

iel/k

5000

r

ice (R

P

4000

3000

2000

1000

0

Aug 03

Sep 03

Oct 03

Nov 03

Dec 03

Jan 04

Feb 04

Month

Figure 10. Monthly prices of the six fi sh species which contributed the most to total catches by

weight. Prices are weighted averages from all sites and gears combined. Clarias batrachus was

uncommon in Feb-04 and no price was recorded.

Page 23

Yield and value of the wild fi shery of rice fi elds in Battambang Province, near the Tonle Sap Lake, Cambodia

3.6 Disposal of the catch

Most fi shers catch what is needed for household consumption and sell the excess, but also tend

to sell larger higher-value fi sh and eat smaller fi sh. Larger specimens of the air-breathing black

fi shes (including Clarias, Channa, and Anabas) can be kept alive for extended periods out of

water, so are easy to transport and sell. Data on catch disposal were incomplete, either because

fi shers did not supply the information or it was not accurately recorded by data collectors,

so a detailed analysis could not be undertaken. Up to about 70% of catches at any time were

reported to be sold by fi shers, with generally higher proportions sold at times of higher catches.

Fishers at Sites 1 4 appeared to be mainly fi shing for income, and sold 50 70% of their

catches, fi shers at Sites 5 7 (close to houses and with more children fi shing) sold only about

10 15% of their catches, and at Sites 8 and 9 fi shers sold 15 60% of their catches, with higher

percentages at times of larger catches. From these data it would be reasonable to estimate

that about half of the weight of all the catches was sold. Thus the value of sales may also be

estimated as about half of the total value of the catch, or about US$11,456 -- or about US$51