Mekong River Commission

Annual Mekong Flood

Report 2008

September 2009

ISBN : 1728 3248

Mekong River Commission

Annual Mekong Flood Report 2008

September 2009

Published in Vientiane in September 2009 by the Mekong River Commission

Cite this document as:

MRC (2009) Annual Mekong Flood Report 2008, Mekong River Commission, Vientiane. 84 pp.

The opinions and interpretation expressed within are those of the authors and do not necessarily

reflect the views of the Mekong River Commission.

Editor: T.J. Burnhill

Graphic design: T.J. Burnhill

Contributing author: P.T. Adamson

© Mekong River Commission

184 Fa Ngoum Road, Unit 18, Ban Sithane Neua, Sikhottabong District,

Vientiane 01000, Lao PDR

Telephone: (856 21) 263 263 Facsimile: (856 21) 263 264

E-mail: mrcs@mrcmekong.org

Website: www.mrcmekong.org

ii

Table of contents

Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................... xi

Summary .................................................................................................................................... xiii

1. Introduction ...............................................................................................................................1

2. Flood benefits ............................................................................................................................3

2.1 Introduction and historical context ..................................................................................3

2.2 Flood benefits -- agriculture ............................................................................................6

2.3 Flood benefits -- the Mekong fishery ............................................................................11

2.4 Flood benefits the creation and maintenance of natural wetlands ...............................14

3. Flood costs ..............................................................................................................................21

3.1 Introduction ....................................................................................................................21

3.2 Flood damage assessment in the Lower Mekong region ...............................................22

3.3 The regional history and pattern of flood damage .........................................................26

3.4 The composition of flood losses ....................................................................................32

4. Comparing the costs and benefits of the annual flood ............................................................35

4.1 General observations......................................................................................................35

4.2 Incremental figures ........................................................................................................36

5. The 2008 flood season.............................................................................................................37

5.1 General observations......................................................................................................37

5.2 Meteorological conditions .............................................................................................39

5.3 Temporal aspects of the 2008 Mekong flood season .....................................................43

5.4 Water levels ....................................................................................................................44

5.5 Flood discharges and flood volumes ..............................................................................46

5.6 Aspects of probability and risk ......................................................................................49

5.7 Conditions on the Cambodian floodplain and in the Delta ............................................51

6. Summary of the 2008 country reports ....................................................................................53

6.1 Cambodia .......................................................................................................................53

6.2 Lao PDR ........................................................................................................................55

6.3 Thailand .........................................................................................................................59

6.4 Viet Nam ........................................................................................................................63

7. Summary conclusions and recommendations .........................................................................67

7.1 Summary conclusions. ...................................................................................................67

7.2 Recommendations. .........................................................................................................67

iii

8. References ...............................................................................................................................69

Appendix 1. Mekong mainstream: summary hydrological statistics for the 2008 food season ..73

Appendix 2. Cambodia. 2008 flood damages compared to those of recent years .......................74

Appendix 3. Lao PDR: August 2008 flood damages ...................................................................75

Appendix 4. Thailand: 2008 flood damages compared to those of recent years .........................76

Appendix 5. Viet Nam: 2008 flood damages compared to those of recent years ........................77

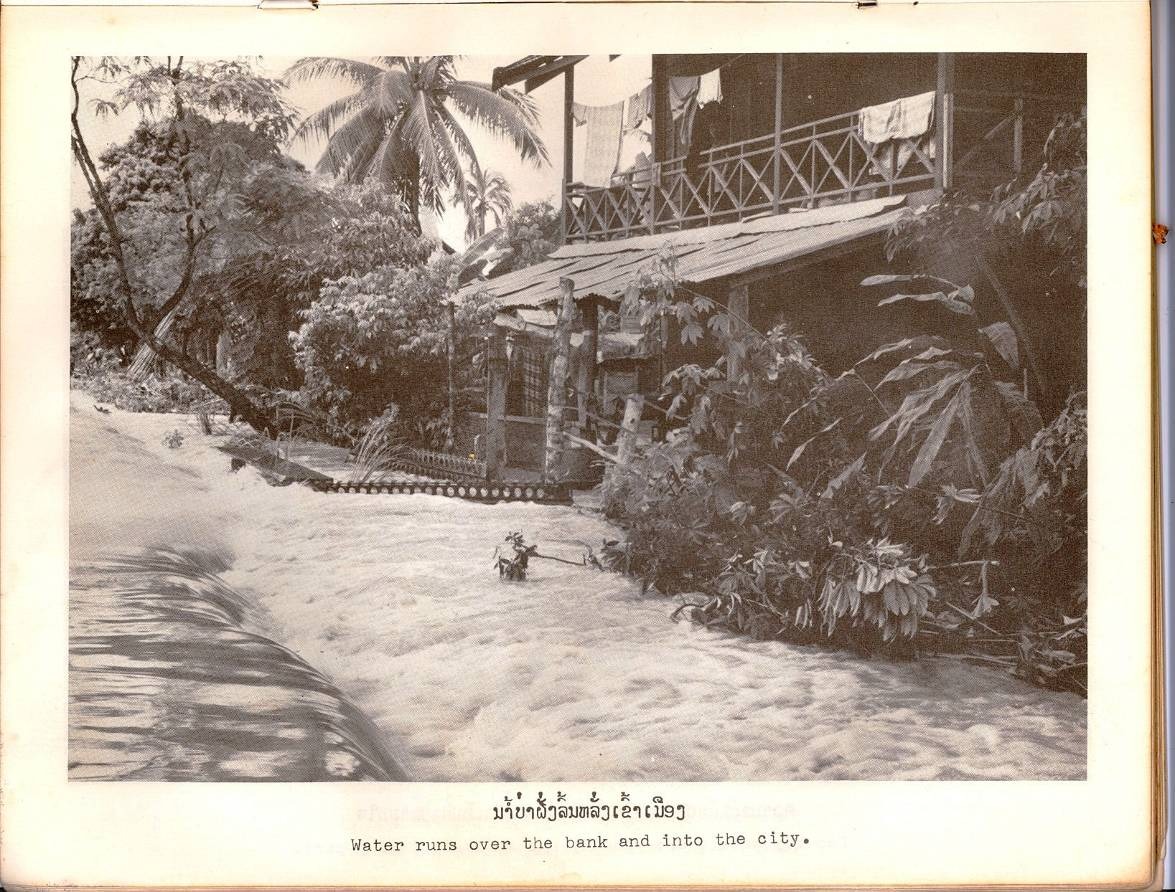

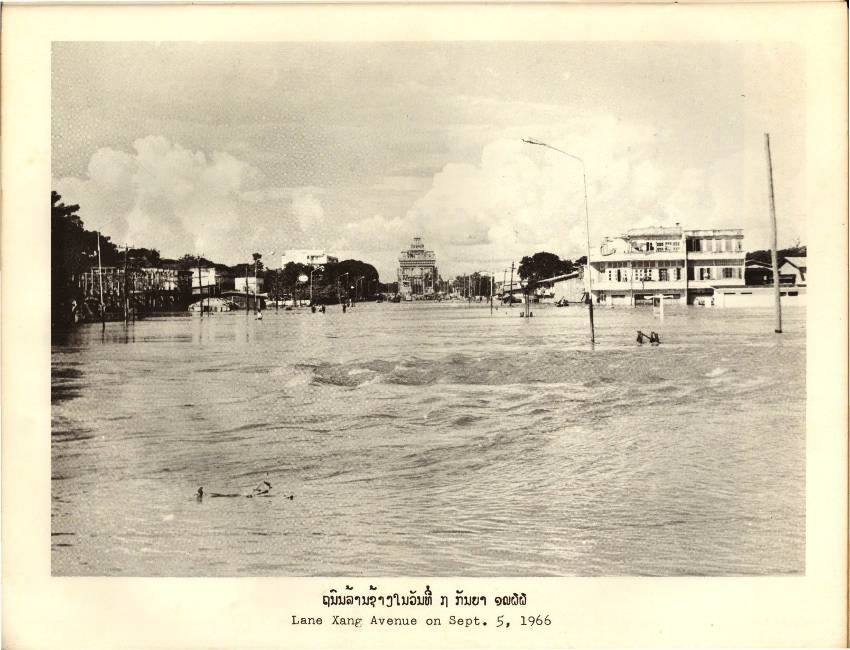

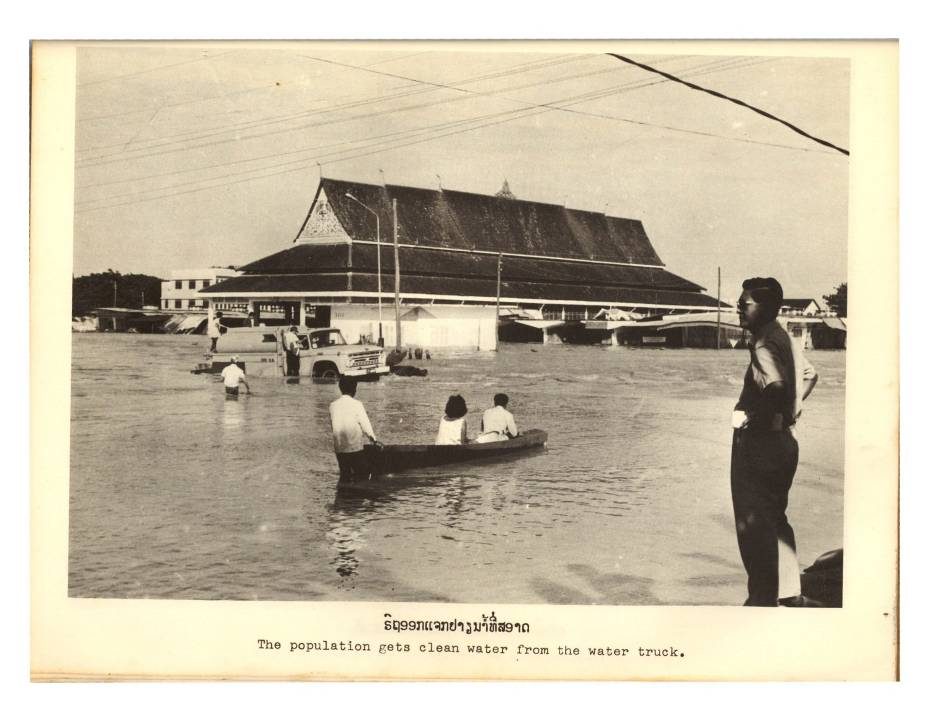

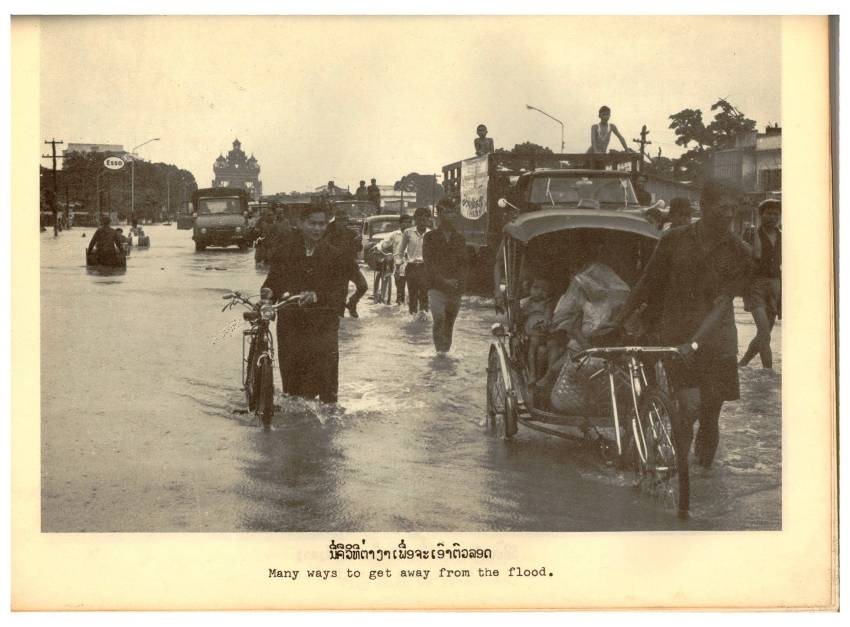

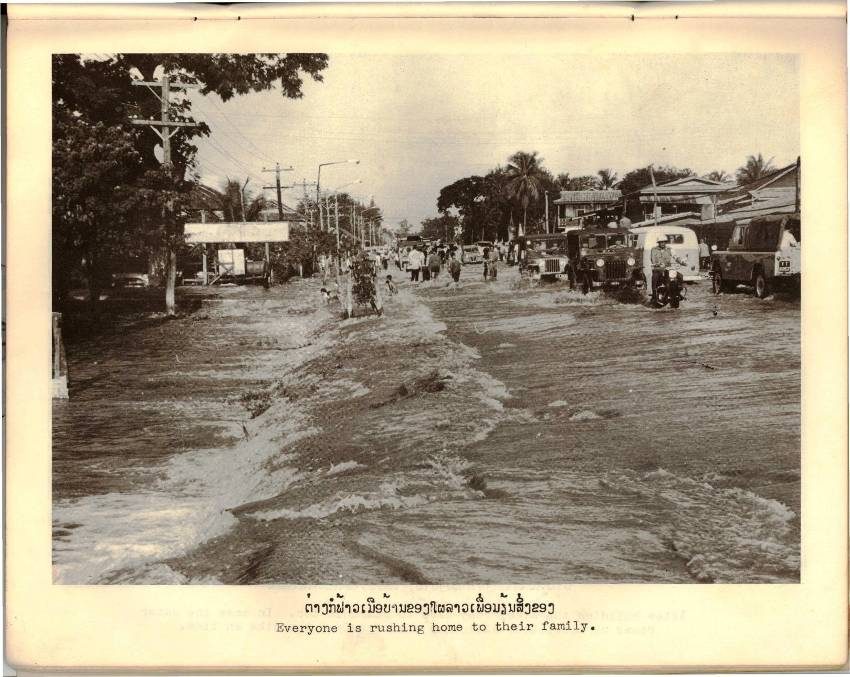

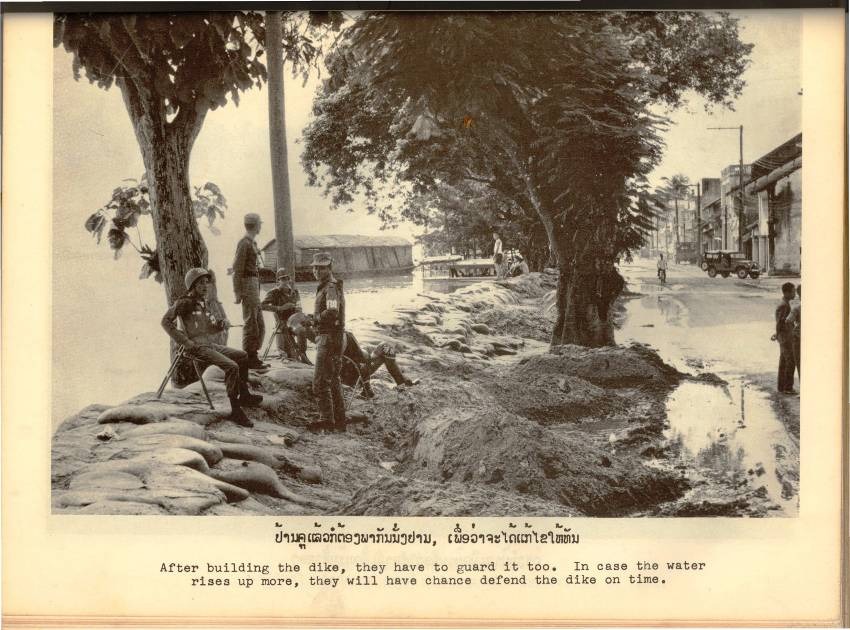

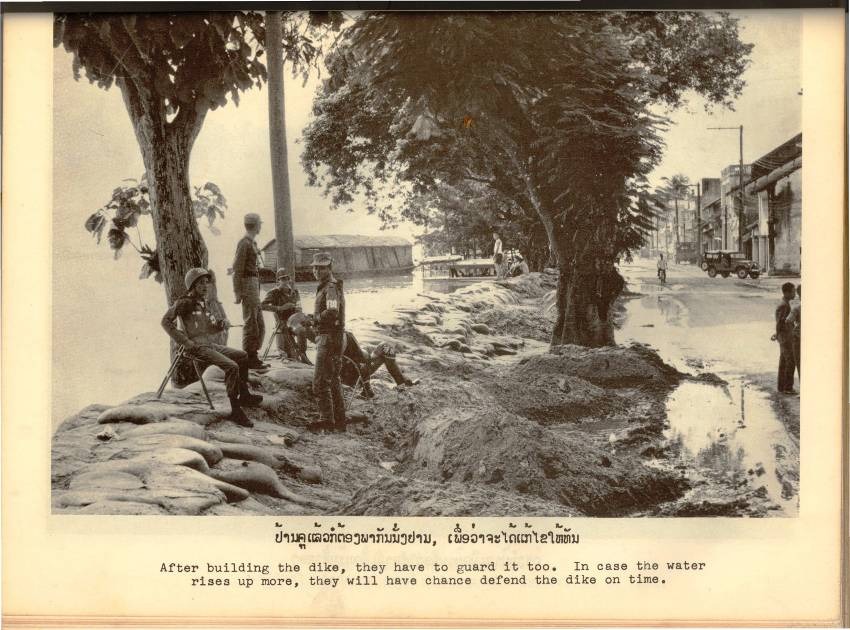

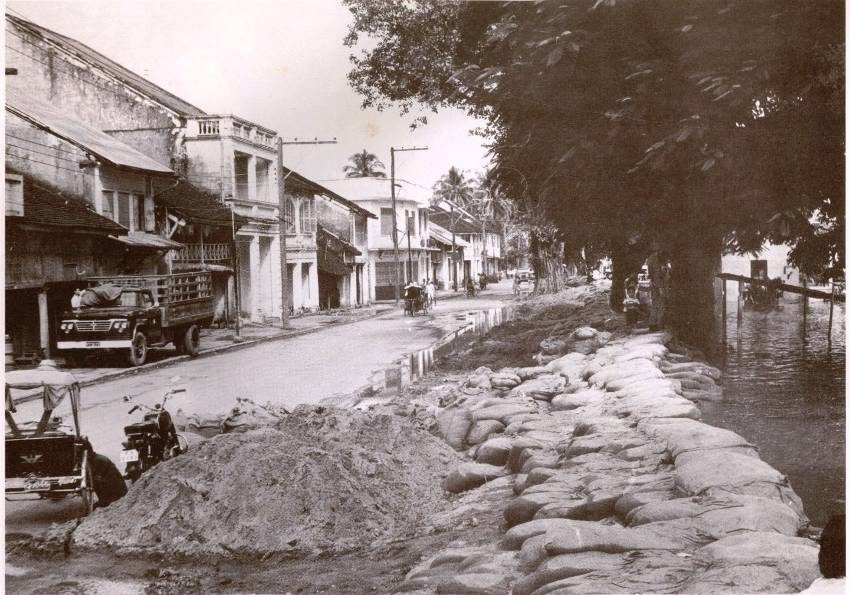

Appendix 6. Photograph archive of the September 1966 flood in Vientiane ...............................78

iv

Table of figures

Figure 2.1 The distribution of flood recession rice cultivation areas and pre-Khmer

archaeological sites in Cambodia. ...................................................................4

Figure 2.2 This bas relief at Angkor Wat is indicative of the importance of fish in the

socioeconomics and culture of the Khmer Empire (800 1300 AD) ..............4

Figure 2.3 The value of agricultural production in the Mekong Delta (1995 2004)

in Viet Nam. ....................................................................................................8

Figure 2.4 Flood recession rice cultivation on the Cambodian floodplain. ......................9

Figure 2.5 An example of the `Tham Nop' flood diversion system from

North East Thailand. .....................................................................................10

Figure 2.6 The dai, or bagnet fishery, on the Tonle Sap, Cambodia. ..............................13

Figure 2.7 Estimates of fish biomass arriving at the dai fishery and the annual flood

index proposed by Halls et al. (2008). ..........................................................13

Figure 2.8 Mekong wetlands at Sipandone, Lao PDR. ...................................................14

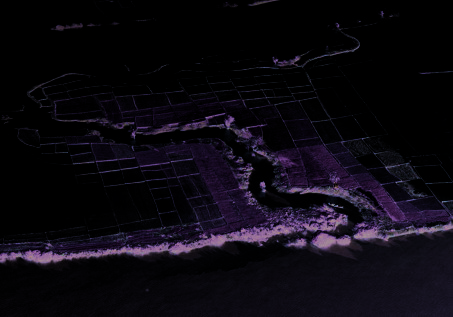

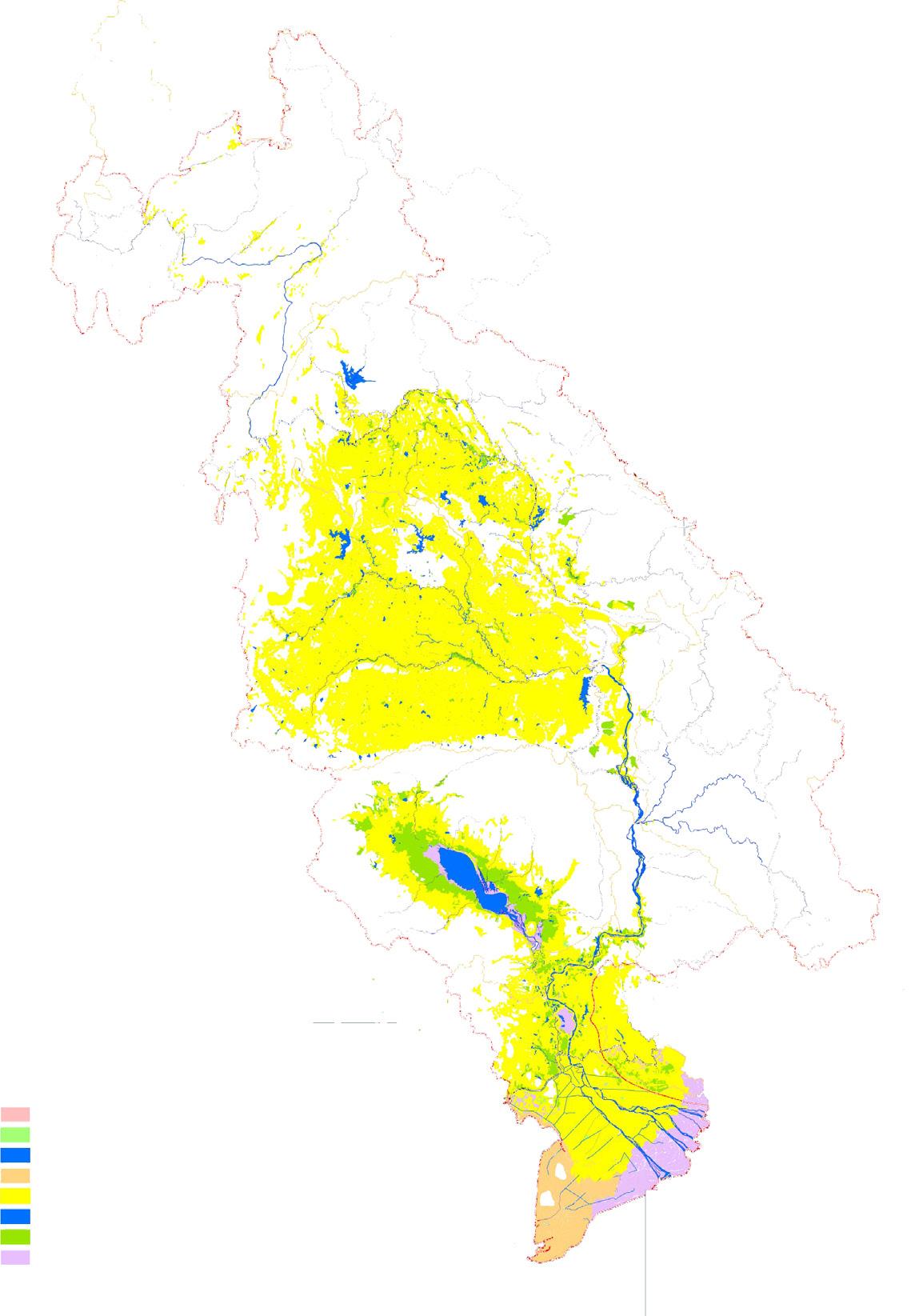

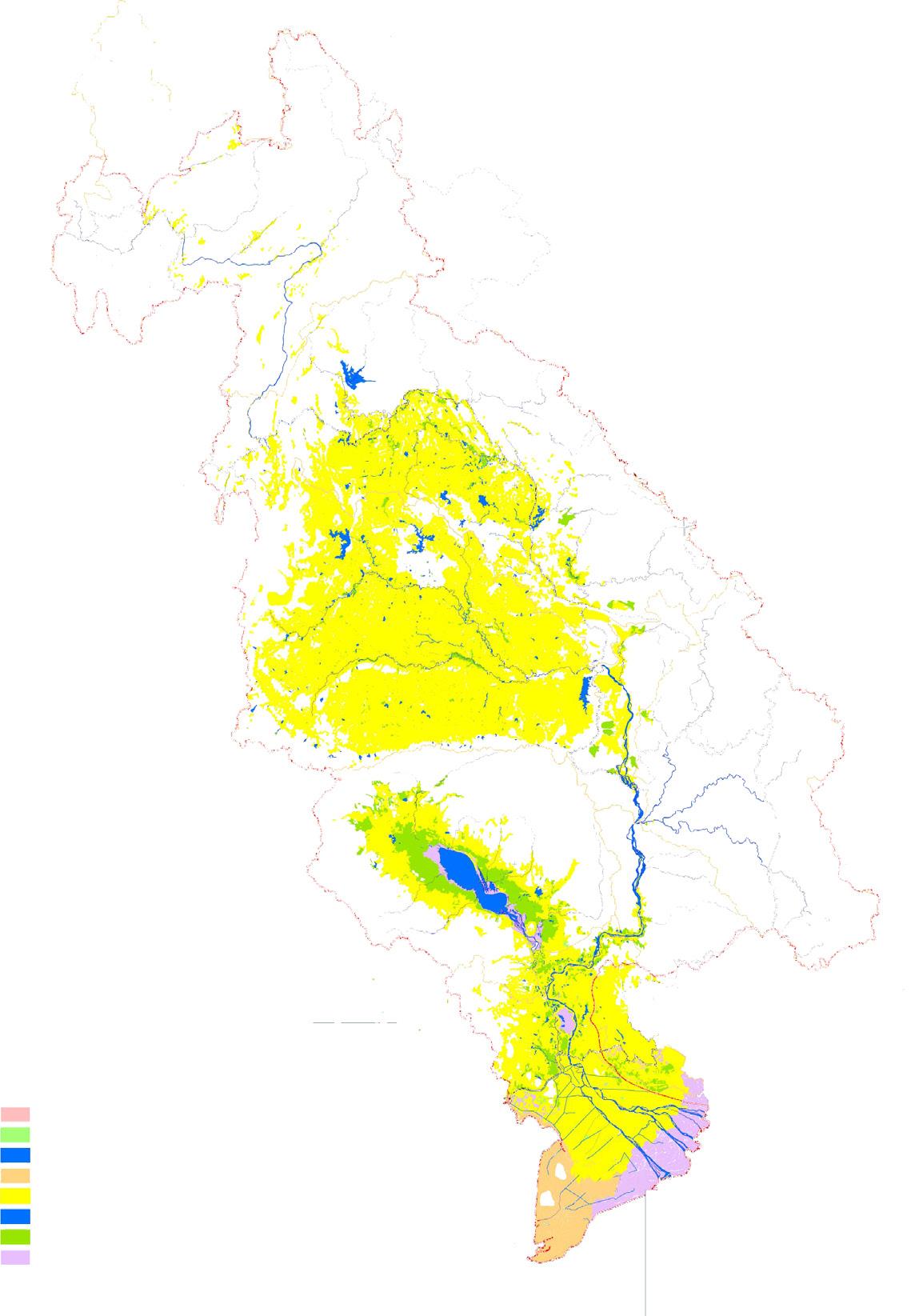

Figure 2.9 Distribution of `wetlands' in the Lower Mekong Basin ...............................16

Figure 3.1 Flooded rice fields near Pakse, September 2008. ..........................................22

Figure 3.2 Growth in agricultural losses in the Mekong delta in Viet Nam as a

function of flood frequency ...........................................................................24

Figure 3.3 Sectoral flood damage curves for the Mekong Delta ....................................25

Figure 3.4 Frequency distribution of annual flood damage in the Mekong Delta .........26

Figure 3.5 Lao PDR, annual flood damage 1966 2008. .................................................27

Figure 3.6 Thai Mekong region, annual flood damage 1989 2008 ...............................27

Figure 3.7 Cambodia, annual flood damage 1996 2008 ...............................................28

Figure 3.8 Mekong Delta, Viet Nam, annual flood damage 1995 2008. ......................28

Figure 3.9 Indicative distribution of average annual regional flood costs

of US$76 million. ..........................................................................................29

v

Figure 3.10 Mekong floods in 2000 and 2008 proportional and total damage. ..............30

Figure 3.11 Scatter plot of the `relationship' between annual maximum discharge on

the Mekong at Vientiane and the reported annual flood damage in

Lao PDR over the years from 1990 to 2008. .................................................31

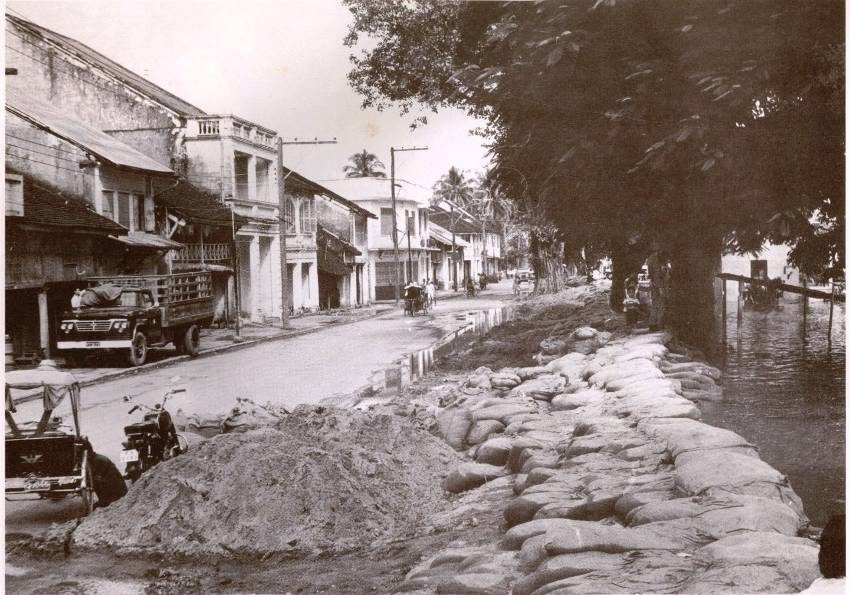

Figure 3.12 Urban flooding Vientiane, Lao PDR, August 2008. ....................................31

Figure 3.13 Total annual flood damage (1996 2008) in Cambodia and the delta in

Viet Nam in relation to the peak and volume of the annual flood

hydrograph recorded at Kratie. ......................................................................32

Figure 3.14 Proportion (%) of total flood damage by sector during 2000. .......................33

Figure 3.15 Primary and secondary flood losses as a proportion of total damage for

business enterprises. ......................................................................................34

Figure 5.1 The `historical geography' of the annual flood on the Mekong mainstream

(1960 2008) between Chaing Saen and Kratie. ...........................................38

Figure 5.2 Cumulative annual rainfall during 2008 at selected sites in the

Lower Mekong Basin ....................................................................................41

Figure 5.3 Track of tropical storm Kammuri first week of August, 2008. ..................42

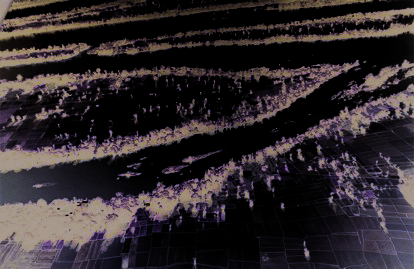

Figure 5.4 Accumulated rainfall over the Mekong Region: 6th to 14th August 2008. ..42

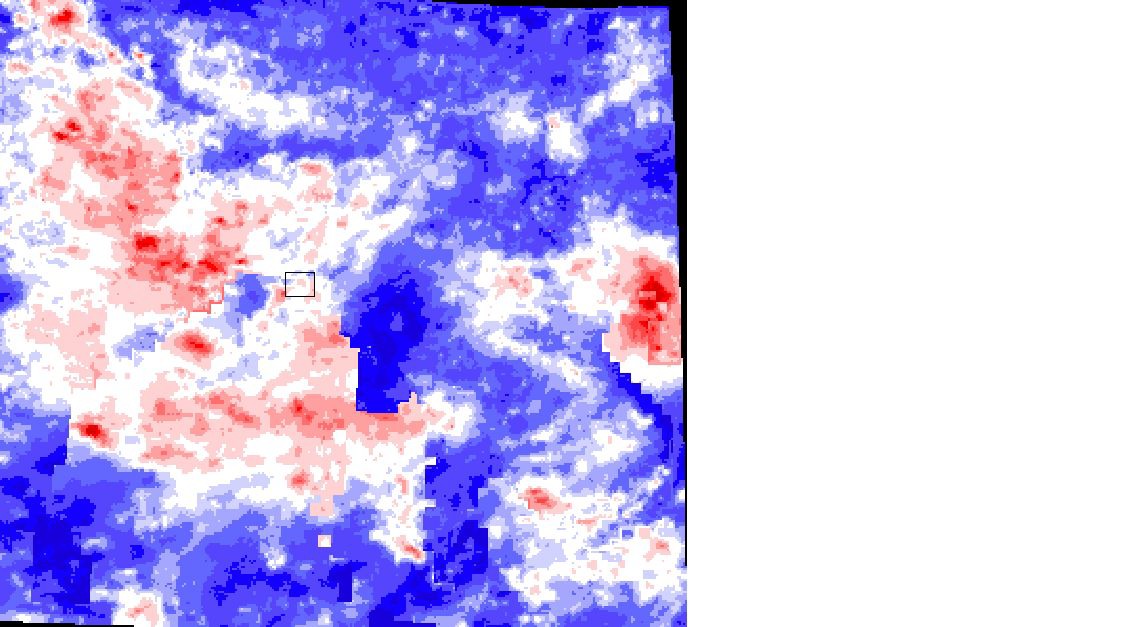

Figure 5.5 Regional soil moisture conditions during early August 2008. ......................43

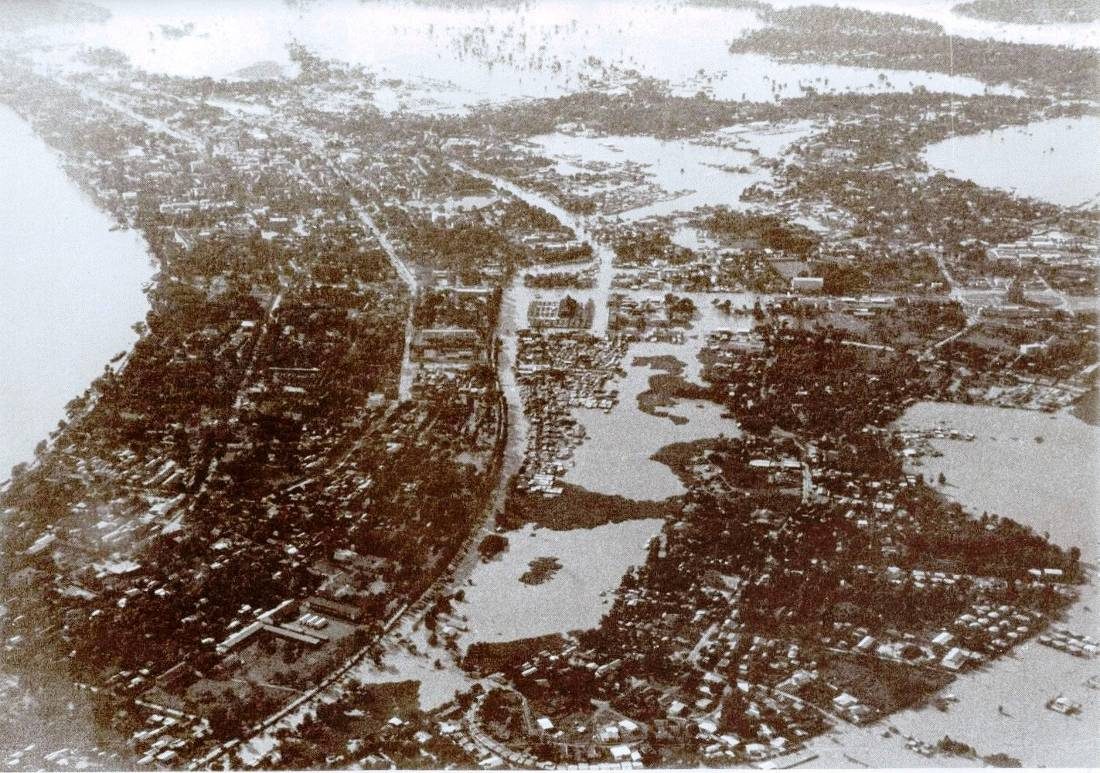

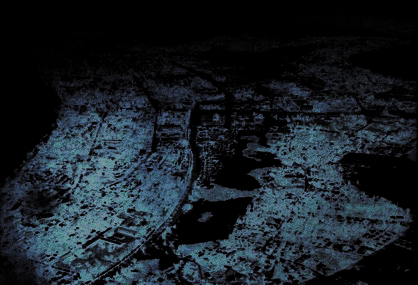

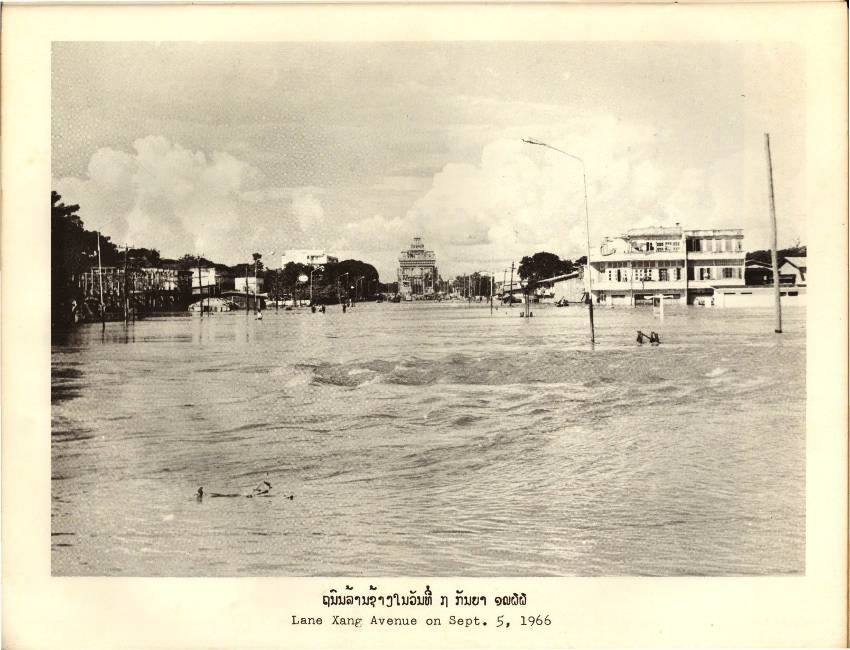

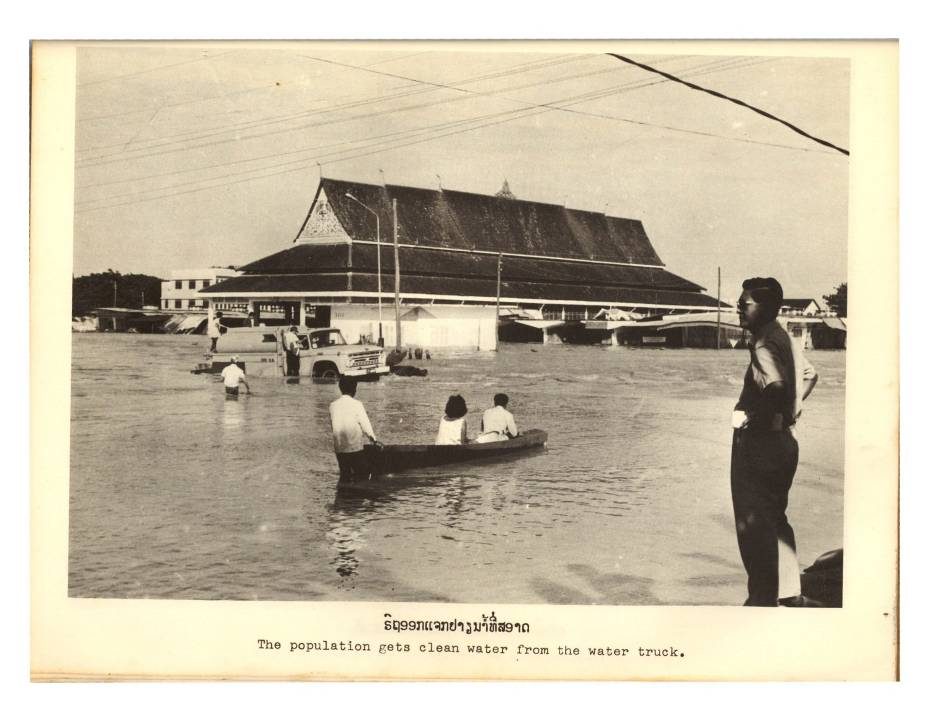

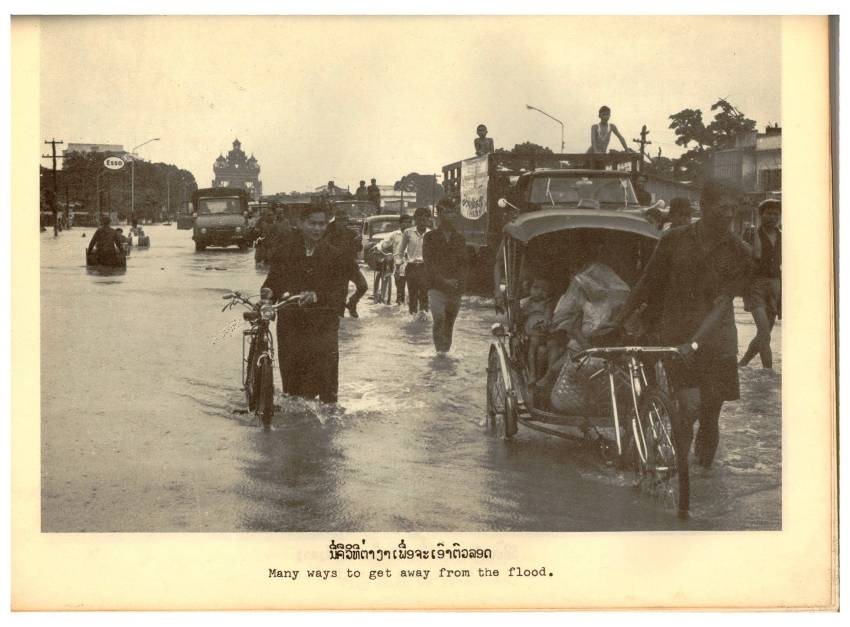

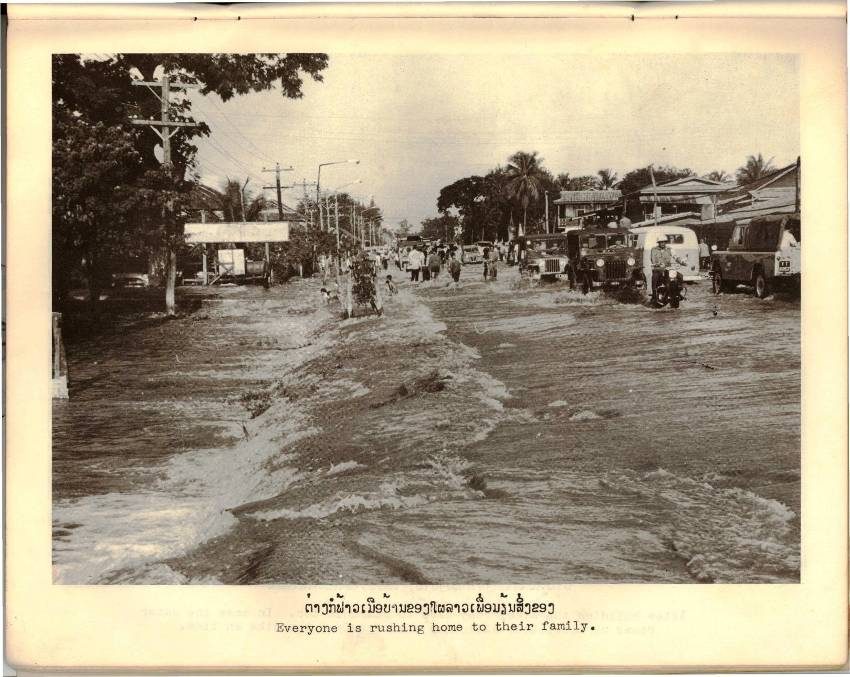

Figure 5.6 The extent of flooding across Vientiane on the 1st September 1966. ...........45

Figure 5.7 August 2008 water levels on the Mekong mainstream between Chiang

Saen and Nakhon Phanom compared to flood alarm levels. .........................45

Figure 5.8 Mekong at Chiang Saen, Luang Prabang and Vientiane comparative

1966 and 2008 daily discharge hydrographs. ................................................46

Figure 5.9 The 2008 daily discharge hydrograph at selected sites on the Mekong

mainstream, compared to the long term average. ..........................................47

Figure 5.10 Scatter plots of the joint distribution of the annual maximum flood

discharge (cumecs) and the volume of the annual flood hydrograph (km3)

at selected sites on the Mekong mainstream. ...............................................48

vi

Figure 5.11 Bivariate probabilities of the joint distribution of flood peak and volume

at selected mainstream sites.. ........................................................................50

Figure 5.12 Mean daily water levels in Cambodia and the Mekong Delta for 2008

compared to their long term daily average. ...................................................51

Figure 6.1 Cambodian flood situation in 2000, the most extreme conditions of

recent decades. .............................................................................................54

Figure 6.2 Lao PDR provinces affected by flooding and local storms during 2008. ....56

Figure 6.3 Central and southern Lao PDR annual maximum 1, 2, 3, 5, and 10 day

rainfalls observed at 29 sites with a combined total of 680 station-years

of data. ...........................................................................................................57

Figure 6.4 Flooding in the Vang Vieng district of Vientiane province after the storms

of mid July, with maximum observed rainfalls of more than 300 mm

over two days. ...............................................................................................57

Figure 6.5 Flooding in Luang Prabang Province as a consequence of the passage of

tropical storm Kammuri in early August. ......................................................58

Figure 6.6 Flooding in Nakhon Phanom Province in mid August. .................................60

Figure 6.7 Khon Kaen: The sample distribution of September rainfall over the

55 years from 1950 to 2004 compared to the reported 2008 monthly

figure of 1,990 mm. .......................................................................................61

Figure 6.8 Flooding in Khon Kaen Province as a result of unprecedented September

rainfall. ..........................................................................................................62

Figure 6.9 Emergency medical provision Lop Buri Province. September 2008. .........63

Figure 6.10 A component of the flash flood and landslide monitoring network. .............63

Figure 6.11 Typical flash flood conditions in the Central Highlands, indicating high

flow velocities and considerable erosive power ............................................65

Figure 6.12 Structural flood mitigation measures implemented in the delta schools

and houses raised on piles. ............................................................................66

vii

List of tables

Table 2.1 Cambodia comparative seasonal rice yields. ...........................................................5

Table 2.2 Summary value of regional agricultural output which benefits directly from the

annual Mekong flood. ..............................................................................................11

Table 2.3 Estimated value of fish production in the Lower Mekong Basin. ...........................12

Table 2.4 Estimated value of other aquatic animals in the Lower Mekong Basin. .................12

Table 2.5 Functions and services provided by natural wetlands. ............................................15

Table 2.6 Summary of the annual value of wetland economic benefits from the

That Luang marsh, Vientiane municipality. ............................................................17

Table 2.7 Estimated wetland and floodplain areas in the Lower Mekong Basin (LMB)

contiguous with the Mekong drainage system. .......................................................19

Table 2.8 Estimated minimum and maximum value of the services provided by the flood

plain/wetland area in the Lower Mekong Basin. .....................................................19

Table 3.1 Average annual flood damage occurring within the Mekong region as a

proportion of national GDP. ....................................................................................30

Table 4.1 Relative costs and benefits of the annual Mekong flood .........................................36

Table 5.1 The onset and end of the SW Monsoon at selected sites in the Lower Mekong

Basin. .......................................................................................................................39

Table 5.2 Start and end dates of the 2008 flood season compared to their historical mean

and standard deviation at selected mainstream locations. .......................................43

Table 5.3 Comparative annual maximum historical flood water levels at Chiang Saen,

Luang Prabang, and Vientiane. ...............................................................................44

Table 5.4 Annual maximum discharge (cumecs) at sites on the Mekong mainstream

primarily affected by the 2008 flood. ......................................................................49

Table 5.5 Estimated annual recurrence interval of the 2008 maximum flood discharge. .......49

Table 5.6 Cambodian floodplain and Mekong Delta onset and end dates of the 2008

flood season compared to their historical mean and standard deviation. ................52

viii

Table 5.7 Maximum water levels reached during 2008 in Cambodia and the Mekong

Delta compared to their long term average. ............................................................52

Table 6.1 Cambodia total national flood damage in recent years (NDCM data). .................53

Table 6.2 Daily rainfalls observed at Paksane over the 10 days between 11th and 20th

June, 2008. ...............................................................................................................56

Table 6.3 Storm rainfall observed in the upper Se San Basin between the 2nd and 8th of

August, 2008. ..........................................................................................................64

Table 6.4 Rainfall observed in the upper Sre Pok: 14 6th November. ..................................65

ix

x

Acknowledgements

This report was prepared by the Regional Flood Management and Mitigation Centre (RFMMC)

of the Mekong River Commission (MRC).

The authors wish to thank the National Flood Experts, National Data Collection Experts and

National FMMP Coordinators at the National Mekong Committee Secretariats of Cambodia,

Lao PDR, Thailand, and Viet Nam for their support and contribution that led to the successful

completion of this report. Particular acknowledgements also go to the staff of the RFMMC for

their coordination of national inputs, overall assistance and guidance provided to the authors.

xi

xii

Summary

Conventionally, floods and flooding are perceived as geophysical hazards within a common

framework of natural disasters that also covers storms and hurricanes, earthquakes, volcanic

eruptions, landslides and tsunami. In each case, socioeconomic losses and damage increase

exponentially with event magnitude and as a function of civil exposure and vulnerability. Such

hazards are perceived as random events that have entirely negative impacts, ignoring the fact

that floods also have a positive ecological and socioeconomic function. Great civilizations

have developed within flood plains where, on the face of it, exposure and vulnerability have

been high. Such societies have included Sumerian Mesopotamia along the Lower Tigris and

Euphrates Rivers, ancient Egypt along the Nile, the Harappan culture of the Indus valley in

Pakisan and India, the founding cultures of China in the Yellow River Valley and the Angkor

civilization of the Lower Mekong Basin itself. Exploiting the benefits and avoiding the

risks brought by the annual flood stimulated such societies to put greater efforts into social

organization and water management systems, which endorsed them as landmark civilizations.

The use of the term `flood' in large tropical rivers and others such as the Nile refers to

a highly predictable seasonal hydrological response to rainfall. The regime comprises two

basic seasons, the `flood' season and the `low flow' season. Issues of scale mean that `flood'

conditions, when flows are considerably above the average for the year as a whole, last for

several months. On much smaller rivers a `flood' lasts only for several days, a duration that is

more consistent with definitions of a `flood' as a short duration geophysical hazard. The annual

Mekong flood, in response to the SW Monsoon, does in some years reach peak discharges

which cause considerable losses and damage. In other years the `flood' is benign and benefits

accrue. Here the term `flood' is used to refer to the several months of increased discharge

conditions, which may or may not in any given year result in large scale economic loss. The

annual Mekong flood has been pivotal to the cultural and socioeconomic evolution of the region

and despite the fact that some loss and damage occurs in most years, those that are significant

at the regional and national scales have a frequency that is low enough to ensure that over time

flood benefits exceed the flood costs by a very considerable margin.

Flood damage arises from a combination of direct losses due to the fact of inundation and

secondary losses as a result of the suspension of normal economic activities in the commercial

and service sectors which can accumulate long after the end of the event itself and until such

time as damage is repaired and stocks and inventory replaced. Assessing these figures in dollar

terms reasonably accurately requires detailed surveys of pilot areas the results of which are

then applied to the flood affected region on a loss per unit area basis. This is the methodology

adopted in each country in the basin and from data available from the relevant National Disaster

Management Agencies the losses that are estimated to arise in an average year amount to a

regional total of US$ 76 million. The most destructive regional flood conditions of recent

decades occurred in 2000 in the south of the basin and in 2008 in the northern parts. By far the

xiii

Annual Mekong flood report 2008

larger overall damages occurred in 2000 and amounted to US$811 million, those of 2008 being

much less at US$135 million.

The major economic flood benefits arise in the agricultural and fisheries sectors, though

by maintaining wetlands the annual flood also ensures that the products and services that such

areas provide are maintained from year to year, though these are difficult to value in financial

terms. On the basis of the value of production the main agricultural region in the basin is the

delta in Viet Nam which contributes 30% of national GDP and is the major source of export

rice, Viet Nam being the second largest contributor to the international rice trade.

In Cambodia flood inundated areas of the Delta are also amongst the most fertile regions

for agricultural production, with extensive double cropping. Rice occupies 90% of the total

cultivated land of which 32% lies in flood prone areas. Because of the fact that only 7% of the

land is irrigated it is only in these naturally flooded areas that a second crop is possible on any

large scale using receding water around lakes and rivers. In Lao PDR and Thailand the link

between agriculture, rice cultivation in particular, and the benefits of the annual flood on the

Mekong is less evident since most crops are rain fed or irrigated.

The link between the regional fisheries production and the annual flood is now well

established. Current estimates regarding the annual value of the regional aquatic resources

exceed US$2.8 billion, though not all of this figure is directly attributable to flood induced

processes.

Other flood benefits accrue but they are much more difficult to value in financial terms. This

applies in particular to wetlands which provide `goods', such as fish and aquatic products, and

`services' such as flood attenuation and the retention, recovery and removal of excess nutrients

and pollutants.

The theme of the AFR 2008 is not to set out a detailed economic analysis of the benefits

and costs of the annual Mekong flood but to compare the two in financial terms based upon the

generally available macro-data. These data, such as those with respect to the annual value of

the Mekong fishery, are widely accepted not least by the MRC's Fisheries Programme itself. In

addition, the annual value figure for the fishery of US$2.85 billion refers only to that at the first

point of sale. In comparison, the estimated average annual costs of flood damage only amount

to US$76 million or just 2.5% of the fisheries benefit alone.

The additional figures for the agricultural benefits are harder to assess since the linkage

between the annual flood is not as clear as it is with the fishery. Flood recession rice production

in Cambodia is reported to account for 32% of national production, valued at US$3.1 billion

in 2006 (based a February 2009 international price of US$500/tonnes). The value of the

agricultural benefit accruing directly from the flood in Cambodia is therefore US$3.1 billion x

0.32 = US$1 billion.

In the Mekong Delta in Viet Nam agricultural production in 2004 had a reported market

value of US$3.5 billion. That this is a benefit of the flood is based on the argument that the

Page xiv

Summary

9 to 13 millions tonnes of sediment deposited annually across the delta, most of it during the

flood season, has over millennia resulted in some of the most productive agricultural land in

Southeast Asia, thus establishing the link.

Separating the proportion of the total benefits in any of the sectors that accrue directly from

the annual flood is simply not possible, but even if they are half of the figures quoted here

with regard the value of the annual Mekong fishery alone, the `benefits' still far outweigh the

`costs'. The major conclusion to be drawn is that in large tropical monsoonal rivers the annual

flood cannot be perceived exclusively in terms of being a geophysical hazard. The comparative

benefit and cost figures presented here should not be seen in any way as a direct economic

comparison but interpreted as broadly indicative measures of the potential socioeconomic value

of flood induced processes.

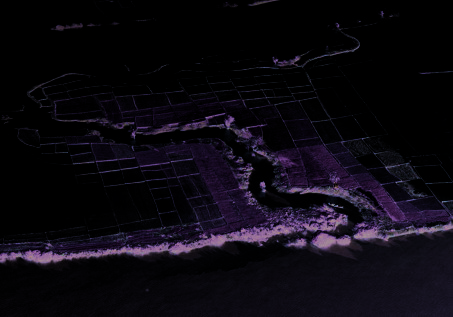

The 2008 flood season across the Lower Mekong Basin illustrated a common feature of the

regional flood hydrology, that is extreme flooding in one part of the basin and average to below

average conditions elsewhere. In 2008 it was the northern parts between the Chinese border and

Vientiane that witnessed flood levels not seen for almost 50 years, while further downstream in

Cambodia and Viet Nam discharges and water levels were average at best.

Volumes of flood runoff, discharges and water levels in the northern part of the region up

until mid July had been average but an intensification of the SW Monsoon saw repeated tropical

storms and higher flood runoff. The storm situation then intensified dramatically during the first

week of August with the passage of tropical storm Kammuri across the northern provinces of

Lao PDR. Only satellite indications of the associated 3 to 5 day rainfalls are available (the rain

gauge network here being very sparse) but cumulative rainfalls considerably in excess of 500

mm are indicted. Volumes of flood runoff in the large northern Lao tributaries such as the Nam

Ou and Nam Khan increased to extreme levels.

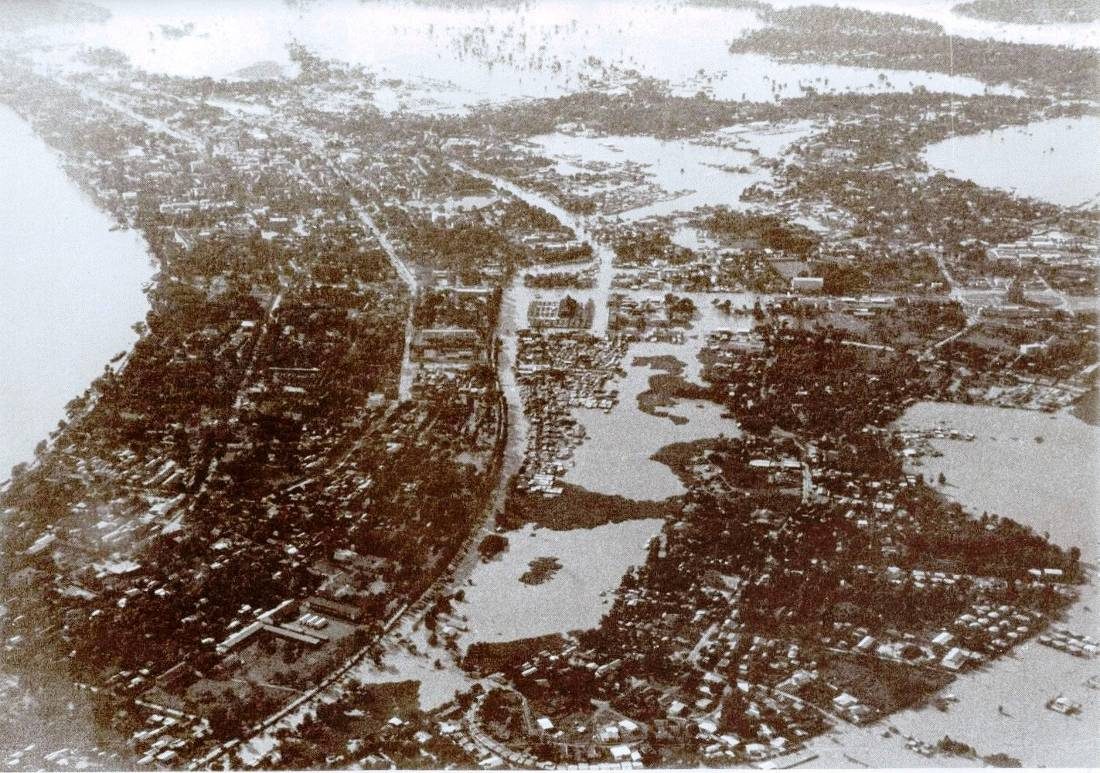

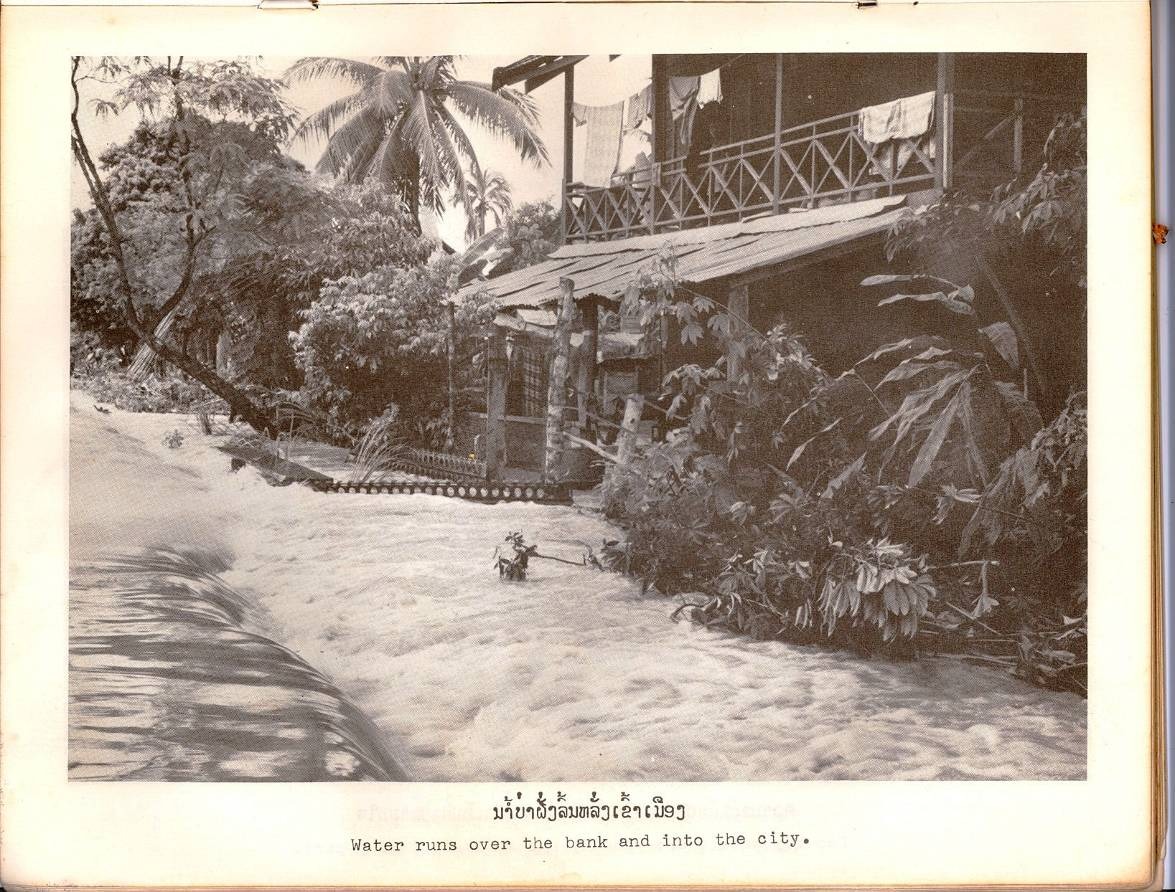

Maximum discharges at Luang Prabang and Vientiane/Nong Khai occurred on the 14th and

15th of the month and were in the region of 23,000 cumecs or 50% above the annual average.

The associated water levels were comparable to those of 1966, when both city centres were

flooded. Some urban flooding again occurred at Luang Prabang since water levels were elevated

due to backwater effects on the Nam Khan upstream of the Mekong confluence. At Vientiane

large scale urban flooding was avoided principally due to the sandbagging of the river bank

adjacent to the central business district, but large areas of suburbs and peri-urban area were

flooded to depths locally exceeding 1.5 m.

These conditions soon dissipated downstream of Vientiane/Nong Khai since flood flows into

the mainstream from the large left-bank tributaries in Lao PDR, starting with the Nam Ngum,

were quite average. This becomes quite clear from the flows at Pakse and Kratie which come

close to those for an average flood season overall, while water levels in the Delta at Tan Chau

and Chau Doc were below average throughout most of the season.

Apart from these events on the mainstream local, and often seriously damaging, flash floods

occurred as they do in most years. In Lao PDR such conditions occurred in Bolikhamxay

Page xv

Annual Mekong flood report 2008

province during June with over 800 mm in 10 days and as much a 200 mm in 1 day. In the Thai

Mekong region during September in the Khon Kaen area heavy rainfall of almost 160 mm. on

the 17th caused of flood inundation and damage to property and crops and the deaths of two

people. In Cambodia no significant flood damage was reported for the year while in Viet Nam

the only events to cause any significant damage occurred in the Upper Sre Prok during May

and in the upper Se San Basin during the first week of August. The former saw two lives lost

and the latter resulted in some bridges being damaged and about 100 ha of rice paddy lost or

seriously damaged. Overall damage from flash floods for the year in Viet Nam amounted to

US$1 million. Regionally, however, the number and severity of flash flood episodes was well

below average.

The events of August 2008 provided the first real opportunity to assess the performance of

the RFMMC's flood forecasting models and expertise and in general they performed reasonably

well, though obviously room for improvement is recognised. The major constraint to accuracy

over lead times in excess of two to three days is the emerging conclusion that the storm rainfalls

indicated by satellite images are probably too low and that the network available for `ground

truthing' needs to be improved in key areas of Lao PDR in particular.

Otherwise the lessons and recommendations put forward in the four country reports

generally repeat those of earlier years and focus up such issues as strengthening community

based flood risk management and self reliance and building capacity within local communities

with regard to flood preparedness and emergency response. A need is also recognized to

improve the channels of communication between the local communities and the relevant flood

forecasting, mitigation and response agencies. In Viet Nam once again attention is drawn to

diverting more financial support for dealing with flash floods in the Central Highlands. Finally,

a call is once more made to consider translating the Annual Flood Report into each of the four

riparian languages.

Page xvi

1. Introduction

Consistent with the format established in the Annual Flood Reports for 2006 and 2007, this

2008 document comprises the following major sections:

Chapters 2, 3, and 4 present the annual theme, which this year considers the benefits and

costs of the annual Mekong flood. The aim is not in any way to provide an in depth economic

assessment but rather to establish the fact that the regional benefits that accrue from the flood

far exceed the losses and damage, which in the past have been the almost exclusive focus of

attention.

Chapter 5 reviews the hydrological aspects of the flood season, which in 2008 witnessed

extreme discharges and water levels in the northern areas of the Lower Mekong Basin between

Vientiane/Nong Khai and the Chinese border.

Chapter 6 gives a brief summary of each of the four annual country reports, for Cambodia, Lao

PDR, Thailand, and Viet Nam.

Chapter 7 details the major lessons learnt over the year, and provides recommendations for

improving the RFMMC's flood forecasting system.

Page 1

Annual Mekong flood report 2008

Page 2

2. Flood benefits

2.1 Introduction and historical context

Conventionally, floods and flooding are perceived as geophysical hazards within a common

framework of natural disasters that also covers storms and hurricanes, earthquakes, volcanic

eruptions, landslides and tsunami. In each case, socio-economic losses and damage increase

exponentially with event magnitude and as a function of civil exposure and vulnerability. Such

hazards are perceived as random events that have entirely negative impacts, ignoring the fact

that floods also have a positive ecological and socio-economic function. Great civilizations

have developed within flood plains where, on the face of it, exposure and vulnerability have

been high. Such societies have included Sumerian Mesopotamia along the Lower Tigris and

Euphrates Rivers, ancient Egypt along the Nile, the Harappan culture of the Indus valley in

Pakisan and India, the founding cultures of China in the Yellow River Valley and the Angkor

civilization of the Lower Mekong Basin itself. Exploiting the benefits and avoiding the

risks brought by the annual flood stimulated such societies to put greater efforts into social

organization and water management systems, which endorsed them as landmark civilizations.

Historically cultures that exploited the benefits of floodplains and contemporary societies

which continue to do so, such as those in the Lower Mekong, have to face a two-tailed flood

hazard (Webby et al., 2007). Either the annual flood is too small, leading to reduced agricultural

output or too large, resulting in inundation, crop losses and general socio-economic damage.

The dis-benefits arising from the `failure' of the flood season must not therefore be ignored or

even made light of. As will be seen, historically some of these deficiencies in the flood season

hydrology of the Mekong have been quite spectacular.

The Mekong Delta and Cambodian floodplain are the site of one of the earliest civilizations

in mainland Southeast Asia. Called Funan by visiting Chinese dignitaries, by the 3rd Century AD

it was centred around two major urban centres, namely Oc Eo in Viet Nam and Angkor Borei

in Cambodia (Jacques, 1979). It has been argued that dry season flood recession rice cultivation

formed the agricultural basis of Angkor Borei and may have dictated the location of the city

itself (Fox and Wood, 1999). The link between the rich agricultural possibilities provided by the

annual Mekong flood and the genesis of such pre-Angkor civilizations is clear from

(Figure 2.1) which compares the location of 2nd and 3rd Century archaeological sites with the

flood recession rice growing areas (see Fox and Wood, 1999). It is entirely likely that this

farming system became the future basis for later Lower Mekong civilizations such as that of

Angkor itself which has its classic period between 800 and 1300 AD. Angkor eventually evolved

into a true `hydraulic civilization' organised around the need to manage water through a vast

system of irrigation canals.

Page 3

Annual Mekong flood report 2008

The ability to maintain soil fertility over time has been a major challenge to Asian

civilizations. The Chinese, for example, developed a sustainable agricultural system based on

meticulous schemes for recycling organic waste; agriculture in Japan, Java and the Philippines

was based on rich volcanic ash soils (Ng, 1979). In Cambodia most soils are not naturally fertile

(Delvert, 1961) but farmers recognised over 1800 years ago that, being located within a flood

plain and deltaic system that allowed rising floodwater to spread out across the landscape and

deposit millions of tonnes of fertile sediment annually, they could develop a highly productive

and sustainable system of agriculture. The enhanced crop yields achievable from flood

recession agriculture are clear from the figures in (Table 2.1).

Lao PDR

Thailand

Siem Reap

Kampong Thom

Kratie

Kampong Chhnang

Kampong Cham

Phnom Penh

Viet Nam

Gulf of Thailand

Prey Veng

Angkor Borei

Dry season rice

Takeo

0

100 Kilometres

South China Sea

Figure 2.1 The distribution of flood recession rice cultivation areas and pre-Khmer archaeological

sites in Cambodia. (Source: Fox and Wood, 1999)

Figure 2.2 This bas relief at Angkor Wat is indicative of the importance of fish in the

socioeconomics and culture of the Khmer Empire (800 1300 AD)

Page 4

Flood benefits

Table 2.1 Cambodia comparative seasonal rice yields.

Land use system

Yield

(tonnes per hectare)

Rain-fed paddy rice wet season

1.6

Flood recession rice cultivation dry season

3.0

These benign effects of the annual Mekong flood with their attendant benefits extend to the

regional fishery which is an imperative component of the basin's economy. The first records

of the importance of fish and fishing is provided by the Bas Reliefs in the temples of Angkor,

dating from the 11th Century (Fox and Wood, 1999). Fish are represented in daily activities in

markets and also appear in agricultural scenes pointing perhaps to early aquaculture. Accounts

provided by Chinese travellers over 700 years ago indicate that fishing practises and the

economic importance of the Mekong fishery have changed little. The next accounts of capture

fisheries come from French and English travellers in Indo China and Thailand during the

late 1800s. They identified the important areas as the Great Lake in Cambodia, the Mekong

mainstream to Khone Falls, and the surrounds of Vientiane and Luang Prabang.

Over this period, the Mekong fishery developed to take advantage of annual fish migrations

at the beginning and end of the flood season. The annual mono-modal flood pulse of large

tropical rivers such as the Amazon, Congo and Mekong is the dominant `trigger' in the annual

cycle of ecological processes within the fluvial system, bringing about a distinct seasonality in

the annual hydro-biological cycle between an aquatic phase and a terrestrial phase (Junk et al.

1989). As a consequence there are highly seasonal bio-geochemical cycles, growth rhythms and

life cycles amongst the many species of ecosystem system biota such as algae, macrophytes,

trees, fish and invertebrates (Junk, 1997; Junk et al., 2000; Junk and Wantzen, 2004) and these

have been exploited much to the benefit of the riparian societies.

This pivotal role that the annual Mekong flood has played in the evolution of the cultures

and economy of the basin therefore negates the concept of a flood exclusively as a (usually)

disastrous overflowing of water onto previously dry areas. In a hydrological, ecological,

economic and social environment such as that which prevails in the Lower Mekong Basin the

annual flood only becomes a hazard if certain hydrological benchmarks are exceeded. Although

important, it would be incorrect to define these thresholds simply in terms of water level or the

associated discharge since these variables only describe one aspect of what is a multivariate

random process. The annual flood in the Mekong arises from the complex interaction between

meteorological conditions and the basin response which generates a seasonal hydrograph which

needs to be defined in much wider terms.

The weight of the evidence, both historical and contemporary, suggests that the benefits of

the annual Mekong flood far outweigh the costs in most years. The balance between the two

is not static, however. When critical hydrological thresholds are exceeded the value at risk

is increasing annually since there is rapidly accelerating development within the flood plain,

its population is increasing and the crops, property and inventory at risk are becoming more

valuable. Such circumstances are in common with those world wide where there appears to

Page 5

Annual Mekong flood report 2008

be a systematic growth in the exposure and vulnerability of society to flooding, particularly in

developing countries, such that annual costs and losses are growing even though there is little

evidence (so far) to suggest that the incidence and severity of the events themselves is on the

increase.

The economic dimension as to whether there is an overall regional cost or benefit accruing

to the annual flood in any given year is complex and fuzzy. The very size of the Lower Mekong

Basin is such that the synoptic events which cause extreme runoff have an area of impact that

can only cover a part of the region, such are the consequences of scale. While the strength of the

SW Monsoon defines the overall character of the flood season it is typhoons and tropical storms

that typically generate the extremes and most damaging events. Historically, there have been

no flood seasons during which the whole basin has been affected by critical conditions. Hence

there can be considerable geographical variation across the region in the annual flood situation,

a fact emphasised during the events of 2008 (details in Chapter 6).

The picture that clearly emerges is that the annual flood has been pivotal to the cultural and

socioeconomic evolution of the Mekong region and that despite the fact that some loss and

damage occurs in most years, those that are significant at the regional and national scales have

a frequency that is low enough to ensure that over time flood benefits exceed the flood costs by

a considerable margin. Arguably therefore, the logical approach is to set out the benefits first

and then consider the losses, which helps to moderate the perspective of floods as an entirely

negative process. This is not to underplay the importance of the need to develop strategies to

manage and mitigate flood losses and damage. In some years they can be catastrophic to the

extent of causing a significant fall in GDP.

2.2 Flood benefits -- agriculture

A key feature of the annual Mekong flood is that in terms of its timing it is highly predictable,

particularly in terms of its onset in early July. This feature it shares with the Nile flood, for

example, which enabled Egyptian society to develop a planned and highly seasonal form of

agriculture with a relatively high level of crop security leading to food surplus in most years.

This said, however, the periodic failure of the annual flood over consecutive years led to

famines of which several are chronicled in the annals of Ancient Egypt. There is little doubt

that droughts would also have occurred and caused food shortages at the time of the ancient

Mekong civilizations, but such events are unrecorded. In Cambodia these societies were largely

rural, supporting ceremonial centres with rice and labour. It has been argued that the later states

and kingdoms that evolved there and in Thailand and Lao PDR took the form of social systems

based on cooperative villages which had a common form of agricultural production based on

monsoon rainfall and to some degree on various forms of flood irrigation. They are referred to

as `agro-cultural complexes'.

This type of rural balance between a subsistence form of agriculture and the provision of

food to political and religious centres largely prevailed in the Mekong region until the colonial

Page 6

Flood benefits

era and the beginning of large scale commercial resource development. French statistics (Van

Liere, 1980) suggest rapid agricultural growth and environmental change during this period.

From 1880 to 1930, the total volume of earth dredged in the Mekong Delta totalled 165 million

cubic metres which compares with 210 million for the Panama Canal and 260 million for the

Suez. These new canals drained large areas and complemented the demands from an increasing

population of ethnic Vietnamese farmers migrating from the north. Cultivated land area rose

from 200,000 hectares in 1879 to 2.4 million in 1929. This represented an increase from

roughly 5% to 60% of the total surface area in the Vietnamese portion of the Mekong Delta.

The aim was, through public works, to drain the delta's swamps, marshes and forests to

exploit the fertile alluvial soils that were the legacy of thousands of years of the flood regime of

the Mekong and transform the landscape into one dominated by highly productive rice paddies.

This impressive rate of growth meant that by the 1930s the delta has already become one of the

world's major rice exporting regions. It was still, however, largely uncontrolled in hydraulic

terms, particularly with regard to flooding and salinity intrusion, which were seen as major

obstacles to the development of intensive farming and multi-cropping systems (Kakonen, 2008).

It was not until the 1980s that the necessary intake and outflow structures were constructed

on a large scale to regulate flows to and from the fields and not until the 1990s that hydraulic

infrastructure was completed that reduced dependence on natural hydrological conditions and

which enabled the control of floods, salinity and the cropping limitations imposed in some areas

by acid sulphate soils. Consequently, by 1997 Viet Nam had become the world's second largest

rice exporter, shipping some 3.5 million tonnes to the global market. A statistical summary

of the contribution that the agricultural outputs of the delta currently make to the Vietnamese

economy (General Statistics Office, 2004) is set out below. It produces:

· About half of the national food output;

· 51% of the total rice paddy production;

· 55% of the national inland fisheries and fruit output;

· 60% of the country's exported aquaculture products;

· 61% of the total national export value.

Of course it would be quite wrong to suggest that these contributions to the national

economy are entirely the result of the Mekong flood regime -- they are the outcome of

converting the natural floodplain into a highly controlled and intensive agricultural landscape.

But the nature of the landscape that provided the opportunity to do so is the result of the

hydrology of the river and the benefits that have accrued from the annual flood over thousands

of years.

Page 7

Annual Mekong flood report 2008

3.5

3.0

alue (US$billion) 2.5

al v

Economic impact of the

2000, 2001, and 2002 floods

A

g

r

icultur

2.0

1.5

1994

1996

1998

2000

2002

2004

2006

Year

Figure 2.3 The value of agricultural production in the Mekong Delta (1995 2004) in Viet Nam.

The chart shows significant annual growth over period, but also that this growth can be

disrupted during years of extreme flood conditions.

Figure 2.3 shows the significant rates of annual growth in agricultural production in the

Mekong Delta to 2004, when its total value reached US$3.3 billion. The figures also illustrate,

however, that this systematic increase in monetary value can be interrupted in years when flood

discharges and water levels exceed critical thresholds, as they did between 2000 and 2002.

These figures refer only to that part of the delta in Viet Nam, though it is generally

regarded as beginning at Phnom Penh in Cambodia, where the Mekong divides into its two

main distributaries, the Bassac and the Mekong (Tien). It comprises a vast triangular plain of

approximately 5.5 million ha of which 1.6 million are in Cambodia and mostly lies below 5 masl.

The 9 to 13 millions tonnes of sediment deposited annually, most of it during the flood season, has

resulted in some of the most productive agricultural land in Southeast Asia.

Unsurprisingly therefore the flood inundated areas of the delta are amongst the most fertile

regions for agricultural production in Cambodia, with extensive double cropping. Rice occupies

90% of the total cultivated land of which 32% lies in flood prone areas. Because of the fact that

only 7% of the land is irrigated it is only in these naturally flooded areas that a second crop

is possible on any large scale using receding water around lakes and rivers. Interestingly this

second dry season flood recession crop usually gives higher yields than the wet season crop due

to more controllable water management, the lower risk of crop losses due to excessive water

depth and the benefits obtained from the deposition of fertile sediment during the flood itself.

Cambodia harvested more than 6,264,000 million tonnes of rice in 2006. Taking current

2008 price of US$ 500/million tonnes and the fact that of the 2006 figure 32% was harvested

from the floodplain areas then the flood benefit value is US$1 billion.

Page 8

Flood benefits

In Lao PDR 80% of the cropped area is planted to rice, of which 75% is rain fed lowland

paddy in areas of low flood risk. The balance is made up of rain-fed upland rice which has quite

low yields. Only about 10% of the planted area is irrigated contributing about 14% to national

production. Although overall, rice production accounts for 20 to 25% of GDP there isn't the

strong linkage between the annual flood in the Mekong Basin and agricultural production

that there is in Cambodia and the Delta in Viet Nam. FAO figures indicate that in 2005 rice

production in Lao PDR totalled 2,600,000 tonnes, of which only 5% is marketed commercially.

The planted area was 736,000 ha giving a yield of 3.5 tonnes/ha.

Figure 2.4 Flood recession rice cultivation on the Cambodian floodplain.

There are local areas of rice paddy close to the Mekong mainstream and in the lower reaches

of the large tributaries in Lao PDR that are inundated during most years and which are exploited

for agricultural production, including the growing of vegetables and maize as well as rice. Most

of the islands in the mainstream are used in this way. Although in total the area is probably

substantial and the economic benefit significant, this sector of the agricultural economy is not

identified separately in the compilation of agricultural statistics since it is generally informal,

with outputs traded locally, if at all. The wider commercial benefits of agriculture in Lao PDR

may therefore be considered to be independent of the Mekong flood.

In the Thai Mekong region traditional forms of agriculture that exploit seasonal floodplain

and wetland inundation are now increasingly scarce, as more intensive forms oriented towards

external markets have taken over from subsistence and small scale farming. According to Fukui

and Hoshikawa (2003) the shift towards large-scale rain-fed production in Isaan only began

during the 1950s, prior to which a flood dispersion system known as Tham Nop, was generally

used, an example of which is illustrated in Figure 2.5. Earthen bunds were constructed across

small tributaries to divert early season floodwater onto pre-prepared paddy fields typically

covering a 300 500 ha area on the flood plain and low lying riparian lands. According to the

Page 9

Annual Mekong flood report 2008

first village economic survey in Thailand in 1930 31 (Zimmerman,1931), the average yield

of rice in the northeast of the country, based on this limited system, was most probably higher

than in the central region, which had become Thailand's rice-bowl for export production (Fukui

and Hoshikawa, 2003). The report goes on to describe the very low density of population in

the northeast and its concentration along rivers where the local economy centred around the

exploitation of aquatic resources.

Figure 2.5 An example of the `Tham Nop' flood diversion system from North East Thailand.

(Fukui and Hoshikawa, 2003). A bund is constructed across the river and early season

flood water diverted onto riparian rice paddy. Water levels are controlled by simple

timber gates. Typically these tradition water control schemes provided flood irrigation to

200 to 500 ha.

Post 1950 rural development policies in the Thai Mekong region, particularly in the

Mun Chi basin, focused on agriculture and the provision of reservoir storage for direct gravity

fed and pumped irrigation from regulated rivers. The population grew five fold in 50 years from

5 to 25 million, of which 70% remains rural and involved to some degree in agriculture. Rain

fed rice production dominates the rural landscape, covering 75% of the agricultural land. In

2006 total rice production in the Thai provinces that lie within the Mekong Basin totalled 10.5

million metric tonnes (FAO Figures), with a current (February 2009) value of US$5.25 billion.

With less than 1% of the regional land classified as flood plain the role of the annual flood

in generating this agricultural benefit in the Thai Mekong region is minimal. Small scale

rice growing systems using flood recession trap ponds do still exist along with instances of

traditional mixed crop farming using flood recession terraces on riverbanks, for example in the

Nam Songkhram river basin. Such activities are, however, usually uncommercial and generate

benefits only at the household or village level.

Summarizing the annual agricultural flood benefit gives a total regional figure of US$4.5

billion, which is generated in Cambodia and Viet Nam alone. In relative terms the outputs of

floodplain agriculture in Lao PDR and Thailand are considered to be insignificant compared

to rain fed and irrigated production (Table 2.2). The overall figure is probably conservative

Page 10

Flood benefits

since, although it is based on a rice price of US$/500 a tonne, which represents a significant

recent increase, the value of other crops has not been included. To do so would be complex

since production and market value figures are not generally available in a form that permits a

breakdown in a way suitable for the present purposes. It is also true to say that fruit, vegetables

and other crops that are grown on a commercial scale are produced in areas not directly at risk

from flood inundation except under the most extreme hydrological conditions. Rice on the other

hand is the archetypical flood plain crop and production clearly benefits from the annual flood

in most years.

Table 2.2 Summary value of regional agricultural output which benefits directly from the annual

Mekong flood.

Country

Estimated annual agricultural value Comments

accruing from the annual Mekong

flood (US$ billion)

Cambodia

1.0

2006 figures. Based on rice occupying 90% of

agricultural area of which 32% lies in flood prone areas.

Only local flood recession agriculture most

Lao PDR

Not significant

production combines rain fed summer and irrigated

winter crops.

Thailand

Not significant

Viet Nam

3.5

2004 figures for production in the delta, which is itself

a long term product of the annual flood.

Total

4.5

Note: The estimates are based on rice production valued at US$500 per tonne (February, 2009 prices).

2.3 Flood benefits -- the Mekong fishery

The annual mono-modal flood-pulse of large tropical rivers such as the Amazon, Congo and

Mekong is the dominant `trigger' in the annual cycle of ecological processes within the fluvial

system, bringing about a distinct seasonality in the annual hydro-biological cycle between an

aquatic phase and a terrestrial phase (Junk et al., 1989). As a consequence there are highly

seasonal biogeochemical cycles, growth rhythms and life cycles amongst the many species

of ecosystem system biota such as algae, macrophytes, trees, fish and invertebrates (Junk,

1997; Junk et al., 2000). The annual inundation of the floodplain, particularly in Cambodia

and specifically around the Tonle Sap and Great Lake, makes available a huge biomass to the

aquatic food web which boosts aquatic productivity and results in a prolific ecosystem.

The major manifestation of this virtually unrivalled level of aquatic productivity is the

Mekong fishery, amongst the largest of its type in the world. Hortle (2007) estimated that

in 2000 the yield of fresh water fish in the basin, minus the aquaculture component, was

approximately 1,860,000 tonnes. Combining this figure with an estimate of the size and first

sale vale of the fish of between US$1.0 and US$1.8/kg, the total value of the fishery is indicated

to be US$2,600 million if a median figure of US$1.4/kg is adopted. Using a proportional

Page 11

Annual Mekong flood report 2008

breakdown of estimated fish yield by country given in (Hortle, 2007), the following national

estimates are obtained:1

Table 2.3 Estimated value of fish production in the Lower Mekong Basin.

Country

Value of national inland fishery

based on 2000 estimates

(US$ million)

Cambodia

608

Lao PDR

212

Thailand

900

Viet Nam

880

Total Lower Mekong Basin

2 600

Note: Base on figures in Hortle (2007).

The figure for Viet Nam reflects the role of aquaculture production, which in effect is

independent of the annual flood pulse. Elsewhere, it is clear that the flood regime plays a

pivotal role, most particularly with regard to migrant fish capture which accounts for 71% of

the total fish yield (Barlow et al., 2008), no more so than in Cambodia. In Thailand the major

basin fishery lies in the Mun/Chi Basin and in tributaries such as the Nam Songkhram while

in Lao PDR it is a significant element in socioeconomics throughout the country, both on the

mainstream and within the tributary systems.

Other aquatic animals (OAAs) such as frogs, crabs and molluscs are also very important in

terms of their contribution to regional diet and livelihoods and their breeding cycle and yield is

closely allied to the seasonal flood cycle. Hortle (2007) provides annual yield estimates which

can be converted to a US$ value by assuming an average sale price, a figure of US$0.50 kg

being a reasonable one according to the MRC Fisheries Programme. As the figures in Table 2.4

indicate their annual regional value could be close to US$250 million.

Table 2.4 Estimated value of other aquatic animals (for example, frogs, crabs and molluscs) in the

Lower Mekong Basin.

Country

Estimated annual yield of other Value based on an average sale price

aquatic resources

of US$0.50 kg

(tonnes)

(US$ million)

Cambodia

105 500

52.75

Lao PDR

40 500

20.25

Thailand

191 000

95.50

Viet Nam

161 000

80.50

Total Lower Mekong Basin

498 000

249.00

Note; Based on figures in Hortle (2007).

1 Though these national yields figures are derived from fish consumption data and therefore ignore cross-border trading they are

nonetheless broadly indicative of production value.

Page 12

Flood benefits

That there is a very strong link between the annual fish catch and the extent and duration of

flooding is intuitively clear. The most researched component of the overall Mekong fishery is

the so called dai, or bagnet, fishery that exploits the annual migration of fish out of the Great

Lake in Cambodia towards the Mekong via the Tonle Sap towards the end of the flood season

(Figure 2.6).

Figure 2.6 The dai, or bagnet fishery, on the Tonle Sap, Cambodia.

Halls et al. (2008) propose a flood index based upon the sum of the number of days that

a given area is flooded during around the Great Lake each flood season, which provides an

indicator in units of km2 days. Figure 2.7 shows the relationship between this statistic and the

annual dai catch in terms of fish biomass.

45000

1200000

40000

1000000

35000

30000

800000

t

o

n

n

e

s

)

25000

d

a

y

s

)

600000

2

a

s

s ( 20000

k

m

F

l (

15000

400000

B

i

o

m

10000

Biomass

200000

5000

Flood Index

0

0

98-99 99-00 00-01 01-02 02-03 03-04 04-05 05-06 06-07 07-08

Season

Figure 2.7 Estimates of fish biomass arriving at the dai fishery and the annual flood index proposed

by Halls et al. (2008).

Page 13

Annual Mekong flood report 2008

The higher fish biomass during years of extensive and longer duration flood inundation, as in

2000, 2001 and 2002, reflects that under such conditions the fish caught are bigger on average

which in turn indicates the longer that they have to breed and feed amongst the rich organic

resources of the flooded areas the larger they grow and the more mature they are once they

begin to migrate.

These huge figures regarding the estimated value of the Mekong aquatic resources,

particularly fish, are regarded as conservative as they do not take account of the economic

benefits that flow from the trade, processing and preservation of fish products. Nor do they

include the very considerable indirect values of the fishery such as its contribution to the

nutrition, employment and well being of millions of rural people who generally have few other

income earning and livelihood options (Barlow et al., 2008).

2.4 Flood benefits the creation and maintenance of natural wetlands

Floodplain and wetland areas which are flooded part of the year or which expand greatly in area

during the flood season can produce much far more aquatic resources than permanent water

bodies of the same size, such as lakes and reservoirs (Figure 2.8). In fact, according to Ringler

and Xai (2006) natural wetlands are amongst the most productive ecosystems in existence and

the benefits from wetland products are often considerably higher per unit area than from other

land uses. The benefits in terms of the regional fishery and other aquatic resources have already

been considered and identified as huge, but wetlands also provide a wide range of additional

ecological goods and natural services as specified in Table 2.5. These include physical benefits

such as natural flood storage and flood attenuation, improved water quality through pollution

control and waste dilution, habitat provision for resident and migratory species and the

maintenance of important biochemical equilibria.

Figure 2.8 Mekong wetlands at Sipandone, Lao PDR.

Page 14

Flood benefits

Table 2.5 Functions and services provided by natural wetlands.

Services

Comments and examples

Provisioning

Food

Production of fish, wild game, fruits, grains.

Fresh water

Storage and retention of water, provision of water for

irrigation and drinking.

Fibre and fuel

Production of timber, fuel wood, peat, fodder, aggregates.

Biochemical products

Extraction of materials from biota.

Genetic materials

Medicine, genes for resistance to plant pathogens,

ornamental species etc.

Regulating

Climate regulation

Regulation of greenhouse gases, temperature, precipitation

and other climatic processes.

Hydrological regime

Groundwater recharge/discharge, water storage.

Pollution control

Retention, recovery and removal of excess nutrients/

pollutants. Waste dilution.

Erosion protection

Retention of soils and prevention of channel erosion

Natural hazards

Flood storage, retention and attenuation

Cultural

Recreational

Opportunities for recreational activities.

Aesthetic

Appreciation of the natural environment.

Educational

Opportunities for formal and informal education and training

Supporting

Biodiversity

Habitats for resident and migratory species.

Soil formation

Sediment retention and accumulation of organic matter.

Nutrient cycling

Storage, recycling, processing and acquisition of nutrients.

Pollination

Support for pollinators.

Note: Based on Mekong Wetlands Conservation and Sustainable Use Programme. (www.mekongwetlands.org)

Wetland goods and services are particularly difficult to value, because:

· Many goods are not marketed but traded or consumed directly:

· Wetland services, such as water quality or groundwater recharge often occur in areas

away from the physical location of the wetland and may not be easily attributable to the

wetland itself;

· Many wetlands are trans-boundary resources and data on the use and consumption of

goods and services are difficult to obtain, and;

· Many wetlands are public property.

Page 15

Annual Mekong flood report 2008

100oE

105oE

Viet Nam

WETLANDS OF THE LOWER MEKONG BASIN

Lao PDR

Thailand

Cambodia

20oN

20oN

Gulf of Tonkin

15oN

15oN

KEY

Bank/beach/bar/esturine

Flooded forest or plantation

Natural or man-made lakes and ponds

10oN

10oN

South China Sea

Marine/costal mangrove or aquaculture

Rice wet/recession and other crops

Rivers and channels

Swamp, backswamp, grassland, marsh

0

100

200

300 kilometres

Other

100oE

105oE

Figure 2.9 Distribution of `wetlands' in the Lower Mekong Basin though here no distinction is

made between natural flood inundated wetlands and rain fed rice paddy. The latter would

account for most of the area specified in the Mun Chi Basin in Thailand.

For these and other related reasons, the economic benefits generated by wetlands and

the economic costs associated their degradation or loss are usually unknown and omitted in

project and policy analysis. As a result, the potential of wetlands to be used as contributors to

economic growth, income generating activities and as sources of goods and services has been

underestimated in many parts of the world resulting in the loss of valuable species, services, and

livelihoods.

Page 16

Flood benefits

The only detailed economic assessment of the value of the goods and services provided

by natural wetlands within the Mekong region is that undertaken of the That Luang marsh in

Vientiane municipality, Lao PDR by Gerrard (2004). Although it collects urban storm water

runoff and some wastewater from the city, has a major flood control role and is not directly

connected to the Mekong in terms of seasonal flood inflow, the results for That Luang provide

an important pointer towards the potential wider regional economic value of natural wetlands.

The total value of the goods and services provided by the 2000 ha marsh on an annual basis is

summarised in terms of direct and indirect use values in Table 2.6:

Table 2.6 Summary of the annual value of wetland economic benefits from the That Luang marsh,

Vientiane municipality.

That Luang Wetland Uses and Services

Annual value (US$)

Wetland Resources Direct use

Rice cultivation

350 000

Garden cultivation

55 000

Aquaculture production

180 000

Capture fisheries.

1 100 000

Other aquatic products

354 000

Sub total

2 040 000

Wetland services Indirect use.

Flood protection

2 850 000

Wastewater purification

70 000

Sub total

2 920 000

Total

4 960 000

Note: figures are rounded from Gerrard (2004).

Gerrard based the monetary value of the flood protection service provided by the marsh on

figures available from the JICA feasibility study on the improvement of the drainage systems in

Vientiane which was undertaken in 1990. This involved the assessment of inundation damage

that would occur as a result of a 10 year storm without an improved drainage system for the city

using unit cost values of damage to property, services and inventory based on surveys and land

use. JICA recommended the construction of urban drainage canals (now completed) into the

marsh as part of the overall plan and calculated the benefit of doing so in terms of the damage

avoided within those areas of the city that would be drained of storm water in this way. Gerrard

updated the cost benefit figures on the basis of the growth in the Gross Regional Domestic

Product of the city over the years since 1990 and obtained the estimate for the flood protection

services provided by That Luang given in Table 2.6.

Since the value of direct wetland uses has already been included in the analysis of

regional agriculture and fisheries the focus here lies with wetland services. For That Luang

the annual monetary benefit of flood protection and wastewater purification is estimated to

be US$2,920,000, giving an annual unit area benefit of US$1,460/ha over the 2,000 ha of

the marshland. In a study of one hundred and ninety wetland valuation studies worldwide

Brander et al. (2006) observed that socioeconomic variables such as income and population

Page 17

Annual Mekong flood report 2008

density are important factors in explaining wetland value. Since in effect That Luang is

providing municipal services directly to a large population its service value is estimated in

terms of replacement costs, for example the construction of sewage treatment facilities and

alternative flood protection and drainage infrastructure. Consequently the service value figure of

US$1,460/ha would be higher than the average for regional wetlands as a whole.

Even so the average value of wetland services at this regional scale is not likely to be

insignificant particularly with regard to their role in mitigating floods. It may seem to be a

circular argument that, since the mainstream and tributary wetlands are by and large a product

of the annual Mekong flood pulse, that one of their key benefits lies with flood attenuation.

This, however, could be seen as positive feedback and simply as one sub-component of the

hydrological dynamics of the system.

Other than the problem of placing a meaningful financial benefit on the services provided

by regional wetlands another complication arises since it is difficult to derive the total area in

the Lower Mekong Basin classified as such. Estimates vary. MacAlister and Mahaxay (2008)

report that 40 million ha are mapped but that the thematic accuracy is poor, which precipitated

their much more detailed mapping though no final figures were quoted for the Basin as a whole.

The figure of 40 million ha is quite clearly unrealistic since it represents more than 60% of the

Lower Basin area. Keskinen et al. (2008) quote a figure of five million hectares for the basin

between Kratie and the South China Sea, which is consistent with estimates available from the

Asean Regional Centre for Biodiversity and those quoted in Do and Bennet (2008). Of this total

area the Cambodian floodplain comprises almost three million hectares.

Determining figures for Lao PDR and Thailand is more problematical. As MacAlister and

Mahaxay (2008) found the categorization of wetlands and floodplain is complex upstream of

Cambodia. Taking a wider view of the available data for the two countries then, excluding

`closed' wetland systems that are not directly connected to the Mekong drainage system, a

figure of 250,000 ha seems reasonable. On this basis the overall regional figures can be broken

down as shown in Table 2.7.

As a working assumption, if a minimum unit area value of the services provided by this area

of floodplain and wetland is set at US$100/ha and a maximum figure of US$500 selected then

the total regional benefit that accrues each year is as reported in Table 2.8.

The natural regulation of floodwater and reduction in peak discharges and water levels is

the major service benefit. Floodwater is in effect stored on the flood plain and in the wetlands

and released once the peak flow has occurred with the effect that flood recession is slower and

therefore longer. This is of advantage particularly in the delta since the period of the year during

which tidal influences dominate the diurnal pattern of water levels and therefore the risk of

extensive saline intrusion is significant becomes shorter.

Page 18

Flood benefits

Table 2.7 Estimated wetland and floodplain areas in the Lower Mekong Basin (LMB) contiguous

with the Mekong drainage system.

Sub area of LMB

Key wetlands

Area (ha)

Lao PDR and Thailand

Nam Songkhram

100 000

Se Champone

24 000

Siphandone

6 000

Se Kong

35 000

Se Pian

30 000

Other

55 000

Cambodia and Viet Nam

Cambodian floodplain

3 000 000

Delta floodplain

2 000 000

Regional Total

5 250 000

Note: Compiled from figures in Keskinen et al, (2005) and the Mekong Wetlands Biodiversity

and Sustainable Use Programme statistics.

Table 2.8 Estimated minimum and maximum value of the services provided by the flood plain/

wetland area in the Lower Mekong Basin.

Flood plain/wetland area

Annual value of services (US$ million)

(million ha)

Minimum based on a unit area

Maximum based on a unit area

service value of US$100/ha

service value of US$500/ha

5.25

525

2 625

Other service benefits include the retention of sediment and organic matter within the

floodplain and wetlands to the obvious advantage of agriculture and the aquatic ecosystem,

pollution control and groundwater recharge and storage.

Page 19

Annual Mekong flood report 2008

Page 20

3. Flood costs

3.1 Introduction

The major challenge to any systematic review of the financial costs of flood damage in the

Mekong region is that national guidelines and methodologies vary, such that building up a

consistent regional database is difficult. The accuracy of the estimates is effectively unknown

since they depend upon the valuation of private property, public infrastructure, crops and

livestock which can vary in line with the economic climate prevailing at the time, though in

general the total value at risk increases from year to year as repair and replacement costs rise.

In addition the property and inventory exposed to flood inundation is growing year on year as

areas at risk are developed.

Primary flood damage arising from the fact of inundation is probably easier to assess. Less

straightforward to evaluate are secondary losses, principally those that accumulate during the

time that normal economic activity is suspended and production and services are suspended.

These secondary losses can accumulate over a very long period after the flood has receded,

usually months and sometimes a year or more depending on the time it takes to fully repair the

damage and for normal services to be resumed.

Issues of scale dictate that in the Lower Mekong Basin flood damage and the associated

financial costs are best considered at the macro level since extreme flooding tends to be regional

in extent. So much so that the impact of the losses can often be measured in terms of reduced

GDP. The major component of total economic damage varies. In rural Lao PDR, for example

the agricultural sector usually suffers the major losses, though the consequences for structural

economic assets such as houses, schools, roads and bridges can also be significant. In the more

densely populated and urbanised delta damage to infrastructure typically exceeds that to crops.

The economics of flood damage are complex since there are a number of damage categories

that have to be valued differently:

· Residential includes physical damage to the structure, clean-up, and damage to the

contents of the house.

· Commercial includes structural damage to shops and industrial premises and the losses

in terms of stock and equipment.

· Agricultural refers not only to crop damage and losses but also to livestock losses and

damage to irrigation infrastructure and on farm property. Also included is the fish farming

sector which in parts of the Mekong region is extensive and a key local economic

activity.

Page 21

Annual Mekong flood report 2008

· Communications and transport covers structural damage to roads, railways and bridges.

· Service facilities encompasses damage to power supply and telecommunications, for

example.

Figure 3.1 Flooded rice fields near Pakse, September 2008.

To these potential sectoral costs and losses must be added the additional costs incurred

during flood emergencies for evacuation, temporary housing, medical supplies, food and

clothing, A significant diversion of resources from other activities during the emergency

response also carries a cost with it. Finally, the secondary losses in terms of ongoing post flood

disruptions to economic activity and reduced agricultural, commercial and industrial production

can in the case of extreme regional events accumulate over time to become a significant

proportion of total damage (Anderson et al., 1993).

3.2 Flood damage assessment in the Lower Mekong region