G

I

W

A R

E

G

I

O

N

A

L A

S

S

E

S

S

M

E

Global International

The Global International Waters Assessment (GIWA) is a holistic, globally

N

T

S

comparable assessment of all the world's transboundary waters that recognises

Waters Assessment

the inextricable links between freshwater and coastal marine environment and

integrates environmental and socio-economic information to determine the

impacts of a broad suite of influences on the world's aquatic environment.

Broad Transboundary Approach

The GIWA not only assesses the problems caused by human activities manifested by

the physical movement of transboundary waters, but also the impacts of other non-

B

hydrological influences that determine how humans use transboundary waters.

R

A

Z

I

Regional Assessment - Global Perspective

L C

U

The GIWA provides a global perspective of the world's transboundary waters by assessing

R

66 regions that encompass all major drainage basins and adjacent large marine ecosystems.

R

E

N

The GIWA Assessment of each region incorporates information and expertise from all

T

countries sharing the transboundary water resources.

Global Comparability

In each region, the assessment focuses on 5 broad concerns that are comprised

of 22 specific water related issues.

Integration of Information and Ecosystems

The GIWA recognises the inextricable links between freshwater and coastal marine

environment and assesses them together as one integrated unit.

The GIWA recognises that the integration of socio-economic and environmental

information and expertise is essential to obtain a holistic picture of the interactions

between the environmental and societal aspects of transboundary waters.

Priorities, Root Causes and Options for the Future

The GIWA indicates priority concerns in each region, determines their societal root causes

and develops options to mitigate the impacts of those concerns in the future.

This Report

This report presents the assessment of the GIWA region Brazil Current, including drainage

basins and their associated coastal/marine zones. Three separate sub-regions have been

assessed within the region: the South/Southeast Atlantic Basins, East Atlantic Basins,

and São Francisco River Basin. Increased anthropogenic pressures due to economic

development and urbanisation in the coastal area have polluted the water environment

and caused severe impact on important ecosystems such as coastal plains and mangrove

ecosystems. Significant changes in the suspended solids transport/sedimentation

dynamics in the river basins due to unsustainable land use practices associated to intense

deforestation and damming has caused increasing erosion of coastal zones, siltation of

riverbeds, and modified the stream flows resulting in periods of water scarcity and flooding

Brazil Current

in some basins. The root causes of pollution and habitat and community modification are

identified for the bi-national Mirim Lagoon Basin, a transboundary freshwater body shared

between Brazil and Uruguay, and Doce River Basin that hosts biomes of global importance.

GIWA Regional assessment 39

Potential remedial policy options are presented.

Marques, M., Knoppers, B., Lanna, A.E., Abdal ah, P.R. and M. Polette

Global International

Waters Assessment

Regional assessments

Global International

Waters Assessment

Regional assessment 39

Brazil Current

GIWA report production

Series editor: Ulla Li Zweifel

Report editor: Marcia Marques

Editorial assistance: Johanna Egerup, Malin Karlsson

Maps & GIS: Niklas Holmgren

Design & graphics: Joakim Palmqvist

Global International Waters Assessment

Brazil Current, GIWA Regional assessment 39

Published by the University of Kalmar on behalf of

United Nations Environment Programme

© 2004 United Nations Environment Programme

ISSN 1651-9404

University of Kalmar

SE-391 82 Kalmar

Sweden

United Nations Environment Programme

PO Box 30552,

Nairobi, Kenya

This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and

in any form for educational or non-profit purposes without

special permission from the copyright holder, provided

acknowledgement of the source is made. No use of this

publication may be made for resale or for any other commercial

purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from the

United Nations Environment Programme.

CITATIONS

When citing this report, please use:

UNEP, 2004. Marques, M., Knoppers, B., Lanna, A.E., Abdallah, P.R.

and Polette, M. Brazil Current, GIWA Regional assessment 39.

University of Kalmar, Kalmar, Sweden.

DISCLAIMER

The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors

and do not necessarily reflect those of UNEP. The designations

employed and the presentations do not imply the expressions

of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNEP or cooperating

agencies concerning the legal status of any country, territory,

city or areas or its authority, or concerning the delimitation of its

frontiers or boundaries.

This publication has been peer-reviewed and the information

herein is believed to be reliable, but the publisher does not

warrant its completeness or accuracy.

Printed and bound in Sweden by Sunds Tryck Öland AB.

CONTENTS

Contents

Preface

9

Executive summary

11

Acknowledgements

15

Abbreviations and acronyms

16

Regional definition

20

Boundaries of the Brazil Current region

20

Physical characteristics of the Brazilian portion of the region

23

Physical characteristics of the Uruguayan portion of the region

33

Socio-economic characteristics of Brazil

35

Socio-economic characteristics of Uruguay

48

Assessment

51

Freshwater shortage

52

Pollution

58

Habitat and community modification

69

Unsustainable exploitation of fish and other living resources

76

Global change

80

Priority concerns

84

Causal chain analysis

86

Patos-Mirim Lagoon system

Introduction

86

System description

87

Methodology

94

Causal chain analysis for Unsustainable exploitation of fish Patos Lagoon

94

Causal chain analysis for Pollution Mirim Lagoon

96

Conclusions

99

Doce River basin

Introduction

100

System description

101

Methodology

104

Causal chain analysis for Pollution Doce River basin

104

Causal chain analysis for Habitat and community modification Doce River basin

108

Conclusions

108

CONTENTS

Policy options

109

Patos-Mirim Lagoon system

Definition of the problems

109

Policy options

110

Recommended policy options

113

Performance of the chosen alternatives

114

Conclusions and recommendations

116

Doce River basin

Definition of the problems

117

Policy options

117

Recommended policy options

118

Performance of the chosen alternatives

119

Conclusions and recommendations

121

Conclusions and recommendations

122

References

126

Annexes

141

Annex I List of contributing authors and organisations involved

141

Annex II Detailed scoring tables

143

Annex III Detailed assessment worksheets

155

Annex IV List of important water-related programmes and assessments in the region

173

Annex V List of conventions and agreements

175

The Global International Waters Assessment

i

The GIWA methodology

vii

Preface

This report presents the results of the strategic impact assessment

The Atlantic Basin of Uruguay (Vertiente Atlántica, in Spanish), a narrow

carried out for marine and freshwater resources and the associated

strip of land with small sub-basins that drain toward the Atlantic Ocean,

living resources of the Brazil Current region, which is part of the

could not be classified as Brazil Current according to oceanographic

Global International Waters Assessment Project GIWA-UNEP/GEF. The

criteria and therefore it is addressed separately in the text. This coastal

scoring procedure was based on: (i) expert opinion obtained during

zone is actual y part of the Patagonian Shelf Large Marine Ecosystem.

workshops, with the participation of experts on the Brazil Current

with different scientific backgrounds and from several institutions

In each sub-region, environmental impacts were assessed and scored

and geographical regions of Brazil Current; (i ) expert advice; and

issue by issue (e.g. modification of stream flow, pol ution of existing

(i i) information and data gathered from different sources. The results

supplies, changes in the water table) and then consolidated with an overal

from the first Scaling & Scoping exercise for the Brazil Current region was

score by concern and sub-region (e.g. Freshwater shortage in South/

based on a workshop with the participation of experts with different

Southeast Atlantic Basins). Final y, based on three scores given to the sub-

backgrounds and regional knowledge. The final scores presented in

regions, an overal score for each concern was given to the Brazil Current

this report resulted from a revision of the preliminary scored, based on

(e.g. Freshwater shortage). If differences in fractions between scores

a more detailed assessment, when impact indicators were col ected

resulting from weighting and averaging procedures are taken into

mostly from local, regional and national documentation and scientific

consideration (e.g. scores 2.1, 2.3, 2.5), it is possible to identify priorities

publications. This information in the format of impact indicators is

among concerns, for each sub-region and for the Brazil Current. Using

presented in the text and/or included in Annex I I (Detailed assessment

this procedure, São Francisco River Basin, for instance, had as the main

worksheets). Few international databases (e.g. Large Marine Ecosystem

concern, Freshwater shortage with the main causative issue being

programme, FAO database) were accessed. This approach was taken

modification of stream flow. South/Southeast Atlantic Basins and East

in order to be as precise as possible in the scoring procedure, using

Atlantic Basins had as the main concern Pol ution, and the main causative

specific catchment basins/coastal zone information to substantiate the

issue, suspended solids. If the fractional differences in the score figures are

degree of severity of impacts given to each issue and concern, both

ignored, impacts caused by four of five GIWA concerns in the Brazil Current

present and future (predictive analysis).

(freshwater shortage, pol ution, habitat and community modification,

overexploitation of fish and other living resources) received moderate

To reduce the difficulty of scoring a largely diverse region such as

overal score. The concern global change, received slight overal score.

the Brazil Current region, a further sub-division was made during the

scaling procedure, leading to the identification of three distinct GIWA

Selection based on differences in fractions of the score figures was not

sub-regions; 39a South/Southeast Atlantic Basins; 39b East Atlantic

considered, in principle, a robust enough procedure to define the main

Basins and 39c São Francisco River Basin. The scoring procedure was

concern. Priority was therefore established according to the precedence

then carried out sub-region by sub-region and the scores obtained

of each concern, compared to the other concerns. Coincidently, the

were subsequently aggregated for the whole GIWA region 39 Brazil

priority based on precedence coincided with the priority previously

Current.

based on differences in fractions among scores. Pol ution was the

concern that met both criteria.

PREFACE

9

This precedence was established from the findings that pol ution causes

increased impacts of freshwater shortage and habitat and community

modification and that pollution is also one of the factors that promote

reduction of fish stocks, which in turn, contributes to increase the

severity of the impacts due to unsustainable exploitation of fish.

Pol ution is also, among al concerns, the one that shows most evidence

of health and economic impacts in the Brazil Current region, mostly

associated to microbiological pol ution, eutrophication, chemical

pollution and spil s. The way pollution contributes to the raising of the

other concerns is illustrated in different sections of the report.

When analysing the impact indicators included in Annex I I, it can be

seen that the information/data gathered varies, regarding reliability

and quality. It is also observed that more information is available for

South/Southeast Atlantic Basins than for the other sub-regions (East

Atlantic Basins and São Francisco River Basin). This reflects the historical

condition of higher socio-economic and scientific development found

in the South and Southeast geographical regions of Brazil, when

compared to other regions of the country, a condition that has been

gradually changed through a policy of investments and incentives to

the other regions of Brazil. Relatively little information was found for

the portion of Mirim Lagoon located in Uruguayan territory, as well

as the Atlantic Basin of Uruguay regarding environmental and socio-

economic impacts associated to water resources, coastal zone and

associated living resources, which indicates the need for closer effective

cooperation between the countries and for generation of primary data

within the area.

10

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 39 BRAZIL CURRENT

Executive summary

Regional definition

between the undeveloped northern Brazil, the often drought-affected

GIWA region 39 Brazil Current is a tropical/sub-tropical ocean margin

northeastern Brazil, and the much more prosperous and industrialised

governed by western boundary currents, a passive continental shelf,

southeastern and southern Brazil. The southeastern and the southern

and moderate continental run-off (Walsh 1988, Ekau & Knoppers in

Brazil are together responsible for more than 75% of the Brazilian GDP.

press). It extends along the Brazilian coast from the São Francisco River

Therefore, although Brazil Current region is almost 100% Brazilian

estuary (10° 30´ S, 32° W) in the northeastern Brazil, to Chui (34° S, 58° W)

territory (excepting 2.3% that belong to Uruguay), it shows an extremely

in the southern Brazil. Its length, excluding contours of bays and islands,

high diversity regarding social, cultural and economic aspects, which in

is 4 150 km, or 58% of the Brazilian coastline (GERCOPNMA 1996). The

turn, reflect on the nature and severity of the impacts.

Brazil Current region's catchment area inside Brazil is 1 403 mil ion km2

and the portion inside Uruguay, corresponding to approximately 52%

In the Brazil Current region, a typical developing economy situation

of the Mirim Lagoon Basin (and 2.3% of the Brazil Current continental

has been established: economic and demographic growth exceed

area), is 33 000 km2. The Brazilian component of the Brazil Current

development of necessary urban and industrial infrastructure (Lacerda

catchment area includes the entire states of Espírito Santo (ES) and

et al. 2002). Littoralisation, a variant of urbanisation with the movement

Rio de Janeiro (RJ) and from northeast to south, part of the states of

of people from the countryside to the coastal cities, is the predominant

Pernambuco (PE), Alagoas (AL), Sergipe (SE), Bahia (BA), Minas Gerais

trend in Latin America, which the Brazil Current il ustrates quite wel .

(MG), Goiás (GO), São Paulo (SP), Paraná (PR), Santa Catarina (SC) and

Anthropogenic pressures exhibit two major features; large cities

Rio Grande do Sul (RG).

either affect the coastal waters or estuaries directly when located

on the coastline, or contribute to coastal change indirectly through

Uruguay is divided in 18 departamentos (political/administrative units).

their location in catchments which carry the urban waste load. In the

Five of them are partial y or entirely included in the Mirim (Merín in

Brazil Current, the main pressures/driving forces and the respective

Spanish) Lagoon basin and subsequently part of the Brazil Current

environmental issues generated by them are:

region. These five departamentos are: Cerro Largo, Lavalleja, Maldonado,

Urbanisation: consumption of water, microbiological pol ution,

Rocha and Treinta y Tres. Two of them (Rocha and Maldonado) also form

eutrophication, suspended solids, habitat and community

the Atlantic Basin of Uruguay with a coastal zone with high potential for

modification;

tourism, that hosts livestock and rice plantation as the main economic

Industry: consumption of water, chemical pollution;

activities.

Agriculture: consumption of water for irrigation, increased nutrient

and suspended solids loads, chemical pol ution, eutrophication,

The Brazil Current region encompasses geographical portions of

habitat and community modification;

"three Brazils" as revealed by the UNDP Human Development Index

Power generation: stream flow modification due to damming,

(UNDP 2001): the northeastern, southeastern and southern Brazil. In

habitat and community modification;

Brazil, the poorest 20% have only 2.6% of the total national wealth;

Mining: chemical pol ution, suspended solids, habitat and

the richest 20% have 65% (IBGE 2001). This extremely uneven wealth

community modification;

distribution has been historical y associated with the contrasts

Fisheries: reduction of fish stocks, pollution;

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

11

Aquaculture: eutrophication, habitat and community modification;

the fact that eutrophication has become a common phenomenon in

Transport: spil s.

reservoirs (Azevedo 1996, Costa & Azevedo 1994, Teixeira et al. 1993,

Proença et al. 1996, Diário do Vale 2001). More frequently recorded has

For the purpose of the GIWA assessment, Brazil Current was divided in

been the association between water pol ution and water-borne diseases

three regions: South/Southeast Atlantic Basins, East Atlantic Basins, and

such as microbiological and parasitic infections (CETESB 1990 in Governo

São Francisco River Basin. Medium-sized basins or groups of smal basins

do Estado de São Paulo 2002, IBGE 2001, COPPE & UFRJ 2002, Governo

in the sub-regions were numbered according to the former classification

do Estado de São Paulo 2002). Increasing gastrointestinal symptoms

by the Brazilian National Agency of Electric Energy (ANEEL) and not the

related to the time of exposure to polluted beaches was described by

newer sub-division of the Brazilian basins, according to the Brazilian

CETESB (1990), in Governo do Estado de São Paulo (2002). In Paraíba do

National Agency of Waters (ANA) (PNRH 2003). This presentation is

Sul River basin (East Atlantic Basins), the incidence of microbiological

intended to help those readers that are not familiar with the Brazilian

infection and parasitic diseases varies among municipalities, from

or Uruguayan geography to locate, on the map, the basins mentioned

0-30% (IBGE 2001) and is seems to be related to the average income.

in different sections and to identify the areas in Brazil Current where the

As regards risks to human health, cases of schistosomiasis have been

issues and impacts are occurring.

registered all over the São Francisco River Basin. In the upper portion

of the Basin, there are health problems resulting from microbiological

Assessment

factors and problems resulting from chemical pollution are suspected,

The assessment of the Brazil Current region identified the fol owing

but not confirmed, due to lack of proper investigations. While the

priority concerns in the three individual sub-regions assessed: South/

percentage of the population affected is smal , the degree of severity

Southeast Atlantic Basins and East Atlantic Basins, Pol ution with

is high, due to the poverty level among those affected.

suspended solids as the main causative issue; São Francisco River

Basin, Freshwater shortage with modification of stream flow as the

Episodes of temporary freshwater scarcity have been registered,

main causative issue.

mostly due to chemical pol ution caused by industrial activities in

some populated basins. In 2003, an accident in a paper-pulp industry

Changes in the suspended solids transport/sedimentation dynamics

located in Minas Gerais state, on a tributary of the Paraíba do Sul River,

due to deforestation and erosion is the main cause of silting,

which flows through Rio de Janeiro state, caused a transboundary issue

modification of stream flow and periods of water scarcity and flooding

due to pollution of the downstream portion of the basin, resulting in

in South/Southeast Atlantic and East Atlantic Basins (e.g. Itajaí Val ey

interruption of the water supplies during weeks, which affected about

and Doce River basin respectively). Diversion of water from one basin

600 000 inhabitants of northern Rio de Janeiro state. Therefore, the

to another to meet the demands for consumption (e.g. transfer of

causative link between Pol ution and other environmental concerns

water from Paraíba do Sul River in East Atlantic Basins to supply the

assessed as equal y severe supported the decision of selecting

Rio de Janeiro littoral basin in South/Southeast Atlantic Basins) has

Pollution as the most important concern for the Brazil Current region.

caused increased sedimentation/silting in the estuary that receives the

The combined assessment of the three sub-regions resulted in the

transposed water (Sepetiba Bay in East Atlantic Basins), which generates

fol owing ranking of concerns:

pol ution and habitat modification. At the same time, significant

1. Pollution;

reduction of sediment transport in the original basin due to damming

2. Habitat and community modification;

has caused extensive erosion of the coastline, destroying fringes of

3. Freshwater shortage;

mangrove forests, dunes and small vil ages around the Paraíba do Sul

4. Overexploitation of fish and other living resources;

River estuary, and promoting depletion of fish stocks.

5. Global change.

Eutrophication in lagoons, estuaries and bays along Brazil Current coast

Causal chain and policy option analyses

placed downstream densely occupied urban areas, industrial activities

The Causal chain analysis methodology was developed special y for

and agriculture fields is currently a serious environmental issue. In

the GIWA project and was previously tested in selected aquatic system

reservoirs for water supply, eutrophication is becoming a serious issue

in Brazil Current (Marques 2002, Marques et al. 2002). The Causal chain

in both South/Southeast Atlantic as wel as East Atlantic Basins. Few, but

and policy option analyses were carried out for two selected aquatic

extremely severe episodes of human intoxication due to hepatotoxins

systems: the transboundary bi-national water body Mirim Lagoon

released in the water after algal blooms have been recorded, as has

(South/Southeast Atlantic Basins), shared by Uruguay and Brazil and the

12

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 39 BRAZIL CURRENT

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

13

Doce River basin, a medium-sized transboundary basin shared by the

In Doce River basin the major environmental and socio-economic

Brazilian states of Minas Gerais and Espírito Santo (East Atlantic Basins).

impacts due to pol ution have a transboundary nature, since

São Francisco River Basin, a natural candidate for further analyses due to

deforestation and land uses practiced by the state responsible for the

the high importance such river has in the national context, has already

upstream portion of the basin (Minas Gerais) during decades has caused

been the focus of an important GEF/UNEP project (Diagnostic analysis

severe environmental and socio-economic impacts to the downstream

and strategic action program for the integrated management of the

portion of the basin, which belongs to another state (Espírito Santo). In

São Francisco River basin and its coastal zone), and only for this reason,

brief, the main environmental problems that lead to socio-economic

was not included in the list of selected aquatic systems. Through these

impacts in the basin arise from the fol owing factors (Gerenciamento

case studies, the causative links and the main root causes responsible

Integrado da Bacia do Rio Doce 2003): (i) generalised deforestation

for pol ution in Brazil Current were addressed. In the particular case

and mismanagement of agricultural soils that led to loss of fertility and

of the Patos-Mirim Lagoon system, although the main focus in terms

speedy erosion, and consequently, to loss of agricultural productivity,

of causal chain and policy options analyses was put on pol ution in

increased rural poverty and migration to the outskirts of large cities;

Mirim Lagoon, a causal chain analysis for the overexploitation of fish

(ii) siltation of riverbeds caused by erosion, leading to reduced stream

was also constructed for the Patos Lagoon. In the case of the Doce

flow during the dry period and increased problems during floods,

River basin, the causal chain was analysed for pollution and the habitat

with effects on urban supply, irrigated agriculture and public safety;

and community modification. It was thus possible to find out that both

(i i) floods, resulting from natural conditions but worsened by the

concerns have some root causes in common. In this model, policy

human flood plain occupation, deforestation, soil erosion and siltation;

options tailored to reduce one of these concerns will also reduce the

(iv) vulnerability of reaches where domestic supply intake points are

other, which represents a desirable win-win situation.

located, considering previous accidental toxic pol ution events, in

several regions in the basin, with potential risks to public health; and

Mirim Lagoon, a truly international freshwater body, is a shal ow Atlantic

(v) the precariousness of basic sanitation (networks, sewage treatment,

tidewater lagoon on the border between Brazil (state of Rio Grande do

disposal of solid wastes) and the lack of drinking water supply in several

Sul) and Uruguay. It is approximately 190 km long and 48 km across

urban agglomerations and rural communities, reflecting on public

at its widest point, covering an area of 3 994 km2. A low, marshy bar

health and on the economy. The main root causes for Doce River basin

containing smal er lagoons, separates the Mirim Lagoon from the

are: (i) Governance (basin-wide management plan not implemented yet,

Atlantic Ocean. It drains northeastward into the Patos Lagoon. Mirim

and lack of legitimacy in negotiations commanding decisions regarding

Lagoon is considered one of the most important water resources in

investments); (i ) Knowledge (insufficient training regarding best land

Uruguay. The main economic activity in the basin is agriculture, mostly

use practices); and (iii) Economic (existing economic distortions, such

rice plantation, which is highly dependent on water from the Mirim

as non-correction of negative externalities resulting in pol ution and

Lagoon for irrigation. The main environmental concern is pol ution due

inefficient use of water).

to the use of chemical fertilisers and pesticides. Root causes behind

agricultural practices are: (i) Governance (lack of ful implementation

Five policy options were proposed and three of them were selected

of the bi-national basin integrated management plan and lack of

as those that should be implemented in the first stage: (i) participatory

autonomy and authority of the control agencies to face pressures

plan for flood control; (i ) production of the manual to prepare City

from economic development); (ii) Knowledge (insufficient information

Statutes (Ordinances); and (i i) pilot project for basin reforestation

regarding environmental functions of wetland and lagoon system

associated with the enhancement of family agriculture.

and insufficient training regarding sustainable use of water and soil);

and (iii) Economic (lack of efficient economic instruments to promote

Challenges and recommendations for future actions

sustainable use of water and land).

The ranking of environmental concerns and issues in Brazil Current

region or any other GIWA region in the world, regarding the severity of

Nine complementary policy options were proposed for Mirim

their impacts is likely to change as time goes by and also as a result of

Lagoon, among them, two were selected as the best candidates to be

policies and initiatives implemented and the development of different

implemented in a first stage: (i) creation of the bi-national Mirim Lagoon

economic sectors. The transformation of the GIWA assessment from

Basin Committee and empowerment of the Brazilian and the Uruguayan

the status of a project into a continuous assessment would represent:

Mirim Lagoon Agencies; and (i ) technical and professional training on

(i) significant and continuous support to the decision making process

pol ution minimisation and control associated to agriculture activities.

towards a more sustainable use of water and associated living resources;

12

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 39 BRAZIL CURRENT

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

13

(ii) better understanding of the environmental problems with updated

and easy-to-access information for increasing cooperation between the

governments that share the water bodies; and (i i) a valuable source

of information/data for development of advanced knowledge and

awareness among stakeholders regarding the importance of rational

land occupation and use of water resources, costal zones and their

associated living resources.

14

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 39 BRAZIL CURRENT

Acknowledgements

The Brazil Current Regional Task Team would

like to acknowledge the following:

The Rio de Janeiro State University (UERJ), the Rio de Janeiro Agricultural

Research Company (PESAGRO-RIO) and the Noel Rosa Culture and

Research Foundation, for hosting and supporting the project.

The institutions included in Annex I (universities, government agencies

and NGOs), the National Agency of Water (ANA), and the Ministry of

Environment (MMA) in Brazil, for facilitating access to information.

The Scientific Director and the Southern Hemisphere Coordinator of

GIWA, for their valuable support during the execution of the project.

The GIWA Core Team and the external peer-reviewers, for editing,

reviewing, and helping to improve this report.

The Global Environment Facility (GEF), the United Nations Environment

Programme (UNEP), and the Swedish International Development

Agency (Sida), for providing the task team with the necessary funding.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

15

Abbreviations and acronyms

AB

Abrolhos Bank

EMBRAPA-CPACT

AL

Alagoas State

Brazilian Company Agriculture Research-Temperate

ANA

National Agency of Water (Brazil)

Climate Agriculture Center

ANEEL

National Agency of Electric Energy (Brazil)

ENSO

El Niño Southern Oscilliation

ANTAQ

National Agency of Water Transport (Brazil)

ES

Espírito Santo State

APA

Environmental Protection Area

FAO

United Nations Food and Agricultural Organization

BA

Bahia State

FAPCZ

Federal Action Plan for the Coastal Zone

BC

Brazil Current

FATMA

Santa Catarina Environment Foundation (Santa Catarina

BOD

Biochemical Oxygen Demand

State)

CADAC Environmental Accident Record

FEAM

State Foundation for the Environment (Minas Gerais state)

CBD

Convention on Biological Diversity

FEPAM

State Foundation for Environmental Protection (Rio Grande

CCA

Causal Chain Analysis

do Sul state)

CDZF

Commission for Joint Development of Transboundary

FUNASA Fundação Nacional de Saúde / Brazil Ministry of Health

Zones

GDP

Gross Domestic Product

CEPERG Centro de Pesquisas e Gestão dos Recursos Lagunares e

GEF

Global Environment Facility

Estuarinos

GERCO

Programa Nacional de Gerenciamento Costeiro

CETESB State Company of Environmental Technology and Basic

GHG

Green House Gas

Sanitation (São Paulo state)

GO

Goiás State

CGC

General Commission of Brazilian-Uruguayan Coordination

HDI

Human Development Index

CIDE

Centro de Informacões e Dados do Rio de Janeiro

IADB

Inter-American Development Bank

CLM

Commission for Development of Mirim Lagoon Basin

IBAMA

Brazilian Institute for the Environment

COD

Chemical Oxygen Demand

IGAM

Minas Gerais Institute of Water Management

CONAMA National Council of Environment

INMET

National Meteorological Institute, Brazil

CPRM

Company of Mineral Resources Research

IPCC

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

CZ

Confluence Zone

ITCZ

Inter-Tropical Convergence Zone

DGRNR General Directory of Renewable Nature Resources

IWC

International Wildlife Coalition

DINAMIGE National Directorate of Mining and Geology

JICA

Japan International Cooperation Agency

DNAEE

National Department of Water and Electrical Energy (Brazil)

MERCOSUR

DNH

Dirección Nacional de Hidrografía (Uruguay)

Mercado Común del Sur / Southern Common Market

DNOCS Brazilian National Department of Works Against the

MG

Minas Gerais State

Drought

MMA

Brazilian Ministry of Environment

EEZ

Exclusive Economic Zone

MRE

Brazilian International Trade Ministry

MSY

Maximum Sustainable Yield

16

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 39 BRAZIL CURRENT

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

17

NBC

North Brazil Current

NGO

Non Governmental Organisation

OSE

National Administration of Sanitary Works (Uruguay)

PARNA National Park of Lagoa do Peixe

PE

Pernambuco State

PLE

Patos Lagoon Estuary

PO

Policy Option

PR

Paraná State

PRENADER

Programa de Manejo de Recursos Naturales y Desarrol o

del Riego (Uruguay)

PROBIDES Conservation of Biodiversity and Sustainable Development

Programme for the Eastern Wetlands (Uruguay)

PRODES Clean-up programme of hydrographic basins

RG

Rio Grande do Sul State

RJ

Rio de Janeiro State

SACW

South Atlantic Central Waters

SACZ

Southwest Atlantic Convergence Zone

SC

Santa Catarina State

SE

Sergipe State

SEAMA State Secretariat for Environmental Issues (Espírito Santo

state)

SEC

South Equatorial Current

SNIU

National Urban Information System (Brazil)

SO

Southern Oscil ation

SP

São Paulo State

STW

Surface tropical Waters

TW

Tropical Water

UFAL

Federal University of Alagoas

UFBA

Federal University of Bahia

UNDP

United Nations Development Programme

UNEP

United Nations Environment Programme

UNESCO United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural

Organization

16

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 39 BRAZIL CURRENT

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

17

List of figures

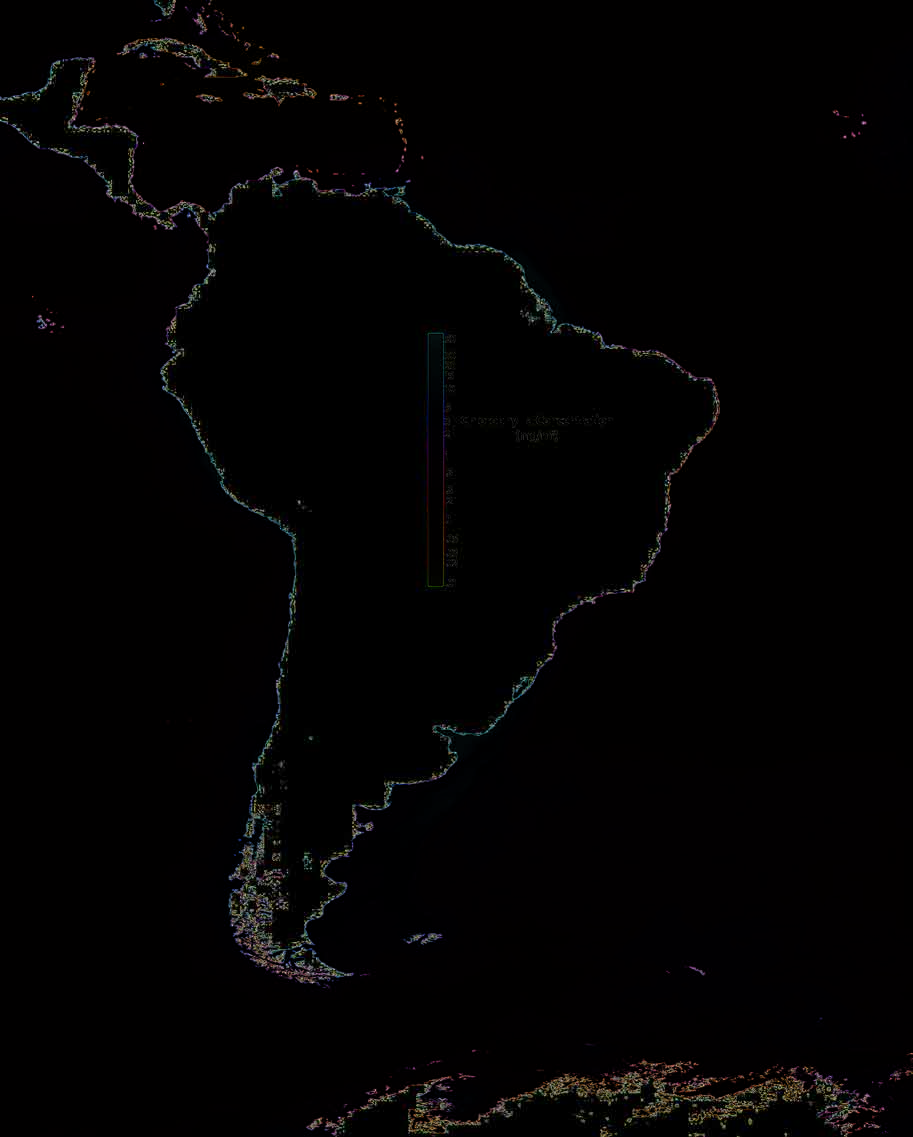

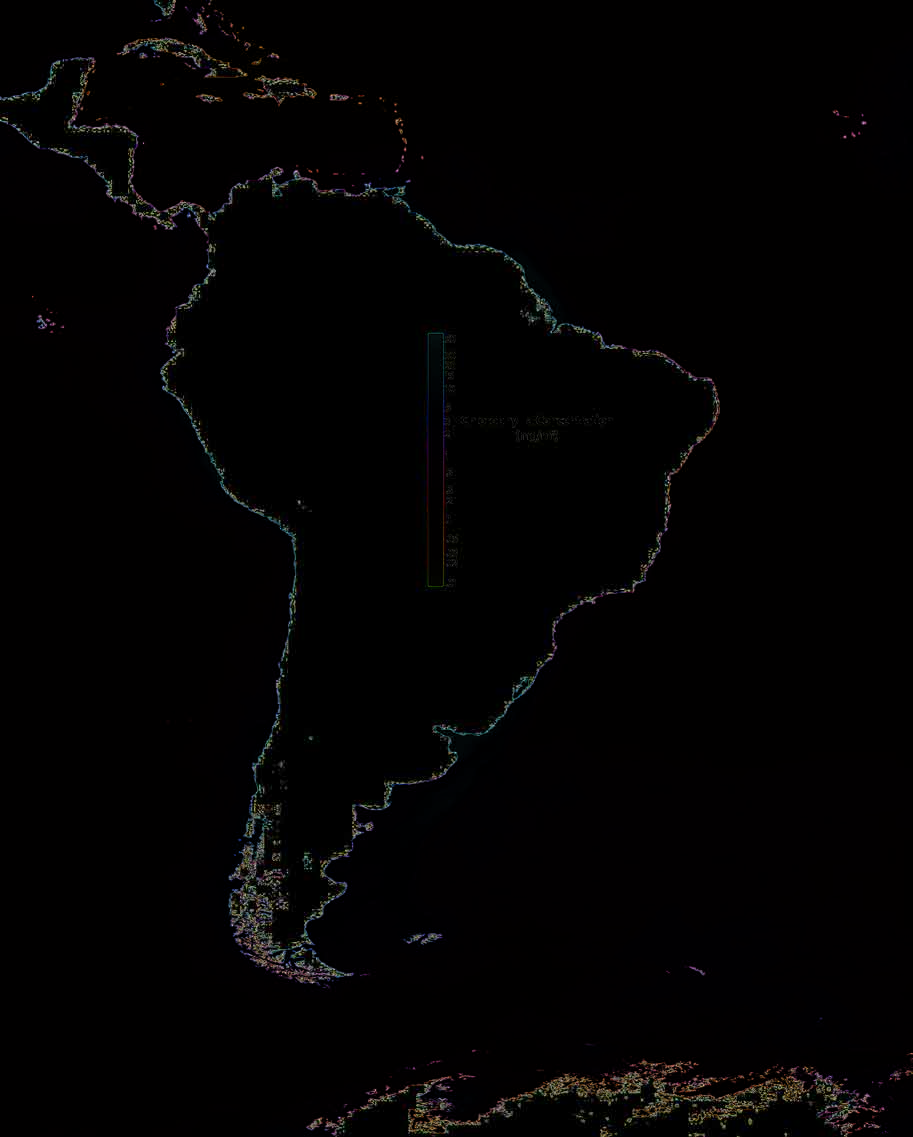

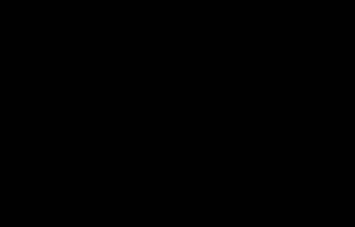

Figure 1

The continent, coast and shelf of the Brazil Current region and surrounding area. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

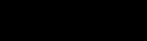

Figure 2

Sub-division of the Brazil Current region: São Francisco River Basin (basins 40-49); East Atlantic Basins (basins 50-59);

and South/Southeast Atlantic Basins (basins 80-88). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

Figure 3

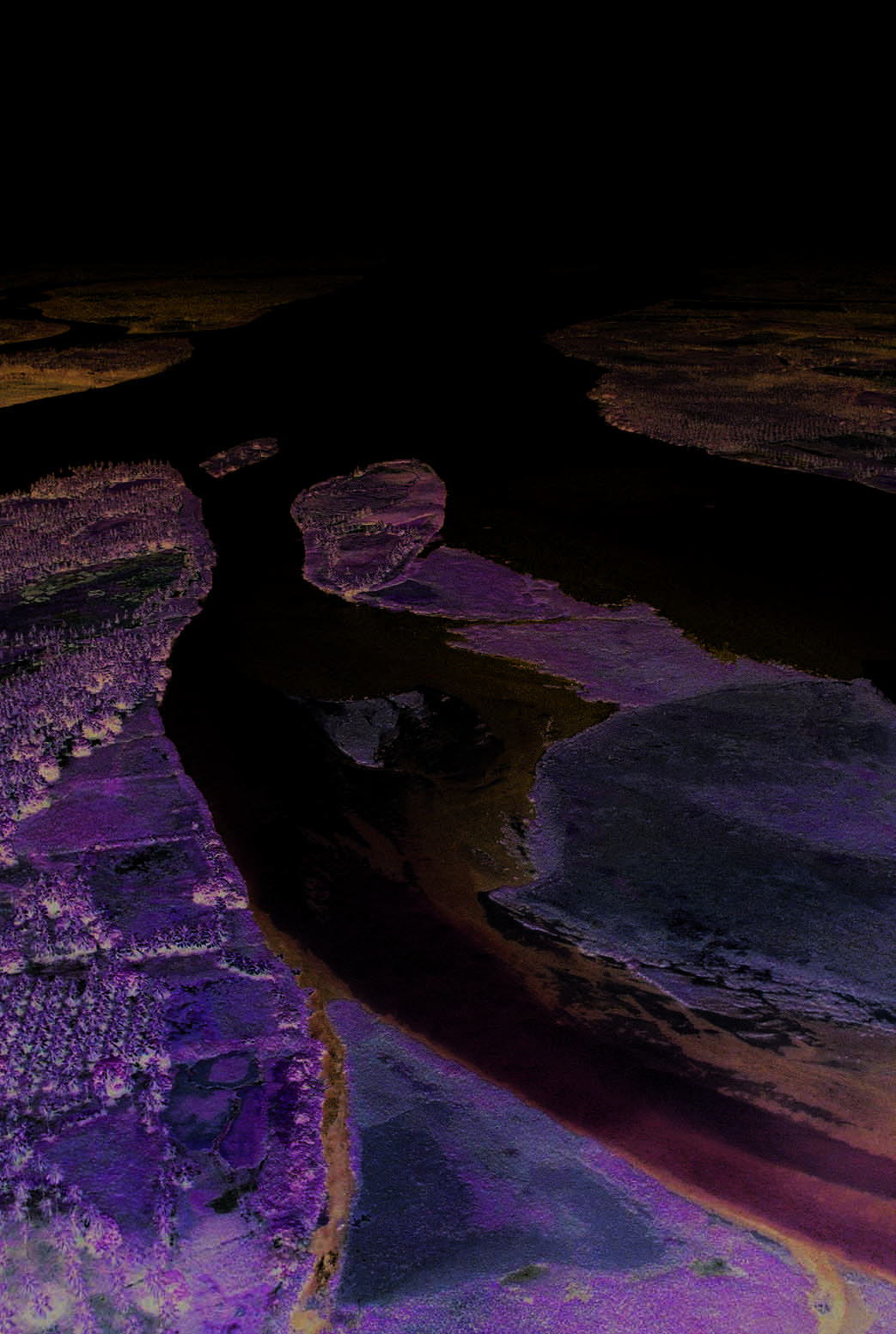

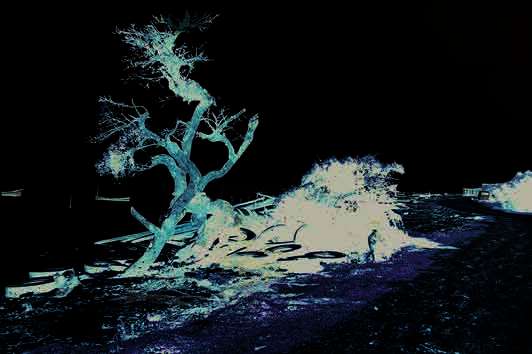

Aerial view of São Francisco River. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23

Figure 4

Köppen type climate classification of Brazil and its coastal zone. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26

Figure 5

Annual precipitation and evapotranspiration.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26

Figure 6

Chlorophyll a concentration in the coastal area. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28

Figure 7

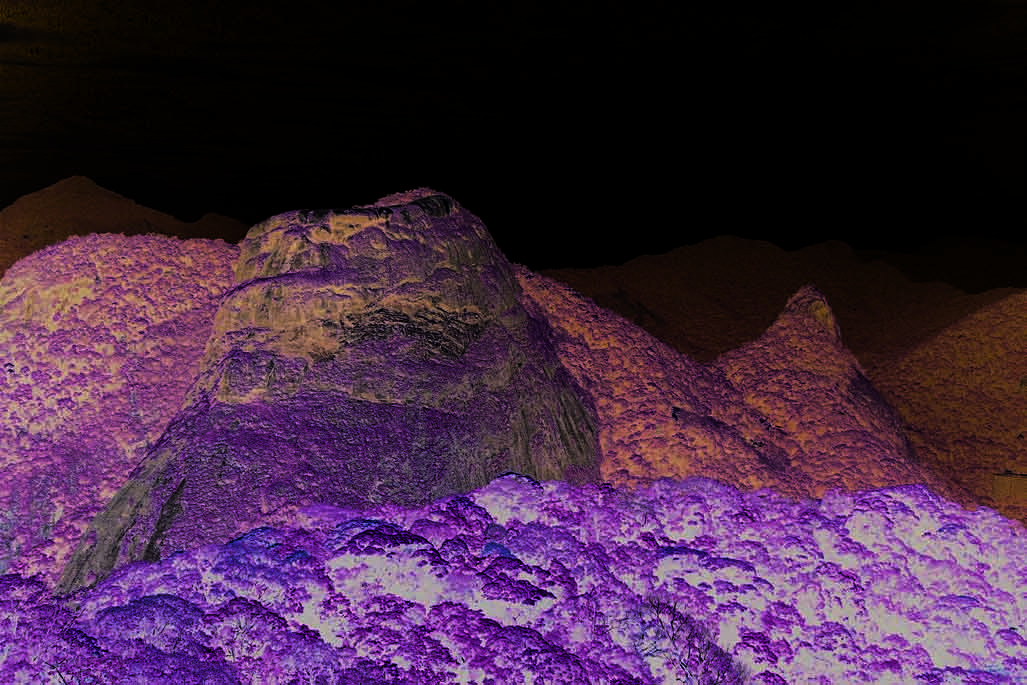

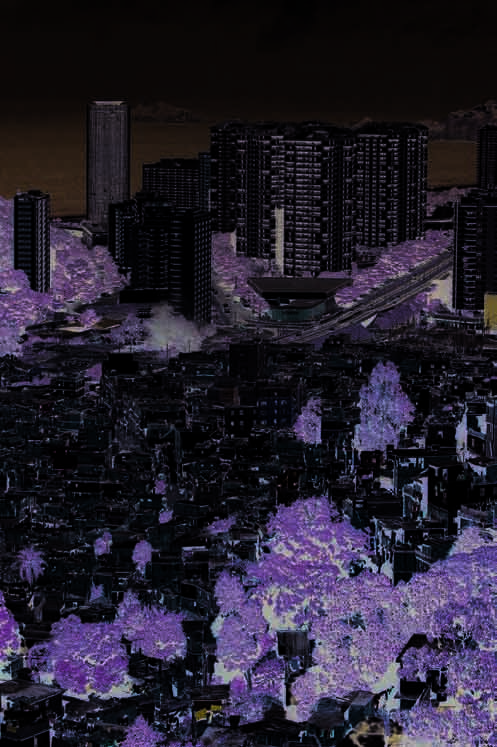

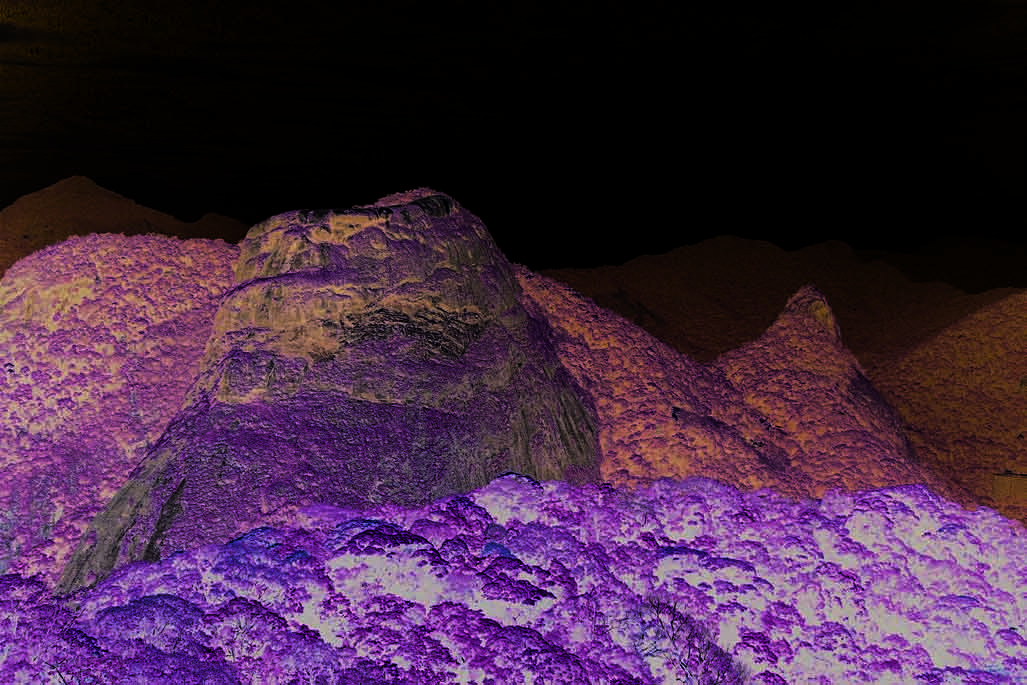

Overview of the Atlantic Forest: Tijuca National Park in Rio, the largest urban forest in the world. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30

Figure 8

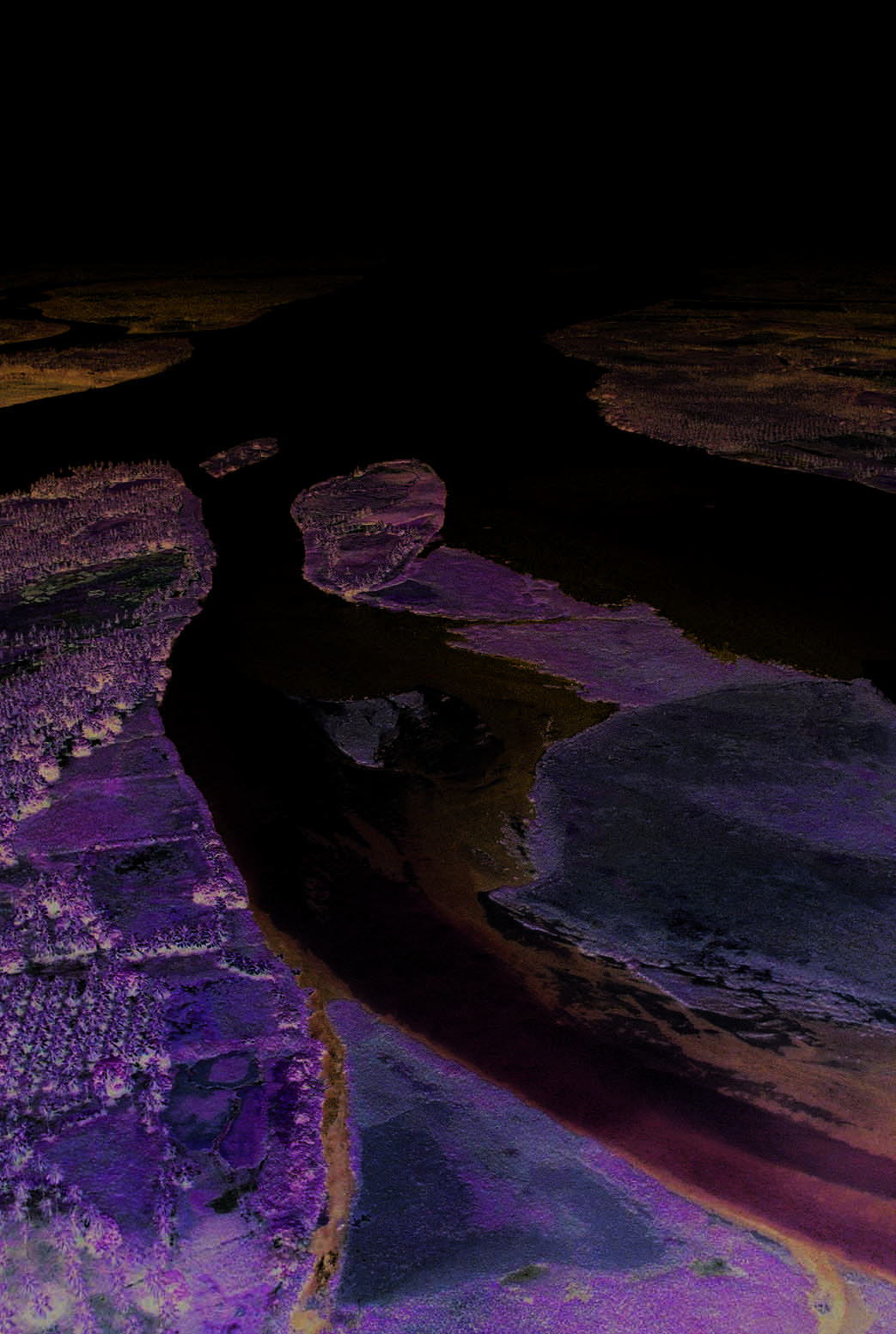

Present and original cover of the Atlantic Rainforest. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31

Figure 9

Red mangrove tree in clear waters. Boipeba Island, southern Bahia state, East Atlantic Basins. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32

Figure 10 Map showing the area of the six hydrographic basins of Uruguay. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34

Figure 11 International protected areas and reserves in Brazil Current region. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35

Figure 12 Brazilian regions.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36

Figure 13 Population growth rate per decade in Brazil and three Brazilian regions partially included in the Brazil Current region: the Northeast,

Southeast and South regions. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 37

Figure 14 Brazil Current population densities. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 37

Figure 15 Ipanema beach, Rio de Janeiro: Example of littoralisation observed along Brazil Current coastal zone (East Atlantic Basins). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 38

Figure 16 Parati, Rio de Janeiro state littoral, one of the cities attractive due to both history/architecture and nature values (East Atlantic Basins).. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 38

Figure 17 Rural workers in Rio Grande do Sul state. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 40

Figure 18

Catch in Large Marine Ecosystem 15, South Brazil Shelf (1950-2000), corresponding to sub-region South/Southeast Atlantic Basins and the Rio de Janeiro littoral.. . . . . 43

Figure 19 Catch in Large Marine Ecosystem 16, East Brazil Shelf (1950-2000), corresponding to East Atlantic Basins excluding the Rio de Janeiro littoral,

plus the GIWA region Brazilian Northeast. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 43

Figure 20 Areas of importance in terms of coastal/marine biodiversity in Brazil Current and some petroleum prospecting areas. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 46

Figure 21 Catch Large Marine Ecosystem LME 14, Patagonian Shelf (1950-2000), where the sub-basin 89 Vertiente Atlántica is included. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 49

Figure 22 Explored areas in the Itajaí River basin and the occurrence of flood events per year in Blumenau city in 20 year intervals (1850-1990). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 54

Figure 23 São Francisco River Basin. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 55

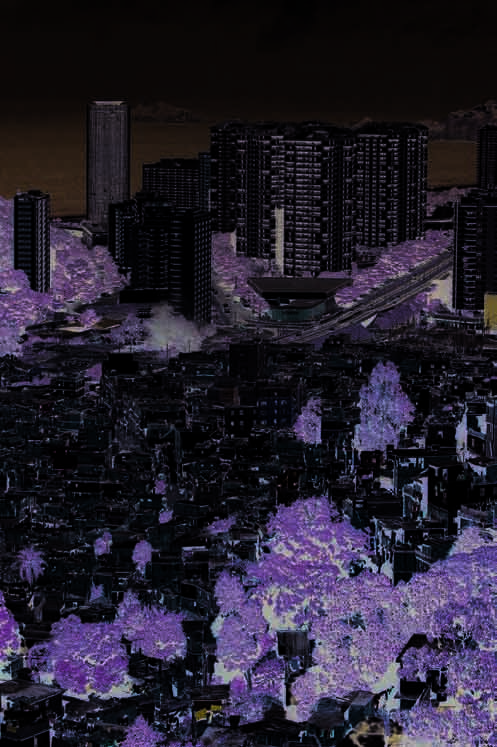

Figure 24 Aerial view of Rio de Janeiro. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 59

Figure 25 Rodrigo de Freitas Lagoon, Rio de Janeiro (East Atlantic Basins).. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 60

Figure 26 Infections and parasitic diseases (% of population affected) in municipalities of Paraíba do Sul River Basin (Minas Gerais, São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro states). 65

Figure 27 Estimated child mortality (<1 year old) per 1 000 births in the municipalities inside each state included in Paraíba do Sul River basin. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 66

Figure 28 True-colour French SPOT-3 satellite image of Rio de Janeiro. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 66

Figure 29 Priority basins in terms of freshwater fish biodiversity/endemism in the Atlantic Rainforest in Brazil Current. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 73

Figure 30 Biomass of phytoplankton in the river, estuary and the sea contiguous to the São Francisco River. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 74

Figure 31 Biomass of microplankton in the river, estuary and the sea contiguous to the São Francisco River. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 74

Figure 32 Biomass of macroplankton in the river, estuary and the sea contiguous to the São Francisco River. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 74

Figure 33 Fish production at the São Francisco River estuary. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 75

Figure 34 Fish production in the Itraipu River, tributary of São Francisco River basin.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 75

Figure 35 The main causal-effect relationships among the five GIWA concerns in the Brazil Current region. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 85

Figure 36 Mirim Lagoon and its drainage basin. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 87

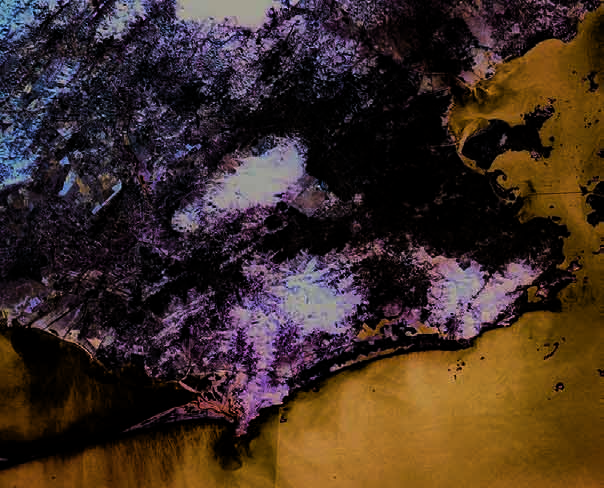

Figure 37 Erosion at Torotama Island. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 92

Figure 38 Causal chain diagram for the concern Unsustainable exploitation of fish and other living resources in Patos-Mirim Lagoon system.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 94

Figure 39 Causal chain diagram for the concern Pollution in Mirim Lagoon. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 97

Figure 40 Doce River basin. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 100

Figure 41 Doce River basin climate types. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 101

Figure 42 Specific stream flows in the Doce River basin. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 102

Figure 43 Water distribution/use in the Doce River basin.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 102

Figure 44 Degree of erosion in the Doce River basin. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 103

Figure 45 Water quality in the Doce River basin. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 103

Figure 46 Doce River basin and its main environmental problems.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 103

Figure 47 Causal chain diagram for the main concern Pollution and its issues in Doce River basin: Comprehensive version. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 106

Figure 48 Causal chain diagram for the main concern Pollution and its issues in Doce River basin: Version focused on the main sectors and root causes. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 107

Figure 49 Causal chain diagram for the main concern Pollution and its issues in Doce River basin: Selected root causes for policy options analysis.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 107

Figure 50 Causal chain diagram for the main concern Habitat and community modification in Doce River basin. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 108

Figure 51 Policy options for mitigating pollution in Mirim Lagoon basin, their links and selected options to be implemented. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 113

18

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 39 BRAZIL CURRENT

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

19

List of tables

Table 1

Hydrological characteristics in the Brazilian part of Brazil Current. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24

Table 2

Physical and chemical characteristics of Brazil Current.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

Table 3

Contribution of each region to the Brazilian GDP.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36

Table 4

Population growth rate in Brazilian states entirely or partially included in the Brazil Current region. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 37

Table 5

Hydroelectric power plants in South/Southeast Atlantic Basins 1997-2006. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 42

Table 6

Ports in Brazil Current with annual movement of goods above 10 million tonnes.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 45

Table 7

Sewage coverage in Brazil. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 46

Table 8

Basic sanitation indicators for urban households in Brazil.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 47

Table 9

Scoring table for South/Southeast Atlantic Basins, East Atlantic Basins and São Francisco River Basin.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 51

Table 10

Water availability and demand per sector. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 53

Table 11

Water demand/water availability ratio in basins of the Brazil Current region where water demand (D) is higher than available water (Q).. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 53

Table 12

Remaining domestic organic load, based on estimated values. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 60

Table 13

Collection and final disposal of municipal solid waste in Brazil Current. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 63

Table 14

Lagoons and wetlands in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil and in the departamentos of Rocha and Maldonado,

Uruguay: Main impact sources and threats to the habitat and ecosystems. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 71

Table 15

Variability and impacts of El Niño and La Niña on different Brazilian and GIWA regions.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 80

Table 16

Priority concerns selected for each basin in GIWA region 39, Brazil Current. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 85

Table 17

Water demand in Patos Lagoon and Mirim Lagoon basins. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 89

Table 18

Main economic activities in the Patos-Mirim Lagoon system. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 92

Table 19

Main root causes associated to the main concerns for Patos-Mirim Lagoon system. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 99

Table 20

Main economic activities in Doce River basin. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 102

Table 21

Summary of root causes for Pollution and Habitat and community modification in Doce River basin. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 108

Table 22

Probable direct, indirect, option, bequest, and existence benefits for PO-5. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 115

Table 23

Probable direct, indirect, option, bequest, and existence benefits for PO-7.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 115

Table 24

The costs for PO-5 and PO-7.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 115

Table 25

Probable direct, indirect, option, bequest, and existence benefits for PO-1. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 120

Table 26

Probable direct, indirect, option, bequest, and existence benefits for PO-2. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 120

Table 27

Probable direct, indirect, option, bequest, and existence benefits for PO-3. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 120

Table 28

The costs for PO-5 and PO-7.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 120

List of boxes

Box 1

Water domain issues in the Doce River basin waters.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 101

18

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 39 BRAZIL CURRENT

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

19

Regional definition

Marques, M. and B. Knoppers

This section describes the boundaries and the main physical and

Boundaries of the Brazil

socio-economic characteristics of the region in order to define the

Current region

area considered in the regional GIWA assessment and to provide

sufficient background information to establish the context within

Brazil Current, GIWA region 39, is a tropical/sub-tropical ocean margin

which the assessment was conducted.

governed by western boundary currents, a passive continental shelf

and moderate continental run-off (Walsh 1988, Ekau & Knoppers 1999).

Elevation/

N o

Depth (m)

r t h B

North Brazil

r

Amazon (40b)

a

0°N

z

Shelf LME (17)

i

4 000

l

North region

C u rr

S o u

2 000

e

t h E q .

n

C u r r e n t

t

3°S

1 000

500

100

Brazil Northeast (40a)

0

Pernambuco

-50

Northeast region

E

Alagoas

10°S

-200

10°S

Sergipe

-1 000

z i l C u r r e n t

East Brazil

Bahia

ra

13°S

São Fransisco

-2 000

Shelf LME (16)

B

River Basin (39c)

Brazil

East Atlantic

Abrolhos

Minas Gerais

Basins (39b)

East region

Bank

egions

Espírito Santo

20°S

Cape São Tomé

Rio de Janeiro

22°S

São Paulo

A r

Paraná

t

Southeast region

S O U T H A T L A N T I C O C E A N

rre n

Santa Catarina

u

C

a

r

i

n

e

-

L

M

South Brazil

Shelf LME (15)

il

South/Southeast

z

Atlantic Basins (39a)

29°S

Rio Grande do Sul

ra

B

30°S

20°C Winter

P

h

y

s

i

o

g

r

a

p

h

i

c

M

South region

GIW

Uruguay

33°S

East Uruguay

Patagonian shelf

East Atlantic Basin

LME (14)

of Uruguay (39)

© GIWA 2004

50°W

40°W

30°W

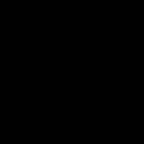

Figure 1

The continent, coast and shelf of the Brazil Current region and surrounding area.

Limits according to: Climate (Nimer 1972); tidal regimes (tide tables, Brazil Navy); western boundary currents NBC, South Equatorial Current SEC and Brazil Current BC (Peterson & Stramma 1990);

geological regions (Gerra 1962); geographical regions (Cruz et al. 1985); Large Marine Ecosystems LME 15, 16, 17 (Large Marine Ecosystems 2003) and; Brazil Current GIWA sub-regions South/

Southeast Atlantic, East Atlantic and São Francisco River Basin (the delta of the São Francisco River Basin is too smal to be shown); and GIWA region 40a Brazilian Northeast and 40b Amazon.

20

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 39 BRAZIL CURRENT

REGIONAL DEFINITION

21

It extends along the Brazilian coast from the São Francisco River delta

In Uruguay, five departamentos (political/administrative units) are

(latitude 10° 30´ S and longitude 32° W) in the northeastern Brazil,

entirely or partial y included in the Mirim's Lagoon catchment area:

to Chui River (latitude 34° S and longitude 58° W) in the southern

Cerro Largo, Treinta y Tres, Laval eja, Rocha and Maldonado.

Brazil (Figure 1). Its length, excluding contours of bays and islands, is

4 150 km or 58% of the Brazilian coastline (GERCO-PNMA 1996). The

The Brazil Current offshore-oceanic boundary fol ows the 200 nautical

total catchment area is 1.403 mil ion km2 inside the Brazilian territory

mile Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), as it encompasses the entire shelf

and 33 000 km2 (Mirim Lagoon portion) inside the Uruguayan territory.

down to its base and the western boundary currents. In the north at

For the purpose of the GIWA assessment, Brazil Current harbours three

about 10° S to 15° S it includes part of the South Equatorial Current

major, physical y and economical y distinct, drainage areas with small

(SEC), which impinges directly upon the shelf, and from about 15° S to

changes from the original division (ANEEL 2002): the São Francisco River

34° S, the southward meandering Brazil Current (BC) up to the reaches

Basin (0.634 mil ion km2), the East Atlantic Basins (0.545 mil ion km2)

of the Southwest Atlantic Convergence Zone (Figure 1). The tectonical y

and the South/Southeast Atlantic Basins (0.224 mil ion km2). The

passive Atlantic coast has only one large-sized basin (>200 000 km2 in

Uruguayan land portion that drains towards Brazilian territory (Mirim

area), which is the São Francisco River Basin (40-49 in Figure 2), a few

Lagoon) corresponds to 2.3% of the total regional area (Figure 2). The

medium-sized basins (10 000-200 000 km2 in area) and a large number

Brazil Current includes the entire Brazilian states of Espírito Santo and

of smal -sized basins (<10 000 km2 in area).

Rio de Janeiro, and part of the states of Pernambuco (PE), Alagoas (AL),

Sergipe (SE), Bahia (BA), Minas Gerais (MG), Goiás (GO), São Paulo (SP),

The GIWA region Brazil Current is essentially compatible with the old

Paraná (PR), Santa Catarina (SC) and Rio Grande do Sul (RG) (Figure 1).

definition of the Brazil Current Large Marine Ecosystem (Sherman 1993).

However, after the recent redefinition of Brazil's LMEs (Ekau & Knoppers

in press), the GIWA region Brazil Current now includes about half of the

Sub-regions

LME 16 East Brazil Shelf and the entire LME 15 South Brazil Shelf (Figure 1).

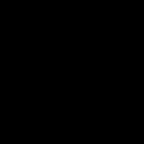

48

39a - South/Southeast Atlantic Basins

o

49

In recognition of the diversity of typological characteristics governing

39b - East Atlantic Basins

São Francisc

39c - São Francisco River Basin

the drainage basins and their adjacent shelf-oceanic realms, as previously

47

50

Aracaju

Grande

46

51

mentioned, the Brazil Current region gained three sub-regions:

Salvador

45

39a South/Southeast Atlantic Basins

52

53

39b East Atlantic Basins

44

43

nhonha

Jequiti

39c São Francisco River Basin

42

Brazil

54

55

41

Belo Horizonte Doce

Recently, the Brazilian coastal basins were sub-divided by the National

40

Vitoria

56

Agency of Water (ANA) (ANA 2002a) in a different number of basins,

57

58

Rio de Janeiro

compared to the former division used by the National Agency of Electric

59

Niteroi

80

Energy (ANEEL) (ANEEL 2002). However, for the objective of the GIWA

Santos

Paraguay

81

assessment and with the sole purpose of facilitating the geographical

82

identification of different basins, it was decided to keep the ANEEL's

83

Florianopolis

classification with numbers representing medium-sized basins (52,

Argentina

86

84

54, 56, 58, 81, 83, 87, 88) or areas encompassing several small basins or

85

Porto Alegre

sub-basins (40-49, 50, 51, 53, 55, 57, 59, 80, 82, 84, 85, 86). Eastern Mirim

Uruguay

87

Melo

Lagoon in the territory of Uruguay, has a small strip of land that forms

88

Treinta Y Tres

the Uruguay Atlantic Basin or Vertiente Atlántica (89 in Figure 2). From

Cebollati

Rocha

89

the oceanographic/marine point of view this area cannot be classified

as Brazil Current and therefore, it was assessed independently from the

© GIWA 2004

rest of the Brazil Current region.

Figure 2

Sub-division of the Brazil Current region: São Francisco

River Basin (basins 40-49); East Atlantic Basins (basins 50-

59); and South/Southeast Atlantic Basins (basins 80-88).

In the next sections, the drainage areas identified with numbers in

Note: Each number in the map (original y used by the National Agency of Electric

Energy-ANEEL) represents either a medium-sized basin or several smal -sized basins.

Figure 2 wil be frequently referred to, to facilitate the geographical

The strip of land marked as 89 in the map forms the Atlantic Basin of Uruguay

(Vertiente Atlántica in Spanish), which is assessed separately from Brazil Current.

location of the assessed impacts.

20

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 39 BRAZIL CURRENT

REGIONAL DEFINITION

21

Geographical settings

the marine environment. A periodical breaching of the sand bars,

The GIWA region Brazil Current covers, entirely or partial y, three of

al ows seawater inflow in some coastal lagoons, connecting them with

Brazil's five main economic regions (Silveira 1964, Cruz et al. 1985, see

the Atlantic Ocean and creating an abundant and cyclic biological

also Socio-economic characteristics of Brazil) and one of Uruguay's

diversity. Important archaeological sites, approximately 5 000 years

regions (Uruguayan East region). Along the Brazilian coast, Brazil Current

old, exist in this area. Evidence is found of the existence of pre-historical

includes a minor fraction (approximately 310 km) of the Northeastern

communities that constructed monuments known as cerritos de indios,

Brazil (from 10° 30´ S, 42° W to 13° S, 38° W) and the entire Eastern Brazil

where people were buried.

(13° S, 39° W to 22° S, 42° W), Southeastern Brazil (22° S, 42° W to 28° 30´ S,

52° W) and Southern Brazil (28° 30´ S, 52° W to 34° S, 58° W) geographical

The East Atlantic Basins (50-59 in Figure 2) extends between latitudes

regions. The lower sector of the inland of São Francisco River Basin

10° and 23° S and longitudes 37° and 46° W with a north-south

belongs to the Northeastern Brazil and the remainder, together with

orientation and is set between the São Francisco River basin and the

the entire East Atlantic Basins (Figure 1), belong to the Eastern Brazil.

coast. It drains parts of the states of Sergipe, Bahia, Minas Gerais and

The southern boundary of the East Atlantic Basins at Cape São Tomé

São Paulo and the entire states of Espírito Santo and Rio de Janeiro.

(22° S) corresponds to the limit between the Eastern and Southeastern

Its southern extent is limited by the Mantiqueira range, state of Rio de

Brazil. The South/Southeast Atlantic Basins includes parts of both the

Janeiro, its western extent by the Espinhaço range and towards the

Southern and the Southeastern Brazil.

north by the Diamantina Plateau and the Trombador range.

The Brazilian portion of South/Southeast Atlantic Basins extends

The São Francisco River Basin (Figure 3) covers the area between

between latitudes 22° and 32°S and longitudes 44° to 54°W with a

latitudes 7° and 21° S and longitudes 35° and 47° 40´ W, and 7.5% of the

northeast-southwest orientation and drains parts of the states of

Brazilian territory. It is an inland drainage basin about 2 700 km long

São Paulo, Paraná, Santa Catarina, Rio Grande do Sul towards the

with a single outlet at the coast. It is divided into the upper, middle,

coast. The Uruguayan portion of South/Southeast Atlantic Basins

lower-middle and lower reaches, including the São Francisco delta

corresponds to the administrative divisions (departamentos) of Cerro

plain. The upper reaches of the São Francisco River Basin in the south,

Largo, Treinta y Tres, Laval eja, Rocha and Maldonado included in Mirim

state of Minas Gerais, are delimited by the Canastra and Vertentes

Lagoon basin that drains through the São Gonçalo channel into the

ranges, which separate it from the Rio Grande River basin. To the east,

Patos Lagoon, which in turn is connected to the Atlantic Ocean. South/

it is separated from the East Atlantic Basins by the Serra do Espinhaço

Southeast Atlantic Basins harbours two distinct sectors: (i) the southern

range and the Diamantina Midlands. From south to north, it traverses

wide sector covering the Uruguay portion of Mirim Lagoon and the

via an extensive depression created by the Atlantic high plain and the

Brazilian area of the state of Rio Grande do Sul, the southern part of

Central Brazilian Plateau, as far as the city of Barra. Henceforth, it diverts

the state of Santa Catarina, between the cities of Chuy and Laguna,

towards the northeast reaching the city of Cabrobó and thereafter to

along the coast, and the inland, river carved, Meridian high plain, up

the southeast until the São Francisco delta, at the frontier of the state

to the border with the Paraná River basin; and (ii) the northern narrow

of Sergipe and Alagoas. The upper and middle reaches in the states of

sector that extends within parts of the states of Santa Catarina, Paraná,

Minas Gerais and Bahia comprise 83% of the basin, 16% comprising its

São Paulo and is backed by the Atlantic range paral el to the coast.

lower-middle and lower reaches, in the states of Pernambuco, Alagoas

and Sergipe, and the remaining 1% to the west, in the state of Goiás and

The Atlantic basin of Uruguay (89 in Figure 2) is one of the five

the Federal District (ANA 2002a).

hydrographical basins of Uruguay. It is formed by part of the Rocha and

Maldonado departamentos. It is a narrow strip of land with a coastline

about 220 km long (from the Brazil-Uruguay border, down to, and

including Punta del Este). This area encompasses part of the Humedales

del Este, and has several dunes and lagoons such as Garzón, Rocha,

Castil os and Negra. This area has in common with the state of Rio

Grande do Sul, southern Brazil, the fact that its dunes are formed by the

action of the winds that promote an accumulation of sand taken from

the surrounding beaches. Due to the intense accumulation of deposits,

these zones became relatively isolated and almost independent from

22

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 39 BRAZIL CURRENT

REGIONAL DEFINITION

23

Figure 3

Aerial view of São Francisco River.

(Photo: José Caldas/SocialPhotos)

Physical characteristics of the

Brazilian portion of the region

Drainage basins

of the entire basin's discharge to the coast. The southern sector (basins

The Brazilian portion of the South/Southeast Atlantic Basins comprises

85 to 87) is more complex, comprising inland and coastal basins, some

nine basin/group of basins (80-88) distributed in two distinct sectors.

of which are interlinked, and approximately half of the basin 88 lies

The average flow in the basins is 4 300 m3/s, the specific flow 19.2 l/s/km2,

outside the boundary of the state of Rio Grande do Sul, in the Uruguayan

the average precipitation 1 394 mm/year and evaporation 789 mm/year

territory. Most of the freshwater input to the coast is delivered via the

(Table 1). The northern sector, between the states of São Paulo (basin 80)

large Patos-Mirim Lagoon system, the average annual freshwater flow

and Santa Catarina (basin 84), is characterised by an array of smal -sized

rate through this estuary is 4 000 m3/s, and the remainder of the coast

rivers. The Ribeira-Iguape (state of São Paulo) and the Itajai rivers (state

receives minor freshwater input via coastal lagoons. The most important

of Santa Catarina) are the most important, they account for about 10%

rivers are the Mampituba, Jacuí, Taquari and Jaguarão.

22

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 39 BRAZIL CURRENT

REGIONAL DEFINITION

23

Table 1

Hydrological characteristics in the Brazilian part of

climatic and flow regimes. About 50% of the drainage basin lies within

Brazil Current.

the Brazil Drought Polygon of the Northeast. Its river sources lie in the

Basins/

Area

Rainfall

Evaporation Average flow Specific flow

humid Canastra Mountains in Minas Gerais. Part of the middle and the

sub-basins1

(km²)

(mm/year)

(mm/year)

(m3/s)

(l/s/km2)

80-88

224 000

1 394

789

4 300

19.2

lower-middle sectors are governed by semi-arid conditions and the

54-59

303 000

1 229

847

3 670

12.1

São Francisco delta by humid conditions. About 84% of the rainfal is

50-53

240 000

895

806

608

2.8

lost by evaporation, 11% corresponds to the river run-off and about 5%

replenishes the water table. São Francisco River Basin has 36 tributaries,

40-49

634 000

916

774

2 850

4.5

Note: 1Used by the National Agency of Electric Energy (ANEEL). (Source: ANEEL 2002)

of which 19 are perennial, the most important being the Paraopeba,

das Velhas and Verde rivers on the right bank, and the Paracatu, Urucuia,

The East Atlantic Basins comprises 10 groups of basins (50-59 in Figure 2)

Caranhanha, Corrente and Grande rivers on the left bank. Except for

with over 35 smal to medium-sized rivers, al oriented towards the coast.

the Verde River, the watersheds of these rivers lie outside the Drought

The mean annual water volume of the East Atlantic Basins is 117 km3

Polygon and, although they represent only 50% of the basin's total area,

and the average flow is 4 350 m3/s. The Basins are characterised by a

they account for 85% of low water flow and 74% of the entire basin's

climatic gradient with dryer conditions in the middle and upper reaches

flow delivered to the coast (ANA 2002a).

of the northern watersheds and humid conditions all along the central

and southern watersheds. The run-off yield of the rivers increases

Lakes are scarce in the Atlantic Rainforest region, but the lower São

considerably from north to south. The small southward located basins

Francisco River and the lower alluvial reaches of the largest rivers of the

of Rio de Janeiro state (basins 59 in Figure 2), which drains the coastal

East Atlantic Basins, contain temporary and permanent flood plain lakes.

lagoons and the Bays of Guanabara, Sepetiba and Angra dos Reis of the

The rivers of the East Atlantic Basins and particularly the São Francisco

state of Rio de Janeiro has been al otted to the South/Southeast Atlantic

River Basin are spiked by many smal , medium and large-sized dam