Global International

Waters Assessment

Regional assessments

Other reports in this series:

Russian Arctic GIWA Regional assessment 1a

Caribbean Sea/Small Islands GIWA Regional assessment 3a

Caribbean Islands GIWA Regional assessment 4

Barents Sea GIWA Regional assessment 11

Baltic Sea GIWA Regional assessment 17

Caspian Sea GIWA Regional assessment 23

Aral Sea GIWA Regional assessment 24

Gulf of California/Colorado River Basin GIWA Regional assessment 27

Oyashio Current GIWA Regional assessment 31

Yellow Sea GIWA Regional assessment 34

East China Sea GIWA Regional assessment 36

Patagonian Shelf GIWA Regional assessment 38

Brazil Current GIWA Regional assessment 39

Amazon Basin GIWA Regional assessment 40b

Canary Current GIWA Regional assessment 41

Guinea Current GIWA Regional assessment 42

Lake Chad Basin GIWA Regional assessment 43

Benguela Current GIWA Regional assessment 44

Indian Ocean Islands GIWA Regional assessment 45b

East African Rift Valley Lakes GIWA Regional assessment 47

South China Sea GIWA Regional assessment 54

Mekong River GIWA Regional assessment 55

Sulu-Celebes (Sulawesi) Sea GIWA Regional assessment 56

Indonesian Seas GIWA Regional assessment 57

Pacifi c Islands GIWA Regional assessment 62

Humboldt Current GIWA Regional assessment 64

Global International

Waters Assessment

Regional assessment 30

Sea of Okhotsk

GIWA report production

Series editor: Ulla Li Zweifel

Editorial assistance: Matthew Fortnam,

Russel Arthurton, Kristin Bertilius

Maps & GIS: Rasmus Göransson

Design & graphics: Joakim Palmqvist

Global International Waters Assessment

Sea of Okhotsk, GIWA Regional assessment 30

Published by the University of Kalmar on behalf of

United Nations Environment Programme

© 2006 United Nations Environment Programme

ISSN 1651-940X

University of Kalmar

SE-391 82 Kalmar

Sweden

United Nations Environment Programme

PO Box 30552,

Nairobi, Kenya

This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and

in any form for educational or non-profi t purposes without

special permission from the copyright holder, provided

acknowledgement of the source is made. No use of this

publication may be made for resale or for any other commercial

purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from the

United Nations Environment Programme.

CITATIONS

When citing this report, please use:

UNEP, 2006. Alekseev, A.V., Baklanov, P.J., Arzamastsev, I.S.,

Blinov, Yu.G., Fedorovskii, A.S., Kachur, A.N., Khrapchenkov, F.F.,

Medvedeva, I.A., Minakir, P.A., Titova, G.D., Vlasov, A.V., Voronov,

B.A. and H. Ishitobi. Sea of Okhotsk, GIWA Regional assessment 30.

University of Kalmar, Kalmar, Sweden.

DISCLAIMER

The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors

and do not necessarily refl ect those of UNEP. The designations

employed and the presentations do not imply the expressions

of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNEP or cooperating

agencies concerning the legal status of any country, territory,

city or areas or its authority, or concerning the delimitation of its

frontiers or boundaries.

This publication has been peer-reviewed and the information

herein is believed to be reliable, but the publisher does not

warrant its completeness or accuracy.

Publishing house: Kirjastusaktsiaselts MATS, Tallinn

Printed in Estonia by Tallinna Raamatutrükikoda, 2006

Contents

Executive summary

9

Abbreviations and acronyms

12

Regional defi nition

14

Boundaries of the Sea of Okhotsk region

14

Physical characteristics

15

Socio-economic characteristics

18

Assessment 24

Freshwater shortage

24

Pollution

25

Habitat and community modifi cation

28

Unsustainable exploitation of fi sh and other living resources

30

Global change

32

Priority concerns for further analysis

32

Causal chain analysis

33

Eutrophication

33

Oil spills

35

Overexploitation of fi sh and other living resources

36

Policy options

39

Eutrophication in the Amur River Basin sub-system

39

Oil spills in the Okhotsk Sea sub-system

40

Overexploitation of fi sh and other living resource in the Sea of Okhotsk region

42

Conclusions and recommendations

44

Recommendations

45

References 46

Annexes 49

Annex I List of contributing authors and organisations

49

Annex II Detailed scoring tables

51

The Global International Waters Assessment

i

The GIWA methodology

vii

CONTENTS

Executive summary

The GIWA Sea of Okhotsk region comprises the Okhotsk Sea and its

and unique ecosystems. The River supports more fi sh species than any

surrounding catchments, the largest of which, by far, is the Amur River

other Russian river, with more than 120 species, 18 of which are endemic

Basin a transboundary basin shared between China, Mongolia, Russia

and eight endangered. The Basin's territory is socially, politically and

and North Korea. Other basins draining into the Okhotsk Sea include

economically diverse, with varying development patterns. These

those of the Khabarovskiy Kray, Magadanskaya and Kamchatskaya

diff erences can be an obstacle to international cooperation in the

oblasts in Russia.

Basin.

For the purpose of this report, the Sea of Okhotsk region can be divided

The population of the Okhotsk Sea sub-system is approximately

into two sub-systems: the Okhotsk Sea (marine) and the Amur River

8.7 million, of which 2.7 million live in Russia and about 6 million

Basin (freshwater).

in Japan. The Russian coast, except for Sakhalin Island, is sparsely

populated, with a population density of approximately 1.5 people per

The Okhotsk Sea sub-system has an area of approximately 1.6 million km2

km². The population of the Amur River Basin sub-system fl uctuates

and a coastline 10 460 km in length. More than 95% of the coast of the

between 70 and 80 million people, 5 million of whom live in Russia, 65-

Sea lies within Russian territory, with Hokkaido Island (Japan) accounting

75 million in China and less than 50 000 in Mongolia. The North Korean

for the remainder. The Sea contains over 50% of the Russian Far East's

part of the Basin is largely unpopulated. The Basin's average population

bio-resources and is regarded as the richest fi shery region in the world,

density is 35 people/km², though 105 people/km² in the catchment

with approxi mately 340 fi sh species. Its continental shelves are rich

of the Songhua River (a tributary of the Amur River in China) which

in hydrocarbon resources. Although the majority of the Sea is within

includes large cities such as Harbin, Jilin and Mudanjiang.

Russia's exclusive economic zone (EEZ), its centre is high seas (neutral

zone), and its southeastern part, adjacent to Hokkaido Island, lies within

This report presents the results of the UNEP/Global International Waters

Japanese territorial waters. The Sea's coast is generally characterised by

Assessment for the Sea of Okhotsk region (GIWA region 30). It is based

mountainous relief which demarks the watershed a narrow land belt

on the outputs of three workshops, conducted in Vladivostok, Russia,

100-150 km wide.

in 2001, 2003 and 2004 respectively. The Task team consisted of local

experts with various specialist backgrounds regarding environmental

The sub-system Amur River Basin known in China as the Heilong Jiang

and socio-economic impact assessments in the Sea of Okhotsk region.

is one of the largest river systems in Asia, covering about 2 million km².

The results are the consensus of the team and other participants of the

The River is one of the ten longest in the world (approximately

workshops (see Annex I) and are substantiated using data obtained from

4 345 km) and its course forms the boundary between Russia and

a number of sources, including international and national programmes

China for 3 000 km. The average annual discharge of the Amur River is

and projects operating within the region. For the Amur River Basin sub-

369 km³. The Amur River Basin hosts some of the world's most diverse

system, this report assesses only the Russian territory and two of the

and productive habitats and encompasses extensive areas of complex

riparian provinces of China (Heilongjiang and Jilin).

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

9

During the Scaling and scoping workshop, the experts prioritised the

and China, threatening biological diversity and endangered species in

GIWA major concerns in the following rank order:

the Basin, notably several migratory bird species.

1 Pollution

2

Unsustainable exploitation of fi sh and other living resources

The immediate causes of eutrophication in the Amur River Basin

3 Freshwater

shortage

sub-system were identifi ed as the considerable quantities of organic

4

Habitat and community modifi cation

matter and biogenic material in domestic and industrial wastewaters

5 Global

change

and surface run-off . Run-off of fertilisers from agricultural areas also

stimulates eutrophication. The sectors responsible for eutrophication

The priority concerns were identifi ed as Pollution, specifi cally the issue

were identifi ed as industry, urbanisation, agriculture and aquaculture. Oil

of eutrophication (for the Amur River Basin sub-system) and oil spills (for

development on the Russian Sakhalin shelf has increased the intensity

Okhotsk Sea sub-system), and the Unsustainable exploitation of fi sh and

of oil-related marine traffi

c transiting the Okhotsk Sea. Although there

other living resources (for the whole Sea of Okhotsk region).

have been relatively few incidents to date, there is always a risk of a spill

through deliberate or accidental discharges. Oil is also discharged by the

In the Okhotsk Sea sub-system, oil and gas exploitation provides

numerous fi shing vessels operating on the Sea. Overfi shing is aff ecting

economic benefi ts for the region but discharges signifi cant quantities

the ecosystems of the Sea of Okhotsk region. Fish catches have declined

of wastewater as by-products of drilling operations. Although only

by one-third due to depleted fi sh stocks. The main cause of the stock

three major oil spills have occurred in the region since the 1990s, the

depletion is overexploitation where the Total Allowable Catches (TACs)

future expansion of the oil industry in the region will increase the risk

of Russia are exceeded by 2 to 10 times.

of spills. In the Amur River Basin, eutrophication has been attributed to

nutrient enrichment caused by the discharge of domestic wastewater

In the future, these aquatic concerns will remain the most signifi cant

and surface run-off from the catchment area. It is expected to increase

anthropogenic threats to the region. Mitigatory actions should include:

in severity over the next 20 years, with the communities of the lower

waste control and treatment in the Amur River Basin sub-system; the

Amur River Basin and Songhua River Basin experiencing the greatest

prevention of oil spills and the development of emergency response

socio-economic impacts. A signifi cant proportion of chemical pollution

measures; and sustainable fi sheries management.

originates from pesticides used in the agricultural sector, as well as

heavy metals released by other human activities.

In the Amur River Basin sub-system, there are a number of

institutional weaknesses which are either promoting or failing to

Over the past 15 years, total fi sh catches in the Sea of Okhotsk have

prevent transboundary pollution. While there is limited basin-wide

drastically reduced. Catches of pollock the major commercial species

cooperation, there is recognition of the need to work together to

in the Okhotsk Sea sub-system have decreased signifi cantly, though

address transboundary issues. There is limited stakeholder involvement

estimating total catches is extremely diffi

cult. In the Amur River Basin

in the decision-making process and public awareness of pollution issues

sub-system, stocks of salmon and sturgeon have declined as a result of

is rather rudimentary. A major hindrance for policy-makers when setting

overfi shing and the degradation of spawning habitats. The problem is

priorities for remediation is the lack of knowledge of the ecological

exacerbated by inappropriate fi shing practices as well as adverse natural

characteristics and their reaction to human activities. A technical

conditions. It is expected that salmon will continue to be overfi shed for

problem is the poor condition of wastewater treatment infrastructure.

the foreseeable future.

In the Sea of Okhotsk region, overcapacity of the fi shing fl eet is a

The concern of Habitat and community modifi cation was assessed as

major factor in the overexploitation of the region's commercial stocks.

having a slight impact. In the Okhotsk Sea, human activities have altered

The introduction of auctions of fi sh quota-rights, in addition to a

the habitats of pollock, Humpback whale and the endangered Gray

burdensome tax system, has reduced the profi tability of the fi sheries,

whale, among other species. Whales are threatened by the increasing

resulting in fi shermen undertaking poaching and illegal fi shing to

exploration and extraction of marine oil and gas reserves. Habitat and

supply a black market for fi sh products. Regional cooperation in

community modifi cation is expected to increase in severity in the future

combating illegal fi shing is limited and national laws and regulations

due to further oil and gas development, which will also necessitate the

are undermined by deep-rooted corruption and weak enforcement.

development of bulk-oil complexes and harbours for large tankers. In

There is a lack of fi sheries statistics and monitoring programmes, and

the Amur River Basin, the extent of wetlands has declined in both Russia

fi shermen lack awareness of the long-term impacts of overfi shing.

10

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 30 SEA OF OKHOTSK

Oil spills in the Okhotsk sub-system were considered to be a

The Policy options recommended to address the water-related problems

considerable future threat because, although there has been rather

of the Sea of Okhotsk region are based on the policies adopted at the

limited oil contamination to date, the extensive oil and gas development,

United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED)

particularly on the continental shelf of Sakhalin (Russia), and increased

and the World Summit on Sustainable Development (WSSD). Russian

shipment of oil across the Sea, will signifi cantly increase the risk of spills.

environmental and development legislation was also considered

While there has been considerable eff ort in rapidly developing the oil

during their formulation. The measures discussed in the conclusions

and gas industry in the region, progress in establishing emergency

and recommendations of this report not only aim to preserve and

contingency plans was considered unsatisfactory.

rehabilitate aquatic ecosystems in the region, but also to prevent future

eutrophication, oil spills and overexploitation of fi sh resources.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

11

Abbreviations and acronyms

BOD Biochemical

Oxygen

Demand

CCA

Causal Chain Analysis

CITES

Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna

DDT Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane

EEZ Exclusive

Economic

Zone

EIA

Environmental Impact Assessment

FAO

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

FEB RAS Far East Branch of Russian Academy of Sciences

GDP Gross

Domestic

Product

GEF Global

Environment

Facility

GIWA

Global International Waters Assessment

GRP Gross

Regional

Product

HCCH Hexachlorocyclohexane

IUCN

The World Conservation Union

MARPOL International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution of Sea by Oil

PICES North

Pacifi

c

Marine

Science

Organization

RSFSR

Russian Soviet Federated Socialist Republic

SOC Stable

Organic

Compounds

TAC Total

Allowable

Catch

TINRO

Pacifi c Scientifi c Research Institute of Fisheries and Oceanography

UNCED

United Nations Conference on Environment and Development

UNCLOS United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea

UNEP

United Nations Environment Programme

USD United

States

Dollar

USSR

Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

WSSD

World Summit on Sustainable Development

WWF World

Wildlife

Fund

12

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 30 SEA OF OKHOTSK

List of figures

Figure 1

Boundaries of the GIWA Sea of Okhotsk region.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

Figure 3

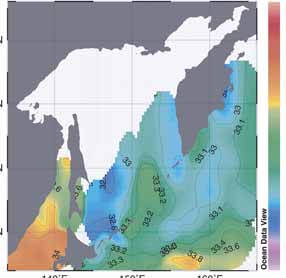

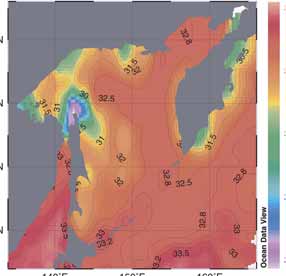

Sea surface water temperatures in February and August. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

Figure 2

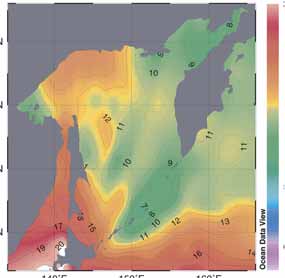

General water circulation. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

Figure 4

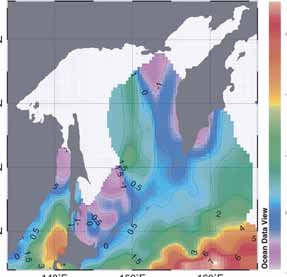

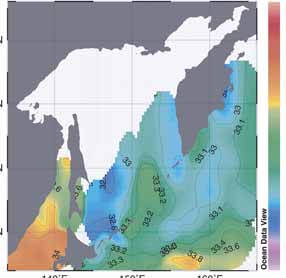

Salinity of surface water in February and August.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

Figure 5

Population density of the Sea of Okhotsk region. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

Figure 6

Distribution of industries in the Sea of Okhotsk Basin. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

Figure 7

Oil production volumes. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

Figure 8

Areas of prospective development of the oil and gas fields in the Sea of Okhotsk region. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

Figure 9

Natural resources of the Sea of Okhotsk sub-system.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

Figure 10

Catches of commercial fish by the Russian fleet in the Okhotsk Sea.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

Figure 11

Distribution of anthropogenic pressures in the Sea of Okhotsk Basin. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28

Figure 12

Synergies and inter-linkages between the GIWA concerns. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32

Figure 13

Causal chain diagram illustrating the causal links for eutrophication in the Amur River Basin. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34

Figure 14

Causal chain diagram illustrating the causal links for oil spills in the Sea of Okhotsk. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36

Figure 15

Causal chain diagram illustrating the causal links for overexploitation in the Sea of Okhotsk region. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 38

List of tables

Table 1

Basic hydrological and water quality characteristics of the Amur River . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

Table 2

Basic economic characteristics of the administrative regions of the Sea of Okhotsk basin. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

Table 3

Sectoral structure of industrial output in the Far East of Russia in 2000. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

Table 4

Consumption of freshwater in the Russian adminstrative regions of the Okhotsk sea. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22

Table 5

Scoring table for Sea of Okhotsk. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24

Table 6

Water discharge and chemical composition of water near the mouth of the Amur River . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25

Table 7

Concentrations of various dissolved and suspended metals in the Amur River . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26

Table 8

Catches of commercial fish from the Sea of Okhotsk between 1992 and 2003 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

13

Regional defi nition

This section describes the boundaries and the main physical and

Boundaries of the Sea of

socio-economic characteristics of the region in order to defi ne the

Okhotsk region

area considered in the regional GIWA Assessment and to provide

suffi

cient background information to establish the context within

The GIWA Sea of Okhotsk region comprises the Okhotsk Sea sub-

which the assessment was conducted.

system and its surrounding catchments (Figure 1), the largest of which,

by far, is the Amur River Basin sub-system a transboundary basin

Uttyakh

Chukotskiy avtonomnyy okrug

Elevation/

ve

Ev

Ev ki

kiy

y

enkiyskiy a

Penzhina

Depth (m)

Oklan

Koryakskiy avtonomnyy okrug

4 000

Krasnoyarskiy kray

Paren'

2 000

Gizhiga

Respublika Sakha(Yakutiya)

Magadanskaya oblast'

1 000

Yakutsk

500

Okh Ku

100

o

Y

k

t

a

a

h

a

m

d

t

Palana

uy U

a

n

l

0

'

Vo

b

eta

e

y

Magadan

ampolk

K

y

In

Kava

a

ya

-50

Tig

a

il'

Urak

-200

Russia

Okhotsk

l'ya

-1 000

U

Irkutsk

ts

t

rkutsk

-2 000

Respublika Buryatiya

Icha

Kamchatskaya oblast'

Ul

Ulan Ude

an Ud

Gulyuy

M

Suchboatar

Chitinskaya oblast'

ay

va

Nercha

Ze

a

Chita

A

iko

rgun'

ya

Selenge

tn

Uda

Shilka

lo

P

Darhan

Chatanga

Ze

Amurskaya

Tov

Aginskoye

Aginskiy

y

oblast'

Buryatskiy

Huma He

a

Ulaanbaatar

Amgun'

Ingoda

avtonomnyy

Selemzdha

Uldz Gol

Onon

okrug

Dzuunmod

Hentiy

G

Dornod

an

Tom'

H

T

e

g

ur

y

Ondorhaan

n

m

Choybalsan

ia

Blagoveshchensk

Khabarovskiy Am

'

J

Ty

kray

r

Dundgovi

Kerulen

xon

Hailar He

en

m

i

Kur

Sakhalinskaya

Or

Y

a

Gol

rm

a

U

oblast'

Mongolia

Bureya

N

C

l

h

u

Nemo

Baruun Urt

a

H

r He

Birobidzhan

o

e

Saynshand

Heilongjiang

r

Yevreyskaya

Suhbaatar

H

Nuyur

e

avtonomnaya oblast'

Khabarovsk

K

Dornogovi

h

China

Qiqihar

or

Hulan He

Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk

ri

Songhua Jiang

Songhua Jiang

ssu

Bikin

U

LHarbin

g

Armu

Nei Mongol

a

n

li

ia

Muling He

Primorskiy

Jilin

n

J

H

kray

Baotou

e

I

l

Changchun

udan

i

Huhot

s

M

t

ri

a

Jilin

ya

ssu

U

Er

Japan

Hebei

d aoJ

Fushun

ia

Vladivostok

Hokkaido

n

0

500 km

Liaoning

Yinma He

Shanxi

Beijing

Sapporo

Ch'ongjin

Anshan

Figure 1

Boundaries of the GIWA Sea of Okhotsk region.

14

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 30 SEA OF OKHOTSK

100-300 km in width and shared between China, Mongolia, Russia and

Changes to the distribution and interactions of baric formations, as well

North Korea. Other basins draining into the Okhotsk Sea include those

as the Sea's position between continental Asia and the Pacifi c Ocean,

of the Khabarovskiy Kray, Magadanskaya and Kamchatskaya oblasts in

are major factors forming the monsoonal climate and Sea's hydrological

Russia.

conditions. The dominant meteorological features that determine

atmospheric circulation in the region are the Aleutian Low, North Pacifi c

The Okhotsk Sea is situated at the margin of the northwestern Pacifi c

High and Siberian anticyclone in winter, and the Far-Eastern depression

Ocean between 43°43' and 62°42' N, and 135°10' and 164°54' E. It is

and Okhotsk anticyclone in summer. The generally monsoonal climatic

separated from the open ocean by the chain of the Kuril Islands and the

conditions are often disturbed by cyclones which traverse the region

Kamchatka Peninsula. The Sea's limits are demarked by Hokkaido Island

from southwest to northeast. The winter, particularly in the northern

to the south and west, and the coast of Sakhalin and the Asian mainland

Sea, is long and severe, with frequent wind and snow storms. In the

to the east. The Sea's maximum length and width are 2 463 km and

summer, high precipitation rates, mist and fog are typical, whereas

1 500 km, respectively. It has an area of approximately 1.6 million km2, a

the spring and autumn seasons are short, cold and cloudy. The cold

coastline 10 460 km in length and a total water volume of approximately

period lasts 120-130 days in the south and 210-220 days in the north

1.3 million km3 (Arzamastsev et al. 2001). The Okhotsk Sea is connected

of the region (Rostov et al. 2002). The cool, northern air masses have

to the Pacifi c Ocean by the numerous straits of the Kuril Islands, to

greater infl uence than the warmer air masses from the south, resulting

the Sea of Japan by La Perouse Strait and to the Amur estuary by the

in a negative heat exchange on the surface. As a result of these distinct

Nevelskoy and Tatar straits. The depth of the sea averages 821 m but

meteorological characteristics, the Okhotsk Sea is the coldest of the

reaches a maximum of between 3 374 m and 3 521 m within the Kuril

Far-Eastern seas.

hollow (Alekseev & Bogdanov 1991, Dobrovol'sky & Zalogin 1982).

From May to September, light southerly winds (2-5 m/s) prevail. These

winds can intensify to over 20 m/s up to four times a year as a result

of cyclones and typhoons, with a maximum frequency from August

Physical characteristics

to September. During the cold season, strong northerly winds with

velocities of 5-10 m/s prevail. Wind speed and direction diff er markedly

Approximately 70% of the region's land is characterised by mountains

in the various areas of the Sea. Maximum wind speeds reach 25-30 m/s

1 000-2 000 m above sea level. Low-lying areas are found mainly in the

in the northeastern and western parts of the Okhotsk Sea, 30-35 m/s in

Kamchatka coastal zone, the Penzhinskaya Gulf and in the middle and

the central and eastern areas, and over 40 m/s in the south. The autumn-

lower reaches of the Amur River. In these regions of low relief there are

winter storm winds are characterised by greater strength and duration

extensive swamps and marshes. The watershed of the Sea of Okhotsk

than those in the summer. The southern and south-eastern areas of

region is formed by the Middle Ridge of the Kamchatka, Koryak and

the Okhotsk Sea are the most prone to unstable weather systems. The

Kolyma highlands, and the Dzugdzur, Stanovoi and Yablonovy ridges.

considerable spatial extent of the Sea, in combination with frequent and

The Sikhote-Alin Mountains separate the Okhotsk Sea from the

strong winds, allows intense seas and swell (waves are 4-11 m high) to

Japanese basins.

develop (Rostov et al. 2002). The hydro-meteorological characteristics

of the region create treacherous conditions for marine-based human

Okhotsk Sea sub-system

activities.

Climate and meteorological characteristics

The Okhotsk Sea sub-system is located within the monsoon climatic

Hydrology

zone of the moderate latitudes. The northern region of the Sea is

The hydrological conditions of the Okhotsk Sea are determined by the

strongly infl uenced by the Arctic climate. Average July temperatures

particularities of its geographical location; its considerable meridional

range from 8 to 16°C, while, in January, temperatures fl uctuate

extent; its vulnerability to severe climatic conditions; the nature of

between 8 and -32°C (Rostov et al. 2002). The Kamchatka coast, the

vertical and horizontal circulation; the seabed relief, and its water

western coast of the Okhotsk Sea and eastern Sakhalin form parts of

exchange with the Pacifi c Ocean and Sea of Japan. The hydrology of

the cold agroclimatic belt. The eastern portion of the Amur River Basin

the coastal waters is additionally infl uenced by continental discharges,

sub-system is within the monsoonal climate zone, whereas its western

tides and the geographic confi guration of the coastline.

portion has continental climatic features.

REGIONAL DEFINITION

15

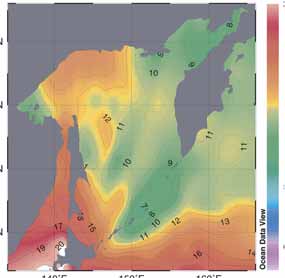

In general, the surface water temperature decreases from south to

north except during certain summer months when a more mixed

pattern is observed (August; Figure 3). Average annual temperatures

in the north and south reach 5-7°C and 2-3°C, respectively. Signifi cant

annual variations of surface water temperatures exist throughout

the Sea (10-19°C) which attenuate with depth. Between May and

Magadan

November, the average monthly water temperatures remain positive.

The warmest waters are found in the southernmost part of the sea

near the La Perouse Strait and Hokkaido Island. In October, the surface

water temperature decreases approximately two-fold and in November

changes to its winter spatial distribution. In February and March, surface

water temperatures of -1.0 to -1.8°C result in a considerable part of the

Uda

Russia

Sea being covered by ice (February; Figure 3) (Rostov et al. 2002). In the

Amgun'

southeastern area of the Sea and to the northwest of the Kuril Islands,

the water temperatures seldom register negative values (PICES 2004).

ur

Am

General cyclonic water circulation occurs around the periphery of the

Khabarovsk

Okhotsk Sea (Figure 2). In addition, there are localised gyres and smaller

Yu

n

h o akhal

k

s

eddies. Stable anti-cyclonic circulation is active over the TINRO hollow, to

ri

ssu

U

the west of the southern extremity of Kamchatka and in close proximity

to the Kuril Hollow fall. The major currents in the region include the

apan

Penzhinskoye, Yamskoye, North-Okhotsk currents and counter-currents,

and the East-Sakhalin, Middle and Soya currents.

Figure 2

General water circulation.

(Source: Arzamastsev et al. 2001)

20

the deepest, 3 000 m and 1 900 m,

February

August

6

respectively (Lapko & Radchenko

60°N

60°N

2000).

15

4

55°N

55°N

The general pattern of water

10

circulation is subject to considerable

2

seasonal variation. In autumn, the

50°N

50°N

fl ow rates of the currents increase,

5

and, in winter, currents fl owing

0

south and southwest are observed

i

ew

i

ew

45°N

V

45°N

V

ta

ta

0

in areas free from sea ice. Periodic

ean Da

ean Da

Oc

Oc

currents have greatest velocity

-2

140°N

150°N

160°N

140°N

150°N

160°N

Figure 3

Sea surface water temperatures in February and August.

in the south and around the

(Source: Arzamastsev et al. 2001)

periphery of the sea, including the

coastal belt, bays, straits and narrow

The straits connecting the Okhotsk Sea to the Sea of Japan and the

waters. Off shore tidal currents are weak, approximately 5-10 cm/s, while

Pacifi c Ocean allow water exchange. The Nevelskoy and La Perouse

tidal currents near the coast, in bays and straits, and over submerged

straits are relatively narrow and shallow, which limits water exchange

shoals are stronger (Zalogin & Kosarev 1999).

with the Sea of Japan. Conversely, the straits of the Kuril Islands ridge

facilitate greater water exchange as they are approximately 500 km wide

Severe winter frosts and sea ice cause intense cooling of sea surface

and are considerably deeper. The Bussol and Kruzenshtern straits are

waters. The sea ice is formed locally, and both stagnant and drift ice are

16

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 30 SEA OF OKHOTSK

present. The severity of ice conditions in the Okhotsk Sea is comparable

Amur River Basin sub-system

to the Arctic seas (Lapko & Radchenko 2000). The annual ice period lasts

The sub-system Amur River Basin, known in China as the Heilong Jiang,

for a maximum of 290 days, an average of 260 days in the northwest,

is one of the largest river systems in Asia, covering about 2 million km².

190-200 days in the north and the Sakhalin coasts, and 110-120 days in

The River is one of the ten longest in the world (approximately

the south. During severe winters, ice cover can occupy up to 99%

4 345 km) and its course forms the

of the water area and, in milder winters, about 65%. Generally, ice

Table 1 Basic

hydrological boundary between Russia and China for

and water quality

formation begins in the northwestern part of the sea in November,

3 000 km. It originates from the Argun/

characteristics of

but as early as October in areas with considerable water freshening.

the Amur River

Urgun (Russia-China border) and Shilka

The ice cover gradually extends southwards along the western and

Characteristic

Value

(Russia) rivers, is joined by the Songhua

eastern coasts, and eventually to the open sea. In December, the

Water run-off, average,

River (China), and later meets the Ussuri/

369.1

long-term, km³

consolidated fast ice is formed in the bays and bights (Lapko &

Wusuli River (Russia-China border) and

Run-off maximum,

459.2

Radchenko 2000). In January and February, the ice fi elds occupy

annual, km³

the Zeya and Bureya Rivers (Russia). The

Run-off minimum,

the northwestern and central parts of the sea. The drift ice

135.0

Amur then fl ows north until it reaches its

annual, km³

reaches a great density and is subject to intense compression and

Maximum water

mouth on the Tatar Strait from where it

40 000

discharge, m³/s

hummocking.

fl ows into the Okhotsk Sea.

Minimum water

153

discharge, m³/s

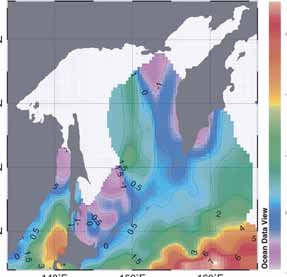

Salinity

Average annual flow

The average discharge of the Amur River

of detritus, millions of

24.0

The salinity of the Okhotsk Sea is largely determined by the

tonnes

is 11 700 m3/s (369 km3/year). During

hydrological cycle in terms of the balance between precipitation

Average annual water

90.0

spring and summer (April-September)

turbidity, mg/dm³

and evaporation; the eff ect of sea ice formation and melting

almost 75% of the annual discharge is

Maximum water

517.0

processes; continental discharges to the coastal zone; and water

turbidity, mg/dm³

recorded, while only about 14-25% fl ows

Average annual flow

exchange with adjacent seas. The salinity of coastal surface waters

during autumn and winter (October-

of dissolved matter,

20.23

in the northwestern part of the Sea has a large annual variance of

millions of tonnes

March). Among the major tributaries

including Ca2+

2.34

20-25 to 30-33. In summer and early autumn, the salinity of the

contributing to the Amur River's total

Mg2+

0.74

Sea is less than in winter when it increases as a result of ice formation

discharge are the Zeya (17%), Ussuri/

Na+ + K+

1.60

and a reduction in continental discharge (see Figure 4). Off shore

Wusuli (12%), Bureya (7.7%), Amgun

HCO -

10.40

and in the southwestern sea, salinity variations are less pronounced

3

(5.7%), Shilka (4.7%), Tunguska (3.5%),

2-

(31.0-33.5) (Rostov et al. 2002) due to water exchange via the La

SO

2.10

4

Argun/Urgun (2.9%), Anyui (1.9%),

Perouse and Kuril straits. The seasonal fl uctuations in salinity diff er

C- 1.10

Gorin (1.6%) and Gur (1.4%). The smaller

Average annual flow of

depending on location. There is a general trend of increasing salinity

tributaries contribute between 0.1

organic matter, millions

5.3

down the water column in all seasons and there are comparably few

of tonnes

and 1.0% to the annual discharge. The

(Source: Estimates of Institute of Water and

spatial and temporal variations.

Ecological Problems, FEB RAS)

smaller river basins of Khabarovskiy Kray,

Magadanskaya and Kamchatskaya

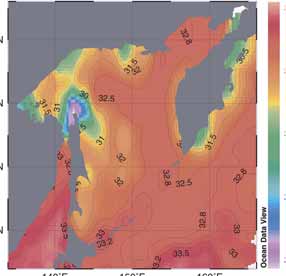

34

February

August

34.5

oblasts also drain into the Okhotsk

60°N

60°N

Sea. Table 1 shows the basic

32

hydrological and water quality

34

characteristics of the Amur River.

55°N

55°N

33.5

30

There are more than 60 000 lakes

50°N

50°N

in the Amur River Basin sub-

33

system, the largest being Khanka,

28

Chukchagirskoye, Bolon, Udyl,

i

ew

i

ew

45°N

V

45°N

V

ta

ta

Bolshoe Kizi, Evoron, Chlya

32.5

ean Da

ean Da

26

(Voronov 2003). The Lake Khanka

Oc

Oc

140°N

150°N

160°N

140°N

150°N

160°N

Basin, known as Lake Xingkai in

Figure 4

Salinity of surface water in February and August.

(Source: Arzamastsev et al. 2001)

China, is located in the upper part

REGIONAL DEFINITION

17

of the Ussuri/Wusuli River system. It is the largest freshwater lake in East

Socio-economic characteristics

Asia shared by China (Heilongjiang province) and Russia (Primorskiy

Kray).

Population

The population of the Okhotsk Sea sub-system is approximately

Biodiversity and critical habitats

8.7 million, of which 2.7 million live in Russia and about 6 million in Japan.

The Amur River Basin sub-system hosts some of the world's most

The Russian coast, except for Sakhalin Island, is sparsely populated, with

diverse and productive habitats and encompasses extensive areas of

a population density of approximately 1.5 people per km2 (Figure 5).

complex and unique ecosystems. The Russian section of the Amur

The only Russian cities with a signifi cant population size (60 000-

River Basin is situated in a temperate mixed broadleaved and coniferous

200 000 inhabitants) are Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk, Magadan, Nikolaevsk-

forest zone, and forest steppe zone. The Amur River supports more fi sh

on-Amur and Okha. The majority of the rural and urban population

species than any other Russian river, with more than 120 species (WWF

lives within the permafrost zone, tolerating severe or extreme natural

2001), 18 of which are endemic and eight are endangered, including

conditions. The far eastern Russian economy experienced a severe

Kaluga sturgeon (Huso dauric). There are also seven migratory salmon

and long recession in the 1990s which led to emigration and a

species (GEF Concept paper 2005). Lake Khanka and its surrounding

decline in population. The largest decline in population out of all the

wetlands have particularly high species diversity. The Lake's basin hosts

Pacifi c coastal regions between 1991 and 2000 was observed in the

342 bird species which account for 65% of the total bird species found

Magadanskaya Oblast' (40% decline), Kamchatskaya Oblast' (20%) and

in Far-Eastern Russia and 48% in Russia. 12 species are included in the

Sakhalinskaya Oblast' (18%).

International Red Book. The variety of fi sh species in the Lake and its

infl ow and outfl ow (only Songacha) rivers represents 73% of the fi sh

Population

density

species in the Amur basin. The wetlands around the lake are used for a

(persons/km²)

<1

spring and autumn resting place for migratory species and for spawning

1-2

grounds for commercial species, such as Predatory carp (Erythroculter

3-5

Russia

6-10

erythropterus) and Mongolian redfi n (Erythroculter mongolicus) (GEF

11-100

>100

Concept paper 2005).

About 61 species of mesopelagic fi sh belonging to 53 genera and

Mongolia

33 families have been recorded in the Okhotsk Sea sub-system (PICES

2004). There are known to be 16 species of squid an important

China

component of the food web of the Sea's ecosystem belonging to

nine genera and six families. Regarding groundfi sh, 50% are fl atfi sh, 21%

Japan

© GIWA 2006

cods, and 11% sculpins. These three groups are a major determinant

Figure 5

Population density of the Sea of Okhotsk region.

of the fi sh productivity of the Okhotsk Sea shelf. The Sea is home

(Source: Data from ORNL 2003)

to 11 endangered species including the Western Pacifi c gray whale

which is critically endangered in this region. At least 16 species of

The population of the Amur River Basin sub-system fl uctuates between

marine mammals inhabit the Okhotsk Sea sub-system. There are four

70 and 80 million people, 5 million of whom live in Russia, 65-75 million

species of the true seal (Phocidae) and two species of eared seal. Whales

in China and less than 50 000 in Mongolia. The North Korean part of

that inhabit the Sea include, among others, Gray whales (Eschtrichtius

the Basin is largely unpopulated (Voronov 2003). The catchment of the

robustus), Southern baleen whales (Eubalaena japonica), Bowhead

Songhua River (a tributary of the Amur River) has a population density of

whales (Balaena mysticetus), Northern fi n whales (Balaenoptera physalus),

105 people/km² (compared to 35 people/km² in the whole of the Amur

Little picked whales (Minke's) (Balaenoptera acutorostrata), Humpback

Basin) and includes most of the large cities in the Amur basin, such as

whales (Megaptera novaeangliae), Baird's beaked whales (Berardius

Harbin, Jilin and Mudanjiang (GEF Concept paper 2005).

baridii) and Killer whales (Orcinus orca).

Economy

In the Russian coastal areas of the Sea of Okhotsk region there is a

developed mining industry. The fi shing industry is found in Kamchatka,

Magadan, Okhotsk, Ayan and Nikolaevsk-on-Amur (Khabarovskiy Kray).

18

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 30 SEA OF OKHOTSK

In Sakhalin, hydrocarbon is exploited and there Table 2

Basic economic characteristics of the administrative regions of the Sea of

are coal mining, and wood and pulp-and-paper

Okhotsk basin.

Cost of basic

industries. Figure 6 shows the distribution of

Share of total

Volume of

Gross regional

Industrial

assets of

Sectors of the Sea Population in

population of

agricultural

industrial activities in the Okhotsk Sea sub-system.

product

output

economics

of Okhotsk basin

sector (people)

administrative

production

(million USD)

(million USD)

branches

In the Amur River Basin sub-system, ship building

territory (%)

(million USD)

(million USD)

and repair, carpentry, construction and coal mining

Sakhalin and Kuril

335 000

61.24

722.9

615.8

38.1

2169.4

are the predominant industries. Further, power

Magadan

125 000

68.41

286.6

244.6

8.5

1110.1

generation using coal, gas and hydroenergy is a

Khabarovsk 407

000

28.4

642.2

557.6

36.4

2931.5

major sector. The sectoral structure of industrial

Kamchatka

24 000

6.3

37.2

32.7

3.5

134.3

output in the Far East of Russia in 2000 is shown

Japanese

310 000

6.1

10 200

(Hokkaido Island)

in Table 3.

(Source: Russian Regions 2001)

Evensk

During a period of market reforms between 1990 and 1998, there was a

signifi cant decrease in investment and industrial production. Since 1999,

Palana

Yamsk

the Russian economy, including that of the Far East, has stabilised and

Magadan

Okhosk

industrial production has increased. GDP growth has averaged 5-7% for

Tigil

the period 2000-2004 (Lvov 2004).

Ayan

Ust-Kharyuzovo

S e a o f O k h o t s k

According to the GIWA regional experts, the socio-economic

Tchumikan

development of the region has been determined by the following:

Mnogovershinnoye

Kolendo

Kherpuchi

Okha

1. The collapse of economic relations with the western regions of

Oktyabrsky

Nikolayevsk-on-Amur

Russia;

Nogliky

Ozernovsky

Katangly

2. Aggravation of social problems. Transport tariff s increased by

Severo-Kurilsk

Tumovskoe

10-12 times making voyages to the western regions of Russia

Poronaisk

unaff ordable for most people;

Makarov

3. Limited market in Far-Eastern Russia for primary and manufactured

Branch of industry

Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk

Fuel

products;

Korsakov

Energy

Vakkanai

4. Factors increasing the cost of production. For example, harsh natural

Kurilsk

Abasiry

Non-ferrous metallurgy

Yuzhno-Kurilsk

conditions, remoteness of settlements and poor infrastructure

Mechanical engineering

Kitamy

Wood-working

development;

Size of industrial node

Building materials

5. Marginal location of region; it is a considerable distance from the

(thousand persons)

Light industry

industrial centres of Russia, thus increasing transportation costs;

Food industry

500-100

100-50 50-10 <10

Fish industry

6. Periodic emigration from the region; and

Figure 6

Distribution of industries in the Sea of Okhotsk Basin.

(Source: Prepared by the authors using Russian Regions 2002)

Table 3

Sectoral structure of industrial output in the Far East of Russia in 2000.

Electric power

Nonferrous Chemical and petro- Mechanical engineering including Wood, woodworking and Food-processing industry

Region

Fuel industry

Other

industry

metallurgy

chemical industry

shipbuilding and ship repair

pulp and paper industry

including fish complex

Primorsky Krai

16.4

2.1

3.7

1.0

16.3

6.8

46.7

7.0

Khabarovsk Krai

8.5

7.9

8.4

1.6

50.4

8.0

8.5

6.7

Amur Oblast

34.4

4.7

29.6

0.1

6.3

5.7

10.2

9.1

Kamchatka Oblast

20.1

0.3

8.3

0.1

4.0

0.6

63.3

3.3

Magadan Oblast

15.3

1.1

66.4

0.0

1.5

0.3

14.0

1.4

Sakhalin Oblast

6.0

60.6

0.2

0.1

1.2

3.2

27.4

1.3

Jewish Autonomous Oblast

13.5

0.2

4.7

0.5

25.4

5.5

13.3

36.9

The Far East as a whole

11.4

13.2

29.8

0.6

16.7

4.1

19.8

4.4

(Russian Regions 2001)

REGIONAL DEFINITION

19

7. The socio-economic conditions contrast with neighbouring

An evaluation of hydrocarbon resources made by Dalmorneftegeofi zika

countries in terms of population density, market characteristics

in 1994, concluded that the Sea of Okhotsk shelf has the equivalent of

and infrastructure development.

14 462 million tonnes of fuel. In Sakhalin Island and on its shelf there

are estimated to be 324 million tonnes of oil and 997 million tonnes of

The Russian section of the Amur River Basin is one of the most

gas. By 2000, 23 oil and gas-oil, and 5 gas fi elds had been developed.

developed territories in the Russian Far East. During the 18th and 19th

Figure 8 shows the areas of prospective development of the oil and gas

centuries, development was concentrated on the north side of the

fi elds in the Sea of Okhotsk region.

Amur River. Economic development was further stimulated following

the construction of the Trans-Siberian Railway in the 20th century, which

4

crosses the Amur River. The Basin has an estimated 35% of the industrial

3.5

onnes)

potential and over 75% of the agricultural potential of the Russian Far

3

East.

(million t

2.5

2

olumes

In Northeast China, the GRPs in 1999 of the Heilongjiang and Jilin

1.5

provinces totalled 2.4 billion USD (14th position out of 32 Chinese

tion v

1

provinces) and 1.4 billion USD (19th position), respectively (Baklanov

oduc

0.5

et al. 2002a). As a result of economic reforms, there has been a shift

Oil pr

0

1970

1975

1980

1985

1990

1995

2000

2002

in the employment structure of the region from the primary to the

Year

secondary and tertiary (service) economic sectors. This trend continued

Figure 7

Oil production volumes.

(Source: Russian Statistical Yearbook 2001)

in subsequent years as a result of the state funded manufacturing

industries of Northeast China (Baklanov et al. 2002a). There has

also been signifi cant investment in transport and communication

infrastructure in order to stimulate trade with regions outside Northeast

China. In Jilin, agriculture remains the largest sector, both in terms of

Magadan

production output and employment rates. There is major domestic and

foreign investment in the Heilongjiang and Jilin provinces, particularly

in agriculture, engineering and transport infrastructure.

Future economic development in the Sea of Okhotsk region will be

based upon the exploitation of the region's mineral resources, such

a

as oil, gas and coal, and possibly the development of hydropower. In

Amgun'

addition, there are abundant forest resources and considerable land

resources.

ur

Am

Economic sectors

Khabarovsk

Oil and gas industry

The Sea of Okhotsk region includes the Okhotsk oil and gas fi elds,

Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk

making its hydrocarbon resources particularly important economically.

Signifi cant reserves of oil and gas are predicted to exist in the

Japan

northeastern and northern shelves of Sakhalin, the western Kamchatka

shelf and in the middle and lower reaches of the Amur River Basin. Only

Figure 8

Areas of prospective development of the oil and gas

a small proportion of the large hydrocarbon reserves of the Russian Far

fi elds in the Sea of Okhotsk region.

(Source: Alekseev et al. 2001)

East is exploited. The dynamics of oil production is shown in Figure 7.

Although the volume of oil exploited continues to increase, with oil

Renewable resources

production reaching 3.4 million tonnes in 2004, only 20% of regional

The region's renewable energy sector also has development potential.

consumption is met by regional production.

Shelikhov Bay and the Penzhinskaya Gulf have large tidal ranges of up

20

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 30 SEA OF OKHOTSK

to 10-12 m and are thus suitable for tidal energy projects. The Amur

Agriculture

River and its tributaries, including the Zeya, Selemdzha and Burea

The agricultural sector (mainly grain and soybean production, and

rivers, have signifi cant hydropower potential (Alekseev et al. 2001). In

cattle-breeding) has been developed primarily in the middle and

the Russian part of the watershed, there are hydroelectric plants such

lower reaches of the Amur. In other areas of the Sea of Okhotsk region,

as the Somninskaya located on the watercourse of the Amgun and the

deer-breeding, local arable farming and cattle-breeding are common,

Zeiskaya on the Zeya. Additionally, the Bureiskaya hydroelectric plant

particularly in the south of Sakhalin and southwestern Kamchatka. The

was recently constructed near the Talakan River mouth and further

Amur River Basin sub-system is a major agricultural zone of the Russian

hydro-electric projects are planned for the Selemzha and Gilyui rivers.

Far East. The most fertile agricultural lands are located on the Zeya-

The region also has an abundance and diversity of wood resources.

Bureinskaya Plain and Lake Khanka lowlands.

Mineral resources

Fisheries

The Sea of Okhotsk region contains a wealth of mineral resources.

The Okhotsk Sea sub-system is regarded as the richest fi shery region

In some of the region's mountains and river valleys, gold has been

in the world. The volume of biological resources in the Sea constitutes

discovered and ferrous and non-ferrous metals and polymetallic

46% of all marine biological resources in the northern Pacifi c. It has

ores are exploited. There is great mining potential in the coastal areas

an estimated 11 million tonnes of biological resources, including

where substantial mineral reserves, particularly of boron, antimony and

approximately 7 million tonnes of cod, 2.5 million tonnes of herring

fl uorspar, are found. Large reserves of brown and hard coal have been

and about 1.5 million tonnes of other seafood (e.g. molluscs and algae)

discovered in Sakhalin and in the Amur River Basin. In a zone adjacent

(Shuntov 2001). Approximately 340 fi sh species inhabit the Okhotsk

to the lower reaches of the Uda, Amgun and Amur rivers there are

Sea (Froese & Pauly 2005). The main fi sh products are fl ounders,

considerable phosphorite reserves. Figure 9 shows the distribution of

herring, capelin, halibut, pollock and crab. Walleye pollock (Theragra

natural resources in the region.

chalcogramma) is the most abundant commercial species in the Sea.

Catch volumes average 1.2-1.5 tonnes per km2, but in productive years

reach between 8 and 22 tonnes per km2 on the western Kamchatka

shelf. In comparison, fi sheries production is about 0.7-1.1 tonnes per km2

in the North Atlantic (The Seas 1998). Russian catches of commercial fi sh

between 1992 and 2003 in the Okhotsk Sea are given in Figure 10.

Until recently, numerous vessels from various countries fi shed intensively

Sea of Okhotsk

in the Okhotsk Sea. The Sea's non-Russian fi shery has been closed since

2003 with the exception of Japanese gill net fi shing for Pacifi c salmon.

In 2005, the foreign fl eet was not allocated any quotas for fi sh in the

Okhotsk Sea sub-system (Governmental Resolution 2004).

Types of resources

3

4

2

5

1

6

2 500

12

7

11

8

10

9

2 000

1 Coal

2 Oil and gas

3 Hydro-energy

onnes) 1 500

4 Ferrous metal

5 Non-ferrous metal

6 Chemical raw materials

7 Non-ore raw materials for

1 000

metallurgy, building materials

(thousand t

h

8 Forest

9 Non-arbareos forest

Catc

500

10 Sea (natural) resources

11 Soils

12 Reindeer pastures

C

0

B

Resource value

1992

1994

1996

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

A

A Natural-economic micro-region

Year

B Levels of region Okhotsk

C Levels of Asia-Pacific region

Figure 10 Catches of commercial fi sh by the Russian fl eet in the

Figure 9

Natural resources of the Sea of Okhotsk sub-system.

Okhotsk Sea.

(Compiled by the authors)

(Source: Barushko 2005)

REGIONAL DEFINITION

21

In 2000, the fi shing industry contributed 1.2 billion USD to the

more than 90% of water resources are used for these purposes. Table 4

economy of the Russian Far-East. It accounted for 18.2% of gross

shows how water consumption generally decreased in the Russian

regional product (GRP) in 1999, and as much as 63.5% in the Koryak

administrative regions during the 1990s.

Autonomous Region, 49.3% in Kamchatka, 27.3% in Primorskiy Kray, and

18.3% in Sakhalinskaya Oblast'. The fi sheries industry therefore plays

Table 4

Consumption of freshwater in the Russian

an important role not only for the local economy, with one fi sherman

adminstrative regions of the Okhotsk sea.

creating 6-7 workplaces onshore, but also in the development of the

1991

1995

2000

2001

Region

(million m³)

(million m³)

(million m³)

(million m³)

social and cultural characteristics of the region and the distribution of

Khabarovsk Kray

714

558

465

467

fi shing settlements.

Kamchatka Oblast

309

276

261

252

Magadan Oblast

144

137

90

96

The riparian population of the Amur River has depended throughout

Sakhalin Oblast

455

376

275

273

history on fi shing and hunting as its major source of food supply. The

(Source: Russian Regions. 2002. Moscow, 2002.)

Amur River Basin sub-system contains one of the largest inland fi shing

industries in Russia. The most important commercial fi sh species in the

Amur are the migratory salmons (Humpback, Oncorhynchus gorbuscha

International cooperation

and Chum, O. keta), sturgeons (Amur, Acipenser schrenckii and Kaluga,

The three riparian countries of the Amur River Basin sub-system have

Huso huso), smelt, and lamprey (Lethenteron sp.). Sturgeon fi shing is an

established bilateral cooperation agreements in the fi eld of protection

important part of the regional fi sh industry but, due to the depletion of

and use of transboundary water resources. These include:

stocks, bans were enforced on Kaluga sturgeon between 1976 and 1991.

The Amur is one of the richest rivers for salmon in the world; in 1910 the

Agreement between the USSR and China on joint research

total catch of salmon was over 100 000 tonnes. The majority of catches

operations to determine the natural resources of the Amur

of salmonids consist of Humpback salmon (Novomodny et al. 2004).

River Basin and the prospects for development of its productive

potentials and on planning and survey operations to prepare a

Aquaculture

scheme for the multi-purpose exploitation of the Argun River and

In Russia, aquaculture is poorly developed. According to the GIWA

the Upper Amur River, 1956;

experts, only 40 fi sh breeding factories operate in the entire Russian

Agreement between the governments of Russia and China on

Far East which release 0.5 billion juvenile fi sh. In comparison, Japan has

cooperation in the fi eld of conservation of transboundary water

350 factories which release approximately 2 billion juvenile fi sh. Most

resources.

commonly, Chum salmon, Humpback salmon and other species of

Agreement between the governments of Russia and China on

salmon are bred, mainly in Sakhalin. Most enterprises have become

cooperating in the preservation of the environment, 1994.

obsolete as they failed to achieve their anticipated production capacities

Agreement between the governments of Russia and China on

due to poor management. Only 1% of the total output of the fi sheries

cooperating in the conservation, regulation and protection of

industry is produced by aquaculture (Baklanov et al. 2002b).

living aquatic resources in the boundary waters of the Amur and

Ussuri Rivers, 1994.

Water use

Agreement between the governments of China and Mongolia

There is an irregular distribution of water resources in the Basin between

on the protection and utilisation of transboundary waters and

the oblasts and krays of Russia and the territories of Mongolia and

environmental management (1994); and

China. The majority of freshwater originates from Khabarovskiy Kray

Agreement between the governments of Mongolia and Russia on

(34%), Amurskaya Oblast' (22%) and from China (28%). Water resources

the protection and use of transboundary waters, 1995.

in the basin are extensively used for agricultural, industrial, energy

production and domestic purposes. In Khabarovskiy and Primorskiy

International treaties relevant to the Okhotsk Sea sub-system:

krays and Priamurye, more than 80% of the total water abstracted is

The international convention for the regulation of whaling, 1946;

used for production and domestic purposes. In other regions, irrigation

The international convention for the prevention of pollution of the

and domestic supply are the most signifi cant consumers. In Chitinskaya

sea by oil, 1954;

Oblast', within the watersheds of Argun/Urgun, Onon and Ingoda rivers,

The convention on the continental shelf, 1958;

as well as practically all the administrative districts of Primorskiy Kray,

The

Ramsar

convention

on

wetlands,

1971;

22

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 30 SEA OF OKHOTSK

The convention on international trade in endangered species of

The convention for the conservation of anadromous stocks in the

wild fauna and fl ora, (CITES), 1973;

North Pacifi c Ocean, (Russia, United States, Canada, Japan, South

The convention on the prohibition of military or any other hostile

Korea), 1992;

use of environmental modifi cation techniques, 1977;

The North Pacifi c Marine Science Organization (PICES), (Russia,

The United Nations convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS),

Canada, United States, Japan, China, South Korea), 1992; and

1982; and

The agreement between the governments of Japan and Russia on

The agreement for the implementation of the United Nations

matters of cooperation in the fi eld of fi shing operations for marine

convention on the Law of the Sea of December 10, 1982, relating

living resources, 1998.

to the conservation and management of straddling fi sh stocks and

highly migratory fi sh stocks, 1995.

Protected areas case of Lake Khanka

The two Lake Khanka basin riparian countries, Russia and China, initiated

Regional agreements relevant to the Okhotsk Sea sub-system

specifi c measures to protect species and their habitats, particularly the

The agreement between the governments of USSR and Japan

wetland areas around the lake. Two protected areas were established

about mutual relations in the sphere of fi shery at coasts of both

for this purpose: Lake Xingkai National Nature Reserve (China) and

countries, 1984;

Khankaisky National Nature Reserve (Russia). The Russian side of the

The agreement between the governments of USSR and Japan

lakeshore wetlands have been designated as a Ramsar site. However, the

about cooperation in the sphere of fi shery, 1985;

national legislations and restricted activities applicable to them diff er,

The agreement between the governments of USSR and North Korea

and it is expected that more harmonised management and regulations

about cooperation in the sphere of fi shery, 1987;

for the protected areas will be developed between the two national

The agreement between the governments USSR and Chinese

nature parks.

about cooperation in the sphere of fi shery, 1988;

The agreement between the governments USSR and South Korea

about mutual relations in the sphere of fi shery, 1991;

REGIONAL DEFINITION

23

Assessment

Table 5

Scoring table for Sea of Okhotsk.

This section presents the results of the assessment of the impacts of

Assessment of GIWA concerns and issues according to

The arrow indicates the likely

each of the fi ve predefi ned GIWA concerns i.e. Freshwater shortage,

scoring criteria (see Methodology chapter)

direction of future changes.

T

T

Pollution, Habitat and community modifi cation, Unsustainable

C

C

Increased impact

A 0

No known impacts

A 2

Moderate impacts

IMP

IMP

T

T

No changes

C

C

exploitation of fi sh and other living resources, Global change,

A 1

Slight impacts

A 3

Severe impacts

IMP

IMP

Decreased impact

and their constituent issues and the priorities identifi ed during

ts

ts

this process. The evaluation of severity of each issue adheres to a

core**

Sea of Okhotsk

ts

ts

set of predefi ned criteria as provided in the chapter describing the

vironmental

t

her community

v

erall S

GIWA methodology. In this section, the scoring of GIWA concerns

En

impac

E

c

onomic impac

Health impac

O

impac

O

Priority***

Freshwater shortage

1*

1

1

1

1

3

and issues is presented in Table 5 and Annex II.

Modification of stream flow

1

Pollution of existing supplies

2

The Sea of Okhotsk region is a large and complex system which, for the

Changes in the water table

1

purpose of this report, can be divided into two sub-systems: the Okhotsk

Pollution

1*

2

2

1

2

1

Sea (marine) and the Amur River Basin (freshwater). Only the sub-system

Microbiological pollution

1

Eutrophication

1

most relevant to each of the GIWA concerns is assessed. For the Amur

Chemical

1

River Basin, this report assesses only the Russian section and two of the

Suspended solids

1

riparian provinces of China (Heilongjiang and Jilin). These provinces of

Solid wastes

1

Thermal

0

China impact the Okhotsk Sea sub-system via the Amur River.

Radionuclides

0

Spills

1

Habitat and community modification

1*

2

1

1

2

4

Loss of ecosystems

1

T

C

A

Freshwater shortage

Modification of ecosystems

1

IMP

Unsustainable exploitation of fish

2*

2

1

1

2

2

Overexploitation

3

2

Freshwater shortage was analysed for the Amur River Basin sub-

Excessive by-catch and discards

2

0

systems.

asin

Destructive fishing practices

2

1

Amur B

Decreased viability of stock

S

e

a of Okhotsk

2

0

Impact on biological and genetic diversity

1

1

Environmental impacts

Global change

1

2

2

1

1

5

The environmental impacts of Freshwater shortage were assessed as

Changes in hydrological cycle

1

slight. The issue of changes in the water table is not further discussed

Sea level change

0

Increased UV-B radiation

0

as there were no known impacts.

Changes in ocean CO source/sink function

0

2

*

This value represents an average weighted score of the environmental issues associated to

the concern.

Modifi cation of stream fl ow

**

This value represents the overall score including environmental, socio-economic and likely

The construction of dams and reservoirs for hydroelectricity production

future impacts.

*** Priority refers to the ranking of GIWA concerns.

has been a major factor in altering the regime of the Amur River. In the

24

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 30 SEA OF OKHOTSK

late 1940s, the Fynman hydroelectric station was constructed on the

is occasionally aff ected by seasonal water shortages (Baklanov et al.

Songhua River (China) and, in 1975, construction began on the Zeiskaya

2002a) and there appear to be no associated health problems of great

hydroelectric station in the Zeya River Basin (Russia). Changes in stream

signifi cance. The pollution of freshwater supplies has, however, caused

fl ow have been detected (Birdlife International 2003). Hydropower

some public health concerns in urban areas. There have been reports

development has reduced the average annual water level variations by

of diarrhoea and other infections linked to the poor water quality of the

1.0-2.3 m along the Blagoveshchensk-Khabarovsk section of the river. In

Amur River system (Baklanov et al. 2002a).

addition, stream fl ow has increased during winter (Shcheka 2005); the

average minimum low water levels in winter rose by 0.3-0.6 m and in

Conclusions and outlook

the Maly Khingan by more than 1.2 metres.

The Amur River and its tributaries have been modifi ed during the 20th

century. The major hydroelectric plants on the Songhua and Zeya rivers

The water regime of the Amur River and its tributaries has also been

have altered the discharge of these tributaries into the Amur River. As

altered by the abstraction of freshwater for industrial and agricultural

a consequence, fl ow rates and seasonal discharge patterns have been

purposes as well as logging and ditching (Novomodny et al. 2004),

modifi ed, which has changed the chemical composition of water bodies

the release of water to reclaim swamps, and increased surface run-off

and altered aquatic habitats. Pollution in the Amur River has increased

due to a loss of vegetation caused by deforestation and fi res (Shcheka

water treatment costs and, in urban areas, the prevalence of diseases.

2005). As a result, downstream wetlands have been depleted (Birdlife

Freshwater shortage, however, is not presently a major problem for the

International 2003, GEF Concept paper 2005) and the frequency of

Sea of Okhotsk region. Therefore, its overall impacts were assessed as

fl ooding has increased (Jen 2003, Shcheka 2005).

slight. There is currently no agreement between China and Russia on

the fl ow rates and discharges of the transboundary rivers in the region.

Pollution of existing supplies

Economic development and population growth, particularly in China,

Urban areas are the major source of freshwater pollution in the

will result in greater demand for water resources, the further diversion

Amur River Basin but agricultural contaminants are also a concern. In

of rivers to supply human uses, and increased pollution loads.

Khabarovskiy Kray, more than 400 million m3 of wastewater is discharged

into the Amur every year, 70 million m3 of which is untreated and 173 mil-

lion m3 is inadequately treated. The Amur River suff ers from transbound-

T

C

A

ary pollution from agrochemicals, phenol, heavy metals and untreated

Pollution

IMP

wastewaters (GEF Concept paper 2005). Agricultural land use has intensi-

fi ed resulting in the increased use of fertilisers and pesticides (Jen 2003).

The following contaminants are found in the Amur River: organic

The deterioration of water quality in the Amur and its large tributaries

substances (BOD ), oil products, phenols, ammonium nitrogen, nitrate

5

has decreased the quantity of potable water in near the Amur River in Pri-

nitrogen, iron, copper, zinc and lead (Chudaeva 2002). Studies by the

amurye (Jen 2003). A considerable proportion of the population is forced

Far-Eastern Hydrometeorological Institute between 1997 and 2000

to use low quality and often contaminated water, especially during the