Global International

Waters Assessment

Regional assessments

Other reports in this series:

Russian Arctic GIWA Regional assessment 1a

Caribbean Sea/Small Islands GIWA Regional assessment 3a

Caribbean Islands GIWA Regional assessment 4

Barents Sea GIWA Regional assessment 11

Baltic Sea GIWA Regional assessment 17

Caspian Sea GIWA Regional assessment 23

Aral Sea GIWA Regional assessment 24

Gulf of California/Colorado River Basin GIWA Regional assessment 27

Sea of Okhotsk GIWA Regional assessment 30

Oyashio Current GIWA Regional assessment 31

Yellow Sea GIWA Regional assessment 34

East China Sea GIWA Regional assessment 36

Patagonian Shelf GIWA Regional assessment 38

Brazil Current GIWA Regional assessment 39

Amazon Basin GIWA Regional assessment 40b

Canary Current GIWA Regional assessment 41

Guinea Current GIWA Regional assessment 42

Lake Chad Basin GIWA Regional assessment 43

Benguela Current GIWA Regional assessment 44

Indian Ocean Islands GIWA Regional assessment 45b

South China Sea GIWA Regional assessment 54

Mekong River GIWA Regional assessment 55

Sulu-Celebes (Sulawesi) Sea GIWA Regional assessment 56

Indonesian Seas GIWA Regional assessment 57

Pacifi c Islands GIWA Regional assessment 62

Humboldt Current GIWA Regional assessment 64

Global International

Waters Assessment

Regional assessment 47

East African Rift Valley Lakes

GIWA report production

Series editor: Ulla Li Zweifel

Report editor: Ulla Li Zweifel

Editorial assistance: Johanna Egerup, Malin Karlsson,

Kristin Bertilius and Russel Arthurton

Maps & GIS: Niklas Holmgren

Design & graphics: Joakim Palmqvist

Global International Waters Assessment

East African Rift Valley Lakes, GIWA Regional assessment 47

Published by the University of Kalmar on behalf of

United Nations Environment Programme

© 2006 United Nations Environment Programme

ISSN 1651-940X

This report has been revised and updated since its fi rst publication 2003.

University of Kalmar

SE-391 82 Kalmar

Sweden

United Nations Environment Programme

PO Box 30552,

Nairobi, Kenya

This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for

educational or non-profi t purposes without special permission from the

copyright holder, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. No

use of this publication may be made for resale or for any other commercial

purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from the United

Nations Environment Programme.

CITATIONS

When citing this report, please use:

UNEP, 2004. Odada, E.O., Olago, D., Kulindwa, K.A.A., Bugenyi, F., West,

K., Ntiba, M., Wandiga, S. and Karimumuryango, J. East African Rift Valley

Lakes, GIWA Regional assessment 47.

University of Kalmar, Kalmar, Sweden.

DISCLAIMER

The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do

not necessarily refl ect those of UNEP. The designations employed and the

presentations do not imply the expressions of any opinion whatsoever

on the part of UNEP or cooperating agencies concerning the legal status

of any country, territory, city or areas or its authority, or concerning the

delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries.

This publication has been peer-reviewed and the information herein

is believed to be reliable, but the publisher does not warrant its

completeness or accuracy.

Publishing house: Kirjastusaktsiaselts MATS, Tallinn

Printed in Estonia by Tallinna Raamatutrükikoda, 2006

Contents

Executive summary

9

Abbreviations and acronyms

12

Boundaries of the East African Rift Valley Lakes region

15

Regional defi nition

15

Physical characteristics

16

Socio-economic characteristics

28

Assessment 37

Lake Turkana Basin

Freshwater shortage

38

Pollution

40

Habitat and community modifi cation

42

Unsustainable exploitation of fi sh and other living resources

43

Global change

44

Priority concerns

45

Lake Victoria Basin

Freshwater shortage

47

Pollution

49

Habitat and community modifi cation

53

Unsustainable exploitation of fi sh and other living resources

55

Global change

59

Priority concerns

60

Lake Tanganyika Basin

Freshwater shortage

61

Pollution

62

Habitat and community modifi cation

64

Unsustainable exploitation of fi sh and other living resources

66

Global change

68

Priority concerns

69

Lake Malawi Basin

Freshwater shortage

70

Pollution

71

Habitat and community modifi cation

73

Unsustainable exploitation of fi sh and other living resources

76

Global change

78

Priority concerns

79

CONTENTS

Causal chain analysis

81

Methodology

81

Unsustainable exploitation of fi sh and other living resources

82

Pollution

87

Summary of the analysis

93

Policy options

94

Problem defi nition

94

Options

97

Recommended policy options

102

Conclusions and recommendations

102

References 103

Annexes 116

Annex I List of contributing authors and organisations involved

116

Annex II Detailed scoring tables

117

Annex III Causal chain analysis Outline of the process

133

Annex IV List of important water-related programmes and assessments in the region

136

Annex V List of conventions and specifi c laws that aff ect water use in the region

137

Annex VI Addendum: A Journalists Diary for a Lake Victoria Tour

138

The Global International Waters Assessment

i

The GIWA methodology

vii

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 47 EAST AFRICAN RIFT VALLEY LAKES

Executive summary

The East African Rift Valley Lakes (EARVL), GIWA region 47, runs from

570 m, with a maximum depth of 1 470 m, making it the world's second

the northern end of Lake Turkana Basin to the southern tip of the Lake

deepest lake. The lake drains westwards through the Lukuga River into

Malawi/Nyasa Basin and includes all the natural habitat and associated

the basin of the Congo River. Lake Malawi is long and narrow, the fourth

human communities found within the Rift Valley and on the adjacent

deepest inland water body in the world (700 m) and the world's fourth

escarpments (Figure 1). It encompasses parts of the following countries;

largest body of freshwater. It drains southwards via the Shire River to

Ethiopia, Kenya, Sudan, Uganda, Tanzania, Rwanda, Burundi, Democratic

the Zambezi Basin.

Republic of Congo (DR Congo), Zambia, Malawi and Mozambique. The

main lakes include Victoria, Tanganyika, Malawi, Turkana, Albert, Edward,

Lakes Victoria, Tanganyika and Malawi are famous for their endemic

George and Kivu. All are tropical and together comprise the African

species fl ocks of cichlid fi shes. Lake Tanganykia hosts a large fl ock,

Great Lakes ecoregion. However, each lake lies within its own separate

estimated to include more than 700 cichlid fi sh species (Snoeks 2000).

drainage basin, with its own assemblage of endemic organisms, most

Lake Malawi's total fi sh fauna comprises some 800 species, more than

notably the cichlid fi sh species-fl ocks. Each lake diff ers substantially

any other lake in the world, and nearly all of its cichlids are endemic

with respect to limnology, catchment dynamics and human impacts

(Ribbink 2001). Lake Victoria's formerly rich cichlid fauna has become

(Hamilton 1982).

drastically reduced in recent decades.

For the purpose of GIWA assessment, the following lakes that are

The EARVL region is home to some of the poorest communities in the

characteristic of most of the transboundary water bodies in the

world. Most of the Lake Turkana Basin is populated with pastoralists,

region were selected for the exercise: Lake Turkana, Lake Victoria, Lake

mostly nomadic, but a few are fi shermen. The lower Omo Valley supports

Tanganyika and Lake Malawi. These are the largest of the East African

subsistence agriculturalists in the north and agro-pastoralists in the

Rift Valley lakes and are among the oldest lakes in the world. All these

south extending to the Kenya border. In the catchment area as a whole,

lakes are extremely sensitive to climate change.

the population is estimated at 15.2 million out of which 12.3 million live in

the Ethiopian part of the catchment. The Basin is the poorest and has the

Lake Turkana, the largest closed-basin lake is up to 115 m deep,

lowest population density and economic activity of all the other large

moderately saline and alkaline, and lies in a topographically closed

lake basins of the region. The Lake Victoria Basin is the most heavily

basin located in the arid northwestern part of Kenya, though the

populated basin, and supports one of the densest rural populations

delta of the Omo River, the principal affl

uent, lies within southwestern

in the world. An estimated population of roughly 30 million people

Ethiopia. Lake Victoria is, by area, the second largest lake in the world

whose incomes are estimated to lie within the ranges of 90-270 USD

and the largest in Africa, though relatively shallow, with a maximum

per capita per year live in the Basin. The catchment is mainly agricultural,

depth of 80-90 m. More than 80% of its water input is derived directly

though most of the population living along the lakeshore relies directly

from rainfall on the lake surface, and about 7% fl ows from the western

or indirectly on the fi shing trade. An estimated 10 million people reside

side of the basin through the Kagera River. It is drained by the Nile River

in the Lake Tanganyika catchment (UNDP 2000); outside urban centres,

from Owen Falls on its northern rim. Lake Tanganyika is the longest lake

subsistence and small-scale commercial fi shing and farming dominate

in the world (673 km) though only 1290 km wide. Its average depth is

people's livelihoods (Quan 1996, Meadows & Zwick 2000). In the Lake

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

9

Malawi Basin, Malawi's land area is densely populated at 116 persons

the concern Unsustainable exploitation of fi sheries and other living

per km2 (UNEP-IETC 2003) representing 80% of the total lakeshore

resources, overexploitation and destructive fi shing practices were

population (World Bank 2003).

identifi ed as key issues; under the concern Pollution, the important

issues identifi ed were microbiological, eutrophication, chemical and

It is only during the past 10 years or so that the East African countries

suspended solids. It was, however, noted that the issue "suspended

have instituted, at government level, policies on the environment

solids" had several components that were interrelated with the

that adopt an integrated and sustainable approach to environmental

microbiological, eutrophication and chemical issues, having both

management. New national environmental policies/acts have been

synergistic and cumulative eff ects in their association. The suspended

enacted in both Ethiopia (1997) and Kenya (1999), and environmental

solids issue was, therefore, nested in the microbiological, eutrophication

authorities have been set up to implement the policies which seek to

and chemical issues.

promote sustainable environmental management and development.

The new Kenya Water Act (2002) provides for the establishment

In the Causal chain analysis for Lake Victoria, the root cause of

of Water Resources Management Authorities that will have wide-

Unsustainable exploitation of fi sh resources was identifi ed as the

ranging powers to manage and protect water resources at river or lake

existence of a market for fi sh, both domestic and, more importantly,

basin scales. International conventions and agreements that Kenya,

export. Other root causes are inadequate regulation, poverty, poor

Uganda and Tanzania are signatories to, or subscribe to, include:

institutional and legal arrangements, low civic education and

Technical Cooperation for the Promotion of the Development and

awareness, low management capacity by communities, availability

Environmental Protection of the Nile Basin (Tecconile), Initiative for

of market for undersized fi sh, and corruption. Whereas these root

Nile Basin Management, the Convention for the Establishment of the

causes lead to unsustainable exploitation practices for subsistence

Lake Victoria Fisheries Organisation (LVFO), the Agreement on the

fi shing, in most cases profi t is the main factor driving the process. The

Preparation of a Tripartite Management Program for Lake Victoria,

environmental degradation of the Lake Victoria Basin over the last three

and the Treaty establishing the EAC. The international conventions

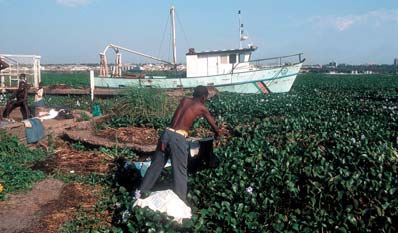

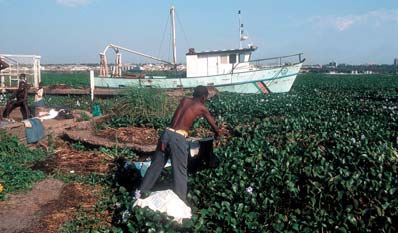

decades (due to high population, massive algal blooms, water-borne

and agreements include: the Convention on Wetlands of International

diseases, water hyacinth infestation, oxygen depletion, introduction of

Importance (Ramsar), the Convention for International Trade in

alien fi sh species etc.) has been determined as placing a present value of

Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), the Convention

270520 million USD at risk to the lake communities, if the large export

on Conservation of Biological Diversity, and the Code of Conduct for

fi shery for Nile perch was lost (World Bank 1996). The collapse of the

Responsible Fisheries (CCRF).

Nile perch fi shery may become a reality sooner rather than later in the

event that things are left in a "business as usual" scenario.

The assessment identifi ed the priority GIWA concerns for Lake Turkana

as Habitat and community modifi cation and freshwater shortage;

The principal causes of Pollution in Lake Victoria lie in its catchment

for Lake Victoria the priorities were Pollution and Unsustainable

areas in both urban and rural settings. The role of the Kagera River as

exploitation of fi sh and other living resources; and for the lakes

a main contributor of suspended solids, nutrients and water hyacinth

Tanganykia and Malawi the priority concerns were identifi ed as

is an extremely important consideration when evaluating policy

Unsustainable exploitation of fi sh and other living resources and Habitat

options for sustainable management of the Lake. Untreated industrial

and community modifi cation.

and municipal effl

uent together with agricultural run-off are the main

contributors of microbiological and chemical pollution and are a

The Lake Victoria Basin was chosen for Causal chain and Policy options

source of nutrients contributing to eutrophication, while suspended

analyses on account of the diverse, linked issues and complexities

solids are derived from erosion of degraded catchments, riverbanks and

that have contributed to its environmental degradation, as well as

lake-edge environments due to poor agricultural practices and high

the interventions that have been initiated in order to address and

grazing intensities. All these contaminants make the Lake water unfi t for

mitigate the environmental degradation. Because of the similarity

recreation, consumption and other uses, unless a huge processing cost

of environmental problems aff ecting the East African Great Lakes, as

is incurred. Pollution destroys habitats for freshwater life forms while at

well as similarities in the socio-political, economic and health status

the same time making them unavailable for nutritional purposes. For the

of the various riparian countries, the Lake Victoria Causal chain and

majority of people living by the lake shore and subsisting by fi shing, this

Policy options analyses presented in this report are considered to be

implies that malnutrition and health problems will entrench themselves

applicable to the other basins of the region. For Lake Victoria, under

and exacerbate the deepening poverty among their ranks.

10

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 47 EAST AFRICAN RIFT VALLEY LAKES

The feasibility of policy options in the Lake Victoria is looked upon

Revision of regulations in urban planning that have not taken into

in conjunction with the establishment of the regional integration of

account environmental issues, and improvement of monitoring and

the East African Community (EAC 2000). The East African Community

enforcement;

off ers a good prospect for the success of the proposed policies, in that

Improvement of natural resource management and farming

it provides a conducive environment for Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania

practices through training, governance and agricultural

to work together towards common goals. Some means are required in

technology;

order to incorporate both Burundi and Rwanda in the management

Stronger vetting of technology promoted by national and

structure of the Lake since, even though they do not share the lake

international agencies;

shore, they form a signifi cant part of the Lake's catchment area and are

Strengthening enforcement of regulations for mandatory effl

uent

a principal polluter, being the source of the highest sediment load and

treatment in municipalities and industries;

the original entry point for water hyacinth.

Incorporating all stakeholders in the drafting of regulations and in

monitoring and enforcing agreed regulations;

Policy options that address overexploitation of fi sh are:

Integration of institutional framework, regulations and laws at two

Quota for fi shing

levels: national and regional;

Quota for processing

Creation of a public complaints institution with powers to

Review of the rules and regulations and existing policies

investigate and recommend prosecution;

Civic education and awareness

Enforcing compliance with international conventions e.g. Ramsar,

CITES, and the Biological Diversity Convention of Agenda 21;

Policy options that address destructive fi shing practices are:

Strengthening the capacity of National Environmental Protection

Strengthening monitoring and enforcement of restrictions;

Authorities to enable a more eff ective enactment of legislation by

enforcing the rule of law;

providing trained manpower and suffi

cient funding.

Provision of civic education and awareness; empowering and

involving more communities in management;

The successful implementation of these policy options will never be

Imposing size restrictions on fi sh processing factories;

achieved without involving, in a participatory manner, the communities

Provision of credit to artisanal fi shers.

living on the lake shores who depend on fi shing as a source of

subsistence livelihood and income generation. Capacity building in

Policy options that address the issues of pollution are:

terms of civic education and leadership and management skills will

Accreditation of analytical laboratories for standards enforcement;

enhance this empowerment.

Liberalisation of waste disposal activities to involve the private

sector and communities;

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

11

Abbreviations and acronyms

BMU Beach

Management

Unit

LVEMP

Lake Victoria Environmental Management Project

BOD

Biological Oxygen Demand

LVFO

Lake Victoria Fisheries Organisation

CCRF

Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries

LVFRP

Lake Victoria Fisheries Research Project

CITES

Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species

LVRLAC

Lake Victoria Regional Local Authorities Cooperation

CPUE

Catch per Unit Eff ort

MCS

Monitoring Control and Surveillance

DRC

Democratic Republic of Congo

MSY Maximum

Sustainable

Yield

EAC

East African Community

NEMC

National Environmental Management Council

EARVL

East African Rift Valley Lakes

NTU Nephelometric

Turbidity

Unit

EIA

Environmental Impact Assessment

PA Protected

Area

ENSO El-Niño-Southern

Oscillation

PPP Purchasing

Power

Parity

EU European

Union

QC Quality

Control

GEF

Global Environment Facility

RRA Rapid

Rural

Appraisal

GDP Gross

Domestic

Product

SADC

Southern Africa Development Community

GNP Gross

National

Product

SAP Strategic

Action

Programme

HACCP

Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point

SSOP

Sanitation Standard Operating Procedures

HDI Human

Development

Index

SST Sea-Surface

Temperature

ITCZ Inter-Tropical

Convergence

Zone

Tecconile Technical Cooperation for the Promotion of the Development

IUCN

International Union for Conservation of Nature

and Environmental Protection of the Nile Basin

LMEMP

Lake Malawi Ecosystem Management Project

UNECIA

Universities of Northern England Consortium for International

LVB Lake

Victoria

Basin

Activities

LVDP Lake

Victoria

Development

Programme

WHO

World Health Organization

12

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 47 EAST AFRICAN RIFT VALLEY LAKES

List of figures

Figure 1

Boundaries of the East African Rift Valley Lakes region. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

Figure 2

Lake Turkana Basin. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

Figure 3

Protected areas in the Lake Turkana Basin. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

Figure 4

Lake Victoria Basin.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

Figure 5

Lake Tanganyika Basin. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

Figure 6

Cichlids. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22

Figure 7

Lake Malawi Basin. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23

Figure 8

Formation of the African Rift Valley Lakes. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24

Figure 9

Temperature, oxygen and dissolved nutrient concentrations in Lake Malawi. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26

Figure 10

Surface winds, water movement and upwelling in Lake Malawi. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27

Figure 11

Protected areas in the Lake Tanganyika Basin. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 33

Figure 12

Human population density in the drainage basin of Lake Malawi. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35

Figure 13

Turkwel River. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 39

Figure 14

Fluctuations in the level of Lake Turkana, 1888-1990. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 45

Figure 15

Linkages between the GIWA concerns in Lake Turkana. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 46

Figure 16 The major drainage basins of Lake Victoria. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 48

Figure 17

Water hyacinths. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 50

Figure 18

Fishermen weighing Nile perch. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 56

Figure 19

Total landings of fish in the three riparian countries of Lake Victoria. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 57

Figure 20

Linkages between the GIWA concerns in Lake Victoria. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 60

Figure 21

Linkages between the GIWA concerns in Lake Tanganyika. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 69

Figure 22

Lake shore of Lake Malawi near Money Bay in Lake Malawi National Park. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 75

Figure 23

Linkages between GIWA concerns in Lake Malawi. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 80

Figure 24

Causal chain diagram illustrating the causal links for Unsustainable exploitation of fish and other living resources. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 82

Figure 25

Trends in catch per unit effort for Nile perch in commercial fisheries of Lake Victoria. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 83

Figure 26

Trends in landings of the major commercial fish species in the riparian countries of Lake Victoria. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 83

Figure 27

The percent contribution by weight of the four major fishing gears to the Kenyan Lake Victoria catches. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 85

Figure 28

Causal chain diagram illustrating the causal links for Pollution. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 89

Figure 29

Comparison of turbidity, nitrogen and phosphorus levels of four Kenyan rivers, rainy season 2001. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 90

List of tables

Table 1

Endangered, endemic and rare fish species of Lake Turkana. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

Table 2

Physiographic statistics for Lake Tanganyika.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

Table 3

Basic limnological parameters for Lake Tanganyika. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

Table 4

Inventory of species in Lake Tanganyika. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23

Table 5

The islands and reefs of Lake Malawi.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24

Table 6

Physical and physico-chemical characteristics of Lake Malawi. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25

Table 7

Land use in the Lake Turkana catchment. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

Table 8

Quantity of fish (tonnes) landed in Kenya, 1965-1968. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

Table 9

Socio-economic statistics for Tanganyika's riparian nations. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32

Table 10

Some socio-economic indicators of the economies of the Lake Malawi Basin. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35

Table 11

Scoring table for Lake Turkana. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 37

Table 12

Fish species and habitats in Lake Turkana.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 44

Table 13

Scoring table for Lake Victoria. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 47

Table 14

Demographic and biophysical characterisation of the inlet drainage basins of Lake Victoria. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 47

Table 15

Scoring table for Lake Tanganyika. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 61

Table 16

Sources of pollution in the Tanganyika catchment. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 63

Table 17

Some water and sediment discharge rates into Lake Tanganyika.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 63

Table 18

Scoring table for Lake Malawi.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 70

Table 19

Unsustainable exploitation of fish in Lake Victoria: percentage contribution of issues and immediate causes of the impacts. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 82

Table 20

Export quantities for Nile perch fillets between 1988 and 1999. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 84

Table 21

Capacity of fish processing factories, annual landings, and maximum sustainable yield for the three riparian countries in 1999. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 85

Table 22

Summary of the processes and actions behind the root causes of overexploitation of fish. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 85

Table 23

Summary of the processes and actions behind the root causes of destructive fishing practices. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 86

Table 24

Pollution in Lake Victoria: percentage contribution of issues and immediate causes of the impacts. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 87

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

13

Table 25

Number of people in urban populations connected to sewerage systems in Lake Victoria Basin. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 87

Table 26

Summary of the processes and actions behind the root causes of microbiological pollution.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 88

Table 27

Agricultural characteristics of Lake Victoria Basin. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 91

Table 28

Summary of the processes and actions behind the root causes of eutrophication (and sedimentation). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 91

Table 29

Summary of the processes and actions behind the root causes of chemical pollution.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 92

Table 30

Policy options analysis matrix: overexploitation and destructive fishing issues. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 95

Table 31

Policy options analysis matrix: Pollution issues.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 100

14

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 47 EAST AFRICAN RIFT VALLEY LAKES

Regional defi nition

This section describes the boundaries and the main physical and

Elevation (m)

socio-economic characteristics of the region in order to defi ne the

Walga

2000-4000

area considered in the regional GIWA assessment and to provide

Ethiopia

1000-2000

suffi

cient background information to establish the context within

500-1000

Wh

Wenz

which the assessment was conducted.

it

Omo

100-500

eNil

Abaya Hayk'

e

Ch'amo Hayk'

Sudan

Ilemi triangle

The Regional defi nition of Lake Tanganyika is excerpted with permission from

- disputed Ch'ew Bahir

the document "Results and Experiences of the UNDP/GEF Conservation Ini-

Ubangi

Lake Tukana

tiative (RAF/92/G32)" compiled by Kelly West in 2001 (West 2001). The GIWA

l

assessment of Lake Tanganyika was based largely on experience gained from

DR Congo

we

rk

Victoria Nile

Lake Kyoga

Tu

this 5-year UN-sponsored project to study the biodiversity of Lake Tangan-

Lake Albert

aut

Uganda

g

Su

yika and the threats to the Lake, and to devise a management plan.

ki

rio

e

Nzoia

Semli

K

Kenya

Lake Edward

Lake

ara

M

Victoria

Rwanda

Boundaries of the East African

Lake Kivu

Lake Natron

Rift Valley Lakes region

Rusizi

Burundi

Lake Eyasi

e

Co

The East African Rift Valley Lakes (EARVL), GIWA region 47, runs from the

ng

Igomb

We

Malag

o

arasi

mber

northern end of Lake Turkana Basin to the southern tip of Lake Malawi/

e

L

Ugall

u

Ka

a

vu

Nyasa Basin and includes all the natural habitat and associated human

alaba

Lake Tanganyika

Shama

Lu

communities found within the Rift Valley and on the adjacent escarp-

fuko

Tanzania

ments (Figure 1). It encompasses parts of the following countries; Ethiopia,

Lukag Lake Rukwa

a

Kenya, Sudan, Uganda, Tanzania, Rwanda, Burundi, Democratic Republic

Songw

of Congo (DR Congo), Zambia, Malawi and Mozambique. The main lakes

e

u

in the region include Victoria, Tanganyika, Malawi, Turkana, Albert, Edward,

uh

Lak Ruh

George and Kivu. All are tropical and together comprise the African Great

Zambia

e

Malawi

Lakes ecoregion. However, each lake lies within its own separate drain-

age basin, with its own assemblage of endemic organisms, most notably

Mozambique

Bua

the cichlid fi sh species-fl ocks. Each lake diff ers

Malawi

substantially with respect to limnology, catch-

Figure 1

Boundaries of the

ment dynamics and human impacts (Hamil-

0

200

Kilometres

e

East African Rift

Shir

ton 1982).

© GIWA 2003

Valley Lakes region.

REGIONAL DEFINITION

15

Physical characteristics

Addis Ababa

The Task team decided that the lakes be tackled separately within

Walga

the context of their respective drainage basins. For the purpose of

GIWA assessment, the following lakes that are characteristic of most

Jima

of the transboundary water bodies in the region were selected for the

Gojeb

'

exercise: Lake Victoria, Lake Tanganyika, Lake Malawi and Lake Turkana.

Shete

These four are the largest of the East African Rift Valley lakes and are

atilB

among the oldest lakes in the world they are all classed as Ancient

Abaya Hayk'

Arba Minch

Lakes (Brooks 1950). All these lakes are extremely sensitive to climate

r

e

Ch'amo Hayk'

r

iv

la

change. Lake Turkana, for example, is a topographically closed basin

Omo

Ba

Sagan

Sudan

(i.e. no outlet) and its level has varied by 20 m within the past century

ana

Ilemi triangle

Gal

alone (Owen et al. 1982). Over 75% of the water lost from Lake Malawi

Ethiopia

- disputed

Ch'ew Bahir

is by evaporation. If annual rainfall over this lake were to decrease by

30%, the lake level would drop 100 m within 150 years (Owen et al.

Lake Turkana

1990). There is abundant geophysical and sedimentological evidence

Ferguson´s

gulf

for its level having been 100-200 m lower than present several times in

the past few thousand years (Scholz & Rosendahl 1988). All the four rift

Lodwar

Tu

rk

lakes are sensitive in this way as well as in their chemical and biological

w

e

l

responses to variation in the hydrological budget.

Uganda

Kenya

rio

Ke

Landcover

Lake Turkana

Barren

Lake Turkana is located in the Great Rift Valley in the arid northwestern

Cropland

part of Kenya at about 3° N and 36° E (Figure 2). Most of the Lake lies in

Forest

Kenya, but part of the Omo River (which supplies about 90% of water

Grassland

to the Lake) delta lies in southwestern Ethiopia. Lake Turkana is the

Savannah

Shrubland

largest closed-basin lake in the East African Rift, and loses water mainly

Nakuru

0

100

Kilometres

by evaporation. It can be considered as the "arid region end-member"

© GIWA 2003

of the large rift valley lakes and a modern analogue for ancient rift

Figure 2 Lake

Turkana

Basin.

environments in Africa and elsewhere (Halfman et al. 1989). The Lake's

(Source: data from Loveland et al. 2000)

catchment area is about 130 860 km2 while the Lake is 250 km long,

has a mean width of 30 km and a surface area of about 6 750 km2. The

the south (Dunkelman et al. 1988). Tertiary volcanic rocks are found

average depth is 35 m while the maximum depth is 115 m. The reason

in the south and along most of the western side of the Lake, while

for Turkana's world-wide fame as the purported "Cradle of Mankind",

Quaternary sediments dominate the western and northern side of the

are the fi ndings of early hominids, including remains of various

Lake. Three volcanic islands are found in the Lake; the North, Central

Australopithecus species, Homo habilis, Homo erectus and Homo sapiens

and South islands.

(Finke 2001).

The only perennial river entering the Lake is Omo River, fl owing

Geology and geomorphology

southwards from Ethiopia into a delta at the northern end of the Lake. All

Lake Turkana lies within a broad depression known as the Turkana

the other rivers of the west area with the exception of the Turkwel River

depression, between the Kenya and Ethiopia domes in that part of the

are dry for most of the year, fl owing for only a few days or even hours

East African Rift Valley System known as the Gregory Rift. The Gregory

after rain (Walsh & Dodson 1969). The Omo River provides about 90%

Rift, which is topographically well-defi ned throughout most of Kenya,

of the water fl owing into the Basin (Cerling 1986), draining southward

splays out into a broader, less distinct zone of rifting within the vicinity

from the Ethiopian plateau where mid-year monsoonal rainfall exceeds

of the Lake. The Turkana Depression has generally been regarded as a

1 500 mm (Halfman & Johnson 1988). The River contributes about 19

diff use zone of faulting, linking the rift segments to the north and to

billion m3 of water each year (Beadle 1981).

16

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 47 EAST AFRICAN RIFT VALLEY LAKES

The western coastal plain extends up to 25 km inland from the lake

River acacia (Acacia elatior), Soapberry tree (Balanites aegyptiaca) and

shore to the Labur-Lothidok ranges, rising gently westwards to over

Doum palm (Hyphaene coriacea) (Hughes & Hughes 1992). Saltbush

100 m above the lake level (Walsh & Dodson 1969). The drainage pat-

(Salvadora persica) forms a bushland on Central and South islands

tern of the western area centres around two major basins: Lake Turkana

(Hughes & Hughes 1992).

and Lotagipi swamp. The Turkwel River carries water into the Lake via

an extensive delta for several months in a normal year. The River is ap-

Physical and chemical limnology

proximately 300 km long, rising on the slopes of Mount Elgon, where

Lake Turkana receives run-off and sediment from a wide geographical

it is known as the Suam (Dodson 1971). The Turkwel River is now being

area. The Omo River provides about 90% of the water that fl ows into

dammed for hydroelectric power generation at Turkwel Gorge, about

the Lake (Cerling 1986). The seasonal Turkwel and Kerio rivers contribute

150 km west of the Lake.

most of the remaining fl uvial input. Other streams, direct rainfall and

subterranean fl ow are considered insignifi cant in the water budget

Most of the lake's southern shoreline is rocky, consisting of layers of lava

(Yuretich & Cerling 1983). All water input is approximately balanced

boulders or minor cliff faces where recent lava fl ows have extended

by evaporation, the surface level lying at approximately 372 m above

to the water line. In the southwest corner of the Lake, however, the

sea level.

shoreline opens out to form a gently curving arc with sandy and shingle

beaches. The eastern area is generally fairly fl at-lying, with ephemeral

The Lake is moderately saline (2.5), alkaline (pH = 9.2), and is well

streams draining into the Lake, but their contribution to the total water

mixed by strong diurnal winds (Yuretich & Cerling 1983). The principal

and sediment fl ux input is very small.

ions are Na+ (sodium), HCO - (bicarbonate), and Cl- (chloride), with

3

relatively low concentrations of Ca2+ (calcium), Mg2+ (magnesium),

The age of Lake Turkana is given a conservative estimate of 4.3 million

and (SO )2- (sulphate) (Halfman et al. 1989). In the north, salinity is

4

years (by K-Ar and 40Ar/39Ar methods), which is recorded from the

seasonally reduced through mixing with dilute Omo River fl oodwaters.

lowermost tuff bed within the Koobi Fora Basin (McDougall 1985).

The evaporation rate has been estimated at 2 335 mm/year. The Lake

Seismic refl ection profi les of Lake Turkana, penetrating about

undergoes far greater changes in salinity than in temperature (Johnson

60 m below the lake fl oor, show that the predominant pattern of

et al. 1990). Its high alkalinity promotes rapid equilibration of CO with

2

sedimentation is one of simple and rapid basin infi lling; the profi le

the atmosphere (Peng & Broecker 1980). The water has a residence time

suggests an abundance of gas (probably methane) in the Holocene

of about 12.5 years (World Lakes Database 2002). The euphotic zone is

sediments, particularly near the major rivers and in the deepest basins

about 6 m, and the Lake is always turbid (Kallqvist et al. 1988). Yuretich

where sedimentation rates are fairly high (Johnson et al. 1987).

(1979) observed that sediment plumes up to 100 km long extend

southward from the Omo River delta during fl ood seasons.

Climate and vegetation

The mean annual temperature is 30°C, mean annual rainfall is below 255

The water level of this closed basin lake is determined by the balance

mm/year (Survey of Kenya 1977), and the evaporation rate is 2 335 mm/

between the infl ux from rivers and groundwater and the evaporation

year (±0.347 mm) (Ferguson & Harbott 1982). The annual mean

from the lake surface, and has an annual water level fl uctuation of

maximum temperature range is 30 to 34°C, while the annual mean

about 1.25 m. The lake level is therefore sensitive to climatic variations,

minimum temperature is 23.7°C (Survey of Kenya 1977). The region is

and is subject to marked seasonal fl uctuations as well as to long-term

semi-arid. The majority of the yearly rainfall occurs in two seasons, from

periodical changes.

March to June, with a peak in April, and from October to December, with

a lesser peak in November or December. The occurrence of rainfall is,

The growth of deltas in Lake Turkana is controlled by the erratic supply

however, erratic and unpredictable.

of sediment, and the short- and long-term fl uctuations in lake level are

brought about by climatic change and tectonic activity (Frostick & Reid

Grassy plains with yellow spear grass (Austrostipa fl avescens) and

1986). Although fl uvial activity is generally infrequent (only the Omo

Commuphera and Acacia sp. characterise the vegetation of the region.

River is perennial), the sediment load is high, in common with other arid

Acacia thorn scrub, with larger acacia trees along the river courses,

environments (up to 1 600 tonnes/km2/year), and delta construction is

grow around the Lake. The fairly high alkali content of the Lake's

rapid (Frostick & Reid 1986). Shoreline features of the Lake include major

waters greatly limits the range of species of vegetation. Galleries of

spits of the western lake shore; the shores around Longech, Lolibekai

forest occur along the affl

uent watercourses, being characterised by

and Menar are associated with high energy (Ferguson & Harbott 1982).

REGIONAL DEFINITION

17

Primary spits of the eastern shore such as Mvite and Koobi Fora are

(Lowe-McConnell 1995). Common species include: Alestes baremose,

subject to relatively little wave action but are maintained by currents

African tetras (A. dentex); Nile perch (Lates niloticus); Snooks, endemic (L.

running along both the river and lake margins, creating extensive

longispinis); Bagrid catfi shes (Bagrus bayad); Squeakers or upside-down

submerged and often steep-sided sand bars (Ferguson & Harbott

catfi shes (Synodontis schall); and Cichlids, such as Oreochromis niloticus,

1982).

O. galilaeus; and Tilapia zillii (Hughes & Hughes 1992). A few endemic

species among the non-cichlids refl ect Lake Turkana's geographical

The modern sediments of Lake Turkana are primarily detrital silicates

isolation for a relatively short time (Table 1) (Lowe-McConnell 1995).

and are dominantly fi ne grained (Yuretich 1979, Olago & Odada 2000).

Table 1

Endangered, endemic and rare fi sh species of Lake

Carbonate is the next most abundant component to the detrital silicate

Turkana.

fraction and has two main components; ostracod carapaces, and

Endangered

Endemic

Rare

micron-sized crystals of carbonate (Yuretich 1979, Halfman 1987). The

Bagrus bayad Forsskål (Catfish)

Lates rudolfianus Worth. (Nile perch)

Hydrocynus forskalii Curier

average sedimentation rate, based on radiocarbon dating by Halfman

Haplochromis rudolfianus Trevaras

Alestes baremose Linn. (Tigerfish)

and Johnson (1988), has been estimated at 2.7 mm/year and constitutes

(Tilapia)

the most reliable rate for Lake Turkana.

Alestes dextrex Linn. (Tigerfish)

Labeo horie Heckel (Barbels)

Alestes imberi Linn. (Tigerfish)

Polypterus bichir Günther (Bichirs)

Alestes minutus (Tigerfish)

P. senegalus (Bichirs)

Biological limnology

Alestes nurse Rüppel(Tigerfish)

Lake Turkana is famous for its colour. It is sometimes referred to as

Citharinus intermedius Warth.

the Jade Sea, which is largely due to the presence of blue-green

(Ray-finned fish)

algae in the phytoplankton community. Today, however the lake

Distochordus niloticus Linn.

Barbus bynni rudolfianus

colour, especially in the north, is brown because of sediment (Haack &

Worthington (Minnows and

Messina 2001). The Lake has a little-modifi ed fauna and a low level of

carps)

endemicity with few cichlid fi sh (Lowe-McConnell 1995). The principal

Barbus hindii Günther (Minnows

and carps)

emergent macrophytes are the grasses Paspalidium germinatum and

Labeo horie Heckel (Minnows

Sporobolus spicatus which cover the seasonally exposed shallows and

and carps)

(Source: National Biodiversity Unit 1992)

provide important nurseries for fi sh (Hughes & Hughes 1992). There are

extensive Potamogeton (pondweed) beds in the shallow bays (Hughes

& Hughes 1992).

Wildlife

On the eastern side of the Lake is Sibiloi National Park (a Natural World

The dominant phytoplankton are the blue-green algae Microcystis

Heritage Site). Mammals include Burchell's and Grevy's zebras (Equus

ceruginosa and the green algae Botryococcus braunii, while in Ferguson's

burchelli) and (E. grevyi), Grants gazelle (Gazella granti), Beisa oryx (Oryx

Gulf the blue-green algae Anabaenopsis arnoldii is dominant (Kallqvist

gazella beisa), Hartebeest (Alcelaphus buselaphus), Topi (Damaliscus

et al. 1988). The development of phytoplankton is limited by the

lunatus), Lesser kudu (Tragelaphus imberbis), Lion (Panthera leo), and

availability of nitrate and light (Hopson 1982). Light limitation is caused

Cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus). There are many crocodiles along the lake

by turbid water and vertical mixing. The zooplankton are dominated by

shore and on Central Island; Crocodylus niloticus and Varanus niloticus

protozoans in terms of numbers, but by crustaceans in terms of biomass

(Hughes & Hughes 1992).

(Hughes & Hughes 1992). The zooplankton community consists mainly

of Copepods (World Lakes Database 2002). There are fi ve gastropod

Lake Turkana is an important fl yway for north-bound migrants. Over

molluscs and two species of shrimp (Hughes & Hughes 1992).

350 species of aquatic and terrestrial birds have been recorded in the

Lake (Hughes & Hughes 1992). Common resident birds in Lake Turkana

Lake Turkana, although no longer in contact with the Nile, evidently was

include pelicans, fl amingos and herons (Gichuki & Gichuki 1992).

so in the recent past and it has a very similar fi sh fauna to that of Lake

Turkana is an important resting site for large numbers of visiting water-

Albert (Uganda) (Lowe-McConnell 1995). Of the 48 species of fi sh that

edge birds such as Kentish plover (Charadrius alexandrinus), Broad-

have been identifi ed in the Lake (36 species) and infl owing Omo River

billed sandpiper (Limicola falcinellus), Long-tailed skua (Stercorarius

(12 species) (Lowe-McConnell 1995), 30 are widespread Sudanian types,

longicaudus) and Pomerine skua (S. pomarinus) (Gichuki & Gichuki

8 have restricted distributions and 10 are endemic (Hughes & Hughes

1992). Central Island has a breeding population of African skimmer

1992). The 10 endemic species all live in the pelagic zone or deep water

(Rhyncops fl avirostris) which nests in banks. It is also an important

18

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 47 EAST AFRICAN RIFT VALLEY LAKES

staging post for migrating birds including warblers, wagtails and little

Lake Victoria

stints (Cunningham Van-Someren 1981).

Lake Victoria (1° S and 32° E) is, by area, the second largest lake in the

world and the largest in Africa, being almost twice the size of Lake

Ethiopia

Tanganyika (32 900 km2) and Lake Malawi (28 760 km2) (Figure 4). It is

perched high (1 134 m above sea level) on the African craton between

the western and eastern rift valleys (Johnson et al. 2000). This equatorial

Omo National Park

lake has a surface area of 68 800 km2 and an adjoining catchment area

of 184 000 km2. Lake Victoria is, however, a relatively shallow lake,

Sudan

with a maximum depth of 80-90 m compared to Tanganyika and

Ilemi triangle

Malawi whose maximum depths are 1 470 m (Capart 1949, Tiercelin &

- disputed

Mondeguer 1991) and 700 m (Johnson & Ng'ang'a 1990), respectively.

Sibiloi National Park

Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania border the Lake and share 6%, 43% and

51%, respectively, of the lake surface.

Lake Turkana

Ferguson´s

gulf

South Island

Kenya

National Park

Mount Kulal

Biosphere Reserve

Uganda

White Nile

Nasolot National

Reserve

South Turkana

Lake Albert

National Reserve

Lake Kyoga

Uganda

Figure 3

Protected areas in the Lake Turkana

Basin.

Nzoia

Kenya

Owen Falls

Kampala

dam

Kisumu

Entebbe

Protected areas and cultural heritage sites

Sondu Miriu

dam

Kavirondo gulf

Omo National Park in southwest Ethiopia is a pro-

Lake Edward

tected area (Figure 3). Koobi Fora, to the north of Alia

Lake Victoria

Bay on the eastern shore of the Lake, is an important

Kagera

archaeological site where extensive palaeontologi-

Bukoba

cal fi nds have been made. Human fossils include the

Rwanda

Mara

remains of Australopithecus rodustus, Homo habilis,

Kigali

i

Homo erectus and Homo sapiens. Central Island is a

Gurumet

part of the protected Sibiloi National Park on the

vu

Mwanza

eastern shore of the Lake. The southeastern sec-

uvu

R

Tanzania

tion of the Lake is also protected in the Mount Kulal

Biosphere Reserve, approved in 1978, and includes

Burundi

the South Island National Park of 3 880 ha. (Hughes

Landcover

& Hughes 1992). Part of the gorge section of the

Barren

Savannah

Turkwel River is protected in the Nasolot National

Cropland

Shrubland

Reserve, and a 25 km section of the left bank of the

Forest

0

100 Kilometres

Dams

Grassland

Kerio River is situated in the South Turkana National

© GIWA 2003

Reserve, 100 km north of Kitale township (Hughes &

Figure 4 Lake

Victoria

Basin.

Hughes 1992).

(Source: data from Loveland 2000)

REGIONAL DEFINITION

19

Climate

Biological limnology

The interannual variability of rainfall is remarkably coherent throughout

Much of the lake margin is swampy; islands of Cyperus papyrus, with

most of eastern Africa despite quite diverse climatic mean conditions.

its typical associates, detach from the fringing swamps (Hughes &

The largest portion of this variability is accounted for by the "short rains"

Hughes 1992). The current phytoplankton community is dominated

season of OctoberDecember. Rainfall variability in the region shows

by the cyanobacteria Cylindrospermopsis and Planktolyngbya, and the

strong teleconnections to the rest of Africa and to the global tropics.

diatom Nitzchia (Komarek & Kling 1991, Hecky 1993). Zooplankton

Rainfall in eastern Africa is strongly quasi-periodic, with a dominant time-

consist of abundant copepods and cladocerans (Branstrator et al.

scale of variability of 5 to 6 years (Nicholson 1996). This is also a dominant

1996). As recently as the 1960s, Lake Victoria supported an endemic

time-scale for the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) phenomenon and

cichlid fi sh species fl ock of more than 500 species (Seehausen 1996),

for Sea Surface Temperatures (SSTs) fl uctuations in the Equatorial Indian

but these have progressively disappeared from the catches to become

and Atlantic oceans. Rainfall variability is closely linked to both ENSO and

poorly represented today.

SSTs in the Indian and Atlantic Oceans, and it tends to be enhanced in

East Africa during ENSO years (Ropelewski & Halpert 1987, Ogallo 1989).

Lake Tanganyika

At 673 km along its major axis, Lake Tanganyika is the longest lake

The water balance is dominated by rainfall on the Lake, evaporation,

in the world and ranges from 12 to 90 km in width with a shoreline

and the Nile River outfl ow, with river infl ow making minor contributions

perimeter of 1 838 km (Figure 5, Table 2, Hanek et al. 1993). The countries

(Spigel & Coulter 1996). More than 80% of the water is derived directly

of Burundi, Democratic Republic of Congo, Tanzania and Zambia share

from rain onto the lake surface, while evaporation from the Lake

Lake Tanganyika. Of the Lake's shoreline perimeter, 9% is in Burundi,

accounts for a signifi cant amount of its annual water loss (Johnson et

43% is in DR Congo, 36% is in Tanzania, and 12% is in Zambia (Hanek

al. 2000). The Kagera River contributes about 7% of the total infl ow.

et al. 1993).

Physical limnology

Hydrological and hydrodynamic data for Lake Victoria (and other

Rwanda

Lake Kivu

R

East African Lakes) are scarce, fragmentary and often not easily

usizi

accessible. A resurgence of work is now underway over a wide range

Burundi

of disciplines since the Lake has been under severe ecological pressure

Uvira Bujumbura

for the last four decades. The Lake has an intricate and highly indented

shoreline of more than 3 500 km. It has numerous islands, shallow

bays and connecting channels, and extensive areas of wetland. These

morphological features are signifi cant for exchange of water between

Kigoma

Tabora

the littoral and pelagic regions of the Lake (Spigel & Coulter 1996). Lake

Malagarasi

Tanzania

Victoria has a fl ushing time of 140 years and a residence time of 23 years

Kalemie

(Bootsma & Hecky 1993).

DR Congo

Lake Tanganyika

Surface water temperature is between 24 and 28°C (Ochumba 1996),

a

g

u

and evaporative cooling during the dry season is important in the

g

Lu

heat balance and mixing regime (Talling 1966). Temperature profi les

Landcover

measured in Lake Victoria show a lack of well-defi ned mixed layers and

bo

Cropland

l

om

Ka

Forest

seasonal thermoclines; the temperature gradients tend to be more

Mpulungu

Grassland

Lu

diff use, and horizontal variability greater, than in Lake Tanganyika and

fubu

Savannah

Lake Malawi (Spigel & Coulter 1996). Measurements carried out in the

Zambia

Kenya sector of the Lake show that anoxic water occurs below a depth

of 35 m, with the oxycline at 10 to 50 m (20 to 30 m for most of the

year) (Ochumba 1996). Sporadic upsurges of the oxycline to depths as

0

100 Kilometres

© GIWA 2003

shallow as 10 m in the open lake have been associated with fi sh kills

Figure 5 Lake

Tanganyika

Basin.

(Ochumba 1996).

(Source: data from Loveland 2000)

20

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 47 EAST AFRICAN RIFT VALLEY LAKES

Table 2

Physiographic statistics for Lake Tanganyika.

world. Modern annual lake level variation is about 1 m (Edmond et

Latitude

03°20' - 08°48' S

al. 1993). Geologic processes have largely determined the shoreline

Longitude

29°03' - 31°12' E

substrates around the Lake. Of the 1 838 km shoreline perimeter, 43%

Age (years)

about 12 million

is rocky substrate, 21% is mixed rock and sand substrate, 31% is sand

Altitude (m)

773 above sea level

substrate and 10% is marshy substrate (Coenen et al. 1993).

Length (km)

673

Width (km)

12-90, average about 50

Climate

Surface area (km2)

32 600

Lake Tanganyika has two wet seasons in a year, March/April and

Volume (km3)

18 880

Shoreline perimeter (km)

1 838

December, with mean annual rainfall ranging from 1 200 mm in the

Maximum depth (m)

1 320 (northern basin), 1 470 (southern basin)

northern part to 1 600 mm in the southern part (Nicholson 1996). The

Mean depth (m)

570

interannual variability of rainfall is remarkably coherent throughout

Catchment (km2)

220 000

most of eastern Africa and is similar to that described for Lake Victoria

Stratification

permanent, meromictic

(see above).

Oxygenated zone (m)

70 (north), 200 (south)

Temperature (°C)

23-27

Physical limnology

pH

8.6-9.2

Most of Lake Tanganyika's water loss is through evaporation. Calcula-

Salinity ()

~0.46

(Source: modified from Coulter 1994)

tions from Lake Tanganyika's water budget suggest a water residence

time of 440 years and a fl ushing time of 7 000 years (Coulter 1991). Lake

A catchment area of 220 000 km2 feeds Lake Tanganyika (Table 2). The

Tanganyika, with an approximate surface area of 32 600 km2 and volume

Lake's average depth is 570 m, with a maximum depth of 1 320 m in

of 18 880 km3, contains 17% of the Earth's free freshwater (statistics from

the northern basin and 1 470 m in the southern basin, making it the

Hutchinson 1975, Edmond et al. 1993, Coulter 1994).

world's second deepest lake, after Lake Baikal. Lake Tanganyika is fed

by numerous small rivers and two major aff fl uent rivers; the Rusizi

Lake Tanganyika can be generally characterised by the limnological

River draining Lake Kivu to the north, and the Malagarasi River draining

parameters in Table 3 (Bailey-Watts 2000, Bailey-Watts et al. 2000).

western Tanzania south of the Lake Victoria Basin. A single outlet, the

Although permanently oligotrophic in appearance (Wetzel 1983),

Lukuga River, drains Lake Tanganyika, though the fl ow of this river

periodic phytoplankton blooms occur (Dubois 1958, Hecky & Kling

has changed direction in historical times (Beadle 1981). This river is a

1981, Coulter 1991, Salonen et al. 1999). It is stratifi ed into an oxygenated

tributary of the Congo River, which belongs to GIWA region 42, Guinea

upper layer, penetrating to about 70 m depth at the north end and 200

Current.

m at the south, and an anoxic lower layer, which constitutes most of

the Lake's water volume (Beauchamp 1939, Hutchinson 1975, Spigel &

Geology and geomorphology

Coulter, 1996). The oxygenated and anoxic layers generally do not mix,

Based on sediment accumulation rates in the Basin, geologists have

though wind-induced upwelling results in some mixing at the Lake's

estimated that Lake Tanganyika has existed for approximately 12 million

southern end (Spigel & Coulter, 1996). The temperature and pH of surface

years (Scholz & Rosendahl 1988, Cohen et al. 1993a). More recent studies

waters vary between 23-28°C and 8.6-9.2, respectively (Coulter 1994).

indicate that between 4.9 million years and 3.6 million years ago, the

proto-Lake Tanganyika corresponded to an approximately 400 km

Table 3

Basic limnological parameters for Lake Tanganyika.

long lake resembling the present-day lake between the latitudes

Parameter

Lakewide

Burundi

Tanzania

Zambia

3° and 7° S (Tiercelin & Lezzar 2002). At about 2 million years ago,

Transparency (m)

7-16

ND

ND

ND

a major episode of rifting associated with intense volcanism in the

Conductivity (µS/cm)

700

ND

ND

ND

Kivu Province resulted in the fi nal development of the Kivu and North

Chlorophyll a concentration (µg/l)

ND

ND

1.5-6

4-14

Tanganyika lake basins (Ebinger et al. 1989, Lezzar et al. 1996) while the

Ammonium-nitrogen (mg/l)

ND

0.5-1.0

ND

ND

southward rift propagation along the Lake Tanganyika Rift resulted in

Nitrate-nitrogen (µg/l)

ND

500-1 000

< 100

75-130

the fi nal morphology of the Mpulungu sub-basins at the southern end

Phosphate-phosphorous (µg/l)

ND

500

7-8

12

of Lake Tanganyika from about 2 million years ago up to the present-day

Total phosphorous (µg/l)

ND

ND

30

12

(Tiercelin & Lezzar 2002). Lake Tanganyika is the oldest of the African

Sulfate (mg/l)

ND

3-4

ND

ND

Lakes, and after Lake Baikal in Russia, it is the second oldest lake in the

Note: ND = No Data. (Source: data from Bailey-Watts 2000)

REGIONAL DEFINITION

21

Biological limnology

copepods, leeches and sponges. Table 4 (modifi ed from Coulter

The Lake's morphology, a steeply sided rift cradling a deep anoxic

1994) lists the numbers of species in Lake Tanganyika by taxonomic

mass capped by a thin oxygenated layer, has profound implications

grouping. The invertebrate species numbers are probably signifi cantly

for the distribution of organisms. Most of Lake Tanganyika's water mass

underestimated, as these groups in general have received relatively little

is uninhabited. Organisms are limited to the Lake's upper oxygenated

attention from taxonomists and in addition, much of Lake Tanganyika's

zone. Because of the steeply sloping sides of the Lake's basin, benthic

coast has not been adequately explored. Nonetheless, it is clear that

organisms (which rely on the substrate for at least some aspect of

this level of invertebrate diversity exceptional. Lake Tanganyika, with

their life cycle) are limited to a thin habitable ring fringing the Lake's

more than 2 000 species of plants and animals, is among the richest

perimeter which extends sometimes only tens of metres off shore.

freshwater ecosystems in the world.

Like lakes Victoria and Malawi, Lake Tanganyika is famous for its

More than 600 of these species are endemic to the Tanganyika Basin,

endemic species fl ocks of cichlid fi shes (Figure 6). It hosts a large fl ock,

i.e. they are not found anywhere else. This includes a remarkable 98%

estimated to include more than 700 cichlid fi sh species (Snoeks 2000).

of the cichlid fi sh species, 59% of the non-cichlid fi sh species, 75% of

More than 250 cichlid species are parsed between several sub-fl ocks

the gastropod species, 60% of the bivalve species, 71% of the ostracod

(Snoeks et al. 1994). However, unlike the other African Great Lakes, Lake

species, 93% of the decapod species, 48% of the copepod species, 60%

Tanganyika also hosts species fl ocks of non-cichlid fi sh and invertebrate

of the leech species, 78% of the sponge species, and others, more than

organisms, including gastropods, bivalves, ostracods, decapods,

600 species in all, are unique to the Tanganyika Basin (Coulter 1994). It

Figure 6 Cichlids.

(Photo: Corbis)

22

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 47 EAST AFRICAN RIFT VALLEY LAKES

Table 4

Inventory of species in Lake Tanganyika.

Taxon

Species

Endemic (%)

Algae

759

ND

Songwe

Aquatic plants

81

ND

Protozoans

71

ND

r

u

Cnidarians

2

ND

u

k

u

R

.

Sponges

9

78

N

u

uh

Ruh

Bryozoans

6

33

Flatworms

11

64

Tanzania

Roundworms

20

35

Segmented worms

28

61

Horsehair worms

9

ND

u

ur

Spiny head worms

1

ND

Ruk

Mzuzu

S.

Pentastomids (small group of parasites)

1

ND

Rotifers

70

7

Lake Malawi

Snails

91

75

Likoma island

Clams

15

60

Arachnids (spiders, scorpions, mites, ticks)

46

37

Crustaceans

219

58

Insects

155

12

angwa

Dw

Mozambique

Fish (family Cichlidae)

250

98

a

Fish (non-cichlids)

75

59

Bu

Lichinga

Amphibians

34

ND

Malawi

Reptiles

29

7

e

gw

Birds

171

ND

Lilon

Lilongwe

Mammals

3

ND

e

ip

Total

2 156

Linth

Note: ND = No Data. (Source: modified from Coulter 1994)

Landcover

Shire

is thought that the proto Lake Tanganyika was colonised by organisms

Mozambique

Barren

from the ancient Congo River system (which pre-dates the Lake), and

Cropland

these pioneer species evolved and radiated within the Lake Basin,

Forest

creating the great diversity (Coulter 1994). In many cases these taxa

Savannah

also represent endemic genera and sometimes endemic families. With

Blantyre

0

50

Kilometres

its great number of species, including endemic species, genera and

© GIWA 2003

families, it is clear that Lake Tanganyika makes an important contribution

Figure 7

Lake Malawi Basin.

(Source: data from Loveland 2000)

to global biodiversity. Lake Tanganyika is an extraordinary biological

system and it provides a natural laboratory for investigating a myriad of

Tanganyika, and the second most voluminous after Lake Tanganyika. The

evolutionary and ecological questions (e.g. Michel et al. 1992).

total catchment area is small for a lake of this magnitude: 126 500 km2 of

which 97 750 km2 is land catchment (Drayton 1984).

Lake Malawi

Lake Malawi is known by a diff erent name in each of its three riparian

A narrow strip along the eastern shore, comprising 7% of the total

countries. In Malawi, it is called Lake Malawi, in Mozambique, it is called

land catchment, is shared between Mozambique and Tanzania

Lake Niassa, and in Tanzania, Lake Nyasa. Lake Malawi is long and narrow

(Eccles 1984). A further 19% consisting of the Ruhuhu Basin (11%), the

and the southernmost of the Western Rift Valley Lakes (Figure 7). The

northern lakeshore and highlands (6%) and part of Songwe Basin (2%)

Lake merits the adjective "great" by almost any measure, e.g. area, depth,