(1,1) -1- Cover 40b_only.indd 2004-04-05, 14:07:25

Global International

Waters Assessment

Amazon Basin

GIWA Regional assessment 40b

Barthem, R. B., Charvet-Almeida, P., Montag, L. F. A. and A. E. Lanna

Global International

Waters Assessment

Regional assessments

Global International

Waters Assessment

Regional assessment 40b

Amazon Basin

GIWA report production

Series editor: Ulla Li Zweifel

Report editor: David Souter

Editorial assistance: Johanna Egerup and Malin Karlsson

Maps & GIS: Niklas Holmgren

Design & graphics: Joakim Palmqvist

Global International Waters Assessment

Amazon Basin, GIWA Regional assessment 40b

Published by the University of Kalmar on behalf of

United Nations Environment Programme

© 2004 United Nations Environment Programme

ISSN 1651-9402

University of Kalmar

SE-391 82 Kalmar

Sweden

United Nations Environment Programme

PO Box 30552,

Nairobi, Kenya

This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and

in any form for educational or non-profit purposes without

special permission from the copyright holder, provided

acknowledgement of the source is made. No use of this

publication may be made for resale or for any other commercial

purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from the

United Nations Environment Programme.

CITATIONS

When citing this report, please use:

UNEP, 2004. Barthem, R. B., Charvet-Almeida, P., Montag, L. F. A.

and Lanna, A.E. Amazon Basin, GIWA Regional assessment 40b.

University of Kalmar, Kalmar, Sweden.

DISCLAIMER

The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors

and do not necessarily reflect those of UNEP. The designations

employed and the presentations do not imply the expressions

of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNEP or cooperating

agencies concerning the legal status of any country, territory,

city or areas or its authority, or concerning the delimitation of its

frontiers or boundaries.

This publication has been peer-reviewed and the information

herein is believed to be reliable, but the publisher does not

warrant its completeness or accuracy.

Printed and bound in Sweden by Sunds Tryck Öland AB.

CONTENTS

Contents

Abbreviations and acronyms

9

Executive summary

11

Regional definition

14

Boundaries of the Amazon region

14

Physical characteristics

15

Socio-economic characteristics

19

Assessment

22

Freshwater shortage

22

Pollution

24

Habitat and community modification

26

Unsustainable exploitation of fish and other living resources

28

Global change

30

Priority concerns

31

Causal chain analysis of the Madeira River Basin

34

Introduction

34

System description

35

Causal model and links

38

Policy options of the Madeira River Basin

43

Definition of the problems

43

Construction of the policy options

45

Identification of the recommended policy options

46

Likely performance of recommended policies

46

References

48

Annexes

53

Annex I List of contributing authors and organisations

53

Annex II Detailed scoring tables

54

Annex III List of important water-related programmes in the region

58

Annex IV List of conventions and specific laws that affect water use in the region

59

The Global International Waters Assessment

i

The GIWA methodology

vii

CONTENTS

Abbreviations and acronyms

ACA

Amazon Conservation Association

ACT

Amazon Cooperation Treaty

ANA

Brazilian National Water Agency

BOD

Biological Oxygen Demand

CENDEPESCA

Bolivian Centre for Fisheries Development

COBRAPHI

Brazilian Committee for the International Hydrological Programme

EMBRAPA

Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation

FAO

Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations

HiBAm

Hydrology and Geochemistry of the Amazon Basin

IBAMA

Brazilian Institute of Environment

IBGE

Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics

INPA

The National Institute for Research in the Amazon

INPE

Brazilian National Institute for Space Research

LBA

Large Scale Biosphere-Atmosphere Experiment in Amazonia

MERCOSUR

Mercado Común del Sur (Southern Common Market)

MINPES

Peruvian Ministry of Fisheries

MPEG

The State of Pará Emílio Goeldi Museum

PPG7

Protection of the Brazilian Rainforest

PROVARZEA

The Amazon Floodplains (Varzea) Project

SECTAM

The Pará State Secretariat for Science, Technology and Environment

SENAMHI

National Service of Meteorology

SINCHI

The Amazonic Institute of Scientific Research

UA

Amazonas University

UFPA

Federal University of Pará

UFPB

Federal University of Paraíba

UNEP

United Nations Environment Programme

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

9

List of figures

Figure 1

Geographical location of the Amazon, Orinoco and Paraná basins. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

Figure 2

The Amazon Basin. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

Figure 3

The drainage basins of the tributaries comprising the Amazon Basin.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

Figure 4

The main Amazon habitats. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

Figure 5

A small urban stream blocked by solid wastes.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25

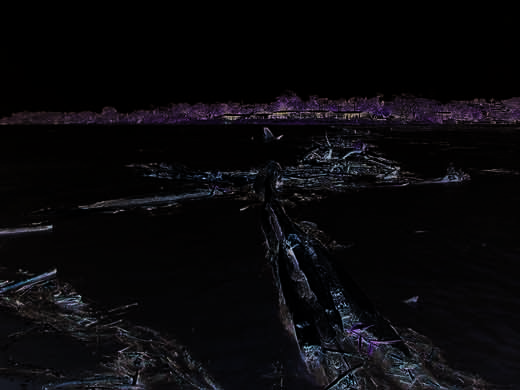

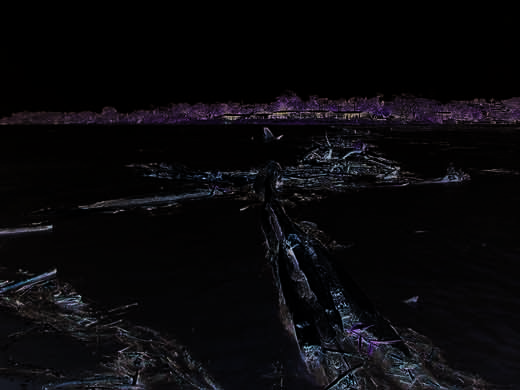

Figure 6

The rivers of the Amazon Basin carry a large volume of trees, pieces of wood, branches, leaves and roots. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25

Figure 7

The Balbina Dam on the Uatumã River.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27

Figure 8

Model indicating the inter-linkage and synergies between the concerns. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 33

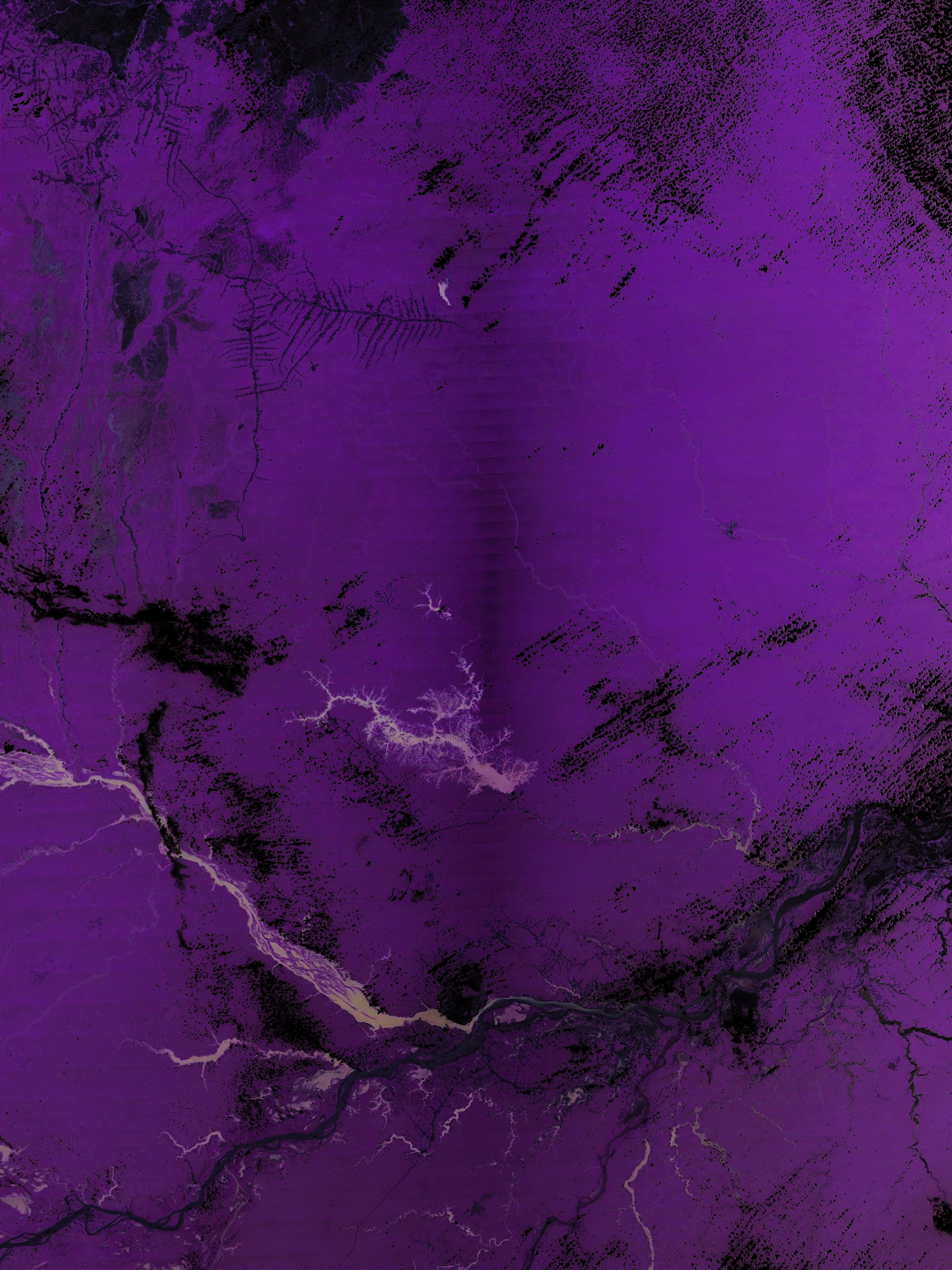

Figure 9

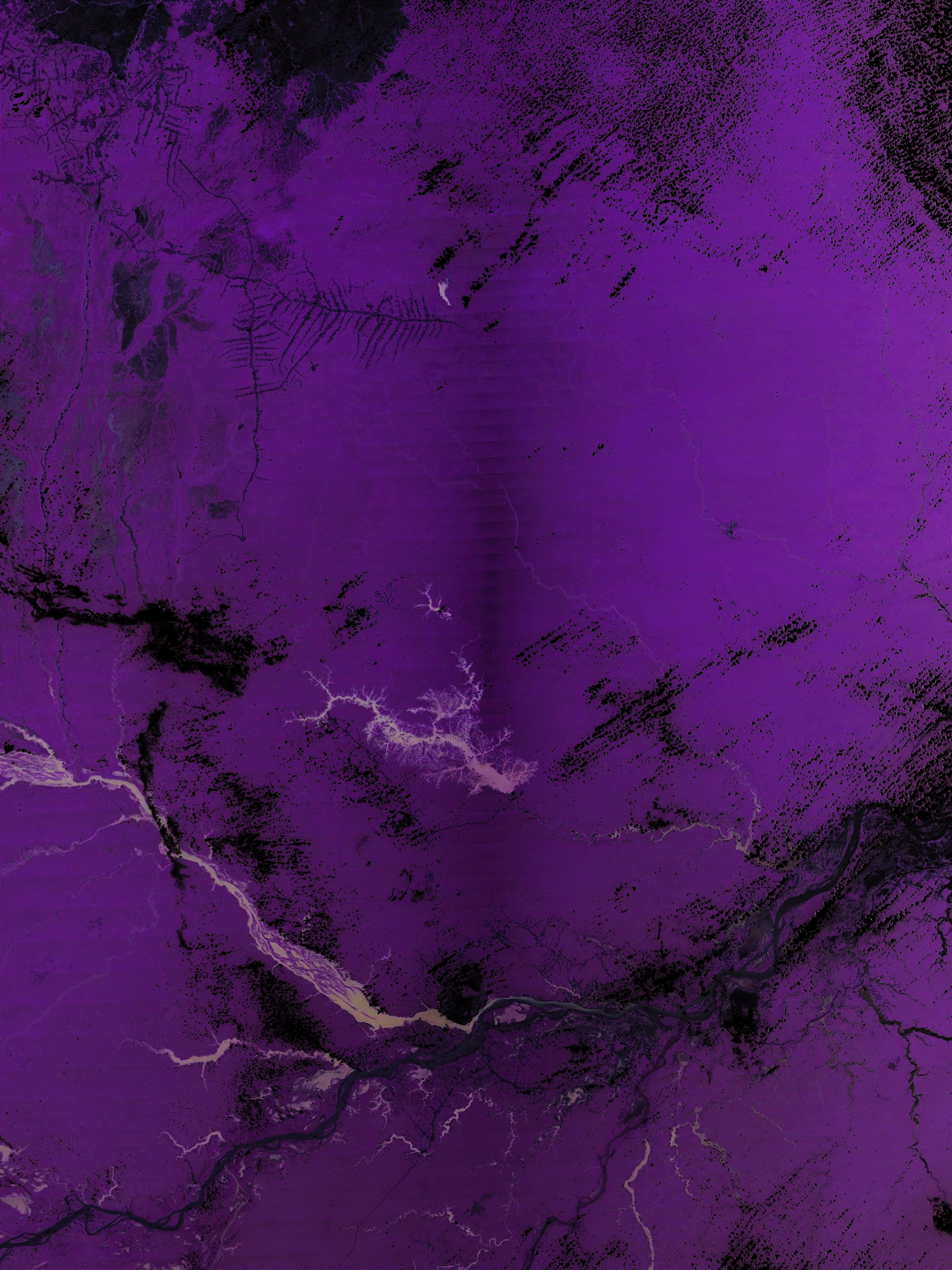

Deforested areas in the Madeira Basin. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35

Figure 10 Anthropogenic pressure in the Madeira River Basin. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36

Figure 11 Gold mining activity in the Madeira River headwaters. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36

Figure 12 Transport of timber (mahogany) in the Peruvian rivers. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 37

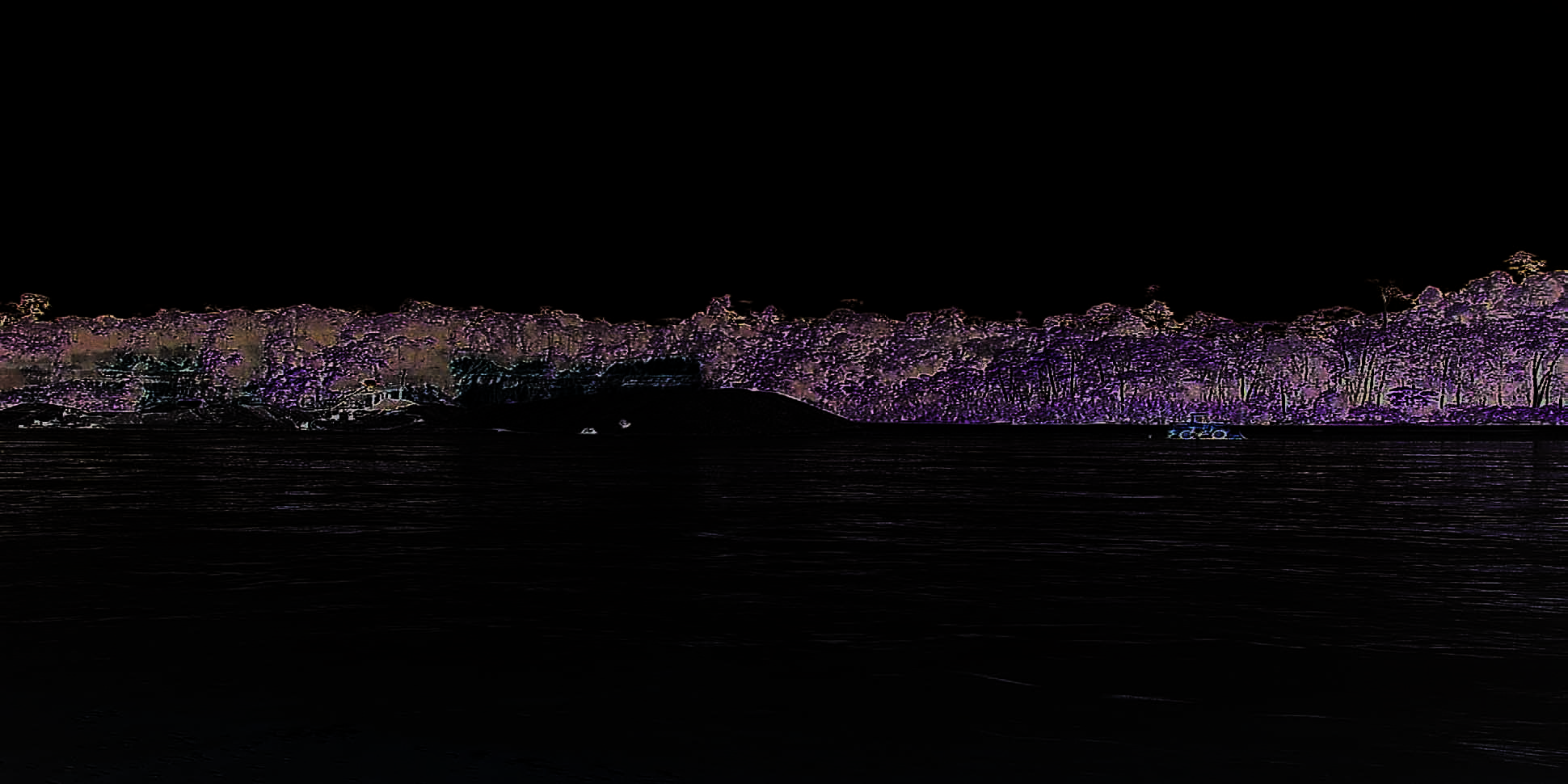

Figure 13 Fishing activity in the Madre de Dios River. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 37

Figure 14 Madeira River Basin causal chain analysis on Pollution. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 41

Figure 15 Madeira River Basin causal chain analysis on Habitat and community modification. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 42

List of tables

Table 1

The Amazon River and its main tributaries. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

Table 2

Countries within the Amazon Basin. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

Table 3

Scoring table for the Amazon region. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22

Table 4

Population in relation to river basins. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35

Table 5

Basic sanitation indicators in the Brazilian part of Madeira and Amazon basins. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 38

Table 6

Water availability in the Brazilian part of the Madeira and Amazon basins.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 38

Table 7

Water demand in the Brazilian part of the Madeira and Amazon basins.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 38

Table 8

Organic load in the Brazilian part of the Madeira and Amazon basins. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 38

10

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 40B AMAZON BASIN

Executive summary

The Amazon Basin is the largest basin on the planet and also one of the

are the most important products exported from the Amazon Basin.

least understood. Its drainage area covers more than one third of the

Timber exploitation focuses on a few species, particularly mahogany

South American continent, and its discharge contributes almost one

(Swietenia macrophyl a). The primary environmental consequence of

fifth of the total discharge of all rivers of the world. The headwaters of

this exploitation is the depletion of natural populations of the exploited

the Amazon River are located about 100 km from the Pacific Ocean and

species. The construction of roads to facilitate the extraction of timber

it runs more than 6 000 km before draining into the Atlantic Ocean. In

from within the forest also provides access to farmers and other groups

addition, the Amazon has 15 tributaries, including the Tocantins River,

that colonise and expand into these newly accessible areas. Mining,

that measure more than 1 000 km in length. The Madeira and Negro

particularly of al uvial gold, and oil extraction activities are scattered

rivers are the most important tributaries, contributing with more than

throughout the Amazon region. The main environmental problems

one third of the total water discharge. The Amazon Basin contains

associated with mining are pol ution and increased suspended

a complex system of vegetation, including the most extensive and

sediment loads caused by erosion which leads to the degradation

preserved rainforest in the world. The rainforest, known as the Amazon

of downstream habitats. Fishing is also an extractive activity that is

Rainforest, is not confined to the Amazon Basin but also extends into

traditional and important in the Amazon plains. Fish is a source of cheap,

the Orinoco Basin and other small basins located between the mouths

high quality protein for inhabitants of the Amazon Basin. Some selected

of the Orinoco and Amazon rivers. In addition, savannah and tundra-

species of fish are exported to other regions outside the Amazon Basin

like vegetation can also be found. Extensive areas of scrub-savannah

and also to other countries. Overexploitation exists but is restricted to

dominate the headwaters of the Brazilian and Guyana shields, while

only a few target species.

the regions of the Basin situated at high altitude in the Andes are

characterised by tundra-like grassy tussocks cal ed the Puna.

The development and expansion of agriculture is modifying the

environment within the region. Large cattle farms are being established

The Amazon Basin is shared by Brazil, Peru, Ecuador, Bolivia, Colombia,

in vast areas along the southern and eastern borders of the Basin. Also,

Venezuela and Guyana. More than half of this basin is located in

large soybean plantations are being established mainly in less humid

Brazilian territory, but the headwaters are located in the Andean

areas near the borders of the Basin. Meat and soybeans may become

portion of the Basin which is shared by Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador and

important export products from this region, but it wil result in the

Colombia. The human density in the Amazon Basin is very low and

replacement of natural forests by pastures and soybean plantation.

people are concentrated in urban centres. In the entire Basin there are

The importance of the Amazon forest in regulating the hydrological

five cities with more than 1 million inhabitants and an additional three

and carbon cycles has only very recently been recognised and the

with more than 300 000 people. However, despite the high proportion

consequences of the large-scale deforestation are not wel understood.

of the population living in urban areas, the economy of the region is

As a consequence, deforestation and pollution were considered to be

stil primarily dependent on the extraction of exportable minerals,

the most critical large-scale environmental problems in this region

oils and forest products. The only exception is the contribution made

leading to the conclusion that Habitat and community modification

by the industrial park established in the duty free zone in the city of

and Pol ution were the most important GIWA concerns in the entire

Manaus. Products from timber, mining and petroleum exploitation

Amazon Basin.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

11

Although the environmental and socio-economic impacts of each

informed about the ecology, economy, socio-economy, hydrology,

of the predefined GIWA issues and concerns were assessed over

meteorology, agriculture and other important aspects related to water

the entire Amazon Basin, the dimension and heterogeneity of the

and land use in the Basin. This action could be implemented in three

region rendered causal chain and policy options analyses of the entire

ways: (i) research, to obtain more and new information; (i ) search,

region impracticable. As a consequence, these analyses focused on

to gather existing information; and (i i) dissemination, to transmit

determining the root causes of and policy options for mitigating Habitat

information to the target audience. The purpose of this project is to

and community modification and Pollution only in the Madeira Basin.

integrate the different countries and stakeholders that support research,

This basin was chosen because of its socio-economic importance to

databases, and social organisations, in the field of water resources

the region and its transboundary nature.

and environmental management in the Madeira Basin. This project

wil represent a first step to develop and implement a basin-wide

The Madeira River Basin is shared by Brazil, Bolivia and Peru and

management programme involving the three countries. This action

therefore, requires a transnational management agreement in order

complies with directives of the Amazon Cooperation Treaty (ACT) and

to ensure appropriate management of aquatic resources and the

will be the basis for the constitution of a Commission or International

establishment of a socio-economic development plan. The Causal

Committee of the Madeira River Basin. Al three countries possess

chain analysis determined that the root causes of Pollution and Habitat

research programmes and database systems to monitor problems and

and community modification in the Madeira Basin were: governance

manage water resources sustainably, but these programmes are not

failures, market and policy failures, poverty, and lack of knowledge and

integrated. The implementation of an integrated information system

information. The lack of information affects the Basin in different ways,

might improve the prediction of floods and the implementation of

from the inability to detect problems and unsustainable practices to the

mechanisms for pol ution control. Also, the scientific community within

lack of environmental warning mechanisms to raise awareness among

these countries could work in association with the information system

decision-makers. The failure of governance was related to the difficulty in

to develop joint research projects in the aquatic sciences.

establishing acceptable mechanisms to settle conflicts among different

interests. The lack of legitimacy of negotiations commanding decisions

The impetus for establishing a sustainable development programme for

regarding investments and the absence of a basin-wide management

fishing activities in the Madeira Basin is the great economic potential of

plan were the two biggest problems associated with governance

fish stocks and the importance of connections between the upper and

failures in the region. The market and policy failures were attributable

lower parts of rivers to enable fish migration. This project aims to gather

to the misconception that natural resources of the Amazon Basin are

fisheries projects and organisations in order to achieve sustainable

inexhaustible which leads to the unsustainable use of those resources.

fishing practices and exploitation of unidentified opportunities. In

The lack of knowledge was associated with inadequate training in best

addition, the project should strive to raise awareness among fishermen

land use practices resulting in the failure to adopt techniques for soil

and stakeholders of how their activities affect and, in turn, are affected

and chemical use in the agriculture and mining industries that make

by the health of the environment of the Basin, thus transforming them

these activities more profitable and less environmental y damaging.

into one of the primary agents monitoring and enforcing the sustainable

Training in best land use practices must be included in the basin-wide

development programme. In the Amazon Basin, some efforts have been

management plan. Final y, poverty is common in the Amazon Basin and

made to integrate fisheries management, mainly to manage the stocks

results in the significant dependence of people living in the region on

of large migratory catfish. Experiences gained from these efforts could

the exploitation of natural resources in order to sustain their livelihoods.

be incorporated directly into a sustainable fisheries development

The Amazon Basin is one of the last frontiers and a land of opportunities

programme for the Madeira Basin. The selection of this project was

for those that do not have good perspectives in their homelands. The

based on the fact that the fishery supports thousands of direct and

poverty-environmental degradation cycle probably represents the

indirect jobs and, as a consequence, the adequate management of the

largest chal enge for the future administration of this region.

fish stocks in the region is more important from a social perspective

than an economic one. Considering the fact that large migratory

The two most promising projects developed to address these root

catfish spawn in the Andean headwaters of the Basin and mature

causes aimed to collate and disseminate information and to implement

in the estuary and in the lower Amazon reaches, the geographic

a fisheries management programme in the Madeira Basin. Information

area in which this project would be implemented is enormous. The

is the key requirement in order to implement actions to ensure

protection of the spawning areas of these species is essential for the

sustainable use of water resources. The Governments must be well

fishery in the entire Amazon Basin. The efficiency of the project is high

12

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 40B AMAZON BASIN

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

13

because the economic feedback resulting from larger fish stocks is

relatively fast. In addition, the equity considerations are also positive

because the development programme for fishing activities would

directly affect both professional and amateur fishermen, as well as the

consumer markets in the largest cities. Furthermore, considering the

increase in the number of conflicts between fishermen during recent

decades, the political feasibility of the project must be addressed. The

necessity of implementing a fishing ordinance to manage fish stocks

in the region has been recognised by both professional fishermen and

by artisanal fisherman living in riparian communities. In some cases,

it is impossible to find an equitable solution for a conflict and it is

necessary to make a decision that could be unfavourable to one party.

If this is done, the political feasibility of the project can be threatened.

However, if the decision is not taken, the conflict may intensify and

become uncontrol able, potential y threatening the project once

again. Unfortunately, despite having the necessary scientific capacity,

the implementation of this project is prevented by inadequate financial

resources in each of the three countries that share the Madeira Basin.

12

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 40B AMAZON BASIN

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

13

Regional definition

This section describes the boundaries and the main physical and

socio-economic characteristics of the region in order to define the

area considered in the regional GIWA assessment and to provide

sufficient background information to establish the context within

which the assessment was conducted.

Boundaries of the

Amazon region

The Amazon Basin is the largest drainage basin on the planet. It is

situated completely within the tropics, between 5° N and 17° S, and

occupies more than one third of the South American continent. Seven

countries, Brazil, Bolivia, Peru, Colombia, Ecuador, Venezuela and

Guyana share this basin. The Orinoco and Paraná rivers represent other

important South American basins, located to the north and south of

the Amazon Basin, respectively (Figure 1).

The headwaters of the Amazon River are located in the Andes Mountains

© GIWA 2003

which are shared among Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador and Colombia, while the

Figure 1

Geographical location of the Amazon, Orinoco and

Paraná basins.

origin of several important tributaries are found in the Brazilian and

Guyana shields, an ancient Precambrian crystalline basement situated

partial y separated by several islands located at their confluence, and it

along the northern and southern border of the Basin (Figure 2). The

may represent a division of the basins. The Marajó Island is the largest

headwaters of rivers situated in the northern Amazon Basin are shared

and it separates the mouth of the Amazon to the north from Marajó

by Venezuela, Guyana and Brazil, while the headwaters of rivers in

Bay and Pará River, which are considered the mouth of the Tocantins

the south are located in Brazil. The central, the lower and the mouth

River and several other smal er rivers located to the south (Barthem &

of the Amazon River fal within the Brazilian territory (Figure 3). The

Schwassmann 1994). The discharge of the Amazon and Tocantins rivers

Amazon discharges into the North Brazil Shelf Large Marine Ecosystem

creates a large area along the northeastern coast of South America where

(LME 17).

fresh and saltwater mix and sustains a 2 700 km stretch of low-lying,

muddy mangrove forests. This environment extends from the Orinoco

The Brazilian Government excludes the Tocantins River from the Amazon

Delta in Venezuela into the Brazilian State of Maranhão and is inhabited

Basin's drainage area (COBRAPHI 1984). The mouths of these rivers are

by several endemic species, genera and sub-families of fishes (Myers

14

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 40B AMAZON BASIN

REGIONAL DEFINITION

15

1960). The volume of water discharged from both these rivers supply

Physical characteristics

around 15% of the total fluvial water into the world's oceans (Mil iman &

Meade 1983, Goulding et al. 2003). However, despite the geographical

The area of the Amazon Basin is estimated to 6 869 000 km2 (Table 1).

separation of the mouths of the Amazon and Tocantins rivers, the water

Although 69% of the Amazon Basin is situated in Brazil; Bolivia and Peru

from both mixes prior to reaching the ocean and therefore has similar

can also be considered as Amazon countries, because 66% and 60%

physical and chemical properties which gives rise to similar freshwater

of the area of these countries respectively is located in the Amazon

fauna on both sides of the archipelago (Barthem 1985, SANYO Techno

Basin (Goulding et al. 2003) (Table 2). The catchment area of the Basin

Marine Inc. 1998, Smith 2002). As a consequence, there are no ecological

extends from 79° W (Chamaya River, Peru) to 46° W (Palma River, Brazil),

or geographical reasons to consider these basins separately.

from 5° N (Cotingo River, Brazil) to 17° S (headwater Araguaia River, Brazil)

and incorporates some of the greatest drainage basins of the world

The boundary of the GIWA Amazon region was considered the limits

(Goulding et al. 2003). Table 1 shows the areas of the most important

of the drainage area of the Amazon and Tocantin Basins. Due to the

catchments within the Amazon Basin and identifies those that are

extension of the Amazon mouth and the influence of the freshwater

considered international and drain an area shared by more than one

discharge on coastal waters close to its mouth, it was necessary to

country, and those that are considered national and drain an area larger

define the eastern limits of the region. Although the distance from the

than a state. The largest catchment within the Amazon Basin in terms

mouth that freshwater is discharged from the Amazon varies more that

of drainage area and discharges of water and sediment is the Madeira

100 km between seasons, the influence of the freshwater is very small

River, which drains an area that covers parts of Brazil, Bolivia and Peru.

beyond 50 m depth (Barthem & Schwassmann 1994, SANYO Techno

The Tocantins River is the second largest catchment in terms of drainage

Marine Inc. 1998). Therefore, the eastern limit of the Amazon Basin

area and is entirely Brazilian. The Negro River, in the northern Amazon

region was designated as the 50 m depth contour and included the

Basin, is the most important tributary in relation to discharge of water

Guamá and Araguari rivers as well as other small basins (Figure 3).

and drainage area, which drains parts of four countries: Brazil, Colombia,

Venezuela

Guyana

LME 17

Suriname

Colombia

French Guiana

G u y a n a

S h i e l d

Boa Vista

Trombetas

o

Branc

Macapá

Negr

Caq

o

ueta

Ecuador

Balbina

Japura

Uatum

Curuá Una

á

Belém

Napo

Putumayo-Içá

Urubu

Amazonas

A

Manaus

Tigr

Santarém

Tucuruí

e

n

Iquitos

A m a z o n i a n l o w l a n d s

Mar

d

añón

Xingu

a

e

Tapajos

Jurua

Madeir

s

Uc

Purus

ayali

Samuel

m

Porto Velho

Rio Branco

Aripuonã

Braço Norte

l d

Elevation (m)

o

Lageado

0

i e

u

Juina

50

Peru

Brazil

n

S h

Tocantins

100

t

Madre de DiosBeni

é

Cuzco

Sierra da Mesa

200

a

Mamor B r a z i l i a n

Culuene

500

i n

1000

Bolivia

s

La Paz

Torixoreu

River

2000

City

Santa Cruz

3000

LME17

de la Sierra

4000

Amazonas estuary

0

500 Kilometres

6561

Hydroelectric dam

© GIWA 2003

Figure 2

The Amazon Basin.

14

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 40B AMAZON BASIN

REGIONAL DEFINITION

15

Table 1

The Amazon River and its main tributaries.

Table 2

Countries within the Amazon Basin.

Basin area

Discharge

Amazon Basin

Country area included in the

Basin

Countries

Category

Country

(km2)

(m3/s)

by country (%)

Amazon Basin (%)

Brazil, Bolivia, Peru, Colombia,

Brazil

69.1

54.7

Amazonas

6 869 000

100%

220 800

International

Ecuador, Venezuela and Guyana

Peru

11.4

59.9

Tributaries

Bolivia

10.7

65.9

Madeira

1 380 000

20%

31 200

Brazil, Bolivia and Peru

International

Colombia

5.9

35.0

Tocantins

757 000

11%

11 800

Brazil

National

Ecuador

2.0

46.8

Brazil, Colombia, Venezuela

Negro

696 808

10%

28 060

International

and Guyana

Venezuela

0.8

6.1

Xingu

504 277

7%

9 680

Brazil

National

Guyana

<0.1

<0.1

(Source: Goulding et al. 2003)

Tapajós

489 628

7%

13 540

Brazil

National

Purus

375 000

5%

10 970

Brazil and Peru

International

The origin of the Amazon lies approximately 100 km from the Pacific

Marañón

358 050

5%

ND

Peru and Ecuador

International

Ocean in the oriental slopes of the Andes Mountains and reaches

Ucayali

337 510

5%

ND

Peru

National

the sedimentary lands of low declivity in Peru before crossing the

Caquetá-Japurá

289 000

4%

18 620

Brazil and Colombia

International

frontier between Colombia and Brazil. The total length of the Amazon

Juruá

217 000

3%

8 420

Brazil and Peru

International

is debated because it is difficult to measure the distance along its

Ecuador, Colombia, Peru and

Putumayo-Içá

148 000

2%

8 760

International

meandering course and also because it is not known exactly where

Brazil

the origin is located. However it is estimated to be between 6 400 and

Trombetas

133 930

2%

2 855

Brazil

National

6 800 km (Goulding et al. 2003). Approximately 15 tributaries and the

Napo

115 000

2%

ND

Peru and Ecuador

International

Tocantins River have lengths greater than 1 000 km and three of them

Uatumã

105 350

2%

1 710

Brazil

National

Note: ND = No Data. (Source: Goulding et al. 2003)

extend more than 3 000 km (Barbosa 1962, Goulding et al. 2003).

Venezuela and Guyana. The origins of other important tributaries in the

The Amazon River discharges approximately 220 800 m3 of water per

Andean zone belong to Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador and Colombia (Figure 3).

second which represents about 15% of the total discharge of al the

Some rivers have their names changed when crossing the border

rivers in the world (Goulding et al. 2003). It transports approximately

between countries. The most important example is the Amazon River,

1.2 billion tonnes of sediments per year, less than Yangtze in China and

which undergoes at least seven name changes between its origin and

Ganges-Brahmaputra in India and Bangladesh (Meade et al. 1979).

its mouth (Barthem & Goulding 1997). In each country, the Amazon has

a different name: Içá and Japurá in Brazil and Putumayo and Caquetá

Most of the Amazon Basin does not exceed an altitude of 250 m, and

in Colombia.

the main humid zones are located below a height of 100 m (Salati &

Vose 1984). The ports located in Iquitos, in the Amazon River (Peru),

and Porto Velho city, in the Madeira River (Brazil), receive ships that

travel more than 3 500 km along the rivers. Otherwise, not all the rivers

of the Amazon Basin are navigable by commercial ships, although, it is

estimated that more than 40 000 km of waterways within the Basin are

içá

iç

navigated by various types of craft.

Climate

Despite its enormous size, the temperature range over the entire

Lageado

Amazon Basin is relatively smal with annual mean temperature varying

from 24 to 26°C. In the mountainous areas, the annual average is below

24°C, while along the Lower and Middle Amazon the mean temperature

exceeds 26°C (Sioli 1975). The homogeneity of temperature is probably

due to the relatively uniform topography of the Basin, the abundance

© GIWA 2003

Figure 3

The drainage basins of the tributaries comprising the

of tropical rainforest, and its location in the north and centre of South

Amazon Basin.

America.

16

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 40B AMAZON BASIN

REGIONAL DEFINITION

17

Other climatic parameters however, exhibit important temporal and

The highly turbid rivers that carry a great amount of material in

spatial variations over the area of the Basin. The area, according to the

suspension, such as the Amazon, Napo, Marañón, Tiger, Juruá, Purus

climatic classification of Köppen, is characterised by several climate

and Madeira rivers, are cal ed white-water rivers and originate in the

types: Type Afi is defined by relatively abundant rains throughout the

Andean slopes. The conductivity of waters in these rivers is elevated

year, with the total precipitation in the driest month always exceeding

(> 60 µS/cm) and the pH is close to neutral (6.5-7) (Meade et al. 1979,

60 mm; Type Ami is defined as a relatively dry season, with elevated total

Schmidt 1982, Guerra et al. 1990).

annual pluviometric rate; and Type Awi has a relatively elevated annual

pluviometric index, but also exhibits a clearly defined dry season (Day

Clear-water rivers are, as the name suggests, general y transparent

& Davies 1986).

and originate in the crystal ine Guyana and Brazilian shields where

the processes of erosion yield few particles that are transported in

Mean annual rainfal exhibits great spatial variations throughout the

suspension. As a result, these waters are chemical y pure, with low

Amazon Basin, general y oscil ating between 1 000 mm and 3 600 mm,

conductivity (6-5 µS/cm) and almost neutral pH (5-6) (Sioli 1967). The

but exceeding 8 000 mm in the Andean coastal region (Day & Davies

visibility within the Tapajós, Xingu and Trombetas rivers is almost 5 m.

1986, Goulding et al. 2003). At the mouth of the Amazon River, the total

annual rainfall exceeds 3 000 mm, while in the less rainy corridor, from

A great amount of humic acid in colloidal form is a characteristic of black-

Roraima through Middle Amazon to the State of Goiás in Brazil, the

water rivers, such as the Negro and Urubu. The chemical properties of

total annual rainfall varies between 1 500 and 1 700 mm (Capobianco

these waters is determined by the sandy soils and a type of vegetation

et al. 2001).

known as Campina and Campinarana that grows in these soils. Campina

and Campinarana habitats are dispersed throughout the sedimentary

The pattern of rainfal throughout the year varies across the Basin. In

basin in which the upper reaches of these black-water rivers are located.

the west, rains are relatively evenly distributed, while the northern Basin

Organic matter, leaves and logs, deposited on the soil are not completely

receives its greatest rainfal in the middle of the year and in regions

decomposed and the porosity of the soils al ows humic acid col oids to

south of Ecuador, maximum precipitation occurs at the end of the year

percolate into the rivers, thus reducing the pH of the water to between

(Simpson & Haffer 1978, Salati 1985). Because more than half of the total

4 and 5.5 and generating the characteristic dark colouration of these

precipitation is recycled by evapotranspiration, the Amazon rainforests

rivers. Despite the elevated concentration of organic matter, the water

maintain the rainfall patterns and the hydrological cycles in the region

in black-water rivers is chemical y more pure than those of white-water

(Salati et al. 1978, Salati & Vose 1984). Medium annual evapotranspiration

rivers, with conductivity up to 8 µS/cm (Junk 1997).

ranges from almost 1 000 mm per year in the proximities of the Juruá

and Purus rivers to more than 2 600 mm per year close to the mouth

Rivers of the Andes

of the Amazon River.

Ucayali and Marañón rivers. The Inca Empire was the most famous

civilization of the Ucayali River. Its capital, Cuzco, was established on

Classification of Amazonian rivers

the Apurimac River, in the Basin's headwaters. The mountains have a

The great environmental heterogeneity of the Amazon Basin can be

long history of human alteration extending thousands of years, but

il ustrated by categorising the different biotopes, considering the

the val ey and the lowlands are well preserved. Fishing is an important

different sub-basins that comprise the Amazon Basin, the landscapes

economic activity in the lowlands, mainly around the cities of Pucallpa

defined by the geological past and the different types of floodplain

and Iquitos. The Marañón River was the principal connection between

areas. The main geological units of the Amazon Basin include high

the Peruvian Amazon and the Pacific in the recent past, and now it is

mountains (Andes), old shields (Brazilian Shield and Guyana Shield)

the main pipeline route for the export of oil. In addition to oil extraction,

and the extensive lowlands (Central Amazonian Lowlands) (Figure 2).

numerous copper, zinc, iron, mercury, antimony and gold mines occur

These three geological structures are of fundamental importance for

in the headwaters of these rivers (Goulding et al. 2003).

the chemical quality of water as wel as the composition and production

of fish in the Amazon rivers. The types of water in the Amazon are

Madeira River. The Madeira River, composed of Mamoré, Beni and Madre

classified as white, clear or black according to their colour, which is

de Dios rivers, is the main source of sediments of the Amazon Basin.

determined by the geological structures where the waters originate

The foothil s of the Andes exhibit a sequence of habitats that change

(Sioli & Klinge 1965, Sioli 1967, Sioli 1975).

from snowfal streams to the large rivers at the base of the mountains.

Although the biodiversity increases downstream, the chemical processes

16

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 40B AMAZON BASIN

REGIONAL DEFINITION

17

and species endemic to the high altitude reaches of these rivers make

archipelago, between Padauari/Demini and Branco rivers (Goulding

them an important area for the Basin. The confluences of the Andean

et al. 1988). In addition, forests in the catchment are periodical y

rivers and the rivers of the Brazilian Shield is observed along a succession

flooded by the rain and, as a consequence, creates another type of

of rapids and fal s located above the city of Porto Velho. Below this point,

flooded environment that covers large contiguous areas close to the

the River is calm and navigable. The largest floodplain areas are located

margins of the Negro and Branco rivers as wel as in the headwaters

in Bolivia, in the flooded savannahs. These areas are inundated with the

of its tributaries. In the Branco River, the savannah that is periodical y

floods of the rivers and by local rainwater (Goulding et al. 2003). One of

flooded by rain is an environment that favours cattle and rice cultivation

the largest al uvial gold mines within the Amazon Basin is located along

and, moreover, it is an area prone to fires during dry periods. The fal s

the Madre de Dios River (Núñez-Barriga & Castañeda-Hurtado 1999).

and headwaters of the rivers are areas subjected to more severe

environmental impacts, such as mining. Conservation depends on

Putumayo-Içá and Caquetá-Japurá. Although, these Andean rivers may

the enforcement of an environmental law, which is hindered by the

have the most preserved catchments in the entire Amazon Basin, the

expansion of mining activities in this area (Barthem 2001).

foothil region has been altered in areas where communities, primarily

of indigenous people, have expanded along the road and cocoa

Brazilian Shield

production has increased. Fishing is an important activity in the lower

The Brazilian Shield is located in the southern Amazon Basin and is

river, mainly in the Caquetá River and gold exploitation occurs along the

located entirely within Brazil.

Colombian and Brazilian border (Férnandez 1991, Goulding et al. 2003).

Tocantins River. The catchment of the Tocantins River is one of the

Purus and Juruá rivers. The Purus and Juruá rivers are different from

most altered areas of the Amazon Basin. This region possesses two large

other white-water rivers in the Andean region because their headwaters

hydroelectric dams, one at Tucuruí in the lower Tocantins River, and the

are situated below 500 m altitude, although, in the past, they were

other at Lageado, in the upper Tocantins River, and the construction of

connected with the Andes. As a result of geological changes these rivers

25 more is predicted (Leite & Bittencourt 1991). Moreover, its headwaters

now drain a desiccated landscape formed by an older alluvium deposit

are altered by agricultural activities to the south of Pará and north of

and carry large quantities of suspended solids (Clapperton 1993). These

Tocantins, as well as by present and past mining activities.

rivers have one of the largest floodplain areas of the Amazon Basin,

which is explored by professional fishermen from Manaus (Batista

Xingu River. The ichthyofauna of the Xingu River above the waterfall

1998, Petrere 1978). In the headwaters, inhabited by Indians and small

at Altamira is completely different from that of the lower sections of

communities, several areas have been designated for ethnic groups and

the River. The fauna and the ecology of this system are not sufficiently

are protected from extractive activities (Goulding et al. 2003).

known and the main impacts are related to mining and agricultural

activities in its headwaters.

Rivers of the Old Shields

Guyana Shield

Tapajós River. Of the rivers that drain the Brazilian Shield, the Tapajós

The Guyana Shield is located in the north of the Amazon Basin and is

River is the most altered by mining activities in its headwaters and

shared by Brazil, Venezuela, Guyana, Suriname and French Guiana.

also by dredging. Unfortunately, knowledge of the ichthyofauna and

ecology of this drainage system is stil insufficient to evaluate the

Trombetas, Jari, Araguari and other rivers. Most of the drainage area of

dimension of the impact of this activity (Barthem 2001).

these rivers is located in the Guyana Shield, which is characterised by the

fal s and headwaters of smal streams. Large industrial operations, such as

The tributaries of Madeira River. The headwaters of the Madeira River are

the extraction of bauxite in the Trombetas River, the extraction of kaolin

located in the Andean slopes, but its tributaries drain the Brazilian Shield.

and paper production in the Jari River and the extraction of manganese

The main impacts in this area are caused by mining, construction of Samuel's

in the Araguari River occur in these basins (Barthem 2001).

Hydroelectric Dam on the Jamari River, and intense agricultural activity in

its headwaters. Information on the fauna and ecology of these tributaries

Negro River. The Negro River is the largest tributary of the Amazon

is lacking. The Madeira River area and regions close to its tributaries have

River located in the Guyana Shield. Several floodplains in the catchment

been studied more often. However, mercury contamination is known in the

that are flooded by overflow from the Negro River are important, such

area and the disturbances of the mining dredges on the migration of the

as the Anavilhanas archipelago in the Negro River and the unnamed

great catfishes have been mentioned by local fishermen.

18

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 40B AMAZON BASIN

REGIONAL DEFINITION

19

The areas of várzea of the white-water rivers are relatively wel conserved

in the area upstream of the confluence of the Purus and Amazon rivers,

in Brazil, without great deforestation caused by cattle or agriculture. On

the other hand, the várzea of the Solimões-Amazon rivers are altered

downstream of the Purus River mainly in the area around Santarém,

in the State of Pará, Brazil. In the area between where the Tapajós and

Xingu rivers join the lower Amazon, there is a different type of várzea,

that is influenced by flooding and river overflow (Barthem 2001).

In Brazil, the várzea of tides are observed along the area between the

confluence of the Xingu and Amazon rivers, and the mangroves. This

Cerrado

vegetation type has been intensely exploited by logging companies

Puna

Dry forest

and smal -scale farmers (Anderson et al. 1999, Barros & Uhl 1999).

Wet forest

However, in spite of this, the condition of habitats in the area of the

Savannah

© GIWA 2003

channels of Breves as well as in the area of the inner delta of Amazon

Figure 4 The main Amazon habitats.

River (Gurupá, Mexiana, Caviana and other islands) is relatively good, as

(Source: WWF 1998-1999)

there are no large agricultural enterprises (Barthem 2001).

Forests

Fields flooded by rain are quite typical within the great islands of

The limits of the Amazon Tropical Forest extend far from the area of the

the Amazon mouth as wel as in the area of the coast of Amapá and

Amazon Basin and covers a great part of Suriname and French Guiana

Pará. This is the most threatened region of the entire Amazon plain

to the north. The Amazon Tropical Forest is composed of complex types

due to ancient human occupation, that had already built dams and

of vegetation such as the highland forest, the cerrado, the flooded

channels, and to the possibility of cattle and agriculture expansion

savannah and the flooded forest (Sioli 1975, Ayres 1993) (Figure 4).

(Smith 2002).

Beyond the limits of the Amazon forest, the Amazon Basin is covered

by an extensive area of savannah and cerrado in the headwaters of

Fish diversity

the Brazilian and Guyana shields. The cloud forest is a special type of

The number of fish species in Amazon remains unknown but estimates

vegetation that grows between 1 500 and 3 000 m on the slopes of the

of the number of fish species in South America vary between 3 000

Andes and is exposed to constant moisture-laden winds. The vegetation

and 8 000, most of them in the Amazon Basin (Menezes 1996, Vari &

changes abruptly at altitudes above 3 000 m. The climate becomes dry

Malabarba 1998).

and cold and a vegetation type known as Puna, which is composed

mainly of grasses and bushes, dominates (Goulding et al. 2003).

The floodplains (várzea and igapó) represent the most important

Socio-economic characteristics

environment for diversity and aquatic productivity (Goulding 1980,

Goulding et al. 1988, Forsberg et al. 1993, Araújo-Lima et al. 1986,

Low human population density is a factor that helps preservation of

Forsberg et al. 1983, Junk 1989 and 1997). These areas extend along

the Amazon Basin. Unfortunately however, this also tends to lead to a

the rivers and appear almost entirely flooded during the rainy

failure to prioritise the col ection and maintenance of data describing

season. Although it is difficult to determine accurately the areas that

basic demographic parameters, such as rates of rural migration, sanitary

are periodical y flooded because of the complexity of the flooding

conditions and the exploitation of timber and fisheries resources,

system which can be influenced by local rains, river overflow and the

among regional administrations. As a consequence, data presented

action of tides (Goulding et al. 2003), it is estimated that within Brazil,

here is often old or does not always cover the entire Amazon Basin.

there is between 70 000 to 100 000 km2 of floodplains and more than

100 000 km2 of lakes and swamps (Goulding et al. 2003). In Bolivia,

Demographic structure

flooded areas occupy between 100 000 and 150 000 km2 of the country

The population density in the Amazon Basin is low and concentrated

(Barthem et al. 1995).

in urban centres (Figure 3). In Brazil, where the Amazon Basin is most

18

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 40B AMAZON BASIN

REGIONAL DEFINITION

19

inhabited, the average population density is 3.3 inhabitants per km2,

In the 1960s, the construction of highways irreversibly modified the

which is considerably lower than the average density of 20 inhabitants

social structure of the region. The road between Belém and Brasília

per km2 in the remainder of Brazil.

connected the Amazon to other areas of Brazil. The opening of the

large highways paral el to the rivers changed the pattern of occupation

The Amazon Basin supports five cities that have more than 1 mil ion

of the Brazilian Amazon. As a consequence, deforestation increased

inhabitants and an additional three that have more than 300 000

along the rivers and in the Terra-Firme (upper-land) along the recently

inhabitants. These major population centres are general y located

open highways (Fearnside 1995). In addition, the logging industry

along the larger rivers, such as Amazon and Madeira rivers. The main

constructed roads deep into forests away from the rivers, which enabled

cities are Manaus, Iquitos and Pucallpa along the Amazon River, Belém,

the extraction and export of timber but also lead to the establishment

in the Amazon estuary and Porto Velho on the Madeira River. Other

of settlement in previously uninhabited areas of the Terra-Firme.

important cities, La Paz, La Santa Cruz Sierra and Cusco, are located

in the headwaters in the Andean Mountains (Goulding et al. 2003)

Hunting for subsistence and sale of skins was concentrated mainly

(Figure 3).

on animals such as the capybara (Hydrochaeris hydrochaeris) and

the al igator (Caiman sp.). The turtle (Podocnemis expansa) and the

Socio-cultural aspects

freshwater manatee (Trichechus inunguis) were easy to capture and, as

The Amazon Basin, with its enormous biodiversity, is also characterised

a consequence of overexploitation, many of these animals practically

by a great socio-cultural diversity, composed of countless indigenous

disappeared in some areas (Neves 1995). In addition, the growing

tribes and traditional populations of riverine, rubber tappers and small

presence of commercial fishermen in the area has generated conflicts

farmers (Neves 1995). The indigenous populations, with more than 100

with the local subsistence fishermen, who try to protect the lakes

different languages, are general y located in reserves that currently

that stil contain healthy stocks from the fishing methods used by

occupy more than 15% of the entire Amazonian territory (Diegues 1989).

commercial fishermen in the várzea and industrial fishermen in the

Until the 1960s, the economy was based on the extraction of natural

estuary (Barthem 1995).

resources, particularly rubber or cocoa and fish. Afterwards, mining

of iron, bauxite and gold became important economic activities and

Extraction of plant resources is another practice that is widespread in

people began to migrate from settlements located along the rivers

the Amazon. The main products are rubber, Brazilian Nuts and açaí. In

and várzeas to areas nearby these new industries (Cardoso & Mul er

addition, a plethora of medicinal and aromatic plants are harvested

1978, Diegues 1989).

for the production of pharmaceuticals and cosmetics. Unfortunately

however, due to indiscriminate col ection, some species are threatened

Human settlement in the Amazon, initial y by the indigenous tribes

to the point of extinction. Timber extraction, primarily for the export

and later on by European and other immigrants, occurred mainly in the

market, is practiced but in an exploratory and disorganised fashion.

várzea due to the resources offered by the rivers and streams as well as

The exploration covers large areas of várzea, where the infrastructure

the high fertility of al uvial soils that were productive for agriculture and

to extract and transport the timber exists. The main exploited species

cattle grazing. A mixture of Europeans, African slaves and indigenous

are: Cedro (Cedrela sp.), Jacareuba (Calophyl um brasiliensis), Mogno

peoples traditional y inhabited the várzea and cultivated corn, rice,

(Swietenia macrophylla), Andiroba (Carapa guianensis), Louro (Aniba sp.),

beans and bananas. Hunting, fishing, growing and harvesting rubber,

Ucuuba (Virola surinamensis) and Copaiba (Copaifera vinifera), among

Brazilian Nuts and açaí, complemented those activities (Neves 1995).

others (Fearnside 1995). The highways facilitate the access in the areas

of Terra-Firme, being the areas more explored than those with a more

Private and governmental planning investments occurred at the end

extensive net of highways (Veríssimo et al. 2001).

of the 19th century with the construction of a railway that aimed to

connect the upper Madeira River with the navigated stretch below the

In recent years, mining has seriously compromised the environment

rapids and fal s between Guajará-Mirim and Porto-Velho and facilitate

and the people that live in it. Gold extraction represents an activity that

the transport and export of rubber, which was the main product of the

most affect the ecosystem.

Amazon Basin during that period. The Madeira-Mamoré railway was

completed in the 1930s but, the inauguration of the railway coincided

Socio-economic aspects

with the economic decline of rubber rendering it economical y

The presentation of the socio-economic aspects of Amazon Basin is

unfeasible to operate.

plagued by a chronic shortage of statistics. However, the quality of life

20

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 40B AMAZON BASIN

REGIONAL DEFINITION

21

of the resident population and the relationships between production

in 1991, to 70.7%, in 1996, overcoming that reported for the Brazilian

and the activities conducted within the area will be summarised on the

North region (IBGE 1996).

basis of the available information.

The quality of life of the population in the Amazon River Basin, based

The occupation of Amazon was intense at the beginning of the

on indicators such as basic sanitation (provisioning of water, sanitary

18th century. Although the Portuguese paid little attention to the

exhaustion and garbage col ection) and incomes, is characterised by

Amazon during their occupation, great international interest in this area

accentuated lack of infrastructure and social investments. These factors

was generated mainly by the English due to their marine and commerce

make the North region in Brazil less favoured than the average situation

tradition. In the 19th century, during the colonial period, the ephemeral

of the other regions in South America.

"agricultural cycle" was progressively replaced by more permanent

production of coffee, cotton, sugar cane and cacao. Later, American

The contribution of the Amazon River Basin to the Brazilian economy

interests were stimulated by the increasing usefulness and demand for

is relatively modest, considering that the North region was responsible

rubber which promoted several private incentives and government

for less than 3.5% of the GDP, in 1990, despite occupying more than

investments in the area. For example, beyond the railway Madeira-

45% of the national territory (IBGE 1991). The GDP of the North and

Mamoré, the North American entrepreneur, Henry Ford, invested in

Middle-West regions of Brazil increased approximately 18 fold between

the plantation of Hevea along the banks of the Tapajós River, Brazil.

1970 and 1990, while the national GDP increased only 11.4 times. The

The urban nucleus known as Fordland was built to extract, process and

growth in per capita income in the Brazilian North region was of the

export the latex obtained from the plantation. Rubber became the main

order of 7.5 times during the same period, from 197 to 1 509 USD

product of the Amazon Basin until the beginning of the 20th century

(Kasznar 1996).

when the low competitiveness of the extractive process and a fungal

plague in the plantation caused the decline of rubber production

Since the 1970s, the agricultural activities of the Brazilian Northern

around 1950. Afterwards, the world centre for rubber exploitation was

region have undergone great transformations that include the spatial

transferred to Southeast Asia, where more productive areas existed and

expansion of crops and growth of bovine flock. Moreover, the changes

fungal infections were able to be control ed (Ribeiro 1990).

in the processes of production, such as the management of resources

and use of different agricultural techniques, as wel as the destination of

In the latter half of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century,

the production are factors that contributed to the development of the

the migration of people assumed a pivotal role in the expansion and

agriculture in the area. Agricultural activities are essential y dedicated to

establishment of new urban centres. Initial y, migration and colonisation

the subsistence cultivation of rice, cassava, corn and beans, while soya,

occurred along navigable waterways but, with the construction of

coffee and cacao are grown as commercial crops.

federal roads during the 1960s, a new route for migration and economic

expansion was established. In Brazil, the most inhabited and impacted

In the region, the supply of electric energy to some specific areas is

area is observed in the regions under the influence of highways

general y generated by isolated hydroelectric systems (dams of Balbina,

constructed between Belém and Brasília and between Cuiaba-Porto

Samuel, Curua-Una and Coaracy-Nunes) and complemented by fuel-

and Velho-Rio Branco, where several consolidated urban nuclei have

burning thermo-electrical centres. The connection of part of the State

been established. However, in the remainder of the Amazon Basin,

of Para to the System Electric Interlinked North-northeast, through

population centres are general y poorly connected. Transport and

Tucuruí Hydroelectric Dam, with a transmission line (1 000 MW)

communication is only between those cities that are located along the

between Venezuela and Balbina Hydroelectric Dam is predicted for

main channel of the Amazon River (IBGE 1991).

the future.

In 1996, the Brazilian population in the Amazon River Basin was

6 706 154 inhabitants and had increased 9.4% since 1991 (IBGE 1996).

This increase correspond with trends reported from the North and

Middle-West regions of Brazil, which exhibited the most significant

growth rates in the country (2.44% and 2.22%, respectively), while

the growth rate of the entire country was 1.38% per year during the

same period. The urbanisation rate in the Basin increased from 60.8%,

20

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 40B AMAZON BASIN

REGIONAL DEFINITION

21

Assessment

Table 3

Scoring table for the Amazon region.

This section presents the results of the assessment of the impacts

Assessment of GIWA concerns and issues according

The arrow indicates the likely

of each of the five predefined GIWA concerns i.e. Freshwater

to scoring criteria (see Methodology chapter)

direction of future changes.

T

T

C

C

Increased impact

shortage, Pollution, Habitat and community modification,

P

A 0 No known impact

P

A 2 Moderate impact

I

M

I

M

T

T

No changes

C

C

Overexploitation of fish and other living resources, Global

P

A 1 Slight impact

P

A 3 Severe impact

I

M

I

M

Decreased impact

change, and their constituent issues and the priorities identified

p

a

c

t

s

u

n

i

t

y

during this process. The evaluation of severity of each issue

Amazon

e

n

t

a

l

m

p

a

c

t

s

m

i

c i

m

c

o

r

e

*

*

o

m

adheres to a set of predefined criteria as provided in the chapter

p

a

c

t

s

p

a

c

t

s

E

n

v

i

r

o

n

m

i

m

E

c

o

n

o

m

H

e

a

l

t

h i

O

t

h

e

r c

i

m

O

v

e

r

a

l

l S

P

r

i

o

r

i

t

y

*

*

*

describing the GIWA methodology. In this section, the scoring of

Freshwater shortage

0.1*

0.3

0.3

0.3

0.2

5

GIWA concerns and issues is presented in Table 3. Detailed scoring

Modification of stream flow

0

information is provided in Annex II of this report.

Pol ution of existing supplies

1

Changes in the water table

0

Pollution

1*

1.7

2.3

1.7

1.4

2

Microbiological pol ution

0

T

C

Freshwater shortage

Eutrophication

0

P

A

I

M

Chemical

2

Suspended solids

2

Freshwater shortage was considered the least important concern for

Solid waste

1

Thermal

1

the Amazon region. A relatively high average annual precipitation of

Radionuclide

0

1 500 to 2 500 mm (Day & Davies 1986) contributes significantly to the

Spil s

1

hydrological balance and reduces the problems of freshwater shortage

Habitat and community modification

1*

2.3

1.7

1.7

1.7

1

in the region. However, the rainfal is not homogenously distributed

Loss of ecosystems

1

Modification of ecosystems

1

throughout the Amazon Basin or during the year. In some areas and/or

Unsustainable exploitation of fish

0.6*

0

0

0

0.5

4

during some months, the rainfall can be very low leading to occasional

Overexploitation

2

shortages of freshwater (Hodnet et al. 1996).

Excessive by-catch and discards

1

Destructive fishing practices

0

Decreased viability of stock

0

More than half of the Amazon population lives in urban centres

Impact on biological and genetic diversity

1

(Becker 1995). The water in these centres is general y col ected from

Global change

0.8*

0

0

0

0.8

3

neighbouring rivers and distributed to residents by local water

Changes in hydrological cycle

2

companies. The rural populations usual y take water directly from the

Sea level change

0

Increased UV-B radiation

0

rivers or from shal ow water wel s.

Changes in ocean CO source/sink function

0

2

* This value represents an average weighted score of the environmental issues associated

to the concern. For further details see Detailed scoring tables (Annex II).

Some issues related to water shortage are not discussed in detail since

** This value represents the overall score including environmental, socio-economic and

they were considered insignificant in the Amazon Basin. Modification

likely future impacts. For further details see Detailed scoring tables (Annex II).

*** Priority refers to the ranking of GIWA concerns.

of stream flow is among the main indicators of water shortage, since

22

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 40B AMAZON BASIN

ASSESSMENT

23

the reduction in water discharge may affect water supplies, the rate

Health impacts associated with freshwater shortage were considered

of dilution of contaminants and the volume of water available in

slight. The number of people affected by occasional seasonal water

underground reservoirs. Some smal streams located near severely

shortage in rural areas is very smal and possibly represents less than

deforested areas may experience a reduction in water flow during the

1% of the total population living in the region and its consequences

dry season. This process is associated with changes in the micro-basin

do not seem to cause significant health problems. On the other hand,

water retention capacity (Hodnet et al. 1996). In such cases, the water

in the urban centres, the pol ution of existing water supplies may

flow is altered and its classification may change from a tropical forest

cause chronic public health problems. Sewage contaminates water

river, which has characteristics of a reservoir river, into a sandbank

supplies and leads to infestations of intestinal parasites and incidences

savannah river that undergoes extreme desiccation during the dry

of diarrhoea that predominantly affects children living in low-income

season (Welcomme 1985). The construction of hydroelectric dams and

areas. This problem is considered serious and more related to urban

water reservoirs has not altered stream flow in the region but potential y

centres of the Amazon region (pers. comm.).

can modify the water discharge cycle. At present, there is no evidence

of annual reductions in the discharges of the Amazon rivers.

Other social and community impacts caused by freshwater shortage

in the Amazon region are presently unnoticed. In areas where seasonal

Impacts associated with changes in the water table were not detected

water shortages are experienced, the population has developed several

in this region. In addition, information describing the effects of the

techniques to solve these problems. Nevertheless, this problem can

natural El Niño phenomena on water levels in wells or spring flow is

be intensified with the increasing deforestation, particularly when the

unavailable. Thus, freshwater shortage associated with changes in the

annual rainfall is less than usual or when regional climate patterns are

water table is not yet considered a problem in the Amazon region.

affected by El Niño events.

Environmental impacts

Conclusions and future outlook

Pollution of existing supplies

Freshwater shortage under present conditions is not a high priority for the

The pollution of existing water supplies has a high but localised impact

Amazon region and, as a result, has few, if any, transboundary implications.

in smal streams or stretches located close to the urban centres (e.g.

The high average annual precipitation maintains stream flow, dilutes

Belém, Santarém, Manaus and neighbourhoods). The general absence

pol utants and guarantees groundwater supplies. If the current supply

of adequate sewage treatment systems and wastewater impoundments

of freshwater is to be maintained in the future, the role of the Amazon

is the main source of pollution of existing supplies. On the other hand,

rainforests in determining climate patterns and hydrological cycles must

the rainfall intensity and the scarcity of large urban centres make this

be conserved (Salati et al. 1978, Salati & Vose 1984). However, the increased

impact local and slight relative to the entire Basin.

deforestation of some parts of the Amazon, such as in the Southeast region

(Brazil), is altering the water cycle and is intensifying the problems related to

Socio-economic impacts

freshwater shortage. Current shortages of water in severely deforested areas

The level of economic impact caused by freshwater shortage is very low

are indicative of what may happen in the region in the future if the present

since the dimension of sectors affected by water shortage is smal and

deforestation rate continues (Lean et al. 1996). In addition to deforestation

limited. During the drier period of the year, there is a reduction in drinking

potential y altering the water cycle, the problem of pol ution of existing

water in smal areas in the rural zone of the southern and southeastern

water supplies can be worsened with the growth in size and number of

regions of the Pará state (Brazil) due to the seasonal declines in stream

smal vil ages and cities scattered on this basin.

flow. This problem can be reduced and is gradual y being solved by the

construction of additional local water reservoirs and wells. The costs

The socio-economics impacts related to freshwater shortage are

incurred through the construction of these wells and reservoirs are very

restricted to smal groups of the population that live in intensively

limited and usual y shared by more than one family.

deforested areas. The impacts of water shortage in those areas are

considered cyclic and occur only during the drier period of the year.

In general, governmental companies are responsible for the treatment

The pollution of water supplies in the urban areas seems more likely to

and distribution of drinking water in the cities. However, recently some

affect health related issues. In the future, it is expected that more people

of these enterprises were privatised and the users observed a slight, but

wil live in the urban centres, but technological improvements might

probably temporary, increase in the cost of water.

provide better conditions for these people. It is also expected that the

drinking water will be supplied from underground reservoirs.

22

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 40B AMAZON BASIN

ASSESSMENT

23

Considering the rate of deforestation and the expansion of urban

Environmental impacts

centres, the prognosis for the Amazon Basin indicates that the Freshwater

Chemical pollution

shortage related issues might become a serious environmental problem

Mercury contamination and chemical agricultural wastes are the

when compared with the present situation.

main sources of chemical pollution in the Amazon Basin. The impacts

caused by these pollutants do not affect large areas because there are

no extensive agricultural areas and because gold mining activities are

established in only a few concentrated locations.

T

C

P

A

Pollution

I

M

The DDT found in Amazon soils originated mainly from the use of this

The human population density in the Amazon Basin is very low and

insecticide against malaria vectors between 1946 and 1993. The present

there are only a few industrial areas established near the cities. Manaus is

level is low compared with previous data obtained from important

the only city in the Amazon that has a duty free industrial area and most

agricultural areas in Brazil (Torres et al. 2002).

of the industries located here are concerned only with the assembly

of machines and electrical goods from components that have been

Contamination of organisms by mercury occurs in the Amazon Basin

manufactured in other countries. Because the individual components

but is not yet completely understood since mercury can originate

are imported, the industrial effluents produced during the manufacture

from both gold mining activities and natural sources. The problematic

of those components are not present in Manaus and, as a result, the

areas for chemical pollution were identified as the regions where gold

assembly industry is considered a "clean industry".

mining activities were intense, such as: the Andean region, the State

of Rondônia (Brazil), and the basins of the Tapajós, Xingu and Madeira

There are two scales of enterprises in the central region of the Amazon

rivers. The mercury levels in most fish species consumed by the Amazon

that can strongly impact water quality: (i) the large and concentrated